Abstract

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is an important type of pathogenic bacteria that causes diarrhea in humans and young livestock. The pathogen has a high morbidity and mortality rate, resulting in significant economic losses in the pig industry. To effectively prevent piglet diarrhea, we developed a new tetravalent genetically engineered vaccine that specifically targets ETEC. To eliminate the natural toxin activity of ST1 enterotoxin and enhance the preventive effect of the vaccine, the mutated ST 1 , K88ac, K99, and LT B genes were amplified by PCR and site-specific mutation techniques. The recombinant strain BL21(DE3)(pXKK3SL) was constructed and achieved high expression. Animal experiments showed that the inactivated vaccine had eliminated the natural toxin activity of ST1. The immune protection test demonstrated that the inclusion body and inactivated vaccine exhibited a positive immune effect. The protection rates of the inclusion body group and inactivated vaccine group were 96 and 98%, respectively, when challenged with 1 minimum lethal dose, indicating that the constructed K88ac-K99-3ST1-LTB vaccine achieved a strong immune effect. Additionally, the minimum immune doses for mice and pregnant sows were determined to be 0.2 and 2 mL, respectively. This study suggests that the novel K88ac-K99-3ST1-LTB vaccine has a wide immune spectrum and can prevent diarrhea caused by ETEC through enterotoxin and fimbrial pathways. The aforementioned research demonstrates that the K88ac-K99-3ST1-LTB vaccine offers a new genetically engineered vaccine that shows potential for preventing diarrhea in newborn piglets.

1 Introduction

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is a significant pathogen that causes diarrhea in young animals, such as piglets, calves, and lambs. ETEC is also among the main pathogens responsible for the high incidence and mortality of bacterial diarrhea in humans and animals [1,2,3,4]. When infected with ETEC, individuals often experience severe watery diarrhea and rapid dehydration, which greatly impacts human health and the sustainable development of aquaculture [5,6]. ETEC-induced diarrhea has become a major contributor to infant diarrhea in developing countries, as well as a cause of diarrhea in children, adults, and tourists [7,8,9,10]. Patients and carriers are the primary sources of infection, which can contaminate the surrounding environment and spread rapidly. Many outbreaks have been linked to water, food, milk, and beverages. People are generally susceptible to ETEC, and many tourists experience severe diarrhea due to food and water contamination by ETEC [11,12]. ETEC belongs to the Enterobacteriaceae genus and is a gram-negative bacterium. The optimal growth temperature for ETEC is 37°C, and the optimal pH value is 7.2–7.4 [13,14]. The antigens within ETEC are complex and primarily include cell O antigen, flagellar H antigen, and capsule K antigen, and the pathogen has different serotypes in different regions. ETEC produces toxic factors, such as adhesin, enterotoxin, endotoxin, and hemolysin. Enterotoxin and adhesin play important roles in pathogenesis and immunology. Adhesion antigens mainly include F4 (K88), F5 (K99), F18, and F41 [15,16]. F5 (K99), F6 (987P), and F41 were almost exclusively found in pigs less than 1 week old. F4 (K88) can cause diarrhea in piglets after they are weaned, and F18 was only discovered in weaned piglets. Based on its antigenicity, F18 was divided into two antigen variants, F18ab and F18ac. The F18ac strain was linked to postweaning diarrhea, while F18ab was associated with edema disease. Infection with F4 or f18 usually leads to sudden death or reduced feed intake and watery diarrhea in one or several pigs, most often in the first week after weaning. Diarrhea can be much more severe after weaning than immediately after birth and usually only results in weight loss.

ETEC fimbriae bind to various receptors in the intestinal mucosal epithelium and attach to intestinal epithelial cells, preventing rapid excretion caused by constant peristalsis in the animal digestive tract. This process creates conditions favorable for a significant increase in bacterial growth and multiplication, leading to the production of enterotoxins that cause disease. Adhesin is a protein-based antigen with strong immunogenicity. Immunizing animals with bacteria or purified adhesin antigen can efficiently produce the corresponding antibodies. ETEC attaches to the epithelial cells of the host’s intestinal mucosa with the assistance of adhesin and produces a large amount of enterotoxin, resulting in pathological changes in the intestinal mucosal epithelial cells and causing diarrhea in piglets [17,18,19]. Enterotoxins can generally be classified as heat-stable enterotoxin (ST) and heat-labile enterotoxin (LT). Strains can produce ST or LT alone or both toxins. Enterotoxin plays a crucial role in ETEC diarrhea, so studying its pathogenesis and immunogenicity is very important for preventing and controlling diarrheal diseases caused by ETEC. Research results have shown that 20–30% of the ETEC strains causing piglet diarrhea were LT+/ST−. Thirty to forty percent of ETEC strains were LT+/ST+, while LT−/ST+ strains accounted for nearly 50% [20]. Therefore, compared to LT, ST plays a vital role in diarrheal diseases in young livestock caused by ETEC. ST is further divided into ST1 and ST2. ST1 includes ST1a (porcine-type, STp) and ST1b (human-type STh). The genes encoding ST enterotoxin are located on the plasmid, and ST does not possess immunogenicity. LT consists of a single A subunit (∼28 kDa) and five B subunits (∼11.5 kDa each). LT and its B subunit exhibit good immunogenicity [21,22,23,24].

The treatment for ETEC disease primarily relies on drugs and vaccines. However, ETEC is often resistant to multiple antibiotics, so vaccination with vaccines, such as F4 or F18, can effectively prevent piglet diarrhea. Additionally, vaccinating sows can prevent colibacillosis in newborn piglets, but it does not completely prevent diarrhea after weaning. More importantly, vaccination remains the most effective method of disease control due to the emergence of drug residues and bacterial resistance, which has resulted from the excessive use of antibiotics in recent years. Commercial or experimental vaccines used to prevent ETEC include inactivated whole vaccines, subunit vaccines, and genetically engineered vaccines. The main virulence factors of ETEC, adhesin and enterotoxin, are crucial factors that cause diarrhea in piglets. Although vaccines are available that provide some preventive protection, all vaccines for ETEC exhibit certain limitations. Some vaccines do not address the toxicity caused by the major enterotoxin ST, while others only target a single adhesin or enterotoxin. The immune effect of the vaccines is not optimal. Therefore, developing a new broad-spectrum vaccine to prevent diarrhea in newborn piglets is very important. Seo et al. constructed BSA-STaA14T and 3xSTaN12S-mnLTR192G/L211A and immunized pigs. The piglets were better protected by the induced anti-STa antibodies [25]. Feng and Guan constructed a recombinant strain expressing LTA-STaA13Q-STb-LTA2-LTB-STaA13Q-STb. After immunization with the bacteria, the serum IgG and fecal sIgA responded against all ETEC enterotoxins and induced F41 antibody in mice. Moreover, there were higher levels of IL-4 than IFN-ϒ, suggesting a T-cell (Th) response [26]. Lu et al. developed the multiepitope fusion antigen (MEFA). The fimbria toxin MEFA generated induced neutralizing antibodies against ETEC fimbriae and all four ETEC toxins. Because MEFA-based vaccines do not carry somatic antigens, they cause fewer side effects [27]. However, the immune response is not ideal, as these vaccines do not address the immunity of ST1, which is the most crucial toxin factor that causes diarrhea in piglets. If this important factor is not effectively resolved, the vaccine will not be effective in preventing the disease and will result in significant economic losses. We created a genetically engineered strain, K88ac-K99-ST1-LTB, through gene mutation and gene fusion technology; this strain targets the main virulence factors of adhesion K88ac and K99, as well as enterotoxin ST1 and LTB of ETEC. This recombinant strain not only rendered ST1 inactive as a natural enterotoxin but also endowed it with immunogenicity. The prepared K88ac-K99-3ST1-LTB tetravalent genetically engineered inactivated vaccine can prevent diarrhea caused by ETEC through enterotoxin and fimbriae. The results demonstrated that the K88ac-K99-3ST1-LTB vaccine was an ideal vaccine for preventing piglet diarrhea, effectively controlling the occurrence of diarrhea in newborn piglets and yielding significant economic and social benefits.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Construction of a candidate strain for a tetravalent genetically engineered vaccine

Corresponding primers were designed according to the reported ST 1 , LT B , K88ac, and K99 gene sequences [10,28]. Three pairs of ST1 site-specific mutation primers were designed and synthesized. The upstream primers the P1, P2, and P3 contained HindIII, NdeI, and EcoRI cleavage sites (italics) and protective bases, respectively, while the downstream primers P4, P5, and P6 contained NdeI, EcoRI, and BamHI cleavage sites (italics) and protective bases, respectively [29]. Two cysteines were mutated to serines (TGT→AGT) at the 3′ end of the ST 1 gene using three pairs of mutant primers. Three ST 1 mutant genes were amplified from the E. coli C83902 plasmid by a PCR site-specific mutation technique. The LT B gene was amplified from the C83902 plasmid by PCR amplification using the P7 and P8 primers. The P7 and P8 primers contained BamH I and Not I cleavage sites. Using P9 and P10 primers, the K88ac gene was amplified from the template C83902 plasmid. The P9 and P10 primers contained Bgl Ⅱ and Nco I cleavage sites [29]. The K99 gene was amplified from the C83539 plasmid using P11 and P12 primers. The P11 and P12 primers contained Nco I and Hind III restriction endonuclease sites [30]. Using DNA ligase, the amplified K88ac, K99, ST 1 , and LT B genes were concatenated into the K88ac-K99-3ST1-LTB fragment. The above primers are shown in Table 1. The PCR system included the following components: 1 µL template, 2 µL 5 mmol/L dNTP, 2 µL 0.1 mol/L primer, 5 µL 10× buffer, 1 µL 3 U/µL Taq DNA polymerase, and 39 µL ddH2O. The PCR amplification procedures were performed as follows: predenaturation at 95°C for 5 min, denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 50°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 1 min, and 30 cycles. After PCR amplification, the product and pET-28a were digested with BglII and NotI, respectively. The mixture was incubated with T4 DNA ligase overnight at 16°C. After the recombinant plasmid was transformed into BL21(DE3), the recombinant bacteria were coated on Kan/LB plates and cultured overnight at 37°C. After overnight cultivation, the recombinant plasmid pXKK3SL was extracted for restriction digestion identification and nucleotide sequence analysis.

Primer sequence

| Primer | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| P1 | 5′-CCC AAGCTT AACAACACATTTTACTGC-3′ |

| P2 | 5′-GGAATTC CATATG ATAACTTCCAGCACTGGC-3′ |

| P3 | 5′-GGAATTC CATATG AACAACACATTTTACTGC-3′ |

| P4 | 5′-CCG GAATTC ATAACTTCCAGCACTGGC–3′ |

| P5 | 5′-CCG GAATTC AACAACACATTTTACTGC-3′ |

| P6 | 5′-CGC GGATCC ATAACTTCCAGCACTGGC-3′ |

| P7 | 5′-GGA AGATCT CATTTACTGACTATGAAGAA-3′ |

| P8 | 5′-CATG CCATGG GAGAATATCATTTCTTGATAG-3′ |

| P9 | 5′-CATG CCATGG A GAT CTT GGG CAG CCT CCT-3′ |

| P10 | 5′-CCC AAGCTT AT ATA AGT GAC TAA GAA-3′ |

| P11 | 5′-CGC GGATCC CCAGACTATTACAGAACTA-3′ |

| P12 | 5′-ATAAGAAT GCGGCCGC AAGCTTGCCCCTCCAGCCTAG C-3′ |

2.2 Induced expression of strain, SDS‒PAGE detection, and ELISA analysis of fusion protein

According to a method described by Sambrook et al. [31], the recombinant strain BL21(DE3)(pXKK3SL) was spread on a Kan/LB plate and incubated overnight at 37°C. Then, a single colony was selected and inoculated into 5 mL of liquid LB medium containing 30 μg/mL kanamycin. The culture was then incubated overnight in a shaking incubator at 37°C with a speed of 170 rpm. Next, the culture was inoculated into a culture bottle containing 250 mL of LB medium at a ratio of 1%. IPTG was added to the culture bottle to a final concentration of 1 mmol/L. The culture was then incubated at 37°C at a speed of 170 rpm for 4 h to reach the logarithmic growth phase (OD600 = 0.4–0.6). The recombinant strain BL21(DE3)(pXKK3SL) was induced and cultured, and 1 mL of the culture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm. The supernatant was discarded, and the bacterial pellet was collected. The precipitate was resuspended in 0.5 mL of 50 mmol/mL Tris-Cl (pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 0°C at 12,000 rpm for 30 s. The supernatant was discarded, and the precipitate was resuspended in 25 μL of water. Once the bacteria were dispersed, 25 μL of 2× SDS gel loading buffer was immediately added. After being oscillated for 20 s, the supernatant was placed in a boiling water bath for 3–5 min and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. Twenty-five microlitres of the supernatant were taken for SDS‒PAGE electrophoresis. BL21(DE3)(pXKK3SL), the negative control BL21(DE3)(pET-28a), the positive control ST+/HB101(pSLM004), and LT+/DH5α(pEWD299) strong strains were split by ultrasonic waves. The lysate was detected by ELISA.

2.3 Fusion protein antigen preparation

The 50 mL culture induced by IPTG for 4 h was centrifuged, and the bacteria were collected and resuspended in 5 mL of TE (50 mmol/L Tris-Cl, 2 mmol/L EDTA). The bacteria were then added to lysozyme at a final concentration of 100 μg/mL and 5 mL of 1% Triton X-100 and incubated at 30℃ for 15 min. The lysate was treated with an ultrasonic wave two times for 10 s each and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. After the precipitate was collected and diluted 10 times, a final concentration of 10% aluminum hydroxide glue was added and mixed as an immune antigen. Additionally, formaldehyde was added to the culture medium of the engineered bacteria at a final concentration of 0.4% to inactivate the bacteria. After 10% aluminum hydroxide glue was added, the mixture was used as an immunological antigen [29].

2.4 Safety test for the recombinant strain BL21(DE3)(pXKK3SL) and minimum lethal dose (MLD)

2.4.1 Determination of challenge strain

To determine whether the K88ac-K99-3ST1-LTB fusion protein had eliminated the natural toxin activity of ST1 enterotoxin, 40 mice weighing 18–22 g were randomly divided into eight groups of five mice. Groups 1–4 were injected with the recombinant strain BL21(DE3)(pXKK3SL) intraperitoneally, and groups 5–8 received the strain through oral inoculation. The clinical response of the test mice was observed daily, and autopsies were performed after continuous observation for three weeks. Fifty mice weighing 18–22 g were randomly divided into five groups of ten mice. Groups 1–4 were separately challenged using different doses of strains (0.5 × 109 CFU, 1.0 × 109 CFU, 1.5 × 109 CFU, 2.0 × 109 CFU). Group 5 was used as the control group. After 3 days of observation, the MLD was determined based on the death of the mice. After birth, 15 piglets that did not receive colostrum were selected and divided into 5 groups, each consisting of 3 piglets. Groups 1–4 were exposed to different doses of strains (1.0 × 1011 CFU, 1.5 × 1011 CFU, 2.0 × 1011 CFU, 2.5 × 1011 CFU). Group 5 served as the control group.

2.4.2 Immune protection test

Three hundred mice weighing 18–22 g were randomly divided into six groups of 50 mice each. Groups 1 and 2 were injected intraperitoneally with inclusion bodies, while groups 3 and 4 were injected intraperitoneally with inactivated vaccines of genetically engineered strains. The animals received two injections at a 14-day interval at a dose of 0.2 mL per animal. Fourteen days after the second immunization, the mice were challenged with 1 MLD and 2 MLD of virulent strains C83902 and C83539. The death of the mice was then observed daily. Groups 5 and 6, injected intraperitoneally with the K88-LTB bivalent vaccine, were used as the negative control.

2.4.3 Determination of the minimum immune dose in mice

Ninety mice were divided into six groups. Groups 1, 3, and 5 (20 each group) were immunized with different doses (0.15, 0.2, 0.25 mL/mouse). All mice were immunized twice with a 14-day interval. As the control group, group 2, group 4, and group 6 (10 each group) were only injected with saline. After the second immunization was completed, all mice were injected with 1 MLD C83902 and C83539 virulent strains and observed for 7 days. The immune protection rates of different groups were recorded in detail.

Eight pregnant sows were divided into four groups, with two sows in each group. Group 1 and group 3 were immunized twice through the neck muscles, 30–35 and 15–20 days before delivery. The immunization doses for group 1 and group 3 were 2 and 4 mL/sow of vaccines, respectively. As the control group, group 2 and group 4 were only injected with saline. Newborn piglets were challenged with 1 MLD C83902 and C83539 virulent strains on the first day after colostrum was administered. The clinical reaction was observed daily after the challenge and the immune protection rates of all groups were recorded in detail.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animal use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals and has been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical and Pharmaceutical College.

3 Results

3.1 Induced expression of the recombinant strain BL21(DE3)(pXKK3SL)

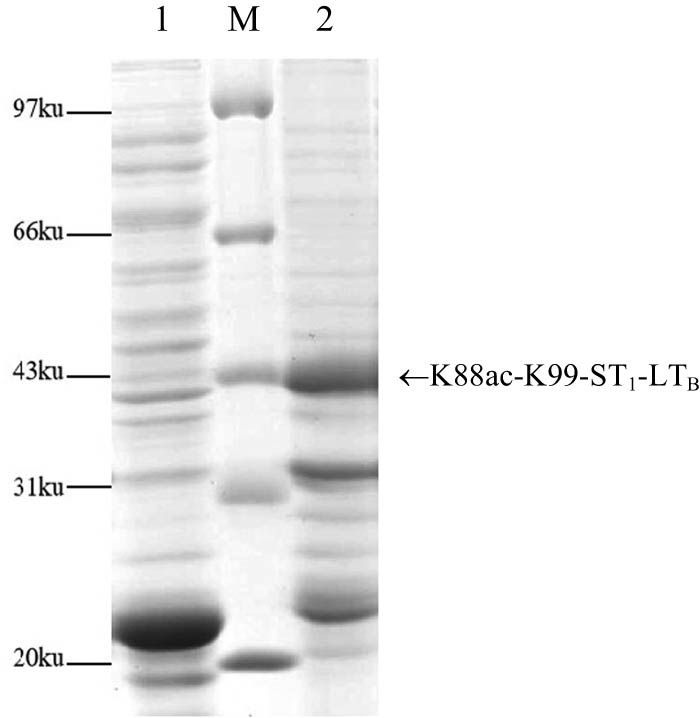

The mutant 180-bp ST1 gene (Cys → Ser) was cloned using the C83902 plasmid as a template through a site-specific mutation technique. The 330-bp K88ac and 500-bp LTB gene fragments were amplified by PCR using the C83902 plasmid as a template. The C83539 plasmid of E. coli was extracted, and the 393-bp K99 gene fragment was amplified by PCR. The 1299-bp K88ac-K99-3ST 1 -LT B fusion gene fragment was constructed using T4 DNA ligase. After the fusion gene K88ac-K99-3ST 1 -LT B was cut by a restriction enzyme, the gene was cloned and inserted into pET-28a to generate the recombinant expression plasmid pXKK3SL. After enzyme digestion and sequence analysis were performed, the plasmid pXKK3SL was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3). The recombinant strain BL21(DE3)(pXKK3SL) was induced by IPTG for 4 h at 37°C. SDS‒PAGE analysis showed that the fusion protein accounted for 35.72% of the total protein content of the bacteria (Figure 1). Therefore, efficient expression of the K88ac-K99-3ST1-LTB fusion gene was achieved. ELISA showed that the K88ac-K99-3ST1-LTB fusion protein can bind to ST1 monoclonal antibody, LTB, K88ac and K99 antibody.

SDS‒PAGE analysis of BL21(DE3)(pXKK3S) expression. M: low molecular protein marker; (1) total cell lysate of BL21(DE3)(pET-28a) and (2) total cell lysate of BL21(DE3)(pXKK3S).

3.2 Safety test for BL21(DE3)(pXKK3SL) and challenge protection test

To confirm whether the K88ac-K99-3ST1-LTB fusion protein had eliminated the natural toxin activity of ST1, mice were inoculated with the BL21(DE3)(pXKK3SL) strain through intraperitoneal injection and orally. After 3 weeks of observation, all mice survived, and no pathological changes were found during autopsy. This result indicated that the recombinant strain had eliminated the natural toxin activity of ST1 and was safe and nonpathogenic to mice. The experimental results showed that the MLD for mice was 1.0 × 109 CFU, and for piglets, the dose was 1.5 × 1011 CFU. Mice were immunized with inclusion bodies and inactivated vaccines separately and were effectively protected when challenged by the virulent strains C83902 and C83539. With 1 MLD challenge to mice, the protection rate of the inclusion body immunization group was 96% (48/50), and the protection rate of the inactivated vaccine immunization group was 98% (49/50). With 2 MLD challenges to mice, the protection rate of the inclusion body immunization group was 94% (47/50), and the protection rate of the inactivated vaccine immunization group was 96% (48/50). The protection rates in the control group were 88% (44/50) and 82% (41/50) (Table 2). The immune protection rate for the 1 and 2 MLD challenge doses exceeded 90%. However, there was no significant difference in immune effect between the inclusion body group and the inactivated vaccine group. There was little difference in the immune protection effect.

Results of the mouse challenge protection test

| Challenge dose (MLD) | Survival/immune number | Immunity way | Immunity frequency | Immunity dose (mL) | Immunization interval (days) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion body group | Inactivated vaccine group | Control group | |||||

| 1 | 48/50 | 49/50 | 44/50 | Intraperitoneal injection | Twice | 0.2 | 14 |

| 2 | 47/50 | 48/50 | 41/50 | Intraperitoneal injection | Twice | 0.2 | 14 |

3.3 Determination of the minimum immune dose

The protection rates for group 1, group 3, and group 5 of mice were 75% (15/20), 85% (17/20), and 95% (19/20), respectively, after being challenged with a 1 MLD dose. All mice in the control group died. The results indicate that the minimum immune dose of the vaccine for mice was 0.2 mL/mouse. The protection rates for group 1 and group 3 of piglets were 86.9% (20/23) and 92.3% (24/26), respectively, after being challenged with a 1 MLD dose. Only four piglets experienced very mild diarrhea. However, all piglets in the control group died. The results indicate that the minimum immune dose of the inactivated vaccine for pregnant sows was 2 mL/pig (Tables 3 and 4). Compared to pigs immunized with a 2 mL dose, pigs immunized with a 4 mL dose achieved a higher immune protection rate; however, the difference was not significant. Therefore, considering the cost factor, the minimum immune dose was determined to be 2 mL.

Results of minimum immunization dose of mice

| Group | Reagent | Immunization dose (mL) | Challenge dose (MLD) | Amount | Number of survivor | Protection rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Inactivated vaccine | 0.15 | 1 | 20 | 15 | 75 |

| Group 2 | Normal saline | 0.15 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Group 3 | Inactivated vaccine | 0.20 | 1 | 20 | 17 | 85 |

| Group 4 | Normal saline | 0.20 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Group 5 | Inactivated vaccine | 0.25 | 1 | 20 | 19 | 95 |

| Group 6 | Normal saline | 0.25 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

Results of minimum immunization dose of pregnant sows

| Group | Reagent | Immunization dose (mL) | Challenge dose (MLD) | Amount | Number of survivor | Protection rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Inactivated vaccine | 2.0 | 1 | 23 | 20 | 86.9 |

| Group 2 | Normal saline | 2.0 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| Group 3 | Inactivated vaccine | 4.0 | 1 | 26 | 24 | 92.3 |

| Group 4 | Normal saline | 4.0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

4 Discussion

Diarrhea is the primary cause of piglet mortality and results in significant economic losses in the pig industry. Viruses, bacteria, and improper diet can contribute to diarrhea in piglets. For instance, soybean can easily lead to weaning diarrhea because trypsin inhibitors or antigens cause a local immune response [31]. Currently, ETEC is the primary pathogen responsible for piglet diarrhea. This condition has consistently impeded progress in the pig industry. The incidence of ETEC can range from 20 to 40%, with mortality rates reaching 30–50% [32,33,34]. Even if pigs are cured with antibiotics, their production performance indicators are greatly reduced, and they completely lose their economic value for feeding, resulting in substantial economic losses for the pig industry. The virulence factors of ETEC include adhesin and enterotoxin. The main adhesins are K88 and K99. With the assistance of these adhesins, ETEC attaches to the epithelial cells of the host’s intestinal mucosa and produces a significant amount of enterotoxin, which causes pathological changes in the intestinal mucosal epithelial cells and leads to piglet diarrhea. The main adhesins of ETEC derived from pigs are K88ac and K99, which indirectly cause diarrhea in piglets. Enterotoxins, such as heat-ST and heat-LT, directly cause diarrhea in piglets. ST is divided into ST1 and ST2 based on antigenicity and host differences. ST1 is a small peptide consisting of 18 or 19 amino acids that remain active even when heated at 100°C for 30 min. ST1 is highly toxic but lacks immunogenicity. LT is composed of an A subunit and a B subunit and both LT and its B subunit exhibit good immunogenicity [35,36].

Diarrhea in piglets caused by ETEC has always been a main focus and challenge in research. The difficulty lies in finding a method to eliminate the biological toxicity of ST1 and generate immunogenic properties. ST1 enterotoxin contains six cysteine residues, which can form three pairs of disulfide bonds within the chain. These disulfide bonds are crucial for the toxicity of ST1. If these bonds are broken, ST1 can lose its biological toxicity. On the other hand, the LTB subunit exhibits strong immunogenic properties. Previous studies have shown that LTB can be used as a carrier protein for ST. As a result, ST can acquire immunogenicity and stimulate an immune response against ST and LT. Therefore, the fusion of LT B and ST genes has become the focus of research for a potential polyvalent vaccine strain. Some researchers constructed a recombinant strain that contained the ST 1 –LT B fusion gene and inserted a 21 bp linker gene between the two genes. The results showed that the ST1–LTB fusion protein lost its ST1 enterotoxin activity and exhibited good immunogenicity [37]. Other researchers also constructed the ST 1 –LT B fusion gene, but the expression product still showed ST1 enterotoxin activity [38]. Additionally, the pro-ST 1 gene, which encodes the ST1 precursor protein, was fused to the 3′-terminus of the LT B gene. The LTB-pro-ST1 fusion protein exhibited good immunogenicity and lost its ST1 enterotoxin activity [39]. Numerous studies have shown that different serotypes of E. coli, which cause piglet diarrhea, have different colonization factors. Among them, K88ac and K99 are the dominant fimbriae [40,41].

Currently, no universal protective ETEC vaccine is available for piglet diarrhea, although adhesion-based vaccines provide some level of protection. However, certain ETEC strains possess one or more enterotoxins but do not contain any known fimbrial or nonfimbrial adhesin. Since adhesin and enterotoxin are key factors that cause diarrhea in piglets, a broad-spectrum vaccine that combines anti-adhesin and anti-enterotoxin would be a highly effective measure for prevention. Therefore, the future direction of vaccine preparations will involve combining heat-resistant and heat-sensitive enterotoxin with major pathogenic adhesin to construct a polyvalent vaccine. This approach aims to prevent piglet diarrhea caused by ETEC through enterotoxin and fimbriae.

Currently, diarrhea caused by ETEC is primarily prevented through drug treatment or immunization using whole-cell vaccines and specific fimbrial vaccines. However, therapeutic and preventive effects of these treatments are not ideal due to the limited effectiveness of the vaccine and the complex and diverse serotypes of pathogenic bacteria. To date, the main preventive measures involve administering the K88–K99 and K88ac-LTB bivalent genetically engineered vaccines. However, the immunogenicity and toxicity issues associated with the main pathogenic factor ST1 enterotoxin are not successfully addressed with these vaccines. As a result, the vaccines cannot achieve a satisfactory preventive effect. Therefore, building upon previous research, we mutated the ST1 gene to eliminate its natural toxin activity. Since the fimbrial antigen, K99 is also a major virulence factor, we amplified the K88ac gene, K99 gene, ST 1 mutant gene, and LT B gene from the plasmids of E. coli C83902 and C83539 using gene mutation, tandem, and fusion techniques. We constructed a recombinant strain BL21(DE3)(pXKK3SL) that contains the K88ac–K99–3ST 1 –LT B fusion gene, and the fusion protein was efficiently expressed. The ELISA test confirmed that the fusion protein could bind to ST1 monoclonal antibody, K88ac, K99, and LTB antibodies. Animal experiments showed that the fusion protein had eliminated the natural toxin activity of ST1. The immune protection test showed that the inclusion body and inactivated vaccine exhibited a good immune effect. The protection rate of the inclusion body immunization group with 1 MLD challenge dose was 96%, and the protection rate of the inactivated vaccine immunization group with 1 MLD challenge dose was 98%. However, the protection rate of the control group that received the K88–LTB bivalent vaccine was 88%. Therefore, the K88ac–K99–3ST1–LTB vaccine we constructed exhibits a positive immune effect. These studies demonstrate that we successfully developed a candidate strain of a tetravalent genetically engineered inactivated vaccine against four major virulence factors of ETEC: K88ac, K99, ST1, and LTB. This vaccine not only eliminates the natural toxin activity of ST1 but also provides immunogenicity. In addition, the inclusion of K88ac and K99 fimbriae further enhances the immune response, preventing diarrhea caused by ETEC through enterotoxin and fimbriae. This study holds significant academic and practical value in effectively controlling diarrhea. In addition, this study establishes a strong foundation for the future development of genetically engineered inactivated vaccines for ETEC, leading to substantial economic and social benefits.

5 Conclusions

Animal experiments showed that the tetravalent genetically engineered inactivated vaccine had eliminated the natural toxin activity of ST1. Therefore, the disulfide bond of ST1 was successfully destroyed by the site-specific mutation technique and the natural toxin activity was lost. The immune protection test demonstrated that the inclusion body and inactivated vaccine exhibited a positive immune effect. The protection rates of the inclusion body group and vaccine group were 96 and 98%, respectively. Therefore, the K88ac–K99–3ST1–LTB vaccine generates a highly effective immune response against piglet diarrhea caused by enterotoxin and fimbriae. These results show that the K88ac–K99–3ST1–LTB vaccine is a promising candidate for preventing diarrhea in newborn piglets. Overall, although the parenteral immunization strategy is promising, the method is expensive and can lead to stress reactions in piglets due to repeated injections. Previous studies have indicated that multiple antigens in ETEC can potentially be combined. To validate these findings, future studies should be conducted with larger sample sizes, focusing on vaccines that target piglet diarrhea caused by E. coli.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Pr. C. Xu, K. Peng, and Y. Lin for their expert assistance and suggestions.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by a grant from the Science and Technology Research Project of Chongqing Education Commission of China (Grant No. KJZD-K202202803).

-

Author contributions: ChongBo Xu and Yimin Lin designed the research. ChongLi Xu and Yuhan She performed the research. Kun Peng, Fengyang Fu and Danni Yang analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Kim K, Song M, Liu Y, Ji P. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection of weaned pigs: Intestinal challenges and nutritional intervention to enhance disease resistance. Front Immunol. 2022;13:885253.10.3389/fimmu.2022.885253Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Choy RKM, Bourgeois AL, Ockenhouse CF, Walker RI, Sheets RL, Flores J. Controlled human infection models to accelerate vaccine development. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2022;35(3):e0000821.10.1128/cmr.00008-21Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Zhang Y, Tan P, Zhao Y, Ma X. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: intestinal pathogenesis mechanisms and colonization resistance by gut microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):2055943.10.1080/19490976.2022.2055943Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Zhao H, Xu Y, Li X, Li G, Zhao H, Wang L. Expression and purification of a recombinant enterotoxin protein using different E.coli host strains and expression vectors. Protein J. 2021;40(2):245–54.10.1007/s10930-021-09973-wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Chakraborty S, Randall A, Vickers TJ, Molina D, Harro CD, DeNearing B, et al. Human experimental challenge with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli elicits immune responses to canonical and novel antigens relevant to vaccine development. J Infect Dis. 2018;218(9):1436–46.10.1093/infdis/jiy312Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Riaz S, Steinsland H, Hanevik K. Human mucosal IgA immune responses against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Pathogens. 2020;9(9):714.10.3390/pathogens9090714Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Smith EM, Grassel CL, Papadimas A, Foulke-Abel J, Barry EM. The role of CFA/I in adherence and toxin delivery by ETEC expressing multiple colonization factors in the human enteroid model. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(7):e0010638.10.1371/journal.pntd.0010638Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Zhang W, Sack DA. Current progress in developing subunit vaccines against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-associated diarrhea. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2015;22(9):983–91.10.1128/CVI.00224-15Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Duan Q, Xia P, Nandre R, Zhang W, Zhu G. Review of newly identified functions associated with the heat-labile toxin of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:292.10.3389/fcimb.2019.00292Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Xu C, Peng K, She Y, Fu F, Shi Q, Lin Y, et al. Preparation of novel trivalent vaccine against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli for preventing newborn piglet diarrhea. Am J Vet Res. 2023;84(2):ajvr.22.10.0183.10.2460/ajvr.22.10.0183Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Abd El Ghany M, Barquist L, Clare S, Brandt C, Mayho M, Joffre E, et al. Functional analysis of colonization factor antigen I positive enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli identifies genes implicated in survival in water and host colonization. Microb Genom. 2021;7(6):000554.10.1099/mgen.0.000554Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Jarocki VM, Heß S, Anantanawat K, Berendonk TU, Djordjevic SP. Multidrug-resistant lineage of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli ST182 with serotype O169:H41 in airline waste. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:731050.10.3389/fmicb.2021.731050Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Khalil I, Walker R, Porter CK, Muhib F, Chilengi R, Cravioto A, et al. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) vaccines: Priority activities to enable product development, licensure, and global access. Vaccine. 2021;39(31):4266–77.10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.04.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Seo H, Duan Q, Upadhyay I, Zhang W. Evaluation of multivalent enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli vaccine candidate MecVax antigen dose-dependent effect in a murine model. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2022;88(17):e0095922.10.1128/aem.00959-22Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Fleckenstein JM. Confronting challenges to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli vaccine development. Front Trop Dis. 2021;2:709907.10.3389/fitd.2021.709907Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Zegeye ED, Govasli ML, Sommerfelt H, Puntervoll P. Development of an enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli vaccine based on the heat-stable toxin. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(6):1379–88.10.1080/21645515.2018.1496768Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Zhao H, Xu Y, Li G, Liu X, Li X, Wang L. Protective efficacy of a novel multivalent vaccine in the prevention of diarrhea induced by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in a murine model. J Vet Sci. 2022;23(1):e7.10.4142/jvs.21068Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Brumfield K, Seo H, Idegwu N, Artman C, Gonyar L, Nataro J, et al. Feasibility of avian antibodies as prophylaxis against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli colonization. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1011200.10.3389/fimmu.2022.1011200Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Dubreuil JD. Pig vaccination strategies based on enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli toxins. Braz J Microbiol. 2021;52(4):2499–509.10.1007/s42770-021-00567-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Rausch D, Ruan X, Nandre R, Duan Q, Hashish E, Casey TA, et al. Antibodies derived from a toxoid MEFA (multiepitope fusion antigen) show neutralizing activities against heat-labile toxin (LT), heat-stable toxins (STa, STb), and Shiga toxin 2e (Stx2e) of porcine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). Vet Microbiol. 2017;202:79–89.10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.02.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Kim N, Gu MJ, Kye YC, Ju YJ, Hong R, Ju DB, et al. Bacteriophage EK99P-1 alleviates enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K99-induced barrier dysfunction and inflammation. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):941.10.1038/s41598-022-04861-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Wang H, Zhong Z, Luo Y, Cox E, Devriendt B. Heat-stable enterotoxins of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and their impact on host immunity. Toxins (Basel). 2019;11(1):24.10.3390/toxins11010024Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Wen C, Zhang H, Guo Q, Duan Y, Chen S, Han M, et al. Engineered Bacillus subtilis alleviates intestinal oxidative injury through Nrf2-Keap1 pathway in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) K88-infected piglet. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2023;24(6):496–509.10.1631/jzus.B2200674Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Wang Z, Li J, Li J, Li Y, Wang L, Wang Q, et al. Protective effect of chicken egg yolk immunoglobulins (IgY) against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88 adhesion in weaned piglets. BMC Vet Res. 2019;15(1):234.10.1186/s12917-019-1958-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Seo H, Lu T, Nandre RM, Duan Q, Zhang W. Immunogenicity characterization of genetically fused or chemically conjugated heat-stable toxin toxoids of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in mice and pigs. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2019;366(4):fnz037.10.1093/femsle/fnz037Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Feng N, Guan W. Expression fusion immunogen by live attenuated Escherichia coli against enterotoxins infection in mice. Microb Biotechnol. 2019;12(5):946–61.10.1111/1751-7915.13447Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Lu T, Moxley RA, Zhang W. Application of a novel epitope- and structure-based vaccinology-assisted fimbria-toxin multiepitope fusion antigen of enterotoxigenic escherichia coli for development of multivalent vaccines against porcine postweaning diarrhea. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2020;86(24):e00274-20.10.1128/AEM.00274-20Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Dykes CW, Halliday IJ, Read MJ, Hobden AN, Harford S. Nucleotide sequences of four variants of the K88 gene of porcine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1985;50(1):279–83.10.1128/iai.50.1.279-283.1985Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Xu C, Wei G. Construction of recombinant strain expressing enterotoxigenic Eischerichia coli K88ac-ST1-LTB fusion protein. Chin J Biotechnol. 2002;18(2):216–20.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Isaacson RE, Start GL. Analysis of K99 plasmids from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;69(2):141–6.10.1016/0378-1097(92)90618-XSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. p. 1–50.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Sauvaitre T, Durif C, Sivignon A, Chalancon S, Van de Wiele T, Etienne-Mesmin L, et al. In Vitro evaluation of dietary fiber anti-infectious properties against food-borne enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Nutrients. 2021;13(9):3188.10.3390/nu13093188Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Ntakiyisumba E, Lee S, Won G. Evidence-based approaches for determining effective target antigens to develop vaccines against post-weaning diarrhea caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in Pigs: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Animals (Basel). 2022;12(16):2136.10.3390/ani12162136Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Seo H, Garcia C, Ruan X, Duan Q, Sack DA, Zhang W. Preclinical characterization of immunogenicity and efficacy against diarrhea from MecVax, a multivalent enterotoxigenic E. coli vaccine candidate. Infect Immun. 2022;89(7):e0010621.10.1128/IAI.00106-21Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Von Mentzer A, Zalem D, Chrienova Z, Teneberg S. Colonization factor CS30 from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli binds to sulfatide in human and porcine small intestine. Virulence. 2020;11(1):381–90.10.1080/21505594.2020.1749497Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Garcia CY, Seo H, Sack DA, Zhang W. Intradermally administered enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli vaccine candidate mecvax induces functional serum immunoglobulin G antibodies against seven adhesins (CFA/I and CS1 through CS6) and both toxins (STa and LT). Appl Environ Microbiol. 2022;88(4):e0213921.10.1128/aem.02139-21Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Cardenas L, Clements JD. Development of mucosal protection against the heat-stable enterotoxin of Escherichia coli by oral immunization with a genetic fusion delivered by a bacterial vector. Infect Immun. 1993;61(11):4629–36.10.1128/iai.61.11.4629-4636.1993Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Zhang Z, Li S, Dong Z, Huang C. Fusion of genes encoding Escherichia coli heat-labile and heat-stable enterotoxins. Chin J Microbiol Immunol. 1994;14(4):219–22.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Aitken R, Hirst TR. Development of an immunoassay using recombinant maltose-binding protein-STa fusions for quantitating antibody responses against STa, the heat-stable enterotoxin of Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(3):732–4.10.1128/jcm.30.3.732-734.1992Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Todnem Sakkestad S, Steinsland H, Skrede S, Kleppa E, Lillebø K, Sævik M, et al. Experimental infection of human volunteers with the heat-stable enterotoxin-producing enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli Strain TW11681. Pathogens. 2019;8(2):84.10.3390/pathogens8020084Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Sakkestad ST, Steinsland H, Skrede S, Lillebø K, Skutlaberg DH, Guttormsen AB, et al. A new human challenge model for testing heat-stable toxin-based vaccine candidates for enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli diarrhea-dose optimization, clinical outcomes, and CD4+ T cell responses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(10):e0007823.10.1371/journal.pntd.0007823Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Systemic investigation of inetetamab in combination with small molecules to treat HER2-overexpressing breast and gastric cancers

- Immunosuppressive treatment for idiopathic membranous nephropathy: An updated network meta-analysis

- Identifying two pathogenic variants in a patient with pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy

- Effects of phytoestrogens combined with cold stress on sperm parameters and testicular proteomics in rats

- A case of pulmonary embolism with bad warfarin anticoagulant effects caused by E. coli infection

- Neutrophilia with subclinical Cushing’s disease: A case report and literature review

- Isoimperatorin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced periodontitis by downregulating ERK1/2 and NF-κB pathways

- Immunoregulation of synovial macrophages for the treatment of osteoarthritis

- Novel CPLANE1 c.8948dupT (p.P2984Tfs*7) variant in a child patient with Joubert syndrome

- Antiphospholipid antibodies and the risk of thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms

- Immunological responses of septic rats to combination therapy with thymosin α1 and vitamin C

- High glucose and high lipid induced mitochondrial dysfunction in JEG-3 cells through oxidative stress

- Pharmacological inhibition of the ubiquitin-specific protease 8 effectively suppresses glioblastoma cell growth

- Levocarnitine regulates the growth of angiotensin II-induced myocardial fibrosis cells via TIMP-1

- Age-related changes in peripheral T-cell subpopulations in elderly individuals: An observational study

- Single-cell transcription analysis reveals the tumor origin and heterogeneity of human bilateral renal clear cell carcinoma

- Identification of iron metabolism-related genes as diagnostic signatures in sepsis by blood transcriptomic analysis

- Long noncoding RNA ACART knockdown decreases 3T3-L1 preadipocyte proliferation and differentiation

- Surgery, adjuvant immunotherapy plus chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary malignant melanoma of the parotid gland (PGMM): A case report

- Dosimetry comparison with helical tomotherapy, volumetric modulated arc therapy, and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for grade II gliomas: A single‑institution case series

- Soy isoflavone reduces LPS-induced acute lung injury via increasing aquaporin 1 and aquaporin 5 in rats

- Refractory hypokalemia with sexual dysplasia and infertility caused by 17α-hydroxylase deficiency and triple X syndrome: A case report

- Meta-analysis of cancer risk among end stage renal disease undergoing maintenance dialysis

- 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase inhibition arrests growth and induces apoptosis in gastric cancer via AMPK activation and oxidative stress

- Experimental study on the optimization of ANM33 release in foam cells

- Primary retroperitoneal angiosarcoma: A case report

- Metabolomic analysis-identified 2-hydroxybutyric acid might be a key metabolite of severe preeclampsia

- Malignant pleural effusion diagnosis and therapy

- Effect of spaceflight on the phenotype and proteome of Escherichia coli

- Comparison of immunotherapy combined with stereotactic radiotherapy and targeted therapy for patients with brain metastases: A systemic review and meta-analysis

- Activation of hypermethylated P2RY1 mitigates gastric cancer by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation

- Association between the VEGFR-2 -604T/C polymorphism (rs2071559) and type 2 diabetic retinopathy

- The role of IL-31 and IL-34 in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic periodontitis

- Triple-negative mouse breast cancer initiating cells show high expression of beta1 integrin and increased malignant features

- mNGS facilitates the accurate diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of suspicious critical CNS infection in real practice: A retrospective study

- The apatinib and pemetrexed combination has antitumor and antiangiogenic effects against NSCLC

- Radiotherapy for primary thyroid adenoid cystic carcinoma

- Design and functional preliminary investigation of recombinant antigen EgG1Y162–EgG1Y162 against Echinococcus granulosus

- Effects of losartan in patients with NAFLD: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial

- Bibliometric analysis of METTL3: Current perspectives, highlights, and trending topics

- Performance comparison of three scaling algorithms in NMR-based metabolomics analysis

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and its related molecules participate in PROK1 silence-induced anti-tumor effects on pancreatic cancer

- The altered expression of cytoskeletal and synaptic remodeling proteins during epilepsy

- Effects of pegylated recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on lymphocytes and white blood cells of patients with malignant tumor

- Prostatitis as initial manifestation of Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia diagnosed by metagenome next-generation sequencing: A case report

- NUDT21 relieves sevoflurane-induced neurological damage in rats by down-regulating LIMK2

- Association of interleukin-10 rs1800896, rs1800872, and interleukin-6 rs1800795 polymorphisms with squamous cell carcinoma risk: A meta-analysis

- Exosomal HBV-DNA for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of chronic hepatitis B

- Shear stress leads to the dysfunction of endothelial cells through the Cav-1-mediated KLF2/eNOS/ERK signaling pathway under physiological conditions

- Interaction between the PI3K/AKT pathway and mitochondrial autophagy in macrophages and the leukocyte count in rats with LPS-induced pulmonary infection

- Meta-analysis of the rs231775 locus polymorphism in the CTLA-4 gene and the susceptibility to Graves’ disease in children

- Cloning, subcellular localization and expression of phosphate transporter gene HvPT6 of hulless barley

- Coptisine mitigates diabetic nephropathy via repressing the NRLP3 inflammasome

- Significant elevated CXCL14 and decreased IL-39 levels in patients with tuberculosis

- Whole-exome sequencing applications in prenatal diagnosis of fetal bowel dilatation

- Gemella morbillorum infective endocarditis: A case report and literature review

- An unusual ectopic thymoma clonal evolution analysis: A case report

- Severe cumulative skin toxicity during toripalimab combined with vemurafenib following toripalimab alone

- Detection of V. vulnificus septic shock with ARDS using mNGS

- Novel rare genetic variants of familial and sporadic pulmonary atresia identified by whole-exome sequencing

- The influence and mechanistic action of sperm DNA fragmentation index on the outcomes of assisted reproduction technology

- Novel compound heterozygous mutations in TELO2 in an infant with You-Hoover-Fong syndrome: A case report and literature review

- ctDNA as a prognostic biomarker in resectable CLM: Systematic review and meta-analysis

- Diagnosis of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis by metagenomic next-generation sequencing: A case report

- Phylogenetic analysis of promoter regions of human Dolichol kinase (DOLK) and orthologous genes using bioinformatics tools

- Collagen changes in rabbit conjunctiva after conjunctival crosslinking

- Effects of NM23 transfection of human gastric carcinoma cells in mice

- Oral nifedipine and phytosterol, intravenous nicardipine, and oral nifedipine only: Three-arm, retrospective, cohort study for management of severe preeclampsia

- Case report of hepatic retiform hemangioendothelioma: A rare tumor treated with ultrasound-guided microwave ablation

- Curcumin induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by decreasing the expression of STAT3/VEGF/HIF-1α signaling

- Rare presentation of double-clonal Waldenström macroglobulinemia with pulmonary embolism: A case report

- Giant duplication of the transverse colon in an adult: A case report and literature review

- Ectopic thyroid tissue in the breast: A case report

- SDR16C5 promotes proliferation and migration and inhibits apoptosis in pancreatic cancer

- Vaginal metastasis from breast cancer: A case report

- Screening of the best time window for MSC transplantation to treat acute myocardial infarction with SDF-1α antibody-loaded targeted ultrasonic microbubbles: An in vivo study in miniswine

- Inhibition of TAZ impairs the migration ability of melanoma cells

- Molecular complexity analysis of the diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome in China

- Effects of maternal calcium and protein intake on the development and bone metabolism of offspring mice

- Identification of winter wheat pests and diseases based on improved convolutional neural network

- Ultra-multiplex PCR technique to guide treatment of Aspergillus-infected aortic valve prostheses

- Virtual high-throughput screening: Potential inhibitors targeting aminopeptidase N (CD13) and PIKfyve for SARS-CoV-2

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients with COVID-19

- Utility of methylene blue mixed with autologous blood in preoperative localization of pulmonary nodules and masses

- Integrated analysis of the microbiome and transcriptome in stomach adenocarcinoma

- Berberine suppressed sarcopenia insulin resistance through SIRT1-mediated mitophagy

- DUSP2 inhibits the progression of lupus nephritis in mice by regulating the STAT3 pathway

- Lung abscess by Fusobacterium nucleatum and Streptococcus spp. co-infection by mNGS: A case series

- Genetic alterations of KRAS and TP53 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma associated with poor prognosis

- Granulomatous polyangiitis involving the fourth ventricle: Report of a rare case and a literature review

- Studying infant mortality: A demographic analysis based on data mining models

- Metaplastic breast carcinoma with osseous differentiation: A report of a rare case and literature review

- Protein Z modulates the metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma cells

- Inhibition of pyroptosis and apoptosis by capsaicin protects against LPS-induced acute kidney injury through TRPV1/UCP2 axis in vitro

- TAK-242, a toll-like receptor 4 antagonist, against brain injury by alleviates autophagy and inflammation in rats

- Primary mediastinum Ewing’s sarcoma with pleural effusion: A case report and literature review

- Association of ADRB2 gene polymorphisms and intestinal microbiota in Chinese Han adolescents

- Tanshinone IIA alleviates chondrocyte apoptosis and extracellular matrix degeneration by inhibiting ferroptosis

- Study on the cytokines related to SARS-Cov-2 in testicular cells and the interaction network between cells based on scRNA-seq data

- Effect of periostin on bone metabolic and autophagy factors during tooth eruption in mice

- HP1 induces ferroptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells through NRF2 pathway in diabetic nephropathy

- Intravaginal estrogen management in postmenopausal patients with vaginal squamous intraepithelial lesions along with CO2 laser ablation: A retrospective study

- Hepatocellular carcinoma cell differentiation trajectory predicts immunotherapy, potential therapeutic drugs, and prognosis of patients

- Effects of physical exercise on biomarkers of oxidative stress in healthy subjects: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Identification of lysosome-related genes in connection with prognosis and immune cell infiltration for drug candidates in head and neck cancer

- Development of an instrument-free and low-cost ELISA dot-blot test to detect antibodies against SARS-CoV-2

- Research progress on gas signal molecular therapy for Parkinson’s disease

- Adiponectin inhibits TGF-β1-induced skin fibroblast proliferation and phenotype transformation via the p38 MAPK signaling pathway

- The G protein-coupled receptor-related gene signatures for predicting prognosis and immunotherapy response in bladder urothelial carcinoma

- α-Fetoprotein contributes to the malignant biological properties of AFP-producing gastric cancer

- CXCL12/CXCR4/CXCR7 axis in placenta tissues of patients with placenta previa

- Association between thyroid stimulating hormone levels and papillary thyroid cancer risk: A meta-analysis

- Significance of sTREM-1 and sST2 combined diagnosis for sepsis detection and prognosis prediction

- Diagnostic value of serum neuroactive substances in the acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease complicated with depression

- Research progress of AMP-activated protein kinase and cardiac aging

- TRIM29 knockdown prevented the colon cancer progression through decreasing the ubiquitination levels of KRT5

- Cross-talk between gut microbiota and liver steatosis: Complications and therapeutic target

- Metastasis from small cell lung cancer to ovary: A case report

- The early diagnosis and pathogenic mechanisms of sepsis-related acute kidney injury

- The effect of NK cell therapy on sepsis secondary to lung cancer: A case report

- Erianin alleviates collagen-induced arthritis in mice by inhibiting Th17 cell differentiation

- Loss of ACOX1 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and its correlation with clinical features

- Signalling pathways in the osteogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells

- Crosstalk between lactic acid and immune regulation and its value in the diagnosis and treatment of liver failure

- Clinicopathological features and differential diagnosis of gastric pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma

- Traumatic brain injury and rTMS-ERPs: Case report and literature review

- Extracellular fibrin promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression through integrin β1/PTEN/AKT signaling

- Knockdown of DLK4 inhibits non-small cell lung cancer tumor growth by downregulating CKS2

- The co-expression pattern of VEGFR-2 with indicators related to proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation of anagen hair follicles

- Inflammation-related signaling pathways in tendinopathy

- CD4+ T cell count in HIV/TB co-infection and co-occurrence with HL: Case report and literature review

- Clinical analysis of severe Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia: Case series study

- Bioinformatics analysis to identify potential biomarkers for the pulmonary artery hypertension associated with the basement membrane

- Influence of MTHFR polymorphism, alone or in combination with smoking and alcohol consumption, on cancer susceptibility

- Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don counteracts the ampicillin resistance in multiple antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by downregulation of PBP2a synthesis

- Combination of a bronchogenic cyst in the thoracic spinal canal with chronic myelocytic leukemia

- Bacterial lipoprotein plays an important role in the macrophage autophagy and apoptosis induced by Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus

- TCL1A+ B cells predict prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer through integrative analysis of single-cell and bulk transcriptomic data

- Ezrin promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression via the Hippo signaling pathway

- Ferroptosis: A potential target of macrophages in plaque vulnerability

- Predicting pediatric Crohn's disease based on six mRNA-constructed risk signature using comprehensive bioinformatic approaches

- Applications of genetic code expansion and photosensitive UAAs in studying membrane proteins

- HK2 contributes to the proliferation, migration, and invasion of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells by enhancing the ERK1/2 signaling pathway

- IL-17 in osteoarthritis: A narrative review

- Circadian cycle and neuroinflammation

- Probiotic management and inflammatory factors as a novel treatment in cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Hemorrhagic meningioma with pulmonary metastasis: Case report and literature review

- SPOP regulates the expression profiles and alternative splicing events in human hepatocytes

- Knockdown of SETD5 inhibited glycolysis and tumor growth in gastric cancer cells by down-regulating Akt signaling pathway

- PTX3 promotes IVIG resistance-induced endothelial injury in Kawasaki disease by regulating the NF-κB pathway

- Pancreatic ectopic thyroid tissue: A case report and analysis of literature

- The prognostic impact of body mass index on female breast cancer patients in underdeveloped regions of northern China differs by menopause status and tumor molecular subtype

- Report on a case of liver-originating malignant melanoma of unknown primary

- Case report: Herbal treatment of neutropenic enterocolitis after chemotherapy for breast cancer

- The fibroblast growth factor–Klotho axis at molecular level

- Characterization of amiodarone action on currents in hERG-T618 gain-of-function mutations

- A case report of diagnosis and dynamic monitoring of Listeria monocytogenes meningitis with NGS

- Effect of autologous platelet-rich plasma on new bone formation and viability of a Marburg bone graft

- Small breast epithelial mucin as a useful prognostic marker for breast cancer patients

- Continuous non-adherent culture promotes transdifferentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells into retinal lineage

- Nrf3 alleviates oxidative stress and promotes the survival of colon cancer cells by activating AKT/BCL-2 signal pathway

- Favorable response to surufatinib in a patient with necrolytic migratory erythema: A case report

- Case report of atypical undernutrition of hypoproteinemia type

- Down-regulation of COL1A1 inhibits tumor-associated fibroblast activation and mediates matrix remodeling in the tumor microenvironment of breast cancer

- Sarcoma protein kinase inhibition alleviates liver fibrosis by promoting hepatic stellate cells ferroptosis

- Research progress of serum eosinophil in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma

- Clinicopathological characteristics of co-existing or mixed colorectal cancer and neuroendocrine tumor: Report of five cases

- Role of menopausal hormone therapy in the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis

- Precisional detection of lymph node metastasis using tFCM in colorectal cancer

- Advances in diagnosis and treatment of perimenopausal syndrome

- A study of forensic genetics: ITO index distribution and kinship judgment between two individuals

- Acute lupus pneumonitis resembling miliary tuberculosis: A case-based review

- Plasma levels of CD36 and glutathione as biomarkers for ruptured intracranial aneurysm

- Fractalkine modulates pulmonary angiogenesis and tube formation by modulating CX3CR1 and growth factors in PVECs

- Novel risk prediction models for deep vein thrombosis after thoracotomy and thoracoscopic lung cancer resections, involving coagulation and immune function

- Exploring the diagnostic markers of essential tremor: A study based on machine learning algorithms

- Evaluation of effects of small-incision approach treatment on proximal tibia fracture by deep learning algorithm-based magnetic resonance imaging

- An online diagnosis method for cancer lesions based on intelligent imaging analysis

- Medical imaging in rheumatoid arthritis: A review on deep learning approach

- Predictive analytics in smart healthcare for child mortality prediction using a machine learning approach

- Utility of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio and platelet–lymphocyte ratio in predicting acute-on-chronic liver failure survival

- A biomedical decision support system for meta-analysis of bilateral upper-limb training in stroke patients with hemiplegia

- TNF-α and IL-8 levels are positively correlated with hypobaric hypoxic pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling in rats

- Stochastic gradient descent optimisation for convolutional neural network for medical image segmentation

- Comparison of the prognostic value of four different critical illness scores in patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy

- Application and teaching of computer molecular simulation embedded technology and artificial intelligence in drug research and development

- Hepatobiliary surgery based on intelligent image segmentation technology

- Value of brain injury-related indicators based on neural network in the diagnosis of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- Analysis of early diagnosis methods for asymmetric dementia in brain MR images based on genetic medical technology

- Early diagnosis for the onset of peri-implantitis based on artificial neural network

- Clinical significance of the detection of serum IgG4 and IgG4/IgG ratio in patients with thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy

- Forecast of pain degree of lumbar disc herniation based on back propagation neural network

- SPA-UNet: A liver tumor segmentation network based on fused multi-scale features

- Systematic evaluation of clinical efficacy of CYP1B1 gene polymorphism in EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer observed by medical image

- Rehabilitation effect of intelligent rehabilitation training system on hemiplegic limb spasms after stroke

- A novel approach for minimising anti-aliasing effects in EEG data acquisition

- ErbB4 promotes M2 activation of macrophages in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Clinical role of CYP1B1 gene polymorphism in prediction of postoperative chemotherapy efficacy in NSCLC based on individualized health model

- Lung nodule segmentation via semi-residual multi-resolution neural networks

- Evaluation of brain nerve function in ICU patients with Delirium by deep learning algorithm-based resting state MRI

- A data mining technique for detecting malignant mesothelioma cancer using multiple regression analysis

- Markov model combined with MR diffusion tensor imaging for predicting the onset of Alzheimer’s disease

- Effectiveness of the treatment of depression associated with cancer and neuroimaging changes in depression-related brain regions in patients treated with the mediator-deuterium acupuncture method

- Molecular mechanism of colorectal cancer and screening of molecular markers based on bioinformatics analysis

- Monitoring and evaluation of anesthesia depth status data based on neuroscience

- Exploring the conformational dynamics and thermodynamics of EGFR S768I and G719X + S768I mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: An in silico approaches

- Optimised feature selection-driven convolutional neural network using gray level co-occurrence matrix for detection of cervical cancer

- Incidence of different pressure patterns of spinal cerebellar ataxia and analysis of imaging and genetic diagnosis

- Pathogenic bacteria and treatment resistance in older cardiovascular disease patients with lung infection and risk prediction model

- Adoption value of support vector machine algorithm-based computed tomography imaging in the diagnosis of secondary pulmonary fungal infections in patients with malignant hematological disorders

- From slides to insights: Harnessing deep learning for prognostic survival prediction in human colorectal cancer histology

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Monitoring of hourly carbon dioxide concentration under different land use types in arid ecosystem

- Comparing the differences of prokaryotic microbial community between pit walls and bottom from Chinese liquor revealed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing

- Effects of cadmium stress on fruits germination and growth of two herbage species

- Bamboo charcoal affects soil properties and bacterial community in tea plantations

- Optimization of biogas potential using kinetic models, response surface methodology, and instrumental evidence for biodegradation of tannery fleshings during anaerobic digestion

- Understory vegetation diversity patterns of Platycladus orientalis and Pinus elliottii communities in Central and Southern China

- Studies on macrofungi diversity and discovery of new species of Abortiporus from Baotianman World Biosphere Reserve

- Food Science

- Effect of berrycactus fruit (Myrtillocactus geometrizans) on glutamate, glutamine, and GABA levels in the frontal cortex of rats fed with a high-fat diet

- Guesstimate of thymoquinone diversity in Nigella sativa L. genotypes and elite varieties collected from Indian states using HPTLC technique

- Analysis of bacterial community structure of Fuzhuan tea with different processing techniques

- Untargeted metabolomics reveals sour jujube kernel benefiting the nutritional value and flavor of Morchella esculenta

- Mycobiota in Slovak wine grapes: A case study from the small Carpathians wine region

- Elemental analysis of Fadogia ancylantha leaves used as a nutraceutical in Mashonaland West Province, Zimbabwe

- Microbiological transglutaminase: Biotechnological application in the food industry

- Influence of solvent-free extraction of fish oil from catfish (Clarias magur) heads using a Taguchi orthogonal array design: A qualitative and quantitative approach

- Chromatographic analysis of the chemical composition and anticancer activities of Curcuma longa extract cultivated in Palestine

- The potential for the use of leghemoglobin and plant ferritin as sources of iron

- Investigating the association between dietary patterns and glycemic control among children and adolescents with T1DM

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Biocompatibility and osteointegration capability of β-TCP manufactured by stereolithography 3D printing: In vitro study

- Clinical characteristics and the prognosis of diabetic foot in Tibet: A single center, retrospective study

- Agriculture

- Biofertilizer and NPSB fertilizer application effects on nodulation and productivity of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) at Sodo Zuria, Southern Ethiopia

- On correlation between canopy vegetation and growth indexes of maize varieties with different nitrogen efficiencies

- Exopolysaccharides from Pseudomonas tolaasii inhibit the growth of Pleurotus ostreatus mycelia

- A transcriptomic evaluation of the mechanism of programmed cell death of the replaceable bud in Chinese chestnut

- Melatonin enhances salt tolerance in sorghum by modulating photosynthetic performance, osmoregulation, antioxidant defense, and ion homeostasis

- Effects of plant density on alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) seed yield in western Heilongjiang areas

- Identification of rice leaf diseases and deficiency disorders using a novel DeepBatch technique

- Artificial intelligence and internet of things oriented sustainable precision farming: Towards modern agriculture

- Animal Sciences

- Effect of ketogenic diet on exercise tolerance and transcriptome of gastrocnemius in mice

- Combined analysis of mRNA–miRNA from testis tissue in Tibetan sheep with different FecB genotypes

- Isolation, identification, and drug resistance of a partially isolated bacterium from the gill of Siniperca chuatsi

- Tracking behavioral changes of confined sows from the first mating to the third parity

- The sequencing of the key genes and end products in the TLR4 signaling pathway from the kidney of Rana dybowskii exposed to Aeromonas hydrophila

- Development of a new candidate vaccine against piglet diarrhea caused by Escherichia coli

- Plant Sciences

- Crown and diameter structure of pure Pinus massoniana Lamb. forest in Hunan province, China

- Genetic evaluation and germplasm identification analysis on ITS2, trnL-F, and psbA-trnH of alfalfa varieties germplasm resources

- Tissue culture and rapid propagation technology for Gentiana rhodantha

- Effects of cadmium on the synthesis of active ingredients in Salvia miltiorrhiza

- Cloning and expression analysis of VrNAC13 gene in mung bean

- Chlorate-induced molecular floral transition revealed by transcriptomes

- Effects of warming and drought on growth and development of soybean in Hailun region

- Effects of different light conditions on transient expression and biomass in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves

- Comparative analysis of the rhizosphere microbiome and medicinally active ingredients of Atractylodes lancea from different geographical origins

- Distinguish Dianthus species or varieties based on chloroplast genomes

- Comparative transcriptomes reveal molecular mechanisms of apple blossoms of different tolerance genotypes to chilling injury

- Study on fresh processing key technology and quality influence of Cut Ophiopogonis Radix based on multi-index evaluation

- An advanced approach for fig leaf disease detection and classification: Leveraging image processing and enhanced support vector machine methodology

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Protein Z modulates the metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma cells”

- Erratum to “BRCA1 subcellular localization regulated by PI3K signaling pathway in triple-negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells and hormone-sensitive T47D cells”

- Retraction

- Retraction to “Protocatechuic acid attenuates cerebral aneurysm formation and progression by inhibiting TNF-alpha/Nrf-2/NF-kB-mediated inflammatory mechanisms in experimental rats”

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Systemic investigation of inetetamab in combination with small molecules to treat HER2-overexpressing breast and gastric cancers

- Immunosuppressive treatment for idiopathic membranous nephropathy: An updated network meta-analysis

- Identifying two pathogenic variants in a patient with pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy

- Effects of phytoestrogens combined with cold stress on sperm parameters and testicular proteomics in rats

- A case of pulmonary embolism with bad warfarin anticoagulant effects caused by E. coli infection

- Neutrophilia with subclinical Cushing’s disease: A case report and literature review

- Isoimperatorin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced periodontitis by downregulating ERK1/2 and NF-κB pathways

- Immunoregulation of synovial macrophages for the treatment of osteoarthritis

- Novel CPLANE1 c.8948dupT (p.P2984Tfs*7) variant in a child patient with Joubert syndrome

- Antiphospholipid antibodies and the risk of thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms

- Immunological responses of septic rats to combination therapy with thymosin α1 and vitamin C

- High glucose and high lipid induced mitochondrial dysfunction in JEG-3 cells through oxidative stress

- Pharmacological inhibition of the ubiquitin-specific protease 8 effectively suppresses glioblastoma cell growth

- Levocarnitine regulates the growth of angiotensin II-induced myocardial fibrosis cells via TIMP-1

- Age-related changes in peripheral T-cell subpopulations in elderly individuals: An observational study

- Single-cell transcription analysis reveals the tumor origin and heterogeneity of human bilateral renal clear cell carcinoma

- Identification of iron metabolism-related genes as diagnostic signatures in sepsis by blood transcriptomic analysis

- Long noncoding RNA ACART knockdown decreases 3T3-L1 preadipocyte proliferation and differentiation

- Surgery, adjuvant immunotherapy plus chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary malignant melanoma of the parotid gland (PGMM): A case report

- Dosimetry comparison with helical tomotherapy, volumetric modulated arc therapy, and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for grade II gliomas: A single‑institution case series

- Soy isoflavone reduces LPS-induced acute lung injury via increasing aquaporin 1 and aquaporin 5 in rats

- Refractory hypokalemia with sexual dysplasia and infertility caused by 17α-hydroxylase deficiency and triple X syndrome: A case report

- Meta-analysis of cancer risk among end stage renal disease undergoing maintenance dialysis

- 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase inhibition arrests growth and induces apoptosis in gastric cancer via AMPK activation and oxidative stress

- Experimental study on the optimization of ANM33 release in foam cells

- Primary retroperitoneal angiosarcoma: A case report

- Metabolomic analysis-identified 2-hydroxybutyric acid might be a key metabolite of severe preeclampsia

- Malignant pleural effusion diagnosis and therapy

- Effect of spaceflight on the phenotype and proteome of Escherichia coli

- Comparison of immunotherapy combined with stereotactic radiotherapy and targeted therapy for patients with brain metastases: A systemic review and meta-analysis

- Activation of hypermethylated P2RY1 mitigates gastric cancer by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation

- Association between the VEGFR-2 -604T/C polymorphism (rs2071559) and type 2 diabetic retinopathy

- The role of IL-31 and IL-34 in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic periodontitis

- Triple-negative mouse breast cancer initiating cells show high expression of beta1 integrin and increased malignant features

- mNGS facilitates the accurate diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of suspicious critical CNS infection in real practice: A retrospective study

- The apatinib and pemetrexed combination has antitumor and antiangiogenic effects against NSCLC

- Radiotherapy for primary thyroid adenoid cystic carcinoma

- Design and functional preliminary investigation of recombinant antigen EgG1Y162–EgG1Y162 against Echinococcus granulosus

- Effects of losartan in patients with NAFLD: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial

- Bibliometric analysis of METTL3: Current perspectives, highlights, and trending topics

- Performance comparison of three scaling algorithms in NMR-based metabolomics analysis

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and its related molecules participate in PROK1 silence-induced anti-tumor effects on pancreatic cancer

- The altered expression of cytoskeletal and synaptic remodeling proteins during epilepsy

- Effects of pegylated recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on lymphocytes and white blood cells of patients with malignant tumor

- Prostatitis as initial manifestation of Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia diagnosed by metagenome next-generation sequencing: A case report

- NUDT21 relieves sevoflurane-induced neurological damage in rats by down-regulating LIMK2

- Association of interleukin-10 rs1800896, rs1800872, and interleukin-6 rs1800795 polymorphisms with squamous cell carcinoma risk: A meta-analysis

- Exosomal HBV-DNA for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of chronic hepatitis B

- Shear stress leads to the dysfunction of endothelial cells through the Cav-1-mediated KLF2/eNOS/ERK signaling pathway under physiological conditions