Abstract

This study investigates the mechanical properties as well as the gamma-ray, neutron, alpha, and proton shielding capabilities of PbO-doped titanium-barium-borate based (TiO2–BaO–B2O3–Al2O3–K2O) glass-ceramic system. Using the Phy-X/PSD program, several gamma-ray shielding parameters such as linear attenuation coefficient (μ), mass attenuation coefficient (μ/ρ), half value layer (HVL), mean free path, effective atomic number (Z eff), exposure buildup factor (EBF) and energy absorption buildup factor (EABF) were theoretically computed in the photon energy range of 0.015–15 MeV. Gamma-ray transmission factors (TFs) were evaluated using Particle and Heavy Ion Transport Code System. Additionally, the projected range (PR) values for protons and alpha in the study were computed using the Stopping and Range of Ions in Matter code. In addition to examining gamma, neutron, alpha, and proton shielding capabilities, the study also assessed elastic modulus, density, and average molecular weight. The mechanical properties for each glass sample were calculated using Makishima–Mackenzie model. The results show an inverse relationship between elasticity and PbO content, indicating a trade-off between mechanical rigidity and radiation shielding effectiveness. A higher PbO concentration (4.5%) significantly raises the molecular weight, density (2.80–3.55 g/cm3), and effective atomic number, which leads to better attenuation. Sample G1, for instance, has HVL = 3.269 cm at 0.662 MeV, while sample G5 exhibits better shielding at 2.538 cm. PbO presence causes buildup factors (EBF/EABF) to rise, particularly at higher photon energies and penetration depths, which suggests increased absorption of secondary photons. Denser, lead-rich glasses are known to promote gamma attenuation, as seen by the continuous reduction in TF with increasing PbO content, thickness (0.5–3.0 cm), and photon energy (0.662, 1.1732, 1.3325 MeV). Neutron shielding effectiveness, measured by the effective removal cross section (ΣR), improved with higher PbO, with G5 (PbO [4.5%], ΣR = 0.071 cm−1) demonstrating the promising performance. The G5 sample has the lowest PR (Φ) values for alpha (Φp) and protons (ΦA) particles, indicating improved stopping power. Finally, comparative benchmarking against literature-reported glass types confirmed the superior protection against gamma rays of the G5 sample. These results demonstrate how PbO-doped titanium-barium-borate based glass-ceramics may be used for sophisticated radiation protection applications by striking a balance between improved shielding and controllable mechanical characteristics.

1 Introduction

In the area of radiation protection, the choice of materials plays a pivotal role in ensuring safety and efficacy. Glass has become a very promising option among the different materials used for shielding because of its special set of qualities [1,2,3,4,5]. High transparency, ease of production, and the flexibility to customize their properties with a variety of modifying agents are key advantages of glass shields [6]. The versatility of glass, coupled with its ability to form stable [7], homogeneous structures [8], makes it an ideal choice for various radiation shielding applications, particularly in environments where both protection and visibility are paramount, such as medical imaging facilities, nuclear power plants, and research laboratories. To enhance the protective capabilities of glass shields, specific oxides are incorporated into the glass matrix [9,10,11].

Each component contributes distinct properties that collectively enhance the overall performance of the glass shield. It is of great importance to know the properties of these components. As a network modifier, potassium oxide (K2O) reduces the glass’ melting point and viscosity while improving its workability. These features make it easier to manufacture and process high-performance shielding glasses, even while specific radiation-shielding data are few [12]. In order to maintain structural integrity, glass’ amorphous network is usually constructed around a network former. Depending on composition, lead oxide (PbO) can behave as an intermediate oxide in certain systems, but it often acts as a network modifier. In order to create non-bridging oxygens (NBOs), Pb2+ ions interact with oxygen atoms at the atomic level, breaking the network and decreasing connection. In addition to increasing amorphousness and changing characteristics like density, these NBOs also reduce structural order. By forming areas of high electron density, Pb2+ also improves photon interactions because of its wide ionic radius and high atomic number. Hence, PbO enhances the glass’ total density and refractive index, greatly enhancing its capacity to attenuate gamma rays. Superior shielding capability is indicated by Pb-doped glasses’ lower half-value layers (HVLs), increased mass, and linear attenuation coefficients (LAC). PbO also improves clarity and brilliance, which is helpful in applications that call for vision through the shield [13]. Barium oxide (BaO) increases glass durability and refractive index [14]. Additionally, it facilitates easier production by lowering viscosity and melting temperature. Adding BaO also improves shielding performance, especially when combined with other modifiers like PbO [13]. Aluminum oxide (Al2O3) strengthens the glass structure by increasing hardness, chemical resistance, and thermal stability especially in the presence of strong radiation doses or harsh environmental conditions [15]. By acting as a glass forming, boron trioxide (B2O3) improves resilience to thermal shock and decreases thermal expansion. Additionally, it facilitates more uniform component mixing during melting. However, as seen in tellurite-glass investigations where heavier oxides provide higher gamma attenuation, adding too much B2O3 can reduce density and shielding capabilities [16,17]. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) increases the refractive index and UV absorption of glass [18]. It also enhances chemical durability and mechanical strength, contributing to the longevity and effectiveness of the glass shield in harsh radiation environments.

The development of glass-ceramics with enhanced radiation shielding properties has been extensively studied. For example, it has been demonstrated that adding heavy metal oxides (HMO), such as PbO and BaO, to the glass matrix greatly increases the gamma-ray attenuation coefficients [19,20]. Lead oxide glasses are particularly noted for their high density and excellent radiation shielding capabilities [21]. Barium titanate-based glasses have also gained attention for their dielectric properties and ability to form stable crystalline phases, which are beneficial for radiation shielding and other electronic applications [22,23]. The addition of Al2O3 has been demonstrated to enhance the mechanical and thermal stability of glass-ceramics, making them more resistant to radiation damage [24]. Boron oxide, a well-known network former in glass chemistry, significantly improves the thermal and chemical stability of glasses [25]. Its incorporation has been shown to reduce the thermal expansion coefficient and enhance resistance to thermal shock, which is critical for maintaining the integrity of the glass shield in fluctuating temperatures [26]. Titanium dioxide, with its high refractive index and UV absorption properties, has been extensively used in the development of photocatalytic materials [27]. In glass-ceramics, TiO2 enhances mechanical strength and chemical durability, contributing to the overall robustness of the shielding material [28]. The inclusion of K2O and B2O3 enhances the workability and thermal stability of the glass, making it more resistant to thermal shocks and easier to fabricate into complex shapes. Barium oxide further contributes to the refractive index and chemical durability, ensuring that the glass remains clear and durable even under prolonged radiation exposure. The synergy of these components can produce a glass with optimized properties, balancing density, durability, and ease of fabrication, making it appropriate for a variety of radiation shielding applications [29,30,31,32,33].

This study investigates the mechanical properties as well as the gamma-ray, neutron, alpha, and proton shielding capabilities of PbO-doped titanium-barium-borate based TiO₂–BaO–B₂O₃–Al₂O₃–K₂O glass-ceramic system. Given the lack of studies on the addition of high-density PbO to titanium-barium-borate based glass-ceramic and the distinctive properties of the compounds in this glass-ceramic system, combining these compounds (K2O, PbO, BaO, Al2O3, B2O3, and TiO2) [34] into a single glass system offers the potential to create a material with superior shielding properties. Also, the addition of HMOs, such as PbO and BaO, to the glass sample significantly increases the gamma-ray attenuation coefficients, which distinguishes this study from other studies. By hypothetically examining the gamma-ray, neutron, alpha, and proton shielding characteristics as well as the elastic modulus of these glasses, this study aims to address this gap. By understanding the synergistic effects of these components, one can design and develop a new class of glass-ceramics with enhanced radiation shielding properties. The findings of this study would open the door for the use of glass-ceramics with tailored properties, paving the way for their application in nuclear medicine, power plants, and other critical areas requiring advanced radiation protection solutions.

2 Materials and methods

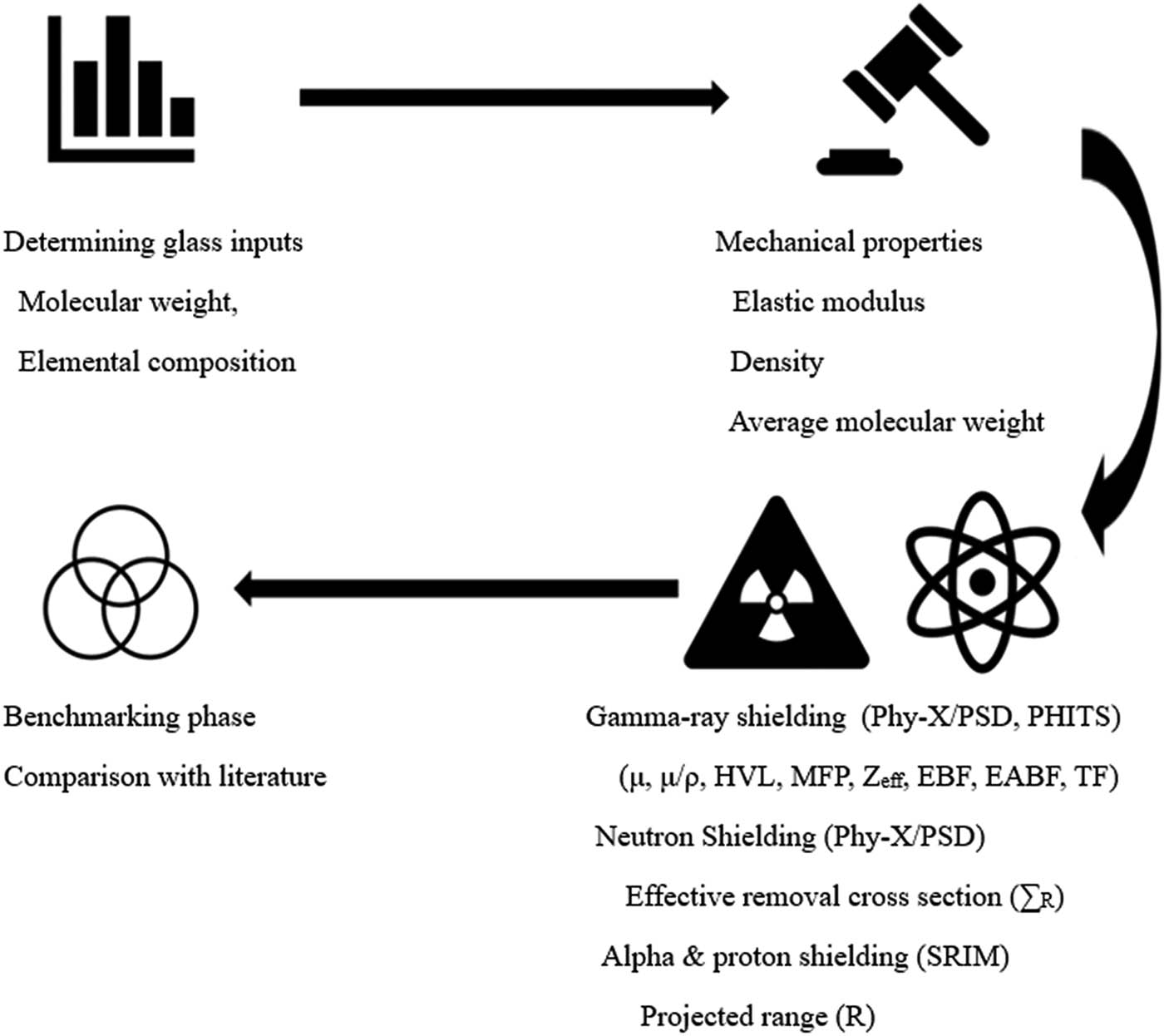

As illustrated in Figure 1, schematic representation of the methodological workflow used for mechanical and radiation shielding analysis of PbO-doped titanium-barium-borate-based glass-ceramic samples was employed. The process begins with determining the glass inputs and calculating the average molecular weights necessary for subsequent analyses. This step is crucial for establishing the foundational properties of glass compositions. Following this, the glass samples’ mechanical characteristics, such as the elastic modulus, are evaluated to assess their structural integrity and suitability for various applications. Concurrently, the gamma-ray, neutron, alpha, and proton shielding properties of the glass samples are analyzed to understand their effectiveness in radiation shielding. The results from these analyses are then benchmarked against existing data to validate and compare the performance of the glass samples.

Schematical representation of the characterization process.

2.1 Elastic modulus calculations

The glass samples, labeled G1 through G5, with specific molar compositions comprising TiO2, K2O, BaO, PbO, Al2O3, and B2O3 were investigated in terms of elastic modulus calculations. The Makishima-Mackenzie (MM) model is a theoretical approach widely applied in materials science to link the elastic properties of glassy systems with their chemical composition and structural parameters [35,36]. Based on the compositional analysis of the investigated glasses, two essential parameters packing density (V t) and dissociation energy per unit volume (G t) were calculated. These values were subsequently used to derive the main mechanical constants, including shear modulus (G), longitudinal modulus (L), Young’s modulus (Y), bulk modulus (K), and Poisson’s ratio (σ). This predictive framework enabled a comprehensive evaluation of the mechanical performance of the glass samples without relying solely on experimental testing, thereby providing valuable insight into the relationship between structure and mechanical behavior.

Here R A and R O are the ionic radius of metal and oxygen, respectively. The mechanical parameters are obtained for PbO-doped titanium-barium-borate-based glass-ceramic samples using the equations given above.

2.2 Gamma-ray shielding parameters

Several gamma-ray shielding parameters were theoretically computed in order to assess the glass samples’ gamma-ray shielding efficacy. These parameters include the LAC (μ), mass attenuation coefficient (MAC) (μ/ρ), mean free path (MFP), HVL, and buildup factors (exposure buildup factor [EBF] and energy absorption buildup factor [EABF] [7,8,9,10]. The calculations were theoretically computed in the photon energy range of 0.015–15 MeV using the Phy-X/PSD [37] software, a robust tool designed for radiation shielding analysis.

2.3 Neutron shielding parameters

Along with gamma-ray shielding parameters, the effectiveness of the synthesized glass samples in attenuating fast neutrons was evaluated. Fast neutrons, with energies typically above 1 MeV, interact with materials primarily through elastic and inelastic scattering, as well as neutron capture reactions. These interactions result in the reduction in neutron energy and eventual removal of neutrons from the beam. The probability that a neutron will be extracted from the incident neutron beam per unit route length is represented by the effective removal cross-section (ΣR) [38]. It is measured in units of cm−1 and indicates how well a material attenuates fast neutrons. A material’s ability to attenuate fast neutrons increases with its ΣR value. The following formula can be used to potentially calculate the ΣR values.

The material’s ith element’s number density (in atoms/cm3) is N i , and its fast neutrons’ microscopic removal cross-section is denoted by σ R,i . The microscopic removal cross-section data (σ R,i ) used in this study were obtained using the Phy-X/PSD software, which is based on NIST-supported cross-section databases and established physical interaction models [37]. Using their number densities and microscopic cross-sections, the contributions from each element were added up to determine the (ΣR) values for each glass sample.

2.4 Heavy-charged particles shielding parameters

A charged particle’s total route length before coming to rest inside a substance is known as its projected range (PR) (R). It is a crucial factor in figuring out how thick the material needs to be to stop the particles entirely. PR of the radiation through the glass samples were evaluated using the Stopping and Range of Ions in Matter (SRIM) codes, developed by Ziegler et al. [39], which is one of the most widely used techniques for such calculations. The PR is computed by integrating the inverse of the stopping power over the particle’s energy and is commonly given in units of g/cm² or cm.

where, R is the PR, E 0 is the initial energy of the particle, and S(E) is the stopping power as a function of energy E.

2.5 Particle and Heavy Ion Transport Code System (PHITS) simulations for transmission factor (TF) values

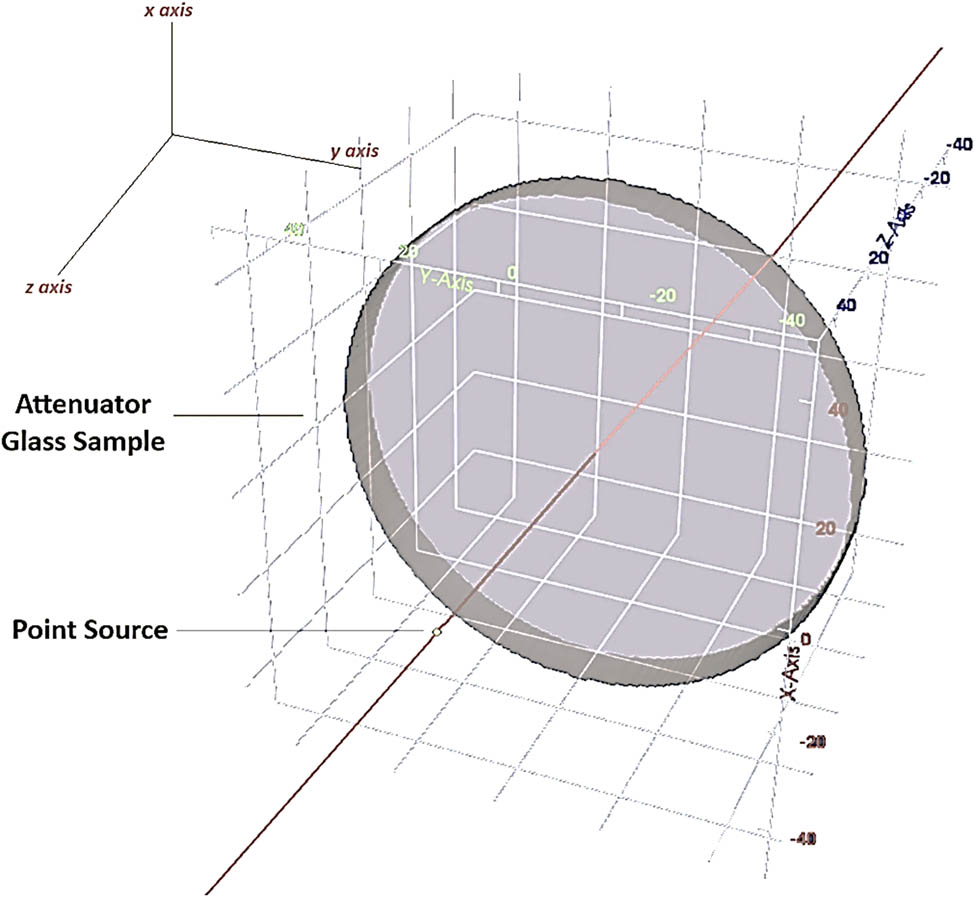

The simulation incorporates physical processes like scattering and absorption to simulate how radiation interacts with the alloy. T-track tallies, which measure photon flux and make it easier to calculate TFs for each alloy, are used to analyze the detector data. A monoenergetic gamma-ray source was used to measure the intensity of primary and secondary photons for the TF calculations. In order to accurately assess the material’s shielding effectiveness, the TF was calculated as the ratio of photon intensity after passing through the alloy sample (I) to the original photon intensity (I 0). The simulated results closely match theoretical expectations and actual findings because of PHITS’s shown dependability in modeling radiation interactions and attenuation processes. The TF values of the PbO-doped titanium-barium-borate-based TiO2–BaO–B2O3–Al2O3–K2O glass-ceramic system were evaluated in this study using PHITS simulations [40,41,42,43]. Figure 2 shows the simulation setup, which includes 2D and 3D models of the glass samples that are modeled and placed inside a lead block that contains a gamma-ray source. Photons with an energy of 1 MeV were to be emitted by the gamma-ray source. The material definition in the input file was modified to represent the unique elemental composition of each glass sample in order to guarantee an accurate simulation of the various glass compositions. A tally mesh was integrated inside the cell with the glass cover for detection and measuring purposes. A significant number of particle histories (NPS 108) were used in each simulation to guarantee statistical reliability. The overall relative error from the simulations is less than 0.1%, demonstrating the accuracy of our results. A high-performance LENOVO® P640 workstation, selected for its capacity to manage the complex numerical computations needed by the PHITS code, was used to carry out the computational operations.

2D and 3D views of modeled setup for TF calculations in PHITS.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Elastic modulus properties of the glasses

The analysis of the calculated values reveals distinct variations in the mechanical performance of the investigated glass samples. The results obtained for each glass sample are given in Table 1. The molar volume is highest in G1 (36.19 cm3/mol) and gradually decreases toward G5 (29.33 cm3/mol). In contrast, V t increases from 0.45 in G1 to 0.56 in G5, indicating the formation of a more compact structure with more efficiently packed atoms. G t values are generally around 19 GPa, with G2 showing the lowest value (16.84 GPa), suggesting weaker bond strength compared to the other samples. Y increases from 73.88 GPa in G1 to above 90 GPa in G4 and G5, clearly reflecting the correlation between higher V t and enhanced rigidity of the glasses. Both K and G follow an increasing trend from G1 to G5. While K rises from 40.14 GPa in G1 to 60.27 GPa in G5, G increases from 33.14 to 38.49 GPa. These results imply that the glasses become less compressible and more resistant to shear deformation as the composition evolves. Similarly, L varies between 82.24 GPa (G2) and 112.11 GPa (G4), with a marked improvement observed in G3–G5, consistent with the increase in density and bonding strength. σ ranges from 0.19 in G1 to 0.25 in G4–G5. Lower values indicate a more brittle nature, whereas higher values close to 0.25 suggest a shift toward a tougher, more ductile behavior. Overall, the findings highlight that G4 and G5 exhibit superior elastic moduli and relatively higher σ values, making them the mechanically strongest glass compositions within the investigated series.

Mechanical parameters of the investigated PbO-doped titanium-barium-borate-based (TiO2–BaO–B2O3–Al2O3–K2O) glass-ceramic system

| Sample | M (g/mol) | Molar volume (cm³/mol) | V t | G t | Young’s Y (Gpa) | Bulk K (Gpa) | Shear G (Gpa) | Longitudinal L (Gpa) | Poisson’s σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 101.34 | 36.19 | 0.45 | 19.45 | 73.88 | 40.14 | 33.14 | 84.34 | 0.19 |

| G2 | 102.04 | 33.13 | 0.50 | 16.84 | 69.83 | 41.42 | 30.62 | 82.24 | 0.22 |

| G3 | 102.74 | 31.32 | 0.52 | 19.39 | 84.92 | 53.23 | 36.75 | 102.24 | 0.23 |

| G4 | 103.44 | 29.30 | 0.56 | 19.35 | 90.54 | 60.61 | 38.62 | 112.11 | 0.25 |

| G5 | 104.13 | 29.33 | 0.56 | 19.32 | 90.21 | 60.27 | 38.49 | 111.59 | 0.25 |

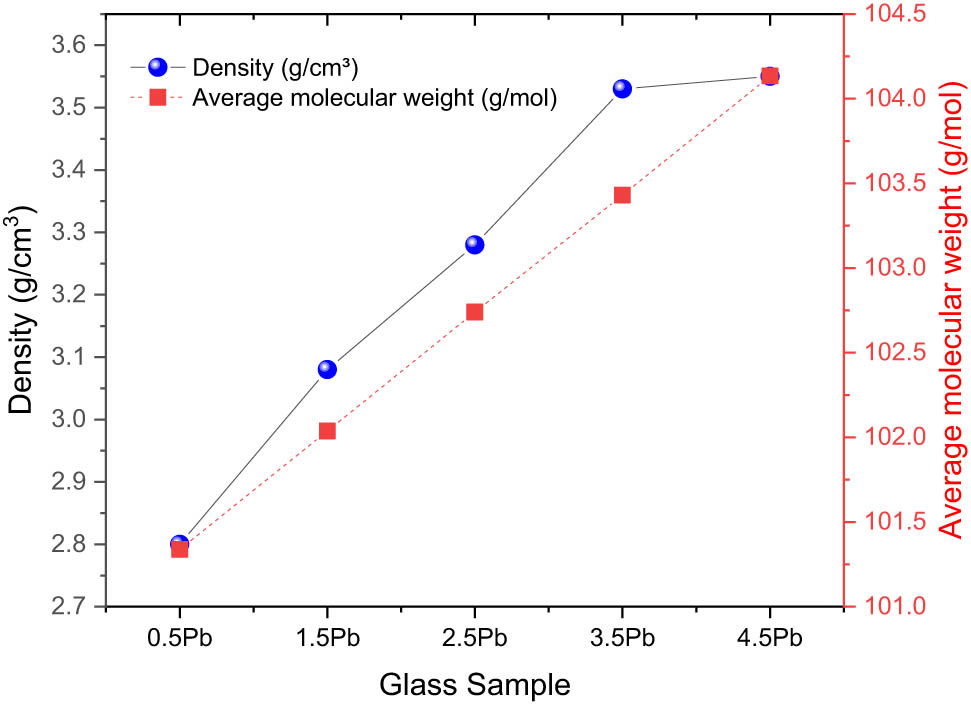

3.2 Average molecular weight and density variations

Figure 3 shows that the density and average molecular weight of glass samples (G1–G5) both dramatically increase when the PbO level rises. The exact compositions of samples G1 through G5, where the proportions of other components stay constant but the PbO level varies, are shown in Table 2. It is clear that there is an increased trend in the density of the glass samples as the PbO content rises. From G1 to G5, the manufactured sample’s ρ rises from 2.80 to 3.55 g/cm3. The rising PbO concentration is the cause of this trend. This finding is consistent with the fact that Pb has a substantially larger atomic mass than the other elements (Ti, K, Ba, Al, B, and O) in the glass matrix. Density increases as a result of raising the PbO fraction since it increases the overall mass per unit volume. Likewise, as the PbO level rises, so does the average molecular weight of the glass samples. Once more, the addition of heavier Pb atoms to the glass network is the cause of this rise. Notable is the close relationship between density and average molecular weight, which both rise with more PbO. This link makes sense because density and molecular weight naturally increase as the glass structure gets denser and contains heavier atoms. This pattern is consistent with research from a variety of glass systems in literature. For example, studies on Lead-Borate (PbO–B2O3) glasses [44,45] have shown that density rises when PbO content increases, and molar volume, which is inversely related to molecular compactness, likewise rises, This confirms our finding that as mass per unit volume rises, heavier PbO additions produce denser glasses. Other studies on different glass systems also report a similar inverse relationship between density and molar volume, reinforcing the correlation with molecular compactness. For instance aluminum lead phosphate glass systems [46], TeO2–CdO–PbO–B2O3 glass system [47], and lead-bismuth tellurite glass systems (TeO2–Bi2O3–PbO) are some of them.

Variation in glass densities and average molecular weights as a function of PbO contribution.

Molar fractions (%) and densities (g/cm3) of PbO-doped titanium-barium-borate-based [TiO2–BaO–B2O3–Al2O3–K2O] glass-ceramic system

| Sample | TiO2 (mol%) | K2O (mol%) | BaO (mol%) | PbO (mol%) | Al2O3 (mol%) | B2O3 (mol%) | Density (g/cm3) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 38 | 9 | 23.5 | 0.5 | 16 | 13 | 2.80 | [34] |

| G2 | 38 | 9 | 22.5 | 1.5 | 16 | 13 | 3.08 | |

| G3 | 38 | 9 | 21.5 | 2.5 | 16 | 13 | 3.28 | |

| G4 | 38 | 9 | 20.5 | 3.5 | 16 | 13 | 3.53 | |

| G5 | 38 | 9 | 19.5 | 4.5 | 16 | 13 | 3.55 |

3.3 Properties of gamma-ray shielding

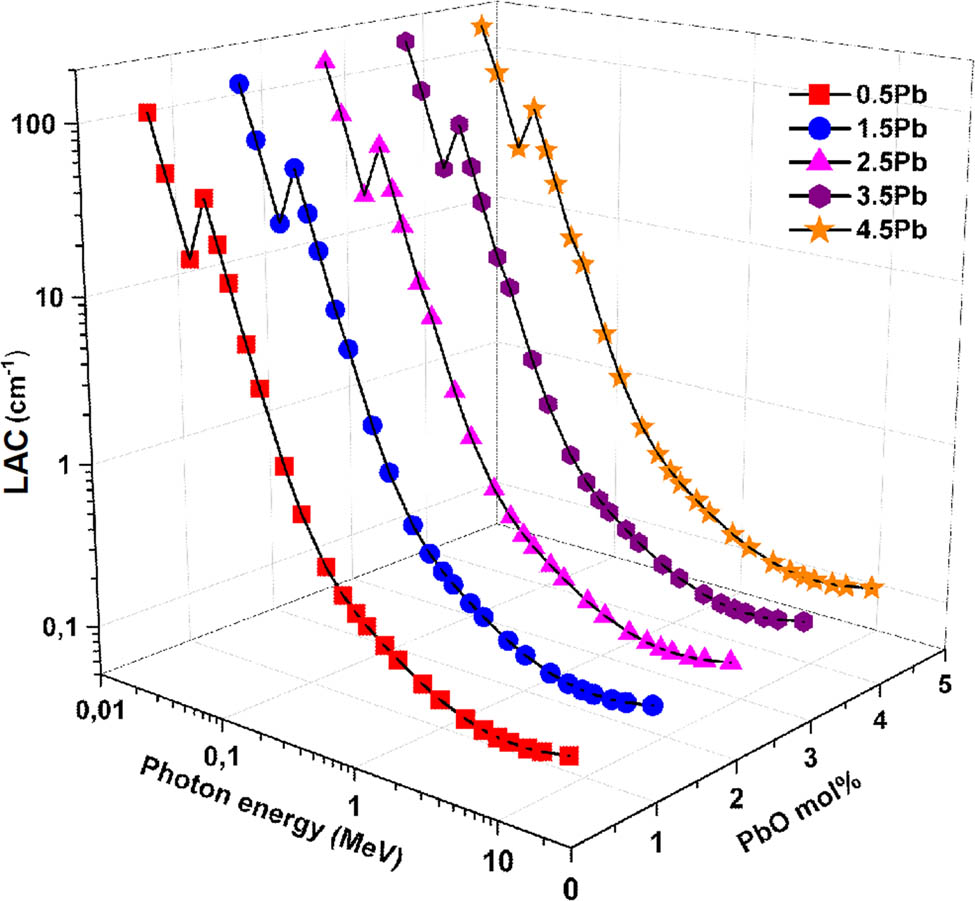

3.3.1 LAC

For the glass samples with compositions listed in Table 2, Figure 4 shows how the LAC change with incident photon energy and PbO contribution. The LAC values are observed to vary significantly with both the photon energy and the PbO content. At lower photon energies (<0.5 MeV), the photoelectric effect is the main process, the LAC values are substantially higher, indicating that the glass samples are highly effective in attenuating low-energy gamma photons. This is consistent across all PbO contributions, although higher PbO contents show more pronounced attenuation. This shows that all glass samples effectively attenuate low-energy photons. This tendency is anticipated as photoelectric absorption, which is heavily reliant on atomic number (Z), predominates at low energies. As the photon energy increases (0.5–1 MeV), the predominant interaction mechanism shifts to Compton scattering, the LAC values decrease sharply but the rate of decrease slows down. In the high energy region (>1 MeV), pair formation is the main process for γ-photons and attenuation exhibits a weak reliance on chemical composition. The reduced interaction probability for higher energy photons explains this tendency. However, samples with higher PbO content maintain higher LAC values compared to those with lower PbO content. The highest PbO content (4.5% PbO, G5) exhibits the highest LAC values, demonstrating superior gamma-ray attenuation properties. This improvement is explained by the fact that lead has a larger atomic number and density, which raises the likelihood of gamma photon interactions inside the glass matrix.

Variation in LAC as a function of incident photon energy and PbO contribution.

3.3.2 HVL and MFP

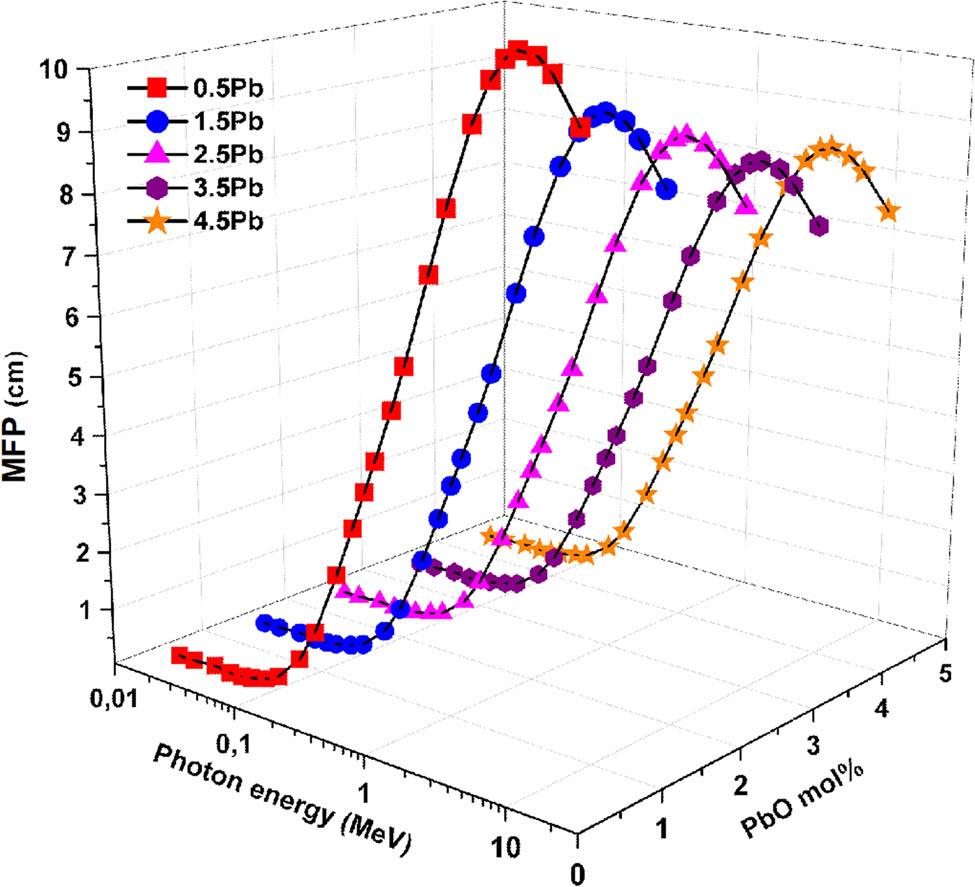

Table 2 details the molar fractions (%) and densities (g/cm3) of the glasses under investigation. Figure 5 illustrates the variation in HVL, and Figure 6 presents the corresponding changes in MFP, both plotted as functions of input photon energy and PbO content. The HVL, which represents the thickness of material needed to cut gamma-ray intensity in half, offers vital information on how well the glass samples shield. The MFP, defined as the average distance travelled by a photon before undergoing an interaction such as absorption or scattering, serves as a crucial metric for assessing a material’s shielding effectiveness. Specifically, a shorter MFP indicates more frequent photon interactions and thus superior radiation attenuation. It is evident from the data that photon energy and PbO content have a considerable impact on both HVL and MFP. HVL and MFP attain their lowest levels at low photon energies (below ∼0.1 MeV), suggesting that all glass samples exhibit excellent attenuation of low-energy photons. Both parameters significantly increase with photon energy, indicating the decreased contact likelihood of higher-energy photons. Furthermore, there is a noticeable impact on the concentration of PbO: glasses with a higher PbO content consistently show improved attenuation performance, with lower HVL and MFP across all energy levels. The glass sample with 0.5% PbO (i.e., G1) has the highest HVL and MFP values, implying the least effective shielding, while the sample with 4.5% PbO (G5) has the lowest HVL and MFP values, suggesting the best shielding efficacy. In this study, for the glass samples G1–G5, the HVL values at 1.173 MeV were found to decrease from 4.419 to 3.464 cm as the PbO content increased from 0.5 to 4.5 mol%. Similarly, in the PbO–MoO₃–B₂O₃ glass system reported in the literature [48], raising the PbO concentration from 30 to 50 mol% decreased the HVL from around 2.693 to 1.752 cm and the MFP from roughly 3.886 to 2.529 cm at the same photon energy. The high atomic mass and density of lead, which facilitate photon interactions and attenuation, are responsible for this enhancement. Consequently, adding more PbO greatly improves glass’ ability to shield against gamma rays, particularly at higher photon energy.

Variation in HVL as a function of incident photon energy and PbO contribution.

Variation in MFP as a function of incident photon energy and PbO contribution.

3.3.3 Effective atomic number (Z eff)

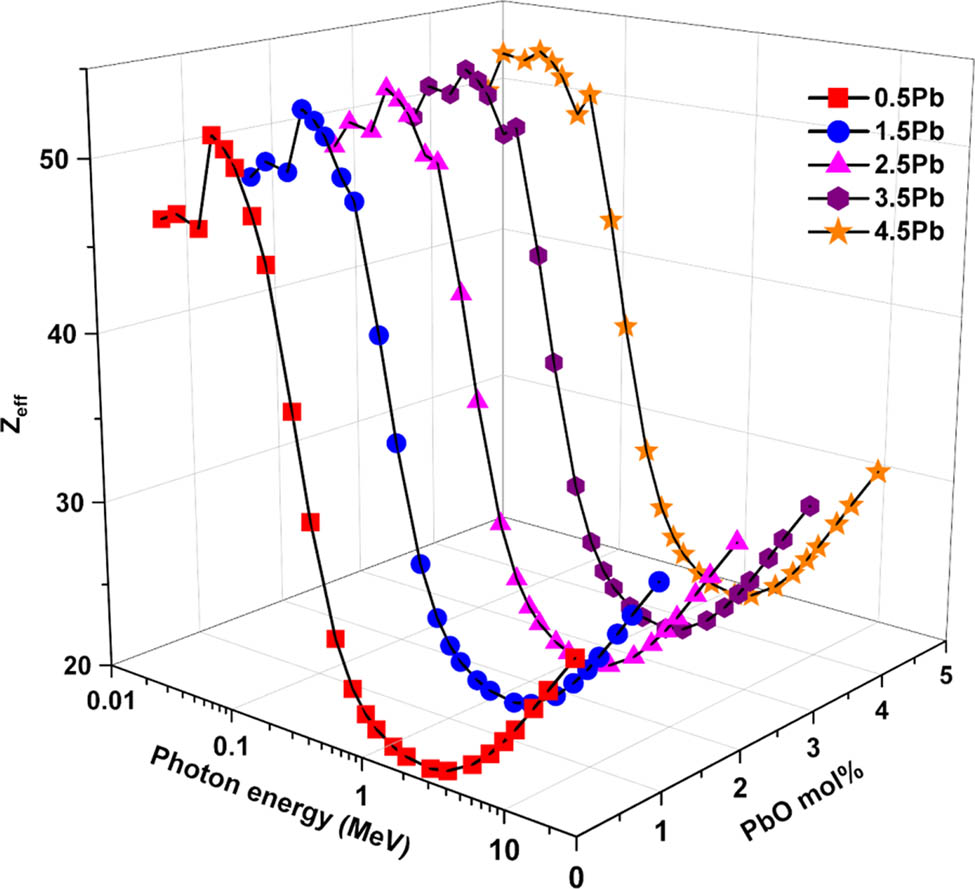

The effective atomic number varies with photon energy and PbO concentration, as seen in Figure 7. Z eff is heavily dependent on both variables, just like other shielding characteristics. Every sample shows high Zₑff values at photon energies <0.1 MeV, indicating strong photon interaction. As energy increases, Zₑff falls, reaches a minimum close to 1 MeV, and then slightly increases at higher energies. Because of the high atomic number of lead, glasses with a greater PbO content specifically, G5 (4.5% PbO) consistently exhibit higher Zₑff values than low-PbO samples, such as G1 (0.5% PbO). This confirms PbO’s role in enhancing photon interaction probability and improving the glass’ overall shielding effectiveness.

Variation in effective atomic number (Z eff) values as a function of incident photon energy and PbO contribution.

3.3.4 EBF and EABF

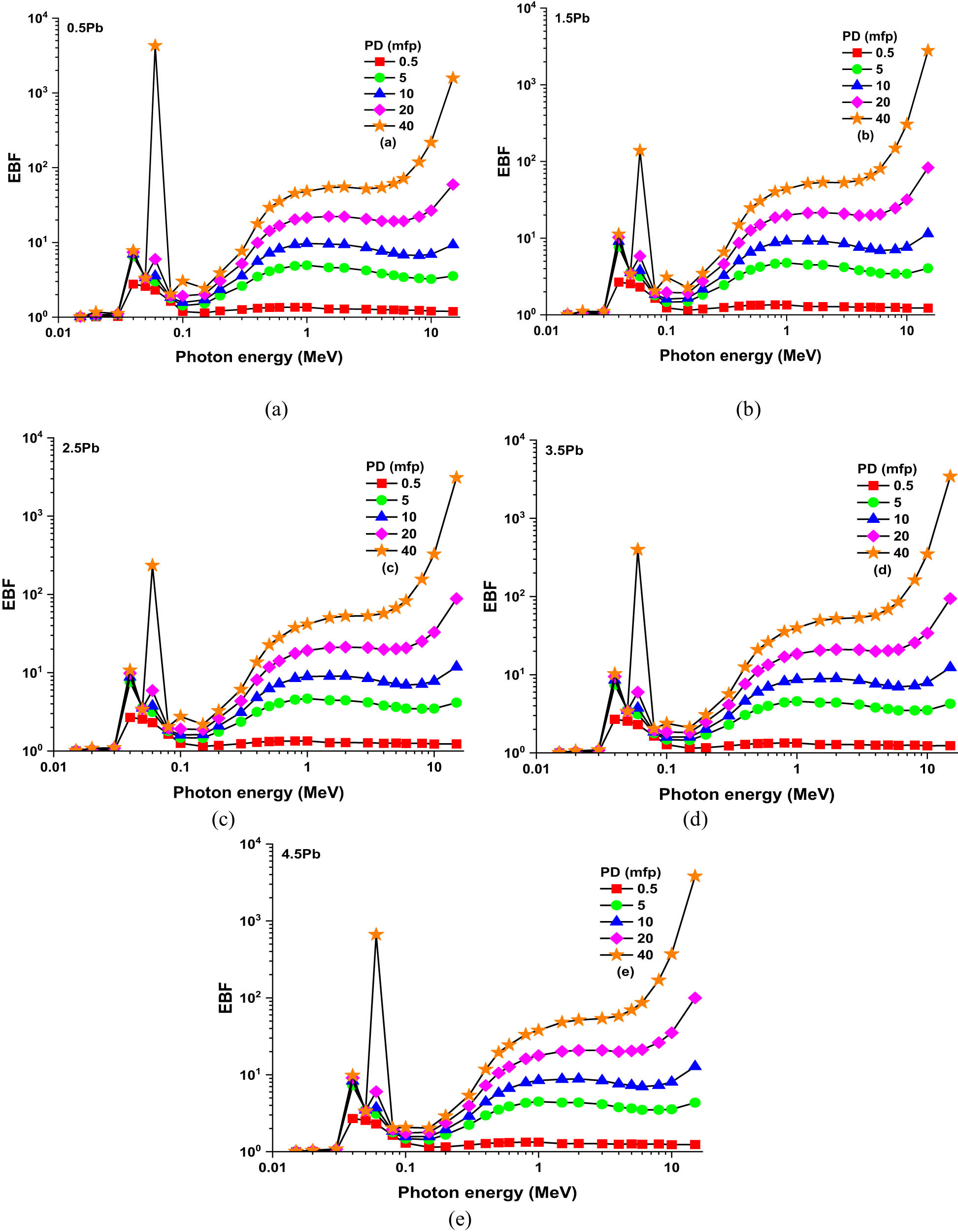

The EBF and EABF values for the glass samples range from 0.5 to 40 MFP, contingent on photon energy and PbO concentration, as shown in Figures 8(a–e) and 9(a–e). The EABF measures the amount of energy absorbed by the interacting material, whereas the EBF indicates the degree of contact between source and detector in the air. At low photon energies (0.01–0.1 MeV), EBF and EABF values are negligible, suggesting little secondary radiation accumulation. Both variables show a large rise with MFP in the intermediate range (0.1–1 MeV), particularly in the 4.5% PbO sample, indicating higher absorption and scattering. EBF and EABF continue to climb steadily at high energies (1–10 MeV), peaking close to 10 MeV. The 4.5% PbO sample once again exhibits the highest values at 40 MFP, demonstrating the significant influence of PbO concentration and penetration depth on radiation accumulation. Secondary radiation buildup is increased by higher PbO levels, particularly at higher MFP and intermediate to high photon energies. This pattern emphasizes how crucial it is to maximize PbO content in glass compositions in order to improve gamma-ray shielding.

(a)–(e): Variation in EBF values as a function of incident photon energy and PbO contribution at different MFPs (i.e., from 0.5 to 40 MFP).

(a)–(e): Variation in EABF values as a function of incident photon energy and PbO contribution at different MFPs (i.e., from 0.5 to 40 MFP).

3.4 Effective removal cross-section (ΣR) values against fast neutrons

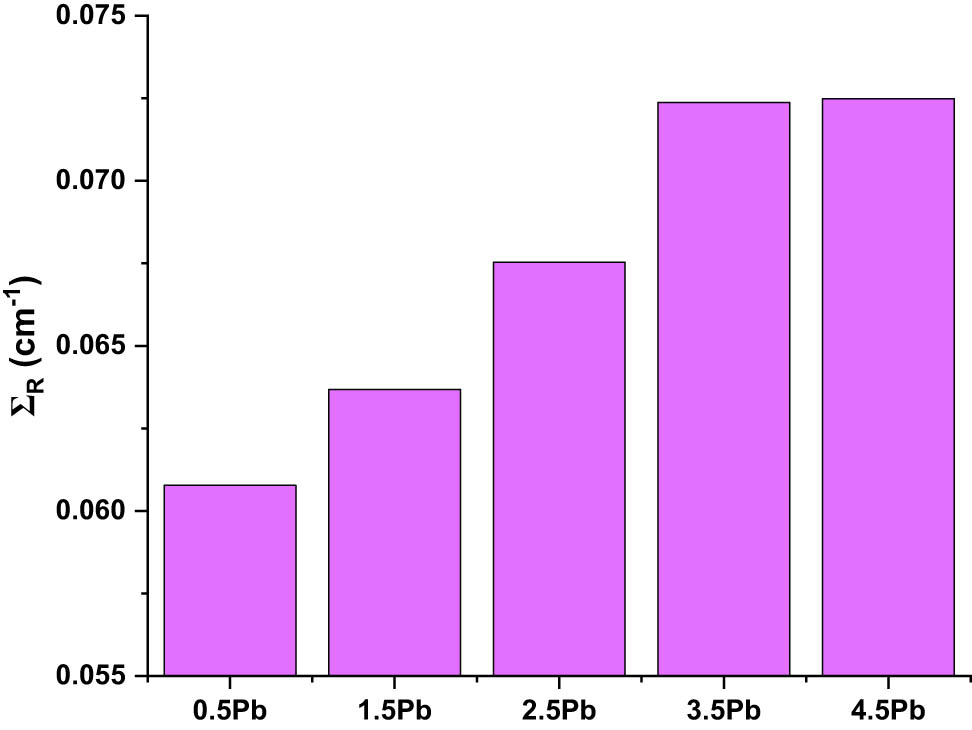

Figure 10 illustrates how the PbO content affects the ΣR values. The attenuation of fast neutrons by the material is measured by ΣR values. According to the findings, the PbO level of the glass samples causes an increase in ΣR values. For instance, ΣR values were reported as 0.5% PbO (G1): ΣR = 0.060 cm−1, 1.5% PbO (G2): ΣR = 0.065 cm−1, 2.5% PbO (G3): ΣR = 0.068 cm−1, 3.5% PbO (G4): ΣR = 0.070 cm−1, 4.5% PbO (G5): ΣR = 0.071 cm−1, respectively. Higher PbO content results in an increase in ΣR, which suggests that PbO improves the glass’ capacity to attenuate fast neutrons. The reason for this is that the high atomic mass and neutron cross-section of lead encourage neutron interactions inside the glass matrix. A higher PbO content considerably enhances neutron shielding, as evidenced by the steady increase in ΣR values, which peaks in the 4.5% PbO sample. These findings highlight how crucial it is to optimize PbO levels for improved shielding effectiveness.

Variation in effective removal cross-section (∑R) values.

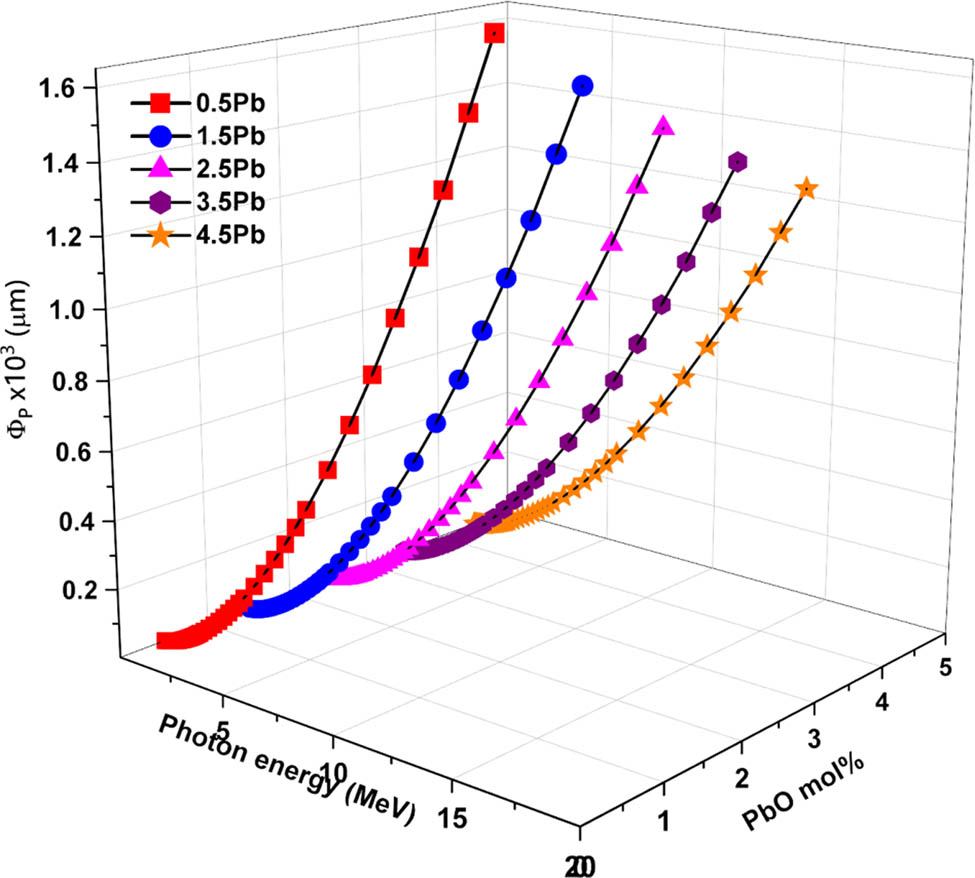

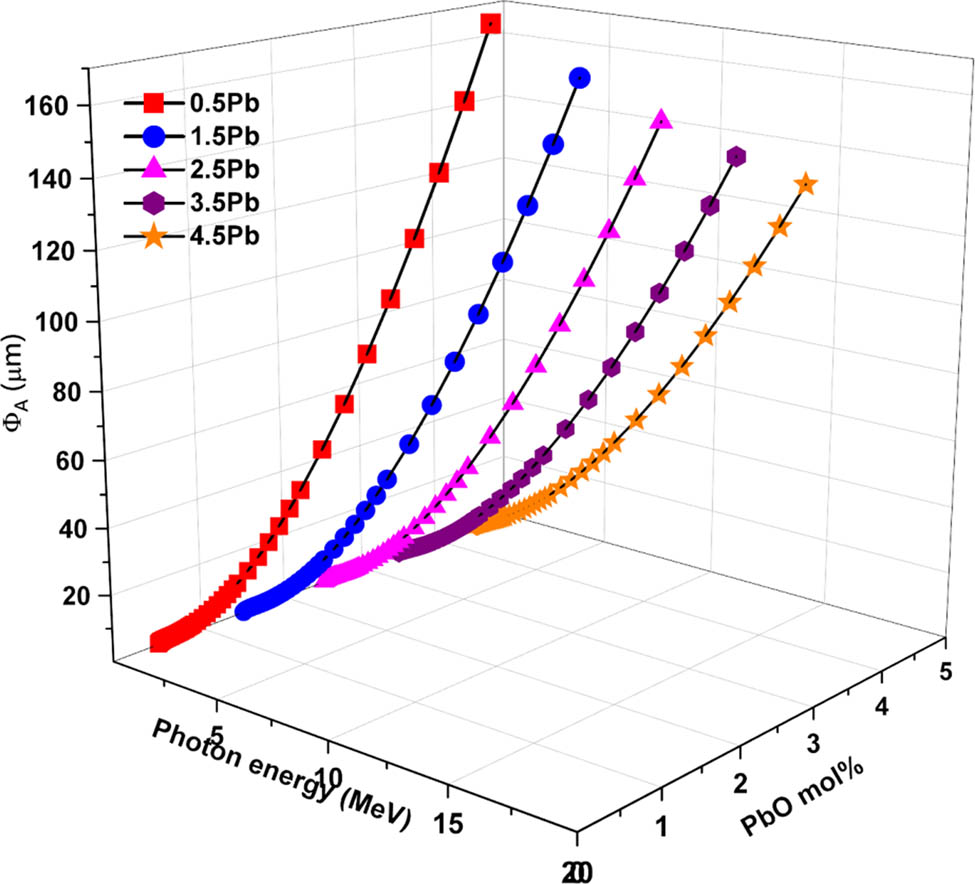

3.5 PR values for proton and alpha particles

PR of the radiation through the glass samples were evaluated using the SRIM codes. Figures 11 and 12 present the PR (Φ) values of the glass samples against energetic protons (ΦP) and alpha particles (ΦA), respectively. These values indicate the depth at which the particles are expected to be stopped within the material, providing insight into the material’s shielding effectiveness. In all glass samples, the PR of protons (ΦP) increases as photon energy increases. Higher PbO-containing samples, on the other hand, consistently exhibit lower ΦP values, indicating improved proton stopping power.

0.5% PbO (G1) shows the highest PR values, suggesting the least effective proton stopping power while the 4.5% PbO (G5) depicts the lowest PR, demonstrating superior proton stopping capability. Likewise, the PR (ΦA) for alpha particles rises with photon energy across all glass samples, with higher PbO content resulting in lower ΦA values. The fact that alpha particles and protons behave similarly emphasizes how more PbO improves attenuation and stopping power. The higher atomic number and density of lead are the main causes of the decreased PR. The 4.5% PbO (G5) sample has the highest PbO content and the lowest PR values for both particle types, as shown in Figures 11 and 12.

PR (ΦP) values of the glasses against energetic protons.

PR (ΦA) values of the glasses against energetic alpha particles.

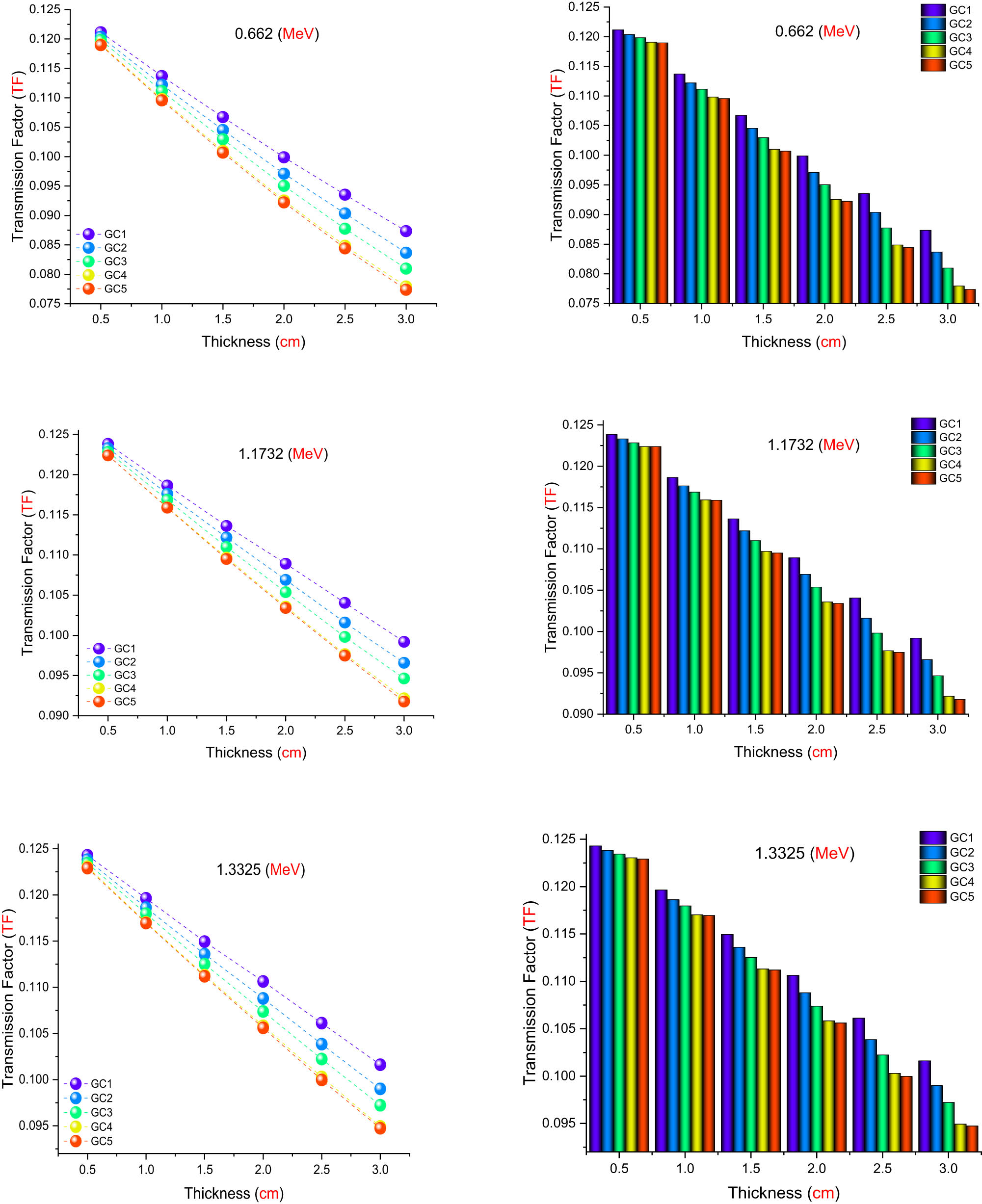

3.6 TF values against energetic photons

As seen in Figure 13, the TF values for samples G1, G2, G3, G4, and G5 were examined for a range of sample thicknesses from 0.5 to 3.0 cm at three different radioisotope photon energies: 0.662, 1.1732, and 1.3325 MeV. These results obtained using PHITS show a similar trend: As sample thickness and PbO content increase across all energy levels, TF values fall. As sample thickness and PbO content increase, TF values drop at all photon energies examined (0.662, 1.1732, and 1.3325 MeV). The 4.5% PbO sample exhibits the lowest TF values, indicating the most effective gamma-ray shielding, whereas the 0.5% PbO sample consistently displays the highest TF values, indicating the poorest attenuation. The high atomic number and density of lead, which improve gamma-ray interaction inside the glass matrix, are responsible for this tendency. Because higher-energy photons have a better ability to penetrate, TF values increase with increasing energy for a given thickness. The highest TF values among the three energies are found at 1.3325 MeV, which is in line with the recognized difficulties of attenuating higher powerful gamma rays. Overall, for all thicknesses and energies, a definite inverse relationship between PbO concentration and TF values is seen. These findings demonstrate how crucial it is to maximize PbO content in glass formulations in order to guarantee effective gamma-ray shielding performance.

TFs for all investigated samples as a function of used radioisotope energy (MeV) at different sample thicknesses.

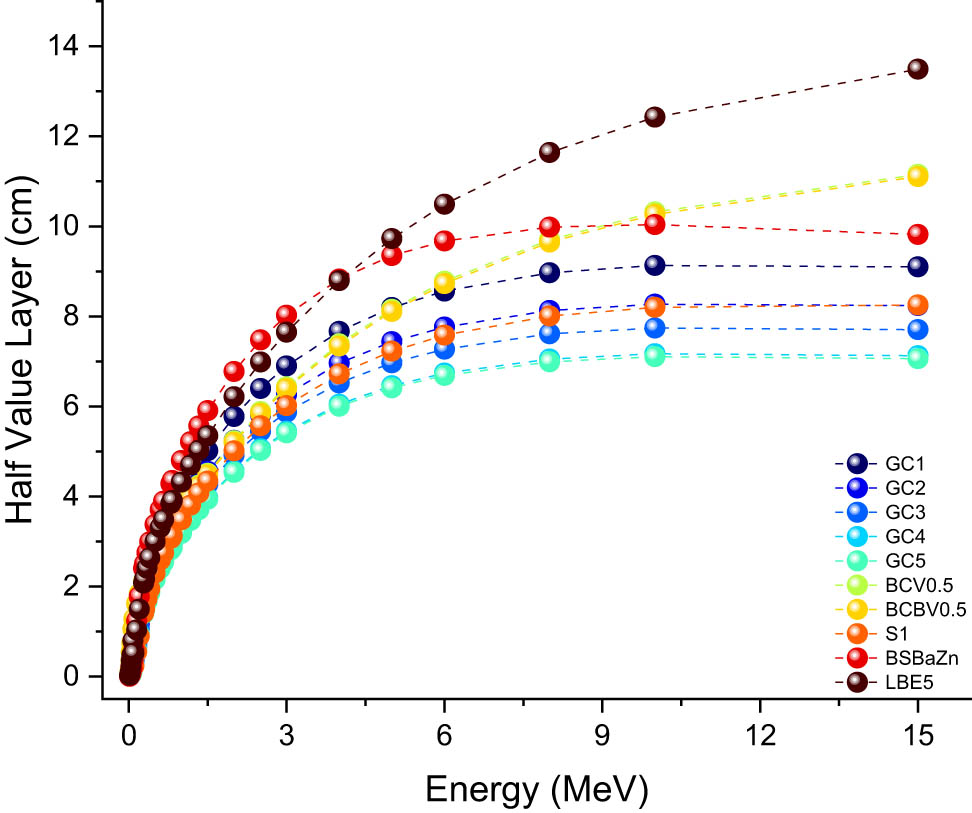

3.7 Benchmarking phase between the G5 (4.5% PbO) and other glasses

Table 3 and Figure 14 provide a comparative analysis of the HVL values for the glass samples G1–G5, alongside various glass compositions reported in the literature, including BCV0.5, BCBV0.5, S1, BSBaZn, and LBE5. Below 0.015 MeV, i.e., at lower photon energies, the HVL values for the G1–G5 samples are notably low, with G1 at 0.010 cm, G2 at 0.009 cm, G3 at 0.008 cm, G4 at 0.007 cm, and G5 at 0.007 cm. In comparison, the HVL values for other glasses such as BCV0.5 (0.025 cm), S1 (0.008 cm), BSBaZn (0.006 cm), and LBE5 (0.028 cm) are significantly higher, indicating that the G1–G5 glasses are more effective at attenuating gamma rays at this energy level. The addition of PbO, which raises the atomic number and density improves the probability of gamma-ray interactions, is responsible for this better performance. The HVL values for every sample increase when the photon energy reaches 0.662 MeV, but the G1–G5 glasses continue to show better performance compared to the other glass types. For instance, at 0.662 MeV, G1 has an HVL of 3.269 cm, while G5 exhibits an HVL of 2.538 cm. In contrast, the HVL values for BCV0.5, BCBV0.5, S1, BSBaZn, and LBE5 are 3.026, 3.006, 2.746, 3.895, and 3.486 cm, respectively. The lower HVL values of G1–G5, particularly G5, indicate more effective attenuation, which is beneficial for radiation shielding applications. At higher photon energies, such as 1.3325 MeV, the trend continues. BSBaZn and BCV0.5 have HVL values of 4.320 and 3.847 cm, respectively, while G5 has an HVL of 3.464 cm. This demonstrates the superior gamma-ray attenuation capability of the G5 glass compared to other formulations. The HVL values for other glass samples from the literature, such as those studied by Ilik et al. [49,50], Barebita et al. [51], Sen Baykal et al. [52], and Chandrashekaraiah et al. [53], are generally higher across various photon energies. For example, Ilik et al. [49] investigated calcium-borate glasses (BCV0.5) doped copper(ii) oxide and found them to have higher HVL values compared to our G5 sample. Similarly, Ilik et al. [50] studied calcium-borate glasses (BCBV0.5) doped vanadium(V) oxide and also reported higher HVL values. Barebita et al. [51] examined Bi2O3–P2O5–B2O3–V2O5 quaternary glass systems (S1) and found them to be less effective than our G5 sample at higher photon energies. Sen Baykal et al. [52] designed a lead-free high-density barium-borosilicate glass (BSBaZn), which also showed higher HVL values. Finally, Chandrashekaraiah et al. [53] studied Li2B4O7 glasses doped with Er3+ and Bi3+ ions (LBE5), which exhibited significantly higher HVL values across the energy spectrum.

Comparison of the HVL (cm) for different types of glass samples [34,43,48,49,50,51,52,53] as a function of photon energy

| Energy (MeV) | G1 [34] | G2 [34] | G3 [34] | G4 [34] | G5 [34] | BCV0.5 [34] | BCBV0.5 [50] | S1 [51] | BSBaZn [52] | LBE5 [53] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.015 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.028 |

| 0.02 | 0.021 | 0.019 | 0.017 | 0.015 | 0.014 | 0.056 | 0.057 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.040 |

| 0.03 | 0.064 | 0.056 | 0.050 | 0.044 | 0.042 | 0.169 | 0.173 | 0.037 | 0.040 | 0.111 |

| 0.04 | 0.041 | 0.038 | 0.036 | 0.034 | 0.035 | 0.341 | 0.347 | 0.078 | 0.061 | 0.220 |

| 0.05 | 0.073 | 0.067 | 0.064 | 0.060 | 0.061 | 0.540 | 0.549 | 0.137 | 0.110 | 0.361 |

| 0.06 | 0.116 | 0.107 | 0.102 | 0.096 | 0.097 | 0.736 | 0.744 | 0.212 | 0.178 | 0.477 |

| 0.08 | 0.237 | 0.218 | 0.207 | 0.195 | 0.197 | 1.056 | 1.060 | 0.398 | 0.363 | 0.792 |

| 0.1 | 0.385 | 0.334 | 0.299 | 0.266 | 0.254 | 1.281 | 1.281 | 0.237 | 0.598 | 0.519 |

| 0.15 | 0.857 | 0.749 | 0.677 | 0.607 | 0.582 | 1.621 | 1.614 | 0.547 | 1.237 | 1.035 |

| 0.2 | 1.312 | 1.158 | 1.057 | 0.955 | 0.925 | 1.839 | 1.829 | 0.894 | 1.775 | 1.498 |

| 0.2835 | 1.895 | 1.693 | 1.562 | 1.427 | 1.396 | 2.117 | 2.104 | 1.411 | 2.405 | 2.078 |

| 0.3 | 1.988 | 1.779 | 1.644 | 1.504 | 1.473 | 2.166 | 2.152 | 1.499 | 2.503 | 2.171 |

| 0.3471 | 2.223 | 1.996 | 1.851 | 1.699 | 1.670 | 2.297 | 2.282 | 1.727 | 2.752 | 2.407 |

| 0.4 | 2.449 | 2.204 | 2.050 | 1.887 | 1.858 | 2.435 | 2.419 | 1.949 | 2.992 | 2.635 |

| 0.5 | 2.803 | 2.531 | 2.362 | 2.180 | 2.154 | 2.675 | 2.657 | 2.297 | 3.376 | 2.999 |

| 0.6 | 3.102 | 2.807 | 2.623 | 2.426 | 2.401 | 2.896 | 2.877 | 2.587 | 3.707 | 3.311 |

| 0.6617 | 3.269 | 2.960 | 2.769 | 2.563 | 2.538 | 3.026 | 3.006 | 2.746 | 3.895 | 3.486 |

| 0.8 | 3.613 | 3.275 | 3.067 | 2.842 | 2.818 | 3.303 | 3.280 | 3.069 | 4.285 | 3.847 |

| 0.8261 | 3.674 | 3.331 | 3.120 | 2.891 | 2.867 | 3.353 | 3.330 | 3.126 | 4.355 | 3.912 |

| 1 | 4.061 | 3.685 | 3.453 | 3.203 | 3.178 | 3.676 | 3.651 | 3.481 | 4.800 | 4.320 |

| 1.173 | 4.419 | 4.011 | 3.761 | 3.489 | 3.464 | 3.981 | 3.953 | 3.805 | 5.213 | 4.699 |

| 1.333 | 4.723 | 4.288 | 4.022 | 3.732 | 3.707 | 4.249 | 4.220 | 4.080 | 5.566 | 5.028 |

| 1.5 | 5.018 | 4.557 | 4.274 | 3.967 | 3.940 | 4.515 | 4.484 | 4.341 | 5.908 | 5.349 |

| 2 | 5.776 | 5.245 | 4.920 | 4.566 | 4.535 | 5.237 | 5.202 | 5.012 | 6.778 | 6.215 |

| 2.506 | 6.400 | 5.811 | 5.450 | 5.057 | 5.023 | 5.884 | 5.844 | 5.571 | 7.477 | 6.988 |

| 3 | 6.899 | 6.263 | 5.873 | 5.449 | 5.411 | 6.436 | 6.394 | 6.019 | 8.026 | 7.649 |

| 4 | 7.668 | 6.959 | 6.523 | 6.050 | 6.005 | 7.389 | 7.342 | 6.726 | 8.831 | 8.796 |

| 5 | 8.197 | 7.437 | 6.968 | 6.461 | 6.411 | 8.159 | 8.109 | 7.227 | 9.350 | 9.729 |

| 6 | 8.562 | 7.765 | 7.274 | 6.742 | 6.688 | 8.780 | 8.728 | 7.583 | 9.677 | 10.491 |

| 8 | 8.971 | 8.131 | 7.613 | 7.053 | 6.992 | 9.702 | 9.649 | 8.007 | 9.980 | 11.639 |

| 10 | 9.132 | 8.274 | 7.743 | 7.170 | 7.106 | 10.321 | 10.268 | 8.200 | 10.038 | 12.423 |

| 15 | 9.101 | 8.239 | 7.705 | 7.129 | 7.060 | 11.153 | 11.104 | 8.256 | 9.821 | 13.492 |

Comparison of HVL values.

4 Conclusion

This study investigates the mechanical properties as well as the gamma-ray, neutron, alpha, and proton shielding capabilities, elastic modulus, density, and average molecular weight of PbO-doped titanium-barium-borate-based [TiO₂–BaO–B₂O₃–Al₂O₃–K₂O] glass-ceramic system labeled G1–G5. Our findings reveal significant insights into the synergistic effects and inverse relationships between the components. The shielding parameters (LAC, HVL, MFP, Z eff, ΣR, EBF, EABF, and PR for proton and alpha particles were theoretically computed using the Phy-X/PSD program in the photon energy range of 0.015–15 MeV. Gamma-ray TF were evaluated using PHITS. Additionally, the PR values for protons and alpha in the study were computed using the SRIM code. The mechanical properties were evaluated using the MM model. An increase in the PbO ratio decreases the molar volume of the glass and increases the relative packing, resulting in a steady increase in Young’s, bulk, shear, and longitudinal moduli. An increase in the Poisson ratio indicates that the glass structure becomes tighter, more rigid, and less flexible. With higher PbO levels, density and average molecular weight increase concurrently, improving radiation shielding due to increased atomic mass and compactness. Low photon energies had the highest LAC values, while higher photon energies resulted in lower values. Samples with higher PbO contents consistently displayed higher LAC values. G5 (4.5% PbO) demonstrated the best shielding performance, as evidenced by its lowest HVL. HVL values climbed with photon energy but fell with increasing PbO content. G5 continuously displayed lower HVL values than other glass compositions documented in the literature, demonstrating its remarkable gamma-ray shielding capability. According to sources [49,50,51,52,53], this benefit is particularly evident when contrasted with glasses like BCV0.5, BCBV0.5, S1, BSBaZn, and LBE5. Effective attenuation was demonstrated by MFP, which rose with energy but was lowest in high PbO samples. Z eff rose in glasses with increased PbO, improving photon interaction, but it fell with energy. G5’s remarkable neutron shielding capabilities was demonstrated by its greatest ΣR value. The PRs (Φ) of protons and alpha particles decreased with increasing PbO content; G5 exhibited the shortest ranges, highlighting its effectiveness in stopping energetic particles. G5’s exceptional performance was further validated by PHITS simulations, which consistently produced the lowest TF values across a range of gamma-ray energy and thicknesses, exhibiting exceptional attenuation.

At the atomic level, the network structure is changed when PbO is added to the glass matrix. It considerably raises the material’s density and radiation-interaction capabilities while decreasing the structural regularity of the glass network. Although the mechanical strength may be slightly diminished as a result of this alteration, the radiation attenuation qualities are significantly improved. Applications in radiation shielding systems and nuclear technologies are especially sensitive to this impact.

It is possible to build and construct a unique class of glass-ceramics with higher radiation shielding qualities by comprehending the synergistic effects of these components. The results open the door for the use of these PbO-doped titanium-barium-borate-based glass-ceramics in nuclear medicine, power plants, and other vital industries that need cutting-edge radiation shielding technologies. These developments make the glass system a viable option for use in high-ionizing radiation settings, such as those found in the nuclear and medical industries, where remarkable shielding effectiveness and structural robustness are required. Its potential for incorporation into next-generation radiation protection systems is highlighted by this combination.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their deepest gratitude to Assoc. Prof. Esra KAVAZ PERİŞANOĞLU for their valuable support and contributions to this work.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Gülfem SÜSOY DOĞAN: writing – review and editing, writing – original draft, visualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, and conceptualization. Ghada ALMisned: methodology, investigation, and formal analysis. Shams A.M. Issa: writing – original draft, validation, software, and investigation. Hesham M.H. Zakaly: material preparation, data collection, and analysis. Duygu Sen Baykal: material preparation, data collection, and analysis. Gokhan Kilic: methodology and investigation. Hessa Alkarrani: investigation, data curation, and writing – review. Antoaneta Ene: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, and investigation. Huseyin Ozan Tekin: writing – original draft, visualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, and conceptualization. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Oto B, Yıldız N, Akdemir F, Kavaz E. Investigation of gamma radiation shielding properties of various ores. Prog Nucl Energy. 2015;85:391–403. 10.1016/j.pnucene.2015.07.016.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Singh VP, Badiger NM, Kaewkhao J. Radiation shielding competence of silicate and borate heavy metal oxide glasses: comparative study. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2014;404:167–73. 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2014.08.003.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Klein RC, Weilandics C. Potential health hazards from lead shielding. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1996;57:1124–6. 10.1080/15428119691014215.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Ersundu Ç, Ersundu AE, Kityk IV. Investigation on gamma and neutron radiation shielding parameters for BaO/SrO‒Bi2O3‒B2O3 glasses. Radiat Phys Chem. 2018;145(4):26–33. 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2017.12.010.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Zanotto ED, Mauro JC. The glassy state of matter: its definition and ultimate fate. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2017;471:490–5. 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2017.05.019.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Mauro JC. Grand challenges in glass science. Front Mater. 2014;1(20):1–5. 10.3389/fmats.2014.00020.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Kurtulus R. Recent developments in radiation shielding glass studies: A mini-review on various glass types. Radiat Phys Chem. 2024;220:111701. 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2024.111701.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Karpuz N. Radiation shielding properties of glass composition. J Radiat Res Appl Sci. 2023;16(4):100689. 10.1016/j.jrras.2023.100689.Search in Google Scholar

[9] ALMisned G, Sen Baykal D, Susoy G, Kilic G, Zakaly MHH, Ene A, et al. Determination of gamma-ray transmission factors of WO3–TeO2–B2O3 glasses using MCPX Monte Carlo code for shielding and protection purposes. Appl Rheol. 2022;32(1):166–77. 10.1515/arh-2022-0132.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Sarihan M. Simulation of gamma-ray shielding properties for materials of medical interest. Open Chem. 2022;20(1):81–7. 10.1515/chem-2021-0118.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Boodaghi Malidarre R, Akkurt I. Evaluation of bioactive borosilicate added Ag glasses in terms of radiation shielding, structural, optical, and electrical properties. Silicon. 2022;14:12371–9. 10.1007/s12633-022-01925-y.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Fernandes HR, Tulyaganov DU, Goel A, Ribeiro MJ, Pascual MJ, Ferreira JMF. Effect of Al2O3 and K2O content on structure, properties and devitrification of glasses in the Li2O–SiO2 system. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2010;30(10):2017–30. 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2010.04.017.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Sayyed MI, Hamad MK, Mhareb MHA, Naseer KA, Mahmoud KA, Khandaker MU, et al. Impact of Modifier Oxides on Mechanical and Radiation Shielding Properties of B2O3-SrO-TeO2-RO Glasses (Where RO = TiO2, ZnO, BaO, and PbO). Appl Sci. 2021;11(22):10904. 10.3390/app112210904.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Kaewjaeng S, Kaewkhao J, Limsuwan P, Maghanemi U. Effect of BaO on Optical, Physical and Radiation Shielding Properties of SiO2-B2O3-Al2O3-CaO-Na2O Glasses System. Procedia Eng. 2012;32:1080–6. 10.1016/j.proeng.2012.02.058.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Al-Ghamdi H, Sayyed I, Kumar A, Yasmin S, Elbashir BO, Almuqrin AH. Effect of PbO and B2O3 on the Physical, Structural, and Radiation Shielding Properties of PbO-TeO2-MgO-Na2O-B2O3 Glasses. Sustainability. 2022;14(15):9695. 10.3390/su14159695.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Yin S, Wang H, Wang S, Zhang J, Zhu Y. Effect of B2O3 on the Radiation Shielding Performance of Telluride Lead Glass System. Crystals. 2022;12(2):178. 10.3390/cryst12020178.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Abouhaswa AS, Abdelghany AM, Alfryyan N, Alsaif NAM, Rammah YS, Nabil IM. The impact of B2O3/Al2O3 substitution on physical properties and γ‑ray shielding competence of aluminum‑borate glasses: comparative study. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron. 2024;35:845. 10.1007/s10854-024-12629-x.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Singh GP, Singh J, Kaur P, Singh T, Kaur R, Kaur S, et al. Impact of TiO2 on radiation shielding competencies and structural, physical and optical properties of CeO2–PbO–B2O3 glasses. J Alloy Compd. 2021;885:160939. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.160939.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Takahashi J, Nakano H, Kageyama K. Fabrication and dielectric properties of barium titanate-based glass-ceramics for tunable microwave LTCC application. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2006;26(10–11):2123–7. 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2005.09.070.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Ruiz-Valdez JJ, Gorokhovsky AV, Escalante-García JI, Mendoza-Suarez G. Glass-ceramics materials with regulated dielectric properties based in the system BaO-PbO-TiO2-B2O3-Al2O3. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2004;24(6):1505–8. 10.1016/S0955-2219(03)00531-4.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Shi R, Pu Y, Wang W, Shi Y, Li J, Guo X, et al. Flash sintering of barium titanate. Ceram Int. 2019;45(5):7085–9. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.12.211.Search in Google Scholar

[22] González MA, Gorokhovsky A, Escalante JI, Ponce P, Escobedo MA. Crystallization and properties of glass-ceramics of the K2O-BaO-B2O3-Al2O3-TiO2 system. Mater Sci Forum. 2013;755:125–32. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.755.125.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Mandal RK, Prasad CD, Parkash O, Kumar D. Dielectric behaviour of glasses and glass ceramics in the system BaO-PbO-TiO2-B2O3-SiO2. Bull Mater Sci. 1987;9(4):255–62. 10.1007/BF02743974.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Huang YX, Senos AMR. Effect of the powder precursor characteristics in the reaction sintering of aluminium titanate. Mater Res Bull. 2002;37(1):99–111. 10.1016/S0025-5408(01)00802-9.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Barbieri L, Karamanov A, Corradi A, Lancellotti I, Pelino M, Rincon JM. Structure, chemical durability and crystallization behavior of incinerator-based glassy systems. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2008;354(6–7):521–8. 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2007.07.080.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Gautam C, Yadav AK, Singh AK. A review on infrared spectroscopy of borate glasses with effects of different additives. ISRN Ceram. 2012;2012:428497. 10.5402/2012/428497.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Escobedo Bretado MA, González Lozano MA, Collins Martínez V, López Ortiz A, Meléndez Zaragoza M, Lara RH, et al. Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic evaluation of potassium hexatitanate (K2Ti6O13) fibers. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2019;44(24):12470–6. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.06.085.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Savio AKPD, Fletcher J, Robles Hernández FC. Sonosynthesis of nanostructured TiO2 doped with transition metals having variable bandgap. Ceram Int. 2013;39(3):2753–65. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2012.09.042.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Oruc Ulas E, Acikgoz A, Aktas B, Kavun Y. Influence of B2O3 incorporation on the structural, mechanical and radiation shielding properties of TeO2 based bioglasses. Appl Radiat Isotopes. 2025;221:111799. 10.1016/j.apradiso.2025.111799.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Rasul SY, Aktas B, Yilmaz D, Pathman AF, Yalcin Ş, Acikgoz A. Impact of HfO2 on the structural, thermal, gamma, and neutron shielding properties of boro-tellurite glasses. Inorg Chem Commun. 2025;174(Part 1):113993. 10.1016/j.inoche.2025.113993.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Dogru K, Aktas B, Acikgoz A, Yilmaz D, Pathman AF, Yalcin Ş, et al. Structural, thermal, and radiation shielding properties of B2O3-TeO2-Bi2O3-CdO-Tm2O3 glasses: The role of Tm2O3. Ceram Int. 2024;50(22Part B):47384–94. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.09.088.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Solak BB, Aktas B, Yilmaz D, Kalecik S, Yalcin Ş, Acikgoz A, et al. Exploring the radiation shielding properties of B2O3-PbO-TeO2-CeO2-WO3 glasses: A comprehensive study on structural, mechanical, gamma, and neutron attenuation characteristics. Mater Chem Phys. 2024;312:128672. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2023.128672.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Aktas B, Yalcin S, Dogru K, Uzunoglu Z, Yilmaz D. Structural and radiation shielding properties of chromium oxide doped borosilicate glass. Radiat Phys Chem. 2019;156:144–9. 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2018.11.012.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Ponce-Peña P, González Lozano MA, Escobedo-Bretado MÁ, Núñez-Ramírez DM, Rodríguez-Pulido A, Quiñones Jurado ZV, et al. Crystallization of Glasses Containing K2O, PbO, BaO, Al2O3, B2O3, and TiO2. Crystals. 2022;12:574. 10.3390/cryst12050574.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Makishima A, Mackenzie JD. Direct calculation of Young’s modulus of glass. J Non-Cryst Solids. 1973;12:35–45. 10.1016/0022-3093(73)90053-7.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Makishima A, Mackenzie JD. Calculation of bulk modulus, shear modulus and Poisson’s ratio of glass. J Non-Cryst Solids. 1975;17:147–57. 10.1016/0022-3093(75)90047-2.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Şakar E, Özpolat ÖF, Alım B, Sayyed MI, Kurudirek M. Phy-X/PSD: Development of a user friendly online software for calculation of parameters relevant to radiation shielding and dosimetry. Radiat Phys Chem. 2020;166:108496. 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2019.108496.Search in Google Scholar

[38] El-Khayatt AM. Calculation of fast neutron removal cross-sections for some compounds and materials. Ann Nucl Energy. 2010;37(2):218–22. ISSN 0306-4549 10.1016/j.anucene.2009.10.022.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Ziegler JF, Ziegler MD, Biersack JP. The stopping and range of ions in matter. New York, NY, USA: Pergamon Press; 1985ISBN 978-0-08-021607-2.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Sato T, Iwamoto Y, Hashimoto S, Ogawa T, Furuta T, Abe S, et al. Features of particle and heavy ion transport code system (PHITS) version 3.02. J Nucl Sci Technol. 2018;55(6):684–90. 10.1080/00223131.2017.1419890.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Iwase H, Niita K, Nakamura T. Development of general purpose particle and heavy ion transport Monte Carlo code. J Nucl Sci Technol. 2002;39(11):1142–51. 10.1080/18811248.2002.9715305.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Niita K, Sato T, Iwase H, Nose H, Nakashima H, Sihver L. Particle and heavy ion transport code system; PHITS. Radiat Meas. 2006;41:1080–90. 10.1016/j.radmeas.2006.07.013.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Sihver L, Mancusi D, Sato T, Niita K, Iwase H, Iwamoto Y, et al. Recent developments and benchmarking of the PHITS code. Adv Space Res. 2007;40:1320–31. 10.1016/j.asr.2007.02.056.Search in Google Scholar

[44] A.Al-Yousef H, Alotiby M, Kumar A, Alotaibi BM, Alsaif NAM, Sayyed MI, et al. Physical, structural, and gamma ray shielding studies on novel (35 + x) PbO-5TeO2-20Bi2O3-(20-x) MgO-20B2O3 glasses. J Aust Ceram Soc. 2021;57:971–81. 10.1007/s41779-021-00600-6.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Alsaif NAM, Al-Ghamdi H, Elsad RA, Abdelghany AM, Shaaban SM, Rammah YS, et al. Fabrication, physical properties and γ-ray shielding factors of high dense B2O3–PbO–Na2O–CdO–ZnO glasses: impact of B2O3/PbO substitution. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron. 2024;35:534. 10.1007/s10854-024-12290-4.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Shaaban KS, Wahab EA, Shaaban ER, Yousef ES, Mahmoud SA. Electronic polarizability, optical basicity and mechanical properties of aluminum lead phosphate glasses. Opt Quantum Electron. 2020;52:125. 10.1007/s11082-020-2191-3.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Sayyed MI, Almuqrin AH, Kumar A, Jecong JFM, Akkurt I. Optical, mechanical properties of TeO2-CdO-PbO-B2O3 glass systems and radiation shielding investigation using EPICS2017 library. Optik. 2021;242:167342. 10.1016/j.ijleo.2021.167342.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Ali AM, Sayyed MI, Rashad M, Kumar A, Kaur R, Aşkın A, et al. Gamma ray shielding behavior of Li2O-doped PbO–MoO3–B2O3 glass system. Appl Phys A. 2019;125:671. 10.1007/s00339-019-2964-3.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Ilik E, Kavaz E, Kilic G, Issa SAM, Zakaly HMH, Tekin HO. A closer-look on Copper(II) oxide reinforced Calcium-Borate glasses: Fabrication and multiple experimental assessment on optical, structural, physical, and experimental neutron/gamma shielding properties. Ceram Int. 2022;48(5):6780–91. ISSN 0272-8842. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.11.229.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Ilik E, Kavaz E, Kilic G, Issa SAM, ALMisned G, Tekin HO. Synthesis and characterization of vanadium(V) oxide reinforced calcium-borate glasses: Experimental assessments on Al2O3/BaO2/ZnO contributions. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2022;580:121397. 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2022.121397.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Barebita H, Ferraa S, Moutataouia M, Baach B, Elbadaoui A, Nimour A, et al. Structural investigation of Bi2O3-P2O5-B2O3-V2O5 quaternary glass system by Raman, FTIR and thermal analysis. Chem Phys Lett. 2020;760:138031. 10.1016/j.cplett.2020.138031.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Sen Baykal D, Kilic G, İlik E, Kavaz E, ALMisned G, Cakirli RB, et al. Designing a Lead-free and high-density glass for radiation facilities: Synthesis, physical, optical, structural, and experimental gamma-ray transmission properties of newly designed barium-borosilicate glass sample. J Alloy Compd. 2023;965:171392. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.171392.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Chandrashekaraiah G, Sivasankara Reddy N, Sujatha B, Viswanatha R, Narayana Reddy C. Role of Er3 + and Bi3 + ions on thermal and optical properties of Li2B4O7 glasses: Structural correlation. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2018;498:252–61. 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2018.06.034.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation

- Single-step fabrication of Mn(iv) oxide-Mn(ii) sulfide/poly-2-mercaptoaniline porous network nanocomposite for pseudo-supercapacitors and charge storage

- Novel constructed dynamical analytical solutions and conserved quantities of the new (2+1)-dimensional KdV model describing acoustic wave propagation

- Tavis–Cummings model in the presence of a deformed field and time-dependent coupling

- Spinning dynamics of stress-dependent viscosity of generalized Cross-nonlinear materials affected by gravitationally swirling disk

- Design and prediction of high optical density photovoltaic polymers using machine learning-DFT studies

- Robust control and preservation of quantum steering, nonlocality, and coherence in open atomic systems

- Coating thickness and process efficiency of reverse roll coating using a magnetized hybrid nanomaterial flow

- Dynamic analysis, circuit realization, and its synchronization of a new chaotic hyperjerk system

- Decoherence of steerability and coherence dynamics induced by nonlinear qubit–cavity interactions

- Finite element analysis of turbulent thermal enhancement in grooved channels with flat- and plus-shaped fins

- Modulational instability and associated ion-acoustic modulated envelope solitons in a quantum plasma having ion beams

- Statistical inference of constant-stress partially accelerated life tests under type II generalized hybrid censored data from Burr III distribution

- On solutions of the Dirac equation for 1D hydrogenic atoms or ions

- Entropy optimization for chemically reactive magnetized unsteady thin film hybrid nanofluid flow on inclined surface subject to nonlinear mixed convection and variable temperature

- Stability analysis, circuit simulation, and color image encryption of a novel four-dimensional hyperchaotic model with hidden and self-excited attractors

- A high-accuracy exponential time integration scheme for the Darcy–Forchheimer Williamson fluid flow with temperature-dependent conductivity

- Novel analysis of fractional regularized long-wave equation in plasma dynamics

- Development of a photoelectrode based on a bismuth(iii) oxyiodide/intercalated iodide-poly(1H-pyrrole) rough spherical nanocomposite for green hydrogen generation

- Investigation of solar radiation effects on the energy performance of the (Al2O3–CuO–Cu)/H2O ternary nanofluidic system through a convectively heated cylinder

- Quantum resources for a system of two atoms interacting with a deformed field in the presence of intensity-dependent coupling

- Studying bifurcations and chaotic dynamics in the generalized hyperelastic-rod wave equation through Hamiltonian mechanics

- A new numerical technique for the solution of time-fractional nonlinear Klein–Gordon equation involving Atangana–Baleanu derivative using cubic B-spline functions

- Interaction solutions of high-order breathers and lumps for a (3+1)-dimensional conformable fractional potential-YTSF-like model

- Hydraulic fracturing radioactive source tracing technology based on hydraulic fracturing tracing mechanics model

- Numerical solution and stability analysis of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to exponential heat source/sink over a Riga sheet

- Numerical investigation of mixed convection and viscous dissipation in couple stress nanofluid flow: A merged Adomian decomposition method and Mohand transform

- Effectual quintic B-spline functions for solving the time fractional coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equation arising in shallow water waves

- Analysis of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow over cone and wedge with exponential and thermal heat source and activation energy

- Solitons and travelling waves structure for M-fractional Kairat-II equation using three explicit methods

- Impact of nanoparticle shapes on the heat transfer properties of Cu and CuO nanofluids flowing over a stretching surface with slip effects: A computational study

- Computational simulation of heat transfer and nanofluid flow for two-sided lid-driven square cavity under the influence of magnetic field

- Irreversibility analysis of a bioconvective two-phase nanofluid in a Maxwell (non-Newtonian) flow induced by a rotating disk with thermal radiation

- Hydrodynamic and sensitivity analysis of a polymeric calendering process for non-Newtonian fluids with temperature-dependent viscosity

- Exploring the peakon solitons molecules and solitary wave structure to the nonlinear damped Kortewege–de Vries equation through efficient technique

- Modeling and heat transfer analysis of magnetized hybrid micropolar blood-based nanofluid flow in Darcy–Forchheimer porous stenosis narrow arteries

- Activation energy and cross-diffusion effects on 3D rotating nanofluid flow in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium with radiation and convective heating

- Insights into chemical reactions occurring in generalized nanomaterials due to spinning surface with melting constraints

- Influence of a magnetic field on double-porosity photo-thermoelastic materials under Lord–Shulman theory

- Soliton-like solutions for a nonlinear doubly dispersive equation in an elastic Murnaghan's rod via Hirota's bilinear method

- Analytical and numerical investigation of exact wave patterns and chaotic dynamics in the extended improved Boussinesq equation

- Nonclassical correlation dynamics of Heisenberg XYZ states with (x, y)-spin--orbit interaction, x-magnetic field, and intrinsic decoherence effects

- Exact traveling wave and soliton solutions for chemotaxis model and (3+1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation

- Unveiling the transformative role of samarium in ZnO: Exploring structural and optical modifications for advanced functional applications

- On the derivation of solitary wave solutions for the time-fractional Rosenau equation through two analytical techniques

- Analyzing the role of length and radius of MWCNTs in a nanofluid flow influenced by variable thermal conductivity and viscosity considering Marangoni convection

- Advanced mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in oscillatory micropolar bio-nanofluid flows via peristaltic waves and electroosmotic effects

- Exact bound state solutions of the radial Schrödinger equation for the Coulomb potential by conformable Nikiforov–Uvarov approach

- Some anisotropic and perfect fluid plane symmetric solutions of Einstein's field equations using killing symmetries

- Nonlinear dynamics of the dissipative ion-acoustic solitary waves in anisotropic rotating magnetoplasmas

- Curves in multiplicative equiaffine plane

- Exact solution of the three-dimensional (3D) Z2 lattice gauge theory

- Propagation properties of Airyprime pulses in relaxing nonlinear media

- Symbolic computation: Analytical solutions and dynamics of a shallow water wave equation in coastal engineering

- Wave propagation in nonlocal piezo-photo-hygrothermoelastic semiconductors subjected to heat and moisture flux

- Comparative reaction dynamics in rotating nanofluid systems: Quartic and cubic kinetics under MHD influence

- Laplace transform technique and probabilistic analysis-based hypothesis testing in medical and engineering applications

- Physical properties of ternary chloro-perovskites KTCl3 (T = Ge, Al) for optoelectronic applications

- Gravitational length stretching: Curvature-induced modulation of quantum probability densities

- The search for the cosmological cold dark matter axion – A new refined narrow mass window and detection scheme

- A comparative study of quantum resources in bipartite Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model under DM interaction and Zeeman splitting

- PbO-doped K2O–BaO–Al2O3–B2O3–TeO2-glasses: Mechanical and shielding efficacy

- Nanospherical arsenic(iii) oxoiodide/iodide-intercalated poly(N-methylpyrrole) composite synthesis for broad-spectrum optical detection

- Sine power Burr X distribution with estimation and applications in physics and other fields

- Numerical modeling of enhanced reactive oxygen plasma in pulsed laser deposition of metal oxide thin films

- Dynamical analyses and dispersive soliton solutions to the nonlinear fractional model in stratified fluids

- Computation of exact analytical soliton solutions and their dynamics in advanced optical system

- An innovative approximation concerning the diffusion and electrical conductivity tensor at critical altitudes within the F-region of ionospheric plasma at low latitudes

- An analytical investigation to the (3+1)-dimensional Yu–Toda–Sassa–Fukuyama equation with dynamical analysis: Bifurcation

- Swirling-annular-flow-induced instability of a micro shell considering Knudsen number and viscosity effects

- Numerical analysis of non-similar convection flows of a two-phase nanofluid past a semi-infinite vertical plate with thermal radiation

- MgO NPs reinforced PCL/PVC nanocomposite films with enhanced UV shielding and thermal stability for packaging applications

- Optimal conditions for indoor air purification using non-thermal Corona discharge electrostatic precipitator

- Investigation of thermal conductivity and Raman spectra for HfAlB, TaAlB, and WAlB based on first-principles calculations

- Tunable double plasmon-induced transparency based on monolayer patterned graphene metamaterial

- DSC: depth data quality optimization framework for RGBD camouflaged object detection

- A new family of Poisson-exponential distributions with applications to cancer data and glass fiber reliability

- Numerical investigation of couple stress under slip conditions via modified Adomian decomposition method

- Monitoring plateau lake area changes in Yunnan province, southwestern China using medium-resolution remote sensing imagery: applicability of water indices and environmental dependencies

- Heterodyne interferometric fiber-optic gyroscope

- Exact solutions of Einstein’s field equations via homothetic symmetries of non-static plane symmetric spacetime

- A widespread study of discrete entropic model and its distribution along with fluctuations of energy

- Empirical model integration for accurate charge carrier mobility simulation in silicon MOSFETs

- The influence of scattering correction effect based on optical path distribution on CO2 retrieval

- Anisotropic dissociation and spectral response of 1-Bromo-4-chlorobenzene under static directional electric fields

- Role of tungsten oxide (WO3) on thermal and optical properties of smart polymer composites

- Analysis of iterative deblurring: no explicit noise

- The influence of anisotropy of InP on its elasticity and phonon properties

- Review Article

- Examination of the gamma radiation shielding properties of different clay and sand materials in the Adrar region

- Erratum

- Erratum to “On Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model (Open Physics 2021;19:679–682)”

- Special Issue on Fundamental Physics from Atoms to Cosmos - Part II

- Possible explanation for the neutron lifetime puzzle

- Special Issue on Nanomaterial utilization and structural optimization - Part III

- Numerical investigation on fluid-thermal-electric performance of a thermoelectric-integrated helically coiled tube heat exchanger for coal mine air cooling

- Special Issue on Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos in Physical Systems

- Analysis of the fractional relativistic isothermal gas sphere with application to neutron stars

- Abundant wave symmetries in the (3+1)-dimensional Chafee–Infante equation through the Hirota bilinear transformation technique

- Successive midpoint method for fractional differential equations with nonlocal kernels: Error analysis, stability, and applications

- Novel exact solitons to the fractional modified mixed-Korteweg--de Vries model with a stability analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Single-step fabrication of Ag2S/poly-2-mercaptoaniline nanoribbon photocathodes for green hydrogen generation from artificial and natural red-sea water

- Abundant new interaction solutions and nonlinear dynamics for the (3+1)-dimensional Hirota–Satsuma–Ito-like equation

- A novel gold and SiO2 material based planar 5-element high HPBW end-fire antenna array for 300 GHz applications

- Explicit exact solutions and bifurcation analysis for the mZK equation with truncated M-fractional derivatives utilizing two reliable methods

- Optical and laser damage resistance: Role of periodic cylindrical surfaces

- Numerical study of flow and heat transfer in the air-side metal foam partially filled channels of panel-type radiator under forced convection

- Water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing CNT nanoparticles over an extending surface with velocity slips, thermal convective, and zero-mass flux conditions

- Dynamical wave structures for some diffusion--reaction equations with quadratic and quartic nonlinearities

- Solving an isotropic grey matter tumour model via a heat transfer equation

- Study on the penetration protection of a fiber-reinforced composite structure with CNTs/GFP clip STF/3DKevlar

- Influence of Hall current and acoustic pressure on nanostructured DPL thermoelastic plates under ramp heating in a double-temperature model

- Applications of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction–diffusion system: Analytical and numerical approaches

- AC electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid in a pH-regulated parallel-plate silica nanochannel

- Interpreting optical effects with relativistic transformations adopting one-way synchronization to conserve simultaneity and space–time continuity

- Modeling and analysis of quantum communication channel in airborne platforms with boundary layer effects

- Theoretical and numerical investigation of a memristor system with a piecewise memductance under fractal–fractional derivatives

- Tuning the structure and electro-optical properties of α-Cr2O3 films by heat treatment/La doping for optoelectronic applications

- High-speed multi-spectral explosion temperature measurement using golden-section accelerated Pearson correlation algorithm

- Dynamic behavior and modulation instability of the generalized coupled fractional nonlinear Helmholtz equation with cubic–quintic term

- Study on the duration of laser-induced air plasma flash near thin film surface

- Exploring the dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear dispersive wave system through homotopy technique

- The mechanism of carbon monoxide fluorescence inside a femtosecond laser-induced plasma

- Numerical solution of a nonconstant coefficient advection diffusion equation in an irregular domain and analyses of numerical dispersion and dissipation

- Numerical examination of the chemically reactive MHD flow of hybrid nanofluids over a two-dimensional stretching surface with the Cattaneo–Christov model and slip conditions

- Impacts of sinusoidal heat flux and embraced heated rectangular cavity on natural convection within a square enclosure partially filled with porous medium and Casson-hybrid nanofluid

- Stability analysis of unsteady ternary nanofluid flow past a stretching/shrinking wedge

- Solitonic wave solutions of a Hamiltonian nonlinear atom chain model through the Hirota bilinear transformation method

- Bilinear form and soltion solutions for (3+1)-dimensional negative-order KdV-CBS equation

- Solitary chirp pulses and soliton control for variable coefficients cubic–quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equation in nonuniform management system

- Influence of decaying heat source and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity on photo-hydro-elasto semiconductor media

- Dissipative disorder optimization in the radiative thin film flow of partially ionized non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid with second-order slip condition

- Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, and traveling wave solutions for the fractional (4+1)-dimensional Davey–Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili model

- New investigation on soliton solutions of two nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics with a dynamical property: Bifurcation analysis

- Mathematical analysis of nanoparticle type and volume fraction on heat transfer efficiency of nanofluids

- Creation of single-wing Lorenz-like attractors via a ten-ninths-degree term

- Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors of nonlinear Schrödinger equation and modulation instability in optical fiber

- Chaotic dynamics and some solutions for the (n + 1)-dimensional modified Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation in plasma physics

- Fractal formation and chaotic soliton phenomena in nonlinear conformable Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation