Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

-

Majid S. Jabir

, Mustafa K. A. Mohammed

, Salim Albukhaty

, Abdallah M. Elgorban

Abstract

Hybrid nanomaterials with unique physiochemical properties have received a lot of attention, making them attractive for application in different fields like cancer treatment. This study was designed to investigate the combined effects of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) hybridized with silver titanium dioxide composite (SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2). Transmission electron microscopy and field emission scanning electron microscopy images demonstrated the accumulation of SWCNTs with Ag–TiO2 due to an increased main grain size with functionalization to 40 nm. The D and G bands in SWCNTs @Ag–TiO2 shifted to 1,366 and 1,534 cm−1, respectively. SWCNTs@Ag-TiO2 were assessed for their cytotoxicity and autophagy induction in liver cancer cells (Hep-G2) using the lactate dehydrogenase assay, MTT assay, and flow cytometry methods. The results showed that SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 exhibited strong anti-cancer activity in vitro against Hep-G2 cells by inducing apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells via controlling the AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. The results show that SWCNTs and SWCNTs coated with silver/titanium dioxide (SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2) reduce the cells’ viability and proliferation. It was shown that an excessive amount of reactive oxygen species was a crucial mediator of both the cell death caused by SWCNTs and the cell death caused by SWCNTs combined with Ag–TiO2. Based on these findings, it appears that SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 have the potential to be developed as nanotherapeutics for the treatment of liver cancer cells.

1 Introduction

Cancer is a disorder characterized by uncontrolled cell differentiation, and in the past few decades, it has been managed using approaches, including chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgical removal of the affected tissue [1]. Although each of these treatments appears to be successful in killing cells, they all have severe and nonselective adverse effects on patients. Recently, there has been a lot of interest shown in cancer therapy involving nanomedicine-mediated modalities due to their active/passive targeting, high solubility/bioavailability, biocompatibility, and multi-functionality. This is to overcome the side effects that are associated with traditional cancer treatments [2,3,4]. Nanotechnology is an exciting new science that has the potential to revolutionize a wide variety of industries, including cancer treatment. The majority of the interactions between biomaterials and cells take place at the nanoscale, which is why efforts have been undertaken to develop new anti-cancer medicines, including the use of nanotechnology. In addition, nanomaterials can engage in interactions with biomolecules located on the surface of cells, embed themselves within cells, and exert their effects on organelles [5,6,7]. The size, shape, surface area, and chemical composition of nanoparticles (NPs) are the primary characteristics that determine their biological activity [8,9,10]. Other important parameters include their surface area. Autophagy, sometimes known as “self-eating,” is a complicated catabolic mechanism that, by way of the lysosome, facilitates the breakdown of cytoplasmic components that are either surplus or undesired. The accumulation of autophagic vesicles, which are responsible for sequestering harmful or foreign material, and the activation of macroautophagy are often induced by nanomaterials [11,12]. Furthermore, nanomaterials act as autophagy activators [13,14]. Autophagy and apoptosis are both characterized by the death of cells. In addition, a variety of nanomaterials were discovered to aggregate inside autophagosomes and even to encourage the development of autophagosomes. Quantum dots were found to have an inducing influence on autophagy, which was initially documented by Seleverstov et al. Silica, gold, alumina, rare earth oxides, and fullerenes were among the several types of nanomaterials that were shown to collect within autophagosomes after further investigation [15,16]. The nanoscale size appears to be a common denominator for accumulation into autophagosomes as well as the possible triggering of autophagy. In addition, it was discovered that the accumulation of autophagosomes that was generated by carbon nanotube (CNT) treatment was connected with the death of cells [17]. Biofunctionalized single- or multi-walled CNTs have the capability of being taken up by a wide variety of cells, moving across a variety of cellular barriers, and interacting with DNA [18,19,20]. Because the ligand-modified surfaces of CNTs make it possible for complexes to be formed with DNA, these NPs are excellent candidates for use as gene-delivery vehicles [21]. CNTs were also utilized to transport tiny proteins such as recombined ricin A chain protein toxin (TAT) to breast cancer cells so that they could be targeted. Because their surfaces were modified, CNTs now have improved biocompatibility and the ability to perform several activities; as a result, the therapeutic effect was greater than it had been in the past, particularly in the treatment of cancer. Because of their needle-like forms, CNTs have high aspect ratios and are very tiny. This gives them large specific surface areas, which enable them to adsorb onto or bind with a wide variety of medicinal compounds [22]. Internalization of CNTs into target cells is made possible, in part, by the needle-like form of the CNTs. As a result, CNTs are seen as potentially useful nanocarriers for the transport of pharmaceuticals, genetic material, and proteins. CNT-based nanocarriers have been the subject of extensive research for the delivery of anticancer drugs [23,24,25]. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) possesses several beneficial biological features, including non-toxicity, chemical stability, and low cost [26,27]. TiO2–Ag biomaterials display a combination of the biocompatibility of TiO2 and the biological characteristics of silver. In addition, numerous studies have been conducted on the electrical, photoactive, and electrochemical characteristics of TiO2 [28,29]. Because of the dual role of Ag sites, the photocatalytic characteristics of TiO2 in particular affect the substance’s biological properties, such as its antibacterial and anticancer activities, and this effect has been the subject of extensive research [30,31]. Second, because its Fermi level is located below the conduction band of TiO2, silver acts as an electron-scavenging center, which separates pairs of electrons and protons. Finally, Ag NPs have the capability of inducing a surface plasmon resonance effect in TiO2 NPs, which ultimately results in a markedly improved photocatalytic activity of TiO2 NPs in the visible range [32,33]. Previous studies demonstrated that an abnormally high level of oxidative stress is hazardous to the cell and results in severe cytotoxicity [34]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated in the mitochondria of a cell. ROS causes severe damage to cellular macromolecules, particularly DNA. The level of DNA damage that a cell sustains either stops the cell cycle, causes DNA repair to take place or activates the pathways that lead to apoptosis [35]. In addition, damage to DNA can lead to the breaking apart of chromosomes and the production of micronuclei. The activation of caspases is caused by the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), which exposes cytochrome c to the intermembrane space. The exposure of cytochrome c is responsible for its leakage, which in turn activates caspases [36]. Consequently, ROS are a prominent and crucial participant in both apoptosis and autophagy, both of which result in the death of cells. The excessive stimulation of autophagy and cellular self-consumption that might result from cellular damage can eventually lead to cell death [37]. A previous study identified autophagy as a significant mode of cell death that can be caused by a wide variety of NP-induced toxicity, although the precise processes that underlie this phenomenon are not fully understood [38]. Previous study has shed light on the relationship between mitochondrial damage and autophagy that was triggered by nanomaterials [38]. This is consistent with the theory that autophagy is a mechanism that reduces damaged mitochondria. This could result in the formation of NPs. Lysosomal dysfunction is an additional significant mechanism that NPs generate as part of the autophagy pathway’s malfunction. Nanomaterials have been shown to produce lysosomal dysfunction in many different investigations [7,39,40]. Inhibition of enzyme capacity and biopersistence are just two of the numerous possible causes of lysosomal dysfunction that can be attributed to NP exposure. In the current study, we demonstrate that exposure to single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposite modulates the ROS signaling pathway in the human liver cancer cell line Hep-G2, which results in the induction of apoptosis and autophagy. The results that were presented have the potential to lead to the development of more effective medicines for the treatment of human liver cancer.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Reagents and antibodies

The following regents were used: Triton X-100 (Sigma, I3021), MTT stain (Sigma, M5655), crystal violet (Sigma, C0775), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (Sigma, L2500), acridine orange (AO) (Sigma, 235474), VitaBright-48TM (Denmark), DCFH-DA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, D399), Rhodamine 123 (Sigma, R8004), RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11835063), paraformaldehyde (Sigma, 441244), SDS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 28362), fetal calf serum (Gibco, A4766801), anti-annexin A1(Invitrogen, 71-3400), anti-NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) (Invitrogen, PA5-53304), anti-cleaved PARP (Abcam, ab32064), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Abcam, E83-77), anti-cleaved caspase-9 (Invitrogen, PA5-105271), anti-LC3 (Abcam, ab192890), anti-tubulin (Sigma, T8328), anti-SQSTM1/p62 (Abcam, ab109012), Alexa fluor 488 (ab194106) (Sorensen’s phosphate buffer, glutaraldehyde, OsO4, ethanol, uranyl acetate lead citrate [all stains from Agar scientific]), Annexin V FITC (Abcam, 14085), and ECL kit (GE Healthcare, RPN2209).

2.2 Functionalization of SWCNTs

Raw SWCNTs with properties of purity of 99%, diameter of 1–2 nm, and length of ∼1–2 μm were purchased from Merck. To make functionalized SWCNTs, 20 mg of raw SWCNTs were treated in 120 mL of sulfuric acid (97%, Merck) and nitric acid (62%, Merck) in a volume ratio of 3:1 v/v. The mixed acid was ultrasonicated for 20 min, then diluted with distilled water, vacuum filtered (0.22 μm), and baked at 90°C overnight [41].

2.3 Synthesis of Ag/TiO2

The Ag-doped TiO2 nanocomposites were synthesized by the sol–gel approach [18]. In a 100-mL volume of absolute ethanol, 15 mL of silver nitrate and titanium (IV) isopropoxide (Ag/TiO2 = 5 vol.%) were mixed using an ultrasonic device. Then, the mixture was rapidly stirred for 20 min at room temperature. About 3 mL of HNO3 was added to the combined solution to adjust the pH to about 4. The mixture was then mixed for 30 min, dried for 24 h at 80°C, and baked for 2 h at 450°C.

2.4 Decoration of Ag–TiO2 onto SWCNTs

Briefly, 10 mg of mixed Ag–TiO2 nanocomposite in 50 mL of ethanol was stirred at 25°C for 25 min. Then, 100 mg of modified-SWCNTs were dispersed in 50 mL of ethanol by sonication for 30 min. Subsequently, SWCNTs were inserted into the Ag–TiO2 nanocomposite solution and stirred for 20 min. By adding 3 mL of HNO3 to the combined solution, the pH was adjusted to around 4. The mixture was filtered before being heated at 100°C for 1 day.

2.5 Characterization of SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2

UV–vis spectroscopy (UV–vis) was utilized to measure the absorption spectra of SWCNTs and Ag–TiO2-functionalized SWCNTs [42]. Rotational, vibrational, and low-frequency modes were examined using Raman spectroscopy to analyze the structural fingerprint [43]. The morphology of all samples was analyzed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Zeiss) and field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) [44].

2.6 LDH release assay

For testing the LDH release, the liver cancer cell line (Hep-G2) was treated with different concentrations (6.25–200 µg/mL) of SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 for 24 h. The cell's supernatant was collected for the next step. LDH release assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols. In brief, for this experiment, a sterile, clean, clear, flat-bottomed 96-well plate was used. In order to guarantee that the liver cancer cell membranes were fully destroyed, 10 µL of 1% Triton X-100 was added to each of the positive control wells. The results were examined using an ELISA plate reader that had a reference wavelength of 490 nm.

2.7 Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of SWCNTs and SWCNTS/Ag–TiO2 was investigated by the MTT protocol. After cultivation overnight, Hep-G2 and L-02 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. After removing the growth medium, it was replaced with 200 µL of new medium containing various concentrations (6.25–200 µg/mL) of SWCNTs and SWCNTS/Ag–TiO2 NPs for 27 h [45]. Then, the cells were washed with PBS and subjected to a 3-h treatment with 2 mg/mL MTT solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After that, the solution was drained out of each well, and then 100 µL of DMSO was added to each one. A microplate reader was utilized to determine each sample’s absorbance at a wavelength of 492 nm [46]. The rate of inhibition of cell growth, also known as the percentage of cytotoxicity, was determined as follows:

where A represents the optical density of the control and B represents the optical density of the samples [47].

2.8 Colony-forming assay

At a density of 100,000 cells/mL, Hep-G2 cells were planted onto 24-well plates and allowed to grow. After 24 h, the cells were treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTS/Ag-TiO2 at inhibitory concentration IC50 concentrations of 28.67 and 19.87 µg/mL, respectively. When the cells attained monolayer confluence, the medium was removed, and the final rinsing was done with PBS. The colonies were preserved using methanol in its purest form. After that, they were dyed for 15 min with crystal violet (Sigma–Aldrich) and then washed with running water to remove any excess dye.

2.9 AO/ethidium bromide staining (AO/EtBr)

In 12-well plates, Hep-G2 cells were collected and plated. Following a 24-h incubation period, the cells were exposed to SWCNTs and SWCNTS/Ag–TiO2 NPs at IC50 concentrations of 28.67 and 19.87 µg/mL, respectively, for 24 h. Following that, the cells were stained with 10 µg/mL AO/EtBr for 2 min at 37°C and detected using a fluorescence microscope.

2.10 Analysis of intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels

The number of free thiols in SWCNTs and SWCNTS/Ag–TiO2-treated liver cancer cells was measured by staining the cells with VitaBright-48TM (VB-48TM). This experiment was done according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.11 Flow cytometry assay

A flow cytometry test was utilized to measure the production of ROS in cells. Hep-G2 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 per well. Following overnight incubation, the cells were treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTS/Ag–TiO2 NPs at IC50 concentrations of 28.67 and 19.87 µg/mL, respectively, for 6 h. After that, a ROS probe DCFH-DA at a concentration of 15 µM was added to the new medium and incubated for another 30 min in the dark. The fluorescence intensity of the cells was measured using a flow cytometer. In addition, flow cytometry assays were used to measure mitochondrial dysfunction using a Rhodamine probe, and MMP using the JC-1 probe, p-JNK, p-AKT, and autophagy marker LC3, SQSTM1/p62, in the liver cell line after treatment with SWCNTs and SWCNTS/Ag–TiO2 NPs at IC50 concentrations 28.67 and 19.87 µg/mL, respectively. The fluorescence intensity of the cells was measured using a flow cytometer and CyAn ADP (Beckman Coulter, CY20030) according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

2.12 Immunofluorescence

Hep-G2 cells were plated at 106/well in a 4-well chamber slide in the RPMI 1640 medium. Then, cells were treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTS/Ag–TiO2 NPs at IC50 concentrations of 28.67 and 19.87 µg/mL, respectively. After that, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Hep-G2 cells were washed twice with PBS and then permeabilized with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 15 min. Fetal calf serum (10%) was used to block the cells for 60 min. After blocking, cells were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with monoclonal primary antibodies against Annexin A1, NOX4, cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase-3, cleaved caspase-9, and LC3. Cells were washed three times using PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin. The secondary antibodies (Alexa fluor 488) were added to the cells and incubated for 1 h. As a final step, cells were washed five times in PBS. Finally, fluorescence images were captured using a confocal microscope [48].

2.13 TEM

Hep-G2 cells treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTS/Ag–TiO2 NPs at IC50 concentrations of 28.67 and 19.87 µg/mL, respectively, for 10 h were washed with Sorensen’s phosphate buffer and prefixed with 1.5% glutaraldehyde, followed by post-fixation with 1% OsO4 in 7 mM Sorensen’s phosphate buffer. All sample pellets were dehydrated stepwise in a graded series of ethanol and embedded in araldite CY212. Ultrathin sections were double-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Sections were examined using a Tecnai transmission electron microscope (model number 943205018411, FEI Company; Czech Republic) equipped with an Olympus digital camera (VELETA).

2.14 Immunoblot analysis

Hep-G2 cells were treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 NPs at IC50 concentrations of 28.67 and 19.87 µg/mL, respectively for 24 h. The following antibodies were used: monoclonal anti-tubulin and anti-LC3B. The bound antibody was visualized using anti-rabbit (Cell Signaling Technology, 7074s) horseradish peroxidase-coupled immunoglobulin and the chemiluminescence ECL kit.

2.15 Apoptosis detection by annexin V/PI assay

Cell apoptosis was investigated using a flow cytometry assay. Liver cancer cells (Hep-G2) were treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 NPs at IC50 concentrations of 28.67 and 19.87 µg/mL, respectively. The cells were taken out and collected after 24 h. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS and stained for 30 min with an Annexin V FITC and PI solution. The labeled cells were then evaluated using a flow cytometry assay.

2.16 Statistical analysis

The presented data are the results of three independent experiments. Data are represented as a mean ± standard deviation (SD). The two-tailed Student’s t-test was utilized so that the significance of the differences could be evaluated. GraphPad Prism was utilized to carry out the statistical analysis (USA). When p < 0.05, statistical significance was recorded [49].

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Characterization

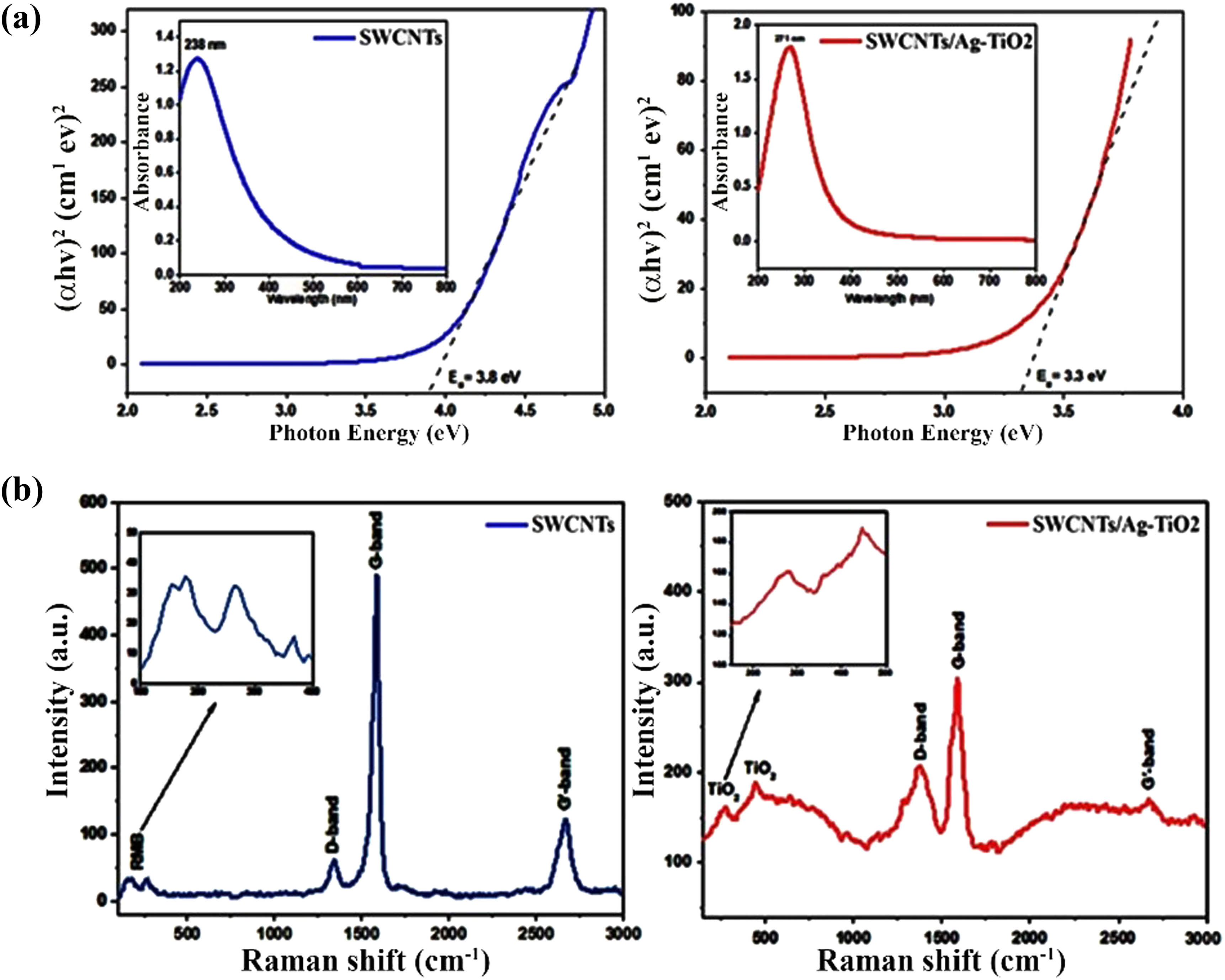

The inset of Figure 1(a) shows the absorbance profiles of SWCNTs (left panel) and the SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposite (right panel) in the range of 200–800 nm. The π–π* transition in the carbon double bonds of the SWCNT’s structure is related to a distinctive absorption band located at a maximum intensity of UV-Vis spectra. When Ag–TiO2 NPs are attached to SWCNTs, the absorption edge shifts to a higher wavelength (red shift). More NPs are attached to SWCNTs, which decorate the surface, increasing the surface area and demonstrating a plasmonic resonance behavior in the absorption. As illustrated in Figure 1a, SWCNTs had a bandgap of 3.8 eV, while the Ag–TiO2-decorated SWCNT nanocomposite had a bandgap of 3.3 eV. The incorporation of Ag–TiO2 on SWCNTs reduces the bandgap of SWCNTs [50], attributed to the development of Ti–O–C chemical bonds between SWCNTs and the nanocomposite. SWCNTs capture the electrons and result in decreasing the electron–hole recombination rate. Besides, Raman spectroscopy was used to better understand the production of SWCNTs and the SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposite. The Raman spectra of SWCNTs and SWCNTs@ Ag-TiO2 samples are shown in Figure 1(b). The distinctive bands known as the G-band, D-band, and 2D-band can be observed in the spectra of carbon nanostructures. The D-band is connected to sp3 bond flaws in SWCNTs. The G-band is the graphitic structure’s distinguishing band and is required for all sp2-hybridized SWCNTs. The 2D band corresponds to the disorder-induced double resonance characteristic, which provides information on the stress on SWCNTs. The spectrum of SWCNTs shows peaks at 1570.4 cm−1 (G-band), 1342.6 cm−1 (D-band), and 2654.8 cm−1 (2D-band), while similar peaks for the SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposite were detected at 1564.8, 1340.1, and 2681.7 cm−1. After decorating Ag–TiO2, these peaks shifted in the spectra of the nanocomposite sample, as shown in Figure 1(b). When compared to SWCNTs, both the shifting of the peak position and an increase in the intensity may be attributed to the increase in disorder. This increasing intensity of the nanocomposite is related to the high energy of Ag–TiO2 NPs, which destroy the nanotube surface and form defect sites. After treatment with a mixture of H2SO4/HNO3, numerous oxygen functional groups are introduced to the walls of SWCNTs, increasing their chemical reactivity and dispersing capacity, as revealed by Raman analysis 1B. Furthermore, via electrostatic interactions, these negatively charged functional groups easily attract positively charged ions in suspension, aiding the interaction between SWCNTs and the Ag–TiO2 precursor.

UV-Vis spectrum of (a) SWCNTs (left panel) and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 (right panel) and (b) Raman spectra of SWCNTs (left panel) and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 (right panel).

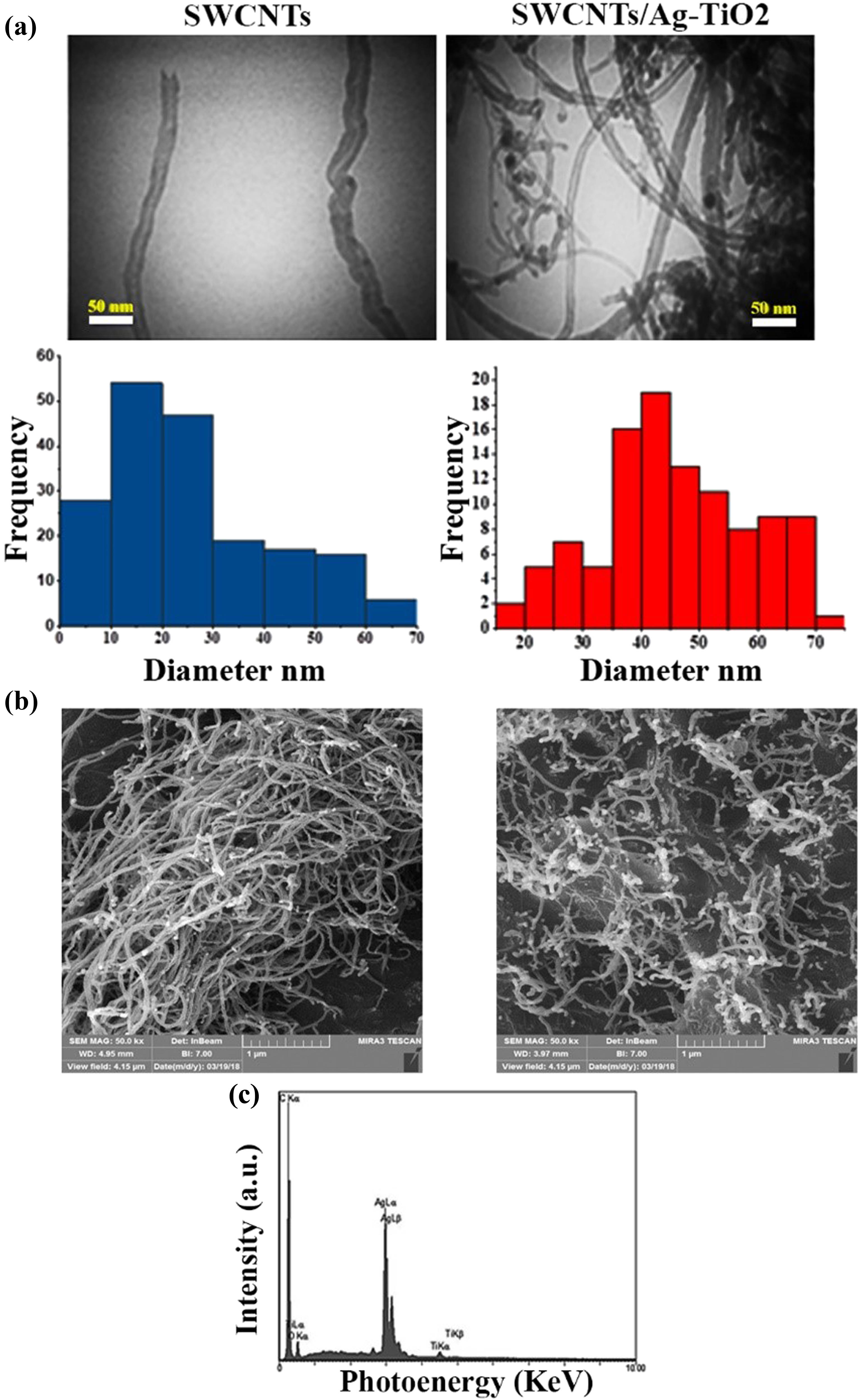

More detailed information on the morphology and microstructure of SWCNTs and the nanocomposite was obtained using TEM and FESEM analyses to confirm the decoration of the Ag–TiO2 nanocomposite on the surface of SWCNTs, as shown in Figure 2(a) and (b). Further, the TEM image of SWCNTs after being functionalized with a mixed acidic solution is shown in Figure 2(a) (left panel). Long SWCNTs with rather well-aligned and curving tubes were examined. Figure 2(a) and (b) (right panel) depict TEM and FESEM images of Ag–TiO2 decorated SWCNTs formed by the sol–gel technique. After Ag–TiO2 was deposited, a semispherical shape of Ag–TiO2 particles of various sizes was seen attached to SWCNTs. Furthermore, the TEM images of SWCNTs demonstrated that the average diameter of nanotubes was about 45.7 nm and the average particle size of the decorated Ag–TiO2 NPs was about 25.5 nm using the ImageJ program, as shown in Figure 2(a). By using EDX analysis, we can verify the presence of Ag–TiO2 NP-decorated SWCNTs as shown in Figure 2(c), which reveals the C, Ag, Ti, and O and confirms the formation of the SWCNT@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposite.

Characterization of SWCNTs (left side), and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposite (right side): (a) TEM, (b) FESEM, and (c) EDX.

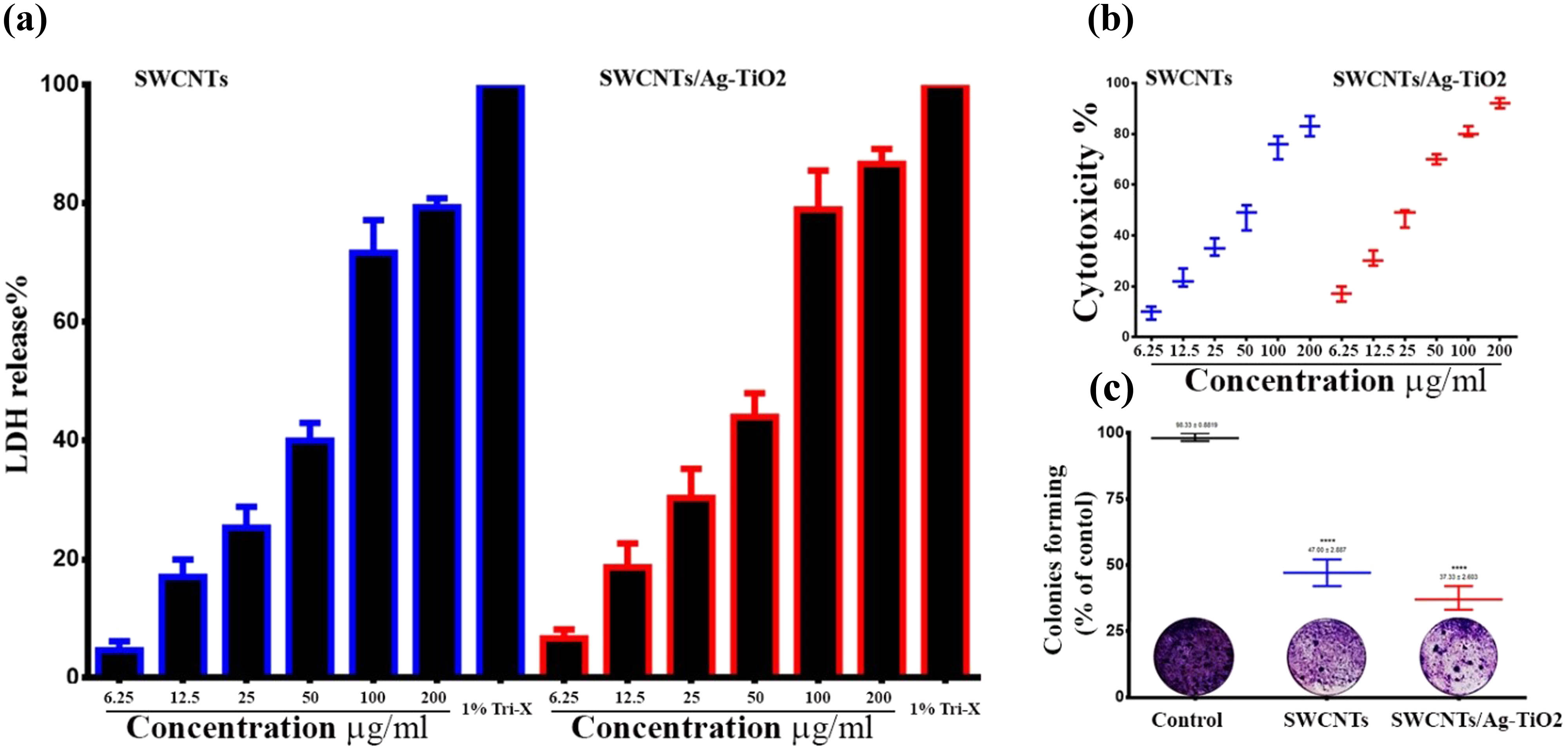

3.2 SWCNTs@SWCNT/Ag–TiO2 increase the release of LDH

The enzyme LDH controls the transition from lactate to pyruvate, which is necessary for the production of cellular energy. The cytotoxic effects of SWCNTs and SWCNT/Ag–TiO2 on liver cancer cell lines were evaluated with LDH. The damage in SWCNTs and SWCNT/Ag–TiO2-exposed Hep-G2 cells leads to the release of LDH from the cytoplasm, which in turn causes the formation of formazan from the tetrazolium salt. The generation of formazan is measured at a wavelength of 490 nm, which provides information about the percentage of LDH release in suffering or dying liver cancer cells after being treated with SWCNTs @SWCNT/Ag–TiO2. This may imply that SWCNTs and SWCNT/Ag–TiO2 can penetrate the treated cells, trigger vesicle development, and then enter the cells. The potential of SWCNTs @SWCNT/Ag–TiO2 to release LDH varies depending on the concentration, as shown in Figure 3(a). SWCNTs @SWCNT/Ag–TiO2 NPs can penetrate cells and other biological components, which can result in considerable cellular breakdown and stimulate the release of LDH. Simultaneously, cells might take in NPs measuring 100–200 nm, which could set off harmful phenomena such as alterations to genetic material or damage to DNA. It is possible that the toxicity of NPs is linked to mechanisms that increase the oxidative stress levels in the body by disrupting the antioxidant system [51]. Free radicals such as ROS are responsible for the damage of several membranes, including those that protect the cell and the mitochondria. As a consequence, the elements of cells, such as proteins, fatty acids, lipids, and nucleic acids, are responsible for the death of cells, which disrupts the process responsible for the electronic transmission of information. There is a possibility that oxidative stress, which leads to cellular disintegration, is responsible for the cytotoxicity of Hep-G2 cells. In addition, cell membrane damage may be involved in the concentration-dependent release of LDH that is caused by SWCNTs and SWCNT/Ag–TiO2. The concentration-dependent LDH release that is produced by SWCNTs and SWCNT/Ag–TiO2 may be connected to the degradation of cellular membranes, which results in the release of cellular enzymes such as LDH into the surrounding environment.

Cytotoxic effects of SWCNTs and SWCNT/Ag–TiO2 NPs in liver cancer cells. (a) SWCNTs and SWCNT/Ag–TiO2 NPs increase LDH release in liver cancer cells. (b) Antiproliferative activity of SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 in liver cancer cells (Hep-G2) by MTT assay. (c) Colony-forming assay.

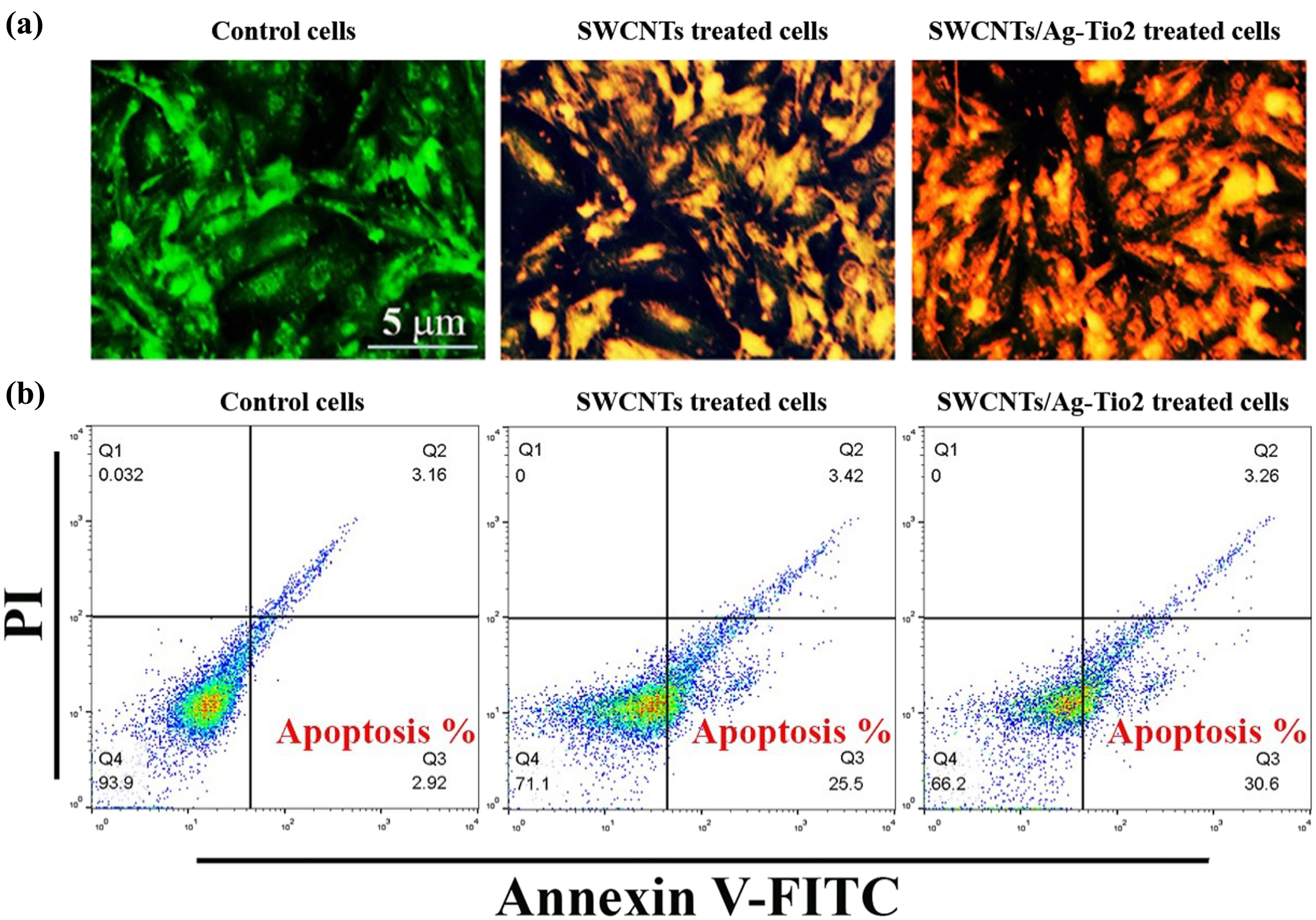

3.3 Anticancer activity of NPs against liver cancer cells

After 72 h of treatment with various concentrations (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 g/mL) of SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2, the ability of SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 to inhibit growth and proliferation of liver cancer cells was determined. This was done in order to determine the inhibitory effects of SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 when compared to the control group. SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 suppressed cell viability in a dose-dependent manner, as shown in Figure 3(b). The IC50 for SWCNTs was 28.67 µg/mL, while that of SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 was 19.87 µg/mL. After 72 h of treatment with high concentrations of SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 at high concentrations, the viability of Hep-G2 cells dropped to practically 10%. Figure 3(c) presents the antiproliferative effects of the prepared SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 on Hep-G2 cells, thus further confirming the cytotoxic effect of SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2.Further, they exhibited high activity in suppressing the colony-formation ability of Hep-G2 cells in comparison with control untreated Hep-G2 cells. The reduction in colony formation suggested that the cells that were subjected to continuous treatment were killed within 24–48 h, which suggested that SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 were taken up by cells, which led to the induction of apoptosis. This was supported by the fact that the cells were killed within 24–48 h after exposure to continuous treatment. This study suggested that the SWCNTs and the SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 caused cell death. In addition, the nuclear morphology of the treated cells was examined using a dual-staining method consisting of AO and EtBr. DNA damage was used as the criterion for evaluating apoptotic cells. Under the scope of this study, the effectiveness of SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 was also determined. The AO–EB staining was utilized so that the various apoptotic characteristics of the nuclear changes could be investigated. After being stained with AO-EtBr, cells that had not undergone apoptosis were green in color, whereas apoptotic cells were orange or red. As can be seen in Figure 4(a), the cells that were treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 had many more apoptotic cells than the control cells. To confirm the current results, the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by staining the cancer cells with annexin V-FITC using flow cytometry. The flow cytometry results showed that the cells undergoing apoptosis were labeled with annexin V in quadrant Q3. Figure 4(b) shows dot plots of Hep-G2 cells treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 for 24 h at IC50 concentrations. In the control Hep-G2 cells, the majority (93.9%) of cells were viable and non-apoptotic, and in Hep-G2 treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2, there was a decrease in viable cells and an increase in cells undergoing apoptosis. The percentage of apoptotic cells in the control Hep-G2 was 2.92%. In Hep-G2 cells treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2, the percentage of apoptotic cells increased to 25.5 and 30.6%, respectively. In addition, the results of this study have demonstrated that there is a non-toxic effect of SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 against the human liver normal cell line (L-02), as shown in Figure 5. CNTs have been hypothesized to harm lung cancer cells via several different processes. One of these mechanisms is that they act as oxidative stimuli, which in turn promote inflammation and DNA damage [52]. When cells were treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2, the results of our study showed that the viability of Hep-G2 cells was significantly reduced. Bisht et al. showed that high dosages of ZnO–Fe3O4 magnetic composite NPs induced a cytotoxic impact in a human breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231) but did not induce this effect in normal mouse fibroblast (NIH 3T3) [53]. A previous study has demonstrated that the production of free radicals and ROS may be responsible for the cytotoxicity of metal NPs [54]. It has also been reported that excessive ROS can cause apoptosis by activating FOXO3a, a protein that can promote apoptosis signaling by inducing the expression of pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl2 family of mitochondria-targeting proteins. This finding supports the hypothesis that excessive ROS can cause apoptosis. This discovery was made feasible as a result of the activation of FOXO3a that occurs when there is an excessive amount of ROS. The results of the ROS assay showed that the amount of ROS generation in the K562 cell line was greatly increased when ZnO/CNT@Fe3O4 was present. It was intriguing to note these results. Significantly, recent research revealed that K562 cells became more sensitive to the lethal action of ZnO/CNT@Fe3O4 when the NF-kB pathway was blocked by the well-known proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. This result confirms the hypothesis that the sensitivity of K562 cells to ZnO/CNT@Fe3O4 is most likely reduced by the activation of the nuclear factor-ƙB pathway.

SWCNTs and SWCNT/Ag–TiO2 NPs induce apoptosis in liver cancer cells. (a) AO/EtBr double staining assay. (b) Apoptosis marker (Annexin V) using flow cytometry assay.

Cytotoxic effect of SWCNTs and SWCNT/Ag–TiO2 NPs in normal liver cell line (L-02). The results are represented as mean ± SD.

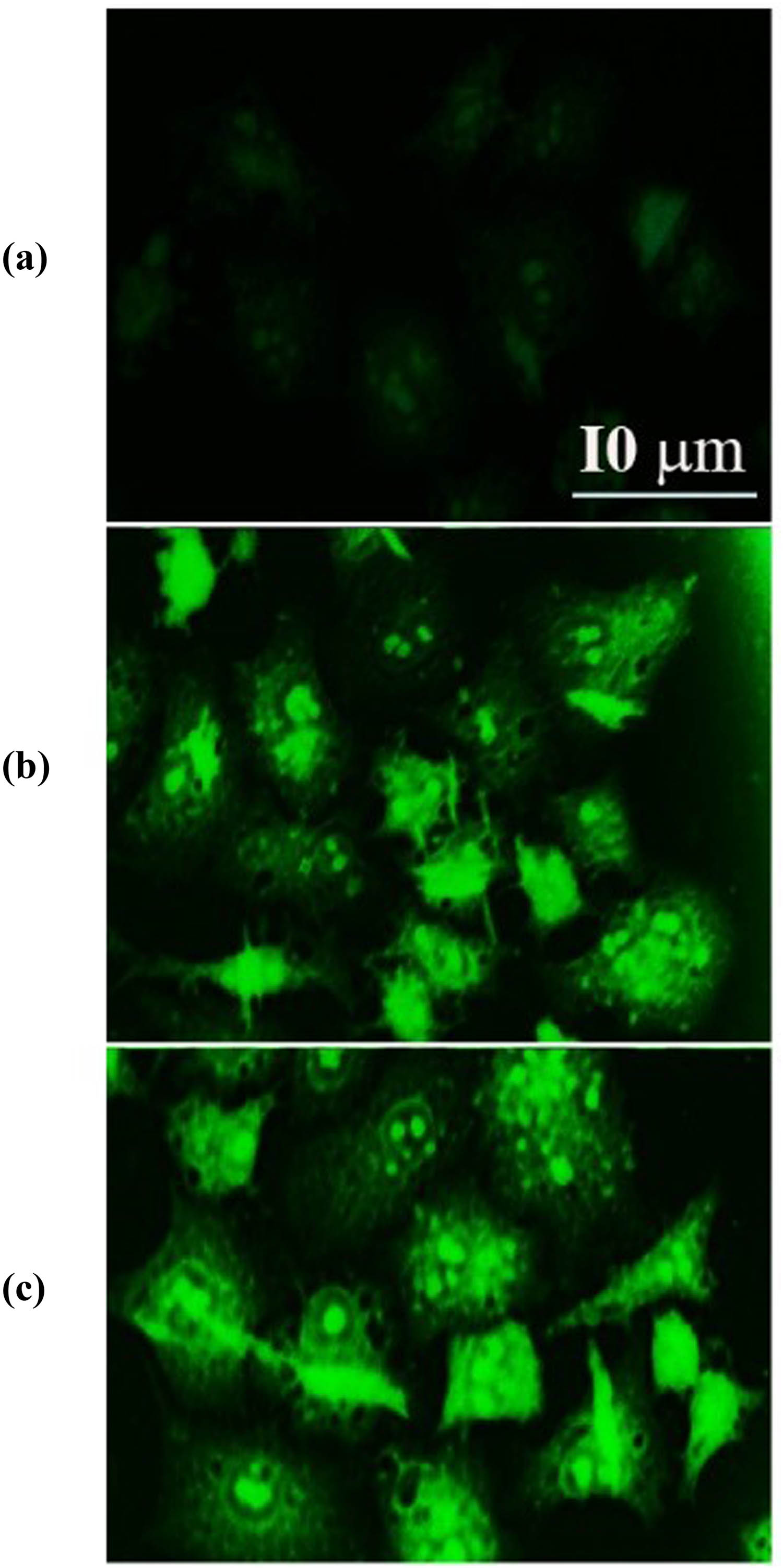

3.4 Internalization of SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2

To study the ability of SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 to internalize inside a HepG2 cell, FITC-labeled SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 were investigated by confocal fluorescence microscopy imaging. As shown in Figure 6(a) (white arrows), green fluorescent SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 were observed FITC-labeled SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 appeared inside the cytoplasmic vesicles of HepG2 cells. Additionally, phase-contrast microscopy was used to determine the presence of SWCNTs, SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 inside the HepG2 cells, as indicated in Figure 6(b) (red arrows). Intracellular aggregates of SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 appear as dark spots in the cell cytoplasm. Furthermore, the cellular vesicles that appeared to contain SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 were further investigated by TEM analysis. SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 were identified in the form of intracellular aggregates, as shown by the red arrows in Figure 6(c).

Internalization and colocalization of SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 in cytoplasmic vesicles of Hep-G2 cells. (a) Confocal images of Hep-G2; the nucleus was stained with DRAQ5-red. Green fluorescence represented internalized SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 into HepG2 cells (exposed for 60 min to 2.5 mg/L FITC SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2. (b) Hep-G2 cells incubated for 60 min with 2.5 mg/L FITC– SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 visualized by phase-contrast microscopy (×200 magnification). (c) TEM images showing aggregates of SWCNTs and SWCNTs/Ag–TiO2 surrounded by cytoplasmic vesicles, confirming the presence of nanomaterial inside the cell (×35,000 magnification).

3.5 SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 disorder oxidative balance in Hep-G2 cells

Oxidative stress-associated parameters were studied to determine if SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 generate ROS production and alter redox equilibrium in treated liver cancer cells. At first, an analysis was performed to determine the total amount of free thiols, which included reduced GSH. As an ROS scavenger, GSH works to maintain intracellular redox balance in cells, and it is widely acknowledged as an important endogenous component in the pathways leading to antioxidant defense. In practice, a decrease in its intracellular level causes cells to undergo an excessive amount of oxidative stress, which ultimately leads to cell death. As shown in Figure 7 (left panel and top right panel), treatment of liver cancer cells with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 led to significant depletion of GSH and a shift in the cellular cytosol from a reducing to an oxidizing environment. This was caused by interference with the GSSG–GSH balance. When compared to untreated cells, the number of cells exhibiting decreased GSH levels increased from 17.33 to 53% and 64.67% (for cells treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2, at IC50), respectively (Figure 7, upper right panel). In a different series of tests, the increased expression of NADPH subunit 4 (NOX4) that was driven by AuP NPs was validated by immunofluorescence staining, as shown in Figure 7 (lower left panel). Upregulation of its expression was found in cancer cells that have been treated with ROS modulators, proving that NOX4 plays an essential part in oxidative stress and that this involvement is important [55]. Because of the treatment of Hep-G2 with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2, we observed a considerable increase in the NADPH levels, as shown in Figure 7 (lower left panel), which validates our theory regarding the disruption of redox balance in treated Hep-G2 cells.

Distraction of oxidative balance in SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-treated Hep-G2 cancer cells. The left panel represented a flow-cytometry analysis of GSH levels. The upper right panel represented a decrease of the intracellular (GSH) levels in SWCNTs, and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-treated Hep-G2 cells. The lower right panel represented immunofluorescence results of NADPH expression in SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-treated Hep-G2 cancer cells. (a) Control untreated cells. (b) SWCNTs-exposed cells. (c) SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-exposed cells.

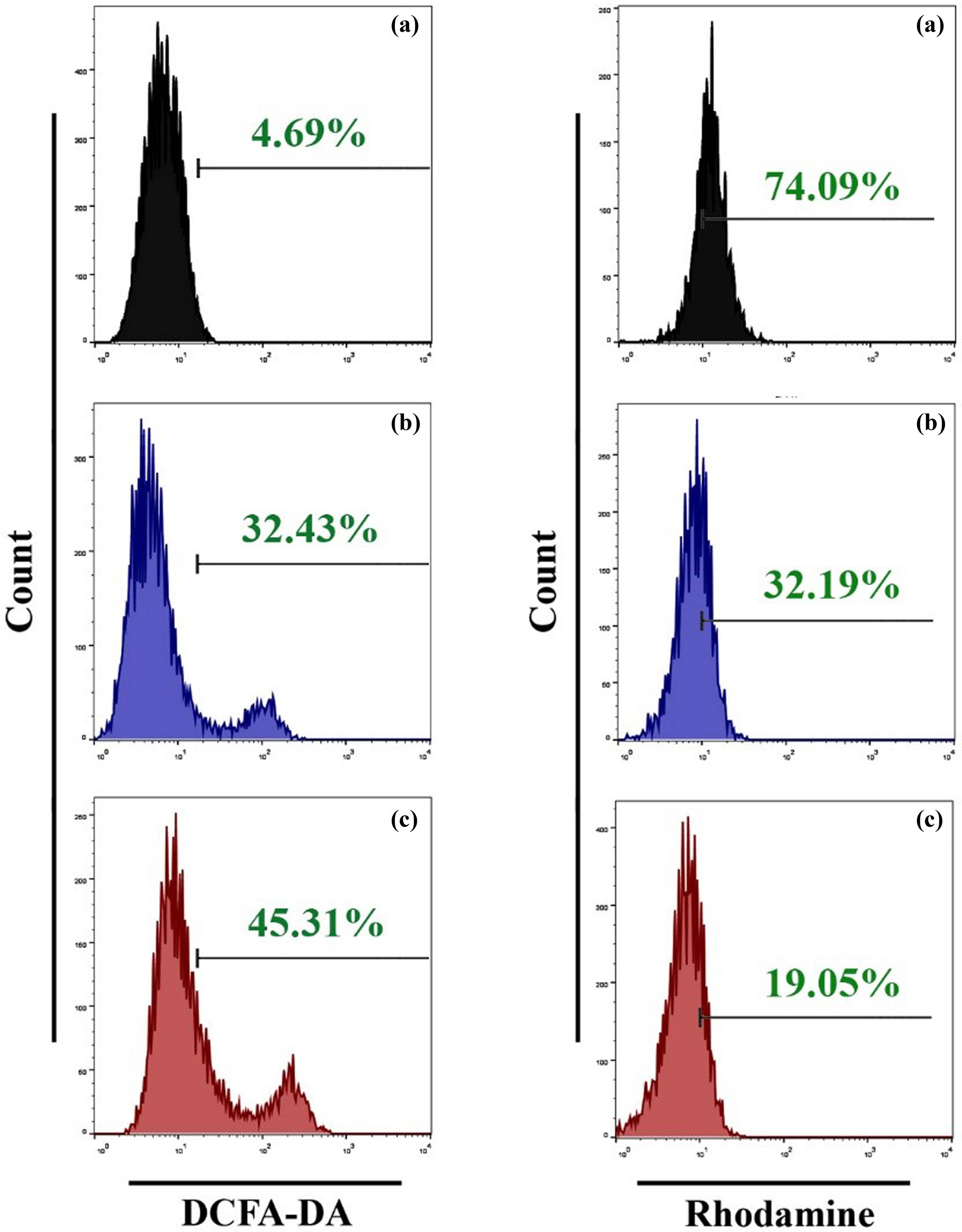

A considerable increase in the generation of ROS was observed in cells treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2. The fluorescence signal resulting from ROS was found to be higher when compared to the control cells. The buildup of ROS in liver cancer cell lines after treatment with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 was investigated in the current study. An increase in ROS was seen in cells that had been treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2. ROS levels were measured with a DCFH-DA probe, as demonstrated in Figure 8 (left panel). When the liver cancer cells were treated with SWCNTs and SWCNT-coated Ag–TiO2, the results revealed that the ROS level was enhanced. In conclusion, this study suggests a loss of mitochondrial potential in cells in which the GSH intracellular level falls below a threshold level, and the findings of another study that highlights crosstalk between mitochondria and NADPH activity [56], we investigated whether or not SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-mediated treatment affects the functioning of mitochondria. Rhodamine dye, which displays potential-dependent accumulation in the mitochondria, was used to identify the loss of the MMP. The findings of the current study showed that the percentages of mitochondrial membrane depolarized cells significantly increased after exposure to SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 at IC50 doses for 24 h, as shown in Figure 8 (right panel). JC-1 staining was performed on Hep-G2 cells in order to assess the healthy and damaged mitochondria. The effect of SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 is evaluated on liver cancer cell lines. For determining whether or not mitochondrial damage has occurred, it is known that MMP (∆Ψ m) is produced by the proton pump of the electron transport chain, which is a component that is required for the production of ATP. For this reason, we additionally assessed MMP using JC-1 staining. As indicated in Figure 9, the promotion of JC-1 monomers increased noticeably depending on the type of treatment given to liver cancer cell lines. According to the findings presented above, the treatment of liver cancer cells Hep-G2 is accompanied by a disruption of the oxidative balance in cancer cells as well as an impairment of protective anti-oxidative molecules. This causes cells to be subjected to excessive oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, which leads to the subsequent release of cytochrome c, which causes the activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 pathways.

SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 induce ROS generation and mitochondrial dysfunction in Hep-G2 cancer cells. (a) Control untreated cells. (b) SWCNTs-exposed cells. (c) SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-exposed cells.

SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 reduce MMP in Hep-G2 cancer cells. (a) Control untreated cells. (b) SWCNTs-exposed cells. (c) SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-exposed cells.

3.6 Effect of SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 in apoptosis-related proteins

Apoptosis begins with a series of processes known as early events, which include a decrease in the cellular GSH concentration and dysregulation of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential [57]. Because we observed both these effects in liver cancer cells that had been treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2, we concluded that the anti-cancer activity of SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 is linked to apoptosis. We investigated the modifications in the expression of selected apoptosis-related proteins that occurred upon exposure to SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 NPs. Our aim was to gain a better understanding of how SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 NPs affect this process. By immunofluorescence staining, we were able to determine whether or not any changes in the functioning of phospholipid-binding proteins from the annexins group, especially annexin A1 (ANXA1), occur in cells that have been treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2. Although it was reported that ANXA1 was involved primarily in inflammatory processes, it also has pro-apoptotic functions. Some of these functions, including the activation of p38 and JNK signaling pathways [58,59], co-localization with LC3-II on the cell’s outer plasma membrane [60], lead to stimulation of caspase-3 [61]. As can be seen in Figure 10, the signal from immunofluorescent ANXA1 is significantly amplified in cells that have been treated with SWCNTs and cells that have been treated with SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2, which is evidence that treated liver cancer cells (Hep-G2) link the apoptotic signaling pathway.

SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 induce annexin 1A protein in Hep-G2 cancer cells. (a) Control untreated cells. (b) SWCNT-exposed cells. (c) SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-exposed cells.

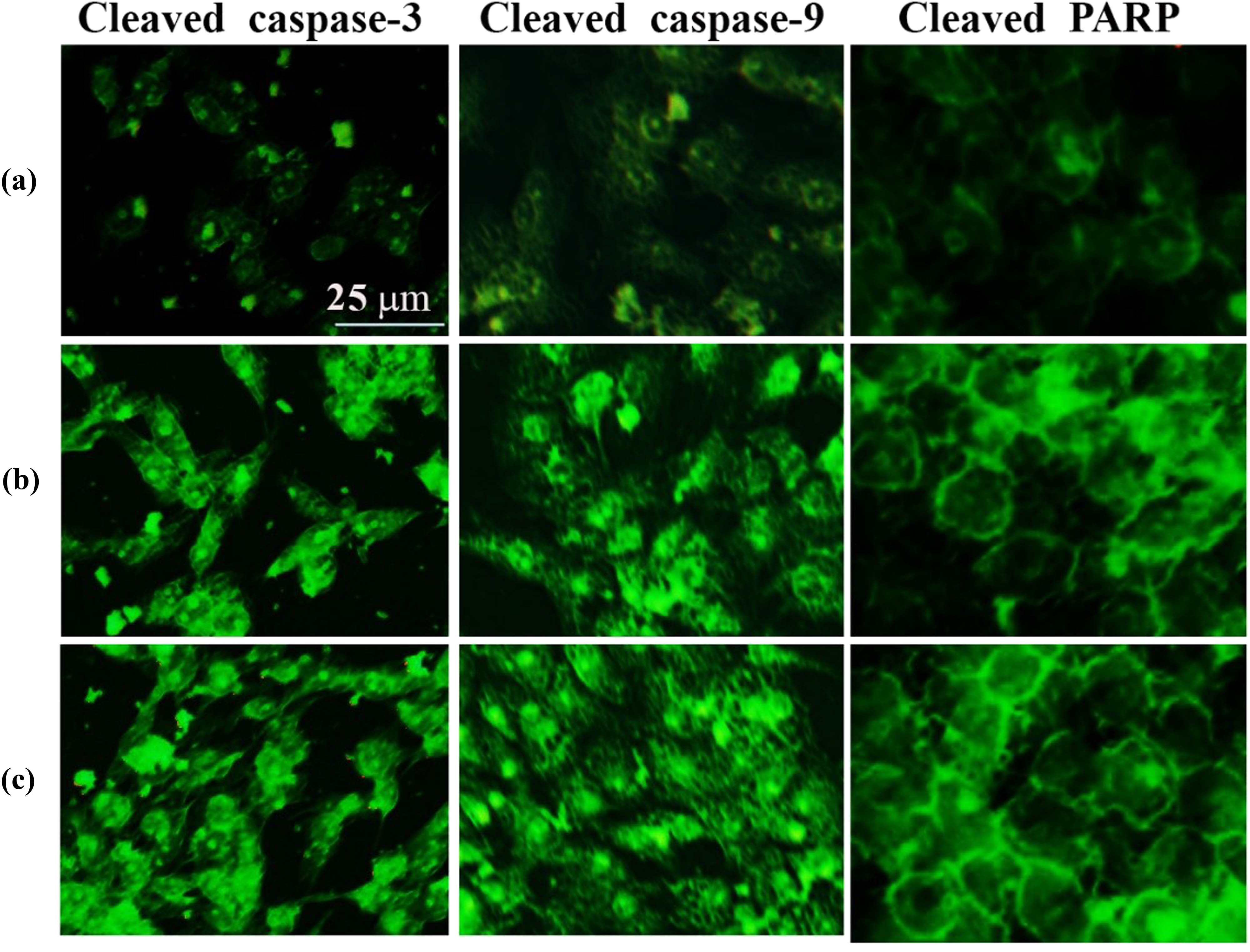

In this study, we confirmed the apoptosis process in liver cancer cells exposed to SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 using an immunofluorescence assay of effector caspases (caspase-3 and caspase-9) and PARP expression. This was done because some caspases are not involved in the initiation of the apoptosis signal, but rather are involved in signaling, which leads to cytokine production during the inflammation process and other types of cell death. As can be seen in Figure 11, cleavage of caspase-3, caspase-9, and PARP was caused by exposure to SWCNTs and SWCNTs-coated Ag–TiO2. The findings suggest that both SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 were responsible for the induction of cell death in Hep-G2 cells by the activation of a pathway involving caspase-dependent apoptotic signaling.

SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 induce apoptotic proteins’ expression: cleaved-caspase-3, cleaved-caspase-9, and cleaved-PARP in Hep-G2 cancer cells. (a) Control untreated cells. (b) SWCNTs-exposed cells. (c) SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-exposed cells.

3.7 SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 induce autophagy in Hep-G2 cells

We examined the expression of LC3, which is an important autophagy-related protein, using western blot, TEM, immunofluorescence, and flow cytometry assays in order to determine whether or not autophagy is induced in SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-treated Hep-G2 cells. To quantify the autophagy process, we monitored the alteration of the protein microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta (LC3) to its lapidated form (LC3 II) by western blot as shown in Figure 12(I). Our results demonstrated a marked increase in the absolute amount of LC3 II relative to β-tubulin following cells exposed to SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2. The TEM technique established the presence of autophagosomes containing cytoplasmic contents (Figure 12(II)). The results showed the double-membrane structure of the autophagosome. To confirm these results, we investigated the localization of endogenous LC3 to autophagocytic vacuoles using immunofluorescence as shown in Figure 12(III). Finally, a flow cytometric assay was used to quantify intracellular LC3 II staining as shown in Figure 12(IV). In addition to LC3 protein, we investigated the role of p62 as an autophagy marker as shown in Figure 12(V). The results of the current study showed that the level of autophagy was increased when Hep-G2 was exposed to SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2, and there was an increase in the expression of the LC3 protein. The expression of LC3 was shown to be higher in SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-treated cells as compared to control cells. In recent years, researchers have discovered that a wide range of nanomaterials can trigger autophagy. In addition, the results of a previous study [62] suggested that CNTs are becoming a class of autophagy inducers. ROS generation was discovered to be capable of providing a signal that might upregulate SIRT1, which is a member of the NAD-dependent class III histone deacetylases [63]. This, in turn, has an effect on the advancement of the cell cycle by inducing an arrest in the G1 or G2/M phase of the cell cycle [64]. ZnO/CNT@Fe3O4 induced an increase in the expression of SIRT1 and blocked the progression of the cells out of the G1 phase of the cell cycle by inducing an increase in the expression level of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p27. This was in agreement with the increased levels of ROS. Based on these findings, the growth-inhibiting impact of ZnO/CNT@Fe3O4 appears to have been mediated, at least in some cases. It has been demonstrated in several studies that the presence of SIRT1 in cancer cells may result in the stimulation of autophagy [65]. This is in addition to the fact that the presence of SIRT1 controls the progression of the cell cycle. The type of cancer cell that is being researched can determine whether or not the induction of autophagy will result in the death of cells or the production of a resistant phenotype [66]. A previous study has demonstrated that silver NPs (Ag NPs) have a significant therapeutic potential against a wide variety of cancer cells. This is accomplished by modulating the action of autophagy either as cytotoxic agents or as nanocarriers that, in conjunction with other treatments, deliver therapeutic molecules [67]. It has been hypothesized that the harmful effects of AgNPs are caused by the lysosome-dependent release of silver ions, which then results in the generation of abundant ROS. These ROS create a breakdown in the integrity of the lysosomal membrane, which in turn facilitates the escape of AgNPs into the cytosolic space, which is the pathway through which they then target other subcellular compartments [68]. In addition, AgNPs-induced lysosomal dysfunction, which can include a loss of membrane integrity or an increase in internal acidity, is associated with an altered autophagosome–lysosome fusion process [69], which significantly disrupts the autophagy machinery’s ability to perform its role. AgNPs have a high affinity for thiol groups, which are essential for protein folding and function as ROS scavengers. AgNPs also have a high surface area. As a result, AgNPs are responsible for the misfolding of proteins, which in turn causes ER stress and GSH depletion, which ultimately results in an imbalance in ROS metabolism. These outcomes collectively speed up the autophagy process, which ultimately leads to the death of the cell. AgNPs are possible sources of oxidative stress, which, when exposed to NIH3T3 mouse embryonic fibroblast cells, results in the generation of ROS and, ultimately, the induction of autophagy. This finding has been supported by a different study that the delivery of AgNPs led to an increase in the expression of the LC3-II protein, which also accumulated in liver tissue [70]. In addition, the use of AgNPs in conjunction with medicines resulted in a synergistic enhancement of the cytotoxicity toward cancer cells. Ag NPs have been shown to inhibit autophagic flux in addition to inducing autophagy; this results in the buildup of autophagosomes, which impedes the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages [71]. It was found that the cytotoxic effect of Ag-NPs was significantly greater on PANC1 cancer cells than it was on non-tumor cells originating from the same tissue. Specifically, compared to non-tumor cells, PANC-1 cells were substantially more susceptible to death from NPs’ stimulation of apoptosis and autophagy, which led to a reduction in the cells’ viability [72]. It has been demonstrated that RAW264.7 cells originating from mouse peritoneal macrophages can be stimulated to undergo pro-survival autophagy when exposed to Fe3O4 NPs. Following the treatment with Fe3O4-NPs, an increase in autophagy markers and ROS levels was seen, which was accompanied by an activation of the ERK pathway, which was necessary for cell survival [73]. Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are key regulatory mechanisms that play a significant part in the biological translation of cell autophagy and apoptosis [74]. We hypothesized that SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 induce autophagy in controlling the AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. To test our hypothesis, a flowcytometry assay was used to measure the protein expression levels of MAPKs, such as p-JNK1/2, and p-AKT in liver cancer cell lines that had been treated with SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2. According to the findings, p-AKT was decreased, while p-JNK was increased in Hep-G2 cells as shown in Figure 13. Based on our outcomes, it appears that the activation of AKT and JNK1/2 may play a role in the regulation of SWCNTs, and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-induced autophagy and apoptosis.

SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 promote autophagy in Hep-G2 cancer cells. (I) Western blot of LC3-I and LC3-II in Hep-G2 exposed to SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2. β-Tubulin is shown as a loading control (of three independent experiments). The graph represents the ratio of LC3-II/β-tubulin in three independent experiments. (II) TEM images of autophagosomes in Hep-G2 cells. (III) Immunofluorescence images of LC3 in Hep-G2. LC3 staining is shown as green and nuclei blue. The scale bar indicates 5 mm. The graph represents the number of LC3 puncta in Hep-G2 cells exposed to SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2. (IV) Expression of LC3 protein using flow cytometric assay. (V) Expression of p62 in Hep-G2 using flow cytometric assay. (a) Control untreated cells. (b) SWCNTs exposed cells. (c) SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-exposed cells. Data are represented by mean ± SD. ***, **** indicates statistically different from control untreated cells.

Role of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in promoting apoptosis and autophagy in Hep-G2 cells. (a) Control untreated cells. (b) SWCNTs-exposed cells. (c) SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2-exposed cells.

4 Conclusions

The findings from the in vitro studies show that SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 can induce apoptosis and autophagy in Hep-G2 cells via ROS-mediated pathways. These findings also suggest that SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 have a significant amount of untapped potential as nanotherapeutics. It is both justifiable and clinically important to pursue more research to elucidate the safety and detailed therapeutic potential of such NPs when used in in vivo situations. In the current study, we demonstrate that exposure to SWCNTs and SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposite modulates the ROS signaling pathway in the human liver cancer cell line Hep-G2, which results in the induction of apoptosis and autophagy. The results presented have the potential to lead to the development of more effective medicines for the treatment of human liver cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers supporting Project (number: RSP2023R56), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by The Researchers supporting Project (number: RSP2023R56), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, M.S.J. and M.K.A.M.; methodology, M.S.J., D.S.A.; software, S.A.; validation, A.S., A.M.E., A. I. A., and H. M. A.; formal analysis, S.G.; investigation, M.S.J., M.K.A.M., D.S.A.; resources, M.S.J.; data curation, F.S.J.; writing – original draft preparation, M.K.A.M., M.A.A.N.; writing – review and editing, D.S.A.; visualization, M.A.A.N.; supervision, M.S.J., M.K.A.M., and S.A; project administration, M.S.J.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Anand U, Dey A, Chandel AKS, Sanyal R, Mishra A, Pandey DK, et al. Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: Current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics. Genes Dis. 2023;10(4):1367–401.10.1016/j.gendis.2022.02.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Tagde P, Najda A, Nagpal K, Kulkarni GT, Shah M, Ullah O, et al. Nanomedicine-based delivery strategies for breast cancer treatment and management. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2856.10.3390/ijms23052856Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Ahmed DS, Mohammed MK. Studying the bactericidal ability and biocompatibility of gold and gold oxide nanoparticles decorating on multi-wall carbon nanotubes. Chem Pap. 2020;74(11):4033–46.10.1007/s11696-020-01223-0Search in Google Scholar

[4] Nadhiya D, Kala A, Sasikumar P, Mohammed MK, Thirunavukkarasu P, Prabhaharan M, et al. Influence of Cu2 + substitution on the Structural, Optical, Magnetic, and Antibacterial behaviour of Zinc Ferrite Nanoparticles. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2023;27:101696.10.1016/j.jscs.2023.101696Search in Google Scholar

[5] Avolio R, D’Albore M, Guarino V, Gentile G, Cocca MC, Zeppetelli S, et al. Pure titanium particle loaded nanocomposites: study on the polymer/filler interface and hMSC biocompatibility. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 2016;27:1–11.10.1007/s10856-016-5765-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Makinde O, Mabood F, Khan W, Tshehla M. MHD flow of a variable viscosity nanofluid over a radially stretching convective surface with radiative heat. J Mol Liq. 2016;219:624–30.10.1016/j.molliq.2016.03.078Search in Google Scholar

[7] Al Rugaie O, Jabir MS, Mohammed MK, Abbas RH, Ahmed DS, Sulaiman GM, et al. Modification of SWCNTs with hybrid materials ZnO–Ag and ZnO–Au for enhancing bactericidal activity of phagocytic cells against Escherichia coli through NOX2 pathway. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):17203.10.1038/s41598-022-22193-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Alhujaily M, Albukhaty S, Yusuf M, Mohammed MK, Sulaiman GM, Al-Karagoly H, et al. Recent advances in plant-mediated zinc oxide nanoparticles with their significant biomedical properties. Bioengineering. 2022;9(10):541.10.3390/bioengineering9100541Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Avalos A, Haza AI, Mateo D, Morales P. Cytotoxicity and ROS production of manufactured silver nanoparticles of different sizes in hepatoma and leukemia cells. J Appl Toxicol. 2014;34(4):413–23.10.1002/jat.2957Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Khan J, Bibi S, Naseem I, Ahmed S, Hafeez M, Ahmed K, et al. Ternary metal (Cu–Ni–Zn) oxide nanocomposite via an environmentally friendly route. ACS Omega. 2023;8(23):21032–41.10.1021/acsomega.3c01896Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Stern ST, Adiseshaiah PP, Crist RM. Autophagy and lysosomal dysfunction as emerging mechanisms of nanomaterial toxicity. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2012;9:1–17.10.1186/1743-8977-9-20Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Kadhim AA, Abbas NR, Kadhum HH, Albukhaty S, Jabir MS, Naji AM, et al. Investigating the effects of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles produced using papaver somniferum extract on oxidative stress, cytotoxicity, and the induction of apoptosis in the THP-1 cell line. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2023;201(10):4697–709.10.1007/s12011-023-03574-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Khan MI, Mohammad A, Patil G, Naqvi S, Chauhan L, Ahmad I. Induction of ROS, mitochondrial damage and autophagy in lung epithelial cancer cells by iron oxide nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2012;33(5):1477–88.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.080Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Liu H, Zhang Y, Yang N, Zhang Y, Liu X, Li C, et al. A functionalized single-walled carbon nanotube-induced autophagic cell death in human lung cells through Akt–TSC2-mTOR signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2(5):e159.10.1038/cddis.2011.27Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Seleverstov O, Zabirnyk O, Zscharnack M, Bulavina L, Nowicki M, Heinrich J-M, et al. Quantum dots for human mesenchymal stem cells labeling. A size-dependent autophagy activation. Nano Lett. 2006;6(12):2826–32.10.1021/nl0619711Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Lee C-M, Huang S-T, Huang S-H, Lin H-W, Tsai H-P, Wu J-Y, et al. C60 fullerene-pentoxifylline dyad nanoparticles enhance autophagy to avoid cytotoxic effects caused by the β-amyloid peptide. Nanomed: Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2011;7(1):107–14.10.1016/j.nano.2010.06.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Ahamed M, AlSalhi MS, Siddiqui M. Silver nanoparticle applications and human health. Clinica Chim acta. 2010;411(23–24):1841–8.10.1016/j.cca.2010.08.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Ahmed DS, Mohammed MK, Mohammad MR. Sol–gel synthesis of Ag-doped titania-coated carbon nanotubes and study their biomedical applications. Chem Pap. 2020;74(1):197–208.10.1007/s11696-019-00869-9Search in Google Scholar

[19] Mohammed MK, Ahmed DS, Mohammad MR. Studying antimicrobial activity of carbon nanotubes decorated with metal-doped ZnO hybrid materials. Materials Research Express. 2019;6(5):055404.10.1088/2053-1591/ab0687Search in Google Scholar

[20] Pantarotto D, Briand J-P, Prato M, Bianco A. Translocation of bioactive peptides across cell membranes by carbon nanotubes. Chem Commun. 2004;(1):16–7.10.1039/b311254cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Ramos-Perez V, Cifuentes A, Coronas N, De Pablo A, Borrós S. Modification of carbon nanotubes for gene delivery vectors. Nanomater Interfaces Biol: Methods Protoc. 2013;261–8.10.1007/978-1-62703-462-3_20Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Mohammad MR, Ahmed DS, Mohammed MK. ZnO/Ag nanoparticle-decorated single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) and their properties. Surf Rev Lett. 2020;27(3):1950123.10.1142/S0218625X19501233Search in Google Scholar

[23] Chen C, Xie X-X, Zhou Q, Zhang F-Y, Wang Q-L, Liu Y-Q, et al. EGF-functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes for targeting delivery of etoposide. Nanotechnology. 2012;23(4):045104.10.1088/0957-4484/23/4/045104Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Huang H, Yuan Q, Shah J, Misra R. A new family of folate-decorated and carbon nanotube-mediated drug delivery system: Synthesis and drug delivery response. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2011;63(14–15):1332–9.10.1016/j.addr.2011.04.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Zhang X, Meng L, Lu Q, Fei Z, Dyson PJ. Targeted delivery and controlled release of doxorubicin to cancer cells using modified single wall carbon nanotubes. Biomaterials. 2009;30(30):6041–7.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Ahamed M, Khan MM, Akhtar MJ, Alhadlaq HA, Alshamsan A. Ag-doping regulates the cytotoxicity of TiO2 nanoparticles via oxidative stress in human cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17662.10.1038/s41598-017-17559-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Piszczek P, Lewandowska Ż, Radtke A, Jędrzejewski T, Kozak W, Sadowska B, et al. Biocompatibility of titania nanotube coatings enriched with silver nanograins by chemical vapor deposition. Nanomaterials. 2017;7(9):274.10.3390/nano7090274Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Mohammed MK. Sol-gel synthesis of Au-doped TiO2 supported SWCNT nanohybrid with visible-light-driven photocatalytic for high degradation performance toward methylene blue dye. Optik. 2020;223:165607.10.1016/j.ijleo.2020.165607Search in Google Scholar

[29] Kadhim AK, Mohammad MR, Abd Ali AI, Mohammed MK. Reduced graphene oxide/Bi2O3 composite as a desirable candidate to modify the electron transport layer of mesoscopic perovskite solar cells. Energy Fuels. 2021;35(10):8944–52.10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c00848Search in Google Scholar

[30] Geng Y, Lei G, Liao Y, Jiang H-Y, Xie G, Chen S. Rapid organic degradation and bacteria destruction under visible light by ternary photocatalysts of Ag/AgX/TiO2. J Environ Chem Eng. 2017;5(6):5566–72.10.1016/j.jece.2017.10.045Search in Google Scholar

[31] Moongraksathum B, Chen Y-W. Anatase TiO2 co-doped with silver and ceria for antibacterial application. Catal Today. 2018;310:68–74.10.1016/j.cattod.2017.05.087Search in Google Scholar

[32] Jiang Z, Wei W, Mao D, Chen C, Shi Y, Lv X, et al. Silver-loaded nitrogen-doped yolk–shell mesoporous TiO 2 hollow microspheres with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. Nanoscale. 2015;7(2):784–97.10.1039/C4NR05963HSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Liu T, Li B, Hao Y, Han F, Zhang L, Hu L. A general method to diverse silver/mesoporous–metal–oxide nanocomposites with plasmon-enhanced photocatalytic activity. Appl Catal B: Environ. 2015;165:378–88.10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.10.041Search in Google Scholar

[34] Pati R, Das I, Mehta RK, Sahu R, Sonawane A. Zinc-oxide nanoparticles exhibit genotoxic, clastogenic, cytotoxic and actin depolymerization effects by inducing oxidative stress responses in macrophages and adult mice. Toxicol Sci. 2016;150(2):454–72.10.1093/toxsci/kfw010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Hussar P. Apoptosis regulators bcl-2 and caspase-3. Encyclopedia. 2022;2(4):1624–36.10.3390/encyclopedia2040111Search in Google Scholar

[36] Jung S, Jeong H, Yu S-W. Autophagy as a decisive process for cell death. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52(6):921–30.10.1038/s12276-020-0455-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Li Y, Ju D. The role of autophagy in nanoparticles-induced toxicity and its related cellular and molecular mechanisms. Cell Mol Toxicol Nanopart. 2018;71–84.10.1007/978-3-319-72041-8_5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Liu X, Tu B, Jiang X, Xu G, Bai L, Zhang L, et al. Lysosomal dysfunction is associated with persistent lung injury in dams caused by pregnancy exposure to carbon black nanoparticles. Life Sci. 2019;233:116741.10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116741Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Fan J, Wang S, Zhang X, Chen W, Li Y, Yang P, et al. Quantum dots elicit hepatotoxicity through lysosome-dependent autophagy activation and reactive oxygen species production. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2018;4(4):1418–27.10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00824Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Zhou H, Gong X, Lin H, Chen H, Huang D, Li D, et al. Gold nanoparticles impair autophagy flux through shape-dependent endocytosis and lysosomal dysfunction. J Mater Chem B. 2018;6(48):8127–36.10.1039/C8TB02390ESearch in Google Scholar

[41] Mohammed MK, Mohammad M, Jabir MS, Ahmed D, editors. Functionalization, characterization, and antibacterial activity of single wall and multi wall carbon nanotubes. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing; 2020.10.1088/1757-899X/757/1/012028Search in Google Scholar

[42] Mohammed MK, Jabir MS, Abdulzahraa HG, Mohammed SH, Al-Azzawi WK, Ahmed DS, et al. Introduction of cadmium chloride additive to improve the performance and stability of perovskite solar cells. RSC Adv. 2022;12(32):20461–70.10.1039/D2RA03776ASearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Sakthivel P, Karuppiah M, Asaithambi S, Balaji V, Pandian MS, Ramasamy P, et al. Electrochemical energy storage applications of carbon nanotube supported heterogeneous metal sulfide electrodes. Ceram Int. 2022;48(5):6157–65.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.11.155Search in Google Scholar

[44] Naji AM, Mohammed IY, Mohammed SH, Mohammed MK, Ahmed DS, Jabir MS, et al. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye using F doped ZnO/polyvinyl alcohol nanocomposites. Mater Lett. 2022;322:132473.10.1016/j.matlet.2022.132473Search in Google Scholar

[45] Jabir MS, Abood NA, Jawad MH, Öztürk K, Kadhim H, Albukhaty S, et al. Gold nanoparticles loaded TNF-α and CALNN peptide as a drug delivery system and promising therapeutic agent for breast cancer cells. Mater Technol. 2022;37(14):3152–66.10.1080/10667857.2022.2133073Search in Google Scholar

[46] Mohammed SA, Khashan KS, Jabir MS, Abdulameer FA, Sulaiman GM, Al-Omar MS, et al. Copper oxide nanoparticle-decorated carbon nanoparticle composite colloidal preparation through laser ablation for antimicrobial and antiproliferative actions against breast cancer cell line, MCF-7. BioMed Res Int. 2022;2022:1–13.10.1155/2022/9863616Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Abbas ZS, Sulaiman GM, Jabir MS, Mohammed SA, Khan RA, Mohammed HA, et al. Galangin/β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex as a drug-delivery system for improved solubility and biocompatibility in breast cancer treatment. Molecules. 2022;27(14):4521.10.3390/molecules27144521Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Jabir MS, Sulaiman GM, Taqi ZJ, Li D. Iraqi propolis increases degradation of IL-1β and NLRC4 by autophagy following Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Microbes Infect. 2018;20(2):89–100.10.1016/j.micinf.2017.10.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Khashan KS, Jabir MS, Abdulameer FA. Carbon Nanoparticles decorated with cupric oxide Nanoparticles prepared by laser ablation in liquid as an antibacterial therapeutic agent. Mater Res Express. 2018;5(3):035003.10.1088/2053-1591/aab0edSearch in Google Scholar

[50] Koli VB, Delekar SD, Pawar SH. Photoinactivation of bacteria by using Fe-doped TiO 2-MWCNTs nanocomposites. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 2016;27:1–10.10.1007/s10856-016-5788-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Samrot AV, Ram Singh SP, Deenadhayalan R, Rajesh VV, Padmanaban S, Radhakrishnan K. Nanoparticles, a double-edged sword with oxidant as well as antioxidant properties—a review. Oxygen. 2022;2(4):591–604.10.3390/oxygen2040039Search in Google Scholar

[52] Cinat D, Coppes RP, Barazzuol L. DNA damage-induced inflammatory microenvironment and adult stem cell response. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:729136.10.3389/fcell.2021.729136Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Bisht G, Rayamajhi S, Kc B, Paudel SN, Karna D, Shrestha BG. Synthesis, characterization, and study of in vitro cytotoxicity of ZnO-Fe3O4 magnetic composite nanoparticles in human breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231) and mouse fibroblast (NIH 3T3). Nanoscale Res Lett. 2016;11:1–11.10.1186/s11671-016-1734-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Kessler A, Hedberg J, Blomberg E, Odnevall I. Reactive oxygen species formed by metal and metal oxide nanoparticles in physiological media—a review of reactions of importance to nanotoxicity and proposal for categorization. Nanomaterials. 2022;12(11):1922.10.3390/nano12111922Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Seo SU, Kim TH, Kim DE, Min K-J, Kwon TK. NOX4-mediated ROS production induces apoptotic cell death via down-regulation of c-FLIP and Mcl-1 expression in combined treatment with thioridazine and curcumin. Redox Biol. 2017;13:608–22.10.1016/j.redox.2017.07.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Di Stefano A, Frosali S, Leonini A, Ettorre A, Priora R, Di Simplicio FC, et al. GSH depletion, protein S-glutathionylation and mitochondrial transmembrane potential hyperpolarization are early events in initiation of cell death induced by a mixture of isothiazolinones in HL60 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Cell Res. 2006;1763(2):214–25.10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.12.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Dikalov S. Cross talk between mitochondria and NADPH oxidases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51(7):1289–301.10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.033Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Matuz-Mares D, González-Andrade M, Araiza-Villanueva MG, Vilchis-Landeros MM, Vázquez-Meza H. Mitochondrial calcium: effects of its imbalance in disease. Antioxidants. 2022;11(5):801.10.3390/antiox11050801Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Hsiang CH, Tunoda T, Whang YE, Tyson DR, Ornstein DK. The impact of altered annexin I protein levels on apoptosis and signal transduction pathways in prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2006;66(13):1413–24.10.1002/pros.20457Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Arur S, Uche UE, Rezaul K, Fong M, Scranton V, Cowan AE, et al. Annexin I is an endogenous ligand that mediates apoptotic cell engulfment. Dev Cell. 2003;4(4):587–98.10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00090-XSearch in Google Scholar

[61] Solito E, De Coupade C, Canaider S, Goulding NJ, Perretti M. Transfection of annexin 1 in monocytic cells produces a high degree of spontaneous and stimulated apoptosis associated with caspase‐3 activation. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133(2):217–28.10.1038/sj.bjp.0704054Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[62] Tsukahara T, Matsuda Y, Haniu H. The role of autophagy as a mechanism of toxicity induced by multi-walled carbon nanotubes in human lung cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;16(1):40–8.10.3390/ijms16010040Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[63] Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Kauppinen A. Crosstalk between oxidative stress and SIRT1: impact on the aging process. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(2):3834–59.10.3390/ijms14023834Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] He X, Maimaiti M, Jiao Y, Meng X, Li H. Sinomenine induces G1-phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in malignant glioma cells via downregulation of sirtuin 1 and induction of p53 acetylation. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2018;17:1533034618770305.10.1177/1533034618770305Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[65] Lee IH, Cao L, Mostoslavsky R, Lombard DB, Liu J, Bruns NE, et al. A role for the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 in the regulation of autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(9):3374–9.10.1073/pnas.0712145105Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[66] Bashash D, Sayyadi M, Safaroghli-Azar A, Sheikh-Zeineddini N, Riyahi N, Momeny M. Small molecule inhibitor of c-Myc 10058-F4 inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in acute leukemia cells, irrespective of PTEN status. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;108:7–16.10.1016/j.biocel.2019.01.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[67] Yuan Y-G, Gurunathan S. Combination of graphene oxide–silver nanoparticle nanocomposites and cisplatin enhances apoptosis and autophagy in human cervical cancer cells. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:6537–58.10.2147/IJN.S125281Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[68] Setyawati MI, Yuan X, Xie J, Leong DT. The influence of lysosomal stability of silver nanomaterials on their toxicity to human cells. Biomaterials. 2014;35(25):6707–15.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Kroemer G, Jäättelä M. Lysosomes and autophagy in cell death control. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(11):886–97.10.1038/nrc1738Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[70] Lee T-Y, Liu M-S, Huang L-J, Lue S-I, Lin L-C, Kwan A-L, et al. Bioenergetic failure correlates with autophagy and apoptosis in rat liver following silver nanoparticle intraperitoneal administration. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2013;10:1–13.10.1186/1743-8977-10-40Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[71] Xu Y, Wang L, Bai R, Zhang T, Chen C. Silver nanoparticles impede phorbol myristate acetate-induced monocyte–macrophage differentiation and autophagy. Nanoscale. 2015;7(38):16100–9.10.1039/C5NR04200CSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[72] Zielinska E, Zauszkiewicz-Pawlak A, Wojcik M, Inkielewicz-Stepniak I. Silver nanoparticles of different sizes induce a mixed type of programmed cell death in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9(4):4675.10.18632/oncotarget.22563Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[73] Park E-J, Umh HN, Kim S-W, Cho M-H, Kim J-H, Kim Y. ERK pathway is activated in bare-FeNPs-induced autophagy. Arch Toxicol. 2014;88:323–36.10.1007/s00204-013-1134-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[74] Song F, Wang Y, Jiang D, Wang T, Zhang Y, Ma H, et al. Cyclic compressive stress regulates apoptosis in rat osteoblasts: involvement of PI3K/Akt and JNK MAPK signaling pathways. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0165845.10.1371/journal.pone.0165845Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface