Abstract

The rapid growth of transportation engineering has led to significant environmental challenges due to the accumulation of building waste and tailings. A promising solution is to utilize these materials to develop high-performance tailings recycled concrete (RFAC) for highway construction, promoting a green circular economy. This study advances existing research by exploring innovative mix design strategies and performance optimization techniques to enhance RFAC’s mechanical properties and industrial applicability. Specifically, this research investigates the effects of various iron tailings admixtures on the mechanical behavior and deformation characteristics of RFAC before and after carbonation, aiming to establish an optimal composition for transportation infrastructure. The materials used include iron tailings, recycled coarse aggregate, natural river sand, and 42.5-grade ordinary silicate cement. Unlike conventional approaches, this study emphasizes the influence of particle morphology and surface characteristics of laboratory-produced recycled fine aggregate, revealing its angular shape, rough texture, and larger specific surface area, which significantly impact fluidity, bulk density, and crushing value. Experimental results demonstrate that fiber type and tailings admixture ratio play a crucial role in improving RFAC’s slump, compressive strength, split tensile strength, and failure modes. Compared to previous studies, this research provides a more refined analysis of mix proportioning and introduces tailings-based performance enhancements, offering new insights for large-scale applications in transportation engineering. By optimizing tailings incorporation and aggregate proportions, this study establishes a systematic approach to improving RFAC’s mechanical performance, durability, and construction adaptability, laying the foundation for sustainable infrastructure development.

1 Introduction

The rapid development of modern civilization has ushered in a new phase in transportation engineering construction, with concrete playing a crucial role in infrastructure projects such as highways, rail transit, and tunnels. However, the simultaneous growth of the construction industry and urbanization has led to an increasing accumulation of building and tailing waste, posing significant environmental challenges [1]. Addressing this issue while promoting sustainable development has become a key concern in both academic and industrial sectors.

Recycled fine aggregate concrete has gained considerable attention due to its potential to reduce carbon emissions, conserve natural resources, and facilitate the reuse of construction waste [2]. While recycled aggregates retain some properties of natural aggregates, they also exhibit drawbacks such as rough surfaces, high water absorption, and reduced strength [3]. These characteristics significantly impact the workability and durability of concrete, necessitating further research and optimization.

Existing studies have explored the mechanical properties of iron tailings concrete, particularly in road engineering applications [4]. Previous research has examined its permeability, shrinkage, slump, and compressive strength [5]. However, most studies have focused on conventional tailings concrete, limiting its environmental and social benefits [6,7]. The adoption of high-performance recycled tailings concrete is hindered by variations in aggregate properties, weak interfacial transition zones, and challenges in cost control and large-scale implementation.

To address these limitations, researchers have explored performance enhancement strategies such as admixture incorporation, surface treatment technologies, and mix ratio optimization [8]. However, these approaches often lack standardized optimization criteria, and surface treatment remains costly for widespread adoption [9,10]. There is still a need for a systematic proportioning design and performance optimization strategy tailored to different application scenarios.

This study aims to develop high-performance tailings recycled concrete by partially replacing fine aggregate with iron tailings and incorporating recycled aggregates [11]. Through systematic testing of its mechanical properties, durability, and environmental adaptability, the research evaluates its feasibility in transportation engineering applications. The findings not only contribute to the resource utilization of construction waste but also provide theoretical support for the engineering application of tailings-based recycled concrete.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

Proposing an optimized mix design incorporating iron tailings and recycled aggregates to enhance concrete performance.

Systematically evaluating the mechanical properties, durability, and environmental adaptability of the developed concrete.

Providing theoretical and practical insights for the application of high-performance tailings recycled concrete in transportation infrastructure.

The rest of this article are structured as follows: Section 2 presents the experimental design and methodology. Section 3 discusses the mechanical properties and durability analysis. Section 4 evaluates the environmental adaptability of the concrete. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the key findings and suggests future research directions.

2 Setting the proportions and test material

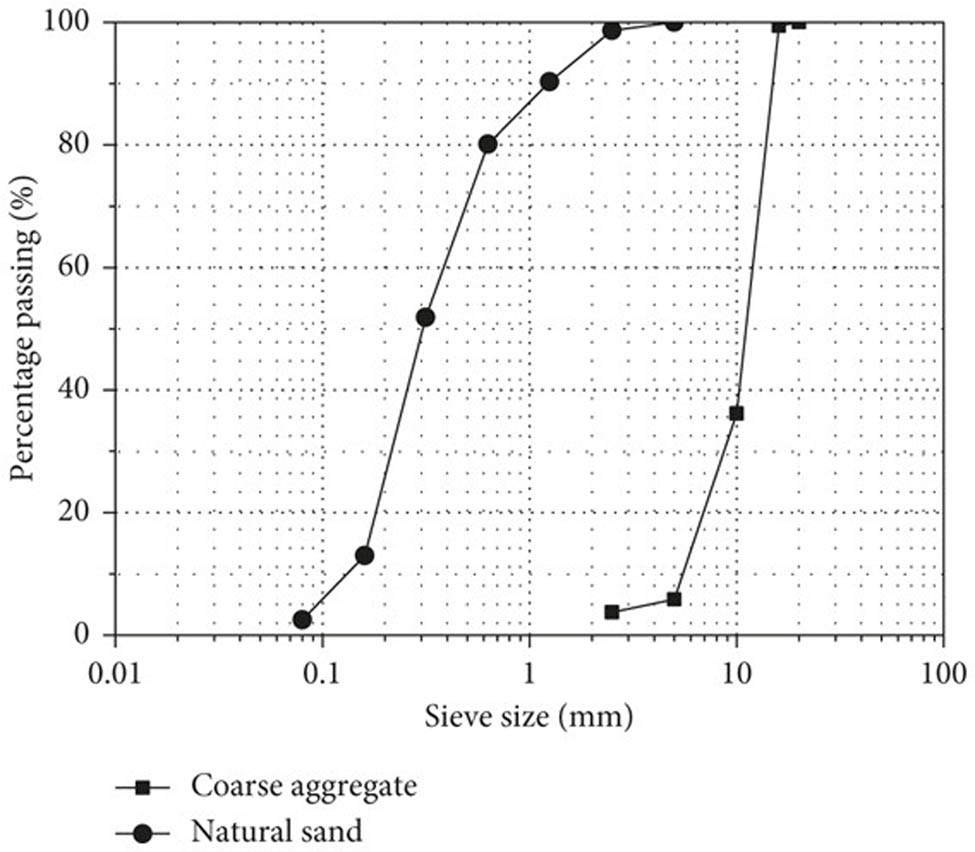

The experimental design is well structured, fully considering the particle size distribution of tailings and their impact on concrete performance. The natural coarse aggregate used in the test was continuously graded artificial gravel with a particle size range of 5–20 mm, while the fine aggregate was natural river sand sourced from the Ba River. The cement used was 42.5-grade ordinary silicate cement, and the foundation concrete’s strength grade was C30. The recycled aggregate, produced by Xi’an Environmental Protection Science and Technology Company Limited, was a widely available material that had been in use for 30 years. It underwent continuous grading, screening, cleaning, drying, and sieving before being bagged for testing.

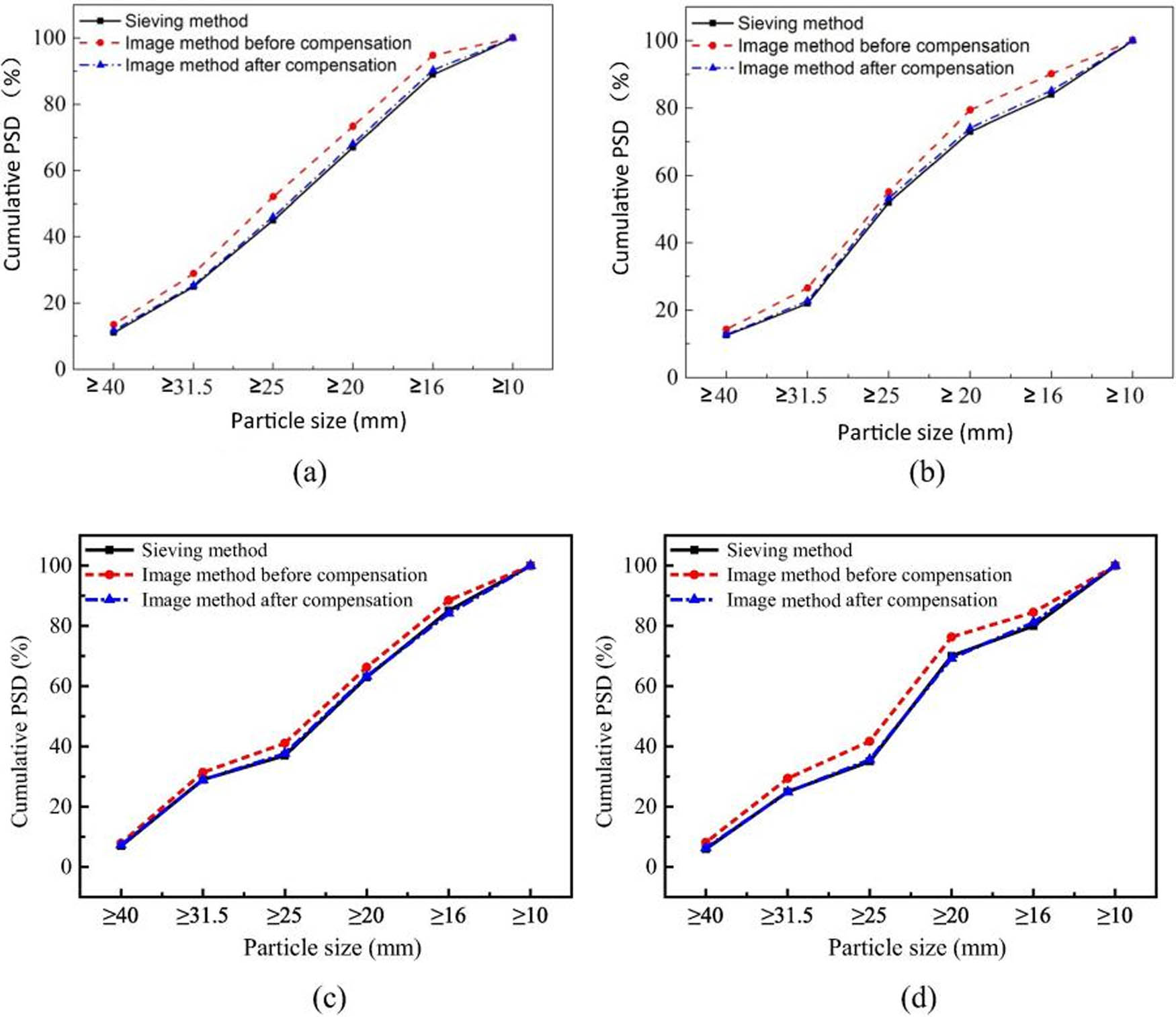

The iron tailings used in the experiment were obtained from Yogou tailings depot, Shaanxi Shangluo Baoming Mining Co. Prior to testing, the gradation of the recycled coarse aggregate and tailings was measured and compared with standard specifications. As shown in Figure 1, the particle gradation meets the required standards [12]. Additionally, Tables 1 and 2 summarize the physical properties of the primary materials before testing.

Aggregate particle grading: (a) limestone-A, (b) granite-A, (c) limestone-B, and (d) granite-B.

Cement’s primary performance indicators

| Water consumption for standard consistency (%) | Set time (min) | Final setting time (min) | Fineness (45) | Stability | Flexural strength (MPa) | Compressive strength (MPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 170 | 285 | 3.0 | Qualified | 4 days | 29 days | 4 days | 29 days |

| 5.5 | 6.9 | 20.5 | 43.6 | |||||

Key materials’ performance indicators

| Performance index | Apparent density (kg/m³) | Bulk density (kg/m³) | Fragmentation value index (%) | Water absorption rate (%) | Mud content (%) | Moisture content (%) | Organic content | Alkali-aggregate reaction | Error range (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural coarse aggregates (NCA) | 2,940 | 1,740 | 10.5 | 1.42 | 0.75 | 0.82 | Qualified | Qualified | ±2.5 |

| Recycled coarse aggregate (RCA) | 2,520 | 1,460 | 15.8 | 7.02 | 1.98 | 3.25 | Qualified | Qualified | ±3.0 |

| Sand | 2,760 | 1,830 | 12.5 | 2.26 | 1.4 | 4.2 | Qualified | Qualified | ±2.0 |

| Iron tailings | 2,740 | 1,826 | 18.6 | 8.85 | 2.8 | 1.52 | Qualified | Qualified | ±3.0 |

While the experimental setup effectively considers the impact of tailings particle distribution, the selection criteria for the tailings replacement rate require further elaboration [13]. To enhance scientific rigor, additional discussion on the rationale behind the chosen replacement percentages, along with supporting experimental data or references, would strengthen the validity of the study’s conclusions.

On the basis of this, high-performance tailings recycled concrete’s mix ratio design was completed. After establishing a 30% recycled aggregate substitution rate based on the pertinent literature, the mix ratios were created in accordance with the specifications [14], accounting for varying tailings mixing quantities. Table 3 displays the concrete mixing ratios under different working conditions following trial mixing and adjustment. For comparison and analysis, a water/cement ratio of 0.45 and a sand rate of 0.55 were chosen for each mixing ratio.

Designing the mixing ratio for inventive concrete under various operating circumstances

| NO | Cement | NCA | RCA | Sand | Iron ore tailings | Tailings replacement rate (%) | Error range (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAC | 530 | 1,062 | 0 | 570 | 0 | 0 | ±2.0 |

| RAC-1 | 530 | 732 | 310 | 560 | 0 | 2 | ±2.5 |

| RAC-2 | 530 | 731 | 315 | 510 | 60 | 8 | ±3.0 |

| RAC-3 | 530 | 745 | 318 | 452 | 116 | 10 | ±3.0 |

| RAC-4 | 530 | 752 | 320 | 450 | 158 | 20 | ±3.5 |

| RAC-5 | 530 | 755 | 320 | 402 | 174 | 25 | ±3.5 |

3 Making and examining the morphology of recycled fine aggregates

3.1 Getting recycled fine aggregate ready

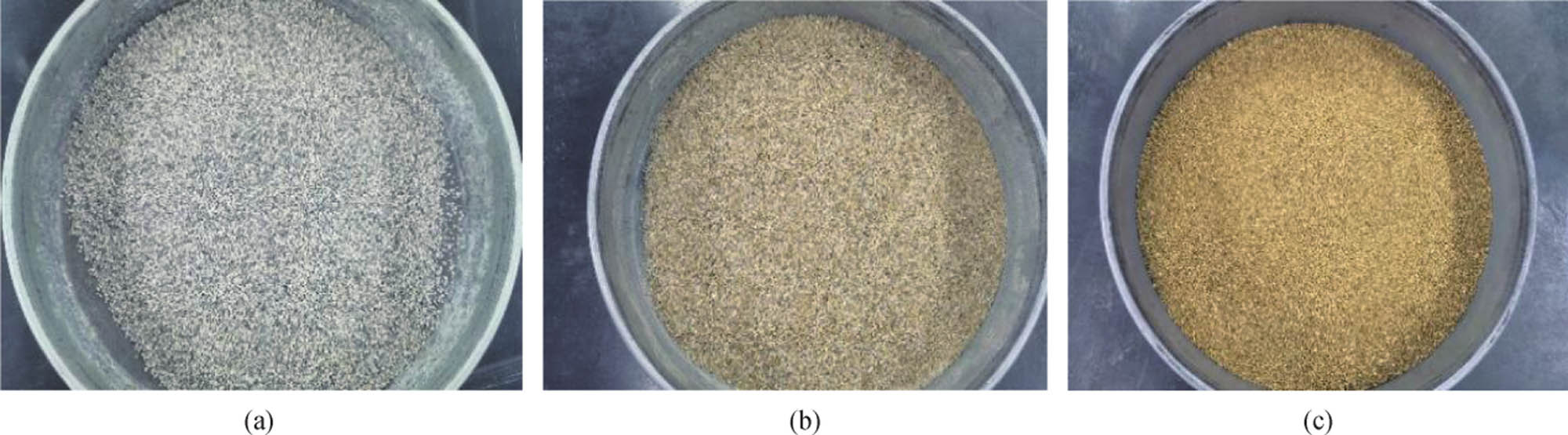

A 150 × 250 jaw crusher made by Henan Zhongke Engineering Technology Co. was used to crush the broken concrete blocks twice after the laboratory waste concrete beams were manually crushed with a hammer. The crushed material was then manually sieved, and the recycled fine aggregate selected for this test had particle sizes ranging from 0.15 to 2.40 mm. To enhance the reproducibility of the experiment, further details on the processing of tailings and recycled fine aggregates are provided. The tailings underwent drying, sieving, and impurity removal to ensure consistency in particle characteristics. Figure 2 presents the specific particle size distribution curves of the recycled fine aggregate, tailings, and other comparison materials. Additionally, standard sand and natural river sand were sieved simultaneously to achieve a gradation curve comparable to the recycled fine aggregate. To systematically analyze the impact of particle characteristics on mortar performance, various fine aggregates were prepared, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Recycled fine aggregate grading curve.

Test made use of three distinct fine aggregates. (a) Recycled fine aggregate, (b) same grade standard sand, and (c) same grade natural river sand.

3.2 Analysis of bluntness and observation of various fine aggregate morphologies

To analyze the differences in particle morphology between recycled fine aggregates and other types of fine aggregates, this study utilized the Occhio Scan700 particle size and shape analyzer. This analyzer operates based on advanced image scanning technology, processing the captured images through Callisto3D graphic analysis software to obtain detailed morphological parameters.

3.2.1 Particle shape and size distribution analysis

To ensure a comprehensive comparison, three different types of fine aggregates were selected for analysis. The Occhio Scan700 provided high-resolution two-dimensional shape parameters, enabling the evaluation of key morphological characteristics, such as:

Sphericity: Reflecting the roundness and angularity of particles, which directly impacts workability and packing density in concrete.

Aspect Ratio: Indicating the elongation of particles, which influences the mechanical interlocking and overall strength of concrete.

Surface Roughness: Affecting the adhesion between the aggregate and cement paste, playing a crucial role in interfacial bonding.

3.2.2 Comparison of morphological differences

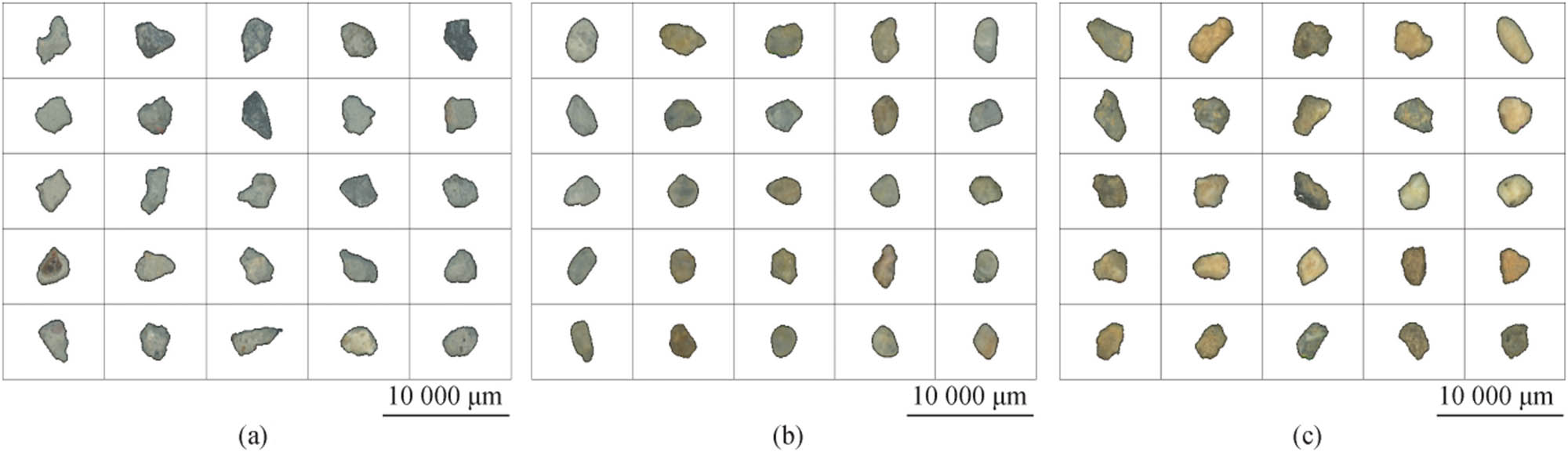

The two-dimensional morphological characteristics of various fine aggregates are illustrated in Figure 4, showcasing the contrast between recycled fine aggregates, natural river sand, and standard sand. Preliminary analysis reveals that:

Recycled fine aggregates exhibit more angular and irregular shapes, with a rougher surface due to residual mortar, which can enhance interfacial bonding but may reduce fluidity.

Natural river sand is generally more rounded and smooth, leading to better workability but potentially weaker interfacial adhesion.

Standard sand maintains a uniform particle shape and size, often serving as a reference material for controlled experimental conditions.

Shape of the particles in various fine aggregates. (a) Recycled fine aggregate, (b) same grade standard sand, and (c) same grade natural river sand.

3.2.3 Impact on concrete performance

The particle shape and size distribution significantly influence the mechanical properties and durability of concrete. The angular and rough texture of recycled fine aggregates may enhance mechanical interlocking, potentially improving compressive and flexural strength, but may also lead to higher water demand and reduced workability. These findings highlight the need for further optimization, such as surface treatment of recycled fine aggregates, to achieve a balance between workability and strength.

By incorporating detailed shape analysis and discussing its implications on concrete performance, this section enhances the scientific rigor and practical significance of the study.

According to the morphological examination, the recycled fine aggregate is more angular, has more long and narrow particles, and is generally uneven when compared to standard sand and natural river sand. The software was used to determine the obtuseness of the particles in order to quantitatively analyze their shape. This involved drawing an internal tangent circle at each protruding part of the projected contour of the particles, dividing its diameter by the maximum diameter of the internal tangent circle of the particles, and taking the average value, which indicates the sharpness of the particles’ surface; the smaller the obtuseness, the sharper the particles’ surface is, and the circle’s obtuseness is 100%. The calculation method is shown in the following equation:

where B is the obtuseness,

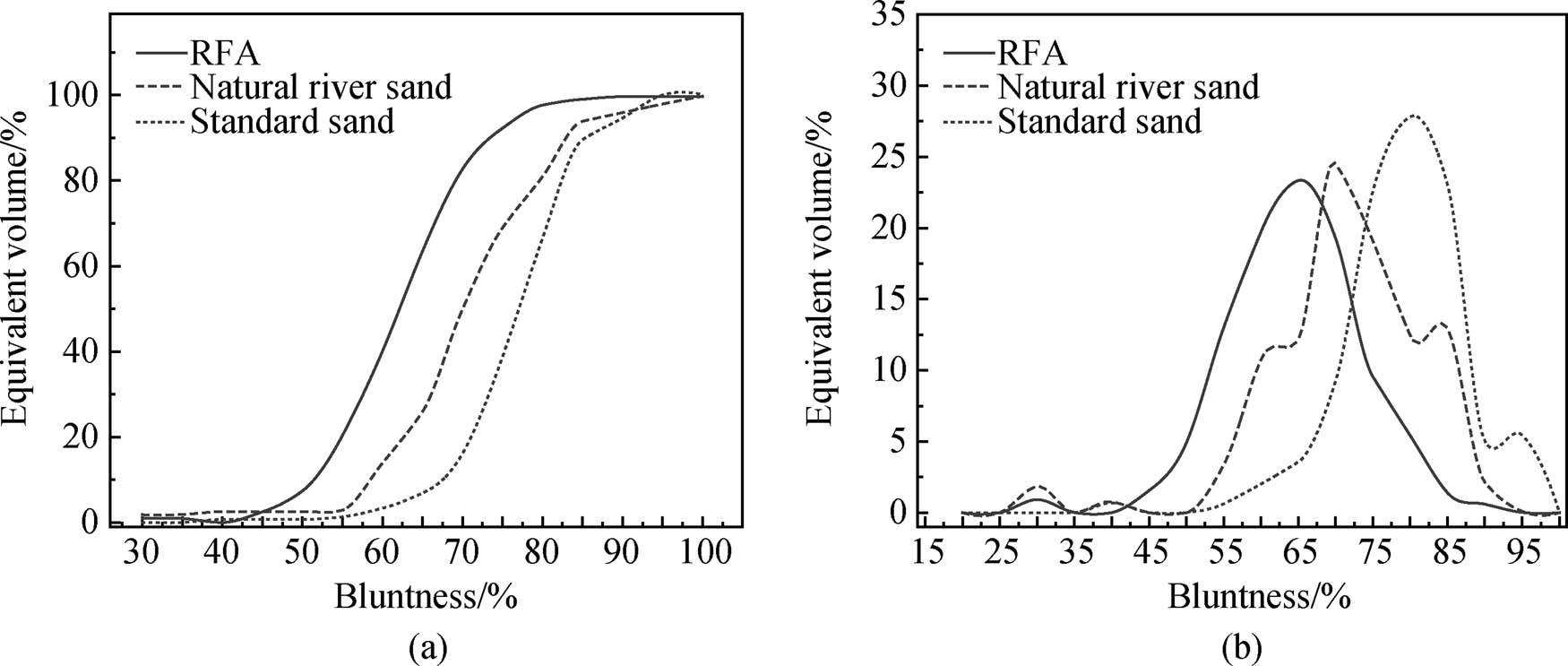

The cumulative and fractional curves of the obtuseness distribution were produced for the three distinct fine aggregates, as well as the equivalent volume percentage of various obtuseness particles in the overall volume, as seen in Figure 5. As illustrated in Figure 5(b), the peak bluntness corresponding to the standard sand and natural river sand is approximately 75 and 90%, respectively, whereas the minimum bluntness corresponding to the peak of recycled fine aggregate is 60%, or nearly 20%, under the same grading conditions. According to the cumulative scaling curves, the natural river sand has less passivation, indicating that there are comparatively few spherical particles in it, whereas the majority of the standard sand is characterized by higher passivation particles, which are less angular and closer to spheres. There are more angular particles with comparatively sharp boundaries in recycled fine aggregate.

Bluntness equivalent volume distribution curves for various fine aggregates: (a) cumulative curves and (b) dividing curves.

3.3 Evaluation and description of the morphological characteristics of various fine aggregates

Digital image processing was utilized to quantitatively describe the morphological characteristics of fine aggregates in order to further study the morphological parameters of the three distinct fine aggregates and to examine the distribution of various aggregates in various particle size intervals [15]. This test’s primary morphological parameters are aspect ratio, sphericity, and firmness. The following are the methods used to calculate the three parameters: Aspect ratio is a parameter that describes the morphology of the particles and assesses the size and shape of a single particle; the closer the aspect ratio is to 100%, the closer the length and width of the particles are; the smaller the aspect ratio, the longer and narrower the shape of the particles is. The following equation illustrates the calculation process:

where

where A is the equivalent plane area of the particle edge,

Wald’s sphericity is denoted by Q, the particles’ actual volume by

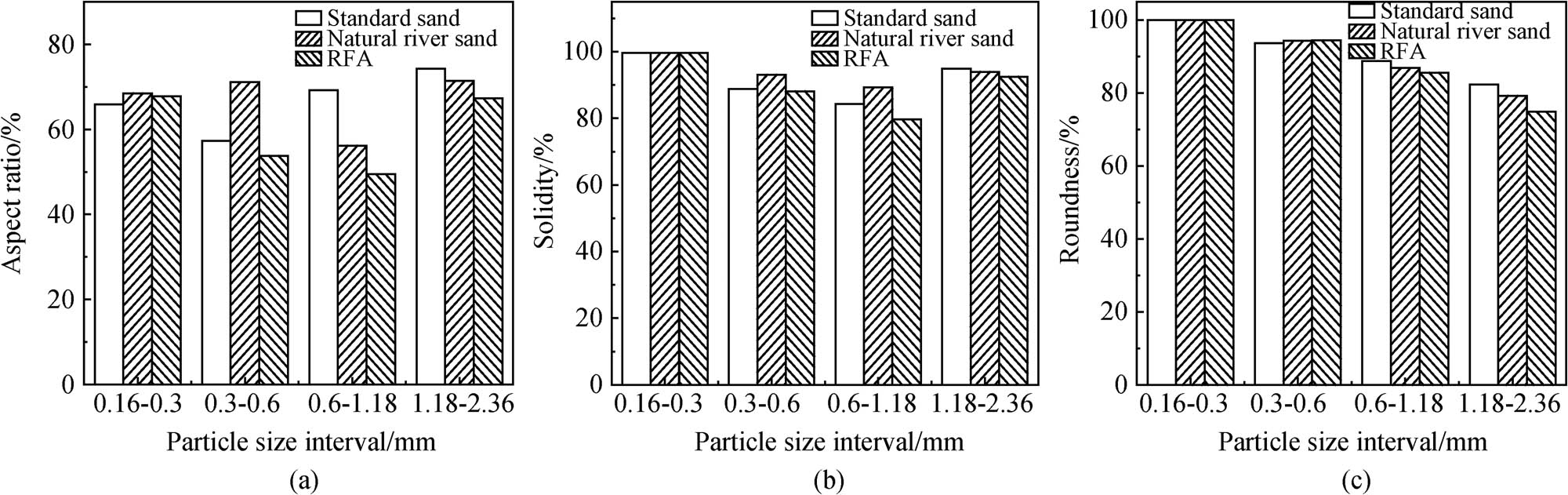

Comparison of several fine aggregates’ morphological characteristics: (a) average aspect ratio, (b) average solidity, and (c) average roundness.

According to the average aspect ratios of three distinct fine aggregates, the recycled fine aggregates exhibit lower aspect ratios in the particle size range above 0.3 mm. Specifically, standard sand has an average aspect ratio of 75%, while recycled fine aggregate, which has the highest proportion within the gradation range, demonstrates an aspect ratio of only 67% for particles in the 1.15–2.35 mm range. This indicates that, compared to ordinary sand and natural river sand, the recycled fine aggregate’s smaller particles possess a relatively low aspect ratio. Moreover, particles larger than 0.3 mm in the recycled fine aggregate show a significantly reduced aspect ratio. This difference suggests that the recycled fine aggregate has a more angular and irregular shape, which could influence the workability and strength characteristics of concrete.

The recycled fine aggregates exhibit less firmness in the particle size range above 0.3 mm, which is consistent with the aspect ratio curves’ trend for the average firmness data. This suggests that throughout the crushing process, the mortar that was adhered to the recycled fine aggregate’s surface was left in place, giving the surface a certain amount of roughness that lessens its firmness. By looking at the sphericity comparison of several fine aggregates in figure, the sphericity of the same gradation of standard sand reaches 83%, that of natural river sand is approximately 80%, and that of recycled aggregate is approximately 73% in the range of 1.15–2.35 mm, which is the largest proportion of gradation. This suggests that the recycled aggregate is less spherical after crushing than the natural river sand because of the mortar that is attached to its surface, while the sphericity of standard sand and natural river sand is nearly equal and spherical particles are more prevalent in natural river sand.

4 Results

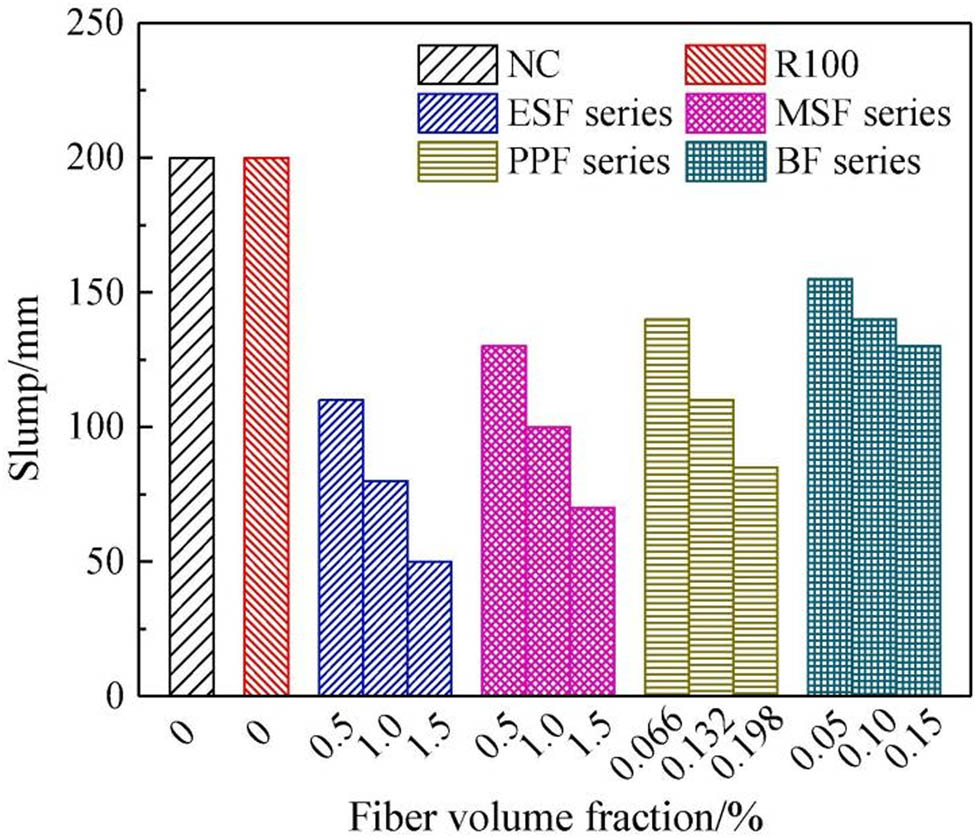

The slump findings for various concretes are displayed in Figure 7, which suggests that fiber significantly affects RFAC’s flowability. All forms of fiber-reinforced RFAC have a droop that is less than that of RFAC without fibers and that considerably lessens as the fiber volume fraction rises. Steel fibers have a bigger impact on RFAC flowability than flexible fibers do. Steel fibers create a skeleton in the combination because of their length and high stiffness, which prevents aggregate slip and lowers slump. The larger surface area of polypropylene fiber (PPF) and basalt fiber (BF), on the other hand, requires more mortar coverage, further reducing RFAC slump. It is worth noting that the slump of R100 is the same as that of normal concrete (200 mm). This is because, when RFAC is cast, the additional water that saturates the fine recycled aggregate (FRA) is added together with the effective water engaged in hydration; yet, the portion of the water does not penetrate the interior of the FRA. The slump of R100 was not decreased because some of the FRA pores were filled with cement particles during the concrete mixing process, increasing the actual water-to-cement ratio and counteracting the friction effect caused by the FRA’s sharpness [16].

Slump of different kinds of concrete.

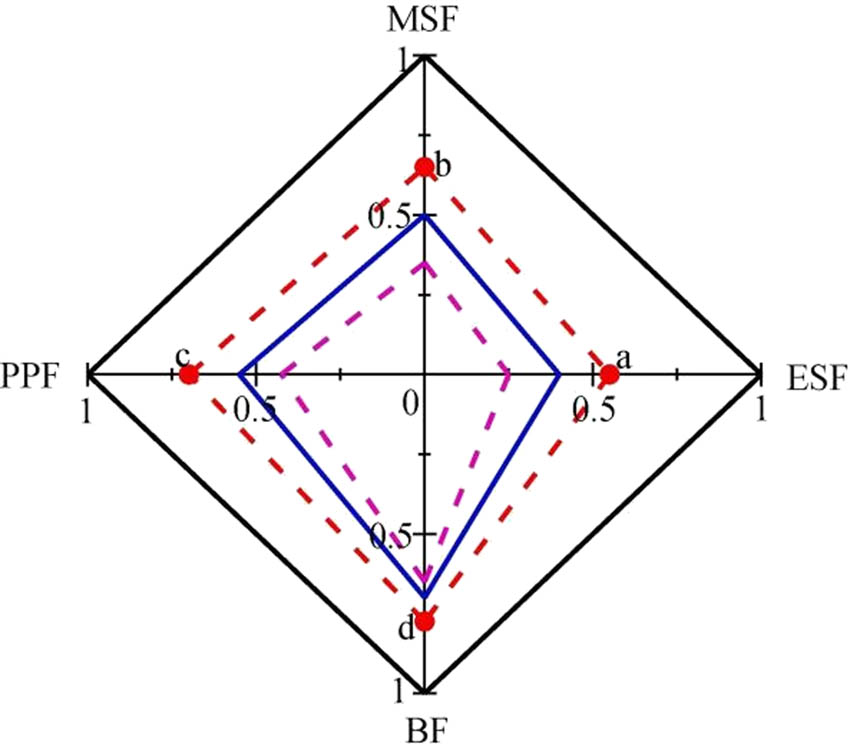

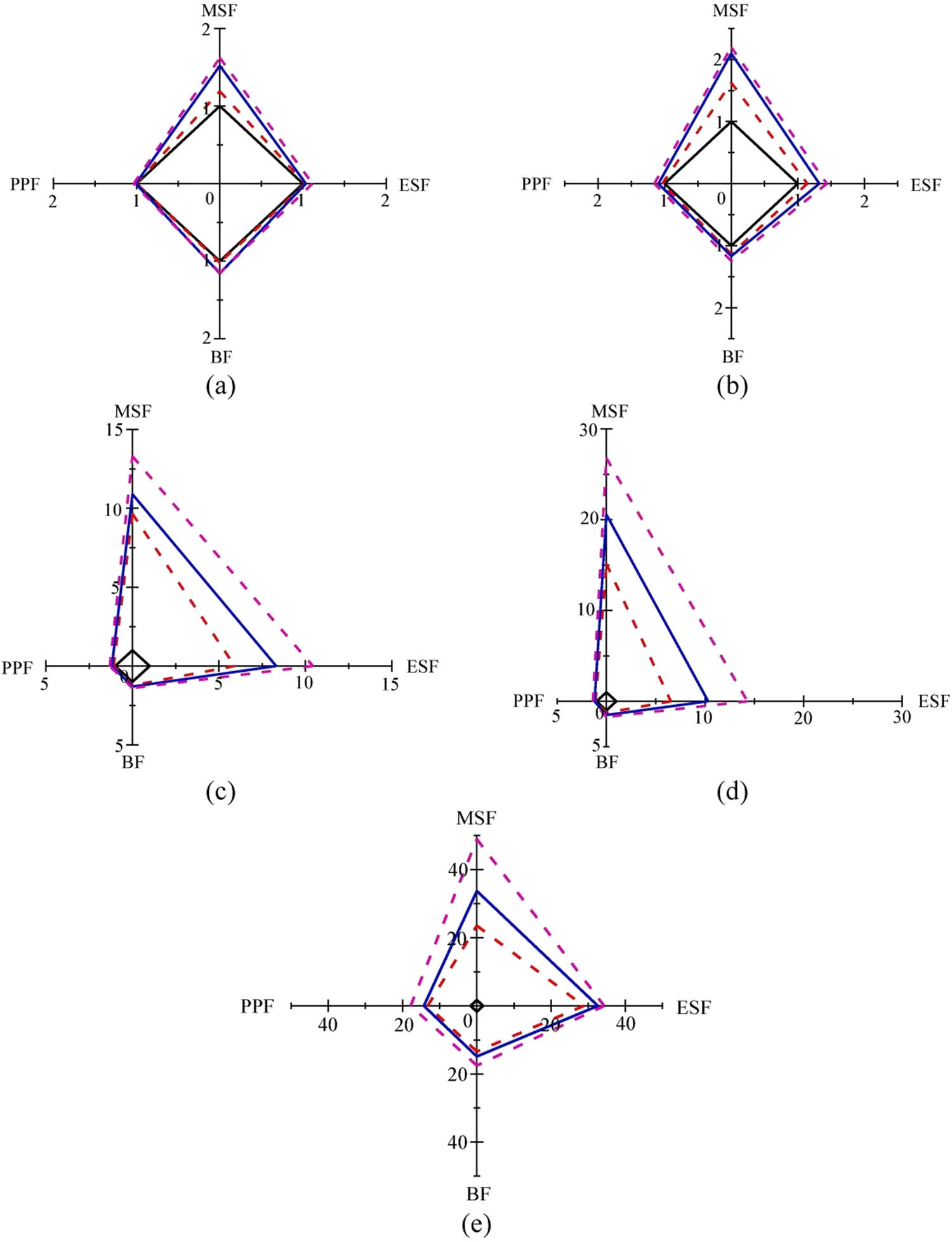

Using the slump of R100 as a reference, the normalized droop of each type of RFAC was analyzed to visually evaluate the effect of fiber type on RFAC flowability. Figure 8 displays the normalized slump vs fiber volume fraction for each fiber-reinforced RFAC, with the closed lines representing different fiber volume percentages from the exterior to the interior (0 to the greatest value), and the normalized droop is the point where the lines cross the coordinate axes. According to the findings, the end-hooked steel fiber (ESF)-reinforced RFAC slump reduced most noticeably as the volume fraction increased, and the fibers’ detrimental impact on RFAC flow was rated as follows: ESF > MSF > PPF > BF. Due to their higher modulus of elasticity, steel fibers had a bigger effect than flexible fibers. Additionally, the majority of the steel fibers formed a skeleton structure after mixing, which further decreased the RFAC flow.

Each fiber-reinforced RFAC with a different fiber volume fraction has a normalized slump.

4.1 Split tensile characteristics, steel fiber distribution, and damage mode

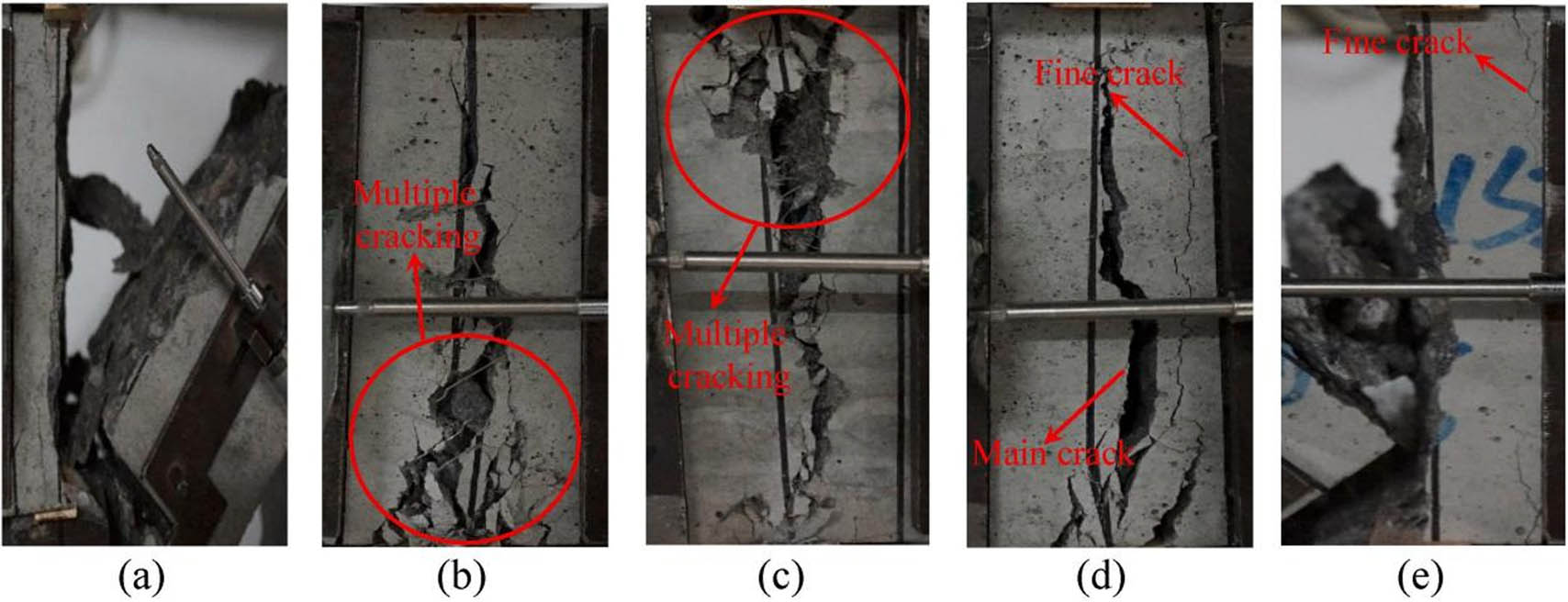

With a single crack running across the cross-section and the specimen shattering into two pieces, the R100 specimen exhibits typical brittle damage (Figure 9(a)). The R100, R100ESF1.0, R100MSF1.0, R100PPF0.132, and R100BF0.10 specimens’ damage under split tensile stress is depicted in Figure 9. The damage pattern of 1.0% ESF- and MSF-reinforced RFAC is shown in Figure 9(b) and (c). The specimen shows repeated cracking and the damage changes from brittle to ductile, mostly as a result of end-hook resistance and bridging loads between the steel fibers and the matrix.

Final failure pictures of different types of specimens: (a) R100, (b) R100ESF1.0, (c) R100MSF1.0, (d) R100PPF0.132, and (e) R100BF0.10.

Although the surface of the R100PPF0.132 and R100BF0.10 specimens had several little fractures, the damage came from the main crack penetration (Figure 9(d), (e)). Because there was not enough bond stress, the majority of the flexible fibers snapped at the fissures. R100PPF0.132 did not break entirely because some of the PPF fibers were still in the elastic stage at the cracking, which is caused by the low modulus of elasticity and high elongation of the flexible fibers (Figure 9(d)).

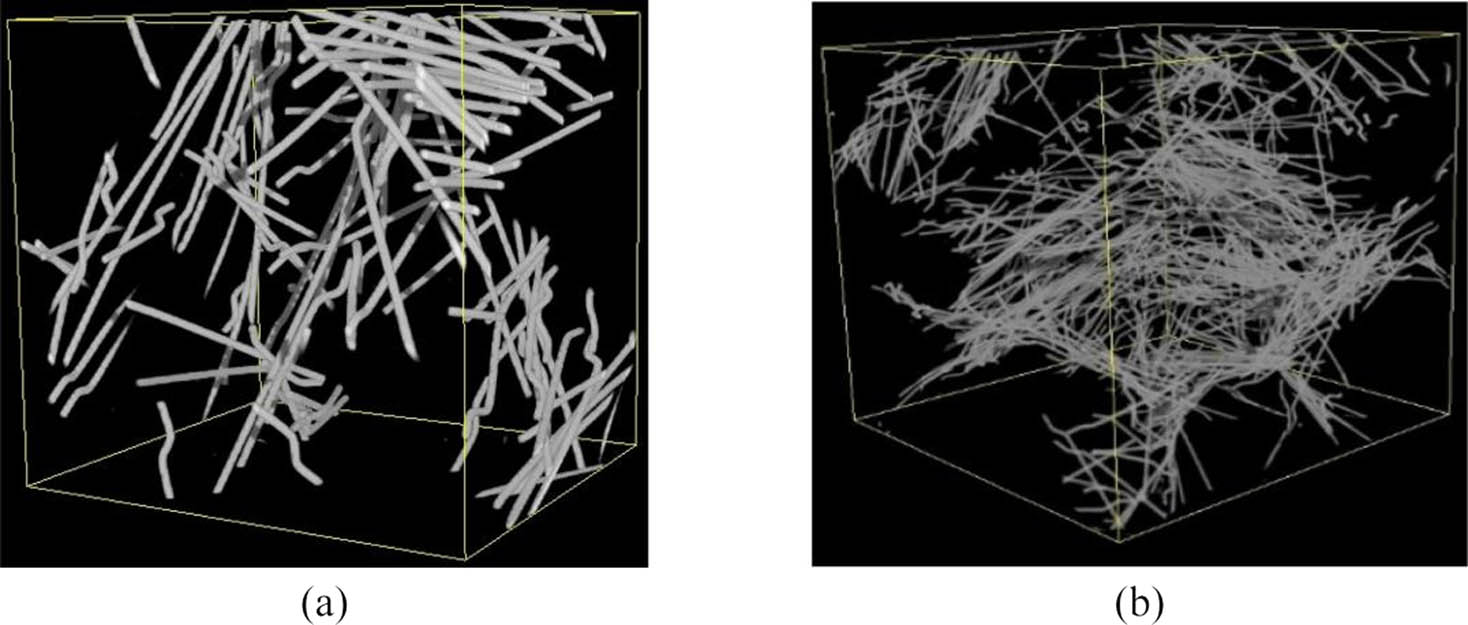

4.2 Steel fiber distribution in RFAC

The distribution of steel fibers in concrete has been shown to have a significant impact on the material’s mechanical qualities. The 1.0% steel fiber-reinforced 150 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm cubic specimens cut with the size of 40 mm × 40 mm × 40 mm in this test were subjected to X-ray computed tomography scanning in order to examine the dispersion of steel fibers in RFAC. The distribution of steel fibers in the R100ESF1.0 and R100MSF1.0 specimens is displayed in Figure 10. The steel fibers are dispersed at random angles throughout the RFAC, and while micro steel fiber (MSF) is smaller than ESF, its distribution is clearly denser.

With a 1.0% fiber volume fraction, the distribution of steel fiber in RFAC is (a) ESF and (b) MSF.

4.3 Load–deformation curve

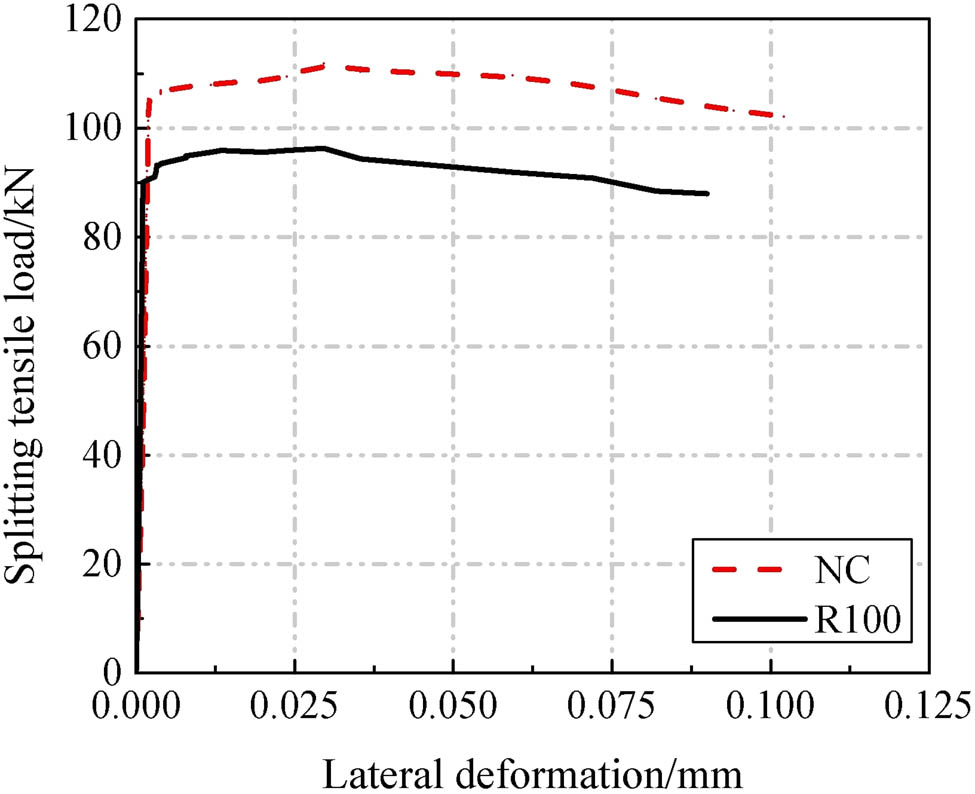

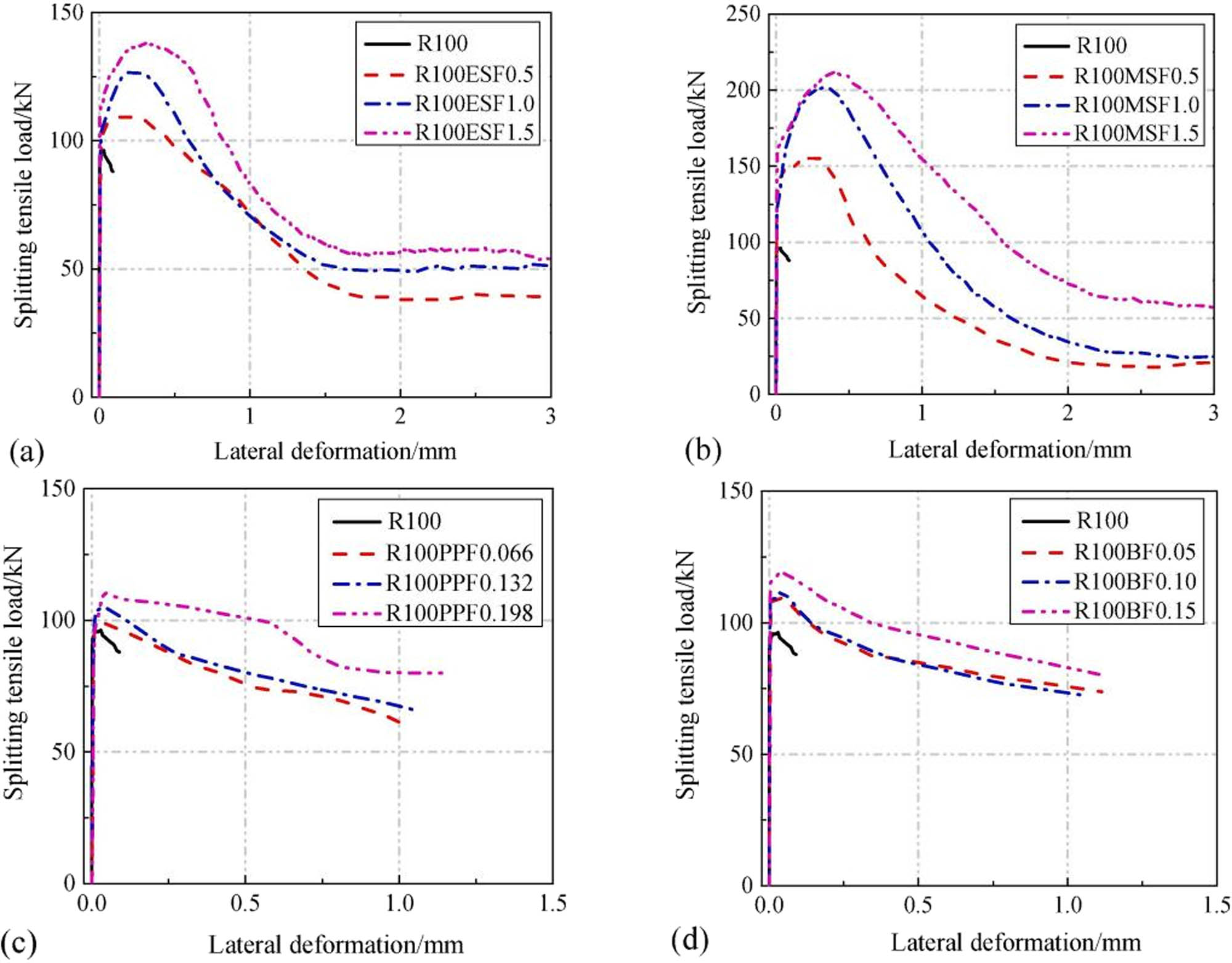

Figure 11 shows the NC and R100 splitting tensile load–deformation curves. Although R100’s peak splitting tensile stress was 13.9% lower than NC’s, no appreciable improvement in toughness was observed, and all specimens displayed brittle damage with mild transverse distortion. Figure 12 displays the splitting tensile load–deflection curves of RFAC reinforced with different fibers. The results demonstrate that the peak splitting tensile load and ductility of RFAC increased as the fiber volume percentage increased. MSF is superior to ESF, and steel fibers toughen and reinforce RFAC more effectively than flexible fibers. MSF-reinforced RFAC exhibits superior splitting tensile capabilities over ESF-reinforced RFAC due to the MSF’s smaller diameter, low aspect ratio, higher MSF at the same volume fraction, and increased likelihood of cracks passing through the MSF. Additionally, Liang et al. [12] found that as the volume % of steel fibers increases, so do the peak splitting tensile load and ductility of steel-fiber-reinforced recycled concrete. The fraction rises, the peak load and critical deformation of steel fiber-reinforced recycled concrete in the shear load–deflection curve rise noticeably, and the load decreases after the peak load, all of which are consistent with the splitting and tensile behavior of steel fiber-reinforced RFAC in this study.

NC and R100 split tensile load–deflection curves.

Tensile load–deflection curves for several fiber-reinforced RFAC types are shown as follows: (a) ESF, (b) MSF, (c) PPF, and (d) BF.

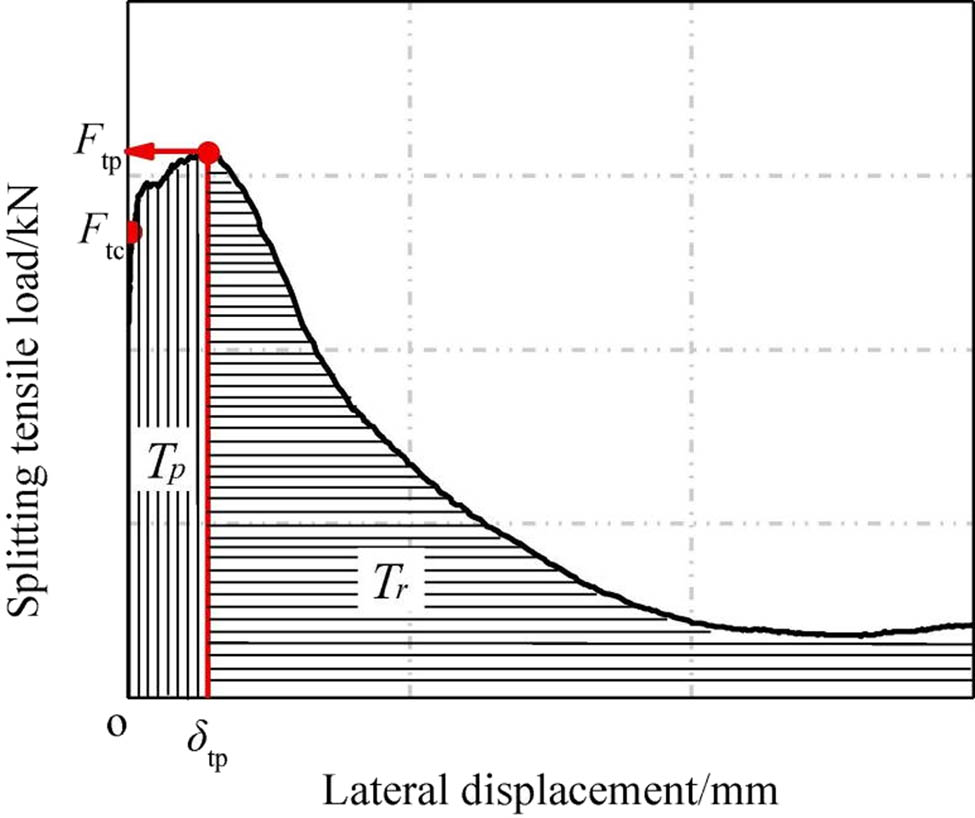

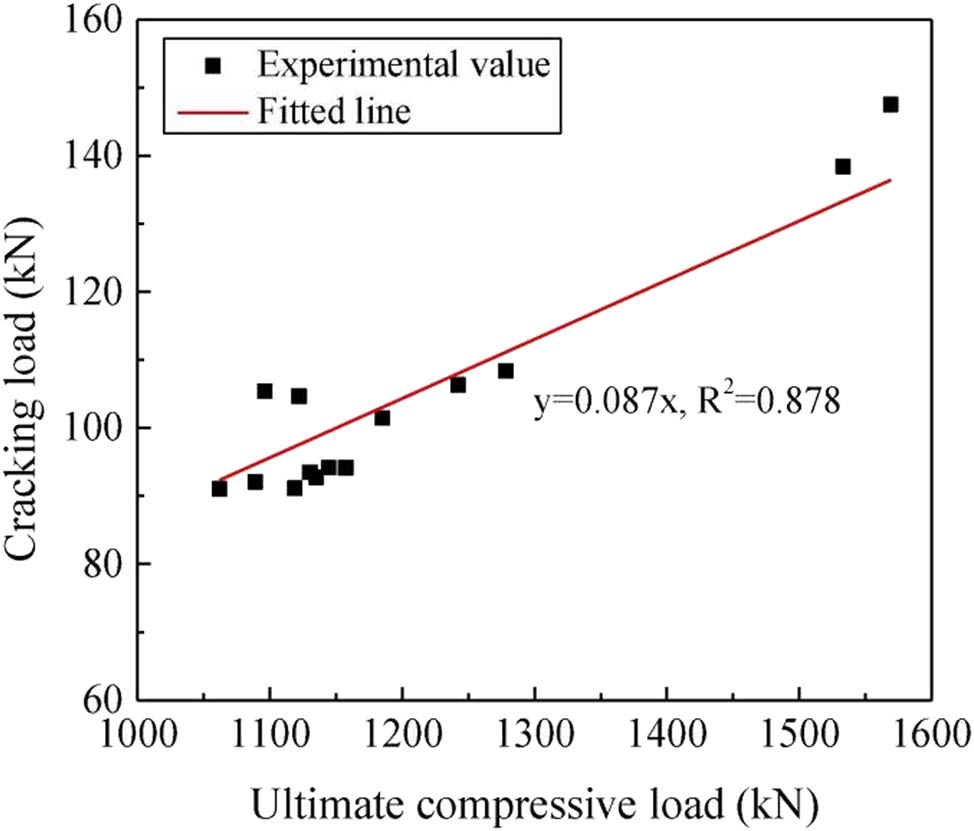

The splitting tensile load–deformation curves of fiber-reinforced RFAC generally exhibit three stages: (1) the elastic stage, in which the load increases linearly with lateral displacement until it reaches the cracking load; (2) the elasto-plastic stage, in which the load increases nonlinearly with displacement until it reaches the peak, during which the fibers are pulled out and the cracks gradually expand; and (3) the softening stage, in which the load gradually decreases, the displacement increases, and the cracks expand until they are destroyed. A typical split tensile load–deformation curve is depicted in Figure 13, where the deformation associated with the peak load is easily visible. The cracking loads for each type of concrete were examined to examine the impact of fiber type on RFAC toughness. The findings indicated that the trend was in line with the ultimate compression load. This is because the damage buildup mechanism for split tensile and compressive stresses is comparable, and the specimens are in the elastic stage prior to cracking. Figure 14 further showed the linear relationship between ultimate compressive load and cracking load, and there was a strong correlation between the experimental data and the fitting results.

Fiber-reinforced RFAC typical load–deflection curves.

Connection between ultimate compression stresses and cracking loads.

4.4 Analysis of characteristic parameters

Figure 15, which is normalized to R100, shows the relationship between the fiber volume percentage and the normalized characteristic parameters of the split tensile load–deflection curves of the various types of fiber-reinforced RFACs. The closed line shows the fiber volume percentage gradually increasing from 0 from inside to outside. The results show that an increase in the fiber volume percentage significantly improves the splitting tensile properties of RFAC. Figure 15(a) and (b) illustrates how different fibers affect the normalized cracking load and peak splitting tensile load, respectively. The highest enhancement impact is seen in the MSF-enhanced RFAC. For an MSF volume fraction of 1.0%, the cracking load is 1.52 times greater than R100, and for a volume fraction of ESF of 1.0%, the peak tensile stress is 2.1 times greater than R100; with a 1.0% increase in volume fraction, the peak tensile load is higher than R100 (R100 by 32.3%); with a PPF volume fraction of 0.198%, the peak tensile load was increased by 15.5%. Fibers have been demonstrated to improve the splitting tensile characteristics of recycled concrete, provided that the PPF volume portion is appropriately managed.

Split tensile load–deflection curves of different fiber-reinforced RFACs with varying fiber volume fractions and their normalized characteristic parameters. (a) Normalized cracking load, (b) normalized peak splitting tensile load, (c) normalized deformation at peak load, (d) normalized peak toughness, and (e) normalized residual toughness.

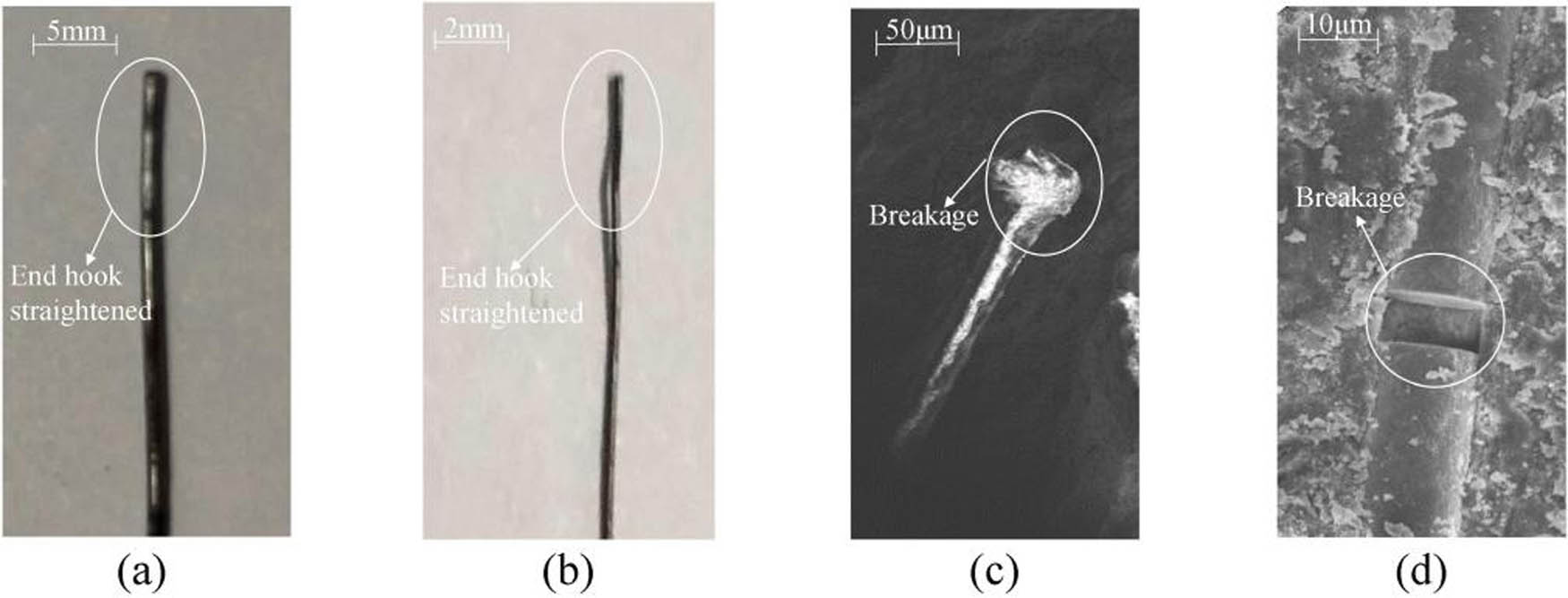

With different fiber volume fractions, Figure 15(c–e) illustrates how the kind of fiber affects the normalized deformation as a function of peak splitting tensile load, peak toughness, and residual toughness of RFAC. The RFAC’s peak splitting tensile load deformation, peak toughness, and residual toughness all increased in tandem with the fiber volume percentage. Fiber toughness and ductility were greatly enhanced by RFAC as compared to split tensile strength. The specimen with a 1% MSF volume fraction had deformation, peak toughness, and residual toughness that were 10.89, 20.54, and 33.7 times greater than R100, respectively [17]; the specimen with a 1% ESF volume fraction had deformation, peak toughness, and residual toughness that were 8.31, 10.31, and 32.61 times greater than R100. Because flexible fibers increase the ductility of RFAC, Figure 15(c) and (d) demonstrates that the improvement of residual toughness by flexible fibers is noticeably superior to the augmentation of peak toughness. The ductility and toughness of RFAC were enhanced with the increase in the volume fraction of PPF and BF fibers, even if the splitting tensile property enhancement of RFAC by flexible fibers was not as excellent as that of steel fibers. Overall, steel fibers outperformed flexible fibers in improving the split tensile properties of RFAC because of their high tensile strength and superior bonding qualities. The split tensile properties of RFAC were improved by several fiber types in the following order: MSF > ESF > BF > PPF. The PPF and BF fibers were primarily broken because of their lower tensile strength, whereas the steel fibers were taken out of the concrete matrix after the specimen fractured under split tensile loading. The tensile property damage patterns of several fiber types under split tensile loading are displayed in Figure 16, and scanning electron microscopy was used to observe the fracture of PPF and BF. The findings indicate that whereas PPF and BF broke, the steel fiber end hooks straightened.

Patterns of failure for various fiber types include (a) ESF, (b) MSF, (c) PPF, and (d) BF.

5 Conclusion

This study investigates the influence of varying iron tailings dosages on the properties of recycled fine aggregate concrete, assessing its feasibility for highway construction. The findings highlight that compared to natural sand, recycled fine aggregate exhibits higher angularity, roughness, and specific surface area, significantly affecting concrete performance. While its use as an aggregate is viable, optimizing the removal of adhered mortar is essential for improving property stability. The damage mode of recycled fine aggregate concrete transitions from brittle to ductile, with steel fibers enhancing crack resistance through bridging effects. However, the toughening effect remains limited due to premature fiber fracture before crack penetration.

Future research should focus on the long-term durability of concrete with varying iron tailings content, particularly in terms of resistance to freeze–thaw cycles, chloride penetration, and fatigue under traffic loads. Additionally, evaluating its applicability across different highway construction environments, including extreme climates and high-load conditions, will help establish comprehensive engineering guidelines and facilitate practical implementation.

-

Funding information: This study was supported by Research on the Integration of Blockchain and Transportation Logistics, Teaching Technology (2023) No. 359; Project Number: 24B580001.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Huang Y, Zhang Y, Ma T, Xiang X, Chen W, Ren X, et al. Study on the mechanical properties and deterioration mechanism of recycled aggregate concrete for low-grade highway pavements. Constr Build Mater. 2024;415:135112.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135112Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Wu CH, Peng HS, Liao CC. Effects of elevated temperature exposure on the mechanical properties of recycled fine aggregate concrete. J Chin Inst Eng. 2024;47(4):359–68.10.1080/02533839.2024.2334206Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Wang F, Luo X, Hai Y, Yu C. Experimental investigation of face mask fiber-reinforced fully recycled coarse aggregate concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2024;447:138141.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.138141Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Panghal H, Kumar A. Sustainable concrete: exploring fresh, mechanical, durability, and microstructural properties with recycled fine aggregates. Period Polytech Civ Eng. 2024;68(2):543–58.10.3311/PPci.22711Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Alyaseen A, Poddar A, Alahmad H, Kumar N, Sihag P. High-performance self-compacting concrete with recycled coarse aggregate: comprehensive systematic review on mix design parameters. Journal of structural integrity and maintenance. 2023;8(3):161–78.10.1080/24705314.2023.2211850Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Zheng S, Liu Q, Han F, Liu S, Han T, Yan H. Basic mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete prepared with Aeolian sand and recycled coarse aggregate. Buildings. 2024;14(9):2949.10.3390/buildings14092949Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Panghal H, Kumar A. Enhancing concrete performance: Surface modification of recycled coarse aggregates for sustainable construction. Constr Build Mater. 2024;411:134432.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134432Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Sadagopan M, Rivera AO, Malaga K, Nagy A. Recycled fine and coarse aggregates’ contributions to the fracture energy and mechanical properties of concrete. Materials. 2023;16(19):6437.10.3390/ma16196437Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Vishnupriyan M, Annadurai R. Investigation of the effect of substituting conventional fine aggregate with PCB powder on concrete strength using artificial neural network. Asian J Civ Eng. 2023;24(8):3155–63.10.1007/s42107-023-00700-7Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Zhong H, Fu H, Feng Y, Li L, Zhang B, Chen Z, et al. Compressive behaviors of high-strength geopolymeric concretes: the role of recycled fine aggregate. Buildings. 2024;14(4):1097.10.3390/buildings14041097Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Hinge P, Shende T, Ralegaonkar R, Nandurkar B, Raut S, Kamath M, et al. An assessment of workability, mechanical and durability properties of high-strength concrete incorporating nano-silica and recycled E-waste materials. Beni-Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci. 2024;13(1):65.10.1186/s43088-024-00521-wSuche in Google Scholar

[12] Liang X, Cheng W, Zhang C, Wang L, Yan X, Chen Q. YOLOD: a task decoupled network based on YOLOv5. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2023;69(4):775–85.10.1109/TCE.2023.3278264Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Sahu A, Kumar S, Srivastava AL, Pratap B. Machine learning approach to study the mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete using copper slag at elevated temperature. Asian J Civ Eng. 2024;25(1):911–21.10.1007/s42107-023-00821-zSuche in Google Scholar

[14] Rout MD, Shubham K, Biswas S, Sinha AK. An integrated evaluation of waste materials containing recycled asphalt fine aggregates using central composite design. Asian J Civ Eng. 2024;25(1):1007–25.10.1007/s42107-023-00828-6Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Xiang YH, Han FX, Liu Q. Effect of salt solution erosion on mechanical properties and micropore structure of recycled fine aggregate ECC. Materials. 2024;17(11):2498.10.3390/ma17112498Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Wu H, Liu X, Ma X, Liu G. Effects of multi-walled carbon nanotubes and recycled fine aggregates on the multi-generational cycle properties of reactive powder concrete. Sustainability. 2024;16(5):2084.10.3390/su16052084Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Khalid MQ, Abbas ZK. Producing sustainable roller compacted concrete by using fine recycled concrete aggregate. J Eng. 2023;29(5):126–45.10.31026/j.eng.2023.05.10Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Generalized (ψ,φ)-contraction to investigate Volterra integral inclusions and fractal fractional PDEs in super-metric space with numerical experiments

- Solitons in ultrasound imaging: Exploring applications and enhancements via the Westervelt equation

- Stochastic improved Simpson for solving nonlinear fractional-order systems using product integration rules

- Exploring dynamical features like bifurcation assessment, sensitivity visualization, and solitary wave solutions of the integrable Akbota equation

- Research on surface defect detection method and optimization of paper-plastic composite bag based on improved combined segmentation algorithm

- Impact the sulphur content in Iraqi crude oil on the mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of carbon steel in various types of API 5L pipelines and ASTM 106 grade B

- Unravelling quiescent optical solitons: An exploration of the complex Ginzburg–Landau equation with nonlinear chromatic dispersion and self-phase modulation

- Perturbation-iteration approach for fractional-order logistic differential equations

- Variational formulations for the Euler and Navier–Stokes systems in fluid mechanics and related models

- Rotor response to unbalanced load and system performance considering variable bearing profile

- DeepFowl: Disease prediction from chicken excreta images using deep learning

- Channel flow of Ellis fluid due to cilia motion

- A case study of fractional-order varicella virus model to nonlinear dynamics strategy for control and prevalence

- Multi-point estimation weldment recognition and estimation of pose with data-driven robotics design

- Analysis of Hall current and nonuniform heating effects on magneto-convection between vertically aligned plates under the influence of electric and magnetic fields

- A comparative study on residual power series method and differential transform method through the time-fractional telegraph equation

- Insights from the nonlinear Schrödinger–Hirota equation with chromatic dispersion: Dynamics in fiber–optic communication

- Mathematical analysis of Jeffrey ferrofluid on stretching surface with the Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Exploring the interaction between lump, stripe and double-stripe, and periodic wave solutions of the Konopelchenko–Dubrovsky–Kaup–Kupershmidt system

- Computational investigation of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS co-infection in fuzzy environment

- Signature verification by geometry and image processing

- Theoretical and numerical approach for quantifying sensitivity to system parameters of nonlinear systems

- Chaotic behaviors, stability, and solitary wave propagations of M-fractional LWE equation in magneto-electro-elastic circular rod

- Dynamic analysis and optimization of syphilis spread: Simulations, integrating treatment and public health interventions

- Visco-thermoelastic rectangular plate under uniform loading: A study of deflection

- Threshold dynamics and optimal control of an epidemiological smoking model

- Numerical computational model for an unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium past an MHD rotating sheet

- Regression prediction model of fabric brightness based on light and shadow reconstruction of layered images

- Dynamics and prevention of gemini virus infection in red chili crops studied with generalized fractional operator: Analysis and modeling

- Qualitative analysis on existence and stability of nonlinear fractional dynamic equations on time scales

- Fractional-order super-twisting sliding mode active disturbance rejection control for electro-hydraulic position servo systems

- Analytical exploration and parametric insights into optical solitons in magneto-optic waveguides: Advances in nonlinear dynamics for applied sciences

- Bifurcation dynamics and optical soliton structures in the nonlinear Schrödinger–Bopp–Podolsky system

- User profiling in university libraries by combining multi-perspective clustering algorithm and reader behavior analysis

- Exploring bifurcation and chaos control in a discrete-time Lotka–Volterra model framework for COVID-19 modeling

- Review Article

- Haar wavelet collocation method for existence and numerical solutions of fourth-order integro-differential equations with bounded coefficients

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Analysis and Design of Communication Networks for IoT Applications - Part II

- Silicon-based all-optical wavelength converter for on-chip optical interconnection

- Research on a path-tracking control system of unmanned rollers based on an optimization algorithm and real-time feedback

- Analysis of the sports action recognition model based on the LSTM recurrent neural network

- Industrial robot trajectory error compensation based on enhanced transfer convolutional neural networks

- Research on IoT network performance prediction model of power grid warehouse based on nonlinear GA-BP neural network

- Interactive recommendation of social network communication between cities based on GNN and user preferences

- Application of improved P-BEM in time varying channel prediction in 5G high-speed mobile communication system

- Construction of a BIM smart building collaborative design model combining the Internet of Things

- Optimizing malicious website prediction: An advanced XGBoost-based machine learning model

- Economic operation analysis of the power grid combining communication network and distributed optimization algorithm

- Sports video temporal action detection technology based on an improved MSST algorithm

- Internet of things data security and privacy protection based on improved federated learning

- Enterprise power emission reduction technology based on the LSTM–SVM model

- Construction of multi-style face models based on artistic image generation algorithms

- Research and application of interactive digital twin monitoring system for photovoltaic power station based on global perception

- Special Issue: Decision and Control in Nonlinear Systems - Part II

- Animation video frame prediction based on ConvGRU fine-grained synthesis flow

- Application of GGNN inference propagation model for martial art intensity evaluation

- Benefit evaluation of building energy-saving renovation projects based on BWM weighting method

- Deep neural network application in real-time economic dispatch and frequency control of microgrids

- Real-time force/position control of soft growing robots: A data-driven model predictive approach

- Mechanical product design and manufacturing system based on CNN and server optimization algorithm

- Application of finite element analysis in the formal analysis of ancient architectural plaque section

- Research on territorial spatial planning based on data mining and geographic information visualization

- Fault diagnosis of agricultural sprinkler irrigation machinery equipment based on machine vision

- Closure technology of large span steel truss arch bridge with temporarily fixed edge supports

- Intelligent accounting question-answering robot based on a large language model and knowledge graph

- Analysis of manufacturing and retailer blockchain decision based on resource recyclability

- Flexible manufacturing workshop mechanical processing and product scheduling algorithm based on MES

- Exploration of indoor environment perception and design model based on virtual reality technology

- Tennis automatic ball-picking robot based on image object detection and positioning technology

- A new CNN deep learning model for computer-intelligent color matching

- Design of AR-based general computer technology experiment demonstration platform

- Indoor environment monitoring method based on the fusion of audio recognition and video patrol features

- Health condition prediction method of the computer numerical control machine tool parts by ensembling digital twins and improved LSTM networks

- Establishment of a green degree evaluation model for wall materials based on lifecycle

- Quantitative evaluation of college music teaching pronunciation based on nonlinear feature extraction

- Multi-index nonlinear robust virtual synchronous generator control method for microgrid inverters

- Manufacturing engineering production line scheduling management technology integrating availability constraints and heuristic rules

- Analysis of digital intelligent financial audit system based on improved BiLSTM neural network

- Attention community discovery model applied to complex network information analysis

- A neural collaborative filtering recommendation algorithm based on attention mechanism and contrastive learning

- Rehabilitation training method for motor dysfunction based on video stream matching

- Research on façade design for cold-region buildings based on artificial neural networks and parametric modeling techniques

- Intelligent implementation of muscle strain identification algorithm in Mi health exercise induced waist muscle strain

- Optimization design of urban rainwater and flood drainage system based on SWMM

- Improved GA for construction progress and cost management in construction projects

- Evaluation and prediction of SVM parameters in engineering cost based on random forest hybrid optimization

- Museum intelligent warning system based on wireless data module

- Optimization design and research of mechatronics based on torque motor control algorithm

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Engineering’s significance in Materials Science

- Experimental research on the degradation of chemical industrial wastewater by combined hydrodynamic cavitation based on nonlinear dynamic model

- Study on low-cycle fatigue life of nickel-based superalloy GH4586 at various temperatures

- Some results of solutions to neutral stochastic functional operator-differential equations

- Ultrasonic cavitation did not occur in high-pressure CO2 liquid

- Research on the performance of a novel type of cemented filler material for coal mine opening and filling

- Testing of recycled fine aggregate concrete’s mechanical properties using recycled fine aggregate concrete and research on technology for highway construction

- A modified fuzzy TOPSIS approach for the condition assessment of existing bridges

- Nonlinear structural and vibration analysis of straddle monorail pantograph under random excitations

- Achieving high efficiency and stability in blue OLEDs: Role of wide-gap hosts and emitter interactions

- Construction of teaching quality evaluation model of online dance teaching course based on improved PSO-BPNN

- Enhanced electrical conductivity and electromagnetic shielding properties of multi-component polymer/graphite nanocomposites prepared by solid-state shear milling

- Optimization of thermal characteristics of buried composite phase-change energy storage walls based on nonlinear engineering methods

- A higher-performance big data-based movie recommendation system

- Nonlinear impact of minimum wage on labor employment in China

- Nonlinear comprehensive evaluation method based on information entropy and discrimination optimization

- Application of numerical calculation methods in stability analysis of pile foundation under complex foundation conditions

- Research on the contribution of shale gas development and utilization in Sichuan Province to carbon peak based on the PSA process

- Characteristics of tight oil reservoirs and their impact on seepage flow from a nonlinear engineering perspective

- Nonlinear deformation decomposition and mode identification of plane structures via orthogonal theory

- Numerical simulation of damage mechanism in rock with cracks impacted by self-excited pulsed jet based on SPH-FEM coupling method: The perspective of nonlinear engineering and materials science

- Cross-scale modeling and collaborative optimization of ethanol-catalyzed coupling to produce C4 olefins: Nonlinear modeling and collaborative optimization strategies

- Unequal width T-node stress concentration factor analysis of stiffened rectangular steel pipe concrete

- Special Issue: Advances in Nonlinear Dynamics and Control

- Development of a cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy design for a nonlinear diabetic patient model

- Big data-based optimized model of building design in the context of rural revitalization

- Multi-UAV assisted air-to-ground data collection for ground sensors with unknown positions

- Design of urban and rural elderly care public areas integrating person-environment fit theory

- Application of lossless signal transmission technology in piano timbre recognition

- Application of improved GA in optimizing rural tourism routes

- Architectural animation generation system based on AL-GAN algorithm

- Advanced sentiment analysis in online shopping: Implementing LSTM models analyzing E-commerce user sentiments

- Intelligent recommendation algorithm for piano tracks based on the CNN model

- Visualization of large-scale user association feature data based on a nonlinear dimensionality reduction method

- Low-carbon economic optimization of microgrid clusters based on an energy interaction operation strategy

- Optimization effect of video data extraction and search based on Faster-RCNN hybrid model on intelligent information systems

- Construction of image segmentation system combining TC and swarm intelligence algorithm

- Particle swarm optimization and fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm for the adhesive layer defect detection

- Optimization of student learning status by instructional intervention decision-making techniques incorporating reinforcement learning

- Fuzzy model-based stabilization control and state estimation of nonlinear systems

- Optimization of distribution network scheduling based on BA and photovoltaic uncertainty

- Tai Chi movement segmentation and recognition on the grounds of multi-sensor data fusion and the DBSCAN algorithm

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part III

- Generalized numerical RKM method for solving sixth-order fractional partial differential equations

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Generalized (ψ,φ)-contraction to investigate Volterra integral inclusions and fractal fractional PDEs in super-metric space with numerical experiments

- Solitons in ultrasound imaging: Exploring applications and enhancements via the Westervelt equation

- Stochastic improved Simpson for solving nonlinear fractional-order systems using product integration rules

- Exploring dynamical features like bifurcation assessment, sensitivity visualization, and solitary wave solutions of the integrable Akbota equation

- Research on surface defect detection method and optimization of paper-plastic composite bag based on improved combined segmentation algorithm

- Impact the sulphur content in Iraqi crude oil on the mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of carbon steel in various types of API 5L pipelines and ASTM 106 grade B

- Unravelling quiescent optical solitons: An exploration of the complex Ginzburg–Landau equation with nonlinear chromatic dispersion and self-phase modulation

- Perturbation-iteration approach for fractional-order logistic differential equations

- Variational formulations for the Euler and Navier–Stokes systems in fluid mechanics and related models

- Rotor response to unbalanced load and system performance considering variable bearing profile

- DeepFowl: Disease prediction from chicken excreta images using deep learning

- Channel flow of Ellis fluid due to cilia motion

- A case study of fractional-order varicella virus model to nonlinear dynamics strategy for control and prevalence

- Multi-point estimation weldment recognition and estimation of pose with data-driven robotics design

- Analysis of Hall current and nonuniform heating effects on magneto-convection between vertically aligned plates under the influence of electric and magnetic fields

- A comparative study on residual power series method and differential transform method through the time-fractional telegraph equation

- Insights from the nonlinear Schrödinger–Hirota equation with chromatic dispersion: Dynamics in fiber–optic communication

- Mathematical analysis of Jeffrey ferrofluid on stretching surface with the Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Exploring the interaction between lump, stripe and double-stripe, and periodic wave solutions of the Konopelchenko–Dubrovsky–Kaup–Kupershmidt system

- Computational investigation of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS co-infection in fuzzy environment

- Signature verification by geometry and image processing

- Theoretical and numerical approach for quantifying sensitivity to system parameters of nonlinear systems

- Chaotic behaviors, stability, and solitary wave propagations of M-fractional LWE equation in magneto-electro-elastic circular rod

- Dynamic analysis and optimization of syphilis spread: Simulations, integrating treatment and public health interventions

- Visco-thermoelastic rectangular plate under uniform loading: A study of deflection

- Threshold dynamics and optimal control of an epidemiological smoking model

- Numerical computational model for an unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium past an MHD rotating sheet

- Regression prediction model of fabric brightness based on light and shadow reconstruction of layered images

- Dynamics and prevention of gemini virus infection in red chili crops studied with generalized fractional operator: Analysis and modeling

- Qualitative analysis on existence and stability of nonlinear fractional dynamic equations on time scales

- Fractional-order super-twisting sliding mode active disturbance rejection control for electro-hydraulic position servo systems

- Analytical exploration and parametric insights into optical solitons in magneto-optic waveguides: Advances in nonlinear dynamics for applied sciences

- Bifurcation dynamics and optical soliton structures in the nonlinear Schrödinger–Bopp–Podolsky system

- User profiling in university libraries by combining multi-perspective clustering algorithm and reader behavior analysis

- Exploring bifurcation and chaos control in a discrete-time Lotka–Volterra model framework for COVID-19 modeling

- Review Article

- Haar wavelet collocation method for existence and numerical solutions of fourth-order integro-differential equations with bounded coefficients

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Analysis and Design of Communication Networks for IoT Applications - Part II

- Silicon-based all-optical wavelength converter for on-chip optical interconnection

- Research on a path-tracking control system of unmanned rollers based on an optimization algorithm and real-time feedback

- Analysis of the sports action recognition model based on the LSTM recurrent neural network

- Industrial robot trajectory error compensation based on enhanced transfer convolutional neural networks

- Research on IoT network performance prediction model of power grid warehouse based on nonlinear GA-BP neural network

- Interactive recommendation of social network communication between cities based on GNN and user preferences

- Application of improved P-BEM in time varying channel prediction in 5G high-speed mobile communication system

- Construction of a BIM smart building collaborative design model combining the Internet of Things

- Optimizing malicious website prediction: An advanced XGBoost-based machine learning model

- Economic operation analysis of the power grid combining communication network and distributed optimization algorithm

- Sports video temporal action detection technology based on an improved MSST algorithm

- Internet of things data security and privacy protection based on improved federated learning

- Enterprise power emission reduction technology based on the LSTM–SVM model

- Construction of multi-style face models based on artistic image generation algorithms

- Research and application of interactive digital twin monitoring system for photovoltaic power station based on global perception

- Special Issue: Decision and Control in Nonlinear Systems - Part II

- Animation video frame prediction based on ConvGRU fine-grained synthesis flow

- Application of GGNN inference propagation model for martial art intensity evaluation

- Benefit evaluation of building energy-saving renovation projects based on BWM weighting method

- Deep neural network application in real-time economic dispatch and frequency control of microgrids

- Real-time force/position control of soft growing robots: A data-driven model predictive approach

- Mechanical product design and manufacturing system based on CNN and server optimization algorithm

- Application of finite element analysis in the formal analysis of ancient architectural plaque section

- Research on territorial spatial planning based on data mining and geographic information visualization

- Fault diagnosis of agricultural sprinkler irrigation machinery equipment based on machine vision

- Closure technology of large span steel truss arch bridge with temporarily fixed edge supports

- Intelligent accounting question-answering robot based on a large language model and knowledge graph

- Analysis of manufacturing and retailer blockchain decision based on resource recyclability

- Flexible manufacturing workshop mechanical processing and product scheduling algorithm based on MES

- Exploration of indoor environment perception and design model based on virtual reality technology

- Tennis automatic ball-picking robot based on image object detection and positioning technology

- A new CNN deep learning model for computer-intelligent color matching

- Design of AR-based general computer technology experiment demonstration platform

- Indoor environment monitoring method based on the fusion of audio recognition and video patrol features

- Health condition prediction method of the computer numerical control machine tool parts by ensembling digital twins and improved LSTM networks

- Establishment of a green degree evaluation model for wall materials based on lifecycle

- Quantitative evaluation of college music teaching pronunciation based on nonlinear feature extraction

- Multi-index nonlinear robust virtual synchronous generator control method for microgrid inverters

- Manufacturing engineering production line scheduling management technology integrating availability constraints and heuristic rules

- Analysis of digital intelligent financial audit system based on improved BiLSTM neural network

- Attention community discovery model applied to complex network information analysis

- A neural collaborative filtering recommendation algorithm based on attention mechanism and contrastive learning

- Rehabilitation training method for motor dysfunction based on video stream matching

- Research on façade design for cold-region buildings based on artificial neural networks and parametric modeling techniques

- Intelligent implementation of muscle strain identification algorithm in Mi health exercise induced waist muscle strain

- Optimization design of urban rainwater and flood drainage system based on SWMM

- Improved GA for construction progress and cost management in construction projects

- Evaluation and prediction of SVM parameters in engineering cost based on random forest hybrid optimization

- Museum intelligent warning system based on wireless data module

- Optimization design and research of mechatronics based on torque motor control algorithm

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Engineering’s significance in Materials Science

- Experimental research on the degradation of chemical industrial wastewater by combined hydrodynamic cavitation based on nonlinear dynamic model

- Study on low-cycle fatigue life of nickel-based superalloy GH4586 at various temperatures

- Some results of solutions to neutral stochastic functional operator-differential equations

- Ultrasonic cavitation did not occur in high-pressure CO2 liquid

- Research on the performance of a novel type of cemented filler material for coal mine opening and filling

- Testing of recycled fine aggregate concrete’s mechanical properties using recycled fine aggregate concrete and research on technology for highway construction

- A modified fuzzy TOPSIS approach for the condition assessment of existing bridges

- Nonlinear structural and vibration analysis of straddle monorail pantograph under random excitations

- Achieving high efficiency and stability in blue OLEDs: Role of wide-gap hosts and emitter interactions

- Construction of teaching quality evaluation model of online dance teaching course based on improved PSO-BPNN

- Enhanced electrical conductivity and electromagnetic shielding properties of multi-component polymer/graphite nanocomposites prepared by solid-state shear milling

- Optimization of thermal characteristics of buried composite phase-change energy storage walls based on nonlinear engineering methods

- A higher-performance big data-based movie recommendation system

- Nonlinear impact of minimum wage on labor employment in China

- Nonlinear comprehensive evaluation method based on information entropy and discrimination optimization

- Application of numerical calculation methods in stability analysis of pile foundation under complex foundation conditions

- Research on the contribution of shale gas development and utilization in Sichuan Province to carbon peak based on the PSA process

- Characteristics of tight oil reservoirs and their impact on seepage flow from a nonlinear engineering perspective

- Nonlinear deformation decomposition and mode identification of plane structures via orthogonal theory

- Numerical simulation of damage mechanism in rock with cracks impacted by self-excited pulsed jet based on SPH-FEM coupling method: The perspective of nonlinear engineering and materials science

- Cross-scale modeling and collaborative optimization of ethanol-catalyzed coupling to produce C4 olefins: Nonlinear modeling and collaborative optimization strategies

- Unequal width T-node stress concentration factor analysis of stiffened rectangular steel pipe concrete

- Special Issue: Advances in Nonlinear Dynamics and Control

- Development of a cognitive blood glucose–insulin control strategy design for a nonlinear diabetic patient model

- Big data-based optimized model of building design in the context of rural revitalization

- Multi-UAV assisted air-to-ground data collection for ground sensors with unknown positions

- Design of urban and rural elderly care public areas integrating person-environment fit theory

- Application of lossless signal transmission technology in piano timbre recognition

- Application of improved GA in optimizing rural tourism routes

- Architectural animation generation system based on AL-GAN algorithm

- Advanced sentiment analysis in online shopping: Implementing LSTM models analyzing E-commerce user sentiments

- Intelligent recommendation algorithm for piano tracks based on the CNN model

- Visualization of large-scale user association feature data based on a nonlinear dimensionality reduction method

- Low-carbon economic optimization of microgrid clusters based on an energy interaction operation strategy

- Optimization effect of video data extraction and search based on Faster-RCNN hybrid model on intelligent information systems

- Construction of image segmentation system combining TC and swarm intelligence algorithm

- Particle swarm optimization and fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm for the adhesive layer defect detection

- Optimization of student learning status by instructional intervention decision-making techniques incorporating reinforcement learning

- Fuzzy model-based stabilization control and state estimation of nonlinear systems

- Optimization of distribution network scheduling based on BA and photovoltaic uncertainty

- Tai Chi movement segmentation and recognition on the grounds of multi-sensor data fusion and the DBSCAN algorithm

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part III

- Generalized numerical RKM method for solving sixth-order fractional partial differential equations