Abstract

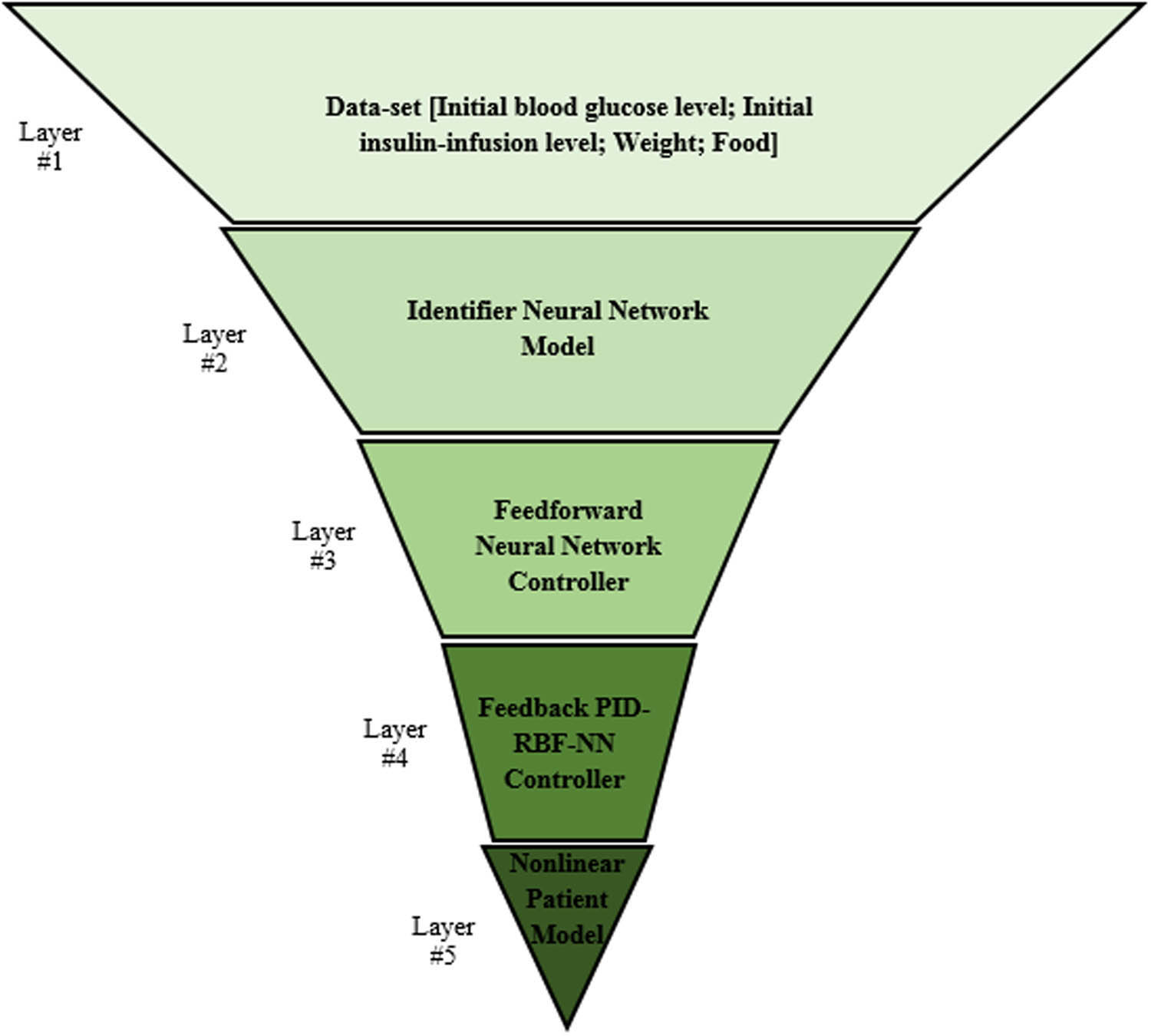

The novel cognitive blood glucose–insulin control technique presented in this work uses five layers in the controller’s structure to monitor and control the blood glucose levels of various diabetic patients’ types. The first layer is the cognitive dataset that represents the attributes of the control system. The second layer is the identifier neural network model that represents the different types of nonlinear Bergman diabetic patient models. The third layer is the feedforward neural network controller based on an identifier neural network model to find the maximum insulin-infusion level for each meal in each sample. The fourth layer is the feedback PID-RBF-NN controller based on the radial basis function neural network model to find the optimal insulin-infusion value and to keep the blood glucose level in the normal state. The fifth layer is the nonlinear patient Bergman minimal model. To train this controller, the grey wolf optimization meta-heuristic technique is employed. The results of the MATLAB simulations for three distinct patients showed the effectiveness and robustness of the suggested control algorithm in monitoring the dynamic behaviour of the diabetic patients’ blood glucose levels. Additionally, the comparison results demonstrated that the suggested cognitive glucose–insulin control algorithm improved the time to reach a normal physiological blood glucose level by 10% compared to the fuzzy logic and the fractional-order proportional integral derivative (PID) control algorithms, by 25% compared to the type-2 fuzzy control algorithm, and by 6% compared to the PID-particle swarm optimization control algorithm.

1 Introduction

One of the most important and common chronic diseases in the world is diabetes, sometimes referred to as diabetes mellitus (DM), which is mostly brought on by elevated blood glucose levels. Diabetes can be fatal or significantly impair a person’s quality of life, regardless of gender. In this regard, diabetes is a chronic illness that only develops when blood glucose levels are too high. In particular, the body uses glucose as an energy source, and the hormone of insulin, which is released by the pancreas and regulates the amount of glucose that the cells may use as fuel [1]. In this context, DM is becoming more and more common worldwide, and by 2045, there will likely be over 783 million cases, mostly in low- and middle-income nations [2]. Specifically, about 90% of cases are Type II diabetes mellitus (TIIDM) [3], with the remaining instances being Type I diabetes mellitus (TIDM) and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Serious side effects include nerve damage and cardiovascular problems, and elevated risks of dying young are linked to these disorders. Thus, accurate, timely, and cost-effective blood glucose monitoring and control are essential for those individuals.

In this regard, experts are specifically studying patients with TIDM in great depth. As a result, a lot of research has been conducted to develop several mathematical models of insulin and glucose that, to a certain degree, accurately depict the physiological behaviour of the human body [4]. In essence, the Bergman minimum model was the most significant. Other glucose–insulin models include the nonlinear glucose metabolism model, as described in Kalaimani and Jeyakumar [4] and Patra and Panigrahi [5], and the Lehman-based diabetic patient model, as described in Kralev and Slavov [6].

Furthermore, various insulin controllers were created to function as an artificial pancreas and maintain a patient’s blood glucose levels between 80 and 120 mg/dl to improve the blood glucose tracking error and control the patient’s blood glucose. For example, Saleem and Iqbal [7] suggested a complex-order proportional integral derivative (PID) controller for elevated blood glucose levels in a TID patient model and employed a fractional-order PID controller. However, the disadvantages of these controllers are that the initial values rely on the designer’s experience and the control parameters are adjusted by numerical optimization. Moreover, using a linear Bergman model, Sharma et al. [8] introduced a digital PID controller for diabetic patients’ blood glucose levels. They utilized the Ziegler–Nichols (Z–N) tuning method to determine the control settings. Nevertheless, the Z–N method is not appropriate for investigating and using the global extreme solution of the problem. Therefore, the control system resulted in an overshoot in the patient’s blood glucose response. Additionally, Benzian et al. [9] employed fuzzy logic and fractional-order PID controllers to control the TID patient’s blood glucose levels. They also used various meta-heuristic techniques to adjust the FOPID’s control parameters. Nonetheless, this work’s drawback is that the controllers were only developed for a single patient using the linear Bergman model. In addition, they employed only five rules for the membership function and the trial-and-error approach to determine the input–output fuzzy logic controller’s gain. As a result, the controller produced an insulin control action value that is too fast and suboptimal, which causes the blood glucose level to respond too quickly. To improve the linear blood glucose–insulin model in type I diabetes, Shenbagam et al. [10] suggested a fractional-order controller. They also used a fractional-order PID controller with a genetic algorithm to adjust the five control parameters, which improved the blood glucose tracking error and maintained the patient’s blood glucose levels. Furthermore, a type-2 fuzzy controller was utilized by Yan et al. [11] and Sayed et al. [12] to monitor and stabilize the blood glucose levels in TID for various patient models. In another work, a radial basis function neural network was employed in Barbosa de Farias and Bessa [13] as an intelligent controller for an automated insulin delivery system for a virtual patient model to monitor and regulate the blood glucose level in a matter of days. In a different study, Khaqan et al. [14] used the University of Virginia/Padova metabolic simulator to demonstrate how to estimate the TID patient model. They also created control algorithms that use an intelligent predictive control model with linear and nonlinear controllers to control the blood glucose level for the linear third-order patient model. To stabilize the patient’s blood glucose level and maintain it at a normal physiological level, Dagher and Haggege [15] suggested a PID-PSO controller for the TIDM patient model. This controller uses the PSO algorithm to adjust the optimal control parameters of the adaptive PID controller, allowing it to quickly and optimally determine the insulin-infusion control action injected into the nonlinear Bergman model of the TIDM patients. Additionally, to achieve a fast response and less chattering in an intravenous glucose tolerance test model of a TIDM patient, Babar et al. [16] designed a control glucose–insulin system using a back-stepping-sliding mode controller with three control parameters that were adjusted by the trial-and-error method. The motivation for this work is that DM patients are becoming more and more common worldwide. Particularly, for type 1 patients, the body cannot adequately use the insulin that it generates and requires insulin injections to survive. To tackle this problem, a lot of research has been done to develop several mathematical glucose–insulin control techniques for patient models. Such techniques were proposed to determine the fast and optimal insulin-infusion control action value to enhance the performance of the blood glucose level in the patient model in terms of regulation and stabilization of the blood glucose at the normal physiological level within a suitable time to avoid the hyperglycemia level which, over a longer period, may cause heart disease, vascular disease, blindness, stroke, nerve damage, kidney disease, and amputation. Conversely, the hypoglycemia state may lead to coma, acute seizure, and death [17]. These lengthy complications lowered life expectancy, increased disability, and raised health care expenses for society. Therefore, all of these numbers demonstrate the critical need for research in diabetes prevention and care, as well as the necessity of developing a control system to enhance the control system for these patients and reduce the rate at which the disease’s financial and physiological expenses are increasing [18]. In particular, the problem definition in this study is that patients with TIDM have a difficult condition that basically entails controlling the blood glucose levels to prevent both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia. Furthermore, controlling and stabilizing the blood glucose level to the normal physiological level in the shortest period is dependent on determining the amount of the insulin-infusion level. By implementing the suggested offline and online cognitive glucose–insulin controller using the grey wolf optimization (GWO) meta-heuristic method, the primary goal of this research is to identify the fastest and best insulin-infusion control action value to improve the blood glucose level performance in various patient models with meal disturbances in terms of regulation and stabilization of the blood glucose at the normal physiological level. This study’s primary contribution involves identifying and adjusting the feedforward neural network controller’s optimal or nearly optimal parameters in addition to the feedback PID-RBF-NN controller’s control gain parameters. This adjustment process will allow for the fast and ideal insulin-infusion control action to be injected into the nonlinear Bergman model of TIDM patients with variable meal disturbances. This process will enable the patient’s blood glucose level to be tracked and stabilized, and it will be kept at a normal physiological level within a suitable time to prevent hyperglycemia and hypoglycaemia. Therefore, the novelty of this research is to design an efficient and robust controller for an artificial pancreas system for blood glucose regulation in TIDM patients.

This article is organized as follows. In Section 2, the Bergman minimum model is introduced. Section 3 describes the cognitive glucose–insulin regulation algorithm. Section 4 presents the simulation’s numerical results, and the primary findings from this study are presented in Section 5.

2 The nonlinear diabetic patient model

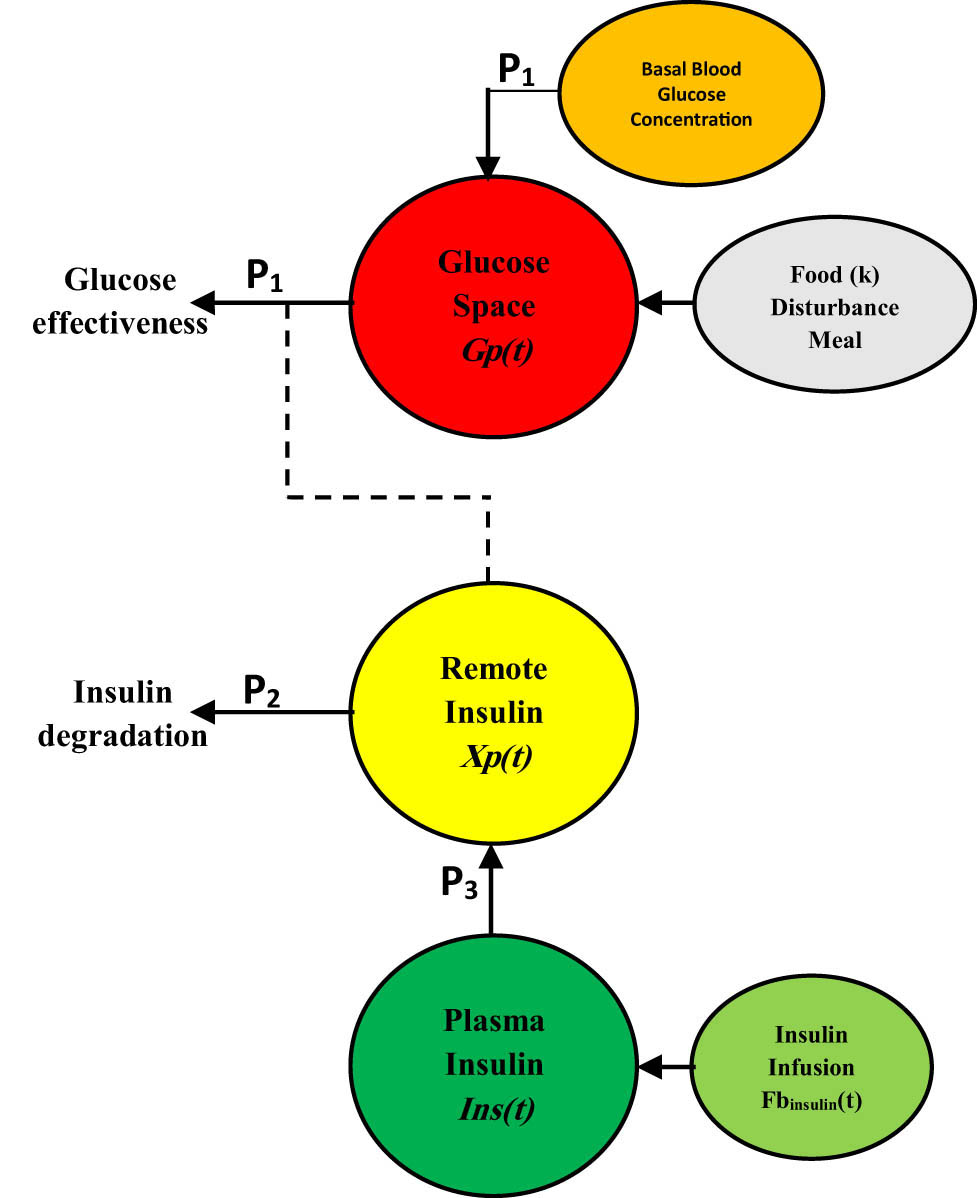

Figure 1 depicts the general diagram of the insulin–glucagon system [19]. The hormones of insulin and glucagon, which regulate the blood glucose levels, are produced in the pancreas, which releases insulin into the bloodstream to lower the blood glucose levels when they are elevated. To raise blood glucose levels when they are low, glucagon promotes the breakdown of glycogen and the synthesis of glucose from circulating precursors. In our work, we will take a model of the insulin–glucose system based on the Bergman glucose insulin minimum model. In particular, the three important compartments in this model are shown in Figure 2, which describes the relationship among the distant insulin compartment level Ins(t) in mU/l, the plasma glucose compartment level Gp(t) in mg/dl, and the remote insulin Xp(t) in 1/min. Blood glucose, a hormone, and insulin were thought to be stored in two separate compartments and to interact with each other.

![Figure 1

The general diagram of the insulin–glucagon system [19].](/document/doi/10.1515/nleng-2025-0135/asset/graphic/j_nleng-2025-0135_fig_001.jpg)

The general diagram of the insulin–glucagon system [19].

The compartments of the Bergman glucose–insulin minimal model.

In this context, several research works used the Bergman glucose–insulin basic model, which lacks the biological complexity shown in Sakulrang et al. [19], to study the distribution of insulin and the regulation of blood glucose [20]. The following representation is a description of this model, which is based on nonlinear ordinary differential equations [21]:

This factor will not be included when establishing the transfer function since diabetic patients cannot control their blood sugar levels

where Xp(t) is the effect of active insulin in the distant compartment variable in 1/min and Gp(t) is the blood glucose concentration variable in mg/dl. Food(t) is the meal disturbance input variable in mg/dl min,

Table 1 demonstrates the parameters of the Bergman model equations that describe the normal person and three patients [15,20,21].

| Parameters units | Normal person | Patient #1 | Patient #2 | Patient #3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P 1 (1/min) | 0.031 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P 2 (1/min) | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.007 | 0.014 |

| P 3 (l/mU min2) | 4.92 × 10−6 | 5.3 × 10−6 | 2.16 × 10−6 | 9.94 × 10−6 |

|

|

0.0039 | 0.0042 | 0.0038 | 0.0046 |

| h (mg/dl) | 79.035 | 80.2 | 77.578 | 82.937 |

| n (min−1) | 0.265 | 0.26 | 0.246 | 0.281 |

| G b (mg/dl) | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| I b (mU/l) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| G o (mg/dl) | 280 | 230 | 220 | 210 |

| I o (mU/l) | 364.8 | 50 | 55 | 60 |

| S I = P 3/P 2 | 492 × 10−6 | 481 × 10−6 | 308 × 10−6 | 710 × 10−6 |

To check whether the nonlinear diabetic patient model based on the Bergman minimal mode is stabile in each patient’s parameters, as given in Table 1, a Lyapunov function [22] is proposed as follows:

Clearly,

The nonlinear Bergman minimal mode can be expressed as shown in Eq. (6) based on Eqs. (1)–(4)

where

By substituting Eq. (6) in (7), the derivative state vector becomes as follows:

Clearly, if all states (

However, when the parameter

The effect of

3 Cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy design

The novelty of this research is to design an efficient and robust controller for the artificial pancreas system for blood glucose regulation in TIDM patients. The general structure of the proposed cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy is shown in Figure 3, which demonstrates the five layers for achieving the optimal insulin-infusion level in the nonlinear diabetic patient model to avoid the hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia states and to keep the blood glucose level in the desired normal state.

The five layers of the proposed cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy for the artificial pancreas system.

This five-layer structure consists of

Layer #1: The cognitive dataset that represents the attributes of the control system.

Layer #2: The identifier model that represents the different types of nonlinear diabetic patients.

Layer #3: The feedforward neural network controller based on the NARMA-L2 neural network model to determine the maximum insulin-infusion level for each meal.

Layer #4: The feedback PID-RBF-NN controller, which is based on the radial basis function neural network model to find the optimal insulin-infusion value and to keep the blood glucose level in the normal state.

Layer #5: The nonlinear patient Bergman minimal model.

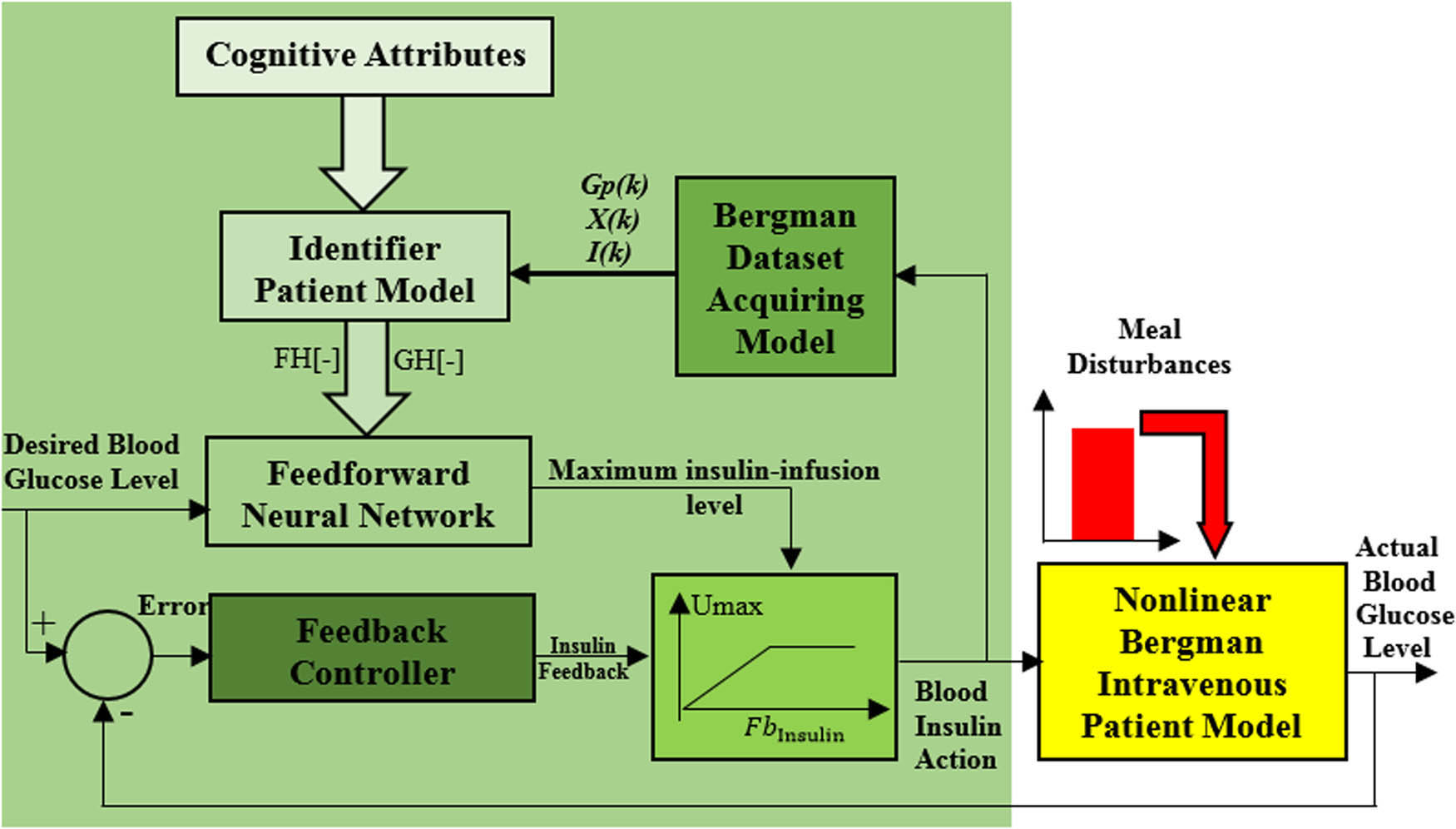

Figure 4 demonstrates the proposed cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy for the nonlinear diabetic patient model.

Cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy for the nonlinear diabetic patient model.

3.1 The cognitive dataset

The cognitive dataset is essential in the structure of the proposed controller because these data are the input set for the controller, including the initial blood glucose level located between the upper level of 250 mg/dl and the lower level of 50 mg/dl to avoid the hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia states, respectively, the initial blood–insulin concentration, and the food input variable that depends on the meal (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) in mg/dl. Moreover, the patient weight determines the maximum insulin-infusion level taken during 1 day for the nonlinear diabetic patient model. Table 2 shows the suggested input attributes of the proposed controller.

The input attributes of the proposed controller

| No. | Input attributes | Values |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | Initial blood glucose level | (210, 220, 230) mg/dl |

| #2 | Hyperglycemia level | 250 mg/dl |

| #3 | Hypoglycemia level | 50 mg/dl |

| #4 | Initial blood–insulin concentration | (50, 55, 60) mU/l |

| #5 | Food as a breakfast meal | (15–20) mg/dl |

| #6 | Food as a lunch meal | (20–25) mg/dl |

| #7 | Food as a dinner meal | (5–8) mg/dl |

| #8 | Maximum insulin-infusion level during 24 h | Weight of the patient divided by 2 |

The cognitive attributes can be expressed as follows:

where

3.2 The patient identifier model

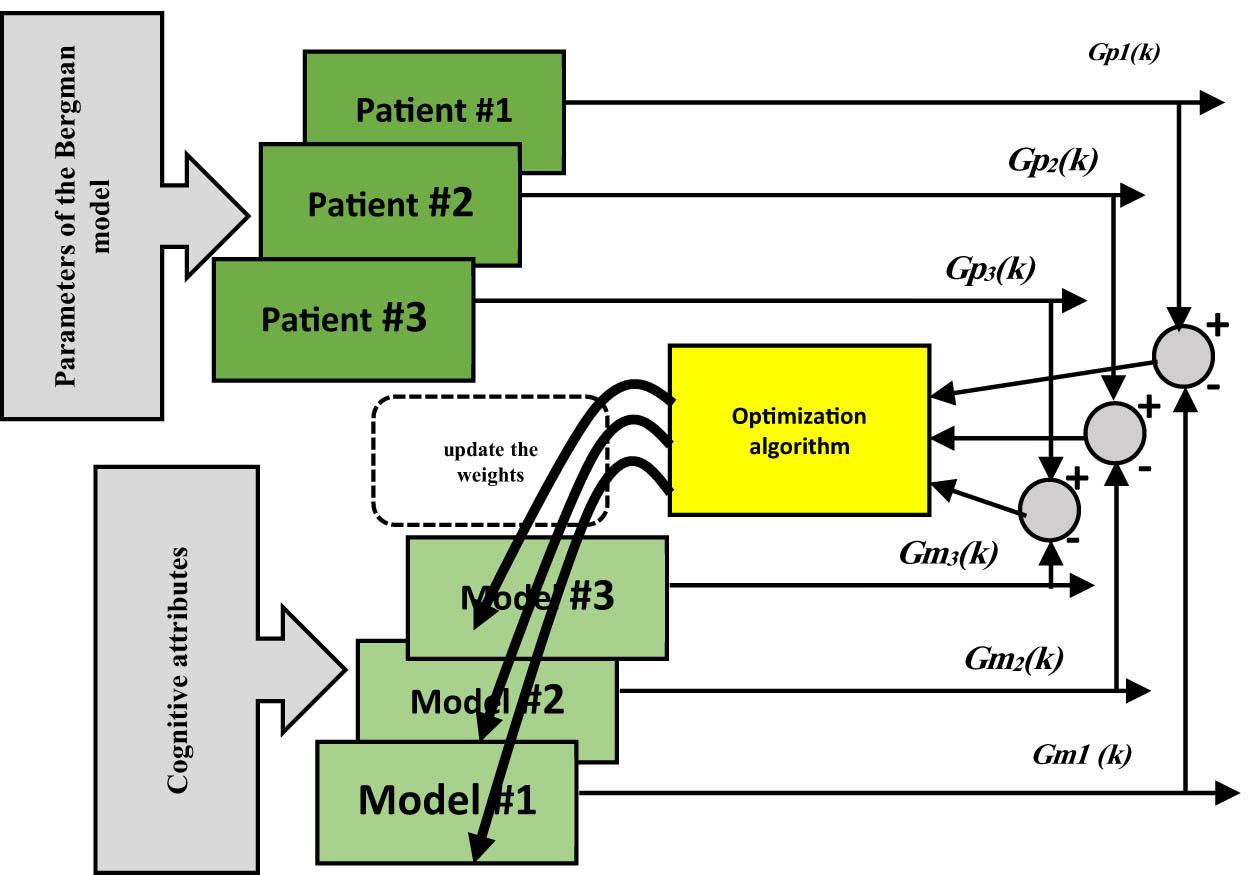

In general, the identifier model is based on the NARMA-L2 neural network model [23] that will represent the different types of the nonlinear diabetic patient model. Specifically, three different types of the nonlinear Bergman glucose–insulin model are used with the input–output dataset, including insulin Iin(k) in mU/dl and glucose Gp(k) in mg/dl, as well as the dataset in layer #1 to build the proposed nonlinear identifier neural network glucose–insulin model. Therefore, the modelling of the nonlinear glucose–insulin is the primary aim of the proposed cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy, which is utilized to provide the preconditions for analysis and will be used in the third layer of the control design. In fact, the purpose of the nonlinear glucose–insulin identification is to find a mathematical model of the different types of the nonlinear Bergman glucose–insulin model whose output corresponds to the output of the nonlinear diabetic patient models. In this regard, neural networks are mathematical models with excellent fault tolerance, adaptiveness, and associative memory capacities that can process data concurrently. To establish the neural network glucose–insulin model, the identifier model of the nonlinear diabetic patient model is constructed using the NARMA-L2 neural network model illustrated in Figure 5.

![Figure 5

FH

[

−

]

\text{FH}{[}-]

and

G

\text{G}

H[−] of the neural network structure.](/document/doi/10.1515/nleng-2025-0135/asset/graphic/j_nleng-2025-0135_fig_005.jpg)

For the proposed identification process, the NARMA-L2 model was selected among several traditional neural networks due to its unique advantages. More specifically, strong robustness performance, no output oscillation, favourable dynamic properties, and an increasing degree of the nonlinear glucose–insulin model performance, are provided by the two networks of FH[−] and GH[−], which are raised in the order of the hidden units. The cognitive attributes input

The proposed NARMA-L2 model of the nonlinear glucose–insulin model can be described in the following equation:

The

where nfh and ngh represent the hidden nodes’ number, which is equal to 15 nodes.

Second, the neuron outputs of both FH a and GH a are calculated as a continuous unipolar sigmoid activation function [24] of the FHnet a and GHnet a , as illustrated in the following equations:

Third, to calculate the weighted sum Fnet o and Gnet o of the output layers, the following equations are used, respectively.

The one linear neuron passes the sum of both (Fnetfo) and (Gnetgo) through a linear function of slope 1, as shown in Eqs. (21) and (22).

The neural network output is the glucose level of the modelling, specifically Gm(k), that can be expressed as given in the following equation:

As depicted in Figure 6, we use the five strategies to address the challenge of recognizing and simulating the nonlinear glucose–insulin patient model.

![Figure 6

The identification and modelling steps for the nonlinear glucose–insulin model [25].](/document/doi/10.1515/nleng-2025-0135/asset/graphic/j_nleng-2025-0135_fig_006.jpg)

The identification and modelling steps for the nonlinear glucose–insulin model [25].

According to the biological description of the nonlinear glucose–insulin patient model, the major physical variable output of the model is the glucose level. Conversely, the cognition attributes in layer #1 are the inputs for the nonlinear glucose–insulin patient model in our work. The structure of the proposed nonlinear glucose–insulin patient identifier model is shown in Figure 7.

The structure of the proposed nonlinear glucose–insulin patient identifier model.

The GWO algorithm is an intelligent algorithm based on the grey wolf predation [26]. Similar to other intelligent algorithms, each grey wolf’s position indicates a feasible response, and the prey indicates the optimal one. Grey wolves are ranked according to the value of their fitness function in an effort to identify the best answer. With three different kinds of grey wolf groups, hierarchical commands can be created.

The grey wolves with the highest fitness function value make up the leader group, often known as the alpha (α) group. The alphas are in charge of making judgments about hunting, waking times, sleeping spots, and other things. Ironically, despite not being the strongest individual in the group, the alpha must be the best pack manager. The wolves in the beta (β) group, the second echelon of leadership, are frequently called co-leaders since they assist the alpha in pack activities and decision-making. The delta (Δ) groups come after them. The probable prey’s location is nearer the wolves α, β, and Δ [27]. The hierarchy of grey wolves during predation is one distinctive feature of GWO. In essence, three primary phases of hunting are conducted to maximize efficiency, including finding the prey, encircling the prey, and attacking the prey. After α groups lead grey wolves to encircle their victim, β and Δ groups assault the prey, and the prey is eventually taken. Because of this process, the approach, which is simple to develop, has few parameters, does not require specialized search parameters, and achieves high convergence performance. At the beginning of the process, a fixed number of grey wolves is used, and their places are selected at random. Each group in the pack will encircle the others according to the following mathematical formuls [26,27]:

Particularly, Eq. (24) represents the distance between the grey wolf and its prey. In Eq. (25), iter indicates the current iteration. A and C are coefficient vectors, and Xp and X are the position vectors of the prey and the grey wolf, respectively, representing the formula for the grey wolf’s position update [28]. The formulas used to determine A and C are as follows:

The convergence factor serves as its representation, and the random vectors r 1 and r 2 are chosen randomly from the interval (0, 1). The total number of iterations is called ItMax. According to the following equations [29], the grey wolf locations α, β, and Δ (the three temporarily ideal solutions) are averaged to determine the prey position X p (iter + 1) update, while the remaining locations are ignored for the position update:

where

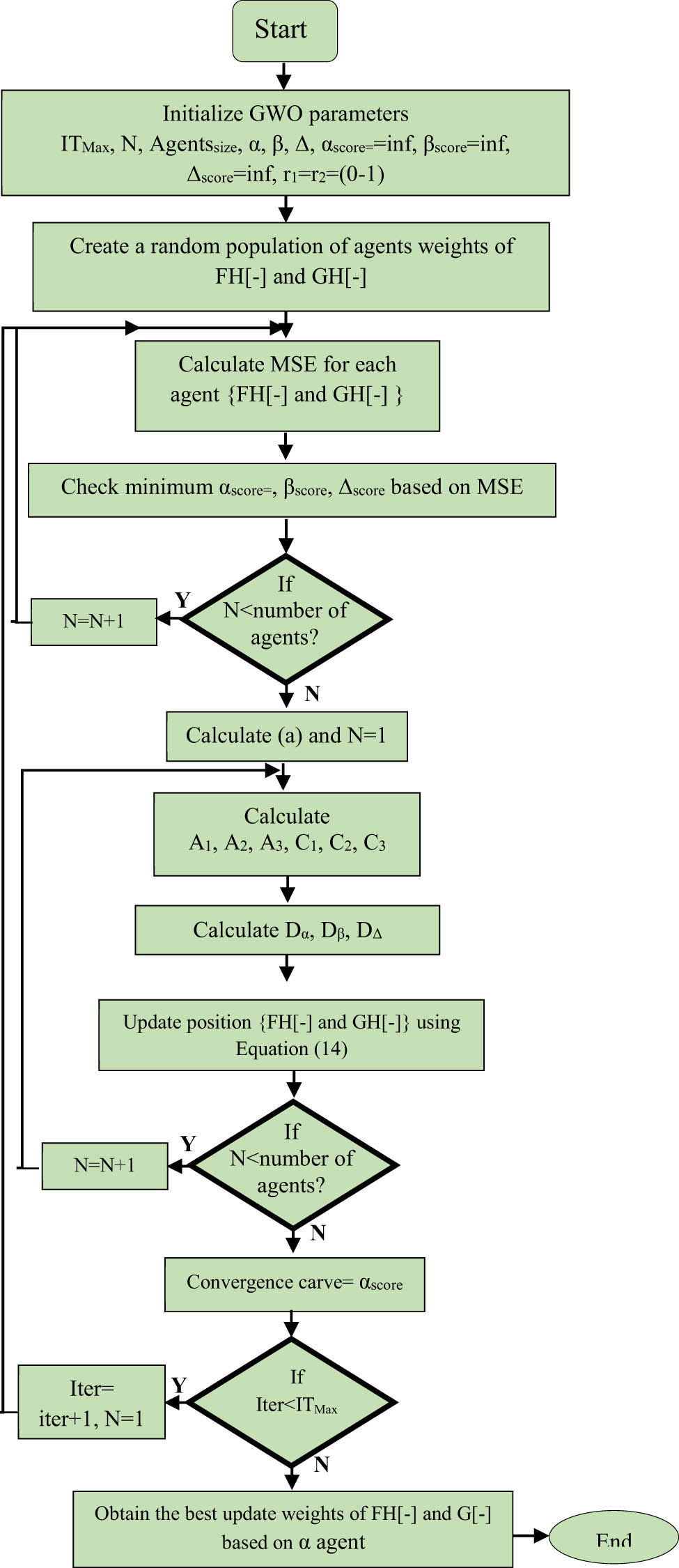

The random vectors C 1, C 2, and C 3 characterize the final positions of the solutions, whereas Dα, Dβ, and DΔ in Eq. (30) indicate the distances between α, β, and Δ and other individuals, respectively. Furthermore, their beginning and finishing positions are specified by Eq. (29). When the victim eventually stops moving, the grey wolf attacks to put an end to the search [26,27,28,29]. The fundamental method for creating a process model is to gradually reduce the value of a, which reduces the range of fluctuations in A. Stated otherwise, the corresponding value of A fluctuates in the interval (−a, b) during the iterative process in a manner akin to the linear decrease in the interval [2, 0]. The identifier model based on NRMA-L2 will produce the same actual response of the glucose level after using the neural network’s training procedure, as shown in Figure 7. Then, the grey wolf learning algorithm is applied to reduce the error of the glaucous level model (the neural network model) Gm(k) and the real glaucous level Gp(k), which is nearly equal to 80 mg/dl. Thus, it will be feasible to confirm that the network is correctly learnt and that the model’s glucose level corresponds to the intended glucose level that characterizes the variation between the glaucous level and the glucose level identity model using a testing set. Particularly, the NARMA-L2 neural network is used to generate the series-parallel identification model. It is clear that the network receives the prior inputs and outputs of the glucose level system at each time instant, and that the network’s output provides the prediction error. Nevertheless, this method can only be applied in conjunction with the series-parallel system, in which the inputs to the neural network (identifier) model in the structure are the outputs of the genuine glucose level model. Figure 8 outlines the basic steps of the GWO method for determining and adjusting the weights of the FH[−] and GH[−] neural networks. The mean square error (MSE) is used as the cost function to evaluate each solution in the GWO algorithm [15]:

where ITmax is the maximum number of iterations and K denotes the maximum number of samples.

The flowchart of updating the weights for the identifier patient model based on the GWO algorithm.

3.3 The feedforward neural network controller

The NARMA-L2 neural network model serves as the foundation for the feedforward neural network controller, which calculates the maximum insulin-infusion amount

where

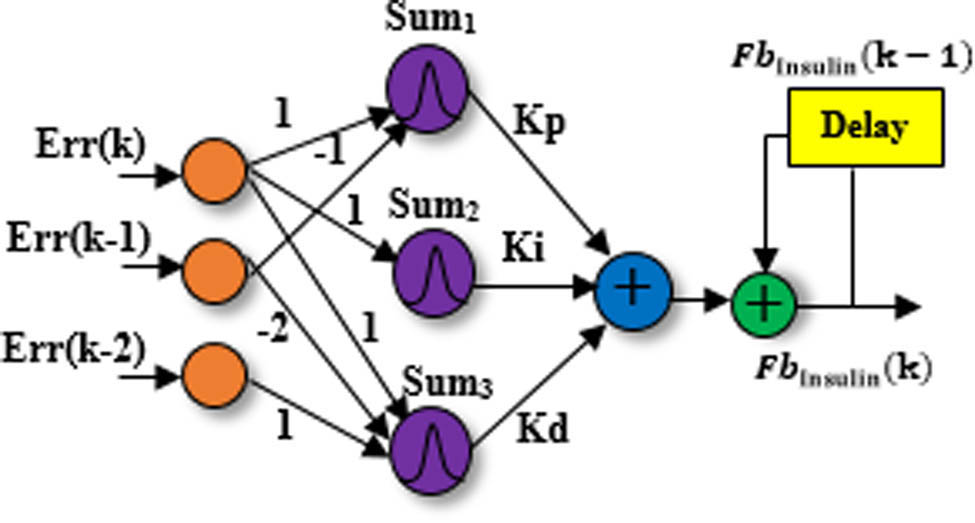

3.4 The feedback controller

The feedback controller’s task is to maintain normal blood glucose levels and determine the ideal insulin infusion value. Based on Gaussian neural networks [30], which have been proven to be effective schemes for learning complex input–output nonlinear mapping and have been employed in the learning and control of nonlinear dynamic systems, the suggested structure of the nonlinear feedback PID-RBF-NN controller is depicted in Figure 9.

The proposed nonlinear feedback PID-RBF-NN controller structure.

The discrete PID controller is described in Eq. (34), which is used to calculate the RBF neural network feedforward algorithm [15]:

where K p, K i, and K d are the control gain parameters of the PID controller. Therefore,

As its input, the nonlinear feedback PID-RBF-NN controller receives the error signal between the desired and the actual blood glucose levels

where

where α and

The final insulin value in Eq. (44), which serves as the control action

In order to obtain the optimal or near-optimal insulin control action for the nonlinear Bergman model, which keeps the blood glucose level in the normal state to prevent the hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia states, the control gain parameters of the PID-RBF-NN controller (K p, K i, and K d) can be found offline, and then, adjusted online using the GWO algorithm, as shown in Figure 8.

The GWO method uses the mean square error with the multi-objective function that reduces the error between the desired glucose level and the patient’s glucose level and, at the same time, reduces the value of the insulin control action for each solution:

where ITmax is the maximum number of iterations and K denotes the maximum number of the samples.

3.5 The nonlinear patient Bergman minimal model

The nonlinear patient Bergman minimal model is explained in Section 2.

4 Numerical simulation results

In this work, the numerical fourth-order Runge–Kutta (4RK) method based on the MATLAB package with a half-minute sampling time was utilized to implement the cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy for the nonlinear diabetic patient model in Figures 3 and 4. This control strategy will achieve the optimal insulin-infusion level for the different types of nonlinear diabetic patient models to avoid the hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia states and to keep the blood glucose level of the patient in the desired normal state. Specifically, five steps are implemented, as illustrated below.

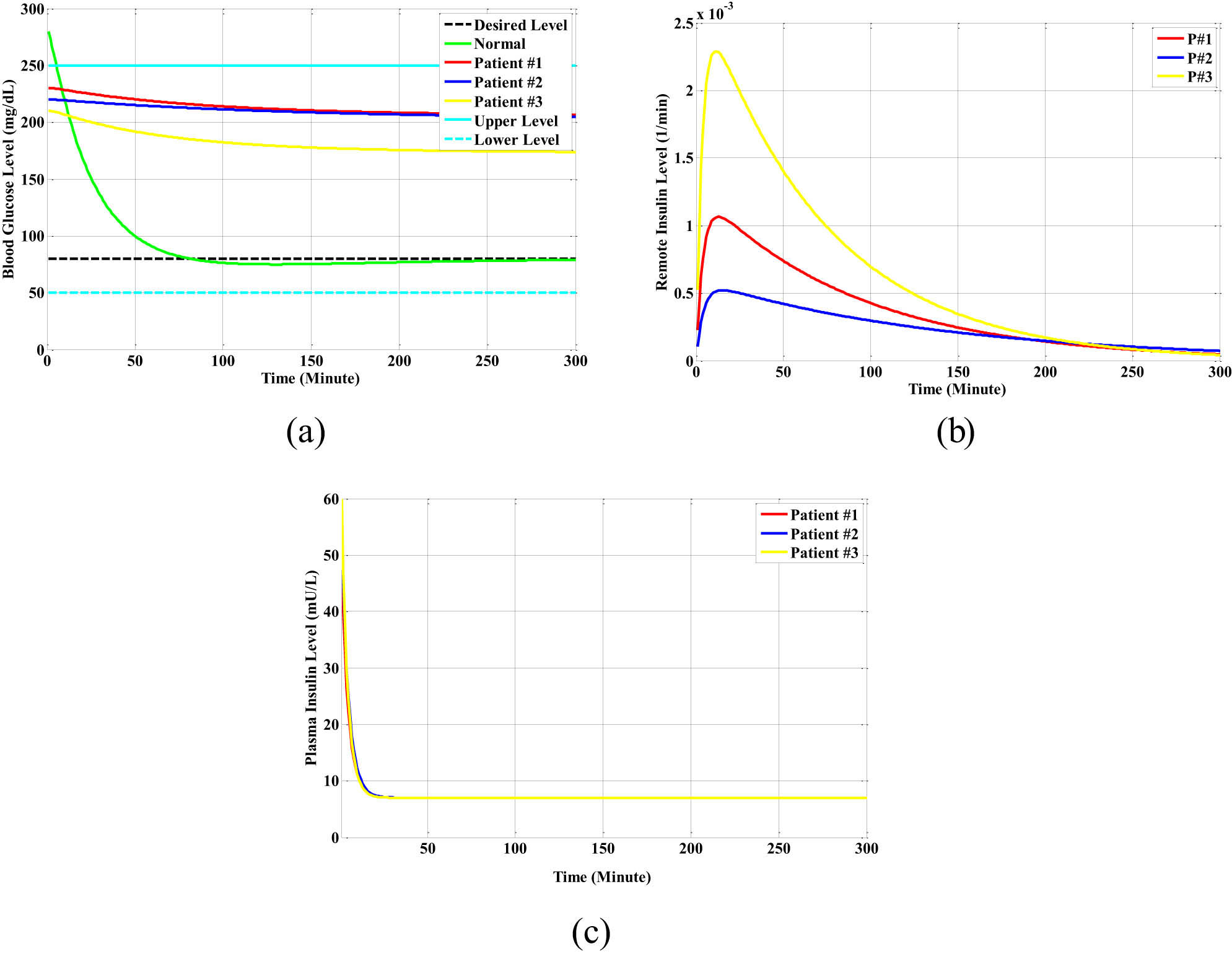

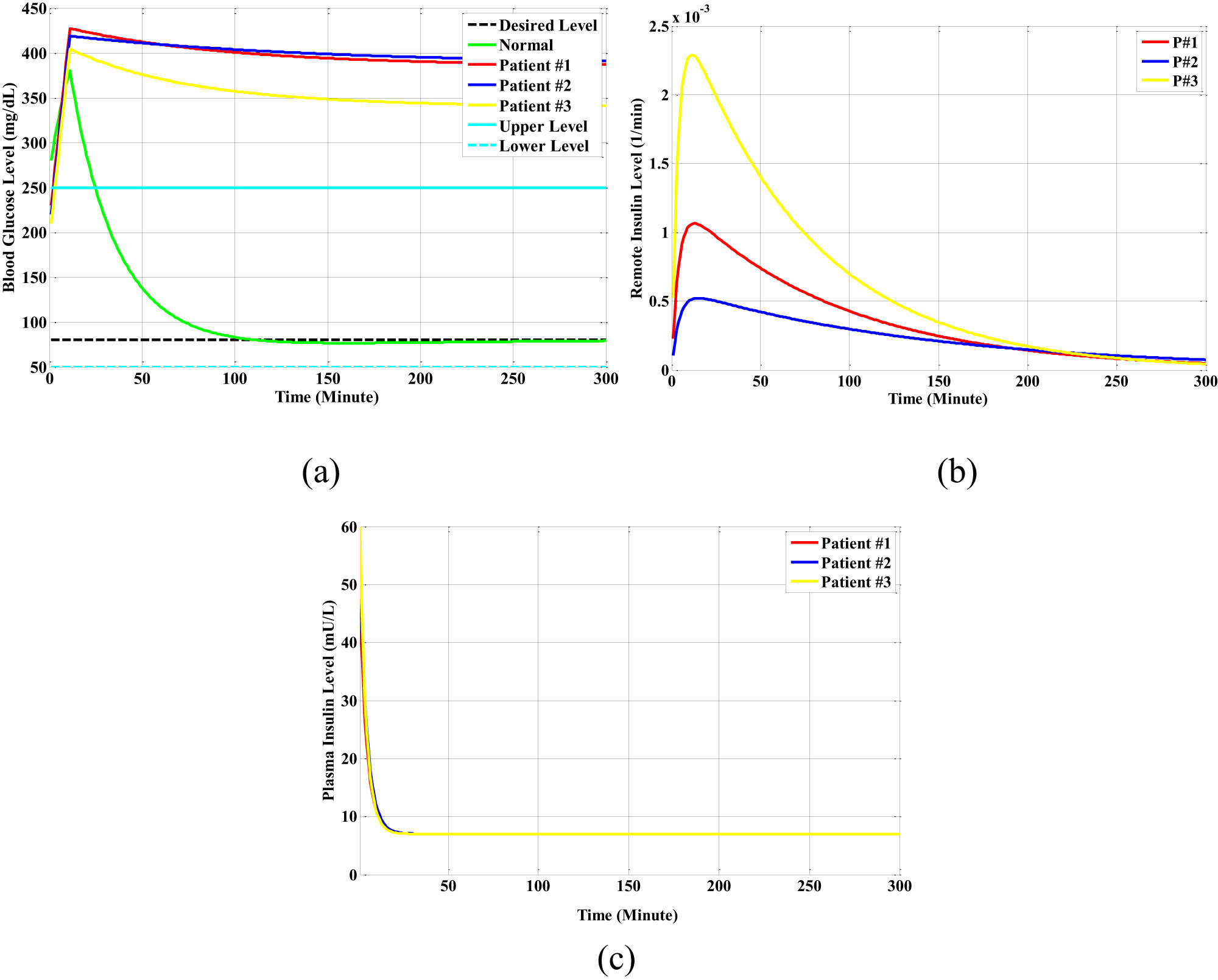

The first step is to determine the cognitive attributes dataset, as given in Table 2, with the blood glucose level of the patient Gp(k), the blood–insulin concentration Ins(k), and the active insulin in the remote compartment performs Xp(k), as an open-loop patient model for a healthy individual as well as for three distinct categories of diabetic patients who are dependent on the glucose starting levels (Go) of (280, 230, 220, and 210) mg/dl, respectively, and without any disturbance meal, as demonstrated in Figure 10a–c. From Figure 10a, the impulse response of the glucose level of the normal person that depends on the initial glucose level of 280 mg/dl reduces the glucose level from 280 mg/dl to the normal state at a value equal to 80 mg/dl during 75 min.

The open-loop responses for a normal person and for different types of diabetic patients in the initial state: (a) the glucose level, (b) the remote insulin level, and (c) the plasma insulin level.

However, for the three different types of diabetic patients, the reduction in the glucose level from the initial levels was very small, and they did not reach the normal glucose level. From Figure 10b, the responses of the remote insulin level of the three different types of diabetic patients are very small values that spread in the blood of the diabetic patients. From Figure 10c, the responses of the plasma insulin level of the three different types of diabetic patients are small values that depend only on the initial plasma insulin level I o(mU/l) in the blood of the diabetic patients due to the inability or insufficiency of the pancreas to generate insulin.

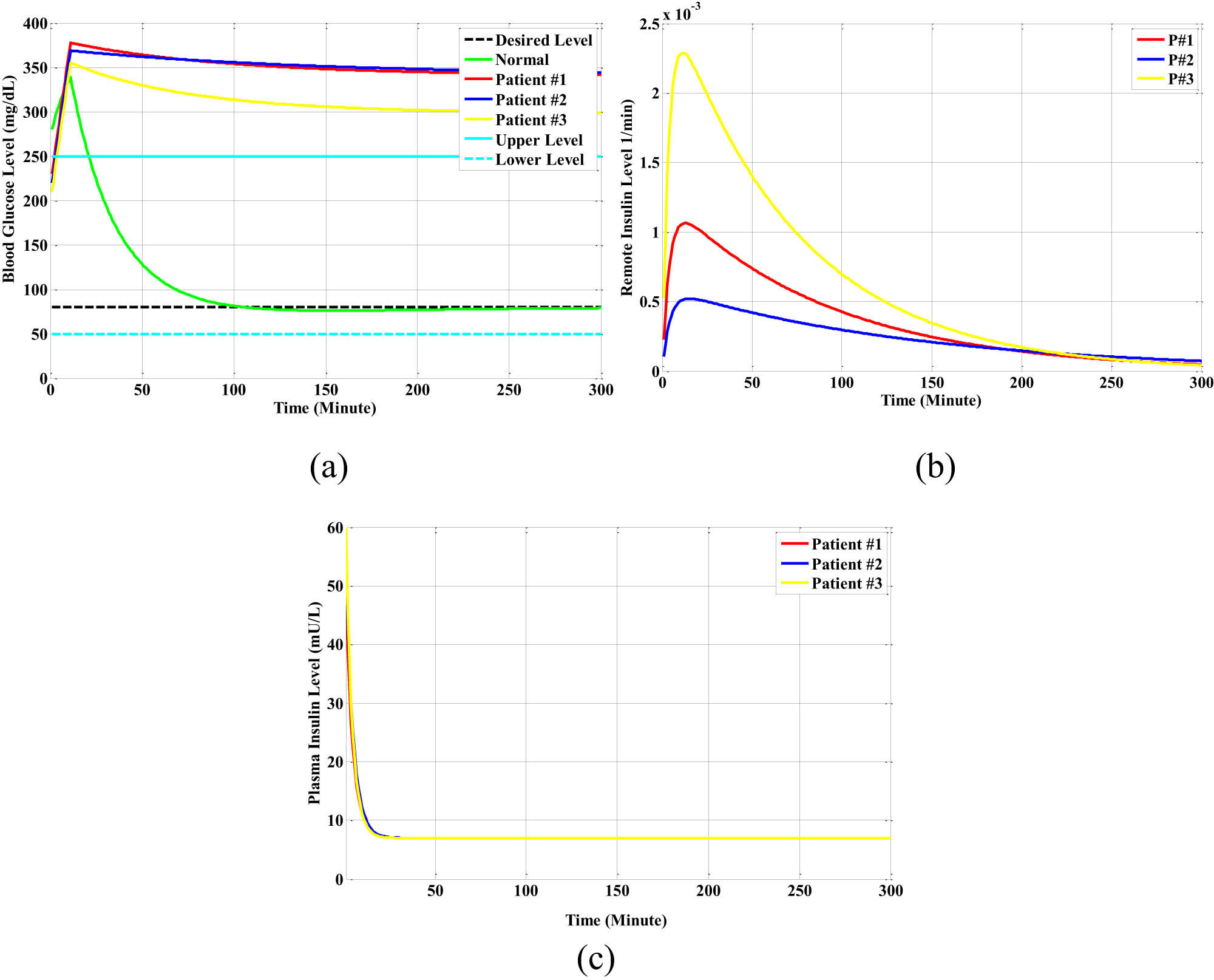

Figure 11a–c demonstrate the blood glucose level of different types of three patients (Gp1(k), Gp2(k), and Gp3(k)), the blood–insulin concentration (Ins1(k), Ins2(k), and Ins3(k)), and the active insulin in the remote compartment for the three different types of diabetic patients (Xp1(k), Xp2(k), and Xp3(k)) with the same initial glucose levels Go. However, the disturbance meal at breakfast is equal to 15 mg/dl blood glucose level.

The open-loop responses for a normal person and for different types of diabetic patients in the breakfast-meal state: (a) the glucose level, (b) the remote insulin level, and (c) the plasma insulin level.

From Figure 11a, the impulse response of the glucose level of the normal person that depends on the initial glucose level and the breakfast meal reduces the glucose level from 350 mg/dl to the normal state at a value equal to 80 mg/dl during 100 min. However, for the three different types of diabetic patients, the glucose levels increased by more than 350 mg/dl during 10 min with a very small decay in the glucose level from the peak levels of 375 mg/dl, and they did not reach the normal glucose level. Nevertheless, the glucose level of the patient at the hyperglycemia is dangerous.

From Figure 11b, the breakfast meal did not affect the response of the remote insulin level of the three different types of diabetic patients, and they are very small values that spread in the blood of the diabetic patients.

From Figure 11c, the responses of the plasma insulin level of the three different types of diabetic patients are small values that depend only on the initial plasma insulin level I o(mU/dl) in the blood of the diabetic patients due to the inability or insufficiency of the pancreas to generate insulin.

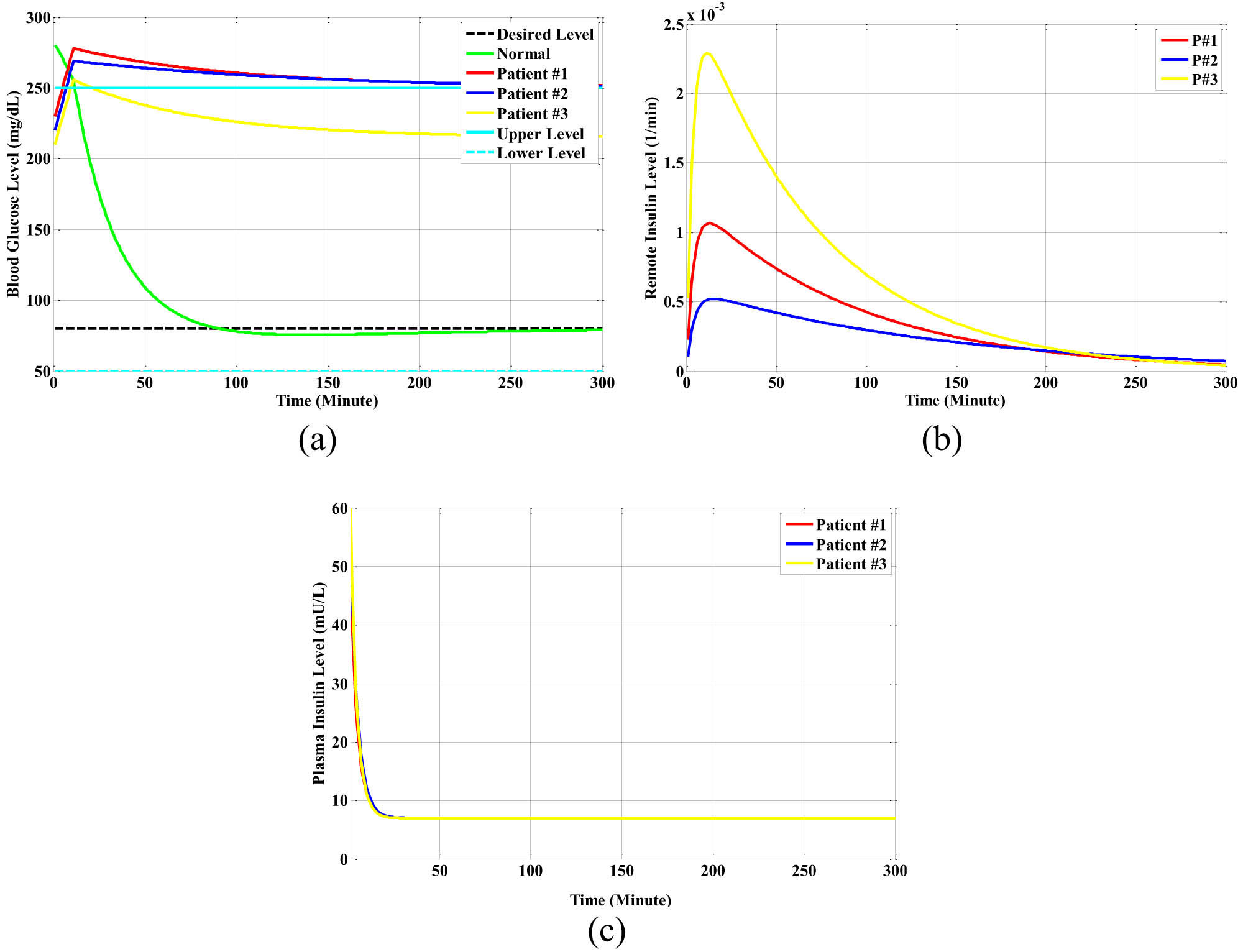

Figure 12a–c demonstrate the dynamic behaviour of the Bergman glucose insulin minimum model for the three different types of diabetic patients representing the blood glucose level, the blood–insulin concentration, and the active insulin in the remote compartment with the same initial glucose levels Go. However, the disturbance meal at lunch is equal to 20 mg/dl blood glucose level.

The open-loop responses for a normal person and for different types of diabetic patients in the lunch-meal state: (a) the glucose level, (b) the remote insulin level, and (c) the plasma insulin level.

From Figure 12a, the impulse response of the glucose level of the normal person that depends on the initial glucose level and the lunch meal reduces the glucose level from 400 mg/dl to the normal state at a value equal to 80 mg/dl during 110 min.

However, for the three different types of diabetic patients, the glucose level increased by more than 400 mg/dl during 10 min with a very small decay in the glucose level from the peak levels of 425 mg/dl, and they did not reach the normal glucose level. Particularly, the glucose level of the patient at the hyperglycemia level is dangerous.

From Figure 12b, the lunch meal did not affect the response of the remote insulin level of the three different types of diabetic patients, and they are very small values that spread in the blood of the diabetic patients.

From Figure 12c, the responses of the plasma insulin level of the three different types of diabetic patients are small values that depend only on the initial plasma insulin level I o(mU/l) in the blood of the diabetic patients due to the inability or insufficiency of the pancreas to generate insulin.

Figure 13a–c demonstrate another dataset, which includes adding the disturbance meal at dinner with a blood glucose level equal to 5 mg/dl for the three different types of diabetic patients with the same initial glucose levels Go.

The open-loop responses for a normal person and for different types of diabetic patients in the dinner-meal state: (a) the glucose level, (b) the remote insulin level, and (c) the plasma insulin level.

From Figure 13a, the impulse response of the glucose level of the normal person that depends on the initial glucose level and the dinner meal reduces the glucose level from 280 mg/dl to the normal state at a value equal to 80 mg/dl during 90 min.

However, for the three different types of diabetic patients, the glucose level increased by more than 250 mg/dl during 10 min with a very small decay in the glucose level from the peak levels of 280 mg/dl, and they did not reach the normal glucose level. In particular, the glucose level of the patient at the hyperglycemia level is dangerous.

From Figure 13b, the dinner meal did not affect the response of the remote insulin level of the three different types of diabetic patients, and they are very small values that spread in the blood of diabetic patients.

From Figure 13c, the responses of the plasma insulin level of the three different types of diabetic patients are small values that only depend on the initial plasma insulin level I o (mU/l) in the blood of the diabetic patients due to the inability or insufficiency of the pancreas to generate insulin.

From Figures 10–13, the responses of the blood glucose levels for the different types of the three patient Bergman models have three real phenomena as follows: they started high, decreased very slowly, and would never return to the normal state, which causes the patient to be in a dangerous state. However, the healthy person curve shows a normal glucose level dropping from a high value to the physiological level, or the normal glucose level (between the upper level of 150 mg/dl and the lower level of 60 mg/dl), in which consuming high blood sugar is not harmful.

Conversely, the glucose value is exceedingly high and well beyond the physiological range, putting the patient in danger mode with hyperglycemia (250 mg/dl) and hypoglycemia (50 mg/dl). In step two, the nonlinear glucose–insulin patient model is displayed in Figure 7 using the structure of the NARMA-L2 neural network described in Figure 5.

Accordingly, the suggested number of nodes in each of the FH[−] and the GH[−] networks, which have three layers, including the input layer, the hidden layer, and the output layer, is as follows: [7:15:1], respectively. The number of nodes in the hidden layer is equal to twice the number of nodes in the input layer plus one. The third step involves learning the identifier model of the nonlinear glucose–insulin patient models using the GWO offline algorithm and then tuning the models online. In order to resolve the numerical problems related to actual values, the signals entering or leaving the neural network (NN) have been treated to lie between (−1) and (+1). Therefore, the scaling functions must be applied at the first layer and the last layer of the neural network terminals (input–output), respectively, such that the ranges of these inputs are as follows: Gp(k) = (50 to 500) mg/dl, Xp(k) = (0 to 0.05) 1/min, Ins(k) = (0 to 700) mU/L, Food(k) = (5 to 25), Io(k) = (50 to 60) mU/L, Go(k) = (210 to 280) mg/dl, and I max(k) = (0 to 700) mU/L·min−1.

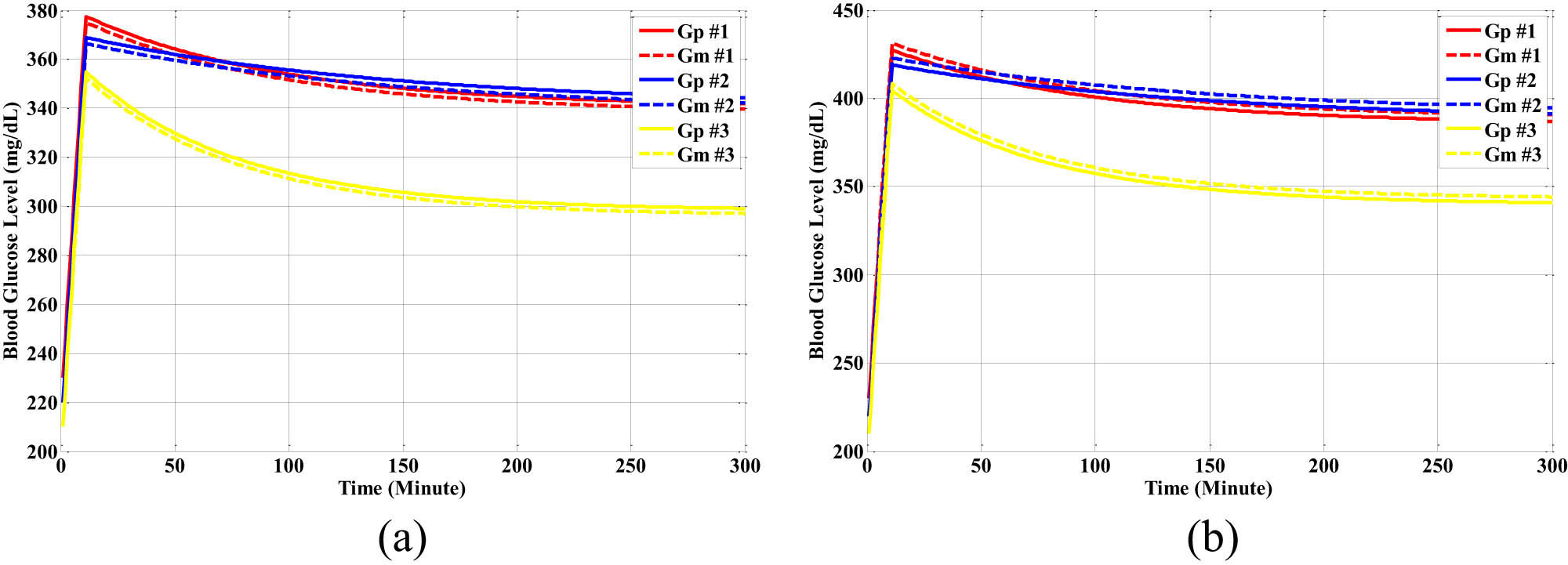

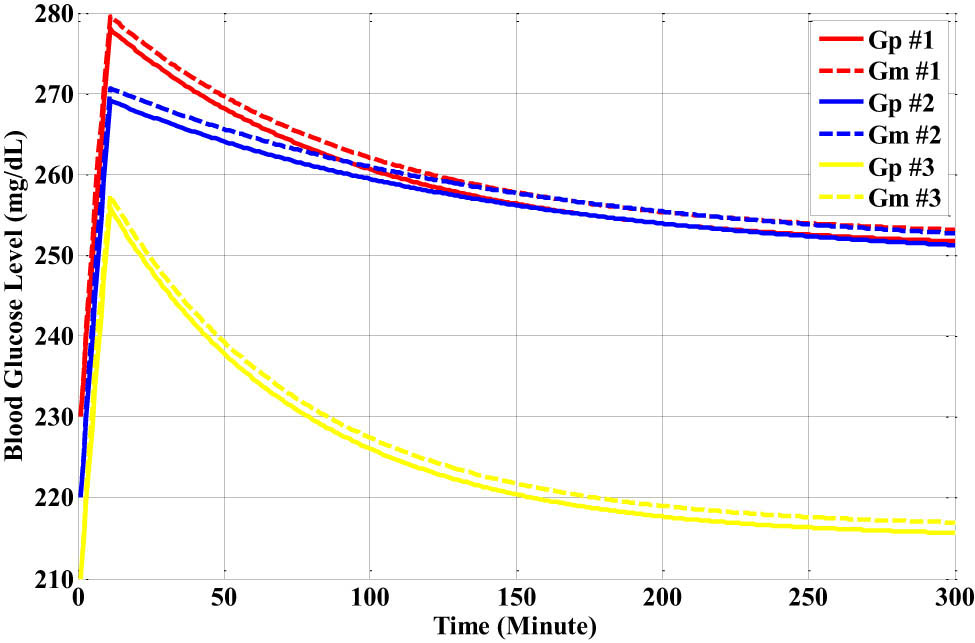

In the learning mode, the responses of the different types of the nonlinear neural network glucose–insulin patient models are shown in Figure 14a and b for two cases, including the breakfast and the lunch meals. These models have a very small error value in the modelling between the Bergman glucose level and the diabetic patient neural network model for 600 patterns as a learning set, and they have good responsiveness of the identifier models with a very good dynamical behaviour during the different cases of disturbance meal inputs (breakfast meal and lunch meal) for the three different types of the nonlinear glucose–insulin patient models.

The response of the different types of the nonlinear neural network glucose–insulin patient models: (a) the breakfast meal learning set and (b) the lunch meal learning set.

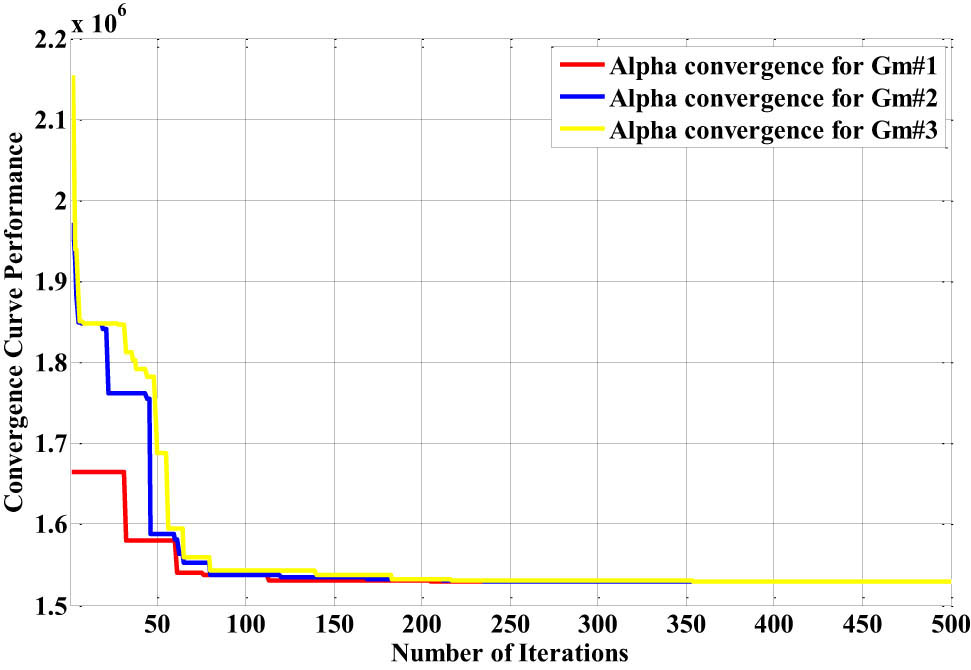

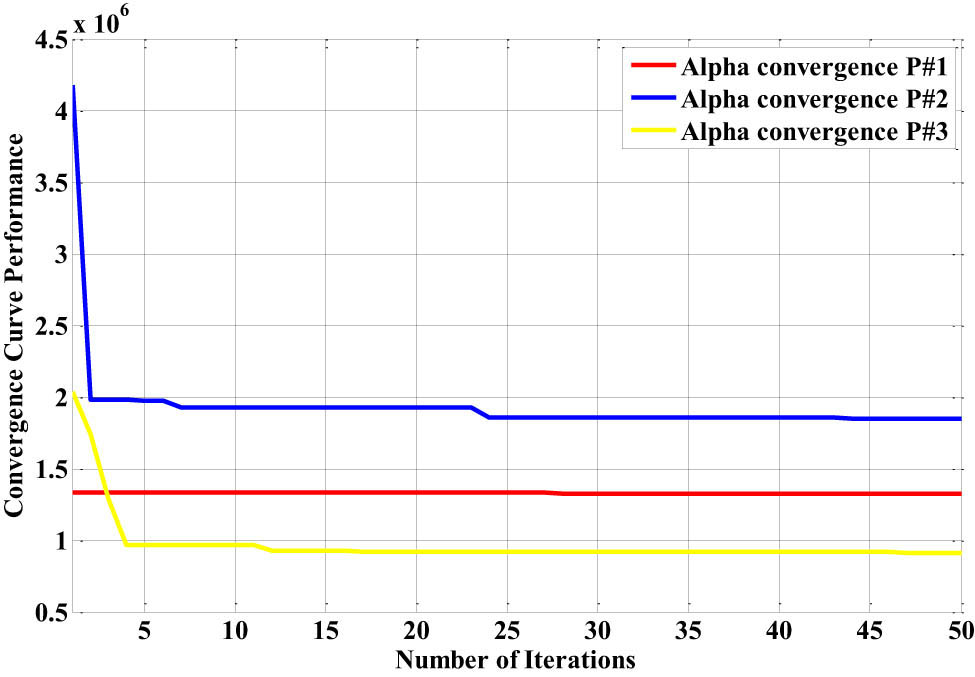

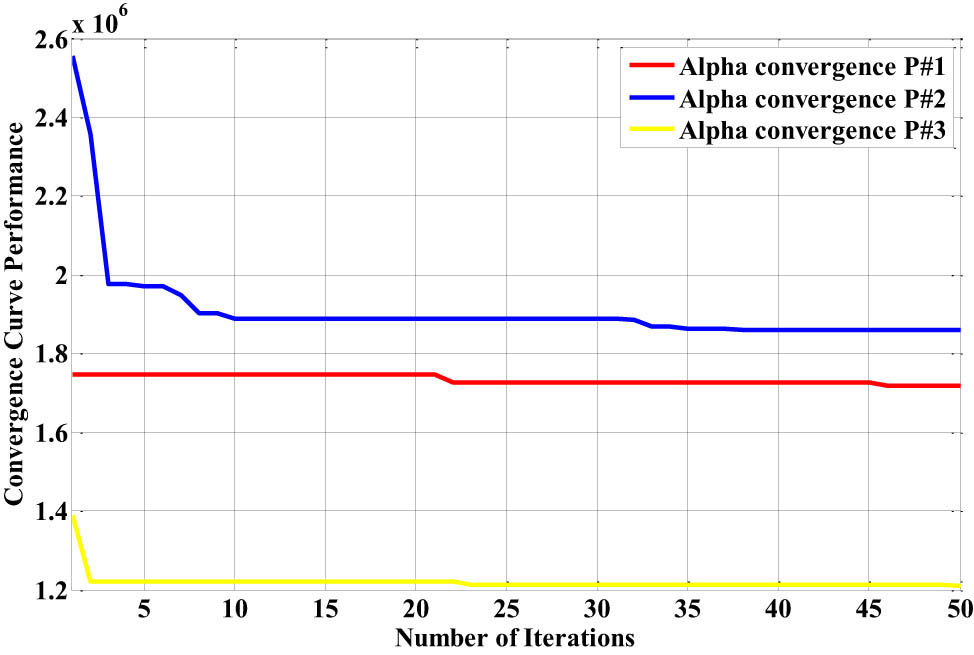

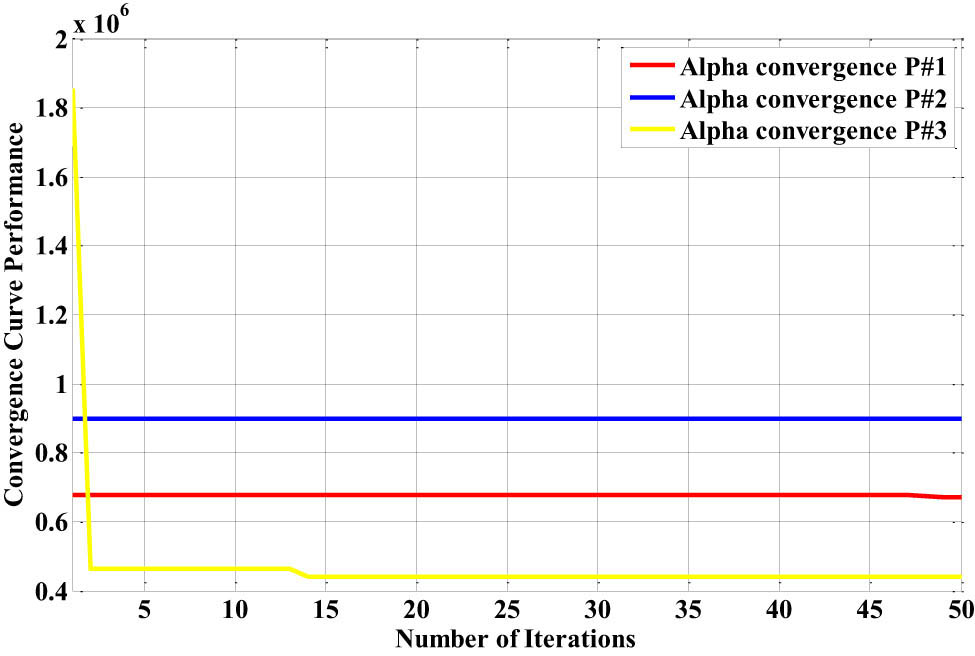

The performance of the best convergence curve is depicted in Figure 15. It is based on the offline GWO algorithm for three different types of patient models with 500 iterations and with an agents’ number equal to 32 for the neural networks of FH[−] and GH[−].

The best alpha convergence curve response of the different types of nonlinear neural network glucose–insulin patient models.

In addition, the number of weights is 120. Specifically, the best alpha convergence curve for the optimal updated weights of the identifier neural network is presented in Figure 15.

To verify that these neural network models have remarkable learning, the testing mode in our work is essentially for the nonlinear glucose–insulin patient models to prove that these neural models have been learned in all the excitation and active regions of the real models and eliminated the overlearning problem. This problem means that the network learns on a part of the region and forgets other regions during the learning mode.

However, the meta-heuristic GWO algorithm learning cycle was excellent because this algorithm is very suitable for exploring and exploiting the global extreme solution of the problems.

Figure 16 demonstrates the dynamical behaviour of the nonlinear glucose–insulin patient models during the testing mode.

The responses of the different types of nonlinear glucose–insulin patient models for the dinner meal testing set.

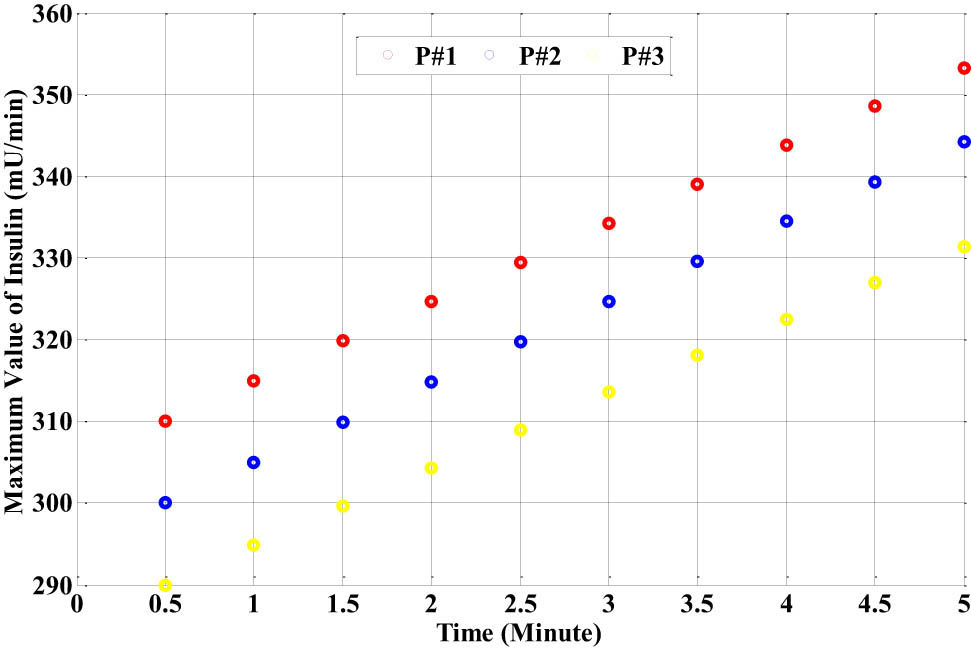

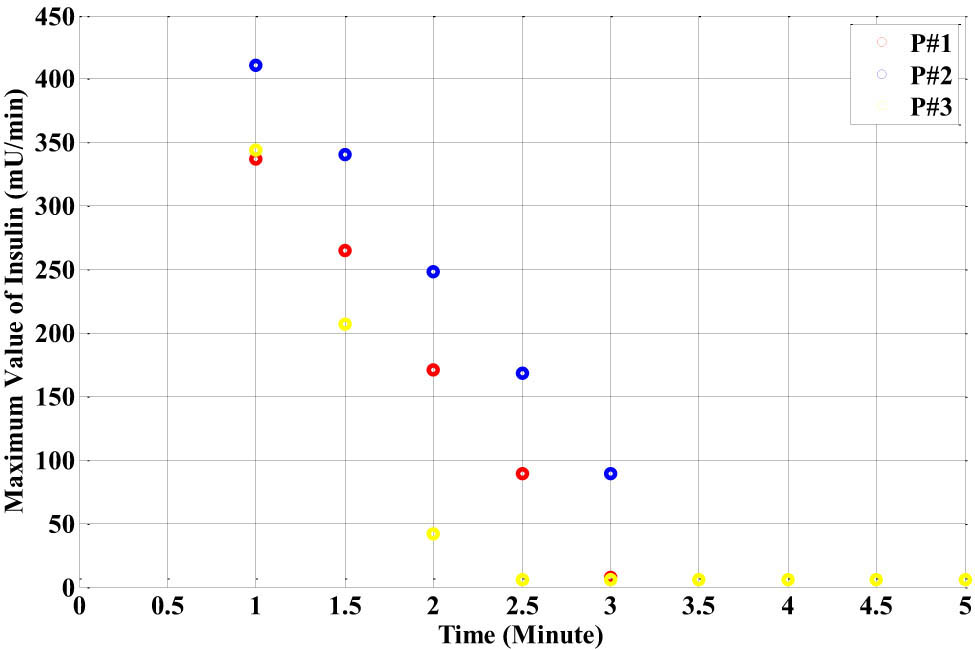

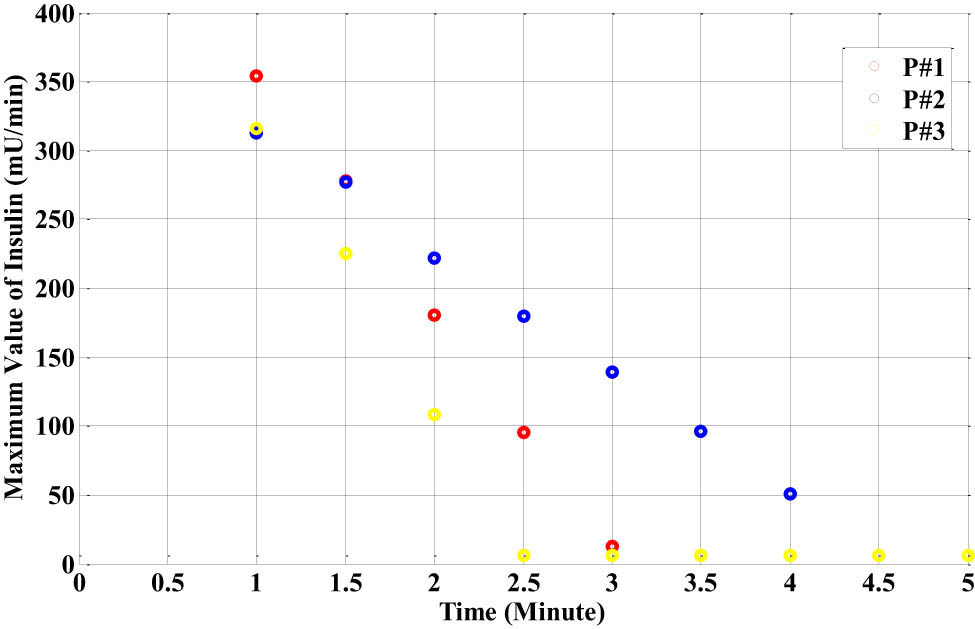

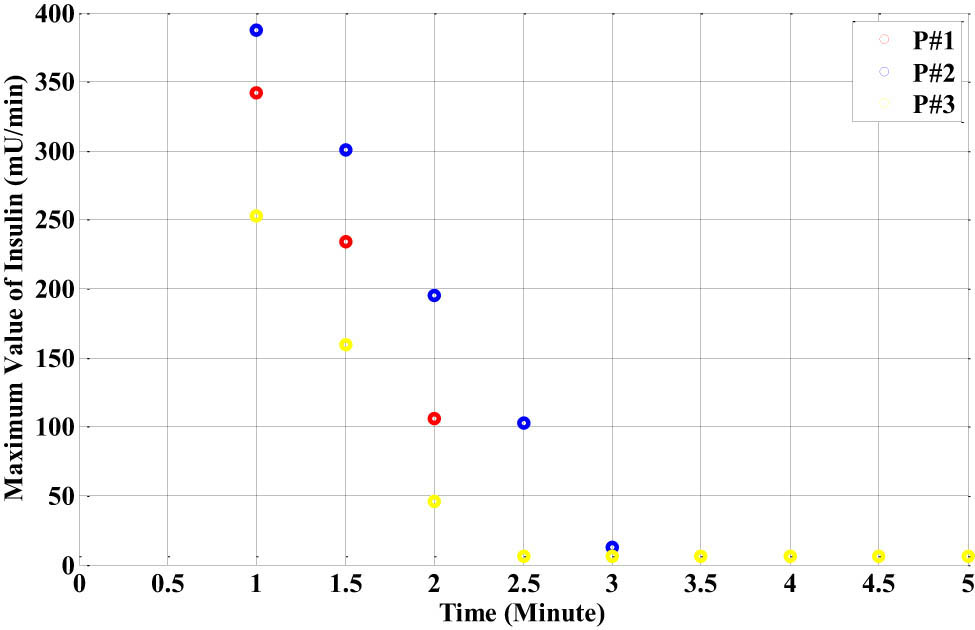

The neural networks glucose level model Gm1,2,3(k) matched the Bergman glucose level Gp1,2,3(k) of the three different types of the nonlinear glucose–insulin patient models when we used 600 patterns for the dinner meal. The fourth step involves representing the feedforward neural network controller based on the NARMA-L2 identifier after sufficient learning and testing for the three different types of the nonlinear neural network glucose–insulin patient identifier models. The aim of this step is to determine the maximum value of the insulin level U max(k) mU/L·min−1 for each meal in the beginning, as shown in Figure 17 with three different patient models.

The response of the maximum insulin level U max for the three different types of the nonlinear neural network glucose–insulin patient identifier models.

From Figure 17, it is clear that the level value of the insulin for each patient is increased for each sample, and only ten samples are taken for example. These values are generated based on the open-loop system, as shown in Eq. (32) without any closed-loop feedback PID-RBF-NN controller. Thus, the error between Gd(k)−FH[−] was not reduced to zero, which led to an increase in the insulin level.

The fifth step involves representing the closed-loop control system for the nonlinear Bergman model based on the proposed PID-RBF-NN controller with the GWO meta-heuristic method using the multi-objective function. This function will reduce the error between the desired glucose level and the patient’s glucose level, and at the same time, it will reduce the value of the insulin control action for each solution of the control gain parameters for the PID-RBF-NN controller (K p, K i, and K d) to find the best value of the insulin-infusion control action in the transient and the steady-state regions.

The suggested PID-RBF-NN controller settings for the search space areas are displayed for each patient in Table 3. These settings are suitable for exploring and exploiting the global extreme solution with different types of patient models and different types of food meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) to find and tune the gain control parameters of the proposed PID-RBF-NN controller.

The active regions of the control parameters’ search spaces for the patient models and the variable disturbance meal

| K p | K i | K d |

|---|---|---|

| −1 to +1 | −0.5 to +0.5 | −5 to +5 |

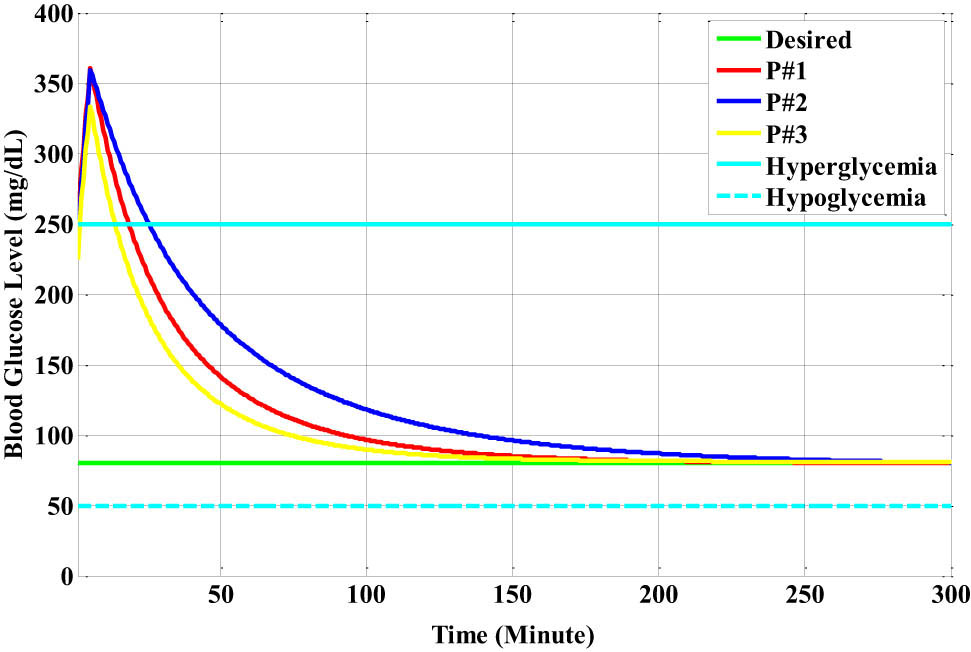

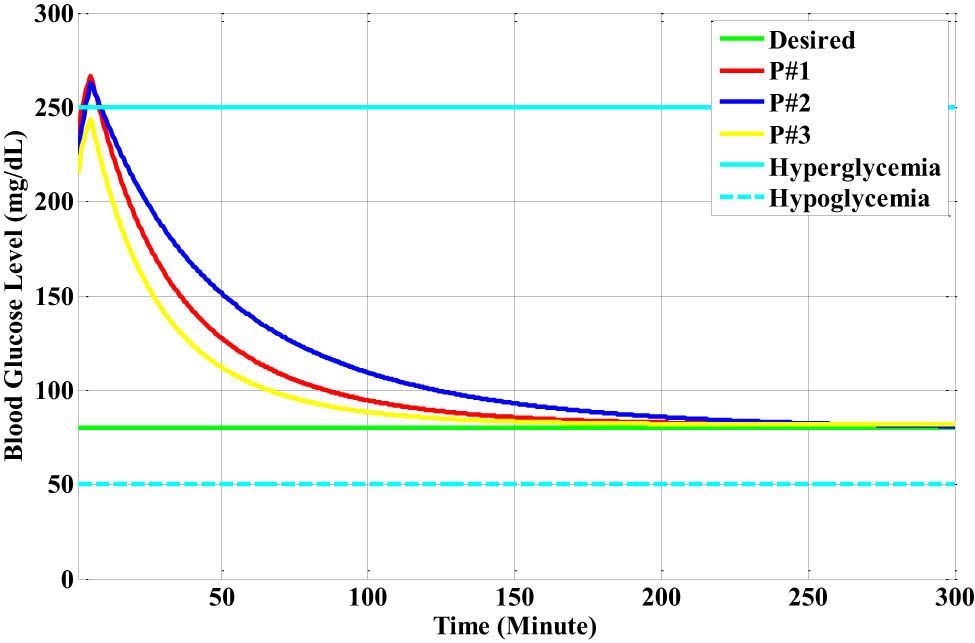

The response of the suggested closed-loop insulin-infusion PID-RBF-NN controller is shown in Figure 18 when the Bergman diabetic patient model adds the breakfast meal as a disturbance.

The glucose responses for each Bergman patient model based on the closed-loop PID-RBF-NN controller with the breakfast disturbance.

The breakfast disturbance effect was introduced for a duration of ten samples for each patient to show the effectiveness of the insulin-infusion control action. In particular, 15 mg/dl is the suggested breakfast disturbance value. The following points indicate that the suggested overall controller improves the patients’ glucose level response:

The insulin-infusion action stabilizes patient #1’s glucose level, as indicated by the red-colour line, which drops from 360 to 250 mg/dl (the hyperglycemia level) and remains there for 18.5 min. Then, it drops to 150 mg/dl (the upper normal physiological level) and remains there for 45.5 min.

Finally, it drops to 80 mg/dl (the normal physiological level) and remains there for 200 min. In contrast, the glucose level of patient #2, which is represented by the blue-colour line, drops from 358 to 250 mg/dl, the hyperglycemia level, and stabilizes there after 24.5 min. It then drops to 150 mg/dl, the upper normal physiological level, and remains there for 67.5 min before dropping to 80 mg/dl, the normal physiological level. Then, it remains there for 220 min.

The third patient’s glucose level, represented by the yellow-colour line, is finally lowered from 333 to 250 mg/dl, or the upper hyperglycemia level, and then, it stabilized there for 14 min. Next, it drops to 150 mg/dl, or the upper normal physiological level, and remains there for 35 min. After that, it drops to 80 mg/dl, or the normal physiological level, and remains there for 150 min.

It is important to note that at 250 min, the blood glucose levels of the first and second patients precisely reached 80 mg/dl at a steady state. They remain at their typical physiological level.

Table 4 shows the time attributes of the blood glucose level of patients #1, #2, and #3 with breakfast meal disturbances.

The time attributes of the blood glucose level of the patients with breakfast meal disturbances

| Patients | G o mg/dl | Maximum blood glucose level after ten samples | Time at 250 mg/dl (min) | Time at 150 mg/dl (min) | Time at 120 mg/dl (min) | Time at 80 mg/dl (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P#1 | 230 | 360 | 18.5 | 45.5 | 67 | 200 |

| P#2 | 220 | 358 | 24.5 | 67.5 | 97.5 | 220 |

| P#3 | 210 | 333 | 14 | 35 | 53 | 150 |

As shown in Table 5, the optimal PID-RBF-NN controller parameters are generated for the Bergman diabetic models of patients #1, #2, and #3 with various meal disturbances (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) using the best-proposed values of the GWO algorithm, including 32 agents and 50 iterations.

The optimal values of the PID-RBF-NN controller parameters for the three different types of patient models with different meal disturbances (breakfast, lunch, and dinner)

| Type of patients | Breakfast meal | Lunch meal | Dinner meal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient #1 | K p = 0.4098 | K p = 0.9804 | K p = 0.2131 |

| K i = 0.3208 | K i = 0.1615 | K i = 0.4620 | |

| K d = 2.6070 | K d = 2.4765 | K d = 2.3509 | |

| Patient #2 | K p = 0.0055 | K p = 0.0079 | K p = 0.3149 |

| K i = 0.1840 | K i = 0.2155 | K i = 0.5372 | |

| K d = 2.1365 | K d = 2.3557 | K d = 3.2244 | |

| Patient #3 | K p = 0.0054 | K p = −0.0079 | K p = 0.3398 |

| K i = 0.2293 | K i = 0.2155 | K i = 0.4808 | |

| K d = 2.4560 | K d = 2.3557 | K d = 2.102 |

The suggested cognitive blood glucose control technique is responsible for generating the optimal or nearly optimal insulin control action for each patient model, which decreases the blood glucose levels and keeps them within a reasonable range.

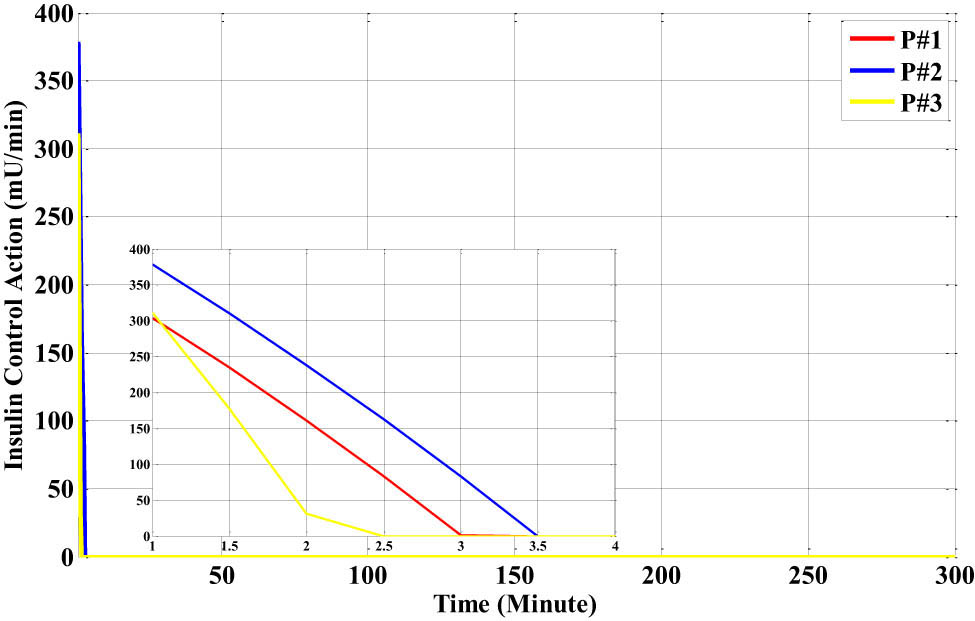

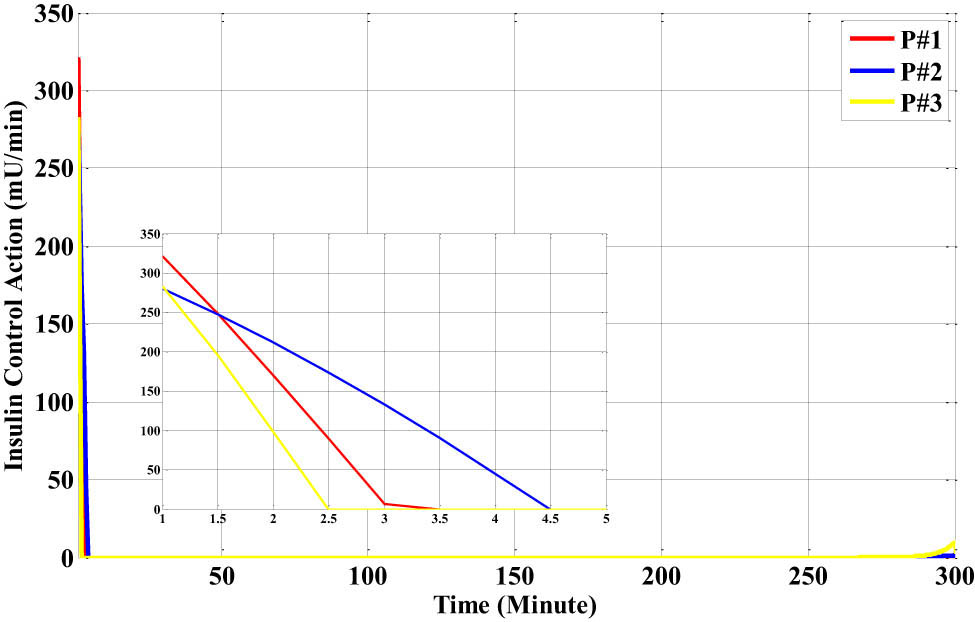

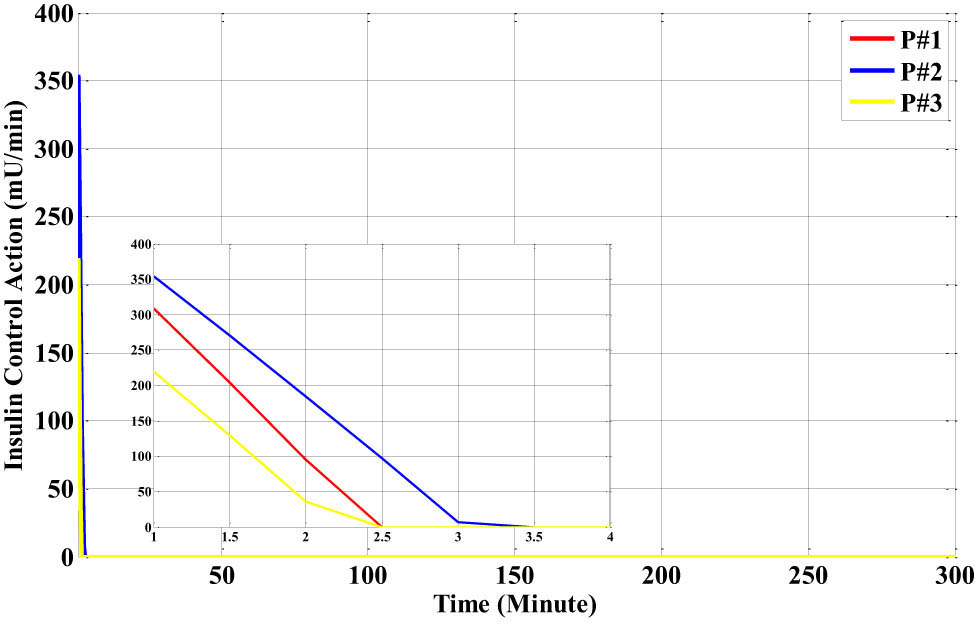

The output response of the insulin-infusion PID-RBF-NN controller during the first ten samples is displayed in Figure 19 when the blood glucose level abruptly rises. The PID-RBF-NN efficiently and rapidly determines the insulin action value for each of the three patients to track the sudden increase in blood glucose levels.

The insulin action of the proposed PID-RBF-NN controller for the three different types of Bergman models with the breakfast disturbance.

The maximum insulin-infusion control action values for patients #1, #2, and #3 are 304, 378, and 311 mU/L·min−1, respectively.

Figure 20 shows the maximum level value of the insulin for each patient, which is a decreased value for each sample, where only ten samples were taken as an example. These values are generated based on the closed-loop feedback PID-RBF-NN controller.

The response of the maximum insulin level U max for the three different types of the nonlinear neural network glucose–insulin patient identifier models with the breakfast disturbance.

Hence, the error between Gd(k) and FH[−] reduces to zero, which leads to a decrease in the U max insulin level to almost zero, which will reduce the insulin control action to zero.

To determine the optimal control gain settings of the PID-RBF-NN controller, Figure 21 shows the response of the best alpha convergence for the three patients.

The best convergence curve response of the PID-RBF-NN controller for the three different types of Bergman patient models with the breakfast disturbance.

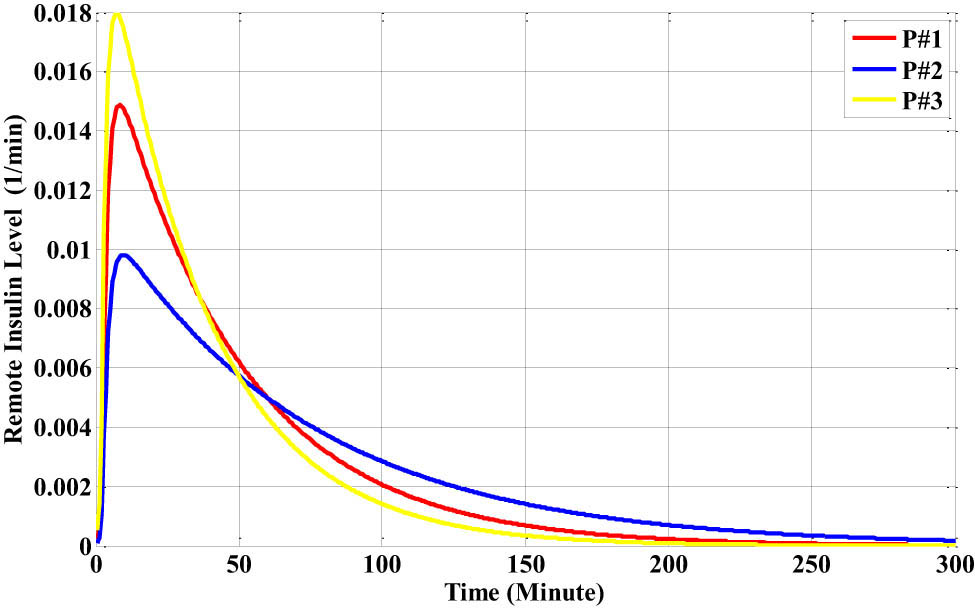

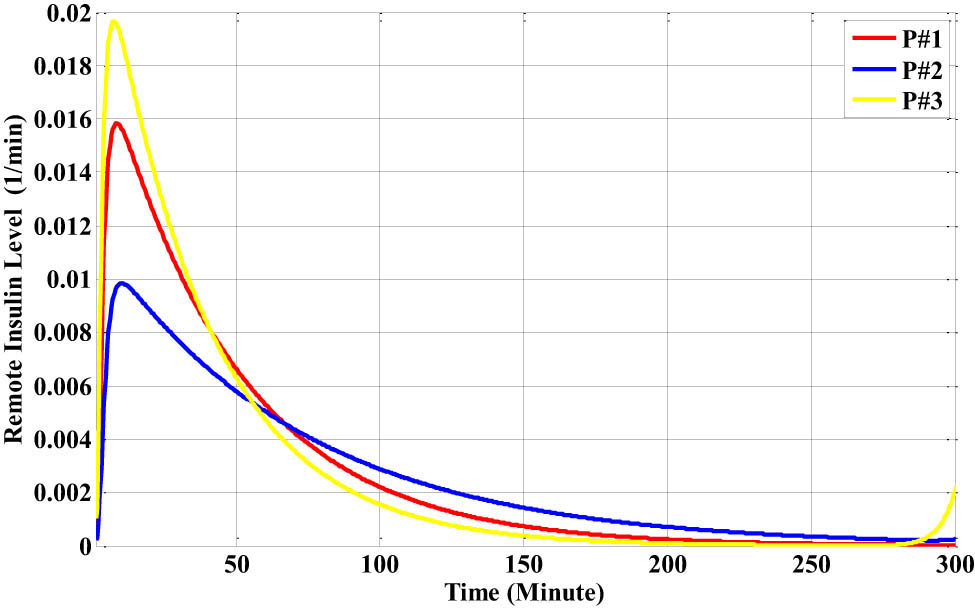

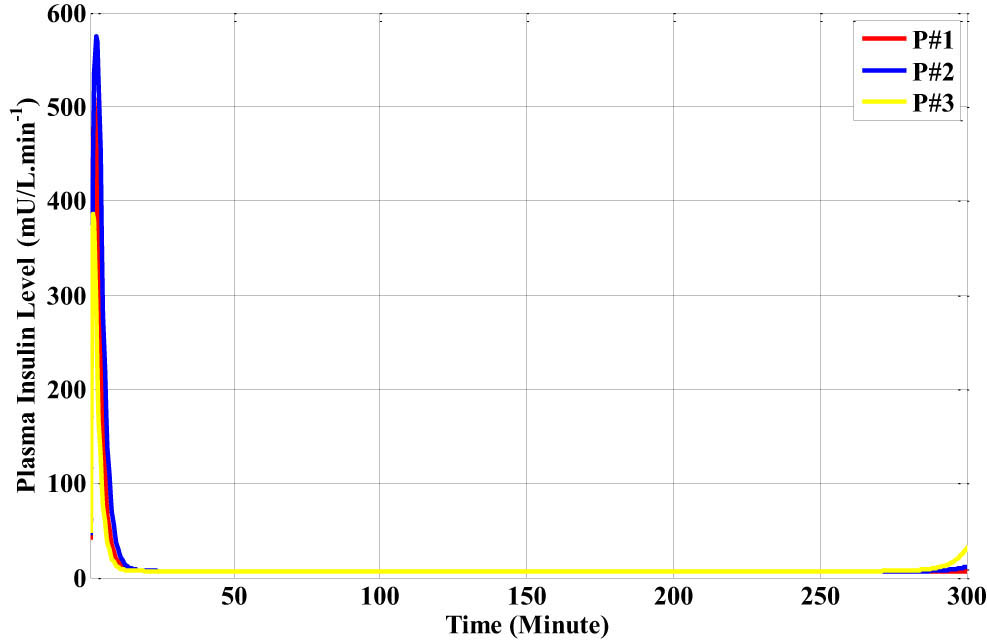

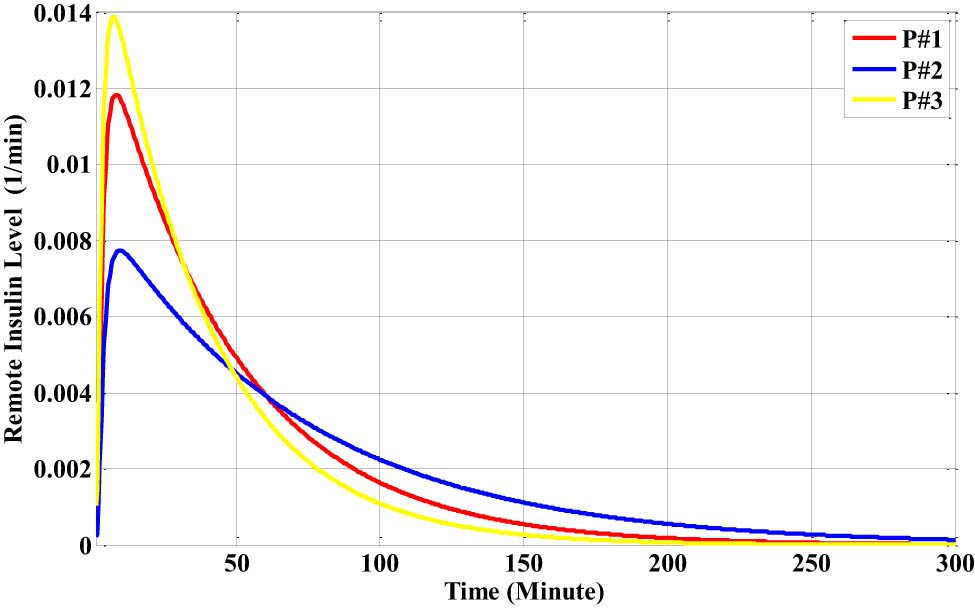

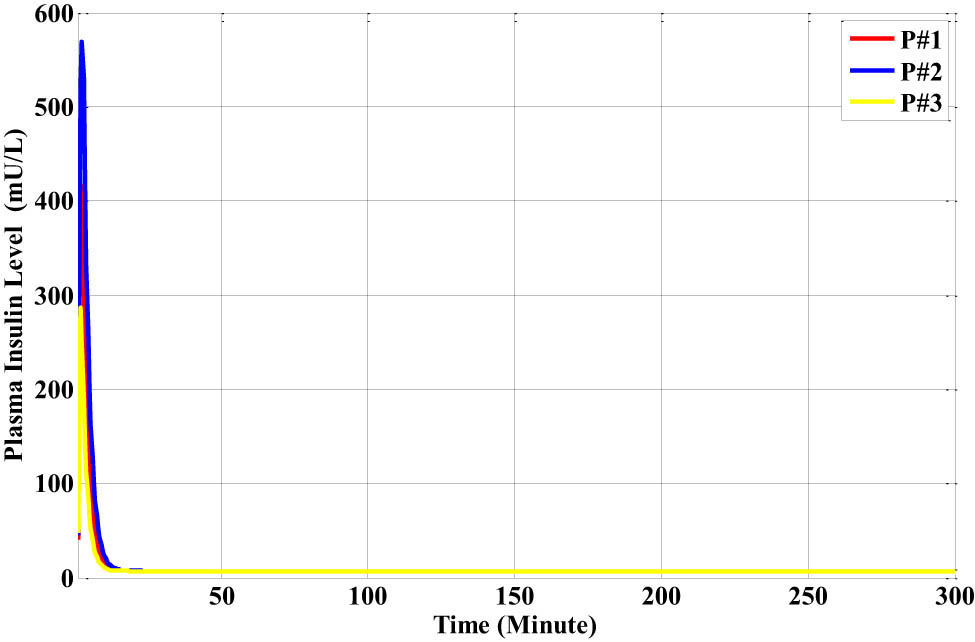

The distant insulin level for each patient, which is a representation of the whole-body insulin level, is displayed in Figure 22. Figure 23 displays the plasma insulin level for each subject and illustrates how quickly the amount spreads throughout the body in a 300-min period.

The distant insulin level for each patient with the breakfast disturbance.

The plasma insulin level for the three different types of the Bergman patient models with the breakfast disturbance.

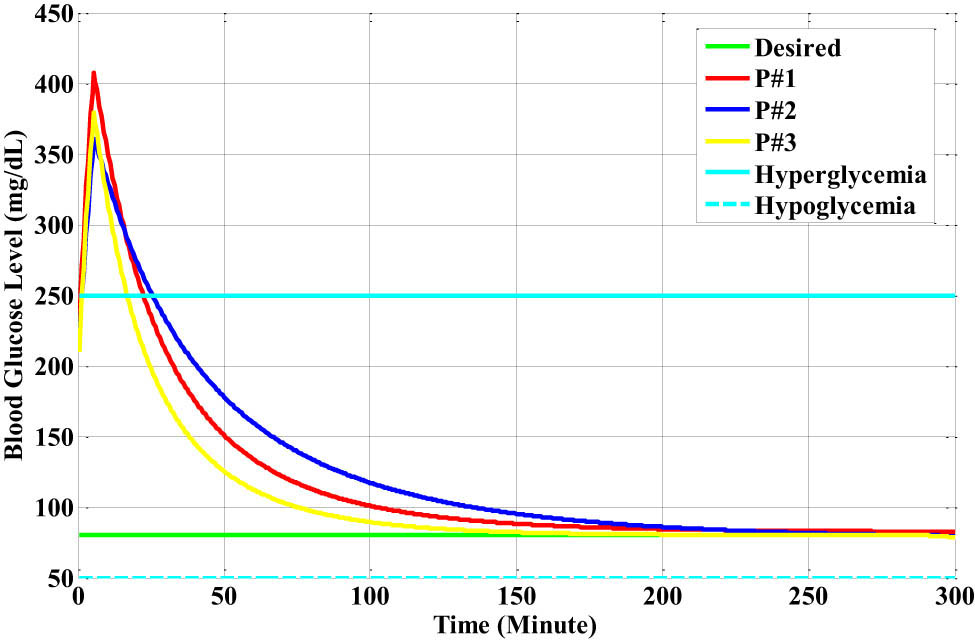

Figure 24 illustrates how the proposed closed-loop insulin-infusion PID-RBF-NN controller reacts when the lunch meal is added as a disturbance in the Bergman diabetic patient model.

The glucose level responses for each Bergman patient model based on the closed-loop PID-RBF-NN controller with the lunch disturbance.

The lunch disturbance effect was introduced for a duration of ten samples for each patient to show the effectiveness of the insulin-infusion control action. In particular, 20 mg/dl is the suggested lunch disturbance value. The following points indicate that the suggested overall controller improves the patients’ glucose level response:

The insulin-infusion action stabilizes patient #1’s glucose level, as indicated by the red-colour line, which drops from 407 to 250 mg/dl (the hyperglycemia level) and remains there for 22.5 min. Then, it drops to 150 mg/dl (the upper normal physiological level) and remains there for 50 min.

Finally, it drops to 80 mg/dl (the normal physiological level) and remains there for 200 min.

In contrast, the glucose level of patient #2, which is represented by the blue-colour line, drops from 409 to 250 mg/dl, the hyperglycemia level, and stabilizes there after 33 min. It then drops to 150 mg/dl, the upper normal physiological level, and remains there for 73.5 min before dropping to 80 mg/dl, the normal physiological level. It remains there for 230 min.

The third patient’s glucose level, represented by the yellow-colour line, is finally lowered from 382 to 250 mg/dl, or the upper hyperglycemia level, and it stabilized there for 17.5 min. Next, it drops to 150 mg/dl, or the upper normal physiological level, and remains there for 40 min. After that, it drops to 80 mg/dl, or the normal physiological level, and remains there for 150 min.

It is important to note that at 250 min, the blood glucose levels of the first and second patients precisely reached 80 mg/dl at a steady state. They remain at their typical physiological level.

Table 6 shows the time attributes of the blood glucose level of patients #1, #2, and #3 with lunch meal disturbances.

The time attributes of the blood glucose level of the patients with lunch meal disturbances

| Patients | G o mg/dl | Maximum blood glucose level after ten samples | Time at 250 mg/dl (min) | Time at 150 mg/dl (min) | Time at 120 mg/dl (min) | Time at 80 mg/dl (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P#1 | 230 | 407 | 22.5 | 50 | 70 | 200 |

| P#2 | 220 | 409 | 33 | 73.5 | 104 | 230 |

| P#3 | 210 | 382 | 17.5 | 40 | 55 | 150 |

The output response of the insulin-infusion PID-RBF-NN controller during the first ten samples is displayed in Figure 25 when the blood glucose level abruptly rises. The PID-RBF-NN efficiently and rapidly determines the insulin action value for each of the three patients to track the sudden increase in blood glucose levels. The maximum insulin-infusion control action values for patients #1, #2, and #3 are 321, 283, and 281 mU/L·min−1, respectively.

The insulin action of the proposed PID-RBF-NN controller for the three different types of the Bergman models with the lunch disturbance.

Figure 26 shows the maximum level value of the insulin for each patient, which is a decreased value for each sample, where only ten samples were taken as an example. These values are generated based on the closed-loop feedback PID-RBF-NN controller. Thus, the error between Gd(k) and FH[−] reduces to zero, which leads to a decrease in the U max insulin level to approximately zero, which will reduce the insulin control action to zero.

The response of the maximum insulin level U max for the three different types of the nonlinear neural network glucose–insulin patient identifier models with the lunch disturbance.

To determine the optimal control gain settings of the PID-RBF-NN controller, Figure 27 shows the response of the best alpha convergence for the three patients.

The best convergence curve response of the PID-RBF-NN controller for the three different types of Bergman patient models with the lunch disturbance.

The distant insulin level for each patient, which is a representation of the whole-body insulin level, is displayed in Figure 28.

The distant insulin level for each patient with the lunch disturbance.

Figure 29 displays the plasma insulin level for each subject and illustrates how quickly the amount spreads throughout the body in a 300-min period.

The plasma insulin level for the three different types of Bergman patient models with the lunch disturbance.

The suggested closed-loop insulin-infusion PID-RBF-NN controller’s response to the addition of dinner as a perturbation in the Bergman diabetic patient model is shown in Figure 30. To demonstrate the efficacy of the insulin-infusion control action, a dinner disturbance effect was created for ten samples per subject. Specifically, the recommended dinner disturbance value is 5 mg/dl. The recommended overall controller enhances the patients’ glucose level response in the following ways:

The glucose level responses for each Bergman patient model based on the closed-loop PID-RBF-NN controller with the dinner disturbance.

The glucose level of patient #1 is the red-colour line, which rises from 271 to 250 mg/dl (the hyperglycemia level) and stays there for 9 min. Then, it falls to 150 mg/dl (the upper normal physiological level) and stays there for 37.5 min. Finally, it falls to 80 mg/dl (the normal physiological level) and stays there for 160 min. This shows that the insulin-infusion action stabilizes patient #1’s glucose level.

Patient #2’s glucose level, shown by the blue-colour line, on the other hand, falls from 265 to 250 mg/dl, the hyperglycemia level, and then stabilizes there after 10 min. Next, it falls to the upper normal physiological level of 150 mg/dl and stays there for 53.5 min. After that, it falls to the normal physiological level of 80 mg/dl and stays there for 235 min.

Finally, the third patient’s glucose level, shown by the yellow line, drops from the upper hyperglycemia level of 250 to 245 mg/dl. It then falls to the top normal physiological level of 150 mg/dl, where it stays for 26.5 min. It then falls to the usual physiological level of 80 mg/dl, where it stays for 150 min.

It should be noted that the first and second patients’ blood glucose levels reached 80 mg/dl at the steady state at 250 min. Their physiological state is still normal.

Table 7 shows the time attributes of the blood glucose level of patients #1, #2, and #3 with dinner meal disturbances.

The time attributes of the blood glucose level of the patients with dinner meal disturbances

| Patients | G o mg/dl | Maximum blood glucose level after ten samples | Time at 250 mg/dl (min) | Time at 150 mg/dl (min) | Time at 120 mg/dl (min) | Time at 80 mg/dl (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P#1 | 230 | 271 | 9 | 37.5 | 56 | 160 |

| P#2 | 220 | 265 | 10 | 53.5 | 83 | 235 |

| P#3 | 210 | 245 | None | 26.5 | 43 | 150 |

When the blood glucose level suddenly rises, Figure 31 shows the output response of the insulin-infusion PID-RBF-NN controller for the first ten samples. To monitor the abrupt rise in blood glucose levels, the PID-RBF-NN quickly and effectively calculates the insulin action value for each of the three patients. Patients #1, #2, and #3 have maximum insulin-infusion control action values of 309, 354, and 219 mU/L·min−1, respectively.

The insulin action of the proposed PID-RBF-NN controller for the three different types of Bergman models with the dinner disturbance.

For instance, only ten samples were collected, and Figure 32 displays the maximum level of insulin for each patient, which is reduced for each sample. Since the closed-loop feedback PID-RBF-NN controller is used to generate these values, the error between Gd(k) and FH[−] falls to zero, lowering the U max insulin level to approximately zero and lowering the insulin control action to zero.

The response of the maximum insulin level U max for the three different types of the nonlinear neural network glucose–insulin patient identifier models with the dinner disturbance.

Figure 33 displays the response of the best alpha convergence for the three patients to identify the PID-RBF-NN controller’s ideal control gain settings. Figure 34 shows each patient’s remote insulin level, which is a representation of the insulin level across the body.

The best convergence curve response of the PID-RBF-NN controller for the three different types of Bergman patient models with the dinner-meal disturbance.

The distant insulin level for each patient with the dinner disturbance.

Each subject’s plasma insulin level is shown in Figure 35, which also shows how quickly the amount circulates throughout the body in a 300-min period.

The plasma insulin level for the three different types of Bergman patient models with the dinner disturbance.

To validate the effectiveness of the optimization algorithm (GWO) for tuning the parameters of the cognitive PID-RBF-NN controller in this work, we compared the simulation results of the proposed cognitive controller with the results of other types of controllers taken from [9,11], and [15], as shown in Table 8 in terms of reaching the blood glucose level at a normal physiological level at a minimum time and for showing the time enhancement percentage by using Eq. (46):

Simulation results comparing the suggested controller to other designs

| Type of control algorithm | Tuning algorithm | Steady-state error overshoot OS (%) time to reach normal physiological level | Enhancing the time to reach the blood glucose level at 100 mg/dl |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fractional order PID and fuzzy logic controllers [9] for 20 mg/dl lunch-meal disturbance | GA, ACO, BAT, IWO | No oscillation | 10% for patient #1 T = 90 min |

| E ss = 0 | |||

| T = 100 min | |||

| Type-2 fuzzy controller [11] for 20 mg/dl lunch-meal disturbance | Trial and error | Small oscillation | 25% for patient #1 T = 90 min |

| E ss = 0 | |||

| T = 120 min | |||

| PID-PSO controller [15] for 20 mg/dl lunch-meal disturbance | PSO | No oscillation E ss = 0 | 6% for patient #1 T = 90 min |

| OS = 0% | |||

| T = 96 min | |||

| The proposed cognitive controller | GWO | No oscillation | |

| E ss = 0 |

Using only five rules for the membership function and the trial-and-error method to determine the gain in the input–output fuzzy logic controller, the fractional-order PID and the fuzzy logic controllers in Benzian et al. [9] were constructed for the linear Bergman model and only for the first patient. As a result, the controller produces an insulin control action value that is too quick and suboptimal, which causes the blood glucose level to respond too quickly.

The suggested controller, on the other hand, employs the nonlinear Bergman model, the feedforward neural controller, and the feedback PID-RBF-NN with the GWO heuristic method. The controller has produced optimal or nearly optimal insulin control action based on the best parameters found by the optimization algorithm, which results in bringing the blood glucose level down to a normal physiological level without overshooting or response oscillation. When compared to the fractional-order PID and the fuzzy logic controller algorithms, the comparison findings demonstrated that the PID-RBF-NN with the GWO algorithm improved the time to attain the blood glucose level in a normal condition for patient #1 by 10% [9].

In Yan et al. [11], the type-2 fuzzy controller was created only for the first patient using the linear patient Bergman model. The four control gains in the control law were obtained through a process of trial and error, which results in a minor oscillation in the blood glucose level response as the controller produces a rapid and suboptimal value of the insulin control action. The proposed cognitive controller, which consists of two controllers, namely the feedforward neural controller and the feedback PID-RBF-NN controller with the heuristic GWO method, works with a nonlinear patient Bergman model. Based on the best parameters identified by the optimization algorithms, the controller generates an optimal or nearly optimal insulin control action, bringing the blood glucose level to a normal physiological level without oscillating or overshooting. When compared to the type-2 fuzzy controller algorithm, the comparison findings demonstrated that the PID-RBF-NN with the GWO algorithm improved the time to attain the blood glucose level in normal conditions for patient #1 by 25% [11].

The offline PSO approach was utilized to determine the three control parameters of the PID-PSO controller in [15], which was constructed for the linear Bergman model. As a result, the insulin control action produced by the controller is fast, but the spike action is high. When compared to the PID-PSO controller algorithm, the comparison findings demonstrated that the PID-RBF-NN with the GWO algorithm improved the time to attain the blood glucose level in normal conditions for patient #1 by 6% [15].

The results of the simulation show that the proposed cognitive glucose–insulin controller with the GWO algorithm can produce the best insulin control action. This action enables the nonlinear patient Bergman model to track the necessary blood glucose level with the least amount of tracking error and to achieve optimal performance without oscillation in the output blood glucose levels of the different patient types.

5 Conclusions

Using a feedforward neural controller and a feedback PID-RBF-NN controller with the GWO algorithm, this study demonstrated the design and simulation of an offline and online cognitive glucose–insulin control strategy for blood glucose level monitoring and control in three distinct nonlinear Bergman patient models with various disturbance meals. Three different patient models were employed as a nonlinear model to solve the problem statement to monitor and stabilize the blood glucose level response in diabetic patients by determining the optimal insulin-infusion level and keeping the blood glucose level at the normal physiological level. The following problems can be effectively resolved by using the glucose–insulin management technique based on the suggested five layers:

The blood glucose level is efficiently monitored and maintained at a normal physiological level of 60–120 mg/dl without oscillation at the goal level of 80 mg/dl.

An ideal or almost ideal smooth value of the insulin-infusion control action was generated to enhance the blood glucose level response in diabetes patients without reaching the saturation condition.

A high tracking precision of the measured blood glucose level is achieved by the proposed controller, which is based on the PID-RBF-NN with the GWO algorithm with offline and online tuning control settings that provide smooth insulin action without a large spike or a saturation state-based feedforward NARMA-L2 identifier.

The maximum tracking error level for monitoring blood glucose approaches zero at intervals longer than 220 min.

By comparing the proposed controller with the fractional-order PID controller, the proposed controller enhanced the time by 10% to reach the blood glucose level at a normal physiological level with the lunch disturbance. Moreover, compared to the type-2 fuzzy control algorithm, the proposed controller enhanced the time by 25% to reach the blood glucose level at a normal physiological level with the lunch disturbance.

Finally, compared to the PID-PSO control algorithm, the proposed controller enhanced the time by 6% to reach the blood glucose level at a normal physiological level with the lunch disturbance.

To create an artificial pancreas, the suggested glucose–insulin control strategy based on offline and online PID-RBF-NN controllers with the GWO algorithm will be experimentally implemented in future works utilizing an FPGA development board with an insulin pump device.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Khulood E. Dagher and Joseph Haggege studied and analyzed the Bergman diabetic patient models. Khulood E. Dagher developed a cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy algorithm using the neural networks and GWO meta-heuristic technique. The Bergman model was described by Joseph Haggege. The suggested numerical simulation results from this work were addressed by the two authors. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author by using MATLAB package.

References

[1] Chinnababu SK, Jayachandra A. Diabetes prediction and classification using self-adaptive evolutionary algorithm with convolutional neural network. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2024;17(3):460–72.10.22266/ijies2024.0630.36Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Gudiño-Ochoa A, García-Rodríguez JA, Cuevas-Chávez JI, Ochoa-Ornelas R, Navarrete-Guzmán A, Vidrios-Serrano C, et al. Enhanced diabetes detection and blood glucose prediction using tiny ML-integrated E-nose and breath analysis: A novel approach combining synthetic and real-world data. Bioengineering. 2024;11(1056):1–26.10.3390/bioengineering11111065Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Wright EE, Shah VN, Miller E, Thach A, Javadi P, Davies S, et al. Prescribed total daily insulin dose and predictors of insulin dose for adults with type 2 diabetes on multiple daily injections of insulin: A retrospective cohort study. Diabetology. 2025;6(13):1–12.10.3390/diabetology6020013Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Kalaimani SC, Jeyakumar V. Design of robust evolving cloud-based controller for type 1 diabetic patients using n-beats algorithm. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2024;67(e24230857):1–19.10.1590/1678-4324-2024230857Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Patra AK, Panigrahi GS. An adaptive control algorithm for blood glucose regulation in type-I diabetes mellitus patients. Decis Anal J. 2023;8(100276):1–12.7.10.1016/j.dajour.2023.100276Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Kralev J, Slavov T. Robust μ-controller for automatic glucose regulation for type I diabetes mellitus. Mathematics. 2023;11(3856):1–26.10.3390/math11183856Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Saleem O, Iqbal J. Complex-order PID controller design for enhanced blood-glucose regulation in type-I diabetes patients. Meas Contr. 2023;56(9):1811–25.10.1177/00202940231189504Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Sharma R, Basu A, Mohanty S. Designing of digital PID controller for blood glucose level of diabetic patient by using various tuning methods. Int J Elect Electr Eng. 2022;9(2):1–5.10.14445/23488379/IJEEE-V9I2P101Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Benzian S, Ameur A, Rebai A. Design an optimal fractional order PID controller based on new algorithm and a fuzzy logic controller to regulate type 1 diabetes patient. J Euro Des Syst Auto. 2021;54(3):381–94.10.18280/jesa.540301Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Shenbagam M, Kanagaraj G, Giri J, Yu VF, Qin H, Mallik S. Optimizing blood glucose regulation in type 1 diabetes: a fractional order controller approach. AIP Adv. 2024;14(045331):1–10.10.1063/5.0199980Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Yan SR, Alattas KA, Bakouri M, Alanazi AK, Mohammadzadeh A, Mobayen S, et al. Generalized type-2 fuzzy control for type-I diabetes: analytical robust system. Mathematics. 2022;10(690):1–20.10.3390/math10050690Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Sayed A, Zalam BA, Elhoushy M, Nabil E. Optimized type-2 fuzzy controller based on IoMT for stabilizing the glucose level in type-1 diabetic patients. Sci Rep. 2023;13(14508):1–21.10.1038/s41598-023-41522-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Barbosa de Farias JLC, Bessa WM. Intelligent control with artificial neural networks for automated insulin delivery systems. Bioengineering. 2022;9(664):1–19.10.3390/bioengineering9110664Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Khaqan A, Nauman A, Shuja S, Khurshaid T, Kim KC. An intelligent model-based effective approach for glycemic control in type-1 diabetes. Sensors. 2022;22(7733):1–18.10.3390/s22207773Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Dagher KE, Haggege J. Enhancement of the blood glucose level for diabetic patients based on an adaptive auto-tuned PID controller via meta-heuristic methods. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2024;17(3):250–61.10.22266/ijies2024.0630.21Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Babar SA, Ahmad I, Mughal IS. Sliding‐mode‐based controllers for automation of blood glucose concentration for type 1 diabetes. IET Syst Bio. 2021;15:72–82.10.1049/syb2.12015Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Hettiarachchi C, Malagutti N, Nolan CJ, Suominen H, Daskalaki E. G2P2C—a modular reinforcement learning algorithm for glucose control by glucose prediction and planning in type 1 diabetes. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;90(105839):1–19.10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105839Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Nasir D, Hatim A, Bourkha ME, El-Beid S, Ez-ziymy S. Closed loop control of blood glucose levels in diabetes using an artificial neural network controller. Proc Comput Sci. 2024;236:444–51.10.1016/j.procs.2024.05.052Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Sakulrang S, Moore EJ, Sungnul S, de-Gaetano A. A fractional differential equation model for continuous glucose monitoring data. Adv Diff Equation. 2017;2017(150):1–11.10.1186/s13662-017-1207-1Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Bergman RN, Phillips LS, Cobelli C. Physiologic evaluation of factors controlling glucose tolerance in man: measurement of insulin sensitivity and beta-cell glucose sensitivity from the response to intravenous glucose. Am Soc Clin Invest. 1981;68:1456–67.10.1172/JCI110398Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Pujol-Vázquez G, Acho L, Gibergans-Báguena J. Commuted PD controller for nonlinear systems: glucose–insulin regulatory case. Appl Sci. 2023;13(8129):1–15.10.3390/app13148129Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Ogata K. Modern control engineering. 4th edn. New Jersey, Prentice Hall: Addison- Wesley Publishing Company, Inc; 2003.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Dagher KE. Design of an adaptive neural voltage-tracking controller for nonlinear proton exchange membrane fuel cell system based on optimization algorithms. J Eng Appl Sci. 2018;13(15):6188–98.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Canoon ZE, Al-Araji AS, Abdullah MN. An intelligent path planning algorithm and control strategy design for multi-mobile robots based on a modified elman recurrent neural network. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2022;15(5):400–15.10.22266/ijies2022.1031.35Suche in Google Scholar

[25] AL-Taie FAS, Al-Araji AS. Development of predictive voltage controller design for PEM fuel cell system based on identifier model. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2023;16(2):343–60.10.22266/ijies2023.0430.28Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Yawale1 NM, Sahu1 N, Khalsa NN. Design of a hybrid GWO CNN model for identification of synthetic images via transfer learning process. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2023;16(3):292–301.10.22266/ijies2023.0630.23Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Jabbar AM, Ku-Mahamud KR. Adaptive grey wolf optimization algorithm with neighborhood search operations: an application for traveling salesman problem. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2021;14(6):539–3.10.22266/ijies2021.1231.48Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Gao B, Guan H, Shen W, Ye Y. Application of the grey wolf optimization algorithm in active disturbance rejection control parameter tuning of an electro-hydraulic servo unit. Machines. 2022;10(599):1–20.10.3390/machines10080599Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Almazini HF, Ku-Mahamud KR, Almazini H. Heuristic initialization using grey wolf optimizer algorithm for feature selection in intrusion detection. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2023;16(1):410–8.10.22266/ijies2023.0228.36Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Pham NT, Le DT A novel FOC vector control structure using RBF tuning PI and SM for SPIM drives. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2020; 13(5):429–40.10.22266/ijies2020.1031.38Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Generalized (ψ,φ)-contraction to investigate Volterra integral inclusions and fractal fractional PDEs in super-metric space with numerical experiments

- Solitons in ultrasound imaging: Exploring applications and enhancements via the Westervelt equation

- Stochastic improved Simpson for solving nonlinear fractional-order systems using product integration rules

- Exploring dynamical features like bifurcation assessment, sensitivity visualization, and solitary wave solutions of the integrable Akbota equation

- Research on surface defect detection method and optimization of paper-plastic composite bag based on improved combined segmentation algorithm

- Impact the sulphur content in Iraqi crude oil on the mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of carbon steel in various types of API 5L pipelines and ASTM 106 grade B

- Unravelling quiescent optical solitons: An exploration of the complex Ginzburg–Landau equation with nonlinear chromatic dispersion and self-phase modulation

- Perturbation-iteration approach for fractional-order logistic differential equations

- Variational formulations for the Euler and Navier–Stokes systems in fluid mechanics and related models

- Rotor response to unbalanced load and system performance considering variable bearing profile

- DeepFowl: Disease prediction from chicken excreta images using deep learning

- Channel flow of Ellis fluid due to cilia motion

- A case study of fractional-order varicella virus model to nonlinear dynamics strategy for control and prevalence

- Multi-point estimation weldment recognition and estimation of pose with data-driven robotics design

- Analysis of Hall current and nonuniform heating effects on magneto-convection between vertically aligned plates under the influence of electric and magnetic fields

- A comparative study on residual power series method and differential transform method through the time-fractional telegraph equation

- Insights from the nonlinear Schrödinger–Hirota equation with chromatic dispersion: Dynamics in fiber–optic communication

- Mathematical analysis of Jeffrey ferrofluid on stretching surface with the Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Exploring the interaction between lump, stripe and double-stripe, and periodic wave solutions of the Konopelchenko–Dubrovsky–Kaup–Kupershmidt system

- Computational investigation of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS co-infection in fuzzy environment

- Signature verification by geometry and image processing

- Theoretical and numerical approach for quantifying sensitivity to system parameters of nonlinear systems

- Chaotic behaviors, stability, and solitary wave propagations of M-fractional LWE equation in magneto-electro-elastic circular rod

- Dynamic analysis and optimization of syphilis spread: Simulations, integrating treatment and public health interventions

- Visco-thermoelastic rectangular plate under uniform loading: A study of deflection

- Threshold dynamics and optimal control of an epidemiological smoking model

- Numerical computational model for an unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium past an MHD rotating sheet

- Regression prediction model of fabric brightness based on light and shadow reconstruction of layered images

- Dynamics and prevention of gemini virus infection in red chili crops studied with generalized fractional operator: Analysis and modeling

- Qualitative analysis on existence and stability of nonlinear fractional dynamic equations on time scales

- Fractional-order super-twisting sliding mode active disturbance rejection control for electro-hydraulic position servo systems

- Analytical exploration and parametric insights into optical solitons in magneto-optic waveguides: Advances in nonlinear dynamics for applied sciences

- Bifurcation dynamics and optical soliton structures in the nonlinear Schrödinger–Bopp–Podolsky system

- User profiling in university libraries by combining multi-perspective clustering algorithm and reader behavior analysis

- Exploring bifurcation and chaos control in a discrete-time Lotka–Volterra model framework for COVID-19 modeling

- Review Article

- Haar wavelet collocation method for existence and numerical solutions of fourth-order integro-differential equations with bounded coefficients

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Analysis and Design of Communication Networks for IoT Applications - Part II

- Silicon-based all-optical wavelength converter for on-chip optical interconnection

- Research on a path-tracking control system of unmanned rollers based on an optimization algorithm and real-time feedback

- Analysis of the sports action recognition model based on the LSTM recurrent neural network

- Industrial robot trajectory error compensation based on enhanced transfer convolutional neural networks

- Research on IoT network performance prediction model of power grid warehouse based on nonlinear GA-BP neural network

- Interactive recommendation of social network communication between cities based on GNN and user preferences

- Application of improved P-BEM in time varying channel prediction in 5G high-speed mobile communication system

- Construction of a BIM smart building collaborative design model combining the Internet of Things

- Optimizing malicious website prediction: An advanced XGBoost-based machine learning model

- Economic operation analysis of the power grid combining communication network and distributed optimization algorithm

- Sports video temporal action detection technology based on an improved MSST algorithm

- Internet of things data security and privacy protection based on improved federated learning

- Enterprise power emission reduction technology based on the LSTM–SVM model

- Construction of multi-style face models based on artistic image generation algorithms

- Research and application of interactive digital twin monitoring system for photovoltaic power station based on global perception

- Special Issue: Decision and Control in Nonlinear Systems - Part II

- Animation video frame prediction based on ConvGRU fine-grained synthesis flow

- Application of GGNN inference propagation model for martial art intensity evaluation

- Benefit evaluation of building energy-saving renovation projects based on BWM weighting method

- Deep neural network application in real-time economic dispatch and frequency control of microgrids

- Real-time force/position control of soft growing robots: A data-driven model predictive approach

- Mechanical product design and manufacturing system based on CNN and server optimization algorithm

- Application of finite element analysis in the formal analysis of ancient architectural plaque section

- Research on territorial spatial planning based on data mining and geographic information visualization

- Fault diagnosis of agricultural sprinkler irrigation machinery equipment based on machine vision