Abstract

In recent years, Airyprime pulses have attracted much attention in the field of nonlinear optics due to their diffraction-free, self-accelerating, and self-healing properties, as well as their unique oscillating tail structure. However, Airyprime pulses are affected by higher-order dispersion and Raman effect in the relaxation nonlinear medium, and their propagation properties have not been thoroughly studied. To this end, the propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media are systematically investigated in this article by using the stepwise Fourier algorithm. The results show that the propagation behavior of the pulse is affected by multiple factors such as dispersion, self-phase modulation, and Raman effect, among which the third-order dispersion and Raman effect play a key role in the propagation characteristics. By adjusting the parameters of the medium and the pulse’s initial conditions, the pulse’s time-domain propagation trajectory and spectral characteristics can be effectively controlled. These research results provide theoretical support for nonlinear optical applications and important guidance for the design of distributed fiber-optic sensing systems in geophysics, showing a broad application prospect.

1 Introduction

In 2014, Zhou et al. proposed a novel light field mode Airyprime beam [1], which satisfies the plane wave equation with a new interference enhancement effect [2]. This unique property and potential application have attracted much attention in optics. Airyprime beams propagating in different media and conditions have different characteristics; Bayraktar’s study in 2020 focused on the propagation of Airyprime beams in uniaxial crystals orthogonal to the axis of propagation and delved into its evolutionary behavior [3]. The performance of Airyprime beams in turbulent atmospheres has also been investigated [4], demonstrating a strong immunity to interference. They have strong immunity to interference and self-recovering properties, but their propagation still faces challenges such as scattering, attenuation, and phase perturbation caused by turbulence. Yang et al. investigated the propagation dynamics of controllable circular Airyprime beams in Kerr media, revealing their potential for modulation [5]. Chen et al. explored the propagation dynamics of controlled circular Airyprime beams in a strongly nonlocalized nonlinear medium with spatiotemporal Airyprime complex-variable functional wave packets, revealing their stabilized rotational motions and discussing the role of Poynting vectors and gradient forces [6]. In addition, the design and implementation of self-focusing Airyprime beam arrays have also been a hot topic of recent research. Zhou et al. designed and implemented an Airyprime beam array with autofocusing characteristics, which is affected by lateral displacement, attenuation factor, and scaling factor, in 2023 [7]. Zang et al. proposed an optimization scheme to enhance the toroidal shape of Airyprime beam arrays by linear chirp Airyprime beam arrays with self-focusing capability and extended focal length, demonstrating a practical approach to improve the performance of these beam arrays [8]. Zhou et al. proposed an optimized design of annular Airyprime beam arrays based on the optimized design of the dimensionless eccentricity position, which enhances the self-focusing capability in a free-space optical communication system while decreasing the influence of turbulence effects [9]. The current study mainly focuses on the propagation characteristics of Airyprime beams or arrays in different media. However, there is a lack of systematic exploration and in-depth analysis of their dynamical behaviors in relaxing nonlinear media containing dispersion, self-phase modulation, and Raman effect.

Raman-induced frequency shifts can generate femtosecond pulses with tunable wavelengths or very high pulse energies, and the resulting solitons have become a commonly used excitation source in multiphoton microscopy [10,11]. Higher-order solitons are destabilized by Raman scattering and dispersion and decompose into multiple elementary solitons, producing multicolor soliton outputs of different wavelengths [12,13]. Experimentally, the emergence of multiple solitons via soliton self-shifting has been widely used in various modalities such as harmonic generation imaging [14] and coherent Raman scattering imaging [15]. Hu et al. proposed an experimental method to control the Raman frequency shift by varying the offsets of the cubic spectral phases of the Airy pulse [16]. Self-accelerating beams usually survive in linear media. Kerr nonlinearities that cause beam distortions often lead to structural failure, and solutions in nonlinear Kerr media have long been found [17]. In practice, nonlinear effects of relaxation are always present in nonlinear media. Current research focuses on studying higher-order dispersion and Raman effects of soliton pulses. However, there are fewer studies on the stability and dynamical behavior of self-accelerating, self-bending, self-recovering, and strongly interference-resistant Airyprime beams subjected to relaxation nonlinearities containing higher-order dispersion and Raman effects and their potential multicolor soliton generation mechanisms.

Most studies have focused on the propagation of Airy pulses, whose linear and nonlinear dynamics have been extensively analyzed theoretically and numerically [18,19,20]. In contrast, Airyprime pulses enhance their responsiveness to nonlinear effects (e.g., Kerr nonlinearity and Raman scattering) by introducing optimized phase or amplitude modulation, which makes them more susceptible to triggering soliton splitting in the medium. In addition, the self-focusing and self-accelerating properties of Airyprime pulses enable the formation of stable multi-soliton structures under the combined effect of dispersion and nonlinearity. This optimized kinetic behavior makes it more conducive to generating and controlling soliton arrays than conventional Airy pulses. The purpose of this article is to explore the propagation characteristics of Airyprime pulse in the relaxation nonlinear medium, focusing on analyzing the influence of the parameters of the relaxation nonlinear medium (such as the third-order dispersion, the Kerr nonlinear effect, and the Raman effect) and the parameters of the Airyprime pulse (such as the truncation coefficient) on the time–frequency splitting mechanism and the evolution characteristics of the Airyprime pulse. Through the in-depth study of the propagation characteristics of Airyprime pulses, this article provides important theoretical guidance and technical reference for distributed fiber-optic sensing systems in geophysics. The study’s results can improve the performance of fiber optic sensing technology in complex environments and promote the development and application of distributed sensors with high accuracy and high sensitivity.

2 Propagation model

In order to concentrate on the effect of relaxing nonlinearity, the self-steepening effect and the role of fiber loss on the pulse propagation process in the optical fiber are not taken into account. Therefore, the modified normalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation with the effect of relaxing nonlinearity is as follows [20]:

where Φ is an approximation of the slow-varying envelope of the optical field normalization, Z denotes the normalized propagation length in the direction of the pulse propagation, β₂ is the second-order dispersion parameter of the optical fiber (fixed to −1 in this article), β 3 is the third-order dispersion parameter of the optical fiber, T R is the parameter related to the Raman response, N is a nonlinear parameter, and T = τ – Z/υ g is the delay time of normalization in the frame of reference moving at the speed of the pulse group υ g .

The split-step Fourier method (SSFM) is a widely used numerical technique for solving fractional Schrödinger equations, particularly in the field of optical fiber communications, where it is employed to simulate the propagation of optical pulses. According to the SSFM, the nonlinear Schrödinger equation can be decomposed into two components: the linear part and the nonlinear part. The linear component accounts for the dispersion effects and is expressed as follows:

The nonlinear part includes the nonlinear effect and its delayed response in the form:

With the SSFM, the evolution of these two components can be computed alternatively. The numerical solution step consists of initializing the field distribution by setting the initial conditions and defining the time grid and the step size. In the second step, the linear evolution is handled by converting the field Φ to the frequency domain denoted as

The frequency-domain results are then transformed back into the time-domain using the inverse Fourier transform, yielding the following:

The next step involves addressing the nonlinear evolution, taking into account the influence of the nonlinear terms in the time domain. The formula for nonlinear evolution is as follows:

Finally, the linear and nonlinear parts of the calculation are alternated, and the above process is repeated until the desired propagation distance is reached. This method effectively combines the computational features of the frequency and time domains to efficiently solve the complex nonlinear Schrödinger equation containing dispersion and nonlinear effects. The input initial Airyprime pulse can be written in the following form:

The parameter 0 < a < 1 represents the truncation coefficient, while Ai′(T) denotes the first derivative of the Airy function. The expression for the Airy function is given by

where ω is the frequency of the pulse. The intensity of the initial pulse in the frequency domain is

From Eq. (9), it can be seen that the frequency influences the intensity properties in the frequency domain ω and the truncation coefficient a. The underlying intensity distribution of the spectrum is determined by the frequency term (a

2 + ω

2), which describes the spectral amplitude at different frequencies. The spectral intensity reaches a minimum at the center frequency ω = 0 and gradually increases with increasing frequency. Meanwhile, the exponential term exp(2a

3/3−2aω

2) modifies the spectrum’s shape, especially in the high-frequency range, where the term leads to a rapid decrease in the spectral intensity. Overall, the spectral distribution of the Airyprime pulse exhibits a frequency dependence: the spectral intensity is lowest near the center frequency, increases first with the absolute value of the frequency |ω|, and then gradually decays in the higher frequency range. In addition, the center frequency corresponds to an intensity minimum of about

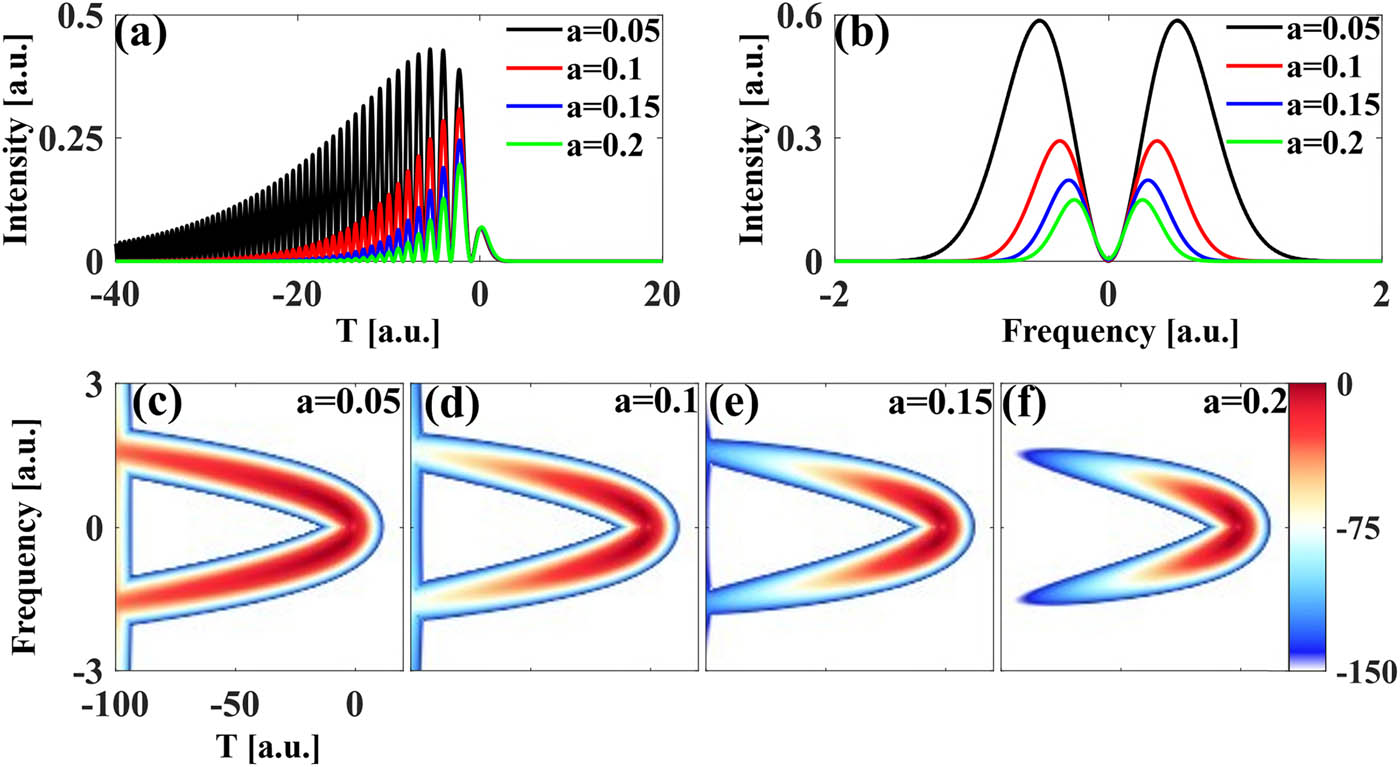

In Figure 1(a), it can be observed that the Airyprime pulse displays a distinctly asymmetric multi-peak waveform feature. The central peak with the most significant peak power appears in the second position on the right side, while the first peak immediately adjacent to it has a significantly smaller peak than the central peak. Multiple oscillatory peaks accompany the left side of the central peak, and the amplitude of the oscillations in this part gradually decreases, forming a more obvious trailing phenomenon. The larger the truncation coefficient, the faster the side flap falls. Figure 1(b) further demonstrates that the initial spectrum of the Airyprime pulse exhibits a double-peak pattern with different truncation coefficients a (0.05, 0.1, 0.15, and 0.2, respectively), and these peaks are symmetrically distributed around the center frequency. As the truncation coefficient a is raised, the maximum intensity of the spectrum gradually decreases while the width also decreases. Figure 1(c)–(e) then presents the X-Frog plots of the Airyprime pulse for different truncation values of a. The X-Frog plots of the Airyprime pulse are shown in Figure 1(c)–(e). As it increases from 0.15 to 0.2, the energy of the Airyprime pulse begins to concentrate significantly in the center frequency interval, and the trailing effect in the rest of the spectrum gradually decreases, the distribution of energy appears more concentrated, and the spectral width becomes significantly narrower.

Comparison of initial waveforms (a) and spectra (b) of Airyprime pulses with different truncation coefficients a, as well as X-Frog plots (c)–(f) of Airyprime pulses with different truncation coefficients.

3 Numerical results

The propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in a relaxing nonlinear medium (containing the Kerr nonlinear effect and Raman effect) are discussed in detail below. The propagation characteristics of Airyprime pulses in free space, Kerr medium by truncation coefficient, Kerr nonlinear coefficient, and third-order dispersion coefficient are discussed first. Then, the propagation characteristics of Airyprime pulses in a Raman medium are discussed using different Raman, truncation, and general nonlinear coefficients.

3.1 The interference enhancement effect of Airyprime pulses in free space

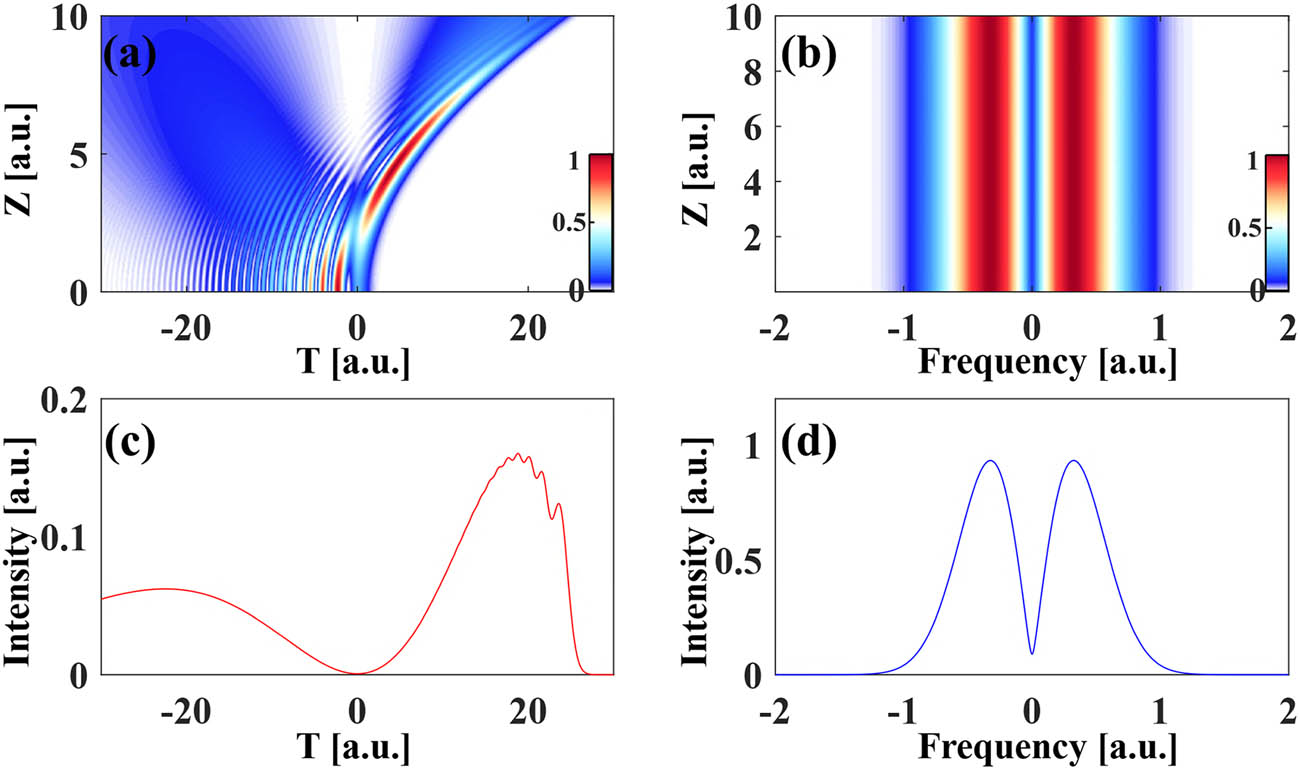

In free space, there are no nonlinear effects, only dispersion effects. As shown in the time-domain evolution diagram (Figure 2(a)), the Airy primer pulse rapidly shifts its energy to the first peak on the right during the initial propagation phase. At Z = 5, the energy of the first peak on the right reaches its maximum value, while the energy of the other peaks gradually decreases. This is due to the interference enhancement effect between the Airy derivative and the Airy correlation mode. The waveform evolves into an Airy-like pulse. Subsequently, the Airyprimer pulse continues to exhibit self-acceleration and self-bending propagation characteristics. From the frequency-domain evolution diagram (Figure 2(b)), it can be seen that the Airyprimer pulse maintains a symmetric double-peak structure during stable propagation. At Z = 10, in the free-space waveform of the Airy primer pulse (Figure 2(c)), the energy of the first peak on the right side is the highest; as observed in the spectrum diagram (Figure 2(d)), the Airy primer pulse still maintains a symmetric double-peak structure.

Time (a) and frequency (b) evolution of the Airyprimer pulse at a = 0.12 in free space; waveform (c) and spectrum (d) of the Airyprimer pulse at Z = 10.

3.2 Properties of Airyprime pulse propagation in Kerr nonlinear media

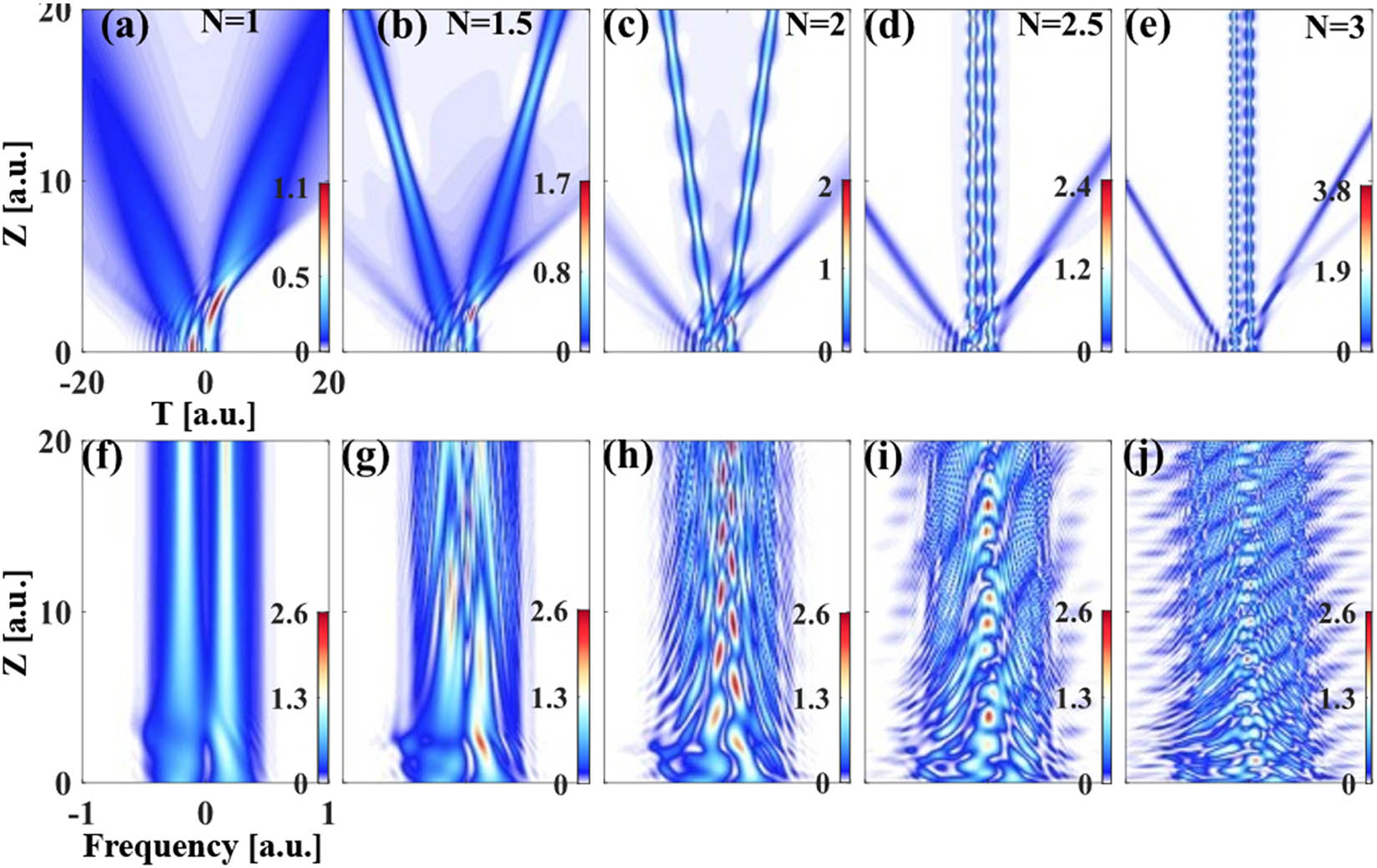

The general nonlinear coefficient is an important parameter for controlling the self-phase modulation of pulses in a medium. Numerical simulations were performed to investigate the effect of the general nonlinear coefficients on the evolutionary properties of the Airyprime pulse. It can be seen from the time-domain evolution diagrams (Figure 3(a)–(e)) that the general nonlinear coefficient N is able to modulate the degree of linear deflection and respiration period of the Airyprime pulse shedding solitons. The self-acceleration and self-bending evolution process of the Airyprime pulse in Kerr medium is a typical nonlinear optical phenomenon. The self-acceleration effect causes the trajectory of the pulse center to maintain a parabolic shape, which generates energy aggregation during propagation and further enhances the local intensity of the pulse. With the propagation, the second peak on the right side is first compressed and sheds solitons, followed by the first peak on the right side also shedding solitons. When N = 1, 1.5, 2 (Figure 3(a)–(c)), the soliton shed by the second peak on the right is linearly deflected to the left, and the soliton shed by the first peak on the right is linearly deflected to the right. In general, the larger the nonlinearity coefficient N, the smaller the degree of deflection. However, when N = 2.5, 3 (Figure 3(d) and (e)), the shed soliton propagates parallel without deflection due to the increased attraction between the two solitons. Meanwhile, the spacing between the shedding solitons gradually decreases when the value of N increases. It is worth noting that the larger the value of N, the smaller the beamwidth and breathing period of the shed soliton. From the frequency-domain evolution diagram (Figure 3(f)–(j)), the notch forms in the high-frequency region at the initial stage of pulse propagation. In contrast, the low-frequency region remains almost unchanged. As the propagation distance increases, the notch gradually deepens while the redshift effect gradually increases. At the stabilization stage, the shape of the notch and the degree of redshift tend to stabilize with the formation of the accelerating pulse, after which they no longer change significantly with the propagation distance (Figure 3(f)). However, when N > 1, the general nonlinear effect produces a positive frequency chirp, while the anomalous dispersion produces a negative frequency chirp. The chirp produced by the general nonlinear effect results in a redshift of the leading edge of the shedding soliton pulse, and the chirp produced by the anomalous dispersion results in a blueshift of the trailing edge of the shedding soliton (Figure 3(g)–(j)). When the width of the spectrum is compressed to a minimum, its width increases abruptly again. Periodic compression and broadening of the spectrum occur all the time during propagation. It is worth noting that the larger the value of N, the greater the change frequency.

Time (a)–(e) and frequency (f)–(j) evolution of Airyprimer pulse at a = 0.3 for different general nonlinear coefficients N under the combined effect of group velocity dispersion and self-phase modulation.

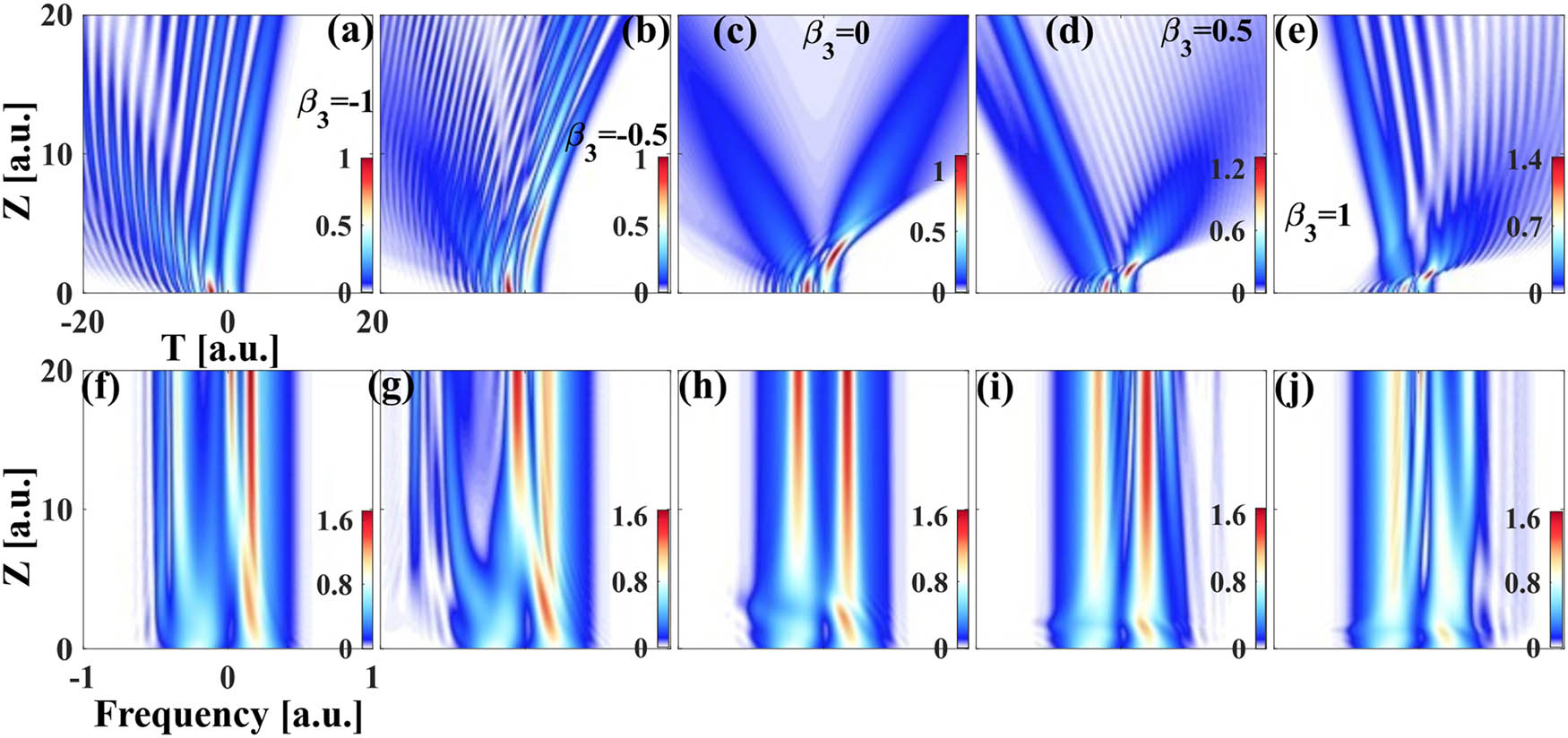

The third-order nonlinear coefficient β 3 can manipulate the linear deflection direction of the pulse propagation as well as control its spectral distribution. Numerical simulations were performed to investigate the general nonlinear coefficients’ effect on the Airyprime pulse’s evolutionary characteristics. From the time-domain evolution diagrams (Figure 4(a)–(e)), it can be seen that when β 3 = −1 (Figure 4(a)), the central peak of the pulse is significantly deflected to the negative time direction, and the tail is enhanced and extended; when β 3 = −0.5 (Figure 4(b)), the deflection is weakened, and asymmetric enhancement of the tail still exists; in the case of β 3 = 0 (Figure 4(c)), the pulse maintains a well-symmetric structure, and propagation presents a stable parabolic trajectory; when β 3 = 0.5 (Figure 4(a)) and β 3 = 1 (Figure 4(a)), the central peak is shifted to favorable time, the tail energy is enhanced and significantly broadened, and the asymmetry is intensified. From the frequency domain evolution diagram (Figure 4(f-j)), it can be seen that when β 3 = −1 (Figure 4f) and β 3 = −0.5 (Figure 4g), the spectrum undergoes red shift, the low-frequency components are enhanced, the spectrum broadens, and asymmetry appears. When β 3 = 0 (Figure 4h), the spectrum exhibits optimal symmetry, minimal broadening, and energy concentrated at the central frequency; when β 3 = 1 (Figure 4i) and β 3 = 0.5 (Figure 4j), the spectrum undergoes blue shift, with high-frequency components dominating, significant broadening, and enhanced asymmetry. In summary, the magnitude and sign of third-order dispersion have a significant influence on the temporal evolution, morphology, and frequency-domain spectral distribution of the pulse. Positive third-order dispersion causes a blue shift and tail enhancement, while negative third-order dispersion causes a red shift and leftward shift of the main peak.

Time-domain (a)–(e) and frequency (f)–(j) evolution of Airyprimer pulses with different third-order dispersion coefficients β 3 under the combined effect of group velocity dispersion and self-phase modulation for N = 1, a = 0.3.

Figures 4(e)–(h) and 5(a)–(d) show the waveform and spectral evolution of the Airyprime pulse in the anomalous dispersion region, respectively. From the time-domain evolution plots (Figure 5(a)–(d)), it can be seen that the Airyprime pulse maintains its original structure at the early stage of evolution and then gradually evolves into a self-accelerating pulse. It is worth noting that during the self-accelerating propagation process, the energy gradually increases due to the focusing of the pulse peak, and a certain number of solitons are eventually shed. When the general nonlinear coefficient N = 1, there is no soliton shedding phenomenon (Figure 5(a)). With the increase of N, the soliton shedding phenomenon gradually appears (Figure 5(b)), and the number of solitons continues to increase with the further increase of the nonlinear coefficient (Figure 5(c) and (d)). From the spectral evolution diagram (Figure 5(e)–(h)), it can be seen that in the anomalous dispersion region, a red-shifted spectral notch appears in the low-frequency region, which is formed during the self-accelerating pulse evolution. In contrast, the high-frequency region remains almost unchanged. When an Airyprime pulse propagates in an anomalously dispersive fiber, the low-frequency component of the pulse front undergoes a more remarkable nonlinear phase shift due to the self-phase modulation effect, resulting in a redshift of the spectrum toward the low frequencies. As the nonlinear intensity increases, the degree of redshift further intensifies, separating the low-frequency component from the high-frequency component in the spectrum and forming a spectral notch that bulges in the low-frequency direction. With increased propagation distance, this spectral notch gradually weakens and eventually disappears. In the anomalous dispersion region, the spectral characteristics of the Airyprime pulse change with the increase of the nonlinear strength N. Specifically, the spectral notch emerges earlier during propagation, and both its depth and width progressively increase, indicating stronger nonlinear interactions (Figure 5(f)–(h)). This controlled frequency shift not only highlights the impact of increasing N on the spectral evolution but also provides a novel and effective method for achieving wavelength conversion and spectral shaping. Such characteristics make it particularly advantageous for applications in optical signal processing, where precise control over spectral properties is crucial.

Time-domain (a)–(e) and frequency-domain (f)–(j) evolution of Airyprimer pulses with different general nonlinear coefficients N under the combined effect of group velocity dispersion and self-phase modulation for a = 0.05.

3.3 Properties of Airyprime pulse propagation under the combination of group velocity dispersion, self-phase modulation, and Raman effect

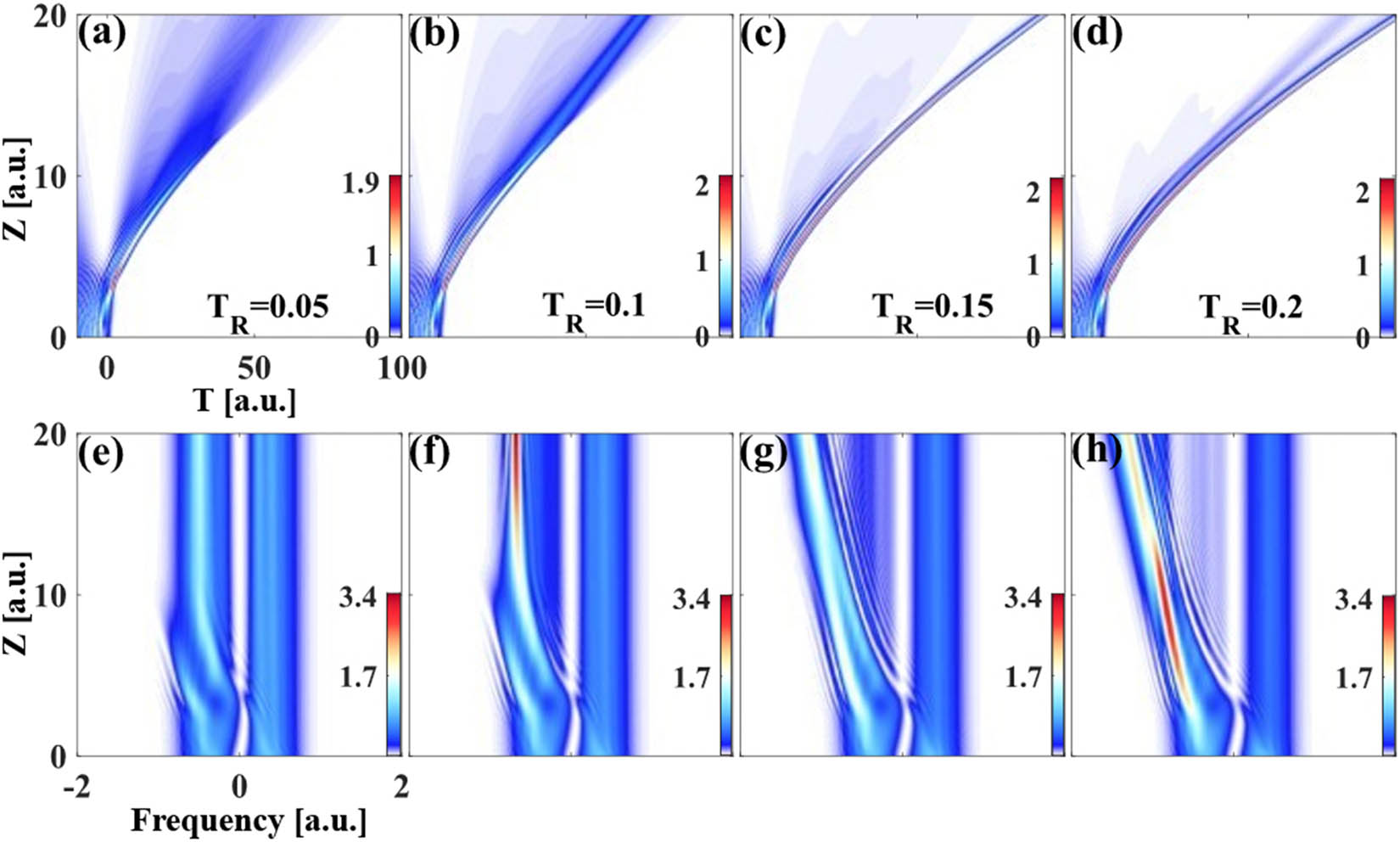

Figure 6 illustrates the time-domain and frequency-domain evolution of the Airyprime pulse at different Raman coefficients under the conditions of a = 0.1 and N = 1. From the time-domain evolution diagrams (Figure 6(a)–(d)), it can be seen that the Airyprime pulse maintains its original structure at the early stage of evolution and then gradually evolves into a self-accelerating pulse that exhibits a curved motion trajectory. During the nonlinear propagation process, part of the soliton energy is dissipated due to the dispersion effect. As the input Raman coefficient increases, a more significant time delay occurs at the main peak position of the shed soliton due to the Raman effect (Figure 6(b)–(d)). From the frequency domain evolution plots (Figure 6(e)–(h)), it can be seen that although the Raman effect leads to a significant shift of the spectrum towards the long-wave direction (redshift), the frequency of the blueshifted portion remains almost unchanged. When the Raman coefficients are 0.05 and 0.1, the Raman effect is weak, and the redshift phenomenon is not obvious after the Airyprime pulses are injected into the ideal lossless fiber (Figure 6(e)–(f)). With the further increase of the Raman coefficient, the Raman effect gradually strengthens and dominates, at which time the frequency redshift becomes more significant (Figure 6(g)–(h)). The Raman effect induces a delay in the leading edge of the pulse spectrum. In contrast, the trailing edge portion remains almost unchanged, resulting in an asymmetric collapsed structure in the frequency domain of the Airyprime pulse, which alters its spectral morphology. In addition, at the early propagation stage, the Raman-induced redshifted frequency interferes with the residual frequency to form a discrete multi-peak structure. This unique behavior can be explained as follows: the Airyprime pulse has a broad spectrum. Due to the frequency chirp induced by self-phase modulation, the pulses may have the same instantaneous frequency at different points. However, phase-length or phase-canceling interference occurs due to phase differences.

Time-domain (a)–(e) and frequency-domain (f)–(j) evolution of group velocity dispersion, self-phase modulation, and Raman effect for different Raman coefficients at a = 0.1, N = 1.

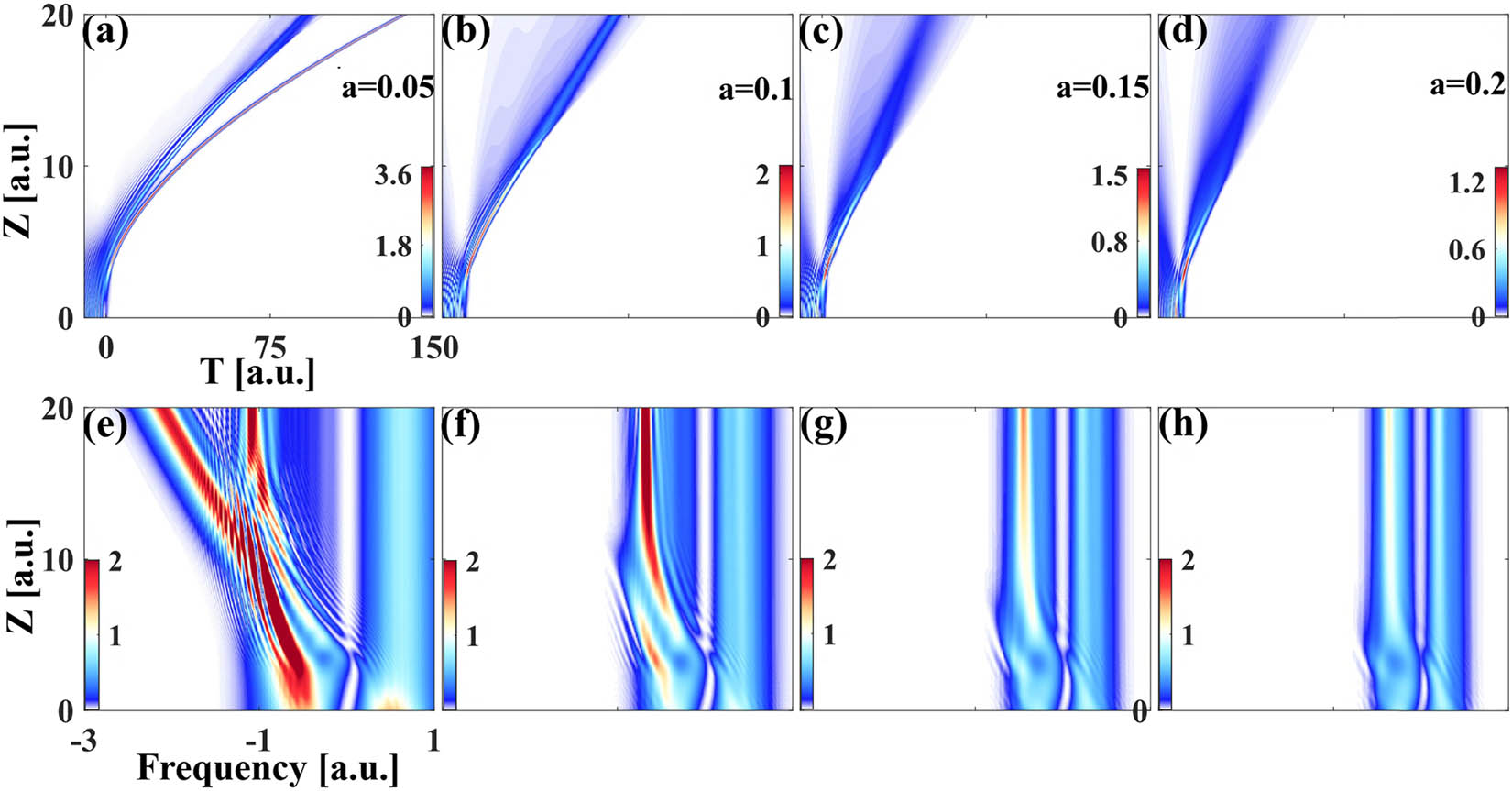

The truncation coefficient is a critical parameter of the Airyprimer pulse, and the main characteristics of the Airyprimer pulse are related to its degree of truncation. When an Airyprimer pulse is strongly truncated, it loses its characteristics and becomes a symmetric soliton pulse. The next section investigates the propagation of low-power Airyprimer pulses with different truncation coefficients under the influence of the Raman effect. Figure 7 illustrates the temporal and spectral evolution of the Airyprimer pulse over 20 dispersion lengths for four different values of the truncation coefficient. The effect of the truncation coefficients on the linear self-accelerating deflection in the time domain and the linear deflection in the frequency domain of the Airyprimer pulse can be seen. The smaller the truncation coefficient is, the larger the time shift of the position of the shed soliton is (Figure 7(a)). As the truncation coefficient decreases, the shed soliton’s peak power and time shift increase (Figure 7(b)–(d)); therefore, the Raman redshift decreases with increasing truncation coefficient (Figure 7(f)–(h)). The truncation coefficient can be used to modulate the Raman redshift in the frequency domain of the Airyprimer pulse, thus realizing a broadly tuned light source.

Time-domain (a)–(e) and frequency-domain (f)–(j) evolution of Airyprimer pulse with T R = 0.1, N = 1, under the combined effect of group velocity dispersion, self-phase modulation, and Raman effect for different truncation coefficients a.

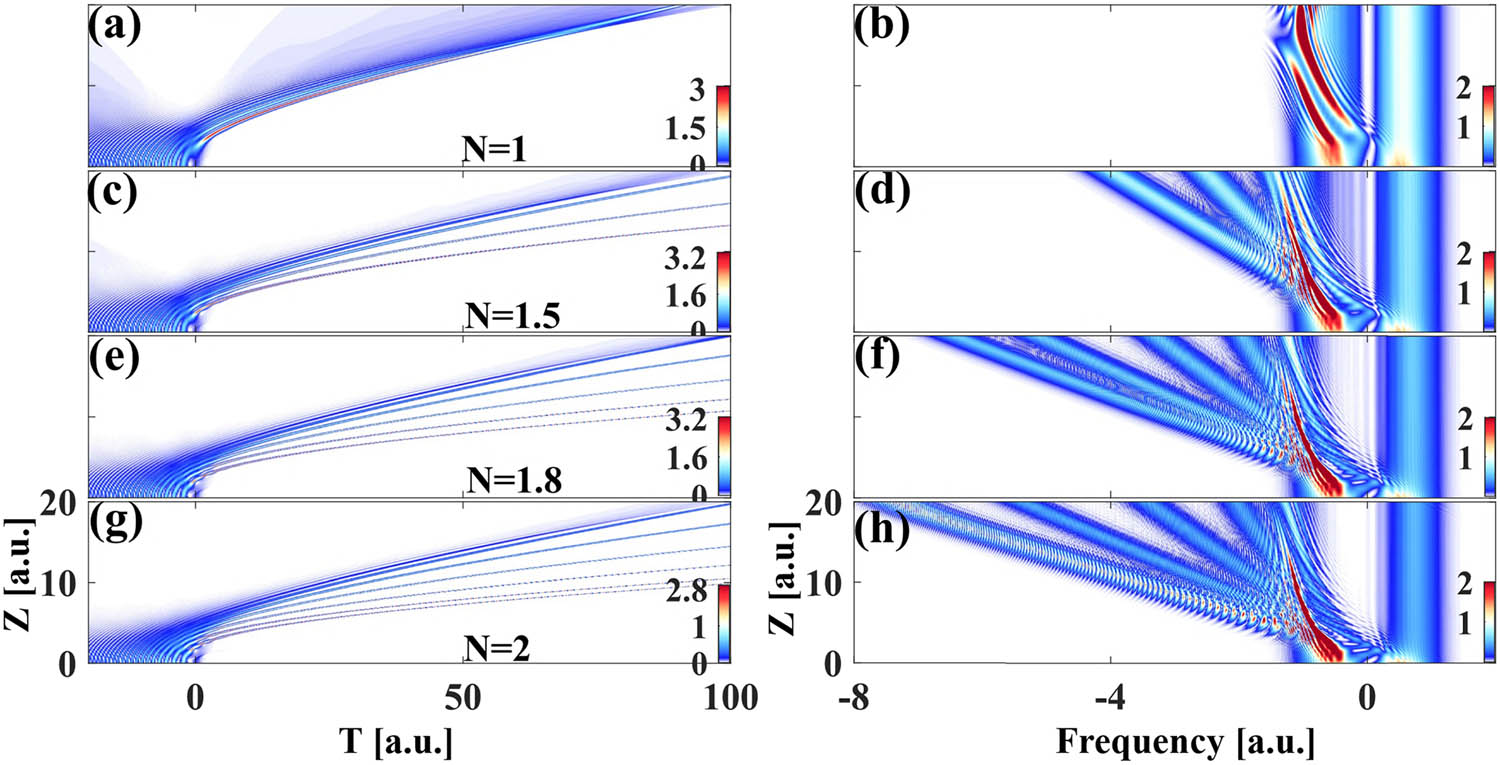

The larger the general nonlinear coefficient N is, the more significant the nonlinear effect of the Airyprimer pulse is in the propagation process, and the spectrum of the pulse undergoes significant redshift phenomenon and energy transfer. Figure 8 demonstrates the evolution of the time-frequency spectroscopic mechanism of the Airyprimer pulse in the anomalous dispersion region for a general nonlinear coefficient N. The time-frequency spectroscopic mechanism of the Airyprimer pulse is shown in Figure 8. When N = 1, the Airyprimer pulse still maintains a relatively stable morphology during the self-accelerating pulse formation, and the Airyprimer pulse shows an obvious red-shifted spectral gap in the low-frequency region, while the high-frequency region remains almost unchanged (Figure 8(a) and (b)). When N = 1, the Airy primer pulse releases Raman solitons from the interference-enhanced region, and a redshift peak appears, strengthening the pulse’s nonlinear features (Figure 8(c) and (d)). More Raman solitons are released from the Airyprimer pulse with increasing N. The Airyprimer pulse forms multiple red-shifted peaks in the spectrum, and the redshift rate of the outermost peaks increases significantly (Figure 8(e)–(h)). The Raman effect-induced frequency shifts continue throughout the fiber, and the larger the value of N is, the wider the red-shifted spectra are. The results show that the number of Raman solitons gradually increases when the general nonlinear coefficient N gradually increases, and the nonlinear interaction of the solitons leads to self-accelerating deflection broadening and multiple linear deflections in the low-frequency part of the Airyprimer pulse in the time domain.

Time-domain (a), (c), (e), (g) and frequency-domain (b), (d), (f), (h) splitting mechanism for different values of N in Airyprime pulses under the combined effects of group velocity dispersion, self-phase modulation, and Raman effect, for T R = 0.05, a = 0.1.

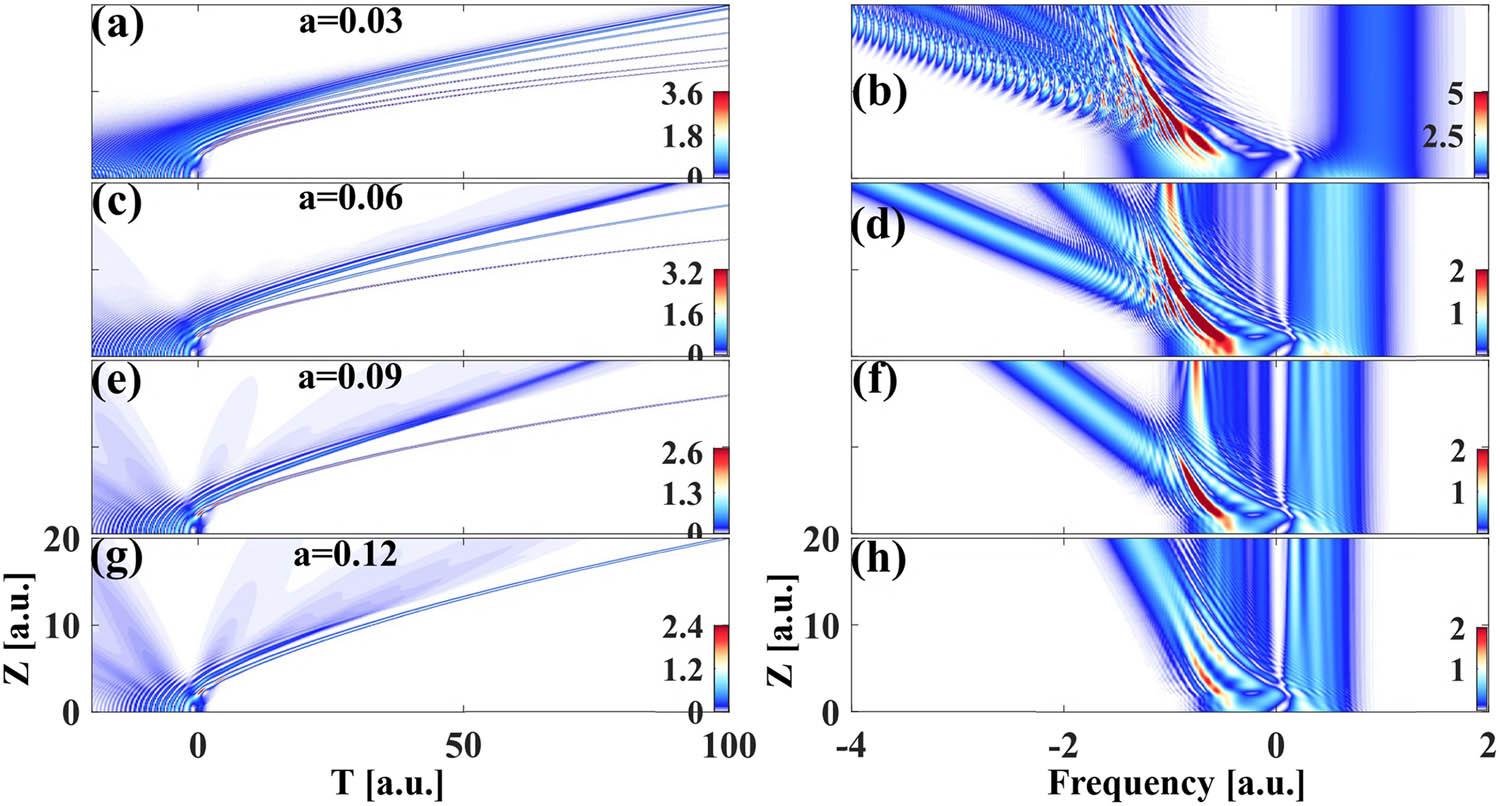

Figure 9 illustrates the effect of different truncation coefficients on the time and frequency domain splitting of the Airyprimer pulse. The redshifted soliton is detached from the incident pump pulse and is slowed down due to Raman scattering effects. This manifests as a change in the pulse trajectory in the time domain and as a redshift in the spectrum in the frequency domain. When a decreases, the Airyprimer pulse can release more Raman solitons and enhance the peak power. Meanwhile, the time interval between the primary and secondary valves significantly increases (Figure 9(a)). In the frequency domain, as a increases, more redshifted peaks are separated from the main spectrum, and the redshifted spectrum becomes larger and smoother. In contrast, the peak power remains constant (Figure 9(c), (e) and (g)). The Raman effect causes the spectrum to be shifted significantly toward the long-wavelength direction, while the blue-shifted spectrum remains almost constant. When a = 0.12, the Airyprimer pulse generates two Raman solitons (Figure 9(h)). As a decreases, the Airyprimer pulse releases more Raman solitons, and more redshifted peaks are separating from the main spectrum, with an increase in the distance between the strong peaks of the main spectrum (Figure 9(b), (d), and (f)). This is attributed to the change in the initial pulse profile for different values of a. An increase in a causes the energy of the incident Airyprimer pulse to increase and the temporal center of mass (manifested as the time-domain position of the strongest wave flap) to move in the direction of T < 0, thus shedding more solitons. The results show that as increases, the time-domain peak power and temporal displacement of the shedding solitons increase, and the number increases, while the frequency-domain peak power remains unchanged.

Time-domain (a), (c), (e), (g) and frequency-domain (b), (d), (f), (h) splitting mechanism under the combined effect of velocity dispersion, self-phase modulation, and Raman effect for pulsed Airyprime pulse group with different a for T R = 0.05, N = 1.5.

4 Conclusion

This article systematically investigates the propagation characteristics of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media, focusing on the influence of group velocity dispersion, self-phase modulation, Raman effect, and third-order dispersion on their evolutionary behavior. It is shown that the Airyprime pulses exhibit remarkable self-acceleration, self-bending, self-recovery, and strong anti-interference ability in nonlinear media. Under the combined effect of group velocity dispersion and self-phase modulation, the central peak of the Airyprime pulse undergoes nonlinear compression. It generates detached solitons with parabolic trajectories, and an increase in the nonlinear coefficient decreases the soliton spacing, causing the propagation to be parallel. The Raman effect has an important impact on the time-frequency evolution of the Airyprime pulse. As the Raman coefficient increases, the spectral redshift and the main peak time delay are significantly enhanced, while the truncation coefficient and the initial peak power play a key role in the degree of redshift. The smaller the truncation coefficient, the more significant the time shift of the shedding soliton, and the wider the range of redshift; the higher the initial peak power, the enhanced energy of the soliton, and the more significant redshift. The size and sign of the third-order dispersion further modulate the pulse’s deflection direction and spectral characteristics, with positive values of the third-order dispersion leading to a blue shift and negative values of the third-order dispersion causing a redshift. By adjusting the nonlinear, Raman, and truncation coefficients, the propagation characteristics of Airyprime pulses can be effectively controlled to optimize their spectral and time-domain properties. These studies provide theoretical guidance for the design of distributed fiber optic sensing, nonlinear optical imaging, and ultrafast laser systems and also show a broad prospect for practical applications in optics. Future work can further explore the stability of Airyprime pulses in complex nonlinear environments and optimized applications in practical systems.

-

Funding information: This work was supported in part by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No. 2021JJ30075), and the Scientific Research Fund of Hunan Provincial Education Department (No. 20A095).

-

Author contributions: D.P. Cheng: conceptualization, writing, review and editing; Z.W. Xiao: data curation and methodology; D.C. Jiang: investigation and software. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Zhou GQ, Chen RP, Ru GY. Airyprime beams and their propagation characteristics. Laser Phys Lett. 2015;12(2):025003.10.1088/1612-2011/12/2/025003Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Xu YQ, Zhou GQ, Zhang LJ, Ru GY. Two kinds of Airy-related beams. Laser Phys. 2015;25(8):085005.10.1088/1054-660X/25/8/085005Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Bayraktar M. Propagation of Airyprime beam in uniaxial crystal orthogonal to propagation axis. Optik. 2021;228:166183.10.1016/j.ijleo.2020.166183Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Bayraktar M. Performance of Airyprime beam in turbulent atmosphere. Photonic Netw Commun. 2021;41:274–9.10.1007/s11107-021-00935-xSuche in Google Scholar

[5] Yang S, Yu PX, Wu JW, Zhang X, Xu Z, Man ZS, et al. Propagation dynamics of the controllable circular Airyprime beam in the Kerr medium. Opt Express. 2023;31(22):35685–96.10.1364/OE.499499Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Chen CD, Zhang LP, Yang S, Li SY, Deng DM. Spatiotemporal Airyprime complex-variable-function wave packets in a strongly nonlocal nonlinear medium. Opt Lett. 2024;49(10):2681–4.10.1364/OL.523374Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Zhou YM, Zang X, Dan WS, Wang F, Chen RP, Zhou GQ. Design and realization of an autofocusing Airyprime beams array. Opt Laser Technol. 2023;162:109303.10.1016/j.optlastec.2023.109303Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Zang X, Dan WS, Zhou YM, Wang F, Cai YJ, Zhou GQ. Simultaneously enhancing autofocusing ability and extending focal length for a ring Airyprime beam array by a linear chirp. Opt Lett. 2023;48(4):912–5.10.1364/OL.482204Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Zhou YM, He J, Dan WS, Wang F, Zhou GQ. An optimum design of a ring Airyprime beam array based on dimensionless eccentric position. Results Phys. 2024;56:107275.10.1016/j.rinp.2023.107275Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Unruh JR, Price ES, Molla RG, Stehnobittel L, Johnson CK, Hui RQ. Two-photon microscopy with wavelength switchable fiber laser excitation. Opt Express. 2006;14(21):9825–31.10.1364/OE.14.009825Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Tong S, Gan MY, Zhuang ZW, Liu HJ, Cheng H, Li J, et al. Manipulating soliton polarization in soliton self-frequency shift and its application to 3-photon microscopy in vivo. J Light Technol. 2020;38(8):2450–5.10.1109/JLT.2020.2973734Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Wai PKA, Menyuk CR, Lee YC, Chen HH. Nonlinear pulse propagation in the neighborhood of the zero-dispersion wavelength of monomode optical fibers. Opt Lett. 1986;11(7):464–6.10.1364/OL.11.000464Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Tai K, Hasegawa A, Bekki N. Fission of optical solitons induced by stimulated Raman effect. Opt Lett. 1988;13(5):392–4.10.1364/OL.13.000392Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Horton NG, Wang K, Kobat D, Clark CG, Wise FW, Schaffer CB, et al. In vivo three-photon microscopy of subcortical structures within an intact mouse brain. Nat Photonics. 2013;7(3):205–9.10.1038/nphoton.2012.336Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Andresen ER, Berto P, Rigneault H. Stimulated Raman scattering microscopy by spectral focusing and fiber-generated soliton as Stokes pulse. Opt Lett. 2011;36(13):2387–9.10.1364/OL.36.002387Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Hu Y, Tehranchi A, Wabnitz S, Kashyap R, Chen Z, Morandotti R. Improved intrapulse Raman scattering control via asymmetric Airy pulses. Phys Rev Lett. 2015;114(7):073901.10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.073901Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Giannini JA, Joseph RI. The role of the second Painlevé transcendent in nonlinear optics. Phys Lett A. 1989;141(8–9):417–9.10.1016/0375-9601(89)90860-8Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Abdollahpour D, Suntsov S, Papazoglou DG, Tzortzakis S. Spatiotemporal Airy light bullets in the linear and nonlinear regions. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;105(25):253901.10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.253901Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Besieris IM, Shaarawi AM. Accelerating Airy wave packets in the presence of quadratic and cubic dispersion. Phys Rev E. 2008;78(4):046605.10.1103/PhysRevE.78.046605Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Fattal Y, Rudnick A, Marom DM. Soliton shedding from Airy pulses in Kerr media. Opt Express. 2011;19(18):17298–307.10.1364/OE.19.017298Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis