Abstract

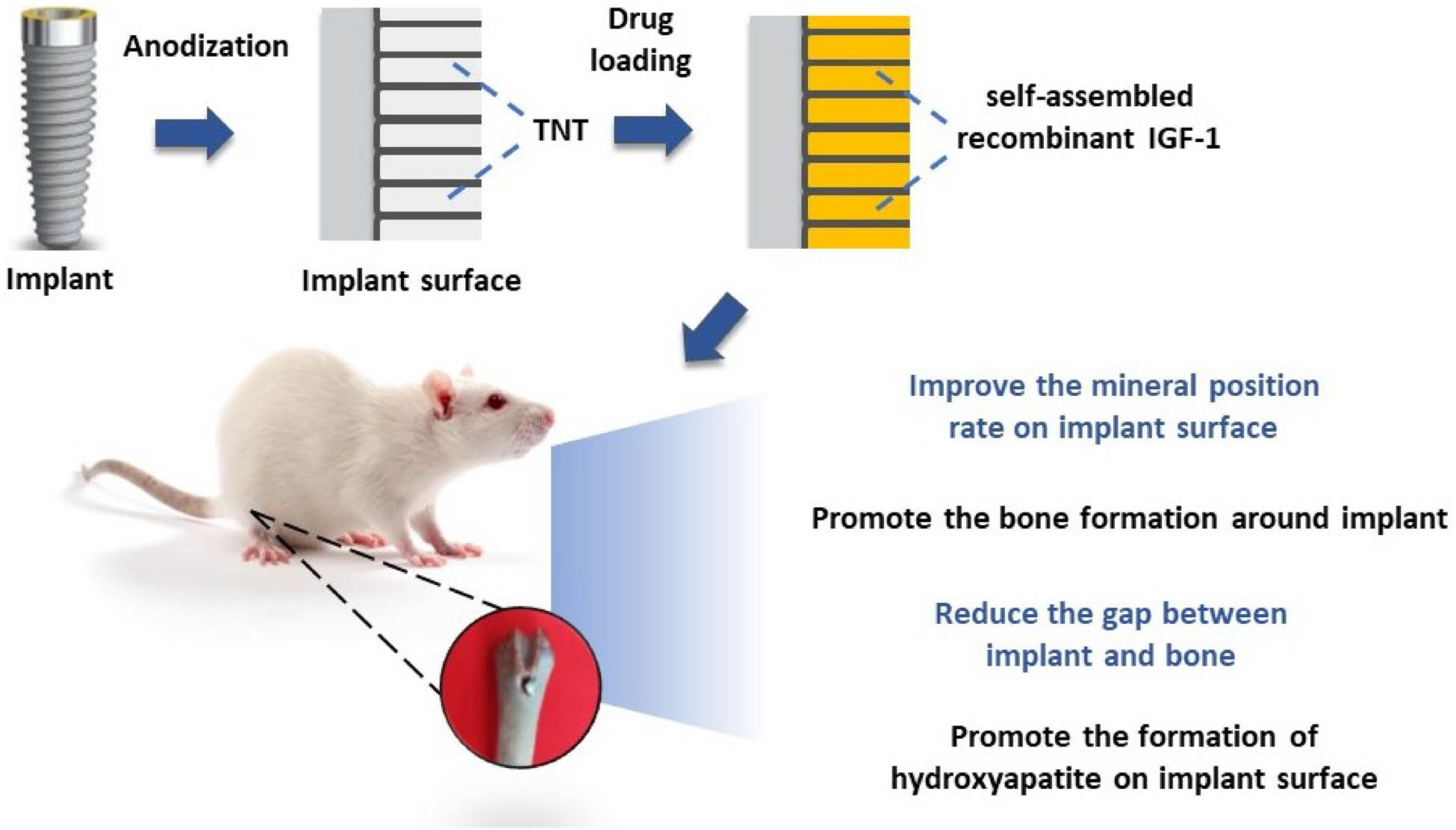

Improvement of poor implant osseointegration under diabetes is always a poser in clinics. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of TiO2 nanotubes (TNTs) and self-assembled minTBP-1-IGF-1 on implant osseointegration in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) rats. There were four groups, the control group, the TNTs group, the minTBP-1-IGF-1 group, and the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group. The atomic force microscopy and scanning electron microscope (SEM) results showed that 500 nm nanotubes were formed by anodic oxidation and minTBP-1-IGF-1 could self-assemble into almost all nanotubes. ELISA assay confirmed that more protein was adsorbed on TNTs surface. The contact angle of the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group was the lowest, confirmed that the hydrophilicity was the highest. The double fluorescence staining was used to evaluate the mineral apposition rate (MAR) at early stage and the MAR of the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group was the highest. Micro-CT images displayed that bone formed around the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs implant was the most homogeneous and dense, and the quantitative analysis of these images at 12 weeks also confirmed these results. The cross-section SEM results showed that the connection between bone and minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs implant was the tightest. All results demonstrated that minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs can significantly improve low implant osseointegration under T2DM condition.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Implants have been used to replace missing teeth by achieving stability through close contact with bone (osseointegration), therefore bone quality and quantity around implant are particularly important [1,2]. However, in some pathological conditions, such as diabetic patients, the osseointegration may be impaired because of the poor bone quality and quantity [3]. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is characterized by high concentration of blood glucose, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) accounts for about 90–95% of all diagnosed cases of DM [4]. T2DM is currently one of the most common systemic diseases affecting implant therapy [3]. T2DM individuals may have reduction in differentiation and proliferation of osteoblasts, which in turn can weaken the expression of bone-matrix genes and cripple production of new bone [5–8].

The latest progress in surface modification of implants is believed to improve bone integration in patients with metabolic disorders, which can impair bone healing [9]. The surface modification can increase bone formation around implant [10]. In recent years, TiO2 nanotubes (TNTs) prepared through anodic oxidation have attracted much attention as they simulate the basic nanoscale structure of bone and exhibit excellent biocompatibility and osseointegration ability [11]. Several studies have confirmed that Ti specimens modified by TNTs exhibit improved cell adhesion and proliferation ability, alkaline phosphatase activity, and bone mineralization [12]. Meanwhile, recent studies have attempted to use TNTs for drug delivery and local administration. Drugs along with TNTs represent an emerging new trend in implantable therapeutics [13].

TNTs have been extensively explored owing to their fainter in vivo immunogenicity, easy preparation, highly controllable topography, mechanical stiffness, chemical resistivity, high loading capability, and eminent surface-to-volume ratio [14–16]. To date, a lot of studies have concentrated on loading hollow TNTs with various therapeutic drugs such as, bone morphogenetic protein 2, metformin, paclitaxel, and vancomycin [17–19]. Insulin-like growth factors 1 (IGF-1), which is considered to participate in the regulation of blood glucose and play a central role in bone remodeling, is produced and reserved in bone matrix [12]. Furthermore, IGF-1 can adjust bone formation and remodeling by influencing the survival and proliferation of osteoblasts [20–22]. In this study, we use protein recombination technology to integrate TiO2 aptamer minTBP-1 with IGF-1, which not only can self-assemble into TNTs but also possess the therapeutic effect of improving bone quality. MinTBP-1 (RKLPDA), a novel peptide aptamer, has been affirmed to possess the high affinity with TiO2, which can connect with TiO2 like a “glue” to introduce bioactive molecules [23–25]. In order to effectively carry the macromolecular protein IGF-1, we connected three minTBP-1 to the N-terminal of IGF-1 [26], which can automatically self-assemble into TNTs.

In this study, TNTs arrays were formed on dental implant surface by anodic oxidation, and these TNTs provided empty spaces for self-assembled minTBP-1-IGF-1 loading. The effects of TNTs and minTBP-1-IGF-1 on bone-implant osseointegration were investigated in T2DM rats.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials processing and surface characterization

Cylindrical screwed Ti implants (1.5 mm2 × 3.5 mm, Zhong Bang Corporation, Xi’an, China) were divided into four groups: the control group (machined surface), the TNTs group, the minTBP-1-IGF-1 group, and the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group. All samples were ultrasonically washed with acetone, ethyl alcohol, and deionized water for 30 min sequentially. For TNTs array, Ti implants were anodized at 10 V for 60 min in an electrolyte solution consisting of HF:H2O at a ratio of 1:99 wt%. Then these samples were washed with deionized water followed by a gentle ultrasonication and sterilized under ethylene oxide. For minTBP-1-IGF-1 self-assembling, machined implants or anodized implants were completely covered by the minTBP-1-IGF-1 solution with a concentration of 1 μg/mL for 6 h at room temperature [15]. Morphological features were characterized by an atomic force microscopy (AFM, Vecco Instrument Dimension, Icon) and field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, JEOL JSM-6460).

2.2 Water contact angle test

The surface hydrophilicity was measured by contact angle measurements employing Automatic Contact Angle Meter Model SL200B (Solon, Shanghai, China) at room temperature. The test was conducted on a flat surface of the upper part of the implant. Droplet volume is 1 μL.

2.3 Assaying adsorbed modified IGF-1s

The adsorbed amount of minTBP-1-IGF-1 was quantified applying a Human IGF-1 ELISA development kit (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ). To measure the amount of adsorbed protein, specimens were submerged into protein solution for 30 min, 1, 6, and 24 h at room temperature. Then the specimens were introduced into 5 M urea, 0.2 M HCl, and 0.1% Tween-20 for 30 min. This eluate was deliquated 1:20 in PBS containing 0.1% BSA before implementing ELISAs.

2.4 Animal model of type 2 diabetes, intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT), and insulin tolerance test (ITT)

The design and implementation of the experiment were consented by the Animal Ethics Committee of Air Force Medical University (052/2019) and reported according to the ARRIVE guidelines with respect to relevant items [27]. The male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (260–300 g, 9 weeks old) were purchased from the animal holding center of the university. As per previous research, a high-carbohydrate–high-fat diet (comprising 48% carbohydrate, 20% protein, and 22% fat, with total calories of 44.3 kJ/kg) and low-level (30 mg/kg) streptozotocin intraperitoneal injection were implemented into 24 SD rats to elicit T2DM [28].

During the experiment, the weight of rats was measured and the weight changes of normal rats and T2DM rats were compared.

For IPGTT, rats were fasted overnight for 15 h, and were administered with glucose load (1.5 g/kg) through IP injection. Blood was collected from the tail vein for glucose measurements at 0, 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after glucose injection and calculated the area under the curve (AUC) [29].

For ITT, rats were fasted overnight for 15 h. The same cohort of rats were injected with insulin at a dose of 2.5 U/kg bw i.p. and then blood was drawn from the tail vein for glycemia measurements at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after insulin administration and calculated the AUC.

The body weight, IPGTT, and ITT of six normal rats were measured for comparison with the T2DM rats.

2.5 In vivo implantation

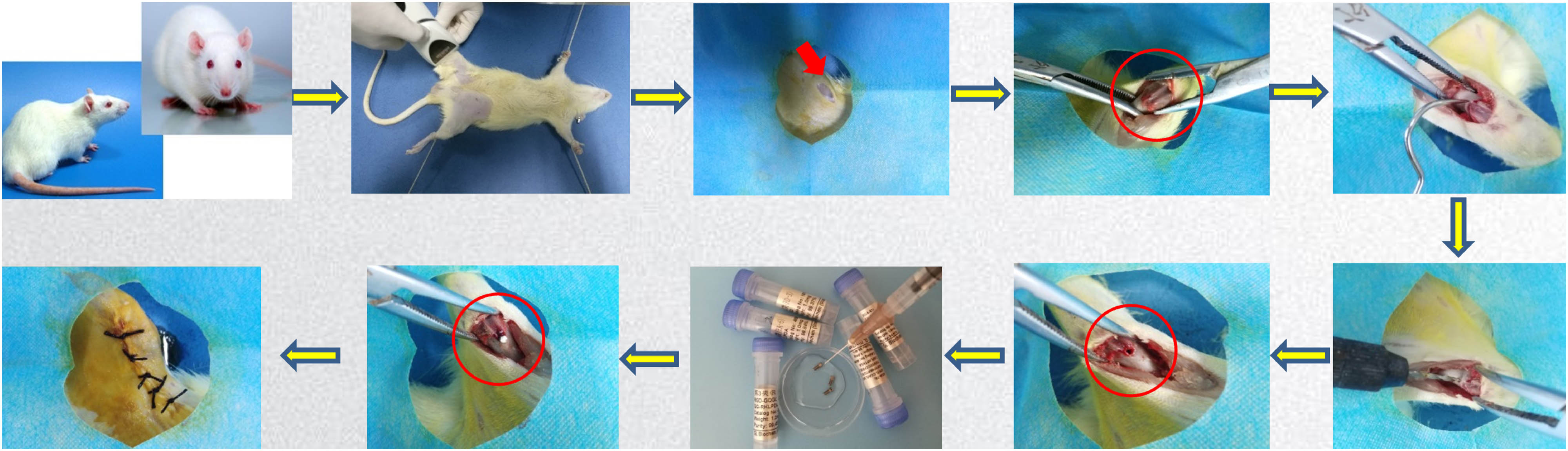

Each rat was anaesthetized with diazepam and pentobarbitalnatrium. Four kinds of implants were implanted into T2DM rat distal femurs at random (Figure 1). After surgery, penicillin was injected daily at a dose of 4 WU/kg for 5 days.

Procedure of implantation surgery.

2.6 Measurement of mineral apposition rate (MAR)

T2DM rats were subcutaneously injected with tetracycline (15 mg/kg, Sigma, USA) and calcein (10 mg/kg, Sigma) at 4 and 8 weeks after implantation. After execution, samples were cleaned of soft tissue and fixed in 70% ethanol, then dehydrated and embedded with acrylic resin. The hard tissue embedded block was properly trimmed and sectioned with a slicer (Leica 2500e, Leica Company). Three slices were obtained for each sample. There were six slices per group. Then, 10 µm thick hard tissue sections were observed under an E-800 fluorescent microscope (Nikon). The ImagePro Plus analysis system was applied to measure the distance between the two labeled fluorescence lines. A grid of crosses was laid over the image and where a grid point met one of the fluorescent bands, the distance was measured from that point to the nearest point on the next band. A minimum of ten measurements were recorded for each slice, and the final value was an average of these measurements. The MAR was calculated by dividing the distance between the two labels by the interlabeling period in days [5].

2.7 Longitudinal, in vivo micro-CT evaluation

Micro-CT (Inveon, Siemens, Germany; 80 kV, 500 μA, 900 ms integration time) scanning at a resolution of 21 μm was performed after anesthesia in T2DM rats at 4, 8, and 12 weeks after implantation. The scanning area included bone within a radius of 1.5 mm with the implant midline as the axis. Bone volume/total volume (BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular number (Tb.N), bone surface/bone volume (BS/BV), and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) were determined.

2.8 SEM/energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) analysis of cross-sections

Few specimens of each group were embedded in acrylic resin, and then intersected intermediately. The cross-section surfaces were characterized by SEM/EDS. The EDS analysis results were only used for qualitative analysis.

2.9 Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and subjected to normality testing. The statistical significance of differences was determined by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s multiple comparison tests using SPSS 16.0 statistical software. Probabilities of less than 0.05 were accepted as significant.

3 Results and discussion

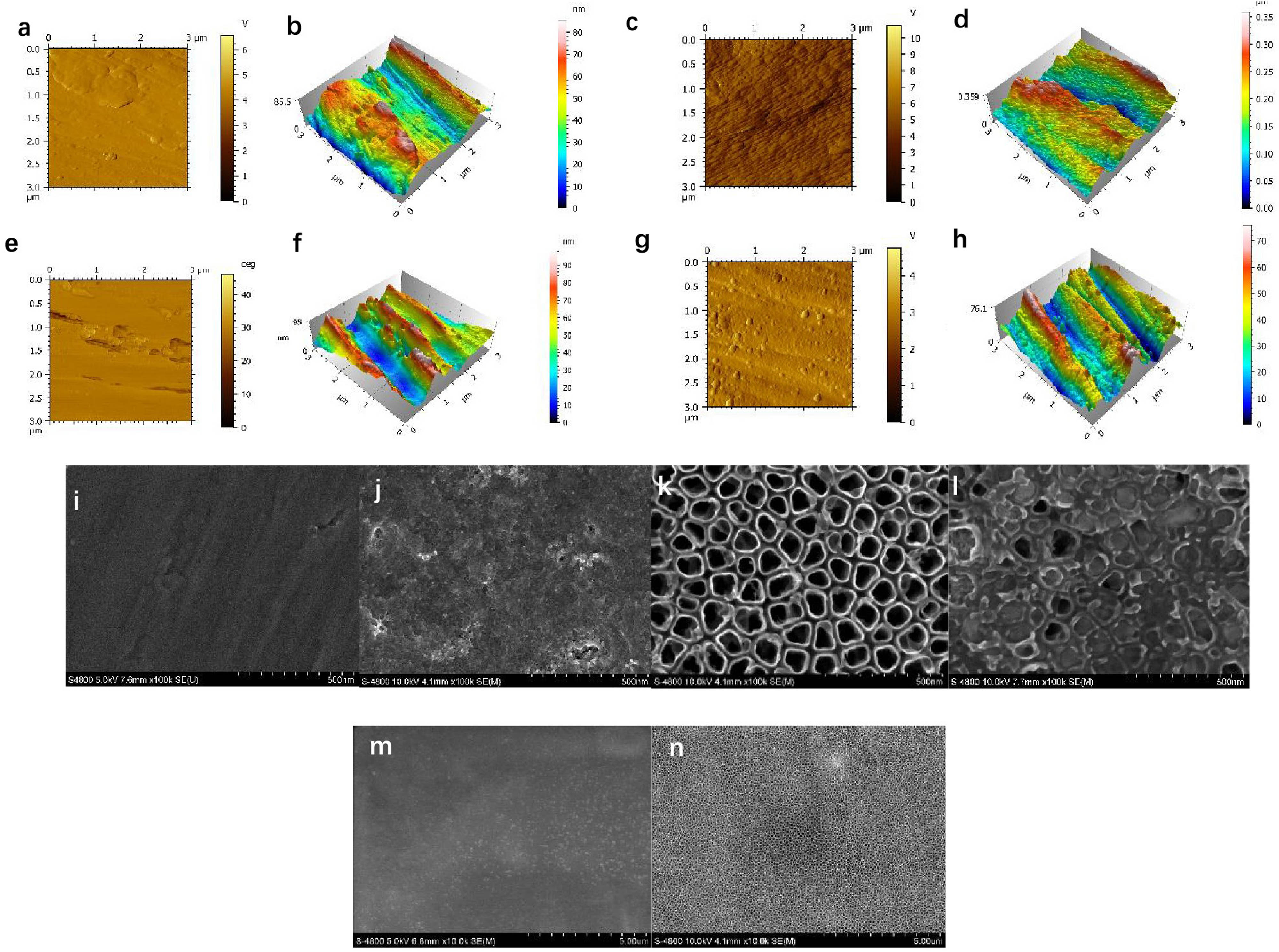

3.1 Surface characterization

To study the surface topography, the interface was analyzed by AFM and SEM. The control group exhibited a coarse surface, many gullies (Figure 2(a), (b), and (i)). After protein adsorption, Ti surface was almost covered by protein, but the adsorbed protein on Ti was uneven (Figure 2(e), (f), and (j)). The AFM images (Figure 2(c) and (d)) of the TNTs samples presented uniformly distributed nano-protrusions; the SEM images (Figure 2(k)) revealed that the highly ordered TNTs were achieved and the nanotubes’ diameter was about 500 nm. The nanotube windows were clean and open. When minTBP-1-IGF-1 was loaded, it can be seen from Figure 2(l) that the fusion protein self-assembled into almost every nanotube. And it demonstrated that the nano-morphology was still visible even after protein adsorption. At low magnification, well-aligned and clean nanotubes can be seen on Ti surface after anodized oxidation (Figure 2(m)); moreover, the nanotubes have been completely covered by protein evenly after protein adsorption (Figure 2(n)). The roughness of the four groups revealing Ra (nm) values from Table 1 was 15.03 (control group), 62.83 (TNTs group), 6.37 (minTBP-1-IGF-1 group), and 14.31 (minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group) in average, respectively.

Surface characterization of the modified implant surface: (a) and (b) AFM images of the machined surface, (c) and (d) AFM images of the TNTs surface, (e) and (f) AFM images of the minTBP-IGF-1 surface, (g) and (h) AFM images of the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs surface, (i)–(l) SEM images of the machined, minTBP-1-IGF-1, TNTs, and minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs surface (scale bars: 500 nm), and (m) and (n) SEM images of TNTs and minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs (scale bars: 5 μm).

Ra values of surface roughness of the four experimental groups

| Group | Ra (nm) |

|---|---|

| Control group | 15.03 ± 2.62 |

| TNTs group | 62.83 ± 6.44** |

| minTBP-1-IGF-1 group | 6.37 ± 2.14** |

| minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group | 14.31 ± 3.95 |

* p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 10.

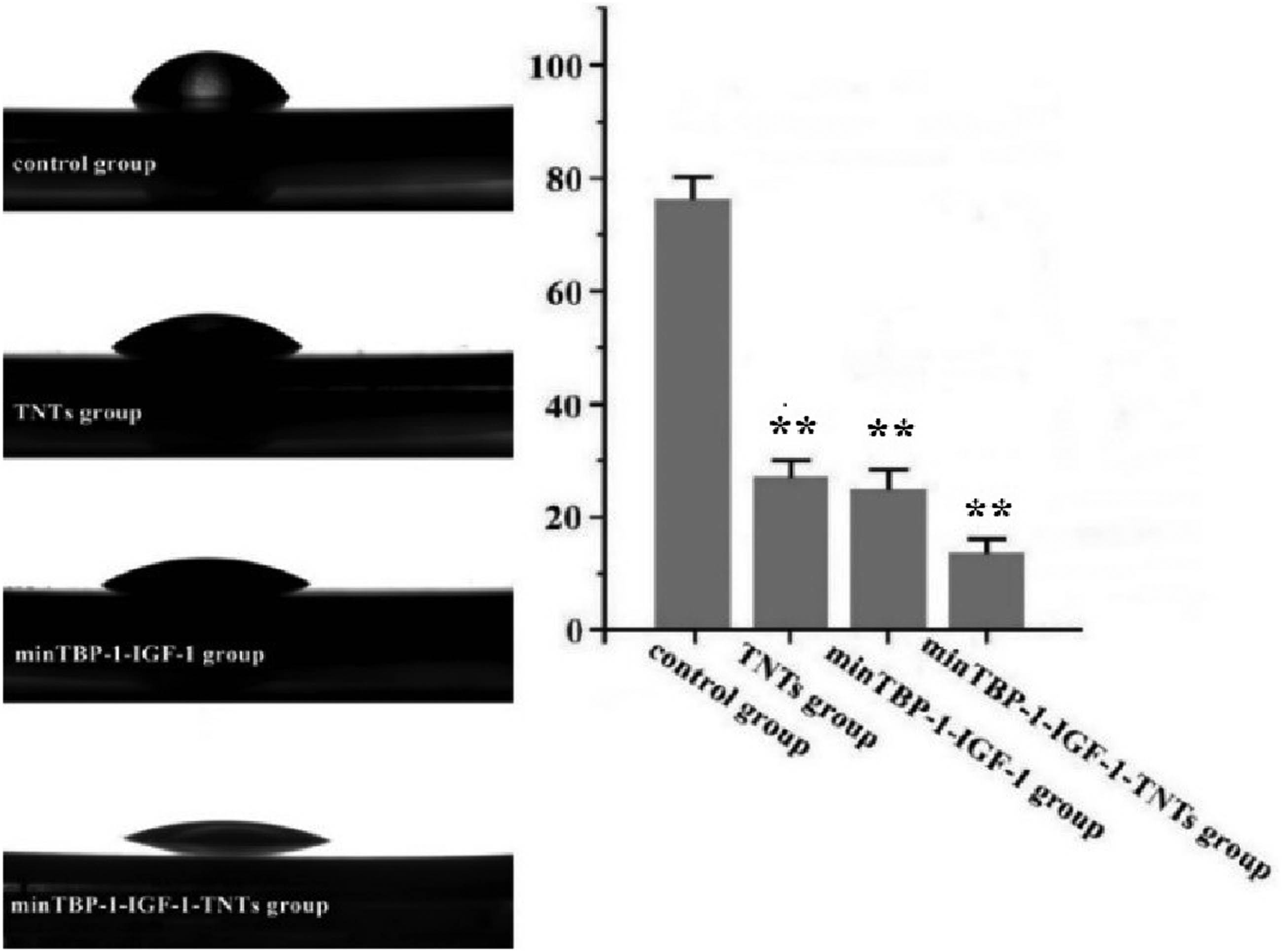

3.2 Water contact angle test

The surface wettability of interface was characterized by water contact angle measurement. Water contact angle measurement results showed that surface wettability changed from 76.2 ± 6.1° (control group) to 27.6 ± 3.2° (TNTs group), 25.2 ± 4.6° (minTBP-1-IGF-1 group), and 13.5 ± 2.7° (minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group), receptively. These results confirmed that the minTBP-1-IGF-1 and TNTs improved surface hydrophilicity (Figure 3) and the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs surface showed the highest hydrophilicity (Table 2).

Water contact angle of the modified interfaces. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 10.

Water contact angle of the four experimental groups

| Group | Water contact angle (°) |

|---|---|

| Control group | 76.2 ± 6.1 |

| TNTs group | 27.6 ± 3.2** |

| minTBP-1-IGF-1 group | 25.2 ± 4.6** |

| minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group | 13.5 ± 2.7** |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 10.

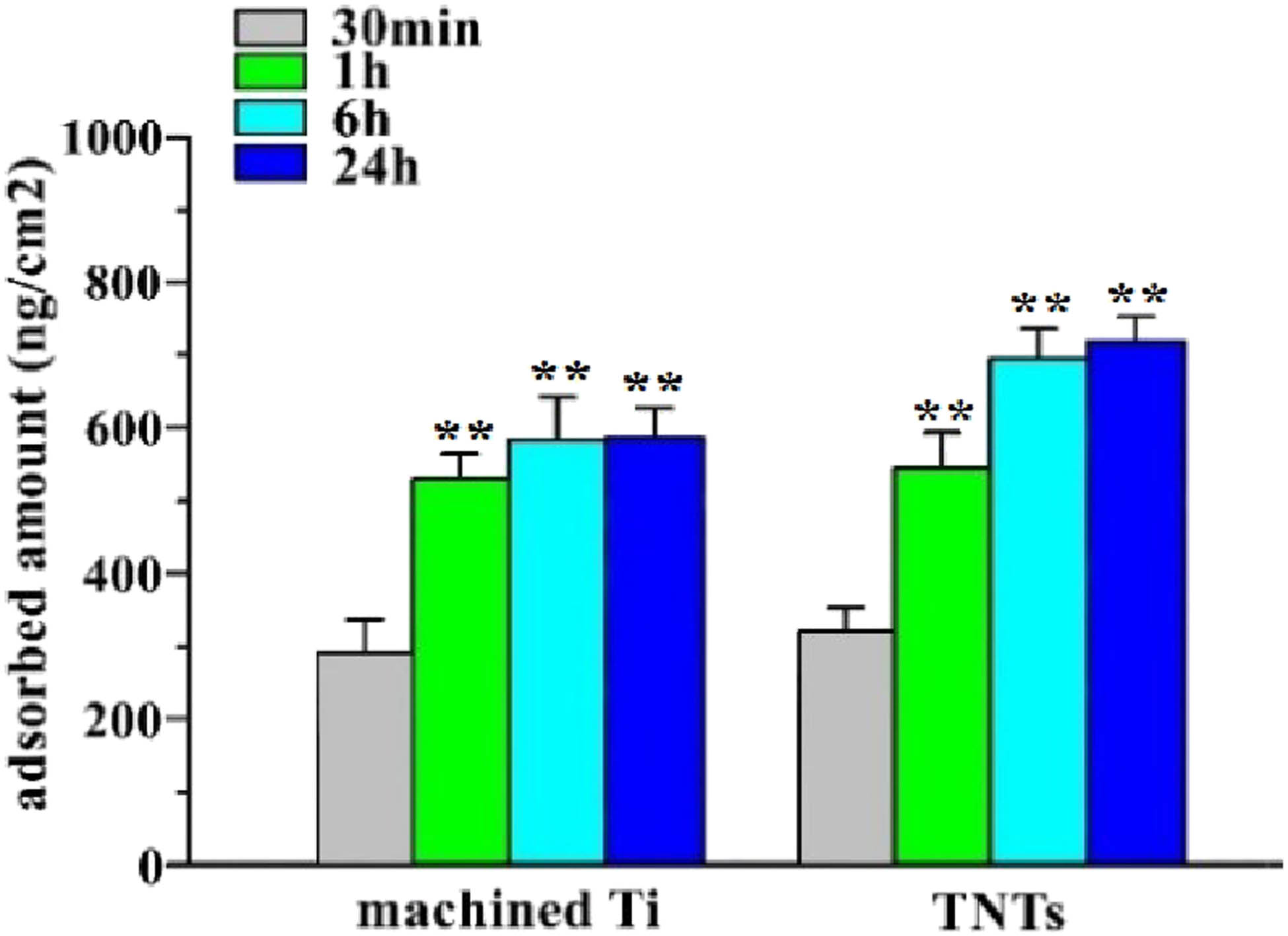

3.3 Assaying adsorbed modified IGF-1s

After immersion for 24 h, the densities of the minTBP-1-IGF-1 adsorbed on machined Ti surface (Table 3) were 587 ± 67 ng/cm2, whereas the densities of minTBP-1-IGF-1 adsorbed on TNTs surface were 726 ± 58 ng/cm2. But there was no significant difference between the 6 and 24 h protein adsorption on the two surfaces within group as shown in Figure 4. Therefore, the soaking time of the specimens in the protein solution was set at 6 h.

Amounts of adsorbed minTBP-1-IGF-1 on machined Ti surfaces and TNTs surface

| Time | Machined Ti (ng/cm2) | TNTs (ng/cm2) |

|---|---|---|

| 30 min | 280.9 ± 45.8 | 312.9 ± 28.4 |

| 1 h | 533.3 ± 39.0** | 544.9 ± 51.0** |

| 6 h | 571.9 ± 72.4** | 702.4 ± 47.2** |

| 24 h | 587.1 ± 67.4** | 726.3 ± 58.5** |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 10.

Amounts of adsorbed minTBP-1-IGF-1 on machined Ti surfaces and TNTs surface were estimated. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 10.

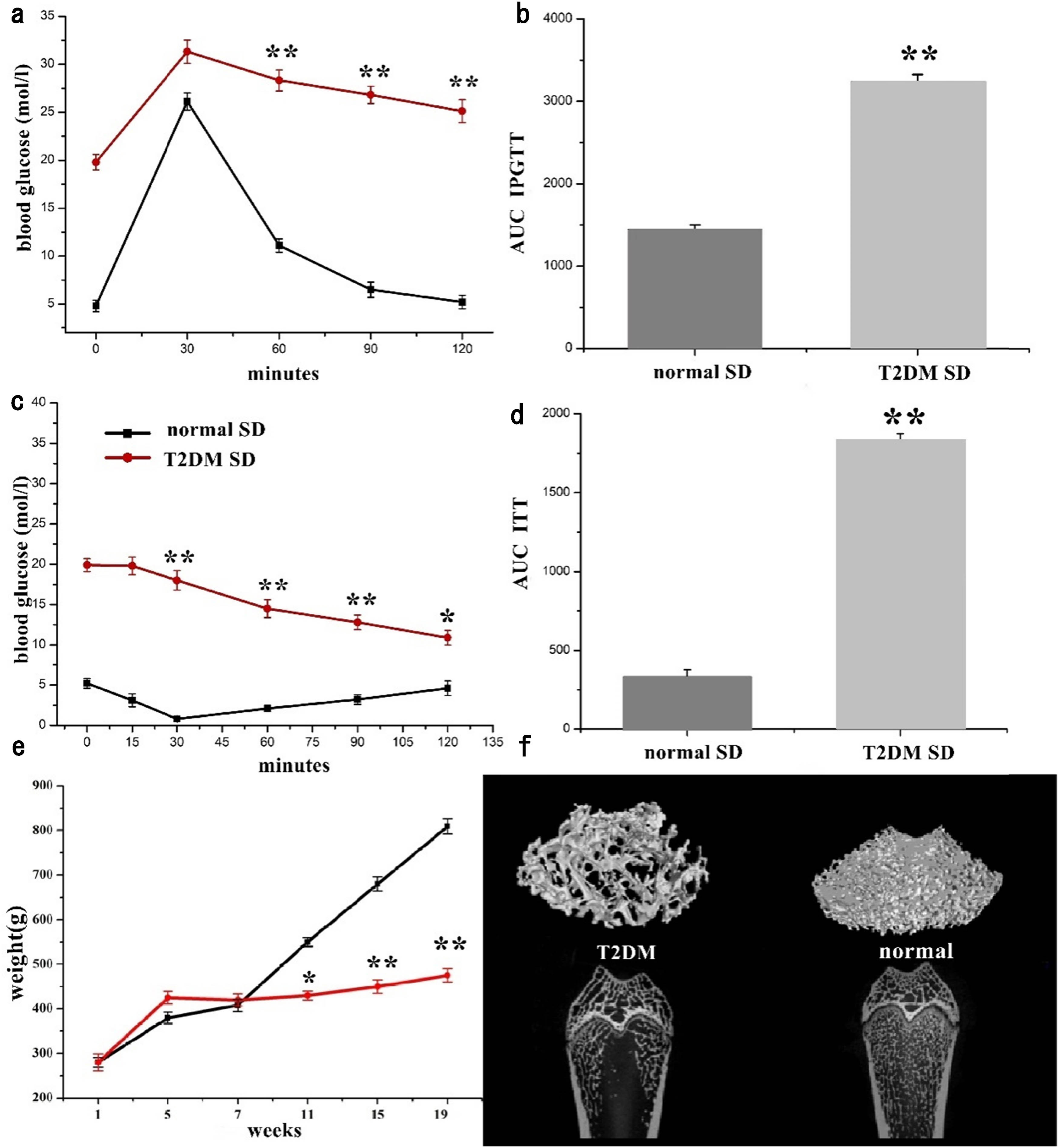

3.4 Construction of the type 2 diabetes model, IPGTT, and ITT

Throughout the experiment, the blood glucose level of the SD rats was stable at around 18.6 mmol/L after diabetes induction and their weight had significantly increased (Figure 5(e), Table 4).

(a) Plasma glucose during IPGTT in rats 4 weeks after injection, (b) AUC of IPGTT assessment, (c) percentage of initial glucose level during ITT in T2DM and normal SD rats, (d) AUC of ITT assessment, (e) body weight changed with time from the beginning to the end of experiment, and (f) micro-CT scan of epiphysis of femoral shaft. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 6.

Body weight changed with time from the beginning to the end of experiment

| Time (weeks) | Normal SD (g) | T2DM SD (g) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 280 ± 11 | 280 ± 19 |

| 5 | 380 ± 13 | 425 ± 14 |

| 7 | 408 ± 14 | 420 ± 14 |

| 11 | 550 ± 10 | 430 ± 10* |

| 15 | 680 ± 16 | 450 ± 15** |

| 19 | 809 ± 17 | 475 ± 15** |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 6.

For the purpose of analyzing glucose tolerance in each group, IPGTTs were performed. The plasma glucose increased to a maximum after 30 min of glucose administration i.p. in both normal and diabetic rats (Table 5), but this increase was higher in diabetic rats (p < 0.01) (Figure 5(a)). There was altogether delay of glucose clearance in diabetic rats, with glucose levels remaining elevated for 120 min (p < 0.01) after glucose administration. AUC (Figure 5(b)) of blood glucose during the IPGTT was more than twice as much as in normal rats (3245.4 vs 1452.0 mmol/L, _120 min in average, p < 0.001, Table 6), thereby qualifying for characterization as glucose intolerance.

Plasma glucose during IPGTT in rats 4 weeks after injection

| Time (min) | Normal SD (mol/L) | T2DM SD (mol/L) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 19.8 ± 0.8 |

| 30 | 26.1 ± 0.9 | 31.3 ± 1.2 |

| 60 | 11.1 ± 0.7 | 28.3 ± 1.1** |

| 90 | 6.5 ± 0.8 | 26.8 ± 0.9** |

| 120 | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 25.1 ± 1.2** |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 6.

AUC of IPGTT and ITT assessment

| IPGTT | ITT | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal SD | T2DM SD | Normal SD | T2DM SD |

| 1452.0 ± 49.9 | 3245.4 ± 79.5** | 334.0 ± 41.3 | 1835.3 ± 38.1** |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 6.

To investigate the differences in insulin sensitivity, an ITT was performed. For ITT (Figure 5(c), Table 7), there was a rapid decline in plasma glucose up to 30 min of insulin administration in normal SD rats. But plasma glucose remained higher in diabetic rats (p < 0.01) at all time-points up to 120 min. The higher AUC (Figure 5(d)) was measured in T2DM rats than that in the normal rats (1835.3 vs 334.0 mmol/L, _120 min in average, p < 0.001, Table 6), characterizing the rats as insulin resistant.

Plasma glucose during ITT in rats 4 weeks after injection

| Time (min) | Normal SD (mol/L) | T2DM SD (mol/L) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 19.9 ± 0.8 |

| 15 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 19.8 ± 1.1 |

| 30 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 18.0 ± 1.2** |

| 60 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 14.5 ± 1.1** |

| 90 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 12.8 ± 0.9** |

| 120 | 4.6 ± 0.9 | 10.9 ± 0.9* |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 6.

The model rats had the characteristics of hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, which indicated that these rats were successfully modeled T2DM [4,6]. The micro-CT evaluation demonstrated that femurs of T2DM rats showed obvious osteoporosis (Figure 5(f)).

3.5 Measurement of MAR

Figure 6 shows fluorescence microscopic images of early bone formation around the implant. From Figure 6(d), the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group had the widest fluorescence spacing, followed by the minTBP-1-IGF-1 group (Figure 6(c)) and the TNTs group (Figure 6(b)), and the control group had the smallest spacing (Figure 6(a)). From Figure 5(e), the MAR value of the control group (Table 8) was the lowest (0.71 ± 0.19 μm/day), followed by the TNTs group (0.88 ± 0.22 μm/day) and the minTBP-1-IGF-1 group (1.27 ± 0.31 μm/day), and the highest was the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group (1.86 ± 0.39 μm/day).

(a)–(d) Fluorescence microscopic images of bone formed around the implant after labeling with alizarin red (red) and calcitrin (green) at 4 and 8 weeks (magnification ×10). (e) MAR was determined by a fluorescent microscope; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 6.

MAR was determined by a fluorescent microscope

| Group | Water contact angle (°) |

|---|---|

| Control group | 0.71 ± 0.19 |

| TNTs group | 0.88 ± 0.22 |

| minTBP-1-IGF-1 group | 1.27 ± 0.31** |

| minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group | 1.86 ± 0.39** |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 6.

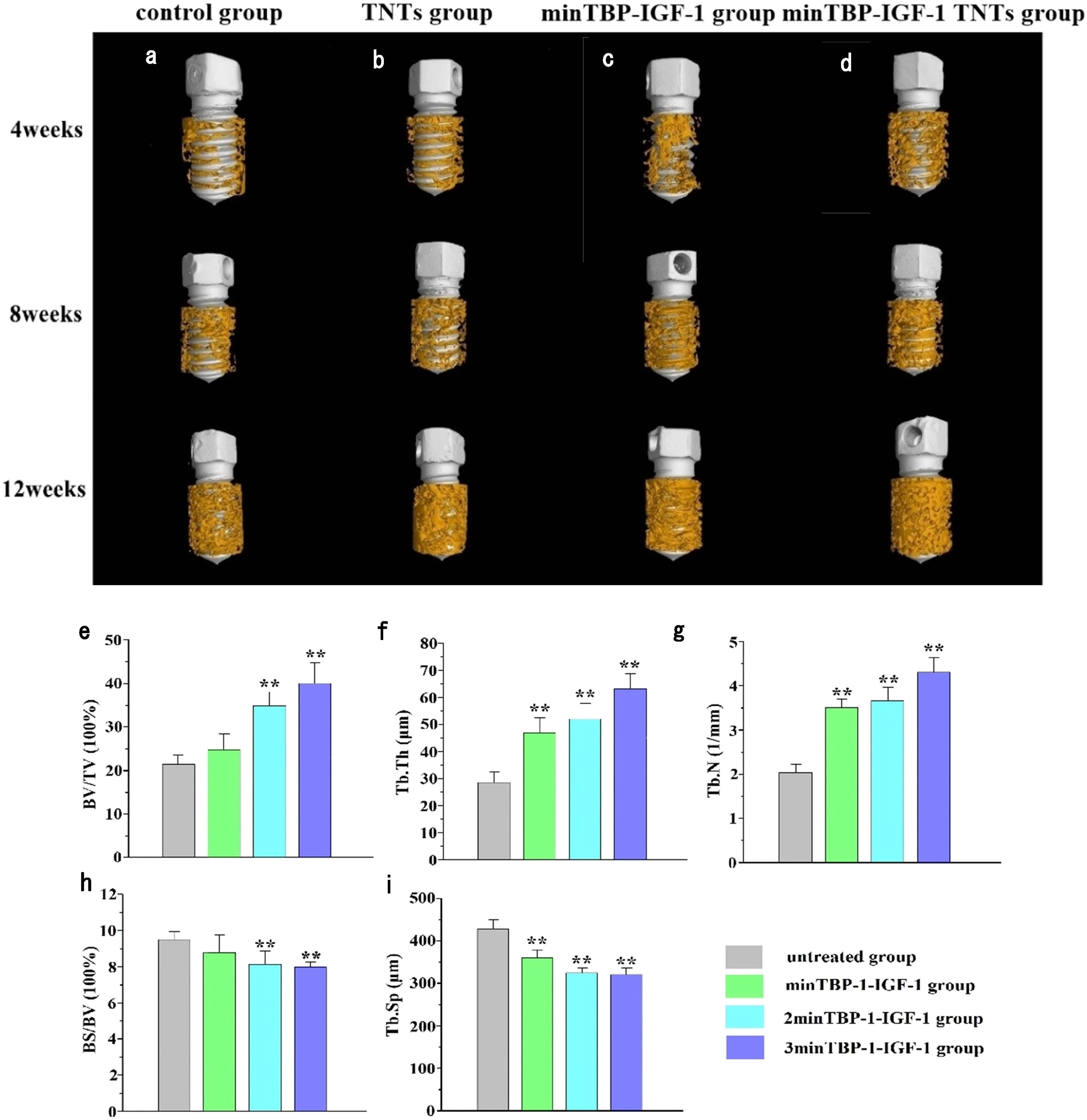

3.6 In vivo micro-CT evaluation

The micro-CT reconstructed images (Figure 7(a)–(d)) clearly demonstrated the architectural changes in trabecular bone around the implant. At each time point, the thickness of the newly formed bone surrounding the implant was obviously denser and more homogeneous in the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group than those in the other groups. At the 12th week, the bone formed around the machined/TNTs/minTBP-1-IGF-1 implant was inconsistent and sparse, while the bone formed in the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group was continuous and dense. The BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, BS/BV, and Tb.Sp were quantified 12 weeks after implantation (Figure 7(e)–(i) and Table 9). Increase of BV/TV, Tb.Th, and Tb.N and decrease of BS/BV and Tb.Sp indicated vigorous bone growth. Among the four groups, the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group had the highest values in BV/TV, Tb.N, and Tb.Th, and the lowest values in BS/BV and Tb.Sp.

(a)–(d) Micro-CT images at 4, 8, and 12 weeks after implantation. (e)–(i) Micro-CT statistical analysis of BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, BS/BV, and Tb.Sp 12 weeks after implantation; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 6.

Micro-CT statistical analysis of BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, BS/BV, and Tb.Sp 12 weeks after implantation

| Group | BV/TV | Tb.Th | Tb.N | BS/BV | Tb.Sp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | 21.7 ± 2.6 | 28.3 ± 4.7 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 9.6 ± 0.4 | 423.2 ± 23.5 |

| TNTs group | 25.2 ± 4.1 | 46.7 ± 6.6** | 3.5 ± 0.2** | 8.9 ± 1.2 | 354.1 ± 21.3** |

| minTBP-1-IGF-1 group | 34.8 ± 3.8** | 51.2 ± 6.2** | 3.7 ± 0.3** | 8.1 ± 0.9** | 319.5 ± 10.9** |

| minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group | 39.5 ± 4.9** | 61.8 ± 7.3** | 4.3 ± 0.4** | 7.9 ± 0.3** | 316.8 ± 19.8** |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 9.

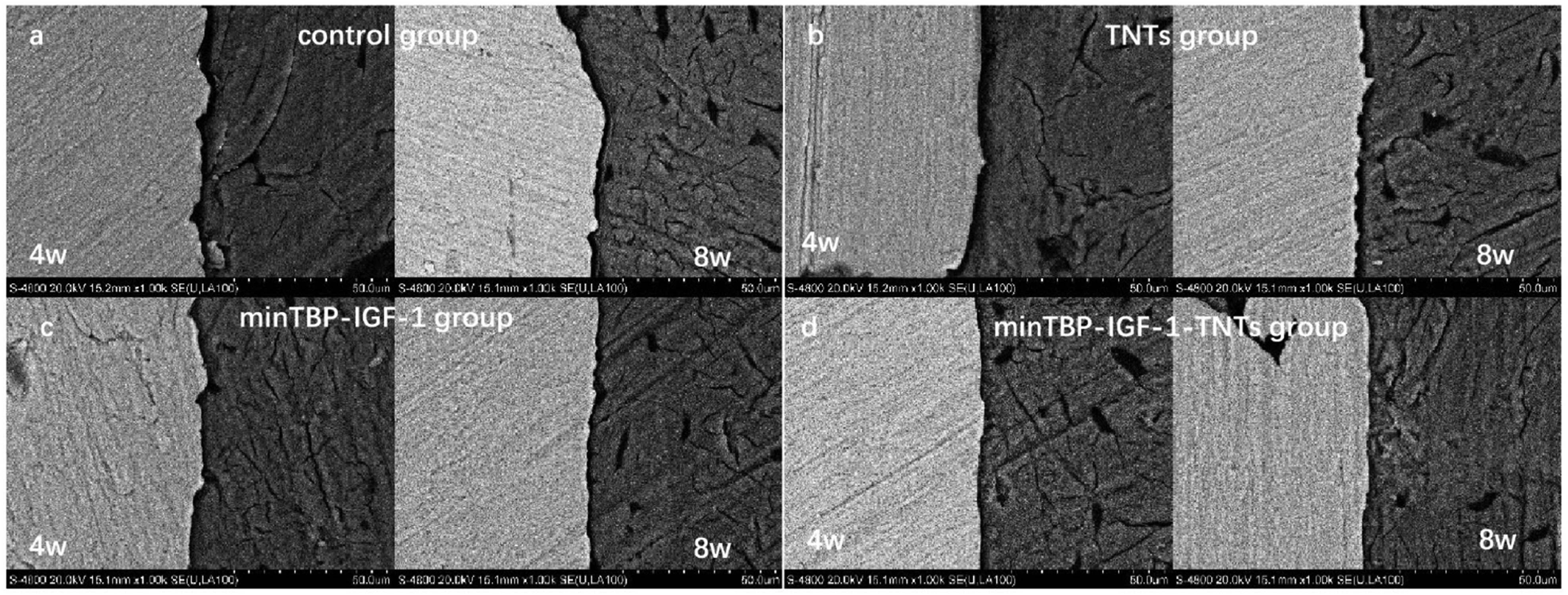

3.7 SEM/EDS analysis of cross-sections

The SEM micrographs (Figure 8) of cross-Section 4 and 8 weeks after implantation showed that in the control group (Figure 8a) there was clear gap between bone and implant. After being modified by TNTs (Figure 8b), minTBP-1-IGF-1 (Figure 8c), and minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs (Figure 8d), the gap between the implant and bone became smaller. And it can be clearly seen that minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group (Figure 8d) has the smallest gap between the implant and bone tissue.

Cross-section SEM photomicrographs 4 and 8 weeks after implantation (n = 6).

The SEM micrographs (Figure 9(a)–(d)) of cross-sections 12 weeks after implantation showed that in the control group there was clear gap between the bone and implant. After being modified by TNTs, minTBP-1-IGF-1, and minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs, the gap between the implant and bone became smaller. In particular, the bone and implant were in close contact with each other in the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group. The EDS analysis of the cross-section (Figure 9(f)–(i)) showed that contents of calcium and phosphor elements increased in order of the control group, the TNTs group, the minTBP-1-IGF-1 group, and the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group. The result of a linear element scanning across the bone–implant interface of the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group (Figure 9e) showed the enrichment of calcium, phosphorus, and oxygen ions at the interface.

(a)–(d) Cross-section SEM photomicrographs, (e) line scan analysis of minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group, and (f)–(i) EDS analysis of Ti–implant interfaces 12 weeks after implantation, n = 6.

4 Discussion

Despite the extensive use of titanium, and the considerably growing body of studies on the advancement of new titanium surfaces and/or modification of available surfaces, implant osseointegration in medically compromised patients still remains a challenge. T2DM is currently the quite common systemic disease affecting implant success [3]. T2DM is characterized by high blood glucose and insulin resistance. In this study, we established a T2DM rat model, which was confirmed to have the characteristics of hyperglycemia and insulin resistance by ITT and IGTT assay (Figure 5(a)–(d)). When normal and T2DM rats were injected with high glucose solution and insulin intraperitoneally, the blood glucose of the T2DM rats was significantly higher than that of the normal rats. The above results confirmed that we successfully prepared the T2DM rat model. In this study, we selected rats as research animals. The reasons are as follows: first, rats are cost-effective and easy to handle, second, its development process and anatomical structure are similar to those of human beings, third, the rat model allows standardized experimental procedure, and finally, the implantation was performed at the distal femur of rats, because there are a large number of cancellous bones, whose tissue structure is similar to that of human jaw, which is easy to operate and observe. At present, embedding the implant into the rat tibia for implant observation has been reported in many literature [3,4,28].

A growing body of evidence indicates that impaired osteoblast-mediated microstructure defects and poor bone quality by T2DM is the important reason for low osseointegration [3]. Our experiment also affirmed that osteoporosis occurred in T2DM rat through the micro-CT examination (Figure 5(f)). Because of the important role of IGF-1 in promoting osteoblast differentiation and mineralization under diabetic condition [25,26], we had prepared a recombinant minTBP-1-IGF-1 for improving implant osseointegration. MinTBP-1 is a TiO2 specific nucleic acid aptamer, which has high affinity with TiO2. Therefore, the recombinant protein can be automatically adsorbed on the implant surface. Through previous in vitro experiments, we confirmed that the recombinant protein can effectively play the biological function of IGF-1 [23]. In order to effectively increase the loading amount of the functional proteins, anodized TNTs were introduced as protein carriers. The preparation of TNTs layer can be easily integrated into the Ti and Ti-alloy implant to increase drug loading and sustained release [13]. The AFM and SEM images showed that the highly ordered TNTs were achieved and the nanotube windows were clean and open. Compared to the amount of the protein adsorbed on the Ti surface, the adsorption amount of fusion protein on the TNTs modified surface was greatly increased. The main reason was that TNTs have high ratio surface areas [13].

Wettability of the modified surface has been known as a significant factor to control the dynamic interactivity between implanted surface and blood or serum in vivo [29,30]. Osteoblasts do not directly interact with biomaterial surface, instead they interact with adsorbed proteins from blood or serum. Therefore, the surface with high hydrophilicity is conducive to protein adhesion and subsequent cell adhesion, spreading, and osteogenic expression [4,31]. The surface hydrophilicity from high to low was the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs surface, the minTBP-1-IGF-1 surface, the TNTs surface, and the machined surface. Therefore, we speculated that because of the highest hydrophilicity, the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs surface was best for osteoblast adhesion and spreading, and the subsequent formation and mineralization of bone tissue.

Osseointegration is a prerequisite for successful implant repair, and it often takes 3–6 months after implantation [32,33]. For oral implants, it has become the key to shorten the osseointegration cycle and improve the osseointegration rate by modifying the implant surface. Poor early osseointegration is considered to be one of the main reasons for implant failure [34]. Therefore, we observed the osseoinducibility in the early stage around the modified implants through observing the distance between the two fluorescent drugs. Previous studies have suggested that the bone-to-implant contact is impaired in patients with DM because the bone formed around implant is incomplete and delayed and the newly formed bone is immature and poorly organized [31,35,36]. It can be seen from Figure 6(a) that the fluorescence spacing of the two colors was the closest, indicating that the formation of bone tissue was the least. And it is clearly seen that the formation of early mineralized bone tissue in the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group (Figure 6(d)) was more than that in the TNTs group (Figure 6(b)) and the minTBP-1-IGF-1 group (Figure 6(c)), which was not only due to the preparation of nanotubes, but also due to the loading of recombinant IGF-1 on implant surface.

Osseointegration is the direct contact between living bone and the surface of a load-bearing synthetic implant, without the interposition of non-bone tissue. Since the direction of 2D slice around the central axis of the implant, the change of tissue morphology measurement is about 30–35%, so one slice of each sample is considered insufficient to fully determine the bone implant contact [37,38]. Micro-CT imaging is fast, non-destructive, and allows three-dimensional evaluation. Butz et al. [39] compared the correlation between micro-CT and histological imaging for cortical and cancellous bones at distances of 0–24, 24–80, 80–160, and 160–240 µm from the implant surface. It also confirmed that this method has revealed to be a feasible alternative to current bone regeneration quantification methods [40]. In order to confirm the effect of different modification methods on the whole period of implant osseointegration, we used micro-CT for qualitative and quantitative analysis. It has been confirmed that the structure and morphology of nanotubes can promote the early response of osteoblasts and facilitate the early bone formation around implants [1,11]. The micro-CT results (Figure 7(a) and (b)) showed that the TNTs modified implant could improve the implant osseointegration under T2DM condition. However, compared with the TNTs group, the bone formed around the implant in the minTBP-1-IGF-1 group and the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group (Figure 7(c) and (d)) from 4 to 12 weeks was more abundant. The highest value of BV/TV, Tb.Th, and Tb.N and the lowest value of BS/BV and Tb.Sp also confirmed that the most bone tissue was formed around the implant in the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group (Figure 7(e)–(i)). Tb.Sp value is related to the stability of bone volume around the implant and a high Tb.Sp value demonstrates that bone resorption is more likely to occur around the implant [2]. Among all groups, the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group had the lowest Tb.Sp value, which indicated that the combination of minTBP-1-IGF-1 and TNTs can effectively enhance the bone maintenance around the implant. In humans, IGF-1 and its binding proteins have positive roles in the acquisition of peak bone mass and the maintenance of bone mineral density [14]. Reduced expression of IGF-I resulted in attenuation of the bone mineralization in diabetic rats and low circulating levels of IGF-1 are associated with osteoporosis and fracture [15,16]. Numerous studies have highlighted the potential of IGF-1 to induce bone regeneration; local administration of IGF-1 has been shown to augment new bone formation and promote bridging bone defects in vivo [41,42]. In this study, it was confirmed that the effect of combined use of minTBP-1-IGF-1 and TNTs in promoting osteogenesis was significantly better than that of minTBP-1-IGF-1 or TNTs alone, and TNTs can be used as an effective carrier of minTBP-1- IGF-1. It can also be confirmed from the cross-section SEM of the implant and bone that the implant in the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group had the closest cohesion to the bone tissue (Figures 8 and 9), and the EDS scanning that hydroxyapatite was formed on the contact surface (Figure 9). Although the analysis of SEM and EDS in this section was qualitative, both indicated that the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs group can effectively promote the formation of bone tissue around the implant in T2DM condition.

5 Conclusion

Low implant osseointegration under T2DM condition is a thorny problem in clinical practice. While the minTBP-1-IGF-1-TNTs is a brand-new method to solve this problem, which is not only effectively enhancing the bone formation around the implant in the short term, but also significantly improving the long-term osseointegration.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by Shaanxi Natural Science Foundation of China (No. S2020-YF-YBSF-0432) and Shaanxi Science and Technology Innovation Team Project (No. 2021TD-46).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animals’ use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals.

References

[1] Yang J, Zhang H, Chan SM, Li R, Wu Y, Cai M, et al. TiO2 nanotubes alleviate diabetes-induced osteogenetic inhibition. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:3523–37. 10.2147/IJN.S237008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Tan N, Liu X, Cai Y, Zhang S, Jian B, Zhou Y, et al. The influence of direct laser metal sintering implants on the early stages of osseointegration in diabetic mini-pigs. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:5433–42. 10.2147/IJN.S138615.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Zhang J, Wang Y-N, Jia T, Huang H, Zhang D, Xu X. Genipin and insulin combined treatment improves implant osseointegration in type 2 diabetic rats. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16:59–69. 10.1186/s13018-021-02210-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Wang B, Song Y, Wang F, Li D, Zhang H, Ma A, et al. Effects of local infiltration of insulin around titanium implants in diabetic rats. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;9:225–9. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2010.03.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Alshahrani A, Al Deeb M, Alresayes S, Mokeem SA, Al-Hamoudi N, Alghamdi O, et al. Comparison of peri-implant soft tissue and crestal bone status of dental impla nts placed in prediabetic, type 2 diabetic, and non-diabetic individuals: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Implant Dent. 2020;6:56–63. 10.1186/s40729-020-00255-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Huang H, Luo L, Liu Z, Li Y, Tong Z, Liu Z. Role of TNF-α and FGF-2 in the fracture healing disorder of type 2 diabetes model induced by high fat diet followed by streptozotocin. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:2279–88. 10.2147/DMSO.S231735.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Chen B, He Q, Yang J, Pan Z, Xiao J, Chen W, et al. Metformin suppresses oxidative stress induced by high glucose via activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway in type 2 diabetic osteoporosis. Life Sci. 2022;312:121092. 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.121092.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Jia T, Wang YN, Feng Y, Wang C, Zhang D, Xu X. Pharmic activation of PKG2 alleviates diabetes-induced osteoblast dysfunction by suppressing PLCβ1-Ca2+-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:5552530. 10.1155/2021/5552530.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Oliveira PGFP, Coelho PG, Bergamo E, Witek L, Borges CA, Bezerra FB, et al. Histological and nanomechanical properties of a new nanometric hydroxiapatite implant surface: an in vivo study in diabetic rats. Materials. 2020;13:5693–709. 10.3390/ma13245693.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Novaes AB Jr, Souza SLSD, de Barros RR, Pereira KK, Iezzi G, Piattelli A. Influence of implant surfaces on osseointegration. Braz Dent J. 2021;21:471–81. 10.1590/S0103-64402010000600001.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Awad NK, Edwards SL, Morsi YS. A review of TiO2 NTs on Ti metal: electrochemical synthesis, functionalization and potential use as bone implants. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017;76:1401–12. 10.1016/j.msec.2017.02.150.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Huang J, Zhang X, Yan W, Chen Z, Shuai X, Wang A, et al. Nanotubular topography enhances the bioactivity of titanium implants. Nanomedicine. 2017;13:1913–23. 10.1016/j.nano.2017.03.017.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Park J, Cimpean A. Anodic TiO2 nanotubes: tailoring osteoinduction via drug delivery. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:2359–99. 10.3390/nano11092359.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Oh S, Brammer KS, Li YS, Teng D, Engler AJ, Chien S, et al. Stem cell fate dictated solely by altered nanotube dimension. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;106:2130–5. 10.1073/pnas.0813200106.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Gulati K, Ramakrishnan S, Aw MS, Atkins GJ, Findlay DM, Losic D. Biocompatible polymer coating of titania nanotube arrays for improved drug elution and osteoblast adhesion. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:449–56. 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.09.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Losic D, Simovic S. Self-ordered nanopore and nanotube platforms for drug delivery applications. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6:1363–81. 10.1517/17425240903300857.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Wang D, Mao J, Zhou B, Liao XF, Gong SQ, Liu Y, et al. A chimeric peptide that binds to titanium and mediates MC3T3-E1 cell adhesion. Biotechnol Lett. 2011;33:191–7. 10.1007/s10529-010-0411-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Gulati K, Santos A, Findlay D, Losic D. Optimizing anodization conditions for the growth of titania nanotubes on curved surfaces. J Phys Chem C. 2015;119:16033–45. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b03383.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Losic D, Aw MS, Santos A, Gulati K, Bariana M. Titania nanotube arrays for local drug delivery: recent advances and perspectives. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015;12:103–27. 10.1517/17425247.2014.945418.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Kawai M, Rosen CJ. The insulin-like growth factor system in bone: Basic and clinical implications. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2012;41:323–33. 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.04.013.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Sheng MH, Lau KH, Baylink DJ. Role of osteocyte-derived insulin-like growth factor I in developmental growth, modeling, remodeling, and regeneration of the bone. J Bone Metab. 2014;21:41–54. 10.11005/jbm.2014.21.1.41.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Niu T, Rosen CJ. The insulin-like growth factor-I gene and osteoporosis: A critical appraisal. Gene. 2005;361:38–56. 10.1016/j.gene.2005.07.016.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Sano K, Shiba K. A hexapeptide motif that electrostatically binds to the surface of titanium. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14234–5. 10.1021/ja038414q.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Sano K, Sasaki H, Shiba K. Specificity and biomineralization activities of Ti-binding peptide-1 (TBP-1). Langmuir. 2005;21:3090–5. 10.1021/la047428m.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Hayashi T, Sano K, Shiba K, Kumashiro Y, Iwahori K, Yamashita I, et al. Mechanism underlying specificity of proteins targeting inorganic materials. Nano Lett. 2006;6:515–9. 10.1021/nl060050n.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Zhang Q, Wang J, Cheng. B. The effects of functionalized titanium with minTBP-1-IGF-1 for improving osteoblast activity. Mater Lett. 2018;227:58–61. 10.1016/j.matlet.2018.05.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Berglundh T, Stavropoulos A, Working Group 1 of the VIII European Workshop on Periodontology. Preclinical in vivo research in implant dentistry. Consensus of the eighth European workshop on periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39(Suppl 12):1–5. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01827.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Sohrabipour S, Sharifi MR, Talebi A, Sharifi M, Soltani N. GABA dramatically improves glucose tolerance in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats fed with high-fat diet. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;826:75–84. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.01.047.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Nath S, Ghosh SK, Choudhury Y. A murine model of type 2 diabetes mellitus developed using a combination of high fat diet and multiple low doses of streptozotocin treatment mimics the metabolic characteristics of type 2 diabetes mellitus in humans. J Pharmacol Toxicol Met. 2017;84:20–30. 10.1016/j.vascn.2016.10.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Choee JH, Lee SJ, Lee YM, Rhee JM, Lee HB, Khang G. Proliferation rate of fibroblast cells on polyethylene surfaces with wettability gradient. J Appl Polym Sci. 2004;92:599–606. 10.1002/app.20048.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Gittens RA, Scheideler L, Rupp F, Hyzy SL, Geis-Gerstorfer J, Schwartz Z, et al. A review on the wettability of dental implant surfaces II: biological and clinical aspects. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:2907–18. 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.03.032.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Zhu X, Chen J, Scheideler L, Reichl R, Geis-Gerstorfer J. Effects of topography and composition of titanium surface oxides on osteoblast responses. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4087–103. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.11.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Smeets R, Stadlinger B, Schwarz F, Beck-Broichsitter B, Jung O, Precht C, et al. Impact of dental implant surface modifications on osseointegration. Biomed Res Int. 2016;628:5620. 10.1155/2016/6285620.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Schwarz F, Derks J, Monje A, Wang H‐L. Peri-implantitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(Suppl 20):S246–66. 10.1111/jcpe.12954.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Ruppa F, Liang L, Geis-Gerstorfer J, Scheideler L, Hüttig F. Surface characteristics of dental implants: a review. Dent Mater. 2018;34:40–57. 10.1016/j.dental.2017.09.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Gulati K, Aw MS, Findlay D, Losic D. Local drug delivery to the bone by drug-releasing implants: perspectives of nano-engineered titania nanotube arrays. Ther Deliv. 2012;3:857–73. 10.4155/tde.12.66.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Bissinger O, Probst FA, Wolff K-D, Jeschke A, Weitz J, Deppe H, et al. Comparative 3D micro-CT and 2D histomorphometry analysis of dental implant osseointegration in the maxilla of minipigs. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44:418–27. 10.1111/jcpe.12693.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Hong JM, Kim UG, Yeo IL. Comparison of three-dimensional digital analyses and two-dimensional histomorphometric analyses of the bone–implant interface. PLoS One. 2022;10:e0276269. 10.1371/journal.pone.0276269.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Butz F, Ogawa T, Chang TL, Nishimura I. Three-dimensional bone–implant integration profiling using micro-computed tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implant. 2006;1:687–95. 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.03.021.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Clozza E, Obrecht M, Dard M, Coelho PG, Dahlin C, Engebretson SP. A novel three-dimensional analysis of standardized bone defects by means of confocal scanner and micro-computed tomography. Clin Oral Investig. 2014;18:1245–50. 10.1007/s00784-013-1081-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Ashpole NM, Herron JC, Estep PN, Logan S, Hodges EL, Yabluchanskiy A, et al. Differential effects of IGF-1 deficiency during the life span on structural and biomechanical properties in the tibia of aged mice. AGE. 2016;38:38–51. 10.1007/s11357-016-9902-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Menendez LG, Sadaba MC, Puche JE, Lavandera JL, Castro LF, Gortazar AR, et al. IGF-I increases markers of osteoblastic activity and reduces bone resorption via osteoprotegerin and RANK-ligand. J Transl Med. 2013;11:271–82. 10.1186/1479-5876-11-271.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery

- The progress of cathode materials in aqueous zinc-ion batteries

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part I

- Effect of polypropylene fiber and nano-silica on the compressive strength and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete

- Mechanochemical design of nanomaterials for catalytic applications with a benign-by-design focus

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery