Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

-

Fadi Althoey

, Adrian A. Șerbănoiu

, Mohamed M. Arbili

Abstract

Utilizing waste materials to produce sustainable concrete has substantial environmental implications. Furthermore, understanding the exceptional durability performance of ultra-high-performance concrete can minimize environmental impacts and retrofitting costs associated with structures. This study presents a systematic experimental investigation of eco-friendly ultra-high-performance self-compacting basalt fiber (BF)-reinforced concrete by incorporating waste nanomaterials, namely nano-wheat straw ash (NWSA), nano-sesame stalk ash (NSSA), and nano-cotton stalk ash (NCSA), as partial substitutes for Portland cement. The research evaluates the effects of varying dosages of nanomaterials (ranging from 5 to 15% as cement replacements) in the presence of BFs. Rheological properties were analyzed, including flow diameter, L-box, and V-funnel tests. Additionally, the study investigated compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths, load-displacement behavior, ultrasonic pulse velocity, and durability performance of the ultra-high-performance self-compacting basalt fiber (BF)-reinforced concrete (UHPSCFRC) samples subjected to sulfate attack, freeze-thaw cycles, autogenous shrinkage, and exposure to temperatures of 150, 300, 450, and 600°C. Microstructural characteristics of the mixtures were examined using X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The findings reveal that self-compacting properties can be achieved in the UHPSCFRC by incorporating NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA. The presence of 10% NWSA significantly improved the mechanical properties of the UHPSCFRC, exhibiting more than 27.55% increase in compressive strength, 17.36% increase in splitting tensile strength, and 21.5% increase in flexural strength compared to the control sample. The UHPSCFRC sample with 10% NWSA demonstrated superior performance across all extreme durability tests, surpassing both the control and other modified samples. XRD analysis revealed the development of microcracking at temperatures of 450 and 600°C due to the evaporation of absorbed and capillary water and the decomposition of ettringites.

Abbreviations

- BFs

-

basalt fibers

- Ca(OH)2

-

calcium hydroxide

- CSH

-

calcium silicate hydrate

- Na2SiO3

-

sulfate solution

- NCSA

-

nano-cotton stalk ash

- NSSA

-

nano sesame stalk ash

- NWSA

-

nano waste straw ash

- OPC

-

ordinary Portland cement

- SF

-

silica fume

- UHPC

-

ultra-high-performance concrete

- UHPSCFRC

-

ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber reinforced concrete

- UPV

-

ultrasonic pulse velocity

1 Introduction

Ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) has gained popularity because of its superior mechanical properties, durability, and resistance to environmental factors [1]. UHPC is a relatively new technology that has been developed and refined over the past few decades [2]. UHPC has compressive and tensile strengths higher than 150 and 10 MPa. UHPC achieves these exceptional engineering characteristics through specialized materials, including a high quantity of cement, silica fume (SF), quartz sand, steel fibers, and superplasticizers [3,4]. The development of UHPC can be traced back to the 1960s when researchers in France developed a high-strength, high-performance concrete called Ductal [5,6]. Using high-strength steel fibers in the mix enabled producing material with superior strength and durability [7]. In the 1990s, research in Germany and Japan led to the development of UHPC with even higher strength and durability properties [8]. UHPC has a wide range of applications due to its superior properties. It is commonly used in bridges, tunnels, and other infrastructure projects where high strength and durability are essential [9,10]. UHPC can also be used in architectural applications, such as constructing façades and cladding, due to its ability to achieve complex shapes and textures [11].

Due to its high strength and durability, UHPC can also be used in precast concrete elements, such as prefabricated panels and columns. Ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete (UHPSCFRC) is a relatively new and advanced form of concrete that combines several key features to create an exceptionally strong, durable material and is easy to work with [12,13,14,15]. The significance of UHPSCFRC lies in its ability to meet the needs of modern construction projects [16]. UHPSCFRC can flow into even the most complex shapes and contours without requiring external vibration or compaction [17,18,19,20]. This makes it ideal for use in structures with intricate shapes or designs, where traditional concrete may not provide sufficient coverage [21,22]. The UHPSCFRC is reinforced with fibers, which help to increase its toughness and resistance to cracking. This makes it ideal for use in structures exposed to significant stress, such as industrial facilities or high-rise buildings [23,24].

Utilization of high quantities of ordinary Portland cement (OPC) in UHPC can contribute to climate change [25] due to its product’s increased carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions [26]. The production of Portland cement is responsible for around 7% of global CO2 emissions, primarily due to the high temperatures required during manufacturing and using fossil fuels to power the kilns [27]. The present trend in lowering the outflow of CO2 is replacing OPC with pozzolanic materials [28]. Agricultural waste products rich in silica, such as wheat straw ash, cotton stalk ash, and sesame stalk, have been significantly used in different concrete types for years [6]. Using these agricultural waste products in concrete substantially lowers the stress on the atmosphere brought on by the development of conventional concrete [29,30,31]. Currently, researchers have been exploring the use of waste nanomaterials, such as nano-wheat straw ash (NWSA), nano-sesame stalk ash (NSSA), and nano-cotton stalk ash (NCSA), as potential alternatives to Portland cement in conventional, self-compacting, and high-performance concrete [32]. These materials are produced from agricultural waste and have the potential to not only reduce the carbon footprint of UHPC production but also provide a use for what would otherwise be waste materials [33].

NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA are all examples of agricultural waste products that can be converted into nano-sized ash through controlled combustion [34,35]. These waste products are extensively available in different places on the planet, and their use in construction materials could help reduce the construction industry’s environmental impact [36,37,38]. The use of these waste nanomaterials in UHPC can also offer several advantages. For example, NWSA has been shown to improve the compressive strength of UHPC while reducing its porosity and water absorption [39]. Similarly, NSSA and NCSA have been found to enhance the mechanical properties of UHPC, including its compressive and flexural strengths and abrasion resistance [40]. Various research has been performed to assess the behavior of agricultural by-products (NWSA, NSSA, NCSA) in concrete subjected to heating conditions. Minnu et al. [41] contrasted the behavior of concrete by adding 20, 30, and 50% slag, nano-sized bagasse ash, and fly ash as a partial substitute for OPC. The authors noted that the heat of hydration and workability reduces as the replacement ratio rises. The authors also revealed that the nano-sized bagasse ash had improved performance in resistance against chloride penetration and elevated temperature compared to fly ash and slag. Faried et al. [35] investigated the impact of various doses of nano agricultural waste ash in concrete subjected to different temperatures (300, 500, 700, and 900°C) for 3, 5, 7, and 9 h of burning. The authors observed that shapeless silica made the concrete stable when subjected to 700°C for 5 h [42].

Fibers play a crucial role in improving the behavior and performance of UHPC. They are typically added to UHPC mixtures to enhance their mechanical properties, durability, and resistance to cracking. The most commonly used fibers in UHPC are steel fibers, polymeric fibers (such as polypropylene and polyethylene fibers), and natural fibers (such as basalt fibers; BFs and coir fibers). Fibers act as reinforcement within the concrete matrix, providing additional tensile strength and improving the overall ductility of UHPC. Fibers enhance the concrete’s resistance to cracking and its toughness by effectively distributing stress and reducing crack propagation. This results in improved resistance against impact, shrinkage, and thermal effects. One of the limitations of UHPC is its low ductility, which can lead to brittle failure and cracking under tensile stresses [43,44,45,46,47,48]. This can be a severe problem in structural applications where the concrete is subjected to high stresses, such as bridges or high-rise buildings [49,50,51,52,53].

Researchers have investigated using BFs as a conventional and high-performance concrete reinforcement material [54]. BFs are derived from volcanic rock and have several attractive properties, including high tensile strength and modulus and good resistance to corrosion and fatigue [55]. Adding BFs to UHPSCFRC can help improve its tensile and flexural strengths, and durability in several ways [56]. The BFs enhance the behavior of concrete by bridging the effect. The bridging development of fibers in concrete refers to fibers’ ability to span across cracks and fissures that may develop within the concrete matrix [57]. The bridging effect occurs when the fibers are distributed evenly throughout the concrete matrix and oriented in a way that allows them to resist the tensile forces that cause cracking. As the concrete cracks, the fibers can bridge the fissure and transfer stress from one side of the crack to the other [58]. This helps to prevent further propagation of the crack and can significantly improve the strength and durability of the concrete. BFs improve the properties of UHPC by reducing the risk of shrinkage cracking. UHPC is a highly dense and compacted material that can cause shrinkage when curing. This shrinkage can cause cracking and degradation of the concrete [59]. However, BFs can help to mitigate this issue by reinforcing the concrete matrix, which helps to resist the forces that cause shrinkage cracking. BFs are highly resistant to corrosion and can help protect the concrete matrix from degradation over time [60]. This can be particularly important in harsh environments, such as marine or industrial settings, where the concrete is exposed to aggressive chemicals or saltwater.

BFs have excellent corrosion resistance properties. BFs are highly corrosion-resistant, unlike traditional steel reinforcements, which are prone to corrosion when exposed to moisture and chemicals. This characteristic makes UHPC reinforced with BF ideal for structures in harsh environments such as marine or coastal areas where corrosion is a significant concern. BFs have high tensile strength. They provide UHPC with enhanced crack resistance and improved structural integrity. Due to their exceptional strength-to-weight ratio, BFs can effectively distribute tensile forces throughout the UHPC matrix, reducing the formation and propagation of cracks. This attribute significantly improves the long-term durability of UHPC structures, ensuring they can withstand heavy loads, thermal cycling, and other external forces without compromising their structural integrity. BFs also offer superior resistance to alkaline environments. UHPC typically has a highly alkaline pH due to the presence of cementitious materials. This alkaline environment can degrade traditional steel reinforcements over time. However, BFs are highly resistant to alkaline attack, making them an excellent choice for UHPC applications. Their resistance to alkaline substances helps maintain the overall durability and lifespan of UHPC structures, even in aggressive environments.

Additionally, BFs have low thermal conductivity. This property reduces the risk of thermal cracking in UHPC exposed to extreme temperature variations. The fibers act as a barrier, inhibiting the transfer of heat within the concrete matrix and minimizing the differential expansion and contraction that can lead to cracks. This thermal stability enhances the durability of UHPC structures, particularly in regions with significant temperature fluctuations or applications where resistance to thermal stress is crucial. The introduction of BFs to UHPSCFRC can also boost its workability. BFs are relatively easy to mix in the concrete matrix, and they can help improve the flow and workability of the material [61]. This can be beneficial during the construction process, as it can help reduce the risk of segregation or blockages in the concrete mix. Compared to other fibers, such as steel or synthetic fibers, BFs have a much higher melting point and are less susceptible to thermal degradation [62]. Concrete with BFs can retain its strength and stiffness at higher temperatures, making the BFs an ideal choice for reinforcing UHPSCFRC in applications where elevated temperatures are a concern. These nano-sized ashes have been investigated for their potential to enhance the performance of UHPC. When added to the UHPC mix, these ashes can affect the concrete mixture’s flowability, workability, and viscosity. The nano-sized particles provide a high surface area, improving pozzolanic reactivity and cementitious properties. This results in better packing of particles and improved particle dispersion, leading to enhanced rheological characteristics [63,64,65,66]. Incorporating NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA in UHPC can lead to improved flowability, reduced segregation, and filling ability, resulting in a more homogeneous and compacted concrete matrix. These rheological enhancements can contribute to better overall performance and durability of UHPC structures, offering potential benefits for sustainable construction practices by utilizing agricultural waste materials as a partial substitute for Portland cement.

Due to the immense demand for high-rise structures and architecturally complex shapes of structures (towers, bridges), the need for ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced is increasing significantly. UHPSCFRC to be suitable for these commercial applications, the UHPSCFRC must be eco-friendly, have enhanced strength, and excellent durability in real-life conditions. Therefore, it is essential to develop an eco-friendly (low binder) UHPSCFRC with improved strength properties and excellent resilience in durability when exposed to extreme environmental conditions using waste industrial or agricultural waste by-products as a substitute for OPC.

2 Research significance

The current research addresses the development of highly improved and eco-friendly UHPSCFRC by incorporating various waste nanomaterials as partial substitutes for OPC. While previous studies have focused on enhancing UHPC properties, limited research has explored using different nano-sized waste materials in UHPSCFRC to achieve exceptional durability under extreme conditions. This study aims to bridge this research gap by evaluating the rheological properties (L-box, V-funnel, and flow diameter), strength properties (compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths, load displacement, and ultrasonic pulse velocity; UPV), durability properties (elevated temperature, sulfate attack, freezing and thawing, and shrinkage), and microstructural analysis (X-ray diffraction; XRD) of UHPSCFRC. BFs were incorporated in all mixtures, while 5, 10, and 15% NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA were utilized as partial replacements for OPC. This research contributes to developing environmentally friendly UHPC materials and helps reduce the construction industry’s carbon footprint. The achieved excellent workability and improved performance (strength and durability under extreme conditions) of UHPSCFRC enable structural engineers to design visually appealing and functionally superior structures, including those with complex shapes.

3 Experimental setup

3.1 Raw materials

The present research used Type I 53-grade cement as per ASTM C150 [67]. Quartz sand was employed as fine aggregates, and natural dolomite stone coarse aggregates were used as coarse aggregates. The physical characteristics of fine and coarse aggregates are provided in Table 1. The Mardan materials factory supplied the BFs (as presented in Figure 1) in the required size, and the BFs’ physical characteristics are displayed in Table 2. A third-generation ViscoCrete 3110 polycarboxylate ether-based superplasticizer admixture as per EFNARC guidelines [68] was employed and mixed in the fresh concrete to make UHPSCFRC.

Physical characteristics of fine and coarse aggregates

| Property | Fine aggregate | Coarse aggregate |

|---|---|---|

| Particle size (mm) | <3.7 | <12 |

| Fineness modulus | 2.7 | 6.5 |

| Specific gravity | 2.8 | 2.9 |

| Water absorption (%) | 1.7 | 0.75 |

| Surface texture | Smooth | Rough and angular |

| Shape | Rounded | Angular and irregular |

| Porosity | Low | Low |

| Density (kg/m³) | 1,600 | 1,750 |

| Color | Light gray | Dark gray |

Physical appearance of straight-BFs.

Physical characteristics of BFs

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Tensile strength | 4.8 GPa |

| Young’s modulus | 85 GPa |

| Elongation at break | 4% |

| Density | 2.8 g/cm³ |

| Thermal conductivity | 0.03–0.04 W/m K |

| Melting point | ∼1,300°C |

| Water absorption | <1% |

| Chemical resistance | Resistant to acids and alkalis |

| Flame resistance | Non-flammable |

| Electrical conductivity | Non-conductive |

The agricultural waste materials, such as NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA, as shown in Figure 2a–c, were all collected from the local farm in Nowshera City, Pakistan. For making nano-sized material for NWSA, the process began with collecting wheat straw residues and thoroughly cleaning them to remove impurities. The cleaned wheat straw was then dried to eliminate moisture. Next controlled combustion (650°C for 3 h) was performed to convert the dried wheat straw into wheat straw ash. To achieve nano-sized particles, high-energy ball milling techniques were employed to reduce the particle size of the ash. For NSSA, a similar approach is followed. Sesame stalk residues were collected and prepared by eliminating any foreign materials. After thoroughly cleaning, the stalks were dried, followed by controlled combustion (650°C for 3 h). A high-energy ball milling method was employed to achieve the desired nano-sized particles.

(a) NCSA, (b) NSSA, and (c) NWSA.

Similarly, for NCSA, cotton stalk residues were collected and cleaned to remove impurities. The stalks were dried, followed by controlled combustion (650°C for 3 h) to produce cotton stalk ash. A specialized method like high-energy ball milling was employed for further nano-sizing. These techniques involve extended milling durations and grinding media to reduce the particle size to the nano-scale range. After ball milling, the materials were sieved, respectively.

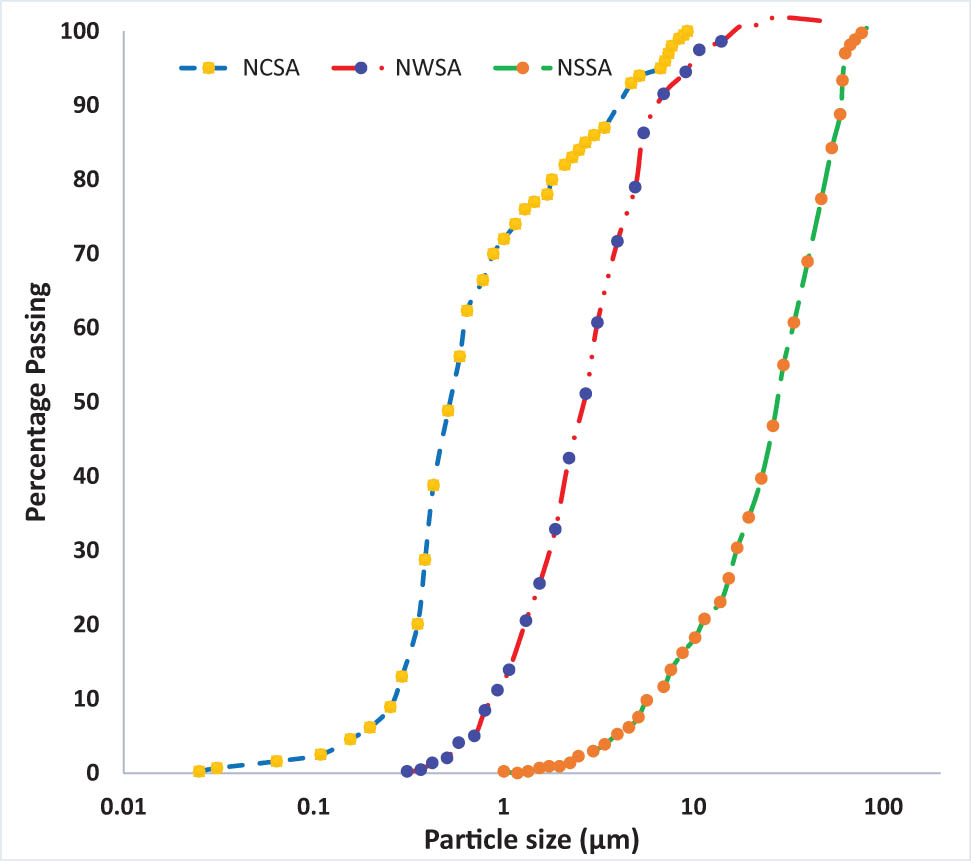

Chemical characterization of NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA was also done, and Table 3 presents the chemical arrangement of OPC, SF, NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA. The specific surface area of OPC, SF, NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA was 358, 14,505, 1,437, 1,213, and 1,581 m2/g, and the particle size gradation of NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA as per ASTM C136 [69] is presented in Figure 3.

Chemical composition of binders

| Chemical composition | OPC (%) | NWSA (%) | NSSA (%) | NCSA (%) | SF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 21.3 | 79.2 | 55.7 | 61.9 | 97.9 |

| Al2O3 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 13.8 | 13.6 | 0.5 |

| Fe2O3 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 0.5 |

| CaO | 63.6 | 1.8 | 14.6 | 12.5 | 0.1 |

| MgO | 2.5 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.1 |

| SO3 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| Na2O | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| K2O | 0.6 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 0.1 |

| TiO2 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.6 | — |

| Mn2O3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | — |

| Loss in Ignition | 0.2 | 2 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

Gradation of NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA.

3.2 Mix proportion and development of UHPSCFRC samples

All the concrete mixes were developed following EFNARC guidelines [68]. Every mixture had the same quantity of OPC + SF (875 + 110 kg/m3). Four diverse batches of concrete were established. The 1st batch was termed a Control sample, which did not have any quantity of NWSA, NSSA, or NCSA. Then, the second, third, and fourth batches of concrete had 5, 10, and 15% of NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA as partial cement substitutes. The water-to-binder ratio was kept at 0.195 with 192 kg/m3 water in every concrete batch with BFs (by binder’s weight) added to the mixture. Complete specifics of the mix design are displayed in Table 4.

Mix design of complete mixtures (kg/m3)

| Batch | Mix ID | OPC | SF | FA | CA | NWSA | NSSA | NCSA | BFs | Water | SP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First batch | Control | 875 | 110 | 465 | 480 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 85 | 192 | 28 |

| Second batch | B2-NWSA-5 | 825.75 | 110 | 465 | 480 | 49.25 | 0 | 0 | 85 | 192 | 28 |

| B2-NWSA-10 | 776.5 | 110 | 465 | 480 | 98.5 | 0 | 0 | 85 | 192 | 28 | |

| B2-NWSA-15 | 727.25 | 110 | 465 | 480 | 147.75 | 0 | 0 | 85 | 192 | 28 | |

| Third batch | B3-NSSA-5 | 825.75 | 110 | 465 | 480 | 0 | 49.25 | 0 | 85 | 192 | 28 |

| B3-NSSA-10 | 776.5 | 110 | 465 | 480 | 0 | 98.5 | 0 | 85 | 192 | 28 | |

| B3-NSSA-15 | 727.25 | 110 | 465 | 480 | 0 | 147.75 | 0 | 85 | 192 | 28 | |

| Fourth batch | B4-NCSA-5 | 825.75 | 110 | 465 | 480 | 0 | 0 | 49.25 | 85 | 192 | 28 |

| B4-NCSA-10 | 776.5 | 110 | 465 | 480 | 0 | 0 | 98.5 | 85 | 192 | 28 | |

| B4-NCSA-15 | 727.25 | 110 | 465 | 480 | 0 | 0 | 147.75 | 85 | 192 | 28 |

OPC – ordinary Portland cement, SF – silica fume, FA – fine aggregate, CA – coarse aggregate, NWSA – nano-wheat straw ash, NSSA – nano-sesame stalk ash, NCSA – nano-cotton stalk ash, BFs – basalt fibers, SP – superplasticizer.

Mixing raw materials was done by following EFNARC guidelines [67] to develop self-compacting concrete. A high-shear mixer was used to create freshly mixed concrete. The high-shear mixer is designed to apply intense shear forces to the mixture, which helps break up agglomerates and ensure that all components are uniformly distributed. This is important because UHPSCFRC is typically used in applications where high strength and durability are critical, such as in bridge construction, precast concrete components, and high-rise buildings. High-shear mixers also reduce the mixing time required to achieve a homogenous mixture, allowing for faster production times and increased efficiency. Additionally, the high-shear mixer can help to prevent the fibers from clumping together, which can cause weak spots in the final product.

First, fine and coarse aggregates were blended for 3 min, then cement and SF were added to the mixer and mixed for 2 min. Then, half of the water was introduced to the mixer, and then nanomaterials for every specific batch of concrete were added to the mixer. The speed of the mixer was increased to ensure the uniform dispersion of nanomaterials in concrete, followed by superplasticizer and mixed for further 2 min. Then, the remaining water was introduced and mixed for 3 min. Finally, BFs were added to the mixer at low speed to certify the consistent spreading of fibers in the concrete, and the mixing was continued for another 3 min. The freshly mixed concrete was poured into plastic molds and placed at ambient conditions. After 24 h, the molds were removed and put in a curing tank. Three samples for each test mixture were prepared and tested to maintain homogeneity and consistency in the test results. The average value of those three samples was taken as a final test value.

4 Test methods

4.1 Fresh properties of UHPSCFRC

In the present study, slump flow, L-box, and V-funnel tests were conducted to assess the fresh concrete properties because these tests are the most common worldwide. The slump flow properties of UHPSCFRC were evaluated as per ASTM C1611 [70]. The L-box test is designed to assess the flowability of the concrete by evaluating the height of the concrete flow through the L-shaped box. The concrete sample is placed in the L-box and permitted to flow through the bottom opening. The height of the concrete flow is then measured and used to calculate the ratio of the height of the concrete on the short side to the height of the concrete on the long side of the box. This ratio is used to determine the flowability of the concrete, with higher ratio indicating better flowability.

The V-funnel test is used to evaluate the workability of the concrete by measuring the time taken for the concrete to flow through the V-funnel apparatus. The concrete sample is poured into the funnel and allowed to flow through the bottom opening. The time taken for the concrete to flow through the funnel is then recorded, and the flow time is used to determine the workability of the concrete. A shorter flow time indicates better workability. It is essential to follow the EFNARC guidelines to ensure accurate and precise testing. The L-box and V-funnel tests were conducted on a level surface to eliminate any bias in the results.

4.2 Strength properties of UHPSCFRC

4.2.1 Compressive strength test

This test is one of the highly common tests for assessing the strength properties of concrete. It was conducted as per ASTM C39 [71] standard and involved preparing cylindrical concrete specimens with a diameter of 150 mm and a length of 300 mm. The loading rate for compressive strength tests was 0.2–0.4 MPa/s. The samples were then placed in a compression testing machine and subjected to a compressive load at a uniform rate until they failed.

4.2.2 Splitting tensile strength test

The splitting tensile strength test is employed to determine the tensile strength of concrete. It was performed as per ASTM C496 [71] standard and involved preparing cylindrical or prismatic specimens with a diameter of 150 mm and a length of 300 mm. The loading rate for splitting tensile strength tests was around 0.02–0.04 MPa/s. Three specimens were then placed in a compression testing machine and subjected to a compressive load along the longitudinal axis of the specimen until they cracked in splitting.

4.2.3 Flexural strength test

The flexural strength test is used to evaluate the modulus of rupture of concrete. The test setup for the flexural strength of UHPSCFRC is presented in Figure 4(a). It was carried out as per ASTM C1609 [72] standard and involved preparing rectangular prismatic specimens with dimensions of 500 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm (length × width × thickness). The loading rate ranged from 0.025 to 0.05 MPa/s as well. The specimens were then placed in a four-point loading fixture and subjected to a third-point load until crack failure occurred. These loading rates ensured a gradual and controlled load application, allowing for accurate measurement of the respective strengths while minimizing the potential for sudden failures or localized stress concentrations.

(a) Test setup for flexural strength of UHPSCFRC. (b) The schematic diagram for the elevated temperature test of UHPSCFRC. (c) Test setup for shrinkage of UHPSCFRC.

4.2.4 Load-displacement test

During the load-displacement test, cylindrical specimens with 150 mm diameter and 300 mm height were prepared and cured for 28 days. The test was then performed using a universal testing machine that applied a vertical load on the specimen and measured the displacement. The loading rate was controlled constantly, and the maximum load capacity was recorded. The specimen’s behavior was monitored during the test, including the load–displacement relationship, the cracking pattern, and the failure mode. The load–displacement curve is usually analyzed to determine the compressive strength, modulus of elasticity, and toughness of the concrete. The crack pattern was studied to evaluate the effectiveness of fiber reinforcement in controlling crack propagation. Finally, the failure mode was analyzed to identify the mechanisms that contributed to the specimen’s failure, which can provide insights into the material’s behavior and the design of structures.

4.2.5 UPV test

UPV testing is a non-destructive method used to evaluate the quality and consistency of concrete. ASTM C597 [73] provides the procedure for performing UPV on UHPSCFRC. The test involves sending an ultrasonic pulse through the concrete and measuring the time taken for the pulse to travel through the concrete. The time taken for the pulse to travel through the concrete is used to calculate the velocity of the wave, which is then used to determine the quality and consistency of the concrete. To perform the test, cube-shaped test specimens are prepared according to the specifications of the standard and allowed to cure for a specified period. The dimensions of the test specimen are then measured, and the surface of the specimen is cleaned to ensure proper transmission of the ultrasonic waves. The transducers are placed at opposite ends of the sample, and the ultrasonic pulse is sent through the sample. The time taken for the pulse to travel through the specimen is measured, and the velocity of the wave is calculated using the equation:

4.3 Durability properties of UHPSCFRC

4.3.1 Exposure of UHPSCFRC to elevated temperature

Exposure to elevated temperatures is a common concern for concrete structures, especially those in high-temperature environments such as furnaces, fire-resistant structures, and nuclear reactors. The loss of mass and residual compressive strength of UHPSCFRC due to high temperatures are determined. The test involves exposing UHPSCFRC specimens to elevated temperatures of up to 600°C and measuring the loss in mass and residual compressive strength. To perform the test, cylindrical UHPSCFRC at 28 days of curing specimens were arranged according to ISO-834 [74]. The schematic diagram for heating and cooling is presented in Figure 4(b). The specimens were then exposed to 150, 300, 450, and 600°C in an electric-powered furnace for 3 h. After 3 h, the specimens were removed from the furnace and cooled to room temperature (18°C). The samples were then weighed to determine the loss in mass due to the high-temperature exposure. To determine the residual compressive strength of the specimens, the specimens were tested using a compression testing machine. The samples were placed in the testing machine, and compressive loads were applied until failure occurred. The compressive strength of the samples was then calculated using the maximum load sustained during the test. The test results were used to evaluate the suitability of UHPSCFRC for use in high-temperature environments. The loss in mass and residual compressive strength of the specimens can provide insight into the performance of UHPSCFRC under high-temperature conditions.

4.3.2 Sulfate attack test

To perform a sulfate attack test on UHPSCFRC, cylindrical samples with a height of 200 mm and diameter of 100 mm were prepared using a UHPSCFRC mixture mixed with sodium sulfate. The mix is then cured for 90 days in standard conditions. A sulfate solution (Na2SiO3) is prepared by dissolving 5% of Na2SiO3 in water. The cured specimens were then placed in a cylindrical mold made of PVC with a height of 200 mm and diameter of 100 mm, and the mold was filled with the prepared sulfate solution. The solution was kept at a temperature of 23 ± 2°C for 90 days. The specimens were observed at regular intervals to check for any surface cracks or damage, and the weight of the samples was measured to determine the compressive strength and loss of mass due to sulfate attack. After 90 days, the specimens were removed from the mold and washed with water. The residual compressive strength and the weight loss due to sulfate attack for 90 days were then calculated.

4.3.3 Freezing and thawing test

During the freeze and thaw test, cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 100 mm and a height of 200 mm were prepared and cured at 90 days. The samples were then subjected to 100, 200, and 300 freezing and thawing cycles. During each cycle, the specimens were immersed in water at −18°C for 4 h and thawed at 20°C for 20 h. After the last cycle, the samples were dried, and their residual compressive strength was calculated. The freezing and thawing test provides insights into the durability of UHPSCFRC under cold weather conditions and can be used to improve the design of structures in cold regions.

4.3.4 Shrinkage

ASTM C157 [75] was followed to evaluate the shrinkage of UHPSCFRC. During this test, strain gauges were attached to those hardened concrete samples (285 mm length × 76 mm width × 76 mm thickness) when the freshly mixed concrete samples were removed from the mold. The instrumented samples were placed in a temperature and humidity-controlled chamber. The test setup for the shrinkage test is displayed in Figure 4(c). The recording data and shrinkage were monitored regularly throughout the testing period of 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 56, 90, 120, and 180 days.

4.4 XRD analysis

The XRD analysis is a powerful technique used to determine the crystallographic structure and composition of materials. For UHPSCFRC, XRD analysis can provide valuable insights into the phase analysis of the concrete. To perform XRD analysis, a representative sample of UHPSCFRC is collected and pulverized to a fine powder. The sample is then mounted onto a glass slide or quartz holder and analyzed using an XRD machine. The XRD machine generates an X-ray beam that is directed onto the sample, and the diffracted X-rays are detected and recorded as a diffraction pattern. The diffraction pattern is then analyzed to identify the crystal structure of the UHPSCFRC, which can be used to determine the type and amount of mineralogical phases present in the concrete. XRD analysis can provide important information about the composition and structure of UHPSCFRC, which can be used to optimize the concrete mixture and improve its performance.

5 Results and discussions

5.1 Fresh characteristics of UHPSCFRC

5.1.1 Flow diameter

Figure 5 shows the flow diameter of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete. Various test trials were tried to maintain and certify the required workability properties. The samples with NWSA had an improved flow diameter than the second and third batches of samples, but still, the flow diameter was lesser than that of the control mixture. The flow diameter of UHPSCFRC was improved from the second and third batches by adding NWSA due to the unique properties of NWSA. Unlike NSSA and NCSA, NWSA contains more silica, alumina, and pozzolanic materials that can contribute to the cementitious reaction. The pozzolanic reaction between NWSA and the cementitious materials in the mix results in the formation of additional reaction products, such as calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gel [76]. This gel can fill the gaps or empty spaces between the aggregate particles, increasing the volume of the paste. As a result, the mix becomes more fluid, leading to a larger flow diameter or improved flowability. Additionally, the use of NWSA can reduce the water demand of the mix due to its ability to adsorb water and increase the workability of the mix, increasing flow diameter. Introducing 5, 10, and 15% NSSA reduced the flow diameter of the control mixture from 812 to 801, 787, and 779 mm, correspondingly. This can be ascribed to the hydrophilic behavior and nano-sized particles of NSSA. When NSSA is added to the fresh concrete, the nano-sized particles can agglomerate and form clusters, leading to an increase in the effective particle size of the mix. These results are also in conformation with the past research [77]. This increase in particle size can reduce the fluidity of the mix, leading to a reduction in flow diameter. Additionally, the presence of NSSA particles can result in a higher water demand to maintain workability, which can further reduce the flow diameter of the UHPSCFRC mix. Adding NCSA, even more reduced the flow diameter of the mixture more than the second batch of mixes.

Flow diameter of UHPSCFRC.

The flow diameter was reduced to 809, 755, and 736 mm by adding 5, 10, and 15% NCSA. This could be attributed to the poor absorption capability of nanomaterials in comparison to OPC. One reason for the decrease in the flow diameter of UHPSCFRC is the pozzolanic reaction between NCSA and the cementitious materials in the mix. NCSA is a waste product from the cotton industry and contains high amounts of silica and alumina, which are pozzolanic materials [78]. When NCSA is added to the UHPSCFRC mix, it undergoes a pozzolanic reaction, forming additional reaction products, such as C–S–H gel [79]. This gel can fill the voids between the particles of aggregate, which increases the paste’s volume and enhances the mix’s flow diameter [80]. However, it is important to note that the reaction between NCSA and the cementitious materials may consume water, which can reduce the mix’s workability and decrease flow [32].

5.1.2 L-box and V-funnel

Figure 6(a) presents the L-box test outcomes of UHPSCFRC. The test results show a reduction in L-box results for all mixtures compared to the control sample. The test results of the L-box ranged from 0.87 to 0.78 for B2, 0.84 to 0.77 for B3, and 0.9 to 0.85 for B4 samples as compared to 0.94 for the control mixture. Hence, NWSA has attained high workability due to the high specific surface area and improved pore distribution than the NSSA and NCSA. NWSA contains more silica, alumina, and pozzolanic materials that can contribute to the cementitious reaction. The pozzolanic reaction that occurs between NWSA and the cementitious materials in the mix results in the formation of additional reaction products, such as C–S–H gel [80]. This gel can increase the paste volume, fill the voids between the aggregate particles, and improve the rheology of the mix [81]. Moreover, NWSA has a high surface area and can absorb water, which can lead to a reduction in the water demand of the mixture and an improvement in the workability of the mix [82]. This improvement in workability can lead to a decrease in the segregation and bleeding of the mix during the L-box test, resulting in an improvement in the L-box test results of UHPSCFRC. Figure 6(b) shows the V-funnel test results of UHPSCFRC. The test outcome shows that all the fresh mixtures of UHPSCFRC have met the conditions required by the self-compacting concrete [32]. The control sample has a v-funnel time of 6.2 s which was increased to 9.5, 9.2, and 8.8 s by adding 5, 10, and 15% NSSA, NCSA, and NWSA, respectively. The increase in v-funnel time can be credited to the high fineness of the nanomaterials than the OPC [83].

(a) L-box and (b) V-funnel test results of UHPSCFRC.

5.2 Strength characteristics of UHPSCFRC

5.2.1 Compressive strength

The compressive strength of all mixtures at 28 and 90 days of curing is presented in Figure 7. The results indicate that the compressive strength of UHPSCFRC can be significantly improved by adding NWSA at various dosages. At 28 and 90 days of curing, the B2-NWSA-10 attained the highest compressive strength among other mixtures, with 149.2 and 172.4 MPa. This is mainly due to the higher content of silica and alumina in NWSA, which are pozzolanic materials that can participate in the cementitious reaction, resulting in the formation of additional reaction products such as C–S–H gel. This gel can fill the voids between the aggregate particles, increasing the strength of the mix. Additionally, the use of NWSA can reduce the water demand of the mix due to its ability to adsorb water and increase the workability of the mix, leading to a denser and more homogenous mixture that can result in higher compressive strength [81].

Compressive strength of UHPSCFRC at 28 and 90 days.

Furthermore, similar studies have shown that the compressive strength of UHPSCFRC with NWSA increases with an increase in the dosage of nanomaterials up to an optimal dosage [41]. For instance, a study conducted by Faried et al. [35] found that the compressive strength of UHPSCFRC increased up to 45% with the addition of nano-sized agricultural ash material compared to the control mix without nanomaterial. However, the compressive strength results of UHPSCFRC at 28 and 90 days with 5% NWSA were 4.39 and 4.17% lower than those with 10% NWSA due to the insufficient pozzolanic reaction. The optimal dosage of NWSA can result in the highest densification and homogenization of the mix, leading to the highest compressive strength results [84,85]. In comparison, using NSSA and NCSA in UHPSCFRC resulted in lower compressive strength than NWSA. With adding 5 and 10% NSSA and NCSA, the compressive strength of concrete was increased to 11.34, 13.67, 9.76, and 11.41%, respectively, at 90 days, but when 15% NSSA and NCSA were added to the UHPSCFRC, the compressive strength was reduced up to 6.06 and 8.17% than B3-NSSA-10 and B4-NCSA-10 at 90 days. Among the modified mixtures, the sample with 15% NCSA had the lowermost compressive strength at 90 days with 120.94 MPa. This is mainly due to the lower silica and alumina content in NSSA and NCSA, which limits their pozzolanic activity and their inability to improve the workability of the mix [86]. For example, a study conducted by Wu et al. [6] showed that the compressive strength of UHPSCFRC with 10% NSSA was 8% lower than that with 10% NWSA.

Similarly, another study conducted by Li et al. [34] found that the compressive strength of UHPSCFRC with 10% nano-limestone ash was 10% lower than that with 10% nano-silica. In addition to the lower silica and alumina content, another reason NSSA and NCSA could not improve the compressive strength as much as NWSA is their chemical composition. Studies have shown that NSSA and NCSA contain higher alkali and alkaline earth metals, such as potassium and magnesium, than NWSA. These metals can have a negative effect on the strength of concrete by causing the formation of expansive reaction products, such as alkali-silica reaction gel, which can result in cracking and deterioration of the concrete over time. Moreover, the presence of these alkali and alkaline earth metals in NSSA and NCSA can also lead to a reduction in the workability of the mix and an increase in the water demand due to their ability to absorb water. This can result in a less dense and homogenous mixture, negatively affecting the compressive strength results [87].

5.2.2 Splitting tensile strength of UHPSCFRC

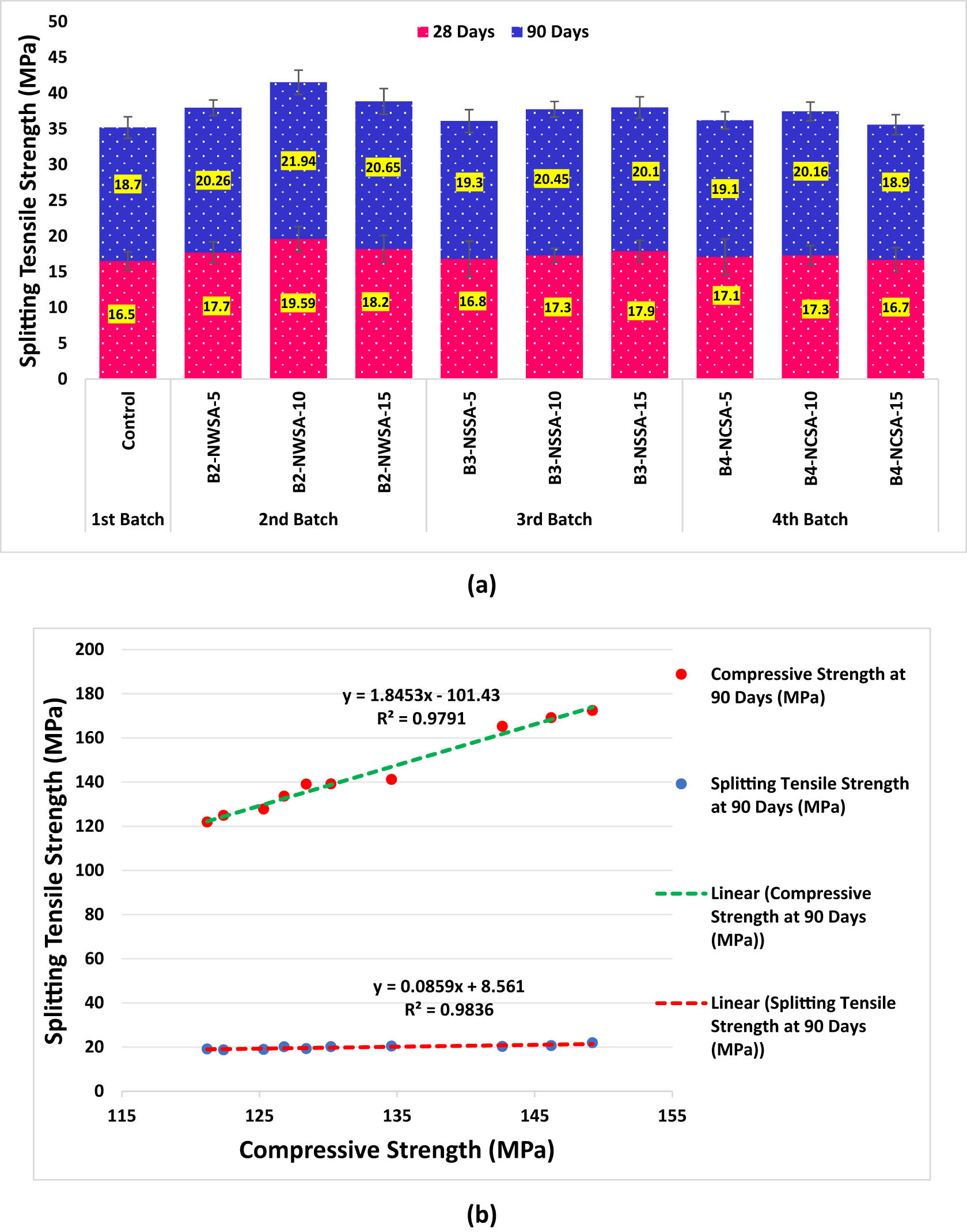

The test results of the splitting tensile strength of UHPSCFRC are presented in Figure 8. Figure 8(a) shows that by adding NWSA, the splitting tensile strength of UHPSCFRC was improved significantly than the samples with NSSA and NCSA. With 10% NWSA, the splitting tensile strength enhanced by 17.36% compared to the control sample at 90 days of curing. While at 5 and 15% NWSA, the splitting tensile strength was improved by 8.37 and 10.46% at 90 days, respectively. Among all mixtures, B4-NWSA-10 had the highest splitting tensile strength of 19.59 and 21.94 MPa at 28 and 90 days. This highlights the importance of carefully selecting the appropriate amount of supplementary cementitious material to achieve the desired properties of the concrete mix. To further support the effectiveness of NWSA in enhancing the splitting tensile strength of UHPSCFRC, it is essential to note that the outcomes align with previous studies on using pozzolanic materials in concrete [23,88,89].

(a) Splitting tensile strength of UHPSCFRC. (b) Linear regression analysis to estimate splitting tensile strength.

Adding 5, 10, and 15% NSSA and NCSA did not lead to the most improved strength. However, the splitting tensile strength of UHPSCFRC was still higher than the control mixture in all combinations, and some percentage of splitting tensile strength was enhanced by adding NSSA and NCSA. At 90 days, the splitting tensile strength of UHPSCFRC with NSSA and NCSA was increased up to 9.36 and 7.85%, and the sample with 15% NCSA had the lowermost splitting tensile strength of 18.9 MPa at 90 days among all other modified mixtures. One potential reason why NSSA and NCSA were not as effective in improving the splitting tensile strength of UHPSCFRC as NWSA could be attributed to differences in their chemical composition [87]. It is known that the chemical composition of supplementary cementitious materials can significantly impact their pozzolanic activity and effects on concrete properties [90]. For instance, NWSA contains a higher percentage of silica and alumina than NSSA and NCSA, which are the key components responsible for the pozzolanic activity of the material. Silica and alumina are known to react with calcium hydroxide, a byproduct of cement hydration, to form additional C–S–H gel, which contributes to the strength and durability of concrete [91]. Additionally, the particle size distribution of the pozzolanic material can also influence its effectiveness in enhancing the properties of concrete. NWSA has a finer particle size distribution than NSSA and NCSA, which may allow for more efficient utilization of the material in the concrete mix and promote a better pozzolanic reaction. Hence, the lower silica and alumina content and larger particle size distribution of NSSA and NCSA may have contributed to their reduced effectiveness in improving the splitting tensile strength of UHPSCFRC compared to NWSA. In addition to the pozzolanic activity of NWSA, using fibers in UHPSCFRC also contributes to the improvement of splitting tensile strength [92]. The BFs act as reinforcement, distributing the tensile stresses more uniformly throughout the concrete and reducing the occurrence and spread of cracking [93].

To evaluate the splitting tensile strength of concrete at 28 and 90 days and to establish a statistical correlation between the compressive strength at 90 days and splitting tensile strength at both 28 and 90 days, a linear regression analysis was conducted, as illustrated in Figure 8(b). This analysis aimed to derive a statistical relationship between the various strength values. The statistical relationship presented in Figure 8(b) enables the estimation of splitting tensile strength at 28 and 90 days based on the corresponding compressive strength values at 90 days. The R-squared values were close to unity, indicating a strong correlation between the compressive strength and splitting tensile strength values. Moreover, the projected values were found to have a consistency of over 90% for splitting tensile strength, confirming the accuracy of the test results.

5.2.3 Flexural strength

Figure 9(a) presents the test outcomes of the flexural strength of UHPSCFRC at 90 days. The flexural strength of UHPSCFRC increased by adding NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA. The observed increase in flexural strength of UHPSCFRC with the addition of NWSA compared to NSSA and NCSA can be attributed to the unique chemical and physical properties of NWSA. NWSA has a high content of SiO2, which acts as a pozzolanic material and reacts with Ca(OH)2 to develop C–S–H gel, the main binder in concrete [94]. Additionally, NWSA has a large specific surface area, which enhances the nucleation and growth of C–S–H gel, leading to better interfacial bonding between the matrix and fibers. The flexural strength of B2-NWSA-10 was 21.5% higher than the control sample (24.6 MPa). At 5 and 10% NSSA and NCSA, the flexural strength of UHPSCFRC was also increased but not higher than samples with 5 and 10% NWSA.

(a) Flexural strength of UHPSCFRC. (b) Linear regression analysis to estimate splitting tensile and flexural strength.

A reduction in flexural strength was observed at 15% NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA. The concept of optimum dosage can explain the higher flexural strength with 10% NWSA compared to 5 and 15%. It is recognized that the effect of pozzolanic materials on concrete strength follows a bell-shaped curve, where an optimal amount of pozzolan is required to achieve maximum strength. In the present study, 10% NWSA seems to be the optimal dosage, where any decrease or increase in NWSA leads to reduced flexural strength. Also, the effectiveness of the BFs in improving the flexural strength of UHPSCFRC has played a role in the observed results [95]. BFs have high tensile strength, excellent adhesion to the matrix, and good chemical and thermal stability [96]. These properties make them a suitable reinforcement material for concrete, particularly in arresting and bridging cracks which stops the dispersal of cracking and ultimately improves the flexural strength [97]. Adding BFs to the concrete matrix resulted in a more efficient load distribution, leading to a higher resistance to bending and cracking [98]. The lower silica content in NSSA and NCSA, compared to NWSA, might explain their less significant improvement in the flexural strength of UHPSCFRC. Silica is vital for creating calcium silicate hydrate gel, the main binder in concrete, and its lower content may result in reduced pozzolanic activity and flexural strength enhancement.

A polynomial regression analysis was conducted to assess the correlation between compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and flexural strength, as shown in Figure 9(b). The purpose was to determine a polynomial relationship between these strength values. The statistical analysis presented in Figure 9(b) allows for estimating splitting tensile and flexural strength values for a given specimen using the corresponding compressive strength values at 90 days. The R-squared values were close to unity, indicating a high degree of correlation between the three strength values. Specifically, the R-squared values were 97 and 91% for splitting tensile and flexural strength, respectively. These high values demonstrate the accuracy of the test results and suggest that the estimated values have a constancy of over 90%.

5.2.4 Load-displacement behavior of UHPSCFRC

Figure 10 illustrates the load-displacement behavior of UHPSCFRC specimens subjected to bending load. Initially, the curve showed a linear slope up to the primary crack, followed by a strain relaxation phase for all UHPSCFRC samples. The load-displacement curve of the control sample exhibited a similar response to the modified sample until the onset of cracking. Notably, adding NWSA up to an optimal concentration of 10% significantly increased the concrete’s ductility. The optimized mix displayed enhanced toughness, high residual strength, and reduced load relaxation compared to NSSA samples and NCSA. The test indicated that UHPSCFRC with 10% NWSA could withstand external loading before cracking. However, adding nanomaterials beyond the optimal dose led to concrete stiffening, reducing the ductility compared to samples with 10% NWSA. The BFs entirely supported the cracked portion of UHPSCFRC during the after-crack process. Adding BFs in UHPSCFRC is crucial in improving the load-displacement test results. BFs have excellent mechanical properties such as high tensile strength, stiffness, and superior chemical and thermal degradation resistance [99]. These properties make them ideal reinforcement materials for UHPSCFRC. BFs can help to prevent cracks from propagating and increase the flexural strength of the concrete. BFs provide toughness to the concrete, enabling it to withstand sudden impact loads and reducing the risk of brittle failure [95].

Load–displacement test of UHPSCFRC.

Another reason NSSA and NCSA did not improve the load-displacement behavior of UHPSCFRC as much as NWSA could be due to differences in their chemical composition and physical properties. For example, NSSA and NCSA may contain lower amorphous silica levels than NWSA, affecting their reactivity and ability to form strong bonds with the cement matrix. The different ashes’ particle size and surface area may also affect their performance. Smaller particles and higher surface areas can lead to better interfacial contact and improved bonding. Furthermore, optimizing the packing density of UHPSCFRC by adding 10% NWSA is a critical factor in enhancing the load-displacement test results. The packing density of concrete refers to the volume fraction of solid particles in the mixture, including aggregate, cement, and other supplementary materials [100]. A higher packing density results in a more homogeneous mixture, improving the interfacial bonding between the cementitious matrix and the reinforcement material. NWSA’s unique properties, such as its high silica content, improve the packing density of the concrete mixture by filling the gaps between the larger particles, resulting in a denser and more uniform microstructure.

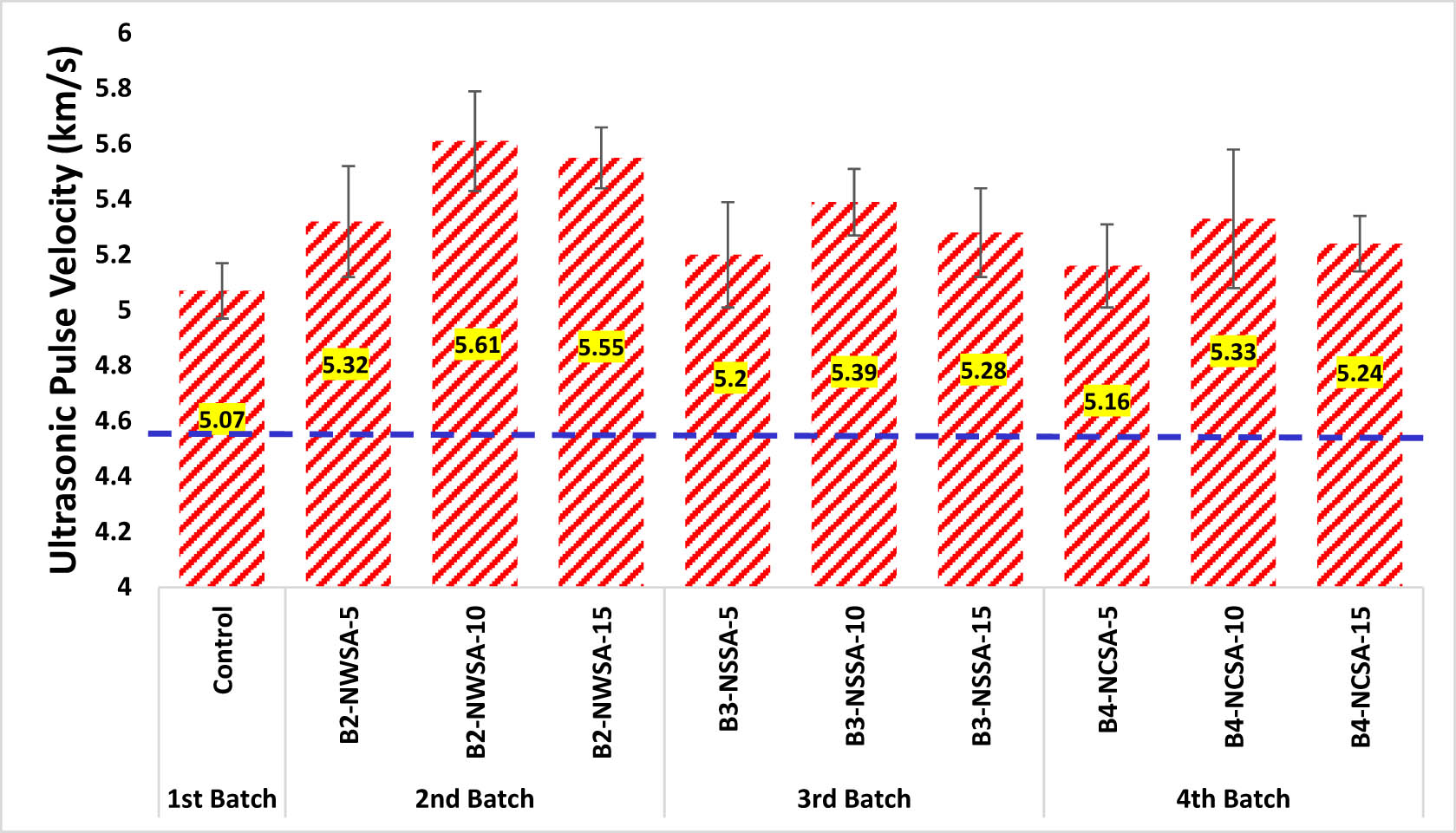

5.2.5 UPVs

The test result of UPV for all samples is exhibited in Figure 11. UPV results show that B2-NWSA-10 had the most improved UPV response among all the samples, followed by B3-NSSA-10 and B4-NCSA-10. The mixture B2-NWSA-10 had a 9.62% higher UPV value than the control sample. It is important to emphasize that all modified UHPSCFRC samples containing NWSA, NSSA, or NCSA showed enhanced performance (5.93 and 4.87%) compared to the control sample. This improvement can be attributed to several factors, including modifying the microstructure, providing additional nucleation sites, and reducing porosity within the concrete matrix [101]. By incorporating these nanomaterials, a denser and more refined microstructure is achieved, contributing to the improved mechanical properties observed in the modified samples. Moreover, the nano-scale particles in these materials provide a larger surface area for the nucleation and growth of hydration products, facilitating the formation of C–S–H gel and other hydration compounds. This, in turn, leads to a more compact and interconnected network within the UHPSCFRC, promoting greater strength and durability. However, the 10% NWSA mixture demonstrates the most significant performance improvement during the UPV test. The unique combination of its physical and chemical properties, including its high silica content and optimized particle size distribution, results in superior pozzolanic characteristics and more effective microstructural development than the other nanomaterials [102].

UPV of UHPSCFRC.

The improved performance of NWSA during the UPV test can also be ascribed to the differences in the chemical and mineralogical composition of these nano-ashes. NSSA and NCSA are derived from agricultural wastes, similar to NWSA. Still, they may have different chemical and mineralogical properties due to variations in the type of plant, growth conditions, and processing methods. For example, when added to concrete, the amount and type of silica, calcium, potassium, and other elements in the ashes can influence their reactivity and pozzolanic activity. NWSA may have a higher content of reactive silica and calcium compounds, which can contribute to the formation of additional C–S–H gel and improve the interfacial transition zone between the fiber and the matrix in UHPSCFRC. This, in turn, can enhance the mechanical and acoustic properties of the composite, including its UPV [103].

5.3 Durability characteristics of UHPSCFRC

5.3.1 Performance of UHPSCFRC under elevated temperature

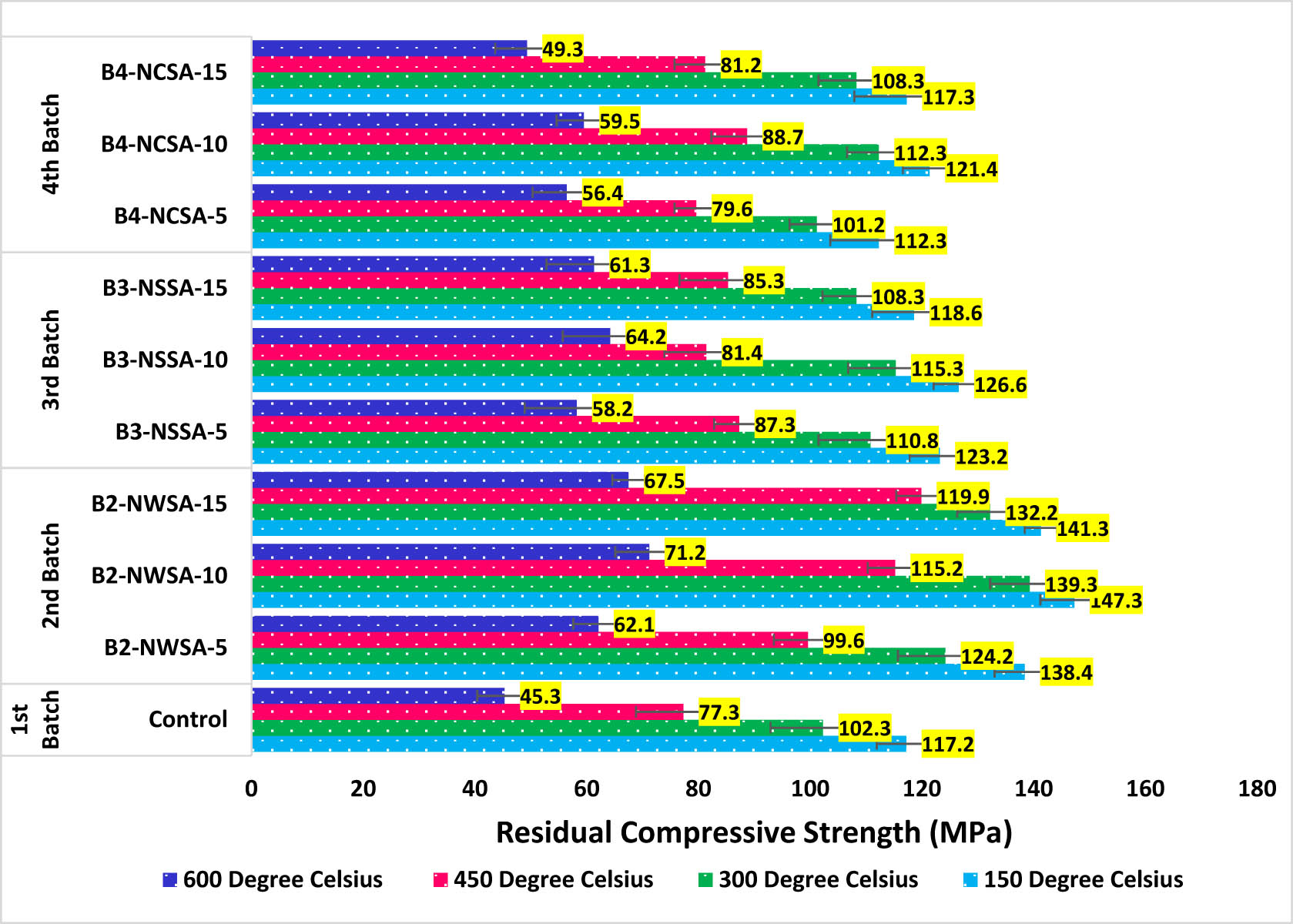

The results of UHPSCFRC, when exposed to high temperatures, are displayed in Figure 12. The result showed that the addition of NWSA to UHPSCFRC has significantly stabilized its residual compressive strength when exposed to elevated temperatures. At 150 and 300°C, the residual compressive strength of all mixtures (control + modified) was stable and reduced by a low percentage. But when the temperature was increased to 450 and 600°C, the residual compressive strength of the mixtures decreased significantly. B2-NWSA-10 had a higher residual compressive strength of 71.2 MPa at 600°C as compared to the control sample of 45.3 MPa. The samples used for the elevated heating tests were first cured for 28 days. The enhanced stability of UHPSCFRC with the introduction of NWSA can be credited to the ash’s chemical composition, making it more effective in preventing the degradation of UHPSCFRC compared to other nano-ashes, such as NSSA and NCSA. Moreover, NWSA has a low water absorption capability, which results in denser forms of UHPSCFRC, leading to a more stable residual compressive strength. The dense formation of UHPSCFRC is attributed to the initial withdrawal of capillary water, which forms a more compact and denser structure in the concrete. This effect is less prominent in NSSA and NCSA due to their higher water absorption capability. The study also revealed that the optimal proportion of NWSA for improving the residual compressive strength of UHPSCFRC is 10% (B2-NWSA-10). A lower percentage of NWSA does not provide enough reinforcement to the concrete, while a higher percentage results in the formation of agglomerates, reducing compressive strength. Therefore, adding 10% NWSA effectively improves the residual compressive strength of UHPSCFRC when exposed to elevated temperatures. NSSA and NCSA contain varying oxides, such as silica, aluminum, iron, and calcium oxide. The presence of these oxides can influence the properties of the ashes and their effectiveness in enhancing the stability of UHPSCFRC when exposed to high temperatures [104]. For instance, NSSA has a higher percentage of Fe2O3 than NWSA, which may lead to the formation of iron oxide in the concrete at high temperatures. This, in turn, may reduce the concrete’s strength due to the formation of cracks and the weakening of the concrete matrix.

Residual compressive strength of UHPSCFRC under high temperature.

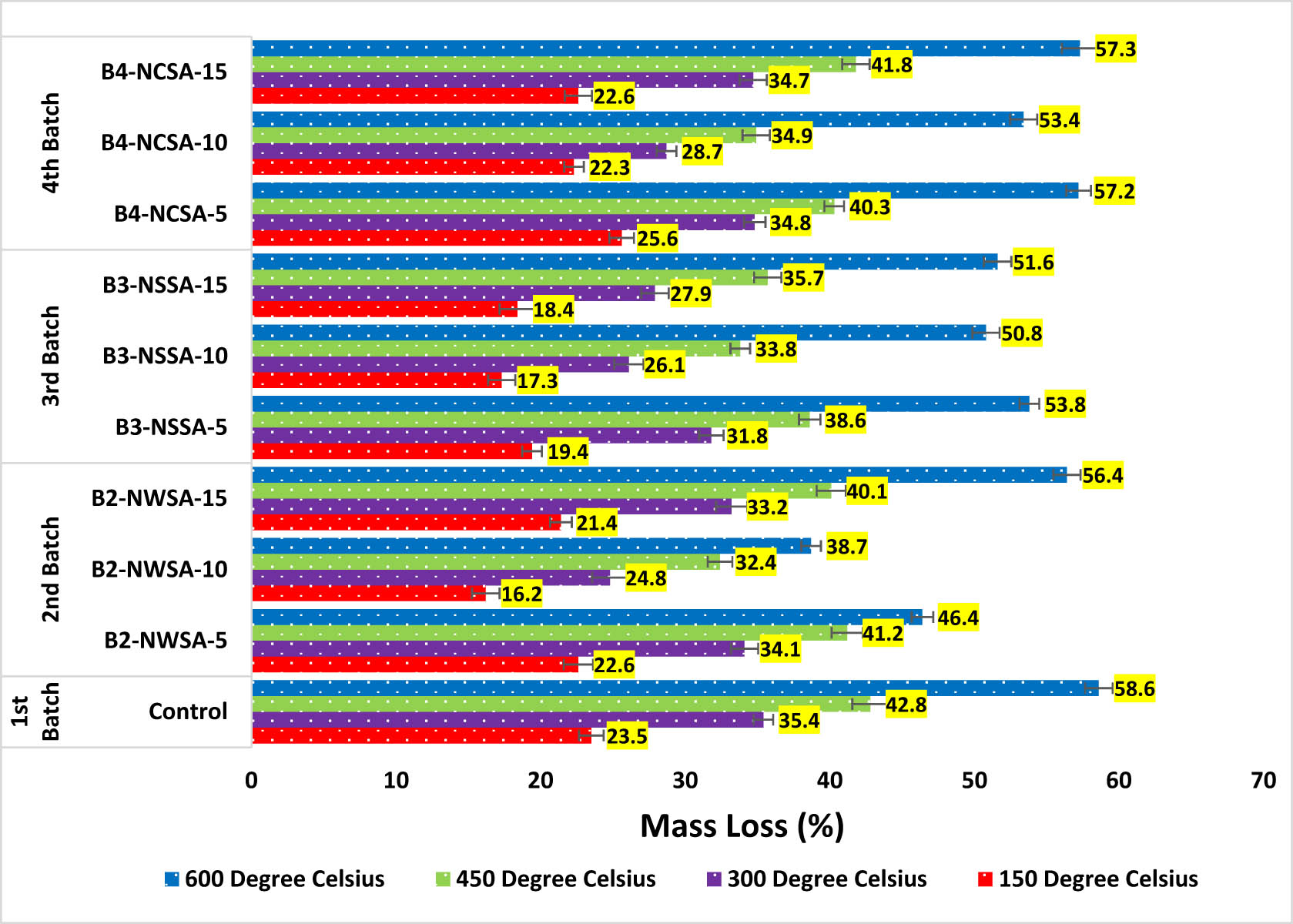

Figure 13 shows the results of loss in mass of UHPSCFRC samples after they were exposed to heating conditions. From the test outcomes, it is evident that the sample with 10% NWSA had the lowermost loss in mass (38.7%) when the concrete was subjected to 600°C, and significant mass loss was observed in the control sample (58.6%). Also, all the modified samples had less mass loss than the control mixture. The less mass loss in NWSA samples can be attributed to the unique physicochemical properties of NWSA. The 10% NWSA optimizes pozzolanic reactivity and porosity reduction, leading to a denser and more robust matrix. At this concentration, NWSA enhances the development of additional C–S–H gel and refines the pore structure of the UHPSCFRC, thereby improving its thermal stability and resistance to mass loss. In comparison, when adding 5% or 15% NWSA, the pozzolanic reactivity and porosity reduction are not as well-balanced, resulting in a less stable matrix. There is insufficient NWSA at lower concentrations to promote the development of the necessary C–S–H gel. In comparison, the increased porosity can adversely affect the concrete’s integrity at higher concentrations, making it more susceptible to mass loss [105]. Therefore, the specific concentration of 10% NWSA provides the most effective enhancement of the UHPSCFRC’s performance under elevated temperatures, outperforming NSSA and NCSA.

Mass loss in UHPSCFRC after high temperature exposure.

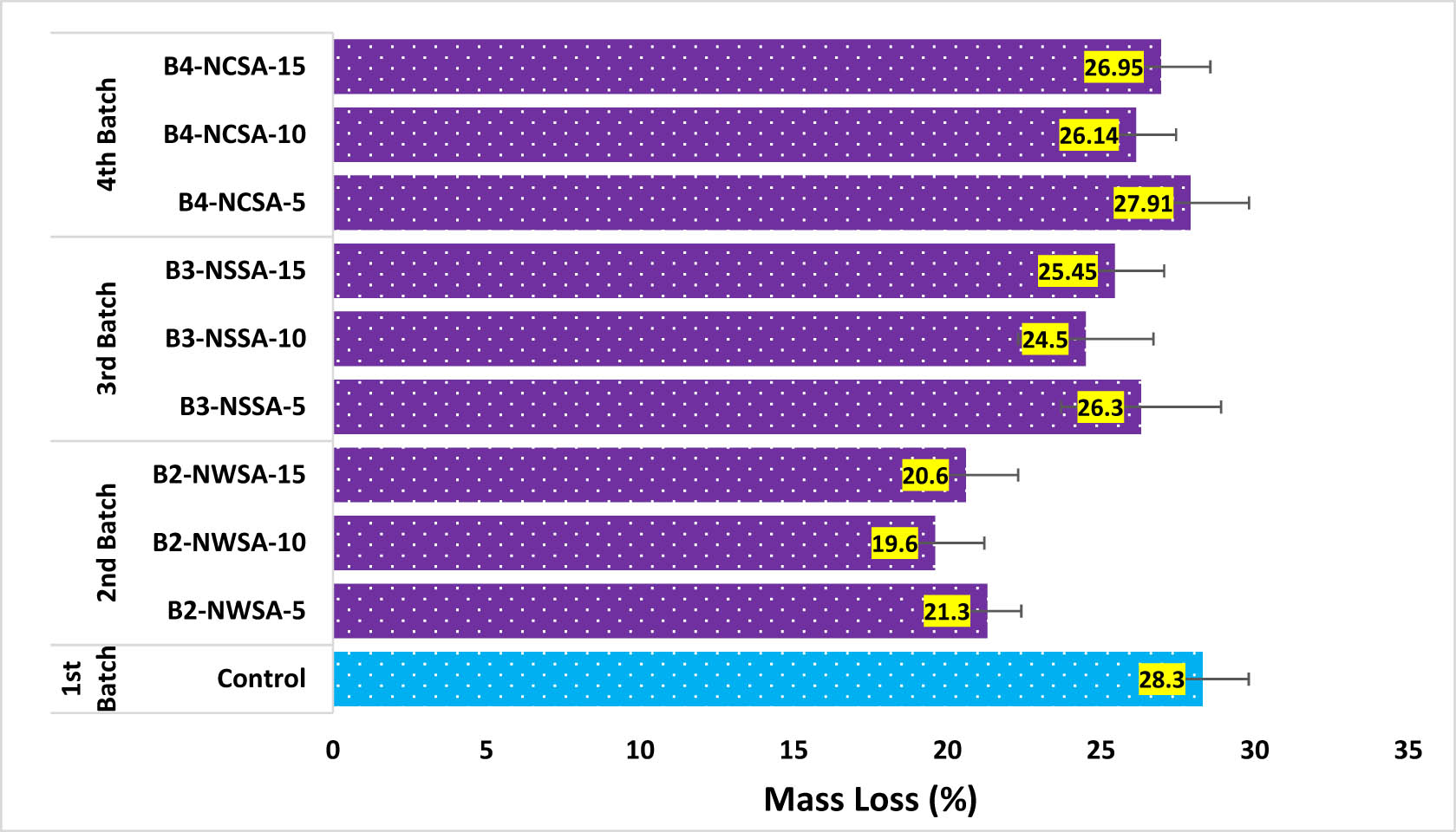

5.3.2 Performance of UHPSCFRC under sulfate attack

The results of UHPSCFRC, when subjected to sulfate attack, are displayed in Figure 14. The test result exhibited that the introduction of NWSA to UHPSCFRC has considerably stabilized its residual compressive strength when subjected to sulfate attack. In the current study, adding 10%, NWSA provided the best performance regarding the residual compressive strength of UHPSCFRC exposed to sulfate attack test. This can be attributed to the high content of reactive silica and calcium oxide in NWSA, which reacts with calcium hydroxide to form cementitious compounds, reducing the amount of free calcium hydroxide in the concrete [106]. The reaction also results in the formation of additional hydration products, contributing to the strength and durability of the concrete. The filler impact of NWSA also boosts the packing density of the concrete, reducing its permeability and susceptibility to sulfate attack. These results suggest that NWSA can be a promising supplementary cementitious materials (SCM) for enhancing the durability of UHPSCFRC while also addressing the issue of agricultural waste disposal. The optimal percentage of NWSA was 10%, as adding more or less than this amount resulted in lower residual compressive strength. When 5% NWSA was used, the pozzolanic material could not react effectively with calcium hydroxide. Adding 15% NWSA resulted in a higher filler effect but lower reactivity, reducing strength. Additionally, the UHPSCFRC containing NSSA and NCSA exhibited lower residual compressive strength than the UHPSCFRC containing NWSA. This can be attributed to the lower reactivity and filler effect of these materials, highlighting the importance of selecting appropriate SCMs for enhancing the durability of concrete [107]. Their particle size and shape influence the nano-ashes’ reactivity and filler effect. NWSA’s smaller, irregular particles may enhance its reactivity and packing density, while the larger, uniform particles of NSSA and NCSA may lower their packing efficiency, reducing sulfate attack resistance. Also, the amount of nano-ash added to the UHPSCFRC matters. The optimal NWSA rate (10%) may not yield the same durability improvements as NSSA or NCSA.

Residual compressive strength of UHPSCFRC after sulfate attack.

The mass loss in UHPSCFRC due to sulfate attack is presented in Figure 15. The results showed that the UHPSCFRC containing 10% NWSA (B2-NWSA-10) exhibited the least mass loss (19.6%), as compared to the UHPSCFRC containing 5 or 15% NWSA (21.3 and 20.6%), as well as compared to the UHPSCFRC containing NSSA, NCSA, or control sample. One possible scientific cause for this can be credited to the pozzolanic behavior and filler impact of NWSA. Among all the samples, the control sample had the highest mass loss (28.3%) due to sulfate attack. The high content of reactive silica and calcium oxide in NWSA allows it to react with calcium hydroxide in the concrete and form additional cementitious compounds, which reduce the amount of free calcium hydroxide that can react with sulfates and lead to mass loss. The filler effect of NWSA also improves the packing density. It reduces the permeability of the concrete, limiting the penetration of sulfate ions into the concrete and minimizing the sulfate attack [108]. The optimal percentage of NWSA, found to be 10%, balances the amount of pozzolanic material and the filler effect, ensuring the best behavior of the UHPSCFRC. On the other hand, the lower mass loss of UHPSCFRC containing NWSA compared to NSSA and NCSA can be attributed to these materials’ lower reactivity and filler effect.

Mass loss in UHPSCFRC after high sulfate attack.

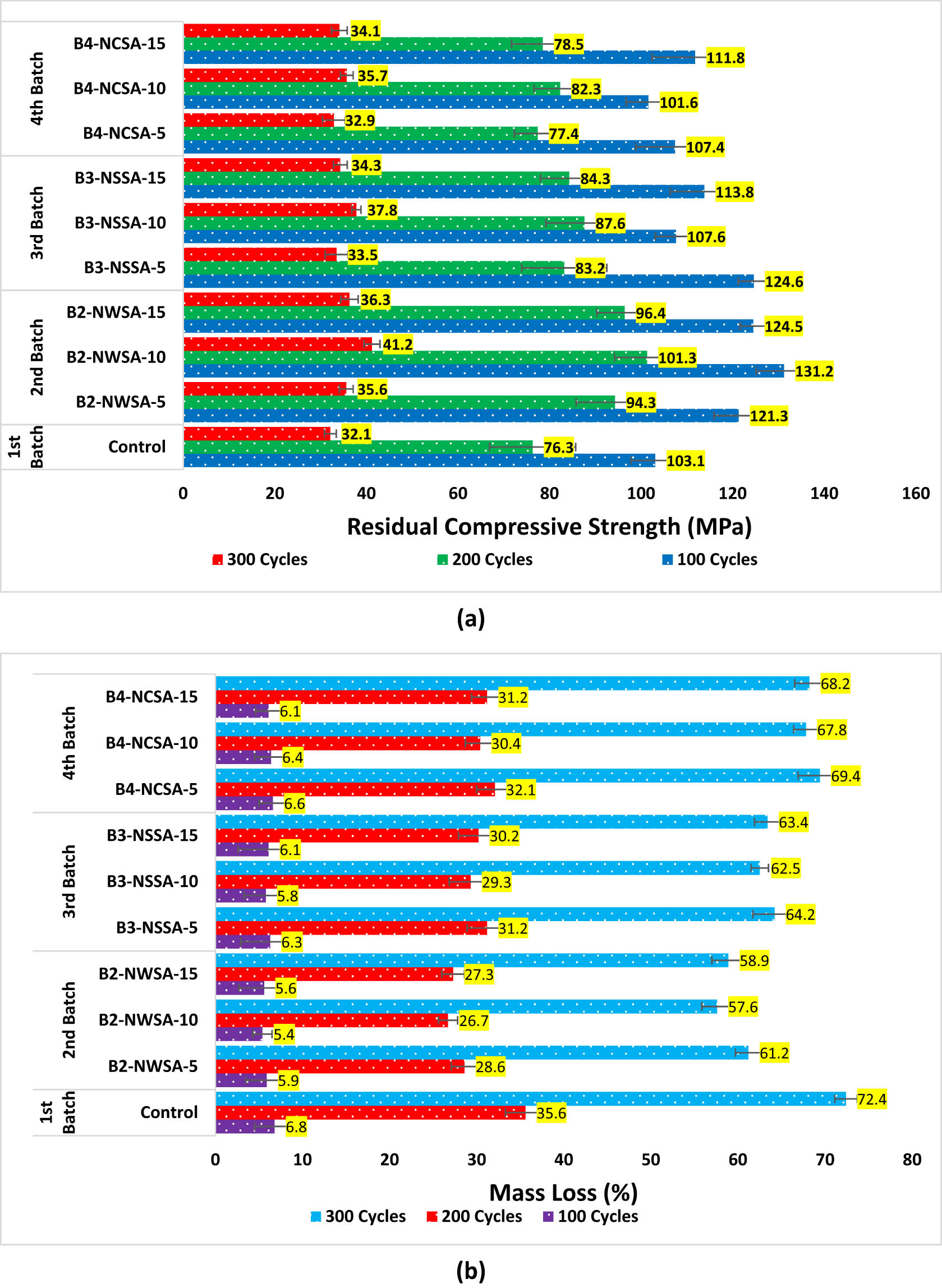

5.3.3 Performance of UHPSCFRC under freezing and thawing test

The results of residual compressive strength of UHPSCFRC, when subjected to freezing and thawing test, are displayed in Figure 16(a). When exposed to freezing and thawing tests, the enhanced stability of the residual compressive strength of UHPSCFRC can be attributed to the optimal addition of 10% NWSA compared to NSSA and NCSA. It can be noted that B2-NWSA-10 had the highest residual compressive strength (131.2, 101.3, and 41.2 MPa) after subjecting to 100, 200, and 300 cycles of freezing and thawing. NWSA demonstrates superior pozzolanic activity and microstructure refinement due to its unique chemical composition and morphology, which results in a more effective and efficient reaction with the calcium hydroxide generated during cement hydration. This pozzolanic reaction leads to an additional C–S–H gel, which contributes to the densification of the cementitious matrix [109]. The improved matrix quality, coupled with a more homogenous distribution of fibers, ultimately offers increased resistance to water ingress and other harmful substances. Consequently, the concrete’s freeze-thaw durability is significantly improved, and the residual compressive strength remains more stable even under harsh environmental conditions. The UHPSCFRC samples with NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA all had higher residual compressive strength, which shows the effectiveness of these waste nanomaterials in improving the durability of UHPSCFRC. The optimal 10% NWSA content provides a delicate balance between workability and mechanical performance. Higher percentages of NWSA may lead to diminishing compressive strength because of the increased porosity instigated by the excessive amounts of fine particles in the mix, potentially offsetting the benefits of the pozzolanic reaction [110]. In contrast, lower percentages may not provide sufficient pozzolanic effect to improve the overall durability and freeze-thaw resistance of the UHPSCFRC.

(a) Residual compressive strength of UHPSCFRC after freezing and thawing test. (b) Mass loss in UHPSCFRC after freezing and thawing.

The results of mass loss of samples, when exposed to freezing and thawing test, are provided in Figure 16(b). The test result showed that the 10% NWSA sample exhibited a more stable mass loss with percentages of 5.4, 26.7, and 57.6% after 100, 200, and 300 cycles of freeze and thaw testing, respectively. The control sample without NWSA had higher mass losses with percentages of 6.8, 35.6, and 72.4% after the same number of freeze and thaw cycles. The reduced mass loss in the 10% NWSA sample suggests that incorporating NWSA enhanced the concrete’s durability and resistance to freeze-thaw damage. The improved performance of UHPSCFRC with 10% NWSA can be attributed to the pozzolanic reaction, resulting in denser microstructure and reduced pore connectivity. This densification restricts water movement during freeze-thaw cycles, minimizing the potential for internal damage and mass loss. The higher mass losses observed in the control sample indicate a higher vulnerability to freeze-thaw damage due to the absence of the beneficial effects imparted by NWSA. The addition of 10% NWSA in UHPSCFRC resulted in more stable mass loss compared to NSSA and NCSA [111], showcasing the potential of NWSA as a beneficial additive for improving the freeze-thaw durability of UHPSCFRC.

Moreover, the incorporation of 10% NWSA enhances the nucleation and growth of hydration products, reducing the size of pores and microcracks and further improving the concrete’s durability. This optimal percentage effectively addresses the challenges of freeze-thaw exposure, resulting in a more stable residual compressive strength compared to the mixtures with 5 and 15% NWSA and those containing NSSA and NCSA.

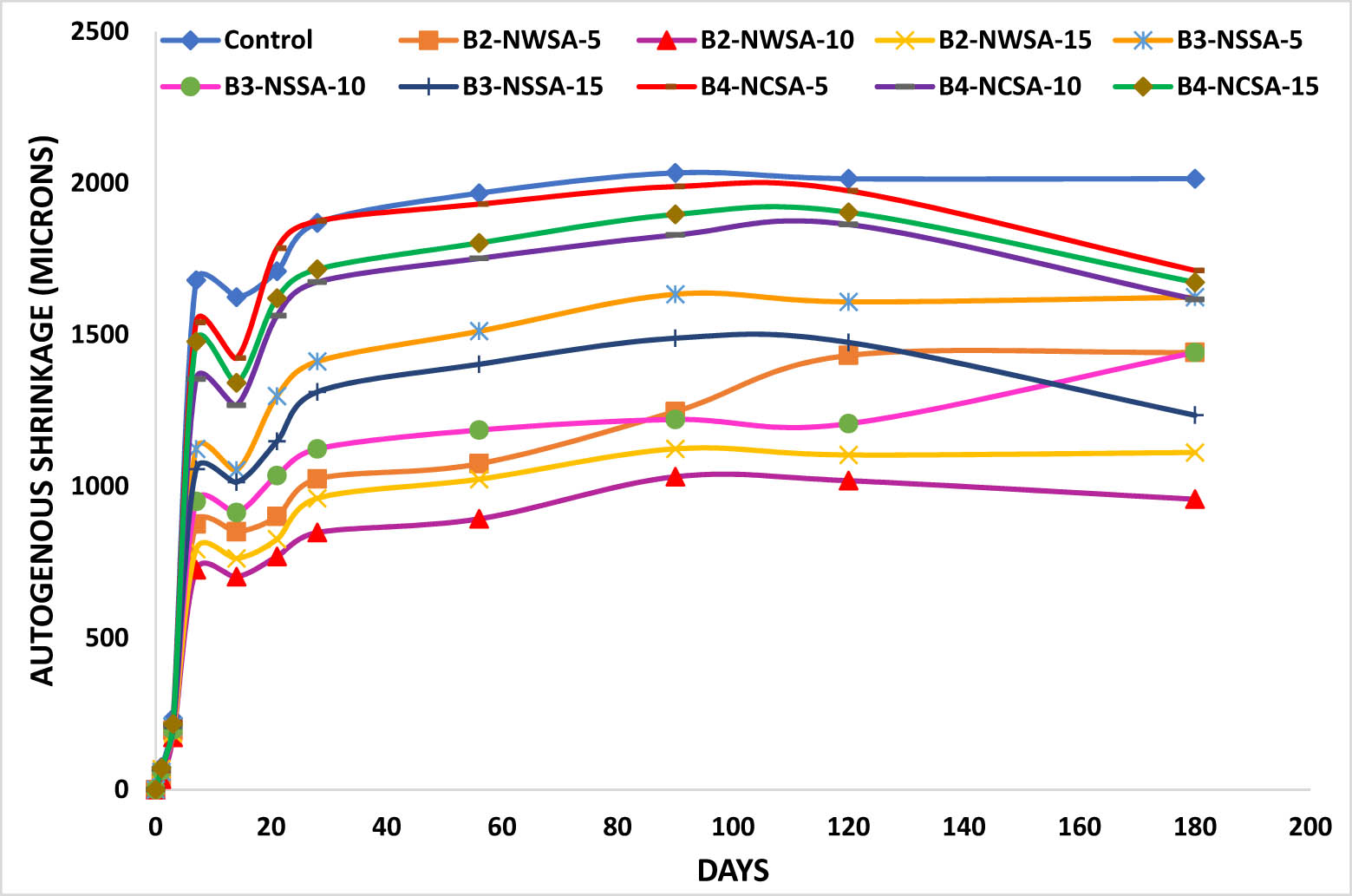

5.3.4 Performance of UHPSCFRC under shrinkage test

The results of the autogenous shrinkage test on UHPSCFRC are displayed in Figure 17. The reduction in autogenous shrinkage of UHPSCFRC is a crucial factor in the durability of structures. Autogenous shrinkage occurs because of the self-desiccation process during the early stages of hydration. This process involves the consumption of water by the cement particles, which decreases the pore volume of the concrete. The reduction in pore volume causes a reduction in the size of the capillary pores, which increases the surface tension and leads to the development of microcracks [112]. These microcracks can eventually lead to the failure of the concrete structure. The addition of pozzolanic materials to the concrete mixture is an effective way to reduce autogenous shrinkage. Pozzolanic materials are finely divided siliceous, and aluminous materials that react with calcium hydroxide to form additional calcium-silicate-hydrate gel. This gel fills up the voids amid the particles of OPC. It reduces the porosity of the concrete, which minimizes the formation of microcracks during the early stages of hydration.

Autogenous shrinkage of UHPSCFRC.

In this context, adding 10% NWSA to UHPSCFRC is an effective way to reduce autogenous shrinkage. NWSA is a pozzolanic material with a high silica and alumina content, which reacts with calcium hydroxide to form additional C–S–H gel. The high pozzolanic activity of NWSA is attributed to its high surface area, which provides more reactive sites for the pozzolanic reaction. The additional C–S–H gel formed by the pozzolanic reaction fills the voids between the cement particles. It reduces the porosity of the concrete, leading to a decrease in autogenous shrinkage [113]. Also, the existence of BFs had a significant part in lowering autogenous shrinkage. The BFs with 10% NWSA in a sample had an optimum bonding between the binder matrix. The reduction in autogenous shrinkage was found to be more significant with 10% NWSA than with 5% or 15% NWSA because the optimal dosage of pozzolanic material is generally between 5 and 15% by weight of the cementitious material. When the dosage is too low, there may not be sufficient pozzolanic reaction to reduce the autogenous shrinkage. In contrast, an excessive dosage may result in excessive water demand, leading to segregation and bleeding of the concrete mixture.

The reason the control sample and samples with NSSA and NCSA could not attain low autogenous shrinkage during the test as much as NWSA is due to their chemical composition. NSSA and NCSA may have a lower pozzolanic activity than NWSA because of their lower silica and alumina contents. Pozzolanic activity depends on the pozzolanic material’s reactivity and ability to react with calcium hydroxide. The lower silica and alumina contents of NSSA and NCSA may result in less efficient pozzolanic reactions. This leads to fewer C–S–H gel products that can fill up the voids between the cement particles and reduce the porosity of the concrete. As a result, the formation of microcracks during the early stages of hydration may not be adequately minimized, leading to a higher degree of autogenous shrinkage. Additionally, the particle size and morphology of the pozzolanic materials can also affect their pozzolanic activity. The smaller the particle size, the larger the surface area available for the reaction with calcium hydroxide, leading to a more efficient pozzolanic reaction [114]. The morphology of the particles can also influence their reactivity, as specific particle shapes may have more reactive sites for the pozzolanic reaction than others.

5.4 XRD analysis of UHPSCFRC

XRD analysis of UHPSCFRC is presented in Figure 18. In the XRD analysis of UHPSCFRC, the higher peaks of C–S–H and Ca(OH)2 observed in samples containing 10% NWSA (B2-NWSA-10) compared to control samples and samples with NSSA and NCSA can be attributed to the unique physicochemical properties of NWSA. The NWSA is rich in reactive silica and has a relatively higher surface area, contributing to increased pozzolanic activity. This enhanced pozzolanic reaction between the reactive silica in NWSA and the calcium hydroxide released during cement hydration results in a denser and more robust C–S–H gel matrix [33]. This denser matrix not only improves the overall mechanical properties of the concrete, such as compressive strength, tensile strength, and durability, but also leads to the observed higher peaks of C–S–H silica and Ca(OH)2 in the XRD analysis. The higher peaks of these hydration products indicate a more significant amount of their formation, which correlates with improved microstructural and performance characteristics of the concrete matrix [32]. Additionally, NWSA’s chemical composition and morphology may differ from NSSA and NCSA, which may also influence the formation of hydration products and the resulting XRD patterns. These differences may be related to the varying mineralogical compositions and the specific surface area of the nano-ashes, which in turn affect their reactivity and interaction with cementitious materials.

XRD spectra of UHPSCFRC.

An alternative scientific reason for the lower peaks of C–S–H, Ca(OH)2, and SiO2 observed in the XRD analysis of control samples and samples containing NSSA and NCSA compared to those with NWSA can be associated with the differences in the chemical composition of amorphous content and pozzolanic activity of the nano-ashes [115]. The chemical compositions of NSSA and NCSA may vary from that of NWSA, with the former having a lower content of reactive silica (SiO2) and higher amounts of unreactive oxides or other impurities. This variation in composition can affect the pozzolanic activity of the ashes and limit their capacity to react with Ca(OH)2 during cement hydration, leading to a lower formation of C–S–H gel. Consequently, the XRD analysis of samples with NSSA and NCSA would display reduced C–S–H and Ca(OH)2 peaks compared to those containing NWSA. Moreover, the amorphous content of NSSA and NCSA may also be lower than that of NWSA. Amorphous materials exhibit higher reactivity in pozzolanic reactions, and their presence in the nano-ashes can significantly influence the formation of C–S–H gel. The reduced amorphous content in NSSA and NCSA may lead to less effective pozzolanic reactions, resulting in lower C–S–H and Ca(OH)2 peaks in the XRD analysis. The pozzolanic activity of NSSA and NCSA may be inherently lower than that of NWSA due to differences in their specific surface area and particle size distribution. A higher specific surface area and finer particle size distribution generally enhance the reactivity of the pozzolanic material by providing a larger contact area for the reaction with calcium hydroxide. Suppose NSSA and NCSA possess lower specific surface areas and larger particle sizes than NWSA, then in that case, their pozzolanic activity will be less effective, leading to a lower formation of C–S–H gel and reduced XRD peaks C–S–H, Ca(OH)2, and SiO2.

6 Sustainability and environmental performance

The present study showed that adding NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA to UHPSCFRC as a partial replacement for Portland cement can provide several sustainability and environmental benefits. First, the production of Portland cement is energy-intensive and releases significant greenhouse gas emissions, which contribute to climate change. By using NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA as partial replacements for Portland cement, the amount of cement needed for UHPSCFRC production can be reduced, thus lowering the carbon footprint of the concrete. Second, using these agricultural waste products in concrete production diverts them from landfills, reducing the amount of waste generated and contributing to waste reduction efforts [116,117]. Moreover, using UHPSCFRC in construction can contribute to the sustainability of buildings and infrastructure. UHPSCFRC is a highly durable material with a long lifespan, requiring less maintenance and repair over time. The durability of UHPSCFRC reduces the need for additional resources, emissions, and energy associated with the repair and maintenance of the structures it is used in. In addition, using agricultural waste products as a partial replacement for Portland cement can also reduce the dependence on natural resources, such as limestone and clay, that are typically used in cement production [118,119]. Using these waste products, the concrete industry can help reduce the environmental impact of mining and processing natural resources [120].

Overall, the use of NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA as partial replacements for Portland cement in UHPSCFRC production can provide significant sustainability and environmental advantages, including reducing greenhouse gas emissions, diverting waste from landfills, reducing natural resource consumption, and contributing to the durability and long-term sustainability of buildings and infrastructure.

7 Recommendations for future research

Based on the findings of the present study, the following recommendations are suggested for future research on the topic:

Investigating other waste materials: Explore the potential of incorporating other agricultural or industrial waste materials as partial substitutes for Portland cement in UHPSCFRC. Research their influence on workability, mechanical properties, and durability performance to identify new sustainable alternatives.

Long-term performance assessment: Conduct long-term studies to evaluate the performance of UHPSCFRC incorporating these waste materials under various environmental conditions. Assess the durability properties, including resistance to chemical attacks, cyclic loading, and exposure to aggressive environments, over an extended period to determine the long-term sustainability and effectiveness of the materials.

Microstructural analysis: Conduct in-depth microstructural analysis, such as scanning electron microscopy and XRD, to gain a deeper understanding of the interaction between the waste materials, cementitious matrix, and fiber reinforcement. Investigate the formation and distribution of reaction products, bonding mechanisms, and overall microstructural characteristics to provide insights into the improved performance of UHPSCFRC.

Life cycle assessment (LCA): Perform comprehensive LCAs to evaluate the environmental impact and sustainability benefits of UHPSCFRC incorporating these waste materials. Analyze the entire life cycle, from raw material extraction to end-of-life, considering energy consumption, carbon emissions, and waste generation. This assessment will provide a holistic perspective on the environmental implications and help make informed decisions in the construction industry.

Field applications and performance monitoring: Conduct field trials and monitor the performance of UHPSCFRC structures incorporating these waste materials in real-world applications. Evaluate their performance under loading conditions, exposure to different climates, and long-term durability. This practical assessment will provide valuable feedback on the feasibility, reliability, and potential challenges of implementing these materials in practical construction projects.

By addressing these recommendations, future research can further advance the understanding and utilization of waste materials in UHPSCFRC, contributing to developing sustainable construction practices and promoting environmental stewardship.

8 Conclusion

The present study evaluates the impact of NWSA, NSSA, and NCSA as a partial substitute for Portland cement on the rheological, mechanical, durability, and microstructural properties of UHPSCFRC. The following conclusions are drawn from the current research: