Abstract

Thiosulfate is a green leaching agent used in the hydrometallurgical process because it is both environmentally benign and can form the required soluble ion complexes. In this article, a novel method for the synthesis of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites from a solution of relevant ion complexes via ultrasound-assisted ultraviolet (UV) photolysis was proposed. An analysis of the mechanism revealed that the complexes undergo a series of photochemical reactions. The CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites were synthesized by photochemical co-precipitation under UV-C irradiation. The microstructure, chemical composition, optical and electrochemical properties of the prepared nanocomposites were analyzed to verify the synthesis and investigate the product. The photodegradation of methyl orange (MO) under a xenon lamp was performed to determine the photocatalytic activity. Under visible light irradiation, the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites undergo the electrons transition (from valence band to conduction band) to form photogenerated electron–hole pairs realizing the effective separation of carriers and finally promote the degradation of MO to water and carbon dioxide. The subsequent degradation efficiency of the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites was found to be 87% after 90 min, and it was larger than 78% for pure CdS prepared via UV photolysis, indicating that the as-developed novel method can effectively fabricate CdS–Ag2S photocatalyst with superior performance.

1 Introduction

Environmental pollution and depleting energy resources have emerged as widespread concerns because of rapid industrialization [1,2]. To effectively solve these key problems, researchers have proposed the use of new solar-driven photocatalytic materials. For example, Mukhopadhyay [3] successfully synthesized CaFe2O4 nanoparticles by a chemical precipitation technique and applied them in the degradation of brilliant green (BG) dye. Bose [4] fabricated the magnetic MgFe2O4 nanoparticles via a facile co-precipitation technique. Tripathy [5] used carbon-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles as a catalyst for the degradation of BG dye. Liexiao [6] adopted a one-step hydrothermal route to synthesize an interesting type of Bi2O2CO3 hierarchical nanotubes. In particular, cadmium sulfide has been widely studied by scientists for this purpose owing to its low price, simple preparation method, and suitable band gap (2.4 eV) [7,8]. However, high photo-generated carrier recombination, poor conductivity, and significant photo-corrosion problems restrict its use in large-scale practical applications [9]. Well-known CdS-containing nanocomposites, such as CdS/MoS2, CdS/Bi4V2O11, CdS/Cu2xSe, and CdS/Bi4Ti3O12, have been constructed to address these issues [10,11,12,13]. Furthermore, silver compounds, such as AgPO4, AgCl, AgBr, AgI, and AgVO4, with very high photocatalytic activity have been used to create excellent photocatalytic systems utilizing these CdS nanocomposites [14,15]. Ag2S, which possesses a bandgap range of 0.9–1.0 eV, is a semiconductor (n-type) with a distinctive structure and good physical properties. Additionally, owing to its excellent photoelectric properties, doping with Ag2S is an effective strategy for enhancing the photocatalytic activity of CdS-supported catalysis because it lowers the photo-generated carrier recombination rate and reduces photo-corrosion. According to numerous reports, combining Ag2S with CdS semiconductors can increase the overall photocatalytic activity. As a result, the synthesis of Ag2S and CdS has recently received significant research attention [16,17,18,19].

The most widely used method for preparing a CdS–Ag2S nanocomposite photocatalyst preparation is to load Ag2S onto CdS carriers via deposition precipitation. However, during the preparation process, Ag2S will self-nucleate, preventing close contact between Ag2S and CdS, thereby hindering the transmission of photogenerated carriers to a certain extent. Several methods have been applied in Ag2S and CdS preparation, such as ion implantation, thermal evaporation technique, and sol–gel methods [20,21]. Among them, the chemical co-precipitation method is an effective and time-efficient method to obtain Ag2S and CdS nanoparticles. As a result, most researchers employ the chemical co-precipitation method with various chemical reagents and conditions to synthesize these nanoparticles. Based on previous studies, this study proposes a novel photochemical co-precipitation method to obtain these nanocomposites. In this proposed method, thiosulfate has been used as a green chemical reagent for the metallurgical leaching of cadmium and silver. The thiosulfate leaching solution containing cadmium and silver thiosulfate complexes can potentially be used as a source of cadmium and silver [22,23]. This thiosulfate complex solution exhibits intense absorption in the ultraviolet (UV)-C region (200–280 nm). The photolysis of the cadmium and silver thiosulfate complexes has been previously studied [24,25]. However, the ultrasound-assisted photolysis of the cadmium and silver thiosulfate complex and the photocatalytic activity of the resulting CdS–Ag2S have not been thoroughly investigated.

In this study, a novel UV photolysis co-precipitation method was applied to fabricate a CdS–Ag2S photocatalyst from cadmium and silver poly-metallic thiosulfate complex solutions. Benefitting from the ion photochemical properties, the poly-metallic thiosulfate complex solution was obtained, which was then subsequently used to generate the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites. In dyeing wastewater, there are three representative pollutants, such as azo dyes, triphenylmethane dyes, and anthraquinone dyes. Among them, azo dyes account for 70–80%. Methyl orange (MO) is a typical azo dye with toxicity, stable chemical properties, and difficult biodegradation. The performance of CdS–Ag2S was evaluated using the typical MO dye as a model compound, and the activity of the nanocomposites was investigated through the visible photocatalytic degradation of MO.

2 Methods

2.1 Reagents

Sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3), cadmium chloride (CdCl2), and silver nitrate (AgNO3) used in the preparation of the simulated leaching solution were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. All the chemicals were of reagent grade. De-ionized (RO or UP) water prepared using a water purification machine was used both as a washing agent and as a solvent.

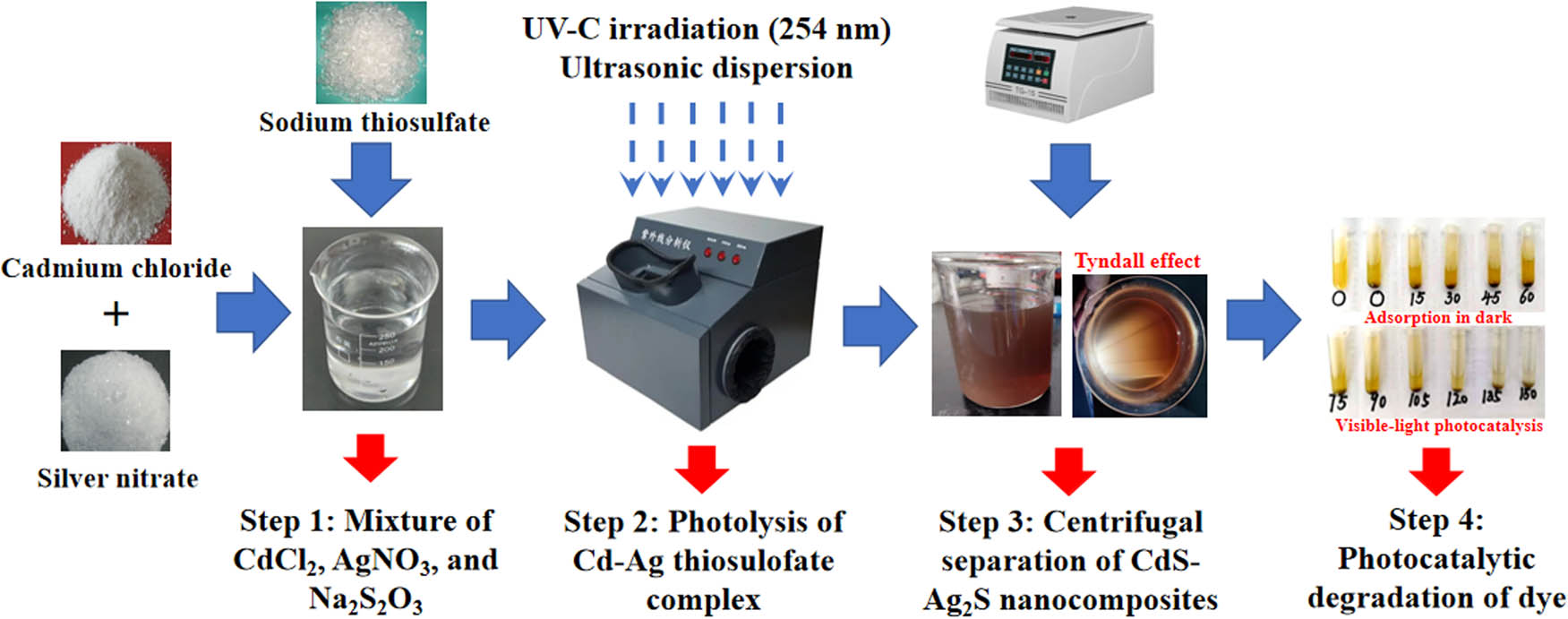

2.2 Procedure

The solution of the simulated Cd–Ag thiosulfate complexes solution was obtained by stoichiometrically mixing cadmium chloride (CdCl2), silver nitrate (AgNO3), and sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3) in a stoichiometric manner, as explained below. The four steps in the CdS–Ag2S composite preparation and testing are elaborated as follows: In Step 1, the simulated Cd–Ag thiosulfate complex solution (250 mL, Cd: 100 mg/L, and Ag: 10 mg/L) was produced in an Erlenmeyer flask through complexation reactions between the Cd2+, Ag+, and

Schematic diagram of the CdS–Ag2S synthesis method.

2.3 Analytical methods

To further clarify the reaction mechanism, the UV decomposition rate of the cadmium/silver-thiosulfate complex was investigated in detail. Accordingly, the UV-induced photolysis rate constant of the Cd–Ag thiosulfate complex was estimated. A Bruker D8 X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to confirm the phase composition of the precipitate. The Highscore software was used to analyze XRD data with a standard card. The surface morphology of the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites was characterized using a JSM-5610LV SEM system. A Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer Spectrum 65) was also used to analyze the prepared sample. An Escalab 250xi XPS system was applied to study the composition and valence state of the elements on the precipitate surface. The analysis was conducted without sputtering or charge neutralization using monochromatic Al Kα X-radiation at a take-off angle of 90°. The C 1s line at 284.6 eV was used to calibrate the binding energies. The XPS Peak software was used to fit the XPS data, and the NIST XPS database was used to cross-check component information. A UV-2550 UV-Vis spectrometer was applied to obtain the UV-Vis DRS of the samples. The electrochemical properties of the samples were characterized by an electrochemical workstation. In the transient photocurrent study, light and dark experiments were performed every 20 s.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Investigation of the UV photolysis precipitation

The thiosulfate leaching solution contains cadmium/silver-thiosulfate complex ions ([CdAg2(S2O3)2n

]4(n–1)−, n = 1 or 2), which are sources of metal and sulfur. A previous study demonstrated the ability of metal-thiosulfate to absorb UV energy and then decompose into metal sulfide. In this work, the UV photolysis mechanism that results in the formation of the cadmium/silver-thiosulfate complex was studied. The step-by-step details of the reaction mechanism are as follows: after absorbing energy from the UV-C (200–280 nm) radiation, the cadmium/silver-thiosulfate complex ions activate and enter an unstable excited state. The primary reaction of the photochemical process is described in equation (1). Subsequently, as shown in equation (2), the water molecule in the solution coordinates this activated Cd–Ag thiosulfate complex into the activated Cd–Ag hydroxide complex and thiosulfate ion. Finally, the activated Cd–Ag thiosulfate complex ions react with the activated state Cd–Ag hydroxide complex in the activated state to dissociate the S–S bond in the latter, resulting in the oxidation product of sulfate ions (

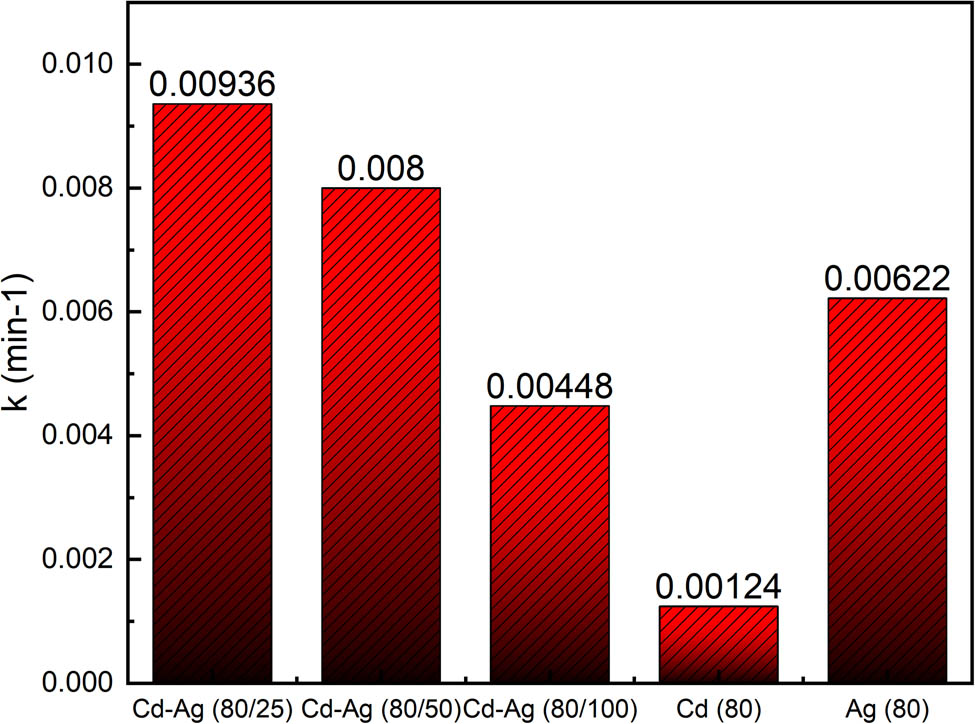

To clarify the UV reaction mechanism, the photolysis rate constant of the Cd–Ag thiosulfate complex was investigated in this reaction together with the UV decomposition rate of the silver cadmium thiosulfate complex. Figure 2 shows the rate constant of the UV-C photolysis of various metal thiosulfate complexes. The photolysis rate constant of a pure Cd–thiosulfate complex (Cd: 80 mg/L) and an Ag–thiosulfate complex (Ag: 80 mg/L) was calculated as 0.00124 and 0.00622 min−1, respectively. Additionally, the ratio of Cd to Ag in the synthesized nanocomposites depends on the decomposition rate of cadmium and silver. Furthermore, in the case of the cadmium–silver thiosulfate complex, the concentration of silver affects the decomposition rate of cadmium. When the concentration of cadmium was fixed (Cd = 80 mg/L), the rate at which cadmium decomposed decreased as the silver concentration increased. The rate constant of Cd photolysis in the Cd–Ag thiosulfate complex (Cd: 80 mg/L, Ag: 25 mg/L) was 0.00936 min−1. This phenomenon can be explained by apparent rate constant (k obs) calculation, which has been studied in the kinetics of Ag-thiosulfate photolysis, and the silver ion concentration is inversely proportional to the k obs. Similarly, when the concentration of cadmium is fixed in this work, the greater the concentration of silver ions, the greater the concentration of Cd–Ag thiosulfate complex ions generated, and the smaller the apparent rate constant.

Rate constant (k) of photolysis of different M-thiosulfate by UV-C (Cd–Ag thiosulfate; Ag–thiosulfate; Cd–thiosulfate).

3.2 Microstructure and chemical composition

To clearly illustrate the microstructure and chemical composition of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites, XRD, SEM, FT-IR, and XPS analyses were performed. XRD studies of pure CdS, pure Ag2S, and photolyzed nanocomposites were conducted. The patterns obtained are shown in Figure 3. Three distinct broad peaks observed in the XRD pattern of the pure CdS (Figure 3b), at approximately 26.7°, 43.9°, and 51.8°, were also detected in the XRD pattern of the nanocomposites (Figure 3a), which are in accordance with the cadmium sulfide phase (PDF:00-002-0454). Similar to the XRD pattern of pure Ag2S (Figure 3c), several peaks were observed in the nanocomposites (Figure 3a) spectrum at 20° and 80°, some of which are in accordance with peaks obtained from the Argentite phase (PDF:01-089-3840). The result demonstrates that cadmium and silver sulfides were predominantly precipitated via photolysis.

XRD patterns of different samples: (a) nanocomposites; (b) CdS; (c) Ag2S.

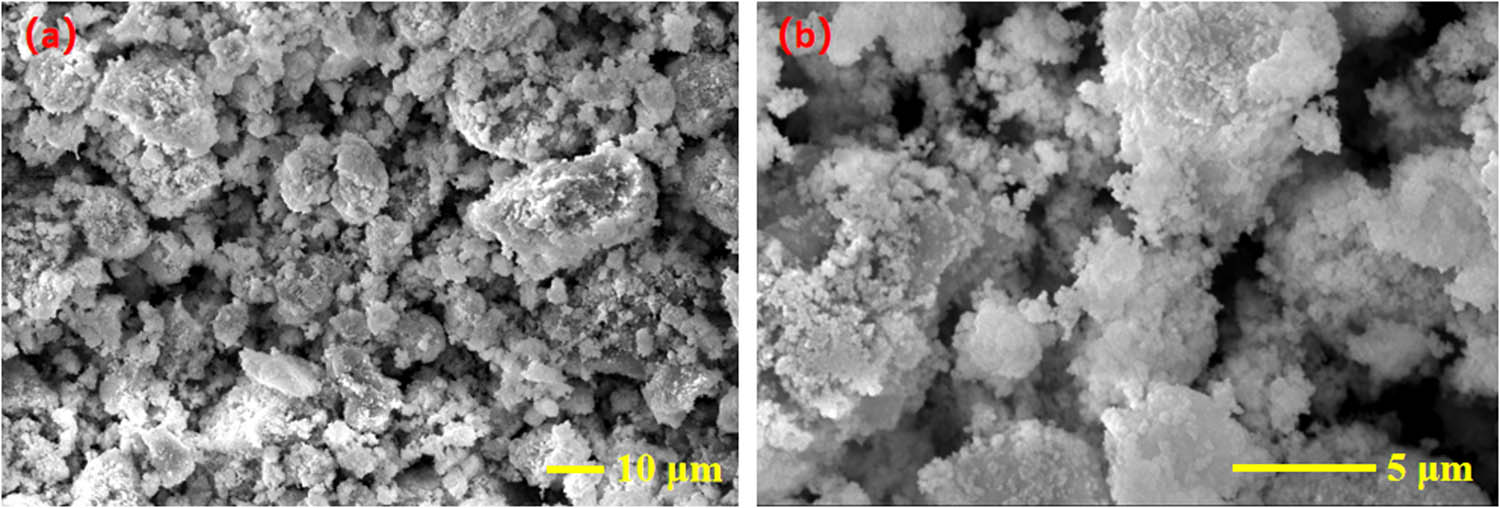

The surface morphology of the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites was observed by SEM, and the results are displayed in Figure 4. The precipitates have different shapes, uneven sizes, and poor dispersion and agglomeration. Owing to the limitations of SEM imaging, it is difficult to determine the exact particle size. However, the Tyndall effect observed for the prepared CdS–Ag2S photocatalyst demonstrated that the particles of the product are in the nanoscale range.

SEM images of the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposite: (a) ×1,000; (b) ×5,000.

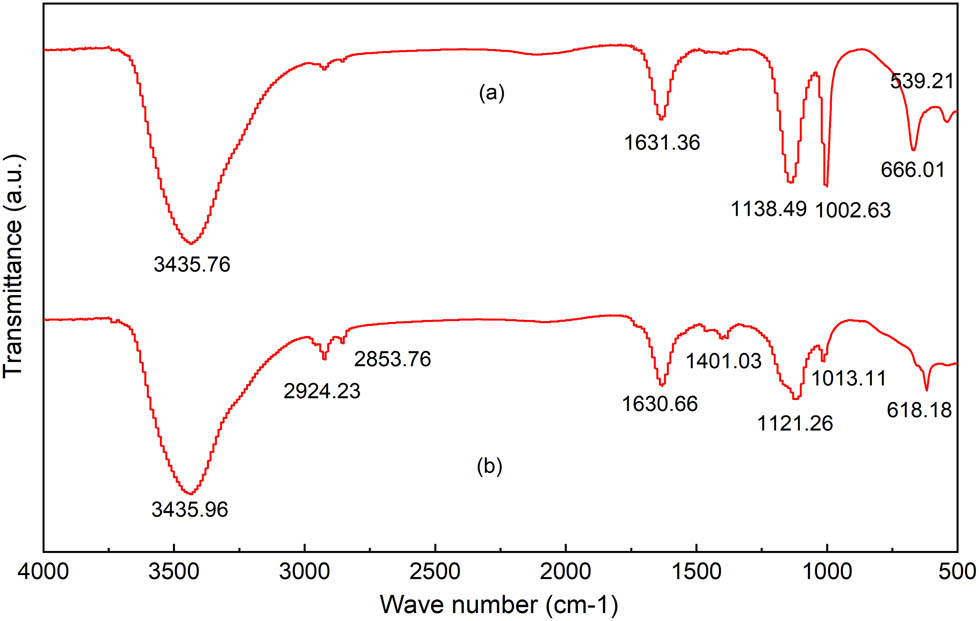

FTIR spectra were collected in the range of 500–4,000 cm−1. The spectra of the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites before and after photocatalysis are shown in Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposite: (a) before photocatalysis; (b) after photocatalysis.

The absorption bands observed in the FTIR spectra at 3435.76 and 3435.96 cm−1 (Figure 5a and b) originate from the O–H group of the H2O present on the surface of the nanocomposites. Figure 5(a) and (b) show absorption bands at 1002.63 and 1013.11 cm−1 that are attributed to sulfate, and the absorption bands at 1631.36 and 1630.66 cm−1 that are attributed to sulfoxide, indicating the presence of the S–O group [26]. Thus, the peaks at 666.01 cm−1 and 618.18 cm−1, which are in the range of 500–750 cm−1, are thus attributed to Ag–S and Cd–S metal-sulfur bonds [17]. No discernible difference was observed in the infrared spectra of the photocatalyst before and after photocatalysis, indicating the stability of the photocatalyst.

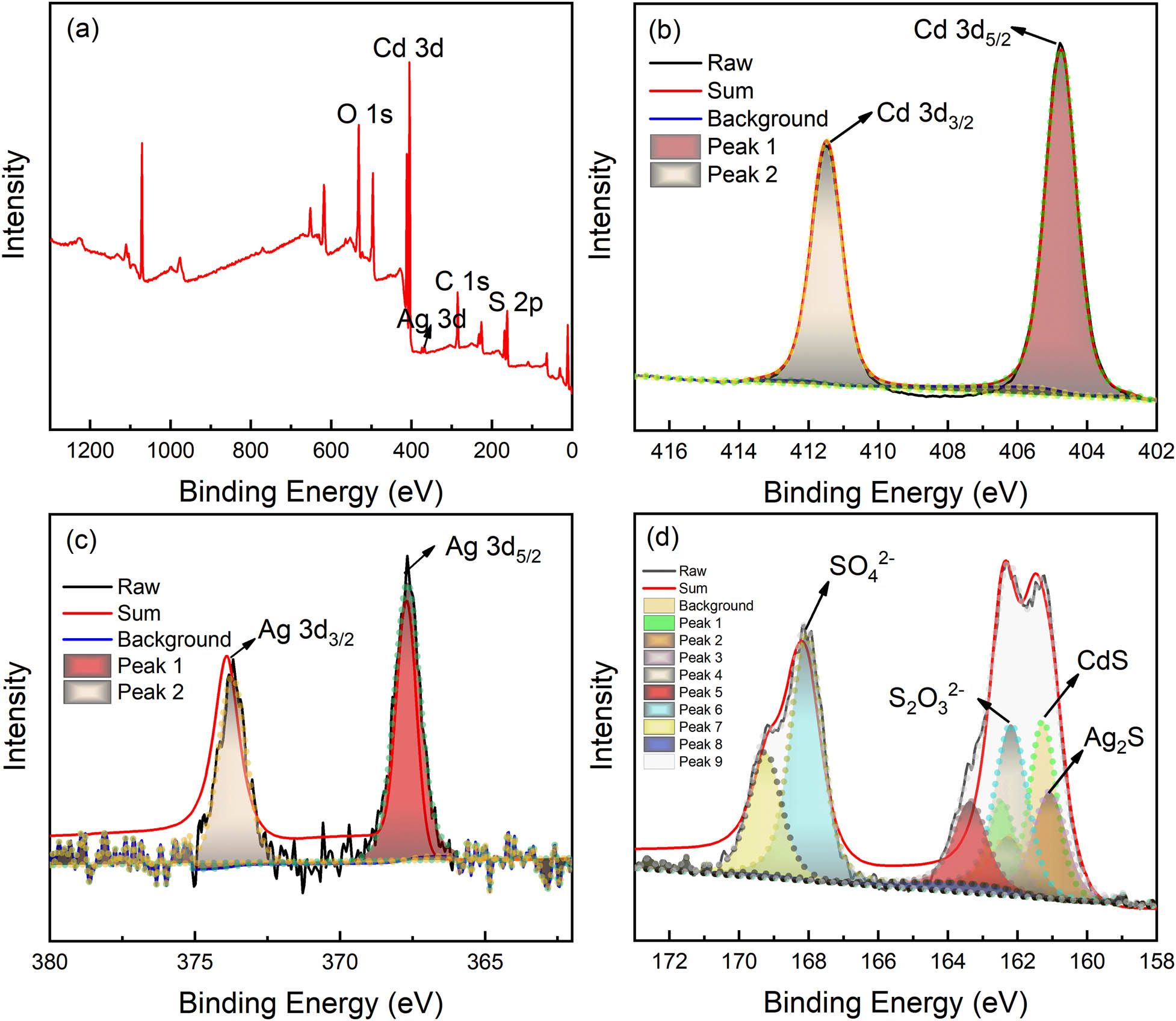

The CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites prepared by photolysis were further analyzed using XPS to determine the valence state of the elements. As shown in Figure 6(a), Cd, Ag, and S were detected in the XPS survey scan. Figure 6(b) shows the XPS profile of Cd 3d, in which two broad peaks are observed. The first peak (411.3 eV) corresponds to Cd 3d3/2, and the second peak (405.0 eV) corresponds to Cd 3d5/2 [27,28]. The peaks of Cd 3d peaks were present at the binding energies of 405.0 eV and 411.3 eV. It can be concluded that Cd appeared as cadmium sulfide in the photoproduct, which agrees with the XRD results. Figure 6(c) shows the XPS profile of Ag-3d, in which two peaks with broad features were identified. Based on the NIST XPS database, the first peak (373.9 eV) corresponds to Ag 3d3/2, and the second peak (367.6 eV) corresponds to Ag 3d5/2 [29]. Therefore, it was verified that Ag appeared as silver sulfide in the photoproduct, which again agrees with the XRD results. The deconvoluted XPS S-2p spectrum displayed in Figure 6(d) shows two peaks in the narrowed bound energy scope. These S 2p peaks occur as doublets, namely S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2. Makhova et al. [30] and Guo et al. [31,32] reported that the S 2p energy level of CdS and Ag2S is at 161.5 and 161.0 eV, respectively. Duret-Thual et al. [33] reported that the S 2p energy level of Na2S2O3 is at 162.4 eV, and the S 2p energy level of Na2SO4 is at 169.2 eV. It has also been reported that the S 2p energy level of

Deconvoluted XPS spectra for photoproduct: (a) survey spectrum; (b) Cd-3d spectrum; (c) Ag-3d spectrum; (d) S-2p spectrum.

3.3 Optical and electrochemical properties

To clearly illustrate the optical and electrochemical properties of the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites, the UV–Vis DRS, transient photocurrent, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were conducted, respectively. The UV–Vis DRS and corresponding bandgap energies were applied to scrupulously investigate the optical properties of the CdS–Ag2S, Ag2S, and CdS nanocomposites.

The UV–Vis spectra of the photolysis products are shown in Figure 7(a), where excellent absorption is observed in the range 200–1200 nm. The bandgap energies were estimated using a plot of (αhv)2 versus photo energy (hv). The intercept of the tangent to this plot provides a good approximation of the indirect bandgap energy. The apparent bandgap can be calculated using the Kubelka–Munk formula, as shown in equation (5).

where α, h, v, A, and E g represent the absorbance coefficient, Plank’s constant, incident photon frequency, absorbance, and apparent bandgap, respectively. Figure 7(b) shows that this curve forms the converted Kubelka–Munk formula curve. The intersection of the curve’s tangent and abscissa determines the apparent bandgap energy. Accordingly, the estimated bandgap energies for Ag2S, CdS, and CdS–Ag2S, are 0.99, 2.37, and 1.72 eV, respectively. The first two values are in accordance with the theoretical values of silver sulfide and cadmium sulfide. The design and development of CdS–Ag2S is to reduce the bandgap and enhance visible light absorption by introducing silver components to adjust the position of valence band (VB) or conduction band (CB), and exhibits better photocatalytic activity.

(a) UV-Vis absorbance spectra of Ag2S, CdS, and CdS–Ag2S; (b) plots of (αhv)2 versus energy (hv) of Ag2S, CdS, and CdS–Ag2S.

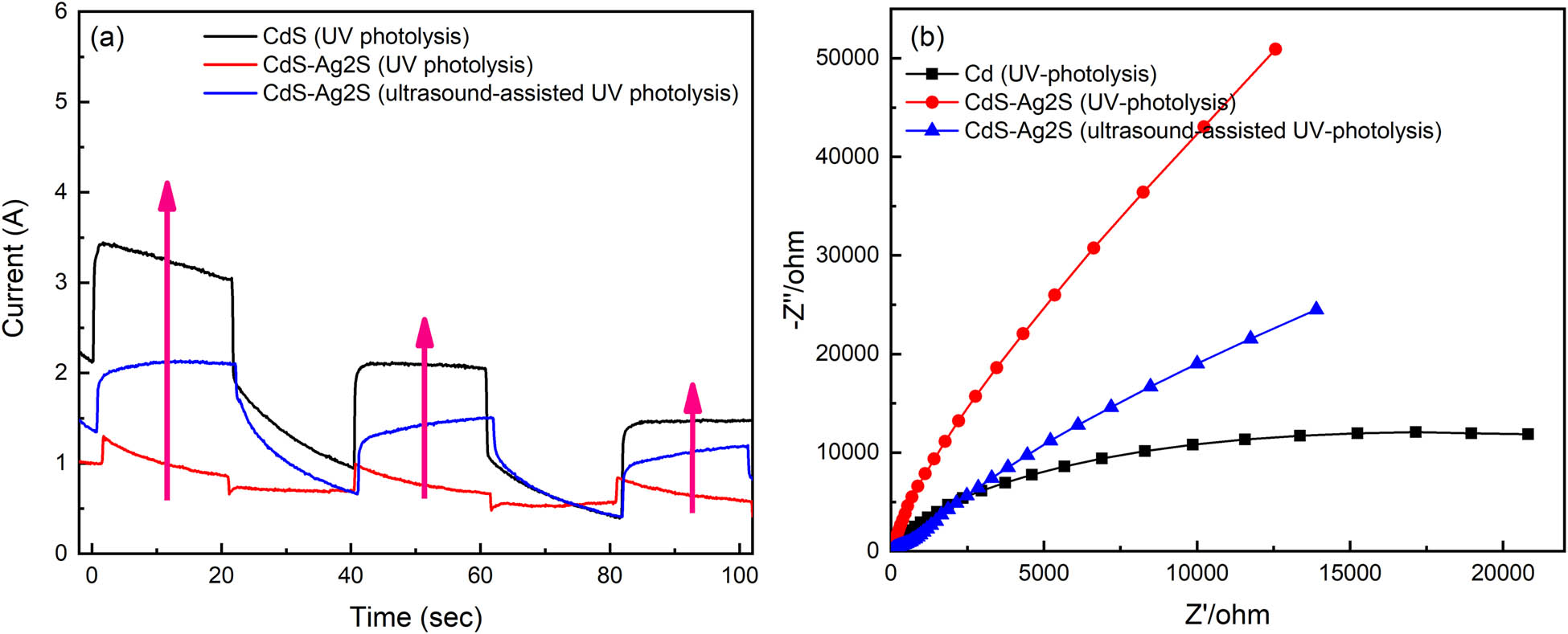

The transient photocurrent was measured using electrochemical workstations to monitor the migration of photogenerated carriers in the nanocomposites. Figure 8(a) displays the transient photocurrent spectra of the cadmium/silver sulfide prepared via ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis, and cadmium/silver sulfide and cadmium sulfide nanocomposites prepared via UV photolysis. The analysis showed that the current value was observed to increase every 20 s of irradiation time, but when blocked, it rapidly decreased in the subsequent 20 s interval. This indicates that the photogenerated charge carriers were transferred to the electrode, thereby generating a photocurrent. Compared with the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites prepared by UV photolysis, the I–t curves of cadmium/silver sulfide synthesized through ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis produced a higher current every 20 s. This demonstrates that the ultrasound treatment improves the dispersion and strengthens the photocatalytic activity. Compared with pure CdS nanocomposites synthesized via pure UV photolysis, the I–t curves of the previously mentioned cadmium/silver sulfide prepared via ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis generated approximately the same or a slightly lower current at every 20 s. This demonstrates that a higher photocurrent improves light absorption and electron extraction, which are in turn beneficial for charge separation [34]. The CdS–Ag2S EIS Nyquist plots of CdS–Ag2S are presented in Figure 8(b). The arc radius of CdS–Ag2S with ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis (presented by the blue line) is smaller than that of CdS–Ag2S without ultrasound (presented by the red line), indicating that the ultrasound can enhance the charge transfer resistance and the interfacial charge separation. However, the arc radius of CdS–Ag2S (ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis) is bigger than that of pure CdS (UV-photolysis, black line), which is consistent with the I–t curves.

(a) Transient photocurrent (I–t curves); (b) electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) of different samples.

3.4 Visible light photocatalysis activity of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites

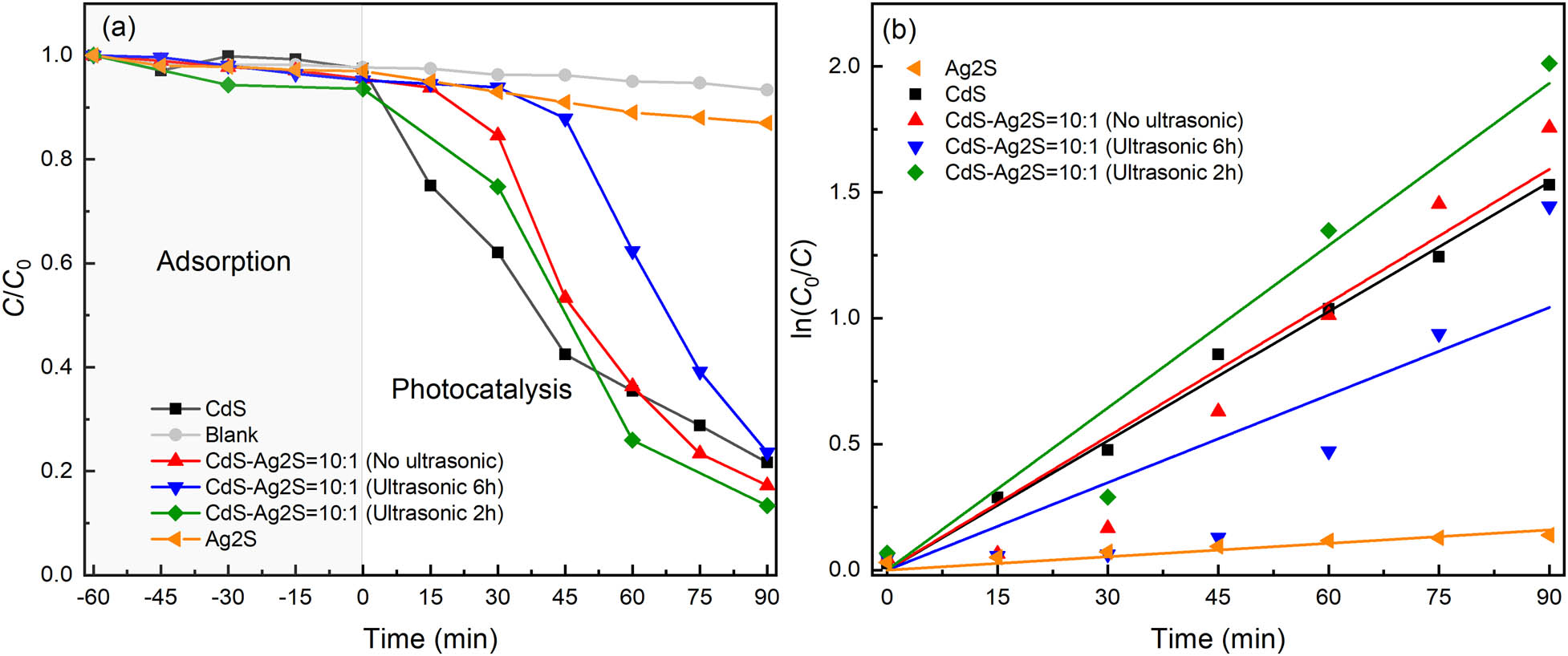

Microstructure, chemical composition, optical, and electrochemical properties of the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites were compared with the photocatalytic activity of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites and pure CdS which are prepared by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis in the photodegradation of MO under visible light irradiation. The degree of degradation was measured by the characteristic absorption wavelength of 465 nm, and the C/C 0 vs irradiation time is plotted in Figure 9. In the photocatalytic activity analysis, the adsorption (−60 to 0 min) and the C/C 0 ratio remained constant, indicating that the MO can hardly adsorb on the surface of the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposite. During photocatalysis (0 to 90 min), the C/C 0 of the blank experiment remained constant, indicating that the MO solutions do not exhibit self-degradation. The C/C 0 of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites decreased with time, but it increased under conditions of ultrasonication for 6 h, no ultrasonication, and ultrasonication for 2 h after 90 min. It possessed a photocatalytic efficiency of 87% after 90 min under the condition of ultrasonication for 2 h, which is higher than that of pure CdS with 78% at the same time. The rate constant of the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites under different conditions, namely ultrasonication for 6 h, no ultrasonication, and ultrasonication for 2 h, was calculated to be 0.01159, 0.01769, and 0.02148 min−1, respectively. The sample ultrasonicated for 2 h with UV photolysis exhibits a fine degradation rate because the ultrasound can contribute to the dispersion of the system and facilitate the formation of nanocomposites. However, a longer ultrasonic treatment time may damage the structure, causing a decrease in the reaction rate. To objectively evaluate the photocatalytic effect of the nanocomposites prepared by this method, and the capabilities of different components were examined. The results show that the catalytic effect of Ag2S is very poor, and the rate constant of the pure Ag2S nanocomposites with UV photolysis was 0.00177 min−1. The rate constant of the pure CdS nanocomposites with UV photolysis was 0.01711 min−1. The rate constant of the synthesized CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites with UV photolysis was increased to 0.02148 min−1 with the formation of the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites, indicating that the ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis method can produce nanocomposites with better properties.

Time-course variation of C/C 0 toward MO: (a) C/C 0 vs time; (b) ln(C 0/C) vs time.

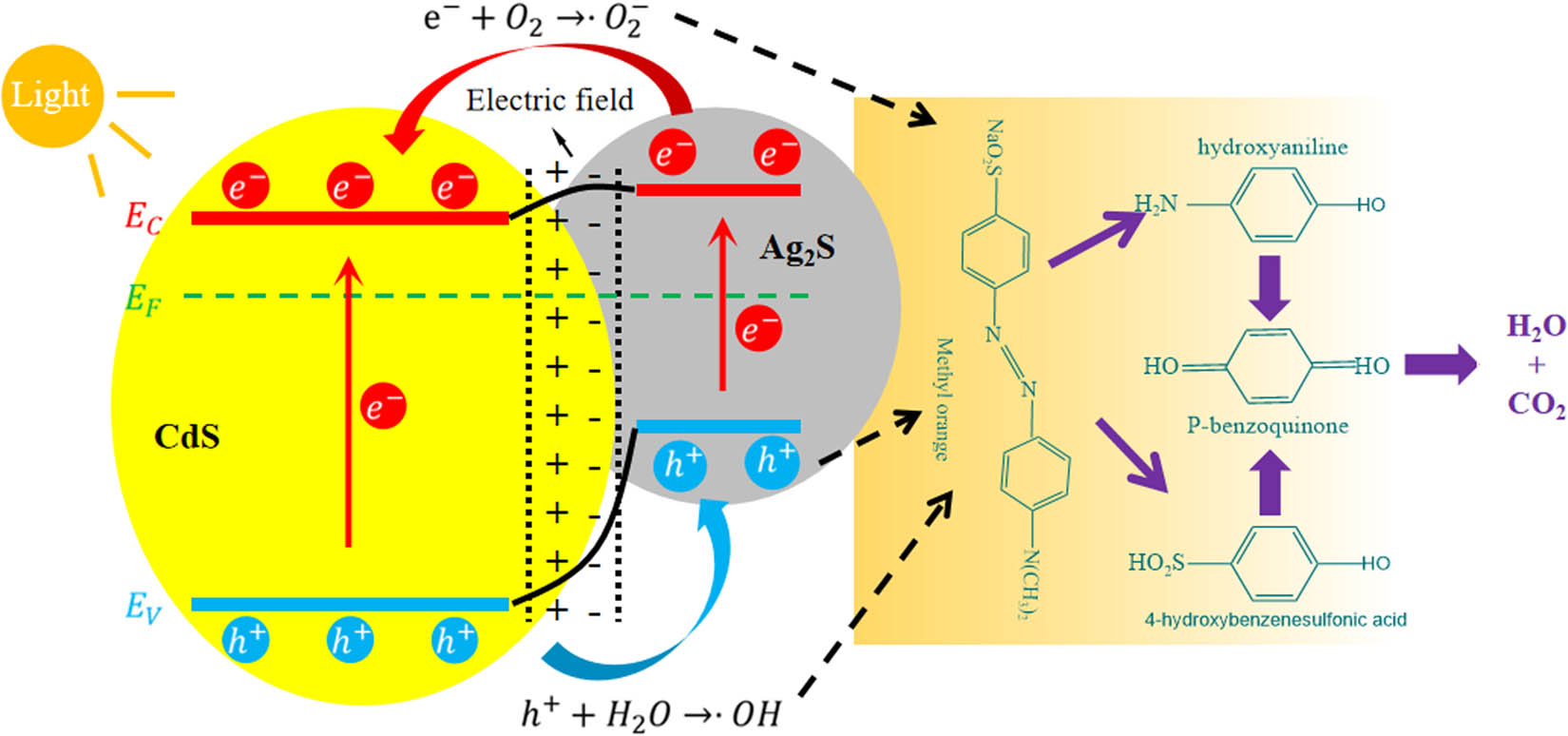

The photocatalytic mechanism of the degradation of MO by CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites is shown in Figure 10. Under visible light irradiation, CdS undergoes electron band-to-band transition, and electrons (e−) transition from valence band (VB) to conduction band (CB), forming photogenerated electron–hole pairs (e−/h+). Photogenerated electron–hole pairs (e−/h+) have strong oxidation and reduction properties. The electrons (e−) on the conduction band (CB) reduce oxygen to superoxide anion (•

Degradation mechanism of MO by CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites under visible light irradiation.

4 Conclusions

In this study, a novel method for synthesizing CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites from complex solutions is presented. The photochemical co-precipitation of the Cd–Ag thiosulfate complex (Cd: 100 mg/L; Ag: 10 mg/L) produced the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites. The XRD and XPS results confirmed that the nanocomposites are chemically composed of CdS and Ag2S. Based on the Tyndall effect, the size of the CdS–Ag2S particles is considered to be in the nanoscale. The DRS result indicated that the bandgap energy of CdS–Ag2S is 1.72 eV. Investigations into the visible-light photocatalytic activity of the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites using the I–t curves demonstrated that they can produce a photocurrent under the conditions of stimulated solar irradiation. Investigations into the photocatalytic degradation of MO using the as-synthesized samples revealed that the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposite possessed a photocatalytic efficiency of 87% after 90 min. According to the kinetic study, which showed that the first-order equation can fit the data, the use of the proposed ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis method can yield nanocomposites with good photocatalytic performance, and the rate constant for the CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites obtained using this method is 0.02148 min−1.

-

Funding information: This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52104349), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2021M690915). This project was also funded by The Key Technologies R&D Program of Henan Province (Grant No. 222102320435), and The Key Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities in Henan Province (Grant No. 21A450001).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Huang J, Luo Y, Weng M, Yu J, Sun L, Zeng H, et al. Advances and applications of phase change materials (PCMs) and PCMs-based technologies. ES Mater Manuf. 2021;13:23–39.10.30919/esmm5f458Search in Google Scholar

[2] Kadam AN, Salunkhe TT, Kim H, Lee SW. Biogenic synthesis of mesoporous N–S–C tri-doped TiO2 photocatalyst via ultrasonic-assisted derivatization of biotemplate from expired egg white protein. Appl Surf Sci. 2020;518:146194.10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.146194Search in Google Scholar

[3] Mukhopadhyay A, Tripathy BK, Debnath A, Kumar M. Enhanced persulfate activated sono-catalytic degradation of brilliant green dye by magnetic CaFe2O4 nanoparticles: Degradation pathway study, assessment of bio-toxicity and cost analysis. Surf Interfaces. 2021;26:101412.10.1016/j.surfin.2021.101412Search in Google Scholar

[4] Bose S, Tripathy BK, Debnath A, Kumar M. Boosted sono-oxidative catalytic degradation of Brilliant green dye by magnetic MgFe2O4 catalyst: Degradation mechanism, assessment of bio-toxicity and cost analysis. Ultrason Sonochem. 2021;75:105592.10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105592Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Tripathy BK, Kumar S, Kumar M, Debnath A. Microwave induced catalytic treatment of brilliant green dye with carbon doped zinc oxide nanoparticles: Central composite design, toxicity assessment and cost analysis. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag. 2020;14:100361.10.1016/j.enmm.2020.100361Search in Google Scholar

[6] Liexiao L, Xiaofeng S, Tao X, Huajing G, Shifa W, Zao Y, et al. Template-free synthesis of Bi2O2CO3 hierarchical nanotubes self-assembled from ordered nanoplates for promising photocatalytic applications. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2022;24:8279–95.10.1039/D1CP05952ASearch in Google Scholar

[7] Supekar A, Kapadnis R, Bansode S, Bhujbal P, Kale S, Jadkar S, et al. Cadmium telluride/cadmium sulfide thin films solar cells:a review. ES Energy Environ. 2020;10:3–12.10.30919/esee8c706Search in Google Scholar

[8] Rahane GK, Jathar SB, Rondiya SR, Jadhav YA, Barma SV, Rokade A, et al. Photoelectrochemical investigation on the cadmium sulfide (CdS) thin films prepared using spin coating technique. ES Mater Manuf. 2020;11:57–64.10.30919/esmm5f1041Search in Google Scholar

[9] Zhao Y, Li L, Zuo Y, He G, Chen Q, Meng Q, et al. Reduced graphene oxide supported ZnO/CdS heterojunction enhances photocatalytic removal efficiency of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solution. Chemosphere. 2022;286:131738.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131738Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Li LL, Yin XL, Sun YQ. Facile synthesized low-cost MoS2/CdS nanodots-on nanorods heterostructures for highly efficient pollution degradation under visible light irradiation. Sep Purif Technol. 2019;212:135–41.10.1016/j.seppur.2018.11.032Search in Google Scholar

[11] Lv T, Li D, Hong Y, Luo B, Xu D, Chen M, et al. Facile synthesis of CdS/Bi4V2O11 photocatalysts with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity for degradation of organic pollutants in water. Dalton Trans. 2017;46:12675–82.10.1039/C7DT02151HSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Liu YP, Shen SJ, Zhang JT, Zhong WW, Huang XH. Cu2xSe/CdS composite photocatalyst with enhanced visible light photocatalysis activity. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;478:762–9.10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.02.010Search in Google Scholar

[13] Tingting C, Huajing G, Guorong L, Zhongsheng P, Shifa W, Zao Y, et al. Preparation of core-shell heterojunction photocatalysts by coating CdS nanoparticles onto Bi4Ti3O12 hierarchical microspheres and their photocatalytic removal of organic pollutants and Cr(VI) ions. Colloids Surf A: Physicochem Eng Aspects. 2022;633:127918.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.127918Search in Google Scholar

[14] Yi Z, Ye J, Kikugawa N, Kako T, Ouyang S, Stuart-Williams H, et al. An orthophosphate semiconductor with photooxidation properties under visible-light irradiation. Nat Mater. 2010;9(7):559–64.10.1038/nmat2780Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Lu HD, Wang JX, Du ZY, Liu YP, Li M, Chen P, et al. In-situ anionexchange synthesis AgCl/AgVO3 hybrid nanoribbons with highly photocatalytic activity. Mater Lett. 2015;157:231–4.10.1016/j.matlet.2015.05.135Search in Google Scholar

[16] Wang C, Zhai J, Jiang H, Liu D, Zhang L. CdS/Ag2S nanocomposites photocatalyst with enhanced visible light photocatalysis activity. Solid State Sci. 2019;98:106020.10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2019.106020Search in Google Scholar

[17] Iqbal T, Ali F, Khalid NR, Bilal Tahir M, IIjaz M. Facile synthesis and antimicrobial activity of CdS-Ag2S nanocomposites. Bioorganic Chem. 2019;90:103064.10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103064Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Han G, Jin YH, Burgess RA, Dickenson NE, Cao XM, Sun Y. Visible-lightdriven valorization of biomass intermediates integrated with H2 production catalyzed by ultrathin Ni/CdS nanosheets. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:15584–7.10.1021/jacs.7b08657Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Di T, Cheng B, Ho W, Yu J, Hua T. Hierarchically CdS-Ag2S nanocomposites for efficient photocatalytic H2 production. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;470:196–204.10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.11.010Search in Google Scholar

[20] El-Nahass MM, Farag AA, Ibrahim EM, Abd-El-Rahman S. Structural, optical and electrical properties of thermally evaporated Ag2S thin films. Vacuum. 2004;72(4):453–60.10.1016/j.vacuum.2003.10.005Search in Google Scholar

[21] Abd-Elkader OH, Shaltout AA. Characterization and antibacterial capabilities of nanocrystalline CdS thin films prepared by chemical bath deposition. Mater Sci Semicond Process. 2015;35:132–8.10.1016/j.mssp.2015.03.003Search in Google Scholar

[22] Sebastián G, Karla G, Ernestode LT, Alicia G. Precious metals recovery from waste printed circuit boards using thiosulfate leaching and ion exchange resin. Hydrometallurgy. 2019;186:1–11.10.1016/j.hydromet.2019.03.004Search in Google Scholar

[23] Wang P, Cheng H, Ding J, Ma J, Jiang J, Huang Z, et al. Cadmium removal with thiosulfate/permanganate (TS/Mn(VII)) system: MnO2 adsorption and/or CdS formation. Chem Eng J. 2020;380:122585.10.1016/j.cej.2019.122585Search in Google Scholar

[24] Egorov NB, Eremin LP, Larionov AM, Usov VF, Tsepenko EA, D’yachenko AS. Products of photolysis of cadmium thiosulfate aqueous solutions. High Energy Chem. 2008;42:119–22.10.1134/S0018143908020100Search in Google Scholar

[25] Han C, Wang G, Cheng C, Shi C, Yang Y, Zou M. A kinetic and mechanism study of silver-thiosulfate complex photolysis by UV-C irradiation. Hydrometallurgy. 2020;191:105212.10.1016/j.hydromet.2019.105212Search in Google Scholar

[26] Zamiri R, Abbastabar Ahangar H, Zakaria A, Zamiri G, Shabani M, Singh B, Ferreira JM. The structural and optical constants of Ag2S semiconductor nanostructure in the Far-Infrared. Chem Cent J. 2015;9(1):28.10.1186/s13065-015-0099-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Di T, Zhu B, Zhang J, Cheng B, Yu J. Enhanced photocatalytic H2 production on CdS nanorod using cobalt-phosphate as oxidation cocatalyst. Appl Surf Sci. 2016;389:775–82.10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.08.002Search in Google Scholar

[28] Yu W, Zhang S, Chen J, Xia P, Richter MH, Chen L, et al. Biomimetic Z-scheme photocatalyst with a tandem solid-state electron flflow catalyzing H2 evolution. J Mater Chem A. 2018;6:15668–74.10.1039/C8TA02922ASearch in Google Scholar

[29] An C, Wang J, Jiang W, Zhang M, Ming X, Wang S, et al. Strongly visiblelight responsive plasmonic shaped AgX: Ag (X = Cl, Br) nanoparticles for reduction of CO2 to methanol. Nanoscale. 2012;4:5646–50.10.1039/c2nr31213aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Makhova L, Mikhlin Y, Romanchenko A. A combined XPS, XANES and STM/STS study of gold and silver deposition on metal sulphides. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res Sect A: Accel Spectrometers Detect Assoc Equip. 2007;575:75–7.10.1016/j.nima.2007.01.029Search in Google Scholar

[31] Guo J, Liang Y, Liu L, Hu J, Wang H, An W, et al. Core-shell structure of sulphur vacancies-CdS@CuS: Enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen generation activity based on photoinduced interfacial charge transfer. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2021;600:138–49.10.1016/j.jcis.2021.05.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Zhang X, Li N, Wu J, Zheng Y, Tao X. Defect-rich O-incorporated 1TMoS2 nanosheets for remarkably enhanced visible-light photocatalytic H2 evolution over CdS: The impact of enriched defects. Appl Catal B. 2018;229:227–36.10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.02.025Search in Google Scholar

[33] Duret-Thual C, Costa D, Yang WP, Marcus P. The role of thiosulfates in the pitting corrosion of Fe-17Cr alloys in neutral chloride solution: Electrochemical and XPS study. Corros Sci. 1997;39(5):913–33.10.1016/S0010-938X(97)81158-4Search in Google Scholar

[34] Yu J, Jin J, Cheng B, Jaroniec M. A noble metal-free reduced graphene oxide–CdS nanorod composite for the enhanced visible-light photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to solar fuel. J Mater Chem A. 2014;2:3407–16.10.1039/c3ta14493cSearch in Google Scholar

[35] Lee J, Lee Y, Bathula C, Kadam AN, Lee SW. A zero-dimensional/two-dimensional Ag-Ag2S-CdS plasmonic nanohybrid for rapid photodegradation of organic pollutant by solar light. Chemosphere. 2022;296:133973.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.133973Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Okla M, Janani B, AL-ghamdi AA, Abdel-Maksoud MA, AbdElgawad H, Das A, et al. Facile construction of 3D CdS-Ag2S nanospheres: A combined study of visible light responsive phtotocatalysis, antibacterial and anti-biofilm activity. Colloids Surf A: Physicochem Eng Aspects. 2022;632:127729.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.127729Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery

- The progress of cathode materials in aqueous zinc-ion batteries

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part I

- Effect of polypropylene fiber and nano-silica on the compressive strength and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete

- Mechanochemical design of nanomaterials for catalytic applications with a benign-by-design focus

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery

- The progress of cathode materials in aqueous zinc-ion batteries

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part I

- Effect of polypropylene fiber and nano-silica on the compressive strength and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete

- Mechanochemical design of nanomaterials for catalytic applications with a benign-by-design focus