Temperature-dependent development, predation, and life table of Sphaerophoria macrogaster (Thomson) (Diptera: Syrphidae) feeding on Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae)

-

Jijun Fan

Abstract

Sphaerophoria macrogaster (Thomson) (Diptera: Syrphidae) is an important predator of Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae). In this study, the morphological characteristics and living habits of S. macrogaster were observed and recorded. It evaluated the variations in developmental rate and predatory capacity of S. macrogaster when preying on M. persicae under five constant temperature regimes (16–32°C). Regression analyses assessing the relationship between temperature and the developmental rates of the egg, first, second, and third larval instars, and pupa of S. macrogaster were performed. In addition, the life table of hoverflies with M. persicae as prey at 28°C was determined. The results demonstrated that development rates at the egg, larval, and pupal stages gradually increased as the temperature increased from 16 to 32°C. The highest threshold temperature occurred at 7.93°C, in the egg stage. The threshold temperature and effective accumulated temperature of the whole generation of S. macrogaster were 5.56°C and 312.50° days, respectively. The larvae consumed more prey at 20°C than at other temperatures; however, the maximum value of the larva predation was 28.3 M. persicae per larva at 28°C, and the average duration of S. macrogaster development was 14.3 days from egg to adult emergence. The mortality of the egg stage of S. macrogaster was 18.0%, and the survival rate from the egg hatch to the adult stage was 58% at 28°C. These results provide valuable information for the release of S. macrogaster into managed systems to reduce M. persicae infestations under a wide range of temperature conditions.

1 Introduction

The green peach aphid, Myzus persicae, is one of the important tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum (L.) [Solanales: Solanaceae]) pests in China and around the world. As a highly polyphagous insect pest, M. persicae boasts an extremely broad host range, inflicting damage on over 40 plant families [1–5]. In spring, after tobacco is cultivated, M. persicae migrates into tobacco fields from other winter hosts (e.g., peach, cabbage, or sweet pepper). M. persicae damages tobacco plants by ingesting phloem, producing honeydew, and transmitting viral diseases (especially tobacco mosaic virus), causing curling and twisting of tender shoots, inducing the growth of black sooty molds, and resulting in the general devitalization of plants [6]. These damages decreased tobacco yield and quality in various tobacco-producing regions of China [7]. Currently, the prevention and control of M. persicae depend on chemical pesticides [8,9]. However, problems related to the use of chemical pesticides (e.g., resistance, residues, and resurgence) [3,10], as well as their negative effects on non-target organisms (e.g., inhibiting the growth, reproduction, and behavior of animals; interfering with physiological processes such as plant photosynthesis, hindering the growth, and reproduction of microorganisms; and damaging their ecological functions) [11–13], must be urgently addressed. As the economic, environmental, and health costs of chemical pesticide use become clearer [16,17], it is important to find other methods of pest control [17]. Encouragingly, in some areas, conventional chemical controls are gradually being replaced by biological controls based on integrated pest management systems [18,19].

Aphidophagous hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) have long been recognized as important natural aphid predators [14,15]. Within the Syrphidae family, the larval stages of species in the Syrphinae and Pipizinae subfamilies exhibit predominant zoophagous behavior, with predation on sternorrhynchous Hemiptera (including aphids) as their primary feeding habit [20]. These two subfamilies collectively account for nearly one-third of all syrphid species [21]. Notably, the predatory role is fulfilled exclusively by the larval stage, whereas adult hoverflies typically rely on nectar and pollen for nutrition [22]. These flies can be found almost everywhere except Antarctica [23]. Because of their high levels of predation, they can effectively reduce aphid abundance [24,25]. Female hoverflies exhibit high mobility, which enables them to disperse eggs over extensive areas [26], and locate aphid communities earlier in the season than other aphidophaga [27,28] and lay their eggs near or directly in aphid colonies [29]. A study by Kakutani et al. [30] revealed that Sphaerophoria macrogaster was the dominant species among aphidophagous hoverflies at Kyoto in Japan. Previous studies have reported on the pollination and feeding behavior [31,32], species abundance [33], life history [34], and morphological characteristics of adults [35] of S. macrogaster. However, detailed reports on their living habits, biological characteristics, and potential biocontrol methods of S. macrogaster have not yet been available.

The study of living habits and morphology is important for field identification and collection efficiency, identifying feeding costs, and assessing the preventive capacity of S. macrogaster. Temperature influences the development and predation of natural prey, and higher and lower temperatures could lead to better or worse growth and development of insects, respectively [36,37]. Therefore, it is necessary to study the effects of temperature on the development and predation of S. macrogaster to determine the optimal temperature range for feeding and biocontrol application. Additionally, to use S. macrogaster as a biological control agent against M. persicae, some life parameters must be evaluated, including development and predation rates. The most important aspect of this evaluation is life table studies, which will provide a systematic understanding of the development and survival of S. macrogaster [38,39]. One of the most important factors contributing to the success of biological control is the coordination between natural enemies and environment [37], where natural enemies adapt to environmental conditions in which pests thrive. Previous research indicated that the optimum growth temperature [40] and development temperature [41] of M. persicae were both 28°C. Therefore, it is necessary to study the population life table of S. macrogaster at 28°C to evaluate its ability to control M. persicae.

The objectives of this study were to (i) observe and record the biological and morphological characteristics of the entire life cycle of S. macrogaster (eggs, larvae, pupae, and adults), (ii) study the effect of temperature on the development and predation capacity of S. macrogaster feeding on M. persicae, and (iii) evaluate the life tables of S. macrogaster feeding on M. persicae at 28°C.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Aphid colonies and syrphid

The M. persicae colony and S. macrogaster of various stages were obtained from October 2016 to October 2018 in the tobacco fields (28°18ʹN, 113°07ʹE) of Changsha, Hunan Province, China. The insects were reared in our laboratory at room temperature (ca. 25 ± 1°C). Tobacco leaves with M. persicae were cut off and brought back to the laboratory, and M. persicae were reared on tobacco plants grown in vermiculite. The third or fourth instar nymphs of M. persicae measuring 1.2–1.5 mm were used in this experiment.

The larvae of S. macrogaster were transferred using a wolf-hair fine-lining brush and placed in Petri dishes (9 cm in diameter) in which the internal surface was covered with moist filter paper, and were fed with M. persicae until pupation. Petri dishes were checked every 12 h to ensure that M. persicae were available for feeding. Adult S. macrogaster were fed in insect cages (30 × 30 × 30 cm3). Fresh pollen (a bouquet of flowers of the oilseed rape plant and absorbent cotton soaked with 10% honey water were used to provide nutrition. The tobacco leaves with M. persicae were placed in each cage to stimulate the oviposition. Leaves were checked every 12 h and leaves with S. macrogaster eggs were replaced. After breeding, the eggs were transferred to Petri dishes (9 cm in diameter, with 1 egg per dish), and the date of oviposition was marked on each Petri dish. All eggs and larvae used in the experiment were obtained by this method.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animal use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals.

2.2 Morphology and living habits of S. macrogaster

The eggs, larvae, pupae, and adults of S. macrogaster were placed under a Soptop SZN71 stereomicroscope (optical magnification range: 6.7–90×) to observe their morphological characteristics, and the adults were photographed using a Nikon stereo microscope Nikon smz18. The living habits of S. macrogaster were observed under both laboratory and field conditions, and the behavior (foraging, mating, and oviposition) were evaluated.

2.3 Effects of temperature on the development and predation of S. macrogaster

The Petri dishes with S. macrogaster eggs were placed into the artificial climate chambers with five treatments at 16, 20, 24, 28, and 32°C, at 75% (±1%) RH, photoperiod L:D = 12:12, and fed daily with 150 third or fourth instar nymphs. The amount of M. persicae consumed was recorded every 24 h, after which each syrphid larva was moved into a new Petri dish and supplied with sufficient M. persicae. The daily predation amount and the developmental time of S. macrogaster were recorded. Four S. macrogaster eggs were placed in Petri dishes (9 cm in diameter, 1 egg per dish) at each temperature, and each treatment was repeated five times.

2.4 Life table study and analysis

The temperature selected to evaluate the ability of S. macrogaster to adapt to environmental conditions in which M. persicae thrive is 28°C [40,41]. One hundred S. macrogaster eggs were placed in Petri dishes (9 cm in diameter, 1 egg per dish) at 28°C, and the date of oviposition was marked on each Petri dish. Each S. macrogaster larva was supplied with approximately 100 third or fourth instar nymphs each day. The pupae were transferred to new Petri dishes at the end of the larval stage, and the emerged adults of S. macrogaster were transferred to the insect cages (30 × 30 × 30 cm3). Fresh pollen (a bouquet of flowers of the oilseed rape plant and absorbent cotton soaked with 10% honey water were used to provide nutrition. The tobacco leaves with M. persicae were placed in each cage to stimulate the oviposition. Leaves were checked every 12 h and leaves with S. macrogaster eggs were replaced. If the eggs did not hatch or the pupae did not emerge for an additional week, they were considered dead. All developmental stages from the egg to the start of the oviposition of the adult were evaluated every day, and the developmental period of each individual spent in each life stage was obtained. Based on the age-stage life table, data on the survivorship and longevity of S. macrogaster were analyzed [24,38]. The age-stage specific survival rate (S xj ) and the age-specific survival rate (lx) were then calculated. The age-stage specific survival rate (S xj ) represents the probability that a single egg will develop to age x and stage j. It was calculated using the following equation:

where n 01 denotes the number of individuals used at the start of the life table study and n xj refers to the number of individuals that survive to age x and stage j.

The age-specific survival rate (lx) is the probability that a newborn will survive to age x. It was calculated using the following equation:

where β stands for the number of stages.

Note that this methodology considers each instar (i.e., first, second, and third instar larva) as distinct “stages” of the syrphid life cycle in the same way that egg, pupa, and adult.

2.5 Statistical methodology

Data were subjected to Kologorov–Smirnov tests and Levene’s tests to assess the normality and homogeneity of the variance, respectively. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to analyze differences in the developmental times of the egg, larval, and pupal stages under five constant temperature conditions. Mean values were statistically compared with the Mann–Whitney test at P < 0.05 since data were not normally distributed. Regression analyses on the relationship between developmental rates and temperature were performed for each life stage and total life cycle. The following linear regression equation

and least-square regression were used to estimate K (the required heat units in degree-days, DD) and C (the minimum developmental thresholds, DT), where V is the developmental rate in days at temperature T (°C).

3 Results

3.1 Morphological characteristics and living habits of S. macrogaster

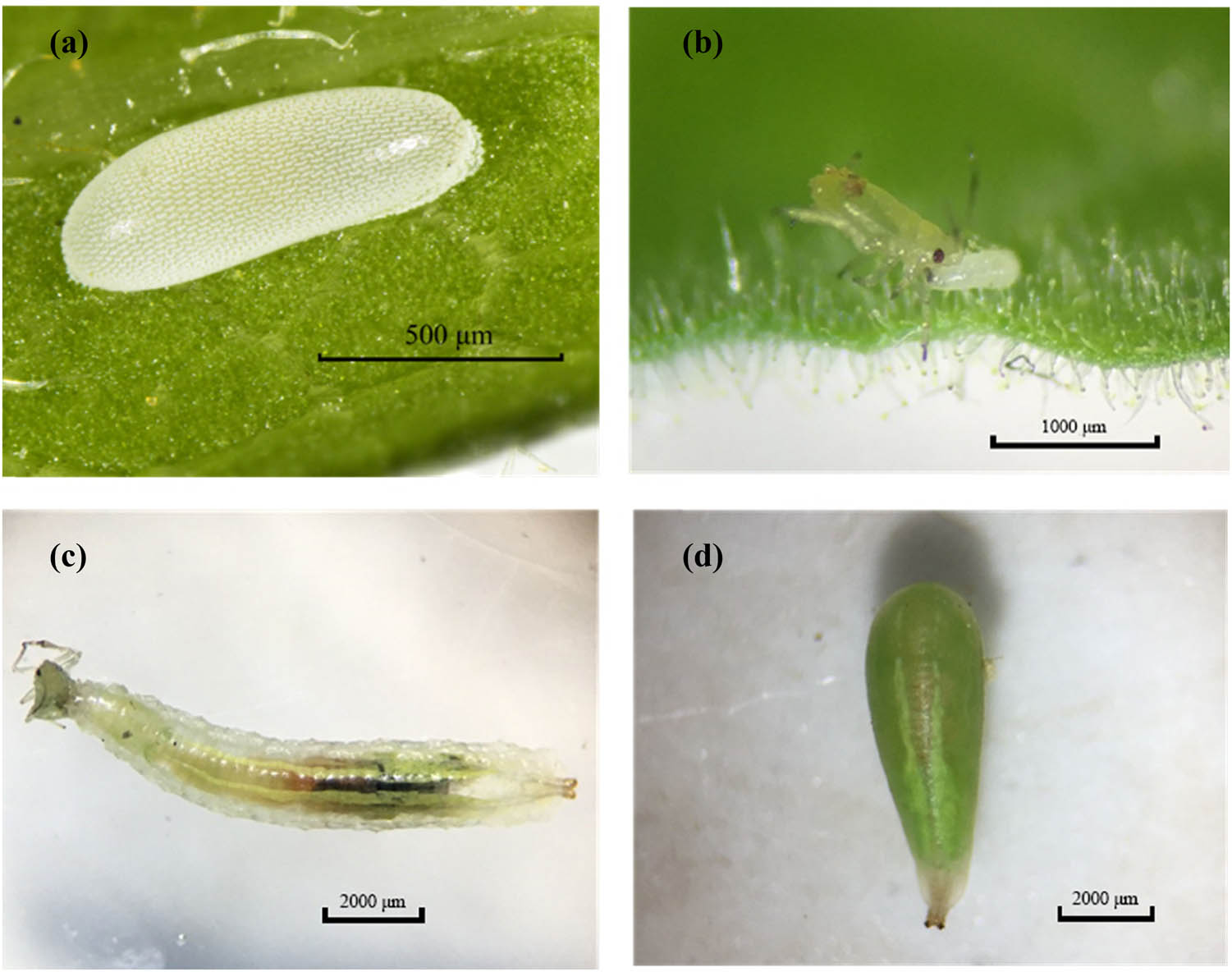

S. macrogaster eggs are oval-shaped and a creamy white color, 0.7–0.9 mm long and 0.3–0.4 mm wide, with rough surfaces (Figure 1a). In nature, adult females of S. macrogaster typically lay eggs on the back of tobacco leaves or buds with M. persicae, and 1–3 eggs are usually distributed in each M. persicae population. However, under laboratory conditions, 13–24 eggs were observed on a tobacco leaf with M. persicae. It takes approximately 3–5 s to lay one egg. S. macrogaster larvae have three instars. First instar larvae are yellowish, 0.7–0.9 mm long. Second instar larvae gradually become translucent light green. The dorsum is characterized by two parallel white bands. Third instar larvae are 8.5–9.5 mm long and 1.5–1.8 mm wide, with a protuberant anus, and the two parallel strips on the dorsum change from white to light green. The newly hatched larva can feed on the adults of M. persicae, which takes over 20 min (Figure 1b), while third larval instars take 30 s to feed the adult aphids (Figure 1c). S. macrogaster adults are 5.9–7.2 mm long, with yellow antennae and legs. The black-yellow stripes are alternately arranged on the abdomen. Adult males and females can be distinguished by their eyes: male eyes are holoptic and female eyes are dichoptic (Figure 2). Different from larvae, adults of S. macrogaster must feed on pollen, nectar, or M. persicae honeydew to obtain nutrients and energy for their growth and development. Females must feed on pollen for their ovaries to mature. Both males and females mate multiple times throughout their lifetime, and the mating duration of adults is typically 3–8 min. A better understanding of the morphological characteristics and living habits of S. macrogaster provides support for the field identification and protection of this natural predator of M. persicae.

Morphological characteristics of egg (a), hatchling larvae (b), juvenile larvae (c), and pupae (d) of S. macrogaster.

Morphological characteristics of adult of S. macrogaster. (a) female head, (b) male head, (c) female, dorsolateral view, (d) male, dorsolateral view, (e) female, ventral view, (f) male, ventral view, (g) female, lateral view, (h) male, lateral view.

3.2 Effects of temperature on the developmental period of S. macrogaster

The mean developmental times of S. macrogaster in different stages at five constant temperatures are shown in Table 1. There were significant differences in the developmental durations at the egg, first, second, third larval instars, pupa, and egg to adult emergence stages of S. macrogaster under the following temperature conditions: 16, 20, and 24°C. However, at 28 and 32°C, only the developmental duration of pupae was significantly different. The developmental period for the egg, first, second, third larval instars, pupa, and egg–adult decreased as the temperature increased from 16 to 32°C. The average recorded duration of S. macrogaster development from egg to adult emergence was 29.8, 22.6, 16.6, 14.2, and 12.0 days at 16, 20, 24, 28, and 32°C, respectively.

Mean (±SE) developmental time (days) of different stages of S. macrogaster at five constant temperatures

| Temperature | Egg | Larval instars | Pupa | Egg–adult | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | Third | ||||

| 16°C | 4.6 ± 0.80a | 4.2 ± 0.68a | 4.0 ± 0.63a | 7.2 ± 0.75a | 9.8 ± 0.40a | 29.8 ± 2.29a |

| 20°C | 2.8 ± 0.81b | 3.2 ± 0.40b | 2.8 ± 0.75b | 5.6 ± 1.02b | 8.2 ± 0.75b | 22.6 ± 1.39b |

| 24°C | 2.0 ± 0.00c | 2.2 ± 0.75c | 1.8 ± 0.75c | 4.4 ± 0.49c | 6.2 ± 0.40c | 16.6 ± 1.20c |

| 28°C | 1.8 ± 0.40c | 2.0 ± 0.63cd | 1.6 ± 0.49cd | 3.6 ± 0.80d | 5.2 ± 0.75c | 14.2 ± 1.40d |

| 32°C | 1.6 ± 0.49c | 1.6 ± 0.49d | 1.6 ± 0.80d | 3.4 ± 0.49d | 3.8 ± 0.40d | 12.0 ± 1.38d |

| K 4,95 | 73.197 | 70.058 | 59.596 | 74.373 | 92.366 | 91.657 |

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

†Mean values in the same column with different letters differ significantly, P<0.05.

3.3 Developmental rates of S. macrogaster at different temperatures

Lower temperature thresholds and degree-day requirements of S. macrogaster (Table 2) (P < 0.001) were calculated according to the linear regression equation (Figure 3), which was used to analyze the relationship between developmental rate and temperature. High coefficients of determination (R 2 > 0.9) were obtained for four stages: egg, third instar, pupa, and egg–adult. The highest threshold temperature for development occurred at 7.93°C in the egg stage. The threshold temperature for the developmental process of S. macrogaster from the egg to the adult stage was 5.56°C, and the effective accumulative temperature was 312.50° days (Table 2). According to the linear fitting model for the different developmental time of S. macrogaster, the developmental rate, sorted from high to low, are second instars > egg > first instars > third instars > pupa > egg–adult at each experiment temperature from 16 to 32°C (Figure 3).

Linear regression analyses of relationship between developmental rates and temperature of different life stages of S. macrogaster

| Stages | Regression equations | R² | F values | P > F | C | K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egg | V = 0.0298T − 0.2363 | 0.9000 | 216.93 | 0.001 | 7.93 | 33.56 |

| First instars | V = 0.0292T − 0.2283 | 0.8447 | 131.58 | 0.001 | 7.82 | 34.25 |

| Second instars | V = 0.0338T − 0.2557 | 0.8536 | 140.96 | 0.001 | 7.57 | 29.59 |

| Third instars | V = 0.0142T − 0.1117 | 0.9461 | 422.25 | 0.001 | 7.87 | 70.42 |

| Pupa | V = 0.0101T − 0.0717 | 0.9178 | 268.88 | 0.001 | 7.10 | 99.01 |

| Egg–adult | V = 0.0032T − 0.0178 | 0.9861 | 1699.19 | 0.001 | 5.56 | 312.50 |

†Calculated after Ding [55], where T is the temperature (°C), V is the developmental rate (1/developmental time), K is the effective accumulative temperature of insect degree-days, and C is the minimum developmental threshold (°C).

Linear fitted models of the development rate (1/development duration) for the total developmental time of S. macrogaster.

3.4 Effects of temperature on the predation amount of S. macrogaster

The daily predation amount of S. macrogaster on M. persicae first increased and then decreased as temperature increased (Figure 4a). The shortest developmental durations (4 days) from the S. macrogaster larvae to the age of the highest daily predation amount was observed at 28°C, and the longest developmental durations (10 days) were observed at 16°C.

Daily predation amount (a), total predation amount (b), and average predation amount (c) of S. macrogaster on M. persicae at five constant temperatures.

The effect of temperature on the predation amount of S. macrogaster larvae can be reflected by the difference in total predation amount (Figure 4b) and average predation amount (Figure 4c) at each developmental stage. The total predation amount and the average predation amount of S. macrogaster on M. persicae first increased and then decreased as temperature increased. The larvae consumed more prey at 20°C compared to other temperatures. The total predation amounts, sorted from high to low, are 261.2 M. persicae (20°C) > 245.0 M. persicae (16°C) > 225.1 M. persicae (24°C) > 203.8 M. persicae (28°C) > 167.0 M. persicae (32°C) (Figure 4b). The minimum predation amount for each developmental stage was observed at 16°C. The maximum value of the predation amount of the second and third larval instars and the total larval stages were all observed at 28°C. However, in the first instar, the maximum predation amount was observed at 24°C. At 28°C, the average predation amount of the total larval stages of S. macrogaster was 28.3 M. persicae/day (Figure 4c).

3.5 Life table of S. macrogaster at 28°C

The mean developmental time of S. macrogaster at different stages at 28°C is shown in Table 3. The successful hatching and emergence rates were 82 and 58%, respectively. Ultimately, 24 males and 34 females successfully emerged, for a sex ratio of 1:1.42. The average duration of S. macrogaster development was 1.9, 7.2, and 5.0 days for eggs, larvae, and pupae, respectively, and 14.3 days from egg to adult emergence.

Mean developmental time (days) of different stages of S. macrogaster

| Parameter | Stage | Mean ± SE | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preadult | Egg | 1.9 ± 0.35 | 100 |

| First instars | 2.0 ± 0.43 | 82 | |

| Second instars | 1.8 ± 0.39 | 76 | |

| Third instars | 3.6 ± 0.79 | 74 | |

| Larva (L1–L3) | 7.2 ± 0.76 | 66 | |

| Pupa | 5.0 ± 0.71 | 66 | |

| Egg–adult | 14.3 ± 1.18 | 58 | |

| Adult | Female | 11.3 ± 6.57 | 34 |

| Male | 10.4 ± 6.00 | 24 |

†Percentage is the number of individuals observed at a certain stage, shows the probability of successful development to a certain stage.

The probability that a newly laid egg will develop to stage j and age x was analyzed by the age-stage specific survival rate (S xj ) (Figure 5a). The survival rate of S. macrogaster from the egg hatch to the larval stage was 82% on the third day. The overlaps in the curves S xj show the variable developmental rates among individuals of S. macrogaster. By ignoring the stage differentiation, the age-specific survival rate (lx) showed the survival percentage from the egg stage to age x (Figure 5b). The mortality rate of S. macrogaster was 18, 7, 3, 11, and 12% for eggs, first, second, third larval instars, and pupae, respectively. The probability of survival from the egg hatch to the adult stage is 58%, while the survival rate of S. macrogaster rapidly decreased at the early adult stage.

Age-stage specific survival rate (S xj ) for each stage (a) and age-specific survival rate (lx) for the cohort (b) of S. macrogaster juvenile larva at 28°C and 75% RH.

4 Discussion

The adults of syrphid are important pollinators in natural ecosystems and the larvae are well-known aphid predators and play an important role in suppressing aphids [24,25,42]. The species identification of syrphids and the morphological characteristics of adults have been described [43,44], but few studies have assessed the eggs and larvae. Tian and Ren [45] briefly summarized the morphological characteristics of larval and adult syrphids, but detailed characteristics of various syrphids were not assessed. Zhang et al. [46] described the morphological characteristics of the egg, larva, pupa, and adult of Scaeva pyrastri (Linnaeus) (Diptera: Syrphidae) and Episyrphus balteatus (De Geer) (Diptera: Syrphidae). Yu et al. [34] reported the biological characteristics of S. macrogaster and pointed out that the first instar larvae could not feed on adult M. persicae. In this study, the morphological characteristics and living habits of S. macrogaster were studied at each life stage, and we found that newly hatched S. macrogaster larvae could feed on adult M. persicae. Temperature is an important factor in the establishment and growth of insect populations [47]. Many studies have also shown that the effect of predatory hoverflies on aphids is closely related to temperature [48,49]. This study demonstrated that the developmental period for eggs, first, second, third larval instars, pupa, and egg–adults decreased as the temperature increased from 16 to 32°C, and the rates of development at each life stage gradually increased as the temperature increased from 16 to 32°C. These results were consistent with the results of previous studies, which found assessed the effect of temperature on the growth and development of hoverflies [50–52]. M. persicae typically harms tobacco in the summer [1], when high temperatures are conducive to the rapid reproduction of the S. macrogaster. This also creates favorable conditions for controlling M. persicae. Notably, across all tested temperatures, the developmental duration of the second larval instar was shorter than that of the first larval instar. These results were consistent with the results of previous studies. Singh et al. [25] reported that the durations of the first and second instars lasted 4.2 and 3.4 days for Eupeodes frequens (Matsmura) (Diptera: Syrphidae) and 4.8 and 3.3 days for E. balteatus, respectively; Arcaya et al. [24] reported that the durations of the both instars lasted 2 days for Allograpta exotica (Wiedemann) (Diptera: Syrphidae), respectively. In contrast, Faheem et al. [37] reported that the durations of the first and second instars lasted 2.67 and 4.70 days for Ischiodon scutellaris (Fabricius) (Diptera: Syrphidae) and 2.63 and 4.45 days for E. balteatus, respectively. This discrepancy may be related to species differences or experimental treatment conditions.

This study assesses S. macrogaster larvae feeding on M. persicae at different temperatures and provides information for future studies assessing whether temperature affects the ability of S. macrogaster to control M. persicae by releasing S. macrogaster into a greenhouse or field. The lower threshold for development and thermal constant are effective indicators for the establishment and growth of insect populations [50]. Our findings demonstrate that the threshold temperature and effective accumulated temperature of S. macrogaster from the egg to adult stage were 5.56°C and 312.50° days, respectively, indicating that S. macrogaster could survive in low-temperature environments. Daily predation levels of S. macrogaster on M. persicae at five constant temperatures first increased and then decreased as temperature increased. S. macrogaster had the highest predation ability at 28°C. Some studies have reported that the optimum growth temperature [40] and the fastest development temperature [38] of M. persicae to both be 28°C, which means that S. macrogaster could effectively control the M. persicae population during the peak reproductive period of M. persicae, though the predatory efficiency of S. macrogaster under fluctuating temperatures is not clear still. Our results suggest that the third instar larvae of S. macrogaster had the largest predation ability compared to first and second instar larvae, which is consistent with previous reports finding that hoverflies had the highest prey-consumption rates of syrphid flies as third instars [36,53,54]. The release of third instar larvae could be a more efficient control approach than the release of eggs or other instar larvae during M. persicae outbreaks. However, difficulties in the preservation and transportation of the third instar larvae remain a challenge for this approach.

To study the feasibility of S. macrogaster as a natural control against M. persicae, the life table of S. macrogaster from the egg stage to the adult’s first egglaying at 28°C was studied. Our results demonstrated that the average recorded duration of S. macrogaster development was 1.9, 7.2, and 5.0 days for eggs, larvae, and pupae, respectively, and 14.26 days from egg to adult emergence. Faheem et al. [37] reported that the average recorded duration of I. scutellaris development was approximately 3.8 and 6.7 days for eggs and pupae, respectively; the average recorded duration of E. balteatus development was approximately 3.1 and 7.7 days for eggs and pupae, respectively; and the average recorded durations of two species were approximately 11.0 days at 27°C. These lower developmental durations mean that the S. macrogaster could complete its life cycle faster than other syrphids. However, Dong et al. [47] reported that the average recorded duration for the development of E. balteatus was 1.80 and 6.08 days for eggs and pupae, respectively, at 27°C, which were lower than the results of Faheem et al. [37]. Arcaya et al. [24] reported a 34% mortality rate for A. exotica at the egg stage, but the mortality rate of the third instar stage of A. exotica was only 2%. Our results demonstrate that the mortality rate of S. macrogaster at the egg stage was 18%, and the mortality rate at the third instar stage was 11%. These phenomena may be ascribed to experimental rearing conditions, including excessively high temperatures or waterlogging induced by overly moist filter paper, or the direct collection of M. persicae to feed the larvae of S. macrogaster. In future studies, researchers should consider how to improve the survival rate of the third instar larvae.

This study was designed to investigate the morphological characteristics, living habits, the effect of temperature on the development and predation capacity, and life tables of S. macrogaster feeding on M. persicae at 28°C. The findings demonstrated that S. macrogaster exhibits sufficient environmental adaptability. These results are useful for rapidly identifying, commercially rearing, and optimizing the climatic conditions of S. macrogaster. However, its control effect against M. persicae requires further investigation.

-

Funding information: This research was supported by the project of modern agricultural industrial technology systems in Hunan Province (HNPR-2024-17020), provincial special project for the construction of the national sustainable development agenda innovation demonstration zone in Chenzhou City, Hunan Province (2023sfq09), and Regional joint fund of Hunan Province (2025JJ70567).

-

Author contributions: JF, YY, LT, and LZ performed the main experiments and analyzed data; JF, YY, QH, and LZ planned and designed the research, wrote the manuscript, with substantial input from WL, JT, YL, and YM.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Blackman RL, Eastop VF. Aphids on the world’s crops, an identification and information guide. 2nd edn. Chichester, New York, USA: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2000.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Ali J. The chemical ecology of a model aphid pest, Myzus persicae, and its natural enemies. Edinburgh, UK: Keele University; 2022.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Bass C, Puinean AM, Zimmer CT, Denholm I, Field LM, Foster SP, et al. The evolution of insecticide resistance in the peach potato aphid, Myzus persicae. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;51:41–51.10.1016/j.ibmb.2014.05.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Edde PA. Field crop arthropod pests of economic importance. Cambridge. MA, USA: Academic Press; 2021.10.1016/B978-0-12-818621-3.00002-1Search in Google Scholar

[5] Ali J, Bayram A, Mukarram M, Zhou F, Karim MF, Hafez MMA, et al. Peach-potato aphid Myzus persicae: current management strategies, challenges, and proposed solutions. In: Holman J. Host plant catalog of aphids: Palaearctic Region. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2023. 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Ali J, Bayram A, Mukarram M, Zhou F, Karim MF, Hafez MMA, et al. Peach-potato aphid Myzus persicae: current management strategies, challenges, and proposed solutions. Sustainability. 2023;15:11150.10.3390/su151411150Search in Google Scholar

[7] Qin XY, Li ZY. Effect of temperature on growth, development, reproduction and survive of Myzus persicae. Chin Agric Sci Bull. 2006;22(4):365–70.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Chohan TA, Chohan TA, Mumtaz MZ, Alam MW, Din S., Naseer I, et al. Insecticidal potential of a-pinene and β-caryophyllene against Myzus persicae and their impacts on gene expression. Phyton-Int J Exp Botany. 2023;92(7):1943–54.10.32604/phyton.2023.026945Search in Google Scholar

[9] Naga KC, Kumar A, Tiwari RK, Kumar R, Subhash S, Verma G, et al. Evaluation of newer insecticides for the management of Myzus persicae (Sulzer). Potato J. 2021;48:161–5.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Cutler GC, Ramanaidu K, Astatkie T, Isman MB. Green peach aphid, Myzus persicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae), reproduction during exposure to sublethal concentrations of imidacloprid and azadirachtin. Pest Manag Sci. 2009;65:205–9.10.1002/ps.1669Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Desneux N, Decourtye A, Delpuech JM. The sublethal effects of pesticides on beneficial arthropods. Annu Rev Entomol. 2007;52:81–106.10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091440Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Bertrand L, Marino DJ, Monferrán MV, Amé MV. Can a low concentration of an organophosphate insecticide cause negative effects on an aquatic macrophyte? Exposure of Potamogeton pusillus at environmentally relevant chlorpyrifos concentrations. Environ Exp Botany. 2017;138:139–47.10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.03.006Search in Google Scholar

[13] Magnoli K, Benito N, Carranza C, Aluffi M, Magnoli C, Barberis C. Effects of chlorpyrifos on growth and aflatoxin B1 production by Aspergillus section Flavi strains on maize-based medium and maize grains. Mycotoxin Res. 2021;37:51–61.10.1007/s12550-020-00412-wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Wojciechowicz-Żytko E, Wilk E. Surrounding semi-natural vegetation as a source of aphidophagous syrphids (Diptera, Syrphidae) for aphid control in apple orchards. Agriculture. 2023;13(5):1040.10.3390/agriculture13051040Search in Google Scholar

[15] Mushtaq S, Maalik S, Rana SA, Majeed W, Ehsan N. Developmental analysis and predatory potential of Eupeodes corollae (fabricius, 1794) (Diptera: Syrphidae) against aphids: a practical approach of biological control. Pak J Agric Sci. 2023;60(1):185–91.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Douglas MR, Rohr JR, Tooker JF. Neonicotinoid insecticide travels through a soil food chain, disrupting biological control of non-target pests and decreasing soya bean yield. J Appl Ecol. 2015;52:250–60.10.1111/1365-2664.12372Search in Google Scholar

[17] Tudi M, Ruan HD, Wang L, Lyu J, Sadler R, Connell D, et al. Agriculture development, pesticide application and its impact on the environment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1112.10.3390/ijerph18031112Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Perez-Hedo M, Pedroche V, Urbaneja A. Temperature-driven selection of predatory Mirid bugs for improving aphid control in sweet pepper crops. Horticulturae. 2023;9(5):572.10.3390/horticulturae9050572Search in Google Scholar

[19] Lin Q, Chen H, Dai X, Yin S, Shi C, Yin Z, et al. Myzus persicae management through combined use of beneficial insects and thiacloprid in pepper seedlings. Insects. 2021;12:791.10.3390/insects12090791Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Burgio G, Dindo ML, Pape T, Whitmore D, Sommaggio D. Diptera as predators in biological control: applications and future perspectives. Biocontrol. 2025;70(1):1–17.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Mengual X, Mayer C, Burt TO, Moran KM, Dietz L, Nottebrock G, et al. Systematics and evolution of predatory flower flies (Diptera: Syrphidae) based on exon-capture sequencing. Syst Entomol. 2023;48(2):250–77.10.1111/syen.12573Search in Google Scholar

[22] Burgio G, Dindo ML, Pape T, Whitmore D, Sommaggio D. Diptera as predators in biological control: applications and future perspectives. In: Rotheray GE, Gilbert F, editors The natural history of hoverflies. Tresaith, UK: Forrest Text; 2025.10.1007/s10526-024-10281-2Search in Google Scholar

[23] Chambers RJ. Preliminary experiments on the potential of hoverflies [Dipt.: Syrphidae] for the control of aphids under glass. Biocontrol. 1986;31:197–204.10.1007/BF02372371Search in Google Scholar

[24] Arcaya E, Perez-Banon C, Mengual X, Zubcoff-vallejo JJ, Rojo S. Life table and predation rates of the syrphid fly Allograpta exotica, a control agent of the cowpea aphid Aphis craccivora. Biol Control. 2017;115:74–84.10.1016/j.biocontrol.2017.09.009Search in Google Scholar

[25] Singh P, Thakur M, Sharma KC, Sharma KH, Nayak RK. Larval feeding capacity and pollination efficiency of the aphidophagous syrphids, Eupeodes frequens (Matsmura) and Episyrphus balteatus (De Geer) (Diptera: Syrphidae) on the cabbage aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae L.) (Homoptera: Aphididae) on mustard crop. Egypt J Biol Pest Control. 2020;30:105.10.1186/s41938-020-00300-6Search in Google Scholar

[26] Chambers RJ. Syrphidae. In: Minks AK, Harrewijn P, editors. Aphids, their biology, natural enemies, and control. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1988. p. 259–70.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Horn DJ. Effect of weedy backgrounds on colonization of collards by green peach aphid, Myzus persicae, and its major predators. Environ Entomol. 1981;10(3):285–9.10.1093/ee/10.3.285Search in Google Scholar

[28] Almohamad R, Verheggen FJ, Haubruge E. Searching and oviposition behavior of aphidophagous hoverflies (diptera: Syrphidae): a review. In: Hagen KS, Van DBR. Impact of pathogens, parasites, and predators on aphids. Annual Rev Entom. 2009;13:325–84.10.1146/annurev.en.13.010168.001545Search in Google Scholar

[29] Chandler AEF. The relation between aphid infestation and oviposition by aphidophagous Syrphidae (Diptera). Ann Appl Biol. 2008;61:425–34.10.1111/j.1744-7348.1968.tb04544.xSearch in Google Scholar

[30] Kakutani T, Inoue T, Kato M, Ichihashi H. Insect–flower relationship in the campus of Kyoto University, Kyoto: an overview of the flowering phenology and the seasonal pattern of insect visits. Contrib Biol Lab Kyoto Univ Kyoto. 1990;27(4):309–76.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Sugiura N. Pollination of the orchid Epipactis thunbergiiby syrphid flies (Diptera: Syrphidae). Ecol Res. 1996;11:249–55.10.1007/BF02347782Search in Google Scholar

[32] Emtia C, Ohno K. Foraging behavior of an aphidophagous hoverfly, Sphaerophoria macrogaster (thomson) on insectary plants. Pak J Biol Sci. 2018;21:323–30.10.3923/pjbs.2018.323.330Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Barkalov AV. New data on the nomenclature and fauna of the genus Sphaerophoria, Le Peletier et Serville, 1828 (Diptera, Syrphidae) from Siberia and adjacent territories. Entomol Rev. 2011;91:898–907.10.1134/S0013873811070104Search in Google Scholar

[34] Yu CR, Pan RY, Yang SH, Lin LL, Guo C. Preliminary study on biological characteristics of Sphaerophoria macrogaster. Wuyi Sci J. 1998;14:73–7. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Veen MPV. Hoverflies of Northwest Europe: identification keys to the Syrphidae. Utrecht: KNNV; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Soleyman-Nezhadiyan E, Laughlin R. Voracity of larvae, rate of development in eggs, larvae and pupae, and flight seasons of adults of the hoverflies Melangyna viridiceps Macquart and Symosyrphus grandicornis Macquart (Diptera: Syrphidae). Aust Entomol. 2010;37:243–8.10.1111/j.1440-6055.1998.tb01578.xSearch in Google Scholar

[37] Faheem M, Saeed S, Sajjad A, Razaq M, Ahmad F. Biological parameters of two syrphid fly species Ischiodon scutellaris (Fabricius) and Episyrphus balteatus (DeGeer) and their predatory potential on wheat aphid Schizaphis graminum (Rondani) at different temperatures. Egypt J Biol Pest Control. 2019;29:e2.10.1186/s41938-019-0105-0Search in Google Scholar

[38] Chi H, Liu H. Two new methods for the study of insect population ecology. Bull Inst Zool Acad Sin. 1985;24:225–40.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Huang YY, Gu XP, Peng XQ, Tao M, Peng L, Chen GH, et al. Effect of short-term low temperature on the growth, development, and reproduction of bactrocera tau (diptera: tephritidae) and Bactrocera cucurbitae. J Econ Entomol. 2020;113:2141–9.10.1093/jee/toaa140Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Zhao HY, Wang SZ, Yuan F, Dong YC, Zhang GS. Life table of Myzus persicae under different temperature and host plant conditions. Chin J Appl Ecol. 1995;6:83–7. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Davis JA, Radcliffe EB, Ragsdale DW. Effects of high and fluctuating temperatures on Myzus persicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Environ Entomol. 2006;35:1461–8.10.1093/ee/35.6.1461Search in Google Scholar

[42] Jauker F, Wolters V. Hover flies are efficient pollinators of oilseed rape. Oecologia. 2008;156:819–23.10.1007/s00442-008-1034-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Jeong SH, Jung JM, Han HY. A taxonomic review of Brachypalpus Macquart and Chalcosyrphus Curran (Insecta: Diptera: Syrphidae) in Korea. J Asia-Pac Entomol. 2017;20:1043–61.10.1016/j.aspen.2017.07.001Search in Google Scholar

[44] Miranda GFG, Moran K. The female abdomen and genitalia of Syrphidae (Diptera). Insect Syst Evol. 2017;48:157–201.10.1163/1876312X-48022153Search in Google Scholar

[45] Tian J, Ren BZ. A conspectus of syrphidae. J Jilin Agric Univ. 2019;41:1–10. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Zhang JM, Wang B, Yu GY. Morphological descriptions of four stages of scaeva pyrastri (Linnaeus) and episyrphus balteatus (De Geer). Vegetables. 2019;12:70–3+85. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Dong K, Dong Y, Luo YZ. Effects of temperatures on development, survival and growth of Episyrphus balteaus De Geer. J Shandong Agric Univ. 2004;35:221–3. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Ankersmit GW, Dijkman H, Keuning NJ, Mertens H, Tacoma HM. Episyrphus balteatus as a predator of the aphid Sitobion avenae on winter wheat. Entomol Exp Appl. 1986;42:271–7.10.1111/j.1570-7458.1986.tb01032.xSearch in Google Scholar

[49] Bianchi FJ, Booij C, Tscharntke T. Sustainable pest regulation in agricultural landscapes: a review on landscape composition, biodiversity and natural pest control. Proc R Soc B-Biol Sci. 2006;273:1715–27.10.1098/rspb.2006.3530Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Campbell A, Frazer BD, Gilbert N, Gutierrez AP, Mackauer M. Temperature requirements of some aphids and their parasites. J Appl Ecol. 1974;11(2):431–8.10.2307/2402197Search in Google Scholar

[51] Lu WM, Bi XH, Shen GT, Luo RC, Shao XZ, Ren Z, et al. Studies on the effective accumulated temperature of Scaeva selenitica Meigen. For Sci Technol. 1994;19:25–6. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Sommaggio D. Syrphidae: can they be used as environmental bioindicators? Agric Ecosyst Environ. 1999;74:343–56.10.1016/B978-0-444-50019-9.50019-4Search in Google Scholar

[53] Völkl W, Mackauer M, Pell JK, Brodeur J. Predators, parasitoids and pathogens. In Aphids as crop pests. Oxford, UK: CAB international; 2007. p. 187–233.10.1079/9780851998190.0187Search in Google Scholar

[54] Singh K, Singh NN. Preying capacity of different established predators of the aphidLipaphis erysimi (Kalt.) infesting rapeseed-mustard crop in laboratory conditions. Plant Prot Sci. 2013;49:84–8.10.17221/66/2011-PPSSearch in Google Scholar

[55] Ding YQ. The theory and application of insect population mathematic ecology. Beijing, China: Science Press; 1980.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Safety assessment and modulation of hepatic CYP3A4 and UGT enzymes by Glycyrrhiza glabra aqueous extract in female Sprague–Dawley rats

- Adult-onset Still’s disease with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and minimal change disease

- Role of DZ2002 in reducing corneal graft rejection in rats by influencing Th17 activation via inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway and downregulation of TRAF1

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome with elevated IgG4 and T-cell clonality: A report of two cases

- Electroacupuncture alleviates sciatic nerve injury in sciatica rats by regulating BDNF and NGF levels, myelin sheath degradation, and autophagy

- Polydatin prevents cholesterol gallstone formation by regulating cholesterol metabolism via PPAR-γ signaling

- RNF144A and RNF144B: Important molecules for health

- Analysis of the detection rate and related factors of thyroid nodules in the healthy population

- Artesunate inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion through OGA-mediated O-GlcNAcylation of ZEB1

- Endovascular management of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: Case report and review of the literature

- Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis

- SATB2 promotes humeral fracture healing in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Overexpression of the ferroptosis-related gene, NFS1, corresponds to gastric cancer growth and tumor immune infiltration

- Understanding risk factors and prognosis in diabetic foot ulcers

- Atractylenolide I alleviates the experimental allergic response in mice by suppressing TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 signalling

- FBXO31 inhibits the stemness characteristics of CD147 (+) melanoma stem cells

- Immune molecule diagnostics in colorectal cancer: CCL2 and CXCL11

- Inhibiting CXCR6 promotes senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells with limited proinflammatory SASP to attenuate hepatic fibrosis

- Cadmium toxicity, health risk and its remediation using low-cost biochar adsorbents

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis with headache as the first presentation: A case report

- Solitary pulmonary metastasis with cystic airspaces in colon cancer: A rare case report

- RUNX1 promotes denervation-induced muscle atrophy by activating the JUNB/NF-κB pathway and driving M1 macrophage polarization

- Morphometric analysis and immunobiological investigation of Indigofera oblongifolia on the infected lung with Plasmodium chabaudi

- The NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex and Hr78 modulate the Lobe2 mutant eye phenotype

- Experimental study on salmon demineralized bone matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: In vitro and in vivo study

- A case of IgA nephropathy treated with a combination of telitacicept and half-dose glucocorticoids

- Analgesic and toxicological evaluation of cannabidiol-rich Moroccan Cannabis sativa L. (Khardala variety) extract: Evidence from an in vivo and in silico study

- Wound healing and signaling pathways

- Combination of immunotherapy and whole-brain radiotherapy on prognosis of patients with multiple brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study

- To explore the relationship between endometrial hyperemia and polycystic ovary syndrome

- Research progress on the impact of curcumin on immune responses in breast cancer

- Biogenic Cu/Ni nanotherapeutics from Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl seeds for the treatment of lung cancer

- Dapagliflozin attenuates atrial fibrosis via the HMGB1/RAGE pathway in atrial fibrillation rats

- Glycitein alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in keratinocytes via ROS-associated PI3K–Akt signalling pathway

- ADH5 inhibits proliferation but promotes EMT in non-small cell lung cancer cell through activating Smad2/Smad3

- Apoptotic efficacies of AgNPs formulated by Syzygium aromaticum leaf extract on 32D-FLT3-ITD human leukemia cell line with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Novel cuproptosis-related genes C1QBP and PFKP identified as prognostic and therapeutic targets in lung adenocarcinoma

- Bee venom promotes exosome secretion and alters miRNA cargo in T cells

- Treatment of pure red cell aplasia in a chronic kidney disease patient with roxadustat: A case report

- Comparative bioinformatics analysis of the Wnt pathway in breast cancer: Selection of novel biomarker panels associated with ER status

- Kynurenine facilitates renal cell carcinoma progression by suppressing M2 macrophage pyroptosis through inhibition of CASP1 cleavage

- RFX5 promotes the growth, motility, and inhibits apoptosis of gastric adenocarcinoma cells through the SIRT1/AMPK axis

- ALKBH5 exacerbates early cardiac damage after radiotherapy for breast cancer via m6A demethylation of TLR4

- Phytochemicals of Roman chamomile: Antioxidant, anti-aging, and whitening activities of distillation residues

- Circadian gene Cry1 inhibits the tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma by the BAX/BCL2-mediated apoptosis pathway

- The TNFR-RIPK1/RIPK3 signalling pathway mediates the effect of lanthanum on necroptosis of nerve cells

- Longitudinal monitoring of autoantibody dynamics in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing surgery

- The potential role of rutin, a flavonoid, in the management of cancer through modulation of cell signaling pathways

- Construction of pectinase gene engineering microbe and its application in tobacco sheets

- Construction of a microbial abundance prognostic scoring model based on intratumoral microbial data for predicting the prognosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Sepsis complicated by haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis triggered by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and human herpesvirus 8 in an immunocompromised elderly patient: A case report

- Sarcopenia in liver transplantation: A comprehensive bibliometric study of current research trends and future directions

- Advances in cancer immunotherapy and future directions in personalized medicine

- Can coronavirus disease 2019 affect male fertility or cause spontaneous abortion? A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis

- Heat stroke associated with novel leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor gene variant in a Chinese infant

- PSME2 exacerbates ulcerative colitis by disrupting intestinal barrier function and promoting autophagy-dependent inflammation

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state with severe hypernatremia coexisting with central diabetes insipidus: A case report and literature review

- Efficacy and mechanism of escin in improving the tissue microenvironment of blood vessel walls via anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects: Implications for clinical practice

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Clinicopathological analysis of three patients and literature review

- Genetic variants in VWF exon 26 and their implications for type 1 Von Willebrand disease in a Saudi Arabian population

- Lipoxin A4 improves myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through the Notch1-Nrf2 signaling pathway

- High levels of EPHB2 expression predict a poor prognosis and promote tumor progression in endometrial cancer

- Knockdown of SHP-2 delays renal tubular epithelial cell injury in diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis

- Exploring the toxicity mechanisms and detoxification methods of Rhizoma Paridis

- Concomitant gastric carcinoma and primary hepatic angiosarcoma in a patient: A case report

- YAP1 inhibition protects retinal vascular endothelial cells under high glucose by inhibiting autophagy

- Identification of secretory protein related biomarkers for primary biliary cholangitis based on machine learning and experimental validation

- Integrated genomic and clinical modeling for prognostic assessment of radiotherapy response in rectal neoplasms

- Stem cell-based approaches for glaucoma treatment: a mini review

- Bacteriophage titering by optical density means: KOTE assays

- Neutrophil-related signature characterizes immune landscape and predicts prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Integrated bioinformatic analysis and machine learning strategies to identify new potential immune biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease and their targeting prediction with geniposide

- TRIM21 accelerates ferroptosis in intervertebral disc degeneration by promoting SLC7A11 ubiquitination and degradation

- TRIM21 accelerates ferroptosis in intervertebral disc degeneration by promoting SLC7A11 ubiquitination and degradation

- Histone modification and non-coding RNAs in skin aging: emerging therapeutic avenues

- A multiplicative behavioral model of DNA replication initiation in cells

- Biogenic gold nanoparticles synthesized from Pergularia daemia leaves: a novel approach for nasopharyngeal carcinoma therapy

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease mimicking Hashimoto’s encephalopathy: steroid response followed by decline

- Impact of semaphorin, Sema3F, on the gene transcription and protein expression of CREB and its binding protein CREBBP in primary hippocampal neurons of rats

- Iron overloaded M0 macrophages regulate hematopoietic stem cell proliferation and senescence via the Nrf2/Keap1/HO-1 pathway

- Revisiting the link between NADPH oxidase p22phox C242T polymorphism and ischemic stroke risk: an updated meta-analysis

- Exercise training preferentially modulates α1D-adrenergic receptor expression in peripheral arteries of hypertensive rats

- Overexpression of HE4/WFDC2 gene in mice leads to keratitis and corneal opacity

- Tumoral calcinosis complicating CKD-MBD in hemodialysis: a case report

- Mechanism of KLF4 Inhibition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer cells

- Dissecting the molecular mechanisms of T cell infiltration in psoriatic lesions via cell-cell communication and regulatory network analysis

- Circadian rhythm-based prognostic features predict immune infiltration and tumor microenvironment in molecular subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Optimization and comparative study of Bacillus consortia for cellulolytic potential and cellulase enzyme activity

- The complete mitochondrial genome analysis of Haemaphysalis hystricis Supino, 1897 (Ixodida: Ixodidae) and its phylogenetic implications

- Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors analysis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among tuberculosis population in Huzhou City, Eastern China

- Indices of human impacts on landscapes: How do they reflect the proportions of natural habitats?

- Genetic analysis of the Siberian flying squirrel population in the northern Changbai Mountains, Northeast China: Insights into population status and conservation

- Diversity and environmental drivers of Suillus communities in Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica forests of Inner Mongolia

- Global assessment of the fate of nitrogen deposition in forest ecosystems: Insights from 15N tracer studies

- Fungal and bacterial pathogenic co-infections mainly lead to the assembly of microbial community in tobacco stems

- Influencing of coal industry related airborne particulate matter on ocular surface tear film injury and inflammatory factor expression in Sprague-Dawley rats

- Temperature-dependent development, predation, and life table of Sphaerophoria macrogaster (Thomson) (Diptera: Syrphidae) feeding on Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae)

- Eleonora’s falcon trophic interactions with insects within its breeding range: A systematic review

- Agriculture

- Integrated analysis of transcriptome, sRNAome, and degradome involved in the drought-response of maize Zhengdan958

- Variation in flower frost tolerance among seven apple cultivars and transcriptome response patterns in two contrastingly frost-tolerant selected cultivars

- Heritability of durable resistance to stripe rust in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Molecular mechanism of follicular development in laying hens based on the regulation of water metabolism

- Molecular identification and control studies on Coridius sp. (Hemiptera: Dinidoridae) in Al-Khamra, south of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 10.1515/biol-2025-1218

- Animal Science

- Effect of sex ratio on the life history traits of an important invasive species, Spodoptera frugiperda

- Plant Sciences

- Hairpin in a haystack: In silico identification and characterization of plant-conserved microRNA in Rafflesiaceae

- Widely targeted metabolomics of different tissues in Rubus corchorifolius

- The complete chloroplast genome of Gerbera piloselloides (L.) Cass., 1820 (Carduoideae, Asteraceae) and its phylogenetic analysis

- Field trial to correlate mineral solubilization activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and biochemical content of groundnut plants

- Correlation analysis between semen routine parameters and sperm DNA fragmentation index in patients with semen non-liquefaction: A retrospective study

- Plasticity of the anatomical traits of Rhododendron L. (Ericaceae) leaves and its implications in adaptation to the plateau environment

- Effects of Piriformospora indica and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on growth and physiology of Moringa oleifera under low-temperature stress

- Effects of different sources of potassium fertiliser on yield, fruit quality and nutrient absorption in “Harward” kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa)

- Comparative efficiency and residue levels of spraying programs against powdery mildew in grape varieties

- The DREB7 transcription factor enhances salt tolerance in soybean plants under salt stress

- Using plant electrical signals of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) for water pollution monitoring

- Response of hybrid grapes (Vitis spp.) to two biotic stress factors and their seedlessness status

- Metabolomic profiling reveals systemic metabolic reprogramming in Alternaria alternata under salt stress

- Effects of mixed salinity and alkali stress on photosynthetic characteristics and PEPC gene expression of vegetable soybean seedlings

- Food Science

- Phytochemical analysis of Stachys iva: Discovering the optimal extract conditions and its bioactive compounds

- Review on role of honey in disease prevention and treatment through modulation of biological activities

- Computational analysis of polymorphic residues in maltose and maltotriose transporters of a wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain

- Optimization of phenolic compound extraction from Tunisian squash by-products: A sustainable approach for antioxidant and antibacterial applications

- Liupao tea aqueous extract alleviates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in rats by modulating the gut microbiota

- Toxicological qualities and detoxification trends of fruit by-products for valorization: A review

- Polyphenolic spectrum of cornelian cherry fruits and their health-promoting effect

- Optimizing the encapsulation of the refined extract of squash peels for functional food applications: A sustainable approach to reduce food waste

- Advancements in curcuminoid formulations: An update on bioavailability enhancement strategies curcuminoid bioavailability and formulations

- Impact of saline sprouting on antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds in chia seeds

- The dilemma of food genetics and improvement

- Causal effects of trace elements on congenital foot deformities and their subtypes: a Mendelian randomization study with gut microbiota mediation

- Honey meets acidity: a novel biopreservative approach against foodborne pathogens

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Impact of hyaluronic acid-modified hafnium metalorganic frameworks containing rhynchophylline on Alzheimer’s disease

- Emerging patterns in nanoparticle-based therapeutic approaches for rheumatoid arthritis: A comprehensive bibliometric and visual analysis spanning two decades

- Application of CRISPR/Cas gene editing for infectious disease control in poultry

- Preparation of hafnium nitride-coated titanium implants by magnetron sputtering technology and evaluation of their antibacterial properties and biocompatibility

- Preparation and characterization of lemongrass oil nanoemulsion: Antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant, and anticancer activities

- Fluorescent detection of sialic acid–binding lectins using functionalized quantum dots in ELISA format

- Smart tectorigenin-loaded ZnO hydrogel nanocomposites for targeted wound healing: synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells”

- Corrigendum to “Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans”

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Down-regulation of miR-539 indicates poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer”

Articles in the same Issue

- Safety assessment and modulation of hepatic CYP3A4 and UGT enzymes by Glycyrrhiza glabra aqueous extract in female Sprague–Dawley rats

- Adult-onset Still’s disease with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and minimal change disease

- Role of DZ2002 in reducing corneal graft rejection in rats by influencing Th17 activation via inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway and downregulation of TRAF1

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease