Abstract

The research aims to solve the problem of data synchronization and redundancy in building information model co-design with blockchain technology. A hyper-ledger fabric federated blockchain, combined with a revolving door compression algorithm, is used for the construction of an intelligent building co-design model. Experiments showed that the method outperformed other blockchain technologies in terms of throughput and response time, with block-out time reduced by 19.31% and transaction throughput increased by 12.38%. The research proposes an innovative cycle division mechanism and utilizes a revolving door compression algorithm for data maintenance of the model, thereby enhancing the security of the design data and the efficiency of collaboration. This is of positive significance for intelligent building design. However, the limitation of the study is that only the blockchain-based model is designed, and further development and example validation are needed in the future.

1 Introduction

As information technology develops, the construction industry is undergoing a profound transformation. Building information modeling (BIM) has accelerated the transformation of this change [1]. BIM mainly represents the physical and functional characteristics of buildings and infrastructure by creating digital information models. This improves design efficiency, construction quality, and intelligent operation and maintenance [2,3]. BIM has the characteristics of 3D visualization, interdisciplinary integration, rich information, design optimization, and conflict detection [4,5]. BIM has a wide range of application significance in the construction industry, project design, and other fields. However, BIM still faces problems such as information silos and low collaboration efficiency in practical applications. The existing BIM collaborative design (BIM co-design) often uses centralized methods for data storage, which can easily lead to data security issues such as loss and tampering with building data [6,7]. The Internet of Things (IoT) provides new ideas for addressing these issues. Blockchain, the most prevalent data storage method utilized in the IoT domain, has been progressively integrated into BIM co-design [8].

BIM has been extensively applied and developed in construction, which brings great opportunities and challenges to building operation and maintenance. BIM co-design, as the foundation and core of BIM collaborative operation and maintenance, has been extensively studied by scholars both domestically and internationally. Reichle et al. proposed a data processing pipeline to address the interruption of information flow for exchanging data between the construction and manufacturing industries. A closed-loop BIM co-design was achieved by utilizing the geometric design information stored in industry basic classes to convert it into product model data exchange specification data format [9]. Meng et al. developed a key technology for the 3D comprehensive design of railway engineering based on a domestic graphics engine to address the software supply interruption in BIM platforms. By constructing a BIM co-design mechanism with a hybrid mode of “central model + link,” theoretical support was provided for the development of BIM software for the entire railway and various specialties [10]. Traditional structural design methods suffer from poor energy-saving and sustainable performance, as well as low energy utilization efficiency. Wang et al. proposed a design method for large-scale building energy-saving structural systems based on the green BIM. The BIM application platform was equipped with functions such as building energy consumption monitoring, safety evacuation, and space management. Ultimately, an energy-saving sustainability coefficient of over 8 was achieved [11]. Chen et al. established a six-dimensional collaborative behavior matrix for the analysis of BIM co-design. This provided a better understanding of the collaboration conditions for BIM construction projects and identified typical collaboration situations for BIM projects. Collaboration data from different construction projects were surveyed through questionnaires, and potential feature analysis was conducted. Finally, a situation-oriented BIM co-design strategic selection framework was developed [12]. Xiao and Bhola compared BIM co-design with traditional design methods to promote BIM application in prefabricated building design. A conceptual model for the collaborative design of professional component processes was established using BIM. The effectiveness of BIM co-design in architecture was validated in parametric design tools [13].

BIM co-design often stores data through centralization, which can lead to security issues such as data loss, while blockchain can securely and reliably store data. Therefore, blockchain has been extensively applied in BIM co-design. Dounas et al. proposed a decentralized architectural design framework to address the constraints of collaboration and trust in BIM. By integrating the BIM design process with blockchain mechanisms, BIM design optimization was achieved, creating new operational and business models for architectural design [14]. Faraji et al. developed a comprehensive project delivery method to better manage construction disputes and improve construction. By generating a blockchain-based dispute management model based on blockchain review, alternative disputes for comprehensive project delivery contacts were resolved [15]. Hijazi et al. proposed a BIM single real source data model using blockchain technology to address the difficulty in identifying and effectively separating valuable building supply chain data. Intervention research on knowledge-induced cases was conducted using data flow graphs, classification methods, and entity relationship graphs. This developed model ensured reliable delivery of building supply chain data [16]. Gigli et al. proposed a sensor-to-cloud monitoring architecture to ensure the efficiency of BIM co-design collaboration. By seamlessly integrating sensors and software technology, different structural health monitoring system components’ software and hardware were jointly designed. Ultimately, the leakage probability in edge-to-cloud data transmission was reduced by over 90% [17].

In summary, relevant scholars have conducted various studies and explorations on BIM co-design and blockchain data storage in BIM. They have achieved many results. However, issues such as real-time updates and repeated transmission of BIM design data among different users, as well as poor security and privacy protection efficiency, have not been fully addressed. Therefore, a BIM smart building design method based on blockchain technology is proposed to solve the real-time updating and collaborative office efficiency of BIM data while simultaneously enhancing the security of design data. The research innovation lies in adopting spinning door transformation (SDT) for incremental updating and maintenance of BIM design data to reduce the redundancy of design data. To further illustrate the validity of the methods proposed by the study, the characteristics of the different methods are compared, as shown in Table 1.

Comparison of different methods

| Research purpose | Method | Shortcomings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive planning for data exchange in the construction industry | Data processing pipeline | Data redundancy not addressed | Reichle et al. [9] |

| To develop 3D comprehensive design technology for railway engineering | Domestic graphics engine | Pure design, not an optimized design method | Meng et al. [10] |

| To design energy-saving structures for large buildings based on the green BIM concept | Green BIM concept | Theoretical research | Wang et al. [11] |

| To understand collaboration conditions in BIM-enabled construction projects | Collaboration behavior matrix | No improvement in the BIM data redundancy problem | Chen et al. [12] |

| To promote the application of BIM in prefabricated building design | Conceptual model comparison | Applied research | Xiao and Bhola [13] |

| To propose a decentralized architectural design framework | Blockchain integration | No synchronization of BIM design data | Dounas et al. [14] |

| To develop a blockchain-based dispute management model for project delivery | Blockchain review | Unsolved BIM data redundancy problem | Faraji et al. [15] |

| To propose a data model integrating BIM and blockchain for the construction of supply chain data delivery | Knowledge induction case | Unsolved BIM data redundancy problem | Hijazi et al. [16] |

| To propose a next-generation edge-cloud architecture for structural health monitoring | Sensor integration | Unsolved BIM data redundancy problem | Gigli et al. [17] |

| Solving data synchronization and redundancy problems in BIM co-design | Hyperledger fabric union blockchain, BIM intelligent building co-design model | — | This paper |

The study proposes a BIM co-design smart building method based on hyperledger fabric federated blockchain (FB) for the data synchronization and redundancy problems of BIM co-design. Blockchain technology is utilized to enhance the data storage security in the BIM co-design process to prevent data loss and tampering. The incremental update of BIM model design data through the SDT algorithm effectively reduces data redundancy and improves the efficiency of data updates. Compared with other methods, the research method demonstrates superior performance in terms of block-out time and transaction throughput. The cycle division mechanism proposed by the study ensures the consistency of BIM model data among different designers. The proposed method has a positive contribution to the field of intelligent building design and provides new ideas and methods for solving collaboration problems in practical design.

This study consists of three parts. First, a BIM co-design smart building model combining IoT is designed. Second, experiments and analysis are conducted on the proposed BIM Co-design smart building model. Finally, the experimental results are summarized, and future research directions are identified.

2 Methods and materials

To enhance the BIM co-design data security, first, BIM co-design’s framework design using blockchain is studied. The BIM co-design is analyzed and described. Second, based on the model framework, model details and processes are developed and designed.

2.1 Establishment of BIM smart building collaborative design model combined with IoT

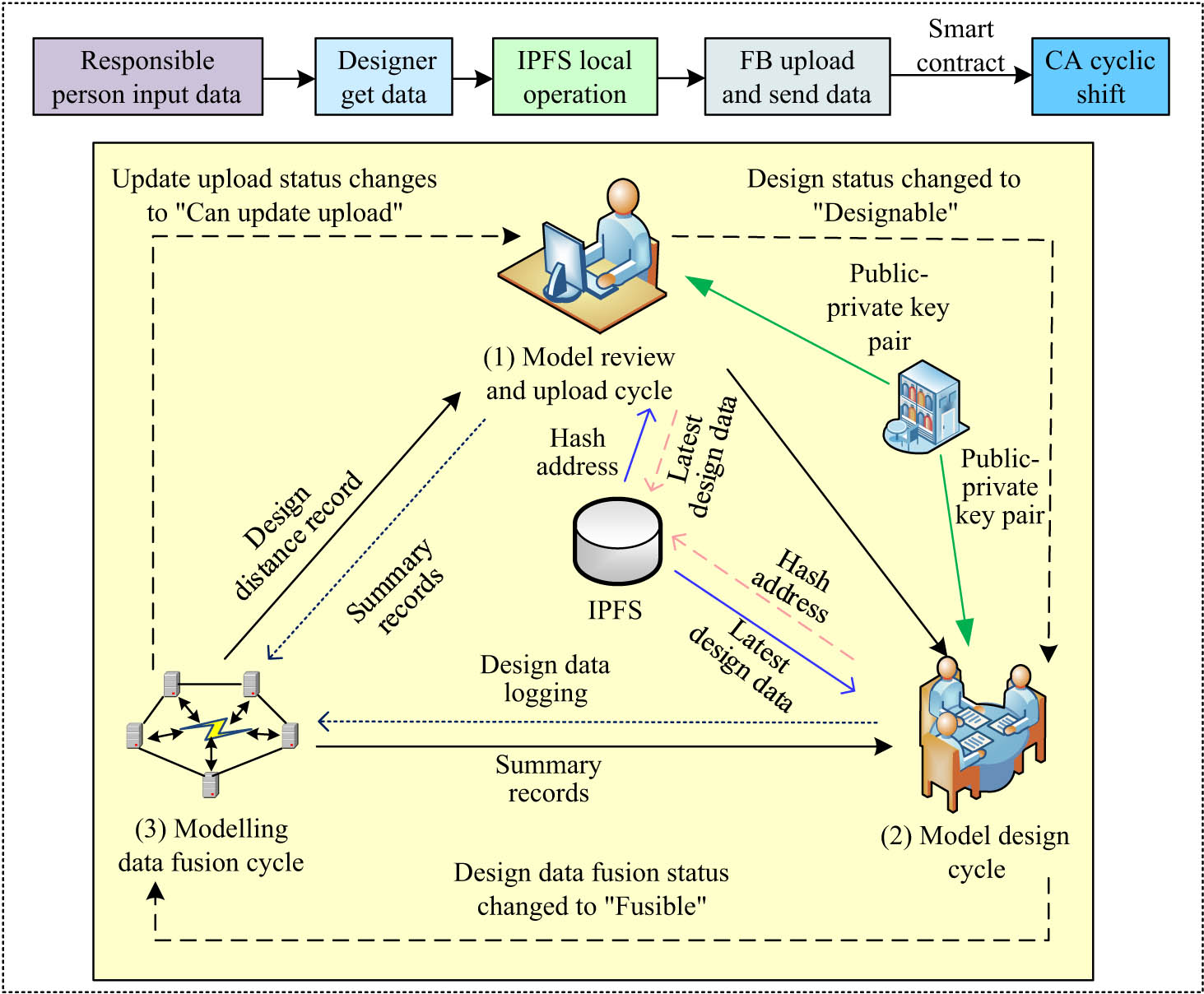

IoT has brought new opportunities for the development of smart buildings. BIM blockchain storage has become a common method in current architectural design. However, in response to the inability to synchronize data and high redundancy in current BIM co-design solutions based on blockchain, a blockchain-based BIM co-design is proposed. This model is implemented in hyperledger fabric FB. Figure 1 shows the specific framework.

Blockchain-based BIM co-design modeling framework.

In Figure 1, the BIM co-design mainly consists of the BIM manager, BIM designer, internet protocol file system (IPFS), smart contract, hyperledger fabric FB, and certification authority (CA). BIM managers are mainly responsible for designing data based on the integrated BIM. BIM designers are mainly responsible for obtaining and designing BIM and uploading the calculated BIM design data. IPFS is responsible for storing the complete BIM. FB is responsible for integrating BIM design data and storing BIM summary records, design data records, and integrated BIM design data records. Meanwhile, FB performs data encryption, signature, and verification operations. CA is responsible for generating public-private key pairs between the responsible person and the designer. Under this framework, the BIM co-design process is divided into three cycles: model review and upload design, and design data fusion. The BIM manager corresponds to the model review and upload cycle, as represented by the following equation:

In Eq. (1),

In Eq. (2),

In Eq. (3)

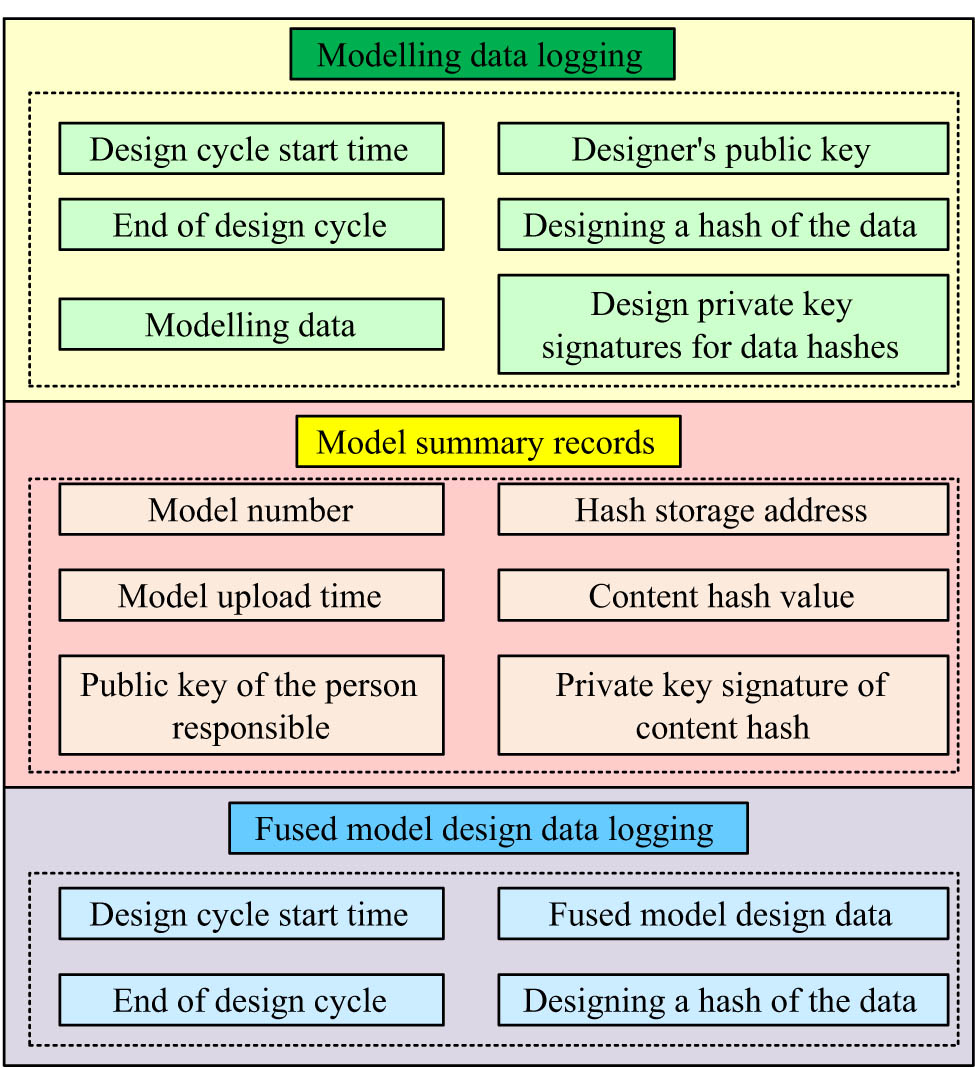

Data content stored in FB on the chain.

From Figure 2, FB mainly stores BIM design data, summary records, and fused BIM design data. In different cycles, different roles upload different data to BC to ensure the security and reliability of all data storage, achieving hybrid storage of FB + IPFS. Based on the above, Figure 3 shows the BIM co-design operation using the proposed blockchain.

Blockchain-based BIM co-design model runtime process.

As shown in Figure 3, this model consists of five stages, including global information configuration, initialization of BIM, acquisition, and design of BIM, fusion of BIM design data, and updating and uploading of BIM. The global information configuration in the first stage is mainly generated by CA for public–private key pairs. The second stage is the model review and upload cycle. The third stage is the BIM design cycle. The fourth stage corresponds to the BIM design data fusion cycle. Finally, the corresponding model review and upload cycle is completed by

2.2 Partial detail design of BIM smart building collaborative design model

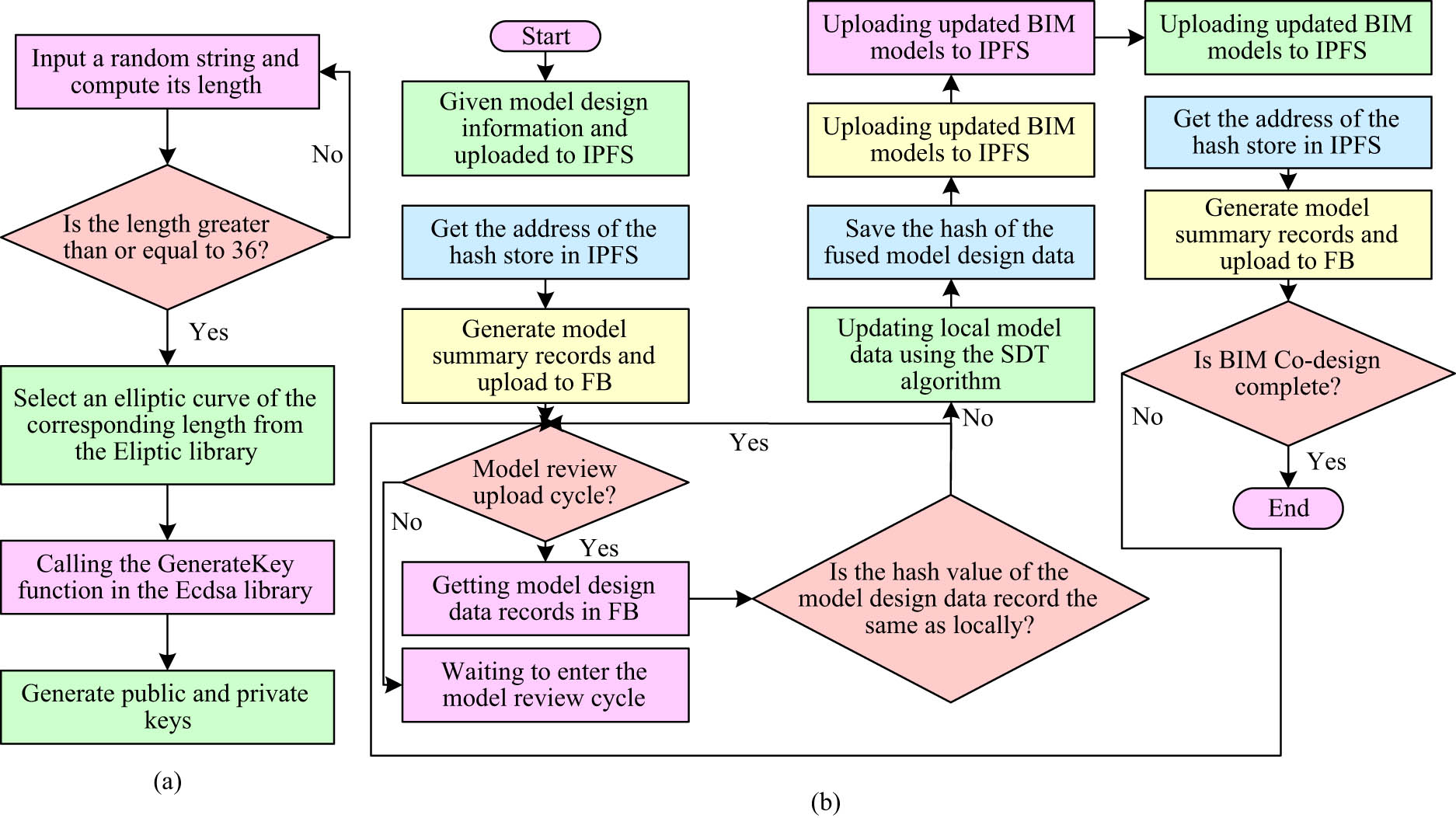

Based on the BIM co-design and operation proposed in the previous section, further detailed design is carried out. In the first stage of CA global configuration, when a new

Execution flow of public–private key pairs and model initialization.

As shown in Figure 4(a), when a new person in charge or designer joins the model, CA inputs a random string and calculates its length to determine if it exceeds 36. If the conditions are met, CA selects the elliptic curve corresponding to the length of the random string from the Eliptic library. At the same time, CA calls the Generate Key function in the Eclsa library based on elliptic curves and random strings to generate public and private key pairs for newly added users. Otherwise, the random string input will be repeated until its corresponding length exceeds 36. Figure 4(b) shows

In Eq. (4),

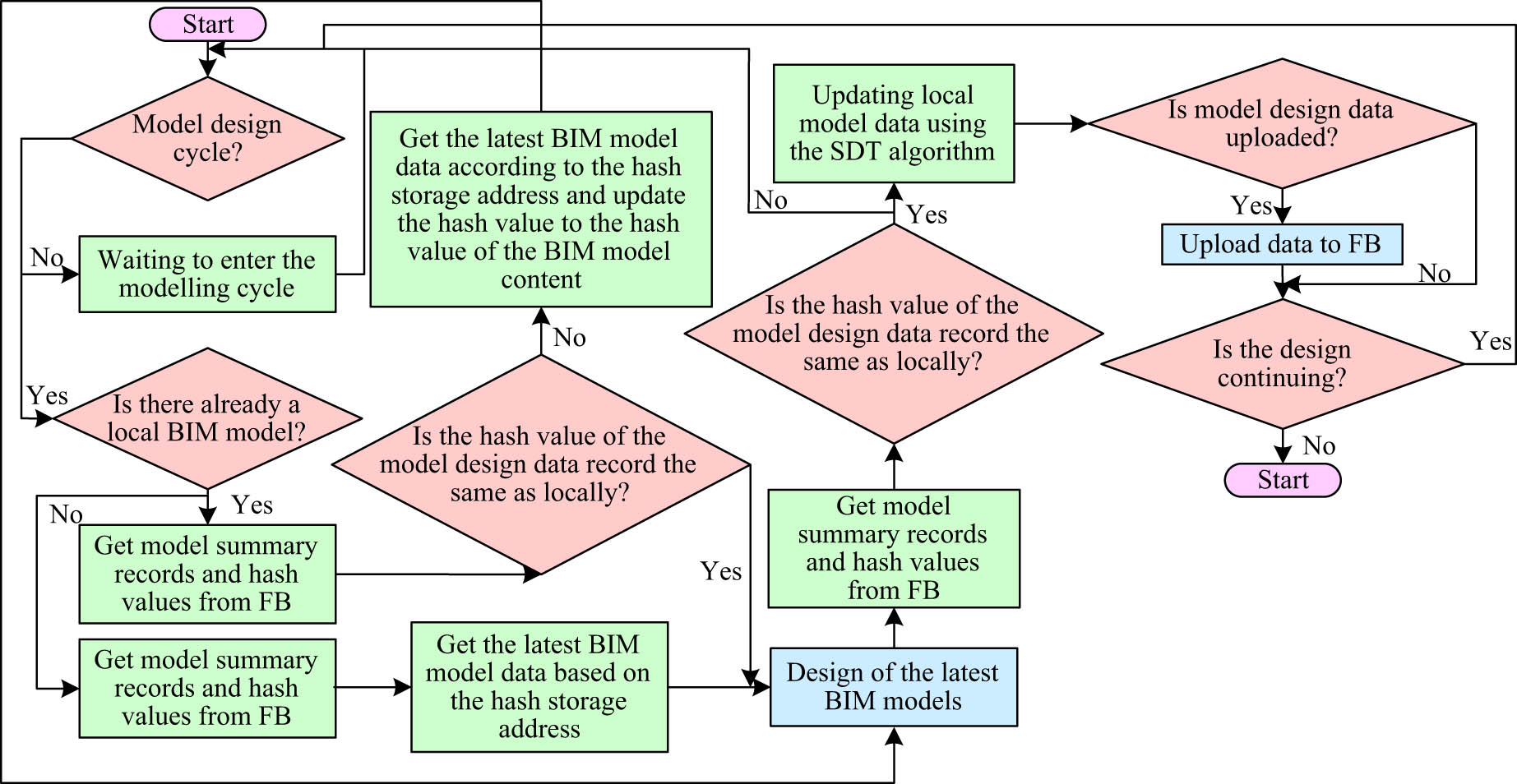

BIM acquisition and design process.

In Figure 5, the experiment sets

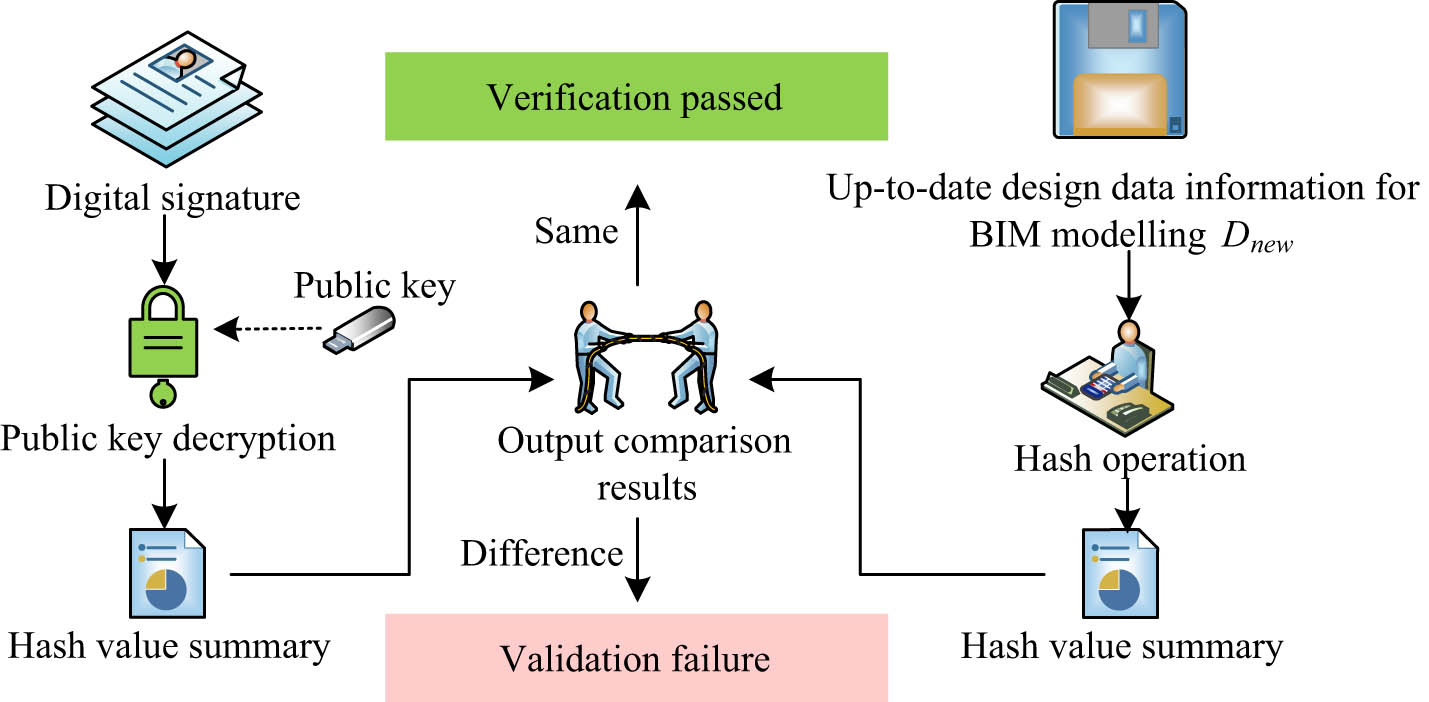

Digital signature verification process.

As shown in Figure 6, this verification process first decrypts the extracted information of the encrypted digital signature using the corresponding user’s public key. The current summary information is compared and analyzed with the previous one through a hash operation to determine whether the information obtained before and after is consistent. If these two messages are consistent,

In Eq. (5)

In Eq. (6),

In Eq. (7),

3 Results

The proposed blockchain-based BIM co-design in architecture was verified. First, the study introduced the experimental simulation environment configuration and compared different blockchains. Second, the model performance was validated. Finally, BIM co-design proposed by other scholars was introduced for performance comparison.

3.1 Experimental simulation environment configuration

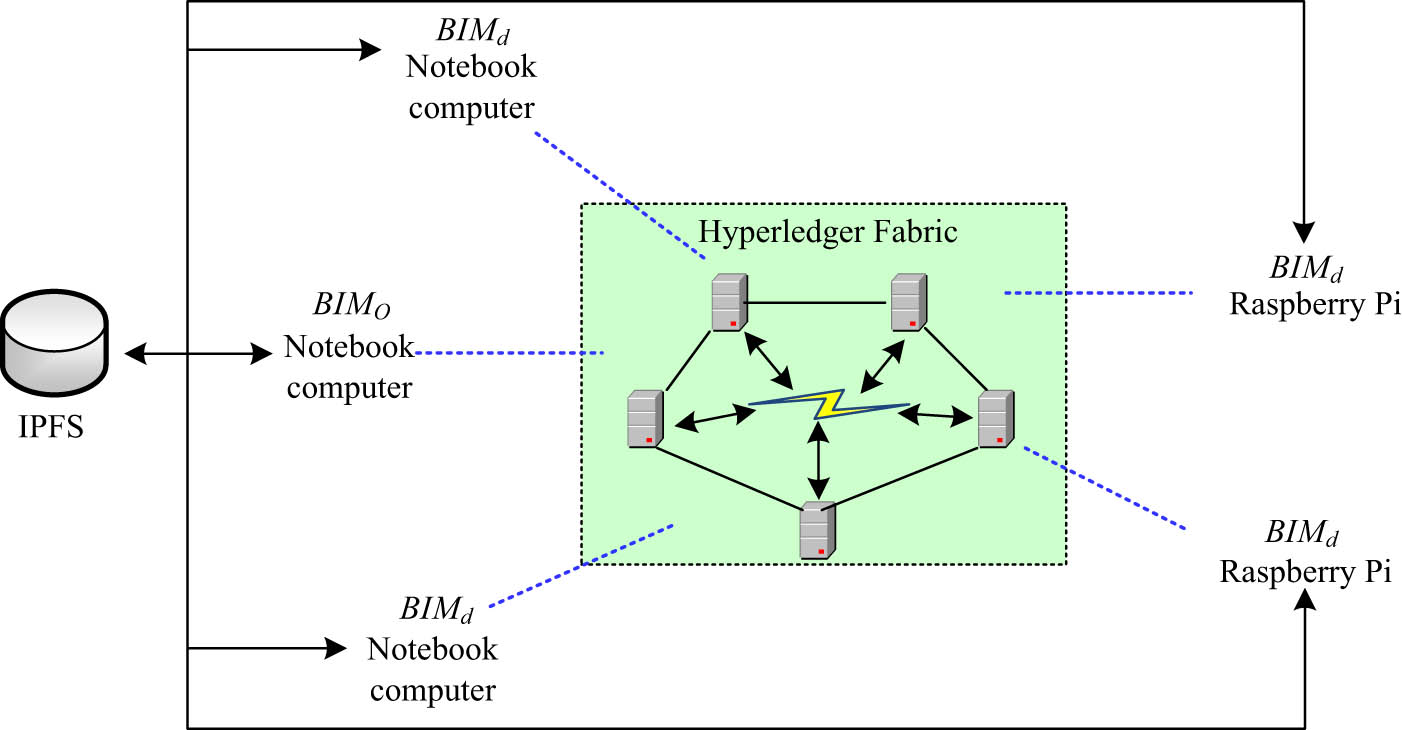

The model is tested and analyzed in an experimental environment built with multiple virtual institutions. The blockchain is hyperledger fabric FB. The simulation equipment consists of one 16 GB, 8-core i7 processor laptop, two 2 GB RAM Raspberry Pi 4B, and three virtual machines running 2 cores and 2 GB RAM. The study employs a simulation of the processes involved in the initialization, acquisition, and design of a BIM, as well as the integration of design data, the updating of the model, and the uploading of the updated model with the associated data. The simulation includes the comparison of the BIM model before and after the design phase, as well as the fusion of the design data within the BIM model. The cycle division mechanism and SDT algorithm are used to ensure the consistency and data synchronization of the BIM model. The Raft consensus algorithm has five Orderer sorting services, five Org organizations, and five Peer nodes each, with each Org organization consisting of one CA service and one Peer node. Figure 7 shows the specific deployment.

Deployment diagram of the simulation environment.

From Figure 7, the study simulates one manager and four designers. Hyperledger fabric consists of an organization of five related nodes and one transmission channel. In addition, all five users are set up locally with IPFS nodes, forming an IPFS private network. In simulation testing, the number of nodes directly affects the concurrent processing capacity and load distribution of the system. An increase in the number of nodes within a system will result in an improvement in throughput. However, this will also lead to an increase in both network delay and the time required to reach consensus. The frequency of sending transactions determines the performance of the system under high load. The high frequency of sending transactions can test the extreme performance and stability of the system. Therefore, the study is mainly adapted to the needs of real application scenarios to achieve the best performance balance.

3.2 Hyperledger fabric FB performance validation

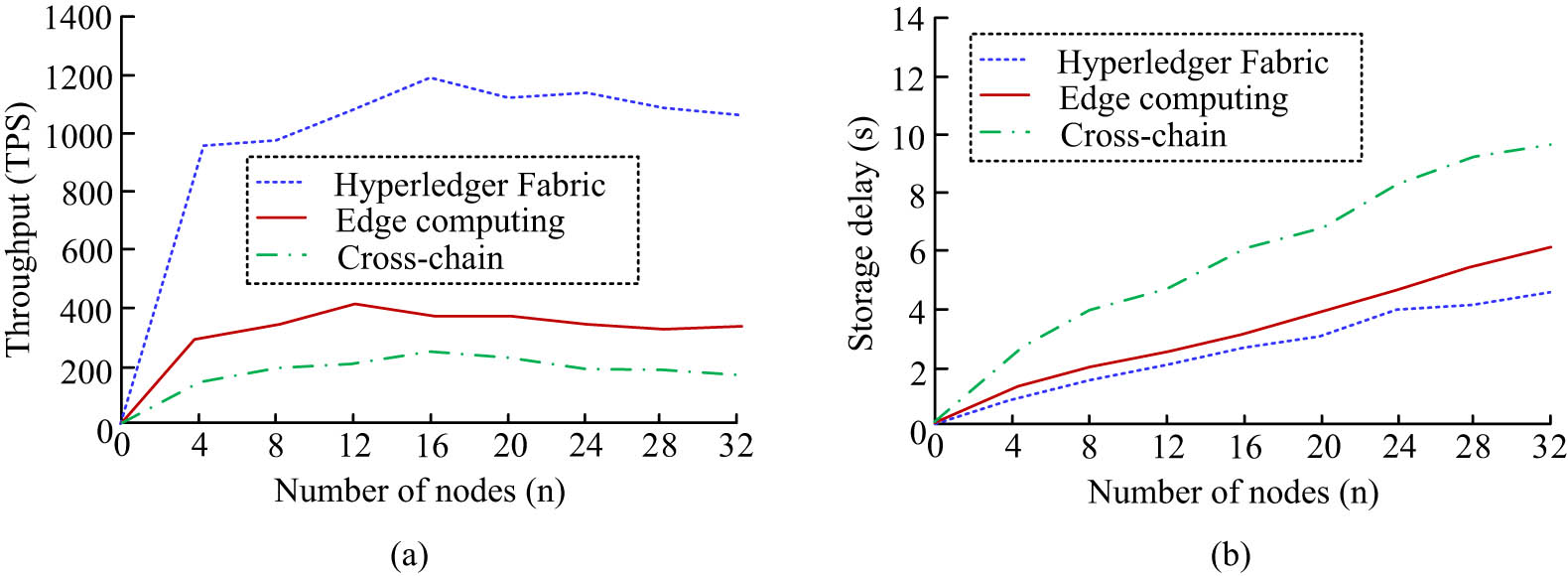

First, the study examined the throughput capability and data storage latency of hyperledger fabric FB. Blockchain and cross-chain technologies based on edge computing were introduced for performance comparison [20,21]. The study conducted 1,500 data storage transactions within a set time frame. Each transaction actually occupied 0.9 kB of storage space. Figure 8 shows the specific comparison results.

Performance comparison of different blockchains. (a) Throughput comparison with different numbers of nodes. (b) Comparison of average storage latency with different numbers of nodes.

In Figure 8(a), the study utilized transaction per second (TPS) to represent different blockchains’ throughput and measured their concurrent processing capabilities. As the nodes increased, the throughput of hyperledger fabric FB showed a continuously increasing trend, but a decrease occurred after 16 nodes. The throughput of blockchain based on edge computing dropped after 12 nodes. The cross-chain technology dropped after 16 nodes. This may be because in FB, such as hyperledger fabric, consensus mechanisms based on Raft or PBFT were usually used, which provide high throughput when the number of nodes is small. However, when the number of nodes increases to a certain level, the above problem might lead to performance degradation. Overall, the maximum throughput of hyperledger fabric FB was 1189.13 TPS, which was 345.06 and 621.32% higher than the other two blockchains, respectively. From Figure 8(b), as nodes increased, the storage latency of the three blockchains continued to increase. However, overall, hyperledger fabric FB had lower latency than the other two blockchains. This indicated that the use of hyperledger fabric FB for BIM Co-design data storage and security protection in research was reasonable and reliable. Figure 9 compares the control latency and response time of three types of blockchains.

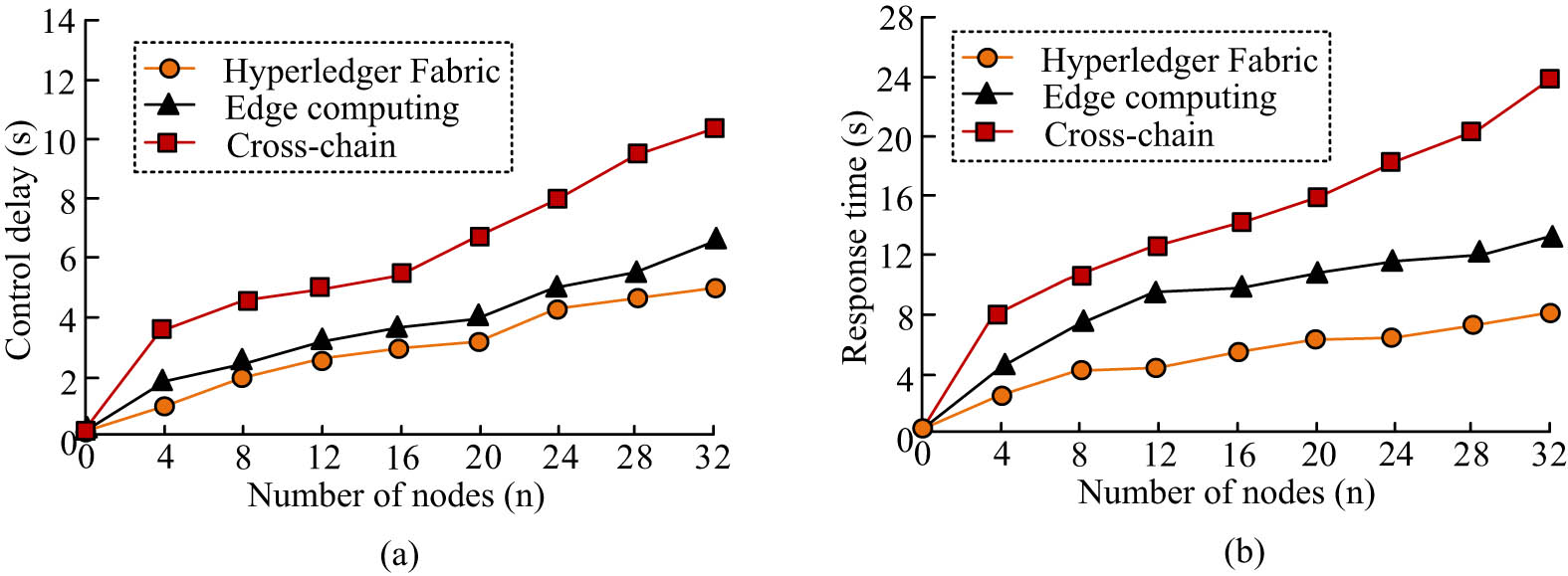

Comparison of control latency and response time of three blockchains. (a) Comparison of average control latency with different numbers of nodes. (b) Comparison of average response time with different numbers of nodes.

Figure 9(a) shows three blockchains’ control latency at different nodes. With the increasing blockchain, hyperledger fabric FB’s control latency was always lower than the other two blockchains. This may be due to the superior throughput and multidimensional scalability of hyperledger fabric FB, which leads to weakening the control latency. From Figure 9(b), the response time required for hyperledger fabric FB was reduced by an average of 48.24% compared to the other two blockchains. This indicated that utilizing hyperledger fabric FB for data security storage had superior capabilities. On this basis, the study further examined the ability of different blockchains to securely protect BIM co-design data, using the F1 score as the evaluation indicator. Table 2 shows the specific results.

Blockchain’s key metrics F1 score (%)

| Blockchain | Authentication mechanisms | Access control | Cryptosystem | Privacy protection | Cryptographic algorithm | Resistance to attack | Smart contract security | Node distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperledger fabric | 97.64 | 100.00 | 99.88 | 99.87 | 98.02 | 98.78 | 97.89 | 95.48 |

| Edge computing | 90.24 | 98.98 | 95.43 | 97.68 | 97.68 | 99.02 | 97.68 | 97.65 |

| Cross-chain | 88.76 | 95.24 | 90.24 | 96.60 | 98.27 | 97.68 | 97.88 | 95.55 |

From Table 2, hyperledger fabric FB had a better F1 score than the other two types of blockchains in terms of authentication mechanism, access control, encryption system, and privacy protection. Hyperledger fabric provides channel functionality that allows the creation of private communication paths between different business entities, thus enhancing privacy protection. The blockchain based on edge computing had more advantages in anti-attack capability and node distribution. This may be because edge computing has improved the blockchain’s ability to identify and resist malicious attacks, thus improving the blockchain’s ability to resist attacks. Cross-chain technologies are needed to deal with interoperability issues between different blockchains, which may be responsible for increasing the complexity and potential security risks of edge computing. However, overall, hyperledger fabric FB was more suitable for BIM co-design.

3.3 Blockchain-based BIM co-design verification

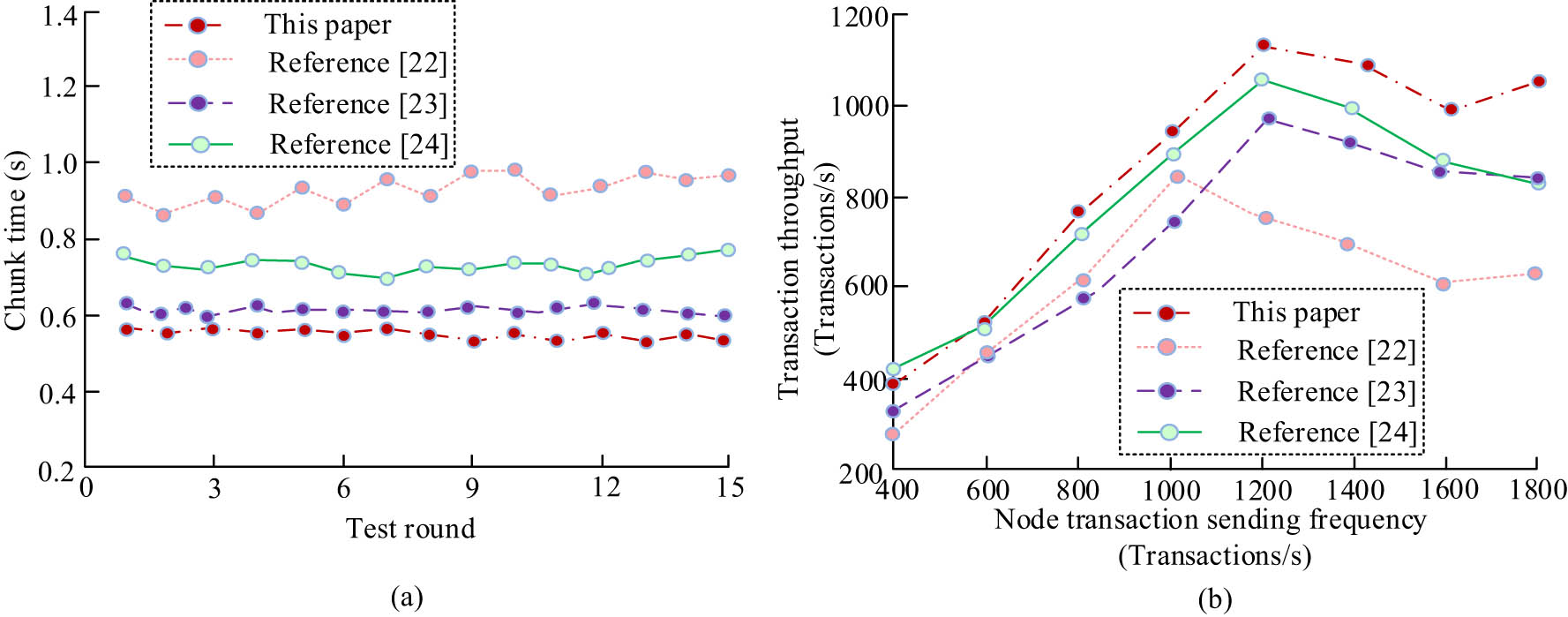

Simulation verification was conducted in the hyperledger fabric FB testing framework to further validate the proposed BIM co-design. The experiment mainly validated the model’s block time testing and transaction throughput. Existing references were introduced for performance comparison. The comparison models all used the hyperledger fabric FB testing framework [22,23,24]. The maximum block time for the model was 2 s. The transaction volume of model data records issued by a single BIM designer per unit time was 400–1,800. Figure 10 shows the specific results.

Performance comparison of different methods. (a) Comparison of chunking times for different methods. (b) Comparison of throughput for different methods.

Figure 10(a) shows the Chunk time comparison of BIM co-design constructed using different methods. All methods were less than the maximum chunk time set by the study. The study of Knippers et al. [22] had an average chunk time of 0.92 s, the study of Tan et al. [23] had an average chunk time of 0.62 s, and the study of Kiu et al. [24] had an average chunk time of 0.77 s. The proposed method had a chunk time of 0.53 s, which was 42.39, 14.53, and 31.17% lower than other methods, respectively. Figure 10(b) shows a comparison of transaction throughput for different methods. The proposed BIM co-design was superior, with a higher maximum number of transactions that could be processed and confirmed within a certain time interval, which had better stability and security. BIM co-design had a transaction throughput of up to 1,115 times, with an average improvement of 12.38% compared to the other three methods. Finally, the study further validated the proposed model’s consistency. Four BIM designers were set up to conduct 1,000 rounds of collaborative design on the given model. Each round ensured that at least one designer operated on the model. There were no restrictions on the model design content, but the content had to be different from the BIM before design. Table 3 shows the specific test results.

BIM consistency simulation test results

| Test round | Number of coherent BIM |

|---|---|

| 1–352 | 4 |

| 353–407 | 3 |

| 408–641 | 4 |

| 642–678 | 3 |

| 679–1,000 | 4 |

According to Table 3, in the 353–407 and 642–678 rounds of testing, the BIM consistency was 3. The nodes in other rounds were all 4. This may be due to network disconnections, crashes, and other issues affecting consistency at individual nodes. After node fault recovery, the BIM consistency was restored to 4. This indicated that the BIM co-design had good robustness. BIM co-design could allow all BIM designers to design in the same BIM, meeting the BIM consistency requirements.

4 Conclusion and future work

A BIM co-design was developed based on hyperledger fabric FB to address the data synchronization and high redundancy in BIM co-design based on current blockchain technology. The BIM consistency between different designers was ensured through the design cycle division mechanism. SDT was utilized for incremental data updates. In experimental verification, hyperledger fabric FB’s throughput increased by 345.06 and 621.32% compared to the other two blockchain technologies, with a maximum throughput of 1189.13 TPS. The response time required for hyperledger fabric FB was reduced by an average of 48.24% compared to the other two blockchains. The proposed BIM co-design method required a chunk time of 0.53 s, which was 42.39, 14.53, and 31.17% less than other methods, respectively. This method had a maximum transaction throughput of 1,115 times, which was an average improvement of 12.38% compared to other methods. The BIM verification consistency confirmed this proposed model’s robustness. Using blockchain technology to implement BIM co-design can improve the model design’s data storage security and efficiency. The proposed hyperledger fabric FB-based BIM co-design model effectively solves the data synchronization and redundancy problems by introducing the cycle division mechanism and SDT algorithm. This approach not only improves the security of design data but also significantly improves the efficiency of BIM co-design. Aiming at the challenges in IoT data management, the proposed Hashgraph-based IoT data management approach significantly improves the data throughput and consensus efficiency by utilizing the high concurrency characteristics of the DAG structure. This approach provides an effective solution for handling large-scale IoT data. Furthermore, the research presents a novel BIM co-design model and IoT data management method, offering a fresh perspective and solution for the operation and maintenance of digital twin smart buildings.

However, the study only conducts BIM co-design based on blockchain technology. The proposed method is based on blockchain and IoT technologies, the maturity and stability of which may vary across regions and industries. This may have an impact on the implementation and performance of the model. Although blockchain offers data security and immutability, additional privacy safeguards need to be considered when handling sensitive data, especially in terms of compliance with data protection regulations. In the case of large-scale deployments and dramatic increases in data volumes, the processing power and response time of the system may be affected, requiring further optimization to handle larger data sizes. Future experiments will consider introducing intelligent algorithms, C-language, and other technologies for model system development. Examples of model optimization and application can be introduced. Future research aims to develop more effective data management algorithms to improve system performance and scalability in handling large-scale data, and enhance system security. Especially in terms of data encryption and user authentication, it is necessary to ensure higher privacy protection standards are met.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Man Feng: data collection, statistical analysis, visualization, and writing the manuscript draft. Hanmei Wu: study design, data collection, statistical analysis, visualization, and revision of the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Hosseini F, Gharehchopogh FS, Masdari M. A botnet detection in IoT using a hybrid multi-objective optimization algorithm. N Gener Comput. 2022;40(3):809–43.10.1007/s00354-022-00188-wSuche in Google Scholar

[2] Disney O, Roupé M, Johansson M, Leto AD. Embracing BIM in its totality: a Total BIM case study. Smart Sustain Built Env. 2024;13(3):512–31.10.1108/SASBE-06-2022-0124Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Kennedy IR, Hodzic M, Crossan AN, Crossan N, Acharige N, Runcie JW. Estimating maximum power from wind turbines with a simple newtonian approach. Arch Adv Eng Sci. 2023;1(1):38–54.10.47852/bonviewAAES32021330Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Moghaddasi K, Rajabi S, Gharehchopogh FS, Ghaffari A. An advanced deep reinforcement learning algorithm for three-layer D2D-edge-cloud computing architecture for efficient task offloading in the Internet of Things. Sustain Comput Inf Syst. 2024;43:100992.10.1016/j.suscom.2024.100992Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Hosseini F, Gharehchopogh FS, Masdari M. MOAEOSCA: an enhanced multi-objective hybrid artificial ecosystem-based optimization with sine cosine algorithm for feature selection in botnet detection in IoT. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(9):13369–99.10.1007/s11042-022-13836-6Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Kylili A, Georgali PZ, Christou P, Fokaides P. An integrated building information modeling (BIM)-based lifecycle-oriented framework for sustainable building design. Constr Innov. 2024;24(2):492–514.10.1108/CI-02-2021-0011Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Pan Y, Zhang L. Integrating BIM and AI for smart construction management: Current status and future directions. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2023;30(2):1081–110.10.1007/s11831-022-09830-8Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Varela L, Putnik G, Romero F. The concept of collaborative engineering: a systematic literature review. Prod Manuf Res. 2022;10(1):784–39.10.1080/21693277.2022.2133856Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Reichle A, Ellwein C, Verl A. Adaptive CAM planning to support co-design in the building industry. Procedia CIRP. 2023;109(1):78–83.10.1016/j.procir.2022.05.217Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Meng H, Yang X, Gao L, Wang C. Research on railway BIM platform framework based on homemade graphics engine. High-Speed Railw. 2023;1(3):204–10.10.1016/j.hspr.2023.08.001Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Wang L, Zhong J, Zhang P. Collaborative design of large-scale building’s energy saving structure based on green BIM concept. Int J Glob Energy Issues. 2022;44(2–3):217–32.10.1504/IJGEI.2022.121401Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Chen G, Chen J, Tang Y, Ning Y, Li Q. Collaboration strategy selection in BIM-enabled construction projects: A perspective through typical collaboration profiles. Eng Constr Archit Manage. 2022;29(7):2689–713.10.1108/ECAM-01-2021-0004Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Xiao Y, Bhola J. Design and optimization of prefabricated building system based on BIM technology. Int J Syst Assur Eng Manag. 2022;13(1):111–20.10.1007/s13198-021-01288-4Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Dounas T, Lombardi D, Jabi W. Framework for decentralised architectural design BIM and Blockchain integration. Int J Archit Comput. 2021;19(2):157–73.10.1177/1478077120963376Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Faraji A, Arya SH, Ghasemi E, Rashidi M, Perera S, Tam V, et al. A conceptual framework of decentralized blockchain integrated system based on building information modeling to steering digital administration of disputes in the IPD contracts. Constr Innov. 2024;24(1):384–406.10.1108/CI-01-2023-0008Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Hijazi AA, Perera S, Calheiros RN, Alashwal A. A data model for integrating BIM and blockchain to enable a single source of truth for the construction supply chain data delivery. Eng Constr Archit Manage. 2023;30(10):4645–64.10.1108/ECAM-03-2022-0209Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Gigli L, Zyrianoff I, Zonzini F, Bogomolov D, Testoni N, Di Felice M, et al. Next generation edge-cloud continuum architecture for structural health monitoring. IEEE Trans Ind Inf. 2023;20(4):5874–87.10.1109/TII.2023.3337391Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Yu Y, Liu M, Chen D, Huo Y, Lu W. Dynamic grouping control of electric vehicles based on improved k-means algorithm for wind power fluctuations suppression. Glob Energy Interconnect. 2023;6(5):542–53.10.1016/j.gloei.2023.10.003Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Wang Y, Qin Y, Liu L, Wei S, Yin S. SWPU: A 126.04 TFLOPS/W edge-device sparse DNN training processor with dynamic sub-structured weight pruning. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst I Regul Pap. 2022;69(10):4014–27.10.1109/TCSI.2022.3184175Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Zhonghua C, Goyal SB, Rajawat AS. Smart contracts attribute-based access control model for security & privacy of IoT system using blockchain and edge computing. J Supercomput. 2024;80(2):1396–425.10.1007/s11227-023-05517-4Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Zook M, McCanless M. Mapping the uneven geographies of digital phenomena: The case of blockchain. Can Geogr. 2022;66(1):23–36.10.1111/cag.12738Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Knippers J, Kropp C, Menges A, Sawodny O, Weiskopf D. Integrative computational design and construction: Rethinking architecture digitally. Civ Eng Des. 2021;3(4):123–35.10.1002/cend.202100027Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Tan JH, Loo SC, Zainon N, Aziz NM, Rahim FA. Potential functionality and workability of blockchain within a building information modelling (BIM) environment. J Facil Manage. 2023;21(4):490–510.10.1108/JFM-10-2021-0131Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Kiu MS, Lai KW, Chia FC, Wong PF. Blockchain integration into electronic document management (EDM) system in construction common data environment. Smart Sustain Built Env. 2024;13(1):117–32.10.1108/SASBE-12-2021-0231Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Generalized (ψ,φ)-contraction to investigate Volterra integral inclusions and fractal fractional PDEs in super-metric space with numerical experiments

- Solitons in ultrasound imaging: Exploring applications and enhancements via the Westervelt equation

- Stochastic improved Simpson for solving nonlinear fractional-order systems using product integration rules

- Exploring dynamical features like bifurcation assessment, sensitivity visualization, and solitary wave solutions of the integrable Akbota equation

- Research on surface defect detection method and optimization of paper-plastic composite bag based on improved combined segmentation algorithm

- Impact the sulphur content in Iraqi crude oil on the mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of carbon steel in various types of API 5L pipelines and ASTM 106 grade B

- Unravelling quiescent optical solitons: An exploration of the complex Ginzburg–Landau equation with nonlinear chromatic dispersion and self-phase modulation

- Perturbation-iteration approach for fractional-order logistic differential equations

- Variational formulations for the Euler and Navier–Stokes systems in fluid mechanics and related models

- Rotor response to unbalanced load and system performance considering variable bearing profile

- DeepFowl: Disease prediction from chicken excreta images using deep learning

- Channel flow of Ellis fluid due to cilia motion

- A case study of fractional-order varicella virus model to nonlinear dynamics strategy for control and prevalence

- Multi-point estimation weldment recognition and estimation of pose with data-driven robotics design

- Analysis of Hall current and nonuniform heating effects on magneto-convection between vertically aligned plates under the influence of electric and magnetic fields

- A comparative study on residual power series method and differential transform method through the time-fractional telegraph equation

- Insights from the nonlinear Schrödinger–Hirota equation with chromatic dispersion: Dynamics in fiber–optic communication

- Mathematical analysis of Jeffrey ferrofluid on stretching surface with the Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Exploring the interaction between lump, stripe and double-stripe, and periodic wave solutions of the Konopelchenko–Dubrovsky–Kaup–Kupershmidt system

- Computational investigation of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS co-infection in fuzzy environment

- Signature verification by geometry and image processing

- Theoretical and numerical approach for quantifying sensitivity to system parameters of nonlinear systems

- Chaotic behaviors, stability, and solitary wave propagations of M-fractional LWE equation in magneto-electro-elastic circular rod

- Dynamic analysis and optimization of syphilis spread: Simulations, integrating treatment and public health interventions

- Visco-thermoelastic rectangular plate under uniform loading: A study of deflection

- Threshold dynamics and optimal control of an epidemiological smoking model

- Numerical computational model for an unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium past an MHD rotating sheet

- Regression prediction model of fabric brightness based on light and shadow reconstruction of layered images

- Dynamics and prevention of gemini virus infection in red chili crops studied with generalized fractional operator: Analysis and modeling

- Qualitative analysis on existence and stability of nonlinear fractional dynamic equations on time scales

- Fractional-order super-twisting sliding mode active disturbance rejection control for electro-hydraulic position servo systems

- Analytical exploration and parametric insights into optical solitons in magneto-optic waveguides: Advances in nonlinear dynamics for applied sciences

- Bifurcation dynamics and optical soliton structures in the nonlinear Schrödinger–Bopp–Podolsky system

- User profiling in university libraries by combining multi-perspective clustering algorithm and reader behavior analysis

- Exploring bifurcation and chaos control in a discrete-time Lotka–Volterra model framework for COVID-19 modeling

- Review Article

- Haar wavelet collocation method for existence and numerical solutions of fourth-order integro-differential equations with bounded coefficients

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Analysis and Design of Communication Networks for IoT Applications - Part II

- Silicon-based all-optical wavelength converter for on-chip optical interconnection

- Research on a path-tracking control system of unmanned rollers based on an optimization algorithm and real-time feedback

- Analysis of the sports action recognition model based on the LSTM recurrent neural network

- Industrial robot trajectory error compensation based on enhanced transfer convolutional neural networks

- Research on IoT network performance prediction model of power grid warehouse based on nonlinear GA-BP neural network

- Interactive recommendation of social network communication between cities based on GNN and user preferences

- Application of improved P-BEM in time varying channel prediction in 5G high-speed mobile communication system

- Construction of a BIM smart building collaborative design model combining the Internet of Things

- Optimizing malicious website prediction: An advanced XGBoost-based machine learning model

- Economic operation analysis of the power grid combining communication network and distributed optimization algorithm

- Sports video temporal action detection technology based on an improved MSST algorithm

- Internet of things data security and privacy protection based on improved federated learning

- Enterprise power emission reduction technology based on the LSTM–SVM model

- Construction of multi-style face models based on artistic image generation algorithms

- Research and application of interactive digital twin monitoring system for photovoltaic power station based on global perception

- Special Issue: Decision and Control in Nonlinear Systems - Part II

- Animation video frame prediction based on ConvGRU fine-grained synthesis flow

- Application of GGNN inference propagation model for martial art intensity evaluation

- Benefit evaluation of building energy-saving renovation projects based on BWM weighting method

- Deep neural network application in real-time economic dispatch and frequency control of microgrids

- Real-time force/position control of soft growing robots: A data-driven model predictive approach

- Mechanical product design and manufacturing system based on CNN and server optimization algorithm

- Application of finite element analysis in the formal analysis of ancient architectural plaque section

- Research on territorial spatial planning based on data mining and geographic information visualization

- Fault diagnosis of agricultural sprinkler irrigation machinery equipment based on machine vision

- Closure technology of large span steel truss arch bridge with temporarily fixed edge supports

- Intelligent accounting question-answering robot based on a large language model and knowledge graph

- Analysis of manufacturing and retailer blockchain decision based on resource recyclability

- Flexible manufacturing workshop mechanical processing and product scheduling algorithm based on MES

- Exploration of indoor environment perception and design model based on virtual reality technology

- Tennis automatic ball-picking robot based on image object detection and positioning technology

- A new CNN deep learning model for computer-intelligent color matching

- Design of AR-based general computer technology experiment demonstration platform

- Indoor environment monitoring method based on the fusion of audio recognition and video patrol features

- Health condition prediction method of the computer numerical control machine tool parts by ensembling digital twins and improved LSTM networks

- Establishment of a green degree evaluation model for wall materials based on lifecycle

- Quantitative evaluation of college music teaching pronunciation based on nonlinear feature extraction

- Multi-index nonlinear robust virtual synchronous generator control method for microgrid inverters

- Manufacturing engineering production line scheduling management technology integrating availability constraints and heuristic rules

- Analysis of digital intelligent financial audit system based on improved BiLSTM neural network

- Attention community discovery model applied to complex network information analysis

- A neural collaborative filtering recommendation algorithm based on attention mechanism and contrastive learning

- Rehabilitation training method for motor dysfunction based on video stream matching

- Research on façade design for cold-region buildings based on artificial neural networks and parametric modeling techniques

- Intelligent implementation of muscle strain identification algorithm in Mi health exercise induced waist muscle strain

- Optimization design of urban rainwater and flood drainage system based on SWMM

- Improved GA for construction progress and cost management in construction projects

- Evaluation and prediction of SVM parameters in engineering cost based on random forest hybrid optimization

- Museum intelligent warning system based on wireless data module

- Optimization design and research of mechatronics based on torque motor control algorithm

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Engineering’s significance in Materials Science

- Experimental research on the degradation of chemical industrial wastewater by combined hydrodynamic cavitation based on nonlinear dynamic model

- Study on low-cycle fatigue life of nickel-based superalloy GH4586 at various temperatures

- Some results of solutions to neutral stochastic functional operator-differential equations

- Ultrasonic cavitation did not occur in high-pressure CO2 liquid

- Research on the performance of a novel type of cemented filler material for coal mine opening and filling

- Testing of recycled fine aggregate concrete’s mechanical properties using recycled fine aggregate concrete and research on technology for highway construction

- A modified fuzzy TOPSIS approach for the condition assessment of existing bridges

- Nonlinear structural and vibration analysis of straddle monorail pantograph under random excitations

- Achieving high efficiency and stability in blue OLEDs: Role of wide-gap hosts and emitter interactions

- Construction of teaching quality evaluation model of online dance teaching course based on improved PSO-BPNN

- Enhanced electrical conductivity and electromagnetic shielding properties of multi-component polymer/graphite nanocomposites prepared by solid-state shear milling

- Optimization of thermal characteristics of buried composite phase-change energy storage walls based on nonlinear engineering methods

- A higher-performance big data-based movie recommendation system

- Nonlinear impact of minimum wage on labor employment in China

- Nonlinear comprehensive evaluation method based on information entropy and discrimination optimization

- Application of numerical calculation methods in stability analysis of pile foundation under complex foundation conditions

- Research on the contribution of shale gas development and utilization in Sichuan Province to carbon peak based on the PSA process

- Characteristics of tight oil reservoirs and their impact on seepage flow from a nonlinear engineering perspective

- Nonlinear deformation decomposition and mode identification of plane structures via orthogonal theory

- Numerical simulation of damage mechanism in rock with cracks impacted by self-excited pulsed jet based on SPH-FEM coupling method: The perspective of nonlinear engineering and materials science

- Cross-scale modeling and collaborative optimization of ethanol-catalyzed coupling to produce C4 olefins: Nonlinear modeling and collaborative optimization strategies

- Unequal width T-node stress concentration factor analysis of stiffened rectangular steel pipe concrete

- Special Issue: Advances in Nonlinear Dynamics and Control

- Development of a cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy design for a nonlinear diabetic patient model

- Big data-based optimized model of building design in the context of rural revitalization

- Multi-UAV assisted air-to-ground data collection for ground sensors with unknown positions

- Design of urban and rural elderly care public areas integrating person-environment fit theory

- Application of lossless signal transmission technology in piano timbre recognition

- Application of improved GA in optimizing rural tourism routes

- Architectural animation generation system based on AL-GAN algorithm

- Advanced sentiment analysis in online shopping: Implementing LSTM models analyzing E-commerce user sentiments

- Intelligent recommendation algorithm for piano tracks based on the CNN model

- Visualization of large-scale user association feature data based on a nonlinear dimensionality reduction method

- Low-carbon economic optimization of microgrid clusters based on an energy interaction operation strategy

- Optimization effect of video data extraction and search based on Faster-RCNN hybrid model on intelligent information systems

- Construction of image segmentation system combining TC and swarm intelligence algorithm

- Particle swarm optimization and fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm for the adhesive layer defect detection

- Optimization of student learning status by instructional intervention decision-making techniques incorporating reinforcement learning

- Fuzzy model-based stabilization control and state estimation of nonlinear systems

- Optimization of distribution network scheduling based on BA and photovoltaic uncertainty

- Tai Chi movement segmentation and recognition on the grounds of multi-sensor data fusion and the DBSCAN algorithm

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part III

- Generalized numerical RKM method for solving sixth-order fractional partial differential equations

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Generalized (ψ,φ)-contraction to investigate Volterra integral inclusions and fractal fractional PDEs in super-metric space with numerical experiments

- Solitons in ultrasound imaging: Exploring applications and enhancements via the Westervelt equation

- Stochastic improved Simpson for solving nonlinear fractional-order systems using product integration rules

- Exploring dynamical features like bifurcation assessment, sensitivity visualization, and solitary wave solutions of the integrable Akbota equation

- Research on surface defect detection method and optimization of paper-plastic composite bag based on improved combined segmentation algorithm

- Impact the sulphur content in Iraqi crude oil on the mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of carbon steel in various types of API 5L pipelines and ASTM 106 grade B

- Unravelling quiescent optical solitons: An exploration of the complex Ginzburg–Landau equation with nonlinear chromatic dispersion and self-phase modulation

- Perturbation-iteration approach for fractional-order logistic differential equations

- Variational formulations for the Euler and Navier–Stokes systems in fluid mechanics and related models

- Rotor response to unbalanced load and system performance considering variable bearing profile

- DeepFowl: Disease prediction from chicken excreta images using deep learning

- Channel flow of Ellis fluid due to cilia motion

- A case study of fractional-order varicella virus model to nonlinear dynamics strategy for control and prevalence

- Multi-point estimation weldment recognition and estimation of pose with data-driven robotics design

- Analysis of Hall current and nonuniform heating effects on magneto-convection between vertically aligned plates under the influence of electric and magnetic fields

- A comparative study on residual power series method and differential transform method through the time-fractional telegraph equation

- Insights from the nonlinear Schrödinger–Hirota equation with chromatic dispersion: Dynamics in fiber–optic communication

- Mathematical analysis of Jeffrey ferrofluid on stretching surface with the Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Exploring the interaction between lump, stripe and double-stripe, and periodic wave solutions of the Konopelchenko–Dubrovsky–Kaup–Kupershmidt system

- Computational investigation of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS co-infection in fuzzy environment

- Signature verification by geometry and image processing

- Theoretical and numerical approach for quantifying sensitivity to system parameters of nonlinear systems

- Chaotic behaviors, stability, and solitary wave propagations of M-fractional LWE equation in magneto-electro-elastic circular rod

- Dynamic analysis and optimization of syphilis spread: Simulations, integrating treatment and public health interventions

- Visco-thermoelastic rectangular plate under uniform loading: A study of deflection

- Threshold dynamics and optimal control of an epidemiological smoking model

- Numerical computational model for an unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium past an MHD rotating sheet

- Regression prediction model of fabric brightness based on light and shadow reconstruction of layered images

- Dynamics and prevention of gemini virus infection in red chili crops studied with generalized fractional operator: Analysis and modeling

- Qualitative analysis on existence and stability of nonlinear fractional dynamic equations on time scales

- Fractional-order super-twisting sliding mode active disturbance rejection control for electro-hydraulic position servo systems

- Analytical exploration and parametric insights into optical solitons in magneto-optic waveguides: Advances in nonlinear dynamics for applied sciences

- Bifurcation dynamics and optical soliton structures in the nonlinear Schrödinger–Bopp–Podolsky system

- User profiling in university libraries by combining multi-perspective clustering algorithm and reader behavior analysis

- Exploring bifurcation and chaos control in a discrete-time Lotka–Volterra model framework for COVID-19 modeling

- Review Article

- Haar wavelet collocation method for existence and numerical solutions of fourth-order integro-differential equations with bounded coefficients

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Analysis and Design of Communication Networks for IoT Applications - Part II

- Silicon-based all-optical wavelength converter for on-chip optical interconnection

- Research on a path-tracking control system of unmanned rollers based on an optimization algorithm and real-time feedback

- Analysis of the sports action recognition model based on the LSTM recurrent neural network

- Industrial robot trajectory error compensation based on enhanced transfer convolutional neural networks

- Research on IoT network performance prediction model of power grid warehouse based on nonlinear GA-BP neural network

- Interactive recommendation of social network communication between cities based on GNN and user preferences

- Application of improved P-BEM in time varying channel prediction in 5G high-speed mobile communication system

- Construction of a BIM smart building collaborative design model combining the Internet of Things

- Optimizing malicious website prediction: An advanced XGBoost-based machine learning model

- Economic operation analysis of the power grid combining communication network and distributed optimization algorithm

- Sports video temporal action detection technology based on an improved MSST algorithm

- Internet of things data security and privacy protection based on improved federated learning

- Enterprise power emission reduction technology based on the LSTM–SVM model

- Construction of multi-style face models based on artistic image generation algorithms

- Research and application of interactive digital twin monitoring system for photovoltaic power station based on global perception

- Special Issue: Decision and Control in Nonlinear Systems - Part II

- Animation video frame prediction based on ConvGRU fine-grained synthesis flow

- Application of GGNN inference propagation model for martial art intensity evaluation

- Benefit evaluation of building energy-saving renovation projects based on BWM weighting method

- Deep neural network application in real-time economic dispatch and frequency control of microgrids

- Real-time force/position control of soft growing robots: A data-driven model predictive approach

- Mechanical product design and manufacturing system based on CNN and server optimization algorithm

- Application of finite element analysis in the formal analysis of ancient architectural plaque section

- Research on territorial spatial planning based on data mining and geographic information visualization

- Fault diagnosis of agricultural sprinkler irrigation machinery equipment based on machine vision

- Closure technology of large span steel truss arch bridge with temporarily fixed edge supports

- Intelligent accounting question-answering robot based on a large language model and knowledge graph

- Analysis of manufacturing and retailer blockchain decision based on resource recyclability

- Flexible manufacturing workshop mechanical processing and product scheduling algorithm based on MES

- Exploration of indoor environment perception and design model based on virtual reality technology

- Tennis automatic ball-picking robot based on image object detection and positioning technology

- A new CNN deep learning model for computer-intelligent color matching

- Design of AR-based general computer technology experiment demonstration platform

- Indoor environment monitoring method based on the fusion of audio recognition and video patrol features

- Health condition prediction method of the computer numerical control machine tool parts by ensembling digital twins and improved LSTM networks

- Establishment of a green degree evaluation model for wall materials based on lifecycle

- Quantitative evaluation of college music teaching pronunciation based on nonlinear feature extraction

- Multi-index nonlinear robust virtual synchronous generator control method for microgrid inverters

- Manufacturing engineering production line scheduling management technology integrating availability constraints and heuristic rules

- Analysis of digital intelligent financial audit system based on improved BiLSTM neural network

- Attention community discovery model applied to complex network information analysis

- A neural collaborative filtering recommendation algorithm based on attention mechanism and contrastive learning

- Rehabilitation training method for motor dysfunction based on video stream matching

- Research on façade design for cold-region buildings based on artificial neural networks and parametric modeling techniques

- Intelligent implementation of muscle strain identification algorithm in Mi health exercise induced waist muscle strain

- Optimization design of urban rainwater and flood drainage system based on SWMM

- Improved GA for construction progress and cost management in construction projects

- Evaluation and prediction of SVM parameters in engineering cost based on random forest hybrid optimization

- Museum intelligent warning system based on wireless data module

- Optimization design and research of mechatronics based on torque motor control algorithm

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Engineering’s significance in Materials Science

- Experimental research on the degradation of chemical industrial wastewater by combined hydrodynamic cavitation based on nonlinear dynamic model

- Study on low-cycle fatigue life of nickel-based superalloy GH4586 at various temperatures

- Some results of solutions to neutral stochastic functional operator-differential equations

- Ultrasonic cavitation did not occur in high-pressure CO2 liquid

- Research on the performance of a novel type of cemented filler material for coal mine opening and filling

- Testing of recycled fine aggregate concrete’s mechanical properties using recycled fine aggregate concrete and research on technology for highway construction

- A modified fuzzy TOPSIS approach for the condition assessment of existing bridges

- Nonlinear structural and vibration analysis of straddle monorail pantograph under random excitations

- Achieving high efficiency and stability in blue OLEDs: Role of wide-gap hosts and emitter interactions

- Construction of teaching quality evaluation model of online dance teaching course based on improved PSO-BPNN

- Enhanced electrical conductivity and electromagnetic shielding properties of multi-component polymer/graphite nanocomposites prepared by solid-state shear milling

- Optimization of thermal characteristics of buried composite phase-change energy storage walls based on nonlinear engineering methods

- A higher-performance big data-based movie recommendation system

- Nonlinear impact of minimum wage on labor employment in China

- Nonlinear comprehensive evaluation method based on information entropy and discrimination optimization

- Application of numerical calculation methods in stability analysis of pile foundation under complex foundation conditions

- Research on the contribution of shale gas development and utilization in Sichuan Province to carbon peak based on the PSA process

- Characteristics of tight oil reservoirs and their impact on seepage flow from a nonlinear engineering perspective

- Nonlinear deformation decomposition and mode identification of plane structures via orthogonal theory

- Numerical simulation of damage mechanism in rock with cracks impacted by self-excited pulsed jet based on SPH-FEM coupling method: The perspective of nonlinear engineering and materials science

- Cross-scale modeling and collaborative optimization of ethanol-catalyzed coupling to produce C4 olefins: Nonlinear modeling and collaborative optimization strategies

- Unequal width T-node stress concentration factor analysis of stiffened rectangular steel pipe concrete

- Special Issue: Advances in Nonlinear Dynamics and Control

- Development of a cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy design for a nonlinear diabetic patient model

- Big data-based optimized model of building design in the context of rural revitalization

- Multi-UAV assisted air-to-ground data collection for ground sensors with unknown positions

- Design of urban and rural elderly care public areas integrating person-environment fit theory

- Application of lossless signal transmission technology in piano timbre recognition

- Application of improved GA in optimizing rural tourism routes

- Architectural animation generation system based on AL-GAN algorithm

- Advanced sentiment analysis in online shopping: Implementing LSTM models analyzing E-commerce user sentiments

- Intelligent recommendation algorithm for piano tracks based on the CNN model

- Visualization of large-scale user association feature data based on a nonlinear dimensionality reduction method

- Low-carbon economic optimization of microgrid clusters based on an energy interaction operation strategy

- Optimization effect of video data extraction and search based on Faster-RCNN hybrid model on intelligent information systems

- Construction of image segmentation system combining TC and swarm intelligence algorithm

- Particle swarm optimization and fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm for the adhesive layer defect detection

- Optimization of student learning status by instructional intervention decision-making techniques incorporating reinforcement learning

- Fuzzy model-based stabilization control and state estimation of nonlinear systems

- Optimization of distribution network scheduling based on BA and photovoltaic uncertainty

- Tai Chi movement segmentation and recognition on the grounds of multi-sensor data fusion and the DBSCAN algorithm

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part III

- Generalized numerical RKM method for solving sixth-order fractional partial differential equations