Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common joint disease affecting approximately 10% of men and 18% of women older than 60. Its pathogenesis is still not fully understood; however, emerging evidence has suggested that chronic low-grade inflammation is associated with OA progression. The pathological features of OA are articular cartilage degeneration in the focal area, including new bone formation at the edge of the joint, subchondral bone changes, and synovitis. Conventional drug therapy aims to prevent further cartilage loss and joint dysfunction. However, the ideal treatment for the pathogenesis of OA remains to be defined. Macrophages are the most common immune cells in inflamed synovial tissues. In OA, synovial macrophages undergo proliferation and activation, thereby releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α, among others. The review article discusses (1) the role of synovial macrophages in the pathogenesis of OA; (2) the progress of immunoregulation of synovial macrophages in the treatment of OA; (3) novel therapeutic targets for preventing the progress of OA or promoting cartilage repair and regeneration.

1 Introduction

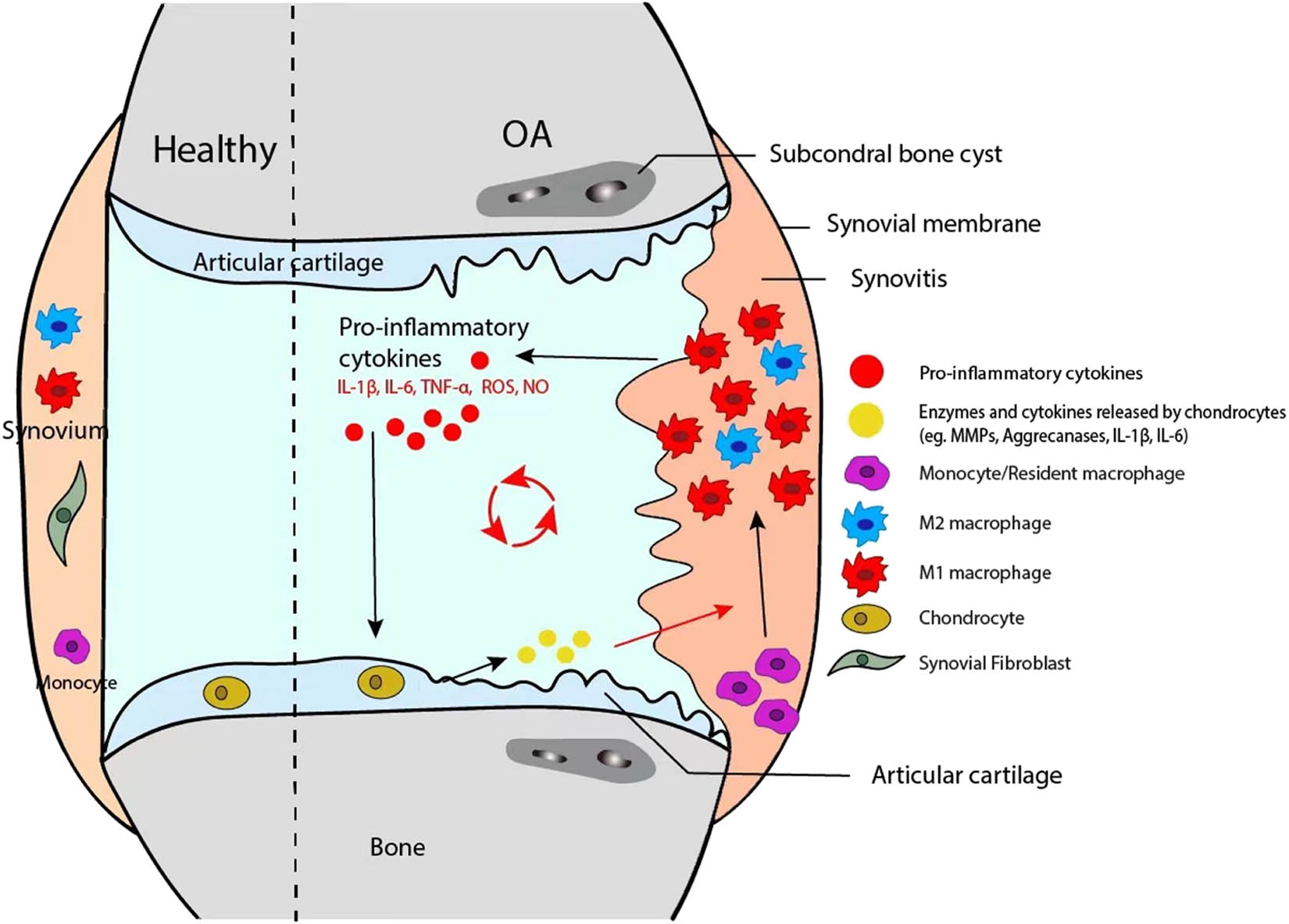

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent form of arthritis and a major cause of disability worldwide, affecting an estimated 10% of men and 18% of women over 60 [1,2]. However, due to the unclear pathogenesis, few treatments are currently available to prevent the onset or progression of OA. Compared to earlier paradigms, OA is now recognized as a low-grade inflammatory disease affecting the entire joint. It is characterized by articular cartilage destruction, subchondral bone remodeling, osteophyte formation, and synovium inflammation (synovitis) [3].

A recent single-cell RNA-seq study has identified various synovial joint immune cell types and characterized their dynamic alterations during the pathological progression of post-traumatic OA in mouse knee joints following anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture [4]. Multiple immune cell types in joints were detected, including neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, B cells, T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and dendritic cells. The monocyte and macrophage populations showed the most dramatic changes after injury. Further characterization of monocytes and macrophages revealed nine major subtypes with distinct transcriptomic signatures, including two macrophage populations with phagocytic genes and enrichment of growth factors [4].

Studies have also found that during the development of OA, many matrix-degrading enzymes, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), are significantly upregulated. The increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines indicated that the synovium undergoes an inflammatory process, leading to the degradation of the cartilage matrix [5]. Furthermore, increasing evidence suggests that persistent low-grade synovial inflammation exacerbates cartilage damage [6], where synovial macrophages have a critical role [7]. Therefore, immunoregulation of macrophages might limit the pro-inflammatory effects and promote anti-inflammatory effects of synovial macrophages, restoring the normal composition of the extracellular chondrocyte matrix and promoting cartilage repair, which in turn improves joint function and facilitate daily activities of patients with OA [8,9,10,11].

The present review discussed the following: (1) the role of synovial macrophages in the pathogenesis of OA; (2) the progress of immunoregulation of synovial macrophages in the treatment of OA; (3) novel therapeutic targets for preventing the progress of OA or promoting cartilage repair and regeneration.

2 Role of synovial macrophages in OA

Different studies have reported on the role of macrophages in the pathogenesis of OA. In normal synovium, macrophages are the predominant cell type [12]. Synovial macrophages are found on the surface of the synovial membrane in healthy joints, providing regulatory factors for cartilage and bone turnover. Similar to other tissue-resident macrophages, they may also remove cell debris and pathogens to prevent sterile and septic inflammation [13]. Increasing evidence highlights the impact of synovitis and macrophage activation on the occurrence and development of OA [14]. A previous study suggested that monocyte/macrophages are the most abundant immune cells in the synovial fluid of OA patients, accounting for ∼36.5% of the total leukocyte. They are also the CD14 + CD16 + double-positive pro-inflammatory cells [15]. Histological studies have also observed more diffusely distributed macrophages in the synovial lining of OA [12]. Yet, studies have also found that alteration in their functionalities may alter the joints of OA patients. It was reported that macrophages produce various cytokines, including interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in the OA synovium [16]. In addition, cytokines such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) produced at the site of inflammation can recruit and activate macrophages [17]. This vicious circle of macrophage activation and pro-inflammatory cytokines production causes deterioration of the inflammatory process and cartilage degradation [18] (Figure 1).

Mechanisms of macrophages in the pathogenesis of OA. Microenvironment stimuli promote synovial macrophage activation and polarization. M1-polarized macrophages in the synovium contribute to OA by releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines that lead to inflammation and subsequent cartilage degradation and osteophyte formation. Polarized macrophages alter the intercellular signaling pathways in chondrocytes, promoting the degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components. ECM, in turn, acts as DAMPs and further stimulates macrophage activation and polarization, resulting in a repeating cycle of inflammation and cartilage degradation. Polarized synovial macrophages and macrophage reprogramming could provide therapeutic targets for OA patients.

The inflammation-targeted treatment has been confirmed to be effective in alleviating the symptoms of OA [19,20]. Inflammation is a predominant risk factor for OA, which can also affect the function of macrophages. The activation and aging of macrophages affect different processes [21], including Toll-like receptor signal transduction [22,23], phenotypic alterations [24,25], phagocytosis [26,27], and wound repair [24].

2.1 Activation of macrophages

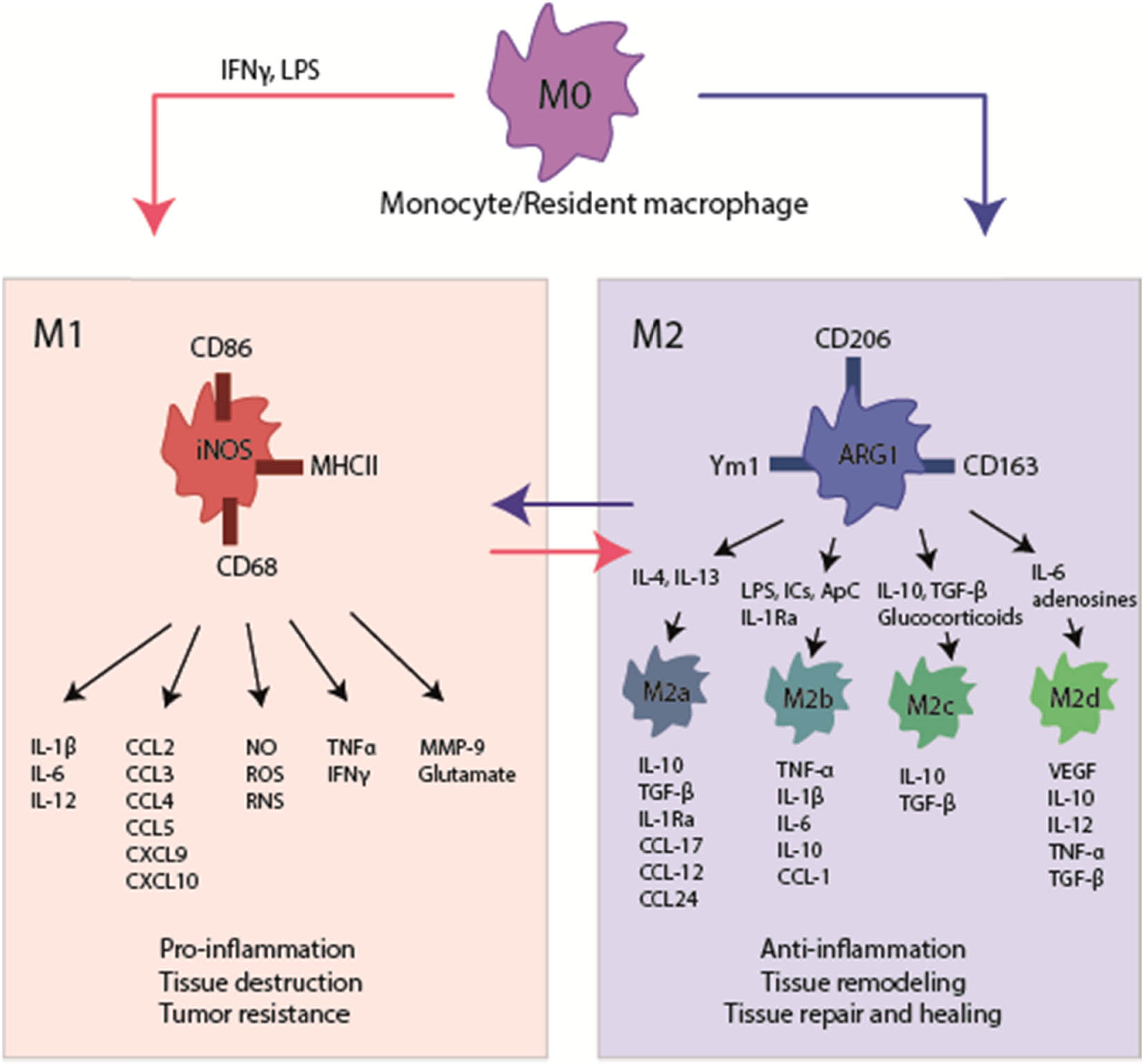

Under healthy conditions, macrophages dynamically and regularly adjust their phenotype and function to stabilize the immune system. However, during pathological conditions, a certain phenotype of macrophages predominates and persists, which is a phenomenon also known as polarization of macrophages [28] (Figure 2).

Schematic representation of macrophage activation and polarization. M1 macrophages (or classical activation pathway) are induced by IFN-γ, LPS, or TNF-α; it promotes the immune response by upregulating pro-inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-1, and downregulating anti-inflammatory factors such as interleukin 10 (IL-10). M2 macrophages (or alternative activation pathway) have four subpopulations: IL-4- and IL-13-induced M2a macrophages, expressing MRC1 and IL-10; M2b macrophages induced by immune complex signaling, expressing IL-10 and major histocompatibility complex class II; M2c macrophages induced by IL-10 and glucocorticoids, expressing MRC1, IL-10 and TGF-β; M2d macrophages can overexpress vascular endothelial growth factor and inducible nitric oxides synthase (iNOS), or lower expression of TNF-α and arginase 1 (arginase 1, Arg1) and participate in angiogenesis and wound healing. Among them, M2a macrophages are mainly related to anti-inflammatory activity, and M2c macrophages are mainly related to tissue repair.

M1 macrophages can be induced by IFN-γ, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), or Toll-like receptors (TLRs) through the production of reactive oxygen intermediates such as NO. M1 macrophages kill and clear pathogens through lysosomal enzymes and other pathways. They also secrete a variety of chemokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, to participate in the inflammatory response, tissue damage, and cell destruction [29,30,31] (Figure 2). At this time, the immune balance is destroyed, and the corresponding tissues are damaged due to the acute and, later on, chronic inflammatory reaction. In their study, Liu et al. examined the phenotypic status of macrophages in the peripheral blood and synovial fluid of 80 patients with knee OA and observed that the M1/M2 was significantly higher in these patients than in healthy controls. Also, this change was significantly associated with the OA classification, indicating the special significance of controlling the activation and polarization of macrophages for guiding the treatment of OA [32].

M2 macrophages are induced by IL-4 and IL-13. M2 can release anti-inflammatory cytokines such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and IL-10, inhibit inflammation, and promote tissue repair (Figure 2). M2 macrophages can be divided into four subpopulations [33]: IL-4 and IL-13-induced M2a macrophages, expressing mannose receptor C-type 1 (MRC1) and IL-10; M2b macrophages induced by immune complex signaling, expressing IL-10 and major histocompatibility complex class II; M2c macrophages induced by IL-10 and glucocorticoids, expressing MRC1, IL-10 and TGF-β; M2d macrophages can overexpress vascular endothelial growth factor and inducible nitric oxides synthase (iNOS), or lower expression of TNF-α and arginase 1 (arginase 1, Arg1), which have a role in angiogenesis and wound healing [34]. Among them, M2a macrophages are mainly related to anti-inflammatory activity, while M2c macrophages have an important role in tissue repair [33,35]. In addition, in mouse models of arthritis, IL-10 was identified to inhibit the occurrence and progression of arthritis [36,37].

A research group found significantly increased M1-type macrophages in OA patients and mouse models [38]. They used two OA mouse models (M1 or M2 macrophage conditional knockouts) to identify the role of M1- or M2-type macrophages in the development of OA. The mouse model with accumulated synovial M1-type macrophages presented with increased OA score, thinner articular cartilage, increased surface fibrosis areas, abnormal distribution of chondrocytes, and significantly increased volume and surface area of periarticular osteophytes, which exacerbated the progression of OA [38]. On the contrary, the mouse model with accumulated synovial M2-type macrophages presented with decreased synovial inflammation of the injured ACL and decreased OA score and osteophytes, indicating that synovial M2-type macrophage polarization prevents the development of collagenase-induced OA [38]. Moreover, gene sequencing analysis showed that M1-type macrophages promote the progression of OA by secreting pro-inflammatory factors IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α, and promote hypertrophic chondrocytes differentiation and maturation, leading to degeneration [38]. Another study reported positive macrophage-specific protein MRP14, indicating the activation of macrophages in an OA animal model [39]. Consecutively, the synovial macrophages were depleted to observe the OA progression. As a result, significantly reduced osteophytes improved the stability of the joints and reduced infiltration of fibroblasts and inflammatory cells (by about 50%) [39]. These findings confirmed the participation of synovial macrophages in the pathological process of OA by promoting synovial fibrosis and osteophyte formation.

In conclusion, macrophages have an important role in the inflammatory response of OA. In the early stage of inflammation, M1-type macrophages phagocytose pathogens, while in the later stage of inflammation, M2-type macrophages regulate the inflammatory tissue microenvironment by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, which is conducive to the regeneration and repair of cartilage tissue. Therefore, timely changes in the polarization state of macrophages are critical for the resolution of inflammation. Therefore, it is of great clinical significance to deeply explore the molecular mechanism of macrophage polarization and achieve targeted induction of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage polarization.

2.2 Macrophages and synovitis

Although synovial macrophages are the major immune cells in synovial tissues, their role in the pathogenesis of OA remains poorly understood. A few studies have shown synovial macrophages’ abnormal accumulation and phenotypic changes in the OA synovium [40,41]. Compared with healthy synovium, the number of F4/8+ (macrophage marker) cells showed a remarkable increase, with an increased number of iNOS + cells (M1 macrophage marker) and a reduced number of CD206 + cells (M2 macrophage marker) in OA synovium [38]. Up to 90% of patients with end-stage OA have synovitis with the infiltration of CD68-positive macrophages [32]. Other studies suggested greater conspicuous macrophage infiltration in patients with early-stage OA [42]. Also, numerous inflammatory factors and chemokines were found to be elevated in the isolated synoviocytes from minced synovial tissue samples extracted from OA patients [43]. After the depletion of macrophages using anti-CD14-conjugated magnetic beads, TNF-α, IL-1, and other cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and MMPs also showed a marked reduction, suggesting that macrophage could secrete pro-inflammatory factors and promote the production of MMPs [16]. Bondeson et al. found that the level of macrophage-secreted pro-inflammatory factor macrophage migration inhibitory factor was positively correlated with the severity of OA-caused pain [16]. Another research group established an in vitro model to study the role of synovial macrophages in OA and found that maintaining the stable phenotype of macrophages is essential for preserving the viability of chondrocytes and maintaining the expression levels of cartilage proteoglycan and collagen [44]. They extracted synovial explants from OA patients for in vitro culture, treated them with different cytokines to stimulate the phenotypic changes of macrophages, and administered dexamethasone, rapamycin, bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP-7) or pravastatin to evaluate the inflammatory state of synovitis. Dexamethasone showed an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting M1 macrophages, while rapamycin inhibited the M2 phenotype to enhance the inflammatory response [44]. These data suggest the use of macrophage phenotypic modulation to guide the treatment of joint inflammation, which could, in turn, help to develop novel therapies for delaying the progression of OA.

2.3 Macrophages and subchondral bone destruction/repair

The subchondral bone in OA undergoes an uncoupled remodeling process characterized by macrophage infiltration, osteoclast formation, and increased osteoblast activity resulting in local remineralization and bone sclerosis of end-stage OA [45]. Utomo et al. injected clodronate-liposomes to deplete macrophages in the synovium and injected different doses of TGF-β into the knee joint seven days later [46]. In mice without macrophage depletion, osteophytes formed on the inner and outer sides of the patella and femur, while in mice with synovial macrophage depletion, the formed osteophytes were reduced by ∼70% [46]. They also discovered that synovial macrophages could lead to bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) and BMP-4 after TGFβ stimulation [46]. These findings suggest that macrophages are a key intermediate factor in TGFβ-induced osteophytes.

Subchondral bone cysts are a common feature in OA [45]. Cysts-derived macrophages promote osteoclast differentiation and contribute to the expansion of OA cysts and osteolysis [47]. Another study reported that the synovial macrophages differentiate into functional osteoclasts, thereby promoting bone resorption and subchondral bone reconstruction [48]. Besides, TNF-α can indirectly induce osteoclast formation by stimulating macrophage differentiation [49]. Furthermore, the M2 polarization of macrophages has been confirmed to be crucial in the regeneration of subchondral bone. In an animal model of the bilateral trochlear cartilage defect, mice were subcutaneously injected with a mixture of chitosan–glycerophosphate and whole blood or serum [50]. This treatment could induce the chemotactic effect of neutrophils and M2 macrophages to concentrate at the injection site and promote trabecular bone repair and bone regeneration by expressing arginase-1 and releasing angiogenic factors [50].

These data suggest macrophages have an important role in the destruction of subchondral bone in OA patients. Therefore, immunoregulation of macrophages, especially polarizing macrophages toward M2 phenotype, might further elucidate the restoring process of subchondral bone.

2.4 Macrophages promote articular cartilage degeneration

The activation of MMPs has been identified as one of the important signs of irreversible damage to articular cartilage. Studies have found that synovial macrophages can mediate the expression of MMPs to induce articular cartilage damage [51]. M1 macrophages induce inflammation and degeneration of OA cartilage explants by up-regulating IL-1, IL-6, and MMP-13, while M2 macrophages have no effect [30]. Utomo et al. established an in vitro three-dimensional co-culture system to evaluate the interaction between activated macrophages and chondrocytes to understand the progression and treatment of OA [30]. It was observed that in the co-culture of activated macrophages and normal chondrocytes, MMPs and pro-inflammatory cytokines were increased while aggrecan and type II collagen were decreased, similar to the microenvironment of early-stage OA in clinical practice; whereas in the co-culture of activated macrophages and OA chondrocytes, the expression levels of MMPs and pro-inflammatory factors were remarkably higher than those in the co-culture system with normal chondrocytes [30]. These results suggest that the activation of pro-inflammatory macrophages is involved in promoting OA development. They also showed that diseased chondrocytes could aggravate the activation of macrophages.

3 Immunomodulatory macrophages in the treatment of OA

3.1 Depletion of macrophages

As macrophages are important in the immune pathogenesis of OA, several studies have tried to deplete macrophages to examine their effect on cartilage health and joint integrity. Previous studies found that depleting the synovial macrophages by intra-articular injection of clodronate-loaded liposomes can significantly decrease the expression of MMP-3 and MMP-9 in the synovium and reduce TGF-β-mediated osteophyte formation in the collagenase-induced OA mouse model [51,52]. In another study, anti-CD14 binding magnetic beads were used to achieve the specific depletion of synovial macrophages in OA synoviocytes in vitro, resulting in downregulation of the expression MMPs and fibroblasts-produced cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 [16]. However, other studies have reported increased synovial inflammation after the depletion of macrophages, which could not prevent the progression of OA [53,54]. Chamberlain et al. showed that compared with the medial collateral ligament (MCL) of untreated rats, the mechanical strength of MCL was decreased in rats with macrophage depletion [55]. These findings demonstrated that depleting macrophages may affect the inflammatory response around the injured joints while inhibiting the function of macrophages could profoundly impact joint inflammation and bone homeostasis after joint injury.

Currently, a variety of in vitro or animal models are available to study macrophage depletion. Yet, these technologies cannot precisely target the specific phenotype of macrophages without affecting other bone marrow lineages, such as dendritic cells and neutrophils. Simply depleting macrophages without considering the polarization of macrophages may not permanently address the OA progression.

3.2 Immunomodulatory macrophages

The continued existence of the pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages is generally thought to be detrimental to tissue repair, while the anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages can benefit tissue regeneration. Several cell or animal studies have attempted to improve or treat OA using immunomodulatory macrophages, including regulating and targeting specific signaling pathways [38,56], and other interventions such as extracts of traditional Chinese medicine [57,58], anti-inflammatory drugs [8], and mesenchymal stem cell therapy [59]. Studies highlighting the potential targets of macrophage immunomodulation are listed in Table 1.

Genes and targets of interest on the immunoregulation of macrophages in OA

| References | Relevant gene/treatment | Disease model | Genotype | Upregulated cytokines | Downregulated cytokines | Effect on macrophages | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [77] | NFAT5 | DMM-induced OA in mice | NFAT5 haplo-insufficient (NFAT5 +/−) mice | CCL2, IL-1β, MMP-13, ADMATS-5 | NA | Macrophage infiltration | NA |

| [78] | Alpha defensin-1 | Meniscal/ligamentous injury, rat | Wistar rats | COL2A1, ACN,MMP3, MMP13 and ADAMTS5 | NA | Promoting M1 to M2 macrophage polarization via insulin and Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | Candidate treatment |

| [79] | Artificial M2 macrophages | Injecting papain, mice | Kunming mice | NA | IL-Iβ, IL-6, IL-17 | A promising strategy | |

| [80] | Basic calcium phosphate crystals | Macrophage isolated from Human blood monocyte | NA | CXCL9, CXCL10, HIF1a, GLUT1and hexokinase 2 | CCL13, MRC1 | Promoting M1 macrophage polarization | Potential therapeutic target |

| [81] | Lumican | Synovial fluid of OA patients | NA | TLR4 | NA | Up-regulating primary macrophage activation and polarization towards the M1-like phenotype | NA |

| [82] | GM-CSF | The collagenase-induced osteoarthritis (CiOA) in mice | C57BL/6 mice | NA | NA | NA | Potential benefits of anti-GM-CSF (and anti-CCL17) mAb therapy in OA |

| [83] | The E3 ubiquitin ligase, Itch | Post-traumatic OA joints | C57BL/6J mice; Itch global knockout (Itch −/−) mice, macrophage-specific Itch knockout (MΔItch) mice | NA | NF-kB, JNK, and MARK12 | Inhibiting macrophage pro-inflammatory polarization | NA |

| [84] | PTP-001 | DMM-induced OA in rat | Rat | NA | MMP-13, TNFa, IL-1b | Inhibiting macrophage polarization | A promising biologic treatment |

| [85] | IL-4 | DMM-induced OA in mice | C57BL/6J, BALB/cJ mice | CD206, CCL24, CCL18 | TNFa | Promoting macrophages polarize towards an M2 phenotype | Could provide therapeutic benefit |

Glucocorticoids can decrease the CD68 + macrophages in the synovial fluid of patients with symptomatic knee OA and increase the expression of CD163 in synovial macrophages [60]. A decreased number of macrophages were reported in advanced knee OA after intra-articular injection of hyaluronic acid (HA) or methylprednisolone [61]. Mechanistically, HA mainly stimulates the repair process, while corticosteroids mainly reduce inflammation. Another study on dexamethasone found its anti-inflammatory effect on the synovial explants of OA patients. Dexamethasone inhibited the pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages and promoted the anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages in the culture of polarized primary human monocytes [46]. This study also carried out similar experiments using rapamycin, BMP-7, and pravastatin, finding that rapamycin and BMP-7 could enhance the inflammatory response of synovial explants and inhibit M2 macrophages. Moreover, pravastatin did not affect the inflammatory state of synovial explants, though it could inhibit M2 macrophages [46]. In the papain-induced OA rat model, triamcinolone acetonide (TA) intra-articular injection limited the osteophyte formation but could not affect cartilage degeneration or subchondral sclerosis [62]. The results indicated that TA could induce the differentiation of monocytes into M2 macrophages.

In animal models of OA, different traditional Chinese medicine extracts, such as ginsenoside [63] and squid type II collagen [58], have been verified to alter the polarization state of synovial macrophages and alleviate cartilage degradation in OA.

Other treatments, such as TissueGene-C (TG-C), a novel cell-mediated gene therapy, can also immunomodulate macrophages through local transduction of TGF-β1. In a rat model of monosodium iodoacetate, IL-10 and other M2 macrophage markers were increased in the knee joints of the TG-C group compared with the control group, indicating that TG-C could induce an anti-inflammatory microenvironment in the knee joint [64]. Furthermore, stem cell therapy could alleviate OA by regulating macrophage activation [65]. The stem cells are effective in cartilage repair, as they can differentiate in chondrocytes and replace degraded or dead chondrocytes [66]. The potential of mesenchymal stem cells to repair OA has been shown to rely on their ability to immunomodulate macrophages [67]. In osteochondral defect models, human embryonic stem cell-derived exosomes increased intra-articular CD163 + macrophages (M2), decreased CD86 + macrophages (M1), and reduced intra-articular pro-inflammatory cytokines [67].

The CCR2 signaling pathway has long been of interest to the rheumatology research community due to its pronounced pro-inflammatory and chemoattractive effects. As a major chemotactic pathway for monocytes, the CCL2/CCR2 axis is critical for recruiting CCR2-expressing circulating monocytes to sites of inflammation. However, studies in Ccr2-null mice reported controversial data in terms of mitigating OA. Miller et al. found severe allodynia and structural knee joint damage in ccr2-null mice equal to wild-type mice; yet, ccr2-null mice did not develop movement-provoked pain behaviors within 8 weeks in a surgical model of OA induced by medial meniscus (DMM) instability [68]. Another study found that the absence of CCR2 strongly suppressed selective inflammatory response genes in the joint with a lower average chondropathy score and delays pain-related behavior DMM [69]. On the contrary, Raghu et al. reported that mice lacking CCR2 were protected against OA by attenuating macrophage accumulation in the synovial joints [70], thus indicating that the CCL2/CCR2 signaling axis preferentially mediates monocyte trafficking and promotes inflammation and tissue damage in OA. These conflicting results might be due to differences in experimental design, including older mice model (20-week-old vs 10-week-old) and duration of OA development (20 weeks after DMM vs 8–12 weeks). Therefore, the function of CCR2 remains unclear in the development of OA, and CCL2/CCR2 inhibition in the treatment of OA should be regarded with caution.

However, there are still some limitations. For instance, diversity and plasticity are hallmarks of macrophages, and the M1/M2 paradigm is a limited attempt to define its complexity. In vivo, macrophages respond to environmental cues by acquiring distinct functional phenotypes. In mice, during the progression of the inflammatory response, the M1-to-M2 switch enables macrophages to perform different activities at different stages [71]. Previous studies have also shown that macrophages can undergo dynamic transitions between different functional states with a mixture of M1 and M2 phenotypes [72,73]. In addition, differences in macrophage biology between mice and humans in terms of phenotype, homology, transcription factors, and functions may confound the interpretation of results. For instance, murine and human macrophages express different cell markers [74]. Macrophages from mice or humans also exhibit differential metabolic responses to LPS [75]. Therefore, study results on mice should be interpreted in relation to the latent differences when implementing potential therapeutic approaches in humans. In addition, inflammatory processes may substantially vary between patients. The role of macrophages in OA pathogenesis differs by disease stage and endotype [76]. A clear understanding of the immunopathological patterns of OA is critical for further research.

4 Summary and future directions

OA is the main cause of lower-limb disability in the elderly [86]. Age is the leading risk factor for OA. Due to the aging population worldwide, an increasing number of patients are at risk of developing OA, which imposes a tremendous economic burden, including productivity and health care. Macrophages have been identified as the main pathological features of OA. They regulate the immune-inflammatory response of synovial tissues, secrete various inflammatory factors such as TNF-α and IL-1β, promote the infiltration of other inflammatory cells, and directly produce cytokines such as MMPs, which in turn accelerate articular cartilage damage and mediate osteophyte formation upon TGFβ stimulation. The damaged articular cartilage fragments subsequently trigger more macrophage activation, forming a vicious circle. Several studies have highlighted the impact of the phenotypic changes of macrophages in the development of OA [76]. The role of macrophages in synovitis and OA has gradually become the focus of therapeutic interventions. Overall, inhibiting the M1 polarization of macrophages and blocking the expression of TNF-α and MMPs may provide novel insights to guide the clinical treatment of OA.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: M.X.: drafted the manuscript; Y.J.: reviewed and made modifications to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Glyn-Jones S, Palmer AJR, Agricola R, Price AJ, Vincent TL, Weinans H, et al. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):376–87.10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60802-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Thomas E, Peat G, Croft P. Defining and mapping the person with osteoarthritis for population studies and public health. Rheumatol (United Kingdom). 2014;53(2):338–45.10.1093/rheumatology/ket346Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Musumeci G, Aiello FC, Szychlinska MA, Di Rosa M, Castrogiovanni P, Mobasheri A. Osteoarthritis in the XXIst century: Risk factors and behaviours that influence disease onset and progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(3):6093–112.10.3390/ijms16036093Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Sebastian A, Hum NR, McCool JL, Wilson SP, Murugesh DK, Martin KA, et al. Single-cell RNA-Seq reveals changes in immune landscape in post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:938075. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.938075.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Tay TL, Béchade C, D’Andrea I, St-Pierre M-K, Henry MS, Roumier A, et al. Microglia Gone Rogue: Impacts on Psychiatric Disorders across the Lifespan. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;10:421. 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00421.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Robinson WH, Lepus CM, Wang Q, Raghu H, Mao R, Lindstrom TM, et al. Low-grade inflammation as a key mediator of the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(10):580–92.10.1038/nrrheum.2016.136Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Xie J, Huang Z, Yu X, Zhou L, Pei F. Clinical implications of macrophage dysfunction in the development of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2019;46:36–44.10.1016/j.cytogfr.2019.03.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Khella CM, Horvath JM, Asgarian R, Rolauffs B, Hart ML. Anti-inflammatory therapeutic approaches to prevent or delay post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA) of the knee joint with a focus on sustained delivery approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:8005.10.3390/ijms22158005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Calabrese G, Zappal A, Dolcimascolo A, Acquaviva R, Parenti R, Malfa GA. (Scrophulariaceae) Leaf extract evaluated in two in vitro models of inflammation and osteoarthritis. Molecules. 2021;26(17):5392.10.3390/molecules26175392Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Conaghan PG, Cook AD, Hamilton JA, Tak PP. Therapeutic options for targeting inflammatory osteoarthritis pain. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019;15(6):355–63.10.1038/s41584-019-0221-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Fernandes TL, Gomoll AH, Lattermann C, Hernandez AJ, Bueno DF, Amano MT. Macrophage: A potential target on cartilage regeneration. Front Immunol. 2020;11:111. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00111.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Menarim BC, Gillis KH, Oliver A, Ngo Y, Werre SR, Barrett SH, et al. Macrophage activation in the synovium of healthy and osteoarthritic equine. Joints. 2020;7(November):1–14.10.3389/fvets.2020.568756Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Kurowska-Stolarska M, Alivernini S. Synovial tissue macrophages: Friend or foe? RMD Open. 2017;3(2):1–10.10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000527Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Rayahin JE, Gemeinhart RA. Activation of macrophages in response to biomaterials. Results Probl Cell Differ. Springer; 2017;62:317–51. 10.1007/978-3-319-54090-0_13.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Gómez-Aristizábal A, Gandhi R, Mahomed NN, Marshall KW, Viswanathan S. Synovial fluid monocyte/macrophage subsets and their correlation to patient-reported outcomes in osteoarthritic patients: A cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):1–10.10.1186/s13075-018-1798-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Bondeson J, Wainwright SD, Lauder S, Amos N, Hughes CE. The role of synovial macrophages and macrophage-produced cytokines in driving aggrecanases, matrix metalloproteinases, and other destructive and inflammatory responses in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(6):1–12.10.1186/ar2099Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Jaguin M, Houlbert N, Fardel O, Lecureur V. Polarization profiles of human M-CSF-generated macrophages and comparison of M1-markers in classically activated macrophages from GM-CSF and M-CSF origin. Cell Immunol. 2013 Jan;281(1):51–61. 10.1016/j.cellimm.2013.01.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Murphy EA, Davis JM, McClellan JL, Steiner JL, Jung D, Carmichael MD, et al. Linking tumor associated macrophages, inflammation, and intestinal tumorigenesis: Role of MCP-1. FASEB J. 2012 Apr 1;26(S1):479.5. 10.1096/fasebj.26.1_supplement.479.5.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Atukorala I, Kwoh CK, Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Boudreau RM, Hannon MJ, et al. Synovitis in knee osteoarthritis: A precursor of disease? Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(2):390–5.10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205894Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Bondeson J, Blom AB, Wainwright S, Hughes C, Caterson B, Van Den Berg WB. The role of synovial macrophages and macrophage-produced mediators in driving inflammatory and destructive responses in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(3):647–57.10.5772/28284Search in Google Scholar

[21] Mathiessen A, Conaghan PG. Synovitis in osteoarthritis: Current understanding with therapeutic implications. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):1–9. 10.1186/s13075-017-1229-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Wang CQ, Udupa KB, Xiao H, Lipschitz DA. Effect of age on marrow macrophage number and function. Aging Clin Exp Res. 1995;7(5):379–84.10.1007/BF03324349Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Jackaman C, Radley-Crabb HG, Soffe Z, Shavlakadze T, Grounds MD, Nelson DJ. Targeting macrophages rescues age-related immune deficiencies in C57BL/6J geriatric mice. Aging Cell. 2013;12(3):345–57.10.1111/acel.12062Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Hearps AC, Martin GE, Angelovich TA, Cheng WJ, Maisa A, Landay AL, et al. Aging is associated with chronic innate immune activation and dysregulation of monocyte phenotype and function. Aging Cell. 2012;11(5):867–75.10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00851.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Chelvarajan RL, Collins SM, Van Willigen JM, Bondada S. The unresponsiveness of aged mice to polysaccharide antigens is a result of a defect in macrophage function. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77(4):503–12. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1189/jlb.0804449.10.1189/jlb.0804449Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Mancuso P, McNish RW, Peters-Golden M, Brock TG. Evaluation of phagocytosis and arachidonate metabolism by alveolar macrophages and recruited neutrophils from F344xBN rats of different ages. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122(15):1899–913.10.1016/S0047-6374(01)00322-0Search in Google Scholar

[27] Aprahamian T, Takemura Y, Goukassian D, Walsh K. Ageing is associated with diminished apoptotic cell clearance in vivo. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;152(3):448–55.10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03658.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Griffin TM, Scanzello CR. Innate inflammation and synovial macrophages in osteoarthritis pathophysiology. Clinical Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37:57–63.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Zhang H, Cai D, Bai X. Macrophages regulate the progression of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2020;28(5):555–61. 10.1016/j.joca.2020.01.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Utomo L, Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM, Verhaar JAN, van Osch GJVM. Cartilage inflammation and degeneration is enhanced by pro-inflammatory (M1) macrophages in vitro, but not inhibited directly by anti-inflammatory (M2) macrophages. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016;24(12):2162–70.10.1016/j.joca.2016.07.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Edwards JP, Zhang X, Frauwirth KA, Mosser DM. Biochemical and functional characterization of three activated macrophage populations. J Leukoc Biol. 2006 Dec 1;80(6):1298–307. 10.1189/jlb.0406249.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Liu B, Zhang M, Zhao J, Zheng M, Yang H. Imbalance of M1/M2 macrophages is linked to severity level of knee osteoarthritis. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16(6):5009–14.10.3892/etm.2018.6852Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Roszer T. Understanding the mysterious M2 macrophage through activation markers and effector mechanisms. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:16–8.10.1155/2015/816460Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(12):953–64.10.1038/nri1733Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Orekhov AN, Orekhova VA, Nikiforov NG, Myasoedova VA, Grechko AV, Romanenko EB, et al. Monocyte differentiation and macrophage polarization. Vessel Plus. 2019;3:10. 10.20517/2574-1209.2019.04.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Tanaka Y, Otsuka T, Hotokebuchi T, Miyahara H, Nakashima H, Kuga S, et al. Effect of IL-10 on collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Inflamm Res. 1996;45(6):283–8. 10.1007/BF02280992.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Mosmann VR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 2016;136(7):2348–57. http://www.jimmunol.org/content/136/7/2348%5Cnhttp://www.jimmunol.org/content/136/7/2348.10.4049/jimmunol.136.7.2348Search in Google Scholar

[38] Zhang H, Lin C, Zeng C, Wang Z, Wang H, Lu J, et al. Synovial macrophage M1 polarisation exacerbates experimental osteoarthritis partially through R-spondin-2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Jul 10;77(10):1524–34.10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213450Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Blom AB, van Lent PLEM, Holthuysen AEM, van der Kraan PM, Roth J, van Rooijen N, et al. Synovial lining macrophages mediate osteophyte formation during experimental osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2004;12(8):627–35.10.1016/j.joca.2004.03.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Thomson A, Hilkens CMU. Synovial macrophages in osteoarthritis: The key to understanding pathogenesis? Front Immunol. 2021;12(June):1–9.10.3389/fimmu.2021.678757Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Sampaio C, Sindrup SH, Stauffer JW, Steigerwald I, Stewart J, Tobias J, et al. Direct in vivo evidence of activated macrophages in human osteoarthritis. 2015;155(9):1683–95.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Roemer FW, Kassim Javaid M, Guermazi A, Thomas M, Kiran A, Keen R, et al. Anatomical distribution of synovitis in knee osteoarthritis and its association with joint effusion assessed on non-enhanced and contrast-enhanced MRI. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18(10):1269–74. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.07.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Chen Y, Jiang W, Yong H, He M, Yang Y, Deng Z, et al. Macrophages in osteoarthritis: Pathophysiology and therapeutics. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12(1):261–8.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Topoluk N, Steckbeck K, Siatkowski S, Burnikel B, Tokish J, Mercuri J. Amniotic mesenchymal stem cells mitigate osteoarthritis progression in a synovial macrophage-mediated in vitro explant coculture model. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12(4):1097–110.10.1002/term.2610Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Li G, Yin J, Gao J, Cheng TS, Pavlos NJ, Zhang C, et al. Subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: Insight into risk factors and microstructural changes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(6):223. http://arthritis-research.com/content/15/6/223%5Cnhttp://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed11&NEWS=N&AN=2013776791.10.1186/ar4405Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Utomo L, van Osch GJVM, Bayon Y, Verhaar JAN, Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM. Guiding synovial inflammation by macrophage phenotype modulation: An in vitro study towards a therapy for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016;24(9):1629–38. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.04.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Sabokbar A, Crawford R, Murray DW, Athanasou NA. Macrophage-osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption in osteoarthrotic subchondral acetabular cysts. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(3):255–61.10.1080/000164700317411843Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Adamopoulos IE, Wordsworth PB, Edwards JR, Ferguson DJ, Athanasou NA. Osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption in multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(9):1176–85.10.1016/j.humpath.2006.04.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Lam J, Takeshita S, Barker JE, Kanagawa O, RossFP SLT. TNF-alpha induces osteoclastogenesis by direct stimulation of macrophages exposed to permissive levels of RANK ligand. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(12):7.10.1172/JCI11176Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] van Meurs J, van Lent P, Holthuysen A, Lambrou D, Bayne E, Singer I, et al. Active matrix metalloproteinases are present in cartilage during immune complex-mediated arthritis: A pivotal role for stromelysin-1 in cartilage destruction. J Immunol. 1999;163(10):5633–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10553093.10.4049/jimmunol.163.10.5633Search in Google Scholar

[51] Blom AB, Van Lent PL, Libregts S, Holthuysen AE, Van Der Kraan PM, Van Rooijen N, et al. Crucial role of macrophages in matrix metalloproteinase-mediated cartilage destruction during experimental osteoarthritis: Involvement of matrix metalloproteinase 3. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(1):147–57.10.1002/art.22337Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Blom AB, van Lent PLEM, Holthuysen AEM, van der Kraan PM, Roth J, van Rooijen N, et al. Synovial lining macrophages mediate osteophyte formation during experimental osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2004;12(8):627–35.10.1016/j.joca.2004.03.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Wu CL, McNeill J, Goon K, Little D, Kimmerling K, Huebner J, et al. Conditional macrophage depletion increases inflammation and does not inhibit the development of osteoarthritis in obese macrophage fas-induced apoptosis–transgenic mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(9):1772–83.10.1002/art.40161Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Bailey KN, Furman BD, Zeitlin J, Kimmerling KA, Wu CL, Guilak F, et al. Intra-articular depletion of macrophages increases acute synovitis and alters macrophage polarity in the injured mouse knee. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2020;28(5):626–38.10.1016/j.joca.2020.01.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Chamberlain CS, Leiferman EM, Frisch KE, Wang S, Yang X, van Rooijen N, et al. The influence of macrophage depletion on ligament healing. Connect Tissue Res. 2011 Jun 30;52(3):203–11. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00682.x.10.3109/03008207.2010.511355Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Lv Z, Xu X, Sun Z, Yang YX, Guo H, Li J, et al. TRPV1 alleviates osteoarthritis by inhibiting M1 macrophage polarization via Ca2+/CaMKII/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(6):504. 10.1038/s41419-021-03792-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[57] Tian Z, Zeng F, Zhao C, Dong S. Angelicin alleviates post-trauma osteoarthritis progression by regulating macrophage polarization via STAT3 signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12(June):1–11.10.3389/fphar.2021.669213Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Dai M, Sui B, Xue Y, Liu X, Sun J. Cartilage repair in degenerative osteoarthritis mediated by squid type II collagen via immunomodulating activation of M2 macrophages, inhibiting apoptosis and hypertrophy of chondrocytes. Biomaterials. 2018;180:91–103. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.07.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Zhang J, Rong Y, Luo C, Cui W. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes prevent osteoarthritis by regulating synovial macrophage polarization. Aging. 2020;12(24):25138–52.10.18632/aging.104110Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Young L, Katrib A, Cuello C, Vollmer-Conna U, Bertouch JV, Roberts-Thomson PJ, et al. Effects of intraarticular glucocorticoids on macrophage infiltration and mediators of joint damage in osteoarthritis synovial membranes: Findings in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(2):343–50.10.1002/1529-0131(200102)44:2<343::AID-ANR52>3.0.CO;2-QSearch in Google Scholar

[61] Pasquali Ronchetti I, Guerra D, Taparelli F, Boraldi F, Bergamini G, Mori G, et al. Morphological analysis of knee synovial membrane biopsies from a randomized controlled clinical study comparing the effects of sodium hyaluronate (Hyalgan®) and methylprednisolone acetate (Depomedrol®) in osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2001 Feb;40(2):158–69. https://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/rheumatology/40.2.158.10.1093/rheumatology/40.2.158Search in Google Scholar

[62] Daghestani HN, Pieper CF, Kraus VB. Soluble macrophage biomarkers indicate inflammatory phenotypes in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(4):956–65.10.1002/art.39006Search in Google Scholar

[63] Zhou F, Mei J, Han X, Li H, Yang S, Wang M, et al. Kinsenoside attenuates osteoarthritis by repolarizing macrophages through inactivating NF-κB/MAPK signaling and protecting chondrocytes. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019;9(5):973–85.10.1016/j.apsb.2019.01.015Search in Google Scholar

[64] Lee H, Kim H, Lee Y, Park K, Lee B, Kim S, et al. INVOSSA-K induces an anti-inflammatory intra-articular environment in a rat MIA model via macrophage polarization. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(2019):S376–7. 10.1016/j.joca.2019.02.371.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Cosenza S, Ruiz M, Toupet K, Jorgensen C, Noël D. Mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomes and microparticles protect cartilage and bone from degradation in osteoarthritis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–12.10.1038/s41598-017-15376-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[66] Kong L, Zheng LZ, Qin L, Ho KKW. Role of mesenchymal stem cells in osteoarthritis treatment. J Orthop Transl. 2017;9:89–103. 10.1016/j.jot.2017.03.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[67] Chahal J, Gómez-Aristizábal A, Shestopaloff K, Bhatt S, Chaboureau A, Fazio A, et al. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Treatment in Patients with Osteoarthritis Results in Overall Improvement in Pain and Symptoms and Reduces Synovial Inflammation. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2019;8(8):746–57.10.1002/sctm.18-0183Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[68] Miller RE, Tran PB, Das R, Ghoreishi-Haack N, Ren D, Miller RJ, et al. CCR2 chemokine receptor signaling mediates pain in experimental osteoarthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(50):20602–7.10.1073/pnas.1209294110Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[69] Miotla Zarebska J, Chanalaris A, Driscoll C, Burleigh A, Miller RE, Malfait AM, et al. CCL2 and CCR2 regulate pain-related behaviour and early gene expression in post-traumatic murine osteoarthritis but contribute little to chondropathy. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2017;25(3):406–12. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.10.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[70] Raghu H, Lepus CM, Wang Q, Wong HH, Lingampalli N, Oliviero F, et al. CCL2/CCR2, but not CCL5/CCR5, mediates monocyte recruitment, inflammation and cartilage destruction in osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(5):914–22.10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210426Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[71] Vogel DYS, Vereyken EJF, Glim JE, Heijnen PDAM, Moeton M, van der Valk P, et al. Macrophages in inflammatory multiple sclerosis lesions have an intermediate activation status. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10(1):809. 10.1186/1742-2094-10-35.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[72] Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ, Hill AM. M-1/M-2 Macrophages and the Th1/Th2 Paradigm. J Immunol. 2017 Oct;199(7):2194–201. 10.4049/jimmunol.1701141.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[73] Mills CD, Ley K. M1 and M2 macrophages: The chicken and the egg of immunity. J Innate Immun. 2014;6(6):716–26. https://europepmc.org/articles/PMC4429858.10.1159/000364945Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[74] Nayak DK, Mendez O, Bowen S, Mohanakumar T. Isolation and in vitro culture of murine and human alveolar macrophages. J Vis Exp. 2018;134:57287. 10.3791/57287.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[75] Vijayan V, Pradhan P, Braud L, Fuchs HR, Gueler F, Motterlini R, et al. Human and murine macrophages exhibit differential metabolic responses to lipopolysaccharide – A divergent role for glycolysis. Redox Biol. 2019;22(January):101147. 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101147.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[76] Mushenkova NV, Nikiforov NG, Shakhpazyan NK, Orekhova VA, Sadykhov NK, Orekhov AN. Phenotype diversity of macrophages in osteoarthritis: implications for development of macrophage modulating therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(15):8381.10.3390/ijms23158381Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[77] Lee J, Lee J, Lee S, Yoo SA, Kim KM, Kim WU, et al. Genetic deficiency of nuclear factor of activated T cells 5 attenuates the development of osteoarthritis in mice. Jt Bone Spine. 2022;89(1):105273. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2021.105273.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[78] Xie JW, Wang Y, Xiao K, Xu H, Luo ZY, Li L, et al. Alpha defensin-1 attenuates surgically induced osteoarthritis in association with promoting M1 to M2 macrophage polarization. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2021;29(7):1048–59.10.1016/j.joca.2021.04.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[79] Ma Y, Yang H, Zong X, Wu J, Ji X, Liu W, et al. Artificial M2 macrophages for disease-modifying osteoarthritis therapeutics. Biomaterials. 2021;274(November 2020):120865. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120865.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[80] Mahon OR, Kelly DJ, McCarthy GM, Dunne A. Osteoarthritis-associated basic calcium phosphate crystals alter immune cell metabolism and promote M1 macrophage polarization. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2020;28(5):603–12. 10.1016/j.joca.2019.10.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[81] Barreto G, Senturk B, Colombo L, Brück O, Neidenbach P, Salzmann G, et al. Lumican is upregulated in osteoarthritis and contributes to TLR4-induced pro-inflammatory activation of cartilage degradation and macrophage polarization. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2020;28(1):92–101. 10.1016/j.joca.2019.10.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[82] Lee KMC, Prasad V, Achuthan A, Fleetwood AJ, Hamilton JA, Cook AD. Targeting GM-CSF for collagenase-induced osteoarthritis pain and disease in mice. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2020;28(4):486–91. 10.1016/j.joca.2020.01.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[83] Lin X, Wang W, McDavid A, Xu H, Boyce BF, Xing L. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch limits the progression of post-traumatic osteoarthritis in mice by inhibiting macrophage polarization. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2021;29(8):1225–36.10.1016/j.joca.2021.04.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[84] Flannery CR, Seaman SA, Buddin KE, Nasert MA, Semler EJ, Kelley KL, et al. A novel placental tissue biologic, PTP-001, inhibits inflammatory and catabolic responses in vitro and prevents pain and cartilage degeneration in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2021;29(8):1203–12. 10.1016/j.joca.2021.03.022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[85] von Kaeppler EP, Wang Q, Raghu H, Bloom MS, Wong H, Robinson WH. Interleukin 4 promotes anti-inflammatory macrophages that clear cartilage debris and inhibits osteoclast development to protect against osteoarthritis. Clin Immunol. 2021;229(June):108784. 10.1016/j.clim.2021.108784.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[86] Samavedi S, Diaz-Rodriguez P, Erndt-Marino JD, Hahn MS. A three-dimensional chondrocyte-macrophage coculture system to probe inflammation in experimental osteoarthritis. Tissue Eng Part A. 2017;23(3–4):101–14. http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/ten.tea.2016.0007.10.1089/ten.tea.2016.0007Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Systemic investigation of inetetamab in combination with small molecules to treat HER2-overexpressing breast and gastric cancers

- Immunosuppressive treatment for idiopathic membranous nephropathy: An updated network meta-analysis

- Identifying two pathogenic variants in a patient with pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy

- Effects of phytoestrogens combined with cold stress on sperm parameters and testicular proteomics in rats

- A case of pulmonary embolism with bad warfarin anticoagulant effects caused by E. coli infection

- Neutrophilia with subclinical Cushing’s disease: A case report and literature review

- Isoimperatorin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced periodontitis by downregulating ERK1/2 and NF-κB pathways

- Immunoregulation of synovial macrophages for the treatment of osteoarthritis

- Novel CPLANE1 c.8948dupT (p.P2984Tfs*7) variant in a child patient with Joubert syndrome

- Antiphospholipid antibodies and the risk of thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms

- Immunological responses of septic rats to combination therapy with thymosin α1 and vitamin C

- High glucose and high lipid induced mitochondrial dysfunction in JEG-3 cells through oxidative stress

- Pharmacological inhibition of the ubiquitin-specific protease 8 effectively suppresses glioblastoma cell growth

- Levocarnitine regulates the growth of angiotensin II-induced myocardial fibrosis cells via TIMP-1

- Age-related changes in peripheral T-cell subpopulations in elderly individuals: An observational study

- Single-cell transcription analysis reveals the tumor origin and heterogeneity of human bilateral renal clear cell carcinoma

- Identification of iron metabolism-related genes as diagnostic signatures in sepsis by blood transcriptomic analysis

- Long noncoding RNA ACART knockdown decreases 3T3-L1 preadipocyte proliferation and differentiation

- Surgery, adjuvant immunotherapy plus chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary malignant melanoma of the parotid gland (PGMM): A case report

- Dosimetry comparison with helical tomotherapy, volumetric modulated arc therapy, and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for grade II gliomas: A single‑institution case series

- Soy isoflavone reduces LPS-induced acute lung injury via increasing aquaporin 1 and aquaporin 5 in rats

- Refractory hypokalemia with sexual dysplasia and infertility caused by 17α-hydroxylase deficiency and triple X syndrome: A case report

- Meta-analysis of cancer risk among end stage renal disease undergoing maintenance dialysis

- 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase inhibition arrests growth and induces apoptosis in gastric cancer via AMPK activation and oxidative stress

- Experimental study on the optimization of ANM33 release in foam cells

- Primary retroperitoneal angiosarcoma: A case report

- Metabolomic analysis-identified 2-hydroxybutyric acid might be a key metabolite of severe preeclampsia

- Malignant pleural effusion diagnosis and therapy

- Effect of spaceflight on the phenotype and proteome of Escherichia coli

- Comparison of immunotherapy combined with stereotactic radiotherapy and targeted therapy for patients with brain metastases: A systemic review and meta-analysis

- Activation of hypermethylated P2RY1 mitigates gastric cancer by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation

- Association between the VEGFR-2 -604T/C polymorphism (rs2071559) and type 2 diabetic retinopathy

- The role of IL-31 and IL-34 in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic periodontitis

- Triple-negative mouse breast cancer initiating cells show high expression of beta1 integrin and increased malignant features

- mNGS facilitates the accurate diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of suspicious critical CNS infection in real practice: A retrospective study

- The apatinib and pemetrexed combination has antitumor and antiangiogenic effects against NSCLC

- Radiotherapy for primary thyroid adenoid cystic carcinoma

- Design and functional preliminary investigation of recombinant antigen EgG1Y162–EgG1Y162 against Echinococcus granulosus

- Effects of losartan in patients with NAFLD: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial

- Bibliometric analysis of METTL3: Current perspectives, highlights, and trending topics

- Performance comparison of three scaling algorithms in NMR-based metabolomics analysis

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and its related molecules participate in PROK1 silence-induced anti-tumor effects on pancreatic cancer

- The altered expression of cytoskeletal and synaptic remodeling proteins during epilepsy

- Effects of pegylated recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on lymphocytes and white blood cells of patients with malignant tumor

- Prostatitis as initial manifestation of Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia diagnosed by metagenome next-generation sequencing: A case report

- NUDT21 relieves sevoflurane-induced neurological damage in rats by down-regulating LIMK2

- Association of interleukin-10 rs1800896, rs1800872, and interleukin-6 rs1800795 polymorphisms with squamous cell carcinoma risk: A meta-analysis

- Exosomal HBV-DNA for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of chronic hepatitis B

- Shear stress leads to the dysfunction of endothelial cells through the Cav-1-mediated KLF2/eNOS/ERK signaling pathway under physiological conditions

- Interaction between the PI3K/AKT pathway and mitochondrial autophagy in macrophages and the leukocyte count in rats with LPS-induced pulmonary infection

- Meta-analysis of the rs231775 locus polymorphism in the CTLA-4 gene and the susceptibility to Graves’ disease in children

- Cloning, subcellular localization and expression of phosphate transporter gene HvPT6 of hulless barley

- Coptisine mitigates diabetic nephropathy via repressing the NRLP3 inflammasome

- Significant elevated CXCL14 and decreased IL-39 levels in patients with tuberculosis

- Whole-exome sequencing applications in prenatal diagnosis of fetal bowel dilatation

- Gemella morbillorum infective endocarditis: A case report and literature review

- An unusual ectopic thymoma clonal evolution analysis: A case report

- Severe cumulative skin toxicity during toripalimab combined with vemurafenib following toripalimab alone

- Detection of V. vulnificus septic shock with ARDS using mNGS

- Novel rare genetic variants of familial and sporadic pulmonary atresia identified by whole-exome sequencing

- The influence and mechanistic action of sperm DNA fragmentation index on the outcomes of assisted reproduction technology

- Novel compound heterozygous mutations in TELO2 in an infant with You-Hoover-Fong syndrome: A case report and literature review

- ctDNA as a prognostic biomarker in resectable CLM: Systematic review and meta-analysis

- Diagnosis of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis by metagenomic next-generation sequencing: A case report

- Phylogenetic analysis of promoter regions of human Dolichol kinase (DOLK) and orthologous genes using bioinformatics tools

- Collagen changes in rabbit conjunctiva after conjunctival crosslinking

- Effects of NM23 transfection of human gastric carcinoma cells in mice

- Oral nifedipine and phytosterol, intravenous nicardipine, and oral nifedipine only: Three-arm, retrospective, cohort study for management of severe preeclampsia

- Case report of hepatic retiform hemangioendothelioma: A rare tumor treated with ultrasound-guided microwave ablation

- Curcumin induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by decreasing the expression of STAT3/VEGF/HIF-1α signaling

- Rare presentation of double-clonal Waldenström macroglobulinemia with pulmonary embolism: A case report

- Giant duplication of the transverse colon in an adult: A case report and literature review

- Ectopic thyroid tissue in the breast: A case report

- SDR16C5 promotes proliferation and migration and inhibits apoptosis in pancreatic cancer

- Vaginal metastasis from breast cancer: A case report

- Screening of the best time window for MSC transplantation to treat acute myocardial infarction with SDF-1α antibody-loaded targeted ultrasonic microbubbles: An in vivo study in miniswine

- Inhibition of TAZ impairs the migration ability of melanoma cells

- Molecular complexity analysis of the diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome in China

- Effects of maternal calcium and protein intake on the development and bone metabolism of offspring mice

- Identification of winter wheat pests and diseases based on improved convolutional neural network

- Ultra-multiplex PCR technique to guide treatment of Aspergillus-infected aortic valve prostheses

- Virtual high-throughput screening: Potential inhibitors targeting aminopeptidase N (CD13) and PIKfyve for SARS-CoV-2

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients with COVID-19

- Utility of methylene blue mixed with autologous blood in preoperative localization of pulmonary nodules and masses

- Integrated analysis of the microbiome and transcriptome in stomach adenocarcinoma

- Berberine suppressed sarcopenia insulin resistance through SIRT1-mediated mitophagy

- DUSP2 inhibits the progression of lupus nephritis in mice by regulating the STAT3 pathway

- Lung abscess by Fusobacterium nucleatum and Streptococcus spp. co-infection by mNGS: A case series

- Genetic alterations of KRAS and TP53 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma associated with poor prognosis

- Granulomatous polyangiitis involving the fourth ventricle: Report of a rare case and a literature review

- Studying infant mortality: A demographic analysis based on data mining models

- Metaplastic breast carcinoma with osseous differentiation: A report of a rare case and literature review

- Protein Z modulates the metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma cells

- Inhibition of pyroptosis and apoptosis by capsaicin protects against LPS-induced acute kidney injury through TRPV1/UCP2 axis in vitro

- TAK-242, a toll-like receptor 4 antagonist, against brain injury by alleviates autophagy and inflammation in rats

- Primary mediastinum Ewing’s sarcoma with pleural effusion: A case report and literature review

- Association of ADRB2 gene polymorphisms and intestinal microbiota in Chinese Han adolescents

- Tanshinone IIA alleviates chondrocyte apoptosis and extracellular matrix degeneration by inhibiting ferroptosis

- Study on the cytokines related to SARS-Cov-2 in testicular cells and the interaction network between cells based on scRNA-seq data

- Effect of periostin on bone metabolic and autophagy factors during tooth eruption in mice

- HP1 induces ferroptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells through NRF2 pathway in diabetic nephropathy

- Intravaginal estrogen management in postmenopausal patients with vaginal squamous intraepithelial lesions along with CO2 laser ablation: A retrospective study

- Hepatocellular carcinoma cell differentiation trajectory predicts immunotherapy, potential therapeutic drugs, and prognosis of patients

- Effects of physical exercise on biomarkers of oxidative stress in healthy subjects: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Identification of lysosome-related genes in connection with prognosis and immune cell infiltration for drug candidates in head and neck cancer

- Development of an instrument-free and low-cost ELISA dot-blot test to detect antibodies against SARS-CoV-2

- Research progress on gas signal molecular therapy for Parkinson’s disease

- Adiponectin inhibits TGF-β1-induced skin fibroblast proliferation and phenotype transformation via the p38 MAPK signaling pathway

- The G protein-coupled receptor-related gene signatures for predicting prognosis and immunotherapy response in bladder urothelial carcinoma

- α-Fetoprotein contributes to the malignant biological properties of AFP-producing gastric cancer

- CXCL12/CXCR4/CXCR7 axis in placenta tissues of patients with placenta previa

- Association between thyroid stimulating hormone levels and papillary thyroid cancer risk: A meta-analysis

- Significance of sTREM-1 and sST2 combined diagnosis for sepsis detection and prognosis prediction

- Diagnostic value of serum neuroactive substances in the acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease complicated with depression

- Research progress of AMP-activated protein kinase and cardiac aging

- TRIM29 knockdown prevented the colon cancer progression through decreasing the ubiquitination levels of KRT5

- Cross-talk between gut microbiota and liver steatosis: Complications and therapeutic target

- Metastasis from small cell lung cancer to ovary: A case report

- The early diagnosis and pathogenic mechanisms of sepsis-related acute kidney injury

- The effect of NK cell therapy on sepsis secondary to lung cancer: A case report

- Erianin alleviates collagen-induced arthritis in mice by inhibiting Th17 cell differentiation

- Loss of ACOX1 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and its correlation with clinical features

- Signalling pathways in the osteogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells

- Crosstalk between lactic acid and immune regulation and its value in the diagnosis and treatment of liver failure

- Clinicopathological features and differential diagnosis of gastric pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma

- Traumatic brain injury and rTMS-ERPs: Case report and literature review

- Extracellular fibrin promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression through integrin β1/PTEN/AKT signaling

- Knockdown of DLK4 inhibits non-small cell lung cancer tumor growth by downregulating CKS2

- The co-expression pattern of VEGFR-2 with indicators related to proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation of anagen hair follicles

- Inflammation-related signaling pathways in tendinopathy

- CD4+ T cell count in HIV/TB co-infection and co-occurrence with HL: Case report and literature review

- Clinical analysis of severe Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia: Case series study

- Bioinformatics analysis to identify potential biomarkers for the pulmonary artery hypertension associated with the basement membrane

- Influence of MTHFR polymorphism, alone or in combination with smoking and alcohol consumption, on cancer susceptibility

- Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don counteracts the ampicillin resistance in multiple antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by downregulation of PBP2a synthesis

- Combination of a bronchogenic cyst in the thoracic spinal canal with chronic myelocytic leukemia

- Bacterial lipoprotein plays an important role in the macrophage autophagy and apoptosis induced by Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus

- TCL1A+ B cells predict prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer through integrative analysis of single-cell and bulk transcriptomic data

- Ezrin promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression via the Hippo signaling pathway

- Ferroptosis: A potential target of macrophages in plaque vulnerability

- Predicting pediatric Crohn's disease based on six mRNA-constructed risk signature using comprehensive bioinformatic approaches

- Applications of genetic code expansion and photosensitive UAAs in studying membrane proteins

- HK2 contributes to the proliferation, migration, and invasion of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells by enhancing the ERK1/2 signaling pathway

- IL-17 in osteoarthritis: A narrative review

- Circadian cycle and neuroinflammation

- Probiotic management and inflammatory factors as a novel treatment in cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Hemorrhagic meningioma with pulmonary metastasis: Case report and literature review

- SPOP regulates the expression profiles and alternative splicing events in human hepatocytes

- Knockdown of SETD5 inhibited glycolysis and tumor growth in gastric cancer cells by down-regulating Akt signaling pathway

- PTX3 promotes IVIG resistance-induced endothelial injury in Kawasaki disease by regulating the NF-κB pathway

- Pancreatic ectopic thyroid tissue: A case report and analysis of literature

- The prognostic impact of body mass index on female breast cancer patients in underdeveloped regions of northern China differs by menopause status and tumor molecular subtype

- Report on a case of liver-originating malignant melanoma of unknown primary

- Case report: Herbal treatment of neutropenic enterocolitis after chemotherapy for breast cancer

- The fibroblast growth factor–Klotho axis at molecular level

- Characterization of amiodarone action on currents in hERG-T618 gain-of-function mutations

- A case report of diagnosis and dynamic monitoring of Listeria monocytogenes meningitis with NGS

- Effect of autologous platelet-rich plasma on new bone formation and viability of a Marburg bone graft

- Small breast epithelial mucin as a useful prognostic marker for breast cancer patients

- Continuous non-adherent culture promotes transdifferentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells into retinal lineage

- Nrf3 alleviates oxidative stress and promotes the survival of colon cancer cells by activating AKT/BCL-2 signal pathway

- Favorable response to surufatinib in a patient with necrolytic migratory erythema: A case report

- Case report of atypical undernutrition of hypoproteinemia type

- Down-regulation of COL1A1 inhibits tumor-associated fibroblast activation and mediates matrix remodeling in the tumor microenvironment of breast cancer

- Sarcoma protein kinase inhibition alleviates liver fibrosis by promoting hepatic stellate cells ferroptosis

- Research progress of serum eosinophil in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma

- Clinicopathological characteristics of co-existing or mixed colorectal cancer and neuroendocrine tumor: Report of five cases

- Role of menopausal hormone therapy in the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis

- Precisional detection of lymph node metastasis using tFCM in colorectal cancer

- Advances in diagnosis and treatment of perimenopausal syndrome

- A study of forensic genetics: ITO index distribution and kinship judgment between two individuals

- Acute lupus pneumonitis resembling miliary tuberculosis: A case-based review

- Plasma levels of CD36 and glutathione as biomarkers for ruptured intracranial aneurysm

- Fractalkine modulates pulmonary angiogenesis and tube formation by modulating CX3CR1 and growth factors in PVECs

- Novel risk prediction models for deep vein thrombosis after thoracotomy and thoracoscopic lung cancer resections, involving coagulation and immune function

- Exploring the diagnostic markers of essential tremor: A study based on machine learning algorithms

- Evaluation of effects of small-incision approach treatment on proximal tibia fracture by deep learning algorithm-based magnetic resonance imaging

- An online diagnosis method for cancer lesions based on intelligent imaging analysis

- Medical imaging in rheumatoid arthritis: A review on deep learning approach

- Predictive analytics in smart healthcare for child mortality prediction using a machine learning approach

- Utility of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio and platelet–lymphocyte ratio in predicting acute-on-chronic liver failure survival

- A biomedical decision support system for meta-analysis of bilateral upper-limb training in stroke patients with hemiplegia

- TNF-α and IL-8 levels are positively correlated with hypobaric hypoxic pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling in rats

- Stochastic gradient descent optimisation for convolutional neural network for medical image segmentation

- Comparison of the prognostic value of four different critical illness scores in patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy

- Application and teaching of computer molecular simulation embedded technology and artificial intelligence in drug research and development

- Hepatobiliary surgery based on intelligent image segmentation technology

- Value of brain injury-related indicators based on neural network in the diagnosis of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- Analysis of early diagnosis methods for asymmetric dementia in brain MR images based on genetic medical technology

- Early diagnosis for the onset of peri-implantitis based on artificial neural network

- Clinical significance of the detection of serum IgG4 and IgG4/IgG ratio in patients with thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy

- Forecast of pain degree of lumbar disc herniation based on back propagation neural network

- SPA-UNet: A liver tumor segmentation network based on fused multi-scale features

- Systematic evaluation of clinical efficacy of CYP1B1 gene polymorphism in EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer observed by medical image

- Rehabilitation effect of intelligent rehabilitation training system on hemiplegic limb spasms after stroke

- A novel approach for minimising anti-aliasing effects in EEG data acquisition

- ErbB4 promotes M2 activation of macrophages in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Clinical role of CYP1B1 gene polymorphism in prediction of postoperative chemotherapy efficacy in NSCLC based on individualized health model

- Lung nodule segmentation via semi-residual multi-resolution neural networks

- Evaluation of brain nerve function in ICU patients with Delirium by deep learning algorithm-based resting state MRI

- A data mining technique for detecting malignant mesothelioma cancer using multiple regression analysis

- Markov model combined with MR diffusion tensor imaging for predicting the onset of Alzheimer’s disease

- Effectiveness of the treatment of depression associated with cancer and neuroimaging changes in depression-related brain regions in patients treated with the mediator-deuterium acupuncture method

- Molecular mechanism of colorectal cancer and screening of molecular markers based on bioinformatics analysis

- Monitoring and evaluation of anesthesia depth status data based on neuroscience

- Exploring the conformational dynamics and thermodynamics of EGFR S768I and G719X + S768I mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: An in silico approaches

- Optimised feature selection-driven convolutional neural network using gray level co-occurrence matrix for detection of cervical cancer

- Incidence of different pressure patterns of spinal cerebellar ataxia and analysis of imaging and genetic diagnosis

- Pathogenic bacteria and treatment resistance in older cardiovascular disease patients with lung infection and risk prediction model

- Adoption value of support vector machine algorithm-based computed tomography imaging in the diagnosis of secondary pulmonary fungal infections in patients with malignant hematological disorders

- From slides to insights: Harnessing deep learning for prognostic survival prediction in human colorectal cancer histology

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Monitoring of hourly carbon dioxide concentration under different land use types in arid ecosystem

- Comparing the differences of prokaryotic microbial community between pit walls and bottom from Chinese liquor revealed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing

- Effects of cadmium stress on fruits germination and growth of two herbage species

- Bamboo charcoal affects soil properties and bacterial community in tea plantations

- Optimization of biogas potential using kinetic models, response surface methodology, and instrumental evidence for biodegradation of tannery fleshings during anaerobic digestion

- Understory vegetation diversity patterns of Platycladus orientalis and Pinus elliottii communities in Central and Southern China

- Studies on macrofungi diversity and discovery of new species of Abortiporus from Baotianman World Biosphere Reserve

- Food Science

- Effect of berrycactus fruit (Myrtillocactus geometrizans) on glutamate, glutamine, and GABA levels in the frontal cortex of rats fed with a high-fat diet

- Guesstimate of thymoquinone diversity in Nigella sativa L. genotypes and elite varieties collected from Indian states using HPTLC technique

- Analysis of bacterial community structure of Fuzhuan tea with different processing techniques

- Untargeted metabolomics reveals sour jujube kernel benefiting the nutritional value and flavor of Morchella esculenta

- Mycobiota in Slovak wine grapes: A case study from the small Carpathians wine region

- Elemental analysis of Fadogia ancylantha leaves used as a nutraceutical in Mashonaland West Province, Zimbabwe