Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

Abstract

This study computationally examines the water-based hybrid nanofluid flow with the impacts of carbon nanotubes on an elongating surface. The flow is influenced by velocity slip constraints, zero-mass flux conditions, and thermal convection. Magnetic effects are applied to the flow system in the normal direction. The activation energy and chemical reactivity effects are used in the concentration equation. The modeled equations have been evaluated numerically through the bvp4c technique after conversion to dimensionless form through a similarity transformation approach. It has been discovered in this work that with expansion in magnetic and porosity factors, the velocities declined. Augmentation in the ratio factor has declined the primary flow velocity while supporting the secondary flow velocity. Thermal profiles have intensified with progression in the Brownian motion factor, thermal Biot number thermophoresis factor, and exponential heat source and radiation factors. Concentration distribution has escalated with the activation energy factor and has declined with an upsurge in Schmidt number and chemical reaction factors. The impact of an upsurge in the thermophoresis factor enhances the concentration distribution, while the upsurge in the Brownian motion factor exhibits a reducing impact on concentration distribution. To ensure the validation of this work, a comparative study is conducted in this work with a fine agreement among the current and established datasets.

1 Introduction

The mixing of small-sized particles into a base fluid for the purpose of supplementing its thermal features results in a nanofluid. This idea was floated initially by Choi and Eastman [1] for enhancing the thermal conductance of normal fluid. Nanofluid flow is studied for its potential to enhance rates of thermal transference in various applications, including cooling of electronic devices, automotive and industrial heat exchangers, and biomedical applications as noticed by Anjum et al. [2] and Khan et al. [3]. Hybrid nanofluid flow involves two or more dissimilar kinds of nanoparticles distributed in a pure fluid, combining the benefits of different materials to further enrich the thermal features of the fluid. For instance, a hybrid nanofluid might include a mixture of metallic nanoparticles, such as copper, and non-metallic nanoparticles, such as graphene, to exploit the extraordinary thermal features of copper and the excellent mechanical and thermal properties of graphene as noticed by Sriharan et al. [4]. Analytical evaluation of temperature in living tissues is performed by Hobiny et al. [5] using the TPL bio-heat model, supported by experimental verification. Their study focuses on understanding thermal behavior in biological tissues, integrating theory and practical data. The results of their work validate the model’s accuracy in predicting temperature distributions, crucial for medical applications such as hyperthermia therapy and diagnostics. Alzahrani and Abbas [6] evaluated analytically the active living tissues’ thermal damage subject to laser irradiations. The synergy between different nanoparticles can lead to improved thermal conductivity, stability, and thermal flow management in comparison with single-component nanofluids [7]. Ibrahim et al. [8] observed that the flow behavior and heat transference characteristics of hybrid nanofluids are influenced by the connections between the diverse kinds of nanoparticles, their concentration ratios, and the properties of pure liquid. Applications include more efficient cooling systems in electronics, automotive radiators, and advanced thermal management systems in renewable energy technologies [9]. Both nanofluids and hybrid nanofluids significantly impact heat transfer by enhancing the thermal conductance and convective heat transfer coefficients of pure fluid [10]. This leads to improved efficiency in heat exchangers and cooling systems, allowing for more effective thermal management. The increased thermal conductivity and improved convective heat transfer result in reduced energy consumption and better performance in systems ranging from microelectronics cooling to industrial heat exchangers and renewable energy applications. Marin et al. [11] numerically examined a nonlinear hyperbolic bio-thermal model under various flow conditions to treat tumor cells. The study aimed to understand the interaction between heat transfer and biological tissue in the context of tumor treatment. Their findings contribute to optimizing therapeutic strategies, enhancing the understanding of heat-induced cell damage, and improving treatment protocols for tumors. The investigation of Saeed and Abbas [12] focuses on mathematical models of bio-heat transfer to analyze the transient phenomena in spherical tissue caused by a laser heat source. Their study aims to understand how the tissue responds to the heat over time, considering the impact of the laser on the thermal behavior of the biological material. Hobiny and Abbas [13] examined the nonlinear analysis of the dual-phase lag model of bio-heat in living tissues under laser irradiation. Their work focuses on understanding heat transfer dynamics, accounting for time delays in heat flux and temperature gradient responses, and offering insights into thermal behavior during laser–tissue interactions for medical and scientific applications.

Porous media describe the materials containing pores within their structure, which allow fluids (liquids or gases) to pass through. These materials occur naturally, such as soils, rocks, and biological tissues, or engineered, such as ceramics, foams, and certain types of filters. The pores in porous media vary significantly in size, shape, and distribution, influencing the material’s permeability and porosity. Fluid flow in porous media involves the movement of fluids through materials that contain numerous pores or voids and is primarily governed by Darcy’s law as observed by Yang et al. [14]. Khalil et al. [15] proved that in permeable media, the fluid flow is affected by the porosity and the permeability of the material, as well as the viscosity and density of the fluid. Wang et al. [16] studied the mass and thermal transportations of thin-film flow on a permeable medium with impressions of the Buongiorno model. Pop et al. [17] discussed time-based flow and thermal transference for mono and hybrid nanoparticle flow on a permeable surface and noted that with progression in porosity factor, there has been a decline in velocity distribution while a growth has noted thermal distribution. In practical applications, such as groundwater hydrology, oil recovery, and filtration, the performance of fluid flow in porous media is crucial for heightening the efficacy and effectiveness of a process [18]. The motion of fluid on a permeable media significantly affects thermal and velocity panels within the medium as noted by Ali et al. [19]. For the heterogeneous nature of permeable media, the fluid velocity is not uniform and varies with the pore size and distribution. This non-uniformity leads to complex velocity profiles, where fluid may accelerate through larger pores and slowdown in smaller ones, creating a range of velocities within the medium. Temperature profiles in porous media are also impacted by the flow as noted by Nadeem et al. [20], the thermal conductance of the porous medium, combined with the convective heat transfer of the fluid, determines the temperature distribution.

The key principle of MHD is the relationship between the magnetic fields and the fluid’s electrical conductivity, which induces currents and affects the fluid motion. Governed by the combined principles of fluid dynamics and electromagnetism, MHD finds applications in astrophysics, fusion reactors, and electromagnetic pumps [21,22]. Ahmad et al. [23] studied the significance of multi-slip constraints with impacts of MHD on fluid flow subject of nonlinear radiations thermally and chemically reactivity. Lone et al. [24] discussed a semi-numerical approach for the evaluation of blood-based trihybrid MHD fluid flow on a bi-directional extending sheet with flow slip constraints. In MHD, the existence of a magnetic field considerably influences the velocity and thermal distributions of the conducted fluid as observed by Tarakaramu et al. [25]. Mahesh et al. [26] proved that the Lorentz force, resulting from the interaction between the magnetic field and the induced electric current, acts on the fluid, modifying its flow characteristics. In some cases, MHD also induces secondary flows, such as swirling or rotational movements, subject to the alignment and strength of the magnetic field [27]. Moreover, Lund et al. [28] noted that the occurrence of the magnetic field in a fluid alters the heat transfer mechanisms. However, in some scenarios, it also suppresses convective motion, leading to increased reliance on conduction for heat transfer. Furthermore, as studied by Nawaz et al. [29], MHD can be utilized to control and optimize thermal management in various applications, such as cooling systems in fusion reactors or electromagnetic braking in metallurgy. The overall impact on velocity and thermal distributions depends on factors such as magnetic field strength, fluid properties, and flow conditions, making MHD a versatile tool in engineering and scientific research. Hobiny and Abbas [30] examined experimentally the thermal response of cylindrical tissues subject to laser irradiations. Abbas et al. [31] evaluated analytically the model of bio-heat for spherical tissues using the impacts of laser irradiations.

Brownian motion describes the random movement of particles mixed in a fluid, resulting from collisions of the molecules of fluids. This phenomenon is more pronounced at smaller scales, such as nanoparticles, where thermal fluctuations cause significant particle displacement. Brownian motion affects fluid dynamics by enhancing the mixing and dispersion of particles within the fluid as proved by Madkhali et al. [32]. Thermophoresis is the migration of particles in a fluid for thermal gradient in the flow phenomenon. Particles tend to move from hotter to cooler regions, driven by the imbalance in kinetic energy between particles in different thermal zones. Both thermophoresis and Brownian motion considerably affect heat and concentration transfer in fluid systems [33]. Shahzad et al. [34] studied that the Brownian motion enhances thermal conductance by promoting the uniform distribution of nanoparticles, leading to better heat transfer in nanofluids. Thermophoresis, in contrast, creates a thermal gradient-driven particle movement, which either enhances or inhibits heat transfer subject to the direction of the temperature gradient relative to the desired heat flow [35]. Brownian motion increases particle dispersion, improving the mixing and homogeneity of the solute concentration in the fluid. This leads to more efficient mass transfer and reaction rates in processes such as chemical reactions or pollutant dispersion. Sharma et al. [36] proved that thermophoresis effects contribute to concentration gradients by causing particles to migrate toward cooler regions, affecting the local concentration profiles and potentially enhancing separation processes or creating regions of high particle concentration. Thabet et al. [37] studied thermal augmentation for MHD fluid flow with impacts of Brownian and thermophoretic diffusions. Hanı et al. [38] discussed the impacts of Brownian and thermophoretic diffusions on boundary-layer MHD fluid flow on an elongating surface. Waqas et al. [39] examined computationally the Brownian motion and thermophoretic effects on gyrating nanomaterial fluid flow with activation energy.

Thermal radiation is electromagnetic radiation emitted by a body due to its temperature. It encompasses a range of wavelengths, including infrared, visible, and ultraviolet light, with intensity and wavelength distribution dependent on the body’s temperature. Thermal radiation significantly impacts the thermal characteristics distribution within the fluid and the boundaries it interacts with [40]. This combined heat transfer mechanism is essential in high-temperature environments, such as combustion chambers, solar collectors, and industrial furnaces. Essam and Abedel-AaL [41] proved that thermal radiation enhances heat transfer by providing a surplus mode of energy transfer, supplementing conduction and convection. Pandey et al. [42] studied thermally radiative and mixed convective fluid flow on a surface. Gul et al. [43] discussed the thin flow of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) with magnetic effects on a belt and have proved that pressure profiles, velocity, and thermal transmission have affected more in the case of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs). Alrehili [44] inspected augmentation in heat transfer for nanoparticle fluid flow on a nonlinear elongating surface with thermal radiations. Wang et al. [45] proved that in high-temperature applications, radiative heat transfer dominates, leading to more uniform temperature distributions and improved thermal efficiency. The presence of thermal radiation affects the fluid’s temperature gradients, often resulting in increased heat transfer rates as noted by Goud et al. [46]. Muhammad et al. [47] inspected the slip flow of mixed convective mono/hybrid nanofluids on a curved sheet. In their study, the authors have conducted a comparative analysis to ensure the precision of their results established. This is particularly important in systems where maintaining high thermal performance is critical, such as in the thermal management of electronic devices, high-temperature industrial processes, and energy systems such as solar thermal collectors. By optimizing the role of thermal radiation, engineers can design more efficient thermal systems with improved performance and energy savings. Swain et al. [48] studied computationally 3D Maxwell fluid flow on a stretching surface with impacts of thermal radiations. Hamad et al. [49] discussed the third-grade fluid flow on an inclined elongating surface with magnetic and thermally radiative effects. Hayat et al. [50] studied the Eyring Powell fluid flow with impacts of nanoparticles on exponential elongating sheet. In their work, the authors have conducted a comparative investigation to ensure the validity of the method used for the solution.

Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) are geometrical structures in cylindrical form with a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice. SWCNTs have remarkable electrical, thermal, and mechanical properties due to their unique structure, making them highly conductive and strong. They are used in various applications, including electronics, materials science, and nanotechnology. SWCNTs, with their single-layer structure, offer superior thermal conductivity along their length, making them ideal for applications requiring efficient heat dissipation. They can be used in thermal interface materials and as fillers in composite materials to improve thermal management in electronics and other devices. MWCNTs consist of numerous concentric layers of carbon atoms, forming a series of coaxial cylinders around a central hollow core. MWCNTs are less conductive than SWCNTs due to interlayer interactions. They offer greater mechanical strength and are easier to produce in large quantities. MWCNTs find applications in composite materials, conductive films, and additives to enhance the properties of various materials. MWCNTs, while slightly less efficient than SWCNTs due to interlayer phonon scattering, still provide excellent thermal conductivity. Their larger diameter and multiple layers make them robust and suitable for bulk applications. MWCNTs enhance the thermal conductivity of polymers and other matrices when used as fillers, improving the performance of thermal management systems in various industrial applications. Both types of CNTs are critical in developing advanced materials for efficient heat transfer and thermal regulation. The adoption of convective and zero-mass flux conditions in this analysis is motivated by their practical applications. Convective conditions account for heat exchange between fluid and the surrounding medium, which is critical in systems for improved heat transfer, such as solar collectors, heat sinks, and cooling devices for electronics. In this analysis, single and MWCNT hybrid nanofluid flow is examined on a bi-directional extending sheet. Velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions are executed to examine the hybrid nanofluid flow. Also, thermal radiation, exponential heat source, Brownian motion, thermophoresis, chemical reaction, and activation energy effects have been used. In this analysis, the authors are encouraged to investigate how the CNT nanoparticles influence the flow behavior of the water-based hybrid nanofluid flow with numerous constraints, such as velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions. How do external factors such as exponential heat source, Brownian motion, thermal radiation, and thermophoresis influence the behavior and efficiency of the water-based hybrid nanofluid flow? What are the effects of the chemical reaction and activation energy on the performance of hybrid nanofluid flow? To answer these questions, the mathematical formulation of the proposed problem is presented in Section 2. The numerical solution of the proposed mathematical model is presented in Section 3. Validation of the present model with published results is presented in Section 4. The present results are discussed in Section 5. The final concluding remarks are shown in Section 6.

2 Problem formulation

A three-dimensional flow of hybrid nanofluid containing SWCNT and MWCNT over an extending sheet using porous media is considered. A Cartesian coordinate system with flow components

With physical conditions at boundaries [54]:

Geometrical view of flow problem.

The velocity slip conditions (

where

The effective qualities of mono and hybrid nanofluids are enumerated as follows [53,56] (Table 1):

Thermophysical features of SWCNT, MWCNT, and water [57]

| Physical property | Water | SWCNT | MWCNT |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

997.1 | 2,600 | 1,600 |

|

|

4,179 | 425 | 796 |

|

|

0.613 | 6,600 | 3,000 |

|

|

5.5 × 10‒6 | 5.96 × 107 | 2.38 × 106 |

So, Eq. (1) is satisfied identically, and the remaining equations are as follows:

with related conditions at the boundary as

Some emerging factors are encountered in the aforementioned equations that are mathematically described as follows:

The physical description and ranges of these factors are given in Table 2.

Symbolic and physical descriptions alongside default values of various factors

| Symbol description | Physical description | Default value |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Magnetic factor | 0.5 |

|

|

Radiation factor | 0.2 |

|

|

Porosity factor | 0.3 |

|

|

Exponential heat source factor | 0.2 |

|

|

Prandtl number | 6.2 |

|

|

Brownian motion factor | 0.2 |

|

|

Thermal Biot number | 0.5 |

|

|

Schmidt number | 2.0 |

|

|

Chemical reaction factor | 1.5 |

|

|

Thermophoresis factor | 0.1 |

|

|

Ratio factor | 0.7 |

|

|

Activation energy factor | 1.0 |

|

|

Velocity slip factor along the x-direction | 0.5 |

|

|

Velocity slip factor along the y-direction | 0.5 |

|

|

Temperature difference factor | 1.0 |

|

|

Power indexes | 1.0 |

The main quantities of interest such as skin friction

where

Thus, Eq. (17) reduces as follows:

Above

3 Numerical solution

To acquire the numerical solution modeled equations, the bvp4c technique is chosen. This is a powerful technique that can solve highly nonlinear problems. The error tolerance of 10−6 is demarcated in the present case. To implement this technique, we must moderate the higher-order nonlinear problem to a first-order problem. Therefore, we assume that

with boundary conditions:

where the subscripts

4 Validation

This section portrays the validation of the current results against the published findings of Hayat et al. [58] and Dawar et al. [54] for variations in ratio, factor (

Assessment of

|

|

0.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Hayat et al. [58] | 1.0 | 1.039495 | 1.075788 | 1.109946 | 1.142488 | 1.17372 |

| Dawar et al. [54] | 1.0 | 1.039495 | 1.075788 | 1.109946 | 1.142488 | 1.17372 | |

| Present results | 1.00000001 | 1.03949504 | 1.07578796 | 1.10994683 | 1.14248856 | 1.17372081 | |

|

|

Hayat et al. [58] | 0.0 | 0.148736 | 0.349208 | 0.590528 | 0.866682 | 1.17372 |

| Dawar et al. [54] | 0.0 | 0.148736 | 0.349208 | 0.590528 | 0.866682 | 1.17372 | |

| Present results | 0.0 | 0.148737 | 0.3492088 | 0.59052911 | 0.86668307 | 1.17372081 | |

5 Discussion of results

This section deals with the physical explanation of the obtained results. A numerical investigation of the presented model is carried out by using the bvp4c approach. The obtained results are shown in Tables 4 and 5 and Figures 2–19. Table 4 shows the variation in

Variation in

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.8516042477 | 0.5763269827 | ||||

| 0.2 | 0.8734369330 | 0.5931297604 | ||||

| 0.3 | 0.8940778848 | 0.6089113376 | ||||

| 0.4 | 0.9136374030 | 0.6237794707 | ||||

| 0.1 | 0.8054190087 | 0.5403678859 | ||||

| 0.2 | 0.8291931255 | 0.5589519547 | ||||

| 0.3 | 0.8516042477 | 0.5763269827 | ||||

| 0.4 | 0.8727793367 | 0.5926253582 | ||||

| 0.1 | 0.8218044946 | 0.0710732979 | ||||

| 0.2 | 0.8273012259 | 0.1467414673 | ||||

| 0.3 | 0.8325488005 | 0.2263762744 | ||||

| 0.4 | 0.8375798184 | 0.3094971954 | ||||

| 0.1 | 1.275599036 | 0.5891556316 | ||||

| 0.2 | 1.130153116 | 0.5850043243 | ||||

| 0.3 | 1.017139509 | 0.5816102207 | ||||

| 0.4 | 0.926366307 | 0.5787628053 | ||||

| 0.1 | 0.863264420 | 0.8379983743 | ||||

| 0.2 | 0.859535940 | 0.7503475045 | ||||

| 0.3 | 0.856452974 | 0.6807050805 | ||||

| 0.4 | 0.853846381 | 0.6238128749 |

Variation in

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.2218436572 | |||

| 0.2 | 0.2311341996 | |||

| 0.3 | 0.2402463468 | |||

| 0.4 | 0.2492002974 | |||

| 0.1 | 0.1948013227 | |||

| 0.2 | 0.2123509435 | |||

| 0.3 | 0.2296660152 | |||

| 0.4 | 0.2467670551 | |||

| 0.1 | 0.1339609864 | |||

| 0.2 | 0.2123509435 | |||

| 0.3 | 0.2793823415 | |||

| 0.4 | 0.3386270997 | |||

| 0.1 | 0.0589262973 | |||

| 0.2 | 0.1081643585 | |||

| 0.3 | 0.1492616108 | |||

| 0.4 | 0.1835942815 |

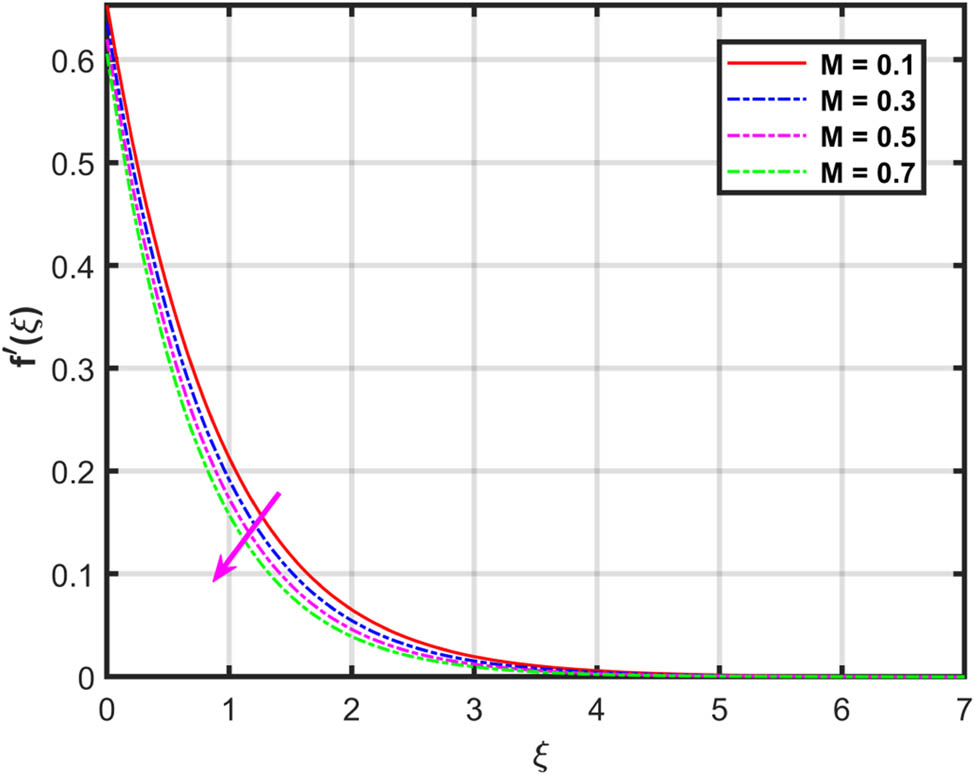

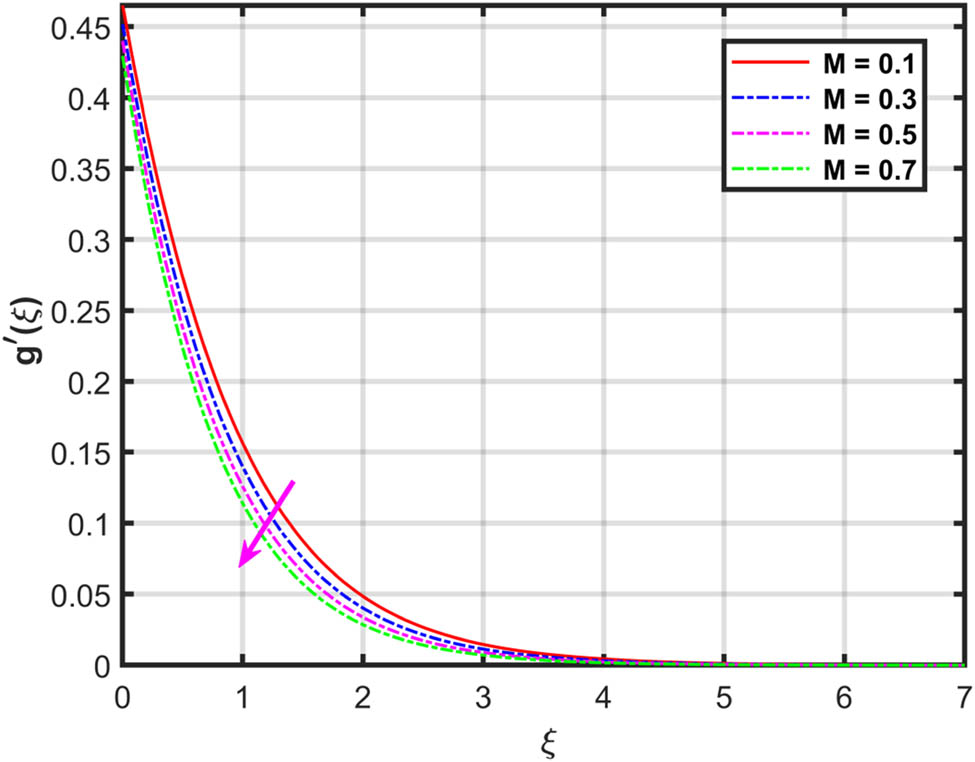

Variation in

Variation in

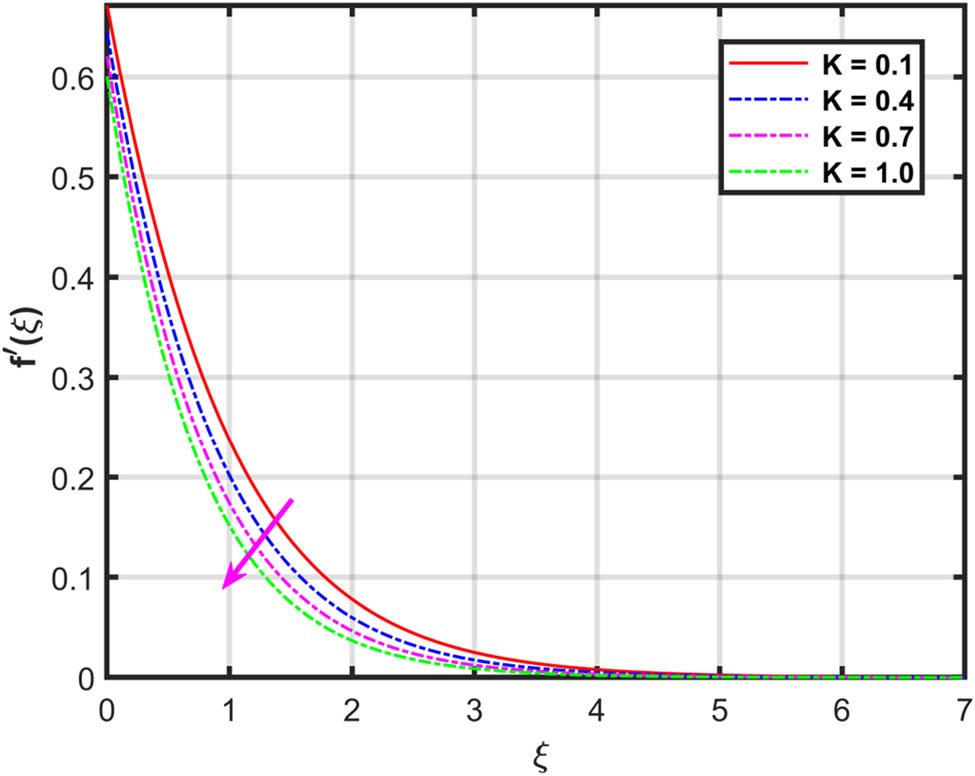

Variation in

Variation in

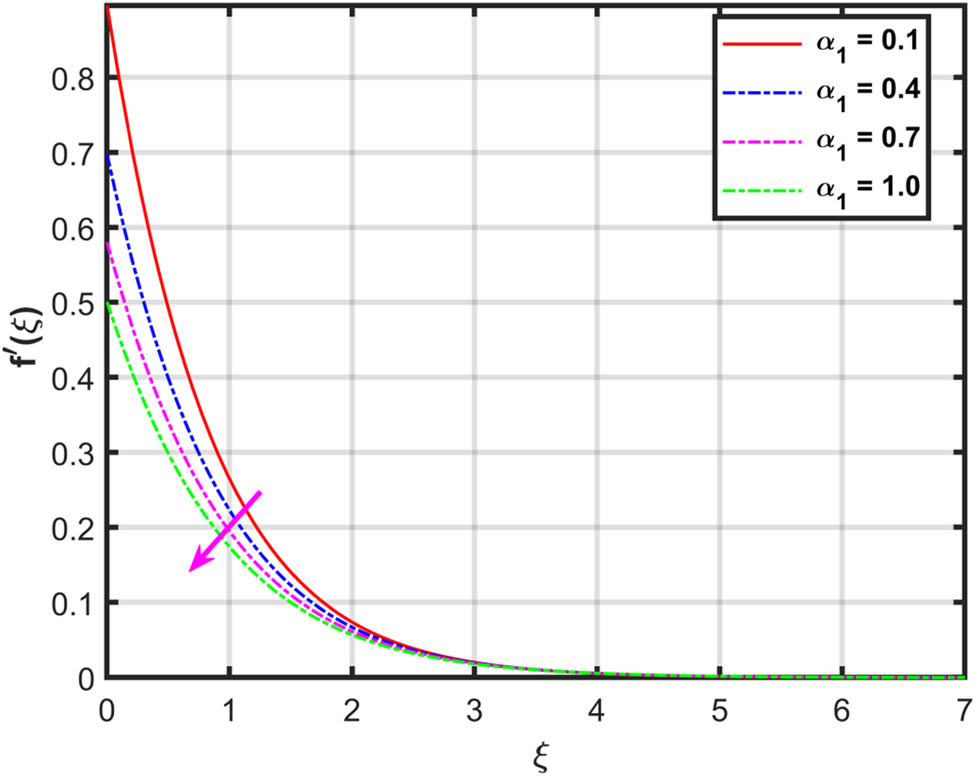

Variation in

Variation in

Variation in

Variation in

Variation in

Variation in

Variation in

Variation in

Variation in

Variation in

Variation in

Variation in

Variation in

Variation in

Figures 2 and 3 show the impact of

Figures 4 and 5 depict the effects of

Figures 6 and 7 depict the effects of

Figures 8 and 9, respectively, portray the impressions of the velocity slip parameter

Figure 10 depicts the influences of thermal Biot number

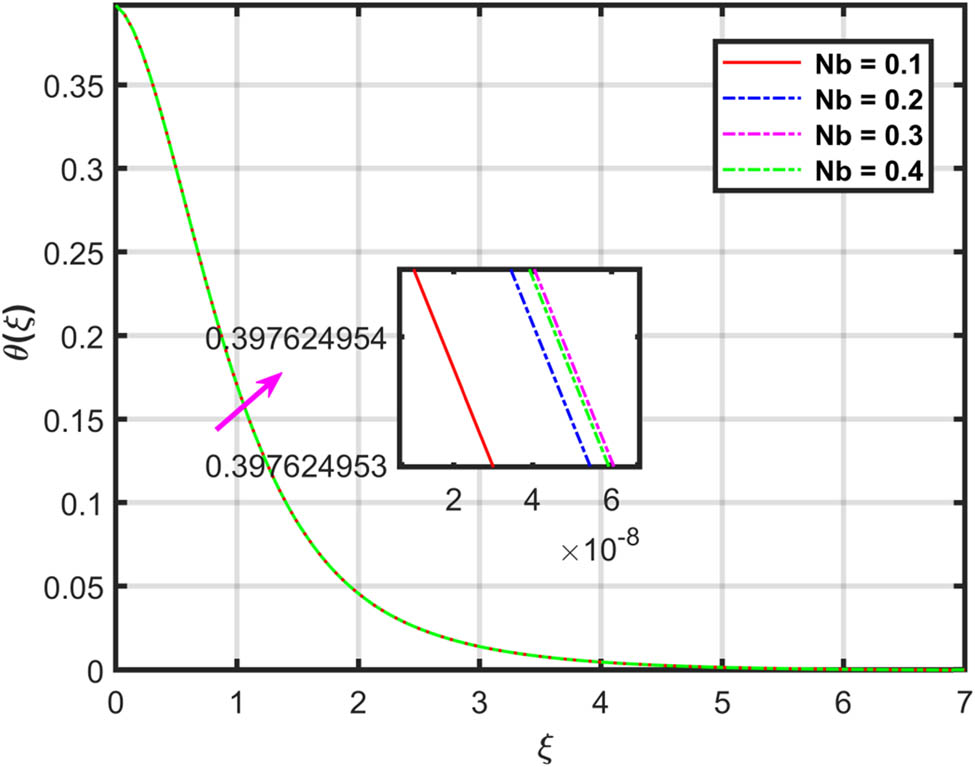

Figure 11 depicts the effects of the Brownian motion factor

Figure 12 depicts the influences of Brownian motion factor

Figure 13 depicts the influences of

Figure 14 depicts the influences of

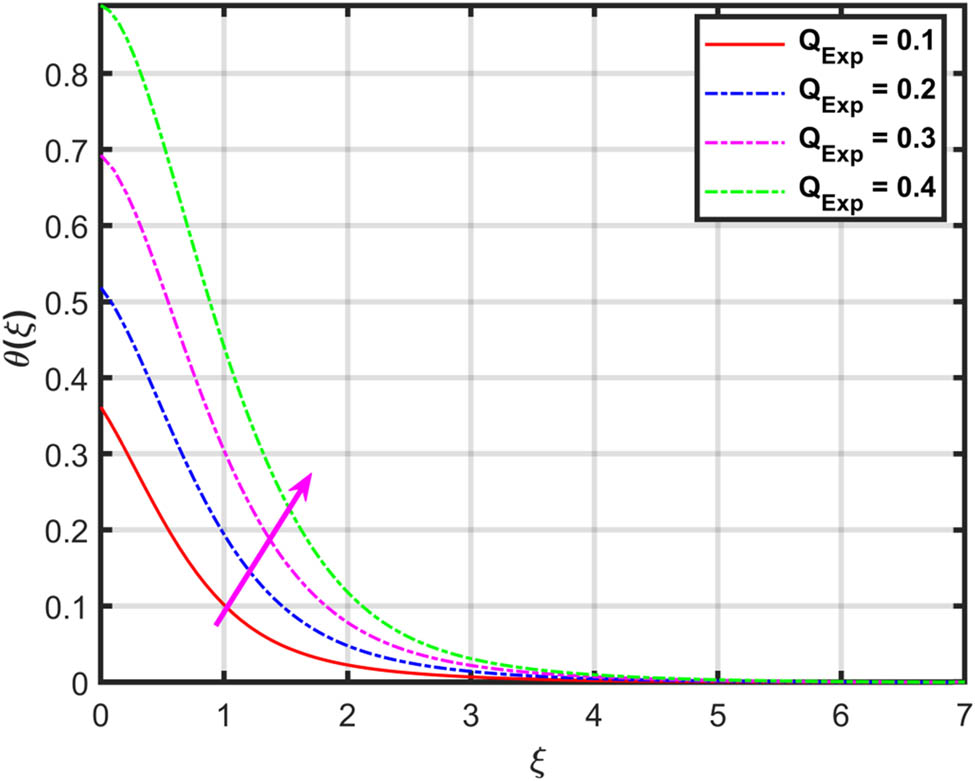

The impact of exponential thermal source factor

The impact of thermal radiation factor

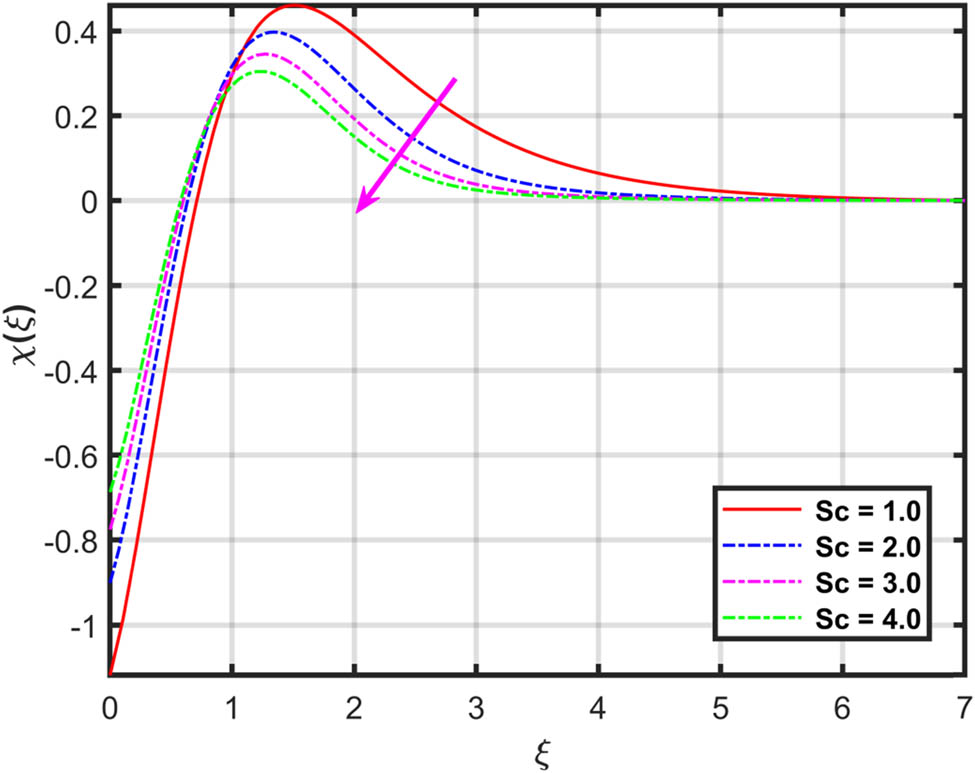

The influence of Schmidt number

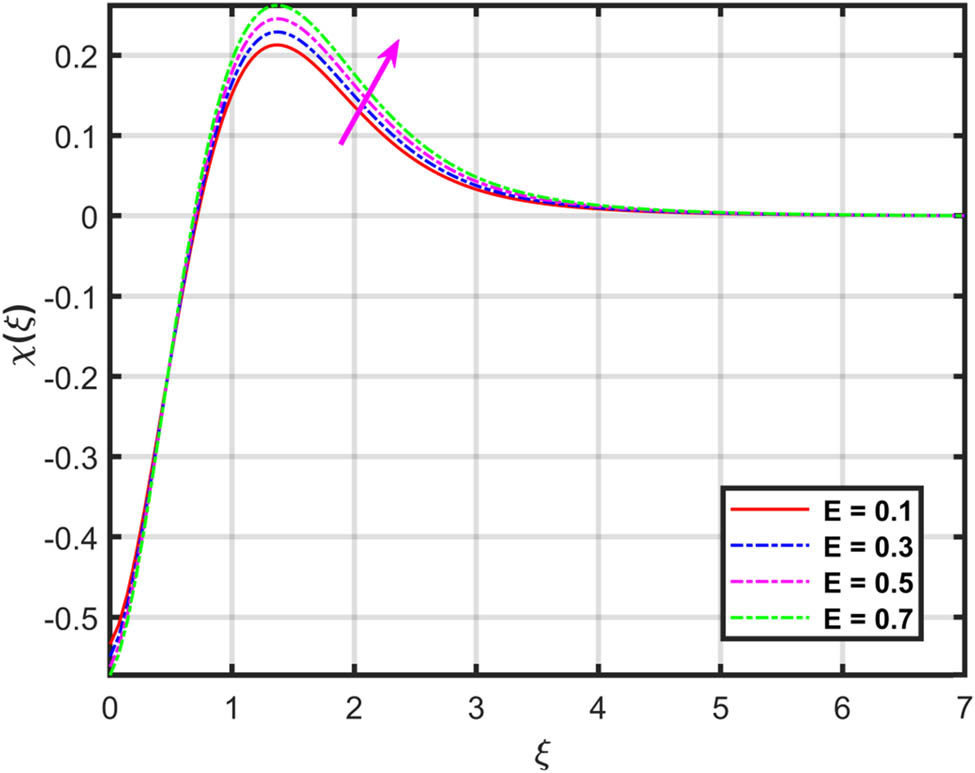

The influence of chemical reactivity parameter

The impacts of activation energy factor

6 Conclusions

This work investigates computationally the water-based hybrid nanofluid flow with impacts of CNTs on an elongating surface. The flow is influenced by velocity slip constraints, zero-mass flux conditions, and thermal convection. A magnetic field of specific strength is applied to the flow system in the normal direction. The activation energy and chemical reactivity effects have been used in the concentration equation. The modeled equations have been evaluated numerically through the bvp4c technique after conversion to dimensionless form through the similarity transformation approach. The novelty of this analysis lies in a comprehensive investigation of hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNTs, incorporating velocity slips, and thermal convective and zero-mass flux conditions. The bvp4c solver ensures higher accuracy and consistency in solving the BVPs, with validation achieved through a comparative analysis presenting a robust agreement with the existing studies. A detailed investigation of the work has revealed that:

With an upsurge in magnetic and porosity factors, the velocities profiles are declined.

Augmentation in ratio factor has declined the primary velocity profile while supported by the secondary velocity profile.

Higher values of velocity slip factor along x- and y-axes have retarded both the primary and secondary velocities.

Thermal distribution has intensified with progression in Brownian motion factor, thermal Biot number thermophoresis factor, and exponential heat source and radiation factors.

Concentration distribution has escalated with the activation energy factor and has declined with the upsurge in Schmidt number and chemical reactivity factor.

The impact of an upsurge in the thermophoresis factor enhanced the concentration distribution, while the upsurge in the Brownian motion factor reduced the concentration distribution.

To ensure the validation of current work, a comparative study has been conducted in this work with a fine agreement among the current and established datasets.

Growth in magnetic, ratio, and porosity factors cause augmentation in the skin frictions along primary and secondary directions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, the Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University Saudi Arabia (Grant No. KFU250260). This study was supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University Project Number (PSAU/2024/R/1446).

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, the Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University Saudi Arabia (Grant No. KFU250260). This study was supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University Project Number (PSAU/2024/R/1446).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Choi SU, Eastman JA. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. 1995 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exhibition, San Francisco, CA (United States), 12–17 Nov 1995; Nov 1995;1995.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Anjum N, Khan WA, Azam M, Ali M, Waqas M, Hussain I. Significance of bioconvection analysis for thermally stratified 3D Cross nanofluid flow with gyrotactic microorganisms and activation energy aspects. Therm Sci Eng Prog. 2023;38:101596.10.1016/j.tsep.2022.101596Search in Google Scholar

[3] Khan A, Alyami MA, Alghamdi W, Alqarni MM, Yassen MF, Tag Eldin E. Thermal examination for the micropolar gold–blood nanofluid flow through a permeable channel subject to gyrotactic microorganisms. Front Energy Res. 2022;10:993247.10.3389/fenrg.2022.993247Search in Google Scholar

[4] Sriharan G, Harikrishnan S, Oztop HF. A review on thermophysical properties, preparation, and heat transfer enhancement of conventional and hybrid nanofluids utilized in micro and mini channel heat sink. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2023;58:103327.10.1016/j.seta.2023.103327Search in Google Scholar

[5] Hobiny A, Alzahrani F, Abbas I. Analytical estimation of temperature in living tissues using the TPL bioheat model with experimental verification. Mathematics. 2020;8:1188.10.3390/math8071188Search in Google Scholar

[6] Alzahrani FS, Abbas IA. Analytical solutions of thermal damage in living tissues due to laser irradiation. Waves Random Complex Media. 2021;31:1443–56.10.1080/17455030.2019.1676934Search in Google Scholar

[7] Hussain M, Sheremet M. Convection analysis of the radiative nanofluid flow through porous media over a stretching surface with inclined magnetic field. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2023;140:106559.10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.106559Search in Google Scholar

[8] Ibrahim IU, Sharifpur M, Meyer JP, Murshed SMS. Experimental investigations of effects of nanoparticle size on force convective heat transfer characteristics of Al2O3-MWCNT hybrid nanofluids in transitional flow regime. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2024;228:125597.10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2024.125597Search in Google Scholar

[9] Alrabaiah H, Iftikhar S, Saeed A, Bilal M, Eldin SM, Galal AM. Numerical calculation of Darcy Forchheimer radiative hybrid nanofluid flow across a curved slippery surface. South Afr J Chem Eng. 2023;45:172–81.10.1016/j.sajce.2023.05.013Search in Google Scholar

[10] Yaseen M, Rawat SK, Shah NA, Kumar M, Eldin SM. Ternary hybrid nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms over three different geometries with Cattaneo–Christov model. Mathematics. 2023;11:1237.10.3390/math11051237Search in Google Scholar

[11] Marin M, Hobiny A, Abbas I. Finite element analysis of nonlinear bioheat model in skin tissue due to external thermal sources. Mathematics. 2021;9:1459.10.3390/math9131459Search in Google Scholar

[12] Saeed T, Abbas I. Finite element analyses of nonlinear DPL bioheat model in spherical tissues using experimental data. Mech Based Des Struct Mach. 2022;50:1287–97.10.1080/15397734.2020.1749068Search in Google Scholar

[13] Hobiny AD, Abbas IA. Nonlinear analysis of dual-phase lag bio-heat model in living tissues induced by laser irradiation. J Therm Stress. 2020;43:503–11.10.1080/01495739.2020.1722050Search in Google Scholar

[14] Yang Y, Horne RN, Cai J, Yao J. Recent advances on fluid flow in porous media using digital core analysis technology. Adv Geo-Energy Res. 2023;9.10.46690/ager.2023.08.01Search in Google Scholar

[15] Khalil S, Yasmin H, Abbas T, Muhammad T. Analysis of thermal conductivity variation in magneto-hybrid nanofluids flow through porous medium with variable viscosity and slip boundary. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;57:104314.10.1016/j.csite.2024.104314Search in Google Scholar

[16] Wang F, Saeed AM, Puneeth V, Shah NA, Anwar MS, Geudri K, et al. Heat and mass transfer of Ag–H2O nano-thin film flowing over a porous medium: A modified Buongiorno’s model. Chin J Phys. 2023;84:330–42.10.1016/j.cjph.2023.01.001Search in Google Scholar

[17] Pop I, Groșan T, Revnic C, Roșca AV. Unsteady flow and heat transfer of nanofluids, hybrid nanofluids, micropolar fluids and porous media: a review. Therm Sci Eng Prog. 2023;46:102248.10.1016/j.tsep.2023.102248Search in Google Scholar

[18] Shu X, Wu Y, Zhang X, Yu F. Experiments and models for contaminant transport in unsaturated and saturated porous media–A review. Chem Eng Res Des. 2023;192:606–21.10.1016/j.cherd.2023.02.022Search in Google Scholar

[19] Ali F, Mahnashi AM, Hamali W, Raizah Z, Saeed A, Khan A. Numerical scrutinization of Darcy–Forchheimer flow for trihybrid nanofluid comprising of $${\text {GO}} + {\text {ZrO}} _ {2} + {\text {SiO}} _ {2} $$/kerosene oil over the curved surface. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2024;1–16.10.1007/s10973-024-13103-wSearch in Google Scholar

[20] Nadeem S, Mushtaq A, Alzabut J, Ghazwani HA, Eldin SM. The flow of an Eyring Powell Nanofluid in a porous peristaltic channel through a porous medium. Sci Rep. 2023;13:9694.10.1038/s41598-023-36136-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Reddy YD, Goud BS, Nisar KS, Alshahrani B, Mahmoud M, Park C. Heat absorption/generation effect on MHD heat transfer fluid flow along a stretching cylinder with a porous medium. Alex Eng J. 2023;64:659–66.10.1016/j.aej.2022.08.049Search in Google Scholar

[22] Mirzaei A, Jalili P, Afifi MD, Jalili B, Ganji DD. Convection heat transfer of MHD fluid flow in the circular cavity with various obstacles: Finite element approach. Int J Thermofluids. 2023;20:100522.10.1016/j.ijft.2023.100522Search in Google Scholar

[23] Ahmad B, Ahmad MO, Farman M, Akgül A, Riaz MB. A significance of multi slip condition for inclined MHD nano-fluid flow with non linear thermal radiations, Dufuor and Sorrot, and chemically reactive bio-convection effect. South Afr J Chem Eng. 2023;43:135–45.10.1016/j.sajce.2022.10.009Search in Google Scholar

[24] Lone SA, Khan A, Raiza Z, Alrabaiah H, Shahab S, Saeed A, et al. A semi-analytical solution of the magnetohydrodynamic blood-based ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a convectively heated bidirectional stretching surface under velocity slip conditions. AIP Adv. 2024;14.10.1063/5.0201663Search in Google Scholar

[25] Tarakaramu N, Satya Narayana PV, Sivakumar N, Harish Babu D, Bhagya Lakshmi K. Convective conditions on 3D Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) non-newtonian nanofluid flow with nonlinear thermal radiation and heat absorption: A numerical analysis. J Nanofluids. 2023;12:448–57.10.1166/jon.2023.1939Search in Google Scholar

[26] Mahesh R, Mahabaleshwar US, Kumar PNV, Öztop HF, Abu-Hamdeh N. Impact of radiation on the MHD couple stress hybrid nanofluid flow over a porous sheet with viscous dissipation. Results Eng. 2023;17:100905.10.1016/j.rineng.2023.100905Search in Google Scholar

[27] Ahmad S, Ali K, Sajid T, Bashir U, Rashid FL, Kumar R, et al. A novel vortex dynamics for micropolar fluid flow in a lid-driven cavity with magnetic field localization–A computational approach. Ain Shams Eng J. 2024;15:102448.10.1016/j.asej.2023.102448Search in Google Scholar

[28] Lund LA, Yashkun U, Shah NA. Magnetohydrodynamics streamwise and cross flow of hybrid nanofluid along the viscous dissipation effect: Duality and stability. Phys Fluids. 2023;35.10.1063/5.0135361Search in Google Scholar

[29] Nawaz Y, Arif MS, Abodayeh K, Mansoor M. Finite difference schemes for MHD mixed convective Darcy–forchheimer flow of Non-Newtonian fluid over oscillatory sheet: A computational study. Front Phys. 2023;11:1072296.10.3389/fphy.2023.1072296Search in Google Scholar

[30] Hobiny A, Abbas I. Thermal response of cylindrical tissue induced by laser irradiation with experimental study. Int J Numer Methods Heat Fluid Flow. 2020;30:4013–23.10.1108/HFF-10-2019-0777Search in Google Scholar

[31] Abbas I, Hobiny A, Alzahrani F. An analytical solution of the bioheat model in a spherical tissue due to laser irradiation. Indian J Phys. 2020;94:1329–34.10.1007/s12648-019-01581-wSearch in Google Scholar

[32] Madkhali HA, Ahmed M, Nawaz M, Alharbi SO, Alqahtani AS, Malik MY. Computational study on the effects of Brownian motion and thermophoresis on thermal performance of cross fluid with nanoparticles in the presence of Ohmic and viscous dissipation in chemically reacting regime. Comput Part Mech. 2023;1–11. 10.1007/S40571-023-00687-7/METRICS.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Sudarmozhi K, Iranian D, Alessa N. Investigation of melting heat effect on fluid flow with brownian motion/thermophoresis effects in the occurrence of energy on a stretching sheet. Alex Eng J. 2024;94:366–76.10.1016/j.aej.2024.03.065Search in Google Scholar

[34] Shahzad A, Imran M, Tahir M, Ali Khan S, Akgül A, Abdullaev S, et al. Brownian motion and thermophoretic diffusion impact on Darcy-Forchheimer flow of bioconvective micropolar nanofluid between double disks with Cattaneo-Christov heat flux. Alex Eng J. 2023;62:1–15. 10.1016/J.AEJ.2022.07.023.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Huang Y, Wu C, Dai J, Liu B, Cheng X, Li X, et al. Tunable self-thermophoretic nanomotors with polymeric coating. J Am Chem Soc. 2023;145:19945–52.10.1021/jacs.3c06322Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Sharma BK, Khanduri U, Mishra NK, Mekheimer KS. Combined effect of thermophoresis and Brownian motion on MHD mixed convective flow over an inclined stretching surface with radiation and chemical reaction. Int J Mod Phys B. 2023;37:2350095.10.1142/S0217979223500959Search in Google Scholar

[37] Thabet EN, Khan Z, Abd-Alla AM, Bayones FS. Thermal enhancement, thermophoretic diffusion, and Brownian motion impacts on MHD micropolar nanofluid over an inclined surface: numerical simulation. Numer Heat Transf Part A Appl. 2023;1–20.10.1080/10407782.2023.2276319Search in Google Scholar

[38] Hanı U, Alı M, Alam MS. MHD boundary layer micropolar fluid flow over a stretching wedge surface: Thermophoresis and brownian motion effect. J Therm Eng. 2024;10:330–49.10.18186/thermal.1448609Search in Google Scholar

[39] Waqas H, Khan SA, Ali B, Liu D, Muhammad T, Hou E. Numerical computation of Brownian motion and thermophoresis effects on rotational micropolar nanomaterials with activation energy. Propuls Power Res. 2023.10.1016/j.jppr.2023.05.005Search in Google Scholar

[40] Shah SA, Hassan A, Karamti H, Alhushaybari A, Eldin SM, Galal AM. Effect of thermal radiation on convective heat transfer in MHD boundary layer Carreau fluid with chemical reaction. Sci Rep. 2023;13:4117.10.1038/s41598-023-31151-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Essam ME, Abedel-AaL EM. Darcy-forchheimer flow of a nanofluid over a porous plate with thermal radiation and Brownian motion. J Nanofluids. 2023;12:55–64.10.1166/jon.2023.1910Search in Google Scholar

[42] Pandey AK, Bhattacharyya K, Gautam AK, Rajput S, Mandal MS, Chamkha AJ, et al. Insight into the relationship between non-linear mixed convection and thermal radiation: The case of Newtonian fluid flow due to non-linear stretching. Propuls Power Res. 2023;12:153–65.10.1016/j.jppr.2022.11.002Search in Google Scholar

[43] Gul T, Bilal M, Shuaib M, Mukhtar S, Thounthong P. Thin film flow of the water‐based carbon nanotubes hybrid nanofluid under the magnetic effects. Heat Transf. 2020;49:3211–27.10.1002/htj.21770Search in Google Scholar

[44] Alrehili M. Improvement for engineering applications through a dissipative Carreau nanofluid fluid flow due to a nonlinearly stretching sheet with thermal radiation. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2023;42:102768.10.1016/j.csite.2023.102768Search in Google Scholar

[45] Wang X, Shan S, Zhang B, Jin G, Yu J, Zhou Z. Parametrical study on spectral radiation characteristics of solid fuel combustion medium for energy cascade utilization. Fuel. 2024;361:130660.10.1016/j.fuel.2023.130660Search in Google Scholar

[46] Goud BS, Srilatha P, Mahendar D, Srinivasulu T, Reddy YD. Thermal radiation effect on thermostatically stratified MHD fluid flow through an accelerated vertical porous plate with viscous dissipation impact. Partial Differ Equ Appl Math. 2023;7:100488.10.1016/j.padiff.2023.100488Search in Google Scholar

[47] Muhammad K, Hayat T, Alsaedi A, Ahmad B, Momani S. Mixed convective slip flow of hybrid nanofluid (MWCNTs + Cu + Water), nanofluid (MWCNTs + Water) and base fluid (Water): a comparative investigation. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2021;143:1523–36.10.1007/s10973-020-09577-zSearch in Google Scholar

[48] Swain K, Ibrahim SM, Dharmaiah G, Noeiaghdam S. Numerical study of nanoparticles aggregation on radiative 3D flow of Maxwell fluid over a permeable stretching surface with thermal radiation and heat source/sink. Results Eng. 2023;19:101208.10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101208Search in Google Scholar

[49] Hamad NH, Bilal M, Ali A, Eldin SM, Sharaf M, Rahman MU. Energy transfer through third‐grade fluid flow across an inclined stretching sheet subject to thermal radiation and Lorentz force. Sci Rep. 2023;13:19643.10.1038/s41598-023-46428-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Hayat T, Ashraf B, Shehzad SA, Abouelmagd E. Three-dimensional flow of Eyring Powell nanofluid over an exponentially stretching sheet. Int J Numer Methods Heat Fluid Flow. 2015;25:593–616.10.1108/HFF-05-2014-0118Search in Google Scholar

[51] Sun X, Animasaun IL, Swain K, Shah NA, Wakif A, Olanrewaju PO. Significance of nanoparticle radius, inter‐particle spacing, inclined magnetic field, and space‐dependent internal heating: The case of chemically reactive water conveying copper nanoparticles. ZAMM‐J Appl Math Mech Für Angew Math Und Mech. 2022;102:e202100094.10.1002/zamm.202100094Search in Google Scholar

[52] Upadhya SM, Raju SSK, Raju CSK, Mnasri C. Arrhenius activation and zero mass flux conditions on nonlinear convective Jeffrey fluid over an electrically conducting and radiated sheet. Arab J Sci Eng. 2020;45:9095–109.10.1007/s13369-020-04687-0Search in Google Scholar

[53] Dawar A, Islam S, Shah Z, Mahmuod SR. A passive control of Casson hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface with alumina and copper nanomaterials: a study on sodium alginate-based fluid. J Mol Liq. 2023;122018.10.1016/j.molliq.2023.122018Search in Google Scholar

[54] Dawar A, Wakif A, Saeed A, Shah Z, Muhammad T, Kumam P. Significance of Lorentz forces on Jeffrey nanofluid flows over a convectively heated flat surface featured by multiple velocity slips and dual stretching constraint: a homotopy analysis approach. J Comput Des Eng. 2022;9:564–82.10.1093/jcde/qwac019Search in Google Scholar

[55] Waqas H, Farooq U, Alqarni MS, Muhammad T. Numerical investigation for 3D bioconvection flow of Carreau nanofluid with heat source/sink and motile microorganisms. Alex Eng J. 2022;61:2366–75.10.1016/j.aej.2021.06.089Search in Google Scholar

[56] Acharya N, Mabood F. On the hydrothermal features of radiative Fe3O4–graphene hybrid nanofluid flow over a slippery bended surface with heat source/sink. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2021;143:1273–89. 10.1007/S10973-020-09850-1/METRICS.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Kumar TP. Heat transfer of SWCNT-MWCNT based hybrid nanofluid boundary layer flow with modified thermal conductivity model. J Adv Res Fluid Mech Therm Sci. 2022;92:13–24.10.37934/arfmts.92.2.1324Search in Google Scholar

[58] Hayat T, Awais M, Obaidat S. Three-dimensional flow of a Jeffery fluid over a linearly stretching sheet. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul. 2012;17:699–707.10.1016/j.cnsns.2011.05.042Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- The influence of anisotropy of InP on its elasticity and phonon properties

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- The influence of anisotropy of InP on its elasticity and phonon properties

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis