Abstract

Based on the Photonpath-length Probability Density Function (PPDF) model and traditional DOAS method, the correction factor (α, ρ, h, γ) is introduced for atmospheric scattering on optical paths. The scattering correction of PPDF factor on 1.6μm band radiation and CO2 retrieval is analyzed. The results show that the influence of α, ρ on radiance is greater than that of h, γ. Increasing α, h will increase the results, and increasing α by 0.1 will increase the retrieval result by about 3 ppm. Increasing ρ, γ will decrease CO2 retrieval, and increasing ρ by 0.1 will decrease the retrieval result by 2 ppm. At the same time, as the surface reflectance increases, its impact on CO2 retrieval becomes smaller and smaller. However, as the aerosol optical thickness increases, the retrieval error increases, which significantly affects the accuracy of CO2 retrieval. The influence of aerosols cannot be ignored and should be corrected to improve the accuracy of CO2 retrieval. The scattering correction of PPDF is verified using the measured GOSAT spectrum, with retrieval accuracy within 0.7 %. Due to the lack of scattering correction in the DOAS method, the scattering correction effect of the PPDF method is also verified.

1 Introduction

Since the industrialization of human society, the greenhouse effect caused by greenhouse gases such as CO2 has become serious, affecting global environment, economy and social development. It has brought significant challenges and threats to human life [1], 2]. Real-time monitoring of CO2 is crucial for studying climate change [3]. However, traditional ground-based greenhouse gas monitoring systems have limitations in spatial scale and coverage, and satellite observations of greenhouse gases can help address these shortcomings [4], 5]. Therefore, satellite monitoring of greenhouse gases has become an important and effective method for addressing these challenges [6], 7]. The defect of using satellite to monitor CO2 gas lies in its retrieval accuracy. Satellite observations in the shortwave infrared band are greatly affected by aerosols and cirrus clouds, and CO2 observation and retrieval accuracy will be significantly affected by scattering. In 2020, Sanghavi et al. [8] pointed out that if the influence of cirrus and aerosol scattering on CO2 retrieval is ignored, the retrieval error can reach 15 ppm. In the desert area with high surface reflectivity, the retrieval error is even as high as 40 ppm [9]. In 2014, Jiang et al. [10] also pointed out that different scattering correction methods have different effects on CO2 retrieval. They pointed out that the PPDF method has a significant effect on correcting the optical path caused by scattering, which can greatly improve the retrieval accuracy. Huo and Duan [11] pointed out that under dust-type fine particle aerosols, aerosol misestimation of 0.1 will cause a retrieval deviation of 4–5 ppm. Ye et al. [12] pointed out that as the surface reflectance in the CO2 band increases, the impact on the retrieval results will be smaller and smaller. Therefore, aerosol scattering effect is important in short-wave near-infrared remote sensing. How to effectively correct aerosol scattering is the key to achieve high-precision satellite remote sensing of CO2.

To achieve high-precision of CO2 retrieval, Crisp has developed a full-physical method [13]. SCIMACHY also developed the retrieval method of WFM-DOAS [14]. A CO2 retrieval algorithm based on PPDF model was developed with the Japanese GOSAT satellite [15]. One of the important factors affecting the accuracy of CO2 retrieval in these mainstream algorithms is the correction of scattering, and the correction effect is directly related to the accuracy of CO2 retrieval. Although the PPDF method can avoid the complex scattering process, the accuracy of PPDF factor in describing the scattering effect of aerosol is directly related to the retrieval accuracy of CO2 concentration. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the influencing factors of the scattering effect of the PPDF method.

Based on the principle of PPDF, the influence of optical path correction factor on CO2 radiance spectrum is first analyzed, and then the error of optical path correction factor on CO2 retrieval. Finally, the influence of PPDF scattering correction effect on CO2 retrieval under different atmospheric conditions is analyzed, aiming to provide a theoretical foundation for achieving high-precision CO2 retrieval.

2 Materials and methods

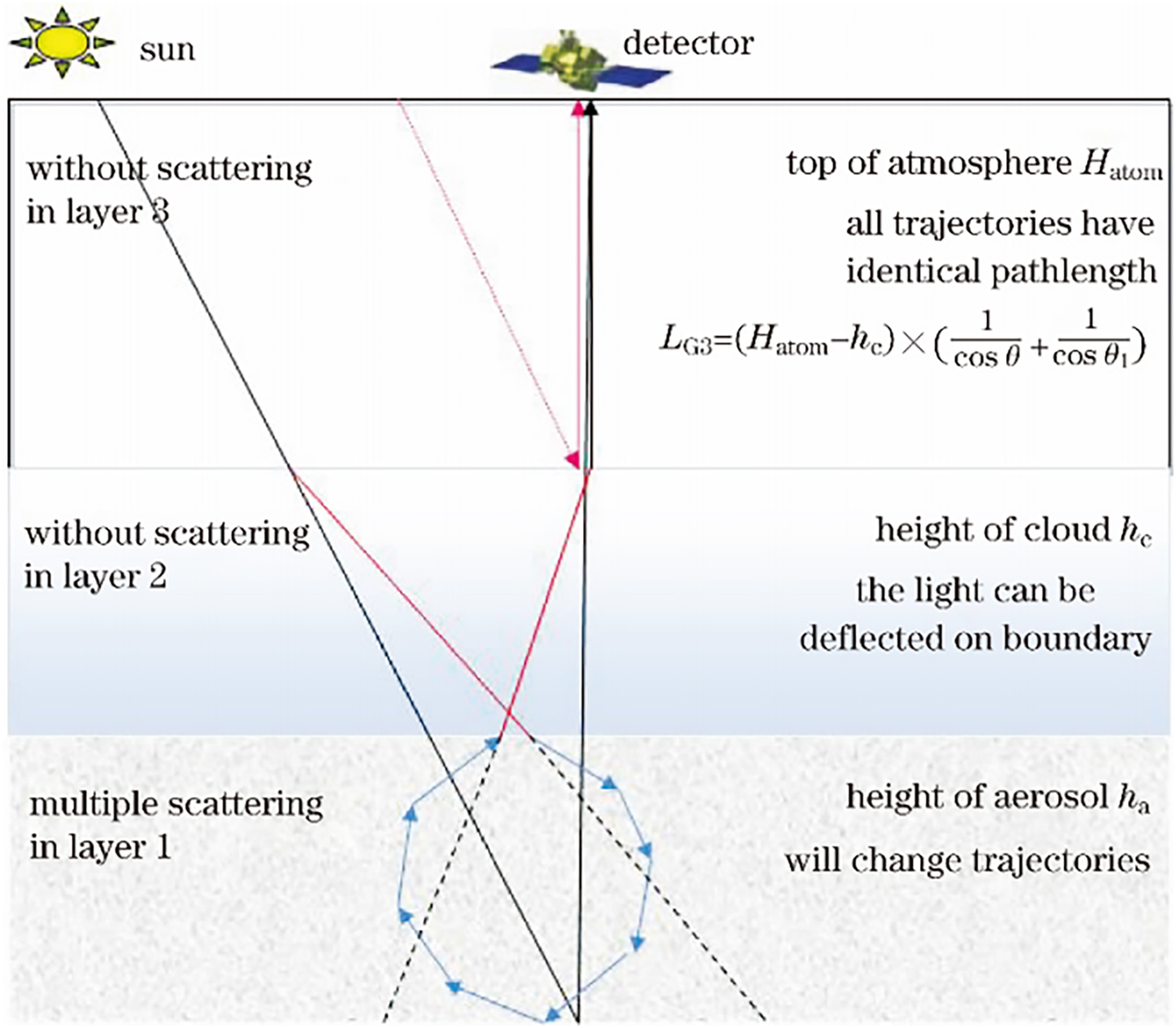

The PPDF model is a greenhouse gas retrieval method based on the equivalence theory. Cloud and aerosol scattering essentially affects the distribution of photon paths. Due to cloud and aerosol scattering, the photon paths are stretched or shortened, leading to an underestimation or overestimation of CO2 concentration. In regions with high surface reflectance, ignoring this path correction effect may result in a particularly noticeable overestimation. Studies have pointed out that in desert areas, ignoring photon path correction can lead to a deviation of more than 15 ppm in CO2. Considering the photon path correction factor in the PPDF model, this method can overcome the limitations of the DOAS method in dealing with scattering. The traditional DOAS method treats gas absorption as a fast-varying component, and aerosol and other influences as slow-varying components for spectral separation. In contrast, the PPDF model converts scattering into fast-varying components through the PPDF factor, thereby theoretically correcting the errors caused by atmospheric scattering in CO2 retrieval. The model diagram is shown in Figure 1.

where α a , α c , ρ a , ρ c , h a , h c , γ a , and γ c are 8 PPDF parameters; k is the molecular absorption coefficient; T eff is the effective transmittance of the whole atmosphere; θ and θ1 are the solar zenith angle and the satellite observation angle, respectively. These PPDF parameters treat the scattering of clouds and aerosols as stretching or shortening the optical path, thereby changing the effective transmittance of the entire atmosphere.

The three-layer PPDF model.

According to the transmittance of Eq. (1) and the instrument response of the detector, the radiance spectrum received by the satellite is as follows:

where R is the radiance spectrum of CO2 in the 1.6 µm band; S is the solar spectrum outside the atmosphere, and < > is the convolution with the instrument linear function.

The scattering is corrected using eight PPDF factors, and the correction effect is directly related to the retrieval accuracy of CO2. The actual effective transmittance of the atmosphere is shown in Eq. (1), and the effect of scattering correction is the deviation of the eight PPDF factors from their true states. Since the PPDF factors of the upper scattering layers α c , ρ c , h c , γ c and α a , ρ a , h a , γ a basically have the same effect on the spectrum, the influence of α c , ρ c , h c , γ c on the effective transmittance in Eq. (1) is discussed. To analyze the influence of α c , ρ c , h c , γ c on radiance, the effect of a small perturbation of a PPDF factor on its effective transmittance is first taken into account, as described by Eqs. (1)– (7). Assuming that α c can change Δα c , the resulting change in transmittance is as follows:

If ρ c changes Δρ c , the change in transmittance is as follows:

If h

c

changes Δh

c

,

If γ c changes Δγ c , the transmittance is as follows:

Therefore, the influence of α c , ρ c , h c , γ c on radiance depends on the values of ΔT 1, ΔT 2, ΔT 3, ΔT 4. If Δα c > 0, then ΔT 1 > 0, the spectrum received by the satellite is enhanced, and the absorption peak becomes shallow. This makes the results of CO2 retrieval larger; otherwise, it is small. If Δρ c > 0, then ΔT 2 < 0, the spectrum received by the satellite weakens and the absorption peak becomes deeper. This makes the CO2 retrieval result smaller; otherwise, the retrieval result is larger. Similarly, the effect of Δh c is similar to that of Δα c , and the effect of Δγ c is similar to that of Δρ c .

The disturbance of the PPDF factor will increase or decrease the effective transmittance in Eq. (1). Consequently, the radiance received by the satellite will also increase or decrease, making the CO2 retrieval result smaller or larger. Therefore, the influence of the scattering correction of the PPDF model on CO2 retrieval is discussed.

3 Results and analysis

3.1 Effect of PPDF factor on 1.6 µm band radiance and CO2 retrieval

From Eqs. (1)– (7) in the PPDF model, it can be seen that the PPDF factor is directly related to the construction of the simulated spectrum and has significant impact on the retrieval accuracy of CO2. The weight of each PPDF factor on the 1.6 µm band radiance of CO2 is obtained using Eqs. (1)– (7). The simulated spectrum is expressed as follows:

The weight function is expressed as follows:

where X is each PPDF factor, and T eff is the calculation result of Eq. (1). The second-order polynomial is calculated as follows:

which is used to fit other slow components except scattering.

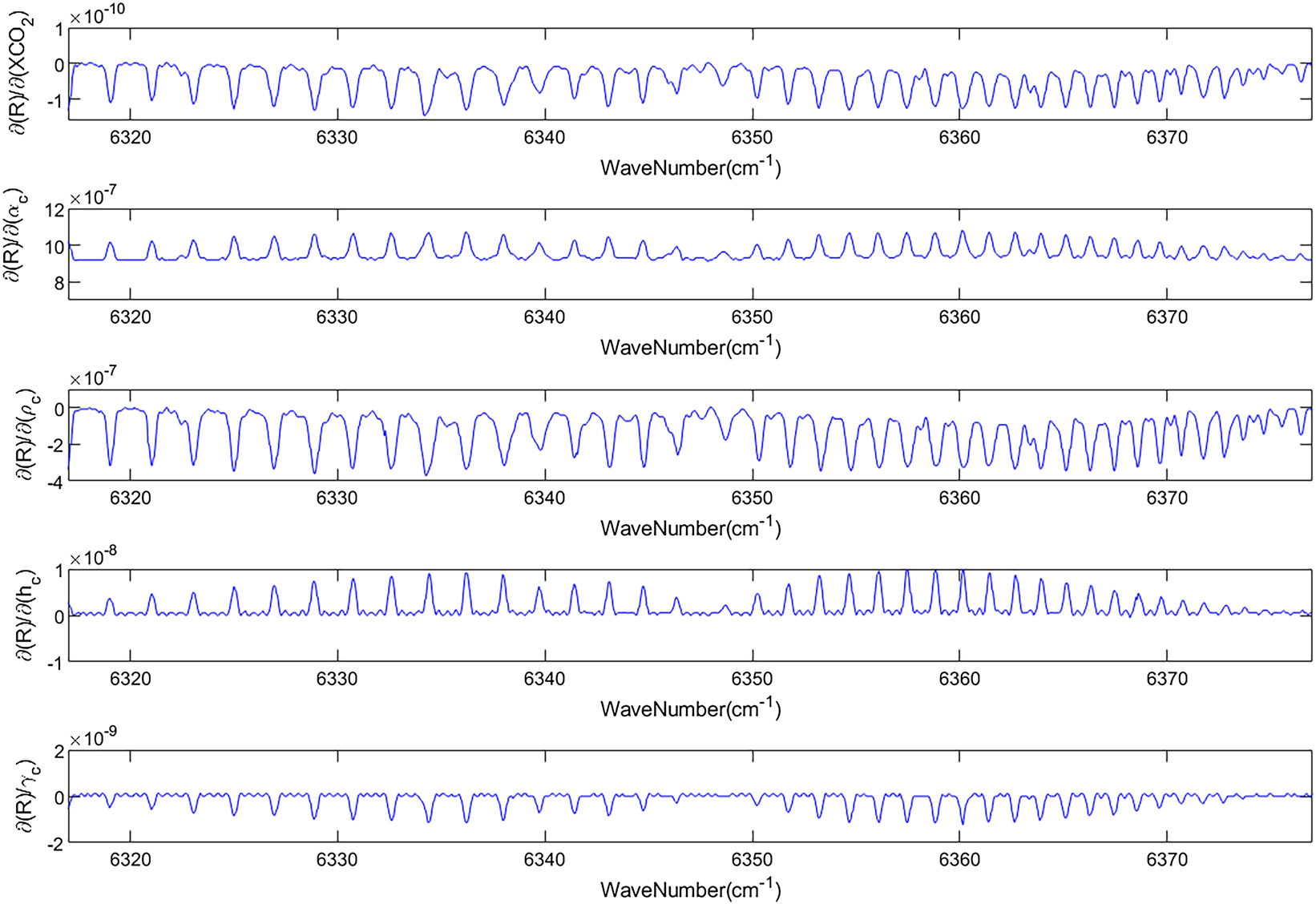

The simulated spectral calculation conditions are shown in Table 1. The weight of each PPDF factor and the CO2 mixing ratio at 1.6 µm are calculated by using Eq. (14). The weight is shown in Figure 2. The x-axis represents the corresponding wave number, and the y-axis represents the weight of each PPDF factor and CO2 mixing ratio.

Simulated spectral factors.

| Parameters | Variation range |

|---|---|

| Viewing zenith angle | 10° |

| Albedo (1.6 μm) | 0.3 |

| AOD (1.6 μm) | 0.5 |

| Solar zenith angle | 65° |

| Atmospheric profile | 76-year standard atmospheric profile |

Weight of CO2 and PPDF factors.

As shown in Figure 2, the weight of each factor is different in the 1.6 µm band. For magnitude, the influence of α c , ρ c on the 1.6 µm band radiance is greater than that on the CO2 column concentration, while the influence of h c , γ c on the 1.6 µm band radiance and the CO2 column concentration is similar. In terms of the impact on CO2 retrieval, α c , h c have the same effect on the spectrum, resulting in shallow absorption peaks in the simulated spectrum and overestimating the retrieval results. On the other hand, ρ c , γ c deepens the absorption peaks in the spectrum, resulting in an underestimation of the retrieval results. Based on the PPDF model, the above results can be understood as: parameter photons are directly scattered back to the satellite by the scattering layer, thereby shortening the actual optical path. This leads to a reduction in CO2 absorption, manifested as a shallower absorption peak, resulting in an increase in the retrieval results. ρ c represents the stretching of the optical path due to atmospheric scattering. The more significant the stretching, the deeper the absorption peak, and the smaller the retrieval result. h c represents the height of the scattering layer. The higher the scattering layer, the lower the absolute probability of photon absorption, the shallower the absorption peak, and the larger the retrieval result. γ c represents the shape of probability distribution of the optical path. The larger γ c , the more photons are stretched due to scattering, the deeper the absorption peak, and the smaller the retrieval.

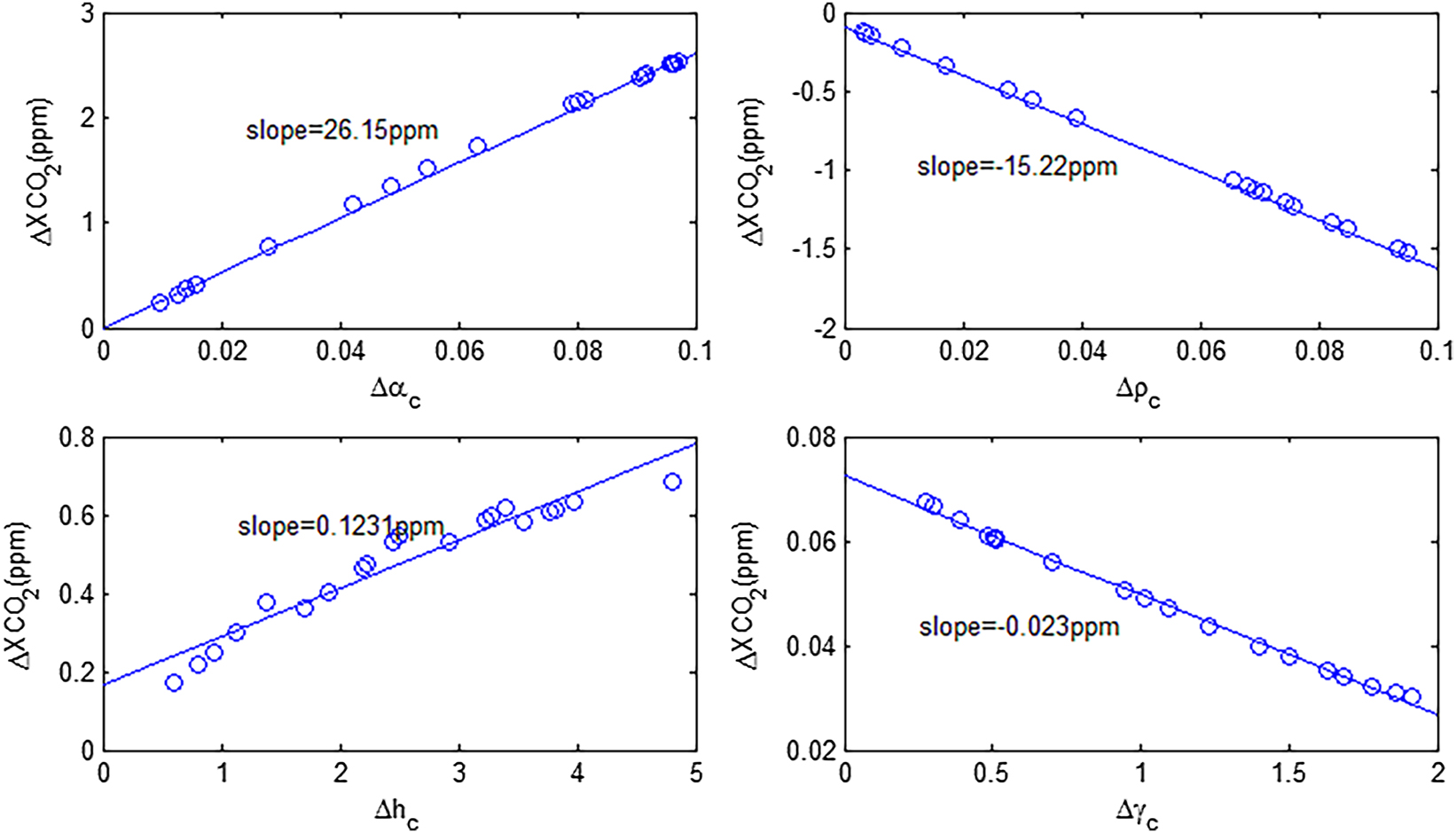

Based on the influence of the weight function (Figure 2) on the radiance of each PPDF factor, how each PPDF factor affects CO2 retrieval is further investigated. In this study, one factor is changed at a time. Since α c , ρ c are usually small and randomly changes between 0 and 0.1, h c is between 0 and 5 km and γ c is between 0 and 2. In the same way, the influence of α c , ρ c , h c , and γ c on CO2 retrieval can be explored. In actual PPDF retrieval, the column concentration is 393.2145 ppm. Figure 3 shows the difference between the retrieved values and the actual PPDF under different factors, helping to determine the influence of each PPDF factor on CO2 retrieval.

The relationship between PPDF factor and the deviation of CO2 retrieval value.

As shown in Figure 3, the impact of α

c

, ρ

c

, h

c

, and γ

c

on CO2 retrieval is approximately linear. A linear fit is performed on the above retrieval results, and the slope of α

c

, h

c

is greater than 0. This indicates that as α

c

, h

c

increases, the retrieval results become larger and larger, and the retrieved value is greater than the real value of ρ

c

, γ

c

; on the contrary, this is consistent with the conclusion of the weight. From the absolute value of the slope, the slope of α

c

, ρ

c

is much larger than that of h

c

, γ

c

, which means that the sensitivity of α

c

, ρ

c

to CO2 retrieval is much stronger than that of h

c

, γ

c

. Therefore, to ensure retrieval accuracy during the inversion process, variable transformations are introduced to constrain the parameters:

3.2 Effects of surface reflectance and aerosol on CO2 retrieval

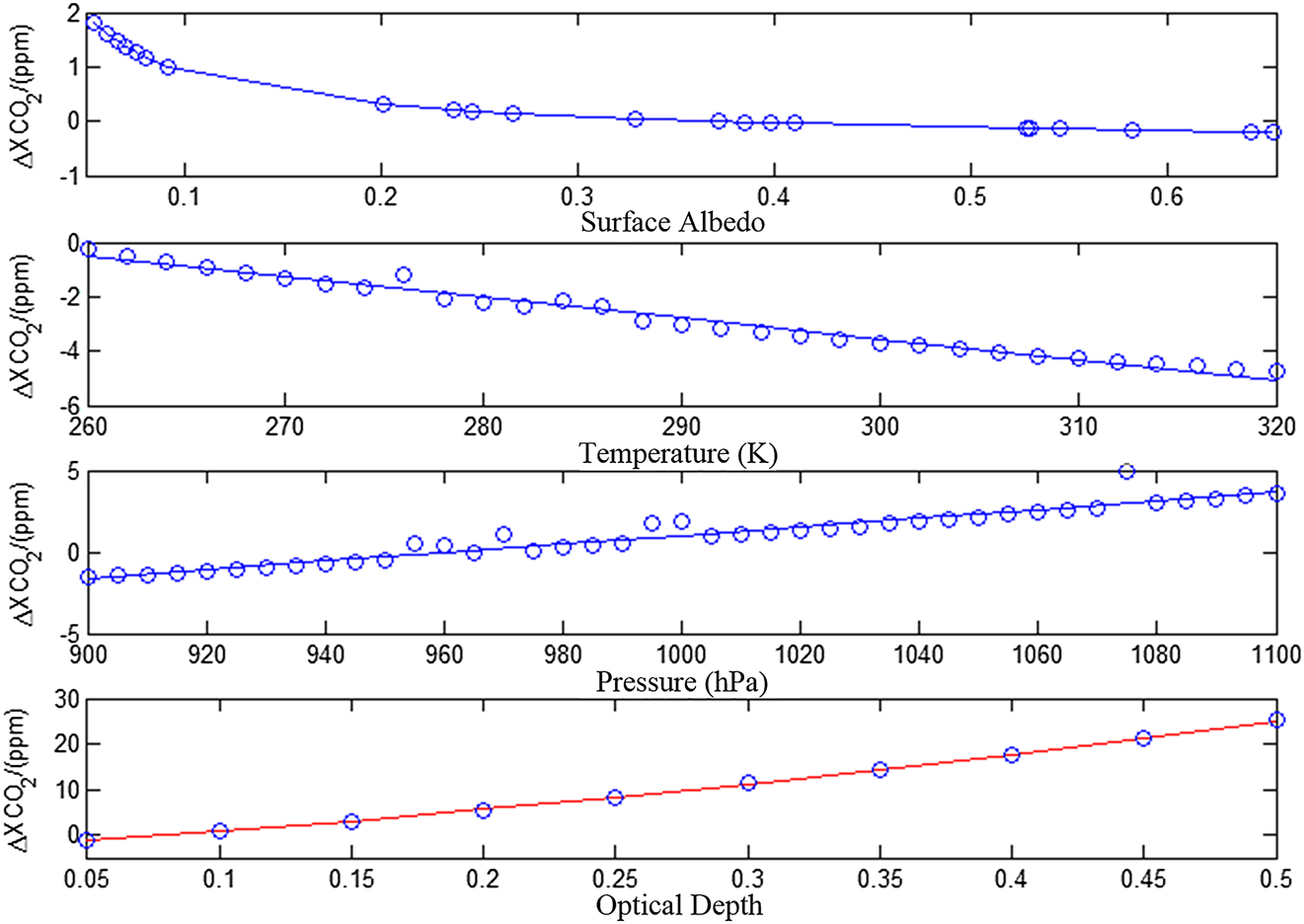

Temperature, pressure, and aerosol optical thickness have a significant impact on the optical path during photon transport. These factors will influence the scattering, absorption, and transmission of photons through the atmosphere, thereby affecting the retrieval of CO2 concentrations. In addition, the surface reflectance characterizes the ability of the Earth’s surface to reflect solar radiation. The coupling of these atmospheric conditions and surface reflectance will influence the accuracy of CO2 retrievals. The PPDF method is used to further analyze the impact of atmospheric parameters and surface reflectance on CO2 retrieval. Table 1 can be used for simulation (The aerosol optical depth is modified to 0.05). The PPDF method is used to retrieve CO2 by changing different temperature, pressure, surface reflectance and aerosol optical thickness. The retrieval results are shown in Figure 4.

Errors of PPDF retrieval under different conditions.

According to the linear fitting of the temperature and surface pressure impacts on the CO2 retrieval results, it is found that the slope of surface pressure is 0.025 ppm/hPa and that of temperature is −0.0753 ppm/K. This means that a pressure difference of 40 hPa from the true value will cause a 1 ppm CO2 retrieval error. About 14 K temperature difference from the true value will result in a 1 ppm CO2 retrieval error. These errors are usually within the acceptable limits in most remote sensing applications. The influence of optical thickness and surface reflectance is not simply linear. As the surface reflectance increase, its influence on CO2 retrieval is small. As the optical thickness increases, the retrieval error increases in the form of quadratic function. To more clearly reflect the retrieval deviation under different surface reflectance and optical thickness conditions, according to the statistical results of MODIS, the deviation of optical thickness can be approximately expressed as Δτ = 0.05 + 0.15τ. The deviation of surface reflectance is usually smaller than 60 %. According to Figure 4, Tables 2 and 3 show the retrieval error caused by optical thickness and surface reflectivity in practical applications.

Retrieval errors of different surface reflectivity.

| Surface reflectivity | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔXCO2 (ppm) | 0.7–1.8 | 0.15–0.88 | 0.56–0.32 | 0.19–0.33 |

Retrieval errors of different aerosol optical thickness.

| Aerosol optical depth | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔXCO2 (ppm) | 2.97 | 4.14 | 6.15 | 8.17 |

From Tables 2 and 3, as the surface reflectivity increases, its influence on the retrieval becomes small. However, as the aerosol optical thickness increases, the retrieval error will increase, which has a significant impact on the CO2 retrieval accuracy.

4 Verification of measured data

To analyze the scattering correction performance of the PPDF method, GOSAT land data from April, June, October, and December, 2022 were selected to represent the four seasons: spring, summer, autumn, and winter. The retrieval deviations of the PPDF results are shown in Figure 5. The results show that the PPDF retrieval show significant fluctuations in June. This is mainly due to high temperatures in summer, increased convective activity, and increased aerosol concentrations of complex types such as biomass burning and urban pollution, resulting in a significant decrease in retrieval accuracy. Most errors are in the range of 0.8–1%. There is also a clear latitudinal variation in retrieval accuracy: the retrieval errors of the PPDF method significantly increase in areas between 30°N and 60°N (temperate continental zone). There are two main reasons for this: (1) This region includes many industrialized countries and densely populated areas. Anthropogenic emission sources such as coal-fired power plants, transportation, and agriculture enhance the near-surface CO2 concentration gradient, which may introduce retrieval bias. In addition, human activities release large amounts of aerosols and pollutants, significantly increasing the uncertainty in atmospheric scattering and absorption; (2) High solar zenith angle in this region increases the complexity of atmospheric scattering, aerosol interference, and surface reflection, thereby greatly affecting the effective detection of CO2 absorption signals.

Retrieval deviations of the PPDF method in different seasons.

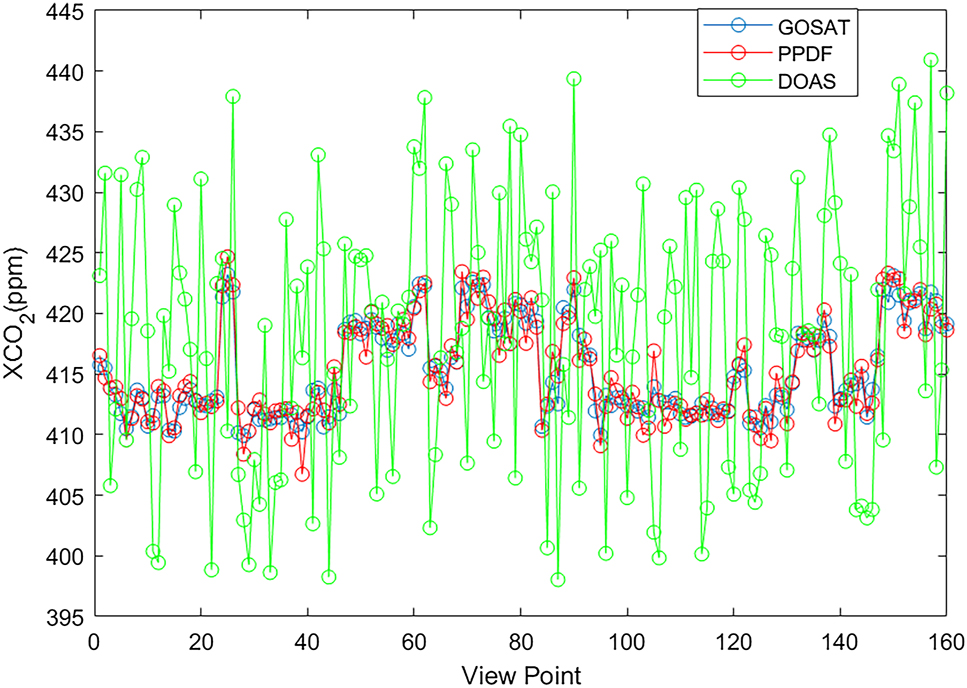

Due to the time-consuming nature of the DOAS retrieval method, this study only applied it to a subset of data in low-latitude regions in May. The retrieval results are compared with those obtained using the PPDF method, as shown in Figure 6, and corresponding means and variances shown in Table 2.

Retrieval results of CO2 infusion concentration obtained by different retrieval methods and GOSAT.

As shown in Figure 6 and Table 4, the deviation between PPDF search results and GOSAT level 2 products is within 0.7 %, and the mean and variance are close to those of GOSAT. This level of retrieval accuracy is suitable for climate studies. In contrast, the DOAS method yields retrieval deviations ranging from 2 to 5 %, with a variance as high as 121, not meeting the accuracy requirements for climate.

Retrieval error of different aerosol optical thickness.

| GOSAT | PPDF | DOAS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/ppm | 415.29 | 415.31 | 418.35 |

| Variance/ppm | 14.85 | 16.37 | 21.34 |

Based on the modeling of photon path length distribution, the PPDF method can better capture multiple scattering effects and significantly reduce retrieval biases under strong atmospheric scattering conditions. It can simplify complex radiative transfer into an integration over path distributions with low computation, making it suitable for large-scale operational processing. It shows high adaptability to different surface albedos and aerosol conditions, reducing sensitivity to scene-dependent parameters. It can also be embedded as a scattering correction module within existing retrieval pipelines without altering the overall framework. These results demonstrate that the PPDF method can correct scattering effects and improve the retrieval accuracy, and it is applicable.

5 Conclusions

Aerosol scattering effect has a significant impact on CO2 satellite remote sensing observation. How to correct aerosol scattering effect is a key scientific problem. Based on the principle of PPDF, the influence of optical path correction factor on CO2 retrieval is analyzed. From the retrieval results, the sensitivity of α, ρ to CO2 in the retrieval process is much stronger than that of h, γ. The influence of α, ρ, h, γ on CO2 retrieval is approximately linear. Increasing α by 0.1 will make the retrieval result increase by about 3 ppm; increasing ρ by 0.1 will make the retrieval results decrease by about 2 ppm; increasing h by 1 km will only increase the retrieval result by 0.12 ppm; increasing γ by 1 km makes the retrieval result decrease by 0.023 ppm. The inversion accuracy of PPDF factor is related to the effect of scattering correction, which further affects the accuracy of CO2 retrieval. To improve the accuracy of CO2 retrieval, the scattering correction effect should be guaranteed in the subsequent retrieval process. To verify the effect of scattering correction, the global data of GOSAT in 2022 is selected for retrieval. The deviation of PPDF retrieval is within 0.7 %, which is better than the accuracy of traditional DOAS method (2–5 %), verifying the effect of scattering correction. Since this method was developed based on GOSAT data, it is also applicable to OCO-2 data. For this case, further validation and some algorithm modifications are still required, and this is also the focus in the future work.

-

Funding information: The authors acknowledge the Key Scientific Research Project of Anhui Education Department (2023AH052104, 2022AH051712, 2023AH052099, KJ2021A1027), The Start-up Fund for High-level Talents (KYDQ-202207, KYQD-202208), College Students’ Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (S202510380077), the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui province (2408085MD102) and the Anhui Provincial Colleges Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars (2022AH020093).

-

Author contribution: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

1. Sun, ZQ, Wang, XH, Ye, HH, Li, C, An, Y, Sun, EC, et al.. Fast retrieval method of atmospheric CO2 based on GF-5 satellite remote sensing data. Acta Opt Sin 2024;44:281–90. https://doi.org/10.3788/AOS231995.Search in Google Scholar

2. Kiel, M, Eldering, A, Roten, DD, Lin, JC, Feng, S, Lei, R, et al.. Urban-focused satellite CO2 observations from the orbiting carbon observatory-3: a first look at the Los Angeles megacity. Rem Sens Environ 2021;258:112314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2021.112314.Search in Google Scholar

3. Li, ZQ, Xie, YS, Shi, YS, Li, Q, Jason, C, Zhang, YZ, et al.. A review of collaborative remote sensing observation of greenhouse gases and aerosol with atmospheric environment satellites. Natl Remote Sens Bull 2022;26:795–816. https://doi.org/10.11834/jrs.20221387.Search in Google Scholar

4. Somkuti, P, Bösch, H, Parker, RJ. The significance of fast radiative transfer for hyperspectral SWIR XCO2 retrievals. Atmosphere 2020;11:1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11111219.Search in Google Scholar

5. Bertaux, JL, Hauchecorne, A, Lefèvre, F, Bréon, FM, Blanot, L, Jouglet, D, et al.. The use of the 1.27 µm O2 absorption band for greenhouse gas monitoring from space and application to MicroCarb. Atmos Meas Tech 2020;13:3329–74. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-13-3329-2020.Search in Google Scholar

6. Lee, KS, Lee, CS, Seo, M, Choi, S, Seong, NH, Jin, D, et al.. Improvements of 6S look-uptable based surface reflectance employing minimum curvature surface method. Asia-Pac J Atmos Sci 2020;56:235–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13143-019-00164-3.Search in Google Scholar

7. Clarisse, L, Van damme, M, Hurtmans, D, Franco, B, Clerbaux, C, Coheur, PF. The diel cycle of NH3 observed from the FY-4A geostationary interferometric infrared sounder (GIIRS). Geophys Res Lett 2021;48:e2021GL093010. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL093010.Search in Google Scholar

8. Sanghavi, S, Nelson, R, Frankenberg, C, Gunson, M. Aerosols in OCO-2/GOSAT retrievals of XCO2: an information content and error analysis. Rem Sens Environ 2020;251:112053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.112053.Search in Google Scholar

9. Sinyuk, A, Holben, BN, Eck, TF, Giles, DM, Slutsker, I, Korkin, S, et al.. The AERONET version 3 aerosol retrieval algorithm, associated uncertainties and comparisons to version 2. Atmos Meas Tech 2020;13:3375–411. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-13-3375-2020.Search in Google Scholar

10. Jiang, XH, Wang, XH, Ye, HH, Wei, QY, Li, ZW, Bu, TT. Correction method of atmospheric scattering effect through optical path in CO2 retrieval. Acta Opt Sin 2014;34:235–41. https://doi.org/10.3788/AOS201434.0801005.Search in Google Scholar

11. Huo, YF, Duan, MZ. Sensitivity studies for CO2 retrieval of aerosol optical depth, type and profile. Remote Sens Technol Appl 2014;29:33–9. https://doi.org/10.11873/j.issn.1004-0323.2014.0033.Search in Google Scholar

12. Ye, H, Shi, H, Li, C, Wang, X, Xiong, W, An, Y, et al.. A coupled BRDF CO2 retrieval method for the GF-5 GMI and improvements in the correction of atmospheric scattering. Remote Sens 2022;14:488. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14030488.Search in Google Scholar

13. Crisp, D, O’dell, C, Granat, R. Orbiting carbon observatory-2 & 3 (OCO-2 & OCO-3) level 2 full physics retrieval algorithm theoretical basis document. NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory; 2021. Report No. OCO D-55207. https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/information/documents?title=OCO-2%20Documents&utm_source=chatgpt.com.Search in Google Scholar

14. Heymann, J, Reuter, M, Hilker, M, Buchwitz, M, Schneising, O, Bovensmann, H, et al.. Consistent satellite XCO2 retrials from SCIAMACHY and GOSAT using the BESD algorithm. Atmos Meas Tech 2015;8:2961–80. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-8-2961-2015.Search in Google Scholar

15. Jiang, F, Wang, H, Chen, JM, Ju, W, Tian, X, Feng, S, et al.. Regional CO2 fluxes from 2010 to 2015 in‐ferred from GOSAT XCO2 retrievals using a new version of the global carbon assimilation system. Atmos Chem Phys 2021;21:1963–85. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-1963-2021.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis