Abstract

A chronic inflammatory skin disorder, psoriasis, affects 2–3% of people worldwide. A bioactive substance, glycitein (GCN), has several pharmacological characteristics. This work aims to evaluate the effects of GCN on the in vitro proliferation and death of human HaCaT keratinocytes. An in vitro model was created to simulate psoriatic features utilizing HaCaT keratinocytes activated by M5 cytokines. The 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide test was used to quantify cell viability, whereas the BrdU assay was used to assess the proliferation rate. Using a DCFH-DA probe and an Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide detection kit, flow cytometry was used to examine the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and apoptosis, respectively. Western blot and quantitative polymerase chain reaction were employed to determine the amounts of phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt) and Akt proteins. GCN dramatically decreased the inflammation and hyperproliferation that cytokines caused in HaCaT keratinocytes. The alteration of mitochondrial membrane potential promoted apoptosis and caused cell cycle arrest at the sub-G1 phase, which indicates apoptotic DNA fragmentation. The suppression of the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway was linked to increased intracellular ROS levels brought on by GCN therapy. These results imply that GCN reduces inflammation and keratinocyte hyperproliferation by controlling cell cycle progression and apoptosis via ROS-associated inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Psoriasis is a persistent, non-contagious, erythematous scaly skin disorder that is defined by epidermal hyperplasia and inflammation. Genetics, spread of infection, allergies, metabolic problems, and autoimmunity are factors in its pathogenesis [1,2,3]. According to Gao et al. [4], it is a common chronic inflammatory illness with a growing frequency of 2–3% globally. Its defining characteristics are rapid proliferation, abnormal keratinocyte differentiation, and inflammatory cell infiltration into the epidermal layer and epidermis [4]. Although the precise pathophysiology of psoriasis is currently unknown, it is widely recognized that aberrant relationships among immune cells and keratinocytes are crucial to the disease’s progression [5]. The stimulating effect of keratinocytes by different cytokines released by immune cells in the lesion can cause hyperproliferation of keratinocytes, which consequently triggers the production of massive proinflammatory mediators by hyperproliferative keratinocytes to maintain or even intensify the inflammatory response [6,7]. Because psoriasis is difficult to treat and vulnerable to recurrence, research into novel therapies linked to keratinocyte proliferation and exacerbated inflammation is beneficial.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediate apoptotic and inflammatory and other intracellular messenger pathways. Emerging evidence implicates ROS as a pivotal regulator of keratinocyte function in psoriasis, with elevated ROS levels promoting apoptosis while suppressing abnormal proliferation [8,9]. The cellular outcome depends on ROS concentration: low levels may promote aberrant proliferation, while higher levels can induce oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis [10,11]. Thus, modulating ROS levels to shift keratinocytes towards apoptosis represents a promising therapeutic avenue [12,13]. Apoptosis, a well-characterized form of programmed cell death, plays a vital role in maintaining tissue homeostasis, and its dysregulation is linked to several skin disorders [14,15]. Several studies have shown a functional connection between ROS and activation or suppression of key apoptotic regulators [16,17].

One of the most important pathways for surviving cells is the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway, a common autophagy-dependent transduction pathway that plays a role in vascular development, cell development, and various additional incorporates [18,19]. Related cytokines may promote PI3K in cells, activating downstream Akt and associated proteins and causing corresponding biological consequences. According to Guo et al. [20] and Mercurio et al. [21], this mechanism can control upward and downward associated targets in psoriasis, causing abnormal proliferation of epidermal cells. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is aberrantly expressed downstream, whereas PTEN expression has decreased upstream. Psoriasis symptoms can be alleviated by suppressing endothelial growth factors by inhibition of the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway [22,23]. Recent findings indicate that elevated ROS may downregulate PI3K/Akt signalling, thereby promoting keratinocyte apoptosis and reducing inflammatory responses, suggesting a mechanistic link between oxidative stress and PI3K/Akt modulation in psoriasis. However, this interaction remains incompletely understood.

Bioflavonoids have been used in healthcare facilities subsequently because of their many biological properties, affordability, and excellent safety record [24]. In soybeans, glycitein (GCN), a 7,4′-dihydroxy-6-methoxyisofavone, is the third commonly encountered isofavone. According to Kim et al. [25], it is also commonly found in many cordyceps species of fungus. According to research, it exhibits anti-inflammatory [26], antioxidant [27], neurologically protective [28,29], liver-protective properties [30], and antitumor [31,32] effects. Despite its known pharmacological benefits, the role of GCN in psoriasis, particularly in regulating ROS-associated PI3K/Akt signalling, has not yet been investigated.

In this study, we employed M5 cytokine-stimulated HaCaT keratinocytes as an in vitro model of psoriasis to evaluate GCN’s antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic effects. We further explored GCN’s influence on the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway in the context of ROS generation, aiming to elucidate the molecular basis of GCN’s potential therapeutic action.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Molecular docking analysis

The 3D structures of GCN were retrieved from the PubChem-NCBI database, while the target proteins Akt (PDB ID: 2UW9) and P13K (PDB ID: 6TNR) were obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. The protein and ligand files were prepared by converting them into PDBQT format using Autodock Tools (v1.5.7 rc1) provided by the Scripps Research Institute. A docking grid was set up, and molecular docking simulations were conducted using Autodock Vina (v1.5.6, available at https://vina.scripps.edu). The docking results were further analysed using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer software to identify interactions.

2.2 Cell culture and in vitro model formation

Human HaCaT keratinocytes were acquired from the Chinese Academy of Science’s Kunming Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection (Kunming, China). Incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2, the cells were kept in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS). By introducing M5 cocktail cytokines (IL-17A, IL-22, oncostatin M, IL-1α, and TNF-α) into the media of HaCaT keratinocytes at the final dosage of 2.5 ng/mL, a psoriasis-like keratinocyte type has been developed.

2.3 Cell viability and proliferation

The viability of HaCaT cells was evaluated using the 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) test. For 24 h, HaCaT cells (2 × 104) were grown in 96-well plates. HaCaT cells were administered with 2.5 ng/mL of combined M5 cytokines and GCN (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μM). After the maker’s instructions, the MTT reagent was utilized. At 490 nm, the absorbance density was determined by a microplate reader. Using the following formula, the cell viability ratio (%) was determined:

Although alternative assays such as cholecystokinin octapeptide (CCK-8) offer improved sensitivity and lower cytotoxicity, the MTT assay remains a robust method for endpoint viability analysis and was used here due to its reproducibility and accessibility in our setup.

2.4 Proliferation assessment using BrdU assay

Using the BrdU Cell Proliferation assessment kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), thymidine monobromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) was used to examine cell proliferation in settings involving de novo-synthesised DNA. In summary, 2 × 103 HaCaT cells/well were scattered onto 96-well plates, and the cells were then incubated for 48 h at 37°C. After that, 20 mL of BrdU was included, and the mixture was incubated for 4 h at 37°C. One hundred millilitres of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine peroxidase substrate was placed in the following mixture, which was incubated with anti-BrdU antibody and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG for 30 min. The mixture was then left in the dark at ambient temperatures. Employing a microplate reader, the intensity of absorption at 450/550 nm was detected.

2.5 Assessment of superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

A solution of 0.033 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid, 3.3 mM methionine, 0.01 mM KCN, and 0.33 μg/mL riboflavin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) has been added to the supernatant. For 10 min, the cuvette holding the reaction solution was put in a box that was lit by a twenty-watt neon bulb. The quantity of SOD enzyme needed to inhibit the synthesis of chromogen (optical density at 560 nm) by 50% in 1 min under the assay circumstances is known as one unit of SOD function. This particular activity is quantified in units/min/mg protein.

2.6 Evaluation of glutathione (GSH) levels

The concentration of GSH was determined by interacting with 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic) acid, which yielded 5′-thio (2-nitrobenzoic) acid (TNBA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), a yellow-colored molecule. A light spectrum of 412 nm was used to quantify the percentage of TNBA, and the quantity of GSH was expressed in nmol GSH/mg protein.

2.7 Catalase (CAT) enzyme assessment

After splitting H2O2 for 1 min, the CAT activity was ascertained. Dichromate/acetic acid reagent was used to halt the reaction, and the amount of H2O2 left behind for chromic acetate was determined at 570 nm. μmol/L H2O2 decomposed/min/mg protein was used to generate the CAT function.

2.8 Assessment of malondialdehyde (MDA) activity

Following the manufacturer’s recommendation, a lipid peroxidation MDA assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China) was employed to measure the MDA activity. GCN treatment (10 and 20 μM) was followed by the harvesting of HaCaT cells, lysing them with cell lysis buffer, and centrifuging them at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. After reacting with thiobarbituric acid in the resulting supernatant, the resulting reaction components were detected at 532 nm using a microplate reader. MDA level was adjusted, and the entire protein value was assessed using a BCA protein detection kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China).

2.9 Analysing apoptosis with fluorescence microscopy

Apoptotic and morphological modifications brought on by GCN were detected by acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EB) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) labelling. Essentially, GCN at 10 and 20 μM was added to HaCaT cells that were seeded in a 12-well plate the day before. Following a 2-h incubation period, cells were stimulated with M5, followed by a 48-h incubation period, 10 s of AO/EB (10 μg/mL each) staining, and two phosphate buffered saline (PBS) washes. For DAPI labelling, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. They were then stained with DAPI (1 μM) in PBS, and fluorescence microscopy (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) images were taken at ×200 magnification.

2.10 Cell cycle analysis

HaCaT cells were cultivated, incubated with M5 for 48 h, and treated with GCN for 2 h. The cells were subsequently trypsinized, fixed in 70% ethanol, and kept at −20°C. Following a PBS wash, the cells were treated for 15 min with propidium iodide (PI) staining buffer before being exposed to flow cytometric analysis (BD C6 Accuri flow cytometry, USA).

2.11 JC-1 staining

Apoptosis is activated by ROS when ΔΨm is lost. At high membrane potential, JC-1 reversibly forms “J aggregates” with red fluorescence, but when ΔΨm is lost, it forms green fluorescence because of “J monomers.” The assay was carried out by seeding HaCaT cells in 12-well plates and stimulating them with M5 cytokines and GCN, respectively. Following 48 h of incubation, cells were stained for 30 min with 1 μM of JC-1 dye and then exposed to flow cytometry.

2.12 Apoptosis assay using flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was used to identify apoptosis. Annexin-V-FITC and PI labelling were used to quantitatively identify phosphatidylserine on the surface of apoptotic cells. Following 24-h incubation, with M5 cytokines and GCN for 2 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 800 rpm for 5 min, followed by a PBS wash, another centrifugation, and resuspension in PBS. After 1 h of Annexin-V-FITC staining and 30 min of PI staining, the cells were examined using a FACScan system.

2.13 Assessment of intracellular ROS concentrations

A peroxide-sensitive fluorescent detector, DCFH-DA, was used to assess ROS levels within the cell following directions provided by the manufacturer. To summarize, HaCaT cells were grown in a six-well plate and stimulated with different doses of GCN and M5 cytokines for the specified durations. After 30 min at 37°C in medium without FBS, cells were treated with DCFH-DA at a final concentration of 10 μM. They were then rinsed three times with media. The ROS contents were measured using a flow cytometer.

2.14 Western blotting analysis

HaCaT keratinocytes were cultivated for 24 h after being seeded in six-well plates. Cells at 60–80% diameter were induced with M5 (5 ng/mL) for 30 min after being treated with GCN for 24 h. Cell lysis buffer containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride was used to harvest and lyse the cells for 20 min on ice. For 15 min, cell lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm. The BCA kit (Pierce, USA) was used to measure the protein level in the final solution. After separating approximately 15 μg of protein using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, the protein was moved to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes and blocked for 2 h at ambient temperature with 5% nonfat milk. The primary antibodies (Akt, p-Akt, pPI3K, PI3K, mTOR) were then reared for the complete night at 4°C at a dilution of 1:1,000. Following three washes with TBS-T washing, the membranes were treated for 2 h at ambient temperature with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. The membranes were then moved to the ChemiDoc™ XRS + System (Bio-Rad, USA) to visualize the protein signals after being treated with chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce, USA). ImageJ software was utilized to measure the protein bands. The internal reference was β-actin.

2.15 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

GCN (10 and 20 μM) was administered to the M5-induced HaCaT cells for 24 h. Then, using an ELISA kit (Abcam Technology, Cambridge, UK) as directed by the manufacturer, inflammatory substances TNF-α (Cat No. ab181421), high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) (Cat No. ab227731), IL-1β (Cat No. ab214025; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and IL-18 (Cat No. ab215539) in the supernatant were identified. In short, a 96-well plate coated with primary antibodies towards cytokines such as TNF-α, HMGB1, IL-18, and IL-1β was filled with 50 mL of typical samples and a control blank. HRP-conjugated detection antibodies (100 mL) were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Following five rounds of washing, substrates A and B were added for an additional 15 min of incubation. In a microplate reader, the absorbance was lastly measured at 450 nm. By creating a standard curve, the levels of cytokines in multiple samples were measured.

2.16 Docking of molecules

The interacting affinities of GCN for PI3K and Akt were evaluated using molecular docking. PubChem was able to determine the molecular structure of GCN (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/5280805). PI3K and Akt’s three-dimensional structures were taken using the Protein Data Bank database (https://www.uniprot.org/). The binding sites among GCN, PI3K, and Akt have been determined using the AutoDock 4.2 software. PyMol 2.2 was used to visualize the outcomes of the docking process.

2.17 Assessment of the data

Each investigation was carried out with a minimum of three biological duplicates in triplicate. Standard error, mean, and median were displayed for the data. For statistical analysis, Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, USA) was used. Analyses of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s post-hoc test were used to examine for variances across various groups. The p-value was deemed substantial provided it was below 0.05.

3 Results

To investigate whether GCN could regulate ROS levels, suppress inflammatory signalling, and modulate the PI3K/Akt pathway in psoriatic keratinocytes, we conducted a series of in vitro experiments using M5-stimulated HaCaT cells.

3.1 GCN impact on the viability of HaCaT keratinocytes

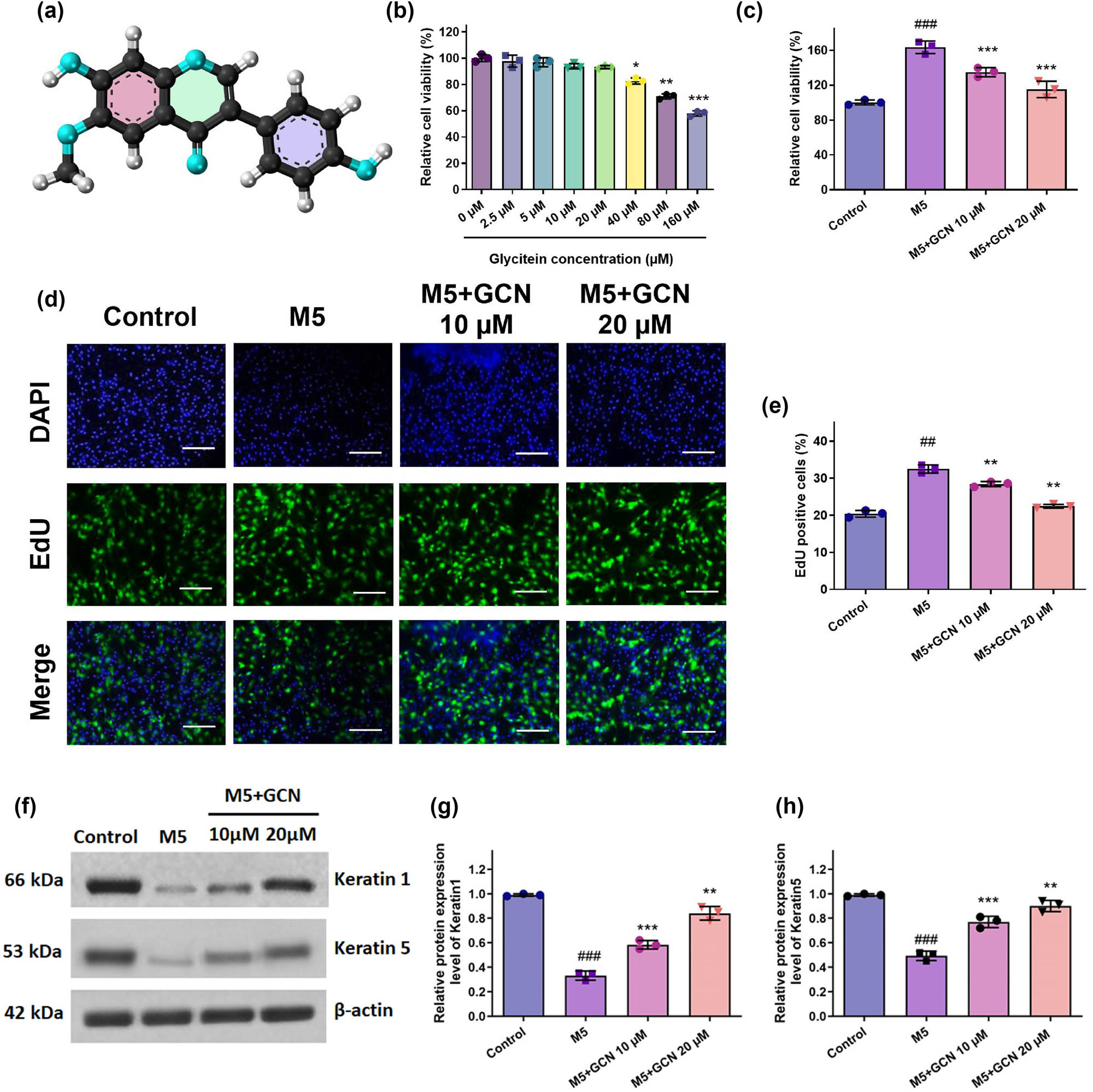

The chemical structure of GCN, a naturally occurring isoflavone having anti-inflammatory qualities, is displayed in Figure 1a. The MTT examination was employed to assess the cell viability of HaCaT keratinocytes subjected to GCN. Following a 48-h GCN administration, no discernible toxicity was seen at values lower than 40 μM. At doses greater than 80 μM, GCN dramatically reduced the cell viability of HaCaT keratinocytes (Figure 1b). Thus, for the following investigations, keratinocytes were exposed to 10–20 μM GCN.

GCN impact on the growth of HaCaT cells proliferation after being activated with M5 cytokines. Cell viability (a) and (b) was assessed using the MTT test; (c) the proliferation rate was assessed using the BrdU assay; (d) the proportion of cells exhibiting BrdU-positive (BrdU+) staining was found. (e) and (f) The levels of KRT1 and KRT5 protein expression were investigated using a Western blot. (g) and (h) Shows band intensities assessed by Image J software evaluation to protein expression levels graphically. Compared to the control, ### p < 0.05 comparing control, **p < 0.01, ***0.05 compared to the M5 group. SEM ± mean was used to express the data.

3.2 GCN attenuates M5-induced hyperproliferation in HaCaT keratinocytes

The widely utilized psoriatic keratinocyte model was employed to create an in vitro model of mixed M5 cytokine-stimulated HaCaT keratinocytes to study the phenotypic characteristics of prevalent psoriasis. Cell viability was assessed using MTT to assess the impact of GCN therapy on M5-stimulated HaCaT keratinocytes. The outcome demonstrated that M5 stimulation greatly increased HaCaT keratinocyte proliferation. However, GCN at 10 and 20 μM reduced the hyperproliferation caused by M5 (Figure 1c). Furthermore, the BrdU staining experiment demonstrated that M5 therapy significantly increased HaCaT cell proliferation. Furthermore, in a dose-related approach, GCN substantially inhibited the proliferation of HaCaT cells caused by M5 in contrast to the untreated group (Figure 1d and e). Therefore, our data validate that M5 promoted cell proliferation, but GCN in administration inhibited this mechanism.

3.3 GCN facilitated the differentiation of HaCaT cells induced by M5

To further evaluate the impact of GCN on the differentiation potential of M5-stimulated HaCaT cells, we employed the Western blotting test to identify the keratinocyte differentiation markers Keratin1 and Keratin5. In comparison with untreated cells, findings demonstrated that M5-stimulated HaCaT cells had lower levels of Keratin1 and Keratin5 protein; however, these lower levels were largely restored after GCN treatment (Figure 1f–h). These outcomes exhibited that the abnormal differentiation of HaCaT cells caused by M5 may be mitigated by GCN.

3.4 GCN reduced keratinocyte inflammation brought on by M5

The pathophysiology of psoriasis is significantly influenced by proinflammatory cytokines. To investigate the impact of GCN on M5-induced a reaction of inflammation, more investigation was carried out on the components associated with inflammation following various therapies (Figure 2). Following M5 cytokine exposition, the expression levels of inflammation-related indicators (TNF-α, HMGB1, IL-18, and IL-1β) in HaCaT cells increased considerably, and following treatment with various doses of GCN, the release of TNF-α, HMGB1, IL-18, and IL-1β was repressed (Figure 2a–d). The findings showed that GCN reduced the M5-induced proinflammatory response’s inflammatory cytokine production.

GCN attenuates M5-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production in HaCaT cells. ELISA was used to measure the levels of inflammatory cytokines in cell culture supernatants. (a) TNF-α, (b) IL-1β, (c) IL-18, and (d) HMGB1 were significantly elevated following M5 treatment compared to the control group. GCN co-treatment (10 and 20 μM) significantly reduced these cytokine levels in a dose-dependent manner. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4). ### p < 0.001 vs control; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs M5-treated group.

3.5 GCN prevents oxidative stress in M5-stimulated keratinocytes

Psoriasis is mostly caused by oxidative stress. As a result, an oxidative stress assay was implemented. The findings showed that M5 stimulated oxidative stress by increasing MDA while decreasing SOD, CAT, and GSH. Nevertheless, GCN administration dramatically reduced MDA levels while dose-dependently raising SOD, CAT, and GSH levels (Figure 3a–d). GCN as a whole prevented HaCaT cells from encountering oxidative stress.

GCN prevented M5-stimulated HaCaT cells from experiencing oxidative damage. (a–d) GCN raised SOD, CAT, and GSH levels in a dose-related way while decreasing MDA levels. ### p < 0.005 vs control; **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.05 vs M5. Differential expression testing was performed with ANOVA.

3.6 GCN induces apoptosis to prevent keratinocyte proliferation

It was also discovered that GCN caused cell death by inducing apoptosis in the cells. At dosages of 10 and 20 μM, GCN-treated cells showed considerable morphological loss, including nuclear pyknosis, apoptotic blebs, and nucleus condensate formation as demonstrated by structural phase-contrast examination, AO/EtBr, and DAPI marking (Figure 4a–c).

GCN inhibits the excessive proliferation of HaCaT cells and causes apoptosis. (a) Phase contrast microscopy visualization of morphological alterations caused by GCN. (b) AO/EB simultaneous staining shows apoptotic alterations brought on by GCN, which result in condensed chromatin and apoptotic structures. (c) Using DAPI labelling, nuclear and apoptotic alterations were observed. The fluorescence microscope was used to take the pictures at a magnification of ×200.

3.7 GCN-induced ROS production disrupts mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm)

Strong formation of ROS causes ΔΨm to be disrupted and further triggers the apoptotic process. To examine the decrease of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) by M5, JC-1 labelling was used. GCN administration over 24 h caused the fluorescence to shift into green, suggesting a reduction in ΔΨm. In contrast, J aggregates in control cells began to show orange fluorescence, whereas the JC-1 monomers, formed as a consequence of the loss of ΔΨm, showed green fluorescence (Figure 5a).

GCN induces human skin cells to experience oxidative damage and a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential. (a) The oxidation and reduction capacity of the membrane of the mitochondria due to GCN was assessed using JC1 staining. (b) DCFDA probing was used to assess the ROS generated by GCN. At a magnification of ×200, the fluorescent pictures were taken. (c) The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was then measured and displayed as a bar graph.

3.8 GCN suppresses the generation of ROS in M5-induced HaCaT cells

The impact of GCN on aggregate intracellular ROS was then assessed using DCFDA labelling in M5-stimulated cells. GCN treatment at 10 and 20 μM substantially elevated ROS levels in cells, and a phenomenon of oxidative stress occurred, as shown in Figure 5b and c. The quantities of ROS generated were measured by flow cytometry, in which groups administered GCN demonstrated a shift of the peak closer to the right side, suggesting that GCN therapy elevated the generation of ROS in HaCaT keratinocytes.

3.9 GCN causes cell cycle arrest and apoptosis

Integrating flow cytometry, the influence on the proportion of cell cycle phase scattering was studied. Sub-G1 phase arrest can be used to evaluate DNA fragmentation, which serves as a powerful indicator of the initiation of apoptosis. According to the flow cytometric evaluation used in this study, the level of GCN treatment elevated the DNA disintegration, which was identified by a distinct and sharp peak that represented the population of “Sub G1” (apoptotic cells). We further noticed that the deposits of cells in the Sub G1 peak rose more substantially at concentrations of 5 and 10 μM in comparison to control cells. The proportion of S and G2/M phases decreased in tandem with this (Figure 6a and c). PI and annexin V-FITC labelling were used in flow cytometry to assess the impact of GCN on the apoptosis of HaCaT keratinocytes. When compared to control cells, the proportion of early and late apoptosis was significantly elevated after 24 h of GCN (10 and 20 μM) treatment (Figure 6b and d).

GCN causes keratinocytes to stop developing in the sub-G1 phase, which triggers earlier apoptosis. Using flow cytometric analysis, it was discovered that GCN induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. The spatial distribution of PI staining in several cell cycle phases is shown in (a), and the histograms’ maxima correspond to these phases. (b) After being labelled with Annexin V-FITC/PI, apoptotic cells were examined using flow cytometry. (c) A graph with bars was used to show the proportion of cells used in every stage. (d) The proportion of live cells and total apoptotic cells in every category was computed. Data are displayed as mean ± standard deviation. Prism 8 was used to calculate the p-values using a one-way ANOVA; *p < 0.01; **p < 0.05.

3.10 Binding interaction of GCN with P13K and Akt

By precisely estimating a ligand’s form inside the boundaries of an attachment pocket, docking aims to evaluate the strength of attachment appropriately. To determine their potential mechanism of action, the bioactive compounds GCN were docked with specific proteins, P13K, and Akt to assess their affinity with their binding sites. Among the top-ranking targets (P13K, Akt), the Akt revealed the highest binding affinity with GCN at −7.65 kcal/mol, followed by P13K at −7.03 kcal/mol. Similarly, the Akt displayed the strongest binding affinity with GCN at −4.66 kcal/mol, followed by P13K at −4.04 kcal/mol (Figure 7a–d).

The two- and three-dimensional interactions between GCN compounds and the key target proteins P13K and Akt were analysed. Specifically, (a) and (b) interactions of GCN with P13K two- and three-dimensional structure and (c) and (d) interactions of GCN with Akt two- and three-dimensional structure were examined. These interactions were visualized using Biovia Discovery Studio, which produced 2D and 3D structural representations.

3.11 GCN downregulates PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling in M5-induced HaCaT keratinocytes

Using Western blotting, we examined the PI3K/Akt signalling systems to better understand the molecular processes behind the anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic impacts of GCN in HaCaT cells. Moreover, M5 activation in keratinocytes was found to be associated with excessive expression of PI3K, Akt, and mTOR. It was discovered that the groups (the untreated and GCN-treated groups) had comparable levels of PI3K, Akt, and mTOR expression. Furthermore, concentration reduction was influenced by the phosphorylated proteins p-PI3K, p-Akt, and p-mTOR. These findings suggested that GCN’s pro-apoptotic and anti-proliferative activities on HaCaT cells contributed to the inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling pathway. Additionally, GCN treatment led to a significant reduction in the protein expression of phosphorylation of PI3K, Akt, and mTOR, according to immunofluorescence assessment (Figure 8d–f). This suggests that GCN downregulates PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling in a transcription-independent mechanism. GCN may target PI3K/Akt to produce its effects, as evidenced by the discovery that residues in PI3K/Akt could be linked to GCN by the use of computer-simulated docking molecules (Figure 7). In M5-treated HaCaT cells, our observations suggested that GCN may target PI3K/Akt to inhibit PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling.

GCN inhibits the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling pathway in M5-stimulated HaCaT cells. (a) and (b) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated and total PI3K, Akt, and mTOR in HaCaT cells following treatment with M5 and GCN (10 and 20 µM). (c–e) Immunofluorescence staining for p-PI3K, p-Akt, and p-mTOR, respectively. DAPI stains the nuclei (blue), and phosphorylated proteins are shown in green. Bar graphs show quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity. Data represent mean ± SE. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, **p < 0.001 vs M5-treated group.

4 Discussion

Preserving good skin condition requires an effective skin barrier, and in recent decades, it has been shown that a variety of botanical medicines provide therapeutic potential for several skin barrier problems [33,34,35]. Based on prior evidence linking oxidative stress and PI3K/Akt signalling to keratinocyte dysfunction in psoriasis, we hypothesized that GCN might exert therapeutic effects by restoring redox balance, inducing apoptosis, and attenuating this key pathway. The antioxidant effect of GCN observed in our study is consistent with prior reports suggesting that isoflavones like daidzein and genistein restore redox balance and protect against oxidative damage in skin cells under inflammatory stress [36,37]. Psoriasis constitutes a common papulosquamous skin condition that can lead to cartilage pathology, psychiatric problems, and skin complaints. Development of new pharmacological agents is therefore needed to lessen the disturbance of the skin barrier linked to psoriasis. These pathophysiological disruptions were the foundation for our hypothesis that GCN could restore epidermal homeostasis by inducing apoptosis and reducing inflammatory signalling in keratinocytes. Numerous cells influence psoriasis, a complicated inflammatory skin condition [38]. One kind of resident skin cell that is capable of contributing to and being affected by psoriasis is the keratinocyte. Skin homeostasis depends on the equilibrium involving keratinocyte growth and apoptosis. Skin equilibrium is disrupted in psoriatic lesions. Apoptosis of keratinocytes is regularly found to be decreased, therefore, invariably results in hyperproliferation [39,40]. To maintain and intensify the inflammatory reaction, hyperproliferative keratinocytes generate a significant quantity of cytokines [41,42,43]. GCN may lessen the hyperproliferation of keratinocytes along with the severe inflammatory process that results from this proliferation. GCN thus becomes a possible treatment option for psoriasis.

Numerous in vitro cell culture variants that resemble psoriasis have been created recently. These efforts included using imiquimod, INF-γ, or cytokines linked to psoriasis and their combination to stimulate the HaCaT cell line. Among these is the model that uses IL-17A, IL-22, oncostatin-M, IL-1α, and TNF-α to stimulate the HaCaT culture simultaneously [44]. In addition to keratinocyte hyperproliferation and pro-inflammatory response, this M5 stimulation model also exhibits suppression of keratinocyte variation and elevated expression of biomarkers associated with psoriasis [45]. To evaluate the therapeutic relevance of GCN in this context, we used a well-established M5 cytokine stimulation model of HaCaT cells that mimics psoriatic phenotypes. A notable influence of influenced by concentration reduction in the flow of M5-stimulated cytokines into the culture medium was the hallmark of GCN’s anti-inflammatory action in this cell model. Alongside this impact, the hyperactive proliferative phenotype induced by the M5 cytokine mix was normalized, and HaCaT apoptosis increased in response to GCN. The impacts of GCN on the cell phenotype changes in the very pro-psoriatic milieu caused by M5 activation have never been examined before, as far as we are aware.

The natural substance melatonin and its metabolites cause stimulated keratinocytes to become more resistant to apoptosis [46]. This has made a pro-apoptotic approach to psoriasis treatment a viable alternative [44]. For instance, sunitinib causes keratinocytes to undergo apoptosis, which reduces imiquimod-induced inflammation that resembles psoriasis [47]. Additionally, via the fabrication of ROS, erianin demonstrated pro-apoptotic and anti-proliferative effects on keratinocytes, downregulating the Akt/mTOR signalling cascades and upregulating the JNK/c-Jun [48]. According to these studies, pro-apoptosis in psoriasis may have positive results. Previous research has emphasized the therapeutic benefit of promoting keratinocyte apoptosis in psoriasis, with compounds like erianin and sunitinib demonstrating efficacy via ROS-mediated and PI3K/Akt-dependent mechanisms [14,47]. Specifically, keratinocytes were stimulated with M5 to simulate their hyperproliferation condition. The cells were subsequently administered GCN, which resulted in a progressive dose-related reduction in cell viability, and it significantly decreased the expression of KRT6, a marker of excessive rate in psoriasis. After that, we looked into how GCN affected the induction of apoptosis. We discovered that the cells’ morphology had changed significantly, exhibiting apoptotic characteristics as nuclear disintegration and intracellular shrinkage, which were visible through phase-contrast imaging and AO/EtBr and DAPI fluorescent staining. GCN demonstrated anti-proliferative effects on HaCaT cells, according to the current study. This could be because GCN caused HaCaT cells to undergo apoptosis. These findings provide cellular-level evidence for GCN’s therapeutic potential in restoring the balance between keratinocyte proliferation and apoptosis in psoriatic conditions.

As suggested in our hypothesis, oxidative stress plays a critical role in psoriasis, and modulation of ROS may influence disease progression. There is evidence linking the aetiology of psoriasis to instabilities in the oxidation and reduction system [8]. ROS, however, has the potential to regulate chronic autoimmune inflammation [49]. Mitochondrial dysfunction and ΔΨm collapse simultaneously as a result of increased ROS production. Conversely, the buildup of intracellular ROS inhibits cell division by stopping cell cycle stages [50]. Lack of ROS may significantly worsen mannan-induced dermatitis and arthritis, whereas increased ROS production may lessen these inflammatory conditions [51,52]. The study mentioned above demonstrates how ROS can help psoriasis. GCN causes human gastric cancer cells to undergo ROS-dependent apoptosis via the NF-κB pathway [53]. However, as of yet, there is currently no convincing proof linking GCN to ROS regulation in psoriasis. Using DCFDA, JC-1, and PI stain-based cell division analysis, the impact of GCN on the redox status of HaCaT cells with M5 was measured. According to our findings, GCN administration considerably raises the ROS levels in M5-stimulated HaCaT cells. By improving regulatory T cell activity, ROS has recently been demonstrated to mitigate IMQ-induced psoriasis eczema [54]. All things considered; it was suggested that GCN-persuaded ROS in HaCaT cells could potentially be helpful in the therapy of psoriasis. Additionally, JC-1 stain illuminates orange-red and produces J aggregates when it integrates into competent mitochondria. JC-1 will continue to be J-monomers and show glowing green when ΔΨm falls. As the depolarizing process of the membranes of the mitochondria increased, we saw an influence on the concentration evaporation of ΔΨm. The molecular characteristics of apoptosis include single-strand breakage events and the creation of smaller base-pair molecules [55,56]. While the present study provides mechanistic insights into the anti-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic effects of GCN in a psoriatic keratinocyte model, one methodological limitation is the use of the MTT assay for cell viability assessment. Although newer alternatives such as CCK-8 offer improved sensitivity and lower cytotoxicity, MTT remains a widely accepted endpoint assay for fixed-time viability evaluation. The duration of MTT exposure was minimized to avoid prolonged cytotoxicity, and viability results were further validated using complementary assays, including apoptosis analysis and cell cycle profiling. Future studies may consider employing more sensitive assays to enhance translational relevance. Additionally, the impact on the proportion of cell cycle phases as a percentage was examined using flow cytometry. Indicating apoptosis due to internucleosomal DNA disintegration, GCN administration dramatically raised the percentage of the sub-G1 phase group at 10 and 20 μM in comparison to untreated controls, according to the cell cycle analysis results.

The pathophysiology of psoriasis is characterized by aberrant keratinocyte death and uncontrolled proliferation [57,58]. In the current investigation, GCN-treated HaCaT cells exhibited increased early-stage and late-stage apoptosis according to concentration. These findings showed that GCN may considerably enhance the aberrant psoriatic keratinocyte development dynamics. All things considered, the current research indicates that GCN works by strongly inducing apoptosis in M5-induced epidermal keratinocytes.

The PI3K–Akt signalling system was found to be significantly inhibited in response to ROS-induced apoptosis [59]. Using ROS-mediated suppression of the PI3K–Akt signalling process, many cytotoxic drugs have pharmacological effects [60–62]. It has been suggested that the skin cells in psoriasis lesions had hyperactivated PI3K–Akt signalling, a critical pathway that regulates survival signals [11,63–65]. This phosphorylated the resulting downstream proteins targeted FOXO and mTOR, which then in turn promoted the proliferation of keratinocytes [20,66]. According to reasonable reasoning, hindering the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway may be a potential anti-psoriatic treatment [67–69]. It is unknown how GCN affects keratinocytes’ PI3K/Akt/mTOR cascade regulation.

Given the established link between oxidative stress and PI3K/Akt signalling, we explored whether GCN could regulate this cascade in psoriatic keratinocytes. Our findings align with previous studies indicating that targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway can effectively reduce keratinocyte proliferation and cytokine release in psoriatic models, supporting its therapeutic relevance [65,70]. Thus, inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling was a suitable approach to psoriasis therapy. Our findings showed that GCN administration significantly reduced PI3K, Akt, and mTOR phosphorylation, which is in line with other studies. Similar to our findings, previous studies have shown that natural flavonoids such as apigenin and myricetin can attenuate keratinocyte hyperproliferation and inflammatory responses via downregulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway [71,72]. Thus, we deduced that GCN n could function by attaching itself to PI3K and Akt to prevent PI3K/Akt from interacting with its intended substrate DNA. All of the results showed that GCN may function in M5-stimulated HaCaT cells via regulating PI3K/Akt signalling.

In summary, this study provides the first evidence that GCN exerts its anti-psoriatic effects through a dual mechanism involving ROS-induced apoptosis and downregulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling in M5-stimulated HaCaT keratinocytes. These findings are in direct alignment with the study’s initial hypothesis and highlight the therapeutic potential of GCN for inflammatory skin disorders such as psoriasis. Although our findings demonstrate that GCN treatment increases ROS levels and downregulates key phosphorylated components of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in HaCaT cells, we acknowledge that a direct causal relationship between ROS modulation and PI3K/Akt signalling was not definitively established. Therefore, future studies employing pathway-specific rescue experiments, such as the use of LY294002, a selective PI3K inhibitor, are warranted to confirm the mechanistic link and further validate the specificity of the GCN-mediated effects on this signalling axis.

5 Conclusion

Despite the fact that existences are several psoriasis therapy options, currently, there is always a requirement for novel medications with no adverse reactions and great effectiveness. To the greatest extent of our knowledge, we are the first to demonstrate that GCN has strong anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative properties that suppress epidermal hyperplasia. GCN can, in summary, reduce the growth and inflammation of HaCaT keratinocytes brought on by M5 cytokines. ROS production and the PI3K–Akt signalling pathway’s subsequent suppression are linked to GCN-mediated HaCaT keratinocyte mortality. Our results point to GCN as a possible pharmaceutical approach to psoriasis therapy; one of its benefits is its biological inflexibility and, therefore, may make it more relevant to psoriasis despite fewer side effects.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: WS: conceptualization and original draft preparation, JC: methodology, LH: data curation and validation, and YC: supervision.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Wu P, Liu Y, Zhai H, Wu X, Liu A. Rutin alleviates psoriasis‐related inflammation in keratinocytes by regulating the JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Skin Res Technol. 2024;30(8):70011.10.1111/srt.70011Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Aquino TM, Calvarido MG, North JP. Interleukin 36 expression in psoriasis variants and other dermatologic diseases with psoriasis‐like histopathologic features. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49(2):123–32.10.1111/cup.14115Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Li J, Ren F, Yan W, Sang H. Kirenol inhibits TNF-α-induced proliferation and migration of HaCaT cells by regulating NF-κB pathway. Qual Assur Saf Crop Foods. 2021;13(4):44–53.10.15586/qas.v13i4.968Search in Google Scholar

[4] Gao J, Chen F, Fang H, Mi J, Qi Q, Yang M. Daphnetin inhibits proliferation and inflammatory response in human HaCaT keratinocytes and ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin lesion in mice. Biol Res. 2020;53(1):48.10.1186/s40659-020-00316-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Keskin S, Acikgoz E. Role of keratinocytes and immune cells as key actors in psoriasis. Int Res Rev Health Sci. 2023;1:202–14.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Albanesi C, Madonna S, Gisondi P, Girolomoni G. The interplay between keratinocytes and immune cells in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Front Immunology. 2018;9:1549.10.3389/fimmu.2018.01549Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Hawkes JE, Chan TC, Krueger JG. Psoriasis pathogenesis and the development of novel targeted immune therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(3):645–53.10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Pleńkowska J, Gabig-Cimińska M, Mozolewski P. Oxidative stress as an important contributor to the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(17):6206.10.3390/ijms21176206Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Medovic MV, Jakovljevic VL, Zivkovic VI, Jeremic NS, Jeremic JN, Bolevich SB, et al. Psoriasis between autoimmunity and oxidative stress: changes induced by different therapeutic approaches. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022(1):2249834.10.1155/2022/2249834Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Zhang D, Li Y, Heims-Waldron D, Bezzerides V, Guatimosim S, Guo Y, et al. Mitochondrial cardiomyopathy caused by elevated reactive oxygen species and impaired cardiomyocyte proliferation. Circ Res. 2018;122(1):74–87.10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311349Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Zhao Y, Xie Y, Li X, Song J, Guo M, Xian D, et al. The protective effect of proanthocyanidins on the psoriasis-like cell models via PI3K/AKT and HO-1. Redox Rep. 2022;27(1):200–11.10.1080/13510002.2022.2123841Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Huang TH, Lin CF, Alalaiwe A, Yang SC, Fang JY. Apoptotic or antiproliferative activity of natural products against keratinocytes for the treatment of psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(10):2558.10.3390/ijms20102558Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Gan L, Duan J, Zhang S, Liu X, Poorun D, Liu X, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasiform dermatitis in mice by mediating antiproliferative effects. Free Radic Res. 2019;53(3):269–80.10.1080/10715762.2018.1564920Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Mo C, Shetti D, Wei K. Erianin inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis of HaCaT cells via ROS-mediated JNK/c-Jun and AKT/mTOR signaling pathways. Molecules. 2019;24(15):2727.10.3390/molecules24152727Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Zamaraev AV, Kopeina GS, Prokhorova EA, Zhivotovsky B, Lavrik IN. Post-translational modification of caspases: the other side of apoptosis regulation. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27(5):322–39.10.1016/j.tcb.2017.01.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Chimenti MS, Sunzini F, Fiorucci L, Botti E, Fonti GL, Conigliaro P, et al. Potential role of cytochrome c and tryptase in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis pathogenesis: focus on resistance to apoptosis and oxidative stress. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2363.10.3389/fimmu.2018.02363Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Holze C, Michaudel C, Mackowiak C, Haas DA, Benda C, Hubel P. Oxeiptosis, a ROS-induced caspase-independent apoptosis-like cell-death pathway. Nat Immunol. 2018;19(2):130–40.10.1038/s41590-017-0013-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Li L, Lu H, Zhang Y, Li Q, Shi S, Liu Y. Effect of azelaic acid on psoriasis progression investigated based on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Protein kinase B (AKT) signaling pathway. Clin Cosmet Invest Dermatol. 2022;15:2523–34.10.2147/CCID.S389760Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Xie Y, Shi X, Sheng K, Han G, Li W, Zhao Q, et al. PI3K/Akt signaling transduction pathway, erythropoiesis and glycolysis in hypoxia. Mol Med Rep. 2019;19(2):783–91.10.3892/mmr.2018.9713Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Guo J, Zhang H, Lin W, Lu L, Su J, Chen X. Signaling pathways and targeted therapies for psoriasis. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):437.10.1038/s41392-023-01655-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Mercurio L, Albanesi C, Madonna S. Recent updates on the involvement of PI3K/AKT/mTOR molecular cascade in the pathogenesis of hyperproliferative skin disorders. Front Med. 2021;8:665647.10.3389/fmed.2021.665647Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Xie X, Zhang L, Li X, Liu W, Wang P, Lin Y, et al. Liangxue jiedu formula improves psoriasis and dyslipidemia comorbidity via PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Front Pharmacology. 2021;12:591608.10.3389/fphar.2021.591608Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Lv H, Liu X, Chen W, Xiao S, Ji Y, Han X, et al. Yangxue jie du fang ameliorates psoriasis by regulating vascular regression via Survivin/PI3K/Akt pathway. J Immunol Res. 2021;2021(1):4678087.10.1155/2021/4678087Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Pandey P, Khan F, Qari HA, Oves M. Rutin (Bioflavonoid) as cell signaling pathway modulator: Prospects in treatment and chemoprevention. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(11):1069.10.3390/ph14111069Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Kim BC, Lim I, Ha J. Metabolic profiling and expression analysis of key genetic factors in the biosynthetic pathways of antioxidant metabolites in mungbean sprouts. Front Plant Sci. 2023;4:1207940.10.3389/fpls.2023.1207940Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Widowati W, Prahastuti S, Ekayanti NLW, Munshy UZ, Kusuma HSW, Wibowo SHB, et al. November. Anti-inflammation assay of black soybean extract and its compounds on lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW 264.7 cell. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series. Vol. 1374, No. 1, 2019. p. 012052.10.1088/1742-6596/1374/1/012052Search in Google Scholar

[27] Luo X, Wan Z, Xu J, Gao Z, Song Z, Wang W. Hemoglobin binding and antioxidant activity in spinal cord neurons: O-methylated isoflavone glycitein as a potential small molecule. Arab J Chem. 2023;16(10):105164.10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105164Search in Google Scholar

[28] Dong N, Yang Z. Glycitein exerts neuroprotective effects in Rotenone-triggered oxidative stress and apoptotic cell death in the cellular model of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Biochim Pol. 2022;69(2):447–52.10.18388/abp.2020_5963Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Hakimi Naeini S, Rajabi-Maham H, Hosseini A, Azizi V. Neuroprotective impact of glycitin on memory impairment in a pentylenetetrazol-induced chronic epileptic rat model: insights into hippocampal histology, oxidative stress, and inflammation. J Nat Med. 2024;79:59–72.10.1007/s11418-024-01846-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Mittal P, Chowdhury A, Arya GC. An Insight into absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity screening, molecular dynamic simulation, and molecular docking of glycitein as hepatoprotective isoflavone. Asian J Pharm Res Health Care. 2024;16(2):124–37.10.4103/ajprhc.ajprhc_76_23Search in Google Scholar

[31] Xiang T, Jin W. Mechanism of glycitein in the treatment of colon cancer based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. Lifestyle Genomics. 2023;16(1):1–10.10.1159/000527124Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Zhu Y. Anticancer effects of soybean bioactive components and anti-inflammatory activities of the soybean peptide lunasin. Belgium: University in Liège; 2018.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Park KD, Kwack MH, Yoon HJ, Lee WJ. Effects of Siegesbeckia herba extract against particulate matter 10 (PM10) in skin barrier‐disrupted mouse models. Skin Res Technol. 2024;30(3):13615.10.1111/srt.13615Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Wang Q, Zhong Y, Li N, Du L, Ye R, Xie Y, et al. Combination of dimethylmethoxy chromanol and turmeric root extract synergically attenuates ultraviolet‐induced oxidative damage by increasing endogenous antioxidants in HaCaT cells. Skin Res Technol. 2023;29(12):13539.10.1111/srt.13539Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Ahmed KAA, Jabbar AA, Galali YM, Al‐Qaaneh A, Akçakavak G, Salehen NA, et al. Cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.) seeds accelerates wound healing in rats: Possible molecular mechanisms. Skin Res Technol. 2024;30(5):13727.10.1111/srt.13727Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Wojciak M, Drozdowski P, Ziemlewska A, Zagorska-Dziok M, Niziol-Lukaszewska Z, Kubrak T, et al. Ros scavenging effect of selected isoflavones in provoked oxidative stress conditions in human skin fibroblasts and keratinocytes. Molecules. 2024;29(5):955.10.3390/molecules29050955Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Bochenska K, Moskot M, Smolinska-Fijołek E, Jakobkiewicz-Banecka J, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Słominski B, et al. Impact of isoflavone genistein on psoriasis in in vivo and in vitro investigations. Sci Rep. 2024;11(1):18297.10.1038/s41598-021-97793-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Vicic M, Kastelan M, Brajac I, Sotosek V, Massari LP. Current concepts of psoriasis immunopathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11574.10.3390/ijms222111574Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Parab S, Doshi G. The experimental animal models in psoriasis research: a comprehensive review. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;117:109897.10.1016/j.intimp.2023.109897Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Khan AQ, Agha MV, Sheikhan KSA, Younis SM, Al Tamimi M, Alam M, et al. Targeting deregulated oxidative stress in skin inflammatory diseases: An update on clinical importance. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;154:113601.10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Chuo WH, Tung YT, Wu CL, Bracci NR, Chang YK, Huang HY, et al. Alantolactone suppresses proliferation and the inflammatory response in human HaCaT keratinocytes and ameliorates imiquimod-induced skin lesions in a psoriasis-like mouse model. Life. 2021;11(7):616.10.3390/life11070616Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Niehues H, Rikken G, van Vlijmen-Willems IM, Rodijk-Olthuis D, van Erp PE, Zeeuwen PL, et al. Identification of keratinocyte mitogens: implications for hyperproliferation in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. JID Innov. 2022;2(1):100066.10.1016/j.xjidi.2021.100066Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Albanesi C, Scarponi C, Giustizieri ML, Girolomoni G. Keratinocytes in inflammatory skin diseases. Curr Drug Targets-Inflammation Allergy. 2005;4(3):329–34.10.2174/1568010054022033Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Bielecka E, Zubrzycka N, Marzec K, Maksylewicz A, Sochalska M, Kulawik-Pióro A, et al. Ursolic acid formulations effectively induce apoptosis and limit inflammation in the psoriasis models in vitro. Biomedicines. 2024;12(4):732.10.3390/biomedicines12040732Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Bocheńska K, Moskot M, Gabig-Cimińska M. Use of cytokine mix-, imiquimod-, and serum-induced monoculture and lipopolysaccharide-and interferon gamma-treated co-culture to establish in vitro psoriasis-like inflammation models. Cells. 2021;10(11):2985.10.3390/cells10112985Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Kleszczyński K, Bilska B, Stegemann A, Flis DJ, Ziolkowski W, Pyza E, et al. Melatonin and its metabolites ameliorate UVR-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress in human MNT-1 melanoma cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(12):3786.10.3390/ijms19123786Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Kuang YH, Lu Y, Liu YK, Liao LQ, Zhou XC, Qin QS, et al. Topical Sunitinib ointment alleviates Psoriasis-like inflammation by inhibiting the proliferation and apoptosis of keratinocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;824:57–63.10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.01.048Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Xin W, Jiajia L, Ziming X, Dan W, Qizhi Z, Qi C, et al. Research progress on the pharmacological mechanism, in vivo metabolism and structural modification of Erianin. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;173:116295.10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116295Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Hoffmann MH, Griffiths HR. The dual role of reactive oxygen species in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases: evidence from preclinical models. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;125:62–71.10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.03.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Wang J, Luo B, Li X, Lu W, Yang J, Hu Y, et al. Inhibition of cancer growth in vitro and in vivo by a novel ROS-modulating agent with ability to eliminate stem-like cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(6):e2887.10.1038/cddis.2017.272Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Xu J, Chen H, Qian H, Wang F, Xu Y. Advances in the modulation of ROS and transdermal administration for anti-psoriatic nanotherapies. J Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20(1):448.10.1186/s12951-022-01651-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Gao J, Guo J, Nong Y, Mo W, Fang H, Mi J, et al. 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid induces human HaCaT keratinocytes apoptosis through ROS-mediated PI3K-Akt signaling pathway and ameliorates IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin lesions in mice. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2020;21:1–11.10.1186/s40360-020-00419-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Zang YQ, Feng YY, Luo YH, Zhai YQ, Ju XY, Feng YC, et al. Glycitein induces reactive oxygen species‐dependent apoptosis and G0/G1 cell cycle arrest through the MAPK/STAT3/NF‐κB pathway in human gastric cancer cells. Drug Dev Res. 2019;80(5):573–84.10.1002/ddr.21534Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Yuan X, Li N, Zhang M, Lu C, Du Z, Zhu W, et al. Taxifolin attenuates IMQ-induced murine psoriasis-like dermatitis by regulating T helper cell responses via Notch1 and JAK2/STAT3 signal pathways. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;123:109747.10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109747Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Higuchi Y. Chromosomal DNA fragmentation in apoptosis and necrosis induced by oxidative stress. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66(8):1527–35.10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00508-2Search in Google Scholar

[56] Gangadevi V, Thatikonda S, Pooladanda V, Devabattula G, Godugu C. Selenium nanoparticles produce a beneficial effect in psoriasis by reducing epidermal hyperproliferation and inflammation. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19:1–19.10.1186/s12951-021-00842-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[57] Zhou X, Chen Y, Cui L, Shi Y, Guo C. Advances in the pathogenesis of psoriasis: from keratinocyte perspective. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(1):81.10.1038/s41419-022-04523-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Wang Z, Zhou H, Zheng H, Zhou X, Shen G, Teng X, et al. Autophagy-based unconventional secretion of HMGB1 by keratinocytes plays a pivotal role in psoriatic skin inflammation. Autophagy. 2021;17(2):529–52.10.1080/15548627.2020.1725381Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Kang J, Wang Y, Guo X, He X, Liu W, Chen H, et al. N-acetylserotonin protects PC12 cells from hydrogen peroxide induced damage through ROS mediated PI3K/AKT pathway. Cell Cycle. 2022;21(21):2268–82.10.1080/15384101.2022.2092817Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Roy T, Boateng ST, Uddin MB, Banang-Mbeumi S, Yadav RK, Bock CR, et al. The PI3K-Akt-mTOR and associated signaling pathways as molecular drivers of immune-mediated inflammatory skin diseases: update on therapeutic strategy using natural and synthetic compounds. Cells. 2023;12(12):1671.10.3390/cells12121671Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[61] Kamel NM, El-Sayed SS, El-Said YA, El-Kersh DM, Hashem MM, Mohamed SS. Unlocking milk thistle’s anti-psoriatic potential in mice: Targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR and KEAP1/NRF2/NF-κB pathways to modulate inflammation and oxidative stress. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;139:112781.10.1016/j.intimp.2024.112781Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Han YH, Feng L, Lee SJ, Zhang YQ, Wang AG, Jin MH, et al. Depletion of peroxiredoxin II promotes keratinocyte apoptosis and alleviates psoriatic skin lesions via the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling axis. Cell Death Discovery. 2023;9(1):263.10.1038/s41420-023-01566-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[63] Wikan N, Hankittichai P, Thaklaewphan P, Potikanond S, Nimlamool W. Oxyresveratrol inhibits TNF-α-stimulated cell proliferation in human immortalized keratinocytes (HaCaT) by suppressing AKT activation. Pharmaceutics. 2021;14(1):63.10.3390/pharmaceutics14010063Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] Varshney P, Saini N. PI3K/AKT/mTOR activation and autophagy inhibition plays a key role in increased cholesterol during IL-17A mediated inflammatory response in psoriasis. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864(5):1795–803.10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.02.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Li C, Xiao L, Jia J, Li F, Wang X, Duan Q, et al. Cornulin is induced in psoriasis lesions and promotes keratinocyte proliferation via phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(1):71–80.10.1016/j.jid.2018.06.184Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Lembo S, Di Caprio R, Balato A, Caiazzo G, Fabbrocini G, Skroza N, et al. The increase of mTOR expression is consistent with FoxO1 decrease at gene level in acne but not in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2020;312:77–80.10.1007/s00403-019-01959-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[67] Zhang M, Zhang X. The role of PI3K/AKT/FOXO signaling in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2019;311:83–91.10.1007/s00403-018-1879-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[68] Chen G, Lv C, Nie Q, Li X, Lv Y, Liao G, et al. Essential oil of Matricaria chamomilla alleviate psoriatic-like skin inflammation by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR and p38MAPK signaling pathway. Clin Cosmet Invest Dermatol. 2024;17:59–77.10.2147/CCID.S445008Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[69] Yue L, Ailin W, Jinwei Z, Leng L, Jianan W, Li L, et al. PSORI-CM02 ameliorates psoriasis in vivo and in vitro by inducing autophagy via inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Phytomedicine. 2019;64:153054.10.1016/j.phymed.2019.153054Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[70] Niu M, Li X, Li M, Chen F, Cao H, Liu Q, et al. Curcumol attenuates hyperproliferation and inflammatory response in a psoriatic HaCaT keratinocyte model by inhibiting the PI3K-Akt pathway and ameliorates skin lesions and inflammatory status in psoriasis-like mice. Inflammopharmacology. 2025;33(4):2165–78.10.1007/s10787-025-01708-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[71] Singh VK, Sahoo D, Agrahari K, Khan A, Mukhopadhyay P, Chanda D, et al. Anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative and anti-psoriatic potential of apigenin in RAW 264.7 cells, HaCaT cells and psoriasis like dermatitis in BALB/c mice. Life Sci. 2023;328:121909.10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121909Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[72] Lee CS. Flavonoid myricetin inhibits TNF-α-stimulated production of inflammatory mediators by suppressing the Akt, mTOR and NF-κB pathways in human keratinocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;784:164–72.10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.05.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Mechanism of triptolide regulating proliferation and apoptosis of hepatoma cells by inhibiting JAK/STAT pathway

- Maslinic acid improves mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative stress and autophagy in human gastric smooth muscle cells

- Comparative analysis of inflammatory biomarkers for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: IL-6, IL-8, SAA, CRP, and PCT

- Post-pandemic insights on COVID-19 and premature ovarian insufficiency

- Proteome differences of dental stem cells between permanent and deciduous teeth by data-independent acquisition proteomics

- Optimizing a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol for fungal DNA extraction: Insights from multilocus gene amplification

- Preliminary analysis of the role of small hepatitis B surface proteins mutations in the pathogenesis of occult hepatitis B infection via the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced UPR-ERAD pathway

- Efficacy of alginate-coated gold nanoparticles against antibiotics-resistant Staphylococcus and Streptococcus pathogens of acne origins

- Battling COVID-19 leveraging nanobiotechnology: Gold and silver nanoparticle–B-escin conjugates as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis

- Impact of fracture fixation surgery on cognitive function and the gut microbiota in mice with a history of stroke

- COLEC10: A potential tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma through modulation of EMT and PI3K-AKT pathways

- High-temperature requirement serine protease A2 inhibitor UCF-101 ameliorates damaged neurons in traumatic brain-injured rats by the AMPK/NF-κB pathway

- SIK1 inhibits IL-1β-stimulated cartilage apoptosis and inflammation in vitro through the CRTC2/CREB1 signaling

- Rutin–chitooligosaccharide complex: Comprehensive evaluation of its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in vitro and in vivo

- Knockdown of Aurora kinase B alleviates high glucose-triggered trophoblast cells damage and inflammation during gestational diabetes

- Calcium-sensing receptors promoted Homer1 expression and osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- ABI3BP can inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer cells

- Changes in blood glucose and metabolism in hyperuricemia mice

- Rapid detection of the GJB2 c.235delC mutation based on CRISPR-Cas13a combined with lateral flow dipstick

- IL-11 promotes Ang II-induced autophagy inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction in atrial fibroblasts

- Short-chain fatty acid attenuates intestinal inflammation by regulation of gut microbial composition in antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pathogens in patients with diabetes complicated by community-acquired pneumonia

- NAT10 promotes radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating KPNB1-mediated PD-L1 nuclear translocation

- Phytol-mixed micelles alleviate dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish: Activation of the MMP3–OPN–MAPK pathway-mediating bone remodeling

- Association between TGF-β1 and β-catenin expression in the vaginal wall of patients with pelvic organ prolapse

- Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma involving bilateral ovaries: Case report and literature review

- Effects of de novo donor-specific Class I and II antibodies on graft outcomes after liver transplantation: A pilot cohort study

- Sleep architecture in Alzheimer’s disease continuum: The deep sleep question

- Ephedra fragilis plant extract: A groundbreaking corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environments – electrochemical, EDX, DFT, and Monte Carlo studies

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient with upper jaw and pulmonary involvement: A case report

- Inhibition of mast cell activation by Jaranol-targeted Pirin ameliorates allergic responses in mouse allergic rhinitis

- Aeromonas veronii-induced septic arthritis of the hip in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Clusterin activates the heat shock response via the PI3K/Akt pathway to protect cardiomyocytes from high-temperature-induced apoptosis

- Research progress on fecal microbiota transplantation in tumor prevention and treatment

- Low-pressure exposure influences the development of HAPE

- Stigmasterol alleviates endplate chondrocyte degeneration through inducing mitophagy by enhancing PINK1 mRNA acetylation via the ESR1/NAT10 axis

- AKAP12, mediated by transcription factor 21, inhibits cell proliferation, metastasis, and glycolysis in lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between PAX9 or MSX1 gene polymorphism and tooth agenesis risk: A meta-analysis

- A case of bloodstream infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis complicated with cervical lymph node and pulmonary tuberculosis

- p-Cymene inhibits pro-fibrotic and inflammatory mediators to prevent hepatic dysfunction

