Abstract

Poor high-temperature stability (HTS) and weak microwave absorption performance (MAP) are a major restriction for wave-absorbing materials in elevated temperature ambient. Consequently, the Stöber process and the sol–gel method are first devised and used to create multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures (MCSNs) on Ti3AlC2 (TAC). The MCSNs with a thickness of 135–215 nm raise the starting oxidation temperature of the matrix by 400°C. Furthermore, the weight gain drops from 17.44 to 2.32% within 1 h at 800°C. The effective absorption bandwidth with a reflection loss (RL) ≤ −10 dB of the MCSNs-coated TAC is 3.25 GHz (8.68–11.27 and 11.63–12.29 GHz) at a thickness of 2.0 mm, which is 4.7 times that of the matrix. The minimum RL is reduced by a factor of 2.77 from −10.68 to −29.55 dB. The enhanced MAP is due to the introduced multiple reflection events and scattering mechanism as well as the enhanced electronic polarization, interface polarization, and polarization relaxation. The growth of the MCSNs provides a reference for the design and preparation of bifunctional materials with good HTS and MAP.

1 Introduction

The extreme electromagnetic environment (including high temperature, high damp heat, and salt fog) have brought high-temperature (>300°C), oxidation-resistant microwave absorbing materials (MAMs) into focus [1,2,3,4]. These materials can be used in civil, military, and aerospace equipment (such as for the nozzle, heat shield, and nose cone) [5,6,7,8]. Therefore, materials with outstanding high-temperature stability (HTS) and microwave absorption performance (MAP) are widely studied [9,10]. In order to meet these requirements, various MAMs have been developed, mainly including magnetic materials (such as magnetic metals [11,12] and ferrites [13]), carbon-based materials (such as carbon nanotubes [14,15], carbon fibers [16], and graphene [5]), and ceramic-based materials (such as SiCnp/Cf [17], PyC–SiCf/SiC [18], and Cf/SiCnw [19]). The general use of magnetic materials in high-temperature situations is severely constrained by the low Curie temperature [20]. Furthermore, once the temperature reaches 300°C, carbon-based materials begin to oxidize [21]. Naturally, SiC-based materials with good HTS and chemical stability become one of the best choice for high-temperature MAMs [22]. However, the low carrier concentration and single polarization mechanism prevent SiC from achieving excellent MAP.

Until now, the introduction of dielectric materials to tune the complex permittivity and polarization mechanism of SiC-based materials has been a commonly used strategy to improve their MAP [18,23]. Han et al. prepared SiC nanowires reinforced SiCf/SiC composites via chemical vapor infiltration [24]. The conductivity and complex permittivity of the composites showed a significant uplift dependence on temperature. Furthermore, the minimum reflection loss (RLmin) was −47.5 dB at a thickness of 2.5 mm at 11.4 GHz and 600°C, and the effective absorption bandwidth (EAB; RL ≤ −10 dB) was 2.8 GHz. Huo et al. prepared heterogeneous SiC/ZrC/SiZrOC hybrid nanofibers containing different highly conductive ZrC phases via electrospinning and high-temperature pyrolysis [25]. When the content of ZrC was up to 10 wt%, the conductivity of the SiC/ZrC/SiZrOC hybrid nanofibers increased from 0.34 to 2.57 S/cm. For SiC/ZrC/SiZrOC hybrid nanofibers containing 7 wt% ZrC, the initial oxidation temperature was around 600°C. When the thickness of the absorber was 3 mm, the EAB was 3 GHz (8.2–11.2 GHz), and the RLmin was −17.5 dB at 10.3 GHz. These results indicate that the inclusion of dielectric materials can considerably improve the MAP of SiC. However, the excellent chemical properties of SiC are degraded, especially its HTS. Therefore, finding a MAM with good HTS and complex polarization mechanism is necessary.

Good electrical characteristics and high-temperature oxidation resistance are displayed by the ternary-layered compound Ti3AlC2 (TAC) [26,27]. TAC is a promising replacement for SiC due to these benefits. The notion that TAC has a good HTS is supported by the modest mass gain at 800°C [28]. The abundant interface and the Ti–C bond endow TAC with a high interface polarization and electronic polarization. Li et al. successfully doped TAC with Fe (xFe-TAC) through high-temperature solid-state sintering [29]. Doping has the ability to improve defect dipole polarization and considerably diversify the phase interface of TAC. They found that when the absorber thickness was 1.5 mm, the RLmin was −33.3 dB, and the EAB was 3.9 GHz. In addition, the core–shell design based on a heterogeneous interface can adjust the complex permittivity and interface polarization mechanism, thus optimizing impedance matching [30]. It is envisaged that TAC with a core–shell structure can achieve not only an excellent MAP but also a good HTS. SiO2 can be exploited in this aspect since it has high thermo-stability, antioxidant properties, and high microwave transmittance characteristics [31]. It hardly inhibits the coupling between matrixes. On the other hand, the antioxidant Al2O3 also holds the potential to maintain the diffusion barrier integrity by supplying adequate environmental protection [32].

Herein the Stöber process (SP) and the sol–gel method (SGM) based on heterogeneous interface engineering were used to construct multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures (MCSNs) in situ on TAC. The results show that the MCNMs with a thickness of 135–215 nm have a significant effect on the HTS and MAP of TAC. In instance, they can nearly double the initial oxidation temperature of TAC (from 400 to 800°C) and reduce the mass gain of TAC by a factor of 6.52 (from 17.44 to 2.32%). Furthermore, the EAB can be broadened by a factor of 4.7 (from 0.69 to 3.25 GHz) with a thickness of 2.0 mm, and the RLmin can be increased by a factor of 2.77 (from −10.68 to −29.55 dB). The results presented in this work can serve as a guide for designing MAMs with good MAP and HTS.

2 Experimental method

2.1 Materials

The high-temperature solid-state sintering method was employed to create the TAC that was used in the current study. Figure S1 displays the comprehensive process and composition analysis. The reagents used mainly include tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS; Si(OC2H5)4), aluminum nitrate (Al(NO3)3·9H2O), ammonia (NH3·H2O), absolute ethanol (EtOH), and deionized water (H2O). The above reagents were analytically pure and were purchased from Sinopharm Group Chemical Agent Co. Ltd.

2.2 Sample synthesis

First, a solution was made by combining 14 ml of deionized water, 56 ml of EtOH, and 2 ml of ammonia. After 5 g TAC was added to the aforementioned solution and mechanically mixed (300 rpm) for 10 min, 14.4 ml of TEOS was added and reacted for 6 h at 30°C. The reaction products were then cleaned, dried for 24 h at 80°C in a vacuum drying oven, and the resulting sample is known as TAC@SiO2.

Next 14 ml of deionized water and 56 ml of EtOH were mixed together in a solution. 5 g TAC@SiO2 and 5 g Al(NO3)3·9H2O were added sequentially, and the solution was mechanically stirred for 10 min at 300 rpm. Then, ammonia water was added dropwise, so that the PH was corrected to 11. The reaction took place for 6 h at 30°C. Furthermore, the product obtained by suction filtration of the solution was repeatedly washed and dried in a vacuum drying oven for 24 h at 80°C. Finally, the dried product was placed in a tube furnace for annealing; the obtained product is named TAC@SiO2@Al2O3. The annealing temperature was 800°C (heated at the rate of 10°C/min). The annealing time was 2 h, the protective gas was N2, and the gas flow was 80 ml/min.

2.3 Characterization

The surface morphology and element distribution of the samples were observed using a Thermo Quattro S (USA) field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) equipped with an EDAX ELECT PLUS spectrometer. The working voltage was 10 kV. A FEI Tecnai G2 F20 (USA) transmission electron microscope (TEM) equipped with an energy spectrometer (Oxford 80 T) was used for the microstructure analysis and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). The acceleration voltage was 200 kV. The phase composition of the samples was analyzed using an Ultima IV (Japan) X-ray diffractometer (XRD) with a Cu Kα radiation source. The scanning rate was 5°/min. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were carried out using a Thermo Fisher Nexsa (USA) spectrometer with a standard Al Kα X-ray source (1486.7 eV). The Raman spectra were acquired using a Thermo DXR2xi (USA), and the laser wavelength was 532 nm. Thermogravimetric (TG), differential thermogravimetric (DTG), and differential scanning calorimetric (DSC) analyses were performed using an STA 449 F3 (Germany) in the temperature range of 30–1,300°C (the heating rate was 10°C/min). The electromagnetic parameters were measured using a N5230A network vector analyzer (USA) in the frequency range of 0.5–18 GHz at room temperature. The samples used for these measurements consisted of a circular workpiece with an outer diameter of 7.0 mm and an inner diameter of 3.0 mm. The samples were composed of the different TAC-based absorbents and paraffin with a mass ratio of 4:1. The dielectric dispersion, power flow, electric field strength, and power loss density of the absorbers were computed from the measured electromagnetic parameters using the CST Studio Suite 2019 program. The simulation model consisted of a square plate with a thickness of 2.0 mm. Incident electromagnetic waves (EWs) were set to transmit in the opposite direction along the z-axis. All directions were open within the boundary conditions.

3 Results and discussion

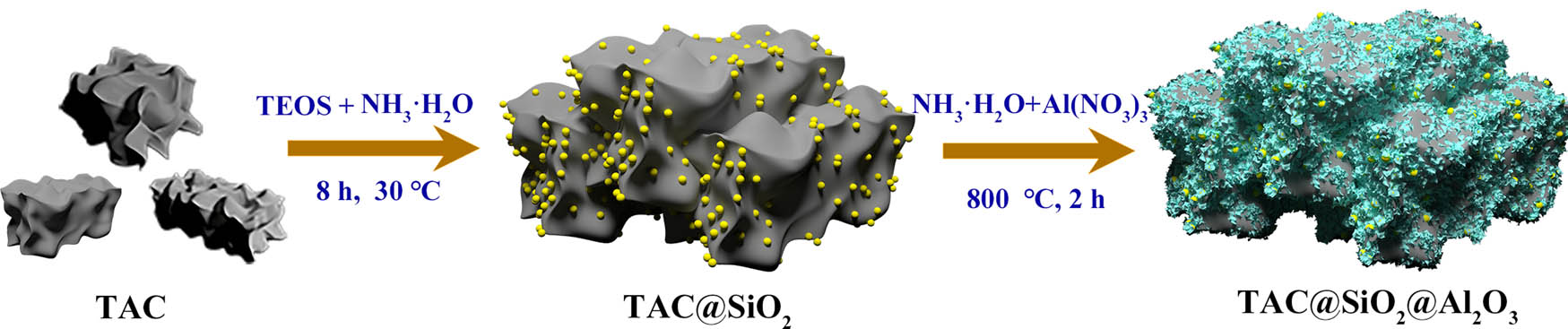

The preparation process of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 is schematically depicted in Figure 1. First, the TAC was coated with SiO2 using the classical SP. In this process, the silanol groups’ bonding and dangling bonds at the TAC surface change the polarity state of the substrate, causing the TAC@SiO2 particles to couple together [33,34]. Second, the surface of the coupled TAC@SiO2 particles was coated with materials containing Al. Furthermore, after annealing at 800°C for 2 h in N2, a flaky Al2O3 coating was formed around the linked TAC@SiO2 particles; this sample is named TAC@SiO2@Al2O3. This is the first report on the preparation of TAC coated with MCSNs using such a simple strategy.

Schematic diagram of the synthesis process of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3.

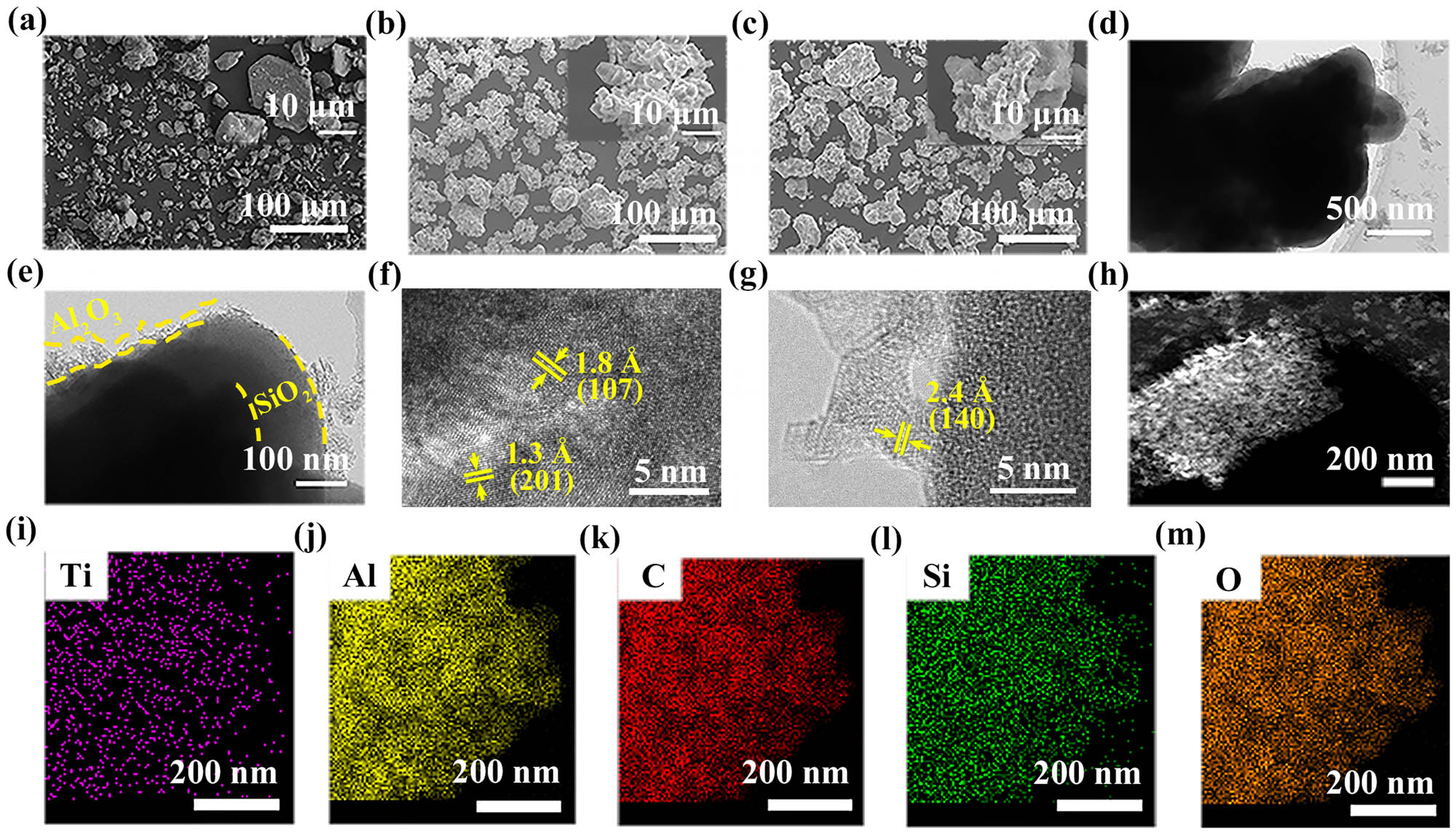

Figure 2 displays the microscopic morphology and composition analyses of the TAC-based absorbents. This graphic demonstrates how significantly different the morphology and structure of TAC@SiO2 are from those of TAC. It can be inferred that a coupling reaction occurred between the TAC@SiO2 particles [35]. Additionally, the TAC@SiO2 surface is covered with rough products during the SGM and subsequent annealing process (AP), as depicted in Figure 2(c). The linked TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 particles’ TEM images are displayed in Figure 2(d) and (e). Amorphous SiO2 has a thickness of around 135 nm. The thickness of the Al2O3 shell is in the range of 10–80 nm. According to Figure 2(f), the (107) and (103) crystal planes of TAC correspond to the crystal plane spacings of 1.8 and 1.3, respectively. The crystal plane spacing of 2.4 Å corresponds to the (140) crystal plane of Al2O3, which reconfirms the presence of Al2O3, as shown in Figure 2(g).

SEM images showing the surface appearance of (a) TAC, (b) TAC@SiO2, and (c) TAC@SiO2@Al2O3. (d) and (e) TEM images and (f) and (g) corresponding high resolution TEM images of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3. (h) TEM image of the as-fabricated TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 and corresponding elemental mapping of (i) Ti, (j) Al, (k) C, (l) Si, and (m) O.

The Ti, Al, C, Si, and Al element mappings for the paired TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 particles are shown in Figure 2(i)–(m). The Al, Si, C, and O elements are uniformly distributed in the coupled TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 particles, indicating that SiO2 and Al2O3 interact to generate a homogeneous heterostructure. The defects in heterostructures can be used as polarization centers to generate a dipole polarization [36].

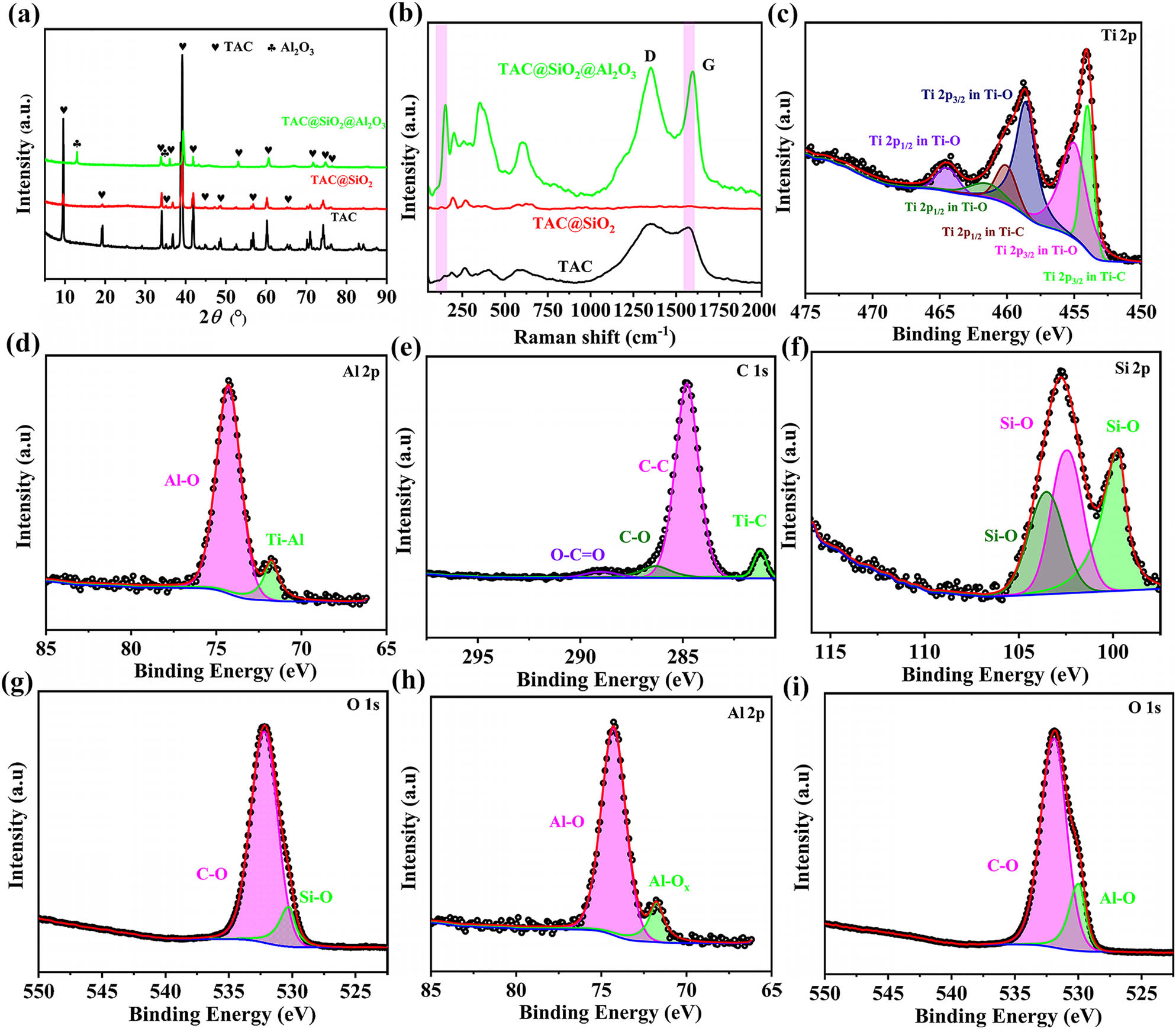

Figure 3(a) shows the XRD patterns of TAC, TAC@SiO2, and TAC@SiO2@Al2O3. It can be seen that the XRD pattern of TAC is made up of 11 diffraction peaks located at 9.5, 19.2, 33.7, 36.8, 39.0, 41.8, 48.5, 56.6, 61.0, 70.6, and 74.1°, corresponding to PDF#52-0875. After the SP, the TAC surface is coated with SiO2; however, SiO2 cannot be detected, which is mainly attributed to its amorphous state. Furthermore, after TAC@SiO2 is subjected to the SGM and the AP, the major diffraction peaks of TAC are retained, and the Al2O3 diffraction peaks appear at 12.8 and 34.5°, correlating to PDF#03-0066. This shows that Al2O3 was successfully deposited on to the TAC surface.

(a) XRD patterns of TAC, TAC@SiO2, and TAC@SiO2@Al2O3. (b) Raman spectra of TAC, TAC@SiO2, and TAC@SiO2@Al2O3. (c) High-resolution Ti 2p spectrum, (d) high-resolution Al 2p spectrum, and (e) high-resolution C 1s spectrum of TAC. (f) High-resolution Si 2p spectrum and (g) high-resolution O 1s spectrum of TAC@SiO2. (h) High-resolution Al 2p spectrum and (i) high-resolution O 1s spectrum of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3.

The Raman shifts of TAC, TAC@SiO2, and TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 were collected in order to more precisely investigate the structure and composition of the TAC-based absorbers, as shown in Figure 3(b). The three Raman bands located at 250, 400, and 600 cm−1 represent the vibration modes of the non-stoichiometric Ti–C bond in TAC. The two broad peaks located between 1,300 and 1,600 cm−1 are the D and G modes of the C atom [37]. Interestingly, the Raman peaks of TAC in TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 appear blue shift and move to a position with higher Raman shift, which will be caused by the high bond energy of the Si–O and Al–O bonds [38]. For TAC@SiO2, there are roughly five Raman shifts in the Raman peak corresponding to the vibration mode of the non-stoichiometric Ti–C bond. For TAC@SiO2@Al2O3, the Raman peak representing the non-stoichiometric Ti–C bond experiences about 25 Raman shifts. In addition, the intensity ration of D and G (I D/I G) peak of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 is 1.02, which is comparable to the I D/I G value of TAC@SiO2. This shows that the MCSNs have not significantly altered the inherent state of the C atom in TAC. The findings further indicate that the MCSNs have no significant influence on the composition and structure of TAC.

Furthermore, the chemical composition and element valence state of the TAC-based absorbents were revealed via XPS, as shown in Figure 3(h)–(j). Figure 3(c) shows the high-resolution Ti 2p spectrum of TAC, which can be fitted with six peaks. The Ti 2p1/2 peak at 454.0 eV and the Ti 2p3/2 peak at 460.1 eV correspond to the Ti–C bond in TAC, confirming the existence of TAC [26,39]. The Ti 2p1/2 peak at 455.0 eV and the Ti 2p3/2 peak at 461.5 eV correspond to the Ti–O bond in non-stoichiometric TiO2 [40]. The Ti 2p1/2 peak at 458.6 eV and the Ti 2p3/2 peak at 464.4 eV correspond to the Ti–O bond in TiO2 [41]. As shown in Figure 3(d), two peaks with binding energies of 71.8 and 74.3 eV are observed in the high-resolution Al 2p spectrum of TAC, corresponding to the Ti–Al bond in TAC and the Al–O bond in Al2O3, respectively [42,43]. The high-resolution C1s spectrum is fitted with four peaks (as shown in Figure 3(e)) located at 281.2, 284.8, 286.4, and 288.9 eV, corresponding to the C–Ti, C–C, C–O, and O–C═O bonds, respectively [44]. These results show that the investigated samples are mainly composed of TAC and contain only small amounts of TiO2 and Al2O3. Figure 3(f) and (g) show the high-resolution Si 2p and O 1s spectra of TAC@SiO2. Figure 3(f) shows that the high-resolution Si 2p spectrum can be decomposed into three peaks with binding energies of 99.7, 102.4, and 103.5 eV, corresponding to SiO x (0 < x < 2), SiO x (0 < x < 2), and SiO2, respectively [45,46,47]. The high-resolution O 1s spectrum of TAC@SiO2 can be divided into two peaks located at 530.2 and 532.2 eV, as shown in Figure 3(g), corresponding to the Si–O and C–O bonds, respectively [48]. The high-resolution Si 2p and O 1s spectra of TAC@SiO2 confirm the existence of SiO2. The position difference in the O 1s peaks of TAC and TAC@SiO2 is mainly caused by the C–O bond in air [49]. In the high-resolution Al 2p spectrum of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3, an intense peak is observed at 75.0 eV, corresponding to Al2O3 [50,51], as shown in Figure 3(h), while the peak at 72.3 eV corresponds to AlO x [52]. The appearance of Al2O3 is derived from the annealing of Al(OH)3 in N2·Al(OH)3 is from the hydrolysis of Al3(NO3)3·9H2O in NH3·H2O. The specific reaction equation is shown in equations (1) and (2).

In the high-resolution O 1s spectrum of the coupled TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 particles (Figure 3(i)), the peaks at 529.9 and 531.9 eV correspond to the Al–O and C–O bonds, respectively [53,54,55]. The above analysis results fully confirm the successful preparation of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3. More importantly, the structural synergy of the three substances is the key to improve the HTS and MAP of the TAC-based absorbents.

The TG analysis can reveal the thermal stability and oxidation stability of samples at different temperatures and atmospheres. Therefore, we examined the HTS of the TAC-based absorbents from room temperature to 1,300°C, as shown in Figure 4. It is evident that all samples exhibit almost the same characteristic curves, as shown in Figure 4(a). It can be observed that the initial oxidation temperature of TAC is approximately 400°C. The initial oxidation temperature of TAC@SiO2 is around 500°C. Furthermore, the initial oxidation temperature of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 is up to 800°C. As demonstrated, the MSCNs raise the TAC’s initial oxidation temperature by 400°C. Thus, it is clear that the MSCNs greatly enhance the HTS of TAC. It is possible mainly because of the MSCNs’ ability to significantly decrease the number of transport channels connecting oxygen and TAC. SiO2@Al2O3 can constitute a dense network structure [56]. This network structure can effectively reduce the number of transport channels between oxygen and the ceramic matrix and restrict oxygen diffusion to the interior, improving TAC’s high-temperature oxidation resistance. Figure 4(b) shows the DTG curves of TAC, TAC@SiO2, and TAC@SiO2@Al2O3. It can be noted that the weight gain rate of TAC is 0.03%/°C. On the other hand, the weight gain rate of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 coated with the MSCNs is only 0.008%/°C. Furthermore, the exothermic peaks of TAC, TAC@SiO2, and TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 are located at 944.59, 1,178, and 1,220°C, respectively, as shown in Figure 4(c). All these point to the fact that MSCN can greatly increase TAC’s high-temperature oxidation resistance. The TAC-based absorbents were submitted to isothermal TG tests at 800°C in air over the course of 1 h to verify that the HTS of TAC is improved, as shown in Figure 4(d). It is obvious that TAC’s mass increase can reach 14.70%, whereas TAC@SiO2@Al2O3’s mass increase is just 2.72%.

HTS analysis of the TAC-based absorbents at high temperature. (a) TG, (b) DTG, and (c) DSC analysis of TAC, TAC@SiO2, and TAC@SiO2@Al2O3. (d) TG curves of TAC, TAC@SiO2, and TAC@SiO2@Al2O3; these curves were obtained at 800°C in air over the period of 1 h.

To establish the MAP of MAMs, electromagnetic characteristics are crucial. As a result, we examined the real part (ɛ′) and imaginary part (ɛ″) of the TAC-based absorbers as well as the dielectric loss tangent (tan δ ε) of the complex permittivity, as shown in Figure S3. ɛ′ represents the capacity of a material to store electric energy, while ɛ″ and tan δ ε indicate the capacity of a material to dissipate the incident EWs. As is well known, TAC, SiO2, and Al2O3 are all non-magnetic materials, and the complex permeability is thus not considered here. The ɛ′ of TAC, TAC@SiO2, and TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 decreases with the increase in frequency, as shown in Figure S3(a) and (b). This is because the dipoles in the TAC-based absorbers rearrange when an electric field is applied. The dielectric polarization caused by the rearranged dipoles is reduced as the frequency rises, preventing them from following the electric field and causing a decrease in the dielectric response. In addition, the ɛ′ of TAC is 15.9–18.0 in the range of 0.5–18 GHz, and the ɛ′ of TAC coated with the MCSNs is 15.1–17.9. The ɛ″ of TAC is 0.007–0.33 at 0.5–18 GHz, and the ɛ″ of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 is 0.04–0.51. It can be seen that the ɛ″ of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 is significantly lower than that of TAC at 7–14 GHz. The TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 has a greater ɛ″ than TAC at 0.5–15 GHz. Additionally, the tan δ ε values of the TAC-based absorbers were determined. It was discovered that the tan δ ε of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 is higher than that of TAC in the range of 0.5–13 GHz. It is clear that TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 has a greater ability than TAC to disperse incident EWs. In addition, the MAP of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 around 11 GHz is almost unaffected by sample thickness. Two main reasons cause this: when the thickness of the absorber layer increases to a certain level, the absorption capacity of the material will reach its limit, i.e., saturation state [57]. Second, due to the particular shape and size of the TAC, there may be a resonance phenomenon at a specific frequency point [58]. That is, when the frequency of the microwave is equal to the resonance frequency of the material, the absorption performance will reach its peak.

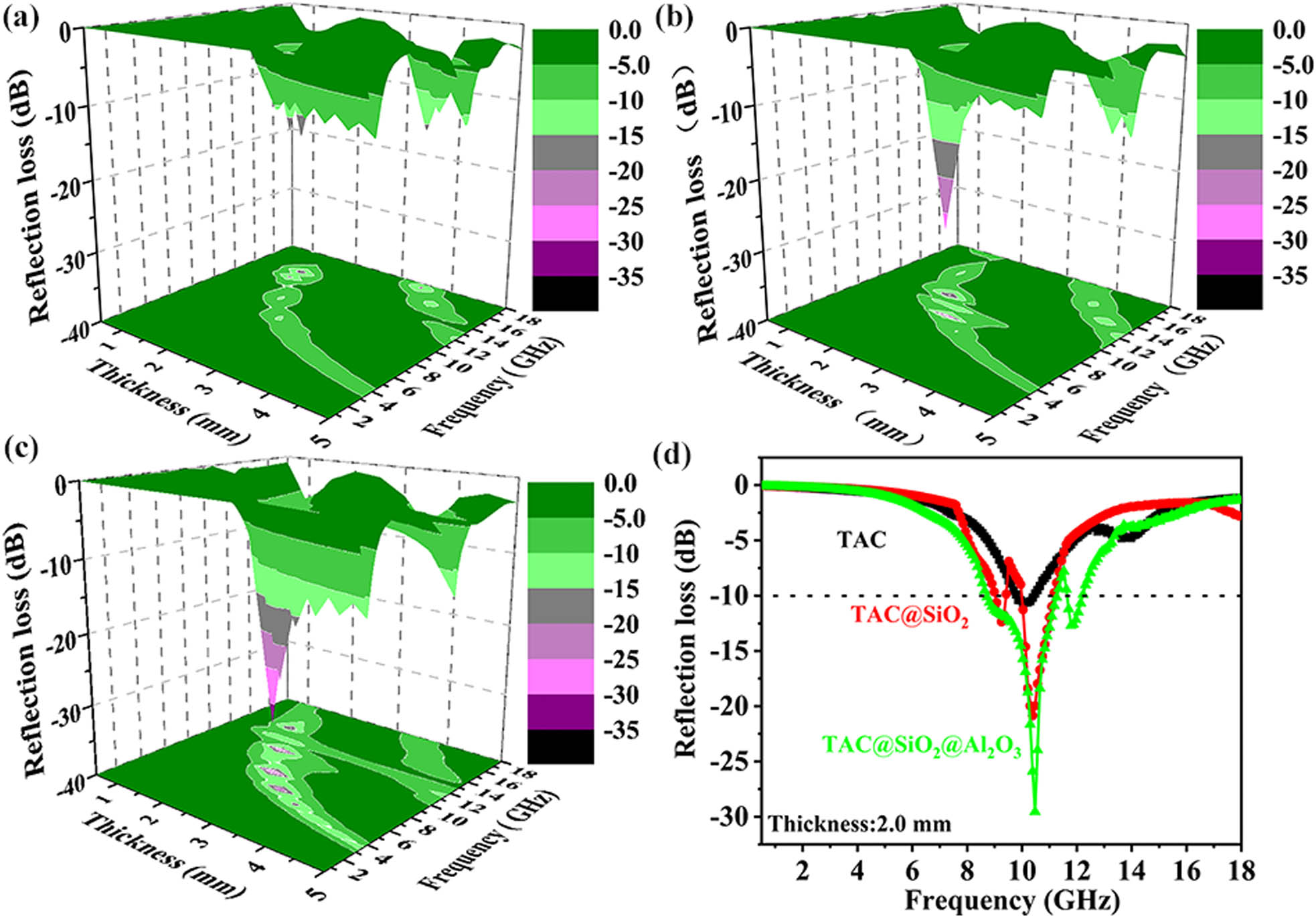

In order to more intuitively analyze the impact of the MCSNs on the properties of the TAC, the RL values of the TAC-based absorbers were calculated using equations (3) and (4). The 3D RL maps of the TAC-based absorbers with a thickness of 0.5–5 mm in the frequency range of 0.5–18 GHz are shown in Figure 5(a)–(c) [59,60].

where Z in and Z 0 stand for the input impedance and internal impedance, respectively. Additionally, μ r stands for the complex permeability, ε r represents the complex dielectric constant, f is the microwave frequency, d marks the thickness of the absorber, and c specifies the speed of light.

Frequency and thickness dependence of the simulated three-dimensional (3D) RL maps of (a) TAC, (b) TAC@SiO2, and (c) TAC@SiO2@Al2O3. (d) RL curves of the TAC-based absorbers with a thickness of 2.5 mm in the range of 0.5–18 GHz.

According to the comparisons of the RL curves of the TAC-based absorbers with a thickness of 2.0 mm at 0.5–18 GHz, it is found that the EAB of TAC is 0.69 GHz (9.75–10.44 GHz), and the RLmin is −10.68 dB (10.09 GHz). The EAB of TAC@SiO2 is 1.50 GHz (9.03–9.42 GHz and 9.99–11.12 GHz), and the RLmin is −20.70 dB (10.39 GHz). The EAB of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 is 3.25 GHz (8.68–11.27 and 11.63–12.29 GHz), and the RLmin is −29.55 dB (10.52 GHz). Compared with pure TAC, the EAB of TAC coated with MCSNs is 4.7 times higher and the RLmin is 2.77 times higher, demonstrating outstanding microwave absorption capabilities. This can be explained by the following two aspects: First, the multi-peak resonances induced by the heterogeneous interfaces broaden the EAB of the TAC. TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 is mainly composed of TAC, amorphous SiO2, and Al2O3. The four resonance peaks located at 6.64, 9.82, 12.64, and 14.56 GHz, as shown in Figure S3(b), are induced by the three-phase interactions, surface geometric enhancement effect, and local space charge accumulation [61,62,63]. Compared with the three resonance peaks of TAC located at 7.48, 11.38, and 13.76 GHz, both the number and intensity of the resonance peaks of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 are higher. It is noteworthy that the resonance peak of TAC coated with the MCSNs moves to a lower frequency. This can be explained by the quarter-wavelength resonance equation

where ε s denotes the static permittivity, and ε ∞ presents the high-frequency limited permittivity.

In the Cole–Cole plot, a semicircle represents a relaxation process. The polarization relaxation loss increases with the semicircle radius. In the Cole–Cole plot, the slope of a straight line represents the strength of conductive loss. The greater the slope of the line, the stronger the conduction loss [18]. As seen in Figure S4, TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 exhibits a stronger polarization loss and conduction loss than TAC. In addition, the numerous heterogeneous interfaces (such as those between TAC, amorphous SiO2, and Al2O3) can heighten the interface polarization. Compared with a single TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 particle, the coupling of different TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 particles gives rise to more heterogeneous interfaces, further enhancing the interfacial polarization. The existence of defect sites (such as Schottky defects and Frenkel defects) in the flaky Al2O3 structure and the SiO2/Al2O3 heterostructure can induce the generation of a dipole polarization and an atomic polarization centered on each defect, thereby boosting the polarization relaxation [67,68,69]. The attenuation constants of TAC, TAC@SiO2, and TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 for incident EWs in the range of 0.5–18 GHz are shown in Figure S5. It is clear that TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 has a much greater attenuation capacity than TAC for incident EWs.

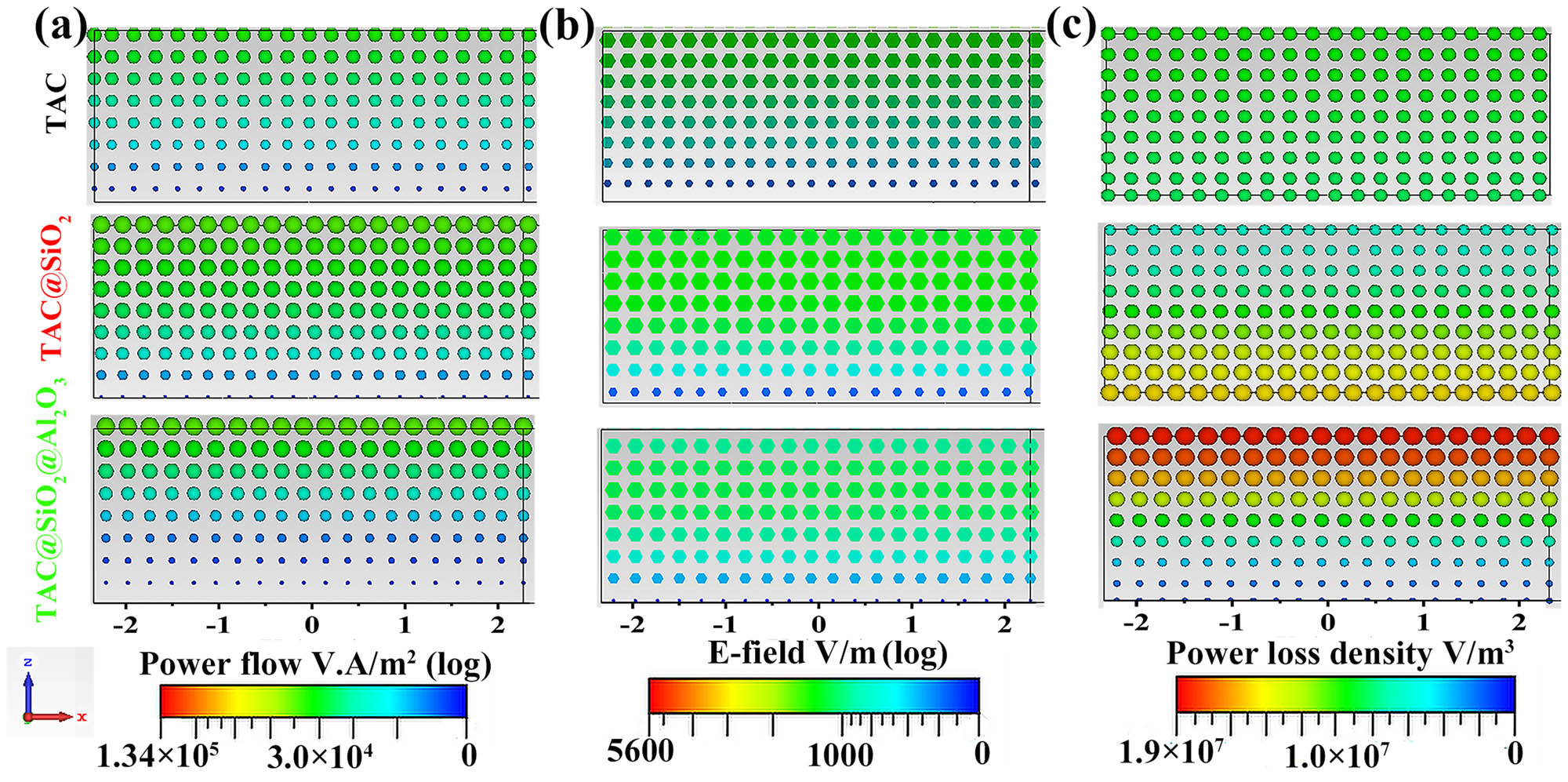

In order to visually depict the positive effects of the MSCNs, the power flow (V·A/m2), electric field (V/m), and power loss density (W/m3) of the TAC-based absorbers were simulated using the CST software, as shown in Figure 6. To guarantee the validity of the result, the simulated S11 coefficient and calculated RL curves of the TAC-based absorbers were compared, as shown in Figure S6. The consistency of the S11 and RL results proves the correctness of the simulation model. The circular spots in Figure 6(a) show that the power flow of TAC@SiO2 is noticeably higher than that of TAC based on their size and color. The power flow of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 is greater in the upper portion of the absorber than that of TAC@SiO2. The power going into TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 at the lower portion of the absorber is less than that flowing into TAC@SiO2. The high conductivity of coupled TAC@SiO2@Al2O3, which results in a potent reflection for the incident EWs, is responsible for this phenomenon. Figure 6(b) shows the electric field (V/m) of the TAC-based absorbers. In the TAC-based absorbers, the electric field intensity decreases from top to bottom. The reduction in the electric field strength (where the electric field represents the microwaves) indicates that the loss ability for EWs of the MAMs becomes gradually stronger [70]. TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 has a lower electric field intensity in the upper portion of the absorber than TAC and TAC@SiO2. Thus, TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 provides the best EW attenuation capability.

(a) Power flow, (b) electric field, and (c) power loss density distribution diagrams of TAC, TAC@SiO2, and TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 with a thickness of 2.0 mm at 10.48 GHz.

4 Conclusion

In this study, a simple combination of the SP and SGM based on heterogeneous interface engineering is first proposed to prepare MCSNs on TAC. The thickness of the MCSNs was roughly 145–215 nm. The HTS and MAP of TAC coated with the MSCNs are significantly enhanced. The starting oxidation temperature of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 is 800°C, which is about 400°C higher than that of TAC. After holding at 800°C for 1 h, the mass gain of TAC is only 2.32%, which is 14.70% less than that of TAC. The EAB of TAC@SiO2@Al2O3 is 3.25 GHz (8.68–11.27 and 11.63–12.29 GHz) at a thickness of 2.0 mm, which is 4.7 times more than that of TAC. The RLmin is reduced by a factor of 2.77, from −10.68 dB at 10.09 GHz to −29.55 dB at 10.52 GHz. This is because there are fewer transport pathways between oxygen and TAC as a result of MSCNs. Additionally, they increase the number of multiple reflection events, strengthen the scattering mechanism, and enhance the electronic polarization, interface polarization, and polarization relaxation. Such a simple strategy to improve the HTS and MAP of the matrix is useful in the design of MAMs with excellent MAP and HTS.

-

Funding information: The present study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52202368), the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan (Nos. 2022NSFSC0347 and 2023NSFSC0586), the Open Projects of Vanadium and Titanium Resource Comprehensive Utilization Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province (Nos. 2021FTSZ05 and 2021FTSZ11), the Open project of Sichuan Vanadium Titanium Materials Engineering Technology Research Center (Nos. 2022FTGC01 and 2022FTGC02), and the guiding science and technology projects of Panzhihua (No. 2021ZD-G-4).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Shao G, Shen X, Huang X. Multilevel structural design and heterointerface engineering of a host–guest binary aerogel toward multifunctional broadband microwave absorption. ACS Mater Lett. 2022;4:1787–97.10.1021/acsmaterialslett.2c00634Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Quan B, Gu W, Sheng J, Lv X, Mao Y, Liu L, et al. From intrinsic dielectric loss to geometry patterns: Dual-principles strategy for ultrabroad band microwave absorption. Nano Res. 2021;14:1495–501.10.1007/s12274-020-3208-8Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Yang G, Li Z, Haipeng L, Longjiang D. Preparation of multi-shell FeSiAl@SiO2@C and its corrosion resistance and electromagnetic properties. Rare Met Mater Eng. 2022;51:2280–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Zhou N, Zhang L, Wang W, Zhang XQ, Zhang KQ, Chen MJ, et al. Stereolithographically 3D printed SiC metastructure for ultrabroadband and high temperature microwave absorption. Adv Mater Technol. 2022;2201222.10.1002/admt.202201222Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Jiang Z, Si H, Li Y, Li D, Chen H, Gong C, et al. Reduced graphene oxide@carbon sphere based metacomposites for temperature-insensitive and efficient microwave absorption. Nano Res. 2022;15:8546–54.10.1007/s12274-022-4674-ySuche in Google Scholar

[6] Ma W, He P, Wang T, Xu J, Liu X, Zhuang Q, et al. Microwave absorption of carbonization temperature-dependent uniform yolk-shell H-Fe3O4@C microspheres. Chem Eng J. 2021;420:129875.10.1016/j.cej.2021.129875Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Li C, Li D, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Gong C, et al. Boosted microwave absorption performance of transition metal doped TiN fibers at elevated temperature. Nano Res. 2023;16:3570–9.10.1007/s12274-023-5398-3Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Gu H, Huang J, Li N, Yang H, Chen G, Dong C, et al. Reactive MnO2 template-assisted synthesis of double-shelled PPy hollow nanotubes to boost microwave absorption. J Mater Sci & Technol. 2023;146:145–53.10.1016/j.jmst.2022.11.010Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Wang H, Li Z, Dong B, Sun W, Yang X, Liu R, et al. Recent progresses of high-temperature microwave-absorbing materials. Nano. 2018;13:1830005.10.1142/S1793292018300050Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Shi Y, Li D, Si H, Jiang Z, Li M, Gong C, et al. TiN/BN composite with excellent thermal stability for efficiency microwave absorption in wide temperature spectrum. J Mater Sci & Technol. 2022;130:249–55.10.1016/j.jmst.2022.04.050Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Guo Y, Jian X, Zhang L, Mu C, Yin L, Xie J, et al. Plasma-induced FeSiAl@Al2O3@SiO2 core–shell structure for exceptional microwave absorption and anti-oxidation at high temperature. Chem Eng J. 2020;384:123371.10.1016/j.cej.2019.123371Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Yang X, Duan Y, Zeng Y, Pang H, Ma G, Dai X. Experimental and theoretical evidence for temperature driving an electric-magnetic complementary effect in magnetic microwave absorbing materials. J Mater Chem C. 2020;8:1583–90.10.1039/C9TC06551BSuche in Google Scholar

[13] Yin P, Zhang L, Feng X, Wang J, Dai J, Tang Y. Recent progress in ferrite microwave absorbing composites. Integr Ferroelectr. 2020;211:82–101.10.1080/10584587.2020.1803677Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Qiu Y, Yang H, Wen B, Ma L, Lin Y. Facile synthesis of nickel/carbon nanotubes hybrid derived from metal organic framework as a lightweight, strong and efficient microwave absorber. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;590:561–70.10.1016/j.jcis.2021.02.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Che RC, Zhi CY, Liang CY, Zhou XG. Fabrication and microwave absorption of carbon nanotubes/CoFe2 O4 spinel nanocomposite. Appl Phys Lett. 2006;88:033105.10.1063/1.2165276Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Wu F, Yang K, Li Q, Shah T, Ahmad M, Zhang Q, et al. Biomass-derived 3D magnetic porous carbon fibers with a helical/chiral structure toward superior microwave absorption. Carbon. 2021;173:918–31.10.1016/j.carbon.2020.11.088Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Yang C, Cheng L. Ultralight and flexible SiC nanoparticle-decorated carbon nanofiber mats for broad-band microwave absorption. Carbon. 2021;171:474–83.10.1016/j.carbon.2020.09.040Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Huang B, Wang Z, Hu H, Xiu-ZhiTang, Huang X, Yue J, et al. Enhancement of the microwave absorption properties of PyC-SiCf/SiC composites by electrophoretic deposition of SiC nanowires on SiC fibers. Ceram Int. 2020;46:9303–10.10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.12.185Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Su J, Wang B, Cao X, Yang R, Zhao H, Zhang P, et al. Simultaneously enhancing mechanical and microwave absorption properties of Cf/SiC composites via SiC nanowires additions. Ceram Int. 2022;48:36238–48.10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.08.181Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Meng L, Zhou Z, Xu M, Yang S, Si K, Liu L, et al. Anomalous thickness dependence of Curie temperature in air-stable two-dimensional ferromagnetic 1T-CrTe2 grown by chemical vapor deposition. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1–8.10.1038/s41467-021-21072-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Saroha R, Oh JH, Lee JS, Kang YC, Jeong SM, Kang DW, et al. Hierarchically porous nanofibers comprising multiple core–shell Co3O4@graphitic carbon nanoparticles grafted within N-doped CNTs as functional interlayers for excellent Li–S batteries. Chem Eng J. 2021;426:130805.10.1016/j.cej.2021.130805Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Zeng X, Li E, Xia G, Xie N, Shen ZY, Moskovits M, et al. Silica-based ceramics toward electromagnetic microwave absorption. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2021;41:7381–403.10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2021.08.009Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Yang J, Liu X, Gong W, Wang T, Wang X, Gong R. Temperature-insensitive and enhanced microwave absorption of TiB2/Al2O3/MgAl2O4 composites: Design, fabrication, and characterization. J Alloy Compd. 2022;894:162144.10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.162144Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Han T, Luo R, Cui G, Wang L. Effect of SiC nanowires on the high-temperature microwave absorption properties of SiCf/SiC composites. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2019;39:1743–56.10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2019.01.018Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Huo Y, Zhao K, Miao P, Kong J, Zhuo X, Wang K, et al. Microwave absorption performance of SiC/ZrC/SiZrOC hybrid nanofibers with enhanced high-temperature oxidation resistance. ACS Sustain Chem & Eng. 2020;8:10490–501.10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c02789Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Ronda-Lloret M, Yang L, Hammerton M, Marakatti VS, Tromp M, Sofer Z, et al. A. Sepúlveda-Escribano, E.V. Ramos-Fernandez, J.J. Delgado, G. Rothenberg, Molybdenum Oxide Supported on Ti3AlC2 is an Active Reverse. Water–Gas Shift Catalyst, ACS Sustain Chem & Eng. 2021;9:4957–66.10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c07881Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Quispe R, Torres C, Eggert L, Ccama GA, Kurniawan M, Hopfeld M, et al. Tribological and mechanical performance of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC2 thin films. Adv Eng Mater. 2022;24:2200188.10.1002/adem.202200188Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Drouelle E, Gauthier-Brunet V, Cormier J, Villechaise P, Sallot P, Naimi F, et al. Microstructure-oxidation resistance relationship in Ti3AlC2 MAX phase. J Alloy Compd. 2020;826:154062.10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.154062Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Li J, Xu T, Bai H, Shen Z, Huang Y, Xing W, et al. Structural modifications and electromagnetic property regulations of Ti3AlC2 MAX for enhancing microwave absorption through the strategy of Fe doping. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2022;9:2101510.10.1002/admi.202101510Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Tong Z, Liao Z, Liu Y, Ma M, Bi Y, Huang W, et al. Hierarchical Fe3O4/Fe@C@MoS2 core-shell nanofibers for efficient microwave absorption. Carbon. 2021;179:646–54.10.1016/j.carbon.2021.04.051Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Gong X, Wang K, Dang Z, Zhang T, Xie F, Zhong B, et al. An easy multiple-layer evaporation method to prepare SiOxCy sub-microwires with notable transmittance properties. Mater Res Bull. 2022;150:111794.10.1016/j.materresbull.2022.111794Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Yang P, Xiao G, Ding D, Ren Y, Yang S, Lv L, et al. Antioxidant properties of low-carbon magnesia-carbon refractories containing AlB2–Al–Al2O3 composites. Ceram Int. 2022;48:1375–81.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.09.223Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Liu B, Zhou H, Meng H, Pan G, Li D. Fresh properties, rheological behavior and structural evolution of cement pastes optimized using highly dispersed in situ controllably grown nano-SiO2. Cem Concr Compos. 2023;135:104828.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2022.104828Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Montaño-Priede JL, Coelho JP, Guerrero-Martínez A, Peña-Rodríguez O, Pal U. Fabrication of monodispersed Au@SiO2 nanoparticles with highly stable silica layers by ultrasound-assisted stober method. J Phys Chem C. 2017;121:9543–51.10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b00933Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Sun J, Shi Z, Dai J, Song X, Hou G. Early hydration properties of Portland cement with lab-synthetic calcined stöber nano-SiO2 particles as modifier. Cem Concr Compos. 2022;132:104622.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2022.104622Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Xiang Z, Wang Y, Yin X, He Q. Microwave absorption performance of porous heterogeneous SiC/SiO2 microspheres. Chem Eng J. 2023;451:138742.10.1016/j.cej.2022.138742Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Li G, Tan L, Zhang Y, Wu B, Li L. Highly efficiently delaminated single-layered MXene nanosheets with large lateral size. Langmuir. 2017;33:9000–6.10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b01339Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Rakhi RB, Ahmed B, Hedhili MN, Anjum DH, Alshareef HN. Effect of postetch annealing gas composition on the structural and electrochemical properties of Ti2CTx MXene electrodes for supercapacitor applications. Chem Mater. 2015;27:5314–23.10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b01623Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Tasleem S, Tahir M, Zakaria ZY. Fabricating structured 2D Ti3AlC2 MAX dispersed TiO2 heterostructure with Ni2P as a cocatalyst for efficient photocatalytic H2 production. J Alloy Compd. 2020;842:155752.10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.155752Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Li H, Cao H, Liu F, Li Y, Qi F, Ouyang X, et al. Microstructure, mechanical and electrochemical properties of Ti3AlC2 coatings prepared by filtered cathode vacuum arc technology. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2022;42:2073–83.10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2021.12.066Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Gao Y, Wang HY, Guan J, Lan L, Zhao C, Xie LY, et al. High-voltage arc erosion behavior and mechanism of Ti3AlC2 under different ambient atmospheres. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2021;41:2263–77.10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.11.041Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Chen J, Cheng J, Li F, Zhu S, Li W, Yang J, et al. Tribological study on a novel wear-resistant AlMgB14-Si composite. Ceram Int. 2017;43:12362–71.10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.06.102Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Liu X, Chen W, Zhang X. Ti3AlC2/Pd composites for efficient hydrogen production from alkaline formaldehyde solutions. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:843.10.3390/nano12050843Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Cao M, Wang F, Wang L, Wu W, Lv W, Zhu J. Room temperature oxidation of Ti3C2 MXene for supercapacitor electrodes. J Electrochem Soc. 2017;164:A3933–42.10.1149/2.1541714jesSuche in Google Scholar

[45] Ryaguzov A, Kudabayeva M, Myrzabekova M, Nemkayeva R, Guseinov N. Influence of Si atoms on the structure and electronic properties of amorphous DLC films. J Non-Crystalline Solids. 2023;599:121956.10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2022.121956Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Hu D, Lu J, Deng J, Yan Q, Long H, Luo Y. The polishing properties of magnetorheological-elastomer polishing pad based on the heterogeneous Fenton reaction of single-crystal SiC. Precis Eng. 2023;79:78–85.10.1016/j.precisioneng.2022.09.006Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Sun H, Xi Y, Tao Y, Zhang J. Facile fabrication of multifunctional transparent glass with superhydrophobic, self-cleaning and ultraviolet-shielding properties via polymer coatings. Prog Org Coat. 2021;158:106360.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2021.106360Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Ferreira-Neto EP, Ullah S, Martinez VP, Yabarrena J, Simões MB, Perissinotto AP, et al. Thermally stable SiO2@TiO2 core@shell nanoparticles for application in photocatalytic self-cleaning ceramic tiles. Mater Adv. 2021;2:2085–96.10.1039/D0MA00785DSuche in Google Scholar

[49] Cao M, Zhao X, Gong X. Ionic liquid-assisted fast synthesis of carbon dots with strong fluorescence and their tunable multicolor emission. Small. 2022;18:2106683.10.1002/smll.202106683Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Kong X, Li Z, Zhao X, Chen XP, Wu ZY, He F, et al. Surface group directed low-temperature synthesis and self-assembly of Al nanostructures for lithium storage. Nano Res. 2023;16:1733–9.10.1007/s12274-022-4776-6Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Kobayashi Y, Tada S, Kikuchi R. Porous intermetallic Ni2XAl (X= Ti or Zr) nanoparticles prepared from oxide precursors. Nanoscale Adv. 2021;3:1901–5.10.1039/D1NA00047KSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Hoque E, DeRose JA, Hoffmann P, Mathieu HJ, Bhushan B, Cichomski M. Phosphonate self-assembled monolayers on aluminum surfaces. J Chem Phys. 2006;124:174710.10.1063/1.2186311Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Huang S, Li X, Zhao Y, Sun Q, Huang H. A novel lapping process for single-crystal sapphire using hybrid nanoparticle suspensions. Int J Mech Sci. 2021;191:106099.10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2020.106099Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Deng Z, Liang J, Liu Q, Ma C, Xie L, Yue L, et al. High-efficiency ammonia electrosynthesis on self-supported Co2AlO4 nanoarray in neutral media by selective reduction of nitrate. Chem Eng J. 2022;435:135104.10.1016/j.cej.2022.135104Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Pan L, Jiang K, Zhai G, Ji H, Li N, Zhu J, et al. A novel 2D conjugated coordination framework with a narrow bandgap for micro‐supercapacitors. Energy Technol. 2022;10:2200133.10.1002/ente.202200133Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Lutpi HA, Mohamad H, Abdullah TK, Ismail H. Effect of ZnO on the structural, physio-mechanical properties and thermal shock resistance of Li2O–Al2O3–SiO2 glass-ceramics. Ceram Int. 2022;48:7677–86.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.11.315Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Jiang D, Yang Y, Huang C, Huang M, Chen J, Rao T, et al. Removal of the heavy metal ion nickel (II) via an adsorption method using flower globular magnesium hydroxide. J Hazard Mater. 2019;373:131–40.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.01.096Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Pan J, Guo H, Wang M, Yang H, Hu H, Liu P, et al. Shape anisotropic Fe3O4 nanotubes for efficient microwave absorption. Nano Res. 2020;13:621–9.10.1007/s12274-020-2656-5Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Xiao J, Qi X, Wang L, Jing T, Yang JL, Gong X, et al. Anion regulating endows core@shell structured hollow carbon spheres@MoSxSe2−x with tunable and boosted microwave absorption performance. Nano Res. 2023;16:1–11.10.1007/s12274-023-5433-4Suche in Google Scholar

[60] Sun H, Che R, You X, Jiang Y, Yang Z, Deng J, et al. Cross-stacking aligned carbon‐nanotube films to tune microwave absorption frequencies and increase absorption intensities. Adv Mater. 2014;26:8120–5.10.1002/adma.201403735Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Guo Y, Zhang L, Lu H, Jian X. In situ regulation of microstructure and microwave-absorbing properties of FeSiAl through HNO3 oxidation. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11:147–57.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0012Suche in Google Scholar

[62] Sun Z, Yan Z, Guo Z, Liu H, Zhao L, Qian L. A synergistic route of heterointerface and metal single-atom configurations towards enhancing microwave absorption. Chem Eng J. 2023;452:139430.10.1016/j.cej.2022.139430Suche in Google Scholar

[63] Wu Z, Cheng HW, Jin C, Yang B, Xu C, Pei K, et al. Dimensional design and core–shell engineering of nanomaterials for electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv Mater. 2022;34:2107538.10.1002/adma.202107538Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Dai YL, Guo AP, Gong MH, Zhang XJ, Wen BY. Rational design of heterointerface between MoO2 and N-doped carbon with tunable electromagnetic interference shielding capacity. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2023;636(15):492–500.10.1016/j.jcis.2023.01.047Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Yang N, Luo ZX, Wu G, Wang YZ. Superhydrophobic hierarchical hollow carbon microspheres for microwave-absorbing and self-cleaning two-in-one applications. Chem Eng J. 2023;454:140132.10.1016/j.cej.2022.140132Suche in Google Scholar

[66] Che RC, Peng LM, Duan XF, Chen Q, Liang X. Microwave absorption enhancement and complex permittivity and permeability of Fe encapsulated within carbon nanotubes. Adv Mater. 2004;16:401–5.10.1002/adma.200306460Suche in Google Scholar

[67] Gao Z, Song Y, Zhang S, Lan D, Zhao Z, Wang Z, et al. Electromagnetic absorbers with Schottky contacts derived from interfacial ligand exchanging metal-organic frameworks. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;600:288–98.10.1016/j.jcis.2021.05.009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[68] Liu Q, Cao Q, Bi H, Liang C, Yuan K, She W, et al. CoNi@SiO2@TiO2 and CoNi@Air@TiO2 microspheres with strong wideband microwave absorption. Adv Mater. 2016;28:486–90.10.1002/adma.201503149Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Rao L, Wang L, Yang C, Zhang R, Zhang J, Liang C, et al. Confined diffusion strategy for customizing magnetic coupling spaces to enhance low‐frequency electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33:2213258.10.1002/adfm.202213258Suche in Google Scholar

[70] Ning M, Kuang B, Wang L, Li J, Jin H. Correlating the gradient nitrogen doping and electromagnetic wave absorption of graphene at gigahertz. J Alloy Compd. 2021;854:157113.10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.157113Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery

- The progress of cathode materials in aqueous zinc-ion batteries

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part I

- Effect of polypropylene fiber and nano-silica on the compressive strength and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete

- Mechanochemical design of nanomaterials for catalytic applications with a benign-by-design focus

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery