Abstract

Based on our previous cold dark matter axion mass proposal and a detection scheme, as well as considering the axion mass ranges suggested by persuasive simulations in recent years, we present in this study a revised non-relativistic axion/ALP search strategy and a pinpoint mass value based upon our calculations, concentrating on a slightly narrower axion mass (and corresponding Compton frequency) window. The suggested mass value and the corresponding frequency, based upon the outcome of calculations presented here, reinforce the earlier mass window and the results (slightly different values from our calculations but within the same window) obtained by the calculations and simulations by Kawasaki et al. and Buschmann et al. The mass window comprises the spectral region of 18.99–19.01 GHz (which falls within the Ku microwave band), with a center frequency of 19.00 GHz (±0.1 GHz), equivalent to an axion mass range of 78.6–79.6 μeV, and a center mass at 78.582 (±5.0) μeV, our suggested most likely value for an axionic/ALP field mass, if these fields exist in nature. Our search strategy, as summarized herewith, is based upon the assumption that the dark matter that exists in the current epoch of our physical universe is dominated by axions and thus the local observable axion density is the density of the light cold dark matter, permeating our local neighborhood (mainly in the Milky Way galactic halo). Some ideas and the design of an experiment, based on the inverse Primakoff effect, and built around a Josephson Parametric Amplifier and Resonant Tunneling Diode combination installed in a resonant RF cavity, are possibly some other useful ideas, as introduced in this study.

1 Introduction

To understand the constituent particles that form the matter in our universe, as well as explain the large-scale structure observed everywhere, it is necessary to get acquainted with the phenomenology of the elusive particles known as Axions or Axion-like particles (ALPs), which seem to lie outside the boundary of or beyond the current Standard Model (SM) of physics. These particles with interesting properties and fundamental importance in the SM also find possible liaisons within the current model of cosmology (the Concordance model or the Cold Dark Matter model), and therefore, have great potential in understanding the nature of matter (and possibly the nature of dark matter as well in our universe). Axions may also be radiated from primordial black holes (PBHs) as a result of their evaporation, as has been argued for some time if PBHs can be found [1,2]. Axion tomography can be carried out combined with gravitational wave detection [3] and their collective signatures could prove valuable in our understanding of the physical universe we inhabit.

A deep analysis of the theory of quantum chromodynamics (QCD), one of the cornerstone constituents of the SM Lagrangian, revealed that a problem existed with the vacuum structure in the theory (specifically by the virtue of the extremely small value of the vacuum angle or

Axionic field replaced the small vacuum angle and emerged as a new quantum field among all the possible fields existing within the quantum vacuum; however, with extremely weak coupling to ordinary matter. It did not take long before axions were identified as plausible new candidates for the proposed (non-baryonic) cold dark matter dominating the matter density of our universe [7,8]. At the same time, nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly plausible after the recent astronomical observations that the unexplained matter responsible for the observed discrepancies in galactic rotation curves and cosmic microwave background (CMB) data could not be a non-baryonic dark matter but instead a conglomeration of ordinary baryonic matter (such as clumps of cold hydrogen gas agglomerating in galactic halos, etc.). The discussion of ordinary or dark matter and its possible forms is beyond the scope of this study, which specifically concentrates on the subject of axion mass and axion detection, and a recent review on the subject can be found elsewhere [8,9].

There has been a lot of theoretical investigation into the physics of axions, and countless models for their existence and properties have been suggested, including the recent suggestions of coherent zero-mode axionic oscillations around their minimum, possibly forming a Bose–Einstein condensate of axions [10,11].

Within the framework of QCD and the string theoretical framework [12], some ideas have been developed during the past three decades in an attempt to understand the formation and evolution of axions soon after the onset of inflation during the epoch. The detailed treatment of the primordial axion formation from the string networks is beyond the scope of this study and can be found in any detailed reviews, such as in previous studies [13,14]. In short, during the Planck epoch, soon after the PQ symmetry breaking, the fundamental axionic string networks form and give way to the formation of string-based domain walls that interact and annihilate around the time of the QCD phase transition [13–17], in turn producing axions that permeate the universe and reach the present epoch as non-thermal Relic Axions [18]. In the beginning, these axions are hot and have much higher kinetic energy; however, their temperatures subside as well as their speeds slow down as well and become non-relativistic (hence the term “cold” dark matter in contrast to the other supposed type, the relativistic or “hot” dark matter, such as neutrinos and other particles), and are thus considered to be one of the most ideal candidates for being the constituent particles of the dark matter. Only a cold form of dark matter could have contributed to the process of structure formation in the universe by agglomerating mass within galactic halos, leading to the formation of cosmic structures, such as galaxies and clusters, we observe today.

However, in addition, axions seem to evolve in a non-linear manner following the onset of QCD transition and have additional effects from cosmological factors, such as the Hubble expansion. Hence, it is difficult to predict their behavior owing to several mathematical and cosmological considerations. Besides, the axion field produced as a result of symmetry breaking (PQ) undergoes time-dependent random fluctuations as the universe evolves, and thus, the field takes the form of an oscillating field around a mean value. An important stage in axion field evolution is the onset and duration of inflation, whether the PQ symmetry is broken before (or during) the onset of inflation or post-inflation, once a minimum has been reached in the inflation, i.e., the inflation field has equilibrated to its minimum value in its potential valley, and the new episode of universe’s evolution, the Reheating, begins.

In this study, we contemplate the second scenario wherein the U(1) PQ symmetry breaks after the onset of inflation, while it has receded and the epoch of Reheating has commenced. As a result, the topological defects in the quantum vacuum produce a network of two-dimensional elementary objects, “Strings” and their corresponding “Domain Walls” [19], known as the “String–Wall” systems, which are formed at the onset of the QCD phase transition following the production of instantons. The formation of these systems and their subsequent collapse, later on through instantonic effects, in turn, produces several successive generations of cosmological axions, collectively forming a large number density of these particles, which later become the relic cold dark matter in our universe [20].

An important step in the cosmological evolution of the axion fields is that during the QCD transition, these fields become massive (as a result of the production of instantons) and undergo oscillations around the minimum of the field’s effective potential. Here, if the value of axion mass exceeds a certain threshold (which, in certain models, has been suggested to be around 5 μeV/c2), then the aforementioned mechanism can result in the production of an ensemble of cold and coherent light axions, forming the collective relic cold dark matter that has traveled since then in space and time to the current epoch. This is the ad hoc hypothesis of axion production from instantonic effects; in short, that is so far the most plausible scenario of the origins of axions in our universe. However, an appropriate detection mechanism and the knowledge of the right mass range are important to detect these particles. Axion mass and its particular value have non-trivial significance in not only the knowledge of elementary particle fields but also in cosmology, where another important parameter, the actual scalar field (that the axion field is a phase of, as explained later in the next section), enters the picture. The axion mass affects the role of the particle as a dark matter candidate as well as its interaction dynamics (mainly through the coupling to other particles and fields), whereas its associated scalar field determines the important elements in the cosmology of the universe, such as cosmic inflation and the equation of state. However, the axion field is a pseudo-scalar field, and the scalar field has different dynamics and interacts differently with other fields. Since we are not aware of the coupling strengths of the fields and also the mass of the axionic fields following mass generation, it is difficult to quantitatively describe the field dynamics as well as provide an experimental framework, which depends on the value of the couplings and an exact mass range.

Thus, we have a serious “axion mass problem” owing to our inability to estimate the mass range that these particles could exist in, which, in turn, determines another important parameter, the axion decay constant (

2 The model

The dynamics of a scalar field evolving in space-time in an expanding universe are described by the Friedmann equations, obtained from the Einstein field equations, using an appropriate metric. These equations laid down with the help of a spatially flat Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) background, while incorporating the FLRW metric, can be expressed along with the metric as follows [21]:

where

We consider bosonic fields arising out of the spontaneous broken PQ symmetry that acquire mass and become axion (or ALPs) particles.

The interaction Lagrangian for these bosonic fields, often termed as the “invisible axion” particles, while ignoring the kinetic and other terms, is given by [6]

Here,

The axion field,

The radial mode of this field, shown here as

The most significant element of the PQ theory and a decisive factor in the emergence of axions is the decay constant,

The value of the axion decay constant is a free parameter in the theory under consideration here, with a broad range of mass values attributed to it. However, given the physical and cosmological considerations, a (broad) realistic window of the coupling’s possible range has been obtained as

The other main parameters in our model are the environmental factor, i.e., the misalignment angle,

Following the PQ symmetry breaking, the axion is created with a spectrum of misalignment angles in various disconnected regions; however, as the onset of inflation occurs during the post-inflation era, the instanton effects cause the value of the misalignment angle to fall to a universal value oscillating in its minimum potential. The accepted value of this minimum is the root-mean square value of

Based on earlier work, following a dilute gas approximation model conceived by Turner [23] (and further developed by Bae et al. [24]), assuming the axions to exist in the form of a dilute instanton gas following the onset of decoupling, the mass of axion/ALPs is described as follows for the dilute gas temperature

The temperature at which the axions slow down and become the non-relativistic cold dark matter and undergo oscillations, as based on the QCD equation of state, is found to be approximately equal to [25]

This corresponds to an upper limit of

However, in the post-inflation scenario, the coupling is endowed with the production of string networks and domain walls, and hence, it is restricted to a lower value, as discussed earlier:

As per the misalignment mechanism [26], the value of the initial misalignment angle,

This produces the viable axion window in the post-inflation scenario of

In view of the measured non-absence of neutron electric dipole moment (nEDM) [27], an upper bound of

Two scenarios of PQ symmetry breaking and axion production are possible here and need to be considered. In the first scenario, the PQ symmetry breaks a priori to the epoch of inflation begins (called the pre-inflation scenario), while in the second one, the PQ symmetry breaks a posteriori when the epoch of inflation has already begun, as the nascent universe evolves during the ensuing highly accelerated inflation epoch, generally known as the post-inflation schemes.

The universal expansion (and, consequently, the change in the scale factor, which is generally gauged with the help of the Hubble parameter) has a direct correlation with the temperature of the universe, which in turn affects the value of the axion potential [11].

As the universe’s temperature decreases, the value of the Hubble parameter also decreases; however, the axion potential becomes deeper, and its value increases. According to the equation of motion (obtained from the Dilute Instanton Gas model approximation [28]), the dynamics of the axion’s field are governed by

As argued in detail in Di Cortona et al. [11], as the temperature cools down further, the attractive axion potential reaches the expansion-driven Hubble friction. When the value of the temperature-dependent axion mass approaches nearly three times the value of the Hubble parameter, the axion field undergoes oscillation at the axion Compton frequency corresponding to the axion mass value. This is soon followed by the axion number density becoming an adiabatic invariant and the axion taking the form of cold dark matter. This occurs assuming the scenario that the PQ symmetry breaks a priori to the epoch of inflation (the pre-inflation scenario), with the value of the misalignment angle

In the alternate scenario, the post-inflation scheme, PQ symmetry breaks following the onset of inflation, as the accelerated episode of inflation begins and the universe undergoes its massive accelerated expansion, and it is not possible to determine the value of

where

The axion mass is bound within the μeV region owing to cosmological considerations (in order not to exceed the observed CDM density), which is known as the so-called “Anthropic window” [6]. This is, thus, the narrow window for ultra-light cold dark matter axion (and axion-like particle) searches:

The critical temperature (

where

Here, g

c

is the relative degrees of freedom at the critical time t, G is Newton’s gravitational constant (which can be alternatively written in terms of the Planck mass,

We follow an approach, similar to Buschmann et al. [29] and Hiramatsu et al. [30–32], in constructing an axion model taking into account the three fundamental mechanisms for axion production, viz., misalignment [33,34], global string decays [35], and domain wall decays [36] since all these three, especially the two principal mechanisms, the axion field misalignment mechanism and the decay of global axion strings and domain walls, equally contribute to post-inflation era axion production.

The energy density with the cosmological constant (Λ) and the susceptibility (

which suppresses the temperature dependence and fixes the value of the zero temperature axion mass as a function of the coupling constant alone, and can be described by the expression [14]

3 Fitting of the model to cosmological parameters

Similar to the earlier calculations by Wantz and Shellard [10], among others, we adopt a high-temperature cosmological model in an era soon after the decoupling has taken place, with a sufficiently high-temperature value of the decoupling temperature, around

We carry out our calculations around the accepted value of axion density (

Based on the WMAP, BAO, and Type 1a Supernova (SNe) data,

On the other hand, the major component of the universe, i.e., the dark energy (or “quintessence”) density,

In addition, it is also assumed in this model, similar to several earlier models, that the value of the radial mass (

We follow an axion string network-based theoretical model similar to the approach of Kawasaki et al. [36], Hindmarsh et al. [39], Yamaguchi et al. [13], Vilenkin [19], and Shellard [40,41], under the String theory framework, using results from their simulations, and work with the calculations and simulations similar in the form to those set up by Gorghetto et al. [14]. However, no string network simulations are carried out; instead, our calculations are set up around the results obtained from those simulations and make use of the accepted values of cosmological parameters, as determined by the latest results of the Planck collaboration [37].

We attempt to fit our calculated results to a power law to estimate the value of

Parameter space for our model

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

|

|

0.120 |

|

|

60 |

|

|

51.04 |

|

|

62 |

|

|

80 |

|

|

75 |

|

|

400 MeV |

|

|

3 |

|

|

1.16667–1.185 |

|

|

|

Following the approach by several investigators before us, we consider it appropriate to adopt a value of the power n as the starting value before parametrizing it:

These parameters were fed into a fitting program (written in C++ language) based upon a multi-parameter space least-squares approximation scheme, and a set of values was obtained for the required decay constant

As a result of our calculations and fitting the parameters to the current dark matter density, we obtain the values of α and

The theoretical value for α is usually obtained as a ratio

Thus, the final expression for

with the value of the axion decay constant

This helps us obtain the corresponding axion mass value as

The corresponding Compton frequency [42] for the suggested axion mass above is obtained appropriately, in a usual manner, as

These are the results we obtained from our calculations and fitting routines based on and modifying the pertinent calculations and simulations carried out elsewhere before us, thus making it feasible to devise a suitable experiment in a narrow frequency range resonant cavity setting.

4 Experiment design and prospective implementation

Based on the short frequency range (falling within the Ku microwave band) obtained from our calculations, the next step is to implement this value and these ideas and probe this tangible range in an actual axion search experiment.

A review of various axion detection strategies based on their electromagnetic detection can be found here [43]. The method here is not novel but just a modification of the usual cavity-based detection methodologies, using some innovations like introducing a resonant tunneling diode element in the detection chain and employing a simple RF-detection-based approach.

We adopt an approach similar to the one devised earlier by Bukhari and Shah [42], based upon the inverse of Primakoff effect [44], which was first discovered for pions, whereby an axion can interact with an ambient powerful magnetic field and convert into a pair of photons and the latter can be detected in an appropriate detection setting using any of various methods.

The two-photon axionic decay width (under this model) is given by

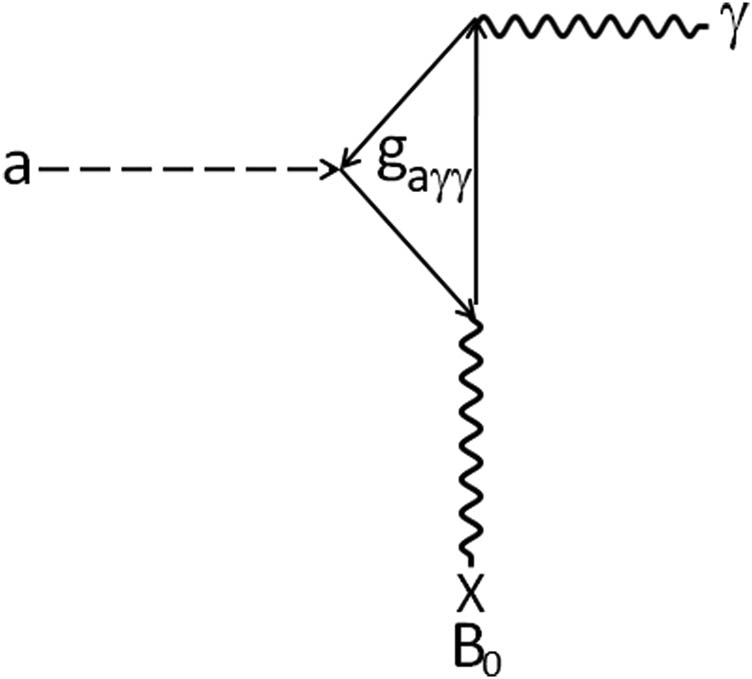

Figure 1 illustrates a magnetic field-induced resonant conversion of an axion into a microwave photon under the inverse Primakoff effect.

Magnetic field-mediated conversion of an axion into a photon under a process inverse to the well-known Primakoff effect.

The interaction is supposedly carried out between an axion and a photon by means of the axion’s two-photon vertex, as shown in the figure. This vertex facilitates a possible interaction of axions with electromagnetic fields, especially in the presence of very strong magnetic fields, as described by the Lagrangian:

Here,

In terms of the vector electric and magnetic fields, this becomes

The model-dependent value of the coupling

The coupling depends on the values of the electromagnetic and color anomalies, E and N, respectively, of the axion-associated axial current. We assume here

Following these lines, the probability of an axion produced in a strong magnetic field, as a result of the inverse Primakoff effect, can be expressed as [42,44]

where B is the intensity of the applied magnetic field, L is the cavity length, and q is the momentum transfer [42].

The signal-to-noise ratio, an important parameter in the experimental detection of any signal, is given by the Dicke Radiometer equation, following the usual microwave signal measurement conventions, as follows [46]:

Here,

Thus, in a nutshell, working under this theoretical framework, the possible detection of axions can be carried out if these particles or such excitations exist in nature.

4.1 Detection scheme

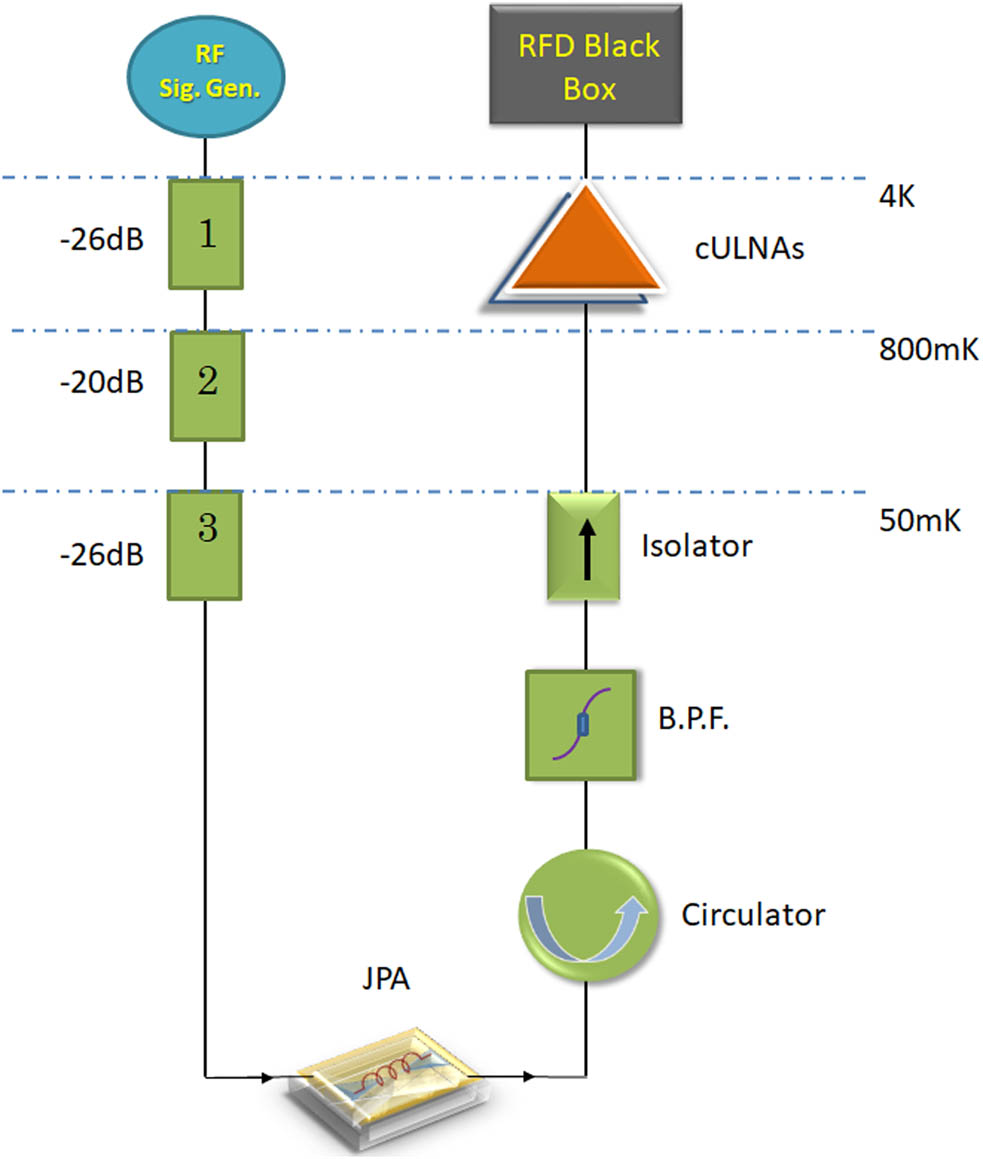

The central part of our detection scheme is a high-finesse resonant RF cavity and an antenna weakly coupled to it, while this setup is mounted in the bore of a high-intensity magnetic field. The output of the antenna is coupled to an extremely sensitive Josephson junction (JJ)-based amplifier device that can amplify the extremely faint electromagnetic signal arising from any possible axion–photon conversion event. To be detected by the antenna and to be read by a measurement system, a signal has to be of a sufficient level. Here, we introduce a new novel addition, which, to our knowledge, has never been used before in such an application: a tunnel diode device in an RF sensing setting. A Tunneling Diode (Resonant Mode) just after the antenna and before the JPA stage further amplifies the detected signal, while in resonance.

The particular JJ device reported here is a flux-driven JPA design [47], implemented with the help of a commercial SQUID-coupled pumped Niobium JPA chip. In addition, as described in an earlier report [42], we employ a new Resonant Tunneling Diode [48,49]-based amplification approach to further increase the sensitivity. We hope for a sensitivity up to around 10−18 W with a noise spectral density down to the order of 10−18 to 10−19 W/Hz1/2. At a highly uniform static magnetic field of approximately 8.0T < B < 10.0 T with a high-resolution (around δT/T < 1 ppb) and an operating temperature of ∼35–55 mK, and taking samples for sufficient longer times, we propose to achieve an operating window just above the Standard Quantum Limit and possibly detect any axion-induced signals within the cavity.

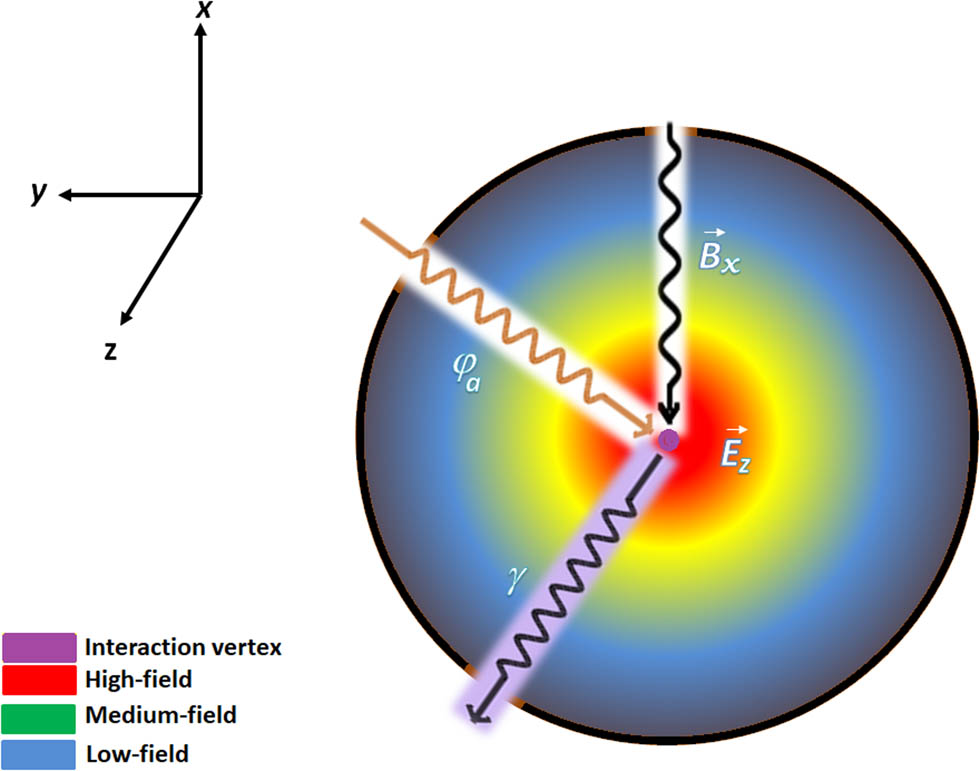

The pertinent parameters of the detection scheme are summarized in Table 2. An image of a simulated response of cavity electromagnetic field obtained from numerical methods (involving the solution of Maxwell equations using finite element method, with the help of COMSOL package, as outlined in our earlier paper [42]) in a transverse slice of the cavity is shown in Figure 2, with a cartoon of the Primakoff conversion process superimposed onto that.

A summary of the cavity-based detection scheme parameters

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Cavity resonance frequency (f) | 17.00–18.99 GHz |

| Pin-point center frequency (f c) | 18.999 GHz |

| Cavity length (l) | Tunable, variable |

| Mean operating temperature (cavity, T) | 35.0 mK |

| Mean magnetic field (B) | 9.0T (δB/B < 1 ppb) |

| Integration time | 120–1,200 s |

| Transmon central frequency (ω/2π) | 4.262 GHz |

| Sensitivity (P) | 10−16 W |

| Mean spectral density (S) | 10−18 W/Hz1/2 |

Cavity electromagnetic field distribution with a cartoon of an axion–photon conversion event facilitated by a strong magnetic field.

Note that the magnetic field (radial) direction is perpendicular to the direction of the electric field (axial).

Figure 3 illustrates an overview of the central element of the detection scheme, i.e., a JJ, and Figures 4 and 5 illustrate block diagrams for the detection scheme and detection electronics for the aforementioned frequency range, with the respective cryogenic and room-temperature sections in an isolated environment individually marked, especially with the cryogenic section (the cavity and cryogenic amplification section) in a low-temperature mu-metal chamber isolated from the strong magnetic field. More details of the experiment, various components, and relevant instrumentation may be found in our earlier report [42]; generic details on microwave measurements can be found elsewhere, such as in Feng et al. [50].

![Figure 3

An overview of the superconducting JJ-based Parametric Amplifier (JPA), the central element of the detection scheme. The details are provided in an earlier report [42].](/document/doi/10.1515/phys-2025-0193/asset/graphic/j_phys-2025-0193_fig_003.jpg)

An overview of the superconducting JJ-based Parametric Amplifier (JPA), the central element of the detection scheme. The details are provided in an earlier report [42].

A block diagram of the detection components in the cryogenic measurement chain, including the respective operating temperatures.

![Figure 5

A block schematic of the RF cavity, detection electronics, amplification and detection components, and relevant instrumentation. As explained in detail in an earlier report [42], a weak electromagnetic signal in the cavity (on resonance) is weakly coupled to a fine gold-plated copper antenna and amplified by a combination of a JJ-based parametric amplifier and a set of cryogenic LNAs in parallel, all operating at cryogenic temperatures, until the signal is amplified sufficiently to be readout by the room-temperature electronics (operated at 10°C). A test signal for calibration is fed from an RF Signal Generator (1–10 GHz). A home-made high-frequency Signal Sensing and Routing Hub (SRH), combines the detected signal with a carrier wave from an Ultra-Low-Distortion Signal Generator (1–100 kHz), feeding it to a Resonant Tunneling Diode (RTD) stage I of the detection chain. From RTD, the signal is amplified by a duo of high-gain Low-Noise Amplifiers until detected by an RF detector.](/document/doi/10.1515/phys-2025-0193/asset/graphic/j_phys-2025-0193_fig_005.jpg)

A block schematic of the RF cavity, detection electronics, amplification and detection components, and relevant instrumentation. As explained in detail in an earlier report [42], a weak electromagnetic signal in the cavity (on resonance) is weakly coupled to a fine gold-plated copper antenna and amplified by a combination of a JJ-based parametric amplifier and a set of cryogenic LNAs in parallel, all operating at cryogenic temperatures, until the signal is amplified sufficiently to be readout by the room-temperature electronics (operated at 10°C). A test signal for calibration is fed from an RF Signal Generator (1–10 GHz). A home-made high-frequency Signal Sensing and Routing Hub (SRH), combines the detected signal with a carrier wave from an Ultra-Low-Distortion Signal Generator (1–100 kHz), feeding it to a Resonant Tunneling Diode (RTD) stage I of the detection chain. From RTD, the signal is amplified by a duo of high-gain Low-Noise Amplifiers until detected by an RF detector.

Figure 6 illustrates a spectral plot of a test signal, acting as a “false axion,” injected into the cavity and detected with the amplification system, showing the measured power spectral density (

A simulated plot of a test signal spectral response, as measured by the detection scheme, measuring an injected ultra-weak signal from an RF generator (power spectral density in W/Hz1/2 vs resonance frequency in MHz).

5 Discussion and conclusion

In this study (and the preprint before [51]), we present some calculations of axion mass and the coupling using standard methods and prescriptions. We assume that axions constitute the majority of the non-baryonic cold dark matter content of the universe, a reasonable assumption given the existing data, and consider three main contributions to axion production within the String theoretical framework, which are the field misalignment mechanism, the decay of global axion strings and domain walls, and the axions radiated from the strings. However, we consider the first two to be the major contributing factors to the total axion density in view of earlier reports. A viable axion mass window is obtained using our fitting routines, and a method to probe this window is also suggested using an approach presented earlier. The value of the axion mass is quite plausible since it is very close and within the window of calculations and simulations carried out in recent times, and also presents a specific center mass value for fixed resonance frequency cavity-based searches.

In particular, the results of our calculations are on similar lines as the recent simulations carried out by Borsanyi et al. [52], Gorghetto et al. [16], and Buschmann et al. [29], especially within the range of 40–180 μeV, as suggested by the important simulations by Buschmann et al. while employing a powerful “Adaptive Mesh Refinement” simulation approach [53]. The proposal of a further narrow axion mass range of around 73–83 μeV, with a center value of 78 μeV (and the corresponding frequency range of 18–20 Giga-Hertz), thus seems to be plausible and valuable to detect an axion, if appropriate experimental methods exist, and subject to the existence of these particles. Recently, Kawasaki et al. [22] have supported the value of

On the other hand, Chang and Cui, in their recent analysis of the dynamics of long-lived axion domain walls [54], have proposed a differing value of decay constant and mass window, one magnitude higher than those in our and other recent proposals. Kim et al. [55], while working on the similar lines of cosmic string networks formation in the post-inflation scenario, but with a new improvisation of the “Tetrahedralization of the Space,” provide their own measures of axion abundance. The mass range proposed by these methods and its corresponding frequencies, reaching the domain of TeraHertz (THz), however, is challenging and extremely difficult to experimentally probe with the precision and low-noise susceptibility of the measurement methods, if not impossible.

Working under a resonant cavity-based detection scheme, and making use of the Primakoff effect, as described in detail in one of our earlier reports [42] and in a recent arXiv report, we have made some viable suggestions for a search for the axions/ALPs to be carried out at or around this frequency, which is slightly difficult due to practical considerations but not impossible to achieve in the contemporary era. It must be mentioned here that this is an extraordinary frequency, just at the end of the microwave “Ku” band.

An important concern is the limitations imposed upon the measurement of the axion signal by the quantum nature of the measurement. These include the Standard Quantum Limit, the Back-Action Noise by the detector, and the quantum fluctuations inherent in the axion and electromagnetic quantum fields. A recent and quite pertinent discussion of these and the relevant parameters is available in the literature by Lasenby [56].

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges valuable discussion with Prof. Willy Fischler, University of Texas, following the publication of the arXiv version of this report. The author also acknowledges the constructive discussions and valuable suggestions by able reviewers in giving the final touches to the report.

-

Funding information: This research was carried out as a part of financial support by the Deanship of Scientific Research of Jazan University, Jazan. Their valuable financial support is duly acknowledged and appreciated in advance.

-

Author contribution: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] Khlopov MY. Primordial black holes. Res Astron Astrophys. 2010;10:495–528.10.1088/1674-4527/10/6/001Search in Google Scholar

[2] Bernal N, Hajkarim F, Xu Y. Axion dark matter in the time of primordial black holes. Phys Rev. 2021;D104:075007.10.1103/PhysRevD.104.075007Search in Google Scholar

[3] Gouttenoire Y, Servant G, Simakachorn P. Kination cosmology from scalar fields and gravitational-wave signatures. arXiv; 2021. [arXiv:2111.01150].Search in Google Scholar

[4] Wilczek F. Problem of strong P and T invariance in the presence of instantons. Phys Rev Lett. 1978;40:279–82.10.1103/PhysRevLett.40.279Search in Google Scholar

[5] Peccei RD, Quinn HR. CP conservation in the presence of instantons. Phys Rev Lett. 1977;38:1440–3.10.1103/PhysRevLett.38.1440Search in Google Scholar

[6] Olive KA. Review of particle physics. Chin Phys. 2014;C38:090001.10.1088/1674-1137/38/9/090001Search in Google Scholar

[7] Dine M, Fischler W. The not so harmless axion. Phys Lett. 1983;B120:137–41; Preskill J, Wise MB, Wilczek F. Cosmology of the invisible axion. Phys Lett. 1983;120B:127; Abbott LF, Sikivie P. A cosmological bound on the invisible axion. Phys Lett. 1983;B120:133.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Seigar MS. The dark matter in the universe, in cold dark matter, hot dark matter, and their alternatives. San Rafael, CA, USA: Morgan and Claypool; 2015.10.1088/978-1-6817-4118-5Search in Google Scholar

[9] Arbey A, Mahmoudi F. Dark matter and the early Universe: a review. Prog Part Nucl Phys. 2021;119:103865.10.1016/j.ppnp.2021.103865Search in Google Scholar

[10] Marsh DJE. Axion cosmology. Phys Rept. 2016;643:1–79; Wantz O, Shellard E. Axion cosmology revisited. Phys Rev D. 2010;82:123508. [ArXiv:0910.1066].Search in Google Scholar

[11] Di Cortona GG, Hardy E, Vega JP, Villadoro G. The QCD axion, precisely. J High Energy Phys. 2016;1:1–37.10.1007/JHEP01(2016)034Search in Google Scholar

[12] Svrcek P, Witten E. Axions in string theory. J High Energ Phys. 2016;2016:051.10.1088/1126-6708/2006/06/051Search in Google Scholar

[13] Yamaguchi M, Kawasaki M, Yokoyama J. Evolution of axionic strings and spectrum of axions radiated from them. Phys Rev Lett. 1999;82:4578–81. [ArXiv: hep-ph/9811311].10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.4578Search in Google Scholar

[14] Gorghetto M, Hardy E, Villadoro G. Axions from strings: the attractive solution. J High Energ Phys. 2018;7:151. [ArXiv:1806.04677].10.1007/JHEP07(2018)151Search in Google Scholar

[15] Gorghetto M, Villadoro G. Topological susceptibility and QCD axion mass: QED and NNLO corrections. J High Energy Phys. 2019;3:33. [arXiv: 1812.01008].10.1007/JHEP03(2019)033Search in Google Scholar

[16] Gorghetto M, Hardy E, Nicolaescu H, Notari A, Reddi M. Early vs late string networks. J High Energy Phys. 2024;2:223.10.1007/JHEP02(2024)223Search in Google Scholar

[17] Gorghetto M, Hardy E, Villadoro G. More axions from strings. Sci Post Phys. 2021;10:050. [ArXiv:2007.04990].10.21468/SciPostPhys.10.2.050Search in Google Scholar

[18] Venegas M. Relic density of axion dark matter in standard and non-standard cosmological scenarios. ArXiv; 2021. [arXiv:2106.07796].Search in Google Scholar

[19] Vilenkin A. Cosmic strings and domain walls. Phys Rept. 1985;121:263–315.10.1016/0370-1573(85)90033-XSearch in Google Scholar

[20] Davis RL. Cosmic axions from cosmic strings. Phys Lett B. 1986;180:225–30.10.1016/0370-2693(86)90300-XSearch in Google Scholar

[21] Garcia-Bellido J. Cosmology and astrophysics. ArXiv. 2005. [arXiv:0502139].Search in Google Scholar

[22] Kawasaki M, Sonomoto E, Yanagida TT. Cosmologically allowed regions for the axion decay constant Fa. Phys Lett B. 2018;782:181–4. [arXiv: 1801.07409].10.1016/j.physletb.2018.05.014Search in Google Scholar

[23] Turner M. Cosmic and local mass density of invisible axions. Phys Rev. 1986;D33:889–96.10.1103/PhysRevD.33.889Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Bae K, Huh J, Kim J. Update of axion CDM energy. JCAP. 2008;0809:005.10.1088/1475-7516/2008/09/005Search in Google Scholar

[25] Ballesteros G, Redondo J, Ringwald A, Tamarit C. Standard model-axion-seesaw-Higgs portal inflation, Five problems of particle physics and cosmology solved in one stroke. arXiv. 2016. [arXiv:1610.01639].10.1088/1475-7516/2017/08/001Search in Google Scholar

[26] Chang C-F, Cui Y. New perspectives on axion misalignment mechanism. arXiv. 2019. [arXiv:1911.11885].Search in Google Scholar

[27] Abel C, Afach S, Ayres NJ, Baker CA, Ban G, Bison G, et al. Measurement of the permanent electric dipole moment of the neutron. Phys Rev Lett. 2020;124:081803.10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.081803Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Borsanyi S, Dierigl M, Fodor Z, Katz SD, Mages SW, Nogradi D, et al. Axion cosmology, lattice QCD and the dilute instanton gas. arXiv. 2015. [arXiv:1508.06917].10.1016/j.physletb.2015.11.020Search in Google Scholar

[29] Buschmann M, Foster JW, Safdi BR. Early-universe simulations of the cosmological axion. Phys Rev Lett. 2020;124:161103.10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.161103Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Hiramatsu T, Kawasaki M, Sekiguchi T, Yamaguchi M, Yokoyama J. Improved estimation of radiated axions from cosmological axionic strings. Phys Rev. 2011;D83:123531.10.1103/PhysRevD.83.123531Search in Google Scholar

[31] Hiramatsu T, Kawasaki M, Saikawa K, Sekiguchi T. Axion cosmology with long-lived domain walls. J Cosmology Astropart Phys. 2013;1301:001.10.1088/1475-7516/2013/01/001Search in Google Scholar

[32] Hiramatsu T, Kawasaki M, Saikawa K, Sekiguchi T. Production of dark matter axions from collapse of string-wall systems. Phys Rev. 2012;D85:105020.10.1103/PhysRevD.85.105020Search in Google Scholar

[33] Co RT, Hall LJ, Harigaya K. Kinetic misalignment mechanism. Phys Rev Lett. 2020;124:251802. [ArXiv: 1910.14152].10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.251802Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Chang C-F, Cui Y. New perspectives on axion misalignment mechanism. Phys Rev. 2020;D102:015003. [ArXiv: 1911.11885].10.1103/PhysRevD.102.015003Search in Google Scholar

[35] Hagmann C. AIP Conference Proceedings. Vol. 1274, 2010. p. 10310.1063/1.3489538Search in Google Scholar

[36] Kawasaki M, Saikawa K, Sekiguchi T. Axion dark matter from topological defects. Phys Rev. 2015;D91:065014. [arXiv:1412.0789].10.1103/PhysRevD.91.065014Search in Google Scholar

[37] Ade PAR, Aghanim N, Arnaud M, Ashdown M, Aumont J, Baccigalupi C, et al. [Planck Collaboration] Planck 2015 results-xiii. Cosmological parameters. Astron Astrophys. 2016;594:A13.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Read JI. The local dark matter density. J Phys G: Nucl Part Phys. 2014;41:063101.10.1088/0954-3899/41/6/063101Search in Google Scholar

[39] Hindmarsh M, Lizarraga J, Lopez-Eiguren A, Urrestilla J. Approach to scaling in axion string networks. Phys Rev. 2021;D103:103534.10.1103/PhysRevD.103.103534Search in Google Scholar

[40] Shellard EPS. Strong network evolution. In: Davis AC, Brandenberger R, editors. Formation and interaction of topological defects, NATO ASI Series. Vol. 349, Boston, MA: Springer; 1995.10.1007/978-1-4615-1883-9_9Search in Google Scholar

[41] Wantz O, Shellard EPS. Axion cosmology revisited. Phys Rev. 2010;D82:123508.10.1103/PhysRevD.82.123508Search in Google Scholar

[42] Bukhari MHS, Shah ZH. An experiment and detection scheme for cavity-based light cold dark matter particle searches. Adv High Energy Phys. 2017;2017:6432354–12.10.1155/2017/6432354Search in Google Scholar

[43] Kim JE, Carosi G. Axions and the strong CP problem. Rev Mod Phys. 2010;82:557–601. [arXiv:0807.3125].10.1103/RevModPhys.82.557Search in Google Scholar

[44] Kahn Y, Safdi BR, Thaler J. Broadband and resonant approaches to axion dark matter detection. Phys Rev Lett. 2016;117:141801.10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.141801Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Tanabashi M, Hagiwara K, Hikasa K, Nakamura K, Sumino Y, Takahashi F, et al. Review of particle physics. Phys Rev. 2018;D98:030001.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Dicke RH. The measurement of thermal radiation at microwave frequencies. In Classics in radio astronomy. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 1946. p. 106.10.1007/978-94-009-7752-5_11Search in Google Scholar

[47] Roy A, Devoret M. Introduction to parametric amplification of quantum signals with Josephson circuits. C R Phys. 2016;17:740–55.10.1016/j.crhy.2016.07.012Search in Google Scholar

[48] Doychinov V, Steenson DP, Patel H. Resonant-tunneling diode based reflection amplifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd European Workshop on Heterostructure Technology (HETECH). Glasgow, UK; 2013. p. 9–11.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Sollner TCLG, Le HQ, Brown EL. Microwave and millimeter-wave resonant tunneling devices, technical report for electronics and electrical engineering. Lexington, MA, USA: NASA; 1988.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Feng X, Zhang YH, Xue W, Zhang H, Fan Y. 6 to 26 GHz detectors for high data rate ASK signal demodulation. Microw J. 2014;57:1–9.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Bukhari MHS. The search for the cosmological axion - A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme. arXiv. 2024. [arXiv:2408.9953].Search in Google Scholar

[52] Borsanyi S, Fodor Z, Guenther J, Kampert KH, Katz SD, Kawanai T, et al. Calculation of the axion mass based on high-temperature lattice quantum chromodynamics. Nature. 2016;69:539–71.10.1038/nature20115Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Drew A, Shellard EPS. Radiation from global topological strings using adaptive mesh refinement: methodology and massless modes. arXiv:1910.01718 [astro-ph.CO]. 2019; Buschmann M, Foster JW, Hook A, et al. Dark matter from axion strings with adaptive mesh refinement. Nat Commun. 2022;13:1049.10.1038/s41467-022-28669-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Chang C-F, Cui Y. Dynamics of long-lived axion domain walls and its cosmological implications. arXiv. 2023. [arXiv: 2309.15920].Search in Google Scholar

[55] Kim H, Park J, Son M. Axion dark matter from cosmic string network. J High Energy Phys. 2024;2024(7):1–53.10.1007/JHEP07(2024)150Search in Google Scholar

[56] Lasenby R. Parametrics of electromagnetic searches for axion dark matter. Phys Rev D. 2021;103:075007.10.1103/PhysRevD.103.075007Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis