Abstract

Electrocardiogram (ECG) recognition systems now play a leading role in the early detection of cardiovascular diseases. However, the explanation of judgments made by deep learning models in these systems is prominent for clinical acceptance. This article reveals the effect of transfer learning in ECG recognition systems on decision precision. This article investigated the role of transfer learning in ECG image classification using a customized convolutional neural network (CNN) with and without a VGG16 architecture. The customized CNN model with the VGG16 achieved a good test accuracy of 98.40%. Gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM), for this model, gave the wrong information because it focused on parts of the ECG that were not important for making decisions instead of features necessary for clinical diagnosis, like the P wave, QRS complex, and T wave. A proposed model that only used customized CNN layers and did not use transfer learning performed 99.08% on tests gave correct Grad-CAM explanations and correctly identified the influencing areas of decision-making in the ECG image. Because of these results, it seems that transfer learning might provide good performance metrics, but it might also make things harder to understand, which could make it harder for deep learning models that use ECG recognition to be reliable for diagnosis. This article concludes with a call for careful consideration when using transfer learning in the medical field, as model explanations resulting from such learning may not be appropriate when it comes to domain-specific interpretations.

1 Introduction

Cardiovascular deaths are still the leading cause of death worldwide, so the development of new diagnostic techniques is an important requirement [1,2,3]. Electrocardiogram (ECG) analysis holds a central place among examining tools because it is a completely non-invasive method that provides information about the state of cardiac activity [4,5]. The application of deep learning, especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs), is the next breakthrough in the ECG interpretation field; it is more precise and more productive than traditional approaches [6]. The suggested approach was chosen because it could shed light on the importance of using explanation methods for deep learning models as well as how transfer learning affects the precision of explanations in deep learning-based ECG recognition systems. As artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare has progressed significantly in recent years, there is a greater reliance on AI models in crucial clinical areas, including ECG analysis. However, the black-box nature of these models hinders their implementation, making it challenging to comprehend the connection between the model and the problem at hand. Also, while transfer learning is considered an effective approach that has been applied in numerous studies and yields promising results in different image recognition tasks, including ECG analysis tasks, the impact of this technique on the interpretability of models has not been sufficiently studied yet. Understanding how transfer learning influences explanation accuracy in deep learning for ECG recognition is as crucial as ever. Solving these problems is vital to ensuring that the AI systems used in the medical field are credible. For instance, imagine that a deep learning model is applied to identify arrhythmias using ECG signals. Despite its high performance in detecting abnormal rhythms, doctors and clinicians only see the final decision made by the model, not how the decision was made. This can be attributed to the lack of clarity in how the model arrived at certain predictions, meaning that there is doubt about using the model for clinical decision-making. Take another example where a deep learning model trained with transfer learning diagnoses arrhythmias perfectly. However, on closer observation, clinicians can determine that the actual reasons offered by the model are not credible based on medical evidence. This brings about doubt and would cause one to pause when trusting an AI-powered system to make life-altering decisions in the context of medical treatment, thus hinting at the larger issue of how to make AI systems trustworthy in healthcare. Therefore, we conducted the current research to tackle these specific issues and illuminate crucial aspects of the advancement of AI in the healthcare sector. To investigate how transfer learning affects the precision of explanations in deep learning-based ECG recognition systems, we selected the application of a CNN trained from scratch, without transfer learning, to a hybrid CNN with VGG16. VGG16, a state-of-the-art deep CNN architecture, has been employed in many image recognition tasks as a pre-trained feature extractor; therefore, the same approach is also used in this research. The purpose of this study was therefore to try and close this gap in the literature and to help more people get to know how various model architectures and training approaches can impact the ability of deep learning models in the identification of complex ECG signals. It is necessary to enhance future research to utilize deep learning models in medical diagnosis in a more comprehensible and trustworthy manner.

2 Background and related work

The application of CNNs and deep transfer learning techniques used in diagnosing heart diseases through ECG analysis have resulted in tremendous changes. Deep learning models have demonstrated their ability to outperform conventional diagnostic modalities, leading to a transformation in how cardiac abnormalities are detected and analyzed [7]. Salehi et al. have made significant contributions in this area by conducting an exhaustive empirical comparison of transfer learning techniques across various ECG datasets and neural structures. They highlight the significant benefits of transfer learning, which infuses the models with information from unrelated large datasets. However, as the training dataset expands, the marginal benefit of transfer learning could potentially decrease [8]. Refereed research like that of Herman et al. has their AI-based systems for reading ECG interpreted as being better than the traditional computerized means. The presented AI systems, which have processed enormous amounts of ECG data, have improved their accuracy and reliability level to such an extent that in individual cases, these systems have turned out to be more reliable and accurate in the diagnosis of ECG than even experienced cardiologists [9]. Albahri et al. specifically focus their systematic study on the reliability and clarity of artificial intelligence in medical technological applications. Their research brings to light the critical feature of building AI with precision, interpretation, and justification in clinical settings to eliminate the chances of bias and error [10]. Qiu et al. and his team focus their study on the explainability challenge, exploring the relevance of gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) across various deep-learning architectures. In this study, they reported that the visualization results from Grad-CAM were highly dependent on the architecture and depth of the underlying neural network model. As such, they highlighted the importance of careful consideration when choosing a network for diagnostic tasks [11].

While ECG interpretation with AI shows much promise, the limitations of transparency and operationalization of these models become apparent in real clinical settings. The question of how the architectural decisions made influence the effectiveness of the models and their clinical relevance is pertinent and therefore must remain an area of continued research. This research will further explore these aspects, with emphasis on learning strategies and advanced explanation techniques in creating more accurate, understandable, and safer ECG recognition models.

3 Research gaps

The following are the research gaps that were filled in our study.

3.1 The lack of explanation techniques is the major challenge when using transfer learning in various applications

Many of the research papers employing transfer learning for ECG and other medical image classification have not used any explanation approaches. This exclusion creates a significant knowledge gap about how these models make decisions, which is vital for the clinical endorsement that enables trust between the general public and AI-based diagnostic systems.

3.2 Marginal use of explanatory methods

Although some research works have used explanation methods, including Grad-CAM, they have not investigated the reliability and depth of these explanations. Determining the level of explanation is critical to avoid misrepresentation of the visualized decision-making process or features of the medical images being investigated.

4 Methodology

4.1 Model architectures

We compare two distinct architectures to assess the transfer learning effect on the explanations generated by CNNs:

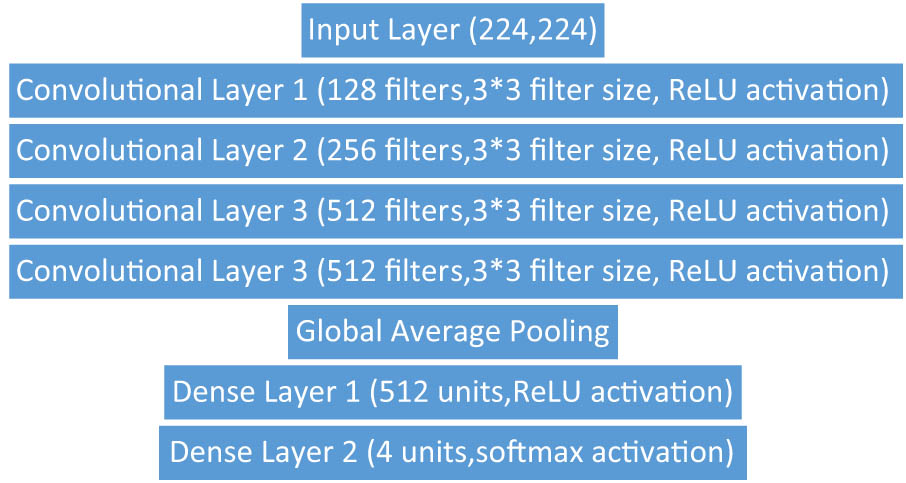

Customized CNN without VGG16: This baseline model’s general goal is to classify ECG images. It consists of the following layers:

Input layer: Takes inputs in 224 × 224 pixel format.

Convolutional layers: To simplify the non-linear process [12], ReLU activation follows each of the four convolutional layers with a number of filters (128, 256, 512, and 512).

Global average pooling: Placed after the customized convolutional layers to lower the feature dimensions and help with classification.

Dense layers: There are two dense layers: the first with 512 units and the second with four units, each corresponding to a class of cardiac condition. The first layer uses ReLU activation, while the second uses the Softmax function to output probabilities for each class.

For a detailed visualization of this model’s configuration, refer to Figure 1.

The proposed CNN architecture.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the customized CNN model without using VGG16 as one of its layers. The architecture is sequential in terms of shape, from the input layers to the dense layers. Variations in the architecture are as follows: the first convolutional layer has various filter sizes, which are essential in the feature extraction of ECG signals for classification.

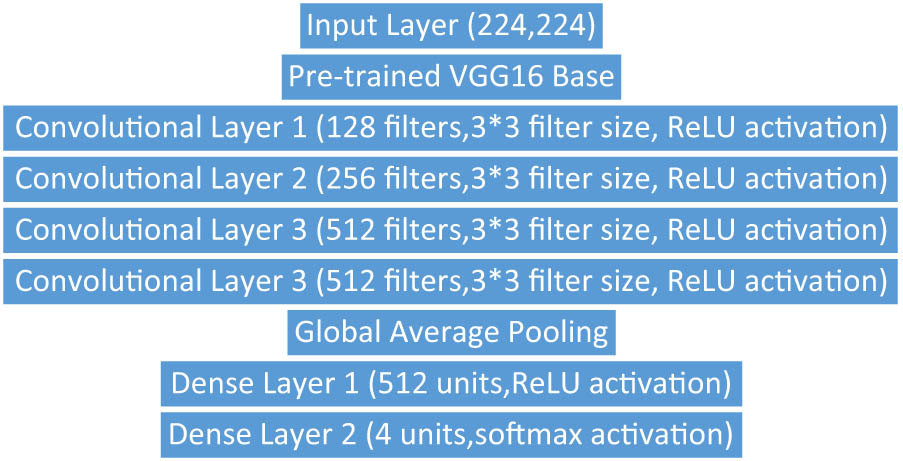

Hybrid CNN with VGG16: This model leverages the robust feature extraction capabilities of the VGG16 architecture, pre-trained with the ImageNet dataset [13]. It consists of the following layers:

Input layer: Takes inputs in 224 × 224 pixel format.

Pre-trained VGG16 base: During the initial stage of training, all layers will remain frozen to preserve the learned features, starting from the model’s base to the “block5_conv3” layer.

Customized top layers: We position four new convolutional layers (128, 256, 512, and 512 filters) at the output of the last retained VGG16 layer to better define the specific features of ECG images. Each of these layers undergoes subsequent ReLU activations.

Global average pooling: Placed after the customized convolutional layers to lower the feature dimensions and help with classification.

Dense layers: There are two dense layers: the first with 512 units and the second with four units, each corresponding to a class of cardiac condition. The first layer uses ReLU activation, while the second uses the Softmax function to output probabilities for each class.

Trainable layers: At first, only the layers after VGG16 are trainable. Later stages unfreeze the layers from VGG16’s “block5” to enable fine-tuning on the ECG dataset.

To understand VGG16 integration, refer to Figure 2.

The hybrid CNN with VGG16 architecture.

This figure represents the structure of the hybrid CNN model, where the VGG16 base model is incorporated with extra customized layers. The shape is a combination of the VGG16 base model and customized layers, and variations include the base VGG16 (freeze layers) and adding more layers with 128/256/512 filters, respectively. This design makes use of the pre-trained features while at the same time learning other features specific to ECG.

4.2 Implementation of Grad-CAM for visual explanations

This study chose Grad-CAM to generate visual explanations of a deep learning model’s decisions [14]. It supports the identification of the regions in the ECG images that models rely on to make their predictions, thus giving useful information about model understandability.

The Grad-CAM implementation includes the following processes:

Layer selection: We used Grad-CAM on the output of each model’s final convolutional layer to identify the most spatial features that determine classification.

Gradient calculation: We used backpropagation to compute the gradients of the target class.

Weighted activation map: By multiplying the feature maps by the established set of weights, we were able to create a localization map with the most features that discriminate between classes.

We then scaled the generated class activation maps to the original ECG images’ size and transformed them into heatmaps. We superimposed the heatmaps over the initial ECG images, effectively adding a visual layer that highlighted the regions the model most distinguished in its predictions. This, in turn, led to a clearer understanding of what the models were looking at, indicating how they came to their conclusions.

4.3 The relation of proposed method parameters to system parameters

The parameters used in the proposed method in this study are carefully selected to correspond with the system parameters of the ECG recognition task, such that there are no discrepancies between the general architecture of the model and the nature of ECG data. The customized CNN model comprises the following architecture: input layer: ECG images are fed into the model after resizing the images to a standard size of 224 × 224 pixels. The convolutional layers have a ReLU activation function, which serves the purpose of feature extraction of important details of ECG signals that include edges and other patterns associated with cardiac conditions such as P waves, QRS complexes, and T waves. The global average pooling layers are applied to avoid overfitting and to summarize the spatial features of the input since the networks will generally be very deep; the dimensions of the feature maps are reduced to provide only the most important features. The dense layers with Softmax activation subsequently evaluate the extracted ECG image features and categorize them into four apparent types of cardiac diseases, namely history of myocardial infarctions (HMI), myocardial infarctions (MI), abnormal heartbeat (AHB), and normal.

In the proposed hybrid CNN model, the pre-trained base that is incorporated in the hybrid CNN model or the CNN architecture is VGG16, which has a strong feature extraction ability from the ImageNet dataset. However, due to the differences in features between ImageNet and ECG, some extra layers are incorporated to optimize the feature extraction of the model for ECG images. The training stages include: first, freezing the VGG16 layers to maintain pre-trained weights and, then, partially, unfreezing some layers to fine-tune the ECG dataset, which enhances the model’s ability to capture specific features of ECG.

The Grad-CAM implementation further improves the interpretability of the model. When Grad-CAM is applied using the last convolutional layers, the method shows which areas of ECG images are crucial for the model’s predictions, thus explaining the decisions made. Backpropagation is applied for calculating gradients, and a weighted activation map helps make the results visible so that one can see which part of the picture has the biggest influence on the model.

4.4 Model evaluation and validation

4.4.1 Quantitative evaluation

Standard performance metrics, including precision, recall, F1 score, precision, and specificity, evaluated both models: the customized CNN model without VGG16 and the hybrid CNN model with VGG16. We calculated these measures for each of the four target categories: HMI, MI, AHB, and normal.

4.4.2 Qualitative validation

A practicing cardiologist evaluated the Grad-CAM output of the customized CNN model without VGG16 to see if it paid attention to diagnostically relevant parameters such as P waves, QRS complexes, and T waves. The cardiologist commented that the model’s visualizations effectively pointed out regions in agreement with clinical knowledge, housing the decision-making logic. This means that the model can help to highlight the most important elements in the ECG data.

5 Experiment design

5.1 Dataset

The present study employed a standard ECG dataset that was made available in the public domain and consists of 1,937 ECG samples annotated for analysis and categorized into four classes: MI, AHB, HMI, and Normal [15]. A total of 77 images describe situations in which patients have MI, which is a sign of serious coronary diseases that might lead to heart attacks and even death. Through the collection of 548 images, the AHB disease category demonstrates people struggling with breathlessness or impaired breathing as a consequence of cardiac diseases. The HMI includes 203 patient images from previous MI. Lastly, normal is the largest category, which includes 859 images from healthy individuals. The dataset comes from medical devices in the EDAN series, with a standard 12 leads and 500 Hz sampling rate. The original dataset included the COVID-19 class, which this research excluded. Normal (548 ECG), MI (548 ECG), HMI (548 ECG), and AHB (548 ECG) images are used in the categorization criteria. This value was chosen to adjust the imbalance in the sample and avoid the inefficiency of classifications that might result.

5.2 Data preprocessing and augmentation

For the preparation of ECG images for analysis, we first do a static crop, selecting only 6–96% of the horizontal region and 21–93% of the vertical region. By performing this step, we eliminate unnecessary elements from the images and retain only those areas that contain the expected diagnostic information. We resize all the images right after cropping and standardize them to 224 × 224 pixels, based on the input into our CNN. Moreover, we adjust the brightness by approximately 5% to enhance the model’s resilience against contrast-induced fluctuations in image lighting.

5.3 Model training

Train-validation-test split: We first split the data into training and testing sets using an 80/20 split. We also created the validation subset within the training set, setting its amount to 20%.

Optimizer and loss function: We compiled them using the Adam optimizer and the categorical cross-entropy loss function.

Training process: Customized CNN without VGG16: We trained the customized CNN for 200 epochs, using early stopping to prevent overfitting and reducing the learning rates if the validation loss plateaued. Hybrid CNN with VGG16: To easily adapt to the new top layers, the VGG16-based model initially trains with the frozen VGG16 layers. In the following step, we unfroze and refined the VGG16-specific layers to ensure fine adaptability.

Validation method: Both models used a validation set held out and performance metrics recorded at each epoch to monitor the learning process during iterations as well as guide adjustments.

6 Results

6.1 The performance of customized CNN model without VGG16

We evaluated the customized CNN model without VGG16’s ability to correctly classify ECG images into the desired four categories. Table 1 displays the performance results.

The performance results of the customized CNN model without VGG16

| Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1 score (%) | Accuracy (%) | Specificity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHB | 98.32 | 98.32 | 98.32 | 99.09 | 99.38 |

| HMI | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| MI | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Normal | 98.20 | 98.20 | 98.20 | 99.09 | 99.39 |

The visualization of Grad-CAM for the customized CNN model without VGG16 (referred to Figure 3a) confirmed that the model successfully highlighted features necessary for clinical diagnosis, like P waves, QRS complexes, and T waves. The visualizations showed the model’s ability to localize precisely on the foundational segments of the image that aimed at providing clinical interpretation to guide its decision-making process.

Grad-CAM visualizations. (a) Grad-CAM visualization for the customized CNN model. The shape of the highlighted regions in the ECG images aims to point at diagnostically significant areas like P-waves, QRS complexes, and T-waves, as well as offer correct visual explanations that match clinical experiences. (b) Grad-CAM visualization for the hybrid CNN model with VGG16. The highlighted regions in the ECG image show that the shape of the regions often emphasizes unimportant areas, which shows that transfer learning adversely affects explanation accuracy. (c) Grad-CAM visualization for the hybrid CNN model with VGG19. The highlighted regions in the ECG image show that the shape of the regions often emphasizes unimportant areas, which shows that transfer learning adversely affects explanation accuracy.

6.2 Hybrid CNN with VGG16 model performance

We also evaluated a hybrid CNN model incorporating VGG16, and Table 2 presents the corresponding results. When compared with the customized CNN, the hybrid model’s Grad-CAM representation (Figure 3b) was clearly out of place. The model pointed out the areas that were not pertinent for clinical interpretation, showing that VGG16 pre-trained features may not have the specific fixings required for the ECG classification.

The performance results of the hybrid CNN with VGG16

| Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1 score (%) | Accuracy (%) | Specificity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHB | 95.16 | 99.16 | 97.12 | 98.41 | 98.12 |

| HMI | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| MI | 100 | 99.06 | 99.53 | 99.77 | 100 |

| Normal | 99.07 | 95.50 | 97.25 | 98.63 | 99.70 |

6.3 Comparison and observations

Customized CNN Model without VGG16: The customized CNN model without VGG16 was successful because of its high ability to spot diagnostically relevant features in the ECG images. This success is reflected in the high-performance metrics achieved (Table 1). The Grad-CAM visualizations showcased the model’s ability to identify regions significantly affected by cardiac conditions, indicating its performance aligns with expectations.

Hybrid CNN with VGG16: The model displayed some regions on Grad-CAM visualizations that do not contain clinically recognized features used in an ECG interpretation. The model performed as well as the customized one, but the Grad-CAM scores did not always reflect a deep comprehension of the data, which means that transfer learning did not necessarily make the model more interpretable in this context.

There is an indication thus that transfer learning can bring certain advantages into play sometimes, but individually designed and trained models for ECG classification, such as customized CNN without VGG16, can be superior in interpretability by focusing on specific Grad-CAM visualizations.

7 Robustness evaluation

Further experiments were conducted as a measure of testing the robustness of the developed ECG recognition system; the experiments included data augmentation and training the model using a different pre-trained model (VGG19).

7.1 Data augmentation

To simulate real-world variations, data augmentation strategies were employed on the original ECG dataset. In particular, the value of 1.3 pixels of blur and changes in exposure from −10 to +10% were applied. These augmentations assist in evaluating how the models perform in context to seemingly different forms of the ECG image.

7.2 Additional pre-trained model (VGG19)

Besides the customized CNN and hybrid CNN with VGG16, the experiment included a hybrid CNN with VGG19. Similar to VGG16, the VGG19 model was also pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset and later adopted for the ECG classification. Table 3 below displays the performance results.

The performance results of the customized CNN model without VGG19

| Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1 score (%) | Accuracy (%) | Specificity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHB | 100 | 91.60 | 95.61 | 97.72 | 100 |

| HMI | 94.87 | 100 | 97.37 | 98.63 | 98.17 |

| MI | 96.26 | 100 | 98.10 | 99.09 | 98.81 |

| Normal | 97.17 | 97.17 | 97.17 | 98.63 | 99.10 |

7.3 Performance metrics with augmented data

We used data augmentation approaches to test the robustness of the models. This was done by evaluating the models on the augmented dataset to test for generalization with slightly different ECG images. Table 4 presents the obtained test results.

Performance metrics with augmented data

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1 score (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customized CNN | 99.24 | 99.25 | 99.22 | 99.23 | 99.74 |

| Hybrid CNN with VGG16 | 96.64 | 96.70 | 96.63 | 96.62 | 98.88 |

| Hybrid CNN with VGG19 | 90.77 | 91.49 | 90.98 | 90.84 | 96.95 |

It is clear from the performance metrics that although the customized CNN had much higher accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and specificity, the hybrid models consisting of VGG16 and VGG19 are also acceptable but not as good as the customized CNN.

7.4 Grad-CAM visualizations with VGG19

We also created Grad-CAM visualizations for the hybrid CNN with VGG19 to identify which regions of the ECG images affected the model’s prediction. Figure 3c displays the Grad-CAM results for the hybrid CNN with VGG19.

Similar to the VGG16 model, the Grad-CAM output of the VGG19 model also displayed falsely highlighted regions.

8 Selectivity of the proposed method for practical systems

The proposed method is based on a comparison between a customized CNN trained without transfer learning and a hybrid CNN with transfer learning. We conducted this comparison to assess the impact of transfer learning on the interpretability of ECG recognition systems. We conclude that the use of transfer learning reduces the interpretability based on the presented Grad-CAM display results. For practical systems and user-specific applications, this method is beneficial for the following reasons:

Improved interpretability without transfer learning: The customized CNN without transfer learning gives better and more explicit visualization of the explanations using Grad-CAM as illustrated in Figure 3(a). This is particularly helpful for more clinical applications where understanding the decision-making process behind a model significantly enhances trust and the overall functionality of the model.

Clinical relevance and trust: Interpretation is a matter of clarity, and accurate interpretability translates to clinical trust. Thus, when the explanations line up with existing clinical cues, clinicians are more likely to use the AI system. The customized CNN’s reliable explanations make it a better candidate for practical application in the real world, hospitals included.

Enhanced model performance: Our investigation shows that the customized CNN is more appropriate for ECG analysis than the hybrid CNN which uses transfer learning. This makes it especially effective when used to address real-world cases in ECG recognition to improve the reliability of the system.

9 Discussion

9.1 Addressing the interpretability issue

The main objective of this article was to investigate how the use of transfer learning affects the interpretability of deep learning-based ECG recognition systems. For models that are implemented in a clinical context, not only the output of the model is important but also the way the model arrives at those decisions. This creates trust and prepares the groundwork for implementing and adopting AI technologies in clinical practice.

9.2 Interpretation of findings

The study’s findings indicate that the customized CNN without transfer learning had improved accuracy and relevant clinical decisions compared to the customized CNN with transfer learning. One of the reasons that the explanations are not accurate for transfer learning with VGG16 and VGG19 could be the variation between the features of the image learned from ImageNet and those of ECG interpretation. VGG16 and VGG19 were pre-trained for images from nature, but ECG signals differ much as regards structure, shapes, and their arrangements. As a result, the features from VGG16 and VGG19 that are captured may not be the best for the ECG image classification, and consequently, the visualization of Grad-CAM might not be very accurate.

The results of the data-augmentation experiments further supported the robustness of the customized CNN model. While we noticed a decrease in the performance of the proposed hybrid models when tested on the new augmented data, the CNN model developed specifically for our purpose was much more robust and explainable. This means that the customized CNN without transfer learning is relatively accurate in identifying the variations that may exist in real ECG images, as opposed to the hybrid models based on transfer learning.

9.3 Implications for clinical applications

The capability for AI models to display outputs that are understandable to end users is of importance for their usage in clinical environments. Correct descriptions that have been illustrated by the customized CNN model can improve clinicians’ trust and help them understand the basis of model predictions. As a result, it may support making informed medical choices. While the hybrid model’s Grad-CAM outputs showed that transfer learning is not generally the optimal choice for interpretability in domains like ECG analysis, it might be the case that it is leading to worse interpretability. This finding emphasizes the necessity of tailoring the model architecture to suit the application’s specific domain of interest to reach a balance between high accuracy and meaningful interpretability.

9.4 Solving the problem

The proposed method has successfully dealt with the issue of interpretability in the following ways:

Enhanced Transparency: The proposed customized CNN model without transfer learning is more accurate and gives clinically useful explanations, which are important for the trust of clinicians.

Reduced Misalignment: Here, the study notes that while pre-trained models such as VGG16 can be employed in medical imaging tasks, they come with several shortcomings that make it important for bespoke medical domain models to be developed.

Improved Trust and Adoption: Hence, it can be said that precise interpretability has a positive influence on the level of clinically applied artificial intelligence trusted by clinicians. With its cleaner and more reliable explanations, the customized CNN model can be deployed in practical health engagements.

9.5 Limitations and confounding factors

This research has some shortcomings that should be taken into account.

Dataset size and diversity: The dataset presented has good coverage, but it might not cover all possible different types of ECG patterns. Therefore, this may influence the model’s generalizability and the relationship between the inputs and the Grad-CAMs produced.

Model architecture: The model complexity can give deeper insights into the data, but at the same time, the architecture of the models could inherently limit their interpretability. The customized model is tailor-made for this case, while VGG16 and VGG19 are not, suggesting that it may have some negative impact on the performance of the hybrid model.

New research needs to be conducted on various architectures of models and data augmentation techniques to improve the interpretability and accuracy of the model in the domain of clinical operation.

10 Conclusion

This research aims to fill the gaps identified in the existing literature by studying the effects of transfer learning on explanation accuracy in deep learning-based ECG recognition systems. The findings could potentially enhance the accuracy of disease identification through artificial intelligence, benefiting researchers in AI and diagnostics, physicians, and developers of diagnostic programs and applications. This research serves as a guide for future studies and developmental work, providing insights into the impact of transfer learning on the interpretability of models. The contributions are long-term, emphasizing AI systems’ explainability to support their implementation and trust in healthcare. Moreover, other subfields of medical image analysis and diagnostic AI can apply the results, offering a broader perspective on explanation techniques across various domains. Since this work focuses on improving the reliability of explanations used in AI models with transfer learning, it provides useful information to researchers, practitioners, and the healthcare sector. Specifically, it fosters the creation of reliable AI systems for healthcare, which will benefit both healthcare providers and patients.

In this study, we compare the performance and interpretability dimensions of a custom-designed CNN and a hybrid CNN with VGG16 to classify ECG images. The customized CNN model without VGG16 showed a more robust performance, along with a more accurate explanatory power indicating diagnostically significant areas in the ECG signals, in distinction from the hybrid model with VGG16, which justified these regions more often with features of less value despite achieving comparable quantitative assessments.

The results demonstrate that the VGG16 network’s learned features from the ImageNet dataset do not effectively extract features from ECG images. The ImageNet dataset primarily includes images of everyday objects, animals, scenes, and so on but excludes medical images like ECGs. Therefore, the weights acquired during transfer learning were less effective compared to those obtained by a custom-made CNN model, mainly in terms of interpretability. This emphasizes the necessity to develop individual models that take into account the specific features of medical data (ECG signals, for example) so that the achieved results have high diagnostic meaning.

Future research will focus on making the models more suitable for ECG analysis and adding domain competence features to the design. Further work on improving the model’s interpretability is needed. Yet, also, the growth of diversity and size of input increases the accuracy of predictions and boosts the reliability of determinations. Through complementing these revelations, future development of ECG recognition systems can have the power to achieve high accuracy as well as robust interpretability, which can then improve their use in clinical practice.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibilityfor the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. Methodology, MSK and AAK; software, MSK; validation, MSK and AAK; formal analysis, MSK; investigation, MSK; resources, MSK; data curation, MSK; writing – original draft preparation, MSK; writing – review and editing, AAK; visualization, MSK; supervision, AAK; project administration, AAK.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Most datasets generated and analyzed in this study are comprised in this submitted manuscript. The other datasets are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author with the attached information.

References

[1] Lorenzini G, Conti A. Numerical transient state analysis of partly obstructed haemodynamics using FSI approach. Open Eng. 2013;3(2):285–305. 10.2478/s13531-012-0052-y.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Abbas AR. Prediction and classification of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) using averaged one-dependence estimators (AODE) classifier. J AL-Turath Univ Coll. 2017;23(1):216–29.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Tripathi PM, Kumar A, Komaragiri R, Kumar M. A review on computational methods for denoising and detecting ECG signals to detect cardiovascular diseases. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2022 May;29(3):1875–914.10.1007/s11831-021-09642-2Search in Google Scholar

[4] Noor A. Potential of cognitive computing and cognitive systems. Open Eng. 2014;5(1):75–88. 10.1515/eng-2015-0008.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Sadiq A, Shukr N. Classification of cardiac arrhythmia using ID3 classifier based on wavelet transform. Iraqi J Sci. 2013;54(4Appendix):1167–75.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Ali AS, Abdulmunem M. Image classification with deep convolutional neural network using tensorflow and transfer of learning. J Coll Educ Women. 2020 Jun;31(2):156–71.10.36231/coedw/vol31no2.9Search in Google Scholar

[7] Cao M, Zhao T, Li Y, Zhang W, Benharash P, Ramezani R. ECG Heartbeat classification using deep transfer learning with Convolutional Neural Network and STFT technique. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series. Vol. 2547, No. 1. IOP Publishing; 2023 Jul. p. 012031.10.1088/1742-6596/2547/1/012031Search in Google Scholar

[8] Salehi AW, Khan S, Gupta G, Alabduallah BI, Almjally A, Alsolai H, et al. A study of CNN and transfer learning in medical imaging: Advantages, challenges, future scope. Sustainability. 2023 Mar;15(7):5930.10.3390/su15075930Search in Google Scholar

[9] Herman R, Demolder A, Vavrik B, Martonak M, Boza V, Kresnakova V, et al. Validation of an automated artificial intelligence system for 12‑lead ECG interpretation. J Electrocardiol. 2024 Jan;82:147–54.10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2023.12.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Albahri AS, Duhaim AM, Fadhel MA, Alnoor A, Baqer NS, Alzubaidi L, et al. A systematic review of trustworthy and explainable artificial intelligence in healthcare: Assessment of quality, bias risk, and data fusion. Inf Fusion. 2023 Aug;96:156–91.10.1016/j.inffus.2023.03.008Search in Google Scholar

[11] Qiu Z, Rivaz H, Xiao Y. Is visual explanation with Grad-CAM more reliable for deeper neural networks? A case study with automatic pneumothorax diagnosis. In International workshop on machine learning in medical imaging. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2023 Oct. p. 224–33.10.1007/978-3-031-45676-3_23Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ahmed WS. The impact of filter size and number of filters on classification accuracy in CNN. In 2020 International Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering (CSASE). IEEE; 2020 Apr. p. 88–93.10.1109/CSASE48920.2020.9142089Search in Google Scholar

[13] Abdulhadi MT, Abbas AR. Human action behavior recognition in still images with proposed frames selection using transfer learning. Int J Online Biomed Eng. 2023;19(6):47–65.10.3991/ijoe.v19i06.38463Search in Google Scholar

[14] Selvaraju RR, Cogswell M, Das A, Vedantam R, Parikh D, Batra D. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017. p. 618–26.10.1109/ICCV.2017.74Search in Google Scholar

[15] Khan AH, Hussain M, Malik MK. ECG images dataset of cardiac and COVID-19 patients. Data Brief. 2021 Feb;34:106762.10.1016/j.dib.2021.106762Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Methodology of automated quality management

- Influence of vibratory conveyor design parameters on the trough motion and the self-synchronization of inertial vibrators

- Application of finite element method in industrial design, example of an electric motorcycle design project

- Correlative evaluation of the corrosion resilience and passivation properties of zinc and aluminum alloys in neutral chloride and acid-chloride solutions

- Will COVID “encourage” B2B and data exchange engineering in logistic firms?

- Influence of unsupported sleepers on flange climb derailment of two freight wagons

- A hybrid detection algorithm for 5G OTFS waveform for 64 and 256 QAM with Rayleigh and Rician channels

- Effect of short heat treatment on mechanical properties and shape memory properties of Cu–Al–Ni shape memory alloy

- Exploring the potential of ammonia and hydrogen as alternative fuels for transportation

- Impact of insulation on energy consumption and CO2 emissions in high-rise commercial buildings at various climate zones

- Advanced autopilot design with extremum-seeking control for aircraft control

- Adaptive multidimensional trust-based recommendation model for peer to peer applications

- Effects of CFRP sheets on the flexural behavior of high-strength concrete beam

- Enhancing urban sustainability through industrial synergy: A multidisciplinary framework for integrating sustainable industrial practices within urban settings – The case of Hamadan industrial city

- Advanced vibrant controller results of an energetic framework structure

- Application of the Taguchi method and RSM for process parameter optimization in AWSJ machining of CFRP composite-based orthopedic implants

- Improved correlation of soil modulus with SPT N values

- Technologies for high-temperature batch annealing of grain-oriented electrical steel: An overview

- Assessing the need for the adoption of digitalization in Indian small and medium enterprises

- A non-ideal hybridization issue for vertical TFET-based dielectric-modulated biosensor

- Optimizing data retrieval for enhanced data integrity verification in cloud environments

- Performance analysis of nonlinear crosstalk of WDM systems using modulation schemes criteria

- Nonlinear finite-element analysis of RC beams with various opening near supports

- Thermal analysis of Fe3O4–Cu/water over a cone: a fractional Maxwell model

- Radial–axial runner blade design using the coordinate slice technique

- Theoretical and experimental comparison between straight and curved continuous box girders

- Effect of the reinforcement ratio on the mechanical behaviour of textile-reinforced concrete composite: Experiment and numerical modeling

- Experimental and numerical investigation on composite beam–column joint connection behavior using different types of connection schemes

- Enhanced performance and robustness in anti-lock brake systems using barrier function-based integral sliding mode control

- Evaluation of the creep strength of samples produced by fused deposition modeling

- A combined feedforward-feedback controller design for nonlinear systems

- Effect of adjacent structures on footing settlement for different multi-building arrangements

- Analyzing the impact of curved tracks on wheel flange thickness reduction in railway systems

- Review Articles

- Mechanical and smart properties of cement nanocomposites containing nanomaterials: A brief review

- Applications of nanotechnology and nanoproduction techniques

- Relationship between indoor environmental quality and guests’ comfort and satisfaction at green hotels: A comprehensive review

- Communication

- Techniques to mitigate the admission of radon inside buildings

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Effect of short heat treatment on mechanical properties and shape memory properties of Cu–Al–Ni shape memory alloy”

- Special Issue: AESMT-3 - Part II

- Integrated fuzzy logic and multicriteria decision model methods for selecting suitable sites for wastewater treatment plant: A case study in the center of Basrah, Iraq

- Physical and mechanical response of porous metals composites with nano-natural additives

- Special Issue: AESMT-4 - Part II

- New recycling method of lubricant oil and the effect on the viscosity and viscous shear as an environmentally friendly

- Identify the effect of Fe2O3 nanoparticles on mechanical and microstructural characteristics of aluminum matrix composite produced by powder metallurgy technique

- Static behavior of piled raft foundation in clay

- Ultra-low-power CMOS ring oscillator with minimum power consumption of 2.9 pW using low-voltage biasing technique

- Using ANN for well type identifying and increasing production from Sa’di formation of Halfaya oil field – Iraq

- Optimizing the performance of concrete tiles using nano-papyrus and carbon fibers

- Special Issue: AESMT-5 - Part II

- Comparative the effect of distribution transformer coil shape on electromagnetic forces and their distribution using the FEM

- The complex of Weyl module in free characteristic in the event of a partition (7,5,3)

- Restrained captive domination number

- Experimental study of improving hot mix asphalt reinforced with carbon fibers

- Asphalt binder modified with recycled tyre rubber

- Thermal performance of radiant floor cooling with phase change material for energy-efficient buildings

- Surveying the prediction of risks in cryptocurrency investments using recurrent neural networks

- A deep reinforcement learning framework to modify LQR for an active vibration control applied to 2D building models

- Evaluation of mechanically stabilized earth retaining walls for different soil–structure interaction methods: A review

- Assessment of heat transfer in a triangular duct with different configurations of ribs using computational fluid dynamics

- Sulfate removal from wastewater by using waste material as an adsorbent

- Experimental investigation on strengthening lap joints subjected to bending in glulam timber beams using CFRP sheets

- A study of the vibrations of a rotor bearing suspended by a hybrid spring system of shape memory alloys

- Stability analysis of Hub dam under rapid drawdown

- Developing ANFIS-FMEA model for assessment and prioritization of potential trouble factors in Iraqi building projects

- Numerical and experimental comparison study of piled raft foundation

- Effect of asphalt modified with waste engine oil on the durability properties of hot asphalt mixtures with reclaimed asphalt pavement

- Hydraulic model for flood inundation in Diyala River Basin using HEC-RAS, PMP, and neural network

- Numerical study on discharge capacity of piano key side weir with various ratios of the crest length to the width

- The optimal allocation of thyristor-controlled series compensators for enhancement HVAC transmission lines Iraqi super grid by using seeker optimization algorithm

- Numerical and experimental study of the impact on aerodynamic characteristics of the NACA0012 airfoil

- Effect of nano-TiO2 on physical and rheological properties of asphalt cement

- Performance evolution of novel palm leaf powder used for enhancing hot mix asphalt

- Performance analysis, evaluation, and improvement of selected unsignalized intersection using SIDRA software – Case study

- Flexural behavior of RC beams externally reinforced with CFRP composites using various strategies

- Influence of fiber types on the properties of the artificial cold-bonded lightweight aggregates

- Experimental investigation of RC beams strengthened with externally bonded BFRP composites

- Generalized RKM methods for solving fifth-order quasi-linear fractional partial differential equation

- An experimental and numerical study investigating sediment transport position in the bed of sewer pipes in Karbala

- Role of individual component failure in the performance of a 1-out-of-3 cold standby system: A Markov model approach

- Implementation for the cases (5, 4) and (5, 4)/(2, 0)

- Center group actions and related concepts

- Experimental investigation of the effect of horizontal construction joints on the behavior of deep beams

- Deletion of a vertex in even sum domination

- Deep learning techniques in concrete powder mix designing

- Effect of loading type in concrete deep beam with strut reinforcement

- Studying the effect of using CFRP warping on strength of husk rice concrete columns

- Parametric analysis of the influence of climatic factors on the formation of traditional buildings in the city of Al Najaf

- Suitability location for landfill using a fuzzy-GIS model: A case study in Hillah, Iraq

