Abstract

The development of architectured nanomaterials has been booming in recent years in part due to their expanded applications in the biomedical field, such as biosensing, bioimaging, drug delivery, and cancer therapeutics. Nanomaterials exhibit a wide variety of shapes depending on both the intrinsic properties of the materials and the synthesis procedures. Typically, the large surface areas of nanomaterials improve the rate of mass transfer in biological reactions. They also have high self-ordering and assembly behaviors, which make them great candidates for various biomedical applications. Some nanomaterials have a high conversion rate in transforming the energy of photons into heat or fluorescence, thus showing promise in cancer treatment (such as hyperthermia) and bioimaging. The nanometric dimension makes them suitable for passing through the biological barriers or interacting with the natural molecules (such as DNA, protein). Nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, and nanodendrites are examples of nano-sized structures, which exhibit unique geometry-dependent properties. Here we reviewed the fabrication methods, features, properties, and biomedical applications of four nano-structured materials including nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves. We further provided our perspectives on employing these novel nanostructures as advanced functional materials for a broad spectrum of applications.

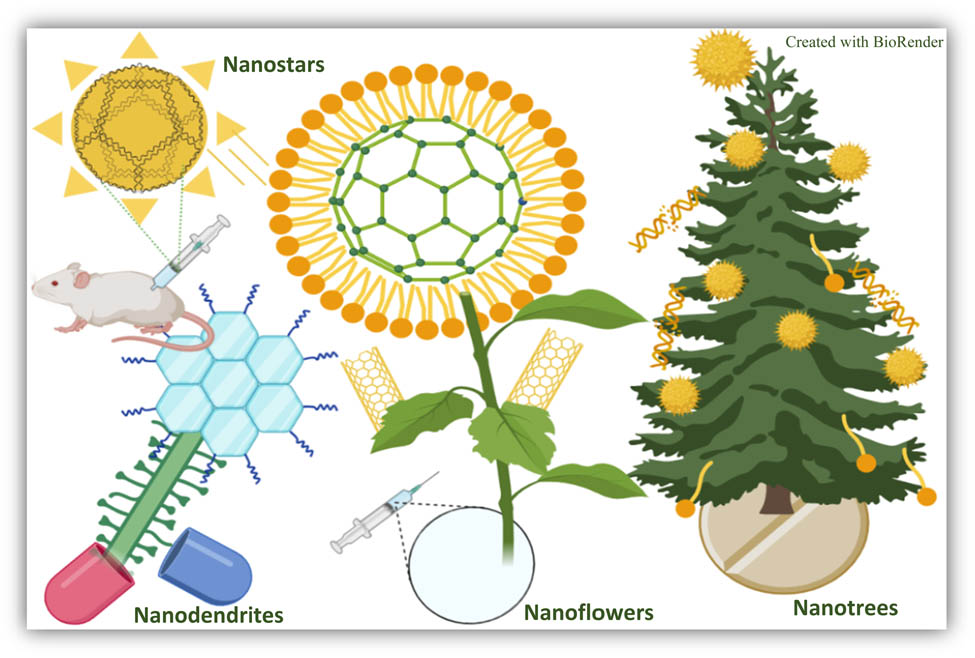

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Nanoparticles (NPs) have attracted much attention due to their unique properties and broad applications in the biomedical field. NPs can differ in shapes, characteristics, reactivity, and functionalization potentials [1]. They can also be made of various types of materials such as noble metals including Au [2], Ag [2], Pt [3], and Pd [4] or semiconductors such as CdS [5], ZnS [6], TiO2 [7], PbS [8], InP [9], and Si [10]. There are also some NPs that are composed of magnetic compounds such as Fe3O4, Co, CoFe2O4, FePt, and CoPt [11]. NPs can be categorized into two main groups: organic NPs such as dendrimer, liposome, and layered biopolymer and inorganic NPs such as iron oxide, quantum dots, mesoporous silica (MS), carbon nanotubes, and gold NPs (Figure 1) [12]. Compared with structures having large particle sizes, NPs exhibit high reactive surface areas, which make them great candidates for therapeutics agents [13]. NPs have a variety of applications such as drug carriers, vectors for gene therapy, hyperthermia therapy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents [11] antiviral application, combating drug resistance bacteria, immunization, and production of vaccine [14].

![Figure 1

Schematic representation of a variety of NPs [12] (Created with BioRender).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0523/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0523_fig_001.jpg)

Schematic representation of a variety of NPs [12] (Created with BioRender).

Using NPs as drug delivery carriers, for example, decrease the undesired side effects and improve drug efficiency [15]. Among different NPs, gold, zinc oxide, and several binary inorganic compounds with applications in electronics have been extensively used [16]. The interactions between nanomaterials and the biological environment can be altered by many factors such as cell type, cell uptake approaches, or different targeted organelles [13]. NPs cellular uptake plays a key role in therapeutic delivery [17–19]. NPs can interact with various types of cells depending on their targeting sites and their physicochemical properties. The morphology of particles can influence the cellular uptake, uptake kinetics and mechanism, intracellular distribution, and cytotoxicity of NPs. So far the effects of the particle shape on cellular internalization in macrophage [20,21], fibroblast [22], endothelial [23], and immune cells have been investigated [24]. The outcomes confirmed that non-spherical shapes inhibit the cellular uptake of NPs by macrophages, which is due to particle adhesion energy, wrapping time, and contact surface area between particles and cells [20]. Aspect ratio (AR) is another determining parameter in cellular uptake [19], and it has been observed that cylindrical NPs with higher AR (AR = 3) internalized faster than those with lower AR (AR = 1) [25]. Furthermore, the NPs morphology can alter the interaction between the cell and NPs. A study was conducted on comparing cell internalization of four different shapes including discoidal, quasi-hemispherical, cylindrical, and spherical shapes [26]. The outcomes indicate that comparing with other shapes, the discoidal particles have the minimum concentration in liver and the maximum concentration in other organs, which resulted from escaping from phagocytosis.

NPs can be synthesized using different chemical, physical, and biological methods (Figure 2) [27]. Coprecipitation, hydrothermal synthesis, micro-emulsion, and sol–gel are representative chemical methods for NPs fabrication [28]. As chemical approaches may result in absorbed toxic chemical on the surface, more ecofriendly alternatives are needed [29]. In order to booster their advantages of synthesizing methods and eliminate or reduce their disadvantages, it is necessary to study the characteristics of NPs morphology and the effect of the construction method on the morphology and the obtained characteristics. In this article, we aim to provide a comprehensive overview of recent advances in four types of novel nanomaterials including: nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites (NDs), and nanoleaves. Different features such as their toxicity, mechanism of action, fabrication approaches, as well as their medical applications are reviewed.

![Figure 2

Schematic illustration of different methods of NP synthesis. Chemical synthesis involves reaction, coating, and synthesis. Physical methods use laser ablation on metal and solvent mixes. Biological methods involve use of biological substances to form metallic NPs [27] (Created with BioRender).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0523/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0523_fig_002.jpg)

Schematic illustration of different methods of NP synthesis. Chemical synthesis involves reaction, coating, and synthesis. Physical methods use laser ablation on metal and solvent mixes. Biological methods involve use of biological substances to form metallic NPs [27] (Created with BioRender).

2 Nanomaterials application in medicine and drug delivery

2.1 Nanoflowers

Nanoflowers are a new class of NPs (size of <100 nm) mimicking the shape of flowers [30]. They have been widely applied in medical applications such as cardiovascular disease treatment, sensors and biosensors, and cancer treatment [31]. Their high surface-to-volume ratios make them desirable agents in biomedical applications [32]. Figure 3 shows a schematic representation of the movement of the flower-like NP into the cell to deliver therapeutic genes. Nanoflowers can be fabricated based on carbon, metals, metal oxides, hydroxides, oxosalts, sulfides, selenides, telluride, nitrides, phosphides, organic, and coordination compounds [33]. There are also hybrid nanoflowers based on deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) [31], protein [34], enzymes [35], and polymers [36].

![Figure 3

Schematic presentation of nanoflowers drug delivery through cell: (1) delivery of DNA-loaded nanoflowers to the cell via endosomal delivery, (2) encapsulated nanoflowers in cell membrane, (3) release of nanoflower and DNA to intracellular environment, and (4) disbanding of DNA and delivery of DNA to the cell [40] (Created with BioRender).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0523/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0523_fig_003.jpg)

Schematic presentation of nanoflowers drug delivery through cell: (1) delivery of DNA-loaded nanoflowers to the cell via endosomal delivery, (2) encapsulated nanoflowers in cell membrane, (3) release of nanoflower and DNA to intracellular environment, and (4) disbanding of DNA and delivery of DNA to the cell [40] (Created with BioRender).

There is a relationship between particles catalytic activities and their morphology [37]. The free electrons in metals can generate different surface plasmon resonance bands depending on particle size, shape, and the corresponding medium [37]. Organic–inorganic hybrid nanoflowers have also attracted much attention in recent years. The organic component includes enzymes, protein, and DNA [32]. They are easy to be fabricated and functionalized, and capable of stabilizing enzyme [38]. The organic–inorganic hybrid nanomaterials show many promising applications as biosensors, drug delivery agents, and in catalysis [38]. Nhung et al. [39] developed gold nanoflowers for surface-enhanced resonance scattering-based sensor. In this study gold nanoflowers were fabricated by seeding Au NPs on films made of cross-linked tripolyphosphate (TPP). Chitosan-TPP template films were considered as the nucleation sites and stabilizing agents to form anisotropic gold nanoflowers. Their size and optical properties were correlated with the ratio of gold salts to chitosan-TPP template films.

A higher content of gold salt can loosen the stabilizing capacity of the template films and Au NPs aggregation which would cause the formation of corners, junctions, and edges on the surface. These physical and geometrical properties made them strong near-infrared (NIR) absorbent and potential candidates for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) applications [39].

Combining the tree-type surfactant – bis(amidoethylcarbamoylethyl) octadecylamine (C18N3) – with multiamine head group has been proposed as a new approach to fabricate hollow gold nanoflowers [41]. This nanostructured material was biologically safe under exposure of visible light and was also highly cytotoxic to HeLa cells when exposed under NIR light irradiation.

The toxicity of Au NPs was also investigated [42]. The fabricated samples consisted of jagged structure with plenty of non-uniform tips. It was assumed that this type of shape leads to non-toxicity in comparison to needle-like carbon nanotubes. The highest toxicity in HeLa cells after 24 h treatment was observed in nanoflowers with a diameter of 340–410 nm at the highest concentration (300 µM). Gold is the one of the most commonly used metallic nanomaterials in biomedical applications.

Moreover, Au NPs with a diameter of 5 nm successfully inhibit proliferation and enhance apoptosis in two lung cancer cell lines. Contrarily Au NPs with dimensions of 10, 20, and 40 nm indicated no cytotoxic effect on lung cancer cells [43].

In some investigations Au NPs reported to be cytotoxic to different cell lines [44–46]. The Au NPs cytotoxic effect depends on the size of NPs and the cell type. The cytotoxic effect in small NPs results from their easy endocytosis into the cells, while no notable cytotoxicity was reported for large particles. Moreover, small NPs would cause upregulation of MMP9 expression [47]. The results of this study indicated that the gold colloid-based monolayers are selectively toxic to certain cells, such as red blood cells (RBCs) [48]. Moreover, the size, composition, and surface properties can also alter the toxicity [49]. The recent studies suggest that diminishing Au NPs size to <2 nm (the size of nanocluster) improves antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [50].

Moreover, the asymmetry shape of nanoflowers enhanced the uptake in cancer cells. The magnetic gold nanoflowers were fabricated with the cancer treatment purpose (Figure 4) [51]. Magnetic NPs have diverse applications as an antimicrobial and anticancer agent and they can also be applied as contrast agents in targeting, imaging, diagnosis, and hyperthermia [52].

![Figure 4

Schematic illustration of developed magnetic nanoflower for cancer treatment. Nanoflowers loaded with Fe2O3 NPs conjugated with polyethylene glycol (PEG) and Raman probe can be used for magnetic detection, or NIR detection of tumors via SERS or MRI imaging [51] (Created with BioRender).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0523/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0523_fig_004.jpg)

Schematic illustration of developed magnetic nanoflower for cancer treatment. Nanoflowers loaded with Fe2O3 NPs conjugated with polyethylene glycol (PEG) and Raman probe can be used for magnetic detection, or NIR detection of tumors via SERS or MRI imaging [51] (Created with BioRender).

To fabricate this structure Au was grown on γFe2O3 NPs, thus a rough surface was achieved. The developed structure demonstrated incredible SERS enhancement, strong PA signals, and enhanced reactivity that are essential for cancer treatment [51].

The extensive use of gold is due to its novel physical and optical features. Their nanoscale dimensions make them suitable candidate for studying and manipulating biological systems [53]. They have been applied as diagnostics agents, photothermal therapy (PTT), biosensing, bioimaging, and drug/gene delivery. Au NPs convert the energy of a photon into heat which makes them an effective photothermal agent in cancer treatment [54]; additionally, the generated heat may have an antibacterial effect [55].

ZnO was also applied in a wide variety of biomedical fields such as delivery vehicles, treatment agent for various diseases such as microbial infection, diabetes, ischemic, cardiovascular diseases, and wound healing [51]. ZnO nanoflower was fabricated via microwave irradiation by Patra and Barui [56]. The proangiogenic property of ZnO nanoflowers via in vivo and in vitro experiments was evaluated. The ZnO nanoflowers stimulated endothelial cells (HUVECs) proliferation which improved proangiogenic property of ZnO nanoflowers. Also, an enhancement in wound healing for endothelial cells was observed. It was assumed that these features are caused by H2O2, which is a redox signaling molecule. In 2015 a biosensor based on ZnO nanoflowers was developed [57]. To fabricate this structure, Zn nanowires were placed on a silicon substrate and then were spotted by Au (Figure 5). The presence of Au NPs eased the thiolated biomolecules binding.

![Figure 5

Schematic illustration and SEM images of fabrication process of biosensor based on Au spotted ZnO nanoflowers by Perumal [57]. Copyright 2015, with permission from Nature Publishing.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0523/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0523_fig_005.jpg)

Schematic illustration and SEM images of fabrication process of biosensor based on Au spotted ZnO nanoflowers by Perumal [57]. Copyright 2015, with permission from Nature Publishing.

The antibacterial features of the ZnO nanoflowers were investigated by Cai et al. [58]. For this purpose, samples were fabricated in three different morphologies: rod flowers, fusiform flowers, and petal flowers via the hydrothermal process. Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli were used to evaluate the antimicrobial activities. Petal flowers, fusiform flowers, and rod flower samples, respectively, demonstrated the highest antimicrobial power.

The differences in anti-microbial power originated from variation in microscopic factors like specific surface area, size of pores, and polar plane of Zn. The mechanisms that result in antimicrobial properties of ZnO can be caused by Zn2+ ion release, either adsorption or generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). It can also damage the cell membrane or DNA breakage and inhibition of the energy metabolism [59]. Furthermore, the neurogenic activity of ZnO nanofibers (NFs) was studied [60]. ZnO NF was fabricated by an advanced microwave irradiation approach and tested in vitro and in vivo. The in vivo investigations in Fischer rats indicated that the neuroprotective efficacy of nanoflowers came from Neurabin-2 and NT-3 upregulation. In in vitro experiments, their study identified the role of PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK1/2 in signaling paths behind nanoflowers mediated neurogenesis.

Other metallic elements like Mo have also been fabricated in the form of nanoflowers. For example, bovine serum albumin (BSA)-coated molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) nanoflowers were developed via a hydrothermal approach [61]. The MoS2 nanoflower had a layered structure which led to an improvement in its heating effect. Layered MoS2 nanoflowers displayed a significant antitumor effect under MW irradiation at 1.8 W, which made them a promising agent for cancer MW thermal therapy. A synergistic antitumor platform was developed using MoS2, azo initiator 2,2′-azobis[2-(2-imidazolin-2-yl) propane] dihydrochloride (AIBI), and phase-change material (PCM) (tetradecanol) (MoS2@AIBI–PCM nanoflowers) [62]. The nanomaterials were fabricated using polyethylene glycol-functionalized molybdenum disulfide (PEG-MoS2) nanoflowers in conjunction with azo initiator and PCM. Under the exposure to NIR laser irradiation, free radicals were produced. This process resulted from the AIBI decomposition initiated by photothermal feature of PEGMoS2. Therefore, MoS2@AIBI–PCM nanoflowers were applied as ROS-based cancer therapy. BSA-modified Ag nanoflowers for sensing DLD-1 human colon cancer cells were also developed [63]. The fabricated structure displayed a suitable cell-immobilization capacity due to its porous structure. The presence of BSA as a natural layer resulted in the acceptable biocompatibility. BSA-incorporated Ag nanoflowers performed well in quantifying DLD-1 cells and the amount of the expressed sialic acid on the surface of a single cell were estimated. The as-developed agent would ease early diagnosis and treatment in human cancer.

DNA nanoflowers are another example of inorganic hybrid materials [64]. They exhibit excellent features such as water solubility, suitable electronegativity, sequence programmability, and automated controllable fabrication approach [65]. These structures are made from long DNA building blocks fabricated via rolling circle replication [66]. The incorporation of functional aptamers, fluorophores, and drug loading capability into DNA-nanoflowers hybrids were investigated [67].

Nano- and micro-scale hybrid nanoflowers carrying various divalent cations such as Mn2+, Co2+, and Zn2+ and DNA were fabricated for drug delivery, sensing, biocatalysis, energy (as super capacitors), and separation technologies. By changing the composition of the enzyme buffers and polymerase enzyme, the as-made structure exhibited versatile properties due to the controllable morphology, size, manipulation of the DNA levels within the particles, and the surface potential [64]. Metal-containing artificial analog-incorporated DNA nanoflowers were developed [66]. These structures were fabricated via three-step approach. In the first step, Ferrocene (Fc)-DNA was fabricated, and then DNA nanoflowers were constructed. In the final step, H2O2-responsive Fc DNA with DNA nanoflowers were incorporated. The as-developed structures were bio-inspired, self-degradable, and size-controllable. For drug delivery evaluations, doxorubicin was loaded and in vitro experiments proved selective uptake of system by protein tyrosine kinase 7 (PTK7)-positive cancer cells. The presence of H2O2 sensitive Fc resulted in quick release, nuclear accumulation, and enhanced cargo cytotoxicity. In vivo studies on mice bearing the PTK7 + HCT-116 tumors confirmed the improvements in targeted delivery and the therapeutic efficacy of doxorubicin [67].

Hybrid nanoflowers containing metals ions and polymers indicated unique features. In an investigation using Cu and Ca ions and elastin-like polypeptide (ELP), it was observed that due to temperature-dependent conformational behavior in ELPs, controllable resultant morphological patterns were achieved. Moreover, ELPs can alter the nucleation and growth process by formation of ordered crystalline nanostructures [36]. The developed nanoflowers are summarized in Table 1.

Summary of developed nanoflowers

| Year | Scientist | Material | Method | Size | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Nhung et al. [39] | Au | Seed-mediated growth | 80–120 nm | SER-based sensor applications |

| 2013 | Zhu et al. [67] | DNA | DNA condensation, self-assembly using rolling cycle replication | 200 nm to several micrometers | Drug delivery |

| 2015 | Cao et al. [63] | Ag | A novel method | Diameter of 500 nm | Sensor |

| 2015 | Perumal et al. [57] | Au-ZnO | Sol–gel, hydrothermal | 2–3 μm long, ∼diameter of 100 mn | DNA capture |

| 2016 | Wang et al. [61] | MoS2 | Hydrothermal process | 130 nm | Antitumor |

| 2016 | Cai et al. [58] | ZnO | Low temperature hydrothermal | Average length of ∼600 nm and the average width of ∼650 nm | Antibacterial agent |

| 2018 | Baker et al. [64] | Mn/Co/Zn/DNA | Crystallization and self-assembly | 15.8–0.312 µm | Drug delivery/sensing/biocatalysis |

| 2019 | Zhang et al. [66] | DNA | Rolling cycle replication reaction | 50–1,000 nm | Drug delivery |

| 2020 | Barui et al. [60] | ZnO | Chemical interaction of zinc(ii) nitrate and NH4OH | Not mentioned | Neuritogenicity |

2.2 Nanotrees

The synthetic approach for nanotrees can be classified into three main groups: one-step growth, sequential branched growth, and template-assisted growth, which are demonstrated and summarized in Figure 6. The solution-based chemical synthesis and vapor phase methods are the common approaches for synthesizing the nanotree platforms. Additionally, full-solution processed synthesis approaches like hydrothermal and solvothermal synthesis have been broadly applied for constructing 3D branched array structures. Vapor-based techniques include vapor oxidization of metal substrates, laser ablation, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), and plasma approaches [68]. Generally, the full-solution processed fabrication approaches like hydrothermal or solvothermal synthesis protocol displayed great potential in fabrication of 3D branched array configuration [69]. The developed tree-like structures exhibited various unique features such as high surface area, quick transfer of electrons, and ideal crystallinity [68].

ZnO@MnO2-ramified nanowire arrays were fabricated via hydrothermal and redox approach [70]. In this structure, ZnO and MnO2 were considered as the core and shell, respectively. Owing to an increase in the surface area the structure can improve the electrical conductivity properties. Also, this core–shell structure displayed an efficient charge–discharge stability.

A 3D nanotree-like ZnO/Si nanocomposite was fabricated by hydrothermal method [71] (Figure 7). In this method, systematically patterned silicon nanorods (SiNRs) were synthesized by merging of polystyrene sphere template with metal-catalyzed etching. The ZnO branches were formed on SiNRs through hydrothermal deposition approach. ZnO nanowires (NWs) improved the electric field of SiNRs, boosted the emitting dots number, and reduced the screening effect due to their high ARs, which made the 3D ZnO/Si a great candidate for application in field emission devices. The 3D jagged ZnO nanotrees (ZNTs) on the ITO–PET substrates were also investigated [72]. Two-step hydrothermal technique was applied for construction of ZNTs. Furthermore, a self-powered piezoelectric nanogenerators based on ZNT was developed. In this structure, nanowire branches affected the electric output and resulted in an enhancement in performance. The highest output of current measurement is about 300 nA. ZnO NPs are biocompatible, non-toxic, self-cleansing, compatible with skin, and antimicrobial. It should be noted that features such as the size, shape, and morphology can affect thermal and electrical properties [73].

![Figure 7

Schematic illustration and FE-SEM images of synthesis of ZnO NWs/SiNRs by Lv et al. [71] (Created with BioRender); Copyright 2015, with permission from ACS Publishing.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0523/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0523_fig_007.jpg)

Schematic illustration and FE-SEM images of synthesis of ZnO NWs/SiNRs by Lv et al. [71] (Created with BioRender); Copyright 2015, with permission from ACS Publishing.

The 3D branched and hyper-branched nanotree structure can be achieved via vapor phase based fabrication approaches [68]. A novel 3D symmetric micro-super capacitor made of polypyrrole (PPy)-coated silicon nanotree (SiNTr) hybrid electrodes were developed via CVD and electrochemical technique [74]. This hybrid structure can be applied as electronic biomedical implants such as neuro-stimulators due to their portability. It was synthesized via precipitating PPy on the surface of SiNTrs. The developed hybrid indicated significant electrochemical features due to electroactive pseudo-capacitive and electric double layer capacitive property of PPy and branched SiNWs, respectively. PPy-coated SiNTr-based micro-supercapacitors displayed an excellent performances in comparison to silicon nanowire hybrid micro-supercapacitors concerning specific capacitance and energy density [75].

Additionally, the Si nanoneedles were grown onto ZnO nanorod arrays and the AgNPs decorations were fabricated as a substrate for SERS detection. In the first step, the Si nanoneedles were implanted onto the ZnO nanorod surface via catalyst-assisted vapor–liquid–solid (VLS) process. This method is based on catalyst droplet losing in plasma-enhanced CVD. In comparison to other techniques such as hydrothermal growth or CVD approach, this method is economical and eco-friendly. In the second step, AgNPs were placed on the surface of ZnO/Si nanomace by a galvanic displacement reaction. Rhodamine 6G (R6G) was applied to evaluate the potential of developed 3D SERS substrate. The Raman enhancement factors are shown to be up to 8.7 × 107, which confirmed the acceptable performance of ZnO/Si heterostructured nanomace arrays as SERS substrate. Other techniques such as thermal evaporation have also been applied for fabrication of nano -tree structures. The PbS-doped ZNTs were investigated as the promising agent for LED, photovoltaic cell, piezoelectric apparatus, and biosensor and gas sensor application [76]. The samples were fabricated via thermal evaporation on silicon and glass substrates. Furthermore, nanotrees have been investigated based on other elements and compounds. Novel treelike two-level Pd x Ag y nanostructures were developed in bifunctional fuel cell electro-catalysis application [77]. The nanostructure made of a tiny Pd1Ag1 alloy NDs and Pd1Ag2 alloy nanobranches provided various active sites and improved the stability of the structure. The Pd3Ag1 NTs were more operative and steadier in comparison to other Pd/Ag ratios. In this investigation 1-naphthol was applied as reductant and structure directing agent. Findings confirmed that the suitable feeding ratio of Pd/Ag forerunner and the introduction of 1-naphthol play key roles in successful fabrication of well-defined Pd x Ag y . The developed nanotrees are summarized in Table 2.

Summary of developed nanotrees

| Year | Scientist | Components | Fabrication method | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Sun et al. [70] | ZnO/MnO2 | Hydrothermal and redox | Average size of 800 nm |

| 2015 | Lv et al. [71] | ZnO/Si | Hydrothermal | Length of 200–800 nm diameter of 50–90 nm |

| 2015 | Aradilla et al. [74] | PPy/Si | CVD and electrochemical | Length of ∼2 µm and diameter of 20–70 nm |

| 2015 | Huang et al. [75] | ZnO/Si | Catalyst-assisted VLS | Length of 300–700 nm diameter of 150 nm |

| 2016 | Yang et al. [72] | ZnO | Two-step hydrothermal | Length of 3–5 µm and diameter of 200 nm |

| 2020 | Abdallah et al. [76] | ZnO/PbS | Thermal evaporation | Diameter less than 15 nm |

2.3 Nanostars

Gold nanostars, with unique structural feature, have been applied in various biomedical applications such as chemical sensing [78], medical imaging [79], cancer treatment, and drug [43] and gene delivery. They have gained much attention owing to their spectacular optical properties and their versatility in surface modification (Figure 8) [80]. They display magnificent features such as high X-ray absorption coefficient, ease of synthetic manipulation, adjustable physicochemical properties of particles, and high affinity to form bonds with thiols, disulfides, and amines [13].

Schematic representation of two types of polymeric nanostars’ structure and their medical application (Created with BioRender).

Parameters such as the size of NP, the nature of the ligand, molecular weight, and grafting density can alter the cellular uptake. Some studies indicated that cellular uptake is not significantly affected by Au NPs size although in multicellular tumor spheroids, Au NPs with smaller size indicated higher cellular uptake and advantages [81].

The cellular uptake is dependent on the shape of Au NPs and the type of cell. In previous studies on Au NPs, Au nanostars exhibited the lowest cellular uptake in RAW264.7 cells in comparison to triangle and rod-shaped NPs [82,83]. In another study, gold nanostars indicated the highest cellular uptake in MCF7 cells compared to other morphology (hollow, rods, and cages) [84].

Furthermore, it was confirmed that size-dependent interaction between sub-nanometer Au NPs and the glycocalyx can affect the cellular uptake. Observations confirmed the higher cytotoxicity of the smaller Au NPs (4–5 nm) in comparison with larger particles (18–20 nm). Besides the size, other factors affecting cytotoxicity include the cell type, tissue distribution, tissue absorption, and penetration capacity [83].

The shape of the NPs on surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) has also been examined [85]. The gold nanostars displayed the highest magnitude of the SERS response in comparison to other shapes such as nanospheres and nanotriangles. It was assumed that the existence of five or more vertices at 30° increased the local field enhancement and sequentially higher SERS. Nanostars are also widely used as drug delivery agents. For example, mitoxantrone (MTX)-loaded gold nanostars were applied as an anti-cancer drug delivery system [86]. MTX was placed on the gold nanostars surface by thiolated and carboxylated PEG spacer. The accumulation of the drug in a healthy mouse heart and lung tumor bearing mice was evaluated. The observations confirmed enrichment in Raman signal from MTX molecules by the plasmonic field of the NPs. The peptide-functionalized gold nanostars were proposed as an agent for cancer treatment [87]. The Au NPs were functionalized by a pH (low) insertion peptide (pHLIPs), which can pass through the pH-dependent transmembrane. This feature eased the crossing of lipid bilayer into tumor cells due to acidic activation. The samples were evaluated via in vitro and in vivo experiments and outcomes showed an improvement in cellular internalization (at pH 6.4), tumor accumulation (after intravenous injection), CT signals, and photoacoustic (PA) imaging compared with GNS-mPEG. The in vivo experiments on tumor-bearing mice indicated an increase in CT signals of the tumors in both GNS-mPEG- and GNS-pHLIP-treated mice which confirmed the accumulation of NPs in tumor. Specifically, CT values in GNS-pHLIP-injected mice were notably higher than that of GNS-mPEG-injected ones.

Coated gold nanostars (AuNSts) were fabricated with the purpose of drug delivery. In this study, MS-coated gold nanostars (AuNSts) that consist of paraffin as a thermo-sensitive factor was used [88]. The AuNSts were synthesized by seed growth technique and then coated with a MS shell and capped with paraffin. Doxorubicin (DOX) was conjugated into porous silica and then covered with thermo-sensitive paraffin. It was found that un-irradiated AuNSt@mSiO2@Dox@paraffin NPs indicate no cytotoxicity to HeLa cells. Under exposure of 808 nm laser, the paraffin layer melted and resulted in cargo release. As-designed drug photo-delivery AuNSts systems demonstrated minimum leakage and low laser power requirements.

The nanostars have also been applied with other coatings. For instance, temperature sensitive liposomes coated nanostar was fabricated as a promising drug delivery agent [89]. The gold composite including siRNA of cyclooxygenase-2 (siCOX-2) that was modified by 2-deoxyglucose (DG) (a tumor targeting ligand) and transmembrane peptide 9-poly-d-arginine (9R) were applied to the siCOX-2(9R/DG-GNS) structure. Gold nanostars were synthesized using the seed growth approach. After successful conjugation of siCOX-2, a paclitaxel (PTX)-TSL-siCOX-2(9R/DG-GNS) co-delivery system was developed. This agent was taken rapidly in high temperatures by tumor. It was found that this system not only defeated PTX resistance, but also improved drug delivery to the cancer cells by photothermal conversion effect.

RBC and platelet membrane-coated gold nanostars loaded by curcumin were also proposed as a promising drug delivery system [90]. The macrophage phagocytosis is avoided in this system. Curcumin was conjugated to the constructed system. Observations proved controlled drug release at high temperature and tumor growth inhibition under exposure of NIR laser irradiation.

The gold nanostar composites have also been applied as a drug delivery agent. Au nanostar@metal–organic framework was evaluated as a stimuli-triggered synergic approach for chemo-photothermal therapy [91]. In this structure, ZIF and Au nanostars were shell and yolk, respectively. The ZIF shell underwent degradation in tumor acidic environment and resulted in cargo release; on the other hand, Au nanostar performed as second near-infrared (NIR-II) responsive photothermal conversion. NIR-II laser penetrated deeply within the tissue and a higher resolution was observed. Furthermore, combining chemo-photothermal therapy achieved an astonishing synergistic effect for preventing tumor growth. Another nanocomposite consisting Au nanostar and ZIF-8 was developed as stimuli responsive active cargo in living cells [92]. In this structure, NSs were considered as seeding sites for the ZIF-8 shell. Developed structure entered into the intracellular environment successfully and was stable in aqueous environment. Nanostars can also be used in antibacterial applications. Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) functionalized gold nanostar (GNS) was proposed as a potential agent for protective antibacterial films and coatings [55]. In this experiment, the photo-thermally-induced local high temperature resulted in antibacterial feature. The temperature increase was contributed to GNS because blank PVA films did not indicate any change in temperature under NIR exposure. Bacterial growth, viability, and proliferation were decreased by about 50% in GNS containing samples under exposure of NIR. Au nanostars and 2D reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite were introduced as cooperative killing multidrug resistant bacteria [93]. Samples were made via seed-mediated growth technique and antibacterial effect was evaluated using methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) bacteria. The results indicated an enhancement in antibacterial feature due to the limited hyperthermal effect of rGO/AuNS. The disintegration of cell walls or membranes caused by the nanocomposite’s prickly and sharp edges can be considered as another factor in the antibacterial capabilities that were obtained. Wang et al. [94] developed a unique agent for Gram-positive bacteria elimination. This system consisted of gold nanostars (AuNSs) and vancomycin (Van). The MRSA was recognized and eliminated by this system under exposure of NIR laser irradiation, but this system demonstrates less efficiency against Van-resistant Gram-positive bacteria so further investigations are needed. PEG-functionalized gold nanostars with multiple sharp branches demonstrated an increase in NIR photothermal conversion efficiency in comparison to other shapes of Au NPs. Surfactant-free fabrication methods resulted in more biocompatible systems. This agent was fabricated via seed-mediated growth method which resulted in ultrasmall dimension, effective metabolizability, and high computed tomography (CT) value [95]. Generally, it has been shown that Au NPs can be incorporated into the Gram-negative bacteria more effectively compared to Gram-positive ones. Also Au NPs are considered safer for mammalian cells due to their ROS-independent mechanism [96].

Apart from metals, nanostars can be made from other materials such as polymers. Star polymers are tree-shaped polymers which are made of a central core and attached linear chains. They are classified based on branches, molecular weights, or topology into three different groups including symmetric stars, asymmetric stars, and miktoarm stars. In symmetric stars all branches are like linear chains, while asymmetric stars referred to NPs consisting of branches differ in molecular weights or topology. In miktoarm stars, branches differ in chemical composition [97].

The star-shaped polymers have attracted much attention. They are synthesized through three different approaches: “arm-first,” “core-first,” and the grafting-onto [98]. A star-shaped hermos responsive amphiphilic copolymer nano-assembly was developed using reversible-addition fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) dispersion polymerization approach [99]. This indicates that the hermos responsive property was highly affected by tethered PNIPAM chains topology. Also gold nanostars with poly dopamine coating were proposed as a candidate for multidrug resistance breast cancer treatment [100]. This agent can be applied as an antitumor and antiangiogenic agent. The methods of synthesizing nanostars are summarized in Table 3.

Summary of developed nanostars for biomedical applications

| Year | Scientist | Components | Method | Size | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Tian et al. [85] | Au | Seed-mediated growth method | 148 ± 11 nm | SERS |

| 2016 | Tian et al. [86] | Au | Seed-mediated route using HEPES buffer | 30–40 nm | Drug delivery |

| 2016 | Cao et al. [99] | PNIPAM/PS | RAFT dispersion polymerization via polymerization-induced self-assembly | Not mentioned | Drug delivery |

| 2017 | Tang et al. [95] | Au | Seed-mediated growth | 50 nm | CT imaging |

| 2017 | Tian et al. [87] | Au | Seed-mediated method | Diameter of 60 nm | Cancer treatment |

| 2018 | Borzenkov et al. [55] | Au | Seed-growth technique | Not mentioned | Antibacterial |

| 2018 | Hernández Montoto et al. [88] | Au | Seeded growth method | 120 nm | Drug delivery |

| 2019 | Wang et al. [94] | Au | Seed-mediated method | 104.4 ± 13.3 nm | Antibacterial |

| 2019 | Feng et al. [93] | Au/reduced graphene oxide | Seed-mediated growth | 78.3 nm | Antibacterial |

| 2019 | Carrillo-Carrion et al. [92] | Au | Seeded growth method | 218 ± 24 nm | Drug delivery |

| 2019 | Zhu et al. [89] | Au/liposome | Seed growth method | 57.23–293.93 nm | Cancer treatment and drug delivery |

| 2019 | You et al. [100] | Au/dopamin | HEPES reductive method | 78 ± 3.4 nm | Drug delivery |

| 2020 | Kim et al. [90] | Au | Seed-mediated growth method | 162.1 ± 3.0 nm | Drug delivery |

2.4 NDs

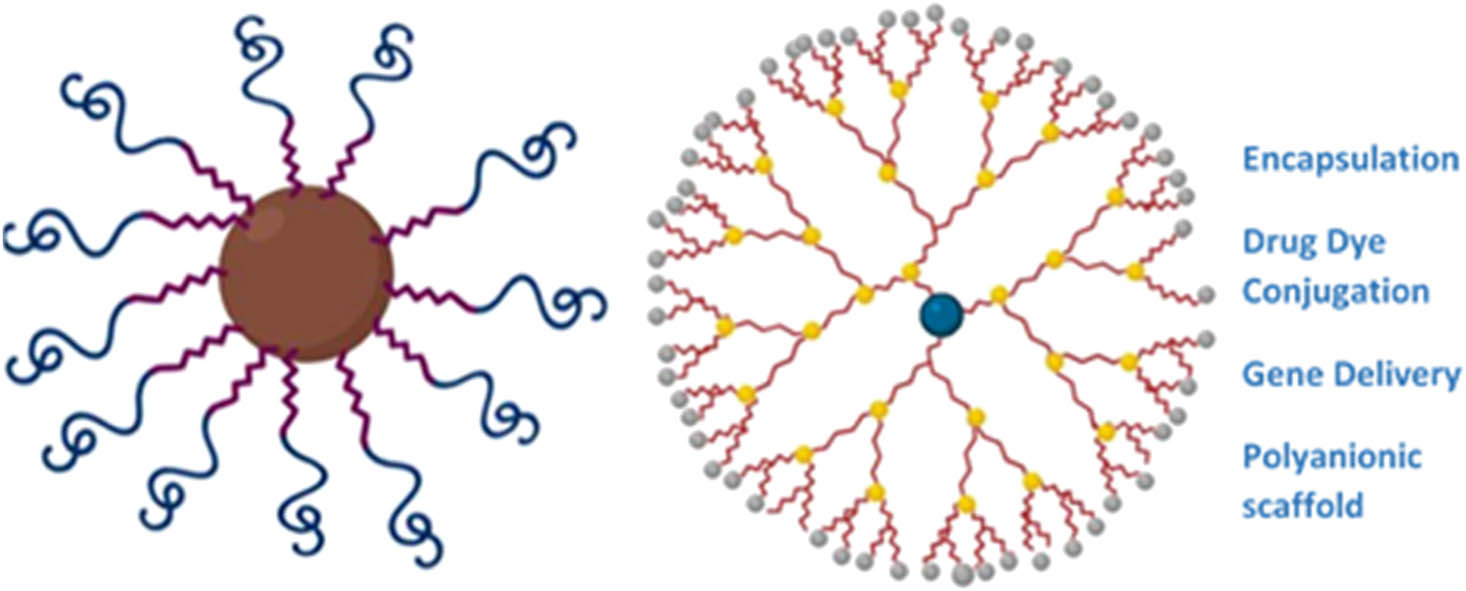

The dendrimers are generally in the shape of connected trees by a common core. The word dendrimers have originated the Greek word “dendron” which means tree (Figure 9). These structures displayed significant bioactive properties. Nanodendrimers have been applied widely in different fields such as drug delivery, gene transfection, material modification, clinical diagnosis, sensors, and MRI [101]. Monometallic, bimetallic, and trimetallic NDs are examples of different ND assemblies [102]. The gold nanodendrites (AuNDs) via novel seed-mediated techniques were fabricated [103]. Observations confirmed that the degree of branching (DB) can influence NPs performance. The higher DB in nanostructure led to the more effective performance in photothermal elimination of tumors at lower NIR wavelengths. On the other hand, NPs with a lower DB functioned well under exposure at a higher wavelength NIR irradiation. Therefore, this versatility of options in applied NIR range results in the selective determination of a laser wavelength, accordingly the best performance in cancer therapeutic is achieved. The correlation between optical and AuNDs DB were also investigated. [104]. The in vivo and in vitro experiments confirmed that the manageable DB led to a wide variety of optical features in a comprehensive range of NIR radiation. The dependence of photothermal features of AuNDs on the applied wavelength was observed.

![Figure 9

Schematic illustration of ND structure [105] (Created with BioRender).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0523/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0523_fig_009.jpg)

Schematic illustration of ND structure [105] (Created with BioRender).

A ND was developed in the core–shell structure. It consisted of gold as a core, palladium as a shell, and PEG as the modifier [106]. The negative charge of PEG and positive charge of DOX created an electrostatic interaction which led to DOX loading. The results confirmed that the DOX desorption depends on various factors such as pH, solvents, temperature, and enzymes; hence, an accurate and controllable stimuli-responsive system was achieved. NDs are also applied as sensors and diagnostic tools. Dendritic NPs made of graphene oxide-based magnetic and bimetallic (Fe/Ag) and modified by vinyl were fabricated [107]. This structure was applied for trace level detection of pyrazinamide (PZA). The nanodendritic shape indicated higher electrocatalytic activity in comparison to NPs with the exact same components. RGO@BMNDs also successfully detected PZA in pharmaceutical, human blood serum, plasma, and urine samples.

The AuND-modified electrode was applied as substrate for preparing hemoglobin (Hb)-imprinted poly(ionic liquid)s (HIPILs) [108]. In this experiment the NDs were applied on the electrode surface as a factor to enhance accessible surface area. The samples were fabricated via electrodeposition approach. HIPILs were applied as a modification agent. Applying ionic liquid as functional monomer decreased the detection limits of developed Hb sensors in comparison with other sensors. In another study [109], platinum NDs were loaded on poly (diallyldimethylammonium chloride) modified and MoS2 nanosheet hybridized PPy nanotubes. Results indicated that the catalytic activity was enhanced by applying Pt NDs and MoS2 nanosheet [109]. Developed nanocomposite was highly active in H2O2 reduction and displayed an appropriate potential to inactivate antibodies, and low detection range of AFP.

Another biosensor was fabricated based on nanodendritic gold/graphene which can be applied for fluorescence, SERS, and electrochemistry tri-mode miRNA detection [110]. This biosensor was fabricated through electrochemical deposition, patterning, and graphene assembly. The microwell is capable of conducting sensitively electrochemical sensing and SERS detection owing to both high surface area and ND hotspot density. The trimetallic AgPtCo NDs and magnetic AgPtCo NDs were also studied as electrochemical signal readout [111]. The AgPtCo NDs were fabricated through convenient one-pot synthesis approach. The NDs with high surface area supplied enough surface for secondary antibodies immobilization. The potential of this electrochemical immune sensor as a POCT platform for sensitive analysis of different biomarkers in clinical samples was confirmed.

Furthermore, a novel multimodal enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (M-ELISA) was developed based on Au@Pt NDs [112]. Cardiac troponin I (cTnI) was tested as biomarker. Due to the properties of Au@Pt NDs such as peroxidase-like activity and photothermal effect, the concentration of cTnI can be successfully quantified by temperature measurement, colorimetric, and ratiometric fluorescent signal responses. These evaluations were precise and well-founded which ensure their usability for clinical assay protein markers. An electrochemical sensing approach for recognition of chiral enantiomers was developed based on AuNDs [113]. This approach was simple, stable, highly efficient, and sophisticated; also the electrode pretreatment in composites synthesis and surface modification was not required. NDs have also been considered as an anti-inflammatory and an antibacterial agent. Bewersdorff et al. [114] in 2017 proposed sulfated dendritic polyglycerol (dPGS)-coated Au NPs as an anti-inflammatory agent and tested in vitro and in vivo. dPGS NPs were highly propended to interact with serum proteins. In 2017 Kienzle et al. [115] proposed dendritic structure as a drug delivery system. A pH triggered block copolymer with dendritic mesoporous silica nanoparticles (DMSNs) coating was developed with the aim of delivering tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) to cancer cell lines and dendritic cells. Polyethylenimine (PEI)-hydrophilic PEG copolymer was applied for coating. It was observed that applying this delivery system reduced systematic toxicity of TNF-α while retaining the pleiotropic antitumor activity.

The pH-responsive DMSNs were developed and loaded with folic acid [115]. The in vitro experiments proved the sustain release of cargo and the developed structure displayed a successful performance.

A two-step method for fabrication of platinum (Pt) NDs was developed [116]. In this technique Pd–Pt core-frame NDs including a compact array of Pt branches and a Pd core was fabricated. Pd cores were removed by selective wet etching and turned into vacant Pt NDs. Developed structure demonstrated remarkable antibacterial features against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and also hastens wound healing process in H2O2 low concentration. Balb/c mice, with wounds on their backs were applied for in vivo experiments. A complete cure of infected wounds was achieved in 6 days after injection.

Furthermore, as the improving theranostic agents, PEGylated Au@Pt NDs was introduced in unique X-ray CT and photothermal PTT/radiation therapy (RT) in cancer treatment [117]. It was observed that with Au and Pt, nanomaterials increased regional radiation dose which resulted in less damage in normal tissue. The nanocomposite consisted of Au as nanocore and Pt as nanobranches. This structure improved PTT and RT synergistically due to vast absorbance of NIR light and strong concentrate of X-ray. The developed NDs are summarized in Table 4.

Summary of developed NDs for medical applications

| Year | Scientist | Components | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Patra et al. [107] | Fe/Ag/graphene | PZA detection |

| 2016 | Qiu et al. [103] | Au | Antitumor agent |

| 2017 | Liu et al. [117] | Au/Pt | CT and theranostic agent |

| 2017 | Bewersdorff et al. [114] | Au/sulfated polyglycerol | Anti-inflammatory |

| 2017 | Kienzle et al. [115] | PEI/PEG/MS | Drug delivery |

| 2018 | Wu et al. [116] | Pd/Pt | Antibacterial agent |

| 2019 | Sun et al. [108] | Au | Sensor |

| 2019 | Pei et al. [109] | Pt/MoS2/poly pyrrole | AFP detection |

| 2019 | Song et al. [110] | Au/graphene | Fluorescence/SERS/electrochemistry tri-mode miRNA detection |

| 2019 | Fan et al. [111] | Ag/Pt/Co | Electrochemical signal readout |

| 2019 | Jiao et al. [112] | Au/Pt | M-ELISA |

| 2020 | Oladipo et al. [106] | Au/Pd/PEG | Drug delivery |

| 2020 | Lian et al. [113] | Au | Sensor |

Azizi et al. investigated the cytotoxicity of a folic acid functionalized terbium-doped dendritic fibrous NP (Tb@KCC-1-NH2-FA) on various cell lines such as MDA breast cancer, HT 29 colon cancer, and HEK 293 normal cell lines. Even in concentration higher than 900 µg/mL no cytotoxicity was observed [118].

2.5 Nanoleaves

In the past few decades, growing interests have emerged in developing and studying two-dimensional nanostructures such as nanoleaves [119–124] due to their high anisotropy structure and unique properties. For example, Xu et al. [120] converted one-dimensional (1D) Cu(OH)2 nanowires into 2D CuO nanoleaves. In their study, polycrystalline Cu(OH)2 nanowires were converted to single crystalline Cu(OH)2 nanoleaves using an oriented attachment. This process consisted of rotation, orientation, and attachment of Cu(OH)2 NPs with a diameter of 3 nm to produce single crystalline Cu(OH)2 nanoleaves. After that single crystalline CuO nanoleaves were obtained from single crystalline Cu(OH)2 nanoleaves via a reconstructive transformation including the nucleation of CuO followed by a two-step oriented attachment of the CuO particles.

In 2019, Warren and LaJeunesse [121] proposed another approach to fabricate CuO nanoleaves. In this study bacterial cellulose (BC) nanofibers were applied as a substrate for deposition of CuO. Obtained CuO nanoleaves were non-uniform and unlike the solution phase CuO nanomaterial synthesis, the nanostructures synthesized by this method were stably integrated in the BC matrix and resist removal even with significant agitation. Another method proposed for fabricating nanoleaves is conventional hydrothermal method. In 2021 Ahmad et al. [122] synthesized hierarchical CuO nanoleaves via the hydrothermal method and developed a nonenzymatic glucose biosensor using engineered hierarchical CuO nanoleaves. The developed biosensor indicated acceptable sensitivity, and detection limit (12 nM) resulted from its excellent electrocatalytic properties. Moreover, it indicated great features such as excellent selectivity, reproducibility, stability, and repeatability in detecting glucose in low glucose level samples. Solid-state ionics method is another method proposed for fabrication of nanoleaves. Xu et al. [123] applied this method to synthesize nanoleaves based on copper. The obtained leaf had the width ranging from 2 to 5 µm. Moreover, numerous NPs with the approximate size of 10–70 nm arranged on the prepared copper nanoleaves resulted in high surface roughness. Also as a consequence of existence of Cu, many hot spots were formed; hence, the developed biosensor based on Cu nanoleaves was significantly accurate with the low limit of detection for CV and R6G. Li et al. [124] studied a novel method to synthesize the leaf-like CuO. In this method the CuO nanoleaves were grown uniformly on the FTO electrode to increase the contact area and decrease the transfer resistance. Moreover, NiO NPs dispersed in the gaps between the leaves enhanced the electron transfer and reduced the diffusion resistance. The results of the electrochemical evaluations confirmed the high sensitivity, broad linear range, and low detection limit of this sensor. Moreover, it indicated not only good reproducibility and stability, but also reflected anti-interference in the detection of actual samples.

3 Perspectives

The variety of NPs morphology makes them suitable for various medical applications including diagnosis tools, smart medicines, and sensors. So far, various NPs have been introduced for medical applications, and each of them displayed different properties according to their unique morphologies and shapes [125].

Morphology can alter the interaction between the biological components and the NPs. Previous studies confirm the effect of fabrication method on the morphology of NPs. NPs have been fabricated in various shapes such as spherical, polygonal, cube, or rod. NPs having sharp edges indicated less biocompatibility due to the induced mechanical damage to cell membrane. Furthermore, the shapes of these NPs are shown to have an impact on the fate and their interaction with the environment. The interaction of NPs with the environment results from either the differences in diffusion rates of the material change with the AR of the material or restriction of the inter-particular interactions by morphology [126].

Lately, nanoflowers have attracted much attention and have been applied in various fields including water purification, photo-anode, enhance redox reaction, and photocatalytic activity as well as medical applications. More specifically, they have been applied as pharmaceuticals agent for protein, drug delivery, anti-cancer therapy, multidrug delivery, detection toxicity, and impurity detection. They can be achieved by eco-friendly approaches [127] and have high surface to volume ratio which results in an improvement in surface reactions [128]. On the other hand, it is difficult to control their structures throughout the reaction. The fabrication process may generate toxic elements and byproducts and also it may result in a reduction in protein and peptide activity [128].

Nanostars are an anisotropic structure consisting of a small core and number of sharp tips. The size of the tips can alter the optical properties and exhibit high absorption cross-sections in the NIR region due to the hybridizations of the plasmons of the core and the tips of NPs [129]. They have exhibited low toxicity and high biocompatibility, which make them as an appropriate potential platform for tissue engineering. The cell entry approach includes two main pathways: phagocytosis and receptor-mediated endocytosis which are determined by their shape and size. Moreover, they show selective optical absorbance, novel electronic properties, and appropriate biocompatibility with low toxicity [54].

Compared with other NPs, nanotrees appear to be understudied. Despite their benefits such as the high surface-to-volume ratio, quick transfer of electron, ideal crystallinity, and efficient charge–discharge stability, their applications in medical field have not been extensively explored.

Last but not least, there are many features of nanodendrimers, which still warrant future investigations. It is predicted that they can be efficiently applied in controllable delivering of drugs and molecular imaging technology [130]. Chemical composition, shape, and size are considered as the main properties which can affect the property-induced functional biomedical applications. The metallic NDs are assumed to be the promising photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy. The high absorption cross-section also makes NDs an appropriate option for PA imaging of cells in a 3D-culture system in real time [102]. NDs have displayed unique physicochemical, optical, and electronic properties. The dendrite structure increased the surface area which resulted in an enhancement in loading efficiency of bioactive molecules. Additionally functional groups such as antibodies and proteins can be added to this structure to improve the targeting. They also have tunable shape-dependent properties [102].

The leaf-shaped nanostructures contain micropores which has significantly improved their performance in some applications, for instance, these pores provide more efficient path for the reactant molecules to shift toward the surface’s active sites [131]. Moreover, these pores can ease the transportation of hole carriers in the sensing process [132]. Table 5 shows the summary of different NPs advantages.

Advantages of developed NPs

| Nanoflowers | Nanotrees | Nanostars | NDs | Nanoleaves |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High surface to volume ratio | High surface area [68] | Low toxicity [54] | High selectivity and sensitivity | Facile and low cost [133,134] |

| Better charge transfer and carrier immobility | Quick transfer of electron [71] | Tunable optical absorbance [53] | Enhanced catalytic activity | |

| Higher efficiency of surface reaction | Ideal crystallinity [71] | Unique electronic features [53] | Improved antimicrobial activity | Containing micropores [131,132] |

| Environment friendly, facile, non-toxic and cost effective synthesize | Efficient charge–discharge stability [70] | High biocompatibility [53] | Enhanced drug loading content | |

| Enhanced stability of enzymes and proteins | ||||

| Favorable enzyme molecules conformation in nanoflowers [128] | Good stability and biocompatibility | Good anti-interferent ability [133] | ||

| Cooperative effects due to nanoscale-entrapped enzyme [125] |

4 Conclusions

Nanoflowers, nanostars, nanotrees, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves have received increasing attention in recent years. They showed various applications in drug delivery, cancer treatment, and have also been applied as antibacterial agents and effective sensors. These wide range of applications have been attributed to their novel physical and optical features. Their specific structures have led to an increase in surface area which can enhance biological reactions and can also improve functionalization process. In addition to their unique structure, various materials such as metals and polymers can be fabricated in these shapes. However, controlling the structure throughout the reaction is non-trivial and toxic elements and byproducts may be generated during the fabrication process. This may result in a reduction in protein and peptide activity. Recently developed nanomaterial platforms are expected to revolutionize the biomedical field due to their unique features. In this article, the advantages and disadvantages of each type of NPs have been systematically reviewed. Areas that warrant further studies are also pointed out in order to fully exploit these novel nanostructures as advanced functional materials with a broad spectrum of applications that will benefit human health.

-

Funding information: Z.C. acknowledges the Fund to Sustain Research Excellence from Brigham Research Institute.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted the responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Abdellatif AAH, Mohammed HA, Khan RA, Singh V, Bouazzaoui A, Yusuf M, et al. Nano-scale delivery: a comprehensive review of nano-structured devices, preparative techniques, site-specificity designs, biomedical applications, commercial products, and references to safety, cellular uptake, and organ toxicity. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10(1):1493–559.10.1515/ntrev-2021-0096Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Abed MA, Mutlak FA-H, Ahmed AF, Nayef UM, Abdulridha SK, Jabir MS. Synthesis of Ag/Au (core/shell) nanoparticles by laser ablation in liquid and study of their toxicity on blood human components. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing; 2021.10.1088/1742-6596/1795/1/012013Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Quinson J, Neumann S, Kacenauskaite L, Bucher J, Kirkensgaard J, Simonsen SB, et al. Solvent‐dependent growth and stabilization mechanisms of surfactant‐free colloidal Pt nanoparticles. Chem Eur J. 2020;26(41):9012–23.10.1002/chem.202001553Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Chen X, Wu G, Chen J, Chen X, Xie Z, Wang X. Synthesis of “clean” and well-dispersive Pd nanoparticles with excellent electrocatalytic property on graphene oxide. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(11):3693–5.10.1021/ja110313dSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Naranthatta S, Janardhanan P, Pilankatta R, Nair SS. Green synthesis of engineered CdS nanoparticles with reduced cytotoxicity for enhanced bioimaging application. ACS Omega. 2021;6(12):8646–55.10.1021/acsomega.1c00519Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Panthi G, Ranjit R, Khadka S, Gyawali KR, Kim HY, Park M. Characterization and antibacterial activity of rice grain-shaped ZnS nanoparticles immobilized inside the polymer electrospun nanofibers. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2020;3(1):8–15.10.1007/s42114-020-00141-9Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Alhadrami HA, Shoudri RA. Titanium oxide (TiO2) nanoparticles for treatment of wound infection; J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2021;15(1):437–51.10.22207/JPAM.15.1.41Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Sadovnikov S, Kuznetsova YV, Rempel A. Synthesis of a stable colloidal solution of PbS nanoparticles. Inorg Mater. 2014;50(10):969–75.10.1134/S0020168514100148Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Haubold S, Haase M, Kornowski A, Weller H. Strongly luminescent InP/ZnS core–shell nanoparticles. ChemPhysChem. 2001;2(5):331–4.10.1002/1439-7641(20010518)2:5<331::AID-CPHC331>3.0.CO;2-0Suche in Google Scholar

[10] O’Farrell N, Houlton A, Horrocks BR. Silicon nanoparticles: applications in cell biology and medicine. Int J Nanomed. 2006;1(4):451–72.10.2147/nano.2006.1.4.451Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Thanh NT, Green LA. Functionalisation of nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Nano Today. 2010;5(3):213–30.10.1016/j.nantod.2010.05.003Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Silva S, Almeida AJ, Vale N. Combination of cell-penetrating peptides with nanoparticles for therapeutic application: a review. Biomolecules. 2019;9(1):22.10.3390/biom9010022Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Elahi N, Kamali M, Baghersad MH. Recent biomedical applications of gold nanoparticles: a review. Talanta. 2018;184:537–56.10.1016/j.talanta.2018.02.088Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Ray SS, Bandyopadhyay J. Nanotechnology-enabled biomedical engineering: current trends, future scopes, and perspectives. Nanotechnol Rev. 2021;10(1):728–43.10.1515/ntrev-2021-0052Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Liang X-J, et al. Circumventing tumor resistance to chemotherapy by nanotechnology. Multi-drug resistance in cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;596:467–88.10.1007/978-1-60761-416-6_21Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Kharissova OV, Kharisov BI, García TH, Méndez UO. A review on less-common nanostructures. Synth React Inorg, Met-Org, Nano-Met Chem. 2009;39(10):662–84.10.1080/15533170903433196Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Guo X, Wang L, Duval K, Fan J, Zhou S, Chen Z. Dimeric drug polymeric micelles with acid‐active tumor targeting and FRET‐traceable drug release. Adv Mater. 2018;30(3):1705436.10.1002/adma.201705436Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Yu X, Trase I, Ren M, Duval K, Guo X, Chen Z. Design of nanoparticle-based carriers for targeted drug delivery. J Nanomater. 2016;2016:1–15.10.1155/2016/1087250Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Guo X, Wei X, Chen Z, Zhang X, Yang G, Zhou S. Multifunctional nanoplatforms for subcellular delivery of drugs in cancer therapy. Prog Mater Sci. 2020;107:100599.10.1016/j.pmatsci.2019.100599Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Mathaes R, Winter G, Besheer A, Engert J. Influence of particle geometry and PEGylation on phagocytosis of particulate carriers. Int J Pharmaceutics. 2014;465(1–2):159–64.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.02.037Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Agarwal R, Singh V, Jurney P, Shi L, Sreenivasan SV, Roy K. Mammalian cells preferentially internalize hydrogel nanodiscs over nanorods and use shape-specific uptake mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110(43):17247–52.10.1073/pnas.1305000110Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Oh WK, Kim S, Yoon H, Jang J. Shape‐dependent cytotoxicity and proinflammatory response of poly (3, 4‐ethylenedioxythiophene) nanomaterials. Small. 2010;6(7):872–9.10.1002/smll.200902074Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Doshi N, Mitragotri S. Needle-shaped polymeric particles induce transient disruption of cell membranes. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7(suppl_4):S403–10.10.1098/rsif.2010.0134.focusSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Jindal AB. The effect of particle shape on cellular interaction and drug delivery applications of micro-and nanoparticles. Int J Pharmaceutics. 2017;532(1):450–65.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.09.028Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Gratton SE, Ropp PA, Pohlhaus PD, Luft JC, Madden VJ, Napier ME, et al. The effect of particle design on cellular internalization pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(33):11613–8.10.1073/pnas.0801763105Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Decuzzi P, Godin B, Tanaka T, Lee SY, Chiappini C, Liu X, et al. Size and shape effects in the biodistribution of intravascularly injected particles. J Controlled Rel. 2010;141(3):320–7.10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.10.014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Jeyaraj M, Gurunathan S, Qasim M, Kang MH, Kim JH. A comprehensive review on the synthesis, characterization, and biomedical application of platinum nanoparticles. Nanomaterials. 2019;9(12):1719.10.3390/nano9121719Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Rane AV, et al. Methods for synthesis of nanoparticles and fabrication of nanocomposites. Synthesis of inorganic nanomaterials. United Kingdom: Woodhead Publishing; 2018. p. 121–39.10.1016/B978-0-08-101975-7.00005-1Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Hasan S. A review on nanoparticles: their synthesis and types. Res. J Recent Sci. 2015;2277:2502.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Heli H, Rahi A. Synthesis and applications of nanoflowers. Recent Pat Nanotechnol. 2016;10(2):86–115.10.2174/1872210510999160517102102Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Negahdary M, Heli H. Applications of nanoflowers in biomedicine. Recent Pat Nanotechnol. 2018;12(1):22–33.10.2174/1872210511666170911153428Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Lee SW, Cheon SA, Kim MI, Park TJ. Organic–inorganic hybrid nanoflowers: types, characteristics, and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnol. 2015;13(1):1–10.10.1186/s12951-015-0118-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Kharisov BI. A review for synthesis of nanoflowers. Recent Pat Nanotechnol. 2008;2(3):190–200.10.2174/187221008786369651Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Ge J, Lei J, Zare RN. Protein–inorganic hybrid nanoflowers. Nat Nanotechnol. 2012;7(7):428–32.10.1038/nnano.2012.80Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Yu Y, Fei X, Tian J, Xu L, Wang X, Wang Y. Self-assembled enzyme–inorganic hybrid nanoflowers and their application to enzyme purification. Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces. 2015;130:299–304.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.04.033Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Ghosh K, Balog ERM, Sista P, Williams DJ, Kelly D, Martinez JS, et al. Temperature-dependent morphology of hybrid nanoflowers from elastin-like polypeptides. Appl Mater. 2014;2(2):021101.10.1063/1.4863235Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Gopal J, Hasan N, Manikandan M, Wu HF. Bacterial toxicity/compatibility of platinum nanospheres, nanocuboids and nanoflowers. Sci Rep. 2013;3(1):1–8.10.1038/srep01260Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Shcharbin D, Halets-Bui I, Abashkin V, Dzmitruk V, Loznikova S, Odabaşı M, et al. Hybrid metal–organic nanoflowers and their application in biotechnology and medicine. Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces. 2019;182:110354.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.110354Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Nhung TT, Kang I-J, Lee S-W. Fabrication and characterization of gold nanoflowers formed via chitosan-tripolyphosphate template films for biomedical applications. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2013;13(8):5346–50.10.1166/jnn.2013.7034Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Liang H, Zhang XB, Lv Y, Gong L, Wang R, Zhu X, et al. Functional DNA-containing nanomaterials: cellular applications in biosensing, imaging, and targeted therapy. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47(6):1891–901.10.1021/ar500078fSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Han J, Li J, Jia W, Yao L, Li X, Jiang L, et al. Photothermal therapy of cancer cells using novel hollow gold nanoflowers. Int J Nanomed. 2014;9:517–26.10.2147/IJN.S55800Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Woźniak A, Malankowska A, Nowaczyk G, Grześkowiak BF, Tuśnio K, Słomski R, et al. Size and shape-dependent cytotoxicity profile of gold nanoparticles for biomedical applications. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2017;28(6):92.10.1007/s10856-017-5902-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Huang P, Zeng B, Mai Z, Deng J, Fang Y, Huang W, et al. Novel drug delivery nanosystems based on out-inside bifunctionalized mesoporous silica yolk–shell magnetic nanostars used as nanocarriers for curcumin. J Mater Chem B. 2016;4(1):46–56.10.1039/C5TB02184GSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Chuang S-M, Lee YH, Liang RY, Roam GD, Zeng ZM, Tu HF, et al. Extensive evaluations of the cytotoxic effects of gold nanoparticles. Biochim Biophys Acta-General Subjects. 2013;1830(10):4960–73.10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.06.025Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Coradeghini R, Gioria S, García CP, Nativo P, Franchini F, Gilliland D, et al. Size-dependent toxicity and cell interaction mechanisms of gold nanoparticles on mouse fibroblasts. Toxicol Lett. 2013;217(3):205–16.10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.11.022Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Goodman CM, McCusker CD, Yilmaz T, Rotello VM. Toxicity of gold nanoparticles functionalized with cationic and anionic side chains. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15(4):897–900.10.1021/bc049951iSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Liu Z, Wu Y, Guo Z, Liu Y, Shen Y, Zhou P, et al. Effects of internalized gold nanoparticles with respect to cytotoxicity and invasion activity in lung cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99175.10.1371/journal.pone.0099175Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Zhang Y, Zhang C, Xu C, Wang X, Liu C, Waterhouse G, et al. Ultrasmall Au nanoclusters for biomedical and biosensing applications: a mini-review. Talanta. 2019;200:432–42.10.1016/j.talanta.2019.03.068Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Makvandi P, Wang C, Zare EN, Borzacchiello A, Niu L, Tay FR. Metal‐based nanomaterials in biomedical applications: antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity aspects. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30(22):1910021.10.1002/adfm.201910021Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Zheng K, Setyawati MI, Leong DT, Xie J. Antimicrobial gold nanoclusters. ACS Nano. 2017;11(7):6904–10.10.1021/acsnano.7b02035Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Huang J, Guo M, Ke H, Zong C, Ren B, Liu G, et al. Rational design and synthesis of γFe2O3@ Au magnetic gold nanoflowers for efficient cancer theranostics. Adv Mater. 2015;27(34):5049–56.10.1002/adma.201501942Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Rastogi A, Yadav K, Mishra A, Singh MS, Chaudhary S, Manohar R, et al. Early diagnosis of lung cancer using magnetic nanoparticles-integrated systems. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):544–74.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0032Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Dardir K. Synthesis and application of SERS active gold nanostar probes to monitor viral evolution. New Jersey, USA: Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, School of Graduate Studies; 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Mousavi SM, Zarei M, Hashemi SA, Ramakrishna S, Chiang WH, Lai CW, et al. Gold nanostars-diagnosis, bioimaging and biomedical applications. Drug Metab Rev. 2020;52(2):299–318.10.1080/03602532.2020.1734021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Borzenkov M, Moros M, Tortiglione C, Bertoldi S, Contessi N, Faré S, et al. Fabrication of photothermally active poly (vinyl alcohol) films with gold nanostars for antibacterial applications. Beilstein J Nanotechnol. 2018;9(1):2040–8.10.3762/bjnano.9.193Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Patra CR, Barui AK. Nanoflowers: a future therapy for cardiac and ischemic disease? Nanomedicine. 2013;8(11):1735–8.10.2217/nnm.13.161Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Perumal V, Hashim U, Gopinath SC, Haarindraprasad R, Foo KL, Balakrishnan SR, et al. ‘Spotted nanoflowers’: gold-seeded zinc oxide nanohybrid for selective bio-capture. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):1–12.10.1038/srep12231Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Cai Q, Gao Y, Gao T, Lan S, Simalou O, Zhou X, et al. Insight into biological effects of zinc oxide nanoflowers on bacteria: why morphology matters. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(16):10109–20.10.1021/acsami.5b11573Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Jin S-E, Jin H-E. Antimicrobial activity of zinc oxide nano/microparticles and their combinations against pathogenic microorganisms for biomedical applications: from physicochemical characteristics to pharmacological aspects. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(2):263.10.3390/nano11020263Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Barui AK, Jhelum P, Nethi SK, Das T, Bhattacharya D, Vinothkumar B, et al. Potential therapeutic application of zinc oxide nanoflowers in the cerebral ischemia rat model through neuritogenic and neuroprotective properties. Bioconjugate Chem. 2020;31(3):895–906.10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.0c00030Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Wang S, Tan L, Liang P, Liu T, Wang J, Fu C, et al. Layered MoS2 nanoflowers for microwave thermal therapy. J Mater Chem B. 2016;4(12):2133–41.10.1039/C6TB00296JSuche in Google Scholar

[62] Wu S, Liu X, Ren J, Qu X. Glutathione depletion in a benign manner by MoS2‐based nanoflowers for enhanced hypoxia‐irrelevant free‐radical‐based cancer therapy. Small. 2019;15(51):1904870.10.1002/smll.201904870Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Cao H, Yang DP, Ye D, Zhang X, Fang X, Zhang S, et al. Protein–inorganic hybrid nanoflowers as ultrasensitive electrochemical cytosensing interfaces for evaluation of cell surface sialic acid. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015;68:329–35.10.1016/j.bios.2015.01.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Baker YR, Chen J, Brown J, El-Sagheer AH, Wiseman P, Johnson E, et al. Preparation and characterization of manganese, cobalt and zinc DNA nanoflowers with tuneable morphology, DNA content and size. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(15):7495–505.10.1093/nar/gky630Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[65] Shi L, Mu C, Gao T, Chen T, Hei S, Yang J, et al. DNA nanoflower blooms in nanochannels: a new strategy for miRNA detection. Chem Commun. 2018;54(81):11391–4.10.1039/C8CC05690KSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Zhang L, Abdullah R, Hu X, Bai H, Fan H, He L, et al. Engineering of bioinspired, size-controllable, self-degradable cancer-targeting DNA nanoflowers via the incorporation of an artificial sandwich base. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141(10):4282–90.10.1021/jacs.8b10795Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[67] Zhu G, Hu R, Zhao Z, Chen Z, Zhang X, Tan W. Noncanonical self-assembly of multifunctional DNA nanoflowers for biomedical applications. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(44):16438–45.10.1021/ja406115eSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[68] Wu W-Q, Feng HL, Chen HY, Kuang DB, Su CY. Recent advances in hierarchical three-dimensional titanium dioxide nanotree arrays for high-performance solar cells. J Mater Chem A. 2017;5(25):12699–717.10.1039/C7TA03521GSuche in Google Scholar

[69] Shi W, Song S, Zhang H. Hydrothermal synthetic strategies of inorganic semiconducting nanostructures. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42(13):5714–43.10.1039/c3cs60012bSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[70] Sun X, Li Q, Lü Y, Mao Y. Three-dimensional ZnO@ MnO2 core@ shell nanostructures for electrochemical energy storage. Chem Commun. 2013;49(40):4456–8.10.1039/c3cc41048jSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[71] Lv S, Li Z, Chen C, Liao J, Wang G, Li M, et al. Enhanced field emission performance of hierarchical ZnO/Si nanotrees with spatially branched heteroassemblies. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(24):13564–8.10.1021/acsami.5b02976Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[72] Yang D, Qiu Y, Wang T, Song W, Wang Z, Xu J, et al. Growth of 3D branched ZnO nanowire for DC-type piezoelectric nanogenerators. J Mater Sci, Mater Electron. 2016;27(7):6708–12.10.1007/s10854-016-4619-xSuche in Google Scholar

[73] Mirzaei H, Darroudi M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles: biological synthesis and biomedical applications. Ceram Int. 2017;43(1):907–14.10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.10.051Suche in Google Scholar

[74] Aradilla D, Gaboriau D, Bidan G, Gentile P, Boniface M, Dubal D, et al. An innovative 3-D nanoforest heterostructure made of polypyrrole coated silicon nanotrees for new high performance hybrid micro-supercapacitors. J Mater Chem A. 2015;3(26):13978–85.10.1039/C5TA03435CSuche in Google Scholar

[75] Huang J, Chen F, Zhang Q, Zhan Y, Ma D, Xu K, et al. 3D silver nanoparticles decorated zinc oxide/silicon heterostructured nanomace arrays as high-performance surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrates. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(10):5725–35.10.1021/am507857xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[76] Abdallah B, Kakhia M, Alsabagh M, Tello A, Kewan F. Synthesis of PbS: ZnO nanotrees by thermal evaporation: morphological, structural and optical properties. Optoelectron Lett. 2020;16(4):241–7.10.1007/s11801-020-9107-0Suche in Google Scholar

[77] Jiang X, Xiong Y, Wang Y, Wang J, Li N, Zhou J, et al. Treelike two-level Pdx Agy nanocrystals tailored for bifunctional fuel cell electrocatalysis. J Mater Chem A. 2019;7(10):5248–57.10.1039/C8TA11538ASuche in Google Scholar

[78] Cennamo N, D'Agostino G, Donà A, Dacarro G, Pallavicini P, Pesavento M, et al. Localized surface plasmon resonance with five-branched gold nanostars in a plastic optical fiber for bio-chemical sensor implementation. Sensors. 2013;13(11):14676–86.10.3390/s131114676Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[79] Abdelhady KR, Moustafa HE-D, Yousif BB. Performance evaluation and enhancement of medical imaging using plasmonic gold nanostars. MEJ. 2021;46(4):18–30.10.21608/bfemu.2021.213113Suche in Google Scholar

[80] Chirico G, Borzenkov M, Pallavicini P. Gold nanostars: synthesis, properties and biomedical application. Germany: Springer; 2015.10.1007/978-3-319-20768-1Suche in Google Scholar

[81] Lu H, Su J, Mamdooh R, Li Y, Stenzel MH. Cellular uptake of gold nanoparticles and their movement in 3D multicellular tumor spheroids: effect of molecular weight and grafting density of poly (2‐hydroxyl ethyl acrylate). Macromol Biosci. 2020;20(1):1900221.10.1002/mabi.201900221Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[82] Xie X, Liao J, Shao X, Li Q, Lin Y. The effect of shape on cellular uptake of gold nanoparticles in the forms of stars, rods, and triangles. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–9.10.1038/s41598-017-04229-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[83] Siddique S, Chow JC. Gold nanoparticles for drug delivery and cancer therapy. Appl Sci. 2020;10(11):3824.10.3390/app10113824Suche in Google Scholar

[84] Pakravan A, Salehi R, Mahkam M. Comparison study on the effect of gold nanoparticles shape in the forms of star, hallow, cage, rods, and Si–Au and Fe–Au core–shell on photothermal cancer treatment. Photodiagnosis Photodynamic Ther. 2021;33:102144.10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.102144Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[85] Tian F, Bonnier F, Casey A, Shanahan AE, Byrne HJ. Surface enhanced Raman scattering with gold nanoparticles: effect of particle shape. Anal Methods. 2014;6(22):9116–23.10.1039/C4AY02112FSuche in Google Scholar

[86] Tian F, Conde J, Bao C, Chen Y, Curtin J, Cui D. Gold nanostars for efficient in vitro and in vivo real-time SERS detection and drug delivery via plasmonic-tunable Raman/FTIR imaging. Biomaterials. 2016;106:87–97.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.08.014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[87] Tian Y, Zhang Y, Teng Z, Tian W, Luo S, Kong X, et al. pH-dependent transmembrane activity of peptide-functionalized gold nanostars for computed tomography/photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(3):2114–22.10.1021/acsami.6b13237Suche in Google Scholar PubMed