Abstract

Jaranol, a bioactive compound derived from various traditional medicinal herbs, has demonstrated significant anti-inflammatory properties. This study investigates its effects and possible mechanisms underlying its anti-inflammatory role in mast cells, as well as ovalbumin (OVA)-induced allergic rhinitis (AR) mice model. Forty mice were randomly divided into blank, AR, dexamethasone (positive control), and Jaranol groups (10 mg/ml), with 10 mice in each group. Jaranol was found to inhibit nasal mucosal inflammation and reduce mast cell numbers in AR models. It also inhibited the secretion of several inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, and CXCR10) from mast cells, as well as mast cell proliferation and migration. Interestingly, Pirin was differentially expressed in blank, AR, and Jaranol groups. Further studies indicated that Jaranol inhibited inflammatory cytokine secretion from mast cells by mediating Pirin and also inhibited mast cell proliferation and migration. Moreover, it inhibited mast cell function by suppressing Pirin expression. These findings suggest that Jaranol exerts its therapeutic effects by inhibiting Pirin expression in mast cells, thereby reducing inflammation and histopathological changes associated with AR.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a chronic inflammation of the nasal mucosa that significantly impairs the quality of life for millions worldwide [1,2]. It is triggered by an IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction to environmental allergens, which causes symptoms such as sneezing, stuffy nose, itching, and runny nose [3,4]. The pathogenesis of AR involves a complex interplay of immune cells, among which mast cells play a pivotal role [5,6]. When exposed to allergen, mast cells release a variety of inflammatory mediators, including histamines [7,8], cytokines [9], and proteases [10,11], leading to AR symptoms and histopathological changes in the nasal tissue.

The nasal administration of Chinese herbal medicine involves applying herbal preparations directly into the nasal cavity, where they are absorbed through the nasal mucosa to provide local or systemic therapeutic effects. This method includes dosage forms such as nasal drops, rinses, emulsions, aerosols, sprays, powders, inhalants, gels, and films. Compared to traditional forms like injections or oral medications, nasal administration of Chinese herbal medicine offers advantages like ease of use, targeted delivery, high safety, and fast absorption. Nasal drop is the commonly used nasal formulation; it can treat various diseases, such as nasal disorders, cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, colds, and migraines. Liu et al. [12] found that Yu-ping-feng nasal drops could treat AR in the rat model. Yip et al. [13] used network pharmacology analysis to test common gene targets in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and confirmed that allergic rhinitis nasal drops have an inhibitory effect on viral infection; moreover, it also reduced the inflammatory response post-infection and potentially lowered the risk of lung fibrosis. Fan et al. [14] conducted a dose-escalation study comparing lentinan nasal drops to a placebo to assess the safety and efficacy of lentinan nasal drops in COVID-19 patients; results indicated that lentinan nasal drops are safe and well-tolerated and can shorten viral clearance time. Qian et al. [15] explored the effects of ketamine nasal drops on postoperative pain in children after cold plasma ablation tonsillectomy; results indicated that ketamine nasal drops are safe, reduce pain, and shorten recovery time. In sum, nasal drops have distinct advantages for treating nasal and pulmonary diseases over traditional formulations (such as granules, pills, and injections), making nasal drop development highly promising.

Pirin, a nuclear protein, has been identified as a significant regulator in the inflammatory response [16] and mast cell activation [17]. Elevated levels of Pirin are associated with increased inflammatory activity, suggesting that targeting Pirin expression may provide a novel therapeutic approach for managing AR. Despite its potential, the modulation of Pirin in allergic conditions remains underexplored. Jaranol, also called Kumatakenin, could be extracted from various traditional medicinal herbs, such as licorice, Psychotria serpens, and Siparuna cristata [18,19]. Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of Jaranol in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 replication [20], exerting anti-cancer [21], alpha-glucosidase inhibitory [22], anti-bacterial [23], anti-oxidant [24], and anti-inflammatory activities [25]. However, the specific effects of Jaranol on Pirin expression in mast cells and its consequent impact on AR have not been thoroughly investigated.

The main objective of this study is to thoroughly investigate the mechanism of action of Jaranol in the treatment of AR, to provide an experimental basis for the discovery of target proteins and pathways regulating AR, and to provide a treatment for AR.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Reagents and experimental animals

Jaranol was obtained from Chengdu Push Biotechnology Co., Ltd (China). Ovalbumin (OVA) was provided by MCE (MedChemExpress, USA), and aluminum hydroxide adjuvant and dexamethasone were provided by Suzhou Boao Long Technology Co., Ltd. (China), recombinant anti-mast cell tryptase antibody, anti-Ki67 primary antibody, 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining solution, crystal violet staining solution, cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay kit, reverse transcription and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay kit, and western blot-related reagents were obtained from Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd. (China). The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit was purchased from Abcam (USA). Pirin interference virus and overexpression virus were obtained from Shanghai Jima Gene (China). P815 mast cells were provided by the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The specific experimental procedures involving the above reagents were performed according to the instructions provided with each assay kit.

A total of 40 BALB/c mice, with equal numbers of males and females, were purchased for this study. All animals were SPF level (Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd., China), aged 6–8 weeks, and weighed 20 ± 2 g. All animals were kept in a controlled environment with 50% humidity and 20°C temperature, with a 12-h light/dark cycle. The water and standard feed were sterilized by high pressure, and the mice had free access to them.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animal use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals and has been approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Children’s Hospital affiliated with Fudan University.

2.2 Modeling methods and experimental groups

Sensitization phase: Mice were raised in SPF-level animal facilities and allowed to acclimate for one week before the experiment. A 1% solution of OVA was prepared by dissolving 10 mg of OVA in 1 ml of saline and then mixed with an equal volume of a 2% aluminum hydroxide adjuvant. The mixture was shaken for 30 min. Each mouse received an intraperitoneal injection of 200 µl of this solution daily for 14 consecutive days. Challenge phase: After 14 days of systemic sensitization, intranasal instillation was initiated using a 5% OVA solution (50 mg OVA in 1 ml of saline). Each nasal cavity received 50 µl of the solution once a day for 14 days. On the final day, mice were observed within 10 min of nasal instillation for symptoms of nasal itching, sneezing, and runny nose. The symptoms of AR in mice were scored according to Table 1, with a score exceeding 5 indicating a successful model.

Scoring criteria for symptoms of AR in mice

| Symptom | Score 1 | Score 2 | Score 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal itching | Scratching nose 1–2 times | Between the two | Continuous scratching of the nose |

| Sneezing | 1–3 times | 4–10 times | >11 times |

| Runny nose | Flowing to the anterior nares | Extending beyond the anterior nares | Covering the whole face |

Forty mice were randomly divided into four groups: blank group, model group, dexamethasone group (positive control), and Jaranol group, with 10 mice in each group, with an equal number of males and females. (1) Blank group: 50 µl of saline was instilled into the nasal cavity during the sensitization stage, and no drug treatment was administered. (2) model group: 50 µl of 5% OVA was instilled into the nasal cavity during the sensitization stage, and no drug treatment was administered. (3) Dexamethasone group: 50 µl of 5% OVA was instilled into the nasal cavity during the sensitization stage, and dexamethasone saline solution (200 µl, 500 µg/ml) was injected intraperitoneally at the same time. (4) Jaranol group: 50 µl of 5% OVA was instilled into the nasal cavity during the sensitization stage, and 50 µl of 10 mg/ml Jaranol was also instilled in the nasal cavity at the same time. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xinhua Hospital and attached to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (XHEC-NSFC-2020-097). The research related to animal use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals.

2.3 Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, immunohistochemical staining, and immunofluorescence staining

After 12 h following the last administration, mice were anesthetized with 2% pentobarbital sodium solution and euthanized. The mouse heads were decalcified with 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and then, tissue samples were collected from three sites (the posterior part of the upper incisor, the incisor papilla, and the second palatal ridge). Tissues were soaked in 80% ethanol for 24 h, then dehydrated, cleared, and embedded in paraffin using a dehydration machine. The thickness of the sections was 5 μm.

HE staining: The paraffin sections were first dewaxed in xylene for 5 min, repeated three times. The sections were then sequentially immersed in anhydrous ethanol, 95% ethanol, and 75% ethanol for 5 min each. After rinsing with distilled water for 10 min, the sections were stained with hematoxylin for 5 min, with staining intensity observed under a microscope and ethanol differentiation time adjusted as needed. The sections were then stained with 0.5% eosin solution for 10–15 s, rinsed with distilled water, and observed under a microscope. Finally, the sections were dehydrated in 75, 95, and 100% ethanol, cleared in xylene, and sealed with neutral gum.

Immunohistochemical staining: The dewaxing and hydration steps were the same as for HE staining. For antigen retrieval, sections were heated at 95°C in antigen retrieval solution (Servicebio) for 15 min and then cooled to room temperature for 30 min. Sections were incubated with immunostaining blocking solution (Servicebio) at room temperature for 1 h. After removing the blocking solution, primary antibodies (anti-Ki67 primary antibody, 1:1,000, anti-Mast Cell Chymase Rabbit pAb, 1:1,000; Servicebio) were added and incubated overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) three times for 10 min each, followed by the addition of the appropriate secondary antibodies and incubation at 37°C for 1 h. After washing with PBS again, 3,3'-diaminobenzidine staining (Servicebio) was performed. Positive staining appeared brown under a microscope. Nuclear staining with hematoxylin followed along with gradient alcohol dehydration, xylene transparency, and neutral gum sealing.

Immunofluorescence staining: The steps of dewaxing, gradient ethanol hydration, and antigen retrieval were the same as for immunohistochemical staining. After blocking, primary antibodies (Servicebio) were added and incubated overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed with PBS three times for 10 min each, followed by the addition of immunofluorescence secondary antibodies and incubation at room temperature for 2 h. After washing with PBS again, the sections were sealed with a mounting medium containing DAPI, and the fluorescence staining was observed under a fluorescence microscope.

2.4 Cell culture and virus infection

P815 mast cells were obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The P815 cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium (Servicebio) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma). The medium was replaced every other day, and the cells were passaged and seeded into appropriate culture vessels according to their growth conditions. For Pirin interference and overexpression experiments, P815 cells were seeded in 6 cm culture dishes (Corning) and infected with the virus once cell density reached approximately 70%. Six micrograms per milliliter of polybrene and 1 × 106 PFU of virus were added to each well, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 3 days. Infection efficiency was observed using a fluorescence microscope, and interference and overexpression were confirmed by western blot. Compound 48/80 (10 μg/ml) (MedChemExpress) was used to activate P815 cells in vitro as a model group, and the concentration of Jaranol for in vitro treatment was 10 μg/ml.

2.5 Real-time PCR

RNA was first extracted from P815 cells seeded in 6 cm culture dishes. One milliliter of TRIzol was added to each dish, and the cells were collected and transferred into 1.5 ml eppendorf (EP) tubes. Two hundred microliters of chloroform was added, mixed, and left at 4°C for 10 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, and the upper aqueous phase was transferred to a new, RNase-free EP tube. Five hundred microliters of pre-cooled isopropanol was added, and the mixture was inverted and mixed. After standing at 4°C for 10 min, the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the RNA precipitate at the bottom of the tube was visible. After washing with 75% ethanol and air drying at room temperature, the RNA turned from white to a colorless, transparent state. Finally, 30 µl of diethyl pyrocarbonate water was added to dissolve the RNA, which was stored at −80°C. Quantitative PCR detection was performed using the 2 × Fast SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix kit (Servicebio) with a 20 μl reaction system. Following an initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, amplification was performed for 45 cycles at 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 45 s. The relative gene expression levels were calculated according to the formula 2−ΔΔCT and compared between groups.

The primer sequences were as follows:

IFN-r forward: 5′-TGAATGTCCAACGCAAAGCA-3′;

reverse: 5′-TCGACCTCGAAACAGCATCT-3′;

TNFa forward: 5′-TTGGAACTTGGAGGGCTAGG-3′;

reverse: 5′-CACTAAGGCCTGTGCTGTTC-3′;

IL-1β forward: 5′-GAAATGCCACCTTTTGACAGTG-3′;

reverse: 5′-TGGATGCTCTCATCAGGACAG-3′;

IL-6 forward: 5′-CTGCAAGAGACTTCCATCCAG-3′;

reverse: 5′-AGTGGTATAGACAGGTCTGTTGG-3′;

MCP-1 forward: 5′-TAAAAACCTGGATCGGAACCAAA-3′;

reverse: 5′-GCATTAGCTTCAGATTTACGGGT-3′;

CXCR10 forward: 5′-CCAAGTGCTGCCGTCATTTTC-3′;

reverse: 5′-TCCCTATGGCCCTCATTCTCA-3′;

GAPDH forward: 5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3′;

reverse: 5′-TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA-3′.

2.6 ELISA

The supernatant from the P815 cell culture was collected and centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 10 min to detect the expression levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. The assay was performed using the Abcam ELISA kit. In brief, standard samples were prepared and added to the ELISA detection plate. The test samples were diluted 2, 5, and 10 times and added to the plate, while sample dilution buffer was added to the blank wells, with 100 μl of diluted sample in each well. The plate was sealed, shaken at 100–300 rpm at room temperature for 2 h, and then washed five times by adding 300 μl of washing solution to each well, leaving it for 5 min. After removing the residual liquid, 100 μl of 1× antibody working solution was added to each well. Following a repeat wash, 100 μl of HRP-conjugated secondary antibody solution was added to each well and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, 90 μl of TMB substrate solution was added to each well, and the plate was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 10 min. Finally, 50 μl of stop solution was added to each well to terminate the reaction. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using an enzyme immunoassay instrument, and the results were compared between groups.

2.7 CCK-8 assay

The cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 10³ cells per well in a 96-well cell culture plate (Corning Inc.) with 200 μl of culture medium per well. A blank control well (without cells) was also included. After incubating in a cell culture incubator for 24 h, 20 μl of CCK-8 solution (Servicebio) was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for an additional 2 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using an enzyme immunoassay instrument, and OD values were compared between groups.

2.8 Transwell assay

The migration of P815 cells was measured using a 24-well Transwell chamber (Corning Inc.) with a 6.5 mm polycarbonate membrane (5 μm pore size). A fresh culture medium containing P815 cells (5 × 10⁴ cells/well) was added to the upper chamber, and the same culture medium was added to the lower chamber. After a 24-h incubation, the fetal bovine serum concentration in the lower chamber was adjusted to 20%, and incubation continued for an additional 24 h. Afterward, non-migratory cells on the membrane surface were removed with a cotton swab. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min, washed three times with PBS for 10 min each, and stained with crystal violet for 10 min. The number of migrated cells was observed under an optical microscope. Ten random fields were selected under a bright-field microscope to count the cells on the underside of the membrane, and the average cell count was taken for comparison between groups.

2.9 Western blot analysis and proteomics

Protein extraction buffer (containing protease inhibitors) was added to the 6 cm culture dish containing P815 cells, which were collected and kept at 4°C for 10 min. The cells were then sonicated on ice at 30 W for 2 min and left at room temperature for 15 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was transferred to a new centrifuge tube. This step was repeated with a second centrifugation under the same conditions, and the supernatant was collected. The protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein quantification kit (Servicebio), after which 5× loading buffer was added, and the mixture was heated at 100°C for 5 min to denature the proteins. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed using a 10% gel, with 30 μg of protein loaded per lane. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane, which was blocked at room temperature for 30 min. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: Pirin (goat anti-rabbit, 1:1,000, Servicebio), p-p65 (goat anti-rabbit, 1:1,000, CST), p65 (goat anti-rabbit, 1:1,000, CST), IκBα (goat anti-rabbit, 1:1,000, CST), and β-actin (goat anti-mouse, 1:2,000, CST). After three washes with TBS-tween (Servicebio) for 15 min each at room temperature, the membrane was incubated with the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 h. Following another set of three washes with TBS-Tween for 10 min each, ECL solution was added, and the PVDF membrane was placed in an automated chemiluminescence imaging system for image acquisition and analysis. The proteomics experiment was conducted by Shanghai Aiputekang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (China), and four tissue samples from each group were used for proteomic analysis.

2.10 Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as means ± standard deviation. A Student’s t-test was used to compare individual data with control values. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Jaranol inhibited nasal mucosal inflammation and reduced mast cell numbers in a mouse model of rhinitis

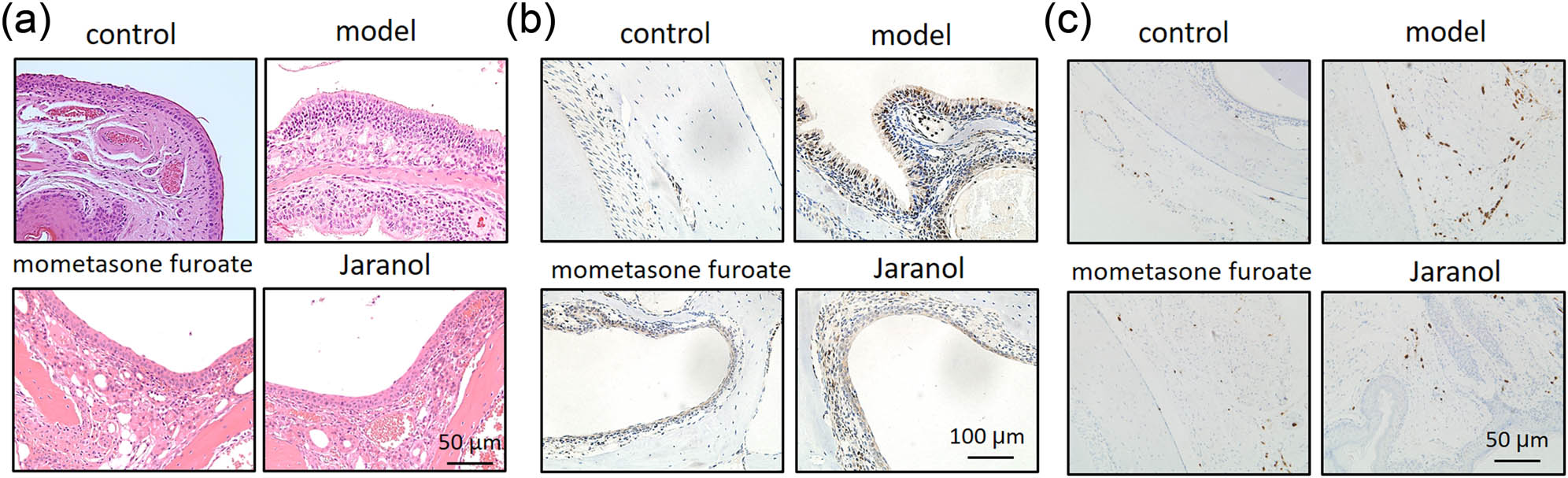

To determine whether Jaranol can alleviate the inflammatory response in rhinitis, we established a rhinitis model in BALB/c mice using OVA nasal drops. As shown in Figure 1, the control group had intact nasal mucosal tissue with columnar epithelium, while the model group (Figure 1, model) had significantly thicker nasal mucosal epithelium with numerous infiltrating inflammatory cells, goblet cell metaplasia, hypertrophy, and increased mucosal interstitial edema. Dexamethasone served as the positive control drug. After treatment with dexamethasone, nasal mucosal hyperplasia and inflammatory cell infiltration were reduced (Figure 1, dexamethasone). Treatment with Jaranol significantly reduced the thickness of the nasal mucosa and decreased inflammatory cell infiltration. The pathological morphology was similar to that of the dexamethasone group (Figure 1, Jaranol). These findings suggest that Jaranol inhibits nasal mucosal damage and inflammation in the mouse model of rhinitis.

Jaranol inhibits nasal mucosal inflammation in a mouse model of rhinitis. (a) HE staining shows successful preparation of a mouse model of rhinitis induced by OVA, and Jaranol and positive control dexamethasone significantly inhibit nasal mucosal damage and inflammation in the model mice. (b) Ki67 immunohistochemistry staining shows that Jaranol inhibits cell proliferation at the site of rhinitis in the model mice. (c) Recombinant Anti-Mast cell tryptase antibody immunohistochemistry staining shows that Jaranol reduces the number of mast cells at the site of nasal mucosal damage. Scale bar: 50 or 100 μm.

Next, we detected the expression of Ki67 (proliferating cell nuclear antigen) in the nasal mucosa of each group. As shown in Figure 1b, the model group showed significantly higher Ki67 expression compared to the control group. After treatment with dexamethasone and Jaranol, Ki67 expression was significantly decreased, indicating that Jaranol inhibits cell proliferation at the site of rhinitis in mice.

Mast cells are the main receptor cells involved in the pathogenesis of AR, triggering early symptoms by releasing substances such as histamine, vascular relaxing peptide, tryptase, and arachidonic acid derivatives. Therefore, we observed the positive staining of mast cells in nasal mucosal tissue. As shown in Figure 1c, mast cell numbers were low in the control group, while significantly increased in the model group. Treatment with mometasone furoate and Jaranol significantly reduced mast cell numbers compared to the model group, indicating that Jaranol can decrease mast cell numbers in the nasal mucosa of mice with AR.

3.2 Jaranol inhibited inflammatory cytokine secretion from mast cells

Based on the above results, we further investigated whether Jaranol could alleviate rhinitis symptoms in mice by inhibiting mast cell infiltration and the secretion of inflammatory cytokine secretion. Therefore, we used the P815 mouse mast cell line in vitro to observe whether Jaranol could reduce inflammatory cytokine secretion from P815 cells. As shown in Figure 2a, real-time PCR results showed that compared to the control group, mRNA levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, and CXCR10 were significantly increased in the model group, while treatment with Jaranol significantly decreased the expression of these inflammatory cytokines. ELISA results further confirmed that Jaranol inhibits the secretion of inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1β from mast cells (Figure 2b).

Jaranol inhibits inflammatory cytokine secretion from mast cells. (a) Real-time PCR shows that Jaranol inhibits the mRNA expression of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, and CXCR10 in mast cells. (b) ELISA shows that Jaranol inhibits the secretion of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 from mast cells. Mod: model; jara: Jaranol. **p < 0.01.

3.3 Jaranol inhibited mast cell proliferation and migration

We used the CCK-8 assay to detect mast cell proliferation and found that Jaranol did not affect normal mast cell proliferation but significantly inhibited proliferation in the model group. The results of Ki67 immunofluorescence staining were consistent with those of the CCK-8 assay. In this experiment, the Ki67-positive signals appeared in red, showing significantly increased Ki67 expression in the model group, while Jaranol significantly downregulated Ki67 expression, thus inhibiting mast cell proliferation (Figure 3a). In rhinitis, mast cells in the lamina propria can migrate toward the mucosal surface due to repeated allergen exposure. We observed the effect of Jaranol on mast cell migration using a transwell assay and found that the migration ability of mast cells in the model group was significantly enhanced compared to the control group, while Jaranol inhibited this phenomenon (Figure 3b).

Jaranol inhibits mast cell proliferation and migration. (a) CCK-8 and Ki67 immunofluorescence staining shows that Jaranol inhibits mast cell proliferation; (b) transwell experiment shows that Jaranol inhibits mast cell migration. Mod: model; jara: aranol. Scale bar: 50 or 100 μm. **p < 0.01.

3.4 Proteomic sequencing screened differential expression and functional genes in mouse nasal mucosal tissue

We conducted proteomic sequencing on mouse nasal mucosal tissue and identified 102 differentially expressed proteins in the model group compared to the control group. Additionally, there were 54 differentially expressed proteins between Jaranol and model groups, and 26 common differentially expressed proteins among the three groups, including 15 upregulated and 11 downregulated proteins. From these 26 proteins, we selected Pirin, which may be involved in regulating mast cell function, to further investigate its role in mast cell function and rhinitis pathogenesis. Figure 4a shows a heatmap of the common proteins expressed across the three groups, with red indicating upregulation and blue indicating downregulation. Figure 4b shows a line graph of the expression trends of each group’s proteins. It also shows the gene ontology (GO) analysis chart, indicating the molecular function, biological process, and cellular component of differentially expressed proteins. Figure 4b shows the Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) analysis chart, showing various functions of differentially expressed proteins.

Differential expression and functional genes screened by proteomic sequencing of mouse nasal mucosal tissue in each group. (a) Heatmap of differentially expressed proteins among the three groups; (b) GO analysis chart of differentially expressed proteins; (c) KEGG analysis chart of differentially expressed proteins.

3.5 Jaranol inhibited inflammatory cytokine secretion from mast cells by mediating Pirin

As shown in Figure 5a, the model group exhibited increased mRNA expression levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, and CXCR10 compared to the control group. However, after Jaranol treatment, these expression levels significantly decreased. When Pirin was silenced in mast cells, mRNA levels of these inflammatory cytokines were also significantly reduced. In contrast, when Jaranol was added to mast cells overexpressing Pirin, cytokine mRNA expression increased compared to the Jaranol-treated group, suggesting that Jaranol inhibited the Pirin-promoted expression of inflammatory cytokines at the mRNA level (Figure 5a). Similarly, Figure 5b shows ELISA results of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, indicating that the secretion of these inflammatory cytokines increased in the model group. Both Jaranol treatment and Pirin silencing inhibited the secretion of these cytokines in mast cells. However, in mast cells with overexpressed Pirin treated with Jaranol, Jaranol still inhibited the secretion of inflammatory cytokines promoted by Pirin. These results suggest that Jaranol may regulate mast cell function by regulating the Pirin expression.

Jaranol inhibits inflammatory cytokine secretion from mast cells by acting on Pirin. (a) Real-time PCR shows that both Jaranol and interference with Pirin can inhibit the mRNA expression of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, and CXCR10 in mast cells, and the inhibitory effect of Jaranol on cytokine secretion is weakened in mast cells overexpressing Pirin. (b) ELISA shows that both Jaranol and interference with Pirin can inhibit the secretion of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 from mast cells, and the inhibitory effect of Jaranol on cytokine secretion is weakened in mast cells overexpressing Pirin. Pir: Pirin; RNAi: interference; OE: overexpression. **p < 0.01.

3.6 Jaranol inhibited mast cell proliferation and migration through Pirin

We further investigated the effect of Jaranol and Pirin on mast cell function. As shown in Figure 6a, the results of the CCK-8 assay demonstrated that both interference with Pirin and the addition of Jaranol could inhibit mast cell proliferation. However, overexpression of Pirin reduced the inhibitory effect of Jaranol on mast cell proliferation. The Ki67 immunofluorescence assay also confirmed this observation, where the number of Ki67-positive cells remained low in both the Pirin interference and Jaranol groups. In contrast, in mast cells overexpressing Pirin and treated with Jaranol, the number of Ki67-positive cells significantly increased, indicating that Pirin promoted mast cell proliferation, and Jaranol partially inhibited Pirin-induced mast cell proliferation. Figure 6b shows that the migration ability of mast cells in the Pirin interference and Jaranol groups was lower, while overexpression of Pirin in mast cells treated with Jaranol significantly increased their migration ability. This suggests that Pirin promoted mast cell migration and that Jaranol partially inhibited Pirin-induced mast cell migration (p < 0.05).

Jaranol inhibits mast cell proliferation and migration through Pirin. (a) CCK-8 and Ki67 immunofluorescence staining show that both Jaranol and interference with Pirin can inhibit mast cell proliferation, and the inhibitory effect of Jaranol on cell proliferation is weakened in mast cells overexpressing Pirin. (b) Transwell experiment shows that both Janroal and interference with Pirin can inhibit mast cell migration, and the inhibitory effect is weakened in mast cells overexpressing Pirin. Pir: Pirin; RNAi: interference; OE: overexpression. Scale bar: 100 μm. **p < 0.01.

3.7 Jaranol inhibited mast cell function by suppressing Pirin expression

Based on the above results, Jaranol regulates the effect of Pirin on mast cell function. Therefore, we further investigated whether Jaranol affects mast cell function by regulating Pirin expression. The western blot (WB) results showed that Pirin expression was increased in the model group while adding Jaranol downregulated Pirin expression (Figure 7a). Both interference with Pirin and the addition of Jaranol inhibited p65 phosphorylation and promoted IκBα expression in mast cells. However, when mast cells overexpressing Pirin were treated with Jaranol, the inhibitory effect on p65 phosphorylation was weakened and IκBα expression was reduced, indicating that Jaranol’s inhibition of p65 phosphorylation was mediated by Pirin, thereby promoting mast cell-mediated inflammatory responses (Figure 7b).

Jaranol inhibits mast cell function by suppressing Pirin expression. (a) WB shows that Jaranol inhibits Pirin expression. (b) WB results show that in mast cells overexpressing Pirin, adding Jaranol weakens the inhibitory effect on p65 phosphorylation and reduces IκBα expression, indicating that Jaranol promotes p65 phosphorylation through Pirin, thereby promoting mast cell-mediated inflammatory responses. RNAi: interference; OE: overexpression. **p < 0.01.

4 Discussion

AR has been treated with Chinese herbal medicine for centuries and has been found to alleviate AR symptoms through immune modulation and anti-allergic or anti-inflammatory effects. Various clinical studies, including those on herbal treatments such as Yu-ping-feng San, Cure-allergic-rhinitis syrup, fermented red ginseng, and Biminne capsules, have been conducted to evaluate their efficacy [26]. In addition to oral administration, Chinese herbal medicine can be used to treat AR through nasal administration, and it can reduce the side effects of orally administered Chinese herbal medicine and improve safety.

We first established a mouse model of AR and performed HE staining on nasal respiratory tissues. The normal nasal respiratory epithelium includes a pseudostratified mucosal layer and submucosal tissue with blood vessels and glands. In the model group, HE staining showed that the mucosal tissue was significantly thickened with abundant inflammatory infiltration. After treatment with dexamethasone or Jaranol, the mice showed reduced nose-scratching symptoms, and HE staining showed a decrease in mucosal layer thickness and a significant decrease in inflammatory cell infiltration. Since mast cells are the main receptors in AR, mast cell staining showed that Jaranol reduced mast cell numbers in the nasal mucosa. Additionally, Ki67 staining of nasal mucosa suggested that Jaranol inhibited cell proliferation. These results suggest that Jaranol is effective in treating AR in mice. The early stage of AR is marked by the release of inflammatory factors by mast cells. Therefore, we conducted in vitro experiments using P815 mast cells. Real-time PCR and ELISA results showed that Jaranol inhibited the secretion of inflammatory factors (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, and CXCR10) in mast cells. Jaranol also inhibited mast cell proliferation and migration. In summary, this study confirmed in vivo and in vitro that Jaranol can treat AR. Research on Jaranol remains limited, and our study has enriched the potential indications of Jaranol.

Next, we explored the mechanism of Jaranol in treating AR. Using proteomic sequencing, we screened for differentially expressed and functional genes in the control, model, and Jaranol groups. Pirin, a nuclear protein with a significant role in inflammation and mast cell activation, showed notable differences in expression among the three groups. This suggests that Pirin could be a key target for Jaranol in treating AR. Further cell and animal experiments confirmed that Jaranol inhibits mast cell inflammatory factor secretion, proliferation, and migration, as well as mast cell function by targeting Pirin.

There is limited study on nasal administration of Chinese herbal medicine, and there is a lack of in-depth studies on individual herbs and compounds suitable for nasal delivery in traditional Chinese medicine formulations. The limitations of nasal delivery for Chinese herbal medicine include: (1) Many herbs used in nasal delivery have strong smells and can be irritating, which may cause nasal allergies or damage. (2) Nasal treatments often focus on symptom relief, leading to frequent recurrence of the illness. (3) Traditional nasal formulations are often made by grinding raw herbs or boiling them, resulting in low drug utilization. (4) In clinical studies, absorption enhancers in formulations can be toxic, strongly irritate the nasal mucosa, and affect ciliary function, leading to adverse reactions. (5) New formulations lack mature preparation methods, leading to unstable product quality and challenges in scaling up for industrial production, which limits the development of nasal delivery for Chinese medicine. The above reasons make it difficult to find suitable drugs for nasal administration. In our study, Jaranol is insoluble in water and can only be formulated as a nasal oil (which has a moisturizing effect), so side effects like nosebleeds and nasal dryness are not a major concern, additionally, Jaranol has a mild odor, is less irritating to the nasal cavity, and has good safety. However, the high viscosity of the oil formulation makes it less convenient for absorption and may affect mucosal absorption. Further optimization of the formulation process is needed to reduce these issues and improve patient use.

Moreover, this study did not explore the safety of Jaranol. An acute toxicity study showed that a single oral dose of Jaranol did not cause any lethal or general behavioral changes in mice. In terms of subacute toxicity, oral administration of 200 mg/kg BW/day of Jaranol significantly affected red blood cells and liver and kidney function in rats [27]. Liver and kidney function damage is a common side effect of Chinese herbal medicine, so to avoid this, our study recommends using Jaranol as nasal drops. Common side effects of clinical nasal drops are nosebleeds, nasal dryness, and long-term use leading to drug resistance. Our study did not find nosebleeds and nasal dryness in the AR mouse model. However, further investigation is needed to determine whether long-term use of Jaranol leads to drug resistance.

5 Conclusion

Jaranol can reduce inflammation and histopathological changes associated with AR, by inhibiting Pirin expression in mast cells, Jaranol presents a promising natural nasal drop for treating AR. However, Jaranol nasal drops are currently in an oil formulation.

In future studies, we will further improve the preparation process to enhance the comfort of clinical use.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the reviewer’s valuable comments that improved the manuscript.

-

Funding information: This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation Youth Fund (No. 82004119).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. (I) Conception and design: Yunfei Zhang and Zhengmin Xu; (II) experiment conduction: Yue Huang and Shuhua Su; (III) data analysis: Yue Huang, Bo Duan, and Shuhua Su; and (IV) manuscript writing: All authors.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors have no conflicts of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Narasimhan G, Deshmukh PT, Gaurkar SS, Khan FQ. A comprehensive review exploring allergic rhinitis with nasal polyps: Mechanisms, management, and emerging therapies. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e59191.10.7759/cureus.59191Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Nur Husna SM, Tan HT, Md Shukri N, Mohd Ashari NS, Wong KK. Allergic rhinitis: A clinical and pathophysiological overview. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:874114.10.3389/fmed.2022.874114Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Li Q, Zhang X, Feng Q, Zhou H, Ma C, Lin C, et al. Common allergens and immune responses associated with allergic rhinitis in China. J Asthma Allergy. 2023;16:851–61.10.2147/JAA.S420328Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Vitte J, Vibhushan S, Bratti M, Montero-Hernandez JE, Blank U. Allergy, anaphylaxis, and nonallergic hypersensitivity: IgE, mast Cells, and beyond. Med Princ Pract. 2022;31(6):501–15.10.1159/000527481Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Zoabi Y, Levi-Schaffer F, Eliashar R. Allergic rhinitis: Pathophysiology and treatment focusing on mast cells. Biomedicines. 2022;10(10):2486.10.3390/biomedicines10102486Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Gelardi M, Giancaspro R, Cassano M, Ribatti D. The underestimated role of mast cells in the pathogenesis of rhinopathies. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2022;183(2):153–9.10.1159/000518924Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Borriello F, Iannone R, Marone G. Histamine release from mast cells and basophils. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;241:121–39.10.1007/164_2017_18Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Baran J, Sobiepanek A, Mazurkiewicz-Pisarek A, Rogalska M, Gryciuk A, Kuryk L, et al. Mast cells as a target-A comprehensive review of recent therapeutic approaches. Cells. 2023;12(8):1187.10.3390/cells12081187Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Theoharides TC. The role of mast cells and their inflammatory mediators in immunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(15):12130.10.3390/ijms241512130Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Hellman L, Akula S, Fu Z, Wernersson S. Mast cell and basophil granule proteases - in vivo targets and function. Front Immunol. 2022;13:918305.10.3389/fimmu.2022.918305Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Caughey GH. Update on mast cell proteases as drug targets. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2023;43(4):777–87.10.1016/j.iac.2023.04.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Liu B, Huang X, Xia L, Wang D, Mu D, Tian L. Effects of Yupingfeng nasal drops on serum cytokines, histopathology and eosinophil cationic protein in nasal mucosa of rats with allergic rhinitis. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2021;34(4):1351–8.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Yip KM, Lee KM, Ng TB, Xu S, Yung KK, Qu S, et al. An anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic proprietary Chinese medicine nasal spray designated as Allergic Rhinitis Nose Drops (ARND) with potential to prevent SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus infection by targeting RBD (Delta)- angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) binding. Chin Med. 2022;17(1):88.10.1186/s13020-022-00635-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Fan W, You B, Wang X, Zheng X, Xu A, Liu Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of lentinan nasal drops in patients infected with the variant of COVID-19: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1292479.10.3389/fphar.2023.1292479Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Qian Q, Liu HX, Li YQ. Effect of esketamine nasal drops on pain in children after tonsillectomy using low temperature plasma ablation. Front Pediatr. 2023;11:1110632.10.3389/fped.2023.1110632Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Ahsan T, Shoily SS, Ahmed T, Sajib AA. Role of the redox state of the Pirin-bound cofactor on interaction with the master regulators of inflammation and other pathways. PLoS One. 2023;18(11):e0289158.10.1371/journal.pone.0289158Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Perez-Dominguez F, Carrillo-Beltrán D, Blanco R, Muñoz JP, León-Cruz G, Corvalan AH, et al. Role of pirin, an oxidative stress sensor protein, in epithelial carcinogenesis. Biol (Basel). 2021;10(2):116.10.3390/biology10020116Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Chen CY. TCM Database@Taiwan: the world’s largest traditional Chinese medicine database for drug screening in silico. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e15939.10.1371/journal.pone.0015939Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Xue R, Fang Z, Zhang M, Yi Z, Wen C, Shi T. TCMID: Traditional Chinese medicine integrative database for herb molecular mechanism analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D1089–95.10.1093/nar/gks1100Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Leal CM, Leitão SG, Sausset R, Mendonça SC, Nascimento PHA, de Araujo R. Cheohen CF, et al. Flavonoids from siparuna cristata as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 replication. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2021;31(5):658–66.10.1007/s43450-021-00162-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Woo JH, Ahn JH, Jang DS, Lee KT, Choi JH. Effect of kumatakenin isolated from cloves on the apoptosis of cancer cells and the alternative activation of tumor-associated macrophages. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65(36):7893–9.10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01543Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Dao TBN, Nguyen TMT, Nguyen VQ, Tran TMD, Tran NMA, Nguyen CH, et al. Flavones from combretum quadrangulare growing in vietnam and their alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity. Molecules. 2021;26(9):2531.10.3390/molecules26092531Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Zhang X, Wang L, Mu H, Wang D, Yu Y. Synergistic antibacterial effects of buddleja albiflora metabolites with antibiotics against Listeria monocytogenes. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2019;68(1):38–47.10.1111/lam.13084Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Quek A, Mohd Zaini H, Kassim NK, Sulaiman F, Rukayadi Y, Ismail A, et al. Oxygen radical antioxidant capacity (ORAC) and antibacterial properties of Melicope glabra bark extracts and isolated compounds. PLoS One. 2021;16(5):e0251534.10.1371/journal.pone.0251534Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] ArenbaoligaoGuo X, Guo X, Xiong J, Zhang S, Yang Y, Chen D, Xie Y. Kumatakenin inhibited iron-ferroptosis in epithelial cells from colitis mice by regulating the Eno3-IRP1-axis. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1127931.10.3389/fphar.2023.1127931Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Zhang X, Lan F, Zhang Y, Zhang L. Chinese herbal medicine to treat allergic rhinitis: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2018;10(1):34–42.10.4168/aair.2018.10.1.34Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Liu T, Zhang Y, Liu J, Peng J, Jia X, Xiao Y, et al. Evaluation of the acute and sub-acute oral toxicity of Jaranol in kunming mice. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:903232.10.3389/fphar.2022.903232Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome with elevated IgG4 and T-cell clonality: A report of two cases

- Electroacupuncture alleviates sciatic nerve injury in sciatica rats by regulating BDNF and NGF levels, myelin sheath degradation, and autophagy

- Polydatin prevents cholesterol gallstone formation by regulating cholesterol metabolism via PPAR-γ signaling

- RNF144A and RNF144B: Important molecules for health

- Analysis of the detection rate and related factors of thyroid nodules in the healthy population

- Artesunate inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion through OGA-mediated O-GlcNAcylation of ZEB1

- Endovascular management of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: Case report and review of the literature

- Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis

- SATB2 promotes humeral fracture healing in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Overexpression of the ferroptosis-related gene, NFS1, corresponds to gastric cancer growth and tumor immune infiltration

- Understanding risk factors and prognosis in diabetic foot ulcers

- Atractylenolide I alleviates the experimental allergic response in mice by suppressing TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 signalling

- FBXO31 inhibits the stemness characteristics of CD147 (+) melanoma stem cells

- Immune molecule diagnostics in colorectal cancer: CCL2 and CXCL11

- Inhibiting CXCR6 promotes senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells with limited proinflammatory SASP to attenuate hepatic fibrosis

- Cadmium toxicity, health risk and its remediation using low-cost biochar adsorbents

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis with headache as the first presentation: A case report

- Solitary pulmonary metastasis with cystic airspaces in colon cancer: A rare case report

- RUNX1 promotes denervation-induced muscle atrophy by activating the JUNB/NF-κB pathway and driving M1 macrophage polarization

- Morphometric analysis and immunobiological investigation of Indigofera oblongifolia on the infected lung with Plasmodium chabaudi

- The NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex and Hr78 modulate the Lobe2 mutant eye phenotype

- Experimental study on salmon demineralized bone matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: In vitro and in vivo study

- A case of IgA nephropathy treated with a combination of telitacicept and half-dose glucocorticoids

- Analgesic and toxicological evaluation of cannabidiol-rich Moroccan Cannabis sativa L. (Khardala variety) extract: Evidence from an in vivo and in silico study

- Wound healing and signaling pathways

- Combination of immunotherapy and whole-brain radiotherapy on prognosis of patients with multiple brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study

- To explore the relationship between endometrial hyperemia and polycystic ovary syndrome

- Research progress on the impact of curcumin on immune responses in breast cancer

- Biogenic Cu/Ni nanotherapeutics from Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl seeds for the treatment of lung cancer

- Dapagliflozin attenuates atrial fibrosis via the HMGB1/RAGE pathway in atrial fibrillation rats

- Glycitein alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in keratinocytes via ROS-associated PI3K–Akt signalling pathway

- ADH5 inhibits proliferation but promotes EMT in non-small cell lung cancer cell through activating Smad2/Smad3

- Apoptotic efficacies of AgNPs formulated by Syzygium aromaticum leaf extract on 32D-FLT3-ITD human leukemia cell line with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Novel cuproptosis-related genes C1QBP and PFKP identified as prognostic and therapeutic targets in lung adenocarcinoma

- Bee venom promotes exosome secretion and alters miRNA cargo in T cells

- Treatment of pure red cell aplasia in a chronic kidney disease patient with roxadustat: A case report

- Comparative bioinformatics analysis of the Wnt pathway in breast cancer: Selection of novel biomarker panels associated with ER status

- Kynurenine facilitates renal cell carcinoma progression by suppressing M2 macrophage pyroptosis through inhibition of CASP1 cleavage

- RFX5 promotes the growth, motility, and inhibits apoptosis of gastric adenocarcinoma cells through the SIRT1/AMPK axis

- ALKBH5 exacerbates early cardiac damage after radiotherapy for breast cancer via m6A demethylation of TLR4

- Phytochemicals of Roman chamomile: Antioxidant, anti-aging, and whitening activities of distillation residues

- Circadian gene Cry1 inhibits the tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma by the BAX/BCL2-mediated apoptosis pathway

- The TNFR-RIPK1/RIPK3 signalling pathway mediates the effect of lanthanum on necroptosis of nerve cells

- Longitudinal monitoring of autoantibody dynamics in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing surgery

- The potential role of rutin, a flavonoid, in the management of cancer through modulation of cell signaling pathways

- Construction of pectinase gene engineering microbe and its application in tobacco sheets

- Construction of a microbial abundance prognostic scoring model based on intratumoral microbial data for predicting the prognosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Sepsis complicated by haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis triggered by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and human herpesvirus 8 in an immunocompromised elderly patient: A case report

- Sarcopenia in liver transplantation: A comprehensive bibliometric study of current research trends and future directions

- Advances in cancer immunotherapy and future directions in personalized medicine

- Can coronavirus disease 2019 affect male fertility or cause spontaneous abortion? A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis

- Heat stroke associated with novel leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor gene variant in a Chinese infant

- PSME2 exacerbates ulcerative colitis by disrupting intestinal barrier function and promoting autophagy-dependent inflammation

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state with severe hypernatremia coexisting with central diabetes insipidus: A case report and literature review

- Efficacy and mechanism of escin in improving the tissue microenvironment of blood vessel walls via anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects: Implications for clinical practice

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Clinicopathological analysis of three patients and literature review

- Genetic variants in VWF exon 26 and their implications for type 1 Von Willebrand disease in a Saudi Arabian population

- Lipoxin A4 improves myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through the Notch1-Nrf2 signaling pathway

- High levels of EPHB2 expression predict a poor prognosis and promote tumor progression in endometrial cancer

- Knockdown of SHP-2 delays renal tubular epithelial cell injury in diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis

- Exploring the toxicity mechanisms and detoxification methods of Rhizoma Paridis

- Concomitant gastric carcinoma and primary hepatic angiosarcoma in a patient: A case report

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Optimization and comparative study of Bacillus consortia for cellulolytic potential and cellulase enzyme activity

- The complete mitochondrial genome analysis of Haemaphysalis hystricis Supino, 1897 (Ixodida: Ixodidae) and its phylogenetic implications

- Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors analysis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among tuberculosis population in Huzhou City, Eastern China

- Indices of human impacts on landscapes: How do they reflect the proportions of natural habitats?

- Genetic analysis of the Siberian flying squirrel population in the northern Changbai Mountains, Northeast China: Insights into population status and conservation

- Diversity and environmental drivers of Suillus communities in Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica forests of Inner Mongolia

- Global assessment of the fate of nitrogen deposition in forest ecosystems: Insights from 15N tracer studies

- Fungal and bacterial pathogenic co-infections mainly lead to the assembly of microbial community in tobacco stems

- Influencing of coal industry related airborne particulate matter on ocular surface tear film injury and inflammatory factor expression in Sprague-Dawley rats

- Temperature-dependent development, predation, and life table of Sphaerophoria macrogaster (Thomson) (Diptera: Syrphidae) feeding on Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae)

- Eleonora’s falcon trophic interactions with insects within its breeding range: A systematic review

- Agriculture

- Integrated analysis of transcriptome, sRNAome, and degradome involved in the drought-response of maize Zhengdan958

- Variation in flower frost tolerance among seven apple cultivars and transcriptome response patterns in two contrastingly frost-tolerant selected cultivars

- Heritability of durable resistance to stripe rust in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Molecular mechanism of follicular development in laying hens based on the regulation of water metabolism

- Animal Science

- Effect of sex ratio on the life history traits of an important invasive species, Spodoptera frugiperda

- Plant Sciences

- Hairpin in a haystack: In silico identification and characterization of plant-conserved microRNA in Rafflesiaceae

- Widely targeted metabolomics of different tissues in Rubus corchorifolius

- The complete chloroplast genome of Gerbera piloselloides (L.) Cass., 1820 (Carduoideae, Asteraceae) and its phylogenetic analysis

- Field trial to correlate mineral solubilization activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and biochemical content of groundnut plants

- Correlation analysis between semen routine parameters and sperm DNA fragmentation index in patients with semen non-liquefaction: A retrospective study

- Plasticity of the anatomical traits of Rhododendron L. (Ericaceae) leaves and its implications in adaptation to the plateau environment

- Effects of Piriformospora indica and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on growth and physiology of Moringa oleifera under low-temperature stress

- Effects of different sources of potassium fertiliser on yield, fruit quality and nutrient absorption in “Harward” kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa)

- Comparative efficiency and residue levels of spraying programs against powdery mildew in grape varieties

- The DREB7 transcription factor enhances salt tolerance in soybean plants under salt stress

- Using plant electrical signals of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) for water pollution monitoring

- Food Science

- Phytochemical analysis of Stachys iva: Discovering the optimal extract conditions and its bioactive compounds

- Review on role of honey in disease prevention and treatment through modulation of biological activities

- Computational analysis of polymorphic residues in maltose and maltotriose transporters of a wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain

- Optimization of phenolic compound extraction from Tunisian squash by-products: A sustainable approach for antioxidant and antibacterial applications

- Liupao tea aqueous extract alleviates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in rats by modulating the gut microbiota

- Toxicological qualities and detoxification trends of fruit by-products for valorization: A review

- Polyphenolic spectrum of cornelian cherry fruits and their health-promoting effect

- Optimizing the encapsulation of the refined extract of squash peels for functional food applications: A sustainable approach to reduce food waste

- Advancements in curcuminoid formulations: An update on bioavailability enhancement strategies curcuminoid bioavailability and formulations

- Impact of saline sprouting on antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds in chia seeds

- The dilemma of food genetics and improvement

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Impact of hyaluronic acid-modified hafnium metalorganic frameworks containing rhynchophylline on Alzheimer’s disease

- Emerging patterns in nanoparticle-based therapeutic approaches for rheumatoid arthritis: A comprehensive bibliometric and visual analysis spanning two decades

- Application of CRISPR/Cas gene editing for infectious disease control in poultry

- Preparation of hafnium nitride-coated titanium implants by magnetron sputtering technology and evaluation of their antibacterial properties and biocompatibility

- Preparation and characterization of lemongrass oil nanoemulsion: Antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant, and anticancer activities

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells”

- Corrigendum to “Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans”

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Down-regulation of miR-539 indicates poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer”

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells