Abstract

Gene regulation is important during tissue formation, but redundant systems make it difficult to study in vivo. The protein Jazf-1 is a member of the NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex, and a transcriptional repressor has been suggested to be important for Drosophila melanogaster eye development. We used the GAL4-UAS system to determine the impact of altering gene expression. GAL4-UAS manipulations of Jazf-1 in the eye caused variable and not fully penetrant phenotypes. Increased expression of Jazf-1 has been shown to suppress a Lobe 2 small eye phenotype. We found that Lobe 2 produces a sensitive background for an in vivo assay to monitor gene regulatory complexes. Depleting Jazf-1 and other NuA4/TIP60 complex members significantly enhanced the eye phenotype. We also tested Hr78, which directly interacts with Jazf-1, and found it inversely modifies the Lobe 2 phenotype. An Hr78 mutation predicted to uncouple the Jazf-1 interaction but still capable of interactions with transcriptional activators further enhanced the Lobe 2 mutant phenotype, suggesting the loss of a repressing complex. We believe that Hr78 is acting as an anchor for repressing and activating complexes and the NuA4/TIP60 complex helps repress genes that can negatively impact eye formation in the context of Lobe 2 .

1 Introduction

Jazf-1 is a transcription factor that has been implicated in both disease pathogenesis and core cellular processes. Certain alleles in humans are widely associated with diabetes susceptibility [1,2,3], and de novo translocations of Jazf-1 are the largest cause of Endometrial Stromal Sarcomas [4,5]. Beyond health implications, the dependance of core cellular processes, such as ribosome biogenesis, on Jazf-1 has been demonstrated in human systems [6]. Furthermore, Jazf-1 is predicted to be an early regulator in the formation of different tissues, such as the nervous system and eyes, in Drosophila melanogaster [7]. In support of the role for Jazf-1 in eye formation, it has previously been detected in a screen for genes that could suppress a mutation in the gene Lobe [8].

Lobe (L) is a transcription factor (Lobe/Oaz) with a classic dominant mutation, L 2 , that causes smaller eyes [9]. The L 2 allele was recently determined to be caused by the presence of a transposable element [10]. This hypermorphic allele results in a smaller eye phenotype due to the overexpression of the Lobe gene [10]. Previous genetic screens with L 2 have investigated enhancers and suppressors to the L 2 allele when gene expression was controlled under an eyeless driver [8]. One of the 33 genes that were found to act as a suppressor of the L 2 mutant phenotype was the gene Jazf-1 (CG12054) [8]. Surprisingly, even though thousands of lines were tested, no other proteins that are known to physically associate with Jazf-1 were detected in this screen [6,11,12,13].

Jazf-1 is part of the NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex in both mammalian and D. melanogaster cells [6,11,12]. Recent studies have demonstrated that in both humans and D. melanogaster, NuA4/TIP60 is responsible for acetylation of Lysine 12 on Histone H4 (H4K12ac), through the histone acetyl transferase TIP-60 [6,12]. RNAi knockdowns of Jazf-1 have also been demonstrated to negatively impact the level of H4K12ac [6]. The NuA4/TIP60 complex also has approximately 14 identified members, including unique members such as TRRAP/Nipped-A and Xbp-1 [12,14,15]. Loss of TRRAP/Nipped-A has been shown to negatively impact the ability of the complex to access different areas of the genome [16]. Jazf-1 has repeatedly been shown to be part of a stable subunit within the NuA4/TIP60 complex [17]. Finally, several members from both complexes were recently identified as being important during tissue formation, including the eye, further supporting the idea that Jazf-1 could regulate eye formation, as part of the NuA4/TIP60 complex [18].

In addition to its role in the NuA4/TIP60 complex, Jazf-1 has been found with NR2C2 (TAK1/TR4/TIP27), a nuclear receptor protein [19]. The interaction between Jazf-1 and NR2C2 was initially detected over 20 years ago via yeast two-hybrid [19]. Since then, it has been repeatedly shown to be an important interacting partner of Jazf-1, and most recently, the interaction has been extensively characterized using X-ray crystallography [19,20,21,22]. Furthermore, Jazf-1 seems to act primarily as a repressor; however, there is conflicting evidence that Jazf-1 may act as a repressor or a co-activator with NR2C2 [6,17]. This interaction occurs through binding with the activation function 2 (AF-2) domain on the C-terminus, a region commonly used by transcription activators [23,24]. While most activators interact through the AF-2 domain of NR2C2, some, such as p300/CREB binding protein, interact through the activation function 1 (AF-1) domain located on the N-terminus of the protein [25]. The nuclear receptors are highly conserved, and Hr78 in D. melanogaster is its closest homolog [26,27]. Like NR2C2, Hr78 was also detected in a yeast two-hybrid screen as having a direct interaction with Jazf-1 in D. melanogaster [13].

While Jazf-1 has been extensively studied biochemically, it is not as well defined genetically [6,12,17,21,28]. To this end, the GAL4-UAS binary expression system has two important features to allow tissue-specific manipulation: the driver and the responder. The driver is responsible for the special and temporal expression of the GAL4 protein, a transcription factor. The driver is often coupled to a specific gene promoter to mimic the endogenous expression of that gene. The responder is the gene that will be activated, as it is located immediately downstream of a DNA sequence known as an upstream activating sequence (UAS). The UAS sequence is a specific DNA sequence that the GAL4 protein binds, leading to transcriptional activation [29].

Given the growing evidence for the role of Jazf-1 in the eye, we wanted to investigate the contribution of Jazf-1 and other members of the NuA4/TIP60 complex during eye development. To do this, we genetically manipulated the expression of Jazf-1 within the D. melanogaster eye. Additionally, we tested NuA4/TIP60 complex members in the context of a sensitive L 2 mutant background. Furthermore, we tested manipulations of Hr78 to determine if this would also have any developmental consequences for the L 2 mutant phenotype.

2 Methods

2.1 Stocks used

All stocks used were obtained through the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. GFP expression in the Jazf-1 locus (RRID:BDSC_605433) (y1 w*; TI[GFP[3xP3.cLa] = CRIMIC.TG4.1]CG12054[CR71307-TG4.1]/TM3, Sb1 Ser1) [30]. Lobe 2 mutant lines are a spontaneous mutant (RRID: BDSC_319) (L 2 /CyO) [9,10]. Hr78 2 mutant lines contain an early stop codon in Hr78 (RRID: BDSC_4436) (w*; Hr782/TM6B, Tb+) [31]. The eyeless GAL4 drivers (RRID:BDSC_8220) (y1 w1118; P[w[+mC] = ey3.5-GAL4.Exel]2) and (RRID:BDSC_8227) (y1 w1118; P[w[+mC] = ey3.5-GAL4.Exel]3) were used as either second or third chromosome drivers respectfully, and we referred to them as eyGAL4. Stocks for overexpression of Jazf-1 (UAS:Jazf-1) (RRID:BDSC_15535) (y1 w67c23; P[EPgy2]CG12054EY01782) [32] and Hr78 (UAS:Hr78) (RRID: BDSC_27214 (y1 w*; P[EP]Hr78G6746) were also used [33]. The RNAi lines used for knockdown were Jazf-RNAi (RRID: BDSC_50910) (y1 v1; P[TRIP.HMJ03134]attP40), Xbp-1-RNAi (RRID: BDSC_36755) (y1 sc* v1 sev21; P[TRiP.HMS03015]attP2), Nipped-A-RNAi (BDSC: 34849) (y1 sc* v1 sev21; P[TRiP.HMS00167]attP2), and Hr78-RNAi (RRID: BDSC_31990) (y1 v1; P[y[+t7.7]v[+t1.8] = TRiP.JF03424]attP2 [34].

2.2 Genetic crosses

UAS-GAL4-manipulated D. melanogaster was crossed as follows. Virgin female L2/CyO; eyGAL4/eyGAL4 flies were crossed with males containing a UAS responder line (either UAS overexpressing or UAS-RNAi lines). Female offspring were measured as eyGAL4 heterozygotes with the appropriate UAS responder, and either containing the L 2 or CyO chromosome.

2.3 Growth conditions

All flies were raised in vials with standard R media [35] purchased from Lab Express (Ann Arbor, MI). Adults were limited to no more than 20 females and no more than 10 males per bottle, and progeny were raised at 25°C with 40–60% humidity.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animal use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals.

2.4 Genetic crosses

All flies were manipulated under standard CO2 conditions using genetic markers from standard balancer chromosomes [36].

2.5 Fluorescent and brightfield microscopy

Zeiss Primo Star trinocular microscopes, Moticam Pro 205A, and Motic Images Plus 3.0 software were used to analyze D. melanogaster lines. Fluorescent microscopy was performed using freshly frozen GFP-expressing flies or those with a UAS:GFP responder and no driver. Flies containing GFP genes were exposed to florescence under a 480 nm filter cube for 30 ms. Brightfield microscopy was used to measure the length of D. melanogaster eyes along the dorsal–ventral axis. In general, flies were frozen prior to use on the microscope and one eye from each fly was measured with the genotype blinded to the researcher making the measurements. Female flies were used for all the data reported due to greater variability with L 2 in male flies.

2.6 Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using a student t-test and ANOVA (Excel Software). P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All measurements were based on 10 female adults, and standard deviation was used for error bars on graphs.

3 Results

3.1 Jazf-1 is expressed in the adult eye and ocelli photoreceptors

To investigate the expression of Jazf-1 in the eye, we used a publicly available inserted GFP trap into the Jazf-1 locus. Briefly, the TI[CRIMIC.TG4.1] is inserted by CRISPR/Cas9 followed by recombination-mediated cassette exchange to insert a GFP trap with a GAL4 trap [37]. This recombination-mediated exchange introduces a splice site to the GFP cassette following the first coding exon of three of the four annotated Jazf-1 isoforms to express GFP (Jazf-1-RA, RE, and RF but not RB) (Figure 1a). This allows expression levels of GFP to be consistent with endogenous expression of Jazf-1 RNA. The Jazf-1 gene trap line coupled with a GFP marker allowed us to investigate gene expression of Jazf-1 within the accumulation of GFP-marked cells. GFP expression using this system was robustly detected in the eyes of Drosophila. In addition, to the eyes, the ocelli, a set of photoreceptors on the top of the Drosophila head, robustly expressed GFP under the Jazf-1 locus (Figure 1).

Jazf-1 locus with GFP expression. (a) Schematic representation of GFP inserted into the Jazf-1 locus. RA, RE, and RF coding sequences will splice in the GFP cassette. Jazf-1 RB is incapable of splicing in the GFP cassette. (b–g) Jazf-1 expression in Drosophila melanogaster eyes and ocelli photoreceptors. (b–d) UAS:GFP responder and a Jazf-1:GAL4 driver were inserted in the Jazf-1 locus. (e–g) UAS:GFP responder inserted in a different location with not responder. Brightfield (b and e), GFP (c and f), and merge (d and g) images demonstrate that expression from the Jazf-1 locus but not responder controls in the eye and ocelli (white arrows).

To further understand the role of Jazf-1 in the formation of the eye, we used two responders, creating either an overexpression or knockdown of Jazf-1 in the eye. The GAL4-UAS binary expression system was used, with an eye-specific driver, eyeless-Gal4 (ey-Gal4). Our first responder was a UAS element inserted into the Jazf-1 locus [32], which had previously been reported to have a phenotypic effect when coupled with an eyeless-GAL4 driver on the L 2 mutant phenotype [8] (Figure 2a). A second driver was engineered to reduce expression of Jazf-1. This driver expresses a shRNA that is complementary to Jazf-1 mRNA, leading to a reduction of Jazf-1 mRNA via RNAi [38] (Figure 2b). Here, we will refer to these as Jazf-1-overexpression and Jazf-1-knockdown, respectively.

Schematic representation of overexpression and knockdown strategy in the eye. (a) Overexpression of a gene of interest in the eye. 1. (a) Gal4 encoding gene with an eyeless-promoter will express the Gal4 transcription factor in the eye (The Driver). 2. The UAS is integrated into the endogenous gene promotor via a transposable element that is stably integrated into the DNA. The Gal4 transcription factor increases the expression of the endogenous gene of interest (The Responder). 3. The overexpression of the endogenous gene of interest increases the gene product. (b) Knockdown of a gene of interest in the eye. 1. (a) Gal4 encoding gene with an eyeless promoter will express the Gal4 transcription factor in the eye (The Driver). 2. The UAS is linked to a shRNA with a complementary sequence to the gene of interest that is to be silenced. 3. The shRNA targets mRNA for degradation based on complementary sequence recognition. 4. Degradation of mRNA leads to decreased protein expression.

Jazf-1-overexpression and Jazf-1-knockdown in the eye lead to no appreciable change in the eye phenotype when both the driver and responder are heterozygous (Figure 3a and b). However, when both the driver and responder elements are homozygous, a phenotype is present, though not fully penetrant. Although this phenotype is not seen in all eyes, a reduction in the eyes can be observed in Jazf-1-overexpression and Jazf-1-knockdown homozygotes. Furthermore, Jazf-1-knockdown can be accompanied by irregular surfaces, eyes that are split, or extra structures. These extra structures are more commonly observed on the posterior end of the eye (Figure 3c–f). Even though heterozygous RNAi has the potential to fully eliminate Jazf-1 expression, we suspect that since Jazf-1 expression occurs early [7], and because heterozygotes would be less effective than homozygotes at quickly eliminating Jazf-1 mRNA before some protein has been synthesized, we see a more severe phenotype with homozygotes.

Jazf-1 overexpression and Jazf-1-RNAi driven in the eye. (a) UAS-Jazf-1 responder and eyeless-GAL4 driver. (b) Jazf-1-RNAi responder and eyeless-Gal4 driver as heterozygotes do not display any obvious phenotype. (c–f) Examples of Jazf-1-RNAi; eyGAL4 homozygotes display variable phenotypes. (c) Extra structures to the posterior of the eye (white arrows). (d and e) Broken sections and a smaller eye field. (f) Arrows point to two different eyes, one fully formed (#), and the other absent (*) in the same organism.

3.2 Jazf-1 reduces the L 2 mutant phenotype

It was previously reported that Jazf-1 overexpression can partially suppress an L 2 mutant phenotype [8]. We recapitulated that finding and demonstrated that Jazf-1 overexpression by itself does not change the eye in any appreciable manner (Figure 4). We anticipated that Jazf-1 knockdown would have the opposite effect and enhance the L 2 phenotype. As suspected, even a heterozygous Jazf-1-knockdown causes a significant loss of the eye when in combination with the L 2 mutant (Figure 5). As previously reported, Jazf-1 overexpression restores part of the normal eye phenotype on an L 2 mutant background [8]. Importantly, we initially observed that these phenotypes did have some degree of variation. As temperature has been previously reported to be a factor in eye development phenotypes [39], all lines that are reported were raised at 25°C, which greatly reduced the level of variation that was observed. Furthermore, females were exclusively measured to eliminate additional variation that might occur due to different sexes or gene doses from males with only one X chromosome.

Lobe2 and Jazf-1 overexpression in the eye. (a–c) Representative images of D. melanogaster eyes. (a) Example of a line containing an eyGAL4 driver with no responder. (b) Lobe2 allele. (c) Lobe2 allele with an eyGal4 driver and UAS:Jazf-1 responder. Jazf-1 overexpression suppresses the eye phenotype of the Lobe2 allele. (d) Graphical representation of the eye sizes measuring the dorsal-ventral axis. All measurements are the average of 10 females; error bars are the standard deviation. A Student’s T-test was conducted between the Lobe2 and the Lobe2 allele rescued with a Jazf-1 overexpression in the eye (p = 5 × 10−7).

Lobe2 is enhanced by NuA4/TIP60 complex member knockdowns. (a–c) Representative images of Drosophila eyes. (a) Lobe2 with a knockdown of Jazf-1. (b) Lobe2 with Xbp-1 knockdown. (c) Lobe2 with Nipped-A knockdown. (d) Graphical representation of the eye sizes measuring the dorsal-ventral axis with members of the NuA4/TIP60 complexed knocked down. No appreciable difference occurred with a single driver and responder present. On a Lobe2 background, knockdown of NuA4/TIP60 complex members enhanced the small eye phenotype. All measurements are the average of 10 females; error bars are the standard deviation. A Student’s T-test was conducted between the Lobe2 and those with Lobe2 and a knocked down NuA4/TIP60 complex member showed a significant enhancement in the eye phenotype with all the members (*p < 0.0005).

3.3 Loss of NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex proteins increase the L 2 eye phenotype

Given the role of Jazf-1 as a member of the NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex, we also tested to see if the reduction of other NuA4/TIP60 members would enhance the L 2 phenotype. Xbp-1 was isolated only in the D. melanogaster NuA4/TIP60 complex [12], and Nipped-A is a well-established core member of the complex whose human homologue TRRAP can disrupt how the NuA4/TIP60 complexes modify histones [12,15,16]. Using the shRNA UAS knockdown responders for Xbp-1 or Nipped-A with an ey-GAL4 driver, these lines demonstrated no appreciable change in the size of the eye (Figure 5). However, siblings carrying the L 2 mutant background had a significant decrease in the size of their eyes when compared to the L 2 mutant alone (Figure 5d).

3.4 Hr78 regulates the L 2 phenotype inversely to Jazf-1

To better understand how the NuA4/TIP60 complex might contribute to the regulation of the L 2 phenotype, we also investigated the nuclear receptor that Jazf-1 is known to bind, Hr78 [13,19]. Hr78 is already known to be expressed in the eye [31]. Again, the same GAL4-UAS binary system was used with ey-Gal4 as the driver and either a UAS Hr78 responder or an Hr78 RNAi system responder. Surprisingly, when Hr78 is overexpressed, the L 2 phenotype is enhanced, and when Hr78 is knocked down by RNAi, the L 2 phenotype is partially suppressed. Therefore, the complete inverse of the same experiment with Jazf-1 was observed (Figure 6). Additionally, while there was variability between completely restored and partially restored eyes, the loss of Hr78 had a significant rescuing effect on the L 2 mutant alone (Figure 6).

Lobe2 and Hr78 expression level changes influence the overall size of the eye. (a and b) Images of phenotypes resulting from Hr78 gene expression level changes with the Lobe 2 allele. (a) Hr78-RNAi in the eye does not significantly change the size of the eye. (b) Hr78-RNAi on a Lobe2 partially restores the eye. (c) Graphical representation of the eye sizes measuring the dorsal-ventral axis with variations in Hr78 expression with Lobe 2 alleles. All measurements are the average of 10 females, error bars are the standard deviation. A Student’s T-test was conducted between the Lobe2 and those with Lobe2 and variations of Hr78 expression levels.

To further understand the role of Hr78, we utilized an allele with an early termination stop codon, Hr78 2 , which produces Hr78 protein with an AF-1 and DNA-binding domain (DBD) but not the AF-2 and ligand-binding domain (LBD) [31]. The AF-2 and LBD of NR2C2 have been well established as the location responsible for binding Jazf-1 [19,20,40]. Therefore, we expected that this would uncouple Jazf-1 from the Hr78 2 allele protein product. Unfortunately, Hr78 2 is homozygous lethal, which prevents the manipulation of its expression level. Hr78 2 heterozygotes had normal eyes, but when L 2 and Hr78 2 heterozygotes were in combination with each other, there was a significant decrease in the size of the eye compared to L 2 allele alone (Figure 7).

(a) Hr782 heterozygous eyes. (b) Lobe 2 and Hr78 2 heterozygotes. Eyes show a decrease in the size of the eye compared with Lobe 2 by itself. (c) Graphical representation of the eye sizes measuring the dorsal-ventral axis. Hr78 2 heterozygotes display a typical eye size. When placed on an Lobe 2 mutant background, the size decreases, including some with no eye formed. All measurements are the average of 10 females; error bars are the standard deviation. A Student’s T-test was conducted between the Lobe 2 and the Lobe 2 ; Hr78 2 mutants displayed a significant enhancement in the eye phenotype (p = 0.0033).

4 Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that the activity of Jazf-1 and NuA4/TIP60 complex members can be measured with eye phenotypes. While using RNAi knockdowns of these genes is often insufficient to create a phenotype with a single eyGAL4 driver, in combination with a sensitized L 2 background, a significant reduction in eye size is observed. This provides us with an in vivo system to test chromatin-modifying proteins such as those in the NuA4/TIP60 complex. Second, the opposing results of NuA4/TIP60 complex members and Hr78 indicate that we can test both repressing and activating factors of gene expression using the L 2 background. Finally, the genetic evidence that NuA4/TIP60 complex members and Hr78 are acting in an inverse regulatory role suggests that Jazf-1 (NuA4/TIP60) is acting as a repressor through Hr78 in this context. In mammalian systems, the relationship between Jazf-1-NR2C2 as a repressor or co-activator has been in question. It is possible that these conflicting studies may depend on the tissue location and context of the gene of interest [6,17].

The expression of Jazf-1 is robust in the adult eye and the ocelli and appears to be important for proper eye formation. While a single copy of the Jazf-1 shRNA was insufficient to cause a visible change, having multiple copies and drivers resulted in a significant phenotype. Although additional copies of GAL4 drivers can also sometimes result in malformations of a tissue, these are not caused by the same eye promoter and happened at higher temperatures than what we tested [41]. It is likely that this is due to incomplete efficiency of the RNAi knockdown and that this is boosted when multiple copies of the eyGAL4 drivers and the Jazf-1 shRNA responders are present. The eyGAL4 driver and Jazf-1 shRNA responder have been verified previously, but the level of efficiency of both in combination has not yet been determined [8,42,43,44,45]. Beyond this, we are confident that the Jazf-1 responder can function as a heterozygote since Jazf-1 can modulate the L 2 mutant phenotype with heterozygous drivers. The data also demonstrate that the shRNA-responding elements alone were insufficient to modify the eye without the proper responder elements. While we and others [8] have found that overexpression of Jazf-1 can rescue the smaller eye, loss of Jazf-1 quickly demonstrates the sensitivity the L 2 background creates that is not present in an otherwise wild-type eye. Furthermore, we confirm that other members of the NuA4/TIP60 complex are required to prevent the additional shrinking of the eye. This yields genetic support to the already well-established biochemical evidence that Jazf-1 is a core component of the NuA4/TIP60 complex, and an in vivo context for how histone modifications can result in phenotypic changes [6,12,17,21].

A clear inverse relationship in the expression of the NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex members and the nuclear receptor Hr78 is seen on the L 2 genetic background. A decrease in the NuA4/TIP60 complex on an L 2 background resulted in a decrease in the overall size of the eye. To date, the only member of the NuA4/TIP60 complex that can partially rescue the L 2 eye phenotype when overexpressed is Jazf-1 [8]. We believe that this is because Jazf-1 provides physical contact with Hr78 that is required to suppress L 2 , likely in conjunction with members of the NuA4/TIP60 complex. In support of this model, the Lobe phenotype is enhanced when Hr78 is increased or Hr78 2 , an allele lacking the AF-2 domain, is used.

We believe that this unique genetic circumstance occurs because the L 2 allele provides an environment in the eye. The L 2 allele has been defined as a hypermorph, expressing Lobe mRNA in a tissue where it is not normally expressed [10]. Since Lobe is a transcription factor, it is likely causing overexpression of multiple genes in the L 2 background. We suspect that the NuA4/TIP60 complex is creating some semblance of typical eye gene expression stability by making the chromatin more typical of the normal eye. When the NuA4/TIP60 complex is compromised, the extra protection is lost, resulting in a smaller eye structure. Conversely, the addition of factors like Jazf-1, or the depletion of Hr78, seems to counteract this abnormal situation and restores the eye. We believe that this is due to the unique ability of Jazf-1 to modulate the activity of the NuA4/TIP60 complex when its expression levels are changed. Similar effects have been seen in other systems where increased Jazf-1 expression can result in changes to normal gene expression [21]. We also believe that Hr78 provides a dual role that may involve the NuA4/TIP60 complex but also other histone-modifying complexes, as well.

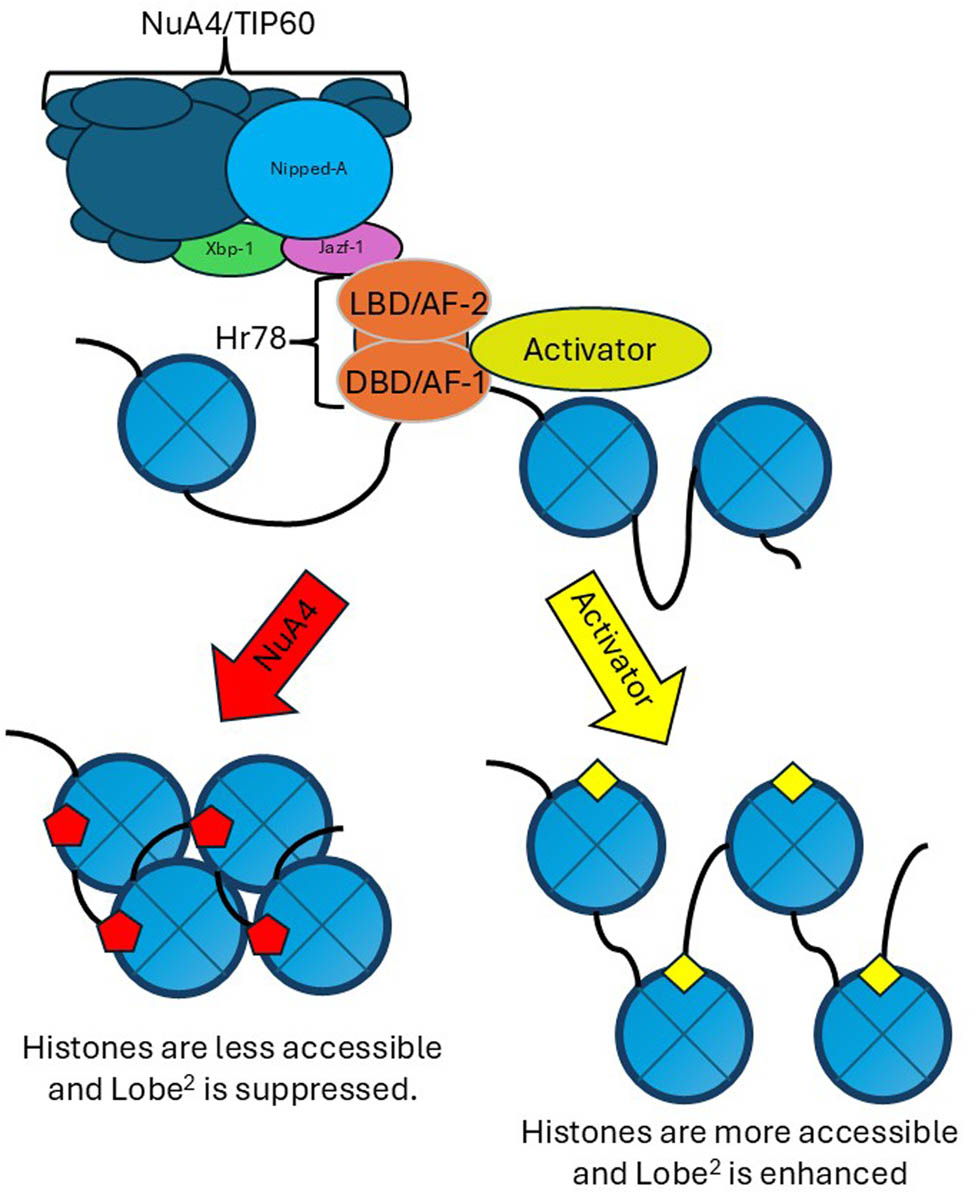

While we can envision several different models, we propose the following model. In this, we propose that the NuA4/TIP60 complex, through its contact with Jazf-1, binds the AF-2 domain of Hr78, repressing the activity of Lobe. If only the AF-1 and DBD of Hr78 are present, an activator can enhance the activity of Lobe (Figure 8). If this is the case, we would further assume that other chromatin modifications could enhance Lobe activity and destabilize the eye. Simply losing a repressor without having an activator does not seem to be enough to cause this change in the eye phenotype of Hr78 2 heterozygous mutants on the L 2 background. We suspect that this activator is likely nejire (nej), the human homologue to p300/CREB-binding protein (CBP). CBP has previously been demonstrated to bind to the AF-1 domain of NR2C2 and acts as an activator of gene expression [24,25]. Furthermore, an investigation into the 33 genes that were uncovered by previous screens of L 2 revealed that the nej was found to be one of seven enhancers of L 2 when overexpressed [8]. Since Jazf-1 and CBP modify the L 2 phenotype in an inverse fashion, and Hr78 can be an enhancer or suppressor of L 2 depending on how it is manipulated, we propose that chromatin modifications are essential to the activity of Lobe. Whether this is at the Lobe locus or some downstream event that Lobe is affecting remains unknown. At this point, these remain untested and will need more extensive genetic analysis of multiple alleles together on the L 2 background. This model also generates other questions about transcriptional control mechanisms involving Lobe. Is it a single gene or multiple genes that lead to the Lobe phenotype? If a downstream gene is repressed, can it overcome the transcriptional control of Lobe? What other chromatin modifications can manipulate the activity of Lobe?

Proposed model of regulation. Hr78 acts as an anchor for chromatin modifiers. The NuA4/TIP60 complex can bind through Jazf-1 to Hr78 via the AF-2 domain. Activators can bind to Hr78, tentatively including nej/CBP through the AF-1 domain. Contact with the NuA4/TIP60 complex allows for histone modifications that typically repress expression. While the activators will enhance gene expression. The Lobe2 allele allows Lobe protein to be expressed in the eye and usually shrinks the eye. Changes in the chromatin modification will enhance or suppress this eye phenotype because they modify the expression changes associated with the Lobe2 allele.

With this in mind, we envision the L 2 in vivo system has potential for the study of the effects of histone-modifying complexes on gene expression through measuring changes in the size of the eye. This could provide answers to difficult questions of how Jazf-1 and CBP help to control gene expression. Furthermore, studies have found that understanding the interplay between different histone-modifying complexes, nuclear receptors, and even signaling pathways all contribute to the understanding of diseases, such as diabetes and endometrial stromal sarcomas [21]. Using an L 2 background and a combination of genetic manipulations, a better understanding of the target genes could provide important key information related to the functioning of these genetic factors, thereby contributing to proper gene expression in an in vivo system.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Angela C. Johnson of Geneva College for providing language editing and proofreading. Stocks obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537) were used in this study.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors accepted responsibility for the entire content of the manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. MLJ designed the experiments. MPS, DAD, ECH, HG, and MLJ carried out the data collection, analysis, and interpretation. MLJ prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R, Voight BF, Marchini JL, Hu T, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2008;40(5):638–45.10.1016/S0084-3741(08)79224-2Search in Google Scholar

[2] Omori S, Tanaka Y, Horikoshi M, Takahashi A, Hara K, Hirose H, et al. Replication study for the association of new meta-analysis-derived risk loci with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes in 6,244 Japanese individuals. Diabetologia. 2009;52(8):1554–60.10.1007/s00125-009-1397-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Rees SD, Hydrie MZ, Shera AS, Kumar S, O’Hare JP, Barnett AH, et al. Replication of 13 genome-wide association (GWA)-validated risk variants for type 2 diabetes in Pakistani populations. Diabetologia. 2011;54(6):1368–74.10.1007/s00125-011-2063-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Hrzenjak A. JAZF1/SUZ12 gene fusion in endometrial stromal sarcomas. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11:15.10.1186/s13023-016-0400-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Samarnthai N, Hall K, Yeh IT. Molecular profiling of endometrial malignancies. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2010;2010:162363.10.1155/2010/162363Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Procida T, Friedrich T, Jack APM, Peritore M, Bonisch C, Eberl HC, et al. JAZF1, a novel p400/TIP60/NuA4 complex member, regulates H2A.Z acetylation at regulatory regions. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(2):678.10.3390/ijms22020678Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Yang Y, Fang Q, Shen HB. Predicting gene regulatory interactions based on spatial gene expression data and deep learning. PLoS Comput Biol. 2019;15(9):e1007324.10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007324Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Singh A, Chan J, Chern JJ, Choi KW. Genetic interaction of Lobe with its modifiers in dorsoventral patterning and growth of the Drosophila eye. Genetics. 2005;171(1):169–83.10.1534/genetics.105.044180Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Morgan TH, Bridges CB, Sturtevant AH. The genetics of Drosophila. Netherlands: M. Nijhoff; 1925. p. 262.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Son W, Choi KW. The classic Lobe eye phenotype of Drosophila is caused by transposon insertion-induced misexpression of a zinc-finger transcription factor. Genetics. 2020;216(1):117–34.10.1534/genetics.120.303486Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Rhee DY, Cho DY, Zhai B, Slattery M, Ma L, Mintseris J, et al. Transcription factor networks in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Rep. 2014;8(6):2031–43.10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.038Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Scacchetti A, Schauer T, Reim A, Apostolou Z, Campos Sparr A, Krause S, et al. Drosophila SWR1 and NuA4 complexes are defined by DOMINO isoforms. Elife. 2020;9:e56325.10.7554/eLife.56325Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Shokri L, Inukai S, Hafner A, Weinand K, Hens K, Vedenko A, et al. A comprehensive Drosophila melanogaster transcription factor interactome. Cell Rep. 2019;27(3):955–70.e7.10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.071Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Eissenberg JC, Wong M, Chrivia JC. Human SRCAP and Drosophila melanogaster DOM are homologs that function in the notch signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(15):6559–69.10.1128/MCB.25.15.6559-6569.2005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Gause M, Eissenberg JC, Macrae AF, Dorsett M, Misulovin Z, Dorsett D. Nipped-A, the Tra1/TRRAP subunit of the Drosophila SAGA and Tip60 complexes, has multiple roles in Notch signaling during wing development. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(6):2347–59.10.1128/MCB.26.6.2347-2359.2006Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Chen K, Wang L, Yu Z, Yu J, Ren Y, Wang Q, et al. Structure of the human TIP60 complex. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7092.10.1038/s41467-024-51259-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Sudarshan D, Avvakumov N, Lalonde ME, Alerasool N, Joly-Beauparlant C, Jacquet K, et al. Recurrent chromosomal translocations in sarcomas create a megacomplex that mislocalizes NuA4/TIP60 to Polycomb target loci. Genes Dev. 2022;36(11–12):664–83.10.1101/gad.348982.121Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Prozzillo Y, Cuticone S, Ferreri D, Fattorini G, Messina G, Dimitri P. In vivo silencing of genes coding for dTip60 chromatin remodeling complex subunits affects polytene chromosome organization and proper development in Drosophila melanogaster. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4525.10.3390/ijms22094525Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Nakajima T, Fujino S, Nakanishi G, Kim YS, Jetten AM. TIP27: a novel repressor of the nuclear orphan receptor TAK1/TR4. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(14):4194–204.10.1093/nar/gkh741Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Liu Y, Ma L, Li M, Tian Z, Yang M, Wu X, et al. Structures of human TR4LBD-JAZF1 and TR4DBD-DNA complexes reveal the molecular basis of transcriptional regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(3):1443–57.10.1093/nar/gkac1259Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Mameri A, Cote J. JAZF1: A metabolic actor subunit of the NuA4/TIP60 chromatin modifying complex. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1134268.10.3389/fcell.2023.1134268Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Kang HS, Okamoto K, Kim YS, Takeda Y, Bortner CD, Dang H, et al. Nuclear orphan receptor TAK1/TR4-deficient mice are protected against obesity-linked inflammation, hepatic steatosis, and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2011;60(1):177–88.10.2337/db10-0628Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Moras D, Gronemeyer H. The nuclear receptor ligand-binding domain: structure and function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10(3):384–91.10.1016/S0955-0674(98)80015-XSearch in Google Scholar

[24] Weikum ER, Liu X, Ortlund EA. The nuclear receptor superfamily: A structural perspective. Protein Sci. 2018;27(11):1876–92.10.1002/pro.3496Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Huq MD, Gupta P, Tsai NP, Wei LN. Modulation of testicular receptor 4 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated phosphorylation. Mol Cell Proteom. 2006;5(11):2072–82.10.1074/mcp.M600180-MCP200Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Laudet V, Hanni C, Coll J, Catzeflis F, Stehelin D. Evolution of the nuclear receptor gene superfamily. EMBO J. 1992;11(3):1003–13.10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05139.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Maglich JM, Sluder A, Guan X, Shi Y, McKee DD, Carrick K, et al. Comparison of complete nuclear receptor sets from the human, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila genomes. Genome Biol. 2001;2(8):RESEARCH0029.10.1186/gb-2001-2-8-research0029Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Li L, Yang Y, Yang G, Lu C, Yang M, Liu H, et al. The role of JAZF1 on lipid metabolism and related genes in vitro. Metabolism. 2011;60(4):523–30.10.1016/j.metabol.2010.04.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118(2):401–15.10.1242/dev.118.2.401Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Kanca O, Zirin J, Garcia-Marques J, Knight SM, Yang-Zhou D, Amador G, et al. An efficient CRISPR-based strategy to insert small and large fragments of DNA using short homology arms. Elife. 2019;8:e51539.10.7554/eLife.51539Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Fisk GJ, Thummel CS. The DHR78 nuclear receptor is required for ecdysteroid signaling during the onset of Drosophila metamorphosis. Cell. 1998;93(4):543–55.10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81184-8Search in Google Scholar

[32] Bellen HJ, Levis RW, Liao G, He Y, Carlson JW, Tsang G, et al. The BDGP gene disruption project: single transposon insertions associated with 40% of Drosophila genes. Genetics. 2004;167(2):761–81.10.1534/genetics.104.026427Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Bellen HJ, Levis RW, He Y, Carlson JW, Evans-Holm M, Bae E, et al. The Drosophila gene disruption project: progress using transposons with distinctive site specificities. Genetics. 2011;188(3):731–43.10.1534/genetics.111.126995Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Perkins LA, Holderbaum L, Tao R, Hu Y, Sopko R, McCall K, et al. The transgenic RNAi project at harvard medical school: resources and validation. Genetics. 2015;201(3):843–52.10.1534/genetics.115.180208Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Wirtz RA, Semey HG. The Drosophila kitchen - equipiment, media preparation, and supplies. Drosoph Inf Serv. 1982;58:176–80.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Greenspan RJ. Fly pushing: the theory and practice of Drosophila genetics. 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2004. p. 191.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Lee PT, Zirin J, Kanca O, Lin WW, Schulze KL, Li-Kroeger D, et al. A gene-specific T2A-GAL4 library for Drosophila. Elife. 2018;7:e35574.10.7554/eLife.35574Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Ni JQ, Zhou R, Czech B, Liu LP, Holderbaum L, Yang-Zhou D, et al. A genome-scale shRNA resource for transgenic RNAi in Drosophila. Nat Methods. 2011;8(5):405–7.10.1038/nmeth.1592Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Zimm GG. An analysis of growth abnormalities associated with the eye-mutant lobe in Drosophila melanogaster. J Exp Zool. 1951;116(2):289–319.10.1002/jez.1401160205Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Rajan S, Yoon HS. Covalent ligands of nuclear receptors. Eur J Med Chem. 2023;261:115869.10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115869Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Kramer JM, Staveley BE. GAL4 causes developmental defects and apoptosis when expressed in the developing eye of Drosophila melanogaster. Genet Mol Res. 2003;2(1):43–7.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Ahmad K, Henikoff S. The H3.3K27M oncohistone antagonizes reprogramming in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2021;17(7):e1009225.10.1371/journal.pgen.1009225Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Huang Y, Jay KL, Yen-Wen Huang A, Wan J, Jangam SV, Chorin O, et al. Loss-of-function in RBBP5 results in a syndromic neurodevelopmental disorder associated with microcephaly. Genet Med. 2024;26(11):101218.10.1101/2024.02.06.578086Search in Google Scholar

[44] Manivannan SN, Roovers J, Smal N, Myers CT, Turkdogan D, Roelens F, et al. De novo FZR1 loss-of-function variants cause developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. Brain. 2022;145(5):1684–97.10.1093/brain/awab409Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Raza Q, Choi JY, Li Y, O’Dowd RM, Watkins SC, Chikina M, et al. Evolutionary rate covariation analysis of E-cadherin identifies Raskol as a regulator of cell adhesion and actin dynamics in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2019;15(2):e1007720.10.1371/journal.pgen.1007720Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome with elevated IgG4 and T-cell clonality: A report of two cases

- Electroacupuncture alleviates sciatic nerve injury in sciatica rats by regulating BDNF and NGF levels, myelin sheath degradation, and autophagy

- Polydatin prevents cholesterol gallstone formation by regulating cholesterol metabolism via PPAR-γ signaling

- RNF144A and RNF144B: Important molecules for health

- Analysis of the detection rate and related factors of thyroid nodules in the healthy population

- Artesunate inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion through OGA-mediated O-GlcNAcylation of ZEB1

- Endovascular management of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: Case report and review of the literature

- Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis

- SATB2 promotes humeral fracture healing in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Overexpression of the ferroptosis-related gene, NFS1, corresponds to gastric cancer growth and tumor immune infiltration

- Understanding risk factors and prognosis in diabetic foot ulcers

- Atractylenolide I alleviates the experimental allergic response in mice by suppressing TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 signalling

- FBXO31 inhibits the stemness characteristics of CD147 (+) melanoma stem cells

- Immune molecule diagnostics in colorectal cancer: CCL2 and CXCL11

- Inhibiting CXCR6 promotes senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells with limited proinflammatory SASP to attenuate hepatic fibrosis

- Cadmium toxicity, health risk and its remediation using low-cost biochar adsorbents

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis with headache as the first presentation: A case report

- Solitary pulmonary metastasis with cystic airspaces in colon cancer: A rare case report

- RUNX1 promotes denervation-induced muscle atrophy by activating the JUNB/NF-κB pathway and driving M1 macrophage polarization

- Morphometric analysis and immunobiological investigation of Indigofera oblongifolia on the infected lung with Plasmodium chabaudi

- The NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex and Hr78 modulate the Lobe2 mutant eye phenotype

- Experimental study on salmon demineralized bone matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: In vitro and in vivo study

- A case of IgA nephropathy treated with a combination of telitacicept and half-dose glucocorticoids

- Analgesic and toxicological evaluation of cannabidiol-rich Moroccan Cannabis sativa L. (Khardala variety) extract: Evidence from an in vivo and in silico study

- Wound healing and signaling pathways

- Combination of immunotherapy and whole-brain radiotherapy on prognosis of patients with multiple brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study

- To explore the relationship between endometrial hyperemia and polycystic ovary syndrome

- Research progress on the impact of curcumin on immune responses in breast cancer

- Biogenic Cu/Ni nanotherapeutics from Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl seeds for the treatment of lung cancer

- Dapagliflozin attenuates atrial fibrosis via the HMGB1/RAGE pathway in atrial fibrillation rats

- Glycitein alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in keratinocytes via ROS-associated PI3K–Akt signalling pathway

- ADH5 inhibits proliferation but promotes EMT in non-small cell lung cancer cell through activating Smad2/Smad3

- Apoptotic efficacies of AgNPs formulated by Syzygium aromaticum leaf extract on 32D-FLT3-ITD human leukemia cell line with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Novel cuproptosis-related genes C1QBP and PFKP identified as prognostic and therapeutic targets in lung adenocarcinoma

- Bee venom promotes exosome secretion and alters miRNA cargo in T cells

- Treatment of pure red cell aplasia in a chronic kidney disease patient with roxadustat: A case report

- Comparative bioinformatics analysis of the Wnt pathway in breast cancer: Selection of novel biomarker panels associated with ER status

- Kynurenine facilitates renal cell carcinoma progression by suppressing M2 macrophage pyroptosis through inhibition of CASP1 cleavage

- RFX5 promotes the growth, motility, and inhibits apoptosis of gastric adenocarcinoma cells through the SIRT1/AMPK axis

- ALKBH5 exacerbates early cardiac damage after radiotherapy for breast cancer via m6A demethylation of TLR4

- Phytochemicals of Roman chamomile: Antioxidant, anti-aging, and whitening activities of distillation residues

- Circadian gene Cry1 inhibits the tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma by the BAX/BCL2-mediated apoptosis pathway

- The TNFR-RIPK1/RIPK3 signalling pathway mediates the effect of lanthanum on necroptosis of nerve cells

- Longitudinal monitoring of autoantibody dynamics in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing surgery

- The potential role of rutin, a flavonoid, in the management of cancer through modulation of cell signaling pathways

- Construction of pectinase gene engineering microbe and its application in tobacco sheets

- Construction of a microbial abundance prognostic scoring model based on intratumoral microbial data for predicting the prognosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Sepsis complicated by haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis triggered by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and human herpesvirus 8 in an immunocompromised elderly patient: A case report

- Sarcopenia in liver transplantation: A comprehensive bibliometric study of current research trends and future directions

- Advances in cancer immunotherapy and future directions in personalized medicine

- Can coronavirus disease 2019 affect male fertility or cause spontaneous abortion? A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis

- Heat stroke associated with novel leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor gene variant in a Chinese infant

- PSME2 exacerbates ulcerative colitis by disrupting intestinal barrier function and promoting autophagy-dependent inflammation

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state with severe hypernatremia coexisting with central diabetes insipidus: A case report and literature review

- Efficacy and mechanism of escin in improving the tissue microenvironment of blood vessel walls via anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects: Implications for clinical practice

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Clinicopathological analysis of three patients and literature review

- Genetic variants in VWF exon 26 and their implications for type 1 Von Willebrand disease in a Saudi Arabian population

- Lipoxin A4 improves myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through the Notch1-Nrf2 signaling pathway

- High levels of EPHB2 expression predict a poor prognosis and promote tumor progression in endometrial cancer

- Knockdown of SHP-2 delays renal tubular epithelial cell injury in diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis

- Exploring the toxicity mechanisms and detoxification methods of Rhizoma Paridis

- Concomitant gastric carcinoma and primary hepatic angiosarcoma in a patient: A case report

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Optimization and comparative study of Bacillus consortia for cellulolytic potential and cellulase enzyme activity

- The complete mitochondrial genome analysis of Haemaphysalis hystricis Supino, 1897 (Ixodida: Ixodidae) and its phylogenetic implications

- Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors analysis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among tuberculosis population in Huzhou City, Eastern China

- Indices of human impacts on landscapes: How do they reflect the proportions of natural habitats?

- Genetic analysis of the Siberian flying squirrel population in the northern Changbai Mountains, Northeast China: Insights into population status and conservation

- Diversity and environmental drivers of Suillus communities in Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica forests of Inner Mongolia

- Global assessment of the fate of nitrogen deposition in forest ecosystems: Insights from 15N tracer studies

- Fungal and bacterial pathogenic co-infections mainly lead to the assembly of microbial community in tobacco stems

- Influencing of coal industry related airborne particulate matter on ocular surface tear film injury and inflammatory factor expression in Sprague-Dawley rats

- Temperature-dependent development, predation, and life table of Sphaerophoria macrogaster (Thomson) (Diptera: Syrphidae) feeding on Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae)

- Eleonora’s falcon trophic interactions with insects within its breeding range: A systematic review

- Agriculture

- Integrated analysis of transcriptome, sRNAome, and degradome involved in the drought-response of maize Zhengdan958

- Variation in flower frost tolerance among seven apple cultivars and transcriptome response patterns in two contrastingly frost-tolerant selected cultivars

- Heritability of durable resistance to stripe rust in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Molecular mechanism of follicular development in laying hens based on the regulation of water metabolism

- Animal Science

- Effect of sex ratio on the life history traits of an important invasive species, Spodoptera frugiperda

- Plant Sciences

- Hairpin in a haystack: In silico identification and characterization of plant-conserved microRNA in Rafflesiaceae

- Widely targeted metabolomics of different tissues in Rubus corchorifolius

- The complete chloroplast genome of Gerbera piloselloides (L.) Cass., 1820 (Carduoideae, Asteraceae) and its phylogenetic analysis

- Field trial to correlate mineral solubilization activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and biochemical content of groundnut plants

- Correlation analysis between semen routine parameters and sperm DNA fragmentation index in patients with semen non-liquefaction: A retrospective study

- Plasticity of the anatomical traits of Rhododendron L. (Ericaceae) leaves and its implications in adaptation to the plateau environment

- Effects of Piriformospora indica and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on growth and physiology of Moringa oleifera under low-temperature stress

- Effects of different sources of potassium fertiliser on yield, fruit quality and nutrient absorption in “Harward” kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa)

- Comparative efficiency and residue levels of spraying programs against powdery mildew in grape varieties

- The DREB7 transcription factor enhances salt tolerance in soybean plants under salt stress

- Using plant electrical signals of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) for water pollution monitoring

- Food Science

- Phytochemical analysis of Stachys iva: Discovering the optimal extract conditions and its bioactive compounds

- Review on role of honey in disease prevention and treatment through modulation of biological activities

- Computational analysis of polymorphic residues in maltose and maltotriose transporters of a wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain

- Optimization of phenolic compound extraction from Tunisian squash by-products: A sustainable approach for antioxidant and antibacterial applications

- Liupao tea aqueous extract alleviates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in rats by modulating the gut microbiota

- Toxicological qualities and detoxification trends of fruit by-products for valorization: A review

- Polyphenolic spectrum of cornelian cherry fruits and their health-promoting effect

- Optimizing the encapsulation of the refined extract of squash peels for functional food applications: A sustainable approach to reduce food waste

- Advancements in curcuminoid formulations: An update on bioavailability enhancement strategies curcuminoid bioavailability and formulations

- Impact of saline sprouting on antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds in chia seeds

- The dilemma of food genetics and improvement

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Impact of hyaluronic acid-modified hafnium metalorganic frameworks containing rhynchophylline on Alzheimer’s disease

- Emerging patterns in nanoparticle-based therapeutic approaches for rheumatoid arthritis: A comprehensive bibliometric and visual analysis spanning two decades

- Application of CRISPR/Cas gene editing for infectious disease control in poultry

- Preparation of hafnium nitride-coated titanium implants by magnetron sputtering technology and evaluation of their antibacterial properties and biocompatibility

- Preparation and characterization of lemongrass oil nanoemulsion: Antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant, and anticancer activities

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells”

- Corrigendum to “Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans”

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Down-regulation of miR-539 indicates poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer”

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome with elevated IgG4 and T-cell clonality: A report of two cases

- Electroacupuncture alleviates sciatic nerve injury in sciatica rats by regulating BDNF and NGF levels, myelin sheath degradation, and autophagy

- Polydatin prevents cholesterol gallstone formation by regulating cholesterol metabolism via PPAR-γ signaling

- RNF144A and RNF144B: Important molecules for health

- Analysis of the detection rate and related factors of thyroid nodules in the healthy population

- Artesunate inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion through OGA-mediated O-GlcNAcylation of ZEB1

- Endovascular management of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: Case report and review of the literature

- Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis

- SATB2 promotes humeral fracture healing in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Overexpression of the ferroptosis-related gene, NFS1, corresponds to gastric cancer growth and tumor immune infiltration

- Understanding risk factors and prognosis in diabetic foot ulcers

- Atractylenolide I alleviates the experimental allergic response in mice by suppressing TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 signalling

- FBXO31 inhibits the stemness characteristics of CD147 (+) melanoma stem cells

- Immune molecule diagnostics in colorectal cancer: CCL2 and CXCL11

- Inhibiting CXCR6 promotes senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells with limited proinflammatory SASP to attenuate hepatic fibrosis

- Cadmium toxicity, health risk and its remediation using low-cost biochar adsorbents

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis with headache as the first presentation: A case report

- Solitary pulmonary metastasis with cystic airspaces in colon cancer: A rare case report

- RUNX1 promotes denervation-induced muscle atrophy by activating the JUNB/NF-κB pathway and driving M1 macrophage polarization

- Morphometric analysis and immunobiological investigation of Indigofera oblongifolia on the infected lung with Plasmodium chabaudi

- The NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex and Hr78 modulate the Lobe2 mutant eye phenotype

- Experimental study on salmon demineralized bone matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: In vitro and in vivo study

- A case of IgA nephropathy treated with a combination of telitacicept and half-dose glucocorticoids

- Analgesic and toxicological evaluation of cannabidiol-rich Moroccan Cannabis sativa L. (Khardala variety) extract: Evidence from an in vivo and in silico study

- Wound healing and signaling pathways

- Combination of immunotherapy and whole-brain radiotherapy on prognosis of patients with multiple brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study

- To explore the relationship between endometrial hyperemia and polycystic ovary syndrome

- Research progress on the impact of curcumin on immune responses in breast cancer

- Biogenic Cu/Ni nanotherapeutics from Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl seeds for the treatment of lung cancer

- Dapagliflozin attenuates atrial fibrosis via the HMGB1/RAGE pathway in atrial fibrillation rats

- Glycitein alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in keratinocytes via ROS-associated PI3K–Akt signalling pathway

- ADH5 inhibits proliferation but promotes EMT in non-small cell lung cancer cell through activating Smad2/Smad3

- Apoptotic efficacies of AgNPs formulated by Syzygium aromaticum leaf extract on 32D-FLT3-ITD human leukemia cell line with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Novel cuproptosis-related genes C1QBP and PFKP identified as prognostic and therapeutic targets in lung adenocarcinoma

- Bee venom promotes exosome secretion and alters miRNA cargo in T cells

- Treatment of pure red cell aplasia in a chronic kidney disease patient with roxadustat: A case report

- Comparative bioinformatics analysis of the Wnt pathway in breast cancer: Selection of novel biomarker panels associated with ER status

- Kynurenine facilitates renal cell carcinoma progression by suppressing M2 macrophage pyroptosis through inhibition of CASP1 cleavage

- RFX5 promotes the growth, motility, and inhibits apoptosis of gastric adenocarcinoma cells through the SIRT1/AMPK axis

- ALKBH5 exacerbates early cardiac damage after radiotherapy for breast cancer via m6A demethylation of TLR4