Abstract

Nanodrug delivery systems (NDDSs) are a hotspot of new drug delivery systems with great development potential. They provide new approaches to fighting against diseases. NDDSs are specially designed to serve as carriers for the delivery of active pharmaceutical ingredients to their target sites, and their unique physicochemical characteristics allow for prolonged circulation time, improved targeting, and avoidance of drug resistance. Despite remarkable progress achieved in the preparation and efficacy evaluation of NDDSs, the understanding of the in vivo pharmacokinetics of NDDSs is still insufficient. Analysis of NDDSs is far more complicated than that for small molecular drugs; thus, almost all conventional techniques are inadequate for accurate profiling of their pharmacokinetic behaviour in vivo. In this article, we systematically reviewed the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of NDDSs and summarized the advanced bioanalytic techniques for tracing the in vivo fate of NDDSs. We also reviewed the physiologically based pharmacokinetic model of NDDS, which has been a useful tool in characterizing and predicting the systemic disposition, target exposure, and efficacy/toxicity of various types of drugs when coupled with pharmacodynamic modelling. We hope that this review will be helpful in improving the understanding of NDDS pharmacokinetics and facilitating the development of NDDSs.

1 Introduction

Nanodrug delivery systems (NDDSs) integrate small molecules into nanometres by encapsulating or adsorbing drugs to form drug nanoparticles (NPs) and achieve effective drug delivery [1,2]. The development of NDDSs includes polymer NPs, micelles, liposomes, dendrimers, metal NPs, and solid lipid NPs. NDDSs have the features of small particle size, large specific surface area, high surface reactivity, and strong adsorption. Using nanomaterials as delivery systems can improve the absorption and utilization rate of drugs, achieve efficient targeted delivery, extend drug half-life, and reduce toxicity and side effects in normal tissues [3]. In the past 30 years, there have been many noteworthy discoveries in disease diagnosis and treatment, drug discovery, and tissue engineering of nanotechnology [4,5]; however, the biological fate of NDDSs remains elusive, and many problems have still not been solved. The pharmacokinetic study of NDDSs is still scattered and superficial due to the complexity of the nanodrug structure.

Pharmacokinetics is a quantitative study modality of the dynamic changes in ADME of drugs and elucidates the relationship between drug concentration and time. Compared with free drugs, NDDSs have special size, structure, and surface properties, which may lead to changes in the physical and chemical properties and biological behaviour of drugs, such as promoting drug transmembrane transport and changing the pharmacokinetic characteristics, in vivo distribution, and tissue selectivity for different organs or cells [6,7]. Pharmacokinetic research on NDDSs is in early stages, and the design and preparation of nanodrugs still lack systematic and comprehensive pharmacokinetic support and guidance. Therefore, concerning the dynamic process from total drugs to free drugs and nanocarriers, finding an appropriate method to monitor the changes to NDDSs that occur in vivo has important guiding significance for promoting the clinical application of nanodrugs.

2 ADME of NDDSs

Pharmacokinetics is the movement of drugs into, through and out of the body – the time course of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. In simple terms, it is what the body does to a drug [8].

2.1 Absorption

Drug absorption is an active or passive process. The drug moves from the application site to the measurement site, which is reflected by measuring the active drug concentration in the systemic circulation [9]. NDDSs are drug-loaded particles, and for such systems, it is necessary to measure the concentrations of free drugs and loaded drugs, as well as the concentrations of carrier materials and drug-loaded particles in blood to further obtain information on drug release kinetics and carrier depolymerization/degradation kinetics in vivo.

NDDSs enter cells mainly through endocytosis, which is affected by the surface charge, particle size, and carrier properties of the NPs. The charge can affect the amount and pathway of NDDS into cells. Drugs with a positive charge have a stronger interaction with cells, more easily enter cells, and are more likely to be endocytosed through the clathrin-mediated pathway [10]. In addition, the particle size has a great influence on the process of NDDSs entering cells. Gratton et al. found that the particle size is inversely proportional to the internalization rate [11]. The larger the particle size, the slower the internalization rate. In addition, carriers can affect the endocytosis and pathway of NDDSs. Previous studies have shown that the hydrophobic segment of polymer micelles plays an important role in the transport amount and speed, and the hydrophilic segment plays an important role in the localization of intracellular organelles [12]. Modification of hydrophobic groups also affects the uptake of nanocarriers. The higher the modification of the palm group, the greater the uptake of chitosan NPs, and caveolin-mediated endocytosis increases significantly with increasing hydrophobicity [13].

2.2 Distribution

Distribution is the reversible transfer of a drug between the blood and the extravascular fluids and tissues of the body. Drug distribution governs the amount of drug reaching target sites compared to the rest of the body and thus plays an important role in drug efficacy and toxicity [14]. The factors affecting drug distribution include diffusion rate, affinity of drug to tissue, blood flow, and binding to plasma protein. Different from free drugs, the distribution of NDDSs in tissues and organs depends on the physicochemical and surface properties of the drug-loaded particles; meanwhile, it is also affected by many factors, such as protein binding in blood, hemodynamics of tissues and organs, and vascular morphology. Our group treated mice with cisplatin and NP-UVA-Pt2 to study the biodistribution of Pt drugs in blood and organs. The results showed that cisplatin accumulated mainly in the liver and kidneys, and the Pt concentrations in the tumour site for NP-UVA-Pt2 increased from 1 to 12 h, while those in the blood decreased. In contrast to cisplatin, NP-UVA-Pt2 gave a higher Pt concentration in tumours at 12 h, which was more than that in the kidneys, blood, and other organs, except the liver [15].

2.3 Metabolism

Due to the metabolism of drugs (in the gut wall and liver) into inactive or less active components before being absorbed into the systemic circulation, the concentration of a drug, especially after oral administration, is significantly reduced before it reaches the bloodstream [16]. A fraction of a drug is lost during absorption, and a fraction is metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes of the liver, and these two processes are accountable for the metabolism or biotransformation of approximately 70–80% of the drugs in clinical use [17]. When NDDS enters the target cell, the nanocarrier is biodegradable, and the drug is released in a targeted manner to exert its effect. Polylactic acid (PLA) is a widely used NP carrier that can be biodegraded. Its degradation in vivo is affected by molecular mass, copolymer monomer ratio, particle size, surface charge, and ionic strength. PLA can be decomposed into lactic acid under the effect of nonenzymatic and enzymatic hydrolyses and then generates carbon dioxide and water through the carboxylic acid metabolic cycle. Therefore, PLA has good biocompatibility in vivo [18].

2.4 Excretion

Due to the efflux proteins, it is difficult for free drugs to aggregate in drug-resistant cells. NDDSs have greatly improved this situation. They can alleviate the efflux and increase the accumulation of drugs in target cells through the addition of excipients to NDDSs or by combining multiple drugs in one NDDS. Li et al. found that the efflux of DOX in drug-resistant cells was greatly reduced by combining DOX prodrug NPs with lornidamine. In vivo, although the plasma concentration of DOX maintained almost the same drug time curve as that of the noncombined preparation, the tumour targeting of DOX in the combined preparation was greatly improved and showed better efficacy [19]. Thus, although there was no significant difference in blood drug concentration, the therapeutic effect on the target was significantly improved.

With advances in the design and synthesis of nanocarrier materials [20,21], many nanodrugs have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for clinical trials [22,23], which shows that nanocarrier materials have been considered nontoxic inert carrier materials. However, new evidence indicates that nanocarrier materials cannot only change the pharmacokinetics of loaded drugs [24,25,26,27] but can also interact with the immune system [28] and affect metabolism, drug distribution, and other processes of the body to produce toxicity and side effects [29,30]. Therefore, when designing and optimizing nanocarrier materials, we should pay attention to the curative effect and their biological fate and analyse their distribution, transport and metabolism in tissues [31]. Meng et al. studied the pharmacokinetics, biological distribution, metabolism, and excretion of polyethylene glycol (PEG)-PLA in rats after intravenous administration. The results showed that unchanged PEG-PLA was mainly distributed in the spleen, liver, and kidney and excreted from urine in the form of PEG metabolites after more than 48 h [32].

3 Analytical method for pharmacokinetic study of NDDS

The analytical methods of NDD pharmacokinetics mainly include high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), radioisotope labelling, liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), and ultrafiltration. These methods with their advantages and disadvantages will briefly be introduced.

3.1 HPLC

HPLC is usually used for the separation of biological macromolecules, medical macromolecules, ionic compounds, unstable natural products, and other macromolecules and unstable compounds due to its high efficiency, automation, accuracy, and simple operation. Using HPLC, Shen et al. analysed the pharmacokinetics of vincristine in rat plasma after a single intravenous injection of vincristine normal saline solution (F-VCR), PLGA-mPEG-loaded VCR NPs (NP1), and PLGA-PEG-folate (NP2). They found that NP1 and NP2 can prolong the residence time of VCR in plasma, increase the area under the concentration-time curve, and reduce systemic clearance (Figure 1) [33]. Our group measured the release kinetics for Pt and capecitabine in the combination drugs in two conditions at pH 5.0 and pH 7.4 using HPLC. we observed that the Pt release was more sensitive to pH compared to the capecitabine release [34]. Calaspargase pegol (Asparlas), first launched in 2019 in the United States, is a polyethylene glycol-l-asparaginase, as part of a multiagent chemotherapeutic regimen for the treatment of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia [35]. Angiolillo et al. determined the pharmacokinetics of calaspargase pegol using validated reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography with double mass spectrometry [36].

![Figure 1

Mean plasma concentration–time profiles of vincristine in rats (n = 6) after a single intravenous injection of F-VCR solution and VCR-loaded nanoparticles (NP1 and NP2) suspension at the dose of 1.2 mg of VCR/kg, respectively [33].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0525/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0525_fig_001.jpg)

Mean plasma concentration–time profiles of vincristine in rats (n = 6) after a single intravenous injection of F-VCR solution and VCR-loaded nanoparticles (NP1 and NP2) suspension at the dose of 1.2 mg of VCR/kg, respectively [33].

HPLC overcomes the shortcomings of the low column efficiency and long analysis cycle of classical liquid chromatography. Meanwhile, RP-HPLC can reflect the situation of the original drug and its metabolites. However, HPLC is not suitable for high-throughput analysis of nanodrugs due to the low sensitivity, long analysis time, and limited selectivity of the detector.

3.2 ELISA

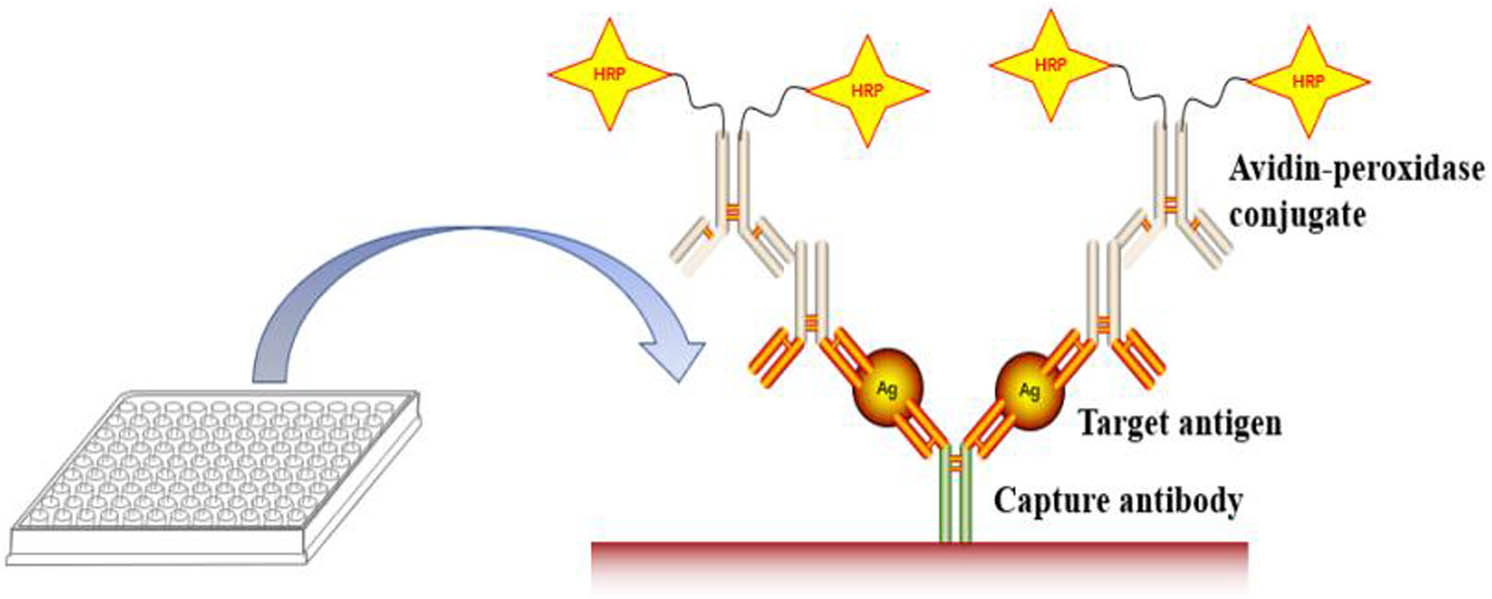

ELISA is a highly sensitive test technology that combines the specific reaction of antigen and antibody with the catalysis of substrates by enzymes [37]. ELISA is a basic tool for immunological, medical, and biochemical research. It is mainly used to detect biological molecules, such as proteins, peptides, antibodies, and cytokines [38,39,40]. At present, the most widely used ELISA method is the “sandwich” method, in which the primary antibody is fixed on the surface of the plate to capture the antigen in the sample, and the captured antigen can be tracked and recognized by the enzyme-linked antigen-specific antibody. The coupled zymogen can be used as an optical detector to amplify and quantify the captured analytical antigen (Figure 2) [41]. Nagasaki et al. used PEG/antibody coimmobilized on magnetic beads as the carrier and combined them with an ALP-assisted fluorescence detection system to construct a new “sandwich” ELISA system to analyse the concentration of AFP antigen [42].

Schematic representation of “sandwich” ELISA.

ELISA requires that the antigen or antibody should have high specificity for the nanodrug being analysed; otherwise, it will react with the structural analogues of the tested object, affect the accuracy of the results, and reduce the detection sensitivity. In addition, nanodrug pharmaceuticals undergo a series of degradation and metabolism processes in vivo, and ELISA cannot distinguish between the fragments and different metabolites of nanodrugs because detection is merely based on the immune response to nanodrugs. The specificity issue and endogenous interference limit a precise evaluation of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs by ELISA.

3.3 Radioisotope labelling

Radioisotope labelling is used to label polymers with radioisotopes and analyse polymers by detecting the radioactive intensity in biological samples. Radioisotope labelling has been increasingly used in the quantitative analysis of polymers in vivo due to its sensitivity and specificity [43]. 89Zr is a radioactive metal with a positive charge pair, and it is widely used in PET research on antibodies because of its long decay period and simple labelling. Ferrara et al. labelled nanoliposomes with 89Zr for in vivo tracing. They prepared three 89Zr-labelled liposomes, with 89Zr being bound to the surface of PEG2k, between the surface and head of PEG2k and on the tail of PEG2k, and then evaluated the pharmacokinetics of these nanoliposomes in NDL tumour-bearing mice by injecting them into the tail vein (Figure 3) [44]. At present, there are still many defects in radioisotope labelling. First, radioactive labelling can only detect the signal of radioisotopes, which makes it difficult to distinguish the polymer prototype and its metabolites in biological samples. Second, radioactive reagents are harmful to the human body and environment, making it difficult to use them in clinical research. These defects seriously limit the application of radioactive labelling in the quantitative analysis of polymer nanomaterials in vivo.

![Figure 3

Time series of small-animal coronal PET images at indicate time points after injection of 89Zr-df liposomes (left), 89Zr-df-PEFlk liposomes (middle), and 89Zr-df-PEG2k liposomes (right) [44].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0525/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0525_fig_003.jpg)

Time series of small-animal coronal PET images at indicate time points after injection of 89Zr-df liposomes (left), 89Zr-df-PEFlk liposomes (middle), and 89Zr-df-PEG2k liposomes (right) [44].

3.4 LC‒MS/MS

Because of its excellent selectivity, sensitivity, and accuracy, LC‒MS/MS is the preferred method for the quantitative analysis of small molecular compounds and polypeptide drugs [45,46,47]. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) is essentially a scanning mode on the mass spectrometer; it selects a specific parent ion under primary scanning and then analyses its specific fragment ions in secondary scanning after collision and fragmentation. Due to the structural specificity of organic molecules and the dual mass screening of ions, MRM analysis can significantly reduce the noise interference of mass spectrometry signals and improve the detection sensitivity and repeatability of target molecules. It has become the preferred method for the quantitative analysis of small molecular biological samples [48,49,50,51,52,53]. However, because the molecular weight of the polymer is not fixed and the polymer has multiple charges under the electrospray ionization mode, the polymer produces numerous precursor ions in mass spectrometry [54,55,56]. MRM can only be used for quantitative analysis of a limited number of precursor ions and is unable to quantitatively analyse polymers with countless precursor ions. Gong et al. combined LC‒MS/MS with collision-induced dissociation with high selectivity and sensitivity to PEG-related materials to produce a series of characteristic fragments of PEG and then selected several characteristic fragments as precursor ions for secondary crushing and MRM scanning analysis to realize the quantitative analysis of PEG [57].

3.5 FRET

FRET chromophores represent a unique class of environment-responsive phosphors. Fluorescence signal switching from the FRET chromophore to the donor receptor mainly depends on the distance between molecules, which is independent of the internal environment. Its response is sensitive and can accurately reflect the relative position between fluorescent molecules. Therefore, FRET can monitor the dynamic changes in drug loading and release [58]. Wu et al. studied the metabolism of intravenous PMs in vivo with a highly sensitive near-infrared environment responsive fluorescent probe. Blood-derived fluorescence analysis showed that PMs could be rapidly removed from the blood in the three-compartment pharmacokinetic model. In vivo imaging showed that PMs could be distributed throughout the body and tended to accumulate in the limbs [59] (Figure 4).

![Figure 4

Live imaging of P2-labelled PMs after i.v. administration to rats (a), plasma pharmacokinetic profile (b), and fractionized quantification of fluorescence of regions of interest as average radiant efficiency [p/s/cm2/sr]/[µW/cm2] (c) [59].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0525/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2022-0525_fig_004.jpg)

Live imaging of P2-labelled PMs after i.v. administration to rats (a), plasma pharmacokinetic profile (b), and fractionized quantification of fluorescence of regions of interest as average radiant efficiency [p/s/cm2/sr]/[µW/cm2] (c) [59].

Despite the described advances in FRET techniques, rigorous challenges remain. The bioactivity of fluorescent dyes may affect the therapeutic actions of NDDSs, and little is known about whether the incorporation of fluorescent dye molecules into NDDSs affects the pharmaceutical properties of the cargo, such as the conformation of the chemical structure, peptide folding, and nucleotide stability [60,61].

3.6 Ultrafiltration

In addition to encapsulated drugs being quantified, nonencapsulated drugs can be separately calculated from the total drug in biological samples. The ultrafiltration method can measure nanomedicine encapsulated and unencapsulated drug fractions in plasma and assess nanomedicine drug release [62,63]. For ultrafiltration dialysis, the primary issue is accounting for the protein-bound component of the non-filterable or dialyzable drug to accurately determine the encapsulated and unencapsulated drug fractions [64]. The Stern group improved the existing ultrafiltration protocols and added a stable isotope tracer into a nanomedicine-containing plasma sample to precisely measure the degree of plasma protein binding. Using this method, protein binding can be determined, and encapsulated and unencapsulated nanomedicine drug fractions and free and protein-bound drug fractions can be calculated accurately. The group used a stable isotope tracer ultrafiltration assay to present the encapsulated, unencapsulated, and unbound drug fraction pharmacokinetic profiles in rats for marketed nanomedicines, representing examples of controlled release, equilibrium binding, and solubilizing nanomedicine formulations [65].

Other examples of analytical methods are summarized in Table 1 [66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75]. Despite the described advances, rigorous challenges remain. For the in vivo fate, it is still unclear how NDDSs cross physiological and pathological barriers, such as the blood–brain barrier, placental barrier, and tumour interstitium. Meanwhile, the exploration of the interaction between NDDSs and the immune system is equally important [76]. We believe that an in-depth understanding of NDDS biological fates will facilitate the generation of effective and safe strategies for clinical treatment and diagnosis.

Analytical methods and their examples for the bioanalysis of NDDS

| Method | Delivery system | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC |

|

[66,67] |

|

[68] | |

|

[69] | |

| ELISA |

|

[70] |

|

[71] | |

| Radioisotope labeling |

|

[72] |

| LC‒MS/MS |

|

[73] |

| Fluorescence labeling |

|

[74] |

|

[75] | |

| Ultrafiltration |

|

[64] |

4 Application of the physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model in the pharmacokinetic analysis of NDDS

The PBPK model is a quantitative support tool for assessing NP hazards recommended by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the new European Union regulatory framework, Registration, Evaluation, and Authorization of Chemicals. The PBPK model, with its distinctive separation of physiology and drug-dependent information, has become a viable option to provide a mechanistic understanding of the influential factors and sources of PK variability, which is thus helpful in predicting drug exposure in various clinically relevant scenarios. When combined with pharmacodynamic (PD) models relating exposure at target tissues to pharmacological effects, the PBPK model can be used to predict efficacy and toxicity [77]. PBPK models have been applied for many types of NPs, including carbon NPs, polymeric NPs, nanocrystals, silver NPs, liposomes, gold/dendrimer composite NPs, and others.

4.1 PBPK model principle

A PBPK model quantitatively describes drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination in the body, facilitating a deep understanding of the effects of these intricate processes on drug exposure and of how these processes interact with each other [20,78]. The advantage of the PBPK model is that it considers the individual anatomical and physiological parameters, including population data, genotype and expression of drug metabolic enzymes and transporters, and receptor genotype. The mathematical model is used to simulate the changes that drugs undergo in vivo, and it can be used to replace some animal experiments or clinical trials [79,80]. The PBPK model consists of a drug characteristic module and a body system module. The drug characteristic module includes the physical and chemical properties and in vitro parameters of the drug itself, such as membrane permeability, inherent clearance of enzyme metabolism, and plasma protein binding rate [81,82]. The body system module integrates the physiological and pathological conditions of the human body or other species, including blood perfusion rate, tissue, and organ volume [81]; the PBPK model combines the two modules to predict the dynamic process of changes that drugs undergo in vivo according to in vitro data parameters and system parameters of drugs. The PBPK model establishes physiological compartments according to the anatomical and physiological characteristics of the body. Each “physiological compartment” represents one or more organs, tissues, or body fluids related to drug distribution and links the compartments in a specific order. Assuming that drugs are evenly distributed in specific tissues or organs, the inflow and outflow of drugs in each atrium are described according to the mass balance differential equation, and then, the calculation process is executed by a computer program [78]. Through computer simulation, the PBPK model can provide the time concentration curve of drugs and their metabolites in plasma and specific tissues and organs. It has great advantages in predicting bioavailability and understanding the dynamic process of drug metabolism in vivo.

4.2 Application of the PBPK model in NDDSs

At present, the PBPK model has been widely used for the analysis of small molecule drugs, including drug research and development, clinical trials, and post-marketing supervision. PBPK models have only recently been applied to NDDSs over the past few years by several large nanodrug research centres. The PBPK model has been increasingly applied to nanodrug research centres, and its advantages have been increasingly recognized.

Lin et al. established a blood flow-limited PBPK model to predict the time concentration curve in mouse quantum dots based on experimental data collected in the same group. Nanodrugs may not have the common tissue blood distribution coefficient (DC). Lin’s team named a specific parameter, the tissue DC, which is the tissue-to-blood affinity ratio of QD705. It changes over time, depending on the transient concentration of QD705 in blood, tissues, and the tissue microenvironment [83]. Pery et al. established the PBPK model of inhaled carbon NPs based on imaging data. The concentration of NPs in organs is determined from imaging data by separating the radioactive overlap in tissues and organs. This work provides a method to use imaging data to establish a PBPK model. This method is convenient in regard to data collection: it does not require collection of data from tissues or organs and allows continuous collection of data from the same subject to complete the experimental study [84]. Cao et al. developed the PBPK model by analysing data from mice. The PBPK model explicitly simulated the multiscale dispositions of doxorubicin in the human heart and tumours to elucidate the potential mechanisms of its cytotoxicity and cardiotoxicity [85].

4.3 PBPK models for the unique disposition properties of NDDSs

Compared to a conventional formulation of the same molecules, NPs can result in distinct and complicated in vivo disposition properties [86]. PBPK modelling has been a useful tool in characterizing and predicting the systemic disposition, target exposure, and efficacy/toxicity of various types of drugs when coupled with PD modelling.

The disposition of active drugs is regulated by the disposition of particulate drugs and by in vivo drug release; the disposition of particulate drugs determines where the active drugs are released. Therefore, ideally, the model should describe the free drug and particulate drug simultaneously. Dual PBPK models can be used to describe the disposition of both NPs and released active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [87]. SNX-2112 is a promising anticancer agent. To develop a nanocrystal formulation for SNX-2112 and determine the pharmacokinetic behaviours of the prepared nanocrystals, Dong et al. used dual PBPK model to characterize the distribution and in vivo drug release of SNX-2112 in rats after IV administration. A two-step strategy was employed. First, a generic perfusion-limited PBPK model was developed for the nonparticulate drug using the PK data of a nonsolvent formulation (a small molecule formulation) in rats. Second, processes describing the particulate drug were included. Using the PBPK modelling strategy, the authors found that the nanocrystal can rapidly release the poorly soluble drug in vivo and presents that minimal systemic risk is associated with particulate injection [88].

In previous studies, few PBPK modelling studies have focused on the important role of MPS in NP distribution and sequestration. Li et al. fitted the PBPK model to the PK data of 14C-labelled PEGylated polyacrylamide NPs (35 nm) in rats after IV administration. As expected, the MPS organs – spleen, liver, bone marrow, and lungs – had the highest phagocytic uptake capacity. They found that sequestration of NPs by MPS may reduce toxicity to tissue cells; however, MPS may also serve as an internal reservoir and slowly release the NPs back to tissues [89].

5 Conclusions and perspectives

The biggest obstacle to clinical transformation in the development of NDDSs is the lack of accurate understanding of their internal behaviour. This review introduces several methods to analyse the pharmacokinetics of NDDSs, discussed how the encapsulated drugs are being quantified, while how can free drugs be separately determined from the total drugs in biological samples. Optimizing the analysis methods should enhance the capacity of the current analytical methodology and therefore provide more comprehensive pharmacokinetics results for NDDSs. In addition, the PBPK model can describe nanoformulation distribution and pharmacokinetic parameters and provide quantitative evaluation of the influence of nanoformulation properties on their absorption, diffusion, and clearance. However, the development and application of PBPK models for nanomedicine is strictly dependent on the analysis of a broad range of information from different scientific disciplines. Knowledge from material chemistry, polymer synthesis, molecular and clinical pharmacology, and mathematical modelling should be integrated to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of nanoformulation pharmacokinetics and ultimately to improve the nanoformulation design. Consequently, an interdisciplinary approach is necessary and collaborative research between chemists, pharmacologists, and modellers should be prioritized for the generation of nanoformulations with optimal pharmacokinetics.

In addition, the targeted delivery and safety assessment of nanodrugs should be considered. After entering the body, nanotherapeutics encounter various biological environments, such as the blood, extracellular matrix, cytoplasm, and cellular organelles [90]. Safety issues for nanotherapeutics are complex. A detailed assessment of the safety of nanotherapeutics is necessary for clinical translation. Methods used for traditional drugs cannot accurately evaluate the safety of nanotherapeutics [91,92]. The Yujun Song group developed Rg3-sheltered dynamic nanocatalysts, which could simultaneously activate ferroptosis and apoptosis based on of CDT-activated apoptosis and ultimately form a combined therapy of ferroptosis–apoptosis to kill tumours. Compared with nanocatalysts alone, Rg3-sheltered dynamic nanocatalysts form hydrophilic nanoclusters, prolonging their circulation lifespan in the blood, protecting the internal nanocatalysts from leakage while allowing their specific release at the tumour site [93]. The group synthesized nanomedicine hydrogel microcapsules to evaluate the release kinetics of nanomedicines from the hydrogel by simulating the pH and temperature of the digestive tract during drug transport and those of the target pathological cell microenvironment. The results showed that nanomedicine-encapsulating hydrogels can undergo rapid decomposition at pH 5.5 and are relatively stable at pH 7.4 and 37°C, which are desirable qualities for drug delivery, controlled release, and residue elimination after achieving target effects [94].

The pharmacokinetics of NDDSs determine their clinical utility. The pharmacokinetics of NDDSs must be well characterized, and imaging modalities and quantitative mass balance methods must be developed to visualize and quantify the biodistribution of NDDSs. Another biological challenge is the heterogeneity of human disease and differences between animals and humans that impact biodistribution and become apparent in clinical studies. Furthermore, NPs often do not directly interact with living cells but instead become coated with a protein corona that alters the biological effects of the NPs and influences cell uptake, biodistribution, clearance, toxicity, and the immune response. Therefore, it is important to also focus on the protein coronas formed around NPs and the resulting biological responses for the clinical translation of nanomedicine [95].

The ideal NDDS should maintain sustained drug release, prolong drug circulation time in vivo, and improve stability, solubility, and targeting. Due to the insufficient understanding of the pharmacokinetics of NDDSs, approved nanodrugs are currently limited. The pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs is more complex than that of common drugs. Studying the ADME process of NDDSs, analysing the dynamic distribution process and metabolic process of nanodrugs by integrating advanced analysis technologies, conducting quantitative research, establishing the pharmacokinetic mathematical model of NDDSs, revealing the pharmacokinetic rules of NDDSs, and further improving the pharmacokinetic analysis of NDDSs are conducive to guiding the design, development, and use of nanodrugs and bringing new opportunities for the advancement of medicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the reviewers’ valuable comments that improved the manuscript.

-

Funding information: This work was funded by the Grant of the Jilin Province Development and Reform Commission (No. 2021C039-3), the Science and Technology Research Planning Project of Jilin Provincial Department of Education (No. JJKH20220460KJ), and the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for Undergraduate of Jilin Medical University (Nos. 202013706055 and S202113706090X).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this article and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors of the references cited in our findings but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the authors of the references cited in our findings.

References

[1] Navya PN, Kaphle A, Srinivas SP, Bhargava SK, Rotello VM, Daima HK. Current trends and challenges in cancer management and therapy using designer nanomaterials. Nano Converg. 2019;6(1):23–53.10.1186/s40580-019-0193-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Komal S, Siddiqui K, Waris A, Akber H, Munir K, Mir M, Khan MW, et al. Physicochemical modifications and nano particulate strategies for improved bioavailability of poorly water soluble drugs. Pharm Nanotechnol. 2017;5(4):276–84.10.2174/2211738506666171226120748Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Malam Y, Loizidou M, Seifalian AM. Liposomes and nanoparticles: Nanosized vehicles for drug delivery in cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30(11):592–9.10.1016/j.tips.2009.08.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Halamoda-Kenzaoui B, Holzwarth U, Roebben G, Bogni A, Bremer Hoffmann S. Mapping of the available standards against the regulatory needs for nanomedicines. WIREs Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology. 2019;11(1):e1531–48.10.1002/wnan.1531Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Cabral H, Miyata K, Osada K, Kataoka K. Block copolymer micelles in nanomedicine applications. Chem Rev. 2018;118(14):6844–92.10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00199Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Xiong XB, Huang Y, Lü W, Zhang X, Zhang H, Zhang Q. Preparation of doxorubicinloaded stealth liposomes modified with RGD mimetic and cellular association in vitro. Acta Pharm Sin. 2005;40:1085–90.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Mu CF, Balakrishnan P, Cui FD, Yin YM, Lee YB, Choi HG, et al. The effects of mixed MPEG-PLA/Pluronic copolymer micelles on the bioavailability and multidrug resistance of docetaxel. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2371–9.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.102Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Shargel L, Andrew B, Wu-Pong S. Applied biopharmaceutics pharmacokinetics. Vol. 264, Stamford, UK: Appleton & Lange Stamford; 1999.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Currie GM. Pharmacology, Part 2: Introduction to pharmacokinetics. J Nucl Med Technol. 2018;46(3):221–30.10.2967/jnmt.117.199638Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Harush-Frenkel O, Debotton N, Benita S, Altschuler Y. Targeting of nanoparticles to the clathrin-mediated endocytic pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353(1):26–32.10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.135Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Gratton SE, Ropp PA, Pohlhaus PD, Luft JC, Madden VJ, Napier ME, et al. The effect of particle design on cellular internalization pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(33):11613–9.10.1073/pnas.0801763105Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Yu C, He B, Xiong MH, Zhang H, Yuan L, Ma L, et al. The effect of hydrophilic and hydrophobic structure of amphiphilic polymeric micelles on their transport in epithelial MDCK cells. Biomaterials. 2013;34(26):6284–98.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.05.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Chiu Y-L, Ho YC, Chen YM, Peng SF, Ke CJ, Chen KJ, et al. The characteristics, cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking of nanoparticles made of hydrophobically-modified chitosan. J Controlled Rel. 2010;146(1):152–9.10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.05.023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Adepu S, Ramakrishna S. Controlled drug delivery systems: Current status and future directions. Molecules. 2021 Sep 29;26(19):5905.10.3390/molecules26195905Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Du R, Xiao H, Guo G, Jiang B, Yan X, Li W, et al. Nanoparticle delivery of photosensitive Pt(iv) drugs for circumventing cisplatin cellular pathway and on-demand drug release. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2014;123:734–41.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.10.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Ekins S, Ring BJ, Grace J, McRobie-Belle DJ, Wrighton SA. Present and future in vitro approaches for drug metabolism. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2000;44:313–24.10.1016/S1056-8719(00)00110-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Jambhekar SS, Breen PJ. Basic pharmacokinetics. Vol. 76, London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Mosqueira VC, Legrand P, Morgat JL, Vert M, Mysiakine E, Gref R, et al. Biodistribution of long-circulating PEG-Grafted nanocapsules in mice: Effects of PEG chain length and density. Pharm Res. 2001;18(10):1411–9.10.1023/A:1012248721523Search in Google Scholar

[19] Li Y, Xu X, Zhang X, Li Y, Zhang Z, Gu Z. Tumor-specific multiple stimuli-activated dendrimeric nanoassemblies with metabolic blockade surmount chemotherapy resistance. ACS Nano. 2017;11(1):416–29.10.1021/acsnano.6b06161Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Zhuang X, Lu C. PBPK modeling and simulation in drug research and development. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6(5):430–40.10.1016/j.apsb.2016.04.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Zhao Q-H, Qiu L-Y. An overview of the pharmacokinetics of polymer-based nanoassemblies and nanoparticles. Curr Drug Metab. 2013;14(8):832–9.10.2174/138920021131400104Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Liu GW, Prossnitz AN, Eng DG, Cheng Y, Subrahmanyam N, Pippin JW, et al. Glomerular disease augments kidney accumulation of synthetic anionic polymers. Biomaterials. 2018;178:317–25.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.06.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Li J, Burgess DJ. Nanomedicine-based drug delivery towards tumor biological and immunological microenvironment. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10(11):2110–24.10.1016/j.apsb.2020.05.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Rafiei P, Haddadi A. Docetaxel-loaded PLGA and PLGA-PEG nanoparticles for intravenous application: Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution profile. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:935–47.10.2147/IJN.S121881Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Balachandra A, Chan EC, Paul JP, Ng S, Chrysostomou V, Ngo S, et al. A biocompatible reverse thermoresponsive polymer for ocular drug delivery. Drug Deliv. 2019;26(1):343–53.10.1080/10717544.2019.1587042Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Singh P, Carrier A, Chen Y, Lin S, Wang J, Cui S, et al. Polymeric microneedles for controlled transdermal drug delivery. J Controlled Rel. 2019;315:97–113.10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.10.022Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Yang Q, Qi R, Cai J, Kang X, Sun S, Xiao H, et al. Biodegradable polymer-platinum drug conjugates to overcome platinum drug resistance. RSC Adv. 2015;5(101):83343–9.10.1039/C5RA11297DSearch in Google Scholar

[28] Rajput MKS, Kesharwani SS, Kumar S, Muley P, Narisetty S, Tummala H. Dendritic cell-targeted nanovaccine delivery system prepared with an immune-active polymer. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(33):27589–602.10.1021/acsami.8b02019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Battistella C, Klok HA. Controlling and monitoring intracellular delivery of anticancer polymer nanomedicines. Macromol Biosci. 2017;17(10):1700022.10.1002/mabi.201700022Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Wang T, Guo Y, He Y, Ren T, Yin L, Fawcett JP, et al. Impact of molecular weight on the mechanism of cellular uptake of polyethylene glycols (PEGs) with particular reference to P-glycoprotein. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10(10):2002–9.10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Drasler B, Vanhecke D, Rodriguez-Lorenzo L, Petri-Fink A, Rothen-Rutishauser B. Quantifying nanoparticle cellular uptake: Which method is best? Nanomedicine. 2017;12(10):1095–9.10.2217/nnm-2017-0071Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Meng X, Zhang Z, Tong J, Sun H, Fawcett JP, Gu J. The biological fate of the polymer nanocarrier material monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(d,l-lactic acid) in rat. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11(4):1003–9.10.1016/j.apsb.2021.02.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Chen J, He H, Li S, Shen Q. An HPLC method for the pharmacokinetic study of vincristine sulfate-loaded PLGA-PEG nanoparticle formulations after injection to rats. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879(21):1967–72.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Xiao X, Wang T, Li L, Zhu Z, Zhang W, Cui G, et al. Co-delivery of cisplatin(iv) and capecitabine as an effective and non-toxic cancer treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:110.10.3389/fphar.2019.00110Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Shan X, Gong X, Li J, Wen J, Li Y, Zhang Z. Current approaches of nanomedicines in the market and various stage of clinical translation. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(7):3028–48.10.1016/j.apsb.2022.02.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Angiolillo AL, Schore RJ, Devidas M, Borowitz MJ, Carroll AJ, Gastier-Foster JM, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of calaspargase pegol Escherichia coli L-asparaginase in the treatment of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Children’s Oncol Group Study AALL07P4J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(34):3874–82.10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5763Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Halewyck H, Schotte L, Oita I, Thys B, Van Eeckhaut A, Vander Heyden Y, et al. Affinity capillary electrophoresis to evaluate the complex formation between poliovirus and nanobodies. J Sep Sci. 2014;37(24):3729–37.10.1002/jssc.201400406Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Liu R, Huang Q, Duan JA, Zhu Z, Liu P, Bian Y, et al. Peptidome characterization of the antipyretic fraction of Bubali Cornu aqueous extract by nano liquid chromatography with orbitrap mass spectrometry detection. J Sep Sci. 2017;40(2):587–95.10.1002/jssc.201600821Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Qu H, Qu B, Wang X, Zhang Y, Cheng J, Zeng W, et al. Rapid, sensitive separation of the three main isoflavones in soybean using immunoaffinity chromatography. J Sep Sci. 2016;39(6):1195–201.10.1002/jssc.201501052Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Zhang Y, Qu H, Zeng W, Zhao Y, Shan W, Wang X, et al. Development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and immunoaffinity chromatography for glycyrrhizic acid using an anti-glycyrrhizic acid monoclonal antibody. J Sep Sci. 2015;38(13):2363–70.10.1002/jssc.201500242Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Tongdee M, Yamanishi C, Maeda M, Kojima T, Dishinger J, Chantiwas R, et al. One-incubation one-hour multiplex ELISA enabled by aqueous two-phase systems. Analyst. 2020;145(10):3517–27.10.1039/D0AN00383BSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Nagasaki Y, Kobayashi H, Katsuyama Y, Jomura T, Sakura T. Enhanced immunoresponse of antibody/mixed-PEG co-immobilized surface construction of high-performance immunomagnetic ELISA system. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2007;309(2):524–30.10.1016/j.jcis.2006.12.079Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Sedlacek O, Kucka J, Svec F, Hruby M. Silver-coated monolithic columns for separation in radiopharmaceutical applications. J Sep Sci. 2014;37(7):798–802.10.1002/jssc.201301325Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Seo JW, Mahakian LM, Tam S, Qin S, Ingham ES, Meares CF, et al. The pharmacokinetics of Zr-89 labeled liposomes over extended periods in a murine tumor model. Nucl Med Biol. 2015;42(2):155–63.10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2014.09.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Su C, Liu Y, Li R, Wu W, Fawcett JP, Gu J. Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of the biomaterials used in Nanocarrier drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;143:97–114.10.1016/j.addr.2019.06.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Zubaidi FA, Choo YM, Tan GH, Hamid HA, Choy YK. A novel liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry technique using multi-period-multi-experiment of mrm-epi-mrm3 with library matching for simultaneous determination of amphetamine type stimulants related drugs in whole blood, urine and dried blood stain (DBS)-application to forensic toxicology cases in Malaysia. J Anal Toxicol. 2019;43(7):528–35.10.1093/jat/bkz017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Shan SW, Do CW, Lam TC, Kong R, Li KK, Chun KM, et al. New insight of common regulatory pathways in human trabecular meshwork cells in response to dexamethasone and prednisolone using an integrated quantitative proteomics: SWATH and MRM-HR mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2017;16(10):3753–65.10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00449Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Doneanu C, Fang J, Fang J, Alelyunas Y, Yu YQ, Wrona M. An HS-MRM assay for the quantification of host-cell proteins in protein biopharmaceuticals by liquid chromatography ion mobility QTOF mass spectrometry. JoVE. 2018;134:e55325–36.10.3791/55325-vSearch in Google Scholar

[49] Vu DL, Ranglová K, Hájek J, Hrouzek P. Quantification of methionine and selenomethionine in biological samples using multiple reaction monitoring high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (MRM-HPLC-MS/MS). J Chromatogr B. 2018;1084:36–44.10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.03.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Mindaye ST, Spiric J, David NA, Rabin RL, Slater JE. Accurate quantification of 5 German cockroach (GCr) allergens in complex extracts using multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry (MRM MS). Clin & Exp Allergy. 2017;47(12):1661–70.10.1111/cea.12986Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Hurtado-Gaitán E, Sellés-Marchart S, Martínez-Márquez A, Samper-Herrero A, Bru-Martínez R. A focused multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) quantitative method for bioactive grapevine stilbenes by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to triple-quadrupole mass spectrometry (UHPLC-QqQ). Molecules. 2017;22(3):418.10.3390/molecules22030418Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Vidova V, Spacil Z. A review on mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomics: Targeted and data independent acquisition. Anal Chim Acta. 2017;964:7–23.10.1016/j.aca.2017.01.059Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Chahrour O, Cobice D, Malone J. Stable isotope labelling methods in mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomics. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2015;113:2–20.10.1016/j.jpba.2015.04.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Liu X, Xie S, Ni T, Chen D, Wang X, Pan Y, et al. Magnetic solid-phase extraction based on carbon nanotubes for the determination of polyether antibiotic and s-triazine drug residues in animal food with LC–MS/MS. J Sep Sci. 2017;40(11):2416–30.10.1002/jssc.201700017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Desfontaine V, Goyon A, Veuthey JL, Charve J, Guillarme D. Development of a LC–MS/MS method for the determination of isomeric glutamyl peptides in food ingredients. J Sep Sci. 2018;41(4):847–55.10.1002/jssc.201701182Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Qian Z, Le J, Chen X, Li S, Song H, Hong Z. High-throughput LC–MS/MS method with 96-well plate precipitation for the determination of arotinolol and amlodipine in a small volume of rat plasma: Application to a pharmacokinetic interaction study. J Sep Sci. 2018;41(3):618–29.10.1002/jssc.201700784Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Gong J, Gu X, Achanzar WE, Chadwick KD, Gan J, Brock BJ, et al. Quantitative analysis of polyethylene glycol (PEG) and PEGylated proteins in animal tissues by LC-MS/MS coupled with in-source CID. Anal Chem. 2014;86(15):7642–9.10.1021/ac501507gSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Chen T, Li C, Li Y, Yi X, Wang R, Lee SM, et al. Small-sized mPEG–PLGA nanoparticles of schisantherin a with sustained release for enhanced brain uptake and anti-parkinsonian activity. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(11):9516–27.10.1021/acsami.7b01171Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] He H, Zhang J, Xie Y, Lu Y, Qi J, Ahmad E, et al. Bioimaging of Intravenous polymeric micelles based on discrimination of integral particles using an environment-responsive probe. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2016;13(11):4013–9.10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00705Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Zhao E, Chen Y, Chen S, Deng H, Gui C, Leung CW, et al. A luminogen with aggregation-induced emission characteristics for wash-free bacterial imaging, high-throughput antibiotics screening and bacterial susceptibility evaluation. Adv Mater. 2015;27(33):4931–7.10.1002/adma.201501972Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Xue X, Zhao Y, Dai L, Zhang X, Hao X, Zhang C, et al. Spatiotemporal drug release visualized through a drug delivery system with tunable aggregation-induced emission. Adv Mater. 2014;26(5):712–7.10.1002/adma.201302365Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Ambardekar VV, Stern ST. NBCD pharmacokinetics and bioanalytical methods to measure drug release. Non-Biol Complex Drugs. 2015;20(6):261–87.10.1007/978-3-319-16241-6_8Search in Google Scholar

[63] Stern ST, Martinez MN, Stevens DM. When is it important to measure unbound drug in evaluating nanomedicine pharmacokinetics? Drug Metab Dispos. 2016;44(12):1934–9.10.1124/dmd.116.073148Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] Skoczen SL, Stern ST. Improved ultrafiltration method to measure drug release from nanomedicines utilizing a stable isotope tracer. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1682:223–39.10.1007/978-1-4939-7352-1_19Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Skoczen SL, Snapp KS, Crist RM, Kozak D, Jiang X, Liu H, et al. Distinguishing pharmacokinetics of marketed nanomedicine formulations using a stable isotope tracer assay. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;3(3):547–58.10.1021/acsptsci.0c00011Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[66] Zabaleta V, Campanero MA, Irache JM. An HPLC with evaporative light scattering detection method for the quantification of PEGs and Gantrez in PEGylated nanoparticles. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2007;44(5):1072–8.10.1016/j.jpba.2007.05.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[67] Liu J, X. Bao, Bao X, Bao X, Kolesnik I, Jia B, et al. Enhancing the in vivo stability of polycation gene carriers by using PEGylated hyaluronic acid as a shielding system. BIO Integr. 2022;3(3):103–11.10.15212/bioi-2021-0033Search in Google Scholar

[68] Díaz-López R, Libong D, Tsapis N, Fattal E, Chaminade P. Quantification of pegylated phospholipids decorating polymeric microcapsules of perfluorooctyl bromide by reverse phase HPLC with a charged aerosol detector. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2008;48(3):702–7.10.1016/j.jpba.2008.06.027Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Chen J, He H, Li S, Shen Q. An HPLC method for the pharmacokinetic study of vincristine sulfate-loaded PLGA-PEG nanoparticle formulations after injection to rats. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879(21):1967–72.10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.05.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[70] Wang B, Guo Y, Chen X, Zeng C, Hu Q, Yin W, et al. Nanoparticle-modified chitosan-agarose-gelatin scaffold for sustained release of SDF-1 and BMP-2. Int J Nanomed. 2018;13:7395–408.10.2147/IJN.S180859Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[71] Azie O, Greenberg ZF, Batich CD, Dobson JP. Carbodiimide conjugation of latent transforming growth factor beta1 to superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for remote activation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(13):3190.10.3390/ijms20133190Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[72] Petersen AL, Binderup T, Rasmussen P, Henriksen JR, Elema DR, Kjær A, et al. 64Cu loaded liposomes as positron emission tomography imaging agents. Biomaterials. 2011;32(9):2334–41.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.11.059Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[73] Zhou X, Meng X, Cheng L, Su C, Sun Y, Sun L, et al. Development and application of an MS(ALL)-based approach for the quantitative analysis of linear polyethylene glycols in rat plasma by liquid chromatography triple-quadrupole/time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2017;89(10):5193–200.10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04058Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[74] Zhao Y, Fay F, Hak S, Manuel Perez-Aguilar J, Sanchez-Gaytan BL, Goode B, et al. Augmenting drug-carrier compatibility improves tumour nanotherapy efficacy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11221–32.10.1038/ncomms11221Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[75] Hu X, Zhang J, Yu Z, Xie Y, He H, Qi J, et al. Environment-responsive aza-BODIPY dyes quenching in water as potential probes to visualize the in vivo fate of lipid-based nanocarriers. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2015;11(8):1939–48.10.1016/j.nano.2015.06.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[76] Wang Y, Zhang Y, Wang J, Liang XJ. Aggregation-induced emission (AIE) fluorophores as imaging tools to trace the biological fate of nano-based drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;143:161–76.10.1016/j.addr.2018.12.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[77] Jones H, Rowland-Yeo K. Basic concepts in physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling in drug discovery and development. CPT Pharmacomet Syst Pharmacol. 2013 Aug 14;2(8):e63.10.1038/psp.2013.41Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[78] Yuan D, He H, Wu Y, Fan J, Cao Y. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of nanoparticles. J Pharm Sci. 2019;108(1):58–72.Search in Google Scholar

[79] Willmann S, Höhn K, Edginton A, Sevestre M, Solodenko J, Weiss W, et al. Development of a physiology-based whole-body population model for assessing the influence of individual variability on the pharmacokinetics of drugs. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacody. 2007;34(3):401–31.10.1007/s10928-007-9053-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[80] Zheng C, Li M, Ding J. Challenges and opportunities of nanomedicines in clinical translation. BIO Integr. 2021;2(2):57–60.10.15212/bioi-2021-0016Search in Google Scholar

[81] Soldin OP, Mattison DR. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacokinetics. 2009;48(3):143–57.10.2165/00003088-200948030-00001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[82] Rodgers T, Rowland M. Mechanistic approaches to volume of distribution predictions: Understanding the processes. Pharm Res. 2007;24(5):918–33.10.1007/s11095-006-9210-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[83] Lin P, Chen JW, Chang LW, Wu JP, Redding L, Chang H, et al. Computational and ultrastructural toxicology of a nanoparticle, quantum dot 705, in mice. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42(16):6264–70.10.1021/es800254aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[84] Péry AR, Brochot C, Hoet PH, Nemmar A, Bois FY. Development of a physiologically based kinetic model for 99m-Technetium-labelled carbon nanoparticles inhaled by humans. Inhalation Toxicol. 2009;21(13):1099–107.10.3109/08958370902748542Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[85] He H, Liu C, Wu Y, Zhang X, Fan J, Cao Y. A multiscale physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model for doxorubicin to explore its mechanisms of cytotoxicity and cardiotoxicity in human physiological contexts. Pharm Res. 2018;35(9):174–96.10.1007/s11095-018-2456-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[86] Asghar MA, Yousuf RI, Shoaib MH, Asghar MA, Mumtaz N. A review on toxicity and challenges in transferability of surface-functionalized metallic nanoparticles from animal models to humans. BIO Integr. 2021;2(2):71–80.10.15212/bioi-2020-0047Search in Google Scholar

[87] Yuan D, He H, Wu Y, Fan J, Cao Y. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of nanoparticles. J Pharm Sci. 2019;108(1):58–72.10.1016/j.xphs.2018.10.037Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[88] Wu B, Dong D, Wang X, Wang H, Zhang X, Wang Y. Elucidating the in vivo fate of nanocrystals using a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model: A case study with the anticancer agent SNX-2112. Int J Nanomed. 2015;10:2521–35.10.2147/IJN.S79734Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[89] Li D, Johanson G, Emond C, Carlander U, Philbert M, Jolliet O. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of polyethylene glycol-coated polyacrylamide nanoparticles in rats. Nanotoxicology. 2014;8(Suppl 1):128–37.10.3109/17435390.2013.863406Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[90] Wolfram J, Zhu M, Yang Y, Shen J, Gentile E, Paolino D, et al. Safety of nanoparticles in medicine. Curr Drug Targets. 2015;16(14):1671–81.10.2174/1389450115666140804124808Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[91] Hua S, de Matos M, Metselaar JM, Storm G. Current trends and challenges in the clinical translation of nanoparticulate nanomedicines: Pathways for translational development and commercialization. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:790.10.3389/fphar.2018.00790Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[92] Agrahari V, Agrahari V. Facilitating the translation of nanomedicines to a clinical product: Challenges and opportunities. Drug Discov Today. 2018 May;23(5):974–91.10.1016/j.drudis.2018.01.047Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[93] Liu R, Wu Q, Huang X, Zhao X, Chen X, Chen Y, et al. Synthesis of nanomedicine hydrogel microcapsules by droplet microfluidic process and their pH and temperature dependent release. RSC Adv. 2021;11(60):37814–23.10.1039/D1RA05207ASearch in Google Scholar

[94] Zhao X, Wu J, Guo D, Hu S, Chen X, Hong L, et al. Dynamic ginsenoside-sheltered nanocatalysts for safe ferroptosis-apoptosis combined therapy. Acta Biomater. 2022;10(151):549–60.10.1016/j.actbio.2022.08.026Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[95] Zhang C, Yan L, Wang X, Zhu S, Chen C, Gu Z, et al. Progress, challenges, and future of nanomedicine. Nano Today. 2020;35:101008.10.1016/j.nantod.2020.101008Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method

- High mechanical performance of 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane/epoxy cured in a sandwich construction of 3D carbon felts foam and woven basalt fibers

- Applying solution of spray polyurea elastomer in asphalt binder: Feasibility analysis and DSR study based on the MSCR and LAS tests

- Study on the chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of iron-based bioabsorbable stents

- Influence of microalloying with B on the microstructure and properties of brazed joints with Ag–Cu–Zn–Sn filler metal

- Thermohydraulic performance of thermal system integrated with twisted turbulator inserts using ternary hybrid nanofluids

- Study of mechanical properties of epoxy/graphene and epoxy/halloysite nanocomposites

- Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction

- Cu and Al2O3-based hybrid nanofluid flow through a porous cavity

- Design of functional vancomycin-embedded bio-derived extracellular matrix hydrogels for repairing infectious bone defects

- Study on nanocrystalline coating prepared by electro-spraying 316L metal wire and its corrosion performance

- Axial compression performance of CFST columns reinforced by ultra-high-performance nano-concrete under long-term loading

- Tungsten trioxide nanocomposite for conventional soliton and noise-like pulse generation in anomalous dispersion laser cavity

- Microstructure and electrical contact behavior of the nano-yttria-modified Cu-Al2O3/30Mo/3SiC composite

- Melting rheology in thermally stratified graphene-mineral oil reservoir (third-grade nanofluid) with slip condition

- Re-examination of nonlinear vibration and nonlinear bending of porous sandwich cylindrical panels reinforced by graphene platelets

- Parametric simulation of hybrid nanofluid flow consisting of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with second-order slip and variable viscosity over an extending surface

- Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles with potent and selective intrinsic activity against the breast cancer cells

- Multi-core/shell SiO2@Al2O3 nanostructures deposited on Ti3AlC2 to enhance high-temperature stability and microwave absorption properties

- Solution-processed Bi2S3/BiVO4/TiO2 ternary heterojunction photoanode with enhanced photoelectrochemical performance

- Electroporation effect of ZnO nanoarrays under low voltage for water disinfection

- NIR-II window absorbing graphene oxide-coated gold nanorods and graphene quantum dot-coupled gold nanorods for photothermal cancer therapy

- Nonlinear three-dimensional stability characteristics of geometrically imperfect nanoshells under axial compression and surface residual stress

- Investigation of different nanoparticles properties on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids by molecular dynamics simulation

- Optimized Cu2O-{100} facet for generation of different reactive oxidative species via peroxymonosulfate activation at specific pH values to efficient acetaminophen removal

- Brownian and thermal diffusivity impact due to the Maxwell nanofluid (graphene/engine oil) flow with motile microorganisms and Joule heating

- Appraising the dielectric properties and the effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding of graphene reinforced silicone rubber nanocomposite

- Synthesis of Ag and Cu nanoparticles by plasma discharge in inorganic salt solutions

- Low-cost and large-scale preparation of ultrafine TiO2@C hybrids for high-performance degradation of methyl orange and formaldehyde under visible light

- Utilization of waste glass with natural pozzolan in the production of self-glazed glass-ceramic materials

- Mechanical performance of date palm fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nano-activated carbon

- Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation

- Graphene nanofibers: A modern approach towards tailored gypsum composites

- Role of localized magnetic field in vortex generation in tri-hybrid nanofluid flow: A numerical approach

- Intelligent computing for the double-diffusive peristaltic rheology of magneto couple stress nanomaterials

- Bioconvection transport of upper convected Maxwell nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganism, nonlinear thermal radiation, and chemical reaction

- 3D printing of porous Ti6Al4V bone tissue engineering scaffold and surface anodization preparation of nanotubes to enhance its biological property

- Bioinspired ferromagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles: Potential pharmaceutical and medical applications

- Significance of gyrotactic microorganisms on the MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow across an elastic slender surface: Numerical analysis

- Performance of polycarboxylate superplasticisers in seawater-blended cement: Effect from chemical structure and nano modification

- Entropy minimization of GO–Ag/KO cross-hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated surface

- Oxygen plasma assisted room temperature bonding for manufacturing SU-8 polymer micro/nanoscale nozzle

- Performance and mechanism of CO2 reduction by DBD-coupled mesoporous SiO2

- Polyarylene ether nitrile dielectric films modified by HNTs@PDA hybrids for high-temperature resistant organic electronics field

- Exploration of generalized two-phase free convection magnetohydrodynamic flow of dusty tetra-hybrid Casson nanofluid between parallel microplates

- Hygrothermal bending analysis of sandwich nanoplates with FG porous core and piezomagnetic faces via nonlocal strain gradient theory

- Design and optimization of a TiO2/RGO-supported epoxy multilayer microwave absorber by the modified local best particle swarm optimization algorithm

- Mechanical properties and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete modified by nano-SiO2

- Self-template synthesis of hollow flower-like NiCo2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution in alkaline media

- High-performance wearable flexible strain sensors based on an AgNWs/rGO/TPU electrospun nanofiber film for monitoring human activities

- High-performance lithium–selenium batteries enabled by nitrogen-doped porous carbon from peanut meal

- Investigating effects of Lorentz forces and convective heating on ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a curved surface using homotopy analysis method

- Exploring the potential of biogenic magnesium oxide nanoparticles for cytotoxicity: In vitro and in silico studies on HCT116 and HT29 cells and DPPH radical scavenging

- Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by heteroatom-doped nickel tungstate nanoparticles

- A facile method to synthesize nZVI-doped polypyrrole-based carbon nanotube for Ag(i) removal

- Improved osseointegration of dental titanium implants by TiO2 nanotube arrays with self-assembled recombinant IGF-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model

- Functionalized SWCNTs@Ag–TiO2 nanocomposites induce ROS-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in liver cancer cells

- Triboelectric nanogenerator based on a water droplet spring with a concave spherical surface for harvesting wave energy and detecting pressure

- A mathematical approach for modeling the blood flow containing nanoparticles by employing the Buongiorno’s model

- Molecular dynamics study on dynamic interlayer friction of graphene and its strain effect

- Induction of apoptosis and autophagy via regulation of AKT and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast cancer cell lines exposed to gold nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α and combined with doxorubicin

- Effect of PVA fibers on durability of nano-SiO2-reinforced cement-based composites subjected to wet-thermal and chloride salt-coupled environment

- Effect of polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical properties of nano-SiO2-reinforced geopolymer composites under a complex environment

- In vitro studies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles modified with glutathione as a potential drug delivery system

- Comparative investigations of Ag/H2O nanofluid and Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with Darcy-Forchheimer flow over a curved surface

- Study on deformation characteristics of multi-pass continuous drawing of micro copper wire based on crystal plasticity finite element method

- Properties of ultra-high-performance self-compacting fiber-reinforced concrete modified with nanomaterials

- Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives

- A novel exploration of how localized magnetic field affects vortex generation of trihybrid nanofluids

- Fabrication and physicochemical characterization of copper oxide–pyrrhotite nanocomposites for the cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and the mechanism

- Thermal radiative flow of cross nanofluid due to a stretched cylinder containing microorganisms

- In vitro study of the biphasic calcium phosphate/chitosan hybrid biomaterial scaffold fabricated via solvent casting and evaporation technique for bone regeneration

- Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface

- Effects of nano-SiO2 additives on carbon fiber-reinforced fly ash–slag geopolymer composites performance: Workability, mechanical properties, and microstructure

- Energy bandgap and thermal characteristics of non-Darcian MHD rotating hybridity nanofluid thin film flow: Nanotechnology application

- Green synthesis and characterization of ginger-extract-based oxali-palladium nanoparticles for colorectal cancer: Downregulation of REG4 and apoptosis induction

- Abnormal evolution of resistivity and microstructure of annealed Ag nanoparticles/Ag–Mo films

- Preparation of water-based dextran-coated Fe3O4 magnetic fluid for magnetic hyperthermia

- Statistical investigations and morphological aspects of cross-rheological material suspended in transportation of alumina, silica, titanium, and ethylene glycol via the Galerkin algorithm

- Effect of CNT film interleaves on the flexural properties and strength after impact of CFRP composites

- Self-assembled nanoscale entities: Preparative process optimization, payload release, and enhanced bioavailability of thymoquinone natural product

- Structure–mechanical property relationships of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane films

- Nonlinear thermal radiation and the slip effect on a 3D bioconvection flow of the Casson nanofluid in a rotating frame via a homotopy analysis mechanism

- Residual mechanical properties of concrete incorporated with nano supplementary cementitious materials exposed to elevated temperature

- Time-independent three-dimensional flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a Riga plate with slips and convective conditions: A homotopic solution

- Lightweight and high-strength polyarylene ether nitrile-based composites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding

- Review Articles

- Recycling waste sources into nanocomposites of graphene materials: Overview from an energy-focused perspective

- Hybrid nanofiller reinforcement in thermoset and biothermoset applications: A review

- Current state-of-the-art review of nanotechnology-based therapeutics for viral pandemics: Special attention to COVID-19

- Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high-incidence cancers, and other diseases: Roles of preparation methods, lipid composition, transitional stability, and release profiles in nanocarriers’ development

- Critical review on experimental and theoretical studies of elastic properties of wurtzite-structured ZnO nanowires

- Polyurea micro-/nano-capsule applications in construction industry: A review

- A comprehensive review and clinical guide to molecular and serological diagnostic tests and future development: In vitro diagnostic testing for COVID-19

- Recent advances in electrocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: Mechanism, catalyst, coupling system

- Research progress and prospect of silica-based polymer nanofluids in enhanced oil recovery

- Review of the pharmacokinetics of nanodrugs

- Engineered nanoflowers, nanotrees, nanostars, nanodendrites, and nanoleaves for biomedical applications

- Research progress of biopolymers combined with stem cells in the repair of intrauterine adhesions

- Progress in FEM modeling on mechanical and electromechanical properties of carbon nanotube cement-based composites

- Antifouling induced by surface wettability of poly(dimethyl siloxane) and its nanocomposites

- TiO2 aerogel composite high-efficiency photocatalysts for environmental treatment and hydrogen energy production

- Structural properties of alumina surfaces and their roles in the synthesis of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)

- Nanoparticles for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A physiopathological approach

- Current status of synthesis and consolidation strategies for thermo-resistant nanoalloys and their general applications

- Recent research progress on the stimuli-responsive smart membrane: A review

- Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in aqueous cementitious materials: A review

- Applications of DNA tetrahedron nanostructure in cancer diagnosis and anticancer drugs delivery

- Magnetic nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for biomedical applications

- An overview of the synthesis of silicon carbide–boron carbide composite powders

- Organolead halide perovskites: Synthetic routes, structural features, and their potential in the development of photovoltaic

- Recent advancements in nanotechnology application on wood and bamboo materials: A review

- Application of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in molecular imaging of tumors

- Recent progress on corrosion mechanisms of graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites

- Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel

- Application of nanomaterials in early diagnosis of cancer

- Plant mediated-green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An insight into biomedical applications

- Recent developments in terahertz quantum cascade lasers for practical applications

- Recent progress in dielectric/metal/dielectric electrodes for foldable light-emitting devices

- Nanocoatings for ballistic applications: A review

- A mini-review on MoS2 membrane for water desalination: Recent development and challenges

- Recent updates in nanotechnological advances for wound healing: A narrative review

- Recent advances in DNA nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis and treatment

- Electrochemical micro- and nanobiosensors for in vivo reactive oxygen/nitrogen species measurement in the brain

- Advances in organic–inorganic nanocomposites for cancer imaging and therapy

- Advancements in aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbides and graphene: A comprehensive review

- Modification effects of nanosilica on asphalt binders: A review

- Decellularized extracellular matrix as a promising biomaterial for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration

- Review of the sol–gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process

- Micro/nano manufacturing aircraft surface with anti-icing and deicing performances: An overview

- Cell type-targeting nanoparticles in treating central nervous system diseases: Challenges and hopes

- An overview of hydrogen production from Al-based materials

- A review of application, modification, and prospect of melamine foam

- A review of the performance of fibre-reinforced composite laminates with carbon nanotubes

- Research on AFM tip-related nanofabrication of two-dimensional materials

- Advances in phase change building materials: An overview

- Development of graphene and graphene quantum dots toward biomedical engineering applications: A review

- Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview

- Photodynamic therapy empowered by nanotechnology for oral and dental science: Progress and perspectives

- Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles: Bioreduction and biomineralization

- Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) and the role of nanomaterial-based theragnosis in combating the pandemic

- Application of two-dimensional black phosphorus material in wound healing

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part I

- Helical fluorinated carbon nanotubes/iron(iii) fluoride hybrid with multilevel transportation channels and rich active sites for lithium/fluorinated carbon primary battery

- The progress of cathode materials in aqueous zinc-ion batteries

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part I

- Effect of polypropylene fiber and nano-silica on the compressive strength and frost resistance of recycled brick aggregate concrete

- Mechanochemical design of nanomaterials for catalytic applications with a benign-by-design focus

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Preparation of CdS–Ag2S nanocomposites by ultrasound-assisted UV photolysis treatment and its visible light photocatalysis activity

- Significance of nanoparticle radius and inter-particle spacing toward the radiative water-based alumina nanofluid flow over a rotating disk

- Aptamer-based detection of serotonin based on the rapid in situ synthesis of colorimetric gold nanoparticles

- Investigation of the nucleation and growth behavior of Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC nano-precipitates in TiAl alloys

- Dynamic recrystallization behavior and nucleation mechanism of dual-scale SiCp/A356 composites processed by P/M method