Abstract

This study aimed to compare the new bone formation, the process of remodeling, and the viability of bone grafts, using a combination of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and Marburg bone graft versus bone grafts without any additional elements. For this study, 48 rabbits (with 24 rabbits in each group) were used. Bone defects were made in the femur, and the bone graft used was the human femoral head prepared according to the Marburg Bone Bank. Rabbits were divided into the following groups: heat-treated bone graft (HTBG group) and HTBG with PRP (HTBG + PRP group). After 14, 30, and 60 days post-surgery, the assessment of the results involved X-ray, histopathological, and histomorphometric analyses. The greater new bone formation was detected in the HTBG + PRP group on the 14 and 30 day (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the group using bone grafts with PRP demonstrated notably enhanced remodeling, characterized by stronger bone integration, more significant graft remineralization, and a circular pattern of newly formed bone. The PRP–bone graft complex improves bone tissue repair in the bone defect in the initial stages of bone regeneration. PRP has been identified to enhance the remodeling process and amplify the osteoconductive and osteoinductive capabilities of HTBGs.

1 Introduction

Bone defects commonly manifest as a result of bone resection, metabolic pathologies, traumatic events, and neoplasms. Annually, these osseous deficiencies necessitate more than one million reconstructive surgical interventions [1,2]. The main principle of treatment of defects of any etiology is their filling with bone substitutes. Autologous bone is the “gold standard” [3,4]. First, this is due to the fact that the autologous bone does not cause any immunological reactions. Second, it has simultaneously both osteoinductive and osteoconductive properties – the former is represented by bone cells and growth factors. The limited availability of autologous bone and the accompanying trauma induced by the harvesting procedure restrict its use in clinical practice [3,4,5]. Synthetic bone grafts serve as an alternative to autologous graft options due to their extensive accessibility, gradual biodegradation, and lack of risks such as donor-site morbidity and viral transmission [6–9]. Yet, their biological role is constrained, particularly in fracture healing, because of their purely osteoconductive nature, mechanical properties, and absence of angiogenic attributes [1,6,10,11]. On the other hand, allogenous bone grafts, sourced from humans or human cadavers, are subject to sterile processing before transplantation to a recipient. The osteoconductive and occasionally osteoinductive potential of these grafts can vary based on the preparation process [1,3,7].

The Marburg Bone Bank-prepared bone graft is a type of bone allograft widely used in orthopedic surgery. These grafts are extensively processed to remove cellular material, leaving behind only the mineralized bone matrix. The processed bone matrix provides a scaffold for new bone growth, which can lead to faster and more complete healing [12–15]. Nevertheless, the osteoinductive capability of processed (chemically or physically) allogeneic bone is not clearly established, given that osteogenic cells are eradicated during the tissue manipulation process. This leads to the partial retention of osteoinductive substances, which may contribute to suboptimal clinical effects. Currently, there has been a surge in interest regarding the use of growth factors and morphogens as potential agents for conferring osteoinductivity to bone substitutes [16–18].

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) obtained from autologous blood represents a significant resource for delivering high levels of growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor beta, epidermal growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and insulin-like growth factor I. These factors are vital in tissue growth and progression, and their introduction to the site of bone defects is crucial [19,20]. PRP has shown potential for use in combination with bone grafts, as in vitro studies have demonstrated a notable increase in osteoblast proliferation upon the addition of PRP [19]. Furthermore, incorporating PRP with graft materials has been shown to reduce the duration required for graft consolidation, maturation, and improvement of trabecular bone density [20–23]. These findings suggest that PRP may compensate for the limited osteogenic potential of thermally disinfected bone grafts to promote osteogenesis in bone defects. However, there is limited information regarding the synergistic effects of PRP and Marburg-prepared bone graft on bone healing. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to perform a comparative assessment of the new bone formation, the process of remodeling, and the viability of bone grafts, using a combination of PRP with bone grafts prepared by the Marburg Bone Bank System versus bone allografts without any additional elements.

2 Methods

2.1 Preparation of Marburg bone grafts

In this study, femoral heads prepared by the Marburg Bank were used as bone graft (Figure 1). These femoral heads were obtained from a living donor who had undergone hip joint arthroplasty surgery in compliance with national regulations [24,25]. During hip joint endoprosthetics, the head of the femur is removed from the operating room and subjected to a series of mechanical cleaning procedures in sterile conditions to eliminate any soft tissue, cartilage, and ligaments. The femoral heads were placed in a disposable sterile container and filled with 0.9% NaCl solution in a volume of 300 ml, and then they were sealed and subjected to a heat treatment process in a Lobator SD-2 (Telos Company, Germany) device for a total of 94 min, maintaining a temperature of 82.5°C in the femoral head for at least 15 min, according to the established protocol. The sterility of the container was verified at the end of the cycle through a specific opening, and then, the liquid was completely drained. The bone allografts were then stored in a freezer at −80°C as per the recommended protocol [13,26]. Two hours before the experiment, the femoral head was unfrozen at room temperature and cut into chips. To ensure a consistent ratio of ingredients, a specific weight was used to standardize the mixture of bone graft with PRP 0.5 g bone allograft/0.5 ml PRP.

Heat-treated femoral head (a) and scanning electron microscopic view of bone graft (b).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to human use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the authors' institutional review board or equivalent committee.

2.2 Preparation of PRP

Prior to each surgical intervention (approximately 30 min before transplantation), 5 ml of blood was collected from the heart into siliconized tubes containing 3.8% sodium citrate at a blood/citrate ratio of 9:1 [27]. PRP was procured via two-step centrifugation [28]. Initial centrifugation involved the separation of blood cell elements using a laboratory centrifuge, with tubes centrifuged at 900 G for 8 min at ambient temperature, yielding two primary components: the blood cell component (BCC) in the lower fraction and in the upper fraction. Subsequent centrifugation entailed marking a point 6 mm beneath the line demarcating the BCC. To augment the total platelet count for the second centrifugation, all contents above the mark were transferred to another 5 ml vacuum tube devoid of anticoagulant. The sample was then centrifuged once more at 1,500 G for 5 min to obtain two components: platelet-poor plasma (PPP) and PRP. Approximately 0.5 ml of PRP was separated from the PPP. The PRP (0.5 ml) was combined with 0.5 g of bone graft and used to fill the created defect.

2.3 Animals and surgical procedures

In this investigation, 48 outbred rabbits were acquired, comprising adult males (6–7 months old) with an average weight of 3,025 ± 87 g. The animals were housed in cages and allowed to acclimate for a duration of 2 weeks. All procedures involving the animals adhered to the protection guidelines of DIRECTIVE 2010/63/EU for animals used in scientific research [29] and were approved by the University Animal Care Committee (UACC) under protocol № 27 dated 27.09.2020. Throughout the study, the rabbits were maintained at room temperature (22 ± 2°C), with 40–50% humidity, and subjected to a 12 h light–dark cycle. The animals were provided with standard rabbit pellets and tap water for sustenance.

Following Russell and Burch’s bioethical principles of replacement, reduction, and refinement, the sample size for animal experimentation in this study was established as the minimum number of animals necessary to yield statistically significant outcomes [30].

The rabbits were randomly allocated into two groups (n = 24 per group) and underwent the same surgical procedure. Three hours before, the rabbits received an intramuscular (i.m.) injection of gentamycin 0.1 ml/kg (Mapichem, Switzerland). Animals were anesthetized with an i.m. injection of Zoletil 0,1 mg/kg (Virbac, USA) and Rometar 5 mg/kg (Bioveta, Czech Republic). Following hip skin disinfection, an incision was made in the distal femur. The periosteum was then lifted, and a 5 mm diameter unicortical bone defect was created in the distal femoral metaphysis using a drill (Figure 2) [31]. Then, based on the experimental group assignment, the bone defects in the first group were treated with a heat-treated bone graft (HTBG group), whereas in the second group, the defects were treated with the HTBG with autologous PRP (HTBG + PRP group). The surgical wound was sutured with absorbable sutures (5-0 Vicryl, Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, USA). After surgery, each animal received i.m. injections of gentamycin 0.1 ml/kg (Mapichem, Switzerland) and ketonal 0.04 ml/kg (Sandoz, Slovenia) for 3 days. Daily postoperative observations were made to monitor the healing progress according to a predetermined schedule for consecutive days. There were no complications or deaths in the postoperative period. At 14, 30, and 60 days, 8 animals from each group (16 rabbits for each time period) were sacrificed according to ethical standards by intravenous administration of lethal doses of Zoletil 50 mg/ml and the distal femur was harvested.

Bone defect in rabbit femur (a) and bone defect after filling with HTBG (b).

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animal use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals and has been approved by the UACC.

2.4 Histopathological examination

Prior to histological analysis, the specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for a duration of 24 h, followed by decalcification in Biodec R solution (Bio-Optica Milano SPA) for an additional 24 h. Subsequently, the samples were rinsed in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4). Upon achieving optimal bone tissue softening (decalcification), a bone incision was executed. The tissue was then fixed in 10% formalin at 4°C for 24 h, washed with tap water, and dehydrated using a series of ascending alcohol concentrations (70, 90, 95, and 100%). The samples were then immersed in xylene and embedded in paraffin blocks. Tissue sections with a thickness of 5 μm were prepared using a Leica SM 2000R sliding microtome. Once prepared, the tissue sections were treated with hematoxylin and eosin for overall tissue morphological analysis, identification of inflammatory infiltrate and necrosis, and Masson’s trichrome to evaluate bone graft remodeling and new bone formation [32].

2.4.1 Hematoxylin and eosin staining process

The tissue slices were submerged in Mayer’s hematoxylin for a quarter of an hour, followed by a 5 min rinse with water. Thereafter, the sections were subjected to a minute-long eosin staining.

2.4.2 Masson’s trichrome staining procedure

A commercial kit (Trichrome Stain (Masson) Biovitrim TU 9398-001-89079081-2012) was used for Masson trichrome staining. After dewaxing and rehydration, the slide specimens were placed in Bouin’s solution at 56°C for a duration of 15 min. This was succeeded by a 5 min tap water rinse. The application of Weigert’s hematoxylin lasted 5 min, followed by another 5 min wash with tap water, and a quick rinse in distilled water. The slides were subsequently stained with Biebrich’s scarlet acid fuchsin for 5 min, rinsed in distilled water, and bathed in phosphoric–tungstic–phosphomolybdenum acid for an additional 5 min. A 5 min application of aniline blue was the next step, and finally, the slides were secured in 1% acetic acid for a period of 2 min.

Microscopic examination of the preparations was carried out on a Zeiss AxioLab 4.0 microscope with a magnification of ×400. AxioVision 7.2 software for Windows was used to analyze and photograph the images.

Two independent investigators with expertise in animal models conducted the morphometric study, uninformed of the group each animal belonged to. The terminology used in the histomorphometric analysis adhered to the guidelines provided by the Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research [33].

The following parameters were determined:

The percentage of newly formed bone tissue

Histopathological pattern of bone graft remodeling.

The morphometric evaluation of bone tissue was carried out within an area defined radially by the defect’s edges and laterally by the native femur along with the outer boundary of the bone graft and/or the newly generated bone tissue. This estimate was represented as a percentage of the total defect zone area. For each bone defect, three histological sections were analyzed and their average value was computed. Tissues indicative of a non-specific reparative process, such as vessels or bone canal width, were not included in the quantification and constituted the smallest percentage in the bone callus area [34,35].

The process of distinguishing between bone graft remodeling, new bone formation, and differentiation from residual and lysed bone grafts was accomplished through different staining characteristics of bones at various stages of maturity and differences in staining between newly formed bone fragments and the graft. The chromatic distinction between the bone graft, which stained more toward red, and the newly formed bone, which stained blue, was examined using Masson’s trichrome.

A morphometric assessment of graft remodeling was conducted by identifying the dominant histomorphometric pattern of the bone graft within the newly formed bone defect.

Histomorphometric patterns of bone graft remodeling included:

Positive bone graft remodeling: this involved remodeling with bone integration, graft remineralization, and the circular formation of new bone tissue.

Negative bone graft remodeling: this represented remodeling with resorption and fibrotic replacement of the bone graft.

These patterns of bone graft remodeling are illustrated in Figure 3.

Histopathologic patterns of bone graft remodeling: (a) positive remodeling with integration, remineralization, and circular formation of newly formed bone tissue (Masson’s trichrome × 40. Scale bar, 500 µm) and (b) negative remodeling with resorption and fibrotic replacement of the bone graft (Masson’s trichrome × 40. scale bar, 500 µm).

Bone graft remodeling was assessed according to a scale: minimal – less than 10%, moderate – 11–50%, and pronounced – more than 50%.

2.5 X-ray imaging

Radiological examinations were conducted 2 h prior to the termination of the animals from the study at the intervals of 14, 30, and 60 days, using frontal and lateral projections on a radiological machine (Platinum, Apelem, France).

The radiological data were analyzed according to the adapted Lane and Sandhu radiograph evaluation method (Table 1) [36]. Average scores were determined for each metric, followed by the aggregation of scores across various metrics (such as periosteal reaction, defect size, presence of new growth in the defect, bone remodeling, and bone allograft remodeling). This cumulative score was used to quantify the degree of healing in each group. The bone formation in each defect was independently scored by three radiologists. The group that achieved the highest overall radiological score was deemed to have experienced the most successful healing.

Radiological assessment of bone defect healing

| No. | Characteristics | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Periosteal reaction | |

| Yes | 1 | |

| No | 0 | |

| 2 | Remodeling and resorption of the bone graft | |

| No change | 0 | |

| Partial | 1 | |

| Full | 2 | |

| 3 | Defect size | |

| No change or increase | 0 | |

| Decrease of less than 25% | 1 | |

| By 25–50% decrease | 2 | |

| By 50–75% decrease | 3 | |

| More than 75% | 4 | |

| No defect | 5 | |

| 4 | Filling bone defect with regenerate | |

| Yes | 1 | |

| No | 0 | |

| 5 | Bone remodeling | |

| Complete | 2 | |

| Bone marrow canal | 1 | |

| No | 0 | |

| Maximum radiological score | 11 | |

2.6 Statistical analysis

All experimental values are displayed as mean and standard deviations. Comparisons between two groups were made using the chi-squared test with Yates continuity correction and Mann–Whitney test, while multiple comparisons were made using Pearson’s chi-squared test. Statistical analysis of the research results was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 and STATISTICA 10. A p-value of <0.05 was deemed to indicate statistical significance.

3 Results

3.1 Histological and morphometric analyses of newly formed bone tissue

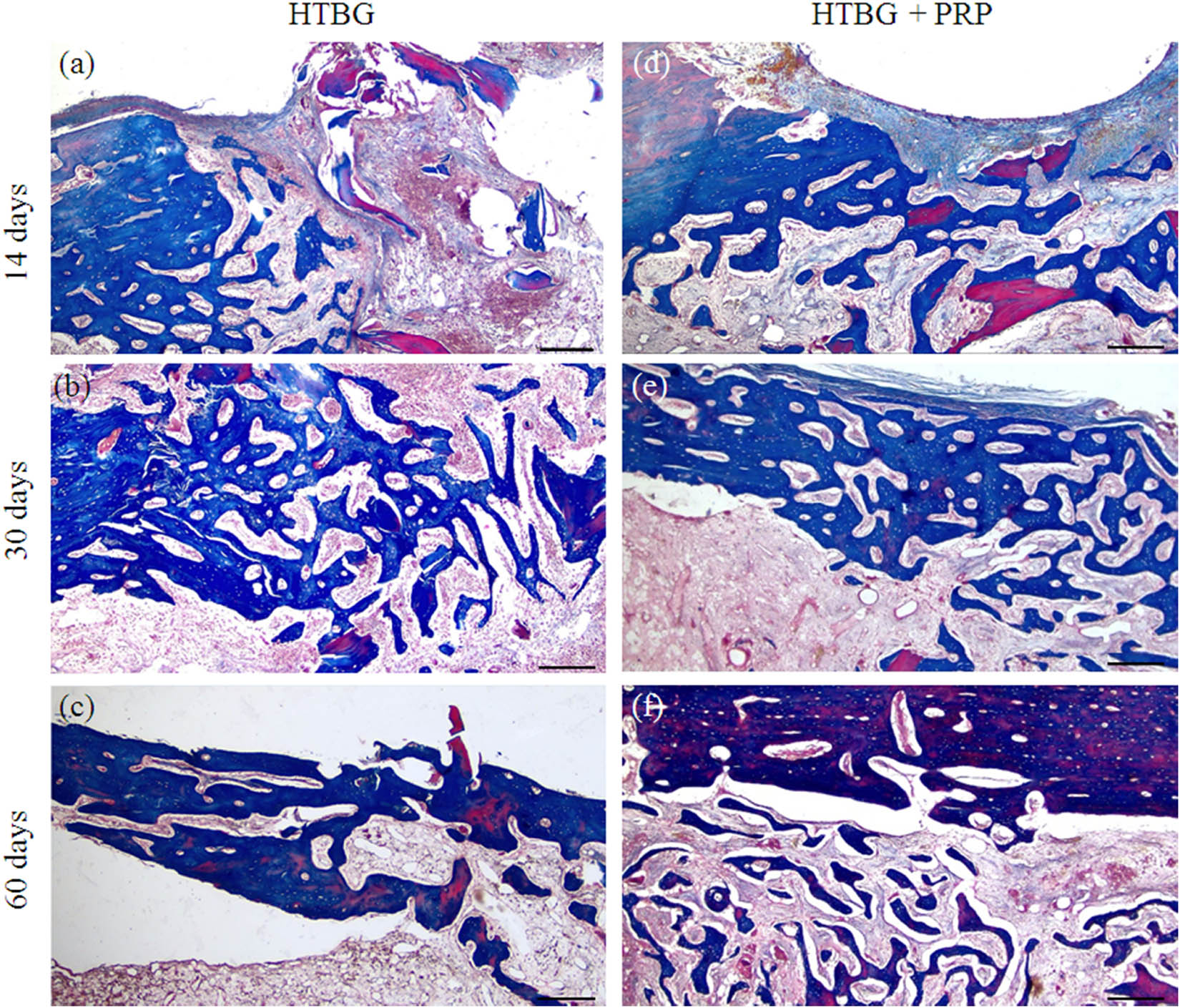

On day 14 for the HTBG group, the newly formed bone tissue constituted 41.5% of the total (Figure 5a). The area of the bone defect was characterized by the development of individual heterogeneous bundles of new bone tissue. These bundles contained lacunae with osteocytes and an abundance of vascular channels. The emerging bone beams were uneven, primarily thin, with focal bridging regions and sporadic contacts, mostly at the ends of bone passages (Figure 4a). In the HTBG + PRP group, the new bone formation made up 58% of the total (Figure 5a). There was a progressive increase in the formed bone tissue, featuring haphazardly arranged Haversian canals and widespread, broad bone trabeculae with numerous extensive bridge-like contacts (Figure 4d).

Microphotographs of stage-specific closure of the cortical plate defect in the study groups 14, 30, and 60 days after implantation (Masson’s trichrome × 40. Scale bar, 500 µm) (a–c) – HTBG group: (a) negative remodeling of the bone graft with lysis and resorption; single heterogeneous bundles of newly formed bone tissue are not integrated with the bone graft; (b) lysed bone graft is replaced by fibrous tissue, and the remaining fragments are integrated with newly formed bone beams; and (c) defect area is closed by newly formed bone tissue with foci of disorderly distribution of mature and immature bone matrix; (d–f) – HTBG with PRP (HTBG + PRP group): (d) positive remodeling of the bone graft with bone integration, remineralization, and circular formation of newly formed bone tissue, partial closure of the defect with newly formed bone beams; (e) the osteotomy site is closed with mature bone tissue with multiple wide bridge-like contacts between newly formed bone beams; and (f) the defect area is closed with mature bone tissue.

Histological image of newly formed bone tissue and positive bone graft remodeling in the defect area after 14, 30, and 60 days: (a) comparison of the amount of newly formed bone tissue between groups (*p < 0.01, **p < 0.001) and (b) comparison of positive bone graft remodeling between groups (*p < 0.01, **p < 0.001).

On the 30th day, the newly formed bone tissue in the HTBG group accounted for 80.5% of the total (Figure 5a). The bone tissue consisted of haphazardly arranged bone trabeculae and tendons that were merging into lamellar structures. The bone tract exhibited significant mineralization and robust longitudinal growth (Figure 4b). Meanwhile, in the HTBG + PRP group on day 30, the bone tissue constituted 84.5% of the total (Figure 5a), with the defect area made up of dense mineralized bone tissue containing Haversian canals of varying sizes.

By day 60 in both HTBG and HTBG + PRP groups, the defect site revealed formed bone tissue with normal development of bone trabeculae, predominantly composed of spindle-shaped osteocytes (Figures 4c,f and 5a).

Neither the HTBG group nor the HTBG + PRP group displayed evidence of chondroid or bone callus hyperplasia on the histological sections. Instead, thin layers of fibrous tissue and blood vessels were visible, along with varying extents of bone graft resorption and the presence of fibrovascular structures. These observations were similar across both groups, and no additional histological alterations were attributable to the use of PRP.

3.2 Comparative analysis of bone graft remodeling

On day 14 in the HTBG group, less than 20% exhibited positive remodeling of the bone graft, while in the HTBG + PRP group, a statistically significant positive remodeling of the bone graft was observed (Figure 5a and b).

On the 30th day in the HTBG group, most of the lysed fragments of the bone graft had been replaced by fibrous tissue, while positive bone graft remodeling was seen in all the remaining fragments. For the HTBG + PRP group, the tissue composition consisted of remaining bone graft fragments closely interacting with the newly formed bone and osteoid tissue. There was noticeable active integration of the bone allograft with the new bone and pronounced positive bone graft remodeling (Figure 5b). No statistically significant difference was observed between the groups at this point.

By day 60 in both HTBG and HTBG + PRP groups, newly formed bone tissue without bone graft fragments was seen at the defect site. However, the histological material in the HTBG group also revealed areas with osteoid tissue (forming bone tissue) and regions with a random distribution of mature and immature bone matrix, while the HTBG + PRP group exhibited a consistent and uniform distribution of mature bone tissue (Figure 5b).

3.3 Comparative characterization of inflammatory and necrotic pattern

At 14 days in both HTBG and HTBG + PRP groups, a single reactive cell infiltrate without necrotic changes was observed at the defect site. At 30 and 60 days, all regions of surgically created defects showed no signs of inflammatory cell infiltration, infection indicators (polymorphonuclear cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, and multinucleated cells), or tissue necrosis.

3.4 Radiographic evaluation

The lateromedial X-ray images illustrated distinct areas of radiolucent bone defect in the femur of all animals after a 2 week period (Figure 6a). The boundaries of the scaffolds began to blur, and a high-density signal appeared on the periphery of the bone defect, suggesting new bone formation in the affected areas for both groups. Notably, the HTBG + PRP group demonstrated a statistically significant (p < 0.01) enhancement in the radiographic score in comparison with the HTBG group after 14 days (Figure 6b).

Radiographic assessment of femoral bone defect healing: (a) radiographic images after 14, 30, and 60 days and (b) comparison radiographic score between groups (*p < 0.05).

By the end of 30 days, the materials implanted in the bone had been substituted by newly grown bone, partially filling in the bone defects (Figure 6a). The defect areas in the bone were largely unobservable in both groups. There was an increased radiopacity in the femur where HTBG + PRP was implanted, demonstrating a higher radiographic score than the adjacent bone and notably greater than that in the HTBG group (Figure 6b).

At the 60 day mark, the areas of bone defect were no longer discernible in either group. All groups exhibited enhanced radiopacity in the femur, with a non-significant uptick in radiographic score (Figure 6b).

4 Discussion

This study provides an examination of bone graft remodeling and the healing pattern of newly formed bone following the application of the Marburg bone graft with and without PRP, based on an animal model experiment. The evaluation incorporates radiological, histopathological, and histomorphometric assessments.

Our findings demonstrate that the use of PRP with thermally disinfected bone graft significantly enhances bone formation when compared to the group using bone graft alone, without additional biocomponents. Particularly, the PRP group displayed a notably larger volume of newly formed bone tissue and higher radiologic scores on the 14th and 30th day, compared to the group without PRP (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the defect area in the PRP group revealed a more pronounced proliferation of mature bone tissue that was integrated with the allograft, and it showed the presence of chaotically arranged Haversian canals and horizontally expanding bone trabeculae. The results we obtained supplement the existing evidence demonstrating that the combination of PRP and thermally treated bone is just as effective as the combination of PRP with other graft materials. Several researchers [22,33] have suggested that combining PRP does not necessarily result in a significant boost in osteogenesis. This could potentially be due to high-temperature treatment of the biomaterial causing irreversible changes, which may diminish the impact of growth factors present in PRP [37]. Drawing on our findings, we postulate that using PRP with heat-treated bone enhances the initial stage of osteogenesis. Consequently, the early phase of fracture healing with a Marburg bone graft could be expedited through appropriate growth factor stimulation, via the synergistic effect of PRP. This process might lower the occurrence of non-unions and infections.

Previously, it was shown that PRP improves the regenerative properties of connective and epithelial tissue by increasing the activity of fibroblast-like cells and stimulating cell proliferation [38–42]. We believe that bone graft in combination with PRP improves osteoconductive potential and induces an osteoinductive effect, which is reflected in the enhancement and acceleration of growth and maturation of bone tissue in the defect area.

On the 14th and 30th day, the group using PRP showed a dominant pattern of positive bone graft remodeling in the histopathological analysis, revealing improved viability of the bone graft and a greater proportion of mature bone matrix compared to the group using only bone graft. Despite being a commonly used and convenient method, bone repair with bone grafts has some drawbacks, such as poor bone graft viability and negative remodeling of the bone graft. These issues can lead to relative delays in bone repair or disjointed, uneven healing of the bone defect. This gradual replacement process might result in persistent zones of bone necrosis [43]. Our findings suggest that PRP can effectively diminish the resorption of a thermally treated bone graft, bolster the integration of newly formed bone with the graft surface, and expedite the bone graft remodeling process. This has promising implications not only for bone grafting, but also for other orthopedic scenarios requiring bone remodeling with minimized necrosis risks.

In earlier studies, PRP has been shown to improve angiogenesis in the area of bone defects [44–46]. The process of angiogenesis is significant and necessary for tropism, growth, and maturation of bone tissue [45,47]. Previously [44], we found that in groups, the formation of more dense zones of maturing and mature bone tissue was observed in zones with a relatively large number of microvessels. We believe that the PRP-induced effect of bone growth and maturation activity is more likely associated with a direct effect on angiogenesis and indirectly on an osteoinductive effect.

Our investigation revealed that, as per the histological and radiological findings, there was no significant difference in bone healing between the HTBG and HTBG + PRP groups at the end of 60 days. We propose that this lack of difference may be attributed to the completion of the active phase of osteogenesis, resulting in complete closure of the bone defect. However, it is important to acknowledge that bone tissue reconstruction and remodeling are complex processes that continue beyond the active phase of osteogenesis [1,6]. These processes involve the reorganization and reshaping of the newly formed bone tissue, ensuring its strength and functionality. Although complete closure of the bone defect may have been achieved, the ongoing reconstruction and remodeling could still be taking place [17,42]. This ongoing process might contribute to the lack of significant difference observed at day 60. This suggests the need for additional research to fully understand these processes.

As previously demonstrated, approximately 90% of the bone lamina is composed of mature lamellar bone tissue, with the remaining 10% comprising lacunae, Haversian canals filled with vessels and nerve fibers, as well as fibrous and cartilaginous tissues [48]. The lamellar structure of the bone lamina, integrated with a system of channels, offers not just nutritional support but also mechanical resilience, as bone’s resistance to deformation relies not merely on its mineral content but also on its intricate internal microstructure, a crucial outcome of successful defect repair. Bone tissue repair conventionally transpires in a stage-specific manner, encompassing a phase of dynamic growth and a maturation phase distinguished by the emergence of channels for nutrition and trophicity. This maturation phase is signaled by a relatively minor decline in bone tissue quantity due to focal resorption. According to our study, the bone plate in the defect zone for the HTBG + PRP group at 60 days displayed a minor reduction in bone tissue quantity. This aligns with the process of bone reconstruction and the formation of Haversian canals and may be perceived as a stage of bone tissue maturation [49]. Conversely, in the group without PRP, at 60 days, there was a tendency toward an increase in bone tissue, accompanied by regions displaying haphazard distribution of immature bone matrix. This suggests an extended potential for bone growth and a relative delay in maturation. We posit that the use of PRP with a HTBG not only enhances the osteoconductive and osteoinductive potential of the graft, but also expedites the maturation process of the newly formed bone tissue.

Furthermore, we showed that in the PRP group, there were no abnormalities in bone repair associated with insufficient or excessive bone formation. Newly formed bone tissue in both groups was characterized by normal histopattern: (1) the bone plate did not extend beyond the thickness of the bone defect and did not pass to the bone plate outside the defect, (2) had a laminar layered structure with a focal chaotic pattern in the area of predominantly Haversian canals, and (3) the relative amount of bone tissue and Haversian canals did not differ both between groups and from the structure of the bone outside the bone defect.

A key advantage of this study lies in the comparative evaluation of using a Marburg bone graft in conjunction with PRP, during both early and late phases of bone defect healing. This approach facilitated the discovery of osteoregeneration stimulation in the early stages through the use of PRP. The use of a standardized rabbit femoral defect model, alongside histological and morphometric analysis, further strengthens the validity of the study.

Limitations: The precise mechanism of PRP’s impact on bone tissue is still subject to debate. Is its role direct, influencing osteosynthesis and bone maturation, or does it indirectly promote a favorable macroenvironment with a high index of angiogenesis? These queries could be addressed in subsequent research. Additionally, the evaluation of bone regeneration relied solely on histological and radiographic analyses, which, although informative, did not fully exhaust all the potential analytical methods. Techniques like micro-computed tomography and immunohistochemistry were not used. These could have contributed to a more well-rounded comprehension of bone regeneration by scrutinizing the structural aspects, cellular elements, and gene expression profiles of the regenerated bone. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the results and should influence the design of future studies to fill these potential knowledge gaps.

5 Conclusions

Thus, our experiment with rabbits demonstrated that the combined application of Marburg bone grafts and PRP enhances the viability of the bone graft within the defect zone. We found that PRP improves the integration of the graft with the bone and accelerates the remodeling process of the bone graft. We believe that the primary effect of enhancing the osteoconductive and osteoinductive potentials, as well as the improvement of bone graft remodeling, is tied to the formation of a locally favorable microenvironment with active perfusion–diffusion potential within the stromal framework. This in turn encourages more active growth and maturation of the bone tissue.

-

Funding information: This research has been funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP09260954).

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, D.S. and E.T.; methodology, Ye.K. and B.T.; software, Ye.K. and E.T.; validation, D.S. and Ye.K.; formal analysis, D.S. and B.T.; investigation, E.T. and Ye.K.; resources, B.T.; data curation, D.S.; writing – original draft preparation, E.T. and Ye.K.; writing – review and editing, D.S. and B.T.; visualization, E.T.; supervision, D.S.; project administration, D.S.; funding acquisition, Ye.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

References

[1] Winkler T, Sass FA, Duda GN, Schmidt-Bleek K. A review of biomaterials in bone defect healing, remaining shortcomings and future opportunities for bone tissue engineering: The unsolved challenge. Bone Joint Res. 2018 May;7(3):232–43.10.1302/2046-3758.73.BJR-2017-0270.R1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Hofmann A, Gorbulev S, Guehring T, Schulz AP, Schupfner R, Raschke M, et al. Autologous iliac bone graft compared with biphasic hydroxyapatite and calcium sulfate cement for the treatment of bone defects in tibial plateau fractures: A prospective, randomized, open-label, multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020 Feb;102(3):179–93.10.2106/JBJS.19.00680Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Schmidt AH. Autologous bone graft: Is it still the gold standard? Injury. 2021 Jun;52(Suppl 2):S18–22.10.1016/j.injury.2021.01.043Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Chiarello E, Cadossi M, Tedesco G, Capra P, Calamelli C, Shehu A, et al. Autograft, allograft and bone substitutes in reconstructive orthopedic surgery. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2013 Oct;25(Suppl 1):101–3.10.1007/s40520-013-0088-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Lauthe O, Soubeyrand M, Babinet A, Dumaine V, Anract P, Biau DJ. The indications and donor-site morbidity of tibial cortical strut autografts in the management of defects in long bones. Bone Joint J. 2018 May;100-B(5):667–74.10.1302/0301-620X.100B5.BJJ-2017-0577.R2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Mauffrey C, Barlow BT, Smith W. Management of segmental bone defects. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(3):143–53.10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Brydone AS, Meek D, Maclaine S. Bone grafting, orthopaedic biomaterials, and the clinical need for bone engineering. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2010;224(12):1329–43.10.1243/09544119JEIM770Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Zhou W, Tangl S, Reich KM, Kirchweger F, Liu Z, Zechner W, et al. The influence of type 2 diabetes mellitus on the osseointegration of titanium implants with different surface modifications-a histomorphometric study in high-fat diet/low-dose streptozotocin-treated rats. Implant Dent. 2019 Feb;28(1):11–9.10.1097/ID.0000000000000836Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Zhou W, Kuderer S, Liu Z, Ulm C, Rausch-Fan X, Tangl S. Peri-implant bone remodeling at the interface of three different implant types: a histomorphometric study in mini-pigs. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28(11):1443–9.10.1111/clr.13009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Black C, Gibbs D, McEwan J, Kanczler J, Fernández MP, Tozzi G, et al. Comparison of bone formation mediated by bone morphogenetic protein delivered by nanoclay gels with clinical techniques (autograft and InductOs®) in an ovine bone model. J Tissue Eng. 2022 Sep;13:20417314221113746.10.1177/20417314221113746Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Kohli N, Sharma V, Orera A, Sawadkar P, Owji N, Frost OG, et al. Pro-angiogenic and osteogenic composite scaffolds of fibrin, alginate and calcium phosphate for bone tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng. 2021 Apr;12:20417314211005610.10.1177/20417314211005610Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Pruss A, Seibold M, Benedix F, Frommelt L, von Garrel T, Gürtler L, et al. Validation of the ‘Marburg bone bank system’ for thermodisinfection of allogenic femoral head transplants using selected bacteria, fungi, and spores. Biologicals. 2003 Dec;31(4):287–94.10.1016/j.biologicals.2003.08.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Katthagen BD, Prub A. Transplantation allogenen Knochens [Bone allografting]. Orthopade. 2008;37(8):764–71.10.1007/s00132-008-1272-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Siemssen N, Friesecke C, Wolff C, Beller G, Wassilew K, Neuner B, et al. Ein klinisch-radiologischer Score für Femurkopftransplantate: Etablierung des Tabea-FK-Scores zur Sicherung der Qualität humaner Femurkopftransplantate [A clinical radiological score for femoral head grafts: Establishment of the Tabea FK score to ensure the quality of human femoral head grafts]. Orthopade. 2021 Jun;50(6):471–80.10.1007/s00132-020-03941-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Mohr J, Germain M, Winters M, Fraser S, Duong A, Garibaldi A, et al. Disinfection of human musculoskeletal allografts in tissue banking: a systematic review. Cell Tissue Bank. 2016 Dec;17(4):573–84.10.1007/s10561-016-9584-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Moreno M, Amaral MH, Lobo JM, Silva AC. Scaffolds for bone regeneration: state of the art. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(18):2726–36.10.2174/1381612822666160203114902Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Dimitriou R, Tsiridis E, Giannoudis PV. Current concepts of molecular aspects of bone healing. Injury. 2005;36(12):1392–404.10.1016/j.injury.2005.07.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Lohmann CH, Andreacchio D, Köster G, Carnes DL Jr, Cochran DL, Dean DD, et al. Tissue response and osteoinduction of human bone grafts in vivo. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001 Oct;121(10):583–90.10.1007/s004020100291Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Foster TE, Puskas BL, Mandelbaum BR, Gerhardt MB, Rodeo SA. Platelet-rich plasma: from basic science to clinical applications. Am J Sports Med. 2009 Nov;37(11):2259–72.10.1177/0363546509349921Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Jurk K, Kehrel BE. Platelets: physiology and biochemistry. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2005 Aug;31(4):381–92.10.1055/s-2005-916671Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Koç S, Çakmak S, Gümüşderelioğlu M, Ertekin TS, Çalış M, Yılmaz MM, et al. Three dimensional nanofibrous and compressible poly(L-lactic acid) bone grafts loaded with platelet-rich plasma. Biomed Mater. 2021 Apr;16(4):045012.10.1088/1748-605X/abef5aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Başdelioğlu K, Meriç G, Sargın S, Atik A, Ulusal AE, Akseki D. The effect of platelet-rich plasma on fracture healing in long-bone pseudoarthrosis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2020 Nov;30(8):1481–6.10.1007/s00590-020-02730-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Walid AA. Evaluation of bone regenerative capacity in rat claverial bone defect using platelet rich fibrin with and without beta tricalcium phosphate bone graft material. Saudi Dent J. 2016 Jul;28(3):109–17.10.1016/j.sdentj.2015.09.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] The Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan on the Health of the People and the Healthcare System of July 7, 2020 No360. Chapter 24 Donation and Transplantation. 2020. https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/K2000000360.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Order of the Minister of Health and Social Development of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated 04.05.2019 on the Approval of the Rules for the Formation and Maintenance of Registers of Tissue Recipients (part of the tissue) and (or) Organs (part of the organs), as well as Tissue Donors (part of the tissue) and (or) Organs (part of organs), Hematopoietic Stem Cells. 2019. https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/V1500011477.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Tuleubaev B, Saginova D, Saginov A, Tashmetov E, Koshanova A. Heat treated bone allograft as an antibiotic carrier for local application. Georgian Med News. 2020 Sep;306:142–6.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Syam S, Chang C-W, Lan W-C, Ou K-L, Huang B-H, Lin Y-Y, et al. An innovative bioceramic bone graft with platelet-rich plasma for rapid bone healing and regeneration in a rabbit model. Appl Sci. 2021;11:5271.10.3390/app11115271Search in Google Scholar

[28] Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Rasmusson L, Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: from pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF). Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27:158–67.10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.11.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] European Parliament and Council. Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Off J Eur Union. 2010;276:33–79.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Cruz-Orive LM, Weibel ER. Recent stereological methods for cell biology: a brief survey. Am J Physiol. 1990;258(4 Pt 1):L148–56.10.1152/ajplung.1990.258.4.L148Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Chiu YL, Luo YL, Chen YW, Wu CT, Periasamy S, Yen KC, et al. Regenerative Efficacy of supercritical carbon dioxide-derived bone graft putty in rabbit bone defect model. Biomedicines. 2022 Nov;10(11):2802.10.3390/biomedicines10112802Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Burkitt HG, Young B, Wheater JW. Wheater’s Functional Histology: A Text and Colour Atlas. 3rd edn. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Dempster DW, Compston JE, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, et al. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(1):2–17.10.1002/jbmr.1805Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Parfitt AM. Bone histomorphometry: proposed system for standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Calcif Tissue Int. 1988 May;42(5):284–6.10.1007/BF02556360Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Compston J. Bone histomorphometry. In: Arnett TR, Henderson B, editors. Methods in bone biology. London, England: Chapman & Hall; 1998. p. 177–99.10.1007/978-0-585-38227-2_7Search in Google Scholar

[36] Lane JM, Sandhu HS. Current approach to experimental bone grafting. Orthop Clin N Am. 1987;18:213–25.10.1016/S0030-5898(20)30385-0Search in Google Scholar

[37] Rocha FS, Ramos LM, Batista JD, Zanetta-Barbosa D, Ferro EA, Dechichi P. Bovine anorganic bone graft associated with platelet-rich plasma: histologic analysis in rabbit calvaria. J Oral Implantol. 2011;37:511–8.10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-09-00091.1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Stievano D, Di Stefano A, Ludovichetti M, Pagnutti S, Gazzola F, Boato C, et al. Maxillary sinus lift through heterologous bone grafts and simultaneous acid-etched implants placement. Five years follow-up. Minerva Chir. 2008;63:79–91.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Slimi F, Zribi W, Trigui M, Amri R, Gouiaa N, Abid C, et al. The effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma gel on full-thickness cartilage defect repair in a rabbit model. Bone Joint Res. 2021 Mar;10(3):192–202.10.1302/2046-3758.103.BJR-2020-0087.R2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Chien CS, Ho HO, Liang YC, Ko PH, Sheu MT, Chen CH. Incorporation of exudates of human platelet-rich fibrin gel in biodegradable fibrin scaffolds for tissue engineering of cartilage. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2012 May;100(4):948–55.10.1002/jbm.b.32657Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Spreafico A, Chellini F, Frediani B, Bernardini G, Niccolini S, Serchi T, et al. Biochemical investigation of the effects of human platelet releasates on human articular chondrocytes. J Cell Biochem. 2009 Dec;108(5):1153–65.10.1002/jcb.22344Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Kaps C, Loch A, Haisch A, Smolian H, Burmester GR, Häupl T, et al. Human platelet supernatant promotes proliferation but not differentiation of articular chondrocytes. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2002 Jul;40(4):485–90.10.1007/BF02345083Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Enneking WF, Burchardt H, Puhl JJ, Piotrowski G. Physical and biological aspects of repair in dog cortical-bone transplants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975 Mar;57(2):237–52.10.2106/00004623-197557020-00018Search in Google Scholar

[44] Saginova D, Tashmetov E, Kamyshanskiy Y, Tuleubayev B, Rimashevskiy D. Evaluation of bone regenerative capacity in rabbit femoral defect using thermally disinfected bone human femoral head combined with platelet-rich plasma, recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2, and zoledronic acid. Biomedicines. 2023 Jun;11(6):1729.10.3390/biomedicines11061729Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Simunovic F, Finkenzeller G. Vascularization strategies in bone tissue engineering. Cells. 2021 Jul;10(7):1749.10.3390/cells10071749Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Dong Z, Li B, Liu B, Bai S, Li G, Ding A, et al. Platelet-rich plasma promotes angiogenesis of prefabricated vascularized bone graft. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012 Sep;70(9):2191–7.10.1016/j.joms.2011.09.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Brownlow HC, Reed A, Simpson AH. The vascularity of atrophic non-unions. Injury. 2002;33(2):145–50.10.1016/S0020-1383(01)00153-XSearch in Google Scholar

[48] Moreira CA, Dempster DW, Baron R Anatomy and Ultrastructure of bone – histogenesis, growth and remodeling. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al. editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2019 Jun.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Maggiano IS, Maggiano CM, Clement JG, Thomas CD, Carter Y, Cooper DM. Three-dimensional reconstruction of Haversian systems in human cortical bone using synchrotron radiation-based micro-CT: morphology and quantification of branching and transverse connections across age. J Anat. 2016 May;228(5):719–32.10.1111/joa.12430Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Systemic investigation of inetetamab in combination with small molecules to treat HER2-overexpressing breast and gastric cancers

- Immunosuppressive treatment for idiopathic membranous nephropathy: An updated network meta-analysis

- Identifying two pathogenic variants in a patient with pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy

- Effects of phytoestrogens combined with cold stress on sperm parameters and testicular proteomics in rats

- A case of pulmonary embolism with bad warfarin anticoagulant effects caused by E. coli infection

- Neutrophilia with subclinical Cushing’s disease: A case report and literature review

- Isoimperatorin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced periodontitis by downregulating ERK1/2 and NF-κB pathways

- Immunoregulation of synovial macrophages for the treatment of osteoarthritis

- Novel CPLANE1 c.8948dupT (p.P2984Tfs*7) variant in a child patient with Joubert syndrome

- Antiphospholipid antibodies and the risk of thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms

- Immunological responses of septic rats to combination therapy with thymosin α1 and vitamin C

- High glucose and high lipid induced mitochondrial dysfunction in JEG-3 cells through oxidative stress

- Pharmacological inhibition of the ubiquitin-specific protease 8 effectively suppresses glioblastoma cell growth

- Levocarnitine regulates the growth of angiotensin II-induced myocardial fibrosis cells via TIMP-1

- Age-related changes in peripheral T-cell subpopulations in elderly individuals: An observational study

- Single-cell transcription analysis reveals the tumor origin and heterogeneity of human bilateral renal clear cell carcinoma

- Identification of iron metabolism-related genes as diagnostic signatures in sepsis by blood transcriptomic analysis

- Long noncoding RNA ACART knockdown decreases 3T3-L1 preadipocyte proliferation and differentiation

- Surgery, adjuvant immunotherapy plus chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary malignant melanoma of the parotid gland (PGMM): A case report

- Dosimetry comparison with helical tomotherapy, volumetric modulated arc therapy, and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for grade II gliomas: A single‑institution case series

- Soy isoflavone reduces LPS-induced acute lung injury via increasing aquaporin 1 and aquaporin 5 in rats

- Refractory hypokalemia with sexual dysplasia and infertility caused by 17α-hydroxylase deficiency and triple X syndrome: A case report

- Meta-analysis of cancer risk among end stage renal disease undergoing maintenance dialysis

- 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase inhibition arrests growth and induces apoptosis in gastric cancer via AMPK activation and oxidative stress

- Experimental study on the optimization of ANM33 release in foam cells

- Primary retroperitoneal angiosarcoma: A case report

- Metabolomic analysis-identified 2-hydroxybutyric acid might be a key metabolite of severe preeclampsia

- Malignant pleural effusion diagnosis and therapy

- Effect of spaceflight on the phenotype and proteome of Escherichia coli

- Comparison of immunotherapy combined with stereotactic radiotherapy and targeted therapy for patients with brain metastases: A systemic review and meta-analysis

- Activation of hypermethylated P2RY1 mitigates gastric cancer by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation

- Association between the VEGFR-2 -604T/C polymorphism (rs2071559) and type 2 diabetic retinopathy

- The role of IL-31 and IL-34 in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic periodontitis

- Triple-negative mouse breast cancer initiating cells show high expression of beta1 integrin and increased malignant features

- mNGS facilitates the accurate diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of suspicious critical CNS infection in real practice: A retrospective study

- The apatinib and pemetrexed combination has antitumor and antiangiogenic effects against NSCLC

- Radiotherapy for primary thyroid adenoid cystic carcinoma

- Design and functional preliminary investigation of recombinant antigen EgG1Y162–EgG1Y162 against Echinococcus granulosus

- Effects of losartan in patients with NAFLD: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial

- Bibliometric analysis of METTL3: Current perspectives, highlights, and trending topics

- Performance comparison of three scaling algorithms in NMR-based metabolomics analysis

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and its related molecules participate in PROK1 silence-induced anti-tumor effects on pancreatic cancer

- The altered expression of cytoskeletal and synaptic remodeling proteins during epilepsy

- Effects of pegylated recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on lymphocytes and white blood cells of patients with malignant tumor

- Prostatitis as initial manifestation of Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia diagnosed by metagenome next-generation sequencing: A case report

- NUDT21 relieves sevoflurane-induced neurological damage in rats by down-regulating LIMK2

- Association of interleukin-10 rs1800896, rs1800872, and interleukin-6 rs1800795 polymorphisms with squamous cell carcinoma risk: A meta-analysis

- Exosomal HBV-DNA for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of chronic hepatitis B

- Shear stress leads to the dysfunction of endothelial cells through the Cav-1-mediated KLF2/eNOS/ERK signaling pathway under physiological conditions

- Interaction between the PI3K/AKT pathway and mitochondrial autophagy in macrophages and the leukocyte count in rats with LPS-induced pulmonary infection

- Meta-analysis of the rs231775 locus polymorphism in the CTLA-4 gene and the susceptibility to Graves’ disease in children

- Cloning, subcellular localization and expression of phosphate transporter gene HvPT6 of hulless barley

- Coptisine mitigates diabetic nephropathy via repressing the NRLP3 inflammasome

- Significant elevated CXCL14 and decreased IL-39 levels in patients with tuberculosis

- Whole-exome sequencing applications in prenatal diagnosis of fetal bowel dilatation

- Gemella morbillorum infective endocarditis: A case report and literature review

- An unusual ectopic thymoma clonal evolution analysis: A case report

- Severe cumulative skin toxicity during toripalimab combined with vemurafenib following toripalimab alone

- Detection of V. vulnificus septic shock with ARDS using mNGS

- Novel rare genetic variants of familial and sporadic pulmonary atresia identified by whole-exome sequencing

- The influence and mechanistic action of sperm DNA fragmentation index on the outcomes of assisted reproduction technology

- Novel compound heterozygous mutations in TELO2 in an infant with You-Hoover-Fong syndrome: A case report and literature review

- ctDNA as a prognostic biomarker in resectable CLM: Systematic review and meta-analysis

- Diagnosis of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis by metagenomic next-generation sequencing: A case report

- Phylogenetic analysis of promoter regions of human Dolichol kinase (DOLK) and orthologous genes using bioinformatics tools

- Collagen changes in rabbit conjunctiva after conjunctival crosslinking

- Effects of NM23 transfection of human gastric carcinoma cells in mice

- Oral nifedipine and phytosterol, intravenous nicardipine, and oral nifedipine only: Three-arm, retrospective, cohort study for management of severe preeclampsia

- Case report of hepatic retiform hemangioendothelioma: A rare tumor treated with ultrasound-guided microwave ablation

- Curcumin induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by decreasing the expression of STAT3/VEGF/HIF-1α signaling

- Rare presentation of double-clonal Waldenström macroglobulinemia with pulmonary embolism: A case report

- Giant duplication of the transverse colon in an adult: A case report and literature review

- Ectopic thyroid tissue in the breast: A case report

- SDR16C5 promotes proliferation and migration and inhibits apoptosis in pancreatic cancer

- Vaginal metastasis from breast cancer: A case report

- Screening of the best time window for MSC transplantation to treat acute myocardial infarction with SDF-1α antibody-loaded targeted ultrasonic microbubbles: An in vivo study in miniswine

- Inhibition of TAZ impairs the migration ability of melanoma cells

- Molecular complexity analysis of the diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome in China

- Effects of maternal calcium and protein intake on the development and bone metabolism of offspring mice

- Identification of winter wheat pests and diseases based on improved convolutional neural network

- Ultra-multiplex PCR technique to guide treatment of Aspergillus-infected aortic valve prostheses

- Virtual high-throughput screening: Potential inhibitors targeting aminopeptidase N (CD13) and PIKfyve for SARS-CoV-2

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients with COVID-19

- Utility of methylene blue mixed with autologous blood in preoperative localization of pulmonary nodules and masses

- Integrated analysis of the microbiome and transcriptome in stomach adenocarcinoma

- Berberine suppressed sarcopenia insulin resistance through SIRT1-mediated mitophagy

- DUSP2 inhibits the progression of lupus nephritis in mice by regulating the STAT3 pathway

- Lung abscess by Fusobacterium nucleatum and Streptococcus spp. co-infection by mNGS: A case series

- Genetic alterations of KRAS and TP53 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma associated with poor prognosis

- Granulomatous polyangiitis involving the fourth ventricle: Report of a rare case and a literature review

- Studying infant mortality: A demographic analysis based on data mining models

- Metaplastic breast carcinoma with osseous differentiation: A report of a rare case and literature review

- Protein Z modulates the metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma cells

- Inhibition of pyroptosis and apoptosis by capsaicin protects against LPS-induced acute kidney injury through TRPV1/UCP2 axis in vitro

- TAK-242, a toll-like receptor 4 antagonist, against brain injury by alleviates autophagy and inflammation in rats

- Primary mediastinum Ewing’s sarcoma with pleural effusion: A case report and literature review

- Association of ADRB2 gene polymorphisms and intestinal microbiota in Chinese Han adolescents

- Tanshinone IIA alleviates chondrocyte apoptosis and extracellular matrix degeneration by inhibiting ferroptosis

- Study on the cytokines related to SARS-Cov-2 in testicular cells and the interaction network between cells based on scRNA-seq data

- Effect of periostin on bone metabolic and autophagy factors during tooth eruption in mice

- HP1 induces ferroptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells through NRF2 pathway in diabetic nephropathy

- Intravaginal estrogen management in postmenopausal patients with vaginal squamous intraepithelial lesions along with CO2 laser ablation: A retrospective study

- Hepatocellular carcinoma cell differentiation trajectory predicts immunotherapy, potential therapeutic drugs, and prognosis of patients

- Effects of physical exercise on biomarkers of oxidative stress in healthy subjects: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Identification of lysosome-related genes in connection with prognosis and immune cell infiltration for drug candidates in head and neck cancer

- Development of an instrument-free and low-cost ELISA dot-blot test to detect antibodies against SARS-CoV-2

- Research progress on gas signal molecular therapy for Parkinson’s disease

- Adiponectin inhibits TGF-β1-induced skin fibroblast proliferation and phenotype transformation via the p38 MAPK signaling pathway

- The G protein-coupled receptor-related gene signatures for predicting prognosis and immunotherapy response in bladder urothelial carcinoma

- α-Fetoprotein contributes to the malignant biological properties of AFP-producing gastric cancer

- CXCL12/CXCR4/CXCR7 axis in placenta tissues of patients with placenta previa

- Association between thyroid stimulating hormone levels and papillary thyroid cancer risk: A meta-analysis

- Significance of sTREM-1 and sST2 combined diagnosis for sepsis detection and prognosis prediction

- Diagnostic value of serum neuroactive substances in the acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease complicated with depression

- Research progress of AMP-activated protein kinase and cardiac aging

- TRIM29 knockdown prevented the colon cancer progression through decreasing the ubiquitination levels of KRT5

- Cross-talk between gut microbiota and liver steatosis: Complications and therapeutic target

- Metastasis from small cell lung cancer to ovary: A case report

- The early diagnosis and pathogenic mechanisms of sepsis-related acute kidney injury

- The effect of NK cell therapy on sepsis secondary to lung cancer: A case report

- Erianin alleviates collagen-induced arthritis in mice by inhibiting Th17 cell differentiation

- Loss of ACOX1 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and its correlation with clinical features

- Signalling pathways in the osteogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells

- Crosstalk between lactic acid and immune regulation and its value in the diagnosis and treatment of liver failure

- Clinicopathological features and differential diagnosis of gastric pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma

- Traumatic brain injury and rTMS-ERPs: Case report and literature review

- Extracellular fibrin promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression through integrin β1/PTEN/AKT signaling

- Knockdown of DLK4 inhibits non-small cell lung cancer tumor growth by downregulating CKS2

- The co-expression pattern of VEGFR-2 with indicators related to proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation of anagen hair follicles

- Inflammation-related signaling pathways in tendinopathy

- CD4+ T cell count in HIV/TB co-infection and co-occurrence with HL: Case report and literature review

- Clinical analysis of severe Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia: Case series study

- Bioinformatics analysis to identify potential biomarkers for the pulmonary artery hypertension associated with the basement membrane

- Influence of MTHFR polymorphism, alone or in combination with smoking and alcohol consumption, on cancer susceptibility

- Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don counteracts the ampicillin resistance in multiple antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by downregulation of PBP2a synthesis

- Combination of a bronchogenic cyst in the thoracic spinal canal with chronic myelocytic leukemia

- Bacterial lipoprotein plays an important role in the macrophage autophagy and apoptosis induced by Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus

- TCL1A+ B cells predict prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer through integrative analysis of single-cell and bulk transcriptomic data

- Ezrin promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression via the Hippo signaling pathway

- Ferroptosis: A potential target of macrophages in plaque vulnerability

- Predicting pediatric Crohn's disease based on six mRNA-constructed risk signature using comprehensive bioinformatic approaches

- Applications of genetic code expansion and photosensitive UAAs in studying membrane proteins

- HK2 contributes to the proliferation, migration, and invasion of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells by enhancing the ERK1/2 signaling pathway

- IL-17 in osteoarthritis: A narrative review

- Circadian cycle and neuroinflammation

- Probiotic management and inflammatory factors as a novel treatment in cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Hemorrhagic meningioma with pulmonary metastasis: Case report and literature review

- SPOP regulates the expression profiles and alternative splicing events in human hepatocytes

- Knockdown of SETD5 inhibited glycolysis and tumor growth in gastric cancer cells by down-regulating Akt signaling pathway

- PTX3 promotes IVIG resistance-induced endothelial injury in Kawasaki disease by regulating the NF-κB pathway

- Pancreatic ectopic thyroid tissue: A case report and analysis of literature

- The prognostic impact of body mass index on female breast cancer patients in underdeveloped regions of northern China differs by menopause status and tumor molecular subtype

- Report on a case of liver-originating malignant melanoma of unknown primary

- Case report: Herbal treatment of neutropenic enterocolitis after chemotherapy for breast cancer

- The fibroblast growth factor–Klotho axis at molecular level

- Characterization of amiodarone action on currents in hERG-T618 gain-of-function mutations

- A case report of diagnosis and dynamic monitoring of Listeria monocytogenes meningitis with NGS

- Effect of autologous platelet-rich plasma on new bone formation and viability of a Marburg bone graft

- Small breast epithelial mucin as a useful prognostic marker for breast cancer patients

- Continuous non-adherent culture promotes transdifferentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells into retinal lineage

- Nrf3 alleviates oxidative stress and promotes the survival of colon cancer cells by activating AKT/BCL-2 signal pathway

- Favorable response to surufatinib in a patient with necrolytic migratory erythema: A case report

- Case report of atypical undernutrition of hypoproteinemia type

- Down-regulation of COL1A1 inhibits tumor-associated fibroblast activation and mediates matrix remodeling in the tumor microenvironment of breast cancer

- Sarcoma protein kinase inhibition alleviates liver fibrosis by promoting hepatic stellate cells ferroptosis

- Research progress of serum eosinophil in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma

- Clinicopathological characteristics of co-existing or mixed colorectal cancer and neuroendocrine tumor: Report of five cases

- Role of menopausal hormone therapy in the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis

- Precisional detection of lymph node metastasis using tFCM in colorectal cancer

- Advances in diagnosis and treatment of perimenopausal syndrome

- A study of forensic genetics: ITO index distribution and kinship judgment between two individuals

- Acute lupus pneumonitis resembling miliary tuberculosis: A case-based review

- Plasma levels of CD36 and glutathione as biomarkers for ruptured intracranial aneurysm

- Fractalkine modulates pulmonary angiogenesis and tube formation by modulating CX3CR1 and growth factors in PVECs

- Novel risk prediction models for deep vein thrombosis after thoracotomy and thoracoscopic lung cancer resections, involving coagulation and immune function

- Exploring the diagnostic markers of essential tremor: A study based on machine learning algorithms

- Evaluation of effects of small-incision approach treatment on proximal tibia fracture by deep learning algorithm-based magnetic resonance imaging

- An online diagnosis method for cancer lesions based on intelligent imaging analysis

- Medical imaging in rheumatoid arthritis: A review on deep learning approach

- Predictive analytics in smart healthcare for child mortality prediction using a machine learning approach

- Utility of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio and platelet–lymphocyte ratio in predicting acute-on-chronic liver failure survival

- A biomedical decision support system for meta-analysis of bilateral upper-limb training in stroke patients with hemiplegia

- TNF-α and IL-8 levels are positively correlated with hypobaric hypoxic pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling in rats

- Stochastic gradient descent optimisation for convolutional neural network for medical image segmentation

- Comparison of the prognostic value of four different critical illness scores in patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy

- Application and teaching of computer molecular simulation embedded technology and artificial intelligence in drug research and development

- Hepatobiliary surgery based on intelligent image segmentation technology

- Value of brain injury-related indicators based on neural network in the diagnosis of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- Analysis of early diagnosis methods for asymmetric dementia in brain MR images based on genetic medical technology

- Early diagnosis for the onset of peri-implantitis based on artificial neural network

- Clinical significance of the detection of serum IgG4 and IgG4/IgG ratio in patients with thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy

- Forecast of pain degree of lumbar disc herniation based on back propagation neural network

- SPA-UNet: A liver tumor segmentation network based on fused multi-scale features

- Systematic evaluation of clinical efficacy of CYP1B1 gene polymorphism in EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer observed by medical image

- Rehabilitation effect of intelligent rehabilitation training system on hemiplegic limb spasms after stroke

- A novel approach for minimising anti-aliasing effects in EEG data acquisition

- ErbB4 promotes M2 activation of macrophages in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Clinical role of CYP1B1 gene polymorphism in prediction of postoperative chemotherapy efficacy in NSCLC based on individualized health model

- Lung nodule segmentation via semi-residual multi-resolution neural networks

- Evaluation of brain nerve function in ICU patients with Delirium by deep learning algorithm-based resting state MRI

- A data mining technique for detecting malignant mesothelioma cancer using multiple regression analysis

- Markov model combined with MR diffusion tensor imaging for predicting the onset of Alzheimer’s disease

- Effectiveness of the treatment of depression associated with cancer and neuroimaging changes in depression-related brain regions in patients treated with the mediator-deuterium acupuncture method

- Molecular mechanism of colorectal cancer and screening of molecular markers based on bioinformatics analysis

- Monitoring and evaluation of anesthesia depth status data based on neuroscience

- Exploring the conformational dynamics and thermodynamics of EGFR S768I and G719X + S768I mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: An in silico approaches

- Optimised feature selection-driven convolutional neural network using gray level co-occurrence matrix for detection of cervical cancer

- Incidence of different pressure patterns of spinal cerebellar ataxia and analysis of imaging and genetic diagnosis

- Pathogenic bacteria and treatment resistance in older cardiovascular disease patients with lung infection and risk prediction model

- Adoption value of support vector machine algorithm-based computed tomography imaging in the diagnosis of secondary pulmonary fungal infections in patients with malignant hematological disorders

- From slides to insights: Harnessing deep learning for prognostic survival prediction in human colorectal cancer histology

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Monitoring of hourly carbon dioxide concentration under different land use types in arid ecosystem

- Comparing the differences of prokaryotic microbial community between pit walls and bottom from Chinese liquor revealed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing

- Effects of cadmium stress on fruits germination and growth of two herbage species

- Bamboo charcoal affects soil properties and bacterial community in tea plantations

- Optimization of biogas potential using kinetic models, response surface methodology, and instrumental evidence for biodegradation of tannery fleshings during anaerobic digestion

- Understory vegetation diversity patterns of Platycladus orientalis and Pinus elliottii communities in Central and Southern China

- Studies on macrofungi diversity and discovery of new species of Abortiporus from Baotianman World Biosphere Reserve

- Food Science

- Effect of berrycactus fruit (Myrtillocactus geometrizans) on glutamate, glutamine, and GABA levels in the frontal cortex of rats fed with a high-fat diet

- Guesstimate of thymoquinone diversity in Nigella sativa L. genotypes and elite varieties collected from Indian states using HPTLC technique

- Analysis of bacterial community structure of Fuzhuan tea with different processing techniques

- Untargeted metabolomics reveals sour jujube kernel benefiting the nutritional value and flavor of Morchella esculenta

- Mycobiota in Slovak wine grapes: A case study from the small Carpathians wine region

- Elemental analysis of Fadogia ancylantha leaves used as a nutraceutical in Mashonaland West Province, Zimbabwe

- Microbiological transglutaminase: Biotechnological application in the food industry

- Influence of solvent-free extraction of fish oil from catfish (Clarias magur) heads using a Taguchi orthogonal array design: A qualitative and quantitative approach

- Chromatographic analysis of the chemical composition and anticancer activities of Curcuma longa extract cultivated in Palestine

- The potential for the use of leghemoglobin and plant ferritin as sources of iron

- Investigating the association between dietary patterns and glycemic control among children and adolescents with T1DM

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Biocompatibility and osteointegration capability of β-TCP manufactured by stereolithography 3D printing: In vitro study

- Clinical characteristics and the prognosis of diabetic foot in Tibet: A single center, retrospective study

- Agriculture

- Biofertilizer and NPSB fertilizer application effects on nodulation and productivity of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) at Sodo Zuria, Southern Ethiopia

- On correlation between canopy vegetation and growth indexes of maize varieties with different nitrogen efficiencies

- Exopolysaccharides from Pseudomonas tolaasii inhibit the growth of Pleurotus ostreatus mycelia

- A transcriptomic evaluation of the mechanism of programmed cell death of the replaceable bud in Chinese chestnut

- Melatonin enhances salt tolerance in sorghum by modulating photosynthetic performance, osmoregulation, antioxidant defense, and ion homeostasis

- Effects of plant density on alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) seed yield in western Heilongjiang areas

- Identification of rice leaf diseases and deficiency disorders using a novel DeepBatch technique

- Artificial intelligence and internet of things oriented sustainable precision farming: Towards modern agriculture

- Animal Sciences

- Effect of ketogenic diet on exercise tolerance and transcriptome of gastrocnemius in mice

- Combined analysis of mRNA–miRNA from testis tissue in Tibetan sheep with different FecB genotypes

- Isolation, identification, and drug resistance of a partially isolated bacterium from the gill of Siniperca chuatsi

- Tracking behavioral changes of confined sows from the first mating to the third parity

- The sequencing of the key genes and end products in the TLR4 signaling pathway from the kidney of Rana dybowskii exposed to Aeromonas hydrophila

- Development of a new candidate vaccine against piglet diarrhea caused by Escherichia coli

- Plant Sciences

- Crown and diameter structure of pure Pinus massoniana Lamb. forest in Hunan province, China

- Genetic evaluation and germplasm identification analysis on ITS2, trnL-F, and psbA-trnH of alfalfa varieties germplasm resources

- Tissue culture and rapid propagation technology for Gentiana rhodantha

- Effects of cadmium on the synthesis of active ingredients in Salvia miltiorrhiza

- Cloning and expression analysis of VrNAC13 gene in mung bean

- Chlorate-induced molecular floral transition revealed by transcriptomes

- Effects of warming and drought on growth and development of soybean in Hailun region

- Effects of different light conditions on transient expression and biomass in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves

- Comparative analysis of the rhizosphere microbiome and medicinally active ingredients of Atractylodes lancea from different geographical origins

- Distinguish Dianthus species or varieties based on chloroplast genomes

- Comparative transcriptomes reveal molecular mechanisms of apple blossoms of different tolerance genotypes to chilling injury

- Study on fresh processing key technology and quality influence of Cut Ophiopogonis Radix based on multi-index evaluation

- An advanced approach for fig leaf disease detection and classification: Leveraging image processing and enhanced support vector machine methodology

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Protein Z modulates the metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma cells”

- Erratum to “BRCA1 subcellular localization regulated by PI3K signaling pathway in triple-negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells and hormone-sensitive T47D cells”

- Retraction

- Retraction to “Protocatechuic acid attenuates cerebral aneurysm formation and progression by inhibiting TNF-alpha/Nrf-2/NF-kB-mediated inflammatory mechanisms in experimental rats”

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Systemic investigation of inetetamab in combination with small molecules to treat HER2-overexpressing breast and gastric cancers

- Immunosuppressive treatment for idiopathic membranous nephropathy: An updated network meta-analysis

- Identifying two pathogenic variants in a patient with pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy

- Effects of phytoestrogens combined with cold stress on sperm parameters and testicular proteomics in rats

- A case of pulmonary embolism with bad warfarin anticoagulant effects caused by E. coli infection

- Neutrophilia with subclinical Cushing’s disease: A case report and literature review

- Isoimperatorin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced periodontitis by downregulating ERK1/2 and NF-κB pathways

- Immunoregulation of synovial macrophages for the treatment of osteoarthritis

- Novel CPLANE1 c.8948dupT (p.P2984Tfs*7) variant in a child patient with Joubert syndrome

- Antiphospholipid antibodies and the risk of thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms

- Immunological responses of septic rats to combination therapy with thymosin α1 and vitamin C

- High glucose and high lipid induced mitochondrial dysfunction in JEG-3 cells through oxidative stress

- Pharmacological inhibition of the ubiquitin-specific protease 8 effectively suppresses glioblastoma cell growth