Abstract

The present study aimed to evaluate the therapeutic potential of Indigofera oblongifolia with silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and chloroquine (CQ) 10 mg/kg in treating lung inflammation caused by Plasmodium chabaudi infection in a mouse model. Fifty female C57BL/6 mice were divided into five groups: control, Indigofera oblongifolia leaf extract (IOLE) AgNPs treated, P. chabaudi infected, infected and IOLE AgNPs treated, infected and CQ 10 mg/kg treated. Lung histopathology was assessed using microscopic analysis and immunohistochemistry investigation for TNF-α and IL-6. The results showed that the positive control of AgNPs slightly triggered proinflammatory cytokines and created an oxidative stress status in lung tissue. The group IOLE AgNPs treatment significantly restored the normal organization of the control lung tissue. It reduced alveolar and septal congestion, edema, and necrosis compared to the infected lung. Therefore I. oblongifolia as a natural medical plant displayed significant antimalarial and anti-oxidant properties effectively, reducing inflammatory signs and cytokine levels in P. chabaudi-infected lungs and treating the harmful impact of AgNPs in P. chabaudi-infected + I. oblongifolia with AgNPs lung. While CQ shows limited efficiency, it showed moderate improvement in the histological architecture such as thicker alveolar and bronchiolar walls and restricted expansion. However, the septal and alveolar congestion, hemosiderin concentration, edema, and necrotic cells were still present. Also, immunohistochemistry expression of proinflammatory cytokines is still expressed. In conclusion, this study highlights the therapeutic potential of I. oblongifolia for malaria management. Also, this study uniquely explored the combined influences of I. oblongifolia leaf extract and AgNPs on lung inflammation caused by P. chabaudi infection. Previous studies may have explored these components separately, but the current study examines their synergistic potential in treating malaria-related lung pathology. Consequently, the study compared the efficacy of I. oblongifolia with that of CQ, revealing that the latter exhibited limited efficiency due to drug resistance and its inability to restore the normal features of its histology. This comparison highlights the potential impact of I. oblongifolia as a more effective alternative in malaria treatment, particularly in cases where conventional drugs fail.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Malaria, caused by parasites of the genus Plasmodium, remains a global health concern, with Plasmodium chabaudi serving as a model for studying the pathogenesis of this disease in mice [1]. This parasite is known to sequester predominantly in the liver and lungs, leading to organ-specific pathology in these organs [2]. The lung is a vital organ in pulmonary circulation, essential for gas exchange and converting deoxygenated blood into oxygenated blood [3]. The lung experiences notable histopathological changes during infection, including increased infiltration of immune cells and cellularity of the alveolar septae [4]. Malaria is widely recognized as the most common epidemic disease globally [5].

Despite the well-documented pathogenesis of malaria-induced lung pathology, there is growing interest in exploring novel therapeutic approaches to mitigate these effects [6]. Recent studies have focused on exploring novel therapeutic approaches to combat malaria and its associated complications [7]. Medical plants have been integral to human history and have diverse therapeutic properties in treating serious diseases [8]. Compounds produced from plants have become viable options for treating malaria, and Indigofera oblongifolia is a promising example of this [9]. I. oblongifolia is a plant that belongs to the Fabaceae family [10]. One such approach involves the use of plant-derived compounds, specifically Indigofera oblongifolia leaf extract (IOLE) silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). These nanoparticles have shown promise in mitigating the effects of P. chabaudi infection in the kidneys [11].

Cytokines are essential in the immunological response to malaria infection [12]. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [13] are important in the pathogenesis of malaria-induced lung pathology [14]. Elevated levels of these cytokines are associated with increased disease severity and mortality in P. chabaudi infections [13]. The modulation of TNF-α and IL-6 by potential therapeutic agents is of significant interest in developing effective treatments for malaria-associated complications.

This study aims to provide a morphometric analysis and immunobiological investigation of the effects of I. oblongifolia leaf extract with AgNPs on lung tissue infected with P. chabaudi. We aim to understand the structural changes in lung tissue following the administration of IOLE AgNPs and investigate how these changes could aid in the fight against malaria through the use of immunobiological techniques and standard histological methods.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 In vivo in the mice and parasites

Fifty female C57BL/6 mice, weighing 22 ± 3 g and 9 ± 2 weeks old, were supplied by the King Faisal Hospital Research Unit in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. We acquired the P. chabaudi strain from the parasitology laboratory at King Saud University’s College of Science. We then transferred P. chabaudi cryopreserved parasites into uninfected mice. A 100 μL PBS solution containing 105 parasitized erythrocytes was delivered intraperitoneally (i.p.) to the mouse.

Five distinct categories were assigned to the animals. Ten mice were included in each of the groups. The first control group that was not infected received PBS by oral administration for 7 days. IOLE AgNPs were given orally to the second group at a dose of 50 mg/kg daily for 7 days. Fifty female C57BL/6 mice, weighing 22 ± 3 g and 9 ± 2 weeks old, were supplied by the King Faisal Hospital Research Unit in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. One hour later, the fourth group got 50 mg/kg of IOLE AgNPs orally for 7 days, while the fifth group received 10 mg/kg chloroquine (CQ) phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) orally for 4 days.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animal use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals, and has been approved by the Ethics Committee of King Saud University (approval number: KSU-SE-21-86).

2.2 Biosynthesized AgNPs

In the literature, a procedure for making the extract is described. Following the methodology described in a previous study, the preparation of AgNPs was carried out.

3 Immunobiological assessment

3.1 Tissue collection and processing

On the seventh day following infection, all mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and then dissected to collect lung tissues. The lung was dissected and sectioned for pathological examination. The tiny fragments were immersed in a solution of neutral buffered formalin (10%) for histological analysis. On Day 8 post-infection, mice were euthanized by CO2, and lungs were harvested. The lung was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histological analysis.

3.2 Lung immunohistopathology

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using antibodies against TNF-α and IL-6. The stained sections were analyzed using image analysis software ImageJ (Version 1.54k) according to the protocols in the literature to quantify TNF-α and IL-6 levels in lung tissue.

3.3 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5. We used a one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. p-Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4 Results

In the current investigation, the pharmacological activity of IOLE AgNPs was studied as a potential therapy for inflammation of the lungs caused by P. chabaudi, which is a parasite that causes malaria sickness. The study investigated the morphometric measurements in addition to the histopathological characteristics of five groups: the control lung, the lung that had been treated with IOLE AgNPs, the lung that had been infected with P. chabaudi, the lung that had been treated with IOLE AgNPs after inflammation with P. chabaudi, and finally, the lung that had been treated with CQ 10 mg/kg after inflammation with P. chabaudi. Positive control of IOLE AgNPs and the lung treated with it showed a considerable improvement in the histoarchitecture of lung tissue, as demonstrated by the current experiment.

4.1 Microscopic examination

The microscopic analysis of five experimental groups revealed that the impact of IOLE AgNPs on lung tissue expressed a significant (p < 0.05) expansion of both bronchiolar (701.70 ± 5.08 µm) and alveolar (214.62 ± 1.33 µm) walls compared to the control ducts. However, the thickness of their walls was reduced (15.78 ± 0.50 µm) and (7.81 ± 0.58 µm), respectively, in a significant way (p < 0.05). Additionally, the diameter of interstitial tissue (219.06 ± 1.63 µm), the intensity of septal (2.78 ± 0.13%), and alveolar (1.64 ± 0.08%) congestion and edema (2.84 ± 0.44%) elevated non-significantly (p > 0.05) compared to those in the normal lung. However, the hemosiderin (4.00 ± 0.10%) and necrosis (1.92 ± 0.02%) intensity increased significantly (p < 0.05). Alternatively, the infected lung with P. chabaudi displayed significant (p < 0.001) restriction in the cavity of pulmonary ducts such as alveolar (58.83 ± 1.37 µm) and bronchiolar (105.69 ± 3.78 µm) ducts comparatively less than the control ducts, and also significant (p < 0.001) thickness in alveolar wall (31.32 ± 0.72 µm) and non-significant (p > 0.05) increase in the thickness of bronchiolar wall (21.26 ± 0.94 µm) in comparison to the control thickness. The P. chabaudi eads to lung severance of increasing intensity (p < 0.001) of pathological inflammatory signs such as septal congestion (35.66 ± 1.39%), alveolar congestion (69.42 ± 2.72%), edema (42.53 ± 1.70%), hemosiderin intensity (20.57 ± 0.6%), and necrosis intensity (14.84 ± 0.6%) more than the normal ranges of these signs in control lung. Therefore, the interstitial tissue expressed an increase in the diameter higher than the normal ones (147.84 ± 3.44 µm) as shown in Table 1.

Morphometric analysis of histopathological parameters of lung tissue: (a) alveolar expansion, (b) alveolar wall thickness, (c) bronchiolar dimensions, (d) bronchiolar wall thickness, (e) hemosiderin intensity, (f) diameter of the interstitium, (g) alveolar congestion, (h) septal congestion, (i) intensity of necrosis, and (j) edema

| Layers | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Alveolar expansion (µm) | Alveolar wall thickness (µm) | Bronchiolar wall thickness (µm) | Bronchiolar dimensions (µm) | Interstitial diameter (µm) | Septal congestion (%) | Alveolar congestion (%) | Edema (%) | Hemosiderin (%) | Necrosis intensity (%) |

| Control | 200.47 ± 2.54 | 10.82 ± 0.46 | 19.60 ± 0.27 | 581.68 ± 6.22 | 128.40 ± 2.65 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 1.28 ± 0.15 | 0.48 ± 0.04 |

| IOLEAgNPs | 214.62 ± 1.33* | 7.81 ± 0.58 | 15.78 ± 0.50* | 701.70 ± 5.08*** | 219.06 ± 1.63** | 2.78 ± 0.13 | 1.64 ± 0.08 | 2.84 ± 0.44 | 4.00 ± 0.10* | 1.92 ± 0.02* |

| Infected | 58.83 ± 1.37 | 31.32 ± 0.72*** | 21.26 ± 0.94** | 105.69 ± 3.78 | 305.69 ± 3.78*** | 35.66 ± 1.39*** | 69.42 ± 2.72** | 42.53 ± 1.70*** | 20.57 ± 0.6*** | 14.84 ± 0.6*** |

| Infected + IOLEAgNPs | 202.91 ± 2.69** | 18.64 ± 0.85** | 16.84 ± 0.75* | 499.69 ± 8.58** | 147.84 ± 3.44* | 7.84 ± 0.73* | 1.84 ± 0.12 | 9.09 ± 0.24* | 4.13 ± 0.12* | 1.97 ± 0.14* |

| Infected + CQ10 | 182.47 ± 0.87* | 22.40 ± 0.28*** | 20.69 ± 1.22** | 396.62 ± 4.44* | 236.48 ± 2.08*** | 17.66 ± 0.62** | 18.93 ± 0.4* | 25.30 ± 1.77** | 6.74 ± 0.30** | 4.48 ± 0.15** |

Among five groups: the control, I. oblongifolia with silver nanoparticles (IOLE AgNPs) group, the group infected by P. chabaudi, the group infected by P. chabaudi and 50 mg/kg of IOLE AgNPs, and the group administrated with P. chabaudi and CQ10. Values are represented as mean ± STD & n = 10 animals. Mean values within the same parameter and not sharing a common superscript symbol(s) differ significantly at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and values that are recorded with the non-significance difference (n.s.) and p-value was calculated according to comparison with the control group.

After treatment with 50 mg/kg of IOLE AgNPs after inflammation with P. chabaudi, the pulmonary ducts displayed a significant recovery compared to the normal dimensions and thickness, and recorded a non-significant (p > 0.05) diameter in alveolar (202.91 ± 2.69 µm) and bronchiolar (499.69 ± 8.58 µm) ducts compared to the control. All pathological inflammatory signs exhibited a significant (p < 0.05) reduction in their intensity in this group. However, the CQ 10 mg/kg therapy after inflammation with P. chabaudi revealed a slow recovery compared to the normal histological architecture, while the alveolar (182.47 ± 0.87 µm) and bronchiolar (396.62 ± 4.44 µm) ducts still had a restricted cavity less than the control diameter. Also, the alveolar wall (22.40 ± 0.28 µm) significantly thickened (p < 0.05) and the bronchiolar wall showed non-significant (p > 0.05) thickness (20.69 ± 1.22 µm). Furthermore, all the pathological inflammatory signs such as septal congestion (17.66 ± 0.62%), alveolar congestion (18.93 ± 0.4%), edema (25.30 ± 1.77%), hemosiderin intensity (6.74 ± 0.30%), and necrosis intensity (4.48 ± 0.15%) still elevated in comparison to normal ranges of these signs in the control lung as shown in Table 1.

5 Immunohistochemistry investigation

5.1 TNF-α assay

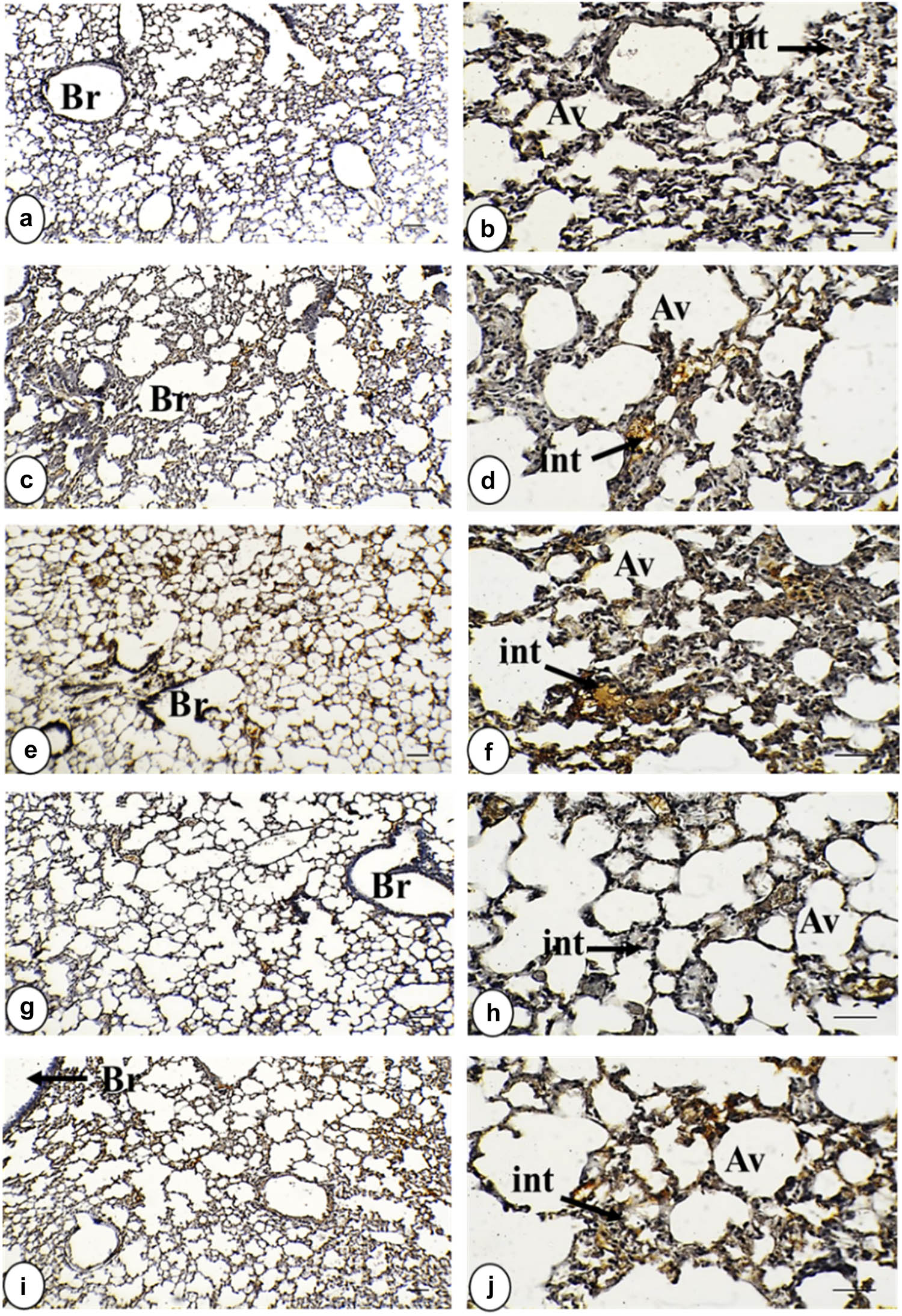

The immunohistochemical sections did not reveal the reactivity of the anti-TNF-α antibody immunostaining in the control lung. Administration of IOLE AgNPs showed a few positive yellowish spots dispersed over the interstitial areas with a significant (p < 0.05) intensity (3.05 ± 0.18%) and around the alveolar wall (1.65 ± 0.18%). However, Plasmodium infection caused intensive (p < 0.01) immunostaining around the bronchiolar (5.78 ± 0.54%) and alveolar wall (2.50 ± 0.24%) and interstitial area (13.35 ± 0.43%) compared to the control intensities. The lung treated with IOLE AgNPs still displayed a significant (p < 0.01) positive interaction with TNF-α immunostaining in the interstitial area (4.56 ± 0.34%), while both bronchiolar (1.80 ± 0.09%) and alveolar (0.67 ± 0.08%) walls exhibited non-significant (p > 0.05) intensities compared to the control tissue. However, yellow patches were still significantly observed (p < 0.05) around the infected + CQ10 bronchiolar wall (4.04 ± 0.23%) and the alveolar wall (1.60 ± 0.23%), but the interstitial tissue displayed higher significant intensity (p < 0.001) in this group (10.18 ± 0.38%) (Figures 1a–j and 3a and Table 2).

Photomicrograph of TNF-α-stained lung tissue in all study groups. (a) and (b) Control group displayed a negative expression of TNF-α within the interstitial tissue, bronchiolar wall, and alveolar wall. (c) and (d) Group of IOLE AgNPs exhibited mild positive expression of TNF-α within the interstitial tissue in the form of yellowish spots. (e) and (f) Infected group shows a strong positive expression of TNF-α in the form of brownish patches in the interstitial tissue, bronchiolar wall, and alveolar wall. (g) and (h) Group infected + 50 mg/kg IOLE AgNPs expressed low positive staining of TNF-α within the interstitial tissue in the form of yellowish spots. (i) and (j) Group with CQ 10 mg/kg presented mild positive expression of TNF-α, within the interstitial tissue and alveolar wall in the form of yellowish patches (TNF-α ×, a, c, e, g, and i = 100 µm and b, d, f, h, and j = 400 µm). TNF-α expression is indicated by black arrows. Stained by DAB-chromogen (brown color) immunostaining.

TNF expression immunohistochemistry in lung tissue stained by DAB-chromogen within a bronchiolar wall, alveolar wall, and interstitial tissue among the five groups

| Groups | Layers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchiolar wall | Alveolar wall | Interstitial tissue | |

| Control | 0.76 ± 0.09 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 1.08 ± 0.07 |

| IOLE AgNPs | 1.78 ± 0.06* | 1.65 ± 0.18* | 3.05 ± 0.18* |

| Infected | 5.78 ± 0.541** | 2.50 ± 0.242** | 13.35 ± 0.43** |

| Infected + IOLE AgNPs | 1.80 ± 0.09 | 0.67 ± 0.08 | 4.56 ± 0.34** |

| Infected + CQ10 | 4.04 ± 0.23* | 1.60 ± 0.23* | 10.18 ± 0.38** |

Control, IOLE AgNPs group, group infected by P. chabaudi, group infected by P. chabaudi and 50 mg/kg of IOLE AgNPs, and the group administrated with P. chabaudi and CQ 10 mg/kg. Values are represented as mean ± STD & n = 10 animals. Mean values within the same parameter and not sharing a common superscript symbol(s) differ significantly at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and values that are recorded with a non-significance difference (n.s.) and p-value was calculated according to comparison with the control group.

5.2 IL-6 assay

The anti-IL-6 antibody immunostaining did not react with any antigen in the control lung. Sections taken from the IOLE AgNPs treated group showed slight upregulation in the anti-IL-6 antibodies (p > 0.05) within the bronchiolar wall (2.75 ± 0.20%) in the form of brownish spots and non-significant expression (p > 0.05) in alveolar wall (1.33 ± 0.09%) and interstitial tissue (4.65 ± 0.30%) compared to control sections. However, a strong positive staining of IL-6 was observed in the bronchiolar wall (6.70 ± 0.39%), alveolar wall (3.32 ± 0.22%), and interstitial tissue (14.44 ± 0.48%) of the plasmodium-infected sections in comparison with normal tissue. The treatment sections of the I. oblongifolia displayed low positive expression of IL-6 in the bronchiolar wall (1.88 ± 0.14%) and alveolar wall (1.40 ± 0.19%) in the form of brownish spots and non-significant expression (p > 0.05) with control sections in the interstitial tissue (4.89 ± 0.25%). On the contrary, the group with infected + CQ 10 mg/kg showed positive staining (p < 0.01) of IL-6 in the bronchiolar wall (4.13 ± 0.15%), and moderate expression (p < 0.05) in the alveolar wall (2.07 ± 0.11%) and the interstitial tissue (6.74 ± 0.52%) in the form of yellowish patches. Our findings of a semi-quantitative analysis of immunostaining for TNF-α and IL-6 proinflammatory cytokines are illustrated in Figures 2a–j and 3b and Table 3.

Photomicrograph of IL-6-stained lung tissue in all study groups. (a) and (b) Control group exhibited a negative expression of IL-6 within the interstitial tissue bronchiolar wall and alveolar wall. (c) and (d) Group of IOLE AgNPs shows a moderate positive expression of IL-6 within the interstitial tissue and alveolar wall as brownish spots. (e) and (f) Infected group displayed strong positive staining of IL-6 within the interstitial tissue, bronchiolar wall, and alveolar wall as brownish patches. (g) and (h) Group with infected + 50 mg/kg IOLE AgNPs presented mild positive expression of IL-6 within the interstitial tissue and alveolar wall as brownish spots. (i) and (j) Group with infected + CQ 10 mg/kg shows a higher positive expression of IL-6 within the interstitial tissue and alveolar wall as yellowish patches (IL-6 × a, c, e, g, and i = 100 µm and b, d, f, h, and j = 400 µm). IL-6 expression is indicated by black arrows. Stained by DAB-chromogen (brown color) immunostaining.

Bar graphs of immunohistochemistry showing (a), (c), (e) TNF expression and (b), (d), (f) IL-6 expression in lung tissue stained by DAB-chromogen (brown color) within a bronchiolar wall (a and b), alveolar wall (c) and (d), and interstitial tissue (e) and (f). Values are represented as mean ± STD & n = 10 animals. Mean values within the same parameter and not sharing a common superscript symbol(s) differ significantly at p < 0.05, and values that are recorded with non-significance difference (n.s.).

IL-6 expression immunohistochemistry in lung tissue stained by DAB-chromogen within a bronchiolar wall, alveolar wall, and interstitial tissue among the five groups

| Layers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Bronchiolar wall | Alveolar wall | Interstitial tissue |

| Control | 1.68 ± 0.10 | 0.84 ± 0.14 | 3.79 ± 0.26 |

| IOLE AgNPs | 2.75 ± 0.20* | 1.33 ± 0.09 | 4.65 ± 0.30 |

| Infected | 6.70 ± 0.39*** | 3.32 ± 0.22** | 14.44 ± 0.48** |

| Infected + IOLE AgNPs | 1.88 ± 0.14* | 1.40 ± 0.19* | 4.89 ± 0.25* |

| Infected + CQ10 | 4.13 ± 0.15** | 2.07 ± 0.11* | 6.74 ± 0.52* |

Control, IOLE AgNPs group, group infected by P. chabaudi, group infected by P. chabaudi and 50 mg/kg of IOLE AgNPs, and the group administrated with P. chabaudi and CQ 10 mg/kg. Values are represented as mean ± STD & n = 10 animals. Mean values within the same parameter and not sharing a common superscript symbol(s) differ significantly at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and values that are recorded with a non-significance difference (n.s.) and p-value was calculated according to comparison with the control group.

5.3 Correlation analysis

The heatmap of TNF-α and IL-6 expression immunohistochemistry in lung regions (bronchiolar wall, alveolar wall, and interstitial regions) indicated strong coordination in the inflammatory response whereas the findings revealed a strong correlation between TNF-α and IL-6 expressions in three different regions in lung tissues. For instance, TNF-α expression in the bronchiolar wall was positively correlated with alveolar wall expression (r = 0.733, p < 0.01) and interstitial expression (r = 0.924, p < 0.01) suggesting that the inflammatory response was coordinated all over the whole tissue and not in a single region. Similarly, IL-6 expression in the bronchiolar wall was strongly correlated with its expression in the alveolar wall (r = 0.855, p < 0.01) and interstitial expression (r = 0.926, p < 0.01), indicating similar coordination in the inflammatory response in the whole regions of the organ. For cross-cytokine relationships, the heatmap exhibited high inter-cytokines correlation among the investigated regions, example.g., the TNF-α expressions in the bronchiolar wall correlated strongly with the expression of IL-6 in the bronchiolar wall (r = 0.841, p < 0.01), alveolar wall (r = 0.879, p < 0.01), and interstitium (r = 0.869, p < 0.01), which indicates that the increase in the TNF-α expression was accompanied by the increase in IL-6 suggesting that there was coordination across the inflammatory response from the beginning of the inflammation to the beginning of the recovery (Table 4 and Figure 4).

Pearson correlation matrix of TNF-α and IL-6 expression immunohistochemistry in lung tissue stained by DAB-chromogen within a bronchiolar wall, alveolar wall, and interstitial tissue among five groups: control, IOLE AgNPs-infected, infected, infected + 50 mg/kg IOLE AgNPs, and CQ10-treated

| Correlated parameter | TNF in bronchiolar wall | TNF in alveolar wall | TNF in interstitial tissue | IL-6 in bronchiolar wall | IL-6 in alveolar wall | IL-6 in interstitial tissue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF in bronchiolar wall | 1 | 0.733** | 0.924** | 0.841** | 0.879** | 0.869** |

| TNF in alveolar wall | 0.733** | 1 | 0.717** | 0.831** | 0.650** | 0.722** |

| TNFin interstitial tissue | 0.924** | 0.717** | 1 | 0.898** | 0.870** | 0.868** |

| IL-6 in bronchiolar wall | 0.841** | 0.831** | 0.898** | 1 | 0.855** | 0.926** |

| IL-6 in alveolar wall | 0.879** | 0.650** | 0.870** | 0.855** | 1 | 0.889** |

| IL-6 in interstitial tissue | 0.869** | 0.722** | 0.868** | 0.926** | 0.889** | 1 |

The heatmap displays the strength and direction of correlations and statistical significance is denoted as p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**).

Triangle heatmap representing Pearson correlation coefficients between TNF-α and IL-6 expression immunohistochemistry in lung tissue stained by DAB-chromogen within a bronchiolar wall, alveolar wall, and interstitial tissue among five groups: control, IOLE AgNPs-infected, infected, infected + 50 mg/kg IOLE AgNPs, and CQ10-treated. The strength and direction of correlations: positive correlations are represented in purple color, while negative correlations are in orange color. The intensity of the color reflects the strength of the correlation, with darker shades indicating stronger associations.

6 Discussion

P. chabaudi is considered a model of the malaria parasite to explore its vigorous impact on different organs such as the lungs. It is known that malaria disease induces multiple inflammatory signs besides several cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 playing a significant role in the inflammatory process. Therefore, the present study indicates the potential impact of I. oblongifolia as an effective therapy for malaria disease, focusing on the microscopic analysis and immunobiological alterations particularly the levels of TNF-α and IL-6.

The current investigation showed that the extraction of I. oblongifolia leaf had significant antimalarial and anti-oxidant properties that could reduce the inflammatory signs caused by P. chabaudi infection via the modulation of inflammatory cytokines and preventing oxidative stress in the infected lung. The present analysis of the study displayed slight restriction in the pulmonary ducts with a thicker wall than the normal thickness in the positive control group of I. oblongifolia with AgNPs. Also, dispersion of necrotic cells and septal congestion besides small spots of edema were observed. De Matteis [15] and Singh et al. [16] explained that these findings are due to the repeated exposure to AgNPs, even at low doses, resulting in cumulative impacts that can lead to chronic inflammation and fibrosis. Consequently, the accumulation of AgNPs in the bronchiolar and alveolar ducts aids in triggering oxidative stress status and inflammation. Several studies validated the previously reported findings of AgNPs, including glomerulosclerosis and necrosis in the kidney [17,18], congestion of white pulp in the spleen [19,20], cardiac ischemic reperfusion injury in the heart [21–23], apoptosis in the thymus [24], and agyria in the skin [25–27]. Also, the present study revealed that the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 assay displayed non-significant expression compared to normal reactions around bronchiolar and alveolar walls while significant yellowish spots in the interstitial tissue. Similar findings were recorded by Alessandrini et al. [28] and Pitchai et al. [29].

The lung infected with P. chabaudi registered a significant obstruction in bronchiolar and alveolar ducts, in addition to elevated rates of alveolar and septal congestion, edema, hemosiderin, and necrosis intensity. Brugat et al. and Nahrendorf et al. [2,30] found a significant increase in dendritic, neutrophil, and macrophage density during acute lung infection with P. chabaudi, as detected by flow cytometry. Moreover, severe cytotoxicity was demonstrated in many organs such as the liver, kidney, spleen, and brain during acute inflammation with malaria [31–33]. Acute malaria inflammation of the liver was characterized by degeneration of hepatocellular tissue, necrosis, and hyperplasia of Kupper cells [34]. Lung injury appeared as an alveolar hemorrhage [35], and kidney failure was associated with tubular hemoglobin casts [2,30]. Similar cytotoxicity in many organs was observed during the acute infection of all species of malaria such as P. falciparum and P. vivax [36,37]. On the other hand, the immunohistochemistry investigation of TNF-α and IL-6 expressed strong positive reactions with pulmonary components that reflected the severity of malaria damage and lung inflammation of P. chabaudi. Similar upregulation was displayed in inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the infected spleen with P. chabaudi [38,39]. There is a noticeable difference in the degree of intensity of TNF-α and IL-6 in lung tissue whereas IL-6 cytokine recorded a heavy stain than TNF-α in the same infected group. Yang et al. [40] and Tomkins-Netzer et al. [41] referred to these intensity variations to the different roles of each cytokine in the inflammatory response, while the TNF-α initiated the inflammatory response rapidly by triggering the immune cells to the inflammatory site; consequently, their expression was not prolonged for a long time. Additionally, Popko et al. [42] and Boulares et al. [43] revealed that IL-6 amplified the immune response, increased the vascular permeability, and was associated with the development of edema, therefore their prolonged expressions were registered.

Treatment with I. oblongifolia leaf extract and AgNPs resulted in rapid recovery from cytotoxicity in the lungs. Respiratory ducts restored to their usual size and thickness. Also, most histopathological signs like congestion, necrosis, and edema returned to their normal levels. The structural reorganization became more evident compared to the infected lung. Lubbad et al. [44] and Al-Quraishy et al. [45] referred this recovery to the anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties of this medical extraction that were able to restore the normal organization of white and red pulps in the spleen after infection with P. chabaudi. Zhang et al. [46] and Khan et al. [47] explained that the antimalarial impact of novel therapy was represented in the disruption of the viability of the parasite through silver ion of AgNPs which in turn suppressed the mitochondrial electron transport chain, and stopped ATP synthesis in plasmodium. In addition to the previous findings Zahra et al. [48] referred to flavonoids of I. oblongifolia that acted on neutralizing the ROS and reducing lipid peroxidation. The anti-inflammatory properties of I. oblongifolia appeared in the suppression of NF-κB activation, which in turn reduced the overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and preserved necessary immune responses according to Almayouf et al. [49]. Moreover, Abdel Moneim [50] and Destro et al. [51] showed the protective, anti-fibrotic, anti-oxidant, and anti-apoptotic activities of I. oblongifolia in restoring the normal organization of hepatocellular cells after hepatocytotoxicity of lead acetate. Furthermore, during the recovery by I. oblongifolia, the immunohistochemistry expression of TNF-α and IL-6 was low in comparison to infected tissue. Analogous expression was registered in cancerous mice treated with I. trita [52].

Conversely, applying CQ 10 mg/kg after inflammation with P. chabaudi as a malaria local medical drug did not achieve full recovery of pulmonary cytotoxicity in the present study. However, the bronchiolar and alveolar ducts still suffered from little obstruction and thicker walls than the normal ones. In addition, cytotoxic signs such as edema and necrosis were still observed with significant intensity in this lung. Alven and Aderibigbe [53] and Tiwari et al. [54] referred the low response of CQ as a conventional antimalarial drug to the molecular resistance of antimalarial drugs in several species of parasites which had polymorphisms in proteins that change the physiological regulation in the parasite. The standard antimalarial medication (CQ, tafenoquine, and primaquine) has a poor response because to its limited water solubility, bioavailability, and short half-life [55,56]. However, Zhou et al. [57] and Ravindar et al. [58] showed the antimalarial, anticancer, and antiviral response of CQ and considered it as a promising therapeutic potential in autoimmune diseases, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases. Also, Chaves et al. [59] added that due to the increasing resistance of local medical drugs like CQ, lumefantrine, and primaquine, there is an urgent need for a diversity of treatment ways and application of nanoscale size of some medical plants to facilitate the penetration and adsorption of therapy. Another implication registered against CQ as an effective therapy for malaria disease was its limited efficiency in restoring normal lung architecture. Yang et al. [60] and Gong et al. [61] reported that CQ was unable to modulate the host inflammatory response and also could not be involved in tissue regeneration that assisted in lung recovery. On the other hand, this mixture of IOLE AgNPs had potent anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties which reduced the oxidative stress status besides suppressing the pro-inflammatory cytokines post-infection, which was responsible for persistent inflammation that mediated lung damage according to Jangid et al. [62] and Parvin et al. [63] who confirmed that the nano-particles modulated chemokines and growth factors like G-CSF and CXCL1 for tissue repair.

The significant coordination in the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 that appeared through the heat map of Pearson correlation demonstrated the well-inflammatory response in the infected tissues with P. chabaudi that was registered in the form of edema, obstruction of pulmonary ducts, and congestion. Also, this coordination was significantly observed in the decrease in their expression after the treatment with IOLE AgNPs which was recorded in the form of withdrawal of majority of histopathological signs from the tissue. Comparable findings were demonstrated in Bhol et al. [64] who showed that curcumin was able to down-regulate the levels of proinflammatory cytokines of TNF-α and IL-6 in various models of acute inflammation. Moreover, Mrityunjaya et al. [65] and Carlson et al. [66] showed that a significant reduction in these levels of cytokines led to the withdrawal of the histopathological signs from the tissues.

7 Conclusion

In conclusion, the accumulation of AgNPs triggered proinflammatory cytokines and created an oxidative stress status in lung tissue. Therefore, I. oblongifolia as a natural medical plant displayed significant antimalarial and anti-oxidant properties effectively reducing inflammatory signs and cytokine levels in P. chabaudi-infected lungs and the harmful impact of AgNPs in P. chabaudi-infected + I. oblongifolia with AgNPs, while CQ (Q 10) shows limited efficiency due to molecular drug resistance. This study highlights the therapeutic potential of I. oblongifolia for malaria management.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ongoing Research Funding Program No. ORF-2025-1081, at King Saud University.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization: S.Q. and M.M.; methodology: M.M; software: M.M.; validation: J.T. and M.M.; formal analysis: J.T.; investigation: H.E.; resources: H.E.; data curation: H.E. and J.T.; writing – original draft preparation: J.T. and M.M.; writing – review and editing: M.M. and J.T.; visualization: M.M.; supervision: S.Q.; project administration: H.E.; funding acquisition: S.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Gozalo AS, Robinson CK, Holdridge J, Mahecha OFL, Elkins WR. Overview of Plasmodium spp. and animal models in malaria research. Comp Med. 2024;74(4):205–30.10.30802/AALAS-CM-24-000019Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Brugat T, Cunningham D, Sodenkamp J, Coomes S, Wilson M, Spence PJ, et al. Sequestration and histopathology in Plasmodium chabaudi malaria are influenced by the immune response in an organ‐specific manner. Cell Microbiol. 2014;16(5):687–700.10.1111/cmi.12212Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Jana S, Manjari P, Hyder I. Physiology of respiration. Textbook of veterinary physiology. Springer Nature; 2023. p. 171–92.10.1007/978-981-19-9410-4_7Search in Google Scholar

[4] Schnadig VJ, Woods GL. Histopathology of fungal infections. Elsevier; 2009. p. 79–108.10.1016/B978-1-4160-5680-5.00005-0Search in Google Scholar

[5] Talapko J, Škrlec I, Alebić T, Jukić M, Včev A. Malaria: the past and the present. Microorganisms. 2019;7(6):179.10.3390/microorganisms7060179Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Dey S, Mohapatra S, Khokhar M, Hassan S, Pandey RK. Extracellular vesicles in malaria: shedding light on pathogenic depths. ACS Infect Dis. 2024;10(3):827–44.10.1021/acsinfecdis.3c00649Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Belete TM. Recent progress in the development of new antimalarial drugs with novel targets. Drug design, development and therapy. Dove press; 2020. p. 3875–89.10.2147/DDDT.S265602Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Süntar I. Importance of ethnopharmacological studies in drug discovery: role of medicinal plants. Phytochem Rev. 2020;19(5):1199–209.10.1007/s11101-019-09629-9Search in Google Scholar

[9] Kamaraj C, Ragavendran C, Prem P, Naveen Kumar S, Ali A, Kazmi A, et al. Exploring the therapeutic potential of traditional antimalarial and antidengue plants: a mechanistic perspective. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2023;2023(1):1860084.10.1155/2023/1860084Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Osman AK, Badry MO, Gafar S. Macromorphological revision of Indigofera L. (Faboideae, Fabaceae) in Egypt. Egyptian Acad J Biol Sci, H Bot. 2023;14(2):43–64.10.21608/eajbsh.2023.329131Search in Google Scholar

[11] Murshed M, Al-Tamimi J, Ibrahim KE, Al-Quraishy S. A histomorphometric study to evaluate the therapeutic effects of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles on the kidneys infected with Plasmodium chabaudi. Open Life Sci. 2024;19(1):20220968.10.1515/biol-2022-0968Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Torre D, Speranza F, Giola M, Matteelli A, Tambini R, Biondi G, et al. Role of Th1 and Th2 cytokines in immune response to uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2002;9(2):348–51.10.1128/CDLI.9.2.348-351.2002Search in Google Scholar

[13] Lyke K, Burges R, Cissoko Y, Sangare L, Dao M, Diarra I, et al. Serum levels of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IL-12 (p70) in Malian children with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria and matched uncomplicated malaria or healthy controls. Infect Immun. 2004;72(10):5630–7.10.1128/IAI.72.10.5630-5637.2004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Simião GM, Parreira KS, Klein SG, Ferreira FB, Freitas FdS, Silva EFd, et al. Involvement of inflammatory cytokines, renal NaPi-IIa cotransporter, and TRAIL induced-apoptosis in experimental malaria-associated acute kidney injury. Pathogens. 2024;13(5):376.10.3390/pathogens13050376Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] De Matteis V. Exposure to inorganic nanoparticles: routes of entry, immune response, biodistribution and in vitro/in vivo toxicity evaluation. Toxics. 2017;5(4):29.10.3390/toxics5040029Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Singh V, Vihal S, Rana R, Rathore C. Nanocarriers for cannabinoid delivery: enhancing therapeutic potential. Recent Adv Drug Deliv Formulat. 2024;18(4):247–61.10.2174/0126673878300347240718100814Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Tiwari R, Singh RD, Khan H, Gangopadhyay S, Mittal S, Singh V, et al. Oral subchronic exposure to silver nanoparticles causes renal damage through apoptotic impairment and necrotic cell death. Nanotoxicology. 2017;11(5):671–86.10.1080/17435390.2017.1343874Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Khayal EE-S, Elhadidy MG, Alnasser SM, Morsy MM, Farag AI, El-Nagdy SA. Podocyte-related biomarkers’ role in evaluating renal toxic effects of silver nanoparticles with the possible ameliorative role of resveratrol in adult male albino rats. Toxicol Rep. 2024;14:101882.10.1016/j.toxrep.2024.101882Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] de Plata DTdN. Morphometric alterations induced by the toxicity of variable sizes of silver nanoparticles. Int J Morphol. 2015;33(2):544–52.10.4067/S0717-95022015000200022Search in Google Scholar

[20] Mohammed ZN, Hussein ZA. Study of the toxicological effects of pentostam and silver nanoparticles on liver and spleen tissue in albino mice infected with cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Posit Sch Psychol. 2022;6(7):5246–52.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Abdal Dayem A, Hossain MK, Lee SB, Kim K, Saha SK, Yang G-M, et al. The role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the biological activities of metallic nanoparticles. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(1):120.10.3390/ijms18010120Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Ferdous Z, Al-Salam S, Greish YE, Ali BH, Nemmar A. Pulmonary exposure to silver nanoparticles impairs cardiovascular homeostasis: effects of coating, dose and time. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2019;367:36–50.10.1016/j.taap.2019.01.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Wang Y-L, Lee Y-H, Chou C-L, Chang Y-S, Liu W-C, Chiu H-W. Oxidative stress and potential effects of metal nanoparticles: a review of biocompatibility and toxicity concerns. Environ Pollut. 2024;346:123617.10.1016/j.envpol.2024.123617Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Jiang X, Lu C, Tang M, Yang Z, Jia W, Ma Y, et al. Nanotoxicity of silver nanoparticles on HEK293T cells: a combined study using biomechanical and biological techniques. ACS Omega. 2018;3(6):6770–8.10.1021/acsomega.8b00608Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Song KS, Sung JH, Ji JH, Lee JH, Lee JS, Ryu HR, et al. Recovery from silver-nanoparticle-exposure-induced lung inflammation and lung function changes in Sprague Dawley rats. Nanotoxicology. 2013;7(2):169–80.10.3109/17435390.2011.648223Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] ALAtawi MK, AlAsmari AA, AlAliany AD, Almajed MM, Sakran MI. Silver nanoparticles forensic uses and toxicity on vital organs and different body systems. Adv Toxicol Toxic Eff. 2024;8(1):015–29.10.17352/atte.000018Search in Google Scholar

[27] Kim JJ, Konkel K, McCulley L, Diak I-L. Cases of argyria associated with colloidal silver use. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(8):867–70.10.1177/1060028019844258Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Alessandrini F, Vennemann A, Gschwendtner S, Neumann AU, Rothballer M, Seher T, et al. Pro-inflammatory versus immunomodulatory effects of silver nanoparticles in the lung: the critical role of dose, size and surface modification. Nanomaterials. 2017;7(10):300.10.3390/nano7100300Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Pitchai A, Shinde A, Swihart JN, Robison K, Shannahan JH. Specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators distinctly modulate silver nanoparticle-induced pulmonary inflammation in healthy and metabolic syndrome mouse models. Nanomaterials. 2024;14(20):1642.10.3390/nano14201642Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Nahrendorf W, Ivens A, Spence PJ. Inducible mechanisms of disease tolerance provide an alternative strategy of acquired immunity to malaria. Elife. 2021;10:e63838.10.7554/eLife.63838Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Machado Siqueira A, Lopes Magalhães BM, Cardoso Melo G, Ferrer M, Castillo P, Martin-Jaular L, et al. Spleen rupture in a case of untreated Plasmodium vivax infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(12):e1934.10.1371/journal.pntd.0001934Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Anstey NM, Tham W-H, Shanks GD, Poespoprodjo JR, Russell BM, Kho S. The biology and pathogenesis of vivax malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2024;40(7):573–90.10.1016/j.pt.2024.04.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Manning L, Rosanas-Urgell A, Laman M, Edoni H, McLean C, Mueller I, et al. A histopathologic study of fatal paediatric cerebral malaria caused by mixed Plasmodium falciparum/Plasmodium vivax infections. Malar J. 2012;11:1–5.10.1186/1475-2875-11-107Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Anstey NM, Russell B, Yeo TW, Price RN. The pathophysiology of vivax malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25(5):220–7.10.1016/j.pt.2009.02.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] David-Vieira C, Carpinter BA, Bezerra-Bellei JC, Machado LF, Raimundo FO, Rodolphi CM, et al. Lung damage induced by Plasmodium berghei ANKA in murine model of malarial infection is mitigated by dietary supplementation with DHA-rich omega-3. ACS Infect Dis. 2024;10(10):3607–17.10.1021/acsinfecdis.4c00482Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Taylor TE, Fu WJ, Carr RA, Whitten RO, Mueller JG, Fosiko NG, et al. Differentiating the pathologies of cerebral malaria by postmortem parasite counts. Nat Med. 2004;10(2):143–5.10.1038/nm986Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] White NJ. Severe malaria. Malar J. 2022;21(1):284.10.1186/s12936-022-04301-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] de Menezes MN, Salles ÉM, Vieira F, Amaral EP, Zuzarte-Luís V, Cassado A, et al. IL-1α promotes liver inflammation and necrosis during blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi malaria. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7575.10.1038/s41598-019-44125-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] MacDonald I, Abbas W, Adedokun O, Benjamin G. Diethyl ether extract of senna siamea exhibits anti-plasmodial polypharmacology activity via modulation of pbEMPI and hepatolipodystrophy genes. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2024;35:1–12.10.1007/s43450-024-00606-8Search in Google Scholar

[40] Yang JY, Goldberg D, Sobrin L. Interleukin-6 and macular edema: a review of outcomes with inhibition. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5):4676.10.3390/ijms24054676Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Tomkins-Netzer O, Niederer R, Greenwood J, Fabian ID, Serlin Y, Friedman A, et al. Mechanisms of blood-retinal barrier disruption related to intraocular inflammation and malignancy. Prog Retinal Eye Res. 2024;99:101245.10.1016/j.preteyeres.2024.101245Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Popko K, Gorska E, Stelmaszczyk-Emmel A, Plywaczewski R, Stoklosa A, Gorecka D, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines Il-6 and TNF-α and the development of inflammation in obese subjects. Eur J Med Res. 2010;15:1–3.10.1186/2047-783X-15-S2-120Search in Google Scholar

[43] Boulares A, Jdidi H, Douzi W. Cold and longevity: can cold exposure counteract aging? Life Sci. 2025;364:123431.10.1016/j.lfs.2025.123431Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Lubbad MY, Al-Quraishy S, Dkhil MA. Antimalarial and antioxidant activities of Indigofera oblongifolia on Plasmodium chabaudi-induced spleen tissue injury in mice. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:3431–8.10.1007/s00436-015-4568-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Al-Quraishy S, Abdel-Maksoud MA, Al-Shaebi EM, Dkhil MA. Botanical candidates from Saudi Arabian flora as potential therapeutics for Plasmodium infection. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28(2):1374–9.10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.11.069Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Zhang P, Gong J, Jiang Y, Long Y, Lei W, Gao X, et al. Application of silver nanoparticles in parasite treatment. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(7):1783.10.3390/pharmaceutics15071783Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Khan AR, Ahmed M, Khan H, Osman NA-HK, Gaafar A-RZ, Shafique T. Beta maritima mediated silver nanoparticles: characterization and evaluation of antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant activities. J King Saud Univ-Sci. 2024;36(6):103219.10.1016/j.jksus.2024.103219Search in Google Scholar

[48] Zahra M, Abrahamse H, George BP. Flavonoids: antioxidant powerhouses and their role in nanomedicine. Antioxidants. 2024;13(8):922.10.3390/antiox13080922Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Almayouf MA, El-Khadragy M, Awad MA, Alolayan EM. The effects of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized using fig and olive extracts on cutaneous leishmaniasis-induced inflammation in female balb/c mice. Biosci Rep. 2020;40(12):BSR20202672.10.1042/BSR20202672Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Abdel Moneim AE. Indigofera oblongifolia prevents lead acetate-induced hepatotoxicity, oxidative stress, fibrosis and apoptosis in rats. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158965.10.1371/journal.pone.0158965Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Destro ALF, da Silva Mattosinhos P, Novaes RD, Sarandy MM, Gonçalves RV, Freitas MB. Impact of plant extracts on hepatic redox metabolism upon lead exposure: a systematic review of preclinical in vivo evidence. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023;30(40):91563–90.10.1007/s11356-023-28620-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Haque ME. In vitro antioxidant and anti-neoplastic activities of Ocimum sanctum leaves in Ehrlich ascites carcinoma bearing mice. Int J Cancer Res. 2011;7(3):209–21.10.3923/ijcr.2011.209.221Search in Google Scholar

[53] Alven S, Aderibigbe BA. Nanoparticles formulations of artemisinin and derivatives as potential therapeutics for the treatment of cancer, leishmaniasis and malaria. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(8):748.10.3390/pharmaceutics12080748Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Tiwari S, Kumar R, Devi S, Sharma P, Chaudhary NR, Negi S, et al. Biogenically synthesized green silver nanoparticles exhibit antimalarial activity. Discov Nano. 2024;19(1):136.10.1186/s11671-024-04098-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Novitt-Moreno A, Martidis A, Gonzalez V, Ransom J, Scott CB, Dow G, et al. Long-term safety of the tafenoquine antimalarial chemoprophylaxis regimen: a 12-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2022;45:102211.10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102211Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Schlagenhauf P, Maier JD, Grobusch MP. Tafenoquine for malaria chemoprophylaxis-Status quo 2022. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2022;46:102268.10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102268Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Zhou W, Wang H, Yang Y, Chen Z-S, Zou C, Zhang J. Chloroquine against malaria, cancers and viral diseases. Drug Discov Today. 2020;25(11):2012–22.10.1016/j.drudis.2020.09.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Ravindar L, Hasbullah SA, Rakesh K, Hassan NI. Recent developments in antimalarial activities of 4-aminoquinoline derivatives. Eur J Med Chem. 2023;256:115458.10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115458Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Chaves JB, Portugal Tavares de Moraes B, Regina Ferrarini S, Noé da Fonseca F, Silva AR, Gonçalves-de-Albuquerque CF. Potential of nanoformulations in malaria treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:999300.10.3389/fphar.2022.999300Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Yang M, Cao L, Xie M, Yu Y, Kang R, Yang L, et al. Chloroquine inhibits HMGB1 inflammatory signaling and protects mice from lethal sepsis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;86(3):410–8.10.1016/j.bcp.2013.05.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[61] Gong Y, Meng T, Lin W, Hu X, Tang R, Xiong Q, et al. Hydroxychloroquine as an add-on therapy for the induction therapy of MPO-AAV: a retrospective observational cohort study. Clin Kidney J. 2024;17(9):sfae264.10.1093/ckj/sfae264Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[62] Jangid H, Singh S, Kashyap P, Singh A, Kumar G. Advancing biomedical applications: an in-depth analysis of silver nanoparticles in antimicrobial, anticancer, and wound healing roles. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1438227.10.3389/fphar.2024.1438227Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[63] Parvin N, Joo SW, Mandal TK. Nanomaterial-based strategies to combat antibiotic resistance: mechanisms and applications. Antibiotics. 2025;14(2):207.10.3390/antibiotics14020207Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] Bhol NK, Bhanjadeo MM, Singh AK, Dash UC, Ojha RR, Majhi S, et al. The interplay between cytokines, inflammation, and antioxidants: mechanistic insights and therapeutic potentials of various antioxidants and anti-cytokine compounds. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;178:117177.10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117177Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Mrityunjaya M, Pavithra V, Neelam R, Janhavi P, Halami P, Ravindra P. Immune-boosting, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory food supplements targeting pathogenesis of COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11:570122.10.3389/fimmu.2020.570122Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[66] Carlson DA, True C, Wilson CG. Oxidative stress and food as medicine. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1394632.10.3389/fnut.2024.1394632Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome with elevated IgG4 and T-cell clonality: A report of two cases

- Electroacupuncture alleviates sciatic nerve injury in sciatica rats by regulating BDNF and NGF levels, myelin sheath degradation, and autophagy

- Polydatin prevents cholesterol gallstone formation by regulating cholesterol metabolism via PPAR-γ signaling

- RNF144A and RNF144B: Important molecules for health

- Analysis of the detection rate and related factors of thyroid nodules in the healthy population

- Artesunate inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion through OGA-mediated O-GlcNAcylation of ZEB1

- Endovascular management of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: Case report and review of the literature

- Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis

- SATB2 promotes humeral fracture healing in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Overexpression of the ferroptosis-related gene, NFS1, corresponds to gastric cancer growth and tumor immune infiltration

- Understanding risk factors and prognosis in diabetic foot ulcers

- Atractylenolide I alleviates the experimental allergic response in mice by suppressing TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 signalling

- FBXO31 inhibits the stemness characteristics of CD147 (+) melanoma stem cells

- Immune molecule diagnostics in colorectal cancer: CCL2 and CXCL11

- Inhibiting CXCR6 promotes senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells with limited proinflammatory SASP to attenuate hepatic fibrosis

- Cadmium toxicity, health risk and its remediation using low-cost biochar adsorbents

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis with headache as the first presentation: A case report

- Solitary pulmonary metastasis with cystic airspaces in colon cancer: A rare case report

- RUNX1 promotes denervation-induced muscle atrophy by activating the JUNB/NF-κB pathway and driving M1 macrophage polarization

- Morphometric analysis and immunobiological investigation of Indigofera oblongifolia on the infected lung with Plasmodium chabaudi

- The NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex and Hr78 modulate the Lobe2 mutant eye phenotype

- Experimental study on salmon demineralized bone matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: In vitro and in vivo study

- A case of IgA nephropathy treated with a combination of telitacicept and half-dose glucocorticoids

- Analgesic and toxicological evaluation of cannabidiol-rich Moroccan Cannabis sativa L. (Khardala variety) extract: Evidence from an in vivo and in silico study

- Wound healing and signaling pathways

- Combination of immunotherapy and whole-brain radiotherapy on prognosis of patients with multiple brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study

- To explore the relationship between endometrial hyperemia and polycystic ovary syndrome

- Research progress on the impact of curcumin on immune responses in breast cancer

- Biogenic Cu/Ni nanotherapeutics from Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl seeds for the treatment of lung cancer

- Dapagliflozin attenuates atrial fibrosis via the HMGB1/RAGE pathway in atrial fibrillation rats

- Glycitein alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in keratinocytes via ROS-associated PI3K–Akt signalling pathway

- ADH5 inhibits proliferation but promotes EMT in non-small cell lung cancer cell through activating Smad2/Smad3

- Apoptotic efficacies of AgNPs formulated by Syzygium aromaticum leaf extract on 32D-FLT3-ITD human leukemia cell line with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Novel cuproptosis-related genes C1QBP and PFKP identified as prognostic and therapeutic targets in lung adenocarcinoma

- Bee venom promotes exosome secretion and alters miRNA cargo in T cells

- Treatment of pure red cell aplasia in a chronic kidney disease patient with roxadustat: A case report

- Comparative bioinformatics analysis of the Wnt pathway in breast cancer: Selection of novel biomarker panels associated with ER status

- Kynurenine facilitates renal cell carcinoma progression by suppressing M2 macrophage pyroptosis through inhibition of CASP1 cleavage

- RFX5 promotes the growth, motility, and inhibits apoptosis of gastric adenocarcinoma cells through the SIRT1/AMPK axis

- ALKBH5 exacerbates early cardiac damage after radiotherapy for breast cancer via m6A demethylation of TLR4

- Phytochemicals of Roman chamomile: Antioxidant, anti-aging, and whitening activities of distillation residues

- Circadian gene Cry1 inhibits the tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma by the BAX/BCL2-mediated apoptosis pathway

- The TNFR-RIPK1/RIPK3 signalling pathway mediates the effect of lanthanum on necroptosis of nerve cells

- Longitudinal monitoring of autoantibody dynamics in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing surgery

- The potential role of rutin, a flavonoid, in the management of cancer through modulation of cell signaling pathways

- Construction of pectinase gene engineering microbe and its application in tobacco sheets

- Construction of a microbial abundance prognostic scoring model based on intratumoral microbial data for predicting the prognosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Sepsis complicated by haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis triggered by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and human herpesvirus 8 in an immunocompromised elderly patient: A case report

- Sarcopenia in liver transplantation: A comprehensive bibliometric study of current research trends and future directions

- Advances in cancer immunotherapy and future directions in personalized medicine

- Can coronavirus disease 2019 affect male fertility or cause spontaneous abortion? A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis

- Heat stroke associated with novel leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor gene variant in a Chinese infant

- PSME2 exacerbates ulcerative colitis by disrupting intestinal barrier function and promoting autophagy-dependent inflammation

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state with severe hypernatremia coexisting with central diabetes insipidus: A case report and literature review

- Efficacy and mechanism of escin in improving the tissue microenvironment of blood vessel walls via anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects: Implications for clinical practice

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Clinicopathological analysis of three patients and literature review

- Genetic variants in VWF exon 26 and their implications for type 1 Von Willebrand disease in a Saudi Arabian population

- Lipoxin A4 improves myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through the Notch1-Nrf2 signaling pathway

- High levels of EPHB2 expression predict a poor prognosis and promote tumor progression in endometrial cancer

- Knockdown of SHP-2 delays renal tubular epithelial cell injury in diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis

- Exploring the toxicity mechanisms and detoxification methods of Rhizoma Paridis

- Concomitant gastric carcinoma and primary hepatic angiosarcoma in a patient: A case report

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Optimization and comparative study of Bacillus consortia for cellulolytic potential and cellulase enzyme activity

- The complete mitochondrial genome analysis of Haemaphysalis hystricis Supino, 1897 (Ixodida: Ixodidae) and its phylogenetic implications

- Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors analysis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among tuberculosis population in Huzhou City, Eastern China

- Indices of human impacts on landscapes: How do they reflect the proportions of natural habitats?

- Genetic analysis of the Siberian flying squirrel population in the northern Changbai Mountains, Northeast China: Insights into population status and conservation

- Diversity and environmental drivers of Suillus communities in Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica forests of Inner Mongolia

- Global assessment of the fate of nitrogen deposition in forest ecosystems: Insights from 15N tracer studies

- Fungal and bacterial pathogenic co-infections mainly lead to the assembly of microbial community in tobacco stems

- Influencing of coal industry related airborne particulate matter on ocular surface tear film injury and inflammatory factor expression in Sprague-Dawley rats

- Temperature-dependent development, predation, and life table of Sphaerophoria macrogaster (Thomson) (Diptera: Syrphidae) feeding on Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae)

- Eleonora’s falcon trophic interactions with insects within its breeding range: A systematic review

- Agriculture

- Integrated analysis of transcriptome, sRNAome, and degradome involved in the drought-response of maize Zhengdan958

- Variation in flower frost tolerance among seven apple cultivars and transcriptome response patterns in two contrastingly frost-tolerant selected cultivars

- Heritability of durable resistance to stripe rust in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Molecular mechanism of follicular development in laying hens based on the regulation of water metabolism

- Animal Science

- Effect of sex ratio on the life history traits of an important invasive species, Spodoptera frugiperda

- Plant Sciences

- Hairpin in a haystack: In silico identification and characterization of plant-conserved microRNA in Rafflesiaceae

- Widely targeted metabolomics of different tissues in Rubus corchorifolius

- The complete chloroplast genome of Gerbera piloselloides (L.) Cass., 1820 (Carduoideae, Asteraceae) and its phylogenetic analysis

- Field trial to correlate mineral solubilization activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and biochemical content of groundnut plants

- Correlation analysis between semen routine parameters and sperm DNA fragmentation index in patients with semen non-liquefaction: A retrospective study

- Plasticity of the anatomical traits of Rhododendron L. (Ericaceae) leaves and its implications in adaptation to the plateau environment

- Effects of Piriformospora indica and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on growth and physiology of Moringa oleifera under low-temperature stress

- Effects of different sources of potassium fertiliser on yield, fruit quality and nutrient absorption in “Harward” kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa)

- Comparative efficiency and residue levels of spraying programs against powdery mildew in grape varieties

- The DREB7 transcription factor enhances salt tolerance in soybean plants under salt stress

- Using plant electrical signals of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) for water pollution monitoring

- Food Science

- Phytochemical analysis of Stachys iva: Discovering the optimal extract conditions and its bioactive compounds

- Review on role of honey in disease prevention and treatment through modulation of biological activities

- Computational analysis of polymorphic residues in maltose and maltotriose transporters of a wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain

- Optimization of phenolic compound extraction from Tunisian squash by-products: A sustainable approach for antioxidant and antibacterial applications

- Liupao tea aqueous extract alleviates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in rats by modulating the gut microbiota

- Toxicological qualities and detoxification trends of fruit by-products for valorization: A review

- Polyphenolic spectrum of cornelian cherry fruits and their health-promoting effect

- Optimizing the encapsulation of the refined extract of squash peels for functional food applications: A sustainable approach to reduce food waste

- Advancements in curcuminoid formulations: An update on bioavailability enhancement strategies curcuminoid bioavailability and formulations

- Impact of saline sprouting on antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds in chia seeds

- The dilemma of food genetics and improvement

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Impact of hyaluronic acid-modified hafnium metalorganic frameworks containing rhynchophylline on Alzheimer’s disease

- Emerging patterns in nanoparticle-based therapeutic approaches for rheumatoid arthritis: A comprehensive bibliometric and visual analysis spanning two decades

- Application of CRISPR/Cas gene editing for infectious disease control in poultry

- Preparation of hafnium nitride-coated titanium implants by magnetron sputtering technology and evaluation of their antibacterial properties and biocompatibility

- Preparation and characterization of lemongrass oil nanoemulsion: Antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant, and anticancer activities

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells”

- Corrigendum to “Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans”

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Down-regulation of miR-539 indicates poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer”

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation