Abstract

Iron is an essential component for the body, but it is also a major cause for the development of many diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and autoimmune diseases. It has been suggested that a diet rich in meat products, especially red meat and highly processed products, constitute a nutritional model that increases the risk of developing. In this context, it is indicated that people on an elimination diet (vegetarians and vegans) may be at risk of deficiencies in iron, because this micronutrient is found mainly in foods of animal origin and has lower bioavailability in plant foods. This article reviews the knowledge on the use of leghemoglobin and plant ferritin as sources of iron and discusses their potential for use in vegetarian and vegan diets.

1 Introduction

The type of diet is one of the main factors affecting human health. It is indicated that a diet rich in meat products, especially red meat and highly processed products, processed products, increases the risk of developing lifestyle diseases such as circulatory system diseases, heart diseases, and cancer. A diet rich in plant products is considered an example of a health-promoting diet. It is estimated that switching to plant-based diets globally could reduce the risk of premature death from non-communicable diseases by 18–21% and additionally reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 54–87% [1].

In contrast, vegetarians and vegans may be at risk of deficiencies in vitamin B12, vitamin D, iron, zinc, and calcium deficits because these micronutrients are found mainly of animal sources or have lower bioavailability in plant foods. Although plant-based diets are described as healthier for the body’s health, they should be balanced to provide the appropriate amount of nutrients needed for a healthy life every day [2,3,4,5,6].

One of the most common deficiencies occurring among human on plant-based diet is iron deficiency (ID) in serum. The reason for such a problem originated mainly in the lower bioavailability of iron from plant sources and the presence of inhibitors of iron absorption in plant-based food. Some plant-based diets are significantly restricted for the application of ingredients or technological processes, including materials from animals in food manufacturing. All those factors, as well as progress in plant-based food technologies, contribute to the development of knowledge about the possibilities of enriching the human diet with alternative iron sources in populations at risk of ID due to the exclusion of animal-based food from the diet.

The purpose of this review is to present recent knowledge about ID and its connection with plant-based diets and information about alternative iron sources such as leghemoglobin (LegH) and (plant)ferritin as a substance that are considered promising in plant-based food fortification.

2 Iron in the diet and its impact on human health

Iron is classified as a microelement that is necessary for the proper functioning of human cells. In the human body, it is a basic component involved in the transport and binding of oxygen and a cofactor of many enzymes, but it also plays an important role in the body’s immune processes. About 2/3 of the human body’s iron is found in hemoglobin, 1/4 is in the liver in the form of ferritin (FT) and hemosiderin, with the remaining sources scattered in the cytoplasm of muscle cells in the form of myoglobin [7,8].

ID is a burden contributing to the development of diseases in a significant part of the population, and the most common disease associated with ID is anemia (iron deficiency anemia, IDA). According to statistical data, the burden of IDA concerns up to 1.2 billion of the population [8]. Women (in the premenopausal period and pregnant women), but also infants and children up to 5 years of age and teenagers, are particularly susceptible to the occurrence and consequences of anemia [8]. The occurrence of ID and IDA also depends on social and demographic factors such as race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religion, eating habits, and diet [9,10]. Due to the high risk of IDA, preventing anemia is one of the tasks of the WHO, which aims to reduce its incidence among women by 50% [11].

ID may cause symptoms in the presence or absence of anemia or may be asymptomatic. Typical symptoms include fatigue, drowsiness, decreased concentration, dizziness, tinnitus, and pallor. In susceptible individuals, ID predisposes to restless legs syndrome [12]. Other symptoms include alopecia, dry hair or skin, and glossitis [13]. ID and anemia can also exacerbate symptoms and worsen prognosis in conditions including heart failure and coronary artery disease [14]. Preoperative anemia increases the risk of blood transfusion and is correlated with a negative course of recovery and postoperative mortality [15]. Even asymptomatic anemia has negative consequences, including impaired physical fitness, neurocognitive development of the child, and the course of pregnancy [16].

However, it is not only ID that is harmful to our health. The most frequently cited causes of iron overload (IO) are red blood cell transfusion, increased gastrointestinal iron absorption, repeated whole blood transfusions, excessive iron supplementation, chronic hepatitis, or hereditary hemochromatosis [17]. The toxicity of excessive iron content leads to serious side effects such as cardiac dysfunction, including arrhythmia and cardiomyopathy [18], liver cirrhosis, liver cancer, hepatitis [19], delayed puberty, impotence, infertility [20], metabolic disorders [21], and development of neurodegenerative diseases, e.g. Alzheimer’s [22].

The primary source of iron is the diet. For a healthy body, without metabolic disorders, achieving an appropriately balanced diet is not difficult in developed countries; therefore, ID in such populations, apart from particularly susceptible groups (children under 5 years of age, pregnant women), is usually the result of metabolic disorders, blood loss (e.g. due to heavy menstruation), as well as the ingestion of a diet with a limited supply of nutrients (e.g. plant-based diets) [23].

Iron in the human diet occurs in two forms: heme iron in organic compounds and non-heme iron occurring in inorganic compounds such as Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions. The different forms of iron found in food differ in their bioavailability. The absorption of heme iron reaches 15–35% and is only slightly dependent on the presence of inhibitors in the consumed food [24]. Heme iron has the highest bioavailability, and its best sources are meat, fish, and seafood. In a diet including products of mixed origin (plant and animal), heme iron usually constitutes approximately 10–15% of the daily iron intake [25]. The best sources of non-heme iron are seeds, grains, nuts, and dark green parts of leafy vegetables [25]. Non-heme iron occurs in various chemical forms (Fe2+ and Fe3+), which significantly affects its absorption, typically reaching levels of 2–20%, with the ferrous ion (Fe2+) being the form with the highest absorption [26]. The forms of iron present in food are low-molecular compounds, such as citrate, phosphate, phytate, oxalate, and iron hydroxide, and high-molecular compounds, such as FT (a protein that combines thousands of iron ions in the mineral core). A specific organic compound that is a source of iron in the diet of infants is lactoferrin (iron transport protein), present in breast milk and infant formulas [27,28].

Iron absorption is strongly dependent on the level of iron in the body. In case of its deficiency, iron absorption usually increases 10-fold, and this applies to both heme and non-heme iron. Moreover, the absorption of non-heme iron is influenced by both its inhibitors (phytic acid, polyphenols, calcium, milk and egg proteins, and albumins) and enhancers such as ascorbic acid and muscle tissue proteins [29]. The absorption of iron is enhanced by MFP (meat, fish, poultry) protein factors, which are present in food of animal origin such as meat, fish, and poultry products. The role of MFP factors in improving the absorption of iron supplied with food of plant origin has been demonstrated. The use of poultry, beef, or fish in the diet improves the absorption of non-heme iron two to three times compared to the absorption from a meal containing the protein equivalent of egg white albumin [30,31,32].

3 Iron in plant-based diets

Nowadays, diets that limit or completely exclude the consumption of meat products are becoming more and more popular. They are most often used by young people, especially women. Their motivation to limit the consumption of meat products is health (reducing the risk of lifestyle diseases), ethics, and the environment. A diet takes different forms depending on the type of products that are not consumed (Table 1). The lightest form is flexitarianizm, which involves limiting meat consumption to a minimum [33].

Types of plant–based diets; the food categories included in each type of diet have been stated in table

| Fruits | Vegetables/grains/legumes | Dairy | Eggs | Meat/poultry | Fish | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetarian | P | P | P | P | A | A |

| Lacto-ovo vegetarian | P | P | P | P | A | A |

| Lacto vegetarian | P | P | P | A | A | A |

| Ovo vegetarian | P | P | A | P | A | A |

| Vegan | P | P | A | A | A | A |

| Flexitarian | P | P | P | P | P | P |

| Pesco-vegetarian | P | P | P | P | A | P |

P – present, A – absent.

There is a variety of diets that eliminate animal products to different extents. Vegetarians are people who do not eat meat, including poultry, fish, seafood, and products containing ingredients derived from the processing of these raw materials. Lacto-ovo vegetarians exclude the consumption of meat, but their diet includes milk, eggs, and products derived from their processing. Lacto-vegetarians also exclude the consumption of eggs, unlike vegetarians, whose diet does not include milk and dairy products. Among all these variants of the vegetarian diet, intermediate variants are described resulting from different scopes of exclusion of animal products (e.g. semi-vegetarianism/flexitarian, pollotarian, pescatarian). The vegan diet does not include any products obtained from raw materials of animal origin [34,35,36]. The use of vegetarian and vegan diets (due to the richness of phytocomponents with health-promoting effects) is believed to provide attractive health-promoting properties, such as the prevention of cancer or ischemic heart disease, a beneficial effect on the reduction of BMI, low levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and glucose [37,38].

According to studies comparing the iron content in the diet of vegetarians, lacto-vegetarians, and non-vegetarians (both among the Seventh-day Adventists population) and the diet of people consuming meat products, the type of diet and the extent to which meat and meat products are eliminated from the diet have a minimal impact on the supply of iron in the diet of the Western population. The average three-day supply of iron in the compared diet variants was 18.0 ± 1.6, 14.2 ± 0.8, 14.4 ± 0.9, and 16.1 ± 1.1 mg Fe/day, respectively [39]. The intake has been computed by the nutrient data bank providing Fe content. In contrast, assessing iron supply solely on the basis of the total Fe content in the diet is not an accurate way to assess the potential of meals to meet nutritional needs for this element. This is due to the different forms and bioavailability of iron depending on the type of food. Therefore, although a vegetarian diet provides similar amounts of iron to a diet including animal products, there are significant differences in the availability of iron for absorption, resulting from the different forms of iron (heme and non-heme) and the amount and profile of the supplied inhibitors and absorption enhancers [40,41]. The main sources of phytic acid, which is an inhibitor of iron absorption, are whole-grain products, legumes, lentils, and nuts [42,43]. Polyphenols, also limiting iron absorption, are additionally supplied with coffee, tea, red wine, and spices [25,44]. Although these factors may suggest a lower degree of meeting iron needs among people on a diet eliminating animal products, the data on this subject are not clear, and future research should include not only intake of Fe but serum analysis also.

The parameter considered appropriate to assess the degree to which the body’s iron needs are met is the analysis of serum iron. Other indicators include hemoglobin, hematocrit, and iron-binding capacity. Regardless of the selected indicators, there are no clear results on the impact of diet on the degree to which the body’s iron needs are met. The described cross-sectional studies often compare iron/FT content in people on an elimination diet and people who include meat in their diet. Some of these comparisons do not indicate statistically significant differences [41,45,46,47]. Others report significantly lower iron stores in people on a vegetarian diet [48,49,50,51]. There are also reports of a higher incidence of ID and IDA among these people, especially in women [48,52,53].

4 New sources of iron for use in plant-based diets

One of the options for supplementing iron in people on a diet eliminating animal products is the use of supplementation. However, no direct data indicates the achievement of long-term beneficial effects from such an action. In this context, there is information suggesting that iron supplementation limits the efficiency of iron absorption from meals, requires long-term use to improve the FT content in serum (observations conducted among women with low iron resources), and may additionally leads to an increase in oxidative stress due to the presence of unabsorbed iron ions in the intestine [54,55,56]. Therefore, it is suggested that a good solution is to enrich food with easily digestible iron and thus meet the demand for this element. Among the sources of iron, food producers most often use iron salts, which, however, can cause negative effects on the organism, e.g. by causing and exacerbating stomach inflammation [54,55]. Therefore, new sources of plant iron are being sought, which will be devoid of negative implications, but with high bioavailability. LegH and FT are described as the most promising.

4.1 Leghemoglobin

LegH is an oxygen-binding phytoglobin with a molecular weight of 16 kDa, first identified in the root nodules of legumes [56]. This symbiotic hemoglobin is composed of protoporphyrin IX (a heme group) and globin (a single peptide). The amino acid sequence of globin depends on the species of legume, while the heme group remains unchanged, regardless of the plant species and bacterial strain. The complex mixture of heme proteins contains two monomeric main components (LegH-a and c) and two less well-characterized minor components (LegH-b and d). Studies using ion exchange chromatography have shown that both LegH-c and LegH-d are mixtures of at least two heme proteins. The ratio of the amounts of various components of LegH depends on the age of the nodules. In the case of young root nodules, a characteristic higher content of LegH-c compared to LegH-a was observed. LegH components can also be classified, using electrophoresis, into fast-moving components (LegH-F), such as LegH-c1 and LegH-c2, and slower-moving components (LegH-S), such as LegH-a [57,58].

This hemoprotein typically consists of seven or eight helical segments A–H, with protoheme (an iron porphyrin molecule) inserted between helices E and F. Between the heme and the E-helix, there is a space called the distal pocket, which allows oxygen to approach and coordinate in a manner reversible with heme iron [59]. Helix D is present only in the β chain of hemoglobin and myoglobin; it is not present in the distal heme pocket. This is replaced by a longer interhelical CD region connecting to the critical E helix, ensuring helix mobility. Research indicates the same structure of the animal and plant hemoglobin gene, which during evolution underwent genetic rearrangement through the loss of an intron and led to changes in the amino acid sequence in approximately 80% of positions [57].

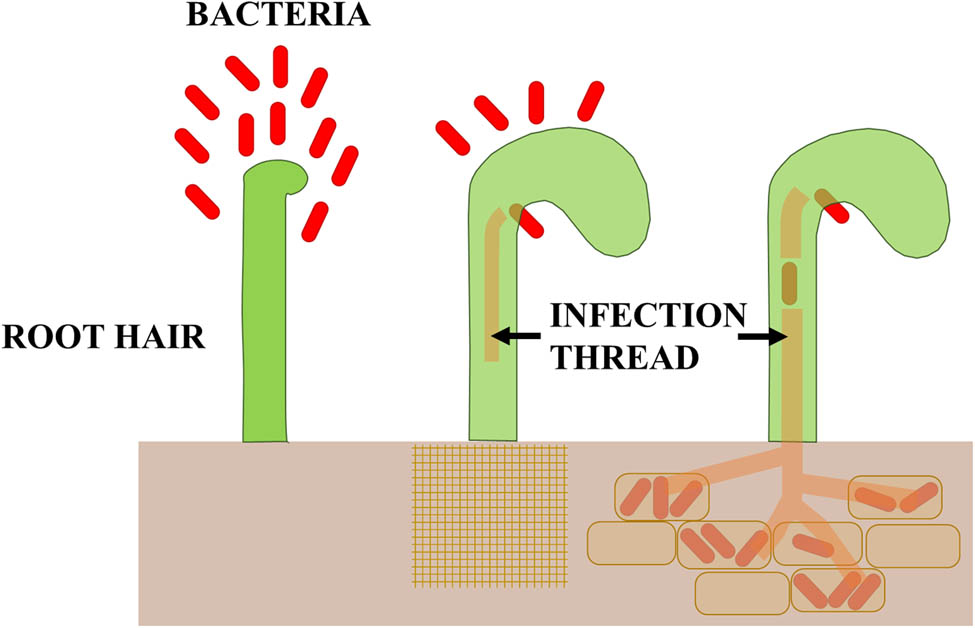

The production of LegH is possible through symbiosis between the bacteroid and the plant (Figure 1). Its synthesis begins immediately after nodulation initiation and just before nitrogenase synthesis. Symbiosis occurs in root nodules resulting from bacterial infections, and a meristem is formed in the root cortex. It divides to give rise to two types of cells – cells filled with bacteroids and smaller interstitial cells devoid of bacteroids. As a result of this division, in mature legume nodules, a structural division into three separate zones can be observed – the outer cortex, the central zone, and the inner cortex [57,60]. Endodermis – the cellular layer separating the outer and inner cortex – acts as a physical barrier to oxygen diffusion. There are no free bacteroids in the cell cytoplasm; after infection and throughout the entire period of symbiosis, bacteroids are surrounded by a symbiosomal membrane (peri-bacteroid) [61].

Scheme of overgrowing the roots of legume plants by bacteria of the Rhizobium genus.

Characteristic properties of LegH include the ability to bind oxygen, similar to human hemoglobin. It binds oxygen in the nodule and establishes sufficient oxygen levels for rhizobia to respire and create ATP. It is responsible for providing bacteria with a sufficient amount of oxygen and protecting nitrogenase – an enzyme that catalyzes the environmental conversion of nitrogen to ammonia – from denaturation. Nitrogenase is an enzyme that is particularly sensitive to oxygen and is irreversibly deactivated when exposed to atmospheric oxygen. Oxygen diffusion through the dense nodule tissue would not be sufficient to meet ATP demand in the absence of LegH. For LegH to release oxygen into the bacteroid respiratory chain, its oxygen affinity must be approximately ten times lower than the oxygen affinity of bacteroid oxidase. This allows oxygen to flow through the tissue and limits the possibility of free oxygen accumulating on the surface of the bacteroid. LegH gives the nodules, which effectively fix nitrogen, their pink color. The presence of LegH in the root nodules of legumes is therefore necessary for the proper functioning of nitrogenase (Figure 2). It takes up as much as 40% of the total share of soluble proteins in papillae [57,62,63]. In addition, LegH may also influence plant metabolism, and some studies suggest that it may influence plant defense responses against pathogens. LegH is completely absent in the intercellular spaces or above other cellular organelles. The concentration of LegH in the root nodules of legumes ranges from 1–5 × 104 M [57,64].

![Figure 2

Participation of LegH in the regulation of bacterial gene expression and nitrogenase functioning (prepared based on [65], available under the CC-BY license). (a) Diagram of the root nodule structure with distinction of the zones formed during the nodule development: 1 – nodule meristem, 2 – infection zone, 3 – intermediate zone, 4 – nitrogen fixation zone, 5 – aging zone. (b) Simplified model of the regulation of some bacterial genes as a result of lowering the oxygen concentration in the infection zone. LegH genes are expressed in the infection, intermediate, and nitrogen fixation zones. LegH transfers oxygen to bacterial oxidases, and these, in turn, to the respiratory chain, enabling the production of ATP in conditions of low oxygen concentration.](/document/doi/10.1515/biol-2022-0805/asset/graphic/j_biol-2022-0805_fig_002.jpg)

Participation of LegH in the regulation of bacterial gene expression and nitrogenase functioning (prepared based on [65], available under the CC-BY license). (a) Diagram of the root nodule structure with distinction of the zones formed during the nodule development: 1 – nodule meristem, 2 – infection zone, 3 – intermediate zone, 4 – nitrogen fixation zone, 5 – aging zone. (b) Simplified model of the regulation of some bacterial genes as a result of lowering the oxygen concentration in the infection zone. LegH genes are expressed in the infection, intermediate, and nitrogen fixation zones. LegH transfers oxygen to bacterial oxidases, and these, in turn, to the respiratory chain, enabling the production of ATP in conditions of low oxygen concentration.

The process of isolating LegH varies depending on the host plant species. The two most commonly used legumes for the production of LegH are soybeans and lupine. The first isolation methods were described already in 1980 [66]. The possibilities of using LegH in the diet are mainly related to its ability to bind oxygen. LegH has great potential as an extremely attractive component of vegetarian and vegan diets. It can be successfully used as an ingredient imitating the sensory properties of meat (texture, taste, smell) despite its plant origin, providing essential nutrients (mainly amino acids, saturated fats, sodium, and iron). The bioavailability of LegH preparations has been studied in animal models and in vitro Caco-2 cell models with different results. However, the Caco-2 model seems to be more reliable in studying the rate of bioavailability in humans. The study of Proulx and Reddy describing the effects of food supplementation with LegH indicates that the bioavailability of hemoglobin from soy root nodules is similar to that of heme iron from animal sources. When tested in the Caco-2 model, the relative biological values exhibited for LegH 27 ± 6% and bovine hemoglobin 33 ± 10% higher bioavailability than FeSO4 (P < 0.05) and with no difference between them [67]. However, future work is needed to confirm the potential ability of soy LegH in plant-based meat alternatives to contribute to iron status in vivo in humans [68]. Introducing legumes containing LegH into the diet can contribute to sustainable development, because growing plants is ecological and has less impact on the environment compared to animal breeding [69,70].

However, the production of LegH for industrial purposes is a process based on genetically modified organisms. The genes responsible for the production of LegH are introduced into plants that do not naturally contain this protein. In July 2016, a Californian company developing substitutes for meat products – Impossible Foods – introduced its flagship product – a vegan alternative to a beef hamburger [71]. In addition to improving taste and providing aroma, soy LegH protein is an excellent source of iron, similar to myoglobin, which is a source of iron in meat [72]. Currently, heme iron in the human diet is almost exclusively iron of animal origin. For the production of meatless burgers, heme is produced by a safe recombinant method using Pichia pastoris yeast genetically modified with the soy LegH gene and using a fermentation process. The yeast releases the globin; the next step is filtration until a minimum of 80% purity of LegH is obtained. It is a routine recombinant method used to produce enzymes or even drugs [73,74].

A number of studies were carried out to assess the safety of LegH obtained using in silico, in vivo, and in vitro methods. Some of them are presented in Table 2. Studies have confirmed that LegH produced in yeast has little or no allergenic potential and does not show mutagenicity in the bacterial reverse mutation test (Ames test) or clastogenicity in the chromosome aberration test under tested in vitro conditions [75]. To exclude potential systemic toxicity, a 28-day in vivo study was also performed introducing prepared LegH into the rat diet, and no negative impact on the health of females or the estrus cycle was observed. The results of all tests performed suggest that the produced protein does not raise toxicological concerns under the tested conditions. This preparation is safe and suitable for human consumption as an ingredient of a simulated meat product, with a maximum soy protein content of 0.8% [75]. The company producing the mentioned burger asked the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for permission to use recombinant soy LegH as an analogue of animal hemoglobin in its products [71]. The FDA granted approval in 2021, and although challenged, the consent was upheld by a decision of the federal appellate court in San Francisco [76,77]. This product has been recognized as a safe food additive (GRAS). Research has confirmed that this vegan alternative to ground beef is a better source of protein, is lower in total fat than a similarly sized beef cutlet, and contains no cholesterol. The developed preparation is produced using Pichia pastoris bacteria, whose genome has a gene encoding a given protein incorporated into it, which is why it is classified as genetically modified food in food law. Therefore, the introduction of food with the addition of LegH is not simple in legal terms, especially in European Union countries. Many countries restrict the introduction of genetically modified foods, and European Union regulations are considered the most restrictive [78]. Therefore, the introduction of LegH into wider production seems highly doubtful, which is why research is ongoing on other sources of iron.

Review of selected studies on the allergological and/or toxicological safety of LegH

| Aim of research | Methods | Conclusions | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| This article focuses on the safety, by means of allergenic potential of Pichia-derived 83 proteins, from a new simplified manufacturing process to produce LegH Prep |

|

A weight-of-evidence approach was used to determine the allergenicity of LegH Prep. No significant matches were found except for the highly evolutionarily conserved GAPDH protein. Results showed that there is an unlikely risk of cross-reactivity between LegH Prep and GAPDH | [72] |

| To check whether food containing recombinant soy LegH produced by Pichia sp. is allergenic or toxic |

|

The results demonstrate that foods containing recombinant soy LegH produced in Pichia sp. are unlikely to present an unacceptable risk of allergenicity or toxicity to consumers | [79] |

| Safety evaluation of soy LegH protein preparation derived from Pichia pastoris, intended for use as a flavor catalyst in plant-based meat |

|

LegH Prep was nonmutagenic and nonclastogenic in each test. There were no mortalities associated with the administration of LegH Prep in a 28-day dietary study in male and female Sprague Dawley rats. Collectively, the results of the studies presented raise no issues of toxicological concern with regard to LegH Prep under the conditions tested | [75] |

| Design of P. pastoris for highly secretory production of LegH without exogenous addition of expensive precursors | CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome editing methods | Increased the secretion of LegH by more than 83-fold, whose maximal LegH titer and heme binding ratio reached as high as 3.5 g/L and 93%, respectively. This represents the highest secretory production of heme-containing proteins ever reported | [80] |

| Determining the regulation of ligand binding imparted by the proximal and distal heme pockets | Spectroscopic and kinetic characterization of wild-type and mutant LegH | The LegH proximal heme pocket exhibits a stronger bond with bound oxygen compared to myoglobin. While myoglobin relies on additional distal pocket stabilization to lower oxygen dissociation, LegH avoids distal oxygen stabilization to prevent an excessively low dissociation rate constant. These differences in regulatory mechanisms for oxygen binding and dissociation demonstrate how LegH and myoglobin, despite their structural similarities, employ distinct strategies to control their rate constants and oxygen affinities. These strategies are tailored to meet the specific demands of their respective biological environments, allowing them to effectively facilitate oxygen diffusion | [81] |

4.2 (Plant)ferritin

FT exists in most plants and animals as a molecule consisting of 24 polypeptide subunits – FT heavy chain (FTH) or light type (FT light chain [FTL]). FT, consisting of 36 subunits, is also found in cardiac and skeletal muscle cells. Depending on the origin, the size of a single subunit is approximately 20 kDa (mammals) to 25–28 kDa (plants). In bacteria, FT exists as a molecule consisting of 12 subunits. The structure of the FT molecule is a protein shell filled with an iron core [82]. Plant FT is similar to the animal variety in both function and structure [83].

FT is a protein that stores Fe3+ iron ions in the cell. The FTH subunit exhibits iron oxidase activity, oxidizing it from the Fe2+ form to Fe3+. The FTL subunit, thanks to its nucleation property, leads to the formation of an iron core. In the case of animals, FT in cells of organs involved in iron storage processes (e.g. liver, spleen) is more rich in FTL subunits [84]. FT in cells maintains iron concentration at the level necessary for proper functioning (10−3–10−5 M). A single FT molecule has the ability to accumulate up to 10−2 M of iron. Typically, the iron content in a single molecule is less than 3,000 atoms [85]. Most cellular iron is stored in FT. In addition to its iron storage function, FT is also crucial in the processes that protect the cell against excess iron. Excessive amounts of iron at the cellular level may lead to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative damage; FT prevents such effects by binding free iron [86]. This protein also has a function in cell detoxification by directly participating in the regulation of cellular concentrations of transition metals and other metal ions apart from iron. In this way, FT limits the formation of ROS and alleviates their impact on cellular structures and macromolecules [87]. FT also plays an important role in defense against pathogen attacks. Overexpression of FT as a result of biotic stress causes complexation of iron circulating in the host body – iron becomes unavailable for the life processes of pathogens [88–90]. There is also a correlation between the FT content and the occurrence of autoimmune diseases and inflammatory conditions. Serum FT levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis may be within the normal range, but synovial fluid and synovial cells have been shown to have elevated FT levels [91]. FT levels decrease during therapy, and FT levels help guide physicians in using glucocorticoids [92]. It has been shown that a high serum FT level is an independent risk factor for severe COVID-19 infection. Assessment of serum FT levels during hospitalization may be helpful in identifying people at high risk of severe COVID-19 disease [93,94].

FT of plant origin is considered important for assessing the possibility of its use as a source of iron in the diet [95–99]. FT from legumes is particularly popular as a source of iron [100]. The bioavailability of a protein of this origin is comparable to FeSO4 [87,101]. It is assumed that the absorption of iron from FT takes place by a mechanism independent of the process of iron absorption from FeSO4. Studies labeled 59Fe derived from FT demonstrated the bioavailability of FT iron as a feature independent of the simultaneous administration of an up to 9-fold higher dose of the mineral form in iron sulfate [102]. The likely mechanism of uptake is AP2 peptide-dependent endocytosis [103].

However, the stability of FT is ambiguously assessed. Selected studies on FT bioavailability and safety are presented in Table 3. Many authors believe that this protein is characterized by very good stability also under digestive conditions (extreme pH values) [87,104,105]. According to other experiments, FT is sensitive to gastric pH (values 1–2), leading to structural changes in the protein. However, these changes may be reversible, and the molecule returns to its native form as the pH in the intestines increases [106]. The food matrix may have a positive effect on maintaining FT stability under digestive conditions [107].

Review of selected studies on the bioavailability and safety of plant FT

| Aim of research | Methods | Conclusions | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of dietary factors on iron uptake from FT by Caco-2 cells |

|

Fe from undigested FT is absorbed by intestinal cells, and this process appears to be minimally affected by common dietary factors. However, once FT is digested, the mineralized core releases Fe, allowing for interactions with dietary factors that can influence absorption. This suggests that while dietary factors can impact the absorption of FT-bound Fe to some extent, their effect is likely comparable to or less than the influence they exert on Fe uptake from more traditional forms of iron supplementation, such as FeSO4. It’s worth noting that FeSO4, while bioavailable, can lead to undesirable changes in the color and organoleptic properties of fortified products. In contrast, FT-bound Fe, encapsulated within a mineral core and protected by a protein shell, minimizes Fe-induced oxidative damage to food products. This finding highlights the potential of using FT for biofortification of staple foods, as it offers a bioavailable source of Fe that is less prone to compromising product quality. In summary, results suggest that FT is a promising candidate for addressing iron deficiency, offering a bioavailable and food-friendly source of this essential nutrient | [101] |

| Assessment of soy FT absorption in nonanemic women | Subjects were randomly assigned to start with either a 59Fe-labeled soybean FT meal or a 59Fe-labeled FeSO4 meal, each containing 1 mg Fe, given with 60 mL of apple juice. They consumed a bagel with cream cheese after fasting for 12 hours overnight | The iron status of the 16 women in the study was generally adequate, with only one participant showing slight anemia and four exhibiting ID based on low serum FT concentrations. The mean concentrations of hemoglobin and serum FT fell within expected ranges. Interestingly, there were no significant differences observed in iron absorption between the two different forms of iron or the two methods used for assessment. Both whole-body counting and RBC incorporation methods provided consistent estimates of iron absorption for both soybean FT and FeSO4. Furthermore, a notable inverse correlation was observed between serum FT levels and iron absorption, regardless of the source of iron. These findings highlight the complex relationship between serum FT and iron absorption, which appears to be consistent across different iron sources and assessment methods | [104] |

| 59Fe incorporation into red blood cells (RBCs) was measured, and after a blood draw, they received the second randomized labeled meal. Radioactivity was measured in a whole-body counter on days 14 and 28 after the second meal. A final blood sample was taken on day 28. Whole-body iron absorption was calculated based on RBC count in 5 mL of blood, assuming a blood volume of 71.4 mL/kg body weight and an 85% incorporation rate into hemoglobin | |||

| Evaluation of soybean FT intake | In vitro by using human intestinal (Caco-2) cells and in vivo by using radiolabeled FT and whole-body counting in human subjects | The research highlights that iron from soybeans is readily absorbed, as supported by multiple human studies. This absorption can occur through receptor-mediated endocytosis of intact FT or via DMT1 as ferrous iron, either released from digested FT or potentially from the FT iron core. Increasing the FT content in soybeans holds promise as a sustainable strategy to enhance iron absorption, particularly in vulnerable populations with ID. This avenue of investigation could contribute significantly to addressing iron-related health challenges | [108] |

| Evaluation of gastric digestion of pea FT and modulation of its iron bioavailability by ascorbic and phytic acids in Caco-2 cells | In vitro digestion/Caco-2 cell model in the presence or absence of ascorbic acid and phytic acid | The study demonstrates that pea FT formation significantly increased iron bioavailability compared to the blank digest, with ascorbic acid enhancing and phytic acid decreasing its availability. However, even with ascorbic acid, the FT content in Caco-2 cells was significantly lower with pea FT compared to FeSO4. Moreover, under gastric pH conditions, no FT bands were observed in the presence of pepsin, indicating structural instability. Gel filtration chromatography and circular dichroism spectroscopy revealed pH-dependent loss of quaternary and secondary structure in pea FT. These findings suggest that the release of iron from pea FT interacts with dietary factors, ultimately affecting its bioavailability in a manner reminiscent of non-heme iron | [109] |

| Evaluation of iron absorption from FT |

|

The study found that a nineold excess of ferrous sulfate did not impact the absorption of iron from FT. This suggests that iron in FT is not absorbed by the same mechanism as ferrous sulfate, and the absorption of FT iron remained unaffected even when saturation kinetics were maintained. Additionally, unlabeled ferrous sulfate had no significant effect on the absorption of 59Fe in FT when administered at a ratio of 9:1 (4.5 mg FeSO4 and 0.5 mg 59Fe as FT iron) in non-gastric-resistant capsules | [102] |

Based on the literature data presented, it can be concluded that the use of plant FT allows to provide absorbable iron, but the bioavailability depends strongly on the diet and compounds consumed in the diet that can bind iron with FT. Moreover, it should be mentioned that the use of plant sprouts containing FT in the recipes of food products may cause unfavorable changes in the appearance of these products, which may translate into their lower acceptance among consumers. However, properly thought-out ingredients of vegan products that can be enriched with FT will enable the development of a full-value product with high bioavailability and attractiveness.

5 Limitation and future perspectives

This review discusses the properties of LegH and FT as sources of Fe, as well as their role in the body. The use of new sources of iron in plant diets seems, on the one hand, necessary, but on the other hand, it poses many new risks both from the point of view of safety and bioavailability. Many countries do not allow the marketing of food containing ingredients subject to genetic modification or obtained from new GM organisms. For this reason, it seems that FT is a much more promising source of Fe for food fortification for vegans and vegetarians. Nevertheless, it is worth clearly pointing out the need to carefully analyze such enriched food, especially in the context of long-term consumption. Long-term analyses can provide valuable data that may indicate the benefits of using novel sources of Fe.

-

Funding information: The National Centre for Research and Development of Poland (NCBR) is acknowledged for funding provided within the program LIDER under grant agreement no. LIDER/27/0105/L-11/19/NCBR/2020 (PI: Przemysław Kowalczewski).

-

Author contributions: Each author has made an equal contribution to the composition and development of the article. Furthermore, all authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the article for publication.

-

Conflict of interest: Przemysław Łukasz Kowalczewski, who is the co-author of this article, is a current Editorial Board member of Open Life Sciences. This fact did not affect the peer-review process.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

[1] Springmann M, Wiebe K, Mason-D’Croz D, Sulser TB, Rayner M, Scarborough P. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: a global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet Heal. 2018;2(10):e451–61. 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30206-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Agnoli C, Baroni L, Bertini I, Ciappellano S, Fabbri A, Papa M, et al. Position paper on vegetarian diets from the working group of the Italian Society of Human Nutrition. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;27(12):1037–52. 10.1016/j.numecd.2017.10.020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Bakaloudi DR, Halloran A, Rippin HL, Oikonomidou AC, Dardavesis TI, Williams J, et al. Intake and adequacy of the vegan diet. A systematic review of the evidence. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(5):3503–21. 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.11.035.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Haider LM, Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G, Ekmekcioglu C. The effect of vegetarian diets on iron status in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58(8):1359–74. 10.1080/10408398.2016.1259210.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Rizzo G, Laganà AS, Rapisarda AM, La Ferrera GM, Buscema M, Rossetti P, et al. Vitamin B12 among vegetarians: Status, assessment and supplementation. Nutrients. 2016;8(12):767. 10.3390/nu8120767.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Saunders AV, Craig WJ, Baines SK. Zinc and vegetarian diets. Med J Aust. 2012;1(2):17–21. 10.5694/mjao11.11493.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2001. 10.17226/10026.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] GBD Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–59. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Barton JC, Wiener HH, Acton RT, Adams PC, Eckfeldt JH, Gordeuk VR, et al. Prevalence of iron deficiency in 62,685 women of seven race/ethnicity groups: The HEIRS Study. Connor JR, ed. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0232125. 10.1371/journal.pone.0232125.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Campbell R, Wang H, Ahmed R. Risk factors contributing to racial/ethnic disparities in iron deficiency in US women. Curr Dev Nutr. 2021;5:725. 10.1093/cdn/nzab046_022.Search in Google Scholar

[11] WHO. Anaemia. https://www.who.int/health-topics/anaemia#tab = tab_1 [Accessed October 4, 2023].Search in Google Scholar

[12] Di Angelantonio E, Thompson SG, Kaptoge S, Moore C, Walker M, Armitage J, et al. Efficiency and safety of varying the frequency of whole blood donation (INTERVAL): a randomised trial of 45 000 donors. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2360–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31928-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Wong C. Iron deficiency anaemia. Paediatr Child Health (Oxford). 2017;27(11):527–9. 10.1016/j.paed.2017.08.004.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Perera CA, Biggers RP, Robertson A. Deceitful red-flag: angina secondary to iron deficiency anaemia as a presenting complaint for underlying malignancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(7):e229942. 10.1136/bcr-2019-229942.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Steenackers N, Van der Schueren B, Mertens A, Lannoo M, Grauwet T, Augustijns P, et al. Iron deficiency after bariatric surgery: what is the real problem. Proc Nutr Soc. 2018;77(4):445–55. 10.1017/S0029665118000149.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Georgieff MK. Iron deficiency in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(4):516–24. 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Entezari S, Haghi SM, Norouzkhani N, Sahebnazar B, Vosoughian F, Akbarzadeh D, et al. Iron chelators in treatment of iron overload. Abd Elhakim Y, editor. J Toxicol. 2022;2022:1–18. 10.1155/2022/4911205.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Shizukuda Y, Rosing DR. Iron overload and arrhythmias: Influence of confounding factors. J Arrhythmia. 2019;35(4):575–83. 10.1002/joa3.12208.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Molina-Sánchez P, Lujambio A. Iron overload and liver cancer. J Exp Med. 2019;216(4):723–4. 10.1084/jem.20190257.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Li X, Duan X, Tan D, Zhang B, Xu A, Qiu N, et al. Iron deficiency and overload in men and woman of reproductive age, and pregnant women. Reprod Toxicol. 2023;118:108381. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2023.108381.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Sachinidis A, Doumas M, Imprialos K, Stavropoulos K, Katsimardou A, Athyros VG. Dysmetabolic iron overload in metabolic syndrome. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(10):1019–24. 10.2174/1381612826666200130090703.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Yan N, Zhang J. Iron metabolism, ferroptosis, and the links with Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2020;13:13. 10.3389/fnins.2019.01443.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] MANTADAKIS E. Iron deficiency anemia in children residing in high and low-income countries: risk factors, prevention, diagnosis and therapy. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2020;12(1):e2020041. 10.4084/mjhid.2020.041.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Fernández-Lázaro D, Mielgo-Ayuso J, Córdova Martínez A, Seco-Calvo J. Iron and Physical activity: Bioavailability enhancers, properties of black pepper (Bioperine®) and potential applications. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1886. 10.3390/nu12061886.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Piskin E, Cianciosi D, Gulec S, Tomas M, Capanoglu E. Iron absorption: factors, limitations, and improvement methods. ACS Omega. 2022;7(24):20441–56. 10.1021/acsomega.2c01833.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Clénin G, Cordes M, Huber A, Schumacher YO, Noack P, Scales J, et al. Iron deficiency in sports – definition, influence on performance and therapy. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145:4344. 10.4414/smw.2015.14196.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Gharibzahedi SMT, Jafari SM. The importance of minerals in human nutrition: Bioavailability, food fortification, processing effects and nanoencapsulation. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2017;62:119–32. 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.02.017.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Shubham K, Anukiruthika T, Dutta S, Kashyap AV, Moses JA, Anandharamakrishnan C. Iron deficiency anemia: A comprehensive review on iron absorption, bioavailability and emerging food fortification approaches. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020;99:58–75. 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.02.021.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Hurrell R, Egli I. Iron bioavailability and dietary reference values. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(5):1461S–7S. 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28674F.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Lynch SR, Hurrell RF, Dassenko SA, Cook JD. The effect of dietary proteins on iron bioavailability in man. In: Dintzis FR, Laszlo JA, eds. Mineral absorption in the monogastric gi tract. Boston, MA: Springer; 1989. p. 117–32. 10.1007/978-1-4684-9111-1_8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Björn-Rasmussen E, Hallberg L. Effect of animal proteins on the absorption of food iron in man. Ann Nutr Metab. 1979;23(3):192–202. 10.1159/000176256.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Reddy MB, Agbemafle I, Armah S. Iron bioavailability: enhancers and inhibitors. In: Karakochuk CD, Zimmermann MB, Moretti D, Kraemer K, eds. Nutritional Anemia. Cham: Springer; 2022. p. 141–9. 10.1007/978-3-031-14521-6_11.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Pyrzyńska E. A Vegetarian diet in the light of the principles of proper nutrition – attitudes and behaviour of vegetarians in poland (in Polish). Zesz Nauk Uniw Ekon w Krakowie. 2013;906:27–36.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Position of the American Dietetic association and dietitians of Canada: Vegetarian diets. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(6):748–65. 10.1053/jada.2003.50142.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Phillips F. Vegetarian nutrition. Nutr Bull. 2005;30(2):132–67. 10.1111/j.1467-3010.2005.00467.x.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Zohoori FV. Chapter 1: Nutrition and diet. The Impact of Nutrition and Diet on Oral Health. 2020;28:1–13. S.Karger AG. 10.1159/000455365.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Dinu M, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A, Sofi F. Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57(17):3640–9. 10.1080/10408398.2016.1138447.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Khalid W, Arshad MS, Ranjha MMAN, Różańska MB, Irfan S, Shafique B, et al. Functional constituents of plant-based foods boost immunity against acute and chronic disorders. Open Life Sci. 2022;17(1):1075–93. 10.1515/biol-2022-0104.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Kurup PA, Jayakumari N, Indira M, Kurup GM, Vargheese T, Mathew A, et al. Diet, nutrition intake, and metabolism in populations at high and low risk for colon cancer. Composition, intake, and excretion of fiber constituents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;40(4):942–6. 10.1093/ajcn/40.4.942.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Hallberg L, Hulthén L. Prediction of dietary iron absorption: an algorithm for calculating absorption and bioavailability of dietary iron. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(5):1147–60. 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1147.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Hunt JR, Roughead ZK. Nonheme-iron absorption, fecal ferritin excretion, and blood indexes of iron status in women consuming controlled lactoovovegetarian diets for 8 wk. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(5):944–52. 10.1093/ajcn/69.5.944.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Zhang YY, Stockmann R, Ng K, Ajlouni S. Revisiting phytate-element interactions: implications for iron, zinc and calcium bioavailability, with emphasis on legumes. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;62(6):1696–712. 10.1080/10408398.2020.1846014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Kumar A, Singh B, Raigond P, Sahu C, Mishra UN, Sharma S, et al. Phytic acid: Blessing in disguise, a prime compound required for both plant and human nutrition. Food Res Int. 2021;142:110193. 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110193.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Cianciosi D, Forbes-Hernández TY, Regolo L, Alvarez-Suarez JM, Navarro-Hortal MD, Xiao J, et al. The reciprocal interaction between polyphenols and other dietary compounds: Impact on bioavailability, antioxidant capacity and other physico-chemical and nutritional parameters. Food Chem. 2022;375:131904. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131904.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Nathan I, Hackett AF, Kirby S. The dietary intake of a group of vegetarian children aged 7-11 years compared with matched omnivores. Br J Nutr. 1996;75(4):533–44. 10.1079/BJN19960157.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Deriemaeker P, Aerenhouts D, De Ridder D, Hebbelinck M, Clarys P. Health aspects, nutrition and physical characteristics in matched samples of institutionalized vegetarian and non-vegetarian elderly (> 65yrs). Nutr Metab (Lond). 2011;8(1):37. 10.1186/1743-7075-8-37.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Harman SK, Parnell WR. The nutritional health of New Zealand vegetarian and non-vegetarian Seventh-day adventists: selected vitamin, mineral and lipid levels. N Z Med J. 1998;111(1062):91–4, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9577459.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Shaw NS, Chin CJ, Pan WH. A vegetarian diet rich in soybean products compromises iron status in young students. J Nutr. 1995;125(2):212–9. 10.1093/jn/125.2.212.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Harvey LJ, Armah CN, Dainty JR, Foxall RJ, John Lewis D, Langford NJ, et al. Impact of menstrual blood loss and diet on iron deficiency among women in the UK. Br J Nutr. 2005;94(4):557–64. 10.1079/BJN20051493.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Obeid R, Geisel J, Schorr H, Hübner U, Herrmann W. The impact of vegetarianism on some haematological parameters. Eur J Haematol. 2002;69(5-6):275–9. 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2002.02798.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Yen C-E, Yen C-H, Huang M-C, Cheng C-H, Huang Y-C. Dietary intake and nutritional status of vegetarian and omnivorous preschool children and their parents in Taiwan. Nutr Res. 2008;28(7):430–6. 10.1016/j.nutres.2008.03.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Bhatti AS, Mahida VI, Gupte SC. Iron status of Hindu brahmin, Jain and Muslim communities in Surat, Gujarat. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2007;23(3-4):82–7. 10.1007/s12288-008-0004-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Kajanachumpol S. Iron status among Thai vegans. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism. Basel: Karger; 2011. p. 213.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Koch RM, Tchernodrinski S, Principe DR. Case report: Rapid onset, ischemic-type gastritis after initiating oral iron supplementation. Front Med. 2022;9:1010897. 10.3389/fmed.2022.1010897.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Mimura ÉCM, Breganó JW, Dichi JB, Gregório EP, Dichi I. Comparison of ferrous sulfate and ferrous glycinate chelate for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in gastrectomized patients. Nutrition. 2008;24(7–8):663–8. 10.1016/j.nut.2008.03.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Downie JA. Legume haemoglobins: Symbiotic nitrogen fixation needs bloody nodules. Curr Biol. 2005;15(6):R196–8. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Singh S, Varma A. Structure, function, and estimation of leghemoglobin. In: Hansen A, Choudhary D, Agrawal P, Varma A, eds. Rhizobium Biology and Biotechnology. Cham: Springer; 2017. 309–30. 10.1007/978-3-319-64982-5_15.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Becana M, Klucas RV. Oxidation and reduction of leghemoglobin in root nodules of leguminous plants. Plant Physiol. 1992;98(4):1217–21. 10.1104/pp.98.4.1217.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Appleby CA. The origin and functions of haemoglobin in plants. Sci Prog. 1992;76(3/4 (301/302)):365–98, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43421309.10.1016/0300-483X(92)90200-XSearch in Google Scholar

[60] Kanu SA, Dakora FD. Symbiotic functioning, structural adaptation, and subcellular organization of root nodules from Psoralea pinnata (L.) plants grown naturally under wetland and upland conditions in the Cape Fynbos of South Africa. Protoplasma. 2017;254(1):137–45. 10.1007/s00709-015-0922-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Emerich DW, Krishnan HB. Symbiosomes: temporary moonlighting organelles. Biochem J. 2014;460(1):1–11. 10.1042/BJ20130271.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Dakora F. A functional relationship between leghaemoglobin and nitrogenase based on novel measurements of the two proteins in legume root nodules. Ann Bot. 1995;75(1):49–54. 10.1016/S0305-7364(05)80008-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[63] Ott T, van Dongen JT, Günther C, Krusell L, Desbrosses G, Vigeolas H, et al. Symbiotic leghemoglobins are crucial for nitrogen fixation in legume root nodules but not for general plant growth and development. Curr Biol. 2005;15(6):531–5. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.042.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Bergersen FJ. Biochemistry of symbiotic nitrogen fixation in legumes. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1971;22(1):121–40. 10.1146/annurev.pp.22.060171.001005.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Stróżycki PM. Functions and evolution of hemoglobins. Plant hemoglobins. Kosmos. 1995;44(3–4):515–25.Search in Google Scholar

[66] Dilworth MJ. [74] Leghemoglobins. In: San Pietro A, ed. Methods in Enzymology. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Academic Press; 1980. p. 812–23. 10.1016/S0076-6879(80)69076-4.Search in Google Scholar

[67] Proulx AK, Reddy MB. Iron bioavailability of hemoglobin from soy root nodules using a caco-2 cell culture model. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54(4):1518–22. 10.1021/jf052268l.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[68] van Vliet S, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Provenza FD, Kronberg SL, Pieper CF, et al. A metabolomics comparison of plant-based meat and grass-fed meat indicates large nutritional differences despite comparable Nutrition Facts panels. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13828. 10.1038/s41598-021-93100-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[69] Pérez-Jiménez F. The future of diet: what will we be eating in the future? Clínica e Investig en Arterioscler (English Ed). 2022;34:17–22. 10.1016/j.artere.2022.06.004.Search in Google Scholar

[70] Vallikkadan MS, Dhanapal L, Dutta S, Sivakamasundari SK, Moses JA, Anandharamakrishnan C. Meat alternatives: Evolution, structuring techniques, trends, and challenges. Food Eng Rev. 2023;15(2):329–59. 10.1007/s12393-023-09332-8.Search in Google Scholar

[71] Food and Drug Administration and Drug Administration. GRAS Notice 737, Soy Leghemoglobin; 2016. https://www.fda.gov/media/124351/download.Search in Google Scholar

[72] Reyes TF, Chen Y, Fraser RZ, Chan T, Li X. Assessment of the potential allergenicity and toxicity of Pichia proteins in a novel leghemoglobin preparation. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2021;119:104817. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2020.104817.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[73] Zeece M. Food colorants. Introduction to the chemistry of food. London, UK: Elsevier; 2020. p. 313–44. 10.1016/B978-0-12-809434-1.00008-6.Search in Google Scholar

[74] Ahmad M, Hirz M, Pichler H, Schwab H. Protein expression in Pichia pastoris: recent achievements and perspectives for heterologous protein production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(12):5301–17. 10.1007/s00253-014-5732-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[75] Fraser RZ, Shitut M, Agrawal P, Mendes O, Klapholz S. Safety evaluation of soy leghemoglobin protein preparation derived from pichia pastoris, intended for use as a flavor catalyst in plant-based meat. Int J Toxicol. 2018;37(3):241–62. 10.1177/1091581818766318.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[76] Shankar D. Impossible Burger could be sold in stores after FDA approves coloring. 2019. https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2019-07-31/impossible-burger-fda-coloring Accessed October 5, 2023.Search in Google Scholar

[77] Zhang JG. Impossible Foods Nabs FDA Approval to Sell in Grocery Stores in September. 2019. https://www.eater.com/2019/7/31/20749247/impossible-foods-fda-approval-grocery-stores-fake-meat-patties. Accessed October 5, 2023.Search in Google Scholar

[78] European Commission. GMO legislation. 2018. https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/genetically-modified-organisms/gmo-legislation_en. Accessed October 5, 2023.Search in Google Scholar

[79] Jin Y, He X, Andoh‐Kumi K, Fraser RZ, Lu M, Goodman RE. Evaluating potential risks of food allergy and toxicity of soy leghemoglobin expressed in Pichia pastoris. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2018;62(1). 10.1002/mnfr.201700297.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[80] Shao Y, Xue C, Liu W, Zuo S, Wei P, Huang L, et al. High-level secretory production of leghemoglobin in Pichia pastoris through enhanced globin expression and heme biosynthesis. Bioresour Technol. 2022;363:127884. 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127884.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[81] Kundu S, Hargrove MS. Distal heme pocket regulation of ligand binding and stability in soybean leghemoglobin. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinforma. 2002;50(2):239–48. 10.1002/prot.10277.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[82] Liu X, Theil EC. Ferritins: Dynamic management of biological iron and oxygen chemistry. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38(3):167–75. 10.1021/ar0302336.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[83] Zhao G. Phytoferritin and its implications for human health and nutrition. Biochim Biophys Acta - Gen Subj. 2010;1800(8):815–23. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.01.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[84] Worwood M, Aherne W, Dawkins S, Jacobs A. The characteristics of ferritin from human tissues, serum and blood cells. Clin Sci. 1975;48(5):441–51. 10.1042/cs0480441.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[85] Michel FM, Hosein H-A, Hausner DB, Debnath S, Parise JB, Strongin DR. Reactivity of ferritin and the structure of ferritin-derived ferrihydrite. Biochim Biophys Acta - Gen Subj. 2010;1800(8):871–85. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.05.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[86] Antosiewicz J, Ziolkowski W, Kaczor JJ, Herman-Antosiewicz A. Tumor necrosis factor-α-induced reactive oxygen species formation is mediated by JNK1-dependent ferritin degradation and elevation of labile iron pool. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43(2):265–70. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.04.023.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[87] Zielińska-Dawidziak M, Hertig I, Piasecka-Kwiatkowska D, Staniek H, Nowak KW, Twardowski T. Study on iron availability from prepared soybean sprouts using an iron-deficient rat model. Food Chem. 2012;135(4):2622–7. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.113.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[88] Briat J-F, Ravet K, Arnaud N, Duc C, Boucherez J, Touraine B, et al. New insights into ferritin synthesis and function highlight a link between iron homeostasis and oxidative stress in plants. Ann Bot. 2010;105(5):811–22. 10.1093/aob/mcp128.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[89] García Mata C, Lamattina L, Cassia RO. Involvement of Iron and Ferritin in the Potato–Phytophthora infestans interaction. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2001;107(5):557–62. 10.1023/A:1011228317709.Search in Google Scholar

[90] Moreira AC, Mesquita G, Gomes MS. Ferritin: an inflammatory player keeping iron at the core of pathogen-host interactions. Microorganisms. 2020;8(4):589. 10.3390/microorganisms8040589.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[91] Abe E, Arai M. Synovial fluid ferritin in traumatic hemarthrosis, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1992;168(3):499–505. 10.1620/tjem.168.499.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[92] Pelkonen P, Swanljung K, Siimes MA. Ferritinemia as an indicator of systemic disease activity in children with systemic juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Paediatr. 1986;75(1):64–8. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1986.tb10158.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[93] Kaushal K, Kaur H, Sarma P, Bhattacharyya A, Sharma DJ, Prajapat M, et al. Serum ferritin as a predictive biomarker in COVID-19. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. J Crit Care. 2022;67:172–81. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2021.09.023.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[94] AbdelFattah EB, Madkour AM, Amer SMI, Ahmed NO. Correlation between the serum level of ferritin and D-dimer and the severity of COVID-19 infection. Egypt J Bronchol. 2023;17(1):45. 10.1186/s43168-023-00218-1.Search in Google Scholar

[95] Zielińska-Dawidziak M. Plant ferritin—a source of iron to prevent its deficiency. Nutrients. 2015;7(2):1184–201. 10.3390/nu7021184.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[96] Makowska A, Zielińska‐Dawidziak M, Niedzielski P, Michalak M. Effect of extrusion conditions on iron stability and physical and textural properties of corn snacks enriched with soybean ferritin. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2018;53(2):296–303. 10.1111/ijfs.13585.Search in Google Scholar

[97] Szymandera‐Buszka K, Zielińska‐Dawidziak M, Makowska A, Majcher M, Jędrusek‐Golińska A, Kaczmarek A, et al. Quality assessment of corn snacks enriched with soybean ferritin among young healthy people and patient with Crohn’s disease: the effect of extrusion conditions. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2021;56(12):6463–73. 10.1111/ijfs.15328.Search in Google Scholar

[98] Zielińska-Dawidziak M, Piasecka-Kwiatkowska D, Warchalewski JR, Makowska A, Gawlak M, Nawrot J. Sprouted wheat grain with ferritin overexpression as a potential source of iron for cereal product fortification. Eur Food Res Technol. 2014;238(5):829–35. 10.1007/s00217-013-2150-3.Search in Google Scholar

[99] Zielińska-Dawidziak M, Hertig I, Staniek H, Piasecka-Kwiatkowska D, Nowak KW. Effect of iron status in rats on the absorption of metal ions from plant ferritin. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2014;69(2):101–7. 10.1007/s11130-014-0413-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[100] Zielińska-Dawidziak M, Siger A. Effect of elevated accumulation of iron in ferritin on the antioxidants content in soybean sprouts. Eur Food Res Technol. 2012;234(6):1005–12. 10.1007/s00217-012-1706-y.Search in Google Scholar

[101] Kalgaonkar S, Lönnerdal B. Effects of dietary factors on iron uptake from ferritin by Caco-2 cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19(1):33–9. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.02.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[102] Theil EC, Chen H, Miranda C, Janser H, Elsenhans B, Núñez MT, et al. Absorption of iron from ferritin is independent of heme iron and ferrous salts in women and rat intestinal segments3. J Nutr. 2012;142(3):478–83. 10.3945/jn.111.145854.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[103] San Martin CD, Garri C, Pizarro F, Walter T, Theil EC, Núñez MT. Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells absorb soybean ferritin by μ2 (AP2)-dependent endocytosis. J Nutr. 2008;138(4):659–66. 10.1093/jn/138.4.659.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[104] Lönnerdal B, Bryant A, Liu X, Theil EC. Iron absorption from soybean ferritin in nonanemic women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(1):103–7. 10.1093/ajcn/83.1.103.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[105] lyu C, Lönnerdal B, Zhao G. Bioavailability of iron from plant and animal ferritins. FASEB J. 2015;29(S1):249.7. 10.1096/fasebj.29.1_supplement.249.7.Search in Google Scholar

[106] Fu X, Deng J, Yang H, Masuda T, Goto F, Yoshihara T, et al. A novel EP-involved pathway for iron release from soya bean seed ferritin. Biochem J. 2010;427(2):313–21. 10.1042/BJ20100015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[107] Zielińska-Dawidziak M, Białas W, Piasecka-Kwiatkowska D, Staniek H, Niedzielski P. Digestibility of protein and iron availability from enriched legume sprouts. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2023;78(2):270–8. 10.1007/s11130-023-01045-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[108] Lönnerdal B. Soybean ferritin: implications for iron status of vegetarians. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):1680S–5S. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736W.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[109] Bejjani S. Gastric digestion of pea ferritin and modulation of its iron bioavailability by ascorbic and phytic acids in Caco-2 cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(14):2083–8. 10.3748/wjg.v13.i14.2083.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Systemic investigation of inetetamab in combination with small molecules to treat HER2-overexpressing breast and gastric cancers

- Immunosuppressive treatment for idiopathic membranous nephropathy: An updated network meta-analysis

- Identifying two pathogenic variants in a patient with pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy

- Effects of phytoestrogens combined with cold stress on sperm parameters and testicular proteomics in rats

- A case of pulmonary embolism with bad warfarin anticoagulant effects caused by E. coli infection

- Neutrophilia with subclinical Cushing’s disease: A case report and literature review

- Isoimperatorin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced periodontitis by downregulating ERK1/2 and NF-κB pathways

- Immunoregulation of synovial macrophages for the treatment of osteoarthritis

- Novel CPLANE1 c.8948dupT (p.P2984Tfs*7) variant in a child patient with Joubert syndrome

- Antiphospholipid antibodies and the risk of thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms

- Immunological responses of septic rats to combination therapy with thymosin α1 and vitamin C

- High glucose and high lipid induced mitochondrial dysfunction in JEG-3 cells through oxidative stress

- Pharmacological inhibition of the ubiquitin-specific protease 8 effectively suppresses glioblastoma cell growth

- Levocarnitine regulates the growth of angiotensin II-induced myocardial fibrosis cells via TIMP-1

- Age-related changes in peripheral T-cell subpopulations in elderly individuals: An observational study

- Single-cell transcription analysis reveals the tumor origin and heterogeneity of human bilateral renal clear cell carcinoma

- Identification of iron metabolism-related genes as diagnostic signatures in sepsis by blood transcriptomic analysis

- Long noncoding RNA ACART knockdown decreases 3T3-L1 preadipocyte proliferation and differentiation

- Surgery, adjuvant immunotherapy plus chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary malignant melanoma of the parotid gland (PGMM): A case report

- Dosimetry comparison with helical tomotherapy, volumetric modulated arc therapy, and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for grade II gliomas: A single‑institution case series

- Soy isoflavone reduces LPS-induced acute lung injury via increasing aquaporin 1 and aquaporin 5 in rats

- Refractory hypokalemia with sexual dysplasia and infertility caused by 17α-hydroxylase deficiency and triple X syndrome: A case report

- Meta-analysis of cancer risk among end stage renal disease undergoing maintenance dialysis

- 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase inhibition arrests growth and induces apoptosis in gastric cancer via AMPK activation and oxidative stress

- Experimental study on the optimization of ANM33 release in foam cells

- Primary retroperitoneal angiosarcoma: A case report

- Metabolomic analysis-identified 2-hydroxybutyric acid might be a key metabolite of severe preeclampsia

- Malignant pleural effusion diagnosis and therapy

- Effect of spaceflight on the phenotype and proteome of Escherichia coli

- Comparison of immunotherapy combined with stereotactic radiotherapy and targeted therapy for patients with brain metastases: A systemic review and meta-analysis

- Activation of hypermethylated P2RY1 mitigates gastric cancer by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation

- Association between the VEGFR-2 -604T/C polymorphism (rs2071559) and type 2 diabetic retinopathy

- The role of IL-31 and IL-34 in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic periodontitis

- Triple-negative mouse breast cancer initiating cells show high expression of beta1 integrin and increased malignant features

- mNGS facilitates the accurate diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of suspicious critical CNS infection in real practice: A retrospective study

- The apatinib and pemetrexed combination has antitumor and antiangiogenic effects against NSCLC

- Radiotherapy for primary thyroid adenoid cystic carcinoma

- Design and functional preliminary investigation of recombinant antigen EgG1Y162–EgG1Y162 against Echinococcus granulosus

- Effects of losartan in patients with NAFLD: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial

- Bibliometric analysis of METTL3: Current perspectives, highlights, and trending topics

- Performance comparison of three scaling algorithms in NMR-based metabolomics analysis

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and its related molecules participate in PROK1 silence-induced anti-tumor effects on pancreatic cancer

- The altered expression of cytoskeletal and synaptic remodeling proteins during epilepsy

- Effects of pegylated recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on lymphocytes and white blood cells of patients with malignant tumor

- Prostatitis as initial manifestation of Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia diagnosed by metagenome next-generation sequencing: A case report

- NUDT21 relieves sevoflurane-induced neurological damage in rats by down-regulating LIMK2

- Association of interleukin-10 rs1800896, rs1800872, and interleukin-6 rs1800795 polymorphisms with squamous cell carcinoma risk: A meta-analysis

- Exosomal HBV-DNA for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of chronic hepatitis B

- Shear stress leads to the dysfunction of endothelial cells through the Cav-1-mediated KLF2/eNOS/ERK signaling pathway under physiological conditions

- Interaction between the PI3K/AKT pathway and mitochondrial autophagy in macrophages and the leukocyte count in rats with LPS-induced pulmonary infection

- Meta-analysis of the rs231775 locus polymorphism in the CTLA-4 gene and the susceptibility to Graves’ disease in children

- Cloning, subcellular localization and expression of phosphate transporter gene HvPT6 of hulless barley

- Coptisine mitigates diabetic nephropathy via repressing the NRLP3 inflammasome

- Significant elevated CXCL14 and decreased IL-39 levels in patients with tuberculosis

- Whole-exome sequencing applications in prenatal diagnosis of fetal bowel dilatation

- Gemella morbillorum infective endocarditis: A case report and literature review

- An unusual ectopic thymoma clonal evolution analysis: A case report

- Severe cumulative skin toxicity during toripalimab combined with vemurafenib following toripalimab alone

- Detection of V. vulnificus septic shock with ARDS using mNGS

- Novel rare genetic variants of familial and sporadic pulmonary atresia identified by whole-exome sequencing

- The influence and mechanistic action of sperm DNA fragmentation index on the outcomes of assisted reproduction technology

- Novel compound heterozygous mutations in TELO2 in an infant with You-Hoover-Fong syndrome: A case report and literature review

- ctDNA as a prognostic biomarker in resectable CLM: Systematic review and meta-analysis

- Diagnosis of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis by metagenomic next-generation sequencing: A case report

- Phylogenetic analysis of promoter regions of human Dolichol kinase (DOLK) and orthologous genes using bioinformatics tools

- Collagen changes in rabbit conjunctiva after conjunctival crosslinking

- Effects of NM23 transfection of human gastric carcinoma cells in mice

- Oral nifedipine and phytosterol, intravenous nicardipine, and oral nifedipine only: Three-arm, retrospective, cohort study for management of severe preeclampsia

- Case report of hepatic retiform hemangioendothelioma: A rare tumor treated with ultrasound-guided microwave ablation

- Curcumin induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by decreasing the expression of STAT3/VEGF/HIF-1α signaling

- Rare presentation of double-clonal Waldenström macroglobulinemia with pulmonary embolism: A case report

- Giant duplication of the transverse colon in an adult: A case report and literature review

- Ectopic thyroid tissue in the breast: A case report

- SDR16C5 promotes proliferation and migration and inhibits apoptosis in pancreatic cancer

- Vaginal metastasis from breast cancer: A case report

- Screening of the best time window for MSC transplantation to treat acute myocardial infarction with SDF-1α antibody-loaded targeted ultrasonic microbubbles: An in vivo study in miniswine

- Inhibition of TAZ impairs the migration ability of melanoma cells

- Molecular complexity analysis of the diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome in China

- Effects of maternal calcium and protein intake on the development and bone metabolism of offspring mice

- Identification of winter wheat pests and diseases based on improved convolutional neural network

- Ultra-multiplex PCR technique to guide treatment of Aspergillus-infected aortic valve prostheses

- Virtual high-throughput screening: Potential inhibitors targeting aminopeptidase N (CD13) and PIKfyve for SARS-CoV-2

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients with COVID-19

- Utility of methylene blue mixed with autologous blood in preoperative localization of pulmonary nodules and masses

- Integrated analysis of the microbiome and transcriptome in stomach adenocarcinoma

- Berberine suppressed sarcopenia insulin resistance through SIRT1-mediated mitophagy

- DUSP2 inhibits the progression of lupus nephritis in mice by regulating the STAT3 pathway

- Lung abscess by Fusobacterium nucleatum and Streptococcus spp. co-infection by mNGS: A case series

- Genetic alterations of KRAS and TP53 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma associated with poor prognosis

- Granulomatous polyangiitis involving the fourth ventricle: Report of a rare case and a literature review

- Studying infant mortality: A demographic analysis based on data mining models

- Metaplastic breast carcinoma with osseous differentiation: A report of a rare case and literature review

- Protein Z modulates the metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma cells

- Inhibition of pyroptosis and apoptosis by capsaicin protects against LPS-induced acute kidney injury through TRPV1/UCP2 axis in vitro

- TAK-242, a toll-like receptor 4 antagonist, against brain injury by alleviates autophagy and inflammation in rats

- Primary mediastinum Ewing’s sarcoma with pleural effusion: A case report and literature review

- Association of ADRB2 gene polymorphisms and intestinal microbiota in Chinese Han adolescents

- Tanshinone IIA alleviates chondrocyte apoptosis and extracellular matrix degeneration by inhibiting ferroptosis

- Study on the cytokines related to SARS-Cov-2 in testicular cells and the interaction network between cells based on scRNA-seq data

- Effect of periostin on bone metabolic and autophagy factors during tooth eruption in mice

- HP1 induces ferroptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells through NRF2 pathway in diabetic nephropathy

- Intravaginal estrogen management in postmenopausal patients with vaginal squamous intraepithelial lesions along with CO2 laser ablation: A retrospective study

- Hepatocellular carcinoma cell differentiation trajectory predicts immunotherapy, potential therapeutic drugs, and prognosis of patients

- Effects of physical exercise on biomarkers of oxidative stress in healthy subjects: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Identification of lysosome-related genes in connection with prognosis and immune cell infiltration for drug candidates in head and neck cancer

- Development of an instrument-free and low-cost ELISA dot-blot test to detect antibodies against SARS-CoV-2

- Research progress on gas signal molecular therapy for Parkinson’s disease

- Adiponectin inhibits TGF-β1-induced skin fibroblast proliferation and phenotype transformation via the p38 MAPK signaling pathway

- The G protein-coupled receptor-related gene signatures for predicting prognosis and immunotherapy response in bladder urothelial carcinoma

- α-Fetoprotein contributes to the malignant biological properties of AFP-producing gastric cancer

- CXCL12/CXCR4/CXCR7 axis in placenta tissues of patients with placenta previa

- Association between thyroid stimulating hormone levels and papillary thyroid cancer risk: A meta-analysis

- Significance of sTREM-1 and sST2 combined diagnosis for sepsis detection and prognosis prediction

- Diagnostic value of serum neuroactive substances in the acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease complicated with depression