Abstract

This article aims to introduce a new three-parameter lifetime distribution called sine power Burr X (SPB-X) distribution. The proposed distribution is obtained by the sine-G class of distributions and the power Burr X distribution. Various properties of the proposed distribution, including explicit expressions for the quantile function, Bowley skewness, Moors kurtosis, ordinary moments, generating function, incomplete and conditional moments, and some numerical and graphical illustrations, are provided. Some various significant reliability metrics for the SPB-X model, including common reliability functions, mean residual life function, mean waiting time function, residual moment, and reversed residual life. Several essential risk measures for the SPB-X distribution. These risk measures include the value at risk, the expected shortfall, the tail value at risk, the tail variance, and the tail variance premium. Four estimation methods were employed to estimate the model’s parameters such as maximum likelihood, least squares, maximum product spacing, and Bayesian. A simulation study is conducted to assess the performance of the estimation methods. Finally, five real data are considered to analyze the usefulness and flexibility of the proposed model.

1 Introduction

Recent years in the field of applied sciences have been characterized by the need and magnitude of data that require analysis. Recently, most statisticians have focused on developing new families that are a generalization of existing distributions to obtain a better fit for data modeling. These families of distributions are derived by compounding multiple distributions or incorporating additional parameters into the baseline model. Recent research has focused on the generation of families of distributions by authors. The beta-G family [1], Kumaraswamy-G [2], T-X family [3], Type II half logistic-G [4], and Topp-Leone odd Fréchet-G [5] are included in this classification. The families described by trigonometric transformations have garnered significant interest due to their applicability and effectiveness in various contexts. These families offer versatility and flexibility as the parameters fluctuate with changes in their values, while the periodic function governs the behavior of the distribution curve. The combination of diverse functions exhibiting distinct behaviors enhances the modeling of real-world phenomena, addressing the limitations of previously established generalized statistical distributions. The sine-G family of distributions, introduced in 2015, is recognized as the pioneering trigonometric family of distributions.

Another method of creating new life distributions by modifying trigonometric functions to produce new statistical distributions was introduced by Kumar et al. [6]. This generated family is called the sine G family and has the following cumulative distribution function (cdf) and probability density function (pdf) as follows:

and

respectively, where

The Burr type

and

where

and

Often, the PB-X distribution is not flexible enough to represent a variety of lifetime data well. To address this limitation, we propose a novel extension of the PB-X distribution. Inspired by the sine-G family, the new suggested distribution is called the sine PB-X (SPB-X) distribution, and it has the same number of parameters as for the PB-X distribution. In this study, the following objectives will be the main focus:

Create a flexible distribution that can represent ft-skewed, right-skewed, decreased, unimodal, heavy-tailed, and closely to symmetric can be seen in its pdf. A variety of shapes, such as increasing, J-shaped, and decreasing patterns, can be seen in its hrf.

Compute some important statistical properties of the suggested distribution, including its quantile function (QF), Bowley skewness, Moors kurtosis, ordinary moments, generating function, incomplete and conditional moments, and some numerical and graphical illustrations.

Some significant reliability metrics are calculated for the SPB-X model, including common reliability functions, mean residual life function, mean waiting time function, residual moment, and reversed residual life.

Several essential risk measures include the value at risk, the expected shortfall (ES), the tail value at risk (TVaR), the tail variance (TV), and the tail variance premium (TVP).

Estimate the unknown parameters of the SPB-X distribution using four estimation methods, including maximum likelihood, least squares, maximum product spacing (MPS), and Bayesian. To evaluate the efficacy of these estimators in varying scenarios, perform a detailed simulation study.

As a result of its adaptability, the SPB-X distribution appears to be a good contender for modeling five datasets taken from the real world in contrast to other alternatives that are currently available. To illustrate its superiority, this present article examines a variety of modern statistical models, such as the PB-X, shifting exponential Weibull exponential (SEWHE), Weibull, gamma, exponentiated Weibull, sine exponentiated Weibull exponential (SEWE) and Burr III (BIII) distributions.

In this study, an idea for an extension of the PB-X model is presented. The sine-G family serves as a framework for its construction, and the distribution is referred to as the sine power Burr

2 Construction of the SPB-X model

In this article, we combine the sine G family and the PB-X distribution by inserting (3) in (1) to obtain the cdf of the SPB-X distribution as follows:

where

Figure 1 illustrates some pdf curves for the SPB-X distribution at

Plots of the pdf for the SPB-X distribution at

To obtain the explicit expression of the distribution, we use the generalized binomial theorem and the Taylor series expansion of the cosine function,

and

One possible way to express the expansion of pdf in Eq. (6) is as follows:

where

3 Statistical and mathematical properties of SPB-X model

Several significant statistical and mathematical metrics for the SPB-X model are presented in this section.

3.1 Quantile function

There are several uses for the QF, including statistical applications, Monte Carlo techniques, and theoretical parts. The QF algorithm is used in Monte Carlo simulations to generate simulated random variables for classical and novel continuous distributions. It is possible to derive the

Bowley skewness, which was defined in [34], is considered one of the early skewness measurements that was offered as

As an alternative, Moors kurtosis [35], which is derived from quantiles, is presented by the following equation:

where

Table 1 displays the values of

Results of

|

|

|

|

|

|

SK | KU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.1559 | 0.2913 | 0.4835 | 0.1733 | 1.2573 |

| 1.8 | 0.2000 | 0.3482 | 0.5502 | 0.1537 | 1.2532 | |

| 2.0 | 0.2278 | 0.3828 | 0.5899 | 0.1441 | 1.2517 | |

| 2.2 | 0.2544 | 0.4150 | 0.6263 | 0.1363 | 1.2507 | |

| 2.4 | 0.2797 | 0.4451 | 0.6600 | 0.1300 | 1.2504 | |

| 2.6 | 0.3038 | 0.4734 | 0.6914 | 0.1246 | 1.2498 | |

| 2.8 | 0.3268 | 0.5002 | 0.7207 | 0.1198 | 1.2497 | |

| 3.0 | 0.3489 | 0.5254 | 0.7482 | 0.1160 | 1.2497 | |

| 3.2 | 0.3699 | 0.5492 | 0.7741 | 0.1126 | 1.2496 | |

| 3.4 | 0.3901 | 0.5720 | 0.7987 | 0.1096 | 1.2496 | |

| 3.6 | 0.4094 | 0.5936 | 0.8219 | 0.1069 | 1.2497 | |

| 3.8 | 0.4280 | 0.6142 | 0.8440 | 0.1045 | 1.2497 | |

| 4.0 | 0.4459 | 0.6340 | 0.8650 | 0.1024 | 1.2498 | |

| 1.6 | 1.5 | 0.5594 | 0.6801 | 0.7968 |

|

1.2289 |

| 1.8 | 0.6047 | 0.7191 | 0.8297 |

|

1.2325 | |

| 2.0 | 0.6299 | 0.7407 | 0.8479 |

|

1.2340 | |

| 2.2 | 0.6520 | 0.7597 | 0.8640 |

|

1.2355 | |

| 2.4 | 0.6716 | 0.7765 | 0.8782 |

|

1.2364 | |

| 2.6 | 0.6891 | 0.7916 | 0.8911 |

|

1.2373 | |

| 2.8 | 0.7051 | 0.8053 | 0.9027 |

|

1.2380 | |

| 3.0 | 0.7196 | 0.8178 | 0.9133 |

|

1.2383 | |

| 3.2 | 0.7329 | 0.8293 | 0.9231 |

|

1.2391 | |

| 3.4 | 0.7451 | 0.8398 | 0.9321 |

|

1.2391 | |

| 3.6 | 0.7565 | 0.8496 | 0.9406 |

|

1.2393 | |

| 3.8 | 0.7670 | 0.8587 | 0.9484 |

|

1.2395 | |

| 4.0 | 0.7769 | 0.8673 | 0.9557 |

|

1.2399 | |

| 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.6895 | 0.7814 | 0.8647 |

|

1.2418 |

| 1.8 | 0.7248 | 0.8098 | 0.8874 |

|

1.2429 | |

| 2.0 | 0.7439 | 0.8252 | 0.8998 |

|

1.2437 | |

| 2.2 | 0.7605 | 0.8387 | 0.9107 |

|

1.2442 | |

| 2.4 | 0.7751 | 0.8505 | 0.9203 |

|

1.2442 | |

| 2.6 | 0.7880 | 0.8611 | 0.9288 |

|

1.2443 | |

| 2.8 | 0.7996 | 0.8706 | 0.9366 |

|

1.2446 | |

| 3.0 | 0.8101 | 0.8792 | 0.9436 |

|

1.2442 | |

| 3.2 | 0.8196 | 0.8871 | 0.9501 |

|

1.2444 | |

| 3.4 | 0.8284 | 0.8943 | 0.9560 |

|

1.2451 | |

| 3.6 | 0.8364 | 0.9009 | 0.9615 |

|

1.2441 | |

| 3.8 | 0.8439 | 0.9071 | 0.9667 |

|

1.2438 | |

| 4.0 | 0.8508 | 0.9129 | 0.9714 |

|

1.2441 |

3.2 Moments and generating functions

The

By letting

The moment generating function of the SPB-X distribution may be defined as follows:

Table 2 presents the numerical values of the first four moments (

Numerical outcomes for the first four moments,

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SK | KU | CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.3538 | 0.1973 | 0.1494 | 0.1432 | 0.0721 | 0.2685 | 1.4774 | 6.3418 | 0.7590 |

| 1.8 | 0.4080 | 0.2462 | 0.1958 | 0.1939 | 0.0797 | 0.2823 | 1.3496 | 5.8230 | 0.6919 | |

| 2.0 | 0.4410 | 0.2784 | 0.2280 | 0.2301 | 0.0839 | 0.2897 | 1.2846 | 5.5792 | 0.6568 | |

| 2.2 | 0.4719 | 0.3102 | 0.2609 | 0.2681 | 0.0876 | 0.2959 | 1.2308 | 5.3877 | 0.6272 | |

| 2.4 | 0.5008 | 0.3416 | 0.2944 | 0.3077 | 0.0908 | 0.3013 | 1.1855 | 5.2339 | 0.6018 | |

| 2.6 | 0.5280 | 0.3724 | 0.3284 | 0.3486 | 0.0937 | 0.3061 | 1.1469 | 5.1080 | 0.5797 | |

| 2.8 | 0.5536 | 0.4027 | 0.3628 | 0.3908 | 0.0962 | 0.3102 | 1.1136 | 5.0031 | 0.5603 | |

| 3.0 | 0.5779 | 0.4325 | 0.3974 | 0.4342 | 0.0985 | 0.3139 | 1.0845 | 4.9147 | 0.5431 | |

| 3.2 | 0.6010 | 0.4618 | 0.4322 | 0.4786 | 0.1006 | 0.3171 | 1.0589 | 4.8391 | 0.5277 | |

| 3.4 | 0.6230 | 0.4905 | 0.4672 | 0.5239 | 0.1024 | 0.3201 | 1.0362 | 4.7739 | 0.5138 | |

| 3.6 | 0.6439 | 0.5187 | 0.5023 | 0.5701 | 0.1041 | 0.3227 | 1.0160 | 4.7172 | 0.5012 | |

| 3.8 | 0.6639 | 0.5465 | 0.5374 | 0.6170 | 0.1057 | 0.3251 | 0.9978 | 4.6673 | 0.4897 | |

| 4.0 | 0.6831 | 0.5737 | 0.5726 | 0.6646 | 0.1071 | 0.3273 | 0.9813 | 4.6233 | 0.4791 | |

| 1.6 | 1.5 | 0.6771 | 0.4888 | 0.3716 | 0.2953 | 0.0302 | 0.1739 |

|

2.8624 | 0.2568 |

| 1.8 | 0.7161 | 0.5402 | 0.4259 | 0.3488 | 0.0275 | 0.1658 |

|

2.9135 | 0.2315 | |

| 2.0 | 0.7377 | 0.5702 | 0.4587 | 0.3821 | 0.0260 | 0.1611 |

|

2.9387 | 0.2184 | |

| 2.2 | 0.7568 | 0.5974 | 0.4892 | 0.4137 | 0.0246 | 0.1570 |

|

2.9587 | 0.2074 | |

| 2.4 | 0.7738 | 0.6223 | 0.5176 | 0.4438 | 0.0235 | 0.1533 |

|

2.9748 | 0.1981 | |

| 2.6 | 0.7891 | 0.6451 | 0.5443 | 0.4725 | 0.0225 | 0.1499 |

|

2.9879 | 0.1900 | |

| 2.8 | 0.8029 | 0.6663 | 0.5694 | 0.4998 | 0.0216 | 0.1469 |

|

2.9987 | 0.1830 | |

| 3.0 | 0.8156 | 0.6859 | 0.5931 | 0.5261 | 0.0208 | 0.1442 |

|

3.0077 | 0.1768 | |

| 3.2 | 0.8272 | 0.7043 | 0.6156 | 0.5512 | 0.0201 | 0.1417 |

|

3.0153 | 0.1713 | |

| 3.4 | 0.8379 | 0.7215 | 0.6369 | 0.5753 | 0.0194 | 0.1394 |

|

3.0218 | 0.1663 | |

| 3.6 | 0.8478 | 0.7376 | 0.6572 | 0.5985 | 0.0188 | 0.1372 |

|

3.0391 | 0.1619 | |

| 3.8 | 0.8571 | 0.7529 | 0.6765 | 0.6209 | 0.0183 | 0.1352 |

|

3.0322 | 0.1578 | |

| 4.0 | 0.8657 | 0.7673 | 0.6950 | 0.6424 | 0.0178 | 0.1334 |

|

3.0364 | 0.1541 | |

| 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.7728 | 0.6145 | 0.5007 | 0.4168 | 0.0172 | 0.1310 |

|

3.1244 | 0.1695 |

| 1.8 | 0.8023 | 0.6585 | 0.5516 | 0.4705 | 0.0149 | 0.1220 |

|

3.1557 | 0.1520 | |

| 2.0 | 0.8184 | 0.6834 | 0.5812 | 0.5025 | 0.0137 | 0.1171 |

|

3.1657 | 0.1431 | |

| 2.2 | 0.8323 | 0.7055 | 0.6080 | 0.5319 | 0.0127 | 0.1128 |

|

3.1704 | 0.1356 | |

| 2.4 | 0.8446 | 0.7253 | 0.6324 | 0.5591 | 0.0119 | 0.1092 |

|

3.1719 | 0.1292 | |

| 2.6 | 0.8556 | 0.7433 | 0.6548 | 0.5844 | 0.0112 | 0.1059 |

|

3.1712 | 0.1238 | |

| 2.8 | 0.8655 | 0.7597 | 0.6755 | 0.6081 | 0.0106 | 0.1030 |

|

3.1691 | 0.1191 | |

| 3.0 | 0.8744 | 0.7747 | 0.6948 | 0.6303 | 0.0101 | 0.1005 |

|

3.1663 | 0.1149 | |

| 3.2 | 0.8826 | 0.7885 | 0.7127 | 0.6511 | 0.0096 | 0.0981 |

|

3.1630 | 0.1112 | |

| 3.4 | 0.8900 | 0.8014 | 0.7295 | 0.6708 | 0.0092 | 0.0960 |

|

3.1594 | 0.1079 | |

| 3.6 | 0.8969 | 0.8134 | 0.7452 | 0.6895 | 0.0089 | 0.0941 |

|

3.1557 | 0.1049 | |

| 3.8 | 0.9033 | 0.8246 | 0.7601 | 0.7072 | 0.0085 | 0.0923 |

|

3.1520 | 0.1022 | |

| 4.0 | 0.9093 | 0.8351 | 0.7741 | 0.7241 | 0.0082 | 0.0907 |

|

3.1484 | 0.0997 |

Furthermore, the values of KU indicate the degree of peakness in the distribution. Higher values correspond to a leptokurtic distribution (more peaked), whereas lower values suggest a platykurtic distribution (flatter). CV reflects the relative dispersion of the data around the mean, with lower values indicating greater homogeneity and higher values suggesting greater variability.

In general, these results highlight the flexibility of the SPB-X distribution and its ability to be customized for different applications by adjusting the shape parameters

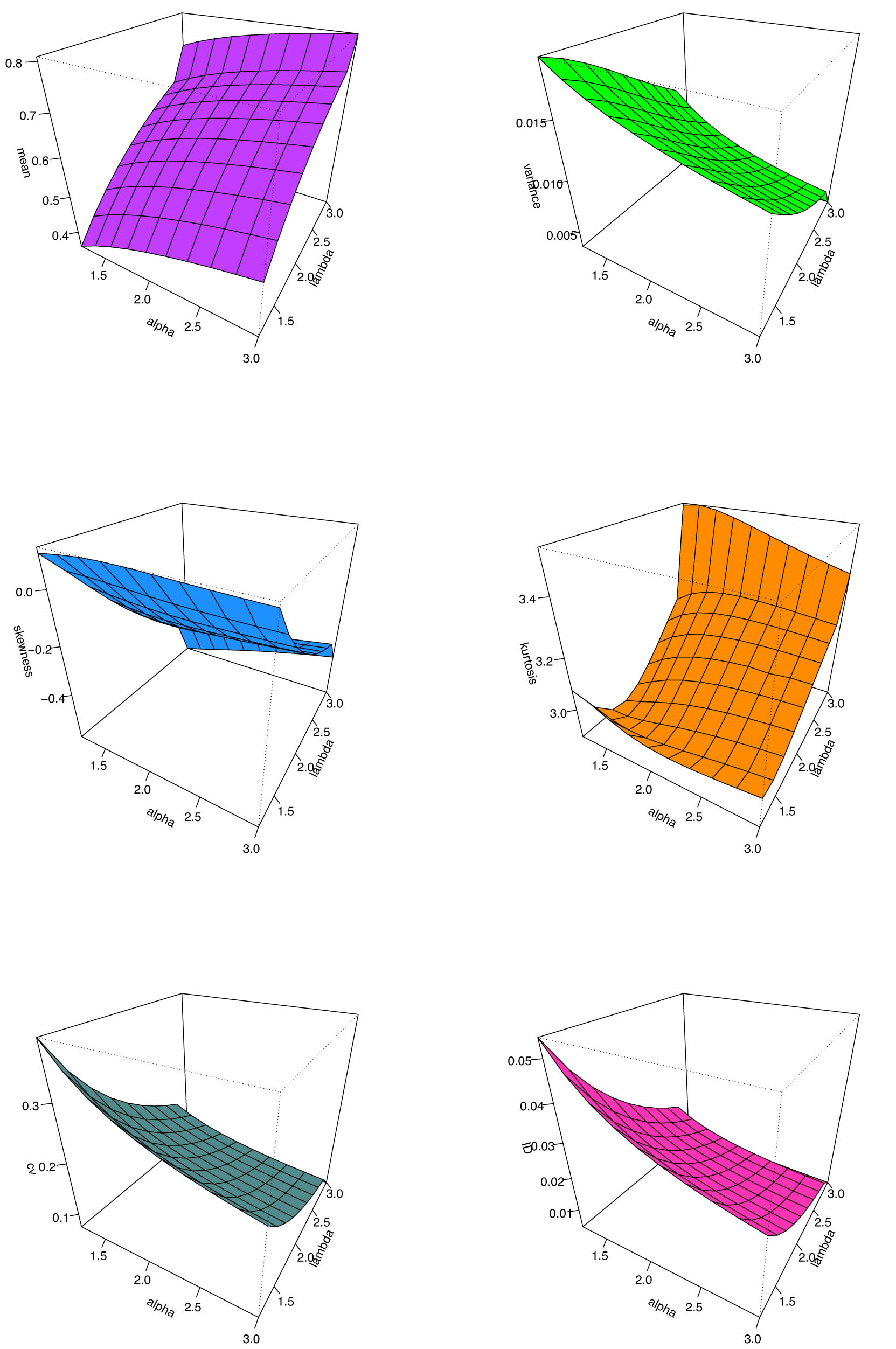

3D plots of the moments measurements for the SPB-X distribution at

3.3 Incomplete moments

The

where

3.4 Conditional moments

For the SPB-X model, the conditional moments defined by

where

and

4 Reliability measures

In this section, we suggested various significant reliability metrics for the SPB-X model, including common reliability functions, mean residual life function, mean waiting time function, residual moment, and reversed residual life.

4.1 Common reliability functions

The common reliability functions of SPB-X distribution are survival, hazard rate function (hrf), and reversed hrf, where the survival or reliability function is given by

The hrf is provided via

and reversed hrf is provided via

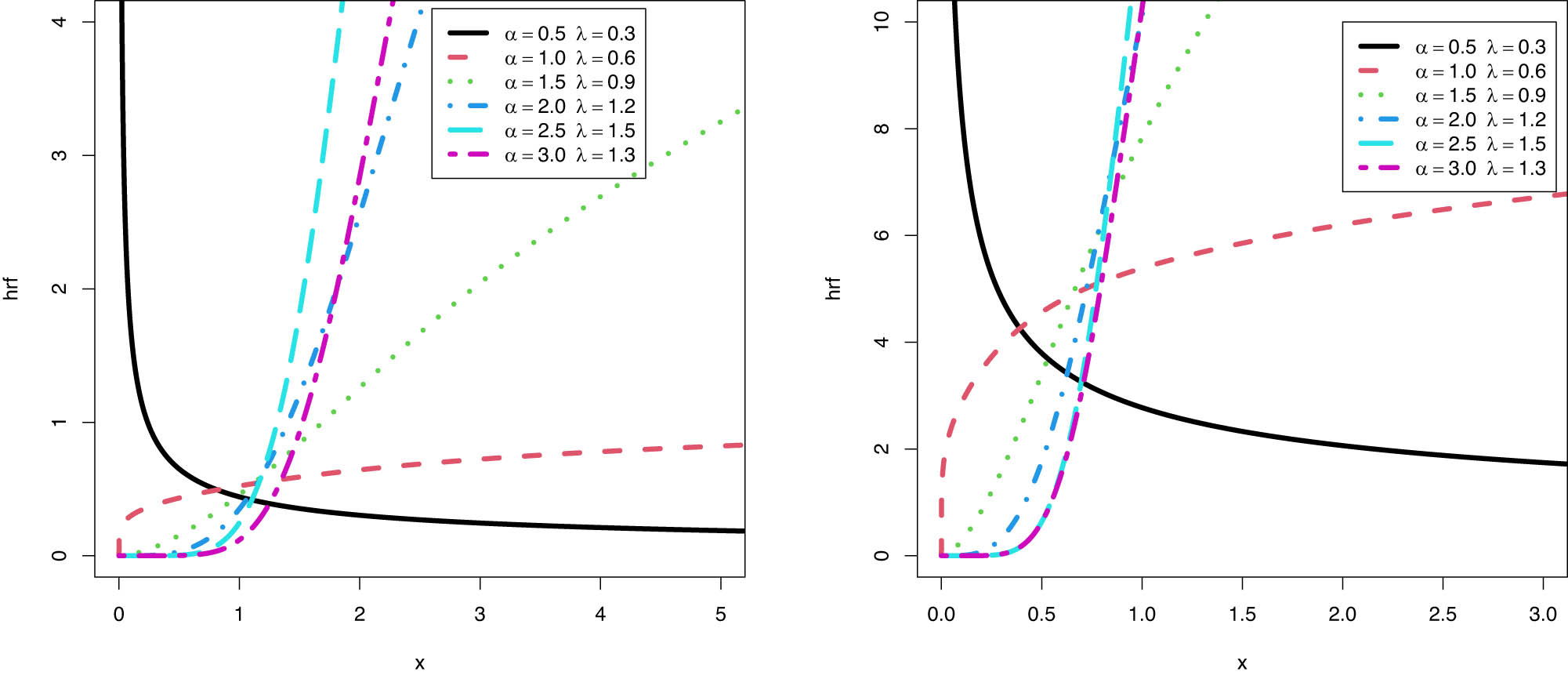

Figure 3 illustrates some hrf curves for the SPB-X distribution at

Plots of the hrf for the SPB-X distribution at

4.2 Mean residual life function

To characterize lifespan distributions, the mean residual life (MRL) function is of critical significance in the fields of dependability, survival analysis, actuarial sciences, economics, and social sciences. In addition, it is an essential component in the repair and replacement methods and provides a comprehensive summary of the residual life function. The MRL function may be derived for the SPB-X distribution from the following:

4.3 Mean inactivity time function

Given that

4.4 Moment of residual and reversed residual lifes

The residual life is the duration beyond

Employing (8) and utilizing the binomial expansion of

On the other hand, the

By utilizing (8) and employing the binomial expansion of

5 Actuarial measures

In actuarial practice, evaluating risk exposures is essential for companies. One of the primary goals of actuarial science institutes is to forecast market risks within a portfolio of instruments. Consequently, assessing risk measures is crucial in purchasing and selling products. In this section, we will explore many essential risk measures for the SPB-X distribution. These risk measures include the value at risk (VaR), the ES, the TVaR, the TV, and the TVP [47].

5.1 VaR measure

Risk managers often focus on the likelihood of an unfavorable result, which can be quantified using VaR at a certain probability level. The VaR [36] is used to assess risk exposure, thereby determining the capital required to endure undesirable outcomes. The VaR of the SPB-X distribution is specified as follows:

5.2 ES measure

Another significant financial metric is the ES, first articulated by [37,38]. The ES is a metric that provides superior justification for trading relative to VaR.

for

5.3 TVaR measure

The TVaR is a crucial risk metric. When an event occurs over a set probability threshold, TVaR is used to assess the expected value of the incurred loss. The TVaR of the SPB-X distribution is explicitly specified as follows:

5.4 TV measure

The TV risk measure, as put up by Landsman [39], is summarized as the variance of the loss distribution above a certain critical threshold. The TV of the SPB-X distribution may be characterized as follows:

where

5.5 TVP measure

The TVP is another important measure that plays an essential role in insurance sciences and is the mixture of central tendency and dispersion statistics. The TVP of SPB-X distribution takes the following form:

where

Key actuarial metrics, such as VaR, ES, Tail TVaR, TV, and TVP, are summarized in Table 3 for various combinations of

Actuarial measures for

|

|

|

|

VaR | ES | TVaR | TV | TVP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.650 | 0.1008 | 0.0298 | 0.2774 | 0.0375 | 0.2961 | 0.3055 | 0.3112 |

| 0.700 | 0.1241 | 0.0357 | 0.3049 | 0.0385 | 0.3242 | 0.3338 | 0.3395 | ||

| 0.750 | 0.1531 | 0.0425 | 0.3383 | 0.0395 | 0.3580 | 0.3679 | 0.3738 | ||

| 0.800 | 0.1904 | 0.0505 | 0.3801 | 0.0405 | 0.4004 | 0.4105 | 0.4166 | ||

| 0.850 | 0.2408 | 0.0601 | 0.4354 | 0.0417 | 0.4563 | 0.4668 | 0.4730 | ||

| 0.900 | 0.3154 | 0.0721 | 0.5155 | 0.0432 | 0.5371 | 0.5479 | 0.5544 | ||

| 0.950 | 0.4498 | 0.0880 | 0.6567 | 0.0450 | 0.6792 | 0.6904 | 0.6972 | ||

| 0.975 | 0.5903 | 0.0989 | 0.8018 | 0.0463 | 0.8250 | 0.8365 | 0.8435 | ||

| 0.990 | 0.7821 | 0.1075 | 0.9976 | 0.0474 | 1.0213 | 1.0332 | 1.0403 | ||

| 0.995 | 0.9302 | 0.1113 | 1.1476 | 0.0481 | 1.1717 | 1.1837 | 1.1909 | ||

| 1.2 | 0.650 | 0.3211 | 0.1485 | 0.5605 | 0.0536 | 0.5873 | 0.6008 | 0.6088 | |

| 0.700 | 0.3601 | 0.1622 | 0.5972 | 0.0531 | 0.6238 | 0.6371 | 0.6450 | ||

| 0.750 | 0.4054 | 0.1768 | 0.6403 | 0.0526 | 0.6666 | 0.6797 | 0.6876 | ||

| 0.800 | 0.4597 | 0.1928 | 0.6924 | 0.0521 | 0.7185 | 0.7315 | 0.7393 | ||

| 0.850 | 0.5285 | 0.2104 | 0.7590 | 0.0516 | 0.7848 | 0.7977 | 0.8055 | ||

| 0.900 | 0.6237 | 0.2305 | 0.8521 | 0.0510 | 0.8776 | 0.8903 | 0.8980 | ||

| 0.950 | 0.7835 | 0.2550 | 1.0094 | 0.0504 | 1.0346 | 1.0472 | 1.0548 | ||

| 0.975 | 0.9409 | 0.2703 | 1.1656 | 0.0499 | 1.1906 | 1.2031 | 1.2106 | ||

| 0.990 | 1.1473 | 0.2818 | 1.3708 | 0.0498 | 1.3957 | 1.4082 | 1.4156 | ||

| 0.995 | 1.3025 | 0.2865 | 1.5257 | 0.0496 | 1.5505 | 1.5629 | 1.5703 | ||

| 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.650 | 0.4882 | 0.2854 | 0.6440 | 0.0146 | 0.6513 | 0.6549 | 0.6571 |

| 0.700 | 0.5210 | 0.3010 | 0.6672 | 0.0133 | 0.6738 | 0.6772 | 0.6792 | ||

| 0.750 | 0.5564 | 0.3169 | 0.6929 | 0.0120 | 0.6989 | 0.7019 | 0.7037 | ||

| 0.800 | 0.5956 | 0.3330 | 0.7223 | 0.0107 | 0.7276 | 0.7303 | 0.7319 | ||

| 0.850 | 0.6409 | 0.3498 | 0.7571 | 0.0093 | 0.7618 | 0.7641 | 0.7655 | ||

| 0.900 | 0.6973 | 0.3674 | 0.8018 | 0.0078 | 0.8057 | 0.8077 | 0.8089 | ||

| 0.950 | 0.7791 | 0.3868 | 0.8689 | 0.0060 | 0.8719 | 0.8735 | 0.8744 | ||

| 0.975 | 0.8482 | 0.3976 | 0.9272 | 0.0050 | 0.9297 | 0.9309 | 0.9317 | ||

| 0.990 | 0.9261 | 0.4050 | 0.9946 | 0.0042 | 0.9967 | 0.9977 | 0.9983 | ||

| 0.995 | 0.9776 | 0.4077 | 1.0409 | 0.0028 | 1.0423 | 1.0430 | 1.0434 | ||

| 1.2 | 0.650 | 0.7012 | 0.5220 | 0.8222 | 0.0089 | 0.8266 | 0.8289 | 0.8302 | |

| 0.700 | 0.7268 | 0.5357 | 0.8402 | 0.0082 | 0.8443 | 0.8463 | 0.8475 | ||

| 0.750 | 0.7541 | 0.5493 | 0.8601 | 0.0074 | 0.8638 | 0.8657 | 0.8668 | ||

| 0.800 | 0.7844 | 0.5631 | 0.8830 | 0.0066 | 0.8863 | 0.8879 | 0.8889 | ||

| 0.850 | 0.8193 | 0.5771 | 0.9102 | 0.0058 | 0.9131 | 0.9145 | 0.9154 | ||

| 0.900 | 0.8629 | 0.5917 | 0.9451 | 0.0051 | 0.9476 | 0.9489 | 0.9497 | ||

| 0.950 | 0.9266 | 0.6075 | 0.9985 | 0.0039 | 1.0004 | 1.0014 | 1.0020 | ||

| 0.975 | 0.9812 | 0.6163 | 1.0455 | 0.0032 | 1.0471 | 1.0480 | 1.0484 | ||

| 0.990 | 1.0439 | 0.6222 | 1.1008 | 0.0027 | 1.1022 | 1.1028 | 1.1033 | ||

| 0.995 | 1.0861 | 0.6245 | 1.1384 | 0.0028 | 1.1398 | 1.1405 | 1.1409 | ||

6 Estimation methods

6.1 Maximum likelihood estimation (MLE)

The MLEs [45,58] is the most widely used method of parameter estimation. Let

To obtain the MLEs of parameters, we differentiate (19) partially with respect to

and

Then the maximum likelihood estimates of the parameters

6.2 Least squares estimators (LSEs)

The LSEs [46,48,49] are key in regression and estimation analysis, with the aim of minimizing the squared differences between observed and predicted values. In linear regression, LSE finds the coefficients that best fit the data. For a RS

This minimization aims to identify the optimal values of

6.3 MPS

MPS estimators are vital in statistical inference, offering efficient parameter estimates for probability distributions, especially useful in survival analysis and reliability modeling with censored data. In survival analysis, where not all failure times in a sample are fully observed, MPS estimators effectively manage such censoring. The method involves MPS between observed failure times to estimate distribution parameters. These estimators are recognized for their robustness against outliers and their strong performance across various distributional assumptions. MPS estimators are widely used in different fields. Further discussions on MPS can be found in papers by previous studies [43,44, 50,51].

The MPS estimators for

where

6.4 Bayesian estimation

In this subsection, we utilize the Bayesian estimation method to estimate the unknown parameters of the SPB-X distribution. The core concept of the Bayesian approach is that the model’s parameters are treated as random variables with a predefined distribution, known as the prior distribution. When prior knowledge is available, selecting an appropriate prior is essential. We choose the gamma conjugate prior for the parameters due to several reasons, such as its flexibility, noninformative nature, and the simplicity, it offers in analytical or computational updates to the posterior. In addition, its positive domain makes it well suited for modeling parameters. We implement the Bayesian inference method to estimate the unknown parameters

The estimates have been derived using the square error loss function. Therefore, the joint prior density of the independent parameters is expressed as follows:

and

where

Since Eq. (24) cannot be solved explicitly, numerical methods are used. One of the most effective numerical approaches in Bayesian estimation is the Monte Carlo Markov chain method. In this case, we propose using the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm, see the study by Tierney [59].

7 Simulation

The simulation of four estimation methods deepens our understanding of statistical techniques, assists in choosing the most appropriate method, and reveals the strengths and weaknesses of various approaches in different contexts. This section utilizes simulation analysis to compare the results of three different parameter estimates for the SPB-X distribution. We carried out simulations by generating 10,000 RS with sizes of

Simulations allow researchers to assess the performance of various estimation methods under different conditions. By generating synthetic datasets with known properties, they can evaluate the accuracy, rank, RMSE, and RAB of each technique.

Simulations serve as a tool to optimize estimation techniques for the parameters of the SPB-X distribution. Researchers can adjust the algorithm parameters or experiment with alternative methodologies to determine the most efficient and accurate approach for specific scenarios.

Through simulation studies, researchers can systematically compare multiple estimators for the SPB-X distribution parameters within a controlled setting. This facilitates an objective assessment of each method’s advantages and limitations, guiding the selection of the most suitable estimator for practical use.

RAB, RMSE, and ranked of estimation methods for parameters of SPB-X distribution

|

|

MLE | LS | MPS | Bayeaisan | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

n | RAB | RMSE | RAB | RMSE | RAB | RMSE | RAB | RMSE | |||||||||

| 1.5 | 25 |

|

0.098349 | 1 | 0.535404 | 1 | 0.008759 | 4 | 0.16359 | 4 | 0.028028 | 3 | 0.525338 | 2 | 0.096516 | 2 | 0.497735 | 3 |

|

|

0.087211 | 1 | 0.159227 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.083594 | 4 | 0.086144 | 2 | 0.14988 | 2 | 0.03257 | 3 | 0.12008 | 3 | ||

|

|

0.014938 | 3 | 0.212967 | 1 | 0.006078 | 4 | 0.130798 | 4 | 0.018591 | 2 | 0.186292 | 2 | 0.063172 | 1 | 0.142277 | 3 | ||

|

|

5 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 9 | ||||||||||

| 70 |

|

0.064606 | 2 | 0.517576 | 1 | 0.004599 | 4 | 0.099651 | 4 | 0.01644 | 3 | 0.325084 | 3 | 0.085276 | 1 | 0.398442 | 2 | |

|

|

0.082028 | 1 | 0.140715 | 1 | 0.006724 | 4 | 0.042627 | 4 | 0.010017 | 3 | 0.090501 | 3 | 0.026713 | 2 | 0.099203 | 2 | ||

|

|

|

3 | 0.084148 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.075748 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.081042 | 3 | 0.024655 | 1 | 0.081247 | 2 | ||

|

|

6 | 3 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 6 | ||||||||||

| 100 |

|

0.016829 | 2 | 0.453821 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.085145 | 4 | 0.015741 | 3 | 0.301315 | 3 | 0.059674 | 1 | 0.389176 | 2 | |

|

|

0.016211 | 1 | 0.124052 | 1 | 0.003828 | 4 | 0.036019 | 4 | 0.009168 | 3 | 0.084335 | 3 | 0.015022 | 2 | 0.091723 | 2 | ||

|

|

|

3 | 0.080529 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.065027 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.079522 | 2 | 0.008973 | 1 | 0.071036 | 3 | ||

|

|

6 | 3 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 7 | ||||||||||

| 200 |

|

0.014146 | 2 | 0.241456 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.031091 | 4 | 0.014128 | 3 | 0.166741 | 2 | 0.030725 | 1 | 0.128756 | 3 | |

|

|

0.002011 | 3 | 0.066863 | 1 | 0.000717 | 4 | 0.02494 | 4 | 0.0082 | 1 | 0.051008 | 3 | 0.005046 | 2 | 0.052854 | 2 | ||

|

|

|

3 | 0.076778 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.047154 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.06048 | 3 | 0.008912 | 1 | 0.068712 | 2 | ||

|

|

8 | 3 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 7 | ||||||||||

| Total rank | 11 | 22 | 16 | 11 | ||||||||||||||

| 0.5 | 25 |

|

0.337683 | 1 | 0.50644 | 1 | 0.090933 | 4 | 0.146 | 4 | 0.336589 | 2 | 0.45835 | 2 | 0.217261 | 3 | 0.258538 | 3 |

|

|

0.111395 | 1 | 0.297497 | 1 | 0.036013 | 4 | 0.166826 | 4 | 0.110824 | 2 | 0.265625 | 2 | 0.100963 | 3 | 0.179842 | 3 | ||

|

|

|

4 | 0.395424 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.143998 | 2 |

|

3 | 0.313146 | 2 |

|

1 | 0.20029 | 3 | ||

|

|

6 | 3 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 9 | ||||||||||

| 70 |

|

0.207274 | 1 | 0.26776 | 2 | 0.05815 | 4 | 0.109132 | 4 | 0.206881 | 2 | 0.301125 | 1 | 0.124303 | 3 | 0.1626 | 3 | |

|

|

0.090973 | 1 | 0.194696 | 1 | 0.034912 | 4 | 0.095431 | 4 | 0.090931 | 2 | 0.192916 | 2 | 0.076127 | 3 | 0.118987 | 3 | ||

|

|

|

3 | 0.284272 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.120023 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.220632 | 2 | 0.001959 | 1 | 0.150957 | 3 | ||

|

|

5 | 4 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 9 | ||||||||||

| 100 |

|

0.192792 | 2 | 0.247364 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.066954 | 4 | 0.193514 | 1 | 0.261325 | 1 | 0.100436 | 3 | 0.156027 | 3 | |

|

|

0.089484 | 2 | 0.176863 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.090415 | 4 | 0.089562 | 1 | 0.176665 | 2 | 0.046063 | 3 | 0.109306 | 3 | ||

|

|

|

4 | 0.229272 | 1 | 0.018205 | 4 | 0.072571 | 1 |

|

3 | 0.202952 | 2 | 0.001209 | 2 | 0.134832 | 3 | ||

|

|

8 | 4 | 12 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 9 | ||||||||||

| 200 |

|

0.149399 | 1 | 0.185062 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.024367 | 4 | 0.148784 | 2 | 0.188903 | 1 | 0.043033 | 3 | 0.092727 | 3 | |

|

|

0.080922 | 1 | 0.148105 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.030511 | 4 | 0.07918 | 2 | 0.13829 | 2 | 0.018522 | 3 | 0.077706 | 3 | ||

|

|

|

4 | 0.202376 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.030395 | 2 |

|

3 | 0.157082 | 2 | 0.001143 | 1 | 0.10759 | 3 | ||

|

|

6 | 4 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 9 | ||||||||||

| Total rank | 10 | 22 | 12 | 16 | ||||||||||||||

|

|

21 | 44 | 28 | 27 | ||||||||||||||

RAB, RMSE, and ranked of estimation methods for parameters of SPB-X distribution

|

|

MLE | LS | MPS | Bayeaisan | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

RAB | RMSE | RAB | RMSE | RAB | RMSE | RAB | RMSE | |||||||||

| 0.5 | 25 |

|

0.237293 | 1 | 0.481939 | 1 | 0.031422 | 4 | 0.140239 | 4 | 0.236122 | 2 | 0.369424 | 2 | 0.148007 | 3 | 0.178753 | 3 |

|

|

0.094034 | 1 | 0.313662 | 1 |

|

3 | 0.159829 | 4 | 0.079784 | 2 | 0.249774 | 2 | 0.069063 | 3 | 0.122545 | 4 | ||

|

|

|

3 | 0.56169 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.191695 | 4 |

|

2 | 0.487931 | 2 |

|

1 | 0.246092 | 3 | ||

|

|

5 | 3 | 11 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 10 | ||||||||||

| 70 |

|

0.135257 | 2 | 0.290683 | 1 | 0.030646 | 4 | 0.086505 | 4 | 0.135534 | 1 | 0.230553 | 2 | 0.071858 | 3 | 0.10814 | 3 | |

|

|

0.065682 | 2 | 0.188634 | 1 | 0.010859 | 3 | 0.083362 | 4 | 0.065696 | 1 | 0.154763 | 2 | 0.035749 | 3 | 0.081059 | 4 | ||

|

|

|

4 | 0.463898 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.166698 | 2 |

|

3 | 0.392399 | 2 |

|

1 | 0.215204 | 3 | ||

|

|

8 | 3 | 11 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 10 | ||||||||||

| 100 |

|

0.108458 | 1 | 0.191718 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.068469 | 4 | 0.108304 | 2 | 0.181584 | 2 | 0.059705 | 3 | 0.097331 | 3 | |

|

|

0.059619 | 1 | 0.129028 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.068863 | 4 | 0.059537 | 2 | 0.126247 | 2 | 0.033491 | 3 | 0.078193 | 3 | ||

|

|

|

4 | 0.373276 | 1 | 0.004215 | 4 | 0.0915 | 1 |

|

3 | 0.345385 | 2 |

|

2 | 0.204391 | 3 | ||

|

|

6 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 9 | ||||||||||

| 200 |

|

0.080716 | 1 | 0.065794 | 2 | 0.002218 | 4 | 0.038939 | 4 | 0.080353 | 2 | 0.12508 | 1 | 0.043635 | 3 | 0.060712 | 3 | |

|

|

0.053007 | 1 | 0.058535 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.038808 | 4 | 0.052625 | 2 | 0.096398 | 1 | 0.028389 | 3 | 0.050202 | 3 | ||

|

|

|

4 | 0.184168 | 2 | 0.00109 | 4 | 0.040365 | 1 |

|

3 | 0.292117 | 1 |

|

2 | 0.179928 | 3 | ||

|

|

6 | 6 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 9 | ||||||||||

| Total rank | 12 | 21 | 10 | 17 | ||||||||||||||

| 1.5 | 25 |

|

|

4 | 0.533336 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.214276 | 2 |

|

3 | 0.434168 | 2 | 0.041754 | 1 | 0.420127 | 3 |

|

|

|

3 | 0.225968 | 1 |

|

3 | 0.200131 | 4 |

|

2 | 0.203626 | 2 | 0.005053 | 1 | 0.082185 | 4 | ||

|

|

|

4 | 0.416789 | 1 | 0.058698 | 3 | 0.228875 | 1 |

|

3 | 0.355903 | 2 | 0.002684 | 2 | 0.208831 | 4 | ||

|

|

11 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 11 | ||||||||||

| 70 |

|

0.036452 | 1 | 0.153281 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.115467 | 4 | 0.00494 | 3 | 0.385402 | 1 | 0.034544 | 2 | 0.131382 | 3 | |

|

|

|

4 | 0.151305 | 2 |

|

3 | 0.12475 | 2 |

|

3 | 0.163303 | 1 | 0.004341 | 1 | 0.065997 | 4 | ||

|

|

|

2 | 0.143572 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.123425 | 4 |

|

3 | 0.292842 | 1 | 0.002335 | 1 | 0.129063 | 3 | ||

|

|

7 | 6 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 10 | ||||||||||

| 100 |

|

0.019642 | 2 | 0.125253 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.08095 | 4 | 0.00382 | 3 | 0.344566 | 1 | 0.031589 | 1 | 0.123064 | 3 | |

|

|

|

3 | 0.137042 | 1 |

|

3 | 0.093568 | 4 |

|

2 | 0.136492 | 2 | 0.003622 | 1 | 0.060676 | 4 | ||

|

|

|

3 | 0.12584 | 2 | 0.001803 | 3 | 0.109926 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.271943 | 1 |

|

2 | 0.108031 | 4 | ||

|

|

8 | 5 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 11 | ||||||||||

| 200 |

|

0.017144 | 2 | 0.123611 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.070877 | 4 | 0.00276 | 3 | 0.300586 | 1 | 0.023573 | 1 | 0.092434 | 3 | |

|

|

0.008163 | 2 | 0.105762 | 1 |

|

3 | 0.081686 | 4 | 0.008167 | 1 | 0.089414 | 2 | 0.001453 | 3 | 0.055692 | 4 | ||

|

|

|

3 | 0.112907 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.086068 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.222332 | 1 |

|

1 | 0.091578 | 3 | ||

|

|

7 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 10 | ||||||||||

| Total rank | 12 | 21 | 12 | 15 | ||||||||||||||

|

|

24 | 42 | 22 | 32 | ||||||||||||||

RAB, RMSE, and ranked of estimation methods for parameters of SPB-X distribution

|

|

MLE | LS | MPS | Bayeaisan | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

RAB | RMSE | RAB | RMSE | RAB | RMSE | RAB | RMSE | |||||||||

| 2 | 25 |

|

|

4 | 0.784902 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.186499 | 3 |

|

2 | 0.618933 | 2 | 0.0798 | 1 | 0.452759 | 3 |

|

|

|

4 | 0.36032 | 1 |

|

2 | 0.286095 | 2 |

|

3 | 0.274264 | 3 | 0.0082 | 1 | 0.191702 | 4 | ||

|

|

0.038 | 2 | 0.756547 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.203331 | 4 | 0.0385 | 1 | 0.599379 | 2 |

|

3 | 0.249373 | 3 | ||

|

|

10 | 3 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 10 | ||||||||||

| 70 |

|

|

4 | 0.675556 | 1 | 0.006 | 4 | 0.178961 | 2 |

|

3 | 0.402374 | 2 | 0.052 | 1 | 0.323463 | 3 | |

|

|

|

3 | 0.203099 | 1 |

|

2 | 0.19451 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.163596 | 3 | 0.0068 | 1 | 0.110154 | 4 | ||

|

|

0.0093 | 1 | 0.711175 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.169255 | 4 | 0.0088 | 2 | 0.353533 | 2 | 0.0037 | 3 | 0.213583 | 3 | ||

|

|

8 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 10 | ||||||||||

| 100 |

|

0.0069 | 2 | 0.466559 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.13176 | 4 | 0.0069 | 2 | 0.361317 | 2 | 0.044 | 1 | 0.295145 | 3 | |

|

|

|

4 | 0.172465 | 1 | 0.0039 | 2 | 0.168627 | 2 |

|

3 | 0.135038 | 3 | 0.0055 | 1 | 0.084145 | 4 | ||

|

|

0.0084 | 1 | 0.553203 | 1 | 0.002 | 4 | 0.142907 | 4 | 0.0075 | 2 | 0.314431 | 2 | 0.0035 | 3 | 0.204128 | 3 | ||

|

|

7 | 3 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 10 | ||||||||||

| 200 |

|

|

3 | 0.452244 | 1 | 0.0043 | 4 | 0.128513 | 2 |

|

3 | 0.26335 | 3 | 0.0434 | 1 | 0.26658 | 2 | |

|

|

|

3 | 0.109653 | 1 |

|

2 | 0.107198 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.093364 | 3 | 0.0055 | 1 | 0.058806 | 4 | ||

|

|

0.0025 | 1 | 0.499037 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.134906 | 4 | 0.0021 | 3 | 0.237421 | 2 | 0.0025 | 1 | 0.191229 | 3 | ||

|

|

7 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 3 | 9 | ||||||||||

| Total rank | 10 | 18 | 18 | 12 | ||||||||||||||

| 4 | 25 |

|

0.0987 | 1 | 0.807114 | 1 |

|

3 | 0.480387 | 4 | 0.0206 | 3 | 0.603981 | 2 | 0.056 | 2 | 0.442574 | 4 |

|

|

|

3 | 0.90611 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.443569 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.68943 | 2 |

|

2 | 0.46061 | 3 | ||

|

|

0.0096 | 2 | 0.416854 | 1 | 0.0241 | 4 | 0.1636 | 1 | 0.0057 | 3 | 0.402546 | 2 | 0.0028 | 4 | 0.210831 | 3 | ||

|

|

6 | 3 | 11 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 10 | ||||||||||

| 70 |

|

0.015 | 2 | 0.405756 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.253711 | 4 | 0.0145 | 3 | 0.429374 | 1 | 0.0523 | 1 | 0.359802 | 3 | |

|

|

|

4 | 0.725479 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.243816 | 2 |

|

3 | 0.462748 | 2 |

|

1 | 0.380727 | 3 | ||

|

|

|

4 | 0.396709 | 1 | 0.0134 | 4 | 0.123397 | 1 |

|

3 | 0.284519 | 2 |

|

2 | 0.185777 | 3 | ||

|

|

10 | 4 | 12 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 9 | ||||||||||

| 100 |

|

0.014 | 2 | 0.327157 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.212561 | 4 | 0.0136 | 3 | 0.382202 | 1 | 0.0466 | 1 | 0.314589 | 3 | |

|

|

|

4 | 0.306385 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.18737 | 2 |

|

3 | 0.385213 | 1 | 0.0014 | 1 | 0.306162 | 3 | ||

|

|

|

4 | 0.155957 | 2 | 0.0061 | 4 | 0.058291 | 1 |

|

3 | 0.227913 | 1 |

|

2 | 0.149529 | 3 | ||

|

|

10 | 6 | 12 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 9 | ||||||||||

| 200 |

|

0.0141 | 2 | 0.323692 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.187806 | 4 | 0.0124 | 3 | 0.28776 | 2 | 0.0426 | 1 | 0.266214 | 3 | |

|

|

|

4 | 0.290651 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.175217 | 1 |

|

3 | 0.302992 | 1 |

|

2 | 0.229806 | 3 | ||

|

|

|

3 | 0.13804 | 2 | 0.0051 | 4 | 0.046913 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.189102 | 1 |

|

2 | 0.126885 | 3 | ||

|

|

9 | 5 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 9 | ||||||||||

| Total rank | 14 | 18 | 14 | 14 | ||||||||||||||

|

|

24 | 36 | 32 | 26 | ||||||||||||||

RAB, RMSE, and ranked of estimation methods for parameters of SPB-X distribution

|

|

MLE | LS | MPS | Bayeaisan | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

RAB | RMSE | RAB | RMSE | RAB | RMSE | RAB | RMSE | |||||||||

| 1.5 | 25 |

|

|

4 |

|

1 |

|

3 |

|

2 | 1.022988 | 1 | 0.247263 | 4 | 0.749682 | 2 | 0.65512 | 3 |

|

|

|

3 |

|

2 |

|

4 |

|

1 | 0.171082 | 2 | 0.263046 | 1 | 0.142879 | 3 | 0.124047 | 4 | ||

|

|

0.03102 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.030965 | 2 | 0.011691 | 3 | 0.721195 | 1 | 0.274253 | 3 | 0.431103 | 2 | 0.210736 | 4 | ||

|

|

8 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 11 | ||||||||||

| 70 |

|

|

4 |

|

2 |

|

3 | 0.021909 | 1 | 0.203063 | 3 | 0.164013 | 4 | 0.601484 | 2 | 0.617428 | 1 | |

|

|

|

4 |

|

1 |

|

3 |

|

2 | 0.063614 | 4 | 0.070686 | 3 | 0.099399 | 1 | 0.085748 | 2 | ||

|

|

0.021379 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.0211 | 2 | 0.005284 | 3 | 0.148033 | 4 | 0.165576 | 3 | 0.292466 | 1 | 0.175084 | 2 | ||

|

|

9 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 11 | 10 | 4 | 5 | ||||||||||

| 100 |

|

|

4 |

|

2 |

|

3 | 0.005074 | 1 | 0.20064 | 3 | 0.153381 | 4 | 0.500061 | 2 | 0.567637 | 1 | |

|

|

|

3 |

|

1 |

|

4 |

|

2 | 0.061136 | 3 | 0.06013 | 4 | 0.078926 | 1 | 0.078552 | 2 | ||

|

|

0.018067 | 1 | 0.001437 | 4 | 0.01782 | 2 | 0.004198 | 3 | 0.127727 | 4 | 0.139024 | 3 | 0.226073 | 1 | 0.167588 | 2 | ||

|

|

8 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 4 | 5 | ||||||||||

| 200 |

|

|

4 |

|

1 |

|

3 |

|

2 | 0.186027 | 3 | 0.148856 | 4 | 0.36416 | 2 | 0.522604 | 1 | |

|

|

|

4 |

|

1 |

|

3 |

|

2 | 0.060114 | 2 | 0.043521 | 4 | 0.055014 | 3 | 0.062995 | 1 | ||

|

|

0.005953 | 1 |

|

4 | 0.005789 | 2 | 0.004023 | 3 | 0.052092 | 4 | 0.100627 | 3 | 0.147558 | 2 | 0.153146 | 1 | ||

|

|

9 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 3 | ||||||||||

| 1.5 | Total rank | 15 | 15 | 20 | 10 | |||||||||||||

| 3 | 25 |

|

|

3 |

|

1 |

|

4 |

|

2 | 1.01585 | 1 | 0.304876 | 4 | 0.685717 | 2 | 0.670245 | 3 |

|

|

|

3 |

|

2 |

|

4 |

|

1 | 0.281515 | 2 | 0.322409 | 1 | 0.134832 | 3 | 0.123108 | 4 | ||

|

|

|

3 |

|

4 |

|

2 | 0.00603 | 1 | 0.954966 | 1 | 0.464819 | 3 | 0.569249 | 2 | 0.250907 | 4 | ||

|

|

9 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 11 | ||||||||||

| 70 |

|

|

4 |

|

2 |

|

3 | 0.011103 | 1 | 0.206847 | 3 | 0.111765 | 4 | 0.553092 | 1 | 0.545158 | 2 | |

|

|

|

4 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

1 | 0.194985 | 1 | 0.152068 | 2 | 0.093001 | 3 | 0.088362 | 4 | ||

|

|

0.002145 | 2 |

|

4 | 0.001838 | 3 | 0.002758 | 1 | 0.247989 | 2 | 0.22598 | 3 | 0.397819 | 1 | 0.219657 | 4 | ||

|

|

10 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 5 | 10 | ||||||||||

| 100 |

|

|

3 |

|

2 |

|

4 | 0.010222 | 1 | 0.189243 | 3 | 0.102759 | 4 | 0.481484 | 2 | 0.511498 | 1 | |

|

|

|

4 |

|

2 |

|

3 | 0.001072 | 1 | 0.156499 | 1 | 0.148069 | 2 | 0.078632 | 3 | 0.075901 | 4 | ||

|

|

0.001646 | 3 |

|

4 | 0.001779 | 1 | 0.001779 | 2 | 0.142582 | 4 | 0.216851 | 3 | 0.344835 | 1 | 0.220094 | 2 | ||

|

|

10 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 7 | ||||||||||

| 200 |

|

|

3 |

|

2 |

|

4 | 0.009103 | 1 | 0.146666 | 3 | 0.091199 | 4 | 0.367609 | 2 | 0.413775 | 1 | |

|

|

|

3 |

|

2 |

|

4 |

|

1 | 0.152245 | 1 | 0.043352 | 4 | 0.054523 | 3 | 0.055331 | 2 | ||

|

|

0.000397 | 3 | 0.000944 | 2 | 0.000335 | 4 | 0.001427 | 1 | 0.137847 | 4 | 0.159341 | 3 | 0.251225 | 1 | 0.186038 | 2 | ||

|

|

9 | 6 | 12 | 3 | 8 | 11 | 6 | 5 | ||||||||||

| Total rank | 15 | 15 | 19 | 11 | ||||||||||||||

|

|

30 | 30 | 39 | 21 | ||||||||||||||

The best-performing estimation method can be determined using the total rank column in the table. The method with the highest total rank is considered the most effective in different scenarios. Based on the ranked values provided in the table, it is clear which method consistently achieves better performance in terms of RMSE and RAB. In the case of

In all cases, the LS method achieved the highest total rank, reaching 546, indicating its superior performance. The Bayesian method followed with a total rank of 494. However, the MLE method had the lowest performance, with a total rank of 327, making it the least effective among the estimation methods compared.

7.1 Approximate confidence intervals (ACIs)

Determining the exact distribution of these estimates becomes problematic when closed-form MLEs and MPS for the unknown parameters cannot be obtained. Therefore, it is not feasible to obtain precise confidence intervals (CIs) for the parameters. Hence, ACIs are built using large sample approximation approaches for the parameters

Using the asymptotic normality features of MLEs and MPS, one may compute the ACIs for

From there, we can obtain the approximate asymptotic variance–covariance matrix, which is:

With a mean of

The

Tables 8 and 9 present confidence intervals for the parameters (

Confidence intervals for parameters of SPB-X distribution

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLE | MPS | MLE | MPS | ||||||||||||

|

|

|

Lower | Upper | LACI | Lower | Upper | LACI |

|

Lower | Upper | LACI | Lower | Upper | LACI | |

| 1.5 | 25 |

|

0.6388 | 2.6563 | 2.0175 | 0.5157 | 2.5684 | 2.0527 | 0.5 | 0.0699 | 1.1674 | 1.0975 | 0.0416 | 1.3042 | 1.3722 |

|

|

0.2435 | 0.8438 | 0.6003 | 0.2617 | 0.8244 | 0.5627 | 0.1030 | 0.9910 | 0.8880 | 0.0566 | 1.0232 | 0.9665 | |||

|

|

0.3444 | 1.1780 | 0.8337 | 0.3998 | 1.1281 | 0.7282 | 0.7828 | 2.8879 | 2.1051 | 0.9352 | 2.7361 | 1.8010 | |||

| 70 |

|

0.6004 | 2.5934 | 1.9930 | 0.8893 | 2.1600 | 1.2707 | 0.0135 | 1.1217 | 1.1082 | 0.1358 | 0.9997 | 0.8638 | ||

|

|

0.2772 | 0.8048 | 0.5277 | 0.3279 | 0.6821 | 0.3542 | 0.1688 | 0.8969 | 0.7282 | 0.2364 | 0.8293 | 0.5928 | |||

|

|

0.5754 | 0.9024 | 0.3270 | 0.5815 | 0.8961 | 0.3146 | 1.0026 | 2.7611 | 1.7585 | 1.1486 | 2.6159 | 1.4673 | |||

| 100 |

|

0.6371 | 2.4134 | 1.7762 | 0.9349 | 2.1124 | 1.1775 | 0.1938 | 0.9147 | 0.7208 | 0.2144 | 0.8939 | 0.6794 | ||

|

|

0.2655 | 0.7507 | 0.4852 | 0.3395 | 0.6696 | 0.3301 | 0.2838 | 0.7759 | 0.4921 | 0.2893 | 0.7702 | 0.4809 | |||

|

|

0.5831 | 0.8961 | 0.3130 | 0.5845 | 0.8931 | 0.3086 | 1.1890 | 2.5813 | 1.3923 | 1.2469 | 2.5245 | 1.2776 | |||

| 200 |

|

1.0498 | 1.9926 | 0.9428 | 1.1970 | 1.8454 | 0.6483 | 0.4385 | 0.6422 | 0.2037 | 0.3080 | 0.7723 | 0.4643 | ||

|

|

0.3700 | 0.6320 | 0.2621 | 0.4044 | 0.6038 | 0.1993 | 0.4242 | 0.6288 | 0.2046 | 0.3445 | 0.7081 | 0.3635 | |||

|

|

0.5979 | 0.8988 | 0.3009 | 0.6253 | 0.8609 | 0.2355 | 1.5951 | 2.2234 | 0.6283 | 1.3652 | 2.4543 | 1.0891 | |||

| 0.5 | 25 |

|

0.0665 | 1.2712 | 1.2047 | 1.1693 | 2.8405 | 1.6712 | 1.5 | 0.3859 | 2.4525 | 2.0666 | 0.4039 | 2.4903 | 2.0864 |

|

|

0.1593 | 0.9520 | 0.7927 | 0.0462 | 1.0646 | 1.0183 | 0.0223 | 0.8921 | 0.8698 | 0.0672 | 0.8478 | 0.7806 | |||

|

|

0.1095 | 1.3135 | 1.2040 | 0.1024 | 1.3207 | 1.2182 | 1.0837 | 2.5686 | 1.4849 | 1.2186 | 2.5007 | 1.2821 | |||

| 70 |

|

0.1197 | 1.0875 | 0.9678 | 0.0492 | 1.1577 | 1.1086 | 1.2740 | 1.8353 | 0.5613 | 0.5488 | 2.4660 | 1.9172 | ||

|

|

0.1744 | 0.9165 | 0.7421 | 0.1780 | 0.9129 | 0.7349 | 0.1899 | 0.7802 | 0.5902 | 0.1667 | 0.8043 | 0.6376 | |||

|

|

0.1630 | 1.2695 | 1.1065 | 0.2888 | 1.1434 | 0.8546 | 1.6939 | 2.2428 | 0.5489 | 1.3969 | 2.5376 | 1.1407 | |||

| 100 |

|

0.1499 | 1.0429 | 0.8930 | 0.1210 | 1.0726 | 0.9516 | 1.2909 | 1.7681 | 0.4772 | 0.6243 | 2.3871 | 1.7628 | ||

|

|

0.2094 | 0.8801 | 0.6708 | 0.2098 | 0.8797 | 0.6699 | 0.2269 | 0.7638 | 0.5369 | 0.2280 | 0.7627 | 0.5347 | |||

|

|

0.2725 | 1.1621 | 0.8896 | 0.3263 | 1.1129 | 0.7866 | 1.7347 | 2.2198 | 0.4852 | 1.4460 | 2.5083 | 1.0623 | |||

| 200 |

|

0.2428 | 0.9066 | 0.6637 | 0.2341 | 0.9147 | 0.6807 | 1.2887 | 1.7627 | 0.4740 | 0.7085 | 2.2998 | 1.5913 | ||

|

|

0.2612 | 0.8197 | 0.5585 | 0.2799 | 0.7993 | 0.5194 | 0.2969 | 0.7112 | 0.4143 | 0.3290 | 0.6792 | 0.3501 | |||

|

|

0.3296 | 1.1156 | 0.7860 | 0.4204 | 1.0277 | 0.6073 | 1.7616 | 2.1965 | 0.4349 | 1.4875 | 2.4698 | 0.9823 | |||

Confidence intervals for parameters of SPB-X distribution:

|

|

MLE | MPS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Lower | Upper | LACI | Lower | Upper | LACI | |

| 2 | 25 |

|

0.1006 | 2.7742 | 2.6736 | 0.2748 | 2.6940 | 2.4193 |

|

|

1.2337 | 2.6145 | 1.3808 | 1.4078 | 2.4416 | 1.0338 | ||

|

|

0.6007 | 3.5513 | 2.9507 | 0.9118 | 3.2420 | 2.3301 | ||

| 70 |

|

0.1529 | 2.7994 | 2.6465 | 0.7049 | 2.2795 | 1.5746 | |

|

|

1.5634 | 2.3334 | 0.7700 | 1.6439 | 2.2519 | 0.6079 | ||

|

|

0.6251 | 3.4119 | 2.7869 | 1.3256 | 2.7097 | 1.3841 | ||

| 100 |

|

0.5962 | 2.4246 | 1.8285 | 0.7955 | 2.2113 | 1.4158 | |

|

|

1.6352 | 2.2989 | 0.6636 | 1.7105 | 2.2241 | 0.5136 | ||

|

|

0.9330 | 3.1006 | 2.1676 | 1.3994 | 2.6305 | 1.2312 | ||

| 200 |

|

0.6048 | 2.3772 | 1.7724 | 0.9811 | 2.0129 | 1.0317 | |

|

|

1.7694 | 2.1929 | 0.4235 | 1.8019 | 2.1603 | 0.3584 | ||

|

|

1.0269 | 2.9830 | 1.9561 | 1.5389 | 2.4695 | 0.9305 | ||

| 4 | 25 |

|

0.0929 | 3.2031 | 3.1102 | 0.3280 | 2.6925 | 2.3645 |

|

|

2.0762 | 5.5530 | 3.4768 | 2.5125 | 5.1142 | 2.6016 | ||

|

|

1.2031 | 2.8354 | 1.6323 | 1.2227 | 2.8000 | 1.5774 | ||

| 70 |

|

0.7285 | 2.3166 | 1.5881 | 0.6667 | 2.3477 | 1.6810 | |

|

|

2.4804 | 5.2877 | 2.8073 | 3.0071 | 4.7654 | 1.7583 | ||

|

|

1.2073 | 2.7611 | 1.5539 | 1.4331 | 2.5478 | 1.1147 | ||

| 100 |

|

0.8811 | 2.1609 | 1.2798 | 0.7588 | 2.2549 | 1.4961 | |

|

|

3.3354 | 4.4815 | 1.1461 | 3.1756 | 4.6432 | 1.4677 | ||

|

|

1.6810 | 2.2896 | 0.6086 | 1.5461 | 2.4390 | 0.8929 | ||

| 200 |

|

0.8880 | 2.1542 | 1.2662 | 0.9434 | 2.0690 | 1.1257 | |

|

|

3.3715 | 4.4646 | 1.0931 | 3.3643 | 4.5357 | 1.1715 | ||

|

|

1.7269 | 2.2679 | 0.5410 | 1.6222 | 2.3629 | 0.7407 | ||

8 Applications

In this section, we present a comprehensive discussion of various statistical metrics used to evaluate the performance of different models [57]. Tables 10, 11, 12, 13, and 15 provide a detailed comparison of key metrics, including estimates, standard errors (StEr), Kolmogorov-Smirnov distance (KSD),

MLE for parameters of SPB-X and each competitive models: latitude for the Southwest of the rain gauge stations

| Estimates | StEr | KSD | PVKS | CVM | PVCVM | AD | PVAD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPB-X |

|

14.5195 | 91.8156 | 0.1684 | 0.9141 | 0.0380 | 0.9417 | 0.3073 | 0.9254 |

|

|

0.8207 | 2.1497 | |||||||

|

|

1.0578 | 2.2285 | |||||||

| PB-X |

|

5.2896 | 19.5810 | 0.1709 | 0.9049 | 0.0385 | 0.9391 | 0.3103 | 0.9207 |

|

|

0.4440 | 1.1365 | |||||||

|

|

1.8414 | 2.6215 | |||||||

| SEWHE |

|

2.5621 | 7.9144 | 0.1740 | 0.8932 | 0.0506 | 0.9341 | 0.3817 | 0.9218 |

|

|

3.1999 | 5.2423 | |||||||

|

|

1.4554 | 4.0546 | |||||||

|

|

0.3341 | 0.1767 | |||||||

| W |

|

8.0720 | 1.9099 | 0.1764 | 0.8834 | 0.0579 | 0.8369 | 0.4090 | 0.8368 |

|

|

2.0251 | 0.0800 | |||||||

| G |

|

51.0781 | 18.4243 | 0.1703 | 0.9042 | 0.03914 | 0.9352 | 0.3116 | 0.9179 |

|

|

0.0374 | 0.0135 | |||||||

| EW |

|

0.6437 | 0.4917 | 0.1709 | 0.9050 | 0.0404 | 0.9391 | 0.3204 | 0.9207 |

|

|

3.6794 | 5.2306 | |||||||

|

|

5.3017 | 19.6086 |

MLE for parameters of SPB-X and each competitive models: latitude for West of rain gauge stations

| Estimates | StEr | KSD | PVKS | CVM | PVCVM | AD | PVAD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPB-X |

|

2.7126 | 9.3506 | 0.1036 | 0.9978 | 0.0196 | 0.9960 | 0.1702 | 0.9949 |

|

|

0.2305 | 0.9371 | |||||||

|

|

1.0543 | 1.9056 | |||||||

| PB-X |

|

1.8090 | 4.3094 | 0.1038 | 0.9976 | 0.0197 | 0.9952 | 0.1703 | 0.9940 |

|

|

0.1305 | 0.4589 | |||||||

|

|

1.4638 | 1.7972 | |||||||

| SEWHE |

|

0.7708 | 2.8499 | 0.1417 | 0.9422 | 0.0329 | 0.9927 | 0.2473 | 0.9913 |

|

|

3.1580 | 9.7527 | |||||||

|

|

0.1476 | 0.6489 | |||||||

|

|

0.1821 | 0.2501 | |||||||

| W |

|

4.0489 | 0.9208 | 0.1201 | 0.9866 | 0.02484 | 0.9926 | 0.1920 | 0.9928 |

|

|

4.6803 | 0.3525 | |||||||

| G |

|

12.5199 | 5.0407 | 0.1129 | 0.9932 | 0.0220 | 0.9954 | 0.1884 | 0.9936 |

|

|

0.3383 | 0.1390 | |||||||

| EW |

|

0.2487 | 0.1808 | 0.1038 | 0.9968 | 0.0223 | 0.9962 | 0.1817 | 0.9920 |

|

|

2.9275 | 3.7318 | |||||||

|

|

1.8087 | 4.4687 |

MLE for parameters of SPB-X and each competitive models: dataset of carbon fibers stress

| Estimates | StEr | KSD | PVKS | CVM | PVCVM | AD | PVAD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPB-X |

|

0.8472 | 0.4571 | 0.0784 | 0.8124 | 0.0809 | 0.8604 | 0.4809 | 0.8972 |

|

|

0.0878 | 0.0994 | |||||||

|

|

1.8287 | 0.6911 | |||||||

| PB-X |

|

0.8006 | 0.3533 | 0.0809 | 0.7801 | 0.0858 | 0.6861 | 0.5084 | 0.7619 |

|

|

0.1009 | 0.0829 | |||||||

|

|

1.9554 | 0.5340 | |||||||

| SEWHE |

|

4.6250 | 2.6478 | 0.0862 | 0.7112 | 0.0868 | 0.8398 | 0.4921 | 0.8694 |

|

|

0.4987 | 0.1811 | |||||||

|

|

0.4402 | 0.2756 | |||||||

|

|

0.9296 | 0.2869 | |||||||

| SEWE |

|

0.9319 | 0.2743 | 0.0812 | 0.7771 | 0.0821 | 0.7176 | 0.4811 | 0.7918 |

|

|

3.3898 | 0.5825 | |||||||

|

|

0.0121 | 0.0107 | |||||||

| BIII |

|

2.2416 | 0.1688 | 0.1941 | 0.0138 | 0.7133 | 0.0076 | 3.9874 | 0.0050 |

|

|

5.8443 | 0.8339 | |||||||

| W |

|

3.4412 | 0.3309 | 0.0822 | 0.7630 | 0.0836 | 0.6727 | 0.4857 | 0.7607 |

|

|

3.0623 | 0.1149 | |||||||

| G |

|

7.4880 | 1.2757 | 0.1328 | 0.1947 | 0.2461 | 0.1935 | 1.3107 | 0.2288 |

|

|

0.3685 | 0.0649 | |||||||

| EW |

|

0.3094 | 0.0331 | 0.0809 | 0.7795 | 0.0813 | 0.6859 | 0.4847 | 0.7618 |

|

|

3.9118 | 1.0682 | |||||||

|

|

0.8000 | 0.3528 |

MLE for parameters of SPB-X and each competitive models: dataset of carbon fibers strength

| Estimates | StEr | KSD | PVKS | CVM | PVCVM | AD | PVAD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPB-X |

|

0.8548 | 0.5113 | 0.0470 | 0.9980 | 0.0238 | 0.9995 | 0.2087 | 0.9981 |

|

|

0.2995 | 0.2240 | |||||||

|

|

1.7155 | 0.7232 | |||||||

| PB-X |

|

0.8131 | 0.3847 | 0.0479 | 0.9974 | 0.0259 | 0.9932 | 0.2236 | 0.9870 |

|

|

0.3759 | 0.1884 | |||||||

|

|

1.8324 | 0.5392 | |||||||

| SEWHE |

|

1.6525 | 2.5956 | 0.0477 | 0.9978 | 0.0239 | 0.9990 | 0.2093 | 0.9978 |

|

|

1.5192 | 2.5144 | |||||||

|

|

0.5202 | 1.5503 | |||||||

|

|

0.5532 | 1.1950 | |||||||

| SEWE |

|

0.8961 | 0.4053 | 0.0478 | 0.9978 | 0.0240 | 0.9959 | 0.2098 | 0.9912 |

|

|

3.2901 | 0.9324 | |||||||

|

|

0.1064 | 0.0914 | |||||||

| BIII |

|

3.2367 | 0.2923 | 0.1407 | 0.1304 | 0.3344 | 0.0782 | 2.1634 | 0.0588 |

|

|

2.0133 | 0.2424 | |||||||

| W |

|

3.2489 | 0.3065 | 0.1201 | 0.9866 | 0.02484 | 0.9926 | 0.2920 | 0.9928 |

|

|

1.6171 | 0.0629 | |||||||

| G |

|

6.9960 | 1.1629 | 0.0884 | 0.6535 | 0.1235 | 0.4824 | 0.8539 | 0.4432 |

|

|

0.2074 | 0.0357 | |||||||

| EW |

|

0.5862 | 0.0712 | 0.0479 | 0.9973 | 0.0232 | 0.9932 | 0.2112 | 0.9870 |

|

|

3.6666 | 1.0799 | |||||||

|

|

0.8124 | 0.3846 |

MLE for parameters of SPB-X and each competitive models: insurance dataset

| Estimates | StEr | KSD | PVKS | CVM | PVCVM | AD | PVAD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPB-X |

|

16.8042 | 0.9714 | 0.0881 | 0.9463 | 0.0505 | 0.8767 | 0.3508 | 0.8949 |

|

|

0.2799 | 0.2559 | |||||||

|

|

1.0771 | 47.5307 | |||||||

| PBX |

|

0.7679 | 0.5972 | 0.0910 | 0.9319 | 0.0518 | 0.8687 | 0.3551 | 0.8910 |

|

|

0.4524 | 0.2740 | |||||||

|

|

7.1741 | 12.1309 | |||||||

| SEWE |

|

0.8713 | 0.5111 | 0.0915 | 0.9291 | 0.0525 | 0.8642 | 0.3583 | 0.8880 |

|

|

0.3280 | 0.4747 | |||||||

|

|

6.7275 | 10.9735 | |||||||

| BIII |

|

15.3663 | 4.8010 | 0.1442 | 0.4749 | 0.1413 | 0.4190 | 0.8172 | 0.4677 |

|

|

2.1054 | 0.2600 | |||||||

| W |

|

2.0483 | 0.2612 | 0.0940 | 0.8939 | 0.0534 | 0.8657 | 0.3771 | 0.8701 |

|

|

5.9411 | 0.5431 | |||||||

| G |

|

4.0985 | 0.9865 | 0.0988 | 0.8954 | 0.0532 | 0.8666 | 0.3898 | 0.8452 |

|

|

1.2798 | 0.3277 | |||||||

| EW |

|

0.5570 | 0.7609 | 0.0909 | 0.9319 | 0.0517 | 0.8688 | 0.3549 | 0.8911 |

|

|

0.9054 | 0.5482 | |||||||

|

|

7.1603 | 12.0956 |

The performance of each model is presented in a detailed perspective, focusing on various distribution models, such as the power Burr X (PB-X) proposed by [22], the SEWHE by [42], Weibull (W) [52], gamma (G) [53], exponentiated Weibull (EW) [54], SEWE [42], and BIII [55] distributions.

8.1 Rainfall data analysis across Peninsular Malaysia

This study analyzed daily rainfall data collected from 50 rain gauge stations in Peninsular Malaysia during the period 1975–2004. Data were sourced from the Malaysian Meteorological Department and the Drainage and Irrigation Department. Following the regional classification by Dale (1959), the area was divided into five distinct rainfall zones: northwest, west, the Port Dickson–Muar coast, southwest, and east (Lim and Azizan [56]). Due to limited data availability, the ports on the port Dickson–Muar coast were grouped with the southwest region.

To ensure data reliability, the dataset was meticulously examined for missing values and homogeneity. Interestingly, less than 10% of the data was missing. The missing values were estimated using enhanced spatial weighting techniques [60], while homogeneity was verified through four robust statistical tests [61]: the standard normal homogeneity test, the Buishand range test, the Pettitt test, and the Von Neumann ratio test, as documented in [62].

Our analysis focused on the latitude data from two key regions, the Southwest and East. The latitude values for the Southwest region are: 1.47, 1.63, 1.63, 1.76, 1.87, 1.88, 1.92, 2.02, 2.25, 2.27, 2.29, and for the east region: 2.45, 2.59, 3.17, 3.56, 3.78, 3.90, 4.23, 4.76, 4.94, 5.32, 5.97, 6.17. In Tables 10 and 11, we provide an in-depth comparison of various models using MLE with StEr, KSD, PVKS, CVM, PVCVM, AD, and PVAD. Among the tested distributions, the SPB-X distribution consistently outperformed others across multiple metrics, including KSD, PVKS, CVM, PVCVM, AD, and PVAD, making it the most suitable model for this rainfall dataset.

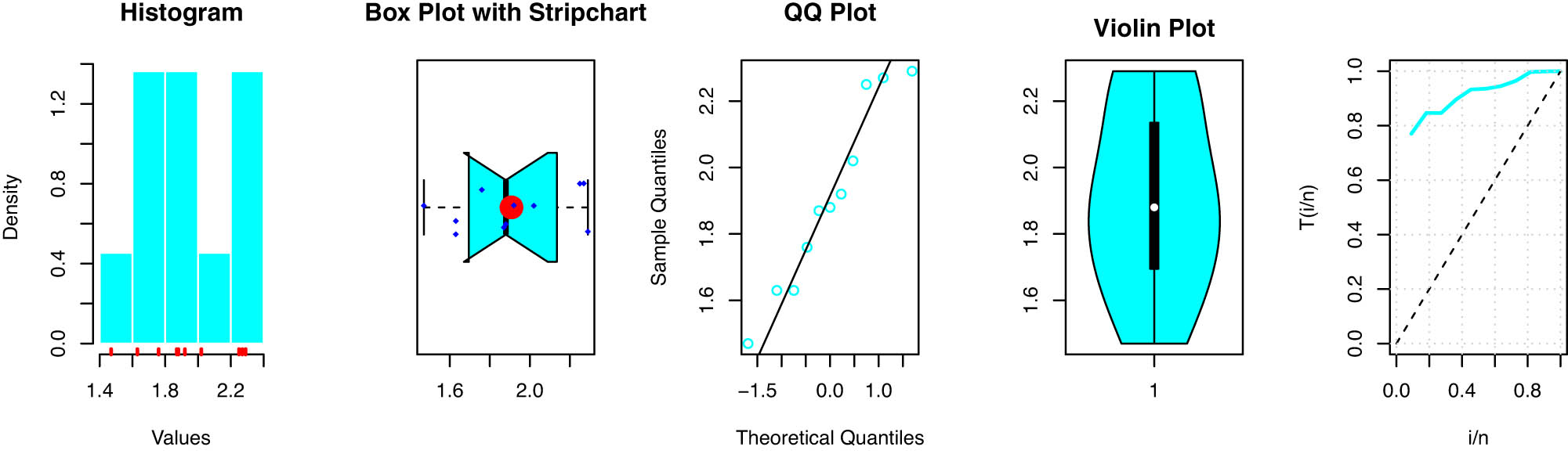

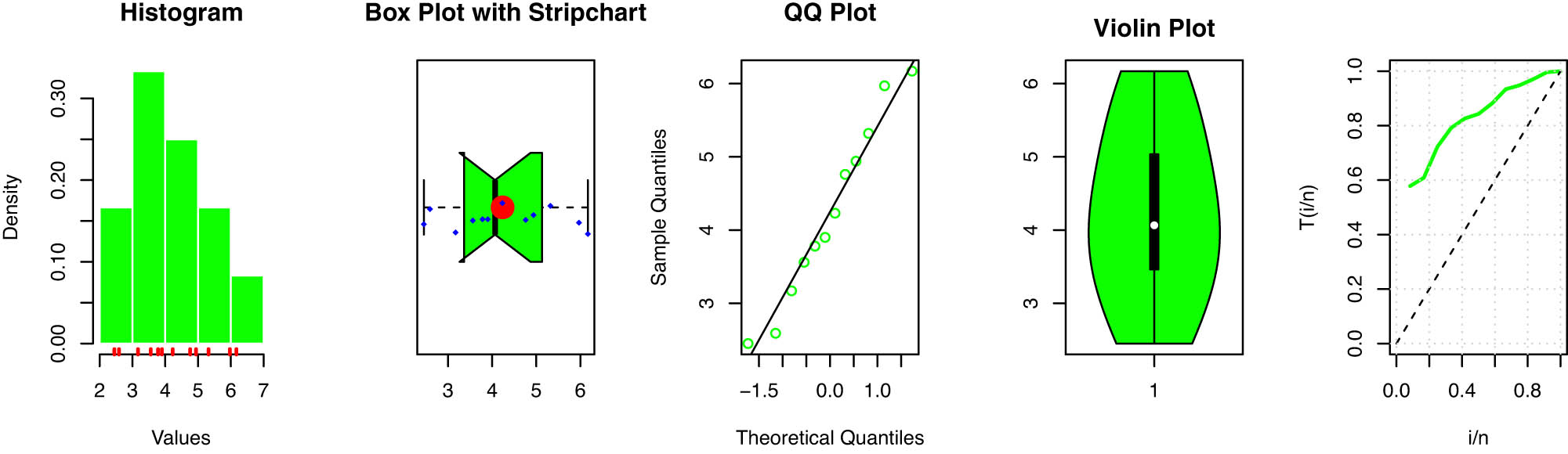

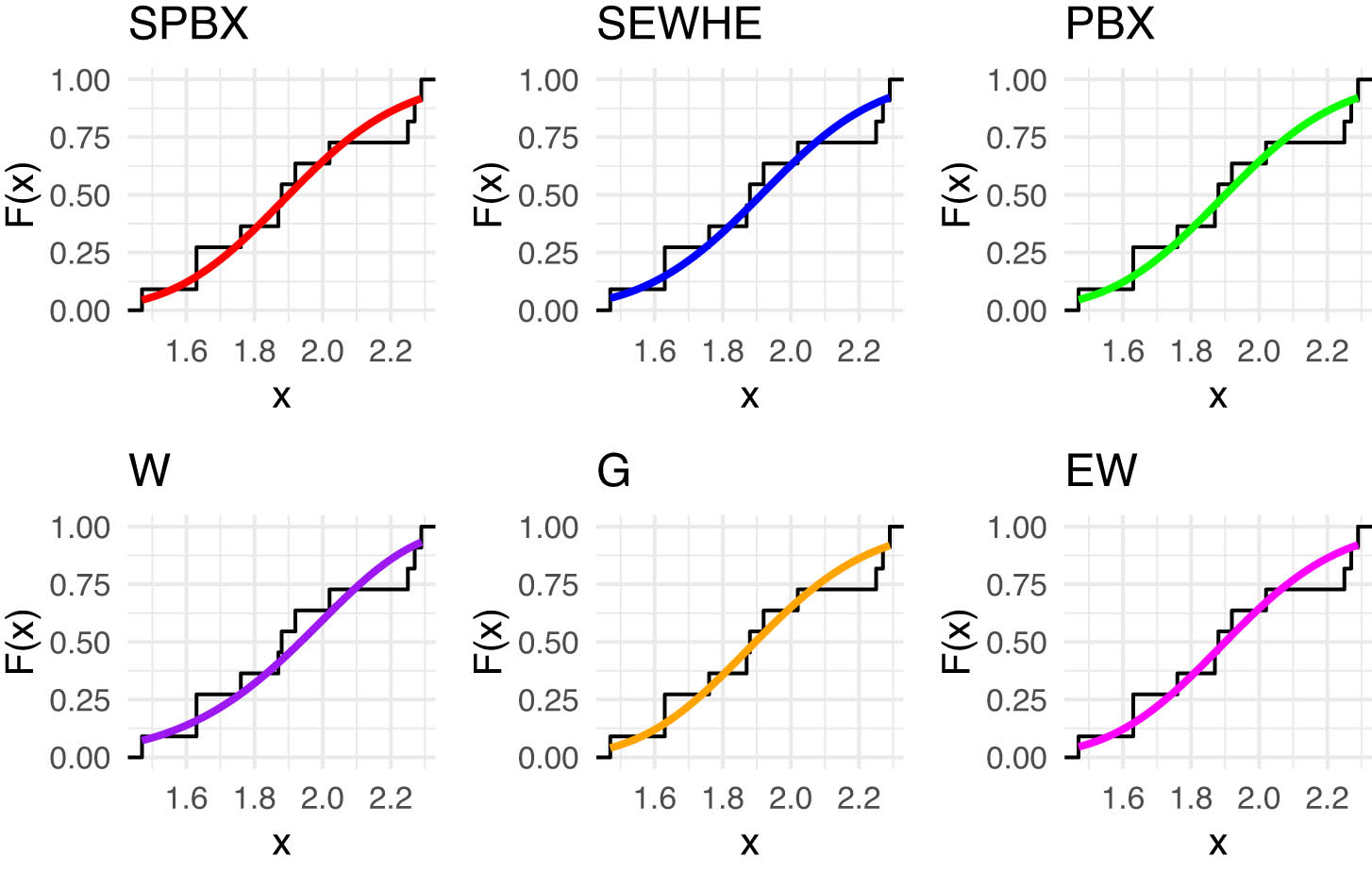

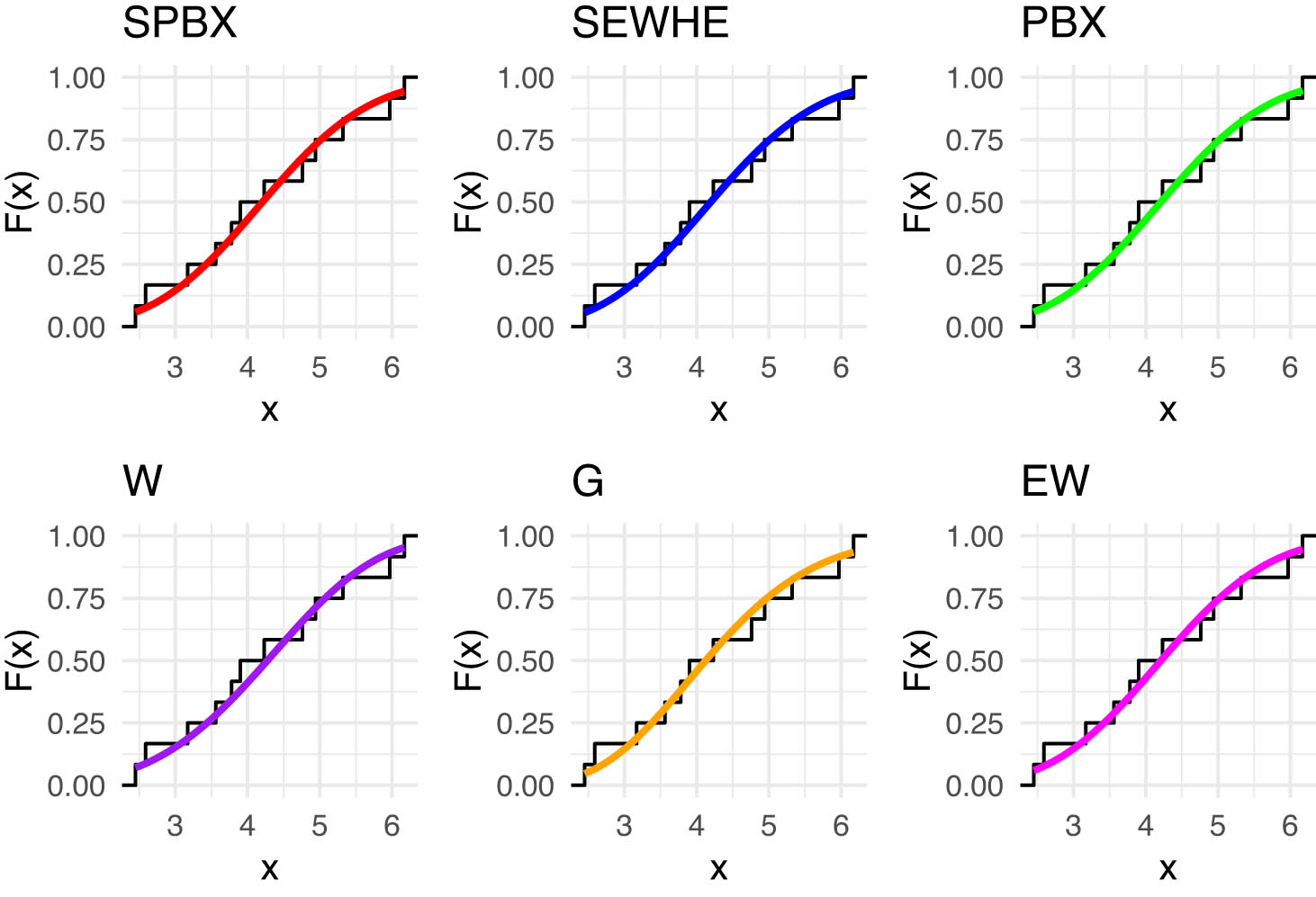

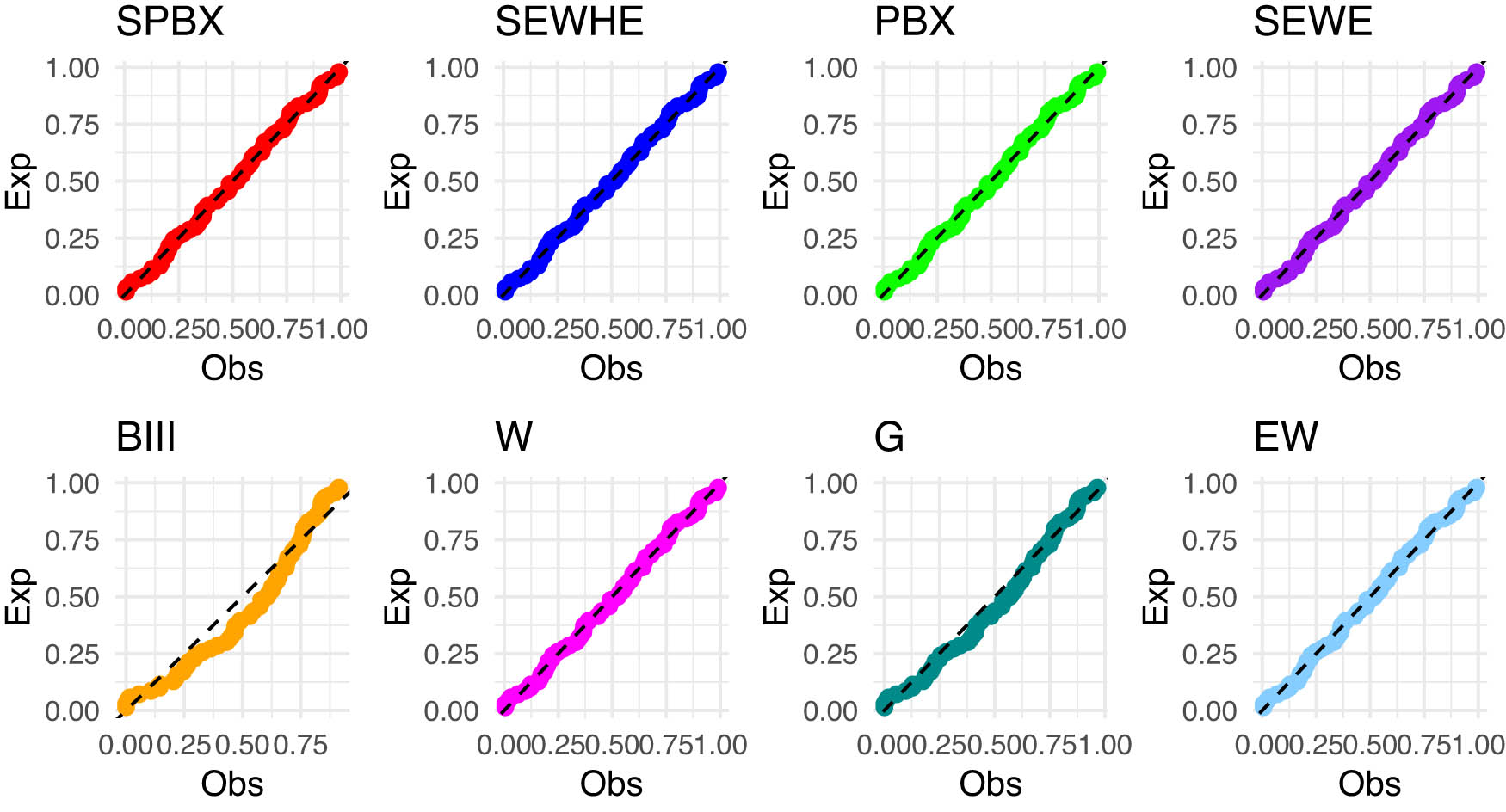

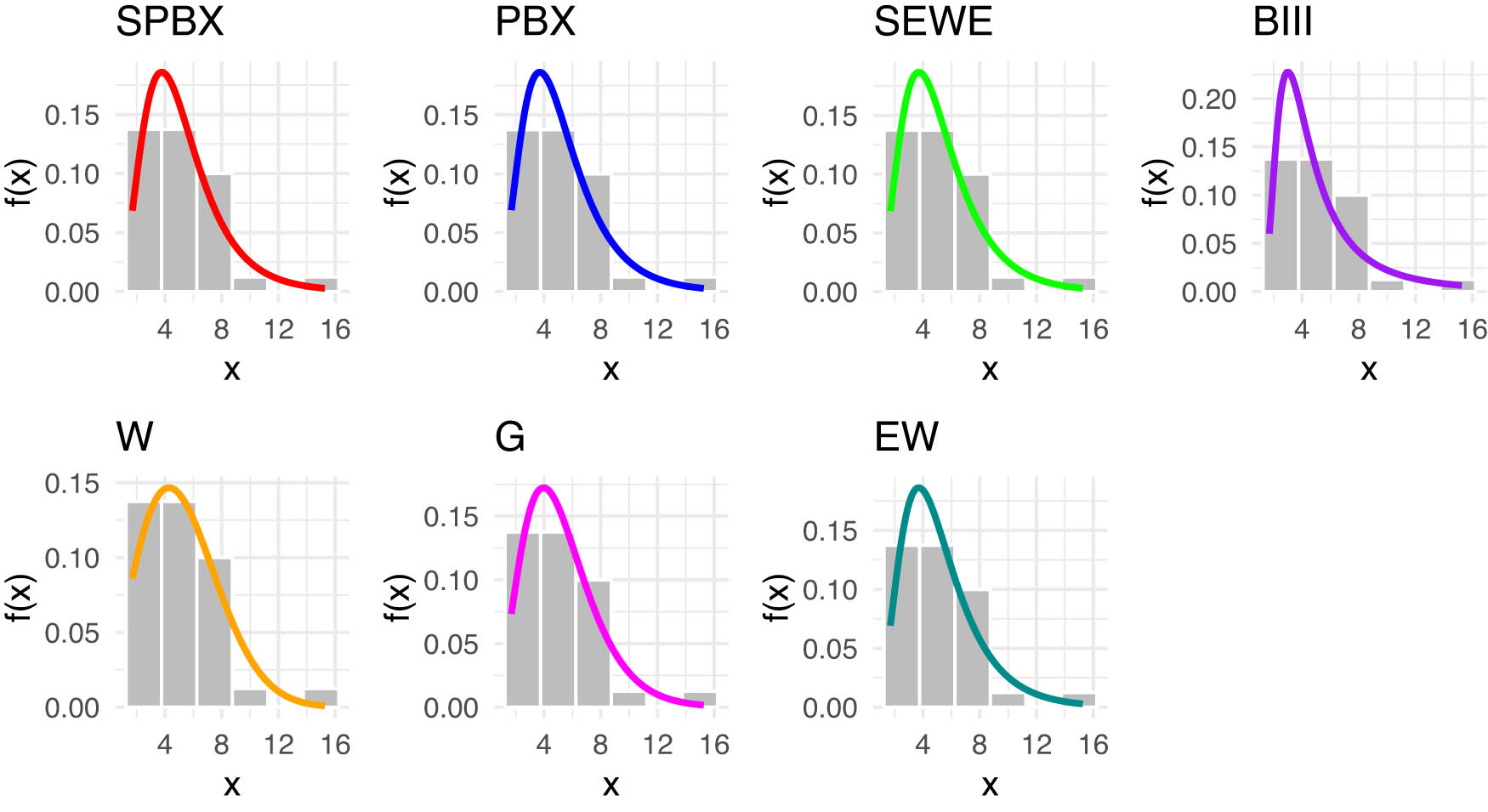

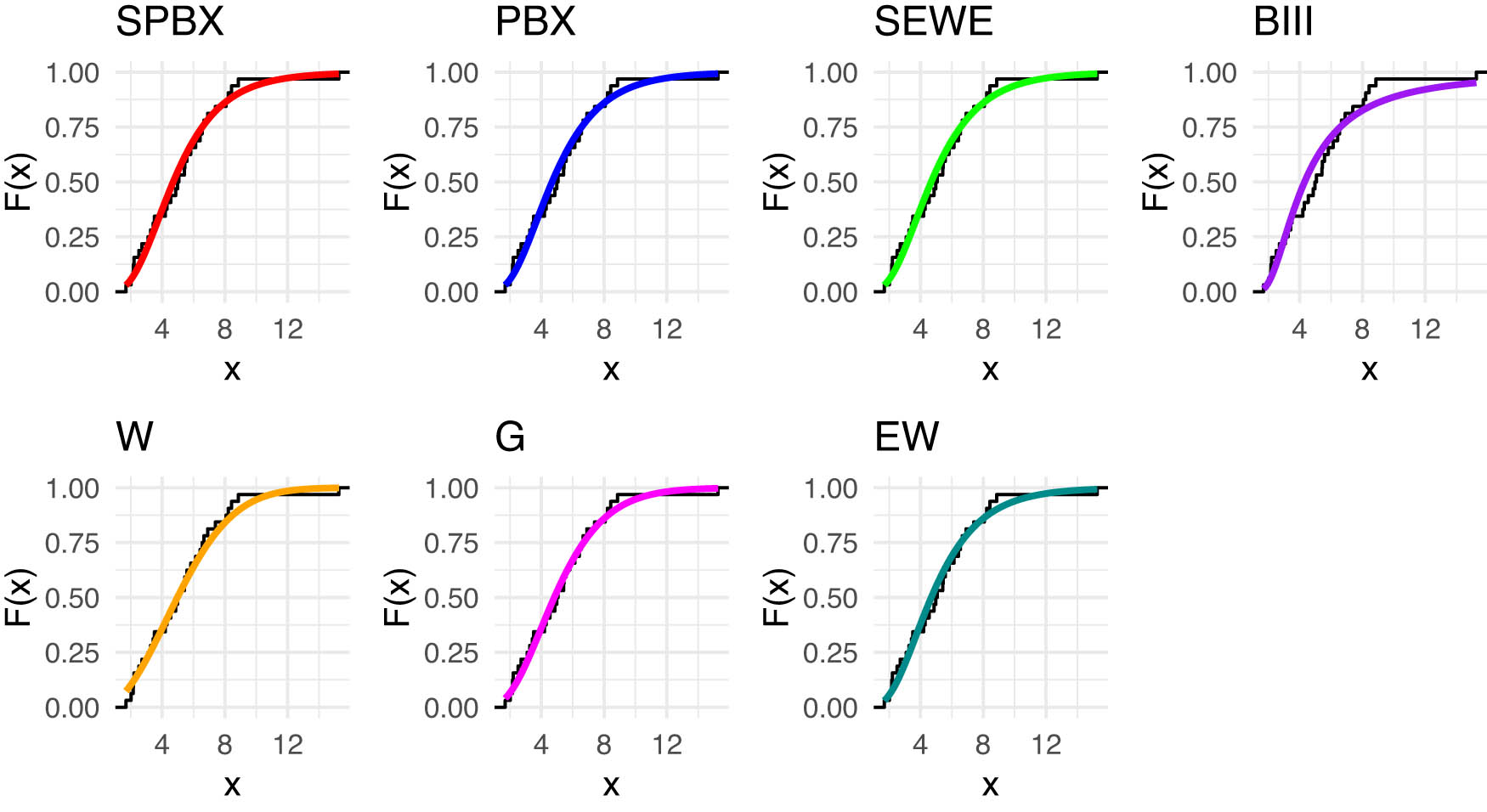

Figures 4 and 5 includes the histogram, violin plot, QQ (quantile-quantile) plot, box plot with stripchart, and TTT (total time in test) plot of dataset of rain gauge stations datasets. The estimated PDFs of competing models for the datasets of rain gauge stations datasets are shown in Figures 6 and 9, while Figures 7 and 10 display the estimated CDFs of the competitive models. Furthermore, Figures 8 and 11 illustrate the PP plots of the competing models. Figures 6–11 demonstrate the fit of our distribution to the actual data.

Some basic nonparametric plots for latitude for southwest of rain gauge stations.

Some basic nonparametric plots for latitude for west of rain gauge stations.

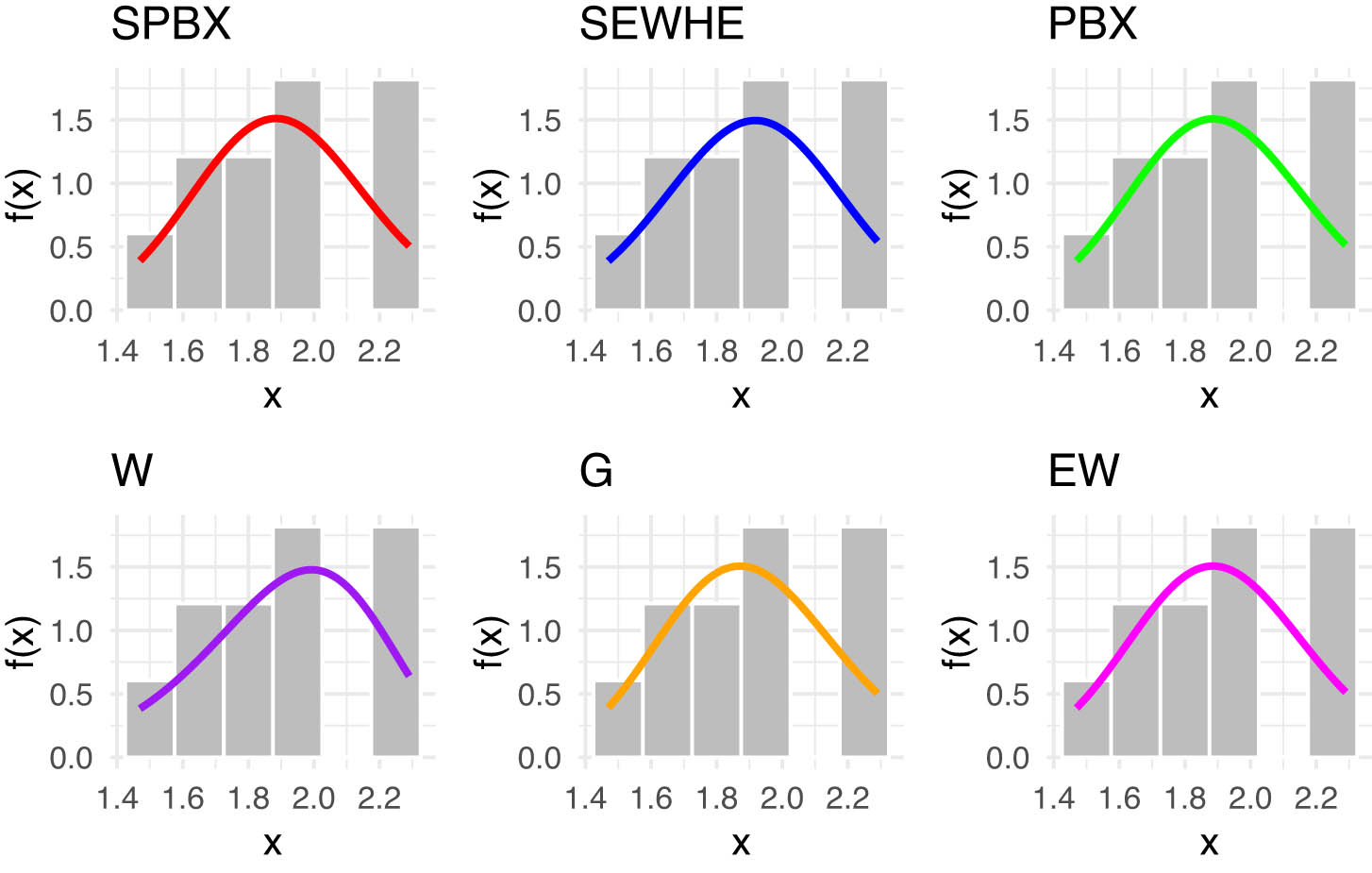

Estimated PDFs for the competing models for latitude for southwest of rain gauge stations.

Estimated CDFs for the competing models for latitude for southwest of rain gauge stations.

The PP plot for the competing models for latitude for southwest of rain gauge stations.

Estimated PDFs for the competing models for latitude for west of rain gauge stations.

Estimated CDFs for the competing models for latitude for west of rain gauge stations.

The PP plot for the competing models for latitude for west of rain gauge stations.

8.2 Breaking stress of carbon fibers dataset

The breaking stress of carbon fibers dataset contains crucial measurements of the maximum stress that carbon fibers can endure before fracturing. This dataset is indispensable for researchers and engineers in the fields of materials science and engineering. It plays a key role in investigating the mechanical properties and performance of carbon fiber-reinforced composites, widely used in industries such as aerospace and automotive manufacturing.

As mentioned by Cordeiro and Lemonte [40], this specific dataset offers valuable insights into the behavior of carbon fibers under stress. Below is the dataset:

{3.15, 1.25, 2.95, 4.38, 2.12, 1.47, 0.39, 2.79, 2.59, 2.05, 2.56, 3.65, 2.74, 1.87, 3.56, 4.42, 3.31, 2.55, 2.03, 3.19, 2.67, 3.22, 2.48, 2.43, 4.70, 3.09, 4.90, 1.61, 3.22, 2.50, 2.93, 3.68, 1.57, 1.80, 2.53, 2.81, 1.84, 2.87, 1.61, 3.11, 2.41, 3.60, 3.75, 3.27, 2.82, 2.35, 2.96, 3.39, 2.55, 0.85, 3.28, 3.11, 2.03, 1.08, 3.27, 2.03, 1.69, 3.39, 2.73, 3.31, 2.88, 4.20, 3.33}.

This dataset allows for deeper analysis into the variability and resilience of carbon fibers under extreme stress conditions. Researchers can apply these data to optimize material performance and design more efficient and durable composites, which are integral to high-stress environments.

In Table 12, we provide an in-depth comparison of various models using MLE with StEr, KSD, PVKS, CVM, PVCVM, AD, and PVAD. Among the tested distributions, the SPB-X distribution consistently outperformed others across multiple metrics, including KSD, PVKS, CVM, PVCVM, AD, and PVAD, making it the most suitable model for breaking stress of carbon fibers dataset.

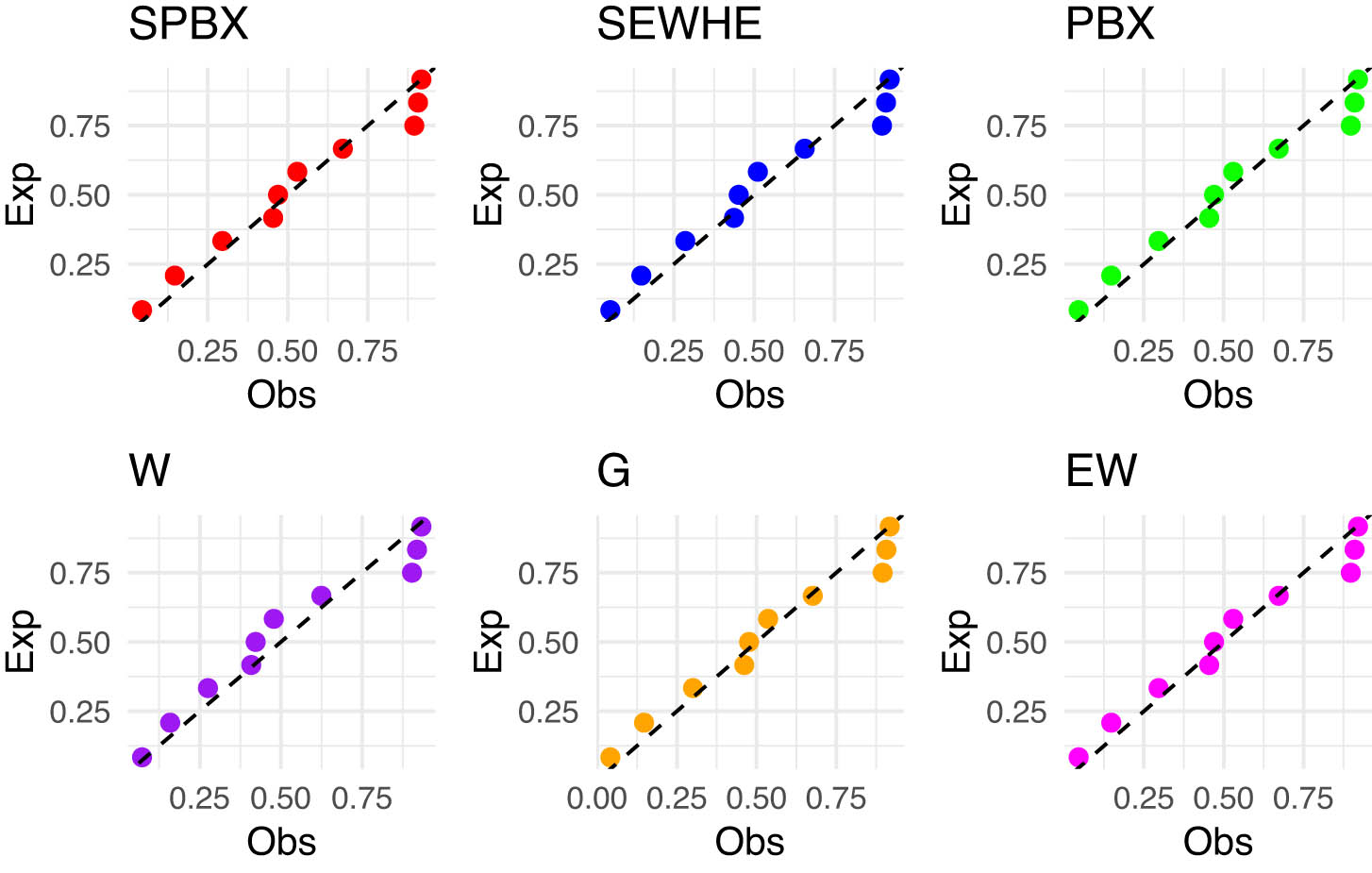

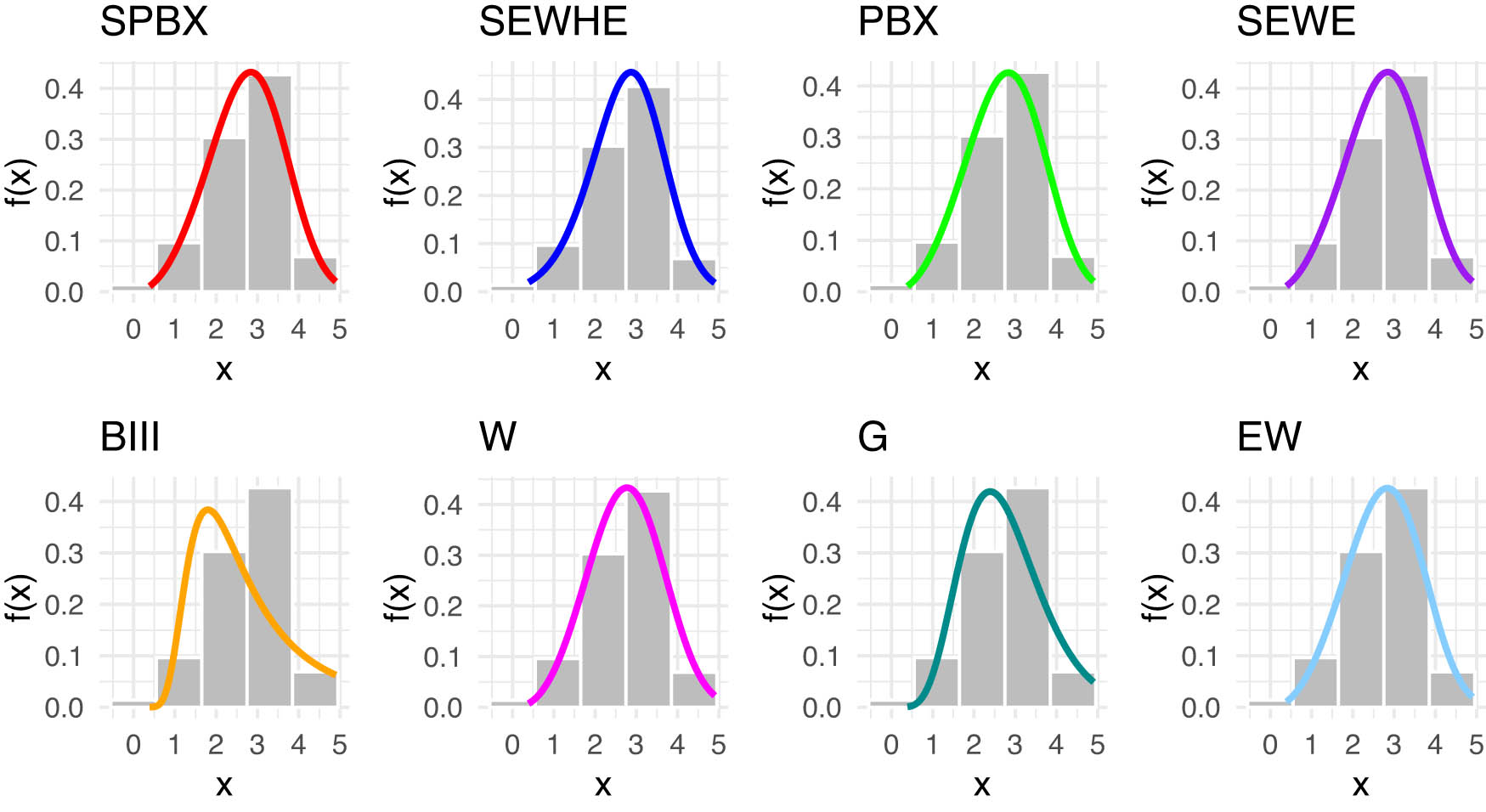

Figure 12 includes the histogram, violin plot, QQ plot, box plot with stripchart, and TTT plot of dataset of breaking stress of carbon fibers datasets. The estimated PDFs of competing models for the of dataset of breaking stress of carbon fibers datasets are shown in Figure 13, while Figure 14 displays the estimated CDFs of the competitive models. In addition, Figure 15 illustrates the PP plots of the competing models. Figures 13–15 demonstrate the fit of our distribution to the actual data.

Some basic nonparametric plots for dataset of carbon fibers stress.

Estimated PDFs for the competing models for dataset of carbon fibers stress.

Estimated CDFs for the competing models for dataset of carbon fibers stress.

The PP plot for the competing models for dataset of carbon fibers stress.

8.3 Tensile strength of carbon fibers dataset

Tensile strength, typically expressed in Gigapascals (GPa), measures the maximum stress a single carbon fiber can withstand before fracturing under tension. This property is essential in evaluating the performance and reliability of carbon fiber-reinforced materials, widely applied across industries such as aerospace, automotive, and sports equipment manufacturing. An in-depth understanding of the tensile strength of carbon fibers directly influences the design and development of more durable and resilient composite structures.

The dataset used in this study, sourced from Kundu and Raqab [41], contains tensile strength measurements for individual carbon fibers, expressed in GPa. The following is the dataset:

{1.098, 1.253, 0.944, 1.055, 1.586, 1.773, 1.554, 2.012, 1.301, 1.179, 1.884, 0.966, 0.552, 1.179, 1.642, 0.312, 1.426, 1.726, 0.865, 1.063, 0.803, 1.514, 1.270, 2.233, 1.301, 1.240, 1.627, 2.096, 1.533, 1.534, 1.321, 1.801, 1.559, 0.865, 0.979, 2.094, 1.300, 0.865, 1.434, 1.235, 2.585, 1.684, 2.012, 1.048, 1.373, 1.633, 1.697, 0.753, 1.726, 1.754}.

This dataset provides critical insights into the variability of tensile strength between individual fibers, allowing engineers and materials scientists to optimize the use of carbon fibers in high-performance applications. Using such data, industries can create composites that push the boundaries of durability and functionality in demanding environments.

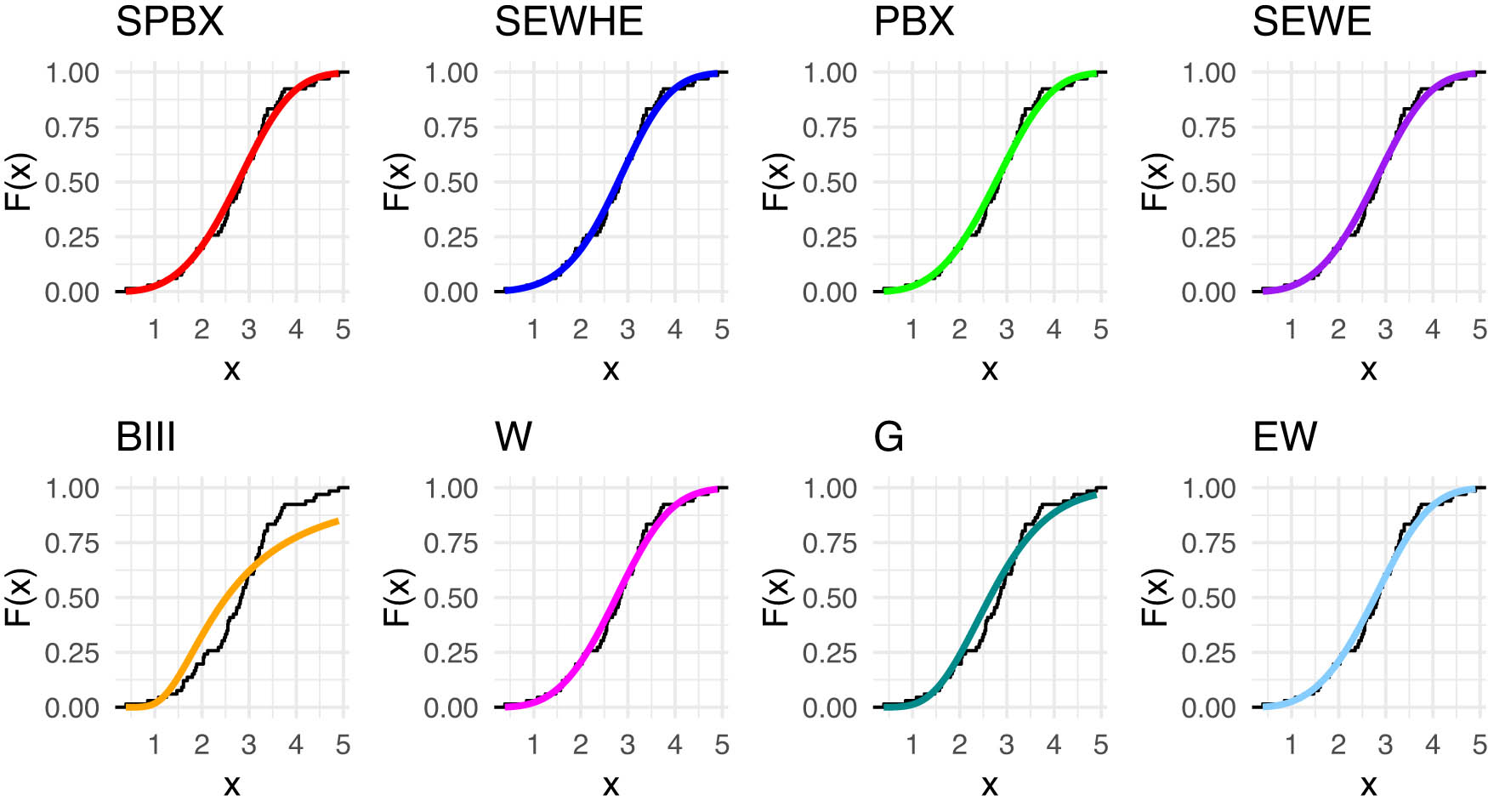

In Table 13, we provide an in-depth comparison of various models using MLE with StEr, KSD, PVKS, CVM, PVCVM, AD, and PVAD. Among the tested distributions, the SPB-X distribution consistently outperformed others across multiple metrics, including KSD, PVKS, CVM, PVCVM, AD, and PVAD, making it the most suitable model for the tensile strength of the carbon fibers dataset.

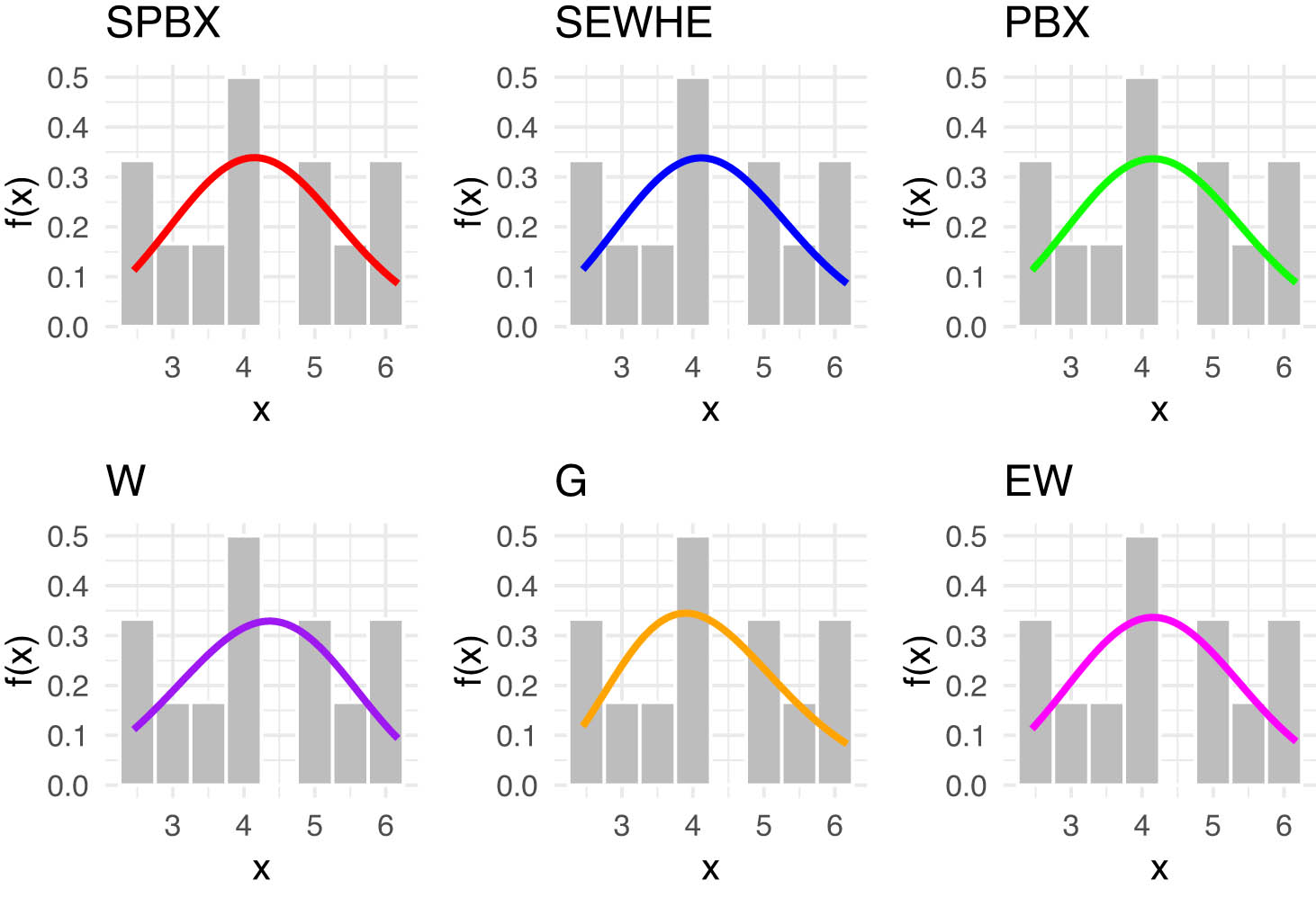

Figure 16 includes the histogram, violin plot, QQ plot, box plot with stripchart, and TTT plot of dataset of tensile stress of carbon fibers datasets. The estimated PDFs of competing models for the of dataset of tensile stress of carbon fibers datasets are shown in Figure 17, while Figure 18 displays the estimated CDFs of the competitive models. In addition, Figure 19 illustrates the PP plots of the competing models. Figures 17–19 demonstrate the fit of our distribution to the actual data.

Some basic nonparametric plots for dataset of carbon fibers strength.

The PDF plot of SPB-X distribution for dataset of carbon fibers strength.

The CDF plot of SPB-X distribution for dataset of carbon fibers strength.

The PP plot of SPB-X distribution for dataset of carbon fibers strength.

8.4 Insurance dataset

The insurance dataset, which spans the years 1987–2017, displays the excess of assets over liabilities for investments made by insurance companies, pension funds, and trusts. The values are expressed in billions of pounds. The following is the electronic address that it was obtained from: The link https://www.ons.gov.uk/ references the aforementioned product. The dataset is reported in Table 14.

Sed Excess of assets over liabilities for investment by insurance companies, and pension funds

| Period | Value | Period | Value | Period | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | 2.151 | 1997 | 4.301 | 2008 | 15.264 |

| 1987 | 2.208 | 1998 | 8.421 | 2009 | 4.547 |

| 1988 | 2.170 | 1999 | 6.661 | 2010 | 3.261 |

| 1989 | 2.707 | 2000 | 6.548 | 2011 | 3.426 |

| 1990 | 2.014 | 2001 | 4.977 | 2012 | 6.418 |

| 1991 | 1.698 | 2002 | 4.202 | 2013 | 7.389 |

| 1992 | 2.512 | 2003 | 5.580 | 2014 | 6.136 |

| 1993 | 4.857 | 2004 | 8.856 | 2015 | 5.820 |

| 1994 | 3.509 | 2005 | 6.902 | 2016 | 3.094 |

| 1995 | 5.066 | 2006 | 5.442 | 2017 | 8.216 |

| 1996 | 5.413 | 2007 | 8.067 |

In Table 15, we provide an in-depth comparison of various models using MLE with StEr, KSD, PVKS, CVM, PVCVM, AD, and PVAD. Among the tested distributions, the SPB-X distribution consistently outperformed others across multiple metrics, including KSD, PVKS, CVM, PVCVM, AD, and PVAD, making it the most suitable model for insurance dataset.

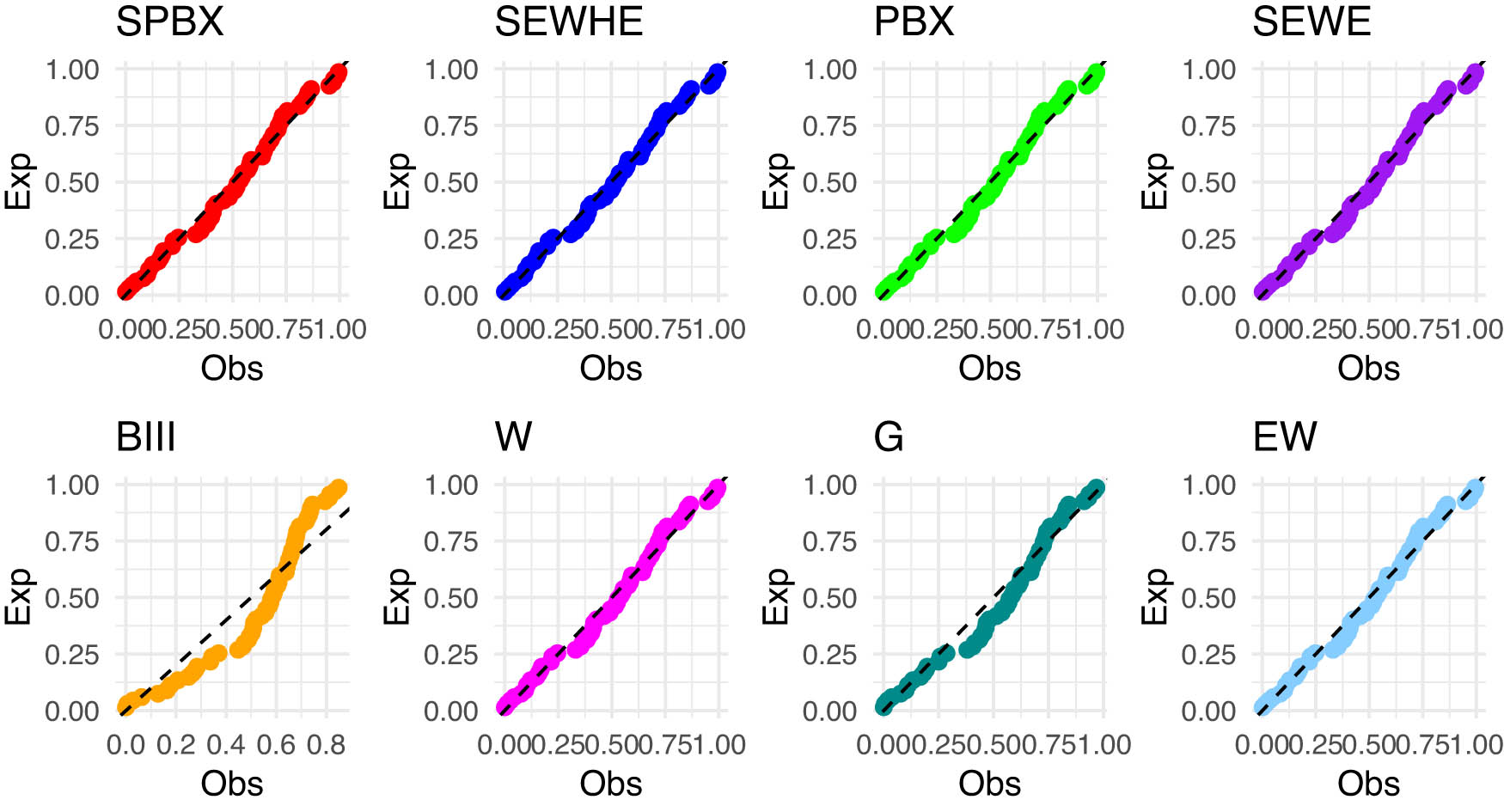

Figure 20 includes the histogram, violin plot, QQ plot, box plot with stripchart, and TTT plot of dataset of insurance datasets. The estimated PDFs of competing models for the of dataset of insurance datasets are shown in Figure 21, while Figure 22 displays the estimated CDFs of the competitive models. In addition, Figure 23 illustrates the PP plots of the competing models. Figures 21–23 demonstrate the fit of our distribution to the actual data.

Some basic nonparametric plots for insurance dataset.

Estimated PDFs for the competing models for insurance dataset.

Estimated CDFs for the competing models for insurance dataset.

Estimated CDFs for the competing models for insurance dataset.

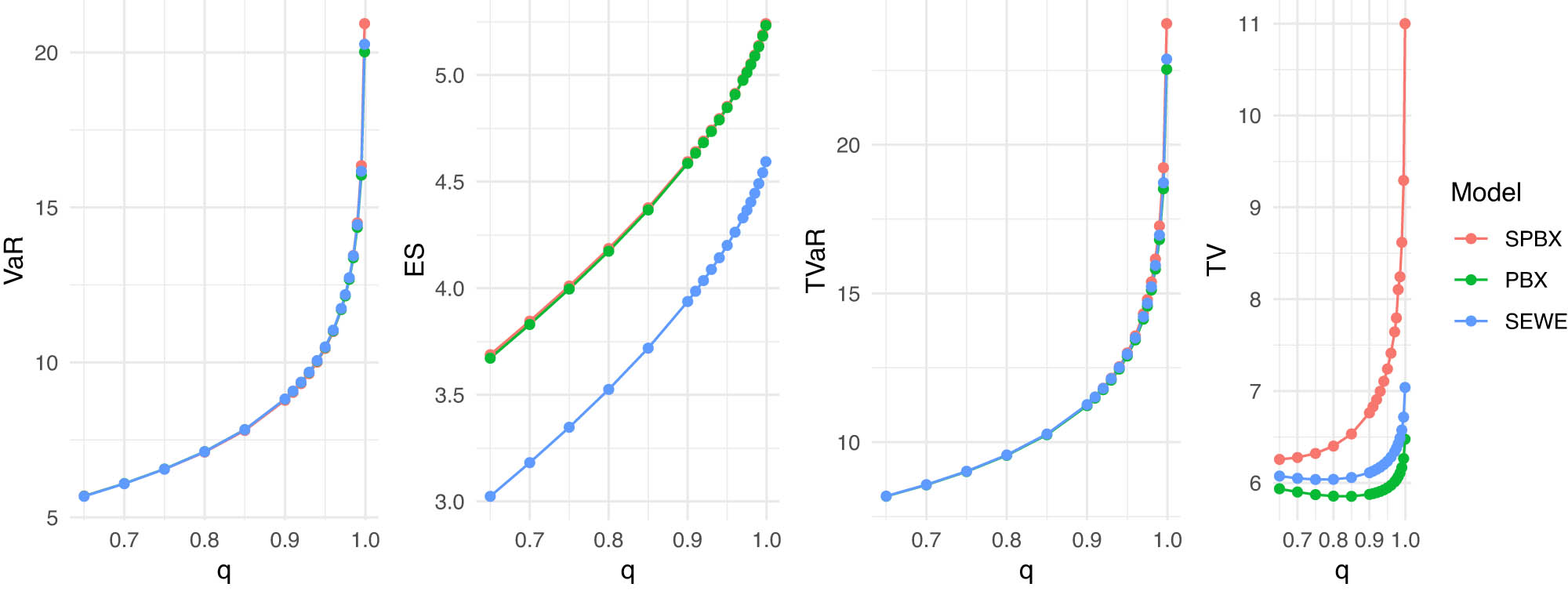

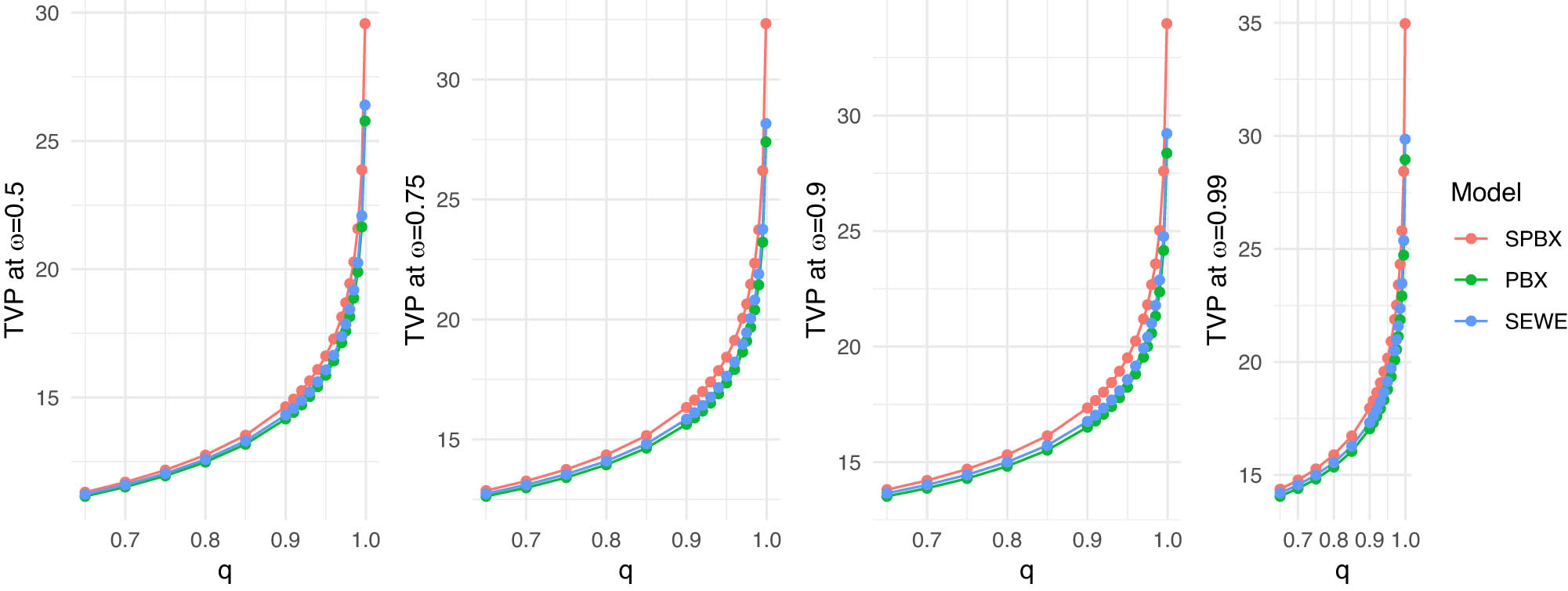

The actuarial measures VaR, ES, TVaR, TV, and TVP of the SPB-X, PBX, and SEWE distributions are computed and compared using the actual dataset in the following. Tables 16 and 17 present the numerical findings.

The actuarial metrics VaR, ES, TVaR, and TV values for the insurance dataset

| Measure |

|

SPB-X | PBX | SEWE | Measure |

|

SPB-X | PBX | SEWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VaR | 0.650 | 5.6930 | 5.6868 | 5.6815 | TVaR | 0.650 | 8.1786 | 8.1798 | 8.1864 |

| 0.700 | 6.0936 | 6.0942 | 6.0883 | 0.700 | 8.5602 | 8.5620 | 8.5707 | ||

| 0.750 | 6.5548 | 6.5636 | 6.5577 | 0.750 | 9.0087 | 9.0100 | 9.0215 | ||

| 0.800 | 7.1068 | 7.1253 | 7.1199 | 0.800 | 9.5554 | 9.5537 | 9.5695 | ||

| 0.850 | 7.8061 | 7.8351 | 7.8317 | 0.850 | 10.2603 | 10.2501 | 10.2728 | ||

| 0.900 | 8.7813 | 8.8196 | 8.8215 | 0.900 | 11.2598 | 11.2275 | 11.2621 | ||

| 0.910 | 9.0343 | 9.0736 | 9.0772 | 0.910 | 11.5214 | 11.4812 | 11.5193 | ||

| 0.920 | 9.3174 | 9.3569 | 9.3629 | 0.920 | 11.8150 | 11.7648 | 11.8070 | ||

| 0.930 | 9.6388 | 9.6776 | 9.6864 | 0.930 | 12.1493 | 12.0863 | 12.1336 | ||

| 0.940 | 10.0109 | 10.0474 | 10.0598 | 0.940 | 12.5376 | 12.4578 | 12.5112 | ||

| 0.950 | 10.4529 | 10.4843 | 10.5016 | 0.950 | 13.0001 | 12.8975 | 12.9586 | ||

| 0.960 | 10.9973 | 11.0190 | 11.0430 | 0.960 | 13.5715 | 13.4364 | 13.5076 | ||

| 0.970 | 11.7060 | 11.7088 | 11.7426 | 0.970 | 14.3173 | 14.1328 | 14.2184 | ||

| 0.975 | 12.1596 | 12.1465 | 12.1873 | 0.975 | 14.7957 | 14.5752 | 14.6705 | ||

| 0.980 | 12.7200 | 12.6832 | 12.7331 | 0.980 | 15.3873 | 15.1177 | 15.2255 | ||

| 0.985 | 13.4515 | 13.3766 | 13.4396 | 0.985 | 16.1607 | 15.8193 | 15.9443 | ||

| 0.990 | 14.5011 | 14.3577 | 14.4412 | 0.990 | 17.2715 | 16.8120 | 16.9634 | ||

| 0.995 | 16.3499 | 16.0457 | 16.1700 | 0.995 | 19.2293 | 18.5203 | 18.7222 | ||

| 0.999 | 20.9308 | 20.0204 | 20.2655 | 0.999 | 24.0749 | 22.5402 | 22.8827 | ||

| ES | 0.650 | 3.6882 | 3.6717 | 3.0239 | TV | 0.650 | 6.2552 | 5.9357 | 6.0739 |

| 0.700 | 3.8454 | 3.8299 | 3.1817 | 0.700 | 6.2759 | 5.9001 | 6.0496 | ||

| 0.750 | 4.0103 | 3.9961 | 3.3478 | 0.750 | 6.3207 | 5.8717 | 6.0364 | ||

| 0.800 | 4.1860 | 4.1735 | 3.5252 | 0.800 | 6.4003 | 5.8557 | 6.0379 | ||

| 0.850 | 4.3774 | 4.3671 | 3.7190 | 0.850 | 6.5323 | 5.8534 | 6.0582 | ||

| 0.900 | 4.5932 | 4.5853 | 3.9378 | 0.900 | 6.7623 | 5.8743 | 6.1107 | ||

| 0.910 | 4.6406 | 4.6332 | 3.9859 | 0.910 | 6.8288 | 5.8828 | 6.1274 | ||

| 0.920 | 4.6898 | 4.6830 | 4.0359 | 0.920 | 6.9061 | 5.8936 | 6.1473 | ||

| 0.930 | 4.7413 | 4.7350 | 4.0881 | 0.930 | 6.9969 | 5.9070 | 6.1710 | ||

| 0.940 | 4.7953 | 4.7895 | 4.1429 | 0.940 | 7.1061 | 5.9239 | 6.1998 | ||

| 0.950 | 4.8525 | 4.8470 | 4.2009 | 0.950 | 7.2404 | 5.9453 | 6.2352 | ||

| 0.960 | 4.9135 | 4.9084 | 4.2628 | 0.960 | 7.4118 | 5.9739 | 6.2815 | ||

| 0.970 | 4.9797 | 4.9748 | 4.3299 | 0.970 | 7.6437 | 6.0116 | 6.3398 | ||

| 0.975 | 5.0153 | 5.0104 | 4.3660 | 0.975 | 7.7954 | 6.0358 | 6.3776 | ||

| 0.980 | 5.0532 | 5.0482 | 4.4043 | 0.980 | 8.1037 | 6.0678 | 6.4260 | ||

| 0.985 | 5.0938 | 5.0886 | 4.4454 | 0.985 | 8.2437 | 6.1081 | 6.4876 | ||

| 0.990 | 5.1385 | 5.1328 | 4.4906 | 0.990 | 8.6181 | 6.1666 | 6.5745 | ||

| 0.995 | 5.1897 | 5.1829 | 4.5421 | 0.995 | 9.2927 | 6.2645 | 6.7159 | ||

| 0.999 | 5.2410 | 5.2322 | 4.5935 | 0.999 | 10.9996 | 6.4753 | 7.0392 |

The actuarial metrics TVP values for the insurance dataset

|

|

|

SPB-X | PBX | SEWE |

|

|

SPB-X | PBX | SEWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.50 | 0.650 | 11.3062 | 11.1476 | 11.2233 | 0.90 | 0.650 | 13.8083 | 13.5219 | 13.6528 |

| 0.700 | 11.6982 | 11.5121 | 11.5955 | 0.700 | 14.2085 | 13.8721 | 14.0153 | ||

| 0.750 | 12.1690 | 11.9459 | 12.0397 | 0.750 | 14.6973 | 14.2946 | 14.4543 | ||

| 0.800 | 12.7555 | 12.4815 | 12.5884 | 0.800 | 15.3156 | 14.8238 | 15.0036 | ||

| 0.850 | 13.5265 | 13.1768 | 13.3019 | 0.850 | 16.1395 | 15.5182 | 15.7251 | ||

| 0.900 | 14.6410 | 14.1646 | 14.3174 | 0.900 | 17.3459 | 16.5143 | 16.7617 | ||

| 0.910 | 14.9358 | 14.4226 | 14.5830 | 0.910 | 17.6674 | 16.7757 | 17.0340 | ||

| 0.920 | 15.2680 | 14.7116 | 14.8807 | 0.920 | 18.0304 | 17.0690 | 17.3396 | ||

| 0.930 | 15.6478 | 15.0398 | 15.2191 | 0.930 | 18.4466 | 17.4026 | 17.6875 | ||

| 0.940 | 16.0906 | 15.4197 | 15.6110 | 0.940 | 18.9331 | 17.7893 | 18.0910 | ||

| 0.950 | 16.6203 | 15.8702 | 16.0762 | 0.950 | 19.5165 | 18.2483 | 18.5702 | ||

| 0.960 | 17.2774 | 16.4234 | 16.6484 | 0.960 | 20.2421 | 18.8129 | 19.1610 | ||

| 0.970 | 18.1391 | 17.1386 | 17.3882 | 0.970 | 21.1966 | 19.5432 | 19.9242 | ||

| 0.975 | 18.6934 | 17.5931 | 17.8593 | 0.975 | 21.8115 | 20.0074 | 20.4103 | ||

| 0.980 | 19.4391 | 18.1517 | 18.4385 | 0.980 | 22.6806 | 20.5788 | 21.0089 | ||

| 0.985 | 20.2825 | 18.8733 | 19.1881 | 0.985 | 23.5800 | 21.3166 | 21.7831 | ||

| 0.990 | 21.5805 | 19.8953 | 20.2507 | 0.990 | 25.0278 | 22.3620 | 22.8805 | ||

| 0.995 | 23.8756 | 21.6525 | 22.0802 | 0.995 | 27.5927 | 24.1583 | 24.7666 | ||

| 0.999 | 29.5747 | 25.7779 | 26.4023 | 0.999 | 33.9745 | 28.3680 | 29.2180 | ||

| 0.75 | 0.650 | 12.8700 | 12.6316 | 12.7418 | 0.99 | 0.650 | 14.3712 | 14.0561 | 14.1995 |

| 0.700 | 13.2672 | 12.9871 | 13.1079 | 0.700 | 14.7734 | 14.4031 | 14.5598 | ||

| 0.750 | 13.7492 | 13.4138 | 13.5488 | 0.750 | 15.2661 | 14.8230 | 14.9976 | ||

| 0.800 | 14.3556 | 13.9454 | 14.0979 | 0.800 | 15.8916 | 15.3508 | 15.5470 | ||

| 0.850 | 15.1596 | 14.6402 | 14.8164 | 0.850 | 16.7274 | 16.0450 | 16.2704 | ||

| 0.900 | 16.3316 | 15.6332 | 15.8451 | 0.900 | 17.9545 | 17.0430 | 17.3116 | ||

| 0.910 | 16.6431 | 15.8933 | 16.1149 | 0.910 | 18.2820 | 17.3052 | 17.5855 | ||

| 0.920 | 16.9945 | 16.1850 | 16.4175 | 0.920 | 18.6520 | 17.5994 | 17.8929 | ||

| 0.930 | 17.3970 | 16.5166 | 16.7619 | 0.930 | 19.0763 | 17.9343 | 18.2429 | ||

| 0.940 | 17.8672 | 16.9007 | 17.1610 | 0.940 | 19.5726 | 18.3224 | 18.6489 | ||

| 0.950 | 18.4304 | 17.3565 | 17.6350 | 0.950 | 20.1681 | 18.7834 | 19.1314 | ||

| 0.960 | 19.1304 | 17.9168 | 18.2187 | 0.960 | 20.9092 | 19.3506 | 19.7263 | ||

| 0.970 | 20.0500 | 18.6415 | 18.9732 | 0.970 | 21.8845 | 20.0843 | 20.4947 | ||

| 0.975 | 20.6422 | 19.1020 | 19.4537 | 0.975 | 22.5131 | 20.5506 | 20.9843 | ||

| 0.980 | 21.4650 | 19.6686 | 20.0450 | 0.980 | 23.4099 | 21.1249 | 21.5873 | ||

| 0.985 | 22.3434 | 20.4004 | 20.8100 | 0.985 | 24.3219 | 21.8663 | 22.3670 | ||

| 0.990 | 23.7351 | 21.4370 | 21.8943 | 0.990 | 25.8034 | 22.9170 | 23.4722 | ||

| 0.995 | 26.1988 | 23.2187 | 23.7592 | 0.995 | 28.4290 | 24.7221 | 25.3710 | ||

| 0.999 | 32.3246 | 27.3967 | 28.1621 | 0.999 | 34.9645 | 28.9508 | 29.8515 |

Figure 24 includes the competing model VaR, ES, TVaR, and TV plots for the insurance dataset. the competing model TVP plots for the insurance dataset shown in Figure 25.

Competing model VaR, ES, TVaR, and TV plots for the insurance dataset.

Competing model TVP plots for the insurance dataset.

We find that for different significance levels

From Table 18, it is observed that both estimation methods produce consistent results with only minor differences in the estimated parameters. In several datasets (Data1, Data3, Data4, and Data5), LSE achieves slightly smaller KS values and higher

Parameter estimates of the SPB-X distribution using MLE and LSE for the five datasets, along with KSD and PVKS

| Data | Method |

|

|

|

KSD | PVKS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data1 | MLE | 14.5195 | 0.8207 | 1.0578 | 0.1684 | 0.9141 |

| LSE | 19.8840 | 1.0673 | 0.7378 | 0.1415 | 0.9803 | |

| Data2 | MLE | 2.7126 | 0.2305 | 1.0543 | 0.1036 | 0.9978 |

| LSE | 1.7772 | 0.1973 | 1.0428 | 0.1088 | 0.9957 | |

| Data3 | MLE | 0.8472 | 0.0878 | 1.8287 | 0.0784 | 0.8124 |

| LSE | 0.5967 | 0.0255 | 2.7033 | 0.0616 | 0.9635 | |

| Data4 | MLE | 0.8548 | 0.2995 | 1.7155 | 0.0470 | 0.9980 |

| LSE | 1.0035 | 0.3514 | 1.5885 | 0.0386 | 0.9999 | |

| Data5 | MLE | 16.8042 | 1.0771 | 0.2799 | 0.0881 | 0.9463 |

| LSE | 0.6613 | 0.0505 | 1.3798 | 0.0791 | 0.9787 |

9 Concluding remarks