Abstract

Photodynamic therapy (PDT), as a noninvasive therapeutic modality, has significantly revolutionized the contemporary management of oral and dental health. Recently, PDT has witnessed significant technological advancements, especially with the introduction of biomaterials and nanotechnologies, thus highlighting its potential as a multi-functional tool in therapeutics. In this review, our objective was to provide a comprehensive overview of the advancements in nanotechnology-enhanced PDT for the treatment of oral diseases, encompassing dental caries, root canal infection, periodontal disease, peri-implant inflammation, tooth staining, and whitening, as well as precancerous lesions and tumors. Furthermore, we extensively deliberated upon the persisting challenges and prospective avenues of nanotechnology-enhanced PDT in the realm of oral diseases, which will open up new possibilities for the application of nanotechnology-enhanced PDT in clinical implementation.

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations

- A. actinomycetemcomitans

-

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans

- AgNC

-

silver nanocluster

- AgNPs

-

silver nanoparticles

- AIE

-

aggregation-induced emission

- ALA

-

5-aminolevulinic acid

- ATP

-

adenosine triphosphate

- AuNPs

-

gold nanoparticles

- CDs

-

carbon dots

- Ce6

-

Chlorin e6

- CeO2NPs

-

cerium oxide nanoparticles

- CS

-

chitosan

- CSNPs

-

chitosan nanoparticles

- Cu2O

-

cuprous oxide

- Cur

-

curcumin

- E. faecalis

-

Enterococcus faecalis

- EDTA

-

ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid

- EPS

-

extracellular polysaccharides

- Esp

-

Enterococcus surface protein

- F. nucleatum

-

Fusobacterium nucleatum

- FDA

-

Food and Drug Administration

- FSR

-

E. faecalis quorum-sensing locus

- GelE

-

gelatinase

- GNRs

-

gold nanorods

- ICG

-

indocyanine green

- LDLR

-

low-density lipoprotein receptor

- MB

-

methylene blue

- Mn

-

manganese

- MOF

-

metal–organic framework

- NGO

-

graphene oxide

- NIR

-

near infrared

- OLK

-

oral leukoplakia

- P. gingivalis

-

Porphyromonas gingivalis

- P. intermedia

-

Prevotella intermedia

- PDA

-

polydopamine

- PDT

-

photodynamic therapy

- PDZ

-

phthalocyanine

- PF-127

-

Pluronic ®F-127

- PLGA

-

poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- P-SACT

-

photoacoustic antibacterial chemotherapy

- PSs

-

photosensitizers

- PTT

-

photothermal therapy

- RB

-

rose bengal

- ROS

-

reactive oxygen species

- S. gordonii

-

Streptococcus gordonii

- S. mutans

-

Streptococcus mutans

- S. sanguis

-

Streptococcus sanguis

- S. sobrinus

-

Streptococcus sobrinus

- SACT

-

sonodynamic antibacterial chemotherapy

- SeNPs

-

selenium nanoparticles

- SOD

-

superoxide dismutase

- SRP

-

scaling and root planning

- TBO

-

toluidine blue

- TiO2

-

titanium dioxide

- UPNPs

-

upconversion nanoparticles

- ZnONPs

-

zinc oxide nanoparticles

1 Introduction

As the human body’s gateway to all the systems, the oral cavity is a complex ecosystem that includes teeth, glandular apparati, vulnerable mucosa, and billions of colonized microorganisms [1]. Disorders of oral health seriously compromise mastication, articulation, physical aesthetics, social integration, and even mental health, imposing a substantial health and economic burden worldwide [2]. The annual global economic burden of poor oral health has been estimated to be approximately 545 billion USD yearly worldwide, encompassing both direct and indirect costs, which is comparable to the two most costly illnesses: cardiovascular disease and diabetes [3]. Currently, the significance of oral health is escalating, highlighting the need for our profession to develop advanced technologies and translate them into practice for global benefit [2,4].

Over the past two decades, photodynamic therapy (PDT) has garnered significant attention in the realm of oral and dental applications due to its minimally invasive nature, potent bactericidal effect, and precise spatiotemporal control [5,6]. PDT relies on three crucial components: an excitation light source, photosensitizers (PSs), and oxygen [5,6]. Under excitation light with an appropriate wavelength, PS can be converted from the ground state to the excited state, where the excited state of PS reacts with oxygen to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), including hydroxyl radicals (˙OH), super oxide anions (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and singlet oxygen (1O2) [7]. Ultimately, these ROS could effectively eliminate malignant cells, eradicate pathogens, bleach pigments, and perform other functions. PDT has been clinically employed for the treatment of multiple oral diseases, encompassing dental caries, root canal infections, periodontitis, and other related ailments [8,9]. However, PDT also presents several significant limitations [10], which impede its further implementation in the treatment of oral diseases. First, in the context of antibacterial treatment, a large proportion of PSs exhibit poor water solubility and negative charge, which may impede their internalization by bacteria and subsequently lead to suboptimal PDT outcomes for disinfection in oral diseases [6,11,12]. Another significant challenge encountered by numerous researchers is the limited ability of small molecule PSs to effectively penetrate deep into the dentinal tubules, pits, and fissures [13], where pathogenic bacteria usually persist and contribute to treatment failure. Meanwhile, the release of ROS during PDT presents a dual nature, potentially leading to detrimental effects on the normal oral mucosa upon successful treatment of oral diseases. In addition, the presence of oxygen is indispensable for the generation of ROS by PDT. The hypoxic nature of our oral cavity, particularly in the root canal and periodontal pocket, significantly hampers the efficacy of the PDT effect [14,15]. To address these limitations of conventional PDT, an interdisciplinary research framework is imperative for augmenting the PDT effect and advancing oral health [16].

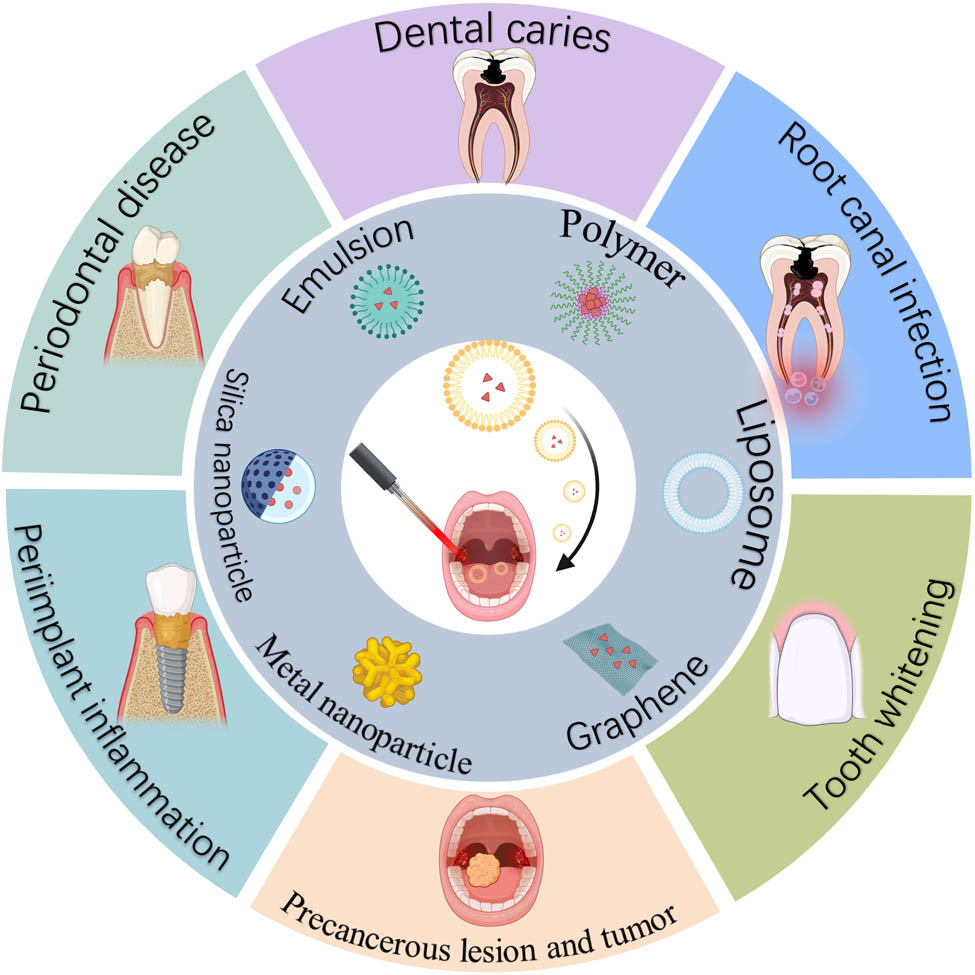

Nanotechnology has been harnessed to optimize treatment efficiency and mitigate adverse effects through various approaches [17,18,19]. The development of novel nanodelivery systems for dental applications is witnessing a growing inclination [20,21,22,23]. Recently, significant advancements have been achieved in the development of novel nanotechnology to optimize the benefits of PDT in oral healthcare. In the present review, we will discuss the recent advances in nanotechnology-enhanced PDT, focusing on the design and treatment efficiency across various oral diseases (Figure 1). Together, considering future optimizations, we will also address the existing challenges and potential perspectives of nanotechnology-enhanced PDT, which would accelerate the corresponding research and clinical transformation for dental care.

Schematic of nanotechnology-enhanced PDT for the treatment of oral diseases. The facilitation of PDT can be achieved through the utilization of diverse nanoparticle types. Six representative types of nanoparticles are shown, including emulsions, polymers, liposomes, graphene, metal nanoparticles, and silica nanoparticles. Nanotechnology-enhanced PDT has been extensively investigated for the treatment of oral diseases, including periodontal diseases, dental caries, root canal infection, tooth whitening, precancerous lesions, and tumors, as well as peri-implant inflammation, created with BioRender.com.

2 General aspects of nanotechnology-empowered PDT in oral diseases

2.1 PDT for oral and dental applications

The majority of oral diseases are directly associated with pathogenic cells, including malignant cells and pathogenic bacteria. Therefore, the primary objective of oral therapies is to eliminate these cells as thoroughly as possible. For instance, the conventional approach for managing oral cancer involves surgical intervention, radiotherapy, and pharmacotherapy to eradicate malignant cells. Certainly, these therapies may have significant systemic side effects and unavoidable damage to surrounding healthy tissues. In terms of microbial infectious diseases, antibiotic therapy is the common choice. However, the widespread abuse of antibiotics has led to a significant rise in microbial drug resistance, posing substantial challenges for its broad clinical application. Consequently, extensive endeavors are being undertaken to refine and optimize these therapeutic approaches, aiming to augment their efficacy while mitigating potential side effects. Over the past decade, PDT has demonstrated escalating potential in antitumor and antibacterial therapy due to its non-invasive feature and high specificity [5,6]. The oral cavity is directly exposed to the external environment. It is easy to conduct PDT for oral diseases. PDT is also non-invasive and thus has great patient compliance. Particularly, for the treatment of oral tumors, the non-invasive PDT can significantly improve the appearance and psychological health, since the traditional surgery may substantially damage the face tissue. Therefore, PDT has shown great potential for the treatment of diverse oral and dental diseases.

Although PDT has shown great promise for oral and dental applications, it also has several drawbacks:

Most PSs are hydrophobic and have poor solubility, which leads to uncontrollable drug release and aggregation-induced quenching.

The tissue penetration of excitation light is limited, which hinders the clinical application of PDT in deeper tissue.

Oxygen is necessary for PDT to produce ROS. However, the lesion sites in the oral cavity are usually hypoxic, which largely limits its effectiveness.

After PDT treatment, some PSs remain in the body for a long time, continuously absorb natural light, and cause side effects such as skin photosensitization or photobleaching.

2.2 Nanotechnology-empowered PDT in oral diseases

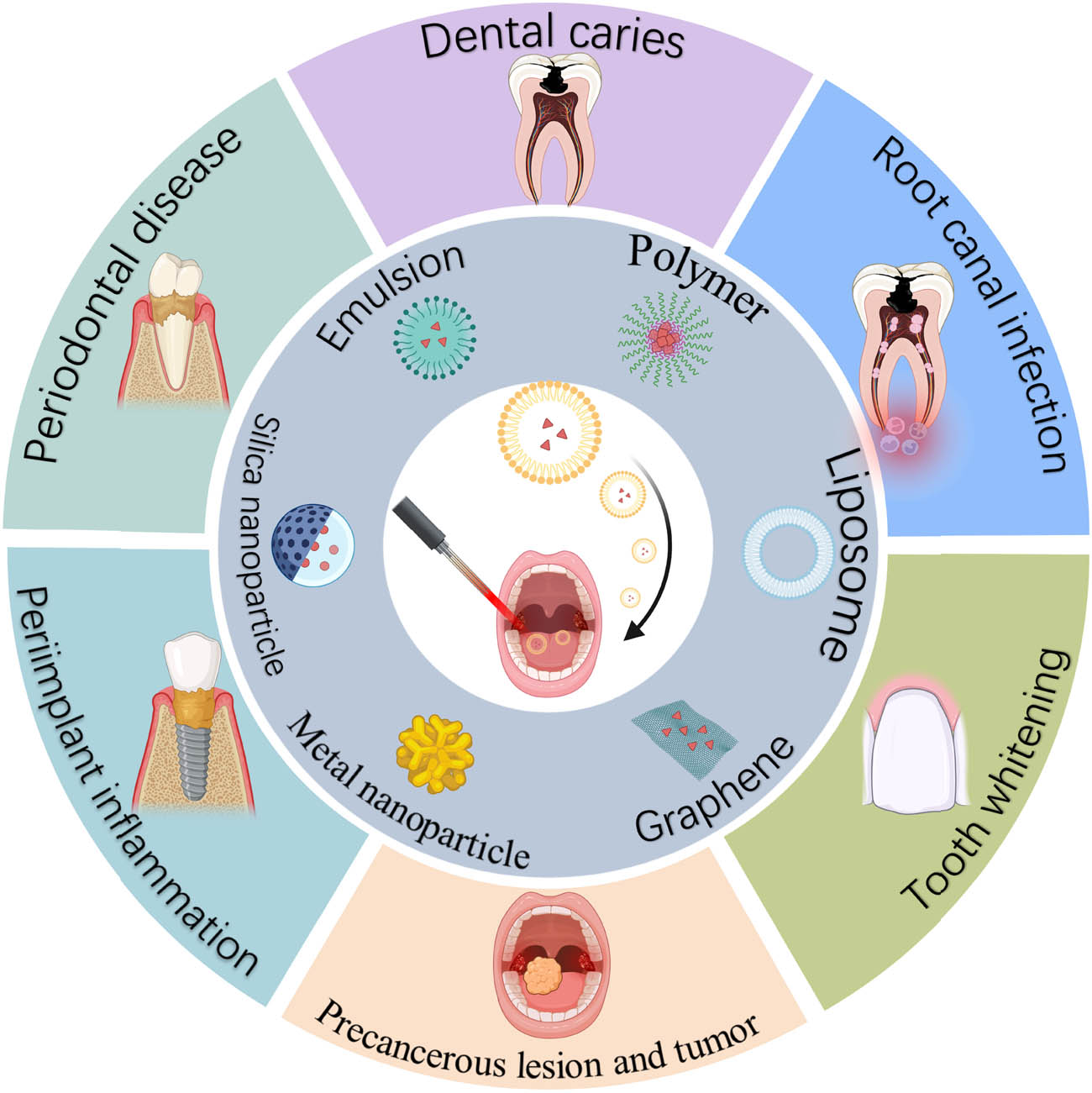

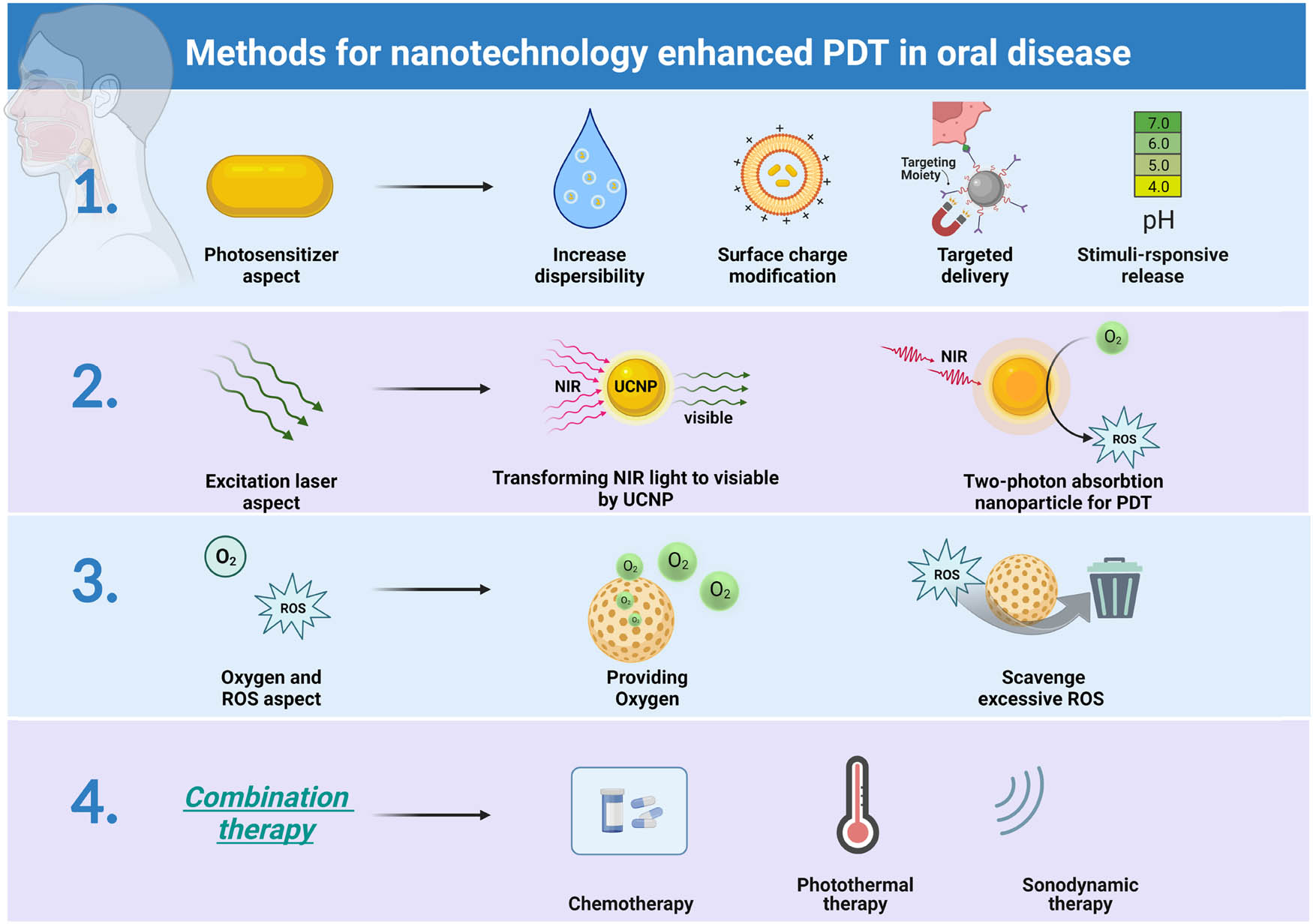

Aiming at addressing the drawbacks of abovementioned PDT, prevailing studies have begun to improve PDT with nanotechnology-based methods for the treatment of oral diseases (Figure 2). Nanotechnology has been developed to promote different aspects of PDT, including PSs, excitation light, oxygen, and combination strategies. In terms of PSs, after the excitation light is irradiated, a significant amount of energy is converted into heat and fluorescence in addition to the production of ROS. Thus, a lot of energy is lost during this process. To enhance the efficiency of PDT, it is essential to keep a sufficient concentration of PSs at the location of the injury. Nanotechnology could promote the accumulation of PS in a variety of ways. First, nanoparticles were applied for encapsulating or decorating PSs to increase the water dispersibility of PSs and change the surface charge of PSs (Figure 2, first panel). Meanwhile, some nanoparticle-loaded PSs have the ability to target specific lesion sites with the guidance of magnets, biological binding, etc. In addition, nanoparticles can endow PSs with the property of stimuli-responsive release, which is able to achieve controlled release of PSs at specific sites and specific times for better disease management. With respect to excitation light, multiple studies have used long-wavelength light to excite PS for deeper tissue penetration; among them, two-photon absorption nanoparticles and upconversion nanoparticles (UPNPs) are two representative methods (Figure 2, second panel). UPNPs can absorb near-infrared (NIR) light and transform it into high-energy photons at shorter wavelengths, which subsequently excite the PSs. Two-photon absorption nanoparticles can serve as PS themselves, absorbing two long-wavelength photons at the same time and thereby generate ROS. In the case of oxygen and ROS, to overcome the hypoxic status in the oral cavity for better ROS generation, nanoparticles could be designed to generate oxygen through different methods (Figure 2, third panel). Sometimes, excessive ROS causes damage to normal tissue, which can be relieved by specific types of nanoparticles that possess the ability to scavenge ROS. Another important aspect of nanotechnology-enhanced PDT is that this method could provide a combination strategy for synergizing PDT with chemotherapy, photothermal therapy (PTT), and sonodynamic therapy (Figure 2, fourth panel).

Schematic diagram of strategies for nanotechnology-enhanced PDT in oral diseases. Nanotechnology could be applied to enhance PDT in four aspects, including the PS, excitation laser, oxygen and ROS, and combination therapy. First, nanotechnology could endow PSs with increased dispersion in water, changeable surface charge, targeted delivery ability, and the function of stimuli-responsive release. Second, UPNP and two-photon absorption nanoparticles can be utilized for generating ROS under the excitation of NIR laser. Third, nanoparticles were exploited for providing oxygen for PDT and scavenging residual ROS to avoid tissue damage. Last, the combination of PDT with chemotherapy, PTT, sonodynamic therapy, or others can be achieved through nanotechnology-based methods, created with BioRender.com.

3 Progress of nanotechnology-empowered PDT in oral diseases

3.1 Dental caries

Dental caries is characterized by chronic and progressive destruction of tooth hard tissue under the action of bacteria and their acid metabolites [29]. The bacterial community is embedded in extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) to form a highly stable ecosystem, the biofilm, which can protect the bacteria from being killed by multiple therapies. Within the biofilm, Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) and Streptococcus sobrinus (S. sobrinus) are the main cariogenic bacteria with the abilities of acid production and acid tolerance [30,31], which results in a stable acidic state in the biofilm (pH = 4.5–5.5) [32]. Due to the limited penetration depth of the excitation light in human tissue, PDT is highly suitable for lesions that occur in superficial areas, including dental caries. Meanwhile, PDT application in dental caries also faces some challenges and could be addressed through nanotechnology (Table 1).

Application of nanotechnology-enhanced PDT for dental caries

| Nanocarrier | PS | Bacteria | PDT parameters | Therapeutic effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSNP | Photoditazine, PDZ | S. mutans | 660 nm, 39.5 J/cm2, 300 s | Increase the absorption of PDZ by S. mutans, reduce the number of S. mutans by 4.5 log10, and inhibit the formation of EPS in biofilms | [41] |

| CSNP | ClAlPc | S. mutans | 660 nm, 100 J/cm2, 175 s | Reduce the number of S. mutans by 1 log10 | [139] |

| Cationic liposomes | Gingival plaque | 660 nm, 250 W/cm2, 3 min | Nanoparticles have a much higher absorption rate in bacteria than in dental pulp cells. Inhibit bacterial growth by 82% | [140] | |

| PLGA-NP | Cur | S. mutans | 405 ± 5 nm, 45 J/cm2 | The inhibition rates of 7% Cur-PLGA-NP on S. mutans biofilm at 15, 30, 60 and 90 days were 4.1, 79.6, 69.6, 69.4, and 55.1%, respectively | [36] |

| Pluronic @ F-127 | Cur | S. mutans and C. albicans | 460 nm, 15 J/cm2, 696 s | Cur-PF-127-mediated PDT has MICs of 270 and 2.1093 μM against S. mutans and C. albicans, respectively, with good anti-biofilm effect | [37] |

| PNP | PhotoAc | S. mutans | 635 nm and 103.12, 68.75 J/cm2 | The formed novel PS exhibited a stronger inhibitory effect on S. mutans biofilm and biofilm formation-related genes (gtfB, gfC, and f0) than photoactive or TBO alone: less toxic to human gingival fibroblasts | [141] |

| AgNP | TBO | S. mutans | 630 nm, 9.1 J/cm2, 70 s | TBO-AgNP-mediated PDT reduced the number of planktonic S. mutans by 4log10, inhibited the formation of S. mutans biofilm, and downregulated the expression of biofilm-related genes | [44] |

| AgNP | RB | S. mutans, A. actinomycetemcomitans, and P. gingivalis | 420–750 nm; 80 mW/cm2; 0、 30, 60, 120 s | The antibacterial effects of RB-AgNP-mediated PDT against S. mutans, A. actinomycetemcomitan, and P. gingivalis were dose-dependent and time-dependent. RB-AgNP still had a stable and durable antibacterial effect after stopping the irradiation effect | [45] |

| AgNP | MB | S. mutans | 650 nm, 400 mW/cm2, 3 min | RB-AgNP-mediated PDT inhibited the S. mutans biofilm constructed on dentin sheets as high as 95.28% | [142] |

| AuNP | MB | S. mutans | 660 nm, 19.23 J/cm2, 10 min | MB-AuNP and free MB-mediated aPDT had the same antibacterial effect on S. mutans | [47] |

| SeNP | TBO | S. mutans | 630 nm, 38.5 J/cm2, 60 s | The inhibition rates of S. mutans biofilms by TBO-SeNP and free TBO-mediated PDT were 60 and 20%, respectively | [46] |

| ZnONP | cCur | S. mutans, S. sobrinus, and L. acidophilus | 435 ± 20 nm, 300–420 J/cm2, 5 min | For up to 90 days, the adhesive containing 7.5% Cur-ZnONP showed no colonization of S. mutans, S. sobrinu, and L. acidophilus after photoactivation | [38] |

| It can 100% inhibit the metabolic growth of these bacteria | |||||

| GO-Car/Hap | ICG | S. mutans | 810 nm, 31.2 J/cm2, 1 min | GO-Car/HAp@ICG-mediated PDT reduced the number of planktonic S. mutans by 93.2%, inhibited the formation of S. mutans biofilm by 56.8%, and the expression of gtfB gene was significantly reduced by 7.9-fold | [35] |

| An amphiphilic polymer | Ce6 | S. mutans, S. sobrinus, and S. sanguinis | 660 nm, 0.5 W/cm2, 3 min | MPP-Ce6-mediated aPDT exhibits significant bacteriostatic effects against cariogenic bacteria while demonstrating negligible systemic toxicity | [42] |

A large proportion of PSs are water-insoluble and possess a negative charge, making them incapable of penetrating deep in the complex structure of biofilm and internalized by negatively charged bacteria [33], which greatly hinders the application of PDT in treating dental caries. Nanotechnology can be exploited to modify those PSs and deliver them more efficiently. First, to overcome the water-insoluble problems of PS, several nanocarriers were developed. Graphene is a unique nanocrystal, characterized by facile modification, high solubility, favorable biocompatibility, and other notable advantages [34]. It exhibits the ability to harness visible light activation for ROS generation, thereby compromising bacterial integrity [34]. Consequently, graphene has garnered significant attention as an antibacterial agent. Gholibegloo et al. loaded indocyanine green (ICG) into a novel graphene oxide (NGO)-based nanodelivery system. Results showed that this system could increase the long-term stability of ICG in water and greatly improve the inhibitory effect of PDT on S. mutans and its biofilm [35]. Curcumin (Cur) is a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug with impressive properties for the treatment of multiple types of diseases, which was also demonstrated to act as a PS for PDT. However, the application of Cur in dental caries is limited by its poor bioavailability caused by poor water solubility and rapid metabolism. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and Pluronic ®F-127 (PF-127) have been developed as Cur carriers, which can increase the bioavailability of Cur and endow Cur with a strong PDT effect [36,37]. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs), which are considered to be one of the most promising next-generation PS for PDT [38], were utilized to evaluate the PDT efficiency for combating cariogenic bacteria and biofilms [38]. Pourhajibagher et al. studied the incorporation of cationic Cur-doped ZnONP into orthodontic adhesives, which can inhibit metabolic activity and biofilm formation up to 90 days [38].

The negative charge of some PSs hampers their further application in the treatment of dental caries. Chitosan (CS), a biocompatible and biodegradable derivative of chitin, exhibits versatile chemical modifications and grafting capabilities [39,40]. The application of CS nanoparticles (CSNPs) demonstrates a significant reduction in bacterial adhesion to the dental surface and effectively eliminates bacterial biofilms. This is attributed to the positive charge of CS, which is able to interact with negatively charged residues on the cytoplasm or cell membrane, enhancing the effect of PSs through the promotion of membrane permeability. de Souza et al. loaded the commercial PS phthalocyanine (PDZ, a derivative of chlorophyll A) into CSNP. Compared with PDZ, nanoparticles formed by PDZ-CSNP could significantly increase the endocytosis of PDZ by S. mutans, which further improved the effect of PDT, reduced the number of S. mutans, and effectively inhibited the formation of EPS in biofilms [41]. Our group also developed a simple but efficient nanodelivery system for eliminating cariogenic biofilms (Figure 3) [42]. Specifically, Chlorin e6 (Ce6) was encapsulated in a type of pH-responsive nanoparticle, which was demonstrated to enhance the penetration depth (by over 75%) and long retention (by over 100%) of Ce6 in the biofilm. Under the irradiation of a 660 nm laser, this method could significantly inhibit the formation of dental caries in a rat model of early childhood caries.

![Figure 3

A novel biofilm-responsive nanoparticle was developed to improve the efficacy of PDT against multispecies cariogenic biofilms. This nanoparticle enhances the penetration of PSs into the biofilms, effectively targeting and eliminating them. Reproduced with permission from Liu et al. [42]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. (a) Schematic diagram illustrating the process in which the nanoparticle releases PSs into the acidic microenvironment of the biofilm and exhibits bactericidal effects when exposed to a 660 nm laser. (b) The nanoparticle can penetrate biofilms to a depth of over 35 μm, surpassing the capability of free PSs.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0163/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0163_fig_003.jpg)

A novel biofilm-responsive nanoparticle was developed to improve the efficacy of PDT against multispecies cariogenic biofilms. This nanoparticle enhances the penetration of PSs into the biofilms, effectively targeting and eliminating them. Reproduced with permission from Liu et al. [42]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. (a) Schematic diagram illustrating the process in which the nanoparticle releases PSs into the acidic microenvironment of the biofilm and exhibits bactericidal effects when exposed to a 660 nm laser. (b) The nanoparticle can penetrate biofilms to a depth of over 35 μm, surpassing the capability of free PSs.

To further enhance the PDT effect, nanotechnology-based combination strategies were exploited for synergizing with PDT in the treatment of dental caries. Metals and metal-oxidized nanomaterials, such as silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), and selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs), are commonly used in the infection control of dental caries and could enhance the effects of PDT. Considering AgNP as an example, it can steadily and persistently release silver ions (Ag+), which subsequently destroy the structure of microorganisms. Moreover, compared with other inorganic nanoparticles, AgNP exhibits stronger broad-spectrum antibacterial properties [43]. Owing to its minute size, AgNP can penetrate the dentin tubules with a diameter ranging from 2.4 to 2.9 μm, thereby aiding in the regulation of bacterial growth and propagation within the root canal system. Additionally, it can induce alterations in bacterial membrane permeability, resulting in leakage of bacterial contents and ultimately leading to bacterial lysis and rupture [43]. Several studies have combined AgNPs with traditional PSs to achieve synergistic antibacterial effects. For example, Misba et al. conjugated toluidine blue (TBO) with AgNP to form TBO-AgNP for PDT under the excitation light, which could destroy the cell membrane of bacteria and cause the leakage of bacterial contents. Compared with free TBO, TBO-AgNP-mediated PDT inhibited the bacterial proliferation and biofilm formation, and significantly downregulated the expression of biofilm formation-related genes (gtfC, ftf, spaP, gbpB, comD, comE, and vicR) [44]. Shitomi et al. developed a nanocomposite of the combination of rose bengal (RB) and silver nanocluster (AgNC), which exhibited dose- and time-dependent bactericidal efficiency against S. mutans, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (A. actinomycetemcomitans), and Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) under the irradiation of excitation light. Moreover, AgNCs/RB showed a greater antibacterial effect compared with the two single components, indicating that the released Ag+ and RB-mediated PDT have a synergistic antibacterial effect [45]. SeNP exhibits potent antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities, making it an ideal nano-carrier for PDT. Furthermore, it synergistically enhances the efficacy of PDT. Biofilm inhibition assay confirmed that TBO-SeNP-mediated PDT had a higher inhibitory effect on S. mutans monospecies biofilm than the free TBO [46]. AuNP can serve as a drug carrier for targeted eradication of diseased cells and microorganisms, making it an ideal candidate for nanomedicine due to its bio-binding surface with suitable molecular probe affinity and exceptional optical properties. However, methylene blue-loaded AuNP (MB-AuNP) was demonstrated to show no significant difference in antibacterial effect against S. mutans after photoactivation compared with free MB [47]. In addition, propolis nanoparticles were loaded with a chlorophyllin mixture (PhotoActive+) and TBO, respectively, to form novel drug-loaded nanoparticles for synergistic effects in the treatment of dental caries. These novel nanoparticles exhibited enhanced inhibitory effects on S. mutans biofilms compared to the original free PhotoActive+ or TBO, thereby holding promise for minimizing therapy-related adverse effects.

3.2 Root canal infection

Root canal infection includes primary root canal infection, secondary root canal infection, and persistent periapical infection. Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) and P. gingivalis have high detection rates in primary root canal infections. E. faecalis is the main cause of root canal treatment failure and can exist in nutrient-depleted root canals for a long time. The main virulence factors, including Enterococcus surface protein (Esp), transcription regulator (BopD), E. faecalis quorum-sensing locus (FSR), and gelatinase (GelE), are involved in the formation of E. faecalis-related biofilms [48,49,50].

The primary goal of endodontic therapy is to eliminate the microbial membrane in the endodontic system and provide a sound endodontic seal. Nanotechnology could effectively deliver PSs into the infection site and increase the internalization of PSs by bacteria, which enables PDT a highly effective bactericidal ability. At the same time, the application of PDT demonstrated minimal bacterial resistance, thereby minimizing the risk of multidrug resistance. Therefore, diverse nanocarriers were recently exploited to deliver PSs for combating root canal infection (Table 2).

Effect of nanotechnology-based aPDT on root canal infection-related pathogens

| Nanocarrier | PS | Bacteria | PDT parameters | Therapeutic effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSNP | RB | E. faecalis | 540 nm, 5–60 J/cm2 | The survival rate of fibroblasts was higher than that of the free RB group, showing higher anti-collagenase degradation ability | [62] |

| CSNP | RB | E. faecalis | 540 nm; 5, 10 J/cm2 | Compared with free RB, RB-CSNP-mediated aPDT still had a residual antibacterial effect after 24 h interaction, which could completely inactivate bacteria | [61] |

| CSNP | RB | E. faecalis, P. intermedia, A. naeslundii, and S. oralis | 540 nm, 5, 60 J/cm2 | RB-CSNP-mediated aPDT can significantly reduce the 21-day mixed biofilm cultured by P. intermedia, A. naeslundii, and S. oralis | [63] |

| CSNP | RB | E. faecalis | 540 nm; 40, 2 J/cm2 | The root canal sealant mixed with RB-CSNP for root canal disinfection can significantly inhibit the E. faecalis biofilm in the root canal for 4 weeks after irradiation | [64] |

| CSNP | RB | E. faecalis | 540 nm; 2, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60 J/cm2 | In the presence of BSA, compared with free RB, RB-CSNP-mediated aPDT effectively destroys the single-strain biofilm formed by E. faecalis | [69] |

| CSNP | ICG | E. faecalis | 810 ± 20 nm; 0.49–1.46 W/cm2; 1, 3, 5 min | After laser irradiation, the longer the laser irradiation time, the higher the inhibition rate of ICG-CSNP against E. faecalis plankton | [65] |

| PLGA-NP | MB | E. faecalis | 665 nm; 0.32 W/cm2; 10 min | MB-PLGA-NP-mediated aPDT reduced planktonic and root canal E. faecalis | [73] |

| PLGA-NP;CSNP | MB, RB | 660, 540 nm; 10 min | Compared with sodium hypochlorite and EDTA irrigant, RB-CSNP, and MB-PLGA-NP-mediated aPDT increased the microhardness of root canal hard tissue and significantly enhanced the elastic modulus of dentin | [70] | |

| Liposomes | mTHPC | E. faecalis | 654 ± 4 nm, 100 J/cm2, 425 s | Compared with chlorhexidine, the antibacterial effect of aPDT mediated by mTHPC-loaded liposome nanoparticles was stronger. E. faecalis biofilm was effectively inhibited at 300 µm in dentinal tubules | [143] |

| AcLi-NP | THPP | E. faecalis | 447 nm, 1.2 mW/cm2, 1 h | THPP-AcLi-NP-mediated aPDT, 0.64 µM can inhibit 90% of E. faecalis growth, and 2.5 µM can completely kill the bacteria | [74] |

| NE | ZnPc | E. faecalis | 670 nm, 30 J/cm2 | Under the excitation of light, ZnPc-NE has more excellent antibacterial ability | [75] |

| NGO | ICG | E. faecalis | 810 nm, 31.2 J/cm2, 60 s | NGO-ICG-mediated aDPT reduced the viability of E. faecalis by 2.8 log10. The inhibition rate of E. faecalis biofilm was 99.4% | [51] |

| NGO | Cur | E. faecalis | 435 ± 20 nm, 360 J/cm2, 300 s | Cur-NGO-mediated aPDT had a significant inhibitory effect on E. faecalis biofilm. The expression of biofilm formation-related virulence factor genes (Efa, Esp, Gel, and FSR) was significantly downregulated | [52] |

| AgNP | ICG | E. faecalis | 810 nm, 200 mW, 30 s | AgNP combined with ICG/DL has a high inhibition rate of 99.12% against E. faecalis in the root canal | [53] |

| AgNP | ICG | E. faecalis | 808 nm, 250 mW, 60 s | AgNP combined with ICG/DL had an inhibition rate of about 70.77% against E. faecalis in the root canal | [54] |

| AgNP | TBO | E. faecalis | 620–640 nm; 2,000–4,000 mW/cm2; 30, 60 s | Simultaneous illumination of TBO and AgNP for 30 or 60 s can inhibit up to 99% of E. faecalis biofilm in root canals | [55] |

| AuNP | MB | E. faecalis | 660 nm; 55, 108, 179 mW/cm2; 30 min | MB-AuNP had a good inhibitory effect on the E. faecalis biofilm | [56] |

| SeNP | MB | E. faecalis | 660 nm, 200 mW/cm2, 1 min | The combined application of SeNP and MB-mediated aPDT not only reduced the number of viable bacteria in the E. faecalis biofilm but also effectively inhibited biofilms in dentinal tubules at a depth of 200–400 µm | [57] |

| MOF | ICG | E. faecalis | 810 nm, 31.2 J/cm2, 60 s | After loading ICG, the inhibition rate of Fe101, Al-101, and Fe-88-mediated aPDT against E. faecalis was increased, and the expression of Esp gene related to biofilm generation was also significantly decreased | [60] |

A number of inorganic nanoparticles were utilized to improve the physical and chemical properties of traditional PSs for antibacterial PDT. NGO has been employed as a nanocarrier due to its exceptional attributes, including substantial surface area, abundant functional group, and cost-effectiveness for large-scale synthesis. The photoactivated bacteria-killing ability of ICG was largely limited due to its negative surface charge. NGO nanoparticle was utilized to conjugate ICG to improve the interaction between ICG and microorganisms. Results have shown that photoactivation of ICG-loaded NGO (ICG-NGO) can prevent the proliferation of E. faecalis (more than 99%) compared with free ICG-mediated PDT, and the compound also exhibits a higher inhibition effect on E. faecalis-related biofilm formation [51]. In addition, the problem of the low solubility of Cur in aqueous media at physiological pH and rapid hydrolysis under alkaline conditions can also be solved by nanotechnology-based delivery systems. Cur-NGO-mediated PDT significantly inhibited E. faecalis biofilm, and the expression of virulence factors related to biofilm formation (Efa, Esp, Gel, and FSR) was significantly downregulated [52].

The combined application of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles, AgNP, AuNP, and metal–organic framework (MOF) materials with PDT can synergistically control pathogens associated with root canal infection. For example, AgNP is widely used as an antibacterial agent in the treatment of root canal infections. AgNP was demonstrated to enter the dentin tubules with a diameter of 2.4–2.9 μm, which causes changes in the bacterial membrane permeability, the leakage of bacterial contents, and finally leads to bacterial lysis and rupture in the root canal system. Afkhami et al. found that the combination of AgNP and ICG/DL inhibited E. faecalis in the root canal at a very high rate (70.77–99.12%) [53,54]. In addition, the combination of TBO and AgNP significantly inhibited 99% of the E. faecalis biofilm in root canals within a short time of irradiation (30 or 60 s) [55]. AuNP and SeNP themselves have antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities, which could also serve as nanocarriers for PDT [56,57]. It was found that PDT mediated by a combination of MB with AuNP or SeNP could reduce the number of E. faecalis in the biofilm. Compared with free MB, MB-AuNP-mediated PDT requires less laser energy to kill the same proportion of bacteria [56]. MB-SeNP was demonstrated to effectively inhibit biofilms at the depth of 200–400 μm of dentin tubules [57].

MOF, a new and promising class of porous material, has received extensive research attention for drug delivery due to its high biodegradability, good biocompatibility, and high drug-loading efficiency [58,59]. Golmohamadpour et al. loaded ICG into different types of MOF nanodelivery systems to form FE-101-ICG, AL-101-ICG, and Fe-88-ICG. The modification of the MOF vector significantly improved the stability of ICG. In addition, the antimicrobial activity of the corresponding novel MOF-mediated PDT loaded into ICG was significantly increased compared with MOF alone after laser irradiation at 810 nm. At the same time, three novel MOF-mediated PDTs significantly decreased the expression of Esp and significantly inhibited the formation of biofilm [60].

Organic nanoplatforms were also introduced to deliver PSs for root canal disinfection through PDT. CS shows a wide range of antibacterial activity, good biocompatibility, and biodegradability, which is suitable for a variety of chemical modifications and grafting. CSNP was demonstrated to effectively reduce the adhesion of bacteria on the dentin surface and eliminate bacterial biofilms. In recent years, CSNP has been used to load PSs, including RB and ICG for root canal infection control [61,62,63,64,65]. After conjugation with CSNP, the adsorption ability of RB by E. faecalis was enhanced, and RB-CSNP could effectively penetrate deep into the biofilm [62]. In addition, CSNP itself has certain antibacterial properties, which can synergistically enhance the antibacterial effect of PDT [62]. Another study showed that RB-CSNP can reduce the number of E. faecalis to 50–65%, while RB-CSNP-mediated PDT can inhibit the number of E. faecalis up to 100% [61]. Moreover, the structure of E. faecalis was significantly destroyed and the bacterial contents leaked out of the cell after RB-CSNP-mediated PDT. For biofilm, after RB-CSNP-mediated PDT, the number and thickness of viable bacteria in the single-species biofilm of E. faecalis and the multi-species biofilm cultured on dentin tablets were significantly reduced [63]. In addition, DaSilva et al. doped RB-CSNP into root canal sealer and found that it had a significant inhibitory effect on the E. faecalis biofilm in root canals after illumination [64]. In most cases, the presence of dentin components, tissue residues, and serum products in the root canal can inhibit the ability of antibiotics to control root canal infection and mediate the degradation of tooth hard tissue, leading to the damage of mechanical integrity and chemical stability of the tooth structure [66,67,68]. Therefore, Shrestha et al. explored whether these inhibitors would affect the RB-CSNP-mediated antimicrobial effects of PDT. Results showed that pulp tissue and serum albumin could inhibit the antibacterial effect of RB-CSNP in the absence of light excitation. After photoactivation, only the RB-CSNP group still had a residual antibacterial effect and was able to completely inactivate the bacteria compared with free RB and MB groups [61,69]. After RB-CSNP-mediated PDT, the microhardness of the inner wall of the root canal was also significantly improved, which enhanced the anti-degradation ability and mechanical strength of dentin collagen. The mechanism may be that 1O2 produced by PDT contributes to the formation of intermolecular or intramolecular covalent cross-links between collagen and protein surface, thereby enhancing the mechanical strength of tooth hard tissue [62,69,70,71,72].

Besides CSNP, other polymeric organic nanocarriers, such as PLGA-NP, acetylated lignin nanoparticles, and clove oil nanoemulsion, have also been used as PS carriers for root canal infection control [73,74,75]. PLGA is a polyester copolymer of polylactic acid and polyglycolic acid, which has gained FDA approval for its exceptional biocompatibility and in vivo degradability and made it an ideal candidate for drug delivery of PSs within the human body, aligning with natural pathways. PLGA exhibits continuous drug release, and high stability in biological fluids, and storage processes. Moreover, it can serve as a carrier to enhance the bioavailability of PSs. MB-loaded PLGA-NP-mediated PDT was found to have strong antibacterial effects and could reduce planktonic and colonizing E. faecalis in root canals [73]. Compared with traditional sodium hypochlorite and ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), MB-PLGA-NP-mediated PDT demonstrated the ability to enhance the microhardness of root canal hard tissue, improve the elastic modulus of dentin, and reduce the damage to dentin structure caused by root canal treatment [70].

Despite these promising results concerning the long-term success of nanotechnology-mediated PDT for eliminating planktonic pathogenic bacteria, questions remain. Disinfection of the root canal is challenging due to its complicated autonomy, and the bacteria penetrate deep into the dentinal tubules [13,76], which requires the nanoparticles to infiltrate deep into the dentinal tubules. Although our and other studies have demonstrated that some microparticles can penetrate deep into the dentinal tubules with the assistance of acoustic or magnetic actuation methods [77,78,79], more effective methods are required for eliminating infections within the profound dental tubules. Therefore, further investigations are warranted to evaluate the potential of nanotechnology-enhanced PDT in eradicating bacteria at concealed sites within root canals through both in vitro and in vivo experiments.

3.3 Periodontitis

Periodontitis is a chronic progressive infectious disease that occurs in periodontal supporting tissue. P. gingivalis is the dominant bacterium in periodontal disease, especially in chronic periodontitis [80]. Traditional periodontal treatments, such as periodontal cleaning, scraping, and root surface leveling, may cause great trauma to the periodontal tissue. Moreover, in the deep part of the periodontal pocket and the rough cementum surface, it is difficult to completely remove subgingival plaque using traditional treatment. PDT has been extensively investigated in the elimination of pathogenic bacteria for the treatment of periodontitis. For example, studies have shown that without adding any PS, irradiation with a laser (380–520 nm) can effectively kill bacteria, which was attributed to endogenous PS (melanin, porphyrins, etc.) produced by P. gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia (P. intermedia) [81]. In addition, researchers have been investigating nanotechnology-based methods for enhancing PDT for periodontitis treatment (Table 3).

Effect of nanotechnology-based aPDT on periodontitis and peri-implantitis-related pathogens

| Nanocarrier | PS | Bacteria | PDT parameters | Therapeutic effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA-NP | MB | Human subgingival plaque biofilm | 665 nm, 100 mW/cm2, 5 min | MB-PLGA-NP-mediated aPDT reduced the number of planktonic bacteria and biofilms by 60 and 48% respectively | [144] |

| PLGA-NP | MB | P. gingivalis | 660 nm, 20 J/cm2 | MB-PLGA-NP increased the antibacterial ability of aPDT mediated by 25% over free MB | [91] |

| CSNP | ICG | A. actinomycetemcomitans | 810 nm, 31.2 J/cm2 | Compared with free ICG, ICG-CSNP-mediated aPDT significantly down-regulated the expression of rcpA gene, a virulence factor associated with biofilm formation in A. actinomycetemcomitans | [90] |

| CSNP | ICG | P. gingivalis | 805 ± 20 nm, 0.5 W, 100 s | The number of P. gingivalis was reduced after 100 s of illumination in continuous-wave repetitive pulse mode. Thermal damage to normal periodontal tissues was avoided | [93] |

| CSNP | ICG | P. gingivalis | 810 ± 20 nm, 4–24 W/cm2, 5 min | ICG-CSNP can inhibit the growth of P. gingivalis. In the bionic gingival model, the temperature rises to 2.74℃ | [92] |

| NPh | Cur | A. actinomycetemcomitans | 450 ± 5 nm, 150 mW/cm2, 2 min | Cur-NPh-mediated PSACT effectively inhibited bacterial growth, biofilm formation, and metabolic activity. Cur-NPh-PSACT inhibited bacterial quorum-sensing virulence factor-related genes (qseB and qseC) and biofilm virulence factor-related genes (rcpA) were down-regulated | [145] |

| GQD | Cur | A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, and P. intermedia | 435 ± 20 nm, 1,000–1,400 mW/cm2, 1 min | Cur-GQD-mediated aPDT can significantly inhibit the viability of A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, and P. intermedia, and also significantly inhibit the formation of related biofilms (76%). The expressions of periodontitis-related virulence factor genes rcpA, fimA, and inpA were down-regulated | [146] |

| Fe3O4-NP | Ce6 | S. sanguis, P. gingivalis, and F. nucleatum | 630 nm, 100 mW/cm2, 3 min | After 3 min of red-light irradiation, three periodontitis-related single-species biofilm bacteria were reduced | [82] |

| UCNP | TiO2 | S. sanguis, P. gingivalis, and F. nucleatum | 980 nm, 2.5 W/cm2, 5 min | Compared with free TBO, aPDT mediated by TiO2-UCNP has a stronger inhibitory ability on the single-strain biofilm, and the viable bacteria of biofilm. The number is reduced by about 4log10 | [84] |

| UCNP | Ce6 | P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, and F. nucleatum | 980 nm, 750 J/cm2, 3 min | 30% Mn-doped Ce6-UCN-mediated aPDT could effectively inhibit the number of viable bacteria in P. gingivalis,P. intermedia, and F. nucleatum and EPS production | [85] |

| CeO2NP | Ce6 | S. gordonii, P. gingivalis, and F. nucleatum | 630 nm, 100 mW/cm2, 3 min | It has a strong antibacterial effect on single- and multi-strain biofilms formed by S. gordonii, P. gingivalis. and F. nucleatum, the number of viable bacteria in the biofilm is reduced and the related virulence factor genes (rgpA, rgpB, and kgp) were significantly downregulated | [87] |

| TiO2-NP | PDA | E. coli, S. aureus, and S. mutans | 5.52, 1.0 W/cm2; 5, 10, 18 min | After irradiation with dual-wavelength light sources (blue light and NIR), CTP-SA has strong antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects and can promote alveolar bone regeneration | [89] |

| TiO2-NP | S. epidermidis | 365 nm, 2.4 J, 2 min | TiO2-NP was deposited on the surface of the implant through the negative electrode, and 90% of S. epidermidis was effectively killed by ultraviolet light irradiation for 2 min | [95] | |

| CSNP | ICG | A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, and P. intermedia | 810 nm, 31.2 J/cm2, 1 min | ICG-CSNP-mediated PSACT can significantly reduce the number of periodontal pathogens by 8.8log10; at the same time, on the implant surface, the therapy can effectively inhibit about 90% of biofilm | [96] |

To increase the accumulation of PSs at the specific lesion site of periodontitis, nanotechnology-based methods were developed to endow traditional PSs with targeting ability. Sun et al. constructed Fe3O4-NP (Fe3O4-Si@Ce6/C6), which is a novel magnetic nanocomposite material. Due to the magnetic properties of Fe3O4, Fe3O4-Si@Ce6/C6 nanoparticles possess lesion site targeting properties when guided by an external magnetic field. Additionally, three individual bacterial biofilms associated with periodontitis (Streptococcus sanguis (S. sanguis), P. gingivalis, and Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum)) were reduced by irradiation with 630 nm red light [82].

P. gingivalis and other pathogenic bacteria primarily reside within the periodontal pocket deeper than 4 mm [83]. Consequently, achieving effective PDT becomes challenging due to the limited penetration of excitation light into the deep periodontal tissue. To increase the penetration depth of PDT, Qi et al. synthesized titanium dioxide (TiO2)-loaded core–shell structure UPNP (TiO2-UPNP) (Figure 4a). UCNP could convert NIR light into high-energy visible or ultraviolet light and realize NIR-mediated PDT in deep periodontal tissue. TiO2 itself has the advantages of low toxicity, good biocompatibility, and high stability. Under ultraviolet irradiation, it can generate ROS and the photocatalytic activity persists even after the light source is removed. Due to its photocatalytic properties and ability to enhance tissue integration, TiO2 can be investigated as a potential implant coating. After irradiation with NIR, TiO2-UCNP had a good antibacterial effect on three kinds of periodontitis-related pathogens (S. sanguis, P. gingivalis, and F. nucleatum) [84]. Zhang et al. loaded Ce6 into manganese (Mn)-doped UCNP and used UCNP as a carrier for PS in an attempt to enhance the penetration of conventional PDT using UCNP [85]. Besides, two-photon absorption nanomaterial-based PDT can also be excited by NIR laser [86], presenting a potential strategy for increasing the penetration depth of PDT in the treatment of periodontitis.

![Figure 4

Nanotechnology-enhanced PDT for the treatment of periodontitis. (a) To combat periodontitis-related pathogens, TiO2-loaded core–shell structure UPNPs were used for inducing PDT under NIR light [84]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. (b) Ce6-CeO2-NP was formed by decorating Ce6 onto the surface of CeO2 nanoparticles, allowing CeO2 to absorb excessive ROS produced by Ce6. This nanosystem can eliminate pathogens while preventing inflammation caused by excessive ROS. Reproduced with permission from Sun et al. [87]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. (c) A guided tissue regeneration membrane was formed by mixing sodium alginate hydrogel, TiO2-NP-PDA, and Cu2O. This membrane exhibits both antibacterial properties and the ability to repair alveolar bone in the treatment of periodontitis. Reproduced with permission from Xu et al. [89]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0163/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0163_fig_004.jpg)

Nanotechnology-enhanced PDT for the treatment of periodontitis. (a) To combat periodontitis-related pathogens, TiO2-loaded core–shell structure UPNPs were used for inducing PDT under NIR light [84]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. (b) Ce6-CeO2-NP was formed by decorating Ce6 onto the surface of CeO2 nanoparticles, allowing CeO2 to absorb excessive ROS produced by Ce6. This nanosystem can eliminate pathogens while preventing inflammation caused by excessive ROS. Reproduced with permission from Sun et al. [87]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. (c) A guided tissue regeneration membrane was formed by mixing sodium alginate hydrogel, TiO2-NP-PDA, and Cu2O. This membrane exhibits both antibacterial properties and the ability to repair alveolar bone in the treatment of periodontitis. Reproduced with permission from Xu et al. [89]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.

ROS-mediated oxidative stress response is the main antibacterial mechanism of PDT. However, an excessive generation of ROS may lead to heightened levels of oxidative stress within the periodontal pocket, resulting in a substantial release of inflammatory factors in the periodontal tissues. Consequently, this process can contribute to the destruction and absorption of periodontal supporting tissues, thereby imposing limitations on the clinical application of PDT. Cerium oxide nanoparticles (CeO2NP) can mimic the effects of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) through chemical reactions so that CeO2NP could combat chronic inflammation and oxidative stress. Sun et al. modified Ce6 on the surface of CeO2-NP (Ce6-CeO2-NP) (Figure 4b) [87]. On the one hand, after red light excitation, Ce6 produces ROS and plays an antibacterial role. On the other hand, CeO2-NP functions similarly to SODs or CAT, effectively scavenging excessive ROS and exerting anti-inflammatory effects. It was found that PDT mediated by Ce6-CeO2-NP had a strong antibacterial effect on Streptococcus gordonii (S. gordonii), P. gingivalis, and F. nucleatum, and significantly reduced the expression of relevant biofilm virulence factor genes (rgpA, rgpB, and kgp); in addition, in vivo and in vitro experiments have proved that PDT mediated by Ce6-CeO2-NP can regulate host immune function, and at the same time inhibit the polarization of macrophages to M1 type that possess proinflammatory effects, thus upregulating M2-type polarization that possesses anti-inflammatory and regenerative effects [87]. Therefore, this nanomaterial-mediated PDT offers promising prospects for the treatment of periodontitis.

In the treatment of periodontitis, effectively eliminating pathogenic bacteria while simultaneously promoting periodontal tissue regeneration poses a significant challenge [88]. For this purpose, Xu et al. added polydopamine-modified TiO2 nanoparticles (TiO2-NP-PDA) together with cubic cuprous oxide (Cu2O) to sodium alginate hydrogels to form a novel guided tissue regeneration membrane (CTP-SA) (Figure 4c) [89]. The CTP-SA membrane undergoes a transition from liquid to solid upon injection, ensuring precise fitting to the damaged area. After blue light irradiation, CTP-SA-mediated PDT has a broad-spectrum antibacterial effect. At the same time, ROS produced by PDT can oxidize Cu+ to Cu2+. After NIR irradiation, CTP-SA can mediate the photothermal effect. Cu2+ and photothermal effects synergistically promote the reconstruction of bone tissue. In a rat model of periodontitis, this novel tissue regeneration membrane was demonstrated to have the functions of antibacterial and regenerating tissue [89].

Recently, owing to the excellent biocompatibility of organic nanomaterials, PS modified by organic nanocarriers has been gradually applied to control periodontal infections in preclinical research and even in the clinic [90,91,92,93]. de Freitas et al. performed PDT in patients with chronic periodontitis by injecting MB-PLGA-NP into the periodontal pocket after ultrasonic cleaning and root planning (scaling and root planning, SRP). The gingival bleeding index of the SRP plus PDT group was significantly lower than that of the SRP group. Therefore, MB-PLGA-NP-mediated PDT can be used as an adjunct to conventional periodontal therapy to enhance its therapeutic effect [91]. Meanwhile, other types of organic nanocarrier functionalized PDT would also be promising for clinical translation.

3.4 Peri-implantitis

Peri-implantitis is an inflammatory lesion occurring in the soft tissue surrounding dental implants, leading to progressive loss of supporting bone tissue. The etiology of peri-implantitis primarily involves colonization by anaerobic bacterial microorganisms on the implant surface [94]. Traditional mechanical treatments damage the integration of the implant with the bone tissue, leading to recession of the marginal ridge and destruction of the esthetic zone. PS can enter anatomical parts such as deep periodontal pockets and root bifurcations. Under the excitation of the light source, it can effectively kill the microorganisms around the implants, thereby reducing traumatic damage to the surrounding normal tissues. PDT has been gradually applied for the treatment of peri-implantitis [8,9]. However, the application of nanotechnology-based PDT in peri-implantitis is still in its infancy (Table 3).

As a type of PS for PDT, TiO2 has good chemical stability, outstanding biosafety, excellent biological compatibility, and other properties, which were deposited on the surface of the implant through a negative electrode [95]. After ultraviolet irradiation for 2 min, TiO2 nanoparticle-induced PDT can effectively kill most of Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis) [95], which is promising for large-scale implant surface modification to avoid peri-implantitis caused by pathogenic bacteria. Researchers also combined sonodynamic antibacterial chemotherapy (SACT) with PDT, known as photoacoustic antibacterial chemotherapy (P-SACT), for the treatment of peri-implantitis. Specifically, ICG was loaded on CSNP (ICG-CSNP) as a PS to explore the synergistic effect of PDT and SACT on the mixed biofilm (A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis and P. intermedia) formed on the surface of implants. It was found that ICG-CSNP-mediated PSACT could significantly reduce the number of periodontal pathogens, which is comparable with the positive control group (0.2% CHX) in terms of antibiofilm ability [96].

3.5 Tooth whitening

The demand for charming smiles is growing and has led to the rapid development of tooth-whitening techniques. In the clinic, tooth-whitening methods include invasive whitening (full crown restoration and veneer restoration) and noninvasive whitening (H2O2 as the most popular tooth-bleaching agent) [97]. Unfortunately, invasive whitening can cause irreversible tooth damage [97]. Noninvasive whitening is usually time-consuming and can lead to tooth hypersensitivity, enamel demineralization, and soft tissue irritation [98]. Thus, there is a tremendous need to develop new strategies for safe and effective tooth whitening. Due to the ability of ROS to decolorize stains on the tooth surface or within the tooth structure [99], PDT is undergoing rapid development in the field of tooth whitening [100,101]. Moreover, nanoparticles could endow PDT with high specificity and safety for decolorizing stains, which makes nanotechnology-enhanced PDT highly promising for the application of tooth whitening [101]. In this section, we will discuss the recent progress of nanotechnology-mediated PDT in tooth whitening.

Safety issues caused by high concentrations of H2O2 have been the main concerns related to its application in tooth whitening [98]. Multiple studies have focused on utilizing nanoparticle-based PDT to solve the related safety problems during tooth whitening [100,101]. As described above, TiO2 possesses high biocompatibility and can generate ROS under light irradiation. PDA-modified TiO2 nanoparticles (TiO2@PDA) were developed as tooth-whitening materials under blue light activation and showed equal efficacy in tooth whitening compared with H2O2 [100]. Interestingly, TiO2@PDA-mediated PDT resulted in minimal surface damage to tooth enamel (Figure 5a) [100]. Moreover, TiO2@PDA-mediated PDT was demonstrated to have minimal toxicity in vitro and in vivo [100]. Clinically, the efficacy of tooth whitening also needs to be improved, where 30–40% H2O2 was applied for approximately 1 h for an acceptable effect [97]. TiO2 was also demonstrated to synergize with H2O2 for tooth whitening and significantly reduce the practice time by 30 min [102]. Recently, PSs with aggregation-induced emission (AIE) properties were demonstrated to have excellent ROS-generating abilities [103], which make it suitable to introduce AIE PSs into nanoparticles for photodynamic tooth whitening. A type of highly efficient AIE PS nanoparticle was developed and demonstrated to have good ROS-generating efficacy and was further proven to have better tooth whitening ability compared with the conventional 40% H2O2 (Figure 5b) [101]. Moreover, as the heat generated by light irradiation during PDT may irritate dental pulp, the authors also monitored the temperature change in the pulp cavity, where the temperature remained under the safe range of 5.5℃ [101].

![Figure 5

Nanotechnology-enhanced PDT for tooth whitening. (a) Nano-TiO2@PDA was used for tooth whitening, which showed less damage to the tooth enamel structure compared with 30% H2O2. Reproduced with permission from Zhang et al. [100]. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society. (b) For tooth whitening, two types of AIE nanoparticle hydrogel-mediated PDT were developed and found to be significantly more efficient than 40% H2O2 [101]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0163/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0163_fig_005.jpg)

Nanotechnology-enhanced PDT for tooth whitening. (a) Nano-TiO2@PDA was used for tooth whitening, which showed less damage to the tooth enamel structure compared with 30% H2O2. Reproduced with permission from Zhang et al. [100]. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society. (b) For tooth whitening, two types of AIE nanoparticle hydrogel-mediated PDT were developed and found to be significantly more efficient than 40% H2O2 [101]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society.

Although nanotechnology-mediated PDT was demonstrated to have superior tooth whitening efficacy than 30–40% H2O2, the studies were mostly confined to extrinsic stains caused by poor oral hygiene, tobacco use, and the color agents of food and drinks, which are highly responsive to bleaching [97]. Although intrinsic stains (deeper internal stains), which are usually caused by metabolic disorders, medical treatments, hereditary diseases, idiopathic diseases, etc., might be more difficult to bleach and remain for testing the efficacy of nanotechnology-mediated PDT. Studies concerning nanotechnology-mediated PDT for tooth whitening are mostly limited to the bleaching on the external tooth surface. However, intracoronal bleaching, another basic method of tooth whitening [104], was rarely studied using nanotechnology-mediated PDT. As multiple studies and our work have proved that nanotechnology could be utilized to enhance the penetration depth of drugs into the dentinal tubules [77,78], we consider that nanotechnology-mediated PDT appears very promising for bleaching stains in the deep dentin. Tooth stains are classified into extrinsic stains and intrinsic stains based on their origins.

3.6 Precancerous and malignant oral diseases

Beyond the teeth and periodontal tissues, the oral mucosa is another major constituent of our oral cavity, where various types of precancerous and malignant diseases may occur. A majority of oral malignancies arise from oral precancerous lesions. including oral leukoplakia (OLK), oral erythroplakia, and oral lichen planus. PDT has been increasingly applied in the treatment of oral precancerous and malignant diseases due to its advantages of noninvasiveness, good safety, ease of use, and high effectiveness. However, in the treatment of precancerous and malignant oral diseases, conventional PSs have several drawbacks including a lack of targeting ability and a high recurrence rate. In view of this, nanotechnology-enhanced PDT has become a popular focus of research for promoting treatment efficacy (Table 4).

Effect of nanotechnology-based aPDT on precancerous and malignant oral diseases

| Nanocarrier | PS | PDT parameters | Therapeutic effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITCH-Th NPs | ITCH-Th NPs | 660 nm, 1 W/cm2, 3 min | In vivo, ITCH-Th NP-mediated PDT/PTT exhibit significant efficacy in inhibiting the malignant transformation of OLK | [108] |

| Amphiphilic polymer | Ce6 | 660 nm, 1 W/cm2, 10 min | Inhibit tumor through the combination of PDT, PTT, and chemotherapy | [110] |

| Lipid polymer | IR700 | 50 J/cm2 | This nano-delivery system was demonstrated to successfully elicit tumor-specific T-cell responses and tumor inhibition | [117] |

| GNRs | RB | 532 nm, 1.79 W/cm2, 10 min | The combination of RB-GNRs with PDT-PTT functionality exhibits enhanced therapeutic efficacy against oral cancer | [120] |

| Liposomal nanoplatform | Evodiamine, ICG | 808 nm, 0.1 W/cm2, 10 min | Liposomal nanoplatform effectively inhibits cancer cell proliferation and ultimately induces apoptosis of cancer cells | [121] |

| CDcf | CDcf | 780 nm, 10 min | CDcf can directly damage DNA, accelerating the destruction of oral cancer cells | [122] |

| S-CDs | S-CDs | 360–600 nm | At the same concentration, S-CDs have higher photo‐oxidative activity than 5-ALA, which is more likely to lead to apoptosis of tumor cells | [147] |

| Mn-CDs | Mn-CDs | 635 nm, 300 mW/cm2, 5 min | The apoptosis rate of Mn-CDs on OSCC-9 cells was 92.88% | [123] |

As one of the most common precancerous diseases occurring in the oral cavity, OLK is defined as a nonscratchable and irreversible lesion with an elevated risk of turning into squamous cell carcinoma [105,106]. Following chemotherapy, surgery, laser ablation, or cryotherapy, PDT mediated by 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) is the fourth alternative therapeutic modality for treating OLK [107]. To further promote the efficacy of PDT for OLK, a new type of photosensitive nanoagent (ITIC-Th nanoparticles, ITCH-Th NPs) was developed for the synergistic of PDT with PTT (Figure 6a) [108]. Under irradiation with a 660 nm laser, ITCH-Th NPs possess good ROS-generating efficacy for PDT and have high photothermal transformation efficacy (38%) for PTT. In the well-established OLK mouse model, ITCH-Th NP-mediated PDT/PTT could significantly block the malignant transformation of OLK. In addition, no obvious topical or systemic toxicity was observed after treatment with ITCH-Th NP-mediated PDT/PTT. This is the first application of nanotechnology-enhanced PDT/PTT in OLK treatment [108]. However, further research is required to test the efficacy of nanotechnology-enhanced PDT in treating other precancerous lesions, including oral erythroplakia and oral lichen planus.

![Figure 6

Nanotechnology-enhanced PDT for combating precancerous and malignant oral diseases. (a) A type of photosensitive nanoagent (ITIC-Th) was developed and demonstrated to possess the dual therapeutic ability of PDT and PTT in the treatment of OLK. Reproduced with permission from Lin et al. [108]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. (b) PDT could trigger cancer cells to release a large amount of ATP, which is a powerful immune stimulator for combating cancer cells. In order to enhance the immune activation effect of ATP, an ATP degradation inhibitor (ARL67156) and a PS were incorporated into nanoparticles. This approach was shown to significantly inhibit the growth of both primary and distant tumors. Reproduced with permission from Mao et al. [117]. Copyright 2022, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. (c) The PS of Ce6 and two chemotherapy drugs (paclitaxel and oxaliplatin) were combined to form a nanocomposite. This nanocomposite was found to induce robust pyroptosis in cancer cells, thus enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy. Reproduced with permission from Wan et al. [119]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0163/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2023-0163_fig_006.jpg)

Nanotechnology-enhanced PDT for combating precancerous and malignant oral diseases. (a) A type of photosensitive nanoagent (ITIC-Th) was developed and demonstrated to possess the dual therapeutic ability of PDT and PTT in the treatment of OLK. Reproduced with permission from Lin et al. [108]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. (b) PDT could trigger cancer cells to release a large amount of ATP, which is a powerful immune stimulator for combating cancer cells. In order to enhance the immune activation effect of ATP, an ATP degradation inhibitor (ARL67156) and a PS were incorporated into nanoparticles. This approach was shown to significantly inhibit the growth of both primary and distant tumors. Reproduced with permission from Mao et al. [117]. Copyright 2022, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. (c) The PS of Ce6 and two chemotherapy drugs (paclitaxel and oxaliplatin) were combined to form a nanocomposite. This nanocomposite was found to induce robust pyroptosis in cancer cells, thus enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy. Reproduced with permission from Wan et al. [119]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH.

In the case of oral cancer, novel nanomaterials and PSs were developed and extensively studied to evaluate their PDT efficiency [83]. In order to improve the PDT effect of traditional PSs, a variety of nanoparticles was used to promote the physical and chemical properties of PSs, which has been reviewed elsewhere comprehensively [109]. Here, we will focus on other obstacles faced by PDT in oral cancer, including targeted delivery methods, tumor immune microenvironment regulation, and combination strategies.

To increase the PDT efficacy and reduce systemic toxicity, PSs should be precisely delivered to the tumor site but not the normal tissue, where targeted delivery methods could be exploited to achieve that. Low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) was found to be a hypoxia marker in oral squamous cell carcinoma and may contribute to malignant transformation and chemoresistance [110]. Thus, anti-LDLR antibody was used to modify a nano-delivery system for targeted delivery of PSs and chemotherapy drugs into the tumor site, where taking advantage of an oral cancer mouse model, this targeted delivery system was demonstrated to improve the therapeutic effects and reduce the side effects caused by chemotherapy [110]. In addition, nanobody was also introduced to decorate nanoparticles and promote the targeted delivery of PSs for PDT in oral cancer treatment [111].

Immune components play an important role in the initiation and progression of oral cancer [112,113]. In an effort to combat cancer, immunotherapy was developed to mobilize the immune system and has served as a pillar of cancer treatment [114]. PDT was also revealed to have the ability to trigger the antitumor immune response [115]. However, the immunosuppressive tumor immune microenvironment was revealed to seriously limit the therapeutic effect of immunotherapy [116]. PDT was demonstrated to trigger the release of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from tumor cells [115,117], which could potently stimulate immune response and ameliorate the suppressive status of the tumor microenvironment [118]. Thus, a type of nanoparticle-mediated PDT was designed and proved to trigger the release of extracellular ATP by oral cancer cells, which was combined with the ATP degradation inhibitor for further elevating the extracellular ATP level in the tumor microenvironment (Figure 6b) [117]. This strategy was demonstrated to successfully elicit tumor-specific T-cell responses and tumor inhibition, prolonging long-term survival in oral cancer mouse models [117].

Combination strategies were also exploited to promote PDT efficacy. For example, chemotherapy was used for synergizing with PDT to induce pyroptosis of cancer cells, which was demonstrated to prime immune response and enhance the therapeutic efficiency of PD-1-based immunotherapy (Figure 6c) [119]. Gold nanorods (GNRs) show good PTT effects under excitation light, which were conjugated with classical PSs of RB for the synergizing of PTT and PDT [120]. In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that this combination strategy could provide better therapeutic effects against oral cancer [120]. In addition, an integrated tri-modal combination of chemotherapy, chemodynamic therapy, and PDT was also introduced [121]. Specifically, evodiamine, a traditional Chinese medicine extraction component widely used for chemotherapy, was found to possess the ability to convert endogenous tumor H2O2 into ROS, which was referred to as chemodynamic therapy. Evodiamine and a type of PS (ICG) were simultaneously encapsulated into a nanoliposome system to achieve tri-modal combination therapy, which showed a significant inhibitory effect on in situ oral cancer [121].

In addition to the above-mentioned nanomaterials, carbon dot (CD), a zero-dimensional nanomaterial, has been utilized as a new type of PS for PDT in combating oral cancer. CDs exhibit good biocompatibility and excellent efficiency in generating ROS, rendering it promising PS. Cur and folic acid were decorated on a CD (CDcf) using the hydrothermal method [122]. The resulting CDcf possesses the ability to target tumor cell nuclei and can be excited by two NIR photons, allowing for deeper penetration in tumor tissue [122]. To enhance PDT in tumors by overcoming the hypoxia status, manganese was doped on CDs, giving it CAT-like activity [123]. This activity leads to the in situ decomposition of acidic H2O2 into oxygen, thereby enhancing the efficacy of PDT against oral cancer cells when exposed to 635 nm irradiation [123].

4 Conclusion and future perspectives

4.1 Biosafety of nanoparticles

Despite the development of multiple types of nanoparticles and their transformation in clinical application, the potential biological toxicity of nanoparticles brought by the unwanted distribution, unclear structure, and other aspects remained unexplored. Therefore, in order to ensure a safe and sustainable future for the application of nanoparticle-enhanced PDT, it is essential to assess their specific structure, pharmacokinetics, and biological interactions, understand the potential risks to human health, and implement effective regulations.

4.2 Oral disease prevention

Prevention is always better than cure. Maintaining daily oral hygiene is critical for preventing dental caries, root canal infections, periodontitis, and other conditions. However, the process of daily oral hygiene is laborious, cumbersome, and time-consuming. In particular, children often have poor oral hygiene, leading to early childhood caries, which has a devastating impact on children’s development and can increase the financial burden on society. Thus, it is urgent to develop strategies to make daily hygiene easier and more efficient. We previously developed a type of bioresponsive nanodrug that has shown effectiveness in preventing early childhood caries in a rat caries model [42]. This method also possesses the potential to be further applied in the clinic, where the nanoparticle can be added to the toothpaste and combined with excitation light attached to the electric tooth brush to synergize with traditional mechanical oral hygiene methods [42]. Our research findings highlight new possibilities that warrant further investigation. For example, can nanoparticles for PDT be added to orthodontic bracket bonding materials to prevent caries in patients with orthodontic treatment? Whether nanoparticles for PDT could be added to mouthwash and promote the daily hygiene effect remains unknown. Future research in this field would be of great help in answering these questions.

4.3 Protecting normal oral flora

The normal oral commensal microbiome has a close symbiotic relationship with its host and is highly important for the host to defend against external threats and maintain oral and systemic health [124,125,126]. Thus, it is of great significance to develop methods that clear pathogenic bacteria and, at the same time, protect normal oral flora. As described above, unlike the neutral pH level of the macroenvironment in the oral cavity, the microenvironment of cariogenic biofilms is acidic. Based on this difference, our group developed a smart nanodelivery system that could release PSs in acidic cariogenic biofilms specifically for PDT. In vitro and in vivo studies showed that this type of nanotherapy could remarkably inhibit the development of dental caries. Thus, further studies on the development of bioresponsive nanotherapeutics for PDT are needed since they would avoid the disturbance of the normal oral flora.

4.4 Eliminating intracellular bacteria

Multiple types of pathogenic bacteria can invade normal oral mucosa cells or other cell types and become intracellular bacteria, which could promote the survival, multiplication, immune escape, and drug resistance of bacteria [127,128,129]. Although mechanical cleaning can eliminate a major portion of microorganisms, it is difficult for these methods to clear intracellular bacteria, which subsequently escape from host cells to recolonize the oral mucosa and restore infection [130]. Most existing antibiotics suffer from limited cellular penetration, poor intracellular retention, and low intracellular activity, making it difficult to kill intracellular bacteria. Therefore, eliminating intracellular bacteria remains a major challenge. Nanotechnology possesses the advantage of targeted drug delivery, which has been exploited for intracellular delivery of bactericidal drugs [128,131]. Meanwhile, PDT with small molecules was demonstrated to be effective in killing intracellular bacteria [132,133]. Therefore, it seems promising to take advantage of nanotechnology-enhanced PDT for treating intracellular pathogens.

4.5 Overcoming hypoxia

The microenvironment of the periodontal pocket and root canal system is hypoxic. However, PDT inherently requires oxygen (O2) to generate ROS [134], which inevitably creates a more hypoxic microenvironment and subsequently hinders the therapeutic effect of PDT. Consequently, there exists a vicious cycle in which PDT consumes oxygen and hypoxia impairs PDT efficiency. To address the hypoxia limitation of PDT in periodontal pockets, a type of oxygen-self-sufficient nanoplatform was developed for combating bacteria in the hypoxic environment of periodontal pockets [135]. However, the hypoxic status in dentinal tubules and periapical tissue also impedes the application of PDT, which is not sufficiently taken into account by researchers. In fact, the obstacle of hypoxia during PDT could be alleviated through multiple ways, including generating O2 in situ, direct delivery of exogenous O2, inhibiting cell respiration to reduce O2 consumption, and inhibiting the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) signaling pathway in relieving hypoxia [136]. The methods of generating O2 in situ and direct delivery of exogenous O2 are suitable for alleviating hypoxia in an oral environment. For direct delivery of exogenous O2, multiple types of materials (hemoglobin, perfluorocarbon, MOF, etc.) could be utilized for carrying and delivering O2 into the hypoxia position. In terms of generating O2 in situ, various strategies have been developed to utilize H2O2 to relieve hypoxia. Further studies that focus on providing O2 during PDT in dentistry are therefore highly warranted [136].

4.6 Deep tissue penetration

Although UPNP and two-photon absorption nanomaterials were exploited to promote the penetration depth of PDT [86,137], there remains a huge unmet need for treating lesions in deep tissue using PDT. The use of functional nanomaterials has shown promise for prolonging the treatment depth of PDT [138]. For instance, the ability of these nanomaterials to either illuminate themselves or respond to external stimulation, such as NIR light or X-rays, offers a versatile and effective approach [138]. However, implantable devices provide a localized and precise means of delivering light for therapy [138]. By implanting devices close to the lesion site, the light can be directly delivered to the affected area, maximizing therapeutic effects and minimizing side effects. However, further research and development are needed to optimize their effectiveness and ensure their safe use in clinical settings. Overall, the constant development of strategies for enhancing the penetration of PDT will surely widen the scope and application of PDT for the treatment of oral diseases.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82303351), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M712880), and Science and Technique Project of He’nan Province (No. 222102310685).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Akintoye SO, Mupparapu M. Clinical evaluation and anatomic variation of the oral cavity. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38(4):399–411.10.1016/j.det.2020.05.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, et al. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet. 2019;394(10194):249–60.10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31146-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Lobbezoo F, Aarab G. Medicine and dentistry working side by side to improve global health equity. J Dent Res. 2022;101(10):1133–4.10.1177/00220345221088237Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] McCauley LK, Robinson M, D’Souza RN. Translating science into improved health for all. J Dent Res. 2022;101(7):744–8.10.1177/00220345221099825Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Konopka K, Goslinski T. Photodynamic therapy in dentistry. J Dent Res. 2007;86(8):694–707.10.1177/154405910708600803Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Jia Q, Song Q, Li P, Huang W. Rejuvenated photodynamic therapy for bacterial infections. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8(14):e1900608.10.1002/adhm.201900608Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Green TJ, Wilson DF, Vanderkooi JM, DeFeo SP. Phosphorimeters for analysis of decay profiles and real time monitoring of exponential decay and oxygen concentrations. Anal Biochem. 1988;174(1):73–9.10.1016/0003-2697(88)90520-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Chambrone L, Wang HL, Romanos GE. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy for the treatment of periodontitis and peri-implantitis: An american academy of periodontology best evidence review. J Periodontol. 2018;89(7):783–803.Search in Google Scholar