Abstract

Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) have recently attracted considerable attention, mainly due to their unique magnetic properties and biocompatibility. Although MNPs have been extensively studied for biomedical applications, there are still very few studies on them as part of three-dimensional (3D)-printed scaffolds. Thus, this review aims to show the potential of MNPs to modulate various properties of 3D-printed scaffolds. 3D Printing is for itself a contemporary method in biomedicine, owing to its ability to produce versatile scaffolds with complex shapes enabling a homogeneous distribution of cells or other entrapped compounds, as well as possible precise control of pore size and shape, porosity, and interconnectivity of pores that contribute to structural stability. All mentioned properties can be upgraded or complemented with the specific properties of MNPs (e.g., biocompatibility and positive effect on cell proliferation). Considering the latest related literature and a steadily increasing number of related publications, the fabrication of magnetically responsive scaffolds is among the most interesting strategies in tissue engineering. According to the literature, incorporating MNPs into scaffolds can improve their mechanical properties and significantly affect biological properties, such as cellular responses. Moreover, under the influence of an external magnetic field, MNPs significantly promoted cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation.

Abbreviations

- AMF

-

alternating magnetic field

- β-TCP

-

beta tri-calcium phosphate

- BMSCs

-

bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- FeHA

-

iron-doped hydroxyapatite

- GC

-

glycol chitosan

- GelMA

-

gelatin methacryloyl

- GO

-

graphene oxide

- HA

-

hydroxyapatite

- hASCs

-

human adipose stem cells

- IONPs

-

iron oxide nanoparticles

- MBG

-

mesoporous bioactive glass

- MGO

-

magnetic graphene oxide

- MH

-

magnetic hyperthermia

- MNPs

-

magnetic nanoparticles

- NPs

-

nanoparticles

- OHA

-

oxidized hyaluronate

- PCL

-

polycaprolactone

- PGA

-

polyglycolic acid

- PLGA

-

poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- PLLA

-

poly-l-lactic acid

- SPIONs

-

super-paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles

- TE

-

tissue engineering

1 Introduction

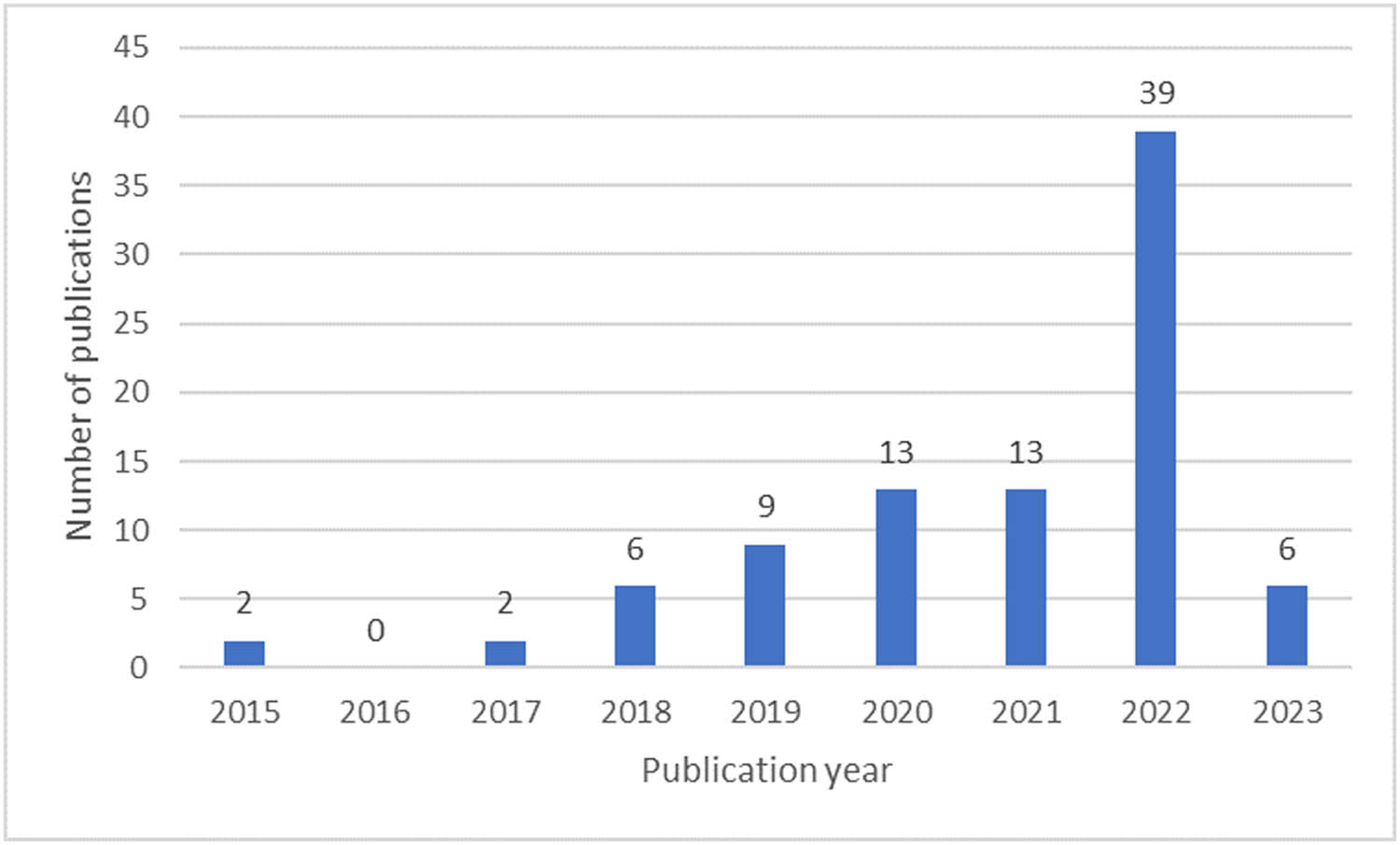

Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), especially iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs), have attracted increasing attention in recent years due to their unique magnetic properties such as appropriate Curie temperature, superparamagnetism, and magnetic hyperthermia (MH), as well as their biocompatibility, which makes them suitable for biomedical applications [1]. In addition, MNPs exhibit many important properties, such as high specific surface area, chemical stability, low intraparticle diffusion rate, and high loading capacity [2,3]. MNPs are usually composed of magnetic elements such as iron (Fe), nickel (Ni), and cobalt (Co), and their oxides such as magnetite (Fe3O4) and its oxidized form maghemite (γ-Fe2O3). Their ability to be remotely controlled with an external magnetic field is one of the most important properties of MNPs [4]. In the last decade, MNPs have been extensively investigated for biomedical applications such as MH, magnetic resonance imaging, and targeted drug delivery [5,6]. Meanwhile, very few studies have been conducted on using MNPs as part of three-dimensional (3D)-printed scaffolds for tissue engineering (TE), although the interest in such applications is steadily rising. Figure 1 shows the increasing number of scientific publications on MNPs use in 3D-printed scaffolds in recent years. This statistic shows that incorporating MNPs into 3D-printed scaffolds is a promising research area that will continue to grow in the coming years. Considering the overall still a low number of related articles and especially the lack of any review articles, related to the use of MNPs to manipulate the properties of 3D-printed scaffolds to improve their properties for biomedical applications, we present a summarized review of the opportunities arising from this combination.

Number of scientific publications per year related to “magnetic nanoparticles” and “3D-printed scaffolds,” according to the ScienceDirect (accessed 25 January 2023).

2 Methods

A literature review was conducted via the biggest medical literature databases (Medline, PubMed, and ScienceDirect) to obtain studies related to MNPs and 3D printing. The employed search terms in the form of keywords were “magnetic nanoparticles” and “3D-printing.” With the help of specific filters (5-year review), we were able to find relevant new impactful studies on MNPs in 3D-printed scaffolds, which were included in this review.

3 General properties of MNPs and 3D printing

Although a wide variety of MNPs can be used for this purpose, most research has focused only on IONPs. This is at least partially related to the approval of their clinical use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [7]. In addition to the general advantages of MNPs, IONPs offer many other benefits like relatively simple synthesis, high saturation magnetization, high magnetic susceptibility, and low cytotoxicity [8]. Moreover, when the size of ferrimagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles (NPs) is reduced below 20 nm, they exhibit super-paramagnetic properties, as each particle becomes a single magnetic domain [9]. Superparamagnetic Fe3O4 NPs exposed to an alternating magnetic field (AMF) can generate heat through mainly Néel and Brownian relaxations, together with hysteresis losses, which are used in MH [10]. However, despite the many advantages of IONPs, there are also some disadvantages, such as a relatively high Curie temperature. The latter might be a problem in biomedical applications (e.g., MH) since it can lead to overheating of the surrounding tissue if there is no external temperature control to turn off the magnetic field [11]. For this reason, nickel–copper (NiCu) NPs with a Curie temperature within the therapeutic range (42–46°C) seem even more promising when using MH [12,13,14,15]. NiCu NPs are chemically stable, biocompatible, and exhibit desired magnetic properties, which makes them highly interesting for use in biomedicine [11]. Many groups have already investigated the use of NiCu MNPs as mediators for MH, but Stergar et al. were the first to report the potential of NiCu NPs as bimodal therapeutic systems, capable of simultaneous MH and targeted drug delivery [16].

Porosity, pore size and interconnectivity, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and mechanical properties are important parameters to be considered in developing suitable scaffolds [17]. Various techniques have been used to fabricate scaffolds, including freeze-drying, solvent casting, particulate leaching, phase separation, electrospinning, melt moulding, and gas foaming [18]. However, in these techniques, it is often difficult to precisely control the pore size, pore geometry, porosity, and connectivity of the pores [19]. Three-dimensional (3D) printing technology is among the methods developed to overcome these limitations through its layer-by-layer deposition, which enables the fabrication of complex and precise structures [20]. 3D Printing brez pomišljaja technology offers several advantages over traditional scaffold fabrication methods. Among them is the ability to fabricate versatile scaffolds with complex geometries and desired overall shapes. Such possibilities are ideal for designing materials for homogeneous cell distribution, mimicry of the extracellular matrix, and fine-tuning the microenvironment to promote cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [21]. 3D Printing technology has revolutionized many areas of biomedical research and clinical practice. From creating patient-specific implants to printing tissue constructs for drug screening, 3D printing has opened up new possibilities for personalized and precision medicine. Extrusion-based 3D printing is one of the simplest and most cost-effective techniques used in 3D printing of polymers with potential application in TE [22]. Other 3D printing technologies currently being used in the preparation of different tissue scaffolds mainly include selective laser sintering, stereolithography, electron beam melting, 3DP technology, and biological 3D printing [23].

Since 3D printing is one of the most widely used techniques nowadays in TE, a lot of related research focuses on tissue-specific material choice. This is crucial from two perspectives: finding the optimum materials to grow specific cell types and suitable printability. Some natural polymers studied for this purpose are collagen, fibrin, chitosan, hyaluronic acid, alginate, gelatin, and gelatin methacrylate [24,25,26]. Despite their excellent bioactivity and biodegradability, low potential for immune defence and ability to form scaffolds that maintain the extracellular matrix composition of host tissues are the reasons that they are not ideal for TE. Their main disadvantages include their low mechanical strength and rapid degradation rate, which hinder their use in load-bearing applications. Although natural materials are beneficial for cellular processes, synthetic polymers are a better choice for tissue support due to their better mechanical properties, easily modifiable biological properties, and controlled degradation rate. Some of the most commonly used synthetic polymers are poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA), polyglycolic acid (PGA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), and polycaprolactone (PCL) [21,27]. Bioceramic materials such as hydroxyapatite (HA) and beta tri-calcium phosphate (β-TCP) are also widely used in 3D printing. Due to their chemical and structural similarity to the mineral phase of natural bone, they exhibit excellent osteoconductivity and biocompatibility. However, they often have disadvantages due to low fracture toughness, extremely high stiffness, and low elasticity [27]. The disadvantages of the above biomaterials, which limit their use in the biomedical field, have led to the development of biocomposite materials that include particles, fibres, or nanomaterials to reinforce their mechanical and functional properties [24].

The use of MNPs for the fabrication of magnetically responsive scaffolds is one of the most recent strategies in the field of TE. Several studies have reported that incorporating MNPs into a scaffold material can improve the mechanical properties of the scaffolds, such as increased strength and toughness [28,29,30,31,32]. In addition, recent studies have shown that the presence of MNPs in scaffolds significantly affects biological properties and cellular responses. Under the influence of an external magnetic field, MNPs were shown to significantly promote cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [33,34,35] (Figure 2).

![Figure 2

Various applications of MNPs in 3D-printed scaffolds in biomedicine. The picture was produced using BioRender. The LEFT BOTTOM graph was taken with permission from [36].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0570/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0570_fig_002.jpg)

Various applications of MNPs in 3D-printed scaffolds in biomedicine. The picture was produced using BioRender. The LEFT BOTTOM graph was taken with permission from [36].

This review focuses on the importance of incorporating MNPs into 3D-printed scaffolds and on the recent advances in the use of MNPs in 3D-printed scaffolds in TE.

4 Contribution of MNPs to specific properties of 3D-printed scaffolds

4.1 Fe3O4 NPs

Considering the advantages of Fe3O4 NPs, several researchers have incorporated Fe3O4 NPs into 3D-printed scaffolds for TE applications. For example, Bin et al. fabricated a magnetic scaffold for bone tissue applications by incorporating Fe3O4 NPs into PLLA by selective laser sintering (Figure 3(a)). The incorporation of Fe3O4 NPs, which acted as nanoscale reinforcement in the polymer matrix, not only improved the mechanical properties of the scaffold, such as compressive strength, modulus, and Vickers hardness, but also significantly improved the biological activity (improved cell adhesion) of the scaffold. The compressive strength and Vickers hardness increased with the Fe3O4 content and reached a maximum value at 7 wt% (Figure 3(b)). The results showed that the PLLA/Fe3O4 scaffold improved MG63 attachment, proliferation, and interaction (Figure 3(c and d)), which promoted the desired cell phenotype [36].

![Figure 3

(a) A schematic of the preparation of PLLA/Fe3O4 magnetic composite scaffolds. (b) Mechanical properties of the PLLA/Fe3O4 scaffolds. (c) SEM pseudocolor image of MG63 cell adhesion on the scaffolds. (d) The relative number of living cells and CCK-8 test in the fluorescence graph. Reproduced with permission from [36].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0570/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0570_fig_003.jpg)

(a) A schematic of the preparation of PLLA/Fe3O4 magnetic composite scaffolds. (b) Mechanical properties of the PLLA/Fe3O4 scaffolds. (c) SEM pseudocolor image of MG63 cell adhesion on the scaffolds. (d) The relative number of living cells and CCK-8 test in the fluorescence graph. Reproduced with permission from [36].

To tailor the degradation rate of PLLA/PGA scaffolds, Shuai et al. incorporated magnetic Fe3O4 NPs into the scaffolds by selective laser sintering. The saturation magnetization of the scaffolds increased from 1.66 to 8.51 emu/g when the content of Fe3O4 NPs increased from 2.5 to 10 wt% and was proportional to the Fe3O4 content. Moreover, the water contact angle decreased with the increase of Fe3O4 NPs, indicating that the incorporation of Fe3O4 NPs significantly improved the hydrophilicity of the scaffold. Although the results indicate that adding Fe3O4 NPs improves the compressive strength and modulus of the scaffold, excessive addition of NPs leads to agglomeration, which reduces the mechanical properties of the matrix. The scaffold with 7.5 wt% was selected for further biological experiments. It was shown that the scaffold promoted cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation in vitro and significantly accelerated the formation of new bone tissue in vivo [37].

Chen et al. investigated the effect of water-based magnetic fluids with different Fe3O4 concentrations on 3D-printed Fe3O4/CaSiO3 composite scaffolds for bone TE and obtained similar results. Scaffolds were prepared with Fe3O4 NPs at concentrations of 2.6, 3.5, 5.4 and 10.5 w/v%. The results showed that the composite scaffolds had the highest surface content of Fe3O4 NPs, the highest saturation magnetization of 69.6 emu/g, and the best stability in dynamically stimulated body fluid when the Fe3O4 concentration was 5.4% [38].

In a recent study, Kao et al. fabricated porous calcium silicate/PCL scaffolds with various concentrations of Fe3O4 NPs (0, 2.5, and 5 wt%) using 3D printing and evaluated their capability to regenerate bone tissue. A favourable combination of compressive strength and rate of decomposition was observed with 5 wt% Fe3O4. Results showed that the incorporation of Fe3O4 into scaffolds further enhanced the mechanical strength and increased the secretion of osteogenic-related markers, such as alkaline phosphatase, bone sialoprotein, collagen I, and osteocalcin [39].

De Santis et al. fabricated magnetic nanocomposite scaffolds based on PCL and poly(ethylene glycol) by 3D fibre deposition technique to regenerate complex tissues such as osteochondral bone. The incorporation of Fe3O4 NPs strongly affected the mechanical properties of both PCL- and poly(ethylene glycol)-based scaffolds by increasing the compressive modulus while decreasing ductility [40].

Han et al. demonstrated that introducing magnetic IONPs into 3D-printed PLGA scaffolds improved osteogenic differentiation in vitro and promoted bone regeneration in vivo. These improvements were attributed to enhanced cell adhesion to the magnetic scaffolds due to changes in hydrophilicity, increased surface roughness, and chemical composition of the scaffold. In addition, magnetic effects may also play a role in cell adhesion [41]. 3D-Printed PLGA scaffolds coated with super-paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) were also used in a recent study by Jia et al. Their palate-bone regeneration was investigated in a rat model. It was found that SPIONs-coated scaffolds improved bone regeneration, which was partly related to a change in the oral microbiota due to the antibacterial effect of SPIONs [42].

In the presence of SPIONs, Ko et al. successfully prepared a self-healing ferrogel based on glycol chitosan (GC) and oxidized hyaluronate (OHA) without using additional chemical crosslinkers. The addition of SPIONs decreased the elastic modulus of the GC/OHA hydrogel, and the storage shear modulus of the GC/OHA/SPIONs ferrogel decreased with an increase in SPIONs concentration. In addition, the properties of the ferrogel also depended on the [GC]/[OHA] ratio and the total polymer concentration. Cytotoxicity was evaluated using ATDC5 cells. Since no significant cytotoxicity of the GC/OHA/SPIONs ferrogel was observed, the authors concluded that the ferrogel could be useful for drug delivery systems and TE applications [43].

In a recent study, adipic acid dihydrazide was added to OHA/GC/SPION ferrogels to improve their 3D printability. By combining a self-healing hydrogel and a self-healing ferrogel without subsequent crosslinking, Choi et al. fabricated a 3D-printed dynamic tissue scaffold that can be used to stimulate and regulate cell phenotype under magnetic stimulation [44].

4.2 Hydroxyapatite in combination with magnetic nanoparticles

In addition to the mentioned natural and synthetic polymers, bioceramic materials such as hydroxyapatite (HA) are also widely used for bone TE due to their chemical and structural similarity to the mineral phase of natural bone.

Saraiva et al. fabricated a novel 3D-printed polylactic acid platform loaded with HA and IONPs to promote bone tissue repair and regrowth. Their results showed that the presence of two types of NPs (IONPs and HA) altered the nanomorphological properties of the 3D platforms and increased the osteogenic functionality of the cells [45].

Petretta et al. used 3D printing technology to develop PCL-based scaffolds to which HA and different concentrations of SPIONs were added. These additions aimed to improve the efficiency and control of cell attachment. Two different concentrations of SPIONs, 0.5 and 1%, were chosen, while HA accounted for 10% of the total weight. The addition of SPIONs resulted in higher cell seeding efficiency, activated through an external magnetic field, which was dependent on the degree of scaffold magnetization. The best results in terms of cell entrapment time and adhesion rates were obtained with the 1% SPIONs formulation with a high degree of magnetization. This study showed that PCL-HA-1% SPIONs scaffolds are promising candidates for bone tissue repair and regeneration because they have no toxic effects on fibroblasts and mesenchymal stromal cells and exhibit good cell proliferation and intrinsic osteogenic potential [46].

De Santis et al. also developed 3D-printed magnetic nanocomposite scaffolds for bone TE by incorporating iron-doped hydroxyapatite (FeHA) NPs into a PCL matrix. Previous studies have shown that incorporating FeHA NPs improves magnetic properties (i.e., saturation magnetization, temperature values due to hyperthermia), hydrophilicity (indicated by lower water contact angle values), and stiffness while decreasing their mechanical strength. Since the introduction of FeHA NPs led to discontinuities at the interface between the NPs and the matrix, which could be due to the difference in ductility between the polymer matrix and the inorganic nanofillers, the mechanical properties of PCL/FeHA scaffolds are limited. However, compared with pure scaffolds, PCL/FeHA scaffolds showed greater bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) growth, resulting in improved bone regeneration [47].

To improve the bacteriostatic properties of the implants, Shokouhimehr et al. incorporated SPIONs into a hyperelastic bone bioink, which consisted of 90 wt% HA and 10 wt% PLGA (Figure 4). Although the incorporation of 200 mg/ml SPIONs increased antibacterial activity compared to the 60 mg/ml SPIONs, the 60 mg/ml group showed the most optimal in vitro cell response [48].

![Figure 4

LEFT: Schematic summary of the experimental method used in this study. RIGHT: Characterization of cellular and bacterial response to bioprinted HB constructs in vitro. (a and b) Cellular growth (normalized to day 3) for C3H10T12 mouse cells (a) and human bone osteoblast (HBO) cells (b), measured by the noninvasive AlamarBlue assay for 17 days of in vitro culture. (c–f) Bacteriostatic effects of SPION in 2D culture (c and d) and SPION-loaded HB constructs (e and f) were evaluated by culturing GFP + S. aureus onto scaffolds for 24 h (c and e) and measuring fluorescence signals (d and f). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and **** p < 0.0001 (reproduced with permission from Shokouhimehr et al. [48]).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0570/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0570_fig_004.jpg)

LEFT: Schematic summary of the experimental method used in this study. RIGHT: Characterization of cellular and bacterial response to bioprinted HB constructs in vitro. (a and b) Cellular growth (normalized to day 3) for C3H10T12 mouse cells (a) and human bone osteoblast (HBO) cells (b), measured by the noninvasive AlamarBlue assay for 17 days of in vitro culture. (c–f) Bacteriostatic effects of SPION in 2D culture (c and d) and SPION-loaded HB constructs (e and f) were evaluated by culturing GFP + S. aureus onto scaffolds for 24 h (c and e) and measuring fluorescence signals (d and f). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and **** p < 0.0001 (reproduced with permission from Shokouhimehr et al. [48]).

In addition to various polymers and HA, 3D-printed porous titanium–aluminium–vanadium (pTi) scaffolds are also promising materials for reconstructing large bone defects due to their good mechanical properties, high corrosion resistance, and excellent biocompatibility. However, their restricted induction of bone ingrowth compared to some other materials limits their application in the clinic. To overcome the limitation of the poor osteogenic activity of 3D-printed porous pTi scaffolds, Huang et al. fabricated a magnetic coating by applying Fe3O4 NPs and polydopamine to the surface of the scaffolds. This new coating significantly improved cell adhesion, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation of human BMSCs in vitro and new bone formation in vivo. Moreover, these improvements could be further enhanced by a static magnetic field [49].

5 Magnetic nanoparticles and their use to manipulate 3D-printed materials

Since induced hyperthermia can cause tumour cell death, MH also presents a potential cancer treatment. Zhang et al. successfully prepared a multifunctional 3D-printed β-TCP bioceramic scaffold by modifying the surface with Fe3O4 NPs/graphene oxide (GO) layers. The resulting β-TCP-Fe-GO scaffold presented a highly ordered macroporous structure with super-paramagnetic behaviour and hyperthermia effects. The porosity of the scaffolds did not change significantly after modification with Fe3O4/GO, while the magnetic intensity of the scaffolds increased with increasing Fe3O4 content, as previously found in other studies. Therefore, by controlling the magnetic intensity and Fe3O4 content, the temperature of the scaffolds could be easily modulated/tailored in the range between 50 and 80°C. The results indicate that such scaffolds have the potential to be used in the therapy and regeneration of bone defects caused by bone tumours due to their excellent magnetic and osteogenic capabilities [50].

In a recent study, Li et al. prepared a novel hydrogel composite scaffold of polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate/HA by 3D printing. They optimized its properties by varying the concentrations of magnetic graphene oxide (MGO), with Fe3O4 NPs uniformly distributed on the surface of GO (Figure 5). Adding MGO improved the composite material’s thermal stability and imparted magnetic properties. The prepared composite scaffolds not only improved the biological functions and supported the differentiation of rat BMSCs in vitro but also showed favourable anti-tumour effects in vivo [51].

![Figure 5

LEFT: Schematic diagrams of MGO hydrogel composite fabrication (above) and application to bone tumour defect regeneration in vitro and in vivo (below). RIGHT: Inhibition of osteosarcoma tumour growth in vivo. (a) In vivo infrared thermography of 143b-tumour-bearing nude mice after intratumorally implantation with MGO hydrogel composite under AMF at various time points. (b) Temperature versus time at the tumour sites implanted with MGO hydrogel composite with and without AMF. (c) Digital photographs of the dissected tumours. (d) Relative tumour volume changes over time after the different treatments (reproduced with permission from Li et al. [51]).](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0570/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0570_fig_005.jpg)

LEFT: Schematic diagrams of MGO hydrogel composite fabrication (above) and application to bone tumour defect regeneration in vitro and in vivo (below). RIGHT: Inhibition of osteosarcoma tumour growth in vivo. (a) In vivo infrared thermography of 143b-tumour-bearing nude mice after intratumorally implantation with MGO hydrogel composite under AMF at various time points. (b) Temperature versus time at the tumour sites implanted with MGO hydrogel composite with and without AMF. (c) Digital photographs of the dissected tumours. (d) Relative tumour volume changes over time after the different treatments (reproduced with permission from Li et al. [51]).

Yang et al. developed implantable magnetocaloric mats capable of hyperthermia for cancer treatment. These properties were achieved by incorporating Fe3O4 NPs into PCL using E-jet 3D printing technology. When the PCL/Fe3O4 mat was exposed to an AMF, it resulted in efficient heating without loss of heating capacity or leakage of Fe3O4 NPs. The mats containing 6 mmol/L Fe3O4 NPs were the most effective, as they peripherally raised the temperature under an AMF to 45°C within 45 min and could inhibit tumour growth in vivo. Such magnetic mats are ideal for hyperthermia treatment of easily accessible tumours [52].

Another interesting study was published by Dong et al., in which the authors report an excellent synergistic therapeutic effect in osteosarcoma treatment. The latter was achieved through a combination of MH with an elaborate catalytic Fenton reaction by Fe3O4 and calcium peroxide (CaO2) NPs. Fe3O4 NPs were loaded into a 3D-printed akermanite scaffold to initiate MH through an AMF and catalyse the generation of hydroxyl radicals from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). At the same time, the co-loaded CaO2 NPs acted as an H2O2 source [53].

In addition to magnetothermal cancer therapies, magnetic field application could also be used to stimulate osteogenesis for bone repair. Shuai et al. fabricated porous super-paramagnetic PGA/Fe3O4 scaffolds that exhibit favourable mechanical, magnetic, and degradation properties. The magnetic moment of Fe3O4 NPs rearranged along the direction of the self-developed external static magnetic field applied as an external magnetic source, resulting in a locally enhanced magnetic field. As a result, cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation were promoted, and bone regeneration was significantly accelerated [54].

Zhang et al. used 3D printing to fabricate mesoporous bioactive glass (MBG)/PCL composite scaffolds containing magnetic Fe3O4 NPs. The saturation magnetization of the Fe3O4/MBG/PCL scaffolds increased with increasing Fe3O4 content, and a positive correlation between the heating rate and Fe3O4 content in the scaffolds was also observed. Although the incorporation of magnetic Fe3O4 NPs into the scaffolds did not affect apatite mineralization ability, it resulted in excellent magnetic heating and significantly stimulated cell proliferation and differentiation. The composite scaffolds also exhibited excellent bioactivity in apatite formation and increased compressive strength. Therefore, there is great potential for using Fe3O4/MBG/PCL scaffolds in the treatment and regeneration of bone defects through a combination of enhanced osteogenic activity, local delivery of anticancer drugs, and MH [55].

The agglomeration potential of IONPs has necessitated the development of strategies to modify the surface of IONPs. Lin et al. chemically modified the IONPs with sodium citrate to obtain a negative charge on the surface before embedding them in a chitosan hydrogel so that the surrounding cells could not directly contact the NPs. The study showed that the inductive coupling magnetic force successfully promoted bone cell growth, as evidenced by higher osteoblast cell proliferation, type I collagen production, alkaline phosphatase expression, and mineralization [56].

6 Magnetic nanoparticles in tailoring delivery of drugs and cells from 3D-printed materials

Scaffolds with incorporated MNPs are also quite interesting for the development of advanced, stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems as they can be guided and triggered by external magnetic fields. In these systems, therapeutic compounds are attached to biocompatible MNPs, which are directed to specific targets in vivo using an external magnetic field, resulting in enhanced delivery to the target site and reduced side effects of drugs by reducing their systemic distribution. For example, when an external magnetic field is applied to MNPs bound to cellular surface receptors, the MNPs generate mechanical forces that can be transmitted to the membrane to activate mechanosensitive ion channels [57]. Zhao et al. incorporated IONPs into alginate hydrogels to control the release of various drugs and cells by causing large deformation and volume change of over 70% under the control of external magnetic field (Figure 6) [58].

![Figure 6

(a) A cylinder of a macroporous ferrogel reduced its height ∼70% when subjected to a vertical magnetic-field gradient of ∼38 A/m2. (b) SEM images of a freeze-dried macroporous ferrogel in the undeformed and deformed states. Scale bar: 500 μm. (c) Cumulative release profiles of mitoxantrone from macroporous ferrogels subject to 2 min of magnetic stimulation every 30 min, or no magnetic stimulation. Reproduced with permission from [58].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0570/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0570_fig_006.jpg)

(a) A cylinder of a macroporous ferrogel reduced its height ∼70% when subjected to a vertical magnetic-field gradient of ∼38 A/m2. (b) SEM images of a freeze-dried macroporous ferrogel in the undeformed and deformed states. Scale bar: 500 μm. (c) Cumulative release profiles of mitoxantrone from macroporous ferrogels subject to 2 min of magnetic stimulation every 30 min, or no magnetic stimulation. Reproduced with permission from [58].

Such on-demand release of cells from porous scaffolds can be also very useful for tissue regeneration and cell therapies.

Wang et al. developed a magnetically driven delivery system for precise control of drug, protein, and cell release based on 3D-printed alginate/IONPs hollow fibre scaffolds. In this system, drugs, proteins, and even cells can be extruded from the core of the hollow fibres based on the deformation of the scaffolds under the magnetic field, which could prove useful for disease treatment and TE applications. The scaffolds’ deformation behaviour (and ability to release on demand) can be influenced by several factors, such as the concentration of alginate inks, crosslink density, and the content of incorporated NPs. A higher amount of NPs resulted in more deformation under magnetic stimulation. Furthermore, adding Fe3O4 NPs to the inks did not significantly affect the printing behaviour of the hollow fibre scaffolds [59].

7 Magnetic nanoparticles for remote magnetic actuation of cells in tissue engineering applications

In addition to already described applications, MNPs have recently been explored to enable remote magnetic actuation for targeting and activating specific mechanosensitive membrane receptors and ion channels to regulate cell signalling pathways and consequently control cell behaviour [60]. In TE, this approach has been applied to different types of stem cells, as stem cell-based therapies offer great potential for regenerating and repairing damaged tissues in vivo [60]. Using 3D printing technology, Gonçalves et al. fabricated the magnetically responsive scaffold from a biodegradable polymer blend of starch, and PCL incorporated with IONPs with potential for tendon tissue engineering. In vitro studies showed that incorporation of MNPs did not negatively affect the viability or differentiation of human adipose stem cells (hASCs) and may even enhance cells’ metabolic activity. Furthermore, applying an external magnetic field enhanced the biological performance of hASCs cultured on developed magnetic scaffolds regarding cell proliferation and differentiation. The developed scaffolds were also cytocompatible in an ectopic rat model [61]. Results of another study suggested that Activin receptor type IIA (ActRIIA) in hASCs is a mechanosensitive receptor that can be remotely activated using anti-ActRIIA functionalized MNPs, whose action is stimulated by an external magnetic field, leading to tenogenic differentiation, which enables successful cell therapy for tendon regeneration [62]. An exciting feature of this approach is the ability of functionalized MNPs to activate cells remotely using bio-magnetic approaches. In a more recent study, this approach was successfully translated into a 3D environment combining magnetically responsive scaffolds, and MNPs-ActRIIA tagged hASCs exposed to the actuation of externally applied AMF, the synergy of which enhanced the tenogenic commitment of hASCs [63]. Their findings, therefore, represent the first step towards the mechanical stimulation of the regeneration of tendon tissue.

8 Other applications of MNPs in the 3D-printed scaffolds

Combinations of scaffolds and MNPs were also shown promising for many other applications [57,64]. In addition to bone TE, Li et al. described a method to fabricate biocompatible artificial bile ducts with 3D printing using a tubular composite scaffold based on PCL as a matrix for the organoid cells of the bile duct. A layer of gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) hydrogel was applied to the outer layer to increase biocompatibility. Ultrasmall super-paramagnetic iron oxide NPs were uniformly dispersed in GelMA to allow monitoring by magnetic resonance imaging [65].

In another recent study, Xiang et al. fabricated a novel bilayered artificial bile duct scaffold with a PLGA inner layer and a GelMA outer layer. PLGA with suitable mechanical properties, slow degradation kinetics, and good biocompatibility was used instead of PCL. Moreover, IKVAV laminin peptide was used to improve cell adhesion and ultrasmall super-paramagnetic iron oxide NPs were used again for magnetic resonance imaging [66].

9 Other magnetic nanoparticles combined with 3D-printed materials

In addition to IONPs, which are the most commonly used due to their relatively simple synthesis, high magnetization, biocompatibility, and chemical stability [8], other MNPs, such as NiCu and CuFeSe2 were also already successfully incorporated into 3D-printed scaffolds to improve their properties [32,67].

To tailor the desired properties of the scaffolds, such as printability, surface roughness, swelling, degradation, and mechanical properties, Milojević et al. incorporated variable concentrations of NiCu NPs into hybrid hydrogel formulations of alginate, carboxymethyl cellulose, and nanofibrillated cellulose. The results showed that NiCu NPs were an effective means of controlling hydrogel viscosity, scaffold swelling, degradation, and topographic properties. In addition, all the scaffolds not only promoted cell adhesion, aggregation, and migration but also supported the long-term growth of pancreatic cells, and thus could be used in the field of pancreas-related disease research [32].

Furthermore, Dang et al. were the first to combine the photothermal performance of semiconductor nanocrystals of CuFeSe2 with the bone-forming activity of bioactive glass (BG) scaffolds. The photothermal performance of the BG-CuFeSe2 scaffolds could be well regulated by controlling the CuFeSe2 content and the laser power density. Due to hyperthermia induced by the CuFeSe2 nanocrystals, the BG-CuFeSe2 scaffolds could not only effectively ablate the bone tumour cells in vitro but also suppress the growth of bone tumour tissue in vivo. Moreover, the BG-CuFeSe2 scaffolds could support the attachment and proliferation of rabbit BMSCs. Finally, the scaffolds were shown to stimulate the formation of new bone in bone defects. The authors concluded that scaffolds with such dual functions (bone tumour therapy and bone defect regeneration) might represent a promising treatment strategy for tumour-induced bone defects [67].

As recently pointed out in a review article by Palenzula and Pumera [68], 3D printing can also be used as a perfect platform for developing sensors and biosensors. An example of the latter is microfluidic platforms for the detection of bacterial pathogens [69]. The vast opportunities enabled by nanoparticle use in the 3D printing of electronic and bioelectronic devices are also highlighted in Hales et al. [70].

10 Conclusion and future perspectives

This review summarizes relevant studies and recent progress on incorporating MNPs into 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications. Several studies have reported that the incorporation of MNPs and their concentration affect the mechanical properties of the scaffolds. MNPs have shown great potential for use in bone TE, as they play several important roles in stimulating and modifying cellular responses that are beneficial for bone formation. The results of several studies indicate that MNPs incorporated into the scaffolds promote cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation in vitro and significantly accelerate the formation of new bone tissue in vivo. Moreover, MNPs can potentially be used in MH and drug delivery. However, as most of the research on 3D-printed scaffolds is limited to bone tissue, more research on other tissues will be needed to prove their worth in TE further. Among additional applications are also studies related to the incorporation of NiCu MNPs into polysaccharide-based dressings with antimelanoma activity, conducted by our research group. In addition to MNPs, which have already been successfully incorporated into 3D-printed scaffolds, other nanocomposites such as FeNi, FeCu, or different ferrites, with appropriate mechanical and hyperthermal properties are being investigated.

MNPs incorporated into 3D-printed scaffolds hold great promise for various biomedical applications, and several future perspectives can be explored. The magnetic properties of MNPs can enable magnetic manipulation of the 3D-printed scaffold and the cells within it, which is a highly interesting property in TE. The magnetic field can be used to guide cell migration and promote tissue regeneration. Furthermore, MNPs can be incorporated into 3D-printed scaffolds as carriers for targeted drug delivery. The drug can be attached to the surface of the MNPs and released in response to an external magnetic field. Incorporating MNPs into 3D-printed scaffolds can also enhance the contrast in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), providing a more detailed and accurate image of the scaffold and the surrounding tissue. It can also enable biosensing applications, such as detecting specific biomolecules or pathogens within the scaffold. MNPs can enhance the sensitivity and selectivity of such biosensors.

Overall, incorporating MNPs into 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications has great potential for enhancing TE, drug delivery, imaging, magnetic manipulation, and biosensing. Continued research in this field will likely lead to further advancements and innovations in the future.

-

Funding information: This study was funded by the Slovenian Research Agency (Grant/Award Numbers: P3-0036, P2-0006, J3-2538, J1-2470, N1-0305, and L7-4494).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Li Y, Ye D, Li M, Ma M, Ning G. Adaptive materials based on iron oxide nanoparticles for bone regeneration. ChemPhysChem. 2018;19:1965–79.10.1002/cphc.201701294Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Chen Z, Wu C, Zhang Z, Wu W, Wang X, Yu Z. Synthesis, functionalization, and nanomedical applications of functional magnetic nanoparticles. Chin Chem Lett. 2018;29(11):1601–8.10.1016/j.cclet.2018.08.007Search in Google Scholar

[3] Kumar CS. Magnetic nanomaterials. Weinheim, Nemčija: Wiley-VCH; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Hauser AK, Wydra RJ, Stocke NA, Anderson KW, Hilt JZ. Magnetic nanoparticles and nanocomposites for remote controlled therapies. J Controlled Release. 2015;219:76–94.10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.09.039Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Roy I, Kritika K. Therapeutic applications of magnetic nanoparticles: recent advances. Mater Adv. 2022;3:7425–44.10.1039/D2MA00444ESearch in Google Scholar

[6] Materón EM, Miyazaki CM, Carr O, Joshi N, Picciani PHS, Dalmaschio CJ, et al. Magnetic nanoparticles in biomedical applications: A review. Appl Surf Sci Adv. 2021;6:100163.10.1016/j.apsadv.2021.100163Search in Google Scholar

[7] Jia Y, Yuan M, Yuan H, Huang X, Sui X, Cui X, et al. Co-encapsulation of magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles and doxorubicin into biodegradable PLGA nanocarriers for intratumoral drug delivery. Int J Nanomed. 2012;7:1697–708.10.2147/IJN.S28629Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Ganapathe LS, Mohamed MA, Mohamad Yunus R, Berhanuddin DD. Magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles in biomedical application: from synthesis to surface functionalisation. Magnetochemistry. 2020;6(4):68.10.3390/magnetochemistry6040068Search in Google Scholar

[9] Koo K, Ismail A, Othman MH, Bidin N, Rahman M. Preparation and characterization of superparamagnetic magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles: A short review. Malays J Fundam Appl Sci. 2019;15:23–31.10.11113/mjfas.v15n2019.1224Search in Google Scholar

[10] Kwizera EA, Stewart S, Mahmud MM, He X. Magnetic nanoparticle-mediated heating for biomedical applications. J Heat Transf. 2022;144(3):030801.10.1115/1.4053007Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Ban I, Stergar J, Maver U. NiCu magnetic nanoparticles: review of synthesis methods, surface functionalization approaches, and biomedical applications. Nanotechnol Rev. 2018;7(2):187–207.10.1515/ntrev-2017-0193Search in Google Scholar

[12] Stergar J, Ban I, Maver U. The potential biomedical application of NiCu magnetic nanoparticles. Magnetochemistry. 2019;5:66.10.3390/magnetochemistry5040066Search in Google Scholar

[13] Chatterjee J, Bettge M, Haik Y, Chen CJ. Synthesis and characterization of polymer encapsulated Cu–Ni magnetic nanoparticles for hyperthermia applications. J Magn Magn Mater. 2005;293(1):303–9.10.1016/j.jmmm.2005.02.024Search in Google Scholar

[14] Ferk G, Stergar J, Makovec D, Hamler A, Jagličić Z, Drofenik M, et al. Synthesis and characterization of Ni–Cu alloy nanoparticles with a tunable Curie temperature. J Alloy Compd. 2015;648:53–8.10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.06.067Search in Google Scholar

[15] Ban I, Stergar J, Drofenik M, Ferk G, Makovec D. Synthesis of copper–nickel nanoparticles prepared by mechanical milling for use in magnetic hyperthermia. J Magn Magn Mater. 2011;323:2254–8.10.1016/j.jmmm.2011.04.004Search in Google Scholar

[16] Stergar J, Maver U, Bele M, Gradisnik L, Kristl M, Ban I. NiCu-silica nanoparticles as a potential drug delivery system. J Sol-Gel Sci Technol. 2022;101:493–504.10.1007/s10971-020-05280-5Search in Google Scholar

[17] Krishani M, Shin WY, Suhaimi H, Sambudi NS. Development of scaffolds from bio-based natural materials for tissue regeneration applications: A review. Gels. 2023;9(2):100.10.3390/gels9020100Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Laird NZ, Acri TM, Chakka JL, Quarterman JC, Malkawi WI, Elangovan S, et al. Applications of nanotechnology in 3D printed tissue engineering scaffolds. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2021;161:15–28.10.1016/j.ejpb.2021.01.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Deng F, Liu L, Li Z, Liu J. 3D printed Ti6Al4V bone scaffolds with different pore structure effects on bone ingrowth. J Biol Eng. 2021;15(1):4.10.1186/s13036-021-00255-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Chung JJ, Im H, Kim SH, Park JW, Jung Y. Toward biomimetic scaffolds for tissue engineering: 3D printing techniques in regenerative medicine. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:586406.10.3389/fbioe.2020.586406Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Do AV, Khorsand B, Geary SM, Salem AK. 3D printing of scaffolds for tissue regeneration applications. Adv Healthc Mater. 2015;4(12):1742–62.10.1002/adhm.201500168Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Socrates R, Nagarajan S, Belaid H, Farha C, Iatsunskyi I, Coy E, et al. Fabrication of 3D printed antimicrobial polycaprolactone scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Mater Sci Eng C. 2021;118:111525.10.1016/j.msec.2020.111525Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Zhang Q, Zhou J, Zhi P, Liu L, Liu C, Fang A, et al. 3D printing method for bone tissue engineering scaffold. Med Nov Technol Devices. 2023;17:100205.10.1016/j.medntd.2022.100205Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Mobaraki M, Ghaffari M, Yazdanpanah A, Luo Y, Mills DK. Bioinks and bioprinting: A focused review. Bioprinting. 2020;18:e00080.10.1016/j.bprint.2020.e00080Search in Google Scholar

[25] Sachdev IVA, Acharya S, Gadodia T, Shukla S, Harshita J, Akre C, et al. A review on techniques and biomaterials used in 3D bioprinting. Cureus. 2022;14(8):e28463.10.7759/cureus.28463Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Su C, Chen Y, Tian S, Lu C, Lv Q. Natural materials for 3D printing and their applications. Gels. 2022;8(11):748.10.3390/gels8110748Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Sinha SK. Additive manufacturing (AM) of medical devices and scaffolds for tissue engineering based on 3D and 4D printing. In: 3D and 4D printing of polymer nanocomposite materials. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2020. p. 119–60.10.1016/B978-0-12-816805-9.00005-3Search in Google Scholar

[28] Perez R, Patel K, Kim HW. Novel magnetic nanocomposite injectables: Calcium phosphate cements impregnated with ultrafine magnetic nanoparticles for bone regeneration. RSC Adv. 2015;5(18):13411–9.10.1039/C4RA12640HSearch in Google Scholar

[29] Kim JJ, Singh RK, Seo SJ, Kim TH, Kim JH, Lee EJ, et al. Magnetic scaffolds of polycaprolactone with functionalized magnetite nanoparticles: physicochemical, mechanical, and biological properties effective for bone regeneration. RSC Adv. 2014;4(33):17325–36.10.1039/C4RA00040DSearch in Google Scholar

[30] Singh RK, Patel KD, Lee JH, Lee EJ, Kim JH, Kim TH, et al. Potential of magnetic nanofiber scaffolds with mechanical and biological properties applicable for bone regeneration. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e91584.10.1371/journal.pone.0091584Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Xia Y, Guo Y, Yang Z, Chen H, Ren K, Weir MD, et al. Iron oxide nanoparticle-calcium phosphate cement enhanced the osteogenic activities of stem cells through WNT/β-catenin signaling. Mater Sci Eng C. 2019;104:109955.10.1016/j.msec.2019.109955Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Milojević M, Gradišnik L, Stergar J, Skelin Klemen M, Stožer A, Vesenjak M, et al. Development of multifunctional 3D printed bioscaffolds from polysaccharides and NiCu nanoparticles and their application. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;488:836–52.10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.05.283Search in Google Scholar

[33] Huang Z, Wu Z, Ma B, Yu L, He Y, Xu D, et al. Enhanced in vitro biocompatibility and osteogenesis of titanium substrates immobilized with dopamine-assisted superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles for hBMSCs. R Soc Open Sci. 2018;5(8):172033.10.1098/rsos.172033Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Li M, Liu J, Cui X, Sun G, Hu J, Xu S, et al. Osteogenesis effects of magnetic nanoparticles modified-porous scaffolds for the reconstruction of bone defect after bone tumor resection. Regen Biomater. 2019;6(6):373–81.10.1093/rb/rbz019Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Aliramaji S, Zamanian A, Mozafari M. Super-paramagnetic responsive silk fibroin/chitosan/magnetite scaffolds with tunable pore structures for bone tissue engineering applications. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017;70(Pt 1):736–44.10.1016/j.msec.2016.09.039Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Bin S, Wang A, Guo W, Yu L, Feng P. Micro magnetic field produced by Fe3O4 nanoparticles in bone scaffold for enhancing cellular activity. Polymers. 2020;12(9):2045.10.3390/polym12092045Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Shuai C, Yang W, He C, Peng S, Gao C, Yang Y, et al. A magnetic micro-environment in scaffolds for stimulating bone regeneration. Mater Des. 2020;185:108275.10.1016/j.matdes.2019.108275Search in Google Scholar

[38] Chen C, Wu J, Wang S, Shao H. Effect of Fe3O4 concentration on 3D gel-printed Fe3O4/CaSiO3 composite scaffolds for bone engineering. Ceram Int. 2021;47(15):21038–44.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.04.105Search in Google Scholar

[39] Kao CY, Lin TL, Lin YH, Lee AK, Ng SY, Huang TH, et al. Synergistic effect of static magnetic fields and 3D-printed iron-oxide-nanoparticle-containing calcium silicate/Poly-ε-caprolactone scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Cells. 2022;11(24):3967.10.3390/cells11243967Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] De Santis R, D’Amora U, Russo T, Ronca A, Gloria A, Ambrosio L. 3D fibre deposition and stereolithography techniques for the design of multifunctional nanocomposite magnetic scaffolds. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 2015;26(10):250.10.1007/s10856-015-5582-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Han L, Guo Y, Jia L, Zhang Q, Sun L, Yang Z, et al. 3D magnetic nanocomposite scaffolds enhanced the osteogenic capacities of rat bone mesenchymal stem cells in vitro and in a rat calvarial bone defect model by promoting cell adhesion. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2021;109(9):1670–80.10.1002/jbm.a.37162Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Jia L, Yang Z, Sun L, Zhang Q, Guo Y, Chen Y, et al. A three-dimensional-printed SPION/PLGA scaffold for enhanced palate-bone regeneration and concurrent alteration of the oral microbiota in rats. Mater Sci Eng C. 2021;126:112173.10.1016/j.msec.2021.112173Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Ko ES, Kim C, Choi Y, Lee KY. 3D printing of self-healing ferrogel prepared from glycol chitosan, oxidized hyaluronate, and iron oxide nanoparticles. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;245:116496.10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116496Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Choi Y, Kim C, Kim HS, Moon C, Lee KY. 3D Printing of dynamic tissue scaffold by combining self-healing hydrogel and self-healing ferrogel. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2021;208:112108.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.112108Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Saraiva AS, Ribeiro IAC, Fernandes MH, Cerdeira AC, Vieira BJC, Waerenborgh JC, et al. 3D-printed platform multi-loaded with bioactive, magnetic nanoparticles and an antibiotic for re-growing bone tissue. Int J Pharm. 2021;593:120097.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.120097Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Petretta M, Gambardella A, Desando G, Cavallo C, Bartolotti I, Shelyakova T, et al. Multifunctional 3D-printed magnetic polycaprolactone/hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Polymers. 2021;13(21):3825.10.3390/polym13213825Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] De Santis R, Russo A, Gloria A, D’Amora U, Russo T, Panseri S, et al. Towards the design of 3D fiber-deposited poly(ε-caprolactone)/lron-doped hydroxyapatite nanocomposite magnetic scaffolds for bone regeneration. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2015;11(7):1236–46.10.1166/jbn.2015.2065Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Shokouhimehr M, Theus AS, Kamalakar A, Ning L, Cao C, Tomov ML, et al. 3D Bioprinted bacteriostatic hyperelastic bone scaffold for damage-specific bone regeneration. Polymers. 2021;13(7):1099.10.3390/polym13071099Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Huang Z, He Y, Chang X, Liu J, Yu L, Wu Y, et al. A magnetic iron oxide/polydopamine coating can improve osteogenesis of 3D-printed porous titanium scaffolds with a static magnetic field by upregulating the TGFβ-smads pathway. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020;9(14):e2000318.10.1002/adhm.202000318Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Zhang Y, Zhai D, Xu M, Yao Q, Chang J, Wu C. 3D-printed bioceramic scaffolds with a Fe3O4/graphene oxide nanocomposite interface for hyperthermia therapy of bone tumor cells. J Mater Chem B. 2016;4(17):2874–86.10.1039/C6TB00390GSearch in Google Scholar

[51] Li Y, Huang L, Tai G, Yan F, Cai L, Xin C, et al. Graphene oxide-loaded magnetic nanoparticles within 3D hydrogel form High-performance scaffolds for bone regeneration and tumour treatment. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2022;152:106672.10.1016/j.compositesa.2021.106672Search in Google Scholar

[52] Yang Y, Tong C, Zhong J, Huang R, Tan W, Tan Z. An effective thermal therapy against cancer using an E-jet 3D-printing method to prepare implantable magnetocaloric mats. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2018;106(5):1827–41.10.1002/jbm.b.33992Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Dong S, Chen Y, Yu L, Lin K, Wang X. Magnetic hyperthermia–synergistic H2O2 self‐sufficient catalytic suppression of osteosarcoma with enhanced bone‐regeneration bioactivity by 3D‐printing composite scaffolds. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30(4):1907071.10.1002/adfm.201907071Search in Google Scholar

[54] Shuai C, Cheng Y, Yang W, Feng P, Yang Y, He C, et al. Magnetically actuated bone scaffold: Microstructure, cell response and osteogenesis. Compos Part B Eng. 2020;192:107986.10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.107986Search in Google Scholar

[55] Zhang J, Zhao S, Zhu M, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Liu Z, et al. 3D-printed magnetic Fe3O4/MBG/PCL composite scaffolds with multifunctionality of bone regeneration, local anticancer drug delivery and hyperthermia. J Mater Chem B. 2014;2(43):7583–95.10.1039/C4TB01063ASearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Lin HY, Huang HY, Shiue SJ, Cheng JK. Osteogenic effects of inductive coupling magnetism from magnetic 3D printed hydrogel scaffold. J Magn Magn Mater. 2020;504:166680.10.1016/j.jmmm.2020.166680Search in Google Scholar

[57] Adedoyin AA, Ekenseair AK. Biomedical applications of magneto-responsive scaffolds. Nano Res. 2018;11(10):5049–64.10.1007/s12274-018-2198-2Search in Google Scholar

[58] Zhao X, Kim J, Cezar CA, Huebsch N, Lee K, Bouhadir K, et al. Active scaffolds for on-demand drug and cell delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(1):67–72.10.1073/pnas.1007862108Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Wang Z, Liu C, Chen B, Luo Y. Magnetically-driven drug and cell on demand release system using 3D printed alginate based hollow fiber scaffolds. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;168:38–45.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.12.023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Rotherham M, Nahar T, Broomhall TJ, Telling ND, El Haj AJ. Remote magnetic actuation of cell signalling for tissue engineering. Curr Opin Biomed Eng. 2022;24:100410.10.1016/j.cobme.2022.100410Search in Google Scholar

[61] Gonçalves AI, Rodrigues MT, Carvalho PP, Bañobre-López M, Paz E, Freitas P, et al. Exploring the potential of starch/polycaprolactone aligned magnetic responsive scaffolds for tendon regeneration. Adv Healthc Mater. 2016;5(2):213–22.10.1002/adhm.201500623Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Gonçalves AI, Rotherham M, Markides H, Rodrigues MT, Reis RL, Gomes ME, et al. Triggering the activation of Activin A type II receptor in human adipose stem cells towards tenogenic commitment using mechanomagnetic stimulation. Nanomed Nanotech Biol Med. 2018;14(4):1149–59.10.1016/j.nano.2018.02.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Matos A, Gonçalves A, Rodrigues M, Miranda M, Haj A, Reis RL, et al. Remote triggering of TGF-β/Smad2/3 signaling in human adipose stem cells laden on magnetic scaffolds synergistically promotes tenogenic commitment. Acta Biomater. 2020;113:488–500.10.1016/j.actbio.2020.07.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Gelmi A, Schutt CE. Stimuli-responsive biomaterials: Scaffolds for stem cell control. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10(1):e2001125.10.1002/adhm.202001125Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Li H, Yin Y, Liu H, Guo R. A novel 3D printing PCL/GelMA scaffold containing USPIO for MRI guided bile duct repair. Biomed Mater. 2020;15:045004.10.1088/1748-605X/ab797aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Xiang Y, Wang W, Gao Y, Zhang J, Zhang J, Bai Z, et al. Production and characterization of an integrated multi-layer 3D printed PLGA/GelMA scaffold aimed for bile duct restoration and detection. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:971.10.3389/fbioe.2020.00971Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[67] Dang W, Li T, Li B, Ma H, Zhai D, Wang X, et al. A bifunctional scaffold with CuFeSe2 nanocrystals for tumor therapy and bone reconstruction. Biomaterials. 2018;160:92–106.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.11.020Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[68] Palenzuela CLM, Pumera M. (Bio)Analytical chemistry enabled by 3D printing: Sensors and biosensors. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2018;103:110–8.10.1016/j.trac.2018.03.016Search in Google Scholar

[69] Park C, Lee J, Kim Y, Kim J, Lee J, Park S. 3D-printed microfluidic magnetic preconcentrator for the detection of bacterial pathogen using an ATP luminometer and antibody-conjugated magnetic nanoparticles. J Microbiol Methods. 2017;132:128–33.10.1016/j.mimet.2016.12.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[70] Hales S, Tokita E, Neupane R, Ghosh U, Elder B, Wirthlin D, et al. 3D printed nanomaterial-based electronic, biomedical, and bioelectronic devices. Nanotechnology. 2020;31(17):172001.10.1088/1361-6528/ab5f29Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery

- The progress of cathode materials in aqueous zinc-ion batteries

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part I

- Effect of polypropylene fiber and nano-silica on the compressive strength and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete

- Mechanochemical design of nanomaterials for catalytic applications with a benign-by-design focus

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects