15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

-

Rong Huang

and Chunyang Zhou

Abstract

15-Lipoxygenase-2 (15-Lox-2) is one of the key enzymes in arachidonic acid (AA) metabolic pathway, which belongs to the unsaturated fatty acid metabolic pathway. This pathway is involved in the foam cell transformation of macrophages during the progression of atherosclerosis (AS). The role of salidroside (SAL) in cardiovascular diseases has been extensively studied, but its impact on macrophage foam cell formation has not yet been clearly clarified. We aimed to determine the effects of 15-Lox-2 deficiency on macrophage (Ana-1 cell) foam cell formation, and those of SAL on 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages. 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages were generated using short hairpin RNA. Results indicated that 15-Lox-2 expression in the aorta of atherosclerotic patients is lower than that of the normal group. Additionally, 15-Lox-2 deficiency dramatically promoted macrophage uptake of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) and increased the Cyclin D1 level while dramatically decreasing caspase3 expression. Furthermore, inflammation, complement, and TNF-α signaling pathways, along with IL1α, IL1β, IL18, and Cx3cl1, were activated in 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages. These changes were alleviated by SAL through inhibiting AA effects, and the effects of AA on macrophages could be inhibited by SAL. Consistently, phospholipase A2-inhibitor arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone (AACOCF3) restored these changes. In summary, SAL reversed the effects of 15-Lox-2 deficiency on macrophages by inhibiting excessive AA and may be a promising therapeutic potential in treating atherosclerosis resulting from 15-Lox-2 deficiency.

1 Introduction

Atherosclerosis (AS), as one of the leading causes of cardiovascular disease, is an inflammatory and dyslipidemic disease [1,2]. Under normal physiological conditions, the body maintains a lipid metabolism homeostasis, many factors can disrupt this homeostasis, causing related diseases such as AS and hyperlipidemia [3]. Monocyte-derived macrophages excessively take up oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) to form foam cells and induce inflammation, which plays an essential role in atherogenesis [4,5]. Emerging studies carried out in cell or animal models of AS and patients with AS have demonstrated that excess polyunsaturated fatty acid could promote the onset and development of AS and increase the risk of cardiovascular disease [6]. Arachidonic acid (AA), a lipid mediator, is one of the most abundant and widely distributed polyunsaturated fatty acids in mammals [7]. AA produces various products through three enzymatic pathways, P-450 epoxygenase, cyclooxygenases, and lipoxygenases (LOXs). LOXs are involved in the biosynthesis of many lipid mediators [8]. Among the LOX family, 15-lipoxygenase-2 (15-Lox-2) shows the highest homology to murine 15-Lox-2 (also named Alox8) and lower identity to human 5-LOX or 15-LOX-1 [9,10]. 15-LOX-2 specifically catalyzes the oxygenation of the 15th carbon (C15) of AA, producing 15(S)-hydroperoxy-eicosatetraenoic acid (15(S)-HpETE). 15(S)-HpETE can be reduced by glutathione peroxidase to form 15(S)-hydroxy-eicosatetraenoic acid (15(S)-HETE), which has more stable biological activity. [11,12]. 15-LOX-2 shows a tissue expression pattern that includes the lymph node, skin, lung, and prostate, and its disorders might contribute to dysfunction in these organs [13,14]. We have shown that 15-Lox-2 deficiency in preB cells might promote lymphomagenesis [15]. 15-Lox-2 acts as a suppressor gene in tumorigenesis [14,16]. Intriguingly, 15-Lox-2 is constitutively active in human monocyte-derived macrophages and participates in the atherosclerotic process [13,17,18]. Salidroside (SAL) is an active component extracted from plants of the genus Rhodiola, which is used in traditional Chinese medicine [19]. SAL has extensive pharmacological activities, such as antioxidant, anti-cancer, and anti-cardiovascular effects, mediated by repressing inflammation and oxidative stress [20–24]. However, the link between 15-Lox-2 and SAL in the progress of macrophage foam cell formation was poorly understood. Here, we aimed to investigate the mechanism of SAL on the improvement of 15-Lox-2 deficiency-induced macrophage foam cell formation.

2 Methods

2.1 Cell lines and tissue samples

The Ana-1 cell line and HEK 293T cells were purchased from Boster Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (China) and maintained in RPMI-1640 and Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, respectively. Cells were incubated in an incubator of 5% CO2 at 37°C. Seventeen patients (10 males and 7 females) with AS were recruited and underwent plaque resection at Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College. Patients did not receive any preoperative medications and treatments.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to human use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies and in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration and has been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College (IRB: 2024ER23-1).

2.2 Generating 15-Lox-2-knockdown macrophages

To create 15-Lox-2 short hairpin RNA (shRNA), the appropriate 15-Lox-2 primers were cloned into the pMSCV-mir30-SV40-GFP retroviral construct. To avoid errors caused by the off-target effects of a single shRNA, we designed two independent shRNAs targeting 15-Lox-2 (sh15-Lox-2.1252 and sh15-Lox-2.2865) to observe the consistency of the phenotypes. Virus packaging and infection were performed as reported previously [25]. Cells stably expressing 15-Lox-2 shRNA were selected using G418.

2.3 Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and immunohistochemistry staining

HE staining was performed as described previously [26]. Immunohistochemistry was used to assay 15-Lox-2 expression in tissues. After being boiled for 2 min to restore the antigen and blocked by 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), the samples were incubated with the primary antibody (15-Lox-2) overnight at 4°C and further incubated with HRP-goat-anti-rabbit IgG for 1 h at 25°C.

2.4 Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS)

A total of 5 × 106 cells were extracted with chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) and washed with 0.9% saline. The lipid-containing chloroform phase was obtained and dried. We then added 100 μL of methanol containing the deuterium-labeled internal standard AA-d8 and 5-HETE-d8 (Cayman Chemical, USA). LC–MS analyses were conducted on the Agilent LC–MS system (USA). Chromatographic separation was achieved on an Agilent ZORBAX RRHD Eclipse XDB C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.8 µm particles) using a flow rate of 0.65 mL/min at 45°C during a 13 min gradient (0–12 min from 68% A to 20% A, 12–13 min 5% A) while using the solvents A, water containing 0.005% formic acid, and B, acetonitrile containing 0.005% formic acid. Electrospray ionization was performed in the negative ion mode using N2 at a pressure of 30 psi for the nebulizer with a flow of 10 L/min and a temperature of 300°C, respectively. Peak determination and peak area integration were performed with the MassHunter WorkStation software (Agilent, Version B.08.00).

2.5 Oil Red O and DiI staining

Cells were stained with Oil Red O (cat: # O8010, Solarbio, China) and the fluorescent probe DiI (cat: # C1036, Beyotime, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, respectively. Furthermore, the value of optical density (OD) was determined for DiI and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), respectively.

