Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency virus (AIDS) have a fatal bidirectional connection with a significant global epidemic overlap. People living with HIV-positive are over 30 times more likely than HIV-negative people to develop TB and active TB causes the chronic immunological activation, which accelerates HIV/AIDS disease development. This gives computational investigation of a TB and HIV/AIDS co-infection in fuzzy environment. The application of fuzzy theory aids in addressing the difficulties associated with measuring uncertainty in mathematical representations of the diseases. Here, the fuzzy reproduction number and fuzzy equilibrium points are obtained by using a model relevant to a specific group described by the triangular membership function. Two numerical techniques, namely, forward Euler’s method and Runge–Kutta method, are developed within a fuzzy framework to address the model. We have also employed the non-standard finite difference scheme, which ensures the preservation of the essential properties such as positivity, convergence, and consistency. Numerical simulations are also conducted to illustrate the applicability of the developed technique.

1 Introduction

In order to comprehend the transmission dynamics of diseases within human populations, mathematical modeling of infectious diseases makes use of numerous mathematical and techniques. The objectives of study of the disease dynamics are to understand patterns of transmission, predict how an epidemic will emerge in the future, evaluate the efficacy of control measures, and provide guidance for public health initiatives. Mathematical models can incorporate a variety of factors, including population demographics, illness characteristics, transmission pathways, and intervention strategies, to simulate and evaluate the evolution of infectious diseases. These models can help researchers and policymakers make informed decisions about mitigating, controlling, and eradicating the diseases. Mathematical modeling is used in epidemiology to explain how illnesses spread and affect communities [1–5]. Epidemiological models facilitate a more profound understanding of the transmission of the disease and its preventive strategies [6]. An extensive array of epidemiological models were created, evaluated, and employed qualitatively and quantitatively to investigate a broad spectrum of infections caused by various types of pathogens. Many traditional schemes, such as Euler’s method, Euler’s improved method, Runge–Kutta method, and related techniques, may face challenges such chaos, oscillations, and false steady states. Another way to get around these numerical instabilities is to build schemes with the non-standard finite-difference (NSFD) approach [7,8]. This approach makes it possible to prevent the problems stated above and provides increased stability when performing numerical calculations. This technique, pioneered by Mickens [9], has resulted in the development of new numerical schemes that preserve essential properties such as stability, positivity, and boundedness. In order to improve our comprehension of transmission dynamics and disease control, a multitude of models have been created and investigated using a variety of approaches [10]. In 1965, Zadeh developed the concept of fuzzy theory [9,11,12]. Fuzzy theory is essential to mathematical modeling, because it provides a way to deal with unclear or ambiguous data inside a mathematical framework. All variables are assumed to be precisely measured or calculated in conventional mathematical models. Taking into account, we have made our interest focusing on co-infection dynamics of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency virus (AIDS) and tuberculosis (TB) [13].

HIV has emerged as one of the leading causes of death and misery around the whole world. In 2019, HIV ranked as the eleventh biggest cause of disease burden worldwide [11]. HIV is the ninth and second major cause of disease worldwide in the age categories 10–24 years and 25–49 years, respectively. This finding highlights the ongoing problem of dealing with HIV globally [14]. The world health organization worldwide HIV program [15] recognizes HIV as a significant issue in global public health, since it has killed about 36.3 million lives. In 2020, the program anticipates 37.7 million individuals living with HIV, 1.5 million newly infected in the previous year, and 0.8 million persons globally died from HIV-related causes.

HIV disrupts functioning of immune system of human body by targeting CD4+ T-cells, which protect the host from infections/pathogens [16]. HIV targets and kills these cells, making it more difficult for the body to fight off additional infections. HIV is mostly transmitted through unprotected sexual contact, infected needles, blood transfusions, and lactation [17]. Heterosexual interaction continues to be the most common way that HIV is spread [18]. HIV can spread depending on how infectious the partner is. In the advanced stages of the illness, higher virus loads are linked to an increased risk of transmission [19]. As the HIV progresses, it is commonly referred to as AIDS. Preventive measures including loyalty, protection, and abstinence are the major ways to fight the disease, even though they cannot be stopped forever [20]. These strategies mostly depend on the level of behavioral change observed in the community and the anti-retroviral treatment (ART) administered to infected patients [21]. ART medication increases life expectancy, improves health, and greatly lowers the risk of HIV transmission.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria causes the TB. It is among the earliest diseases that have been identified, and it is brought on by inhaling aerosolized bacilli of the causing agent. It is acquired by sharing a closed, communal space with contagious individuals. Lung infections from TB are common. However, it can also infect other tissues and organs. To treat TB, a variety of anti-TB medications are taken. Every year, millions of individuals still develop TB [22]. Approximately 25% of the population has latent TB, which is the infection that has not yet resulted in illness [23]. Latently infected persons cannot spread TB. Latent TB infections frequently do not result in TB disease. Some of them become infected with TB when their immune systems deteriorate for other reasons. Approximately 10 million individuals are affected, comprising around 5.6 million men, 3.2 million women, and 1.2 million children. In 2017, 6.4 million new cases worldwide were reported to national authorities; this amounts to only 64% of the 10 million new cases that were expected. Underreporting of detected cases and underdiagnosis cases combine to cause the discrepancy between the number of newly reported cases that are actually reported and the estimated number of cases [23].

Using a comparative table in research, such as the one presented in “A GPT-Based Approach for Sentiment Analysis and Bakery Rating Prediction” by Magdaleno et al., is crucial for clearly presenting differences between methodologies, such as a fuzzy model versus deterministic models. Comparative tables allow researchers to systematically showcase key performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, flexibility, robustness) in an organized format, highlighting the advantages and trade-offs of each approach [24–26].

The fuzzy model offers significant advantages over deterministic models and previous studies by better handling uncertainty and imprecision in data. Unlike deterministic models that rely on precise inputs and outputs, fuzzy models can manage ambiguous or incomplete information through degrees of membership, resulting in more adaptable and realistic predictions in complex, real-world scenarios. Studies comparing the two approaches often show that fuzzy models outperform deterministic ones in environments where uncertainty, variability, or linguistic ambiguity exists, making them more flexible and robust for decision-making in fields such as engineering, economics, and control systems. This flexibility provides more accurate results where deterministic models may struggle with oversimplification or rigid assumptions.

The various co-dynamics of numerous illnesses are studied by several epidemiologists [27–31]. Various techniques have been used to reduce the effect of co-infections on the host’s health and the spread of diseases in the human society. Numerous investigations have been carried out on the co-dynamics of the TB with other illnesses. Depending on the goal and direction of the research; various models of TB and HIV/AIDS co-infections have been studied earlier [32]. This study examines the spatial and temporal patterns of COVID-19 spread by leveraging a self-organizing neural network for spatial mapping and a fuzzy fractal approach to capture temporal dynamics across various countries. Based on self-organization, and neural networks, countries with a similar COVID-19 spread can be spatially categorized; this way, we may assess whether countries have comparable characteristics. As a result, similar tactics for preventing virus spread may be advantageous. Furthermore, a fuzzy fractal technique is employed for the temporal analysis of time-series trends of the researched countries [33]. Fuzzy logic was used to describe the intrinsic uncertainty in the decision-making required to achieve the control aim. The method uses a fuzzy model with fuzzy rules to input fractal dimensions and calculate control actions for countries based on COVID-19 data over time [34]. A thorough integration of fuzzy numerical and co-infection mathematical methodologies is absent from the current models. Keeping this in mind, we have created an NSFD scheme to solve a fuzzy parameter co-infection model of HIV/AIDS and TB. We address the difficulties of quantifying uncertainty or ambiguity in mathematical modeling using fuzzy theory [35]. Fuzzy parameters provide a more accurate explanation of the spread of the disease dynamics. We shall develop numerical techniques utilizing the forward Euler’s method, Runge–Kutta method, and NSFD scheme for the problem under investigation. The remainder part of this study is organized in the following manner: preliminaries of the fuzzy set theory is included in the section “Preliminaries of Fuzzy Set.” In the section “TB and HIV/AIDS Co-infection Model with Fuzzy Parameters,” the formulation of the proposed co-infection model is discussed along with the formulation and analysis of TB fuzzy sub-model by including TB basic reproduction number (BRN), fuzzy equilibrium analysis of TB. In the section “Numerical techniques for TB fuzzy sub-model,” forward Euler’s method, Runge–Kutta method, and NSFD scheme were employed for TB fuzzy sub-model. In the same section, convergence and consistency analysis of the model is carried out. Similarly, all the sections of the HIV/AIDS sub-model is also discussed. In the section “Numerical Simulation,” applicability of the developed techniques was discussed. Finally, conclusion is drawn in the last section.

2 Preliminaries of fuzzy set theory

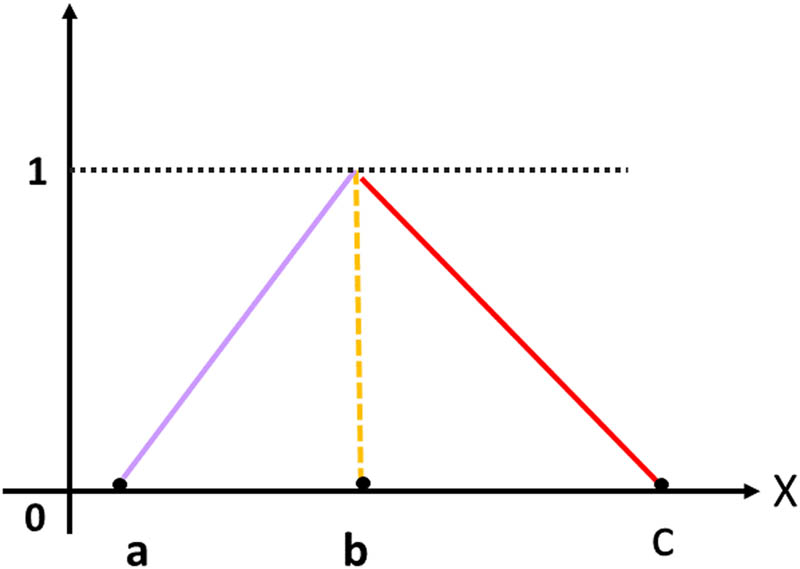

2.1 Triangular fuzzy number (TFN)

A fuzzy number

where

Triangular fuzzy number.

2.2 Expected value of a TFN

Liu and Liu [37] proposed the concept of expected value for a fuzzy number. It is represented by

where

Now, the expected value of a triangular fuzzy number is given by [38]

2.3 Fuzzy BRN

R

0

f

The fuzzy BRN

where the expected value of a TFN described in Eq. (2.2) is

3 TB and HIV/AIDS co-infection model with fuzzy parameters

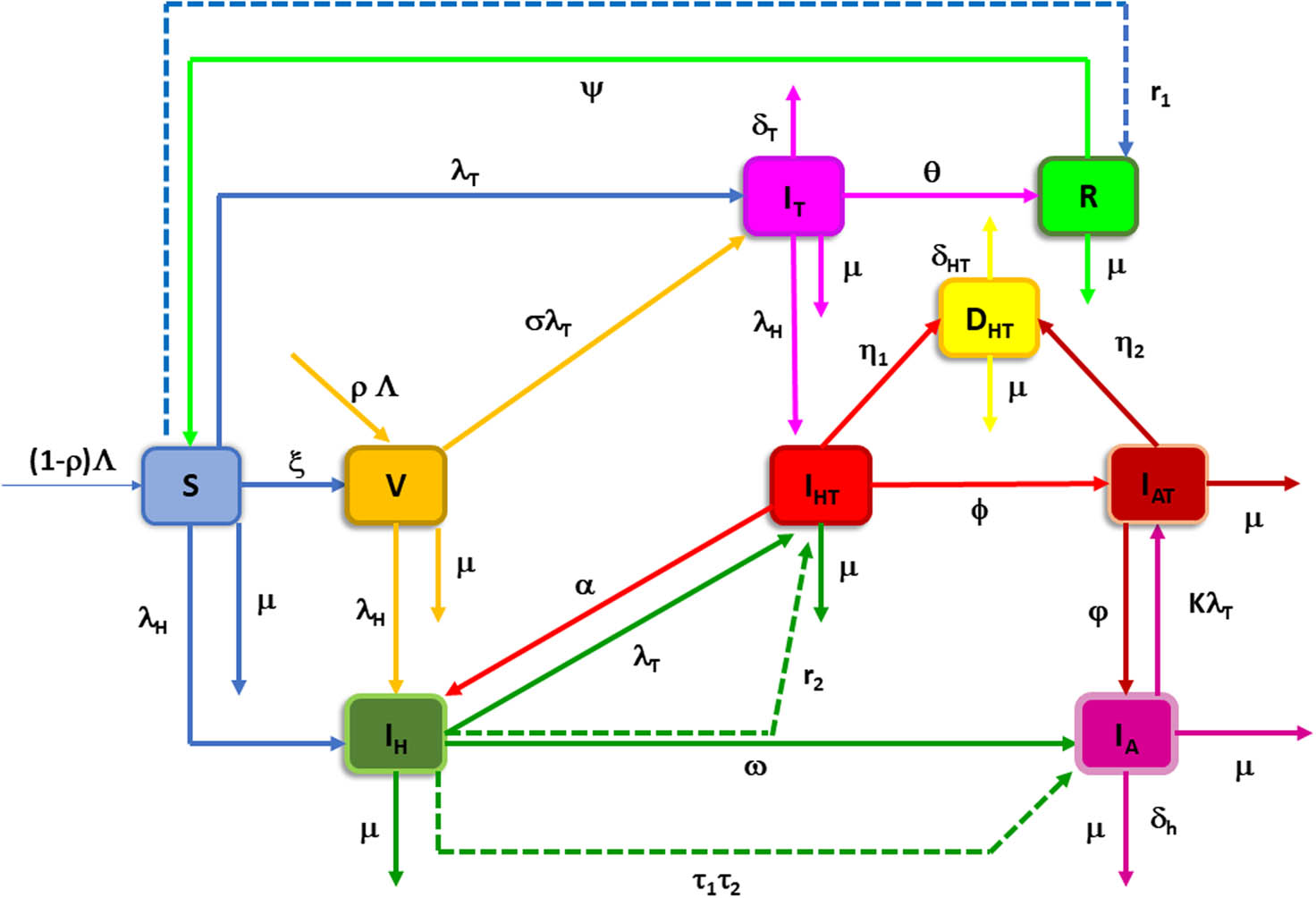

The total population at any time

The proposed model is described by the following system of differential equations:

where

The fuzzy model associated with fuzzy parameters can be represented as follows:

where

The description of the model parameter is given in Table 1.

Description of model parameters

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

|

|

Recruitment rate of susceptible population |

|

|

Fraction of recruitment to the vaccinated population |

|

|

Efficacy of vaccination |

|

|

Vaccination rate for susceptible individuals |

|

|

Modification parameters |

|

|

Effective transmission rate of TB |

|

|

Effective transmission rate of HIV/AIDS |

|

|

Recovery rate of the TB-infected population |

|

|

Natural death rate |

|

|

Death due to TB disease |

|

|

Rate of losing immunity after TB recovery |

|

|

HIV progression rate for individuals in

|

|

|

HIV induced death rate |

|

|

Rate at which co-infected individuals risked to death |

|

|

Recovery rate from TB for

|

|

|

Recovery rate from TB for

|

|

|

Co-infection-induced death rate |

|

|

HIV progression rate for individuals in

|

|

|

Proportion of screening of HIV-infected population selected from

|

|

|

Proportion of HIV-infected population with no symptoms of AIDS after screening |

|

|

Rate at which TB recovered individuals in R move back into the class of susceptible |

|

|

Rate at which dually infected individuals in class

|

Now, we assume that the effective transmission rate

where the lowest recovery rate is

Moreover, as these rates increase as the disease progresses, the death rates

Schematic representation of fuzzy model.

The death rates

For the purpose to analyze the fuzzy model, we split the model into two sub-models: first the TB sub-model and second the HIV/AIDS sub-model. We discuss these two submodels separately to analyze them in better means.

3.1 Feasibility of the model solution

The feasible region is the positive region

Thus, the solution is feasible and positive in the region

Solving this differential inequalities gives

As

Thus, the model solution is bounded and positively invariant in

3.2 Formulation of TB fuzzy sub-model

For this sub-model,

where

3.3 TB fuzzy BRN

R

0

T

f

:

Here, we compute the BRN

Then,

Inserting the disease-free equilibrium (DFE) point

The analysis of

Case 1. Weak amount of virus load: If

Case 2. Medium amount of virus load: If

Case 3. Strong amount of virus load: If

The BRN

Now, we obtain the fuzzy reproduction number

or,

3.4 Equilibrium analysis of TB fuzzy sub-model

The following three cases exist while discussing equilibrium analysis of TB fuzzy sub-model:

Case 1. Weak amount of virus load: If

which is the DFE point. In this instance, there is no virus present in the entire population. Regarding biology, the disease is eradicated when the population’s viral load decreases below the threshold necessary for disease spread.

Case 2. Medium amount of virus load: If

where

where

Solving (3.27), we obtain

where

Case 3. Strong amount of virus load: If

In this case,

4 Numerical techniques for TB fuzzy sub-model

We find the numerical solution of fuzzy TB sub-model by using the following schemes:

4.1 Forward Euler’s scheme for TB sub-model

The forward Euler’s scheme for the TB sub-model (3.17) can be written as follows:

Now, we discuss the following three cases.

Case 1. Weak amount of virus load: If

Case 2. Medium amount of virus load: If

Case 3. Strong amount of virus load: If

4.2 Runge–Kutta method for TB sub-model

The Runge–Kutta method of order 4 is commonly used to solve ordinary differential equations. It is more precise than the Euler’s and other techniques. This method is extensively utilized because it establishes a compromise between simplicity and precision. Here, we give Runge–Kutta method of order 4 for the investigated model as follows:

Step 1:

Step 2:

Step 3:

Step 4:

Final step:

4.3 NSFD scheme for TB sub-model

The NSFD scheme combines numerical approaches to solve differential equations using a discrete model. Mickens [9] introduced the NSFD scheme to improve numerical solutions’ precision and stability. The NSFD scheme for the specified model can be expressed specifically as follows:

Now, we discuss the following three cases:

Case 1. Weak amount of virus load: If

Case 2. Medium amount of virus load: If

Case 3. Strong amount of virus load: If

4.4 Positivity of the NSFD scheme

If all state variables (

Proof

Taking into account the state variables (

By inserting

Assume next that the aforementioned system of equations guarantees that the variable values have the quality of positivity for

We now analyze the positivity for a random positive integer

For all positive integer values of

4.5 Convergence analysis of TB NSFD scheme

Convergence analysis examines whether the numerical solution obtained by a numerical approaches the actual solution of the underlying mathematical model. The behavior of the system’s convergence is largely determined by the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix at an equilibrium point. If all of the eigenvalues are strictly less than unity, then the system’s trajectories will eventually converge to the equilibrium point. If any eigenvalue has a magnitude greater than unity, then the corresponding trajectories will deviate from the equilibrium point. When this happens, the system will not be able to achieve equilibrium, and its behavior could turn erratic or chaotic. Now, we will examine the NSFD scheme’s convergence for the aforementioned model. For this purpose, we can express the system (4.37)–(4.40) as follows:

Jacobian matrix of the aforementioned system of equations is given by

which is discussed in the following in three cases:

Case 1. Weak amount of virus load: If

where

and

and

Case 2. Medium amount of virus load: If

where

Case 3. Strong amount of virus load: If

where

4.6 Consistency analysis of TB NSFD scheme

Consistency is important in numerical schemes because it connects the discrete equations to the continuous system that they describe. Differential equations derivative operators are discretized using Taylor’s series, and higher-order terms are intentionally eliminated to achieve the necessary accuracy. The removed terms cause a truncation or discretization error in the specified system’s solution. As the mesh size and time steps approach zero, consistency is a key property that guarantees the discretization error will eventually reduce to zero.

Thus, the Taylor series for the susceptible compartment can be written as follows:

From Eq. (4.37), we have

or

or

Taking

Similarly, applying the Taylor series for Eqs. (4.38)–(4.40), we obtain

5 Formulation of HIV/AIDS fuzzy sub-model

For this sub-model,

where

5.1 HIV/AIDS fuzzy BRN

R

0

H

f

Here, we compute the BRN

Let

The following result is obtained by substituting the DFE point

Here, we compute the BRN

Case 1. Weak amount of virus load: If

Case 2. Medium amount of virus load: If

Case 3. Strong amount of virus load: If

As a well-defined fuzzy variable, the BRN

Now, we obtain the fuzzy reproduction number

or

5.2 Equilibrium analysis of HIV/AIDS fuzzy sub-model

The following three cases exist while discussing equilibrium analysis of HIV/AIDS model fuzzy sub-model.

Case 1. Weak amount of virus load: If

which is the DFE point. In this instance, there is no virus present in the entire population. Regarding biology, the disease is eradicated when the population’s viral load falls below the threshold value necessary for disease spread.

Case 2. Medium amount of virus load: If

where

where

and

where

Case 3. Strong amount of virus load: If

Substituting

6 Numerical techniques for HIV/AIDS fuzzy sub-model

We find the numerical solution of fuzzy HIV/AIDS sub-model by using the following schemes:

6.1 Forward Euler’s scheme for HIV/AIDS sub-model

The forward Euler’s scheme for HIV/AIDS sub-model (5.1) can be expressed as follows:

Now, we discuss the following three cases:

Case 1. Weak amount of virus load: If

Case 2. Medium amount of virus load: If

Case 3. Strong amount of virus load: If

6.2 Runge–Kutta method of order 4 for HIV/AIDS sub-model

Here, we give Runge–Kutta method of order 4 for the investigated HIV/AIDS sub-model as follows:

Step 1:

Step 2:

Step 3:

Step 4:

Final step:

6.3 NSFD scheme for HIV/AIDS sub-model

The NSFD scheme for the given HIV/AIDS model can be expressed as follows:

Now, we discuss the following three cases:

Case 1. Weak amount of virus load: If

Case 2. Medium amount of virus load: If

Case 3. Strong amount of virus load: If

6.4 Positivity of the NSFD scheme

Theorem 1

If all the state variables (

Proof

Taking into account the state variables (

By inserting

Assume next that the aforementioned system of equations guarantees that the variable values have the quality of positivity for

We now analyze the positivity for a random positive integer

For all positive integer values of

6.5 Convergence analysis of the NSFD scheme of HIV/AIDS

Now, we will examine the NSFD scheme’s convergence for the aforementioned model. For this purpose, we can express system (6.37)–(6.40) as follows:

Jacobian matrix of the aforementioned system of equations is given by

which is discussed in the following in three cases:

Case 1. Weak amount of virus load: If

where

and

and

where

Case 2. Medium amount of virus load: If

where

Case 3. Strong amount of virus load: If

where

6.6 Consistency analysis of HIV/AIDS fuzzy sub-model

Thus, the Taylor series for susceptible compartment can be written as follows:

From Eq. (6.37), we have

or

or

Taking

Similarly, applying the Taylor series for Eqs (6.38)–(6.40), we obtain

Table 2 contains detailed information on the model parameters.

Values and sources of model parameters

| Parameter | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

|

|

200 | Fitted |

|

|

0.99 | Fitted |

|

|

0.99 | Estimated |

|

|

0.935 | Fitted |

|

|

0.0998, 0.0224 | Fitted |

|

|

0.009768 | Fitted |

|

|

0.00798 | Fitted |

|

|

0.21 | Estimated |

|

|

0.009 | Fitted |

|

|

0.009 | Fitted |

|

|

0.89 | Estimated |

|

|

0.011 | Fitted |

|

|

7.99 | Fitted |

|

|

0.0001 | Fitted |

|

|

0.009 | Fitted |

|

|

0.9 | Fitted |

7 Numerical simulation

Numerical simulations validate the findings of the co-infection model of TB and HIV/AIDS with fuzzy parameters. The effects of factors on the spread and control co-infection of TB and HIV/AIDS are evaluated. Parameter values from Table 2 are used to perform simulations using MATLAB software. Various types of plots are shown and explained in the following [40].

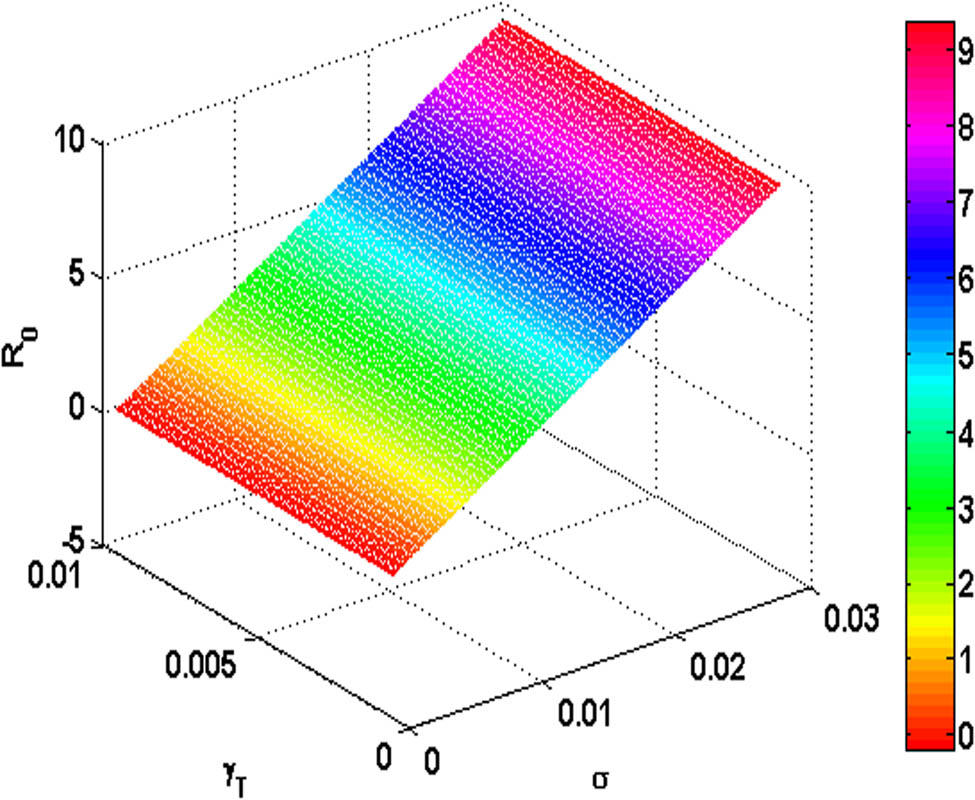

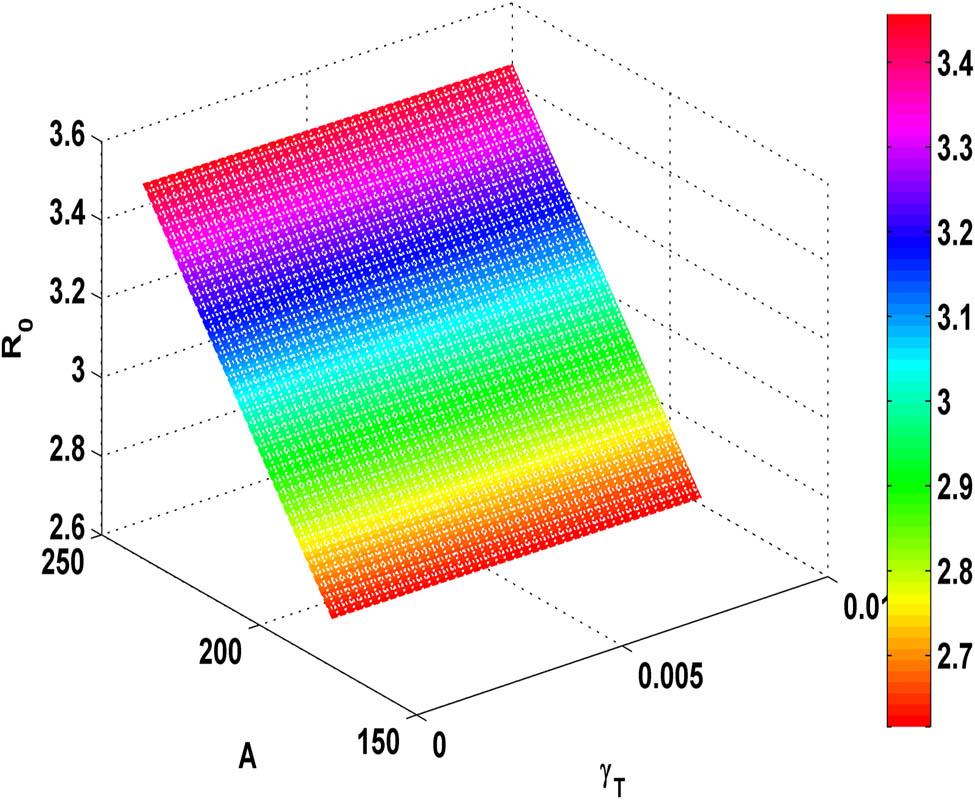

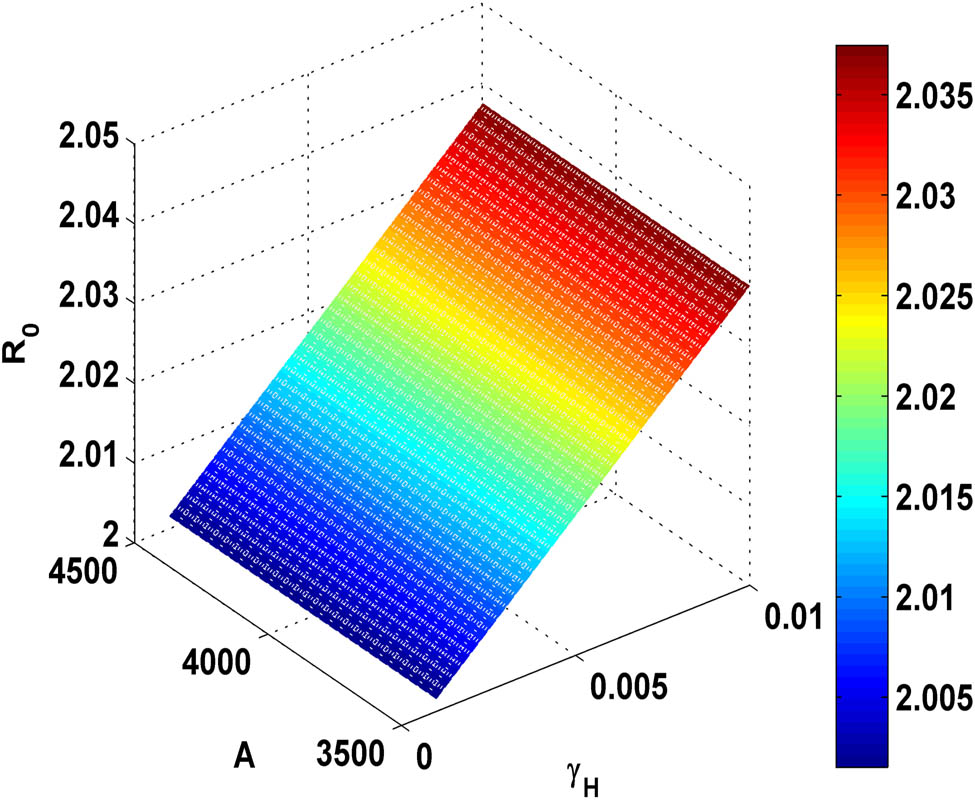

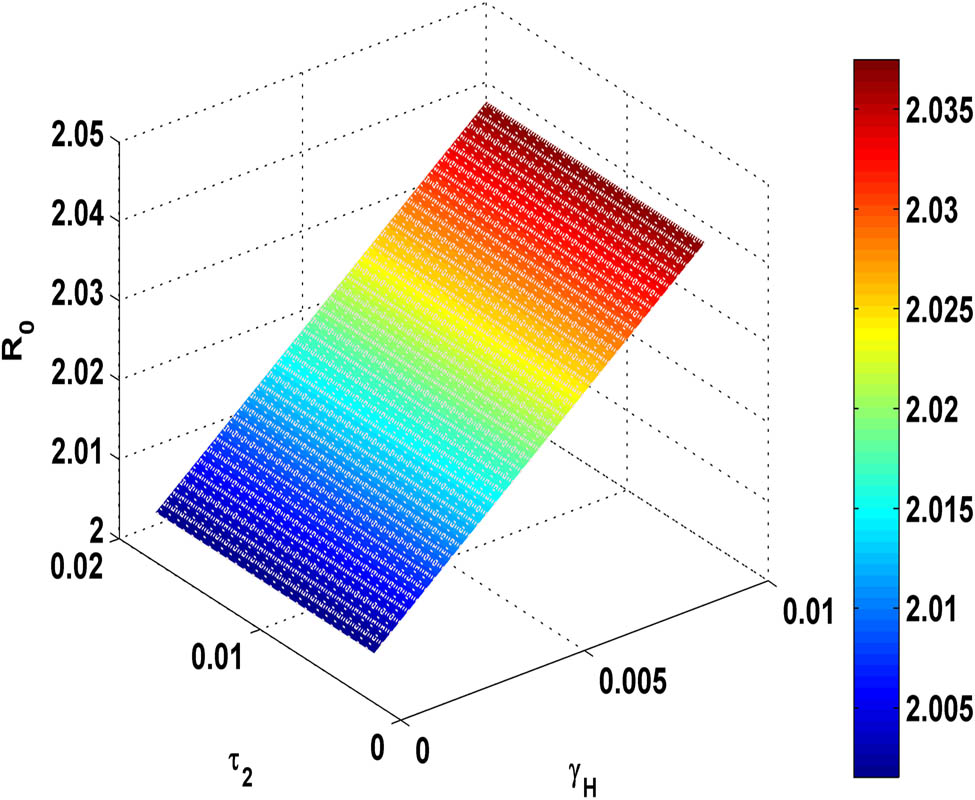

Figure 3 demonstrates that as the value of

Variation of

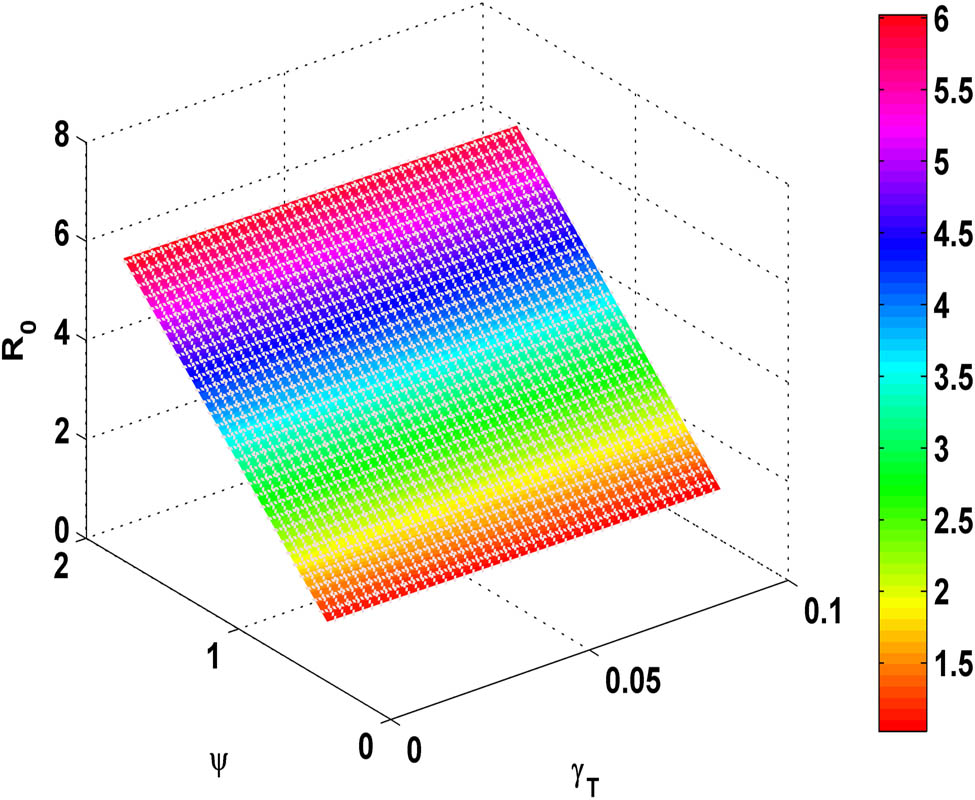

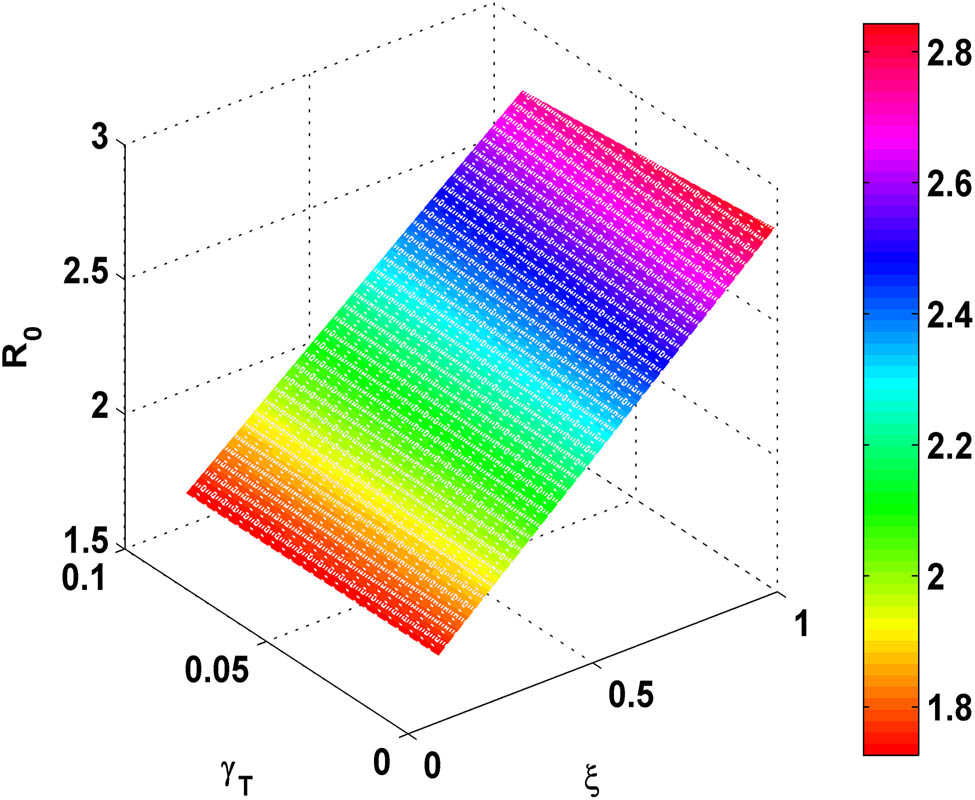

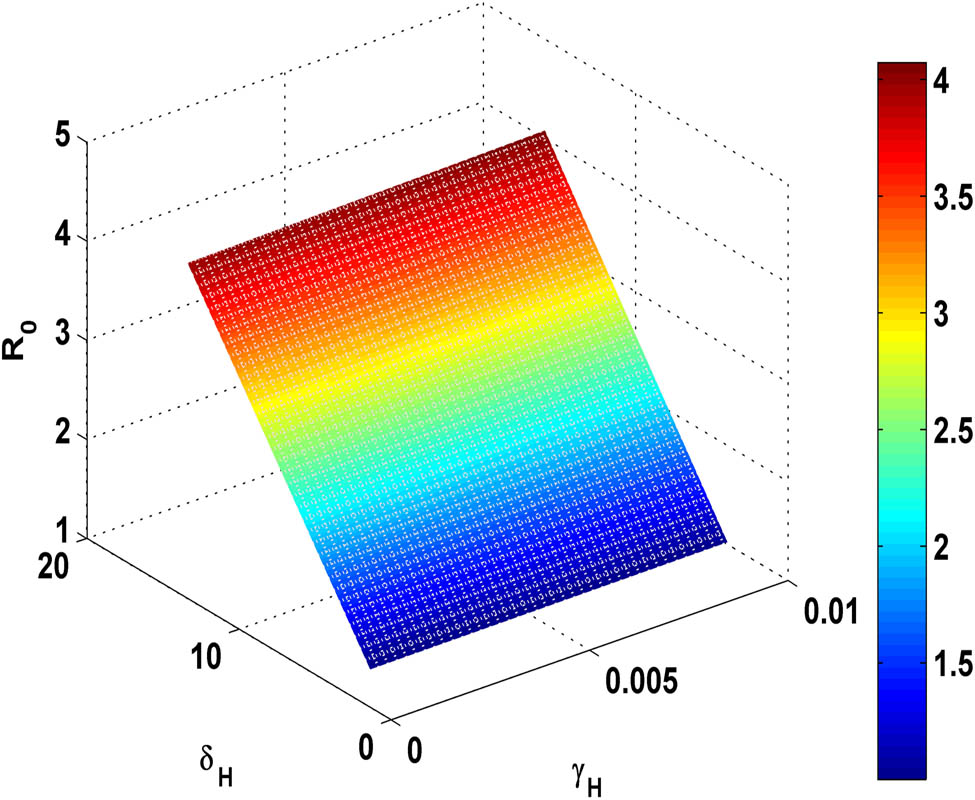

Figure 4 illustrates that the increment in the value of

Variation of

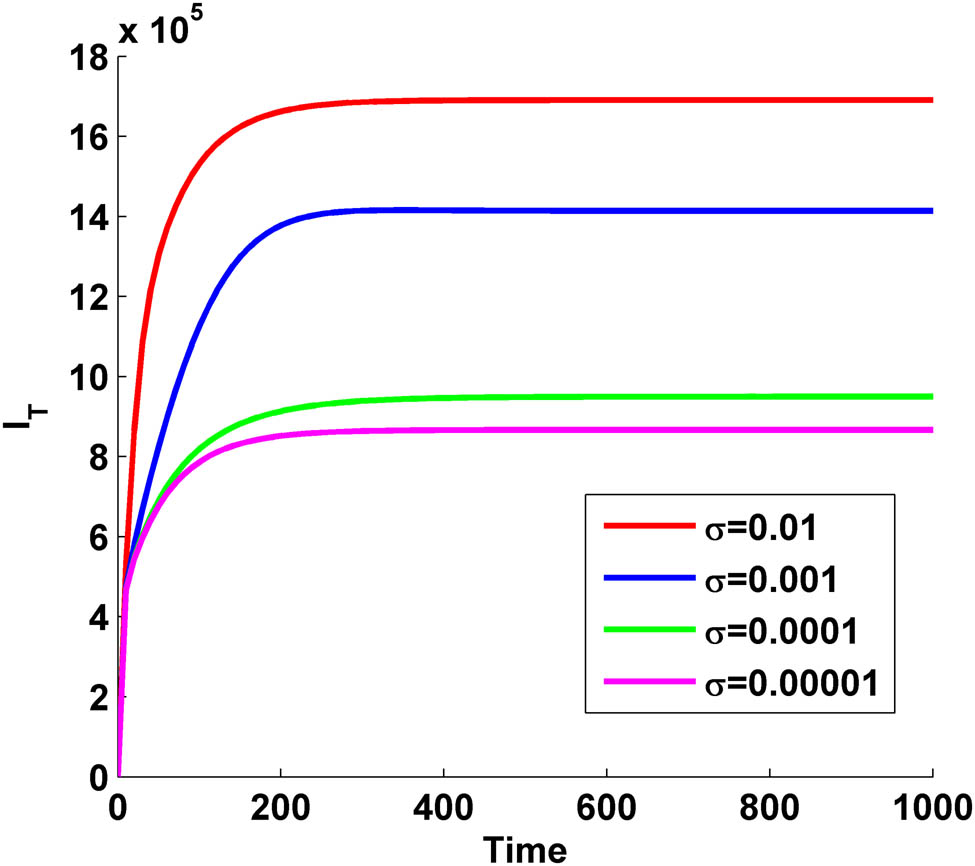

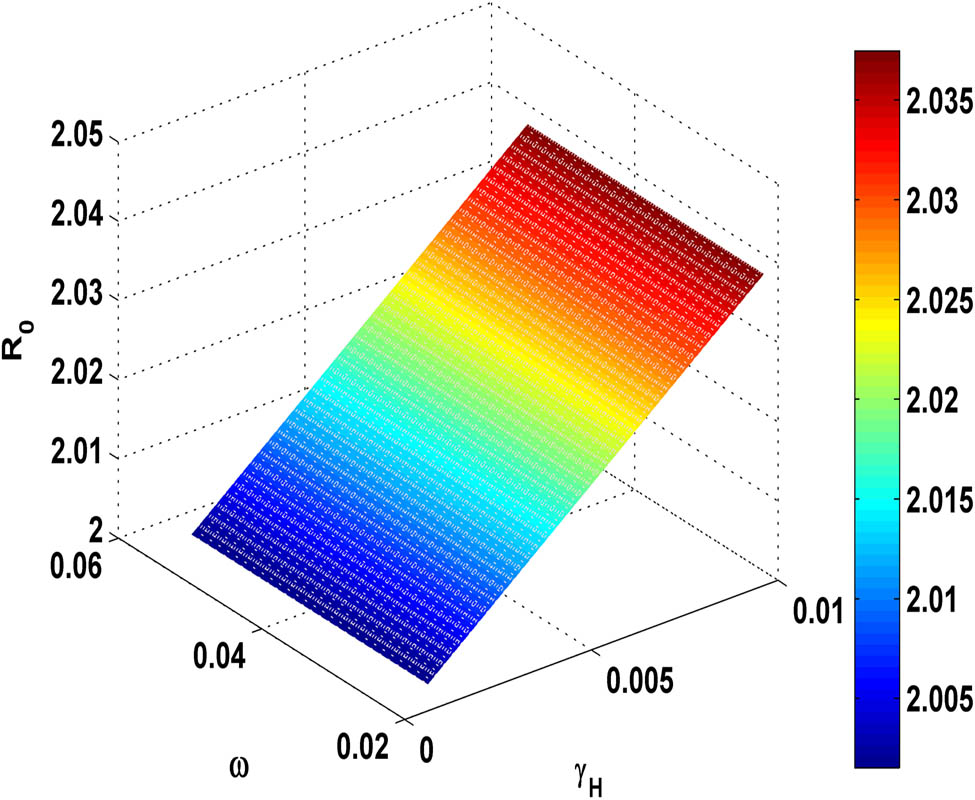

Figure 5 shows that as the value of

Variation of

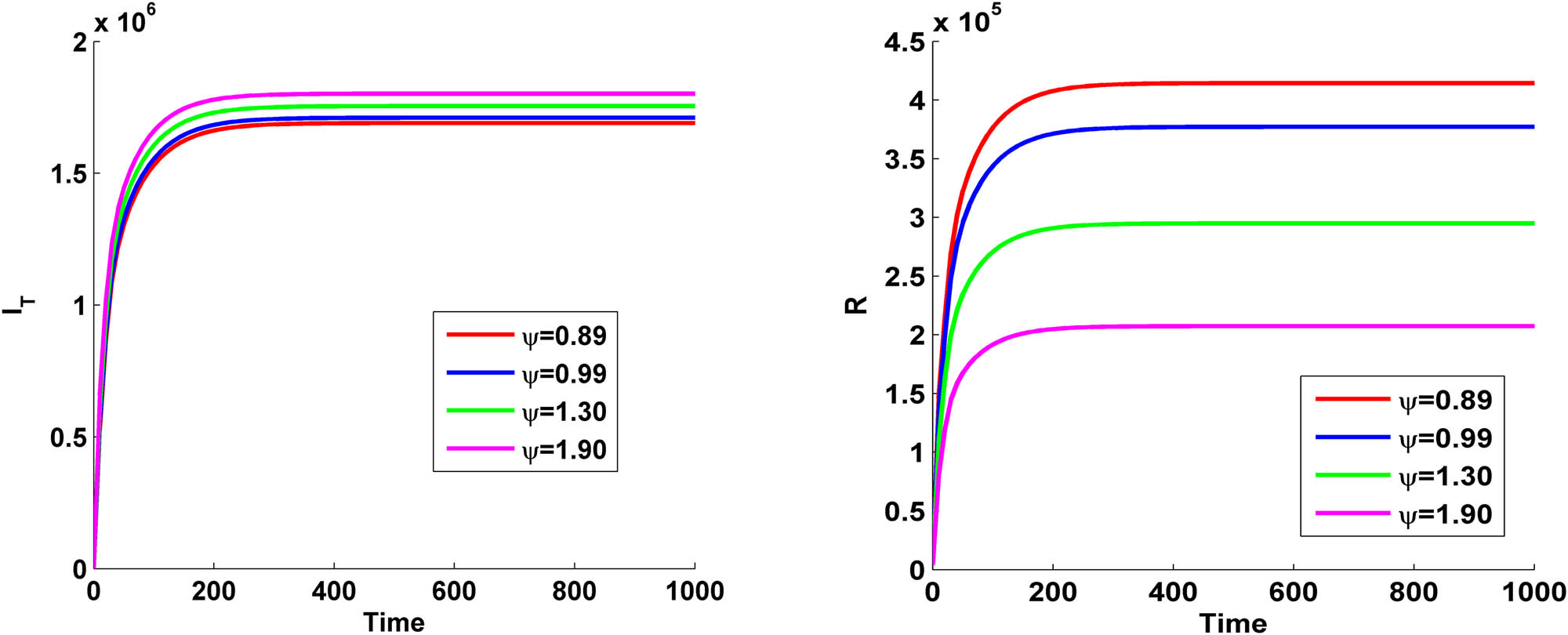

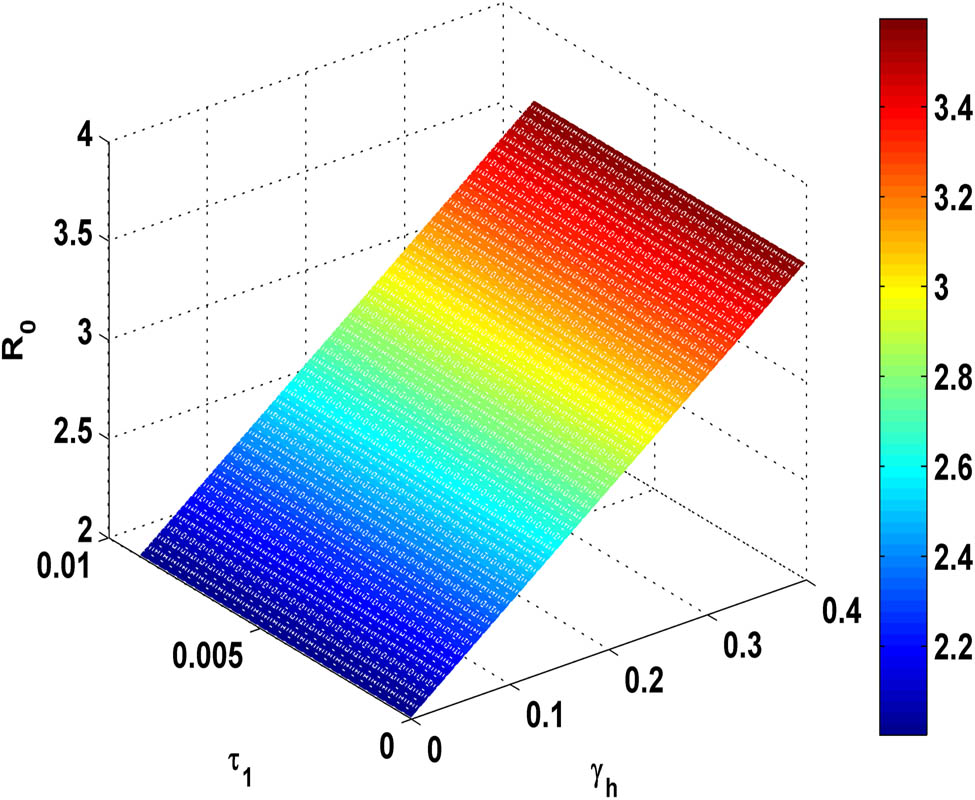

Figure 6 illustrates that as we increment in value of vaccination rate,

Variation of

In Figure 7, we have drawn the variation of TB-infected population with time for HIV/AIDS infection. From the figure, we observe that as we increase the vaccine efficacy

Variation of

Figure 8 shows the variation of TB-infected population and recovered population with time for different values of

Variation of

Figure 9 illustrates that as the value of effective transmission rate

Variation of

Figure 10 demonstrates that if the transmission rate

Variation of

Figure 11 shows that as the value of transmission rate

Variation of

Figure 12 demonstrates that as the proportion

Variation of

Figure 13 demonstrates that as the proportion

Variation of

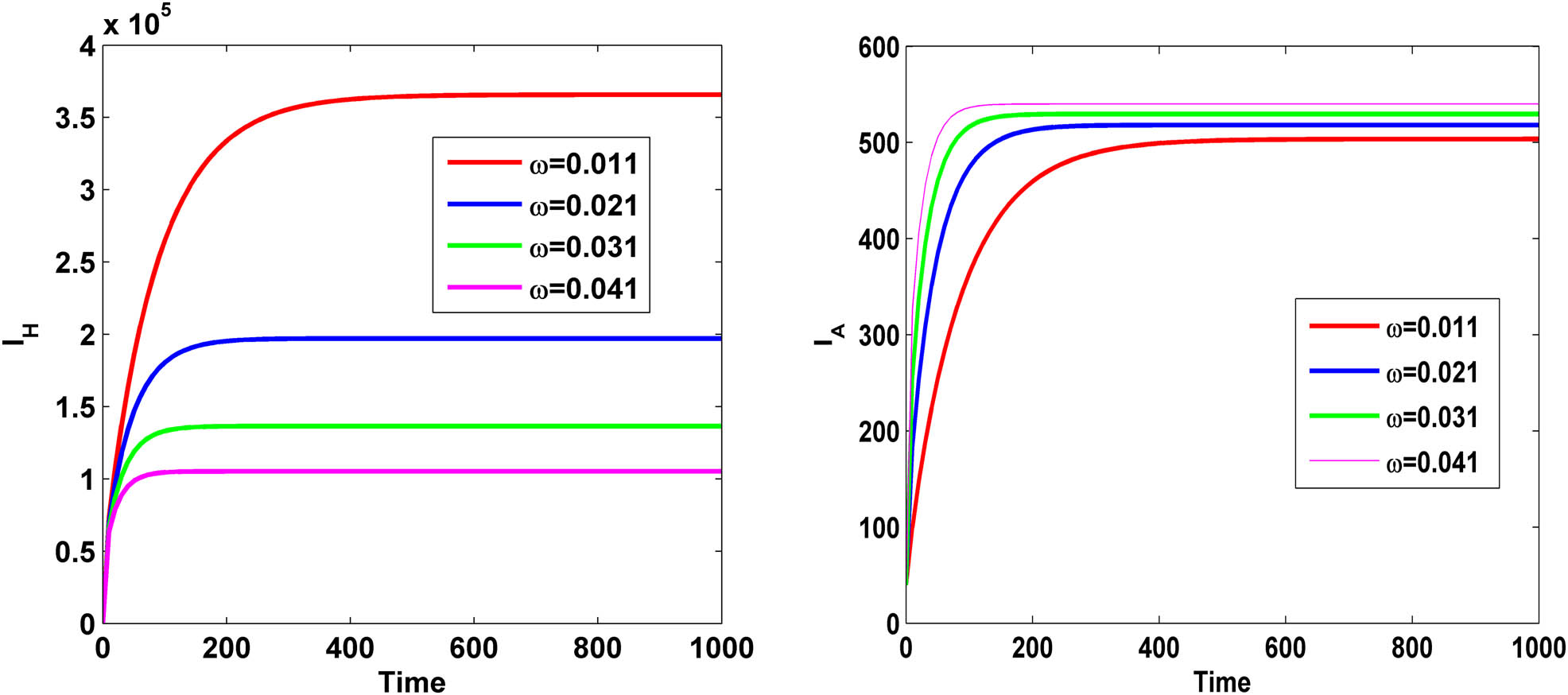

Figure 14 demonstrates that as the HIV progression rate

Variation of

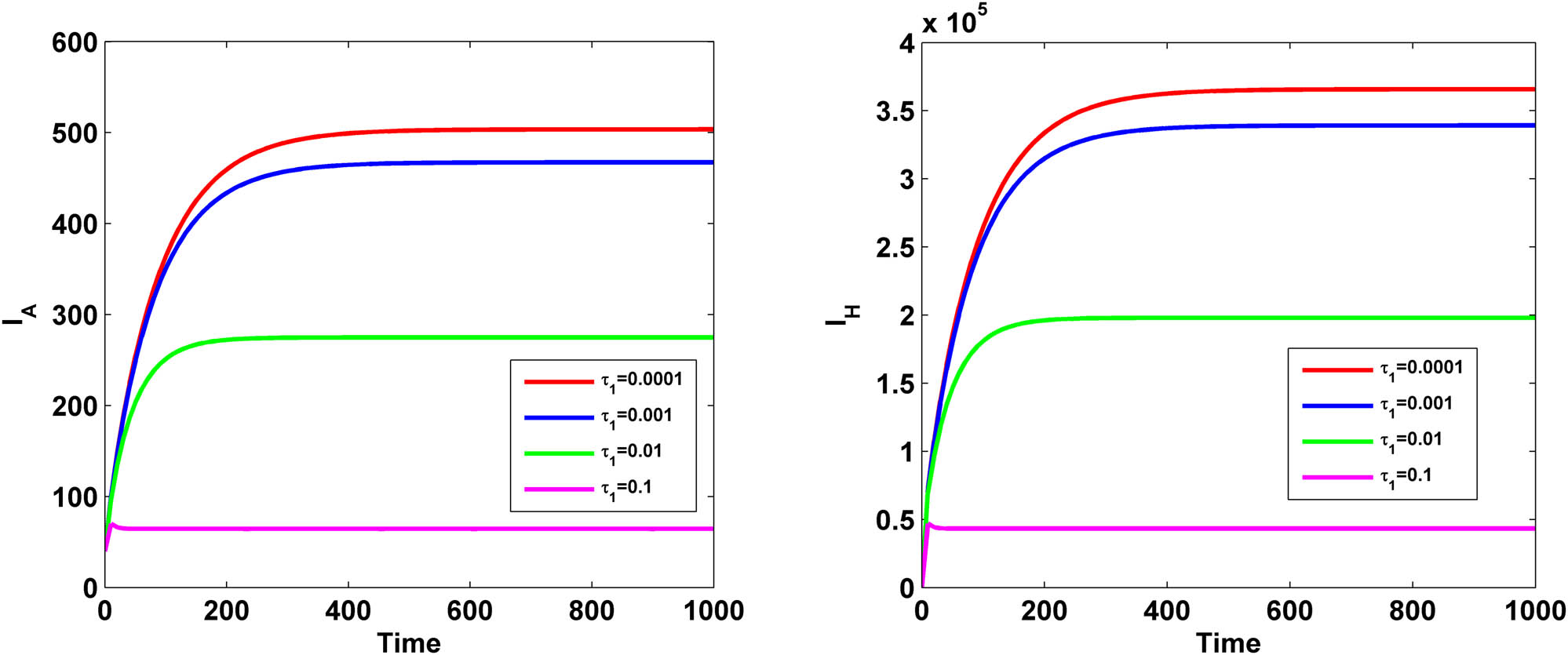

Figure 15 demonstrates the variation of both HIV-infected population

Variation of

8 Conclusion

In this study, we have presented a co-infection model of HIV/AIDS and TB using fuzzy parameters. We have assumed that the infection is not spread uniformly among individuals in the entire population. Similarly, the recovery and death rates are also assumed to vary per individual. We have treated the HIV/AIDS and TB transmission rates

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at the Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

-

Funding information: The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at the Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

-

Author contributions: All Authors have equally contributed to this paper.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the curent study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Jain S, El-Khatib Y. Modelling chaotic dynamical attractor with fractal-fractional differential operators. AIMS Math. 2021 Jan 1;1(12):13689–725. 10.3934/math.2021795Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Jain S. Numerical analysis for the fractional diffusion and fractional Buckmaster equation by the two-step Laplace Adam-Bashforth method. Europ Phys J Plus. 2018 Jan 19;133(1):19. 10.1140/epjp/i2018-11854-xSuche in Google Scholar

[3] Owolabi KM, Jain S. Spatial patterns through diffusion-driven instability in modified predator-prey models with chaotic behaviors. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2023;174:113839. Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Owolabi KM, Jain S. Spatial patterns through diffusion-driven instability in modified predator-prey models with chaotic behaviors. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2023 Sep 1;174:113839. 10.1016/j.chaos.2023.113839Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Atangana A, Jain S. The role of power decay, exponential decay and Mittag-Leffler function’s waiting time distribution: application of cancer spread. Phys A Stat Mech Appl. 2018 Dec 15;512:330–51. 10.1016/j.physa.2018.08.033Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Brauer F, Castillo-Chavez C, Castillo-Chavez C. Mathematical models in population biology and epidemiology. New York: Springer; 2012. 10.1007/978-1-4614-1686-9Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Verma AK, Kayenat S. On the convergence of Mickens’ type nonstandard finite difference schemes on Lane-Emden type equations. J Math Chem. 2018 Jun;56:1667–706. 10.1007/s10910-018-0880-ySuche in Google Scholar

[8] Conte D, Guarino N, Pagano G, Paternoster B. On the advantages of nonstandard finite difference discretizations for differential problems. Numer Anal Appl. 2022 Sep;15(3):219–35. 10.1134/S1995423922030041Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Mickens RE. Advances in the applications of nonstandard finite difference schemes. Singapore: World Scientific; 2005 Oct 25. 10.1142/9789812703316Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Cresson J, Pierret F. Non standard finite difference scheme preserving dynamical properties. J Comput Appl Math. 2016 Sep 1 303:15–30. 10.1016/j.cam.2016.02.007Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Goguen JA, Zadeh LA. Fuzzy sets. Information and control. 1965;8:338–53. Zadeh LA. Similarity relations and fuzzy orderings. Information sciences, vol. 3 (1971), pp. 177-200. J Symb Log. 1973 Dec;38(4):656–7. 10.2307/2272014Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Mondal PK, Jana S, Haldar P, Kar TK. Dynamical behavior of an epidemic model in a fuzzy transmission. Int J Uncertainty Fuzziness Knowl-Based Syst. 2015 Oct;23(05):651–65. 10.1142/S0218488515500282Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Lefevr N, Kanavos A, Gerogiannis VC, Iliadis L, Pintelas P. Employing fuzzy logic to analyze the structure of complex biological and epidemic spreading models. Mathematics. 2021 Apr 27;9(9):977. 10.3390/math9090977Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Vos T. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (vol. 396, p. 1204, 2020). Lancet. 2020 Nov 14;396:(10262):1562. Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Batu TD, Obsu LL, Deressa CT. Co-infection dynamics of COVID-19 and HIV/AIDS. Scientif Reports. 2023 Oct 27;13(1):18437. 10.1038/s41598-023-45520-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] WHO. Global HIV Programme 2020 estimates. 2022. https://bit.ly/3HmxDpQ. Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Maartens G, Celum C, Lewin SR. HIV infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. The Lancet. 2014 Jul 19;384(9939):258–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60164-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Morison L. The global epidemiology of HIV/AIDS. British Med Bulletin. 2001 Sep 1;58(1):7–18. 10.1093/bmb/58.1.7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Simon V, Ho DD, Karim QA. HIV/AIDS epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. The Lancet. 2006 Aug 5;368(9534):489–504. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69157-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] d’Arminio Monforte A, Cozzi-Lepri A, Castagna A, Antinori A, De Luca A, Mussini C, et al. Risk of developing specific AIDS-defining illnesses in patients coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C virus with or without liver cirrhosis. Clin Infect Diseases. 2009 Aug 15;49(4):612–22. 10.1086/603557Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Centers for disease control and prevention. Evidence of HIV treatment and viral suppression in preventing the sexual transmission of HIV. Dep Heal Hum Serv. 2018 Dec;4:15. Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Rwezaura H, Diagne ML, Omame A, de Espindola AL, Tchuenche JM. Mathematical modeling and optimal control of SARS-CoV-2 and tuberculosis co-infection: a case study of Indonesia. Model Earth Syst Environ. 2022 Nov;8(4):5493–520. 10.1007/s40808-022-01430-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] World Health Organisation. www.who.int/tb/publications/glob-al_report/en/. Suche in Google Scholar

[24] World Health Organisation. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis. Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Centers for disease control and prevention. www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/basics/tbinfectiondisease.htm. Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Magdaleno D, Montes M, Estrada B, Ochoa-Zezzatti A. A GPT-based approach for sentiment analysis and bakery rating prediction. InMexican International Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2023 Nov 13. pp. 61–76. 10.1007/978-3-031-51940-6_7Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Tilahun GT. Modeling co-dynamics of pneumonia and meningitis diseases. Adv Differ Equ. 2019 Dec;2019(1):1–8. 10.1186/s13662-019-2087-3Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Omame A, Okuonghae D, Umana RA, Inyama SC. Analysis of a co-infection model for HPV-TB. Appl Math Model. 2020 Jan 1;77:881–901. 10.1016/j.apm.2019.08.012Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Varshney KG, Dwivedi YK. Mathematical modeling of influenza-meningitis under the quarantine effect of influenza. Turkish J Comput Math Educ. 2021;12(11):7214–25. Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Omame A, Okuonghae D. A co-infection model for oncogenic human papillomavirus and tuberculosis with optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis. Opt Control Appl Methods. 2021 Jul;42(4):1081–101. 10.1002/oca.2717Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Faniran TS, Adewole MO, Ahmad H, Abdullah FA. Dynamics of tuberculosis in HIV-HCV co-infected cases. Int J Biomath. 2023 Apr 28;16(3):2250091. 10.1142/S1793524522500917Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Sil N, Mahata A, Roy B. Dynamical behavior of HIV infection in fuzzy environment. Results Control Optim. 2023 Mar 1;10:100209. 10.1016/j.rico.2023.100209Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Melin P, Castillo O. Spatial and temporal spread of the COVID-19 pandemic using self organizing neural networks and a fuzzy fractal approach. Sustainability. 2021 Jul 24;13(15):8295. 10.3390/su13158295Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Castillo O, Melin P. A new fuzzy fractal control approach of non-linear dynamic systems: The case of controlling the COVID-19 pandemics. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2021 Oct 1;151:111250. 10.1016/j.chaos.2021.111250Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Ahmed N, Shahid N, Iqbal Z, Jawaz M, Rafiq M, Tahira SS, et al. Numerical modeling of SEIQV epidemic model with saturated incidence rate. J Appl Environ Biol Sci. 2018;8(4):67–82. Suche in Google Scholar

[36] De Barros LC, Bassanezi RC, Lodwick WA. First course in fuzzy logic, fuzzy dynamical systems, and biomathematics. Berlin: Springer-Verlag: 2016. 10.1007/978-3-662-53324-6Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Liu B, Liu YK. Expected value of fuzzy variable and fuzzy expected value models. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2002 Aug;10(4):445–50. 10.1109/TFUZZ.2002.800692Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Mangongo YT, Bukweli JD, Kampempe JD. Fuzzy global stability analysis of the dynamics of malaria with fuzzy transmission and recovery rates. Am J Operat Res. 2021 Oct 13;11(6):257–82. 10.4236/ajor.2021.116017Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Salahshour S, Ahmadian A, Mahata A, Mondal SP, Alam S. The behavior of logistic equation with alley effect in fuzzy environment: fuzzy differential equation approach. Int J Appl Comput Math. 2018 Apr;4:1–20. 10.1007/s40819-018-0496-8Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Panda A, Pal M. A study on pentagonal fuzzy number and its corresponding matrices. Pacific Sci Rev B Human Soc Sc. 2015 Nov 1;1(3):131–9. 10.1016/j.psrb.2016.08.001Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Generalized (ψ,φ)-contraction to investigate Volterra integral inclusions and fractal fractional PDEs in super-metric space with numerical experiments

- Solitons in ultrasound imaging: Exploring applications and enhancements via the Westervelt equation

- Stochastic improved Simpson for solving nonlinear fractional-order systems using product integration rules

- Exploring dynamical features like bifurcation assessment, sensitivity visualization, and solitary wave solutions of the integrable Akbota equation

- Research on surface defect detection method and optimization of paper-plastic composite bag based on improved combined segmentation algorithm

- Impact the sulphur content in Iraqi crude oil on the mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of carbon steel in various types of API 5L pipelines and ASTM 106 grade B

- Unravelling quiescent optical solitons: An exploration of the complex Ginzburg–Landau equation with nonlinear chromatic dispersion and self-phase modulation

- Perturbation-iteration approach for fractional-order logistic differential equations

- Variational formulations for the Euler and Navier–Stokes systems in fluid mechanics and related models

- Rotor response to unbalanced load and system performance considering variable bearing profile

- DeepFowl: Disease prediction from chicken excreta images using deep learning

- Channel flow of Ellis fluid due to cilia motion

- A case study of fractional-order varicella virus model to nonlinear dynamics strategy for control and prevalence

- Multi-point estimation weldment recognition and estimation of pose with data-driven robotics design

- Analysis of Hall current and nonuniform heating effects on magneto-convection between vertically aligned plates under the influence of electric and magnetic fields

- A comparative study on residual power series method and differential transform method through the time-fractional telegraph equation

- Insights from the nonlinear Schrödinger–Hirota equation with chromatic dispersion: Dynamics in fiber–optic communication

- Mathematical analysis of Jeffrey ferrofluid on stretching surface with the Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Exploring the interaction between lump, stripe and double-stripe, and periodic wave solutions of the Konopelchenko–Dubrovsky–Kaup–Kupershmidt system

- Computational investigation of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS co-infection in fuzzy environment

- Signature verification by geometry and image processing

- Theoretical and numerical approach for quantifying sensitivity to system parameters of nonlinear systems

- Chaotic behaviors, stability, and solitary wave propagations of M-fractional LWE equation in magneto-electro-elastic circular rod

- Dynamic analysis and optimization of syphilis spread: Simulations, integrating treatment and public health interventions

- Visco-thermoelastic rectangular plate under uniform loading: A study of deflection

- Threshold dynamics and optimal control of an epidemiological smoking model

- Numerical computational model for an unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium past an MHD rotating sheet

- Regression prediction model of fabric brightness based on light and shadow reconstruction of layered images

- Dynamics and prevention of gemini virus infection in red chili crops studied with generalized fractional operator: Analysis and modeling

- Qualitative analysis on existence and stability of nonlinear fractional dynamic equations on time scales

- Fractional-order super-twisting sliding mode active disturbance rejection control for electro-hydraulic position servo systems

- Analytical exploration and parametric insights into optical solitons in magneto-optic waveguides: Advances in nonlinear dynamics for applied sciences

- Bifurcation dynamics and optical soliton structures in the nonlinear Schrödinger–Bopp–Podolsky system

- User profiling in university libraries by combining multi-perspective clustering algorithm and reader behavior analysis

- Exploring bifurcation and chaos control in a discrete-time Lotka–Volterra model framework for COVID-19 modeling

- Review Article

- Haar wavelet collocation method for existence and numerical solutions of fourth-order integro-differential equations with bounded coefficients

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Analysis and Design of Communication Networks for IoT Applications - Part II

- Silicon-based all-optical wavelength converter for on-chip optical interconnection

- Research on a path-tracking control system of unmanned rollers based on an optimization algorithm and real-time feedback

- Analysis of the sports action recognition model based on the LSTM recurrent neural network

- Industrial robot trajectory error compensation based on enhanced transfer convolutional neural networks

- Research on IoT network performance prediction model of power grid warehouse based on nonlinear GA-BP neural network

- Interactive recommendation of social network communication between cities based on GNN and user preferences

- Application of improved P-BEM in time varying channel prediction in 5G high-speed mobile communication system

- Construction of a BIM smart building collaborative design model combining the Internet of Things

- Optimizing malicious website prediction: An advanced XGBoost-based machine learning model

- Economic operation analysis of the power grid combining communication network and distributed optimization algorithm

- Sports video temporal action detection technology based on an improved MSST algorithm

- Internet of things data security and privacy protection based on improved federated learning

- Enterprise power emission reduction technology based on the LSTM–SVM model

- Construction of multi-style face models based on artistic image generation algorithms

- Research and application of interactive digital twin monitoring system for photovoltaic power station based on global perception

- Special Issue: Decision and Control in Nonlinear Systems - Part II

- Animation video frame prediction based on ConvGRU fine-grained synthesis flow

- Application of GGNN inference propagation model for martial art intensity evaluation

- Benefit evaluation of building energy-saving renovation projects based on BWM weighting method

- Deep neural network application in real-time economic dispatch and frequency control of microgrids

- Real-time force/position control of soft growing robots: A data-driven model predictive approach

- Mechanical product design and manufacturing system based on CNN and server optimization algorithm

- Application of finite element analysis in the formal analysis of ancient architectural plaque section

- Research on territorial spatial planning based on data mining and geographic information visualization

- Fault diagnosis of agricultural sprinkler irrigation machinery equipment based on machine vision

- Closure technology of large span steel truss arch bridge with temporarily fixed edge supports

- Intelligent accounting question-answering robot based on a large language model and knowledge graph

- Analysis of manufacturing and retailer blockchain decision based on resource recyclability

- Flexible manufacturing workshop mechanical processing and product scheduling algorithm based on MES

- Exploration of indoor environment perception and design model based on virtual reality technology

- Tennis automatic ball-picking robot based on image object detection and positioning technology

- A new CNN deep learning model for computer-intelligent color matching

- Design of AR-based general computer technology experiment demonstration platform

- Indoor environment monitoring method based on the fusion of audio recognition and video patrol features

- Health condition prediction method of the computer numerical control machine tool parts by ensembling digital twins and improved LSTM networks

- Establishment of a green degree evaluation model for wall materials based on lifecycle

- Quantitative evaluation of college music teaching pronunciation based on nonlinear feature extraction

- Multi-index nonlinear robust virtual synchronous generator control method for microgrid inverters

- Manufacturing engineering production line scheduling management technology integrating availability constraints and heuristic rules

- Analysis of digital intelligent financial audit system based on improved BiLSTM neural network

- Attention community discovery model applied to complex network information analysis

- A neural collaborative filtering recommendation algorithm based on attention mechanism and contrastive learning

- Rehabilitation training method for motor dysfunction based on video stream matching

- Research on façade design for cold-region buildings based on artificial neural networks and parametric modeling techniques

- Intelligent implementation of muscle strain identification algorithm in Mi health exercise induced waist muscle strain

- Optimization design of urban rainwater and flood drainage system based on SWMM

- Improved GA for construction progress and cost management in construction projects

- Evaluation and prediction of SVM parameters in engineering cost based on random forest hybrid optimization

- Museum intelligent warning system based on wireless data module

- Optimization design and research of mechatronics based on torque motor control algorithm

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Engineering’s significance in Materials Science

- Experimental research on the degradation of chemical industrial wastewater by combined hydrodynamic cavitation based on nonlinear dynamic model

- Study on low-cycle fatigue life of nickel-based superalloy GH4586 at various temperatures

- Some results of solutions to neutral stochastic functional operator-differential equations

- Ultrasonic cavitation did not occur in high-pressure CO2 liquid

- Research on the performance of a novel type of cemented filler material for coal mine opening and filling

- Testing of recycled fine aggregate concrete’s mechanical properties using recycled fine aggregate concrete and research on technology for highway construction

- A modified fuzzy TOPSIS approach for the condition assessment of existing bridges

- Nonlinear structural and vibration analysis of straddle monorail pantograph under random excitations

- Achieving high efficiency and stability in blue OLEDs: Role of wide-gap hosts and emitter interactions

- Construction of teaching quality evaluation model of online dance teaching course based on improved PSO-BPNN

- Enhanced electrical conductivity and electromagnetic shielding properties of multi-component polymer/graphite nanocomposites prepared by solid-state shear milling

- Optimization of thermal characteristics of buried composite phase-change energy storage walls based on nonlinear engineering methods

- A higher-performance big data-based movie recommendation system

- Nonlinear impact of minimum wage on labor employment in China

- Nonlinear comprehensive evaluation method based on information entropy and discrimination optimization

- Application of numerical calculation methods in stability analysis of pile foundation under complex foundation conditions

- Research on the contribution of shale gas development and utilization in Sichuan Province to carbon peak based on the PSA process

- Characteristics of tight oil reservoirs and their impact on seepage flow from a nonlinear engineering perspective

- Nonlinear deformation decomposition and mode identification of plane structures via orthogonal theory

- Numerical simulation of damage mechanism in rock with cracks impacted by self-excited pulsed jet based on SPH-FEM coupling method: The perspective of nonlinear engineering and materials science

- Cross-scale modeling and collaborative optimization of ethanol-catalyzed coupling to produce C4 olefins: Nonlinear modeling and collaborative optimization strategies

- Unequal width T-node stress concentration factor analysis of stiffened rectangular steel pipe concrete

- Special Issue: Advances in Nonlinear Dynamics and Control

- Development of a cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy design for a nonlinear diabetic patient model

- Big data-based optimized model of building design in the context of rural revitalization

- Multi-UAV assisted air-to-ground data collection for ground sensors with unknown positions

- Design of urban and rural elderly care public areas integrating person-environment fit theory

- Application of lossless signal transmission technology in piano timbre recognition

- Application of improved GA in optimizing rural tourism routes

- Architectural animation generation system based on AL-GAN algorithm

- Advanced sentiment analysis in online shopping: Implementing LSTM models analyzing E-commerce user sentiments

- Intelligent recommendation algorithm for piano tracks based on the CNN model

- Visualization of large-scale user association feature data based on a nonlinear dimensionality reduction method

- Low-carbon economic optimization of microgrid clusters based on an energy interaction operation strategy

- Optimization effect of video data extraction and search based on Faster-RCNN hybrid model on intelligent information systems

- Construction of image segmentation system combining TC and swarm intelligence algorithm

- Particle swarm optimization and fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm for the adhesive layer defect detection

- Optimization of student learning status by instructional intervention decision-making techniques incorporating reinforcement learning

- Fuzzy model-based stabilization control and state estimation of nonlinear systems

- Optimization of distribution network scheduling based on BA and photovoltaic uncertainty

- Tai Chi movement segmentation and recognition on the grounds of multi-sensor data fusion and the DBSCAN algorithm

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part III

- Generalized numerical RKM method for solving sixth-order fractional partial differential equations

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Generalized (ψ,φ)-contraction to investigate Volterra integral inclusions and fractal fractional PDEs in super-metric space with numerical experiments

- Solitons in ultrasound imaging: Exploring applications and enhancements via the Westervelt equation

- Stochastic improved Simpson for solving nonlinear fractional-order systems using product integration rules

- Exploring dynamical features like bifurcation assessment, sensitivity visualization, and solitary wave solutions of the integrable Akbota equation

- Research on surface defect detection method and optimization of paper-plastic composite bag based on improved combined segmentation algorithm

- Impact the sulphur content in Iraqi crude oil on the mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of carbon steel in various types of API 5L pipelines and ASTM 106 grade B

- Unravelling quiescent optical solitons: An exploration of the complex Ginzburg–Landau equation with nonlinear chromatic dispersion and self-phase modulation

- Perturbation-iteration approach for fractional-order logistic differential equations

- Variational formulations for the Euler and Navier–Stokes systems in fluid mechanics and related models

- Rotor response to unbalanced load and system performance considering variable bearing profile

- DeepFowl: Disease prediction from chicken excreta images using deep learning

- Channel flow of Ellis fluid due to cilia motion

- A case study of fractional-order varicella virus model to nonlinear dynamics strategy for control and prevalence

- Multi-point estimation weldment recognition and estimation of pose with data-driven robotics design

- Analysis of Hall current and nonuniform heating effects on magneto-convection between vertically aligned plates under the influence of electric and magnetic fields

- A comparative study on residual power series method and differential transform method through the time-fractional telegraph equation

- Insights from the nonlinear Schrödinger–Hirota equation with chromatic dispersion: Dynamics in fiber–optic communication

- Mathematical analysis of Jeffrey ferrofluid on stretching surface with the Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Exploring the interaction between lump, stripe and double-stripe, and periodic wave solutions of the Konopelchenko–Dubrovsky–Kaup–Kupershmidt system

- Computational investigation of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS co-infection in fuzzy environment

- Signature verification by geometry and image processing

- Theoretical and numerical approach for quantifying sensitivity to system parameters of nonlinear systems

- Chaotic behaviors, stability, and solitary wave propagations of M-fractional LWE equation in magneto-electro-elastic circular rod

- Dynamic analysis and optimization of syphilis spread: Simulations, integrating treatment and public health interventions

- Visco-thermoelastic rectangular plate under uniform loading: A study of deflection

- Threshold dynamics and optimal control of an epidemiological smoking model

- Numerical computational model for an unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium past an MHD rotating sheet

- Regression prediction model of fabric brightness based on light and shadow reconstruction of layered images

- Dynamics and prevention of gemini virus infection in red chili crops studied with generalized fractional operator: Analysis and modeling

- Qualitative analysis on existence and stability of nonlinear fractional dynamic equations on time scales

- Fractional-order super-twisting sliding mode active disturbance rejection control for electro-hydraulic position servo systems

- Analytical exploration and parametric insights into optical solitons in magneto-optic waveguides: Advances in nonlinear dynamics for applied sciences

- Bifurcation dynamics and optical soliton structures in the nonlinear Schrödinger–Bopp–Podolsky system

- User profiling in university libraries by combining multi-perspective clustering algorithm and reader behavior analysis

- Exploring bifurcation and chaos control in a discrete-time Lotka–Volterra model framework for COVID-19 modeling

- Review Article

- Haar wavelet collocation method for existence and numerical solutions of fourth-order integro-differential equations with bounded coefficients

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Analysis and Design of Communication Networks for IoT Applications - Part II

- Silicon-based all-optical wavelength converter for on-chip optical interconnection

- Research on a path-tracking control system of unmanned rollers based on an optimization algorithm and real-time feedback

- Analysis of the sports action recognition model based on the LSTM recurrent neural network

- Industrial robot trajectory error compensation based on enhanced transfer convolutional neural networks

- Research on IoT network performance prediction model of power grid warehouse based on nonlinear GA-BP neural network

- Interactive recommendation of social network communication between cities based on GNN and user preferences

- Application of improved P-BEM in time varying channel prediction in 5G high-speed mobile communication system

- Construction of a BIM smart building collaborative design model combining the Internet of Things

- Optimizing malicious website prediction: An advanced XGBoost-based machine learning model

- Economic operation analysis of the power grid combining communication network and distributed optimization algorithm

- Sports video temporal action detection technology based on an improved MSST algorithm

- Internet of things data security and privacy protection based on improved federated learning

- Enterprise power emission reduction technology based on the LSTM–SVM model

- Construction of multi-style face models based on artistic image generation algorithms

- Research and application of interactive digital twin monitoring system for photovoltaic power station based on global perception

- Special Issue: Decision and Control in Nonlinear Systems - Part II

- Animation video frame prediction based on ConvGRU fine-grained synthesis flow

- Application of GGNN inference propagation model for martial art intensity evaluation

- Benefit evaluation of building energy-saving renovation projects based on BWM weighting method

- Deep neural network application in real-time economic dispatch and frequency control of microgrids

- Real-time force/position control of soft growing robots: A data-driven model predictive approach

- Mechanical product design and manufacturing system based on CNN and server optimization algorithm

- Application of finite element analysis in the formal analysis of ancient architectural plaque section

- Research on territorial spatial planning based on data mining and geographic information visualization

- Fault diagnosis of agricultural sprinkler irrigation machinery equipment based on machine vision

- Closure technology of large span steel truss arch bridge with temporarily fixed edge supports

- Intelligent accounting question-answering robot based on a large language model and knowledge graph

- Analysis of manufacturing and retailer blockchain decision based on resource recyclability

- Flexible manufacturing workshop mechanical processing and product scheduling algorithm based on MES

- Exploration of indoor environment perception and design model based on virtual reality technology

- Tennis automatic ball-picking robot based on image object detection and positioning technology

- A new CNN deep learning model for computer-intelligent color matching

- Design of AR-based general computer technology experiment demonstration platform

- Indoor environment monitoring method based on the fusion of audio recognition and video patrol features

- Health condition prediction method of the computer numerical control machine tool parts by ensembling digital twins and improved LSTM networks

- Establishment of a green degree evaluation model for wall materials based on lifecycle

- Quantitative evaluation of college music teaching pronunciation based on nonlinear feature extraction

- Multi-index nonlinear robust virtual synchronous generator control method for microgrid inverters

- Manufacturing engineering production line scheduling management technology integrating availability constraints and heuristic rules

- Analysis of digital intelligent financial audit system based on improved BiLSTM neural network

- Attention community discovery model applied to complex network information analysis

- A neural collaborative filtering recommendation algorithm based on attention mechanism and contrastive learning

- Rehabilitation training method for motor dysfunction based on video stream matching

- Research on façade design for cold-region buildings based on artificial neural networks and parametric modeling techniques

- Intelligent implementation of muscle strain identification algorithm in Mi health exercise induced waist muscle strain

- Optimization design of urban rainwater and flood drainage system based on SWMM

- Improved GA for construction progress and cost management in construction projects

- Evaluation and prediction of SVM parameters in engineering cost based on random forest hybrid optimization

- Museum intelligent warning system based on wireless data module

- Optimization design and research of mechatronics based on torque motor control algorithm

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Engineering’s significance in Materials Science

- Experimental research on the degradation of chemical industrial wastewater by combined hydrodynamic cavitation based on nonlinear dynamic model

- Study on low-cycle fatigue life of nickel-based superalloy GH4586 at various temperatures

- Some results of solutions to neutral stochastic functional operator-differential equations

- Ultrasonic cavitation did not occur in high-pressure CO2 liquid

- Research on the performance of a novel type of cemented filler material for coal mine opening and filling

- Testing of recycled fine aggregate concrete’s mechanical properties using recycled fine aggregate concrete and research on technology for highway construction

- A modified fuzzy TOPSIS approach for the condition assessment of existing bridges

- Nonlinear structural and vibration analysis of straddle monorail pantograph under random excitations

- Achieving high efficiency and stability in blue OLEDs: Role of wide-gap hosts and emitter interactions

- Construction of teaching quality evaluation model of online dance teaching course based on improved PSO-BPNN

- Enhanced electrical conductivity and electromagnetic shielding properties of multi-component polymer/graphite nanocomposites prepared by solid-state shear milling

- Optimization of thermal characteristics of buried composite phase-change energy storage walls based on nonlinear engineering methods

- A higher-performance big data-based movie recommendation system

- Nonlinear impact of minimum wage on labor employment in China

- Nonlinear comprehensive evaluation method based on information entropy and discrimination optimization

- Application of numerical calculation methods in stability analysis of pile foundation under complex foundation conditions

- Research on the contribution of shale gas development and utilization in Sichuan Province to carbon peak based on the PSA process

- Characteristics of tight oil reservoirs and their impact on seepage flow from a nonlinear engineering perspective

- Nonlinear deformation decomposition and mode identification of plane structures via orthogonal theory

- Numerical simulation of damage mechanism in rock with cracks impacted by self-excited pulsed jet based on SPH-FEM coupling method: The perspective of nonlinear engineering and materials science

- Cross-scale modeling and collaborative optimization of ethanol-catalyzed coupling to produce C4 olefins: Nonlinear modeling and collaborative optimization strategies

- Unequal width T-node stress concentration factor analysis of stiffened rectangular steel pipe concrete

- Special Issue: Advances in Nonlinear Dynamics and Control

- Development of a cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy design for a nonlinear diabetic patient model

- Big data-based optimized model of building design in the context of rural revitalization

- Multi-UAV assisted air-to-ground data collection for ground sensors with unknown positions

- Design of urban and rural elderly care public areas integrating person-environment fit theory

- Application of lossless signal transmission technology in piano timbre recognition

- Application of improved GA in optimizing rural tourism routes

- Architectural animation generation system based on AL-GAN algorithm

- Advanced sentiment analysis in online shopping: Implementing LSTM models analyzing E-commerce user sentiments

- Intelligent recommendation algorithm for piano tracks based on the CNN model

- Visualization of large-scale user association feature data based on a nonlinear dimensionality reduction method

- Low-carbon economic optimization of microgrid clusters based on an energy interaction operation strategy

- Optimization effect of video data extraction and search based on Faster-RCNN hybrid model on intelligent information systems

- Construction of image segmentation system combining TC and swarm intelligence algorithm

- Particle swarm optimization and fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm for the adhesive layer defect detection

- Optimization of student learning status by instructional intervention decision-making techniques incorporating reinforcement learning

- Fuzzy model-based stabilization control and state estimation of nonlinear systems

- Optimization of distribution network scheduling based on BA and photovoltaic uncertainty

- Tai Chi movement segmentation and recognition on the grounds of multi-sensor data fusion and the DBSCAN algorithm

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part III

- Generalized numerical RKM method for solving sixth-order fractional partial differential equations