Abstract

Klotho is a recently discovered protein that has positive effects on all systems of the body, for example, regulating calcium and phosphorus metabolism, protecting nerves, delaying aging and so on. Fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) are a group of polypeptides that function throughout the body by binding with cell surface FGF receptors (FGFRs). Endocrine FGFs require Klotho as a co-receptor for FGFRs. There is increasing evidence that Klotho participates in calcium and phosphorus regulation and metabolic regulation via the FGF–Klotho axis. Moreover, soluble Klotho can function as a separate hormone to regulate homeostasis on various ion channels and carrier channels on the cell surface. This review mainly explains the molecular basis of the membrane signaling mechanism of Klotho.

1 Introduction

The Klotho protein was discovered in 1997, and its name is derived from Clotho, the goddess of fate who determines the length of life, as per Greek mythology. Klotho protein was first found in the distal convoluted tubules of transgenic mice [1–4]. There are three types of Klotho in the human body, namely α-Klotho (KLA), β-Klotho (KLB), and γ-Klotho. Moreover, Klotho can also be divided into the membrane-binding type (mKL), secretory or soluble type (sKL), and intracellular type. These different forms of klotho are involved in different physiological processes [5]. The KLA gene is located on chromosome 13q12; it has five exons and four introns and encodes a type I single transmembrane protein (mKLA) with a molecular weight of 135 kDa which comprises 1,012 amino acids [6,7]. mKLA is mainly found in the kidney and comprises the extracellular domain (KL1 and KL2), N-terminal signal, ten amino acids at the C-terminal of the transmembrane helix, and the intracellular cytoplasmic domain [8]. mKLA is cleaved by a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 10/17(ADAM10/17) at the proximal end of the cell surface (α-cutting) and forms an isomer called the secretory-type KLA (sKLA), which has a molecular weight of 130 kDa. sKLA only contains KL1 and KL2 domains and is predominantly obtained by the hydrolysis of mKLA on the cell membrane of distal renal tubules. Therefore, the expression of sKLA is the most abundant in distal renal tubules. β-cleavage can also occur between the KL1 and KL2 domains of sKLA to form a 60 kDa isomer containing only the KL1 domain (intracellular type). Besides, the 3C end of the exon of the Klotho gene carries alternative splicing sites, and the translation of alternative mRNA splicing sites may lead to premature termination of codon translation and the formation of an inactive protein comprising KL1. Except for sKLA, all isomers of Klotho have limited blood circulation. The KLB gene is located on chromosome 4. Compared to KLA, KLB is only membrane-bound and has no secretory form; it is mainly found in the liver and white adipose tissue [8,9]. γ-Klotho is predominantly expressed in the kidney and skin; however, its function remains unclear. Thus, sKL in the human body is mainly sKLA. The sKL mentioned below is sKLA. Klotho expression is affected by many physiological and pathological conditions. The levels of Klotho are reportedly significantly reduced in the animal and human brain, kidney, atrial node, liver, and serum [10–18]. In addition, oxidative stress, inflammation, angiotensin II, aldosterone, and proteinuria inhibit Klotho expression [19]. This protein expression is also decreased in many diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease [20–22], acute and chronic kidney disease [22,23], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [24], diabetes mellitus (bamboo medium) [25–27], some cancers, and various vascular cancer pathologies, including arteriosclerosis, atherosclerosis, and stroke [28,29].

The fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family comprises 22 polypeptides that play important roles in embryonic development and normal tissue homeostasis by binding with FGF receptors (FGFRs) [30]. Endocrine FGFs, including FGF19, 21, and 23, are powerful endocrine hormones that regulate various aspects of physiological homeostasis [31]. The binding of endocrine FGFs and FGFRs requires KLA or KLB as a co-receptor [32]. FGF19 is a satiety hormone secreted in the intestine during food intake, which in combination with the KLB–FGFR4 complex of hepatocytes promotes the metabolic response of food intake [33]. Conversely, under fasting conditions, FGF21 is secreted by the liver; it binds to the KLB–FGFR complex of adipocytes and the suprachiasmatic nucleus to activate the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system, consequently regulating the metabolic response to fasting and stress [34–38]. FGF23 is secreted by osteoblasts in response to phosphate uptake; it binds with the KLA–FGFR complex to regulate mineral metabolism [39–42].

2 Molecular structure of KLA/KLB

The KLA domains KL1 and KL2 comprise an inner eight-stranded parallel α-barrel and eight surrounding β-helices. The two domains of KLA are connected by a proline-rich rigid chain, N-terminal of β1chain, α7 helix of KL1, β5α5 rings, β6α6 rings, and α7 helix of KL2 [43]; furthermore, a special inter-domain contact is mediated by zinc ions, which promotes the activity of the co-receptor KLA–FGFR by minimizing the flexibility between domains. KLB is structurally similar to KLA. KL1 and KL2 domains of KLB comprise eight units each of β-slice and α7 helix; the inter-action domain of KLB has a wide network of hydrophobicity and polar interactions. KL1 and KL2 domains of both KLA and KLB are homologous with glucosidase-1 (GH1). GH1 contains two highly conserved glutamate residues, which are necessary for glucosidase to function. The first glutamate is a nucleophilic residue, and the second glutamate has the activity of acid–base catalysis double substitution mechanism [44–46]. GH1 hydrolyzes carbohydrates through a double substitution mechanism mediated by the two conservative glutamate residues. However, Asn241 replaces the first glutamate in the KL1 domain of KLB, whereas in the KL2 domain, Ala889 replaces the second glutamate [47], indicating that the glycoside hydrolase-like domains (KL1 and KL2) of KLB are not real glycoside hydrolases. KL1 and KL2 domains of KLA also have no glycoside hydrolase activity, possibly due to the replacement of the two conservative glutamates.

3 Molecular structure of FGF23–KLA–FGFR

3.1 Structural association between KLA and FGFR

The individual entities of the ternary complex FGF23–KLA–FGFR have close interaction with each other, and the molecular conformation is shown in Figure 1a. FGFR comprises an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a transmembrane helix domain, and a cytoplasmic part with tyrosine kinase activity. The extracellular ligand-binding domain comprises three immunoglobulin-like domains (D1–D3). KLA is bound to FGFR primarily through the binding of the KL2 and D3 domains. The long β1α1 loop of KL2, which is a 35 kDa amino acid sequence extending from the KL2 nucleus, is locked in the FGFR D3 domain; it is called the receptor-binding arm (RBA). A short β-chain pair (RBA-β1: RBA-β2) is formed by the binding of distal residues of RBA (547Tyr–Leu–Trp549 and 556Ile–Leu–Arg558) and the FGFR D3 domain. RBA-β1: RBA-β2, the βC′–βC–βF–βG slice, and broad hydrophobic channels between the βC–βC′ rings of the FGFR D3 domain together form a large hydrophobic surface. In addition, the binding of RBA-β1 and βC of the FGFR D3 domain forms three hydrogen bonds to further strengthen the interface (Figure 1b). Although the RBA proximal residue is bound to a second smaller binding pocket at the bottom of D3, the disulfide bond between Cys-572 of the RBA N-terminal and Cys-621 of the KL2 α2 helix endows the interface with a certain degree of conformational rigidity, thus making the interface more stable [43,48].

![Figure 1

(a) View of the ternary complex FGF23–KLA–FGFR. The circular frame shows the binding of the RBA of Klotho with D3 domain of FGFR. The square frame shows the binding of FGF23CT with KLA. (b) Close-up view of the circular frame of panel (a). (c) Close-up view of the square frame of panel (a). Yellow surface represents hydrogen bonding and the gray translucent surface represents hydrophobicity. This image has been reproduced with permission from Chen et al. [43].](/document/doi/10.1515/biol-2022-0655/asset/graphic/j_biol-2022-0655_fig_001.jpg)

(a) View of the ternary complex FGF23–KLA–FGFR. The circular frame shows the binding of the RBA of Klotho with D3 domain of FGFR. The square frame shows the binding of FGF23CT with KLA. (b) Close-up view of the circular frame of panel (a). (c) Close-up view of the square frame of panel (a). Yellow surface represents hydrogen bonding and the gray translucent surface represents hydrophobicity. This image has been reproduced with permission from Chen et al. [43].

3.2 Structural association between KLA and FGF23CT

FGF23CT is noted to have two KLA-binding sites, one of which is a KL-binding peptide, namely FGF23180–205 (C26, also known as the first KL site), and the other is a potential KL interaction site, namely FGF23212–239 (C28, also known as the second KL site); C26 and C28 have only 40% homology, and both contain DPL motifs; thus, they may interact differently with KLA [49,50]. In this article, we mainly introduce the interaction between KLA and the first KL site of FGF23. In the interface between KLA and FGF23CT, the DPL motif of FGF23 residues (188Asp–Pro–Leu–Asn–Val–Leu193) is the most important and is bound to residues between KL1 and KL2 through an unusual “cage” structure to form hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic bonds. Notably, Tyr-433 in the KL1 α7 helix plays an important role in fastening the “cage” structure of FGF23CT, which is required for accurate alignment of KL1 and KL2 residues. Zn2+ is the auxiliary group of KLA and promotes accurate alignment of residues by minimizing the flexibility between KL1 and KL2 domains (Figure 1c). In the downstream FGF23CT, the side chains of basic amino acids (Lys-194, Arg-196, and Arg-198) combine with the residues in the center of KL2 to form multiple hydrogen bonds. At the interface between the β-trefoil nucleus and KLA, the α-C helix of FGF23 is bound to short β7–ɑ7 rings and β8–ɑ8 rings in the upper margin of KL2 cavity to form hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic bonds. The combination of the three points mentioned above improves the stability of FGF23–KLA [43,48].

3.3 Structural association between FGFR and FGF23

The N-terminal of FGF23 is mainly bound to D2 and D3 domains of FGFR, albeit weakly, and the interaction between D2 and D3 domains is also weak, which results in low intrinsic affinity of FGF23 and FGFR. Therefore, FGF23 is equivalent to a linker of D2 and D3 domains. KLA is a non-enzyme scaffold and combines with FGF23 and FGFR, which makes FGF23 and FGFR adjacent to each other, thus allowing an increased affinity between them [43]. Currently, the molecular mechanism of interaction between FGF23 and FGFRs remains unclear.

There are two forms of KLA: mKLA and sKLA. However, FGF23 mainly interacts with mKLA and not so prominently with sKLA because sKLA contains only KL1 and KL2 domains and does not contain the AA transmembrane structure or an intracellular short domain, thus weakening the interaction between FGF23 and sKLA. This may reduce the signal transduction efficiency of FGF23. Perhaps FGF23 and sKLA combine in a different way to play a unique physiological role; however, this remains to be elucidated.

The FGF23–KLA–FGFR complex plays an important role in maintaining a balanced state of phosphate metabolism in the body. First, it can reduce vitamin D biosynthesis and cellular reabsorption of phosphorus, accelerate urinary phosphorus excretion, and thereby reduce the incidence of vascular calcification [51]. Second, it can inhibit the expression of proteins related to calcium and phosphorus metabolism in the proximal tubules, play a role in inhibiting renal reabsorption of phosphorus, and regulate the overexpression of phosphorus [52]. Finally, besides acting on the kidneys to regulate phosphorus absorption, it can also prevent intestinal absorption of phosphorus by regulating the expression of the related proteins in intestinal cells and reducing the concentration of phosphorus in urine and blood in the body [53]. In summary, abnormal expression of FGF23–KLA–FGFR can severely affect the balance of calcium and phosphorus metabolism in the body (Figure 4).

4 Molecular structure of FGF21/FGF19–FGFR–KLB

4.1 FGF19CT and FGF21CT bind to KL1 domain of KLB through DPL motif

FGF21CT and FGF19CT bind to both the KL1 and KL2 domains of KLB. The binding sites of FGF19CT and FGF21CT in the KL1 and KL2 domains of KLB are called site 1 and site 2, respectively (Figure 2a). The KL1 domain of KLB could bind to the amino acid (186Pro–Val197) of FGF21CT via hydrophobic interaction. Two kinds of type I turns comprising 187Asp–Val–Gly–Ser190 and 192Asp–Pro–Seu–Ser195 and the ST-turn formed by 190Ser–Ser–Asp192 are combined to form the ligand region of FGF21CT, which could bind to the KL1 domain of KLB [47]. Meanwhile, the DPL motif (192Asp–Pro–Leu194) included in the type I turn may play an important role in the binding of the KL1 domain of KLB with the ligand (Figure 2c). Similarly, DPL motifs are noted to exist in the P191–V203 motif of FGF19CT, and they form a large hydrophobic surface with the KL1 domain of KLB [47,50,54] (Figure 2b). However, it is currently not clear whether the ligand region of FGF19CT, like FGF21CT, has the structural rigidity to promote stable binding.

![Figure 2

(a) There are two binding sites of KLB to FGF19/21 – sites 1 and 2. (b) Residue of FGF19 binds to the KLB site 1. (c) Residue of FGF21 binds to KLB site 1. (d) Residue of FGF19 binds to KLB site 2. (e) Residue of FGF21 binds to KLB site 2. (f) KLB binds to FGF19/21. The spatial structure of KL1 and KL2 changes. This image has been reproduced with permission from Kuzina et al. [54].](/document/doi/10.1515/biol-2022-0655/asset/graphic/j_biol-2022-0655_fig_002.jpg)

(a) There are two binding sites of KLB to FGF19/21 – sites 1 and 2. (b) Residue of FGF19 binds to the KLB site 1. (c) Residue of FGF21 binds to KLB site 1. (d) Residue of FGF19 binds to KLB site 2. (e) Residue of FGF21 binds to KLB site 2. (f) KLB binds to FGF19/21. The spatial structure of KL1 and KL2 changes. This image has been reproduced with permission from Kuzina et al. [54].

4.2 FGF19CT and FGF21CT bind to the KL2 domain of KLB through the S–P–S motif

Half of the FGF21CT sequence (S–Q–G–R–S–P–S–Y–A–S) contains hydroxyl side chains and could bind to KL2 of KLB; therefore, this region of FGF21 appears to mimic the glucoside substrate [55,56]. This sequence also contains the S–P–S sequence (204Ser–Pro–Ser206), which is key for the binding of FGF21CT and the KL2 domain of KLB (Figure 2e). The hydroxyl groups of Ser204 and Ser206 in FGF21CT interact with the carboxyl group of Glu693 in KLB to simulate the reaction between GH1 and glucoside substrate. In the Koshland disubstitution reaction of GH1, Glu693 is one of the two conserved catalytic glutamic acids and acts as a general acid–base catalyst. Pro205 of FGF21CT combines with Phe826, Phe931, and Phe942 of KLB through hydrophobic interaction to further strengthen the interface [47,54]. The S–P–S motif (S211–P212–S213) of FGF19 binds to the KL2 domain of KLB (Figure 2d) [54]; however, the specific combination method remains unidentified. They all bind to the substrate-binding region of the KL2 domain through the S–P–S motif (similar to sugar sequence).

4.3 Binding of FGF19CT and FGF21CT to KLB was affected by the change of spatial conformation and electrostatic potential distribution

The combination of FGF21CT/FGF19CT with KLB requires KL1 and KL2 domains to interact with each other, which changes the distance and angle between KL1 and KL2 domains. The main features are as follows: the connection of KL1 and KL2 domains is flexible, the binding of FGF21CT with KLB results in the inter-domain angle of KL1 and KL2 rotating 6°, and the binding of FGF21CT with KLB results in the inter-domain angle of KL1 and KL2 rotating 17° (Figure 2f), which may affect the binding of FGF19CT/FGF21CT with KLB. In terms of electrostatic potential distributions, the electrostatic potential distribution is different for KLB and KLA, but their crystal structures almost overlap (Figure 3c), which may be attributed to the different structures of the KL2 domains of KLA and KLB. The tyrosine (Y809 and Y915) of KLA is the key amino acid responsible for the negative electrostatic potential. In the KL2 domain of KLB, tyrosine (Y809 and Y915) is replaced by phenylalanine (F826 and F931), resulting in positive electrostatic potential. The KL2 domain of KLA, which has negative electrostatic potential, is bound to FGF23CT, which shows positive electrostatic potential centered on R196 and R198 (Figure 3a and b); conversely, owing to the S–P–S motif, FGF23CT shows negative electrostatic potential and combines with the KL2 domain of KLB with positive electrostatic potential, which may at least partly explain why the KL2 domain of KLA does not bind to FGF23CT through the S–P–S motif. This also indirectly proves that the difference in the electrostatic potentials of KL2 domains is instrumental in determining the specificity of ligand binding. Due to the differences in amino acids on both sides of the S–P–S motif, FGF19CT shows a slightly stronger negative electrostatic potential than FGF21CT (Figure 3d and e). Therefore, the combination of FGF21CT and KLB is closer than that of FGF19CT and KLB [54,57]. KLB is the main receptor of FGF21, a hormone produced during starvation. FGF21 can combine with FGFR and KLB to increase insulin sensitivity, enhance glucose metabolism, reduce blood sugar, and induce weight loss. At the same time, KLB can also bind FGF19 and FGFR to activate extrahepatic tissues, mainly acting on skeletal muscles, promoting muscle glycogen synthesis, inhibiting gluconeogenesis, and promoting glucose homeostasis, and it may thus become a new treatment target for diabetes and obesity (Figure 4).

![Figure 3

(a) Electrostatic potential distribution of sKLA and sKLB. Red is the negative potential and blue is the positive potential. Orange dotted box: the main difference of electrostatic potential distribution between them. (b) Comparison of the crystal structures of sKLA and sKLB, which almost overlap each other. (c) Comparison of crystal structures of sKLB and sKLA. (d) Relationship between sKLB and FGF19/21CT. (e) Electrostatic interaction between sKLA and FGF23CT. Reproduced with permission from Kuzina et al. [54].](/document/doi/10.1515/biol-2022-0655/asset/graphic/j_biol-2022-0655_fig_003.jpg)

(a) Electrostatic potential distribution of sKLA and sKLB. Red is the negative potential and blue is the positive potential. Orange dotted box: the main difference of electrostatic potential distribution between them. (b) Comparison of the crystal structures of sKLA and sKLB, which almost overlap each other. (c) Comparison of crystal structures of sKLB and sKLA. (d) Relationship between sKLB and FGF19/21CT. (e) Electrostatic interaction between sKLA and FGF23CT. Reproduced with permission from Kuzina et al. [54].

Schematic of the biological effects of FGF–Klotho axis and sKLA.

5 Connection and difference between FGF23 and FGF19/21

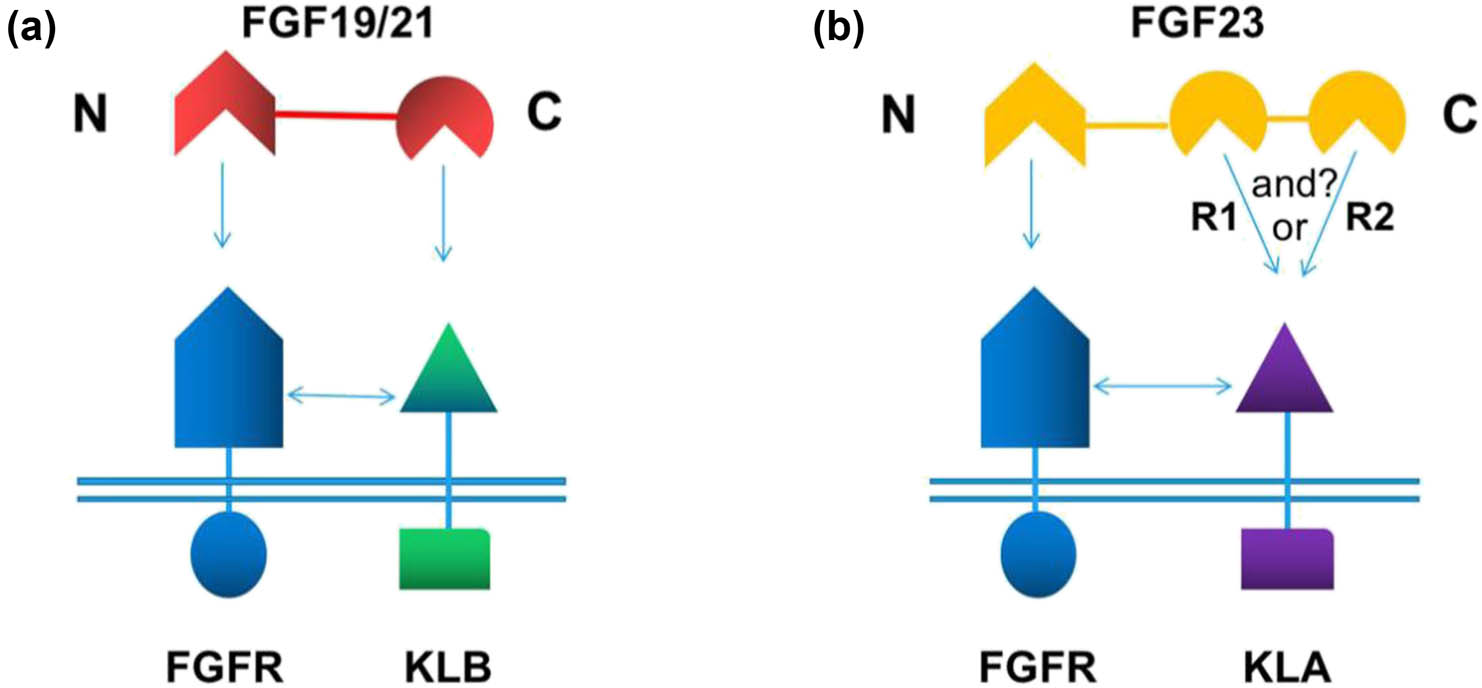

FGF23, FGF19, and FGF21 are bound to the KL1 domain of KLA and KLB through the DPL/F motif. The sugar mimetic pro-tease (S–P–S) motif of sucrose phosphate synthase in FGF19 and FGF21 is bound to the KL2 domain of KLA. FGF23CT does not contain the S–P–S sequence but is bound to the KL2 domain of KLB through some basic amino acids [43,47,58]. However, the biggest difference between FGF23 and FGF19/FGF21 is structural diversity. Previous studies have shown that FGF23CT has 89 amino acids and two tandem repeats (R1 and R2) with high affinity for KLA; therefore, the binding between FGF23 and KLA is called divalent binding. The C-terminal tail of FGF19 and FGF21 could only bind to one KLB (Figure 5a and b). Divalent FGF23 could stimulate dimerization between pre-existing KLA–FGFR and a free KLA molecule or another pair of pre-existing KLA–FGFR. Although the binding affinity of R1 and R2 to free KLA is very similar, KLA–FGFR may preferentially interact with R1, whereas the two cysteines connected by disulfide bonds on both sides of R2 may tend to bind with the free KLA molecule [50]. When one active site of FGF23 is lost, the other action site would compensate, and FGF23 would be inactivated only when two action sites are lost at the same time [49]. The formation of a dimer requires two FGF23, but due to the bivalent interactions of the two sites of FGF23, one FGF23 active site may satisfy the formation of a dimer (Figure 5b). In our opinion, the formation of a dimer would require the participation of both FGF23 binding sites because the spatial structure of R1 and R2 of FGF23CT is almost identical, and R1 of FGF23 has high affinity to KLA–FGFR. Nevertheless, these problems still warrant further study.

(a) Schematic diagram of the combination of FGF19/21 and KLB. (b) Schematic diagram of the combination of FGF23 and KLA. The “or” represents the combination of R1 and R2 with KLA, and “and” represents the combination of R1 and R2 with KLA; however, it is not yet clear whether this mechanism exists.

6 Formation of 2:2:2:2 FGF–FGFR–Klotho–heparin sodium (HS) dimer

HS is essential for FGFR dimerization, activation, and cell proliferation [32,59,60]. Considering the classic FGF as an example, in the 2:2:2 FGF–FGFR–HS model, HS is closely bound to 1:1 FGF–FGFR and interacts with the D2 domain of FGFR in the adjacent 1:1 FGF–FGFR. HS is bound to the dimer by 30 hydrogen bonds, 25 of which are between the 1:1 FGF–FGFR complex and HS, and the remaining 5 are formed between the adjacent 1:1 FGF–FGFR complex and HS.

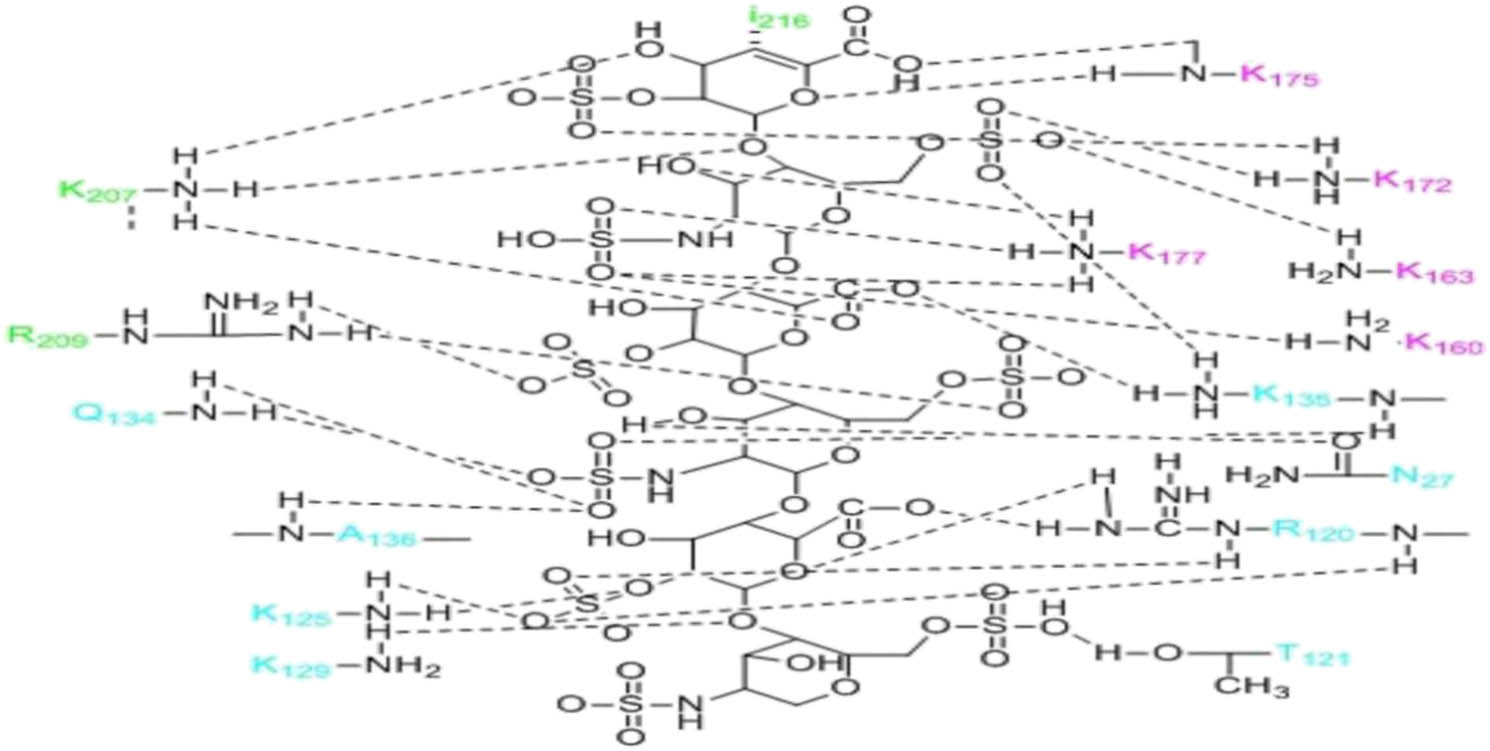

Notably, FGF is bound to HS by 16 hydrogen bonds, 10 of which are mediated by sulfate and 6 by heparin carboxylate, linker, and epoxide. FGF surface residues (e.g., Asn-27, Arg-120, Thr-121, Lys-125, Lys129, Gln-134, Lys-135, and Ala-136) constitute heparin-binding sites [61,62]. The binding of the FGFR D2 domain with HS involves nine hydrogen bonds, which are mediated by heparin N-sulfate, 2-O-sulfate, and 6-O-sulfate. At the interface between HS and the adjacent 1:1 FGF–FGFR, the A–D ring of HS is only bound to the amino acids in the D2 domain of FGFR (e.g., Lys-207, Arg-209, and Il-216) to form five hydrogen bonds. The hydrogen bond between Lys-207 and HS is mediated by heparin carboxylate, linker, and epoxide. Arg-209 forms hydrogen bonds with the 2-O-sulfate group of ring C and the 6-O-sulfate group of ring D. Hydrophobic contact between Il-216 and ring A further enhances the interaction (Figure 6) [62,63]. However, in the above process, only FGF23 from the members of the FGF19 subfamily has been confirmed to require the involvement of HS [64]. Whether HS participates in the formation of FGF19/21 signal complexes remains to be studied. Although the possibility of FGF19/21 binding to HS is very low, there may be other molecules besides HS involved in the formation of signal complexes.

FGF, FGFRD2 domains, adjacent FGFR2 domains, and other amino acids interact with HS. Blue is the residue of FGF, green is the residue of the adjacent FGFRD2 domain, and pink is the residue of the FGFD2 domain. There are six rings from top to bottom, which are A, B, C, D, E, and F rings.

The HS-binding region of the FGFR D2 domain is highly conserved, whereas the HS binding of FGF shows considerable diversity [62,65,66]. There is a large distance between the 1–2 ring and 10–12 ring of the FGF19 subfamily that lacks the GXXXXGXX (T/S) motif, which results in greatly reduced binding ability of FGF19 subfamily members with HS. The nuclear homologous region of classical FGF is folded into 12 antiparallel chains (β1–β12) to form a spherical area called Trifolium. All members of the FGF19 subfamily lack β11 chains containing the T/S motif. Although the residues Lys149 to Lys155 of FGF19 form an α11 spiral to replace β11 chains and FGF23 uses g11 helix to replace β11 chains, the affinity of FGF19 subfamily to HS is still very low [67]. Therefore, HS is not enough to promote the formation of 1:1 FGF–FGFR, at this time, some assistance from Klotho is needed. The affinity between HS and FGFR remains unchanged, which plays a role in the dimerization of two adjacent ternary complexes (FGF19s–Klotho–FGFR) (Figure 7).

(a) Classical FGF, HS, and FGFR form a ternary complex and then form a dimer. (b) Endocrine FGF-19 subfamily and HS, Klotho, and FGFR form a ternary complex and then form a dimer. Solid lines represent a close relationship between substances, and dotted lines represent a weak relationship between substances.

7 Functions of sKLA are independent of FGF–FGFR forms

As mentioned above, ternary complexes are formed by mKLA, FGF23, and FGFR, and the two ternary complexes form a dimer in the presence of heparin. The tyrosine kinase in FGFR is phosphorylated, and the FGFR substrate 2 and the downstream targets ERK1 and ERK2 are phosphorylated as well, thus resulting in corresponding physiological effects. KLB only has a membrane-bound type, and therefore, the sKL mentioned here is sKLA. sKLA, a circulating anti-aging hormone, functions independently of FGF23 and is considered to lack co-receptor activity. Although sKLA could form complexes with FGF23 and FGFR, the signal transduction level of sKLA is far lower than that of mKLA. Furthermore, the physiological concentration of sKLA is too low to meet the formation of FGF23 co-receptor. Therefore, we speculate that the physiological function of sKLA may not be related to FGF23 [68,69]. Studies have found that sKLA and heparin mediate the binding of FGF23 with different types of FGFRs. Heparin specifically mediates FGF23 binding to FGFR4, whereas sKLA mediates FGF23 binding to other types of FGFRs. The specific type of FGFR needs to be studied. sKLA and HS have the opposite effect in regulating myocardial hypertrophy. In other words, decreased sKLA and increased heparin can induce myocardial hypertrophy. Therefore, sKLA is also involved in the formation of the FGF23–FGFR complex under certain conditions [70]. KL1 and KL2 domains of sKLA are homologous to mammalian lactose hydrolase 1 (GH1) but lack two conserved glutamate residues with acid–base catalysis [46,71]; therefore, sKLA may not have real glycosidase activity but worked as a lectin instead.

sKL regulates the activities of various ion channels and transporters, including transient receptor potential cation channel V5 (TRPV5) and the renal outer medullary potassium (ROMK1) channel. The membrane receptor of sKLA is a ganglioside containing α-2,3-sialic lactulose. sKLA exerts pseudoglucosidase activity and hydrolyzes the glycosylated chain of α-2,3-sialiclactulose on the cell surface [72,73], which exposes the disaccharide N-acetolactate amine (LacNAc). The binding of calectin-1 with LacNAc causes the accumulation of functional changes of plasma membrane channels, which results in increased calcium absorption and potassium secretion [74]. However, recent studies have suggested that sKLA is a lectin and not an enzyme. sKLA, which has the galectin1 ligand, perhaps binds to the α-2,3-sialic lactulose of channel protein indirectly through galectin1, which increases the abundance of TRPV5 and ROMK1 [26,75]. sKLA promotes the function of most transporters and channel proteins; however, there are exceptions, such as the presence of transient receptor potential cation channel 6 (TRPC6), long-term high pressure, abnormal calcium signal, activated calcineurin and the nuclear factor of activated T cell, upregulated expression of the TRPC6 gene, and increased TRPC channel protein on the cell surface, which lead to increased calcium influx and long-term enhancement of myocardial contractility, eventually causing cardiac hypertrophy [26,75]. sKLA is bound to TRPC6 through the action of pseudoglucosidase and inhibits the function of TRPC6, and simultaneously, it inhibits the binding of IGF-1 to its receptor, inhibits P13K, and blocks the exocytosis of TRPC6. Therefore, sKLA could inhibit the quantity and function of the TRPC6 channel protein and may play a therapeutic role in hypertrophic heart disease induced by various stressors [76–78] (Figure 4).

8 Conclusion

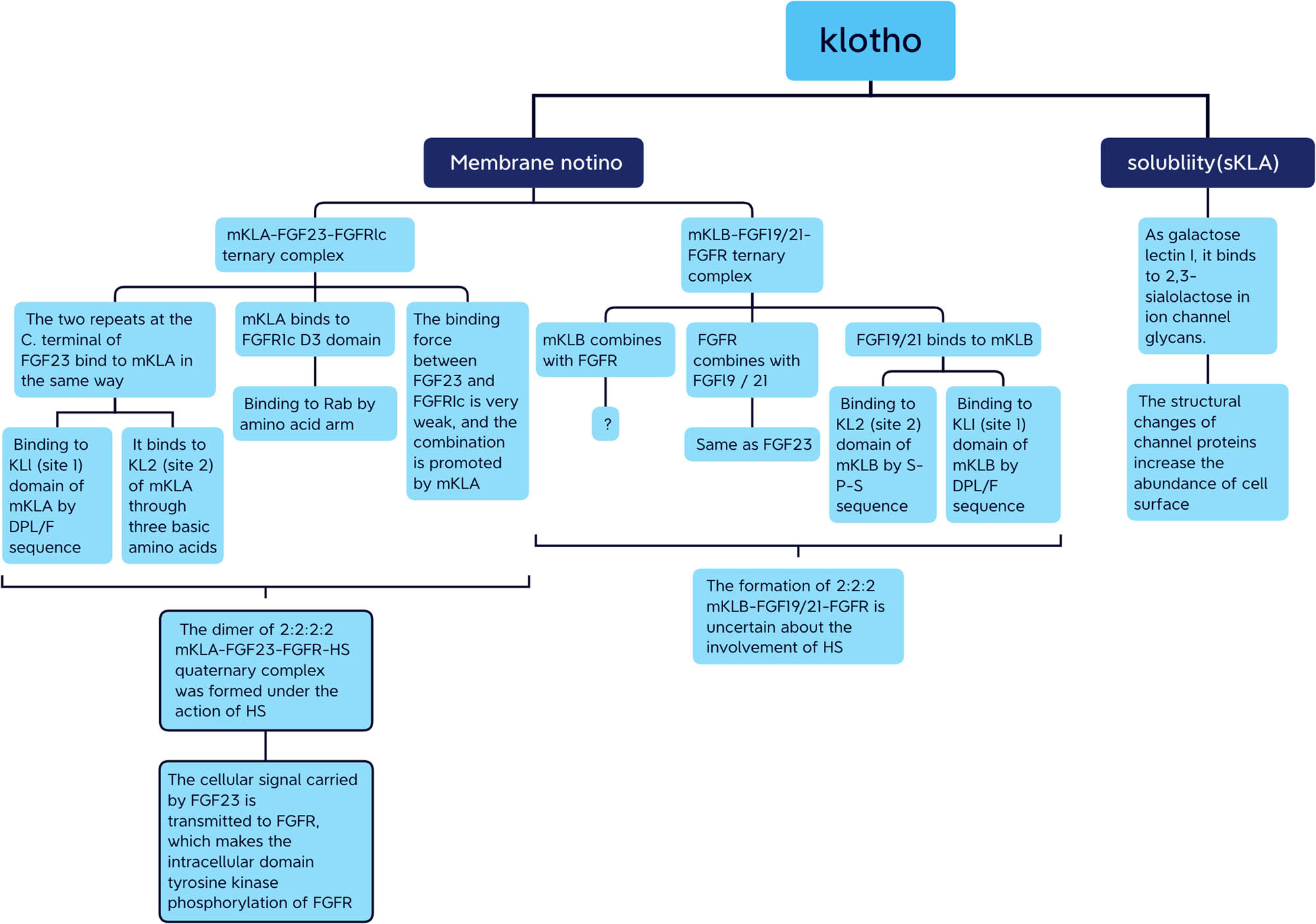

mKL is a co-receptor of endocrine FGFs and has a role similar to that of HS in the signal transduction of classical FGFs. The binding affinity of endocrine FGFs and Klotho is 1,000–10,000 times higher than that of endocrine FGFs and FGFRs. Therefore, Klotho is the main surface receptor of endocrine FGFs, and FGFRs are the catalytic subunit of the activated signal complexes. However, the acid–base catalytic principle of FGFR and the role of acid–base catalysis in the process of signal transduction remain unclear. sKL breaks away from this mode of action and uses its own KL1 and KL2 domain pseudoglycosidase activities to bind to the receptor on the cell surface via enzyme–substrate binding, thus activating the cell physiological response. sKL is widely distributed and transported to various organs and tissues through blood circulation, leading to important physiological effects with anti-aging, anti-inflammatory, and anti-oxidative properties (Figure 8). Although many hypotheses have been put forward to explain the interaction of the FGF–Klotho–FGFR complex, the crystal structure of the FGF–Klotho–FGFR complex still needs to be explored to better understand their interaction, which will help elucidate the role of Klotho in the FGF–Klotho axis.

Flow chart summarizes two types of Klotho which play corresponding physiological roles in their respective modes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Medjaden Inc. for scientific editing of this manuscript. The authors also thank the support from Weifang Medical University, School of Anesthesiology, Shandong Provincial Medicine and Health Key Laboratory of Clinical Anesthesia.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Writing – original draft: Fuqiang Sun; writing – review and editing: Panpan Liang, Wenbo Liu; formal analysis: Bo Wang; financial support: Wenbo Liu.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

[1] Zhou X, Wang X. Klotho: a novel biomarker for cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141(6):961–9.10.1007/s00432-014-1788-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390(6655):45–51.10.1038/36285Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Kuro OM. The Klotho proteins in health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15(1):27–44.10.1038/s41581-018-0078-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Xiao Z, King G, Mancarella S, Munkhsaikhan U, Cao L, Cai C, et al. FGF23 expression is stimulated in transgenic α-Klotho longevity mouse model. JCI Insight. 2019;4(23):e132820.10.1172/jci.insight.132820Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Landry T, Shookster D, Huang H. Circulating α-klotho regulates metabolism via distinct central and peripheral mechanisms. Metabolism. 2021;121:154819.10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154819Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Andrade L, Rodrigues CE, Gomes SA, Noronha IL. Acute kidney injury as a condition of renal senescence. Cell Transplant. 2018;27(5):739–53.10.1177/0963689717743512Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Dalton G, Xie J, An S, Huang C. New insights into the mechanism of action of soluble klotho. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:323.10.3389/fendo.2017.00323Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Kuro-o M. Klotho and βKlotho. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;728:25–40.10.1007/978-1-4614-0887-1_2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Ito S, Kinoshita S, Shiraishi N, Nakagawa S, Sekine S, Fujimori T, et al. Molecular cloning and expression analyses of mouse betaklotho, which encodes a novel Klotho family protein. Mech Dev. 2000;98:115–9.10.1016/S0925-4773(00)00439-1Search in Google Scholar

[10] Nabeshima Y. Ectopic calcification in Klotho mice. Clin Calcium. 2002;12(8):1114–7.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Xiao NM, Zhang YM, Zheng Q, Gu J. Klotho is a serum factor related to human aging. Chin Med J (Engl). 2004;117(5):742–7.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Shih PH, Yen GC. Differential expressions of antioxidant status in aging rats: the role of transcriptional factor Nrf2 and MAPK signaling pathway. Biogerontology. 2007;8(2):71–80.10.1007/s10522-006-9033-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Duce JA, Podvin S, Hollander W, Kipling D, Rosene DL, Abraham CR. Gene profile analysis implicates Klotho as an important contributor to aging changes in brain white matter of the rhesus monkey. Glia. 2008;56(1):106–17.10.1002/glia.20593Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Yamazaki Y, Imura A, Urakawa I, Shimada T, Murakami J, Aono Y, et al. Establishment of sandwich ELISA for soluble alpha-Klotho measurement: age-dependent change of soluble alpha-Klotho levels in healthy subjects. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398(3):513–8.10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.110Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Semba RD, Moghekar AR, Hu J, Sun K, Turner R, Ferrucci L, et al. Klotho in the cerebrospinal fluid of adults with and without Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2014;558:37–40.10.1016/j.neulet.2013.10.058Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Akasaka-Manya K, Manya H, Endo T. Function and change with aging of α-Klotho in the kidney. Vitam Horm. 2016;101:239–56.10.1016/bs.vh.2016.02.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Behringer V, Stevens JMG, Deschner T, Sonnweber R, Hohmann G. Aging and sex affect soluble alpha klotho levels in bonobos and chimpanzees. Front Zool. 2018;15:35.10.1186/s12983-018-0282-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Zhou HJ, Zeng CY, Yang TT, Long FY, Kuang X, Du JR. Lentivirus-mediated klotho up-regulation improves aging-related memory deficits and oxidative stress in senescence-accelerated mouse prone-8 mice. Life Sci. 2018;200:56–62.10.1016/j.lfs.2018.03.027Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Kanbay M, Demiray A, Afsar B, Covic A, Tapoi L, Ureche C, et al. Role of Klotho in the development of essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2021;77(3):740–50.10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.16635Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Zeng CY, Yang TT, Zhou HJ, Zhao Y, Kuang X, Duan W, et al. Lentiviral vector-mediated overexpression of Klotho in the brain improves Alzheimer's disease-like pathology and cognitive deficits in mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;78:18–28.10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.02.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Kuang X, Zhou HJ, Thorne AH, Chen XN, Li LJ, Du JR. Neuroprotective effect of ligustilide through induction of α-secretase processing of both APP and Klotho in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:353.10.3389/fnagi.2017.00353Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Hu MC, Kuro-o M, Moe OW. Klotho and chronic kidney disease. Contrib Nephrol. 2013;180:47–63.10.1159/000346778Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Kitagawa M, Sugiyama H, Morinaga H, Inoue T, Takiue K, Ogawa A, et al. A decreased level of serum soluble Klotho is an independent biomarker associated with arterial stiffness in patients with chronic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56695.10.1371/journal.pone.0056695Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Gao W, Yuan C, Zhang J, Li L, Yu L, Wiegman CH, et al. Klotho expression is reduced in COPD airway epithelial cells: effects on inflammation and oxidant injury. Clin Sci (Lond). 2015;129(12):1011–23.10.1042/CS20150273Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Typiak M, Piwkowska A. Antiinflammatory actions of Klotho: implications for therapy of diabetic nephropathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(2):956.10.3390/ijms22020956Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Ohtsubo K, Takamatsu S, Minowa MT, Yoshida A, Takeuchi M, Marth JD. Dietary and genetic control of glucose transporter 2 glycosylation promotes insulin secretion in suppressing diabetes. Cell. 2005;123(7):1307–21.10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.041Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Takenaka T, Kobori H, Miyazaki T, Suzuki H, Nishiyama A, Ishii N, et al. Klotho protein supplementation reduces blood pressure and renal hypertrophy in db/db mice, a model of type 2 diabetes. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2019;225(2):e13190.10.1111/apha.13190Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Lim K, Halim A, Lu TS, Ashworth A, Chong I. Klotho: a major shareholder in vascular aging enterprises. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(18):4637.10.3390/ijms20184637Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Memmos E, Sarafidis P, Pateinakis P, Tsiantoulas A, Faitatzidou D, Giamalis P, et al. Soluble Klotho is associated with mortality and cardiovascular events in hemodialysis. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):217.10.1186/s12882-019-1391-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Itoh N, Ohta H, Konishi M. Endocrine FGFs: evolution, physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacotherapy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2015;6:154.10.3389/fendo.2015.00154Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Degirolamo C, Sabbà C, Moschetta A. Therapeutic potential of the endocrine fibroblast growth factors FGF19, FGF21 and FGF23. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(1):51–69.10.1038/nrd.2015.9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Eswarakumar VP, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16(2):139–49.10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Lin B, Wang M, Blackmore C, Desnoyers L. Liver-specific activities of FGF19 require Klotho beta. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(37):27277–84.10.1074/jbc.M704244200Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Kir S, Be Dd OwSA, Samuel VT, Miller P, Previs SF, Suino-Powell K, et al. FGF19 as a postprandial, insulin-independent activator of hepatic protein and glycogen synthesis. Science. 2011;331(6024):1621–4.10.1126/science.1198363Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Kir S, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. Roles of FGF19 in liver metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:139–44.10.1101/sqb.2011.76.010710Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Owen BM, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. Tissue-specific actions of the metabolic hormones FGF15/19 and FGF21. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(1):22–9.10.1016/j.tem.2014.10.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Fisher FM, Maratos-Flier E. Understanding the physiology of FGF21. Annu Rev Physiol. 2016;78(1):223.10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105339Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Ogawa Y, Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Nandi A, Rosenblatt KP, Goetz R, et al. BetaKlotho is required for metabolic activity of fibroblast growth factor 21. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(18):7432–7.10.1073/pnas.0701600104Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Kuro-O M, Moe OW. FGF23-αKlotho as a paradigm for a kidney-bone network. Bone. 2017;100:4–18.10.1016/j.bone.2016.11.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Razzaque MS. The FGF23-Klotho axis: endocrine regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5(11):611–9.10.1038/nrendo.2009.196Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Kolek OI, Hines ER, Jones M, Lesueur LK, Lipko MA, Kiela PR, et al. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 upregulates FGF23 gene expression in bone: the final link in a renal–gastrointestinal–skeletal axis that controls phosphate transport. Am J Physio Gastro Liver Physiol. 2005;289(6):G1036.10.1152/ajpgi.00243.2005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Smith E, Holt S, Hewitson T. αKlotho-FGF23 interactions and their role in kidney disease: a molecular insight. Cellular Mol Life Sci: CMLS. 2019;76(23):4705–24.10.1007/s00018-019-03241-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Chen G, Yang L, Goetz R, Fu L, Mohammadi M. α-Klotho is a non-enzymatic molecular scaffold for FGF23 hormone signalling. Nature. 2018;553(7689):461–6.10.1038/nature25451Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] DE Koshland jr. Stereochemistry and the mechanism of enzymatic reactions. Biol Rev. 2010;28(4):416–36.10.1111/j.1469-185X.1953.tb01386.xSearch in Google Scholar

[45] Davies G, Henrissat B. Structures and mechanisms of glycosyl hydrolases. Structure. 1995;3(9):853–9.10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00220-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Mian IS. Sequence, structural, functional, and phylogenetic analyses of three glycosidase families. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 1998;24(2):83–100.10.1006/bcmd.1998.9998Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Lee S, Choi J, Mohanty J, Sousa LP, Tome F, Pardon E, et al. Structures of beta-klotho reveal a 'zip code'-like mechanism for endocrine FGF signalling. Nature. 2018;553:501–5.10.1038/nature25010Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Shimada T, Iijima K, Hasegawa H, Okawa K, et al. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature. 2006;444(7120):770–4.10.1038/nature05315Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Agrawal A, Ni P, Agoro R, White KE, DiMarchi RD. Identification of a second Klotho interaction site in the C terminus of FGF23. Cell Rep. 2021;34(4):108665.10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108665Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Suzuki Y, Kuzina E, An S, Tome F, Schlessinger J. FGF23 contains two distinct high-affinity binding sites enabling bivalent interactions with α-Klotho. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(50):31800–7.10.1073/pnas.2018554117Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Kuro OM. The FGF23 and Klotho system beyond mineral metabolism. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2017;21(Suppl 1):64–9.10.1007/s10157-016-1357-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Andrukhova O, Bayer J, Schüler C, Zeitz U, Murali SK, Ada S, et al. Klotho lacks an FGF23-independent role in mineral homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(10):2049–61.10.1002/jbmr.3195Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Muñoz-Castañeda JR, Rodelo-Haad C, Pendon-Ruiz de Mier MV, Martin-Malo A, Santamaria R, Rodriguez M. Klotho/FGF23 and Wnt signaling as important players in the comorbidities associated with chronic kidney disease. Toxins (Basel). 2020;12(3):185.10.3390/toxins12030185Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Kuzina ES, Ung MU, Mohanty J, Tome F, Lee S. Structures of ligand-occupied β-Klotho complexes reveal a molecular mechanism underlying endocrine FGF specificity and activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116(16) 201822055.10.1073/pnas.1822055116Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Chuenchor W, Pengthaisong S, Robinson RC, Yuvaniyama J, Svasti J, Cairns J. The structural basis of oligosaccharide binding by rice BGlu1 beta-glucosidase. J Struct Biol. 2011;173(1):169–79.10.1016/j.jsb.2010.09.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Isorna P, Polaina J, Latorre-Garcia L, Canada FJ, Gonzalez B, Sanz-Aparicio J. Crystal structures of Paenibacillus polymyxa beta-glucosidase B complexes reveal the molecular basis of substrate specificity and give new insights into the catalytic machinery of family I glycosidases. J Mol Biol. 2007;371(5):1204–18.10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.082Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Lee RA, Razaz M, Hayward S. The DynDom database of protein domain motions. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(10):1290–1.10.1093/bioinformatics/btg137Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Kharitonenkov A, Dunbar J, Bina H, Bright S, Moyers J, Zhang C, et al. FGF-21/FGF-21 receptor interaction and activation is determined by betaKlotho. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215(1):1–7.10.1002/jcp.21357Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Spivak-Kroizman T, Lemmon MA, Dikic I, Ladbury JE, Pinchasi D, Huang J, et al. Heparin-induced oligomerization of FGF molecules is responsible for FGF receptor dimerization, activation, and cell proliferation. Cell. 1994;79(6):1015–24.10.1016/0092-8674(94)90032-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Belov AA, Mohammadi M. Molecular mechanisms of fibroblast growth factor signaling in physiology and pathology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(6):239–49.10.1101/cshperspect.a015958Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[61] Faham S, Hileman RE. Heparin structure and interactions with basic fibroblast growth factor. Science. 1996;271(5252):1116.10.1126/science.271.5252.1116Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Schlessinger J, Plotnikov AN, Ibrahimi OA, Eliseenkova AV, Yeh BK, Yayon A, et al. Crystal structure of a ternary FGF–FGFR–heparin complex reveals a dual role for heparin in FGFR binding and dimerization. Mol Cell. 2000;6(3):743–50.10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00073-3Search in Google Scholar

[63] Guimond S. Activating and inhibitory heparin sequences for FGF-2 (basic FGF). Distinct requirements for FGF-1, FGF-2, and FGF-4. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(32):23906.10.1016/S0021-9258(20)80471-2Search in Google Scholar

[64] Martinez-Calle M, David V. Heparin, klotho, and FGF23: the 3-beat waltz of the discordant heart. Kidney Int. 2022;102(2):228–30.10.1016/j.kint.2022.05.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Faham A, Linhardt RJ, Rees DC. Diversity does make a difference: fibroblast growth factor–heparin interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8(5):578–86.10.1016/S0959-440X(98)80147-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Davis JC, Venkataraman G, Shriver Z, Raj PA, Sasisekharan R. Oligomeric self-association of basic fibroblast growth factor in the absence of heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. Biochem J. 1999;341(3):613–20.10.1042/bj3410613Search in Google Scholar

[67] Goetz R, Beenken A, Ibrahimi OA, Kalinina J, Olsen SK, Eliseenkova AV, et al. Molecular insights into the klotho-dependent, endocrine mode of action of fibroblast growth factor 19 subfamily members. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(9):3417–28.10.1128/MCB.02249-06Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[68] Bloch L, Sineshchekova O, Reichenbach D, Reiss K, Saftig P, Kuro-O M, et al. Klotho is a substrate for alpha-, beta- and gamma-secretase. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(19):3221–4.10.1016/j.febslet.2009.09.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[69] Chen CD, Podvin S, Gillespie E, Leeman SE, Abraham CR. Insulin stimulates the cleavage and release of the extracellular domain of Klotho by ADAM10 and ADAM17. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(50):19796–801.10.1073/pnas.0709805104Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[70] Yanucil C, Kentrup D, Campos I, Czaya B, Heitman K, Westbrook D, et al. Soluble α-klotho and heparin modulate the pathologic cardiac actions of fibroblast growth factor 23 in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2022;102(2):261–79.10.1016/j.kint.2022.03.028Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[71] Ito S, Fujimori T, Hayashizaki Y, Nabeshima YI. Identification of a novel mouse membrane-bound family 1 glycosidase-like protein, which carries an atypical active site structure. BBA – Gene Struct Exp. 2002;1576(3):341–5.10.1016/S0167-4781(02)00281-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[72] Cha SK, Ortega B, Kurosu H, Rosenblatt KP, Kuro-O M, Huang CL. Removal of sialic acid involving Klotho causes cell-surface retention of TRPV5 channel via binding to galectin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(28):9805–10.10.1073/pnas.0803223105Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[73] Cha SK, Hu MC, Kurosu H, Kuroo M, Moe O, Huang CL. Regulation of ROMK1 channel and renal K+ excretion by Klotho. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76(1):38–46.10.1124/mol.109.055780Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[74] Sopjani M, Dërmaku-Sopjani M. Klotho-dependent cellular transport regulation. Vitam Horm. 2016;101:59–84.10.1016/bs.vh.2016.02.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[75] Partridge EA, Le Roy C, Di Guglielmo GM, Pawling J, Cheung P, Granovsky M, et al. Regulation of cytokine receptors by Golgi N-glycan processing and endocytosis. Science. 2004;306(5693):120–4.10.1126/science.1102109Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[76] Wright JD, An S, Xie J, Lim C, Huang C. Soluble klotho regulates TRPC6 calcium signaling via lipid rafts, independent of the FGFR‐FGF23 pathway. FASEB J. 2019;33:9182.10.1096/fj.201900321RSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[77] Chen K, Zhang B, Sun Z. MicroRNA 379 regulates klotho deficiency-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis via repression of smurf1. Hypertension (Dallas, TX: 1979). 2021;78(2):342–52.10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.16888Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[78] Navarro-García J, Rueda A, Romero-García T, Aceves-Ripoll J, Rodríguez-Sánchez E, González-Lafuente L, et al. Enhanced Klotho availability protects against cardiac dysfunction induced by uraemic cardiomyopathy by regulating Ca handling. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177(20):4701–19.10.1111/bph.15235Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Systemic investigation of inetetamab in combination with small molecules to treat HER2-overexpressing breast and gastric cancers

- Immunosuppressive treatment for idiopathic membranous nephropathy: An updated network meta-analysis

- Identifying two pathogenic variants in a patient with pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy

- Effects of phytoestrogens combined with cold stress on sperm parameters and testicular proteomics in rats

- A case of pulmonary embolism with bad warfarin anticoagulant effects caused by E. coli infection

- Neutrophilia with subclinical Cushing’s disease: A case report and literature review

- Isoimperatorin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced periodontitis by downregulating ERK1/2 and NF-κB pathways

- Immunoregulation of synovial macrophages for the treatment of osteoarthritis

- Novel CPLANE1 c.8948dupT (p.P2984Tfs*7) variant in a child patient with Joubert syndrome

- Antiphospholipid antibodies and the risk of thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms

- Immunological responses of septic rats to combination therapy with thymosin α1 and vitamin C

- High glucose and high lipid induced mitochondrial dysfunction in JEG-3 cells through oxidative stress

- Pharmacological inhibition of the ubiquitin-specific protease 8 effectively suppresses glioblastoma cell growth

- Levocarnitine regulates the growth of angiotensin II-induced myocardial fibrosis cells via TIMP-1

- Age-related changes in peripheral T-cell subpopulations in elderly individuals: An observational study

- Single-cell transcription analysis reveals the tumor origin and heterogeneity of human bilateral renal clear cell carcinoma

- Identification of iron metabolism-related genes as diagnostic signatures in sepsis by blood transcriptomic analysis

- Long noncoding RNA ACART knockdown decreases 3T3-L1 preadipocyte proliferation and differentiation

- Surgery, adjuvant immunotherapy plus chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary malignant melanoma of the parotid gland (PGMM): A case report

- Dosimetry comparison with helical tomotherapy, volumetric modulated arc therapy, and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for grade II gliomas: A single‑institution case series

- Soy isoflavone reduces LPS-induced acute lung injury via increasing aquaporin 1 and aquaporin 5 in rats

- Refractory hypokalemia with sexual dysplasia and infertility caused by 17α-hydroxylase deficiency and triple X syndrome: A case report

- Meta-analysis of cancer risk among end stage renal disease undergoing maintenance dialysis

- 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase inhibition arrests growth and induces apoptosis in gastric cancer via AMPK activation and oxidative stress

- Experimental study on the optimization of ANM33 release in foam cells

- Primary retroperitoneal angiosarcoma: A case report

- Metabolomic analysis-identified 2-hydroxybutyric acid might be a key metabolite of severe preeclampsia

- Malignant pleural effusion diagnosis and therapy

- Effect of spaceflight on the phenotype and proteome of Escherichia coli

- Comparison of immunotherapy combined with stereotactic radiotherapy and targeted therapy for patients with brain metastases: A systemic review and meta-analysis

- Activation of hypermethylated P2RY1 mitigates gastric cancer by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation

- Association between the VEGFR-2 -604T/C polymorphism (rs2071559) and type 2 diabetic retinopathy

- The role of IL-31 and IL-34 in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic periodontitis

- Triple-negative mouse breast cancer initiating cells show high expression of beta1 integrin and increased malignant features

- mNGS facilitates the accurate diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of suspicious critical CNS infection in real practice: A retrospective study

- The apatinib and pemetrexed combination has antitumor and antiangiogenic effects against NSCLC

- Radiotherapy for primary thyroid adenoid cystic carcinoma

- Design and functional preliminary investigation of recombinant antigen EgG1Y162–EgG1Y162 against Echinococcus granulosus

- Effects of losartan in patients with NAFLD: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial

- Bibliometric analysis of METTL3: Current perspectives, highlights, and trending topics

- Performance comparison of three scaling algorithms in NMR-based metabolomics analysis

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and its related molecules participate in PROK1 silence-induced anti-tumor effects on pancreatic cancer

- The altered expression of cytoskeletal and synaptic remodeling proteins during epilepsy

- Effects of pegylated recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on lymphocytes and white blood cells of patients with malignant tumor

- Prostatitis as initial manifestation of Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia diagnosed by metagenome next-generation sequencing: A case report

- NUDT21 relieves sevoflurane-induced neurological damage in rats by down-regulating LIMK2

- Association of interleukin-10 rs1800896, rs1800872, and interleukin-6 rs1800795 polymorphisms with squamous cell carcinoma risk: A meta-analysis

- Exosomal HBV-DNA for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of chronic hepatitis B

- Shear stress leads to the dysfunction of endothelial cells through the Cav-1-mediated KLF2/eNOS/ERK signaling pathway under physiological conditions

- Interaction between the PI3K/AKT pathway and mitochondrial autophagy in macrophages and the leukocyte count in rats with LPS-induced pulmonary infection

- Meta-analysis of the rs231775 locus polymorphism in the CTLA-4 gene and the susceptibility to Graves’ disease in children

- Cloning, subcellular localization and expression of phosphate transporter gene HvPT6 of hulless barley

- Coptisine mitigates diabetic nephropathy via repressing the NRLP3 inflammasome

- Significant elevated CXCL14 and decreased IL-39 levels in patients with tuberculosis

- Whole-exome sequencing applications in prenatal diagnosis of fetal bowel dilatation

- Gemella morbillorum infective endocarditis: A case report and literature review

- An unusual ectopic thymoma clonal evolution analysis: A case report

- Severe cumulative skin toxicity during toripalimab combined with vemurafenib following toripalimab alone

- Detection of V. vulnificus septic shock with ARDS using mNGS

- Novel rare genetic variants of familial and sporadic pulmonary atresia identified by whole-exome sequencing

- The influence and mechanistic action of sperm DNA fragmentation index on the outcomes of assisted reproduction technology

- Novel compound heterozygous mutations in TELO2 in an infant with You-Hoover-Fong syndrome: A case report and literature review

- ctDNA as a prognostic biomarker in resectable CLM: Systematic review and meta-analysis

- Diagnosis of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis by metagenomic next-generation sequencing: A case report

- Phylogenetic analysis of promoter regions of human Dolichol kinase (DOLK) and orthologous genes using bioinformatics tools

- Collagen changes in rabbit conjunctiva after conjunctival crosslinking

- Effects of NM23 transfection of human gastric carcinoma cells in mice

- Oral nifedipine and phytosterol, intravenous nicardipine, and oral nifedipine only: Three-arm, retrospective, cohort study for management of severe preeclampsia

- Case report of hepatic retiform hemangioendothelioma: A rare tumor treated with ultrasound-guided microwave ablation

- Curcumin induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by decreasing the expression of STAT3/VEGF/HIF-1α signaling

- Rare presentation of double-clonal Waldenström macroglobulinemia with pulmonary embolism: A case report

- Giant duplication of the transverse colon in an adult: A case report and literature review

- Ectopic thyroid tissue in the breast: A case report

- SDR16C5 promotes proliferation and migration and inhibits apoptosis in pancreatic cancer

- Vaginal metastasis from breast cancer: A case report

- Screening of the best time window for MSC transplantation to treat acute myocardial infarction with SDF-1α antibody-loaded targeted ultrasonic microbubbles: An in vivo study in miniswine

- Inhibition of TAZ impairs the migration ability of melanoma cells

- Molecular complexity analysis of the diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome in China

- Effects of maternal calcium and protein intake on the development and bone metabolism of offspring mice

- Identification of winter wheat pests and diseases based on improved convolutional neural network

- Ultra-multiplex PCR technique to guide treatment of Aspergillus-infected aortic valve prostheses

- Virtual high-throughput screening: Potential inhibitors targeting aminopeptidase N (CD13) and PIKfyve for SARS-CoV-2

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients with COVID-19

- Utility of methylene blue mixed with autologous blood in preoperative localization of pulmonary nodules and masses

- Integrated analysis of the microbiome and transcriptome in stomach adenocarcinoma

- Berberine suppressed sarcopenia insulin resistance through SIRT1-mediated mitophagy

- DUSP2 inhibits the progression of lupus nephritis in mice by regulating the STAT3 pathway

- Lung abscess by Fusobacterium nucleatum and Streptococcus spp. co-infection by mNGS: A case series

- Genetic alterations of KRAS and TP53 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma associated with poor prognosis

- Granulomatous polyangiitis involving the fourth ventricle: Report of a rare case and a literature review

- Studying infant mortality: A demographic analysis based on data mining models

- Metaplastic breast carcinoma with osseous differentiation: A report of a rare case and literature review

- Protein Z modulates the metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma cells

- Inhibition of pyroptosis and apoptosis by capsaicin protects against LPS-induced acute kidney injury through TRPV1/UCP2 axis in vitro

- TAK-242, a toll-like receptor 4 antagonist, against brain injury by alleviates autophagy and inflammation in rats

- Primary mediastinum Ewing’s sarcoma with pleural effusion: A case report and literature review

- Association of ADRB2 gene polymorphisms and intestinal microbiota in Chinese Han adolescents

- Tanshinone IIA alleviates chondrocyte apoptosis and extracellular matrix degeneration by inhibiting ferroptosis

- Study on the cytokines related to SARS-Cov-2 in testicular cells and the interaction network between cells based on scRNA-seq data

- Effect of periostin on bone metabolic and autophagy factors during tooth eruption in mice

- HP1 induces ferroptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells through NRF2 pathway in diabetic nephropathy

- Intravaginal estrogen management in postmenopausal patients with vaginal squamous intraepithelial lesions along with CO2 laser ablation: A retrospective study

- Hepatocellular carcinoma cell differentiation trajectory predicts immunotherapy, potential therapeutic drugs, and prognosis of patients

- Effects of physical exercise on biomarkers of oxidative stress in healthy subjects: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Identification of lysosome-related genes in connection with prognosis and immune cell infiltration for drug candidates in head and neck cancer

- Development of an instrument-free and low-cost ELISA dot-blot test to detect antibodies against SARS-CoV-2

- Research progress on gas signal molecular therapy for Parkinson’s disease

- Adiponectin inhibits TGF-β1-induced skin fibroblast proliferation and phenotype transformation via the p38 MAPK signaling pathway

- The G protein-coupled receptor-related gene signatures for predicting prognosis and immunotherapy response in bladder urothelial carcinoma

- α-Fetoprotein contributes to the malignant biological properties of AFP-producing gastric cancer

- CXCL12/CXCR4/CXCR7 axis in placenta tissues of patients with placenta previa

- Association between thyroid stimulating hormone levels and papillary thyroid cancer risk: A meta-analysis

- Significance of sTREM-1 and sST2 combined diagnosis for sepsis detection and prognosis prediction

- Diagnostic value of serum neuroactive substances in the acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease complicated with depression

- Research progress of AMP-activated protein kinase and cardiac aging

- TRIM29 knockdown prevented the colon cancer progression through decreasing the ubiquitination levels of KRT5

- Cross-talk between gut microbiota and liver steatosis: Complications and therapeutic target

- Metastasis from small cell lung cancer to ovary: A case report

- The early diagnosis and pathogenic mechanisms of sepsis-related acute kidney injury

- The effect of NK cell therapy on sepsis secondary to lung cancer: A case report

- Erianin alleviates collagen-induced arthritis in mice by inhibiting Th17 cell differentiation

- Loss of ACOX1 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and its correlation with clinical features

- Signalling pathways in the osteogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells

- Crosstalk between lactic acid and immune regulation and its value in the diagnosis and treatment of liver failure

- Clinicopathological features and differential diagnosis of gastric pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma

- Traumatic brain injury and rTMS-ERPs: Case report and literature review

- Extracellular fibrin promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression through integrin β1/PTEN/AKT signaling

- Knockdown of DLK4 inhibits non-small cell lung cancer tumor growth by downregulating CKS2

- The co-expression pattern of VEGFR-2 with indicators related to proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation of anagen hair follicles

- Inflammation-related signaling pathways in tendinopathy

- CD4+ T cell count in HIV/TB co-infection and co-occurrence with HL: Case report and literature review

- Clinical analysis of severe Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia: Case series study

- Bioinformatics analysis to identify potential biomarkers for the pulmonary artery hypertension associated with the basement membrane

- Influence of MTHFR polymorphism, alone or in combination with smoking and alcohol consumption, on cancer susceptibility

- Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don counteracts the ampicillin resistance in multiple antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by downregulation of PBP2a synthesis

- Combination of a bronchogenic cyst in the thoracic spinal canal with chronic myelocytic leukemia

- Bacterial lipoprotein plays an important role in the macrophage autophagy and apoptosis induced by Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus

- TCL1A+ B cells predict prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer through integrative analysis of single-cell and bulk transcriptomic data

- Ezrin promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression via the Hippo signaling pathway

- Ferroptosis: A potential target of macrophages in plaque vulnerability

- Predicting pediatric Crohn's disease based on six mRNA-constructed risk signature using comprehensive bioinformatic approaches

- Applications of genetic code expansion and photosensitive UAAs in studying membrane proteins

- HK2 contributes to the proliferation, migration, and invasion of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells by enhancing the ERK1/2 signaling pathway

- IL-17 in osteoarthritis: A narrative review

- Circadian cycle and neuroinflammation

- Probiotic management and inflammatory factors as a novel treatment in cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Hemorrhagic meningioma with pulmonary metastasis: Case report and literature review

- SPOP regulates the expression profiles and alternative splicing events in human hepatocytes

- Knockdown of SETD5 inhibited glycolysis and tumor growth in gastric cancer cells by down-regulating Akt signaling pathway

- PTX3 promotes IVIG resistance-induced endothelial injury in Kawasaki disease by regulating the NF-κB pathway

- Pancreatic ectopic thyroid tissue: A case report and analysis of literature

- The prognostic impact of body mass index on female breast cancer patients in underdeveloped regions of northern China differs by menopause status and tumor molecular subtype

- Report on a case of liver-originating malignant melanoma of unknown primary

- Case report: Herbal treatment of neutropenic enterocolitis after chemotherapy for breast cancer

- The fibroblast growth factor–Klotho axis at molecular level

- Characterization of amiodarone action on currents in hERG-T618 gain-of-function mutations

- A case report of diagnosis and dynamic monitoring of Listeria monocytogenes meningitis with NGS

- Effect of autologous platelet-rich plasma on new bone formation and viability of a Marburg bone graft

- Small breast epithelial mucin as a useful prognostic marker for breast cancer patients

- Continuous non-adherent culture promotes transdifferentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells into retinal lineage

- Nrf3 alleviates oxidative stress and promotes the survival of colon cancer cells by activating AKT/BCL-2 signal pathway

- Favorable response to surufatinib in a patient with necrolytic migratory erythema: A case report

- Case report of atypical undernutrition of hypoproteinemia type

- Down-regulation of COL1A1 inhibits tumor-associated fibroblast activation and mediates matrix remodeling in the tumor microenvironment of breast cancer

- Sarcoma protein kinase inhibition alleviates liver fibrosis by promoting hepatic stellate cells ferroptosis

- Research progress of serum eosinophil in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma

- Clinicopathological characteristics of co-existing or mixed colorectal cancer and neuroendocrine tumor: Report of five cases

- Role of menopausal hormone therapy in the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis

- Precisional detection of lymph node metastasis using tFCM in colorectal cancer

- Advances in diagnosis and treatment of perimenopausal syndrome

- A study of forensic genetics: ITO index distribution and kinship judgment between two individuals

- Acute lupus pneumonitis resembling miliary tuberculosis: A case-based review

- Plasma levels of CD36 and glutathione as biomarkers for ruptured intracranial aneurysm

- Fractalkine modulates pulmonary angiogenesis and tube formation by modulating CX3CR1 and growth factors in PVECs

- Novel risk prediction models for deep vein thrombosis after thoracotomy and thoracoscopic lung cancer resections, involving coagulation and immune function

- Exploring the diagnostic markers of essential tremor: A study based on machine learning algorithms

- Evaluation of effects of small-incision approach treatment on proximal tibia fracture by deep learning algorithm-based magnetic resonance imaging

- An online diagnosis method for cancer lesions based on intelligent imaging analysis

- Medical imaging in rheumatoid arthritis: A review on deep learning approach

- Predictive analytics in smart healthcare for child mortality prediction using a machine learning approach

- Utility of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio and platelet–lymphocyte ratio in predicting acute-on-chronic liver failure survival

- A biomedical decision support system for meta-analysis of bilateral upper-limb training in stroke patients with hemiplegia

- TNF-α and IL-8 levels are positively correlated with hypobaric hypoxic pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling in rats

- Stochastic gradient descent optimisation for convolutional neural network for medical image segmentation

- Comparison of the prognostic value of four different critical illness scores in patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy

- Application and teaching of computer molecular simulation embedded technology and artificial intelligence in drug research and development

- Hepatobiliary surgery based on intelligent image segmentation technology

- Value of brain injury-related indicators based on neural network in the diagnosis of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- Analysis of early diagnosis methods for asymmetric dementia in brain MR images based on genetic medical technology

- Early diagnosis for the onset of peri-implantitis based on artificial neural network

- Clinical significance of the detection of serum IgG4 and IgG4/IgG ratio in patients with thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy

- Forecast of pain degree of lumbar disc herniation based on back propagation neural network

- SPA-UNet: A liver tumor segmentation network based on fused multi-scale features

- Systematic evaluation of clinical efficacy of CYP1B1 gene polymorphism in EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer observed by medical image

- Rehabilitation effect of intelligent rehabilitation training system on hemiplegic limb spasms after stroke

- A novel approach for minimising anti-aliasing effects in EEG data acquisition

- ErbB4 promotes M2 activation of macrophages in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Clinical role of CYP1B1 gene polymorphism in prediction of postoperative chemotherapy efficacy in NSCLC based on individualized health model

- Lung nodule segmentation via semi-residual multi-resolution neural networks

- Evaluation of brain nerve function in ICU patients with Delirium by deep learning algorithm-based resting state MRI

- A data mining technique for detecting malignant mesothelioma cancer using multiple regression analysis

- Markov model combined with MR diffusion tensor imaging for predicting the onset of Alzheimer’s disease

- Effectiveness of the treatment of depression associated with cancer and neuroimaging changes in depression-related brain regions in patients treated with the mediator-deuterium acupuncture method

- Molecular mechanism of colorectal cancer and screening of molecular markers based on bioinformatics analysis

- Monitoring and evaluation of anesthesia depth status data based on neuroscience

- Exploring the conformational dynamics and thermodynamics of EGFR S768I and G719X + S768I mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: An in silico approaches

- Optimised feature selection-driven convolutional neural network using gray level co-occurrence matrix for detection of cervical cancer

- Incidence of different pressure patterns of spinal cerebellar ataxia and analysis of imaging and genetic diagnosis

- Pathogenic bacteria and treatment resistance in older cardiovascular disease patients with lung infection and risk prediction model

- Adoption value of support vector machine algorithm-based computed tomography imaging in the diagnosis of secondary pulmonary fungal infections in patients with malignant hematological disorders

- From slides to insights: Harnessing deep learning for prognostic survival prediction in human colorectal cancer histology

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Monitoring of hourly carbon dioxide concentration under different land use types in arid ecosystem

- Comparing the differences of prokaryotic microbial community between pit walls and bottom from Chinese liquor revealed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing

- Effects of cadmium stress on fruits germination and growth of two herbage species

- Bamboo charcoal affects soil properties and bacterial community in tea plantations

- Optimization of biogas potential using kinetic models, response surface methodology, and instrumental evidence for biodegradation of tannery fleshings during anaerobic digestion

- Understory vegetation diversity patterns of Platycladus orientalis and Pinus elliottii communities in Central and Southern China

- Studies on macrofungi diversity and discovery of new species of Abortiporus from Baotianman World Biosphere Reserve

- Food Science

- Effect of berrycactus fruit (Myrtillocactus geometrizans) on glutamate, glutamine, and GABA levels in the frontal cortex of rats fed with a high-fat diet

- Guesstimate of thymoquinone diversity in Nigella sativa L. genotypes and elite varieties collected from Indian states using HPTLC technique

- Analysis of bacterial community structure of Fuzhuan tea with different processing techniques

- Untargeted metabolomics reveals sour jujube kernel benefiting the nutritional value and flavor of Morchella esculenta

- Mycobiota in Slovak wine grapes: A case study from the small Carpathians wine region

- Elemental analysis of Fadogia ancylantha leaves used as a nutraceutical in Mashonaland West Province, Zimbabwe

- Microbiological transglutaminase: Biotechnological application in the food industry

- Influence of solvent-free extraction of fish oil from catfish (Clarias magur) heads using a Taguchi orthogonal array design: A qualitative and quantitative approach

- Chromatographic analysis of the chemical composition and anticancer activities of Curcuma longa extract cultivated in Palestine

- The potential for the use of leghemoglobin and plant ferritin as sources of iron

- Investigating the association between dietary patterns and glycemic control among children and adolescents with T1DM

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Biocompatibility and osteointegration capability of β-TCP manufactured by stereolithography 3D printing: In vitro study

- Clinical characteristics and the prognosis of diabetic foot in Tibet: A single center, retrospective study

- Agriculture

- Biofertilizer and NPSB fertilizer application effects on nodulation and productivity of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) at Sodo Zuria, Southern Ethiopia

- On correlation between canopy vegetation and growth indexes of maize varieties with different nitrogen efficiencies

- Exopolysaccharides from Pseudomonas tolaasii inhibit the growth of Pleurotus ostreatus mycelia

- A transcriptomic evaluation of the mechanism of programmed cell death of the replaceable bud in Chinese chestnut

- Melatonin enhances salt tolerance in sorghum by modulating photosynthetic performance, osmoregulation, antioxidant defense, and ion homeostasis

- Effects of plant density on alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) seed yield in western Heilongjiang areas

- Identification of rice leaf diseases and deficiency disorders using a novel DeepBatch technique

- Artificial intelligence and internet of things oriented sustainable precision farming: Towards modern agriculture

- Animal Sciences

- Effect of ketogenic diet on exercise tolerance and transcriptome of gastrocnemius in mice

- Combined analysis of mRNA–miRNA from testis tissue in Tibetan sheep with different FecB genotypes

- Isolation, identification, and drug resistance of a partially isolated bacterium from the gill of Siniperca chuatsi

- Tracking behavioral changes of confined sows from the first mating to the third parity

- The sequencing of the key genes and end products in the TLR4 signaling pathway from the kidney of Rana dybowskii exposed to Aeromonas hydrophila

- Development of a new candidate vaccine against piglet diarrhea caused by Escherichia coli

- Plant Sciences

- Crown and diameter structure of pure Pinus massoniana Lamb. forest in Hunan province, China

- Genetic evaluation and germplasm identification analysis on ITS2, trnL-F, and psbA-trnH of alfalfa varieties germplasm resources

- Tissue culture and rapid propagation technology for Gentiana rhodantha

- Effects of cadmium on the synthesis of active ingredients in Salvia miltiorrhiza

- Cloning and expression analysis of VrNAC13 gene in mung bean

- Chlorate-induced molecular floral transition revealed by transcriptomes

- Effects of warming and drought on growth and development of soybean in Hailun region

- Effects of different light conditions on transient expression and biomass in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves

- Comparative analysis of the rhizosphere microbiome and medicinally active ingredients of Atractylodes lancea from different geographical origins

- Distinguish Dianthus species or varieties based on chloroplast genomes

- Comparative transcriptomes reveal molecular mechanisms of apple blossoms of different tolerance genotypes to chilling injury

- Study on fresh processing key technology and quality influence of Cut Ophiopogonis Radix based on multi-index evaluation

- An advanced approach for fig leaf disease detection and classification: Leveraging image processing and enhanced support vector machine methodology

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Protein Z modulates the metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma cells”

- Erratum to “BRCA1 subcellular localization regulated by PI3K signaling pathway in triple-negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells and hormone-sensitive T47D cells”

- Retraction