Abstract

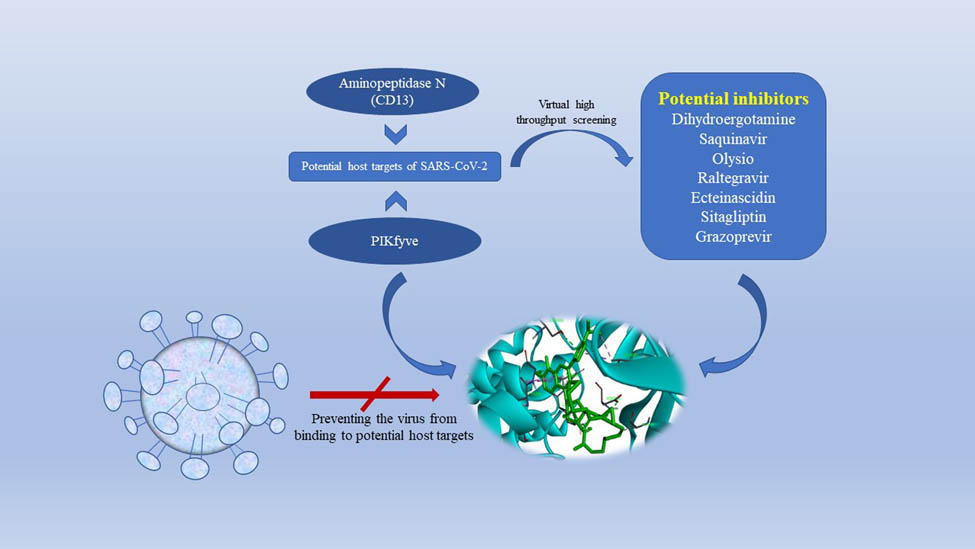

Since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus nearly 3 years ago, the world’s public health has been under constant threat. At the same time, people’s travel and social interaction have also been greatly affected. The study focused on the potential host targets of SARS-CoV-2, CD13, and PIKfyve, which may be involved in viral infection and the viral/cell membrane fusion stage of SARS-CoV-2 in humans. In this study, electronic virtual high-throughput screening for CD13 and PIKfyve was conducted using Food and Drug Administration-approved compounds in ZINC database. The results showed that dihydroergotamine, Saquinavir, Olysio, Raltegravir, and Ecteinascidin had inhibitory effects on CD13. Dihydroergotamine, Sitagliptin, Olysio, Grazoprevir, and Saquinavir could inhibit PIKfyve. After 50 ns of molecular dynamics simulation, seven compounds showed stability at the active site of the target protein. Hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces were formed with target proteins. At the same time, the seven compounds showed good binding free energy after binding to the target proteins, providing potential drug candidates for the treatment and prevention of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

COVID-19, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has been circulating worldwide since 2019 [1]. According to statistics from the World Health Organization, as of May 5, 2023, the number of global deaths caused by this epidemic has reached 6,800,000, involving 35 countries. SARS-CoV-2 bel to the genus Betacoronavirus, which is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus with 26–32 kb genome [2,3]. In addition, the genus includes the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), which was endemic in 2002–2003, Middle East Respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), human coronaviruses (HCoV)-OC43, and HCoV-HKU1 [4]. Among them, SARS-CoV-2 shares 80% identity with SARS-CoV and 50% similarity with MERS-CoV, which caused global outbreaks in 2011 [5]. The outbreak of these coronaviruses, especially SARS-CoV-2, has caused serious impacts on human health around the world, and at the same time, it has also caused huge losses to the global economy. So far, more than 30 vaccines worldwide have been approved for marketing or urgently authorized for use. At the same time, there are nearly 30 drugs globally approved for COVID-19, including neutralizing antibodies, monoclonal antibodies, neuropeptide hormones, and small-molecule drugs. Among them, the approved small-molecule antiviral drugs are represented by Remdesivir, Paxlovid, Molnupiravir, and Azvudine. Although vaccines and drugs against SARS-CoV-2 have been developed to prevent the outbreak of the virus pandemic, due to the high mutagenicity of the novel coronavirus genome, such as the rapidly spreading Omicron variant, the existing strategies cannot fully guarantee the subsequent effectiveness [6]. Therefore, we urgently need to find new targets and develop small-molecule antiviral drugs for the huge threat posed by COVID-19. The development of small-molecule drugs is also the reuse or repositioning of drugs, with low cost and high accessibility.

Aminopeptidase N (CD13), an extracellular enzyme, is also a zinc-dependent metalloproteinase whose N-terminus is anchored to the cell membrane and faces the extracellular catalytic domain [7]. Expression of this cell-surface glycoprotein is found in many human tissues, including the lung [8]. In addition, the protease is involved in peptide cleavage, viral infection, endocytosis, and cell signal transduction [9]. Studies have shown that CD13 is not only a receptor for human coronavirus 229E, but also a receptor for gut-borne coronavirus, which also indicates that CD13 may also be involved in COVID-19 invasion [10,11]. Therefore, as one of the host receptors of coronavirus, CD13 can also be considered a potential target for SARS-CoV-2 to deal with the possible emergence of coronavirus variants in the future.

PIKfyve, a phosphoinositol 5-kinase, synthesizes PtdIns5P and PtdIns(3,5) diphosphate, which in turn regulates membrane homeostasis [6]. PIKfyve plays a key role in endocytosis of viral entry into host cells [12]. Studies have shown that PIKfyve inhibitors may prevent the viral/cell membrane fusion stage, resulting in the failure of viral single-stranded RNA release into the cytoplasm, thereby terminating SARS-CoV-2 entry into host cells. In addition to this, the rapid generation of vacuoles and inactivated tissue proteins induced by PIKfyve inhibitors also severely disrupted the new life cycle of the virus, thereby reducing infection [6]. Therefore, drug targeting PIKfyve to interfere with the endocytosis of host cells is an effective way to block virus infection [13]. It is a good idea to use PIKfyve as a potential target against SARS-CoV-2.

Therefore, in this study, CD13 and PIKfyve were used as two target proteins for drug screening, to find potential drugs against SARS-CoV-2. A computer virtual screen in a database of known drugs can help rapidly identify potential drug candidates for COVID-19 prevention and treatment. More importantly, previous literature has shown that some of the virtually screened compounds, such as ribavirin and ritonavir, have been shown to be effective in the treatment of COVID-19 [14]. It takes approximately a decade of research to develop new drugs. Therefore, reusing small-molecule drugs may be an effective strategy to deal with SARS-CoV-2 infection [15]. Through high-throughput screening methods, we hope to find potential antiviral drug candidates.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Construction of small molecular ligands and preparation of target proteins

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) compound sublibrary was downloaded from the zinc database (http://zinc.docking.org/substances/subsets/). Then, the model was converted to pdbqt format by prepare_receptor4.py script by assigning atomic types and atomic charges. All rotatable bonds in the molecule are set to be flexible for flexible docking. The crystal structure of CD13 (PDB ID: 4FYT) was used as the target protein of SARS‐CoV‐2. The crystal structure of PIKfyve (PDB ID: 7K1W) was used as the target protein of SARS‐CoV-2.

2.2 Molecular docking

First, the 3D structure of the FDA-approved compound was saved after energy minimization, and the pdbqt format was generated by AutoDock Tools software. Log in to the PDB database to download the 3D crystal structure of the target protein and recalculate the charge after dewatering, ligand, and hydrogenation. Then, the compound structure file is imported to detect the total charge, assign the charge, and check the flexible rotatable. Finally, AutoDock Vina was used for molecular docking and the binding energy was calculated. The absolute value of binding energy >4.25 indicates that the molecule has initial binding ability with the target, >5.0 indicates strong binding ability, and >7.0 indicates strong binding ability.

2.3 Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation and binding free energy calculation

The Gromacs 2020 software package was used to simulate the MD of the screened receptor protein–small molecule complex. AMBER99SB-ILDN field parameters were used for proteins and gaff general field parameters were used for small-molecule ligands. The sobtop program was used to construct the small-molecule topology and RESP was used for charge fitting. The TIP3P dominant water model was selected, and the minimum distance between the atoms in the protein and the edge of the water box was 1.0 nm. Sodium or chloride ions were used to neutralize the system charge depending on the docking result. The work flow of MD simulation includes four steps: energy minimization, heating, balancing, and production dynamics simulation. Target equilibrium temperature is 300 K. Finally, MD simulations were performed for 50 ns, calculating and recording conformations every 2 ps. In the simulation process, the simulated unframe is isotropic and periodic boundary conditions are applied. After the MD simulation, we calculated the root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), radius of gyration (R g), and solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of the protein. Finally, the hydrogen bond interaction between the target protein and the compound was calculated. The g_MMPBSA method using the Gromacs 2020 program was used to calculate the binding free energy of ligands and proteins.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Docking results of 2631 drugs on CD13 and PIKfyve, potential targets of SARS-CoV-2

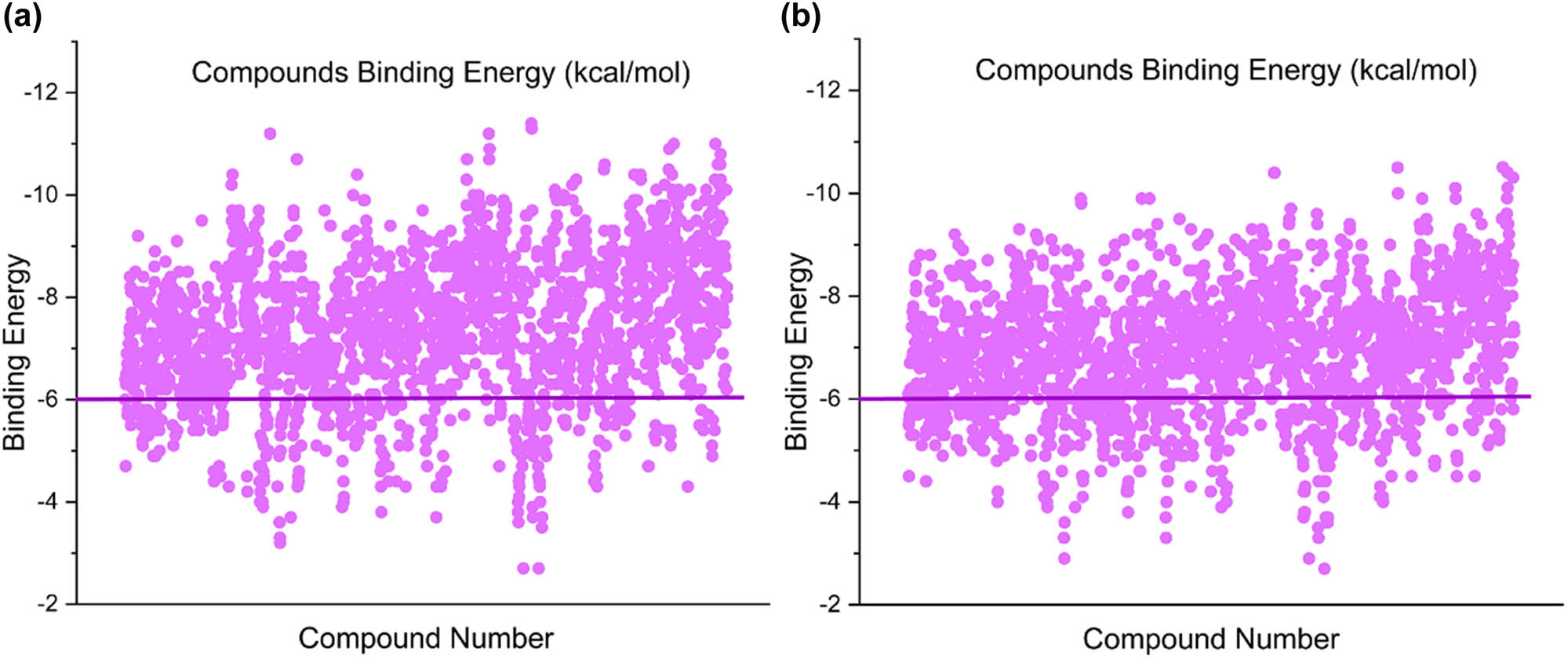

A total of 2,631 FDA-approved small molecules were screened for molecular docking. The AutoDock tool was used to calculate the binding energy of the compound. The compound selected according to the determined cutoff value −6.00 kcal/mol is shown in Figure 1. The purple line shows the cutoff range. The results showed that 1,801 FDA-approved compounds showed binding energies higher than −6.00 kcal/mol with potential target CD13. Meanwhile, 1666 FDA-approved compounds showed binding energies higher than −6.00 kcal/mol with potential targets PIKfyve. According to the results of molecular docking between APN and compounds, the 10 top compounds with affinities between −10.1 and −11.4 kcal/mol were selected (Table 1). In the same way, the 10 top compounds with affinities between −9.5 and −10.4 kcal/mol were selected from the results of molecular docking between PIKfyve and the compounds (Table 2). According to the selected compounds, dihydroergotamine, Saquinavir, and Olysio showed high affinity for both target proteins CD13 and PIKfyve with good docking scores. In addition, Saquinavir, Olysio, Raltegravir, and Grazoprevir were all strongly associated with antiviral activity.

Binding energies for virtual hit compounds. The violet line shows the cut-off range for the compounds selected. (a) Binding energy of CD13 with FDA-approved compounds. (b) Binding energy of PIKfyve with FDA-approved compounds.

Ten compounds screened with CD13 as the target protein

| Compounds name | ID | Data | Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nilotinib | ZINC000006716957 | FDA | −11.4 |

| Dihydroergotamine | ZINC000003978005 | FDA | −11.2 |

| Lumacaftor | ZINC000064033452 | FDA | −11 |

| Ergotamine | ZINC000052955754 | FDA | −10.9 |

| Saquinavir | ZINC000003914596 | FDA | −10.7 |

| Olysio | ZINC000164760756 | FDA | −10.6 |

| Raltegravir | ZINC000013831130 | FDA | −10.2 |

| Ecteinascidin | ZINC000150338708 | FDA | −10.2 |

| Grazoprevir | ZINC000095551509 | FDA | −10.1 |

| Tipranavir | ZINC000100016058 | FDA | −10.1 |

Ten compounds screened with PIKfyve as the target protein

| Compounds name | ID | Data | Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dihydroergotamine | ZINC000003978005 | FDA | −10.4 |

| Ergotamine | ZINC000052955754 | FDA | −10.1 |

| Sitagliptin | ZINC000001489478 | FDA | −9.9 |

| Olysio | ZINC000164760756 | FDA | −9.9 |

| Nilotinib | ZINC000006716957 | FDA | −9.6 |

| Grazoprevir | ZINC000095551509 | FDA | −9.6 |

| Saquinavir | ZINC000029416466 | FDA | −9.5 |

| Ecteinascidin | ZINC000150338708 | FDA | −9.4 |

| Haloperidol | ZINC000000537822 | FDA | −9.3 |

| Naldemedine | ZINC000100378061 | FDA | −9.5 |

3.2 Docking results of dihydroergotamine against CD13 and PIKfyve

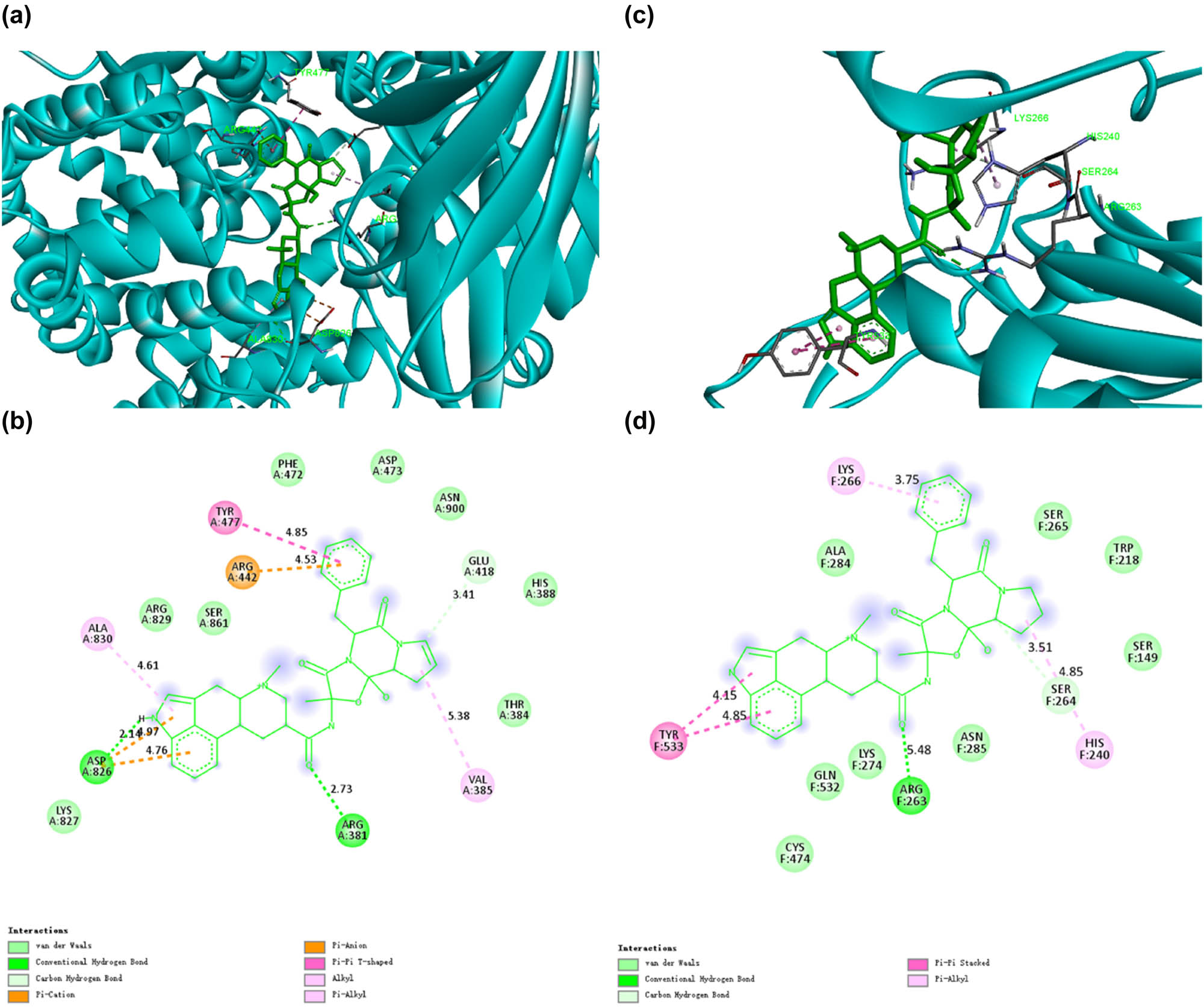

Dihydroergotamine (DHE), as an alpha-adrenergic antagonist, is structurally similar to many neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and epinephrine, so it can bind to many receptors. Until now, DHE is still the drug of choice for cluster headache, migraine state, and acute migraine [16]. Recent studies have shown that DHE also plays a certain role in potential antiviral [17,18]. Our docking study showed that DHE had high binding capacity with CD13 and PIKfyve, potential targets of SARS-CoV-2, with binding energies −11.2 and −10.4 kcal/mol, respectively. According to Figure 2a and b, when DHE binds to CD13, two conventional hydrogen bonds are formed, involving ASP862 and ARG381. One carbon–hydrogen bond is formed with GLU418. It also formed eight van der Waals, which involve LYS827, ARG829, SER861, PHE472, ASP473, ASN900, HIS388, and THR384. In addition, DHE made one cation and anion Pi interaction with ARG442 and one Pi–Pi T-shaped interaction with TYR477. Besides, DHE had two Pi-alkyl with ALA830 and VAL385. According to Figure 2c and d, when DHE binds to PIKfyve, eight van der Waals are formed with CYS474, GLN532, LYS274, ASN285, SER149, TRP218, SER265, and ALA284. Besides, DHE had one conventional hydrogen bond with ARG263 and one carbon–hydrogen bond with SER264. In addition, DHE made two Pi-alkyl with LYS266 and HIS240. It also had one Pi–Pi stacked with TYR533. Previously, studies have shown that DHE has strong binding ability with SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease (3CLpro) and viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), thereby inhibiting the activities of these two enzymes [19]. Our screening study further found that DHE can bind to CD13 and PIKfyve and, thus, may block the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with potential human targets.

The binding model of dihydroergotamine against CD13 and PIKfyve. (a) Interactions between dihydroergotamine (green) and associated residues (purple) in the CD13 protein interface pocket (cyan) for SARS‐CoV‐2. (b) Two-dimensional interaction diagram of dihydroergotamine binding to the CD13 active site. (c) Interactions between dihydroergotamine (green) and associated residues (purple) in the PIKfyve protein interface pocket (cyan) for SARS‐CoV‐2. (d) Two-dimensional interaction diagram of dihydroergotamine binding to the PIKfyve active site. The numbers next to the dotted line indicate the interaction distance.

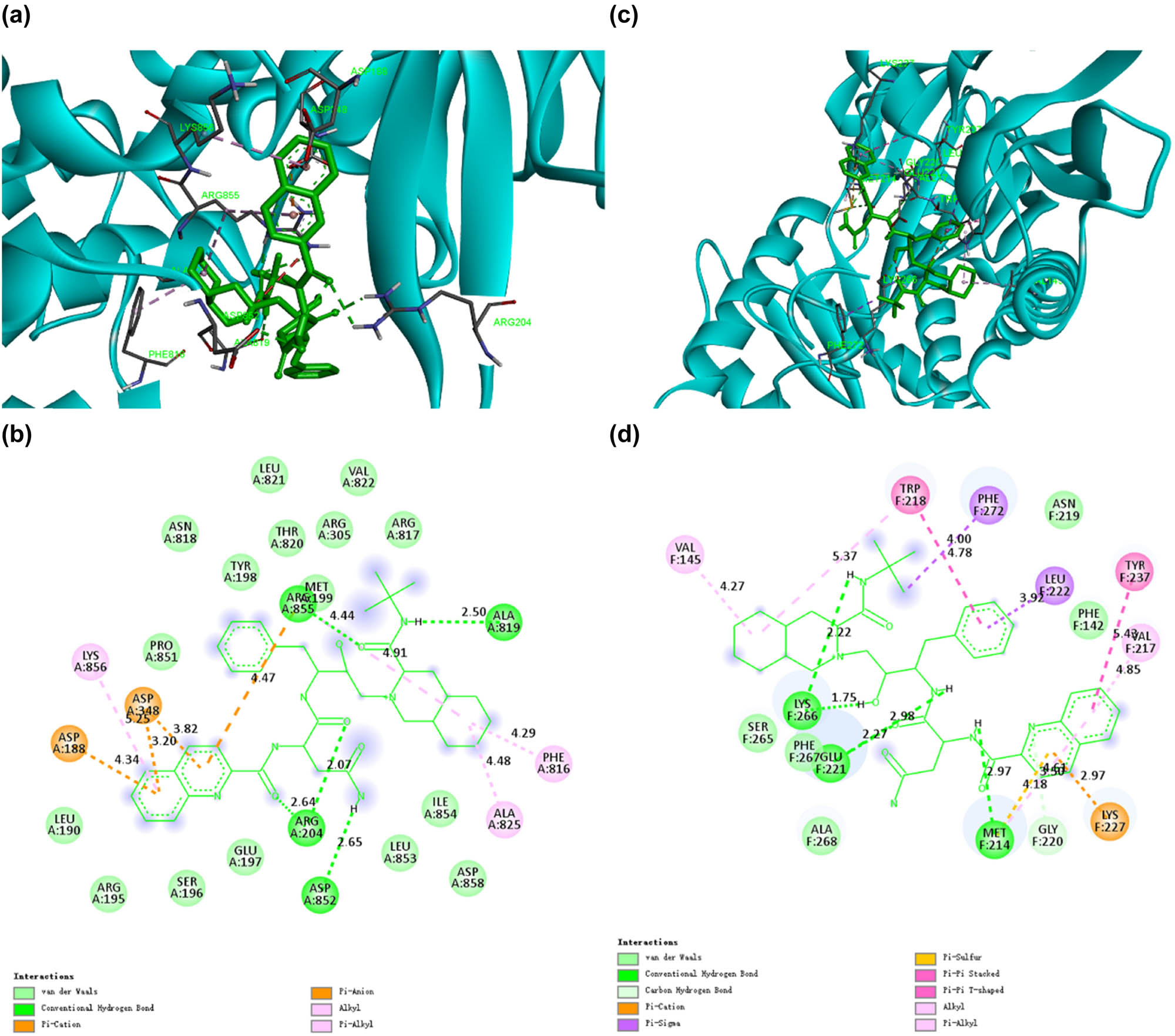

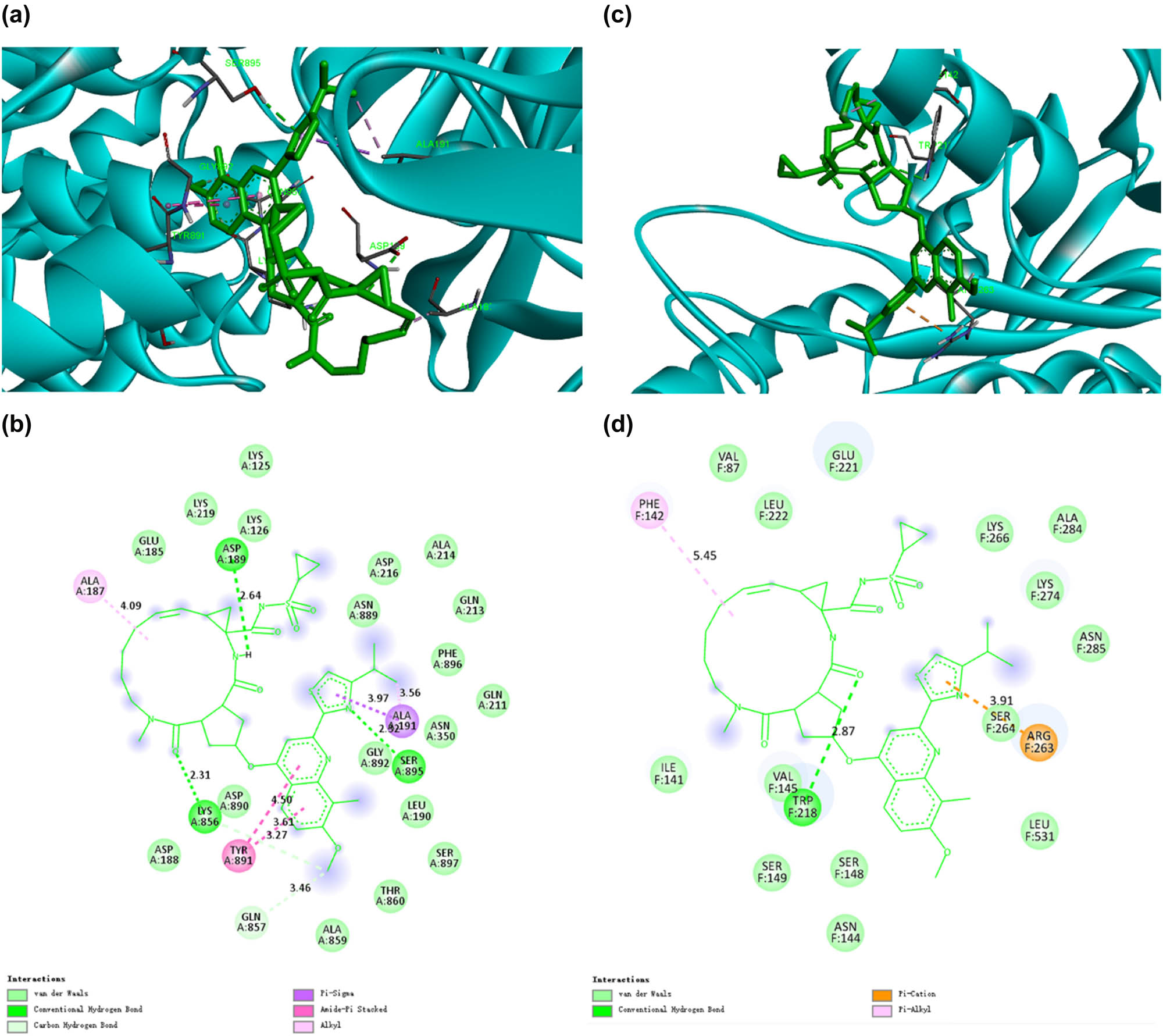

3.3 Docking results of Saquinavir against CD13 and PIKfyve

Saquinavir, first approved by the US FDA in 1995, was the first PI to be used to treat HIV. Saquinavir is a protease inhibitor that can bind strongly with protease, resulting in competitive inhibition of its activities required for maturation and proliferation, thus forming an immature provirus that cannot infect cells [20]. Many studies have shown that Saquinavir plays an important role in antiviral treatment [21,22]. Our docking results showed that Saquinavir could bind closely to CD13 and PIKfyve, potential targets of SARS-CoV-2, with binding energies of −10.7 and −9.5 kcal/mol, respectively. As shown in Figure 3a and b, when Saquinavir binds to CD13, it forms 16 van der Waals forces with amino acid residues LEU190, ARG195, SER196, GLU197, LEU853, ILE854, ASP858, PRO851, ASN818, TYR198, MET199, THR820, LEU821, ARG305, ARG817, and VAL822, respectively. Meanwhile, four conventional hydrogen bonds were formed with residues ARG204, ASP852, ARG855, and ALA819, respectively. It also made two cation and anion Pi interactions with ASP188 and ASP348. Besides, Saquinavir had three Pi-alkyl with LYS856, ALA825, and PHE816. According to Figure 3c and d, when Saquinavir binds to PIKfyve, it forms five van der Waals interactions with SER265, PHE267, ALA268, ASN219, and PHE142. It also forms three conventional hydrogen bonds and one carbon–hydrogen bond with LYS266, GLU221, MET214, and GLY220. Moreover, two Pi-sigma are formed between Saquinavir and PIKfyve, involving PHE272 and LEU222. In addition, Pi–Pi stacked and Pi–Pi t-shaped are formed with TRP218 and TYR237. Meanwhile, Pi-alkyl is formed between Saquinavir and the amino acid residue VAL217 of PIKfyve. Chiou et al. showed that Saquinavir blocks the proteolytic activity of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro [23]. Halder et al. found that Saquinavir can target 12 non-structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2, especially key enzymes [24]. Our screening study further revealed that Saquinavir could bind closely to CD13 and PIKfyve, potential targets of SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, Saquinavir could be a potential candidate against COVID-19.

The binding model of Saquinavir against CD13 and PIKfyve. (a) Interactions between Saquinavir (green) and associated residues (purple) in the CD13 protein interface pocket (cyan) for SARS‐CoV‐2. (b) Two-dimensional interaction diagram of dihydroergotamine binding to the CD13 active site. (c) Interactions between Saquinavir (green) and associated residues (purple) in the PIKfyve protein interface pocket (cyan) for SARS‐CoV‐2. (d) Two-dimensional interaction diagram of dihydroergotamine binding to the PIKfyve active site. The numbers next to the dotted line indicate the interaction distance.

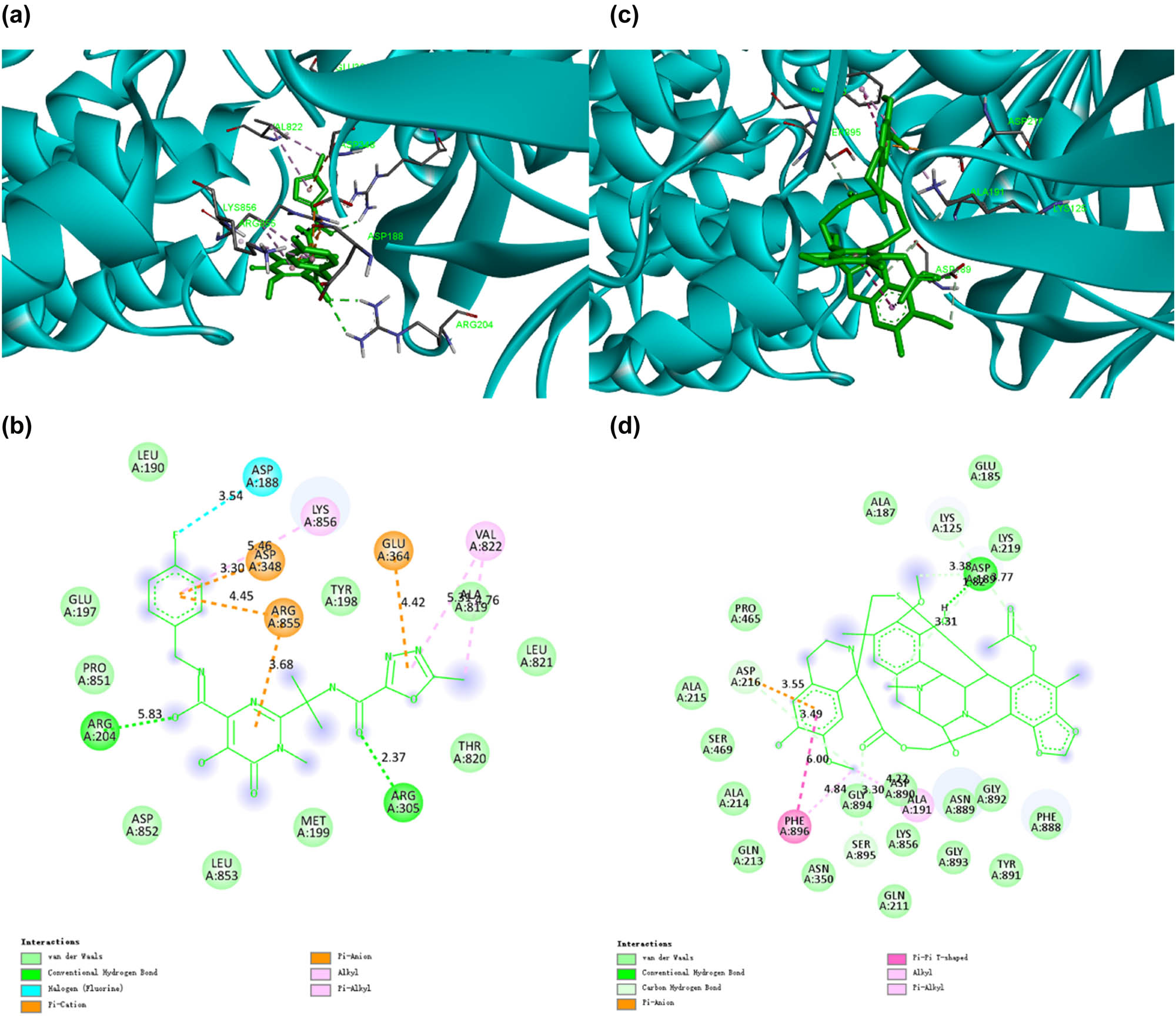

3.4 Docking results of Olysio against CD13 and PIKfyve

Olysio, an HCV inhibitor that targets the NS3/4A protease, is a direct-acting antiviral agent that has been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of HCV infection alone or in combination with other agents [25]. MD simulations have shown that Olysio can bind not only non-structural proteins of SARS but also side chains of residues in the receptor-binding domain binding pocket to inhibit the interaction of viral spike proteins with receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) [26]. In this study, Olysio binding to CD13, a potential SARS‐CoV‐2 target, resulted in 18 van der Waals interactions involving ASP188, ASP890, ALA859, THR860, SER897, LEU190, GLY892, ASN350, GLN211, PHE896, GLN213, ASN889, ASP216, ALA214, LYS126, LYS219, GLU185, and LYS125. It also forms three conventional hydrogen bonds and one carbon–hydrogen bond, involving LYS856, SER895, ASP189, and GLN857. In addition to that, Pi-sigma, amide-Pi stacked, and alkyl are formed with amino acid residues ALA191, TYR891, and ALA187, respectively (Figure 4a and b). For PIKfyve, a potential SARS‐CoV‐2 target, Olysio formed 14 van der Waals interactions when combined with PIKfyve with ILE141, VAL145, SER149, SER148, ASN144, LEU531, SER264, ASN285, LYS274, ALA284, LYS266, GLU221, LEU222, and VAL87. Meanwhile, it made one conventional hydrogen bond with TRP218, one Pi-cation with ARG263, and one Pi-alkyl with PHE142 (Figure 4c and d). Lo et al. found that Olysio could effectively inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication, reduce SARS-CoV-2 viral load, and synergistically interact with remdesivir in vitro. In addition, cimeprvir not only inhibits major proteolytic enzymes (MPRO) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) but also modulates host immune responses [27]. The results of this study also indicate that Olysio is a multitarget inhibitor. Therefore, Olysio has great potential as an anti-COVID-19 drug in the future.

The binding model of Olysio against CD13 and PIKfyve. (a) Interactions between Olysio (green) and associated residues (purple) in the CD13 protein interface pocket (cyan) for SARS‐CoV‐2. (b) Two-dimensional interaction diagram of dihydroergotamine binding to the CD13 active site. (c) Interactions between Olysio (green) and associated residues (purple) in the PIKfyve protein interface pocket (cyan) for SARS‐CoV‐2. (d) Two-dimensional interaction diagram of dihydroergotamine binding to the PIKfyve active site. The numbers next to the dotted line indicate the interaction distance.

3.5 Docking results of Raltegravir and Ecteinascidin against CD13

Raltegravir was the first integrase chain transfer inhibitor (INSTI), which allows integration into the host cell DNA, approved by the US FDA in 2017 [28]. Akcora-Yildiz et al. showed that Raltegravir is a relatively safe antiviral drug with mild adverse reactions [29]. Ecteinascidin, also known as trabectedin, was discovered in 1969 during screening for antitumor activity in the Caribbean mangrove tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinate and was the first marine-derived drug clinically used to treat cancer [30,31]. Our molecular docking studies showed that both Raltegravir and Ecteinascidin could bind to CD13, a potential target of SARS‐CoV‐2, with binding energies of −10.2 kcal/mol, both. When Raltegravir binds to CD13, ten van der Waals interactions are formed, involving amino acid residues LEU190, GLU197, PRO851, ASP852, LEU853, MET199, THR820, LEU821, ALA819, and TYR198. Meanwhile, two conventional hydrogen bonds are formed with ARG204 and ARG305. It also made one Halogen with ASP188. In addition, three cation and anion Pi interactions with amino acid residues ASP348, ARG855, and GLU364 are present. Raltegravir also formed two Pi-alkyl with LYS856 and VAL822 (Figure 5a and b). When Ecteinascidin binds to CD13, 18 van der Waals interactions are formed. What is more, it also formed one conventional hydrogen bond with ASP189 and two carbon hydrogen bonds with SER895 and LYS125. Besides, Ecteinascidin with amino acid residues formed one Pi–Pi t-shaped with PHE896 and one Pi-alkyl with ALA191. Thus, both remdesivir and ascidians bind closely to CD13 (Figure 5c and d). Remdesivir has previously been shown to be effective against SARS-CoV-2 non-structural proteins [32]. Ecteinascidin, a natural Marine drug, showed good binding ability to CD13, suggesting the potential of Marine products as anti-SARS‐CoV‐2 agents. In the future, more ideas for anti-SARS‐CoV‐2 drugs can also be explored along the direction of Marine products.

The binding model of Raltegravir and Ecteinascidin against CD13. (a) Interactions between Raltegravir (green) and associated residues (purple) in the CD13 protein interface pocket (cyan) for SARS‐CoV‐2. (b) Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Raltegravir binding to the CD13 active site. (c) Interactions between Ecteinascidin (green) and associated residues (purple) in the CD13 protein interface pocket (cyan) for SARS‐CoV‐2. (d) Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Ecteinascidin binding to the CD13 active site. The numbers next to the dotted line indicate the interaction distance.

3.6 Docking results of Sitagliptin and Grazoprevir against PIKfyve

Sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, plays an important role in immune regulation, antidiabetes, and anti-inflammation [33,34]. Grazoprevir (MK-5172) is an NS3/4A PI that is highly active against all hepatitis C viruses except genotype 3 [35,36]. Our molecular docking studies showed that both Sitagliptin and Grazoprevir could bind to PIKfyve, a potential target of SARS‐CoV‐2, with binding energies of −9.9 and −9.6 kcal/mol, respectively. When Sitagliptin binds to PIKfyve, 12 van der Waals interactions are formed with amino acid residues. Sitagliptin also made two conventional hydrogen bonds and one carbon–hydrogen bond, involving HIS110, LEU170, and GLY108, respectively. Besides, Sitagliptin and PIKfyve have three Halogen with ILE107, ASN166, and MET172. Meanwhile, one Pi-sigma with LEU163 and one Pi-alkyl with TYR306 are formed (Figure 6a and b). According to Figure 6c and d, when Grazoprevir binds to PIKfyve, 15 van der Waals are formed with amino acid residues. What is more, two conventional hydrogen bonds are formed, involving ARG275 and ARG376. One carbon–hydrogen bond is formed with CYS477. It also formed two Pi-alkyl which involve ILE324 and TYR533. Remarkably, Sitagliptin has been found not only to reduce hepatitis C virus replication in diabetic patients but also to inhibit the production of interferon-induced-protein 10 (CXCL10) chemokine in AIDS patients. However, there is a high level of CXCL10 chemokine in the alveolar microenvironment of patients with COVID-19 [37,38]. Thus, Sitagliptin and Grazoprevir can be used as good potential drugs against SARS‐CoV‐2 and also provide Linchuan researchers with new ideas for drug development.

The binding model of Sitagliptin and Grazoprevir against PIKfyve. (a) Interactions between Sitagliptin (green) and associated residues (purple) in the PIKfyve protein interface pocket (cyan) for SARS‐CoV‐2. (b) Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Sitagliptin binding to the PIKfyve active site. (c) Interactions between Grazoprevir (green) and associated residues (purple) in the PIKfyve protein interface pocket (cyan) for SARS‐CoV‐2. (d) Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Grazoprevir binding to the PIKfyve active site. The numbers next to the dotted line indicate the interaction distance.

3.7 MD simulation for CD13

We further used MD simulations to investigate the binding stability of protein–ligand docking complexes. We used MD simulations to analyze the docking files between the top five selected compounds and CD13 target proteins to determine the stability and intermolecular interactions between proteins and molecules over a 50-ns time interval. Figure 7a shows the RMSD plots of the five selected CD13 compound complexes. RMSD results showed that the RMSD values of the five complexes ranged from 0.1 to 0.2 nm. The system of the five complexes reached equilibrium after 40 ns, which reflected the good stability of the whole system to a certain extent.

MD trajectory analysis for the selected top five compound–CD13 complexes. (a) RMSD, root mean square deviation. (b) RMSF, root mean square fluctuation. (c) R g, radius of gyration. (d) SASA, solvent accessible surface area. (e) Hydrogen bonds’ interaction between CD13 and compounds.

RMSF values for all sampled conformations during the 50 ns simulation were also calculated to determine the degree of ligand deviation from the initial position and protein residue movement. In Figure 7b, the initial residue of the protein (0–100 residues) is not very stable. The final imaging results of the five systems basically overlap between 0.05 and 0.2 nm, and all five CD13 complex complexes have almost similar RMSF patterns. This indicates to some extent that the flexibility of the five systems is low, and the overall effect of composite bundling is better. RMSF results of the five complexes confirmed strong binding to CD13 target proteins.

We evaluated the compactness of the CD13-compound complex by RG analysis. The lower R g value indicated that the complex was more compact. We evaluated the compactness of the CD13-compound complex by RG analysis. The lower R g value indicated that the complex was more compact. As can be seen from Figure 7c, the five complexes maintained between 2.85 and 2.89 nm at 0–30 ns. However, R g values of the five compounds increased slightly after 30 ns. After 45 ns, the R g value is basically stable between 2.86 and 2.92 nm. This also shows that the compactness of the protein is constant when the compound binds to the protein and shows a constant interaction during the simulation. R g results showed that the selected compounds were tightly bound to CD13 protein.

In Figure 7d, the SASA values of the five complexes varied between 345 and 375 nm2. CD13–dihydroergotamine complex and CD13–Olysio complex showed high SASA values compared to other complexes. As we can see from Figure 7e, the formation of hydrogen bonds in the CD13 compound complex shows that hydrogen bond formation is constant when the CD13 compound complex is simulated for 50 ns. Most compounds form more than one hydrogen bond.

3.8 MD simulation for PIKfyve

The first five PIKfyve compounds were simulated by RMSD, RMSF, RG, and SASA for 50 ns MD (Figure 8). As shown in Figure 8a, the RMSD value of dihydroergotamine fluctuates greatly from 0 to 15 ns, exceeding 0.3 nm; after 15 ns, the RMSD value is above 0.55 nm, and the overall fluctuation is relatively stable. The other four compounds were also stable after 10 ns. The fluctuation of the root mean square function of five PIKfyve compounds indicates that the compounds have strong binding to the active center of PIKfyve (Figure 8b). All PIKfyve-compound complexes had R g values ranging from 2.4 to 2.55 nm. When the compound was bound to PIKfyve, the R g values of all complexes showed protein compactness, and all complexes were stable and compact (Figure 8c). In addition, it can be seen from Figure 8d that the reported SASA flat value varies between 230 and 280 nm2. After 20 ns, the SASA values of all complexes tended to be stable. Finally, we also calculated the hydrogen bond formation between PIKfyve and the compound. The results showed that all complexes formed more than one hydrogen bond (Figure 8e).

MD trajectory analysis for the selected top five compound–CD13 complexes. (a) RMSD, root mean square deviation. (b) RMSF, root mean square fluctuation. (c) R g, radius of gyration. (d) SASA, solvent accessible surface area. (e) Hydrogen bonds interaction between CD13 and compounds.

3.9 Binding free energy analyses

The binding free energy of seven drugs was calculated by MM/GBSA method through the simulation trajectories of 50 ns MD simulation. The calculated binding free energies of Saquinavir, dihydroergotamine, Raltegravir, Ecteinascidin, and Olysio for the potential target CD13 of SARS‐CoV‐2 were −101.21 ± 11.69, −106.87 ± 13.29, −50.86 ± 18.42, −94.55 ± 15.54, and −84.80 ± 25.66 kcal/mol, respectively, which highlighted dihydroergotamine as the most active one. The van der Waals force was the main driving force for the combination of Saquinavir, dihydroergotamine, Ecteinascidin, and Olysio with CD13 (Table 3). Besides, The calculated binding free energies of Sitagliptin, dihydroergotamine, Saquinavir, Grazoprevir, and Olysio for the potential target PIKfyve of SARS‐CoV‐2 were 93.94 ± 22.86, −107.73 ± 17.65, −184.28 ± 14.22, −119.29 ± 20.82, and −124.35 ± 12.03 kcal/mol. This also indicates that Saquinavir has strong binding activity with PIKfyve. What is more, van der Waals force was the main driving force for the binding of the five compounds to the target protein of PIKfyve (Table 4).

Calculation results of MM/PBSA of 5 CD13–compound complexes

| Saquinavir | Dihydroergotamine | Raltegravir | Ecteinascidin | Olysio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE vdW | −205.34 ± 14.53 | −192.69 ± 12.79 | −184.90 ± 11.61 | −191.89 ± 13.01 | −254.20 ± 9.71 |

| ΔE ele | −50.55 ± 8.075 | −23.73 ± 12.11 | −57.62 ± 12.52 | −27.35 ± 8.15 | −52.36 ± 13.18 |

| ΔE GB | 179.31 ± 16.65 | 130.19 ± 14.33 | 212.58 ± 18.87 | 145.37 ± 19.67 | 248.69 ± 33.87 |

| ΔE SA | −24.64 ± 1.23 | −20.62 ± 0.93 | −20.92 ± 1.15 | −20.68 ± 1.30 | −26.93 ± 1.41 |

| Binding energy | −101.21 ± 11.69 | −106.87 ± 13.29 | −50.86 ± 18.42 | −94.55 ± 15.54 | −84.80 ± 25.66 |

*ΔE vdW = van der Waals energy terms; ΔE ele = electrostatic energy; ΔG GB = polar solvation free energy; ΔG SA = non-polar contribution to solvation (kcal/mol).

Calculation results of MM/PBSA of five PIKfyve–compound complexes

| Sitagliptin | Dihydroergotamine | Saquinavir | Grazoprevir | Olysio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE vdW | −172.20 ± 12.19 | −203.74 ± 15.84 | −307.57 ± 12.20 | −229.80 ± 16.06 | −267.46 ± 14.81 |

| ΔE ele | −58.11 ± 28.35 | −17.88 ± 8.00 | −95.44 ± 7.72 | −16.86 ± 15.56 | 33.36 ± 16.10 |

| ΔE GB | 146.09 ± 20.13 | 136.56 ± 11.41 | 248.91 ± 14.48 | 153.34 ± 27.14 | 206.32 ± 38.48 |

| ΔE SA | −19.73 ± 1.07 | −22.66 ± 1.76 | −30.18 ± 1.02 | −25.97 ± 1.22 | −29.86 ± 1.62 |

| Binding energy | −93.94 ± 22.86 | −107.73 ± 17.65 | −184.28 ± 14.22 | −119.29 ± 20.82 | −124.35 ± 12.03 |

4 Conclusion

At present, we need to urgently find a specific drug for SARS-CoV-2, so as to ease the inconvenience brought by the novel coronavirus pneumonia to people all over the world. In this study, inhibitors against CD13 and PIKfyve, potential targets of SARS-CoV-2 in the human body, were screened from the FDA-approved compound database through electronic virtual high-throughput screening. Dihydroergotamine, Saquinavir, Olysio, Raltegravir, Ecteinascidin, Sitagliptin, and Grazoprevir have been shown to be candidates for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Besides, dihydroergotamine, Saquinavir, and Olysio can simultaneously inhibit CD13 and PIKfyve. Therefore, this study suggested that seven compounds could be further tested for anti-SARS-CoV-2 in vitro, providing more options for the clinical treatment and prevention of COVID-19.

-

Funding information: The study was funded by Project of Sichuan Science and Technology Department. (No. 2020YFQ0010).

-

Author contributions: All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Ruan Z. and Tang J. designed the study. Ruan Z. performed most studies, but a few were carried out by Mingtang Z. Fan P. did a literature search. Ruan Z. collected the data. Tang J. analyzed and interpreted the data. Ruan Z. wrote the text, and the other authors contributed to the final text presentation. All authors have proved the submission.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Ahmad W, Gull B, Baby J, Panicker NG, Khader TA, Akhlaq S, et al. Differentially-regulated miRNAs in COVID-19: A systematic review. Rev Med Virol. 2023;e2449.10.1002/rmv.2449Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Egri SB, Wang X, Diaz-Salinas MA, Luban J, Dudkina NV, Munro JB, et al. Detergent modulates the conformational equilibrium of SARS-CoV-2 Spike during cryo-EM structural determination. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):2527.10.1038/s41467-023-38251-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Yu X, Juraszek J, Rutten L, Bakkers MJG, Blokland S, Melchers JM, et al. Convergence of immune escape strategies highlights plasticity of SARS-CoV-2 spike. PLoS Pathog. 2023;19(5):e1011308.10.1371/journal.ppat.1011308Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Jackson CB, Farzan M, Chen B, Choe H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23(1):3–20.10.1038/s41580-021-00418-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Muralidar S, Ambi SV, Sekaran S, Krishnan UM. The emergence of COVID-19 as a global pandemic: Understanding the epidemiology, immune response and potential therapeutic targets of SARS-CoV-2. Biochimie. 2020;179:85–100.10.1016/j.biochi.2020.09.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Su J, Zheng J, Huang W, Zhang Y, Lv C, Zhang B, et al. PIKfyve inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 and its variants including Omicron. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):167.10.1038/s41392-022-01025-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Lu CY, Amin MA, Fox DA. CD13/aminopeptidase N Is a potential therapeutic target for inflammatory disorders. J Immunol. 2020;204(1):3–11.10.4049/jimmunol.1900868Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Barnieh FM, Loadman PM, Falconer RA. Is tumour-expressed aminopeptidase N (APN/CD13) structurally and functionally unique? Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2021;1876(2):188641.10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188641Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Wang R, Simoneau CR, Kulsuptrakul J, Bouhaddou M, Travisano KA, Hayashi JM, et al. Genetic screens identify host factors for SARS-CoV-2 and common cold coronaviruses. Cell. 2021;184(1):106–19, e14.10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Tortorici MA, Walls AC, Joshi A, Park YJ, Eguia RT, Miranda MC, et al. Structure, receptor recognition, and antigenicity of the human coronavirus CCoV-HuPn-2018 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2022;185(13):2279–91, e17.10.1016/j.cell.2022.05.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Fuochi V, Floresta G, Emma R, Patamia V, Caruso M, Zagni C, et al. Heparan sulfate and enoxaparin interact at the interface of the spike protein of HCoV-229E but not with HCoV-OC43. Viruses. 2023;15(3):663.10.3390/v15030663Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Ou X, Liu Y, Lei X, Li P, Mi D, Ren L, et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1620.10.1038/s41467-020-15562-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Bouhaddou M, Memon D, Meyer B, White KM, Rezelj VV, Correa Marrero M, et al. The global phosphorylation landscape of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell. 2020;182(3):685–712, e19.10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.034Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Artese A, Svicher V, Costa G, Salpini R, Di Maio VC, Alkhatib M, et al. Current status of antivirals and druggable targets of SARS CoV-2 and other human pathogenic coronaviruses. Drug Resist Update. 2020;53:100721.10.1016/j.drup.2020.100721Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Romeo I, Mesiti F, Lupia A, Alcaro S. Current updates on naturally occurring compounds recognizing SARS-CoV-2 druggable targets. Molecules. 2021;26(3):632.10.3390/molecules26030632Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Silberstein SD, Shrewsbury SB, Hoekman J. Dihydroergotamine (DHE) - then and now: A narrative review. Headache. 2020;60(1):40–57.10.1111/head.13700Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Molavi Z, Razi S, Mirmotalebisohi SA, Adibi A, Sameni M, Karami F, et al. Identification of FDA approved drugs against SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro), drug repurposing approach. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;138:111544.10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111544Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Gurung AB, Ali MA, Lee J, Abul Farah M, Al-Anazi KM. In silico screening of FDA approved drugs reveals ergotamine and dihydroergotamine as potential coronavirus main protease enzyme inhibitors. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2020;27(10):2674–82.10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.06.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Gul S, Ozcan O, Asar S, Okyar A, Baris I, Kavakli IH. In silico identification of widely used and well-tolerated drugs as potential SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease and viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors for direct use in clinical trials. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39(17):6772–91.10.1080/07391102.2020.1802346Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Pereira M, Vale N. Saquinavir: From HIV to COVID-19 and cancer treatment. Biomolecules. 2022;12(7):944.10.3390/biom12070944Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Mohamed K, Yazdanpanah N, Saghazadeh A, Rezaei N. Computational drug discovery and repurposing for the treatment of COVID-19: A systematic review. Bioorg Chem. 2021;106:104490.10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104490Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Bello M, Martinez-Munoz A, Balbuena-Rebolledo I. Identification of saquinavir as a potent inhibitor of dimeric SARS-CoV2 main protease through MM/GBSA. J Mol Model. 2020;26(12):340.10.1007/s00894-020-04600-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Chiou WC, Hsu MS, Chen YT, Yang JM, Tsay YG, Huang HC, et al. Repurposing existing drugs: identification of SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease inhibitors. J Enzym Inhib Med Ch. 2021;36(1):147–53.10.1080/14756366.2020.1850710Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Halder UC. Predicted antiviral drugs Darunavir, Amprenavir, Rimantadine and Saquinavir can potentially bind to neutralize SARS-CoV-2 conserved proteins. J Biol Res-Thessalon. 2021;28(1):18.10.1186/s40709-021-00149-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Islam MA, Kibria MK, Hossen MB, Reza MS, Tasmia SA, Tuly KF, et al. Bioinformatics-based investigation on the genetic influence between SARS-CoV-2 infections and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) diseases, and drug repurposing. Sci Rep. 2023 Mar 22;13(1):4685.10.1038/s41598-023-31276-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Muturi E, Hong W, Li JH, Yang W, He J, Wei HP, et al. Effects of simeprevir on the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro and in transgenic hACE2 mice. Int J Antimicrob Ag. 2022;59(1):106499.10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2021.106499Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Lo HS, Hui KPY, Lai HM, He X, Khan KS, Kaur S, et al. Simeprevir potently suppresses SARS-CoV-2 replication and synergizes with Remdesivir. ACS Central Sci. 2021;7(5):792–802.10.1021/acscentsci.0c01186Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Jain P, Thota A, Saini PK, Raghuvanshi RS. Comprehensive review on different analytical techniques for HIV 1-integrase inhibitors: Raltegravir, Dolutegravir, Elvitegravir and Bictegravir. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 2022;1–15.10.1080/10408347.2022.2080493Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Akcora-Yildiz D, Gonulkirmaz N, Ozkan T, Beksac M, Sunguroglu A. HIV-1 integrase inhibitor raltegravir promotes DNA damage-induced apoptosis in multiple myeloma. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2023.10.1111/cbdd.14237Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Sanfilippo R, Hindi N, Cruz Jurado J, Blay JY, Lopez-Pousa A, Italiano A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of trabectedin and radiotherapy for patients with myxoid liposarcoma: A nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(5):656–63.10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.0056Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Gao Y, Tu N, Liu X, Lu K, Chen S, Guo J. Progress in the total synthesis of antitumor tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids. Chem Biodivers. 2023;20(5):e202300172.10.1002/cbdv.202300172Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Aleebrahim-Dehkordi E, Ghoshouni H, Koochaki P, Esmaili-Dehkordi M, Aleebrahim E, Chichagi F, et al. Targeting the vital non-structural proteins (NSP12, NSP7, NSP8 and NSP3) from SARS-CoV-2 and inhibition of RNA polymerase by natural bioactive compound naringenin as a promising drug candidate against COVID-19. J Mol Struct. 2023;1287:135642.10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.135642Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Narayanan A, Narwal M, Majowicz SA, Varricchio C, Toner SA, Ballatore C, et al. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors targeting Mpro and PLpro using in-cell-protease assay. Commun Biol. 2022;5(1):169.10.1038/s42003-022-03090-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Qi JH, Chen PY, Cai DY, Wang Y, Wei YL, He SP, et al. Exploring novel targets of sitagliptin for type 2 diabetes mellitus: Network pharmacology, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, and SPR approaches. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;13:1096655.10.3389/fendo.2022.1096655Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Hill DD, Kramer JR, Chaffin KR, Mast TC, Robertson MN, Kanwal F, et al. Effectiveness of elbasvir/grazoprevir plus ribavirin for hepatitis C virus genotype 1a infection and baseline NS5A resistance. Ann Hepatol. 2023;28(2):100899.10.1016/j.aohep.2023.100899Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Prabhu AR, Rao IR, Nagaraju SP, Rajwar E, Venkatesh BT, Nair NS, et al. Interventions for dialysis patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;4(4):CD007003.10.1002/14651858.CD007003.pub3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Bardaweel SK, Hajjo R, Sabbah DA. Sitagliptin: A potential drug for the treatment of COVID-19? Acta Pharmaceut. 2021;71(2):175–84.10.2478/acph-2021-0013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Albogami SM, Jean-Marc S, Nadwa EH, Hafiz AA, et al. Potential therapeutic benefits of metformin alone and in combination with sitagliptin in the management of type 2 diabetes patients with COVID-19. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(11):1361.10.3390/ph15111361Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Systemic investigation of inetetamab in combination with small molecules to treat HER2-overexpressing breast and gastric cancers

- Immunosuppressive treatment for idiopathic membranous nephropathy: An updated network meta-analysis

- Identifying two pathogenic variants in a patient with pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy

- Effects of phytoestrogens combined with cold stress on sperm parameters and testicular proteomics in rats

- A case of pulmonary embolism with bad warfarin anticoagulant effects caused by E. coli infection

- Neutrophilia with subclinical Cushing’s disease: A case report and literature review

- Isoimperatorin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced periodontitis by downregulating ERK1/2 and NF-κB pathways

- Immunoregulation of synovial macrophages for the treatment of osteoarthritis

- Novel CPLANE1 c.8948dupT (p.P2984Tfs*7) variant in a child patient with Joubert syndrome

- Antiphospholipid antibodies and the risk of thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms

- Immunological responses of septic rats to combination therapy with thymosin α1 and vitamin C

- High glucose and high lipid induced mitochondrial dysfunction in JEG-3 cells through oxidative stress

- Pharmacological inhibition of the ubiquitin-specific protease 8 effectively suppresses glioblastoma cell growth

- Levocarnitine regulates the growth of angiotensin II-induced myocardial fibrosis cells via TIMP-1

- Age-related changes in peripheral T-cell subpopulations in elderly individuals: An observational study

- Single-cell transcription analysis reveals the tumor origin and heterogeneity of human bilateral renal clear cell carcinoma

- Identification of iron metabolism-related genes as diagnostic signatures in sepsis by blood transcriptomic analysis

- Long noncoding RNA ACART knockdown decreases 3T3-L1 preadipocyte proliferation and differentiation

- Surgery, adjuvant immunotherapy plus chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary malignant melanoma of the parotid gland (PGMM): A case report

- Dosimetry comparison with helical tomotherapy, volumetric modulated arc therapy, and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for grade II gliomas: A single‑institution case series

- Soy isoflavone reduces LPS-induced acute lung injury via increasing aquaporin 1 and aquaporin 5 in rats

- Refractory hypokalemia with sexual dysplasia and infertility caused by 17α-hydroxylase deficiency and triple X syndrome: A case report

- Meta-analysis of cancer risk among end stage renal disease undergoing maintenance dialysis

- 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase inhibition arrests growth and induces apoptosis in gastric cancer via AMPK activation and oxidative stress

- Experimental study on the optimization of ANM33 release in foam cells

- Primary retroperitoneal angiosarcoma: A case report

- Metabolomic analysis-identified 2-hydroxybutyric acid might be a key metabolite of severe preeclampsia

- Malignant pleural effusion diagnosis and therapy

- Effect of spaceflight on the phenotype and proteome of Escherichia coli

- Comparison of immunotherapy combined with stereotactic radiotherapy and targeted therapy for patients with brain metastases: A systemic review and meta-analysis

- Activation of hypermethylated P2RY1 mitigates gastric cancer by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation

- Association between the VEGFR-2 -604T/C polymorphism (rs2071559) and type 2 diabetic retinopathy

- The role of IL-31 and IL-34 in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic periodontitis

- Triple-negative mouse breast cancer initiating cells show high expression of beta1 integrin and increased malignant features

- mNGS facilitates the accurate diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of suspicious critical CNS infection in real practice: A retrospective study

- The apatinib and pemetrexed combination has antitumor and antiangiogenic effects against NSCLC

- Radiotherapy for primary thyroid adenoid cystic carcinoma

- Design and functional preliminary investigation of recombinant antigen EgG1Y162–EgG1Y162 against Echinococcus granulosus

- Effects of losartan in patients with NAFLD: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial

- Bibliometric analysis of METTL3: Current perspectives, highlights, and trending topics

- Performance comparison of three scaling algorithms in NMR-based metabolomics analysis

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and its related molecules participate in PROK1 silence-induced anti-tumor effects on pancreatic cancer

- The altered expression of cytoskeletal and synaptic remodeling proteins during epilepsy

- Effects of pegylated recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on lymphocytes and white blood cells of patients with malignant tumor

- Prostatitis as initial manifestation of Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia diagnosed by metagenome next-generation sequencing: A case report

- NUDT21 relieves sevoflurane-induced neurological damage in rats by down-regulating LIMK2

- Association of interleukin-10 rs1800896, rs1800872, and interleukin-6 rs1800795 polymorphisms with squamous cell carcinoma risk: A meta-analysis

- Exosomal HBV-DNA for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of chronic hepatitis B

- Shear stress leads to the dysfunction of endothelial cells through the Cav-1-mediated KLF2/eNOS/ERK signaling pathway under physiological conditions

- Interaction between the PI3K/AKT pathway and mitochondrial autophagy in macrophages and the leukocyte count in rats with LPS-induced pulmonary infection

- Meta-analysis of the rs231775 locus polymorphism in the CTLA-4 gene and the susceptibility to Graves’ disease in children

- Cloning, subcellular localization and expression of phosphate transporter gene HvPT6 of hulless barley

- Coptisine mitigates diabetic nephropathy via repressing the NRLP3 inflammasome

- Significant elevated CXCL14 and decreased IL-39 levels in patients with tuberculosis

- Whole-exome sequencing applications in prenatal diagnosis of fetal bowel dilatation

- Gemella morbillorum infective endocarditis: A case report and literature review

- An unusual ectopic thymoma clonal evolution analysis: A case report

- Severe cumulative skin toxicity during toripalimab combined with vemurafenib following toripalimab alone

- Detection of V. vulnificus septic shock with ARDS using mNGS

- Novel rare genetic variants of familial and sporadic pulmonary atresia identified by whole-exome sequencing

- The influence and mechanistic action of sperm DNA fragmentation index on the outcomes of assisted reproduction technology

- Novel compound heterozygous mutations in TELO2 in an infant with You-Hoover-Fong syndrome: A case report and literature review

- ctDNA as a prognostic biomarker in resectable CLM: Systematic review and meta-analysis

- Diagnosis of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis by metagenomic next-generation sequencing: A case report

- Phylogenetic analysis of promoter regions of human Dolichol kinase (DOLK) and orthologous genes using bioinformatics tools

- Collagen changes in rabbit conjunctiva after conjunctival crosslinking

- Effects of NM23 transfection of human gastric carcinoma cells in mice

- Oral nifedipine and phytosterol, intravenous nicardipine, and oral nifedipine only: Three-arm, retrospective, cohort study for management of severe preeclampsia

- Case report of hepatic retiform hemangioendothelioma: A rare tumor treated with ultrasound-guided microwave ablation

- Curcumin induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by decreasing the expression of STAT3/VEGF/HIF-1α signaling

- Rare presentation of double-clonal Waldenström macroglobulinemia with pulmonary embolism: A case report

- Giant duplication of the transverse colon in an adult: A case report and literature review

- Ectopic thyroid tissue in the breast: A case report

- SDR16C5 promotes proliferation and migration and inhibits apoptosis in pancreatic cancer

- Vaginal metastasis from breast cancer: A case report

- Screening of the best time window for MSC transplantation to treat acute myocardial infarction with SDF-1α antibody-loaded targeted ultrasonic microbubbles: An in vivo study in miniswine

- Inhibition of TAZ impairs the migration ability of melanoma cells

- Molecular complexity analysis of the diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome in China

- Effects of maternal calcium and protein intake on the development and bone metabolism of offspring mice

- Identification of winter wheat pests and diseases based on improved convolutional neural network

- Ultra-multiplex PCR technique to guide treatment of Aspergillus-infected aortic valve prostheses

- Virtual high-throughput screening: Potential inhibitors targeting aminopeptidase N (CD13) and PIKfyve for SARS-CoV-2

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients with COVID-19

- Utility of methylene blue mixed with autologous blood in preoperative localization of pulmonary nodules and masses

- Integrated analysis of the microbiome and transcriptome in stomach adenocarcinoma

- Berberine suppressed sarcopenia insulin resistance through SIRT1-mediated mitophagy

- DUSP2 inhibits the progression of lupus nephritis in mice by regulating the STAT3 pathway

- Lung abscess by Fusobacterium nucleatum and Streptococcus spp. co-infection by mNGS: A case series

- Genetic alterations of KRAS and TP53 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma associated with poor prognosis

- Granulomatous polyangiitis involving the fourth ventricle: Report of a rare case and a literature review

- Studying infant mortality: A demographic analysis based on data mining models

- Metaplastic breast carcinoma with osseous differentiation: A report of a rare case and literature review

- Protein Z modulates the metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma cells

- Inhibition of pyroptosis and apoptosis by capsaicin protects against LPS-induced acute kidney injury through TRPV1/UCP2 axis in vitro

- TAK-242, a toll-like receptor 4 antagonist, against brain injury by alleviates autophagy and inflammation in rats

- Primary mediastinum Ewing’s sarcoma with pleural effusion: A case report and literature review

- Association of ADRB2 gene polymorphisms and intestinal microbiota in Chinese Han adolescents

- Tanshinone IIA alleviates chondrocyte apoptosis and extracellular matrix degeneration by inhibiting ferroptosis

- Study on the cytokines related to SARS-Cov-2 in testicular cells and the interaction network between cells based on scRNA-seq data

- Effect of periostin on bone metabolic and autophagy factors during tooth eruption in mice

- HP1 induces ferroptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells through NRF2 pathway in diabetic nephropathy

- Intravaginal estrogen management in postmenopausal patients with vaginal squamous intraepithelial lesions along with CO2 laser ablation: A retrospective study

- Hepatocellular carcinoma cell differentiation trajectory predicts immunotherapy, potential therapeutic drugs, and prognosis of patients

- Effects of physical exercise on biomarkers of oxidative stress in healthy subjects: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Identification of lysosome-related genes in connection with prognosis and immune cell infiltration for drug candidates in head and neck cancer

- Development of an instrument-free and low-cost ELISA dot-blot test to detect antibodies against SARS-CoV-2

- Research progress on gas signal molecular therapy for Parkinson’s disease

- Adiponectin inhibits TGF-β1-induced skin fibroblast proliferation and phenotype transformation via the p38 MAPK signaling pathway

- The G protein-coupled receptor-related gene signatures for predicting prognosis and immunotherapy response in bladder urothelial carcinoma

- α-Fetoprotein contributes to the malignant biological properties of AFP-producing gastric cancer

- CXCL12/CXCR4/CXCR7 axis in placenta tissues of patients with placenta previa

- Association between thyroid stimulating hormone levels and papillary thyroid cancer risk: A meta-analysis

- Significance of sTREM-1 and sST2 combined diagnosis for sepsis detection and prognosis prediction

- Diagnostic value of serum neuroactive substances in the acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease complicated with depression

- Research progress of AMP-activated protein kinase and cardiac aging

- TRIM29 knockdown prevented the colon cancer progression through decreasing the ubiquitination levels of KRT5

- Cross-talk between gut microbiota and liver steatosis: Complications and therapeutic target

- Metastasis from small cell lung cancer to ovary: A case report

- The early diagnosis and pathogenic mechanisms of sepsis-related acute kidney injury

- The effect of NK cell therapy on sepsis secondary to lung cancer: A case report

- Erianin alleviates collagen-induced arthritis in mice by inhibiting Th17 cell differentiation

- Loss of ACOX1 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and its correlation with clinical features

- Signalling pathways in the osteogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells

- Crosstalk between lactic acid and immune regulation and its value in the diagnosis and treatment of liver failure

- Clinicopathological features and differential diagnosis of gastric pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma

- Traumatic brain injury and rTMS-ERPs: Case report and literature review

- Extracellular fibrin promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression through integrin β1/PTEN/AKT signaling

- Knockdown of DLK4 inhibits non-small cell lung cancer tumor growth by downregulating CKS2

- The co-expression pattern of VEGFR-2 with indicators related to proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation of anagen hair follicles

- Inflammation-related signaling pathways in tendinopathy

- CD4+ T cell count in HIV/TB co-infection and co-occurrence with HL: Case report and literature review

- Clinical analysis of severe Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia: Case series study

- Bioinformatics analysis to identify potential biomarkers for the pulmonary artery hypertension associated with the basement membrane

- Influence of MTHFR polymorphism, alone or in combination with smoking and alcohol consumption, on cancer susceptibility

- Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don counteracts the ampicillin resistance in multiple antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by downregulation of PBP2a synthesis

- Combination of a bronchogenic cyst in the thoracic spinal canal with chronic myelocytic leukemia

- Bacterial lipoprotein plays an important role in the macrophage autophagy and apoptosis induced by Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus

- TCL1A+ B cells predict prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer through integrative analysis of single-cell and bulk transcriptomic data

- Ezrin promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression via the Hippo signaling pathway

- Ferroptosis: A potential target of macrophages in plaque vulnerability

- Predicting pediatric Crohn's disease based on six mRNA-constructed risk signature using comprehensive bioinformatic approaches

- Applications of genetic code expansion and photosensitive UAAs in studying membrane proteins

- HK2 contributes to the proliferation, migration, and invasion of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells by enhancing the ERK1/2 signaling pathway

- IL-17 in osteoarthritis: A narrative review

- Circadian cycle and neuroinflammation

- Probiotic management and inflammatory factors as a novel treatment in cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Hemorrhagic meningioma with pulmonary metastasis: Case report and literature review

- SPOP regulates the expression profiles and alternative splicing events in human hepatocytes

- Knockdown of SETD5 inhibited glycolysis and tumor growth in gastric cancer cells by down-regulating Akt signaling pathway

- PTX3 promotes IVIG resistance-induced endothelial injury in Kawasaki disease by regulating the NF-κB pathway

- Pancreatic ectopic thyroid tissue: A case report and analysis of literature

- The prognostic impact of body mass index on female breast cancer patients in underdeveloped regions of northern China differs by menopause status and tumor molecular subtype

- Report on a case of liver-originating malignant melanoma of unknown primary

- Case report: Herbal treatment of neutropenic enterocolitis after chemotherapy for breast cancer

- The fibroblast growth factor–Klotho axis at molecular level

- Characterization of amiodarone action on currents in hERG-T618 gain-of-function mutations

- A case report of diagnosis and dynamic monitoring of Listeria monocytogenes meningitis with NGS

- Effect of autologous platelet-rich plasma on new bone formation and viability of a Marburg bone graft

- Small breast epithelial mucin as a useful prognostic marker for breast cancer patients

- Continuous non-adherent culture promotes transdifferentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells into retinal lineage

- Nrf3 alleviates oxidative stress and promotes the survival of colon cancer cells by activating AKT/BCL-2 signal pathway

- Favorable response to surufatinib in a patient with necrolytic migratory erythema: A case report

- Case report of atypical undernutrition of hypoproteinemia type

- Down-regulation of COL1A1 inhibits tumor-associated fibroblast activation and mediates matrix remodeling in the tumor microenvironment of breast cancer

- Sarcoma protein kinase inhibition alleviates liver fibrosis by promoting hepatic stellate cells ferroptosis

- Research progress of serum eosinophil in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma

- Clinicopathological characteristics of co-existing or mixed colorectal cancer and neuroendocrine tumor: Report of five cases

- Role of menopausal hormone therapy in the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis

- Precisional detection of lymph node metastasis using tFCM in colorectal cancer

- Advances in diagnosis and treatment of perimenopausal syndrome

- A study of forensic genetics: ITO index distribution and kinship judgment between two individuals

- Acute lupus pneumonitis resembling miliary tuberculosis: A case-based review

- Plasma levels of CD36 and glutathione as biomarkers for ruptured intracranial aneurysm

- Fractalkine modulates pulmonary angiogenesis and tube formation by modulating CX3CR1 and growth factors in PVECs

- Novel risk prediction models for deep vein thrombosis after thoracotomy and thoracoscopic lung cancer resections, involving coagulation and immune function

- Exploring the diagnostic markers of essential tremor: A study based on machine learning algorithms

- Evaluation of effects of small-incision approach treatment on proximal tibia fracture by deep learning algorithm-based magnetic resonance imaging

- An online diagnosis method for cancer lesions based on intelligent imaging analysis

- Medical imaging in rheumatoid arthritis: A review on deep learning approach

- Predictive analytics in smart healthcare for child mortality prediction using a machine learning approach

- Utility of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio and platelet–lymphocyte ratio in predicting acute-on-chronic liver failure survival

- A biomedical decision support system for meta-analysis of bilateral upper-limb training in stroke patients with hemiplegia

- TNF-α and IL-8 levels are positively correlated with hypobaric hypoxic pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling in rats

- Stochastic gradient descent optimisation for convolutional neural network for medical image segmentation

- Comparison of the prognostic value of four different critical illness scores in patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy

- Application and teaching of computer molecular simulation embedded technology and artificial intelligence in drug research and development

- Hepatobiliary surgery based on intelligent image segmentation technology

- Value of brain injury-related indicators based on neural network in the diagnosis of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- Analysis of early diagnosis methods for asymmetric dementia in brain MR images based on genetic medical technology

- Early diagnosis for the onset of peri-implantitis based on artificial neural network

- Clinical significance of the detection of serum IgG4 and IgG4/IgG ratio in patients with thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy

- Forecast of pain degree of lumbar disc herniation based on back propagation neural network

- SPA-UNet: A liver tumor segmentation network based on fused multi-scale features

- Systematic evaluation of clinical efficacy of CYP1B1 gene polymorphism in EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer observed by medical image

- Rehabilitation effect of intelligent rehabilitation training system on hemiplegic limb spasms after stroke

- A novel approach for minimising anti-aliasing effects in EEG data acquisition

- ErbB4 promotes M2 activation of macrophages in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Clinical role of CYP1B1 gene polymorphism in prediction of postoperative chemotherapy efficacy in NSCLC based on individualized health model

- Lung nodule segmentation via semi-residual multi-resolution neural networks

- Evaluation of brain nerve function in ICU patients with Delirium by deep learning algorithm-based resting state MRI

- A data mining technique for detecting malignant mesothelioma cancer using multiple regression analysis

- Markov model combined with MR diffusion tensor imaging for predicting the onset of Alzheimer’s disease

- Effectiveness of the treatment of depression associated with cancer and neuroimaging changes in depression-related brain regions in patients treated with the mediator-deuterium acupuncture method

- Molecular mechanism of colorectal cancer and screening of molecular markers based on bioinformatics analysis

- Monitoring and evaluation of anesthesia depth status data based on neuroscience

- Exploring the conformational dynamics and thermodynamics of EGFR S768I and G719X + S768I mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: An in silico approaches

- Optimised feature selection-driven convolutional neural network using gray level co-occurrence matrix for detection of cervical cancer

- Incidence of different pressure patterns of spinal cerebellar ataxia and analysis of imaging and genetic diagnosis

- Pathogenic bacteria and treatment resistance in older cardiovascular disease patients with lung infection and risk prediction model

- Adoption value of support vector machine algorithm-based computed tomography imaging in the diagnosis of secondary pulmonary fungal infections in patients with malignant hematological disorders

- From slides to insights: Harnessing deep learning for prognostic survival prediction in human colorectal cancer histology

- Ecology and Environmental Science

- Monitoring of hourly carbon dioxide concentration under different land use types in arid ecosystem

- Comparing the differences of prokaryotic microbial community between pit walls and bottom from Chinese liquor revealed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing

- Effects of cadmium stress on fruits germination and growth of two herbage species

- Bamboo charcoal affects soil properties and bacterial community in tea plantations

- Optimization of biogas potential using kinetic models, response surface methodology, and instrumental evidence for biodegradation of tannery fleshings during anaerobic digestion

- Understory vegetation diversity patterns of Platycladus orientalis and Pinus elliottii communities in Central and Southern China

- Studies on macrofungi diversity and discovery of new species of Abortiporus from Baotianman World Biosphere Reserve

- Food Science

- Effect of berrycactus fruit (Myrtillocactus geometrizans) on glutamate, glutamine, and GABA levels in the frontal cortex of rats fed with a high-fat diet

- Guesstimate of thymoquinone diversity in Nigella sativa L. genotypes and elite varieties collected from Indian states using HPTLC technique

- Analysis of bacterial community structure of Fuzhuan tea with different processing techniques

- Untargeted metabolomics reveals sour jujube kernel benefiting the nutritional value and flavor of Morchella esculenta

- Mycobiota in Slovak wine grapes: A case study from the small Carpathians wine region

- Elemental analysis of Fadogia ancylantha leaves used as a nutraceutical in Mashonaland West Province, Zimbabwe

- Microbiological transglutaminase: Biotechnological application in the food industry

- Influence of solvent-free extraction of fish oil from catfish (Clarias magur) heads using a Taguchi orthogonal array design: A qualitative and quantitative approach

- Chromatographic analysis of the chemical composition and anticancer activities of Curcuma longa extract cultivated in Palestine

- The potential for the use of leghemoglobin and plant ferritin as sources of iron

- Investigating the association between dietary patterns and glycemic control among children and adolescents with T1DM

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Biocompatibility and osteointegration capability of β-TCP manufactured by stereolithography 3D printing: In vitro study

- Clinical characteristics and the prognosis of diabetic foot in Tibet: A single center, retrospective study

- Agriculture

- Biofertilizer and NPSB fertilizer application effects on nodulation and productivity of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) at Sodo Zuria, Southern Ethiopia

- On correlation between canopy vegetation and growth indexes of maize varieties with different nitrogen efficiencies

- Exopolysaccharides from Pseudomonas tolaasii inhibit the growth of Pleurotus ostreatus mycelia

- A transcriptomic evaluation of the mechanism of programmed cell death of the replaceable bud in Chinese chestnut

- Melatonin enhances salt tolerance in sorghum by modulating photosynthetic performance, osmoregulation, antioxidant defense, and ion homeostasis

- Effects of plant density on alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) seed yield in western Heilongjiang areas

- Identification of rice leaf diseases and deficiency disorders using a novel DeepBatch technique

- Artificial intelligence and internet of things oriented sustainable precision farming: Towards modern agriculture

- Animal Sciences

- Effect of ketogenic diet on exercise tolerance and transcriptome of gastrocnemius in mice

- Combined analysis of mRNA–miRNA from testis tissue in Tibetan sheep with different FecB genotypes

- Isolation, identification, and drug resistance of a partially isolated bacterium from the gill of Siniperca chuatsi

- Tracking behavioral changes of confined sows from the first mating to the third parity

- The sequencing of the key genes and end products in the TLR4 signaling pathway from the kidney of Rana dybowskii exposed to Aeromonas hydrophila

- Development of a new candidate vaccine against piglet diarrhea caused by Escherichia coli

- Plant Sciences

- Crown and diameter structure of pure Pinus massoniana Lamb. forest in Hunan province, China

- Genetic evaluation and germplasm identification analysis on ITS2, trnL-F, and psbA-trnH of alfalfa varieties germplasm resources

- Tissue culture and rapid propagation technology for Gentiana rhodantha

- Effects of cadmium on the synthesis of active ingredients in Salvia miltiorrhiza

- Cloning and expression analysis of VrNAC13 gene in mung bean

- Chlorate-induced molecular floral transition revealed by transcriptomes

- Effects of warming and drought on growth and development of soybean in Hailun region

- Effects of different light conditions on transient expression and biomass in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves

- Comparative analysis of the rhizosphere microbiome and medicinally active ingredients of Atractylodes lancea from different geographical origins

- Distinguish Dianthus species or varieties based on chloroplast genomes

- Comparative transcriptomes reveal molecular mechanisms of apple blossoms of different tolerance genotypes to chilling injury

- Study on fresh processing key technology and quality influence of Cut Ophiopogonis Radix based on multi-index evaluation

- An advanced approach for fig leaf disease detection and classification: Leveraging image processing and enhanced support vector machine methodology

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Protein Z modulates the metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma cells”

- Erratum to “BRCA1 subcellular localization regulated by PI3K signaling pathway in triple-negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells and hormone-sensitive T47D cells”

- Retraction

- Retraction to “Protocatechuic acid attenuates cerebral aneurysm formation and progression by inhibiting TNF-alpha/Nrf-2/NF-kB-mediated inflammatory mechanisms in experimental rats”

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Systemic investigation of inetetamab in combination with small molecules to treat HER2-overexpressing breast and gastric cancers

- Immunosuppressive treatment for idiopathic membranous nephropathy: An updated network meta-analysis

- Identifying two pathogenic variants in a patient with pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy

- Effects of phytoestrogens combined with cold stress on sperm parameters and testicular proteomics in rats

- A case of pulmonary embolism with bad warfarin anticoagulant effects caused by E. coli infection

- Neutrophilia with subclinical Cushing’s disease: A case report and literature review

- Isoimperatorin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced periodontitis by downregulating ERK1/2 and NF-κB pathways

- Immunoregulation of synovial macrophages for the treatment of osteoarthritis

- Novel CPLANE1 c.8948dupT (p.P2984Tfs*7) variant in a child patient with Joubert syndrome

- Antiphospholipid antibodies and the risk of thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms

- Immunological responses of septic rats to combination therapy with thymosin α1 and vitamin C

- High glucose and high lipid induced mitochondrial dysfunction in JEG-3 cells through oxidative stress

- Pharmacological inhibition of the ubiquitin-specific protease 8 effectively suppresses glioblastoma cell growth

- Levocarnitine regulates the growth of angiotensin II-induced myocardial fibrosis cells via TIMP-1

- Age-related changes in peripheral T-cell subpopulations in elderly individuals: An observational study

- Single-cell transcription analysis reveals the tumor origin and heterogeneity of human bilateral renal clear cell carcinoma

- Identification of iron metabolism-related genes as diagnostic signatures in sepsis by blood transcriptomic analysis

- Long noncoding RNA ACART knockdown decreases 3T3-L1 preadipocyte proliferation and differentiation

- Surgery, adjuvant immunotherapy plus chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary malignant melanoma of the parotid gland (PGMM): A case report

- Dosimetry comparison with helical tomotherapy, volumetric modulated arc therapy, and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for grade II gliomas: A single‑institution case series

- Soy isoflavone reduces LPS-induced acute lung injury via increasing aquaporin 1 and aquaporin 5 in rats

- Refractory hypokalemia with sexual dysplasia and infertility caused by 17α-hydroxylase deficiency and triple X syndrome: A case report

- Meta-analysis of cancer risk among end stage renal disease undergoing maintenance dialysis

- 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase inhibition arrests growth and induces apoptosis in gastric cancer via AMPK activation and oxidative stress

- Experimental study on the optimization of ANM33 release in foam cells

- Primary retroperitoneal angiosarcoma: A case report

- Metabolomic analysis-identified 2-hydroxybutyric acid might be a key metabolite of severe preeclampsia

- Malignant pleural effusion diagnosis and therapy

- Effect of spaceflight on the phenotype and proteome of Escherichia coli

- Comparison of immunotherapy combined with stereotactic radiotherapy and targeted therapy for patients with brain metastases: A systemic review and meta-analysis

- Activation of hypermethylated P2RY1 mitigates gastric cancer by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation

- Association between the VEGFR-2 -604T/C polymorphism (rs2071559) and type 2 diabetic retinopathy

- The role of IL-31 and IL-34 in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic periodontitis

- Triple-negative mouse breast cancer initiating cells show high expression of beta1 integrin and increased malignant features

- mNGS facilitates the accurate diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of suspicious critical CNS infection in real practice: A retrospective study

- The apatinib and pemetrexed combination has antitumor and antiangiogenic effects against NSCLC

- Radiotherapy for primary thyroid adenoid cystic carcinoma

- Design and functional preliminary investigation of recombinant antigen EgG1Y162–EgG1Y162 against Echinococcus granulosus

- Effects of losartan in patients with NAFLD: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial

- Bibliometric analysis of METTL3: Current perspectives, highlights, and trending topics

- Performance comparison of three scaling algorithms in NMR-based metabolomics analysis

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and its related molecules participate in PROK1 silence-induced anti-tumor effects on pancreatic cancer

- The altered expression of cytoskeletal and synaptic remodeling proteins during epilepsy

- Effects of pegylated recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on lymphocytes and white blood cells of patients with malignant tumor

- Prostatitis as initial manifestation of Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia diagnosed by metagenome next-generation sequencing: A case report

- NUDT21 relieves sevoflurane-induced neurological damage in rats by down-regulating LIMK2

- Association of interleukin-10 rs1800896, rs1800872, and interleukin-6 rs1800795 polymorphisms with squamous cell carcinoma risk: A meta-analysis

- Exosomal HBV-DNA for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of chronic hepatitis B

- Shear stress leads to the dysfunction of endothelial cells through the Cav-1-mediated KLF2/eNOS/ERK signaling pathway under physiological conditions

- Interaction between the PI3K/AKT pathway and mitochondrial autophagy in macrophages and the leukocyte count in rats with LPS-induced pulmonary infection

- Meta-analysis of the rs231775 locus polymorphism in the CTLA-4 gene and the susceptibility to Graves’ disease in children

- Cloning, subcellular localization and expression of phosphate transporter gene HvPT6 of hulless barley

- Coptisine mitigates diabetic nephropathy via repressing the NRLP3 inflammasome

- Significant elevated CXCL14 and decreased IL-39 levels in patients with tuberculosis

- Whole-exome sequencing applications in prenatal diagnosis of fetal bowel dilatation