- Hybrid approach for cost estimation of sustainable building projects using artificial neural networks

- Assessment of indirect tensile stress and tensile–strength ratio and creep compliance in HMA mixes with micro-silica and PMB

- Density functional theory to study stopping power of proton in water, lung, bladder, and intestine

- A review of single flow, flow boiling, and coating microchannel studies

- Effect of GFRP bar length on the flexural behavior of hybrid concrete beams strengthened with NSM bars

- Exploring the impact of parameters on flow boiling heat transfer in microchannels and coated microtubes: A comprehensive review

- Crumb rubber modification for enhanced rutting resistance in asphalt mixtures

- Special Issue: AESMT-6

- Design of a new sorting colors system based on PLC, TIA portal, and factory I/O programs

- Forecasting empirical formula for suspended sediment load prediction at upstream of Al-Kufa barrage, Kufa City, Iraq

- Optimization and characterization of sustainable geopolymer mortars based on palygorskite clay, water glass, and sodium hydroxide

- Sediment transport modelling upstream of Al Kufa Barrage

- Study of energy loss, range, and stopping time for proton in germanium and copper materials

- Effect of internal and external recycle ratios on the nutrient removal efficiency of anaerobic/anoxic/oxic (VIP) wastewater treatment plant

- Enhancing structural behaviour of polypropylene fibre concrete columns longitudinally reinforced with fibreglass bars

- Sustainable road paving: Enhancing concrete paver blocks with zeolite-enhanced cement

- Evaluation of the operational performance of Karbala waste water treatment plant under variable flow using GPS-X model

- Design and simulation of photonic crystal fiber for highly sensitive chemical sensing applications

- Optimization and design of a new column sequencing for crude oil distillation at Basrah refinery

- Inductive 3D numerical modelling of the tibia bone using MRI to examine von Mises stress and overall deformation

- An image encryption method based on modified elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol and Hill Cipher

- Experimental investigation of generating superheated steam using a parabolic dish with a cylindrical cavity receiver: A case study

- Effect of surface roughness on the interface behavior of clayey soils

- Investigated of the optical properties for SiO2 by using Lorentz model

- Measurements of induced vibrations due to steel pipe pile driving in Al-Fao soil: Effect of partial end closure

- Experimental and numerical studies of ballistic resistance of hybrid sandwich composite body armor

- Evaluation of clay layer presence on shallow foundation settlement in dry sand under an earthquake

- Optimal design of mechanical performances of asphalt mixtures comprising nano-clay additives

- Advancing seismic performance: Isolators, TMDs, and multi-level strategies in reinforced concrete buildings

- Predicted evaporation in Basrah using artificial neural networks

- Energy management system for a small town to enhance quality of life

- Numerical study on entropy minimization in pipes with helical airfoil and CuO nanoparticle integration

- Equations and methodologies of inlet drainage system discharge coefficients: A review

- Thermal buckling analysis for hybrid and composite laminated plate by using new displacement function

- Investigation into the mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight mortar using commercial beads or recycled expanded polystyrene

- Experimental and theoretical analysis of single-jet column and concrete column using double-jet grouting technique applied at Al-Rashdia site

- The impact of incorporating waste materials on the mechanical and physical characteristics of tile adhesive materials

- Seismic resilience: Innovations in structural engineering for earthquake-prone areas

- Automatic human identification using fingerprint images based on Gabor filter and SIFT features fusion

- Performance of GRKM-method for solving classes of ordinary and partial differential equations of sixth-orders

- Visible light-boosted photodegradation activity of Ag–AgVO3/Zn0.5Mn0.5Fe2O4 supported heterojunctions for effective degradation of organic contaminates

- Production of sustainable concrete with treated cement kiln dust and iron slag waste aggregate

- Key effects on the structural behavior of fiber-reinforced lightweight concrete-ribbed slabs: A review

- A comparative analysis of the energy dissipation efficiency of various piano key weir types

- Special Issue: Transport 2022 - Part II

- Variability in road surface temperature in urban road network – A case study making use of mobile measurements

- Special Issue: BCEE5-2023

- Evaluation of reclaimed asphalt mixtures rejuvenated with waste engine oil to resist rutting deformation

- Assessment of potential resistance to moisture damage and fatigue cracks of asphalt mixture modified with ground granulated blast furnace slag

- Investigating seismic response in adjacent structures: A study on the impact of buildings’ orientation and distance considering soil–structure interaction

- Improvement of porosity of mortar using polyethylene glycol pre-polymer-impregnated mortar

- Three-dimensional analysis of steel beam-column bolted connections

- Assessment of agricultural drought in Iraq employing Landsat and MODIS imagery

- Performance evaluation of grouted porous asphalt concrete

- Optimization of local modified metakaolin-based geopolymer concrete by Taguchi method

- Effect of waste tire products on some characteristics of roller-compacted concrete

- Studying the lateral displacement of retaining wall supporting sandy soil under dynamic loads

- Seismic performance evaluation of concrete buttress dram (Dynamic linear analysis)

- Behavior of soil reinforced with micropiles

- Possibility of production high strength lightweight concrete containing organic waste aggregate and recycled steel fibers

- An investigation of self-sensing and mechanical properties of smart engineered cementitious composites reinforced with functional materials

- Forecasting changes in precipitation and temperatures of a regional watershed in Northern Iraq using LARS-WG model

- Experimental investigation of dynamic soil properties for modeling energy-absorbing layers

- Numerical investigation of the effect of longitudinal steel reinforcement ratio on the ductility of concrete beams

- An experimental study on the tensile properties of reinforced asphalt pavement

- Self-sensing behavior of hot asphalt mixture with steel fiber-based additive

- Behavior of ultra-high-performance concrete deep beams reinforced by basalt fibers

- Optimizing asphalt binder performance with various PET types

- Investigation of the hydraulic characteristics and homogeneity of the microstructure of the air voids in the sustainable rigid pavement

- Enhanced biogas production from municipal solid waste via digestion with cow manure: A case study

- Special Issue: AESMT-7 - Part I

- Preparation and investigation of cobalt nanoparticles by laser ablation: Structure, linear, and nonlinear optical properties

- Seismic analysis of RC building with plan irregularity in Baghdad/Iraq to obtain the optimal behavior

- The effect of urban environment on large-scale path loss model’s main parameters for mmWave 5G mobile network in Iraq

- Formatting a questionnaire for the quality control of river bank roads

- Vibration suppression of smart composite beam using model predictive controller

- Machine learning-based compressive strength estimation in nanomaterial-modified lightweight concrete

- In-depth analysis of critical factors affecting Iraqi construction projects performance

- Behavior of container berth structure under the influence of environmental and operational loads

- Energy absorption and impact response of ballistic resistance laminate

- Effect of water-absorbent polymer balls in internal curing on punching shear behavior of bubble slabs

- Effect of surface roughness on interface shear strength parameters of sandy soils

- Evaluating the interaction for embedded H-steel section in normal concrete under monotonic and repeated loads

- Estimation of the settlement of pile head using ANN and multivariate linear regression based on the results of load transfer method

- Enhancing communication: Deep learning for Arabic sign language translation

- A review of recent studies of both heat pipe and evaporative cooling in passive heat recovery

- Effect of nano-silica on the mechanical properties of LWC

- An experimental study of some mechanical properties and absorption for polymer-modified cement mortar modified with superplasticizer

- Digital beamforming enhancement with LSTM-based deep learning for millimeter wave transmission

- Developing an efficient planning process for heritage buildings maintenance in Iraq

- Design and optimization of two-stage controller for three-phase multi-converter/multi-machine electric vehicle

- Evaluation of microstructure and mechanical properties of Al1050/Al2O3/Gr composite processed by forming operation ECAP

- Calculations of mass stopping power and range of protons in organic compounds (CH3OH, CH2O, and CO2) at energy range of 0.01–1,000 MeV

- Investigation of in vitro behavior of composite coating hydroxyapatite-nano silver on 316L stainless steel substrate by electrophoretic technic for biomedical tools

- A review: Enhancing tribological properties of journal bearings composite materials

- Improvements in the randomness and security of digital currency using the photon sponge hash function through Maiorana–McFarland S-box replacement

- Design a new scheme for image security using a deep learning technique of hierarchical parameters

- Special Issue: ICES 2023

- Comparative geotechnical analysis for ultimate bearing capacity of precast concrete piles using cone resistance measurements

- Visualizing sustainable rainwater harvesting: A case study of Karbala Province

- Geogrid reinforcement for improving bearing capacity and stability of square foundations

- Evaluation of the effluent concentrations of Karbala wastewater treatment plant using reliability analysis

- Adsorbent made with inexpensive, local resources

- Effect of drain pipes on seepage and slope stability through a zoned earth dam

- Sediment accumulation in an 8 inch sewer pipe for a sample of various particles obtained from the streets of Karbala city, Iraq

- Special Issue: IETAS 2024 - Part I

- Analyzing the impact of transfer learning on explanation accuracy in deep learning-based ECG recognition systems

- Effect of scale factor on the dynamic response of frame foundations

- Improving multi-object detection and tracking with deep learning, DeepSORT, and frame cancellation techniques

- The impact of using prestressed CFRP bars on the development of flexural strength

- Assessment of surface hardness and impact strength of denture base resins reinforced with silver–titanium dioxide and silver–zirconium dioxide nanoparticles: In vitro study

- A data augmentation approach to enhance breast cancer detection using generative adversarial and artificial neural networks

- Modification of the 5D Lorenz chaotic map with fuzzy numbers for video encryption in cloud computing

- Special Issue: 51st KKBN - Part I

- Evaluation of static bending caused damage of glass-fiber composite structure using terahertz inspection

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Methodology of automated quality management

- Influence of vibratory conveyor design parameters on the trough motion and the self-synchronization of inertial vibrators

- Application of finite element method in industrial design, example of an electric motorcycle design project

- Correlative evaluation of the corrosion resilience and passivation properties of zinc and aluminum alloys in neutral chloride and acid-chloride solutions

- Will COVID “encourage” B2B and data exchange engineering in logistic firms?

- Influence of unsupported sleepers on flange climb derailment of two freight wagons

- A hybrid detection algorithm for 5G OTFS waveform for 64 and 256 QAM with Rayleigh and Rician channels

- Effect of short heat treatment on mechanical properties and shape memory properties of Cu–Al–Ni shape memory alloy

- Exploring the potential of ammonia and hydrogen as alternative fuels for transportation

- Impact of insulation on energy consumption and CO2 emissions in high-rise commercial buildings at various climate zones

- Advanced autopilot design with extremum-seeking control for aircraft control

- Adaptive multidimensional trust-based recommendation model for peer to peer applications

- Effects of CFRP sheets on the flexural behavior of high-strength concrete beam

- Enhancing urban sustainability through industrial synergy: A multidisciplinary framework for integrating sustainable industrial practices within urban settings – The case of Hamadan industrial city

- Advanced vibrant controller results of an energetic framework structure

- Application of the Taguchi method and RSM for process parameter optimization in AWSJ machining of CFRP composite-based orthopedic implants

- Improved correlation of soil modulus with SPT N values

- Technologies for high-temperature batch annealing of grain-oriented electrical steel: An overview

- Assessing the need for the adoption of digitalization in Indian small and medium enterprises

- A non-ideal hybridization issue for vertical TFET-based dielectric-modulated biosensor

- Optimizing data retrieval for enhanced data integrity verification in cloud environments

- Performance analysis of nonlinear crosstalk of WDM systems using modulation schemes criteria

- Nonlinear finite-element analysis of RC beams with various opening near supports

- Thermal analysis of Fe3O4–Cu/water over a cone: a fractional Maxwell model

- Radial–axial runner blade design using the coordinate slice technique

- Theoretical and experimental comparison between straight and curved continuous box girders

- Effect of the reinforcement ratio on the mechanical behaviour of textile-reinforced concrete composite: Experiment and numerical modeling

- Experimental and numerical investigation on composite beam–column joint connection behavior using different types of connection schemes

- Enhanced performance and robustness in anti-lock brake systems using barrier function-based integral sliding mode control

- Evaluation of the creep strength of samples produced by fused deposition modeling

- A combined feedforward-feedback controller design for nonlinear systems

- Effect of adjacent structures on footing settlement for different multi-building arrangements

- Analyzing the impact of curved tracks on wheel flange thickness reduction in railway systems

- Review Articles

- Mechanical and smart properties of cement nanocomposites containing nanomaterials: A brief review

- Applications of nanotechnology and nanoproduction techniques

- Relationship between indoor environmental quality and guests’ comfort and satisfaction at green hotels: A comprehensive review

- Communication

- Techniques to mitigate the admission of radon inside buildings

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Effect of short heat treatment on mechanical properties and shape memory properties of Cu–Al–Ni shape memory alloy”

- Special Issue: AESMT-3 - Part II

- Integrated fuzzy logic and multicriteria decision model methods for selecting suitable sites for wastewater treatment plant: A case study in the center of Basrah, Iraq

- Physical and mechanical response of porous metals composites with nano-natural additives

- Special Issue: AESMT-4 - Part II

- New recycling method of lubricant oil and the effect on the viscosity and viscous shear as an environmentally friendly

- Identify the effect of Fe2O3 nanoparticles on mechanical and microstructural characteristics of aluminum matrix composite produced by powder metallurgy technique

- Static behavior of piled raft foundation in clay

- Ultra-low-power CMOS ring oscillator with minimum power consumption of 2.9 pW using low-voltage biasing technique

- Using ANN for well type identifying and increasing production from Sa’di formation of Halfaya oil field – Iraq

- Optimizing the performance of concrete tiles using nano-papyrus and carbon fibers

- Special Issue: AESMT-5 - Part II

- Comparative the effect of distribution transformer coil shape on electromagnetic forces and their distribution using the FEM

- The complex of Weyl module in free characteristic in the event of a partition (7,5,3)

- Restrained captive domination number

- Experimental study of improving hot mix asphalt reinforced with carbon fibers

- Asphalt binder modified with recycled tyre rubber

- Thermal performance of radiant floor cooling with phase change material for energy-efficient buildings

- Surveying the prediction of risks in cryptocurrency investments using recurrent neural networks

- A deep reinforcement learning framework to modify LQR for an active vibration control applied to 2D building models

- Evaluation of mechanically stabilized earth retaining walls for different soil–structure interaction methods: A review

- Assessment of heat transfer in a triangular duct with different configurations of ribs using computational fluid dynamics

- Sulfate removal from wastewater by using waste material as an adsorbent

- Experimental investigation on strengthening lap joints subjected to bending in glulam timber beams using CFRP sheets

- A study of the vibrations of a rotor bearing suspended by a hybrid spring system of shape memory alloys

- Stability analysis of Hub dam under rapid drawdown

- Developing ANFIS-FMEA model for assessment and prioritization of potential trouble factors in Iraqi building projects

- Numerical and experimental comparison study of piled raft foundation

- Effect of asphalt modified with waste engine oil on the durability properties of hot asphalt mixtures with reclaimed asphalt pavement

- Hydraulic model for flood inundation in Diyala River Basin using HEC-RAS, PMP, and neural network

- Numerical study on discharge capacity of piano key side weir with various ratios of the crest length to the width

- The optimal allocation of thyristor-controlled series compensators for enhancement HVAC transmission lines Iraqi super grid by using seeker optimization algorithm

- Numerical and experimental study of the impact on aerodynamic characteristics of the NACA0012 airfoil

- Effect of nano-TiO2 on physical and rheological properties of asphalt cement

- Performance evolution of novel palm leaf powder used for enhancing hot mix asphalt

- Performance analysis, evaluation, and improvement of selected unsignalized intersection using SIDRA software – Case study

- Flexural behavior of RC beams externally reinforced with CFRP composites using various strategies

- Influence of fiber types on the properties of the artificial cold-bonded lightweight aggregates

- Experimental investigation of RC beams strengthened with externally bonded BFRP composites

- Generalized RKM methods for solving fifth-order quasi-linear fractional partial differential equation

- An experimental and numerical study investigating sediment transport position in the bed of sewer pipes in Karbala

- Role of individual component failure in the performance of a 1-out-of-3 cold standby system: A Markov model approach

- Implementation for the cases (5, 4) and (5, 4)/(2, 0)

- Center group actions and related concepts

- Experimental investigation of the effect of horizontal construction joints on the behavior of deep beams

- Deletion of a vertex in even sum domination

- Deep learning techniques in concrete powder mix designing

- Effect of loading type in concrete deep beam with strut reinforcement

- Studying the effect of using CFRP warping on strength of husk rice concrete columns

- Parametric analysis of the influence of climatic factors on the formation of traditional buildings in the city of Al Najaf

- Suitability location for landfill using a fuzzy-GIS model: A case study in Hillah, Iraq

- Hybrid approach for cost estimation of sustainable building projects using artificial neural networks

- Assessment of indirect tensile stress and tensile–strength ratio and creep compliance in HMA mixes with micro-silica and PMB

- Density functional theory to study stopping power of proton in water, lung, bladder, and intestine

- A review of single flow, flow boiling, and coating microchannel studies

- Effect of GFRP bar length on the flexural behavior of hybrid concrete beams strengthened with NSM bars

- Exploring the impact of parameters on flow boiling heat transfer in microchannels and coated microtubes: A comprehensive review

- Crumb rubber modification for enhanced rutting resistance in asphalt mixtures

- Special Issue: AESMT-6

- Design of a new sorting colors system based on PLC, TIA portal, and factory I/O programs

- Forecasting empirical formula for suspended sediment load prediction at upstream of Al-Kufa barrage, Kufa City, Iraq

- Optimization and characterization of sustainable geopolymer mortars based on palygorskite clay, water glass, and sodium hydroxide

- Sediment transport modelling upstream of Al Kufa Barrage

- Study of energy loss, range, and stopping time for proton in germanium and copper materials

- Effect of internal and external recycle ratios on the nutrient removal efficiency of anaerobic/anoxic/oxic (VIP) wastewater treatment plant

- Enhancing structural behaviour of polypropylene fibre concrete columns longitudinally reinforced with fibreglass bars

- Sustainable road paving: Enhancing concrete paver blocks with zeolite-enhanced cement

- Evaluation of the operational performance of Karbala waste water treatment plant under variable flow using GPS-X model

- Design and simulation of photonic crystal fiber for highly sensitive chemical sensing applications

- Optimization and design of a new column sequencing for crude oil distillation at Basrah refinery

- Inductive 3D numerical modelling of the tibia bone using MRI to examine von Mises stress and overall deformation

- An image encryption method based on modified elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol and Hill Cipher

- Experimental investigation of generating superheated steam using a parabolic dish with a cylindrical cavity receiver: A case study

- Effect of surface roughness on the interface behavior of clayey soils

- Investigated of the optical properties for SiO2 by using Lorentz model

- Measurements of induced vibrations due to steel pipe pile driving in Al-Fao soil: Effect of partial end closure

- Experimental and numerical studies of ballistic resistance of hybrid sandwich composite body armor

- Evaluation of clay layer presence on shallow foundation settlement in dry sand under an earthquake

- Optimal design of mechanical performances of asphalt mixtures comprising nano-clay additives

- Advancing seismic performance: Isolators, TMDs, and multi-level strategies in reinforced concrete buildings

- Predicted evaporation in Basrah using artificial neural networks

- Energy management system for a small town to enhance quality of life

- Numerical study on entropy minimization in pipes with helical airfoil and CuO nanoparticle integration

- Equations and methodologies of inlet drainage system discharge coefficients: A review

- Thermal buckling analysis for hybrid and composite laminated plate by using new displacement function

- Investigation into the mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight mortar using commercial beads or recycled expanded polystyrene

- Experimental and theoretical analysis of single-jet column and concrete column using double-jet grouting technique applied at Al-Rashdia site

- The impact of incorporating waste materials on the mechanical and physical characteristics of tile adhesive materials

- Seismic resilience: Innovations in structural engineering for earthquake-prone areas

- Automatic human identification using fingerprint images based on Gabor filter and SIFT features fusion

- Performance of GRKM-method for solving classes of ordinary and partial differential equations of sixth-orders

- Visible light-boosted photodegradation activity of Ag–AgVO3/Zn0.5Mn0.5Fe2O4 supported heterojunctions for effective degradation of organic contaminates

- Production of sustainable concrete with treated cement kiln dust and iron slag waste aggregate

- Key effects on the structural behavior of fiber-reinforced lightweight concrete-ribbed slabs: A review

- A comparative analysis of the energy dissipation efficiency of various piano key weir types

- Special Issue: Transport 2022 - Part II

- Variability in road surface temperature in urban road network – A case study making use of mobile measurements

- Special Issue: BCEE5-2023

- Evaluation of reclaimed asphalt mixtures rejuvenated with waste engine oil to resist rutting deformation

- Assessment of potential resistance to moisture damage and fatigue cracks of asphalt mixture modified with ground granulated blast furnace slag

- Investigating seismic response in adjacent structures: A study on the impact of buildings’ orientation and distance considering soil–structure interaction

- Improvement of porosity of mortar using polyethylene glycol pre-polymer-impregnated mortar

- Three-dimensional analysis of steel beam-column bolted connections

- Assessment of agricultural drought in Iraq employing Landsat and MODIS imagery

- Performance evaluation of grouted porous asphalt concrete

- Optimization of local modified metakaolin-based geopolymer concrete by Taguchi method

- Effect of waste tire products on some characteristics of roller-compacted concrete

- Studying the lateral displacement of retaining wall supporting sandy soil under dynamic loads

- Seismic performance evaluation of concrete buttress dram (Dynamic linear analysis)

- Behavior of soil reinforced with micropiles

- Possibility of production high strength lightweight concrete containing organic waste aggregate and recycled steel fibers

- An investigation of self-sensing and mechanical properties of smart engineered cementitious composites reinforced with functional materials

- Forecasting changes in precipitation and temperatures of a regional watershed in Northern Iraq using LARS-WG model

- Experimental investigation of dynamic soil properties for modeling energy-absorbing layers

- Numerical investigation of the effect of longitudinal steel reinforcement ratio on the ductility of concrete beams

- An experimental study on the tensile properties of reinforced asphalt pavement

- Self-sensing behavior of hot asphalt mixture with steel fiber-based additive

- Behavior of ultra-high-performance concrete deep beams reinforced by basalt fibers

- Optimizing asphalt binder performance with various PET types

- Investigation of the hydraulic characteristics and homogeneity of the microstructure of the air voids in the sustainable rigid pavement

- Enhanced biogas production from municipal solid waste via digestion with cow manure: A case study

- Special Issue: AESMT-7 - Part I

- Preparation and investigation of cobalt nanoparticles by laser ablation: Structure, linear, and nonlinear optical properties

- Seismic analysis of RC building with plan irregularity in Baghdad/Iraq to obtain the optimal behavior

- The effect of urban environment on large-scale path loss model’s main parameters for mmWave 5G mobile network in Iraq

- Formatting a questionnaire for the quality control of river bank roads

- Vibration suppression of smart composite beam using model predictive controller

- Machine learning-based compressive strength estimation in nanomaterial-modified lightweight concrete

- In-depth analysis of critical factors affecting Iraqi construction projects performance

- Behavior of container berth structure under the influence of environmental and operational loads

- Energy absorption and impact response of ballistic resistance laminate

- Effect of water-absorbent polymer balls in internal curing on punching shear behavior of bubble slabs

- Effect of surface roughness on interface shear strength parameters of sandy soils

- Evaluating the interaction for embedded H-steel section in normal concrete under monotonic and repeated loads

- Estimation of the settlement of pile head using ANN and multivariate linear regression based on the results of load transfer method

- Enhancing communication: Deep learning for Arabic sign language translation

- A review of recent studies of both heat pipe and evaporative cooling in passive heat recovery

- Effect of nano-silica on the mechanical properties of LWC

- An experimental study of some mechanical properties and absorption for polymer-modified cement mortar modified with superplasticizer

- Digital beamforming enhancement with LSTM-based deep learning for millimeter wave transmission