Abstract

The present study proposes a monolayer graphene metamaterial fabricated with periodic patterns, composed of three graphene nanostrips and a graphene rectangle (GR). The transmission spectra of the proposed metamaterial are calculated by means of the Finite-Difference Time-Domain (FDTD) simulation and the coupled mode theory (CMT). And double plasmon-induced transparency (DPIT) in the terahertz (THz) spectrum is achieved. Its spectral properties with different geometrical parameters, Fermi energy levels, and carrier mobility values are explored. In addition, we examine how adjusting the Fermi energy and carrier mobility influences the slow light phenomenon. An elevation of the group index to 600 is achieved by optimizing carrier mobility to

1 Introduction

Over the recent years, the scientific community has witnessed a remarkable upsurge in the research enthusiasm regarding surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs). This burgeoning interest stems from their unique capacity to surmount the constraints imposed by traditional optical diffraction [1], 2]. Specifically, SPPs hold great promise for manipulating light at the sub-wavelength scale, which has far-reaching implications for various fields such as nanophotonics [3], all-optical switch [4], and integrated optical circuits [5]. As a result, numerous studies have been dedicated to exploring the fundamental properties of SPPs, as well as devising novel strategies to harness and control them for practical applications [6], [7], [8].

Graphene has several remarkable attributes, namely its dynamic tunability, an extensive frequency operating range, and a substantially more pronounced locality of SPPs [9], 10]. Notably, the SPPs propagating along the surface of graphene exhibit properties that outshine those on metal surfaces. For instance, owing to the absence of a saturation point in the dispersion relation of graphene surface plasmons, a broadband optical response spanning from the mid-infrared to the THz regime is enabled [11]. Additionally, when the Fermi level of graphene is elevated to a higher value, the loss associated with graphene SPPs waves is significantly mitigated [12]. Experimental investigations have demonstrated that the graphene Fermi level can be effectively modulated by applying an appropriate applied voltage [13]. In light of these advantageous characteristics, graphene has emerged as the preeminent candidate in the development of plasmonic metamaterials. Consequently, graphene plasmonics has found significant applications in diverse areas such as light sensing [14], absorption [15], switching [16], and the generation of slow light [17], [18], [19]. In many instances, these applications are predicated on the mechanism of plasmonically induced transparency (PIT) [20], 21].

PIT arises from the quantum interference effects induced by the coupling between the bright-state and dark-state plasmons. A key feature of PIT is the presence of distinct transparent windows within the transmission spectra. This window effectively nullifies the resonance absorption that would otherwise be generated by Fano interference occurring in intense local fields [22]. To date, an extensive array of PIT based plasmonic devices has been put forward. These include optical switches, holographic imaging systems, and structures enabling ultra-slow light propagation [23]. The designs of these plasmonic devices exhibit great diversity. For example, they can be based on single-layer graphene, nanostructured metamaterials, or waveguide-graphene hybrid metamaterials. Nevertheless, the majority of these plasmonic devices are rather complex in their construction and pose challenges in terms of practical implementation [24]. Moreover, they predominantly display only a single PIT effect, limiting their functionality and versatility in more advanced applications [25]. This situation calls for the development of more simplified yet efficient strategies for fabricating PIT-based plasmonic devices with enhanced multi-functionality.

This study presents a novel graphene-based metastructure featuring a single-layer structure. At terahertz frequencies, the Double-PIT (DPIT) effect is attained via the interaction between a graphene rectangle and three graphene nanostrips within the structure. The metamaterial under investigation is modeled as an ideal, perfectly periodic patterned configuration. The outcomes from Finite-Difference Time-Domain (FDTD) numerical simulations are in close accordance with those derived from the coupled mode theory (CMT). When the proposed structure is contrasted with other existing structures, this particular graphene-based metamaterial showcases distinct advantages with regard to its simple structure and relative ease of manufacturing. By modulating the Fermi energy of graphene, active control over the DPIT windows can be effectively realized, thereby obviating the need for structural redesign. Additionally, this structure demonstrates excellent slow light performance. As a result, the proposed graphene-based metastructure holds great promise for enabling the development of modulation devices, slow light devices, and other associated devices, contributing to the advancement of terahertz based optoelectronic applications.

2 Model and theoretical method

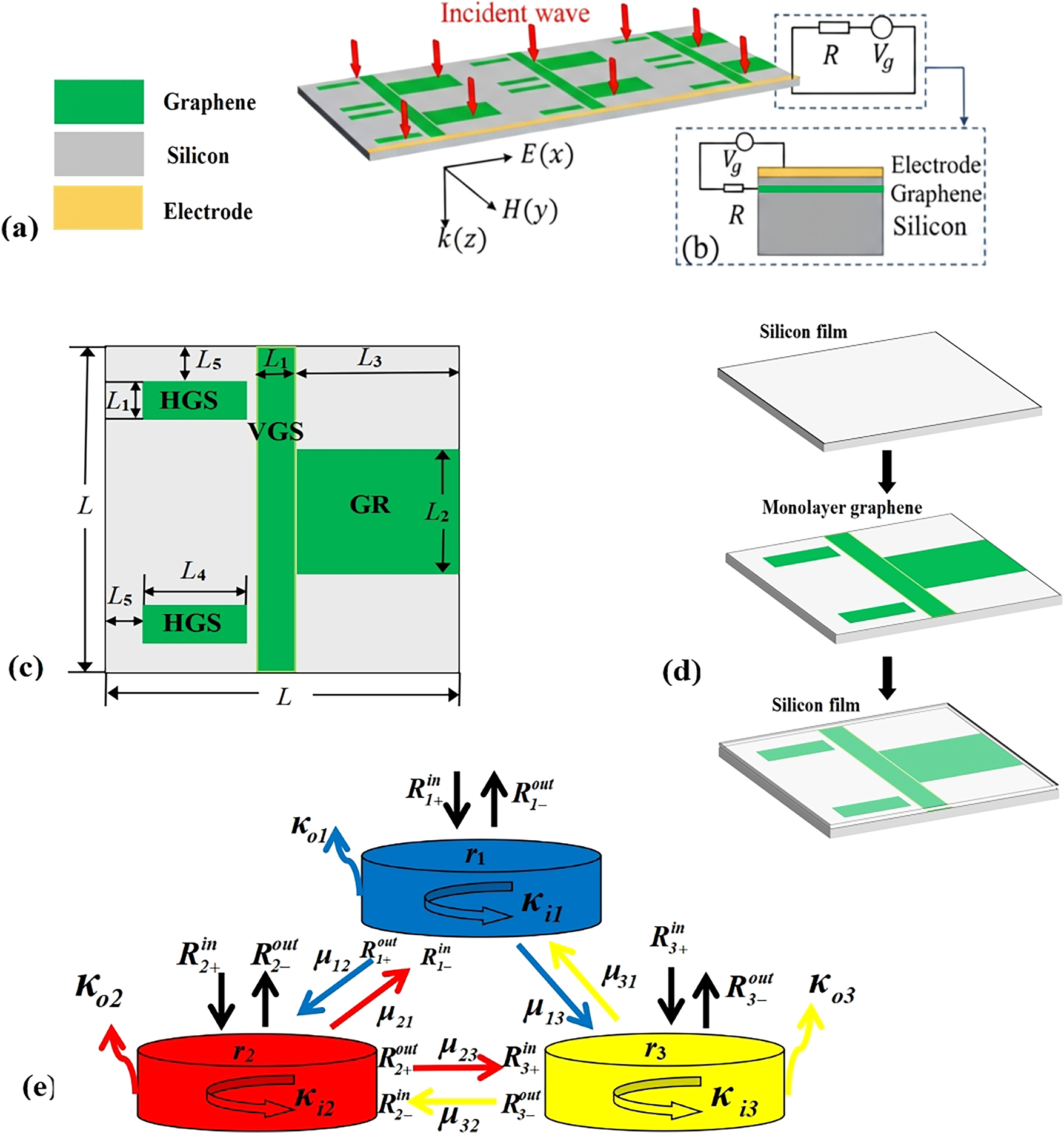

The schematic diagram of the proposed periodic structure of the graphene metamaterial is shown in Figure 1(a). The Fermi levels E f of the graphene structures can be dynamically tuned by gate voltage V g between the electrode and the monolayer graphene, as illustrated in Figure 1(b). To achieve uniform impact of the gate voltage on all graphene sheets, they are linked with thin metal wires, ensuring consistent modulation across the entire graphene structure. As shown in Figure 1(c), the periodic unit is depicted from an overhead perspective. The monolayer graphene structures discussed in the article include a graphene rectangle (GR), a vertical graphene strip (VGS), and two aligned horizontal graphene strips (HGSs). Dielectric silicon layers with relative permittivity of 11.7, each having a thicknesses of 0.05 μm for top level and 0.25 μm for bottom level, encase the monolayer graphene. Details of the geometric parameters are given below: L = 6.0 μm, L 1 = 0.6 μm, L 2 = 3.0 μm, L 3 = 2.7 μm, L 4 = 2.0 μm, and L 5 = 0.5 μm.

Schematic diagrams of the periodic metamaterial structure, Fermi energy-voltage relation, fabrication process and CMT representation. (a) Three-dimension illustration of the proposed periodic metastructure. (b) A diagram of the variation of the Fermi energy in relation to voltage. (c) Overhead view of a structural unit. (d) Fabrication process schematic of the designed metamaterial structure. (e) Schematic representation of CMT.

The fabrication process for our proposed structure is outlined in the schematic of Figure 1(d), which provides key information about how the structure is assembled. First, a graphene layer is grown on a copper foil via chemical vapor deposition, with the process carried out at a temperature of 1,050 °C [26]. After this step, the graphene is carefully transferred onto a 250 nm-thick silicon substrate, and acetone is used to remove any leftover photoresist from its surface [27]. Subsequently, following the approach detailed by reference [28], a 50 nm-thick silicon layer is accurately deposited on top of the graphene. These sequential steps help clarify the detailed preparation work involved in creating the structure.

In FDTD simulation calculations, the input x-polarized plane light wave propagates in the z-axis. Along the z-coordinate axis, perfectly matched layer (PML) boundary conditions are implemented, while periodic boundary conditions are imposed to the x and y directional boundaries. For the grid of the entire simulated structure, an accuracy of 50 nm is specified. A simulated environmental temperature of 300 K is adopted in the study. Under the above conditions, the conductivity σ g of graphene layer can be written as:

Here, the electron charge corresponds to e, the graphene Fermi level is indicated by E

f

, the angular frequency of incident light is reflected by ω, and the carrier relaxation time is embodied by

Here, k

0 denotes the electromagnetic wave vector transmitting in vacuum, ɛ

d

signifies permittivity of dielectric layer silicon, and Z

0 represents the intrinsic impedance in free space. Thus, it’s possible to determine the effective refractive index

Using the multi-mode interference CMT, investigation of transmission characteristics is also feasible. CMT stands out in photonic research for its notable strengths. It simplifies complex electromagnetic analyses by focusing on key resonant modes, avoiding computationally heavy full-wave simulations. As a well-developed theoretical research approach, CMT is capable of investigating the coupling interactions between two or more resonant modes, and it has been extensively applied in numerous academic studies [31], [32], [33]. In the diagram of Figure 1(e), we assume that the three resonators represent three modes. The notation

Here, μ

nm

(m = 1, 2, 3, n = 1, 2, 3, m ≠ n) indicates the resonator-to-resonator coupling coefficients,

Here, the phase difference of the plasmonic wave between R 1 and R 2, as well as R 2 and R 3, is represented by φ 1 and φ 2. Due to the fact that the three resonators are positioned in the identical plane, there is no phase difference among them. Thus, the aforementioned relationship can be utilized to determine the total transmission coefficient across the system:

Here,

Ultimately, the CMT can be used to determine the system transmittance: T = t 2.

3 Results and theoretical analysis

In this section, we will discuss different impacts of parameters E

f

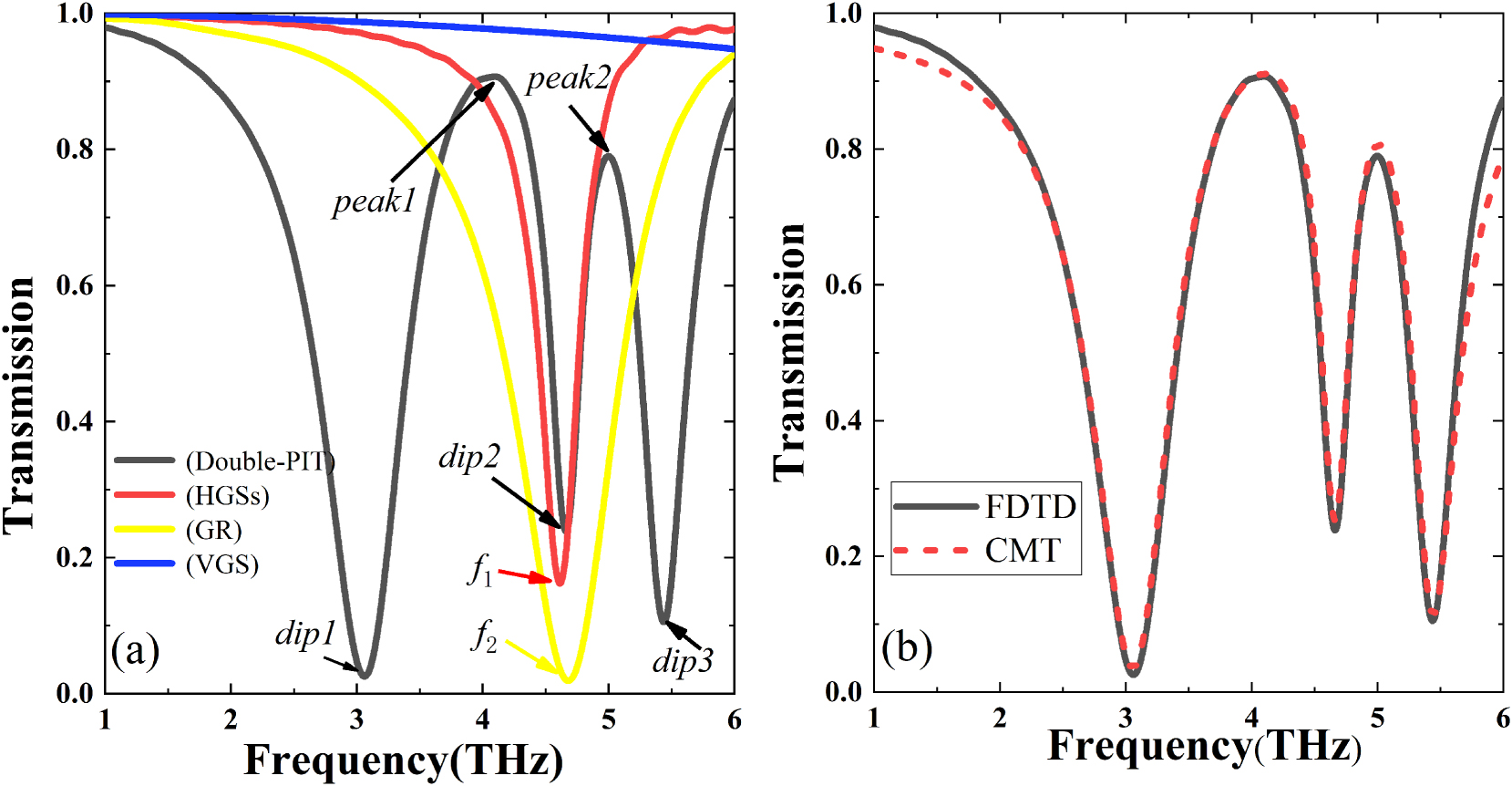

, L

2 and μ on the transparency windows. When the terahertz light is directly irradiated onto the proposed structure, different graphene structures have various spectral transmissions, as demonstrated in Figure 2(a) with E

f

= 1 eV,

Transmission spectra of various graphene configurations and FDTD-CMT comparisons. (a) Transmission spectra of HGSs (red line), GR (yellow line), VGS (blue line), and combined graphene structure (black line). (b) Transmission spectra of FDTD simulation result and CMT theory. (E

f

= 1 eV,

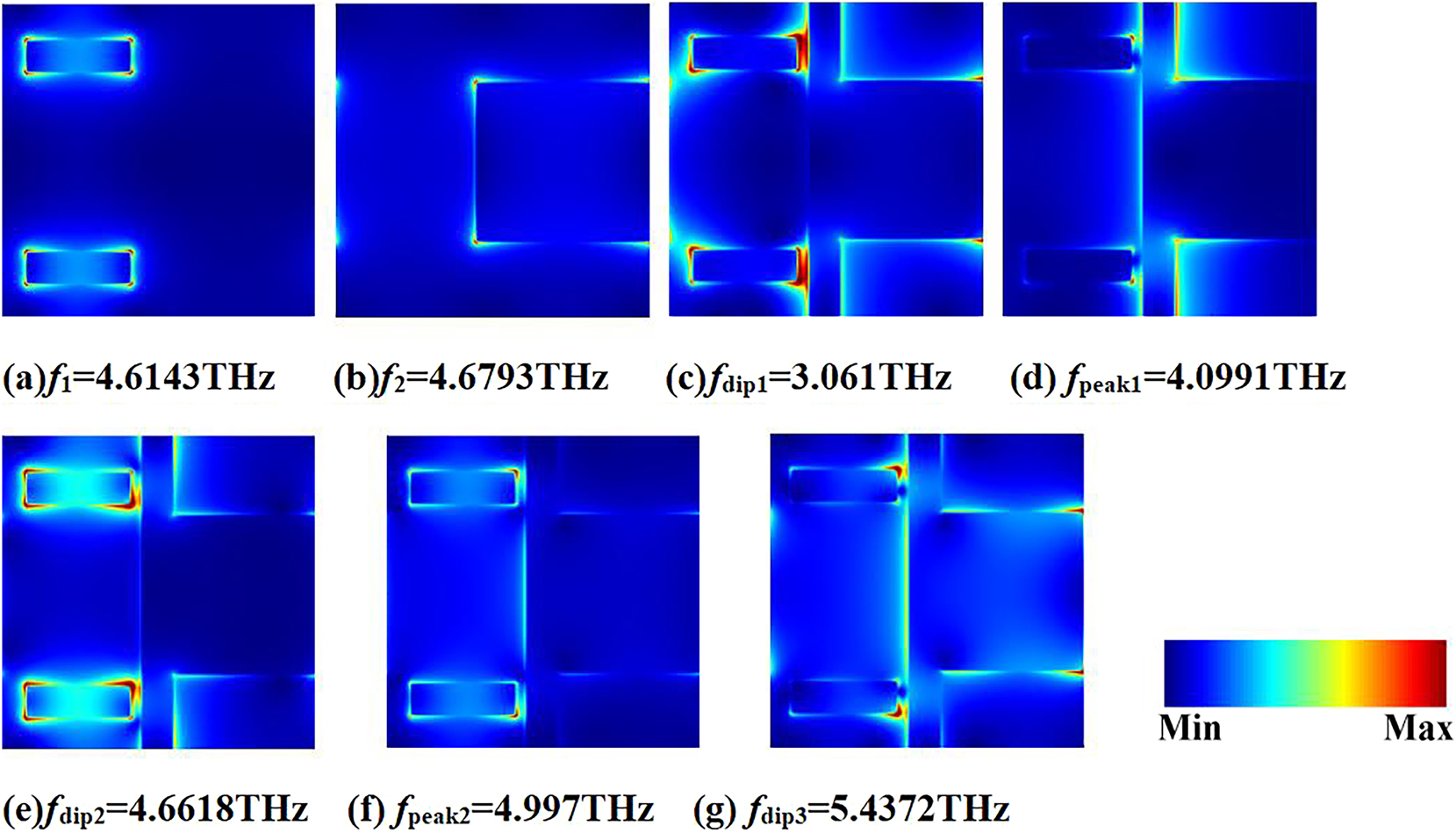

The underlying physical mechanism of the double PIT production is reflected in the structural electric field distribution at the relevant resonant frequencies. Figure 3 displays the distribution of the electric field

The electric field distributions of different resonant frequencies which are marked by arrows in Figure 2.

