Abstract

The Raman spectra, thermal conductivity, and related physical properties of three MAB materials HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB are investigated by using first-principles calculations. The results reveal that all three materials possess a metallic layered structure, characterized by alternating stacks of network layers composed of transition metals M, B, and Al layers. The strong covalent bonds between B atoms and the metallic bonds of M−Al collectively determine the stability and electrical conductivity of these materials. In terms of lattice thermal conductivity, TaAlB (34.0 W/(m K)) and HfAlB (16.9 W/(m K)) exhibit relatively high values, while WAlB (3.5 W/(m K)) shows significantly smaller thermal conductivity due to enhanced phonon scattering resulting from strong anharmonicity. Raman spectroscopic analysis reveals the presence of nine Raman-active modes in each material. The peaks at low frequencies correspond to the vibrational modes of M and Al atoms, whereas the peaks at high frequencies are associated with the stretching vibrations of covalent bonds within B atoms. Furthermore, HfAlB and TaAlB demonstrate reduced phonon scattering, which aligns with their thermal conductivity results. Notably, this study elucidates the intrinsic relationships among atomic structures, chemical bonds, and thermal transport properties, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for the use of MAB materials in high-temperature applications, including thermal conduction and thermal barrier coatings.

1 Introduction

MAB materials, where M represents a transition metal, A stands for aluminum, and B denotes boron, are emerging as a class of layered ternary borides. Due to their unique crystal structures and potentially exceptional properties, such as high melting points and excellent electrical conductivity [1], [2], [3], they have garnered significant research interest. MAB materials exhibit characteristics of both metals and ceramics, including high melting points, favorable thermal and electrical conductivity, and remarkable high-temperature resistance [4], [5], [6]. These properties provide them with extensive application prospects in high-temperature fields, such as coatings for thermal barrier applications, high-temperature structural materials, and nuclear reactor components [7].

Investigating the Raman spectra and thermal conductivity of MAB materials is of significant scientific importance and holds considerable potential for applications, particularly in the field of high-temperature materials. Raman spectra is an effective tool for studying the vibrational modes of materials. By simulating Raman spectra both experimentally and theoretically (through first-principles calculations), researchers can gain in-depth insights into the phonon vibrational modes of materials, thereby revealing the relationships between their microscopic structures and vibrational characteristics [8]. This information is essential for understanding the thermal properties of materials.

The first-principles approach allows for an accurate description of the electronic structures and vibrational properties of materials at the quantum mechanical level. This method provides a solid theoretical foundation for exploring the physical properties of materials [9]. First-principles calculations can predict the thermal conductivity of MAB materials and analyze key factors that influence thermal conductivity, such as phonon scattering and lattice structures [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. By guiding experimental research with theoretical predictions, the thermal conductivity of materials can be optimized to meet specific application requirements. Additionally, by integrating first-principles studies of Raman spectra and thermal conductivity, a comprehensive understanding of the relationships among the structural, vibrational, and thermal transport properties of MAB materials can be attained. This approach offers theoretical guidance for exploring novel high-temperature materials, directing experimental research, and facilitating material design, ultimately advancing both material design and applications [16], [17], [18].

The unique properties of MAB phase materials, including their high-temperature mechanical performance, resistance to high-temperature oxidation, low-temperature synthesis capability, and machinability, provide significant application potential across multiple fields [19], [20], [21]. Research has shown that MAB phase materials, such as WAlB, exhibit metallic characteristics. By analyzing the electronic band structure and density of states (DOS), one can gain comprehensive insights into the electronic behavior of these materials. Methods such as the electron localization function (ELF) and Bader’s quantum theory of atoms in molecules have the potential to elucidate the nature of B–B covalent bonds, as well as the intermediate covalent-metallic bonding between M and B [22]. Thermal conductivity is a critical physical property of MAB phase materials, especially in high-temperature applications [23], [24], [25]. When combined with the Boltzmann transport equation (BTE), first-principles calculations can accurately predict the thermal conductivity of materials and offer insights for optimizing their thermal performance [26], [27], [28], [29]. Furthermore, first-principles calculations can predict Raman spectra and assist in interpreting experimental results [30], [31], [32].

Although some studies have been conducted on MAB phases, first-principles investigations into the Raman spectra and thermal conductivity of representative MAB materials – namely HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB – remain relatively scarce. Therefore, employing first-principles methods to study the Raman spectra and thermal conductivity of MAlB (M = Hf, Ta, and W) serves a dual purpose. On one hand, it allows for precise predictions of the lattice vibrational modes and thermal conductivity of these materials, thereby bridging gaps in experimental research. On the other hand, it enables a comprehensive analysis of the intrinsic relationships among atomic structures, chemical bonding characteristics, Raman spectra, and thermal conductivity, thereby providing theoretical support for interpreting experimental phenomena. Furthermore, theoretical calculations can guide the design and performance optimization of novel boride materials, assisting in overcoming performance bottlenecks in existing materials for practical applications. This, in turn, fosters technological innovations in fields such as high-temperature structural materials and electronic heat dissipation materials.

2 Methodology

In this study, first-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) were executed via the VASP software package for simulations. The exchange-correlation energy was addressed with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional in conjunction with the generalized gradient approximation (GGA). The plane-wave cutoff energy was set to 700 eV. For both geometric optimization and electronic property calculations, a 13 × 13 × 13 Monkhorst-Pack k-point sampling scheme was employed. To ensure computational accuracy, the energy convergence criterion for structural optimization was established at 1 × 10−8 eV, while the atomic force convergence criterion was set to 1 × 10−7 eV/Å [33], [34], [35]. And the valence electron configurations for each element in the calculation are as follows: Hf has a configuration of 5d 26s 2, Ta has 5d 36s 2, W has 5d 4 6s 2, Al has 3s 23p 1, and B has 2s 22p 1.

The thermal properties and phonon-related characteristics were calculated using VASP in conjunction with software ShengBTE [36], 37]. During the calculation process, Phonopy and Thirdorder software played crucial roles [38]. By employing VASP alongside Phonopy, Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) was utilized to perform 4 × 4 × 4 supercell calculations with 17 × 17 × 17 Monkhorst-Pack k-point and 20 × 20 × 20 q-mesh (MP) for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB. The second-order force constant matrices was obtained. The force constant matrix is constructed using Phonopy. The symmetry reduction function is enabled to minimize redundant calculations, while built-in symmetry constraints ensure that the force constant matrix satisfies translational invariance. At the same time, the LESPILON = TRUE keyword is used in the article to account for LO-TO splitting and to calculate Raman and infrared spectra. And the Thirdorder program was utilized to perform 3 × 3 × 3 supercell calculations with 13 × 13 × 13 Monkhorst-Pack k-point for these materials, considering at least 13 neighboring atoms to ensure convergence. Subsequently, by integrating the second-order and third-order force constant matrices, the ShengBTE program was employed to evaluate the thermal transport properties of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB. For the calculation of Raman and IR spectroscopic properties, a methodology that combined Phonopy, Phono3py, and Phonopy-spectroscopy software was adopted [39].

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Crystal structure

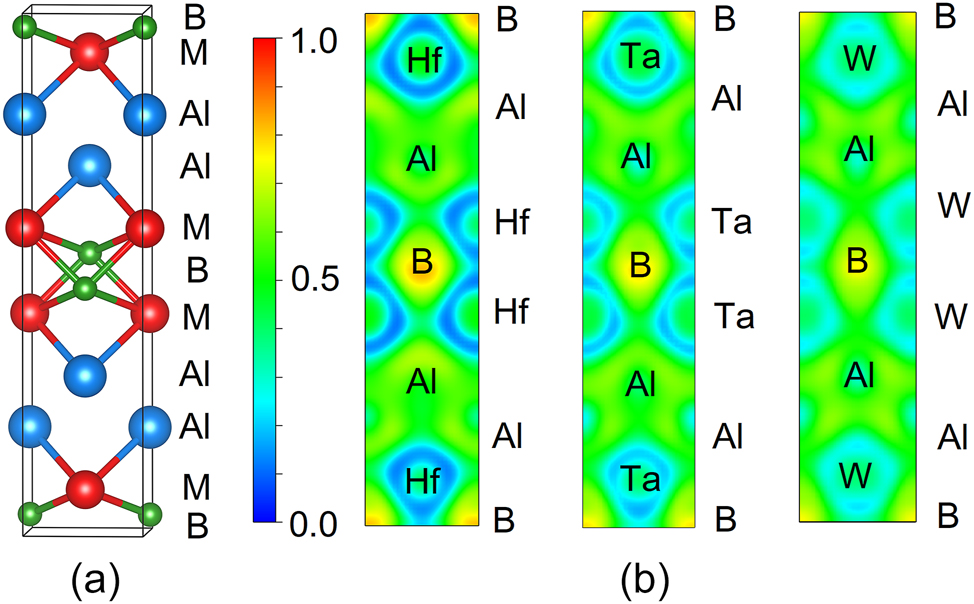

As illustrated in Figure 1(a), the schematic diagrams of the unit cells for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB are presented. These diagrams show a two-dimensional network of layers composed of metal M (depicted in red) and boron (shown in green) atoms, which alternate with aluminum (represented in blue) layers.

Structure diagram (a), and ELF (b) of HfAlB, TaAlB and WAlB.

The lattice parameters of MAlB are detailed in Table 1, with α = β = γ = 90°. For HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB, the values of parameters a and b exhibit a successive decrease as the M element transitions from Hf to Ta and then to W. This trend is closely related to the reduction in the atomic radius of the M element. The decrease in parameters a and b results in a closer packing of atoms along these directions, which in turn affects the chemical bonds and other related properties. This modification has the potential to cause changes in both the atomic arrangement density and the interlayer interactions. Additionally, parameter c decreases in the order of HfAlB, WAlB, and TaAlB. HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB exhibit a nanolayered ternary boride structure characterized by a space group of Cmcm (No. 63).

Calculated lattice parameters of MAlB materials.

| MAlB materials | a(Å) | b(Å) | c(Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HfAlB | 3.455 | 15.539 | 3.153 |

| TaAlB | 3.341 | 14.643 | 3.100 |

| WAlB | 3.220 | 13.999 | 3.123 |

The crystal structures HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB display distinctive features. From the perspective of crystal structural characteristics, the fundamental structural unit of the MAlB phase consists of network layers formed by transition metal M and B atoms, alternating with stacked Al atomic layers. This layered architecture is the underlying reason for the unique properties exhibited by MAlB compounds.

The transition metal M atoms are arranged in a prismatic configuration, with chains of B atoms positioned at the centers of these prisms, creating a distinctive prismatic coordination environment. This environment significantly influences the interactions between M and B, thereby impacting the overall properties of the material. In the MAlB structure, boron atoms form chain-like structures, where they are tightly bonded to one another through covalent bonds. This strong interaction provides a solid foundation for the structural stability and hardness of the material. Additionally, the two layers of Al atoms intercalated between the M−B layers play a crucial role. The aluminum layers not only facilitate close atomic bonding through metallic interactions but also contribute electrons, significantly affecting the material’s electrical conductivity and other physical properties.

In terms of bonding characteristics, the bonding nature of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB is relatively complex, resulting from a hybrid interaction of covalent, metallic, and ionic bonds. The covalent bonds between the metal and boron atoms within the M−B layers, as well as those among the boron atoms themselves, constitute the primary bonding interactions in the MAlB structure, endowing the material with high hardness and exceptional stability. The aluminum atoms within the aluminum layers are bonded through metallic bonds, which not only provide the material with excellent electrical conductivity but also, in conjunction with transition metal atoms, further enhance the overall strength and toughness of the material. Additionally, there is a degree of charge transfer between the M−B layers and the Al layers, resulting in ionic bonding. This ionic interaction contributes to the structural stability and influences the electronic properties of the material. As illustrated in Figure 1(b), the bonding characteristics on the MAlB (001) surface can be analyzed using the ELF. In the ELF distribution graph, different values represent specific electron behaviors. A value of 1 indicates that electrons are fully localized in one region. A value of 0.5 signifies that electrons are evenly delocalized, while a value of 0 means there are virtually no electrons present in that area [40]. Studies have found that in this structure, all the ions – M, Al, and B – are surrounded by a uniformly distributed electron “cloud,” represented by the green area in the graph. The B atoms are connected by covalent bonds, which are strong chemical bonds. The bond between M and B is also covalent but relatively weaker. Between M and Al, there exists a special type of electron “gas” exhibiting properties similar to those of a metallic bond. The presence of an M atom may disrupt the interaction between Al and B, thereby promoting the formation of localized electrons. However, due to this unique nano-layered ternary boride structure, Al can be easily exfoliated or etched to form MBene materials.

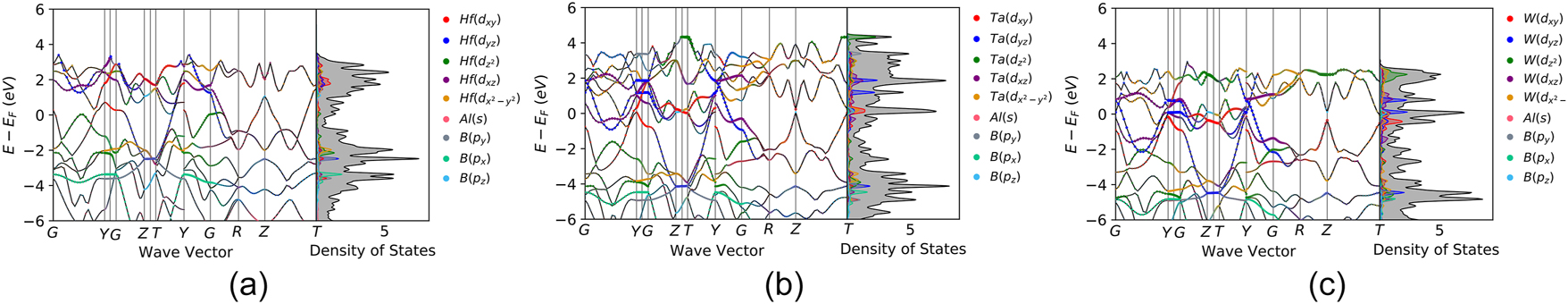

Electronic band of HfAlB (a), TaAlB (b), WAlB (c).

3.2 Electronic band properties

As shown in Figure 2, the electronic band diagrams of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB show no bandgap near the Fermi level, with multiple overlaps between the valence band and the conduction band, confirming their metallic nature. The projected density of states (PDOS) analysis for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB indicates that the density of states (DOS) near the Fermi level is primarily contributed by the d-orbital electrons of Hf, Ta, and W, with a minor contribution from the p-orbitals of B, while the contribution from Al is negligible. This suggests that the first three elements significantly influence the electrical conductivity of MAlB materials. Within the energy range of the valence band near the Fermi level, the hybridization between the p-orbital of B and the d-orbitals of hafnium (Hf), tantalum (Ta), and tungsten (W) is stronger than that between the p-orbital of Al and the d-orbitals of Hf, Ta, and W. This suggests that there is a stronger covalent bonding between Hf, Ta, W, and B. Such differences in bonding may influence the elastic modulus of the materials, as stronger covalent bonds typically enhance hardness and stiffness. Although HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB share similar crystal structures, subtle differences exist in their energy band structures and density of states (DOS) due to the unique electronic configurations of the transition metals Hf, Ta, and W. These differences may subsequently affect their electrical conductivity, thermal stability, and mechanical properties.

3.3 Crystal stability

3.3.1 Phonon dispersion

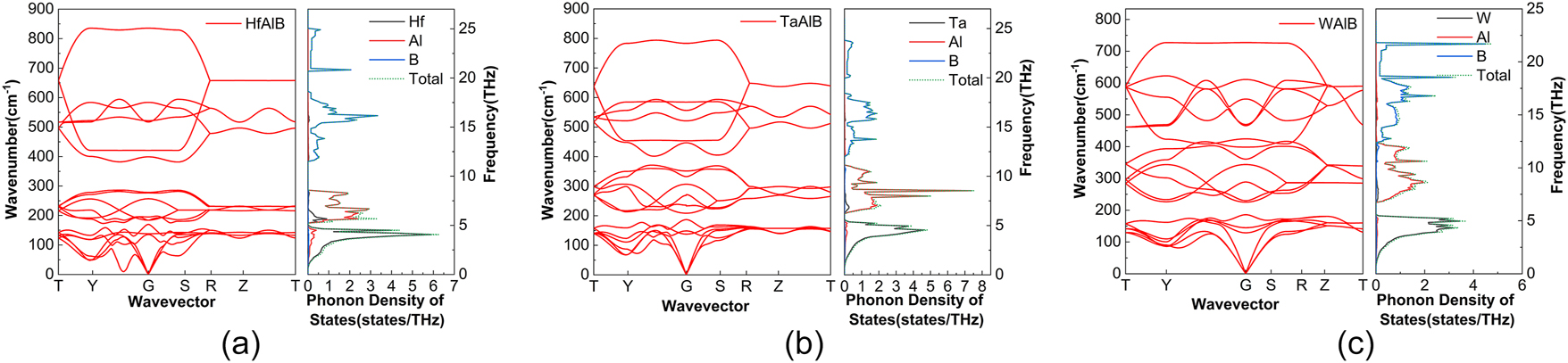

As shown in Figure 3, the phonon dispersion of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB show no imaginary frequencies, indicating their dynamical stability. The primitive cells of these compounds consist of 2 metal (Hf, Ta, or W) atoms, 2 Al atoms, and 2 B atoms. Their phonon dispersion include 3 acoustic branches and 15 optical branches. The acoustic branches exhibit approximately linear behavior near the Γ point, which is consistent with the characteristics of typical acoustic modes. In HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB, the lower vibrations are primarily attributed to the M and Al atoms, while the high-frequency region is predominantly influenced by the lighter B atoms. This indicates that B atoms, due to their small mass and strong covalent bonds, tend to vibrate at higher frequencies, whereas the heavier M and Al atoms dominate the low-frequency acoustic branches. The relatively low mass and strong bonding of B atoms result in high vibrational frequencies, while the heavier Hf, Ta, and W atoms exhibit lower vibrational frequencies. This characteristic presents significant potential for tuning the phonon bandgap by adjusting the types or ratios of atoms, thereby influencing the material’s thermal properties, such as thermal conductivity and the coefficient of thermal expansion.

Phonon dispersion of HfAlB (a), TaAlB (b), WAlB (c).

3.3.2 Mechanical stability

The mechanical stability assessment of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB materials with the Cmcm (No. 63) structure is presented in Table 2. In the Cmcm crystal system, nine independent elastic constants – C 11, C 12, C 13, C 22, C 23, C 33, C 44, C 55, and C 66 – are critical. Ensuring that a material satisfies the conditions outlined in Equation (1) is a fundamental step in confirming its mechanical stability, which is essential for the practical application and further development of these materials. The detailed calculation results of the elastic constants for these three materials, presented in Table 2, indicate that HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB all satisfy the prerequisites for achieving mechanical stability, confirming their mechanical stability.

Calculated material elastic constants.

| Materials | C11 | C12 | C13 | C22 | C23 | C33 | C44 | C55 | C66 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HfAlB | 248.71 | 103.29 | 83.78 | 177.05 | 79.94 | 326.80 | 102.61 | 136.95 | 92.59 |

| TaAlB | 293.68 | 139.02 | 159.07 | 272.57 | 117.28 | 359.59 | 162.62 | 181.11 | 179.39 |

| WAlB | 356.27 | 156.25 | 175.33 | 351.71 | 146.09 | 397.70 | 194.70 | 169.41 | 180.79 |

3.4 Lattice thermal conductivity

In fact, the temperature gradient ∇T can produce a non-zero heat flux J. In the linear range, the thermal conductivity κ is defined by the equation

where p is the category identifier of the phonon branch. q is the wave vector. The variable ω

λ employed to denote the angular frequency of phonon mode λ,

v

λ

denotes the group velocity of phonon mode λ, and f

λ

is the phonon distribution function. In the case of thermal equilibrium with no temperature gradient, phonons are distributed according to Bose–Einstein statistics

Here

The relaxation time of the mode obtained through perturbation theory is denoted as

where

Among them, f

λ′ is the abbreviation for

These phonons adhere to the law of conservation of energy and momentum. By incorporating concepts such as phonon group velocity and phonon relaxation time, the lattice thermal conductivity κ l is ultimately calculated as follows [41]:

where N is the number of sampled q points in the Brillouin zone, and V is the volume of the unit cell. k

B

is the Boltzmann constant. T is absolute temperature.

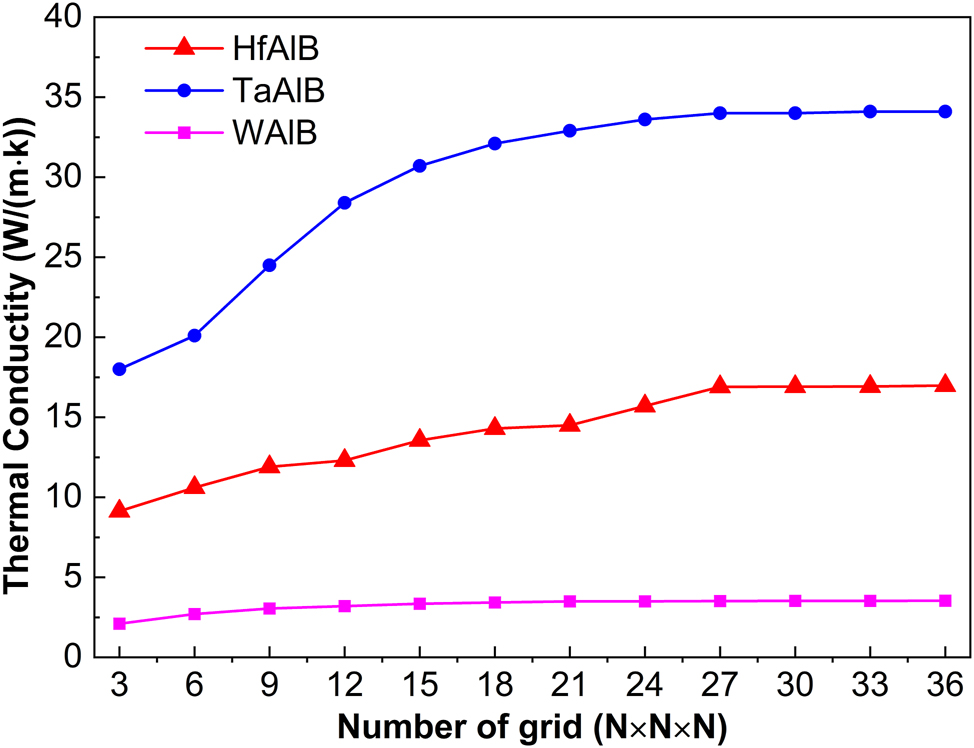

As shown in Figure 4, the variation of thermal conductivity values of MAlB with different grid densities during the solution process of the BTE. The inset illustrates the thermal conductivity of WAlB for clarity. The results indicate that when the grid density in all three dimensions is N × N × N ≥ 27 × 27 × 27, the fluctuation in thermal conductivity remains stable within 3 %. To ensure calculation accuracy, this paper selects a grid density of 35 × 35 × 35. And the final result can be compared to similar materials found in the reference [42].

Convergence test for mesh density.

3.4.1 Thermal conductivity

There is a physical relationship between

Figure 5 illustrates the cumulative variation trend of lattice thermal conductivity in relation to the phonon mean free path (MFP) for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB at a temperature of 300 K. Material size is a critical factor influencing lattice thermal conductivity. For these three materials – HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB – when the phonon mean free paths exceed 231.0 nm, 278.3 nm, and 2,595.0 nm, respectively, their lattice thermal conductivity remain constant. This phenomenon indicates that the phonons primarily responsible for heat conduction have mean free paths that are smaller than the corresponding critical dimensions. When the material sizes exceed these critical dimensions (231.0 nm, 278.3 nm, and 2,595.0 nm), the lattice thermal conductivity of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB show minimal changes, with almost no observable phonon scattering, leading to a stabilization of the lattice thermal conductivity. Ultimately, the lattice thermal conductivity of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB stabilize at 16.9 W/(m K), 34.0 W/(m K), and 3.5 W/(m K), respectively.

Lattice thermal conductivity of HfAlB (a), TaAlB (b), WAlB (c).

3.4.2 Phonon relaxation time

The phonon relaxation time τ

λ

is determined by the reciprocal of the anharmonic scattering rate of three phonons, while

where

As shown in Figure 6(a)–(c), the results demonstrate the variation of relaxation times with frequency for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB at 300 K. In Figure 6(a), it is evident that the relaxation times of the acoustic branches for HfAlB are greater than those of the optical branches. Notably, the LA mode displays the longest relaxation time of 185.6 ps. The phonon relaxation times for the TA1 and TA2 modes are relatively short, all measuring below 68.1 ps. Within the frequency range of 3.1–25.1 THz, the phonon relaxation times are primarily influenced by the optical branches, with all values remaining below 21.4 ps.

Phonon relaxation time of HfAlB (a), TaAlB (b), WAlB (c).

It can be observed from Figure 6(b) that TaAlB exhibits shorter relaxation times compared to HfAlB. In TaAlB, the relaxation times associated with the majority of its acoustic branches are longer than those of its optical branches, with only a small fraction of the optical branches attaining significantly high relaxation times. Specifically, the relaxation time for the LA mode of TaAlB is less than 130.9 ps. The phonon relaxation times for both the TA1 and TA2 modes are relatively large, remaining below 152.3 ps. Within the frequency range of 3.4–23.6 THz, the phonon relaxation times of TaAlB are primarily influenced by its optical branches, all of which stay below the maximum value of 49.7 ps.

It can be observed from Figure 6(c) that WAlB exhibits significantly shorter relaxation times compared to both HfAlB and TaAlB. For WAlB, the relaxation times for most of its acoustic branches are comparable to those of its low optical branches, with only a few acoustic branches reaching notably high values. Specifically, the relaxation time for the TA1 mode of WAlB is below 77.6 ps. The phonon relaxation times for both the TA2 and LA modes are relatively short, remaining below 57.5 ps. Within the frequency range of 3.4–21.6 THz, the phonon relaxation times of WAlB are primarily influenced by its optical branches, all of which remain below the peak value of 59.5 ps.

At 300 K, the TA1, TA2, LA, and optical phonons of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB all demonstrate relatively high relaxation times. The extended phonon relaxation times suggest that phonons significantly contribute to the thermal transport process over longer durations. As a result, this enhances the lattice thermal conductivity. On the whole, although mid-to-high frequency optical phonon modes contribute to thermal transport, the lattice thermal conductivity is primarily dominated by contributions from acoustic phonon modes and low-frequency optical modes. As shown in the figures, the relaxation times for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB generally follow the trend of τ HfAlB > τ TaAlB > τ WAlB. However, this trend does not completely align with the conclusions drawn from their thermal conductivity patterns.

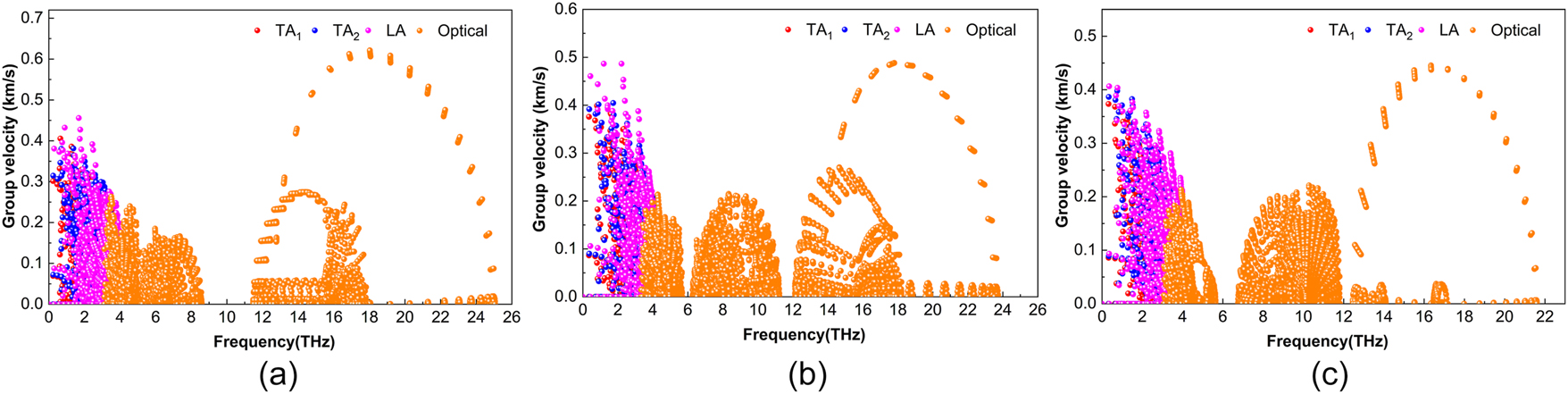

3.4.3 Phonon group velocity

The phonon group velocity υ is the derivative of frequency with respect to the wave vector, which is a crucial factor in evaluating heat transport capacity. The phonon group velocity can be calculated from the trend of the phonon dispersion [45].

As shown in Figure 7, the phonon group velocities of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB are quite similar. In Figure 7(a), the acoustic branches TA1, TA2, and LA of HfAlB exhibit low group velocities, predominantly concentrated near 2 THz. Among these, the TA2 mode shows the lowest phonon group velocity, with a peak value of approximately 0.38 km/s. In the low-frequency domain, the LA mode exhibits the highest group velocity, with certain phonons reaching speeds of up to 0.46 km/s. Meanwhile, a limited number of phonons in the TA1 mode achieve group velocities of approximately 0.41 km/s. Optical phonons within the frequency range of 3.1–8.6 THz have group velocities lower than those of acoustic phonons, with a maximum value of 0.26 km/s. In contrast, optical branches in the high-frequency region, spanning 11.5 to 25.1 THz, exhibit higher group velocities, reaching a maximum of 0.62 km/s.

Phonon group velocity of HfAlB (a), TaAlB (b), WAlB (c).

As shown in Figure 7(b) for TaAlB, the acoustic branches TA1, TA2, and LA exhibit slightly elevated group velocities, with most velocities concentrated around 2.5 THz. Among these, the LA mode has the highest phonon group velocity, reaching approximately 0.49 km/s. In the low-frequency region, several phonons in the TA1 mode achieve a group velocity of 0.39 km/s, and a similar velocity is observed for a small fraction of phonons in the TA2 mode, closely approaching the maximum value of the TA1 mode. The optical phonons near 4.3 THz exhibit group velocities of 4.3 km/s, which are lower than those of the acoustic phonons. Within the frequency range of 6.3–11.2 THz, the group velocities of certain optical branches reach a partial maximum of 0.21 km/s. In contrast, the optical branches in the high-frequency region, from 12.1 to 23.7 THz, attain a significantly higher maximum group velocity of 0.49 km/s.

As depicted in Figure 7(c), WAlB generally exhibits lower phonon group velocities compared to HfAlB and TaAlB. The group velocities of the TA1, TA2, and LA modes in WAlB are comparable to those of the high-frequency optical branches, predominantly clustered around 2.6 THz. Among these modes, the LA mode shows the highest phonon group velocity, reaching a maximum value of approximately 0.41 km/s. In the low-frequency region, the TA1 mode displays a relatively slow group velocity, with only a limited number of phonons achieving a velocity of 0.37 km/s. A similar group velocity, approximately 0.39 km/s, is observed for a small fraction of phonons in the TA2 mode. The group velocities of the optical branches within the frequency range of 3.2–5.6 THz are notably low, with a maximum value of only 0.21 km/s. As the frequency range shifts to 6.8 to 11.8 THz, the group velocities of the optical phonons increase slightly, reaching a maximum of 0.22 km/s. In contrast, the optical branches in the high-frequency region, spanning 12.5 to 21.6 THz, exhibit significantly higher group velocities, peaking at 0.45 km/s. This variation in group velocities across different frequency ranges provides valuable insights into the dynamic behavior of optical phonons in the material.

Overall, the relationship among the phonon group velocities associated with the TA1, TA2, and LA modes of the three materials is as follows: ν TaAlB > ν HfAlB > ν WAlB. The results align with the experimental findings concerning their thermal conductivity.

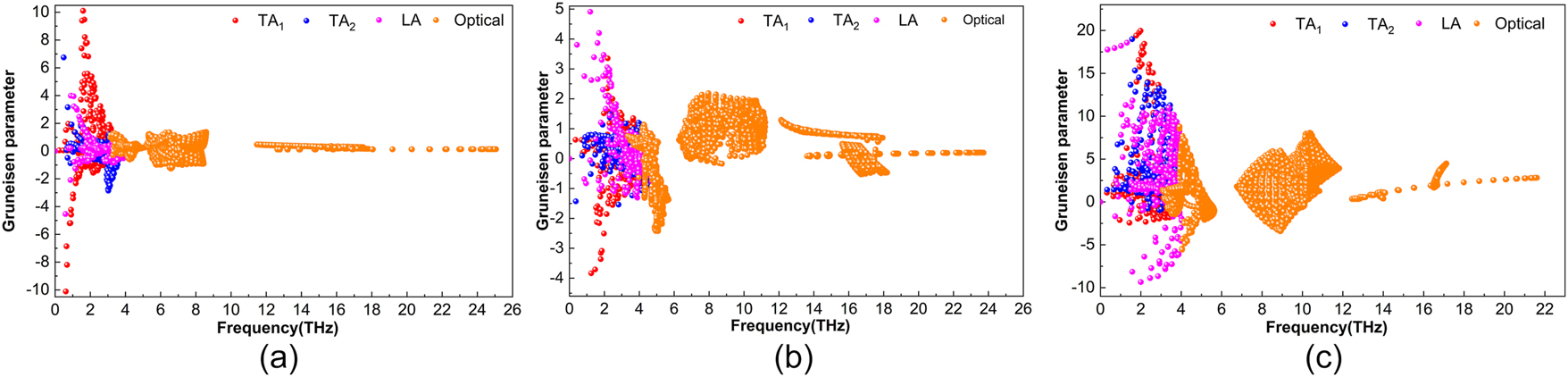

3.4.4 Grüneisen parameter

In equations (7) and (8),

Here, i, j, and k are atomic indices, while α, β, and γ denote Cartesian coordinates. In the summation process, i runs only over the atoms in the central unit cell, while j and k cover the entire system. −λ″ is the abbreviated form of

q

and

R

. M

i

represents the mass of the i-th atom.

where

where k is the atomic index in unit cell l′. At the same time, the strength of the interaction is typically determined by the anharmonicity interaction, which is characterized by the Grüneisen parameter (γ). This means the greater the anharmonicity, the stronger the phonon-phonon interaction, and the lower the thermal conductivity of the lattice.

Figure 8(a)–(c) illustrate the γ parameters for various phonon modes of the HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB materials, respectively. Both the acoustic and optical phonons of HfAlB and TaAlB exhibit relatively low absolute values of γ. In contrast, WAlB demonstrates a significantly higher absolute value of γ. For HfAlB and TaAlB, the highest absolute values of γ, approximately 10.1 and 4.9, are associated with the TA1 and LA mode respectively. This indicates that these two compounds exhibit relatively weaker anharmonicity compared to WAlB. Additionally, the absolute value of γ in the optical mode is slightly lower for HfAlB, reaching a maximum of 1.38, while for TaAlB, it is comparatively lower in the optical mode, with a peak value of 2.43.

Grüneisen parameter of HfAlB (a), TaAlB (b), WAlB (c).

In contrast, the WAlB material demonstrates an exceptionally high maximum absolute value of γ, reaching 19.96, which is associated with the TA1 mode. The absolute values of γ for the TA2 and LA modes are relatively smaller, ranging from 0 to 4.1 THz, with maximum values of 18.98 and 18.57, respectively. For the optical branches distributed within the frequency range of 3.2 THz to 21.6 THz, the maximum absolute value of γ is 8.79, indicating significant anharmonicity in WAlB. Furthermore, there is an overlap between the acoustic and optical branches in WAlB, which corresponds to the phonon dispersion diagram presented earlier. This overlap also suggests potential crossings between the acoustic and optical branches, which may lead to increased scattering and a possible reduction in lattice thermal conductivity.

The pronounced peaks observed in WAlB are likely attributed to stronger anharmonic vibrations of atoms within its lattice, which lead to intense phonon-phonon scattering and, consequently, high anharmonicity. WAlB exhibits particularly strong anharmonicity, enhancing phonon scattering and thereby reducing the thermal conductivity of the WAlB compound. In contrast, HfAlB and TaAlB exhibit the opposite behavior, as their relatively lower anharmonicity contributes to higher thermal conductivity. Notably, the distribution of γ values in TaAlB appears more dispersed. Furthermore, the high

In general, when examining the Grüneisen parameters (γ) of the MAlB compounds, the relationship is as follows: |γ WAlB| > |γ HfAlB| > |γ TaAlB|, with |γ WAlB| being significantly larger than both |γ HfAlB| and |γ TaAlB|. This trend partially aligns with the conclusions drawn from thermal conductivity measurements. Interestingly, |γ HfAlB| is greater than |γ TaAlB|, then the lattice thermal conductivity of HfAlB is lower than that of TaAlB. This observation contradicts the assumption that lattice thermal conductivity would decrease sequentially according to the order of the metal M elements in the periodic table (Hf, Ta, W). This observation suggests a potential antagonistic relationship among the Grüneisen parameter, phonon relaxation time, and phonon group velocity. For the three materials – HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB – the Grüneisen parameter appears to be a dominant factor influencing their lattice thermal conductivity, although phonon relaxation time and group velocity also contribute to some extent. Based on the thermal conductivity data, TaAlB and HfAlB may be more suitable for thermal conduction applications, whereas WAlB, with its lower thermal conductivity, is better suited for thermal barrier coating materials.

3.4.5 Variation of lattice thermal conductivity with temperature

The variation in lattice thermal conductivity of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB with temperature is shown in Figure 9. Specifically, at 200 K, the thermal conductivity values for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB are 24.4 W/(m K), 52.0 W/(m K), and 5.7 W/(m K), respectively. In contrast, when the temperature increases to 950 K, these values decrease to 13.7 W/(m K), 6.1 W/(m K), and 1.1 W/(m K), respectively. Analysis of the thermal conductivity data reveals a consistent trend: as temperature increases, the lattice thermal conductivity of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB initially decreases gradually and eventually stabilizes. This behavior can be attributed to the following mechanism: elevated temperatures induce more intense lattice vibrations, which increase the likelihood of phonon-phonon scattering and the frequency of phonon collisions. Additionally, anharmonic effects within the materials are enhanced at higher temperatures. Together, these factors cause the thermal conductivity curve to gradually flatten.

The variation of lattice thermal conductivity in HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB with temperature.

4 Infrared and Raman spectra

The phonon vibrational frequencies via DFPT method [46]. The infrared intensity of a phonon eigenmode is given by the square of the scalar product between the Born effective charge tensor and the normalized eigenvector, as defined in equation:

where

In equation (15), the I

αβ was used in place of

There are three types of irreducible representations for the acoustic branches, corresponding to three lattice waves:

There are 15 irreducible representations for the optical branches, corresponding to 15 lattice waves.

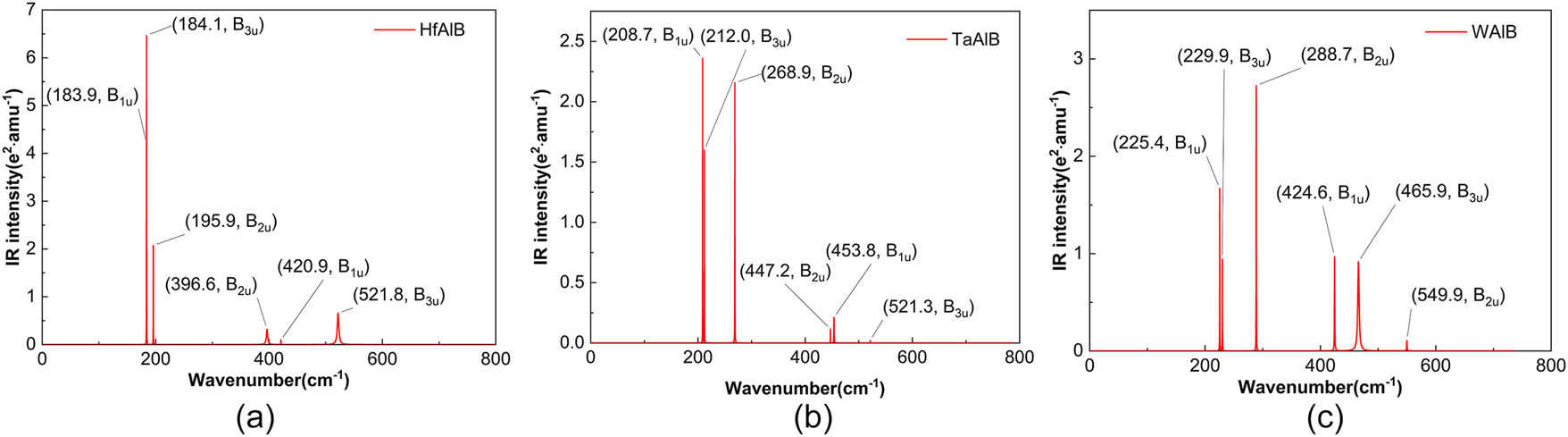

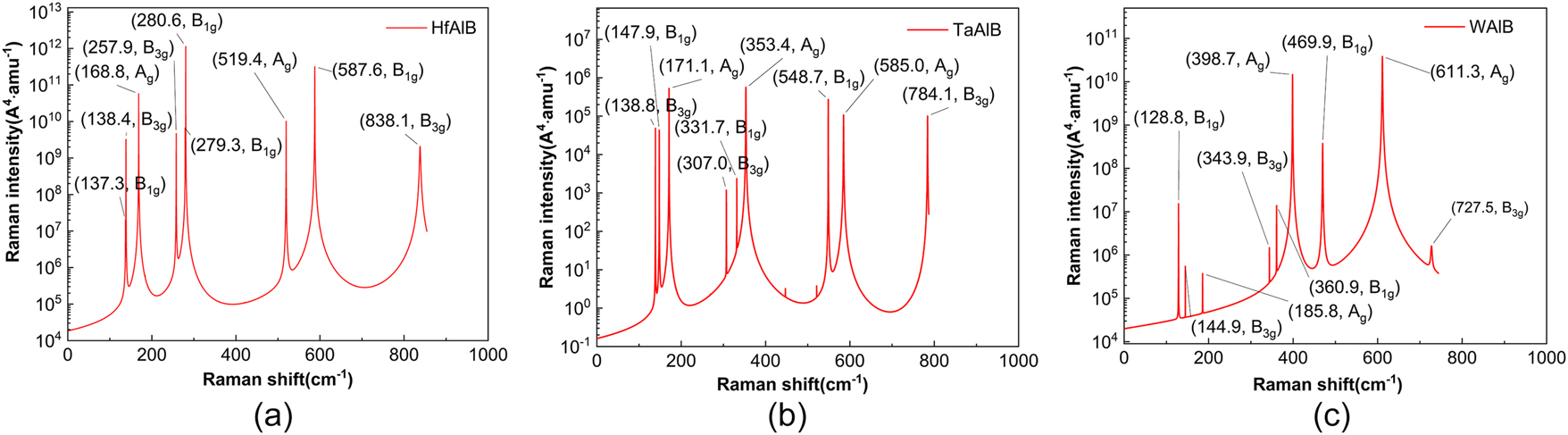

Based on the character tables of the point groups, it can be observed that among the optical modes of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB, there are a total of six infrared-active modes: 2B1u+ 2B2u+ 2B3u. Additionally, there are nine Raman-active modes: 3Ag+ 3B1g + 3B3g. Following structural optimization, we calculated the phonon dispersion and infrared/Raman spectra of the ternary borides HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB, as shown in Figures 10 and 11.

Infrared spectra of HfAlB (a), TaAlB (b), WAlB (c).

Raman spectra of HfAlB (a), TaAlB (b), WAlB (c).

4.1 Infrared spectra

Figure 10(a) illustrates the positions and vibration intensities of the six infrared vibrational mode peaks for the HfAlB material. Among these, the modes at 184.1 cm−1(B3u) and 195.9 cm−1(B2u) in the HfAlB structure exhibit strong infrared vibration intensities and are easily distinguishable. The modes at 195.9 cm−1(B2u), 396.6 cm−1(B2u), and 521.8 cm−1(B3u) display lower infrared vibration intensities but can still be clearly identified. The mode at 420.9 cm−1(B1u) exhibits a relatively low infrared vibrational intensity, necessitating careful observation for accurate identification. Furthermore, the infrared peak of the 183.9 cm−1(B1u) mode is very close to that of the 184.1 cm−1(B3u) mode, rendering them nearly indistinguishable from one another.

Figure 10(b) illustrates the positions and vibration intensities of the six infrared vibrational mode peaks for the TaAlB material. Among these modes in the TaAlB structure, those at 208.7 cm−1(B1u), 212.0 cm−1(B3u), and 268.9 cm−1(B2u) demonstrate strong infrared vibration intensities and are easily identifiable. In contrast, the modes at 447.2 cm−1(B2u), 453.8 cm−1(B1u), and 521.3 cm−1(B3u) exhibit lower infrared vibrational intensities, yet they remain distinguishable. The peaks at 208.7 cm−1(B1u) and 212.0 cm−1(B3u) are closely spaced, requiring careful discrimination to differentiate between them.

Figure 10(c) illustrates the positions and vibration intensities of the six infrared vibrational mode peaks for the WAlB material. Among these modes in the WAlB structure, those at 225.4 cm−1(B1u), and 288.7 cm−1(B2u) demonstrate relatively strong infrared vibration intensities and are comparatively easier to identify. The modes at 229.9 cm−1(B3u), 424.6 cm−1(B1u), and 465.9 cm−1(B3u) exhibit lower infrared vibrational intensities but are still identifiable. The mode at 549.9 cm−1(B2u) also presents a low infrared vibrational intensity, requiring careful observation for accurate identification. Notably, the infrared peak of the 225.4 cm−1(B1u) mode is very close to that of the 229.9 cm−1(B3u) mode, necessitating meticulous scrutiny and confirmation to differentiate between the two peaks.

From a structural perspective, MAlB exhibits a layered architecture, consisting of alternating metal layers (M/Al) and boron layers. Within this structure, the boron atoms can form chain-like or two-dimensional network configurations. In terms of vibrational characteristics, low-frequency vibrations are primarily induced by interlayer shearing or out-of-plane vibrations of the metal M atomic layers, with these vibrational modes predominantly influenced by metallic bonding interactions. Mid- to high-frequency vibrations are significantly contributed to by the vibrations of M atoms, Al atoms, and B atoms. These vibrations may arise from weak metal-boron interactions between M/Al and B, such as lateral vibrations of M-B/Al–B bonds, or from in-plane bending and torsional vibrations of boron chains. Within the mid-frequency range, these vibrations exhibit coupling effects. The high-frequency vibrations primarily originate from the movements of B atoms, especially those related to the stretching of the strong covalent bonds between B–B atoms.

4.2 Raman spectra

As shown in Figure 11(a), the HfAlB material exhibits nine Raman-active modes at specific frequencies: 137.3 cm−1(B1g), 138.4 cm−1(B3g), 168.8 cm−1(Ag), 257.9 cm−1(B3g), 279.3 cm−1(B1g), 280.6 cm−1(B1g), 519.4 cm−1(Ag), 587.6 cm−1(B1g), and 838.1 cm−1(B3g). Figure 10(a) presents the detailed peak positions and intensities of the Raman vibrational modes. Among these modes, the cases where 137.3 cm−1(B1g) is very close to 138.4 cm−1(B3g) and 279.3 cm−1(B1g) is near 280.6 cm−1(B1g) result in mutual masking, making these particular modes difficult to distinguish. In contrast, the other modes exhibit relatively high vibrational intensities and are easily identifiable.

As shown in Figure 11(b), the TaAlB material exhibits nine Raman-active modes at the following frequencies: 138.8 cm−1(B3g), 147.9 cm−1(B1g), 171.1 cm−1(Ag), 307.0 cm−1(B3g), 331.7 cm−1(B1g), 353.4 cm−1(Ag), 548.7 cm−1(B1g), 585.0 cm−1(Ag), and 784.1 cm−1(B3g). Figure 10(b) presents the detailed peak positions and intensities of the Raman vibrational modes. Among these modes, the peaks at 138.8 cm−1(B3g) and 147.9 cm−1(B1g) are in close proximity, necessitating careful discrimination to differentiate between them. All nine Raman modes of the TaAlB material exhibit relatively high vibrational intensities and are easily distinguishable. As illustrated in Figure 10(b), the Raman spectrum also reveals several “spikes” (minor peaks) that may only become apparent or identifiable with advanced Raman spectroscopy equipment.

As shown in Figure 11(c), the WAlB material exhibits nine Raman-active modes at the following frequencies: 128.8 cm−1(B1g), 144.9 cm−1(B3g), 185.8 cm−1(Ag), 343.9 cm−1(B3g), 360.9 cm−1(B1g), 398.7 cm−1(Ag), 469.9 cm−1(B1g), 611.3 cm−1(Ag), and 727.5 cm−1(B3g). Figure 10(c) illustrates the specific peak positions and intensities of the Raman vibrational modes. Among these modes, the peaks at 128.8 cm−1(B1g), 398.7 cm−1(Ag), 469.9 cm−1(B1g), and 611.3 cm−1(Ag) are easily distinguishable due to their relatively high intensities. The peaks at 144.9 cm−1(B3g), 185.8 cm−1(Ag), 343.9 cm−1(B3g), and 360.9 cm−1(B1g) are relatively weak, but they can still be accurately distinguished. Although the peak at 727.5 cm−1(B3g) has a lower intensity, it remains identifiable because it is sufficiently separated from the other peaks.

From a holistic perspective, there is a notable similarity between Raman spectra and infrared (IR) spectra. The presence of lower vibrational frequencies can primarily be attributed to the relatively large masses of the metal M and Al atoms, as well as the bending vibrations of M−Al bonds. In the mid-frequency range, it is hypothesized that these vibrations may arise from interactions between the metallic M layers and the boron layers, or from the in-plane bending and torsional vibrations of B–B chains. On the other hand, high-frequency vibrations are likely associated with the stretching vibrations of strong covalent bonds between B atoms, as well as the coupled vibrations of Al and B atoms. In high-frequency vibrations, the contributions from the vibrations of metal M atoms and Al atoms are relatively minor. This may be due to the strength of the M−B bonds and the relatively low mass of the B atoms, which results in these stretching vibration modes exhibiting higher vibrational frequencies.

Through the Raman spectroscopic analysis of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB materials, we can derive characteristics closely related to lattice vibrational properties (phonon behavior). These characteristics can indirectly reflect the influence of phonon transport efficiency, scattering mechanisms, and lattice dynamics on the thermal conductivity of HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB materials. The Raman spectra of HfAlB and TaAlB materials display a series of sharp low-frequency phonon peaks at 137.3 cm−1(B1g), 138.4 cm−1(B3g), 168.8 cm−1(Ag) of HfAlB and 138.8 cm−1(B3g), 147.9 cm−1(B1g), 171.1 cm−1(Ag) of TaAlB, all exhibiting relatively high vibrational intensities. This observation suggests that phonons encounter minimal scattering as they propagate through the HfAlB and TaAlB lattices, which facilitates thermal conduction and contributes to the attainment of higher lattice thermal conductivity. In contrast, the Raman spectrum of the WAlB material exhibits low-frequency peaks at 128.8 cm−1(B1g), 144.9 cm−1(B3g), and 185.8 cm−1(Ag), each with significant vibrational intensities. This finding reflects the low thermal conductivity of WAlB and illustrates the strong connection between Raman spectroscopy and thermal conductivity.

5 Conclusions

The study reveals that HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB are layered ternary borides belonging to the Cmcm space group, exhibiting metallic properties. Their performance is influenced by a combination of M−B covalent bonds, metallic bonds within the aluminum layers, and interlayer ionic bonds. phonon dispersion indicate that these materials are dynamically stable, with boron atoms primarily contributing to high-frequency vibrations, while M/Al atoms predominantly govern low-frequency vibrations. Additionally, lattice thermal conductivity is significantly affected by anharmonicity. TaAlB (34.0 W/(m K)) and HfAlB (16.9 W/(m K)) exhibit high thermal conductivity due to their weak anharmonicity and long phonon relaxation times. In contrast, WAlB (3.5 W/(m K)) shows significant phonon scattering as a result of strong anharmonicity, which leads to its lower thermal conductivity. In the Raman spectra, each of the three materials displays nine active modes. The low-frequency modes correspond to M/Al vibrations, while the high-frequency modes are associated with the covalent bonds of B atoms. The presence of strong low-frequency peaks in HfAlB and TaAlB indicates minimal phonon scattering, which is consistent with their thermal conductivity results. This research offers theoretical guidance for the application of MAlB materials in high-temperature structural components, electronic thermal management, and thermal barrier coatings.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Dr. Juliusz Skoryna and all the editors and reviewers for their kind support and insightful feedback.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Research Project of Henan Province Science and Technology (grant number 252102230086) and the Interdisciplinary Sciences Project of Nanyang Institute of Technology (grant number 230072).

-

Author contributions: Shengzhao Wang: investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Jinfan Song: conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal). Bin Liu: formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal). All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

1. Potanin, AY, Bashkirov, EA, Karpenkov, AY, Levashov, EA. Fabrication of high-strength magnetocaloric Fe2AlB2 MAB phase ceramics via combustion synthesis and hot pressing. Materialia 2024;33:101993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtla.2023.101993.Search in Google Scholar

2. Wang, Z, Qin, S, Gao, J, Mao, J, Wang, M, Xin, B, et al.. Microstructure evolution of MAB-phase WAlB during helium irradiation and post-irradiation annealing. Ceram Int 2025;51:1674–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.11.143.Search in Google Scholar

3. Zhang, Y, Zhang, G, Wang, T, Wang, C, Xie, Z, Wang, W, et al.. Synthesis, microstructure and properties of MoAlB MAB phase films. Ceram Int 2023;49:23714–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.04.207.Search in Google Scholar

4. Samanta, B, Dilanga Siriwardane, EM, Çakır, D. Ab initio prediction of phase stability of quaternary Mo1−xMxAlB (M = Cr, Fe, Mn, Nb, Sc, Ta, Ti, V, and W) MAB solid solutions. J Appl Phys 2024;136:065104. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0214978.Search in Google Scholar

5. Lu, Z, Qi, X, He, X, Zhang, J, Fan, Y, Yin, H, et al.. Lattice dynamics, Raman and IR vibrations of stable Al/Si-containing MAB phases: an ab initio and experimental study. J Am Ceram Soc 2024;107:6853–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.19954.Search in Google Scholar

6. Rezaie, AA, Yan, Z, Scheifers, JP, Zhang, J, Guo, J, Fokwa, BPT. Synthesis and Li-ion electrode properties of layered MAB phases Nin+1ZnBn (n = 1, 2). J Mater Chem A 2020;8:1646–51. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TA12937E.Search in Google Scholar

7. Zhang, D, Richardson, P, Wang, M, He, L, Shi, L, Gao, J. Experimental and theoretical investigation of the damage evolution of irradiated MoAlB and WAlB MAB phases. J Alloys Compd 2023;942:169099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.169099.Search in Google Scholar

8. Muhammad, Z, Usman, M, Ullah, S, Zhang, B, Lu, Q, Zhu, L, et al.. Lattice dynamics, optical and thermal properties of quasi-two-dimensional anisotropic layered semimetal ZrTe2. Inorg Chem Front 2021;8:3885–92. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1qi00553g.Search in Google Scholar

9. Zhang, X, Zhou, J, Fu, W, Chen, L. Research on materials of solar selective absorption coating based on the first principle. Open Phys 2021;19:477–85. https://doi.org/10.1515/phys-2021-0037.Search in Google Scholar

10. Akande, SO, Samanta, B, Sevik, C, Cakir, D. First-principles investigation of mechanical and thermal properties of MAlB (M = Mo, W), Cr2AlB2, and Ti2InB2. Phys Rev Appl 2023;20:044064. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.20.044064.Search in Google Scholar

11. Wang, C, Wang, H, Chen, YB, Yao, S-H, Zhou, J. First-principles study of lattice thermal conductivity in ZrTe5 and HfTe5. J Appl Phys 2018;123:175104. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5020615.Search in Google Scholar

12. Muthaiah, R, Tarannum, F, Annam, RS, Nayal, AS, Danayat, S, Garg, J. Thermal conductivity of hexagonal BC2P – a first-principles study. RSC Adv 2020;10:42628–32. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0ra08444a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Liu, G, Sun, HY, Zhou, J, Li, QF, Wan, X-G. First-principles study of lattice thermal conductivity of Td–WTe2. New J Phys 2016;18:033017. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/18/3/033017.Search in Google Scholar

14. Ren, Q, Li, Y, Lun, Y, Tang, G, Hong, J. First-principles study of the lattice thermal conductivity of the nitride perovskite LaWN3. Phys Rev B 2023;107:125206. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.107.125206.Search in Google Scholar

15. Peng, Q, Yuan, X, Zhao, S, Chen, X-J. Lattice thermal conductivity of Mg3(Bi,Sb)2 nanocomposites: a first-principles study. Nanomaterials 2023;13:2938. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13222938.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Kirtley, J, Leichner, V, Anderson, BR, Eilers, H. A comparison of pulsed and continuous lasers for high‐temperature Raman measurements of anhydrite. J Raman Spectrosc 2018;49:862–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.5356.Search in Google Scholar

17. Song, D, Ryu, M, Pyeon, J, Jeon, H-B, Song, T, Paik, U, et al.. Phase-reassembled high-entropy fluorites for advanced thermal barrier materials. J Mater Res Technol 2023;23:2740–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.01.170.Search in Google Scholar

18. Liu, F, Wei, Z, Hu, X, Cai, Y, Chen, Z, Yang, C, et al.. Asymmetric segregated network design of ultralight and thermal insulating polymer composite foams for green electromagnetic interference shielding. Compos Commun 2023;38:101492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coco.2022.101492.Search in Google Scholar

19. Mondal, S, Roy, C, Bhattacharyya, S. Unravelling formation mechanism, thermal and oxidation stabilities of layered sub-micron MAB phase WAlB synthesized at open atmosphere. Mater Today Chem 2024;37:102004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtchem.2024.102004.Search in Google Scholar

20. Zhang, H, Ren, G, Jia, P, Zhao, X, Ni, N. Development of machine learning force field for thermal conductivity analysis in MoAlB: insights into anisotropic heat transfer mechanisms. Ceram Int 2024;50:13740–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.01.288.Search in Google Scholar

21. Merz, J, Cuskelly, D, Richardson, P. MAB phase-alumina composite formation via aluminothermic exchange reactions. Mater Lett 2024;360:135869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2024.135869.Search in Google Scholar

22. Li, X-H, Cui, H-L, Yong, Y-L, Zhang, R-Z. Theoretical investigation of electronic, bonding and optical properties of nanolaminated boride WAlB. Mater Chem Phys 2018;212:122–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2018.03.048.Search in Google Scholar

23. Liu, Y, Jiang, Z, Jiang, X, Zhao, J. New refractory MAB phases and their 2D derivatives: insight into the effects of valence electron concentration and chemical composition. RSC Adv 2020;10:25836–47. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0ra04385k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Li, H, Fan, H, Su, Y, Li, Z, Chen, S, Wei, W, et al.. Quaternary layered boride Ti4MoSiB2: a structure‐function integrated high‐temperature self‐lubricating and negative‐wear material. Adv Mater 2025;37:2418995. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202418995.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Zhang, D, Richardson, P, Tu, H, O’Connor, J, Kisi, E, Zhang, H, et al.. Radiation damage of MoAlB at elevated temperatures: investigating MAB phases as potential neutron shielding materials. J Eur Ceram Soc 2022;42:1311–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2021.11.017.Search in Google Scholar

26. Guo, Z, Han, Z, Alkandari, A, Khot, K, Ruan, X. First-principles prediction of thermal conductivity of bulk hexagonal boron nitride. Appl Phys Lett 2024;124:163906. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0210935.Search in Google Scholar

27. Zhou, X-F, Zhou, J. First-principles study on ultralow lattice thermal conductivity in HfGeTe4. Mod Phys Lett B 2022;36:2250123. https://doi.org/10.1142/s0217984922501238.Search in Google Scholar

28. Luo, X, Zhang, T, Hu, C-E, Cheng, Y, Geng, H-Y. First-principles studies on the structural, electronic and thermal transport characteristics of half-Heusler compounds LiXN (X=Mg, Zn). Solid State Commun 2023;366–367:115156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssc.2023.115156.Search in Google Scholar

29. Katre, A, Togo, A, Tanaka, I, Madsen, GKH. First principles study of thermal conductivity cross-over in nanostructured zinc-chalcogenides. J Appl Phys 2015;117:045102. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4906461.Search in Google Scholar

30. Yan, S, Liu, Z, Zhang, J-H, Wei, S, Zhang, S, Chen, X, et al.. Raman spectrum and phonon thermal transport in van der Waals semiconductor GaPS4. Appl Phys Lett 2024;125:022202. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0216986.Search in Google Scholar

31. Guo, Z, Wang, L, Wang, K, Ren, C, Guo, R, Zhang, Y, et al.. Temperature dependent thermal conductivity of IIa diamond by laser excited Raman spectroscopy. Appl Phys Lett 2021;118:192104. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0046656.Search in Google Scholar

32. Devipriya, CP, Deepa, S, Udayaseelan, J, Chandrasekaran, R, Aravinthraj, M, Sabari, V. Quantum chemical and MD investigations on molecular structure, vibrational (FT-IR and FT-Raman), electronic, thermal, topological, molecular docking analysis of 1-carboxy-4-ethoxybenzene. Chem Phys Impact 2024;8:100495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chphi.2024.100495.Search in Google Scholar

33. Xu, X, Goddard, WA. The extended Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional with improved accuracy for thermodynamic and electronic properties of molecular systems. J Chem Phys 2004;121:4068–82. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1771632.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Perdew, JP, Burke, K, Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys Rev Lett 1998;77:3865–8. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Kresse, G, Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys Rev B 1996;54:11169–86. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Li, W, Carrete, J, Katcho, NA, Mingo, N. ShengBTE: a solver of the Boltzmann transport equation for phonons. Comput Phys Commun 2014;185:1747–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2014.02.015.Search in Google Scholar

37. Chen, S-B, Guo, S-D, Zeng, Z-Y, Lv, B, Xu, M, Chen, X-R, et al.. Ultra-low lattice thermal conductivity induces high-performance thermoelectricity in Janus group-VIA binary monolayers: a comparative investigation. Vacuum 2023;213:112075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacuum.2023.112075.Search in Google Scholar

38. Togo, A. First-principles phonon calculations with phonopy and Phono3py. J Phys Soc Jpn 2023;92:012001. https://doi.org/10.7566/JPSJ.92.012001.Search in Google Scholar

39. Kroumova, E, Aroyo, MI, Perez-Mato, JM, Kirov, A, Capillas, C, Ivantchev, S, et al.. Bilbao crystallographic server: useful databases and tools for phase-transition studies. Phase Transit 2003;76:155–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141159031000076110.Search in Google Scholar

40. Hadi, MA, Kelaidis, N, Filippatos, PP, Christopoulos, S-RG, Chroneos, A, Naqib, SH, et al.. Optical response, lithiation and charge transfer in Sn-based 211 MAX phases with electron localization function. J Mater Res Technol 2022;18:2470–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.03.083.Search in Google Scholar

41. Li, W, Lindsay, L, Broido, DA, Stewart, DA, Mingo, N. Thermal conductivity of bulk and nanowire Mg2SixSn1−x alloys from first principles. Phys Rev B 2012;86:174307. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.86.174307.Search in Google Scholar

42. Xu, L, Shi, O, Liu, C, Zhu, D, Grasso, S, Hu, C. Synthesis, microstructure and properties of MoAlB ceramics. Ceram Int 2018;44:13396–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.04.177.Search in Google Scholar

43. Keshri, SP, Pati, SK. d-Orbital-Driven low lattice thermal conductivity in TiRhBi: a root for potential thermoelectric and microelectronic performance. ACS Appl Energy Mater 2022;5:13590–9. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.2c02304.Search in Google Scholar

44. Peng, B, Zhang, H, Shao, H, Xu, Y, Ni, G, Zhang, R, et al.. Phonon transport properties of two-dimensional group-IV materials from ab initio calculations. Phys Rev B 2016;94:245420. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.94.245420.Search in Google Scholar

45. Ouyang, T, Hu, M. First-principles study on lattice thermal conductivity of thermoelectrics HgTe in different phases. J Appl Phys 2015;117:245101. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4922978.Search in Google Scholar

46. Palumbo, M, Kisu, K, Gulino, V, Nervi, C, Maschio, L, Casassa, S, et al.. Ion conductivity in a magnesium borohydride ammonia borane solid-state electrolyte. J Phys Chem C 2022;126:15118–27. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.2c04934.Search in Google Scholar

47. Smith, KA, Ramkumar, SP, Harms, NC, Clune, AJ, Cheong, S-W, Liu, Z, et al.. Pressure-induced phase transition and phonon softening in h−Lu0.6Sc0.4FeO3. Phys Rev B 2021;104:094109. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.104.094109.Search in Google Scholar

48. Lai, H-E, Yoo, RMS, Djire, A, Balbuena, PB. Investigation of the vibrational properties of 2D titanium nitride MXene using DFT. J Phys Chem C 2024;128:3327–42. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.3c06717.Search in Google Scholar

49. Skelton, JM, Burton, LA, Jackson, AJ, Oba, F, Parker, SC, Walsh, A. Lattice dynamics of the tin sulphides SnS2, SnS and Sn2S3: vibrational spectra and thermal transport. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2017;19:12452–65. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7CP01680H.Search in Google Scholar

50. Porezag, D, Pederson, MR. Infrared intensities and Raman-scattering activities within density-functional theory. Phys Rev B 1996;54:7830–6. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.54.7830.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- The influence of anisotropy of InP on its elasticity and phonon properties

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber