Abstract

Co-occurring symptoms such as depression, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep disorders are frequently comorbid with cancer. The causes of these cancer-related symptom clusters are hypothesized sharing a common biological mechanism. This study explored pattern differences of some gut metabolites (glucocorticoids, short-chain fatty acids, gut microbial metabolites from tryptophan) in plasma samples from patients with four types of cancer. Metabolomics analysis was performed to indicate the differences of metabolites. Discrimination model and diagnostic model were constructed using orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis, and differential metabolites were screened, then receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis was performed to evaluate the performance of these models. Melatonin (MLT), indole propionic, and skatole were screened as the common differential metabolites shared by four types of cancer, indicating that the intestinal microbial metabolic pathway of tryptophan plays a key role in the occurrence and development of malignant tumors. The area under the curve values for the potential candidate biomarker predictors in univariate analysis ranged from 0.771 to 0.989, and in multivariate analysis ranged from 0.985 to 1.00. The sensitivity and specificity of the multivariable model were 94.7–100 and 96.4–100%, respectively. These biomarkers also had good performance in discriminating different pairs of cancer. The analysis of gut microbiota metabolites allows us to characterize the common metabolic characteristics of patients with various cancers. The intestinal microbial metabolic pathway of tryptophan plays a key role in the occurrence and development of malignant tumors.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

The incidence of cancer is mainly attributed to two aspects, including genetic predisposition and exposure to environmental risk factors, but what these exact environmental factors are remains unknown [1,2]. A great deal of evidence is accumulating that psychosocial stress may be one of the factors, yet the mechanisms for this association are poorly understood [3]. Cortisol is the primary stress hormone, where gradually increasing studies have demonstrated that cortisol levels positively correlate with high mortality rate and recurrence of cancer [4,5].

In recent years, an additional environmental risk factor in cancer has drawn keen interest as the gut microbiota [6]. The intestines of mammals are home to a complex ecological system comprising thousands of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms [7]. A multitude of factors, including the host’s diet, hormonal levels, medication use, and environmental conditions, influence the dynamic composition of this gut microbiota, which, in turn, may contribute to the development of a variety of diseases [8]. Despite many studies on the relationship between gut microbiota and carcinogenesis, the exact mechanisms of this interaction are not very clear. Our gut microbiota is capable of producing metabolites, including a wide range of molecules with a variety of biological activities: short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate [9]; tryptophan (Trp) metabolites, such as indole (IND), indole propionic acid (IPA), melatonin (MLT), skatole (SKT), etc. [10]; amino acids, such as threonine, isoleucine, glutamine [11], and l-norvaline [12]; other substances, such as hormones, neurotransmitters, etc. [9]. Similar to human hormones, these metabolites are produced in the intestinal tract and subsequently transferred to distant sites of action through circulation. It is fluctuations of these molecules in the body that determine the beneficial or harmful role of the gut microbiota in the tumor progression, immunity, and therapy prediction by reshaping the tumor microenvironment [13]. These molecules act on target organs through blood circulation, forming the gut–organ axis, such as the microbiota–gut–liver axis or microbiota–gut–brain (MGB) axis [9].

The MGB axis refers to the bidirectional communication network linking the gut, microbiota, and brain [9]. This system enables information to be shared between the microbe and the brain, allowing the brain to communicate with the gut [14]. Cortisol receptors are expressed on various cells of the gut, indicating that cortisol can impact the MGB axis through multiple pathways, which in turn impact the composition and diversity of the gut microbiota [4,15]. Therefore, understanding the relationship between cortisol and various types of intestinal microbial metabolites is of great significance for the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis assessment of cancer. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have examined both cortisol and representative intestinal microbial metabolites in different kinds of tumors.

This study chose to look at digestive system cancer (gastric cancer [GC], esophageal cancer [EC], and colon cancer [CC]) and lung cancer (LC) because most earlier research on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and cancer focused on women with gynecological cancer, aiming to see if the HPA axis affects cancer development in a similar way across different types of cancer. Therefore, this study aimed to select several types of metabolites related to the MGB axis, including the HPA axis, for targeted metabolomics analysis. The purpose of this analysis was to investigate whether the common side effects of fatigue, insomnia, and depression observed in cancers are due to shared metabolic characteristics. Our goals were to measure the levels of two corticosteroids (cortisol and cortisone) and two groups of metabolites, SCFAs and Trp metabolites, in the blood of patients with four types of cancer (colorectal, esophageal, stomach, and LC) and healthy individuals. Metabolomics analysis was used to study how the two hormones and metabolites changed and to see if cancer types have similar biological processes. Multiple sets of potential biomarkers were identified that could be used in the diagnosis of different types of cancer.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study participants and sample collection

The investigation was performed with plasma samples derived from patients with GC (n = 29), LC (n = 23), EC (n = 19), CC (n = 26), and a group of healthy controls (CT) (n = 28). All participants in the study were acquainted with its aim and signed a written consent. Patients were recruited among patients of the Ward of Oncology Department, Jiangsu Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, China. The sixth edition of the International Union against Cancer Classification was used to classify each cancer group, and no other coexisting cancers. All cancer patients had not received therapeutic drugs, radiation therapy, or other treatments, and blood samples were taken before treatment. The control group consisted of healthy individuals with no cancer and no chronic diseases. They were recruited among people subjected to the routine periodic medical examinations. The control group matched the cancer groups in terms of age and ethnicity (China) (Table 1). Plasma samples were obtained when the participants were waked up in the morning at about 6:00 am and immediately stored at −20℃ until being analyzed. The demographic characteristics of 97 patients and 28 age-matched health control (CT) are shown in Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | EC | LC | Colorectal cancer | GC | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 19 | 23 | 26 | 28 | 28 | |

| Sex | Male | 13 | 16 | 14 | 16 | 16 |

| Female | 6 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 12 | |

| Age (years) | Mean | 63.2 | 60.1 | 58.2 | 57.8 | 58.5 |

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to human use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the IRB of the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine by Decision no. 2023NL-KS002.

2.2 Cortisol and cortisone concentrations in plasma

Based on the established method for the determination of cortisol in urine [16], we briefly optimized the detection method for the analysis of target substances in plasma. Plasma cortisol was extracted using a solid phase extraction (SPE) column packed with 5 mg of polystyrene nanofiber. The simple process is as follows: the column is rinsed with 200 µL methanol and water successively to activate the extraction column. To a 100 µL of plasma, 10 µL of internal standard solution (200 ng/mL deuterated cortisol in water) was added and vortexed, the mixture was added to the small column filled with polystyrene nanofibers, and the liquid was slowly pressed out drop by drop using a barometric SPE instrument, so that the target compounds could be adsorbed on the nanofiber material. After the liquid was drained, 100 µL of methanol was added for elution in the same way. The eluted target solution was injected with 10 µL into a liquid chromatograph–mass spectrometer for the determination, and the optimized instrumental settings were presented in ref. [16] (Figure S1).

2.3 SCFAs concentration in plasma

Based on the SCFAs analytic method established by our research group [17], we briefly optimized the detection method for the analysis of target substances in plasma. Sample pretreatment was accomplished by a packed-fiber SPE method using 5 mg of polystyrene/polypyrrole (PS/PPy) nanofibers as the sorbent. Before SPE, 5.0 mg nanofibers were loaded into the extraction column. The nanofibers in the extraction column were activated with 200 μL of methanol and 200 μL of water, respectively. After the extraction column was activated, a plasma sample of 100 μL was added, and the fluid was pushed through the nanofibers using a barometric solid phase extractor. After passing through the column, the target substances were eluted from the column with 100 μL of eluent, which was an ethanol solution containing 0.01 mol/L hydrochloric acid. In order to remove the residue of protein precipitation contained in the eluted liquid, a gun tip column filled with 1 mg of polystyrene nanofibers was used to filter the eluted liquid again, and the filtered filtrate was collected and fed into a gas chromatography–mass spectrometer for the determination. Other instruments and experimental conditions remained unchanged (Figure S2).

2.4 Trp metabolites concentration in plasma

Based on the analytic method for Trp metabolites established by our research group [18], we briefly optimized the detection method for the analysis of target substances in plasma. About 100 μL of plasma sample was added with concentrated HCl (hydrochloric acid: plasma = 1:1, v/v). The acidified samples were centrifuged at a rotational speed of 12,000 rpm for 3.0 min and then the supernatant was separated. Before SPE, columns packed with 5.0 mg of PS/PPy nanofibers were activated with 100 μL of methanol and 100 μL of water, respectively. After the extraction column was activated, 100 μL of the treated sample supernatant was added, and then the sample liquid was pressurized through the nanofibers using a barometric solid phase extractor. After passing through the column, the target substance adsorbed was eluted from the column with 100 μL of eluent containing methanol and 0.2 mol/L sulfuric acid (95:5). Finally, the eluent was injected into a liquid chromatograph for the determination (Figure S3).

2.5 Statistical analysis

Urinary creatinine concentrations were measured to correct urinary metabolite concentrations and control the influence of urinary volume fluctuations. Data were analyzed by Statistical Product and Service Solutions (IBM SPSS 27.0.1), and Mann–Whitney test was used to conduct descriptive statistics on creatinine adjusted urinary target compound levels of subjects. Mean ± SD was calculated to determine the overall gut microbiota metabolite profiles. The p-values <0.05 were used to assess statistical significance. Natural ln transformation of all target compounds was performed using GraphPad Prism 10.1.2 for mapping purposes. The metabolomics dataset was processed using MetaboAnalyst 6.0. All missing values were replaced by the average of each variable within the group, and a natural logarithmic transformation of the variable was performed. Principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) were used to visualize metabolic changes between HC and cancer groups. MetaboAnalyst 6.0 was used for biomarker analysis of differential metabolites, including classic univariate receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) analysis and multivariate ROC analysis. In biomarkers analysis, the sample first passed normalization, data transformation, and data scaling to make the normalized data normally distributed, and biomarker analysis was then performed. Finally, pathway analysis was performed and visualized using the MetaboAnalyst 6.0 software package.

3 Results

3.1 Characterizing the biochemical composition of plasma in four type of cancer patients

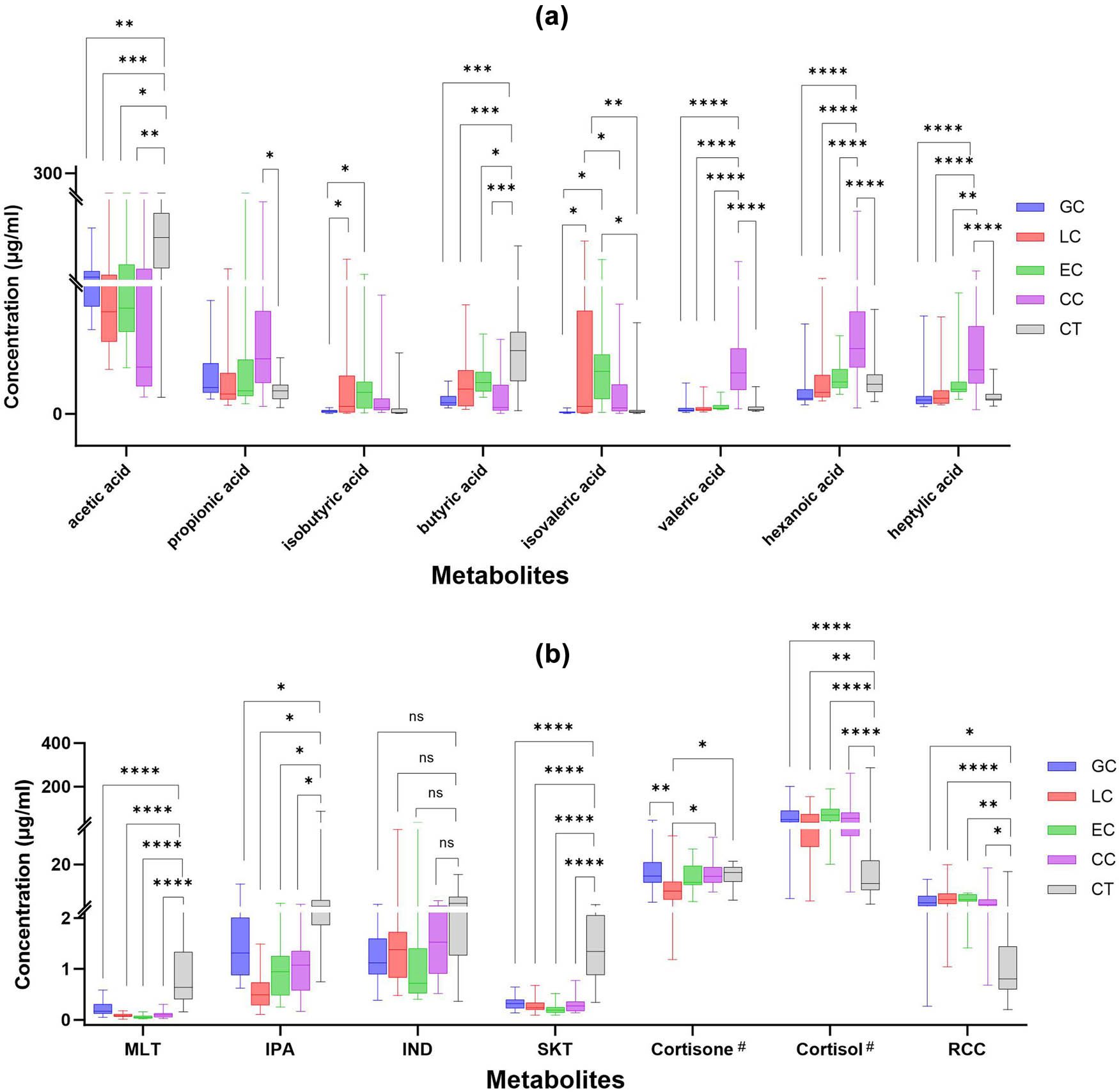

A total of 14 targeted metabolites in each sample of cancers and health controls were determined, including acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid, valeric acid, hexanoic acid, heptylic acid, MLT, IPA, IND, and SKT, cortisone, and cortisol. Since the ratio of cortisol to cortisone (RCC) characterizes the enzyme 11β-HSD1 that catalyzes the transformation of these two corticosteroids in vivo, RCC was also included as an indicator in the data calculation. All metabolite concentrations are as shown in Figure 1.

Univariate multivariate analysis of metabolite concentrations of patient groups and health control group. (a) metabolites of short-chain fatty acid; (b) metabolites of Indoleamine and corticosteroid; Boxplots illustrate the upper quartile, median (central transverse line), and lower quartile, with whiskers indicating the maximum and minimum values. # Concentration unit of cortisol and cortisone in plasma is ng/mL. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns p > 0.05. GC, gastric cancer; LC, lung cancer; EC, esophageal cancer; CC, colon cancer; CT, healthy controls. IND, indole, IPA, indole propionic acid, MLT, melatonin, SKT, skatole.

As shown in Figure 1a, the concentrations of acetic acid and butyric acid across the cancers were significantly lower than those of the control group (p < 0.05); on the contrary, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, and isovaleric acid were mostly higher than those of the control group; however, the increases were not significant in most disease groups. The concentrations of valeric acid, caproic acid, and heptanoic acid were significantly higher in colorectal cancer than that of other types of cancers and the control group (p < 0.01).

As shown in Figure 1b, the concentrations of MLT, IPA, and SKT were significantly lower in all types of cancers than those of the control group (p < 0.05), while the concentrations of IND were not significantly different. The concentrations of cortisol and RCC across cancers were significantly different from those of the control group, with the former significantly higher (p < 0.01) and the latter significantly lower (p < 0.05), and the changes of cortisone level in all groups were not very obvious.

3.2 Correlations between metabolites in plasma

The correlations of the 14 compounds within five groups are presented in Figure 2. Pearson’s correlation was used to test for the correlation of the 14 metabolites measured in plasma. Compared with the control group, the correlations between metabolites were changed, except for the EC group, the other three groups showed a significantly enhanced positive correlation between SCFAs. The relationship between SCFAs and Trp metabolites were changed from negative correlation in normal group to slightly positive correlation for some metabolites in cancer groups. And the correlations of cortisol, cortisone, and their ratio (RCC) with SCFAs and Trp metabolites were also changed, and the changes were different in each type of cancer. Except for individual material pairs, the general trend toward enhanced positive correlation was observed.

Correlation map calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient of metabolites in blood plasma. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is reported with color gradient, and blue color indicates a positive association, while red indicates a negative association. Only the significant correlations (p < 0.05) of two corticosteroids are illustrated with asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001). GC, gastric cancer; LC, lung cancer; EC, esophageal cancer; CC, colon cancer; CT, healthy controls. IND, indole, IPA, indole propionic acid, MET, melatonin, SKT, skatole.

3.3 Multivariate statistical analysis for control and cancer subjects

The absolute quantitative data of 14 accurately measured data were grouped into four cancers and a control group and brought into MetaboAnalyst 6.0 for statistical analysis and mapping. PCA was carried out to generate an overview of the variations between groups. Figure 3a shows the PC1 vs PC2 score plot for all the samples. The PCA distribution did not exhibit any significant trend or difference across the groups. In order to determine the metabolites that contributed to the differences between five groups, partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was employed to examine the data; however, the score plots among the five groups indicated that the groups could not be distinctly differentiated (Figure 3b).

(a) PCA score plots and (b) PLS-DA score plots based on the plasma samples from five patient groups with different cancers in comparison with the healthy control group (GC, gastric cancer; LC, lung cancer; EC, esophageal cancer; CC, colon cancer; CT, healthy controls).

However, if OPLS-DA was carried out to generate an overview of the variations between control and each cancer group. The data revealed significant differences between the normal and disease groups (Figure 4a–d). The subsequent parameters of cross validation and permutation tests met the requirements (Q2, 0.752–0.827; R2Y, 0.845–0.868), indicating that the model was reliable in predicting performance. The results showed that there were significant metabolic differences between cancers and the healthy control group.

OPLS-DA score plots based on the plasma samples from each patient group in comparison with healthy control group: (a) colon cancer, (b) EC, (c) GC, and (d) LC.

3.4 Differential metabolites and biomarker analysis

The variable importance in projection (VIP) value was calculated according to the established OPLS-DA model. Among the 14 endogenous metabolites detected, metabolites with p values <0.05 serve as potential biomarkers. The observed differences were attributable to significant differences between the concentrations of the metabolites represented in the VIP scores (Figure 5a–d). The |log2FC| ≥ 1 and VIP ≥ 1 were used as the selection criteria for deferential metabolites. Figure 5a’–d’ down-regulated (blue dot) and up-regulated metabolites (red dot). The differential metabolites between cancers and control group are presented in Table 2. It was found that MLT, SKT, and IPA were down-regulated in all cancer groups (except IND replaces IPA in GC group), acetic acid and butyric acid down-regulated, while heptylic acid and valeric acid up-regulated in CC groups, isovaleric acid up-regulated in EC, and RCC and cortisol up-regulated only in EC group.

Important features identified by the OPLS-DA and volcanic map of metabolites: (a, a’) CC, (b, b’) EC, (c, c’) GC, and (d d’) LC (IND, indole, IPA, indole propionic acid, MET, melatonin, SKT, skatole).

Differential metabolites found in the metabolomic analysis and AUC values of the metabolites by ROC curve analysis of the normal group and the disease groups

| Group | Compound | FC | log2(FC) | VIP | Type | Univariate (AUC) | Multivariate (AUC) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | IPA | 0.1131 | −3.1443 | 1.104 | Down | 0.893 | 0.999 | 96.2 | 100 |

| MLT | 0.1113 | −3.1674 | 1.324 | Down | 0.989 | ||||

| SKT | 0.2096 | −2.2541 | 1.360 | Down | 0.967 | ||||

| Acetic acid | 0.4654 | −1.1033 | 1.032 | Down | 0.793 | ||||

| Butyric acid | 0.2515 | −1.9914 | 1.148 | Down | 0.861 | ||||

| Heptylic acid | 3.2437 | 1.6976 | 1.135 | Up | 0.875 | ||||

| Valeric acid | 9.0989 | 3.1857 | 1.367 | Up | 0.952 | ||||

| EC | IPA | 0.0996 | −3.3282 | 1.178 | Down | 0.929 | 0.996 | 94.7 | 96.6 |

| MLT | 0.0665 | −3.9097 | 1.516 | Down | 0.996 | ||||

| SKT | 0.1512 | −2.7252 | 1.521 | Down | 0.985 | ||||

| Isovaleric acid | 2.9094 | 1.5407 | 1.221 | Up | 0.853 | ||||

| RCC | 2.2523 | 1.1714 | 1.323 | Up | 0.895 | ||||

| Cortisol | 2.1647 | 1.1142 | 1.288 | Up | 0.895 | ||||

| GC | IND | 0.2982 | −1.7455 | 1.108 | Down | 0.771 | 0.985 | 89.7 | 96.4 |

| MLT | 0.2274 | −2.1366 | 1.527 | Down | 0.909 | ||||

| SKT | 0.2368 | −2.0784 | 1.690 | Down | 0.950 | ||||

| Butyric acid | 0.1966 | −2.3468 | 1.520 | Down | 0.935 | ||||

| LC | IPA | 0.0567 | −4.14 | 1.584 | Down | 0.985 | 1.00 | 100 | 100 |

| MLT | 0.0979 | −3.353 | 1.712 | Down | 0.988 | ||||

| SKT | 0.1846 | −2.4378 | 1.702 | Down | 0.981 | ||||

| Acetic acid | 0.4209 | −1.2486 | 1.016 | Down | 0.825 |

CC: colon cancer; EC: esophageal cancer; GC: stomach cancer; LC: lung cancer; IPA: indole propionic acid; MET: melatonin; SKT: skatole; RCC: ratio of cortisol to cortisone.

ROC curve analysis was performed to further characterize the predictive value of differential metabolites in differentiating tumor patients from healthy controls. The predictive utility of the ROC curve was measured by the area under the curve (AUC). An AUC of 0.5 or <0.5 for the metabolite indicates that the difference between the groups were not significant, and AUC close to 1 is considered a perfect discriminant test. As shown in Table 2, the AUC values for the predictors in univariate analysis ranged from 0.771 to 0.989, and in multivariate analysis ranged from 0.985 to 1.00. The sensitivity and specificity of the multivariable model were 94.7–100 and 96.4–100%, respectively.

In addition to differentiating between patients with each type of cancer and the controls, pairings between the four cancer groups were also identified by multivariate ROC analysis. The accuracies of all discriminant analyses using the concentrations of differential metabolites as explanatory variables were better than 55% (Table 3).

Multivariate ROC analysis between different pairs of cancer

| Group | Compound | Another cancer | Multivariate (AUC) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | IPA, MLT, SKT, acetic acid, butyric acid, heptylic acid, valeric acid | EC | 0.947 | 88.5 | 100 |

| GC | 0.952 | 88.5 | 96.4 | ||

| LC | 0.962 | 88.5 | 95.7 | ||

| EC | IPA, MLT, SKT, isovaleric RCC, cortisol | CC | 0.721 | 78.9 | 69.2 |

| GC | 0.917 | 89.5 | 96.4 | ||

| LC | 0.667 | 78.9 | 56.5 | ||

| GC | IND, MLT, SKT, butyric acid | CC | 0.774 | 82.1 | 69.2 |

| EC | 0.912 | 85.7 | 89.5 | ||

| LC | 0.944 | 85.7 | 90.0 | ||

| LC | IPA, MLT, SKT, acetic acid | CC | 0.639 | 69.2 | 78.3 |

| EC | 0.652 | 57.9 | 78.3 | ||

| GC | 0.930 | 82.6 | 82.1 |

CC: colon cancer; EC: esophageal cancer; GC: stomach cancer; LC: lung cancer; IPA: indole propionic acid; MET: melatonin; SKT: skatole; RCC: ratio of cortisol to cortisone.

3.5 Altered metabolic pathways

When we analyzed pathways with differential metabolites (shown in Table 2) for cancers vs control group, several metabolic pathways showed cancer-related changes. As shown in Figure 6, changes in steroid hormone biosynthesis and Trp metabolism were significant and common across cancers, and changes in pyruvate metabolism, glycolysis, or gluconeogenesis were also significant except GC.

Metabolome view of pathway changes observed by differential metabolites in plasma of four types of cancer patients. GC, gastric cancer; LC, lung cancer; EC, esophageal cancer; CC, colon cancer.

4 Discussion

4.1 Determination methods and application

Cancer-related fatigue [19], sleep difficulties [20], depressive symptoms [21], and cognitive impairment [22] are common side effects of cancer. The often co-occurring and interdependent nature of these symptoms suggests that a common underlying mechanism may exist [23]. The discovery of shared mechanisms of action pathways may help develop new strategies to manage multiple symptoms.

In this study, three classes of metabolites related to MGB axis were detected in plasma samples from four tumor groups and healthy control group, so as to investigate the changing characteristics of the three classes of indicators in different tumor groups and explore whether there may be some common biological mechanisms shared in different tumor groups, and evaluate its possibility as multiple clinical markers and prognostic evaluation indicators. To achieve the goal, we used the electrospinning technology to prepare nanofiber solid-phase extraction materials that can interact with target substances through hydrogen bonds, electrostatics, hydrophobicity, coordination, host–guest, etc. Combined with the nanofiber-based solid-phase extraction established by our research group, analytical methods for three classes of metabolites related to MGB axis in plasma samples was established based on slightly modified analytical methods that have been reported [16–18]. These methods were applied to the detection of metabolic profiles of flora-related metabolites in plasma samples from four groups of patients with cancer. Based on metabolomics analysis, it could be possible to explore the changing trends and patterns of intestinal flora metabolic-related target substances in the human body after being affected by cancer, and to explore the possible mechanisms of flora metabolic disorder in cancer patients.

4.2 Cortisol and cortisone alternations

Multiple evidence suggests that the immunosuppressive effect of cortisol may reduce cancer immune surveillance, promote immune escape, and induce carcinogenic mutations [24]. Cortisol can induce obesity and insulin resistance, and is associated with an increased risk of a range of malignant tumors [25]. In addition, chronic stress from exposure to environmental factors leads to an increased risk of cancer [26].

A recent review of HPA axis dysfunction in cancer reports that most studies report increased baseline cortisol or hyperactive cortisol response, while a few report decreased baseline cortisol or cortisol response in cancers. However, the authors also point out some limitations of the listed studies, such as the heterogeneity of assay methods and sampling protocols, and they conclude that a standardized approach is needed to study the mechanisms of HPA disorders and their health outcomes in order to develop appropriate tools to diagnose and manage HPA dysfunction in cancers [27].

In this study, the results of endogenous cortisol and cortisone in four groups of cancer patients showed that the plasma cortisol levels were significantly increased compared with the control group, and the cortisol/cortisone ratios were increased, indicating that the activity of 11β-HSD1 may be enhanced and the activity of 11β-HSD2 may be weakened. This suggests that there may be common mechanisms of change for various types of cancers in glucocorticoid metabolism, and it is necessary to evaluate patients’ cortisol levels before and after cancer diagnosis and treatment, respectively.

4.3 Trp metabolite alternations

MLT is an active metabolite of Trp produced by host’s own cells in the serotonergic pathway in a circadian rhythm under the control of various enzymes [28]. MLT exerts considerable functional versatility with antioxidant, oncostatic, anti-aging, anti-stress, and immunomodulatory properties [29]. Decreased melatonin levels increase the risk of certain cancers such as breast cancer, endometrial cancer, colorectal cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and prostate cancer [30]. There is current interest in exogenous MLT as a potential anti-proliferative agent in some cancers [30].

This study found that compared with the control group, the concentrations of MLT across the cancers were significantly lower than those in the control group (p < 0.05). Many previous studies have typically focused on a single type of cancer, for example, several studies have found that MLT concentrations in cancer patients are lower than in healthy controls, including prostate cancer [31], breast cancer [32], cervical cancer [32], LC [33,34], and colorectal cancer [35]. In this work, the MLT level in all types of cancers was detected simultaneously, the results showed that they were similar to those in individual cancer studies. Therefore, significantly reduced plasma MLT levels may be common in cancers and could potentially serve as a biomarker for early detection. Further research is warranted to explore the underlying mechanisms contributing to these diminished levels and their implications for cancer progression and treatment outcomes.

In addition to MLT, other Trp metabolites also have an impact on cancer development, such as IND, IPA, and SKT are active metabolites of Trp produced by gut microbes [28]. Sári et al.’s study on breast cancer found that 3-indoleacetic acid has anti-tumor properties, and IPA reduces the proportion of cancer stem cells and the proliferation, movement, and metastasis of cancer cells [36]. Sári also points out that IPA supplementation can reduce the invasion of the surrounding tissue by the primary tumor, the number of metastases, cell movement, and blood exudation. IND derivatives support the survival of breast cancer patients, and their levels are down-regulated as the disease progresses. Our test results showed that IPA and SKT were significantly lower in the plasma of four cancer groups than in the control group, which is similar to the results reported in the literature, suggesting that supplementation with certain Trp metabolites may be beneficial for the treatment of cancers.

4.4 SCFAs alternation

SCFAs are a class of metabolites produced by gut microbes, which can reduce inflammation, maintain intestinal barrier, mediate colonization resistance of intestinal pathogens, and enhance host health. Studies have shown that SCFAs can prevent and improve various malignant tumors, such as adenocarcinoma [37] and colorectal cancer [38].

Acetic acid inhibits the proliferation of human cancer cell lines by reducing glycolysis [39]. The potential benefits of the combination of acetate and propionate in tumor growth inhibition have raised concerns [40]. Butyrate is the most studied SCFA that inhibits the progression and proliferation of cancer cells by regulating metabolic, endocrine, and immune functions [41]. Butyrate and propionate can enhance the effectiveness of chemotherapy drugs by increasing tumor sensitivity or enhancing anti-tumor immune response [42].

Acetate, butyrate, and propionate have been widely studied due to their high abundance, while SCFAs, isobutyrate, valerate, and isovalerate, in less abundance, have received less attention. Recent studies have shown that isobutyric acid can inhibit the growth of colorectal cancer cells and synergistically improve the efficacy of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy [43].

Zhu et al. collected stool samples from breast cancer patients to detect SCFAs, and found that compared with the control group, the contents of acetic acid and butyric acid were lower, while the contents of isobutyric acid and valeric acid were higher (p < 0.05) [12].

This study found that the concentrations of acetic acid and butyric acid in the plasma samples of the four tumors were significantly lower than those of the control group (p < 0.05), and propionic acid, isobutyric acid, and isovaleric acid were mostly higher than those of the control group. However, the results were not significant in some cancer groups. These results were consistent with Zhu’s study, although the types of tumors studied were different. For valeric acid, hexanoic acid, and heptylic acid, these molecules with more carbon atoms, the changes of these SCFAs in colorectal cancer samples were distinctive, and the concentrations were significantly higher than that of other cancer groups and control group (p < 0.01).

4.5 Relationships between the metabolites

There was also a correlation between the three types of metabolites investigated in this study. For example, under stress conditions, glucocorticoids reduce the synthesis of MLT in the pineal gland, and the production of MLT at night can only be activated under low stress conditions [44,45].

MLT is also thought to counteract the immunosuppressive effect of glucocorticoids, on the one hand up-regulating the expression of MLT receptors on the surface of lymphoid organs cells, and on the other hand decreasing the sensitivity of immunoactive cells to glucocorticoids [46].

Xu et al. found that MLT is associated with its metabolites. In addition, MLT and its metabolites are also associated with cortisol and several steroid hormones upstream and downstream of cortisol metabolism [47].

Dalile et al. administered a colonic SCFAs mixture (acetate, propionic acid, butyrate) to healthy participants, and the results showed a significant reduction in cortisol levels and stress responses. This study supports the mechanistic role of SCFAs in the human MGB axis, particularly in relation to stress reactivity dominated by the HPA axis where cortisol is the marker [48].

In this study, it was observed that the relationships between the metabolites were changed by comparing the healthy group with the patient groups, and most of Pearson’s correlation coefficients were increased in the same group of metabolites, such as in SCFAs (except EC group) and glucocorticoids groups, while in the group of Trp metabolites, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were mostly reduced. The correlations between metabolites of different classes were mostly changed slightly from negative to positive between SCFAs and metabolites of Trp. The changes in Pearson’s correlation coefficients between glucocorticoids and the other two groups of metabolites were different in different disease groups, but the changes were not significant.

4.6 Potential biomarkers

In this study, 14 target compounds were analyzed targeting the MGB axis, and four groups of potential candidate biomarkers were found on the basis of screening differential metabolites. These biomarkers had good performance in discriminating between disease and healthy groups, and most of them showed acceptable effects in discriminating different pairs of cancer.

4.7 Metabolic pathway alternations

Tumor cells increase their metabolic rate to maintain rapid growth through “metabolic reprogramming,” which is most often caused by increased glycolysis. Pyruvate is the end product of the anaerobic glycolytic energy production pathway, and the anaerobic decomposition of pyruvate produces lactic acid or ethanol as a byproduct. Glycolytic enzymes and products have been shown to be closely associated with tumor progression, including proliferation, invasion, metastasis, autophagy, and immune escape. Diagnostic imaging such as positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance spectrum, and the detection of glycolytic enzymes have been developed to provide evidence for accurate diagnosis and disease management in cancer patients [49]. This study also provides information on abnormal glycolysis and pyruvate metabolism in cancer patients through the detection of several metabolites in plasma.

The association between stress and cortisol reactivity is well known. Exposure to stress causes HPA axis to activate and release glucocorticoids from the adrenal cortex. As the end product of the HPA axis, cortisol is widely used as a marker of neuroendocrine stress responses [50]. A recent literature suggests that glucocorticoids produced by immune and tumor cells within tumors have been shown to support tumor immune escape [24]. The HPA axis is an important regulator of the immune system, and its potential inhibitory effect on immune function may affect the occurrence and progression of cancer. Previous studies on the relationship between glucocorticoids and cancer have mostly focused on female tumor patients. Adding cortisol to cultured breast cancer cells in vitro has been shown to enhance or inhibit the growth of breast cancer cells. A small number of studies have reported elevated cortisol in breast cancer patients, and the amount raised is positively correlated with the severity of the cancer [51]. We found that plasma glucocorticoid production and metabolism were active in patients with EC, GC, LC, and colorectal cancer, suggesting that this may be a potential mechanism for the co-occurrence and development of malignant tumors.

In addition, we found down-regulated plasma Trp metabolites and an imbalance in Trp metabolism that is common in patients with four types of cancer. It has been reported that dysregulated Trp metabolism promotes tumor growth and immune escape by creating immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment [52].

4.8 Shortcomings and advantages

This study had some limitations, such as a small sample size and lack of clinical personal information, such as IBM and cancer stage, which made more detailed clinically relevant analyses difficult to carry out. In addition, our samples were all from Han Chinese derived from a single-center, which may have influenced the results and limited external validity. Confounding factors such as diet and drug use were not strictly controlled. Further studies are needed to expand the study to include different ethnic, sample sizes to provide more accurate and meaningful results.

The advantage of this study was that the quantitative determination method was relatively sensitive and accurate, and the sample pretreatment with nanofiber materials was conducive to eliminate the possible sample matrix effect in the usual detection, making the results more reliable.

5 Conclusion

Many previous studies have typically focused on a single type of cancer. This approach screened valuable gut microbiota markers for different types of cancer, contributing to a deeper understanding of the biology, pathogenesis, and treatment strategies of specific cancers. However, this approach also has certain limitations, as it may overlook commonalities and differences between different cancer types.

In this study, metabolomic analysis targeting SCFAs, four Trp metabolites, and two glucocorticoids was performed using Packed-nanofiber SPE coupled with chromatography–mass method. MLT, IPA, and SKT were screened as the common differential metabolites shared by four types of cancer indicating that the intestinal microbial metabolic pathway of Trp plays a key role in the occurrence and development of malignant tumors. In addition, some SCFAs can also be used as potential biomarkers for diagnostic models. All four disease groups showed significant increases in cortisol and RCC levels. These results suggest that paying close attention to the changes in these three types of metabolites will play a potential role in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Four groups of potential candidate biomarkers were found on the basis of screening differential metabolites for discriminating disease and healthy groups, and these biomarkers also play a role in models that classify different cancers.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82173575) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2242023k30022).

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization: YQZ and LX; sample collection and clinical analysis: YQZ and KWS; resources: WH and YQZ; data analysis: KWS and LX; methodology: LX and XJK; original draft: YQZ; writing, reviewing, and editing: LX and XJK; supervision: XJK and QL; funding acquisition and project administration: XJK All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Blackadar CB. Historical review of the causes of cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2016;7:54–86.10.5306/wjco.v7.i1.54Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Urbaniak C, Gloor GB, Brackstone M, Scott L, Tangney M, Reid G. The microbiota of breast tissue and its association with breast cancer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:5039–48.10.1128/AEM.01235-16Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Giudice A, Aliberti SM, Barbieri A, Pentangelo P, Bisogno I, D’Arena G, et al. Potential mechanisms by which glucocorticoids induce breast carcinogenesis through Nrf2 inhibition. Front Biosci-Landmark. 2022;27:223.10.31083/j.fbl2707223Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] errera RA, Deshpande K, Martirosian V, Saatian B, Julian A, Eisenbarth R, et al. Cortisol promotes breast-to-brain metastasis through the blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier. Cancer Rep. 2022;5:e1351.10.1002/cnr2.1351Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Hsiao FH, Jow GM, Kuo WH, Huang CS, Lai YM, Liu YF, et al. The partner’s insecure attachment, depression and psychological well-being as predictors of diurnal cortisol patterns for breast cancer survivors and their spouses. Stress Amst Neth. 2014;17(2):169–75.10.3109/10253890.2014.880833Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Ruo SW, Alkayyali T, Win M, Tara A, Joseph C, Kannan A, et al. Role of gut microbiota dysbiosis in breast cancer and novel approaches in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Cureus. 2021;13:e17472.10.7759/cureus.17472Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Álvarez J, Fernández Real JM, Guarner F, Gueimonde M, Rodríguez JM, Saenz De Pipaon M, et al. Gut microbes and health. Gastroenterol Hepatol (Engl Ed). 2021;44:519–35.10.1016/j.gastre.2021.01.002Search in Google Scholar

[8] Wargo JA. Modulating gut microbes. Science. 2020;369:1302–3.10.1126/science.abc3965Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Álvarez-Mercado AI, Del Valle Cano A, Fernández MF, Fontana L. Gut microbiota and breast cancer: the dual role of microbes. Cancers. 2023;15:443.10.3390/cancers15020443Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Tsvetikova SA, Koshel EI. Microbiota and cancer: host cellular mechanisms activated by gut microbial metabolites. Int J Med Microbiol. 2020;310:151425.10.1016/j.ijmm.2020.151425Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Plaza-Diaz J, Álvarez-Mercado AI. The interplay between microbiota and chemotherapy-derived metabolites in breast cancer. Metabolites. 2023;13:703.10.3390/metabo13060703Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Zhu Q, Zai H, Zhang K, Zhang X, Luo N, Li X, et al. L-Norvaline affects the proliferation of breast cancer cells based on the microbiome and metabolome analysis. J Appl Microbiol. 2022;133:1014–26.10.1111/jam.15620Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Zhou Y, Han W, Feng Y, Wang Y, Sun T, Xu J. Microbial metabolites affect tumor progression, immunity, and therapy prediction by reshaping the tumor microenvironment. Int J Oncol. 2024;65:73.10.3892/ijo.2024.5661Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Alpert O, Begun L, Issac T, Solhkhah R. The brain–gut axis in gastrointestinal cancers. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;12(Suppl 2):S301–10.10.21037/jgo-2019-gi-04Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Priego-Parra BA, Remes-Troche JM. Bidirectional relationship between gastrointestinal cancer and depression: the key is in the microbiota–gut–brain axis. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30(48):5104–10.10.3748/wjg.v30.i48.5104Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Li C, Zhang Z, Liu X, Shen K, Gu P, Kang X. Simultaneous quantification of cortisol and cortisone in urines from infants with packed-fiber solid-phase extraction coupled to HPLC–MS/MS. J Chromatogr B. 2017;1061–1062:163–8.10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.07.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Zhao R, Chu L, Wang Y, Song Y, Liu P, Li C, et al. Application of packed-fiber solid-phase extraction coupled with GC–MS for the determination of short-chain fatty acids in children’s urine. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;468:120–5.10.1016/j.cca.2017.02.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Wei L, Kang X. Packed-nanofiber solid-phase extraction coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography fluorescence for determining gut microbiota–host cometabolites and indoleamines in human urine. Separations. 2024;11:153.10.3390/separations11050153Search in Google Scholar

[19] Goto T, Saligan LN. Mechanistic insights into behavioral clusters associated with cancer-related systemic inflammatory response. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2024;18(3):161–7.10.1097/SPC.0000000000000706Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Lowery-Allison AE, Passik SD, Cribbet MR, Reinsel RA, O’Sullivan B, Norton L, et al. Sleep problems in breast cancer survivors 1–10 years posttreatment. Palliat Support Care. 2018;16:325–34.10.1017/S1478951517000311Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Saeki Y, Sumi Y, Ozaki Y, Hosonaga M, Kenmotsu Y, Onoe T, et al. Proposal for managing cancer-related insomnia: a systematic literature review of associated factors and a narrative review of treatment. Cancer Med. 2024;13(22):e70365.10.1002/cam4.70365Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Aspelund SG, Halldorsdottir T, Agustsson G, Sigurdardottir Tobin HR, Wu LM, Amidi A, et al. Biological and psychological predictors of cognitive function in breast cancer patients before surgery. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc. Support Care Cancer. 2024;32(1):88.10.1007/s00520-023-08282-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Amidi A, Wu LM. Circadian disruption and cancer- and treatment-related symptoms. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1009064.10.3389/fonc.2022.1009064Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Schwarzlmueller P, Triebig A, Assié G, Jouinot A, Theurich S, Maier T, et al. Steroid hormones as modulators of anti-tumoural immunity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2025;01102:2.10.1038/s41574-025-01102-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Nead KT, Sharp SJ, Thompson DJ, Painter JN, Savage DB, Semple RK, et al. Evidence of a causal association between insulinemia and endometrial cancer: a Mendelian randomization analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(9):djv178.10.1093/jnci/djv178Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Bratborska AW, Piotrowski I. The impact of yoga practice on cortisol levels in breast cancer patients – a comprehensive review. Oncol Clin Pract. 2024;20(6):420–7.10.5603/ocp.98177Search in Google Scholar

[27] Kanter NG, Cohen‐Woods S, Balfour D, Burt MG, Waterman AL, Koczwara B. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysfunction in people with cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Med. 2024;13(22);e70366. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cam4.70366.10.1002/cam4.70366Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Konopelski P, Mogilnicka I. Biological effects of indole-3-propionic acid, a gut microbiota-derived metabolite, and its precursor tryptophan in mammals’ health and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:1222.10.3390/ijms23031222Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Simonneaux V, Ribelayga C. Generation of the melatonin endocrine message in mammals: a review of the complex regulation of melatonin synthesis by norepinephrine, peptides, and other pineal transmitters. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55(37):325–95.10.1124/pr.55.2.2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Jung-Hynes B, Huang W, Reiter RJ, Ahmad N. Melatonin resynchronizes dysregulated circadian rhythm circuitry in human prostate cancer cells: melatonin and the circadian clock. J Pineal Res. 2010;49:60–8.10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00767.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Lozano-Lorca M, Olmedo-Requena R, Rodríguez-Barranco M, Redondo-Sánchez D, Jiménez-Pacheco A, Vázquez-Alonso F, et al. Salivary melatonin rhythm and prostate cancer: CAPLIFE study. J Urol. 2022;207:565–72.10.1097/JU.0000000000002294Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Bartsch C, Bartsch H, Jain AK, Laumas KR, Wetterberg L. Urinary melatonin levels in human breast cancer patients. J Neural Transm. 1981;52:281–94.10.1007/BF01256753Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Chang WP, Lin CC. Relationships of salivary cortisol and melatonin rhythms to sleep quality, emotion, and fatigue levels in patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2017;29:79–84.10.1016/j.ejon.2017.05.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Hu S, Shen G, Yin S, Xu W, Hu B. Melatonin and tryptophan circadian profiles in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Adv Ther. 2009;26:886–92.10.1007/s12325-009-0068-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Khoory R, Stemme D. Plasma melatonin levels in patients suffering from colorectal carcinoma. J Pineal Res. 1988;5:251–8.10.1111/j.1600-079X.1988.tb00651.xSearch in Google Scholar

[36] Sári Z, Mikó E, Kovács T, Jankó L, Csonka T, Lente G, et al. Indolepropionic acid, a metabolite of the microbiome, has cytostatic properties in breast cancer by activating AHR and PXR receptors and inducing oxidative stress. Cancers. 2020;12:2411.10.3390/cancers12092411Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Sivaprakasam S, Prasad PD, Singh N. Benefits of short-chain fatty acids and their receptors in inflammation and carcinogenesis. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;164:144–51.10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.04.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Zhang Z, Cao H, Song N, Zhang L, Tai J. Long-term hexavalent chromium exposure facilitates colorectal cancer in mice associated with changes in gut microbiota composition. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;138:111237.10.1016/j.fct.2020.111237Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Sahuri-Arisoylu M, Mould RR, Shinjyo N, Bligh SWA, Nunn AVW, Guy GW, et al. Acetate induces growth arrest in colon cancer cells through modulation of mitochondrial function. Front Nutr. 2021;8:588466.10.3389/fnut.2021.588466Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Tang Y, Chen Y, Jiang H, Nie D. The role of short-chain fatty acids in orchestrating two types of programmed cell death in colon cancer. Autophagy. 2011;7:235–7.10.4161/auto.7.2.14277Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Portincasa P, Bonfrate L, Vacca M, De Angelis M, Farella I, Lanza E, et al. Gut microbiota and short chain fatty acids: implications in glucose homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:1105.10.3390/ijms23031105Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Al-Qadami GH, Secombe KR, Subramaniam CB, Wardill HR, Bowen JM. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids: impact on cancer treatment response and toxicities. Microorganisms. 2022;10:2048.10.3390/microorganisms10102048Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Murayama M, Hosonuma M, Kuramasu A, Kobayashi S, Sasaki A, Baba Y, et al. Isobutyric acid enhances the anti-tumour effect of anti-PD-1 antibody. Sci Rep. 2024;14:11325.10.1038/s41598-024-59677-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Da Silveira Cruz-Machado S, Tamura EK, Carvalho-Sousa CE, Rocha VA, Pinato L, Fernandes PAC, et al. Daily corticosterone rhythm modulates pineal function through NFκB-related gene transcriptional program. Sci Rep. 2017;7:2091.10.1038/s41598-017-02286-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Fernandes PA, Tamura EK, D’Argenio-Garcia L, Muxel SM, Da Silveira Cruz-Machado S, Marçola M, et al. Dual effect of catecholamines and corticosterone crosstalk on pineal gland melatonin synthesis. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;104:126–34.10.1159/000445189Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Singh AK, Haldar C. Melatonin modulates glucocorticoid receptor mediated inhibition of antioxidant response and apoptosis in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;436:59–67.10.1016/j.mce.2016.07.024Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Xu W, Cui Y, Guo D, Wang W, Xu H, Qiao S, et al. UPLC-MS/MS simultaneous quantification of urinary circadian rhythm hormones and related metabolites: application to air traffic controllers. J Chromatogr B. 2023;1222:123664.10.1016/j.jchromb.2023.123664Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Dalile B, Vervliet B, Bergonzelli G, Verbeke K, Van Oudenhove L. Colon-delivered short-chain fatty acids attenuate the cortisol response to psychosocial stress in healthy men: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:2257–66.10.1038/s41386-020-0732-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Qiao Q, Hu S, Wang X. The regulatory roles and clinical significance of glycolysis in tumor. Cancer Commun Lond Engl. 2024;44(7):761–86.10.1002/cac2.12549Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Ahabrach H, El Mlili N, Mafla-España MA, Cauli O. Hair cortisol concentration associates with insomnia and stress symptoms in breast cancer survivors. Int J Psychophysiol. 2023;191:49–56.10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2023.07.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Luecken LJ, Compas BE. Stress, coping, and immune function in breast cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(4):336–44.10.1207/S15324796ABM2404_10Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Zhang HL, Zhang AH, Miao JH, Sun H, Yan GL, Wu FF, et al. Targeting regulation of tryptophan metabolism for colorectal cancer therapy: a systematic review. RSC Adv. 2019;9(6):3072–80.10.1039/C8RA08520JSearch in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome with elevated IgG4 and T-cell clonality: A report of two cases

- Electroacupuncture alleviates sciatic nerve injury in sciatica rats by regulating BDNF and NGF levels, myelin sheath degradation, and autophagy

- Polydatin prevents cholesterol gallstone formation by regulating cholesterol metabolism via PPAR-γ signaling

- RNF144A and RNF144B: Important molecules for health

- Analysis of the detection rate and related factors of thyroid nodules in the healthy population

- Artesunate inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion through OGA-mediated O-GlcNAcylation of ZEB1

- Endovascular management of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: Case report and review of the literature

- Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis

- SATB2 promotes humeral fracture healing in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Overexpression of the ferroptosis-related gene, NFS1, corresponds to gastric cancer growth and tumor immune infiltration

- Understanding risk factors and prognosis in diabetic foot ulcers

- Atractylenolide I alleviates the experimental allergic response in mice by suppressing TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 signalling

- FBXO31 inhibits the stemness characteristics of CD147 (+) melanoma stem cells

- Immune molecule diagnostics in colorectal cancer: CCL2 and CXCL11

- Inhibiting CXCR6 promotes senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells with limited proinflammatory SASP to attenuate hepatic fibrosis

- Cadmium toxicity, health risk and its remediation using low-cost biochar adsorbents

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis with headache as the first presentation: A case report

- Solitary pulmonary metastasis with cystic airspaces in colon cancer: A rare case report

- RUNX1 promotes denervation-induced muscle atrophy by activating the JUNB/NF-κB pathway and driving M1 macrophage polarization

- Morphometric analysis and immunobiological investigation of Indigofera oblongifolia on the infected lung with Plasmodium chabaudi

- The NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex and Hr78 modulate the Lobe2 mutant eye phenotype

- Experimental study on salmon demineralized bone matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: In vitro and in vivo study

- A case of IgA nephropathy treated with a combination of telitacicept and half-dose glucocorticoids

- Analgesic and toxicological evaluation of cannabidiol-rich Moroccan Cannabis sativa L. (Khardala variety) extract: Evidence from an in vivo and in silico study

- Wound healing and signaling pathways

- Combination of immunotherapy and whole-brain radiotherapy on prognosis of patients with multiple brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study

- To explore the relationship between endometrial hyperemia and polycystic ovary syndrome

- Research progress on the impact of curcumin on immune responses in breast cancer

- Biogenic Cu/Ni nanotherapeutics from Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl seeds for the treatment of lung cancer

- Dapagliflozin attenuates atrial fibrosis via the HMGB1/RAGE pathway in atrial fibrillation rats

- Glycitein alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in keratinocytes via ROS-associated PI3K–Akt signalling pathway

- ADH5 inhibits proliferation but promotes EMT in non-small cell lung cancer cell through activating Smad2/Smad3

- Apoptotic efficacies of AgNPs formulated by Syzygium aromaticum leaf extract on 32D-FLT3-ITD human leukemia cell line with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Novel cuproptosis-related genes C1QBP and PFKP identified as prognostic and therapeutic targets in lung adenocarcinoma

- Bee venom promotes exosome secretion and alters miRNA cargo in T cells

- Treatment of pure red cell aplasia in a chronic kidney disease patient with roxadustat: A case report

- Comparative bioinformatics analysis of the Wnt pathway in breast cancer: Selection of novel biomarker panels associated with ER status

- Kynurenine facilitates renal cell carcinoma progression by suppressing M2 macrophage pyroptosis through inhibition of CASP1 cleavage

- RFX5 promotes the growth, motility, and inhibits apoptosis of gastric adenocarcinoma cells through the SIRT1/AMPK axis

- ALKBH5 exacerbates early cardiac damage after radiotherapy for breast cancer via m6A demethylation of TLR4

- Phytochemicals of Roman chamomile: Antioxidant, anti-aging, and whitening activities of distillation residues

- Circadian gene Cry1 inhibits the tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma by the BAX/BCL2-mediated apoptosis pathway

- The TNFR-RIPK1/RIPK3 signalling pathway mediates the effect of lanthanum on necroptosis of nerve cells

- Longitudinal monitoring of autoantibody dynamics in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing surgery

- The potential role of rutin, a flavonoid, in the management of cancer through modulation of cell signaling pathways

- Construction of pectinase gene engineering microbe and its application in tobacco sheets

- Construction of a microbial abundance prognostic scoring model based on intratumoral microbial data for predicting the prognosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Sepsis complicated by haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis triggered by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and human herpesvirus 8 in an immunocompromised elderly patient: A case report

- Sarcopenia in liver transplantation: A comprehensive bibliometric study of current research trends and future directions

- Advances in cancer immunotherapy and future directions in personalized medicine

- Can coronavirus disease 2019 affect male fertility or cause spontaneous abortion? A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis

- Heat stroke associated with novel leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor gene variant in a Chinese infant

- PSME2 exacerbates ulcerative colitis by disrupting intestinal barrier function and promoting autophagy-dependent inflammation

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state with severe hypernatremia coexisting with central diabetes insipidus: A case report and literature review

- Efficacy and mechanism of escin in improving the tissue microenvironment of blood vessel walls via anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects: Implications for clinical practice

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Clinicopathological analysis of three patients and literature review

- Genetic variants in VWF exon 26 and their implications for type 1 Von Willebrand disease in a Saudi Arabian population

- Lipoxin A4 improves myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through the Notch1-Nrf2 signaling pathway

- High levels of EPHB2 expression predict a poor prognosis and promote tumor progression in endometrial cancer

- Knockdown of SHP-2 delays renal tubular epithelial cell injury in diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis

- Exploring the toxicity mechanisms and detoxification methods of Rhizoma Paridis

- Concomitant gastric carcinoma and primary hepatic angiosarcoma in a patient: A case report

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Optimization and comparative study of Bacillus consortia for cellulolytic potential and cellulase enzyme activity

- The complete mitochondrial genome analysis of Haemaphysalis hystricis Supino, 1897 (Ixodida: Ixodidae) and its phylogenetic implications

- Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors analysis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among tuberculosis population in Huzhou City, Eastern China

- Indices of human impacts on landscapes: How do they reflect the proportions of natural habitats?

- Genetic analysis of the Siberian flying squirrel population in the northern Changbai Mountains, Northeast China: Insights into population status and conservation

- Diversity and environmental drivers of Suillus communities in Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica forests of Inner Mongolia

- Global assessment of the fate of nitrogen deposition in forest ecosystems: Insights from 15N tracer studies

- Fungal and bacterial pathogenic co-infections mainly lead to the assembly of microbial community in tobacco stems

- Influencing of coal industry related airborne particulate matter on ocular surface tear film injury and inflammatory factor expression in Sprague-Dawley rats

- Temperature-dependent development, predation, and life table of Sphaerophoria macrogaster (Thomson) (Diptera: Syrphidae) feeding on Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae)

- Eleonora’s falcon trophic interactions with insects within its breeding range: A systematic review

- Agriculture

- Integrated analysis of transcriptome, sRNAome, and degradome involved in the drought-response of maize Zhengdan958

- Variation in flower frost tolerance among seven apple cultivars and transcriptome response patterns in two contrastingly frost-tolerant selected cultivars

- Heritability of durable resistance to stripe rust in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Molecular mechanism of follicular development in laying hens based on the regulation of water metabolism

- Animal Science

- Effect of sex ratio on the life history traits of an important invasive species, Spodoptera frugiperda

- Plant Sciences

- Hairpin in a haystack: In silico identification and characterization of plant-conserved microRNA in Rafflesiaceae

- Widely targeted metabolomics of different tissues in Rubus corchorifolius

- The complete chloroplast genome of Gerbera piloselloides (L.) Cass., 1820 (Carduoideae, Asteraceae) and its phylogenetic analysis

- Field trial to correlate mineral solubilization activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and biochemical content of groundnut plants

- Correlation analysis between semen routine parameters and sperm DNA fragmentation index in patients with semen non-liquefaction: A retrospective study

- Plasticity of the anatomical traits of Rhododendron L. (Ericaceae) leaves and its implications in adaptation to the plateau environment

- Effects of Piriformospora indica and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on growth and physiology of Moringa oleifera under low-temperature stress

- Effects of different sources of potassium fertiliser on yield, fruit quality and nutrient absorption in “Harward” kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa)

- Comparative efficiency and residue levels of spraying programs against powdery mildew in grape varieties

- The DREB7 transcription factor enhances salt tolerance in soybean plants under salt stress

- Using plant electrical signals of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) for water pollution monitoring

- Food Science

- Phytochemical analysis of Stachys iva: Discovering the optimal extract conditions and its bioactive compounds

- Review on role of honey in disease prevention and treatment through modulation of biological activities

- Computational analysis of polymorphic residues in maltose and maltotriose transporters of a wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain

- Optimization of phenolic compound extraction from Tunisian squash by-products: A sustainable approach for antioxidant and antibacterial applications

- Liupao tea aqueous extract alleviates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in rats by modulating the gut microbiota

- Toxicological qualities and detoxification trends of fruit by-products for valorization: A review

- Polyphenolic spectrum of cornelian cherry fruits and their health-promoting effect

- Optimizing the encapsulation of the refined extract of squash peels for functional food applications: A sustainable approach to reduce food waste

- Advancements in curcuminoid formulations: An update on bioavailability enhancement strategies curcuminoid bioavailability and formulations

- Impact of saline sprouting on antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds in chia seeds

- The dilemma of food genetics and improvement

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Impact of hyaluronic acid-modified hafnium metalorganic frameworks containing rhynchophylline on Alzheimer’s disease

- Emerging patterns in nanoparticle-based therapeutic approaches for rheumatoid arthritis: A comprehensive bibliometric and visual analysis spanning two decades

- Application of CRISPR/Cas gene editing for infectious disease control in poultry

- Preparation of hafnium nitride-coated titanium implants by magnetron sputtering technology and evaluation of their antibacterial properties and biocompatibility

- Preparation and characterization of lemongrass oil nanoemulsion: Antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant, and anticancer activities

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells”

- Corrigendum to “Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans”

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Down-regulation of miR-539 indicates poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer”

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis