Abstract

Catalytic synthesis of value-added chemicals from sustainable biomass or biomass-derived platform chemicals is an essential strategy for reducing dependency on fossil fuels. As a precursor for the synthesis of important polymers such as polyesters, polyurethanes, and polyamides, FDCA is a monomer with high added value. Meanwhile, due to its widespread use in chemical industry, 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA) has gained significant interest in recent years. In this review, we discuss the electrochemical oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) and summarize the most recent advances in electrode materials from the past 5 years, including reaction mechanisms, catalyst structures, and coupling reactions. First, the effect of pH on the electrocatalytic oxidation of furfural is presented, followed by a systematic summary of the reaction mechanism (direct and indirect oxidation). Then, the advantages, disadvantages, and research progress of precious metal, non-precious metal, and non-metallic HMF electrooxidation catalysts are discussed. In addition, a coupled dual system that combines HMF electrooxidation with hydrogen reduction reaction, CO2 reduction, or N2 reduction for more effective energy utilization is discussed. This review can guide the electrochemical oxidation of furfural and the development of advanced electrocatalyst materials for the implementation and production of renewable resources.

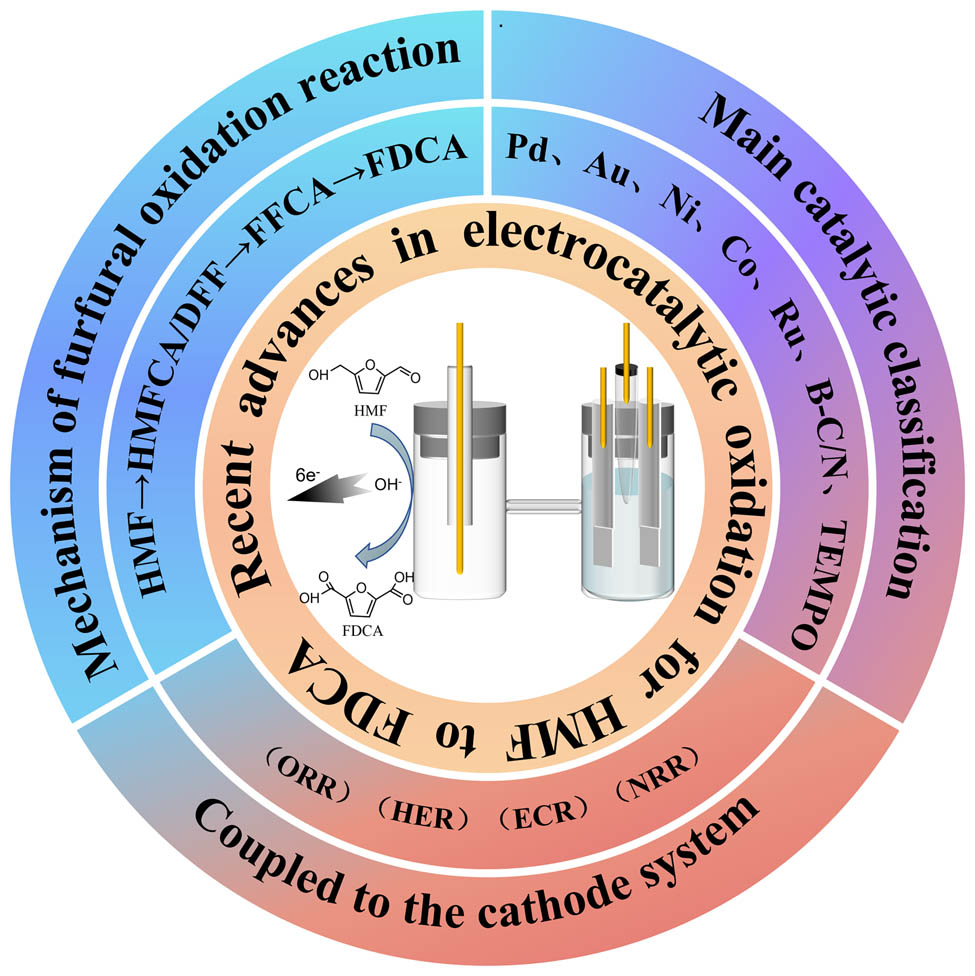

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

The increasing global energy demand, the depletion of non-renewable resources, and the worsening climate change resulting from the use of fossil fuels have prompted efforts to develop sustainable and environmentally friendly clean energy storage and conversion technologies. The only renewable and abundant carbon-containing resource that can be used to produce fuels and value-added chemicals is biomass. Since annual global production is approximately 1.7 × 1011 t, it is frequently used as an alternative to finite fossil resources [1]. Lignocellulosic biomass, the most abundant form of biomass, is a highly efficient renewable and sustainable alternative to conventional fossil fuels. Furfural acid is the most important oxidation product of the biomass molecule furfural. Furfural acid [2] is a crucial raw material in the pharmaceutical, agrochemical, flavor, and fragrance industries. As an alternative to terephthalic acid as a raw material for the synthesis of 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA), furfural acid is also regarded as promising. In recent years, the electrooxidation process of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) [3,4,5], a typical biomass-based platform compound, has been extensively investigated. FDCA, one of the products of the oxidation reaction of hydroxymethyl furfural (HMFOR), is receiving increasing attention as a monomer for the production of important polymeric materials such as polyethylene furan dicarboxylic acid ester [6]. The core literature on the electrocatalytic oxidation of HMF to FDCA has been limited in the last decade (Figure 1). Currently, FDCA can be synthesized from HMF by hydrothermal [7,8,9,10,11], biocatalytic, photocatalytic [12], and electrochemical oxidation [13]. During hydrothermal oxidation, HMF is initially oxidized to 2,5-diformylfuran (DFF) or 5-hydroxymethyl-2-frantic acid (HMFCA), which is further converted to 5-formyl-2-furan carboxylic acid (FFCA) and FDCA under aerobic conditions [9]. The hydrothermal redox method usually uses tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) as the oxidant, whereas tert-butanol is also the most suitable solvent when TBHP is used as the oxidant [10]. The hydrothermal catalysis is more commonly used because of its efficient and convenient procedure. However, catalyst deactivation is usually unavoidable in the presence of strong acids or bases. In addition, thermal catalysis is usually performed at higher reaction temperatures leading to increased degradation of the substrate HMF [14]. The reaction pathway for the conversion of HMF to FDCA such as through electrochemical oxidation is similar to that of hydrothermal oxidation. Electrochemical oxidation provides favorable operating conditions, controlled selectivity and scalability, while it is a cleaner and safer method of FDCA production as it eliminates the use of high pressure oxidising atmospheres or other environmentally unfriendly chemical oxidants [15]. Driven by an external electrical potential, electrocatalysis offers significant advantages in solving thermodynamic and/or kinetic problems in thermal and photocatalysis, using inexpensive transition metals as highly active catalysts [14]. By controlling the electrode potential and circuit current, the management of electrocatalytic reaction parameters can be more accurate and easily achieved compared to thermal catalysis. At the same time, one should not overlook that electrocatalysis often requires a conductive electrolyte due to the poor conductivity of aqueous HMF solutions, leading to energy consumption for product separation in downstream processes compared to base-free multiphase catalysis. Depending on whether the applied potential drives the oxidation of HMF directly, the mechanism of electrochemical oxidation of HMF can be classified as either direct or indirect. There are six electron transfers in the reaction process, and both types of oxidation can occur separately or simultaneously [3].

Number of annual core ensemble publications related to HMF and FDCA. Search engine: Web of Science. Keywords: HMF, FDCA; 19.05.2022.

1.1 Direct oxidation

If the applied potential drives the oxidation of the substrate directly, the valence state of the catalyst remains constant throughout the reaction; this is referred to as direct oxidation. The electrocatalytic reaction system is activated when the applied external voltage reaches the reaction’s overpotential [16]. As shown in Figure 2, there are two possible direct oxidation pathways for the oxidation of HMF to FDCA: (i) the formyl group of HMF is first oxidized to give HMFCA (pH ≥ 13), while the hydroxymethyl group of HMFCA is oxidized to produce FFCA, and then the formyl group of FFCA is oxidized to form FDCA (HMF → HMFCA → FFCA → FDCA); (ii) the hydroxymethyl group was first oxidized to DFF (pH < 13), then oxidized to FFCA, and finally FDCA was obtained (HMF → DFF → FFCA → FDCA). The stability of the catalysts at different pH is different to the extent that different intermediates are produced, but both DFF and HMFCA are further oxidized to form 5-formyl-2-furan carboxylic acid (FFCA) and FDCA. Based on non-in situ detection, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), the reaction pathways of HMF at different pH can be determined [17,18]. In addition, theoretical calculations can be used as a useful aid to gain insight into the oxidation process of hydroxymethyl furfural [19,20].

Two direct oxidation pathways of HMF.

1.2 Indirect oxidation

In contrast to direct oxidation, in indirect oxidation, the applied potential does not directly drive substrate oxidation, and the valence state of the catalyst changes during the oxidation process. The catalyst actually acts as a redox mediator to drive the oxidation of the substrate, which is a chemical process that does not require an applied potential [16]. Since this oxidation is referred to as indirect oxidation, it applies only to redox. As demonstrated in Figure 3, indirect oxidation is comprised of two sequential processes. The difference between a non-homogeneous medium and a homogeneous medium is that the former requires OH– to participate in its oxidation. Therefore, strongly alkaline conditions (pH ≥ 13) are more conducive to the oxidation of heterogeneous media.

(a) Indirect oxidation reaction mechanism diagram of non-homogeneous oxidation medium (Mn+ represents the low valence state and Mn+1 represents the high valence state) and (b) homogeneous oxidation medium (TEMPO-oxidation as an example).

This article provides a comprehensive review of HMF electrochemical oxidation. After proposing a pH-dependent reaction pathway and summarizing the reaction mechanism (direct and indirect oxidation), HMF electrooxidation catalyst materials are introduced, the brief classification of HMF electrocatalysts is shown in Figure 4. This paper introduces the development of precious metals, non-precious metals, and even non-metallic materials, with a focus on catalysts made of non-precious metals. In addition, a number of representative coupling reactions (e.g., HMF electrooxidation coupled with H2 precipitation, CO2 reduction, N2 reduction [21], and organic reduction) for efficient energy conversion are discussed.

A brief classification of electrocatalysts for HMF conversion.

2 Detection method

Using linear scanning voltammetry (LSV), the electrocatalytic activity was analyzed. Chronoamperometry was used to monitor the electrochemical performance of the catalysts, and HPLC was used to analyze the electrolytes. Using the following equations, the HMF conversion, FDCA yield, and Faraday efficiency (FE) were calculated:

3 Precious metal catalysts

Typically, noble metal catalysts are highly active in many chemical processes due to the unique electronic and orbital properties of noble metals [22]. For this reason noble metals are also used for HMF electrochemical oxidation, from single noble metals (e.g., Pd [23], Pt [13], Au [24], and Ru [25]) to noble metal alloys (e.g., PtRu and AuPd [26]). Table 1 displays the performance of HMF electrocatalytic oxidation of noble metal catalysts. As Au is combined with another precious metal to form an alloy catalyst, the catalyst will combine the benefits of both metals [27], this is because the electronic properties of Au are altered during the preparation of the alloy system, resulting in high activity, selectivity, and stability. The electronic properties of Au are altered during the preparation of the alloy system, resulting in a coordinated effect that improves the catalytic performance of the monometallic system [28]. Au and Pt are mainly present in the metallic state, with small amounts of Au+ and Au3+ or Pt2+ cationic states, which may be related to the surface oxidation of the metallic state or the interaction of the nanoparticles with the carrier [29,30]. Zhong’s team developed an efficient and stable zeolite-supported Pt–Au alloy catalyst [11] for the selective oxidation of HMF to FDCA. The XPS results confirmed the formation of a Pt–Au alloy on the support. The binding energy of Au 4 f in the 1.5Pt1Au4/N-HNT bimetal is lower than that of 1.5Au/N-HNT, but higher than that in 1.5Pt/N-HNT. The shift in binding energy is attributed to the regio-electron interaction between the Au and Pt atomic orbitals during the formation of the alloy [31,32]. The Fermi energy level of Pt is higher than that of Au. The higher electronegativity of Pt and the tendency of electrons to shift towards Au lead to changes in d-electron density and binding energy [33]. Verdeguer et al. demonstrated that alkalinity has a significant effect on the catalytic activity (and selectivity) of Pt/Pb-loaded catalysts [34]. On phosphorus-functionalized carbon nanofibers (CNF) [35], Au–Pt nanoparticles were deposited and proved to be an effective catalyst for the oxidation of HMF to FDCA. The activity and selectivity to FDCA were significantly influenced by the P content of the CNF surface, with the highest P content catalyst producing the best results (98% selectivity to FDCA at 80% conversion after 1 h). The authors demonstrated that Au–P interactions may have an impact on the electronic properties of the active site. Despite the fact that noble metal-based electrocatalysts have low initial potentials for HMF oxidation, they can only provide very low current densities, not even 10 mA cm−2 in the applied potential range. In addition, complete oxidation of HMF to FDCA on a single noble metal is difficult. Due to the unique catalytic properties of Pd and Au for the competitive oxidation of hydroxyl and aldehyde groups in HMF, the Au–Pd alloy was able to generate higher yields of FDCA than single noble metal catalysts. Bonincontro et al. [28] reported an efficient and stable Au–Pd alloy catalyst containing nNiO. There is a significant synergistic effect between Au and Pd in the alloy and NiO, allowing the catalyst to achieve high conversion (95%), high activity, high FDCA yield (70%), and good stability. Using a layer-by-layer assembly technique, Park et al. fabricated a three-dimensional hybrid bimetallic electrocatalytic [13] electrode for simultaneous HMF conversion and hydrogen precipitation reaction (HER) and discovered that the thickness and structure of the LBL-assembled multilayer electrode largely determined its electrocatalytic activity. In HER, the structure consisting of adjacent Pd and Au(AuPd)7 electrodes is optimal for the rapid diffusion of hydrogen from Pd NPs to Au NPs. In addition, the full-cell electrochemical system containing HMF oxidation electrodes and HER was successfully regulated utilizing an optimized electrode combination.

Comparison of the performance of different noble metal catalysts for the oxidation of HMF

| Type | Catalyst | Electrolyte | T (°C) | HMF conversion (%) | FDCA yield (%) | FE (%) | Reaction time (h) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt | Pt | 1.0 M H2SO4 | 25 | 88.3 | — | — | — | [36] |

| Pt | 0.3 M NaClO4 | 25 | 9.0 | — | 9.0 | — | [37] | |

| Au | Au | 1.0 M KOH | 25 | 41.5 | — | 45.8 | 2 | [13] |

| Au/CeO2 | 2 equiv of Na2CO3 | 140 | 99 | 91 | — | 15 | [38] | |

| AuPd | Au–Pd/IRA-743 | 2 equiv of Na2CO3 | 100 | 100 | 93 | — | 4 | [39] |

| Au–Pd/nNiO | 0.1 M NaBH4 | 90 | 100 | 99 | — | 14 | [28] | |

| Pd | Pd | 1.0 M KOH | 25 | 16 | — | 85.8 | 2 | [13] |

| Pd/CNT | 2 equiv of K2CO3 | 160 | 100 | 60 | — | 5 | [40] | |

| Ru | Ru(iii) | 0.1 M KOH | 25 | — | — | 94 | 27 | [41] |

| Ru/C | 2 equiv of NaHCO3 | 75 | 100 | 93 | — | 12 | [25] | |

| Ru/HAP | H2O | 120 | 100 | 99 | — | 24 | [42] | |

| Ru/MgAlO | H2O | 160 | 100 | 99 | — | 4 | [43] |

4 Non-precious metal catalysts

Taking cost into account, the development of efficient non-precious metal or non-metallic catalysts remains the norm. Co [44], Cu [45], Fe [46,47], Mo, W, V [48], Pb, and Mn [49,50] are examples of non-precious metals that have been studied. In particular, nickel-based [3] and Cobalt-based materials represent non-precious metal catalysts with exceptionally high catalytic activity, far exceeding other metals, including noble metal alloys. For nickel-based catalysts, the catalytic mechanism follows an “electrochemical-chemical” reaction pathway, whereby divalent nickel species are electrochemically oxidized to trivalent nickel species, followed by a spontaneous redox reaction between the trivalent nickel species and the HMF as an oxidant [51,52]. By combining the electrochemical test, in situ Raman spectroscopy test, product characterization and theoretical calculations, Deng et al. [53] explored in depth the intrinsic link between the oxidation states of surface cobalt species and the kinetics of the HMF oxidation reaction and product selectivity under electrochemical oxidation conditions, and elucidated the different intrinsic catalytic activities of the in situ generated high-valent Co3+ and Co4+ species as oxidants involved in the selective oxidation of HMF. It is shown that Co3+ is only able to catalyze the slow oxidation of aldehyde groups to carboxyl groups in HMF molecules, whereas Co4+ is able to achieve the rapid oxidation of hydroxyl/aldol groups. Based on this feature, this work has achieved the first modulation of the selectivity of the HMF electrochemical oxidation products, i.e., when the applied voltage is low, Co3+ is the main active species and the resulting product is 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxylic acid (HMFCA); when the applied voltage is high, Co4+ is the main active species and the resulting product is FDCA. A Ni–Co-based sulfide (NiCo–S) was prepared by Zhao’s group [54], and the bimetallic site and coordination effects of the layered NiCo–S catalyst on HMF electrooxidation were demonstrated at the atomic level. Electrochemical experiments and theoretical results show that Ni–Co synergistically participates in HMF oxidation, where the Co site has strong diatomic adsorption (O and C atoms) on the aldehyde group, thereby facilitating the conversion of the aldehyde group to the carboxyl group, while the Ni site accelerates the reaction rate of FDCA. Also, the ligand S species contributes to the formation of strong diatomic adsorption with the aldehyde group of HMF, and the density of states (DOS) of NiCo–S has a higher carrier transfer conductivity than NiCo–O. This confirms the effect of the Ni–Co double active site and S coordination on accelerating the reaction and lowering the energy potential barrier, thus promoting catalytic activity to achieve 98.0% selectivity and 97.1% yield.

Homogeneous catalysis is considered to be an inexpensive and effective method of converting biomass derivatives into value-added chemicals, although it has separation and reuse problems [55]. Homogeneous metal bromides are widely used as catalysts for the aerobic oxidation of hydrocarbons [56]. Manganese based catalysts are the most active of the various catalytic systems due to the different oxidation states of Mn and the high oxygen storage capacity of the metal and the faster uptake and reduction of oxygen. Mn shows significant results in terms of HMF conversion and FDCA selectivity, both directly and in combination with other metals [57]. Zuo et al. [58] investigated the rate of oxidation of FDCA by HMF in acetic acid media with a Co/Mn/Br catalyst. The transient concentration distributions of the reactants (HMF) intermediates 2,5-diformylfuran (DFF), and FFCA and final product (FDCA) were obtained by rapid on-line sampling in a stirred semi-batch reactor. They showed experimentally that spray reactors in which the liquid is dispersed as fine droplets in the oxygen-containing phase can help to alleviate the oxygen shortage in the liquid phase, thereby increasing the overall reaction rate. Chen’s team [59] developed a free radical chain reaction mechanism containing primary and secondary reactions over Co/Mn/Br catalysts to describe in detail the liquid phase air oxidation of HMF to FDCA. Parallel reactions of HMF with DFF and HMFCA intermediating during MC were demonstrated for the first time. The majority of HMF tended to convert to DFF rather than HMFCA, which can be attributed to the retarding effect of the alcohol group on the oxidation of the aldehyde group and the low C–H bond dissociation energy on the hydroxymethyl group. The high activity of hydroxymethyl groups over aldehyde groups for the oxidation of HMF is explained for the first time on the basis of the inhibitory effect of alcohols on free radical reactions and the reactivity of reactive hydrogen on both HMF substituents. The team systematically evaluated the effects of temperature, pressure, substrate solvent ratio, catalyst composition and concentration, and water concentration on the primary and secondary reactions of HMF oxidation. Under optimal conditions, at 150°C, 0.8 MPa air pressure, Co/Mn/Br molar ratio of 29/1/30, and HMF/HAc mass ratio of 1/9, the occurrence of side reactions could be reduced and the yield of FDCA maximized, resulting in a selectivity of 92% for FDCA and complete conversion of HMF with a total conversion time of less than 20 min, The purity of FDCA exceeded 99.8% [60]. The experimental results provide new ideas for the in-depth study of the oxidation process of hydroxymethyl furfural, and are of great significance for the large-scale production of FDCA. In addition, a comparison of the performance of different non-precious metal catalysts for the oxidation of hydroxymethyl furfural is shown in Table 2.

Comparison of performance of different non-precious metal catalysts for the oxidation of HMF

| Type | Catalyst | Electrolyte | T (°C) | HMF conversion (%) | FDCA yield (%) | FE (%) | Reaction time (h) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni | Ni3N@C | 1.0 M KOH | 25 | 100 | 98 | — | — | [36] |

| NixB-modified NF | 1.0 M KOH | 25 | 100 | 98.5 | 100 | 0.5 | [64] | |

| NiSe@NiOx | 1.0 M KOH | 25 | 100 | 99 | 99 | 2 | [65] | |

| NiFe LDH | 1.0 M KOH | — | 99 | 98 | 94.4 | — | [66] | |

| NiCoFe LDHs | 1.0 M NaOH | 55 | 95.5 | 84.9 | ∼90 | 1 | [67] | |

| Ni2S3/NF | 1.0 M KOH | — | 100 | 98 | 94 | 2 | [68] | |

| Ni(OH)2/NF | 1.0 M KOH | — | 100 | 100 | 99 | 1.5 | [69] | |

| Co | Co–P_DES | 0.5 M NaHCO3 | 25 | 99 | 85.3 | 77.3 | — | [70] |

| CoO–CoSe | 1.0 M KOH | 25 | 100 | 99 | 97.9 | ∼1 | [62] | |

| NiCo2O4 | 1.0 M KOH | 25 | 99.6 | — | 87.5 | ∼1 | [71] | |

| NiCo2O4/NF | 1.0 M KOH | 25 | 99.6 | 90.8 | 87.5 | ∼1 | [71] | |

| Co3O4 nanowires/NF | 1.0 M KOH | — | 100 | 96.8 | 96.6 | 5.73 | [72] | |

| NiCo-MOFs | pH = 13 | — | — | 99 | 78.8 | 6 | [73] | |

| Cu | CuxS@NiCo-LDH | 1.0 M KOH | — | ∼100 | 99 | 100 | — | [74] |

| Cu(OH)2NWs/CuF | 0.1 M KOH | 25 | 96.4 | 80.3 | 80.5 | ∼3.4 | [75] | |

| CuO NWs/CuF | 0.1 M KOH | 25 | 99.4 | 90.9 | 90.4 | ∼1.5 | [75] | |

| CuNi(OH)2/C | 1.0 M KOH | 25 | 100 | 93.3 | ∼95 | 5 | [76] | |

| CuMn2O4(Cu/Mn-1) | MeCN | 80 | 100 | 90.5 | — | 12 | [77] | |

| Mo | NF@Mo-Ni0.85Se | 1.0 M KOH | 25 | 100 | 95 | — | 2 | [78] |

| MoO2-FeP | 1.0 M KOH | 25 | 99.4 | — | 97.8 | 2.7 | [47] | |

| Mn | MnO2 | 0.6 mM NaHCO3 | 100 | 100 | 91 | — | 24 | [49] |

| MnOx | 1.0 M H2SO4 | 25 | 99.9 | 53.8 | 33.8 | — | [36] | |

| MnFe2O4 | H2O | 100 | — | 85 | — | 5 | [79] | |

| V | 3D VN HNs | 1.0 M KOH | 25 | 98 | — | 84 | ∼0.9 | [48] |

| Fe | FeOOH | 0.1 M KOH | 25 | 16 | ∼1.6 | ∼1.6 | 2.3 | [80] |

It was demonstrated that the introduction of abundant oxygen vacancies can enhance the catalytic activity and selectivity of FDCA by increasing the electrochemical surface area and decreasing charge transfer resistance. Density flooding theory (DFT) calculations [61] show that increasing the amount of oxygen vacancy (Ov) not only improves the alcohol activity of the catalyst by reducing the generation energy of Ov, but also promotes the adsorption and activation of O2 on the catalyst by significantly reducing the adsorption energy of O2, thus improving the oxidation activity of the catalyst towards HMF. Since the introduction of oxygen vacancies can enhance the activity of the catalyst against hydroxymethylfurfural, Han’s group [62] was the first to develop highly stable metal oxides. They introduced oxygen vacancies via Se doping, and the resulting CoO/CoSe2 with a molar ratio of 23:1 exhibited excellent performance and stability in the electrooxidation of HMF to FDCA, achieving a 99.0% yield of FDCA and a 97.9% FE at a potential of 1.43 V vs reversible hydrogen electrode potential (RHE). Huang’s team [63] synthesized two-dimensional (2D) polycrystalline cobalt oxide (Co3O4) nanosheets without surfactant, independent, and graded with oxygen-rich vacancies (Co3O4 VO) by topological transformation through rapid calcination of ultrathin cobalt oxide nanosheets synthesized by solvent heat. The nanosheets preserved the 2D structure and reduced the number of P123 surface active sites that are exposed. Furthermore, we suggest that strain-induced oxygen vacancies at the grain boundaries of Co3O4 nanocrystals are responsible for the enhanced electrooxidation properties. Co3O4-VO nanosheets exhibited significantly higher catalytic activity in oxygen evolution reaction (OER), particularly in the electrooxidation of HMF to FDCA, compared to conventionally synthesized CoOxHy nanosheets and conventionally calcined Co3O4 nanosheets.

In recent years, the majority of research has centered on the high performance oxidation of HMF utilizing electrocatalysts (such as 3D Ni foam [81], 3D Cu foam [82], and carbon paper [83]) deposited on high surface area 3D porous substrates. Metal foams with three-dimensional (3D) open pore structures have a high specific surface area and structural stiffness [82], making them suitable self-supporting substrates for in situ growth or coating of active materials. Pang et al. reported that CF-coated Cu(OH)2 is an effective electrocatalyst for HMF oxidation [84], enabling FDCA production with close to 100 percent FE (yield: 98.7%). Using a polyethylene glycol template, Hu’s team synthesized a 3D porous WO3/Ni electrode [1] in a controlled manner at low temperature. The electrochemically active surface area of the electrode can reach 40 cm2 if it has a high electrochemical catalytic performance. It is possible to achieve a good catalytic effect in a mild environment at room temperature and pressure. In 1.0 M KOH electrolyte, the HMF conversion was 99.4%, the FDCA yield was 88.3%, and the FE was 88.0%. Sun’s team [82] reviewed the recent progress of CF-derived electrodes as low-cost and efficient electrocatalysts in combination with the advantages of 3D mesh structure of metal foams, and focused on their applications in conventional and hybrid water electrolysis. Ni-based [85] catalysts are considered as one of the best candidates as a catalyst for HMF electrooxidation due to the rich 3D electron number and unique electron orbitals that enhance the covalency of transition metal–oxygen bonds, and have been extensively studied. Liu’s team [86] reported the efficient electrocatalytic oxidation of HMF to FDCA and furfural to furandicarboxylic acid using easily synthesized NiCoMn layered double hydroxide (LDH) nanosheets, rich in oxygen vacancies, loaded on nickel foam (NF). The effects of different metal ratios, reaction temperatures, and reactant concentrations on FDCA yields were systematically investigated. Niu team [66] reported the vertical electrochemical growth of NiSe@NiOx core-shell nanowires on NF as a non-precious metal electrocatalyst for the preparation of FDCA by electrooxidation of HMF (Figure 5). The core-shell NiSe@NiOx catalyst achieved 100% yield and 99% FE due to the unique structure of the core-shell exposing more active sites and favoring high electron transfer capability. In addition to the efficiency and activity, the catalytic mechanism is currently an important factor. The electrochemical oxidation of HMF on nickel-based materials closely resembles the indirect oxidation process [87,88]. Even though there are numerous advanced strategies for HMF electrooxidation on Ni-based catalysts, achieving high current densities at low potentials remains a challenge. Therefore, future research should focus on enhancing the kinetics of HMF electrooxidation and decreasing the reaction time while maintaining high catalytic efficiency.

Schematic diagram of the electrochemical system for simultaneous HMF oxidation and hydrogen reduction over a bifunctional core-shell NiSe@NiOx catalyst.

Studies have demonstrated that interfacial effects can generate a large number of cationic vacancies and that cationic vacancies play a crucial role in catalyzing the electrooxidation of HMF. Lu et al. [18] successfully prepared graded nanostructured NiO–Co3O4 electrodes with abundant interfacial defects using a simple hydrothermal annealing technique. Due to the dissimilar crystal structures of Co3O4 (spinel) and NiO (face-centered cubic), the atomic arrangement at the interface is not one-to-one, resulting in an abundance of defects and vacancies (Figure 6). With a high FDCA yield of 98% and a FE of 96%, the nanosheets exhibited superior HMF oxidation activity and stability. For this reason, interfacial engineering is an effective strategy for designing high-quality and highly effective electrocatalysts. Qi’s team [89] successfully prepared self-supporting cation-defect-rich NiFe-LDH (d-NiFe LDH/CP) catalysts through a hydrothermal process and alkaline etching treatment. A series of physical characterization studies confirmed the successful removal of the zinc component and the introduction of cationic vacancies. Among them, NiFe-LDH (d-NiFe LDH/CP) is the best catalyst for the reaction of electrochemical oxidation of HMF to FDCA. The catalyst showed excellent catalytic performance at 1.48 V, obtained 97.35% conversion of HMF, 96.8% yield of FDCA, and 84.47% of FE, and the catalytic performance was maintained even after ten cycles. The introduction of a large number of cationic vacancies is the key to achieve high catalytic activity, which greatly tunes the electronic structure of NiFe LDH. This greatly increased the electrochemically active surface area and reduced the charge transfer resistance. This provides insight into the design of defect-rich catalysts and their application in the upgrading of electrochemical biomass derivatives. Due to the rich oxygen vacancy structure and high surface area of the nanosheets, Gu’s team [90] successfully generated a defect-rich high-entropy oxide (HEO) nanosheet with high surface area utilizing a low-temperature plasma method and for the first time employed it for the electrooxidation of HMF (Figure 6). In comparison to HEO made using the high-temperature method, the binary (FeCrCoNiCu)3O4 nanosheets demonstrated excellent electrocatalytic performance for the oxidation of HMF with lower onset potential and faster kinetics, opening up new possibilities for the synthesis of nanostructured HEO with great application potential and electrocatalytic oxidation of furfural.

(a) The traditional synthesis method and (b) low-temperature plasma strategy for HEOs. (c) XRD patterns, (d) Raman spectra, and (e) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm of P-HEOs and C-HEOs. (f) and (i) TEM, (g) and (j) HRTEM, and (h) and (k) EDX mapping of P-HEOs and C-HEOs, respectively. Copyright © 2021 Wiley-VCH GmbH.

It has also been demonstrated that metal–organic framework (MOF) nanosheets are effective catalysts for the electrochemical oxidation of HMF. Cai et al. were the first to investigate the use of nickel-based 2D MOFs (2D-MOFs) [73] as electrocatalysts for HMF oxidation. Their prepared co-doped 2D-MOFs-NiCoBDC (Ni2+, BDC = terephthalic acid) exhibited a high FDCA yield of 99% and a FE of 78.8% in an electrolyte at pH 13. Due to their abundant exposed active sites and the coupling effect between Ni and Co atoms, the 2D NiCo-MOFs exhibited high catalytic activity and strong electrochemical stability. Chamberlain’s team [91] discovered that the oxidation-active MIL-100(Fe) MOF synthesized in water is an effective, stable, and recoverable MOF catalyst. Within 24 h, HMF was completely converted as a result of the synergistic effect of the MOF and the co-catalyst TEMPO. Under optimal reaction conditions, the maximum yields of FDCA and FFCA, respectively, were 57 and 17%, with an overall selectivity of 74%. Compared to other HMF oxidation catalysts using TEMPO as a co-catalyst, this is the only example of using water as a solvent. The porosity and abundance of active sites in 2D MOF make it a promising catalyst.

5 Non-metallic catalysts

Non-metallic catalysts can circumvent metallic catalysts’ disadvantages, such as high cost and product contamination. Two types of non-metallic catalysts have been studied for the electrochemical oxidation of HMF: non-homogeneous carbon-based materials [92,93] and homogeneous N-oxyl materials (i.e., TEMPO [94] and its derivatives). 4-acetamido-TEMPO [95] (ACT TEMPO = 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yloxy) has been identified as a highly promising homogeneous electrocatalyst for alcohol oxidation; TEMPO derivatives offer superior activity at a lower price. It permits the indirect electrochemical oxidation of HMF to FDCA [17] with close to 100% FE. The properties of the non-metallic HMF electrooxidation catalysts are listed in Table 3.

HMF electrooxidation performance of non-metallic catalysts

| Type | Catalyst | Electrolyte | T (°C) | HMF conversion (%) | FDCA yield (%) | FE (%) | Reaction time (h) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon | B–N co-doped porous carbons (BNC-2) | 0.1 M NaOH | 25 | 71 | 57 | — | 6 | [96] |

| TEMPO | TEMPO | 0.5 M sodium borate buffer | 25 | 99.9 | 93.8 | 93.8 | — | [97] |

| BiVO4/CoPi-30 | 5.0 mM TEMPO | — | 95 | 88 | — | 2.7 | [98] | |

| Hub-TEMPO | 0.5 mM LiClO4 | 25 | 99 | 78 | — | 20 | [99] |

6 Coupling with cathode system

In recent years, more and more people have turned their attention from uncoupled 5-HMF oxidation catalytic system to its coupling system. This is because the coupled system can first improve the energy utilization efficiency of the whole system. Second, the coupling system is promising to upgrade biomass derivatives into value-added products at the same time. Finally, the coupling system can further promote the industrialization of electrocatalytic furfural oxidation. The OER is a common anodic half-reaction that acts as a counter electrode in a range of electrocatalytic conversion technologies, such as electrocatalytic water separation, carbon dioxide reduction reaction (CO2RR), nitrogen reduction reaction (NRR), and nitrate reduction reaction (NO3-RR). However, the slow kinetics of the anode OER leads to a significant overpotential, which largely restricts the rate of the entire electrocatalytic reaction. For example, hydrogen generation in water splitting is limited due to the four-electron transfer of the anode OER, requiring a high cell voltage to drive the overall water electrolysis. Therefore, the replacement of OER with thermodynamically more favorable organic oxidation reactions has attracted great interest.

In recent years, oxidation reaction (OER) is a common anodic half-reaction, similar to electrocatalytic decomposition of water, and electroreduction of organic small molecules such as CO2 and N2 for energy or fine chemicals is gradually becoming a hot topic [100,101,102]. Furthermore, this series of electrocatalytic conversion technologies frequently acts as counter electrodes. Numerous studies have combined the commonly employed hydrogen precipitation reactions, CO2RRs, NRRs [96], and NO3-RR with anodic oxidation reactions, and the design of electrochemically coupled systems is emerging as a promising area of research. However, the slow kinetics of the anodic OER leads to a high overpotential, which largely limits the overall electrocatalytic reaction rate, consequently, substituting the OER with a thermodynamically more favorable organic oxidation reaction, which has drawn great interest. Theoretically, this coupled reaction system is twice as efficient (200%) as a conventional reaction system, but consumes the same amount of energy. The anodic oxidation kinetics of HMF is better than OER, so the starting voltage for HMF oxidation is lower than OER. By replacing OER with HMF oxidation at the anode, organic substrate reduction, H2 production, CO2RR, and NRR can be achieved simultaneously at a lower voltage [16]. The bifunctional linked system consisting of furfural oxidation and reduction reactions can not only maximize the return on energy investment but also provide value-added products for both parties. Table 4 shows the properties of different catalysts in the coupled system for the HMF electrooxidation catalyst.

Comparison of performance of different catalysts for the oxidation of HMF in coupled systems

| Type | Catalyst | Electrolyte | T (°C) | HMF conversion (%) | FDCA yield (%) | FE (%) | Reaction time (h) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru | Ru(iii)-PEI@MWCNT | 1.0 M KOH | — | — | — | 94 | 27 | [41] |

| Ru/MgO | Aqueous conditions | 160 | 100 | 90 | — | 4 | [43] | |

| Co | CuxS@NiCo-LDH | 1.0 M KOH | — | 87 | ∼99 | ∼99 | 20 | [74] |

| NiCo2O4 | 1.0 M KOH | — | >99 | >99 | >99 | 2 | [44] | |

| CoNiP-NIE | 1.0 M KOH | — | — | 87.2 | 87.2 | — | [103] | |

| Co3O4/CF | 1.0 M KOH | — | 100 | 93.2 | 92.9 | 1.67 | [104] | |

| BNC | BNC-2 | 0.1 M NaOH | 25 | 71 | 57 | — | 6 | [96] |

| Ti | Ti-MOF | 0.7 M MEA electrolyte (pH 11.0) | — | 35 | 30 | — | 6 | [105] |

| Ni | NiBx@NF | 1.0 M KOH | — | 99 | 99 | 99 | 1.67 | [19] |

| NiMoP/NF | 1.0 M KOH | 30 | 91.9 | 99.7 | 107.1 | 2 | [106] | |

| NiO NPs | 0.5 M KHCO3(pH 7.2) | — | 90 | 30 | 35 | — | [107] | |

| CoOOH/Ni | 1.0 M KOH | — | — | 90.2 | 92.3 | — | [108] | |

| NiCo–S | 1.0 M KOH | — | 99.1 | 97.1 | 96.4 | 0.67 | [54] | |

| CoFe@NiFe | 1.0 M KOH | — | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 1 | [83] | |

| Co0.4NiS@NF | 1.0 m KOH | — | 98.8–100 | 96.3–99.9 | 100 | — | [87] |

6.1 Coupling with CO2RRs

In CO2 reduction reactions (CO2RRs), typical CO2RR electrolyzers tend to use slow kinetic and high overpotential anodic OER, resulting in low anodic product values and wasteful operating costs. To address the problems of low space utilization and low energy utilization of the currently commonly used monopole CO2 electroreduction reaction process (cathode CO2 reduction and anode water oxidation to oxygen), it is crucial to construct a paired electrochemical reaction system with cathode CO2 reduction coupled with anode organic oxidation. It was discovered that partial oxidation of furfural coupled with H2 precipitation or other reduction reactions (such as CO2 [109]) in an electrochemical cell permits electrolysis at lower voltages while yielding a more valuable product than O2. The introduction of biomass oxidation as an alternative anode reaction in an electrolyte saturated with CO2 and near neutral allows for an efficient CO2 electrolysis system. The Nam team [107] designed and synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles (NPs) 3D transition metal-based catalysts NiO, Mn3O4, and Co3O4 NPs using a thermal injection method in order to establish an efficient HMF-CO2 double electrolysis system. Native electrolysis in 0.5 M KHCO3 saturated with CO2 was performed at 2 mA cm−2 for 3 h. The cell voltage was 2.5 V. The FE from biomass conversion was 36% and the FE from formate (HCOO−) production was 81%. They successfully demonstrated a formate production system combined with biomass oxidation for the simultaneous production of liquid fuels and synthesis of valuable polymer feedstocks. Han’s team [110] used PdOx/ZIF-8 as the cathode catalyst and PdO as the anode catalyst to efficiently catalyse the reduction of CO2 to CO at the cathode and the oxidation of HMF to organic acids at the anode. Figure 7a–d shows that the CO2RR–HMFOR system has higher current density and efficiency at the same tank voltage. Furthermore, the paired CO2RR–HMFOR system only requires a starting tank voltage of 1.06 V, which is much lower than the CO2RR–OER system (1.77 V) (Figure 7e). The tank voltage could be reduced by 0.71 V compared to the conventional paired OER reaction, and at a tank voltage of 2.70 V, a current density of 103.5 mA cm−2 was achieved at a cathodic CO FE of 97.0% using 8-PZ as the catalytic material; meanwhile, 84.3% organic acid yields were achieved on the anode, including 20.0% maleic acid (MA) and 64.3% formic acid (FA) (Figure 7f and g).

Performance of CO2RR–OER and CO2RR–HMFOR. (a) Current density vs cell voltage curves of CO2RR with OER or HMFOR over 8-PZ cathode and 8-PdO anode (scan rate: 20 mV s–1); (b) CO2RR vs OER: FE of CO and current density at different cell voltages for 8-PZ; (c) CO2RR vs HMFOR cathode: FE of CO and current density at different cell voltages for 8-PZ; (d) CO2RR vs HMFOR anode: the conversion of HMF and the yield of products at different cell voltages for 8-PdO (electrolysis time: 5 h; temperature: 40°C); (e) the comparison between a traditional single reaction and paired electrolysis system; (f) current density, FECO, the conversion of HMF, and the yield of anodic products on various catalysts (cell voltage: 2.70 V; electrolysis time: 5 h; temperature: 40°C); (g) long-term electrolysis results of CO2RR and HMFOR over 8-PZ cathode and 8-PdO anode (cell voltage: 2.70 V; temperature: 40°C). Copyright © 2022 American Chemical Society.

6.2 Coupling with NRRs

Since the thermodynamics of HMF oxidation are more favorable than OER, the first attempt to combine ammonia production with biomass upgrading was made by Xu et al. [41] who investigated a straightforward and effective technique for the production of Ru(iii)-PEI@MWCNT catalysts for the electrocatalytic oxidation of NRR and HMF in alkaline environments. During 27 h of stable electrolysis, the current density was 0.50 mA cm−2 and the cell voltage dropped from 1.56 to 1.34 V compared to the OER. And the yields and FEs of NH3 and FDCA were high, and the oxidation products obtained, FDCA, were more valuable than the HMF and O2 obtained by water cracking. The team of Oschatz [96] reported the synthesis of nitrogen and boron co-doped porous carbons,which has a unique structure with porosity, a high amount of heteroatom doping, and a high oxidation potential. As the created B–N motif combined a large number of unpaired electrons and frustrated Lewis pairs (FLPs), the B–N motif was extremely reactive. In the absence of metal auxiliaries, they performed well in both the electrochemical oxidation and NRR of HMF. The yield of NH3 was steady at 21.3 μg h−1 mg−1, and the FE reached 15.2%. Additionally, FDCA was generated for the first time utilizing a non-metal electrocatalyst with a 71% conversion and a 57% yield. Gas adsorption investigations clarified the link between the structure of the catalyst and its ability to activate substrate molecules. They shed light on the logical design of non-metal-based catalysts for prospective electrocatalytic applications and the increase in their activity through the introduction of FLP and grain boundary point defects (Figure 8).

Schematic diagram of the electrochemical system used for electrocatalytic NRR with HMF oxidation and the whole cell reaction.

6.3 Coupling with hydrogen evolution reaction

Electrochemical hydrogen production is considered to be an efficient and forward-looking sustainable technology, but its anodic oxygen precipitation reaction OER kinetics are slow and the value added to the product is low. Although the overpotential of OER can be reduced by developing advanced electrocatalysts, a qualitative breakthrough in overall reaction efficiency is yet to be achieved. Systems using biomass-derived chemicals such as glucose, furfural, and HMF as substrates for oxidation reactions are particularly attractive because the electricity and organic feedstock used are renewable and the hydrogen generation process is fully sustainable [54]. The use of new anodic oxidation reactions with good thermodynamics and kinetics in combination with cathodic hydrogen precipitation reactions (HER) can reduce the voltage required for electrolytic systems. Deng et al. developed and produced low-energy CuxS@NiCo-LDH core-shell nanoarray electrocatalysts [74] for HMF oxidation and water reduction, while simultaneously producing FDCA and hydrogen fuel with additional value. Zhou et al. produced and fabricated a variety of NixCo3-xO4 electrodes using a simple hydrothermal technique [44]. At 1.45 V (relative to RHE), a highly selective conversion of HMF to FDCA was accomplished with >99% conversion and FE efficiency, as well as a considerable increase in hydrogen production of 8.16 times that of pure water oxidation. Song et al. [103] reported a bifunctional nickel–titanium alloy nanosheet integrated electrode (CoNiP-NIE) to enhance HER and replace OER by 5-hydroxymethylfurfural oxidation reaction (HMFOR) to obtain high-value FDCA. As can be seen from Figure 9, FEFDCA on CoNiP-NIE could reach 87.2% at 1.50 VRHE and FEFDCA exceeded 82% over a wide potential range from 1.40 VRHE to 1.70 VRHE. CoNiP-NIE also showed good HER activity with overpotentials as low as 107.56 mV at −10 mA cm−2 current density. Furthermore, the CoNiP-NIE-based bifunctional EHCO system exhibited an ultra-low cell potential (1.46 V) and a higher H2 precipitation rate (41.2 L h−1 m−2) compared to the hydrolysis system (1.76 V, 16.1 L h−1 m−2). This ECHO system achieved a high FDCA yield (85.5 g h−1 m−2), further improving the economic efficiency of hydrogen production. The bilayer hydroxide (CoFe@NiFe) [83], synthesized by the electrodeposition method of Zhao’s team, can selectively react with six electrons of HMF to produce FDCA via an anodic half-reaction in a two-chamber system with cathodic HER. The overall reaction reaches 38 mA cm−2 at 1.40 V and exhibits 100% selectivity, producing FDCA and almost 100% FE with a hydrogen yield of 901 µmol cm−2. Sun’s team [87] developed a convenient route based on in situ heteroatom doping to prepare co-doped Ni3S2 electrocatalysts on NF substrates. The optimized electrocatalyst (Co0.4NiS@NF) electrode requires only a very low starting potential and achieves high current density at a lower potential. Very high production rates of cathodic H2 and anodic value-added chemicals were achieved in the HMFOR-assisted conventional HER cathodic reaction process, providing a reference for the development of industrial-scale electrocatalytic production of H2.

(a) LSV curves of CoNiP-NIE and CoNi-LDH-NIE for EHCO and water splitting. (b) FEFDCA and yield at different potentials of CoNiP-NIE and CoNi-LDH-NIE for EHCO. (c) H2 evolution rate and FDCA yield rate of CoNiP-NIE for EHCO system and water splitting system (the inset shows HPLC chromatogram and digital photograph of FDCA powders). (d) I–V curve of commercial Si solar cell under illumination together with polarization curve of the catalytic cell. (e) LSV curves of CoNiP-NIE and CoNiP-P in 1 M KOH in the presence and absence of 10 mM HMF. The connect angles of (f1) CoNiP-NIE and (f2) CoNiP-P. Microscope photographs of H2 bubbles on the surface of (g1) CoNiP-NIE and (g2) CoNiP-P. © 2022 Published by Elsevier.

6.4 Coupling with other reactions

In electrocatalytic processes, metal sulfides [111] (sulfides and selenides) have also been widely explored. They can exhibit an extensive range of crystalline phases and oxidation states, and can be used to catalyze UOR and HMF-EOR reactions by constructing multiphase structures and doping non-homogeneous atoms to generate new active centers that enhance intrinsic activity and accelerate electron transfer. Zhang et al. [19] prepared NiBx catalysts to oxygenate HMF to FDCA while hydrogenating p-nitrophenol to p-aminophenol in a 1 M KOH electrolyte, achieving 99% conversion efficiency and selectivity. This paired electro-synthetic cell was also coupled to a solar cell as a stand-alone reactor to cope with sunlight. The Liang team [106] demonstrated the use of paired electrolysis of acrylonitrile (AN) and HMF for the simultaneous production of acetonitrile (ADN) and FDCA. Their paired electrolysis reaction system, using electrodeposited NiMoP amorphous film-covered NF as the anode, effectively increased HMFOR activity and expanded ECSA by in situ selective removal of surface Mo and P. By adding DMF to the cathode chamber, the solubility of ADN was increased and the resulting single-phase solution provided better mass transfer for the hydrolysis of AN. DMF as co-solvent increased the solubility of ADN and the resulting single-phase solution provided better mass transfer for the hydrolysis of AN. The ANEHD-HMFOR pairing system allowed the production of FDCA and ADN at high currents (160 mA) as the cathode and anode simultaneously increased the conversion of the substrate molecules, achieving 83.7% FDCA yield for the anode and 62.3% ADN yield, with a FE of 107.1% for the whole cell. Román et al. [112] optimized FA production by limiting the coupling to the Pt electrode surface, thereby prevented decarbonylation/decarboxylation (and the associated complete oxidation of furan groups) and induced aggregate effects of modifiers such as Bi or Pb (which adsorb irreversibly to Pt under electrooxidation conditions) or self-assembled monolayers [113]. The selectivity of MA and HFN is optimized by doping the Pt surface with an oxygen-loving metal (such as Ru), thereby increasing the concentration of active OH* species at the surface. These “bifunctional” Pt alloys or composites can increase CO oxidation at lower potentials and can release the metallic Pt surface at steady state, producing C4 products (via the decarbonization pathway). A paired photoelectrochemical cell (PEC) was successfully constructed by Bharath et al. [114]. They employed Au/α-Fe2O3/RGO as the photoelectric cathode and Ru/RGO-modified Pt as the anode, reducing CO2 at the cathode to CH3OH and oxidizing furfural at the anode to 2-FA and 5-HFA. Both PEC CO2 reduction and furfural oxidation at various anode solution concentrations produced high CH3OH yield (63 μmol L−1 cm−2), 82% FF conversion, 63% yield of 2-FA, and 19% yield of 5-HFA with good stability. Electrocatalytic reductive amination and simultaneous oxidation (ERAO) was proposed to convert biomass-derived HMF to valuable 2-hydroxymethyl-5-(ethanolamine methyl) furan (HEMF) and FDCA at the cathode and anode, respectively. Zhang’s team [105] suggested an ERAO approach to convert biomass-derived HMF to useful HEMF at the cathode and FDCA at the anode. They devised and produced titanium-based MOF (Ti-MOF) cubes and NiCoF-LDH nanosheets as cathode and anode materials, respectively. ERAO showed very good performance overall, with 67.8% conversion of HMF in ERAO, 99% selectivity for HEMF (cathode), and 35% selectivity for FDCA after 6 h of reaction (anode), which is closely related to the additional internal site access provided by the Ti-MOF exposed N–Ti–O active center and the porous structure.

6.5 Coupling with photovoltaic electrolysis

In addition, the coupling reaction of hydroxymethyl furfural oxidation with photovoltaic electrolysis has also become a hot topic of interest. Chen’s [104] team used in situ electrochemical modulation to prepare a highly efficient multifunctional hydrangea-like CoO electrocatalyst. The defective structure and abundance of electroactive sites enabled the catalyst to achieve photovoltaic electrocatalysis for the simultaneous production of FDCA and H2. The team constructed the first solar-driven integrated reaction using photovoltaic electrocatalysis (PVEC) of 2,5-Bis(hydroxymethyl)furan (BHMF), effectively improving the overall sustainability. Takanabe’s [108] team believes that efficient electrochemical devices can convert electrical energy from intermittent renewable energy sources into chemical form. The different targets and the choice of combinations provide different thermodynamics and kinetics for redox reactions. They demonstrate a promising approach for the production of H2 using an intermediate redox medium in combination with sulfide remediation. For the first time, Zhang’s team used the more stable furan molecule BHMF as the reaction substrate for the coupling system and prepared vertical CoOOH nanosheet electrocatalysts [108] by simple electrodeposition and subsequent oxidative activation, achieving complete conversion of BHMF with 90.2% FDCA yield and 100% current efficiency for H2 evolution, providing a green coupling electrolysis for industrial applications.

7 Summary and outlook

FDCA is a viable biomass-derived feedstock, and its most attractive application is as a substitute for terephthalic acid derived from petroleum for the synthesis of valuable biobased polymers, polyethylene-2,5-furandicarboxylate. In recent years, the electrocatalytic synthesis of FDCA from bio-based HMF has garnered increased interest due to its substantial economic and sustainable benefits. Meanwhile coupling furfural oxidation with numerous reduction reactions can be used for a variety of energy-related applications, with remarkable achievements in the catalytic synthesis of FDCA and its derivatives by different methods. The selective catalytic oxidation of HMF to FDCA is therefore seen as a promising process that can effectively reduce energy consumption and environmental pollution issues. However, there are still some practical problems:

In the oxidation of HMF to FDCA, most of the current methods are carried out in water in the presence of excess alkali, which is an environmentally unfriendly and expensive process, and various by-products such as furan compounds are formed, so there is a need to develop greener catalytic systems and find milder conditions to achieve high FDCA selectivity.

From a practical application point of view, it is vital to produce more efficient, active, and stable transition metal catalysts for the aerobic oxidation of HMF to FDCA compared to expensive precious metal materials.

The design of electrochemically coupled systems is becoming a promising area of research. Bifunctional coupled systems consisting of furfural oxidation reactions not only maximize the return on energy investment, but also provide value-added products for both parties. But few research has integrated the anodic furfural oxidation and reduction reactions to produce a double-coupled system, so the creation of an efficient double-coupled electrocatalytic system is important for energy consumption. Finally, further developments are still needed to accomplish industrial large-scale and economic production of FDCA and its derivatives.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.22005269); the National Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LQ21B030007); the National Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LTGS23B030002) and the Open Research Subject of Zhejiang Key Laboratory of Petrochemical Environmental Pollution Control (Grant 2022Z02).

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22005269); the National Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LQ21B030007), and the Science and Technological program of Ningbo (Grant 2021S136).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Hu K, Zhang M, Liu B, Yang Z, Li R, Yan K. Efficient electrochemical oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid using the facilely synthesized 3d porous WO3/Ni electrode. Mol Catal. 2021;504:111459.10.1016/j.mcat.2021.111459Search in Google Scholar

[2] Wang T, Huang Z, Liu T, Tao L, Tian J, Gu K, et al. Transforming electrocatalytic biomass upgrading and hydrogen production from electricity input to electricity output. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2022;61(12):e202115636.10.1002/anie.202115636Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Yang Y, Mu T. Electrochemical oxidation of biomass derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF): Pathway, mechanism, catalysts and coupling reactions. Green Chem. 2021;23(12):4228–54.10.1039/D1GC00914ASearch in Google Scholar

[4] You B, Liu X, Jiang N, Sun Y. A general strategy for decoupled hydrogen production from water splitting by integrating oxidative biomass valorization. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(41):13639–46.10.1021/jacs.6b07127Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Giannakoudakis DA, Colmenares JC, Tsiplakides D, Triantafyllidis KS. Nanoengineered electrodes for biomass-derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural electrocatalytic oxidation to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2021;9(5):1970–93.10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c07480Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zhang Z, Deng K. Recent advances in the catalytic synthesis of 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid and its derivatives. ACS Catal. 2015;5(11):6529–44.10.1021/acscatal.5b01491Search in Google Scholar

[7] Yu L, Chen H, Wen Z, Jin M, Ma X, Li Y, et al. Efficient aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid over a nanofiber globule La-MnO2 catalyst. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2021;60(4):1624–32.10.1021/acs.iecr.0c05561Search in Google Scholar

[8] Zhang M, Yu Z, Xiong J, Zhang R, Liu X, Lu X. One-step hydrothermal synthesis of CdxInyS(x + 1.5y) for photocatalytic oxidation of biomass-derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-diformylfuran under ambient conditions. Appl Catal B. 2022;300:120738.10.1016/j.apcatb.2021.120738Search in Google Scholar

[9] Kandasamy P, Gogoi P, Venugopalan AT, Raja T. A highly efficient and reusable Ru-NaY catalyst for the base free oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. Catal Today. 2021;375:145–54.10.1016/j.cattod.2020.05.009Search in Google Scholar

[10] Cheng F, Guo D, Lai J, Long M, Zhao W, Liu X, et al. Efficient base-free oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid over copper-doped manganese oxide nanorods with tert-butanol as solvent. Front Chem Sci Eng. 2021;15(4):960–8.10.1007/s11705-020-1999-5Search in Google Scholar

[11] Zhong X, Yuan P, Wei Y, Liu D, Losic D, Li M. Coupling natural halloysite nanotubes and bimetallic Pt-Au alloy nanoparticles for highly efficient and selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(3):3949–60.10.1021/acsami.1c18788Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Li C, Na Y. Recent advances in photocatalytic oxidation of 5hydroxymethylfurfural. ChemPhotoChem. 2021;5:1–11.10.1002/cptc.202000261Search in Google Scholar

[13] Park M, Gu M, Kim BS. Tailorable electrocatalytic 5-hydroxymethylfurfural oxidation and H2 production: Architecture-performance relationship in bifunctional multilayer electrodes. ACS Nano. 2020;14(6):6812–22.10.1021/acsnano.0c00581Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Chen C, Wang L, Zhu B, Zhou Z, El-Hout SI, Yang J, et al. 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid production via catalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural: Catalysts, processes and reaction mechanism. J Energy Chem. 2021;54:528–54.10.1016/j.jechem.2020.05.068Search in Google Scholar

[15] Zhong Y, Ren R-Q, Qin L, Wang J-B, Peng Y-Y, Li Q, et al. Electrodeposition of hybrid nanosheet-structured NiCo2O4 on carbon fiber paper as a non-noble electrocatalyst for efficient electrooxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. N J Chem. 2021;45(25):11213–21.10.1039/D1NJ01489GSearch in Google Scholar

[16] Meng Y, Yang S, Li H. Electro- and photocatalytic oxidative upgrading of bio-based 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. ChemSusChem. 2022;15(13):e202102581.10.1002/cssc.202102581Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Chadderdon XH, Chadderdon DJ, Pfennig T, Shanks BH, Li W. Paired electrocatalytic hydrogenation and oxidation of 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural for efficient production of biomass-derived monomers. Green Chem. 2019;21(22):6210–9.10.1039/C9GC02264CSearch in Google Scholar

[18] Lu Y, Dong C-L, Huang Y-C, Zou Y, Liu Y, Li Y, et al. Hierarchically nanostructured NiO–Co3O4 with rich interface defects for the electro-oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Sci China Chem. 2020;63(7):980–6.10.1007/s11426-020-9749-8Search in Google Scholar

[19] Zhang P, Sheng X, Chen X, Fang Z, Jiang J, Wang M, et al. Paired electrocatalytic oxygenation and hydrogenation of organic substrates with water as the oxygen and hydrogen source. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2019;58(27):9155–9.10.1002/anie.201903936Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Huang X, Song J, Hua M, Xie Z, Liu S, Wu T, et al. Enhancing electrocatalytic activity of CoO for oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural by introducing oxygen vacancy. Green Chem. 2020;22(3):843–9.10.1039/C9GC03698ASearch in Google Scholar

[21] Tao H, Choi C, Ding L-X, Jiang Z, Han Z, Jia M, et al. Nitrogen fixation by Ru single-atom electrocatalytic reduction. Chem. 2019;5(1):204–14.10.1016/j.chempr.2018.10.007Search in Google Scholar

[22] Du Y, Sheng H, Astruc D, Zhu M. Atomically precise noble metal nanoclusters as efficient catalysts: A bridge between structure and properties. Chem Rev. 2020;120(2):526–622.10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00726Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Capelli S, Villa A. Biomass processing via metal catalysis. Biomass Valoriz. 2021;81–112.10.1002/9783527825028.ch4Search in Google Scholar

[24] Zhu Z, Gao X, Wang X, Yin M, Wang Q, Ren W, et al. Rational construction of metal–base synergetic sites on Au/Mg-beta catalyst for selective aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. J Energy Chem. 2021;62:599–609.10.1016/j.jechem.2021.04.022Search in Google Scholar

[25] Liu H, Cao X, Wang T, Wei J, Tang X, Zeng X, et al. Efficient synthesis of bio-monomer 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid from concentrated 5-hydroxymethylfurfural or fructose in DMSO/H2O mixed solvent. J Ind Eng Chem. 2019;77:209–14.10.1016/j.jiec.2019.04.038Search in Google Scholar

[26] Chadderdon DJ, Xin L, Qi J, Qiu Y, Krishna P, More KL, et al. Electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid on supported Au and Pd bimetallic nanoparticles. Green Chem. 2014;16(8):3778–86.10.1039/C4GC00401ASearch in Google Scholar

[27] Xu H, Li X, Hu W, Yu Z, Zhou H, Zhu Y, et al. Research progress of highly efficient noble metal catalysts for the oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. ChemSusChem. 2022;15(13):e202200352.10.1002/cssc.202200352Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Bonincontro D, Lolli A, Villa A, Prati L, Dimitratos N, Veith GM, et al. AuPd-nNiO as an effective catalyst for the base-free oxidation of HMF under mild reaction conditions. Green Chem. 2019;21(15):4090–9.10.1039/C9GC01283DSearch in Google Scholar

[29] Han X, Geng L, Guo Y, Jia R, Liu X, Zhang Y, et al. Base-free aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid over a Pt/C–O–Mg catalyst. Green Chem. 2016;18:1597–604.10.1039/C5GC02114FSearch in Google Scholar

[30] Gao Z, Xie R, Fan G, Yang L, Li F. Highly efficient and stable bimetallic AuPd over La-doped Ca−Mg−Al layered double hydroxide for base-free aerobic oxidation of 5‑hydroxymethylfurfural in water. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2017;5(7):5852–61.10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b00573Search in Google Scholar

[31] Zhang B, Zhu H, Zou M, Liu X, Yang H, Zhang M, et al. Design and fabrication of size-controlled Pt–Au bimetallic alloy nanostructure in carbon nanofibers: A bifunctional material for biosensors and the hydrogen evolution reaction. J Mater Sci. 2017;52:8207–18.10.1007/s10853-017-1030-9Search in Google Scholar

[32] Wang P, Zhou F, Wang Z, Lai C, Han X. Substrate-induced assembly of PtAu alloy nanostructures at choline functionalized monolayer interface for nitrite sensing. J Electroanal Chem. 2015;750:36–42.10.1016/j.jelechem.2015.05.006Search in Google Scholar

[33] Xiao F, Mo Z, Zhao F, Zeng B. Ultrasonic-electrodeposition of gold–platinum alloy nanoparticles on multi-walled carbon nanotubes – ionic liquid composite film and their electrocatalysis towards the oxidation of nitrite. Electrochem Commun. 2008;10(11):1740–3.10.1016/j.elecom.2008.09.004Search in Google Scholar

[34] Verdeguer P, Merat N, Gaset A. Oxydation catalytique du HMF en acide 2,5-furane dicarboxylique. J Mol Catal A: Chem. 1993;85(3):44–327.10.1016/0304-5102(93)80059-4Search in Google Scholar

[35] Campisi S, Capelli S, Motta D, Trujillo F, Davies T, Prati L, et al. Catalytic performances of Au–Pt nanoparticles on phosphorous functionalized carbon nanofibers towards HMF oxidation. C. 2018;4(3):1–17.10.3390/c4030048Search in Google Scholar

[36] Kubota SR, Choi KS. Electrochemical oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA) in acidic media enabling spontaneous FDCA separation. ChemSusChem. 2018;11(13):2138–45.10.1002/cssc.201800532Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Latsuzbaia R, Bisselink R, Anastasopol A, van der Meer H, van Heck R, Yagüe MS, et al. Continuous electrochemical oxidation of biomass derived 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural into 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. J Appl Electrochem. 2018;48(6):611–26.10.1007/s10800-018-1157-7Search in Google Scholar

[38] Kim M, Su Y, Fukuoka A, Hensen EJM, Nakajima K. Aerobic oxidation of 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural cyclic acetal enables selective furan-2,5-dicarboxylic acid formation with CeO2-supported gold catalyst. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57(27):8235–9.10.1002/anie.201805457Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Antonyraj CA, Huynh NTT, Park S-K, Shin S, Kim YJ, Kim S, et al. Basic anion-exchange resin (AER)-supported Au-Pd alloy nanoparticles for the oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural (HMF) into 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA). Appl Catal A. 2017;547:230–6.10.1016/j.apcata.2017.09.012Search in Google Scholar

[40] Espinosa JC, Contreras RC, Navalón S, Rivera‐Cárcamo C, Álvaro M, Machado BF, et al. Influence of carbon supports on palladium nanoparticle activity toward hydrodeoxygenation and aerobic oxidation in biomass transformations. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2019;2019(14):1979–87.10.1002/ejic.201900190Search in Google Scholar

[41] Xu G-R, Batmunkh M, Donne S, Jin H, Jiang J-X, Chen Y, et al. Ruthenium(III) polyethyleneimine complexes for bifunctional ammonia production and biomass upgrading. J Mater Chem A. 2019;7(44):25433–40.10.1039/C9TA10267ASearch in Google Scholar

[42] Gao T, Yin Y, Fang W, Cao Q. Highly dispersed ruthenium nanoparticles on hydroxyapatite as selective and reusable catalyst for aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid under base-free conditions. Mol Catal. 2018;450:55–64.10.1016/j.mcat.2018.03.006Search in Google Scholar

[43] Antonyraj CA, Huynh NTT, Lee KW, Kim YJ, Shin S, Shin JS, et al. Base-free oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural to 2,5-furan dicarboxylic acid over basic metal oxide-supported ruthenium catalysts under aqueous conditions. J Chem Sci (Bangalore, India). 2018;130(11):156.10.1007/s12039-018-1551-zSearch in Google Scholar

[44] Zhou Z, Xie Y-N, Sun L, Wang Z, Wang W, Jiang L, et al. Strain-induced in situ formation of NiOOH species on Co–Co bond for selective electrooxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and efficient hydrogen production. Appl Catal B. 2022;305:121072.10.1016/j.apcatb.2022.121072Search in Google Scholar

[45] Dutta S, Yu IKM, Tsang DCW, Ng YH, Ok YS, Sherwood J, et al. Green synthesis of gamma-valerolactone (GVL) through hydrogenation of biomass-derived levulinic acid using non-noble metal catalysts: A critical review. Chem Eng J. 2019;372:992–1006.10.1016/j.cej.2019.04.199Search in Google Scholar

[46] Liu W-J, Dang L, Xu Z, Yu H-Q, Jin S, Huber GW. Electrochemical oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural with NiFe layered double hydroxide (LDH) nanosheet catalysts. ACS Catal. 2018;8(6):5533–41.10.1021/acscatal.8b01017Search in Google Scholar

[47] Yang G, Jiao Y, Yan H, Xie Y, Wu A, Dong X, et al. Interfacial engineering of MoO2-FEP heterojunction for highly efficient hydrogen evolution coupled with biomass electrooxidation. Adv Mater. 2020;32(17):e2000455.10.1002/adma.202000455Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Li S, Sun X, Yao Z, Zhong X, Cao Y, Liang Y, et al. Biomass valorization via paired electrosynthesis over vanadium nitride-based electrocatalysts. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;29(42):1904780.10.1002/adfm.201904780Search in Google Scholar

[49] Hayashi E, Yamaguchi Y, Kamata K, Tsunoda N, Kumagai Y, Oba F, et al. Effect of MnO2 crystal structure on aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141(2):890–900.10.1021/jacs.8b09917Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Pal P, Saravanamurugan S. Heterostructured manganese catalysts for the selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-diformylfuran. ChemCatChem. 2020;12(8):2324–32.10.1002/cctc.202000086Search in Google Scholar

[51] Fleischmann M, Korinek K, Pletcher D. The kinetics and mechanism of the oxidation of amines and alcohols at oxide-covered nickel, silver, copper, and cobalt electrodes. J Electroanal Chem Interfacial Electrochem. 1971;31:39–49.10.1039/p29720001396Search in Google Scholar

[52] Chen W, Xie C, Wang Y, Zou Y, Dong C-L, Huang Y-C, et al. Activity origins and design principles of nickel-based catalysts for nucleophile electrooxidation. Chem. 2020;6(11):2974–93.10.1016/j.chempr.2020.07.022Search in Google Scholar

[53] Deng X, Xu GY, Zhang YJ, Wang L, Zhang J, Li JF, et al. Understanding the roles of electrogenerated Co3+ and Co4+ in selectivity-tuned 5-hydroxymethylfurfural oxidation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2021;60(37):20535–42.10.1002/anie.202108955Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Zhao Z, Guo T, Luo X, Qin X, Zheng L, Yu L, et al. Bimetallic sites and coordination effects: Electronic structure engineering of NiCo-based sulfide for 5-hydroxymethylfurfural electrooxidation. Catal Sci Technol. 2022;12:3817–25.10.1039/D2CY00281GSearch in Google Scholar

[55] Deuss PJ, Barta K, de Vries JG. Homogeneous catalysis for the conversion of biomass and biomass-derived platform chemicals. Catal Sci &Technology. 2014;4:1174–96.10.1002/9783527651733.ch36Search in Google Scholar

[56] Partenheimer W. Methodology and scope of metal/bromide autoxidation of hydrocarbons. Catal Today. 1995;23:69–158.10.1016/0920-5861(94)00138-RSearch in Google Scholar

[57] Tang W, Wu X, Li D, Wang Z, Liu G, Liu H, et al. Oxalate route for promoting activity of manganese oxide catalysts in total VOCs’ oxidation: Effect of calcination temperature and preparation method. J Mater Chem A. 2014;2:2544–54.10.1039/C3TA13847JSearch in Google Scholar

[58] Zuo X, Chaudhari AS, Snavely K, Niu F, Zhu H, Martin KJ, et al. Kinetics of homogeneous 5-hydroxymethylfurfural oxidation to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co/Mn/Br catalyst. AIChE J. 2016;63(1):1–44.10.1002/aic.15497Search in Google Scholar

[59] Chen S, Guo X, Ban H, Pan T, Zheng L, Cheng Y, et al. Reaction mechanism and kinetics of the liquid-phase oxidation of 5‑hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2021;60:16887–98.10.1021/acs.iecr.1c02730Search in Google Scholar

[60] Chen S, Cheng Y, Ban H, Zhang Y, Zheng L, Wang L, et al. Liquid phase aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid over Co/Mn/Br catalyst. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2020;59(39):17076–84.10.1021/acs.iecr.0c01309Search in Google Scholar

[61] Liu H, Jia W, Yu X, Tang X, Zeng X, Sun Y, et al. Vitamin C‑assisted synthesized Mn−Co oxides with improved oxygen vacancy concentration: Boosting lattice oxygen activity for the air-oxidation of 5‑(hydroxymethyl)furfural. ACS Catal. 2021;11:7828–44.10.1021/acscatal.0c04503Search in Google Scholar

[62] Huang X, Song J, Hua M, Xie Z, Liu S, Wu T, et al. Enhancing the electrocatalytic activity of CoO for the oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural by introducing oxygen vacancies. Green Chem. 2020;22(3):843–9.10.1039/C9GC03698ASearch in Google Scholar

[63] Zhong R, Wang Q, Du L, Pu Y, Ye S, Gu M, et al. Ultrathin polycrystalline Co3O4 nanosheets with enriched oxygen vacancies for efficient electrochemical oxygen evolution and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural oxidation. Appl Surf Sci. 2022;584:152553.10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.152553Search in Google Scholar

[64] Zhang N, Zou Y, Tao L, Chen W, Zhou L, Liu Z, et al. Electrochemical oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural on nickel nitride/carbon nanosheets: Reaction pathway determined by in situ sum frequency generation vibrational spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2019;58(44):15895–903.10.1002/anie.201908722Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Barwe S, Weidner J, Cychy S, Morales DM, Dieckhofer S, Hiltrop D, et al. Electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural using high-surface-area nickel boride. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57(35):11460–64.10.1002/anie.201806298Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Gao L, Liu Z, Ma J, Zhong L, Song Z, Xu J, et al. NiSe@NiOx core-shell nanowires as a non-precious electrocatalyst for upgrading 5-hydroxymethylfurfural into 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. Appl Catal B. 2020;261:118235.10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118235Search in Google Scholar

[67] Zhang M, Liu Y, Liu B, Chen Z, Xu H, Yan K. Trimetallic NiCoFe-layered double hydroxides nanosheets efficient for oxygen evolution and highly selective oxidation of biomass-derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. ACS Catal. 2020;10(9):5179–89.10.1021/acscatal.0c00007Search in Google Scholar

[68] Wang W, Kong F, Zhang Z, Yang L, Wang M. Sulfidation of nickel foam with enhanced electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. Dalton Trans. 2021;50(31):10922–27.10.1039/D1DT02025KSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Zhang J, Gong W, Yin H, Wang D, Zhang Y, Zhang H, et al. In situ growth of ultrathin Ni(OH)2 nanosheets as catalyst for electrocatalytic oxidation reactions. ChemSusChem. 2021;14(14):2935–42.10.1002/cssc.202100811Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[70] Kang MJ, Yu HJ, Kim HS, Cha HG. Deep eutectic solvent stabilised Co–P films for electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural into 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. N J Chem. 2020;44(33):14239–45.10.1039/D0NJ01426ESearch in Google Scholar

[71] Kang MJ, Park H, Jegal J, Hwang SY, Kang YS, Cha HG. Electrocatalysis of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural at cobalt based spinel catalysts with filamentous nanoarchitecture in alkaline media. Appl Catal B. 2019;242:85–91.10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.09.087Search in Google Scholar

[72] Zhou Z, Chen C, Gao M, Xia B, Zhang J. In situ anchoring of a Co3O4 nanowire on nickel foam: An outstanding bifunctional catalyst for energy-saving simultaneous reactions. Green Chem. 2019;21(24):6699–706.10.1039/C9GC02880CSearch in Google Scholar

[73] Cai M, Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Liu Q, Li Y, Li G. Two-dimensional metal–organic framework nanosheets for highly efficient electrocatalytic biomass 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural (HMF) valorization. J Mater Chem A. 2020;8(39):20386–92.10.1039/D0TA07793CSearch in Google Scholar

[74] Deng X, Kang X, Li M, Xiang K, Wang C, Guo Z, et al. Coupling efficient biomass upgrading with H2 production via bifunctional CuxS@NiCo-LDH core–shell nanoarray electrocatalysts. J Mater Chem A. 2020;8(3):1138–46.10.1039/C9TA06917HSearch in Google Scholar

[75] Pham HM, Kang MJ, Kim K-A, Im CG, Hwang SY, Cha HG. Which electrode is better for biomass valorization: Cu(OH)2 or CuO nanowire? Korean J Chem Eng. 2020;37(3):556–62.10.1007/s11814-020-0474-9Search in Google Scholar

[76] Chen H, Wang J, Yao Y, Zhang Z, Yang Z, Li J, et al. Cu−Ni bimetallic hydroxide catalyst for efficient electrochemical conversion of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. ChemElectroChem. 2019;6(23):5797–801.10.1002/celc.201901366Search in Google Scholar

[77] Wang F, Lai J, Liu Z, Wen S, Liu X. Copper-manganese oxide for highly selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to bio-monomer 2, 5-furandicarboxylic acid. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2022:1–12.10.1007/s13399-021-02143-zSearch in Google Scholar

[78] Yang C, Wang C, Zhou L, Duan W, Song Y, Zhang F, et al. Refining d-band center in Ni0.85Se by Mo doping: A strategy for boosting hydrogen generation via coupling electrocatalytic oxidation 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Chem Eng J. 2021;422:130125.10.1016/j.cej.2021.130125Search in Google Scholar

[79] Gawade AB, Nakhate AV, Yadav GD. Selective synthesis of 2, 5-furandicarboxylic acid by oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural over MnFe2O4 catalyst. Catal Today. 2018;309:119–25.10.1016/j.cattod.2017.08.061Search in Google Scholar

[80] Taitt BJ, Nam D-H, Choi K-S. A comparative study of nickel, cobalt, and iron oxyhydroxide anodes for the electrochemical oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. ACS Catal. 2018;9(1):660–70.10.1021/acscatal.8b04003Search in Google Scholar

[81] You B, Liu X, Liu X, Sun Y. Efficient H2 evolution coupled with oxidative refining of alcohols via a hierarchically porous nickel bifunctional electrocatalyst. ACS Catal. 2017;7(7):4564–70.10.1021/acscatal.7b00876Search in Google Scholar

[82] Sun H, Kim H, Song S, Jung W. Copper foam-derived electrodes as efficient electrocatalysts for conventional and hybrid water electrolysis. Mater Rep Energy. 2022;2(2):100092.10.1016/j.matre.2022.100092Search in Google Scholar

[83] Xie Y, Zhou Z, Yang N, Zhao G. An overall reaction integrated with highly selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and efficient hydrogen evolution. Adv Funct Mater. 2021;31(34):2102886.10.1002/adfm.202102886Search in Google Scholar

[84] Pang X, Bai H, Zhao H, Fan W, Shi W. Efficient electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural coupled with 4-nitrophenol hydrogenation in a water system. ACS Catal. 2022;12(2):1545–57.10.1021/acscatal.1c04880Search in Google Scholar

[85] Formenti D, Ferretti F, Scharnagl FK, Beller M. Reduction of nitro compounds using 3D-non-noble metal catalysts. Chem Rev. 2019;119(4):2611–80.10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00547Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[86] Liu B, Xu S, Zhang M, Li X, Decarolis D, Liu Y, et al. Electrochemical upgrading of biomass-derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and furfural over oxygen vacancy-rich NiCoMn-layered double hydroxides nanosheets. Green Chem. 2021;23(11):4034–43.10.1039/D1GC00901JSearch in Google Scholar

[87] Sun Y, Wang J, Qi Y, Li W, Wang C. Efficient electrooxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural using Co-doped Ni3S2 catalyst: Promising for H2 production under industrial-level current density. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2022;9(17):e2200957.10.1002/advs.202200957Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[88] Zheng R, Zhao C, Xiong J, Teng X, Chen W, Hu Z, et al. Construction of a hierarchically structured, NiCo–Cu-based trifunctional electrocatalyst for efficient overall water splitting and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural oxidation. Sustain Energy Fuels. 2021;5(16):4023–31.10.1039/D1SE00697ESearch in Google Scholar

[89] Qi Y-F, Wang K-Y, Sun Y, Wang J, Wang C. Engineering the electronic structure of NiFe layered double hydroxide nanosheet array by implanting cationic vacancies for efficient electrochemical conversion of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2021;10(1):645–54.10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c07482Search in Google Scholar

[90] Gu K, Wang D, Xie C, Wang T, Huang G, Liu Y, et al. Defect-rich high-entropy oxide nanosheets for efficient 5-hydroxymethylfurfural electrooxidation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2021;60(37):20253–8.10.1002/anie.202107390Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[91] Chamberlain TW, Degirmenci V, Walton RI. Oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl furfural to 2,5-furan dicarboxylic acid under mild aqueous conditions catalysed by MIL-100(Fe) metal-organic framework. ChemCatChem. 2022;14(7):e202200135.10.1002/cctc.202200135Search in Google Scholar

[92] Ilic IK, Oschatz M. The functional chameleon of materials chemistry-combining carbon structures into all-carbon hybrid nanomaterials with intrinsic porosity to overcome the “functionality-conductivity-dilemma” in electrochemical energy storage and electrocatalysis. Small. 2021;17(19):e2007508.10.1002/smll.202007508Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[93] Wang J, Kumar P, Zhao H, Kibria MG, Hu J. Polymeric carbon nitride-based photocatalysts for photoreforming of biomass derivatives. Green Chem. 2021;23(19):7435–57.10.1039/D1GC02307ASearch in Google Scholar