Abstract

Halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons, owing to the stable structure imparted by their halogen substituents and benzene ring, are among the Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) with relatively high toxicity and are notoriously resistant to degradation. In this work, the density functional method with the B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) level set was employed to investigate the effects of external electric fields on the total energy, LUMO(lowest unoccupied molecular orbital), HOMO, (highest occupied molecular orbital), EG (energy gap) and dissociation characteristics of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene molecule. The results show that the electric field along the X axis changes from −0.025 a.u. to 0.025 a.u. During the process, the C–Br bond length of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene molecule increases gradually, while the C–Cl bond length changes inversely. The dipole moment initially decreases and then increases, while the total energy of the molecular system shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. The EG first increases and then decreases with the strengthening with the external electric field. The positive external electric field causes the C–Br bond vibration peak to redshift, and the C–Cl bond vibration peak to blue shift. Simultaneously, the first 9 excited states undergo a red shift in wavelength, resulting in a decrease in excitation energy. In addition, C–Br and C–Cl are found to break in sequence by scanning in the external electric field, which provides a theoretical basis for the dissociation of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene molecule.

1 Introduction

The ozone layer, situated in the stratosphere, absorbs nearly all ultraviolet (UV) radiation below 300 nm [1]. However, halogen atoms generated from UV-induced decomposition of anthropogenic organic pollutants react catalytically with ozone, contributing to ozone depletion [2]. This process increases ground-level UV exposure, posing global health risks to ecosystems. International agreements like the “On ozone layer destruction and protection” reflect growing efforts to mitigate this issue [3]. Halogenated organic compounds are particularly concerning due to their persistence, mobility, bioaccumulation potential, and toxicity [4], 5]. For instance, 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene (C6H4BrCl), widely used in industrial processes, undergoes UV-driven atmospheric decomposition to release bromine radicals. These radicals initiate a chain reaction: first converting ozone (O3) to bromine oxide (BrO) and oxygen (O2), then regenerating bromine radicals through further BrO–O3 interactions, perpetuating ozone destruction [6]. Current degradation strategies include mechanochemical methods. Yu et al. [5]. optimized milling parameters (600 rpm rotation speed, 12.6:1 ball-to-material ratio, 102:1 reagent ratio) for dehalogenation efficiency, identifying CaO as the most effective reagent. Similarly, Liu [7] demonstrated mechanochemical degradation but noted limitations: solvent-free requirements complicate operational scalability, while mechanical force may induce undesirable side reactions. Despite these advances, electric field-assisted degradation remains unexplored for 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene, suggesting a novel pathway for sustainable pollutant mitigation.

The physical and chemical transformations of molecules under external electric fields remain a central focus in theoretical research [8]. Zhang et al. [9] demonstrated through density functional theory (DFT) calculations that arsenic chloride undergoes structural modifications under electric fields. Time-dependent DFT analysis of the first nine excited states revealed that strong fields induce molecular dissociation. Zhou et al. [10] investigated vinyl bromide using DFT under an electric field oriented at 11.2° relative to the C–Br bond. Their results showed intensified vibrations in C=C, C–Br, and C–H bonds with increasing field strength, culminating in C–Br bond cleavage. Complete decomposition occurred at 154.26 V nm−1 when the energy barrier vanished. Xia et al. [11] observed that phenol molecules exhibit elongated C–C and C–O bonds under increasing electric fields. Enhanced electronegativity at adjacent carbon and oxygen atoms, reduced energy gaps, and infrared spectral red shifts collectively indicate heightened chemical reactivity. Dissociation occurs as energy barriers diminish. Comparative analyses confirm that external fields substantially alter molecular geometry, energy states, spectral characteristics, and charge distribution, inducing profound molecular transformations [12], [13], [14]. Electric field application emerges as an effective molecular degradation strategy. Unlike experimental approaches, theoretical investigations eliminate the need for chemical reagents or catalysts, streamlining processes and reducing costs. Furthermore, electric fields enable precise control over reaction pathways, rates, and selectivity. This offers innovative solutions for chemical manufacturing and environmental protection, aligning with contemporary strategies for green chemistry and sustainable development.

This study employs density functional theory (DFT) [15] with the B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) basis set to systematically investigate the properties of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under external electric fields. The study began with geometry optimization of the ground-state structure, followed by calculations of bond lengths (C–Br and C–Cl), dipole moments, energy levels, frontier molecular orbitals (HOMO-LUMO), energy gaps, infrared spectra, and dissociation characteristics under electric fields ranging from −0.025 to 0.025 atomic units. In this study, we investigate the degradation behavior of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene in the bulk phase under external electric fields ranging from −0.025 a.u. to +0.025 a.u. The molecule is modeled using a molecular cluster model to simulate the behavior in a bulk-like environment without surface effects. The calculated properties include bond lengths (C–Br and C–Cl), dipole moments, atomic charges, infrared spectra, excitation states, and dissociation behaviors. A comprehensive analysis of the optimized structure, spectral features, and dissociation behavior revealed critical insights into the molecule’s physicochemical properties. These findings advance fundamental understanding of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene while establishing a theoretical framework for its targeted degradation, demonstrating significant practical implications.

2 Theory and computational method

The Hamiltonian H of the 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene molecule under the influence of an external electric field is:

where H 0 is the Hamiltonian without the electric field and H int is the Hamiltonian of the interaction between the electric field and the molecular system. Based on the dipole approximation:

where μ is the dipole moment and F is the external electric field The electric field selected in this work is −0.025 a.u. ∼ 0.025 a. u. where 1 a.u = 5.14225 × 1011 V m−1 [16].

For all field strengths examined, the energy gap between frontier molecular orbitals was calculated using Eq. (3)

Theoretical calculations were conducted using Gaussian16 software [17]. Multiple computational methods and basis sets were evaluated for optimizing 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under zero-field conditions. The B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) methodology [8] demonstrated the closest agreement with experimental C–Br bond lengths and was selected for further analysis. Using this optimized structure, external electric fields ranging from −0.025 to 0.025 atomic units were systematically applied. Key parameters including C–Br and C–Cl bond lengths, total energy, dipole moment, frontier molecular orbital energies (HOMO-LUMO), energy gap, infrared spectra, and dissociation characteristics were calculated. These results provide critical insights into the structural and electronic behavior of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Geometric configuration of C6H4BrCl at ground state

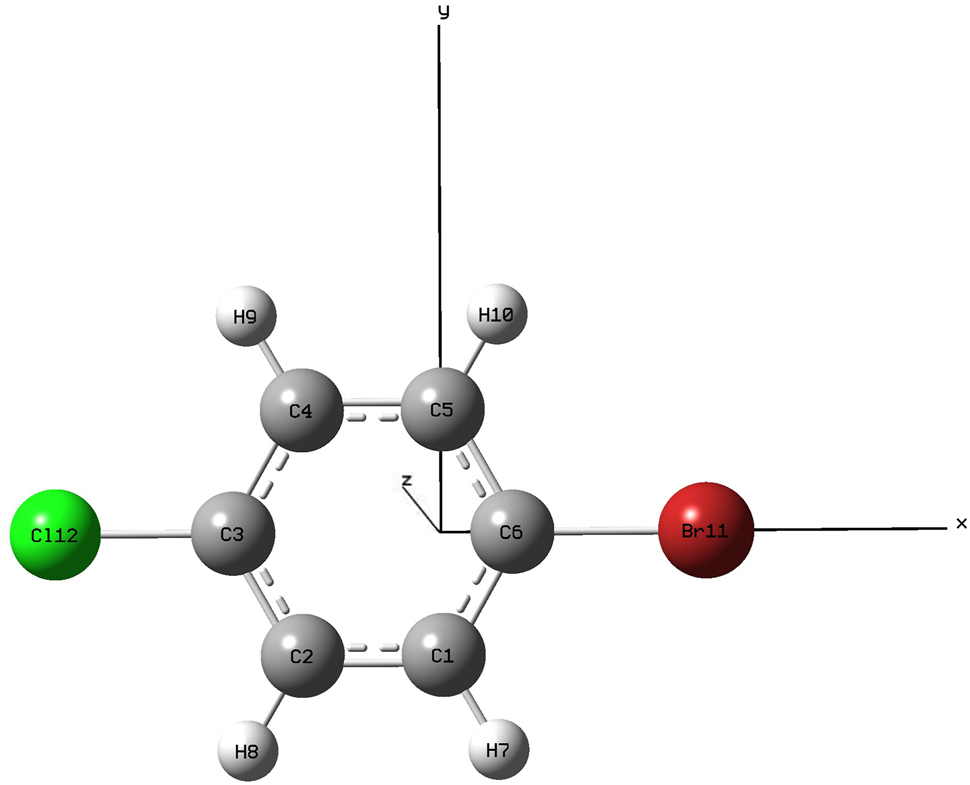

Initial structural optimizations of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene were performed using the methods and basis sets listed in Table 1 under zero-field conditions. The B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) methodology demonstrated optimal agreement with experimental bond lengths (R) and bond angles (A) from the NIST Chemistry WebBook database, and was therefore selected for subsequent electric field simulations. As shown in Figure 1, the optimized molecular geometry adopts a Cartesian coordinate system (x, y, z), with halogen atoms (Br and Cl) aligned along the X-axis. This spatial arrangement guided the application of external electric fields along the ±X-axis to systematically probe the molecule’s electronic behavior and dissociation mechanisms.

Partial bond lengths (Å) and bond angles (°) of C6H4BrCl molecules calculated using various methods and basis sets.

| HF/6-311G+(d,p) | BPV86/6-31G | B3LYP/6-311G | B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) | B3LYP/6-31G++(d,p) | Experimental value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R(3,12)/Å | 1.74223 | 1.82879 | 1.82726 | 1.75735 | 1.75751 | 1.75660 |

| R(6,11)/Å | 1.89824 | 1.94836 | 1.95153 | 1.91609 | 1.89909 | 1.90999 |

| R(5,6)/Å | 1.38240 | 1.40082 | 1.39245 | 1.39122 | 1.39454 | 1.39369 |

| R(1,7)/Å | 1.07337 | 1.09117 | 1.07911 | 1.08203 | 1.08486 | 1.08438 |

| A(5,6,11)/(°) | 119.54167 | 119.10547 | 119.42424 | 119.45743 | 119.78781 | 119.46619 |

| A(2,3,12)/(°) | 119.50973 | 118.97974 | 119.02597 | 119.46083 | 119.48048 | 119.46867 |

| A(6,1,7)/(°) | 120.47521 | 120.43382 | 120.47582 | 120.48746 | 120.10182 | 120.29372 |

Stable structure of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene molecule without external electric field (DFT B3LYP 6-311G(d,p)basis, 6C–11Br bond length is 1.91609 Å, 3C–12Cl bond length is 1.75736 Å, energy is −3265.471570 a.u.).

It should be emphasized that density functional theory (DFT) calculations fundamentally depend on the harmonic oscillator approximation. This approach may introduce errors due to truncation of the potential energy surface’s Taylor expansion, particularly affecting predicted bond dissociation and molecular degradation pathways in systems exhibiting significant anharmonic effects. Computational accuracy – especially for Raman spectra and vibrational properties – is substantially influenced by methodological choices, particularly the selection of functionals and basis sets [18]. To evaluate this sensitivity, we employed the B3LYP functional (demonstrating <0.3 ppm mean absolute error and >0.98 correlation with experimental Raman intensities [19]) with comparative basis sets (def-TZVP and 6-311G(d,p)), with detailed benchmarking data provided in Supplementary Materials.

3.2 Physical properties of C6H4BrCl molecule under an applied external electric fields

The 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene molecule was optimized using the B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) methodology. External electric fields ranging from −0.025 to 0.025 atomic units were systematically applied along the ±X-axis. The resulting geometric parameters of the molecule under these conditions are comprehensively detailed in Table 2.

Variation of bond lengths (Å), total energy (a.u.), dipole moment (Debye), HOMO-LUMO levels (a,u,), and energy gap (eV) of C6H4BrCl under different external electric fields.

| F/a.u. | C–Br/Å | C–Cl/Å | E/a.u. | μ/Debye | E L/a,u, | E H/a.u. | E G/eV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.025 | 1.87362 | 1.85637 | −3265.523317 | 10.693100 | −0.11755 | −0.24104 | 3.358928 |

| −0.020 | 1.88110 | 1.82625 | −3265.504583 | 8.390500 | −0.08933 | −0.24531 | 4.242656 |

| −0.015 | 1.88785 | 1.80259 | −3265.490223 | 6.228600 | −0.06243 | −0.24965 | 5.092384 |

| −0.010 | 1.89645 | 1.78410 | −3265.480016 | 4.154900 | −0.05058 | −0.25320 | 5.511264 |

| −0.005 | 1.90574 | 1.77016 | −3265.473826 | 2.142200 | −0.04521 | −0.25491 | 5.706288 |

| 0 | 1.91609 | 1.75736 | −3265.471570 | 0.151900 | −0.03962 | −0.25353 | 5.818352 |

| 0.005 | 1.92825 | 1.74599 | −3265.473223 | 1.835900 | −0.03406 | −0.24848 | 5.832224 |

| 0.010 | 1.94287 | 1.73500 | −3265.478808 | 3.850100 | −0.04228 | −0.24055 | 5.379344 |

| 0.015 | 1.96103 | 1.72547 | −3265.488398 | 5.913000 | −0.05545 | −0.22929 | 4.728448 |

| 0.020 | 1.98457 | 1.71578 | −3265.502129 | 8.064200 | −0.06957 | −0.21710 | 4.012816 |

| 0.025 | 2.01996 | 1.70751 | −3265.520230 | 10.366400 | −0.08516 | −0.20444 | 3.244416 |

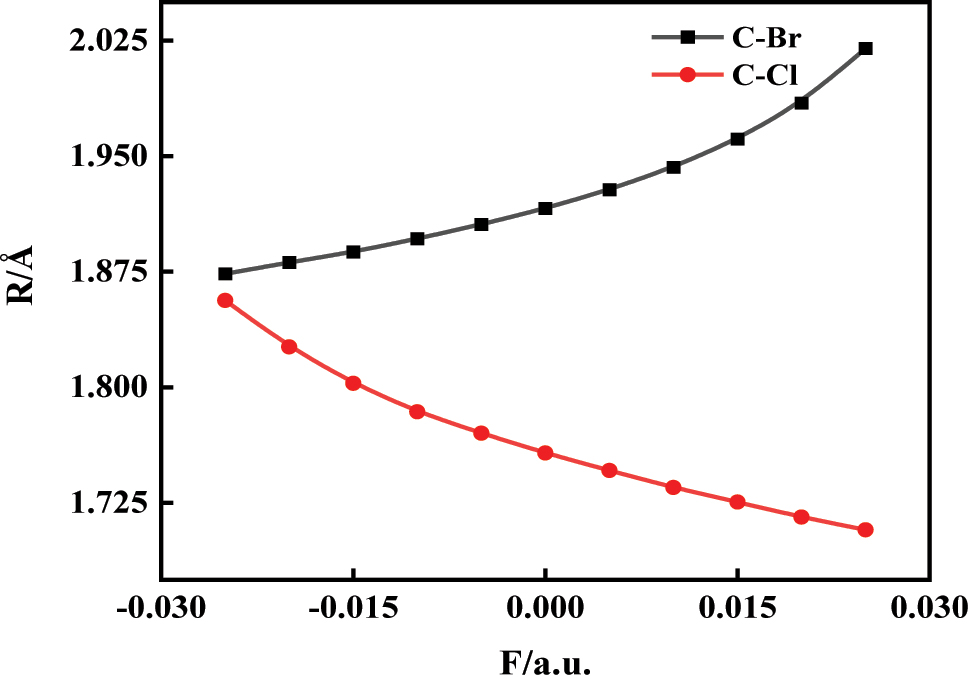

As shown in Figure 2, the C–Br bond length increases progressively with increasing electric field strength, while the C–Cl bond length decreases accordingly. This anisotropic trend arises from the directional application of the electric field along the C–Br bond axis. Under this field, the electron density within the molecule is redistributed asymmetrically, generating an internal polarization field that enhances the asymmetry of the bonding environment [20], 21]. Specifically, the C–Br bond, being more polar and associated with the more polarizable Br atom, experiences a net weakening under the applied field, leading to bond elongation and a reduction in dissociation energy. In contrast, the C–Cl bond lies opposite to the field direction and is subjected to a compressive electrostatic effect, resulting in bond shortening and potential strengthening [22]. This field-induced differential response is further supported by the polar nature of the molecule and the Stark-like modulation of frontier orbital energies, which alters the bonding–antibonding orbital overlap. Such asymmetric structural evolution under the electric field provides mechanistic insight into bond-selective weakening and offers a theoretical basis for the field-controlled dissociation pathways discussed in later sections.

The change of C6H4BrCl bond length under different external electric field.

Our comparative analysis of B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) and B3LYP/def2-TZVP computational results (Supplementary Tables S1) reveals minimal dependence on methodology for C–Br and C–Cl bond length variations. Both methods show identical directional changes, demonstrating consistent bond elongation trends regardless of functional or basis set selection. Although slight differences exist in absolute bond length values between methods, these variations fall within accepted computational tolerances. Thus, qualitative dissociation trends remain reliable while absolute values may exhibit minor method-dependent fluctuations.

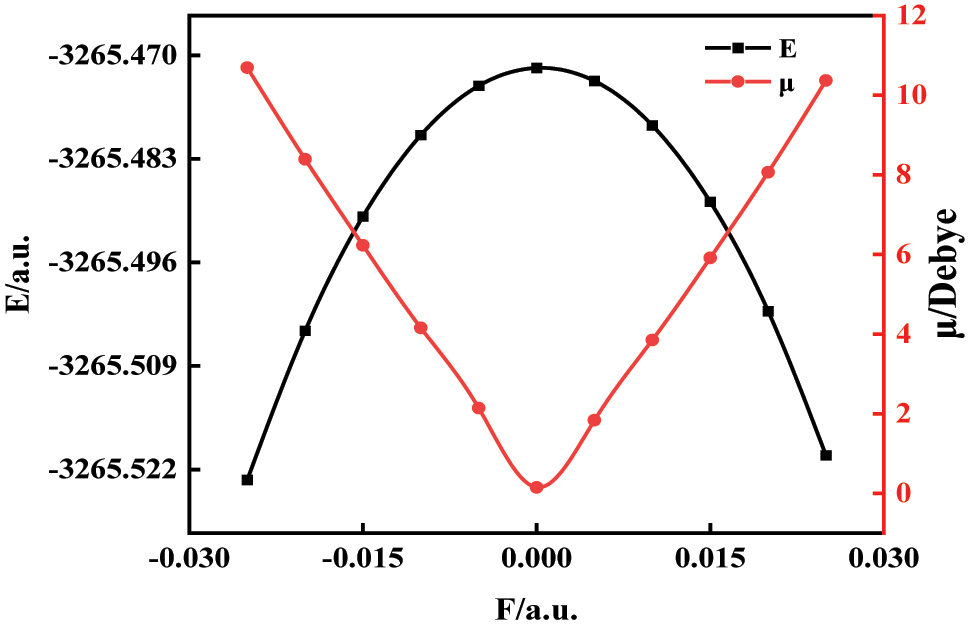

Figure 3 demonstrates a progressive increase in molecular dipole moment with rising electric field strength (±X-axis). This polarization effect arises from charge separation – positive and negative charges migrate in opposing field directions, elongating the molecular structure and enhancing polarity [23]. Total molecular energy initially increases then decreases with field intensification, following the potential energy relationship.

The change of C6H4BrCl total energy and dipole moment under different external electric fields.

At 0.025 atomic units field strength, directional electron migration significantly enhances Coulombic attraction between charged moieties. Concurrent dipole moment amplification increases the absolute potential energy value in the Hamiltonian (H), thereby reducing total system energy. The inverse relationship holds for field reversal, confirming the bidirectional control of electronic behavior through applied fields. This behavior reflects a second-order (quadratic) Stark effect in the total energy, where the external electric field perturbs the molecular Hamiltonian through the dipole interaction term (μ·F) and higher-order polarizability contributions. At higher field strengths (e.g., ±0.025 a.u.), enhanced charge redistribution and field-induced orbital reordering reduce the net system energy by stabilizing the dipolar configuration aligned with the field. Consequently, the dipole moment and total energy exhibit inverse trends, indicating that the system becomes more stable as its polarization increases [21]. Moreover, the asymmetric energy profile with respect to field direction highlights the critical role of the intrinsic dipole orientation, confirming that the applied field can be exploited to bidirectionally tune the electronic structure, potential energy surface, and molecular reactivity [22].

3.3 The effect of an external electric field on molecular charge and molecular orbitals

Using the aforementioned methodology and basis set, we analyzed the Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) charge distribution of 1-bromo-4-chlorobenzene under external electric fields ranging from −0.025 to +0.025 a.u., as summarized in Table 3. The results indicate that the applied electric field significantly modulates intramolecular electron distribution. Pairs of symmetry-related atoms (e.g., 1C–5C, 2C–4C, 7H–10H, 8H–9H) maintain nearly identical charge values throughout the field range, confirming the molecule’s partial symmetry. Notably, the halogen atoms respond strongly to the applied field. At +0.025 a.u., atom 12Cl exhibits the most negative charge (−0.358), while 11Br displays the largest positive charge (+0.313) at −0.025 a.u. With increasing positive field strength (aligned along the C–Br bond axis), 11Br accumulates additional negative charge, while the adjacent carbon atom 6C becomes more electron-deficient. This charge redistribution reflects the electrostatic polarization of the molecule, wherein the external field enhances the electron-withdrawing effect of Br. As a result, electron density is pulled toward 11Br, effectively elongating the C–Br bond due to increased Coulombic repulsion and weakened orbital overlap between C and Br. Conversely, 12Cl shows a gradual increase in positive charge at higher positive fields, intensifying its electrostatic interaction with 3C and thus contributing to a shortening of the C–Cl bond. These trends are consistent with the bond length variations observed in Figure 2 and further confirm the field-induced charge-driven mechanism underlying bond asymmetry. Such analysis links localized atomic charges to global structural reorganization, and reveals the essential role of electronic polarization in determining field-responsive reactivity.

Charge distribution of C6H4BrCl molecules under different external electric fields.

| F a.u. | Atom | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1C | 2C | 3C | 6C | 7H | 8H | 11Br | 12Cl | |

| −0.025 | −0.021 | 0.018 | 0.199 | −0.223 | 0.169 | 0.069 | 0.313 | −0.358 |

| −0.020 | −0.020 | 0.018 | −0.210 | −0.217 | 0.159 | 0 | 0.242 | −0.291 |

| −0.015 | −0.019 | 0.019 | −0.219 | −0.211 | 0.149 | 0.092 | 0.176 | −0.230 |

| −0.010 | −0.018 | 0.020 | −0.226 | −0.204 | 0.140 | 0.104 | 0.111 | −0.172 |

| −0.005 | −0.018 | 0.021 | −0.231 | −0.198 | 0.130 | 0.115 | 0.048 | −0.117 |

| 0 | −0.017 | 0.022 | −0.236 | −0.191 | 0.121 | 0.127 | −0.015 | −0.062 |

| 0.005 | −0.017 | 0.023 | −0.241 | −0.184 | 0.111 | 0.138 | −0.078 | −0.007 |

| 0.010 | −0.017 | 0.023 | −0.245 | −0.176 | 0.101 | 0.149 | −0.142 | 0.048 |

| 0.015 | −0.016 | 0.023 | −0.248 | −0.168 | 0.092 | 0.160 | −0.208 | 0.105 |

| 0.020 | −0.015 | 0.023 | −0.250 | −0.158 | 0.082 | 0.171 | −0.278 | 0.163 |

| 0.025 | −0.013 | 0.022 | −0.252 | −0.146 | 0.074 | 0.183 | −0.355 | 0.224 |

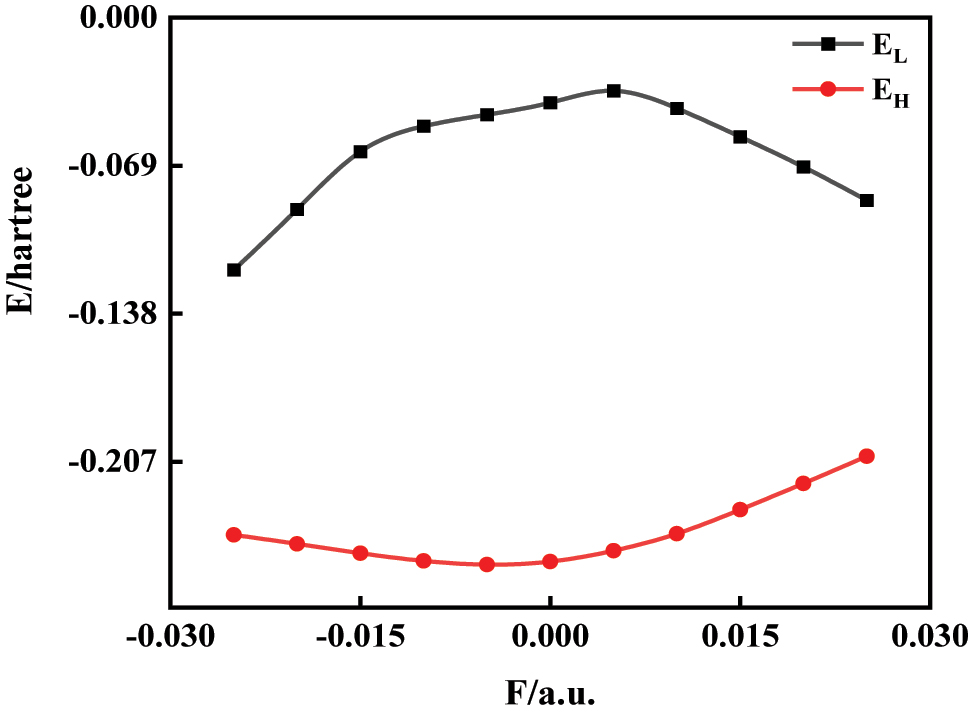

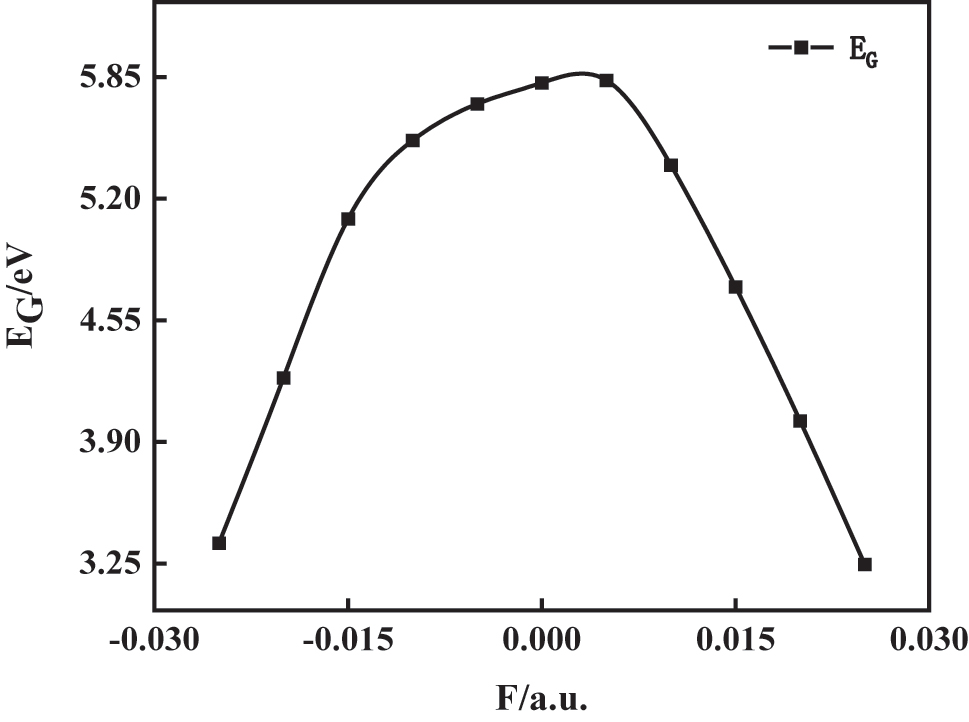

Using the same method and basis set, we computed the LUMO energy (E L), HOMO energy (E H), and the energy gap (E G) for the C6H4BrCl molecule under varying external electric fields ranging from −0.025 a.u. to 0.025 a.u. where the energy gap (E G) was calculated by Eq (3).

Variations in the LUMO energy (E L) reflect a molecule’s electron-accepting capacity, with lower EL values indicating enhanced electron affinity and a greater tendency for reduction reactions. Conversely, shifts in the HOMO energy (E H) reveal electron-donating tendencies, where elevated E H values correlate with reduced electron retention and increased likelihood of oxidation processes [24]. The HOMO-LUMO energy gap (EG) further serves as a critical indicator of chemical reactivity: narrower EG values correspond to diminished molecular stability and heightened propensity for chemical interactions [25]. Together, these parameters provide a comprehensive framework for understanding redox behavior and reaction dynamics under external stimuli.

As shown in Figures 4 and 5, the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital energy (E L) initially increases before decreasing with rising field strength, while the highest occupied molecular orbital energy (E H) follows an inverse trend, decreasing first and then increasing. This field-induced modulation of orbital energies reflects a second-order Stark effect, where the spatial redistribution of electron density in response to the field perturbs the molecular Hamiltonian. As a result, the energy gap (E G) widens near zero field and narrows significantly as the field strength approaches ±0.025 a.u. The reduced energy gap facilitates electronic excitation, enhancing the probability of charge transfer and exciton generation. This is particularly relevant for optical absorption and photoreactivity, as lower excitation thresholds increase the likelihood of π → π* or n → π* transitions under external stimuli. Moreover, the narrowing of E G under strong electric fields correlates with structural distortions – such as C–Br bond elongation and C–Cl bond contraction – observed in Figure 2. This indicates a coupled electronic–structural response: field-induced polarization not only reshapes the molecular geometry but also modifies its electronic reactivity landscape. The observed trends underline the potential for precise field control over reactivity, optical behavior, and electron transport in polar π-conjugated molecules like 1-bromo-4-chlorobenzene [22].

Changes of E L and E H in C6H4BrCl under different external electric fields.

Variation of C6H4BrCl molecular energy gap in external electric fields.

To achieve more accurate characterization of charge-transfer excitations and long-range electron interactions, we employed the CAM-B3LYP functional with long-range correction. This method effectively mitigates known deficiencies in electronic gap prediction associated with conventional DFT approaches such as B3LYP [26]. Supporting Information S4 presents the CAM-B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) calculated energy gap (E G) evolution of 1-bromo-4-chlorobenzene under electric fields (−0.025 to +0.025 a.u.). The gap exhibits non-monotonic behavior – initially widening before narrowing, with maximum values occurring near zero field. This response pattern originates from electric-field-induced molecular polarization and frontier orbital reorganization. Notably, while CAM-B3LYP yields systematically larger E G values than B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) due to enhanced treatment of long-range electron interactions, both methods demonstrate consistent gap modulation trends. This consistency confirms the intrinsic nature of field-responsive gap variation rather than computational artifacts. The observed agreement with GW method predictions further validates the theoretical framework for electric-field-controlled molecular responses [27].

3.4 The infrared spectral characteristics of the molecule under different external electric field

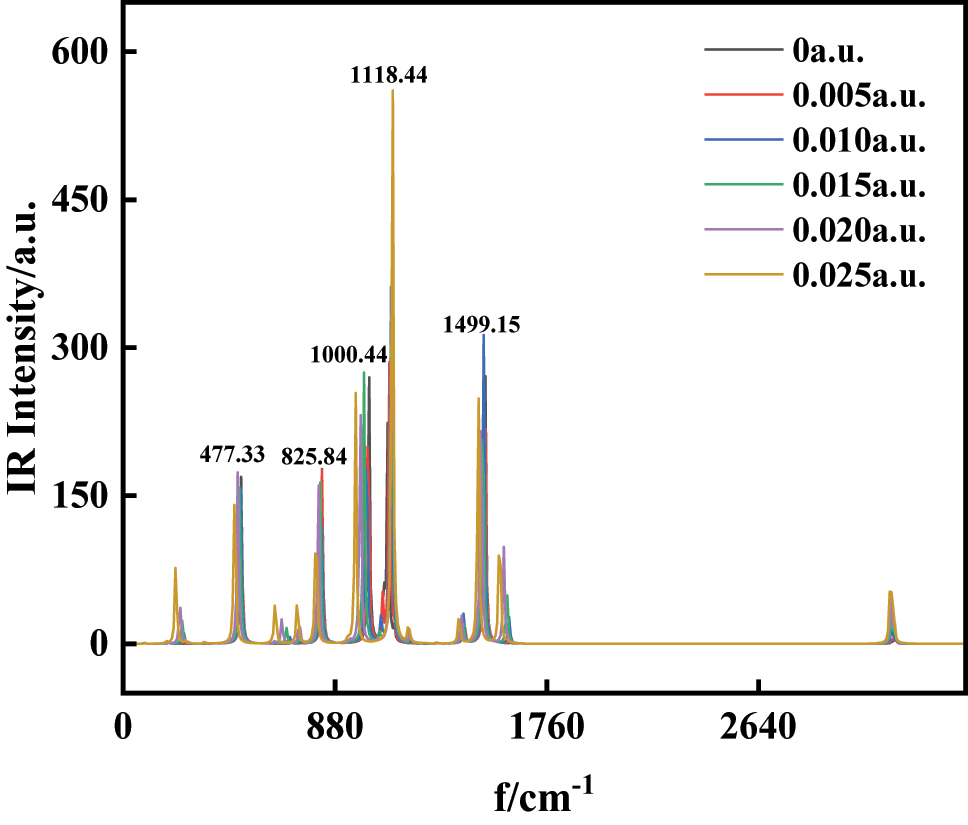

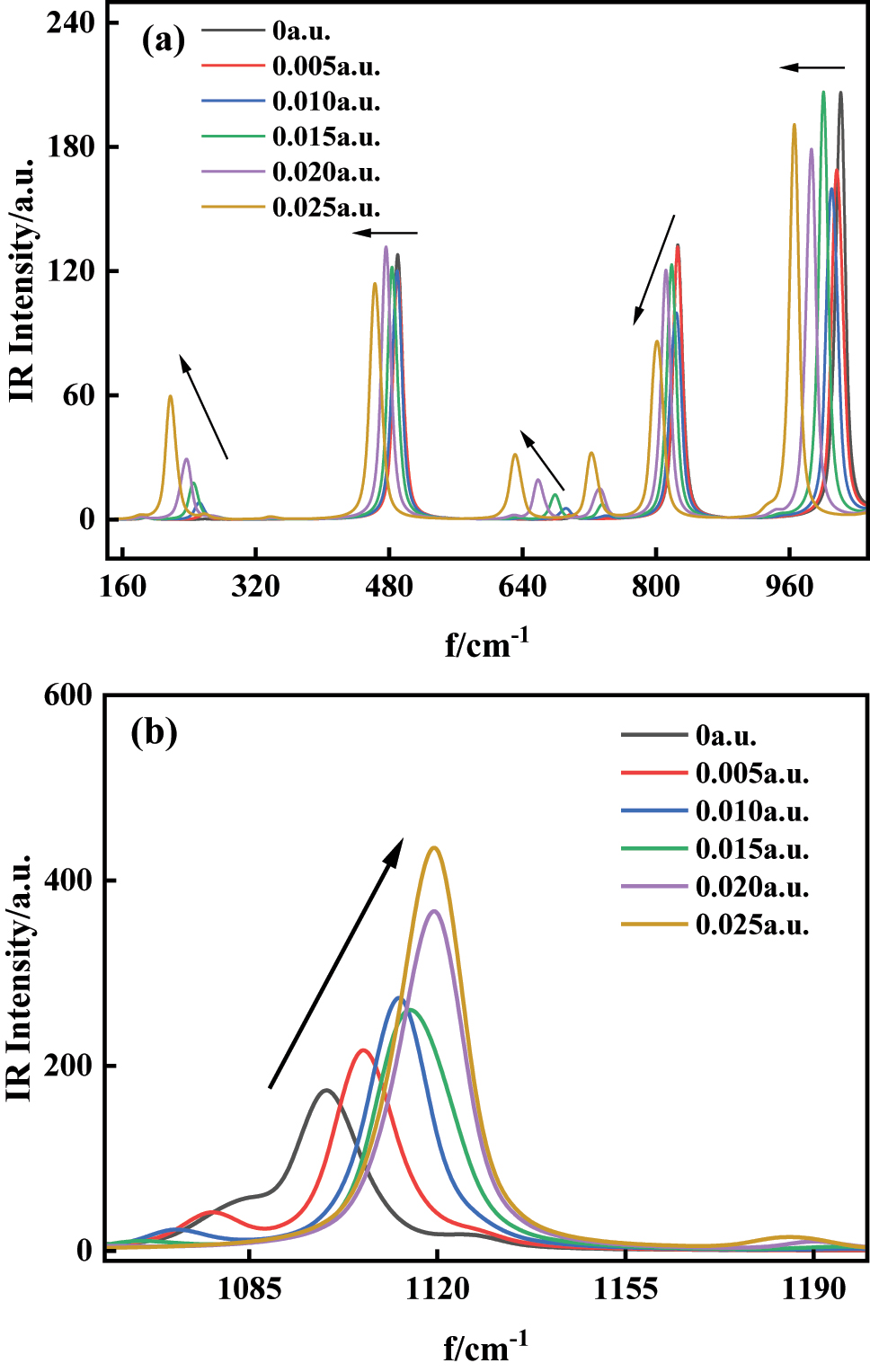

Structural optimization of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene was performed using the B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) methodology. Subsequent analysis under external electric fields (0 a.u.∼0.025 a.u.) applied along the +X-axis revealed significant field-dependent modifications to the infrared spectral profile. As shown in Figure 6, the IR spectrum exhibits five prominent absorption bands. The strongest peak at 1,118.44 cm−1 arises from 3C–12Cl stretching vibrations coupled with collective bending modes of 4C–9H, 5C–10H, 2C–8H, and 1C–7H. A secondary peak at 1,499.15 cm−1 originates from bending vibrations of the aromatic 4C–9H, 5C–10H, 2C–8H, and 1C–7H groups. The 1,000.44 cm−1 band corresponds to in-plane deformation vibrations of 3C–4C and 2C–3C bonds, combined with 5C–11Br stretching. Out-of-plane deformation modes of aromatic C–C and C–H bonds dominate the 825.84 cm−1 absorption, while stretching vibrations of the 3C–12Cl and 6C–11Br bonds contribute to the 477.33 cm−1 feature. These vibrational assignments highlight the interplay between molecular symmetry, bond dynamics, and external field effects.

The variations of IR spectra of C6H4BrCl in external.

Magnified spectral analysis (Figure 7a) reveals a systematic redshift across the 142∼1,054 cm−1 range under increasing electric fields, indicating reduced vibrational frequencies for all modes in this region. At 218.70 cm−1, the enhanced Coulombic interaction between 6C and 11Br intensifies the C–Br stretching vibration amplitude. Conversely, the dominant 1,118.44 cm−1 peak (3C–12Cl stretching mode) exhibits a blueshift with field intensification, as shown in Figure 7b. This counterintuitive blueshift arises from 12Cl’s electron-withdrawing nature. The X-axis-aligned field redistributes electron density toward 11Br, increasing net positive charge on 3C–12Cl. The amplified charge disparity elevates the C–Cl bond’s force constant, thereby increasing its vibrational frequency through the relationship

The variations of IR spectra of C6H4BrCl in external field (a) 142∼1,054 cm−1; (b) 1,058∼1,200 cm−1.

3.5 The Effect of an external electric field on the excited states of C6H4BrCl

To elucidate field effects on 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene properties, we employed TD-DFT/B3LYP with the 6-311G(d,p) basis set to calculate excitation energies, wavelengths, and oscillator strengths for the first nine excited states under positive-oriented electric fields (0 a.u.∼0.025 a.u.). These computational results are systematically presented in Table 4.

Changes of excitation energy (eV), excitation wavelength (nm), and oscillator strength for C6H4BrCl molecules under different applied electric fields.

| F a.u. | Excited state | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| 0 | E/eV | 4.9843 | 5.2769 | 5.5133 | 6.1871 | 6.2205 | 6.2379 | 6.2760 | 6.4319 | 6.4974 |

| λ/nm | 248.75 | 234.96 | 224.88 | 200.39 | 199.32 | 198.76 | 197.55 | 192.76 | 190.82 | |

| f | 0.0096 | 0 | 0.2568 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0001 | 0.0733 | 0.0259 | |

| 0.005 | E/eV | 4.8985 | 5.3686 | 5.3691 | 5.7656 | 5.7893 | 5.9272 | 6.1782 | 6.2881 | 6.4105 |

| λ/nm | 253.11 | 230.94 | 230.92 | 215.04 | 214.16 | 209.18 | 200.68 | 197.17 | 193.41 | |

| f | 0.0104 | 0 | 0.2506 | 0 | 0.0001 | 0 | 0.0434 | 0.0018 | 0 | |

| 0.010 | E/eV | 4.7254 | 5.1166 | 5.2170 | 5.2788 | 5.3043 | 5.6527 | 5.9448 | 6.0101 | 6.3038 |

| λ/nm | 262.38 | 242.32 | 237.66 | 234.87 | 233.74 | 219.34 | 208.56 | 206.29 | 196.68 | |

| f | 0.0108 | 0.2354 | 0 | 0 | 0.0001 | 0 | 0.0176 | 0.0048 | 0 | |

| 0.015 | E/eV | 4.4616 | 4.7297 | 4.7818 | 4.7917 | 4.8223 | 5.3825 | 5.4400 | 5.8059 | 5.9090 |

| λ/nm | 277.89 | 262.14 | 259.28 | 258.75 | 257.11 | 230.35 | 227.91 | 213.55 | 209.82 | |

| f | 0.0097 | 0 | 0 | 0.2164 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0 | 0.011 | 0.0003 | |

| 0.020 | E/eV | 4.0373 | 4.1255 | 4.2734 | 4.3431 | 4.4197 | 4.4979 | 5.1514 | 5.4679 | 5.5737 |

| λ/nm | 307.10 | 300.53 | 290.13 | 285.47 | 280.52 | 275.65 | 240.68 | 226.75 | 222.45 | |

| f | 0 | 0.0074 | 0 | 0.0001 | 0.1981 | 0 | 0 | 0.0001 | 0 | |

| 0.025 | E/eV | 3.1944 | 3.4996 | 3.7282 | 3.7465 | 3.8500 | 4.0069 | 4.6865 | 4.9098 | 5.0974 |

| λ/nm | 388.13 | 354.28 | 332.56 | 330.93 | 322.04 | 309.43 | 264.56 | 252.53 | 243.23 | |

| f | 0 | 0 | 0.0049 | 0 | 0.0001 | 0.1781 | 0.0002 | 0 | 0 | |

Excitation energy, defined as the energy difference between the ground and excited states, provides direct insight into the electronic excitation characteristics of 1-bromo-4-chlorobenzene under external electric fields. As shown in Table 4, all excitation energies (except the second excited state) decrease monotonically with increasing field strength, indicating that the applied field facilitates electronic excitation by lowering the energy barriers to higher-lying states. This trend is particularly pronounced for low-lying states, whose energy values decrease from 4.9843 eV to 3.1944 eV (S1) as the field increases from 0 to 0.025 a.u. The corresponding redshift in excitation wavelengths – from 248.75 nm to 388.13 nm for S1 – further confirms this behavior. The origin of this redshift lies in the field-induced narrowing of the energy gap (as seen in Figure 5), which reduces the energy required for π → π* transitions. Additionally, changes in oscillator strength (f) reveal that several transitions become allowed or forbidden depending on field intensity. For example, the S8 state has a finite oscillator strength at 0 a.u. but vanishes at 0.025 a.u., suggesting that the field modulates transition dipole moments via changes in orbital symmetry and spatial overlap. From a physical standpoint, these observations can be attributed to the external field’s ability to polarize the molecular electron cloud and distort its geometry. This affects both the delocalization of frontier orbitals and the charge-transfer characteristics of excited states.

To address the systematic underestimation of excited-state energies by conventional hybrid functionals like B3LYP and approach GW-level accuracy, we performed complementary calculations using the long-range corrected CAM-B3LYP functional. As shown in Supporting Information S5, significant differences exist between B3LYP and CAM-B3LYP predictions for both absolute excitation energies and field-response trends of 1-bromo-4-chlorobenzene. The incorporation of long-range exchange in CAM-B3LYP raises excitation energies by 0.3∼1.0 eV compared to B3LYP, substantially improving descriptions of charge-transfer states and long-range excitations. Regarding field responses: while B3LYP shows a continuous decrease (redshift) in S1 excitation energy with increasing field strength, CAM-B3LYP exhibits non-monotonic behavior – reaching a minimum at 0.020 a.u. before rising at 0.025 a.u. – reflecting heightened sensitivity to orbital reorganization and polarization effects. For higher excited states, B3LYP predicts more pronounced energy reductions versus CAM-B3LYP’s gradual variations, highlighting inherent methodological differences. Crucially, both functionals effectively capture essential field-responsive excitation phenomena relevant to optoelectronic studies.

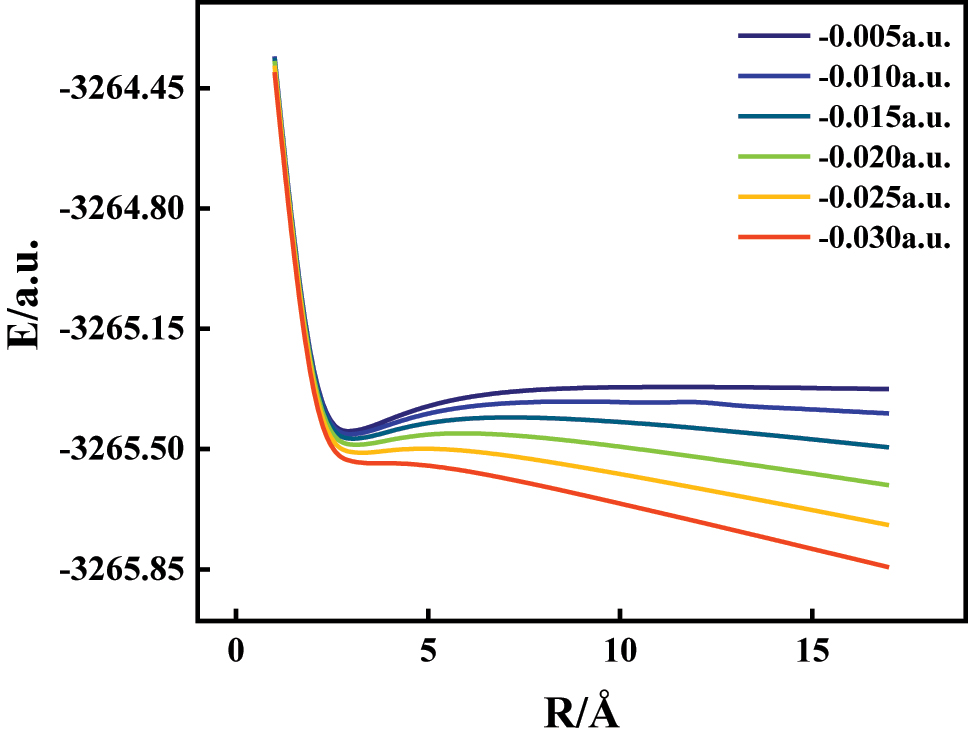

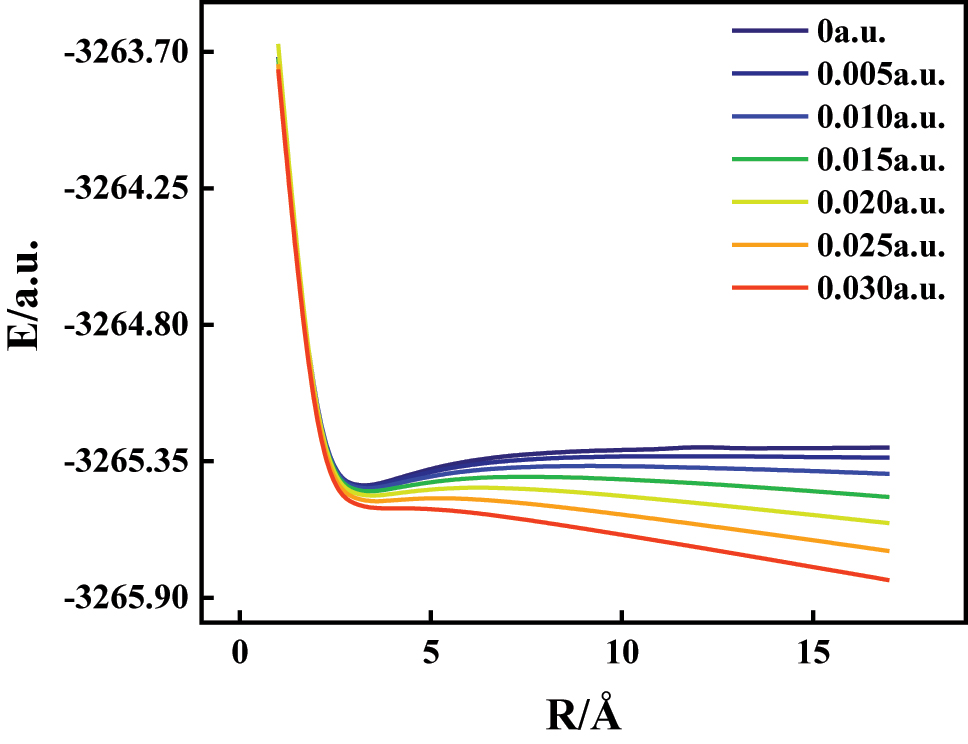

3.6 Stepwise dissociation of molecules under external electric field

To investigate the electric field-driven dissociation behavior of 1-bromo-4-chlorobenzene, we conducted potential energy surface (PES) scans along the C–Cl and C–Br bond coordinates under varying external electric fields using the B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) level of theory. Figures 8 and 9 show the energy profiles for bond lengths ranging from ∼1 Å to ∼17 Å under field strengths between −0.030 and +0.030 a.u., with the field direction oriented along the C–Br bond axis. Under zero-field conditions, both bonds exhibit steep energy descents to global minima, followed by gradual increases in energy as the bond extends – reflecting their intrinsic covalent stability. However, the application of external fields alters this stability significantly and directionally. For the C–Cl bond (Figure 8), increasing negative electric fields progressively destabilize the bond. As the field strength grows from −0.005 to −0.030 a.u., the depth of the energy well shallows, and the dissociation energy drops notably. This is attributed to field-induced polarization, which drives electron density away from the C–Cl region, weakening orbital overlap and reducing the energy barrier for dissociation [28], 29]. Conversely, the C–Br bond (Figure 9) responds to positive electric fields, showing a clear reduction in dissociation energy as field strength increases from 0 to +0.030 a.u. Here, the highly polarizable Br atom accumulates excess negative charge under the field, increasing repulsion with the adjacent carbon and weakening the C–Br bond [30]. This effect becomes pronounced at field strengths beyond 0.020 a.u., where the dissociation process becomes nearly barrierless. These findings establish a field-dependent and directionally selective bond cleavage mechanism: negative fields facilitate C–Cl bond rupture, while positive fields promote C–Br dissociation. This behavior arises from asymmetric charge redistribution and modified electrostatic forces, illustrating the external field’s role in modulating molecular potential energy surfaces [31]. Such insights are valuable for designing field-assisted reaction pathways, targeted halogen bond cleavage, and environmental degradation of halogenated pollutants.

The potential energy curves of C6H4BrCl along 3C–12Cl bond at various external electric fields.

The potential energy curves of C6H4BrCl along 6C–11Br bond at various external electric fields.

As noted, the harmonic approximation in DFT calculations may introduce errors affecting predicted bond dissociation and degradation pathways. Our comparative calculations using B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) and B3LYP/def2-TZVP basis sets (Supplementary Materials, Tables S2-S3) reveal that C–Br bond dissociation energy exhibits minimal variation (<2 % difference), indicating its relative insensitivity to computational methodology. In contrast, C–Cl dissociation energy shows greater basis set dependence. Crucially, both basis sets produce consistent potential energy curves for bond elongation and dissociation pathways. This demonstrates that while absolute dissociation energies are method-dependent, the qualitative field-induced degradation mechanisms remain robust across computational approaches. Therefore, the findings of this study demonstrate robust reliability.

3.7 Comparison with pevious studies

Furthermore, our results were compared with previous studies on chlorobenzene under electric fields Liu et al. [32]. Their work reported progressive C–Cl bond elongation, HOMO–LUMO gap narrowing, and spectral redshifts with increasing positive field strength, which are fully consistent with our findings. By additionally considering the C–Br bond, the present study reveals field-selective degradation behavior: C–Cl bonds are preferentially destabilized under negative fields, whereas C–Br bonds are more susceptible under positive fields. This provides a more comprehensive mechanistic picture of field-controlled halogen bond rupture and extends the applicability of external-field modulation strategies to halogenated aromatic systems.

4 Conclusions

This study employed density functional theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) level to investigate the structural and electronic properties of 1-bromo-4-chlorobenzene under external electric fields. Key parameters analyzed include bond lengths, dipole moments, total energy, frontier molecular orbitals (HOMO–LUMO), energy gaps, infrared spectra, and dissociation pathways of C–Cl and C–Br bonds. Time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) with the same basis set was used to characterize the first nine excited states. The applied electric field redistributes electron density, leading to elongation of the C–Br bond and contraction of the C–Cl bond due to charge accumulation on bromine and electron attraction by chlorine. The dipole moment and total energy exhibit opposite trends, both reaching extreme values at zero field. The LUMO energy rises initially before declining, while the HOMO energy shows the reverse trend, resulting in a narrowed energy gap that promotes electron transitions. Under positive fields, C–Br vibrational modes redshift whereas C–Cl modes blueshift. Directional fields selectively reduce dissociation barriers: negative fields destabilize the C–Cl bond, while positive fields weaken the C–Br bond. Excitation energies decrease under positive fields, accompanied by spectral redshift and modulated oscillator strength that switches between allowed and forbidden transitions. With increasing field strength, both C–Br and C–Cl bonds elongate, ultimately leading to bond dissociation and molecular degradation. These effects are observed in the bulk phase, where the field uniformly influences the entire molecule without surface-specific interactions.

The present results are consistent with previous findings on chlorobenzene under electric fields [32], while further extending the analysis to bromine-containing systems to uncover field-selective degradation pathways.

Overall, these results demonstrate that external electric fields can act as precise tools for tuning electronic structure, controlling reaction pathways, optimizing industrial processes, and enabling targeted degradation of halogenated pollutants.

Funding source: Xinjiang Natural Science Foundation for General Program

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2023D01A40

-

Funding information: Xinjiang Natural Science Foundation for General Program (No. 2023D01A40), Research Program of Xinjiang Higher Education (No. XJEDU2023J030), The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22363011), Tianshan Talent Training Program of Xinjiang (No. 2024TSYCCX0064), University of Science and Technology of China- Xinjiang Normal University Counterpart Cooperation and Development Joint Fund (No. XJNULH2503).

-

Author contributions: Haoran Ma: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Software, Writing-original draft. Reyihanguli Tudi: Validation, Resources. Jiajun Ma: Validation, Investigation. Mei Xiang: Supervision, Writing-review & editing. Bumaliya Abulimiti: Supervision, Writing-review & editing. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30463247. Tables 2 and 3, and Figures 2–7 in the manuscript are sourced from the data file in Manuscripts\Field. Table 4 in the manuscript is sourced from the data file in Manuscripts\Excited state. Figures 8 and 9 in the manuscript are sourced from the Manusripts\Scan data file. Supplementary Material S1 is sourced from the Supplementary materials\B3LYP-def2tzvp\Field folder. Supplementary Material S2 is sourced from the Supplementary materials\B3LYP-def2tzvp\Scan folder. Supplementary Material S3 is sourced from the Supplementary materials\BDE folder. Supplementary Material S4 is sourced from the Supplementary materials\CAM-B3LYP-6-311G(dp)\Field folder. Supplementary Material S5 is sourced from the Supplementary materials\CAM-B3LYP-6-311G(dp)\Excited state folder.

References

1. Chi, Y, Zhao, C. Progress and challenges of ozone satellite remote sensing inversion. Acta Opt Sin 2023;43:72–89.Search in Google Scholar

2. Zhang, Y, Hang, X, Wang, Y, Wang, X. A review of ozone-depleting substances and fluorinated greenhouse gases in China. Bulletin of Mineralogy. Petrol Geochem. 2024;43:921–45+896.10.3724/j.issn.1007-2802.20240042Search in Google Scholar

3. Hu, L, Yan, W. On ozone layer destruction and protection. Geogr Teach Guide 2001:32–3.Search in Google Scholar

4. Chen, J, Yang, R, Zhao, N, Ying, G, Huang, P, Jiang, Y, et al.. Experimental system for in-situ rapid detection of benzene series fluorescence in groundwater in chemical industry park design and experimental research. Acta Opt Sin 2024;44:154–64.Search in Google Scholar

5. Yu, J, Feng, Z, Liu, J, Hu, J. Degradation of 4-bromochlorobenzene by mechanochemical technology. J Zhejiang Univ Technol 2018;46:418–22.Search in Google Scholar

6. An, H, Yan, H, Xiang, M, Bumaliya, A, Zheng, J. Spectral and dissociation characteristics of p-Dibromobenzene based on external electric field. Spectrosc Spectr Anal 2023;43:405–11.Search in Google Scholar

7. Liu, J. Studies on degradation and dehalogenation of halogenated aromatics by mechanochemical treatment. ZJUT; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

8. Gulimire, Y, Yan, H, Bumaliya, A, Xiang, M, Zheng, J, An, H. Study on physical properties and stepwise dissociation characteristics of dibromomethane molecules under external electric field. J Atom Mol Phys 2023;40:7–14.Search in Google Scholar

9. Zhang, C, Wu, H, Wang, Y, Wen, Z, Shi, Z. Molecular structure and dissociation characteristics of Arsenic Trichloride under external electric field. Comput Phys 2025;42:481–9.Search in Google Scholar

10. Zhou, H, Han, B, Nuerbiye, A, Zhang, W, Zhu, Y, Liu, Y. Study on dissociation properties of vinyl bromide in an external electric field. J Atom Mol Phys 2025;42:26–32.Search in Google Scholar

11. Xia, M, Pang, Y, Yue, L, Lai, S. Molecular structures and dissociation properties of phenol under enternal electric field. J Univ Sci Technol Liaoning 2024;47:105–11.Search in Google Scholar

12. Du, J, Feng, Z, Zhang, Q, Han, L, Tang, Y, Li, Q. Molecular structure and electronic spectrum of MoS2 under external electric field. Acta Phys Sin 2019;68:98–103. https://doi.org/10.7498/aps.68.20190781.Search in Google Scholar

13. Du, J, Zang, Q, Li, Q, Tang, Y. Investigation of external electric field effect on C24H38O4 molecule by density functional theory. Acta Phys Sin 2018;67:81–8.10.7498/aps.67.20172022Search in Google Scholar

14. An, Y, Xiong, B, Xing, Y, Shen, J, Li, P, Zhu, Z, et al.. Structural properties of ZnO molecules under an external electric field. Acta Phys Sin 2013;62:156–61.10.7498/aps.62.073103Search in Google Scholar

15. Tang, N, Zhang, S, Li, Q. Basic algorithms research progress of density functional theory. J Chengdu Text Coll 2015;32:39–43.Search in Google Scholar

16. Zheng, J, Bumaliya, A, Xiang, M, An, H. Molecular structure and dissociation characteristics of 4-fluorophenol under external electric field. J Atom Mol Phys 2023;40:59–65.Search in Google Scholar

17. Wan, J. Application of gaussian software in pharmacy teaching. Strait Pharm J 2022;34:91–4.Search in Google Scholar

18. Malgorzata, B, Pawel, P, Giovanni, S, Julien, B, Vincenzo, B. Harmonic and anharmonic vibrational frequency calculations with the double-hybrid B2PLYP method: analytic second derivatives and benchmark studies. J Chem Theor Comput 2010;6:2115–25. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct100212p.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Stephens, PJ, Devlin, FJ, Chabalowski, CF, Frisch, MJ. Ab initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular dichroism spectra using density functional force fields. J Phys Chem 1994;98:11623–7. https://doi.org/10.1021/j100096a001.Search in Google Scholar

20. Zhu, Z. The atomic and molecular reaction statics. Sci China Ser G 2007;50:581–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11433-007-0054-6.Search in Google Scholar

21. Brieger, M. Stark effect, polarizabilities and the electric dipole moment of heteronuclear diatomic molecules in 1Σ states. Chem Phys 1984;89:275–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-0104(84)85316-1.Search in Google Scholar

22. Tokatlı, A, Tunç, F, Ucun, F. Effect of external electric field on C-X⋯π halogen bonds. J Mol Model 2019;25:57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-019-3938-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Li, Y, Zhou, X, Sun, L, Zhang, X, Meng, F, Mei, Y. Molecular structures and properties of C4F7N under the external electric field. J Atom Mol Phys 2020;37:494–500.Search in Google Scholar

24. Amudha, G, Santhakumari, R, Chandrika, D, Mugeshini, S, Rajeswari, N, Sagadevan, S. Synthesis, growth, DFT, and HOMO-LUMO studies on pyrazolemethoxy benzaldehyde single crystals. Chin J Phys 2022;76:44–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjph.2021.10.038.Search in Google Scholar

25. Li, X, Zhang, L, Zheng, M, Zhou, L, Kong, X. Density functional theory study of the structural and electronic characteristics of C6H5OH(H2O)n(n=1-6) clusters. J Atom Mol Phys 2019;36:184–92.Search in Google Scholar

26. Vydrov, OA, Scuseria, GE. Assessment of a long-range corrected hybrid functional. J Chem Phys 2006;125:234109. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2409292.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Körzdörfer, T, Brédas, JL. Organic electronic materials: recent advances in the DFT description of the ground and excited states using tuned range-separated hybrid functionals. Acc Chem Res 2014;47:3284–91. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar500021t.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Meir, R, Chen, H, Lai, W, Shaik, PS. Corrigendum: oriented electric fields accelerate diels-alder reactions and control the endo/exo selectivity. ChemPhysChem 2020;21:1737. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.201900495.Search in Google Scholar

29. Aragones, AC, Haworth, NL, Darwish, N, Ciampi, S, Mannix, EJ, Wallace, GG, et al.. Electrostatic catalysis of a Diels-Alder reaction. Nature 2016;531:88–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16989.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Shaik, S, Danovich, D, Joy, J, Wang, Z, Stuyver, T. Electric-field mediated chemistry: uncovering and exploiting the potential of (oriented) electric fields to exert chemical catalysis and reaction control. J Am Chem Soc 2020;142:12551–62. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.0c05128.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Shaik, S, Ramanan, R, Danovich, D, Mandal, D. Structure and reactivity/selectivity control by oriented-external electric fields. Chem Soc Rev 2018;47:5125–45. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cs00354h.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Lin, H, Liu, Y, Yin, W, Yan, Y, Ma, L, Jin, Y, et al.. The studies on the physical and dissociation properties of chlorobenzene under external electric fields. J Theor Comput Chem 2018;17:1850029. https://doi.org/10.1142/s0219633618500293.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/phys-2025-0250).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- The influence of anisotropy of InP on its elasticity and phonon properties

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- The influence of anisotropy of InP on its elasticity and phonon properties

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II