- GFPT2 promotes paclitaxel resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells via activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-36 modulates varicose vein progression via human vascular smooth muscle cell Notch signaling

- RTA-408 attenuates the hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in mice possibly by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway

- Decreased serum TIMP4 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Sirt1 protects lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 signaling pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells

- Sodium butyrate aids brain injury repair in neonatal rats

- Interaction of MTHFR polymorphism with PAX1 methylation in cervical cancer

- Convallatoxin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis of glioma cells via regulating JAK/STAT3 pathway

- The effect of the PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine, on the replication of influenza A virus, and segment 8 mRNA splicing

- Effects of Ire1 gene on virulence and pathogenicity of Candida albicans

- Small cell lung cancer with small intestinal metastasis: Case report and literature review

- GRB14: A prognostic biomarker driving tumor progression in gastric cancer through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by interacting with COBLL1

- 15-Lipoxygenase-2 deficiency induces foam cell formation that can be restored by salidroside through the inhibition of arachidonic acid effects

- FTO alleviated the diabetic nephropathy progression by regulating the N6-methyladenosine levels of DACT1

- Clinical relevance of inflammatory markers in the evaluation of severity of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study

- Zinc valproic acid complex promotes osteoblast differentiation and exhibits anti-osteoporotic potential

- Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in the bronchial cavity: A case report

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid improves the detection of pulmonary infection

- Uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor with extensive rhabdoid differentiation: A case report

- Genomic analysis of a novel ST11(PR34365) Clostridioides difficile strain isolated from the human fecal of a CDI patient in Guizhou, China

- Effects of tiered cardiac rehabilitation on CRP, TNF-α, and physical endurance in older adults with coronary heart disease

- Changes in T-lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with colorectal cancer before and after acupoint catgut embedding acupuncture observation

- Modulating the tumor microenvironment: The role of traditional Chinese medicine in improving lung cancer treatment

- Alterations of metabolites related to microbiota–gut–brain axis in plasma of colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, and lung cancer patients

- Research on individualized drug sensitivity detection technology based on bio-3D printing technology for precision treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- CEBPB promotes ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by stimulating tumor growth and activating the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway

- Oncolytic bacteria: A revolutionary approach to cancer therapy

- A de novo meningioma with rapid growth: A possible malignancy imposter?

- Diagnosis of secondary tuberculosis infection in an asymptomatic elderly with cancer using next-generation sequencing: Case report

- Hesperidin and its zinc(ii) complex enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Research progress on the regulation of autophagy in cardiovascular diseases by chemokines

- Anti-arthritic, immunomodulatory, and inflammatory regulation by the benzimidazole derivative BMZ-AD: Insights from an FCA-induced rat model

- Immunoassay for pyruvate kinase M1/2 as an Alzheimer’s biomarker in CSF

- The role of HDAC11 in age-related hearing loss: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications

- Evaluation and application analysis of animal models of PIPNP based on data mining

- Therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis by targeting pyroptosis

- Fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Ruellia tuberosa leaf extract induces apoptosis through P53 and STAT3 signalling pathways in prostate cancer cells

- Haplo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunoradiotherapy for severe aplastic anemia complicated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report

- Modulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway by Erianin: A novel approach to reduce psoriasiform inflammation and inflammatory signaling

- The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and clinical pathological features in breast cancer patients

- Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights

- BAP1 complexes with YY1 and RBBP7 and its downstream targets in ccRCC cells

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome with elevated IgG4 and T-cell clonality: A report of two cases

- Electroacupuncture alleviates sciatic nerve injury in sciatica rats by regulating BDNF and NGF levels, myelin sheath degradation, and autophagy

- Polydatin prevents cholesterol gallstone formation by regulating cholesterol metabolism via PPAR-γ signaling

- RNF144A and RNF144B: Important molecules for health

- Analysis of the detection rate and related factors of thyroid nodules in the healthy population

- Artesunate inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion through OGA-mediated O-GlcNAcylation of ZEB1

- Endovascular management of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: Case report and review of the literature

- Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis

- SATB2 promotes humeral fracture healing in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Overexpression of the ferroptosis-related gene, NFS1, corresponds to gastric cancer growth and tumor immune infiltration

- Understanding risk factors and prognosis in diabetic foot ulcers

- Atractylenolide I alleviates the experimental allergic response in mice by suppressing TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 signalling

- FBXO31 inhibits the stemness characteristics of CD147 (+) melanoma stem cells

- Immune molecule diagnostics in colorectal cancer: CCL2 and CXCL11

- Inhibiting CXCR6 promotes senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells with limited proinflammatory SASP to attenuate hepatic fibrosis

- Cadmium toxicity, health risk and its remediation using low-cost biochar adsorbents

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis with headache as the first presentation: A case report

- Solitary pulmonary metastasis with cystic airspaces in colon cancer: A rare case report

- RUNX1 promotes denervation-induced muscle atrophy by activating the JUNB/NF-κB pathway and driving M1 macrophage polarization

- Morphometric analysis and immunobiological investigation of Indigofera oblongifolia on the infected lung with Plasmodium chabaudi

- The NuA4/TIP60 histone-modifying complex and Hr78 modulate the Lobe2 mutant eye phenotype

- Experimental study on salmon demineralized bone matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: In vitro and in vivo study

- A case of IgA nephropathy treated with a combination of telitacicept and half-dose glucocorticoids

- Analgesic and toxicological evaluation of cannabidiol-rich Moroccan Cannabis sativa L. (Khardala variety) extract: Evidence from an in vivo and in silico study

- Wound healing and signaling pathways

- Combination of immunotherapy and whole-brain radiotherapy on prognosis of patients with multiple brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study

- To explore the relationship between endometrial hyperemia and polycystic ovary syndrome

- Research progress on the impact of curcumin on immune responses in breast cancer

- Biogenic Cu/Ni nanotherapeutics from Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl seeds for the treatment of lung cancer

- Dapagliflozin attenuates atrial fibrosis via the HMGB1/RAGE pathway in atrial fibrillation rats

- Glycitein alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in keratinocytes via ROS-associated PI3K–Akt signalling pathway

- ADH5 inhibits proliferation but promotes EMT in non-small cell lung cancer cell through activating Smad2/Smad3

- Apoptotic efficacies of AgNPs formulated by Syzygium aromaticum leaf extract on 32D-FLT3-ITD human leukemia cell line with PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Novel cuproptosis-related genes C1QBP and PFKP identified as prognostic and therapeutic targets in lung adenocarcinoma

- Bee venom promotes exosome secretion and alters miRNA cargo in T cells

- Treatment of pure red cell aplasia in a chronic kidney disease patient with roxadustat: A case report

- Comparative bioinformatics analysis of the Wnt pathway in breast cancer: Selection of novel biomarker panels associated with ER status

- Kynurenine facilitates renal cell carcinoma progression by suppressing M2 macrophage pyroptosis through inhibition of CASP1 cleavage

- RFX5 promotes the growth, motility, and inhibits apoptosis of gastric adenocarcinoma cells through the SIRT1/AMPK axis

- ALKBH5 exacerbates early cardiac damage after radiotherapy for breast cancer via m6A demethylation of TLR4

- Phytochemicals of Roman chamomile: Antioxidant, anti-aging, and whitening activities of distillation residues

- Circadian gene Cry1 inhibits the tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma by the BAX/BCL2-mediated apoptosis pathway

- The TNFR-RIPK1/RIPK3 signalling pathway mediates the effect of lanthanum on necroptosis of nerve cells

- Longitudinal monitoring of autoantibody dynamics in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing surgery

- The potential role of rutin, a flavonoid, in the management of cancer through modulation of cell signaling pathways

- Construction of pectinase gene engineering microbe and its application in tobacco sheets

- Construction of a microbial abundance prognostic scoring model based on intratumoral microbial data for predicting the prognosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma

- Sepsis complicated by haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis triggered by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and human herpesvirus 8 in an immunocompromised elderly patient: A case report

- Sarcopenia in liver transplantation: A comprehensive bibliometric study of current research trends and future directions

- Advances in cancer immunotherapy and future directions in personalized medicine

- Can coronavirus disease 2019 affect male fertility or cause spontaneous abortion? A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis

- Heat stroke associated with novel leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor gene variant in a Chinese infant

- PSME2 exacerbates ulcerative colitis by disrupting intestinal barrier function and promoting autophagy-dependent inflammation

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state with severe hypernatremia coexisting with central diabetes insipidus: A case report and literature review

- Efficacy and mechanism of escin in improving the tissue microenvironment of blood vessel walls via anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects: Implications for clinical practice

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Clinicopathological analysis of three patients and literature review

- Genetic variants in VWF exon 26 and their implications for type 1 Von Willebrand disease in a Saudi Arabian population

- Lipoxin A4 improves myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through the Notch1-Nrf2 signaling pathway

- High levels of EPHB2 expression predict a poor prognosis and promote tumor progression in endometrial cancer