Exploring bifurcation and chaos control in a discrete-time Lotka–Volterra model framework for COVID-19 modeling

-

Elhadi E. Elamir

, Ibrahim M.E. Abdelsatar

Abstract

This study investigates the dynamics of a discrete-time epidemic model of COVID-19 formulated on the basis of the Lotka–Volterra framework. The positivity and boundedness of solutions are established to ensure biological feasibility. A stability analysis identifies equilibrium points and reveals critical bifurcations that influence disease transmission. Numerical simulations confirm the occurrence of flip and Neimark–Sacker bifurcations, leading to complex periodic and quasi-periodic oscillations. The analysis of Lyapunov exponents further highlights the transition from stable dynamics to chaotic behavior as key parameters vary. In addition, effective chaos-control strategies are explored to stabilize the system, thereby mitigating unpredictable epidemic oscillations and promoting reliable long-term disease dynamics. These findings underscore the importance of controlling epidemiological factors to prevent irregular epidemic waves and to maintain long-term stability in disease transmission.

1 Introduction

Infectious diseases have long posed one of the most serious threats to human survival, with pandemics repeatedly reshaping societies, economies, and public health systems. Classic examples, such as the Black Death of the 14th century and the Spanish flu of 1918 [1], 2], illustrate how rapidly spreading pathogens can devastate populations. Even lesser-known pandemics have had devastating health, social, and economic consequences [3], underscoring the continued vulnerability of human societies to emerging infectious diseases.

The emergence of COVID-19 in late 2019 in Wuhan, China, once again highlighted the global threat of novel pathogens. Within weeks, the virus spread across international borders, prompting the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a global health emergency in early 2020 [4]. Since then, COVID-19 has caused millions of deaths worldwide and unprecedented disruption to healthcare, economic systems, and daily life. Biologically, the virus primarily targets the respiratory system by binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors on lung epithelial cells [5]. This interaction often leads to severe lung injury, with approximately 10 % of patients experiencing long-term respiratory complications [6], 7]. Disease progression varies widely – from a mild influenza-like illness to acute respiratory distress syndrome, respiratory failure, and death [8].

Despite remarkable advances in vaccination, antiviral therapy, and public health measures, containing pandemics remains a formidable challenge. Interventions such as quarantine, isolation, and vaccination are critical, yet their effectiveness is often limited by biological uncertainties, delayed responses, and ethical or logistical barriers. These limitations underscore the need for complementary approaches that can anticipate epidemic behavior and guide timely interventions.

Mathematical modeling has emerged as one of the most powerful tools for understanding and controlling infectious diseases. By formalizing the interactions between susceptible, infected, and recovered populations, models can predict epidemic trajectories, estimate transmission potential, and evaluate the effectiveness of intervention strategies [9], 10]. Beyond simple forecasting, mathematical models help policymakers quantify outbreak risks and assess the potential impact of measures such as vaccination campaigns, quarantine enforcement, or pharmaceutical treatments [11], 12].

1.1 Contribution

Building on existing modeling frameworks, this study introduces a discrete-time epidemic model of COVID-19 based on the Lotka–Volterra system, designed to capture the interaction dynamics between healthy and infected populations. The analysis establishes the existence, positivity, and boundedness of solutions to guarantee biological feasibility and provides a comprehensive characterization of equilibrium stability. The model further demonstrates rich dynamical behaviors through bifurcations, including flip and Neimark–Sacker types, which generate periodic and quasi-periodic epidemic patterns. The influence of the discretization parameter is examined, highlighting its role in flattening infection curves and shaping epidemic control strategies. In addition, the detection of chaotic oscillations via Lyapunov exponents and their stabilization through chaos-control methods underscores the capacity of the model to address complex epidemic dynamics. Collectively, these contributions advance the theoretical understanding of disease transmission while offering practical insights for effective public health intervention and epidemic management.

Together, these contributions provide both a deeper theoretical understanding of epidemic dynamics and practical tools that may inform effective public health interventions.

2 Lotka–Volterra discrete-time model

Mathematical models of infectious diseases have been widely employed to capture the dynamics of transmission and to evaluate intervention strategies. Among these, Lotka–Volterra (L–V) type formulations have been particularly useful for describing interactions between healthy and infected populations. Wael et al. [13] proposed a COVID-19 model based on the L–V framework, which incorporates the infection rate, recovery rate, migration, and mortality. Their continuous-time formulation takes the form

where U(t) and V(t) denote the healthy and infected individual population respectively. The parameter β represents the infection rate. The term μU(t) corresponds to the per-capita recruitment of healthy individuals into the system, which can be interpreted as natural births or as external influx, depending on the epidemiological context. The parameter c denotes the migration (or outflow) of infected individuals from the considered population, capturing processes such as relocation, isolation, or emigration rather than recovery or death. The parameter d represents the natural death rate, while r is the recovery rate. In this model, the recovery term rV(t) returns recovered individuals to the healthy class, reflecting the assumption that immunity is temporary and the model therefore has an SIS-type structure.

The model (2.1) admits a trivial equilibrium E

0 = (0, 0) and a coexistence equilibrium

2.1 Discrete-time approximation

To investigate new dynamical behaviors, the continuous-time system (2.1) is reformulated in discrete time. By applying the Euler discretization method [14], one obtains

where h > 0 is the time-step size, with U n , V n ≥ 0 for all n ≥ 0.

Theorem 2.1.

If the initial populations satisfy U

n

≥ 0, V

n

≥ 0, then the solution

Proof.

Define the total population at step n as

Summing the two equations of (2.2) gives:

Since U n ≥ 0, V n ≥ 0, the growth and decay terms can be examined to establish boundedness. If μU n ≤ (d − c)V n , then N n+1 ≤ N n , meaning the population is non-increasing and hence bounded. Otherwise, if μU n > (d − c)V n , then

Applying the standard iterative bound:

For biologically realistic models, external constraints (such as resource limits or carrying capacity) impose an upper bound M, ensuring that N n remains finite for all n. Thus, U n and V n are bounded.□

To analyze the dynamical behavior of system (2.2), the Jacobian matrix

Theorem 2.2.

E 0 is always unstable.

Proof.

Substituting

The Jacobian matrix

To characterize the stability of the coexistence equilibrium E 1, the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix (2.3) are analyzed. The following theorem establishes the stability conditions of the discrete-time system (2.2).

Theorem 2.3.

(i) E

1 is asymptotically stable (sink) if 0 < h < h

1 or 0 < h < h

2,

(ii) E

1 is unstable (source) if h > h

3 or h > h

2,

(iii) E 1 is unstable (saddle) if h 1 < h < h 3, Δ ⩾ 0.

(iv) Non-hyperbolic if h = h

1, h = h

3, Δ ⩾ 0 or h = h

2, Δ < 0, where

Proof.

Substituting

Define

3 Bifurcation

In this section, the bifurcation behavior of the system (2.2) at the coexistence point E 1 is investigated. The analysis follows standard results for discrete-time dynamical systems [16], where bifurcations occur when eigenvalues of the Jacobian cross the unit circle in the complex plane. In particular, we focus on flip (period-doubling) bifurcations, which occur when an eigenvalue passes through −1, and Neimark–Sacker bifurcations, which arise when a complex-conjugate pair of eigenvalues crosses the unit circle [17]. The center manifold theorem [18] is applied to investigate the conditions of flip bifurcation while the normal form method [19] is used to investigate the analysis of N–S bifurcation at E 1.

3.1 Flip bifurcations

The flip bifurcation analysis associated with E

1 is introduced in this section when the constant values

where,

Let

where,

Then, it follows that

where,

for x n , δ sufficiently small such that

which must satisfy

Solving (3.4), the following result is obtained as

Hence, the function f is defined as

where,

The discriminatory quantities χ 1 and χ 2 are given by

Thus, χ

1 = φ

1 and

3.2 Neimark–Sacker bifurcation

A Neimark–Sacker bifurcation at E

1 occurs when the parameters

where,

where

The characteristic equation associated with the linearized system of (3.8) at

where,

Therefore, there are two eigenvalues ω

1,2 at

Next, the normal form of the system (3.10) when ɛ = 0 is studied. Let

Consider the translation below

Applying L −1 on both sides of (3.12) yields

where

Thus, it follows that

The quantity ℏ is given as

where

From the above analysis and the N–S bifurcation conditions [21], the following theorem is stated.

Theorem 3.2.

[21] If conditions (3.10) and (3.16) are satisfied, then the model (2.2) undergoes a Neimark–Sacker bifurcation at the equilibrium E 1 when the parameter ɛ varies within a small neighborhood of h. Moreover, if ℏ < 0 (respectively, ℏ > 0), an attracting, (respectively, repelling) invariant closed curve bifurcates from E 1 for h > ɛ (respectively, h < ɛ).

4 Numerical simulation

Periodic epidemic patterns can emerge in the system as well. Once h ≥ h 3, instability occurs at the epidemic interior equilibrium, which results in the continued transmission of the disease across the community. According to the above analysis of local stability and bifurcations at E 1, the constant values of the system (2.2) will be examined in two case

Case 1. Take μ = β = 0.01, r = 0.98, d = 0.02, c = 0.0001. Then the model (2.2) has an interior point

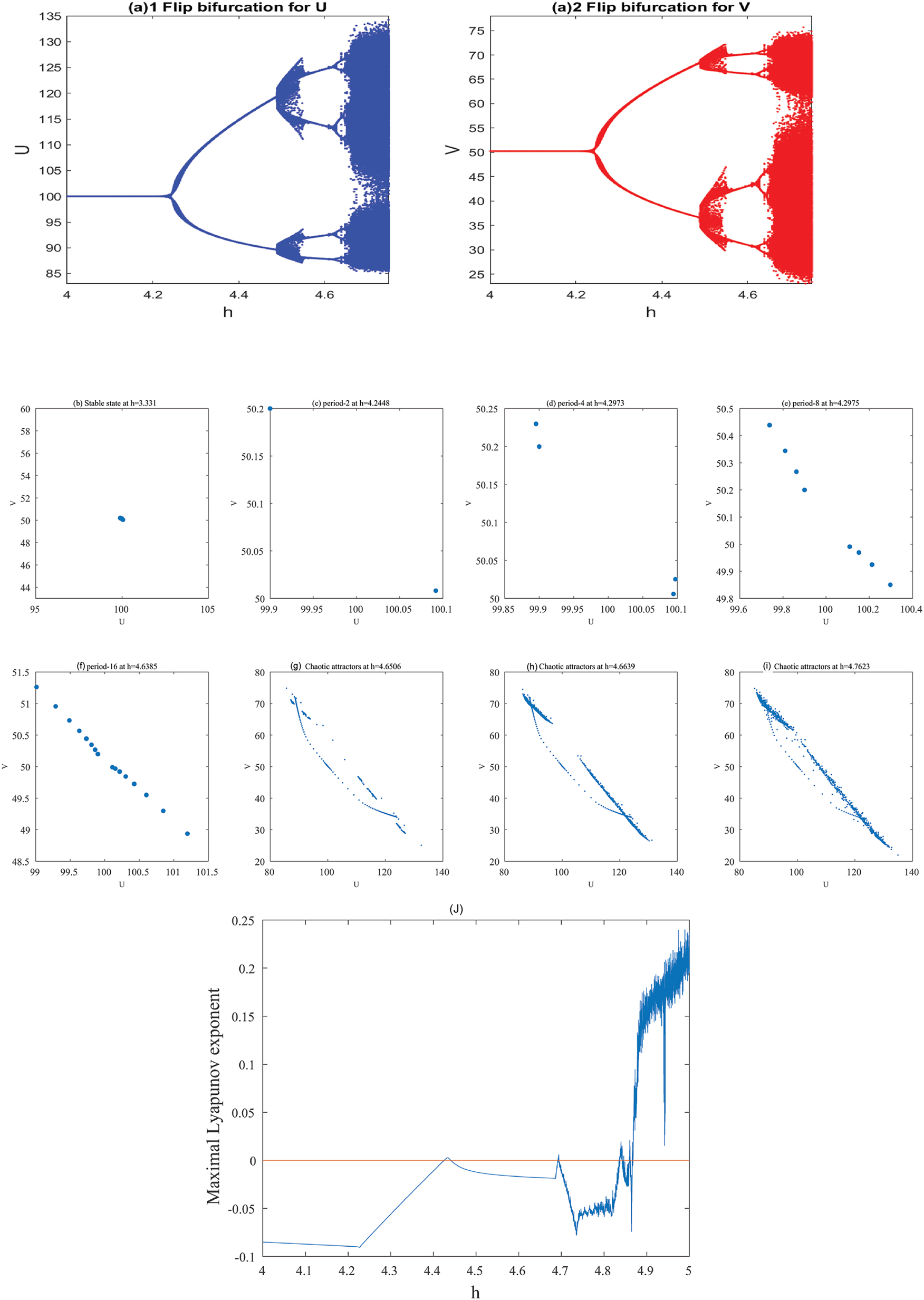

Varying h in range 4.3 ≤ h ⩽ 5 with initial conditions

Flip bifurcation behavior of system (2.2) with respect to the step size. (a1) Bifurcation diagram of the state variable; (a2) bifurcation diagram of the state variable; (b–i) phase portraits illustrating the transition from a stable equilibrium to periodic and chaotic dynamics; (j) maximal Lyapunov exponent corresponding to the bifurcation diagram shown in panel (a).

The phase portraits for

From an epidemiological viewpoint, it is understood that when s exceeds the critical value h 3, the disease outbreak persists and becomes pandemic. It is also possible for the system to exhibit periodic outbreaks. For h ≥ h 3, the epidemic interior equilibrium loses stability, allowing the disease to propagate throughout the population.

The flip bifurcation analysis indicates that in certain parameter regimes, the epidemic model does not settle into a steady state but instead exhibits periodic or chaotic outbreaks. In real-world scenarios, this could correspond to recurrent epidemics where infection levels rise and fall cyclically. Understanding these bifurcations is crucial for epidemic control strategies, as it highlights the conditions under which disease prevalence may become unstable.

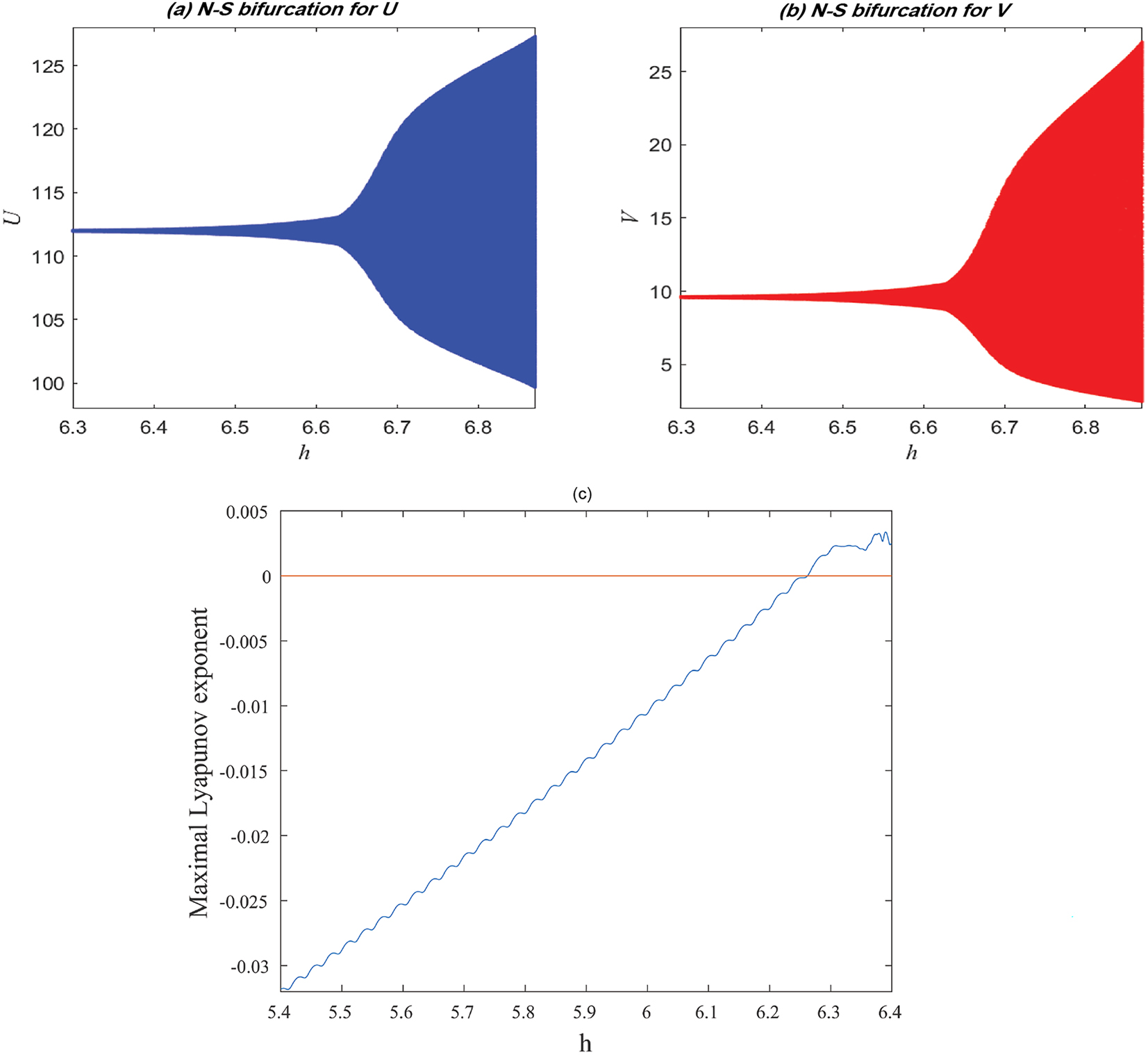

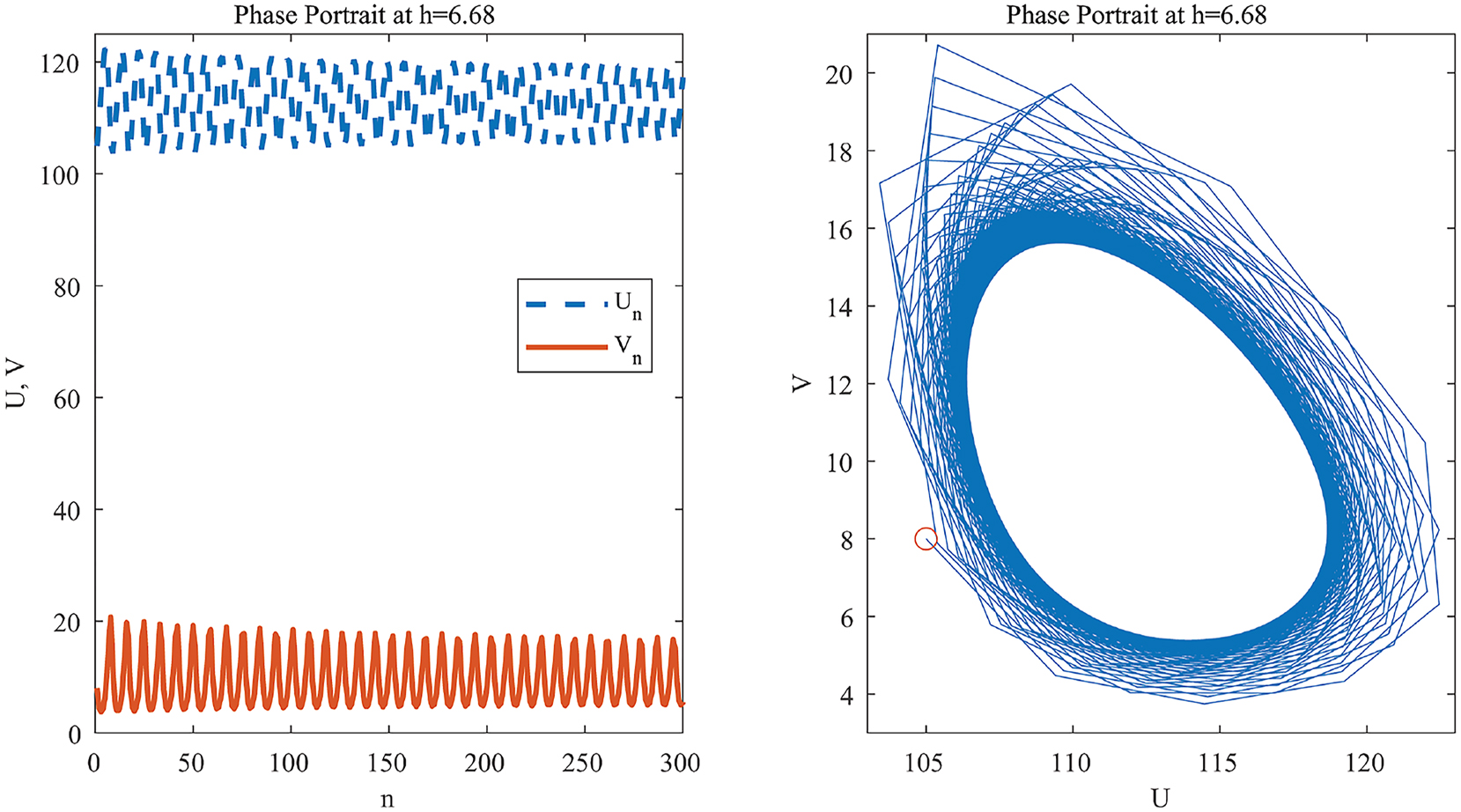

Case 2. Varying s in range 6.3 ≤ h ⩽ 6.875 and fixing μ = 0.012, β = 0.01, r = 0.98, d = 0.014, c = 0.0001 with initial conditions

Neimark–Sacker bifurcation of system (2.2) induced by variation of the step size. (a) Bifurcation diagram of the model; (b) bifurcation diagram of the model; (c) maximal Lyapunov exponent confirming the transition from stable to quasi-periodic dynamics.

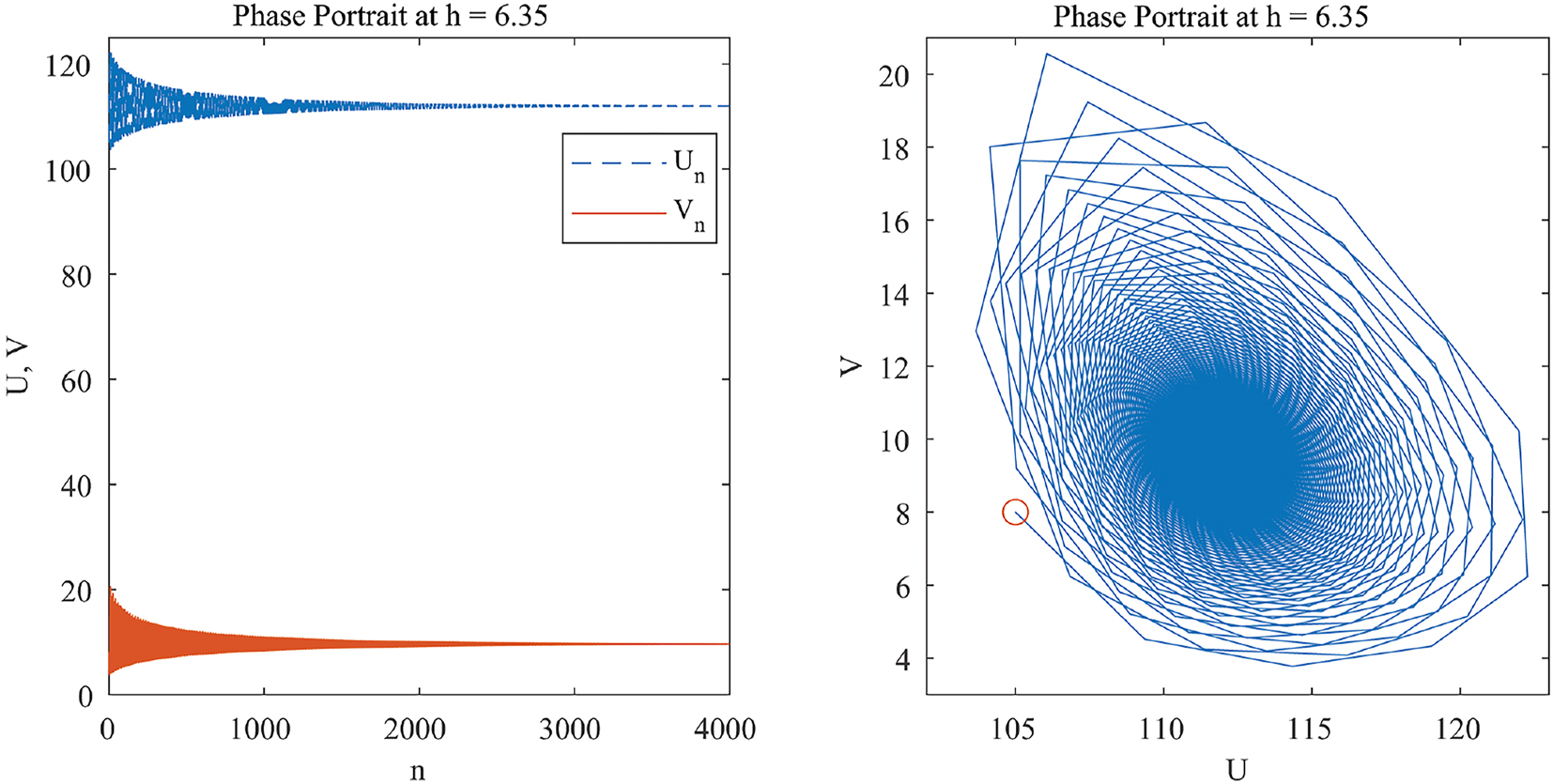

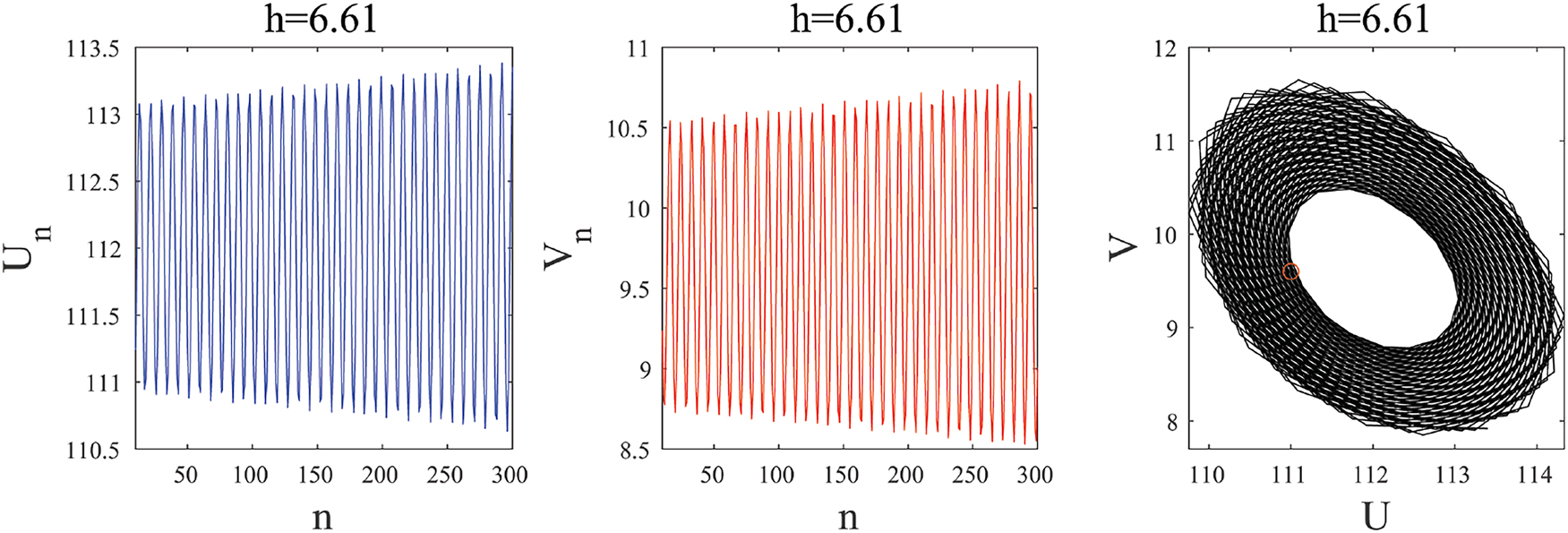

The phase portraits for various h − values corresponding to Figure 2 are plotted in Figures 3–5 to illustrate these observations. Stable steady state E 1 is shown when h < h 2 in Figure 3 at h = 6.6. A closed invariant circle begins to form at a value of h less than the critical value h 2 (Figure 4). The repelling invariant circle is completely formed at h = h 2 (Figure 5). An unstable equilibrium point E 1 bifurcates when h exceeds the critical N–S bifurcation value h 2. Chaotic region attractors form as h-value increases. The trajectory of system (2.2) converges to an asymptotically stable limit cycle around E 2. Figure 2(c) presents the computed maximal Lyapunov exponents corresponding to the observations illustrated in Figure 2. It is observed some positive and negative LE values. These observations say that when h > h 2, the disease is spreading and persist in the population and a pandemic will occur. Measures that are taken by decision-makers to combat epidemics, such as treatment, vaccination, or quarantine, make the epidemic stop spreading sometimes, but this is not necessary to stop the epidemic permanently. That may be interpreted as the oscillating of pandemic observed through the periodic windows which appear within the chaotic regions. When h = h 2, epidemic equilibrium is unstable and the disease spread in the community. When h < h 2, epidemic equilibrium is stable and the disease is eradicated.

At h = 6.35, the trajectory of system (2.2) converges to E 1.

At h = 6.61, the trajectory of system (2.2) converges to an asymptotically stable limit cycle around E 1.

At h = 6.68, the trajectory of system (2.2) converges to an asymptotically stable limit cycle around E 1.

5 Chaos control

Managing chaos and bifurcation is vital in population models, particularly those related to the biological reproduction of species. Discrete-time models often display more intricate dynamics than their continuous counterparts. To avoid unpredictable outcomes in population dynamics, applying chaos control methods is imperative.

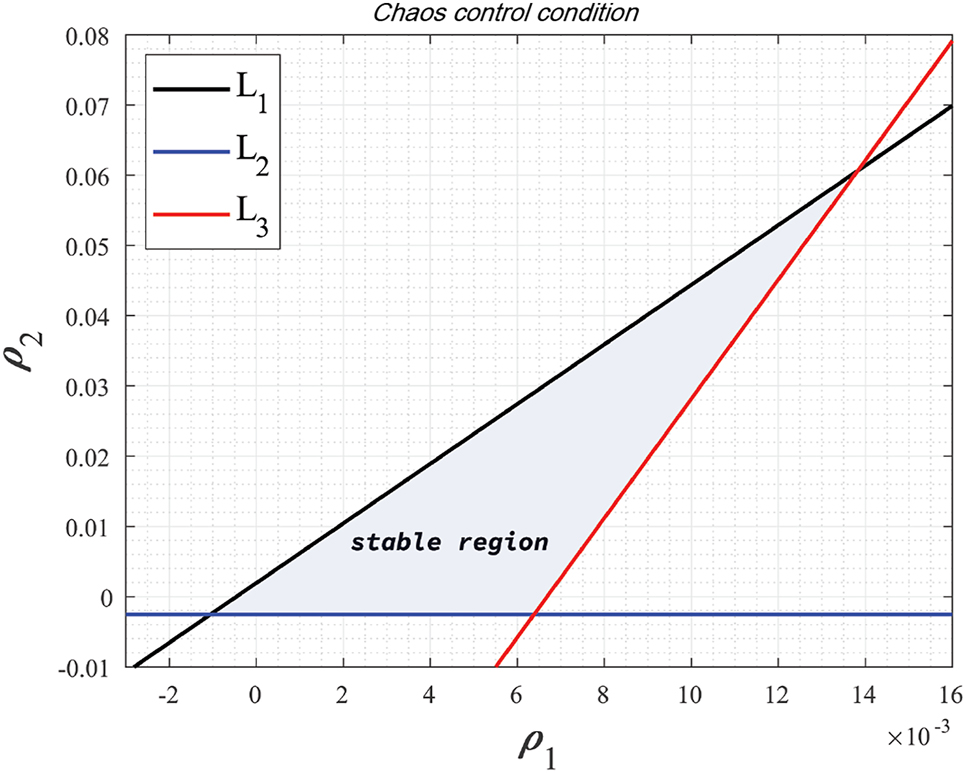

Triangular stability region bounded by L 1, L 2 and L 3 for the controlled system (5.1).

5.1 Pole placement technique

In this subsection, two feedback control strategies are examined, aimed at steering unstable trajectories toward stable ones. As an initial approach, system (2.2) is stabilized by applying the OGY control method [22], with the parameter μ serving as the control parameter. The system in (2.2) can be written in the form

where μ is chosen as the control parameter, enabling the achievement of desired chaos control by applying only minimal perturbations. For this purpose, μ is restricted to lie within a small interval

where

and

Additionally, system (5.1) is controllable under the condition that the following matrix satisfies:

is of rank 2. Moreover, taking

In addition, the controlled form associated with system (2.2) can be written as:

The equilibrium E* attains local asymptotic stability precisely when the eigenvalues of

The characteristic equation of the Jacobian matrix J − MK is given by

where

where Let λ c1 and λ c2 are the roots of characteristic equation (5.6).

Consider the case where λ c1 = ±1 and λ c1 λ c2 = 1. Under these constraints, the lines of marginal stability for the controlled system are determined, and λ c1 together with λ c2 remain confined within the open unit disk. Under the assumption that λ c1 λ c2 = 1, then (5.7) implies the following.

Moreover, it is assumed that λ c1 = 1, then (5.7) yields that:

Finally by setting λ c1 = −1, equation (5.7) give the following relation:

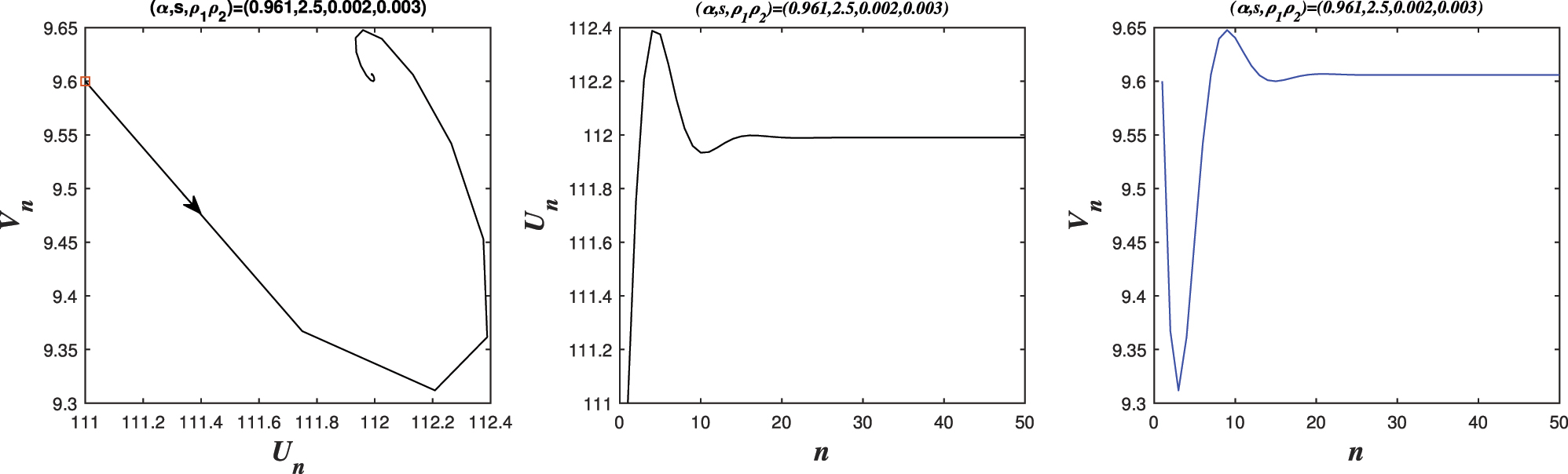

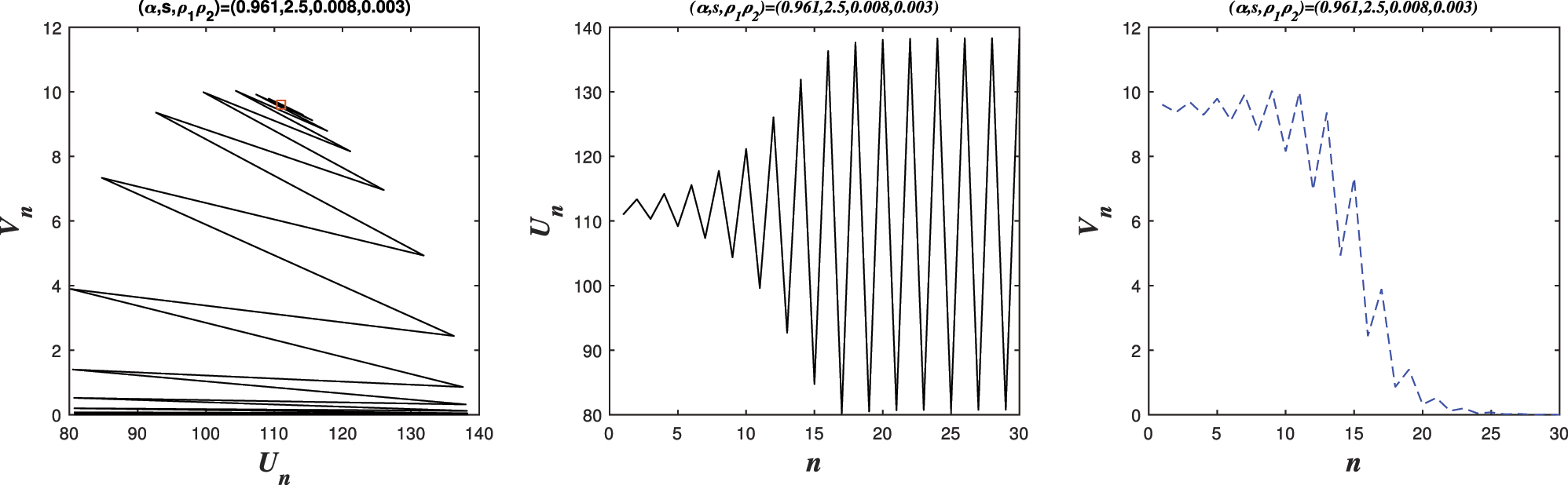

Figure 6 illustrates the stability region in the (ρ 1, ρ 2)-plane; specifically, the triangular domain bounded by L 1, L 2, L 3 and corresponds to control gains that place the controlled eigenvalues inside the unit circle. Figures 7 and 8 then show representative trajectories inside and outside this stability region.

Phase portraits of system (5.1) for parameter values (ρ 1, ρ 2) = (0.002, 0.003), corresponding to a point inside the triangular stability region defined by the lines L 1, L 2, L 3. The trajectories converge to the stable equilibrium, confirming that the control parameters lie within the stability domain and successfully suppress chaotic oscillations.

Phase portraits of system (5.1) for parameter values (ρ 1, ρ 2) = (0.008, 0.003), corresponding to a point outside the triangular stability region defined by L 1, L 2, L 3. In this case, trajectories diverge or exhibit irregular oscillations, indicating loss of stability when the control parameters are chosen outside the admissible region.

5.2 Hybrid control method

The hybrid control feedback method [23] is employed to address the chaos induced by bifurcation in system (2.2). This technique was initially designed to manage period-doubling bifurcations. In [23], the authors applied the hybrid control feedback approach to control chaos arising from Neimark–Sacker bifurcations. If system (2.2) undergoes bifurcation at the equilibrium point E*, the corresponding controlled system can be formulated as:

where 0 < ρ < 1. The control strategy in (5.8) combines both parameter perturbation and feedback control. A suitable adjustment of the control parameter ρ makes it possible to advance, postpone, or eliminate the occurrence of period-doubling and Neimark–Sacker bifurcations at the equilibrium E* of the controlled system (5.8). At the positive equilibrium, the Jacobian matrix of the controlled system (5.8) takes the following form:

It follows that:

For the stability of the system (5.8),

The following result provides the conditions for the local asymptotic stability of E 1 in the controlled system (5.8). Specifically, the coexistence point E 1 is locally asymptotically stable if the following conditions are satisfied:

5.3 State feedback control

An efficient way to regulate chaotic dynamics is through state feedback control [24]. In this approach, an optimal controller is applied to reshape the chaotic system into a piecewise linear structure. The procedure lowers the upper bound and, under defined circumstances, guarantees controllability. When an appropriate feedback strategy is implemented, the resulting controlled form of system (2.2) is obtained as:

where

corresponds to the control force defined by the feedback control law, with q 1 and q 2 acting as the respective feedback gains. From the Jacobian matrix of system (5.13), the resulting characteristic equation is obtained as:

Let λ 1fd and λ 2fd be two roots of the characteristic equation (5.14) then sum and product of the roots are

Now the conditions for the marginal stability lines are given as

then for second condition (5.14) gives

Under another stability condition, setting λ 1fd = 1 yields

Similarly for λ 1fd = −1, it is obtained

Stability requires that every eigenvalue falls within the triangular domain defined by the lines FC 1, FC 2, and FC 3. Accordingly, system (5.13) achieves stability if the associated eigenvalues are confined to the interior of the open unit disk.

6 Conclusions

In this study, the dynamics of a discrete-time epidemic model of COVID-19 based on the Lotka–Volterra model were investigated. To ensure biological feasibility, the positivity and boundedness of solutions are demonstrated, thereby preventing the emergence of negative or unbounded populations within the model. The stability analysis revealed the existence of equilibrium points, and numerical simulations confirmed the occurrence of bifurcations leading to oscillatory and chaotic epidemic dynamics. Our bifurcation analysis highlighted the presence of flip bifurcations, which result in alternating infection levels, and N–S bifurcations, which lead to quasiperiodic epidemic cycles. The Lyapunov exponent analysis provided further evidence of the transition from stable to chaotic dynamics, indicating the loss of predictability in disease spread at critical parameter values. Chaotic dynamics were mitigated and epidemic spread stabilized through the implementation of three chaos-control strategies – Pole Placement Technique, Hybrid Control Method, and State Feedback Control. These approaches proved effective in restoring stable disease dynamics and preventing unpredictable epidemic oscillations. From a biological perspective, these results suggest that disease outbreaks may follow complex, unpredictable oscillations if key parameters-such as infection rates-exceed stability thresholds. This has significant implications for public health interventions, emphasizing the need for controlled policies to prevent instability in disease transmission. Future work could explore optimal control strategies to mitigate chaos in epidemic dynamics and extend the model to incorporate additional real-world factors such as vaccination or spatial heterogeneity.

Acknowledgments

The research team thanks the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Najran University for supporting the research project through the Nama’a program, with the project code NU/GP/SERC/13/590-1.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, A. A. Elsadany, Mahmoud A. M. Abdelaziz, Mona Alsulami; Methodology, Mahmoud A. M. Abdelaziz, Mona Alsulami, Ibrahim M.E. Abdelsatar, Elhadi E. Elamir; Writing – original draft preparation, Mahmoud A. M. Abdelaziz, Mona Alsulami, Ibrahim M.E. Abdelsatar, Elhadi E. Elamir; Writing – review and editing, Mahmoud A. M. Abdelaziz, Ibrahim M.E. Abdelsatar, Elhadi E. Elamir, A. A. Elsadany, Manal Alqhtani, Hamada F. El-Mekawy. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

1. McNeill, WH. Plagues and peoples. Garden City, NY: Anchor; 1976.Search in Google Scholar

2. Aassve, A, Alfani, G, Gandolfi, F, Le Moglie, M. Epidemics and trust: the case of the Spanish Flu. Health Econ 2021;30:840–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4218.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Kaur, H, Garg, S, Joshi, H, Ayaz, S, Sharma, S, Bhandari, M. A review: epidemics and pandemics in human history. Int J Pharma Res Health Sci 2020;8:3139–42. https://doi.org/10.21276/ijprhs.2020.02.01.Search in Google Scholar

4. Ciotti, M, Ciccozzi, M, Terrinoni, A, Jiang, WC, Wang, CB, Bernardini, S. The COVID-19 pandemic. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2020;57:365–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2020.1783198.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Desai, AD, Lavelle, M, Boursiquot, BC, Wan, EY. Long-term complications of COVID-19. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2022;322:C1–11. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00375.2021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Salian, VS, Wright, JA, Vedell, PT, Nair, S, Li, C, Kandimalla, M, et al.. COVID-19 transmission, current treatment, and future therapeutic strategies. Mol Pharm 2021;18:754–71. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00608.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. John, AE, Joseph, C, Jenkins, G, Tatler, AL. COVID-19 and pulmonary fibrosis: a potential role for lung epithelial cells and fibroblasts. Immunol Rev 2021;302:228–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12977.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Li, T, Lu, H, Zhang, W. Clinical observation and management of COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microb Infect 2020;9:687–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1741327.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). [Internet]; 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/.Search in Google Scholar

10. Yuan, LG, Yang, QG. Bifurcation, invariant curve and hybrid control in a discrete-time predator–prey system. Appl Math Model 2015;39:2345–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2014.10.040.Search in Google Scholar

11. Carlson, K. Mathematical modeling of infectious diseases with latency: homogeneous mixing and contact network [Ph.D. thesis]; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

12. Abdelaziz, MA, Ismail, AI, Abdullah, MHM, Mohd, MH. Bifurcations and chaos in a discrete SI epidemic model with fractional order. Adv Differ Equ 2018;2018:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-018-1481-6.Search in Google Scholar

13. Zakia, AS, Yousef, AM, Rida, SZ, Gouda, YG. On the dynamics of an SIR epidemic model with a saturated incidence rate. J Adv Stud Topol 2017;8:97–110. https://doi.org/10.20454/jast.2017.1333.Search in Google Scholar

14. Brauer, F, Castillo-Chavez, C, Feng, Z. Mathematical models in epidemiology. New York: Springer; 2019, vol 32.10.1007/978-1-4939-9828-9Search in Google Scholar

15. Sahaminejad, F, Nyamoradi, N, Eskandari, Z. Developing a continuous SIR epidemic model and its discrete version using Euler method: analyzing dynamics with analytical and numerical methods. Math Methods Appl Sci 2024;47:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/mma.10124.Search in Google Scholar

16. Li, B, Yuan, Z, Eskandari, Z. Dynamics and bifurcations of a discrete-time Moran–Ricker model with a time delay. Mathematics 2023;11:2446. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11112446.Search in Google Scholar

17. Li, X, Shao, X. Flip bifurcation and Neimark–Sacker bifurcation in a discrete predator–prey model with Michaelis–Menten functional response. Electron Res Arch 2023;31:37–57. https://doi.org/10.3934/era.2023003.Search in Google Scholar

18. Du, X, Han, X, Lei, C. Behavior analysis of a class of discrete-time dynamical system with capture rate. Mathematics 2022;10:2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10142410.Search in Google Scholar

19. Reja, S, Al Basir, F, Aldawsari, K. A discrete-time mathematical model for mosaic disease dynamics in cassava: Neimark–Sacker bifurcation and sensitivity analysis. AIMS Math 2025;10:18295–320. https://doi.org/10.3934/math.2025817.Search in Google Scholar

20. Abdelaziz, MA, Ismail, AI, Abdullah, FA, Mohd, MH. Codimension one and two bifurcations of a discrete-time fractional-order SEIR measles epidemic model with constant vaccination. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020;140:110104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110104.Search in Google Scholar

21. Zhou, X, Li, X, Wang, WS. Bifurcations for a deterministic SIR epidemic model in discrete time. Adv Differ Equ 2014;2014:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-1847-2014-168.Search in Google Scholar

22. Priyanka, M, Muthukumar, P. Bifurcation patterns and chaos control in discrete-time coral reef model. arXiv preprint 2024. arXiv:2405.07491.Search in Google Scholar

23. Aldosary, SF, Ahmed, R. Stability and bifurcation analysis of a discrete Leslie predator–prey system via piecewise constant argument method. AIMS Math 2024;9:4684–706. https://doi.org/10.3934/math.2024226.Search in Google Scholar

24. Din, Q. Complexity and chaos control in a discrete-time prey–predator model. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul 2017;49:113–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnsns.2017.01.025.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Generalized (ψ,φ)-contraction to investigate Volterra integral inclusions and fractal fractional PDEs in super-metric space with numerical experiments

- Solitons in ultrasound imaging: Exploring applications and enhancements via the Westervelt equation

- Stochastic improved Simpson for solving nonlinear fractional-order systems using product integration rules

- Exploring dynamical features like bifurcation assessment, sensitivity visualization, and solitary wave solutions of the integrable Akbota equation

- Research on surface defect detection method and optimization of paper-plastic composite bag based on improved combined segmentation algorithm

- Impact the sulphur content in Iraqi crude oil on the mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of carbon steel in various types of API 5L pipelines and ASTM 106 grade B

- Unravelling quiescent optical solitons: An exploration of the complex Ginzburg–Landau equation with nonlinear chromatic dispersion and self-phase modulation

- Perturbation-iteration approach for fractional-order logistic differential equations

- Variational formulations for the Euler and Navier–Stokes systems in fluid mechanics and related models

- Rotor response to unbalanced load and system performance considering variable bearing profile

- DeepFowl: Disease prediction from chicken excreta images using deep learning

- Channel flow of Ellis fluid due to cilia motion

- A case study of fractional-order varicella virus model to nonlinear dynamics strategy for control and prevalence

- Multi-point estimation weldment recognition and estimation of pose with data-driven robotics design

- Analysis of Hall current and nonuniform heating effects on magneto-convection between vertically aligned plates under the influence of electric and magnetic fields

- A comparative study on residual power series method and differential transform method through the time-fractional telegraph equation

- Insights from the nonlinear Schrödinger–Hirota equation with chromatic dispersion: Dynamics in fiber–optic communication

- Mathematical analysis of Jeffrey ferrofluid on stretching surface with the Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Exploring the interaction between lump, stripe and double-stripe, and periodic wave solutions of the Konopelchenko–Dubrovsky–Kaup–Kupershmidt system

- Computational investigation of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS co-infection in fuzzy environment

- Signature verification by geometry and image processing

- Theoretical and numerical approach for quantifying sensitivity to system parameters of nonlinear systems

- Chaotic behaviors, stability, and solitary wave propagations of M-fractional LWE equation in magneto-electro-elastic circular rod

- Dynamic analysis and optimization of syphilis spread: Simulations, integrating treatment and public health interventions

- Visco-thermoelastic rectangular plate under uniform loading: A study of deflection

- Threshold dynamics and optimal control of an epidemiological smoking model

- Numerical computational model for an unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium past an MHD rotating sheet

- Regression prediction model of fabric brightness based on light and shadow reconstruction of layered images

- Dynamics and prevention of gemini virus infection in red chili crops studied with generalized fractional operator: Analysis and modeling

- Qualitative analysis on existence and stability of nonlinear fractional dynamic equations on time scales

- Fractional-order super-twisting sliding mode active disturbance rejection control for electro-hydraulic position servo systems

- Analytical exploration and parametric insights into optical solitons in magneto-optic waveguides: Advances in nonlinear dynamics for applied sciences

- Bifurcation dynamics and optical soliton structures in the nonlinear Schrödinger–Bopp–Podolsky system

- User profiling in university libraries by combining multi-perspective clustering algorithm and reader behavior analysis

- Exploring bifurcation and chaos control in a discrete-time Lotka–Volterra model framework for COVID-19 modeling

- Review Article

- Haar wavelet collocation method for existence and numerical solutions of fourth-order integro-differential equations with bounded coefficients

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Analysis and Design of Communication Networks for IoT Applications - Part II

- Silicon-based all-optical wavelength converter for on-chip optical interconnection

- Research on a path-tracking control system of unmanned rollers based on an optimization algorithm and real-time feedback

- Analysis of the sports action recognition model based on the LSTM recurrent neural network

- Industrial robot trajectory error compensation based on enhanced transfer convolutional neural networks

- Research on IoT network performance prediction model of power grid warehouse based on nonlinear GA-BP neural network

- Interactive recommendation of social network communication between cities based on GNN and user preferences

- Application of improved P-BEM in time varying channel prediction in 5G high-speed mobile communication system

- Construction of a BIM smart building collaborative design model combining the Internet of Things

- Optimizing malicious website prediction: An advanced XGBoost-based machine learning model

- Economic operation analysis of the power grid combining communication network and distributed optimization algorithm

- Sports video temporal action detection technology based on an improved MSST algorithm

- Internet of things data security and privacy protection based on improved federated learning

- Enterprise power emission reduction technology based on the LSTM–SVM model

- Construction of multi-style face models based on artistic image generation algorithms

- Research and application of interactive digital twin monitoring system for photovoltaic power station based on global perception

- Special Issue: Decision and Control in Nonlinear Systems - Part II

- Animation video frame prediction based on ConvGRU fine-grained synthesis flow

- Application of GGNN inference propagation model for martial art intensity evaluation

- Benefit evaluation of building energy-saving renovation projects based on BWM weighting method

- Deep neural network application in real-time economic dispatch and frequency control of microgrids

- Real-time force/position control of soft growing robots: A data-driven model predictive approach

- Mechanical product design and manufacturing system based on CNN and server optimization algorithm

- Application of finite element analysis in the formal analysis of ancient architectural plaque section

- Research on territorial spatial planning based on data mining and geographic information visualization

- Fault diagnosis of agricultural sprinkler irrigation machinery equipment based on machine vision

- Closure technology of large span steel truss arch bridge with temporarily fixed edge supports

- Intelligent accounting question-answering robot based on a large language model and knowledge graph

- Analysis of manufacturing and retailer blockchain decision based on resource recyclability

- Flexible manufacturing workshop mechanical processing and product scheduling algorithm based on MES

- Exploration of indoor environment perception and design model based on virtual reality technology

- Tennis automatic ball-picking robot based on image object detection and positioning technology

- A new CNN deep learning model for computer-intelligent color matching

- Design of AR-based general computer technology experiment demonstration platform

- Indoor environment monitoring method based on the fusion of audio recognition and video patrol features

- Health condition prediction method of the computer numerical control machine tool parts by ensembling digital twins and improved LSTM networks

- Establishment of a green degree evaluation model for wall materials based on lifecycle

- Quantitative evaluation of college music teaching pronunciation based on nonlinear feature extraction

- Multi-index nonlinear robust virtual synchronous generator control method for microgrid inverters

- Manufacturing engineering production line scheduling management technology integrating availability constraints and heuristic rules

- Analysis of digital intelligent financial audit system based on improved BiLSTM neural network

- Attention community discovery model applied to complex network information analysis

- A neural collaborative filtering recommendation algorithm based on attention mechanism and contrastive learning

- Rehabilitation training method for motor dysfunction based on video stream matching

- Research on façade design for cold-region buildings based on artificial neural networks and parametric modeling techniques

- Intelligent implementation of muscle strain identification algorithm in Mi health exercise induced waist muscle strain

- Optimization design of urban rainwater and flood drainage system based on SWMM

- Improved GA for construction progress and cost management in construction projects

- Evaluation and prediction of SVM parameters in engineering cost based on random forest hybrid optimization

- Museum intelligent warning system based on wireless data module

- Optimization design and research of mechatronics based on torque motor control algorithm

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Engineering’s significance in Materials Science

- Experimental research on the degradation of chemical industrial wastewater by combined hydrodynamic cavitation based on nonlinear dynamic model

- Study on low-cycle fatigue life of nickel-based superalloy GH4586 at various temperatures

- Some results of solutions to neutral stochastic functional operator-differential equations

- Ultrasonic cavitation did not occur in high-pressure CO2 liquid

- Research on the performance of a novel type of cemented filler material for coal mine opening and filling

- Testing of recycled fine aggregate concrete’s mechanical properties using recycled fine aggregate concrete and research on technology for highway construction

- A modified fuzzy TOPSIS approach for the condition assessment of existing bridges

- Nonlinear structural and vibration analysis of straddle monorail pantograph under random excitations

- Achieving high efficiency and stability in blue OLEDs: Role of wide-gap hosts and emitter interactions

- Construction of teaching quality evaluation model of online dance teaching course based on improved PSO-BPNN

- Enhanced electrical conductivity and electromagnetic shielding properties of multi-component polymer/graphite nanocomposites prepared by solid-state shear milling

- Optimization of thermal characteristics of buried composite phase-change energy storage walls based on nonlinear engineering methods

- A higher-performance big data-based movie recommendation system

- Nonlinear impact of minimum wage on labor employment in China

- Nonlinear comprehensive evaluation method based on information entropy and discrimination optimization

- Application of numerical calculation methods in stability analysis of pile foundation under complex foundation conditions

- Research on the contribution of shale gas development and utilization in Sichuan Province to carbon peak based on the PSA process

- Characteristics of tight oil reservoirs and their impact on seepage flow from a nonlinear engineering perspective

- Nonlinear deformation decomposition and mode identification of plane structures via orthogonal theory

- Numerical simulation of damage mechanism in rock with cracks impacted by self-excited pulsed jet based on SPH-FEM coupling method: The perspective of nonlinear engineering and materials science

- Cross-scale modeling and collaborative optimization of ethanol-catalyzed coupling to produce C4 olefins: Nonlinear modeling and collaborative optimization strategies

- Unequal width T-node stress concentration factor analysis of stiffened rectangular steel pipe concrete

- Special Issue: Advances in Nonlinear Dynamics and Control

- Development of a cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy design for a nonlinear diabetic patient model

- Big data-based optimized model of building design in the context of rural revitalization

- Multi-UAV assisted air-to-ground data collection for ground sensors with unknown positions

- Design of urban and rural elderly care public areas integrating person-environment fit theory

- Application of lossless signal transmission technology in piano timbre recognition

- Application of improved GA in optimizing rural tourism routes

- Architectural animation generation system based on AL-GAN algorithm

- Advanced sentiment analysis in online shopping: Implementing LSTM models analyzing E-commerce user sentiments

- Intelligent recommendation algorithm for piano tracks based on the CNN model

- Visualization of large-scale user association feature data based on a nonlinear dimensionality reduction method

- Low-carbon economic optimization of microgrid clusters based on an energy interaction operation strategy

- Optimization effect of video data extraction and search based on Faster-RCNN hybrid model on intelligent information systems

- Construction of image segmentation system combining TC and swarm intelligence algorithm

- Particle swarm optimization and fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm for the adhesive layer defect detection

- Optimization of student learning status by instructional intervention decision-making techniques incorporating reinforcement learning

- Fuzzy model-based stabilization control and state estimation of nonlinear systems

- Optimization of distribution network scheduling based on BA and photovoltaic uncertainty

- Tai Chi movement segmentation and recognition on the grounds of multi-sensor data fusion and the DBSCAN algorithm

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part III

- Generalized numerical RKM method for solving sixth-order fractional partial differential equations

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Generalized (ψ,φ)-contraction to investigate Volterra integral inclusions and fractal fractional PDEs in super-metric space with numerical experiments

- Solitons in ultrasound imaging: Exploring applications and enhancements via the Westervelt equation

- Stochastic improved Simpson for solving nonlinear fractional-order systems using product integration rules

- Exploring dynamical features like bifurcation assessment, sensitivity visualization, and solitary wave solutions of the integrable Akbota equation

- Research on surface defect detection method and optimization of paper-plastic composite bag based on improved combined segmentation algorithm

- Impact the sulphur content in Iraqi crude oil on the mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of carbon steel in various types of API 5L pipelines and ASTM 106 grade B

- Unravelling quiescent optical solitons: An exploration of the complex Ginzburg–Landau equation with nonlinear chromatic dispersion and self-phase modulation

- Perturbation-iteration approach for fractional-order logistic differential equations

- Variational formulations for the Euler and Navier–Stokes systems in fluid mechanics and related models

- Rotor response to unbalanced load and system performance considering variable bearing profile

- DeepFowl: Disease prediction from chicken excreta images using deep learning

- Channel flow of Ellis fluid due to cilia motion

- A case study of fractional-order varicella virus model to nonlinear dynamics strategy for control and prevalence

- Multi-point estimation weldment recognition and estimation of pose with data-driven robotics design

- Analysis of Hall current and nonuniform heating effects on magneto-convection between vertically aligned plates under the influence of electric and magnetic fields

- A comparative study on residual power series method and differential transform method through the time-fractional telegraph equation

- Insights from the nonlinear Schrödinger–Hirota equation with chromatic dispersion: Dynamics in fiber–optic communication

- Mathematical analysis of Jeffrey ferrofluid on stretching surface with the Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Exploring the interaction between lump, stripe and double-stripe, and periodic wave solutions of the Konopelchenko–Dubrovsky–Kaup–Kupershmidt system

- Computational investigation of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS co-infection in fuzzy environment

- Signature verification by geometry and image processing

- Theoretical and numerical approach for quantifying sensitivity to system parameters of nonlinear systems

- Chaotic behaviors, stability, and solitary wave propagations of M-fractional LWE equation in magneto-electro-elastic circular rod

- Dynamic analysis and optimization of syphilis spread: Simulations, integrating treatment and public health interventions

- Visco-thermoelastic rectangular plate under uniform loading: A study of deflection

- Threshold dynamics and optimal control of an epidemiological smoking model

- Numerical computational model for an unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium past an MHD rotating sheet

- Regression prediction model of fabric brightness based on light and shadow reconstruction of layered images

- Dynamics and prevention of gemini virus infection in red chili crops studied with generalized fractional operator: Analysis and modeling

- Qualitative analysis on existence and stability of nonlinear fractional dynamic equations on time scales

- Fractional-order super-twisting sliding mode active disturbance rejection control for electro-hydraulic position servo systems

- Analytical exploration and parametric insights into optical solitons in magneto-optic waveguides: Advances in nonlinear dynamics for applied sciences

- Bifurcation dynamics and optical soliton structures in the nonlinear Schrödinger–Bopp–Podolsky system

- User profiling in university libraries by combining multi-perspective clustering algorithm and reader behavior analysis

- Exploring bifurcation and chaos control in a discrete-time Lotka–Volterra model framework for COVID-19 modeling

- Review Article

- Haar wavelet collocation method for existence and numerical solutions of fourth-order integro-differential equations with bounded coefficients

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Analysis and Design of Communication Networks for IoT Applications - Part II

- Silicon-based all-optical wavelength converter for on-chip optical interconnection

- Research on a path-tracking control system of unmanned rollers based on an optimization algorithm and real-time feedback

- Analysis of the sports action recognition model based on the LSTM recurrent neural network

- Industrial robot trajectory error compensation based on enhanced transfer convolutional neural networks

- Research on IoT network performance prediction model of power grid warehouse based on nonlinear GA-BP neural network

- Interactive recommendation of social network communication between cities based on GNN and user preferences

- Application of improved P-BEM in time varying channel prediction in 5G high-speed mobile communication system

- Construction of a BIM smart building collaborative design model combining the Internet of Things

- Optimizing malicious website prediction: An advanced XGBoost-based machine learning model

- Economic operation analysis of the power grid combining communication network and distributed optimization algorithm

- Sports video temporal action detection technology based on an improved MSST algorithm

- Internet of things data security and privacy protection based on improved federated learning

- Enterprise power emission reduction technology based on the LSTM–SVM model

- Construction of multi-style face models based on artistic image generation algorithms

- Research and application of interactive digital twin monitoring system for photovoltaic power station based on global perception

- Special Issue: Decision and Control in Nonlinear Systems - Part II

- Animation video frame prediction based on ConvGRU fine-grained synthesis flow

- Application of GGNN inference propagation model for martial art intensity evaluation

- Benefit evaluation of building energy-saving renovation projects based on BWM weighting method

- Deep neural network application in real-time economic dispatch and frequency control of microgrids

- Real-time force/position control of soft growing robots: A data-driven model predictive approach

- Mechanical product design and manufacturing system based on CNN and server optimization algorithm

- Application of finite element analysis in the formal analysis of ancient architectural plaque section

- Research on territorial spatial planning based on data mining and geographic information visualization

- Fault diagnosis of agricultural sprinkler irrigation machinery equipment based on machine vision

- Closure technology of large span steel truss arch bridge with temporarily fixed edge supports

- Intelligent accounting question-answering robot based on a large language model and knowledge graph

- Analysis of manufacturing and retailer blockchain decision based on resource recyclability

- Flexible manufacturing workshop mechanical processing and product scheduling algorithm based on MES

- Exploration of indoor environment perception and design model based on virtual reality technology

- Tennis automatic ball-picking robot based on image object detection and positioning technology

- A new CNN deep learning model for computer-intelligent color matching

- Design of AR-based general computer technology experiment demonstration platform

- Indoor environment monitoring method based on the fusion of audio recognition and video patrol features

- Health condition prediction method of the computer numerical control machine tool parts by ensembling digital twins and improved LSTM networks

- Establishment of a green degree evaluation model for wall materials based on lifecycle

- Quantitative evaluation of college music teaching pronunciation based on nonlinear feature extraction

- Multi-index nonlinear robust virtual synchronous generator control method for microgrid inverters

- Manufacturing engineering production line scheduling management technology integrating availability constraints and heuristic rules

- Analysis of digital intelligent financial audit system based on improved BiLSTM neural network

- Attention community discovery model applied to complex network information analysis

- A neural collaborative filtering recommendation algorithm based on attention mechanism and contrastive learning

- Rehabilitation training method for motor dysfunction based on video stream matching

- Research on façade design for cold-region buildings based on artificial neural networks and parametric modeling techniques

- Intelligent implementation of muscle strain identification algorithm in Mi health exercise induced waist muscle strain

- Optimization design of urban rainwater and flood drainage system based on SWMM

- Improved GA for construction progress and cost management in construction projects

- Evaluation and prediction of SVM parameters in engineering cost based on random forest hybrid optimization

- Museum intelligent warning system based on wireless data module

- Optimization design and research of mechatronics based on torque motor control algorithm

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Engineering’s significance in Materials Science

- Experimental research on the degradation of chemical industrial wastewater by combined hydrodynamic cavitation based on nonlinear dynamic model

- Study on low-cycle fatigue life of nickel-based superalloy GH4586 at various temperatures

- Some results of solutions to neutral stochastic functional operator-differential equations

- Ultrasonic cavitation did not occur in high-pressure CO2 liquid

- Research on the performance of a novel type of cemented filler material for coal mine opening and filling

- Testing of recycled fine aggregate concrete’s mechanical properties using recycled fine aggregate concrete and research on technology for highway construction

- A modified fuzzy TOPSIS approach for the condition assessment of existing bridges

- Nonlinear structural and vibration analysis of straddle monorail pantograph under random excitations

- Achieving high efficiency and stability in blue OLEDs: Role of wide-gap hosts and emitter interactions

- Construction of teaching quality evaluation model of online dance teaching course based on improved PSO-BPNN

- Enhanced electrical conductivity and electromagnetic shielding properties of multi-component polymer/graphite nanocomposites prepared by solid-state shear milling

- Optimization of thermal characteristics of buried composite phase-change energy storage walls based on nonlinear engineering methods

- A higher-performance big data-based movie recommendation system

- Nonlinear impact of minimum wage on labor employment in China

- Nonlinear comprehensive evaluation method based on information entropy and discrimination optimization

- Application of numerical calculation methods in stability analysis of pile foundation under complex foundation conditions

- Research on the contribution of shale gas development and utilization in Sichuan Province to carbon peak based on the PSA process

- Characteristics of tight oil reservoirs and their impact on seepage flow from a nonlinear engineering perspective

- Nonlinear deformation decomposition and mode identification of plane structures via orthogonal theory

- Numerical simulation of damage mechanism in rock with cracks impacted by self-excited pulsed jet based on SPH-FEM coupling method: The perspective of nonlinear engineering and materials science

- Cross-scale modeling and collaborative optimization of ethanol-catalyzed coupling to produce C4 olefins: Nonlinear modeling and collaborative optimization strategies

- Unequal width T-node stress concentration factor analysis of stiffened rectangular steel pipe concrete

- Special Issue: Advances in Nonlinear Dynamics and Control

- Development of a cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy design for a nonlinear diabetic patient model

- Big data-based optimized model of building design in the context of rural revitalization

- Multi-UAV assisted air-to-ground data collection for ground sensors with unknown positions

- Design of urban and rural elderly care public areas integrating person-environment fit theory

- Application of lossless signal transmission technology in piano timbre recognition

- Application of improved GA in optimizing rural tourism routes

- Architectural animation generation system based on AL-GAN algorithm

- Advanced sentiment analysis in online shopping: Implementing LSTM models analyzing E-commerce user sentiments

- Intelligent recommendation algorithm for piano tracks based on the CNN model

- Visualization of large-scale user association feature data based on a nonlinear dimensionality reduction method

- Low-carbon economic optimization of microgrid clusters based on an energy interaction operation strategy

- Optimization effect of video data extraction and search based on Faster-RCNN hybrid model on intelligent information systems

- Construction of image segmentation system combining TC and swarm intelligence algorithm

- Particle swarm optimization and fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm for the adhesive layer defect detection

- Optimization of student learning status by instructional intervention decision-making techniques incorporating reinforcement learning

- Fuzzy model-based stabilization control and state estimation of nonlinear systems

- Optimization of distribution network scheduling based on BA and photovoltaic uncertainty

- Tai Chi movement segmentation and recognition on the grounds of multi-sensor data fusion and the DBSCAN algorithm

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part III

- Generalized numerical RKM method for solving sixth-order fractional partial differential equations