2.6 RNA-seq

Total RNA was sequenced using BGISEQ500, and the results were analyzed using 50-bp single-end reads. The reads were aligned to the reference genome (GRCm38) using STAR_2.6.0. Transcript abundance was normalized and measured in reads/fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads. DESeq2 was used to analyze differential gene expression. Genes with absolute fold-changes in expression levels greater than 1 and a false discovery rate of ≤0.05 were considered differentially expressed. The characteristic differences between samples were assessed using principal component analysis (PCA). Based on the designated clusters, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed to statistically analyze similarities and differences between the two types of samples.

2.7 Proliferation assay

The cells were assayed for proliferation using a Cell-Light™ Edu Apollo643 In Vitro Kit (cat: # C10310-2, Ribobio, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and further detected using flow cytometry (Agilent, USA), and data were analyzed using FlowJo v10.

2.8 Apoptosis assay

Cell proliferation was assessed using an Annexin V PE Apoptosis Dtec Kit (cat: # 559763, BD Biosciences, USA) according to the instructions. Samples were analyzed using flow cytometry (BD, USA).

2.9 Western blot

Proteins were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA and incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies (Table 1) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with the appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive proteins were detected using the Vilber Lourmat Imaging System (France).

Antibodies used in WB

| Antibodies | Source | Identification |

|---|---|---|

| 15-Lox-2 | Novus | Cat: # NBP2-92668 |

| Caspase3 | CST | Cat: # 9662S |

| CCND1 | Abcam | Cat: # ab16663 |

| β-Tubulin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat: # MA5-16308 |

2.10 RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using RNAiso Plus reagent (cat: # 9109, Takara, China) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (cat: # K1622, Thermo Fisher Scientific). All primers (Table 2) were designed using https://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/. RT-qPCR was performed using the LightCycler96 system (Roche, Switzerland).

Primers used in RT-qPCR

| Primers | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| β-Actin | F: 5′-ATGGAGGGGAATACAGCCC-3′ |

| β-Actin | R: 5′-TTCTTTGCAGCTCCTTCGTT-3′ |

| Cx3cl1 | F: 5′-ACGAAATGCGAAATCATGTGC-3′ |

| Cx3cl1 | R: 5′-CTGTGTCGTCTCCAGGACAA-3′ |

| IL18 | F: 5′-CTCTGTGGTTCCATGCTTTCT-3′ |

| IL18 | R: 5′-GTTTGAGGCGGCTTTCTTTG-3′ |

| IL1α | F: 5′-CAGATCAGCACCTTACACCTAC-3′ |

| IL1α | R: 5′-GAGATAGTGTTTGTCCACATCCT-3′ |

| IL1β | F: 5′-GGCAGGCAGTATCACTCATT-3′ |

| IL1β | R: 5′-GAAGGTGCTCATGTCCTCATC-3″ |

2.11 Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed three times independently. All data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism6.0. Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between groups were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed t-tests and one-way analysis of variance. Differences were expressed as p-values; p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The number of samples or events in the study was denoted in the figure legends.

3 Results

3.1 The 15-Lox-2 expression decreased in AS

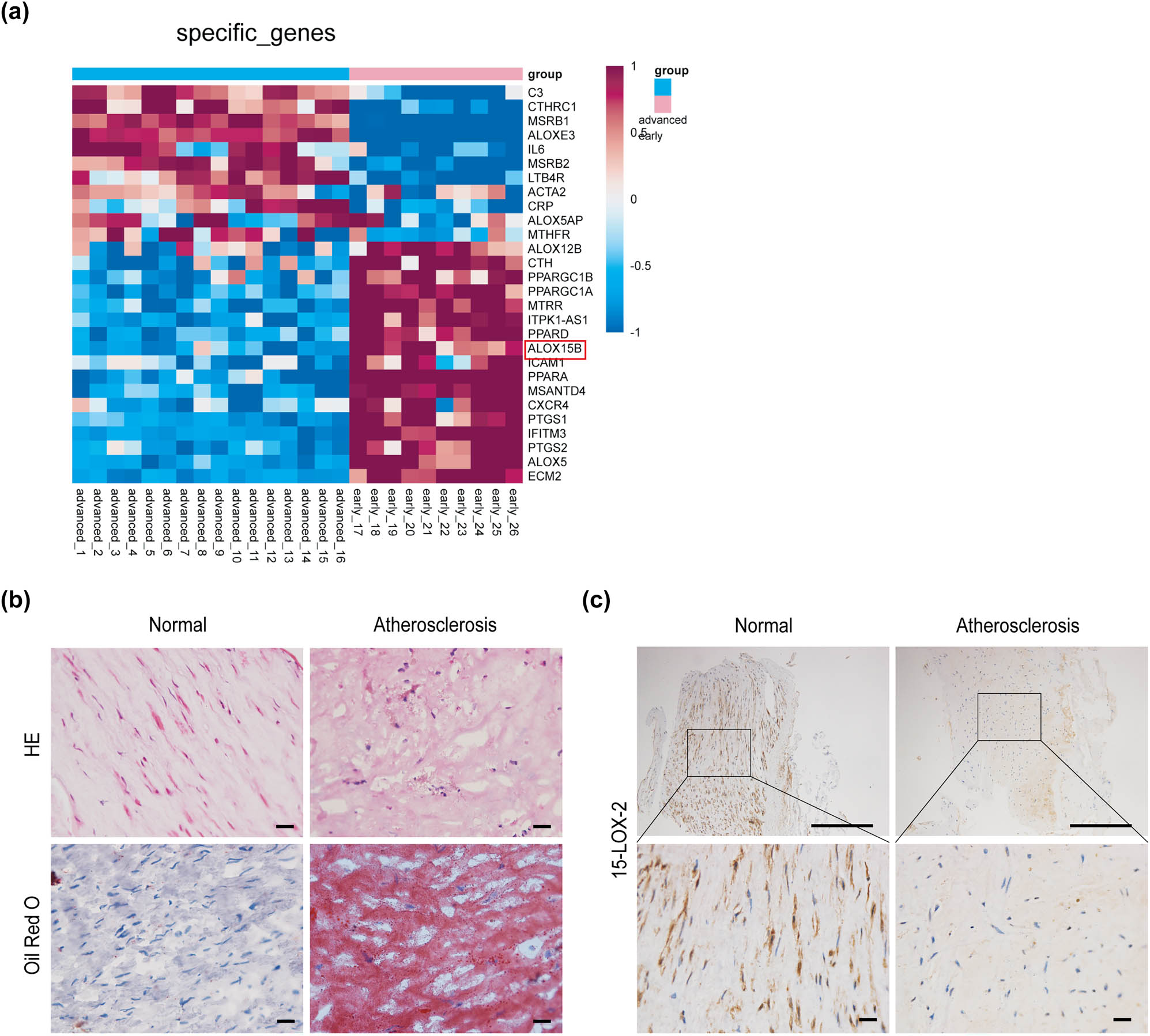

Variance analysis was used to explore the expression of 15-Lox-2 in the different stages of AS. As shown in Figure 1a, the expression of 15-Lox-2 was significantly decreased in advanced AS as compared to normal, while increased in early AS. Subsequently, advanced AS endarterectomy specimens and non-atherosclerotic specimens were harvested (Figure 1b). Immunohistochemistry analyses showed that the 15-Lox-2 expression was significantly higher in atherosclerotic plaque than normal (Figure 1c).

The expression of 15-Lox-2 decreased in advanced AS. (a) The differential expression of 15-Lox-2 in early and advanced AS. (b) The vessels of patients with AS were monitored by HE or Oil Red O staining, scale bar: 100 μm. (c) The 15-Lox-2 expression in vessels was detected by immunohistochemistry, scale bar: 100 μm.

3.2 15-Lox-2 deficiency-induced macrophage foam cell formation

To validate the role of 15-Lox-2 in macrophage foam cell formation, two independent 15-Lox-2 shRNAs (sh15-Lox-2.1252 and sh15-Lox-2.2865) and shRen were introduced into GFP and Neo vectors (Figure 2a). Then, the 15-Lox-2 shRNAs were introduced into Ana-1 macrophages to construct stable cell lines with 15-Lox-2 deficiency. As shown in Figure 2b, the expression of 15-Lox-2 in sh15-Lox-2 macrophages was lower than that in shRen. Furthermore, the level of AA was higher in 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages than those in controls (Figure 3a), whereas 15(S)-HETE was decreased in 15-Lox-2-deficient cells (Figure 3b).

The model of sh15-Lox-2 macrophages. (a) Schematic representation of virus vector; shRNAs were cloned into the backbone named mir30. (b) The knockdown efficiency of sh15-Lox-2.1252 and sh15-Lox-2.2865 was detected by WB, compared with shRen. shRen is used as a control due to its sequence that does not target any genes.

15-Lox-2 deficiency promoted foam cell formation and survival of macrophages. (a) The levels of AA and (b) 15(S)-HETE were analyzed by mass spectrometry. (c) Representative images of Oil Red O staining images of cells, scale bar: 100 μm; black arrows show lipid droplets in cells. (d) Representative images of DiI staining images of cells, scale bar: 25 μm; white arrows show lipid droplets. (e) DiI and DAPI OD were determined using a fluorescence microplate reader. (f) and (g) The percentage of Edu-positive cells and (h) and (i) AnnexinV/7-AAD-positive cells was detected by flow cytometry and quantified by FlowJo V10. (j) The levels of CCND1 and (k) caspase3 were measured by WB and quantitated by ImageJ. (l) The levels of caspase3 mRNA were detected by RT-qPCR. (m) The CCND1 expression of Ana-1 cells treated with AA or 15(S)-HETE was detected by WB. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs shRen.

As is known, macrophages can consume a substantial amount of ox-LDL and transform into foam cells, which is a key factor in atherosclerotic lesion progression [2]. To examine the phagocytosis of 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages, we monitored the uptake of ox-LDL in macrophages. As shown in Figure 3c and d, the cytoplasm of 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages was filled with ox-LDL, whereas few ox-LDL were observed in controls. The fluorescence OD results also showed that ox-LDL was markedly more abundant in 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages than in controls (Figure 3e). These data suggested that the phagocytosis of ox-LDL by 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages was enhanced, and macrophages tended to form foam cells following 15-Lox-2 deficiency.

We found that the 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages have a faster proliferation than those of controls within the entire culture duration. As a result, we further assessed the effect of 15-Lox-2 deficiency on Ana-1 proliferation and apoptosis, respectively. The percentages of cells in the S phase were increased in 5-Lox-2-deficient macrophages when compared to controls (Figure 3f and g). Additionally, the percentages of early apoptotic macrophages were lower in 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages than in controls (Figure 3h and i). Next, we tested the levels of proteins related to cell survival. The levels of Cyclin D1 (CCND1) were measured because an increase in CCND1 would indicate cell commitment to proliferation through cellular G1/S transition. 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages showed a significant increase in CCND1 expression (Figure 3j), indicating that the deficiency of 15-Lox-2 promoted cellular proliferation. Caspase3 encodes a cysteine protease that has been linked to the promotion of cell apoptosis. As shown in Figure 3k, compared with those in controls, caspase3 levels were significantly reduced in 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages. Caspase3 mRNA level also decreased in sh15-Lox-2 macrophages relative to that in controls (Figure 3l). These data suggested that 15-Lox-2 deficiency might promote macrophage activity. Moreover, the expression of CCND1 in Ana-1 cells treated with AA was upregulated, but it was downregulated in cells treated with 15(S)-HETE (Figure 3m), which suggested that the product and substrate of 15-Lox-2 may impact the fate of macrophages.

3.3 15-Lox-2 deficiency is associated with enhanced inflammation-related pathways

To further explore the mechanisms of 15-Lox-2 in macrophage function, RNA-seq was performed to analyze the transcriptomes of Ana-1 macrophages expressing sh15-Lox-2 and shRen. Both unsupervised clustering and PCA plots showed that macrophages expressing sh15-Lox-2.1252 and sh15-Lox-2.2865 were grouped together and clearly separated from shRen cells, indicating that the off-target effects of these two shRNAs were minimal (Figure 4a and b). Notably, compared with those in the controls, multiple gene sets related to inflammation, the complement pathway, and the TNF-α signaling pathway were activated in sh15-Lox-2-expressing cells (Figure 4c–e). RT-qPCR results revealed that IL18, IL1α, IL1β, and Cx3cl1, all related to the pathways identified, were upregulated in 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages (Figure 4f). These data indicated that 15-Lox-2 deficiency regulates the inflammatory response in Ana-1 macrophages.

15-Lox-2 deficiency associated with activation of inflammation-related signaling pathways. (a) Unsupervised clustering of 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages. (b) PCA of 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages. (c) GSEA of the hallmark gene sets showed positive enrichment of inflammatory response, (d) the complement signaling pathway, and (e) the TNF-α signaling via NF-κB. NES, normalized enrichment score; FDR, false discovery rate. (f) The mRNA level of IL18, IL1α, IL1β, and Cx3cl1 was performed by RT- qPCR. Results are presented as the mean ± SD, n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs shRen.

3.4 15-Lox-2 deficiency leads to an increase in AA, which may result in macrophage dysfunction

AA, a common 20-carbon polyunsaturated fatty acid, is mainly located in the plasma membrane and plays a remarkable role in the progress of AS [27]. Based on the above research shown in Figure 3a, b, and j, we presume that the effect of 15-Lox-2 deficiency on macrophages may be attributed to its metabolic substrate called AA. Then, arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone (AACOCF3) was used to treat macrophages. As shown in Figure 5a, after treatment with AACOCF3, AA level in 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages was decreased near to the level in controls. Furthermore, AACOCF3 decreased the fluorescence intensity of DiI-ox-LDL in 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages to a level close to that of the controls (Figure 5b and c), suggesting that AACOCF3 could ameliorate the phagocytosis of 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages via decreasing AA level. Additionally, the increased CCND1 expression of 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages was attenuated by AACOCF3, and the reduced caspase3 expression was increased by AACOCF3 to near controls (Figure 5d). These results suggested that the cell activity and phagocytosis were activated in an AA-dependent manner in Ana-1 macrophages.

AACOCF3 alleviated the abnormal function of 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages. (a) The levels of AA were analyzed by mass spectrometry. (b) Representative DiI staining images of cells, scale bar: 25 μm. White arrows show lipid droplets located in the cytoplasm. (c) DiI and DAPI OD were determined using a fluorescence microplate reader. (d) The CCND1 and caspase3 expression of cells treated with AACOCF3 were detected by WB and quantitated by ImageJ. Results are presented as the mean ± SD, n = 3, *p < 0.05, vs shRen.

3.5 SAL alleviated the phagocytosis of 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages by inhibiting AA effects

SAL has been shown to exert various pharmacological effects, including antioxidative stress and anti-inflammatory properties [28–30]. SAL can reduce de novo lipogenesis to attenuate AS [29]. The dosage of SAL selected in this study was based on its dose-dependent effect of SAL on the expression of 15-Lox-2 in Ana-1 cells and the results of the cell viability assay (Figure 6a) [29]. As shown in Figure 6b and c, the levels of ox-LDL observed in the 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages were close to those in shRen macrophages after treatment with SAL. The fluorescence OD also showed that ox-LDL in 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages were decreased to similar levels observed in controls (Figure 6d). These results suggested that SAL could alleviate the effect of 15-Lox-2 deficiency on phagocytosis of macrophages. Furthermore, after treatment with SAL, the increased proliferation of 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages was attenuated by SAL (Figure 6e). The reduced apoptosis of 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages was dramatically restored to normal levels by SAL (Figure 6f). Similar results were obtained from the analysis of proteins associated with proliferation and apoptosis in 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages treated with SAL. The upregulation of CCND1 expression and the decline in caspase3 protein caused by 15-Lox-2 deficiency were significantly reversed, returning to levels close to those in controls (Figure 6g and h). These results revealed that SAL may restore the abnormal cellular activity of 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages. Moreover, the mRNA levels of IL18, IL1α, IL1β, and Cx3cl1 in macrophages treating with SAL, which were all restored levels similar to those in controls (Figure 6i), indicating that SAL significantly decreased inflammatory response induced by 15-Lox-2 deficiency.

SAL reversed the phagocytosis of macrophages activated by 15-Lox-2 deficiency via acting on AA. (a–j) Macrophage-derived foam cells were treated with SAL. (a) The 15-Lox-2 expression of Ana-1 treated with 0–200 μM SAL was measured by WB. (b) Representative Oil Red O staining images of cells, scale bar: 100 μm; black arrows show lipid droplets in cells. (c) Representative DiI staining images of cells, scale bar: 25 μm. White arrows show lipid droplets located in the cytoplasm. (d) DiI and DAPI OD were determined using a fluorescence microplate reader. (e) The percentage of Edu-positive cells and (f) AnnexinV/7-AAD-positive cells was detected by flow cytometry and quantified by FlowJo V10. (g) The CCND1 and (h) caspase3 expression of cells were determined by WB and quantitated by ImageJ. (i) The levels of IL18, IL1α, IL1β, and Cx3cl1 mRNA were detected by RT-qPCR. (j) The levels of AA were tested by Mass Spectrometry. (k) Representative DiI staining images of cells co-treated with AACOCF3 and SAL, scale bar: 25 μm. White arrows show lipid droplets located in the cytoplasm. (l) DiI and DAPI OD were determined using a fluorescence microplate reader. (m) The levels of CCND1 in macrophages treated with AA, 15(S)-HETE, SAL, SAL plus AA, or SAL plus 15(S)-HETE were performed by WB. Results are presented as the mean ± SD, n = 3, *p < 0.05 vs shRen.

To determine whether SAL could decrease AA levels that were increased in 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages, AA levels were detected. After treatment with SAL, the AA levels in the 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages were decreased and got close to those in controls (Figure 6j). Moreover, after treating with both SAL and AACOCF3, there were no differences in ox-LDL density between controls and 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages, which were similar to that of cells treated with AACOCF3 alone (Figure 6k and l), indicating that SAL may inhibit the activity of phospholipase A2 (PLA2), thereby exerting its pharmacological effects. Subsequently, the CCND1 expression of macrophages treated with SAL alone or in combination with AA or 15(S)-HETE was tested by WB. As shown in Figure 6m, AA alone could upregulate the expression of CCND1 in cells. In contrast to AA, SAL combined with AA or 15(S)-HETE downregulated the expression of CCND1 in macrophages, indicating that SAL not only decreased the expression of CCND1 increased by AA but also enhanced the effects of 15(S)-HETE on CCND1 expression. All the data indicated that SAL may ameliorate the changes in macrophages caused by 15-Lox-2 deficiency via inhibiting AA effects.

4 Discussion

In this study, we found that 15-Lox-2 deficiency was prone to undergo foam cell formation and inflammatory response. SAL restored the changes in macrophages caused by 15-Lox-2 deficiency via inhibiting AA effects.

Macrophages are now known to have diverse and context-dependent functions in a variety of pathophysiological settings [31]. There is a rapidly growing interest in understanding how metabolic process-related genes, including lipoxygenases, can affect the appropriate activation of macrophages to enable host defense mechanisms. Multiple studies proved that 15-LOX-2 participated in various functions of macrophages, such as playing a key role in cancer and diseases of lipid metabolism [17,32]. Moreover, lipids regulate the inflammatory responses and phagocytosis of macrophages [33,34]. However, little is known about the importance of 15-LOX-2 and its relationship to physiological events in macrophage foam cell formation. In this study, using the loss-of-function way and transcriptomics approach, we highlighted the fact that the 15-Lox-2 deficiency had an impact on the phagocytosis of ox-LDL in macrophages, which might impact foam cell formation during the development of AS.

15-LOX-2 was found to affect the development of tumors through the regulation of AA levels in cells to impact tumor cell apoptosis and proliferation [35]. Here, we found that 15-Lox-2 deficiency increased AA levels in cells, inhibited apoptosis, and promoted the proliferation of macrophages. It has also been reported that 15-Lox-2 products (15(S)-HETE) might suppress immunosuppressive properties of ovarian tumor-associated macrophages and markedly inhibit the growth of tumor cells [36]. We found that 15(S)-HETE might downregulate the expression of the proliferative protein CCND1, but AA had the opposite effects on those proteins. It is known that AA is mainly located in the cell membrane and released by PLA2 [37,38]. Here, the AA level of 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages was decreased close to those of controls by the PLA2 inhibitor AACOCF3. The phagocytosis induced by ox-LDL in 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages was moderated by AACOCF3, suggesting that AA acted as a promoter in phagocytosis of 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages, which was consistent with previous research on the role of AA in promoting atherosclerotic onset and progression [39]. Environmental and Intrinsic stimulation activates LOXs to produce significant amounts of downstream eicosanoids, such as leukotrienes (LTs) and lipoxins (LXs), and many aspects of the inflammatory response are regulated by LTs and LXs [40,41]. We showed that 15-Lox-2 was a crucial anti-inflammatory regulator, the down-regulation of 15-Lox-2 expression served as a positive feedback mechanism to activate inflammatory, complement, and TNF-α signaling pathways. All these results indicated that 15-Lox-2 deficiency might increase levels of AA to activate inflammatory response in macrophages.

Statins are the primary medicines used in clinical settings for the treatment of AS [42]. The anti-atherosclerotic effect of Statins is achieved by reducing cholesterol through the competitive inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme of endogenous cholesterol synthesis [43,44]. Therefore, statins are commonly prescribed as lipid-reducing medications [45]. However, statin therapy has limited effectiveness on various AS conditions due to adverse reactions and application constraints [46]. SAL, a safe medication, possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and has been used for a long time to prevent aging and cardiovascular diseases [29,30]. This study showed that SAL restored abnormal phagocytosis and survival among inflammatory pathways and related genes (IL18, IL1α, IL1β, and Cx3cl1) of macrophages caused by 15-Lox-2 deficiency. Moreover, our previous study demonstrated that SAL had low toxic effects and significant pharmacological effects on macrophages, as well as exhibited anti-atherosclerotic effects in vivo [29], which was consistent with literature supporting the protective effect of SAL on AS [24,47]. Otherwise, previous studies have shown that omega-3 fatty acids possess immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, anti-platelet, and vascular protective effects in patients with AS [48,49]. However, there are many debates regarding the role of omega-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular disease [50,51]. Therefore, SAL may be a novel strategy to treat patients with AS who cannot effectively respond to other known anti-atherosclerotic medicines. Here, we found that SAL not only reversed the effects induced by AA but also enhanced the effects of 15(S)-HETE in macrophages. Notably, there were minimal differences in phagocytosis between 15-Lox-2-deficient macrophages treated with both SAL and AACOCF3 and cells treated with AACOCF3 alone. These data indicated that SAL reversed the dysfunction of macrophages caused by 15-Lox-2 deficiency by inhibiting the effects of AA and blocking PLA2 activity. Some natural medicinal ingredients also exerted anti-atherosclerotic effects by inhibiting the secretion of AA and the inflammatory response[52], suggesting that the AA metabolic pathway may be an important avenue for natural medicine in AS treatment. AS, a chronic disease, primarily involves inflammatory response and disorders of lipid metabolism. Long-term use of medications is associated with numerous adverse reactions and limited efficacy [53]. Due to its extensive and effective pharmacological effects, low cost, and minimal side effects, SAL is anticipated to be utilized clinically as a foundational drug for the treatment of AS.

This study highlighted that 15-Lox-2 deficiency promoted macrophage foam cell formation, which could be alleviated by SAL via inhibiting the AA effects. SAL might be a promising therapeutic strategy to treat AS resulting from 15-Lox-2 deficiency. Nonetheless, our experiments were mainly carried out in vitro, accurate and comprehensive experiments need to be performed to further verify our results.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the reviewers’ valuable comments that improved the manuscript.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by projects for the key project of North Sichuan Medical College (CBY21-ZD05), the Doctoral initiation fund of North Sichuan Medical College (740/75001013), Scientific Research Project of Nanchong Municipal Science and Technology Bureau, Sichuan Province (19SXHZ0443), and National College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program Project (XJ202310634319 and S202410634100).

-

Author contributions: Rong Huang designed the experiments. Xi Yong, Tingting Li, and Huling Wen generated 15-Lox-2-knockdown macrophages and analyzed the data. Xing Zhou, Jun You, Peng Xu, and Tianqin Xia cultured the cells and performed the flow cytometry. Chunlei Yu, Yuquan Wang, and Dan Wen collected clinical samples and performed the pathological analysis. Hao Yang, Yanqin Chen, and Lei Xu performed the WB and RT-qPCR. Xiaorong Zhong and Xianfu Li performed the LC–MS and analyzed the data; Yichen Liao contributed to the RNA-seq analysis; Zhengmin Xu, Chunyang Zhou, and Rong Huang organized the data and wrote the manuscript. All co-authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Weber C, Habenicht AJR, von Hundelshausen P. Novel mechanisms and therapeutic targets in atherosclerosis: Inflammat ion and beyond. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(29):2672–81.10.1093/eurheartj/ehad304Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Zheng WC, Chan W, Dart A, Shaw JA. Novel therapeutic targets and emerging treatments for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2024;10(1):53–67.10.1093/ehjcvp/pvad074Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Wu X, Pan J, Yu JJ, Kang J, Hou S, Cheng M, et al. DiDang decoction improves mitochondrial function and lipid metabolism via the HIF-1 signaling pathway to treat atherosclerosis and hyperlipi demia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;308:116289.10.1016/j.jep.2023.116289Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Guo X, Li B, Wen C, Zhang F, Xiang X, Nie L, et al. TREM2 promotes cholesterol uptake and foam cell formation in atheroscl erosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2023;80(5):137.10.1007/s00018-023-04786-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Blagov AV, Markin AM, Bogatyreva AI, Tolstik TV, Sukhorukov VN, Orekhov AN. The role of macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cells. 2023;12(4):522.10.3390/cells12040522Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Busnelli M, Manzini S, Colombo A, Franchi E, Lääperi M, Laaksonen R, et al. Effect of diets on plasma and aorta lipidome: A study in the apoE Knoc kout mouse model. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2023;67(2):e2200367.10.1002/mnfr.202200367Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Qian C, Wang Q, Qiao Y, Xu Z, Zhang L, Xiao H, et al. Arachidonic acid in aging: New roles for old players. J Adv Res. 2024;(70):79–101.10.1016/j.jare.2024.05.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Broos JY, van der Burgt RTM, Konings J, Rijnsburger M, Werz O, de Vries HE, et al. Arachidonic acid-derived lipid mediators in multiple sclerosis pathoge nesis: fueling or dampening disease progression? J Neuroinflammation. 2024;21(1):21.10.1186/s12974-023-02981-wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Nemri J, Morales C, Gilbert NC, Majewski J, Newcomer ME, Vander Zanden CM. Structure of a model lipid membrane oxidized by human 15-lipoxygenase- 2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024;737:150533.10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.150533Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Palmer MA, Benatzy Y, Brüne B. Murine Alox8 versus the human ALOX15B ortholog: differences and simila rities. Pflug Arch. 2024;476(12):1817–32.10.1007/s00424-024-02961-wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Li J, DeNicola GM, Ruffell B. Metabolism in tumor-associated macrophages. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2022;367:65–100.10.1016/bs.ircmb.2022.01.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Shinu P, Sharma M, Gupta GL, Mujwar S, Kandeel M, Kumar M, et al. Computational design, synthesis, and pharmacological evaluation of nap roxen-guaiacol chimera for gastro-sparing anti-inflammatory response by selective COX2 Inhibition. Molecules. 2022;27(20):6905.10.3390/molecules27206905Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Benatzy Y, Palmer MA, Lütjohann D, Ohno R-I, Kampschulte N, Schebb NH, et al. ALOX15B controls macrophage cholesterol homeostasis via lipid peroxidation, ERK1/2 and SREBP2. Redox Biol. 2024;72:103149.10.1016/j.redox.2024.103149Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Palmer MA, Kirchhoff R, Buerger C, Benatzy Y, Schebb NH, Brüne B. RNAi-based ALOX15B silencing augments keratinocyte inflammation in vit ro via EGFR/STAT1/JAK1 signalling. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16(1):39.10.1038/s41419-025-07357-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Liu Y, Chen C, Xu Z, Scuoppo C, Rillahan CD, Gao J, et al. Deletions linked to TP53 loss drive cancer through p53-independent mec hanisms. Nature. 2016;531(7595):471–5.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Korbecki J, Rębacz-Maron E, Kupnicka P, Chlubek D, Baranowska-Bosiacka I. Synthesis and significance of arachidonic acid, a substrate for cycloo xygenases, lipoxygenases, and cytochrome P450 pathways in the tumorige nesis of glioblastoma multiforme, including a pan-cancer comparative analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(3):946.10.3390/cancers15030946Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Rao Z, Brunner E, Giszas B, Iyer-Bierhoff A, Gerstmeier J, Börner F, et al. Glucocorticoids regulate lipid mediator networks by reciprocal modulat ion of 15-lipoxygenase isoforms affecting inflammation resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(35):e2302070120.10.1073/pnas.2302070120Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Benatzy Y, Palmer MA, Brüne B. Arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase type B: Regulation, function, and its role in pathophysiology. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1042420.10.3389/fphar.2022.1042420Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Sęczyk Ł, Sugier D, Dervişoğlu G, Özdemir FA, Kołodziej B. Phytochemical profile, in vitro bioaccessibility, and anticancer potential of golden root (Rhodiola rosea L.) extracts. Food Chem. 2023;404(Pt B):134779.10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134779Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Hou Y, Zhang Y, Jiang S, Xie N, Zhang Y, Meng X, et al. Salidroside intensifies mitochondrial function of CoCl2-dam aged HT22 cells by stimulating PI3K-AKT-MAPK signaling pathway. Phytomedicine. 2023;109:154568.10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154568Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Gao Z, Zhan H, Zong W, Sun M, Linghu L, Wang G, et al. Salidroside alleviates acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity via Sirt1- mediated activation of Akt/Nrf2 pathway and suppression of NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome axis. Life Sci. 2024;327:121793.10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121793Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Jin G, Ma M, Yang C, Zhen L, Feng M. Salidroside suppresses the multiple oncogenic activates and immune escape of lung adenocarcinoma through the circ_0009624-mediated PD-L1 pathway. Thorac Cancer. 2023;14(24):2493–503.10.1111/1759-7714.15034Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Liu Q, Chen J, Zeng A, Song L. Pharmacological functions of salidroside in renal diseases: facts and perspectives. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1309598.10.3389/fphar.2023.1309598Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Zhilan T, Zengyu Z, Pengpeng J, Hualan Y, Chao L, Yan X, et al. Salidroside promotes pro-angiogenesis and repair of blood brain barrier via Notch/ITGB1 signal path in CSVD model. J Adv Res. 2025;68:429–44.10.1016/j.jare.2024.02.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Liu Y, Chen C, Xu Z, Scuoppo C, Rillahan CD, Gao J, et al. Deletions linked to TP53 loss drive cancer through p53-independent mechanisms. Nature. 2016;531(7595):471–5.10.1038/nature17157Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Xiang X, Tian Y, Hu J, Xiong R, Bautista M, Deng L, et al. Fangchinoline exerts anticancer effects on colorectal cancer by inducing autophagy via regulation AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;186:114475.10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114475Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Xu SS, Zhang XL, Liu SS, Feng ST, Xiang GM, Xu CJ, et al. Multi-omic analysis in a metabolic syndrome porcine model implicates arachidonic acid metabolism disorder as a risk factor for atherosclerosis. Front Nutr. 2022;9:807118.10.3389/fnut.2022.807118Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Song T, Wang P, Li C, Jia L, Liang Q, Cao Y, et al. Salidroside simultaneously reduces de novo lipogenesis and cholesterol biosynthesis to attenuate atherosclerosis in mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;134:111137.10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111137Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Guo W, Huang R, Bian J, Liao Q, You J, Yong X, et al. Salidroside ameliorates macrophages lipid accumulation and atherosclerotic plaque by inhibiting Hif-1α-induced pyroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2025;742:151104.10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.151104Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Ji S, Chen D, Ding F, Gu X, Xue Q, Zhou C, et al. Salidroside exerts neuroprotective effects on retrograde neuronal death following neonatal axotomy via activation of PI3K/Akt pathway and deactivation of p38 MAPK pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2025;494:117178.10.1016/j.taap.2024.117178Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Wu J, He S, Song Z, Chen S, Lin X, Sun H, et al. Macrophage polarization states in atherosclerosis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1185587.10.3389/fimmu.2023.1185587Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Radmark O. Formation of eicosanoids and other oxylipins in human macrophages. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022;204:115210.10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115210Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Canfrán-Duque A, Rotllan N, Zhang X, Andrés-Blasco I, Thompson BM, Sun J, et al. Macrophage-derived 25-hydroxycholesterol promotes vascular inflammation, atherogenesis, and lesion remodeling. Circulation. 2023;147(5):388–408.10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.059062Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Kaba M, Carreras-Sureda A, Nunes-Hasler P, Demaurex N. The lipid transfer proteins Nir2 and Nir3 sustain phosphoinositide signaling and actin dynamics during phagocytosis. J Cell Sci. 2023;136(14):jcs260902.10.1242/jcs.260902Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Wei C, Li L, Qiao Y, Chen Y, Zhang C, Xie J, et al. Ferroptosis-related genes DUOX1 and HSD17B11 affect tumor microenvironment and predict overall survival of lung adenocarcinoma patients. Med (Baltim). 2024;103(22):e38322.10.1097/MD.0000000000038322Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Prat M, Coulson K, Blot C, Jacquemin G, Romano M, Renoud ML, et al. PPARγ activation modulates the balance of peritoneal macrophage populations to suppress ovarian tumor growth and tumor-induced immunosuppression. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11(8):e007031.10.1136/jitc-2023-007031Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Hayashi D, Mouchlis VD, Dennis EA. Omega-3 versus Omega-6 fatty acid availability is controlled by hydrophobic site geometries of phospholipase A(2)s. J Lipid Res. 2021;62:100113.10.1016/j.jlr.2021.100113Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Putta P, Smith AH, Chaudhuri P, Guardia-Wolff R, Rosenbaum MA, Graham LM. Activation of the cytosolic calcium-independent phospholipase A(2) β isoform contributes to TRPC6 externalization via release of arachidonic acid. J Biol Chem. 2021;297(4):101180.10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101180Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Wang B, Wu L, Chen J, Dong L, Chen C, Wen Z, et al. Metabolism pathways of arachidonic acids: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):94.10.1038/s41392-020-00443-wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Heydeck D, Reisch F, Schäfer M, Kakularam KR, Roigas SA, Stehling S, et al. The reaction specificity of mammalian ALOX15 orthologs is changed during late primate evolution and these alterations might offer evolutionary advantages for hominidae. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:871585.10.3389/fcell.2022.871585Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Biernacki M, Skrzydlewska E. Metabolic pathways of eicosanoids-derivatives of arachidonic acid and their significance in skin. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2025;30(1):7.10.1186/s11658-025-00685-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Wang A, Ning J, Zhao L, Xu R. Lipid-lowering effect and oral transport characteristics study of curculigoside. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1426379.10.3389/fcvm.2024.1426379Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Fularski P, Krzemińska J, Lewandowska N, Młynarska E, Saar M, Wronka M, et al. Statins in chronic kidney disease-effects on atherosclerosis and cellular senescence. Cells. 2023;12(13):1679.10.3390/cells12131679Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Lee MCM, Kachura JJ, Vlachou PA, Dzulynsky R, Di Tomaso A, Samawi H, et al. Evaluation of adjuvant chemotherapy-associated steatosis (CAS) in colorectal cancer. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(4):3030–40.10.3390/curroncol28040265Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Khatiwada N, Hong Z. Potential benefits and risks associated with the use of statins. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16(2):214.10.3390/pharmaceutics16020214Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Maged K, El-Henawee MM, Abd El-Hay SS. Development and validation of an eco-friendly HPLC-UV method for determination of atorvastatin and vitamin D(3) in pure form and pharmaceutical formulation. BMC Chem. 2023;17(1):62.10.1186/s13065-023-00975-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Wang XL, Sun RX, Li DX, Chen ZG, Li XF, Sun SY, et al. Salidroside regulates mitochondrial homeostasis after polarization of RAW264.7 macrophages. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2023;81(1):85–92.10.1097/FJC.0000000000001362Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Shibabaw T. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: Anti-inflammatory and anti-hypertriglyceridemia mechanisms in cardiovascular disease. Mol Cell Biochem. 2021;476(2):993–1003.10.1007/s11010-020-03965-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Bae JH, Lim H, Lim S. The potential cardiometabolic effects of long-chain ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: Recent updates and controversies. Adv Nutr. 2023;14(4):612–28.10.1016/j.advnut.2023.03.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Sherratt SCR, Libby P, Budoff MJ, Bhatt DL, Mason RP. Role of omega-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular disease: The debate continues. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2023;25(1):1–17.10.1007/s11883-022-01075-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Sherratt SCR, Mason RP, Libby P, Steg PG, Bhatt DL. Do patients benefit from omega-3 fatty acids? Cardiovasc Res. 2024;119(18):2884–901.10.1093/cvr/cvad188Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Al-Khayri JM, Sahana GR, Nagella P, Joseph BV, Alessa FM, Al-Mssallem MQ. Flavonoids as potential anti-inflammatory molecules: A review. Molecules. 2022;27(9):2901.10.3390/molecules27092901Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Zhu Y, Xian X, Wang Z, Bi Y, Chen Q, Han X, et al. Research progress on the relationship between atherosclerosis and inflammation. Biomolecules. 2018;8(3):80.10.3390/biom8030080Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome with elevated IgG4 and T-cell clonality: A report of two cases

- Electroacupuncture alleviates sciatic nerve injury in sciatica rats by regulating BDNF and NGF levels, myelin sheath degradation, and autophagy

- Polydatin prevents cholesterol gallstone formation by regulating cholesterol metabolism via PPAR-γ signaling

- RNF144A and RNF144B: Important molecules for health

- Analysis of the detection rate and related factors of thyroid nodules in the healthy population

- Artesunate inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion through OGA-mediated O-GlcNAcylation of ZEB1

- Endovascular management of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: Case report and review of the literature

- Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis

- SATB2 promotes humeral fracture healing in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Overexpression of the ferroptosis-related gene, NFS1, corresponds to gastric cancer growth and tumor immune infiltration

- Understanding risk factors and prognosis in diabetic foot ulcers

- Atractylenolide I alleviates the experimental allergic response in mice by suppressing TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 signalling

- FBXO31 inhibits the stemness characteristics of CD147 (+) melanoma stem cells

- Immune molecule diagnostics in colorectal cancer: CCL2 and CXCL11

- Inhibiting CXCR6 promotes senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells with limited proinflammatory SASP to attenuate hepatic fibrosis

- Cadmium toxicity, health risk and its remediation using low-cost biochar adsorbents

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis with headache as the first presentation: A case report

- Solitary pulmonary metastasis with cystic airspaces in colon cancer: A rare case report

- RUNX1 promotes denervation-induced muscle atrophy by activating the JUNB/NF-κB pathway and driving M1 macrophage polarization

- Morphometric analysis and immunobiological investigation of Indigofera oblongifolia on the infected lung with Plasmodium chabaudi

- The NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex and Hr78 modulate the Lobe2 mutant eye phenotype

- Experimental study on salmon demineralized bone matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: In vitro and in vivo study

- A case of IgA nephropathy treated with a combination of telitacicept and half-dose glucocorticoids

- Analgesic and toxicological evaluation of cannabidiol-rich Moroccan Cannabis sativa L. (Khardala variety) extract: Evidence from an in vivo and in silico study

- Wound healing and signaling pathways

- Combination of immunotherapy and whole-brain radiotherapy on prognosis of patients with multiple brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study

- To explore the relationship between endometrial hyperemia and polycystic ovary syndrome

- Research progress on the impact of curcumin on immune responses in breast cancer

- Biogenic Cu/Ni nanotherapeutics from Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl seeds for the treatment of lung cancer

- Dapagliflozin attenuates atrial fibrosis via the HMGB1/RAGE pathway in atrial fibrillation rats

- Glycitein alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in keratinocytes via ROS-associated PI3K–Akt signalling pathway

- ADH5 inhibits proliferation but promotes EMT in non-small cell lung cancer cell through activating Smad2/Smad3

- Apoptotic efficacies of AgNPs formulated by Syzygium aromaticum leaf extract on 32D-FLT3-ITD human leukemia cell line with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Novel cuproptosis-related genes C1QBP and PFKP identified as prognostic and therapeutic targets in lung adenocarcinoma

- Bee venom promotes exosome secretion and alters miRNA cargo in T cells

- Treatment of pure red cell aplasia in a chronic kidney disease patient with roxadustat: A case report

- Comparative bioinformatics analysis of the Wnt pathway in breast cancer: Selection of novel biomarker panels associated with ER status

- Kynurenine facilitates renal cell carcinoma progression by suppressing M2 macrophage pyroptosis through inhibition of CASP1 cleavage

- RFX5 promotes the growth, motility, and inhibits apoptosis of gastric adenocarcinoma cells through the SIRT1/AMPK axis

- ALKBH5 exacerbates early cardiac damage after radiotherapy for breast cancer via m6A demethylation of TLR4

- Phytochemicals of Roman chamomile: Antioxidant, anti-aging, and whitening activities of distillation residues

- Circadian gene Cry1 inhibits the tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma by the BAX/BCL2-mediated apoptosis pathway

- The TNFR-RIPK1/RIPK3 signalling pathway mediates the effect of lanthanum on necroptosis of nerve cells

- Longitudinal monitoring of autoantibody dynamics in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing surgery

- The potential role of rutin, a flavonoid, in the management of cancer through modulation of cell signaling pathways

- Construction of pectinase gene engineering microbe and its application in tobacco sheets

- Construction of a microbial abundance prognostic scoring model based on intratumoral microbial data for predicting the prognosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Sepsis complicated by haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis triggered by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and human herpesvirus 8 in an immunocompromised elderly patient: A case report

- Sarcopenia in liver transplantation: A comprehensive bibliometric study of current research trends and future directions

- Advances in cancer immunotherapy and future directions in personalized medicine

- Can coronavirus disease 2019 affect male fertility or cause spontaneous abortion? A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis

- Heat stroke associated with novel leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor gene variant in a Chinese infant

- PSME2 exacerbates ulcerative colitis by disrupting intestinal barrier function and promoting autophagy-dependent inflammation

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state with severe hypernatremia coexisting with central diabetes insipidus: A case report and literature review

- Efficacy and mechanism of escin in improving the tissue microenvironment of blood vessel walls via anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects: Implications for clinical practice

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Clinicopathological analysis of three patients and literature review

- Genetic variants in VWF exon 26 and their implications for type 1 Von Willebrand disease in a Saudi Arabian population

- Lipoxin A4 improves myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through the Notch1-Nrf2 signaling pathway

- High levels of EPHB2 expression predict a poor prognosis and promote tumor progression in endometrial cancer

- Knockdown of SHP-2 delays renal tubular epithelial cell injury in diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis

- Exploring the toxicity mechanisms and detoxification methods of Rhizoma Paridis

- Concomitant gastric carcinoma and primary hepatic angiosarcoma in a patient: A case report

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Optimization and comparative study of Bacillus consortia for cellulolytic potential and cellulase enzyme activity

- The complete mitochondrial genome analysis of Haemaphysalis hystricis Supino, 1897 (Ixodida: Ixodidae) and its phylogenetic implications

- Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors analysis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among tuberculosis population in Huzhou City, Eastern China

- Indices of human impacts on landscapes: How do they reflect the proportions of natural habitats?

- Genetic analysis of the Siberian flying squirrel population in the northern Changbai Mountains, Northeast China: Insights into population status and conservation

- Diversity and environmental drivers of Suillus communities in Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica forests of Inner Mongolia

- Global assessment of the fate of nitrogen deposition in forest ecosystems: Insights from 15N tracer studies

- Fungal and bacterial pathogenic co-infections mainly lead to the assembly of microbial community in tobacco stems

- Influencing of coal industry related airborne particulate matter on ocular surface tear film injury and inflammatory factor expression in Sprague-Dawley rats

- Temperature-dependent development, predation, and life table of Sphaerophoria macrogaster (Thomson) (Diptera: Syrphidae) feeding on Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae)

- Eleonora’s falcon trophic interactions with insects within its breeding range: A systematic review

- Agriculture

- Integrated analysis of transcriptome, sRNAome, and degradome involved in the drought-response of maize Zhengdan958

- Variation in flower frost tolerance among seven apple cultivars and transcriptome response patterns in two contrastingly frost-tolerant selected cultivars

- Heritability of durable resistance to stripe rust in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Molecular mechanism of follicular development in laying hens based on the regulation of water metabolism

- Animal Science

- Effect of sex ratio on the life history traits of an important invasive species, Spodoptera frugiperda

- Plant Sciences

- Hairpin in a haystack: In silico identification and characterization of plant-conserved microRNA in Rafflesiaceae

- Widely targeted metabolomics of different tissues in Rubus corchorifolius

- The complete chloroplast genome of Gerbera piloselloides (L.) Cass., 1820 (Carduoideae, Asteraceae) and its phylogenetic analysis

- Field trial to correlate mineral solubilization activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and biochemical content of groundnut plants

- Correlation analysis between semen routine parameters and sperm DNA fragmentation index in patients with semen non-liquefaction: A retrospective study

- Plasticity of the anatomical traits of Rhododendron L. (Ericaceae) leaves and its implications in adaptation to the plateau environment

- Effects of Piriformospora indica and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on growth and physiology of Moringa oleifera under low-temperature stress

- Effects of different sources of potassium fertiliser on yield, fruit quality and nutrient absorption in “Harward” kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa)

- Comparative efficiency and residue levels of spraying programs against powdery mildew in grape varieties

- The DREB7 transcription factor enhances salt tolerance in soybean plants under salt stress

- Using plant electrical signals of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) for water pollution monitoring

- Food Science

- Phytochemical analysis of Stachys iva: Discovering the optimal extract conditions and its bioactive compounds

- Review on role of honey in disease prevention and treatment through modulation of biological activities

- Computational analysis of polymorphic residues in maltose and maltotriose transporters of a wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain

- Optimization of phenolic compound extraction from Tunisian squash by-products: A sustainable approach for antioxidant and antibacterial applications

- Liupao tea aqueous extract alleviates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in rats by modulating the gut microbiota

- Toxicological qualities and detoxification trends of fruit by-products for valorization: A review

- Polyphenolic spectrum of cornelian cherry fruits and their health-promoting effect

- Optimizing the encapsulation of the refined extract of squash peels for functional food applications: A sustainable approach to reduce food waste

- Advancements in curcuminoid formulations: An update on bioavailability enhancement strategies curcuminoid bioavailability and formulations

- Impact of saline sprouting on antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds in chia seeds

- The dilemma of food genetics and improvement

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Impact of hyaluronic acid-modified hafnium metalorganic frameworks containing rhynchophylline on Alzheimer’s disease

- Emerging patterns in nanoparticle-based therapeutic approaches for rheumatoid arthritis: A comprehensive bibliometric and visual analysis spanning two decades

- Application of CRISPR/Cas gene editing for infectious disease control in poultry

- Preparation of hafnium nitride-coated titanium implants by magnetron sputtering technology and evaluation of their antibacterial properties and biocompatibility

- Preparation and characterization of lemongrass oil nanoemulsion: Antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant, and anticancer activities

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Utilization of convolutional neural networks to analyze microscopic images for high-throughput screening of mesenchymal stem cells”

- Corrigendum to “Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans”

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Down-regulation of miR-539 indicates poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer”

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells