Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

-

Görkem Ozankaya

, Mohamed Yasin Alibar

, Vincent Kvocak

Abstract

In this study, graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs) and titanium dioxide nanofillers were added to epoxy resin P-5005 at five different weight percentages (wt%), viz., 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 wt%. The tensile properties of the nanocomposites were experimentally tested following ASTM D638-14. Then, the above-mentioned nanocomposites were applied as adhesives for an overlap joint of two A5055 aluminum sheets. The apparent shear strength behavior of joints was tested following ASTM D1002-01. Moreover, experimentally obtained results were applied to train and test machine learning and deep learning models, i.e., adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system, support vector machine, multiple linear regression, and artificial neural network (ANN). The peak tensile strength (TS) and joint failure load (FL) values were observed in epoxy/GNP samples. The ANN model exhibited the least error in predicting the TS and FL of the considered nanocomposites. The epoxy/GNP nanocomposites exhibited the highest TS of 28.49 MPa at 1 wt%, and the peak overlap joints exhibited an FL of 3.69 kN at 15 wt%.

1 Introduction

Epoxy resin is one of the most vital structural adhesives, widely popular in aerospace, automotive, electronics, civil, and packaging industries. Recently, the adhesive industry has changed significantly by including new formulations, raw materials, substrates, operation conditions, applications, and curing processes [1]. Therefore, properties such as resistance to failure at vibration and fatigue loading, resistance to thermal cycling and high service temperatures, and optimum curing conditions have to be considered in epoxy adhesives. Numerous studies aimed to develop multi-functional epoxy adhesives by mixing epoxy with a second material as a filler, such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, Al2O3, CaCO3, SiO2, ZrO2, titanium dioxide (TiO2) and so on. In recent years, the size of fillers has shifted from micro- to nano-scale, resulting in much superior multifunctional characteristics in nanocomposite adhesives compared to neat adhesives and their composites having conventional micro-particles [2,3]. The addition of nanoparticles to epoxy adhesive joints improves their mechanical properties, joints’ failure load (FL), thermal stability, and electrical conductivity [4,5,6,7]. However, it varies based on several parameters, such as particle characteristics, functional groups on the nanoparticle surface, size distribution, size, content, and shape, defining its compatibility with the epoxy matrix [8,9,10,11,12].

Graphene is a carbon allotrope that consists of a one-atom layer and its lattice nanostructure is arranged in a 2D honeycomb structure. Since 2004, it has been considered one of the most stiff and strong materials. The Young’s modulus and tensile strength (TS) of graphene are around 1 TPa and 130 GPa, respectively [13]; moreover, the thermal conductivity is around 5,000 W/mK [14]. Multilayered graphene, also known as graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs), has become a very desirable polymer matrix filler with a great price-to-performance ratio and is utilized in diverse fields, i.e., energy, defense, electronics, transport, medicine, etc. TiO2, which is also known as titanium, is a natural mineral available in various crystalline structures, and its applications include the textile industry, food products, coatings, plastics, pharmaceuticals, and so on.

Multiple research studies have investigated the mechanical, thermal, and electrical characteristics of epoxy adhesives reinforced with GNP and metal-based TiO2. Singh et al. [15] studied the effect of GNP and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) on the mechanical characteristics of epoxy-based nanocomposites, and the results showed that the epoxy/GNP composite provided greater tensile and compressive strengths compared to MWCNT/epoxy composites, while the latter exhibited a greater toughness compared to epoxy/GNP. Hence, graphene possesses an outstanding specific surface area, in addition to significant mechanical and electrical properties, which makes graphene the greatest compared to other carbon allotropes for developing multifunctional and structural-reinforced composites [16,17]. Moreover, the dispersion of graphene in the composites and the surface friction force of graphene are the two main properties that have an impact on the ability of graphene to improve damping [18,19,20].

Mustafa et al. [21] have studied the influence of MWCNTs on mechanical characteristics and thermal stability of hybrid nanocomposites. The hybrid polymer structure was made from epoxy resin mixed with different weight percentages of zirconium dioxide (ZrO2) and yttrium oxide (Y2O3). The structure was further strengthened with 0.1 wt% MWCNT through a hand lay-up casting process. It was reported that the TS and Young’s modulus were improved by 24 and 37% in comparison with pure epoxy resin. Kumar et al. [22] investigated the tensile and dynamic mechanical properties of epoxy/MWCNT/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, and 1.5 wt%. The results revealed that the TS of epoxy was increased by 24% by the addition of 1 wt% MWCNTs. Modeling and simulation as well as artificial intelligence have emerged in a wider spectrum for diverse science and engineering applications [23,24,25]. Even though experimental testing is drastically crucial for the development of new material, machine learning reduces the computational time and cost, since the needed platforms to run machine learning algorithms mainly have free access and can be found easily [26,27,28]. Artificial intelligence was recently implemented by numerous studies to analyze the characteristics of composite materials, natural fiber composites, and nanocomposites [29,30,31,32,33]. Pati [34] utilized artificial neural networks (ANNs) to predict the wear properties of glass/epoxy composites, and the input data included the RBD content, erodent size, erodent temperature, impact velocity, and impingement angle. Antil et al. [35] applied the response surface metamodel and ANN to evaluate the erosion characteristics of S glass composites, and the input parameters consisted of the impingement angle, nozzle diameter, and slurry pressure. Jayaganthan et al. [36] classified the conductivity of epoxy reinforced with 66 wt% silica fillers, 0.7 wt% ion trapping particles and coated with four different coal types by implementing a support vector machine (SVM), logistic regression model, K-nearest neighbors, and a multi-layer perceptron approach in their LIBS spectral data. Rahman et al. [37] applied a convolutional neural network for the analysis of the pull-out force of epoxy/CNT nanocomposites.

The goal of the current research was to study the characteristics of epoxy reinforced with GNP and TiO2 nanoparticles for aluminum single-lap joint application by testing the tensile properties of the considered nanocomposites, examining nanocomposite joints’ FL, and developing an SVM, multiple linear regression (MLR)-based metamodel, adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS), and ANNs. The effect of increasing filler weight percentages of 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 wt% was examined.

2 Methodology

TiO2 and GNP nano-particles were added into an epoxy matrix with five different percentages, i.e. 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 wt%. First, the tensile behaviors of these nanocomposites were evaluated following the ASTM D638-14 tensile testing standard, followed by scanning electron microscopy for testing the fracture surface morphology. Moreover, the aforementioned nanocomposites were applied as an overlap adhesive between two aluminum plates. The apparent shear strength properties of the adhesives were tested following ASTM D1002-01. The experimental results were utilized to train and test machine learning and deep learning models, i.e., ANFIS, SVM, MLR, and ANN to evaluate the ability of the aforementioned to predict the mechanical properties of nanocomposites.

2.1 Experiment

Epoxy resin P-5005 by Polymex was utilized in this study as a matrix for the nanocomposite adhesive. The resin-to-hardener mixing ratio (2:1) and matrix-to-filler compositions were prepared using a high-precision electronic balance. Thus, in order to achieve a homogeneous nanocomposite, the nanocomposites were prepared via the following steps: a specific amount of epoxy was added into the mixing container, then nanoparticles were added upon a desired weight percentage, and the mixture was stirred with a plastic spoon for 25 min. To ensure that the nanoparticles in the epoxy were evenly distributed, the mixture was left at room temperature for an extra 2 h. After the addition of the curing agent, the mixture was mixed for 3 min, and then poured into a mold to develop tensile test specimens and to prepare lap-shear test samples The A5055 aluminum sheets (1 mm thick) were considered as an adherent material. Moreover, the sheets’ surfaces were wiped and treated aiming to enhance the bonding between the nanocomposite material and the aluminum sheets. GNPs and TiO2 were supplied from Nanografi. GNPs had a purity of 99.9%, 5 nm thickness, 30 μm diameter, gray in color, a conductivity between 1,100 and 1,600 s/m, and a specific surface area of 170 m2/g. TiO2 nanoparticles were of 20 nm size, 99.9% purity, 4.26 g/cm3 density, white in color, and 79.87 g/mol molecular weight.

2.1.1 Tensile test

The TS values of GNP and TiO2-reinforced epoxy nanocomposites were tested following the ASTM standard D638-14. Dog bone-shaped samples were prepared with 200 mm length, 57 mm width, 3.2 mm thickness, and a gauge length of 50 mm. First, the epoxy resin and its hardener were mixed in a 2:1 ratio and then the nanoparticles were added and stirred until the mixture became homogeneous. A layer of releasing agent was sprayed into the wooden mold before pouring the mixture. Then, the samples were cured at room temperature for 12 h. The test was conducted on an INSTRAM 338571 tensile machine with a testing speed of 5 mm/min.

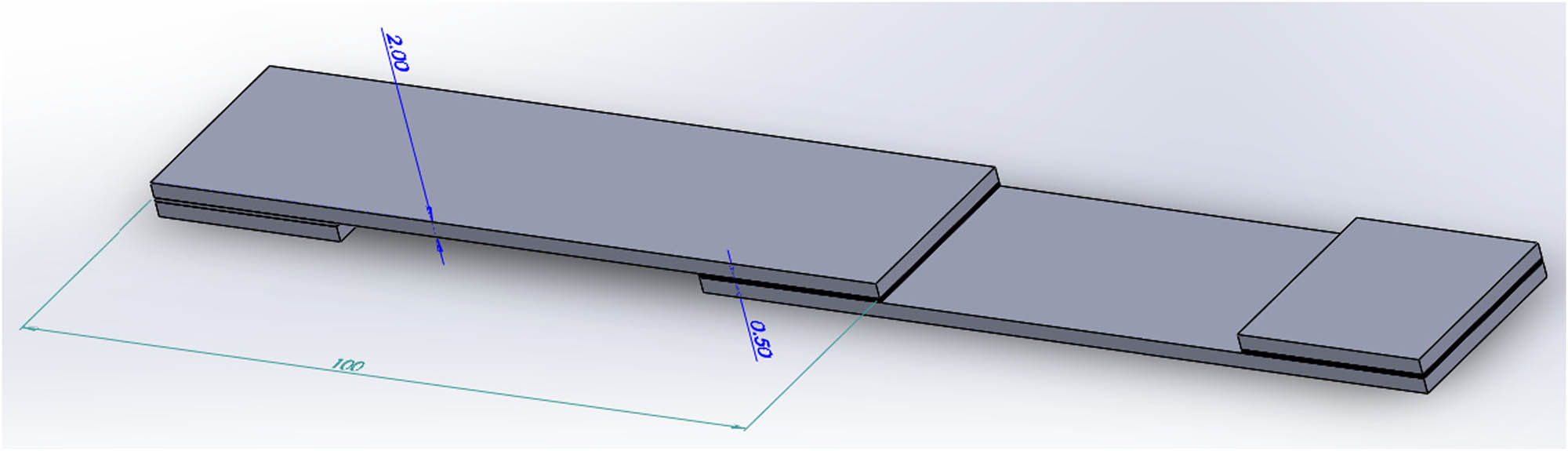

2.1.2 Lap joint

A5055 aluminum was selected as a substrate material. Single lap joint specimens were prepared by first slightly roughening the overlap area using an emery cloth to strengthen the bonding between the adhesive and substrates, followed by immersing the latter in a detergent to prevent any unwanted dirt, grease, or oil. Then, the samples were removed from the solution, washed with deionized water, and dried using a tissue. An epoxy/nanoparticles mixture was then spread for a 25 mm × 25 mm overlap area, keeping a grip length of 200 mm (Figure 1). Thus, the thickness of the cured adhesive was around 0.5 mm. In order to ensure the results’ accuracy and avoid undesired errors, three replicates were prepared for each nanocomposite’s composition, i.e., 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 wt%. An INSTRAM 338571 tensile machine (10 kN) was utilized for conducting the single lap joint test at a testing rate of 1 mm/min.

The geometry of adhesively bonded aluminum joints.

2.2 Machine learning and deep learning predictions

Machine learning is derived from artificial intelligence, which is a method that trains the computer to perform tasks that are usually specific for humans and acquired through experience. Increasing the amount of learning samples usually enhances the precision of the algorithm. Moreover, the implementation of deep learning in research attained wide popularity since 2006, as it was applied to object recognition, machine translations, speech recognition, and image segmentation. Basically, due to their neural network structures, most deep learning methods could be considered deep neural networks. Although there are supervised and unsupervised machine learning algorithms, the former is more suitable for manufacturing implementations due to the labeled data it provides:

An easy approach for evaluating the training model precision is called prediction error, where the aforementioned is validated using novel input data, which were not considered in the testing stage, which thereby contributes to defining the error percentage. Hence, root mean square error (RMSE) is a prevalent method used to define a model’s error:

where N is the whole training data, p i is the predicted deliberate information, and q i is the real value.

In this study, ANFIS, SVM, ANNs, and the response surface metamodel were applied to evaluate and define the most suitable approach for the prediction of the lap shear strength and TS for input parameters not considered in the experiment, as well as to determine the design space based on the considered parameters. The proposed model employs nanoparticle types and weight percentages as input. The tensile test and shear lap experimentally obtained results were considered for training, validation, and testing. The precision of the prediction models was assessed by the mean value of absolute percentage error.

3 Results and discussion

The tensile and shear characteristics obtained from experimental and machine learning of TiO2 and GNP-reinforced epoxy are presented in this section.

3.1 Tensile test

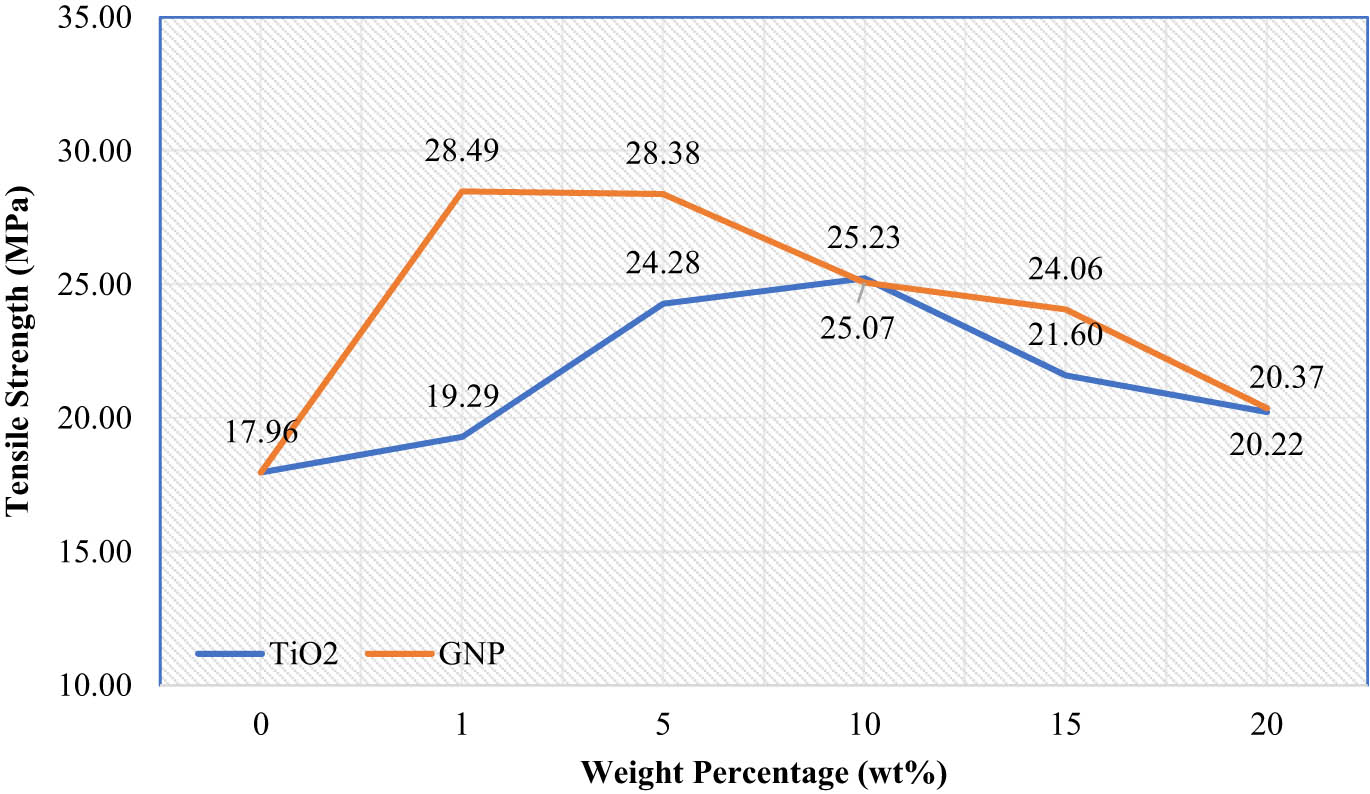

In this section, tensile test results are presented, which mainly highlight the TS values of epoxy/GNP and epoxy/TiO2 nanocomposites for five different compositions. Figure 2 illustrates the impact of increasing TiO2 and GNP nanoparticles from 1 to 20 wt% on the TS of the end nanocomposites.

TS of epoxy/TiO2 and epoxy/GNP for 5 wt%.

As exhibited in Figure 2, increasing the TiO2 content increased the TS from 17.96 to 25.23 MPa at 10 wt%, which was the highest TS observed in TiO2-reinforced nanocomposites. Meanwhile, the addition of GNP in the epoxy matrix reached the highest TS value of 28.49 MPa at 1 wt% followed by a gradual decrease to reach 20.22 MPa at 20 wt%. Close TS values of 25.23 and 25.07 MPa were observed in both nanocomposites at 10 wt%, respectively. Thereby, GNP and TiO2 nanocomposites followed a descending trend to reach 20.22 and 20.37 MPa at 20 wt%. The highest TS value recorded in this study was observed in GNP-reinforced epoxy at 1 wt%, which was quite similar to the results obtained by Nitesh et al. [38], where a 1 wt% nanoparticle concentration exhibited the highest tensile behavior, which was ∼60% higher than the corresponding values obtained for neat epoxy. The decrease in the TS when the filler content is further increased above the optimal concentration is caused by the agglomeration of the nanofillers, which thereby leads to weaker interface bonding between the matrix and the fillers. Figure 3 illustrates SEM micrographs of the epoxy fracture surface at 1, 20, 5, 10, and 15 wt% GNP.

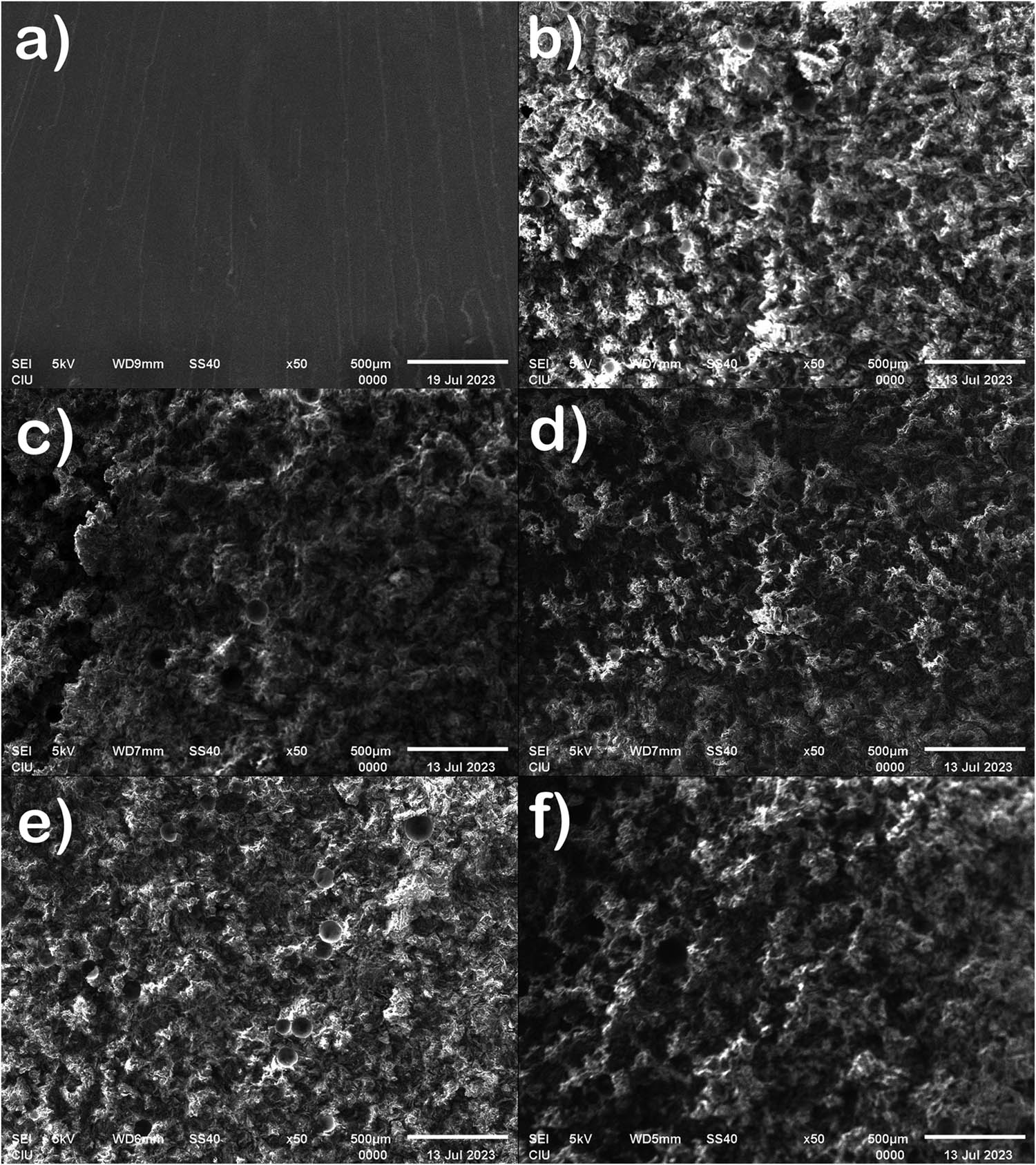

Fracture surface of nanocomposite epoxy with different GNP contents: (a) 0 wt%, (b) 1 wt%, (c) 5 wt%, (d) 10 wt%, (e) 15 wt%, and (f) 20 wt%.

Larger agglomerates were observed when the GNP content exceeded 1%. The 20% GNP ductile epoxy specimen exhibited a significant agglomeration. Referring to the tensile test results, GNP/epoxy samples with GNP contents exceeding 5% exhibited decreased tensile modulus and TS, which could be due to the increase in the size and amount of agglomerates inside the nanocomposite [39]. The fracture surface of the nanocomposites became markedly rougher upon the increase of the nanofiller content. Figure 4 shows the SEM of epoxy/TiO2 at five different weight percentages.

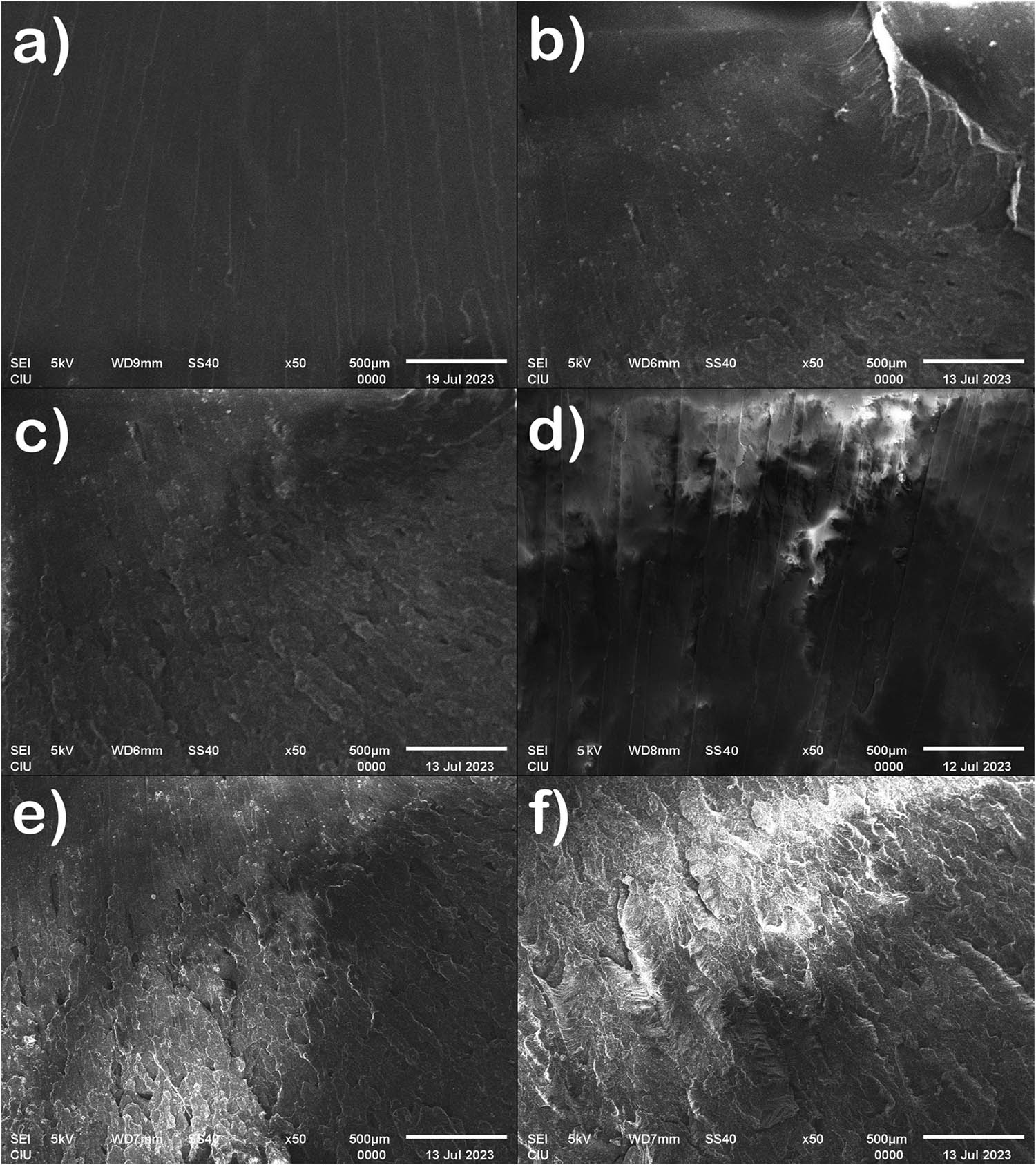

Fracture surface of the nanocomposite epoxy with different TiO2 contents: (a) 0 wt%, (b) 1 wt%, (c) 5 wt%, (d) 10 wt%, (e) 15 wt%, and (f) 20 wt%.

As clearly shown in Figure 4, TiO2 exhibited a good dispersion along with a good interface compatibility with the epoxy matrix. Furthermore, scanning electron micrography of TiO2 showed that the manufactured nanoparticles were made up of small, irregularly shaped, fine particles. Peeling away from the grain boundaries indicates brittle fracture, whereas the presence of many dimples indicates ductile fracture surface. Fracture in composites is caused by the initiation and expansion of dimples, fracture of the layers or reinforcing particles, and interface detachment. The SEM graphs show that these fracture surfaces exhibit ductile and cleavage modes of fracture.

3.2 Lap joint

The results of the apparent shear strength of aluminum specimens adhesively bonded with single lap joints are given in this section. GNP and TiO2 nanocomposites at five different weight fractions were considered adhesives for aluminum overlap joints. Figure 5 shows FL versus displacement of epoxy/TiO2 at 10 wt%.

Force vs displacement of the epoxy/TiO2 lap joint at 10 wt%.

As exhibited in Figure 5, ductile behavior was observed in epoxy/TiO2 overlap joints; the force vs displacement behavior started with a linear elastic increase to reach a force of 1.108 kN at 0.075 mm. Then, the force increased gradually along with a notable increase in the displacement, where it attained a maximum value of 1.877 kN at 0.567 mm, right before its failure. Figure 6 displays the FL and displacement behavior of the epoxy/GNP lap joint at 15 wt%.

Force vs displacement of the epoxy/GNP lap joint at 15 wt%.

As shown in Figure 6, the force vs displacement of the epoxy/GNP nanocomposite at 15 wt% increased linearly to reach a value of 1.553 kN at 0.119 mm. Then, it followed an ascending trend to exhibit its peak force of 3.081 kN at 0.806 mm, which was straight before its ductile failure. Although the nanoparticles were evenly distributed throughout the hardened resin, the TS of the corresponding modified resin likewise significantly decreased [40]. The poorer interlocking system caused by inadequate dispersion within the composite matrix may be the cause of the decreased bond strength shown in specimens.

Figure 7 shows the comparison of the impact of increasing the filler content on the maximum FL.

Joint FL of the epoxy/TiO2 and epoxy/GNP for 5 wt%.

As displayed in Figure 7, the addition of 1 and 5 wt% TiO2 nanoparticles decreased the joint shear strength compared to pure epoxy, revealing average FLs of 1.73 and 1.57 kN, respectively. Further increasing the weight percentage of TiO2 led to an increase in the FL, which exhibited its peak value of 3.07 kN at 20 wt%. A common behavior was observed at 1 wt% GNP, where the joint FL decreased to 1.52 kN, which was around 60% lower than that of pure epoxy joints. Hence, increasing the GNP content contributed to increasing joint FL to reach its highest FL of 3.69 kN in the nanocomposite with 15 wt% GNP, followed by a decrease at 20 wt%. Throughout the considered compositions, 20 wt% revealed peak FL in TiO2 nanocomposites, whereas 15 wt% was an optimum composition for epoxy/GNP nanocomposites, which was also considered as highest FL in this study (3.69 kN). The opposite FL behavior of both nanocomposites at 20 wt% can be explained by adapting some of the important properties of nanocomposites, i.e., matrix to particle interface quality. In other words, if the interaction between the matrix and nanoparticles is weak, the particles are unable to withstand a part of the applied external loads to the nanocomposite, thereby the yielding of amorphous glassy polymers switches from cavitational to shear, leading to a brittle to ductile transition. It is worth mentioning that there are two types of damage, i.e., adhesion and cohesion, and their occurrence is strongly correlated to the homogeneous dispersion of nanoparticles in the epoxy matrix. Therefore, the adhesion strength can be affected by physical and chemical reactions between the epoxy and nanofiller materials.

3.3 Machine learning and deep learning

MLR, ANNs, ANFIS, and SVM were applied in the current study to define the most suitable machine learning method to predict shear force and TS of nanocomposites, as well as specify design spaces of corresponding parameters. The results of the aforementioned machine learning tools in predicting TS and overlap joint FL of GNP and TiO2 nanocomposites are listed in this section. A regression model was applied in this study by the curve fitting tool (Cftool) in MATLAB. Response surface models of GNP and TiO2 nanocomposites were projected via cubic polynomial prediction functions. Moreover, output data were TS and FL, while input data were weight percentage and fiber type. Furthermore, the response surface metamodel creates a surface fit, which considers the whole design space, providing the ability to predict responses using input parameters not considered in the experiment. Figure 8a and b shows the developed response surfaces.

Response surface fitting for the (a) TS and (b) joint FL.

The Cftool in MATLAB was used to develop the RSM for the TS and overlap FL of TiO2 and GNP nanocomposites. The RMSE, R-square adjusted, and sum of square error (SSE) were considered to evaluate goodness of fit. For proper surface fit, the values of SSE and RMSE should be as close as possible to 0. Meanwhile, the adjusted value of the R-square ranges from 0 and 1, and a good fit should be close to 1. Moreover, the function utilized to develop the response surface of the TS of nanocomposites is

where x is the nanoparticle type, y is the weight percent, and p00 =12.92, p10 = 4.418, p01 = 285.6, p11 = −22.2, p02 = −2,560, p12 = 7.554, and p03 = 6,555. The goodness of fit attained an RMSE of 2.896, adjusted R-square of 0.3909, R-square of 0.7232, and SSE of 41.94.

For the RSM model of overlap joints FL, the applied function was

where x is the nanoparticle types, y is the weight percent, and p00 = 2.708, p10 = −0.3022, p01 = −62.74, p11 = 22.09, p02 = 555, p12 = −97.93, and p03 = −1,213. In addition, SSE = 1.168, RMSE = 0.4832, adjusted R-square = 0.4671, and R-square = 0.7578.

All components of the prediction model in this study were trained using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm, which exhibited a stable and swift convergence. Figure 9 illustrates the ANN model design: it consisted of 2 inputs, 10 hidden layers, and a single output.

The ANN model structure.

A neural network fitting tool in MATLAB was utilized for the generation of the ANN models. Nanoparticle types and weight percentages were considered as input data, whereas the TS and FL were the model outputs. Experimental results of the tensile test and overlap shear test were considered to generate two corresponding models, and 70% of the data were utilized for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. Figure 10 shows the schemes of TS regressions for TiO2 and GNP nanocomposites for five different weight percentages, i.e., 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 wt%. This graph provides a correlation between experimental data (target) and ANN output data.

Regression plot of the ANN model.

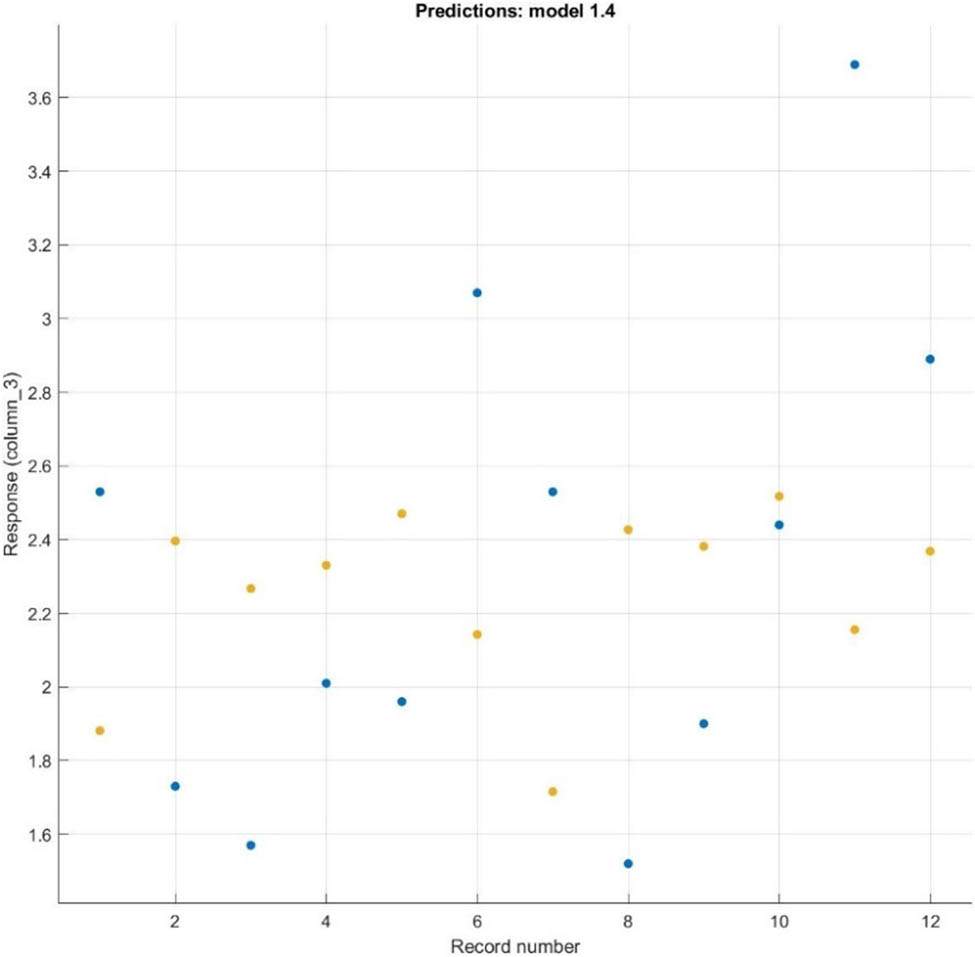

As shown in Figure 10, the dotted line denotes the best achievable correlation, while the solid line represents the correlation between output and target values. The overall regression coefficient of the TS ANN model was 0.93712 and that of the FL ANN model was 0.92341, which can be considered satisfactory as the values are close to 1. The MATLAB regression learner tool was used to generate the SVM model, and input parameters included two nanoparticle types and five weight percentages. Testing and training output datasets created by the FL SVM model are shown in Figure 11: yellow dots illustrate predicted data, while blue dots are the true data.

FL predict versus real SVM data.

Furthermore, SVM models were trained using tensile and FL experimental results, Gaussian was considered as the kernel function, and fine Gaussian SVM was the selected preset. However, for the TS SVM model RMSE = 4.2839, MSE = 18.352, and R-square = −0.36, while for the FL SVM model RMSE = 0.75973, MSE = 0.57719, and R-square = −0.13. The considered ANFIS models include two inputs (nanoparticle type and weight percentage), and two and five membership functions for the first and second inputs, respectively. Figure 12 illustrates the ANFIS model structure.

The ANFIS model structure.

ANFIS models were generated using the MATLAB Neuro-fuzzy designer tool. The models were trained using 75% of tensile and joint FL experimental results, yet the remaining 25% were for testing. The Gaussmf membership function with fixed output was used to create the FIS model. Training was completed at epoch 1, with an average testing error of 1.5265 × 10−6. Figure 13 displays the TS ANFIS model plot, which shows the FIS output and training data.

Plot of ANFIS for TS prediction.

3.3.1 ML vs experimental results

Table 1 lists TS results and predicted data using machine learning models of TiO2 and GNP nanocomposites. As shown in Table 1, the predicted TS using ANN showed a drastic compliance with experimental TS results, exhibiting 3.67% prediction error, while TS values obtained from MLR, SVM, and ANFIS revealed a significant agreement with errors of 5.27, 5.37, and 6.74%, respectively. This highlights the ability of these models to be trained and used for the prediction of the TS of nanocomposites. Moreover, GNP nanocomposite at 5 wt% exhibited the highest TS between all implemented machine learning models. The most convenient machine learning technique for the prediction of the TS of nanocomposites is ANN as it exhibited the least prediction error of 3.67%. Table 2 displays experimental overlap FL results and predicted data using machine learning techniques of TiO2 and GNP nanocomposites.

Predicted TS values using MLR, ANN, SVM, and ANFIS

| Matrix | Wt% | Experiment (MPa) | MLR (MPa) | ANN (MPa) | SVM (MPa) | ANFIS (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | 0 | 17.96 | 17.34 | 18.3 | 18.9419 | 17.96 |

| TiO2 | 1 | 19.29 | 19.72 | 17.8 | 19.5465 | 19.29 |

| TiO2 | 5 | 24.28 | 24.95 | 24.44 | 23.8802 | 22.3731 |

| TiO2 | 10 | 25.23 | 24.71 | 24.91 | 24.8235 | 25.23 |

| TiO2 | 15 | 21.60 | 21.54 | 20.52 | 22.0001 | 21.6 |

| TiO2 | 20 | 20.22 | 20.36 | 20.26 | 20.623 | 20.22 |

| GNP | 0 | 17.96 | 21.76 | 21.24 | 22.5004 | 17.96 |

| GNP | 1 | 28.49 | 23.92 | 26.4 | 23.8548 | 21.1485 |

| GNP | 5 | 28.38 | 28.27 | 28.41 | 27.2574 | 28.38 |

| GNP | 10 | 25.07 | 26.98 | 24.86 | 24.6729 | 13.2474 |

| GNP | 15 | 24.06 | 22.80 | 24.11 | 23.667 | 24.06 |

| GNP | 20 | 20.37 | 20.64 | 20.5 | 20.7634 | 20.37 |

| Error% | 5.27% | 3.67% | 5.37% | 6.74% | ||

Predicted joint FL values using MLR, ANN, SVM, and ANFIS

| Matrix | Wt% | Experiment (kN) | MLR (kN) | ANN (kN) | SVM (kN) | ANFIS (kN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | 0 | 2.53 | 2.41 | 2.475 | 2.459 | 2.53 |

| TiO2 | 1 | 1.73 | 2.04 | 1.909 | 2.2343 | 1.73 |

| TiO2 | 5 | 1.57 | 1.36 | 1.573 | 1.6695 | 1.57 |

| TiO2 | 10 | 2.01 | 1.70 | 2.014 | 2.0799 | 1.3538 |

| TiO2 | 15 | 1.96 | 2.50 | 1.959 | 2.0263 | 1.96 |

| TiO2 | 20 | 3.07 | 2.85 | 2.664 | 3.0036 | 3.07 |

| GNP | 0 | 2.53 | 2.10 | 1.952 | 2.4637 | 2.53 |

| GNP | 1 | 1.52 | 1.95 | 1.937 | 2.2611 | 1.52 |

| GNP | 5 | 1.90 | 1.92 | 1.901 | 1.9664 | 1.5719 |

| GNP | 10 | 2.44 | 2.63 | 2.223 | 2.3993 | 2.44 |

| GNP | 15 | 3.69 | 3.31 | 3.692 | 3.0663 | 3.69 |

| GNP | 20 | 2.89 | 3.05 | 2.887 | 2.8201 | 0.8201 |

| Error% | 13.00% | 7.21% | 10.33% | 10.24% | ||

As shown in Table 2, MLR, SVM, and ANFIS models exhibited prediction errors of 13.00, 10.33, and 10.24%, respectively. However, the overlap FL obtained from the ANN model showed the least prediction error, a value of 7.21%, which therefore can be considered the most suitable prediction approach across all the utilized models for predicting the overlap joint FL of the nanocomposites. Peak FL values were observed in the GNP nanocomposite joints at 15 wt%.

4 Conclusion

In this study, the tensile properties of TiO2 and GNP nanocomposite were evaluated following the ASTM standard D638-14. Moreover, the considered nanocomposites were utilized as an adhesive for an overlap joint of two A5055 aluminum sheets. Then, their apparent shear strength properties were evaluated following the ASTM D1002-01 standard. Five weight percentages of different nanoparticles were considered (1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 wt%). Furthermore, for evaluating the capability of deep learning and machine learning models in predicting the mechanical characteristics of nanocomposites, the results obtained from the experiment were applied to train and test the considered models, i.e., ANFIS, SVM, MLR, and ANN.

However, a maximum TS behavior was witnessed in epoxy/GNP at 1 wt%, which exhibited a value of 28.49 MPa, whereas for the overlap joints FL, the highest value recorded in this study was 3.69 kN, which was observed in epoxy with 15 wt% GNP. ANN can be considered a convenient machine learning model for the prediction of the joint failure shear load and TS of nanocomposites since it showed the least prediction error of 3.67% in predicting TS and 7.21% in the prediction of FL.

-

Funding information: This study was supported by the projects: VEGA 1/0172/20 and VEGA 1/0307/23 of the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: David Hui, who is the co-author of this article, is a current Editorial Board member of Nanotechnology Reviews. This fact did not affect the peer-review process. The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

References

[1] Moriche R, Prolongo SG, Sánchez M, Jiménez-Suárez A, Sayagués MJ, Ureña A. Morphological changes on graphene nanoplatelets induced during dispersion into an epoxy resin by different methods. Compos Part B. 2015;72:199–205.10.1016/j.compositesb.2014.12.012Search in Google Scholar

[2] Khoee S, Hassani N. Adhesion strength improvement of epoxy resin reinforced with nanoelastomeric copolymer. Mater Sci Eng A. 2010;527(24–25):6562–7.10.1016/j.msea.2010.07.013Search in Google Scholar

[3] Zhai LL, Ling GP, Wang YW. Effect of nano-Al2O3 on adhesion strength of epoxy adhesive and steel. Int J Adhes. 2008;28(1–2):23–8.10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2007.03.005Search in Google Scholar

[4] Ekrem M, Ataberk N, Avcı A, Akdemir A. Improving electrical and mechanical properties of a conductive nano adhesive. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2017;31(7):699–712.10.1080/01694243.2016.1229881Search in Google Scholar

[5] Zhai L, Ling G, Li J, Wang Y. The effect of nanoparticles on the adhesion of epoxy adhesive. Mater Lett. 2006;60(25–26):3031–3.10.1016/j.matlet.2006.02.038Search in Google Scholar

[6] May M, Wang HM, Akid R. Effects of the addition of inorganic nanoparticles on the adhesive strength of a hybrid sol–gel epoxy system. Int J Adhes. 2010;30(6):505–12.10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2010.05.002Search in Google Scholar

[7] Lee DG, Kim JK, Cho DH. Effects of adhesive fillers on the strength of tubular single lap adhesive joints. J Adhes Sci Technol. 1999;13(11):1343–60.10.1163/156856199X00244Search in Google Scholar

[8] Akbari V, Jouyandeh M, Paran SMR, Ganjali MR, Abdollahi H, Vahabi H, et al. Effect of surface treatment of halloysite nanotubes (HNTs) on the kinetics of epoxy resin cure with amines. Polymers. 2020;12(4):930.10.3390/polym12040930Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Saeb MR, Rastin H, Shabanian M, Ghaffari M, Bahlakeh G. Cure kinetics of epoxy/β-cyclodextrin-functionalized Fe3O4 nanocomposites: Experimental analysis, mathematical modeling, and molecular dynamics simulation. Prog Org Coat. 2017;110:172–81.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2017.05.007Search in Google Scholar

[10] Aliakbari M, Jazani OM, Sohrabian M, Jouyandeh M, Saeb MR. Multi-nationality epoxy adhesives on trial for future nanocomposite developments. Prog Org Coat. 2019;133:376–86.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.04.076Search in Google Scholar

[11] Alhijazi M, Safaei B, Zeeshan Q, Arman S, Asmael M. Prediction of elastic properties of thermoplastic composites with natural fibers. J Text Inst. 2023;114(10):1488–96.10.1080/00405000.2022.2131352Search in Google Scholar

[12] Alhijazi M, Safaei B, Zeeshan Q, Asmael M. Modeling and simulation of the elastic properties of natural fiber‐reinforced thermosets. Polym Compos. 2021;42(7):3508–17.10.1002/pc.26075Search in Google Scholar

[13] Lee C, Wei X, Kysar JW, Hone J. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science. 2008;321(5887):385–8.10.1126/science.1157996Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Balandin AA, Ghosh S, Bao W, Calizo I, Teweldebrhan D, Miao F, et al. Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett. 2008;8(3):902–7.10.1021/nl0731872Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Singh S, Srivastava VK, Prakash R. Influences of carbon nanofillers on mechanical performance of epoxy resin polymer. Appl Nanosci. 2015;5(3):305–13.10.1007/s13204-014-0319-0Search in Google Scholar

[16] Araby S, Li J, Shi G, Ma Z, Ma J. Graphene for flame-retarding elastomeric composite. Compos Part A. 2017;101:254–64.10.1016/j.compositesa.2017.06.022Search in Google Scholar

[17] Araby S, Qiu A, Wang R, Zhao Z, Wang C-H, Ma J. Aerogels based on carbon nanomaterials. J Mater Sci. 2016;51(20):9157–89.10.1007/s10853-016-0141-zSearch in Google Scholar

[18] Li H, Liu Y, Zhang H, Qin Z, Wang Z, Deng Y, et al. Amplitude-dependent damping characteristics of all-composite sandwich plates with a foam-filled hexagon honeycomb core. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2023;186:109845.10.1016/j.ymssp.2022.109845Search in Google Scholar

[19] Feng J, Safaei B, Qin Z, Chu F. Nature-inspired energy dissipation sandwich composites reinforced with high-friction graphene. Compos Sci Technol. 2023;233:109925.10.1016/j.compscitech.2023.109925Search in Google Scholar

[20] Pan S, Feng J, Safaei B, Qin Z, Chu F, Hui D. A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):1658–69.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0107Search in Google Scholar

[21] Mustafa BS, Jamal GM, Abdullah OG. The impact of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the thermal stability and tensile properties of epoxy resin hybrid nanocomposites. Results Phys. 2022;43:106061.10.1016/j.rinp.2022.106061Search in Google Scholar

[22] Kumar A, Ghosh PK, Yadav KL, Kumar K. Thermo-mechanical and anti-corrosive properties of MWCNT/epoxy nanocomposite fabricated by innovative dispersion technique. Compos Part B. 2017;113:291–9.10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.01.046Search in Google Scholar

[23] Safaei B, Chukwueloka EO, Gören M, Kotrasova K, Yang Z, Arman S, et al. Free vibration investigation on RVE of proposed honeycomb sandwich beam and material selection Optimization. Facta Univ Ser: Mech Eng. 2023;21:31–50.10.22190/FUME220806042SSearch in Google Scholar

[24] Sarkon GK, Safaei B, Kenevisi MS, Arman S, Zeeshan Q. State-of-the-art review of machine learning applications in additive manufacturing; from design to manufacturing and property control. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2022;29(7):5663–721.10.1007/s11831-022-09786-9Search in Google Scholar

[25] Alhijazi M, Zeeshan Q, Qin Z, Safaei B, Asmael M. Finite element analysis of natural fibers composites: A review. Nanotechnol Rev. 2020;9(1):853–75.10.1515/ntrev-2020-0069Search in Google Scholar

[26] Pattnaik P, Sharma A, Choudhary M, Singh V, Agarwal P, Kukshal V. Role of machine learning in the field of Fiber reinforced polymer composites: A preliminary discussion. Mater Today. 2020;44(6):4703–8.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.11.026Search in Google Scholar

[27] Alhijazi M, Safaei B, Zeeshan Q, Asmael M, Harb M, Qin Z. An Experimental and metamodeling approach to tensile properties of natural fibers composites. J Polym Environ. 2022;30:4377–93.10.1007/s10924-022-02514-1Search in Google Scholar

[28] Albu A, Precup RE, Teban TA. Result and challenges of artificial neural networks used for decision-making and control in medical application. Facta Univ Ser: Mech Eng. 2019;17(3):24.10.22190/FUME190327035ASearch in Google Scholar

[29] Jamshidi MB, Daneshfar F, editors. A hybrid echo state network for hypercomplex pattern recognition, classification, and big data analysis. 2022 12th International Conference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering (ICCKE). Mashhad, Iran: IEEE Xplore; 2022. p. 7–12.10.1109/ICCKE57176.2022.9960125Search in Google Scholar

[30] Khalaj O, Jamshidi MB, Saebnoori E, Mašek B, Štadler C, Svoboda J. Hybrid machine learning techniques and computational mechanics: Estimating the dynamic behavior of oxide precipitation hardened steel. IEEE Access. 2021;9:156930–46.10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3129454Search in Google Scholar

[31] Jamshidi MB, Talla J, Peroutka Z, Roshani S, editors. Neuro-Fuzzy approaches to estimating thermal overstress behavior of IGBTs. 2021 IEEE 19th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (PEMC). Gliwice, Poland: IEEE Xplore; 2021. p. 843–50.10.1109/PEMC48073.2021.9432584Search in Google Scholar

[32] Alhijazi M, Zeeshan Q, Safaei B, Asmael M, Qin Z. Recent developments in palm fibers composites: a review. J Polym Environ. 2020;28:3029–54.10.1007/s10924-020-01842-4Search in Google Scholar

[33] Alhijazi M, Safaei B, Zeeshan Q, Asmael M, Eyvazian A, Qin Z. Recent developments in Luffa natural fiber composites. Sustainability. 2020;12(18):7683.10.3390/su12187683Search in Google Scholar

[34] Pati PR. Prediction and wear performance of red brick dust filled glass–epoxy composites using neural networks. Int J Plast Technol. 2019;23(2):253–60.10.1007/s12588-019-09257-0Search in Google Scholar

[35] Antil SK, Antil P, Singh S, Kumar A, Pruncu CI. Artificial neural network and response surface methodology based analysis on solid particle Erosion behavior of polymer matrix composites. Materials. 2020;13(6):1381.10.3390/ma13061381Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Jayaganthan S, Babu MS, Vasa NJ, Sarathi R, Imai T. Classification of coal deposited epoxy micro-nanocomposites by adopting machine learning techniques to LIBS analysis. J Phys Commun. 2021;5(10):105006.10.1088/2399-6528/ac2b5dSearch in Google Scholar

[37] Rahman A, Deshpande P, Radue MS, Odegard GM, Gowtham S, Ghosh S, et al. A machine learning framework for predicting the shear strength of carbon nanotube-polymer interfaces based on molecular dynamics simulation data. Compos Sci Technol. 2021;207:108627.10.1016/j.compscitech.2020.108627Search in Google Scholar

[38] Nitesh, Kumar A, Saini S, Yadav KL, Ghosh PK, Rathi A. Morphology and tensile performance of MWCNT/TiO2-epoxy nanocomposite. Mater Chem Phys. 2022;277:125336.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2021.125336Search in Google Scholar

[39] Ahmadi-Moghadam B, Taheri F. Fracture and toughening mechanisms of GNP-based nanocomposites in modes I and II fracture. Eng Fract Mech. 2014;131:329–39.10.1016/j.engfracmech.2014.08.008Search in Google Scholar

[40] Ning N, Liu W, Hu Q, Zhang L, Jiang Q, Qiu Y, et al. Impressive epoxy toughening by a structure-engineered core/shell polymer nanoparticle. Compos Sci Technol. 2020;199:108364.10.1016/j.compscitech.2020.108364Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery

- The progress of cathode materials in aqueous zinc-ion batteries

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part I

- Effect of polypropylene fiber and nano-silica on the compressive strength and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete

- Mechanochemical design of nanomaterials for catalytic applications with a benign-by-design focus

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery

- The progress of cathode materials in aqueous zinc-ion batteries

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part I

- Effect of polypropylene fiber and nano-silica on the compressive strength and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete

- Mechanochemical design of nanomaterials for catalytic applications with a benign-by-design focus