Abstract

This article conducts a meta-analysis to evaluate the safety and efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (R/R DLBCL). A total of 63 papers were initially retrieved, and eight clinical studies were collected. The estimated effect of ORR was [OR = 0.40, 95% CI 0.29–0.51; p = 0.08], the estimated effect of complete response rate was [OR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.14–0.31; p < 0.001], while the estimated effect of 1-year progression-free survival was [OR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.22–0.47; p = 0.01]. The estimated effect of 1-year OS was [OR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.55–0.77; p = 0.05]. In addition, the estimated effect of grade 3 adverse events was [OR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.22–0.46; p = 0.01]. Overall, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors demonstrated suboptimal therapeutic efficacy in the selected trials for R/R DLBCL. However, combining PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with CAR-T showed potential for improved treatment outcomes. Additionally, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors were found to be safe and well-tolerated in patients with R/R DLBCL.

1 Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) represents the most prevalent subtype of aggressive lymphoma, where approximately 60–65% of patients achieve remission after initial treatment. Nevertheless, the prognosis for relapsed or refractory cases continues to pose significant clinical challenges, with the optimal therapeutic strategy remaining under active investigation. While autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) has emerged as a cornerstone therapeutic intervention for relapsed/refractory (R/R) DLBCL in recent years, clinical evidence reveals suboptimal outcomes: Patients achieving partial response (PR) after second-line salvage chemotherapy who subsequently undergo ASCT demonstrate a strikingly limited median overall survival (OS) of 4.4 months, accompanied by 1-year and 2-year OS rates of 23 and 16%, respectively [1]. Notably, even in transplant-eligible populations, ASCT fails to achieve long-term disease-free survival rates exceeding 50%. Beyond ASCT, the therapeutic landscape for R/R DLBCL encompasses multiple emerging modalities, including chimeric antigen receptor T-cell immunotherapy (CAR-T) therapy, next-generation monoclonal antibodies, antibody–drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies, targeted small molecule inhibitors, and allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Critical questions regarding the optimal sequencing paradigms and combination strategies for these interventions persist as focal points of contemporary clinical research.

Programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1), a pivotal immune checkpoint receptor, orchestrates peripheral tissue T cell activity while maintaining immune tolerance during infection-induced inflammatory responses. Emerging evidence highlights substantial infiltration of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in diverse tumor microenvironments (TMEs), where tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes exhibit marked PD-1 upregulation. This molecular signature promotes Treg expansion through PD-1/ligand interaction. The receptor engages two structurally distinct ligands: programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) (B7-H1/CD274) and PD-L2 (B7-DC/CD273), with PD-L1 overexpression being extensively characterized in multiple malignancies. Clinical studies have consistently demonstrated aberrant PD-L1 expression patterns in solid tumors including non-small cell lung cancer [2], melanoma [3], renal cell carcinoma [4], as well as hematological neoplasms such as relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma [5,6]. Of particular clinical relevance, the spatial distribution and quantitative expression of PD-1/PD-L1 within both tumor parenchyma and infiltrating immune cells have gained recognition as predictive biomarkers for patient outcomes in contemporary oncology.

Therapeutic inhibitors targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis abrogate the interaction between PD-1 receptors and their ligand PD-L1 expressed by activated T cells, thereby rescuing T cell exhaustion and reinvigorating antitumor immunity [7]. Pivotal clinical trials have established the clinical precedence of PD-1 inhibitors surpassing conventional therapies across malignancies, notably advanced melanoma [8], non-small cell lung cancer [9,10], and multiple myeloma [11]. Mechanistic studies reveal that anti-PD-L1 antibodies achieve precision targeting of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway while preserving PD-1/PD-L2 signaling critical for peripheral immune homeostasis, thereby reducing immune-related toxicities [12]. Illustratively, a phase 1 trial evaluating Nivolumab in R/R DLBCL demonstrated an overall response rate of 36% and complete response (CR) rate of 18%, with median progression-free survival (PFS) limited to 7 weeks after 2-year treatment [13]. Younes et al. reported a combination regimen of Ibrutinib plus Nivolumab yielding ORR and CR rates of 36 and 16%, respectively, in R/R DLBCL [14]. Similarly, Armand et al. conducted a phase 2 study showing Pidilizumab monotherapy achieved ORR of 51% and CR of 34% in this population [15]. Notably, the existing evidence landscape lacks comprehensive systematic evaluations assessing both efficacy profiles and safety parameters of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors specifically in DLBCL. This study undertakes a rigorous meta-analysis to address this knowledge gap, aiming to provide evidence synthesis for optimizing clinical decision-making in this challenging patient cohort.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Retrieval strategy

We executed a systematic search strategy across PubMed, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE databases to identify studies published from January 1, 2014 through January 1, 2024. To account for regional therapeutic variations, particularly the commercial availability of multiple PD-1 inhibitors in China, our search incorporated both generic terms (“PD-1 blockade” or “programmed death-1 blockade”) and proprietary agent nomenclature: Pembrolizumab, Nivolumab, Sintilimab, Camrelizumab, Tislelizumab, and Toripalimab. To enhance search specificity, we employed combinatorial search strings integrating these target keywords with disease-specific terms including “diffuse large B-cell lymphoma” and “refractory or relapsed (R/R)” during secondary screening of the preliminary search results.

2.2 Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included: (1) the study population consisted of patients diagnosed with R/R DLBCL, (2) the study investigated the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in treating R/R DLBCL, (3) the article presented data on ORR, PFS, OS, and drug-related adverse events (AEs), and (4) literature included in the review was restricted to English and Chinese languages.

2.3 Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included: (1) irrelevant articles were excluded from consideration; (2) articles lacking the specified outcome measures and data on adverse drug reactions were also excluded; (3) letters, case reports, and reviews were not included in the analysis; (4) republished articles were not included in the review; and (5) conference articles and abstracts presenting only stage summaries were excluded from the analysis.

2.4 Quality evaluation and data extraction

Two independent investigators performed the study selection process using predefined eligibility criteria, with screening conducted in duplicate to ensure reproducibility. Discrepancies were resolved through deliberation or adjudication by a third researcher when consensus could not be reached. Data extraction focused on capturing key parameters: patient demographics (age distribution in case and control cohorts), sample size, therapeutic outcomes (ORR, CR, OS, PFS), first author identification, and publication timeline. AEs were systematically classified into hematologic toxicities (neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia) and non-hematologic events. Methodological rigor was evaluated using the validated Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) tool [16], which assesses eight critical domains: (1) explicitly defined study objective, (2) consecutive patient enrollment, (3) prospective data acquisition, (4) endpoint alignment with research aims, (5) blinded endpoint assessment, (6) clinically appropriate follow-up duration, (7) follow-up completion rate ≥95%, and (8) a priori sample size calculation.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The ORR represented the proportion of patients achieving CR and PR. All data processing was conducted utilizing RevMan 5.4 software. The combined OR and its corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using the formula: pf = OR/(1 + OR), lower limit of 95% CI (LL) = LLOR/(1 + LLOR), and upper limit of 95% CI (UL) = ULOR/(1 + ULOR). Heterogeneity analysis was performed using two methods: the I 2 test and the Q test. Heterogeneity was deemed small if I 2 was less than 50% and Q test had a p-value greater than 0.1, in which case the fixed-effect model was employed for analysis. Conversely, if there was significant heterogeneity (I 2 ≥ 50% or Q test p-value ≤0.1), the random-effects model was utilized for combined analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Study characteristics and quality assessment

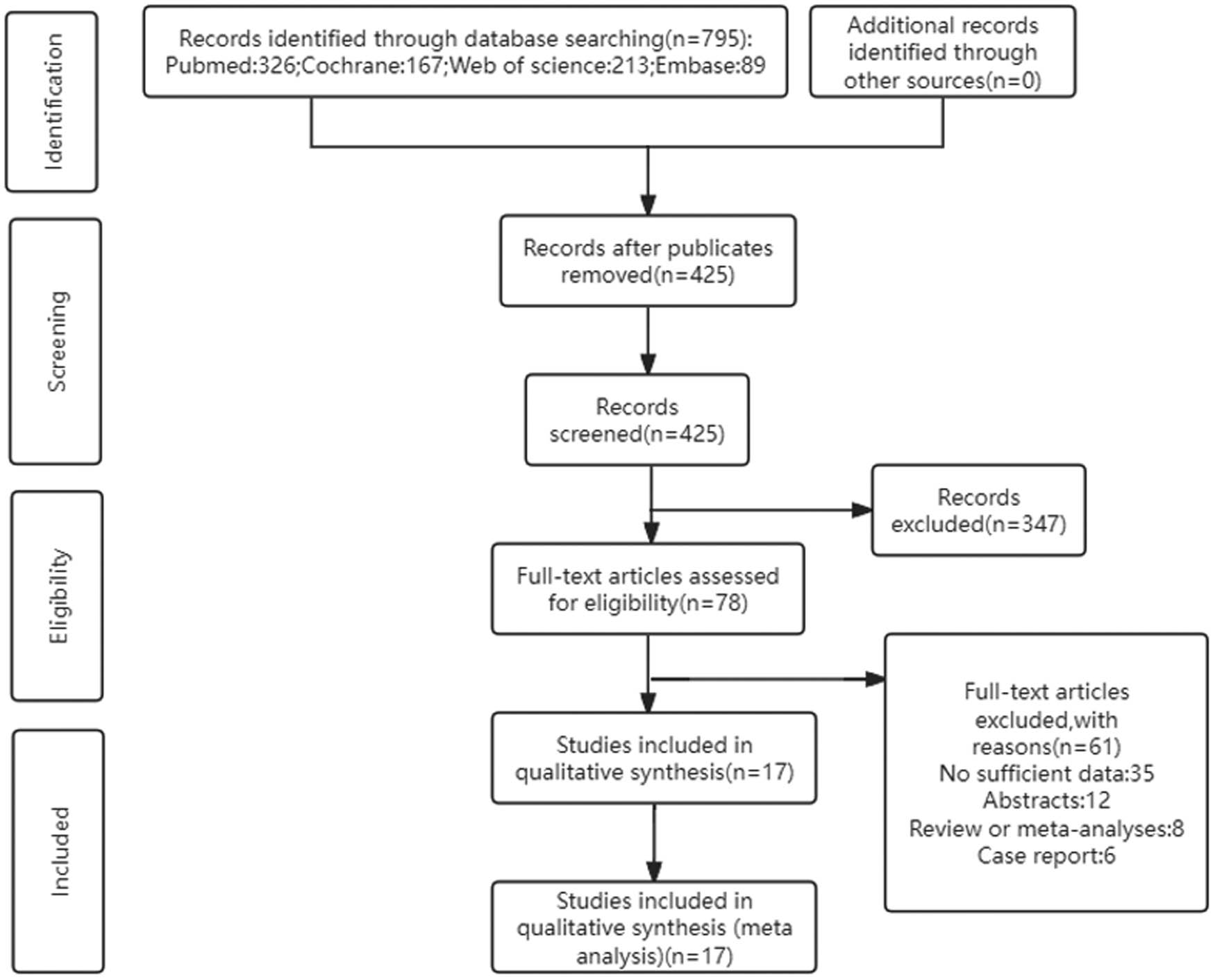

A total of 63 papers retrieved from the four databases underwent screening based on the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Ultimately, 17 clinical case–control studies [14,17–28] were selected, comprising 576 cases with R/R DLBCL. All included studies assessed the impact of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies on R/R DLBCL. The study screening process is depicted in Figure 1. Detailed information for each included study is provided in Table 1. The quality assessment of papers using the MINORS revealed moderate quality, with scores ranging from 10 to 13. The MINORS scores for the included papers are presented in Table S1.

Flow chart of the literature search and study selection.

Included in the article baseline table

| Author & year | Trial phase | Number | Age | Follow-up duration | Treatment | ORR (%) | CRR (%) | Adverse events (>grade 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Philippe Armand (2013) | 2 | 66 | 57 (19–80) | 16 months | Pidilizumab | 51.5 | 34.0 | Neutropenia: 19% |

| Thrombocytopenia: 8% | ||||||||

| Anas Younes (2019) | 1/2a | 65 | 65 (54–71) | 18.4 months (15.6–19.4) | Ibrutinib + Nivolumab | 44.6 | 13.8 | Anemia: 26% |

| Neutropenia: 20% | ||||||||

| Rash: 12% | ||||||||

| Stephen M. Ansell (2018) | 2 | 121 | a: 62 (24–75) b: 68 (28–86) | 9 months | Nivolumab | 8.0 | 2.0 | Neutrophils decreased: 4% |

| Platelets decreased: 3% | ||||||||

| Lipase increased: 3% | ||||||||

| Alexander M. Lesokin (2016) | 1b | 11 | 65 (23–74) | 7 weeks (6–29) | Nivolumab | 36.0 | 18.0 | Pneumonia: 4% |

| Anemia: 4%, | ||||||||

| Low white blood cells: 4% | ||||||||

| Vincent Ribrag (2021) | 1b | 32 | 68 (41–87) | — | Durvalumab + Tremelimumab | 6.0 | 0.0 | — |

| Alex F. Herrera (2018) | 1b/2 | 34 | GCB:68 (22–82) non-GCB 67 (39–82) | 17.5 months (0.2–23.6) | Ibrutinib + Durvalumab | 24.0 | 18.0 | Neutropenia: 26% |

| Fatigue: 12% | ||||||||

| Dyspnea: 12% | ||||||||

| Liqin Ping (2023) | — | 67 | 54 (23–74) | 24.7 months (1.4–39.6) | Sintilimab/Camrelizumab/Toripalimab/Pembrolizumab + ICE | 62.7 | 43.3 | Neutropenia: 7.5% |

| Anemia: 5.0% | ||||||||

| Thrombocytopenia: 9.0% | ||||||||

| Yan Qin (2021) | 2 | 30 | 56.5 (20–78) | 21.3 months (9.6–24.2) | Toripalimab/Pembrolizumab/Nivolumab/Sintilima + Rituximab | 53.3 | 6.7 | Interstitial pneumonia: 7% |

| Hypophysitis: | ||||||||

| 3% | ||||||||

| A. Davies (2021) | 2 | 41 | 73 (23–85) | — | Atezolizumab + R-GemOx | 39.0 | 13.0 | Thrombocytopenia: 32% |

| Neutropenia: 10% | ||||||||

| Pneumonia: 10% | ||||||||

| Fever: 10% | ||||||||

| Juan Mu (2021) | 2 | 26 | 52 | — | CD19 CAR-T + Sintilimab | 65.39 | 42.31 | Neutropenia: 54% |

| Thrombocytopenia: 35% | ||||||||

| Fatigue: 31% | ||||||||

| Fever: 27% | ||||||||

| Chills: 23% | ||||||||

| Teng Yu (2023) | 1b | 11 | 50 (40–70) | 31 months (2–34) | CD19 CAR-T + Tislelizumab | 72.7 | 45.5 | CRS: 19% |

| Chunmeng Wang (2021) | — | 5 | 40 (35–54) | 21.8 months | After failure of CD19/20 CAR-T therapy, Sintilimab/Camrelizumab | 60.0 | 40.0 | — |

| Qian W. (2021) | 1b | 8 | 45.5 (38–65) | — | CD19 CAR-T + Tislelizumab | 75.0 | 57.1 | ICANS: 25% |

| James Godfrey (2023) | 1 | 6 | 51 (21–79) | 3.8 years (2.9–5.1) | Vorinostat + Pembrolizumab | 33.0 | 17.0 | Neutropenia: 17% |

| Hypertension: 17% | ||||||||

| Carmelo Carlo‐Stella (2022) | 1/2 | 17 | 64 (23–75) | 24 weeks | Isatuximab + Cemiplimab | 5.9 | 5.9 | Decreased appetite: 12% |

| Abdominal pain: 6% | ||||||||

| Peripheral edema: 6% | ||||||||

| U. Jaeger (2021) | 1b | 12 | 62 (35–79) | 4 months | CD19 CAR-T + Pembrolizumab | 33.3 | 16.7 | Neutropenia: 33% |

| Nitin Jain (2023) | 2 | 24 | 64.5 (47–88) | 46.3 months (1.2–61.3) | Nivolumab + Ibrutinib | 42.0 | 34.0 | Lung infection: 4% |

| Lipase: 4% | ||||||||

| Uveitis: 4% | ||||||||

| transaminase: 4% |

3.2 Heterogeneity test and estimated effect analysis of ORR

The heterogeneity test results for the level of ORR were as follows: Q = 89.51 (p < 0.001) and I 2 = 82%. These findings indicate substantial heterogeneity among the studies, warranting the use of a random-effects model for analysis. The estimated effect of ORR was [OR = 0.40, 95% CI 0.29–0.51; p = 0.08]. Figure 2a illustrates the forest plot depicting the level of ORR.

![Figure 2

(a) The forest plot of the level of ORR. The heterogeneity test result was Q = 89.51 (p < 0.001) and I

2 = 82%. The estimated effect was [OR = 0.40, 95% CI 0.29–0.51; p = 0.08]. (b) The forest plot of the level of CRR. The heterogeneity test result was Q = 67.76 (p < 0.001) and I

2 = 76%. The estimated effect was [OR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.14–0.31; p < 0.001].](/document/doi/10.1515/biol-2025-1129/asset/graphic/j_biol-2025-1129_fig_002.jpg)

(a) The forest plot of the level of ORR. The heterogeneity test result was Q = 89.51 (p < 0.001) and I 2 = 82%. The estimated effect was [OR = 0.40, 95% CI 0.29–0.51; p = 0.08]. (b) The forest plot of the level of CRR. The heterogeneity test result was Q = 67.76 (p < 0.001) and I 2 = 76%. The estimated effect was [OR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.14–0.31; p < 0.001].

3.3 Heterogeneity test and estimated effect analysis of CRR

The heterogeneity analysis for the level of CRR yielded Q = 67.76 (p < 0.001) and I 2 = 76%, indicating significant heterogeneity among the studies. Therefore, a random-effects model was employed for analysis. The estimated effect of CRR was [OR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.14–0.31; p < 0.001]. Figure 2b depicts the forest plot illustrating the level of CRR.

3.4 Heterogeneity test and estimated effect analysis of 1-year PFS

The heterogeneity analysis for the level of PFS yielded Q = 96.64 (p < 0.001) and I 2 = 84%, indicating significant heterogeneity among the studies. Therefore, a random-effects model was employed for analysis. The estimated effect of PFS was [OR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.22–0.47; p = 0.01]. Figure 3a depicts the forest plot illustrating the level of PFS.

![Figure 3

(a) The forest plot of the level of 1-year PFS. The heterogeneity test result was Q = 96.64 (p < 0.001) and I

2 = 84%. The estimated effect was [OR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.22–0.47; p = 0.01]. (b) The forest plot of the level of 1-year OS. The heterogeneity test result was Q = 68.33 (p < 0.001) and I

2 = 81%.The estimated effect was [OR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.55–0.77; p = 0.05].](/document/doi/10.1515/biol-2025-1129/asset/graphic/j_biol-2025-1129_fig_003.jpg)

(a) The forest plot of the level of 1-year PFS. The heterogeneity test result was Q = 96.64 (p < 0.001) and I 2 = 84%. The estimated effect was [OR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.22–0.47; p = 0.01]. (b) The forest plot of the level of 1-year OS. The heterogeneity test result was Q = 68.33 (p < 0.001) and I 2 = 81%.The estimated effect was [OR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.55–0.77; p = 0.05].

3.5 Heterogeneity test and estimated effect analysis of 1-year OS

The heterogeneity analysis for the level of OS yielded Q = 68.33 (p < 0.001) and I 2 = 81%, indicating significant heterogeneity among the studies. Therefore, a random-effects model was employed for analysis. The estimated effect of OS was [OR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.55–0.77; p = 0.05]. Figure 3b depicts the forest plot illustrating the level of OS.

3.6 Heterogeneity assessment and analysis of estimated effects on AEs

The heterogeneity test revealed significant heterogeneity among studies for AEs of grades 1, 2 and 3, with Q = 40.29 (p < 0.001) and I 2 = 70%. Thus, a random-effects model was applied for analysis. The estimated OR for AEs was [OR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.70–0.89; p < 0.001], Figure 4a displays the forest plot illustrating AEs. Similarly, for grade 3 AEs, the heterogeneity test showed substantial heterogeneity, with Q = 49.65 (p < 0.001) and I 2 = 78%. Therefore, a random-effects model was employed. The estimated OR for grade 3 AEs was [OR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.22–0.46; p = 0.01]. Figure 4b depicts the forest plot of grade 3 AEs.

![Figure 4

(a) The forest plot of the level of AEs. The heterogeneity test result was Q = 40.29 (p < 0.001) and I

2 = 70%. The estimated effect was [OR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.70–0.89; p<0.001]. (b) The forest plot of the level of grade 3 AEs. The heterogeneity test result was Q = 49.65 (p < 0.001) and I

2 = 78%. The estimated effect was [OR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.22–0.46; p = 0.01].](/document/doi/10.1515/biol-2025-1129/asset/graphic/j_biol-2025-1129_fig_004.jpg)

(a) The forest plot of the level of AEs. The heterogeneity test result was Q = 40.29 (p < 0.001) and I 2 = 70%. The estimated effect was [OR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.70–0.89; p<0.001]. (b) The forest plot of the level of grade 3 AEs. The heterogeneity test result was Q = 49.65 (p < 0.001) and I 2 = 78%. The estimated effect was [OR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.22–0.46; p = 0.01].

3.7 Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was conducted based on whether CAR-T was combined, as illustrated in Figure 5. The overall heterogeneity across the included studies was significant, with Q = 89.51 (p < 0.001) and I 2 = 82%. This indicates substantial heterogeneity among the studies, necessitating the utilization of a random-effects model for analysis. Subgroup findings revealed that the PD-1 inhibitor combined with CAR-T group [OR = 0.61, 95% CI 0.43–0.77; p = 0.23], while the PD-1 inhibitor combined with other groups [OR = 0.34, 95% CI 0.22–0.47; p = 0.02]. The combination of PD-1 inhibitor with CAR-T demonstrated a significant improvement in ORR among R/R DLBCL patients.

Subgroup analysis conducted based on whether CAR-T was combined.

3.8 Bias analysis

As depicted in Figure S1a and b respectively, the plots reveal that all data points are evenly distributed and symmetrical regarding the ORR and CRR. This symmetry suggests the absence of publication bias, thereby bolstering the credibility of the results. However, for the outcomes of 1-year PFS, 1-year OS, and AEs, as shown in Figures S2a, b, and S3, respectively, the symmetry among data points is notably poor. This discrepancy implies the presence of significant publication bias in these aspects.

4 Discussion

R/R DLBCL manifests as a biologically complex malignancy driven by multifactorial pathogenesis. Mounting evidence implicates viral triggers, dysregulated immune responses (both immunosuppressive states and hyperactive immunity), and environmental exposures as key etiological contributors [29]. Despite therapeutic advances, the prognosis remains dismal, with 5-year survival rates persisting below 30% in contemporary series. This persistent clinical challenge underscores the critical unmet need for rational development of novel combinatorial approaches and dynamic sequencing algorithms to overcome therapeutic resistance.

Contemporary oncology has witnessed immunotherapy revolutionize the therapeutic landscape through strategic immune system reprogramming. This paradigm harnesses host immunity to reinvigorate antitumor responses via three cardinal mechanisms: immune checkpoint modulation, T cell activation potentiation, and TME remodeling ultimately achieving durable tumor control [30,31]. At the molecular level, PD-1 and PD-L1, both immunoglobulin superfamily members, constitute co-inhibitory type I transmembrane proteins that orchestrate immune evasion. Functionally, PD-1 expressed on activated T lymphocytes engages PD-L1 expressed by malignant cells or stromal antigen-presenting cells, initiating inhibitory signaling cascades that attenuate T cell effector functions while establishing immune privileged niches for tumor progression [32].

At the molecular level, PD-1 activation on stimulated T lymphocytes initiates a sophisticated biochemical cascade: following ligand engagement, the receptor recruits SHP-1/SHP-2 phosphatases and downstream adaptor proteins, triggering catalytic dephosphorylation events that disrupt proximal signaling networks. This biochemical interplay culminates in three cardinal immunosuppressive effects: (1) blunted cytokine secretion (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2); (2) proliferative arrest of antigen-specific T cell clones; and (3) breakdown of immune homeostasis through Treg/Th17 axis dysregulation collectively establishing a tumor permissive microenvironment [33,34]. These mechanistic insights have propelled monoclonal antibody based checkpoint blockade to the forefront of cancer immunotherapy, where PD-1/PD-L1 antagonists precisely intercept this co-inhibitory axis to restore immune-mediated tumor eradication.

Immunohistochemical profiling reveals distinct expression patterns of checkpoint molecules across lymphoma subtypes. PD-1 immunoreactivity is consistently detected in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL [35]. Conversely, PD-L1 expression demarcates a separate pathological spectrum, being prevalent in Hodgkin lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, while remaining undetectable in mantle cell lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, and Burkitt lymphoma [36]. Prognostically, multivariate analyses demonstrate a significant inverse correlation between PD-1 tumor infiltration density and survival outcomes in DLBCL (HR = 2.1, 95% CI 1.4–3.2; p < 0.01), whereas PD-L1 expression lacks comparable predictive value [37]. Intriguingly, the TME exhibits heightened PD-1+ cell infiltration in non-GCB DLBCL subsets characterized by CD30-/CD5-/EBER-phenotypes (72% vs 28%, p = 0.003), mirroring the striking survival disparity between GCB and non-GCB subtypes (5-year OS: 68% vs 41%, p < 0.001) [37]. Clinically, dual negative (PD-1−/PD-L1−) patients demonstrate superior treatment response rates (ORR: 84% vs 52%, p = 0.01) and 3-year survival (72% vs 35%, p < 0.001), a prognostic advantage mechanistically linked to the predominant PD-1+ phenotype in non-GCB biology [38].

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors can disrupt the interaction between PD-1 and its ligand PD-L1 on activated T cells, reversing T cell senescence and enhancing anti-tumor immune responses [7]. The meta-analysis results revealed an ORR of 0.40 (95% CI 0.29–0.51) and a CRR of 0.21 (95% CI 0.14–0.31) for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in treating R/R DLBCL, consistent with the findings of Ding et al.’s study [39].

CAR-T cell therapy is a genetically engineered cellular treatment that offers a novel possibility for achieving long-lasting remission or even cure, acknowledged by the American Society of Clinical Oncology as the “2018 Advance” [40]. The first approved products include axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel), tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel), and lisocabtagenemaraleucel (liso-cel) [41–43], which function by programming autologous T cells to express CAR targeting the B-cell marker CD19.

Landmark phase 2 trials ZUMA-1, JULIET, and TRANSFORM demonstrated durable clinical benefit of CD19 directed CAR T-cell therapies in multiply R/R DLBCL [41]. Notably, the three FDA approved constructs (axi-cel, tisa-cel, liso-cel) achieved sustained remission in 30–40% of heavily pretreated patients (median 3 prior lines) over 24-month follow-up, including ASCT-refractory populations. However, emerging translational data elucidate TME-mediated resistance mechanisms particularly PD-L1 upregulation, Treg infiltration, and myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation that compromise CAR T-cell persistence and effector function in vivo [44,45].

Immunohistochemical analyses have consistently demonstrated pathological upregulation of PD-L1 in DLBCL TME, which correlates with adverse clinical outcomes including reduced PFS (median 8.2 vs 24.6 months, p < 0.001) and elevated relapse rates (HR = 3.4, 95% CI 2.1–5.5) [46]. Mechanistically, targeted disruption of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis serves as a dual-pronged immunotherapeutic strategy: not only potentiating host anti-lymphoma immunity through checkpoint reversal, but also enhancing CAR-T cell effector functions by mitigating terminal exhaustion phenotypes thereby synergistically improving therapeutic efficacy in B-cell malignancies [47,48].

Subgroup analysis indicated that the ORR of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors combined with CAR-T cell therapy was higher compared to monotherapy or combinations with other treatments, with rates of 0.61 and 0.34, respectively. Among the 17 studies analyzed, the phase 1b clinical trial by Qian et al. (NCT04381741) [24] reported the highest ORR and CRR following PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment. This trial involved eight patients aged 18–75 years with R/R DLBCL. Thirty days after modified T-cell infusion, the patients received six cycles of Tislelizumab (200 mg) every 3 weeks as an anti-PD-1 antibody.

Safety assessment revealed two patients (25%) developed grade ≥3 cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and two (25%) experienced grade 3 neurotoxicity, all managed effectively with protocol directed interventions. At 3-month follow-up (n = 7 evaluable), treatment responses stratified as five CR (71.4%), one PR (14.3%), and two progressive disease (28.6%), demonstrating enhanced therapeutic synergy between CAR-T and PD-(L)1 blockade in R/R DLBCL. This synergistic mechanism likely stems from CAR-T cells’ precision targeting capability selectively eliminating CD19+ malignant cells while preserving healthy tissues contrasted with conventional non-targeted therapies (e.g., chemotherapy) that indiscriminately damage proliferating cells. Despite these promising signals, current evidence remains limited by small cohort sizes (median n = 8 per study), necessitating validation through large-scale randomized controlled trials to establish clinical benefit risk profiles.

In terms of safety, research indicates that the incidence of fatal toxic reactions, such as myocarditis and pulmonary toxicity, associated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in lymphoma treatment is relatively low, with grade 3–4 AEs occurring in 1–14% of cases [49]. Overall, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors exhibit favorable tolerability among patients with R/R DLBCL. However, it is essential to note that while combination therapy may enhance clinical efficacy to some extent, it also brings about increased safety risks that warrant careful consideration. This is particularly relevant when approaching the threshold of drug efficacy, which may trigger severe autoimmune conditions and elevate the incidence of immune-related AEs [50].

This study reports an overall incidence rate of AEs at 0.81 (95% CI 0.70, 0.89), with a grade ≥3 AE incidence rate of 0.33 (95% CI 0.22, 0.46), aligning with the findings of Ding et al. [39]. None of the studies included in this analysis reported treatment-related deaths. The most prevalent AEs observed were fatigue, neutropenia, rash, nausea, diarrhea, and anemia, with anemia and neutropenia being the most common among the grade ≥3 AEs. Immune-related AEs, including rash, renal dysfunction, diarrhea, and hepatic dysfunction, were observed in only a small subset of patients.

The limitations of this study include: (1) the restricted pool of eligible studies (n = 17) with marked protocol heterogeneity – variability in therapeutic regimens and dosing schedules – resulted in substantial methodological heterogeneity (I² = 76.00%); (2) incorporation of two retrospective observational studies introduced baseline characteristic disparities and selection bias risks inherent to non-randomized designs; (3) critical survival endpoints (OS/PFS) were compromised by incomplete data granularity, precluding time-to-event meta-analysis via parametric survival models. These constraints collectively undermine the robustness of pooled effect estimates and limit generalizability of conclusions, necessitating cautious interpretation of therapeutic recommendations.

5 Conclusions

In summary, the meta-analysis of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in the treatment of R/R DLBCL indicates limited therapeutic efficacy while demonstrating consistent safety profiles. Furthermore, the combination of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with CAR-T cell therapy for R/R DLBCL yields satisfactory treatment outcomes. However, the lack of measurements for PD-1/PD-L1 expression levels in the TME and peripheral blood across the included studies precludes validation of their correlation with prognosis. Therefore, further research is warranted to elucidate this relationship.

-

Funding information: This work was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2021MH115), Projects of medical and health technology development program in Shandong province (202203040454), and Natural Science Foundation of Dongying (2023ZR028).

-

Author contributions: Liang Wang conceptualized the study design. Jiawen Zhang and Lei Xu analyzed the data, performed statistical analyses, Jiawen Zhang wrote the manuscript. Jiawen Zhang, Lei Xu, Caifeng Sun, and Zonghua Huang acquired the data and managed the patients. Ji Ma and Liang Wang revised the manuscript critically and approved the final version.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Van Den Neste E, Schmitz N, Mounier N, Gill D, Linch D, Trneny M, et al. Outcomes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients relapsing after autologous stem cell transplantation: an analysis of patients included in the CORAL study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;52:216–21. 10.1038/bmt.2016.213.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Spigel DR, Chaft JE, Gettinger S, Chao BH, Dirix L, Schmid P, et al. FIR: efficacy, safety, and biomarker analysis of a phase II open-label study of atezolizumab in PD-L1-selected patients with NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:1733–42. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.05.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Lee J, Kefford R, Carlino M. PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in melanoma treatment: past success, present application and future challenges. Immunotherapy. 2016;8:733–46. 10.2217/imt-2016-0022.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] McKay RR, Bossé D, Xie W, Wankowicz SAM, Flaifel A, Brandao R, et al. The clinical activity of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in metastatic non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6:758–65. 10.1158/2326-6066.Cir-17-0475.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Kasamon YL, de Claro RA, Wang Y, Shen YL, Farrell AT, Pazdur R. FDA approval summary: nivolumab for the treatment of relapsed or progressive classical hodgkin lymphoma. Oncologist. 2017;22:585–91. 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Vinay DS, Ryan EP, Pawelec G, Talib WH, Stagg J, Elkord E, et al. Immune evasion in cancer: mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35(Suppl):S185–98. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.03.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Voena C, Chiarle R. Advances in cancer immunology and cancer immunotherapy. Discovery Med. 2016;21:125–33.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Guan X, Wang H, Ma F, Qian H, Yi Z, Xu B. The efficacy and safety of programmed cell death 1 and programmed cell death 1 ligand inhibitors for advanced melanoma: a meta-analysis of clinical trials following the PRISMA guidelines. Medicine. 2016;95:e3134. 10.1097/md.0000000000003134.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crinò L, Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Inman BA, Sebo TJ, Frigola X, Dong H, Bergstralh EJ, Frank I, et al. PD-L1 (B7-H1) expression by urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and BCG-induced granulomata: associations with localized stage progression. Cancer. 2007;109:1499–505. 10.1002/cncr.22588.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, Dutriaux C, Maio M, Mortier L, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320–30. 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Xiao Y, Yu S, Zhu B, Bedoret D, Bu X, Francisco LM, et al. RGMb is a novel binding partner for PD-L2 and its engagement with PD-L2 promotes respiratory tolerance. J Exp Med. 2014;211:943–59. 10.1084/jem.20130790.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Manson G, Mear JB, Herbaux C, Schiano JM, Casasnovas O, Stamatoullas A, et al. Long-term efficacy of anti-PD1 therapy in Hodgkin lymphoma with and without allogenic stem cell transplantation. Eur J Cancer. 2019;115:47–56. 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.04.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Younes A, Brody J, Carpio C, Lopez-Guillermo A, Ben-Yehuda D, Ferhanoglu B, et al. Safety and activity of ibrutinib in combination with nivolumab in patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a phase 1/2a study. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6:e67–78. 10.1016/s2352-3026(18)30217-5.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Armand P, Nagler A, Weller EA, Devine SM, Avigan DE, Chen YB, et al. Disabling immune tolerance by programmed death-1 blockade with pidilizumab after autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results of an international phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4199–206. 10.1200/jco.2012.48.3685.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Gore S, Goldberg A, Huang MH, Shoemaker M, Blackwood J. Development and validation of a quality appraisal tool for validity studies (QAVALS). Physiother Theory Pract. 2021;37:646–54. 10.1080/09593985.2019.1636435.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Davies AJ, Tansley Hancock O, Cummin T, Caddy J, Stanton L, Burton C, et al. ARGO: a randomised phase II study of atezolizumabwith rituximab, gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who are not candidates for high-dose therapy. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37:555–6. 10.1002/hon.1_2632.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Godfrey J, Mei M, Chen L, Song JY, Bedell V, Budde E, et al. Results from a phase I trial of pembrolizumab plus vorinostat in relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Haematologica. 2024;109:533–42. 10.3324/haematol.2023.283002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Herrera AF, Goy A, Mehta A, Ramchandren R, Pagel JM, Svoboda J, et al. Safety and activity of ibrutinib in combination with durvalumab in patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:18–27. 10.1002/ajh.25659.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Jain N, Senapati J, Thakral B, Ferrajoli A, Thompson P, Burger J, et al. A phase 2 study of nivolumab combined with ibrutinib in patients with diffuse large B-cell Richter transformation of CLL. Blood Adv. 2023;7:1958–66. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008790.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Lesokhin AM, Ansell SM, Armand P, Scott EC, Halwani A, Gutierrez M, et al. Nivolumab in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancy: preliminary results of a phase Ib study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2698–704. 10.1200/jco.2015.65.9789.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Mu J, Deng H, Lyu C, Yuan J, Li Q, Wang J, et al. Efficacy of programmed cell death 1 inhibitor maintenance therapy after combined treatment with programmed cell death 1 inhibitors and anti-CD19-chimeric antigen receptor T cells in patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and high tumor burden. Hematol Oncol. 2023;41:275–84. 10.1002/hon.2981.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Ping L, Gao Y, He Y, Bai B, Huang C, Shi L, et al. PD-1 blockade combined with ICE regimen in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2023;102:2189–98. 10.1007/s00277-023-05292-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Qian W, Zhao A, Liu H, Lei W, Liang Y, Yuan X. Safety and efficacy of CD19 CAR-T cells co-expressing IL-7 and CCL19 in combination with anti-PD-1 antibody for refractory/relapsed DLBCL: preliminary data from the phase Ib trial (NCT04381741). Blood. 2021;138:3843. 10.1182/blood-2021-144523.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Qin Y, He X, Yang S, Liu P, Zhou S, Yang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of PD-1 inhibitor plus rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2021;138:2485. 10.1182/blood-2021-152094.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Ribrag V, Lee ST, Rizzieri D, Dyer MJS, Fayad L, Kurzrock R, et al. A Phase 1B study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of durvalumab in combination with tremelimumab or danvatirsen in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21:309–17.e303. 10.1016/j.clml.2020.12.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Sacks D, Baxter B, Campbell BCV, Carpenter JS, Cognard C, Dippel D, et al. Multisociety consensus quality improvement revised consensus statement for endovascular therapy of acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2018;13:612–32. 10.1177/1747493018778713.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Wang C, Shi F, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Dong L, Li X, et al. Correction to: Anti-PD-1 antibodies as a salvage therapy for patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma who progressed/relapsed after CART19/20 therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:150. 10.1186/s13045-021-01154-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Liu Y, Barta SK. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:604–16. 10.1002/ajh.25460.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Weiss SA, Djureinovic D, Jessel S, Krykbaeva I, Zhang L, Jilaveanu L, et al. A phase I study of APX005M and cabiralizumab with or without nivolumab in patients with melanoma, kidney cancer, or non-small cell lung cancer resistant to anti-PD-1/PD-L1. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:4757–67. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-21-0903.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Zhang L, Chen Y, Wang H, Xu Z, Wang Y, Li S, et al. Massive PD-L1 and CD8 double positive TILs characterize an immunosuppressive microenvironment with high mutational burden in lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(6):e002356. 10.1136/jitc-2021-002356.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, Bourque K, Chernova T, Nishimura H, et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1027–34. 10.1084/jem.192.7.1027.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Wang L, Liu Z, Zhang W, Zhang A, Qu P. PD-1 coexpression gene analysis and the regulatory network in endometrial cancer based on bioinformatics analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:9923434. 10.1155/2021/9923434.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Abunasser AAA, Xue J, Balawi EJA, Zhu Y. Combination of the EP and anti-PD-1 pathway or anti-CTLA-4 for the phase III trial of small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. J Oncol. 2021;2021:6662344. 10.1155/2021/6662344.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Xerri L, Chetaille B, Serriari N, Attias C, Guillaume Y, Arnoulet C, et al. Programmed death 1 is a marker of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and B-cell small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1050–8. 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.11.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Wilcox RA, Feldman AL, Wada DA, Yang ZZ, Comfere NI, Dong H, et al. B7-H1 (PD-L1, CD274) suppresses host immunity in T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 2009;114:2149–58. 10.1182/blood-2009-04-216671.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Dai X, Wang K, Chen H, Huang X, Feng Z. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of 1-methyl-1H-pyrazolo[4,3-b]pyridine derivatives as novel small-molecule inhibitors targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction. Bioorg Chem. 2021;114:105034. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105034.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Liu L, Yao Z, Wang S, Xie T, Wu G, Zhang H, et al. Syntheses, biological evaluations, and mechanistic studies of benzo[c][1,2,5]oxadiazole derivatives as potent PD-L1 inhibitors with in vivo antitumor activity. J Med Chem. 2021;64:8391–8409. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00392.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Ding X, Guan C, Ding X. Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a meta-analysis. J Biol Regulators Homeost Agents. 2023;37:4479–89. 10.23812/j.biol.regul.homeost.agents.20233708.438.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Heymach J, Krilov L, Alberg A, Baxter N, Chang SM, Corcoran RB, et al. Clinical cancer advances 2018: annual report on progress against cancer from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1020–44. 10.1200/jco.2017.77.0446.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, Lekakis LJ, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2531–44. 10.1056/NEJMoa1707447.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, Waller EK, Borchmann P, McGuirk JP, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:45–56. 10.1056/NEJMoa1804980.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, Lunning MA, Wang M, Arnason J, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. Lancet. 2020;396:839–52. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31366-0.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Enblad G, Karlsson H, Loskog AS. CAR T-cell therapy: the role of physical barriers and immunosuppression in lymphoma. Hum Gene Ther. 2015;26:498–505. 10.1089/hum.2015.054.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] John LB, Kershaw MH, Darcy PK. Blockade of PD-1 immunosuppression boosts CAR T-cell therapy. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e26286. 10.4161/onci.26286.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Vari F, Arpon D, Keane C, Hertzberg MS, Talaulikar D, Jain S, et al. Immune evasion via PD-1/PD-L1 on NK cells and monocyte/macrophages is more prominent in Hodgkin lymphoma than DLBCL. Blood. 2018;131:1809–19. 10.1182/blood-2017-07-796342.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] McCord R, Bolen CR, Koeppen H, Kadel 3rd EE, Oestergaard MZ, Nielsen T, et al. PD-L1 and tumor-associated macrophages in de novo DLBCL. Blood Adv. 2019;3:531–40. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018020602.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Grosser R, Cherkassky L, Chintala N, Adusumilli PS. Combination immunotherapy with car t cells and checkpoint blockade for the treatment of solid tumors. Cancer Cell. 2019;36:471–82. 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.09.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Hawkes EA, Grigg A, Chong G. Programmed cell death-1 inhibition in lymphoma. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e234–45. 10.1016/s1470-2045(15)70103-8.Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Rosenblatt J, Glotzbecker B, Mills H, Vasir B, Tzachanis D, Levine JD, et al. PD-1 blockade by CT-011, anti-PD-1 antibody, enhances ex vivo T-cell responses to autologous dendritic cell/myeloma fusion vaccine. J Immunother. 2011;34:409–18. 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31821ca6ce.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome with elevated IgG4 and T-cell clonality: A report of two cases

- Electroacupuncture alleviates sciatic nerve injury in sciatica rats by regulating BDNF and NGF levels, myelin sheath degradation, and autophagy

- Polydatin prevents cholesterol gallstone formation by regulating cholesterol metabolism via PPAR-γ signaling

- RNF144A and RNF144B: Important molecules for health

- Analysis of the detection rate and related factors of thyroid nodules in the healthy population

- Artesunate inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion through OGA-mediated O-GlcNAcylation of ZEB1

- Endovascular management of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: Case report and review of the literature

- Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis

- SATB2 promotes humeral fracture healing in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Overexpression of the ferroptosis-related gene, NFS1, corresponds to gastric cancer growth and tumor immune infiltration

- Understanding risk factors and prognosis in diabetic foot ulcers

- Atractylenolide I alleviates the experimental allergic response in mice by suppressing TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 signalling

- FBXO31 inhibits the stemness characteristics of CD147 (+) melanoma stem cells

- Immune molecule diagnostics in colorectal cancer: CCL2 and CXCL11

- Inhibiting CXCR6 promotes senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells with limited proinflammatory SASP to attenuate hepatic fibrosis

- Cadmium toxicity, health risk and its remediation using low-cost biochar adsorbents

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis with headache as the first presentation: A case report

- Solitary pulmonary metastasis with cystic airspaces in colon cancer: A rare case report

- RUNX1 promotes denervation-induced muscle atrophy by activating the JUNB/NF-κB pathway and driving M1 macrophage polarization

- Morphometric analysis and immunobiological investigation of Indigofera oblongifolia on the infected lung with Plasmodium chabaudi

- The NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex and Hr78 modulate the Lobe2 mutant eye phenotype

- Experimental study on salmon demineralized bone matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: In vitro and in vivo study

- A case of IgA nephropathy treated with a combination of telitacicept and half-dose glucocorticoids

- Analgesic and toxicological evaluation of cannabidiol-rich Moroccan Cannabis sativa L. (Khardala variety) extract: Evidence from an in vivo and in silico study

- Wound healing and signaling pathways

- Combination of immunotherapy and whole-brain radiotherapy on prognosis of patients with multiple brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study

- To explore the relationship between endometrial hyperemia and polycystic ovary syndrome

- Research progress on the impact of curcumin on immune responses in breast cancer

- Biogenic Cu/Ni nanotherapeutics from Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl seeds for the treatment of lung cancer

- Dapagliflozin attenuates atrial fibrosis via the HMGB1/RAGE pathway in atrial fibrillation rats

- Glycitein alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in keratinocytes via ROS-associated PI3K–Akt signalling pathway

- ADH5 inhibits proliferation but promotes EMT in non-small cell lung cancer cell through activating Smad2/Smad3

- Apoptotic efficacies of AgNPs formulated by Syzygium aromaticum leaf extract on 32D-FLT3-ITD human leukemia cell line with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Novel cuproptosis-related genes C1QBP and PFKP identified as prognostic and therapeutic targets in lung adenocarcinoma

- Bee venom promotes exosome secretion and alters miRNA cargo in T cells

- Treatment of pure red cell aplasia in a chronic kidney disease patient with roxadustat: A case report

- Comparative bioinformatics analysis of the Wnt pathway in breast cancer: Selection of novel biomarker panels associated with ER status

- Kynurenine facilitates renal cell carcinoma progression by suppressing M2 macrophage pyroptosis through inhibition of CASP1 cleavage

- RFX5 promotes the growth, motility, and inhibits apoptosis of gastric adenocarcinoma cells through the SIRT1/AMPK axis

- ALKBH5 exacerbates early cardiac damage after radiotherapy for breast cancer via m6A demethylation of TLR4

- Phytochemicals of Roman chamomile: Antioxidant, anti-aging, and whitening activities of distillation residues

- Circadian gene Cry1 inhibits the tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma by the BAX/BCL2-mediated apoptosis pathway

- The TNFR-RIPK1/RIPK3 signalling pathway mediates the effect of lanthanum on necroptosis of nerve cells

- Longitudinal monitoring of autoantibody dynamics in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing surgery

- The potential role of rutin, a flavonoid, in the management of cancer through modulation of cell signaling pathways

- Construction of pectinase gene engineering microbe and its application in tobacco sheets

- Construction of a microbial abundance prognostic scoring model based on intratumoral microbial data for predicting the prognosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Sepsis complicated by haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis triggered by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and human herpesvirus 8 in an immunocompromised elderly patient: A case report

- Sarcopenia in liver transplantation: A comprehensive bibliometric study of current research trends and future directions

- Advances in cancer immunotherapy and future directions in personalized medicine

- Can coronavirus disease 2019 affect male fertility or cause spontaneous abortion? A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis

- Heat stroke associated with novel leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor gene variant in a Chinese infant

- PSME2 exacerbates ulcerative colitis by disrupting intestinal barrier function and promoting autophagy-dependent inflammation

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state with severe hypernatremia coexisting with central diabetes insipidus: A case report and literature review

- Efficacy and mechanism of escin in improving the tissue microenvironment of blood vessel walls via anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects: Implications for clinical practice

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Clinicopathological analysis of three patients and literature review

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Optimization and comparative study of Bacillus consortia for cellulolytic potential and cellulase enzyme activity

- The complete mitochondrial genome analysis of Haemaphysalis hystricis Supino, 1897 (Ixodida: Ixodidae) and its phylogenetic implications

- Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors analysis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among tuberculosis population in Huzhou City, Eastern China

- Indices of human impacts on landscapes: How do they reflect the proportions of natural habitats?

- Genetic analysis of the Siberian flying squirrel population in the northern Changbai Mountains, Northeast China: Insights into population status and conservation

- Diversity and environmental drivers of Suillus communities in Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica forests of Inner Mongolia

- Global assessment of the fate of nitrogen deposition in forest ecosystems: Insights from 15N tracer studies

- Fungal and bacterial pathogenic co-infections mainly lead to the assembly of microbial community in tobacco stems

- Influencing of coal industry related airborne particulate matter on ocular surface tear film injury and inflammatory factor expression in Sprague-Dawley rats

- Temperature-dependent development, predation, and life table of Sphaerophoria macrogaster (Thomson) (Diptera: Syrphidae) feeding on Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae)

- Eleonora’s falcon trophic interactions with insects within its breeding range: A systematic review

- Agriculture

- Integrated analysis of transcriptome, sRNAome, and degradome involved in the drought-response of maize Zhengdan958

- Variation in flower frost tolerance among seven apple cultivars and transcriptome response patterns in two contrastingly frost-tolerant selected cultivars

- Heritability of durable resistance to stripe rust in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Molecular mechanism of follicular development in laying hens based on the regulation of water metabolism

- Animal Science

- Effect of sex ratio on the life history traits of an important invasive species, Spodoptera frugiperda

- Plant Sciences

- Hairpin in a haystack: In silico identification and characterization of plant-conserved microRNA in Rafflesiaceae

- Widely targeted metabolomics of different tissues in Rubus corchorifolius

- The complete chloroplast genome of Gerbera piloselloides (L.) Cass., 1820 (Carduoideae, Asteraceae) and its phylogenetic analysis

- Field trial to correlate mineral solubilization activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and biochemical content of groundnut plants

- Correlation analysis between semen routine parameters and sperm DNA fragmentation index in patients with semen non-liquefaction: A retrospective study

- Plasticity of the anatomical traits of Rhododendron L. (Ericaceae) leaves and its implications in adaptation to the plateau environment

- Effects of Piriformospora indica and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on growth and physiology of Moringa oleifera under low-temperature stress

- Effects of different sources of potassium fertiliser on yield, fruit quality and nutrient absorption in “Harward” kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa)

- Comparative efficiency and residue levels of spraying programs against powdery mildew in grape varieties

- The DREB7 transcription factor enhances salt tolerance in soybean plants under salt stress

- Using plant electrical signals of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) for water pollution monitoring

- Food Science

- Phytochemical analysis of Stachys iva: Discovering the optimal extract conditions and its bioactive compounds

- Review on role of honey in disease prevention and treatment through modulation of biological activities

- Computational analysis of polymorphic residues in maltose and maltotriose transporters of a wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain

- Optimization of phenolic compound extraction from Tunisian squash by-products: A sustainable approach for antioxidant and antibacterial applications

- Liupao tea aqueous extract alleviates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in rats by modulating the gut microbiota

- Toxicological qualities and detoxification trends of fruit by-products for valorization: A review

- Polyphenolic spectrum of cornelian cherry fruits and their health-promoting effect

- Optimizing the encapsulation of the refined extract of squash peels for functional food applications: A sustainable approach to reduce food waste

- Advancements in curcuminoid formulations: An update on bioavailability enhancement strategies curcuminoid bioavailability and formulations

- Impact of saline sprouting on antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds in chia seeds

- The dilemma of food genetics and improvement

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Impact of hyaluronic acid-modified hafnium metalorganic frameworks containing rhynchophylline on Alzheimer’s disease

- Emerging patterns in nanoparticle-based therapeutic approaches for rheumatoid arthritis: A comprehensive bibliometric and visual analysis spanning two decades

- Application of CRISPR/Cas gene editing for infectious disease control in poultry

- Preparation of hafnium nitride-coated titanium implants by magnetron sputtering technology and evaluation of their antibacterial properties and biocompatibility

- Preparation and characterization of lemongrass oil nanoemulsion: Antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant, and anticancer activities

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells”

- Corrigendum to “Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome with elevated IgG4 and T-cell clonality: A report of two cases

- Electroacupuncture alleviates sciatic nerve injury in sciatica rats by regulating BDNF and NGF levels, myelin sheath degradation, and autophagy

- Polydatin prevents cholesterol gallstone formation by regulating cholesterol metabolism via PPAR-γ signaling

- RNF144A and RNF144B: Important molecules for health

- Analysis of the detection rate and related factors of thyroid nodules in the healthy population

- Artesunate inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion through OGA-mediated O-GlcNAcylation of ZEB1

- Endovascular management of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: Case report and review of the literature

- Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis

- SATB2 promotes humeral fracture healing in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Overexpression of the ferroptosis-related gene, NFS1, corresponds to gastric cancer growth and tumor immune infiltration

- Understanding risk factors and prognosis in diabetic foot ulcers

- Atractylenolide I alleviates the experimental allergic response in mice by suppressing TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 signalling

- FBXO31 inhibits the stemness characteristics of CD147 (+) melanoma stem cells

- Immune molecule diagnostics in colorectal cancer: CCL2 and CXCL11

- Inhibiting CXCR6 promotes senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells with limited proinflammatory SASP to attenuate hepatic fibrosis