Abstract

In this work, we study the corrosion performance of coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying of metal wires. 316L metal wire with a diameter of 1.5 mm is used as spray material, and the coating is prepared on the 45# steel substrate by electrical explosion spraying. The oil–water corrosion experiment of the coating is carried out in a constant temperature water bath of 60°C for 168 h. The scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive spectroscopy results of the experimental samples have shown that some metal oxides are found inside the coating, most of which are distributed at the grain boundaries with a size range of 30–50 nm. The corrosion rate of the coating is measured by weight loss method with a corrosion rate of 0.079 mm/annum. XRD results show that the corrosion generates CaCO3, Fe3O4, and MgFe2O4. Coating corrosion is mainly caused by the formation of electrochemical corrosion between oxides and non-oxides in the coating, and pitting corrosion and intergranular corrosion in the presence of chloride ions.

1 Introduction

Steel materials are widely used in automotive, aerospace, transportation, and equipment manufacturing industries due to their good toughness, easy processing, and high strength. Most steel materials, however, have poor corrosion resistance and are easily affected by environmental factors, leading to corrosion under actual working conditions. The metal and equipment materials scrapped globally due to corrosion account for about 1/3 of the annual production, giving rise to direct economic loss of about 700 billion US dollars, which is 6 times the total loss caused by natural disasters, such as earthquakes, floods, and typhoons [1,2]. Among the current methods to avoid the corrosion of steel materials, coating is one of the most economical, simplest, and most effective methods to improve the corrosion resistance of steel materials [3,4,5].

The current methods in preparing corrosion-resistant coatings on steel materials mainly include electroplating, electroless plating, and thermal spraying by coating the surfaces of steel materials with alloys containing nickel, zinc, and chromium as corrosion-resistant materials [6,7]. The methods of electroplating and electroless plating can, however, only use soluble metals as coating materials, and the generated liquid wastes in electroplating process can cause environmental pollution, which increases the cost in environmental protection. Moreover, traditional thermal spraying technology will heat the surfaces of steel materials during the coating process, which affects inevitably the surfaces of the substrates, resulting in decreases in both compactness and bonding force of the coatings [7,8].

Electric explosion spraying of metal wire is a process of rapid melting, vaporization, and plasmaization of the metal wire through which a current density of higher than 107 cm−2 passes within pretty short time. Meanwhile, the material states and parameters of the metal wire change sharply accompanied by strong light radiation and explosion sound, which is thereby called the electric explosion [9,10,11].

Electrical explosion spraying, as a kind of thermal spraying, uses metal wires as spraying materials on which large current with high energy density is applied to generate ohmic heating. The metal wires rapidly undergo phase transition of solid → liquid → vapor → plasma, resulting in an electrical explosion. With the help of explosion shock wave, metal droplets that are partially molten but not vaporized are sprayed onto surfaces of workpieces at high speeds to form high-temperature resistant and anti-ablative coatings [12,13]. Due to its unique spraying method, electrical explosion spraying has good adaptability to the spraying in pipes and holes. The spraying speed is fast, normally finished in about 1 ms, thus posing negligible thermal effects on workpieces. The generated metal grains are mostly microcrystalline and nanocrystalline, which can greatly improve the strength plasticity, abrasion resistance, corrosion resistance, and other properties of materials [14].

Currently, electrical explosion spraying is mainly used in the preparation of nano-powders and abrasion-resistant coatings [15,16,17,18]. Mizusako successfully coated Mo, W, and stainless steel on aluminum and steel plates by carrying out electrical explosion spraying on inner holes of pipe fittings in the atmospheric environments [19]. Padgurskas et al. used the same method to prepare low friction coatings [20]. Romanov et al. improved abrasion resistance and galvanic corrosion resistance of surfaces of copper alloys with ZnO–Ag coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying [21]. In addition, researchers have reported anti-corrosion coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying to improve the corrosion resistance of substrates, which, however, lacks in-depth research to clarify their corrosion performance under certain conditions [22,23].

Unlike previous study, in this work, we prepare coatings of the spray material 316L metal wires on 45# steel substrates by electrical explosion spraying. A corrosion experiment is carried out on the coatings for 168 h. Based on the analyses of original structures, the diffusion of elements, the corrosion products, and the corrosion rate of the coating section after the corrosion test, we obtain the main factors affecting the corrosion performance of the coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying.

2 Experiments

2.1 Preparation of the coatings

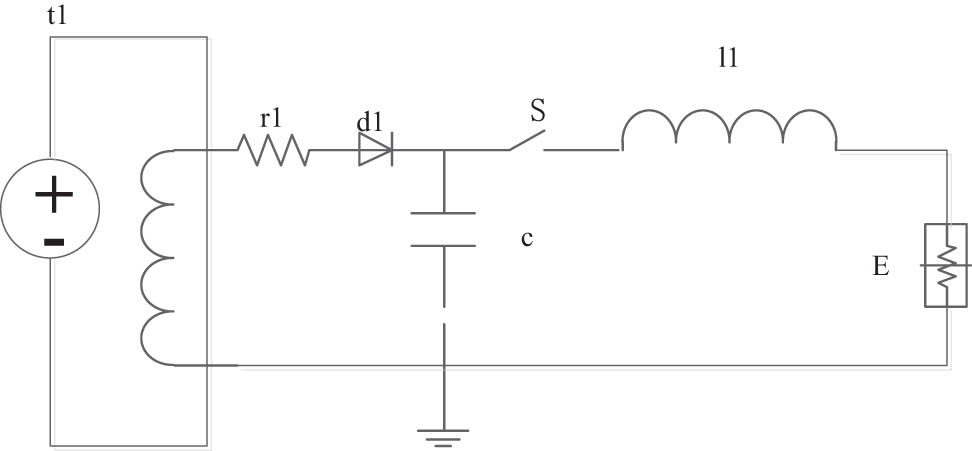

45# steel with a sample size of 10 mm × 10 mm × 20 mm was used as substrate with related composition shown in Table 1. 316L metal wires with a diameter of 1.5 mm were used as the spraying material with related composition shown in Table 2. Coatings were prepared by electrical explosion spraying with 20 times of spraying on the surfaces of the substrates under appropriate parameters of power supply. Figure 1 shows the working principle of electrical explosion spraying of metal wires.

Chemical composition of 45# steel

| Element | C | Si | Mn | Cr | Ni | Cu | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (wt%) | 0.45 | 0.21 | 0.6 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.1 | Bal. |

Chemical composition of 316L steel

| Element | C | Si | Mn | Cr | Ni | S | P | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (wt%) | 0.03 | 0.1 | 2.5 | 16 | 13 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.045 | Bal. |

Schematic diagram of working principle of electrical explosion spraying.

Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of working principle of electrical explosion spraying, where t1 is the charging module, d1 is the diode, r1 is the resistance value of the metal wire, c is the capacitance value of the electric quantity released during the electric explosion spraying of metal wires, S is the switch, L1 is the energy storage inductance, and E is the electrical explosion wire.

2.2 Characterization of the coatings

The phase of the coatings was detected by X-ray diffraction (XRD; smartlab, Rigaku) with a scanning angle of 20–90° and a speed of 2θ/min. The surfaces and cross-sectional morphologies of the coatings were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Zeiss Sigma300, Germany) and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS; OXFORD X-MAXN). The bonding force between the coatings and the substrates was measured with a film FM1000 and a universal testing machine. The microhardness of coating was measured by automatic microhardness tester (Q10A+, Austria).

2.3 Corrosion test

The surfaces of the samples were polished smooth. The unsprayed surfaces were covered with epoxy resin and the boundary was sealed with silica gel. Then, the sample was immersed in the corrosion solution for 168 h at a constant temperature of 60°C in water bath. The components of the corrosion solution are shown in Table 3. The experiment was carried out according to NACE TM0284-2003 standard. The sample was weighed every 24 h, based on which the kinetic curve was plotted.

Components of medium that mimics oilfield conditions (g/L)

| Compound | Concentration | Ionic form | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| CaCl2 | 1.665 | Ca2+ | 0.6 |

| NaHCO3 | 0.826 |

|

0.6 |

| NaCl | 30.715 |

|

20 |

| Na2SO4 | 1.775 |

|

1.2 |

| MgCl2·6H2O | 0.846 | Mg2+ | 0.1 |

3 Results

3.1 Properties of the coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying

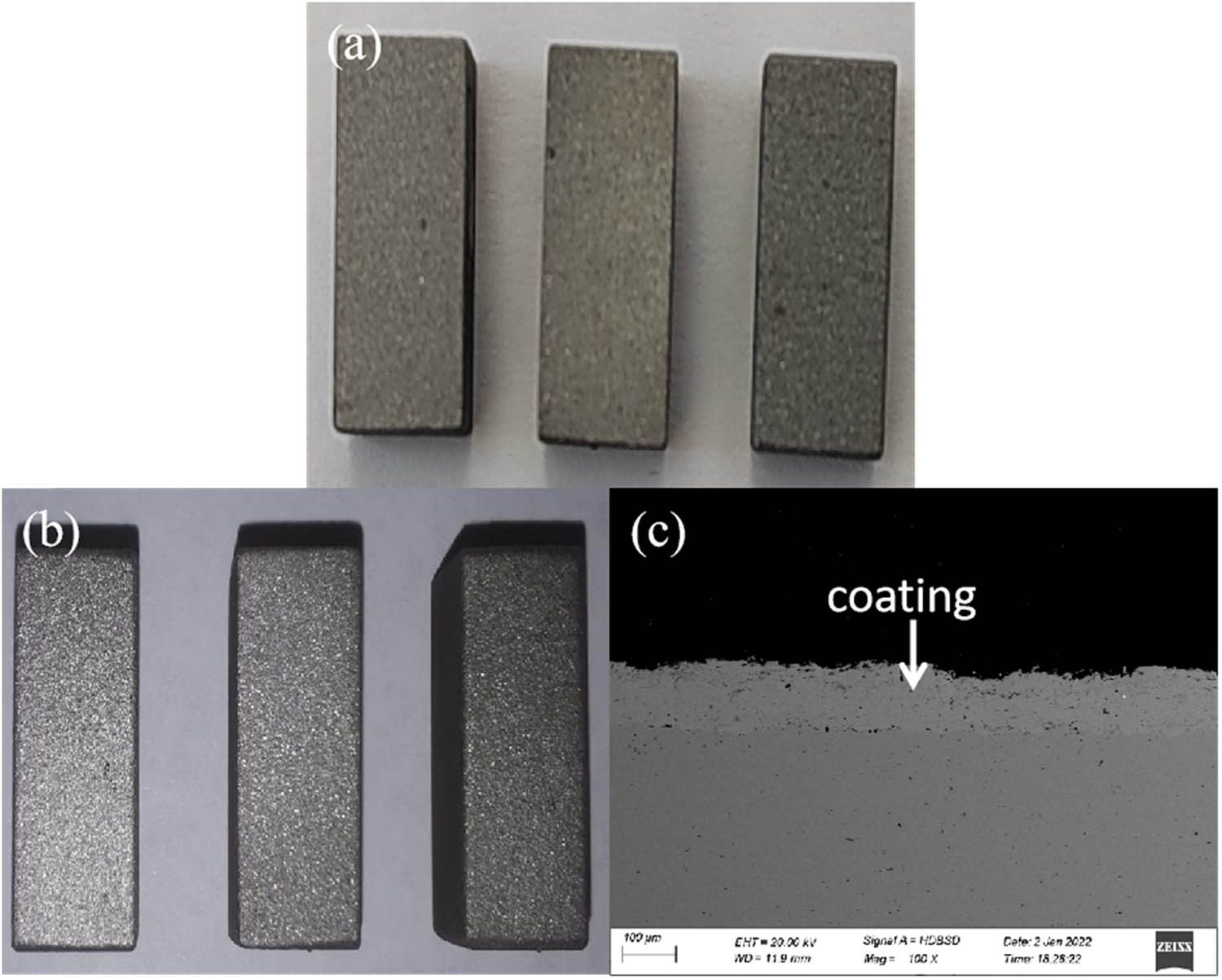

The macro-morphology and micro cross-sectional morphology of the coatings can reflect quality of the prepared coatings. Figure 2a shows the macro-morphology of base material, and Figure 2b and c shows the macro-morphology and micro cross-sectional morphology of 316L metal wire coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying, revealing that the metal coatings with white metallic luster are deposited densely and uniformly on the surfaces of the substrates with a thickness of about 125 μm. The coatings have been tested by thermal vibration (heating to 350°C for 30 min and then cooling to room temperature with water) 50 times without detachment or peeling. Table 4 shows the results of bonding strength between the coatings and the substrates. All samples in the experiment show detachment between the coatings and the substrates, and no detachment is found within the coatings (Figure 3). The average value of the measured bonding strength is about 48 MPa, as is shown in Table 4. The microhardness of the coating is 246HV.

(a) The macro-morphology of base material. (b) Photos and (c) cross-section scanning electron microscope images of 316L wire coatings by explosive spraying.

Bonding strength of the coatings

| Coating | Bonding strength (MPa) |

|---|---|

| Sample 1 | 45.532 |

| Sample 2 | 38.496 |

| Sample 3 | 59.986 |

| Average | 48.005 |

Macro-morphology of the coatings in bonding strength test.

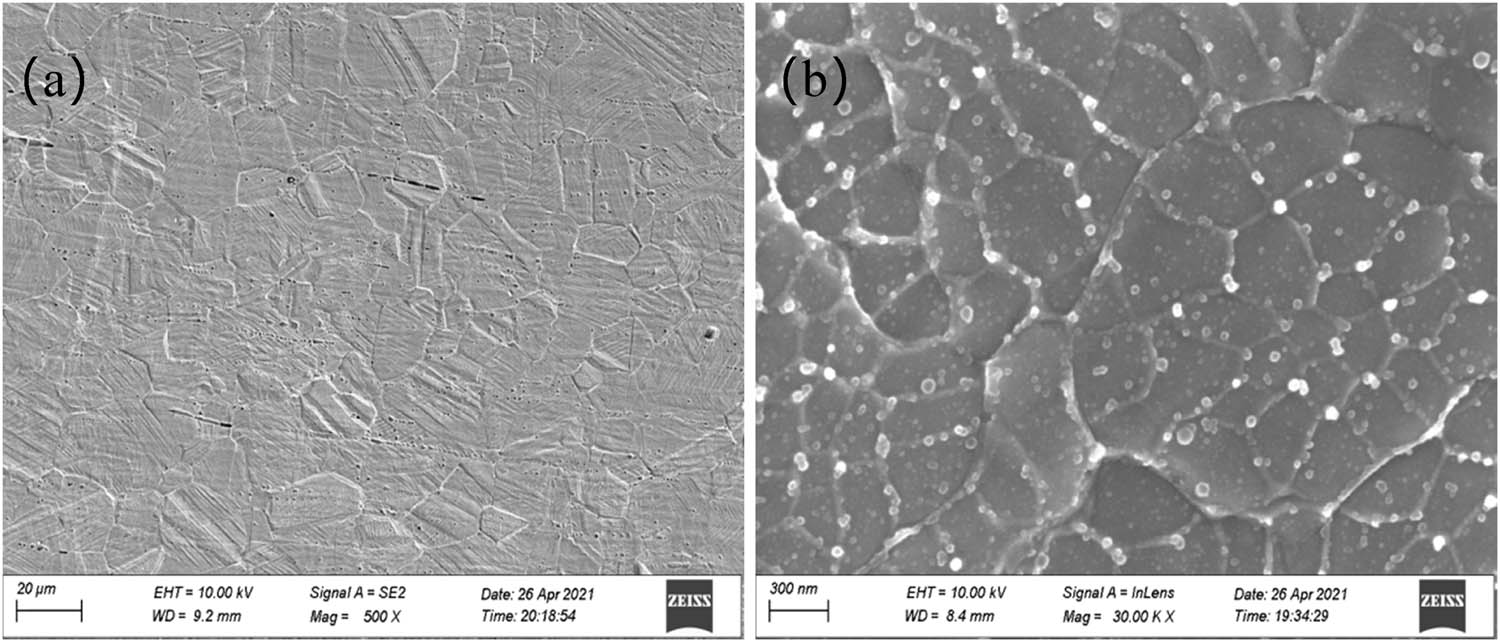

Figure 4 shows the structures of 316L metal wire before and after electrical explosion spraying. It can be seen that the grain size of the 316L metal wire is 15–20 μm. After electrical explosion spraying, the grain size of the coating is 150–300 nm. White granular substances with inhomogeneous size of 30–50 nm can be observed in the coatings, most of them near the grain boundaries.

The structures of 316L metal wire (a) before and (b) after electrical explosion spraying.

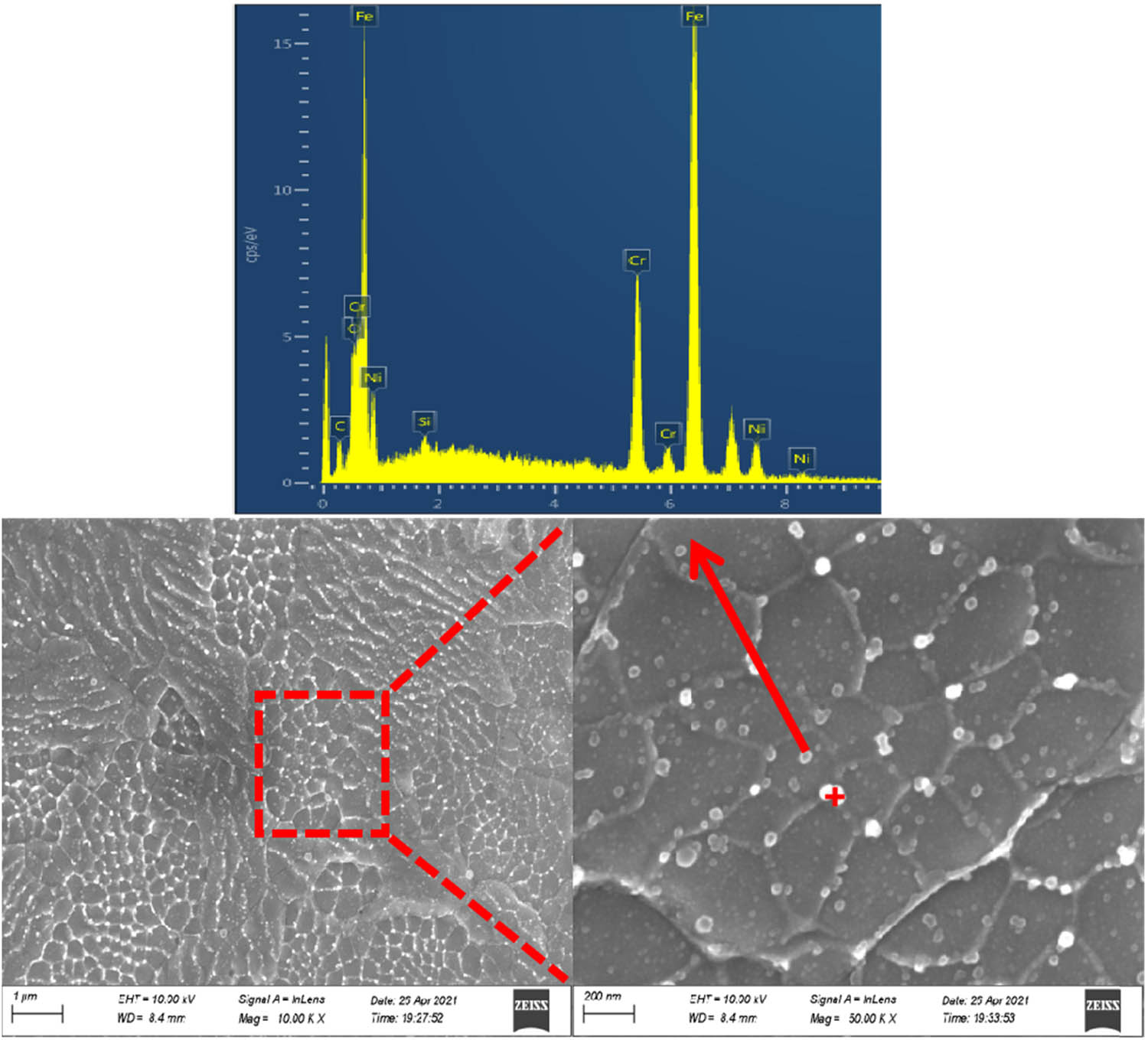

Figure 5 shows the XRD spectrum of the coating surface. As can be seen from the XRD results, the phase composition of the coatings is Fe–Cr and Fe–Ni. Figure 6 shows the SEM images and EDS spectrum of the surfaces of the coatings. The EDS result shows that oxygen element that is not from the original metal appears in the coatings. Analysis of point energy spectrum reveals that the white granular materials are oxides mostly distributed in the grain boundaries, which cannot be detected by XRD due to its low content and small grain size. The formation of oxides can be attributed to the reaction of the high-temperature metal droplets generated during electrical explosion spraying process and oxygen in the air. The molten metal droplets form some oxides, which hit the substrate at high speed and spread out on the substrate. Most of the oxides are distributed near the grain boundaries because of higher solubility of oxides at the grain boundaries than in the grains [24,25,26,27].

XRD spectrum of the coating surface.

SEM images and EDS spectrum of the coating prepared by electrical explosion spraying.

3.2 Corrosion performance of the coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying

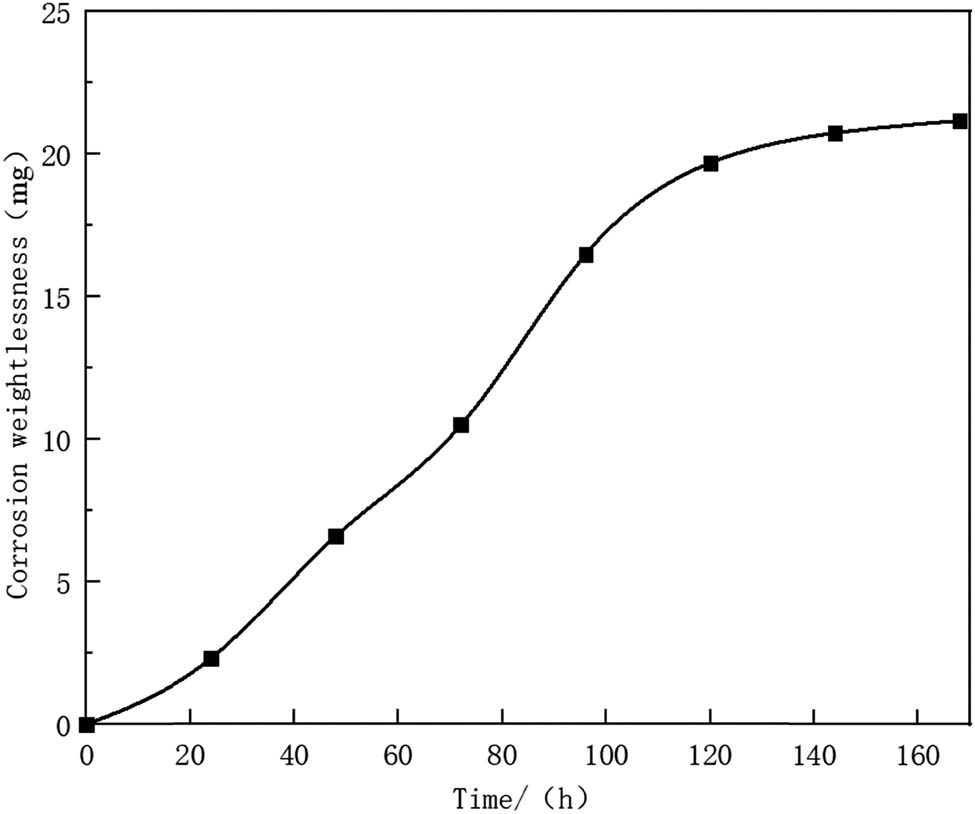

Figure 7 shows the kinetic curve of the coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying with the treatment of corrosion solution at a constant temperature of 60°C in the medium shown in Table 3 for 168 h. It can be seen that the overall curve is in parabolic shape, and the corrosion rate increases linearly before 120 h and gradually tends to be stable after 120 h, indicating a decrease of corrosion rate after 120 h. Based on formula (1), the average corrosion rate within 7 days is calculated to be 0.079 mm/annum.

where R is the corrosion rate (mm/annum), m 0 is the mass before the test (g), m 1 is the mass after the test (g), S is the total area of the sample (cm2), T is the test time (h), and D is the density of the material (kg/m3).

Kinetic curve of the coatings in corrosion test.

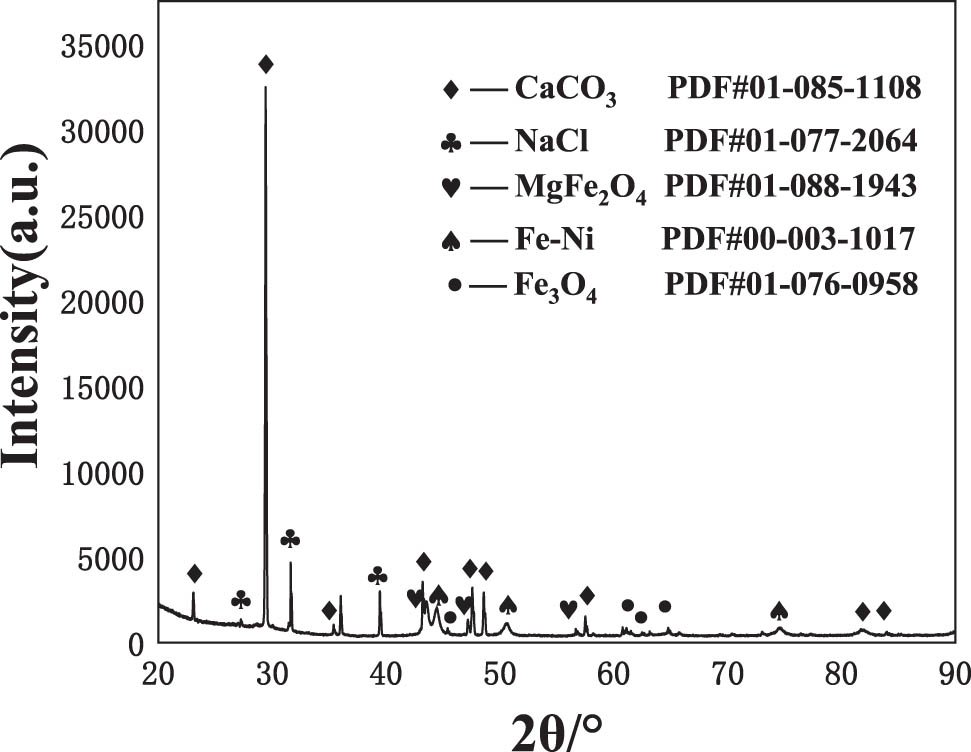

Figure 8 shows XRD spectrum of the coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying after the corrosion test at 60°C for 168 h in oil–water system. It can be seen that the corrosion of the coatings produces CaCO3, Fe3O4 and MgFe2O4. The Fe–Ni phase in the map is derived from the coatings, and NaCl is the residue of the solute in the corrosion solution.

XRD spectrum of the coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying after corrosion test at 60°C for 168 h in oil–water system.

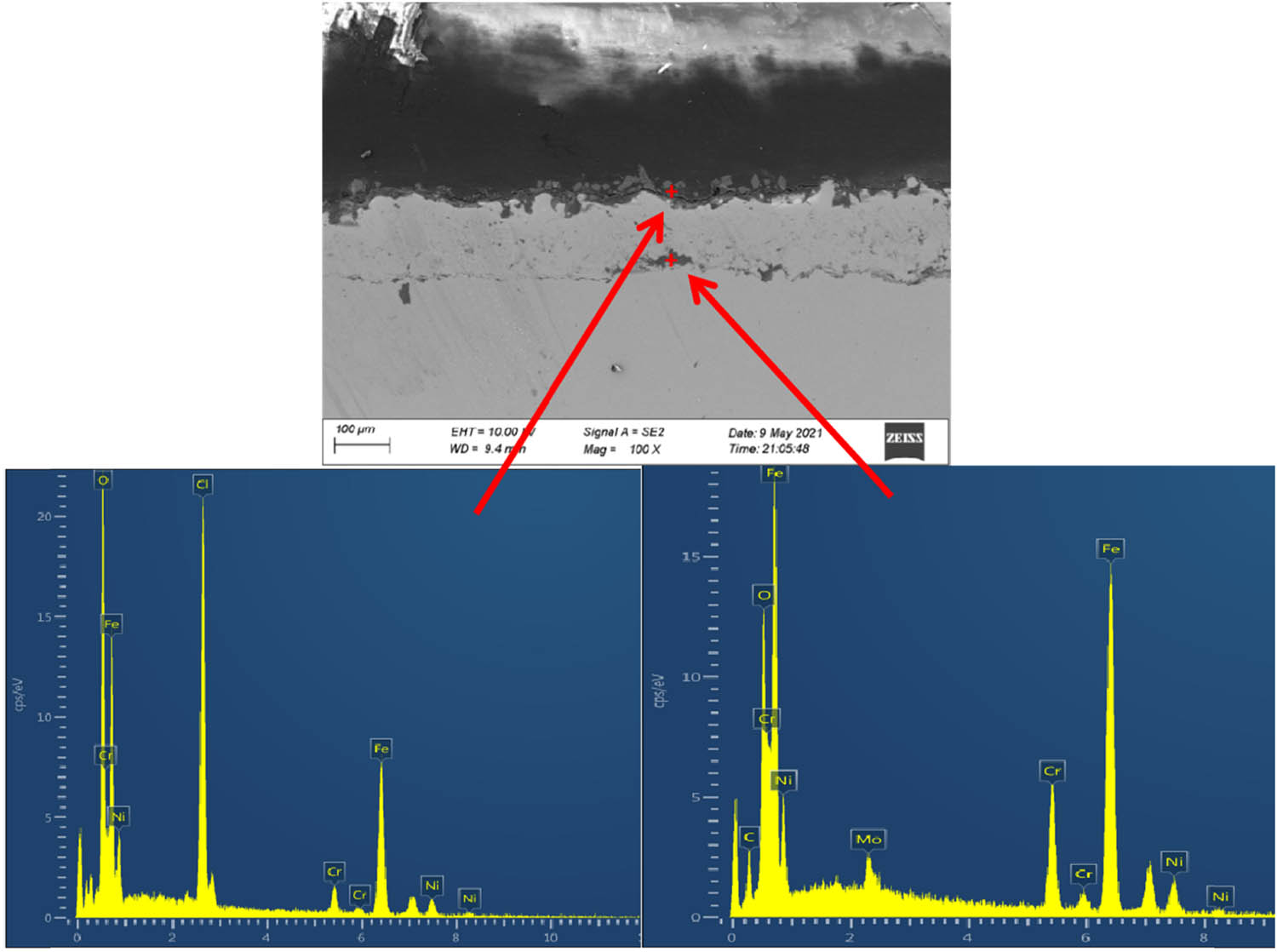

Figure 9 shows the SEM image and EDS spectra of the cross-section of the coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying after corrosion test at 60°C for 168 h in oil–water system. The results show the presence of oxygen and chloride elements on the surfaces of the coatings after corrosion, and the formation of oxides between the coatings and the substrates. The presence of oxygen and chlorine elements on the surfaces is consistent with the results in the XRD spectrum in Figure 8, which indicates possible micro-crevices in the coatings, allowing the corrosion elements like chloride in the solution to penetrate between the coatings and the substrates and forming a “corrosion zone” between the coatings and the substrates.

SEM image and EDS spectra of the cross-section of the coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying after corrosion test at 60°C for 168 h in oil–water system.

4 Discussion

The corrosion of coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying is mainly attributed to the presence of oxides near the grain boundaries. These oxides can form protrusions, depressions, or holes on the surfaces and inside of the coating and react with solutes in the corrosion solution to cause detachment and dissolution, resulting in the formation of tiny pores, and further the formation of microgalvanic corrosion inside and outside the pores of the coatings and near the oxides. The following reactions then occur [28].

Fe element in the pores works as the anode:

Dissolved oxygen and water molecules in the pores work as the cathode:

The unstable Fe(OH)2 will have a further reaction:

Fe(OH)3 forms iron oxides in the presence of oxygen, which adhere to the surfaces of the coatings [29,30].

Meanwhile, with the increase in pH, the

At the same time, Mg2+ in the solution reacts with oxygen to form MgO, which then combines with Fe2O3 to form MgFe2O4 with a spinel structure.

The back-and-forth cycles of the above reactions form an autocatalytic process of the occluded corrosion cell, and the progress of such corrosion is the result of a combination of chemical and electrochemical interactions.

5 Conclusion

In this work, we have studied the corrosion properties of coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying of 316L metal wires in oil–water system and obtained the following results:

Electrical explosion spraying method can refine the grains in the obtained coatings. The grain size of the coating structure is 150–300 nm after electrical explosion spraying, while the grain size of the original structure is 15–20 μm.

The bonding force between the coatings and the substrates can reach 48 MPa by electrical explosion spraying of 316L metal wire.

CaCO3, Fe3O4, and MgFe2O4 are generated in an oil–water corrosion test of coatings prepared by electrical explosion spraying of 316L metal wire at a temperature of 60°C for 168 h, with the corrosion rate being about 0.079 mm/annum.

The preparation of coatings by electrical explosion spraying can generate oxides, which are mostly distributed near the grain boundaries. The presence of these oxides is the main factor accounting for the corrosion of coatings.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the reviewer’s valuable comments that improved the manuscript.

-

Funding information: This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 11521062) and State Key Laboratory of Explosion Science and Technology, Beijing Institute of Technology (Grant No. QNKT21-7).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Li X, Zhang D, Liu Z, Li Z, Du C, Dong C. Materials science: Share corrosion data. Nature. 2015;527(7579):441–2.10.1038/527441aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Loto RT. Localized corrosion susceptibility of 434 ferritic stainless steel in acid chloride media. Mater Sci Forum. 2022;1059:1059–34.10.4028/p-36uwatSearch in Google Scholar

[3] Hou B, Li X, Ma X, Du C, Zhang D, Zheng M, et al. The cost of corrosion in China. npj Mater Degrad. 2017;1(5779):4.10.1038/s41529-017-0005-2Search in Google Scholar

[4] Kim H, Yang HJ, Kim J, Cho WJ, Hwang W, Ann KY. Corrosion Behavior of Steel in Mortar Containing Ferronickel Slag. ACI Mater J. 2022;119(2):10–28.10.14359/51734351Search in Google Scholar

[5] Kong Z, Jin Y, Sabbir Hossen GM, Hong S, Wang Y, Vu QV, et al. Experimental and theoretical study on mechanical properties of mild steel after corrosion. Ocean Eng. 2022;246(246-Feb.15):110652.10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.110652Search in Google Scholar

[6] Feng L, Li S, Luo H, Zhao X. Study on the oxidisation behaviour of particles during thermal spray process. Mater Res Innov. 2016;19(13):806–11.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Vardelle A, Moreau C, Themelis NJ, Chazelas C. A perspective on plasma spray Technology. Plasma Chem Plasma Process. 2015;35:491–509.10.1007/s11090-014-9600-ySearch in Google Scholar

[8] Roohi AH, Mirsadeghi A, Sadooghi A. Investigation of structural, mechanical, and corrosion properties of steel 316L reinforcement by hBN and TiC particles. Mater Res Express. 2022;9:065006. IOP Publishing Ltd.10.1088/2053-1591/ac6d4aSearch in Google Scholar

[9] Furnberg CM. Computer modeling of detonators. Proceedings of the 1994 37th Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems; 1994.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Shicheng W, Binshi X, Haidou W, Guo J. Development and key technology analysis of electrothermal explosive spraying. China Surf Eng. 2008;21(4):8–13.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Jia-zhi Y, Zhong-yang L. Research progress of electro-explosive spraying technology to prepare coating on material surface. Mater Guide. 2008;22(2):82–9.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Tkachenko SI, Barishpoltsev DV, Ivanenkov GV, Romanova VM, Ter-Oganesyan AE, Mingaleev AR, et al. Analysis of the discharge channel structure upon nanosecond electrical explosion of wires. Phys Plasmas. 2007;14:123502.10.1063/1.2817961Search in Google Scholar

[13] Kotov YA. Electric explosion of wires as a method for preparation of nanopowders. J Nanopart Res. 2003;5:539–50.10.1023/B:NANO.0000006069.45073.0bSearch in Google Scholar

[14] Huang K, Song Q, Chen P, Liu Y. Preparation and performance of Mo/Cu/Fe multi-layer composite coating with staggered spatial structure by electro-explosive spraying technology. Materials. 2022;15(10):3552.10.3390/ma15103552Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Gryaznova E, Pustovalov A. Iron nanoparticle production by the method of electric explosion of wire. Micro Nanosyst. 2022;14(1):14–58.10.2174/1876402913666210126144945Search in Google Scholar

[16] Han F, Zhu L, Liu Z, Gong L. The study of refractory Ta10W and non-refractory Ni60A coatings deposited by wire electrical explosion spraying. Surf Coat Technol. 2019;374:44–51.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2019.05.065Search in Google Scholar

[17] Zhou H, Wang X, He C, Li Z, Zhu L. Tantalum coatings deposited on Ti6Al4V alloy by self-designed wire electrical explosion spraying. J Therm Spray Technol. 2022;31(3):636–43.10.1007/s11666-022-01333-zSearch in Google Scholar

[18] Glazkova EA, Bakina OV, Rodkevich NG, Mosunov AA, Vornakova EA, Chzhou VR, et al. Copper ferrite/copper oxides (I, II) nanoparticles synthesized by electric explosion of wires for high performance photocatalytic and antibacterial applications. Mater Sci Eng B Solid-State Mater Adv Technol. 2022;283:115845.10.1016/j.mseb.2022.115845Search in Google Scholar

[19] Mizusako F, Tamura H, Horioka K, Harada K. Zr-O-B ceramics/Ni-20%Cr alloy graded coating produced by electrothermal explosion spraying. Surf Coat Technol; 2004;187(2–3):257–64.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2004.02.031Search in Google Scholar

[20] Padgurskas J, Snitka V, Jankauskas V, Andriušis A. Selective transfer phenomenon in lubricated sliding surfaces with copper and its alloy coatings made by electro-pulse spraying. Wear. 2006;260(6):652–61.10.1016/j.wear.2005.03.033Search in Google Scholar

[21] Romanov D, Moskovskii S, Konovalov S, Sosnin K, Gromov V, Ivanov Y. Improvement of copper alloy properties in electro-explosive spraying of ZnO–Ag coatings resistant to electrical erosion. J Mater Res Technol. 2019;8(6):5515–23.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Pu ZL, Yang K, Liu ZD, Xu L. Experimental Study on Wire Explosion Directional Spraying. 2004 International Thermal Spray Conference and Exposition (ITSC 2004); 2004. p. 670–2.10.31399/asm.cp.itsc2004p0670Search in Google Scholar

[23] Romanov D, Moskovskii S, Konovalov S, Sosnin K, Gromov V, Ivanov Y. Improvement of copper alloy properties in electro-explosive spraying of ZnO–Ag coatings resistant to electrical erosion - ScienceDirect. J Mater Res Technol. 2019;8(6):5515–23.10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.09.019Search in Google Scholar

[24] Dajun C, Fu C. Applied chemistry of oil and gas fields. 2nd edn. Beijing: Petroleum Industry Press; 2015. p. 467–93.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Zhiyong L, Xiaogang L, Cuiwei D. Evaluation method of corrosion experiment for oil and gas fields with typical materials. Beijing: Science Press; 2016. p. 86–93.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Fengping W, Wanli K. Principle, method and application of corrosion electrochemistry. Beijing: Chemical Industry Press; 2008. p. 12–118.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Jinshan Z. Principle of liquid metal forming. Beijing: Chemical Industry Press; 2011. p. 170–1.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Lin H, Guo X, Song K, Feng J, Li S, Zhang X. Synergistic strengthening mechanism of copper matrix composite reinforced with nano-Al2O3 particles and micro-SiC whiskers. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10(1):62–72.10.1515/ntrev-2021-0006Search in Google Scholar

[29] Jing X, Ping D, Jun G, Zhao Y. First-principles study on corrosion of austenitic stainless steel in liquid lead-bismuth medium. Sci Technol Innov. 2022;44(10):53–6.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Pu Y, Lifeng H, Huayun D, Xiaoda L, Jianwen J, Yang L, et al. Study on NaCl corrosion behavior of new austenitic stainless steel at high temperature. Chin J Corros Prot. 2022;42(2):288–94.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Gazrati IB, Vansinvin NZ, Nefedov AN. Study of the rate of corrosion of steel 20 in the presence of increased content of organic chlorinous compounds in oil. J Appl Solut Chem Modeling. 2022;11(11):11–4.10.6000/1929-5030.2022.11.01Search in Google Scholar

[32] Saraireh S, Altarawneh M, Tarawneh M. Nanosystem’s density functional theory study of the chlorine adsorption on the Fe(100) surface. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10(1):719–27.10.1515/ntrev-2021-0051Search in Google Scholar

[33] Mingxian Z. Study on intergranular corrosion and grain boundary characteristic distribution optimization of 316L(N) austenitic stainless steel. Beijing: University of Science and Technology Beijing; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Kesheng W. Study on Corrosion and Corrosion-Fatigue Properties of AISI 304L Austenitic Stainless Steel by Plasma-based Low Energy Nitrogen Ion Implantation. Dalian: Dalian University of Technology; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Xiaomei W, Fangrong L, Zhang Y, Aiying C, Deng P. Research progress on corrosion mechanism of nano/ultra-fine grained austenitic stainless steel. Corros Prot. 2014;35(11):1069–73.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery

- The progress of cathode materials in aqueous zinc-ion batteries

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part I

- Effect of polypropylene fiber and nano-silica on the compressive strength and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete

- Mechanochemical design of nanomaterials for catalytic applications with a benign-by-design focus

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery

- The progress of cathode materials in aqueous zinc-ion batteries

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part I

- Effect of polypropylene fiber and nano-silica on the compressive strength and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete

- Mechanochemical design of nanomaterials for catalytic applications with a benign-by-design focus