Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

-

Ioannis Foukarakis

Abstract

As sleep appears to be closely related to cognitive status, we aimed to explore the association between the percentage of deep sleep, cognitive state, and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarker amyloid-beta 42 in non-demented individuals. In this cross-sectional study, 90 non-demented participants from the Aiginition Longitudinal Biomarker Investigation of Neurodegeneration cohort underwent a one-night WatchPAT sleep evaluation. Participants were categorized by cognitive status (patients with mild cognitive impairment [MCI] or cognitively normal [CN] individuals) and CSF Aβ42 status (Aβ42 ≤ 1,030 pg/mL [A+] or Ab42 > 1,030 pg/mL [A−]). After controlling for age, sex, and years of education, a significant inverse association was found between the percentage of deep sleep and the odds of being classified as MCI compared to CN (OR = 0.86, 95% CI [0.76–0.97], p = 0.012). However, a non-significant trend for an inverse association between the percentage of deep sleep and the odds of being classified as A+ was observed (OR = 0.92, 95% CI [0.84–1.01], p = 0.092). This study demonstrates a significant link between deep sleep and MCI. Although more longitudinal studies are needed, deep sleep could potentially serve as a novel biomarker of cognitive decline and an intervention target for dementia prevention.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

In 2023, dementia was the seventh leading cause of death and one of the major causes of disability among older adults globally, while Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, representing 60–70% of all cases [1]. Between dementia and normal cognitive aging there is an intermediate stage, namely mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [2]. Although MCI can result from a variety of diseases, AD accounts for many cases, thus MCI constitutes a well-recognized part of AD clinical continuum [2]. At the same time, AD biomarkers, and especially amyloid-beta (Aβ42), which can precede clinical symptoms by years [3], are considered a hallmark in AD pathophysiological continuum [4]. Consequently, research interest has shifted to these preclinical and prodromal stages of the disease and the possible associations with lifestyle factors.

Regarding lifestyle factors, apart from diet [5] and physical activity [6], cognitive decline is also closely associated with sleep [7]. Notably, the prevalence of sleep disturbances in patients with pathological cognitive decline is significantly higher compared to cognitively normal (CN) individuals [8], while numerous cross-sectional and prospective studies have demonstrated that poor sleep quality is linked to cognitive impairment [7,9,10]. However, existing evidence suggests a bidirectional relationship between sleep and AD pathology [11,12]. Beyond overall sleep quality and self-reported sleep disturbances, a particularly intriguing area of research is deep sleep, also known as slow wave sleep (SWS) or N3 (non-rapid eye movement, NREM) sleep, and its impact on cognition. Its crucial role in the consolidation of declarative memories has been firmly established in healthy older adults [13,14], although the exact underlying physiology of this procedure remains debated [14]. In CN older adults, SWS has been positively associated with cognitive functions, especially episodic memory performance [15], whereas several studies suggest that enhancing deep sleep activity or duration may lead to performance improvements in various cognitive domains [16].

However, data regarding the association between deep sleep and MCI have provided conflicting results. Some cross-sectional studies have provided evidence of such a relationship [17,18,19,20], while other studies have failed to detect any significant correlation [21,22,23,24,25,26]. Two meta-analyses [27,28] which have compared the sleep macroarchitecture in CN and MCI subjects, concluded that there were no significant differences between the two groups regarding deep sleep. As far as the association between amyloid-beta burden and deep sleep in non-demented individuals is concerned, there are a few studies dealing with this topic. In patients with amnestic MCI (aMCI) a positive correlation between disrupted deep sleep and plasma Aβ42 levels has been documented [29], while in cognitively healthy individuals a link between diminished deep sleep duration and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ42 was found [30].

Nonetheless, the above-mentioned studies are not without limitations. First, the majority of studies concerning cognitive status included a low number of non-demented participants (less than 50) [17,18,19,23,24,26], limiting their power. Additionally, in many studies, participants were on average over 70 years old [17,18,19,20,26], indicating the need for more comprehensive data on younger non-demented individuals within the AD continuum and only two of them have presented data regarding the participants’ amyloid-beta status [25,26]. Studies regarding the relationship between amyloid-beta and deep sleep included a small number of participants (less than 50) as well, while Aβ42 evaluation was either performed through plasma [29], where there is no consensus for the cut-offs criteria [31], or did not include individuals with pathological Aβ42 values [30].

Within this theoretical framework, our aim in undertaking this specific cross-sectional study was to enhance current understanding of sleep macroarchitecture in non-demented people, placing emphasis on deep sleep percentage. Specifically, our goal was to investigate differences in the percentage of deep sleep, as measured by a WatchPAT device, among CN individuals and patients with MCI and to explore the association between the fraction of deep sleep and amyloid-beta burden.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants and study design

Data for the analysis were drawn from Aiginition Longitudinal Biomarker Investigation of Neurodegeneration (ALBION) study, a longitudinal ongoing study in the Cognitive Disorders Clinic of Aiginition Hospital of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens [32]. Our sample consisted of individuals aged ≥40 years, referred by other specialists or self-referred to the cognitive disorders’ outpatient clinic of Aiginition, Athens, Greece. Patients with neurological and psychiatric diseases, including dementia, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Huntington’s disease, severe traumatic brain injury, and normal pressure hydrocephalus, as well as those with active alcohol or drug abuse, major psychiatric conditions such as major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder, or other medical conditions associated with cognitive impairment, were excluded from ALBION. All subjects underwent a standardized physical and neurological examination, comprehensive neuropsychological assessment, a lumbar puncture, blood sampling, and one-night sleep activity assessment by WatchPAT as part of their baseline evaluation. All participants provided written informed consent at the time of enrollment. More details regarding ALBION study protocol can be found elsewhere [32].

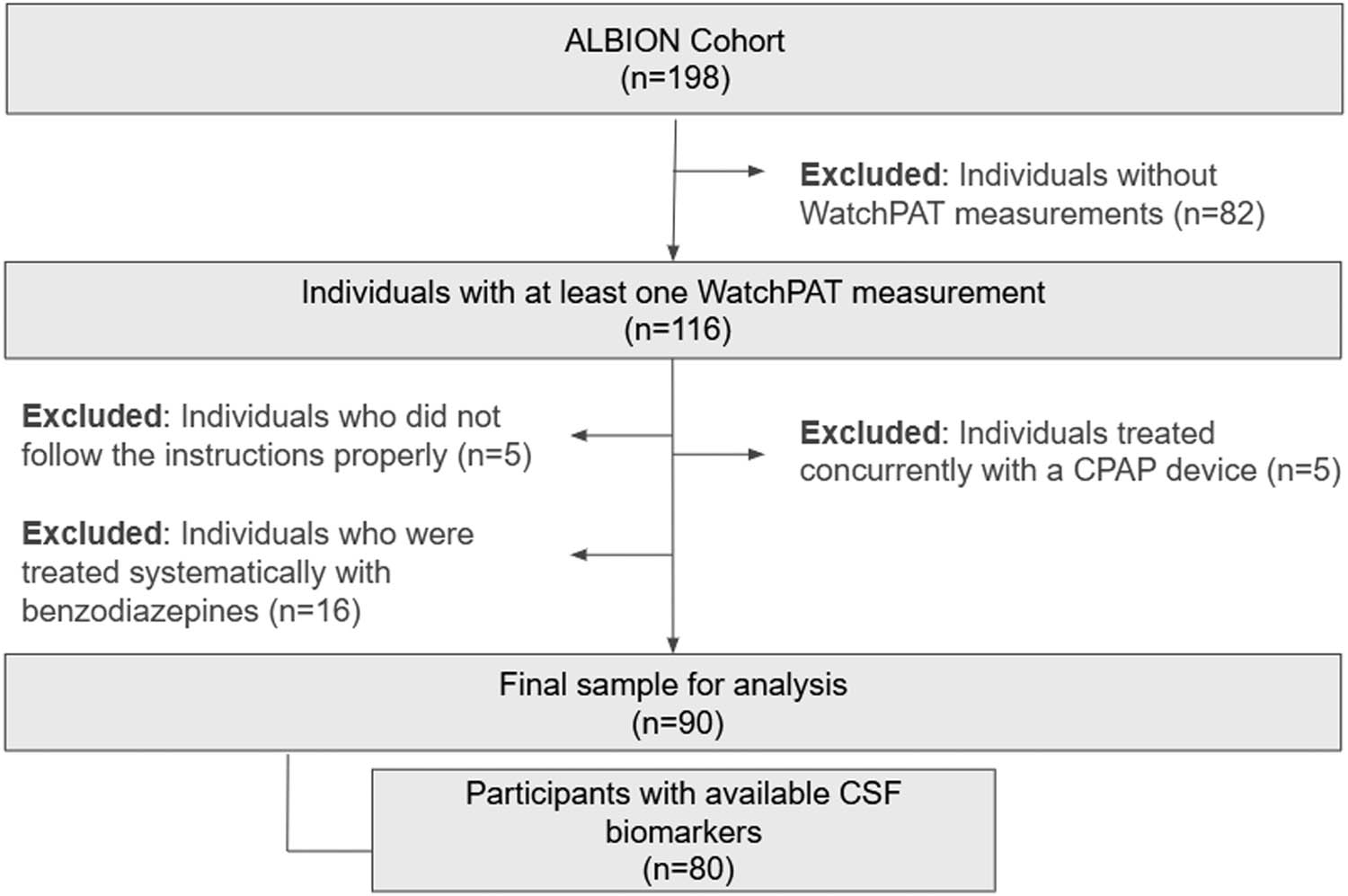

Initially, a total of 116 participants in the ALBION cohort underwent sleep evaluation using a WatchPAT device. Five participants provided incomplete data because they did not adhere to the instructions for proper WatchPAT measurement, which impacted the calculated total sleep time (TST) (e.g., WatchPAT activation failure, incomplete measurements, or activation occurring extremely early in the morning). Furthermore, five participants diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome by a polysomnography study and subsequently treated with continuous positive airway pressure device were excluded from this study. Also, considering the potential influence of benzodiazepines on sleep macro-architecture [33], particularly on deep sleep, we excluded 16 participants who were systematically treated with benzodiazepines.

In total, our study consisted of 90 participants, with CSF analysis data available for 80, as depicted in our flowchart (Figure 1).

Flowchart.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to human use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the Aiginition University Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece (Protocol code: 255, A∆A: ΨΘ6K46Ψ8N2-8HΩ, date of approval: 10 May 2021).

2.2 Clinical diagnosis, neurological, and neuropsychological assessment

All participants have successfully completed a thorough standardized neuropsychological assessment conducted by trained clinical neuropsychologists who administered a battery of neuropsychological tests assessing five cognitive domains: attention-speed, executive functioning, memory, language, and visuospatial perception. Global cognition was assessed using Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [34] and the Revised Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (ACE-R) [35]. Further information regarding the neuropsychological evaluation in ALBION study can be found elsewhere [32]. Subsequently, a neurological examination was performed by a specialist neurologist who recorded detailed information regarding demographics, medical history, medication, and family history.

A diagnosis of MCI and MCI subtypes (aMCI and non-amnestic [naMCI]) was assigned using standard criteria [36] when the participant had cognitive complaints and a measurable deficit in cognition with a standard deviation (SD) below 1.5 in at least one domain, in the absence of dementia or impairment in everyday functioning.

We defined cognitive status (either CN or MCI) of each participant based on the clinical status corresponding to the visit when they successfully completed the WatchPAT evaluation.

2.3 CSF collection and analysis

Eighty (n = 80) participants underwent a lumbar puncture during their first visit, according to ALBION’s study protocol [32], and had available CSF data by the time of our analysis. The lumbar puncture procedure, as well as the collection, processing, and storage of CSF, followed international guidelines [37]. CSF was primarily processed for Aβ42 biomarker, which is indicative of AD. Analysis of CSF neurodegenerative biomarkers was performed using the Roche Diagnostics Elecsys© Platform (Elecsys® β-Amyloid (1-42) CSF II). The provided reference ranges for a positive result were as follows: Aβ42 ≤ 1,030 pg/mL based on the established cut-off explicitly provided by the assay manufacturer [38]. Participants were classified as amyloid positive (A+) if the CSF Aβ42 value was less than 1,030 pg/mL; otherwise, they were classified as amyloid negative (A−).

2.4 Sleep measures

The WatchPAT device is an objective, battery-powered, wrist-worn ambulatory sleep recorder equipped with sensors that detect peripheral arterial tone (PAT) signal, pulse rate, actigraphy, and pulse oximetry. The PAT signal measures pulsatile volume changes at the fingertip, reflecting variations in sympathetic tone. The recorded signals from the WatchPAT device are automatically analyzed using advanced software, which categorizes sleep into wake, light sleep, deep sleep, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep [39,40]. This classification is based on evaluations of body movements and their occurrence, as well as spectral components of the PAT signal. The WatchPAT algorithm stratifies sleep into light, deep, and REM stages, with light sleep corresponding to sleep stages N1 and N2, and deep sleep corresponding to sleep stage N3. Further details on the algorithm can be found elsewhere [39,40,41]. A multicenter validation study comparing the WatchPAT device to polysomnography (PSG) demonstrated an overall agreement of 88.6 ± 5.9% for detecting light/deep sleep and 88.7 ± 5.5% for detecting REM sleep across a varied population [42]. Cohen κ coefficients were calculated to adjust for random agreement and suggested moderate agreement between polysomnography and WatchPAT recordings [43].

In the current study, WatchPAT300 device was used to assess participants’ nighttime sleep macroarchitecture, focusing on TST, sleep latency, number of awakenings, and sleep stages, as reported above. The time spent in each sleep stage (deep sleep, light sleep, and REM sleep) was expressed as a percentage of TST (%TST) of every participant to ensure that our data regarding deep sleep were comparable across all subjects. All individuals included in this analysis received detailed written and illustrated instructions on the proper use of the WatchPAT device. Subjects were instructed to activate the WatchPAT recorder just before bedtime and to deactivate it upon waking up.

Fifty-eight participants (64.0%) completed the WatchPAT evaluation during the first evaluation in the ALBION Cohort, coinciding with CSF collection and analysis. Additionally, 11 participants (12.0%) completed the WatchPAT evaluation within 1 year after the CSF evaluation, 13 participants (14.0%) within 2 years, 5 participants (5.5%) within 3 years, and 3 participants (3.3%) within 4 years.

2.5 Blood sampling and gene-apolipoprotein E (APOE) genetic outcomes

APOE genotyping was conducted using genomic DNA extracted from blood buffy coat, employing Qiamp DNA Blood Mini Kits (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). The genotyping method utilized is polymerase chain reaction-DNA sequencing, carried out with LightCycler 2 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) and LightMix TIB MOLBIOL reagents. Data from APOE genotyping analysis were available for 77 individuals. Participants with one or more APOE-ε4 alleles were considered APOE-ε4 carriers whereas those without APOE-ε4 alleles were regarded as APOE-ε4 non-carriers.

2.6 Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed with SPSS version 28.0. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.050.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median with interquartile range (IQR), while categorical variables were represented as frequencies and percentages. Normality of all continuous variables was assessed using the Sharipo–Wilk normality test.

A positive family history of dementia was considered if either parent had late-onset dementia (after age 65); otherwise, it was considered negative.

The initial sample was stratified into two distinct sets of groups: first into MCI versus CN and subsequently into A+ versus A− groups. Differences in variables between CN subjects and MCI patients, as well as between amyloid negative (A−) and amyloid positive (A+) groups, were tested using independent samples t-test for continuous variables following the normal distribution (age, BMI, TST, CSF Aβ42 levels, percentage of deep sleep, percentage of light sleep, and percentage of REM sleep); otherwise, they were compared using independent samples – Mann Whitney U-test (education, ACE-R, MMSE, sleep latency, and number of awakenings). Chi-square (X²) test was used for comparing categorical variables (sex, APOE-ε4 carrier, family history).

Subsequently, two separate binary logistic regression analyses were conducted. One aimed to examine the association between deep sleep and cognitive function, while the other explored the relationship between deep sleep and amyloid-beta status. Regarding cognitive status, clinical diagnosis was selected as the outcome variable (CN = 0 and MCI = 1) with percentage of deep sleep, age, sex, and education years as predictor variables. Similarly, regarding amyloid-beta status, amyloid category was selected as the dependent variable (A− = 0/A+ = 1), with percentage of deep sleep, age, sex, and education years as independent variables. All independent variables were introduced in the model as continuous variables except for sex, which was treated as categorical variable (female as reference). Results are represented as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of logistic regression coefficients.

In the unadjusted model, each independent variable was individually introduced into the regression analysis. In the adjusted model, all independent variables were simultaneously introduced into the regression analysis. The Omnibus tests of model coefficients were used to evaluate the extent to which the model improved over the baseline model. Nagelkerke R square value was used as a method of calculating the explaining variation. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used as a goodness of fit test. All binary logistic regression assumptions were checked.

A sensitivity analysis assessed the impact of different MCI types (aMCI and naMCI) on our results. After excluding naMCI individuals, we compared subjects based on their demographic, clinical, and sleep characteristics concerning cognitive status. Subsequently, we performed a corresponding regression analysis, with cognitive status as an outcome (CN = 0 and aMCI = 1) and age, sex, and years of education as predictor variables.

3 Results

3.1 Demographics, clinical characteristics, and sleep measures

3.1.1 Cognitive status classification

A total of 90 individuals were included in our analysis. Patients’ demographic, clinical characteristics, and sleep measures are reported in Table 1.

Demographics, clinical characteristics, and sleep measures classified by cognitive status

| All | CN | MCI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 90) | (n = 72) | (n = 18) | p-value | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 63.43 ± 9.16 | 62.49 ± 9.06 | 67.22 ± 8.80 | 0.049 |

| Sex, female (%) | 63 (70.0) | 52 (72.2) | 11 (61.0) | 0.358 |

| Education (years), mean ± SD (min–max) | 13.72 ± 3.85 (6–22) | 14.06 ± 3.71 (6–22) | 12.39 ± 4.20 (6–19) | 0.158 |

| ACE-R, mean ± SD (min–max) | 92.21 ± 6.39 (61–100) | 94.24 ± 4.04 (81–100) | 84.11 ± 7.63 (61–94) | <0.001 |

| MMSE, mean ± SD (min–max) | 28.50 ± 1.84 (21–30) | 29.01 ± 1.13 (25–30) | 26.44 ± 2.59 (21–30) | <0.001 |

| APOE-ε4 carrier, positive (%) | 19 (24.6) [n = 77] | 13 (21.3) [n = 61] | 6 (37.5) [n = 16] | 0.181 |

| Family history of dementia, positive (%) | 49 (54.4) | 41 (56.9) | 8 (44.4) | 0.341 |

| CSF Aβ42 (pg/mL), Mean ± SD | 1.221 (501) [n = 80] | 1.276 (477) [n = 65] | 983 (550) [n = 15] | 0.040 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 25.99 ± 3.96 | 25.69 ± 4.17 | 27.19 ± 2.79 | 0.154 |

| TST (min), mean ± SD (min–max) | 364 ± 74 (196–519) | 356 ± 71 (196–498) | 398 ± 79 (217–519) | 0.030 |

| Sleep latency (min), median (IQR) | 19.00 (11.50) | 19.00 (15.75) | 20.00 (19.00) | 0.481 |

| Number of awakenings, median (IQR) | 7.5 (5.25) | 7 (5.00) | 10 (12.50) | 0.152 |

| Percentage of deep sleep (%TST), mean ± SD | 14.31 ± 5.69 | 15.18 ± 5.51 | 10.87 ± 5.16 | 0.003 |

| Percentage of light sleep (%TST), mean ± SD | 65.17 ± 12.16 | 63.73 ± 12.28 | 70.90 ± 10.06 | 0.024 |

| Percentage of REM sleep (%TST), Mean ± SD | 20.52 ± 8.69 | 21.09 ± 8.92 | 18.23 ± 7.53 | 0.214 |

All p-values are significant at the 0.050 level. Significant results are indicated with bold values.

CN, cognitively normal; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; ACE-R, Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination – revised; MMSE, mini-mental state examination; APOE, gene-apolipoprotein E; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; BMI, body mass index; TST, total sleep time; REM, rapid eye movement.

Regarding cognitive status, 18 individuals were diagnosed with MCI, while 72 participants were classified as CN. No significant difference in sex ratio was found between the two groups. The participants with MCI were significantly older (p = 0.049) and, as expected, cognitive scores (MMSE, ACE) were lower in the MCI group compared to CN subjects (p < 0.001). Between the two groups, CSF Aβ levels were, on average, significantly lower in individuals diagnosed with MCI (p = 0.040). Regarding sleep characteristics, patients with MCI showed, on average, significantly longer TST by 42 min (p = 0.030), a lower percentage of deep sleep by 4.31% (p = 0.004), and a higher percentage of light sleep by 7.17% (p = 0.025) compared to CN individuals.

A sensitivity analysis, where only aMCI patients were included, showed that differences between the compared groups (CN/aMCI) regarding demographic, clinical characteristics, and sleep measures did not considerably alter and the statistically significant results remained unchanged (Table S1).

3.1.2 Amyloid status classification

In total, 80 individuals successfully completed lumbar puncture and had available CSF biomarkers. Patients’ demographic, clinical characteristics, and sleep measures based on amyloid status are reported in Table 2.

Demographics, clinical characteristics, and sleep measures classified by amyloid status

| All | Amyloid negative (A−) | Amyloid positive (A+) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 80) | (n = 49) | (n = 31) | p-value | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 63.60 ± 8.95 | 61.41 ± 8.00 | 67.06 ± 9.39 | 0.005 |

| Sex, female (%) | 57 (71.2) | 35 (71.4) | 22 (70.9) | 0.965 |

| Education (years), mean ± SD (min–max) | 13.64 ± 4.02 (6–22) | 14.33 ± 3.98 (6–22) | 12.55 ± 3.91 (6–22) | 0.027 |

| ACE, mean ± SD (min–max) | 92.34 ± 6.61 (61–100) | 93.39 ± 5.22 (80–100) | 90.68 ± 8.17 (61–98) | 0.135 |

| MMSE, mean ± SD (min–max) | 28.49 ± 1.88 (21–30) | 28.57 ± 1.81 (22–30) | 28.35 ± 2.01 (21–30) | 0.548 |

| APOE-ε4 carrier, positive (%) | 17 (22.9) [ n = 74] | 9 (19.5) [ n = 46] | 8 (28.5) [ n = 28] | 0.372 |

| Family history of dementia, positive (%) | 43 (53.7) | 27 (55.1) | 16 (51.6) | 0.760 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 25.73 ± 3.90 | 25.85 ± 4.08 | 25.55 ± 3.66 | 0.742 |

| TST (min), mean ± SD (min–max) | 364 ± 73 (196–504) | 360 ± 72 (196–498) | 369 ± 76 (217–504) | 0.595 |

| Sleep latency (min), median (IQR) | 19.00 (7.00) | 19.00 (16.00) | 21.00 (11.00) | 0.059 |

| Number of awakenings, median (IQR) | 7.5 (5.00) | 7 (6.50) | 8 (5.00) | 0.898 |

| Percentage of deep sleep (%TST), mean ± SD | 14.45 ± 5.77 | 15.64 ± 5.70 | 12.56 ± 5.44 | 0.019 |

| Percentage of light sleep (%TST), mean ± SD | 65.41 ± 12.34 | 63.60 ± 12.63 | 68.26 ± 11.48 | 0.100 |

| Percentage of REM sleep (%TST), mean ± SD | 20.15 ± 8.77 | 20.76 ± 9.09 | 19.18 ± 8.30 | 0.437 |

All p-values are significant at the 0.050 level. Significant results are indicated with bold values.

ACE-R, Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination – revised; MMSE, mini-mental state examination; APOE, gene-apolipoprotein E; BMI, body mass index, TST, total sleep time, REM, rapid eye movement.

Thirty-one participants were classified as amyloid positive (A+). The amyloid positive group was, on average, significantly older by 5.65 years (p = 0.005) and had less years of education (p = 0.039) than the amyloid negative group (A−). Concerning sleep parameters, only the percentage of deep sleep was significantly different between groups. A+ subjects had on average, a significantly lower percentage of deep sleep by 3.08% (p = 0.019) than A− individuals.

3.2 Regression analysis

3.2.1 Cognitive status

Results from multiple logistic regression are shown in Table 3. The unadjusted model revealed that for every 1% decrease in the percentage of deep sleep, there was approximately a 14% increase in the odds of being classified as MCI (95% CI [0.76, 0.96], p = 0.006). This association remained significant after controlling for age, sex, and years of education in the adjusted model (OR = 0.86, 95% CI [0.76–0.97], p = 0.012).

Binary logistic regression analysis – cognitive status

| Dependent variable: CN = 0, MCI = 1 CN (n = 72)/MCI (n = 18) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model | Adjusted model* adjusted for age, sex, and years of education | |||||

| Independent variables | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Percentage of deep sleep (% TST) | 0.86 | 0.76–0.96 | 0.006 | 0.86 | 0.76–0.97 | 0.012 |

*Adjusted model: Omnibus tests, X²(4) = 13.325, p = 0.01, Hosmer–Lemeshow test, X²(8) = 13.769, p = 0.09, Nagelkerke R² = 0.218.

All p-values are significant at the 0.050 level. Significant results are indicated with bold values.

Overall, after adjusting for potential confounders, a lower percentage of deep sleep was linked to an increased likelihood of MCI.

In sensitivity analysis excluding naMCI patients, logistic regression outcomes were similar (OR = 0.82, 95% CI [0.71–0.96], p = 0.011) in the adjusted model (Table S2).

3.2.2 Amyloid status

As presented in Table 4, the unadjusted model showed that each 1% decrease in the percentage of deep sleep was associated, on average, with a 10% increase in the odds of being classified as A+ (OR = 0.90, 95% CI [0.83–0.99], p = 0.023). However, after controlling for age, sex, and years of education, the association became non-significant (OR = 0.92, 95% CI [0.84–1,01], p = 0.092).

Binary logistic regression analysis – amyloid status

| Dependent variable: amyloid negative = 0, amyloid positive = 1 A− (n = 49)/A+ (n = 31) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model | Adjusted model* adjusted for age, sex, and years of education | |||||

| Independent variables | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Percentage of deep sleep (% TST) | 0.90 | 0.83–0.99 | 0.023 | 0.92 | 0.84–1.01 | 0.092 |

*Adjusted Model : Omnibus Tests, X 2(4) = 12.441 (p = 0.014) , Hosmer-Lemeshow test, X 2(8) = 10.077 (p = 0.26), Nagelkerke R 2 = 0.195.

All p-values are significant at the level of 0.050. Significant results are indicated with bold values.

Overall, after adjusting for potential confounders, a lower percentage of deep sleep was linked to a higher likelihood of amyloid positivity (A+); however, this association was not statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

4 Discussion

Overall, our analyses indicate that in non-demented individuals, a shorter duration of deep sleep, as a percentage of TST, is associated with higher odds of being MCI, even after controlling for age, sex, and years of education. In contrast, no statistically significant association between deep sleep and amyloid-beta status was found after adjusting for the above-mentioned confounding factors. Regarding other sleep measurements, in this study, subjects with MCI had a significantly longer TST compared to CN individuals. Additionally, the percentage of light sleep, defined as a combination of N1 and N2 NREM sleep stages, differed significantly among MCI and CN individuals; however, we considered this as a mirroring effect of the reduction of deep sleep stage and thus we did not further examine this parameter.

Our results regarding the relationship between MCI and deep sleep are consistent with several studies, although literature has also presented contradictory findings. Compared to this study, existing literature has primarily provided evidence from PSG studies involving participants predominantly over the age of 70, which contrasts with the younger age of participants in this study. First of all, Westerberg et al. [17] observed that individuals with aMCI spent less time in SWS compared to normal controls, suggesting a potential link between memory processing and deep sleep. However, the sample size of this analysis was considerably small, posing considerable limitations. Another study [18], which included CN individuals, aMCI, and AD subjects, revealed a significant difference in SWS percentage but post-hoc analysis indicated significance only in the comparison between CN and AD subjects, possibly due to the limited number of participants. Reda et al. [19] found a reduction in SWS percentage among those with aMCI compared to normal subjects and stated that this reduction in SWS could differentiate between cognitively impaired and CN older individuals. In a large cohort, with a high predominance of aMCI patients, Brunetti et al. [20] found that patients with MCI due to AD had a lower percentage of SWS compared to CN individuals. It is important to highlight the fact that in the aforementioned studies which found an association between MCI and deep sleep, the majority of the participants were classified as aMCI [17,18,19,20]. The majority of participants in this study were aMCI (66%) as well, which may explain why our findings are in accordance with similar studies. Specifically, our results remained robust after conducting a sensitivity analysis based on patients with aMCI despite the considerable limitations posed by the small number of aMCI cases, albeit predominant in this cohort (Supplementary material). Recently, a prospective study has associated reductions in SWS, as measured by PSG, with an increased incidence of dementia over a 17-year follow-up [44]. Similarly, a retrospective cohort study linked a decrease in deep sleep percentage to a higher risk of neurodegenerative disorders, such as AD [45]. Although the longitudinal nature of these studies provides evidence suggestive of causality, the absence of biomarkers, such as amyloid-beta42, which were included in our analysis, limits their ability to clarify the potential connection between deep sleep reduction and the underlying pathology of the disease.

In contrast, other studies [21,22,23,26] found no difference in SWS between individuals with different cognitive status. Kim et al. [21], although they did not report any differences between the MCI and CN regarding deep sleep percentage, noted that the amount of SWS was positively associated with the performance on language function tests in both groups. In comparison to our findings, another study [22] primarily reported differences in REM sleep, which were also associated with the APOE status of the individual. To a lesser extent they reported higher fragmentation of SWS in patients with MCI. Potential differences between our findings and these studies could be explained by the fact that we used a WatchPAT device to assess sleep stages instead of PSG, which provides a more thorough examination of sleep structure and architecture. Additionally, although these studies had larger sample sizes, they did not specify the MCI subtypes, such as aMCI and naMCI. Brayet et al. [24], in a study including patients with aMCI, concluded that the percentage of SWS did not significantly differ compared to CN individuals. Liguori et al. [26], in a large cohort, where CSF biomarkers were included, compared CN individuals, subjects with subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), patients with MCI due to AD, and patients with dementia of AD type. Despite observing a significant difference in the percentage of N3 (NREM sleep stage) across groups, a post-hoc analysis revealed no noticeable difference between MCI due to AD and CN individuals. In contrast to our study, this study provided evidence that REM sleep is altered in the preclinical stage of AD, namely MCI and subjects with SCI, and that it is linked to β-amyloid pathology and memory loss. Two meta-analyses were conducted on this topic as well; one regarding sleep measurements in all MCI groups and the other focusing on sleep structure exclusively in aMCI. A meta-analysis by D’Rozario et al. [27], which included several studies mentioned earlier, failed to identify differences in deep sleep characteristics between MCI and CN individuals. Another meta-analysis by Cai et al. [28], which included polysomnographic data on SWS from four studies, similarly found no difference between aMCI and CN, but it hinted at a trend toward lower deep sleep percentages in aMCI, while acknowledging the limitation of study’s sample size. However, apart from deep sleep percentage, authors reported a significant reduction in the total minutes of SWS between aMCI and CN individuals. However, in this study, we examined only the percentages of deep sleep, as we believe this approach is more consistent, reduces individual differences regarding TST, and enhances methodological accuracy. It is worth mentioning that these meta-analyses did not include newer studies on the topic [20,26].

The exact pathophysiological mechanism potentially connecting cognitive impairment to disrupted deep sleep remains unknown. The role of slow waves during deep sleep in the consolidation of memories has been investigated in cognitive normal individuals [13,14,16,46] noting the effects of SWS enhancement on various cognitive domains through auditory, electrical, or pharmaceutical stimulation in normal aging subjects. A potential link between the reduction of deep sleep and subsequent cognitive decline could involve amyloid beta (Aβ42). Sanchez-Espinosa et al. [29] found that an increased arousals index in SWS is associated with higher plasma Aβ42 in aMCI patients. However, AD pathophysiology is associated with lower (not higher) levels of Aβ42 in plasma and CSF [32] which makes the interpretation of this study as well as the comparison with our findings challenging. Additionally, it is important to highlight here that in contrast to the CSF amyloid biomarker included in our analysis, plasma Aβ42 may not be the most reliable plasma biomarker for AD pathology [47]. Another study by Varga et al. [30] revealed that in CN elderly, higher CSF Aβ42 values were associated with lower duration of SWS, in patients with normal CSF measurements. The authors proposed that disrupted deep sleep could potentially worsen the elevation of soluble brain Aβ levels prior to amyloid deposition. Meanwhile, Ju et al. [9] proposed that a lower percentage of deep sleep may result in increased amyloid in the interstitial space, thereby enhancing amyloid deposition and potentially leading to cognitive decline. According to this study, such a process could be explained by the fact that neurons tend to remain mostly silent, hyperpolarized, and exhibit reduced activity during deep sleep, whereas more amyloid beta is produced during periods of activation. Nevertheless, our results regarding amyloid status contradict this hypothesis, as a lower percentage of deep sleep did not significantly increase the odds of being A+ when confounders were adjusted for. This can be explained by the fact that amyloid-positive (A+) group was on average older than amyloid-negative (A−) group and it is generally accepted that age is associated with both reduction of time spent in deep sleep [8] and Aβ42 burden [48].

This study is not without limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, causality regarding the above-mentioned associations could not be determined. Second, there could be a selection bias as some of the participants were self-referred to the outpatient clinic, due to concerns about their memory. Furthermore, the gold standard technique used to acquire sleep data and accurately monitor sleep activity is polysomnography, which was not performed in this study. The sole validation study on sleep staging for WatchPAT [42] provided evidence for a specific age group younger than the cohort analyzed in this study. Therefore, the possibility of underestimating the deep sleep percentage in older adults due to inherent limitations of WatchPAT cannot be excluded. However, polysomnography is difficult to implement in population studies. Additionally, only 64% of our participants in this study completed WatchPAT sleep evaluation simultaneously (within a week) with lumbar puncture. This percentage increased to 90% when considering individuals that completed a WatchPAT study up to 3 years after CSF analysis. This mismatch in synchrony might have affected our implications, as Aβ42 values in CSF may not be constant over time. Finally, the relatively small sample size of this study, the notable predominance of CN individuals compared to MCI patients, 80 and 20%, respectively, and the fact that not all subjects selected were drug-naive regarding CNS-affecting medication might constrain the significance of our results.

Nevertheless, our approach possesses several strengths. First of all, our sample consisted of individuals who were, on average, younger (less than 70 years old) than participants in previous studies, allowing us to expand current knowledge regarding deep sleep during a crucial age zone concerning cognitive decline and Aβ42 aggregation. Second, we have adjusted our results for age considering the extensive literature regarding changes in sleep architecture, especially sleep stages, through normal aging [8]. Moreover, we presented both clinical and biomarker data from the same cohort, including a multifaceted sample of non-demented individuals and we used automated methods for CSF biomarkers assessment, which have demonstrated high agreement with amyloid PET scan imaging [49]. Additionally, WatchPAT is a portable device and thus a comfortable and affordable objective method for measuring sleep architecture, although not gold-standard. Clinical evaluation and neuropsychological assessment were conducted by experienced clinicians with subspecialty training and highly qualified neuropsychologists.

5 Conclusion

A potential bidirectional relationship between sleep and dementia is widely acknowledged in existing literature. However, the exact characteristics, the pathophysiology, and the prospective significance of such an association are yet to be fully determined. Deep sleep undoubtedly constitutes a fertile research field, given the emerging evidence on its role in memory consolidation, cognitive functions, and its interaction with amyloid beta (Aβ42). In this study, we explored the interplay between different aspects of AD continuum and deep sleep macroarchitecture in non-demented individuals. We found a considerable association between deep sleep and MCI. To confirm this evidence, longitudinal studies on non-demented patients should be conducted in order to unveil the relationship among disturbance in deep sleep patterns, cognitive decline, and biomarkers changes. After a comprehensive conjunction of these three fields, deep sleep could potentially serve as a new biomarker of cognitive decline as well as an open field for intervention for dementia prevention.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the reviewer’s valuable comments that improved the manuscript.

-

Funding information: This work was partially supported by the National Network for Research of Neurodegenerative Diseases on the basis of Medical Precision (Grant 2018 E01300001), funded by the General Secretariat of Research and Innovation (GSRI), and by Brain Precision (TAEDR-0535850), funded by the GSRI, through funds provided by the European Union (Next Generation EU) to the National Recovery and Resilience Plan.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. I.F. and N.S. conceptualized the study and developed the methodology. I.F. conducted the investigation and statistical analysis, while E.M. and E.N. performed the formal analysis and data acquisition. I.F. prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors. S.N.S., A.K., A.T., M.Y., and K.R. contributed to writing – review, editing, and critical revision of the work. N.S. supervised the work and managed project administration.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] World Health Organization. Dementia. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023, [cited 2024 Sep 25] Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment. Continuum (Minneap Minn). vol. 22, No. 2, 2016 Apr. p. 404–18, 10.1212/CON.0000000000000313, PMID: 27042901; PMCID: PMC5390929.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Jack Jr CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, et al. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 2010 Jan;9(1):119–28. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6, PMID: 20083042; PMCID: PMC2819840.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Jack Jr CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dementia. 2018 Apr;14(4):535–62. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018, PMID: 29653606; PMCID: PMC5958625.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Scarmeas N, Anastasiou CA, Yannakoulia M. Nutrition and prevention of cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):1006–15. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30338-7, Epub 2018 Sep 21. PMID: 30244829.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Clouston SA, Brewster P, Kuh D, Richards M, Cooper R, Hardy R, et al. The dynamic relationship between physical function and cognition in longitudinal aging cohorts. Epidemiol Rev. 2013;35(1):33–50. 10.1093/epirev/mxs004, Epub 2013 Jan 24 PMID: 23349427; PMCID: PMC3578448.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Xu W, Tan CC, Zou JJ, Cao XP, Tan L. Sleep problems and risk of all-cause cognitive decline or dementia: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020 Mar;91(3):236–44. 10.1136/jnnp-2019-321896, Epub 2019 Dec 26 PMID: 31879285; PMCID: PMC7035682.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Casagrande M, Forte G, Favieri F, Corbo I. Sleep quality and aging: a systematic review on healthy older people, mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jul;19(14):8457. 10.3390/ijerph19148457, PMID: 35886309; PMCID: PMC9325170.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Ju YE, Lucey BP, Holtzman DM. Sleep and alzheimer disease pathology – a bidirectional relationship. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014 Feb;10(2):115–9. 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.269, Epub 2013 Dec 24. PMID: 24366271; PMCID: PMC3979317.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Blackwell T, Yaffe K, Ancoli-Israel S, Redline S, Ensrud KE, Stefanick ML, et al. Association of sleep characteristics and cognition in older community-dwelling men: the MrOS sleep study. Sleep. 2011 Oct;34(10):1347–56. 10.5665/SLEEP.1276, PMID: 21966066; PMCID: PMC3174836.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Wang C, Holtzman DM. Bidirectional relationship between sleep and Alzheimer’s disease: role of amyloid, tau, and other factors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020 Jan;45(1):104–20. 10.1038/s41386-019-0478-5, Epub 2019 Aug 13. PMID: 31408876; PMCID: PMC6879647.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Spira AP, Gamaldo AA, An Y, Wu MN, Simonsick EM, Bilgel M, et al. Self-reported sleep and β-amyloid deposition in community-dwelling older adults. JAMA Neurol. 2013 Dec;70(12):1537–43. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4258, PMID: 24145859; PMCID: PMC3918480.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Walker MP. The role of slow wave sleep in memory processing. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009 Apr;5(2 Suppl):S20–6, PMID: 19998871; PMCID: PMC2824214.10.5664/jcsm.5.2S.S20Search in Google Scholar

[14] Léger D, Debellemaniere E, Rabat A, Bayon V, Benchenane K, Chennaoui M. Slow-wave sleep: from the cell to the clinic. Sleep Med Rev. 2018 Oct;41:113–32. 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.01.008, Epub 2018 Feb 5. PMID: 29490885.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Ourry V, Rehel S, André C, Mary A, Paly L, Delarue M, et al. Effect of cognitive reserve on the association between slow wave sleep and cognition in community-dwelling older adults. Aging. 2023 Sep;15(18):9275–92. 10.18632/aging.204943, Epub 2023 Sep 28 PMID: 37770186; PMCID: PMC10564409.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Zhang Y, Gruber R. Can slow-wave sleep enhancement improve memory? A review of current approaches and cognitive outcomes. Yale J Biol Med. 2019 Mar;92(1):63–80, PMID: 30923474; PMCID: PMC6430170.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Westerberg CE, Mander BA, Florczak SM, Weintraub S, Mesulam MM, Zee PC, et al. Concurrent impairments in sleep and memory in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2012 May;18(3):490–500. 10.1017/S135561771200001X, Epub 2012 Feb 3 PMID: 22300710; PMCID: PMC3468412.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Gorgoni M, Lauri G, Truglia I, Cordone S, Sarasso S, Scarpelli S, et al. Parietal fast sleep spindle density decrease in Alzheimer’s disease and amnesic mild cognitive impairment. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:8376108. 10.1155/2016/8376108, Epub 2016 Mar 15 PMID: 27066274; PMCID: PMC4811201.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Reda F, Gorgoni M, Lauri G, Truglia I, Cordone S, Scarpelli S, et al. In search of sleep biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: k-complexes do not discriminate between patients with mild cognitive impairment and healthy controls. Brain Sci. 2017 Apr;7(5):51. 10.3390/brainsci7050051, PMID: 28468235; PMCID: PMC5447933.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Brunetti V, D’Atri A, Della Marca G, Vollono C, Marra C, Vita MG, et al. Subclinical epileptiform activity during sleep in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Clin Neurophysiol. 2020 May;131(5):1011–8. 10.1016/j.clinph.2020.02.015, Epub 2020 Mar 5. PMID: 32193162.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Kim SJ, Lee JH, Lee DY, Jhoo JH, Woo JI. Neurocognitive dysfunction associated with sleep quality and sleep apnea in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011 Apr;19(4):374–81. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181e9b976, PMID: 20808148.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Hita-Yañez E, Atienza M, Gil-Neciga E, Cantero JL. Disturbed sleep patterns in elders with mild cognitive impairment: the role of memory decline and ApoE ε4 genotype. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012 Mar;9(3):290–7. 10.2174/156720512800107609, PMID: 22211488.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Maestri M, Carnicelli L, Tognoni G, Di Coscio E, Giorgi FS, Volpi L, et al. Non-rapid eye movement sleep instability in mild cognitive impairment: a pilot study. Sleep Med. 2015 Sep;16(9):1139–45. 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.04.027, Epub 2015 Jun 25. PMID: 26298791.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Brayet P, Petit D, Frauscher B, Gagnon JF, Gosselin N, Gagnon K, et al. Quantitative EEG of rapid-eye-movement sleep: a marker of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2016 Apr;47(2):134–41. 10.1177/1550059415603050, Epub 2015 Aug 30. PMID: 26323578.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Liguori C, Nuccetelli M, Izzi F, Sancesario G, Romigi A, Martorana A, et al. Rapid eye movement sleep disruption and sleep fragmentation are associated with increased orexin-A cerebrospinal-fluid levels in mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;40:120–6. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.01.007. Epub 2016 Jan 21. PMID: 26973111.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Liguori C, Placidi F, Izzi F, Spanetta M, Mercuri NB, Di Pucchio A, et al. Sleep dysregulation, memory impairment, and CSF biomarkers during different levels of neurocognitive functioning in Alzheimer’s disease course. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020 May 8;12(1):53. 10.1186/s13195-020-00624-3, PMID: 31901236; PMCID: PMC6942389.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] D’Rozario AL, Chapman JL, Phillips CL, Palmer JR, Hoyos CM, Mowszowski L, et al. Objective measurement of sleep in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2020 Aug;52:101308. 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101308, Epub 2020 Mar 13. PMID: 32302775.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Cai S, Li T, Zhang L, Shi L, Liao J, Li W, et al. Characteristics of sleep structure assessed by objective measurements in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2020 Nov;11:577126. 10.3389/fneur.2020.577126, PMID: 33281712; PMCID: PMC7689212.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Sanchez-Espinosa MP, Atienza M, Cantero JL. Sleep deficits in mild cognitive impairment are related to increased levels of plasma amyloid-β and cortical thinning. Neuroimage. 2014 Sep;98:395–404. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.05.027, Epub 2014 May 16. PMID: 24845621.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Varga AW, Wohlleber ME, Giménez S, Romero S, Alonso JF, Ducca EL, et al. Reduced slow-wave sleep is associated with high cerebrospinal fluid aβ42 levels in cognitively normal elderly. Sleep. 2016 Nov;39(11):2041–8. 10.5665/sleep.6240, PMID: 27568802; PMCID: PMC5070758.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Pais MV, Forlenza OV, Diniz BS. Plasma biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: a review of available assays, recent developments, and implications for clinical practice. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2023 May;7(1):355–80. 10.3233/ADR-230029, PMID: 37220625; PMCID: PMC10200198.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Kalligerou F, Ntanasi E, Voskou P, Velonakis G, Karavasilis E, Mamalaki E, et al. Aiginition longitudinal biomarker investigation of neurodegeneration (albion): study design, cohort description, and preliminary data. Postgrad Med. 2019Sep;131(7):501–8. 10.1080/00325481.2019.1663708, Epub 2019 Sep 16. PMID: 31483196.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] de Mendonça FMR, de Mendonça GPRR, Souza LC, Galvão LP, Paiva HS, de Azevedo Marques Périco C, et al. Benzodiazepines and sleep architecture: a systematic review. CNS Neurol Disord:Drug Targets. 2023;22(2):172–9. 10.2174/1871527320666210618103344, PMID: 34145997.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–98. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6, PMID: 1202204.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Mioshi E, Dawson K, Mitchell J, Arnold R, Hodges JR. The Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination revised (ACE-R): a brief cognitive test battery for dementia screening. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006 Nov;21(11):1078–85. 10.1002/gps.1610, PMID: 16977673.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rabins PV, et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2001 Dec;58(12):1985–92. 10.1001/archneur.58.12.1985, PMID: 11735772.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Teunissen CE, Tumani H, Engelborghs S, Mollenhauer B. Biobanking of CSF: international standardization to optimize biomarker development. Clin Biochem. 2014 Mar;47(4-5):288–92. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.12.024, Epub 2014 Jan 2. PMID: 24389077.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Roche Diagnostics. Elecsys® β-Amyloid (1-42) CSF II -–Method Sheet. Version 08821941500V2.0. 2023. Available from: https://elabdoc-prod.roche.com/eLD/web/global/en/documents/download/7a9a7998-938e-ee11-2191-005056a772fd. pp. 6.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Herscovici S, Pe’er A, Papyan S, Lavie P. Detecting REM sleep from the finger: an automatic REM sleep algorithm based on peripheral arterial tone (PAT) and actigraphy. Physiol Meas. 2007 Feb;28(2):129–40. 10.1088/0967-3334/28/2/002, Epub 2006 Dec 12. PMID: 17237585.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Bresler M, Sheffy K, Pillar G, Preiszler M, Herscovici S. Differentiating between light and deep sleep stages using an ambulatory device based on peripheral arterial tonometry. Physiol Meas. 2008 May;29(5):571–84. 10.1088/0967-3334/29/5/004, Epub 2008 May 7. PMID: 18460762.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Hedner J, Pillar G, Pittman SD, Zou D, Grote L, White DP. A novel adaptive wrist actigraphy algorithm for sleep-wake assessment in sleep apnea patients. Sleep. 2004 Dec;27(8):1560–6. 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1560, PMID: 15683148.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Hedner J, White DP, Malhotra A, Herscovici S, Pittman SD, Zou D, et al. Sleep staging based on autonomic signals: a multi-center validation study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011 Jun;7(3):301–6. 10.5664/JCSM.1078, PMID: 21677901; PMCID: PMC3113970.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull. 1968 Oct;70(4):213–20. 10.1037/h0026256, PMID: 19673146.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Himali JJ, Baril AA, Cavuoto MG, Yiallourou S, Wiedner CD, Himali D, et al. Association between slow-wave sleep loss and incident dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2023 Dec;80(12):1326–33. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.3889, PMID: 37902739; PMCID: PMC10616771.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Ibrahim A, Cesari M, Heidbreder A, Defrancesco M, Brandauer E, Seppi K, et al. Sleep features and long-term incident neurodegeneration: a polysomnographic study. Sleep. 2024 Mar;47(3):zsad304. 10.1093/sleep/zsad304, PMID: 38001022; PMCID: PMC10925953.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Mittermaier FX, Kalbhenn T, Xu R, Onken J, Faust K, Sauvigny T, et al. Membrane potential states gate synaptic consolidation in human neocortical tissue. Nat Commun. 2024 Dec 12;15(1). 10.1038/s41467-024-53901-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Therriault J, Janelidze S, Benedet AL, Ashton NJ, Arranz Martínez J, Gonzalez-Escalante A, et al. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease using plasma biomarkers adjusted to clinical probability. Nat Aging. 2024 Nov;4(11):1529–37. 10.1038/s43587-024-00731-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Park DC. Beta-amyloid deposition and the aging brain. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009 Dec;19(4):436–50. 10.1007/s11065-009-9118-x, Epub 2009 Nov 12 PMID: 19908146; PMCID: PMC2844114.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Doecke JD, Ward L, Burnham SC, Villemagne VL, Li QX, Collins S, et al. Elecsys CSF biomarker immunoassays demonstrate concordance with amyloid-PET imaging. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020 Mar;12(1):36. 10.1186/s13195-020-00595-5, PMID: 32234072; PMCID: PMC7110644.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome with elevated IgG4 and T-cell clonality: A report of two cases

- Electroacupuncture alleviates sciatic nerve injury in sciatica rats by regulating BDNF and NGF levels, myelin sheath degradation, and autophagy

- Polydatin prevents cholesterol gallstone formation by regulating cholesterol metabolism via PPAR-γ signaling

- RNF144A and RNF144B: Important molecules for health

- Analysis of the detection rate and related factors of thyroid nodules in the healthy population

- Artesunate inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion through OGA-mediated O-GlcNAcylation of ZEB1

- Endovascular management of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: Case report and review of the literature

- Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis

- SATB2 promotes humeral fracture healing in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Overexpression of the ferroptosis-related gene, NFS1, corresponds to gastric cancer growth and tumor immune infiltration

- Understanding risk factors and prognosis in diabetic foot ulcers

- Atractylenolide I alleviates the experimental allergic response in mice by suppressing TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 signalling

- FBXO31 inhibits the stemness characteristics of CD147 (+) melanoma stem cells

- Immune molecule diagnostics in colorectal cancer: CCL2 and CXCL11

- Inhibiting CXCR6 promotes senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells with limited proinflammatory SASP to attenuate hepatic fibrosis

- Cadmium toxicity, health risk and its remediation using low-cost biochar adsorbents

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis with headache as the first presentation: A case report

- Solitary pulmonary metastasis with cystic airspaces in colon cancer: A rare case report

- RUNX1 promotes denervation-induced muscle atrophy by activating the JUNB/NF-κB pathway and driving M1 macrophage polarization

- Morphometric analysis and immunobiological investigation of Indigofera oblongifolia on the infected lung with Plasmodium chabaudi

- The NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex and Hr78 modulate the Lobe2 mutant eye phenotype

- Experimental study on salmon demineralized bone matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: In vitro and in vivo study

- A case of IgA nephropathy treated with a combination of telitacicept and half-dose glucocorticoids

- Analgesic and toxicological evaluation of cannabidiol-rich Moroccan Cannabis sativa L. (Khardala variety) extract: Evidence from an in vivo and in silico study

- Wound healing and signaling pathways

- Combination of immunotherapy and whole-brain radiotherapy on prognosis of patients with multiple brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study

- To explore the relationship between endometrial hyperemia and polycystic ovary syndrome

- Research progress on the impact of curcumin on immune responses in breast cancer

- Biogenic Cu/Ni nanotherapeutics from Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl seeds for the treatment of lung cancer

- Dapagliflozin attenuates atrial fibrosis via the HMGB1/RAGE pathway in atrial fibrillation rats

- Glycitein alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in keratinocytes via ROS-associated PI3K–Akt signalling pathway

- ADH5 inhibits proliferation but promotes EMT in non-small cell lung cancer cell through activating Smad2/Smad3

- Apoptotic efficacies of AgNPs formulated by Syzygium aromaticum leaf extract on 32D-FLT3-ITD human leukemia cell line with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Novel cuproptosis-related genes C1QBP and PFKP identified as prognostic and therapeutic targets in lung adenocarcinoma

- Bee venom promotes exosome secretion and alters miRNA cargo in T cells

- Treatment of pure red cell aplasia in a chronic kidney disease patient with roxadustat: A case report

- Comparative bioinformatics analysis of the Wnt pathway in breast cancer: Selection of novel biomarker panels associated with ER status

- Kynurenine facilitates renal cell carcinoma progression by suppressing M2 macrophage pyroptosis through inhibition of CASP1 cleavage

- RFX5 promotes the growth, motility, and inhibits apoptosis of gastric adenocarcinoma cells through the SIRT1/AMPK axis

- ALKBH5 exacerbates early cardiac damage after radiotherapy for breast cancer via m6A demethylation of TLR4

- Phytochemicals of Roman chamomile: Antioxidant, anti-aging, and whitening activities of distillation residues

- Circadian gene Cry1 inhibits the tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma by the BAX/BCL2-mediated apoptosis pathway

- The TNFR-RIPK1/RIPK3 signalling pathway mediates the effect of lanthanum on necroptosis of nerve cells

- Longitudinal monitoring of autoantibody dynamics in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing surgery

- The potential role of rutin, a flavonoid, in the management of cancer through modulation of cell signaling pathways

- Construction of pectinase gene engineering microbe and its application in tobacco sheets

- Construction of a microbial abundance prognostic scoring model based on intratumoral microbial data for predicting the prognosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Sepsis complicated by haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis triggered by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and human herpesvirus 8 in an immunocompromised elderly patient: A case report

- Sarcopenia in liver transplantation: A comprehensive bibliometric study of current research trends and future directions

- Advances in cancer immunotherapy and future directions in personalized medicine

- Can coronavirus disease 2019 affect male fertility or cause spontaneous abortion? A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis

- Heat stroke associated with novel leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor gene variant in a Chinese infant

- PSME2 exacerbates ulcerative colitis by disrupting intestinal barrier function and promoting autophagy-dependent inflammation

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state with severe hypernatremia coexisting with central diabetes insipidus: A case report and literature review

- Efficacy and mechanism of escin in improving the tissue microenvironment of blood vessel walls via anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects: Implications for clinical practice

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Clinicopathological analysis of three patients and literature review

- Genetic variants in VWF exon 26 and their implications for type 1 Von Willebrand disease in a Saudi Arabian population

- Lipoxin A4 improves myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through the Notch1-Nrf2 signaling pathway

- High levels of EPHB2 expression predict a poor prognosis and promote tumor progression in endometrial cancer

- Knockdown of SHP-2 delays renal tubular epithelial cell injury in diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis

- Exploring the toxicity mechanisms and detoxification methods of Rhizoma Paridis

- Concomitant gastric carcinoma and primary hepatic angiosarcoma in a patient: A case report

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Optimization and comparative study of Bacillus consortia for cellulolytic potential and cellulase enzyme activity

- The complete mitochondrial genome analysis of Haemaphysalis hystricis Supino, 1897 (Ixodida: Ixodidae) and its phylogenetic implications

- Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors analysis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among tuberculosis population in Huzhou City, Eastern China

- Indices of human impacts on landscapes: How do they reflect the proportions of natural habitats?

- Genetic analysis of the Siberian flying squirrel population in the northern Changbai Mountains, Northeast China: Insights into population status and conservation

- Diversity and environmental drivers of Suillus communities in Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica forests of Inner Mongolia

- Global assessment of the fate of nitrogen deposition in forest ecosystems: Insights from 15N tracer studies

- Fungal and bacterial pathogenic co-infections mainly lead to the assembly of microbial community in tobacco stems

- Influencing of coal industry related airborne particulate matter on ocular surface tear film injury and inflammatory factor expression in Sprague-Dawley rats

- Temperature-dependent development, predation, and life table of Sphaerophoria macrogaster (Thomson) (Diptera: Syrphidae) feeding on Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae)

- Eleonora’s falcon trophic interactions with insects within its breeding range: A systematic review

- Agriculture

- Integrated analysis of transcriptome, sRNAome, and degradome involved in the drought-response of maize Zhengdan958

- Variation in flower frost tolerance among seven apple cultivars and transcriptome response patterns in two contrastingly frost-tolerant selected cultivars

- Heritability of durable resistance to stripe rust in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Molecular mechanism of follicular development in laying hens based on the regulation of water metabolism

- Animal Science

- Effect of sex ratio on the life history traits of an important invasive species, Spodoptera frugiperda

- Plant Sciences

- Hairpin in a haystack: In silico identification and characterization of plant-conserved microRNA in Rafflesiaceae

- Widely targeted metabolomics of different tissues in Rubus corchorifolius

- The complete chloroplast genome of Gerbera piloselloides (L.) Cass., 1820 (Carduoideae, Asteraceae) and its phylogenetic analysis

- Field trial to correlate mineral solubilization activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and biochemical content of groundnut plants

- Correlation analysis between semen routine parameters and sperm DNA fragmentation index in patients with semen non-liquefaction: A retrospective study

- Plasticity of the anatomical traits of Rhododendron L. (Ericaceae) leaves and its implications in adaptation to the plateau environment

- Effects of Piriformospora indica and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on growth and physiology of Moringa oleifera under low-temperature stress

- Effects of different sources of potassium fertiliser on yield, fruit quality and nutrient absorption in “Harward” kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa)

- Comparative efficiency and residue levels of spraying programs against powdery mildew in grape varieties

- The DREB7 transcription factor enhances salt tolerance in soybean plants under salt stress

- Using plant electrical signals of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) for water pollution monitoring

- Food Science

- Phytochemical analysis of Stachys iva: Discovering the optimal extract conditions and its bioactive compounds

- Review on role of honey in disease prevention and treatment through modulation of biological activities

- Computational analysis of polymorphic residues in maltose and maltotriose transporters of a wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain

- Optimization of phenolic compound extraction from Tunisian squash by-products: A sustainable approach for antioxidant and antibacterial applications

- Liupao tea aqueous extract alleviates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in rats by modulating the gut microbiota

- Toxicological qualities and detoxification trends of fruit by-products for valorization: A review

- Polyphenolic spectrum of cornelian cherry fruits and their health-promoting effect

- Optimizing the encapsulation of the refined extract of squash peels for functional food applications: A sustainable approach to reduce food waste

- Advancements in curcuminoid formulations: An update on bioavailability enhancement strategies curcuminoid bioavailability and formulations

- Impact of saline sprouting on antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds in chia seeds

- The dilemma of food genetics and improvement

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Impact of hyaluronic acid-modified hafnium metalorganic frameworks containing rhynchophylline on Alzheimer’s disease

- Emerging patterns in nanoparticle-based therapeutic approaches for rheumatoid arthritis: A comprehensive bibliometric and visual analysis spanning two decades

- Application of CRISPR/Cas gene editing for infectious disease control in poultry

- Preparation of hafnium nitride-coated titanium implants by magnetron sputtering technology and evaluation of their antibacterial properties and biocompatibility

- Preparation and characterization of lemongrass oil nanoemulsion: Antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant, and anticancer activities

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells”

- Corrigendum to “Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans”

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Down-regulation of miR-539 indicates poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer”

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins