Abstract

Energy poverty is a global challenge that demands sustainable and affordable solutions. This study investigates the use of commercial graphene nanofibers (GNFs) as a reinforcing agent in gypsum composites for energy-efficient building retrofitting. The GNFs were manually dispersed in the gypsum matrix, and the composites were fabricated by casting and curing. The thermomechanical properties were systematically studied using various characterization techniques, including scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, and thermal analysis. The results show that the addition of 1% GNFs reduces the thermal conductivity of the composites by more than 40% and improves their flexural and compressive strength by up to 23 and 42%, respectively, compared to neat gypsum. The enhancements are attributed to the effective phonon scattering of the GNFs and their ability to act as crystal seeding sites, resulting in a denser and more homogeneous structure. The dynamic thermal analysis further demonstrates that the GNF-reinforced composites could reduce heating and cooling requirements by 14 and 11%, respectively, indicating their potential for energy-efficient building retrofitting. However, the cost effectiveness and safety issues of the GNF-reinforced composites should be carefully considered before their large-scale implementation. Achieving uniform dispersion of nanoparticles in high concentrations is also a significant challenge that will be addressed in future studies.

1 Introduction

The construction industry is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption, which is especially concerning in developed countries, where it accounts for 40% of energy consumption and emissions. This contributes to energy poverty and environmental degradation. As a result, sustainable practices are becoming increasingly important in the industry. Gypsum-based materials (CaSO4·2H2O) have emerged as a promising solution due to their abundant availability, eco-friendly properties, and affordability. However, the durability and resistance of gypsum-based materials are critical features that affect their lifespan and performance [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8].

In recent years, many studies have aimed to develop gypsum-based composites with lower environmental impacts and improved thermal and acoustic properties. However, these developments have come at the cost of reduced mechanical properties, as observed by researchers, and documented in Table 1. Various additives, such as expanded polystyrene (EPS) [9], polypropylene fibers (PP) [10], polyamide fibers (PA) [11], textile fibers [12], cellulose fibers [13], chicken feathers [14], copper slags [15], graphite [16], and even rubber particles [17], have been explored to enhance the physical and mechanical attributes of these composites. Nonetheless, it has been observed that these additives can adversely affect the bonding between the gypsum matrix and the additives, particularly at higher concentrations. As a result, the most promising outcomes have been achieved at low additive concentrations (less than 10%) and by employing a w/g ratio of 0.65–0.75.

Summary of properties of gypsum-based composites obtained from the literature

| Author | Year | Additive | % | w/g | Density (kg/m3) | Flexural strength (Mpa) | Compressive strength (Mpa) | λ (W/mK) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bouzit et al. [9] | 2021 | EPS | 10 | 0.80 | * | 3.4 | 1 | 0.191 |

| Eve et al. [11] | 2002 | PA fiber | 5 | 0.68 | * | 2 | 6 | * |

| Vasconcelos et al. [12] | 2015 | Cork/textiles | 7/3 | 0.88 | 714 | * | 2.13 | * |

| Serna et al. [17] | 2012 | Rubber particles | 5 | 0.70 | * | 3.26 | 5.54 | * |

| Barbero-Barrera et al. [16] | 2017 | Graphite | 15 | 0.74 | 1,190 | * | 4.8 | 0.600 |

| Flores Medina and Barbero-Barrera [10] | 2017 | PP fibers | 0.6 | 0.60 | 940 | 0.50 | 0.98 | 0.167 |

| Hagiri and Honda [15] | 2021 | Copper slag | 20 | 0.67 | 1,010 | 2.57 | * | * |

| Ouakarrouch et al. [14] | 2020 | Chicken feathers | 5 | 0.60 | 1048.9 | * | * | 0.309 |

| Senff et al. [13] | 2018 | Cellulose/n-TiO2 | 2/1 | 0.37 | * | 0.48 | * | 0.770 |

| Gordina et al. [18] | 2013 | CNT | 0.001 | 0.60 | * | 4 | 15 | * |

*Not provided.

While the use of wastes and other additives has shown promise in improving the physical and thermal properties of gypsum-based composites, there is still room for improvement. Carbon nanomaterials (NMT) such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene have garnered attention in the building industry for their ability to provide new applications and improve the overall quality and characteristics of common materials [18,19,20,21,22].

Given their small size, these materials exhibit increased reactivity, greater surface area, and distinct characteristics compared to materials at a larger scale. Previous studies have observed that CNTs can increase crystallization centers in a gypsum matrix, contributing to a denser matrix and improved electronics properties, which could be beneficial in terms of electromagnetic shielding or sensing. However, exceeding the optimal value resulted in a decrease in mechanical properties due to the formation of a structure with higher porosity [23,24,25,26,27].

As such, the implementation of nanomaterials (NMTs) in construction presents several challenges including issues with availability, consistency, quality, market trends, dispersion issues, and cost. The use of NMTs in large quantities also raises concerns about potential health and environmental risks, limiting their widespread implementation in the industry. To overcome these challenges, researchers suggest using low concentrations, ranging from 0.001 to 1%. This approach helps to prevent negative impacts on the properties, cost, and recyclability of the composite [1,18,19,20,21,22].

To date, there is limited research on the use of graphene nanofibers (GNFs) in gypsum composites, and their impact on the properties of these materials. GNFs are a promising candidate due to their high aspect ratio, large surface area, and excellent mechanical, thermal, and electronic properties. GNFs have already been shown to improve the strength and durability of isotactic polypropylene (iPP), offering potential applications in various fields such as electronics, energy, and biomedicine [18,27,28].

The present study developed an eco-friendly and safe gypsum composite that incorporated GNFs to improve their mechanical and thermal properties while examining the potential risks and costs associated with their use. The incorporation of GNFs in gypsum composites could lead to the development of tailored building materials and retrofits that meet market requirements, such as controlled porosity, high or low thermal conductivity, electromagnetic shielding, carbon capture, and building monitoring. The physical and mechanical properties of the composites were evaluated, including their strength, hardness, thermal conductivity, water absorption, porosity, and their thermal values were used to assess their performance in a typical southern Spanish dwelling. Furthermore, this study also examined the dispersion issues and potential risks associated with low concentrations of GNFs in order to ensure their proper implementation in the construction industry. These results could provide a better understanding of how GNFs affect the properties of gypsum composites and contribute to existing knowledge in this area.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The present work designed a gypsum composite using GNFs as a reinforcing agent. Commercial building gypsum type B1-YG/L from PLACO-Saint Gobain was used as a matrix, while the GNFs-LS class was supplied by the company Graphenano, located in Murcia, Spain. Technical specifications of both raw materials are shown in Table 2.

Technical specifications of building gypsum type B1-YG/L and GNFs

| Material | Density (g/cm3) | Melting point (°C) | Particle size | Electrical resistivity (Ωm) | λ (W/mK) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building gypsum B1 YG/L | 2.3 | 100–150 | ≤1 mm | 3.4 × 104 | 0.34 |

| GNFs-LS | 0.2–0.3 | 3650 -3,700 | ≥20 nm | 4.6 × 10−6 | 1,400–1,600 |

2.2 Experimental procedure

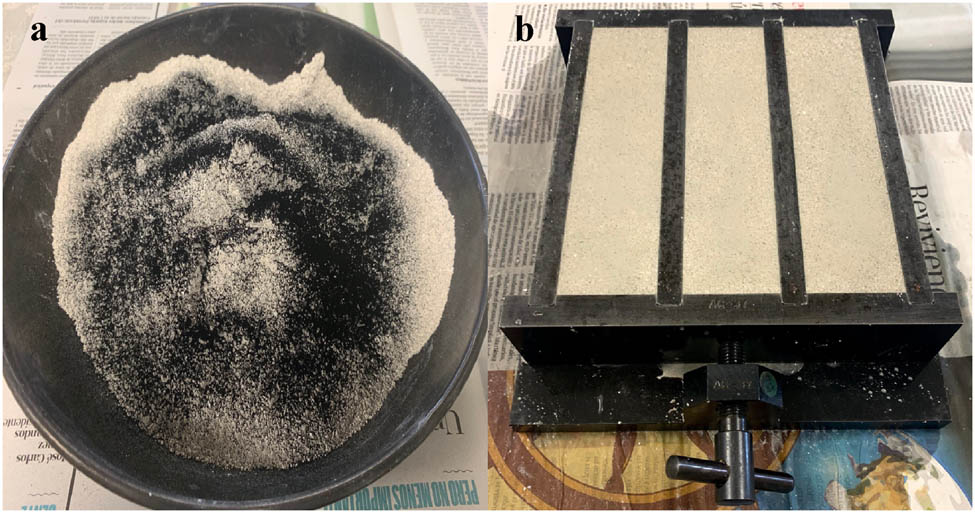

Composites were elaborated by manually mixing up to 1% of GNFs with dry-building gypsum until a well-dispersed distribution was achieved. GNFs were handled at all times with the proper individual protection equipment, including safety glasses, facemasks, and gloves. All samples presented a w/g of 0.75, determined in accordance with European regulation EN 13279 [29,30]. Water was added to the dry mixture, and the resulting slurry was then casted in 40 × 40 × 160 mm3 molds, as seen in Figure 1. After 1 h, the samples were removed from the molds and were kept at room conditions for 7 days before testing. The composition of each sample is listed in Table 3.

Dry mixture of gypsum and GNFs (a) and mold containing casted slurry (b).

Designation and detailed composition of each mixture

| Sample | GNFs (%) | Gypsum (g) | Water (g) | GNFs (g) | w/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref | 0 | 800 | 600 | 0 | 0.75 |

| LS-0.25 | 0.25 | 800 | 600 | 2 | 0.75 |

| LS-0.50 | 0.50 | 800 | 600 | 4 | 0.75 |

| LS-0.75 | 0.75 | 800 | 600 | 6 | 0.75 |

| LS-1.00 | 1.00 | 800 | 600 | 8 | 0.75 |

2.3 Physical and mechanical properties

The bulk density and the void content (V c) were determined through the Archimedes method. The immersion absorption coefficient (W Abs) was also measured at 24 h, following the indications of the EN 13279-2:2014 standard [50]. V c and W Abs were determined using equations (1) and (2), respectively,

where w s represents the saturated weight after 24 h of immersion, w sub is the submerged weight, and w d is the dry weight of the samples after retrieving them from the stove. Crystal size, morphology, and structure of the composites were also studied by means of scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Energy dispersive spectrometry (EDS) was used to examine the local elemental composition while observing the samples. Crystalline phases present in the composites were determined by means of X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Bruker D8 ADVANCE diffractometer.

The values of hardness index at the Shore C scale, flexural and compressive strength were obtained in accordance with the EN 13279-2:2014 standard [30]. Values for superficial hardness were obtained after taking a total of 18 measurements, 6 for each smooth side of the sample. Flexural and compressive strength were measured using a universal testing machine IBERTEST MIB60-AM with a preload of 0.5 kN and a loading rate of 10 mm/min, as shown in Figure 2. For each designation, three identical samples were tested, and the average value was reported.

Flexural test (a) and insulating cube employed to measure thermal properties (b).

Thermal conductivity testing was performed at the physics laboratory located in the school of building engineering of the Technical University of Madrid. Thermal properties were measured using a 400 × 400 × 400 mm3 insulating cube used in other studies [10,31,32]. Samples were fixed in the 21 × 21 cm2 openings located on each wall; afterwards, they were sealed from external conditions by adding a 3 cm EPS board. The stationary state was reached 5 h after placing the samples in the cube. Thermocouples recorded the temperature in a 30 min span, and the thermal conductivity was determined using Fourier’s law.

2.4 Dynamic thermal simulation

This section presents the simulation of environmental and energy-saving characteristics when gypsum plasterboards with and without GNFs are implemented as retrofit components in a poorly insulated dwelling. The simulations took place using the Energy plus module within the Design Builder software. Yearly consumption values (kWh), utility use per total area (kWh/m2), and CO2 emissions (kg) were obtained for all envelope arrangements.

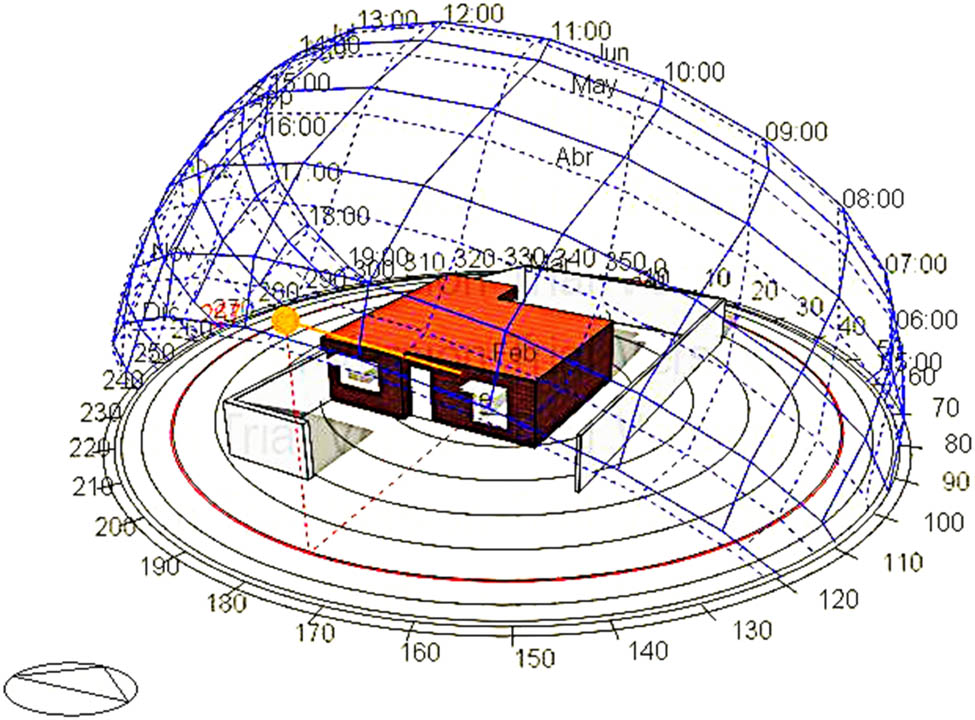

The building studied is a typical Spanish dwelling in the city of Almería, situated in southern Spain, 21 m above sea level in the Mediterranean basin. Almería is known for its year-round dry environment with very warm winters and low precipitation. A model of the building consisting of one floor and a total area of 72 m2 is shown in Figure 3. Parameter settings and building components are listed in Tables 4–7. For this home, a yearly heating and cooling schedule was selected. The system was activated when the indoor temperature fell below 18°C during winter and exceeded 25°C during the summer.

Simulated building model, solar trajectory, and shades.

Parameter settings for the studied dwelling

| Location | Almería, Spain |

|---|---|

| Total area (m2) | 72 |

| Occupancy (Hab/m2) | 0.0277 |

| Window type | Preferred height, 30% glazed |

| Shading | Blinds w/high reflectivity |

| Local shading | 1 m Overhang |

| Humidity control | Dehumidification |

| Lighting type | Suspended |

| Power density (W/m2) | 5.0 |

Original building components and thermal properties of the simulated building model

| Component | Material | Thickness (m) | λ (W/mK) |

|---|---|---|---|

| External wall | Outer bricks | 0.100 | 0.840 |

| Hollow concrete bricks | 0.200 | 0.480 | |

| Gypsum plasterboard | 0.030 | 0.341 | |

| Roof | Roofing tiles | 0.016 | 0.840 |

| Asphalt | 0.010 | 0.300 | |

| Concrete roofing slab | 0.145 | 0.160 | |

| Gypsum plasterboard | 0.025 | 0.341 | |

| Partitions | Gypsum plasterboard | 0.025 | 0.341 |

| Hollow concrete bricks | 0.080 | 0.480 | |

| Gypsum plasterboard | 0.025 | 0.341 | |

| Inner floor | Timber flooring | 0.015 | 0.140 |

| Gypsum plasterboard | 0.025 | 0.341 | |

| Concrete slab | 0.250 | 0.380 |

Building components including 1% gypsum-GNFs composites as insulating surfaces

| Component | Material | Thickness (m) | λ (W/mK) |

|---|---|---|---|

| External wall | Outer bricks | 0.100 | 0.840 |

| Hollow concrete bricks | 0.200 | 0.480 | |

| Gypsum-GNF 1% | 0.030 | 0.199 | |

| Roof | Roofing tiles | 0.016 | 0.840 |

| Asphalt | 0.010 | 0.300 | |

| Concrete roofing slab | 0.145 | 0.160 | |

| Gypsum-GNF 1% | 0.025 | 0.199 | |

| Partitions | Gypsum-GNF 1% | 0.025 | 0.199 |

| Hollow concrete bricks | 0.080 | 0.480 | |

| Gypsum-GNF 1% | 0.025 | 0.199 | |

| Inner Floor | Timber flooring | 0.015 | 0.140 |

| Gypsum-GNF 1% | 0.025 | 0.199 | |

| Concrete slab | 0.250 | 0.380 |

Building components including the benefits of both 0.50 and 1% gypsum-GNFs composites

| Component | Material | Thickness (m) | λ (W/mK) |

|---|---|---|---|

| External wall | Outer bricks | 0.100 | 0.840 |

| Hollow concrete bricks | 0.200 | 0.480 | |

| Gypsum-GNFs 1% | 0.030 | 0.199 | |

| Roof | Roofing tiles | 0.016 | 0.840 |

| Asphalt | 0.010 | 0.300 | |

| Concrete roofing slab | 0.145 | 0.160 | |

| Gypsum-GNFs 1% | 0.025 | 0.199 | |

| Partitions | Gypsum GNFs 1% | 0.025 | 0.199 |

| Hollow concrete bricks | 0.080 | 0.480 | |

| Gypsum GNFs 1% | 0.025 | 0.199 | |

| Inner floor | Timber flooring | 0.015 | 0.140 |

| Gypsum-GNFs 0.5% | 0.025 | 0.574 | |

| Concrete slab | 0.250 | 0.380 |

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Physical and mechanical properties

The workability and initial setting times of the samples were not affected by adding GNFs and remained above 50 min. There were no issues with sedimentation or dispersion during the entire process, and no signs of detachment or loss of material were detected when handling the samples. However, the color of the composite turned gray as the concentration of GNFs in the mixture increased. Nevertheless, since GNF content was low, it is not expected to have a negative impact on the recyclability of common gypsum since GNFs are unaffected by thermal treatments. The hemihydrate powder containing GNFs can then be reconstituted into Gypsum-GNF composites by adding water to the mixture and casting the slurry into molds.

In Table 8, the results for bulk density, void content, and water absorption are given. It can be seen that the bulk density increases with GNF concentration up to 6%, obtaining values within the range of common gypsum-based products, usually oscillating between 700 and 1,100 kg/m3 [33].

Physical and thermomechanical properties of different gypsum samples

| Sample | Bulk density (kg/m3) | V c (%) | W Abs (%) | Shore C hardness index | Flexural strength (MPa) | Compressive strength (MPa) | λ (W/mK) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref | 1,031 | 40.6 | 39.4 | 65 ± 4 | 2.30 ± 0.07 | 4.06 ± 0.01 | 0.341 |

| LS-0.25 | 1,063 | 39.4 | 37.0 | 66 ± 5 | 2.37 ± 0.09 | 4.56 ± 0.05 | 0.372 |

| LS-0.50 | 1,095 | 38.5 | 35.1 | 70 ± 3 | 2.61 ± 0.03 | 5.20 ± 0.01 | 0.574 |

| LS-0.75 | 1,094 | 38.7 | 35.4 | 73 ± 5 | 2.71 ± 0.02 | 5.37 ± 0.01 | 0.327 |

| LS-1.00 | 1,092 | 39.0 | 35.7 | 75 ± 5 | 2.82 ± 0.03 | 5.77 ± 0.03 | 0.199 |

The void content decreased by approximately 2% in samples that contained GNFs. The highest void content was observed in the reference sample, whereas the lowest belonged to the composite containing 0.50% GNFs. A slight reduction in void content was expected since GNFs can fill the microstructure to some extent. These voids are the result of entrapped gas molecules that continuously forms bubbles and will only be ejected from the mixture by periodic and gentle agitation of the molds or if the size and growth kinetics of the bubbles allows them to reach the liquid–air interface before setting takes place [34].

Water absorption by immersion was also reduced by introducing carbon NMT in the mixture, reaching values, on average, 4% lower than those obtained by the reference sample. This reduction is a direct consequence of the concurrent filling and densifying effects of GNFs when introduced to the calcium sulfate matrix. This type of behavior has also been observed with different additives and other binders, as the introduction of well-dispersed additives can refine the bulk density, durability, and pore structure in traditional materials providing additional features in the process. However, higher concentrations are known to cause agglomerations, poor bonding, and workability due to their uneven distribution within the mixture [7,10,16,18,35,36,37].

Building materials play a vital role in this modern era; although usually considered for construction works, most applications will require these materials to function properly. In addition, their capacity, quality, and implementation are generally dictated by their own properties. Surface hardness, flexural, and compressive strength are among the most important attributes in building materials, and the values for these features are also expressed in Table 8.

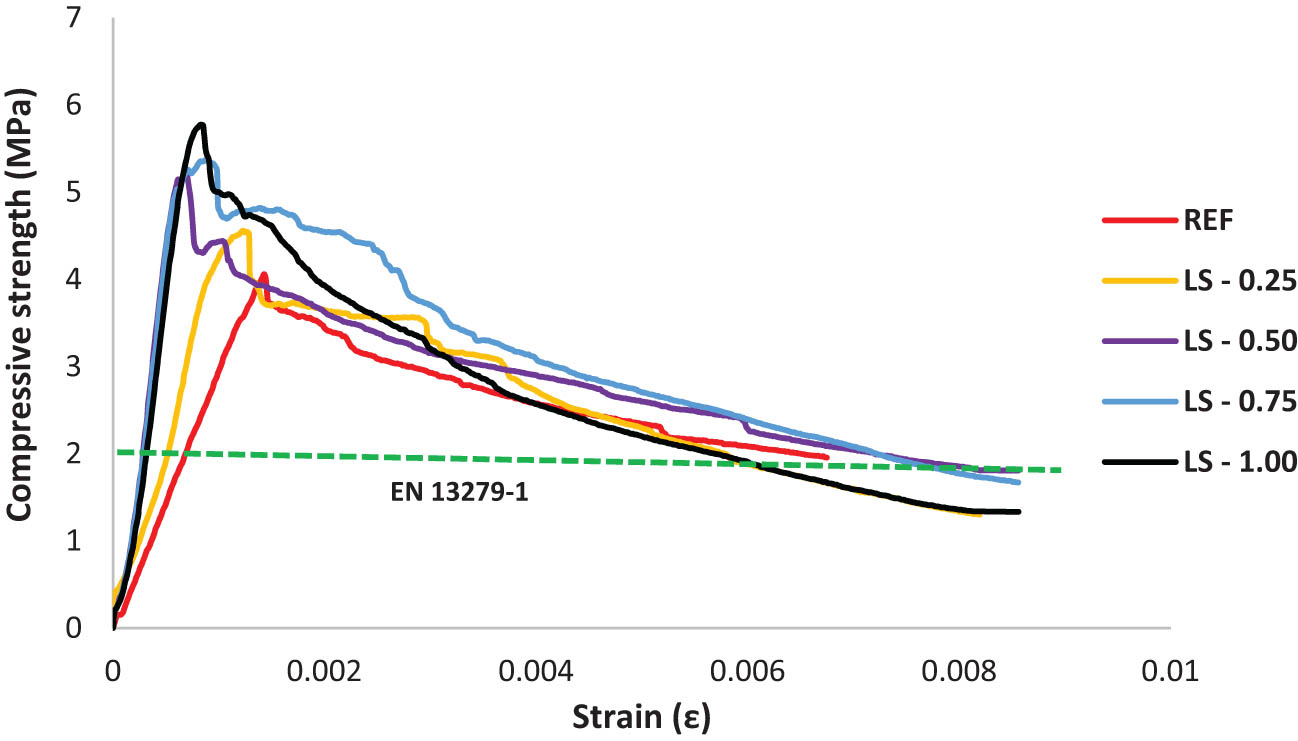

Neat gypsum reached values for flexural and compressive strength of 2.30 and 4.06 MPa, respectively. While all composite samples presented a steady increase in GNF content in both flexural and compressive strength, as expressed in Figures 4 and 5. Samples containing 1% of GNF’s achieved the highest values for flexural and compressive strength with increments of 23 and 42%, in comparison to common gypsum. As a result, these composites are lighter and required less amounts of additive to achieve greater values for compressive strength when compared to gypsum samples containing isostatic graphite [16].

Stress–strain curves of all studied samples.

Compressive strength in the function of GNF content in the mixture.

Strength in gypsum products stems from several reasons, such as binder and additive quality, w/g ratio, curing conditions, and porosity. That said, it is worth noting that all studied properties were in total compliance with the requirements, as well as the criteria, established by Spanish standard EN 13279-1 and Lushnikova et al. [8,29]. However, most properties of gypsum products and building materials will mainly be determined by the structure of their matrix [4,9,38].

3.2 Morphology and composition analysis (SEM and XRD)

Microstructural analysis revealed that samples without GNFs presented needle-like crystals spread along the matrix with an average size of 21.4 μm, as seen in Figure 6. In this case, the structure displayed a higher amount of porosity that resulted in lower durability and mechanical properties, in comparison to other samples. When GNFs are implemented in the mixture, an ordered and uniform structure emerges with longer crystals, decreased porosity, and improved mechanical properties.

Microstructural analysis (1,000×) of the reference sample (a) and samples containing 0.25% (b), 0.50% (c), and 1% (d) of GNFs.

These nanodispersed additives, as in other works, acted as crystallization centers introducing excess energy into the system, hence, improving crystal seeding and growth rate. More contact and interaction within the crystals translates into a higher overall strength of the composite, resulting in a denser, durable, and stronger matrix. Therefore, GNFs prove to be a viable option to modify and regulate, to some extent, the properties of traditional materials such as gypsum, paving the road for new tailored composites specifically designed to address certain market needs [18,19,39,40].

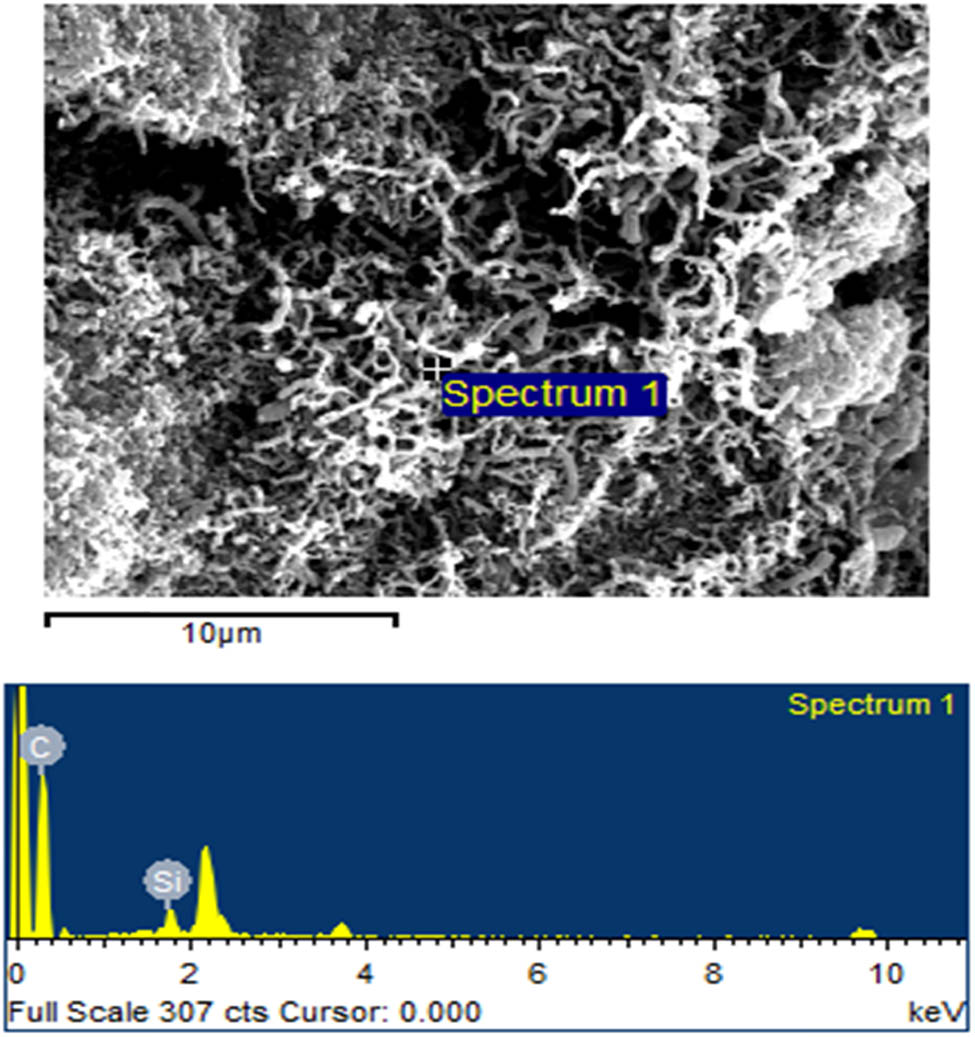

While studying these NMT, it was revealed that they present themselves as clusters along the gypsum matrix, with filaments of several nanometers in length, as shown in Figure 7. Furthermore, small amounts of Si (<4%) were detected to be present within GNFs, which might indicate that silicon carbide (SiC) wafers were employed as a production method to produce this graphene additive. Since graphitic layers are known to be grown either on the silicon or carbon faces of a SiC wafer by sublimating Si atoms, thus leaving a graphitized surface. The quality of such graphene can be very high, with crystallites approaching hundreds of micrometers in size. Unfortunately, due to high temperatures, high substrate cost, and small-diameter wafers, the use of graphene on SiC will probably be limited to low-requirement applications [26,41,42].

Microstructure and EDS analysis of GNFs (5,000×).

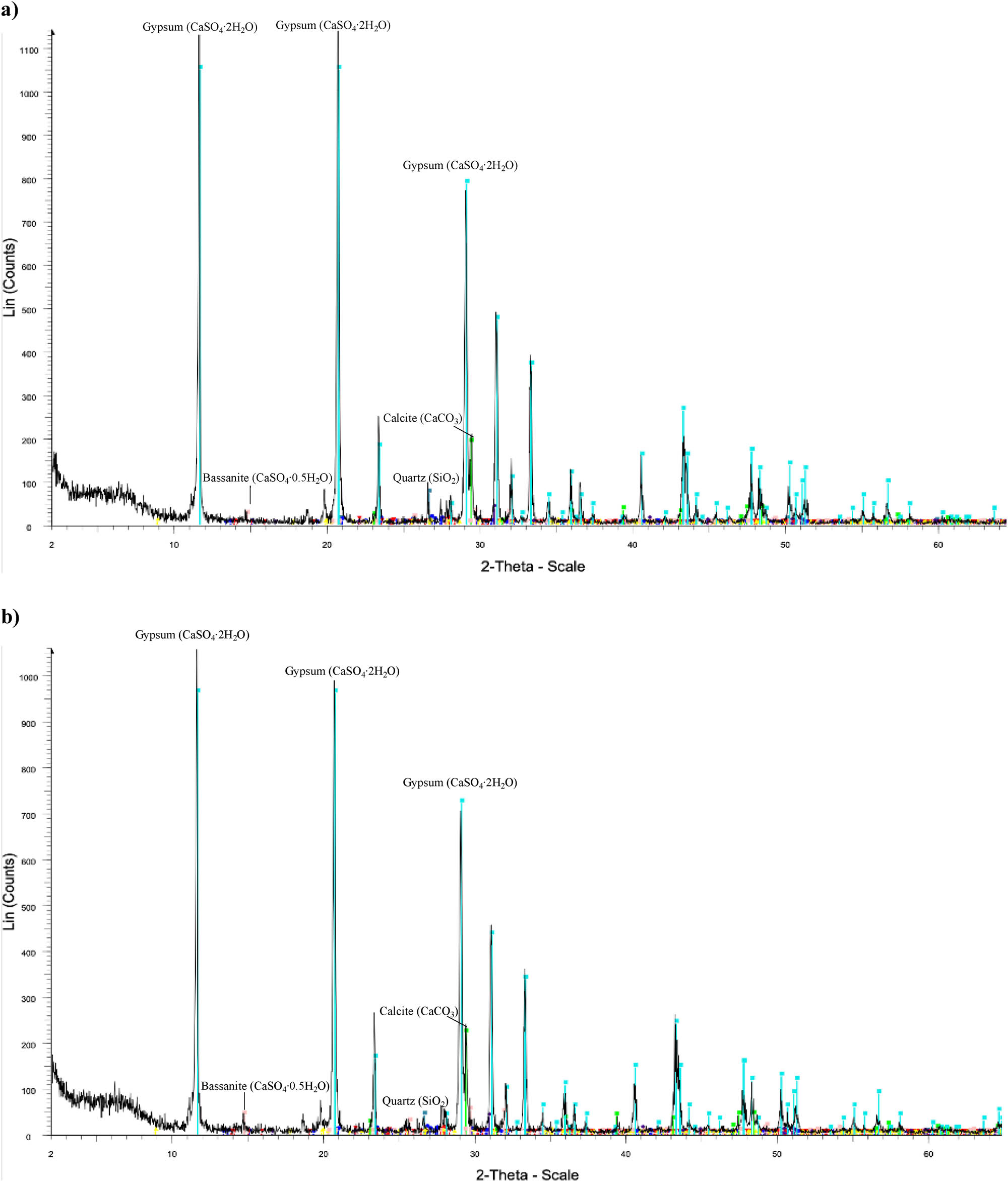

XRD analysis was performed exposing changes in the crystalline phases present in the test samples. Patterns of samples with and without additives are shown in Figure 8. The main reflections correspond to the peaks of gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O) followed by calcite (CaCO3), quartz (SiO2), bassanite (CaSO4·½H2O), dolomite (CaMg (CO3)2), along with lower quantities of alkali-feldspars and phyllosilicates, as seen in Table 9.

XRD patterns for the reference sample (a) and the composite containing 0.50% GNFs (b).

Crystalline phases present in all samples by means of XRD

| Sample | SiO2 | KAlSi3O8 | NaAlSi3O8 | KAl2(AlSi3O10)(OH)2 | CaCO3 | CaMg(CO3)2 | CaSO4·½H2O | CaSO4·2H2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref | 3.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 78.5 |

| LS-025 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 8.9 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 78.3 |

| LS-050 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 9.9 | 2.0 | 4.1 | 76.2 |

| LS-1.00 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 11.1 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 75.7 |

No carbon peaks were detected due to our additive being highly amorphous, hence, poorly detectable by our equipment. When compared, it was revealed that, when GNFs are introduced, the intensity of reflections for gypsum slightly drops while those of bassanite tend to increase in all samples (2θ ≈ 15), indicating a frail drop in hydration conditions.

Nanoparticles are generally characterized as being highly reactive and hydrophobic; thus, an increase in the intensity peaks for bassanite can be explained by a drop in hydration conditions. On this matter, Wigley [38] mentions that a decrease in the solubility of gypsum, at any temperature, is to be expected when applying other minerals or additives in the mixture. Therefore, introducing higher concentrations of this additive (>1%) could seriously affect the overall performance of the composites if no changes are implemented in the mixture to ensure proper particle distribution and hydration [18,19,21,22].

3.3 Thermal properties

In Figure 9, the values for thermal conductivity (λ) at different concentrations of GNFs are presented. The reference sample achieved a value of 0.341 W/mK, while those containing 0.50% of GNFs reached a value of 0.574 W/mK; thus, an increase of almost 70% was achieved at very low percentages. Hence, when this type of additive is employed in very small amounts, λ will tend to increase progressively.

Thermal conductivity in the function of GNF content.

However, as GNF content continues to increase within the mixture, a sudden drop in thermal conductivity was reported. Incorporating 1% of these NMT resulted in a remarkable reduction in λ by more than 40%, reaching a value of 0.199 W/mK. In contrast, these values for thermal conductivity remained within the range of those obtained by implementing 10% of EPS or silica granules without compromising mechanical properties [4,33,43].

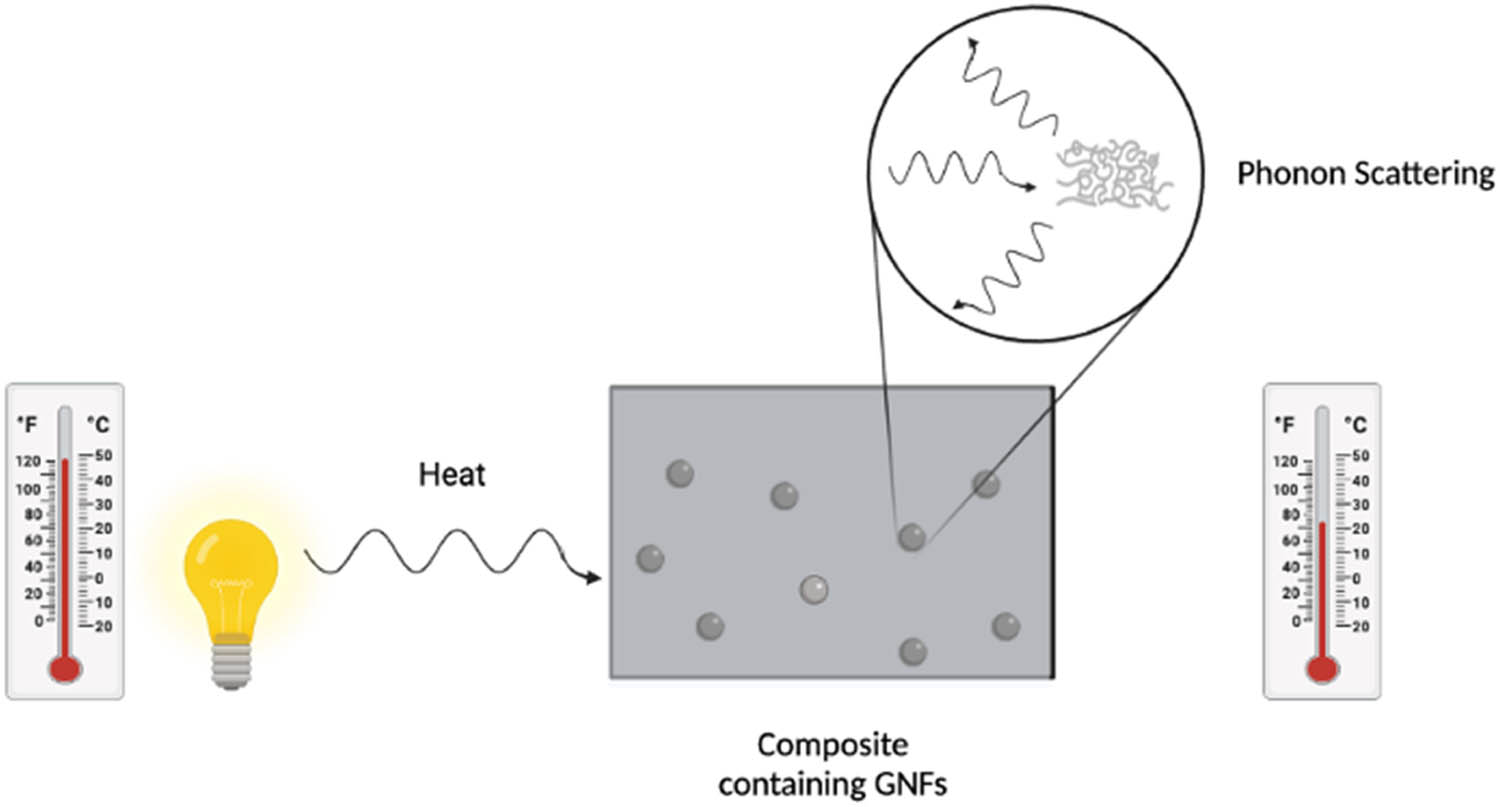

This reduction in λ may be due to the effects of intensified phonon scattering, as shown in Figure 10. Since thermal energy in insulating solids is mainly transported by these quasiparticles, whose interactions with impurities, interfaces, or other phonons can produce different scattering events of this incident energy. Thus, heat transport along these composites can be regulated by employing nanoparticles such as GNFs. These composites could be implemented in new proposals or retrofits as false ceilings, internal walls, or even heating tiles depending on the GNF content [44,45,46].

Phonon scattering events in gypsum composites containing GNFs. Own image-Biorender.

By refining the thermal features of common materials, we could further address user comfort, as well as reduce heating and cooling requirements. This could be a first step toward mitigating the current difficulties established by EP, since energy prices, inflation, occupancy, and residential demands have risen while incomes and employment rates have lowered due to the persisting effects of COVID-19 and nearby conflicts [2,47,48]

3.4 Dynamic thermal analysis

Andalusia is one of Spain’s most populated regions, but also one of the Spanish communities with the highest levels of EP, outdated homes, and lowest employment rates. A 2021 census indicated that 8,472,407 residents live here. Moreover, recent surveys revealed that more than 20% of these habitants claimed that they currently live in uncomfortable homes with signs of humidity and leaks. This only demonstrates the fragile situation of this region and the need to act upon this with proper answers in order to lower energy demands and improve inner room conditions. Therefore, modifying the building envelope is considered one of the most decisive actions to ensure adequate air quality and good insulation [49,50,51,52].

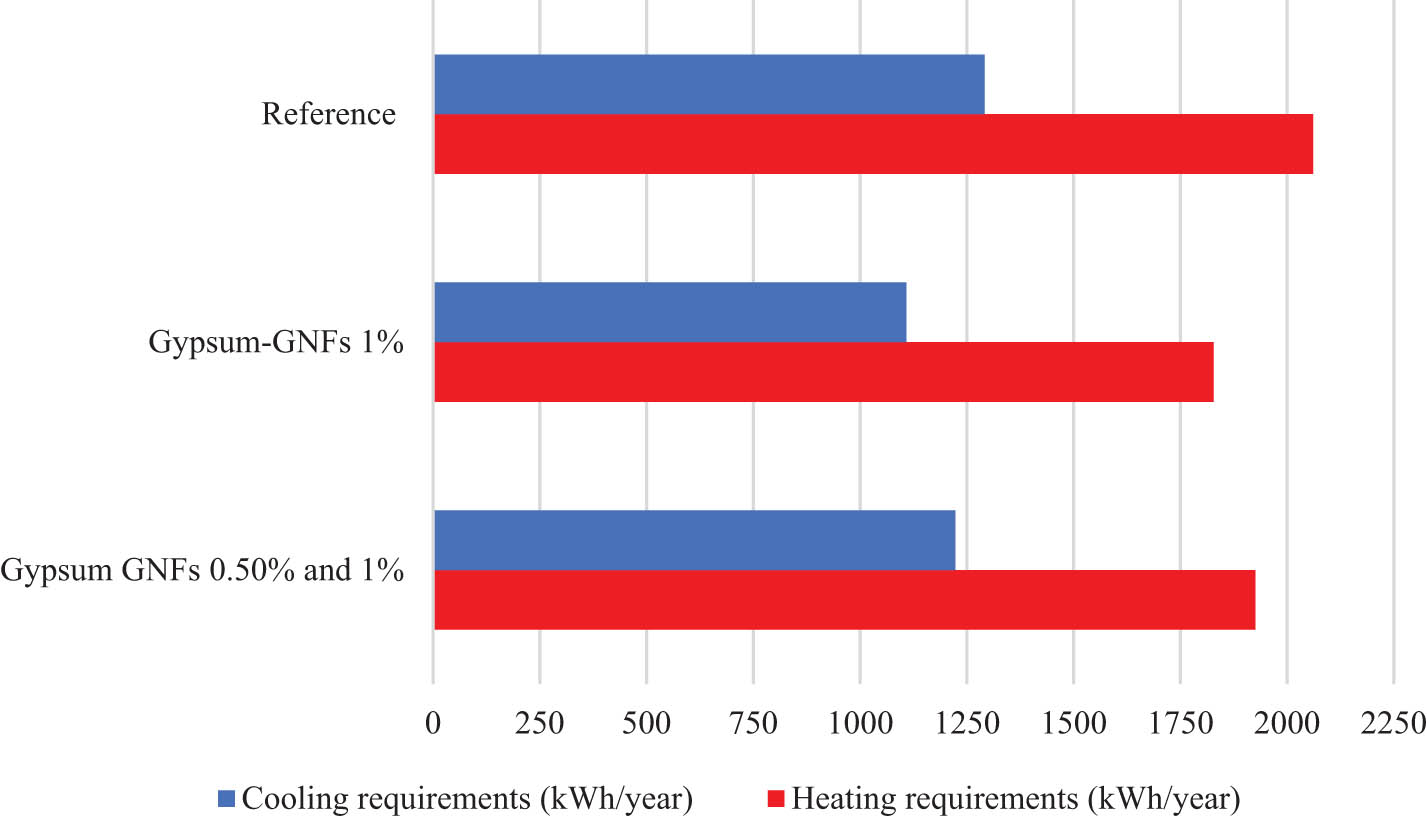

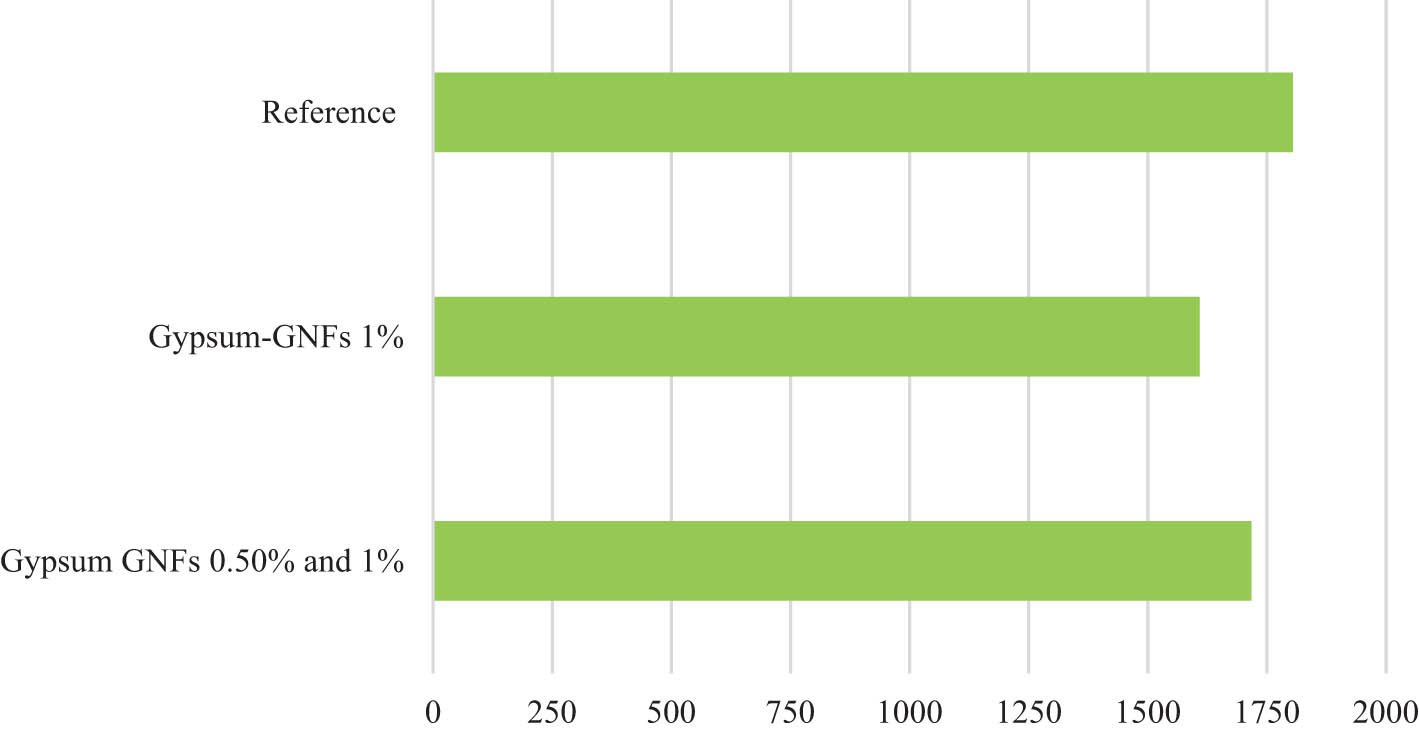

The values for annual heating and cooling requirements are shown in Table 10. Composites containing 1% GNFs resulted as the most efficient solution for this building when implemented in all surfaces. Reductions of 11 and 14% were obtained for heating and cooling demands, when compared to common gypsum. Furthermore, a decrease in CO2 emissions and total energy per building area of 11 and 9% was also reported, as illustrated in Figures 11 and 12.

Dynamic thermal simulation results of a building in Almeria implementing different arrangements

| Arrangement | Heating requirements (kWh/year) | Cooling requirements (kWh/year) | CO2 emissions (kg/year) | Total energy per building area (kWh/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | 2060.5 | 1291.4 | 1804.3 | 62.2 |

| Gypsum-GNFs 1% | 1827.8 | 1108.2 | 1608.8 | 56.6 |

| Gypsum GNFs 0.50 and 1% | 1925.3 | 1223.1 | 1717.4 | 60.2 |

Annual heating and cooling demands implementing different envelope arrangements.

Annual CO2 emissions at different envelope arrangements.

4 Conclusions

This work has performed a thermomechanical characterization of a gypsum composite containing the benefits of GNFs focused on the development of building components capable of improving user comfort while lowering energy requirements, and the main conclusions are summed up as follows:

Introducing GNFs in a gypsum mixture will change the final coloration to gray in the function of the content of the additive present in the system. Furthermore, the bulk density increases with GNF concentration up to 6%, obtaining values within the range of common gypsum-based products, usually oscillating between 700 and 1,100 kg/m3.

Samples containing 1% of GNFs achieved the highest values for flexural and compressive strength with increments of 23 and 42%, reaching values of 2.82 and 5.77 MPa. As a result, these composites are lighter and required less amount of additive to achieve greater values for compressive strength when compared to gypsum samples containing isostatic graphite.

Microstructural analysis revealed that the addition of GNFs resulted in the emergence of a more ordered, uniform, and denser structure with longer crystals, reduced porosity, and enhanced mechanical properties. Similar to other studies, these nanodispersed additives served as crystallization centers, introducing extra energy into the system, which led to improved crystal seeding and growth rate.

The addition of 1% of these nanoparticles achieved a significant reduction in thermal conductivity by >40%, reaching values of 0.199 W/mK due to the effects of intensified phonon scattering. In contrast, these values for thermal conductivity remained within the range of those obtained by implementing 10% of EPS or silica granules without compromising mechanical properties.

Implementing these components could lead to significant reductions in energy requirements for heating and cooling by 11 and 14%, respectively, along with an 11% decrease in CO2 emissions. This indicates that improving the building envelope can be an effective approach to enhance the air quality, insulation, and comfort of households.

GNFs could offer the potential to create new building components with improved mechanical properties, porosity, high or low thermal conductivity, electromagnetic shielding, and building monitoring. The addition of GNFs did not result in any sedimentation or dispersion problems during the entire process. Moreover, the use of low concentrations of GNFs is not expected to severely impact costs or the recyclability of the composite. Overall, this research demonstrates the potential for the use of GNFs in gypsum composites to create new and tailored building components that can meet the current market needs and reduce the impacts of energy poverty.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all members of the Physics and Building Materials Lab of the Technical Building School of Madrid.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted all responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Verma A, Yadav M. Application of nanomaterials in architecture – An overview. Mater Today Proc. 2021;43:2921–5.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.01.268Search in Google Scholar

[2] Sharifi NP, Shaikh AAN, Sakulich AR. Application of phase change materials in gypsum boards to meet building energy conservation goals. Energy Build. 2017 Mar;138:455–67.10.1016/j.enbuild.2016.12.046Search in Google Scholar

[3] Mastropietro P. Energy poverty in pandemic times: Fine-tuning emergency measures for better future responses to extreme events in Spain. Energy Res Soc Sci. 2022 Feb;84:102364.10.1016/j.erss.2021.102364Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Karni J, Karni E. Gypsum in construction: Origin and properties. Mater Struct. 1995 Mar;28(2):92–100.10.1007/BF02473176Search in Google Scholar

[5] Harrell JA. Amarna gypsite: A new source of gypsum for ancient Egypt. J Archaeol Sci Rep. 2017 Feb;11:536–45.10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.12.031Search in Google Scholar

[6] Herrero MJ, Escavy JI, Bustillo M. The Spanish building crisis and its effect in the gypsum quarry production (1998–2012). Resour Policy. 2013 Jun;38(2):123–9.10.1016/j.resourpol.2013.02.005Search in Google Scholar

[7] Jia R, Wang Q, Feng P. A comprehensive overview of fibre-reinforced gypsum-based composites (FRGCs) in the construction field. Compos Part B: Eng. 2021 Jan;205:108540.10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108540Search in Google Scholar

[8] Lushnikova N, Dvorkin L. Sustainability of gypsum products as a construction material. In: Khatib JM, editor. Sustainability of Construction Materials (2nd edition). Woodhead Publishing; 2016. p. 643–81.10.1016/B978-0-08-100370-1.00025-1Search in Google Scholar

[9] Bouzit S, Merli F, Sonebi M, Buratti C, Taha M. Gypsum-plasters mixed with polystyrene balls for building insulation: Experimental characterization and energy performance. Constr Build Mater. 2021 May;283:122625.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122625Search in Google Scholar

[10] Flores Medina N, Barbero-Barrera MM. Mechanical and physical enhancement of gypsum composites through a synergic work of polypropylene fiber and recycled isostatic graphite filler. Constr Build Mater. 2017 Jan;131:165–77.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.11.073Search in Google Scholar

[11] Eve S, Gomina M, Gmouh A, Samdi A, Moussa R, Orange G. Microstructural and mechanical behaviour of polyamide fibre-reinforced plaster composites. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2002 Dec;22(13):2269–75.10.1016/S0955-2219(02)00014-6Search in Google Scholar

[12] Vasconcelos G, Lourenço PB, Camões A, Martins A, Cunha S. Evaluation of the performance of recycled textile fibres in the mechanical behaviour of a gypsum and cork composite material. Cem Concr Compos. 2015 Apr;58:29–39.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2015.01.001Search in Google Scholar

[13] Senff L, Ascensão G, Ferreira VM, Seabra MP, Labrincha JA. Development of multifunctional plaster using nano-TiO2 and distinct particle size cellulose fibers. Energy Build. 2018 Jan;158:721–35.10.1016/j.enbuild.2017.10.060Search in Google Scholar

[14] Ouakarrouch M, El Azhary K, Laaroussi N, Garoum M, Kifani-Sahban F. Thermal performances, and environmental analysis of a new composite building material based on gypsum plaster and chicken feathers waste. Therm Sci Eng Prog. 2020 Oct;19:100642.10.1016/j.tsep.2020.100642Search in Google Scholar

[15] Hagiri M, Honda K. Preparation and evaluation of gypsum plaster composited with copper smelter slag. Clean Eng Technol. 2021 Jun;2:100084.10.1016/j.clet.2021.100084Search in Google Scholar

[16] Barbero-Barrera M, del M, Flores-Medina N, Pérez-Villar V. Assessment of thermal performance of gypsum-based composites with revalorized graphite filler. Constr Build Mater. 2017 Jul;142:83–91.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.03.060Search in Google Scholar

[17] Serna Á, Río M, del, Palomo JG, González M. Improvement of gypsum plaster strain capacity by the addition of rubber particles from recycled tyres. Constr Build Mater. 2012 Oct;35:633–41.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.04.093Search in Google Scholar

[18] Gordina A, Tokarev Y, Yakovlev G, Keriene J, Sychugov S, Mohamed AES. Evaluation of the Influence of ultradisperse dust and carbon nanostructures on the structure and properties of gypsum binders. Procedia Eng. 2013;57:334–42.10.1016/j.proeng.2013.04.045Search in Google Scholar

[19] Yakovlev G, Polyanskikh I, Fedorova G, Gordina A, Buryanov A. Anhydrite and gypsum compositions modified with ultrafine man-made admixtures. Procedia Eng. 2015;108:13–21.10.1016/j.proeng.2015.06.195Search in Google Scholar

[20] Papadaki D, Kiriakidis G, Tsoutsos T. Applications of nanotechnology in construction industry. In: Barhoum A, Hamdy Makhlouf AS, editors. Fundamentals of Nanoparticles. Elsevier; 2018. p. 343–70.10.1016/B978-0-323-51255-8.00011-2Search in Google Scholar

[21] Tokarev Y, Ginchitsky E, Sychugov S, Krutikov V, Yakovlev G, Buryanov A, et al. Modification of gypsum binders by using carbon nanotubes and mineral additives. Procedia Eng. 2017;172:1161–8.10.1016/j.proeng.2017.02.135Search in Google Scholar

[22] Pervyshin GN, Yakovlev GI, Gordina AF, Keriene J, Polyanskikh IS, Fischer HB, et al. Water-resistant gypsum compositions with man-made modifiers. Procedia Eng. 2017;172:867–74.10.1016/j.proeng.2017.02.087Search in Google Scholar

[23] Rafique M, Tahir MB, Rafique MS, Hamza M. History and fundamentals of nanoscience and nanotechnology. In: Tahir MB, Rafique M, Rafique MS, editors. Nanotechnology and Photocatalysis for Environmental Applications. Elsevier; 2020. p. 1–25.10.1016/B978-0-12-821192-2.00001-2Search in Google Scholar

[24] Novoselov KS. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science. 2004 Oct 22;306(5696):666–9.10.1126/science.1102896Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Geim AK, Novoselov KS. The rise of graphene. Nat Mater. 2007 Mar;6(3):183–91.10.1038/nmat1849Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Novoselov KS, Fal′ko VI, Colombo L, Gellert PR, Schwab MG, Kim K. A roadmap for graphene. Nature. 2012 Oct;490(7419):192–200.10.1038/nature11458Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Young RJ, Kinloch IA, Gong L, Novoselov KS. The mechanics of graphene nanocomposites: A review. Compos Sci Technol. 2012 Jul;72(12):1459–76.10.1016/j.compscitech.2012.05.005Search in Google Scholar

[28] Novo S, Fonseca C, Benavente R, Blázquez-Blázquez E, Cerrada ML, Pérez E. Effect of graphene nanofibers on the morphological, structural, thermal, phase transitions and mechanical characteristics in metallocene iPP based nanocomposites. J Compos Sci. 2022 Jun 1;6(6):161.10.3390/jcs6060161Search in Google Scholar

[29] AENOR. EN 13279-1, Gypsum binders and gypsum plasters – Part 1: Definitions and requirements. 2008.Search in Google Scholar

[30] AENOR. EN 13279-2, Gypsum binders and gypsum plasters – Part 2: Test methods. 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Herrero S, Mayor P, Hernández-Olivares F. Influence of proportion and particle size gradation of rubber from end-of-life tires on mechanical, thermal and acoustic properties of plaster–rubber mortars. Mater & Des. 2013 May;47:633–42.10.1016/j.matdes.2012.12.063Search in Google Scholar

[32] Navacerrada MA, Fernández P, Díaz C, Pedrero A. Thermal and acoustic properties of aluminium foams manufactured by the infiltration process. Appl Acoust. 2013 Apr;74(4):496–501.10.1016/j.apacoust.2012.10.006Search in Google Scholar

[33] Cao W, Yi W, Yin S, Peng J, Li J. A novel low-density thermal insulation gypsum reinforced with superplasticizers. Constr Build Mater. 2021 Apr;278:122421.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122421Search in Google Scholar

[34] Smirnov BM, Berry RS. Growth of bubbles in liquid. Chem Cent J. 2015 Sep 21;9(1):1–8.10.1186/s13065-015-0127-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Biswal A, Swain SK. Smart composite materials for civil engineering applications. In: Bouhfid R, Kacem Qaiss A, Jawaid, editors. Polymer Nanocomposite-Based Smart Materials. Woodhead Publishing; 2020. p. 197–210.10.1016/B978-0-08-103013-4.00011-XSearch in Google Scholar

[36] Suresh Babu K, Ratnam Ch. Mechanical and thermophysical behavior of hemp fiber reinforced gypsum composites. Mater Today Proc. 2021 Jan;259:126858.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.12.363Search in Google Scholar

[37] Tao J, Wang J, Zeng Q. A comparative study on the influences of CNT and GNP on the piezoresistivity of cement composites. Mater Lett. 2020 Jan;259:126858.10.1016/j.matlet.2019.126858Search in Google Scholar

[38] Wigley TML. Chemical evolution of the system calcite–gypsum–water. Can J Earth Sci. 1973 Feb 1;10(2):306–15.10.1139/e73-027Search in Google Scholar

[39] Kondratieva N, Barre M, Goutenoire F, Sanytsky M, Rousseau A. Effect of additives SiC on the hydration and the crystallization processes of gypsum. Constr Build Mater. 2020 Feb;235:117479.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117479Search in Google Scholar

[40] Ahmadi Moghadam H, Mirzaei A. Comparing the effects of a retarder and accelerator on properties of gypsum building plaster. J Build Eng. 2020 Mar;28:101075.10.1016/j.jobe.2019.101075Search in Google Scholar

[41] Virojanadara C, Syväjarvi M, Yakimova R, Johansson LI, Zakharov AA, Balasubramanian T. Homogeneous large-area graphene layer growth on6H-SiC(0001). Phys Rev B. 2008 Dec 1;78(24):245403.10.1103/PhysRevB.78.245403Search in Google Scholar

[42] Forbeaux I, Themlin J-M, Debever J-M. Heteroepitaxial graphite on6H−SiC(0001): Interface formation through conduction-band electronic structure. Phys Rev B. 1998 Dec 15;58(24):16396–406.10.1103/PhysRevB.58.16396Search in Google Scholar

[43] Capasso I, Pappalardo L, Romano RA, Iucolano F. Foamed gypsum for multipurpose applications in building. Constr Build Mater. 2021 Nov;307:124948.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124948Search in Google Scholar

[44] Xu C, Miao M, Jiang X, Wang X. Thermal conductive composites reinforced via advanced boron nitride nanomaterials. Compos Commun. 2018 Dec;10:103–9.10.1016/j.coco.2018.08.002Search in Google Scholar

[45] Lee KH, Kim H-S, Shin WH, Kim SY, Lim J-H, Kim SW, et al. Nanoparticles in Bi0.5Sb1.5Te3: A prerequisite defect structure to scatter the mid-wavelength phonons between Rayleigh and geometry scatterings. Acta Materialia. 2020 Feb;185:271–8.10.1016/j.actamat.2019.12.001Search in Google Scholar

[46] Tan WK, Hakiri N, Yokoi A, Kawamura G, Matsuda A, Muto H. Controlled microstructure and mechanical properties of Al2O3-based nanocarbon composites fabricated by electrostatic assembly method. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2019 Jul 23;14(1):1–7.10.1186/s11671-019-3061-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Carfora A, Scandurra G, Thomas A. Forecasting the COVID-19 effects on energy poverty across EU member states. Energy Policy. 2021 Sep;161:112597.10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112597Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Čekon M, Čurpek J. A transparent insulation façade enhanced with a selective absorber: A cooling energy load and validated building energy performance prediction model. Energy Build. 2019 Jan;183:266–82.10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.10.032Search in Google Scholar

[49] Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía. Padrón municipal de habitantes [Internet]. [cited 2022 Oct 18]. https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/badea/operaciones/consulta/anual/6782?CodOper=b3_128&codConsulta=6782.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Clavijo-Núñez S, Herrera-Limones R, Rey-Pérez J, Torres-García M. Energy poverty in Andalusia. An analysis through decentralised indicators. Energy Policy. 2022 Aug;167:113083.10.1016/j.enpol.2022.113083Search in Google Scholar

[51] Domínguez-Amarillo S, Fernández-Agüera J, Sendra JJ, Roaf S. The performance of Mediterranean low-income housing in scenarios involving climate change. Energy Build. 2019 Nov;202:109374.10.1016/j.enbuild.2019.109374Search in Google Scholar

[52] Bienvenido-Huertas D, Sanz Fernández A, Sánchez-Guevara Sánchez C, Rubio-Bellido C. Assessment of energy poverty in Andalusian municipalities. Application of a combined indicator to detect priorities. Energy Rep. 2022 Nov;8:5100–16.10.1016/j.egyr.2022.03.045Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery

- The progress of cathode materials in aqueous zinc-ion batteries

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part I

- Effect of polypropylene fiber and nano-silica on the compressive strength and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete

- Mechanochemical design of nanomaterials for catalytic applications with a benign-by-design focus

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview