Abstract

We assess the thermal resilience of key quantum resources-(

1 Introduction

Quantum coherence, emerging from the superposition of quantum states, serves as the foundation for all nonclassical phenomena, quantified by the off-diagonal elements of the density matrix within a specified basis [1,2]. This coherence is formalized through a resource-theoretic framework, where the

Nonlocality, validated through Bell inequality violations in photonic [13] and superconducting circuits [14], challenges classical realism by rejecting local hidden variable models [15]. However, its relationship with entanglement is nuanced, illustrating their ambiguous correspondence [16,17]. Steering [18–20], an asymmetric phenomenon in which one party remotely manipulates another’s state through local measurements, further stratifies these correlations [19,21,22]. The coexistence of coherence, entanglement, Bell nonlocality, quantum discord, and quantum steering resists unambiguous distinction even in bipartite systems. The lack of connections between these measures, combined with the inherent difficulty of separating entangled and separable states – implies that optimizing one resource does not inherently amplify others. This necessitates a multimeasure approach, as distinct correlations dominate in specific parameter regimes. Within the bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick (LMG) framework, we map their hierarchical relationships, identifying critical thresholds where spin–spin coupling (

In the field of quantum information science, the LMG model has served as a prominent platform for investigating quantum correlations, particularly in the context of quantum phase transitions (QPTs). Extensive studies have been conducted on two-spin entanglement [36–39], entanglement entropy [40,41], and multipartite entanglement [42–44], alongside analyses of multipartite nonlocality [45], quantum discord [46,47], and quantum correlations [48]. Furthermore, critical phenomena in the

We investigate the intricate dynamics of quantum resources:

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the used quantifiers, including coherence, discord, entanglement, Bell nonlocality, and steering. Section 3 investigates the Hamiltonian structure and the thermal density matrix of the bipartite LMG system. In Section 4, the interplay between system parameters and key measures dynamics is investigated, with theoretical insights supported by numerical simulations. Finally, Section 5 summarizes key findings, discusses implications for emerging quantum technologies, and outlines promising avenues for future research.

2 Quantum resources

This section investigates quantum resources within the bipartite LMG model. Entanglement is measured using the LN, while quantum discord evaluates nonclassical correlations that extend beyond entanglement. Bell nonlocality is identified through violations of the Clauser–Horne–Shimony–Holt (CHSH) inequality, and quantum steering is assessed via the Cavalcanti–Jones–Wiseman–Reid steering criterion [62]. These metrics are examined as functions of temperature

2.1

l

1

-norm of coherence function

Quantum coherence is an important feature derived from the principle of superposition in quantum physics. A well-established framework for quantifying coherence, has been extensively developed in recent studies [1,2]. This theory determines the set of incoherent states

Incoherent operations that transform incoherent states into other incoherent states are known as free operations. Detecting and quantifying quantum coherence plays a vital role in enabling quantum correlations and facilitating information processing in the quantum system. In this sense, Baumgratz et al. [2] introduced the

with

2.2 Quantum discord function

Quantum discord (QD) [8] provides a rigorous measure of nonclassical correlations that persist even in separable quantum states. For a bipartite system, QD is operationally defined as the discrepancy between total quantum mutual information

where

and

Here,

The computational complexity of this minimization restricts analytical solutions to specific state classes. For the bipartite X-state, the density matrix adopts the structured form:

where the diagonal elements

with correlation measures:

where

employ the binary entropy function:

The critical parameter

2.3 LN function

LN serves as a practical entanglement quantifier due to its computational simplicity and operational interpretation [5,7]. For a bipartite system described by the density matrix

where

which quantifies the degree of positive partial transpose violation [65]. Equivalently, negativity can be expressed using the eigenvalues

where negative eigenvalues (

Entanglement, as quantified by

2.4 Bell nonlocality function

To assess the nonlocality in our system, one can use the Bell inequality violation [66–69]. Bell nonlocality provides a stricter criterion for quantumness through experimentally testable inequalities. Here, we employ the CHSH inequality for any system of two qubits [68]

where

In order to achieve the maximal value for the

where

2.5 Quantum steering function

The notion of steering, an extension of the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen paradox, was introduced by Schrödinger [18]. Quantum states that exhibit steering offer key advantages in various applications, including secure quantum teleportation [70], device-independent quantum cryptography [71], and randomness certification [72]. A fundamental approach to identifying and quantifying steering, particularly in two-qubit systems, is the three-setting linear steering inequality [62,73]. This formulation assumes that both Alice and Bob can conduct three distinct measurements on their respective subsystems. The inequality is formulated as follows [73]:

Here, the operators

which quantifies the degree of steering present in the system. The steerability

where

such that

3 LMG model

The LMG model [23–25] represents a fully connected system of spin-1/2 particles, characterized by infinite-range interactions and a tunable anisotropy parameter

where

Owing to its inherent symmetries and infinite-range interactions, the LMG model has emerged as a paradigmatic testbed in quantum information science, underpinning studies of entanglement scaling, quantum coherence, and the intricate hierarchy of many-body correlations. Notably, experimental breakthroughs have begun to bridge theory and practice: superconducting quantum circuits have demonstrated spontaneous symmetry breaking alongside the generation of multipartite entanglement [78], while neutral-atom quantum processors have accurately reconstructed LMG ground-state properties via variational algorithms [79]. Complementing these advances, recent quantum-computational investigations have further illuminated LMG physics: the ground-state energy of a two-spin system was computed on the IBM quantum experience [77], the energy spectrum of systems up to four spins was resolved [80], a suite of hybrid quantum-classical simulation strategies of the LMG model has been formulated [81–83]. In this article, we consider the bipartite LMG model (N = 2), where the Hamiltonian (27) writes as follows:

The parameter

The DM interaction, characterized by the vector

Thus, the matrix representation of

The eigenvalues

where

At zero temperature (

where

with matrix elements parameterized by spin–spin coupling

where the partition function

The parameter

4 Results and discussion

This section examines how critical parameters, spin–spin coupling strength (

4.1 The impact of spin–spin coupling strength

λ

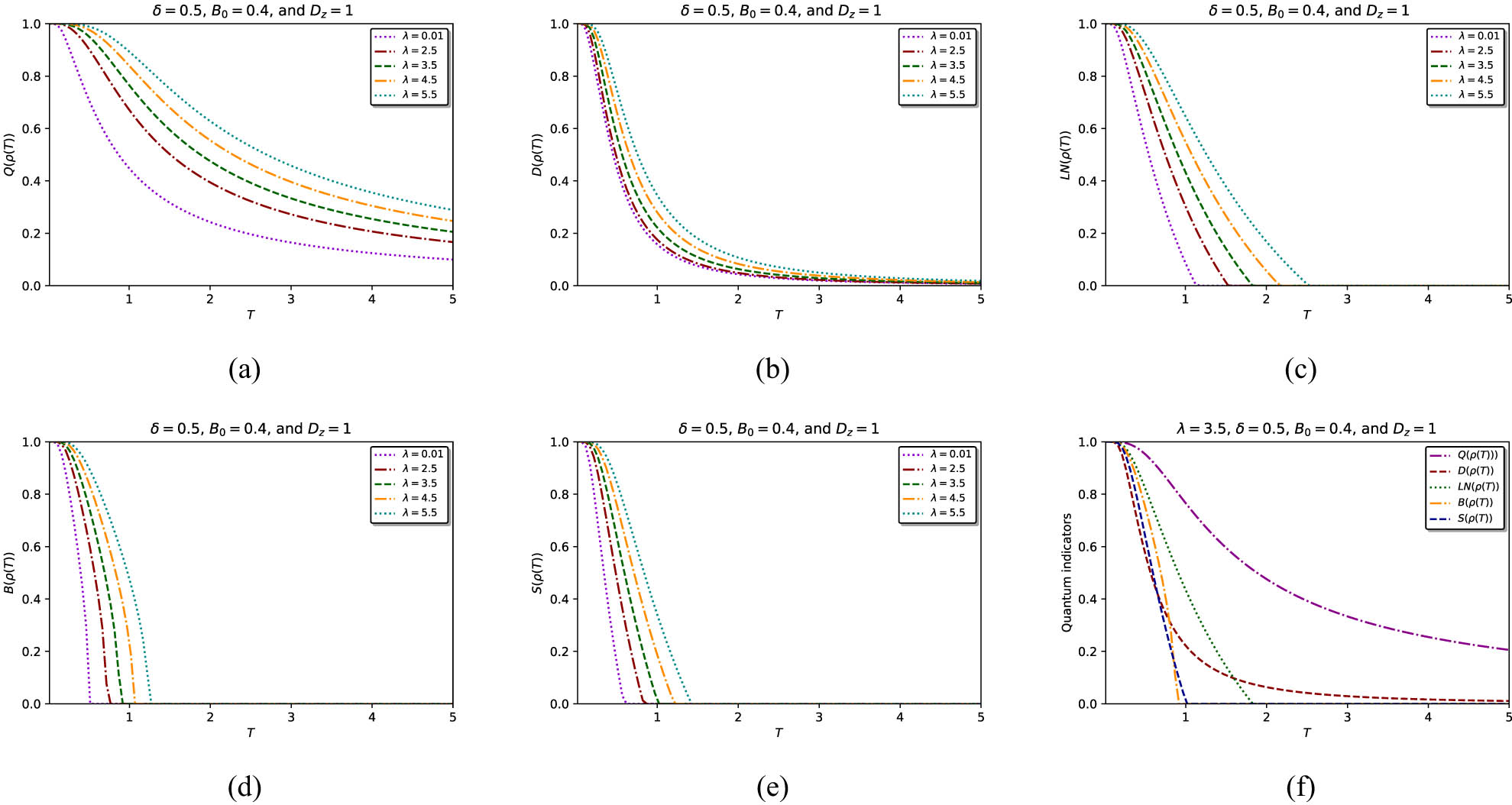

We illustrate in Figure 1, the influence of the coupling strength,

Dynamics of quantum coherence (a), quantum discord (b), entanglement (c), nonlocality (d), and quantum steering (e) versus

By varying the spin–spin coupling strength

4.2 The impact of the Zeeman splitting

B

0

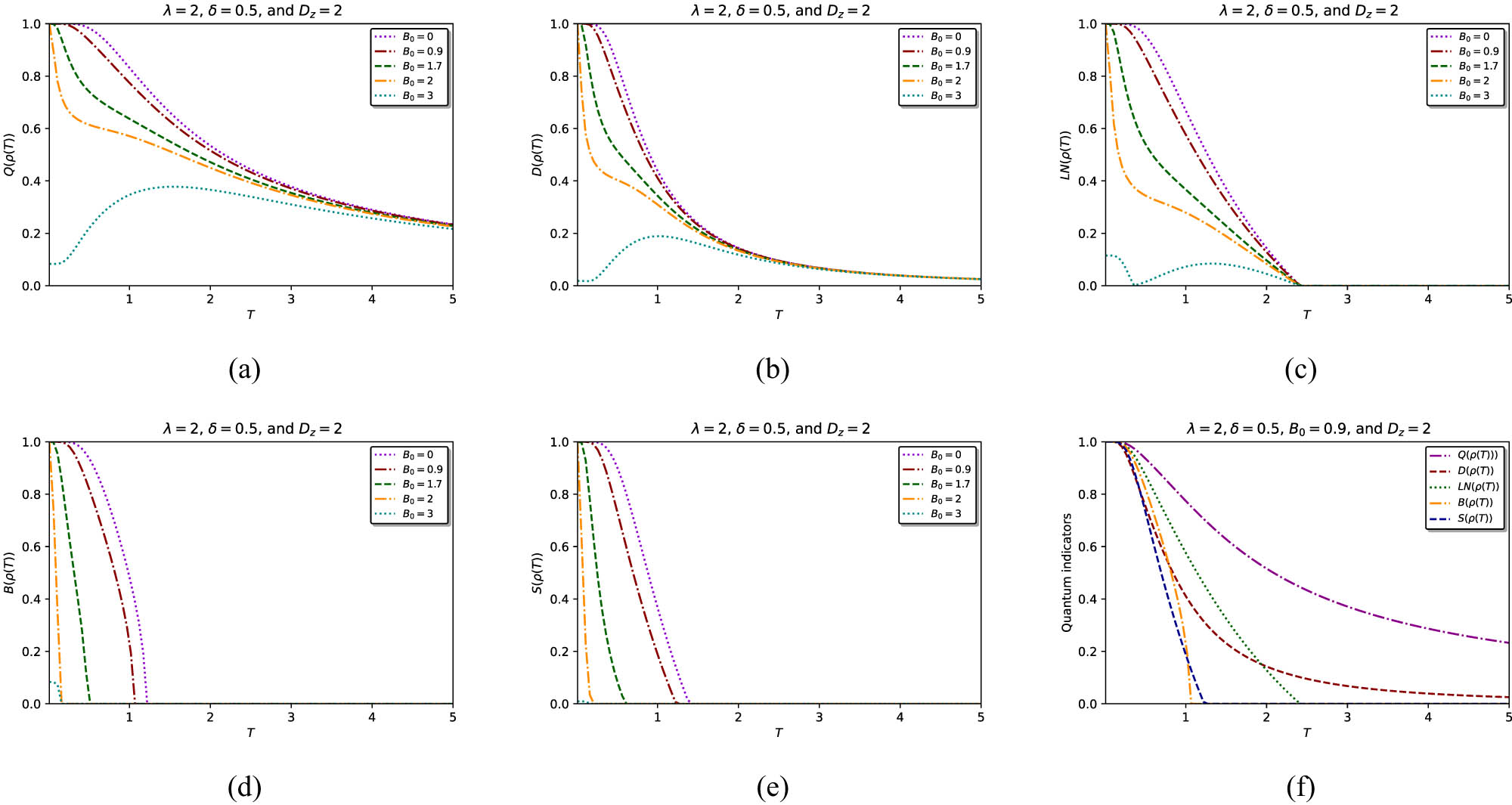

Next, we examine the roles of Zeeman splitting (

Evolution of quantum coherence (a), quantum discord (b), entanglement (c), nonlocality (d), and quantum steering (e) versus temperature

Figure 2 investigates how quantum resources in the bipartite LMG model are influenced by the DM interaction (

4.3 The impact of the interaction DM

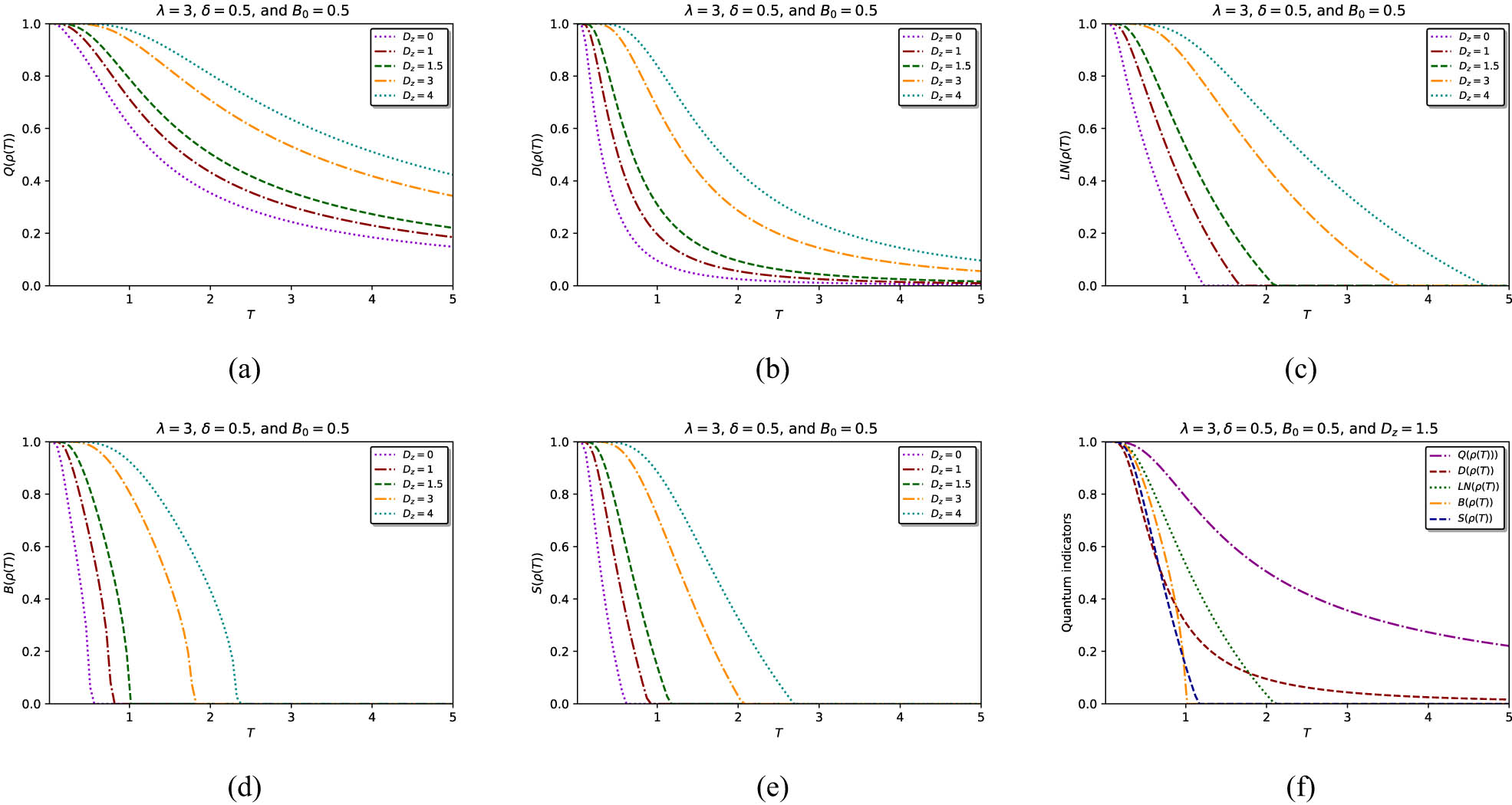

Finally, we analyze the impact of the DM interaction on the dynamics of quantum resources as shown in Figure 3. The selected metrics are plotted as functions of temperature for varying DM interaction strengths

Dynamics of quantum coherence (a), quantum discord (b), entanglement (c), nonlocality (d), and quantum steering (e) versus temperature

As evidenced by the temperature-dependent evolution of quantum resources in Figure 3, all measures, coherence

5 Conclusion

In this work, we examined how key quantum resources, Bell nonlocality, quantum steering, entanglement (via LN

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to the referees for their important remarks which improve the manuscript. This work was supported by the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R906), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This study is supported via funding from Prince sattam bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2024/R/1446).

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R906), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: M.B., H.A, and F.A. contributed to the writing of the manuscript and played a role in software development and conceptualization. M.M. and ABA.M. provided supervision throughout the process and carefully reviewed the manuscript. M.B., H.A,F.A., M.M., and ABA.M. revised final draft of the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] Streltsov A, Adesso G, Plenio MB. Colloquium: Quantum coherence as a resource. Rev Modern Phys. 2017;89(4):041003. 10.1103/RevModPhys.89.041003Search in Google Scholar

[2] Baumgratz T, Cramer M, Plenio MB. Quantifying coherence. Phys Rev Lett. 2014;113(14):140401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.140401Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Wootters WK. Entanglement of formation of an arbitrary state of two qubits. Phys Rev Lett. 1998;80(10):2245. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.2245Search in Google Scholar

[4] Wootters WK. Entanglement of formation and concurrence. Quantum Inf Comput. 2001;1(1):27–44. 10.26421/QIC1.1-3Search in Google Scholar

[5] Vidal G, Werner RF. Computable measure of entanglement. Phys Rev A. 2002;65(3):032314. 10.1103/PhysRevA.65.032314Search in Google Scholar

[6] Horodecki M, Horodecki P, Horodecki R. On the necessary and sufficient conditions for separability of mixed quantum states. Phys Lett A. 1996;223(1):1–8. 10.1016/S0375-9601(96)00706-2Search in Google Scholar

[7] Plenio MB, Virmani SS. An introduction to entanglement theory. In: Quantum information and coherence. Scottish Graduate Series. Cham: Springer; 2014. p. 173–209. 10.1007/978-3-319-04063-9_8Search in Google Scholar

[8] Ollivier H, Zurek WH. Quantum discord: a measure of the quantumness of correlations. Phys Rev Lett. 2001;88(1):017901. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.017901Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Ali M, Rau A, Alber G. Quantum discord for two-qubit X states. Phys Rev A-Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2010;81(4):042105. 10.1103/PhysRevA.81.042105Search in Google Scholar

[10] Luo S. Quantum discord for two-qubit systems. Phys Rev A-Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2008;77(4):042303. 10.1103/PhysRevA.77.042303Search in Google Scholar

[11] Dahbi Z, Oumennana M, Mansour M. Intrinsic decoherence effects on correlated coherence and quantum discord in XXZ Heisenberg model. Opt Quant Electr. 2023;55(5):412. 10.1007/s11082-023-04604-3Search in Google Scholar

[12] Baba H, Kaydi W, Daoud M, Mansour M. Entanglement of formation and quantum discord in multipartite j-spin coherent states. Int J Modern Phys B. 2020;34(26):2050237. 10.1142/S0217979220502379Search in Google Scholar

[13] Aspect A, Dalibard J, Roger G. Experimental test of Bell’s inequalities using time-varying analyzers. Phys Rev Lett. 1982;49(25):1804. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.49.1804Search in Google Scholar

[14] Storz S, Schär J, Kulikov A, Magnard P, Kurpiers P, Lütolf J, et al. Loophole-free Bell inequality violation with superconducting circuits. Nature. 2023;617(7960):265–70. 10.1038/s41586-023-05885-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Bell JS. On the einstein podolsky rosen paradox. Phys Phys Fizika. 1964;1(3):195. 10.1103/PhysicsPhysiqueFizika.1.195Search in Google Scholar

[16] Bennett CH, DiVincenzo DP, Fuchs CA, Mor T, Rains E, Shor PW, et al. Quantum nonlocality without entanglement. Phys Rev A. 1999;59(2):1070. 10.1103/PhysRevA.59.1070Search in Google Scholar

[17] Halder S, Banik M, Agrawal S, Bandyopadhyay S. Strong quantum nonlocality without entanglement. Phys Rev Lett. 2019;122(4):040403. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.040403Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Schrödinger E. Discussion of probability relations between separated systems. In: Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. vol. 31. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1935. p. 555–63. 10.1017/S0305004100013554Search in Google Scholar

[19] Uola R, Costa AC, Nguyen HC, Gühne O. Quantum steering. Rev Modern Phys. 2020;92(1):015001. 10.1103/RevModPhys.92.015001Search in Google Scholar

[20] Duuuu MM, Tong D. Relationship between first-order coherence and the maximum violation of the three-setting linear steering inequality for a two-qubit system. Phys Rev A. 2021;103(3):032407. 10.1103/PhysRevA.103.032407Search in Google Scholar

[21] Obada AS, Abd-Rabbou MY, Haddadi S. Does conditional entropy squeezing indicate normalized entropic uncertainty relation steering? Quant Inform Proces. 2024;23(3):90. 10.1007/s11128-024-04298-wSearch in Google Scholar

[22] Chouiba A, Elghaayda S, Ait Chlih A, Mansour M. Unveiling quantum resources in dimeric perylene-based arrays. J Phys A Math Theoret. 2025;58(12):125302. 10.1088/1751-8121/adbf77Search in Google Scholar

[23] Lipkin HJ, Meshkov N, Glick A. Validity of many-body approximation methods for a solvable model: (I). Exact solutions and perturbation theory. Nuclear Phys. 1965;62(2):188–98. 10.1016/0029-5582(65)90862-XSearch in Google Scholar

[24] Meshkov N, Glick A, Lipkin H. Validity of many-body approximation methods for a solvable model: (II). Linearization procedures. Nuclear Phys. 1965;62(2):199–210. 10.1016/0029-5582(65)90863-1Search in Google Scholar

[25] Glick A, Lipkin H, Meshkov N. Validity of many-body approximation methods for a solvable model: (III). Diagram summations. Nuclear Phys. 1965;62(2):211–24. 10.1016/0029-5582(65)90864-3Search in Google Scholar

[26] Dreiss GJ, Klein A. The algebra of currents as a complete dynamical method in the nuclear many-body problem: Application to an exactly soluble model. Nuclear Phys A. 1969;139(1):81–99. 10.1016/0375-9474(69)90261-9Search in Google Scholar

[27] Schuck P, Ethofer S. Self-consistent (nuclear) phonons. Nuclear Phys A. 1973;212(2):269–86. 10.1016/0375-9474(73)90563-0Search in Google Scholar

[28] Catara F, Dang ND, Sambataro M. Ground-state correlations beyond RPA. Nuclear Phys A. 1994;579(1–2):1–12. 10.1016/0375-9474(94)90790-0Search in Google Scholar

[29] Wahlen-Strothman JM, Henderson TM, Hermes MR, Degroote M, Qiu Y, Zhao J, et al. Merging symmetry projection methods with coupled cluster theory: Lessons from the Lipkin model Hamiltonian. J Chem Phys. 2017;146:054110. 10.1063/1.4974989Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Turbiner A. Quasi-exactly-solvable problems and sl (2) algebra. Commun Math Phys. 1988;118:467–74. 10.1007/BF01466727Search in Google Scholar

[31] Ulyanov V, Zaslavskii O. New methods in the theory of quantum spin systems. Phys Reports. 1992;216(4):179–251. 10.1016/0370-1573(92)90158-VSearch in Google Scholar

[32] Botet R, Jullien R. Large-size critical behavior of infinitely coordinated systems. Phys Rev B. 1983;28(7):3955. 10.1103/PhysRevB.28.3955Search in Google Scholar

[33] Gatteschi D, Sessoli R, Villain J. Molecular Nanomagnets. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2006. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198567530.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

[34] Bogani L, Wernsdorfer W. Molecular spintronics using single-molecule magnets. Nature Materials. 2008;7(3):179–86. 10.1038/nmat2133Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Cirac JI, Lewenstein M, Mølmer K, Zoller P. Quantum superposition states of Bose–Einstein condensates. Phys Rev A. 1998;57(2):1208. 10.1103/PhysRevA.57.1208Search in Google Scholar

[36] Vidal J, Palacios G, Mosseri R. Entanglement in a second-order quantum phase transition. Phys Rev A. 2004;69(2):022107. 10.1103/PhysRevA.69.022107Search in Google Scholar

[37] Vidal J, Mosseri R, Dukelsky J. Entanglement in a first-order quantum phase transition. Phys Rev A Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2004;69(5):054101. 10.1103/PhysRevA.69.054101Search in Google Scholar

[38] Vidal J. Concurrence in collective models. Phys Rev A Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2006;73(6):062318. 10.1103/PhysRevA.73.062318Search in Google Scholar

[39] Vidal J, Palacios G, Aslangul C. Entanglement dynamics in the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Phys Rev A Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2004;70(6):062304. 10.1103/PhysRevA.70.062304Search in Google Scholar

[40] Latorre JI, Orús R, Rico E, Vidal J. Entanglement entropy in the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Phys Rev A Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2005;71(6):064101. 10.1103/PhysRevA.71.064101Search in Google Scholar

[41] Barthel T, Dusuel S, Vidal J. Entanglement entropy beyond the free case. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;97(22):220402. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.220402Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Cui H. Multiparticle entanglement in the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Phys Rev A Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2008;77(5):052105. 10.1103/PhysRevA.77.052105Search in Google Scholar

[43] Lourenço AC, Calegari S, Maciel TO, Debarba T, Landi GT, Duzzioni EI. Genuine multipartite correlations distribution in the criticality of the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Phys Rev B. 2020;101(5):054431. 10.1103/PhysRevB.101.054431Search in Google Scholar

[44] Orús R, Dusuel S, Vidal J. Equivalence of critical scaling laws for many-body entanglement in the Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model. Phys Rev Lett 2008;101(2):025701. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.025701Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Bao J, Guo B, Cheng HG, Zhou M, Fu J, Deng YC, et al. Multipartite nonlocality in the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Phys Rev A. 2020;101(1):012110. 10.1103/PhysRevA.101.012110Search in Google Scholar

[46] Sarandy MS. Classical correlation and quantum discord in critical systems. Phys Rev A Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2009;80(2):022108. 10.1103/PhysRevA.80.022108Search in Google Scholar

[47] Wang C, Zhang YY, Chen QH. Quantum correlations in collective spin systems. Phys Rev A Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2012;85(5):052112. 10.1103/PhysRevA.85.052112Search in Google Scholar

[48] Ye BL, Li B, Li-Jost X, Fei SM. Quantum correlations in critical XXZ system and LMG model. Int J Quant Inform. 2018;16(03):1850029. 10.1142/S0219749918500296Search in Google Scholar

[49] Kwok HM, Ning WQ, Gu SJ, Lin HQ. Quantum criticality of the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model in terms of fidelity susceptibility. Phys Rev E-Stat Nonl Soft Matter Phys. 2008;78(3):032103. 10.1103/PhysRevE.78.032103Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Ma J, Xu L, Xiong HN, Wang X. Reduced fidelity susceptibility and its finite-size scaling behaviors in the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Phys Rev E Stat Nonl Soft Matter Phys. 2008;78(5):051126. 10.1103/PhysRevE.78.051126Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Ma J, Wang X. Fisher information and spin squeezing in the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Phys Rev A Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2009;80(1):012318. 10.1103/PhysRevA.80.012318Search in Google Scholar

[52] Wang Q, Wang P, Yang Y, Wang WG. Decay of quantum Loschmidt echo and fidelity in the broken phase of the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Phys Rev A. 2015;91(4):042102. 10.1103/PhysRevA.91.042102Search in Google Scholar

[53] Abd-Rabbou M, Khalil E, Al-Awfi S. Quantum otto machine in Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model with magnetic field and a symmetric cross interaction. Opt Quantum Electron. 2024;56(6):940. 10.1007/s11082-024-06444-1Search in Google Scholar

[54] Micheli A, Jaksch D, Cirac JI, Zoller P. Many-particle entanglement in two-component Bose–Einstein condensates. Phys Rev A. 2003;67(1):013607. 10.1103/PhysRevA.67.013607Search in Google Scholar

[55] Morrison S, Parkins A. Dynamical quantum phase transitions in the dissipative Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick Model with proposed realization in optical cavity QED. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;100(4):040403. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.040403Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Chen G, Liang JQ, Jia S. Interaction-induced Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model in a Bose–Einstein condensate inside an optical cavity. Optics Express. 2009;17(22):19682–90. 10.1364/OE.17.019682Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Larson J. Circuit QED scheme for the realization of the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Europhys Lett. 2010;90(5):54001. 10.1209/0295-5075/90/54001Search in Google Scholar

[58] Unanyan R, Fleischhauer M. Decoherence-free generation of many-particle entanglement by adiabatic ground-state transitions. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;90(13):133601. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.133601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Russomanno A, Iemini F, Dalmonte M, Fazio R. Floquet time crystal in the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Phys Rev B. 2017;95(21):214307. 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.214307Search in Google Scholar

[60] Zhou Y, Ma SL, Li B, Li XX, Li FL, Li PB. Simulating the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model in a hybrid quantum system. Phys Rev A. 2017;96(6):062333. 10.1103/PhysRevA.96.062333Search in Google Scholar

[61] Xu K, Sun ZH, Liu W, Zhang YR, Li H, Dong H, et al. Probing dynamical phase transitions with a superconducting quantum simulator. Sci Adv. 2020;6(25):eaba4935. 10.1126/sciadv.aba4935Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[62] Cavalcanti EG, Jones SJ, Wiseman HM, Reid MD. Experimental criteria for steering and the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox. Phys Rev A Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2009;80(3):032112. 10.1103/PhysRevA.80.032112Search in Google Scholar

[63] Henderson L, Vedral V. Classical, quantum and total correlations. J Phys A Math General. 2001;34(35):6899. 10.1088/0305-4470/34/35/315Search in Google Scholar

[64] Fanchini F, Werlang T, Brasil C, Arruda L, Caldeira A. Non-Markovian dynamics of quantum discord. Phys Rev A Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2010;81(5):052107. 10.1103/PhysRevA.81.052107Search in Google Scholar

[65] Peres A. Separability criterion for density matrices. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77(8):1413. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.1413Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Bartkiewicz K, Horst B, Lemr K, Miranowicz A. Entanglement estimation from Bell inequality violation. Phys Rev A Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2013;88(5):052105. 10.1103/PhysRevA.88.052105Search in Google Scholar

[67] Bartkiewicz K, Lemr K, Černoch A, Miranowicz A. Bell nonlocality and fully entangled fraction measured in an entanglement-swapping device without quantum state tomography. Phys Rev A. 2017;95(3):030102. 10.1103/PhysRevA.95.030102Search in Google Scholar

[68] Horodecki R, Horodecki P, Horodecki M. Violating Bell inequality by mixed spin-12 states: necessary and sufficient condition. Phys Lett A. 1995;200(5):340–4. 10.1016/0375-9601(95)00214-NSearch in Google Scholar

[69] Huuuu ML. Relations between entanglement, Bell-inequality violation and teleportation fidelity for the two-qubit X states. Quant Inform Proces. 2013;12(1):229–36. 10.1007/s11128-012-0371-1Search in Google Scholar

[70] He Q, Rosales-Zárate L, Adesso G, Reid MD. Secure continuous variable teleportation and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen steering. Phys Rev Lett. 2015;115(18):180502. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.180502Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[71] Branciard C, Cavalcanti EG, Walborn SP, Scarani V, Wiseman HM. One-sided device-independent quantum key distribution: Security, feasibility, and the connection with steering. Phys RevA Atomic Mol Opt Phys. 2012;85(1):010301. 10.1103/PhysRevA.85.010301Search in Google Scholar

[72] Law YZ, Bancal JD, Scarani V, et al. Quantum randomness extraction for various levels of characterization of the devices. J Phys A Math Theoret. 2014;47(42):424028. 10.1088/1751-8113/47/42/424028Search in Google Scholar

[73] Costa A, Angelo R. Quantification of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen steering for two-qubit states. Phys Rev A. 2016;93(2):020103. 10.1103/PhysRevA.93.020103Search in Google Scholar

[74] Vidal J, Dusuel S, Barthel T. Entanglement entropy in collective models. J Stat Mech Theory Experiment. 2007;2007(1):P01015. 10.1088/1742-5468/2007/01/P01015Search in Google Scholar

[75] Dusuel S, Vidal J. Finite-size scaling exponents of the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93(23):237204. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.237204Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[76] Dusuel S, Vidal J. Continuous unitary transformations and finite-size scaling exponents in the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Phys Rev B-Condensed Matter Materials Phys. 2005;71(22):224420. 10.1103/PhysRevB.71.224420Search in Google Scholar

[77] Cervia MJ, Balantekin A, Coppersmith S, Johnson CW, Love PJ, Poole C, et al. Lipkin model on a quantum computer. Phys Rev C. 2021;104(2):024305. 10.1103/PhysRevC.104.024305Search in Google Scholar

[78] Zheng RH, Ning W, Lü JH, Yu XJ, Wu F, Deng CL, et al. Experimental demonstration of spontaneous symmetry breaking with emergent multiqubit entanglement. Phys Rev Lett. 2025;134(15):150406. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.150406Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[79] Chinnarasu R, Poole C, Phuttitarn L, Noori A, Graham T, Coppersmith S, et al. Variational simulation of the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model on a neutral atom quantum computer. 2025. arXiv: http://arXiv.org/abs/arXiv:250106097. 10.1103/PRXQuantum.6.020350Search in Google Scholar

[80] Hlatshwayo MQ, Zhang Y, Wibowo H, LaRose R, Lacroix D, Litvinova E. Simulating excited states of the Lipkin model on a quantum computer. Phys Rev C. 2022;106(2):024319. 10.1103/PhysRevC.106.024319Search in Google Scholar

[81] Hengstenberg SM, Robin CE, Savage MJ. Multi-body entanglement and information rearrangement in nuclear many-body systems: a study of the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Europ Phys J A. 2023;59(10):231. 10.1140/epja/s10050-023-01145-xSearch in Google Scholar

[82] Robin CE, Savage MJ. Quantum simulations in effective model spaces: Hamiltonian-learning variational quantum eigensolver using digital quantum computers and application to the Lipkin-Meshkov-Glick model. Phys Rev C. 2023;108(2):024313. 10.1103/PhysRevC.108.024313Search in Google Scholar

[83] Beaujeault-Taudière Y, Lacroix D. Solving the Lipkin model using quantum computers with two qubits only with a hybrid quantum-classical technique based on the generator coordinate method. Phys Rev C. 2024;109(2):024327. 10.1103/PhysRevC.109.024327Search in Google Scholar

[84] Chen G, Robertson M, Hoffmann M, Ophus C, Fernandes Cauduro AL, Lo Conte R, et al. Observation of hydrogen-induced Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction and reversible switching of magnetic chirality. Phys Rev X. 2021;11(2):021015. 10.1103/PhysRevX.11.021015Search in Google Scholar

[85] Oumennana M, Rahman AU, Mansour M. Quantum coherence versus non-classical correlations in XXZ spin-chain under Dzyaloshinsky-Moriya (DM) and KSEA interactions. Appl Phys B. 2022;128(9):162. 10.1007/s00340-022-07881-0Search in Google Scholar

[86] Oumennana M, Dahbi Z, Mansour M, Khedif Y. Geometric measures of quantum correlations in a two-qubit heisenberg xxz model under multiple interactions effects. J Russian Laser Res. 2022;43(5):533–45. 10.1007/s10946-022-10079-6Search in Google Scholar

[87] Bouafia Z, Oumennana M, Mansour M, Ouchni F. Thermal entanglement versus quantum-memory-assisted entropic uncertainty relation in a two-qubit Heisenberg system with Herring-Flicker coupling under Dzyaloshinsky-Moriya interaction. Appl Phys B. 2024;130(6):94. 10.1007/s00340-024-08228-7Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- The influence of anisotropy of InP on its elasticity and phonon properties

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- The influence of anisotropy of InP on its elasticity and phonon properties

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis