Abstract

Metal oxide films have received a lot of scientific research interest over the past few years because of their excellent optical and electrical properties needed for optoelectronic devices as well as their low cost and non-toxicity. Plasma enhanced-pulsed laser deposition (PE-PLD) is utilized for the growth of thin films on flexible, thermally sensitive polymer surfaces. A background oxygen plasma gas is required for PLD to enhance the control process and to prevent oxygen deficiency during metal oxide film formation. Simulation results using COMSOL Multiphysics show that a radiofrequency-driven inductively coupled plasma (ICP) model generates reactive oxygen species, like O and O2 ∗, with densities of 1019–1020 m−3, which significantly affect film deposition. As the applied power and pressures are increased, the electron temperature decreases and the oxygen ion density diminishes, which enhances the deposition rate and minimizes defects in oxide films. Furthermore, as power increases, oxygen atoms gain energy leading to higher atom excitation, while increasing pressure declines the total ion flux. Also, the crystal construction, stoichiometry, and characteristics of the metal oxide films on polymer foils are affected by the O/O2 ratio. Based on the numerical model developed in this article, stoichiometric metal oxide thin films are achieved, and materials are transferred to polymer substrates at high rates.

1 Introduction

Metal oxide materials, such as copper oxides (CuO and Cu2O) and zinc oxide (ZnO), have been the subject of extensive research in recent decades for their unique optical, electrical, chemical, and electronic properties. Copper oxide thin films (CuO and Cu2O) are p-type semiconductors that find applications in thin film transistors, solar cells, supercapacitors, and gas sensors [1]. In addition, ZnO is an n-type semiconductor with a wide bandgap of 3.3 eV, a high melting point at 2,000°C, and elevated exciton binding energy. Due to their non-toxicity, low cost, and ecofriendliness [2], ZnO films are mainly investigated for many applications, such as solar cells, polymer coating, antibacterial agents, microelectronics, and optical waveguides [3]. Despite the variety of metal oxide applications, the film quality, substrate temperature, and control of stoichiometry remain challenging issues. Hence, controlled and more complex processes are required to produce high-quality metal oxide thin films [4,5].

Thermo-evaporation is easy to use and reasonably priced but may not be feasible without a high enough temperature and good supply of electricity. Moreover, thin films cannot adhere effectively to surfaces during thermal deposition, and their thickness and composition are difficult to control [6]. In contrast, excellent film uniformity and composition control are provided by sputtering, which blasts atoms or molecules out of a target substance using high-energy ions and then deposits them onto a substrate. However, it takes time and has complicated equipment [7]. The chemical vapor deposition (CVD) which combines gases on a surface to form a solid layer can provide exact control over composition and thickness. Nonetheless, CVD is expensive, requires specialized equipment, and uses high temperatures. Additionally, many chemical precursors employed in CVD are extremely hazardous [8].

In comparison, pulsed laser deposition (PLD) offers distinct advantages over the other deposition methods [9] with outstanding adhesion, superior quality, and precise composition control. It is a very adaptable process and can deposit a wide variety of materials, including complex chemicals and multilayer structures with limited stoichiometry control, high deposition rates, and easy material interchangeability. Despite their advantages, these methods utilize higher substrate temperatures for film deposition and sample post-treatment on sapphire or glass surfaces.

Solar cells and plastic electronic devices require the use of pure ZnO or aluminum-doped ZnO films generated on flexible, thermally sensitive polymer substrates like polyethylene terephthalate [10]. Hence, different additives have been increasingly used to enhance film growth, such as the use of plasmas to produce reactive species during film deposition [11]. Alternatively, reactive oxygen plasma at low temperatures is used to enhance PLD, a process recognized as plasma-enhanced pulsed laser deposition (PE-PLD) [12]. This technology intends to improve stoichiometric control of thin layers from the target material to the substrate by combining a typical PLD setup with a low-temperature, electrically generated oxygen plasma. During deposition, a mixture of ions, atoms, and neutral oxygen molecules is produced in the background plasma independent of interaction with the ablation plume, allowing surface reorganization and preparation. This is beneficial to prevent the production of oxygen-deficient metal oxide coatings which can be deposited on flexible plastic substrates without substrate heating or film annealing [13]. Also, metal targets are simpler to manage and cheaper to produce than oxides or compound targets, and the radiofrequency (RF) plasma offers more control over the growth of the film. Further, control of the structure and expansion of the plume during the process of ablation are feasible, and the system can also be expanded to include other gases for achieving more diverse films (like N2 for nitrides) [14].

However, PE-PLD still has some disadvantages, such as greater expense and complexity, and a restricted deposition area. So, this field remains under research because of its intricacy and unclear process definitions. According to Huang et al. [15], radiofrequency parallel plate discharge is used as the PLD background. Also, ZnO films are observed with a (0 02) c-axis direction and higher deposition rates than the traditional PLD. Scarisorneau et al. [16] have used an oxygen plasma source to deposit thin oxide films. They have demonstrated that by altering oxygen plasma beam relative orientations, different crystal orientations could be obtained. With the use of a directional RF plasma beam over a PLD setup, Nistor et al. [17] have demonstrated that high quality c-axis and a-axis ZnO films can be grown. This research has focused on the film generation by oxygen plasma, rather than analyzing or modeling the plasma properties.

In this work, the method for PE-PLD of metal oxide films using a heat-sensitive substrate material is presented. A numerical simulation of PE-PLD with RF inductively coupled oxygen plasma is performed through COMSOL Multiphysics [18]. The model using the Gaseous Electronics Conference radiofrequency (GEC-RF) reference cell is employed to examine the quantity and type of deposited oxygen reactive species and to control film crystallization and stoichiometry of metal oxide thin films. Reactive oxygen species are investigated to provide insight into the type and concentration of reactive oxygen species that contribute to thin film formation. Additionally, different operating conditions, like power and pressure deposition and temperature, are explored for analyzing the influence of plasma parameters on oxide thin film deposition on flexible and thermally sensitive polymer substrates. The current article focuses on the optimal operation process for the deposition of metal oxide thin coatings to achieve higher quality of conductive thin coatings adhering to the polymeric substrate and to enhance the structure, morphology, and deposition rate of generated films.

2 PE-PLD process

An experimental setup for PE-PLD for the generation of ZnO films is presented in Figure 1. In this setup, a focused pulsed laser beam is coupled to a stainless-steel vacuum chamber, and the oxygen gas flow into the chamber is controlled with a mechanical pump. In order to ablate the ZnO targets (purity, 99.99%; frequency, 10 Hz), the pulsed laser is operated under the following conditions: pulse energy, 35 mJ; wavelength, 532 nm; pulse duration, 5 ns. This wavelength is commonly employed in PLD using the Nd:YAG laser system. A quartz window is used to direct the laser beam at an incident angle of 90° to the target. RF plasma discharge is produced by connecting a 300 W power supply at 13.56 MHz to the top electrode. The target and substrate are separated by 6 cm [19]. Indeed, incorporating oxygen gas into the background atmosphere of PLD enhances the film oxygen content and crystallization structure. Plasma plumes generated by lasers travel through the oxygen background gas and interact with it before being deposited on the substrate. With background gas molecules, complex interactions occur and oxygen molecules are dissociated into highly reactive oxygen atoms interacting with the target or depositing on the substrate [20].

PE-PLD system for thin film deposition.

3 Numerical model

A simulation of inductively coupled plasma (ICP) model at low pressure is performed using a 2D fluid model derived from the continuity equation, the mean electron energy equation balance, and Maxwell equations. The plasma module and laminar flow are coupled through Navier–Stokes equations for neutral background gas [21].

3.1 Modeling equations

In terms of electron densities, the continuity equation is defined as follows:

where

Drift diffusion equations are used to compute the electron density and average energy of electrons, expressed as follows:

Here,

The energy equation for electrons is given by

Here,

where

The mass fractions of non-electron species are calculated using the following equation:

where

Equations for electromagnetic fields are formulated as follows [23]:

In these equations,

where

and

Here,

Combining Eqs. (9) and (10), the coil current density

where s represents the position along the induction coil, and the capacitive current flowing through the coil

For neutral background gas, Navier–Stokes equations are as follows:

Mass conservation:

Momentum conservation:

where

Species on the surface are determined from their deposition height [24]:

where

3.2 Plasma boundary conditions

The electron flow into the reactor wall is determined by:

where

Electrons transfer energy to walls through:

As a result of surface reactions, heavy species lose ions to the wall since the electric field is directed toward the wall [25].

Here, (

3.3 Chemical model

Identification of species and reactions in plasma chemistry is critical. The species and reaction used for inductively coupled oxygen plasma enhanced atomic layer deposition are taken from the study of Christophorou and Olthoff [26]. The chemical model includes electrons and 11 different oxygen species, such as O2, O, O+, O−, O2 +, O2 −, O*(1D), O*(1S), O2 *(v), O2 *(1Δ), and O2 *(1Σ). In this case, the O*(1S) and O*(1D) states are the atomic oxygen exciting states. The vibrationally excited state of O2 is represented by O2 *(v), which refers to the O245 state. The excited states of molecular oxygen are given by (O2a1d) and (O2b1s), which refer to O2 *(1Δ) and O2 *(1Σ), respectively. O3 is not included in the model since it has a minor effect on these plasma types [27]. A total of 62 reactions are included in the model [24]. The electron impact reaction rates are given in the study of Kropotkin and Voloshon [28,29].

The reactor walls neutralize and reflect all the O+, O−, and O2 + ions in the plasma. In addition, O*(1D), O*(1S), O2 *(v), O2 *(1Δ), and O2 *(1Σ) are returned to the ground state after being de-excited and reflected back into the plasma after colliding with the wall. A reaction rate of 0.2 is assumed for atomic oxygen to recombine at the wall to produce O2 [30].

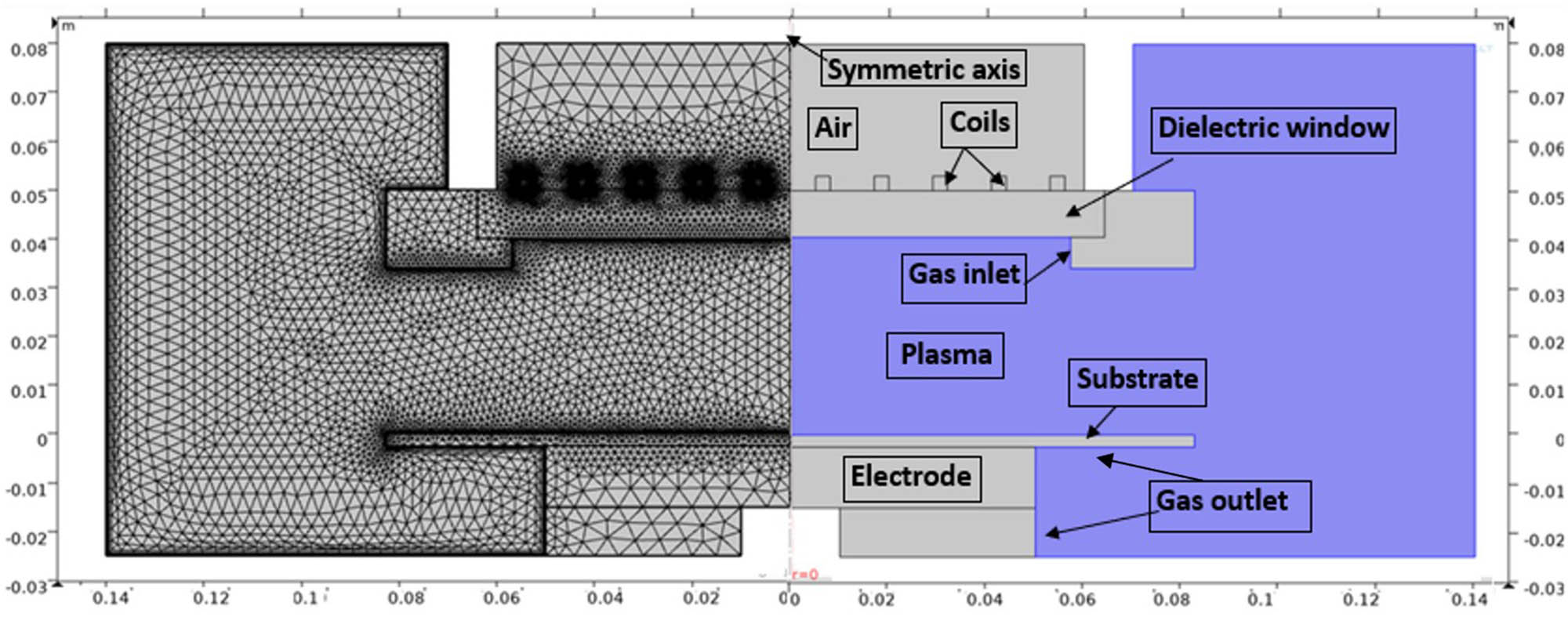

3.4 Geometry of the discharge model

Figure 2 (right) illustrates the simulated geometry. Plasma is confined in a vacuum chamber mounted by a metal electrode and a five-turn planar copper coil antenna. Using a quartz cylinder (1 cm thick and 3.2 cm in radius), electrical power is inductively coupled to the plasma volume. A grounded electrode with a radius of 4.12 cm and made of stainless steel is used. The quartz cylinder and the lower electrode are separated by a space of 4 cm. Oxygen gas is injected into the discharge volume at 400 W applied power with 13.56 MHz sinusoidal frequency and pressures between 3 and 100 Pa. Figure 2 (left) shows the meshing of the reference cell with 14,460 triangular elements.

Cell coupled GEC reference structure (right) and structure meshing of GEC-ICP (left).

3.5 Computational process

COMSOL Multiphysics is used to implement a 2D axisymmetric simulation model of ICP generated in a GEC reference cell reactor [31]. Models with axial symmetry perform better than their isotropic counterparts. Nonetheless, due to its inability to scale, the axisymmetric-based approach is impractical when dealing with large data sets. As a result, subsampling or providing computationally practical likelihood estimates is necessary [32]. It is typically found that inductively coupled discharges generated at low pressure provide high charge densities (>1016 m−3) [33,34]. Furthermore, surface anisotropy is achieved with low pressure ion bombardment, which makes high density plasma sources appealing. The negative ion temperature is equal to 0.3 eV when calculating negative ion mobility and diffusivity since the ions are held within the plasma core, where they acquire energy from the electromagnetic field at high frequencies [35,36]. Three steps are involved in calculating plasma properties. As a first step, the electromagnetic field inside the discharge reactor must be determined using Maxwell’s equations. In the second step, based on these fields, Boltzmann solvers are used to determine electron energy distribution functions and electron impact reaction rates. In the third step, on the basis of the reaction rates, different species of oxygen plasma gas and distribution of electron density are determined. Finally, electromagnetic fields are re-calculated based on the electrostatic field derived from Poisson’s equation, and the calculation loop is closed. An iterative process is carried out until a model is convergent. The model simulation requires a 64-bit machine with at least 4 GB of memory because of the large number of reactions and species.

4 Results and discussion

A GEC reactor is used to study inductively coupled plasma-enhanced plasma laser deposition (PE-PLD). The plasma discharge is sustained at a temperature of 500 K by operating at 13.56 MHz [37]. The results of the modeling are compared with those of the experiments. The influence of implemented power and gas pressure on the quality of the metal oxide films is examined in this section. Working power from 100 to 1,000 W and gas pressure from 0.5 to 100 Pa (3 to 750 mTorr) are considered.

4.1 Validation of the numerical model

Figure 3 shows the variation of electron density with the applied power at various pressures 0.5, 7, and 14 Pa (3, 50, and 100 mTorr) in inductively coupled oxygen plasma. The results are compared with the experimental electron density obtained from the literature [38] using a Langmuir probe with uncertainty measurements between 5 and 10%. There is a linear relationship between electron density and power, while a weak decrease of electron density is observed with pressure. The agreement is good; however, the chemical model did not adjust experimental chemical coefficient rates and there are no inelastic electron collisions, which can explain the simple disagreement between simulation and experiment.

Variation of numerical and experimental electron densities with the applied power in RF-inductively coupled oxygen plasma.

4.2 Reactive oxygen plasma

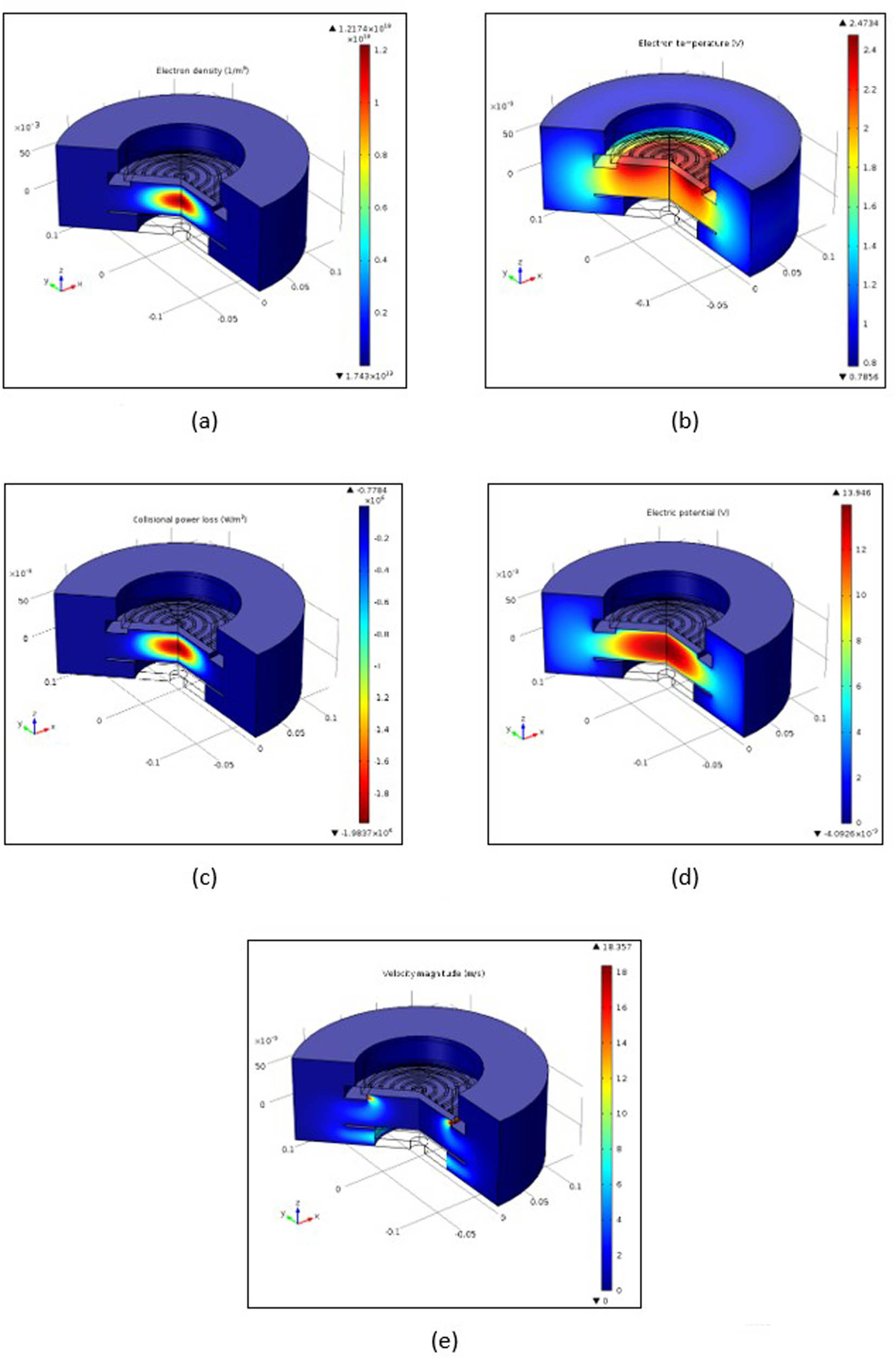

Figure 4 presents the 2D spatial distribution in electron density, electron temperature, collisional power loss, electric potential, and velocity field in the discharge volume at 400 W power, 10 Pa (75 mTorr) pressure, and oxygen gas.

2D distribution of (a) electron density, (b) electron temperature, (c) collisional power loss, (d) electric potential, and (e) velocity field.

The maximum electron density is about 1.21 × 1018 m−3 and is located at the center of the reactor under the RF coil (Figure 4a). Azimuthal electric field shielding occurs and is high in this case because of the density of electrons. The temperature of electrons is displayed in Figure 4b. In the reactor center, the density of electrons and temperature are elevated, and the dissipated power (Figure 4c) is increased at 0.77 × 106 W/m3. Most power deposition occurs at an arc length of 35 mm below the third and fourth coils of the reactor. Figure 4d displays the distribution of electric potential, and Figure 4e presents the velocity field, where gas cannot penetrate deep into the plasma core at these flow rates. Through the pump, the gas flows down toward the wafer, then around it, and out to the pump. Gas flow has a relatively small effect on ICPs which operate at very low pressures.

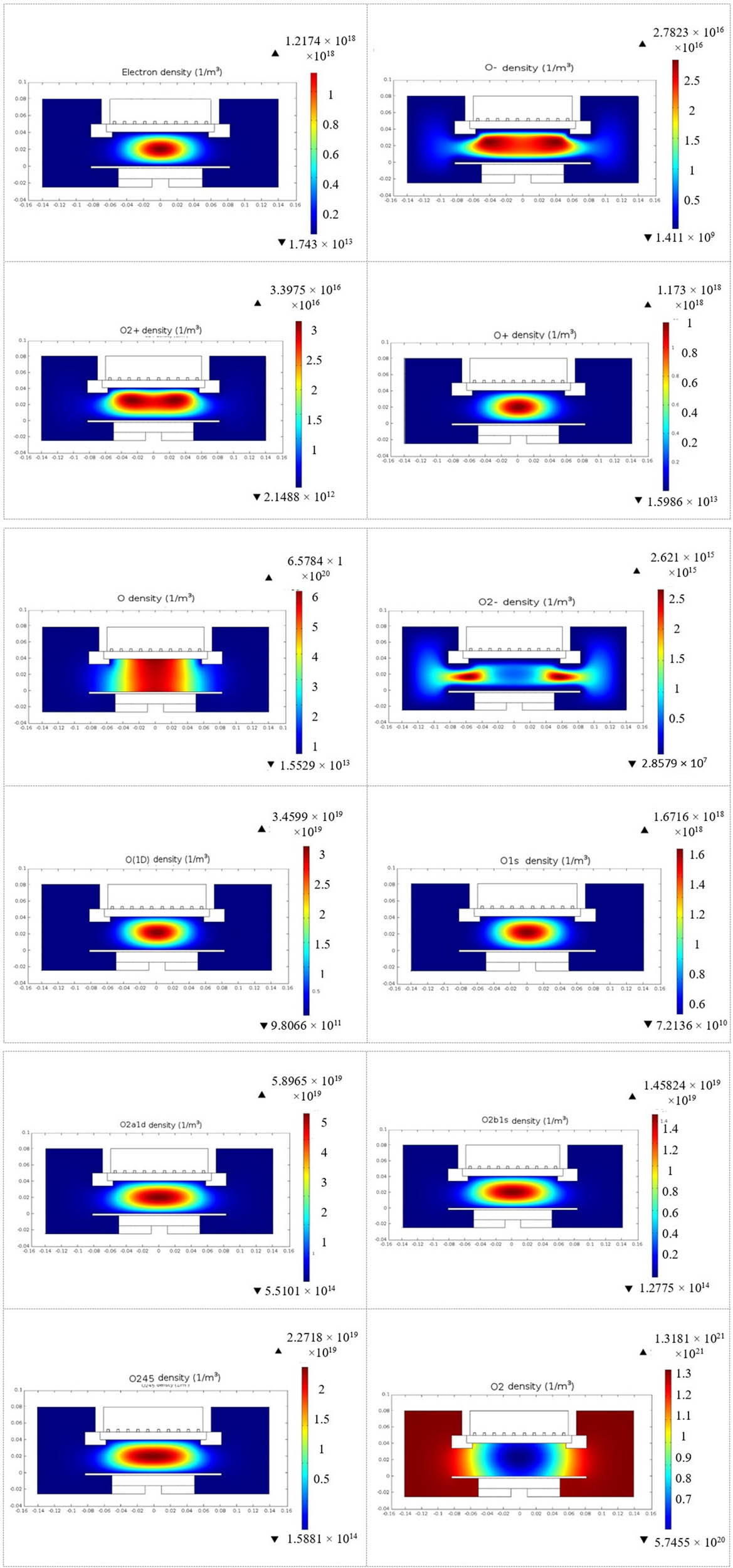

The surface distribution of reactive oxygen density at 400 W RF input power and 10 Pa (75 mTorr) is shown in Figure 5. The distributions of charged particles (electrons, O+, O−, and O2 +) indicate that most of the power is dissipated just below the coil, in front of the quartz cylinder. The predominant positive oxygen ion is O+, with a maximum density of 1.17 × 1018 m−3. O2 + has a density that is nearly two orders of magnitude lower. Due to the presence of a considerable number of negative ions O−, the plasma is electronegative.

Surface distribution of reactive oxygen plasma (electron, O2, O, O2 +, O+, O2 −, O−, O*, O2 *(1∆), O2 *(v), and O2 *(1∑)) in 10 Pa oxygen gas at 400 W in a GEC-ICP reactor.

The neutral oxygen atom (O), excited atomic oxygen species (O*(1D) and O*(1S)), and excited molecular oxygen species (O2 *(1Δ), O2 *(1Σ), and O2 *(v)) identified in the model as O2a1d, O2b1s, and O245, respectively, have peak densities that are two or three orders of magnitude higher than those of charged particles [39]. In addition, the neutral species distribution across the inter-electrode gap is more homogeneous. These reactive neutral species dominate the impact of charged particles in PE-PLD, emphasizing higher importance in thin film deposition. The singlet delta oxygen O2 *(1Δ) identified as O2a1d and atomic oxygen (O) are chemically highly reactive. So, in PLDs with an O2 gas background, these species are critical in thin film deposition.

Plasma plumes as well as background gases react to create reactive O and O2 *(1Δ) species. As a result, reactive oxygen species are directly correlated with the ablation process limiting the control of reactive oxygen species properties [40].

O− ions have a higher density than O2 − ions, since O2 is produced by the dissociative attachment reaction (e + O2 → O− + O) which is greater than the three-body attachment reaction (e + 2O2 → O2 + O2 −).

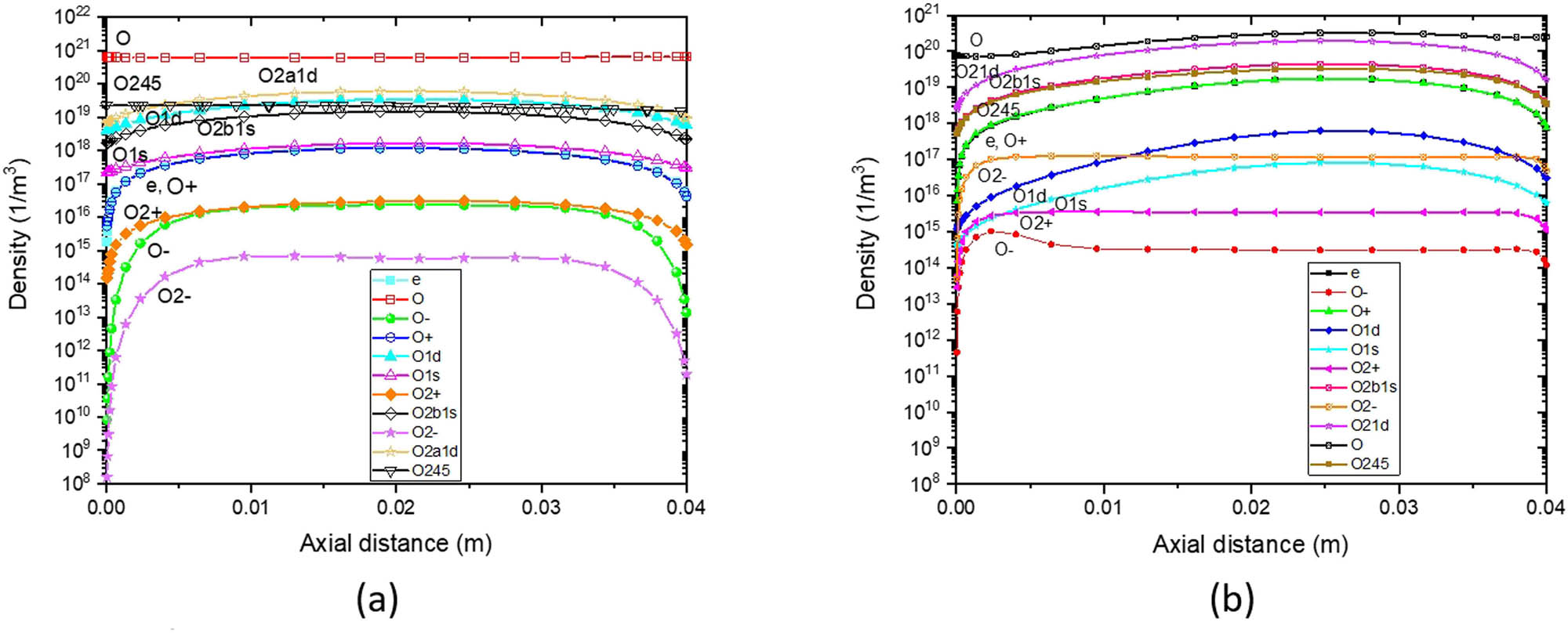

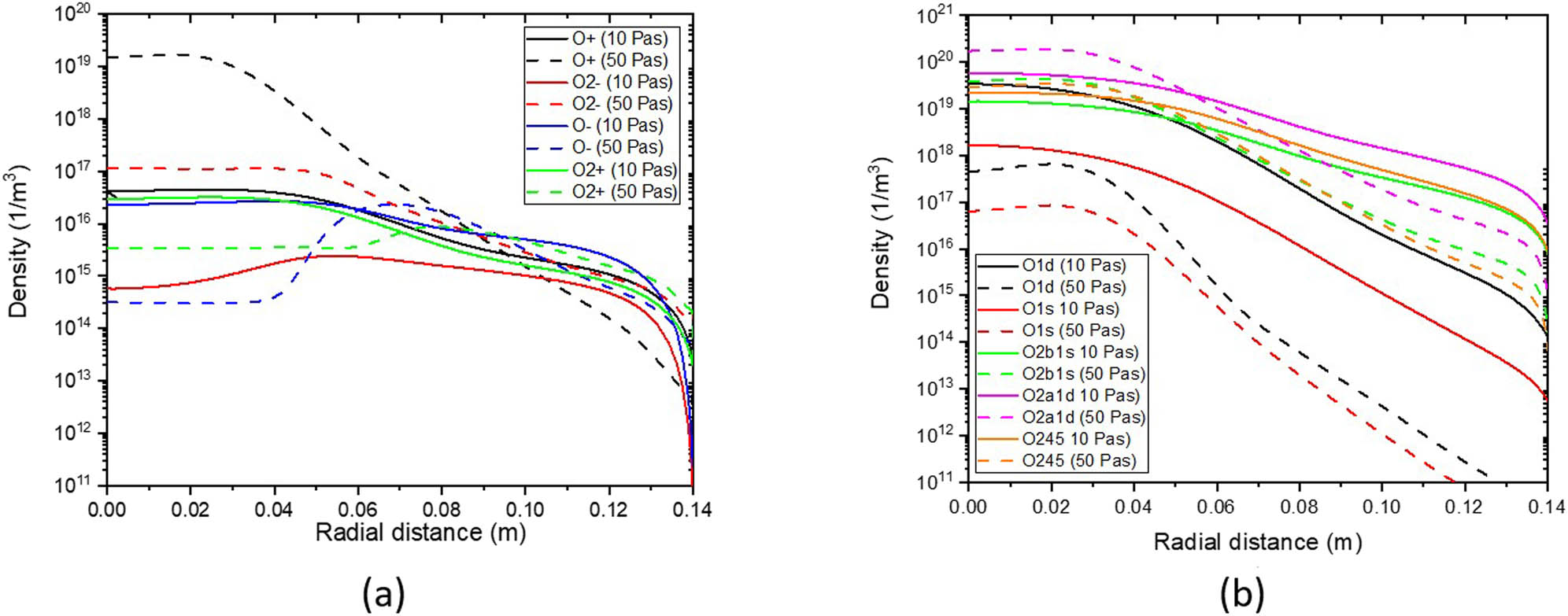

Figure 6 illustrates the axial distribution of oxygen density at 400 W-RF and varied O2 pressures of 10 Pa (75 mTorr) and 50 Pa (375 mTorr). In Figure 6a, a doughnut shape is formed by the charged species, which is even more localized in front of the quartz cylinder in the 10 Pa case. In Figure 6b, the reactor-averaged density of all charged species is higher at 50 Pa than at 10 Pa. Reactive neutral oxygen atom species have lower peaks, and reactor average densities are reduced by a factor of 10 orders for O. The maximum oxygen species densities are localized under the quartz window.

Axial density distribution in reactive oxygen gas (electron, O2, O, O2 +, O+, O2 −, O−, O*, O2 *(1∆), O2 *(v), and O2 *(1∑)) with 400 W input power for (a) 10 Pa and (b) 50 Pa.

O2 *, O*, and O are no longer homogeneously distributed across the reactor. They are localized in the same region as the charged species. During the PLD process, the oxygen content is optimized by exploring these differences in density with pressure.

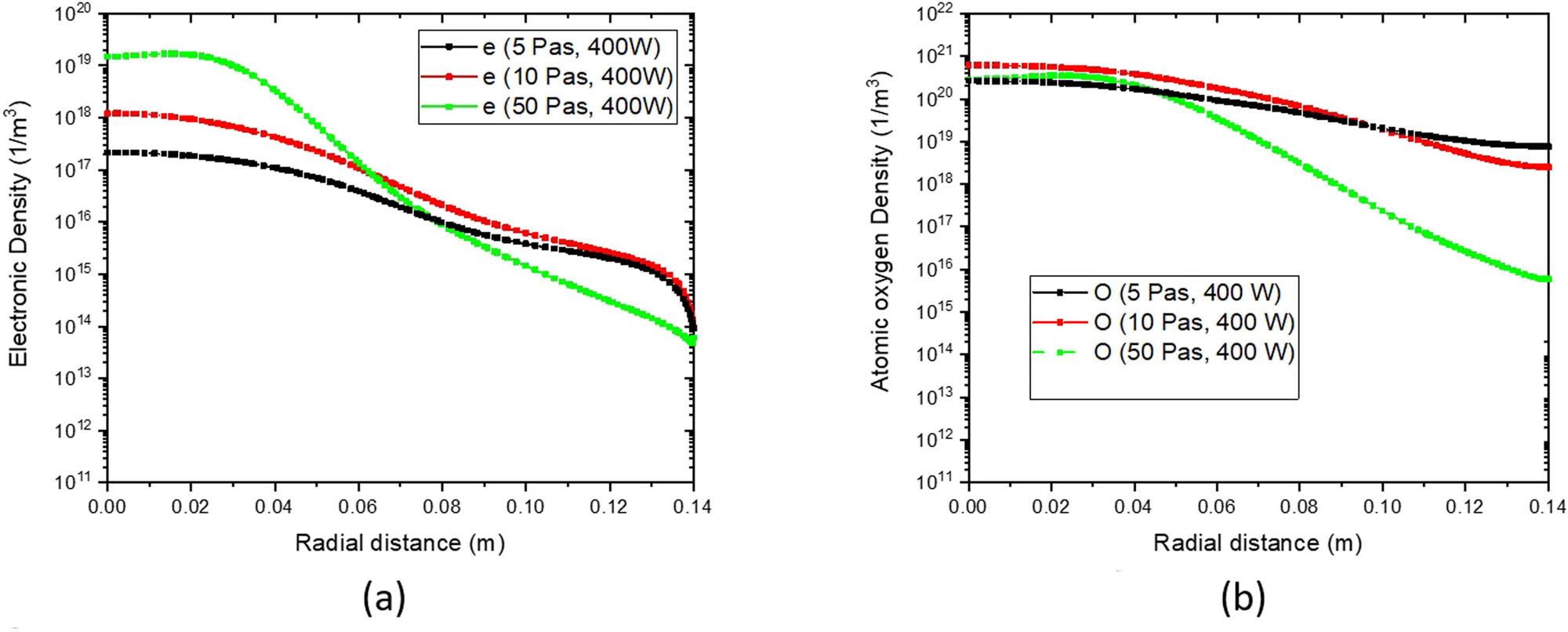

During deposition, oxygen atoms are generated by both the target and collisions in the plasma plume and have a greater oxidation power compared to molecular oxygen [41]. Figure 7 shows the evolution of oxygen atoms O and electron density under various pressures. Figure 7a shows that the electron density varies linearly with pressure. Figure 7b shows that with increasing pressure, the oxygen atom density increases and then decreases.

Radial distribution of (a) electron density and (b) atomic oxygen density for different pressures.

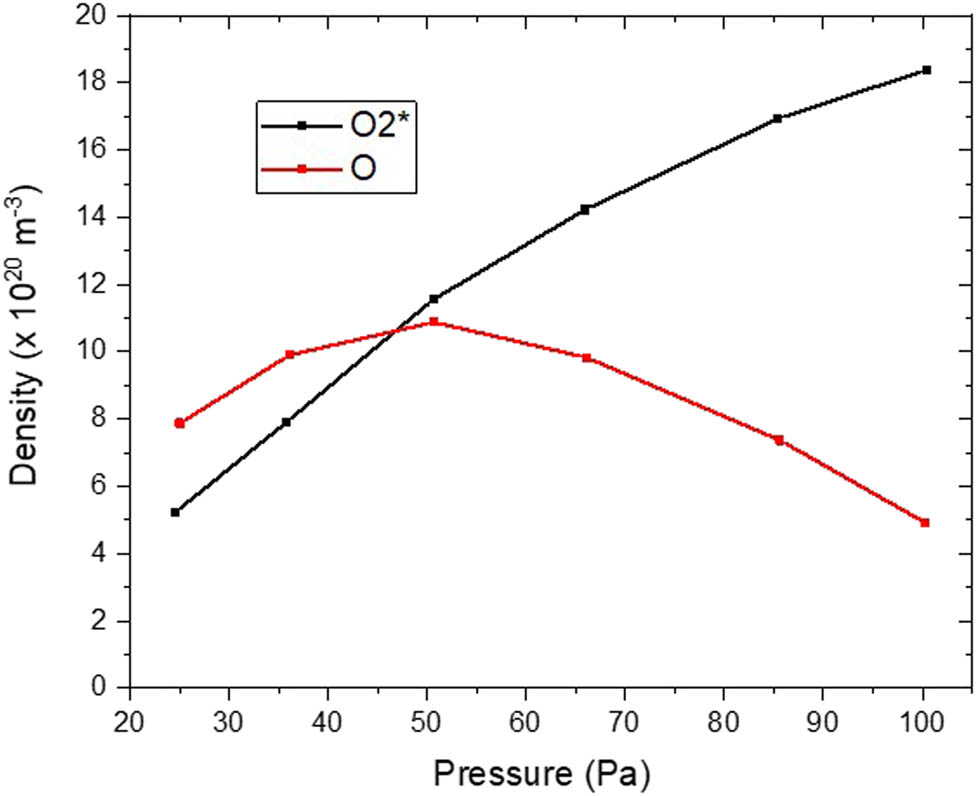

To explain more the variation of atomic oxygen density with pressure, the pressure is varied between 3 and 100 Pa (22–750 mTorr), which is a suitable domain to activate the deposition substrate. Figure 8 displays the density distribution of oxygen atoms and metastable molecular oxygen close to the metal electrode. It indicates that the O2 * density increases from 4 × 1013 cm−3 to 1 × 1015 cm−3 when the pressure is increased from 3 Pa to 100 Pa. In contrast, O exhibits a different behavior with pressure, varying between 3 × 1013 cm−3 and 2 × 1014 cm−3, with an elevated density at 10 Pa (75 mTorr) and the lowest at 100 Pa. Hence, the dominant species at 3 Pa is O, which has a density that is twice as high as O2 *. By increasing the pressure to 100 Pa, the dominant reactive species is O2. This change in reactive oxygen species impacts on thin film properties. A similar result is found in simulations by Blackwell et al. [42], wherein the crystal composition, stoichiometry, and quality of metal oxide films are affected by the O/O2 ratio.

Density distribution of O2* and O with pressure in front of the lower electrode.

The plasma medium has a high density of ionized particles which affects its diagnosis. Figure 9 illustrates the radial distribution of charged and metastable species of oxygen gas with 400 W input power at 10 Pa (75 mTorr) and 50 Pa (375 mTorr). The peaks of reactive ion oxygen density increase with pressure. Also, with increasing pressure, the ion drift flux depending on the electron temperature and the diffusion flux of ions decline together, resulting in a decline of the total ion flux.

Radial distribution of (a) oxygen particles and (b) metastable oxygen particles for different pressures at z = 0.02 m with 400 W input power.

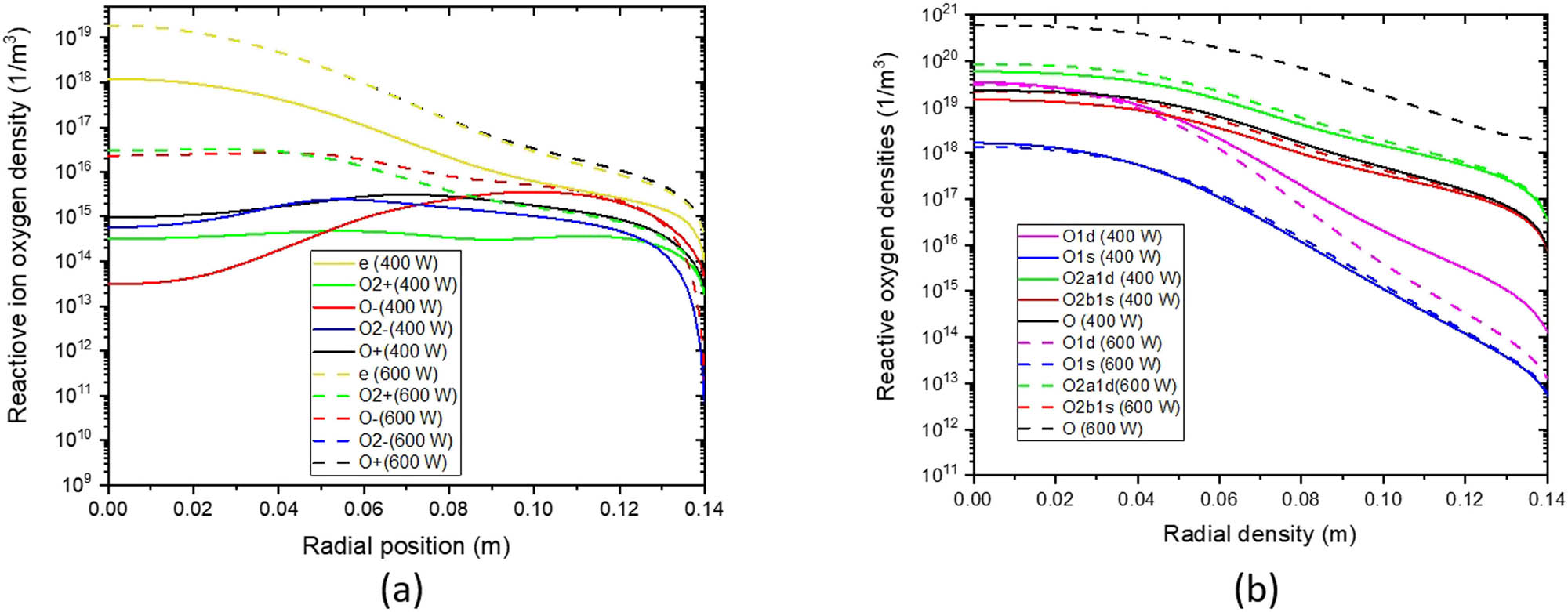

Figure 10 shows how charged, neutral, and metastable oxygen species density evolve with applied power. In Figure 10a, electron densities vary linearly with power. This trend is also supported by experiments [43]. According to Figure 10b, increasing the power values under the RF coil increases the density of excited oxygen atoms and oxygen molecules. Increasing power causes oxygen atoms to gain energy, leading to higher atom excitation.

Radial distribution of densities of (a) oxygen particles and (b) neutral oxygen particles for different powers at z = 0.02 m with 10 Pa pressure.

The electron temperature and ion density are important parameters influencing the deposition of oxide thin films. The electron temperature is proportional to bombardment energy, causing oxide films homogeneity defect. Furthermore, ion density affects the deposition rate. Hence, the oxygen ion density and electron temperature in Figure 11 are displayed as functions of power and pressure in the middle of the reactor. Figure 11a illustrates the applied power affecting the ion density and electron temperature at 10 Pa (75 mTorr). As the applied power increases between 100 and 600 W, the oxygen ion density increases and the electron temperature decreases. Increasing power causes higher ionization rates, which result in a plasma rich in electrons and ions. While a decline in the electron temperature is observed in the plasma zone because of energy loss [44,45].

Ion oxygen density and electron thermal distribution in films deposited by PE-PLD under different (a) applied powers and (b) pressures of the ICP.

According to Figure 11b, when the pressure varies from 10 to 40 Pa (75 to 300 mTorr), the oxygen ion density increases, while the electron temperature decreases. Furthermore, the oxygen density in the plasma region becomes higher as the pressure rises. As collisions increase at high pressure, particles per unit volume increase [46,47]. A proportional increase in collision rate with pressure results in energy loss by collisions, which lowers the temperature of electrons. There is an agreement between these results and those of Ojeda et al. [48] in terms of density and electron temperature.

A simulation of oxide film growth rate in response to applied power and gas pressure is presented. Figure 12 shows how applied power affects ZnO film deposition rates for different operating pressures. With increasing power and pressure, the deposition rate increases almost linearly [49].

Variation of deposition rate with applied power at different values of pressure.

4.3 Correlation analysis

This article focuses on the growth of metal oxide thin films on a polymer substrate through PE-PLD to overcome some limitations of the conventional PLD method, such as the need to use multi-element targets and elevated substrate temperatures. The standard PLD setup with a metal target will be combined with an electrically produced low-temperature oxygen background plasma. Crucially, oxygen plasma is a pulsed non-equilibrium plasma to maintain a low temperature, which prevents the substrate from being significantly heated by the plasma’s conductivity and enables the deposition of coatings onto delicate substrates.

The results show that the direct contact between the active plasma and the ablation plume results in more reactive, energetic plasma particles impinging on the substrate, instead of an afterglow plasma beam. In contrast, in the plasma beam assisted PLD system presented by Dinescu et al. [17], an additional oxygen plasma beam impinges on the substrate to form ZnO films. This system provides high-quality ZnO films only when combined with 800 K substrate heating.

In addition, since these particles are more energetic in PE-PLD than an afterglow plasma or a neutral background gas, where electrons present a high temperature proportional to the energy of bombardment of the substrate, their diffusion lengths are longer, resulting in more crystalline films [50].

A background plasma plume also provides particles for a longer period of time than a laser-produced plume. As a result, polycrystalline films can be deposited at room temperature because incoming particles are more likely to find good sites on the surface for crystalline growth. Our results are in accordance with the work of Tricot et al. [51], which concludes that using pulsed-electron beam deposition systems delivers plasma species to substrates for much longer periods of time than conventional PLD systems.

In addition, De Giacomo et al. [52] studied TiO2 films made via PE-PLD, while Huang et al. [15] reported ZnO films deposited at ambient temperature using the RF-PE-PLD technique. These systems similar to our work use a plasma backdrop to decrease the droplets in the PLD plume rather than using the background plasma to provide oxygen for the film.

5 Conclusions

The use of PE-PLD for metal oxide thin film deposition is presented in this article. Cold oxygen plasma is used instead of neutral gas to enhance process control and check polymer stability issues. A two-dimensional model of an RF-inductively coupled oxygen plasma is developed using COMSOL Multiphysics to understand the dynamics of inductively coupled oxygen discharge. The electron density, electron temperature, electric potential, as well as oxygen ion and excited oxygen atom densities are calculated inside the GEC-ICP reference cell reactor. According to simulation results, a low-pressure RF-ICP plasma generates significant quantities of reactive oxygen species including O and O2, at densities of up to 1019 m−3, compared to a conventional oxygen gas background. Due to the similar density of these plasma plumes and background plasma, it appears plausible that similar rates of oxygen and metal deposition can result. The temperature of electrons is proportional to the energy of bombardment. As a result, the substrate receives chemical energy from the oxygen plasma to enhance the growth of the film without the need for further substrate heating. PE-PLD has comparable stoichiometry and crystallinity to PLD, but it does not heat the substrate and uses pure metal targets instead of metal oxide ones. Metal oxide films were polycrystalline, and their stoichiometry could be adjusted by adjusting the ICP power. The results show that densities of electrons, excited oxygen atoms, and oxygen ions increase with power. However, the electric potential and electron temperature decrease as the input power increases and increasing power causes oxygen atoms to gain energy, leading to higher atom excitation. Moreover, the oxygen gas pressure plays a crucial role in determining the properties of films. As the pressure increases, the oxygen ion density increases and the electron temperature decreases, which enhance the deposition rate. In contrast to O2, the O density decreases at pressures above 10 Pa .

The film deposition is significantly affected by reactive species O and O2, and the results show that with increasing power and pressure, the deposition rate increases almost linearly.

PE-PLD is a powerful method with a wide range of uses in several domains. Its accuracy and adaptability make it a useful instrument for engineers and researchers, propelling developments in fields like technology, healthcare, and energy.

Acknowledgments

This research project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research and Libraries, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, through the Program of Research Project Funding After Publication, grant no. RPFAP-63-1445.

-

Funding information: This research project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research and Libraries, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, through the Program of Research Project Funding After Publication, grant no. RPFAP-63-1445.

-

Author contributions: Samira Elaissi and Norah A.M. Alsaif – methodology, writing, supervision, project management, and data revision. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Devaraj P, Peranantham P, Devarani Devi K, Siva Kumar VV, Jeyachandran YL. Oxidation characteristics of copper oxide thin films deposited by direct current sputtering under substrate temperature and post-deposition copper-ion implantation. Thin Solid Films. 2024;804:140485.10.1016/j.tsf.2024.140485Search in Google Scholar

[2] Patil PR, Borse HP, Chaware NP, Huse DNP. Study of optoelectronic properties of ZnO thin film grown by facile solution growth technique. Int J Sci Res Sci Techn. 2024;11(9):322–9.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Fasquelle D, Députier S, Bouquet V, Guilloux-Viry M. Effect of the microstructure of ZnO thin films prepared by PLD on their performance as toxic gas sensors. Chemosensors. 2022;10(7):285.10.3390/chemosensors10070285Search in Google Scholar

[4] Rakhimkulov S, Absattorov D, Borikhonov B, Yakubov E. Synthesis and application of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Res J Chem Env. 2024;28(1):1–20.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Dosmailov M, Leona LN, Patek J, Roth D, Bauer P, Scharber MC, et al. Transparent conductive ZnO layers on polymer substrates: Thin film deposition and application in organic solar cells. Thin Solid Films. 2015;591(Part A):97–104.10.1016/j.tsf.2015.08.015Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zaier A, Meftah A, Jaber AY, Abdelaziz AA, Aida MS. Annealing effects on the structural, electrical and optical properties of ZnO thin films prepared by thermal evaporation technique. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2015;27(4):356–60.10.1016/j.jksus.2015.04.007Search in Google Scholar

[7] Faramawy A, Elsayed H, Scian C, Mattei G. Structural, optical, magnetic and electrical properties of sputtered ZnO and ZnO: Fe Thin films: The role of deposition power. Ceramics. 2022;5(4):1128–53.10.3390/ceramics5040080Search in Google Scholar

[8] Tiwari C, Pandey A, Dixit A. Precursor mediated and defect engineered ZnO nanostructures using thermal chemical vapor deposition for green light emission. Thin Solid Films. 2022;762:139539.10.1016/j.tsf.2022.139539Search in Google Scholar

[9] Haider AJ, Jabbar AA, Ali GA. Pure and doped ZnO nanostructure production and its optical properties using pulsed laser deposition technique. J Phys: Conf Ser. 2021;1795:012015.10.1088/1742-6596/1795/1/012015Search in Google Scholar

[10] Escalona M, Bhuyan H, Valenzuela JC, Ibacache S, Wyndham E, Favre M, et al. Comparative study on the dynamics and the composition between a pulsed laser deposition (PLD) and a plasma enhanced PLD (PE-PLD). Results Phys. 2021;24:104066.10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104066Search in Google Scholar

[11] Hacini N, Ghamnia M, Dahamni MA, Boukhachem AB, Pireaux JJ, Houssiau L. Compositional, structural, morphological, and optical properties of ZnO thin films prepared by PECVD technique. Coatings. 2021;11(2):202.10.3390/coatings11020202Search in Google Scholar

[12] Rajendiran S, Meehan D, Wagenaars E. Plasma-enhanced pulsed laser deposition of copper oxide and zinc oxide thin films. AIP Adv. 2020;10(6):065323.10.1063/5.0008938Search in Google Scholar

[13] Bukharia SA, Kumarb S, Kumarc P, Gumfekara SP, Chunga HJ, Thundata T, et al. The effect of oxygen flow rate on metal–insulator transition (MIT) characteristics of vanadium dioxide (VO2) thin films by pulsed laser deposition (PLD). Appl Surf Sci. 2020;529:146995.10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.146995Search in Google Scholar

[14] Chou CM, Lai CC, Chang CW, Wen KH, Hsiaom VKS. Radio-frequency oxygen-plasma-enhanced pulsed laser deposition of IGZO films. AIP Adv. 2017;7:075309.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Huang SH, Chou YC, Chou CM, Hsiao VKS. Room temperature radio-frequency plasma-enhanced pulsed laser deposition of ZnO thin films. Appl Surf Sci. 2013;226:194–8.10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.11.138Search in Google Scholar

[16] Scarisoreanu N, Matei DG, Dinescu G, Epurescu G, Ghica C, Nistor LC, et al. Properties of ZnO thin films prepared by radio-frequency plasma beam assisted laser ablation. Appl Surf Sci. 2005;247(1–4):518–25.10.1016/j.apsusc.2005.01.140Search in Google Scholar

[17] Nistor LC, Ghica C, Matei D, Dinescu G, Dinescu M, Van Tendeloo G. Growth and characterization of a-axis textured ZnO thin films. J Cryst Growth. 2005;277(1–4):26–31.10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2004.12.162Search in Google Scholar

[18] COMSOL Multiphysics® v.5.1. www.comsol.com. COMSOL AB, Stockholm, Sweden.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Zhang CY, Zhong XL, Wang JB, Yang GW. Room-temperature growth of cubic nitride boron film by RF plasma enhanced pulsed laser deposition. Chem Phys Lett. 2003;370(3–4):522–7.10.1016/S0009-2614(02)01987-5Search in Google Scholar

[20] Siari K, Rebiai S, Bahouh H, Bouanaka F. Plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition of silicon films at low pressure in GEC reference cell. Plasma Phys Rep. 2020;46:667–74.10.1134/S1063780X20060094Search in Google Scholar

[21] Ramamurthi B, Economou DJ. Pulsed-power plasma reactors: Two-dimensional electropositive discharge simulation in a GEC reference cell. Plasma Sources Sci Technol. 2002;11(3):324–32.10.1088/0963-0252/11/3/315Search in Google Scholar

[22] Hagelaar GJM, Pitchford LC. Solving the Boltzmann equation to obtain electron transport coefficients and rate coefficients for fluid models. Plasma Sources Sci Technol. 2005;14:722–33.10.1088/0963-0252/14/4/011Search in Google Scholar

[23] Jaeger EF, Berry LA, Tolliver JS, Batchelor DB. Power deposition in high‐density inductively coupled plasma tools for semiconductor processing. Phys Plasmas. 1995;2:2597.10.1063/1.871222Search in Google Scholar

[24] Kropotkin A, Chukalovsky A, Kurnosov A, Rakhimova T, Palov A. Modelling of an icp discharge in oxygen with full kinetics scheme with newly calculated vv/vt rate constants. Publ Astron Obs Belgrade. 2024;103:130–3.10.69646/aob103p130Search in Google Scholar

[25] Application Gallery: Model of an Argon/Oxygen inductively coupled plasma reactor [Internet]. COMSOL Multiphysics® v.5.1. www.comsol.com. COMSOL AB, Stockholm, Sweden; 2025 [cited 2025 May 10]. https://www.comsol.com/model/model-of-an-argonoxygen-inductively-coupled-plasma-reactor-109191. Search in Google Scholar

[26] Christophorou GL, Olthoff JK. Fundamental electron interactions with plasma processing gases. 2nd edn. New York: Springer; 2003.10.1007/978-1-4419-8971-0Search in Google Scholar

[27] Koster G, Blank DHA, Rijnders GAJHM. Oxygen in complex oxide thin films grown by pulsed laser deposition: A perspective. J Supercond Nov Magn. 2020;33:205–12.10.1007/s10948-019-05276-5Search in Google Scholar

[28] Kropotkin AN, Voloshin DG. ICP argon discharge simulation: The role of ion inertia and additional RF bias. Phys Plasmas. 2020;27(5):053507.10.1063/5.0003735Search in Google Scholar

[29] Miller PA, Hebner GA, Greenberg KE, Pochan PD, Aragon BP. An inductively coupled plasma source for the gaseous electronics conference RF reference cell. J Res Natl Inst Stand Technol. 1995;100(4):427.10.6028/jres.100.032Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Wang J, Rijnders G, Koster G. Complex plume stoichiometry during pulsed laser deposition of SrVO3 at low oxygen pressures. Appl Phys Lett. 2018;113(22):223103.10.1063/1.5049792Search in Google Scholar

[31] Seadawy AR. Ion acoustic solitary wave solutions of two-dimensional nonlinear Kadomtsev–Petviashvili–Burgers equation in quantum plasma. Math Method Appl Sci. 2017;40(5):1598–607.10.1002/mma.4081Search in Google Scholar

[32] Porcu E, Castruccio S, Alegría A, Crippa P. Axially symmetric models for global data: A journey between geostatistics and stochastic generators. Environmetrics. 2019;30(1):e2555.10.1002/env.2555Search in Google Scholar

[33] Seadawy AR. Stability analysis solutions for nonlinear three-dimensional modified Korteweg–de Vries–Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in a magnetized electron–positron plasma. Phys A. 2016;455:44–51.10.1016/j.physa.2016.02.061Search in Google Scholar

[34] Seadawy AR. Solitary wave solutions of two-dimensional nonlinear Kadomtsev–Petviashvili dynamic equation in dust-acoustic plasmas. Pramana– J Phys. 2017;89:49.10.1007/s12043-017-1446-4Search in Google Scholar

[35] Abdullah A, Seadawy AR, Wang J. Stability analysis and applications of traveling wave solutions of three-dimensional nonlinear modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in a magnetized plasma. Mod Phys Lett A. 2018;33(25):1850145.10.1142/S0217732318501456Search in Google Scholar

[36] Cheemaa N, Seadawy AR, Chen S. Some new families of solitary wave solutions of the generalized Schamel equation and their applications in plasma physics. Eur Phys J Plus. 2019;134(117):12467.10.1140/epjp/i2019-12467-7Search in Google Scholar

[37] Ponnamma D, Cabibihan JJ, Rajan M, Pethaiah SS, Deshmukh K, Gogoi JP, et al. Synthesis, optimization and applications of ZnO/polymer nanocomposites. Mat Sci Eng C-Solid. 2019;98:1210–40.10.1016/j.msec.2019.01.081Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Kiehlbauch MW, Graves DB. Inductively coupled plasmas in oxygen: Modeling and experiment. J Vac Sci Technol A. 2003;21(3):660–70.10.1116/1.1564024Search in Google Scholar

[39] Rajendiran S, Rossall AK, Gibson A, Wagenaars E. Modelling of laser ablation and reactive oxygen plasmas for pulsed laser deposition of zinc oxide. Surf Coat Tech. 2014;260:417–23.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2014.06.062Search in Google Scholar

[40] Singh J, Srivastava PK, Siwach PK, Singh HK, Tiwari RS, Srivastava ON. PLD deposited ZnO films on different substrates and oxygen pressure: A study of surface morphology and optical properties. Sci Adv Mater. 2012;4(3–4):467–74.10.1166/sam.2012.1303Search in Google Scholar

[41] Chou CM, Lai CC, Chang CW, Wen KS, Hsiao VKS. Radio-frequency oxygen-plasma-enhanced pulsed laser deposition of IGZO films. AIP Adv. 2017;7:075309.10.1063/1.4994677Search in Google Scholar

[42] Blackwell S, Smith R, Kenny SD, Walls JM, Sanz-Navarro CF. Modelling the growth of ZnO thin films by PVD methods and the effects of post-annealing. J Phys Condens Matter. 2013;25:135002.10.1088/0953-8984/25/13/135002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Marza HH, Khalaf TH. The effect of power on inductively coupled plasma parameters. Iraqi J Phys. 2022;20(3):98–108.10.30723/ijp.v20i3.1017Search in Google Scholar

[44] Gu Y, Li X, Yu W, Gao X, Zhao J, Yang C. Microstructures, electrical and optical characteristics of ZnO thin films by oxygen plasma-assisted pulsed laser deposition. J Cryst Growth. 2007;305(1):36–9.10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2007.03.050Search in Google Scholar

[45] Orsel K. Analysis of transient plasmas for pulsed laser deposition using spatiotemporally resolved laser-induced fluorescence. PhD dissertation. Enschede, The Netherlands: University of Twente; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Escalona M, Bhuyan H, Ibacache S, Retamal MJ, Saikia P, Borgohain C, et al. Study of titanium nitride film growth by plasma enhanced pulsed laser deposition at different experimental conditions. Surf Coat Tech. 2020;405:126492.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2020.126492Search in Google Scholar

[47] Bogaerts A, Chen Z. Effect of laser parameters on laser ablation and laser-induced plasma formation: A numerical modeling investigation. Spectrochim Acta B. 2005;60(9–10):1280–307.10.1016/j.sab.2005.06.009Search in Google Scholar

[48] OjedaGP A, Schneider CW, Lippert T, Wokaun A. Pressure and temperature dependence of the laser-induced plasma plume dynamics. J Appl Phys. 2016;120(22):225301.10.1063/1.4971251Search in Google Scholar

[49] Wise RS, Lymberopoulos DP, Economou DJ. Rapid two-dimensional self-consistent simulation of inductively coupled plasma and comparison with experimental data. Appl Phys Lett. 1996;68(18):2499–501.10.1063/1.115834Search in Google Scholar

[50] Nistor M, Mandache NB, Perrière J. Pulsed electron beam deposition of oxide thin films. J Phys D: Appl Phys. 2008;41:165205.10.1088/0022-3727/41/16/165205Search in Google Scholar

[51] Tricot S, Boulmer-Leborgne C, Nistor M, Millon E, Perrière J. Dynamics of a pulsed-electron beam induced plasma: application to the growth of zinc oxide thin films. J Phys D: Appl Phys. 2008;41:175205.10.1088/0022-3727/41/17/175205Search in Google Scholar

[52] De Giacomo A, Shakhatov V, Senesi GS, Orlando S. Spectroscopic investigation of the technique of plasma assisted pulsed laser deposition of titanium dioxide. Spectrochim Acta B. 2001;56(8):1459–72.10.1016/S0584-8547(01)00274-9Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- The influence of anisotropy of InP on its elasticity and phonon properties

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- The influence of anisotropy of InP on its elasticity and phonon properties

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis