Abstract

The study of silicon-based all-optical wavelength converters (SAOWCs) for on-chip optical interconnect applications holds potential research value and application horizons. The study proposes a SAOWC for on-chip optical interconnect technology. It also designs and optimizes an all-optical wavelength converter based on a quantum dot semiconductor optical amplifier and a Mach-Zönder interferometer in conjunction with photonic integrated circuit technology. The interlayer coupling efficiency is simulated by the finite-difference time-domain method, and the performance of the system is verified in conjunction with experiments. The experimental results showed that the coupling efficiency was as high as 98.44% at 1,550 nm wavelength. The bit error rate (BER) test results showed that the BER rose from 10−17 to 10−4 when the pulse width increased from 0.1 to 1.0 ps. Meanwhile, the temperature fluctuation and signal strength degradation tests further validated the stability of the device under different operating conditions. These results demonstrate that the converter has significant potential to enhance data transmission capability. The study provides a valuable reference for further improving and optimizing data transmission over all-optical networks, which is expected to promote scientific advancement and technological applications in this field.

1 Introduction

The development of the information society has driven the demand for data transmission rate and bandwidth, especially in large data centers and mobile internet. With the increasing demand for data communication, traditional electronic interconnection technology has faced challenges, making optical interconnection technology (OIT) a cutting-edge research field [1,2]. Among them, silicon-based all-optical wavelength converters (SAOWCs) for on-chip optical interconnection (OCOI) play an important role in solving data transmission bottlenecks. An all-optical wavelength converter (AOWC) can achieve wavelength conversion without electronic devices, allowing multiple signals of different wavelengths to be transmitted in the same fiber, greatly improving data transmission capacity [3,4]. SAOWC has become a research focus due to its excellent integration and compatibility. However, the research on SAOWC faces many challenges, involving issues such as nonlinear optics, material science, and integrated circuit design that require in-depth exploration. The innovation is to propose a new design scheme for SAOWC, aimed at improving the conversion efficiency and bandwidth of the device. The device incorporates novel silicon-based materials and process technology to enhance its integration and performance stability. Additionally, it investigates innovative optical wavelength modulation techniques to achieve more precise wavelength conversion. This study promotes the technological progress of SAOWC and the development of OIT, thereby improving the performance of data communication [5,6]. The study is conducted in four sections. Section 1 discusses numerous research works on SAOWC methods for OCOI. Section 2 is the model construction of OCOI’s SAOWC research. Section 3 is the experimental verification. Section 4 summarizes the content and points out the shortcomings.

2 Related works

With the growth of multi-core processors, efficient on-chip communication plays an essential role in improving the system performance of multiprocessors. The traditional on-chip interconnection (OCI) method not only fulfills the communication requirements but also results in a significant increase in energy consumption, thereby creating a challenge in achieving an equilibrium between latency, power consumption, and reliability. The emergence of optical networks on chip (ONOC) provides new ideas for solving this difficulty. ONOC has more advantages in transmission speed, communication bandwidth, energy efficiency, and is the most promising solution for chip level communication. To reduce the hardware overhead of ONOC and improve the performance of optical networks, Jinyang et al. proposed a 16-port passive H-tree optical interconnection network based on micro ring resonators. The passive optical H-tree network required only 72 micro ring resonators in a 16 × 16 array scale. This demonstrated its excellent performance compared to passive network structures such as Crossbar, λ-Router, GWOR, LACE, and Light. The average insertion loss of the network was only 1.49 dB, which was 21.5, 10.7, and 59.7% lower than that of λ-Router, GWOR, and TAONoC, respectively. This study has made significant breakthroughs by optimizing the use of micro ring resonators and organizing network structures [7]. The quantum and neural morphology computing platforms in integrated photonic circuits required next-generation optical capabilities. Usually, increasingly complex on-chip optical paths allowed for overlays that could not be achieved by planar techniques, which is crucial for artificial neural networks. Multifunctional 3D wave-guides could be achieved through micro printing based on two-photon polymerization (TPP). Adao et al. proposed a 3D shape prediction tool that considers experimental TPP parameters, achieving simulation of 3D wave-guide performance on chip. This simulation could reduce the cost intensive optimization process of system experiments. The optical transmission characteristics of the prepared 3D wave-guide were consistent with the simulation results, indicating that the developed morphology prediction method was conducive to the development of universal on-chip and inter-chip photon interconnection technologies [8]. Li et al. proposed the method of adding excessive methyl ammonium bromide (MABr) to its precursor. They studied self-passivating perovskite films with excessive doping of MABr by changing the stoichiometric ratio of perovskite precursors. As the MABr content increased, the interaction between free charges and longitudinal optical phonons increased, thereby reducing the exciton binding energy, leading to emission broadening and blue shift of the photoluminescence spectroscopy spectrum. When the molar ratio of PbBr2 to MABr was 1:1.315, PeLED achieved a good balance between brightness and stability, exhibiting a maximum brightness of 9,981 CD·m(−2), a lifespan of 14 min, and a maximum current efficiency of 6.59 CD·A(−1) [9]. Mode division multiplexing (MDM) for OCI has received widespread attention as a degree of freedom that can further expand communication ability. However, the selective loading of multi-mode optical carriers in MDM was not as easy as wavelength division multiplexing (WDM).

Hao and Xin designed a scalable mode selection device for OCI. It had two functional blocks. In one module, the carrier depletion plus silicon micro ring resonator was used to achieve simultaneous mode demultiplexing of multi-mode bus wave-guides and high-speed modulation functions. In another module, a mode multiplexer based on an asymmetric directional coupler restored the modulated signal from the fundamental mode to the original mode sequence. Through this, each channel was separated from the input port and could proceed separately. Researchers can selectively modulate any mode channel as needed, and this structure can be extended to multiple channels. As a concept proof, researchers designed and manufactured a device with 4 micro ring resonators and channel mode multiplexers. This method could provide greater operational flexibility for multi-mode optical interconnects [10]. Long wave infrared covers a rich range of molecular absorption fingerprints and has great potential in chemical sensing. Wave-guides provide an attractive chip level miniaturization solution for optical sensors. However, the exploration of wave-guide sensors within this wavelength range is limited. Weixin et al. developed a photon platform for fast and sensitive on-chip gas sensing utilizing suspended silicon wave-guides. It gave a feasible method for fully utilizing the transparent window of silicon. The subwavelength grating (SWG) presented a potential solution for designing patterns of interaction between strong light analytes. The field research covered the issues of transmission loss and bending loss in the wide wavelength range of 6.4–6.8 µm, and has achieved satisfactory results. In addition, the performance of functional devices such as grating couplers, Y-junctions, and directional couplers also proved their high performance. In view of vapor detection, the sensing function based on this platform was demonstrated. The test results showed that it could reach the detection limit of 75 ppm toluene, with a response time of 0.8 s and a recovery of 3.4 s for 75 ppm toluene, respectively. This powerful and efficient performance had huge potential for developing the SWG structures in on-site medical and environmental applications, making it a highly promising platform [11]. Huang et al. proposed a model for predicting human gait reaction forces and energy metabolism under a spring-loaded suspension backpack. The model was subsequently validated through experimentation, demonstrating that the discrepancy between the model-predicted energy cost and the experimental data was less than 7%. This outcome substantiated the efficacy of the model in optimizing the system performance [12]. Similarly, Sharma et al. developed a brain signal classification method based on multiple machine learning algorithms. The results showed that by combining multiple signal processing techniques, the performance of the model in complex signal processing was significantly improved, which further contributed to the optimization of complex systems. These works share some similarities with the study of complex signal processing challenges encountered in SAOWC design. These novel modeling techniques provide more scalability and robustness support in complex optical signal processing compared to traditional approaches [13].

In summary, ONOC has the advantages of fast transmission speed, large communication bandwidth, and high energy efficiency, and is considered a powerful solution to chip-level communication problems. However, the development and implementation of this technology also face many challenges, including device size, power consumption, reliability, and manufacturing complexity. Considering the complexity and cost of the manufacturing process, it is necessary to develop new manufacturing and packaging technologies to improve production efficiency and output quality. Despite these challenges, with the continuous development and optimization of photonic technology, it is expected that ONOC will occupy an increasingly vital position in future computing and communication systems. It is looked forward to achieving more efficient, reliable, and cost-effective ONOC solutions through continuous research and innovation.

3 Design of SAOWC method for OCOI

The research on the SAOWC method of OCOI mainly adopts the theories and methods of nonlinear optics, material science, and integrated circuit design to design and manufacture AOWC. This converter can achieve wavelength conversion of light without the involvement of electronic devices, thereby transmitting multiple signals of different wavelengths in the same optical fiber.

3.1 Optical waveguide construction of 3D interlayer silicon waveguide coupler

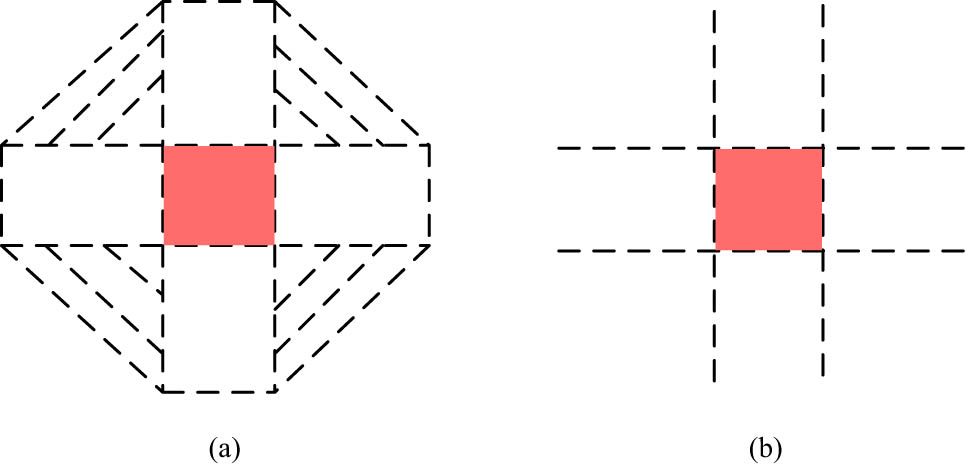

The construction of 3D interlayer silicon waveguide couplers began with precise etching techniques to prepare silicon waveguides. Then, through a specially designed interlayer coupling scheme, precise docking of silicon waveguides is achieved. In this process, the optimization of coupling efficiency is particularly concerned, by adjusting the geometric parameters and material properties of the waveguide to maximize coupling performance [14]. To ensure the implementation of final device performance, relying on advanced simulation tools for detailed simulation and optimization is an essential step. In this context, the propagation of electromagnetic waves along metal lines can be considered the construction of a minimalist waveguide structure, whereby the propagation of electromagnetic waves is restricted to this specific route. Similarly, visual light is a part of electromagnetic waves, and its wave nature can be utilized to confine light to a material with a specific shape, making it an optical waveguide. This is the basic construction method of optical waveguides in 3D interlayer silicon waveguide couplers. There are multiple commonly used methods for solving strip waveguides, including the Marcatili approximation and Kumar method for effective refractive index. The two methods are shown in Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of (a) Marcatili approximation method and (b) Kumar method.

In Figure 1(a), due to the relatively low influence of four specific regions R1, R2, R3, and R4 on the refractive index of the core layer, the Marcatili method chooses to ignore these regions. This strategy helps to reduce the number of boundary conditions that need to be processed, thereby reducing computational complexity. However, in Figure 1(b), although Kumar’s method is similar in core ideas to Marcatili, it takes into account the influence of these four corner regions on refractive index, which is ignored in Marcatili. Waveguides have two intrinsic polarization states, transverse electric (TE) and transverse magnetic (TM). Electromagnetic waves have three directions: electric field component, magnetic field component, and transmission, which are perpendicular to each other. If the direction of the electric field is parallel to the transmission plane and the direction of the magnetic field is perpendicular to the transmission plane, it is called the TE mode. If the magnetic field direction is parallel to the transmission plane and the electric field direction is perpendicular to the transmission plane, it is called the TM mode [15]. The eigenmode equations of TE and TM are shown in Eq. (1).

In Eq. (1), light propagates along the z direction in the waveguide.

where

where

where

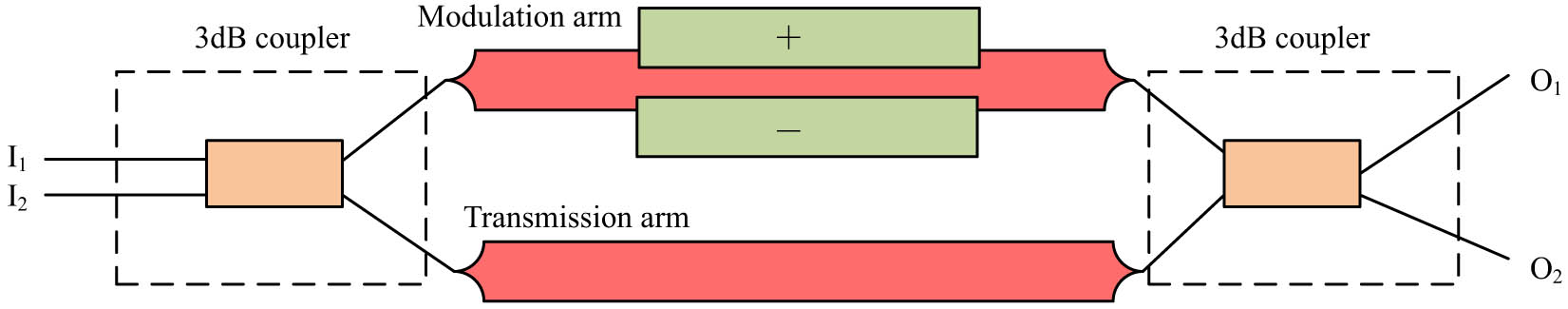

Schematic diagram of 2 × 2 optical switch structure.

In Figure 2, a beam of light enters from input port I1, passes through the first 3-dB coupler, and is evenly divided into two beams with π/2 phase difference. These two beams of light continue to enter the modulation region. If no additional modulation is applied, the two beams of light maintain a π/2 phase difference and enter the second 3-dB coupler. The coupler is designed symmetrically and can compensate for the phase difference between two beams of light, so that the two beams are combined into one beam and output at the O2 port. However, if modulation is applied, it will cause the π/2 phase difference between the two beams of light to become −π/2, resulting in phase inversion. Therefore, light will be output from the O1 port. If the two states are light input from I1 and output from O2, it is known as the “Cross” state. On the contrary, if the two states are input from I1 and output from O1, it is named as the “Bar” state. This forms two states of a 2 × 2 optical switch. The distribution of guided modes in multi-mode waveguides is shown in Figure 3.

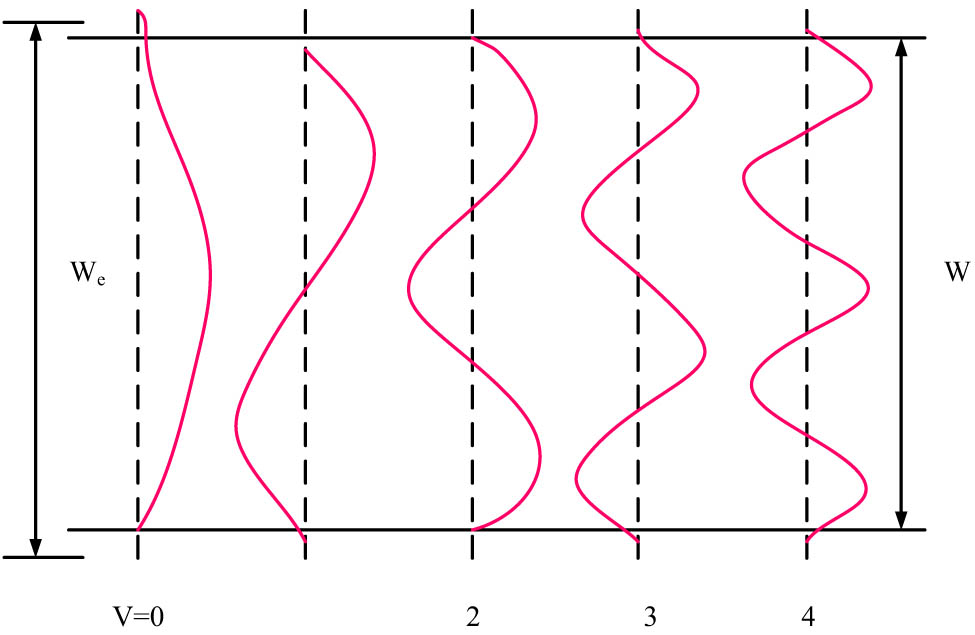

Distribution of guided modes in multi-mode waveguides.

In Figure 3, the self-imaging effect (SIE) plays a crucial role in the design of a multi-mode interferometer (MMI). SIE is a fundamental optical phenomenon in multi-mode waveguides, which is achieved through complex interactions between phase consistency and geometric shape. Essentially, it describes the process of how light replicates its incident mode in the propagation of matter, while also reproducing the shape and structure of the scene. According to SIE, by cleverly designing MMI, the research can achieve the generation of input mode images at the waveguide exit. This is why in the design of MMI, the target size parameters are determined based on SIE. Geometric size parameters are key elements that determine the generation of functional images, including the length and width of MMI, as well as the width of the designed multi-mode zone. Each parameter is greatly affected by the interferometer, including loss, phase error, crosstalk, and bandwidth. Based on the guided mode distribution in SIE, it is possible to design a MMI with specific characteristics and performance. Especially in optical communication and integrated photonics, it has extensive applications, such as being able to achieve complex optical signal processing functions, WDM devices, MDM devices, etc. [16,17]. The distribution mode of guided modes under SIE directly determines the output characteristics and application range of MMIs. The optical field intensity at the input of the multi-mode interference region is given by Eq. (5).

where

where

where L

π

represents the beat length and

3.2 Building an AOWC model based on quantum dot semiconductor optical amplifier Mach Zehnder interferometer (QD-SOA-MZI)

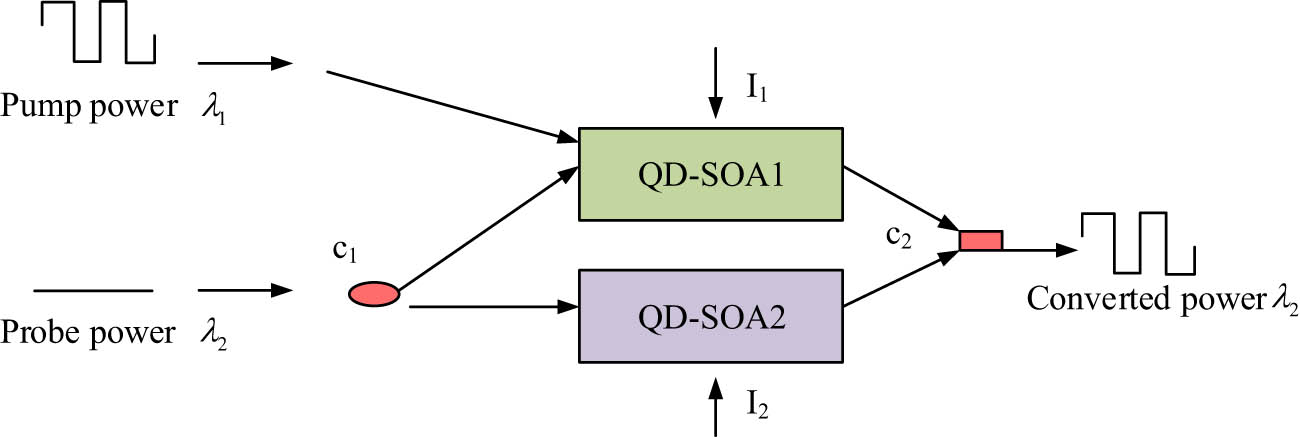

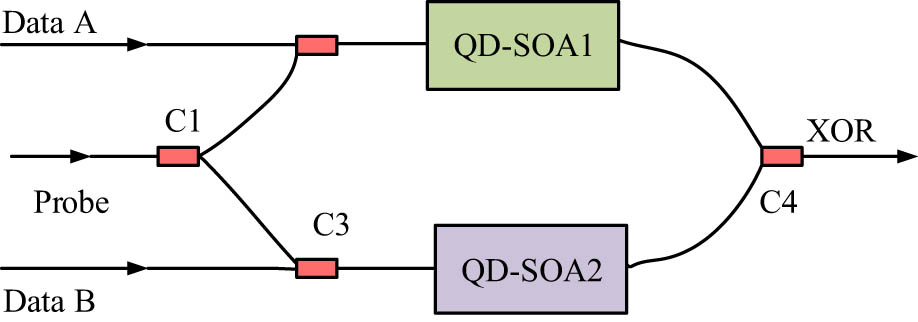

This study explores the construction methods of AOWC. The converter is based on the QD-SOA-MZI [18,19]. First, the QD-SOA is designed to accurately control the parameters of quantum dots to optimize broadband wavelength conversion performance. On this basis, a MZI is built to provide an optical architecture for AOWC. In the process of designing and constructing this device, theoretical analysis and experimental verification are deeply integrated. On the one hand, detailed theoretical analysis provides accurate guidance for design, predicts experimental results, and provides theoretical basis for system optimization through multiple iterations. In addition, experimental verification provides theoretical analysis with real-world references. The blind spots and unknown problems can also be identified and solved during the experimental process. The working diagram of the converter is shown in Figure 4.

Working principle diagram of cross-phase modulation (XPM) type wavelength converter based on QD-SOA-MZI.

In Figure 4, two identical QD-SOAs (QD-SOA1 and QD-SOA2) are placed in the arms of MZI. In this design, the pump light is input into QD-SOA1, and the continuous detection light is decomposed by a splitter and then input into two QD-SOAs, respectively. Due to the fact that the detection light in QD-SOA1 is modulated by pump light, there is a phase difference in the detection light compared to the one that is not modulated by pump light. Furthermore, through interference, this phase difference is converted into an intensity change, allowing the detection light at the output port to have pump light information, achieving wavelength conversion. In modern optical communication systems, bit error rate (BER) is usually used as one of the parameters to measure the accuracy of signal transmission. Subsequently, through interference, this phase difference is converted into an intensity change, and the probe light carries pump light information in the output port, thus achieving wavelength conversion. In today’s optical communication systems, the

The transformation extinction ratio, as an important indicator of system robustness and sensitivity, is defined as the ratio of the average power of output signal “1” to “0”, as shown in Eq. (9).

where ER is the extinction ratio of the transformed light, and

AoL-XORg principle based on QD-SOA-MZI.

In Figure 5, two identical QD-SOAs are placed on both arms of the interferometer. The detection light is divided into two identical beams through the wavelength divider C1, and is input into QD-SOA through couplers C2 and C3 along with the signal light Data A and Data B. Due to the higher input power of Data A and Data B compared to the maximum linear input power of QD-SOA, the probe light is modulated by Data A and Data B in QD-SOA. These modulated lights undergo interference to achieve an AoL-XORg. To achieve logical XOR operation, the output optical power is given by Eq. (10).

where

4 Predictive analysis of OCOI’s SAOWC application

The application prospects of SAOWC are broad, especially in data communication and silicon photonics. In data communication, AOWC can achieve wavelength conversion of light without the involvement of electronic devices, thereby transmitting multiple signals of different wavelengths in the same optical fiber, greatly improving data transmission capacity. It can effectively reduce signal interference and improve signal quality and system stability. The method is highly scalable due to the maturity of silicon photonics technology, which allows for seamless integration with existing photonic systems, particularly in standard silicon-based chip fabrication processes without extensive process modifications. This makes it suitable for mass production. However, commercial implementation still faces a number of challenges, especially in the manufacturing and packaging processes. Although the cost of integrated silicon photonic systems has been gradually decreasing, the complex design and high-precision fabrication requirements of wavelength converters may increase the cost, especially in the early stages. Further cost reductions are expected with advances in manufacturing technology and the realization of mass production, but initial capital investment remains a major obstacle to commercial implementation.

4.1 Application analysis of AOWC in data communication

The application of AOWC in data communication will be of great significance. By using optical wavelength conversion without the involvement of electronic devices, the same optical fiber can transmit multiple signals of different wavelengths, greatly improving the ability of data communication. In addition, AOWC can effectively reduce signal interference and improve signal quality and system stability. In comparison to conventional electronic wavelength converters, SAOWC exhibits a notable advantage in terms of energy consumption. This is due to the fact that its operation is primarily based on optical signal processing, which eliminates the necessity for photovoltaic conversion. This significantly reduces the energy consumption issues that are commonly observed in electronic devices. However, despite the excellent energy-saving characteristics of SAOWC, its overall energy efficiency is still dependent on the use of light sources and amplifiers. In some application scenarios, it may be necessary to additionally optimize the energy-efficient design of the device to reduce system power consumption, thus preventing it from becoming a limiting factor in large-scale applications. In conducting experiments on the application of AOWC in data communication, the selection of parameters and equipment is crucial. Table 1 shows the details of the model.

System parameters

| Parameter name | Parameter value | Equipment selection |

|---|---|---|

| Fiber type | Multi-mode fiber | Fiber suitable for multi-wavelength signal transmission |

| Optical wavelength converter | AOWC | Device with high-performance optical wavelength conversion ability |

| Fiber coupler | High precision fiber coupler | Used to reduce signal interference and improve signal quality |

| Optical detector | High performance optical detector | Used to detect optical signals |

| Power supply | Stable power supply | Used to ensure system stability |

| Temperature control equipment | High precision temperature control equipment | Used to ensure the normal operation of the device |

In Table 1, first, it is necessary to select optical fibers that can support multi-wavelength signal transmission, as well as AOWC with high-performance optical wavelength conversion capabilities. In addition, to reduce signal interference and improve signal quality, it is also necessary to choose high-precision fiber optic couplers and high-performance photodetectors. At the same time, to achieve the system operation stably, a stable power supply and high-precision temperature control equipment are also needed. The curve of the coupling efficiency of the inverted cone waveguide interlayer coupler with wavelength variation is shown in Figure 6.

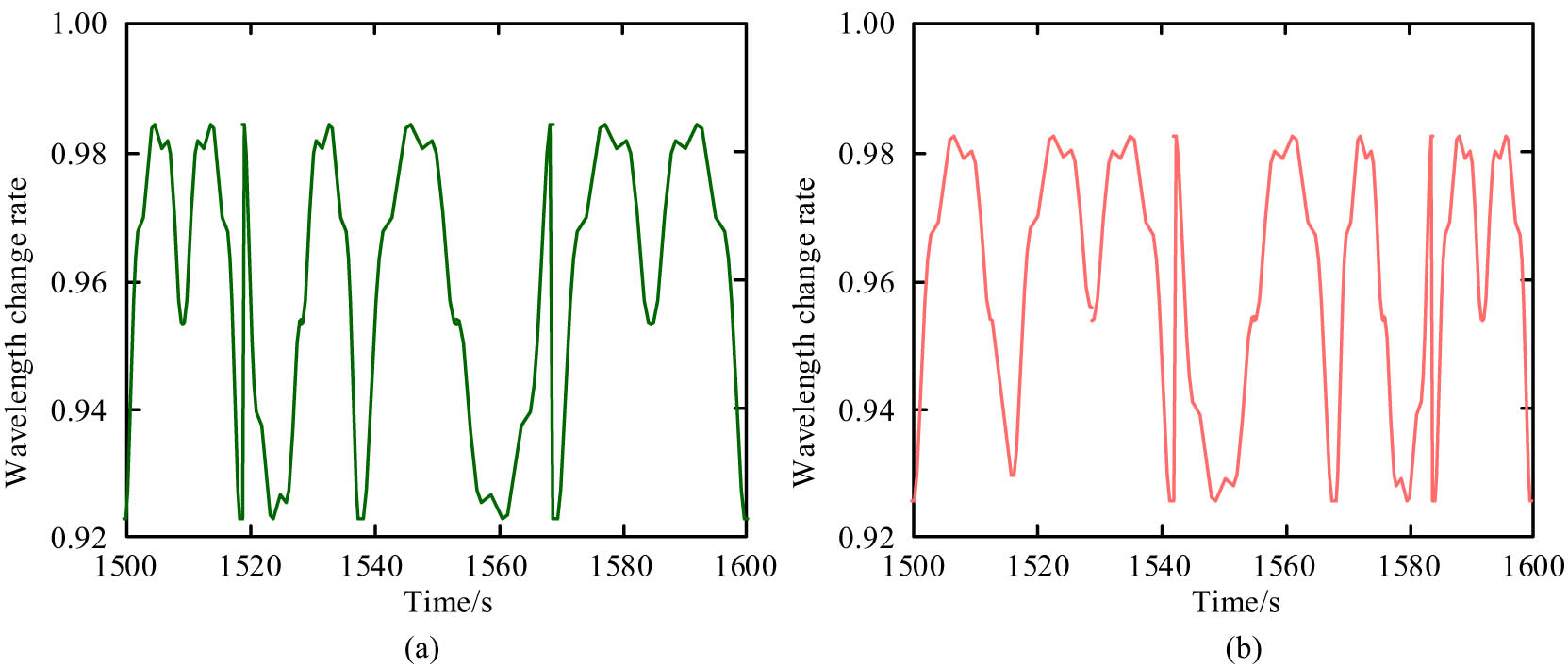

Curve of coupling efficiency of inverted cone waveguide interlayer coupler changing with wavelength. (a) Wavelength change rate curve 1. (b) Wavelength change rate curve 2.

In Figure 6, through simulation calculations, there is a clear pattern in the rate of change of wavelength within a specific time interval using the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method. At t = 0 s, the wavelength is 1,550 nm, while at t1 seconds, the wavelength increases to 1,600 nm. During this time interval, the rate of change in wavelength (i.e., the amount of change in wavelength per second) remains within a certain range, demonstrating the stability of the device’s operation throughout the C-band. This high coupling efficiency not only demonstrates the excellent performance of the converter in OCOIs but also hints at its potential for applications in biomedical imaging. For example, the depth of photon penetration in biological tissues and the quality of imaging are directly related to the coupling efficiency. Higher coupling efficiency means more stable signal transmission, which can provide sharper biomedical images, especially within the infrared band, which penetrates deeper into biological tissues. The curve of the coupling efficiency of the rectangular waveguide interlayer coupler with wavelength variation is shown in Figure 7.

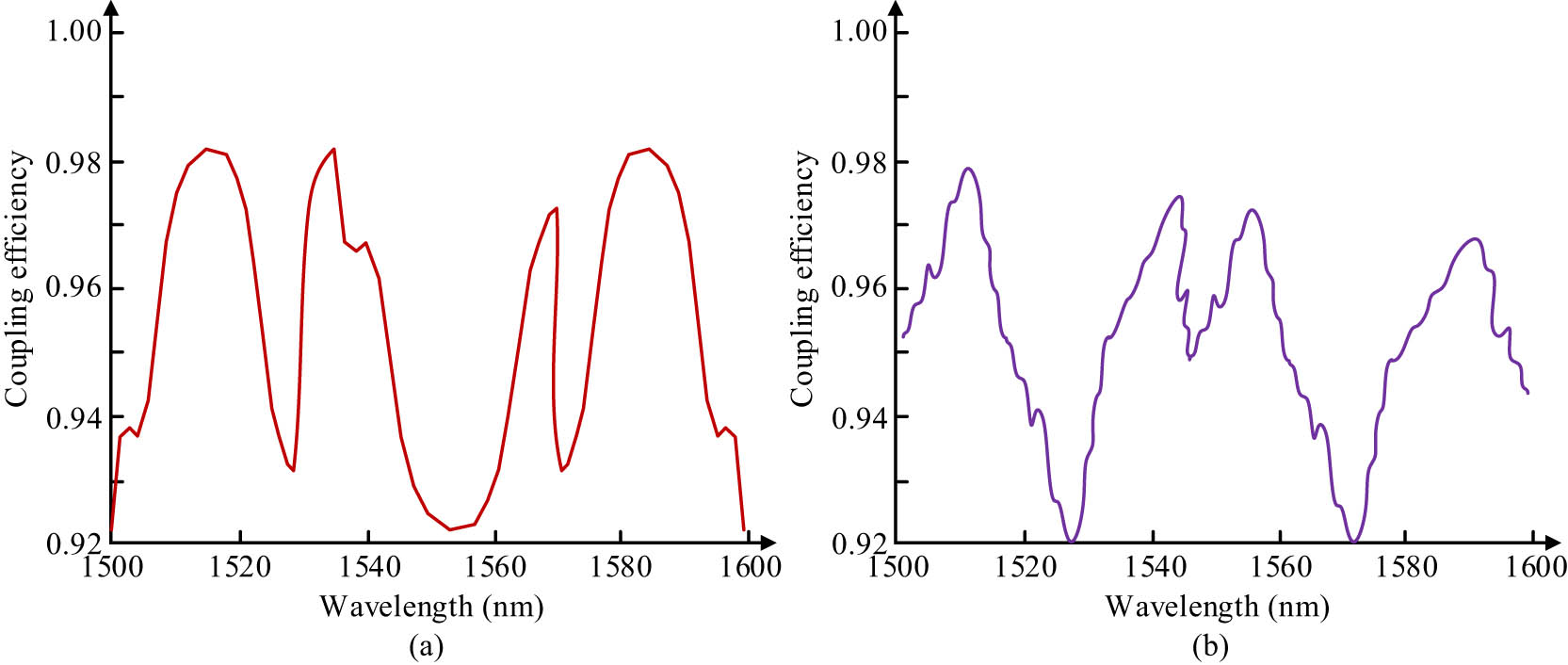

Curve of coupling efficiency of rectangular waveguide interlayer coupler with wavelength variation. (a) Curve 1 of the coupling efficiency of rectangular waveguide interlayer couplers with wavelength variation. (b) Curve 2 of the coupling efficiency of rectangular waveguide interlayer couplers with wavelength variation.

Figure 7 simulates the interlayer coupling efficiency at different wavelengths using the FDTD method. At a wavelength of 1,550 nm, the interlayer coupling efficiency can reach 98.14%, and the coupling efficiency range of over 90% corresponds to a bandwidth of greater than 100 nm, which can cover the entire C-band.

4.2 Application analysis of AOWC in silicon photonics

The application of AOWC in silicon photonics will also have a profound impact. Through SAOWC, more efficient photonic integrated circuits can be achieved, further improving the performance of optoelectronic devices. This will promote the development of silicon photonics and provide new possibilities for the design and manufacturing of optoelectronic devices. The research and application of AOWC will open up new research fields and application prospects for the development of silicon photonics. Table 2 shows the parameters of the model.

System parameters of all-optical wavelength converters

| Parameter name | Parameter value | Equipment selection |

|---|---|---|

| Optical wavelength converter | SAOWC | Device with high-efficiency wavelength conversion performance |

| Photonic integrated circuit | Photonic integrated circuit | Device for simulating and testing optoelectronic device performance |

| Light source device | Laser | Stable, moderate intensity light source device |

| Optical detector | Photodiode | High sensitivity, fast response optical detector |

| Power supply | Direct current power supply | Stable output, low current fluctuation power supply |

| Temperature control equipment | Digital temperature controller | High precision, fast response temperature control equipment |

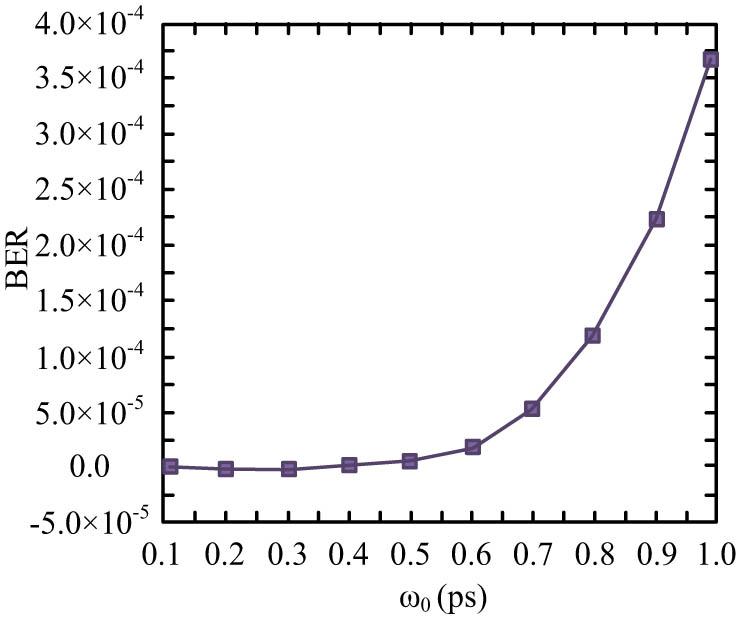

In Table 2, when choosing AOWC, SAOWC with high efficiency wavelength conversion performance is preferred. Meanwhile, to simulate and test the performance of optoelectronic devices, photonic integrated circuits have been selected as the preferred equipment. In terms of the selection of light source equipment, a stable and moderately strong laser is considered as the best option. In addition, due to its high sensitivity and fast response speed, photodiodes have been selected as the most ideal photodetectors. On the power supply, a DC power supply with stable output and small current fluctuations is selected. In addition, digital temperature controllers with high accuracy and fast response speed have been selected as temperature control devices to ensure the accuracy and effectiveness of the experiment. The relationship between error rate and pulse width is shown in Figure 8.

The relationship between BER and pulse width.

In Figure 8, when Λ = 0.1 ps, BER is 4.341310−17. When Λ = 1.0 ps, BER is 3.666410−4. In view of this, when Λ increases from 0.1 to 1.0 ps, the order of 10−17 is increased to the order of 10−4. An increase in BER can mean more interference or loss of data during the transmission of biological signals, similar to the loss of information in neural signaling. Therefore, the BER results underscore the necessity for additional optimization of the technique when processing biological data, aiming to ensure the maintenance of high signal accuracy in complex environments. The simulation results of XPM type wavelength converter based on QD-SOA-MZI are shown in Figure 9.

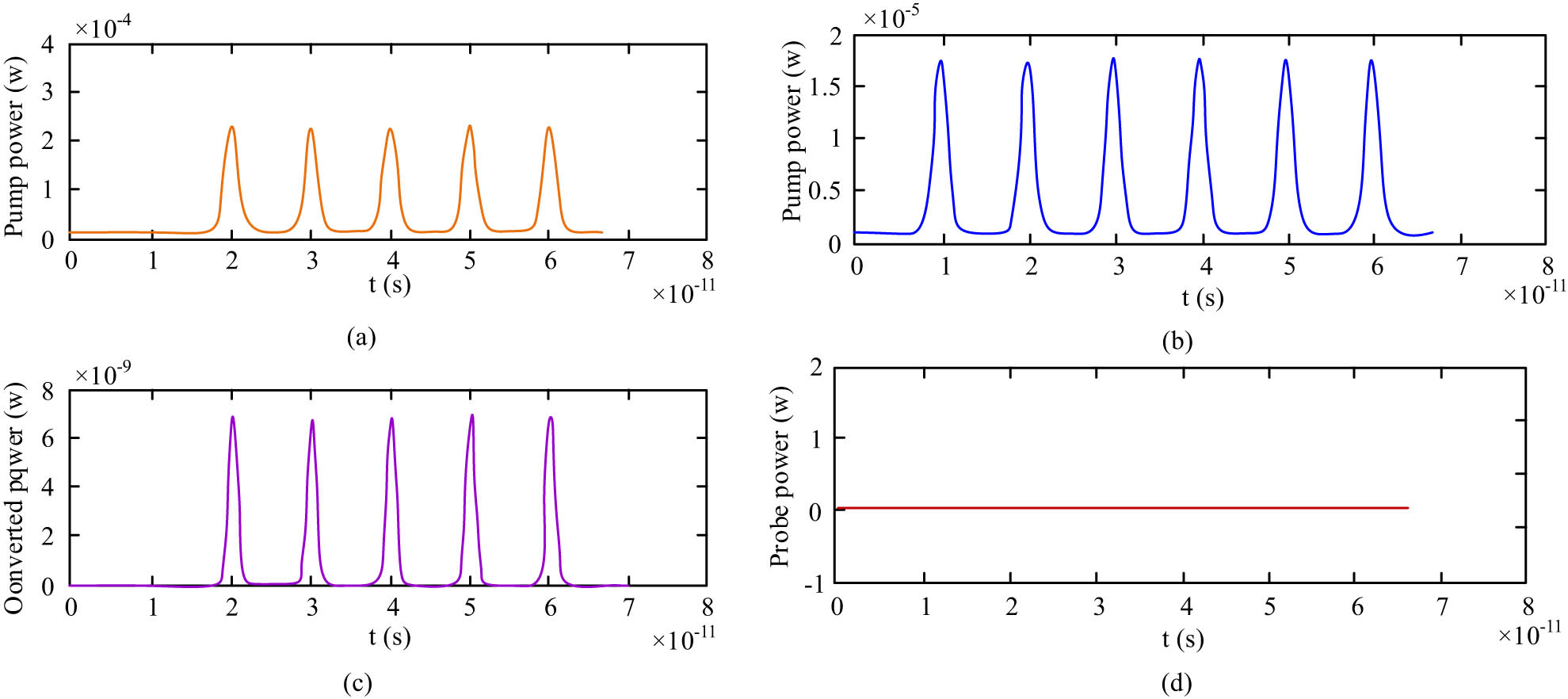

Simulation results of XPM wavelength converter based on QD-SOA-MZI. (a) Pump power before conversion. (b) Pump power after conversion. (c) Conversion power before conversion. (d) Conversion power after conversion.

In Figure 9, during the simulation of the all-optical wavelength converter, it is assumed that the pump light wavelength is 1,500 nm and the detection light wavelength is 1,550 nm. When the injection current 1I of QD-SOA1 is 40 mA and the injection current 2I of QD-SOA2 is 35 mA, in-phase conversion is achieved. The selection of these two types of injection currents is mainly based on the preliminary simulation analysis of the gain characteristics of the quantum dot semiconductor optical amplifier (QD-SOA) and the reference values in the literature. The specific reason is that the 40 mA injection current can provide sufficient optical gain for QD-SOA1, while the 35 mA injection current ensures the steady-state output of QD-SOA2. The difference between the two also helps to realize the phase modulation in the interferometer. The simulation under these environmental conditions reveals the performance of the AOWC under specific operating conditions. The relationship between pulse width and influence factor is shown in Figure 10.

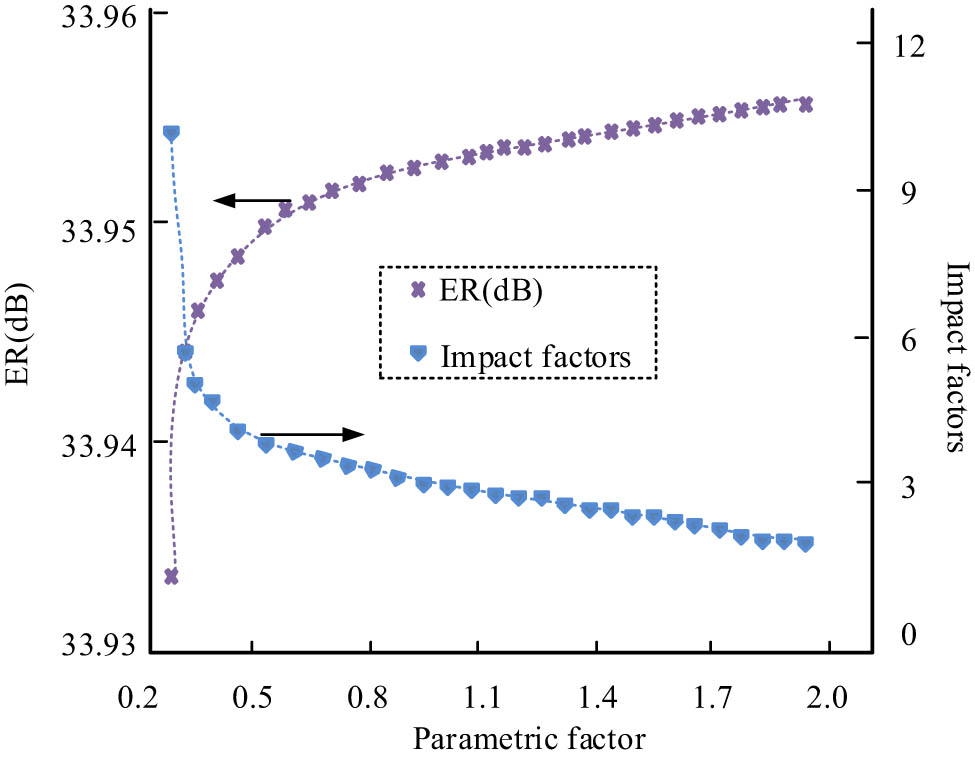

Relationship between pulse width and influence factor.

In Figure 10, during the process of reducing the parameter factor from 2.0 to 0.5 ps, the error rate (ER) increases from 33.9738 to 33.9537 dB, while the impact factor increases from 5.6898 to 11.1202 dB. This process reveals a phenomenon of mutual hindrance, namely, the difficulty in attempting to increase both ER and influence factors by changing parameter factors. When determining the parameter factor, this factor should be considered to ensure that while improving the influence factor, the obtained ER value can also meet the requirements. This is a strategy to balance optimization indicators, aiming to maintain a high level of ER while meeting the improvement of impact factors. In addition, when optimizing the injection current, a dual-objective optimization method based on BER and coupling efficiency is used, and the test results for QD-SOA1 and QD-SOA2 are shown in Figure 11.

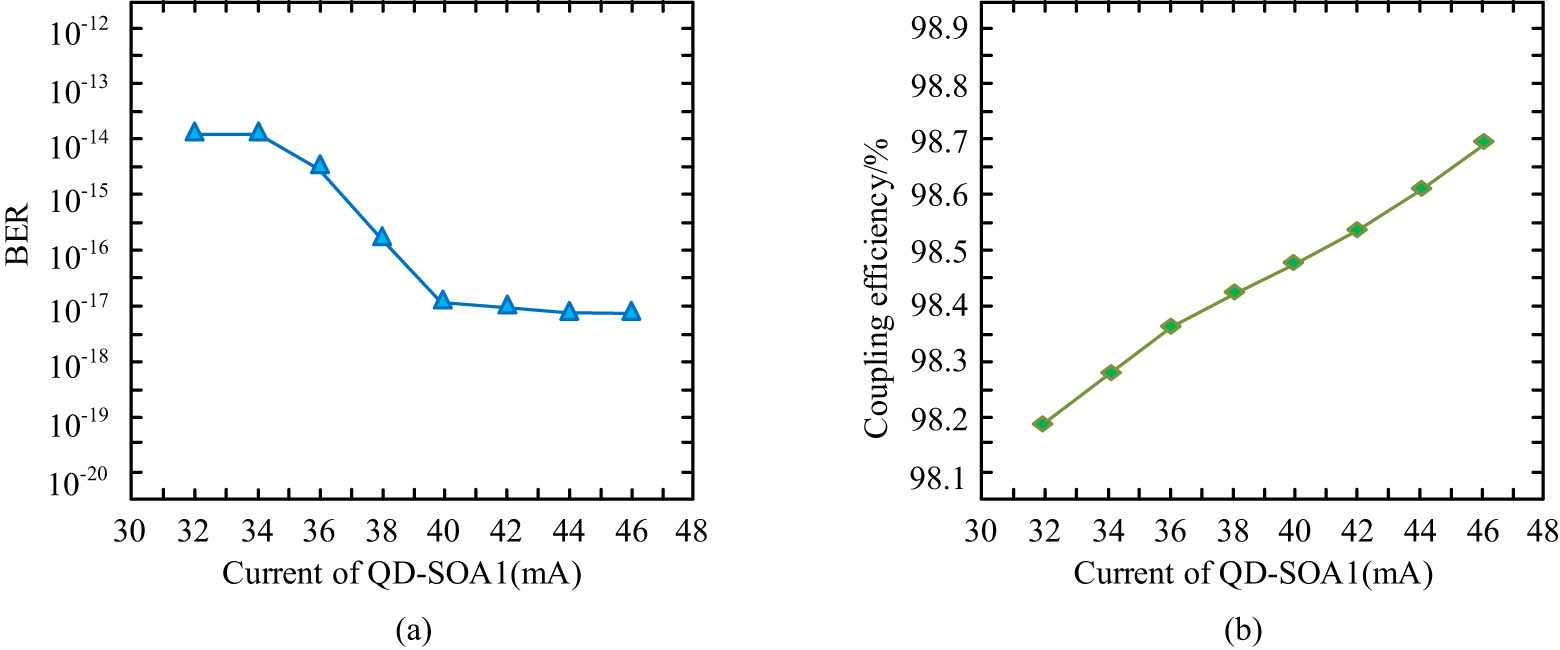

ER and coupling efficiency testing of different injected currents. (a) Error rate testing. (b) Coupling efficiency test.

Figure 11 shows the results of the ER and coupling efficiency at different injection currents. From Figure 11(a), the ER decreases significantly with the increase in QD-SOA1 injection current. When the injection current is increased from 35 to 45 mA, the BER decreases from 10 to 17 levels to nearly 10–18 levels, proving that the ER can be effectively reduced by adjusting the current. In Figure 11(b), the coupling efficiency gradually increases from 98.44% to more than 98.7% with the increase in injection current. This proves that the reasonable adjustment of injection current helps to improve the coupling performance of the optical path. In addition, the study conducts the temperature fluctuation test and optical signal intensity degradation test in the stress test, and the results are shown in Figure 12.

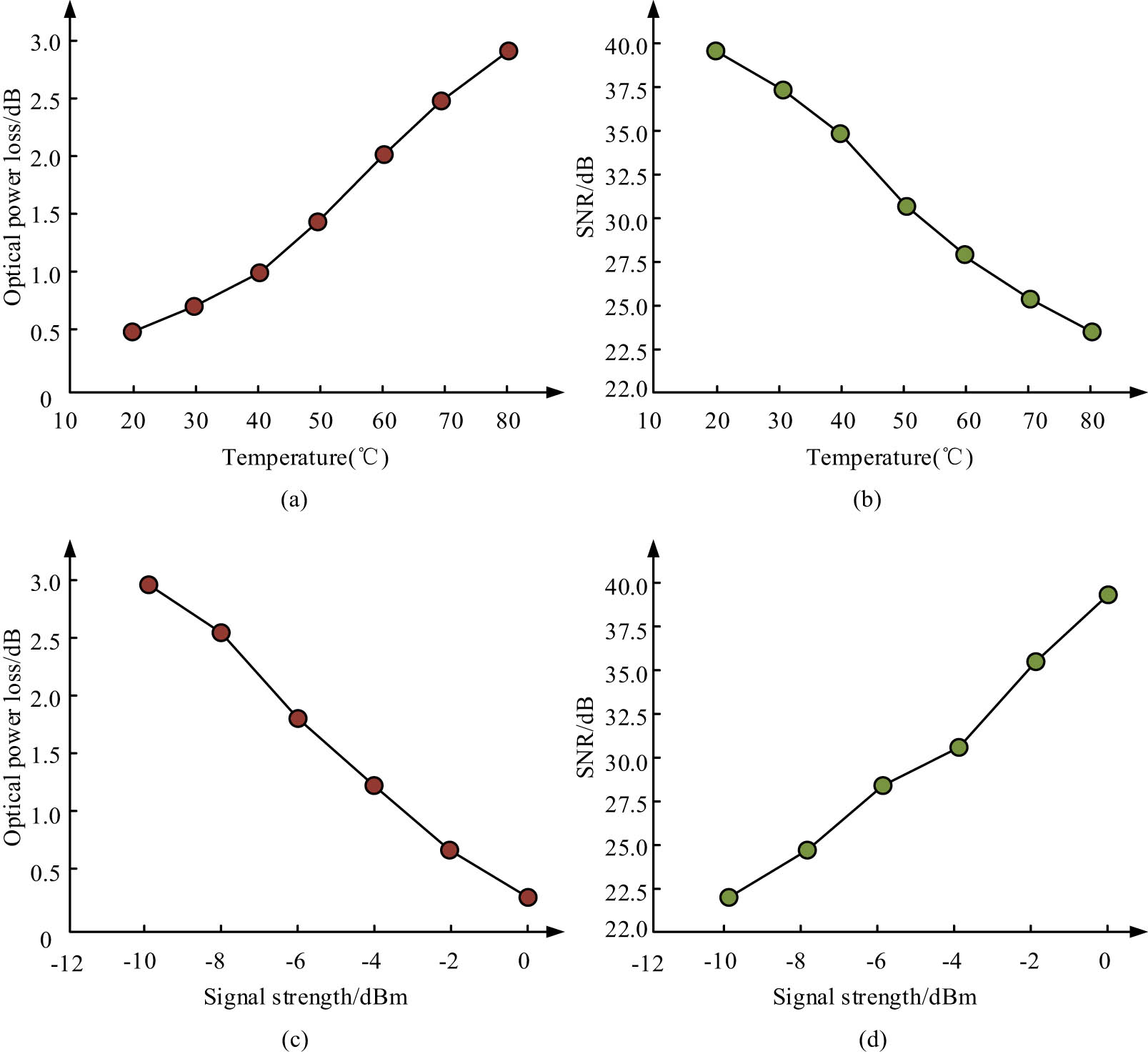

Temperature fluctuation test and light signal intensity degradation test. (a) Optical power loss under temperature and pressure. (b) Signal to noise ratio under temperature and pressure. (c) Optical power loss caused by degradation of optical signal intensity. (d) Signal to noise (SNR) ratio of degraded optical signal intensity.

Figure 12(a) and (b) show the test results of optical power loss and SNR under temperature stress. Figure 12(c) and (d) show the test results of optical power loss and SNR ratio with degradation of optical signal strength. From Figure 12(a) and (b), the optical power loss gradually increases from 0.5 to 3.0 dB as the temperature rises from 20 to 80°C, while the SNR gradually decreases from 40 to 22 dB. This indicates that the temperature rise negatively affects the transmission efficiency of the system, resulting in more signal loss. At the same time, the temperature fluctuation leads to the degradation of the signal quality, and the noise relative to the signal becomes more pronounced. This phenomenon can also be compared to temperature sensitivity in biological systems. For example, neural signaling and enzymatic reactions change in efficiency and accuracy at different temperatures. Increased molecular vibrations in biological systems at high temperatures can lead to signal distortion. Similarly, the effect of temperature on the photon transport system suggests that the performance of the converter in different biological environments may also need to be optimized for temperature changes. From Figure 12(c) and (d), the optical power loss increases from 0.5 to 3.2 dB and the SNR decreases from 40 to 20 dB as the signal strength decreases from 0 to 10 dBm. This indicates that the decreasing of the signal strength has a large impact on the loss in the transmission process. At the same time, the quality of the signal with an increase in the noise component is significantly reduced. The optical power loss increases with the temperature, while the SNR decreases with the temperature. In addition, the optical power loss increases with the weakening of the signal strength, while the SNR decreases significantly. It illustrates that temperature fluctuation needs to be controlled in practical applications to avoid system reliability degradation, while keeping the intensity of the optical signal within a certain range is the key to ensure the stability of the system.

5 Conclusion

In the current field of high-speed data transmission and communication, on-chip OIT has received widespread attention due to its characteristics such as low latency and energy consumption, and high bandwidth. Among them, efficient optical wavelength converters are a key component of smooth information transmission and play a crucial role in supporting the comprehensive operation of OCOIs. Therefore, the research on SAOWC for OCOIs has remarkable significance. The existing research mainly uses the FDTD method for simulation calculations. During this process, attempts are made to achieve in-phase conversion at different wavelengths by adjusting the injection current 1I of QD-SOA1 and the injection current 2I of QD-SOA2.

Through simulation and experimental verification, the study successfully demonstrated the efficient performance of SAOWCs in OCOIs. First, the FDTD simulation results showed that the interlayer coupling efficiency reached 98.44% at 1,550 nm wavelength, and this performance was consistent with the experimental data, proving the high efficiency of the proposed converter. Second, the BER test clearly showed that the increase in pulse width had a significant effect on the BER, which rose from 10−17 to 10−4 when the pulse width increased from 0.1 to 1.0 ps. This further illustrated the criticality of the pulse parameter on the system performance. In addition, the test results for temperature fluctuation and optical signal strength degradation showed the stability of the system in different environments, where the optical power loss increased with temperature rise and signal strength degradation, while the SNR decreased. This indicated that the converter performed well in complex environments with good operational stability as predicted by simulations. In the high wavelength range, existing silicon-based materials will experience increased losses and nonlinear effects, which will affect conversion efficiency and signal quality. The design of wavelength converters must be adapted to accommodate the varying wavelengths of light waves, encompassing the engineering of waveguide structures and resonant cavities. This is essential to enhance the coupling and transmission of light. The experimental equipment used for testing and validation also needs to be updated to enable accurate measurement and analysis in a higher wavelength range. The application of SAOWC in on-chip OIT has demonstrated extremely high interlayer coupling efficiency and reliable in-phase conversion performance. It is expected to have more optimization research works in the future to promote the deeper development of optical wavelength converters and on chip OITs.

-

Funding information: The research was supported by 2021 Shaanxi Provincial Department of Education Project, Research on silicon-based all-optical wavelength converters for on-chip optical interconnection Project No. “21JK0513.”

-

Author contributions: All the contributions in the article are attributed to Shuhong Liu.

-

Conflict of interest: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data used to support the findings of the research are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

[1] Huang X, Li Z. Multi-scale analyses on mechano-electric degradation of film interconnects in flexible electronics. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 2023;46(1):259–70.10.1111/ffe.13861Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Bharat S, Chaudhari S, Patil S. Optimized designs of low loss non-blocking optical router for ONoC applications. Int J Inf Technol. 2020;12(1):91–6.10.1007/s41870-019-00298-7Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Cao XP, Zheng S, Zhou N. On-chip multidimensional 1 × 4 selective switch with simultaneous mode-/polarization-/wavelength-division multiplexing. IEEE J Quantum Electron. 2020;56(5):1–8.10.1109/JQE.2020.3004821Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Zhang Y, Zhang RH, Zhu QM. Architecture and devices for silicon photonic switching in wavelength, polarization and mode. J Lightw Technol. 2019;38(2):215–25.10.1109/JLT.2019.2946171Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Zhang J, Kuo BPP, Radic S. 64 Gb/s PAM4 and 160 Gb/s 16QAM modulation reception using a low-voltage Si-Ge waveguide-integrated APD. Opt Express. 2020;28(16):23266–73.10.1364/OE.396979Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Fang Y, Luo B, Zhao T, He D, Jiang B, Liu Q. ST-SIGMA: Spatio-temporal semantics and interaction graph aggregation for multi-agent perception and trajectory forecasting. CAAI Trans Intell Technol. 2022;7(4):744–57.10.1049/cit2.12145Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Jinyang H, Lin J, Yan Z. Design of passive H tree network for on-chip optical interconnection. J Optoelectron Laser. 2022;33(June):570–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Adao RMR, Alves TL, Maibohm C. Two-photon polymerization simulation and fabrication of 3D microprinted suspended waveguides for on-chip optical interconnects. Opt Express. 2022;30(1):9623–42. Optica Publ Group.10.1364/OE.449641Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Li G, Li M, Zuo Y, Suo X, Su H, Wang Y. Self-passivated perovskite film by overdoping MABr to enhance the luminescence efficiency of MAPbBr3-based light-emitting diodes. Opt Eng. 2022;61(8):1–10.10.1117/1.OE.61.8.087104Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Hao J, Xin F. Mode-selective modulation by silicon microring resonators and mode multiplexers for on-chip optical interconnect. Opt Express. 2019;27(Jan):2915–25.10.1364/OE.27.002915Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Weixin L, Yiming M. Suspended silicon waveguide platform with subwavelength grating metamaterial cladding for long-wave infrared sensing applications. Nanophotonics. 2021;10(May):1861–70.10.1515/nanoph-2021-0029Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Huang L, Yang Z, Wang R, Xie L. A model for predicting ground reaction force and energetics of human locomotion with an elastically suspended backpack. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng. 2022;25(14):1554–64.10.1080/10255842.2021.2023808Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Sharma H, Raj R, Juneja M. An empirical comparison of machine learning algorithms for the classification of brain signals to assess the impact of combined yoga and Sudarshan Kriya. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng. 2022;25(7):721–8.10.1080/10255842.2021.1975682Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Huang L, Gu H, Tian Y, Zhao T. Universal method for constructing the on-chip optical router with wavelength routing technology. J Lightw Technol. 2020;38(15):3815–21.10.1109/JLT.2020.2986237Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Mere V, Dash A, Kallega R, Pratap R, Naik A, Selvaraja SK. On-chip silicon photonics based grating assisted vibration sensor. Opt Express. 2020;28(19):27495–505.10.1364/OE.394393Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Zhang K, Hu H. An experimental study on the transient runback characteristics of wind-driven film/rivulet flows. Phys Fluids. 2021;33(11):1–14.10.1063/5.0067672Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Dabaghyan G. Modification of a silicon surface visible light reflectivity by the carbon nanofilm. Int J Mod Phys B. 2021;35(26):1–5.10.1142/S0217979221502647Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Guo PX, Hou WG, Guo L. Fault tolerant routing mechanism in 3D optical network-on-chip based on node reuse. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2020;31(3):547–64.10.1109/TPDS.2019.2939240Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Mahmood T, Ali Z. Prioritized Muirhead mean aggregation operators under the complex single-valued neutrosophic settings and their application in multi-attribute decision-making. J Comput Cogn Eng. 2022;1(2):56–73.10.47852/bonviewJCCE2022010104Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Muhiuddin G, Mahboob A, Elnair MEA. A new study based on fuzzy bi-Γ-ideals in ordered-Γ-semigroups. J Comput Cogn Eng. 2022;1(1):42–6.10.47852/bonviewJCCE19919205514Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Waziri TA, Yakasai BM. Assessment of some proposed replacement models involving moderate fix-up. J Comput Cogn Eng. 2023;2(1):28–37.10.47852/bonviewJCCE2202150Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Generalized (ψ,φ)-contraction to investigate Volterra integral inclusions and fractal fractional PDEs in super-metric space with numerical experiments

- Solitons in ultrasound imaging: Exploring applications and enhancements via the Westervelt equation

- Stochastic improved Simpson for solving nonlinear fractional-order systems using product integration rules

- Exploring dynamical features like bifurcation assessment, sensitivity visualization, and solitary wave solutions of the integrable Akbota equation

- Research on surface defect detection method and optimization of paper-plastic composite bag based on improved combined segmentation algorithm

- Impact the sulphur content in Iraqi crude oil on the mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of carbon steel in various types of API 5L pipelines and ASTM 106 grade B

- Unravelling quiescent optical solitons: An exploration of the complex Ginzburg–Landau equation with nonlinear chromatic dispersion and self-phase modulation

- Perturbation-iteration approach for fractional-order logistic differential equations

- Variational formulations for the Euler and Navier–Stokes systems in fluid mechanics and related models

- Rotor response to unbalanced load and system performance considering variable bearing profile

- DeepFowl: Disease prediction from chicken excreta images using deep learning

- Channel flow of Ellis fluid due to cilia motion

- A case study of fractional-order varicella virus model to nonlinear dynamics strategy for control and prevalence

- Multi-point estimation weldment recognition and estimation of pose with data-driven robotics design

- Analysis of Hall current and nonuniform heating effects on magneto-convection between vertically aligned plates under the influence of electric and magnetic fields

- A comparative study on residual power series method and differential transform method through the time-fractional telegraph equation

- Insights from the nonlinear Schrödinger–Hirota equation with chromatic dispersion: Dynamics in fiber–optic communication

- Mathematical analysis of Jeffrey ferrofluid on stretching surface with the Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Exploring the interaction between lump, stripe and double-stripe, and periodic wave solutions of the Konopelchenko–Dubrovsky–Kaup–Kupershmidt system

- Computational investigation of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS co-infection in fuzzy environment

- Signature verification by geometry and image processing

- Theoretical and numerical approach for quantifying sensitivity to system parameters of nonlinear systems

- Chaotic behaviors, stability, and solitary wave propagations of M-fractional LWE equation in magneto-electro-elastic circular rod

- Dynamic analysis and optimization of syphilis spread: Simulations, integrating treatment and public health interventions

- Visco-thermoelastic rectangular plate under uniform loading: A study of deflection

- Threshold dynamics and optimal control of an epidemiological smoking model

- Numerical computational model for an unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium past an MHD rotating sheet

- Regression prediction model of fabric brightness based on light and shadow reconstruction of layered images

- Dynamics and prevention of gemini virus infection in red chili crops studied with generalized fractional operator: Analysis and modeling

- Qualitative analysis on existence and stability of nonlinear fractional dynamic equations on time scales

- Fractional-order super-twisting sliding mode active disturbance rejection control for electro-hydraulic position servo systems

- Analytical exploration and parametric insights into optical solitons in magneto-optic waveguides: Advances in nonlinear dynamics for applied sciences

- Bifurcation dynamics and optical soliton structures in the nonlinear Schrödinger–Bopp–Podolsky system

- User profiling in university libraries by combining multi-perspective clustering algorithm and reader behavior analysis

- Exploring bifurcation and chaos control in a discrete-time Lotka–Volterra model framework for COVID-19 modeling

- Review Article

- Haar wavelet collocation method for existence and numerical solutions of fourth-order integro-differential equations with bounded coefficients

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Analysis and Design of Communication Networks for IoT Applications - Part II

- Silicon-based all-optical wavelength converter for on-chip optical interconnection

- Research on a path-tracking control system of unmanned rollers based on an optimization algorithm and real-time feedback

- Analysis of the sports action recognition model based on the LSTM recurrent neural network

- Industrial robot trajectory error compensation based on enhanced transfer convolutional neural networks

- Research on IoT network performance prediction model of power grid warehouse based on nonlinear GA-BP neural network

- Interactive recommendation of social network communication between cities based on GNN and user preferences

- Application of improved P-BEM in time varying channel prediction in 5G high-speed mobile communication system

- Construction of a BIM smart building collaborative design model combining the Internet of Things

- Optimizing malicious website prediction: An advanced XGBoost-based machine learning model

- Economic operation analysis of the power grid combining communication network and distributed optimization algorithm

- Sports video temporal action detection technology based on an improved MSST algorithm

- Internet of things data security and privacy protection based on improved federated learning

- Enterprise power emission reduction technology based on the LSTM–SVM model

- Construction of multi-style face models based on artistic image generation algorithms

- Research and application of interactive digital twin monitoring system for photovoltaic power station based on global perception

- Special Issue: Decision and Control in Nonlinear Systems - Part II

- Animation video frame prediction based on ConvGRU fine-grained synthesis flow

- Application of GGNN inference propagation model for martial art intensity evaluation

- Benefit evaluation of building energy-saving renovation projects based on BWM weighting method

- Deep neural network application in real-time economic dispatch and frequency control of microgrids

- Real-time force/position control of soft growing robots: A data-driven model predictive approach

- Mechanical product design and manufacturing system based on CNN and server optimization algorithm

- Application of finite element analysis in the formal analysis of ancient architectural plaque section

- Research on territorial spatial planning based on data mining and geographic information visualization

- Fault diagnosis of agricultural sprinkler irrigation machinery equipment based on machine vision

- Closure technology of large span steel truss arch bridge with temporarily fixed edge supports

- Intelligent accounting question-answering robot based on a large language model and knowledge graph

- Analysis of manufacturing and retailer blockchain decision based on resource recyclability

- Flexible manufacturing workshop mechanical processing and product scheduling algorithm based on MES

- Exploration of indoor environment perception and design model based on virtual reality technology

- Tennis automatic ball-picking robot based on image object detection and positioning technology

- A new CNN deep learning model for computer-intelligent color matching

- Design of AR-based general computer technology experiment demonstration platform

- Indoor environment monitoring method based on the fusion of audio recognition and video patrol features

- Health condition prediction method of the computer numerical control machine tool parts by ensembling digital twins and improved LSTM networks

- Establishment of a green degree evaluation model for wall materials based on lifecycle

- Quantitative evaluation of college music teaching pronunciation based on nonlinear feature extraction

- Multi-index nonlinear robust virtual synchronous generator control method for microgrid inverters

- Manufacturing engineering production line scheduling management technology integrating availability constraints and heuristic rules

- Analysis of digital intelligent financial audit system based on improved BiLSTM neural network

- Attention community discovery model applied to complex network information analysis

- A neural collaborative filtering recommendation algorithm based on attention mechanism and contrastive learning

- Rehabilitation training method for motor dysfunction based on video stream matching

- Research on façade design for cold-region buildings based on artificial neural networks and parametric modeling techniques

- Intelligent implementation of muscle strain identification algorithm in Mi health exercise induced waist muscle strain

- Optimization design of urban rainwater and flood drainage system based on SWMM

- Improved GA for construction progress and cost management in construction projects

- Evaluation and prediction of SVM parameters in engineering cost based on random forest hybrid optimization

- Museum intelligent warning system based on wireless data module

- Optimization design and research of mechatronics based on torque motor control algorithm

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Engineering’s significance in Materials Science

- Experimental research on the degradation of chemical industrial wastewater by combined hydrodynamic cavitation based on nonlinear dynamic model

- Study on low-cycle fatigue life of nickel-based superalloy GH4586 at various temperatures

- Some results of solutions to neutral stochastic functional operator-differential equations

- Ultrasonic cavitation did not occur in high-pressure CO2 liquid

- Research on the performance of a novel type of cemented filler material for coal mine opening and filling

- Testing of recycled fine aggregate concrete’s mechanical properties using recycled fine aggregate concrete and research on technology for highway construction

- A modified fuzzy TOPSIS approach for the condition assessment of existing bridges

- Nonlinear structural and vibration analysis of straddle monorail pantograph under random excitations

- Achieving high efficiency and stability in blue OLEDs: Role of wide-gap hosts and emitter interactions

- Construction of teaching quality evaluation model of online dance teaching course based on improved PSO-BPNN

- Enhanced electrical conductivity and electromagnetic shielding properties of multi-component polymer/graphite nanocomposites prepared by solid-state shear milling

- Optimization of thermal characteristics of buried composite phase-change energy storage walls based on nonlinear engineering methods

- A higher-performance big data-based movie recommendation system

- Nonlinear impact of minimum wage on labor employment in China

- Nonlinear comprehensive evaluation method based on information entropy and discrimination optimization

- Application of numerical calculation methods in stability analysis of pile foundation under complex foundation conditions

- Research on the contribution of shale gas development and utilization in Sichuan Province to carbon peak based on the PSA process

- Characteristics of tight oil reservoirs and their impact on seepage flow from a nonlinear engineering perspective

- Nonlinear deformation decomposition and mode identification of plane structures via orthogonal theory

- Numerical simulation of damage mechanism in rock with cracks impacted by self-excited pulsed jet based on SPH-FEM coupling method: The perspective of nonlinear engineering and materials science

- Cross-scale modeling and collaborative optimization of ethanol-catalyzed coupling to produce C4 olefins: Nonlinear modeling and collaborative optimization strategies

- Unequal width T-node stress concentration factor analysis of stiffened rectangular steel pipe concrete

- Special Issue: Advances in Nonlinear Dynamics and Control

- Development of a cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy design for a nonlinear diabetic patient model

- Big data-based optimized model of building design in the context of rural revitalization

- Multi-UAV assisted air-to-ground data collection for ground sensors with unknown positions

- Design of urban and rural elderly care public areas integrating person-environment fit theory

- Application of lossless signal transmission technology in piano timbre recognition

- Application of improved GA in optimizing rural tourism routes

- Architectural animation generation system based on AL-GAN algorithm

- Advanced sentiment analysis in online shopping: Implementing LSTM models analyzing E-commerce user sentiments

- Intelligent recommendation algorithm for piano tracks based on the CNN model

- Visualization of large-scale user association feature data based on a nonlinear dimensionality reduction method

- Low-carbon economic optimization of microgrid clusters based on an energy interaction operation strategy

- Optimization effect of video data extraction and search based on Faster-RCNN hybrid model on intelligent information systems

- Construction of image segmentation system combining TC and swarm intelligence algorithm

- Particle swarm optimization and fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm for the adhesive layer defect detection

- Optimization of student learning status by instructional intervention decision-making techniques incorporating reinforcement learning

- Fuzzy model-based stabilization control and state estimation of nonlinear systems

- Optimization of distribution network scheduling based on BA and photovoltaic uncertainty

- Tai Chi movement segmentation and recognition on the grounds of multi-sensor data fusion and the DBSCAN algorithm

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part III

- Generalized numerical RKM method for solving sixth-order fractional partial differential equations

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Generalized (ψ,φ)-contraction to investigate Volterra integral inclusions and fractal fractional PDEs in super-metric space with numerical experiments

- Solitons in ultrasound imaging: Exploring applications and enhancements via the Westervelt equation

- Stochastic improved Simpson for solving nonlinear fractional-order systems using product integration rules

- Exploring dynamical features like bifurcation assessment, sensitivity visualization, and solitary wave solutions of the integrable Akbota equation

- Research on surface defect detection method and optimization of paper-plastic composite bag based on improved combined segmentation algorithm

- Impact the sulphur content in Iraqi crude oil on the mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of carbon steel in various types of API 5L pipelines and ASTM 106 grade B

- Unravelling quiescent optical solitons: An exploration of the complex Ginzburg–Landau equation with nonlinear chromatic dispersion and self-phase modulation

- Perturbation-iteration approach for fractional-order logistic differential equations

- Variational formulations for the Euler and Navier–Stokes systems in fluid mechanics and related models

- Rotor response to unbalanced load and system performance considering variable bearing profile

- DeepFowl: Disease prediction from chicken excreta images using deep learning

- Channel flow of Ellis fluid due to cilia motion

- A case study of fractional-order varicella virus model to nonlinear dynamics strategy for control and prevalence

- Multi-point estimation weldment recognition and estimation of pose with data-driven robotics design

- Analysis of Hall current and nonuniform heating effects on magneto-convection between vertically aligned plates under the influence of electric and magnetic fields

- A comparative study on residual power series method and differential transform method through the time-fractional telegraph equation

- Insights from the nonlinear Schrödinger–Hirota equation with chromatic dispersion: Dynamics in fiber–optic communication

- Mathematical analysis of Jeffrey ferrofluid on stretching surface with the Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Exploring the interaction between lump, stripe and double-stripe, and periodic wave solutions of the Konopelchenko–Dubrovsky–Kaup–Kupershmidt system

- Computational investigation of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS co-infection in fuzzy environment

- Signature verification by geometry and image processing

- Theoretical and numerical approach for quantifying sensitivity to system parameters of nonlinear systems

- Chaotic behaviors, stability, and solitary wave propagations of M-fractional LWE equation in magneto-electro-elastic circular rod

- Dynamic analysis and optimization of syphilis spread: Simulations, integrating treatment and public health interventions

- Visco-thermoelastic rectangular plate under uniform loading: A study of deflection

- Threshold dynamics and optimal control of an epidemiological smoking model

- Numerical computational model for an unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium past an MHD rotating sheet

- Regression prediction model of fabric brightness based on light and shadow reconstruction of layered images

- Dynamics and prevention of gemini virus infection in red chili crops studied with generalized fractional operator: Analysis and modeling

- Qualitative analysis on existence and stability of nonlinear fractional dynamic equations on time scales

- Fractional-order super-twisting sliding mode active disturbance rejection control for electro-hydraulic position servo systems

- Analytical exploration and parametric insights into optical solitons in magneto-optic waveguides: Advances in nonlinear dynamics for applied sciences

- Bifurcation dynamics and optical soliton structures in the nonlinear Schrödinger–Bopp–Podolsky system

- User profiling in university libraries by combining multi-perspective clustering algorithm and reader behavior analysis

- Exploring bifurcation and chaos control in a discrete-time Lotka–Volterra model framework for COVID-19 modeling

- Review Article

- Haar wavelet collocation method for existence and numerical solutions of fourth-order integro-differential equations with bounded coefficients

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Analysis and Design of Communication Networks for IoT Applications - Part II

- Silicon-based all-optical wavelength converter for on-chip optical interconnection

- Research on a path-tracking control system of unmanned rollers based on an optimization algorithm and real-time feedback

- Analysis of the sports action recognition model based on the LSTM recurrent neural network

- Industrial robot trajectory error compensation based on enhanced transfer convolutional neural networks

- Research on IoT network performance prediction model of power grid warehouse based on nonlinear GA-BP neural network

- Interactive recommendation of social network communication between cities based on GNN and user preferences

- Application of improved P-BEM in time varying channel prediction in 5G high-speed mobile communication system

- Construction of a BIM smart building collaborative design model combining the Internet of Things

- Optimizing malicious website prediction: An advanced XGBoost-based machine learning model

- Economic operation analysis of the power grid combining communication network and distributed optimization algorithm

- Sports video temporal action detection technology based on an improved MSST algorithm

- Internet of things data security and privacy protection based on improved federated learning

- Enterprise power emission reduction technology based on the LSTM–SVM model

- Construction of multi-style face models based on artistic image generation algorithms

- Research and application of interactive digital twin monitoring system for photovoltaic power station based on global perception

- Special Issue: Decision and Control in Nonlinear Systems - Part II

- Animation video frame prediction based on ConvGRU fine-grained synthesis flow

- Application of GGNN inference propagation model for martial art intensity evaluation

- Benefit evaluation of building energy-saving renovation projects based on BWM weighting method

- Deep neural network application in real-time economic dispatch and frequency control of microgrids

- Real-time force/position control of soft growing robots: A data-driven model predictive approach

- Mechanical product design and manufacturing system based on CNN and server optimization algorithm

- Application of finite element analysis in the formal analysis of ancient architectural plaque section

- Research on territorial spatial planning based on data mining and geographic information visualization

- Fault diagnosis of agricultural sprinkler irrigation machinery equipment based on machine vision

- Closure technology of large span steel truss arch bridge with temporarily fixed edge supports

- Intelligent accounting question-answering robot based on a large language model and knowledge graph

- Analysis of manufacturing and retailer blockchain decision based on resource recyclability

- Flexible manufacturing workshop mechanical processing and product scheduling algorithm based on MES

- Exploration of indoor environment perception and design model based on virtual reality technology

- Tennis automatic ball-picking robot based on image object detection and positioning technology

- A new CNN deep learning model for computer-intelligent color matching

- Design of AR-based general computer technology experiment demonstration platform

- Indoor environment monitoring method based on the fusion of audio recognition and video patrol features

- Health condition prediction method of the computer numerical control machine tool parts by ensembling digital twins and improved LSTM networks

- Establishment of a green degree evaluation model for wall materials based on lifecycle

- Quantitative evaluation of college music teaching pronunciation based on nonlinear feature extraction

- Multi-index nonlinear robust virtual synchronous generator control method for microgrid inverters

- Manufacturing engineering production line scheduling management technology integrating availability constraints and heuristic rules

- Analysis of digital intelligent financial audit system based on improved BiLSTM neural network

- Attention community discovery model applied to complex network information analysis

- A neural collaborative filtering recommendation algorithm based on attention mechanism and contrastive learning

- Rehabilitation training method for motor dysfunction based on video stream matching

- Research on façade design for cold-region buildings based on artificial neural networks and parametric modeling techniques

- Intelligent implementation of muscle strain identification algorithm in Mi health exercise induced waist muscle strain

- Optimization design of urban rainwater and flood drainage system based on SWMM

- Improved GA for construction progress and cost management in construction projects

- Evaluation and prediction of SVM parameters in engineering cost based on random forest hybrid optimization

- Museum intelligent warning system based on wireless data module

- Optimization design and research of mechatronics based on torque motor control algorithm

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Engineering’s significance in Materials Science

- Experimental research on the degradation of chemical industrial wastewater by combined hydrodynamic cavitation based on nonlinear dynamic model

- Study on low-cycle fatigue life of nickel-based superalloy GH4586 at various temperatures

- Some results of solutions to neutral stochastic functional operator-differential equations

- Ultrasonic cavitation did not occur in high-pressure CO2 liquid

- Research on the performance of a novel type of cemented filler material for coal mine opening and filling

- Testing of recycled fine aggregate concrete’s mechanical properties using recycled fine aggregate concrete and research on technology for highway construction

- A modified fuzzy TOPSIS approach for the condition assessment of existing bridges

- Nonlinear structural and vibration analysis of straddle monorail pantograph under random excitations

- Achieving high efficiency and stability in blue OLEDs: Role of wide-gap hosts and emitter interactions

- Construction of teaching quality evaluation model of online dance teaching course based on improved PSO-BPNN

- Enhanced electrical conductivity and electromagnetic shielding properties of multi-component polymer/graphite nanocomposites prepared by solid-state shear milling

- Optimization of thermal characteristics of buried composite phase-change energy storage walls based on nonlinear engineering methods

- A higher-performance big data-based movie recommendation system

- Nonlinear impact of minimum wage on labor employment in China

- Nonlinear comprehensive evaluation method based on information entropy and discrimination optimization

- Application of numerical calculation methods in stability analysis of pile foundation under complex foundation conditions

- Research on the contribution of shale gas development and utilization in Sichuan Province to carbon peak based on the PSA process

- Characteristics of tight oil reservoirs and their impact on seepage flow from a nonlinear engineering perspective

- Nonlinear deformation decomposition and mode identification of plane structures via orthogonal theory

- Numerical simulation of damage mechanism in rock with cracks impacted by self-excited pulsed jet based on SPH-FEM coupling method: The perspective of nonlinear engineering and materials science

- Cross-scale modeling and collaborative optimization of ethanol-catalyzed coupling to produce C4 olefins: Nonlinear modeling and collaborative optimization strategies

- Unequal width T-node stress concentration factor analysis of stiffened rectangular steel pipe concrete

- Special Issue: Advances in Nonlinear Dynamics and Control

- Development of a cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy design for a nonlinear diabetic patient model

- Big data-based optimized model of building design in the context of rural revitalization

- Multi-UAV assisted air-to-ground data collection for ground sensors with unknown positions

- Design of urban and rural elderly care public areas integrating person-environment fit theory

- Application of lossless signal transmission technology in piano timbre recognition

- Application of improved GA in optimizing rural tourism routes

- Architectural animation generation system based on AL-GAN algorithm

- Advanced sentiment analysis in online shopping: Implementing LSTM models analyzing E-commerce user sentiments

- Intelligent recommendation algorithm for piano tracks based on the CNN model

- Visualization of large-scale user association feature data based on a nonlinear dimensionality reduction method

- Low-carbon economic optimization of microgrid clusters based on an energy interaction operation strategy

- Optimization effect of video data extraction and search based on Faster-RCNN hybrid model on intelligent information systems

- Construction of image segmentation system combining TC and swarm intelligence algorithm

- Particle swarm optimization and fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm for the adhesive layer defect detection

- Optimization of student learning status by instructional intervention decision-making techniques incorporating reinforcement learning

- Fuzzy model-based stabilization control and state estimation of nonlinear systems

- Optimization of distribution network scheduling based on BA and photovoltaic uncertainty

- Tai Chi movement segmentation and recognition on the grounds of multi-sensor data fusion and the DBSCAN algorithm

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part III

- Generalized numerical RKM method for solving sixth-order fractional partial differential equations