Because of its low ohmic losses and flexible modulation characteristics, graphene metamaterial is widely used and provides notable benefits in a variety of applications. Common techniques for achieving these tuning characteristics include chemical doping and field-based tuning via electric and magnetic field. A widely adopted method consists of utilizing a gate voltage V g to modify the Fermi levels of graphene metamaterial [35], 36]. The relation between V g and E f can be given by [37]

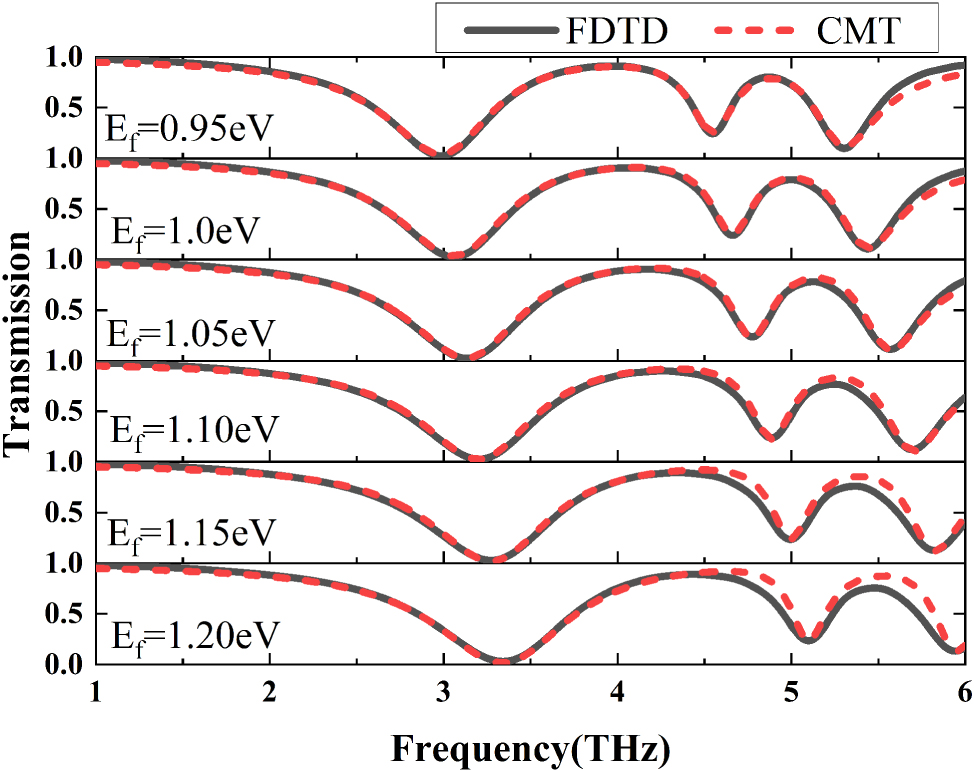

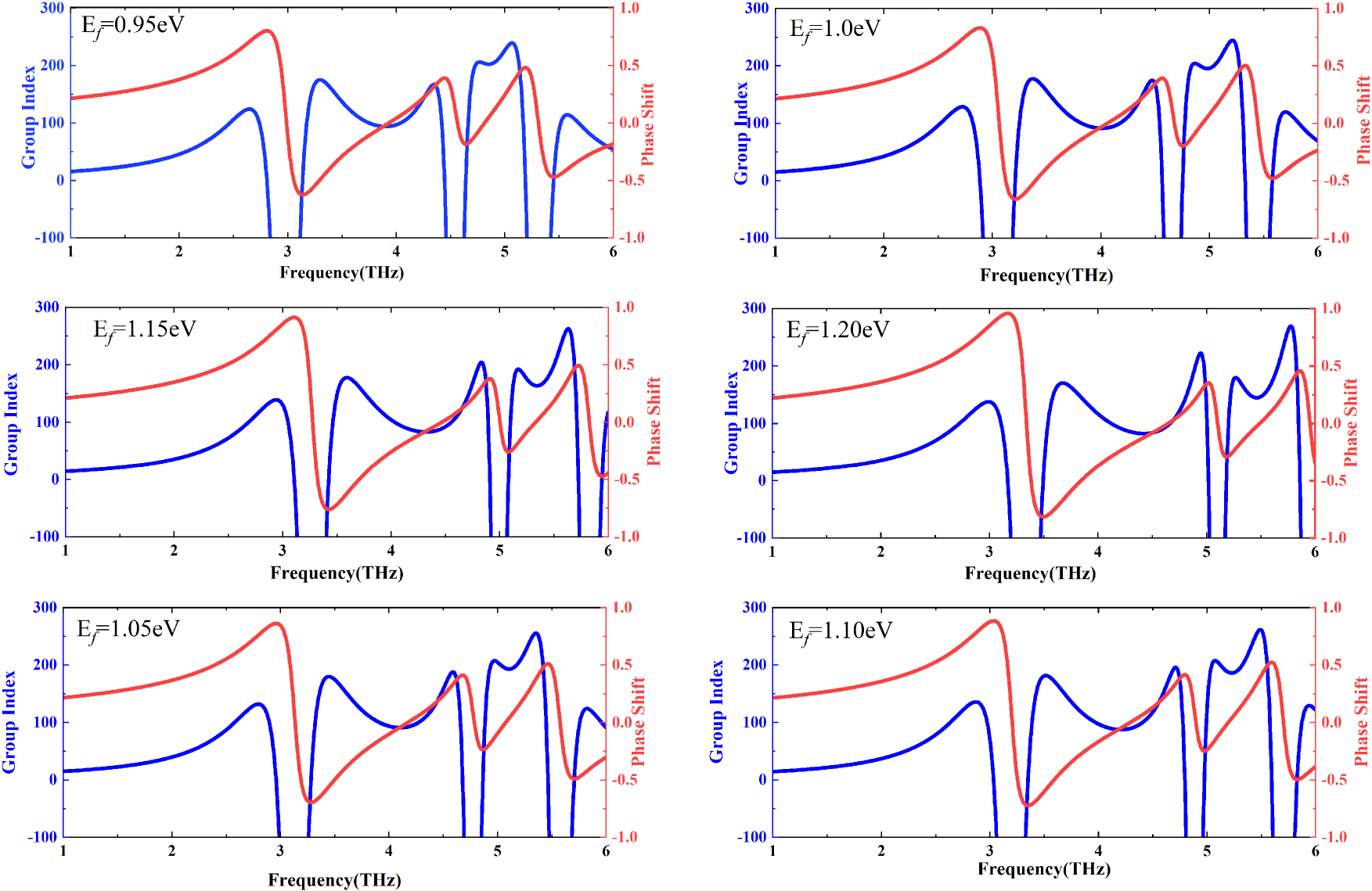

Where ɛ 0 represents the vacuum dielectric constant, and d denotes the distance separating the electrode from the graphene plane. Figure 4 illustrates various DPIT spectral lines produced by the proposed structure for different Fermi levels to demonstrate the tunability of PIT windows. It is clear that with the increase of the Fermi levels, two transparency windows shift gradually toward higher frequencies. For example, when E f increases from 0.95 eV to 1.20 eV, peak1 shifts from 3.9815 THz to 4.4342 THz, and peak2 blue-shifts from 4.8694 THz to 5.4772 THz, respectively. This phenomenon stems from the requirement that graphene electrons necessitate a higher energy input to resonate with increasing Fermi level. It is evident that Figure 4 demonstrates the adjustability of transparency windows through the manipulation of the Fermi level.

Transmission spectra of FDTD results and CMT data at different Fermi levels. (

Analogous to the atomic system, the plasmonic system exhibits the capability to reduce group velocities. Leveraging the notable dispersion characteristics of monolayer graphene, we can utilize it in plasmonic nanostructures to manipulate electromagnetic fields. Regarding adjustable slow-light phenomena, controllable group delay is feasible via Fermi level modulation. Theoretical calculation of the group index (n g ), which signifies the slow-light effect, is performed using the following formula [38]:

Here c is the light speed in vacuum, the group velocity is denoted by v g , h stands for the thickness of the proposed nanostructure, and φ is the transmission phase shift. The graphs in Figure 5 display the modulation of group index and phase shift across frequencies when the graphene Fermi level is tuned from 0.95 eV to 1.2 eV. It reveals that the group index demonstrates a stable increase with the escalation of the Fermi level of graphene, on the condition that the remaining parameters remain constant. The group index is observed to be 239 when the Fermi level is at 0.95 eV, whereas the value increases to 270 as the Fermi level ascends to 1.20 eV. The sharp phase shift and intense dispersion of the SP wave, originating from the near-field interaction of bright-dark mode coupling, result in a remarkable augmentation of the group index close to the DPIT windows.

Frequency-dependent modulation of group index and phase shift during the transition of graphene Fermi level from 0.95 eV to 1.2 eV.

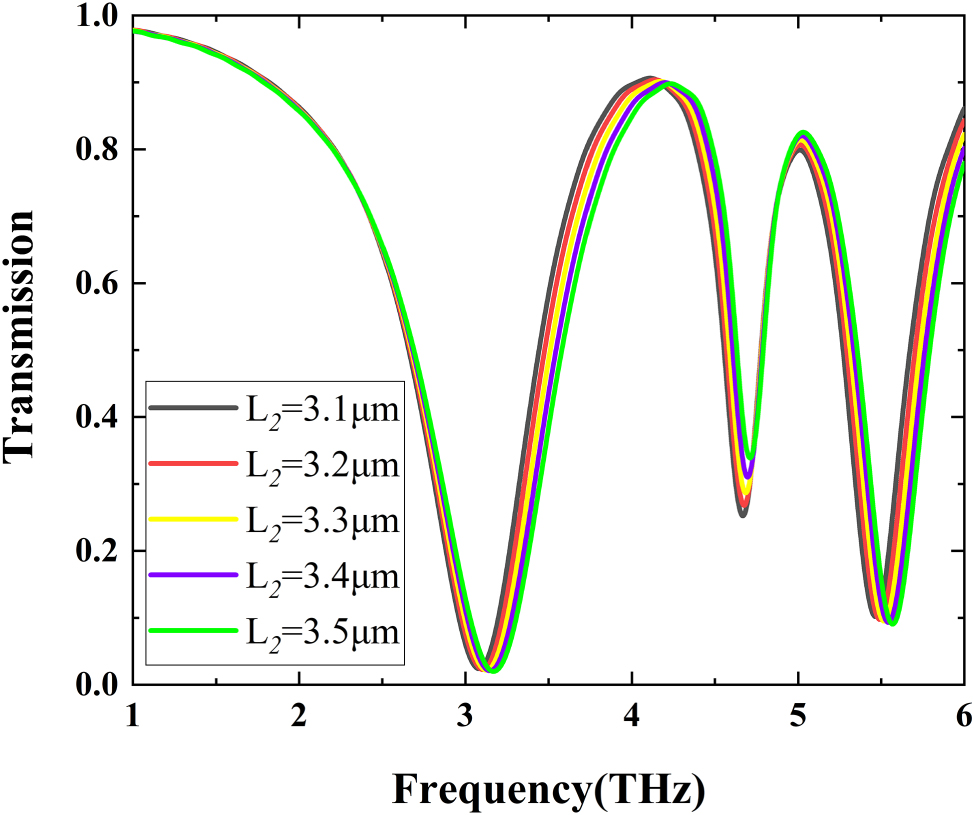

To investigate how structure geometry impacts DPIT windows, we set the Fermi level at 1.0 eV. The transmission characteristics of the graphene nanostructure for varying lengths of L 2 are illustrated in Figure 6. It can be seen that with the gradual increase of L 2, the transmission spectrum exhibits a minor blue shift. Additionally, the magnitude of peak1 experiences a slight diminishment, whereas the magnitude of peak2 undergoes a minor augmentation. Even in the presence of L 2 variations of ±200 nm, the alterations to the transmission spectrum are minor. This observation indicates that during the fabrication process, the performance of this graphene structure exhibits resilience to minor discrepancies that potentially occur. The robustness has a certain value in practical implementations where maintaining consistent precision can be challenging.

Transmission spectra of FDTD results at different lengths of L

2. (

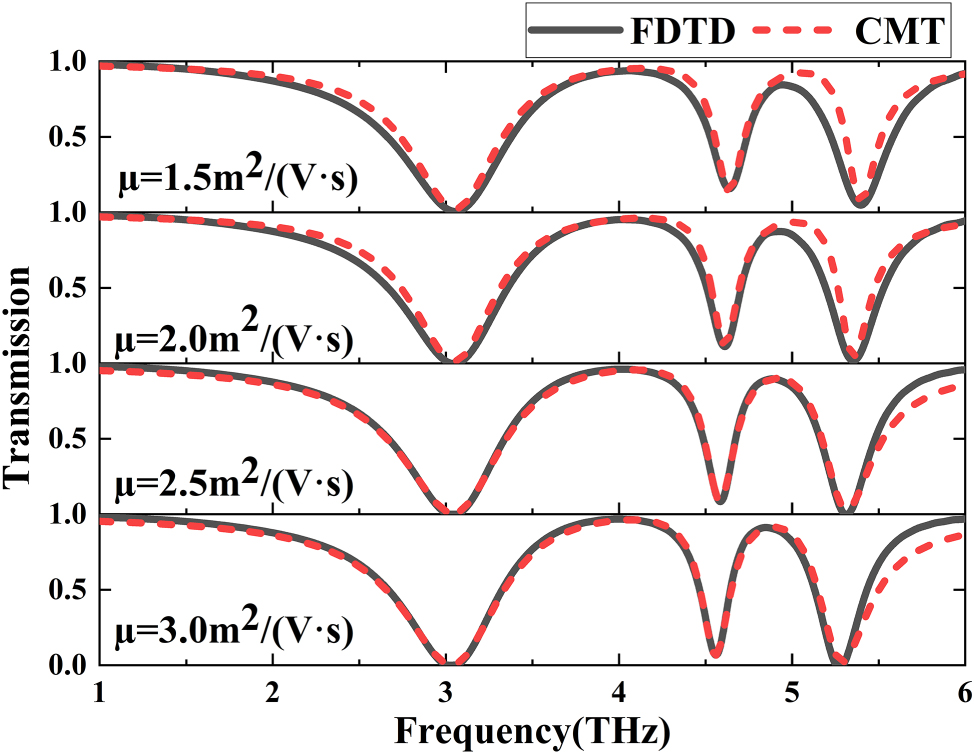

Chemical doping can modify the carrier mobility within graphene, thereby influencing its spectral characteristics. In order to ascertain this correlation, we maintained the Fermi level at 1.0 eV while changing the graphene carrier mobility (µ). Figure 7 provides the transmission spectra of FDTD results and CMT data when the graphene carrier mobility is varied from

Transmission spectra of FDTD results and CMT data when the graphene carrier mobility is changed from

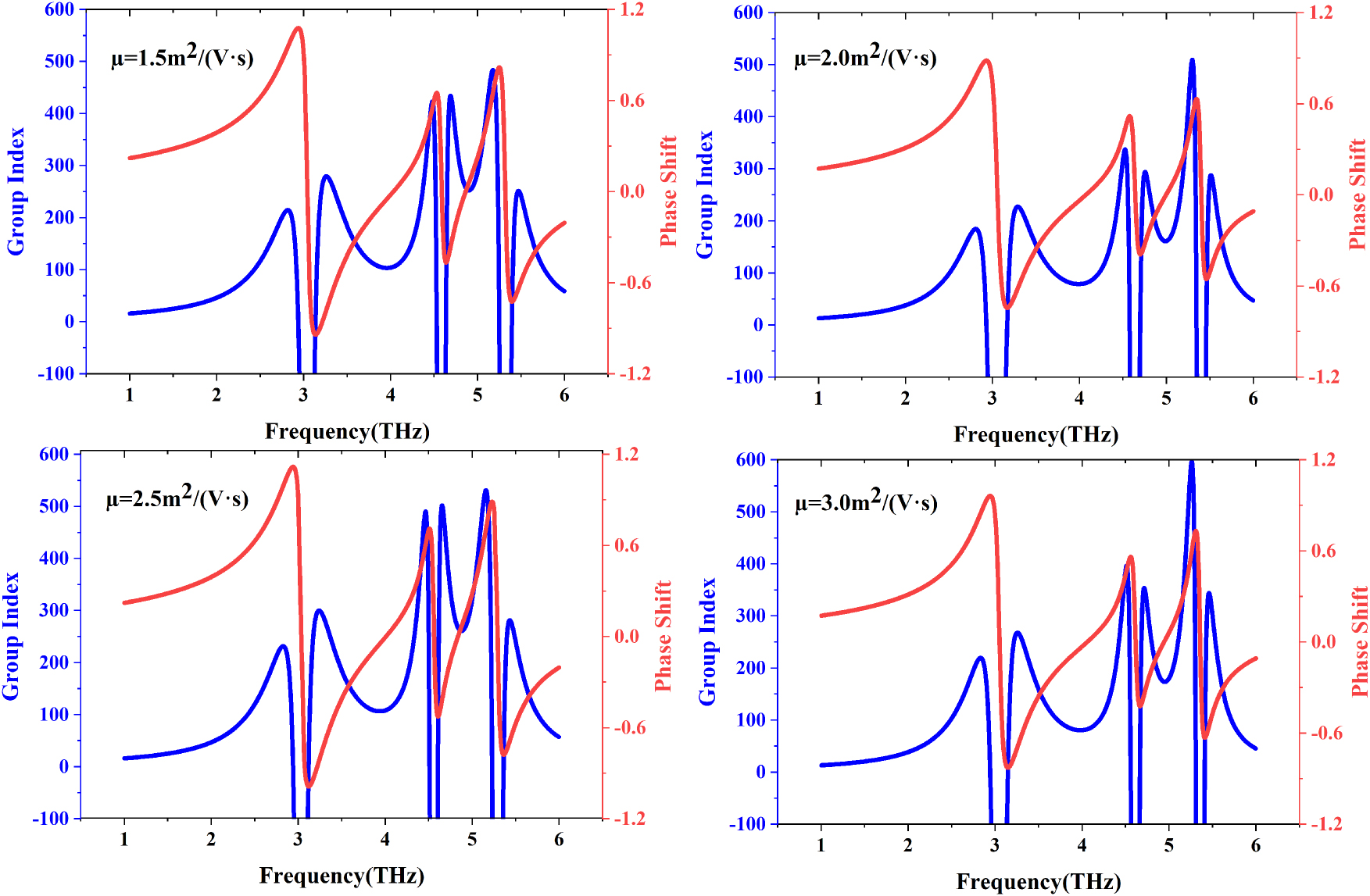

Figure 8 exhibits the variation of group index and phase shift in relation to frequency when the graphene carrier mobility is increased. It reveals that the group index of the proposed structure at the resonance points increases significantly with the Fermi level fixed at 1.0 eV. Notably, the group index even reaches 600 as

Frequency-dependent modulation of group index and phase shift during the transition of graphene carrier mobility from

Comparison of graphene-based metamaterial slow-light.

| References/year | Material structure | Group index |

|---|---|---|

| [34]/2019 | Single-layer patterned graphene | 382 |

| [35]/2021 | Dual-layer patterned graphene | 515 |

| [24]/2021 | Single-layer patterned graphene | 321 |

| [20]/2023 | Single-layer patterned graphene | 424 |

| [12]/2023 | Single-layer patterned graphene | 430 |

| [42]/2024 | Single-layer patterned graphene | 320 |

| This work | Single-layer patterned graphene | 600 |

4 Conclusions

In this work, we present a monolayer patterned graphene composed of three graphene nanostrips and a graphene rectangle for the realization of a DPIT, and explore its spectral properties with different geometrical parameters L

2, Fermi energy level E

f

, and carrier mobility μ. The spectral properties obtained from FDTD calculations show consistency with those derived from CMT theory calculations. In addition, we examine how adjusting the Fermi energy and carrier mobility influences the slow light phenomenon. Significantly, enhancing the mobility of carriers in graphene emerges as the most effective means to optimize the slow light effect. As demonstrated by the numerical results, the group index reaches 600 as

-

Funding information: This work was funded by the Open Fund of Hunan High Speed Railway Operation Safety Assurance Engineering Technology Research Center (2025 Annual, Grant no. KFJJ2025-03), and Hunan provincial Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 2025JJ80381).

-

Author contributions: Methodology: Xin Zhou; software: Guozheng Nie; writing-original draft: Xin Zhou; writing-review and editing: Fengling Jiang; visualization: Xiuying Yi; supervision: Fengling Jiang and Xiuying Yi. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflicts of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

1. Guo, Y, Xu, Z, Curto, AG, Zeng, YJ, Van Thourhout, D. Plasmonic semiconductors: materials, tunability and applications. Prog Mater Sci 2023;138:101158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2023.101158.Search in Google Scholar

2. Khonina, SN, Kazanskiy, NL, Skidanov, RV, Butt, MA. Advancements and applications of diffractive optical elements in contemporary optics: a comprehensive overview. Adv Mater Technol 2024;10:2401028. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.202401028.Search in Google Scholar

3. Shi, J, Guo, Q, Shi, Z, Zhang, S, Xu, S. Nonlinear nanophotonics based on surface plasmon polaritons. Appl Phys Lett 2021;119:130501. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0061726.Search in Google Scholar

4. Khatooni, HS, Abbasian, K, Nurmohammadi, T. A tunable band-stop plasmonic waveguide filter and switch designing with triangular resonator based on Kerr non-linearity. Optik 2020;224:165708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2020.165708.Search in Google Scholar

5. Maier, SA. Plasmonics: the promise of highly integrated optical devices. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum 2007;12:1671–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/jstqe.2006.884086.Search in Google Scholar

6. Alshanski, I, Bentolila, M, Gitlin-Domagalska, A, Zamir, D, Zorsky, S, Joubran, S, et al.. Enhancing the efficiency of the solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) process by high shear mixing. Org Process Res Dev 2018;22:1318–22. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.oprd.8b00225.Search in Google Scholar

7. Katzmarek, DA, Pradeepkumar, A, Ziolkowski, RW, Iacopi, F. Review of graphene for the generation, manipulation, and detection of electromagnetic fields from microwave to terahertz. 2D Mater 2022;9:022002. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1583/ac59d1.Search in Google Scholar

8. Liu, J, Khan, ZU, Sarjoghian, S. Layered THz waveguides for SPPs, filter and sensor applications. J Opt 2019;48:567–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12596-019-00569-3.Search in Google Scholar

9. Zhang, F, Yang, K, Liu, G, Chen, Y, Wang, M, Li, S, et al.. Recent advances on graphene: synthesis, properties and applications. Composites, Part A: Appl Sci 2022;160:107051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2022.107051.Search in Google Scholar

10. Sun, YW, Papageorgiou, DG, Humphreys, CJ, Dunstan, DJ, Puech, P, Proctor, JE, et al.. Mechanical properties of graphene. Appl Phys Rev 2021;8:021310. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0040578.Search in Google Scholar

11. Gao, E, Liu, Z, Li, H, Xu, H, Zhang, Z, Zhang, X, et al.. Dual plasmonically induced transparency and ultra-slow light effect in m-shaped graphene-based terahertz metasurfaces. Appl Phys Express 2019;12:126001. https://doi.org/10.7567/1882-0786/ab5602.Search in Google Scholar

12. Li, M, Xu, H, Yang, X, Xu, H, Liu, P, He, L, et al.. Tunable plasma-induced transparency of a novel graphene-based metamaterial. Results Phys 2023;52:106798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2023.106798.Search in Google Scholar

13. Li, X, Wei, Y, Lu, G, Mei, Z, Zhang, G, Liang, L, et al.. Gate-tunable contact-induced Fermi-level shift in semimetal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2022;119:e2119016119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2119016119.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Xu, Y, Wang, Z, Yang, Y, Huang, X, Zeng, X, Cheng, S, et al.. Dynamically tunable highly sensitive sensor based on graphene and black phosphorus composite metamaterial. Phys Scripta 2024;99:105568. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/ad7aba.Search in Google Scholar

15. Nong, J, Tang, L, Lan, G, Luo, P, Li, Z, Huang, D, et al.. Enhanced graphene plasmonic mode energy for highly sensitive molecular fingerprint retrieva. Laser Photonics Rev 2021;15:2000300. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202000300.Search in Google Scholar

16. Zhou, X, Xu, Y, Li, Y, Cheng, S, Yi, Z, Xiao, G, et al.. Multi-frequency switch and excellent slow light based on tunable triple plasmon-induced transparency in bilayer graphene metamaterial. Commun Theor Phys 2022;74:115501. https://doi.org/10.1088/1572-9494/ac8a41.Search in Google Scholar

17. Zhou, X, Xu, Y, Li, Y, Cheng, S, Yi, Z, Xiao, G, et al.. High-sensitive refractive index sensing and excellent slow light based on tunable triple plasmon-induced transparency in monolayer graphene based metamaterial. Commun Theor Phys 2022;75:015501. https://doi.org/10.1088/1572-9494/aca084.Search in Google Scholar

18. Li, Y, Xu, Y, Jiang, J, Ren, L, Cheng, S, Yang, W, et al.. Quadruple plasmon-induced transparency and tunable multi-frequency switch in monolayer graphene terahertz metamaterial. J Phys D Appl Phys 2022;55:155101. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/ac48b0.Search in Google Scholar

19. Nurmohammadi, T, Abbasian, K, Mashayekhi, MZ. Tunable modulators based on single and double graphene-based resonator systems in the mid-infrared spectrum. Optik 2022;271:170195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2022.170195.Search in Google Scholar

20. Wang, X, Chen, C, Gao, P, Dai, Y, Zhao, J, Lu, X, et al.. Slow-light and sensing performance analysis based on plasmon-induced transparency in terahertz graphene metasurface. IEEE Sens J 2023;23:4794–801. https://doi.org/10.1109/jsen.2023.3238388.Search in Google Scholar

21. Xu, H, Li, M, Chen, Z, He, L, Dong, Y, Li, X, et al.. Optical tunable multifunctional applications based on graphene metasurface in terahertz. Phys Scripta 2023;98:045511. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/acc3c9.Search in Google Scholar

22. Zhao, X, Yuan, C, Zhu, L, Yao, J. Graphene-based tunable terahertz plasmon-induced transparency metamaterial. Nanoscale 2016;8:15273–80. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5nr07114c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Zheng, S, Zhao, Q, Peng, L, Jiang, X. Tunable plasmon induced transparency with high transmittance in a two-layer graphene structure. Results Phys 2021;23:104040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104040.Search in Google Scholar

24. Zhang, X, Zhou, F, Liu, Z, Zhang, Z, Qin, Y, Zhuo, S, et al.. Quadruple plasmon-induced transparency of polarization desensitization caused by the Boltzmann function. Opt Express 2021;29:29387–401. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.433258.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Li, Z, Nie, G, Wang, J, Zhong, F, Zhan, S. Polarization-modulating switchable and selectable image display through an ultrathin quasi-bound-state-in-the-continuum metasurface. Phys Rev Appl 2024;21:034039. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.21.034039.Search in Google Scholar

26. Zheng, L, Cheng, X, Cao, D, Wang, Z, Xu, D, Xia, C, et al.. Effects of rapid thermal annealing on properties of HfAlO fflms directly deposited by ALD on graphene. Mater Lett 2014;137:200–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2014.08.146.Search in Google Scholar

27. Jin, R, Huang, L, Zhou, C, Guo, J, Fu, Z, Chen, J, et al.. Toroidal dipole BIC-driven highly robust perfect absorption with a GrapheneLoaded metasurface. Nano Lett 2023;23:9105–13. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c02958.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Müller, M, Bouša, M, Hájková, Z, Ledinský, M, Fejfar, A, Drogowska-Horná, K, et al.. Transferless inverted graphene/silicon heterostructures prepared by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition of amorphous silicon on CVD graphene. Nanomaterials 2020;10:589. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10030589.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Vakil, A, Engheta, N. Transformation optics using graphene. Science 2011;332:1291–4. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1202691.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Xu, H, Li, H, Chen, Z, Zheng, M, Zhao, M, Xiong, C, et al.. Novel tunable terahertz graphene metamaterial with an ultrahigh group index over a broad bandwidth. Appl Phys Express 2018;11:042003. https://doi.org/10.7567/apex.11.042003.Search in Google Scholar

31. Li, Y, Xu, Y, Jiang, J, Ren, L, Cheng, S, Wang, B, et al.. Dual dynamically tunable plasmon-induced transparency and absorption in I-type-graphene-based slow-light metamaterial with rectangular defect. Optik 2021;246:167837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2021.167837.Search in Google Scholar

32. Li, Y, Xu, Y, Jiang, J, Cheng, S, Yi, Z, Xiao, G, et al.. Polarization-sensitive multi-frequency switches and high-performance slow light based on quadruple plasmon-induced transparency in a patterned graphene-based terahertz metamaterial. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2023;25:3820–33. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2cp05368c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Yao, P, Zeng, B, Gao, E, Zhang, H, Liu, C, Li, M, et al.. Tunable dual plasmon-induced transparency and slow-light analysis based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial. J Phys D Appl Phys 2022;55:155105. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/ac485a.Search in Google Scholar

34. Zhang, B, Li, H, Xu, H, Zhao, M, Xiong, C, Liu, C, et al.. Absorption and slow-light analysis based on tunable plasmon-induced transparency in patterned graphene metamaterial. Opt Express 2019;27:3598–608. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.27.003598.Search in Google Scholar

35. Xu, H, Wang, X, Chen, Z, Li, X, He, L, Dong, Y, et al.. Optical tunable multifunctional slow light device based on double monolayer graphene grating-like metamaterial. New J Phys 2021;23:123025. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/ac3d50.Search in Google Scholar

36. Wang, F, Zhang, Y, Tian, C, Girit, C, Zettl, A, Crommie, M, et al.. Gate-variable optical transitions in graphene. Science 2008;320:206–9. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1152793.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Hu, X, Zhang, Y, Chen, D, Xiao, X, Yu, S. Design and modeling of high efficiency graphene intensity/phase modulator based on ultra-thin silicon strip waveguide. J Lightwave Technol 2019;37:2284–92. https://doi.org/10.1109/jlt.2019.2901916.Search in Google Scholar

38. Cao, G, Li, H, Zhan, S, He, Z, Guo, Z, Xu, X, et al.. Uniform theoretical description of plasmon-induced transparency in plasmonic stub waveguide. Opt Lett 2014;39:216–19. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.39.000216.Search in Google Scholar

39. Hwang, EH, Das Sarma, S. Screening-induced temperature-dependent transport in two-dimensional graphene. Phys Rev B 2009;79:165404. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.79.165404.Search in Google Scholar

40. Lei, P, Nie, G, Li, H, Li, Z, Peng, L, Tang, X, et al.. Multifunctional terahertz device based on plasmon-induced transparency. Phys Scripta 2024;99:075512. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/ad5120.Search in Google Scholar

41. Chen, JH, Jang, C, Xiao, S, Ishigami, M, Fuhrer, MS. Intrinsic and extrinsic performance limits of graphene devices on SiO2. Nat Nanotechnol 2008;3:206–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2008.58.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Wang, Y, Luo, G, Yan, Z, Wang, J, Tang, C, Liu, F, et al.. Silicon ultraviolet high-Q plasmon induced transparency for slow light and ultrahigh sensitivity sensing. J Lightwave Technol 2024;42:406–13. https://doi.org/10.1109/jlt.2023.3305875.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis