Abstract

The Siberian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans) is an arboreal, nocturnal, and gliding rodent. It is crucial for maintaining ecosystem balance and the dispersal of forest seeds. In Northeast China, the number of Siberian flying squirrels is decreasing and their habitats are shrinking due to logging and habitat loss. To make more targeted and effective measures to protect and manage the population, there is an urgent need to study the genetic changes in the population, particularly looking at genetic diversity and gene flow. In this study, we collected hair samples from 91 Siberian flying squirrels in a way that did not harm them. Then, we analyzed the DNA in these samples, specifically using cytochrome b and microsatellite loci, and examined the genetic diversity and population structure of flying squirrels living in the northern Changbai Mountains of Northeast China. The results indicated that the genetic diversity in the populations was high. However, a high proportion of rare haplotypes and a low frequency of alleles indicated that the genetic diversity might decline in the future. There were significantly low to moderate levels of genetic differentiation among the four populations. According to our STRUCTURE analysis, the four geographical populations belonged to three genetic clusters (Fangzheng, Bin County, and Weihe–Muling). The isolation by distance model could not effectively explain the current pattern of the population genetic structure. The haplotype network showed no clear phylogeographic pattern among the four geographic populations, indicating that the geographic barriers between the flying squirrels might have formed only recently. To better protect the Siberian flying squirrels, conservation methods should be further improved. For example, habitat restoration and ecological corridor construction should be carried out to increase gene exchange and help the population recover and grow faster.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

The Siberian flying squirrels (Pteromys volans) are nocturnal, tree-dwelling rodents that can glide through the air. They are mostly found in the northern Eurasia, in places like Latvia, Estonia, Finland, Russia, Mongolia, Japan, South Korea, North Korea, and China [1]. The species is under threat to varying degrees in many areas due to habitat loss and fragmentation. The species is on the verge of extinction in Latvia, and is listed as endangered (EN), vulnerable (VU), and near threatened (NT) in South Korea, Estonia, and Finland [2], respectively. In China, the Siberian flying squirrel is the only species belonging to the Pteromys genus of the Sciuridae family. It lives primarily in the northern forests of Northeast China, North China, and Northwest China [1]. As a key indicator species for sustainable forest management [3], the Siberian flying squirrel is of great ecological, scientific, and social value, and has been included in China’s catalogue of terrestrial wildlife. Furthermore, it is classified as VU in China’s Vertebrate Red List [4]. The Siberian flying squirrel reproduces at a low rate, usually bearing one or two litters per year, with 2–4 offspring per litter. Most individuals live only 1–2 years [5], which slows population growth and makes the species even more vulnerable. Globally, numerous studies have been conducted on various aspects of the Siberian flying squirrel, including its morphology, home range, nest-site utilization, habitat selection, genetic diversity, and molecular evolution [6–11]. These studies have provided critical insights to support its protection. In contrast, research in China remains limited. Early studies in China primarily focused on tree-hollow insulation mechanisms, activity rhythm in captivity, molecular marker screening, and taxonomic status of the flying squirrels. Notably, most of these studies have been published in Chinese, which limits their accessibility to the broader scientific community [12–15].

The northeastern region of China, including the Greater Khingan Mountains, Lesser Khingan Mountains, Changbai Mountains, Songnen Plain, and Sanjiang Plain, has historically experienced extensive deforestation and habitat degradation. These environmental pressures have disrupted gene flow among wildlife populations leading to inbreeding, lower genetic diversity, and the accumulation of harmful mutations in small populations. The survival of local wildlife is thus under threat [15–17]. Siberian flying squirrel is a typical tree-dwelling forest species that nests primarily in tree cavities. It is particularly vulnerable to habitat changes [2]. Since modern times, large-scale deforestation, activities that transformed natural landscapes into farmland, and rapid population growth in the Northeast China have all reduced the size of the mature forest habitats, which the Siberian flying squirrel rely on for nesting and foraging. Consequently, the species’ population and distribution are declining [15–17]. To prevent forest degradation, China has implemented a series of effective measures, including the launch of the Natural Forest Protection Program in 2000 and a comprehensive ban on commercial logging of natural forests in 2014 [16]. Research indicates that Siberian flying squirrels prefer to live in trees that are 20–50 years old [2]. Even though there have been efforts of reforestation in the Northeast, it is still hard to find suitable habitats for Siberian flying squirrels. According to field surveys, Siberian flying squirrels are not as active in many forests as they used to be. Their populations are shrinking due to habitat loss and fragmentation. As forests are getting cut down or broken into smaller patches, squirrels in one area may be isolated, leading to hindered gene flow and weaker genetic diversity. To better protect the species and its habitats, it is urgent to study how their genetics are responding to these changes. This study uses two genetic tools: mitochondrial DNA (cytochrome b) and nuclear DNA (microsatellite markers) to analyze the genetic diversity, the demographic history, and the genetic differentiation of the Siberian flying squirrels in the northern Changbai Mountains. The findings provide valuable insights for scientists to protect the species and its habitats.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area and sampling

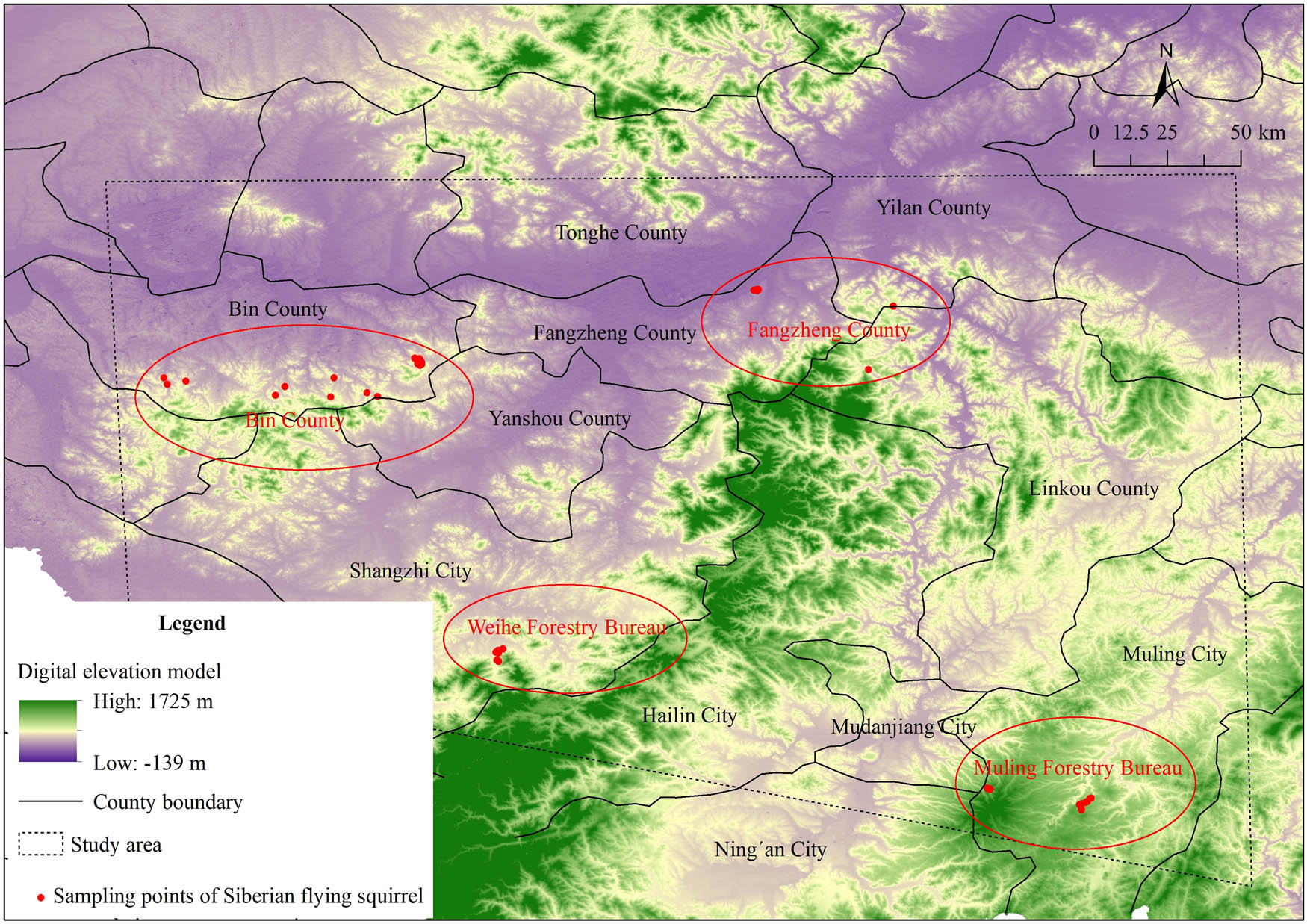

During 2022–2024, we conducted field surveys in both autumn and winter in the northern part of the Changbai Mountains, specifically in forests of the Zhangguangcai Mountains and Laoye Mountains. We found four main regions where the Siberian flying squirrels still have notable populations: Bin County, Fangzheng County, Weihe Forestry Bureau, and Muling Forestry Bureau. These four regions together span about 50,000 km2 and they are all located in the southern part of Heilongjiang Province, China. Each of these locations is about 110–250 km apart from the others (Figure 1).

Sampling sites of this study.

In this study, we used nondestructive methods to collect hair samples. When we found a Siberian flying squirrel nest in a tree cavity, we used a net at the entrance to catch the squirrel when it came out. We plucked about 20 hairs from the tail of each Siberian flying squirrel and stored the hairs in sealed bags. GPS coordinates were recorded at the sampling locations. To avoid taking samples from the same squirrel twice, we clipped a small patch of tail hair as a marking. After sampling, we released the squirrels safely back into the wild. A total of 91 hair samples were collected from the four study sites. These samples were stored at −20°C (in a freezer) for further analysis (Table 1).

Information about collected samples

| Study area | Population | Geographic position | Individual number | Coordinate range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fangzheng County | Fangzheng | Northeastern Zhangguangcai Mountains | 20 | 45°40′–45°55′N, 129°09′–129°34′E |

| Bin County | Bin County | Northwestern Zhangguangcai Mountains | 29 | 45°30′–46°01′N, 126°55′–128°19′E |

| Weihe Forestry Bureau | Weihe | Southern Zhangguangcai Mountains | 15 | 44°47′–44°49′N, 128°21′–128°22′E |

| Muling Forestry Bureau | Muling | Southern Laoye Mountains | 27 | 44°19′–44°24′N, 129°51′–130°11′E |

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animal use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals, and has been approved by the Experimental Animal Welfare Ethics Committee of Mudanjiang Normal University, 15 September 2022 (Review number: IACUC-MNU-0-901).

2.2 DNA extraction and PCR amplification

For genetic analysis, we extracted DNA from 20 hair roots per sample and used a stereoscope to cut off the hair roots and transfer them to a 2.0 mL tube. Using the “TIANamp Micro DNA Kit” (Tiangen, China), we extracted DNA based on the manufacturer’s instructions. To amplify the complete sequence of mtDNA cytochrome b gene, we adopted primers CBF: ACATGGAATCTAACCATGACCAA and CBR: AGACTTCATTGTTGGTTTACAAGAC [15]. Eight specific microsatellite loci of the Siberian flying squirrel were studied [14,15] (Table 2). PCR amplification of cytochrome b and microsatellite loci was performed using the following conditions: an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of strand denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for cytochrome b and 50–59°C for microsatellites for 30 s, and elongation at 72°C for 30 s. A final elongation step was carried out at 72°C for 10 min.

Primer sequence and size range of the eight microsatellite loci (Ta: Annealing temperature)

| Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Size range (bp) | Ta (°C) | Fluorophores |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pvol10 | F: GTCATAACATCAGTCTTTGG | 76–130 | 50 | FAM |

| R: ATCACAAAAAAATAAATAAAAGTC | ||||

| Pvol41 | F: AGGAAATAGGTCTAGTATATGG | 108–144 | 50 | ROX |

| R: TGGAGTATATAATTTTTCCTG | ||||

| PvolE5 | F: GCACAATTTCAGCTGCTTACC | 139–177 | 50 | HEX |

| R: TGAGCTAGGGACTACATGATATGG | ||||

| PvolE6 | F: TCCTTACTAATGTGAACCCTGACA | 161–209 | 50 | TAMRA |

| R: CAGTCTTCAAGCACACTTCCT | ||||

| Hlep59 | F: AATAAATGCTGCTGAAACAAACTC | 294–360 | 59 | FAM |

| R: GCTGTGCATTAGCCTCAAAG | ||||

| Hlep72 | F: GCCAAACCACTGCTATCC | 194–236 | 55 | ROX |

| R: GKGRTAATCCTAGCCACTTG | ||||

| Hph17 | F: GAGTCCAKKGCCAAAKGAGA | 158–186 | 59 | HEX |

| R: AGCCTGGAAACTAGGACAGTG | ||||

| ScnFO35 | F: GATGGACATCTGAAATAGTGAGA | 152–180 | 55 | ROX |

| R: ACACTGGGCTAAACAACAAA |

Amplifications were performed with a 20 μL reaction volume, containing 2 μL of 10× reaction buffer, 1.6 μL of 2.5 mmol/L dNTPs, 0.5 μL of 10 μmol/L each primer, 0.5 units of Ex Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa, Japan), and about 0.1 μg of template DNA. The PCR products were visualized via electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel. To precisely determine the length of each successfully amplified microsatellite locus, capillary electrophoresis was conducted using the ABI 3730XL sequencer (Applied Biosystems Inc., America). To make sure the obtained genotypes were highly accurate, we used a multi-tube PCR amplification protocol with three positive PCR amplifications per microsatellite locus. In three positive PCR amplifications, two distinct alleles appeared in at least two tests, so it was recorded as heterozygous. Moreover, the same allele appeared in all three tests, so it was recorded as homozygous [15,18]. The paired-end sequencing and genotyping work on all the amplified products were done by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

2.3 Data analysis

To evaluate population genetic diversity, we used Clustal X 2.1 [19] to align the mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences from different individuals. Then we adopted DnaSP 5.10 [20] to calculate the total number of mutation sites, the number of haplotypes, haplotype diversity (H d), and nucleotide diversity (P i). During the microsatellite data analysis, we used GenAlEx 6.0 [21] to calculate the number of alleles (N a) and the number of effective alleles (N e). We also calculated the observed heterozygosity (H o) and the expected heterozygosity (H e) in the populations. Additionally, using the Excel Microsatellite Toolkit v3.1 program (MS Tools) [22], we determined the polymorphic information content (PIC) of each locus and population.

With the microsatellite data, we evaluated the demographic history of populations and used the GenAlEx 6.0 [21] to compute the inbreeding coefficient (F is) in the population. We also used Genepop 4.0 with statistical tests to see if the real data fits Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium prediction. Deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was tested using Fisher’s exact tests with unbiased p-values derived by a Markov chain method [23]. To test recent genetic bottlenecks, we should first measure the deviations from expected heterozygosity under the assumption of mutation drift equilibrium. The Bottleneck 1.2 software was adopted in this process [24]. When choosing between the stepwise mutation model and the two-phase model (TPM), we found that TPM was the most suitable model for microsatellite analysis [25]. The data were then analyzed with the recommended settings [24].

To assess the structure of the population, we analyzed cytochrome b sequences. Arlequin 3.11 [26] was used to calculate the genetic differentiation coefficient (F ST) and associated p-value, gene flow (N m), and analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) between populations. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered a significant level of genetic differentiation. Network 4.6 [27] was used to build a median-joining network, and analyze the evolutionary relationship between haplotypes. Second, we conducted an in-depth analysis of the population structure using microsatellite data. Population differentiation was assessed using two methods. The first method was using traditional F ST to compare the observed averaged allele distributions among a priori defined four populations. F ST, p-value, N m, and AMOVA across the study area and between pairs of sampling sites were calculated using the GenAlEx 6.0 [21]. Although robust population structure analysis can be obtained with F ST, the a priori subdivision of populations can be very subjective and may greatly affect the estimates of population structure [28]. The second method implemented individual-based Bayesian clustering in the program STRUCTURE 2.3.4 [29], in which the number of potential genetic clusters (K) was inferred instead of defining populations as a priori. The most likely number of populations (K) was estimated by conducting 20 independent runs for K = 1–6 using a burn-in of 100,000 replications, 10,000 Markov chain Monte Carlo steps. The results from the STRUCTURE program were then uploaded to Structure Harvester Web [30] to analyze and visualize the output. The optimal K of population genetic structure was determined based on the maximum value of the ΔK and Ln Pr (X|K).

To check if genetic differentiation between sampling sites followed the isolation–by-distance (IBD) model, we performed the Mantel test in GenAlEx 6.0 [21]. During the tests, the significance of the regression between pairwise genetic distances, expressed as F ST/(1 − F ST), was assessed in relation to the natural log-transformed geographical distance [28]. Statistical significance was determined through 10,000 permutation tests.

3 Results

3.1 Genetic diversity

A total of 91 mtDNA cytochrome b sequences (1,140 bp) were analyzed. According to the results, there were 63 mutations, of which 25 were singleton variable sites and 38 were parsimony informative sites. With an average transition/transversion ratio of 33.5, the majority of base substitutions were transitions. There were no insertions or missing found. Among the 91 cytochrome b sequences, 48 distinct haplotypes were identified with 10, 14, 10, and 21 haplotypes found in the populations from Fangzheng, Bin County, Weihe, and Muling, respectively. According to the genetic diversity parameters, the average haplotype diversity (H d) across the populations was 0.955 (ranging from 0.859 to 0.980) and the average nucleotide diversity (P i) was 0.509% (ranging from 0.339 to 0.616%) (Table 3).

Genetic diversity of Siberian flying squirrel populations based on cytochrome b gene

| Population | Individual number | Haplotype number | Haplotype diversity | Nucleotide diversity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fangzheng | 20 | 10 | 0.863 | 0.339 |

| Bin County | 29 | 14 | 0.909 | 0.616 |

| Weihe | 15 | 10 | 0.859 | 0.376 |

| Muling | 27 | 21 | 0.980 | 0.530 |

| The whole population | 91 | 48 | 0.955 | 0.509 |

According to the microsatellite analysis, two populations – the Fangzheng and Bin County populations deviated significantly from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, which suggests a degree of heterozygote deficiency (p < 0.05). The inbreeding coefficients (F is) were positive for the Fangzheng and Bin County populations (F is = 0.008 and 0.046, respectively), while negative for the Weihe and Muling populations (F is = −0.061 and −0.066, respectively). The overall inbreeding coefficient was negative (F is = −0.018). This means inbreeding is occurring in the Fangzheng and Bin County populations (Table 4). Tests for genetic bottleneck showed that the Fangzheng population had a statistically significant bottleneck under the TPM model Wilcoxon test (p < 0.05), and the Bin County population was close to critical significance (p = 0.057), indicating that both populations had recent genetic bottlenecks.

Details of the studied microsatellite loci

| Population | N a | N e | H o | H e | PIC | F is | P HW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fangzheng | 12.4 | 8.8 | 0.869 | 0.898 | 0.864 | 0.008 | 0.015 |

| Bin County | 12.8 | 8.1 | 0.832 | 0.887 | 0.860 | 0.046 | 0.021 |

| Weihe | 12.0 | 8.5 | 0.925 | 0.903 | 0.861 | −0.061 | 0.999 |

| Muling | 14.4 | 8.8 | 0.921 | 0.882 | 0.853 | −0.066 | 0.982 |

| The whole population | 12.9 | 8.6 | 0.887 | 0.892 | 0.891 | −0.018 | 0.269 |

Mean number of different alleles (N a), mean number of effective alleles (N e), polymorphic information content (PIC), observed and expected heterozygosity (H o, H e), inbreeding coefficient value (F is), probability value for Hardy–Weinberg tests (P HW).

The PIC for the eight microsatellite loci ranged from 0.862 to 0.945, showing a high polymorphism (PIC > 0.5). The PIC values across the four populations ranged from 0.853 to 0.864, with an overall PIC of 0.891. On average, the number of alleles (N a) was 12.9 (ranging from 12.0 to 14.4), and the effective number of alleles (N e) was 8.6 (ranging from 8.1 to 8.8). The average effective number of alleles in the four populations was significantly lower than the observed allele number (p < 0.01). Across the populations, the average observed heterozygosity (H o) was 0.887 (ranging from 0.832 to 0.925), and the average unbiased expected heterozygosity (H e) was 0.892 (ranging from 0.882 to 0.903) (Table 4).

3.2 Population structure

The cytochrome b analysis showed that the genetic differentiation coefficient (F ST) among the populations ranged from 0.036 to 0.065. This is a significant genetic differentiation among the four geographic populations of Siberian flying squirrel (p < 0.05) (Table 5). The gene flow (N m) between the populations ranged from 7.18 to 13.22. According to the Mantel test, there was no significant correlation between genetic distance and geographical distance (r = −0.164, p > 0.05). The haplotype network diagram revealed a mixed distribution of haplotypes across the four geographic populations, without a clear systematic geographic pattern observed. Of the 48 haplotypes, only five (Hap5, Hap11, Hap15, Hap20, and Hap45) were shared between two or more populations. The genetic variation was not evenly distributed across the populations, as most of the haplotypes were found only in some specific geographic populations. In other words, 31 rare haplotypes, found in just one sample each, represented 64.58% of the total (Figure 2).

Pairwise genetic differentiation coefficient (F ST) (below diagonal) and associated p values (above diagonal) between populations based on cytochrome b gene

| Population | Fangzheng | Bin County | Weihe | Muling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fangzheng | 0.042 | 0.036 | 0.009 | |

| Bin County | 0.046 | 0.045 | 0.027 | |

| Weihe | 0.042 | 0.051 | 0.009 | |

| Muling | 0.065 | 0.036 | 0.046 |

Haplotype network for Siberian flying squirrel based on cytochrome b gene. The small hollow circles indicate missing haplotypes, and short bars crossing network branches indicate mutation steps.

According to the microsatellite analysis, the F ST values range from 0.017 to 0.060. Since all values had p < 0.05, the genetic differentiation among the four geographic populations were statistically significant (Table 6). The gene flow (N m) between the populations ranged from 3.92 to 14.46 (Table 7). The Mantel testing showed no significant positive correlation between genetic distance and geographical distance (r = 0.751, p > 0.05). According to the STRUCTURE analysis, the optimal grouping of the 91 samples was into three genetic clusters (K), as indicated by the highest values of ΔK and Ln Pr (X|K). These clusters matched the locations of Fangzheng, Bin County, and Weihe-Muling. This was closely aligned with the geographic distribution of the samples. However, there was notable gene flow (introgression) among the clusters, particularly between the Fangzheng population and the other two (Figures 3 and 4).

Pairwise genetic differentiation coefficient (F ST) (below diagonal) and associated p values (above diagonal) between populations based on microsatellite loci

| Population | Fangzheng | Bin County | Weihe | Muling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fangzheng | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | |

| Bin County | 0.039 | 0.030 | 0.001 | |

| Weihe | 0.027 | 0.017 | 0.012 | |

| Muling | 0.060 | 0.049 | 0.020 |

Gene flow (N m) (below diagonal) and geographical distance (km) (above diagonal) between populations based on microsatellite loci

| Population | Fangzheng | Bin County | Weihe | Muling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fangzheng | 139.8 | 133.2 | 183.6 | |

| Bin County | 6.16 | 115.9 | 253.9 | |

| Weihe | 9.01 | 14.46 | 147.1 | |

| Muling | 3.92 | 4.85 | 12.25 |

Changing trends of Ln Pr(X|K) and Delta K from STRUCTURE clustering results for the microsatellite.

Bayesian clustering result (K = 3) of Siberian flying squirrel populations for the microsatellite. Each individual (n = 91) is represented by a vertical bar, and the proportions of different colors in the bars are the probability an individual assigned to a certain population. Numbers at the bottom of the graph correspond to the numbers of individual for the sampling estates.

4 Discussion

Since modern times, frequent forest harvesting activities and rapid urbanization in Northeast China have reduced the habitat of Siberian flying squirrel, leading to great changes in its genetic diversity and population structure. Genetic diversity is a fundamental aspect of biodiversity, and understanding its levels, formation, and distribution patterns can help to understand the origin and evolution of this species. It also indicates a species’ ability to adapt to its environment and its potential for future evolution. With our analysis, we can make well-planned and scientifically supported approaches aimed at preserving biodiversity, protecting ecosystems, and ensuring the long-term survival of species [31,32]. Two key metrics in assessing genetic diversity are haplotype diversity (H d) and nucleotide diversity (P i). While H d measures the variety of distinct haplotypes within a population, P i provides a more accurate measure by considering the frequency of these haplotypes. It more accurately reflects the genetic variability within the population [15,33]. In this study, the P i for the Siberian flying squirrel populations was found to be 0.509%. This value is lower than that observed in the Russian Primorye population (P i = 0.950%) and slightly below the Korean population (P i = 0.616%). However, it is significantly higher than the populations in Estonia (P i = 0), Finland (P i = 0.027%), Karelia in Russia (P i = 0.097%), and Hokkaido, Japan (P i = 0.219%) [10,34,35]. This indicates that the Siberian flying squirrel populations in the northern Changbai Mountains show a relatively high genetic diversity compared to other regions. The observed values of haplotype diversity (H d = 0.955) and nucleotide diversity (P i = 0.509%) meet the criteria for populations with high genetic diversity (H d ≥ 0.5, P i ≥ 0.5%) [36,37]. Furthermore, microsatellite analysis revealed that the average observed heterozygosity (H o) and expected heterozygosity (H e) for these populations were 0.887 and 0.892, respectively. These values are notably higher than those reported for populations in Finland (H o = 0.410–0.772, H e = 0.430–0.748) and Estonia (H o = 0.608, H e = 0.764) [10,34,38]. These results indicate that the Siberian flying squirrel populations in the northern Changbai Mountains have a high genetic diversity, a strong capacity to adapt to environmental changes, and a good evolutionary potential. The analysis provides a solid foundation for future efforts to preserve the species’ resilience and long-term survival.

The study suggests that populations from refugia during glacial periods tend to have higher genetic diversity compared to populations in other areas [39,40]. The Siberian flying squirrel population observed in this study shows notably higher genetic diversity than foreign populations. This implies that the Changbai Mountain may have provided sanctuary for these squirrels when much of their typical forest habitat was rendered uninhabitable during the ice age. Based on the analysis of the cytochrome b gene, we have identified three distinct genetic lineages of Siberian flying squirrel: the Far Eastern lineage, Northern Eurasian lineage, and Hokkaido (Japan) lineage. Populations from regions belonging to the Far Eastern lineage, such as Heilongjiang in China, Korea, and the Russian Primorye, all display high levels of genetic diversity than other lineages [15,41]. Multiple refugia for Siberian flying squirrel are proposed to have existed across Eurasia during the Quaternary glaciations, with these populations then expanding over northern Eurasia following the ice age, hence influencing the geographic distribution of lineages of present days. Arboreal species, which rely on forested environments for shelter and food, would have been confined to the remaining forested areas during the Pleistocene. Thus, the refugia of arboreal species like the Siberian flying squirrel may have been more dependent on forest dynamics than terrestrial rodents [41]. According to phylogeographic studies, during the Last Glacial Maximum, certain regions in Northeast Asia, specifically the Changbai Mountains, the Korean Peninsula, and the Russian Far East, may have mixed coniferous-broadleaf forests, which provided stable refugia [42]. This further supports our observation of high genetic diversity in the populations of the Far Eastern lineage. Despite the high genetic diversity of the population studied, a high proportion of rare haplotypes in the cytochrome b gene (31/48) was also detected. In addition, the number of effective alleles at microsatellite loci was significantly lower than the actual number of alleles (p < 0.01). This indicates a risk of haplotype and allele loss in future population development. The high proportion of rare haplotypes and alleles in the population may be a sign of genetic bottlenecks and inbreeding, where the flying squirrel population is drastically reduced. This hypothesis is further confirmed by genetic bottlenecks and inbreeding observed in the Fangzheng and Bin County populations. Therefore, it is important to further protect and manage Siberian flying squirrel populations in Northeast China against the decrease in genetic diversity.

Genetic differentiation and gene flow are crucial indicators for evaluating the genetic structure of populations [43]. The genetic differentiation coefficient, F ST, is used to assess the genetic divergence between populations. F ST ≤ 0.05 indicates low genetic differentiation; 0.05 < F ST ≤ 0.15 reflects moderate genetic differentiation; and F ST > 0.15 represents great genetic differentiation between populations [44]. In this study, the F ST values from two molecular markers reveal significant, low, or moderate levels of genetic differentiation among the four geographical populations of Siberian flying squirrel. Mantel tests failed to detect the correlation between genetic and geographical distances. This suggests that the IBD model does not fully explain the current genetic structure of the populations, so we need to evaluate isolation-by-environment factors. The species’ dispersal ability and the landscape configuration are among the most important factors that influence population genetic structure [15,28,37]. Although Siberian flying squirrel is a gliding species, it has a relatively weak dispersal ability for its small size. Thus, it is more susceptible to the effects of environmental isolation [7,34]. According to the STRUCTURE results, the populations of Weihe and Muling in the southern part of the study area form a distinct genetic cluster. This suggests that there is frequent gene flow between these two populations. Although a portion of the Ning’an farmland is located between the Weihe and Muling populations, continuous forest on both the northern and southern sides of this region act as natural corridors that facilitate the movement of individuals between the two populations. In contrast, the presence of agricultural land corridors in the northern regions, especially between Fangzheng and Shangzhi, along with extensive road networks acts as barriers that limit the movement of the Siberian flying squirrel populations. Studies have also shown that habitat fragmentation is more severe in the northern regions [45], which further restricts individual dispersal and gene flow between the northern populations and those in the south (Figure 1).

There is a noticeable genetic differentiation among populations of the Siberian flying squirrel, but the gene flow (N m) values between populations all exceed 1.0, and the haplotype network shows a mixed distribution of haplotypes. This suggests that these groups of flying squirrels have only recently become isolated. There has not been sufficient time for the populations to form a monophyletic group. Similar genetic patterns have been observed among populations in Estonia, Russian Karelia, and Finland, which can be attributed to the widespread deforestation that has taken place in these areas [34]. As a typical arboreal forest species that primarily nests in tree cavities, the Siberian flying squirrel populations are highly susceptible to habitat changes [2]. However, the mature forest habitats that they rely on for nesting and foraging have quickly shrunk in recent years, due to the rapid growth in population, logging, agriculture, road construction, and urban development in Northeast China. Field surveys have revealed that the Siberian flying squirrel’s activity is now difficult to detect in many forested areas [15]. The significant genetic differentiation, isolation among populations, and impeded gene flow can lead to a decline in genetic diversity. Thus, we need to carry out fundamental ecological research on Siberian flying squirrel to analyze its population size, distribution patterns, habitat preferences, and evaluations of their status. Moreover, landscape genetics approaches are also essential to identify the environmental factors that affect genetic differentiation. To enhance population growth and genetic exchange of the Siberian flying squirrel, conservation efforts should prioritize the development of landscape-friendly forest areas. This involves integrating natural habitat restoration with targeted artificial interventions such as installing nest boxes, creating crossing structures, and implementing rewilding programs [46,47]. Additionally, improving habitat suitability and connectivity is essential to prevent further decline in genetic diversity and fitness resulting from genetic differentiation.

5 Conclusion

The populations of the Siberian flying squirrel located in the Changbai Mountains show a high genetic diversity, indicating that the Changbai Mountains may have served as a glacial refugium during the last ice age. However, due to the decline and fragmentation of suitable habitats, the populations have also experienced severe genetic differentiation, a high proportion of rare haplotypes and alleles, genetic bottlenecks, and inbreeding. The IBD alone may not adequately account for the limited gene flow between populations. Therefore, future research should further assess isolation by environment as a complementary approach. To enhance gene exchange among individuals and accelerate population recovery, it is essential to restore the habitats of the Siberian flying squirrel and build more ecological corridors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Wenlong Jiao and Long Yang for their help in collecting hair samples. They would also like to thank the leaders and all staff of Heilongjiang Provincial Forest Department for their strong support and assistance in this research.

-

Funding information: This study was supported by the Natural Science Fund of Heilongjiang Province (no. LH2022C101), the Heilongjiang Provincial Basic Research Business Support Project (no. 1453ZD021), and the Mudanjiang Normal College Project (no. MNUGP202302).

-

Author contributions: Xinmin Tian: conception, design and analysis of data, performed the field sample collection, data analyses, and wrote the manuscript; Lanying Shi, Xiaozhen Bai, and Ze Wang: contributed to the field sample collection and experimental analysis. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Wei FW, Yang QS, Wu Y, Jiang XL, Liu SY, Hu YB, et al. Catalogue of mammals in China (2024). Acta Theriol Sin. 2025;45(1):1–16 Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Lim SJ, Kim KY, Kim EK, Han CW, Park YC. Distribution and habitat use of the endangered Siberian flying squirrel Pteromys volans (Rodentia: Sciuridae). J Ecol Env. 2021;45(4):163–9.10.1186/s41610-021-00190-1Search in Google Scholar

[3] Hurme E, Monkkonen M, Sippola AL, Ylinen H, Pentinsaari M. Role of the Siberian flying squirrel as an umbrella species for biodiversity in northern boreal forests. Ecol Indic. 2007;8(3):246–55.10.1016/j.ecolind.2007.02.001Search in Google Scholar

[4] Jiang ZG, Wu Y, Liu SY, Jiang XL, Zhou KY, Hu HJ, et al. China’s red list of biodiversity vertebrates (Vol. I): mammals. Beijing: Science Press; 2021 Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Hoset KS, Villers A, Wistbacka R, Selonen V. Pulsed food resources, but not forest cover, determine lifetime reproductive success in a forest-dwelling rodent. J Anim Ecol. 2017;86(5):1235–45.10.1111/1365-2656.12715Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Kim JS, Jeon JH, Lee WS, Kim JU. Morphological characteristics of Siberian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans): sexual dimorphism and comparison of morphological characteristics in different latitudes. J Korean Soc Sci. 2019;108(1):133–7.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Lim CW, Kim SC, Shin G, Jeon YS, Lee R, Chung CU. Study on home range of Siberian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans) using GPS tag. J Environ Sci Int. 2024;33(6):427–34.10.5322/JESI.2024.33.6.427Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kikuchi H, Akasaka T, Asari Y, Yanagawa H, Oshida T. Communal nesting behaviour of Siberian flying squirrels during the non-winter season. Ethology. 2023;129(10):499–506.10.1111/eth.13386Search in Google Scholar

[9] Ahtikoski A, Nikula A, Nivala V, Haikarainen S, Juutinen A. Cost-efficient forest management for safeguarding Siberian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans) habitats in Central Finland. Scand J Res. 2023;38(4):197–207.10.1080/02827581.2023.2208875Search in Google Scholar

[10] Lampila S, Kvist L, Wistbacka R, Orell M. Genetic diversity and population differentiation in the endangered Siberian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans) in a fragmented landscape. Eur J Wildl Res. 2009;55(4):397–406.10.1007/s10344-009-0259-2Search in Google Scholar

[11] Yalkovskaya LE, Bol’shakov VN, Sibiryakov PA, Borodin AV. Phylogeography of the Siberian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans L., 1785) and the history of the formation of the modern species range: new data. Dokl Biochem Biophys. 2015;462(1):181–4.10.1134/S1607672915030114Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Chen L. Study on the insulation mechanism of tree cavities, as exampled from wintering cavity of Pteromys volans in northern Greater Hingan Mt’s. PhD thesis. Harbin: Northeast Forestry University; 2018 Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Tian XM, Sha ST, Yang MP, Lian MD, Shi LY. Effects of photoperiods on activity rhythm of Pteromys volans. Hubei Agric Sci. 2020;59(14):8–11 Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Tian XM, Yang MP, Song YQ, Liu XH, Lian MD, Chen H. Microsatellite loci screening and genetic characterization of Pteromys volans. Chin J Wildl. 2022;43(2):379–85 Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Tian XM, Lian MD, Song YQ, Liu XH, Yang MP, Chen H. Genetic diversity and demographic history of Siberian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans) population in northern Zhangguangcai Mountains, Heilongjiang, China. Acta Theriol Sin. 2022;42(4):398–409 Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Tian XM. Studies on population genetics and factors driving differentiation of Cervus canadensis xanthopygus. PhD thesis. Harbin: Northeast Forestry University; 2021 Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Chen SY, Holyoak M, Liu H, Bao H, Ma YJ, Dou HJ, et al. Effects of spatially heterogeneous warming on gut microbiota, nutrition and gene flow of a heat-sensitive ungulate population. Sci Total Environ. 2022;806:150537.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150537Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Wang D, Zhang D, Bu HL, Hopkins JB, Xiong MY, Wang DJ, et al. Estimating the population size of masked palm civets using hair-snaring in Southwest China. Diversity. 2024;16(7):421.10.3390/d16070421Search in Google Scholar

[19] Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(11):2947–8.10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1451–2.10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Peakall R, Smouse PE. GENALEX 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol Ecol Notes. 2006;6(1):288–95.10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005.01155.xSearch in Google Scholar

[22] Park SDE. Trypanotolerance in West African cattle and the population genetic effects of selection. Ph D thesis. Dublin: University of Dublin; 2001.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Raymond M, Rousset F. GENEPOP (version 1.2): population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J Hered. 1995;86(3):248–9.10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111573Search in Google Scholar

[24] Piry S, Luikart G, Cornuet JM. BOTTLENECK: a computer program for detecting recent reductions in the effective size using allele frequency data. J Hered. 1999;90(4):502–3.10.1093/jhered/90.4.502Search in Google Scholar

[25] Vinod U, Punyakumari B, Sushma G, Cherryl DM. Molecular evidences of mutation-drift equilibrium in Punganur breed of cattle. J Livest Sci. 2024;15(2):174–80.10.33259/JLivestSci.2024.174-180Search in Google Scholar

[26] Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S. Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol Bioinform. 2005;1:47–50.10.1177/117693430500100003Search in Google Scholar

[27] Pukhrambam M, Dutta A, Das PJ, Chanda A, Sarkar M. Phylogenetic and population genetic analysis of Arunachali Yak (Bos grunniens) using mitochondrial DNA D-loop region. Mol Biol Rep. 2024;51(1):1125.10.1007/s11033-024-10076-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Pérez-Espona S, Pérez-Barbería FJ, Mcleod JE, Jiggins CD, Gordon IJ, Pemberton JM. Landscape features affect gene flow of Scottish Highland red deer (Cervus elaphus). Mol Ecol. 2008;17(4):981–96.10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03629.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155(2):945–59.10.1093/genetics/155.2.945Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Earl DA, vonHoldt BM. Structure harvester: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour. 2012;4(2):359–61.10.1007/s12686-011-9548-7Search in Google Scholar

[31] Snead AA, Tatarenkov A, Taylor DS, Marson K, Earley RL. Centrality to the metapopulation is more important for population genetic diversity than habitat area or fragmentation. Biol Lett. 2024;20(7):20240158.10.1098/rsbl.2024.0158Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Hoban S, Paz-Vinas I, Shaw RE, Castillo-Reina L, Silva JMDA, Dewoody JA, et al. DNA-based studies and genetic diversity indicator assessments are complementary approaches to conserving evolutionary potential. Conserv Genet. 2024;25:1147–53.10.1007/s10592-024-01632-8Search in Google Scholar

[33] Clark RD, Pinsky ML. Global patterns of nuclear and mitochondrial genetic diversity in marine fishes. Ecol Evol. 2024;14(5):e11365.10.1002/ece3.11365Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Nummert G, Aaspollu A, Kuningas K, Timm U, Hanski IK, Maran T. Genetic diversity in Siberian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans) in its western frontier with a focus on the Estonian population. Mammal Res. 2020;65(4):767–78.10.1007/s13364-020-00509-8Search in Google Scholar

[35] Lee MY, Park SK, Hong YJ, Kim YJ, Voloshina I, Myslenkov A, et al. Mitochondrial genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships of Siberian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans) populations. ACS. 2008;12(4):269–77.10.1080/19768354.2008.9647182Search in Google Scholar

[36] Grant WS, Bowen BW. Shallow population histories in deep evolutionary lineages of marine fishes: insights from sardines and anchovies and lessons for conservation. J Hered. 1998;89(5):415–26.10.1093/jhered/89.5.415Search in Google Scholar

[37] Xiong DM, Meng YX, Zhang XM, Wang JL, Feng GP, Shao J, et al. The validity of species of Brachymystax tsinlingensis Li based on mitochondria control region and microsatellite. Acta Hydrobiol Sin. 2023;47(5):809–18 Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Selonen V, Painter JN, Hanski IK. Microsatellite variation in the Siberian flying squirrel in Finland. Ann Zool Fenn. 2005;42(5):505–11.Search in Google Scholar

[39] García-Rodríguez O, Hardouin EA, Pedreschi D, Richards MB, Stafford R, Searle JB, et al. Contrasting patterns of genetic diversity in European mammals in the context of glacial refugia. Diversity. 2024;16(10):611.10.3390/d16100611Search in Google Scholar

[40] Márquez AM, Ríncon ROM, Guzmán RH, De León FJG. Implications of the Last Glacial Maximum on the genetic diversity of six co-distributed taxa in the Baja California Peninsula. J Biogeogr. 2025;52(4):e15075.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Oshida T, Abramov A, Yanagawa H. Phylogeography of the Russian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans): implication of refugia theory in arboreal small mammal of Eurasia. Mol Ecol. 2005;14(4):1191–6.10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02475.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Ye JW, Yuan YG, Cai L, Wang XJ. Research progress of phylogeographic studies of plant species in temperate coniferous and broadleaf mixed forests in Northeastern China. Biodiv Sci. 2017;25(12):1339–49 Chinese.10.17520/biods.2017265Search in Google Scholar

[43] Wang JC, Xu TJ, Xu W, Zhang GJ, You YJ, Ruan HH, et al. Impact of urban landscape pattern on the genetic structure of Thereuopoda clunifera population in Nanjing, China. Biodiv Sci. 2025;33(1):24251 Chinese.10.17520/biods.2024251Search in Google Scholar

[44] Zhang Z, Zhang R, Li XY, Sai H, Yang ZD, Han ZQ, et al. Genetic diversity and sex structure of red deer population in Saihanwula Nature Reserve, Inner Mongolia. Acta Theriol Sin. 2021;41(1):42–50 Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Qi JZ, Gu JY, Ning Y, Miquelle DG, Holyoak M, Wen DS, et al. Integrated assessments call for establishing a sustainable meta-population of Amur tigers in northeast Asia. Biol Conserv. 2021;261(12):109250.10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109250Search in Google Scholar

[46] Kim KY, Lim SJ, Hong MJ, Kim HR, Kim EK, Park YC. Artificial nest usage patterns of the endangered Siberian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans) released in natural habitat. Sci Technol. 2021;17(4):225–31.10.1080/21580103.2021.2007172Search in Google Scholar

[47] Howard JM. Gap crossing in flying squirrels: mitigating movement barriers through landscape management and structural implementation. Forests. 2022;13(12):2027.10.3390/f13122027Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome with elevated IgG4 and T-cell clonality: A report of two cases

- Electroacupuncture alleviates sciatic nerve injury in sciatica rats by regulating BDNF and NGF levels, myelin sheath degradation, and autophagy

- Polydatin prevents cholesterol gallstone formation by regulating cholesterol metabolism via PPAR-γ signaling

- RNF144A and RNF144B: Important molecules for health

- Analysis of the detection rate and related factors of thyroid nodules in the healthy population

- Artesunate inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion through OGA-mediated O-GlcNAcylation of ZEB1

- Endovascular management of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: Case report and review of the literature

- Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis

- SATB2 promotes humeral fracture healing in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Overexpression of the ferroptosis-related gene, NFS1, corresponds to gastric cancer growth and tumor immune infiltration

- Understanding risk factors and prognosis in diabetic foot ulcers

- Atractylenolide I alleviates the experimental allergic response in mice by suppressing TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 signalling

- FBXO31 inhibits the stemness characteristics of CD147 (+) melanoma stem cells

- Immune molecule diagnostics in colorectal cancer: CCL2 and CXCL11

- Inhibiting CXCR6 promotes senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells with limited proinflammatory SASP to attenuate hepatic fibrosis

- Cadmium toxicity, health risk and its remediation using low-cost biochar adsorbents

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis with headache as the first presentation: A case report

- Solitary pulmonary metastasis with cystic airspaces in colon cancer: A rare case report

- RUNX1 promotes denervation-induced muscle atrophy by activating the JUNB/NF-κB pathway and driving M1 macrophage polarization

- Morphometric analysis and immunobiological investigation of Indigofera oblongifolia on the infected lung with Plasmodium chabaudi

- The NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex and Hr78 modulate the Lobe2 mutant eye phenotype

- Experimental study on salmon demineralized bone matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: In vitro and in vivo study

- A case of IgA nephropathy treated with a combination of telitacicept and half-dose glucocorticoids

- Analgesic and toxicological evaluation of cannabidiol-rich Moroccan Cannabis sativa L. (Khardala variety) extract: Evidence from an in vivo and in silico study

- Wound healing and signaling pathways

- Combination of immunotherapy and whole-brain radiotherapy on prognosis of patients with multiple brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study

- To explore the relationship between endometrial hyperemia and polycystic ovary syndrome

- Research progress on the impact of curcumin on immune responses in breast cancer

- Biogenic Cu/Ni nanotherapeutics from Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl seeds for the treatment of lung cancer

- Dapagliflozin attenuates atrial fibrosis via the HMGB1/RAGE pathway in atrial fibrillation rats

- Glycitein alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in keratinocytes via ROS-associated PI3K–Akt signalling pathway

- ADH5 inhibits proliferation but promotes EMT in non-small cell lung cancer cell through activating Smad2/Smad3

- Apoptotic efficacies of AgNPs formulated by Syzygium aromaticum leaf extract on 32D-FLT3-ITD human leukemia cell line with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Novel cuproptosis-related genes C1QBP and PFKP identified as prognostic and therapeutic targets in lung adenocarcinoma

- Bee venom promotes exosome secretion and alters miRNA cargo in T cells

- Treatment of pure red cell aplasia in a chronic kidney disease patient with roxadustat: A case report

- Comparative bioinformatics analysis of the Wnt pathway in breast cancer: Selection of novel biomarker panels associated with ER status

- Kynurenine facilitates renal cell carcinoma progression by suppressing M2 macrophage pyroptosis through inhibition of CASP1 cleavage

- RFX5 promotes the growth, motility, and inhibits apoptosis of gastric adenocarcinoma cells through the SIRT1/AMPK axis

- ALKBH5 exacerbates early cardiac damage after radiotherapy for breast cancer via m6A demethylation of TLR4

- Phytochemicals of Roman chamomile: Antioxidant, anti-aging, and whitening activities of distillation residues

- Circadian gene Cry1 inhibits the tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma by the BAX/BCL2-mediated apoptosis pathway

- The TNFR-RIPK1/RIPK3 signalling pathway mediates the effect of lanthanum on necroptosis of nerve cells

- Longitudinal monitoring of autoantibody dynamics in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing surgery

- The potential role of rutin, a flavonoid, in the management of cancer through modulation of cell signaling pathways

- Construction of pectinase gene engineering microbe and its application in tobacco sheets

- Construction of a microbial abundance prognostic scoring model based on intratumoral microbial data for predicting the prognosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Sepsis complicated by haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis triggered by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and human herpesvirus 8 in an immunocompromised elderly patient: A case report

- Sarcopenia in liver transplantation: A comprehensive bibliometric study of current research trends and future directions

- Advances in cancer immunotherapy and future directions in personalized medicine

- Can coronavirus disease 2019 affect male fertility or cause spontaneous abortion? A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis

- Heat stroke associated with novel leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor gene variant in a Chinese infant

- PSME2 exacerbates ulcerative colitis by disrupting intestinal barrier function and promoting autophagy-dependent inflammation

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state with severe hypernatremia coexisting with central diabetes insipidus: A case report and literature review

- Efficacy and mechanism of escin in improving the tissue microenvironment of blood vessel walls via anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects: Implications for clinical practice

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Clinicopathological analysis of three patients and literature review

- Genetic variants in VWF exon 26 and their implications for type 1 Von Willebrand disease in a Saudi Arabian population

- Lipoxin A4 improves myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through the Notch1-Nrf2 signaling pathway

- High levels of EPHB2 expression predict a poor prognosis and promote tumor progression in endometrial cancer

- Knockdown of SHP-2 delays renal tubular epithelial cell injury in diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis

- Exploring the toxicity mechanisms and detoxification methods of Rhizoma Paridis

- Concomitant gastric carcinoma and primary hepatic angiosarcoma in a patient: A case report

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Optimization and comparative study of Bacillus consortia for cellulolytic potential and cellulase enzyme activity

- The complete mitochondrial genome analysis of Haemaphysalis hystricis Supino, 1897 (Ixodida: Ixodidae) and its phylogenetic implications

- Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors analysis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among tuberculosis population in Huzhou City, Eastern China

- Indices of human impacts on landscapes: How do they reflect the proportions of natural habitats?

- Genetic analysis of the Siberian flying squirrel population in the northern Changbai Mountains, Northeast China: Insights into population status and conservation

- Diversity and environmental drivers of Suillus communities in Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica forests of Inner Mongolia

- Global assessment of the fate of nitrogen deposition in forest ecosystems: Insights from 15N tracer studies

- Fungal and bacterial pathogenic co-infections mainly lead to the assembly of microbial community in tobacco stems

- Influencing of coal industry related airborne particulate matter on ocular surface tear film injury and inflammatory factor expression in Sprague-Dawley rats

- Temperature-dependent development, predation, and life table of Sphaerophoria macrogaster (Thomson) (Diptera: Syrphidae) feeding on Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae)

- Eleonora’s falcon trophic interactions with insects within its breeding range: A systematic review

- Agriculture

- Integrated analysis of transcriptome, sRNAome, and degradome involved in the drought-response of maize Zhengdan958

- Variation in flower frost tolerance among seven apple cultivars and transcriptome response patterns in two contrastingly frost-tolerant selected cultivars

- Heritability of durable resistance to stripe rust in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Molecular mechanism of follicular development in laying hens based on the regulation of water metabolism

- Animal Science

- Effect of sex ratio on the life history traits of an important invasive species, Spodoptera frugiperda

- Plant Sciences

- Hairpin in a haystack: In silico identification and characterization of plant-conserved microRNA in Rafflesiaceae

- Widely targeted metabolomics of different tissues in Rubus corchorifolius

- The complete chloroplast genome of Gerbera piloselloides (L.) Cass., 1820 (Carduoideae, Asteraceae) and its phylogenetic analysis

- Field trial to correlate mineral solubilization activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and biochemical content of groundnut plants

- Correlation analysis between semen routine parameters and sperm DNA fragmentation index in patients with semen non-liquefaction: A retrospective study

- Plasticity of the anatomical traits of Rhododendron L. (Ericaceae) leaves and its implications in adaptation to the plateau environment

- Effects of Piriformospora indica and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on growth and physiology of Moringa oleifera under low-temperature stress

- Effects of different sources of potassium fertiliser on yield, fruit quality and nutrient absorption in “Harward” kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa)

- Comparative efficiency and residue levels of spraying programs against powdery mildew in grape varieties

- The DREB7 transcription factor enhances salt tolerance in soybean plants under salt stress

- Using plant electrical signals of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) for water pollution monitoring

- Food Science

- Phytochemical analysis of Stachys iva: Discovering the optimal extract conditions and its bioactive compounds

- Review on role of honey in disease prevention and treatment through modulation of biological activities

- Computational analysis of polymorphic residues in maltose and maltotriose transporters of a wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain

- Optimization of phenolic compound extraction from Tunisian squash by-products: A sustainable approach for antioxidant and antibacterial applications

- Liupao tea aqueous extract alleviates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in rats by modulating the gut microbiota

- Toxicological qualities and detoxification trends of fruit by-products for valorization: A review

- Polyphenolic spectrum of cornelian cherry fruits and their health-promoting effect

- Optimizing the encapsulation of the refined extract of squash peels for functional food applications: A sustainable approach to reduce food waste

- Advancements in curcuminoid formulations: An update on bioavailability enhancement strategies curcuminoid bioavailability and formulations

- Impact of saline sprouting on antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds in chia seeds

- The dilemma of food genetics and improvement

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Impact of hyaluronic acid-modified hafnium metalorganic frameworks containing rhynchophylline on Alzheimer’s disease

- Emerging patterns in nanoparticle-based therapeutic approaches for rheumatoid arthritis: A comprehensive bibliometric and visual analysis spanning two decades

- Application of CRISPR/Cas gene editing for infectious disease control in poultry

- Preparation of hafnium nitride-coated titanium implants by magnetron sputtering technology and evaluation of their antibacterial properties and biocompatibility

- Preparation and characterization of lemongrass oil nanoemulsion: Antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant, and anticancer activities

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells”

- Corrigendum to “Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans”

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Down-regulation of miR-539 indicates poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer”

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling