Abstract

The current work has further elucidated the expression and functional implication of cysteine desulfurase (NFS1) in gastric cancer (GC), the prognostic value, and therapeutic target because of the interaction with tumor immune infiltration and ferroptosis. Transcriptomic data from TCGA and GTEX were analyzed to assess mRNA expression and survival correlation with NFS1 among GC patients. A total of 152 GC cases were retrospectively analyzed. The level of NFS1 expression was upregulated in GC tissues compared to non-tumor gastric tissues, which was related to clinical characteristics and poor prognosis. Downregulation of the NFS1 protein in the GC cell line had an adverse effect on the migration, invasion, and proliferation of cells. In addition, NFS1 and immune correlation analysis showed that the level of NFS1 expression was related to a variety of immune cells and characteristics of the immune microenvironment. Based on functional enrichment analysis, NFS1 may have a role in ferroptosis and the tumor microenvironment (TME), such as epithelial–mesenchymal transition control, and the stromal and immunologic responses. NFS1 is a potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker linked to ferroptosis and the TME, and provides a novel target for cancer treatment and immunotherapy.

1 Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is still one of the most common and lethal types of cancers worldwide [1]. The burden from this disease is highest in China, accounting for approximately one-half of the new cases worldwide (total = 478,000) [2,3]. Most patients are diagnosed at a late stage and therefore miss the optimal surgical window for disease intervention [4,5]. Consequently, the detection of characteristic biomarkers at an early stage is essential for improving prognosis.

Cysteine desulfurase (NFS1), a ferroptosis suppressor, is the product of a gene located on human chromosome 20q11.22, which helps catalyze the release of sulfur from cysteine to produce an iron–sulfur cluster (ISC) assembly [6,7]. NFS1 is involved in the biosynthesis of ISCs, which are essential in various cellular processes, including maintaining iron homeostasis. Previous research has demonstrated that the ISC enzyme, NFS1, functions as a ferroptosis suppressor involved in ferroptosis and tumor growth [8,9,10,11,12]. Targeting NFS1 to induce ferroptosis has been under investigation as a potential therapeutic strategy in several types of cancers [13].

Because NFS1 can inhibit ferroptosis, targeting NFS1 might enhance treatment efficiency by increasing cancer cell death. Recent studies have shown that NFS1 is highly expressed in GC tissues and is related to a poor prognosis [14]. NFS1 inhibits ferroptosis in GC by upregulating the STAT3 signaling pathway. This inhibition helps GC cells survive and proliferate, making NFS1 a potential target for therapeutic strategies aimed at inducing ferroptosis to combat GC [14]. Knockdown of NFS1 increases the sensitivity of colorectal cancer cells to the ferroptosis inducer, RSL3, and the chemotherapeutic drug, oxaliplatin, enhancing treatment outcomes [15,16]. Previous research has highlighted that high expression of NFS1 is related to poor prognosis [6,17,18,19], which makes NFS1 a potentially good target for early diagnosis and therapeutic intervention in GC.

Few studies have investigated NFS1 in GC patients. The current study was designed to determine the expression of NFS1 in GC tissues, observe the impact of NFS1 downregulation on GC cells, and analyze the relationship with clinical features and the prognostic value.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 NFS1 mRNA expression analysis

Transcriptomic data, including mRNA and clinical information, were obtained from the Cancer Genome Atlas database (TCGA [https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov]) and the Genotype-Tissue Expression database (GTEX [https://gtexportal.org/home/]). The Kaplan–Meier Plotter (https://kmplot.com/analysis/) was used to determine the relationship between NFS1 mRNA expression and overall survival (OS) in GC patients. mRNA sequencing data from level 3 in the HTSeq-TPM format were converted to the TPM format for further analysis. Statistical analysis and visualization were performed using R (version 4.2.1) and the ggplot2 package.

2.2 Tissue microarrays and immunohistochemical analysis

A total of 152 (46 males and 106 females) GC and paired adjacent tissues were obtained from patients who received treatment in the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University (Nantong, China) between 2005 and 2010 to evaluate NFS1 expression in relation to clinicopathologic features. Patients were divided into two groups (high and low/no expression) based on the status of NFS1 expression. The following information was collected: gender, age, and tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage (tumor invasion [T], lymph node involvement [N], and metastasis [M]). Patients were grouped by age (<60 years [n = 37] and ≥60 years (n = 115). The TNM staging classified the patients into TNM stages I/II (n = 55) and III/IV (n = 97). Tumor invasion was as follows: Tis/T1/T2 (n = 40) and T3/T4 (n = 112). Lymph node involvement was categorized as N0 (n = 35), N1a (n = 31), N1b (n = 37), and N2a/b (n = 49). Metastasis was classified as M0 (n = 118) and M1 (n = 34). None of the patients had preoperative radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy.

Clinical data and follow-up information were retrieved from medical records. Tissue specimens of gastric tissues were paraffin-embedded, and tissue specimens were constructed. Immunohistochemical staining was performed to detect NFS1 expression. Tissue specimen chips were dewaxed and dehydrated, and treated with antigen retrieval using 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a microwave. Inhibition of endogenous peroxidase activity was achieved using 3% H2O2 for 10 min. Sections were incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies to NFS1 (MG815491S, 1:150 dilution; ABmart), followed by incubation with the secondary antibodies. The nuclei were stained with hematoxylin. NFS1 expression was evaluated using a Vectra Automated Quantitative Pathology Imaging System (version 3.0; PerkinElmer, USA). The degree of staining was rated as follows: 0 (no staining), 1 (pale yellow), 2 (brown-yellow), and 3 (tan). The percentage of positively stained cells was multiplied by the intensity score to provide a final immunohistochemistry score ranging from 0 to 300. Three biological and technical replicates were used for each assay.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to human use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the authors' institutional review board or equivalent committee and has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University (Approval Number: 2022-L025).

2.3 Cell culture and NFS1 knockdown

The HGC-27, AGS, MKN-1, and BGC-823 human GC cell lines and the normal gastric epithelial cell line, GES-1, were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Corning, Manassas, VA, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), and incubated in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting NFS1 for NFS1 knockdown (designed and synthesized by GenePharma). The siRNA sequences targeting NFS1 were as follows: si-NFS1-1 (5′-CCCTTACCTAATCAACTACTATG-3′) and si-NFS1-2 (5′-ATCCAACAACATAGCAATTAAGG-3′). GC cells were seeded at 50–60% confluence in 6-well plates before transfection using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were subsequently subjected to cell collection for use in western blot analysis, as well as invasion and migration assays.

2.4 Cell proliferation and colony formation assays

The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) was used to evaluate the number of proliferating viable cells. The transfected cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 1 × 103 cells/well and incubated for the specified length of time. CCK-8 solution (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was added to each well, and the cells were subsequently incubated at 37°C. Two hours after administering the CCK-8 reagent, every 24 h thereafter, cell vitality was evaluated at 450 nm (OD450). Transfected cells were seeded onto 6-well plates at a density of 400 cells/well in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS for colony formation experiments. After 2 weeks, the cells were rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline, fixed in methanol, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. Visible colonies were manually counted.

2.5 Migration and invasion assays

Transwell inserts (8 μm pore size; Millipore, NY, USA) were used for the migration tests. The top chambers of 24-well plates were filled with 100 μl of the transfected cells, which had been resuspended in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium at a density of 2 × 105 cells/ml. The top chambers were pre-coated with diluted Matrigel (BD) for invasion experiments. The bottom chambers were filled with 500 μl/well of RPMI-1640 medium, which included 20% FBS. Cells that had moved or invaded the bottom surface of the membrane were fixed, stained, and photographed following incubation (16 h for invasion and 24 h for migration). Three randomly chosen fields of vision were used to count the cells. Fifty microliters of Matrigel (30 mg/well; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) were used to pre-coat the Transwell membranes.

2.6 NFS1 functional enrichment analysis

A network of protein–protein interactions (PPIs) was created based on STRING. The following Metascape analyses (https://metascape.org/gp/index.html#/) were performed on co-expressed genes for gene ontology (GO) enrichment: cellular components (CCs), molecular functions (MFs), and biological pathways. The R packages, “ggplot2” and “clusterProfiler,” were utilized for the abovementioned analyses.

2.7 Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

Using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) gene sets (c2 v7.5.1), Hallmark (v7.5.1), GO (c5 v7.5.1) BPs, CCs, MFs, and pathway enrichment analysis, an effort was made to demonstrate the role of NFS1 expression in biological processes and signaling pathways in GC. The R package “clusterProfiler” was used to perform the statistical analysis and display the results.

2.8 Immune infiltration analysis

The ssGSEA method in the GSVA package (v1.46.0) was used to assess Spearman correlations between NFS1 and immune cells for the TCGA datasets. The Tumor Immune Estimation Resource 2 portal (TIMER2 [https://timer.cistrome.org]) provided the purity-adjusted Spearman correlations between NFS1 and tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Correlation scatter plots were created to visualize results. The stromal, immune, and ESTIMATE scores were calculated using SangerBox3.0 and the ESTIMATE package.

2.9 Statistical analysis

X-tile software (v3.6.1) was used to determine the cut-off values for low and high NFS1 expression and statistical analysis of OS (Rimm Lab, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA). A χ 2 test was used to analyze the correlations between clinical parameters and NFS1 expression. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier technique and compared using the log-rank test. The Cox regression method was adopted in both univariate and multivariate analyses to estimate the prognostic value of NFS1 expression. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (v22.0; IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). All continuous data are presented as the mean ± SD or mean ± 95% CI. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Identification of NFS1 mRNA expression and the diagnostic significance

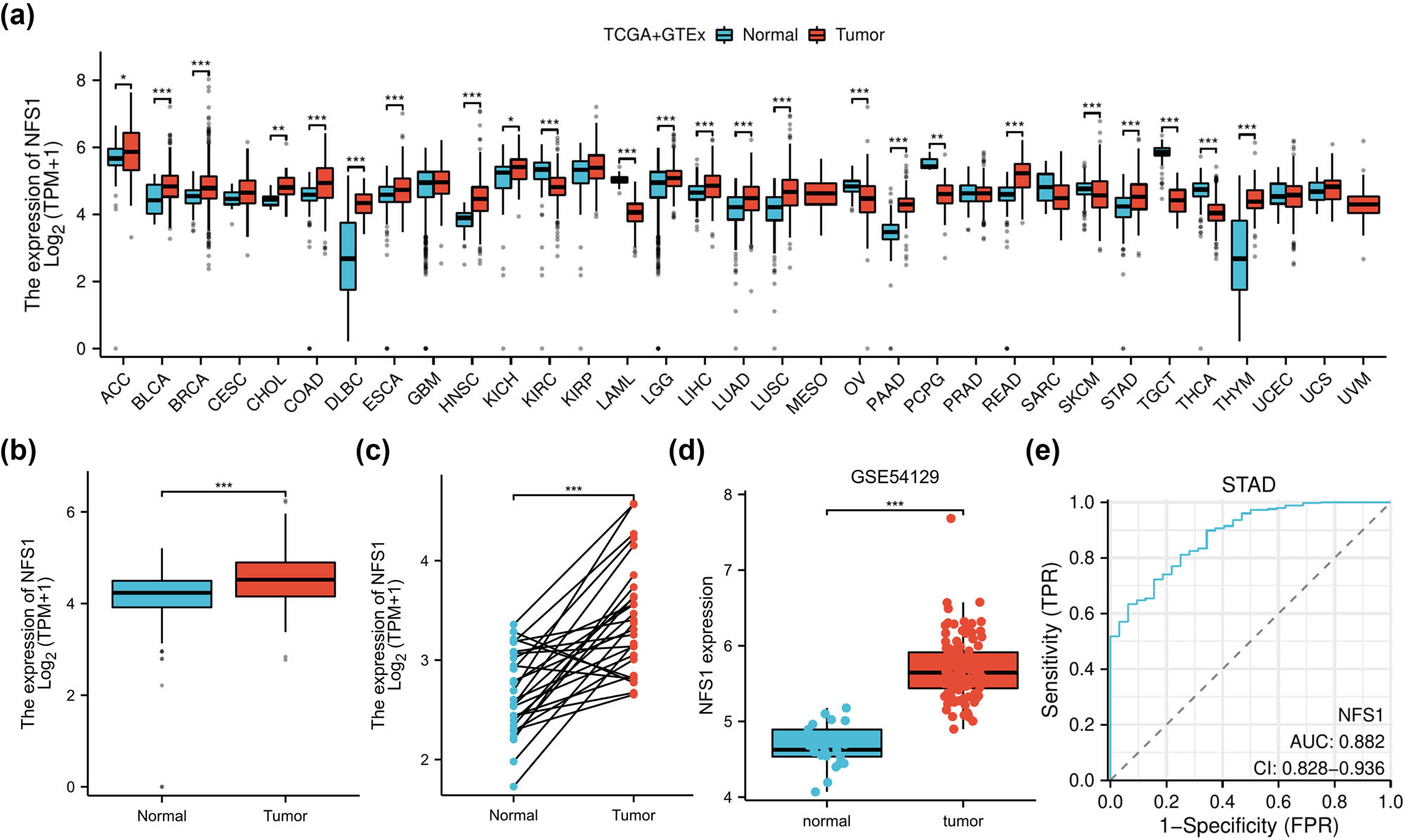

NFS1 mRNA expression was analyzed in various types of tumors and normal tissues using TCGA and GTEx. NFS1 expression was higher in most types of tumors, including stomach adenocarcinoma (Figure 1a). Specifically, NFS1 mRNA was significantly higher in GC tissue samples compared to matched adjacent normal tissues (Figure 1b and c; P < 0.001). Furthermore, in support of these findings, upregulation of NFS1 in GC was confirmed when analyzing the GSE54129 dataset (Figure 1d; P < 0.001). Then, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to further determine the diagnostic value of NFS1. The area under the ROC (AUC) was 0.882 (Figure 1e; 95% CI = 0.828–0.936), suggesting that NFS1 has the potential to serve as a diagnostic biomarker in GC.

NFS1 mRNA expression in tissues. (a) NFS1 mRNA expression in different tumor types was obtained from the UCSCXenaShiny database. (b) and (c) NFS1 mRNA expression in GC patients and matched adjacent normal samples in The Cancer Genome Atlas databases. (d) NFS1 expression in GC was determined by the GEO dataset. (e) ROC curve analysis for NFS1 expression in GC patients. *P < 0.05.

3.2 Correlation of NFS1 protein expression with clinicopathologic features in GC patients

Immunohistochemical labeling was used on a tissue microarray that had 152 pairs of GC and nearby normal tissues because post-transcriptional regulation of mRNA expression is not necessarily indicative of protein levels in vivo [20]. Tumor tissues had substantially greater NFS1 protein levels than peritumoral tissues based on mRNA expression patterns (Figure 2a and b). The association between NFS1 expression and clinicopathologic features in patients with GC is shown in Table 1. NFS1 expression and the TNM stage were significantly correlated (P = 0.002); patients with advanced stages (III and IV) exhibited greater NFS1 expression. Similarly, because greater expression is more common in patients without metastases (M0), there was a significant correlation between the M stage and NFS1 expression (P = 0.033). NFS1 expression, however, did not significantly correlate with age (P = 0.953), gender (P = 0.599), nerve/vascular invasion (P = 0.104), T stage (P = 0.138), or N stage (P = 0.465). These findings implied that NFS1 expression is impacted by disease severity, especially cancer stage, although other clinical characteristics, including age and gender, do not appear to have a major impact on NFS1 expression.

Histochemical analysis and survival data of NFS1 expression in GC tissues. (a) and (b) Histochemical staining results of NFS1 in GC tissues and para-cancerous tissues taken with original 40× magnification (bar = 50 μm) and 400× magnification (bar = 500 μm), respectively. (c) OS curves of NFS1 mRNA expression in GC. (d) High NFS1 protein expression was correlated with a poor prognosis in the clinical GC patient cohort (n = 152).

Relationship between NFS1 expression and clinicopathological characteristics in GC patients

| Characteristic | n | Low and no expression | High expression | Pearson χ 2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 152 | ||||

| Gender | 0.0277 | 0.599 | |||

| Male | 46 | 17(37.0) | 29(63.0) | ||

| Female | 106 | 44(41.5) | 62(58.5) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.003 | 0.953 | |||

| <60 | 37 | 15 (40.5) | 22(59.5) | ||

| ≥60 | 115 | 46(40.0) | 69(60.0) | ||

| TNM stage | 9.451 | 0.002 | |||

| I + II | 55 | 31(56.4) | 24(43.6) | ||

| III + IV | 97 | 30(30.9) | 67(69.1) | ||

| T | 2.2 | 0.138 | |||

| Tis + T1 + T2 | 40 | 20(50.0) | 20(50.0) | ||

| T3, 4b | 112 | 41(36.6) | 71(63.4) | ||

| N | 2.560 | 0.465 | |||

| N0 | 35 | 18(51.4) | 17(48.6) | ||

| N1a | 31 | 11(35.5) | 20(64.5) | ||

| N1b | 37 | 13(35.1) | 24(64.9) | ||

| N2a,b | 49 | 19(38.8) | 30(61.2) | ||

| M | 4.522 | 0.033 | |||

| M0 | 118 | 42(35.6) | 76(64.4) | ||

| M1 | 34 | 19(55.9) | 15(44.1) | ||

| Nerve/vascular invasion | 4.521 | 0.104 | |||

| Positive | 104 | 45(43.3) | 59(56.7) | ||

| Negative | 27 | 12(44.4) | 15(55.6) | ||

| Unknown | 21 | 4(19.0) | 17(81.0) |

Tis: Carcinoma in situ.

3.3 Prognostic potential of NFS1 protein expression in GC

NFS1 expression (HR = 5.546, 95% CI: 2.723–11.293; P < 0.001), T stage (HR = 2.142, 95% CI: 1.085–4.230; P = 0.028), N stage (HR = 1.329, 95% CI: 1.056–1.673; P = 0.015), and M stage (HR = 0.329, 95% CI: 0.141–0.766; P = 0.01) were significantly associated with survival (Table 2). Age (HR = 0.824; P = 0.499) and gender (HR = 0.931; P = 0.797) were not significantly relevant to OS based on univariate analysis (P > 0.05; Table 2).

Univariate analysis of prognostic factors for OS in GC

| Factors | Univariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | P | 95% CI | ||

| NFS1 expression | 5.546 | <0.001 | 2.723 | 11.293 |

| High vs low and no | ||||

| Age (years) | 0.824 | 0.499 | 0.469 | 1.445 |

| <60 vs ≥60 | ||||

| Gender | 0.931 | 0.797 | 0.540 | 1.604 |

| Male vs female | ||||

| TNM stage | 4.391 | <0.001 | 2.156 | 8.942 |

| I and II vs III and IV | ||||

| T: Tis + T1 + T2 vs T3 + T4 | 2.142 | 0.028 | 1.085 | 4.230 |

| N: N0 vs N1a vs N1b and N2a + 2b | 1.329 | 0.015 | 1.056 | 1.673 |

| M: M0 vs M1 | 0.329 | 0.01 | 0.141 | 0.766 |

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; Tis: carcinoma in situ.

High NFS1 expression represented a powerful independent prognostic factor for poor OS in GC based on multivariate analysis (HR = 4.607, 95% CI: 2.251–9.462; P < 0.001; Table 3). Advanced TNM stage (III/IV) was significantly associated with an increased risk of mortality (HR = 3.463, 95% CI: 1.692–7.088; P < 0.001; Table 3). The same finding was further verified by the Kaplan–Meier analysis, in which overexpression of NFS1 was significantly related to poor OS in GC patients (Figure 2c and d).

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for OS in GC

| Factors | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | P | 95% CI | ||

| NFS1 expression | 4.607 | <0.001 | 2.251 | 9.462 |

| High vs low and no | ||||

| TNM stage | 3.463 | <0.001 | 1.692 | 7.088 |

| I and II vs III and IV | ||||

| T: Tis + T1 + T2 vs T3 + T4 | ||||

| N: N0 vs N1a vs N1b and N2a + 2b | ||||

| M: M0 vs M1 | 0.3362 | 0.019 | 0.155 | 0.848 |

3.4 Upregulated NFS1 expression in GC cell lines

NFS1 expression was assessed with a reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction and western blot analysis in four human GC cell lines (HGC-27, AGS, MKN-1, and BGC-823) and one normal gastric epithelial cell line (GES-1) to determine the phenotypic consequence of NFS1 in GC. NFS1 was highly expressed in GC cell lines compared to GES-1 (Figure 3a–c). Specifically, HGC-27 and AGS had the highest NFS1 levels but the NFS1 levels were low for MKN-1 and BGC-823. Thus, high expression NFS1 and the cell lines with high NFS1 expression (HGC-27 and AGS) were selected. Construction of stable NFS1 knockdown was performed in cells to ascertain knockdown efficacy by qPCR and western blot analysis (Figure 3d–i). The original western blot results are shown in the Supplemental file, WB-NFS1.

NFS1 expression in GC cell lines. (a) Relative NFS1 expression in GC cell lines (HGC-27, AGS, MKN-1, and BGC-823) compared to a normal gastric epithelial cell line (GES-1). (b) and (c) Western blot showing levels of NFS1 in GC cell lines with GAPDH as a loading control. (d)–(f) qRT-PCR and western blot analysis of knockdown and overexpression efficiency in HGC-27 cells. (g)–(i) qRT-PCR and western blot analysis of knockdown and overexpression efficiency in AGS cells.

3.5 NFS1 promoted cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in vitro

Cell viability was measured using CCK-8 and colony-forming assays to determine the role of NFS1 in GC cell proliferation. siRNA-mediated knockdown of NFS1 significantly repressed the growth of HGC-27 and AGS cells compared to the negative control, as shown in Figure 4a and b (P < 0.05). Similarly, colony formation was significantly reduced in such cells following NFS1 knockdown (P < 0.05; Figure 4c and d). Then, we determined whether NFS1 had a potential role in GC metastasis by using the Transwell assay to assess cell migration and invasion. We demonstrated that NFS1 knockdown significantly reduced the migratory and invasive capabilities of GC cells (Figure 4e–h). These results point to a critical role for NFS1 in GC tumorigenesis and progression.

NFS1 promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of GC cells in vitro. (a) and (b) CCK-8 assays were used to determine the cell viability of GC cells transfected with si-RNA or si-NC with relative control. (c) and (d) Representative images of colony formation induced by si-NC and si-RNA cells. (e)–(h) Migration and invasion assays were used to investigate the vertical migration and invasion abilities with NFS1 knockdown in GC cells.

3.6 NFS1 expression related to TME score and immune cell infiltration

The amount and proportion of tumor-infiltrating immune cells are major determinants in patient selection for immunotherapy [21]. The ESTIMATE algorithm was used to calculate the immune, stromal, and estimated scores of GC patients to further elucidate the association between NFS1 expression and tumor microenvironment (TME). The above scores were negatively correlated with NFS1 expression, suggesting that tumor immune activity may be more powerful in patients with lower NFS1 expression, as shown in Figure 5a–c. Moreover, the ssGSEA algorithm was used to investigate the relationship between NFS1 and 24 types of immune cells in GC. NFS1 had a significant correlation with most types of immune cells and may be implicated in the modulation of immune cell infiltration into the TME (Figure 5d).

Influence of NFS1 on infiltration of stromal and immune cells. (a)–(c) Relationship between NFS1 expression and immune score, estimated score, and stromal score in GC. (d) Differences of 24 immune cells between the NFS1 high- and low-expression groups. (e)–(g) NFS1 expression associated with 12 kinds of immune cells in TIMER2.0.

3.7 Correlation between NFS1 expression and tumor-infiltrating immune cells

The TIMER2.0 database was analyzed to provide a deeper understanding of the relationship between the level of NFS1 expression and tumor-infiltrating immune cells, and the tumor purity had a significant positive correlation (r = 0.124; P = 1.55 × 10−2). NFS1 was positively correlated with myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (r = 0.331; P = 3.64 × 10−11; Figure 5e), Th1 cells (r = 0.256; P = 4.33 × 10−7; Figure 5e), and Tfh cells (r = 0.209; P = 4.01 × 10−5; Figure 5f). Stromal cell infiltration, including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and endothelial cells, had a negative correlation trend with NFS1 expression but without adequate statistical support (CAFs [r = −0.237; P = 3.06 × 10−6; Figure 5f] and endothelial cells [r = −0.158; P = 2.03 × 10−3; Figure 5e]). In contrast, the negative relevance of NFS1 expression was observed with immune cell types, such as CD8+ T cells (r = −0.19; P = 2.06 × 10−4; Figure 5g), CD4+ T cells (r = −0.133; P = 9.33 × 10−3; Figure 5g), and myeloid dendritic cells (r = −0.102; P = 4.63 × 10−2; Figure 5g). These results suggested that NFS1 expression might influence the tumor immune microenvironment by altering the infiltrating density of immune and stromal cells.

3.8 Functional enrichment analysis of NFS1

A functional enrichment analysis was performed to determine the potential functions and pathways related to NFS1 in GC. The STRING database was used to construct the PPI network, and 20 genes interacted with NFS1. The correlations of NFS1 with these genes are represented as a heat map in Figure 6a and b. GO enrichment analysis showed that NFS1 took part in BP, like “ISC assembly,” “metal–sulfur cluster assembly,” “protein maturation by ISC transfer,” “ISC binding,” and “sulfur transferase activity.” The MFs enriched significantly included “iron ion binding.” At the CC level, high NFS1 expression was highly associated with “mitochondrial matrix” and “mitochondrial outer membrane translocase complex” (Figure 6c). All these observations suggest that NFS1 primarily participates in ISC binding and assembly, mitochondrial function, and metabolic processes linked to ferroptosis.

Pathway enrichment analysis of NFS1. (a) PPI network of NFS1 with its 20 interacting proteins. (b) A heatmap of the correlation between NFS1 and the co-expressed genes. ***P < 0.001. (c) GO enrichment analysis of NFS1 and co-expressed genes. (d) Enrichment analysis of the NFS1 GSEA gene in the TCGA database. P < 0.05 was considered a meaningful pathway. Red and blue indicate immune- and ferroptosis-related metabolic pathways, respectively.

3.9 NFS1-related signaling pathways and the possible role in ferroptosis and the TME

We also conducted GSEA to explore the biological processes and signaling pathways associated with NFS1 expression. In hallmark gene sets, NFS1 expression was positively correlated with cell cycle-related pathways, such as “E2F targets,” “G2/M checkpoint,” and “mitotic spindle.” In contrast, NFS1 expression was negatively correlated with KRAS signaling, TGF-α signaling, EMT, and inflammatory responses. The identified DEGs related to NFS1 in GO and KEGG gene sets were involved in the pathway related to the cell cycle checkpoint, signaling that included sister chromatid segregation, cancer pathways, focal adhesion, immune responses, and B- and T-cell-mediated immunity. In addition, a significant positive correlation between NFS1 expression and metabolic processes involving ferroptosis was detected (steroid metabolism, steroid biosynthesis, and terpenoid backbone biosynthesis; Figure 6d). These enrichment results suggested that NFS1 exerts influence on the modulation of GC biological processes through involvement in ferroptosis and TME.

4 Discussion

The current study demonstrated significantly upregulated NFS1 expression in GC tissues compared to non-tumor stomach tissues. Downregulation of the NFS1 protein in the GC cell line had a suppressive effect on the migration, invasion, and proliferation of cells. In addition, it was observed that the level of NFS1 expression was related to a variety of immune cells and characteristics of the TME.

In contrast to normal and benign tissues, the level of NFS1 expression in GC tissues was much higher (χ 2 = 9.451; P = 0.002) and the proportion of patients with high expression (n = 67 [69.1%]) in patients with TNM stages III + IV was considerably greater than patients with low expression (n = 30 [30.9%]). These results suggested that NFS1 may have a role in tumor development [22]. The biological behavior of the tumor likely changes as cancer progresses to a more advanced stage, leading to increased NFS1 expression, which might have a role in tumor migration, resistance, or proliferation [14,15,16,17,18,19]. The level of NFS1 expression was inversely correlated with the tumor stage and OS in GC patients. Knockdown of NFS1 greatly decreased invasion, migration, and proliferation of the GC cell line according to in vitro experiments, which is consistent with previous results in other cancer types and indicates the role of NFS1 in carcinogenesis [14,15,16,17,18,19]. These results suggested that during the early and late stages of tumors, NFS1 might serve as an important marker for the development and progression of cancer.

GO enrichment analysis suggested that NFS1 is involved in the biological processes of ISC binding and assembly, cysteine metabolism, and pathways of ferroptosis metabolism. GSEA based on NFS1 expression is related to the cell cycle, cancer, stroma, inflammatory responses, and ferroptosis metabolic pathways. These findings suggested that the potential pathways of NFS1 affecting GC biological processes could be related to ferroptosis and TME-related pathways [6,7,15,16,17].

NFS1 is the key participant in ISC biosynthesis, according to earlier research, and forms ISCs by binding to certain molecular conformations [23]. ISCs have a role in energy conversion, protein translation, and DNA maintenance. When NFS1 is depleted, the iron starvation response is triggered, which causes ferroptosis [6]. Unlike apoptosis, necroptosis, autophagy, pyroptosis, and necrosis, the process-named ferroptosis by Dixon et al. presented a new form of lipid peroxidation-driven regulatory iron-dependent cell death [24]. Ferroptosis has recently gained much attention. Either direct inhibition of lipid peroxidation or iron deprivation prevents iron-dependent phospholipid peroxidation, which is an imbalance between redox homeostasis and cell metabolism [25]. Recent studies have shown that iron death is implicated in various physiologic processes of illness, including organ damage [26], infectious diseases [27], autoimmune disorders [28], and tumorigenesis [29]. Tumor immune activity was higher in patients with low expression of NFS1 than in patients with high expression of NFS1, according to the association between NFS1 expression and immunologic, estimation, and stromal scores in GC. Therefore, tumor cells might develop strategies to inhibit immune function in patients with elevated NFS1 expression. This finding was consistent with previous studies, indicating that NFS1 could be important for immune regulation in the TME [30].

By targeting the OPA3–NFS1 axis, suppression of iron death for protecting cardiac toxicity induced by dox [31,32] and depletion of NFS1 while targeting CAIX enhanced ferroptosis and significantly inhibited tumor growth [12,33]. Based on this study, differential expression of NFS1 in GC tissues may be associated with the ferroptosis pathway. The involvement of NFS1 in the iron metabolism pathway may modulate ISC synthesis, affecting cell sensitivity to ferroptosis. Further investigation is needed to give a more detailed explanation of the mechanism underlying NFS1-regulated ferroptosis in GC.

The TME influences the growth of tumors and is made up of stromal cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, immune cells, and various chemokines. The tumor immunotherapy therapeutic response and patient prognosis are determined by the TME [34]. Using the TIMER database, we showed that NFS1 expression had a positive correlation with Th1 cells, Tfh cells, MDSCs, and M0 macrophages but a negative correlation with infiltration of the majority of immune cells, including CD8+ T cells. Numerous investigations have shown that ferroptosis may be one of the ways tumor suppressors partially carry out tumor-suppressive activity. For example, CD8+ T lymphocytes suppress SLC7A11 in tumor cells and secrete IFN-γ to induce ferroptosis [35]. Th1 cells produce IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α, playing a major role in tumor immunity [36]. In liver cancer, the combination of ferroptosis induction and MDSC blockade was shown to be beneficial for effective tumor suppression [37,38]. Additionally, targeting the selenium-GPX4-ferroptosis axis can regulate TFH cell homeostasis, enhancing humoral immunity [38]. These results indicate that NFS1 expression may be an important biomarker for prognosis and is closely related to clinical parameters in GC patients. These findings still need further clinical validation in patients with GC.

Understanding how NFS1 modulates ferroptosis could lead to novel ferroptosis-based therapies, enhancing GC cell sensitivity to this process and improving treatment outcomes [19,39,40]. NFS1 has emerged as an important protein in different cancers and hence represents a promising target for therapeutic intervention. In lung cancer, depletion of NFS1 in combination with cysteine transport inhibition disrupts ISCs, inducing ferroptosis and impairing tumor growth, and may represent a potential therapeutic intervention by targeting NFS1 [41]. High NFS1 expression is associated with poor prognosis, increased tumor aggressiveness, and resistance to ferroptosis in breast cancer, highlighting the role in tumor progression [42]. Similarly, elevated NFS1 expression correlates with poor outcomes in prostate cancer, and targeting NFS1 may enhance the sensitivity of cancer cells to ferroptosis-based therapies [18]. Knockdown of NFS1 increases sensitivity to the ferroptosis inducer, RSL3, and to the chemotherapy drug, oxaliplatin, which leads to better treatment outcomes [43]. These findings showed the broad impact of NFS1 in various cancers. The current study revealed that NFS1 knockdown suppresses GC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, which is consistent with previous studies [18,19,40,41,42,43]. A significant association was demonstrated between NFS1 expression and TNM and M stages in this study, with higher expression in advanced stages (III and IV) and patients without metastases. These findings suggested that a relationship between NFS1 and tumor progression is required to determine the possible effects of NFS1 in GC patients. The lack of significant correlation with other factors, such as gender, age, and T or N stages, implies that the NFS1 role in the GC population warrants additional study.

The association between NFS1 and the TME was evaluated using the ESTIMATE, stromal, and immune scores to determine the role of NFS1 in the immune microenvironment of GC. The results indicated that NFS1 is negatively correlated with the ESTIMATE, stromal, and immune scores, suggesting that the tumor immune activity of patients with low NFS1 expression was stronger than patients with high NFS1 expression. The ssGSEA algorithm was used to study the relationship between the high and low NFS1 expression groups in the TCGA database and 24 immune cell subsets in GC. More B cells, CD8+ T cells, cytotoxic cells, dendritic cells, eosinophils, immature dendritic cells, macrophages, mast cells, neutrophils, natural killer cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, T cells, effector memory T cells, Tfh cells, Th1 cells, and Th2 cells were present in the high NFS1 expression group than in the low NFS1 expression group. The above results indicate that NFS1 may be involved in the TME and affect tumor growth by influencing the infiltration of immune cells. NFS1 appeared to regulate both immune and stromal cell infiltration within TME, with high NFS1 expression associated with lower immune, stromal, and TME scores, suggesting suppressed immune infiltration and poor tumor prognosis. Then, the relationship between NFS1 expression and immune cell infiltration was studied using the TIMER2.0 database. NFS1 was positively correlated with tumor purity (r = 0.124; P = 1.55 × 10−2) and negatively correlated with CD8+ T cells (r = −0.19; P = 2.06 × 10−4), CD4+ T cells (r = −0.133; P = 9.33 × 10−3), myeloid dendritic cells (r = −0.102; P = 4.63 × 10−2), and activated NK cells (r = −0.238; P = 2.79 × 10−6). The results indicated that NFS1 was positively correlated with MDSC (r = 0.331; P = 3.64 × 10−11), Th1 cells (r = 0.256; P = 4.33 × 10−7), and Tfh cells (r = 0.209; P = 4.01 × 10−5). The infiltration of stromal cells was evaluated from the TIMER portal, mainly including CAF and endothelial cells. NFS1 was negatively correlated with CAFs (r = −0.237; P = 3.06 × 10−6) and endothelial cells (r = −0.158; P = 2.03 × 10−3) in GC (Figure 5e–g). Based on the above analysis, the level of NFS1 expression positively correlated with Th1 and Tfh cells, and negatively correlated with CD8+ T cells, mast cells, Th17 cells, B cells, and pDCd. These findings indicated that anti-tumor immunity may have a role in NFS1-mediated carcinogenesis in GC and positioned NFS1 as a potential target of immunotherapy.

The present study provided valuable insight into the relationship between NFS1, immune cell infiltration, and prognosis. However, the present study had some limitations. First, the role of NFS1 in ferroptosis was only inferred from bioinformatics analysis, and the investigation of the underlying mechanisms may be insufficient. Second, immune cell profiling (ssGSEA and TIMER2.0) showed a correlation, but the biological implications remain vague. Further experiments, such as BODIPY-C11 staining, lipid ROS, iron accumulation, and GPX4 levels through in vitro ferroptosis assays, are required to illustrate how NFS1 regulates immune and stromal cell infiltration. Third, the current study had a limited sample of GC tissues from a retrospective review of patients. Adding more samples and diversity in further research could affect generalization and the reliability of results, and increasing both would strengthen the power of the study. Testing cytokine profiles or immune checkpoint molecules in vitro or from public datasets can be considered in the next step. Fourth, ROC curves and the AUC lacked comparison with standard GC biomarkers. Multivariate ROC curves or combination marker analysis highlighted the diagnostic potential. Finally, clinical validation was lacking in this study, which limits the applicability of the results. Clinical trials to verify the effects in actual patients would give further credence to the conclusions of this research.

5 Conclusion

For the first time, the current study showed that NFS1 may function as a possible biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis associated with ferroptosis and TME. NFS1 may also offer a novel target for immunotherapy and medication therapy based on ferroptosis in GC. There were certain restrictions. The direct mechanisms by which NFS1 influences cancer development and prognosis by controlling ferroptosis and TME need to be further studied using more fundamental studies with additional clinical samples.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Zhiyun Mao: guarantor of integrity of the entire study, definition of intellectual content, data acquisition, statistical analysis, manuscript preparation, and manuscript editing. Zhongmei Shi: study design, data analysis, statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation; Ming Cui: literature research, data analysis, and manuscript editing. Xiaohong Ma: data acquisition. Yan Wan: literature research. Rongrong Jing: guarantor of integrity of the entire study, study design, and manuscript review. Jingchun Wang: study concepts, definition of intellectual content, and manuscript review. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Morgan E, Arnold M, Camargo MC, Gini A, Kunzmann AT, Matsuda T, et al. The current and future incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in 185 countries, 2020-40: A population-based modelling study. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;47:101404.10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101404Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.10.3322/caac.21660Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van Grieken NC, Lordick F. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2020;396(10251):635–48.10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31288-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Ouyang S, Li H, Lou L, Huang Q, Zhang Z, Mo J, et al. Inhibition of STAT3-ferroptosis negative regulatory axis suppresses tumor growth and alleviates chemoresistance in gastric cancer. Redox Biol. 2022;52:102317.10.1016/j.redox.2022.102317Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Tian S, Peng P, Li J, Deng H, Zhan N, Zeng Z, et al. SERPINH1 regulates EMT and gastric cancer metastasis via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(4):3574–93.10.18632/aging.102831Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Alvarez SW, Sviderskiy VO, Terzi EM, Papagiannakopoulos T, Moreira AL, Adams S, et al. NFS1 undergoes positive selection in lung tumours and protects cells from ferroptosis. Nature. 2017;551(7682):639–43.10.1038/nature24637Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Stehling O, Wilbrecht C, Lill R. Mitochondrial iron-sulfur protein biogenesis and human disease. Biochimie. 2014;100:61–77.10.1016/j.biochi.2014.01.010Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Berndt C, Alborzinia H, Amen VS, Ayton S, Barayeu U, Bartelt A, et al. Ferroptosis in health and disease. Redox Biol. 2024;75:103211.10.1016/j.redox.2024.103211Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Chen F, Kang R, Tang D, Liu J. Ferroptosis: principles and significance in health and disease. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17(1):41.10.1186/s13045-024-01564-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Rouault TA. Biogenesis of iron-sulfur clusters in mammalian cells: new insights and relevance to human disease. Dis Model Mech. 2012;5(2):155–64.10.1242/dmm.009019Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Fujihara KM, Zhang BZ, Jackson TD, Ogunkola MO, Nijagal B, Milne JV, et al. Eprenetapopt triggers ferroptosis, inhibits NFS1 cysteine desulfurase, and synergizes with serine and glycine dietary restriction. Sci Adv. 2022;8(37):eabm9427.10.1126/sciadv.abm9427Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Chafe SC, Vizeacoumar FS, Venkateswaran G, Nemirovsky O, Awrey S, Brown WS, et al. Genome-wide synthetic lethal screen unveils novel CAIX-NFS1/xCT axis as a targetable vulnerability in hypoxic solid tumors. Sci Adv. 2021;7(35):eabj0364.10.1126/sciadv.abj0364Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Lee J, Roh JL. Targeting iron-sulfur clusters in cancer: opportunities and challenges for ferroptosis-based therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(10):2694.10.3390/cancers15102694Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Jiang Y, Li L, Li W, Liu K, Wu Y, Wang Z. NFS1 inhibits ferroptosis in gastric cancer by regulating the STAT3 pathway. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2024;56(5):573–87.10.1007/s10863-024-10038-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Du S, Zeng F, Sun H, Liu Y, Han P, Zhang B, et al. Prognostic and therapeutic significance of a novel ferroptosis related signature in colorectal cancer patients. Bioengineered. 2022;13(2):2498–512.10.1080/21655979.2021.2017627Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Lin JF, Hu PS, Wang YY, Tan YT, Yu K, Liao K, et al. Phosphorylated NFS1 weakens oxaliplatin-based chemosensitivity of colorectal cancer by preventing PANoptosis. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):54.10.1038/s41392-022-00889-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Sviderskiy VO, Blumenberg L, Gorodetsky E, Karakousi TR, Hirsh N, Alvarez SW, et al. Hyperactive CDK2 activity in basal-like breast cancer imposes a genome integrity liability that can be exploited by targeting DNA polymerase ε. Mol Cell. 2020;80(4):682–98.e7.10.1016/j.molcel.2020.10.016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Lv Z, Wang J, Wang X, Mo M, Tang G, Xu H, et al. Identifying a ferroptosis-related gene signature for predicting biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:666025.10.3389/fcell.2021.666025Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Jiang Y, Li W, Zhang J, Liu K, Wu Y, Wang Z. NFS1 as a candidate prognostic biomarker for gastric cancer correlated with immune infiltrates. Int J Gen Med. 2024;17:3855–68.10.2147/IJGM.S444443Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Lee LJ, Papadopoli D, Jewer M, Del Rincon S, Topisirovic I, Lawrence MG, et al. Cancer plasticity: the role of mRNA translation. Trends Cancer. 2021;7(2):134–45.10.1016/j.trecan.2020.09.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Chen Y, Jia K, Sun Y, Zhang C, Li Y, Zhang L, et al. Predicting response to immunotherapy in gastric cancer via multi-dimensional analyses of the tumour immune microenvironment. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4851.10.1038/s41467-022-32570-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Zhang C, Liu X, Jin S, Chen Y, Guo R. Ferroptosis in cancer therapy: a novel approach to reversing drug resistance. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):47.10.1186/s12943-022-01530-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Cai K, Frederick RO, Kim JH, Reinen NM, Tonelli M, Markley JL. Human mitochondrial chaperone (mtHSP70) and cysteine desulfurase (NFS1) bind preferentially to the disordered conformation, whereas co-chaperone (HSC20) binds to the structured conformation of the iron-sulfur cluster scaffold protein (ISCU). J Biol Chem. 2013;288(40):28755–70.10.1074/jbc.M113.482042Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060–72.10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Gao M, Monian P, Pan Q, Zhang W, Xiang J, Jiang X. Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell Res. 2016;26(9):1021–32.10.1038/cr.2016.95Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Ide S, Kobayashi Y, Ide K, Strausser SA, Abe K, Herbek S, et al. Ferroptotic stress promotes the accumulation of pro-inflammatory proximal tubular cells in maladaptive renal repair. Elife. 2021;10:e68603.10.7554/eLife.68603Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Yamane D, Hayashi Y, Matsumoto M, Nakanishi H, Imagawa H, Kohara M, et al. FADS2-dependent fatty acid desaturation dictates cellular sensitivity to ferroptosis and permissiveness for hepatitis C virus replication. Cell Chem Biol. 2022;29(5):799–810.e4.10.1016/j.chembiol.2021.07.022Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Li P, Jiang M, Li K, Li H, Zhou Y, Xiao X, et al. Glutathione peroxidase 4-regulated neutrophil ferroptosis induces systemic autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2021;22(9):1107–17.10.1038/s41590-021-00993-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Wu W, Li D, Feng X, Zhao F, Li C, Zheng S, et al. A pan-cancer study of selenoprotein genes as promising targets for cancer therapy. BMC Med Genomics. 2021;14(1):78.10.1186/s12920-021-00930-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Gok Yavuz B, Gunaydin G, Gedik ME, Kosemehmetoglu K, Karakoc D, Ozgur F, et al. Cancer associated fibroblasts sculpt tumour microenvironment by recruiting monocytes and inducing immunosuppressive PD-1(+) TAMs. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):3172.10.1038/s41598-019-39553-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Wang Y, Ying X, Wang Y, Zou Z, Yuan A, Xiao Z, et al. Hydrogen sulfide alleviates mitochondrial damage and ferroptosis by regulating OPA3-NFS1 axis in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Cell Signal. 2023;107:110655.10.1016/j.cellsig.2023.110655Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Zhang H, Pan J, Huang S, Chen X, Chang ACY, Wang C, et al. Hydrogen sulfide protects cardiomyocytes from doxorubicin-induced ferroptosis through the SLC7A11/GSH/GPx4 pathway by Keap1 S-sulfhydration and Nrf2 activation. Redox Biol. 2024;70:103066.10.1016/j.redox.2024.103066Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Venkateswaran G, McDonald PC, Chafe SC, Brown WS, Gerbec ZJ, Awrey SJ, et al. A carbonic anhydrase IX/SLC1A5 axis regulates glutamine metabolism dependent ferroptosis in hypoxic tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2023;22(10):1228–42.10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-23-0041Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Wang R, Song S, Qin J, Yoshimura K, Peng F, Chu Y, et al. Evolution of immune and stromal cell states and ecotypes during gastric adenocarcinoma progression. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(8):1407–26.e9.10.1016/j.ccell.2023.06.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Wang W, Green M, Choi JE, Gijón M, Kennedy PD, Johnson JK, et al. CD8( +) T cells regulate tumour ferroptosis during cancer immunotherapy. Nature. 2019;569(7755):270–4.10.1038/s41586-019-1170-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Huang M, Xiong D, Pan J, Zhang Q, Sei S, Shoemaker RH, et al. Targeting glutamine metabolism to enhance immunoprevention of EGFR-driven lung cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2022;9(26):e2105885.10.1002/advs.202105885Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Conche C, Finkelmeier F, Pešić M, Nicolas AM, Böttger TW, Kennel KB, et al. Combining ferroptosis induction with MDSC blockade renders primary tumours and metastases in liver sensitive to immune checkpoint blockade. Gut. 2023;72(9):1774–82.10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327909Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Yao Y, Chen Z, Zhang H, Chen C, Zeng M, Yunis J, et al. Selenium-GPX4 axis protects follicular helper T cells from ferroptosis. Nat Immunol. 2021;22(9):1127–39.10.1038/s41590-021-00996-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Li Y, Liu J, Wu S, Xiao J, Zhang Z. Ferroptosis: opening up potential targets for gastric cancer treatment. Mol Cell Biochem. 2024;479(11):2863–74.10.1007/s11010-023-04886-xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Zhou Q, Meng Y, Li D, Yao L, Le J, Liu Y, et al. Ferroptosis in cancer: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):55.10.1038/s41392-024-01769-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Zang J, Cui M, Xiao L, Zhang J, Jing R. Overexpression of ferroptosis-related genes FSP1 and CISD1 is related to prognosis and tumor immune infiltration in gastric cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2023;25(8):2532–44.10.1007/s12094-023-03136-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Ge A, Xiang W, Li Y, Zhao D, Chen J, Daga P, et al. Broadening horizons: the multifaceted role of ferroptosis in breast cancer. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1455741.10.3389/fimmu.2024.1455741Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Song YQ, Yan XD, Wang Y, Wang ZZ, Mao XL, Ye LP, et al. Role of ferroptosis in colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2023;15(2):225–39.10.4251/wjgo.v15.i2.225Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome with elevated IgG4 and T-cell clonality: A report of two cases

- Electroacupuncture alleviates sciatic nerve injury in sciatica rats by regulating BDNF and NGF levels, myelin sheath degradation, and autophagy

- Polydatin prevents cholesterol gallstone formation by regulating cholesterol metabolism via PPAR-γ signaling

- RNF144A and RNF144B: Important molecules for health

- Analysis of the detection rate and related factors of thyroid nodules in the healthy population

- Artesunate inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion through OGA-mediated O-GlcNAcylation of ZEB1

- Endovascular management of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: Case report and review of the literature

- Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis

- SATB2 promotes humeral fracture healing in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Overexpression of the ferroptosis-related gene, NFS1, corresponds to gastric cancer growth and tumor immune infiltration

- Understanding risk factors and prognosis in diabetic foot ulcers

- Atractylenolide I alleviates the experimental allergic response in mice by suppressing TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 signalling

- FBXO31 inhibits the stemness characteristics of CD147 (+) melanoma stem cells

- Immune molecule diagnostics in colorectal cancer: CCL2 and CXCL11

- Inhibiting CXCR6 promotes senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells with limited proinflammatory SASP to attenuate hepatic fibrosis

- Cadmium toxicity, health risk and its remediation using low-cost biochar adsorbents

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis with headache as the first presentation: A case report

- Solitary pulmonary metastasis with cystic airspaces in colon cancer: A rare case report

- RUNX1 promotes denervation-induced muscle atrophy by activating the JUNB/NF-κB pathway and driving M1 macrophage polarization

- Morphometric analysis and immunobiological investigation of Indigofera oblongifolia on the infected lung with Plasmodium chabaudi

- The NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex and Hr78 modulate the Lobe2 mutant eye phenotype

- Experimental study on salmon demineralized bone matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: In vitro and in vivo study

- A case of IgA nephropathy treated with a combination of telitacicept and half-dose glucocorticoids

- Analgesic and toxicological evaluation of cannabidiol-rich Moroccan Cannabis sativa L. (Khardala variety) extract: Evidence from an in vivo and in silico study

- Wound healing and signaling pathways

- Combination of immunotherapy and whole-brain radiotherapy on prognosis of patients with multiple brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study

- To explore the relationship between endometrial hyperemia and polycystic ovary syndrome

- Research progress on the impact of curcumin on immune responses in breast cancer

- Biogenic Cu/Ni nanotherapeutics from Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl seeds for the treatment of lung cancer

- Dapagliflozin attenuates atrial fibrosis via the HMGB1/RAGE pathway in atrial fibrillation rats

- Glycitein alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in keratinocytes via ROS-associated PI3K–Akt signalling pathway

- ADH5 inhibits proliferation but promotes EMT in non-small cell lung cancer cell through activating Smad2/Smad3

- Apoptotic efficacies of AgNPs formulated by Syzygium aromaticum leaf extract on 32D-FLT3-ITD human leukemia cell line with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Novel cuproptosis-related genes C1QBP and PFKP identified as prognostic and therapeutic targets in lung adenocarcinoma

- Bee venom promotes exosome secretion and alters miRNA cargo in T cells

- Treatment of pure red cell aplasia in a chronic kidney disease patient with roxadustat: A case report

- Comparative bioinformatics analysis of the Wnt pathway in breast cancer: Selection of novel biomarker panels associated with ER status

- Kynurenine facilitates renal cell carcinoma progression by suppressing M2 macrophage pyroptosis through inhibition of CASP1 cleavage

- RFX5 promotes the growth, motility, and inhibits apoptosis of gastric adenocarcinoma cells through the SIRT1/AMPK axis

- ALKBH5 exacerbates early cardiac damage after radiotherapy for breast cancer via m6A demethylation of TLR4

- Phytochemicals of Roman chamomile: Antioxidant, anti-aging, and whitening activities of distillation residues

- Circadian gene Cry1 inhibits the tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma by the BAX/BCL2-mediated apoptosis pathway

- The TNFR-RIPK1/RIPK3 signalling pathway mediates the effect of lanthanum on necroptosis of nerve cells

- Longitudinal monitoring of autoantibody dynamics in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing surgery

- The potential role of rutin, a flavonoid, in the management of cancer through modulation of cell signaling pathways

- Construction of pectinase gene engineering microbe and its application in tobacco sheets

- Construction of a microbial abundance prognostic scoring model based on intratumoral microbial data for predicting the prognosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Sepsis complicated by haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis triggered by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and human herpesvirus 8 in an immunocompromised elderly patient: A case report

- Sarcopenia in liver transplantation: A comprehensive bibliometric study of current research trends and future directions

- Advances in cancer immunotherapy and future directions in personalized medicine

- Can coronavirus disease 2019 affect male fertility or cause spontaneous abortion? A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis

- Heat stroke associated with novel leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor gene variant in a Chinese infant

- PSME2 exacerbates ulcerative colitis by disrupting intestinal barrier function and promoting autophagy-dependent inflammation

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state with severe hypernatremia coexisting with central diabetes insipidus: A case report and literature review

- Efficacy and mechanism of escin in improving the tissue microenvironment of blood vessel walls via anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects: Implications for clinical practice

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Clinicopathological analysis of three patients and literature review

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Optimization and comparative study of Bacillus consortia for cellulolytic potential and cellulase enzyme activity

- The complete mitochondrial genome analysis of Haemaphysalis hystricis Supino, 1897 (Ixodida: Ixodidae) and its phylogenetic implications

- Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors analysis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among tuberculosis population in Huzhou City, Eastern China

- Indices of human impacts on landscapes: How do they reflect the proportions of natural habitats?

- Genetic analysis of the Siberian flying squirrel population in the northern Changbai Mountains, Northeast China: Insights into population status and conservation

- Diversity and environmental drivers of Suillus communities in Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica forests of Inner Mongolia

- Global assessment of the fate of nitrogen deposition in forest ecosystems: Insights from 15N tracer studies

- Fungal and bacterial pathogenic co-infections mainly lead to the assembly of microbial community in tobacco stems

- Influencing of coal industry related airborne particulate matter on ocular surface tear film injury and inflammatory factor expression in Sprague-Dawley rats

- Temperature-dependent development, predation, and life table of Sphaerophoria macrogaster (Thomson) (Diptera: Syrphidae) feeding on Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae)

- Eleonora’s falcon trophic interactions with insects within its breeding range: A systematic review

- Agriculture

- Integrated analysis of transcriptome, sRNAome, and degradome involved in the drought-response of maize Zhengdan958

- Variation in flower frost tolerance among seven apple cultivars and transcriptome response patterns in two contrastingly frost-tolerant selected cultivars

- Heritability of durable resistance to stripe rust in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Molecular mechanism of follicular development in laying hens based on the regulation of water metabolism

- Animal Science

- Effect of sex ratio on the life history traits of an important invasive species, Spodoptera frugiperda

- Plant Sciences

- Hairpin in a haystack: In silico identification and characterization of plant-conserved microRNA in Rafflesiaceae

- Widely targeted metabolomics of different tissues in Rubus corchorifolius

- The complete chloroplast genome of Gerbera piloselloides (L.) Cass., 1820 (Carduoideae, Asteraceae) and its phylogenetic analysis

- Field trial to correlate mineral solubilization activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and biochemical content of groundnut plants

- Correlation analysis between semen routine parameters and sperm DNA fragmentation index in patients with semen non-liquefaction: A retrospective study

- Plasticity of the anatomical traits of Rhododendron L. (Ericaceae) leaves and its implications in adaptation to the plateau environment

- Effects of Piriformospora indica and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on growth and physiology of Moringa oleifera under low-temperature stress

- Effects of different sources of potassium fertiliser on yield, fruit quality and nutrient absorption in “Harward” kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa)

- Comparative efficiency and residue levels of spraying programs against powdery mildew in grape varieties

- The DREB7 transcription factor enhances salt tolerance in soybean plants under salt stress

- Using plant electrical signals of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) for water pollution monitoring

- Food Science

- Phytochemical analysis of Stachys iva: Discovering the optimal extract conditions and its bioactive compounds

- Review on role of honey in disease prevention and treatment through modulation of biological activities

- Computational analysis of polymorphic residues in maltose and maltotriose transporters of a wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain

- Optimization of phenolic compound extraction from Tunisian squash by-products: A sustainable approach for antioxidant and antibacterial applications

- Liupao tea aqueous extract alleviates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in rats by modulating the gut microbiota

- Toxicological qualities and detoxification trends of fruit by-products for valorization: A review

- Polyphenolic spectrum of cornelian cherry fruits and their health-promoting effect

- Optimizing the encapsulation of the refined extract of squash peels for functional food applications: A sustainable approach to reduce food waste

- Advancements in curcuminoid formulations: An update on bioavailability enhancement strategies curcuminoid bioavailability and formulations

- Impact of saline sprouting on antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds in chia seeds

- The dilemma of food genetics and improvement

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Impact of hyaluronic acid-modified hafnium metalorganic frameworks containing rhynchophylline on Alzheimer’s disease

- Emerging patterns in nanoparticle-based therapeutic approaches for rheumatoid arthritis: A comprehensive bibliometric and visual analysis spanning two decades

- Application of CRISPR/Cas gene editing for infectious disease control in poultry

- Preparation of hafnium nitride-coated titanium implants by magnetron sputtering technology and evaluation of their antibacterial properties and biocompatibility

- Preparation and characterization of lemongrass oil nanoemulsion: Antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant, and anticancer activities

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells”

- Corrigendum to “Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans