Abstract

Buildings in service are severely affected by the complex environment with multiple coupled factors such as high temperatures, humidity, and inorganic salt attack. In this work, the mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites (NSGPC) incorporated with varying dosages of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibers were investigated under a complex environment. A simulated environmental chamber was employed to simulate the complex environment with relative humidity, temperature, and NaCl solution concentration of 100%, 45°C, and 5%, respectively. Fly ash/metakaolin geopolymer composites (GPCs) were fabricated by utilizing 1.5% nano-SiO2 by weight and five various dosages of PVA fibers by volume (0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8%). The compressive strength, tensile strength, elastic modulus, and impact resistance of NSGPC eroded in a simulated environmental chamber for 60 days were determined. Then, the impact of the PVA fiber dosage on the mechanical properties of NSGPC under complex coupled environments was analyzed. In addition, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to evaluate and analyze the microstructural behavior of NSGPC under complex environments. Results indicated that the compressive strength, tensile strength, elastic modulus, and impact resistance of NSGPC increased with increasing PVA fiber to 0.6% and then decreased with a continuous increase to 0.8% but remained higher than those of the reference specimen. NSGPC exhibited the best performance at a PVA fiber dosage of 0.6%, which increased by 13.3, 12.0, 17.2, and 522%, respectively. The outcomes of SEM analysis indicated that the usage of PVA fiber and NS remarkably improved the mechanical properties and microstructural behavior of GPC by making the inner structure of GPCs more robust and compact under a complex environment. The outcomes of this work can provide theoretical guidance for buildings serving under a complex environment.

1 Introduction

As urbanization and industrialization further develop, cement is widely used in the construction field due to its excellent mechanical performance and low price. Nevertheless, during the mass production of cement, large dosages of toxic and harmful greenhouse gases are produced, which has a very serious impact on the ecological environment and human society [1–3]. Recent studies indicate that the annual global consumption of concrete is about 40 billion tons and CO2 emissions are about 10% of the total global CO2 emissions [4–6]. Hence, it is imperative to search for a low-carbon, environmentally friendly, green, and reliable material that can replace ordinary cement for reducing CO2 emissions and global sustainable development in the construction and industrial sectors.

Geopolymer has drawn considerable attention from researchers in recent decades owing to its excellent properties in compression strength and impact resistance [7–10]. It is usually made from industrial by-products rich in silica-aluminates or natural raw materials (i.e., metakaolin [MK], fly ash [FA], blast furnace slag, etc.) activated with alkali solutions (NaOH, Na2CO3, or Na2SiO3, etc.). During the mixing process, the silicon–aluminum bond is broken in the alkaline environment, and then the free silicate ions and [AlO4]4− undergo a condensation reaction to form Si–O–Al bonds, resulting in a stable three-dimensional net-like structure. Many studies have revealed that geopolymers have high early strength, high densification, and excellent erosion resistance [11,12]. However, similar to concrete, geopolymer, as a brittle material, has many disadvantages such as low tensile strength and poor toughness, which limit its application in practical projects with relatively high requirements for strength.

A variety of approaches have been employed to compensate for the lack of performance of the geopolymer composite (GPC). Among them, the utilization of nanoparticles (NPs) to enhance the properties of GPC is one of the most common methods used by researchers. The commonly employed nanomaterials include nano-SiO2 (NS), nano-TiO2, nano-CaCO3, and nano-Al2O3. Many reports have demonstrated that using a certain dosage of NPs instead of raw materials in concrete is convincing for enhancing the performance of the concrete composite [1,13,14,15]. Due to the unique properties of NPs in terms of small size effect, and surface effect, after being incorporated into GPC, NPs can fill in the tiny pores in GPC and improve its internal structure [16]. Also, NPs can be used as reactants to enhance the polymerization reaction and improve the interfacial bonding behavior of cementitious materials and aggregates [17].

Related research results indicate that the addition of fibers can improve the mechanical performance of GPCs, and enhance cracking resistance and toughness of GPCs [18–21]. The fibers commonly blended in the GPC matrix are steel fibers [22–24], polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibers [25,26], basalt fibers [27], polyethylene fibers [28], etc. Among them, the PVA fiber is an excellent choice to strengthen the toughness of GPCs owing to its good hydrophilicity, high toughness, green environment, and excellent acid and alkaline resistance [29–32]. When the PVA fiber is incorporated into the GPC, the uniform distribution of fibers in the matrix can bear part of the external force, effectively reducing the weak areas in the inner structure of the GPC, also limiting its plastic deformation, reducing the number of cracks, and delaying the evolution of cracks [18,33]. Hence, PVA fiber is widely utilized as a reinforcement material in the field of construction for the preparation of PVA fiber-reinforced GPCs. It has been shown that the mechanical properties of GPCs with an appropriate dosage of PVA fibers were remarkably higher than those of the reference specimens without PVA fibers [34].

Greenhouse gas is making the external environment more complex. In such a complex environment, buildings in service, especially those in coastal areas, are most severely affected by multiple coupled factors (i.e., high temperatures, humidity, high salt concentration, etc.). Inorganic ions (e.g., Cl−,

Though there are many studies on the performance of nano-SiO2 or PVA fiber-reinforced GPCs, studies on the use of nano-SiO2 in conjunction with PVA fibers in GPC under complex environments are still inadequate. This work aims to investigate the influence of PVA fiber dosage (by volume) on the mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites (NSGPC) under complex environments. The compressive strength, tensile strength, elastic modulus, and impact resistance of NSGPC specimens after 60 days of erosion in a simulated environmental chamber were studied and analyzed. The microstructural characteristics of NSGPC were evaluated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The outcomes of this work can provide theoretical guidance for buildings serving in complex environments.

2 Experiments

2.1 Materials

The fibers with different properties made of high-quality PVA, shown in Table 1, were used as additives with four varying dosages (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8% by volume) in GPCs. The appearance of PVA fibers is shown in Figure 1.

Properties of PVA fibers

| Length (mm) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Specific gravity (g/cm3) | Elongation at fracture (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 1,400 | 1.32 | 15 |

Appearance of PVA fibers.

In this work, low-calcium FA and MK have been employed as geopolymer precursors. MK is a fine, pink-white, highly reactive mineral admixture with a mean particle size of 1.26 μm. FA is a fine-gray powdery solid ash with a density of approximately 2.16 g/cm3. The chemical composition of the precursor obtained from the X-ray fluorescence analysis is provided in Table 2.

Chemical composition of precursors

| Composition (wt%) | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO + CaO | K2O + Na2O | SO3 | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MK | 54.0 | 43.0 | ≤1.3 | ≤0.8 | ≤0.7 | — | ≥0.2 |

| FA | 60.98 | 24.47 | 6.70 | 5.58 | — | 0.52 | 1.75 |

The alkali activator for preparing GPCs contained Na2SiO3 (light-yellow liquid, about 40% solid, modulus: 3.2) and NaOH (pure white flaky solid, 99% purity). The dosage of NS in GPC is 1.5% by weight, which is due to the best mechanical properties of GPC at this dosage [39]. The performance of NS used in this work is given in Table 3.

Properties of NS

| Content (%) | Specific surface area (m2/g) | Mean particle size (nm) | pH | Bulk density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99.5 | 200 | 30 | 6 | 0.035 |

2.2 Mix proportions and geopolymer synthesis

The proportions of GPCs prepared in this study are shown in Table 4. Five different GPCs were prepared by adding varying dosages of PVA fibers and an equal dosage of NS. The compressive strength, tensile strength, elastic modulus, and impact resistance of each group of GPCs were tested. In this work, the ratio of MK/FA was kept at 1.5, the water/binder ratio was 0.52, the aggregate/binder was considered 3.0, and the modulus of the alkali activator was kept at 1.3 for all samples. All GPCs were made with 1.5% NS (by weight) and PVA fibers (by volume) in dosages of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8%, respectively.

Mix design

| Mix ID | Precursor (kg/m3) | Alkali activator (kg/m3) | Water (kg/m3) | Coarse aggregate (kg/m3) | Fine aggregate (kg/m3) | NS (%) | PVA fibers (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MK | FA | Na2SiO3 | NaOH | ||||||

| C | 273 | 195 | 286 | 53.2 | 79 | 1,072 | 577 | 0 | 0 |

| NP-0.2 | 269 | 192 | 286 | 53.2 | 79 | 1,072 | 577 | 1.5 | 0.2 |

| NP-0.4 | 269 | 192 | 286 | 53.2 | 79 | 1,072 | 577 | 1.5 | 0.4 |

| NP-0.6 | 269 | 192 | 286 | 53.2 | 79 | 1,072 | 577 | 1.5 | 0.6 |

| NP-0.8 | 269 | 192 | 286 | 53.2 | 79 | 1,072 | 577 | 1.5 | 0.8 |

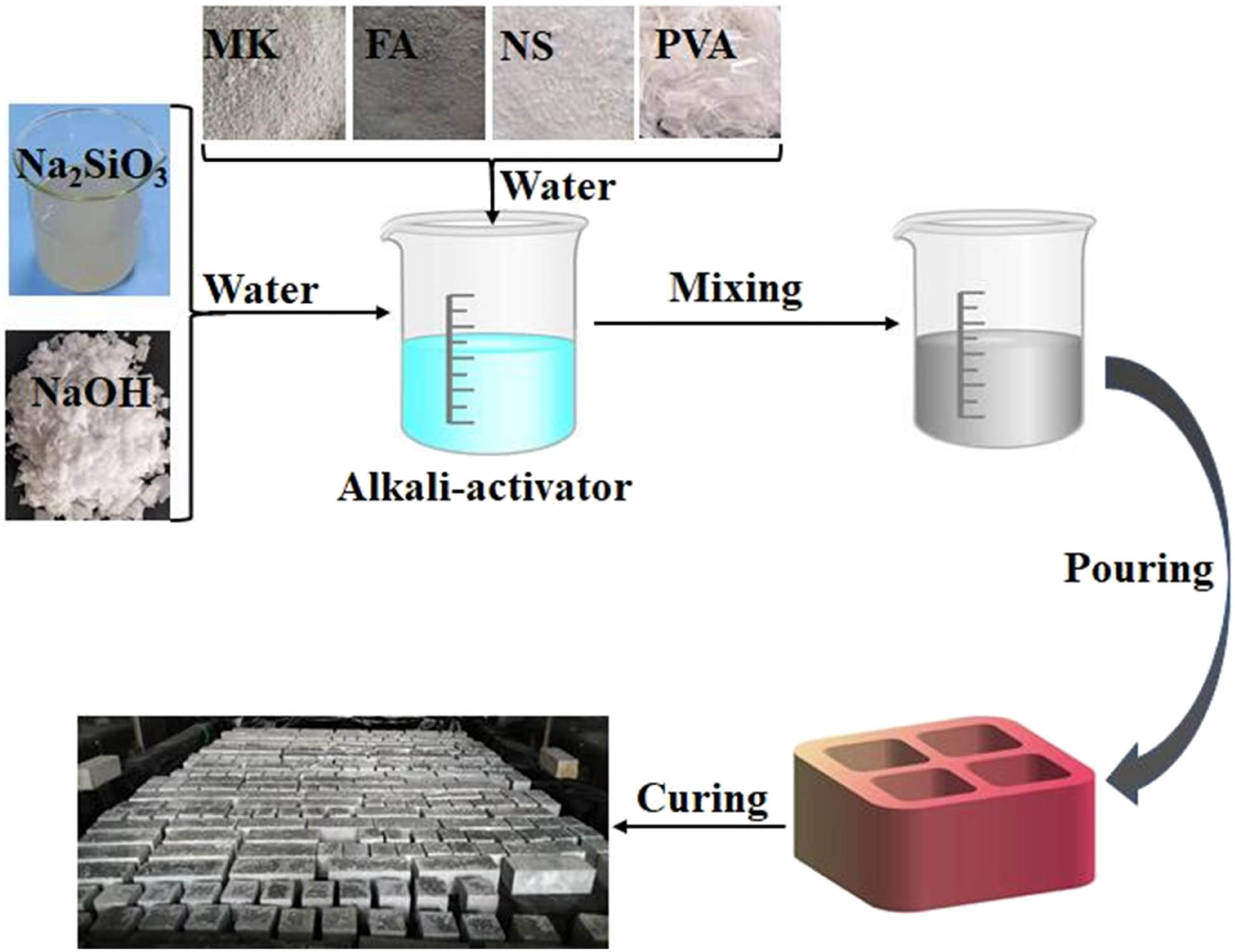

In this study, a 50 L capacity mechanical mixer was employed for mixing in order to obtain a homogeneous and workable paste. First of all, in order to disperse the fibers, PVA fibers were incorporated into the mixtures and stirred for 2 min before the precursor and river sand were added to the alkali-activator solution. Then, the alkali activator, NS, and water were incorporated into the mix and mixed for 1 min, and subsequently, the graded gravel was added to the mixer and mixed for 2 min. Finally, the prepared GPC paste was poured into different kinds of molds to form the desired specimens. Each GPC specimen was maintained for 28 days at room temperature. Subsequently, the fabricated specimens were placed in an environmental simulation oven to perform a series of mechanical tests. Figure 2 provides the flow chart for fabricating the GPC.

Preparation process of NSGPC.

2.3 Environment simulation and test methods

2.3.1 Simulation of the complex environment

With reference to the complex environment of the southeastern coastal region of China, the effects of three coupled factors, namely humidity, temperature, and chloride salt erosion, on NSGPC were studied comprehensively. In this work, a simulated environmental test chamber produced by Shanghai Tong Rui Instrument and Equipment Co., Ltd. was employed to simulate the complex environment. Inside the test chamber, heaters and sprayers were adopted to simulate the changes in temperatures and humidity under external conditions. A reservoir was built in the simulated environmental chamber to store NaCl solution at a concentration of 5% for simulating the effect of chloride salt erosion on the specimens. Figure 3 presents the exterior and inner structure of the test chamber.

Simulated environmental test chamber. (a) Overall apperance and (b) inner layout.

For the complex environment simulation, the relative humidity, temperature, concentration of the salt solution, and duration of the chamber were kept at 100%, 45°C, 5%, and 60 days, respectively. In addition, in order to simulate the complex outdoor environment more imaginatively and objectively, the dry–wet cycle method was employed in this experiment, i.e., each GPC specimen was dried for 3 days and immersed for 3 days in each cycle. Meanwhile, sprayers were employed to spray NaCl solution or water on the specimen to make the humidity and NaCl concentration meet the test requirements.

2.3.2 Compressive and splitting tensile strength test

A total of 15 cube specimens having sizes of 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm were fabricated to perform the compressive strength test of NSGPC according to GB/T50081-2019. A testing machine having a range of 2,000 kN was employed to load the NSGPC specimens at a uniform rate of 0.5 MPa/s until the specimens were damaged. For the objectivity of the results, three specimens were prepared for each proportion, and the mean value of the three NSGPC specimens was set as the compressive strength value of the group for the analysis and discussion of the effect of PVA fiber dosage on compressive strength.

Fifteen cube samples of NSGPC with sizes of 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm were prepared for the tensile strength test. NSGPC specimens were loaded by the test machine at a steady rate of 0.07 MPa/s until the specimens were destroyed. Each ratio consisted of three NSGPC specimens and the mean result was set as the final value for analysis and discussion in this work.

2.3.3 Elastic modulus test

Fifteen prismatic samples of NSGPC with sizes of 300 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm were fabricated to perform the elastic modulus test. The test machine was employed to load and unload the load continuously and uniformly at a rate of 0.5 MPa/s. For each proportion, three specimens were prepared and their mean results were used as the final values. The elastic modulus is obtained by

where

2.3.4 Impact resistance test

Similar to previous tests, a total of 25 cube samples of NSGPC with sizes of 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm were manufactured to perform the impact resistance test. A drop hammer tester with a 4.5 kg impact hammer was applied to determine the impact toughness of the NSGPC specimens. In detail, the number of impacts corresponding to the first crack in the specimen was defined as the number of initial crack impacts (N 1), the number of impacts corresponding to complete damage was defined as the number of damage impacts (N 2), and the impact toughness was the difference between N 2 and N 1. Each proportion consisted of five NSGPC specimens, and the mean findings after removing the maximum and minimum values were set as the standard values to ensure the objectivity of the results.

2.3.5 SEM test

In this work, SEM was employed to characterize the cracking characteristics of NSGPC specimens under complex environments. Before the test, fractured cubic samples with dimensions of 15 mm × 15 mm × 15 mm were placed in a drying oven and dried for 24 h. Subsequently, the NSGPC was sprayed with gold for the microscopic test. The microstructure of the NSGPC specimen was studied by SEM, the micro-morphology was analyzed, and the microform of the NSGPC specimen damage was explored to reveal the mechanism of the influence of the PVA fiber dosage on NSGPC at the microscopic level.

3 Experimental results and discussion

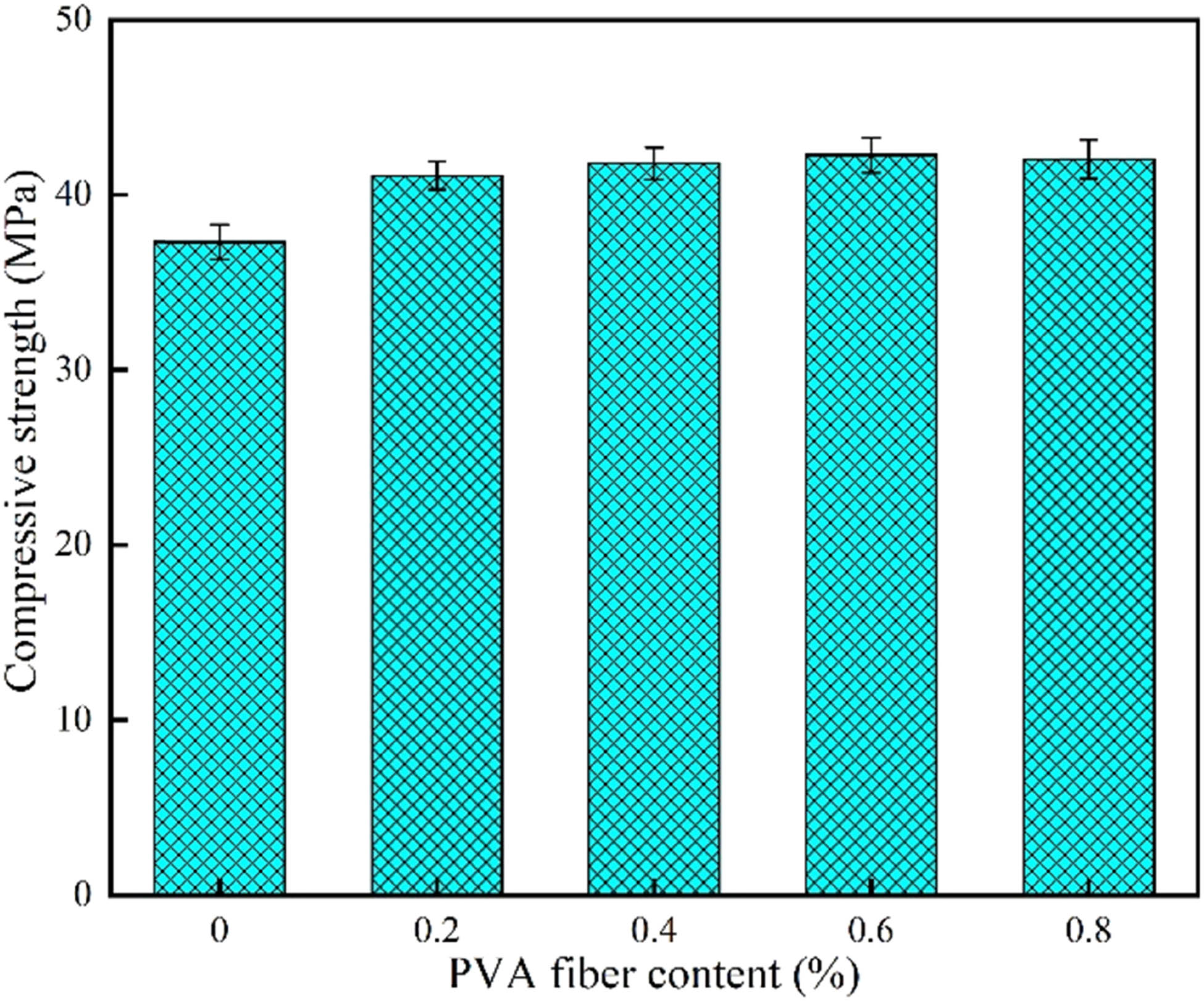

3.1 Compressive strength

The influence of the PVA fiber dosage on the compressive strength of NSGPC under the complex environment is depicted in Figure 4. The compressive strength of the reference GPC specimen under the complex environment is 37.32 MPa. The results indicated that an increase in the PVA fiber dosage to 0.6% led to an increase in the compressive strength of NSGPC, whereas the continuous increase of PVA fiber content to 0.8% caused a decrease in the compressive strength but still greater than the compressive strength of the reference GPC specimens. The compressive strengths of NSGPC specimens dosed with PVA fibers of 0.2% (NSGPC-0.2% PVA), 0.4% (NSGPC-0.4% PVA), and 0.6% (NSGPC-0.6% PVA) by volume enhanced by 10.2, 12.0, and 13.3%, respectively, compared with the reference specimens under the complex environment. Similarly, Yuan et al. [40] revealed that the compressive strength of the geopolymer concrete blended with 50% slag with 0.3% PVA fibers under a complex environment was 14.7% higher than that of the reference specimen. This can be attributed to the fact that the PVA fibers are uniformly dispersed in the NSGPC and inhibit crack initiation and crack propagation by a bridging effect [41,42,43]. Yet, the compressive strength of the specimens was only 12.6% higher than that of the reference NSGPC specimens when the dosage of PVA fibers was 0.8%, but it was still higher than that of the reference specimens under the complex environment. This may be the result of excessive PVA fiber aggregation inside the matrix destroying the dense, strong internal structure of NSGPC.

Effect of the PVA fiber dosage on the compressive strength of NSGPC.

From the findings of a previous study, it was evident that the compressive strength of GPC specimens mixed with NS was all higher than that of GPC specimens without NS [44]. This strongly demonstrates the advantage of incorporating 1.5% NS and varying dosages of PVA fibers in the GPC specimens. The enhancement of the compressive strength of GPC specimens with NS can be attributed to the homogeneous dispersion of NS in the matrix, which participates in the polymerization reaction and produces a large dosage of N–A–S–H gels resulting in a compact internal structure of GPC [39,45]. Therefore, it can be concluded that the addition of an appropriate content of PVA fibers and NS into the matrix can enhance the compressive strength of GPC specimens under a complex environment.

3.2 Splitting tensile strength

The influence of the PVA fiber dosage on the tensile strength of NSGPC specimens with 1.5% NS under the complex environment is shown in Figure 5. The findings indicated that the addition of PVA fibers had a certain degree of impact on the tensile strength of NSGPC under the complex environment. Specifically, the tensile strength of the NSGPC specimens having different contents of PVA fibers was higher than that of the reference specimens, and the NSGPC mixed with 0.6% PVA fibers obtained the highest tensile strength, which was 1.12 times higher than that of reference GPC specimens under the complex environment. Notably, Wang et al. [46] and Wang et al. [47] also discovered that incorporating a certain dosage of fibers in GPCs under complex environments can dramatically improve the tensile strength of NSGPC. Enhancement in tensile strength of NSGPC may be related to the dispersion of PVA fibers in the matrix of the specimen [48,49]. However, when the dosage of PVA fibers was 0.8%, the splitting tensile strength of the specimen was only 9% higher than that of the reference NSGPC specimen, but still higher than that of the reference specimen under the complex environment. This may be due to the excessive aggregation of PVA fibers that damaged the dense and strong internal structure of NSGPC.

Effect of PVA fiber dosage on the tensile strength of NSGPC.

Similar to the enhancement of the compressive strength, the tensile strength of NSGPC containing different dosages of PVA fibers had a similar effect. In a previous study, the maximum tensile strength of the specimen was 1.95 MPa when 0.6% PVA fibers were added to the geopolymer without NS at high temperatures [50]. Similarly, the maximum compressive strength was 3.37 MPa with 0.6% of PVA fibers in this study, which was much greater than the previous results. Interestingly, the use of PVA fibers along with NS was more beneficial in improving the tensile strength of GPC compared to the reference specimen under the complex environment.

3.3 Elastic modulus

The elastic modulus is one of the crucial factors in evaluating the performance of engineering materials. Specifically, from a macroscopic perspective, the elastic modulus is a measurement of the capacity of a mixture to resist deformation, while from a microscopic perspective, it is a response to the strength of the bonds between molecules and atoms within the structure. Hence, it is vital to analyze and discuss the effect of the dosage of PVA fibers on the elastic moduli of NSGPC and its mechanism under the complex environment. Figure 6 exhibits the influence of PVA fiber dosage on the elastic moduli of GPC blended with 1.5% NS under the complex environment. The PVA fiber dosage has a remarkable impact on the modulus of elasticity of NSGPC under a complex environment. In detail, the increase in the PVA fiber dosage to 0.6% resulted in an improvement in the elastic modulus of the GPC specimens, while the continuous increase in the PVA fiber dosage to 0.8% led to a decrease in the elastic modulus but still higher than that of the reference specimens. With a PVA fiber dosage of 0.6%, the maximum elastic modulus of 20.2 GPa was obtained for NSGPC, which was 17.2% higher than that of the reference GPC under the complex environment. Incorporating 1.5% NS along with 0.6% PVA fiber in GPC can substantially improve the deformation resistance of GPC under a complex environment.

Effect of PVA fiber dosage on the elastic modulus of NSGPC.

The enhancement mechanism of the elastic modulus of NSGPC incorporating varied contents of PVA fibers is the same as that of the compressive and tensile strength of NSGPC under a complex environment. When the dosage of PVA fibers in the GPC matrix is less than 0.6%, the PVA fibers can be uniformly dispersed around the interfacial transition zone of NSGPC. Due to the excellent tensile properties of PVA fibers, the ability of GPC to resist deformation can be greatly increased when subjected to external loads. Meanwhile, NS with a mass fraction of 1.5% can be involved in the polymerization reaction to yield considerable N–A–S–H or C–A–S–H, which can improve the microstructure of GPC and play a synergistic effect with PVA fibers [34,51]. Yet, once the dosage of PVA fibers exceeds 0.6%, the excess PVA fibers agglomerate inside the matrix, causing an increasing number of pores in the GPC matrix, which leads to a reduced synergistic effect. However, the negative effect of excess PVA fibers on the elastic moduli of GPCs is weakened due to the presence of NS inside the matrix [52]. This is the reason why the elastic modulus of NSGPC with 0.8% PVA fiber is still higher than that of the reference GPC under the complex environment.

3.4 Impact resistance

Impact toughness refers to the ability of the material to resist plastic deformation and fracture damage under impact loads, which reflects the internal defects and impact resistance of the material to a certain extent. In this work, the difference between the number of damage impacts (N 2) and the number of initial fracture impacts (N 1) was adopted as the index of NSGPC impact toughness. Figure 7 demonstrates the influence of PVA fiber dosage on the impact resistance of NSGPC under a complex environment. The findings revealed that the impact toughness of GPC under the complex environment increased as the PVA fiber dosage increased to 0.6%, and decreased with the continuous increase to 0.8%. That is, NSGPC incorporated with 0.6% PVA fiber exhibited the maximum impact toughness of 18.67 times, which was 6.22 times higher than that of the reference GPC under the complex environment. Similar outcomes for fiber-reinforced impact resistance have also been reported elsewhere [53,54]. In addition, in this work, note that the impact toughness of all NSGPCs with PVA fibers was greater than that of the reference GPC. It can be deduced that incorporating a certain dosage of PVA fibers in NSGPC could effectively enhance the impact resistance of the specimens under the complex environment.

Effect of PVA fiber dosage on the impact resistance of NSGPC.

The enhanced impact toughness of NSGPC with a small dosage of PVA fibers (less than 0.6%) can be ascribed to the association formed between the PVA fiber and the surrounding matrix, leading to an improvement in the ability of the GPC to resist deformation. The bridging effect of PVA fibers improved the structure of the matrix, and limited crack initiation and propagation, which caused an enhancement in the impact toughness of NSGPC under the complex environment. Besides, owing to the excellent properties of NS, NS can effectively fill in the cracks between PVA fibers and the matrix and the micropores inside the matrix, making the structure of GPC much denser and stronger [55,56].

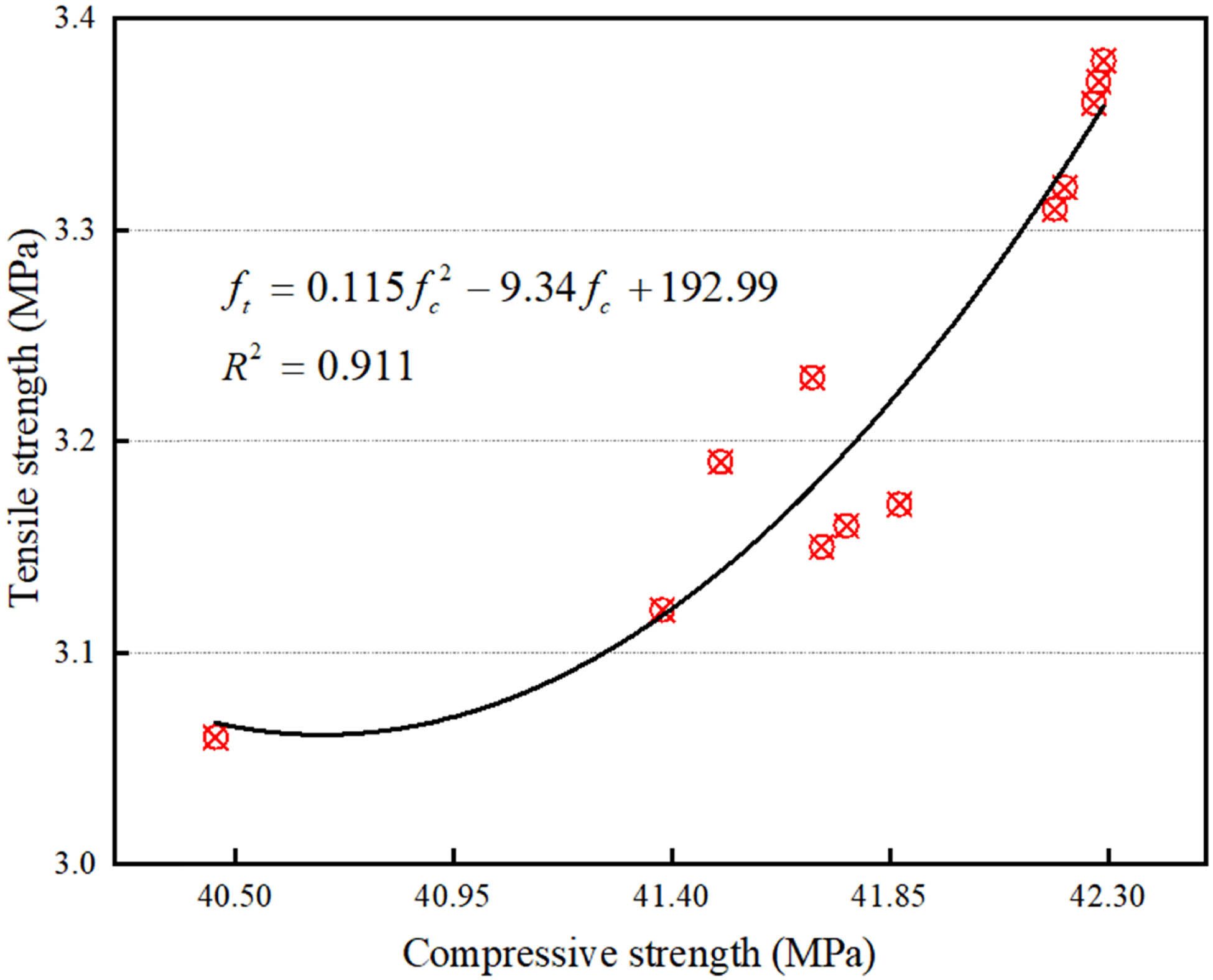

3.5 Relationship between compressive and tensile strength

In previous studies, it was found that there was a correlation between the tensile (f t) and compressive strength (f c) of concrete or geopolymer [57,58]. Various fitting models, e.g. linear function fitting model, quadratic function fitting model, and logarithmic function fitting model, were employed to reveal the relationship between f t and f c based on the experimental findings [58,59,60,61]. In this work, a quadratic function fitting model was employed to characterize the relationship between f t and f c of GPC. The fitted curve of f t versus f c for NSGPC blended with 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8% PVA fibers based on the experimental outcomes is illustrated in Figure 8. Equation (2) exhibits the equation used to fit the f t and f c of NSGPC containing varying dosages of PVA fibers. It can be observed that there is a strong relationship between f t and f c for NSGPC containing various contents of PVA fibers:

where f t represents the tensile strength and f c represents the compressive strength.

Relationship between tensile and compressive strength of NSGPC containing various dosages of PVA fibers.

In the fitting process, the correlation coefficient (R 2) is employed to evaluate the merit of the fitted equation with respect to the experimental outcomes. When R 2 of the fitted equation is around 1, the fitting function is considered reliable. It is acceptable when the R 2 of the fitted function is above 0.9. In this investigation, the R 2 of the GPC fitting equation is 0.911; thus, it can be assumed that the fitting function obtained based on the experimental findings can reflect the relationship between f t and f c of GPC to some extent. The results of this study are similar to those of Sofi et al. [62], where the f t and f c of GPC are enhanced to some extent compared to the strength of the reference specimens. This can be attributed to the involvement of NS in the polymerization reaction in an alkaline environment, which produces a sufficient dosage of gels to form a dense structure and the bridging mechanism of PVA fibers in the interfacial transition zone [63,64].

3.6 Microstructural behavior

The microstructural images of NSGPC blended with varying dosages of PVA fibers under the complex environment are depicted in Figure 9. As shown in the SEM micrographs of GPC, the damage behavior of NSGPC and its strength enhancement mechanism could be clearly understood and analyzed under the complex environment. It can be noted clearly that the microstructure of the reference GPC is remarkably dissimilar to that of the NSGPC with various dosages of PVA fibers. Specifically, in the SEM images of the reference GPC (Figure 9a and b), it is found that the inner structure of the GPC is relatively loose and that numerous cracks and pores appear on the fracture surface, along with a large variety of chloride crystals and corrosion products around the cracks and pores. In contrast, a significant improvement in the internal microstructure of the specimens is observed in NSGPC prepared with 0.6% PVA fibers (Figure 9c and d). In the NSGPC matrix, NS as a filler filled inside the cracks and voids is capable of significantly reducing the porosity of the internal structure and making the structure of the GPC matrix stronger and more compact, thus inhibiting the erosion of the specimens by chlorides as well as various salts [65,66].

SEM image of GPC. (a and b) Reference GPC, (c and d) NSGPC-0.6%PVA.

Similarly, the microstructural images demonstrate that the PVA fibers are capable of binding effectively to the matrix, which may be related to the particular performance of NS (i.e., small size, large specific surface area, and strong adsorption capacity). As found by Zhang et al. [36], the PVA fibers cross over the cracks and prevent the cracks from propagating to the surrounding area. When the applied external load exceeds a certain threshold value, the weak tensile strength of the PVA fiber and the smooth surface properties cause the PVA fibers to be pulled off or pulled out. Moreover, as the dosages of PVA fibers are too high, the agglomeration and interlacing effect of PVA fibers leads to a considerable number of pores and cracks in the inner structure of GPCs, thus reducing the erosion resistance of GPCs. Nevertheless, owing to the presence of NS, the negative effects of excessive PVA fibers can be weakened to some extent [34,67].

3.7 Mechanisms of effects for complex coupled environments

GPC, as a multi-component composite material, has many micro-cracks and pores inside the structure (Figure 9a and b). In a complex environment of humidity, high temperatures, and high salt concentration, inorganic salt ions erode the surface of the specimen by diffusion and osmosis. The water molecules in the humid environment act as a carrier for the diffusion of inorganic salt ions in the matrix. High temperatures can both increase the solubility of inorganic salt ions in water and make inorganic salt ions and water molecules more active. Due to the erosion of inorganic salts, the dissolution of water, and the acceleration of temperature, the existing cracks and pores inside the GPC are further developed, and more new cracks and pores are created [35,38,39,68,69,70]. With the superposition of the coupling effect, the damage to the specimen goes from the surface to the interior.

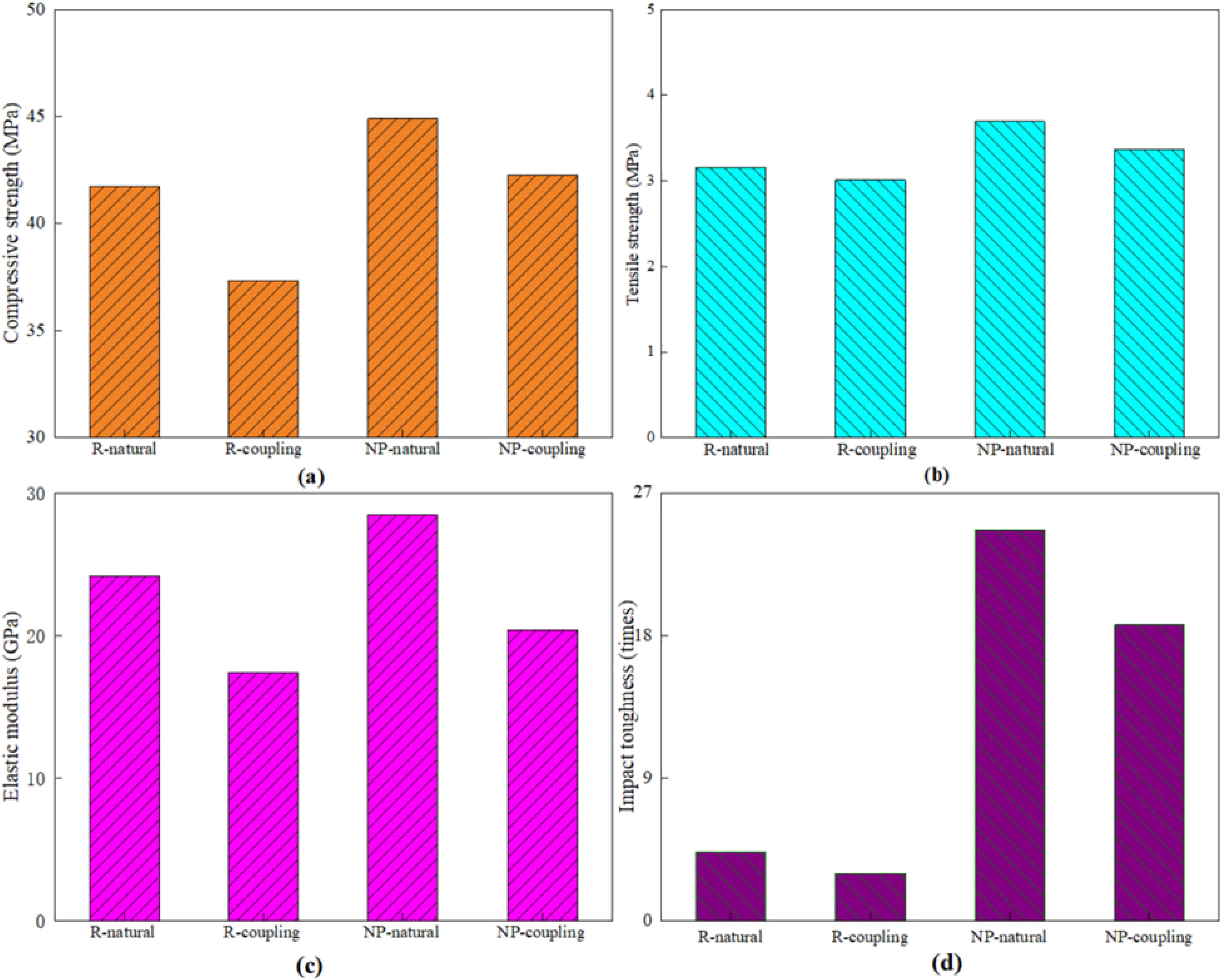

Figure 10(a)–(d) illustrates the appearance of GPC in the natural environment and complex environment, respectively. It can be found that the appearance of the GPC specimens in the complex environment is considerably different from that under the natural environment. Specifically, the surface of GPCs in the natural environment appeared light gray, whereas the surface of the GPC in the complex environment appeared dark gray and was accompanied by visible pores, inorganic salt crystals, and corrosion products. Among them, the area of surface patches of GPC incorporated with NS and PVA fibers in the complex environment was smaller than that of the surface patches of the reference GPC.

Appearance of GPC in the natural environment and complex environment. (a) Control GPC in the natural environment; (b) control GPC in the complex environments; (c) NSGPC-0.6%PVA in the natural environment; and (d) NSGPC-0.6%PVA in the complex environment.

The mechanical behaviors of GPC in natural and complex environments are depicted in Figure 11. In this work, R-natural and R-coupling represent reference GPC specimens under natural and complex environments, respectively; and NP-natural and NP-coupling represent GPC specimens containing 0.6% PVA fiber and 1.5% NS under natural and complex environments, respectively. It can be realized that the mechanical performance of GPC containing PVA fibers and NS is generally higher than the mechanical performance of the corresponding reference specimens, both in natural and complex environments. In addition, it was found that the compressive strength, tensile strength, elastic module, and impact resistance of specimens containing no PVA fiber and NS under complex environments were 10.61, 4.44, 27.98, and 30.72% lower than those of the reference GPC under natural environments, respectively. The compressive strength, tensile strength, elastic module, and impact resistance of specimens containing 0.6% PVA fibers and 1.5% NS in complex environments were 5.81, 8.67, 28.30, and 24.32% lower than those of the corresponding GPC, respectively. This implied that the usage of NS and PVA fiber under a complex environment had an inhibiting impact on the decrease of compressive strength and impact resistance of GPC, while it did not have a remarkable impact on the decrease of tensile strength and elastic module of GPCs. Nevertheless, on the whole, the use of PVA fibers along with NS in GPCs remarkably improved the mechanical performance of GPC under complex environments.

Varying mechanical performances of NSGPC in natural and complex environments. (a) Compressive strength, (b) tensile strength, (c) elastic modulus, and (d) impact toughness.

4 Conclusions and further work

This work focuses on the mechanical properties of NSGPC under complex environments reinforced by various contents of PVA fibers. The main conclusions obtained are the following.

The compressive strength, tensile strength, and elastic modulus of GPCs blended with 1.5% NS (by weight) initially improved and then reduced with the dosage of PVA fibers (by volume) varying from 0.2 to 0.8% but remained higher than those of the reference specimens under the complex environment. NSGPC with 0.6% PVA fiber yielded the maximum compressive and tensile strength, and elastic modulus, which were 13.3, 12.0, and 17.2% higher than those of the reference specimen, respectively.

The impact toughness of NSGPC was first enhanced and then reduced with the PVA fiber dosage in the range of 0.2–0.8% but was still higher than that of the reference specimen under the complex environment. The highest impact resistance was also achieved for NSGPC with 0.6% PVA fiber, which was 6.22 times higher than that of the reference specimen.

The enhancement in strength and erosion resistance of the GPC under the complex environment was due to the PVA fibers incorporated in the NSGPC matrix limiting crack generation and propagation through the bridging effect. PVA fibers could effectively bind to the matrix, owing to the NS improving and providing a stronger and more compact inner structure of the GPC.

Buildings in service are not only subjected to temperatures, humidity, and chloride attack but also subjected to long-term loads and variable loads. Under the complex environment, long-term loads or variable loads cause varying degrees of damage to geopolymer concrete structures. Therefore, it is important to further investigate the long-term performance (such as impermeability, frost resistance, and chloride erosion resistance) of geopolymer concrete under a complex environment.

-

Funding information: The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support received from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52278283, U2040224), Natural Science Foundation of Henan (Grant No. 212300410018), and Project Special Funding of Yellow River Laboratory (Grant No. YRL22LT02).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Alomayri T, Raza A, Shaikh F. Effect of nano SiO2 on mechanical properties of micro-steel fibers reinforced geopolymer composites. Ceram Int. 2021;47(23):33444–53.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.08.251Search in Google Scholar

[2] Han X, Zhang P, Zheng Y, Wang J. Utilization of municipal solid waste incineration fly ash with coal fly ash/metakaolin for geopolymer composites preparation. Constr Build Mater. 2023;403:133060.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133060Search in Google Scholar

[3] Zhang P, Wang C, Wang F, Yuan P. Influence of sodium silicate to precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of the metakaolin/fly ash alkali-activated sustainable mortar using manufactured sand. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2023;62(1):20220310.10.1515/rams-2022-0330Search in Google Scholar

[4] Zhang CY, Han R, Yu BY, Wei YM. Accounting process-related CO2 emissions from global cement production under shared socioeconomic pathways. J Clean Prod. 2018;184:451–65.10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.284Search in Google Scholar

[5] Van Damme H. Concrete material science: Past, present, and future innovations. Cem Concr Res. 2018;112:5–24.10.1016/j.cemconres.2018.05.002Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zhang P, Su J, Guo J, Hu S. Influence of carbon nanotube on properties of concrete: A review. Constr Build Mater. 2023;369:130388.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130388Search in Google Scholar

[7] Tang Z, Li W, Tam VWY, Luo Z. Investigation on dynamic mechanical properties of fly ash/slag-based geopolymeric recycled aggregate concrete. Compos Part B-Eng. 2020;185:107776.10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.107776Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kong DLY, Sanjayan JG. Damage behavior of geopolymer composites exposed to elevated temperatures. Cem Concr Compos. 2008;30(10):986–91.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2008.08.001Search in Google Scholar

[9] Chan CL, Zhang MZ. Behaviour of strain hardening geopolymer composites at elevated temperatures. Cem Concr Compos. 2022;132:104634.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2022.104634Search in Google Scholar

[10] Nis A, Eren NA, Cevik A. Effects of recycled tyre rubber and steel fibre on the impact resistance of slag-based self-compacting alkali-activated concrete. Eur J Environ Civ Eng. 2023;27(1):519–37.10.1080/19648189.2022.2052967Search in Google Scholar

[11] Zhang ZM, Chen R, Hu J, Wang YY, Huang HL, Ma YW, et al. Corrosion behavior of the reinforcement in chloride-contaminated alkali-activated fly ash pore solution. Compos Part B-Eng. 2021;224:109215.10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109215Search in Google Scholar

[12] Behera P, Baheti V, Militky J, Naeem S. Microstructure and mechanical properties of carbon microfiber reinforced geopolymers at elevated temperatures. Constr Build Mater. 2018;160:733–43.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.11.109Search in Google Scholar

[13] Zhang P, Wang MH, Han X, Zheng YX. A review on properties of cement-based composites doped with graphene. J Build Eng. 2023;70:106367.10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106367Search in Google Scholar

[14] Zhang P, Sun YW, Wei JD, Zhang TH. Research progress on properties of cement-based composites incorporating graphene oxide. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2023;62(1):20220329.10.1515/rams-2022-0329Search in Google Scholar

[15] Nis A, Eren NA, Cevik A. Effects of nanosilica and steel fibers on the impact resistance of slag based self-compacting alkali-activated concrete. Ceram Int. 2021;47(17):23905–18.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.05.099Search in Google Scholar

[16] Wang C, Zhang P, Guo JJ, Wang J, Zhang TH. Durability and microstructure of cementitious composites under the complex environment: Synergistic effects of nano-SiO2 and polyvinyl alcohol fiber. Constr Build Mater. 2023;400:132621.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132621Search in Google Scholar

[17] Phoo-ngernkham T, Chindaprasirt P, Sata V, Hanjitsuwan S, Hatanaka S. The effect of adding nano-SiO2 and nano-Al2O3 on properties of high calcium fly ash geopolymer cured at ambient temperature. Mater Des. 2014;55:58–65.10.1016/j.matdes.2013.09.049Search in Google Scholar

[18] Zhang P, Han X, Hu SW, Wang J, Wang TY. High-temperature behavior of polyvinyl alcohol fiber-reinforced metakaolin/fly ash-based geopolymer mortar. Compos Part B-Eng. 2022;244:110171.10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.110171Search in Google Scholar

[19] Tanyildizi H, Yonar Y. Mechanical properties of geopolymer concrete containing polyvinyl alcohol fiber exposed to high temperature. Constr Build Mater. 2016;126:381–7.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.09.001Search in Google Scholar

[20] Shirai K, Horii J, Nakamuta K, Teo W. Experimental investigation on the mechanical and interfacial properties of fiber-reinforced geopolymer layer on the tension zone of normal concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2022;360:129568.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129568Search in Google Scholar

[21] Zhang P, Wei SY, Wu JJ, Zhang Y, Zheng YX. Investigation of mechanical properties of PVA fiber-reinforced cementitious composites under the coupling effect of wet-thermal and chloride salt environment. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2022;17:e01325.10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01325Search in Google Scholar

[22] Zhang P, Wang C, Gao Z, Wang F. A review on fracture properties of steel fiber reinforced concrete. J Build Eng. 2023;67:105975.10.1016/j.jobe.2023.105975Search in Google Scholar

[23] Chen G, Zheng D-P, Chen Y-W, Lin J-X, Lao W-J, Guo Y-C, et al. Development of high performance geopolymer concrete with waste rubber and recycle steel fiber: A study on compressive behavior, carbon emissions and economical performance. Constr Build Mater. 2023;393:131988.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131988Search in Google Scholar

[24] Lin JX, Su JY, Pan HS, Peng YQ, Guo YC, Chen WS, et al. Dynamic compression behavior of ultra-high performance concrete with hybrid polyoxymethylene fiber and steel fiber. J Mater Res Technol-JMRT. 2022;20:4473–86.10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.08.139Search in Google Scholar

[25] Al-Majidi MH, Lampropoulos AP, Cundy AB, Tsioulou OT, Al-Rekabi S. A novel corrosion resistant repair technique for existing reinforced concrete (RC) elements using polyvinyl alcohol fibre reinforced geopolymer concrete (PVAFRGC). Constr Build Mater. 2018;164:603–19.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.213Search in Google Scholar

[26] Lin JX, Song Y, Xie ZH, Guo YC, Yuan B, Zeng JJ, et al. Static and dynamic mechanical behavior of engineered cementitious composites with PP and PVA fibers. J Build Eng. 2020;29:101097.10.1016/j.jobe.2019.101097Search in Google Scholar

[27] Zheng Y, Zhuo J, Zhang P, Ma M. Mechanical properties and meso-microscopic mechanism of basalt fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete. J Clean Prod. 2022;370:133555.10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133555Search in Google Scholar

[28] Peng YQ, Zheng DP, Pan HS, Yang JL, Lin JX, Lai HM, et al. Strain hardening geopolymer composites with hybrid POM and UHMWPE fibers: Analysis of static mechanical properties, economic benefits, and environmental impact. J Build Eng. 2023;76:107315.10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107315Search in Google Scholar

[29] Zhao N, Wang SL, Quan XY, Xu F, Liu KN, Liu Y. Behavior of polyvinyl alcohol fiber reinforced geopolymer composites under the coupled attack of sulfate and freeze-thaw in a marine environment. Ocean Eng. 2021;238:109734.10.1016/j.oceaneng.2021.109734Search in Google Scholar

[30] Si W, Cao ML, Li L. Establishment of fiber factor for rheological and mechanical performance of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fiber reinforced mortar. Constr Build Mater. 2020;265:120347.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120347Search in Google Scholar

[31] Xu F, Deng X, Peng C, Zhu J, Chen JP. Mix design and flexural toughness of PVA fiber reinforced fly ash-geopolymer composites. Constr Build Mater. 2017;150:179–89.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.05.172Search in Google Scholar

[32] Zhang P, Gao Z, Wang J, Guo JJ, Wang TY. Influencing factors analysis and optimized prediction model for rheology and flowability of nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber reinforced alkali-activated composites. J Clean Prod. 2022;366:132988.10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132988Search in Google Scholar

[33] Choi JI, Song KI, Song JK, Lee BY. Composite properties of high-strength polyethylene fiber-reinforced cement and cementless composites. Compos Struct. 2016;138:116–21.10.1016/j.compstruct.2015.11.046Search in Google Scholar

[34] Wang KX, Zhang P, Guo JJ, Gao Z. Single and synergistic enhancement on durability of geopolymer mortar by polyvinyl alcohol fiber and nano-SiO2. J Mater Res Technol-JMRT. 2021;15:1801–14.10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.09.036Search in Google Scholar

[35] Tang LP. Concentration dependence of diffusion and migration of chloride ions - Part 1. Theoretical considerations. Cem Concr Res. 1999;29(9):1463–8.10.1016/S0008-8846(99)00121-0Search in Google Scholar

[36] Zhang P, Yuan P, Guan JF, Guo JJ. Fracture behavior of multi-scale nano-SiO2 and polyvinyl alcohol fiber reinforced cementitious composites under the complex environments. Theor Appl Fract Mech. 2022;122:103584.10.1016/j.tafmec.2022.103584Search in Google Scholar

[37] Yang CC. On the relationship between pore structure and chloride diffusivity from accelerated chloride migration test in cement-based materials. Cem Concr Res. 2006;36(7):1304–11.10.1016/j.cemconres.2006.03.007Search in Google Scholar

[38] Jiang WQ, Shen XH, Xia J, Mao LX, Yang J, Liu QF. A numerical study on chloride diffusion in freeze-thaw affected concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2018;179:553–65.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.05.209Search in Google Scholar

[39] Jin QQ, Zhang P, Wu JJ, Sha DH. Mechanical properties of nano-SiO2 reinforced geopolymer concrete under the coupling effect of a wet-thermal and chloride salt environment. Polymers. 2022;14(11):2298.10.3390/polym14112298Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Yuan Y, Zhao RD, Li R, Wang YB, Cheng ZQ, Li FH, et al. Frost resistance of fiber-reinforced blended slag and Class F fly ash-based geopolymer concrete under the coupling effect of freeze-thaw cycling and axial compressive loading. Constr Build Mater. 2020;250:118831.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118831Search in Google Scholar

[41] Humur G, Cevik A. Effects of hybrid fibers and nanosilica on mechanical and durability properties of lightweight engineered geopolymer composites subjected to cyclic loading and heating-cooling cycles. Constr Build Mater. 2022;326:126846.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126846Search in Google Scholar

[42] Zhong H, Zhang MZ. Dynamic splitting tensile behaviour of engineered geopolymer composites with hybrid polyvinyl alcohol and recycled tyre polymer fibres. J Clean Prod. 2022;379:134779.10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134779Search in Google Scholar

[43] Noushini A, Samali B, Vessalas K. Effect of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibre on dynamic and material properties of fibre reinforced concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2013;49:374–83.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.08.035Search in Google Scholar

[44] Cheng ZJ, Lu YY, An JP, Zhang HJ, Li S. Multi-scale reinforcement of multi-walled carbon nanotubes/polyvinyl alcohol fibers on lightweight engineered geopolymer composites. J Build Eng. 2022;57:104889.10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104889Search in Google Scholar

[45] Xu H, Van Deventer JSJ. The geopolymerisation of alumino-silicate minerals. Int J Miner Process. 2000;59(3):247–66.10.1016/S0301-7516(99)00074-5Search in Google Scholar

[46] Wang Y, Zhang SH, Niu DT, Fu Q. Quantitative evaluation of the characteristics of air voids and their relationship with the permeability and salt freeze-thaw resistance of hybrid steel-polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete composites. Cem Concr Compos. 2022;125:104292.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2021.104292Search in Google Scholar

[47] Wang L, He TS, Zhou YX, Tang SW, Tan JJ, Liu ZT, et al. The influence of fiber type and length on the cracking resistance, durability and pore structure of face slab concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2021;282:122706.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122706Search in Google Scholar

[48] Xu SL, Malik MA, Qi Z, Huang BT, Li QH, Sarkar M. Influence of the PVA fibers and SiO2 NPs on the structural properties of fly ash based sustainable geopolymer. Constr Build Mater. 2018;164:238–45.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.227Search in Google Scholar

[49] Zhang P, Wei SY, Zheng YX, Wang F, Hu SW. Effect of single and synergistic reinforcement of PVA fiber and nano-SiO2 on workability and compressive strength of geopolymer composites. Polymers. 2022;14(18):3765.10.3390/polym14183765Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Deng ZM, Yang ZF, Bian J, Lin JJ, Long ZS, Hong GZ, et al. Advantages and disadvantages of PVA-fibre-reinforced slag- and fly ash-blended geopolymer composites: Engineering properties and microstructure. Constr Build Mater. 2022;349:128690.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128690Search in Google Scholar

[51] Gulsan ME, Alzeebaree R, Rasheed AA, Nis A, Kurtoglu AE. Development of fly ash/slag based self-compacting geopolymer concrete using nano-silica and steel fiber. Constr Build Mater. 2019;211:271–83.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.228Search in Google Scholar

[52] Zhang P, Wang KX, Wang J, Guo JJ, Ling YF. Macroscopic and microscopic analyses on mechanical performance of metakaolin/fly ash based geopolymer mortar. J Clean Prod. 2021;294:126193.10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126193Search in Google Scholar

[53] Xiao SH, Liao SJ, Zhong GQ, Guo YC, Lin JX, Xie ZH, et al. Dynamic properties of PVA short fiber reinforced low-calcium fly ash-slag geopolymer under an SHPB impact load. J Build Eng. 2021;44:103220.10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103220Search in Google Scholar

[54] Li WM, Xu JY. Impact characterization of basalt fiber reinforced geopolymeric concrete using a 100-mm-diameter split Hopkinson pressure bar. Mater Sci Eng A-Struct Mater Prop Microstruct Process. 2009;513–514:145–53.10.1016/j.msea.2009.02.033Search in Google Scholar

[55] Li WG, Long C, Tam VWY, Poon CS, Duan WH. Effects of nano-particles on failure process and microstructural properties of recycled aggregate concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2017;142:42–50.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.03.051Search in Google Scholar

[56] Shaikh FUA, Shafaei Y, Sarker PK. Effect of nano and micro-silica on bond behaviour of steel and polypropylene fibres in high volume fly ash mortar. Constr Build Mater. 2016;115:690–8.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.04.090Search in Google Scholar

[57] Ryu GS, Lee YB, Koh KT, Chung YS. The mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete with alkaline activators. Constr Build Mater. 2013;47:409–18.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.05.069Search in Google Scholar

[58] Choi Y, Yuan RL. Experimental relationship between splitting tensile strength and compressive strength of GFRC and PFRC. Cem Concr Res. 2005;35(8):1587–91.10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.09.010Search in Google Scholar

[59] Zhao SB, Ding XX, Zhao MS, Li CY, Pei SW. Experimental study on tensile strength development of concrete with manufactured sand. Constr Build Mater. 2017;138:247–53.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.01.093Search in Google Scholar

[60] Yildirim H, Ozturan T. Impact resistance of concrete produced with plain and reinforced cold-bonded fly ash aggregates. J Build Eng. 2021;42:102875.10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102875Search in Google Scholar

[61] Gesoglu M, Guneyisi E, Alzeebaree R, Mermerdas K. Effect of silica fume and steel fiber on the mechanical properties of the concretes produced with cold bonded fly ash aggregates. Constr Build Mater. 2013;40:982–90.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.11.074Search in Google Scholar

[62] Sofi M, van Deventer JSJ, Mendis PA, Lukey GC. Engineering properties of inorganic polymer concretes (IPCs). Cem Concr Res. 2007;37(2):251–7.10.1016/j.cemconres.2006.10.008Search in Google Scholar

[63] Zanotti C, Borges PHR, Bhutta A, Banthia N. Bond strength between concrete substrate and metakaolin geopolymer repair mortar: Effect of curing regime and PVA fiber reinforcement. Cem Concr Compos. 2017;80:307–16.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2016.12.014Search in Google Scholar

[64] Ibrahim M, Johari MAM, Maslehuddin M, Rahman MK. Influence of nano-SiO2 on the strength and microstructure of natural pozzolan based alkali activated concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2018;173:573–85.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.04.051Search in Google Scholar

[65] Yin SP, Jing L, Yin MT, Wang B. Mechanical properties of textile reinforced concrete under chloride wet-dry and freeze-thaw cycle environments. Cem Concr Compos. 2019;96:118–27.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2018.11.020Search in Google Scholar

[66] Yip CK, Lukey GC, Provis JL, van Deventer JSJ. Effect of calcium silicate sources on geopolymerisation. Cem Concr Res. 2008;38(4):554–64.10.1016/j.cemconres.2007.11.001Search in Google Scholar

[67] Escalante-Garcia JI, Sharp JH. The chemical composition and microstructure of hydration products in blended cements. Cem Concr Compos. 2004;26(8):967–76.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2004.02.036Search in Google Scholar

[68] Ozyurt N, Soylev TA, Ozturan T, Pehlivan AO, Nis A. Corrosion and chloride diffusivity of reinforced concrete cracked under sustained flexure. Tek Dergi. 2020;31(6):10315–37.10.18400/tekderg.430536Search in Google Scholar

[69] Niş A, Çevik A. 18-Seawater resistance of alkali-activated concrete. In: Pacheco-Torgal F, Chindaprasirt P, Ozbakkaloglu T, editors. Handbook of advances in alkali-activated concrete. Sawston, United Kingdom: Woodhead Publishing; 2022. p. 451–69.10.1016/B978-0-323-85469-6.00005-2Search in Google Scholar

[70] Kurtoglu AE, Alzeebaree R, Aljumaili O, Nis A, Gulsan ME, Humur G, et al. Mechanical and durability properties of fly ash and slag based geopolymer concrete. Adv Concr Constr. 2018;6(4):345–62.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery

- The progress of cathode materials in aqueous zinc-ion batteries

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part I

- Effect of polypropylene fiber and nano-silica on the compressive strength and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete

- Mechanochemical design of nanomaterials for catalytic applications with a benign-by-design focus

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells