Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

-

Nurul Huda Abd Kadir

and Mahboob Alam

Abstract

The goal of this work was to assess the cytotoxicity, chemical characteristics, thermal stability, and antioxidant activity of green-synthesized MgO nanoparticles (MgO NPs) produced from pumpkin seed extract for their potential therapeutic implications in cancer treatment. The shape, chemical properties, and thermal stability of MgO NPs made with green synthesis were looked at with Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopic analysis, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopic (TEM) imaging, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), ultraviolet-visible, X-ray diffraction (XRD), and thermogravimetric analysis. Three cell lines, HCT-116, HT29, and Vero, were used to test the cytotoxicity of MgO NPs. The AlamarBlue® assay was used for HCT-116 and Vero cells, and the Neutral Red (NR) Uptake Assay was used for HT29 cells. A molecular docking study was done to find out how MgO nanoparticles and cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), a protein linked to cancerous cells growing out of control, interact. The morphological properties, size, aggregation, shapeless pores, and high surface-to-area volume ratio of biosynthesized MgO NPs were shown using SEM and TEM imagings. The elemental composition of Mg and O in green-synthesized MgO NPs was validated using EDX. The AlamarBlue® assay did not yield IC50 values for HCT-116 and Vero cells, suggesting minimal cytotoxicity in these cell lines. However, the NR Uptake Assay showed an IC50 of 164.1 µg/mL for HT29 cells, indicating a significant impact. The DPPH experiment revealed that MgO nanoparticles had high antioxidant activity, with a scavenging capacity of 61% and an IC50 of 170 μg/mL. In conclusion, MgO nanoparticles produced utilizing green chemistry demonstrated a wide range of biological features, including antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity against three cell lines. According to molecular docking studies, these nanoparticles may interact with CDK2, a protein implicated in cancer cell growth. These findings emphasize MgO nanoparticles’ potential for cancer treatment. However, further study is needed to understand the underlying processes and investigate therapeutic applications.

1 Introduction

Cancer is a devastating medical condition characterized by uncontrolled growth and genetic mutations in cells, leading to the formation of tumors and interference with normal cellular function [1,2]. It is the second leading cause of death worldwide after heart disease, with an estimated 10 million deaths recorded in 2020 [3,4]. Breast cancer and colorectal cancer are among the most common types of cancer in Malaysia in 2021 [5]. Despite the availability of commercial anticancer drugs, there is still a need for better therapies. This is necessary because of the drawbacks of existing medications, which include things like high toxicity, restricted solubility, decreased stability, and a lack of selectivity [6]. As an example, it is worth noting that methotrexate has the potential to induce significant adverse effects, such as renal impairment [7], whereas paclitaxel encounters challenges associated with inadequate absorption [8]. Moreover, a multitude of currently available medications exhibit little efficacy in treating diverse forms of cancer. The lack of selectivity in current chemotherapeutic drugs also requires the use of pharmaceutical carriers to deliver drugs to cancer cells, further complicating their efficacy and safety [9]. In response to global concerns and the need for sustainability, the United Nations has introduced the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which encompass 17 goals aimed at promoting political, scientific, economic, and sociological reform [10]. The 13th goal of the SDGs focuses on combating climate change and its impacts, such as rising global temperatures and sea levels. As part of this goal, it is imperative to explore environmentally friendly approaches to drug production, including green synthesis, which aims to reduce toxic waste, minimize energy consumption, and utilize ecological solvents [11,12]. Green synthesis has been widely applied in the field of nanotechnology to produce nanoparticles from sustainable sources such as yeast, fungi, bacteria, and plants, with potential applications in anticancer medications due to their precision in targeting antigens and activating immune cells [13,14]. Magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgO NPs) have shown favorable properties in biomedical applications, including antimicrobial activity, antioxidant activity, and use as a health supplement for indigestion, heartburn, and stimulant laxatives [15,16]. Magnesium oxide nanoparticles have been widely explored in numerous sectors due to their unique features and prospective uses. MgO NPs increase agricultural yield and sustainability in agriculture by improving plant growth and biochemical parameters. MgO NPs-containing resin cement has shown antibacterial activity and enhanced physical qualities, making it efficient at controlling bacteria and biofilm near prosthesis margins. MgO NPs may be beneficial in medicinal applications in addition to their bactericidal effect against both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. In thermal management and renewable energy systems, nanofluids containing MgO nanoparticles demonstrated higher thermal characteristics and improved heat transfer qualities. Because of their antimicrobial qualities, MgO nanoparticles have also been employed in medicine, water purification, catalysis, and gas sensors. They have been investigated for possible use in membrane applications, food packaging, sensors, and supercapacitors, in addition to membrane applications. Recently, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) containing ZnO and a carbon shell have aroused the curiosity of photocatalysis researchers. This interest stems primarily from the novel properties and potential applications that arise from this synergistic combination [17]. Previous research has demonstrated the potential of MgO NPs as antimicrobial agents against S. aureus, as evidenced by an increase in dead cell concentration over time [18]. However, their potential as anticancer agents has not been fully explored. Cancer, being a disease characterized by uncontrolled cell proliferation and genetic mutations, poses a significant global health challenge. It is estimated that by 2025, there will be an increase of over 20 million new cancer cases annually [19]. Although chemotherapy and radiation therapy are commonly used in cancer treatment, they often come with undesirable side effects such as diarrhea, mucositis, peripheral neuropathy, xerostomia, and sexual dysfunction [20,21]. Therefore, the field of nanotechnology, specifically the production of nanoparticles as cytotoxic agents, has gained increasing attention due to their potential for selective toxicity. The use of plant extracts represents the prevailing approach in the synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles (NPs). Algae, fungi, and bacteria are utilized less frequently for this particular objective. Table 1 presents a comprehensive overview of the many plant species that have been employed in the synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgO NPs), along with the corresponding impacts of these plants on the size and shape of the nanoparticles.

Comparison between cytotoxicity and antioxidant activity of MgO NPs obtained from different parts of natural product extracts

| S. no | Name of nanomaterials | Species | Cytotoxicity/antioxidant activity | Shape/size | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | MgO NPs | Saussurea costus biomasses | MCF-7 breast cancer cells | 34–30 nm, cubic | [22] |

| 2. | MgO NPs | Ajwain (Trachyspermum ammi) | Antioxidant | 78.48 nm | [23] |

| 3. | MgO NPs | Pumpkin seed extract | Cytotoxicity | Spherical, 100 nm | [24] |

| 4. | MgO NPs | Abrus precatorius bark extract | Antioxidant/cytotoxicity | 100 nm/irregular | [25] |

| 5. | MgO NPs | Piper nigrum | Antioxidant | 20 nm/rod-shaped | [26] |

| 6. | MgO NPs | Sargassum wightii | Anticancer | 68.06 nm | [27] |

| 7. | MgO NPs | Melia azedarach seed extract | Antioxidant | Spherical 73.29–62.4, and 44.29 nm | [28] |

| 8. | MgO NPs | Date pits/plants | Anticancer/antioxidant | Spherical, 23.4 nm | [29] |

| 9. | MgO NPs | Cystoseira crinita | Cytotoxicity | Spherical, 3–18 nm | [16] |

| 10. | MgO NPs | Moringa oleifera | Cytotoxicity assessment | Irregular, 100–200 nm | [30] |

| 11. | MgO NPs | Pumpkin seeds extract | Antioxidant/cytotoxicity | Spherical, 50–100 nm | Present work |

Green production of bio-inspired magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgO NPs) and better characterization techniques are examples of significant breakthroughs in antioxidant agents. MgO NPs are made in an ecologically friendly way by using plant extracts as dual reducing and capping agents. Because of their small size, increased surface area, and unique surface chemistry, these bio-inspired MgO NPs have antioxidative potential. The use of characterization approaches such as ultraviolet-visible (UV–Vis) spectrum, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) leads to a thorough understanding of the structure and properties of MgO NPs. More research is needed to understand the unique properties of green MgO NP synthesis for antioxidant applications. The current investigation involved the synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles with bioinspiration, utilizing an aqueous extract derived from pumpkin seeds. The confirmation of nanoparticle production, as well as the determination of their shape, size, geometry, and stability, was achieved by the utilization of modern analytical techniques including UV–Vis spectroscopy, FTIR, X-ray diffraction (XRD), SEM with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX), transmission electron microscopy with selected area electron diffraction (TEM-SAED), and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). The nanoparticles that were generated were employed to assess the cytotoxicity against HCT116 and HT29 cell lines, as well as normal cell lines, utilizing the Alomar blue test and the NRU cytotoxicity assay. Docking research was conducted to investigate the interaction between magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgO NPs) and cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), a crucial factor in understanding the inhibitory mechanism of CDK2 in cancer cells. Furthermore, the DPPH experiment was conducted in order to validate the antioxidant capacity of biogenic nanoparticles, with a comparative analysis conducted using ascorbic acid as the reference medication. The results obtained in this study have the possibility of helping improve the nanoparticle production technique and its use in the field of pharmacology.

2 Material and methods

Accutase, Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), and RPMI 1640 were purchased from Nacalai Tech, Japan. However, Penicillin–streptomycin and phosphate buffer saline (PBS) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, UK. 70% ethanol, Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and Deionized water were purchased from Merck, USA. Apparatus used were T-25 cell culture flasks, 5 and 10 mL serological pipettes, micropipettes, micropipette tips, 15-mL falcon tubes, 50-mL centrifuge tube, 1 mL cryovials, Class II biohazard cabinet, inverted microscope, −80 and −20°C freezer, 4°C refrigerator, centrifuge and humid CO₂ incubator.

2.1 Preparation of pumpkin seed extract

A powder form of the sample was obtained by grinding and drying process of 5.0 g pumpkin seeds. The powdered-form sample was then condensed in 75 mL of deionized water in a 250-mL round bottom flask for 1 h under reflux. The solution was cooled and filtered using Whatman filter paper to produce the extract. The filtered sample was stored in a cold place until it was used.

2.2 Biosynthesis of MgO NPs

A mixture of 20 mL of pumpkin seed extract mixed with 80 mL of Mg (NO3)2 (aqueous, with 0.1 M concentration) was prepared and stirred using continuous magnetic stirring at a temperature range of 60–80°C for 4 h. The brownish solution was centrifuged for ten minutes at 10,000 rpm, then oven-dried (50–60°C), and calcinated (500°C). White-colored fine powder of MgO NP was obtained and was kept until further use.

2.3 Characterization of MgO NPs

FTIR spectroscopy study was done using FTIR-ATR to evaluate the functional group present in MgO NPs. The spectra of FTIR-ATR will give fingerprinting of the chemical characterization of the MgO NPs. The MgO NPs sample was crushed and compressed into the KBr pellet and the spectra of the was recorded in the range between 400 and 4,000 cm−1. The morphological characterization of green synthesized MgO NPs was observed using a TESCAN VEGA Microscope. A small amount of sample was fixed on a carbon stud and coated with a thin line of gold by an auto fine coater. The SEM study was carried out under X7000 magnification, and EDX analysis was done in the range of 0–10 keV of electrons to evaluate the presence of elements in the samples. The size and shape of the biogenic nanoparticles were also investigated through the utilization of TEM with integrated selected area electron diffraction (SAED) on a JEM-2100 TEM instrument. The pellets were dispersed again in sterile double-distilled water for 10 min, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. After air drying at 50°C in an oven, the pellets were analyzed using XRD with a Cu–Kα radiation source on a Pan Analytical X-pert Pro instrument from the Netherlands. The instrument was operated at a voltage of 45 kV and a current of 40 mA, with a 2θ scan range of 20–80°. The average crystallite size of MgO nanoparticles was determined using Scherrer’s equation, which takes into account the line broadening (β) of the peak in radians, the X-ray wavelength (λ), the Braggs angle (θ), and a constant (K) with a geometric factor of 0.94 [D = (Kλ/βcosθ)].

The UV–vis spectrum of the MgO NPs that were synthesized was analyzed using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UV-2450, Shimadzu, Japan) with a resolution of 1 nm. The spectrum was measured in the range of 200–800 nm to study the conversion of metal oxide ions to metal oxide nanoparticles. Double-distilled water was used as a blank reference for background correction.

2.4 Molecular docking

The molecular docking study investigated the interaction between nanoparticles and the CDK2 enzyme receptor (PDB ID: 6GUE), which was downloaded from the RCSB PDB. The complexation of the ligand (4-(1-isopropyl-2-methyl-1H-imidazol-5-yl)-N-(4-(methylsulfonyl)phenyl)pyrimidin-2-amine) with the active amino acids of the receptor revealed the location of the receptor’s active site. Before docking, the receptor was prepared by removing heteromolecules and water molecules from the protein using Discovery Studio [31]. The MgO nanoparticles were constructed using the crystallographic information of MgO with Material Studio. The constructed structure of MgO nanoparticles was minimized, optimized, and dynamically simulated using a COMPASS (condensed phase optimized molecular potential for atomistic simulation) force field to determine the proper packing and orientation of MgO nanoparticles in the geometric structure, and was saved in pdb format. To obtain the docking results, the prepared receptor and the energy-minimized structure of MgO nanoparticles were added to MGLTools at the interface of Autodock 4.0 [32, 33]. The best docking model from the results was then used to study the interaction analysis between amino acids and nanoparticles using Discovery Studio.

2.5 Thermal and stability analysis of magnesium oxide nanoparticle, MgO NP

2.5.1 TGA

The thermal stability of MgO NP was assessed using TGA analysis. TA 2050 instrument was used. The sample was placed in the platinum crucible inside the instrument and the analysis was conducted in a nitrogen environment with a temperature range between 20 and 800°C, with 10°C/min of heating temperature.

2.6 Cytotoxicity test

In our laboratory, we assessed the cytotoxicity of the HCT116 and Vero cell lines using the Alamar blue assay. For the HT29 cell line, the cytotoxicity was determined using the Neutral Red Uptake (NRU) assay in a professional laboratory. Both assays are commonly used to evaluate the toxicity of chemical compounds and drugs on cell viability. The results obtained from these assays will help us better understand the potential effects of the tested substances on human health and inform future research directions.

2.7 Alamar blue assay

2.7.1 Sample preparation for cytotoxicity test

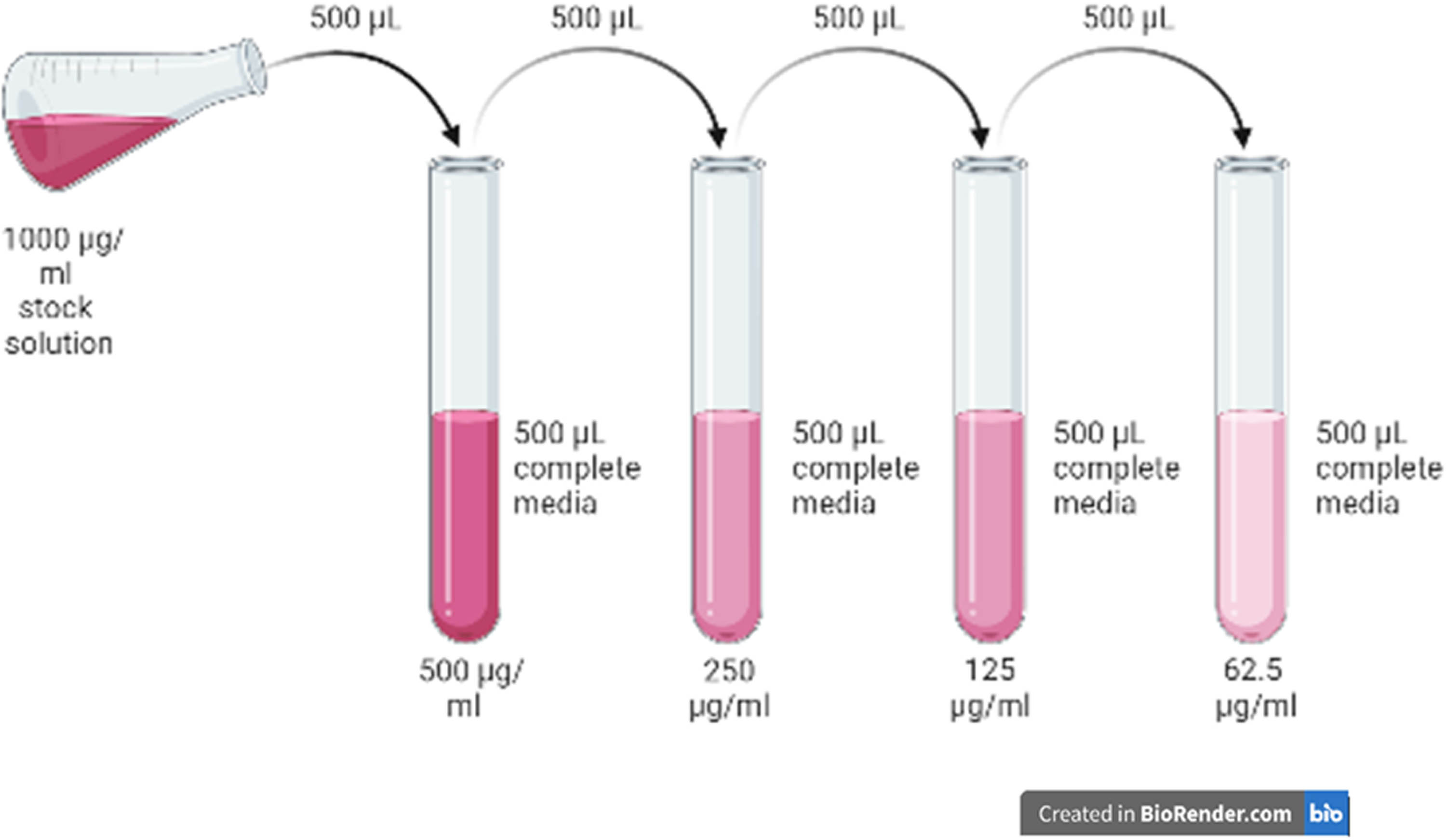

Different concentration of MgO NPs (1,000, 500, 250, 125, and 62.5) µg/mL was prepared via two-fold dilution (Figure 1). A 1,000 µg MgO NPs sample was diluted with 1 mL of double distilled water to produce a 1,000 µg/mL stock solution. About 500 µL of stock solution was diluted with 500 µL of RPMI 1640 media, producing a diluted MgO NP to a concentration of 500 µg/mL. The steps were repeated three times to give rise to (250, 125, and 62.5) µg/mL of solution.

Two-fold dilution of pumpkin seed-derived MgO NPs.

2.8 Preparation of media chemical solutions for cell culture

2.8.1 Preparation of complete media (RPMI 1640)

About 50 mL of FBS and 5 mL Pen–Strep Penicillin–Streptomycin were added to an empty sterile bottle containing 500 mL of RPMI 1640 media. The prepared media was stored in a refrigerator at 4°C.

2.8.2 Preparation of phosphate buffer saline (PBS)

Two PBS tablets (Sigma Aldrich, USA) were added to an empty sterile bottle containing 400 mL of deionized water. The PBS solution was priorly autoclaved before being stored in a refrigerator at 4°C.

2.8.3 Preparation of cryopreservation chemical

DMSO (0.1 mL) was mixed with media-containing cells (0.9 mL) in a cryovial tube. The solution was stored at −20°C overnight and −80°C until future use.

2.9 Cell culture

2.9.1 Cell thawing

Cryopreserved HCT 116 and Vero cells were thawed from a −80°C freezer. The thawed cells were transferred from the cryovial into 15-mL centrifuge tubes with 2 mL of RPMI 1640 media. The cells were centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant obtained was taken out, and the pellet was suspended with 1 mL of RPMI 1640 media. The cells were incubated in a CO2 incubator until the cells achieved 90% confluency.

2.10 Neutral red (NR) uptake assay

This can determine the rate of cell growth inhibition using this assay, which relies on the ability of living cells to absorb red dye in their lysosomes, while dead or damaged cells are unable to do so [34]. To begin the experiment, cells were seeded into 96 plates at a density of 5,000–8,000 cells per well and cultured in a DMEM medium containing 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic solution. The cells were then incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h, after which fresh culture medium was added to each well. Treatment dilutions (5 µL) with varying concentrations were added to the designated wells, and the treated plates were incubated for an additional 24 h. Next, 100 µL of NRU (dissolved in PBS at a concentration of 40 µg/mL) was added to the assigned wells and incubated for 1 h. After removing the medium, NRU was dissolved in 100 µL of NRU-destained solution, and the plates were read at 550/660 nm.

2.11 DPPH radical scavenging assay

The antioxidant activity of the sample was determined using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical assay. In the antioxidant study, in the first step, 0.06 mM DPPH reagent was prepared before 24 h to protect it from sunlight. Methanol was used as blank and ascorbic acid as standard. Then, 3 mL of methanol was added to each of the test tubes, and different concentrations of the test sample obtained by twofold serial dilution (25, 50, 100, 200, and 400 μg/mL) were added and mixed thoroughly. To this, 0.5 mL of DPPH was added in the dark and incubated for 30 min [35]. The antioxidant activity of the sample was calculated at 517 nm as a percentage of the decolonization of DPPH, and this value is referred to as the radical scavenging activity (RSA), using the following equation:

where Abcontrol is the absorbance of the DPPH solution and Absample is the absorbance of the DPPH solution in a sample.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Characterization of MgO NPs

3.1.1 FTIR

FTIR was done to evaluate the compounds and chemical bonds contained in the MgO NPs sample. The sample was observed in the range between 400 and 4,000 cm−1. Figure 2 demonstrates the peak obtained at 668 cm−1 was due to the vibrating interaction between the magnesium and oxygen bond (Mg–O). The bonds observed at 3,374 and 1,137 cm−1 were caused by the OH group and carbonate ion vibration (C–O), respectively. The presence of a band corresponding to the alcohol group (OH) in the sample was due to phytochemicals that act as the capping agent to stabilize the nanoparticle [36]. Similar findings were obtained from an FTIR analysis of MgO NPs synthesized from leaf extract of Annona muricata where the peaks obtained in the range 3,440–3,450 cm−1 were due to −OH group stretching, while bands in the 588–694 cm−1 area were due to stretching vibration of Mg–O bond [37].

FTIR Spectrum of pumpkin seed-derived MgO NPs.

The FTIR analysis substantiated the involvement of bioactive compounds as agents for reducing, capping, and stabilizing the biosynthesis of MgO NPs. The FTIR spectrum showed similarity and agreement with previous studies reported by Pugazhendhi et al. [27], Amina et al. [22], and Fouda et al. [16]. The proposed mechanism for the biosynthesis of MgO NPs is explained in Scheme 1 based on literature reviews and IR spectrum analysis, indicating the plant extract plays a reducing and capping role in green synthesis approaches (Scheme 1a). Phytochemicals in the extract bind to Mg2+ ions results in particle growth via coalescence or Ostwald ripening. Secondary metabolites, possibly phenolic compounds (Scheme 1b) present in the extracts, reduce magnesium ions. This reduction in magnesium ions causes the particles to cluster. The amount of MgO salt consumed and the extracted biomolecules affect the particle size as explained in the literature [38]. The presence of bioactive substances in the extract, particularly phenolic compounds that have a role in the reduction and capping of metal (Mg2+) into nanoscale metal particles (Mg0), was emphasized and corroborated by a gas chromatography mass spectroscopy (GC-MS) analysis [39].

Proposed mechanism for the biosynthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgO NPs) from seed extracts: (a) various bioactive compounds in the extract of pumpkin seeds, and (b) possible bioactive compound participating in reducing and capping nanoparticles.

3.1.2 SEM-EDX

To confirm the element observed in the previous FTIR analysis is presented in the sample, SEM-EDX analysis was done. SEM was done to identify the surface morphology of the green-synthesized MgO NPs while EDX was done to determine its elemental composition. Figure 3 illustrates the morphological characteristics of MgO NPs where there were agglomerations, the presence of shapeless pores, and a large surface-to-area volume ratio observed. This surface characteristic possessed by the MgO NPs is useful in anticancer studies as they help in catalysis applications, defined as the usage of a catalyst to speed up a chemical reaction by reacting with the surrounding substrates or reagents [40,41]. The same morphological characteristics were observed with a green-synthesized MgO NP derived from P. marsupium heartwood extract where the nanoparticles illustrate a large surface area-to-volume ratio with the presence of clumped clusters [42].

(a) SEM of pumpkin seed-derived MgO NPs and (b) EDX of pumpkin seed-derived MgO NPs.

Distinct peaks in the EDX spectrum are important as they determine the quality of the produced nanomaterials [24]. Figure 4 presents the EDX analysis observed in the range of 0–10 keV of electron illumination. Magnesium element presented a distinct peak at 1.25 keV with the highest elemental percentage (56.53%). Meanwhile, oxygen showed a peak at 0.5 keV with an elemental percentage of 43.47, Similar findings of green-synthesized MgO NPs derived from Costus plant, Saussurea costus, observed a prominent peak of Mg and O with an average elemental percentage mass of 85.23 and 38.15, respectively [22].

The scale bar in (a) represents 50 nm of a TEM micrograph of the biosynthesized MgO NPs, and (b) the SAED pattern of the MgO NPs.

3.1.3 TEM and SAED patterns

The size and shape of the biogenic MgONPs were investigated using TEM. TEM images in Figure 4a revealed that MgO NPs are polydispersed, spherical in shape, and range in size from 25 to 40 nm. The single-crystalline nature of the nanoparticles was further confirmed by the TEM micrograph. The analysis showed that MgO NPs exhibit a wide range of sizes at the nanoscale, with the majority of particles being spherical and having an average diameter of less than 50 nm.

The SAED pattern of biogenic MgO NPs, as shown in Figure 5b, confirms the crystalline nature of the synthesized nanoparticles, resembling a polycrystalline metallic oxide. The diffraction rings in the SAED pattern can be indexed to a hexagonal MgO phase, which is consistent with the XRD study. The nanoparticles exhibit a high surface area-to-volume ratio and are uniformly distributed throughout the sample.

(a) UV–Vis spectrum of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles and (b) XRD pattern with reference.

3.1.4 UV–Vis spectroscopy and XRD analyses

The structural properties of the nanoparticles were analyzed by UV–vis spectroscopy. According to Figure 5a, single-surface plasmon resonance bands have been found at low wavelengths (265 nm), indicating the appearance of nanosized particles. It corresponds to the MgO nanosphere dipole resonance. The outcome of UV–Vis demonstrates that the reductive biomolecules in the pumpkin seed extract were capable of bio-reduction, resulting in the formation of MgO NPs. Therefore, we assume that such compounds in pumpkin seed extracts are highly likely to exhibit important organic capping and reducing agents, engaging in the biosynthesis of MgO NPs.

The XRD diffraction pattern of the magnesium oxide nanoparticles, synthesized using pumpkin seed extract, revealed a crystalline structure and diffractogram as shown in Figure 5b. The diffraction pattern exhibited peaks at 2θ values of 37.02, 42.94, 62.38, 74.68, and 78.78, corresponding to the refractive planes (111), (200), (220), (311), and (222), respectively. These peaks were indexed to five significant peaks and matched those in the standard reference file (JCDPS file no. 78-0430), indicating the formation of a hexagonal MgO phase [43]. The average crystalline size (D) of nanoparticles can be calculated using the Debye–Scherrer equation. A simple equation to calculate D is: D = Kλ/Bcosθ. Using a high-intensity Bragg peak, the nanoparticles were estimated to have a crystalline size of 20.093 nm.

3.2 Thermal analysis of MgO NPs

3.2.1 TGA

TGA Analysis was done to determine the thermal stability of the green synthesized MgO NPs by observing their weight loss over exposure to temperature in a certain period. TGA Analysis conducted in a nitrogen environment (temperature range, 20–800°C; 10°C/min of heating temperature) resulted in three stages of decomposition at 48.5–160, 250–490, and 490–900°C as presented in Figure 6. In the first stage of decomposition at 48.5–160°C, 5.7% weight loss occurred due to evaporation of the hydrogen molecule together with the oxygen molecule. In the second stage of decomposition at 250–490°C, 18.7% mass reduction occurred due to the crystallization of MgO NPs. Similarly, two steps of MgO NPs derived from Camellia sinensis extract were obtained, which were at 43.39–157.27 and 309.84–475.24°C and occurred due to water dehydration and formation of MgO via the decomposition process of organic moieties, respectively [44]. The third stage of weight loss occurred at 490–900°C, with 23.17% weight reduction occurring due to the phase transition of MgO [36].

MgO nanoparticle TGA analysis with a temperature range of 20–900°C, weight losses of MgO NPs were seen in an oxygen atmosphere at a heating rate of 10°C/min (the graph displays the percentage of weight reduction for Steps A, B, and C).

3.3 Alamar blue assay analysis

Based on the characterization analyses done via FTIR, SEM-EDX, and TGA, we confirmed that the nanoparticle sample obtained was MgO NPs. However, the AlamarBlue® assay was conducted to study the potential of pumpkin seed-derived MgO NPs as an anticancer agent. Pumpkin seed-derived MgO NPs showed negligible cytotoxicity effect on HCT116 cancer cells as no IC50 level was reached after both 24 and 48 h of treatment, as illustrated in Figure 7(a). Similarly, MgO NPs treated on HCT116 human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line did not cause any significant alteration of cell number [45]. In this experiment, cells were treated via a sequential seeding method, where cells were seeded and then incubated first for 24 h prior treatment with different concentrations of MgO NPs, instead of the co-seeding method that involves simultaneous treatment of MgO NPs during the seeding procedure. Thus, there was a potential for negligible cytotoxicity effects of MgO NPs on the cells observed were influenced by the chosen sequential seeding method, as MgO NPs showed a lower toxicity effect on the sequential seeding method than the co-seeding method [46].

Percentage viability (%) of (a) HCT 116; (b) Vero cells after being treated with different concentrations of MgO NP (6.25–100 μg/mL) at 24 and 48 h. Measurement of AlamarBlue® reduction level was performed fluorometrically at 570 nm (excitation) and 590 nm (emission) wavelength. One-way ANOVA (Dunnet post-test) was done.

Based on our results in Figure 7(b), a negligible effect was found in normal cell treatment, implying that selective cytotoxicity events occurred on normal cells after both 24 and 48 h of treatment. It is suggested that MgO NPs can be toxic to normal cells, but with exposure of higher concentration than 100 μg/mL as reported by other journals [47,48]. Overall, the results obtained in both Figure 7(a) and (b) illustrated that the HCT116 and Vero cell lines were neither dose-dependent nor time-dependent toward our pumpkin seed-derived MgO NP samples.

3.4 NRU cytotoxicity assay analysis

The NRU colorimetric assay was used to determine the cytotoxicity of NPs synthesized via the green method. The assay is based on the ability of viable cells to incorporate neutral red into lysosomes [49]. The concentration-dependent cytotoxicity of biogenic nanoparticles was assessed by observation. The level of cytotoxicity was determined by the extent of reduction in the uptake of neutral red observed after NP exposure. This reduction is an indicator of impaired cell growth and integrity, and the IC50 value, which represents the concentration required to inhibit 50% of cell growth, was also determined using this assay. The results in Figure 8a demonstrate that the viability of HT29 cells decreased with increasing concentrations of NPs compared to untreated control cells (DMSO). All concentrations of NPs (ranging from 1 to 1,000 µg/mL) inhibited the growth of HT29 cells, and the number of viable cells decreased as the concentration of NPs increased. At the highest concentration (1,000 µg/mL), the number of viable cells fell below 18%. Using a dose-dependent curve (Figure 8b), the IC50 value of NPs was calculated as 164.1 µg/mL.

(a) The NRU assay depicting a dose-dependent increase in cytotoxicity in HT-29 cell lines and (b) the data presented as a percentage of viable cells compared to the untreated control cells (treated with DMSO, without MgO NPs). The estimated IC50 value was 164.1 µg/mL.

3.5 Antioxidant activity of MgO NPs

The free radical scavenging activity of drugs and extracts can often be tested using a solution of free radical DPPH in methanol. DPPH is a free radical that does not react with metal ions or enzymes, unlike laboratory-generated free radicals such as hydroxyl radicals and superoxide anions. This makes DPPH a more reliable indicator of antioxidant activity. The antioxidant activity of the biogenic nanoparticles was determined by the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical, which was reflected by the reduction of the absorbance of the DPPH methanol solution of MgO NPs. The bio-fabricated magnesium oxide nanoparticles were combined with DPPH giving strong absorbance at 517 nm with changing color from deep violet to pale yellow due to the transfer of electrons from the fabricated nanoparticles and the transformation of free radical to nonradical form. The fabricated magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgONPs) exhibited a DPPH radical scavenging reduction of 29–61% at a maximum dose of 400 μg/mL, as shown in Figure 9.

DPPH radical scavenging capacity of MgONPs at various concentrations (mean ± SD) (n = 3) applies to each value.

Figure 9 shows the relationship between the concentration of magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgONPs) on the x-axis and the corresponding DPPH radical scavenging capacity on the y-axis. The observed trend suggests that as the concentration of MgO NPs increases, so does the DPPH radical scavenging capacity. It should be noted that the IC50 (inhibitory rate reaches 50% of the DPPH radical scavenging activity) was determined to be 170 μg/mL, which is consistent with the established efficacy of the standard drug ascorbic acid as reported in the literature [50]. The antioxidant capacity of as-prepared magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgO NPs) to scavenge free radicals and reduce oxidative stress is tested. Our findings, along with those of others, reveal that MgO NPs biosynthesized from plant extracts had higher antioxidant activity than plant extracts or ascorbic acid. The electron-donating capability of magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgO NPs) can be ascribed to the existence of functional groups and chemical residues on their surface, as evidenced by Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) research. This observation is substantiated by the use of the DPPH test, wherein it was demonstrated that the magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgO NPs) exhibited the capability to convert the purple-colored DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical to its yellow-colored reduced form, DPPH-H [25,26]. These findings have important implications for understanding the potential antioxidant properties of MgO NPs and their potential applications in fields ranging from medicine to food science.

3.6 Molecular docking analysis

The molecular docking technique was employed to investigate the interaction between MgO nanoparticles and the CDK2 receptor, with the evaluation of results based on parameters such as Gibbs free energy (∆G) and the types of bonds formed with amino acid residues on the surface of the nanoparticles. The docking results of the nanoparticles with the CDK2 receptor are depicted in Figure 10. Overexpression of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), a protein involved in cell cycle regulation, contributes to uncontrolled cell proliferation. Inhibition of CDK2 is a recognized mechanism of action for several anticancer drugs. After analyzing the docking results, the most favorable docking pose with highly negative energy was chosen to visualize the interactions and the involvement of amino acids.

(a) The receptor interacting with (b) the ligand (MgO NPs), (c) the active amino acids of the receptor around MgO NPs, and (d) and (e) various nonbonding interactions between the amino acids and MgO NPs.

The lower binding energy model, which was found to be −7.5 kcal/mol, suggests a stronger affinity between the components, as it indicates an easier and more favorable interaction. The involvement of active amino acids of human cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (PDB:6GUE) is the primary factor that induces a proper orientation of the active site geometry, particularly in the region where these crucial residues (GLY27, GLU28, VAL29, GLU81, PHE82, HIS84, ASN136, THR137, and GLU138) are located. Among these residues, ASN136, THR137, PHE82, and VAL29 are directly engaged in forming hydrogen bonds with MgO NPs, making them potential interaction sites for inhibitor nanoparticles. Additionally, these amino acids also contribute to the formation of electrostatic attraction with the magnesium atoms of the nanoparticles.

4 Conclusions

In conclusion, pumpkin seed-derived MgO NPs possess a similar characteristic with other green-synthesized MgO NPs, as well as commercial MgO NPs, promising a high possibility of them being utilized in the biomedical field. The cytotoxicity of MgO NPs derived from pumpkin seeds was evaluated on normal and cancer cells, and it was found to be negligible, indicating their potential as anticancer agents. However, the effects of MgO NPs on colon adenocarcinoma cells (HT 29) were investigated, and dose-dependent cytotoxicity was observed with an IC50 dose of 164.1 µg/mL. Despite these encouraging results with HT-29, the exact mechanism of action of MgO NPs remains unclear and requires further investigation. It is worth noting that the limited amount of MgO NPs used in this study resulted in a restricted range of characterization and cytotoxicity assessment. Based on the results of the investigation, it was observed that the Alamar blue test and NRU cytotoxicity assay analyses indicate that the introduction of MgO NPs induces cytotoxicity in HCT 116 and HT 29 cells, respectively, in a way that is dependent on the dosage administered. Additionally, future studies should explore the bioactivity of MgO NPs using other cell lines and antimicrobial assays to determine their full potential. These additional experiments will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the potential of MgO NPs as a therapeutic agent. This study has also demonstrated that environmentally friendly MgO nanoparticles have strong antioxidant activity that is comparable to that of the well-known antioxidant ascorbic acid. These results imply that MgO nanoparticles could be utilized in a variety of applications as a potential antioxidant agent. More study is needed to investigate the toxicity of MgO nanoparticles and improve their production parameters to increase their antioxidant efficiency. The study concluded that bioinspired MgO nanoparticles (NPs) have promise for usage in cosmetics due to their significant anti-aging properties. Furthermore, because of their high antioxidant capacity, they have the potential to be used in cancer treatment. However, more extensive research is required to evaluate the in vitro and in vivo properties of MgO nanoparticles for possible biological applications. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that MgO nanoparticles hold promise as a reliable and harmless antioxidant treatment.

-

Funding information: This work was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2023R339) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: Nurul Huda Abd Kadir: conceptualization; methodology; investigation; validation; formal analysis. Nur Anniesa Farhana Mohd Roza: conceptualization; methodology; validation; writing – original draft. Azmat Ali Khan: conceptualization; investigation; methodology. Azhar U. Khan: resources; supervision; investigation. Mahboob Alam: validation; software; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the first and corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

[1] Martincorena I. Somatic mutation and clonal expansions in human tissues. Genome Med. 2019;11(1):35.10.1186/s13073-019-0648-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Pashaei Y, Mehrabi M, Shekarchi M. A review on various analytical methods for determination of anthracyclines and their metabolites as anti–cancer chemotherapy drugs in different matrices over the last four decades. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2020;130:115991.10.1016/j.trac.2020.115991Search in Google Scholar

[3] Ahmad FB, Anderson RN. The leading causes of death in the US for 2020. JAMA. 2021;325(18):1829–30.10.1001/jama.2021.5469Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.10.3322/caac.21660Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Teh H, Woon Y. Burden of cancers attributable to modifiable risk factors in Malaysia. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–10.10.1186/s12889-021-10412-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Elbagory AM, Marima RM, Dlamini Z. Role and merits of green based nanocarriers in cancer treatment. Cancers. 2021;13(22):5686.10.3390/cancers13225686Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Basak D, Arrighi S, Darwiche Y, Deb S. Comparison of anticancer drug toxicities: paradigm shift in adverse effect profile. Life (Basel, Switz). 2021;12(1):48.10.3390/life12010048Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Gala UH, Miller DA, Williams RO III. Harnessing the therapeutic potential of anticancer drugs through amorphous solid dispersions. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020;1873(1):188319.10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.188319Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Sivadasan D, Hadi M, Madkhali OA, Alsabei SH, Alessa AA. Stealth liposomes (PEGylated) containing an anticancer drug camptothecin: In vitro characterization and In Vivo pharmacokinetic and tissue distribution study. Molecules. 2022;27(3):1086–102.10.3390/molecules27031086Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Purnell PJ. A comparison of different methods of identifying publications related to the United Nations sustainable development goals: Case study of SDG 13—Climate action. Quant Sci Stud. 2022;3(4):1–56.10.1162/qss_a_00215Search in Google Scholar

[11] Bedlovičová Z. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using actinomycetes. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanomaterials. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. p. 547–69.10.1016/B978-0-12-824508-8.00001-0Search in Google Scholar

[12] Stone V, Johnston H, Clift MJ. Air pollution, ultrafine and nanoparticle toxicology: cellular and molecular interactions. IEEE Trans Nanobioscience. 2007;6(4):331–40.10.1109/TNB.2007.909005Search in Google Scholar

[13] Buabeid MA, Arafa E-SA, Murtaza G. Emerging prospects for nanoparticle-enabled cancer immunotherapy. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020:9624532.10.1155/2020/9624532Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Hussain I, Singh N, Singh A, Singh H, Singh S. Green synthesis of nanoparticles and its potential application. Biotechnol Lett. 2016;38:545–60.10.1007/s10529-015-2026-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Shabbir N, Hassan SM, Mughal SS, Pando A, Rafiq A. Eletteria cardamomum and greenly synthesized MgO NPs: a detailed review of their properties and applications. Eng Sci. 2022;7(1):15–22.10.11648/j.es.20220701.12Search in Google Scholar

[16] Fouda A, Eid AM, Abdel-Rahman MA, El-Belely EF, Awad MA, Hassan SE-D, et al. Enhanced antimicrobial, cytotoxicity, larvicidal, and repellence activities of brown algae, Cystoseira crinita-mediated green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:849921.10.3389/fbioe.2022.849921Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Li Y, Xia Y, Liu K, Ye K, Wang Q, Zhang S, et al. Constructing Fe-MOF-derived Z-scheme photocatalysts with enhanced charge transport: Nanointerface and carbon sheath synergistic effect. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(22):25494–502.10.1021/acsami.0c06601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Das B, Moumita S, Ghosh S, Khan MI, Indira D, Jayabalan R, et al. Biosynthesis of magnesium oxide (MgO) nanoflakes by using leaf extract of Bauhinia purpurea and evaluation of its antibacterial property against Staphylococcus aureus. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2018;91:436–4.10.1016/j.msec.2018.05.059Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Zugazagoitia J, Guedes C, Ponce S, Ferrer I, Molina-Pinelo S, Paz-Ares L. Current challenges in cancer treatment. Clin therapeutics. 2016;38(7):1551–66.10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.03.026Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Stubbe CE, Valero M. Complementary strategies for the management of radiation therapy side effects. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2013;4(4):219–31.10.6004/jadpro.2013.4.4.3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Sun CC, Bodurka DC, Weaver CB, Rasu R, Wolf JK, Bevers MW, et al. Rankings and symptom assessments of side effects from chemotherapy: insights from experienced patients with ovarian cancer. Supportive Care Cancer: Off J Multinatl Assoc Supportive Care Cancer. 2005;13:219–27.10.1007/s00520-004-0710-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Amina M, Al Musayeib NM, Alarfaj NA, El-Tohamy MF, Oraby HF, Al Hamoud GA, et al. Biogenic green synthesis of MgO nanoparticles using Saussurea costus biomasses for a comprehensive detection of their antimicrobial, cytotoxicity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells and photocatalysis potentials. PLoS one. 2020;15(8):e0237567.10.1371/journal.pone.0237567Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Dabhane H, Ghotekar S, Zate M, Kute S, Jadhav G, Medhane V. Green synthesis of MgO nanoparticles using aqueous leaf extract of Ajwain (Trachyspermum ammi) and evaluation of their catalytic and biological activities. Inorg Chem Commun. 2022;138:109270.10.1016/j.inoche.2022.109270Search in Google Scholar

[24] Tabrez S, Khan AU, Hoque M, Suhail M, Khan MI, Zughaibi TA. Investigating the anticancer efficacy of biogenic synthesized MgONPs: An in vitro analysis. Front Chem. 2022;10:1–14.10.3389/fchem.2022.970193Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Ali S, Sudha KG, Thirumalaivasan N, Ahamed M, Pandiaraj S, Rajeswari VD, et al. Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles by using abrus precatorius bark extract and their photocatalytic, antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity activities. Bioeng (Basel, Switz). 2023;10(3):302.10.3390/bioengineering10030302Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Periakaruppan R, Naveen V, Danaraj J. Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles with antioxidant potential using the leaf extract of piper nigrum. JOM. 2022;74(12):4817–22.10.1007/s11837-022-05548-xSearch in Google Scholar

[27] Pugazhendhi A, Prabhu R, Muruganantham K, Shanmuganathan R, Natarajan S. Anticancer, antimicrobial and photocatalytic activities of green synthesized magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgONPs) using aqueous extract of Sargassum wightii. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2019;190:86–97.10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.11.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Dinga E, Ekennia A, Ogbonna CU, Udu DA, Mthiyane DMN, Marume U, et al. Phyto-mediated synthesis of MgO nanoparticles using Melia azedarach seed extract: Larvicidal and antioxidant activities. Sci Afr. 2022;17:e01366.10.1016/j.sciaf.2022.e01366Search in Google Scholar

[29] Thakur N, Ghosh J, Pandey SK, Pabbathi A, Das J. A comprehensive review on biosynthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles, and their antimicrobial, anticancer, antioxidant activities as well as toxicity study. Inorg Chem Commun. 2022;146:110156.10.1016/j.inoche.2022.110156Search in Google Scholar

[30] Vijayakumar S, Chen J, Sánchez ZIG, Tungare K, Bhori M, Durán-Lara EF, et al. Moringa oleifera gum capped MgO nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, cyto-and ecotoxicity assessment. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;233:123514.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123514Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Biovia DS. Dassault systemes BIOVIA, Discovery studio modelling environment, Release 4.5. Dassault systemes. San Diego, California, USA: BIOVIA; 2015; p. 98–104.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, et al. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J Comput Chem. 1998;19(14):1639–62.10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19981115)19:14<1639::AID-JCC10>3.0.CO;2-BSearch in Google Scholar

[33] Eberhardt J, Santos-Martins D, Tillack AF, Forli S. AutoDock Vina 1.2. 0: New docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J Chem Inf Model. 2021;61(8):3891–8.10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203Search in Google Scholar

[34] Widakdo J, Chen T-M, Lin M-C, Wu J-H, Lin T-L, Yu P-J, et al. Evaluation of the antibacterial activity of eco-friendly hybrid composites on the base of oyster shell powder modified by metal Ions and LLDPE. Polymers. 2022;14(15):3001.10.3390/polym14153001Search in Google Scholar

[35] Anandalakshmi K, Venugobal J, Ramasamy VJ. Characterization of silver nanoparticles by green synthesis method using Pedalium murex leaf extract and their antibacterial activity. Appl Nanosci. 2016;6:399–408.10.1007/s13204-015-0449-zSearch in Google Scholar

[36] Jeevanandam J, San Chan Y, Wong YJ, Hii YS, editors. Biogenic synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using Aloe barbadensis leaf latex extract. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. Bristol, England: IOP Publishing; 2020.10.1088/1757-899X/943/1/012030Search in Google Scholar

[37] Abd Karim NZAB, Yusoff HBM, Bhat IUH, Yusoff F, Asari A, Izham NZBM. Green synthesis and characterisation of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using annona muricata leaves extract. Universiti Malays Terengganu J Undergrad Res. 2022;4(1):117–30.10.46754/umtjur.v4i1.265Search in Google Scholar

[38] Shu M, Mahdavi B, Balčiūnaitienė A, Goorani S, Mahdavi AA. Novel green synthesis of tin nanoparticles by medicinal plant: Chemical characterization and determination of cytotoxicity, cutaneous wound healing and antioxidant properties. Micro Nano Lett. 2023;18(2):e12157.10.1049/mna2.12157Search in Google Scholar

[39] Monica SJ, John S, Madhanagopal R, Sivaraj C, Khusro A, Arumugam P, et al. Chemical composition of pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima) seeds and its supplemental effect on Indian women with metabolic syndrome. Arab J Chem. 2022;15(8):103985.10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103985Search in Google Scholar

[40] Essien ER, Atasie VN, Okeafor AO, Nwude DO. Biogenic synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using Manihot esculenta (Crantz) leaf extract. Int Nano Lett. 2020;10(1):43–8.10.1007/s40089-019-00290-wSearch in Google Scholar

[41] Navalón S, García H. Nanoparticles for Catalysis. Nanomaterials. 2016;6:123.10.3390/nano6070123Search in Google Scholar

[42] Ammulu MA, Vinay Viswanath K, Giduturi AK, Vemuri PK, Mangamuri U, Poda S, et al. Phytoassisted synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles from Pterocarpus marsupium rox. b heartwood extract and its biomedical applications. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2021;19:1–18.10.1186/s43141-021-00119-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Karam L, Armandi M, Casale S, El Khoury V, Bonelli B, Massiani P, et al. Comprehensive study on the effect of magnesium loading over nickel-ordered mesoporous alumina for dry reforming of methane. Energy Convers Manag. 2020;225:113470.10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113470Search in Google Scholar

[44] Kumar SA, Jarvin M, Inbanathan S, Umar A, Lalla N, Dzade NY, et al. Facile green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using tea (Camellia sinensis) extract for efficient photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye. Environ Technol Innov. 2022;28:102746.10.1016/j.eti.2022.102746Search in Google Scholar

[45] Mittag A, Schneider T, Westermann M, Glei M. Toxicological assessment of magnesium oxide nanoparticles in HT29 intestinal cells. Arch Toxicol. 2019;93:1491–500.10.1007/s00204-019-02451-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Wetteland CL, Nguyen N-YT, Liu H. Concentration-dependent behaviors of bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells and infectious bacteria toward magnesium oxide nanoparticles. Acta Biomater. 2016;35:341–56.10.1016/j.actbio.2016.02.032Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Mahmoud A, Ezgi Ö, Merve A, Özhan G. In vitro toxicological assessment of magnesium oxide nanoparticle exposure in several mammalian cell types. Int J Toxicol. 2016;35(4):429–37.10.1177/1091581816648624Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Majeed S, Danish M, Muhadi NFBB. Nanotechnology. Genotoxicity and apoptotic activity of biologically synthesized magnesium oxide nanoparticles against human lung cancer A-549 cell line. Adv Nat Sci: Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2018;9(2):025011.10.1088/2043-6254/aac42cSearch in Google Scholar

[49] Abd-Elhady HM, Ashor MA, Hazem A, Saleh FM, Selim S, El Nahhas N, et al. Biosynthesis and characterization of extracellular silver nanoparticles from Streptomyces aizuneusis: antimicrobial, anti larval, and anticancer activities. Molecules (Basel, Switz). 2021;27(1):212.10.3390/molecules27010212Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Dar RA, Brahman PK, Khurana N, Wagay JA, Lone ZA, Ganaie MA, et al. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of crocin, podophyllotoxin and kaempferol by chemical, biochemical and electrochemical assays. Arab J Chem. 2017;10:S1119–28.10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.02.004Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery

- The progress of cathode materials in aqueous zinc-ion batteries

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part I

- Effect of polypropylene fiber and nano-silica on the compressive strength and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete

- Mechanochemical design of nanomaterials for catalytic applications with a benign-by-design focus

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities